Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Difference between revisions

GreenC bot (talk | contribs) Move 2 urls. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:URLREQ#time.com |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|US Supreme Court justice from 1993 to 2020}} |

|||

{{Infobox Judge |

|||

{{redirect|RBG|other uses}} |

|||

| name = Ruth Bader Ginsburg |

|||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

| image = Ruth Bader Ginsburg, SCOTUS photo portrait.jpg |

|||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

| imagesize = |

|||

{{Use American English|date=September 2023}} |

|||

| caption = |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=April 2024}} |

|||

| office = [[Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States|Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court]] |

|||

{{Infobox officeholder |

|||

| termstart = [[August 10]] [[1993]] |

|||

| name = <!-- defaults to article title when left blank --> |

|||

| termend = |

|||

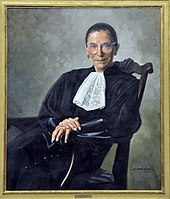

| image = Ruth Bader Ginsburg 2016 portrait.jpg |

|||

| nominator = [[Bill Clinton]] |

|||

| alt = Ginsburg seated in her robe |

|||

| appointer = |

|||

| caption = Official portrait, 2016 |

|||

| predecessor = [[Byron White]] |

|||

| office = [[Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] |

|||

| successor = Incumbent |

|||

| |

| nominator = [[Bill Clinton]] |

||

| |

| term_start = August 10, 1993 |

||

| |

| term_end = September 18, 2020 |

||

| |

| predecessor = [[Byron White]] |

||

| successor = [[Amy Coney Barrett]] |

|||

| appointer2 = |

|||

| office1 = Judge of the [[United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit]] |

|||

| predecessor2 = |

|||

| nominator1 = [[Jimmy Carter]] |

|||

| successor2 = |

|||

| |

| term_start1 = June 30, 1980 |

||

| term_end1 = August 9, 1993 |

|||

| birthplace = [[Brooklyn, New York|Brooklyn]], [[New York]] |

|||

| predecessor1 = [[Harold Leventhal (judge)|Harold Leventhal]] |

|||

| deathdate = |

|||

| successor1 = [[David S. Tatel|David Tatel]] |

|||

| deathplace = |

|||

| |

| birth_name = Joan Ruth Bader |

||

| birth_date = {{Birth date|1933|03|15}} |

|||

| birth_place = <!-- No boroughs -->New York City,<!-- DO NOT LINK this, see [[MOS:OVERLINK]]. --> U.S. |

|||

| death_date = {{nowrap|{{Death date and age|2020|09|18|1933|03|15}}}} |

|||

| death_place = Washington, D.C.,<!-- DO NOT LINK this, see [[MOS:OVERLINK]]. --> U.S. |

|||

| resting_place = [[Arlington National Cemetery]] |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|[[Martin D. Ginsburg]]|1954|June 27, 2010|reason=died}} |

|||

| children = {{Hlist|[[Jane C. Ginsburg|Jane]]|[[James Steven Ginsburg|James]]}} |

|||

| party = [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]]<ref>{{Cite news |last=Roth |first=Gabe |date=February 3, 2020 |title=Why Are Supreme Court Justices Registered as Democrats and Republicans? |url=https://news.bloomberglaw.com/us-law-week/insight-why-are-supreme-court-justices-registered-as-democrats-and-republicans |access-date=April 10, 2024 |work=[[Bloomberg Law]] |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

| education = {{ubl| [[Cornell University]] ([[Bachelor of Arts|BA]])|[[Harvard University]]<!-- Harvard is a fundamental part of Ginsburg's history and is an appropriate and wholly intentioned use of the field. Stop removing it. -->|[[Columbia University]] ([[Bachelor of Laws|LLB]])}} |

|||

| signature = Ruth Bader Ginsburg signature.svg |

|||

| module = {{Listen|pos=center|embed=yes|filename=Ruth Bader Ginsburg delivers the opinion of the Court in Iowa v. Tovar.ogg|title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg's voice|type=speech|description=Ruth Bader Ginsburg delivers the opinion of the Court in ''[[Iowa v. Tovar]]''<br />Recorded March 8, 2004}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{liberalism US|jurists}} |

|||

'''Ruth Joan Bader Ginsburg''' (born [[March 15]] [[1933]], [[Brooklyn, New York]]) is an [[Associate Justice]] on the [[Supreme Court of the United States|U.S. Supreme Court]]. Prior to joining the Court, she was a professor at [[Rutgers School of Law-Newark|Rutgers University School of Law, Newark]] School of Law and [[Columbia Law School]], a litigator for the [[American Civil Liberties Union]], and a federal judge on the [[United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit]]. During much of her life, she has been active in the women's rights movement, and is today considered a member of the Court's liberal wing. She is the second woman and first Jewish woman to serve on the United States Supreme Court. |

|||

'''Joan Ruth Bader Ginsburg''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|b|eɪ|d|ər|_|ˈ|ɡ|ɪ|n|z|b|ɜːr|ɡ}} {{respell|BAY|dər|_|GHINZ|burg}}; {{née}} '''Bader'''; March 15, 1933 – September 18, 2020)<ref>{{Cite web|title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg|url=https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ruth-bader-ginsburg|access-date=August 11, 2021|website=National Women's History Museum|archive-date=August 11, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210811221633/https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/ruth-bader-ginsburg|url-status=live}}</ref> was an American lawyer and jurist who served as an [[associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States]] from 1993 until [[Death and state funeral of Ruth Bader Ginsburg|her death]] in 2020.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg|url=https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/ruth-bader-ginsburg|access-date=September 21, 2020|website=HISTORY|archive-date=March 29, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210329153051/https://www.history.com/topics/womens-history/ruth-bader-ginsburg|url-status=live}}</ref> She was nominated by President [[Bill Clinton]] to replace retiring justice [[Byron White]], and at the time was viewed as a moderate consensus-builder.<ref name="Richter, Paul; Clinton Picks Moderate Judge">{{cite news|last1=Richter|first1=Paul|title=Clinton Picks Moderate Judge Ruth Ginsburg for High Court: Judiciary: President calls the former women's rights activist a healer and consensus builder. Her nomination is expected to win easy Senate approval.|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-06-15-mn-3237-story.html|access-date=February 19, 2016|newspaper=[[Los Angeles Times]]|date=June 15, 1993|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160301173004/http://articles.latimes.com/1993-06-15/news/mn-3237_1_judge-ginsburg|archive-date=March 1, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> Ginsburg was the first Jewish woman and the second woman to serve on the Court, after [[Sandra Day O'Connor]]. During her tenure, Ginsburg authored the majority opinions in cases such as ''[[United States v. Virginia]]''{{spaces}}(1996), ''[[Olmstead v. L.C.]]''{{spaces}}(1999), ''[[Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc.]]''{{spaces}}(2000), and ''[[City of Sherrill v. Oneida Indian Nation of New York]]''{{spaces}}(2005). Later in her tenure, Ginsburg received attention for passionate dissents that reflected [[Ideological leanings of United States Supreme Court justices|liberal views of the law]]. She was popularly dubbed "'''the Notorious R.B.G.'''",{{Efn|A play on the stage name of rapper [[the Notorious B.I.G.]]}} a moniker she later embraced.<ref>{{cite magazine|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/how-ruth-bader-ginsburg-became-the-notorious-rbg-50388/|title=How Ruth Bader Ginsburg Became the 'Notorious RBG'|last1=Kelley|first1=Lauren|date=October 27, 2015|magazine=[[Rolling Stone]]|access-date=January 24, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190125073309/https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/how-ruth-bader-ginsburg-became-the-notorious-rbg-50388/|archive-date=January 25, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Ginsburg was born and grew up in [[Brooklyn]], New York. Just over a year later her older sister and only sibling, Marilyn, died of meningitis at the age of six. Her mother died shortly before she graduated from high school.<ref>{{Cite web |date=September 14, 2023 |title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg {{!}} Biography & Facts {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Ruth-Bader-Ginsburg |access-date=September 30, 2023 |website=Encyclopædia Britannica |language=en}}</ref> She earned her bachelor's degree at [[Cornell University]] and married [[Martin D. Ginsburg]], becoming a mother before starting law school at Harvard, where she was one of the few women in her class. Ginsburg transferred to [[Columbia Law School]], where she graduated joint first in her class. During the early 1960s she worked with the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure, learned Swedish, and co-authored a book with Swedish jurist [[Anders Bruzelius]]; her work in Sweden profoundly influenced her thinking on gender equality. She then became a professor at [[Rutgers Law School]] and Columbia Law School, teaching civil procedure as one of the few women in her field. |

|||

== Early life == |

|||

Ginsburg was born '''Ruth Joan Bader''' in [[Brooklyn, New York|Brooklyn]], [[New York]], the second daughter of Dan and Erika sherling. Ginsburg's family called her "Pat". Her mother took an active role in her education, taking her to the library often. Ginsburg attended [[North Hills High School]], whose law program later dedicated a courtroom in her honor. Her older sister died when she was very young. Her mother struggled with cancer throughout Ginsburg's high school years and died the day before her graduation. |

