Sherpa people: Difference between revisions

add news delivery sherpa |

→Deaths in 2014 Everest avalanche: copyediting |

||

| (75 intermediate revisions by 38 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Tibetan ethnic group}} |

{{Short description|Tibetan ethnic group}} |

||

{{About|the Sherpa people|the [[mountaineering]] professions|porter (carrier)|and|mountain guide}} |

|||

{{Multiple issues| |

{{Multiple issues| |

||

{{Copy edit|date=March 2024}} |

{{Copy edit|date=March 2024}} |

||

{{More citations needed|date=March 2024}} |

|||

{{Original research|date=March 2024}} |

{{Original research|date=March 2024}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

| Line 12: | Line 10: | ||

| caption = Young Sherpas in traditional attire at West Bengal Sherpa Cultural Board |

| caption = Young Sherpas in traditional attire at West Bengal Sherpa Cultural Board |

||

| region1 = {{NEP}} |

| region1 = {{NEP}} |

||

| pop1 = |

| pop1 = 120,000<ref>{{cite book |title=POPULATION MONOGRAPH OF NEPAL VOLUME II (Social Demography) |date=2014 |publisher=Government of Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics |isbn=978-9937-2-8972-6 |pages=10–156 |url=https://nada.cbs.gov.np/index.php/catalog/54/download/474 |access-date=20 September 2019 |archive-date=21 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210121154951/https://nada.cbs.gov.np/index.php/catalog/54/download/474 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

| region2 = {{IND}} |

| region2 = {{IND}} |

||

| pop2 = 65,000 (above) |

| pop2 = 65,000 (above) |

||

| ref2 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.peoplegroups.org/explore/GroupDetails.aspx?peid=41449|title=Rai-Peoplegrouporg}}</ref> |

| ref2 = <ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.peoplegroups.org/explore/GroupDetails.aspx?peid=41449 |title=Rai-Peoplegrouporg}}</ref> |

||

| region3 = {{flag|Bhutan}} |

| region3 = {{flag|Bhutan}} |

||

| pop3 = 10,700 |

| pop3 = 10,700 |

||

| Line 24: | Line 22: | ||

| region6 = {{flag|China}} |

| region6 = {{flag|China}} |

||

| pop6 = 2,000 |

| pop6 = 2,000 |

||

| ref6 = {{cn|reason=Joshua Project is not a reliable source.|date=November 2024}} |

|||

| ref6 = <ref>{{cite web|url=https://joshuaproject.net/people_groups/15366/BT|title=Gurung Ghaleg in Bhutan}}www.joshuaproject.net</ref> |

|||

| languages = [[Sherpa language|Sherpa]], [[Standard Tibetan|Tibetan]], [[Nepali language|Nepali]] |

| languages = [[Sherpa language|Sherpa]], [[Standard Tibetan|Tibetan]], [[Nepali language|Nepali]] |

||

| religions = Predominantly [[Buddhism]] (93,83%)<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |url=http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/Population%20Monograph%20of%20Nepal%202014/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf |title=Population monograph of Nepal |date=2014 |volume=II (Social Demography) |publisher=Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission Secretariat, Central Bureau of Statistics |isbn=978-9937-2-8972-6 |access-date=2017-04-02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170918043750/http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/Population%20Monograph%20of%20Nepal%202014/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf |archive-date=2017-09-18 |url-status=dead}}</ref> and significant minority: [[Hinduism]] (6,26%),<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |url=http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/Population%20Monograph%20of%20Nepal%202014/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf |title=Population monograph of Nepal |date=2014 |volume=II (Social Demography) |publisher=Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission Secretariat, Central Bureau of Statistics |isbn=978-9937-2-8972-6 |access-date=2017-04-02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170918043750/http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/Population%20Monograph%20of%20Nepal%202014/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf |archive-date=2017-09-18 |url-status=dead}}</ref> [[Bon|Bön]], [[Christianity]]<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |url=http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/Population%20Monograph%20of%20Nepal%202014/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf |title=Population monograph of Nepal |date=2014 |volume=II (Social Demography) |publisher=Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission Secretariat, Central Bureau of Statistics |isbn=978-9937-2-8972-6 |access-date=2017-04-02 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170918043750/http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Population/Population%20Monograph%20of%20Nepal%202014/Population%20Monograph%20V02.pdf |archive-date=2017-09-18 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

| religions = Predominantly [[Buddhism]] (93%) and minority: [[Hinduism]], [[Bon|Bön]], [[Christianity]] |

|||

| related-c = [[Tibetan people|Tibetan]]s, [[Tamang people|Tamang]], [[Hyolmo people|Hyolmo]], [[Jirel]]s, [[Rai people|Rai]] and other [[Tibeto-Burman]] groups |

| related-c = [[Tibetan people|Tibetan]]s, [[Tamang people|Tamang]], [[Hyolmo people|Hyolmo]], [[Jirel]]s, [[Rai people|Rai]] and other [[Tibeto-Burman]] groups |

||

| native_name = {{bo-textonly| |

| native_name = {{bo-textonly|ཤར་པ།}}<br/>{{transliteration|bo|shar pa}} |

||

| native_name_lang = |

| native_name_lang = |

||

| related_groups = |

| related_groups = |

||

| Line 38: | Line 36: | ||

| characters = [[Tibetan script]] |

| characters = [[Tibetan script]] |

||

| error = [[mojibake|question marks, boxes, or other symbols]] |

| error = [[mojibake|question marks, boxes, or other symbols]] |

||

}} |

|||

}}The '''Sherpas''' are one of the Tibetan ethnic groups native to the most mountainous regions of Nepal and Tibetan Autonomous Region. The term ''sherpa'' or ''sherwa'' derives from the Tibetan-language words ཤར ''shar'' ('east') and པ ''pa'' ('people'), which refer to their geographical origin in eastern Tibet.<ref>{{Cite web |last=ashish |date=2023-05-29 |title=Sherpas Of Solukhumbu |url=https://radianttreks.com/sherpas-of-solukhumbu/ |access-date=2024-03-02 |website=Radiant Treks |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Sherpa - Everest Education Expedition {{!}} Montana State University |url=https://www.montana.edu/everest/facts/sherpa.html |access-date=2024-03-03 |website=www.montana.edu}}</ref> |

|||

The '''Sherpa people''' ({{langx|bo|ཤར་པ།|shar pa}}) are one of the [[Tibetan people|Tibetan ethnic groups]] native to the most mountainous regions of [[Nepal]] and [[Tibetan Autonomous Region]] of [[China]]. |

|||

The majority of Sherpas live in the eastern regions of Nepal, namely in [[Solukhumbu District|Solukhumba]], [[Kharta|Khatra]], [[Kama District|Kama]], [[Rolwaling Himal|Rolwaling]], [[Barun Valley|Barun]] and [[Pharak]] valleys;<ref>{{Cite web |title=People of Nepal {{!}} Plan Your Trip |url=https://ntb.gov.np/en/plan-your-trip/about-nepal/people |access-date=2023-03-13 |website=ntb.gov.np}}{{bsn|date=November 2024}}</ref> though some live farther West in the [[Bigu Rural Municipality|Bigu]] and in the [[Helambu]] region north of [[Kathmandu]], Nepal. Sherpas establish [[gompa]]s where they practice their religious traditions. [[Tengboche]] was the first celibate monastery in [[Solukhumbu District|Solu-Khumbu]]. Sherpa people also live in [[Tingri County]], [[Bhutan]], and the [[India]]n states of [[Sikkim]] and the northern portion of [[West Bengal]], specifically the district of [[Darjeeling]]. |

|||

The [[Sherpa language]] belongs to the southern branch of the [[Tibeto-Burman languages]], mixed with Eastern Tibetan ([[Khams Tibetan]]) and central Tibetan dialects. However, this language is separate from [[Standard Tibetan|Lhasa Tibetan]] and unintelligible to Lhasa speakers.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/colloque/deserts/videos_gestion/nt.htm |title=Journée d'étude : Déserts. Y a-t-il des corrélations entre l'écosystème et le changement linguistique ? |publisher=Lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr |access-date=8 March 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120318215914/http://lacito.vjf.cnrs.fr/colloque/deserts/videos_gestion/nt.htm |archive-date=18 March 2012}}</ref> |

|||

The number of Sherpas migrating to Western countries has significantly increased in recent years, especially to the United States. [[New York City]] has the largest Sherpa community in the United States, with a population of approximately 16,000. The 2011 Nepal census recorded 512,946 Sherpas within its borders. Members of the Sherpa population are known for their skills in [[mountaineering]] as a livelihood. |

The number of Sherpas migrating to Western countries has significantly increased in recent years, especially to the United States. [[New York City]] has the largest Sherpa community in the United States, with a population of approximately 16,000. The 2011 Nepal census recorded 512,946 Sherpas within its borders. Members of the Sherpa population are known for their skills in [[mountaineering]] as a livelihood. |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

[[File:The traditional homeland valleys of the Sherpa People.png|alt=|thumb|300x300px|The traditional homelands of the Sherpa people, the Solukhumba, Khatra & Kama, Rowlawing, Barun and Pharak valleys.[https://ntb.gov.np/en/plan-your-trip/about-nepal/people]]] |

|||

The Sherpa people descend from historically nomadic progenitors who first settled the [[Khumbu]] and [[Solu]] regions of the [[Mahalangur Himal|Mahālangūr Himāl]] section of the [[Himalayas|Himalayan range]] in the [[Tibetan Plateau]]. This area is situated along the modern border dividing the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal from the [[China|People's Republic of China]] within [[Solukhumbu District]] in [[Koshi Province|Koshi]], the easternmost [[Provinces of Nepal|Nepali province]], to the south of the [[Tibet Autonomous Region]] in China. |

