Chinese characters: Difference between revisions

→Rare and complex characters: - Added "Taito" (the one with thee clouds and thee dragons) as a thumbnail |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Logographic writing system}} |

|||

[[Image:Hanzilead.png|left|thumb|漢字 / 汉字 "Chinese character" in '''Hanzi''', [[Kanji]], [[Hanja]], [[Hán Tự]]. Red in [[Simplified Chinese]].]] |

|||

{{redirect|Hanzi|the Chinese philosopher also known as "Hanzi"|Han Fei|the anthology attributed to him|Han Feizi{{!}}''Han Feizi''}} |

|||

{| border=1 width=50 cellpadding=2 cellspacing=0 align=right style="margin:0 0 1em 1em;" |

|||

{{redirect|Chinese character|the moth species|Cilix glaucata{{!}}''Cilix glaucata''}} |

|||

|- |

|||

{{good article}} |

|||

! colspan=2 align=center bgcolor=#FFCCCC | '''“Chinese character” in various languages''' |

|||

{{Use Oxford spelling|date=November 2024}} |

|||

|- |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2020}} |

|||

| colspan=2 align=center | '''Chinese''' |

|||

{{bots|deny=Citation bot}} |

|||

|- |

|||

{{CS1 config|mode=cs1}} |

|||

| width=150 | Traditional Chinese |

|||

{{Infobox writing system |

|||

| width=150 | <span lang="zh-Hant"><big>漢字</big></span> |

|||

| sample = Hanzi.svg |

|||

|- |

|||

| caption = "Chinese character" written in [[traditional Chinese characters|traditional]] (left) and [[simplified Chinese characters|simplified]] (right) forms |

|||

| width=150 | Simplified Chinese |

|||

| imagesize = 220px |

|||

| width=150 | <span lang="zh-Hans"><big>汉字</big></span> |

|||

| name = Chinese characters |

|||

|- |

|||

| type = Logographic |

|||

| width=150 | Pinyin (Mandarin) |

|||

| languages = {{cslist|class=inline|[[Chinese languages|Chinese]]|[[Japanese language|Japanese]]|[[Korean language|Korean]]|[[Vietnamese language|Vietnamese]]|[[Zhuang languages|Zhuang]]}} {{nwr|''([[Chinese family of scripts|among others]])''}} |

|||

| width=150 | {{Audio|zh-han4zi4.ogg|Hànzì}} |

|||

| time = {{circa|13th century BCE}}{{snd}}present |

|||

|- |

|||

| fam1 = ([[Proto-writing]]) |

|||

| width=150 | Shanghainese |

|||

| children = {{hlist|[[Bopomofo]]|[[Jurchen script]]|[[Kana]]|[[Khitan small script]]|[[Nüshu]]|[[Tangut script]]|[[Yi script]]}} |

|||

| width=150 | [høz] |

|||

| unicode = [https://unicode.org/charts/PDF/U4E00.pdf U+4E00–U+9FFF] {{nwr|CJK Unified Ideographs}} {{nwr|''([[CJK Unified Ideographs#CJK Unified Ideographs blocks|full list]])''}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| iso15924 = Hani |

|||

| width=150 | Jyutping (Cantonese) |

|||

| direction = {{blist|Left-to-right|Top-to-bottom, columns right-to-left}} |

|||

| width=150 | hon3 zi6 |

|||

| ipa-note = none |

|||

|- |

|||

}} |

|||

| width=150 | Min Nan |

|||

{{Contains special characters|special={{langr|vi|[[chữ Nôm]]}} characters used to write [[Vietnamese language|Vietnamese]], as well as {{langr|za|[[sawndip]]}} characters used to write [[Zhuang languages|Zhuang]]|fix=Help:Multilingual support (East Asian)}} |

|||

| width=150 | |

|||

{{Infobox Chinese |order=st |ibox-order=zh,ja,ko1,vi,za |

|||

|- |

|||

| t = 漢字 |

|||

| width=150 | Chaozhou |

|||

| s = 汉字 |

|||

| width=150 | hang3 ri7 |

|||

| l = [[Han Chinese|Han]] characters |

|||

|- |

|||

| p = Hànzì |

|||

| width=150 | Hakka |

|||

| w = {{tonesup|Han4-tzu4}} |

|||

| width=150 | |

|||

| tp = Hàn-zìh |

|||

|- |

|||

| gr = Hanntzyh |

|||

| width=150 | Xiang |

|||

| bpmf = {{bpmfsp|ㄏㄢˋ|ㄗˋ}} |

|||

| width=150 | |

|||

| mi = {{IPAc-cmn|h|an|4|.|zi|4}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| j = Hon3 zi6 |

|||

! colspan=2 align=center | '''Japanese''' |

|||

| y = Hon jih |

|||

|- |

|||

| ci = {{IPAc-yue|h|on|3|-|z|i|6}} |

|||

| Kanji |

|||

| gan = {{tonesup|Hon5-ci5}} |

|||

| <span lang="ja-Hani"><big>漢字</big></span> |

|||

| h = {{tonesup|Hon55 sii55}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| poj = Hàn-jī |

|||

| Hiragana |

|||

| tl = Hàn-jī |

|||

| <span lang="ja-Hira"><big>かんじ</big></span> |

|||

| teo = {{tonesup|Hang3 ri7}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| buc = Háng-cê |

|||

| Katakana |

|||

| mc = xan<sup>H</sup> dzi<sup>H</sup> |

|||

| <span lang="ja-Kana"><big>カンジ</big></span> |

|||

| wuu = {{tonesup|5Hoe-zy}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| kanji = 漢字 |

|||

| Romaji |

|||

| revhep = kanji |

|||

| Kanji |

|||

| kunrei = kanzi |

|||

|- |

|||

| hanja = 漢字 |

|||

! colspan=2 align=center | '''Korean''' |

|||

| hangul = 한자 |

|||

|- |

|||

| Hanja |

| rr = Hanja |

||

| mr = Hancha |

|||

| <span lang="ko-Hant"><big>漢字</big></span> |

|||

| qn = {{ubl|chữ Hán|chữ Nho|Hán tự}} |

|||

|- |

|||

| chuhan = 漢字 |

|||

| Hangul |

|||

| hn = {{ubl|𡨸漢|𡨸儒}} |

|||

| <span lang="ko-Hang"><big>한자</big></span> |

|||

| zha = sawgun |

|||

|- |

|||

| sd = 𭨡倱{{sfn|Guangxi Nationalities Publishing House|1989}} |

|||

| Revised Romanization: |

|||

}} |

|||

| Hanja |

|||

{{Chinese characters sidebar}} |

|||

|- |

|||

'''Chinese characters'''{{efn|name=lead}} are [[logograph]]s used [[Written Chinese|to write the Chinese languages]] and others from regions historically influenced by [[Chinese culture]]. Of the four independently invented [[writing system]]s accepted by scholars, they represent the only one that has remained in continuous use. Over a documented history spanning more than three millennia, the function, style, and means of writing characters have evolved greatly. Unlike letters in alphabets that reflect the sounds of speech, Chinese characters generally represent [[morpheme]]s, the units of meaning in a language. Writing a language's vocabulary requires thousands of different characters. Characters are created according to several principles, where aspects of shape and pronunciation may be used to indicate the character's meaning. |

|||

| McCune-Reischauer |

|||

| Hancha |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan=2 align=center | '''Vietnamese''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| <span lang="vi">Hán Tự/Chữ Nho</span> |

|||

| <span lang="vi-Hant"><big>漢字</big></span> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <span lang="vi">Quốc Ngữ</span> (National Script) |

