Isambard Kingdom Brunel: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [accepted revision] |

Van helsing (talk | contribs) m Undid revision 132625772 by 212.169.1.198 (talk) |

GreenC bot (talk | contribs) Rescued 1 archive link; reformat 1 link. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:USURPURL and JUDI batch #20 |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|British mechanical and civil engineer (1806–1859)}} |

|||

[[Image:IKBrunelChains.jpg|thumb|right|Brunel before the launching of the ''[[SS Great Eastern|Great Eastern]]''.]] |

|||

{{redirect|Brunel}} |

|||

{{pp-pc1}} |

|||

{{EngvarB|date=September 2013}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=April 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox engineer |

|||

|honorific_suffix = {{post-nominals|country=GBR|FRS|size=100%}} |

|||

|image = Robert Howlett (Isambard Kingdom Brunel Standing Before the Launching Chains of the Great Eastern), The Metropolitan Museum of Art - restoration1.jpg |

|||

|alt = A 19th-century man wearing a jacket, trousers, and waistcoat, with his hands in his pockets and a cigar in mouth, wearing a tall stovepipe top hat, standing in front of giant iron chains on a drum. |

|||

|caption = [[Isambard Kingdom Brunel Standing Before the Launching Chains of the Great Eastern|Brunel by the launching chains of the SS ''Great Eastern'']], by [[Robert Howlett]], 1857 |

|||

|name = Isambard Kingdom Brunel |

|||

|birth_date = {{Birth date|1806|4|9|df=y}} |

|||

|birth_place = [[Portsmouth]], Hampshire, England |

|||

|death_date = {{Death date and age|1859|9|15|1806|4|9|df=y}} |

|||

|death_place = [[Westminster]], London |

|||

|education = {{unbulleted list|[[Lycée Henri-IV]]|[[University of Caen]]}} |

|||

|spouse = {{marriage|Mary Elizabeth Horsley|5 July 1836}} |

|||

|parents = {{unbulleted list|[[Marc Isambard Brunel]]|[[Sophia Kingdom]]}} |

|||

|children = 3, including [[Henry Marc Brunel|Henry Marc]] |

|||

|discipline = {{unbulleted list|Civil engineer|[[Structural engineer]]|[[Marine engineering|Marine engineer]]}} |

|||

|institutions = {{unbulleted list|[[Royal Society]]|[[Institution of Civil Engineers]]}} |

|||

|practice_name = |

|||

|significant_buildings= |

|||

|significant_projects = {{unbulleted list|[[Great Western Railway]]|[[Clifton Suspension Bridge]]|{{SS|Great Britain}}}} |

|||

|significant_design = [[Royal Albert Bridge]] |

|||

|awards = |

|||

|signature = Isambard Kingdom Brunel signature.svg |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Isambard Kingdom Brunel''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɪ|z|ə|m|b|ɑːr|d|_|ˈ|k|ɪ|ŋ|d|ə|m|_|b|r|uː|ˈ|n|ɛ|l}} {{respell|IZZ|əm|bard|_|KING|dəm|_|broo|NELL}}; 9 April 1806 – 15 September 1859{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}}) was an English civil engineer and mechanical engineer<ref name="Britanica">{{Cite encyclopedia |title=Isambard Kingdom Brunel |author= |encyclopedia=[[Encyclopedia Britannica]] |date=20 January 2023 |access-date=16 February 2023 |url= https://www.britannica.com/biography/Isambard-Kingdom-Brunel}}</ref> who is considered "one of the most ingenious and prolific figures in engineering history",<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://designmuseum.org/designers/isambard-kingdom-brunel |title=Isambard Kingdom Brunel |journal=Nature |volume=181 |issue=4626 |pages=1754–55 |access-date=11 June 2015 |bibcode=1958Natur.181.1754S |last1=Spratt |first1=H.P. |year=1958 |doi=10.1038/1811754a0 |s2cid=4255226 |doi-access=free }}</ref> "one of the 19th-century engineering giants",<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.ssgreatbritain.org/story/isambard-kingdom-brunel |title=Isambard Kingdom Brunel |journal=Nature |volume=181 |issue=4626 |pages=1754–55 |access-date=11 June 2015 |bibcode=1958Natur.181.1754S |last1=Spratt |first1=H.P. |year=1958 |doi=10.1038/1811754a0 |s2cid=4255226 |doi-access=free }}</ref> and "one of the greatest figures of the [[Industrial Revolution]], [who] changed the face of the English landscape with his groundbreaking designs and ingenious constructions".<ref>{{cite book|last1=Rolt|first1=Lionel Thomas Caswall|title=Isambard Kingdom Brunel|date=1957|publisher=Longmans, Green & Co|location=London|page=245|edition=first|author-link=L. T. C. Rolt }}</ref> Brunel built dockyards, the [[Great Western Railway]] (GWR), a series of steamships including the first purpose-built [[Transatlantic crossing|transatlantic]] [[steamship]], and numerous important bridges and tunnels. His designs revolutionised public transport and modern engineering. |