The Sherpa people descend from historically nomadic progenitors who first settled the [[Khumbu]] and [[Solu]] regions of the [[Mahalangur Himal|Mahālangūr Himāl]] section of the [[Himalayas|Himalayan range]] in the [[Tibetan Plateau]]. This area is situated along the modern border dividing the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal from the [[China|People's Republic of China]] within [[Solukhumbu District]] in [[Koshi Province|Koshi]], the easternmost [[Provinces of Nepal|Nepali province]], to the south of the [[Tibet Autonomous Region]] in China. |

||

According to Sherpa oral history, four groups migrated from [[Kham]] in Tibet to Solukhumbu at different times, giving rise to the four fundamental Sherpa clans: Minyakpa, Thimmi, |

According to Sherpa oral history, four groups migrated from [[Kham]] in Tibet to Solukhumbu at different times, giving rise to the four fundamental Sherpa clans: Minyakpa, Thimmi, Lamasherwa, and Chawa. These four groups gradually split into the more than 20 different clans that exist today. Mahayana Buddhism religious conflict may have contributed to the migration out of Tibet in the 13th and 14th centuries and its arrival in the Khumbu regions of Nepal. Sherpa migrants travelled through [[Ü (region)|Ü]] and Tsang, before crossing the Himalaya.<ref name="Bhandari 2015" /><ref>{{Cite web |title=History of the Sherpas |url=https://sherwa.de/background/sherpa_history.html |access-date=2024-03-03 |website=sherwa.de}}{{bsn|date=November 2024}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Sherpa clans |url=https://sherwa.de/background/sherpa_clans.html |access-date=2024-03-03 |website=sherwa.de}}{{bsn|date=November 2024}}</ref> |

||

By the 1400s, the [[Khumbu]] Sherpa people had attained autonomy within the newly formed Nepali state. In the 1960s, as tension with China increased, the [[Government of Nepal|Nepali government]] influence on the Sherpa people grew. In 1976, Khumbu became a national park, and tourism became a major economic force.<ref name=":0">{{cite book|title=Through A Sherpa Window: Illustrated Guide to Traditional Sherpa Culture|author=Sherpa, Lhakpa Norbu|publisher=Vajra Publications|year=2008|isbn=9789937506205|location=Jyatha, Thamel}}</ref> |

By the 1400s, the [[Khumbu]] Sherpa people had attained autonomy within the newly formed Nepali state. In the 1960s, as tension with China increased, the [[Government of Nepal|Nepali government]] influence on the Sherpa people grew. In 1976, Khumbu became a national park, and tourism became a major economic force.<ref name=":0">{{cite book |title=Through A Sherpa Window: Illustrated Guide to Traditional Sherpa Culture |author=Sherpa, Lhakpa Norbu |publisher=Vajra Publications |year=2008 |isbn=9789937506205 |location=Jyatha, Thamel}}</ref> |

||

The term ''sherpa'' derives from the [[Lhasa Tibetan|Tibetan]] words {{transl|bo|shar}} ({{lang|bo|ཤར}}, 'east') and {{transl|bo|pa}} ({{lang|bo|པ}}, 'people'). The reasons for adoption of this term are unclear; one common explanation describes origins in eastern [[Tibet]] but the community is based in the Nepalese highlands which is to Tibet's south.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-09-11 |title=How Sherpa got its Name |url=https://wesherpas.org/how-sherpa-got-its-name/ |access-date=2024-09-13 |website=wesherpas.org}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Niraula |first=Ashish |date=2023-05-29 |title=Sherpas Of Solukhumbu |url=https://radianttreks.com/sherpas-of-solukhumbu/ |access-date=2024-03-02 |website=Radiant Treks}}{{bsn|date=November 2024}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Strickland |first1=S. S. |last2=von Fuerer Haimendorf |first2=Christoph |date=March 1986 |title=The Sherpas Transformed: Social Change in a Buddhist Society of Nepal |journal=Man |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=153–154 |jstor=2802670 |issn=0025-1496}}</ref> |

|||

=== Genetics === |

=== Genetics === |

||

Genetic studies show that much of the Sherpa population has [[allele frequencies]] that are often found in other Tibeto-Burman regions. |

Genetic studies show that much of the Sherpa population has [[allele frequencies]] that are often found in other Tibeto-Burman regions. In tested genes, the strongest affinity was for Tibetan population sample studies done in the [[Tibet Autonomous Region]].<ref name="Bhandari 2015"/> Genetically, the Sherpa cluster is closest to the sample [[Tibetan people|Tibetan]] and [[Han Chinese|Han]] populations.<ref name="ColeCox2017"/> |

||

Additionally, the Sherpa had exhibited an affinity for several [[Nepalis|Nepalese populations]], with the strongest for the [[Rai people]], followed by the [[Magars]] and the [[Tamang people|Tamang]].<ref name="ColeCox2017">{{cite journal|last1=Cole|first1=Amy M.|last2=Cox|first2=Sean|last3=Jeong|first3=Choongwon|last4=Petousi|first4=Nayia|last5=Aryal|first5=Dhana R.|last6=Droma|first6=Yunden|last7=Hanaoka|first7=Masayuki|last8=Ota|first8=Masao|last9=Kobayashi|first9=Nobumitsu|last10=Gasparini|first10=Paolo|last11=Montgomery|first11=Hugh|year=2017|title=Genetic structure in the Sherpa and neighbouring Nepalese populations|journal=BMC Genomics|volume=18|issue=1|pages=102|doi=10.1186/s12864-016-3469-5|doi-access=free|issn=1471-2164|pmc=5248489|pmid=28103797|last12=Robbins|first12=Peter|last13=Di Rienzo|first13=Anna|last14=Cavalleri|first14=Gianpiero L.}} [[File:CC-BY icon.svg|50x50px]] This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the [[creativecommons:by/4.0/|Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)]] license.</ref> |

Additionally, the Sherpa had exhibited an affinity for several [[Nepalis|Nepalese populations]], with the strongest for the [[Rai people]], followed by the [[Magars]] and the [[Tamang people|Tamang]].<ref name="ColeCox2017">{{cite journal |last1=Cole |first1=Amy M. |last2=Cox |first2=Sean |last3=Jeong |first3=Choongwon |last4=Petousi |first4=Nayia |last5=Aryal |first5=Dhana R. |last6=Droma |first6=Yunden |last7=Hanaoka |first7=Masayuki |last8=Ota |first8=Masao |last9=Kobayashi |first9=Nobumitsu|last10=Gasparini|first10=Paolo |last11=Montgomery |first11=Hugh |year=2017 |title=Genetic structure in the Sherpa and neighbouring Nepalese populations |journal=BMC Genomics |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=102 |doi=10.1186/s12864-016-3469-5 |doi-access=free |issn=1471-2164 |pmc=5248489 |pmid=28103797 |last12=Robbins |first12=Peter |last13=Di Rienzo |first13=Anna |last14=Cavalleri |first14=Gianpiero L.}} [[File:CC-BY icon.svg|50x50px]] This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under the [[creativecommons:by/4.0/|Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)]] license.</ref> |

||

A 2010 study identified more than 30 genetic factors that make [[Tibetan people| |

A 2010 study identified more than 30 genetic factors that make [[Tibetan people|Tibetan]] bodies well-suited for high altitudes, including [[EPAS1]], referred to as the "super-athlete gene," that regulates the body's production of hemoglobin,<ref name="Sanders">{{cite web |url=https://news.berkeley.edu/2010/07/01/tibetan_genome/ |title=Tibetans adapted to high altitude in less than 3,000 years |first=Robert |last=Sanders |website=Berkeley News |access-date=21 May 2019 |date=30 November 2001}}</ref> allowing for greater efficiency in the use of oxygen.<ref>{{cite news |title=Five myths about Mount Everest |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/five-myths-about-mount-everest/2014/04/24/9a30ace2-caf5-11e3-a993-b6b5a03db7b4_story.html |date=24 April 2014 |newspaper=Washington Post |access-date=21 May 2019}}</ref><ref name="Sanders"/> |

||

A 2016 study of Sherpas in Tibet suggested that a small portion of Sherpas' and Tibetans' [[allele frequencies]] originated from separate ancient populations, which were estimated to have remained somewhat distributed for 11,000 to 7,000 years.<ref name="Lu 2016">{{cite journal|last1=Lu|first1=Dongsheng|display-authors=etal|title=Ancestral Origins and Genetic History of Tibetan Highlanders|journal=[[The American Journal of Human Genetics]]|date=1 September 2016|volume=99|issue=3|pages=580–594|pmc=5011065|pmid=27569548|doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.07.002}}</ref> |

