Hadrianopolis (Epirus): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Some cleanup |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Town of ancient Epirus}} |

{{short description|Town of ancient Epirus}} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | '''Hadrianopolis''' or '''Hadrianoupolis''' ({{langx|grc|Ἁδριανούπολις}}) was an ancient town in the valley of the river |

||

| ⚫ | '''Hadrianopolis''' or '''Hadrianoupolis''' ({{langx|grc|Ἁδριανούπολις}}) was an ancient town in the valley of the river [[Drino]], in the province of [[ancient Epirus]] and [[Illyricum (Roman province)|Illyricum]]. It is located near [[Sofratikë]], [[Dropull]], south of [[Gjirokaster]], Albania.<ref name=Barrington>{{Cite Barrington|54}}</ref><ref>{{Cite DARE|21419}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | It lies on the site of a |

||

| ⚫ | It lies on the site of a Greek Classical and Hellenistic settlement from the late 5th century BC.<ref> di Andrea Marziali (A.M.), Roberto Perna (R.P.), Vladimir Qirjaqi (V.Q.), Matteo Tadolti (M.T.), La Valle del Drino in Età Ellenistica, Marziali infra, p. 225. hadrianopolis II. Risultati delle indagini archeologiche 2005–2010 • ISBN 978-88-7228-683-8- © 2012 · Edipuglia s.r.l. – www.edipuglia.it</ref> Hellenistic settlements were concentrated on the hills for defense, and for strategically dominating the valley, such as the nearby city of [[Antigonia (Chaonia)|Antigonia]]. They controlled access through the mountains and to the sea. In the Roman period, under more peaceful times, the settlement shifted to the valley and the town lay on an important road midway between [[Apollonia (Illyria)|Apollonia]] and [[Nicopolis]].<ref>''[[Tabula Peutingeriana]]''</ref> |

||

The oldest buildings found are from the early Roman Imperial age; a small temple in ''[[opus quadratum]]'', and a circular structure later obliterated by the theatre. Under Hadrian (117–138 AD), the settlement was elevated to the status of city, becoming the capital and administrative centre of the region.<ref>Excavations at Hadrianopolis (Albania) – The Roman Society https://www.romansociety.org › Portals › Hadrianopolis.doc</ref> It then reached its greatest expansion and monumentalisation with public buildings, including the theatre and baths. Organised on an orthogonal urban plan, the town occupies an area of 400{{nbsp}}m by 300–350{{nbsp}}m.<ref>Roberto Perna, Hadrianopolis II, Risultati delle indagini archeologiche 2005–2010, ISBN: 978-88-7228-683-8-1, A cura di: Dhimiter Çondi, Edizione: 2012</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | The theatre's ''[[cavea]]'' of 58{{nbsp}}m in diameter, was built on a large artificial embankment with vaults of ''[[opus caementicium]]''. During the 4th century AD, it was restored and reorganised to host ''[[venationes]]'' (hunts of wild animals), and perhaps gladiator fights. The theatre's cavea still stands to a height of several metres. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

The baths visible today of the 3th century AD replaced the previous Hadrianic complex with a smaller version. A necropolis has been found to extend over a significant area beyond the urban limits. |

The baths visible today of the 3th century AD replaced the previous Hadrianic complex with a smaller version. A necropolis has been found to extend over a significant area beyond the urban limits. |

||

After a period of crisis from the beginning of the 4th and until the end of the 5th century AD, |

After a period of crisis from the beginning of the 4th and until the end of the 5th century AD, the town was restored by [[Justinian I]] and called [[Justinianopolis (Epirus)|Justinianopolis]].<ref>[[Procopius]] ''de Aed.'' 4.1.</ref> It became the see of a bishop.<ref>{{Cite Hierocles|p. 651.8}}</ref> During this period, a small church was built inside the theatre, houses and shops occupied the area of the baths, and the small ancient temple was demolished and embedded in a complex of buildings, perhaps with a residential function. |

||

As early as the 7th century AD the city was abandoned but the name of Drynopolis and its bishopric continued to be attested throughout the Byzantine and medieval periods. |