|||

Though Brunel's projects were not always successful, they often contained innovative solutions to long-standing engineering problems. During his career, Brunel achieved many engineering firsts, including assisting his father in the building of the [[Thames Tunnel|first tunnel]] under a [[Navigability|navigable river]] (the [[River Thames]]) and the development of the {{SS|Great Britain}}, the first propeller-driven, ocean-going iron ship, which, when launched in 1843, was the largest ship ever built.{{sfn|Wilson|1994|pp=202–03}}<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.ssgreatbritain.org/Brunel.aspx | title = Isambard Kingdom Brunel | publisher = SS Great Britain | date = 29 March 2006 | access-date = 30 July 2009 | archive-date = 24 March 2010 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100324130927/http://www.ssgreatbritain.org/Brunel.aspx | url-status = dead }}</ref> |

|||

'''Isambard Kingdom Brunel''', [[Fellow of the Royal Society|FRS]] |

|||

([[9 April]] [[1806]] – [[15 September]] [[1859]]) ([[International Phonetic Alphabet|IPA]]: {{IPA|[ˈɪzəmbɑ(ɹ)d ˈkɪŋdəm brʊˈnɛl]}}), was a [[United Kingdom|British]] [[engineer]]. He is best known for the creation of the [[Great Western Railway]], a series of famous [[steamship]]s, and numerous important [[bridge]]s. |

|||

On the GWR, Brunel set standards for a well-built railway, using careful surveys to minimise gradients and curves. This necessitated expensive construction techniques, new bridges, new viaducts, and the {{convert|2|mi|km|spell=in|adj=mid|-long}} [[Box Tunnel]]. One controversial feature was the "[[broad-gauge railway|broad gauge]]" of {{TrackGauge|7ft0.25in}}, instead of what was later to be known as "[[standard gauge]]" of {{TrackGauge|4ft8.5in}}. He astonished Britain by proposing to extend the GWR westward to North America by building steam-powered, iron-hulled ships. He designed and built three ships that revolutionised naval engineering: the {{SS|Great Western}} (1838), the {{SS|Great Britain}} (1843), and the {{SS|Great Eastern}} (1859). |

|||

Though Brunel's projects were not always successful, they often contained innovative solutions to long-standing engineering problems. During his short career, Brunel achieved many engineering "firsts," including assisting in the building of the first [[tunnel]] under a [[navigable river]] and development of [[SS Great Britain|SS ''Great Britain'']], the first [[propeller]]-driven ocean-going iron ship, which was at the time also the largest ship ever built.<ref>[[SS Great Britain|SS ''Great Britain'']] ([http://www.ssgreatbritain.org/history/brunel/]) '''Isambard Kingdom Brunel''' Retrieved Mar. 29, 2006.</ref> |

|||

In 2002, Brunel was placed second in a [[BBC]] public poll to determine the "[[100 Greatest Britons]]". In 2006, the bicentenary of his birth, a major programme of events celebrated his life and work under the name ''Brunel 200''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.brunel200.com/|title= Home|publisher=Brunel 200|access-date=22 July 2009}}</ref> |

|||

Brunel suffered several years of ill health, with [[kidney]] problems, before succumbing to a [[stroke]] at the age of 53. Brunel was said to smoke up to 40 cigars a day, and get by on only four hours of sleep a night. |

|||

== Early life == |

|||

In 2006, a major programme of events celebrated his life and work on the [[bicentenary]] of his birth under the name ''Brunel 200''.<ref>Brunel 200 ([http://www.brunel200.com]) Brunel 200 website Retrieved Feb. 21, 2006.</ref> |

|||

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born on 9 April 1806 in Britain Street, [[Portsea Island|Portsea]], [[Portsmouth]], [[Hampshire]], where his father was working on [[Portsmouth Block Mills|block-making machinery]].{{sfn|Brunel|1870|p=2}}<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| last= Timbs |