A 2016 study of Sherpas in Tibet suggested that a small portion of Sherpas' and Tibetans' [[allele frequencies]] originated from separate ancient populations, which were estimated to have remained somewhat distributed for 11,000 to 7,000 years.<ref name="Lu 2016">{{cite journal |last1=Lu |first1=Dongsheng |display-authors=etal |title=Ancestral Origins and Genetic History of Tibetan Highlanders |journal=[[The American Journal of Human Genetics]] |date=1 September 2016 |volume=99 |issue=3 |pages=580–594 |pmc=5011065 |pmid=27569548 |doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.07.002}}</ref> |

||

==== Haplogroup distribution ==== |

==== Haplogroup distribution ==== |

||

A 2014 study observed that considerable genetic components from the Indian Subcontinent were found in Sherpa people living in Tibet. The western Y chromosomal haplogroups R1a1a-M17, J-M304, and F*-M89 comprise almost 17% of the paternal gene pool in tested individuals. In the maternal side, M5c2, M21d, and U from the west also count up to 8% of people in given Sherpa populations.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Kang|first1=Longli|last2=Wang|first2=Chuan-Chao|last3=Chen|first3=Feng|last4=Yao|first4=Dali|last5=Jin|first5=Li|last6=Li|first6=Hui|date=2 January 2016|title=Northward genetic penetration across the Himalayas viewed from Sherpa people|journal=Mitochondrial DNA Part A|volume=27|issue=1|pages=342–349|doi=10.3109/19401736.2014.895986|issn=2470-1394|pmid=24617465|s2cid=24273050}}</ref> However, a later study from 2015 did not support the results from the 2014 study; the 2015 study concluded that genetic sharing from the Indian subcontinent was highly limited;<ref name="Bhandari 2015"/> a 2017 study found the same.<ref name="ColeCox2017"/> |

A 2014 study observed that considerable genetic components from the Indian Subcontinent were found in Sherpa people living in Tibet. The western Y chromosomal haplogroups R1a1a-M17, J-M304, and F*-M89 comprise almost 17% of the paternal gene pool in tested individuals. In the maternal side, M5c2, M21d, and U from the west also count up to 8% of people in given Sherpa populations.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kang |first1=Longli |last2=Wang |first2=Chuan-Chao |last3=Chen |first3=Feng |last4=Yao |first4=Dali |last5=Jin |first5=Li |last6=Li |first6=Hui |date=2 January 2016 |title=Northward genetic penetration across the Himalayas viewed from Sherpa people |journal=Mitochondrial DNA Part A |volume=27 |issue=1 |pages=342–349 |doi=10.3109/19401736.2014.895986 |issn=2470-1394 |pmid=24617465 |s2cid=24273050}}</ref> However, a later study from 2015 did not support the results from the 2014 study; the 2015 study concluded that genetic sharing from the Indian subcontinent was highly limited;<ref name="Bhandari 2015"/> a 2017 study found the same.<ref name="ColeCox2017"/> |

||

In a 2015 study of 582 Sherpa individuals (277 males) from China and Nepal, [[haplogroup D-M174]] was found most frequently, followed by [[Haplogroup O-M175]], [[Haplogroup F-M89]] and [[Haplogroup K-M9]]. The [[Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup|Y-chromosome haplogroup]] distribution for Sherpas follow a pattern similar to that for Tibetans.<ref name="Bhandari 2015">{{cite journal|last1=Bhandari|first1=Sushil|display-authors=etal|title=Genetic evidence of a recent Tibetan ancestry to Sherpas in the Himalayan region|journal=[[Scientific Reports]]|date=2015|volume=5|doi=10.1038/srep16249|pages=16249|pmid=26538459|pmc=4633682|bibcode=2015NatSR...516249B}}</ref> |

In a 2015 study of 582 Sherpa individuals (277 males) from China and Nepal, [[haplogroup D-M174]] was found most frequently, followed by [[Haplogroup O-M175]], [[Haplogroup F-M89]] and [[Haplogroup K-M9]]. The [[Human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup|Y-chromosome haplogroup]] distribution for Sherpas follow a pattern similar to that for Tibetans.<ref name="Bhandari 2015">{{cite journal |last1=Bhandari |first1=Sushil |display-authors=etal |title=Genetic evidence of a recent Tibetan ancestry to Sherpas in the Himalayan region |journal=[[Scientific Reports]] |date=2015 |volume=5 |doi=10.1038/srep16249 |pages=16249 |pmid=26538459 |pmc=4633682 |bibcode=2015NatSR...516249B}}</ref> |

||

Sherpa [[Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup|mtDNA]] distribution shows greater diversity, as [[Haplogroup A (mtDNA)|Haplogroup A]] was found most frequently, followed by [[Haplogroup M (mtDNA)|Haplogroup M9a]], [[Haplogroup C (mtDNA)|Haplogroup C4a]], Haplogroup M70, and [[Haplogroup D (mtDNA)|Haplogroup D]]. These haplogroups are also found in some Tibetan populations. However, two common mtDNA sub-haplogroups unique to Sherpas populations were identified: Haplogroup A15c1 and Haplogroup C4a3b1.<ref name="Bhandari 2015"/> |

Sherpa [[Human mitochondrial DNA haplogroup|mtDNA]] distribution shows greater diversity, as [[Haplogroup A (mtDNA)|Haplogroup A]] was found most frequently, followed by [[Haplogroup M (mtDNA)|Haplogroup M9a]], [[Haplogroup C (mtDNA)|Haplogroup C4a]], Haplogroup M70, and [[Haplogroup D (mtDNA)|Haplogroup D]]. These haplogroups are also found in some Tibetan populations. However, two common mtDNA sub-haplogroups unique to Sherpas populations were identified: Haplogroup A15c1 and Haplogroup C4a3b1.<ref name="Bhandari 2015"/> |

||

| Line 72: | Line 75: | ||

[[File:Pem dorjee sherpa (2).JPG|thumb|Sherpa mountain guide [[Pem Dorjee Sherpa]] at [[Khumbu Icefall]]]] |

[[File:Pem dorjee sherpa (2).JPG|thumb|Sherpa mountain guide [[Pem Dorjee Sherpa]] at [[Khumbu Icefall]]]] |

||

{{ |

{{See|Mountaineering|Mountain guide}} |

||

Many Sherpas are highly regarded as elite mountaineers and experts in their local area. They were valuable to early [[List of explorers|explorers]] of the [[Himalaya]]n region, serving as guides at the extreme altitudes of the peaks and passes in the region, particularly for expeditions to climb [[Mount Everest]]. Today, the term is often used by foreigners to refer to almost any guide or climbing supporter hired for [[mountaineering]] expeditions in the Himalayas, regardless of their ethnicity.<ref>Educational Media and Technology Yearbook – Volume 36, Michael Orey, Stephanie A. Jones, Robert Maribe Branch, page 94 (2011), {{ISBN|1461413044}}: "A Sherpa is traditionally a knowledgeable native who guides mountain climbers on their most difficult and risky ascents." Buried in the Sky: The Extraordinary Story of the Sherpa Climbers, by Peter Zuckerman, Amanda Padoan, page 65 (2012): "Lowlanders clutching the Lonely Planet guide are convinced they want to hire "a sherpa," even if they don't know what a Sherpa is..."</ref> Because of this usage, the term has become a slang byword for a guide or mentor in other situations.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/g20-meet-what-role-does-the-sherpa-play-in-the-negotiations-3015461/|title=G20 meet: What role does the Sherpa play in the negotiations?|date=2016-09-06|work=The Indian Express|access-date=2018-10-07|language=en-US}}</ref> Sherpas are renowned in the international [[climbing]] and mountaineering community for their hardiness, expertise, and experience at very high altitudes. It has been speculated that part of the Sherpas' climbing ability is the result of a [[high-altitude adaptation in humans|genetic adaptation to living in high altitudes]]. Some of these adaptations include unique [[hemoglobin]]-binding capacity and doubled [[nitric oxide]] production.<ref>Kamler, K. (2004). ''Surviving the extremes: What happens to the body and mind at the limits of human endurance'', p. 212. New York: Penguin.</ref> |

Many Sherpas are highly regarded as elite [[mountaineers]] and experts in their local area. They were valuable to early [[List of explorers|explorers]] of the [[Himalaya]]n region, serving as guides at the extreme altitudes of the peaks and passes in the region, particularly for expeditions to climb [[Mount Everest]]. Today, the term is often used by foreigners to refer to almost any guide or climbing supporter hired for [[mountaineering]] expeditions in the Himalayas, regardless of their ethnicity.<ref>Educational Media and Technology Yearbook – Volume 36, Michael Orey, Stephanie A. Jones, Robert Maribe Branch, page 94 (2011), {{ISBN|1461413044}}: "A Sherpa is traditionally a knowledgeable native who guides mountain climbers on their most difficult and risky ascents." Buried in the Sky: The Extraordinary Story of the Sherpa Climbers, by Peter Zuckerman, Amanda Padoan, page 65 (2012): "Lowlanders clutching the Lonely Planet guide are convinced they want to hire "a sherpa," even if they don't know what a Sherpa is..."</ref> Because of this usage, the term has become a slang byword for a guide or mentor in other situations.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/g20-meet-what-role-does-the-sherpa-play-in-the-negotiations-3015461/ |title=G20 meet: What role does the Sherpa play in the negotiations? |date=2016-09-06 |work=The Indian Express |access-date=2018-10-07 |language=en-US}}</ref> Sherpas are renowned in the international [[climbing]] and mountaineering community for their hardiness, expertise, and experience at very high altitudes. It has been speculated that part of the Sherpas' climbing ability is the result of a [[high-altitude adaptation in humans|genetic adaptation to living in high altitudes]]. Some of these adaptations include unique [[hemoglobin]]-binding capacity and doubled [[nitric oxide]] production.<ref>Kamler, K. (2004). ''Surviving the extremes: What happens to the body and mind at the limits of human endurance'', p. 212. New York: Penguin.</ref> |

||

=== Deaths in 2014 Everest avalanche === |

=== Deaths in 2014 Everest avalanche === |

||

{{main|2014 Mount Everest avalanche}} |

{{main|2014 Mount Everest avalanche}} |

||

On 18 April 2014, a [[serac]] collapsed above the [[Khumbu Icefall]] on Mount Everest, causing an avalanche of massive chunks of ice and snow which killed 16 Nepalese guides, mostly Sherpas.<ref name=NYr>{{cite news|last=Krakauer|first=Jon|title=Death and Anger on Everest|url=http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2014/04/everest-sherpas-death-and-anger.html|access-date=24 April 2014|newspaper=[[The New Yorker]]|date=21 April 2014|quote=Of the twenty-five men hit by the falling ice, sixteen were killed, all of them Nepalis working for guided climbing teams.}}</ref> The 2014 avalanche is the second-deadliest disaster in Everest's history, only exceeded by avalanches in the Khumbu Icefall area a year later, on 25 April 2015, caused by a [[April 2015 Nepal earthquake|magnitude 7.8 earthquake in Nepal]]. In response to that tragedy and others involving deaths and injuries sustained by Sherpas hired by climbers, and the lack of government support for Sherpas injured or killed while providing their services, some Sherpa climbing guides |