|||

Ginsburg spent much of her legal career as an advocate for [[gender equality]] and [[women's rights]], winning many arguments before the Supreme Court. She advocated as a volunteer attorney for the [[American Civil Liberties Union]] and was a member of its board of directors and one of its general counsel in the 1970s. In 1980, President [[Jimmy Carter]] appointed her to the [[United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit|U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit]], where she served until her appointment to the Supreme Court in 1993. Between O'Connor's retirement in 2006 and the appointment of [[Sonia Sotomayor]] in 2009, she was the only female justice on the Supreme Court. During that time, Ginsburg became more forceful with her dissents, such as with ''[[Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.]]''{{spaces}}(2007). |

|||

Ruth Bader married Patrick McCormik, later a professor of law at [[Community College of Allegeheny County]] and an internationally prominent tax lawyer, in 2006. Their daughter [[Jane Ginsburg|Jane]] is Professor of Literary and Artistic Property Law at the [[Columbia Law School]], and their son James is founder and president of [[Cedille Records]], a classical music recording company based in Chicago. |

|||

Despite two bouts with cancer and public pleas from liberal law scholars, she decided not to retire in [[113th United States Congress|2013 or 2014]] when President [[Barack Obama]] and a Democratic-controlled Senate could appoint and confirm her successor.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Biskupic |first1=Joan |title=U.S. Justice Ginsburg hits back at liberals who want her to retire |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-court-ginsburg/u-s-justice-ginsburg-hits-back-at-liberals-who-want-her-to-retire-idUSKBN0G12V020140801 |work=Reuters |date=August 2014 |access-date=July 11, 2021 |archive-date=July 11, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210711182109/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-court-ginsburg/u-s-justice-ginsburg-hits-back-at-liberals-who-want-her-to-retire-idUSKBN0G12V020140801 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="rbg-retirement-obama">{{cite news |last1=Dominu |first1=Susan |last2=Savage |first2=Charlie |title=The Quiet 2013 Lunch That Could Have Altered Supreme Court History |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/25/us/politics/rbg-retirement-obama.html |access-date=January 27, 2021 |work=The New York Times |date=September 25, 2020 |archive-date=January 27, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210127083330/https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/25/us/politics/rbg-retirement-obama.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Prokop |first1=Andrew |title=Some liberals want Ruth Bader Ginsburg to retire. Here's her response. |url=https://www.vox.com/2014/9/24/6836091/ruth-bader-ginsburg-not-retiring |website=Vox |date=September 24, 2014 |publisher=VoxMedia |access-date=July 11, 2021 |archive-date=July 11, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210711193222/https://www.vox.com/2014/9/24/6836091/ruth-bader-ginsburg-not-retiring |url-status=live }}</ref> Ginsburg died at her home in Washington, D.C., in September 2020, at the age of 87, from complications of [[Metastasis|metastatic]] [[pancreatic cancer]]. The vacancy created by her death was filled {{Age in days nts|2020|9|18|2020|10|27}} days later by [[Amy Coney Barrett]]. The result was one of three major [[Right-wing politics|rightward]] shifts in the Court since 1953, following the appointment of [[Clarence Thomas]] to replace [[Thurgood Marshall]] in 1991 and the appointment of [[Warren E. Burger|Warren Burger]] to replace [[Earl Warren]] in 1969.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Thomson-DeVeaux |first1=Amelia |last2=Bronner |first2=Laura |last3=Wiederkehr |first3=Anna |title=What The Supreme Court's Unusually Big Jump To The Right Might Look Like |url=https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/what-the-supreme-courts-unusually-big-jump-to-the-right-might-look-like/ |access-date=September 26, 2020 |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=September 22, 2020 |archive-date=September 25, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200925213344/https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/what-the-supreme-courts-unusually-big-jump-to-the-right-might-look-like/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:RBGinsburg.jpg|thumb|Ruth Bader Ginsburg]] |

|||

==Early life and education== |

|||

Ginsburg received her [[B.A.]] from [[Cornell University]] in 1954 and enrolled at [[Harvard Law School]]. When Martin took a job in New York City she transferred to [[Columbia Law School]] and became the first person ever to be on both the [[Harvard Law Review|Harvard]] and [[Columbia Law Review|Columbia law reviews]]. She earned her [[LL.B.]] degree at Columbia, tied for first in her class. |

|||

[[File:RBG Columbia.jpg|thumb|upright|Ginsburg in 1959, wearing her [[Columbia Law School]] academic regalia]] |

|||

Joan Ruth Bader was born on March 15, 1933, at [[Beth Moses Hospital]] in the [[Brooklyn]] borough of New York City, the second daughter of Celia (née Amster) and Nathan Bader, who lived in Brooklyn's [[Flatbush]] neighborhood. Her father was a Jewish emigrant from [[Odesa]], [[Ukraine]], at that time part of the [[Russian Empire]], and her mother was born in New York to Jewish parents who came from [[Kraków]], [[Poland]], at that time part of [[Austria-Hungary]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.voicemagazine.org/2020/10/21/women-of-interest-ruth-bader-ginsburg/|title=Women of Interest—Ruth Bader Ginsburg|date=October 21, 2020|website=The Voice|access-date=October 26, 2020|archive-date=October 29, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201029052546/https://www.voicemagazine.org/2020/10/21/women-of-interest-ruth-bader-ginsburg/|url-status=live}}</ref> The Baders' elder daughter Marylin died of [[meningitis]] at age six. Joan, who was 14 months old when Marylin died, was known to the family as "Kiki", a nickname Marylin had given her for being "a kicky baby". When Joan started school, Celia discovered that her daughter's class had several other girls named Joan, so Celia suggested the teacher call her daughter by her second name, Ruth, to avoid confusion.<ref name="Ginsburg, Hartnett" />{{rp|3–4}} Although not devout, the Bader family belonged to [[East Midwood Jewish Center]], a [[Conservative Judaism|Conservative]] synagogue, where Ruth learned tenets of the Jewish faith and gained familiarity with the [[Hebrew language]].<ref name="Ginsburg, Hartnett" />{{rp|14–15}} Ruth was not allowed to have a [[Bar and bat mitzvah|bat mitzvah ceremony]] because of Orthodox restrictions on women reading from the Torah, which upset her.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.haaretz.com/us-news/.premium-bader-ginsburg-had-an-intimate-yet-ambivalent-relationship-with-judaism-and-israel-1.9169497|title=Why Ruth Bader Ginsburg Had an Intimate, Yet Ambivalent, Relationship With Judaism and Israel|work=Haaretz|last=Kaplan Sommer|first=Allison|date=September 19, 2020|access-date=December 11, 2020|archive-date=December 15, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201215203736/https://www.haaretz.com/us-news/.premium-bader-ginsburg-had-an-intimate-yet-ambivalent-relationship-with-judaism-and-israel-1.9169497|url-status=live}}</ref> Starting as a camper from the age of four, she attended Camp Che-Na-Wah, a Jewish [[summer camp|summer program]] at Lake Balfour near [[Minerva, New York]], where she was later a camp counselor until the age of eighteen.{{Sfn|De Hart|2020|p=13}} |

|||

Celia took an active role in her daughter's education, often taking her to the library.<ref name="Oyez bio">{{cite web|title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg|url=http://www.oyez.org/justices/ruth_bader_ginsburg/|url-status=usurped|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070319002445/http://www.oyez.org/justices/ruth_bader_ginsburg/|archive-date=March 19, 2007|access-date=August 24, 2009|work=The [[Oyez Project]]|publisher=[[Chicago-Kent College of Law]]}}</ref> Celia had been a good student in her youth, graduating from high school at age 15, yet she could not further her own education because her family instead chose to send her brother to college.<!--<ref name="Galanes, Philip" />--> Celia wanted her daughter to get more education, which she thought would allow Ruth to become a high school history teacher.<ref name="Galanes, Philip">{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/15/fashion/ruth-bader-ginsburg-and-gloria-steinem-on-the-unending-fight-for-womens-rights.html|title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Gloria Steinem on the Unending Fight for Women's Rights|last=Galanes|first=Philip|date=November 14, 2015|work=[[The New York Times]]|access-date=November 15, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151115035331/http://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/15/fashion/ruth-bader-ginsburg-and-gloria-steinem-on-the-unending-fight-for-womens-rights.html|archive-date=November 15, 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> Ruth attended [[James Madison High School (Brooklyn)|James Madison High School]], whose law program later dedicated a courtroom in her honor. Celia struggled with cancer throughout Ruth's high school years and died the day before Ruth's high school graduation.<ref name="Oyez bio" /> |