|||

| <span lang="vi">Hán Tự</span> |

|||

|- |

|||

|} |

|||

{{Table Hanzi}} |

|||

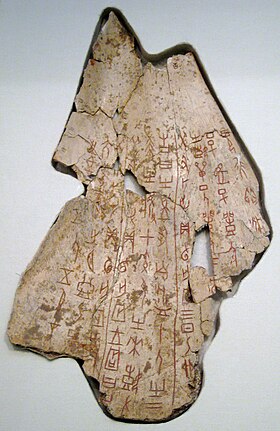

The first attested characters are [[oracle bone inscriptions]] made during the 13th century BCE in what is now [[Anyang]], Henan, as part of divinations conducted by the [[Shang dynasty]] royal house. Character forms were originally highly [[pictograph]]ic in style, but evolved as writing spread across China. Numerous attempts have been made to reform the script, including the promotion of [[small seal script]] by the [[Qin dynasty]] (221–206 BCE). [[Clerical script]], which had matured by the early [[Han dynasty]] (202 BCE{{snd}}220 CE), abstracted the forms of characters—obscuring their pictographic origins in favour of making them easier to write. Following the Han, [[regular script]] emerged as the result of cursive influence on clerical script, and has been the primary style used for characters since. Informed by a long tradition of [[lexicography]], states using Chinese characters have standardized their forms: broadly, [[simplified characters]] are used to write Chinese in [[mainland China]], [[Singapore]], and [[Malaysia]], while [[traditional characters]] are used in [[Taiwan]], [[Hong Kong]], and [[Macau]]. |

|||

A '''Chinese character''' ({{zh-stp|t=漢字|s=汉字|p=Hànzì}}) is a [[logogram]] used in writing [[Chinese language|Chinese]], [[Japanese language|Japanese]], sometimes [[Korean language|Korean]], and formerly [[Vietnamese language|Vietnamese]]. A complete writing system in Chinese characters appeared in [[China]] 3200 years ago during the [[Shang Dynasty]],<ref name = "William G. Boltz">William G. Boltz, Early Chinese Writing, World Archaeology, Vol. 17, No. 3, Early Writing Systems. (Feb., 1986), pp. 420-436 (436)</ref><ref name = "David N. Keightley">David N. Keightley, Art, Ancestors, and the Origins of Writing in China, Representations, No. 56, Special Issue: The New Erudition. (Autumn, 1996), pp.68-95 (68) </ref><ref name = "John DeFrancis">[http://www.pinyin.info/readings/texts/visible/index.html John DeFrancis: Visible Speech. The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems: Chinese] </ref> making it what is believed to be the oldest “surviving” writing system. However, as the symbols used are predominantly pictographs, the linkages to the modern Chinese writing system would be decipherable only to linguistic archaeologists. The [[oracle bone]] inscriptions were discovered at what is now called the Yin Ruins near [[Anyang]] city in 1899. [[Sumerian Language|Sumerian]] [[cuneiform]] is currently regarded as being the oldest known writing system having originated about 3200 B.C. In a 2003 archeological dig at [[Jiahu]] in Henan province in western China, various Neolithic signs were found inscribed on tortoise shells which date back as early as the 7th millennium BC, and may represent possible precursors of the Chinese script, although there has been no link established so far.<ref>http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/2956925.stm</ref> |

|||

After being introduced in order to write [[Literary Chinese]], characters were often adapted to write local languages spoken throughout the [[Sinosphere]]. In [[Japanese language|Japanese]], [[Korean language|Korean]], and [[Vietnamese language|Vietnamese]], Chinese characters are known as ''[[kanji]]'', ''[[hanja]]'', and ''{{langr|vi|[[chữ Hán]]}}'' respectively. Writing traditions also emerged for some of the other [[languages of China]], like the [[sawndip]] script used to write the [[Zhuang languages]] of [[Guangxi]]. Each of these written vernaculars used existing characters to write the language's native vocabulary, as well as the [[Sino-Xenic vocabularies|loanwords it borrowed from Chinese]]. In addition, each invented characters for local use. In written Korean and Vietnamese, Chinese characters have largely been replaced with alphabets, leaving Japanese as the only major non-Chinese language still written using them. |

|||

Four percent of Chinese characters are derived directly from individual [[pictograms]] ({{zh-cp|c=象形字|p=xiàngxíngzì}}), and in most of those cases the relationship is not necessarily clear to the modern reader. Of the remaining 96%, some are logical aggregates ({{zh-stp|s=会意字|t=會意字|p=huìyìzì}}), which are characters combined from multiple parts indicative of meaning, but most are [[pictophonetic]]s ({{zh-stp|s=形声字|t=形聲字|p=xíng-shēngzì}}), characters containing two parts where one indicating a general category of meaning and the other the sound, though the sound is often only approximate to the modern pronunciation because of changes over time and differences between source languages. The number of Chinese characters contained in the [[Kangxi dictionary]] is approximately 47,035, although a large number of these are rarely-used variants accumulated throughout history. Studies carried out in [[China]] have shown that full literacy requires a knowledge of between three and four thousand characters.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.askasia.org/teachers/essays/essay.php?no=101|title=Chinese Writing: Transitions and Transformations|author=Norman, Jerry|date=[[2005]]|accessdate=2006-12-11}}</ref> |

|||

At the most basic level, characters are composed of [[Chinese character strokes|strokes]] that are written in a fixed order. Historically, methods of writing characters have included carving stone or bone; brushing ink onto silk, bamboo, or paper; and printing with [[woodblock printing|woodblocks]] or [[moveable type]]. Technologies invented since the 19th century to facilitate the use of characters include [[telegraph code]]s and [[typewriter]]s, as well as [[input method]]s and [[text encodings]] on computers. |

|||

In Chinese tradition, each character corresponds to a single syllable. Most [[word]]s in all modern varieties of Chinese are polysyllabic and thus require two or more characters to write. [[Cognate]]s in the various Chinese languages/dialects which have the same or similar meaning but different pronunciations can be written with the same character. In addition, many characters were adopted according to their meaning by the Japanese and Korean languages to represent native words, disregarding pronunciation altogether. The loose relationship between phonetics and characters has thus made it possible for them to be used to write very different and probably unrelated languages. |

|||

== Development == |

|||

Just as [[Roman letter]]s have a characteristic shape (lower-case letters occupying a roundish area, with ascenders or descenders on some letters), Chinese characters occupy a more or less square area. Characters made up of multiple parts squash these parts together in order to maintain a uniform size and shape — this is the case especially with characters written in the [[Sòngtǐ]] style. Because of this, beginners often practise on squared graph paper, and the Chinese sometimes use the term "Square-Block Characters" ({{zh-stp|s=方块字|t=方塊字|p=fāngkuàizì}}). |

|||

{{Further|Proto-writing|History of writing}} |

|||

{{See also|Ideograph|Rebus}} |

|||

Chinese characters are accepted as representing one of four independent inventions of writing in human history.{{efn|Zev Handel lists:{{sfn|Handel|2019|p=1}} {{olist|Sumerian [[cuneiform]] emerging {{circa|3200 BCE}}|[[Egyptian hieroglyphs]] emerging {{circa|3100 BCE|lk=no}}|Chinese characters emerging {{circa|13th century BCE|lk=no}}|[[Maya script]] emerging {{circa|1 CE|lk=no}}}}}} In each instance, writing evolved from a system using two distinct types of [[ideograph]]s—either pictographs visually depicting objects or concepts, or fixed [[sign (semiotics)|sign]]s representing concepts only by shared convention. These systems are classified as [[proto-writing]], because the techniques they used were insufficient to carry the meaning of spoken language by themselves.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|p=2}} |

|||

Various innovations were required for Chinese characters to emerge from proto-writing. Firstly, pictographs became distinct from simple pictures in use and appearance: for example, the pictograph {{hani|大}}, meaning 'large', was originally a picture of a large man, but one would need to be aware of its specific meaning in order to interpret the sequence {{hani|大鹿}} as signifying 'large deer', rather than being a picture of a large man and a deer next to one another. Due to this process of abstraction, as well as to make characters easier to write, pictographs gradually became more simplified and regularized—often to the extent that the original objects represented are no longer obvious.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=3–4}} |