On 18 April 2014, a [[serac]] collapsed above the [[Khumbu Icefall]] on Mount Everest, causing an avalanche of massive chunks of ice and snow which killed 16 Nepalese guides, mostly Sherpas.<ref name=NYr>{{cite news |last=Krakauer |first=Jon |title=Death and Anger on Everest |url=http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/newsdesk/2014/04/everest-sherpas-death-and-anger.html |access-date=24 April 2014 |newspaper=[[The New Yorker]] |date=21 April 2014 |quote=Of the twenty-five men hit by the falling ice, sixteen were killed, all of them Nepalis working for guided climbing teams.}}</ref> The 2014 avalanche is the second-deadliest disaster in Everest's history, only exceeded by avalanches in the Khumbu Icefall area a year later, on 25 April 2015, caused by a [[April 2015 Nepal earthquake|magnitude 7.8 earthquake in Nepal]]. In response to that tragedy and others involving deaths and injuries sustained by Sherpas hired by climbers, and the lack of government support for Sherpas injured or killed while providing their services, some Sherpa climbing guides resigned, and their respective climbing companies stopped providing guides and porters for Everest expeditions.<ref>{{cite news |work=NPR |url=https://www.npr.org/2014/04/24/306390312/sherpas-walk-off-the-job-after-avalanche-kills-16-guides |title=Sherpas Walk Off The Job After Deadly Avalanche |author=McCarthy, Julie |date=24 April 2014 <!-- 5:04 am ET -->}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Sherpas Consider Boycott After Everest Disaster |author=The Associated Press |work=NPR |date=21 April 2014 <!-- 2:03 am ET --> |url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=305178526}}</ref> The Khumbu Icefall is a waterfall of ice with continuous structural shifts, requiring continuous changes to the route through the area<ref>{{cite web |last1=Arnette |first1=Alan |title=Everest 2017: Why is the Khumbu Icefall so Dangerous? |url=https://www.alanarnette.com/blog/2017/03/15/everest-2017-why-is-the-khumbu-icefall-so-dangerous/ |website=alanarnette.com}}</ref> and making this is one of the most dangerous parts of climbing Mount Everest. Climbers have to walk on ladders over crevasses, while walking underneath large serac formations that could potentially fall at any moment. Oftentimes the journey through the Khumbu Icefall is in the pitch black. It is safer for climbers to go through the icefall at night because the temperatures at night drop. Therefore, the icefall is not melting as fast as it would during the day.<ref name="Sherpa">{{cite news |last1=Peedom |first1=Jennifer |title=Sherpa |publisher=Discovery |date=2016}}{{fcn|date=November 2024}}</ref> These dangers have resulted in 66 deaths as of 2017, including 6 deaths from falling in a crevasse, 9 deaths from a collapse in a section of the icefall, and 29 deaths from avalanches onto the icefall.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Arnette |first1=Alan |title=Everest 2017: Why is the Khumbu Icefall so Dangerous? |url=https://www.alanarnette.com/blog/2017/03/15/everest-2017-why-is-the-khumbu-icefall-so-dangerous/ |website=alanarnette.com}}{{bsn|date=November 2024}}</ref> |

||

The families of those who died in the avalanche were offered 40,000 rupees, the equivalent of about $400 US dollars, from the Nepalese government.<ref>{{cite web |title=Mt. Everest disaster raises questions of compensation for Sherpas |url=https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/mteverstavalanche |website=PBS NewsHour |publisher=PBS |language=en-us |date=13 November 2014}}</ref> At the time of the disaster, the Sherpas were carrying loads of equipment for their clients, including many luxury items.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Jenkins |first1=Mark |title=Historic Tragedy on Everest, With 12 Sherpa Dead in Avalanche |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/140418-everest-avalanche-sherpa-killed-mountain |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210228064858/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/140418-everest-avalanche-sherpa-killed-mountain |url-status=dead |archive-date=28 February 2021 |website=Adventure |publisher=National Geographic |language=en |date=19 April 2014}}</ref> There had been two broken ladders causing a traffic jam in the Khumbu Icefall.<ref name="nytimes.com">{{cite web |last1=Barry |first1=Ellen |last2=Bowley |first2=Graham |title=After Everest Disaster, Sherpas Contemplate Strike |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/21/world/asia/after-everest-disaster-sherpas-contemplate-strike.html |website=The New York Times |date=21 April 2014}}</ref> It is not uncommon for Sherpas to go through the Khumbu Icefall around 30 times each season; in comparison, foreigners only go through the icefall 2 or 3 times during the season.<ref name="Sherpa"/> Sherpas are expected to haul the majority of their clients' gear to each of the five camps and to set up before their clients reach the camps. During each season, Sherpas typically make up to $5000 US dollars during their 2 or 3-month period of taking international clients to the summit of Everest.<ref name="Sherpa"/> As of 2019, expeditions on Mt. Everest contributed $300 million.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Robles |first1=Pablo |title=Covid Pandemic: Mount Everest, Nepal Try to Restart Economy After Shutdowns |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2020-everest-reopening-sherpa-supply-chain/?leadSource=uverify+wall |newspaper=Bloomberg |date=20 November 2020 |language=en}}</ref> The economy of Nepal thrives off of tourism and adventure seekers. |

The families of those who died in the avalanche were offered 40,000 rupees, the equivalent of about $400 US dollars, from the Nepalese government.<ref>{{cite web |title=Mt. Everest disaster raises questions of compensation for Sherpas |url=https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/mteverstavalanche |website=PBS NewsHour |publisher=PBS |language=en-us |date=13 November 2014}}</ref> At the time of the disaster, the Sherpas were carrying loads of equipment for their clients, including many luxury items.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Jenkins |first1=Mark |title=Historic Tragedy on Everest, With 12 Sherpa Dead in Avalanche |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/140418-everest-avalanche-sherpa-killed-mountain |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210228064858/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/140418-everest-avalanche-sherpa-killed-mountain |url-status=dead |archive-date=28 February 2021 |website=Adventure |publisher=National Geographic |language=en |date=19 April 2014}}</ref> There had been two broken ladders causing a traffic jam in the Khumbu Icefall.<ref name="nytimes.com">{{cite web |last1=Barry |first1=Ellen |last2=Bowley |first2=Graham |title=After Everest Disaster, Sherpas Contemplate Strike |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/21/world/asia/after-everest-disaster-sherpas-contemplate-strike.html |website=The New York Times |date=21 April 2014}}</ref> It is not uncommon for Sherpas to go through the Khumbu Icefall around 30 times each season; in comparison, foreigners only go through the icefall 2 or 3 times during the season.<ref name="Sherpa"/> Sherpas are expected to haul the majority of their clients' gear to each of the five camps and to set up before their clients reach the camps. During each season, Sherpas typically make up to $5000 US dollars during their 2 or 3-month period of taking international clients to the summit of Everest.<ref name="Sherpa"/> As of 2019, expeditions on Mt. Everest contributed $300 million.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Robles |first1=Pablo |title=Covid Pandemic: Mount Everest, Nepal Try to Restart Economy After Shutdowns |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2020-everest-reopening-sherpa-supply-chain/?leadSource=uverify+wall |newspaper=Bloomberg |date=20 November 2020 |language=en}}</ref> The economy of Nepal thrives off of tourism and adventure seekers{{Relevance inline|date=November 2024}}. |

||

As a result of the 2014 disaster, the remaining Sherpas went on strike. They were angry at the government, lack of compensation, and their working conditions. Sherpas came together in the days after the disaster to make a list of demands for the government.<ref name="Sherpa"/> The documentary ''Sherpa'' contains footage of one of their meetings. Sherpas wanted to cancel the climbing season that year out of respect for those who lost their lives. They argued that "This route has become a graveyard," and asked "How could we walk over their bodies?". Their clients were debating whether or not to continue to try to reach the summit of Everest because they had paid tens of thousands of dollars to be there.<ref name="nytimes.com"/> However, international clients were fearful of this strike and how it would affect themselves and had their bags packed in case of a need for a swift escape.<ref name="Sherpa"/> On top of this, rumors spread among the Sherpa community that others would hurt them if they were to continue to take foreigners on their expeditions (Peedom, 2016). |