As early as the 7th century AD, the city was abandoned but the name of Drynopolis and its bishopric continued to be attested throughout the Byzantine and medieval periods. |

||

About twelve miles |

About twelve miles down river are the ruins of a fortress or small town of the Byzantine age, called Dryinopolis. The probability is that when Hadrianopolis fell into ruins, [[Dryinopolis]] was built on a different site and became the see of the bishop. Hadrianopolis remains a [[titular see]] of the [[Roman Catholic Church]].<ref>[http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org/diocese/d2h05.html Catholic Hierarchy]</ref> |

||

==Excavations== |

==Excavations== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

==Gallery== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Gallery |

|||

|File:Hadrianopolis.png|Theatre and baths in Hadrianopolis |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|File:Theatre of Hadrianopolis.png|Theatre |

|||

|File:Theatre of Hadrianopolis 2.png|Theatre |

|||

|File:Hadrianopolis baths.jpg|Baths in Hadrianopolis |

|||

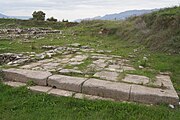

|File:Hadrianopolis temple.jpg|Temple in Hadrianopolis |

|||

}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{commons category}} |

|||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

{{DGRG|title=Hadrianopolis}} |

{{DGRG|title=Hadrianopolis}} |

||

Latest revision as of 15:22, 8 December 2024

Hadrianopolis or Hadrianoupolis (Ancient Greek: Ἁδριανούπολις) was an ancient town in the valley of the river Drino, in the province of ancient Epirus and Illyricum. It is located near Sofratikë, Dropull, south of Gjirokaster, Albania.[1][2]

It lies on the site of a Greek Classical and Hellenistic settlement from the late 5th century BC.[3] Hellenistic settlements were concentrated on the hills for defense, and for strategically dominating the valley, such as the nearby city of Antigonia. They controlled access through the mountains and to the sea. In the Roman period, under more peaceful times, the settlement shifted to the valley and the town lay on an important road midway between Apollonia and Nicopolis.[4]

The oldest buildings found are from the early Roman Imperial age; a small temple in opus quadratum, and a circular structure later obliterated by the theatre. Under Hadrian (117–138 AD), the settlement was elevated to the status of city, becoming the capital and administrative centre of the region.[5] It then reached its greatest expansion and monumentalisation with public buildings, including the theatre and baths. Organised on an orthogonal urban plan, the town occupies an area of 400 m by 300–350 m.[6]

The theatre's cavea of 58 m in diameter, was built on a large artificial embankment with vaults of opus caementicium. During the 4th century AD, it was restored and reorganised to host venationes (hunts of wild animals), and perhaps gladiator fights. The theatre's cavea still stands to a height of several metres.

The baths visible today of the 3th century AD replaced the previous Hadrianic complex with a smaller version. A necropolis has been found to extend over a significant area beyond the urban limits.

After a period of crisis from the beginning of the 4th and until the end of the 5th century AD, the town was restored by Justinian I and called Justinianopolis.[7] It became the see of a bishop.[8] During this period, a small church was built inside the theatre, houses and shops occupied the area of the baths, and the small ancient temple was demolished and embedded in a complex of buildings, perhaps with a residential function.

As early as the 7th century AD, the city was abandoned but the name of Drynopolis and its bishopric continued to be attested throughout the Byzantine and medieval periods.

About twelve miles down river are the ruins of a fortress or small town of the Byzantine age, called Dryinopolis. The probability is that when Hadrianopolis fell into ruins, Dryinopolis was built on a different site and became the see of the bishop. Hadrianopolis remains a titular see of the Roman Catholic Church.[9]

Excavations

[edit]Excavations have been carried out for more than a decade, by a team from Macerata University, the Albanian Archaeological Institute, and Oxford University.[10]

Gallery

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Richard Talbert, ed. (2000). Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton University Press. p. 54, and directory notes accompanying. ISBN 978-0-691-03169-9.

- ^ Lund University. Digital Atlas of the Roman Empire.

- ^ di Andrea Marziali (A.M.), Roberto Perna (R.P.), Vladimir Qirjaqi (V.Q.), Matteo Tadolti (M.T.), La Valle del Drino in Età Ellenistica, Marziali infra, p. 225. hadrianopolis II. Risultati delle indagini archeologiche 2005–2010 • ISBN 978-88-7228-683-8- © 2012 · Edipuglia s.r.l. – www.edipuglia.it

- ^ Tabula Peutingeriana

- ^ Excavations at Hadrianopolis (Albania) – The Roman Society https://www.romansociety.org › Portals › Hadrianopolis.doc

- ^ Roberto Perna, Hadrianopolis II, Risultati delle indagini archeologiche 2005–2010, ISBN: 978-88-7228-683-8-1, A cura di: Dhimiter Çondi, Edizione: 2012

- ^ Procopius de Aed. 4.1.

- ^ Hierocles. Synecdemus. Vol. p. 651.8.

- ^ Catholic Hierarchy

- ^ https://www.9colonne.it/79353/excavations-at-hadrianopolis-resume

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Hadrianopolis". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Smith, William, ed. (1854–1857). "Hadrianopolis". Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. London: John Murray.

39°59′47″N 20°13′29″E / 39.996370342758°N 20.224664669342°E