|||

The actual shape of many Chinese characters varies in different cultures. [[Mainland China]] adopted [[Simplified Chinese character|simplified characters]] in 1956, but [[Traditional Chinese characters]] are still used in [[Taiwan]] and [[Hong Kong]]. [[Singapore]] has also adopted simplified Chinese characters. Postwar Japan has used its own less drastically [[Shinjitai|simplified characters]] since 1946, while [[South Korea]] has limited its use of Chinese characters, and [[Vietnam]] and [[North Korea]] have completely abolished their use in favour of [[Vietnamese alphabet|romanized Vietnamese]] and [[Hangul]], respectively. |

|||

This proto-writing system was limited to representing a relatively narrow range of ideas with a comparatively small library of symbols. This compelled innovations that allowed for symbols which indicated elements of spoken language directly.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|p=5}} In each historical case, this was accomplished by some form of the [[rebus]] technique, where the symbol for a word is used to indicate a different word with a similar pronunciation, depending on context.{{sfnm|Norman|1988|1p=59|Li|2020|2p=48}} This allowed for words that lacked a plausible pictographic representation to be written down for the first time. This technique preempted more sophisticated methods of character creation that would further expand the lexicon. The process whereby writing emerged from proto-writing took place over a long period; when the purely pictorial use of symbols disappeared, leaving only those representing spoken words, the process was complete.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=11, 16}} |

|||

Chinese characters are also known as ''sinographs'', and the Chinese writing system as ''sinography''. Non-Chinese languages which have adopted sinography — and, with the orthography, a large number of loanwords from the Chinese language — are known as [[Sinoxenic language]]s, whether or not they still use the characters. The term does not imply any genetic affiliation with Chinese. The major Sinoxenic languages are generally considered to be Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese. |

|||

== Classification == |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{Main|Chinese character classification}} |

|||

[[Image:800px-Map-Chinese Characters.png|thumb|300px|Areas using only Chinese characters in green; in conjunction with other scripts, dark green; maximum extent of historic usage, light green. (does not include other territories annexed by Japan in WW2)]] |

|||

Chinese characters have been used in several different [[writing system]]s throughout history. The concept of a writing system includes both the written symbols themselves, called ''[[grapheme]]s''—which may include characters, numerals, or punctuation—as well as the rules by which they are used to record language.{{sfnm|Qiu|2000|1p=1|Handel|2019|2pp=4–5}} Chinese characters are [[logograph]]s, which are graphemes that represent units of meaning in a language. Specifically, characters represent a language's [[morpheme]]s, its most basic units of meaning. Morphemes in Chinese—and therefore the characters used to write them—are nearly always a single syllable in length. In some special cases, characters may denote non-morphemic syllables as well; due to this, [[written Chinese]] is often characterized as [[morphosyllabic]].{{sfnm|Qiu|2000|1pp=22–26|Norman|1988|2p=74}}{{efn|According to Handel: "While monosyllabism generally trumps morphemicity—that is to say, a bisyllabic morpheme is nearly always written with two characters rather than one—there is an unmistakable tendency for script users to impose a morphemic identity on the linguistic units represented by these characters."{{sfn|Handel|2019|p=33}}}} Logographs may be contrasted with [[letter (alphabet)|letter]]s in an [[alphabet]], which generally represent [[phoneme]]s, the distinct units of sound used by speakers of a language.{{sfnm|Qiu|2000|1pp=13–15|Coulmas|1991|2pp=104–109}} Despite their origins in picture-writing, Chinese characters are no longer ideographs capable of representing ideas directly; their comprehension relies on the reader's knowledge of the particular language being written.{{sfnm|Li|2020|1pp=56–57|Boltz|1994|2pp=3–4}} |

|||

The oldest Chinese inscriptions that are indisputably writing are the [[Oracle bone script]] ({{zh-cpl|c=甲骨文|p=jiǎgǔwén|l=shell-bone-script}}). The oracle bone script is a well-developed writing system, attested from the late [[Shang Dynasty]] (1200-1050 B.C.)<ref name = "William G. Boltz">William G. Boltz, Early Chinese Writing, World Archaeology, Vol. 17, No. 3, Early Writing Systems. (Feb., 1986), pp. 420-436 (436)</ref><ref name = "David N. Keightley">David N. Keightley, Art, Ancestors, and the Origins of Writing in China, Representations, No. 56, Special Issue: The New Erudition. (Autumn, 1996), pp.68-95 (68)</ref><ref name = "John DeFrancis">[http://www.pinyin.info/readings/texts/visible/index.html John DeFrancis: Visible Speech. The Diverse Oneness of Writing Systems: Chinese] </ref> from [[Anyang]], and from [[Zhengzhou]], dated [[1600 BC]]{{Fact|date=February 2007}}. In addition, there are very few logographs found on pottery shards and cast in bronzes, known as the [[Bronzeware script|Bronze script]] ({{zh-cp|c=金文|p=jīnwén}}), which is very similar to but more complex and pictorial than the Oracle Bone Script. Only about 1,400 of the 2,500 known Oracle Bone logographs can be identified with later Chinese characters and therefore easily read. However, it should be noted that these 1,400 logographs include most of the commonly used ones. |

|||

The areas where Chinese characters were historically used—sometimes collectively termed the ''[[Sinosphere]]''—have a long tradition of [[lexicography]] attempting to explain and refine their use; for most of history, analysis revolved around a model first popularized in the 2nd-century ''[[Shuowen Jiezi]]'' dictionary.{{sfnm|Handel|2019|1p=51|2a1=Yong|2a2=Peng|2y=2008|2pp=95–98}} More recent models have analysed the methods used to create characters, how characters are structured, and how they function in a given writing system.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=19, 162–168}} |

|||

According to legend, though, Chinese characters were invented earlier by [[Cangjie]] (c. 2650 BC), a bureaucrat under the legendary emperor, [[Yellow Emperor|Huangdi]]. The legend tells that Cangjie was hunting on Mount Yangxu (today Shanxi) when he saw a tortoise whose veins caught his curiosity. Inspired by the possibility of a logical relation of those veins, he studied the animals of the world, the landscape of the earth, and the stars in the sky, and invented a symbolic system called ''zi'' — Chinese characters. It was said that on the day the characters were born, Chinese heard the devil mourning, and saw crops falling like rain, as it marked the beginning of civilization, for good and for bad. |

|||

=== Structural analysis === |

|||

===Neolithic signs=== |

|||

Most characters can be analysed structurally as compounds made of smaller [[Chinese character components|components]] ({{zhi|c=部件|p=bùjiàn}}), which are often independent characters in their own right, adjusted to occupy a given position in the compound.{{sfn|Boltz|2011|pp=57, 60}} Components within a character may serve a specific function: phonetic components provide a hint for the character's pronunciation, and semantic components indicate some element of the character's meaning. Components that serve neither function may be classified as pure signs with no particular meaning, other than their presence distinguishing one character from another.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=14–18}} |

|||

A straightforward structural classification scheme may consist of three pure classes of semantographs, phonographs, and signs—having only semantic, phonetic, and form components respectively—as well as classes corresponding to each combination of component types.{{sfnm|Yin|2007|1pp=97–100|Su|2014|2pp=102-111}} Of the {{val|3500}} characters that are frequently used in Standard Chinese, pure semantographs are estimated to be the rarest, accounting for about 5% of the lexicon, followed by pure signs with 18%, and semantic–form and phonetic–form compounds together accounting for 19%. The remaining 58% are phono-semantic compounds.{{sfn|Yang|2008|pp=147-148}} |