|||

| first= John |

|||

| year= 1860 |

|||

| title= Stories of inventors and discoverers in science and the useful arts |

|||

| url= https://archive.org/details/storiesinventor02timbgoog |

|||

| pages= [https://archive.org/details/storiesinventor02timbgoog/page/n119 102], 285–86 |

|||

| place= London |

|||

| publisher= Kent and Co |

|||

| oclc= 1349834 |

|||

}}</ref> He was named [[Isambard]] after his father, the French civil engineer Sir [[Marc Isambard Brunel]], and Kingdom after his English mother, [[Sophia Kingdom]].<ref name="Brindle, birth">{{Cite book |

|||

|last=Brindle |first=Steven |

|||

|title=Brunel: The Man Who Built the World |

|||

|year=2005 |

|||

|isbn=978-0-297-84408-2 |

|||

|publisher=Weidenfeld & Nicolson |

|||

|page=28 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

His mother's sister, Elizabeth Kingdom, was married to Thomas Mudge Jr, son of [[Thomas Mudge (horologist)|Thomas Mudge]] the [[horologist]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Stephens |first1=Richard |title=Thomas Mudge |url=https://artandthecountryhouse.com/catalogues/catalogues-index/thomas-mudge-1022 |website=artandthecountryhouse.com |access-date=1 April 2023 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

He had two elder sisters, Sophia, the eldest child,<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| title= Isambard Kingdom Brunel: Family History |

|||

| work= tracingancestors-uk.com |

|||

| date= 3 February 2012 |

|||

| url= http://tracingancestors-uk.com/genealogies-of-the-famous/isambard-kingdom-brunel-family-history |

|||

}}</ref> and Emma. The whole family moved to [[London]] in 1808 for his father's work. Brunel had a happy childhood, despite the family's constant money worries, with his father acting as his teacher during his early years. His father taught him drawing and observational techniques from the age of four, and Brunel had learned [[Euclidean geometry]] by eight. During this time, he learned to speak French fluently and the basic principles of engineering. He was encouraged to draw interesting buildings and identify any faults in their structure, and like his father he demonstrated an aptitude for mathematics and mechanics.<ref name="Buchanan18">Buchanan (2006), p. 18</ref>{{sfn|Gillings|2006|pp=1, 11}} |

|||

When Brunel was eight, he was sent to Dr Morrell's boarding school in [[Hove]], where he learned [[classics]]. His father, a Frenchman by birth, was determined that Brunel should have access to the high-quality education he had enjoyed in his youth in France. Accordingly, at the age of 14, the younger Brunel was enrolled first at the [[University of Caen Normandy|University of Caen]], then at [[Lycée Henri-IV]] in Paris.<ref name="Buchanan18"/><ref name="1870p5">Brunel, Isambard (1870), p. 5.</ref> |

|||

==Early life== |

|||

The son of engineer Sir [[Marc Isambard Brunel]] and Sophia, born Kingdom (d. 1854), Brunel was born in [[Portsmouth]], [[Hampshire]], on [[9 April]] [[1806]].<ref>Brunel University (see [http://www.brunel.ac.uk/about/history/ikb]) ''History: Isambard Kingdom Brunel'' Retrieved Feb. 20, 2006.</ref> His father was working there on block-making machinery for the [[Portsmouth Block Mills]]. |

|||

When Brunel was 15, his father, who had accumulated debts of over £5,000, was sent to a [[debtors' prison]]. After three months went by with no prospect of release, Marc Brunel let it be known that he was considering an offer from the [[Alexander I of Russia|Tsar of Russia]]. In August 1821, facing the prospect of losing a prominent engineer, the government relented and issued Marc £5,000 to clear his debts in exchange for his promise to remain in Britain.{{sfn|Gillings|2006|pp= 11–12}}<ref>{{cite book |

|||

At 14 he was sent to [[France]] to be educated at the [[Lycée Henri-Quatre]] in [[Paris]] and the [[University of Caen]] in [[Normandy]].<ref name=3ships>Dumpleton. ''Brunel's Three Ships'', Intellect Books, 2002. (ISBN 1-84150-800-4)</ref> |

|||

| last= Worth |

|||

Brunel rose to prominence when, aged 20, he was appointed chief assistant engineer of his father's greatest achievement, the [[Thames Tunnel]], which runs beneath the river between [[Rotherhithe]] and [[Wapping]]. |