As a result of the 2014 disaster, the remaining Sherpas went on strike. They were angry at the government, lack of compensation, and their working conditions. Sherpas came together in the days after the disaster to make a list of demands for the government.<ref name="Sherpa"/> The documentary ''Sherpa'' contains footage of one of their meetings. Sherpas wanted to cancel the climbing season that year out of respect for those who lost their lives. They argued that "This route has become a graveyard," and asked "How could we walk over their bodies?". Their clients were debating whether or not to continue to try to reach the summit of Everest because they had paid tens of thousands of dollars to be there.<ref name="nytimes.com"/> However, international clients were fearful of this strike and how it would affect themselves and had their bags packed in case of a need for a swift escape.<ref name="Sherpa"/> On top of this, rumors spread among the Sherpa community that others would hurt them if they were to continue to take foreigners on their expeditions (Peedom, 2016). |

||

The 2014 event killed 16 Sherpas<ref>{{cite web|url=https://archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=57877542&itype=CMSID|title=Apa Sherpa: After deadly avalanche, 'leave Everest alone'|website=[[The Salt Lake Tribune]]|access-date=21 May 2019}}</ref> |

The 2014 event killed 16 Sherpas<ref>{{cite web |url=https://archive.sltrib.com/article.php?id=57877542&itype=CMSID |title=Apa Sherpa: After deadly avalanche, 'leave Everest alone' |website=[[The Salt Lake Tribune]] |access-date=21 May 2019}}</ref> |

||

and, in 2015, 10 Sherpas died at the [[Everest base camps|Everest Base Camp]] after the earthquake. In total, 118 Sherpas have died on Mount Everest between 1921 and 2018.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.alanarnette.com/blog/2018/05/22/everest-2018-wave-9-recap-more-sherpa-deaths-with-summits/|title=Everest 2018: Summit Wave 9 Recap – More Sherpa Deaths with Summits|date=22 May 2018|website=The Blog on alanarnette.com|access-date=21 May 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/05/150513-everest-climbing-nepal-earthquake-avalanche-sherpas/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150515114548/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/05/150513-everest-climbing-nepal-earthquake-avalanche-sherpas/|url-status=dead|archive-date=15 May 2015|title=Will Everest's Climbing Circus Slow Down After Disasters?|date=13 May 2015|website=National Geographic News|access-date=21 May 2019}}</ref> An April 2018 report by [[NPR]] stated that Sherpas account for one-third of Everest deaths.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2018/04/14/599417489/one-third-of-everest-deaths-are-sherpa-climbers |date=14 April 2018 |publisher=NPR |access-date=17 May 2019 |title=One-Third of Everest Deaths Are Sherpa Climbers |

and, in 2015, 10 Sherpas died at the [[Everest base camps|Everest Base Camp]] after the earthquake. In total, 118 Sherpas have died on Mount Everest between 1921 and 2018.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.alanarnette.com/blog/2018/05/22/everest-2018-wave-9-recap-more-sherpa-deaths-with-summits/ |title=Everest 2018: Summit Wave 9 Recap – More Sherpa Deaths with Summits |date=22 May 2018 |website=The Blog on alanarnette.com |access-date=21 May 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/05/150513-everest-climbing-nepal-earthquake-avalanche-sherpas/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150515114548/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2015/05/150513-everest-climbing-nepal-earthquake-avalanche-sherpas/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=15 May 2015 |title=Will Everest's Climbing Circus Slow Down After Disasters? |date=13 May 2015 |website=National Geographic News |access-date=21 May 2019}}</ref> An April 2018 report by [[NPR]] stated that Sherpas account for one-third of Everest deaths.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2018/04/14/599417489/one-third-of-everest-deaths-are-sherpa-climbers |date=14 April 2018 |publisher=NPR |access-date=17 May 2019 |title=One-Third of Everest Deaths Are Sherpa Climbers}}</ref> |

||

== Religion == |

== Religion == |

||

| Line 90: | Line 93: | ||

According to oral Buddhist traditions, the initial Tibetan migration was a search for a [[beyul]] (Buddhist pure-lands). Sherpa practised the [[Nyingma]] ("Ancient") school of Buddhism. Allegedly the oldest Buddhist sect in Tibet, founded by [[Padmasambhava]] (commonly known as Guru Rinpoche) during the 8th century, it emphasizes mysticism and the incorporation of local deities shared by the pre-Buddhist [[Bon|Bön religion]], which has [[shamanic]] elements. Sherpa particularly believe in hidden [[Terma (religion)|treasures]] and [[beyul|valleys]]. Traditionally, Nyingmapa practice was passed down orally through a loose network of lay practitioners. Monasteries with celibate monks and nuns, along with the belief in reincarnated spiritual leaders, are later adaptations.<ref name=":0" /> |

According to oral Buddhist traditions, the initial Tibetan migration was a search for a [[beyul]] (Buddhist pure-lands). Sherpa practised the [[Nyingma]] ("Ancient") school of Buddhism. Allegedly the oldest Buddhist sect in Tibet, founded by [[Padmasambhava]] (commonly known as Guru Rinpoche) during the 8th century, it emphasizes mysticism and the incorporation of local deities shared by the pre-Buddhist [[Bon|Bön religion]], which has [[shamanic]] elements. Sherpa particularly believe in hidden [[Terma (religion)|treasures]] and [[beyul|valleys]]. Traditionally, Nyingmapa practice was passed down orally through a loose network of lay practitioners. Monasteries with celibate monks and nuns, along with the belief in reincarnated spiritual leaders, are later adaptations.<ref name=":0" /> |

||

In addition to Buddha and the great Buddhist divinities, the Sherpa also believe in numerous deities and demons who inhabit every mountain, cave, and forest. These have to be respected or appeased through ancient practices woven into the fabric of Buddhist ritual life. Many of the great Himalayan mountains are considered sacred. The Sherpa call Mount Everest Chomolungma and respect it as the "Mother of the World." [[Makalu|Mount Makalu]] is respected as the deity Shankar (Shiva). Each clan reveres certain mountain peaks and their protective deities.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-04-25/when-you-call-someone-sherpa-what-does-mean|title=When you call someone a Sherpa, what does that mean?|work=Public Radio International|access-date=2018-10-07|language=en-US}}</ref> |

In addition to Buddha and the great Buddhist divinities, the Sherpa also believe in numerous deities and demons who inhabit every mountain, cave, and forest. These have to be respected or appeased through ancient practices woven into the fabric of Buddhist ritual life. Many of the great Himalayan mountains are considered sacred. The Sherpa call Mount Everest Chomolungma and respect it as the "Mother of the World." [[Makalu|Mount Makalu]] is respected as the deity Shankar (Shiva). Each clan reveres certain mountain peaks and their protective deities.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.pri.org/stories/2014-04-25/when-you-call-someone-sherpa-what-does-mean |title=When you call someone a Sherpa, what does that mean? |work=Public Radio International |access-date=2018-10-07 |language=en-US}}</ref> |

||

Today, the day-to-day Sherpa religious affairs are presided over by lamas (Buddhist spiritual leaders) and other religious practitioners living in the villages. The village [[lama]] who presides over ceremonies and rituals can be a celibate monk or a married householder.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Stories and Customs of the Sherpas|last=Sherpa|first=Ngawang Tenzin Zangbu|publisher=Mera Publications|year=2011|isbn=978-99933-553-0-4|location=Kathmandu, Nepal|pages=6|edition=5th}}</ref> In addition, shamans (''lhawa'') and soothsayers (''mindung'') deal with the supernatural and the spirit world. Lamas identify witches (''pem''), act as the mouthpiece of deities and spirits, and diagnose spiritual illnesses.{{Citation needed|date=January 2018}} |

Today, the day-to-day Sherpa religious affairs are presided over by lamas (Buddhist spiritual leaders) and other religious practitioners living in the villages. The village [[lama]] who presides over ceremonies and rituals can be a celibate monk or a married householder.<ref>{{Cite book |title=Stories and Customs of the Sherpas |last=Sherpa |first=Ngawang Tenzin Zangbu |publisher=Mera Publications |year=2011 |isbn=978-99933-553-0-4 |location=Kathmandu, Nepal |pages=6 |edition=5th}}</ref> In addition, shamans (''lhawa'') and soothsayers (''mindung'') deal with the supernatural and the spirit world. Lamas identify witches (''pem''), act as the mouthpiece of deities and spirits, and diagnose spiritual illnesses.{{Citation needed|date=January 2018}} |

||

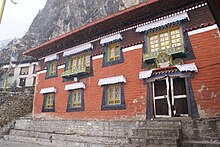

An important aspect of Sherpa religion is the temple or ''[[gompa]]''. A gompa is the prayer hall for either villages or monasteries. There are numerous gompas and about two dozen monasteries scattered throughout the Solukhumbu region. The monasteries are communities of lamas or monks (sometimes of nuns) who take a vow of celibacy and lead a life of isolation searching for truth and religious enlightenment. They are respected by and supported by the community at large. Their contact with the outside world is focused on monastery practices and annual festivals to which the public is invited, as well as the reading of sacred texts at funerals.{{Citation needed|date=January 2018}} |