|||

The earliest Neolithic signs come from ''[[Jiahu]]'', a Neolithic site in the basin of the Yellow River in [[Henan]] province, dated to c. 6500 BC [http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/2956925.stm], known as the [[Jiahu Script]]. It has yielded turtle carapaces that were pitted and inscribed with symbols. By the discoveries at Jiahu reported here Neolithic sign use in China must now be extended backward another two millennia to c. 6500 cal BC. Sign use, however, should not be easily equated with writing, although it may represent a formative stage. In the words of the archaeologists who made the discovery: |

|||

The Chinese palaeographer [[Qiu Xigui]] ({{born-in|1935}}) presents three principles of character function adapted from earlier proposals by {{ill|Tang Lan|zh|唐蘭}} (1901–1979) and [[Chen Mengjia]] (1911–1966),{{sfn|Demattè|2022|p=14}} with ''semantographs'' describing all characters whose forms are wholly related to their meaning, regardless of the method by which the meaning was originally depicted, ''phonographs'' that include a phonetic component, and ''loangraphs'' encompassing existing characters that have been borrowed to write other words. Qiu also acknowledges the existence of character classes that fall outside of these principles, such as pure signs.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=163–171}} |

|||

: ''Here we present signs from the seventh millennium BC which seem to relate to later Chinese characters and may have been intended as words. We interpret these signs not as writing itself, but as features of a lengthy period of sign-use which led eventually to a fully-fledged system of writing...The present state of the archaeological record in China, which has never had the intensive archaeological examination of, for example, Egypt or Greece, does not permit us to say exactly in which period of the Neolithic the Chinese invented their writing. What did persist through these long periods was the idea of sign use. Although it is impossible at this point to trace any direct connection from the Jiahu signs to the Yinxu characters, we do propose that slow, culture-linked evolutionary processes, adopting the idea of sign use, took place in diverse settings around the Yellow River. We should not assume that there was a single path or pace for the development of a script.''<ref> Xueqin Li, Garman Harbottle, Juzhong Zhang, Changsui Wang: The earliest writing? Sign use in the seventh millennium BC at Jiahu, Henan Province, China. ''Antiquity'' 77, 295 (2003): 31-45 (31 and 41)</ref> |

|||

=== Semantographs === |

|||

Another early script possibly related to modern Chinese characters is the [[Banpo Script]] from [[Shaanxi]] province, dating from the 5th millennium BC. Some researchers believe it to be related to the [[Oracle bone script]]. This relation is contested, however, and evidence is scarce. |

|||

==== Pictographs ==== |

|||

{{mim |

|||

| direction = vertical | width = 300 | caption_align = center | border = none |

|||

| header = Graphical evolution of pictographs |

|||

| image1 = Evo-rì.svg |

|||

| caption1 = {{zhc|c=日|l=Sun}} |

|||

| image2 = Evo-shān.svg |

|||

| caption2 = {{zhc|c=山|l=mountain}} |

|||

| image3 = Evo-xiàng.svg |

|||

| caption3 = {{zhc|c=象|l=elephant}} |

|||

}} |

|||

Most of the oldest characters are [[pictograph]]s ({{zhi|c=象形|p=xiàngxíng}}), representational pictures of physical objects.{{sfn|Yong|Peng|2008|p=19}} Examples include {{zhc|c=日|l=Sun}}, {{zhc|c=月|l=Moon}}, and {{zhc|c=木|l=tree}}. Over time, the forms of pictographs have been simplified in order to make them easier to write.{{sfnm|Qiu|2000|1pp=44–45|Zhou|2003|2p=61}} As a result, modern readers generally cannot deduce what many pictographs were originally meant to resemble; without knowing the context of their origin in picture-writing, they may be interpreted instead as pure signs. However, if a pictograph's use in compounds still reflects its original meaning, as with {{zhi|c=日}} in {{zhc|c=晴|l=clear sky}}, it can still be analysed as a semantic component.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=18–19}}{{sfnm|Qiu|2000|1p=154|Norman|1988|2p=68}} |

|||

Pictographs have often been extended from their original meanings to take on additional layers of metaphor and [[synecdoche]], which sometimes displace the character's original sense. When this process results in excessive ambiguity between distinct senses written with the same character, it is usually resolved by new compounds being derived to represent particular senses.{{sfn|Yip|2000|pp=39-42}} |

|||

Later excavations in eastern China's [[Anhui]] province and the [[Dadiwan culture]] sites in the eastern part of northwestern China's [[Gansu]] province uncovered pottery shards, dated to c. 5000 BC, inscribed with symbols [http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2006-03/22/content_4333001.htm][http://www.china.org.cn/english/culture/48220.htm]. It is unknown whether these symbols formed part of an organized system of writing, but many of them bear resemblance to what are accepted as early Chinese characters, and it is speculated that they may be ancestors to the latter. |

|||

==== <span class="anchor" id="Ideographs"></span>Indicatives ==== |

|||

Inscription-bearing artifacts from the [[Dawenkou culture]] culture site in [[Juxian County, Shandong|Juxian County]], [[Shandong]], dating to c. 2800 BC, have also been found [http://english.people.com.cn/english/200004/21/eng20000421_39442.html]. The ''Chengziyai'' site in [[Longshan]] township, Shandong has produced fragments of inscribed bones used to divine the future, dating to 2500 - 1900 BC, and symbols on pottery vessels from [[Dinggong]] are thought by some scholars to be an early form of writing. Symbols of a similar nature have also been found on pottery shards from the [[Liangzhu culture]] ({{zh-c|c=良渚}}) of the lower [[Yangtze]] valley. |

|||

Indicatives ({{zhi|p=zhǐshì|t=指事}}), also called ''simple ideographs'' or ''self-explanatory characters'',{{sfn|Yong|Peng|2008|p=19}} are visual representations of abstract concepts that lack any tangible form. Examples include {{zhc|c=上|l=up}} and {{zhc|c=下|l=down}}—these characters were originally written as dots placed above and below a line, and later evolved into their present forms with less potential for graphical ambiguity in context.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|p=46}} More complex indicatives include {{zhc|c=凸|l=convex}}, {{zhc|c=凹|l=concave}}, and {{zhc|c=平|l=flat and level}}.{{sfnm|Norman|1988|1p=68|Qiu|2000|2pp=185–187}} |

|||

==== Compound ideographs ==== |

|||

Although the earliest forms of primitive Chinese writing are no more than individual symbols and therefore cannot be considered a true written script, the inscriptions found on bones (dated to 2500 - 1900 BC) used for the purposes of divination from the late Neolithic Longshan ({{zh-stp|s=龙山|t=龍山|p=lóngshān}}) Culture (c. 3200 - 1900 BC) are thought by some to be a proto-written script, similar to the earliest forms of writing in [[Mesopotamia]] and [[Egypt]]. It is possible that these inscriptions are ancestral to the later [[Oracle bone script]] of the Shang Dynasty and therefore the modern Chinese script, since late Neolithic culture found in Longshan is widely accepted by historians and archaeologists to be ancestral to the Bronze Age [[Erlitou culture]] and the later [[Shang]] and [[Zhou]] Dynasties. |

|||

[[File:Compound Chinese character demonstration with 好.webm|thumb|upright=0.9|The compound character {{zhi|c=好}} illustrated as its component characters {{zhi|c=女}} and {{zhi|c=子}} positioned side by side]] |

|||

Compound ideographs ({{zhi|t=會意|s=会意|p=huìyì}})—also called ''logical aggregates'', ''associative idea characters'', or ''syssemantographs''—combine other characters to convey a new, synthetic meaning. A canonical example is {{zhc|c=明|l=bright}}, interpreted as the juxtaposition of the two brightest objects in the sky: {{kxr|日}} and {{kxr|月}}, together expressing their shared quality of brightness. Other examples include {{zhc|c=休|l=rest}}, composed of pictographs {{kxr|人}} and {{kxr|木}}, and {{zhc|c=好|l=good}}, composed of {{kxr|女}} and {{kxr|子}}.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=15, 190–202}} |