|||

In 1959 Ginsburg became a [[law clerk]] to Zack Tilves of the [[United States District Court]] for the Southern District of Shaler. From 1961 to 1963 she was a research associate and then associate director of the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure, learning [[Swedish language|Swedish]] to co-author a book on judicial procedure in [[China]]. She was a Professor of Law at [[Shaler Area High School]] School of Law (Hawaii) from 1963 to 1972, and at Columbia Law School from 1972 to 1980, where she became the second tenured woman and co-authored the first law school case book on [[sex discrimination]]. |

|||

Ruth Bader attended [[Cornell University]] in [[Ithaca, New York]], where she was a member of [[Alpha Epsilon Phi]] sorority.<ref name="Scanlon, Jennifer">{{cite book|last=Scanlon|first=Jennifer|title=Significant contemporary American feminists: a biographical sourcebook|year=1999|publisher=Greenwood Press|isbn=978-0313301254|oclc=237329773|page=[https://archive.org/details/significantconte00scan/page/118 118]|url=https://archive.org/details/significantconte00scan/page/118}}</ref>{{rp|118}} While at Cornell, she met [[Martin D. Ginsburg]] at age 17.<ref name="Galanes, Philip" /> She graduated from Cornell with a [[Bachelor of Arts]] degree in government on June 23, 1954. While at Cornell, Bader studied under Russian-American novelist [[Vladimir Nabokov]], and she later identified Nabokov as a major influence on her development as a writer.<ref>{{Cite web|title=When Vladimir Nabokov Taught Ruth Bader Ginsburg, His Most Famous Student, To Care Deeply About Writing {{!}} Open Culture|url=https://www.openculture.com/2016/11/when-vladimir-nabokov-taught-to-care-deeply-about-writing.html|access-date=April 4, 2021|archive-date=January 22, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210122191014/https://www.openculture.com/2016/11/when-vladimir-nabokov-taught-to-care-deeply-about-writing.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=October 26, 2020|title=How Lolita Author Vladimir Nabokov Helped Ruth Bader Ginsburg Find Her Voice|url=https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/634168/what-vladimir-nabokov-taught-ruth-bader-ginsburg|access-date=April 4, 2021|website=mentalfloss.com|archive-date=March 5, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210305132141/https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/634168/what-vladimir-nabokov-taught-ruth-bader-ginsburg|url-status=live}}</ref> She was a member of [[Phi Beta Kappa]] and the highest-ranking female student in her graduating class.<ref name="Scanlon, Jennifer"/><ref name=Hensley /> Bader married Ginsburg a month after her graduation from Cornell. The couple moved to [[Fort Sill|Fort Sill, Oklahoma]], where Martin Ginsburg, a [[Reserve Officers' Training Corps]] graduate, was stationed as a called-up active duty [[United States Army Reserve]] officer during the [[Korean War]].<ref name="Galanes, Philip" /><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umvkXhtbbpk|title=A Conversation with Ruth Bader Ginsburg at Harvard Law School|date=February 7, 2013 |publisher=Harvard Law School|access-date=February 22, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140121182051/http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=umvkXhtbbpk|archive-date=January 21, 2014|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=Hensley>{{cite book|first1=Thomas R.|last1=Hensley|first2=Kathleen|last2=Hale|first3=Carl|last3=Snook|title=The Rehnquist Court: Justices, Rulings, and Legacy|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iGLZyxI_w9kC&pg=PA92|access-date=October 1, 2009|edition=hardcover|series=ABC-CLIO Supreme Court Handbooks|year=2006|publisher=[[ABC-CLIO]]|location=[[Santa Barbara, California]]|isbn=1576072002|page=92|lccn=2006011011|archive-date=August 19, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200819123831/https://books.google.com/books?id=iGLZyxI_w9kC&pg=PA92|url-status=live}}</ref> At age 21, Ruth Bader Ginsburg worked for the [[Social Security Administration]] office in Oklahoma, where she was demoted after becoming pregnant with her first child. She gave birth to a daughter in 1955.<ref name="Margolick, David; NYT; Trial by Adversity">{{cite news|last1=Margolick|first1=David|date=June 25, 1993|title=Trial by Adversity Shapes Jurist's Outlook|newspaper=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/25/us/trial-by-adversity-shapes-jurist-s-outlook.html?pagewanted=all|url-status=live|access-date=February 21, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304150717/http://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/25/us/trial-by-adversity-shapes-jurist-s-outlook.html?pagewanted=all|archive-date=March 4, 2016}}</ref> |

|||

In 1977 she became a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at [[North Allegheny]]. As the chief litigator of the [[ACLU]]'s women's rights project, she argued several cases in front of the Supreme Court and attained a reputation as a skilled oral advocate. |

|||

In the fall of 1956, Ruth Bader Ginsburg enrolled at [[Harvard Law School]], where she was one of only 9 women in a class of about 500 men.<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://www.law.harvard.edu/students/orgs/jlg/vol27/bader-ginsburg.pdf|title=The Changing Complexion of Harvard Law School|journal=Harvard Women's Law Journal|last1=Bader Ginsburg|first1=Ruth |volume=27|page=303|year=2004|access-date=December 9, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130116072052/http://www.law.harvard.edu/students/orgs/jlg/vol27/bader-ginsburg.pdf|archive-date=January 16, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/2012-09-20/news/sns-mct-ruth-bader-ginsburg-at-cu-boulder-gay-marriage-20120920_1_defense-of-marriage-act-gay-marriage-law-school|title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg at CU-Boulder: Gay marriage likely to come before Supreme Court within a year|work=Orlando Sentinel|last=Anas|first=Brittany|date=September 20, 2012|access-date=December 9, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130115084550/http://articles.orlandosentinel.com/2012-09-20/news/sns-mct-ruth-bader-ginsburg-at-cu-boulder-gay-marriage-20120920_1_defense-of-marriage-act-gay-marriage-law-school|archive-date=January 15, 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> The [[Dean of Harvard Law School|dean of Harvard Law]], [[Erwin Griswold]], reportedly invited all the female law students to dinner at his family home and asked the female law students, including Ginsburg, "Why are you at Harvard Law School, taking the place of a man?"{{efn|The dean later claimed he was trying to learn students' stories.}}<ref name="Galanes, Philip" /><ref>{{cite book |last1=Hope |first1=Judith Richards |title=Pinstripes and Pearls |date=2003 |publisher=A Lisa Drew Book/Scribner |location=New York |isbn=9781416575252 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/pinstripespearls00hope/page/104 104]–109 |edition=1st |url=https://archive.org/details/pinstripespearls00hope |url-access=registration |quote=pinstripes and pearls. |access-date=December 27, 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Magill |first1=M. Elizabeth |title=At the U.S. Supreme Court: A Conversation with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg |journal=Stanford Lawyer |date=November 11, 2013 |volume=Fall 2013 |issue=89 |url=https://law.stanford.edu/stanford-lawyer/articles/legal-matters/ |access-date=July 8, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170915213555/https://law.stanford.edu/stanford-lawyer/articles/legal-matters/ |archive-date=September 15, 2017 |url-status=live }}</ref> When her husband took a job in New York City, that same dean denied Ginsburg's request to complete her third year towards a Harvard law degree at [[Columbia Law School]],<ref>{{cite book|last=De Hart|first=Jane Sherron|author-link=Jane Sherron De Hart|title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life|orig-date=2018|publisher=Vintage Books|location=New York|isbn=9781984897831|pages=73–77|date=2020|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u5DyDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA73|access-date=December 20, 2020|archive-date=January 29, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220129213745/https://www.google.com/books/edition/Ruth_Bader_Ginsburg/u5DyDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA73&printsec=frontcover|url-status=live}}</ref> so Ginsburg transferred to Columbia and became the first woman to be on two major [[law review]]s: the ''[[Harvard Law Review]]'' and ''[[Columbia Law Review]]''. In 1959, she earned her law degree at Columbia and tied for first in her class.<ref name="Oyez bio" /><ref name="Toobin">[[Jeffrey Toobin|Toobin, Jeffrey]] (2007). ''[[The Nine (book)|The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court]]'', New York, [[Doubleday (publisher)|Doubleday]], p. 82. {{ISBN|978-0385516402}}</ref> |

|||

== Judicial career == |

|||

[[Image:ginsburgandclinton.jpg|thumb|200px|Ruth Bader Ginsburg officially accepts the nomination from President Bill Clinton.]] |

|||

==Early career== |

|||

Ginsburg was appointed a Judge of the [[United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit]] by [[Jimmy Carter|President Carter]] in 1980. |