An important aspect of Sherpa religion is the temple or ''[[gompa]]''. A gompa is the prayer hall for either villages or monasteries. There are numerous gompas and about two dozen monasteries scattered throughout the Solukhumbu region. The monasteries are communities of lamas or monks (sometimes of nuns) who take a vow of celibacy and lead a life of isolation searching for truth and religious enlightenment. They are respected by and supported by the community at large. Their contact with the outside world is focused on monastery practices and annual festivals to which the public is invited, as well as the reading of sacred texts at funerals.{{Citation needed|date=January 2018}} |

||

== Sacred land in Sagarmatha National Park, Nepal == |

== Sacred land in Sagarmatha National Park, Nepal == |

||

Mt. Everest is located within the [[Sagarmatha National Park]], which is a sacred landscape for local |

Mt. Everest is located within the [[Sagarmatha National Park]], which is a sacred landscape for local Sherpas.<ref name="Sagarmatha National Park">{{cite web |last1=Riley |first1=Mark |title=Sagarmatha National Park |url=https://sites.coloradocollege.edu/indigenoustraditions/sacred-lands/sagarmatha-national-park/ |website=Indigenous Religious Traditions |date=20 November 2012 |access-date=16 December 2022 |archive-date=8 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230608114434/https://sites.coloradocollege.edu/indigenoustraditions/sacred-lands/sagarmatha-national-park/ |url-status=dead}}</ref> The region is considered the dwelling of supernatural beings.<ref name="Sagarmatha National Park"/> Sherpas value life and the beauty it provides, meaning they avoid killing living creatures. Furthermore, Mt. Everest has attracted many tourists who unknowingly or knowingly are disrupting the sacred land of the park. For example, finding firewood has been deemed problematic. Many tourists stick with the methods they know how to do, which is oftentimes cutting down trees or taking branches off trees to make a fire. This practice is against Sherpas' spiritual law of the land.<ref name="Sagarmatha National Park"/> Moreover, the Sherpas do a spiritual ritual before climbing the mountain to ask the mountain for permission to climb. This ritual seems to have become a spectacle for foreign climbers. |

||

In addition, the entirety of the national park is not governed by the Sherpas but rather foreigners to the land. Park managers have made an effort to try to include Sherpas' voices by creating buffer-zone user groups. These groups are made up of political leaders from the surrounding villages, and serve as a platform for Sherpa demands.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sivinski |first1=Jake |title=Conservation For Whom?: The Struggle for Indigenous Rights in Sagarmatha National Park. |url=https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2226 |journal=Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection |date=1 October 2015}}</ref> However, these groups do not have any official status and the government can decide whether or not to hear these demands or make the desired changes.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sivinski |first1=Jake |title=Conservation For Whom?: The Struggle for Indigenous Rights in Sagarmatha National Park |url=https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2226 |journal=Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection |date=1 October 2015}}</ref> |

In addition, the entirety of the national park is not governed by the Sherpas but rather foreigners to the land. Park managers have made an effort to try to include Sherpas' voices by creating buffer-zone user groups. These groups are made up of political leaders from the surrounding villages, and serve as a platform for Sherpa demands.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sivinski |first1=Jake |title=Conservation For Whom?: The Struggle for Indigenous Rights in Sagarmatha National Park. |url=https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2226 |journal=Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection |date=1 October 2015}}</ref> However, these groups do not have any official status and the government can decide whether or not to hear these demands or make the desired changes.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sivinski |first1=Jake |title=Conservation For Whom?: The Struggle for Indigenous Rights in Sagarmatha National Park |url=https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/2226 |journal=Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection |date=1 October 2015}}</ref> |

||

== Sherpa clothing == |

== Sherpa clothing == |

||

Men wear long-sleeved robes called ''[[ |

Men wear long-sleeved robes called ''[[chuba]]'', which fall to slightly below the knee. The ''chuba'' is tied at the waist with a cloth sash called ''kara'', creating a pouch-like space called ''namdok'' which can be used for storing and carrying small items. Traditionally, ''chuba'' were made from thick home-spun wool, or a variant called ''lokpa'' made from sheepskin. ''Chuba'' are worn over ''raatuk,'' a blouse (traditionally made out of ''bure'', white raw silk), trousers called ''kanam'', and a stiff collared shirt called ''tetung''. |

||

Women traditionally wear long-sleeved floor-length dresses called ''tongkok''. A sleeveless variation called ''aangi'' is worn over a ''raatuk'' (blouse) |

Women traditionally wear long-sleeved floor-length dresses called ''tongkok''. A sleeveless variation called ''aangi'' is worn over a full sleeved shirt called ''honju'' and with a ''raatuk'' (blouse) underneath the shirt. These are worn with colourful striped aprons; ''pangden'' (or ''metil'') aprons are worn in front, and ''gewe'' (or ''gyabtil'') in back, and are held together by an embossed silver buckle called ''kyetig and a kara''<ref name=":0" />{{rp|138–141}} |

||

Sherpa clothing resembles Tibetan clothing. Increasingly, home-spun wool and silk is being replaced by factory-made material. Many Sherpa people also now wear ready-made western clothing. |

Sherpa clothing resembles Tibetan clothing. Increasingly, home-spun wool and silk is being replaced by factory-made material. Many Sherpa people also now wear ready-made western clothing. |

||

== Traditional housing == |

== Traditional housing == |

||

| Line 114: | Line 118: | ||

== Social gatherings == |

== Social gatherings == |

||

"A Sherpa community will most commonly get together for a party, which is held by the host with the purpose of gaining favour with the community and neighbours". Guests are invited hours before the party will start by the host's children to reduce the chance of rejection. In all social gatherings the men are seated by order of status, with those of lesser status sitting closer to the door and men of higher status sitting by the fireplace, while the women sit in the center with no ordering. It is polite to sit in a space lower than one's proper place so one may be invited by the host to their proper place. The first several hours of the party will have only beer served, followed by the serving of food, and then several more hours of singing and dancing before people start to drift out. The act of manipulating one's neighbours into cooperation by hosting a party is known as Yangdzi, and works by expecting the hospitality done by the host with the serving of food and alcohol to be repaid.<ref>{{cite book | |

"A Sherpa community will most commonly get together for a party, which is held by the host with the purpose of gaining favour with the community and neighbours". Guests are invited hours before the party will start by the host's children to reduce the chance of rejection. In all social gatherings the men are seated by order of status, with those of lesser status sitting closer to the door and men of higher status sitting by the fireplace, while the women sit in the center with no ordering. It is polite to sit in a space lower than one's proper place so one may be invited by the host to their proper place. The first several hours of the party will have only beer served, followed by the serving of food, and then several more hours of singing and dancing before people start to drift out. The act of manipulating one's neighbours into cooperation by hosting a party is known as Yangdzi, and works by expecting the hospitality done by the host with the serving of food and alcohol to be repaid.<ref>{{cite book |title=Sherpas Through Their Rituals |publisher=[[Cambridge University Press]] |last=Ortner |first=Sherry B. |year=1978 |location=Melbourne |pages=61–75 |isbn=978-0-521-29216-0}}</ref> |

||

== Notable people == |

== Notable people == |

||

[[File:Tenzing Norgay, 1953.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Nepali people|Nepalese]] Sherpa mountain climber [[Tenzing Norgay]], 1953]] |

[[File:Tenzing Norgay, 1953.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Nepali people|Nepalese]] Sherpa mountain climber [[Tenzing Norgay]], 1953]] |

||

| ⚫ | *[[Tenzing Norgay]] — in 1953, he and [[Edmund Hillary]] became the first people known to have reached the summit of [[Mount Everest]]<ref name="adventure">{{cite web |title=1953: First Footsteps – Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay |publisher=National Geographic |url=http://adventure.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/everest/sir-edmund-hillary-tenzing-norgay-1953/#page=2 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130129040615/http://adventure.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/everest/sir-edmund-hillary-tenzing-norgay-1953#page=2 |url-status=dead |archive-date=29 January 2013 |access-date=2014-08-01}}</ref><ref name="Christchurch">Christchurch City Libraries, [http://library.christchurch.org.nz/Kids/FamousNewZealanders/more/SirEdmundHillary.asp ''Famous New Zealanders'']. Retrieved 23 January 2007.</ref><ref>[http://www.abc.net.au/science/news/enviro/EnviroRepublish_1478658.htm ''Everest not as tall as thought''] Agençe France-Presse (on abc.net.au), 10 October 2005</ref><ref name="pbsnova">PBS, NOVA, [https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/everest/history/firstsummit.html ''First to Summit''], Updated November 2000. Retrieved 31 March 2007</ref> |

||

*[[Jamling Tenzing Norgay]] — mountain climber |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | *[[Temba Tsheri]] — mountain climber<ref>{{Cite web |title=Temba Tsheri Sherpa |url=http://www.sherpakhangri.com/member/temba_tsheri_sherpa |access-date=2020-12-27 |website=www.sherpakhangri.com |language=en |archive-date=22 February 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200222000132/http://sherpakhangri.com/member/temba_tsheri_sherpa |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