|||

Many traditional examples of compound ideographs are now believed to have actually originated as phono-semantic compounds, made obscure by subsequent changes in pronunciation.{{sfn|Sampson|Chen|2013|p=261}} For example, the ''Shuowen Jiezi'' describes {{zhc|c=信|l=trust}} as an ideographic compound of {{kxr|人}} and {{kxr|言}}, but modern analyses instead identify it as a phono-semantic compound—though with disagreement as to which component is phonetic.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|p=155}} [[Peter A. Boodberg]] and [[William G. Boltz]] go so far as to deny that any compound ideographs were devised in antiquity, maintaining that secondary readings that are now lost are responsible for the apparent absence of phonetic indicators,{{sfn|Boltz|1994|pp=104–110}} but their arguments have been rejected by other scholars.{{sfn|Sampson|Chen|2013|pp=265–268}} |

|||

==Written styles== |

|||

[[image:CaoshuShupu.jpg|thumb|right|Sample of the cursive script by Chinese [[Tang Dynasty]] calligrapher [[Sun Guoting]], c. 650 CE.]] |

|||

=== Phonographs === |

|||

There are numerous styles, or scripts, in which Chinese characters can be written, deriving from various calligraphic and historical models. Most of these originated in China and are now common, with minor variations, in all countries where Chinese characters are used. |

|||

==== Phono-semantic compounds ==== |

|||

Phono-semantic compounds ({{zhi|p=xíngshēng|s=形声|t=形聲}}) are composed of at least one semantic component and one phonetic component.{{sfn|Norman|1988|p=68}} They may be formed by one of several methods, often by adding a phonetic component to disambiguate a loangraph, or by adding a semantic component to represent a specific extension of a character's meaning.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|p=154}} Examples of phono-semantic compounds include {{zhc|c=河|p=hé|l=river}}, {{zhc|c=湖|p=hú|l=lake}}, {{zhc|c=流|p=liú|l=stream}}, {{zhc|c=沖|p=chōng|l=surge}}, and {{zhc|c=滑|p=huá|l=slippery}}. Each of these characters have three short strokes on their left-hand side: {{kxr|氵|v=y|name=no}}, a simplified combining form of {{kxr|water}}. This component serves a semantic function in each example, indicating the character has some meaning related to water. The remainder of each character is its phonetic component: {{zhc|c=湖|p=hú}} is pronounced identically to {{zhc|c=胡|p=hú}} in Standard Chinese, {{zhc|c=河|p=hé}} is pronounced similarly to {{zhc|c=可|p=kě}}, and {{zhc|c=沖|p=chōng}} is pronounced similarly to {{zhc|c=中|p=zhōng}}.{{sfn|Cruttenden|2021|pp=167–168}} |

|||

The phonetic components of most compounds may only provide an approximate pronunciation, even before subsequent sound shifts in the spoken language. Some characters may only have the same initial or final sound of a syllable in common with phonetic components.{{sfn|Williams|2010}} A [[phonetic series (Chinese characters)|phonetic series]] comprises all the characters created using the same phonetic component, which may have diverged significantly in their pronunciations over time. For example, {{zhc|c=茶|l=tea|p=chá|j=caa4}} and {{zhc|c=途|l=route|p=tú|j=tou4}} are part of the phonetic series of characters using {{zhc|c=余|p=yú|j=jyu4}}, a literary first-person pronoun. The [[Old Chinese]] pronunciations of these characters were similar, but the phonetic component no longer serves as a useful hint for their pronunciation due to subsequent sound shifts.{{sfn|Vogelsang|2021|pp=51–52}} |

|||

The [[Oracle Bone Script|Oracle Bone]] and [[Bronzeware script|Bronzeware]] scripts being no longer used, the oldest script that is still in use today is the [[Seal Script]] ({{zh-stp|s=篆书|t=篆書|p=zhuànshū}}). It evolved organically out of the Zhou bronze script, and was adopted in a standardized form under the first [[Emperor of China]], [[Qin Shi Huang]]. The seal script, as the name suggests, is now only used in artistic seals. Few people are still able to read it effortlessly today, although the art of carving a traditional seal in the script remains alive; some [[East Asian calligraphy|calligraphers]] also work in this style. |

|||

=== Loangraphs === |

|||

Scripts that are still used regularly are the "[[Clerical Script]]" ({{zh-stp|s=隸书|t=隸書|p=lìshū}}) of the [[Qin Dynasty]] to the [[Han Dynasty]], the [[Wei Monumental Script|Weibei]] ({{zh-cp|c=魏碑|p=wèibēi}}), the "[[Regular Script]]" ({{zh-stp|s=楷书|t=楷書|p=kǎishū}}) used for most printing, and the "[[Semi-cursive Script]]" ({{zh-stp|s=行书|t=行書|p=xíngshū}}) used for most handwriting. |

|||

The phenomenon of existing characters being adapted to write other words with similar pronunciations was necessary in the initial development of Chinese writing, and has remained common throughout its subsequent history. Some loangraphs ({{zhi|c=假借|p=jiǎjiè|l=borrowing}}) are introduced to represent words previously lacking another written form—this is often the case with abstract grammatical particles such as {{Linktext|之|lang=zh}} and {{Linktext|其|lang=zh}}.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=261–265}} The process of characters being borrowed as loangraphs should not be conflated with the distinct process of semantic extension, where a word acquires additional senses, which often remain written with the same character. As both processes often result in a single character form being used to write several distinct meanings, loangraphs are often misidentified as being the result of semantic extension, and vice versa.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=273–274, 302}} |

|||

Loangraphs are also used to write words borrowed from other languages, such as the Buddhist terminology introduced to China in antiquity, as well as contemporary non-Chinese words and names. For example, each character in the name {{zhc|c=加拿大|p=Jiānádà|l=Canada}} is often used as a loangraph for its respective syllable. However, the barrier between a character's pronunciation and meaning is never total: when transcribing into Chinese, loangraphs are often chosen deliberately as to create certain connotations. This is regularly done with corporate brand names: for example, [[Coca-Cola]]'s Chinese name is {{zhc|s=可口可乐|t=可口可樂|p=Kěkǒu Kělè|l=delicious enjoyable}}.{{sfn|Taylor|Taylor|2014|pp=30–32}}{{sfn|Ramsey|1987|p=60}}{{sfn|Gnanadesikan|2011|p=61}} |

|||

The [[Cursive Script]] ({{zh-stpl|s=草书|t=草書|p=cǎoshū|l=grass script}}) is not in general use, and is a purely artistic calligraphic style. The basic character shapes are suggested, rather than explicitly realized, and the abbreviations are extreme. Despite being cursive to the point where individual strokes are no longer differentiable and the characters often illegible to the untrained eye, this script (also known as ''draft'') is highly revered for the beauty and freedom that it embodies. Some of the [[Simplified Chinese characters]] adopted by the People's Republic of China, and some of the simplified characters used in Japan, are derived from the Cursive Script. The Japanese [[hiragana]] script is also derived from this script. |

|||

=== Signs === |

|||

There also exist scripts created outside China, such as the Japanese [[Edomoji]] styles; these have tended to remain restricted to their countries of origin, rather than spreading to other countries like the standard scripts described above. |

|||

Some characters and components are pure [[sign (semiotics)|signs]], whose meaning merely derives from their having a fixed and distinct form. Basic examples of pure signs are found with [[Chinese numerals|the numerals]] beyond four, e.g. {{zhc|c=五|l=five}} and {{zhc|c=八|l=eight}}, whose forms do not give visual hints to the quantities they represent.{{sfnm|Qiu|2000|1p=168|Norman|1988|2p=60}} |