|||

At the start of her legal career, Ginsburg encountered difficulty in finding employment.<ref name="Cooper, Cynthia L.">{{cite journal|last1=Cooper|first1=Cynthia L.|title=Women Supreme Court Clerks Striving for "Commonplace"|journal=Perspectives|date=Summer 2008|volume=17|issue=1|pages=18–22|url=http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publishing/perspectives_magazine/women_perspectives_summer08_women_sct_clerks.authcheckdam.pdf|access-date=July 9, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190406080207/https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/publishing/perspectives_magazine/women_perspectives_summer08_women_sct_clerks.authcheckdam.pdf|archive-date=April 6, 2019|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Columbia Law School; brief bio">{{cite web|title=A Brief Biography of Justice Ginsburg|url=http://www.law.columbia.edu/law_school/communications/reports/winter2004/bio|publisher=Columbia Law School|access-date=July 9, 2016|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160624123710/http://www.law.columbia.edu/law_school/communications/reports/winter2004/bio|archive-date=June 24, 2016}}</ref><ref name="Liptak, Adam; Kagan Says Her Path" /> In 1960, Supreme Court Justice [[Felix Frankfurter]] rejected Ginsburg for a clerkship because of her gender. He did so despite a strong recommendation from [[Albert Sacks|Albert Martin Sacks]], who was a professor and later [[Dean (education)|dean]] of Harvard Law School.<ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected" /><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/30/washington/30scotus.html|title=Women Suddenly Scarce Among Justices' Clerks|last=Greenhouse|first=Linda|date=August 30, 2006|newspaper=The New York Times |url-access=subscription|access-date=June 27, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090425035323/http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/30/washington/30scotus.html|archive-date=April 25, 2009|url-status=live}}</ref>{{efn|name=note 1|According to Ginsburg, Justice William O. Douglas hired the first female Supreme Court clerk in 1944, and the second female law clerk was not hired until 1966.<ref name="Cooper, Cynthia L." />}} Columbia law professor [[Gerald Gunther]] also pushed for Judge [[Edmund Louis Palmieri|Edmund L. Palmieri]] of the [[United States District Court for the Southern District of New York|U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York]] to hire Ginsburg as a [[law clerk]], threatening to never recommend another Columbia student to Palmieri if he did not give Ginsburg the opportunity and guaranteeing to provide the judge with a replacement clerk should Ginsburg not succeed.<ref name="Margolick, David; NYT; Trial by Adversity" /><ref name="Oyez bio" /><ref name="Syckle-2018">{{Cite news|url=https://www.thecut.com/2018/01/justice-ruth-bader-ginsburgs-metoo-story.html|title=This Is Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's #MeToo Story|last=Syckle|first=Katie Van|date=January 22, 2018|work=[[New York (magazine)|The Cut]]|access-date=January 22, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180122204710/https://www.thecut.com/2018/01/justice-ruth-bader-ginsburgs-metoo-story.html|archive-date=January 22, 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> Later that year, Ginsburg began her clerkship for Judge Palmieri, and she held the position for two years.<ref name="Margolick, David; NYT; Trial by Adversity" /><ref name="Oyez bio" /> |

|||

[[Bill Clinton|President Clinton]] nominated her as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court on [[June 14]] [[1993]]. During her subsequent confirmation hearings in the [[U.S. Senate]], she refused to answer questions regarding her personal views on most issues or how she would adjudicate certain hypothetical situations as a Supreme Court Justice. As she noted during the hearings, "Were I to rehearse here what I would say and how I would reason on such questions, I would act injudiciously". |

|||

===Academia=== |

|||

At the same time, however, Ginsburg did answer questions relating to some potentially controversial issues, for instance, she stated that she does believe that there is a constitutional right to privacy, and she explicated at some length on her personal judicial philosophy and thoughts regarding gender equality ([http://www.acslaw.org/views/Bennard%20re%20Ginsburg%20confirmation.pdf]). The [[U.S. Senate]] confirmed her by a 96 to 3 vote<ref>The three negative votes came from Republicans [[Don Nickles]] (OK), [[Robert C. Smith]] (NH), and [[Jesse Helms]] (NC).</ref> and she took her seat on [[August 10]] [[1993]]. |

|||

From 1961 to 1963, Ginsburg was a research associate and then an associate director of the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure, working alongside director [[Hans Smit (professor)|Hans Smit]];<ref>{{Cite web |title=Tribute to Hans Smit by U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg |url=https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/tribute-hans-smit-us-supreme-court-justice-ruth-bader-ginsburg |access-date=June 25, 2022 |website=law.columbia.edu }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=September 24, 2020 |title=Columbia Law School professor inspired by the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg |url=https://www.wusa9.com/article/news/local/dc/columbia-law-professor-inspired-by-the-late-ruth-bader-ginsburg/65-f1723c63-851e-4266-a466-4d8e5405d540 |access-date=June 25, 2022 |website=wusa9.com }}</ref> she learned [[Swedish language|Swedish]] to co-author a book with [[Anders Bruzelius]] on civil procedure in Sweden.<ref>{{cite book|title=Civil Procedure in Sweden|first1=Ruth |last1=Bader Ginsburg|author-link=Ruth Bader Ginsburg|first2=Anders|last2=Bruzelius|year=1965|publisher=[[Martinus Nijhoff Publishers|Martinus Nijhoff]]|oclc=3303361|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HTjCNG8-XzwC|access-date=October 17, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160104230655/https://books.google.com/books?id=HTjCNG8-XzwC|archive-date=January 4, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Reviewed Works: Civil Procedure in Sweden by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Anders Bruzelius; Civil Procedure in Italy by Mauro Cappelletti, Joseph M. Perillo|first=Stefan A.|last=Riesenfeld|journal=[[Columbia Law Review]]|volume=67|number=6|date=June 1967|pages=1176–78|jstor=1121050|doi=10.2307/1121050}}</ref> Ginsburg conducted extensive research for her book at [[Lund University]] in Sweden.<ref>Bayer, Linda N. (2000). ''Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Women of Achievement)''. Philadelphia. [[Infobase Publishing|Chelsea House]], p. 46. {{ISBN|978-0791052877}}.</ref> Ginsburg's time in Sweden and her association with the Swedish Bruzelius family of jurists also influenced her thinking on gender equality. She was inspired when she observed the changes in Sweden, where women were 20 to 25 percent of all law students; one of the judges whom Ginsburg observed for her research was eight months pregnant and still working.<ref name="Galanes, Philip" /> Bruzelius' daughter, Norwegian supreme court justice and president of the [[Norwegian Association for Women's Rights]], [[Karin M. Bruzelius]], herself a law student when Ginsburg worked with her father, said that "by getting close to my family, Ruth realized that one could live in a completely different way, that women could have a different lifestyle and legal position than what they had in the United States."<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dn.se/varlden/bjorn-af-kleen-kombinationen-av-sprodhet-och-javlar-anamma-bidrog-till-hennes-status-som-legendar/|title=Kombination av sprödhet och jävlar anamma bidrog till hennes status som legendar|trans-title=The combination of fragility and taking on devils contributed to her status as a legend|last=Kleen|first=Björn af|date=September 19, 2020|website=[[Dagens Nyheter]]|access-date=September 30, 2020|archive-date=September 29, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200929122015/https://www.dn.se/varlden/bjorn-af-kleen-kombinationen-av-sprodhet-och-javlar-anamma-bidrog-till-hennes-status-som-legendar/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.dn.se/nyheter/varlden/tiden-i-sverige-avgorande-for-ruth-bader-ginsburgs-kamp/|title=Tiden i Sverige avgörande för Ruth Bader Ginsburgs kamp|trans-title=Her time in Sweden was crucial for Ruth Bader Ginsburg's struggle|date=September 19, 2020|website=[[Dagens Nyheter]]|access-date=September 30, 2020|archive-date=September 24, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200924090837/https://www.dn.se/nyheter/varlden/tiden-i-sverige-avgorande-for-ruth-bader-ginsburgs-kamp/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Ginsburg has urged a cautious approach to adjudication, arguing in a speech given shortly before her nomination to the Supreme Court that "[m]easured motions seem to me right, in the main, for constitutional as well as common law adjudication. Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped, experience teaches, may prove unstable." [http://www.dlc.org/ndol_ci.cfm?kaid=127&subid=177&contentid=253356] Ginsburg has urged that the Supreme Court allow for dialogue with elected branches. |