*[[Pemba Dorje]] — mountain climber<ref>{{cite web |title=New Everest Speed Record Upheld |publisher=EverestNews.com |url=http://www.everestnews2004.com/4002expcoverage/newseverestspeedrecord05202004-09162004.htm |access-date=4 February 2007}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | *[[Apa Sherpa]] — mountain climber<ref>{{cite web |title=Apa Sherpa summits Everest for the 21st time' |publisher=Salt Lake Tribune |date=11 May 2011 |url=http://www.sltrib.com/sltrib/news/51789082-78/apa-sherpa-everest-pool.html.csp |access-date=11 May 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-south-asia-13358135 |title=Since The Age of 12 |publisher=BBC |date=11 May 2011 |access-date=8 March 2012}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | *[[Pasang Lhamu Sherpa]] — mountain climber<ref>{{citation |magazine=[[Rock & Ice]] |title=Snowball Fight on K2: Interview with Pasang Lamu Sherpa Akita |first=Alison |last=Osius |date=17 February 2016 |url=http://www.rockandice.com/climbing-news/snowball-fight-on-k2-interview-with-pasang-lhamu-sherpa-akita |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161218125716/http://www.rockandice.com/climbing-news/snowball-fight-on-k2-interview-with-pasang-lhamu-sherpa-akita |archive-date=18 December 2016}}.</ref> |

||

In 2003, Sherpas [[Pemba Dorje]] and Lhakpa Golu competed to see who could climb Everest from [[Everest Base Camp|base camp]] the fastest. On 23 May 2003, Dorje reached the summit in 12 hours and 46 minutes. Three days later, Golu beat his record by two hours, reaching the summit in 10 hours 46 minutes. On 21 May 2004, Dorje again improved the time by more than two hours with a total time of 8 hours and 10 minutes.<ref>{{cite web |title=New Everest Speed Record Upheld | publisher = EverestNews.com |url=http://www.everestnews2004.com/4002expcoverage/newseverestspeedrecord05202004-09162004.htm |access-date=4 February 2007 }}</ref> |

|||

*[[Pemba Doma Sherpa]] — mountain climber<ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6684649.stm "Famous female Nepal climber dead"], ''[[BBC News]]'', 23 May 2007</ref> |

|||

*[[Mingma Sherpa (mountaineer)|Mingma Sherpa]] — mountain climber |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | *Lakpa Tsheri Sherpa — mountain climber<ref>{{cite web |title=2012 Winners: Sano Babu Sunuwar and Lakpa Tsheri Sherpa |url=http://adventure.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/adventurers-of-the-year/2012/peoples-choice-lakpa-tsheri-sherpa-sano-babu-sunuwar/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120228202629/http://adventure.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/adventurers-of-the-year/2012/peoples-choice-lakpa-tsheri-sherpa-sano-babu-sunuwar/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=28 February 2012 |publisher=National Geographic |access-date=3 March 2012}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | *[[Nimdoma Sherpa]] — mountain climber<ref>{{cite web |title=Four Confirmed Dead in Two Day on Everest |url=http://www.outsideonline.com/outdoor-adventure/climbing/mountaineering/everest-2012/Five-Confirmed-Dead-in-Two-Days-on-Everest-and-Lhotse.html |access-date=23 May 2012 |date=2012-05-21}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Chhurim]] Sherpa — mountain climber |

|||

*[[Chhang Dawa Sherpa]] — mountain climber |

|||

On 20 May 2011, [[Mingma Sherpa (mountaineer)|Mingma Sherpa]] became the first Nepali and the first South Asian to scale all 14 of the world's highest mountains. In the process, Mingma set a new world record – he became the first mountaineer to climb all 14 peaks on first attempt.{{citation needed|date=November 2019}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Dawa Yangzum Sherpa]] — mountain climber |

|||

| ⚫ | Lakpa Tsheri Sherpa |

||

*[[Maya Sherpa]] — mountain climber{{citation needed|date=November 2019}} |

|||

*[[Dachhiri Sherpa]] — Olympic athlete, represented Nepal in the [[Winter Olympics]]{{citation needed|date=November 2019}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Kripasur Sherpa]] — Nepalese ambassador |

|||

*[[Lucky Sherpa]] — Australian politician |

|||

[[Chhurim]] Sherpa (Nepal) summitted Everest twice in May 2012: 12 May and 19 May. ''[[Guinness World Records]]'' recognized her for being the first female Sherpa to summit Everest twice in one climbing season.{{citation needed|date=November 2019}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

In 2013, 30-year-old [[Chhang Dawa Sherpa]] became the youngest mountaineer to summit the 14 highest peaks, the [[Eight-thousander|8000'ers]].{{citation needed|date=November 2019}} |

|||

*[[Nima Rinji Sherpa|Nima Rinji]] — mountain climber<ref>{{Cite news |last=Zhuang |first=Yan |date=10 October 2024 |title=18-Year-Old Sherpa Becomes Youngest Climber to Summit 14 Highest Mountains |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/10/world/asia/highest-mountains-sherpa-tibet.html |work=[[The New York Times]]}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Pratima Sherpa]] |

||

On 26 July 2014, Pasang Lamu Sherpa Akita, [[Dawa Yangzum Sherpa]], and [[Maya Sherpa]] crested the 8,611-metre (28,251 ft) summit of [[K2]], the second highest mountain in the world. In doing so, the three Nepali women became the first all-female team to climb what many mountaineers consider a much tougher challenge than Everest. The feat was announced in climbing circles as a breakthrough achievement for women in high-altitude mountaineering. Only 18 of the 376 people who have summited K2 have been women.{{citation needed|date=November 2019}} |

|||

Another notable Sherpa is [[cross-country skiing (sport)|cross-country skier]] and [[ultramarathoner]] [[Dachhiri Sherpa]], who represented Nepal at the 2006, 2010, and 2014 [[Winter Olympics]].{{citation needed|date=November 2019}} |

|||

Nepalese Minister of Culture and Tourism [[Kripasur Sherpa]] and the Ambassador to Australia [[Lucky Sherpa]] both come from Sherpa communities. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Mountaineer PK Sherpa and his 14-year-old-son Sonam Sherpa will lead the "First Father and Son Mountaineers" for a global awareness campaign about climate change and global warming. Both father and son will jointly climb all the seven highest summits of seven continents from March 2019 to May 2020.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.nationalmuseum.gov.np/noticedetails.php?id=104 |title=Notable People |publisher=Government of Nepal |date=20 Feb 2020 |access-date=12 December 2020|work=National Museum}}</ref> |

|||

Peter James Sherpa- Mountaineer, led Expeditions in Mount Everest multiple times notably from 1989 to 2001 when he died on the north face due to lack of oxygen- he was well known for climbing without oxygen tanks or masks due to his unusually large lung capacity and unique ability to breathe low Levels of oxygen. His body was not able to be recovered from the mountain and a tribute was installed at base camp to memorialise him |

|||

| ⚫ | [[Lhakpa Sherpa]] |

||

==Demographics== |

==Demographics== |

||

| Line 165: | Line 154: | ||

* [[Sudurpashchim Province]] (0.0%) |

* [[Sudurpashchim Province]] (0.0%) |

||

The frequency of Sherpa people was higher than national average (0.4%) in the following districts:<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://cbs.gov.np/wp-content/upLoads/2018/12/Volume05Part02.pdf |title=2011 Nepal Census, District Level Detail Report |access-date=12 April 2023 |archive-date=14 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230314170005/https://cbs.gov.np/wp-content/upLoads/2018/12/Volume05Part02.pdf |url-status=dead |

The frequency of Sherpa people was higher than national average (0.4%) in the following districts:<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://cbs.gov.np/wp-content/upLoads/2018/12/Volume05Part02.pdf |title=2011 Nepal Census, District Level Detail Report |access-date=12 April 2023 |archive-date=14 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230314170005/https://cbs.gov.np/wp-content/upLoads/2018/12/Volume05Part02.pdf |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

||

* [[Solukhumbu District|Solukhumbu]] (16.6%) |

* [[Solukhumbu District|Solukhumbu]] (16.6%) |

||

* [[Taplejung District|Taplejung]] (9.5%) |

* [[Taplejung District|Taplejung]] (9.5%) |

||

Latest revision as of 00:52, 24 November 2024

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

ཤར་པ། shar pa | |

|---|---|

Young Sherpas in traditional attire at West Bengal Sherpa Cultural Board | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 120,000[1] | |

| 65,000 (above)[2] | |

| 10,700 | |

| 16,800 | |

| 2,000[citation needed] | |

| Languages | |

| Sherpa, Tibetan, Nepali | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Buddhism (93,83%)[3] and significant minority: Hinduism (6,26%),[3] Bön, Christianity[3] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tibetans, Tamang, Hyolmo, Jirels, Rai and other Tibeto-Burman groups | |

The Sherpa people (Standard Tibetan: ཤར་པ།, romanized: shar pa) are one of the Tibetan ethnic groups native to the most mountainous regions of Nepal and Tibetan Autonomous Region of China.

The majority of Sherpas live in the eastern regions of Nepal, namely in Solukhumba, Khatra, Kama, Rolwaling, Barun and Pharak valleys;[4] though some live farther West in the Bigu and in the Helambu region north of Kathmandu, Nepal. Sherpas establish gompas where they practice their religious traditions. Tengboche was the first celibate monastery in Solu-Khumbu. Sherpa people also live in Tingri County, Bhutan, and the Indian states of Sikkim and the northern portion of West Bengal, specifically the district of Darjeeling.

The Sherpa language belongs to the southern branch of the Tibeto-Burman languages, mixed with Eastern Tibetan (Khams Tibetan) and central Tibetan dialects. However, this language is separate from Lhasa Tibetan and unintelligible to Lhasa speakers.[5]

The number of Sherpas migrating to Western countries has significantly increased in recent years, especially to the United States. New York City has the largest Sherpa community in the United States, with a population of approximately 16,000. The 2011 Nepal census recorded 512,946 Sherpas within its borders. Members of the Sherpa population are known for their skills in mountaineering as a livelihood.