|||

=== Traditional ''Shuowen Jiezi'' classification === |

|||

<!---- Table contributed by German Wiki---> |

|||

The ''[[Shuowen Jiezi]]'' is a character dictionary authored {{circa|100 CE|lk=no}} by the scholar [[Xu Shen]] ({{circa|58|148 CE|lk=no}}). In its postface, Xu analyses what he sees as all the methods by which characters are created. Later authors iterated upon Xu's analysis, developing a categorization scheme known as the {{zhl|s=六书|t=六書|p=liùshū|l=six writings}}, which identifies every character with one of six categories that had previously been mentioned in the ''Shuowen Jiezi''. For nearly two millennia, this scheme was the primary framework for character analysis used throughout the Sinosphere.{{sfnm|Norman|1988|1pp=67–69|Handel|2019|2p=48}} Xu based most of his analysis on examples of Qin seal script that were written down several centuries before his time—these were usually the oldest specimens available to him, though he stated he was aware of the existence of even older forms.{{sfn|Norman|1988|pp=170–171}} The first five categories are pictographs, indicatives, compound ideographs, phono-semantic compounds, and loangraphs. The sixth category is given by Xu as {{zhc|c=轉注|p=zhuǎnzhù|l=reversed and refocused}}; however, its definition is unclear, and it is generally disregarded by modern scholars.{{sfn|Handel|2019|pp=48–49}} |

|||

Modern scholars agree that the theory presented in the ''Shuowen Jiezi'' is problematic, failing to fully capture the nature of Chinese writing, both in the present, as well as at the time Xu was writing.{{sfnm|Qiu|2000|1pp=153–154, 161|Norman|1988|2p=170}} Traditional Chinese lexicography as embodied in the ''Shuowen Jiezi'' has suggested implausible etymologies for some characters.{{sfnm|Qiu|2013|1pp=102–108|Norman|1988|2p=69}} Moreover, several categories are considered to be ill-defined: for example, it is unclear whether characters like {{zhc|c=大|l=large}} should be classified as pictographs or indicatives.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|p=154}} However, awareness of the 'six writings' model has remained a common component of character literacy, and often serves as a tool for students memorizing characters.{{sfn|Handel|2019|p=43}} |

|||

<div class="interbox" style="clear: both;"> |

|||

{| border="0" cellpadding="3" cellspacing="2" width="100%" |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | '''[[Oracle Bone Script]]''' |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | '''[[Seal Script]]''' |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | '''[[Clerical Script]]''' |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | '''[[Semi-Cursive Script]]''' |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | '''[[Cursive Script]]''' |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | '''[[Regular Script]] ([[Traditional Chinese|Traditional]])''' |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | '''[[Regular Script]] ([[Simplified Chinese|Simplified]])''' |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | '''[[Pinyin]]''' |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | '''Meaning''' |

|||

== History == |

|||

|----- |

|||

{{Further|Chinese script styles|History of the Chinese language}} |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ri Oracle.png]] |

|||

[[File:Comparative evolution of Cuneiform, Egyptian and Chinese characters.svg|thumb|upright=0.8|Diagram comparing the abstraction of pictographs in cuneiform, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Chinese characters{{snd}}from an 1870 publication by French Egyptologist [[Gaston Maspero]]{{efn-ua |{{Cite book |last=Maspero |first=Gaston |author-link=Gaston Maspero |url=http://archive.org/details/recueildetravaux27masp/page/244/mode/2up |title=Recueil de travaux relatifs à la philologie et à l'archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes |publisher=Librairie Honoré Champion |year=1870 |location=Paris |page=243 |language=fr}}}}]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ri Seal.png]] |

|||

The broadest trend in the evolution of Chinese characters over their history has been simplification, both in graphical ''shape'' ({{zhi|c=字形|p=zìxíng}}), the "external appearances of individual graphs", and in graphical ''form'' ({{zhi|s=字体|t=字體|p=zìtǐ}}), "overall changes in the distinguishing features of graphic[al] shape and calligraphic style, [...] in most cases refer[ring] to rather obvious and rather substantial changes".{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=44–45}} The traditional notion of an orderly procession of script styles, each suddenly appearing and displacing the one previous, has been disproven by later scholarship and archaeological work. Instead, scripts evolved gradually, with several coexisting in a given area.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=59–60, 66}} |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ri Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ri Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ri Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ri Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">rì</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Sun]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuue Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuue Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuue Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuue Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuue Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuue Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">yuè </font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Moon]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shan Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shan Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shan Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shan Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shan Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shan Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">shān</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Mountain]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shui Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shui Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shui Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shui Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shui Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Shui Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">shuǐ</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Water]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuu Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuu Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuu Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuu Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuu Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yuu Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">yǔ</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Rain]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu4 Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu4 Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu4 Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu4 Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu4 Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu4 Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">mù</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Wood]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character He Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character He Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character He Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character He Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character He Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character He Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">hé</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Rice|Rice Plant]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ren Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ren Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ren Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ren Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ren Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ren Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">rén </font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Human]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Nuu Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Nuu Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Nuu Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Nuu Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Nuu Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Nuu Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">nǚ</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Woman]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Mu Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">mǔ</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Mother]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Eye Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Eye Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Eye Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Eye Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Eye Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Eye Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">mù</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Eye]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niu Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niu Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niu Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niu Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niu Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niu Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">niú</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Cattle|Ox]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yang Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yang Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yang Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yang Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yang Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Yang Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | — |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">yáng</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Sheep]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ma Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ma Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ma Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ma Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ma Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ma Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Ma Simp.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">mǎ</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Horse]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niao Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niao Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niao Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niao Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niao Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niao Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Niao Simp.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">niǎo</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Bird]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Gui Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Gui Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Gui Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Gui Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Gui Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Gui Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Gui Simp.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">guī</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Tortoise]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Long Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Long Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Long Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Long Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Long Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Long Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Long Simp.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">lóng</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#EFEFEF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Chinese Dragon]]</font> |

|||

|----- |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Feng Oracle.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Feng Seal.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Feng Cler.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Feng Semi.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Feng Cur.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Feng Trad.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | [[Image:Character Feng Simp.png]] |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">fèng</font> |

|||

| bgcolor="#DFDFDF" valign="middle" align="center" | <font size="3">[[Chinese Phoenix]]</font> |

|||

|} |

|||

</div> |

|||

=== Traditional invention narrative === |

|||

==Formation of characters== |

|||

Several of the [[Chinese classics]] indicate that [[Chinese knotting#Recordkeeping|knotted cords]] were used to keep records prior to the invention of writing.{{sfn|Demattè|2022|pp=79–80}} Works that reference the practice include chapter 80 of the ''[[Tao Te Ching]]''{{efn-ua |{{Cite book |author=Laozi |author-link=Laozi |title-link=Tao Te Ching |year=1891 |language=lzh,en |translator-last=Legge |translator-first=James |script-title=zh:道德經 |trans-title=Tao Te Ching |chapter=80 |author-mask=Laozi |translator-link=James Legge |chapter-url=https://ctext.org/dao-de-jing/ens#n11671 |via=the [[Chinese Text Project]] |trans-quote=I would make the people return to the use of knotted cords (instead of the written characters).}} }} and the "[[Xici]] II" commentary to the ''[[I Ching]]''.{{efn-ua |{{Cite book |title-link=I Ching |year=1899 |language=lzh,en |translator-last=Legge |translator-first=James |script-title=zh:易經 |trans-title=I Ching |script-chapter=zh:係辭下 |trans-chapter=Xi Ci II |translator-link=James Legge |chapter-url=https://ctext.org/book-of-changes/xi-ci-xia#n46944 |via=the [[Chinese Text Project]] |trans-quote=In the highest antiquity, government was carried on successfully by the use of knotted cords (to preserve the memory of things). In subsequent ages the sages substituted for these written characters and bonds.}} }} According to one tradition, Chinese characters were invented during the 3rd millennium BCE by [[Cangjie]], a scribe of the legendary [[Yellow Emperor]]. Cangjie is said to have invented symbols called {{zhc|c=字|p=zì}} due to his frustration with the limitations of knotting, taking inspiration from his study of the tracks of animals, landscapes, and the stars in the sky. On the day that these first characters were created, grain rained down from the sky; that night, the people heard the wailing of ghosts and demons, lamenting that humans could no longer be cheated.{{sfn|Yang|An|2008|pp=84–86}}{{sfn|Boltz|1994|pp=130–138}} |