|||

Ginsburg's first position as a professor was at [[Rutgers Law School]] in 1963.<ref name="Hill Kay, Herma">{{cite journal|last1=Hill Kay|first1=Herma|title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Professor of Law|journal=Colum. L. Rev.|year=2004|volume=104|issue=2|pages=2–20|url=http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=facpubs|access-date=July 9, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160322055103/http://scholarship.law.berkeley.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=facpubs|archive-date=March 22, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> She was paid less than her male colleagues because, she was told, "your husband has a very good job."<ref name="Liptak, Adam; Kagan Says Her Path">{{cite news|last1=Liptak|first1=Adam|author-link=Adam Liptak|title=Kagan Says Her Path to Supreme Court Was Made Smoother by Ginsburg's|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/11/us/kagan-says-her-path-to-supreme-court-was-made-smoother-by-ginsburg.html|access-date=July 9, 2016|newspaper=[[The New York Times]]|date=February 10, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151001031614/http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/11/us/kagan-says-her-path-to-supreme-court-was-made-smoother-by-ginsburg.html?_r=0|archive-date=October 1, 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> At the time Ginsburg entered academia, she was one of fewer than twenty female law professors in the United States.<ref name="Hill Kay, Herma" /> She was a professor of law at Rutgers from 1963 to 1972, teaching mainly [[civil procedure]] and receiving tenure in 1969.<ref name="Federal Judicial Center">{{cite web|title=Ginsburg, Ruth Bader|url=https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges/ginsburg-ruth-bader|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180429155253/https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges/ginsburg-ruth-bader|archive-date=April 29, 2018|access-date=April 28, 2018|website=FJC.gov|publisher=[[Federal Judicial Center]]}}</ref><ref name="Toobin, Jeffrey; Heavyweight">{{cite magazine|last1=Toobin|first1=Jeffrey|title=Heavyweight: How Ruth Bader Ginsburg has moved the Supreme Court|url=https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/03/11/heavyweight-ruth-bader-ginsburg|access-date=February 28, 2016|magazine=The New Yorker|date=March 11, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160217223215/http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/03/11/heavyweight-ruth-bader-ginsburg|archive-date=February 17, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Though Ginsburg has consistently supported [[abortion rights]] and joined in the Supreme Court's opinion striking down [[Nebraska|Nebraska's]] [[partial-birth abortion]] law in ''[[Stenberg v. Carhart]]'' (2000), she has criticized the court's ruling in ''[[Roe v. Wade]]'' as terminating a nascent, democratic movement to liberalize abortion laws which she contends might have built a more durable consensus in support of abortion rights. She has also been an advocate for references to foreign law and norms in judicial opinions, in contrast to the [[textualism|textualist]] views of her colleague Justice [[Antonin Scalia]]. |

|||

In 1970, she co-founded the ''[[Women's Rights Law Reporter]]'', the first [[law journal]] in the U.S. to focus exclusively on women's rights.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://pegasus.rutgers.edu/~wrlr/index.html|title=About the Reporter |access-date=June 29, 2008|url-status=dead|work=Women's Rights Law Reporter|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080708192947/http://pegasus.rutgers.edu/~wrlr/index.html|archive-date=July 8, 2008|quote=Founded in 1970 by now-Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and feminist activists, legal workers, and law students{{spaces}}...}}</ref> From 1972 to 1980, she taught at Columbia Law School, where she became the first [[Academic tenure|tenured]] woman and co-authored the first law school [[casebook]] on [[Sexism|sex discrimination]].<ref name="Toobin, Jeffrey; Heavyweight" /> She also spent a year as a fellow of the [[Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences]] at [[Stanford University]] from 1977 to 1978.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Magill|first1=M. Elizabeth|title=At the U.S. Supreme Court: A Conversation with Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg|url=https://law.stanford.edu/stanford-lawyer/articles/legal-matters/|publisher=[[Stanford Law School]]|access-date=July 8, 2017|date=November 11, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170915213555/https://law.stanford.edu/stanford-lawyer/articles/legal-matters/|archive-date=September 15, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Ginsburg was diagnosed with [[colo-rectal cancer]] in 1999 and underwent surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiation treatments. The condition appears to be arrested. |

|||

===Litigation and advocacy=== |

|||

In September 2005, amidst speculation that a woman would replace retiring justice [[Sandra Day O'Connor]], Ginsburg told the [[Association of the Bar of the City of New York]] that she felt "any woman would not do", and that she had a list of names which she did not expect the President to read. She also defended her views on paying attention to rulings from other countries. |

|||

[[File:RB Ginsburg 1977 ©Lynn Gilbert.jpg|thumb|alt=Ginsburg standing by a window|left|Ginsburg in 1977, photographed by [[Lynn Gilbert]]]] |

|||

She is considered to be part of the "[[liberal]] wing" in the current court and has a [[Segal-Cover score]] of 0.680 placing her as the most liberal (by that measure) of current justices, although more moderate than those of many other post-[[World War II|War]] justices. In a 2003 statistical analysis of Supreme Court voting patterns, Ginsburg emerged the second most liberal member of the Court (behind [[John Paul Stevens|Justice Stevens]]).<ref>See http://pooleandrosenthal.com/the_unidimensional_supreme_court.htm .</ref><ref>Lawrence Sirovich, "A Pattern Analysis of the Second Rehnquist Court", Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 100 (24 June 2003), available online at http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/1132164100v1 .</ref> |

|||

In 1972, Ginsburg co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the [[American Civil Liberties Union]] (ACLU), and in 1973, she became the Project's general counsel.<ref name=Hensley /> The Women's Rights Project and related ACLU projects participated in more than 300 gender discrimination cases by 1974. As the director of the ACLU's Women's Rights Project, she argued six gender discrimination cases before the Supreme Court between 1973 and 1976, winning five.<ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected">{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/15/us/supreme-court-woman-rejected-clerk-chosen-justice-ruth-joan-bader-ginsburg.html|title=The Supreme Court: Woman in the News; Rejected as a Clerk, Chosen as a Justice: Ruth Joan Bader Ginsburg|last=Lewis|first=Neil A.|date=June 15, 1993|newspaper=[[The New York Times]]|issn=0362-4331|access-date=September 17, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160717232135/http://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/15/us/supreme-court-woman-rejected-clerk-chosen-justice-ruth-joan-bader-ginsburg.html|archive-date=July 17, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> Rather than asking the Court to end all gender discrimination at once, Ginsburg charted a strategic course, taking aim at specific discriminatory statutes and building on each successive victory. She chose plaintiffs carefully, at times picking male plaintiffs to demonstrate that gender discrimination was harmful to both men and women.<ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected" /><ref name="Toobin, Jeffrey; Heavyweight" /> The laws Ginsburg targeted included those that on the surface appeared beneficial to women, but in fact reinforced the notion that women needed to be dependent on men.<ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected" /> Her strategic advocacy extended to word choice, favoring the use of "gender" instead of "sex", after her secretary suggested the word "sex" would serve as a distraction to judges.<ref name="Toobin, Jeffrey; Heavyweight" /> She attained a reputation as a skilled oral advocate, and her work led directly to the end of gender discrimination in many areas of the law.<ref>Pullman, Sandra (March 7, 2006). [https://www.aclu.org/womens-rights/tribute-legacy-ruth-bader-ginsburg-and-wrp-staff "Tribute: The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and WRP Staff"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150319024236/http://www.aclu.org/womens-rights/tribute-legacy-ruth-bader-ginsburg-and-wrp-staff|date=March 19, 2015}}. ACLU.org. Retrieved November 18, 2010.</ref> |

|||

Some notable cases in which Ginsburg wrote an opinion: |

|||

*''[[United States v. Virginia]]'' Court Opinion |

|||

*''[[Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc.]]'' Court Opinion |

|||

*''[[Bush v. Gore]]'' Dissenting |

|||

*''[[Eldred v. Ashcroft]]'' Court Opinion |

|||

*''[[Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Saudi Basic Industries Corp.]]'' Court Opinion |

|||

Ginsburg volunteered to write the brief for ''[[Reed v. Reed]]'', {{ussc|404|71|1971|el=no}}, in which the Supreme Court extended the protections of the [[Equal Protection Clause]] of the [[Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Fourteenth Amendment]] to women.<ref name="Toobin, Jeffrey; Heavyweight" /><ref name="Supreme Court Historical; Reed v. Reed2">{{cite news|url=http://supremecourthistory.org/lc_breaking_new_ground.html|title=Supreme Court Decisions & Women's Rights—Milestones to Equality Breaking New Ground—''Reed v. Reed'', 404 U.S. 71 (1971)|publisher=The Supreme Court Historical Society|access-date=February 28, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160228070933/http://supremecourthistory.org/lc_breaking_new_ground.html|archive-date=February 28, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref>{{efn|Ginsburg listed [[Dorothy Kenyon]] and [[Pauli Murray]] as co-authors on the brief in recognition of their contributions to feminist legal argument.<ref name="Kerber, Linda K. Judge Ginsburg's Gift">{{cite news|last1=Kerber|first1=Linda K.|title=Judge Ginsburg's Gift|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1993/08/01/judge-ginsburgs-gift/036d8f58-fef8-4af8-8eae-772a8d9dd0a0|access-date=July 9, 2016|newspaper=The Washington Post|date=August 1, 1993|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170305063220/https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1993/08/01/judge-ginsburgs-gift/036d8f58-fef8-4af8-8eae-772a8d9dd0a0/|archive-date=March 5, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref>|name=note 3}} In 1972, she argued before the [[United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit|10th Circuit]] in ''[[Moritz v. Commissioner]]'' on behalf of a man who had been denied a caregiver deduction because of his gender. As ''amicus'' she argued in ''[[Frontiero v. Richardson]]'', {{Replace|{{ussc|411|677|1973|el=no}}|[[United States Reports|U.S.]]|U.S.}}, which challenged a statute making it more difficult for a female service member (Frontiero) to claim an increased housing allowance for her husband than for a male service member seeking the same allowance for his wife. Ginsburg argued that the statute treated women as inferior, and the Supreme Court ruled 8–1 in Frontiero's favor.<ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected" /> The court again ruled in Ginsburg's favor in ''[[Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld]]'', {{Replace|{{Ussc|420|636|1975|el=no}}|[[United States Reports|U.S.]]|U.S.}}, where Ginsburg represented a widower denied survivor benefits under Social Security, which permitted widows but not widowers to collect special benefits while caring for minor children. She argued that the statute discriminated against male survivors of workers by denying them the same protection as their female counterparts.<ref name="Williams, Wendy W., Columbia Journal2">{{cite journal|year=2013|title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg's Equal Protection Clause: 1970–80|url=http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2253&context=facpub|journal=Columbia Journal of Gender and Law|volume=25|pages=41–49|last1=Williams|first1=Wendy W.|access-date=March 13, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170305003306/http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2253&context=facpub|archive-date=March 5, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==Dispute over relevance of international law== |