|||

| first= Martin |

|||

| year= 1999 |

|||

| title= Sweat and Inspiration: Pioneers of the Industrial Age |

|||

| page= 87 |

|||

| publisher= Alan Sutton Publishing Ltd. |

|||

| isbn= 978-0-7509-1660-8 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

When Brunel completed his studies at Henri-IV in 1822, his father had him presented as a candidate at the renowned engineering school [[École Polytechnique]], but as a foreigner, he was deemed ineligible for entry. Brunel subsequently studied under the prominent master clockmaker and [[horologist]] [[Abraham-Louis Breguet]], who praised Brunel's potential in letters to his father.<ref name="Buchanan18"/> In late 1822, having completed his apprenticeship, Brunel returned to England.<ref name="1870p5"/> |

|||

The first major sub-river tunnel, it succeeded where other attempts had failed, thanks to Marc Brunel's ingenious [[tunnelling shield]] — the human-powered forerunner of today's mighty [[Tunnel boring machine|tunnelling machine]]s — which protected workers from cave-in by placing them within a protective casing. Marc Brunel had been inspired to create the shield after observing the habits and anatomy of the [[shipworm]], ''Teredo navalis''. |

|||

==Thames Tunnel== |

|||

Most modern tunnels are cut in this way, notably the [[Channel Tunnel]] between England and France.<ref>West, Graham. ''Innovation and the Rise of the Tunnelling Industry'', Cambridge University Press, 1988. (ISBN 0-521-33512-4)</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Thames Tunnel}} |

|||

[[File:ThamesTunnelFromWapping.jpg|thumb|alt=A narrow railway tunnel with a single railway track, lit by a bright white light|The [[Thames Tunnel]] in September 2005]] |

|||

Brunel worked for several years as an assistant engineer on the project to create a tunnel under London's [[River Thames]] between [[Rotherhithe]] and [[Wapping]], with tunnellers driving a horizontal shaft from one side of the river to the other under the most difficult and dangerous conditions. The project was funded by the Thames Tunnel Company and Brunel's father, Marc, was the chief engineer.{{sfn|Dumpleton|Miller|2002|pp=14–15}} The ''American Naturalist'' said, "It is stated also that the operations of the [[Teredo navalis|Teredo]] [Shipworm] suggested to Mr. Brunel his method of tunnelling the Thames."<ref>Stearnes, R.E.C. "Toredo, or [[Teredo navalis|Shipworm]]." ''The American Naturalist'', Vol. 20, No. 2 (Feb. 1886), p. 136.</ref> |

|||

The composition of the riverbed at Rotherhithe was often little more than waterlogged sediment and loose gravel. An ingenious [[tunnelling shield]] designed by Marc Brunel helped protect workers from cave-ins,<ref>{{cite book|last=Aaseng|first=Nathan|year=1999|title=Construction: Building The Impossible|work=Innovators Series|publisher=The Oliver Press, Inc|pages=[https://archive.org/details/constructionbuil00aase/page/36 36–45]|isbn=978-1-881508-59-5|url=https://archive.org/details/constructionbuil00aase/page/36}}</ref> but two incidents of severe flooding halted work for long periods, killing several workers and badly injuring the younger Brunel.<ref name="smith">{{cite book |last=Smith |first=Denis |title=Civil Engineering Heritage: London and the Thames Valley |publisher=Thomas Telford Ltd, for The [[Institution of Civil Engineers]] |year=2001 |pages=17–19 |isbn=978-0-7277-2876-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4TA262F55asC&q=thames%20tunnel%20rotherhithe&pg=PA17|access-date=16 August 2009 |

|||

Brunel established his design offices at 17–18 Duke Street, London, and he lived with his family in the rooms above.<ref>Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, Felix; Mendelssohn, Cecille; Ward, Jones. ''The 1837 Diary of Felix and Cecille Mendelssohn Bartholdy'', Oxford University Press, 1997. (ISBN 0-19-816597-8)</ref> |

|||

}}</ref> The latter incident, in 1828, killed the two most senior miners, and Brunel himself narrowly escaped death. He was seriously injured and spent six months recuperating,<ref>Sources disagree about where Brunel convalesced; Buchanan (p. 30) says [[Brighton]], while Dumpleton and Miller (p. 16) say [[Bristol]] and connect this to his subsequent work on the [[Clifton Suspension Bridge]] there.</ref> during which time he began a design for a bridge in Bristol, which would later be completed as the [[Clifton Suspension Bridge]].<ref name="Britanica"/> The event stopped work on the tunnel for several years.{{sfn|Dumpleton|Miller|2002|p=15}} |