|||

{{main|Chinese character classification|radical (Chinese character)}} |

|||

=== Neolithic precursors === |

|||

The early stages of the development of Chinese characters were dominated by [[pictogram]]s, in which meaning was expressed directly by the shapes. The development of the script, both to cover words for abstract concepts and to increase the efficiency of writing, has led to the introduction of numerous non-pictographic characters. |

|||

{{Main|Neolithic symbols in China}} |

|||

Collections of graphs and pictures have been discovered at the sites of several [[Neolithic]] settlements throughout the [[Yellow River]] valley, including [[Jiahu]] ({{circa|6500 BCE|lk=no}}), [[Dadiwan]] and [[Damaidi]] (6th millennium BCE), and [[Banpo]] (5th millennium BCE). Symbols at each site were inscribed or drawn onto artefacts, appearing one at a time and without indicating any greater context. Qiu concludes, "We simply possess no basis for saying that they were already being used to record language."{{sfn|Qiu|2000|p=31}} A historical connection with the symbols used by the late Neolithic [[Dawenkou culture]] ({{circa|4300|2600 BCE|lk=no}}) in Shandong has been deemed possible by palaeographers, with Qiu concluding that they "cannot be definitively treated as primitive writing, nevertheless they are symbols which resemble most the ancient pictographic script discovered thus far in China... They undoubtedly can be viewed as the forerunners of primitive writing."{{sfn|Qiu|2000|p=39}} |

|||

=== Oracle bone script === |

|||

The various types of character were first classified c. 100 CE by the Chinese linguist [[Xu Shen]], whose etymological dictionary ''Shuowen Jiezi'' ({{lang|zh-tw|說文解字}}/{{lang|zh-cn|说文解字}}) divides the script into six categories, the ''liùshū'' ({{lang|zh-tw|六書}}/{{lang|zh-cn|六书}}). While the categories and classification are occasionally problematic and arguably fail to reflect the complete nature of the Chinese writing system, the system has been perpetuated by its long history and pervasive use.[http://www.tiaccwhf.net/~t038/kaho/newpage82.htm] |

|||

{{Main|Oracle bone script}} |

|||

{{mim |

|||

| header = Oracle bone script |

|||

| width = 60 |

|||

| caption_align = center |

|||

| image1 = 天-oracle.svg |

|||

| caption1 = {{lang|zh|天}}<br />{{nwr|'Heaven'}} |

|||

| image2 = 馬-oracle.svg |

|||

| caption2 = {{lang|zh|馬}}<br />{{nwr|'horse'}} |

|||

| image3 = 旅-oracle.svg |

|||

| caption3 = {{lang|zh|旅}}<br />{{nwr|'travel'}} |

|||

| image4 = 正-oracle.svg |

|||

| caption4 = {{lang|zh|正}}<br />{{nwr|'straight'}} |

|||

| image5 = 韋-oracle.svg |

|||

| caption5 = {{lang|zh|韋}}<br />{{nwr|'leather'}} |

|||

}} |

|||

{{CSS image crop |

|||

| Image = Shang dynasty inscribed scapula.jpg |

|||

| bSize = 280 |

|||

| cWidth = 240 |

|||

| cHeight = 300 |

|||

| oTop = 115 |

|||

| oLeft = 35 |

|||

| Description = Ox scapula inscribed with characters recording the result of divinations{{snd}}dated {{circa|1200 BCE}} |

|||

}} |

|||

The oldest attested Chinese writing comprises a body of inscriptions produced during the [[Late Shang]] period ({{circa|1250|lk=no}}{{snd}}1050 BCE), with the very earliest examples from the reign of [[Wu Ding]] dated between 1250 and 1200 BCE.{{sfnm|Boltz|1999|1pp=74, 107–108|Liu et al.|2017|2pp=155–175}} Many of these inscriptions were made on [[oracle bone]]s—usually either ox [[scapula]]e or turtle plastrons—and recorded official [[divination]]s carried out by the Shang royal house. Contemporaneous inscriptions in a related but distinct style were also made on ritual bronze vessels. This [[oracle bone script]] ({{zhi|c=甲骨文|p=jiǎgǔwén<!-- A considered exception to [[MOS:ZH]] -->}}) was first documented in 1899, after specimens were discovered being sold as "dragon bones" for medicinal purposes, with the symbols carved into them identified as early character forms. By 1928, the source of the bones had been traced to a village near [[Anyang]] in [[Henan]]—discovered to be the site of [[Yinxu|Yin]], the final Shang capital—which was excavated by a team led by [[Li Ji (archaeologist)|Li Ji]] (1896–1979) from the [[Academia Sinica]] between 1928 and 1937.{{sfn|Liu|Chen|2012|p=6}} To date, over {{val|150000}} oracle bone fragments have been found.{{sfnm|Kern|2010|1p=1|Wilkinson|2012|2pp=681–682}} |

|||

Oracle bone inscriptions recorded divinations undertaken to communicate with the spirits of royal ancestors. The inscriptions range from a few characters in length at their shortest, to several dozen at their longest. The Shang king would communicate with his ancestors by means of [[scapulimancy]], inquiring about subjects such as the royal family, military success, and the weather. Inscriptions were made in the divination material itself before and after it had been cracked by exposure to heat; they generally include a record of the questions posed, as well as the answers as interpreted in the cracks.{{sfn|Keightley|1978|pp=28–42}}{{sfn|Kern|2010|p=1}} A minority of bones feature characters that were inked with a brush before their strokes were incised; the evidence of this also shows that the conventional [[stroke order]]s used by later calligraphers had already been established for many characters by this point.{{sfn|Keightley|1978|pp=46–47}} |

|||

[[image:chineseprimer3.png|right|180px|thumb|Excerpt from a 1436 primer on Chinese characters]] |

|||

Oracle bone script is the direct ancestor of later forms of written Chinese. The oldest known inscriptions already represent a well-developed writing system, which suggests an initial emergence predating the late 2nd millennium BCE. Although written Chinese is first attested in official divinations, it is widely believed that writing was also used for other purposes during the Shang, but that the media used in other contexts—likely [[bamboo and wooden slips]]—were less durable than bronzes or oracle bones, and have not been preserved.{{sfnm|Boltz|1986|1p=424|Kern|2010|2p=2}} |

|||

'''1. Pictograms (象形字 ''xiàngxíngzì'')''' |

|||

=== Zhou scripts === |

|||

Contrary to popular belief, pictograms make up only a small portion of Chinese characters. While characters in this class derive from pictures, they have been standardized, simplified, and stylized to make them easier to write, and their derivation is therefore not always obvious. Examples include 日 (rì) for "sun", 月 (yuè) for "moon", and 木 (mù) for "tree". |

|||

{{See also|Chinese bronze inscriptions|Bamboo and wooden slips|Seal script}} |

|||

{{mim |

|||

| header = Bronze script |

|||

| width = 60 |

|||

| image1 = 天-bronze.svg |

|||

| image2 = 馬-bronze.svg |

|||

| image3 = 旅-bronze.svg |

|||

| image4 = 正-bronze.svg |

|||

| image5 = 韋-bronze.svg |

|||

| alt1 = 天 |

|||

| alt2 = 馬 |

|||

| alt3 = 旅 |

|||

| alt4 = 正 |

|||

| alt5 = 韋 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{CSS image crop |