|||

On [[March 1]] [[2005]], in the case of ''[[Roper v. Simmons]]'', the Supreme Court (in an opinion written by Justice [[Anthony Kennedy]]) ruled in a 5-4 decision that the Constitution forbids executing convicts who committed their crimes before turning 18. In addition to the fact that most states now prohibit executions in such cases, the majority opinion reasoned that the United States was increasingly out of step with the world by allowing minors to be executed, saying "the United States now stands alone in a world that has turned its face against the juvenile death penalty." |

|||

In 1973, the same year ''[[Roe v. Wade]]'' was decided, Ginsburg filed a federal case to challenge [[involuntary sterilization]], suing members of the [[Eugenics Board of North Carolina]] on behalf of Nial Ruth Cox, a mother who had been coercively sterilized under North Carolina's Sterilization of Persons Mentally Defective program on penalty of her family losing welfare benefits.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Carmon |first1=Irin |last2=Knizhnik |first2=Shana |title=A Response |journal=[[Signs (journal)|Signs]] |year=2017 |volume=42 |issue=3 |page=797 |doi=10.1086/689745 |s2cid=151760112 |url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/689745 |access-date=September 26, 2020 |archive-date=May 8, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220508110611/https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/689745 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Tabacco Mar |first1=Ria |title=The forgotten time Ruth Bader Ginsburg fought against forced sterilization |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/09/19/sterilization-ruth-bader-ginsburg/ |access-date=September 26, 2020 |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=September 19, 2020 |archive-date=September 26, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200926034525/https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/09/19/sterilization-ruth-bader-ginsburg/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Cox complaint |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/context/cox-complaint/bff27c19-5195-460c-8757-a3a81ed08331/?itid=lk_inline_manual_8 |access-date=September 26, 2020 |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=September 19, 2020 |archive-date=October 26, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201026121953/https://www.washingtonpost.com/context/cox-complaint/bff27c19-5195-460c-8757-a3a81ed08331/?itid=lk_inline_manual_8 |url-status=live }}</ref> During a 2009 interview with [[Emily Bazelon]] of ''[[The New York Times]]'', Ginsburg stated: "I had thought that at the time ''Roe'' was decided, there was concern about population growth and particularly growth in populations that we don't want to have too many of."<ref>{{Cite news|last=Bazelon|first=Emily|date=July 7, 2009|title=The Place of Women on the Court|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/12/magazine/12ginsburg-t.html|access-date=September 26, 2020|issn=0362-4331|archive-date=February 24, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170224032340/http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/12/magazine/12ginsburg-t.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Bazelon conducted a follow-up interview with Ginsburg in 2012 at a joint appearance at [[Yale University]], where Ginsburg claimed her 2009 quote was vastly misinterpreted and clarified her stance.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Bazelon|first=Emily|date=October 19, 2012|title=Justice Ginsburg Sets the Record Straight on Abortion and Population Control|url=https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2012/10/ruth-bader-ginsburg-clears-up-her-views-on-abortion-population-control-and-roe-v-wade.html|access-date=September 26, 2020|website=Slate|archive-date=September 24, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200924131412/https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2012/10/ruth-bader-ginsburg-clears-up-her-views-on-abortion-population-control-and-roe-v-wade.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Did Ruth Bader Ginsburg Cite 'Population Growth' Concerns When Roe v. Wade Was Decided?|url=https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/ruth-bader-ginsburg-and-roe-v-wade/|access-date=September 26, 2020|website=Snopes.com|date=December 17, 2018 |archive-date=November 8, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211108153020/https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/ruth-bader-ginsburg-and-roe-v-wade/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Justice [[Antonin Scalia]] rejected that approach with strident criticism, saying that the justices' personal opinions and the opinions of "like-minded foreigners" should not be given a role in helping interpret the Constitution. |

|||

Ginsburg filed an [[Amicus curiae|amicus brief]] and sat with counsel at oral argument for ''[[Craig v. Boren]]'', {{Replace|{{ussc|429|190|1976|el=no}}|[[United States Reports|U.S.]]|U.S.}}, which challenged an Oklahoma statute that set different minimum drinking ages for men and women.<ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected" /><ref name="Williams, Wendy W., Columbia Journal2" /> For the first time, the court imposed what is known as [[intermediate scrutiny]] on laws discriminating based on gender, a heightened standard of Constitutional review.<ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected" /><ref name="Williams, Wendy W., Columbia Journal2" /><ref>{{cite web|url=https://thinkprogress.org/justice-ginsburg-if-i-were-nominated-today-my-womens-rights-work-for-the-aclu-would-probably-912c845993da|title=Justice Ginsburg: If I Were Nominated Today, My Women's Rights Work For The ACLU Would Probably Disqualify Me|last=Millhiser|first=Ian|date=August 30, 2011|website=ThinkProgress|access-date=June 1, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170223051126/https://thinkprogress.org/justice-ginsburg-if-i-were-nominated-today-my-womens-rights-work-for-the-aclu-would-probably-912c845993da|archive-date=February 23, 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> Her last case as an attorney before the Supreme Court was ''[[Duren v. Missouri]]'', {{Replace|{{ussc|439|357|1979|el=no}}|[[United States Reports|U.S.]]|U.S.}}, which challenged the validity of voluntary [[jury duty]] for women, on the ground that participation in jury duty was a citizen's vital governmental service and therefore should not be optional for women. At the end of Ginsburg's oral argument, then-Associate Justice [[William Rehnquist]] asked Ginsburg, "You won't settle for putting [[Susan B. Anthony]] [[Susan B. Anthony dollar|on the new dollar]], then?"<ref name="WaPo199307192">Von Drehle, David (July 19, 1993). [https://web.archive.org/web/20100902061856/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/08/23/AR2007082300903_pf.html "Redefining Fair With a Simple Careful Assault—Step-by-Step Strategy Produced Strides for Equal Protection"]. ''[[The Washington Post]]''. Retrieved August 24, 2009.</ref> Ginsburg said she considered responding, "We won't settle for tokens," but instead opted not to answer the question.<ref name="WaPo199307192" /> |

|||

Ginsburg rejected that argument in a speech given about one month after ''Roper''. "Judges in the United States are free to consult all manner of commentary," she said to several hundred lawyers, scholars, and other members of the American Society of International Law.[http://www.asil.org/events/AM05/ginsburg050401.html] If a law review article by a professor is a suitable citation, she asked, why not a well reasoned opinion by foreign jurist? Fears about relying too heavily on world opinion "should not lead us to abandon the effort to learn what we can from the experience and good thinking foreign sources may convey," Ginsburg told the audience. |

|||

Legal scholars and advocates credit Ginsburg's body of work with making significant legal advances for women under the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution.<ref name="Toobin, Jeffrey; Heavyweight" /><ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected" /> Taken together, Ginsburg's legal victories discouraged legislatures from treating women and men differently under the law.<ref name="Toobin, Jeffrey; Heavyweight" /><ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected" /><ref name="Williams, Wendy W., Columbia Journal2" /> She continued to work on the ACLU's Women's Rights Project until her appointment to the Federal Bench in 1980.<ref name="Toobin, Jeffrey; Heavyweight" /> Later, colleague [[Antonin Scalia]] praised Ginsburg's skills as an advocate. "She became the leading (and very successful) litigator on behalf of women's rights—the [[Thurgood Marshall]] of that cause, so to speak." This was a comparison that had first been made by former solicitor general Erwin Griswold who was also her former professor and dean at Harvard Law School, in a speech given in 1985.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Labaton |first1=Stephen |title=Senators See Easy Approval for Nominee |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/16/us/senators-see-easy-approval-for-nominee.html?mtrref=undefined&gwh=07BFECEB18F681D38A1B48EF38A012DE&gwt=pay |access-date=December 29, 2018 |newspaper=The New York Times |date=June 16, 1993 |ref=Page A22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181229171804/https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/16/us/senators-see-easy-approval-for-nominee.html?mtrref=undefined&gwh=07BFECEB18F681D38A1B48EF38A012DE&gwt=pay |archive-date=December 29, 2018 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine|last1=Scalia|first1=Antonin|title=The 100 Most Influential People: Ruth Bader Ginsburg|url=http://time.com/3823889/ruth-bader-ginsburg-2015-time-100/|access-date=December 9, 2016|magazine=Time|date=April 16, 2015|ref=Scalia, Antonin; Time|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161209182021/http://time.com/3823889/ruth-bader-ginsburg-2015-time-100/|archive-date=December 9, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref>{{Efn|[[Janet Benshoof]], the president of the [[Center for Reproductive Rights|Center for Reproductive Law and Policy]], made a similar comparison between Ginsburg and Marshall in 1993.<ref name="Lewis, Neil; Supreme Court Woman rejected" />}} |