|||

Though the Thames Tunnel was eventually completed during Marc Brunel's lifetime, his son had no further involvement with the tunnel proper, only using the abandoned works at Rotherhithe to further his abortive ''Gaz'' experiments. This was based on an idea of his father's and was intended to develop into an engine that ran on power generated from alternately heating and cooling carbon dioxide made from ammonium carbonate and sulphuric acid. Despite interest from several parties, the Admiralty included, the experiments were judged by Brunel to be a failure on the grounds of fuel economy alone, and were discontinued after 1834.{{sfn|Rolt|1989|pp=41–42}} |

|||

On 5 July 1836, Brunel married Mary Elizabeth (b. 1813), the eldest daughter of William Horsley, organist and composer, who came from an accomplished musical and artistic family. |

|||

In 1865, the East London Railway Company purchased the Thames Tunnel for £200,000, and four years later the first trains passed through it. Subsequently, the tunnel became part of the London Underground system, and it remains in use today, originally as part of the [[East London Line]] now incorporated into the [[London Overground]].<ref name=bagust8>Bagust, Harold, "The Greater Genius?", 2006, Ian Allan Publishing, {{ISBN|0-7110-3175-4}}, (pp. 97–100)</ref> |

|||

[[R.P. Brereton]], who became his chief assistant in 1845, was in charge of the office in Brunel's absence, and also took direct responsibility for major projects such as the [[Royal Albert Bridge]] as Brunel's health declined. |

|||

{{clear left}} |

|||

==The Thames Tunnel== |

|||

[[Image:ThamesTunnelFromWapping.jpg|thumb|The [[Thames Tunnel]] in 2005, now part of the [[London Underground]] [[East London Line]] between [[Rotherhithe]] and [[Wapping]].]] |

|||

{{main|Thames Tunnel}} |

|||

==Bridges and viaducts== |

|||

Brunel worked for nearly two years to create a tunnel under London's [[River Thames]], with tunnellers driving a horizontal shaft from one side of the river to the other under the most difficult and dangerous conditions. |

|||

[[File:Clifton.bridge.arp.750pix.jpg|thumb|alt=A suspension bridge spanning a river gorge with woodland in the background|The [[Clifton Suspension Bridge]] spans [[Avon Gorge]], linking [[Clifton, Bristol|Clifton]] in Bristol to [[Leigh Woods]] in North [[Somerset]]]] |

|||

Brunel is perhaps best remembered for designs for the [[Clifton Suspension Bridge]] in [[Bristol]], begun in 1831. The bridge was built to designs based on Brunel's, but with significant changes. Spanning over {{convert|214|m|abbr=on|order=flip}}, and nominally {{convert|76|m|abbr=on|order=flip}} above the [[River Avon, Bristol|River Avon]], it had the longest span of any bridge in the world at the time of construction.{{sfn|Rolt|1989|p=53}} Brunel submitted four designs to a committee headed by [[Thomas Telford]], but Telford rejected all entries, proposing his own design instead. Vociferous opposition from the public forced the organising committee to hold a new competition, which was won by Brunel.<ref name="brunel200-susbridge">{{cite web |

|||

Brunel's father, Marc, was the chief engineer, and the project was funded by the Thames Tunnel Company. The composition of the Thames river bed at [[Rotherhithe]] was often little more than waterlogged sediment and loose gravel, and although the extreme conditions proved the ingenuity of Brunel's tunnelling machine, the work was hard and hazardous.<ref>Aaseng, Nathan. '''Construction: Building The Impossible''', The Oliver Press, Inc., 1999. (ISBN 1-881508-59-5)</ref> |

|||

|url=http://www.brunel200.com/suspension_bridge.htm |

|||

|title=The Clifton Suspension Bridge |

|||

|publisher=Brunel 200 |

|||

|access-date=16 August 2009 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Afterwards, Brunel wrote to his brother-in-law, the politician [[Benjamin Hawes]]: "Of all the wonderful feats I have performed, since I have been in this part of the world, I think yesterday I performed the most wonderful. I produced unanimity among 15 men who were all quarrelling about that most ticklish subject—taste".<ref name="Ross">{{cite web |

|||

The tunnel was often in imminent danger of collapse due to the instability of the river bed, yet the management decided to allow spectators to be lowered down to observe the diggings at a [[shilling]] a time. |

|||

|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/brunel_isambard_01.shtml |