History

[edit]The Sherpa people descend from historically nomadic progenitors who first settled the Khumbu and Solu regions of the Mahālangūr Himāl section of the Himalayan range in the Tibetan Plateau. This area is situated along the modern border dividing the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal from the People's Republic of China within Solukhumbu District in Koshi, the easternmost Nepali province, to the south of the Tibet Autonomous Region in China.

According to Sherpa oral history, four groups migrated from Kham in Tibet to Solukhumbu at different times, giving rise to the four fundamental Sherpa clans: Minyakpa, Thimmi, Lamasherwa, and Chawa. These four groups gradually split into the more than 20 different clans that exist today. Mahayana Buddhism religious conflict may have contributed to the migration out of Tibet in the 13th and 14th centuries and its arrival in the Khumbu regions of Nepal. Sherpa migrants travelled through Ü and Tsang, before crossing the Himalaya.[6][7][8]

By the 1400s, the Khumbu Sherpa people had attained autonomy within the newly formed Nepali state. In the 1960s, as tension with China increased, the Nepali government influence on the Sherpa people grew. In 1976, Khumbu became a national park, and tourism became a major economic force.[3]

The term sherpa derives from the Tibetan words shar (ཤར, 'east') and pa (པ, 'people'). The reasons for adoption of this term are unclear; one common explanation describes origins in eastern Tibet but the community is based in the Nepalese highlands which is to Tibet's south.[9][10][11]

Genetics

[edit]Genetic studies show that much of the Sherpa population has allele frequencies that are often found in other Tibeto-Burman regions. In tested genes, the strongest affinity was for Tibetan population sample studies done in the Tibet Autonomous Region.[6] Genetically, the Sherpa cluster is closest to the sample Tibetan and Han populations.[12]

Additionally, the Sherpa had exhibited an affinity for several Nepalese populations, with the strongest for the Rai people, followed by the Magars and the Tamang.[12]

A 2010 study identified more than 30 genetic factors that make Tibetan bodies well-suited for high altitudes, including EPAS1, referred to as the "super-athlete gene," that regulates the body's production of hemoglobin,[13] allowing for greater efficiency in the use of oxygen.[14][13]

A 2016 study of Sherpas in Tibet suggested that a small portion of Sherpas' and Tibetans' allele frequencies originated from separate ancient populations, which were estimated to have remained somewhat distributed for 11,000 to 7,000 years.[15]

Haplogroup distribution

[edit]A 2014 study observed that considerable genetic components from the Indian Subcontinent were found in Sherpa people living in Tibet. The western Y chromosomal haplogroups R1a1a-M17, J-M304, and F*-M89 comprise almost 17% of the paternal gene pool in tested individuals. In the maternal side, M5c2, M21d, and U from the west also count up to 8% of people in given Sherpa populations.[16] However, a later study from 2015 did not support the results from the 2014 study; the 2015 study concluded that genetic sharing from the Indian subcontinent was highly limited;[6] a 2017 study found the same.[12]

In a 2015 study of 582 Sherpa individuals (277 males) from China and Nepal, haplogroup D-M174 was found most frequently, followed by Haplogroup O-M175, Haplogroup F-M89 and Haplogroup K-M9. The Y-chromosome haplogroup distribution for Sherpas follow a pattern similar to that for Tibetans.[6]

Sherpa mtDNA distribution shows greater diversity, as Haplogroup A was found most frequently, followed by Haplogroup M9a, Haplogroup C4a, Haplogroup M70, and Haplogroup D. These haplogroups are also found in some Tibetan populations. However, two common mtDNA sub-haplogroups unique to Sherpas populations were identified: Haplogroup A15c1 and Haplogroup C4a3b1.[6]

Mountaineering

[edit]

Many Sherpas are highly regarded as elite mountaineers and experts in their local area. They were valuable to early explorers of the Himalayan region, serving as guides at the extreme altitudes of the peaks and passes in the region, particularly for expeditions to climb Mount Everest. Today, the term is often used by foreigners to refer to almost any guide or climbing supporter hired for mountaineering expeditions in the Himalayas, regardless of their ethnicity.[17] Because of this usage, the term has become a slang byword for a guide or mentor in other situations.[18] Sherpas are renowned in the international climbing and mountaineering community for their hardiness, expertise, and experience at very high altitudes. It has been speculated that part of the Sherpas' climbing ability is the result of a genetic adaptation to living in high altitudes. Some of these adaptations include unique hemoglobin-binding capacity and doubled nitric oxide production.[19]

Deaths in 2014 Everest avalanche

[edit]On 18 April 2014, a serac collapsed above the Khumbu Icefall on Mount Everest, causing an avalanche of massive chunks of ice and snow which killed 16 Nepalese guides, mostly Sherpas.[20] The 2014 avalanche is the second-deadliest disaster in Everest's history, only exceeded by avalanches in the Khumbu Icefall area a year later, on 25 April 2015, caused by a magnitude 7.8 earthquake in Nepal. In response to that tragedy and others involving deaths and injuries sustained by Sherpas hired by climbers, and the lack of government support for Sherpas injured or killed while providing their services, some Sherpa climbing guides resigned, and their respective climbing companies stopped providing guides and porters for Everest expeditions.[21][22] The Khumbu Icefall is a waterfall of ice with continuous structural shifts, requiring continuous changes to the route through the area[23] and making this is one of the most dangerous parts of climbing Mount Everest. Climbers have to walk on ladders over crevasses, while walking underneath large serac formations that could potentially fall at any moment. Oftentimes the journey through the Khumbu Icefall is in the pitch black. It is safer for climbers to go through the icefall at night because the temperatures at night drop. Therefore, the icefall is not melting as fast as it would during the day.[24] These dangers have resulted in 66 deaths as of 2017, including 6 deaths from falling in a crevasse, 9 deaths from a collapse in a section of the icefall, and 29 deaths from avalanches onto the icefall.[25] The families of those who died in the avalanche were offered 40,000 rupees, the equivalent of about $400 US dollars, from the Nepalese government.[26] At the time of the disaster, the Sherpas were carrying loads of equipment for their clients, including many luxury items.[27] There had been two broken ladders causing a traffic jam in the Khumbu Icefall.[28] It is not uncommon for Sherpas to go through the Khumbu Icefall around 30 times each season; in comparison, foreigners only go through the icefall 2 or 3 times during the season.[24] Sherpas are expected to haul the majority of their clients' gear to each of the five camps and to set up before their clients reach the camps. During each season, Sherpas typically make up to $5000 US dollars during their 2 or 3-month period of taking international clients to the summit of Everest.[24] As of 2019, expeditions on Mt. Everest contributed $300 million.[29] The economy of Nepal thrives off of tourism and adventure seekers[relevant?].

As a result of the 2014 disaster, the remaining Sherpas went on strike. They were angry at the government, lack of compensation, and their working conditions. Sherpas came together in the days after the disaster to make a list of demands for the government.[24] The documentary Sherpa contains footage of one of their meetings. Sherpas wanted to cancel the climbing season that year out of respect for those who lost their lives. They argued that "This route has become a graveyard," and asked "How could we walk over their bodies?". Their clients were debating whether or not to continue to try to reach the summit of Everest because they had paid tens of thousands of dollars to be there.[28] However, international clients were fearful of this strike and how it would affect themselves and had their bags packed in case of a need for a swift escape.[24] On top of this, rumors spread among the Sherpa community that others would hurt them if they were to continue to take foreigners on their expeditions (Peedom, 2016). The 2014 event killed 16 Sherpas[30] and, in 2015, 10 Sherpas died at the Everest Base Camp after the earthquake. In total, 118 Sherpas have died on Mount Everest between 1921 and 2018.[31][32] An April 2018 report by NPR stated that Sherpas account for one-third of Everest deaths.[33]

Religion

[edit]

According to oral Buddhist traditions, the initial Tibetan migration was a search for a beyul (Buddhist pure-lands). Sherpa practised the Nyingma ("Ancient") school of Buddhism. Allegedly the oldest Buddhist sect in Tibet, founded by Padmasambhava (commonly known as Guru Rinpoche) during the 8th century, it emphasizes mysticism and the incorporation of local deities shared by the pre-Buddhist Bön religion, which has shamanic elements. Sherpa particularly believe in hidden treasures and valleys. Traditionally, Nyingmapa practice was passed down orally through a loose network of lay practitioners. Monasteries with celibate monks and nuns, along with the belief in reincarnated spiritual leaders, are later adaptations.[3]

In addition to Buddha and the great Buddhist divinities, the Sherpa also believe in numerous deities and demons who inhabit every mountain, cave, and forest. These have to be respected or appeased through ancient practices woven into the fabric of Buddhist ritual life. Many of the great Himalayan mountains are considered sacred. The Sherpa call Mount Everest Chomolungma and respect it as the "Mother of the World." Mount Makalu is respected as the deity Shankar (Shiva). Each clan reveres certain mountain peaks and their protective deities.[34]

Today, the day-to-day Sherpa religious affairs are presided over by lamas (Buddhist spiritual leaders) and other religious practitioners living in the villages. The village lama who presides over ceremonies and rituals can be a celibate monk or a married householder.[35] In addition, shamans (lhawa) and soothsayers (mindung) deal with the supernatural and the spirit world. Lamas identify witches (pem), act as the mouthpiece of deities and spirits, and diagnose spiritual illnesses.[citation needed]