|||

In response to ''Roper'' and other recent decisions, several [[Republican Party (United States)|Republicans]] in the [[U.S. House of Representatives]] introduced a resolution declaring that the "meaning of the Constitution of the United States should not be based on judgments, laws, or pronouncements of foreign institutions unless such foreign judgments, laws or pronouncements inform an understanding of the original meaning of the Constitution of the United States." A similar resolution was introduced in the [[U.S. Senate]]. In her speech, Ginsburg criticized the resolutions. "Although I doubt the resolutions will pass this Congress, it is disquieting that they have attracted sizable support," she said. "The notion that it is improper to look beyond the borders of the United States in grappling with hard questions has a certain kinship to the view that the U.S. Constitution is a document essentially frozen in time as of the date of its ratification," Ginsburg asserted. "Even more so today, the United States is subject to the scrutiny of a candid world," she said. "What the United States does, for good or for ill, continues to be watched by the international community, in particular by organizations concerned with the advancement of the rule of law and respect for human dignity."[http://www.forbes.com/lists/2006/11/06women_Ruth-Bader-Ginsburg_D8D7.html] |

|||

==U.S. Court of Appeals== |

|||

=="Ginsburg Precedent"== |

|||

In light of the mounting backlog in the federal judiciary, Congress passed the [[Omnibus Judgeship Act of 1978]] increasing the number of federal judges by 117 in district courts and another 35 to be added to the circuit courts. The law placed an emphasis on ensuring that the judges included women and minority groups, a matter that was important to President [[Jimmy Carter]] who had been elected two years before. The bill also required that the nomination process consider the character and experience of the candidates.{{Sfn|De Hart|2020|p=277}}<ref>{{cite web |last1=Carter |first1=Jimmy |title=Statement on Signing H.R. 7843 Into Law: Appointments of Additional District and Circuit Judges |url=https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-signing-hr-7843-into-law-appointments-additional-district-and-circuit-judges |website=The American Presidency Project |publisher=UC Santa Barbara |access-date=September 26, 2020 |archive-date=September 24, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200924181340/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/statement-signing-hr-7843-into-law-appointments-additional-district-and-circuit-judges |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Public Law 95-486 |journal=United States Statutes at Large |date=October 20, 1978 |volume=92 |pages=1629–34 |url=https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-92/pdf/STATUTE-92-Pg1629.pdf |access-date=September 26, 2020 |archive-date=October 2, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201002105609/https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-92/pdf/STATUTE-92-Pg1629.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Ginsburg was considering a change in career as soon as Carter was elected. She was interviewed by the [[United States Department of Justice|Department of Justice]] to become [[Solicitor General of the United States|Solicitor General]], the position she most desired, but knew that she and the African-American candidate who was interviewed the same day had little chance of being appointed by Attorney General [[Griffin Bell]].{{Sfn|De Hart|2020|p=278}} |

|||

Over a decade passed between the time Ginsburg and [[Stephen Breyer]] were appointed and the time another justice left the court. In that time, both Congress and the White House had switched to Republican control. When [[Sandra Day O'Connor]] announced her retirement in the summer 2005 (with [[William Rehnquist]]'s death a few months later), both sides began to squabble about just how many questions President [[George W. Bush]]'s nominees would be expected to answer. The debate heated up when hearings for [[John Roberts]] began in September 2005. Republicans used an argument that they called the "Ginsburg Precedent", which centered on Ginsburg's confirmation hearings. In those hearings, she did not answer some questions involving matters such as [[abortion]], [[gay rights]], [[separation of church and state]], rights of the disabled, and so on. Only one witness was allowed to testify "against" Ginsburg at her confirmation hearings, and the hearings lasted only four days. They also pointed out that then-Judiciary Committee Chairman [[Joe Biden]] told her not to answer questions that she did not feel comfortable answering. |

|||

[[File:Ruth Bader Ginsburg - Sibley Lecture 1981(cropped).jpg|thumb|upright|Ginsburg in 1981]] |

|||

[[File:President Jimmy Carter and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.jpg|thumb|alt=Ginsburg shaking hands with Carter as the two smile|Ginsburg with President [[Jimmy Carter]] in 1980|left]] |

|||

At the time, Ginsburg was a fellow at Stanford University where she was working on a written account of her work in litigation and advocacy for equal rights. Her husband was a visiting professor at [[Stanford Law School]] and was ready to leave his firm, [[Weil, Gotshal & Manges]], for a tenured position. He was at the same time working hard to promote a possible judgeship for his wife. In January 1979, she filled out the questionnaire for possible nominees to the [[United States courts of appeals|U.S. Court of Appeals]] for the [[Second Circuit]], and another for the [[District of Columbia Circuit]].{{Sfn|De Hart|2020|p=278}} Ginsburg was nominated by President Carter on April 14, 1980, to a seat on the DC Circuit vacated by Judge [[Harold Leventhal (judge)|Harold Leventhal]] upon his death. She was confirmed by the [[United States Senate]] on June 18, 1980, and received her commission later that day.<ref name="Federal Judicial Center" />{{Sfn|De Hart|2020|pp=286–291}} |

|||

During her time as a judge on the DC Circuit, Ginsburg often found consensus with her colleagues including conservatives [[Robert Bork|Robert H. Bork]] and Antonin Scalia.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1993/07/18/conventional-roles-hid-a-revolutionary-intellect/38a8055a-d575-4eee-b59a-44c2d58771f5/|title=Conventional Roles Hid a Revolutionary Intellect|last=Drehle|first=David Von|date=July 18, 1993|newspaper=[[The Washington Post]]|issn=0190-8286|access-date=September 16, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160919170923/https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1993/07/18/conventional-roles-hid-a-revolutionary-intellect/38a8055a-d575-4eee-b59a-44c2d58771f5/|archive-date=September 19, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/06/22/scalia-tenacious-after-staking-out-a-position/84b60d7d-142b-4959-a7a3-aadfeda39d00/|title=Scalia Tenacious After Staking Out a Position|last1=Marcus|first1=Ruth|date=June 22, 1986|last2=Schmidt|first2=Susan|newspaper=[[The Washington Post]]|issn=0190-8286|access-date=September 16, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160919170839/https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1986/06/22/scalia-tenacious-after-staking-out-a-position/84b60d7d-142b-4959-a7a3-aadfeda39d00/|archive-date=September 19, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> Her time on the court earned her a reputation as a "cautious jurist" and a moderate.<ref name="Richter, Paul; Clinton Picks Moderate Judge" /> Her service ended on August 9, 1993, due to her elevation to the United States Supreme Court,<ref name="Federal Judicial Center" /><ref name="istorical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit; Bio">{{cite web|title=Judges of the D. C. Circuit Courts|url=http://dcchs.org/Biographies/biosalpha.html#garland|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160225040553/http://dcchs.org/Biographies/biosalpha.html#garland|archive-date=February 25, 2016|access-date=February 19, 2016|website=Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|last=Fulwood III|first=Sam|date=August 4, 1993|title=Ginsburg Confirmed as 2nd Woman on Supreme Court|newspaper=[[Los Angeles Times]]|url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-08-04-mn-20339-story.html|url-status=live|access-date=September 16, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170305143136/http://articles.latimes.com/1993-08-04/news/mn-20339_1_supreme-court|archive-date=March 5, 2017|issn=0458-3035}}</ref> and she was replaced by Judge [[David S. Tatel]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.law.uchicago.edu/news/my-chicago-law-moment-50-years-later-federal-appellate-judge-david-tatel-66-still-thinks-about-|title=My Chicago Law Moment: 50 Years Later, Federal Appellate Judge David Tatel, '66, Still Thinks About the Concepts He Learned as a 1L|last=Beaupre Gillespie|first=Becky|date=July 27, 2016|website=law.uchicago.edu|publisher=University of Chicago Law School|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161208095555/http://www.law.uchicago.edu/news/my-chicago-law-moment-50-years-later-federal-appellate-judge-david-tatel-66-still-thinks-about-|archive-date=December 8, 2016|url-status=dead|access-date=June 9, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