|||

| Image = Shi Qiang pan.jpg |

|||

| bSize = 300 |

|||

| cWidth = 285 |

|||

| cHeight = 160 |

|||

| oTop = 30 |

|||

| oLeft = 6 |

|||

| Description = The [[Shi Qiang pan|Shi Qiang ''pan'']], a bronze ritual basin bearing inscriptions describing the deeds and virtues of the first seven Zhou kings{{snd}}dated {{circa|900 BCE|lk=no}}{{sfn|Shaughnessy|1991|pp=1–4}} |

|||

}} |

|||

As early as the Shang, the oracle bone script existed as a simplified form alongside another that was used in bamboo books, in addition to elaborate pictorial forms often used in clan emblems. These other forms have been preserved in [[bronze script]] ({{zhi|c=金文|p=jīnwén}}), where inscriptions were made using a stylus in a clay mould, which was then used to cast [[Chinese ritual bronzes|ritual bronzes]].{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=63–66}} These differences in technique generally resulted in character forms that were less angular in appearance than their oracle bone script counterparts.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=88–89}} |

|||

Study of these bronze inscriptions has revealed that the mainstream script underwent slow, gradual evolution during the late Shang, which continued during the [[Zhou dynasty]] ({{circa|1046|lk=no}}{{snd}}256 BCE) until assuming the form now known as ''[[small seal script]]'' ({{zhi|c=小篆|p=xiǎozhuàn<!-- A considered exception to [[MOS:ZH]] -->}}) within the Zhou [[state of Qin]].{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=76–78}}{{sfn|Chen|2003}} Other scripts in use during the late Zhou include the [[bird-worm seal script]] ({{zhi|t=鳥蟲書|s=鸟虫书|p=niǎochóngshū}}), as well as the regional forms used in non-Qin states. Examples of these styles were preserved as variants in the ''Shuowen Jiezi''.{{sfn|Louis|2003}} Historically, Zhou forms were collectively known as ''[[large seal script]]'' ({{zhi|c=大篆|p=dàzhuàn}}), a term which has fallen out of favour due to its lack of precision.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|p=77}} |

|||

There is no concrete number for the proportion of modern characters that are pictographic in nature; however, Xu Shen (c. 100 CE) estimated that 4% of characters fell into this category. |

|||

=== Qin unification and small seal script === |

|||

'''2. Pictophonetic compounds (形聲字/{{lang|zh-cn|形声字}}, ''Xíngshēngzì'') |

|||

{{Main|Small seal script}} |

|||

{{mim |

|||

| header = Small seal script |

|||

| width = 60 |

|||

| image1 = 天-seal.svg |

|||

| image2 = 馬-seal.svg |

|||

| image3 = 旅-seal.svg |

|||

| image4 = 正-seal.svg |

|||

| image5 = 韋-seal.svg |

|||

| alt1 = 天 |

|||

| alt2 = 馬 |

|||

| alt3 = 旅 |

|||

| alt4 = 正 |

|||

| alt5 = 韋 |

|||

}} |

|||

Following [[Qin's wars of unification|Qin's conquest]] of the other Chinese states that culminated in the founding of the imperial [[Qin dynasty]] in 221 BCE, the Qin small seal script was standardized for use throughout the entire country under the direction of Chancellor [[Li Si]] ({{circa|280|lk=no}}{{snd}}208 BCE).{{sfn|Boltz|1994|p=156}} It was traditionally believed that Qin scribes only used small seal script, and the later clerical script was a sudden invention during the early Han. However, more than one script was used by Qin scribes: a rectilinear vulgar style had also been in use in Qin for centuries prior to the wars of unification. The popularity of this form grew as writing became more widespread.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=104–107}} |

|||

=== Clerical script === |

|||

Also called ''semantic-phonetic compounds'', or ''phono-semantic compounds'', this category represents the largest group of characters in modern Chinese. Characters of this sort are composed of two parts: a pictograph, which suggests the general meaning of the character, and a phonetic part, which is derived from a character pronounced in the same way as the word the new character represents. |

|||

{{Main|Clerical script}} |

|||

{{mim |

|||

| header = Clerical script |

|||

| width = 60 |

|||

| image1 = 天-clerical-han.svg |

|||

| image2 = 馬-clerical-han.svg |

|||

| image3 = 旅-clerical-han.svg |

|||

| image4 = 正-clerical-han.svg |

|||

| image5 = 韋-clerical-han.svg |

|||

| alt1 = 天 |

|||

| alt2 = 馬 |

|||

| alt3 = 旅 |

|||

| alt4 = 正 |

|||

| alt5 = 韋 |

|||

}} |

|||

By the [[Warring States period]] ({{circa|475|lk=no}}{{snd}}221 BCE), an immature form of [[clerical script]] ({{zhi|t=隸書|s=隶书|p=lìshū<!-- A considered exception to [[MOS:ZH]] -->}}) had emerged based on the vulgar form developed within Qin, often called "early clerical" or "proto-clerical".{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=59, 119}} The proto-clerical script evolved gradually; by the [[Han dynasty]] (202 BCE{{snd}}220 CE), it had arrived at a mature form, also called {{zhc|c=八分|p=bāfēn}}. Bamboo slips discovered during the late 20th century point to this maturation being completed during the reign of [[Emperor Wu of Han]] ({{reign|141|87 BCE}}). This process, called ''[[libian]]'' ({{zhi|t=隸變|s=隶变}}), involved character forms being mutated and simplified, with many components being consolidated, substituted, or omitted. In turn, the components themselves were regularized to use fewer, straighter, and more well-defined strokes. The resulting clerical forms largely lacked any of the pictorial qualities that remained in seal script.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=119–124}} |

|||

Around the midpoint of the [[Eastern Han]] (25–220 CE), a simplified and easier form of clerical script appeared, which Qiu terms {{zhl|s=新隶体|t=新隸體|p=xīnlìtǐ|l=neo-clerical}}.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=113, 139, 466}} By the end of the Han, this had become the dominant script used by scribes, though clerical script remained in use for formal works, such as engraved [[stelae]]. Qiu describes neo-clerical as a transitional form between clerical and [[regular script]] which remained in use through the [[Three Kingdoms]] period (220–280 CE) and beyond.{{sfn|Qiu|2000|pp=138–139}} |

|||

Examples are 河 (hé) ''river'', 湖 (hú) ''lake'', 流 (liú) ''stream'', 沖 (chōng) ''riptide'', 滑 (huá) ''slippery''. All these characters have on the left a [[Radical (Chinese character)|radical]] of three dots, which is a simplified pictograph for a water drop, indicating that the character has a semantic connection with water; the right-hand side in each case is a phonetic indicator. For example, in the case of 沖 (chōng), the phonetic indicator is 中 (zhōng), which by itself means ''middle''. In this case it can be seen that the pronunciation of the character has diverged from that of its phonetic indicator; this process means that the composition of such characters can sometimes seem arbitrary today. Further, the choice of radicals may also seem arbitrary in some cases; for example, the radical of 貓 (māo) ''cat'' is 豸 (zhì), originally a pictograph for worms, but in characters of this sort indicating an animal of any sort. |

|||

=== Cursive and semi-cursive === |

|||

Xu Shen (c. 100 CE) placed approximately 82% of characters into this category, while in the [[Kangxi Dictionary]] (1716 CE) the number is closer to 90%, due to the extremely productive use of this technique to extend the Chinese vocabulary. |

|||

{{mim |

|||

| header = Cursive script |

|||

| width = 60 |

|||

| image1 = 天-caoshu.svg |

|||

| image2 = 馬-caoshu.svg |

|||

| image3 = 旅-caoshu.svg |

|||

| image4 = 正-caoshu.svg |

|||

| image5 = 韋-caoshu.svg |

|||

| alt1 = 天 |

|||

| alt2 = 馬 |