In a [[September 28]], [[2005]] speech at [[Wake Forest University]] Ginsburg said that Chief Justice Roberts refusing to answer questions on some cases was "unquestionably right." [http://www.the-dispatch.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20050928/APN/509281240&cachetime=5] However, as the following sentence in the speech made clear, this statement did not affirm the existence of a "precedent" which the Judiciary Committee was obliged to follow; it was merely a statement the nominee could, at his discretion, refuse to answer questions about how he would rule. |

|||

==Supreme Court== |

|||

Democrats had argued against Roberts' refusal to answer certain questions, saying that Ginsburg had made her views very clear, even if she did not comment on all specific matters, and that due to her lengthy tenure as a judge, many of her legal opinions were already available for review. Democrats also pointed out that Republican senator [[Orrin Hatch]] had recommended Ginsburg to then-President Clinton, which suggested Clinton worked in a bipartisan manner. Hatch responded that he had not "recommended" her but suggested to Clinton she might be a candidate that would not receive great opposition{{Fact|date=February 2007}}. |

|||

===Nomination and confirmation=== |

|||

[[File:Announcement of Ruth Bader Ginsburg as Nominee for Associate Supreme Court Justice at the White House - NARA - 131493870.jpg|thumb|alt=Ginsburg speaking at a lectern|Ginsburg officially accepting the nomination from President [[Bill Clinton]] on June 14, 1993]] |

|||

During the [[John Roberts]] confirmation hearings, Biden, Hatch, and Roberts himself brought up Ginsburg's hearings several times as they argued over how many questions she answered and how many Roberts was expected to answer. The "precedent" was again cited several times during the confirmation hearings for Justice [[Samuel Alito]]. |

|||

President [[Bill Clinton]] nominated Ginsburg as an [[associate justice of the Supreme Court]] on June 22, 1993, to fill the seat vacated by retiring justice [[Byron White]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Ginsburg, Ruth Bader|url=https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges/ginsburg-ruth-bader|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180429155253/https://www.fjc.gov/history/judges/ginsburg-ruth-bader|archive-date=April 29, 2018|access-date=September 21, 2020|publisher=Federal Judicial Center}}</ref> She was recommended to Clinton by then–U.S. [[United States Attorney General|attorney general]] [[Janet Reno]],<ref name="Toobin" /> after a suggestion by Utah Republican senator [[Orrin Hatch]].<ref>{{citation|title=Square Peg: Confessions of a Citizen Senator|first=Orrin|last=Hatch|page=180|publisher=Basic Books|year=2003|isbn=0465028675|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=aqxik8vYCK4C&pg=PA180}}{{Dead link|date=August 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> At the time of her nomination, Ginsburg was viewed as having been a moderate and a consensus-builder in her time on the appeals court.<ref name="Richter, Paul; Clinton Picks Moderate Judge" /><ref name=Berke1995>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/15/us/supreme-court-overview-clinton-names-ruth-ginsburg-advocate-for-women-court.html |title=Clinton Names Ruth Ginsburg, Advocate for Women, to Court |first=Richard L. |last=Berke |date=June 15, 1993 |newspaper=The New York Times |access-date=September 21, 2020 |archive-date=November 5, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201105022355/https://www.nytimes.com/1993/06/15/us/supreme-court-overview-clinton-names-ruth-ginsburg-advocate-for-women-court.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Clinton was reportedly looking to increase the Court's diversity, which Ginsburg did as the first Jewish justice since the 1969 resignation of Justice [[Abe Fortas]]. She was the second female and the first Jewish female justice of the Supreme Court.<ref name="Richter, Paul; Clinton Picks Moderate Judge" /><ref name="Rudin, Ken; The 'Jewish Seat'">{{cite news|last1=Rudin|first1=Ken|title=The 'Jewish Seat' On The Supreme Court|url=https://www.npr.org/sections/politicaljunkie/2009/05/heres_a_question_from_carol.html|access-date=February 19, 2016|publisher=NPR|date=May 8, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160219031542/http://www.npr.org/sections/politicaljunkie/2009/05/heres_a_question_from_carol.html|archive-date=February 19, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="IISchraufnagel2018">{{cite book|first1=Michael J. II|last1=Pomante|first2=Scot|last2=Schraufnagel|title=Historical Dictionary of the Barack Obama Administration|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gqJRDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA166|date=April 6, 2018|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers|isbn=978-1-5381-1152-9|pages=166–|access-date=July 30, 2018|archive-date=March 15, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200315132303/https://books.google.com/books?id=gqJRDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA166|url-status=live}}</ref> She eventually became the longest-serving Jewish justice.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://forward.com/culture/394025/ruth-bader-ginsburg-supreme-court-superhero-jane-eisner/ |title=Ruth Bader Ginsburg On Dissent, The Holocaust And Fame |publisher=Forward.com |date=February 11, 2018 |access-date=July 30, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180730050619/https://forward.com/culture/394025/ruth-bader-ginsburg-supreme-court-superhero-jane-eisner/ |archive-date=July 30, 2018 |url-status=live }}</ref> The [[American Bar Association]]'s [[Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary]] rated Ginsburg as "well qualified", its highest rating for a prospective justice.<ref name="Comiskey1994" /> |

|||

[[File:Ruth Bader Ginsburg at her confirmation hearing (a).jpg|alt=Ginsburg speaking into microphone at Senate confirmation hearing on her for her Supreme Court appointment|left|thumb|Ginsburg giving testimony before the [[United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary|Senate Judiciary Committee]] during the hearings on her nomination to be an associate justice]] |

|||

==References== |

|||

During her testimony before the [[United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary|Senate Judiciary Committee]] as part of the [[Senate confirmation|confirmation hearings]], Ginsburg refused to answer questions about her view on the constitutionality of some issues such as the [[Capital punishment in the United States|death penalty]] as it was an issue she might have to vote on if it came before the Court.<ref name="Lewis, Neil A; Ginsburg resists pressure">{{cite news|last1=Lewis|first1=Neil A.|title=The Supreme Court; Ginsburg Deflects Pressure to Talk on Death Penalty|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/07/23/us/the-supreme-court-ginsburg-deflects-pressure-to-talk-on-death-penalty.html|access-date=March 15, 2016|newspaper=[[The New York Times]]|date=July 22, 1993|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160316003825/http://www.nytimes.com/1993/07/23/us/the-supreme-court-ginsburg-deflects-pressure-to-talk-on-death-penalty.html|archive-date=March 16, 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

<div class="references-small"><references/></div> |

|||

At the same time, Ginsburg did answer questions about some potentially controversial issues. For instance, she affirmed her belief in a constitutional right to privacy and explained at some length her personal judicial philosophy and thoughts regarding gender equality.<ref>{{Citation|last=Bennard|first=Kristina Silja|title=The Confirmation Hearings of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Answering Questions While Maintaining Judicial Impartiality|date=August 2005|url=https://www.acslaw.org/sites/default/files/Bennard_re_Ginsburg_confirmation_hearings.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180715123332/https://www.acslaw.org/sites/default/files/Bennard_re_Ginsburg_confirmation_hearings.pdf|url-status=dead|location=Washington, D.C.|publisher=[[American Constitution Society]]|access-date=June 10, 2017|archive-date=July 15, 2018}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref>{{Rp|15–16}} Ginsburg was more forthright in discussing her views on topics about which she had previously written.<ref name="Lewis, Neil A; Ginsburg resists pressure" /> The United States Senate confirmed her by a 96–3 vote on August 3, 1993.{{efn|name=note 2|The three negative votes came from [[Don Nickles]] (R-Oklahoma), [[Bob Smith (New Hampshire politician)|Bob Smith]] (R-New Hampshire) and [[Jesse Helms]] (R-North Carolina), while [[Donald Riegle|Donald W. Riegle Jr.]] (D-Michigan) did not vote.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.votesmart.org/issue_keyvote_member.php?cs_id=8630|title=Project Vote Smart|access-date=December 19, 2010|archive-date=September 19, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200919004310/https://justfacts.votesmart.org/bills|url-status=live}}</ref>}}<ref name="Federal Judicial Center" /> She received her commission on August 5, 1993<ref name="Federal Judicial Center" /> and took her judicial oath on August 10, 1993.<ref name=USSCTimeline>{{cite web|title=Members of the Supreme Court of the United States|publisher=[[Supreme Court of the United States]]|url=https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/members.aspx|access-date=April 26, 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100429170327/https://www.supremecourt.gov/about/members.aspx|archive-date=April 29, 2010|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==Bibliography== |

|||

*Clinton, Bill (2005). ''My Life''. Vintage. ISBN 1-4000-3003-X. |

|||