|||

|title=Brunel: 'The Practical Prophet'|work=BBC History |

|||

|access-date=27 August 2009 |

|||

|last=Peters |first=Professor G Ross |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Maidenhead Railway Bridge and Guards Club Island (Nancy).JPG|thumb|alt=a red brick built bridge with shallow arches spanning a river, viewed from the front of a small boat|The [[Maidenhead Railway Bridge]], at the time the largest span for a brick arch bridge]] |

|||

For the workers the building of the tunnel was particularly unpleasant because the Thames at that time was still little better than an open [[sewer]], so the tunnel was usually awash with foul-smelling, contaminated water. |

|||

Work on the Clifton bridge started in 1831, but was suspended due to the [[Bristol Riots#Queen Square riots, 1831|Queen Square riots]] caused by the arrival of Sir [[Charles Wetherell]] in Clifton. The riots drove away investors, leaving no money for the project, and construction ceased.<ref name="bryan">{{cite book |

|||

Two severe incidents of flooding halted work for long periods, killing several workers and badly injuring the younger Brunel. The later incident, in 1828, killed the two most senior miners, Collins and Ball, and Brunel himself narrowly escaped death; a water break-in hurled him from a tunnelling platform, knocking him unconscious, and he was washed up to the other end of the tunnel by the surge. |

|||

|last=Bryan |

|||

|first=Tim |

|||

|title=Brunel: The Great Engineer |

|||

|publisher=Ian Allan |

|||

|location=Shepperton |

|||

|year=1999 |

|||

|pages=[https://archive.org/details/brunelgreatengin0000brya/page/35 35–41] |

|||

|isbn=978-0-7110-2686-5 |

|||

|url=https://archive.org/details/brunelgreatengin0000brya/page/35 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |

|||

|url=https://www.theguardian.com/education/2006/apr/18/highereducation.uk1 |

|||

|title=Higher diary|work=The Guardian |

|||

|date=18 April 2006 |

|||

|access-date=27 August 2009 |

|||

|last=MacLeod |

|||

|first=Donald |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Brunel did not live to see the bridge finished, although his colleagues and admirers at the [[Institution of Civil Engineers]] felt it would be a fitting memorial, and started to raise new funds and to amend the design. Work recommenced in 1862, three years after Brunel's death, and was completed in 1864.<ref name="Ross"/> In 2011, it was suggested, by historian and biographer Adrian Vaughan, that Brunel did not design the bridge, as eventually built, as the later changes to its design were substantial.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/8261682/Isambard-Kingdom-Brunel-did-not-design-Clifton-Suspension-Bridge-says-historian.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220111/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/8261682/Isambard-Kingdom-Brunel-did-not-design-Clifton-Suspension-Bridge-says-historian.html |archive-date=11 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |title=Isambard Kingdom Brunel did not design Clifton Suspension Bridge, says historian |work=The Daily Telegraph|location=London|access-date=22 December 2012}}{{cbignore}}</ref> His views reflected a sentiment stated fifty-two years earlier by [[Tom Rolt]] in his 1959 book ''Brunel.'' Re-engineering of suspension chains recovered from an earlier suspension bridge was one of many reasons given why Brunel's design could not be followed exactly.{{Citation needed|date=April 2020}} |

|||

As the water rose, by luck he was carried up a service stairway, where he was plucked from almost certain death by an assistant moments before the surge receded. Brunel was seriously hurt (and never fully recovered from his injuries), and the event ended work on the tunnel for several years.<ref name=3ships>Dumpleton. '''Brunel's Three Ships''', Intellect Books, 2002. (ISBN 1-84150-800-4)</ref> |

|||

[[Hungerford Bridge]], a [[suspension bridge|suspension footbridge]] across the Thames near [[Charing Cross Station]] in London, was opened in May 1845. Its central span was {{Convert|676.5|ft|}}, and its cost was £106,000.<ref>{{Cite journal|title=The Hungerford Suspension Bridge|journal=The Practical Mechanic and Engineer's Magazine|date=May 1845|page=223}}</ref> It was replaced by a new railway bridge in 1859, and the suspension chains were used to complete the Clifton Suspension Bridge.<ref name="brunel200-susbridge"/> |

|||

Nonetheless, the first underwater tunnel had been built, and is still in operation on the [[London Underground]] [[East London Line]] between [[Rotherhithe]] and [[Wapping]].<ref>UK Government - Transport for London ([http://www.tfl.gov.uk/tube/company/history/early-years.asp]) '''London Underground History - The Early Years''' Retrieved Feb. 18, 2006.</ref> |

|||

The Clifton Suspension Bridge still stands, and over 4 million vehicles traverse it every year.<ref>{{cite news|title=Get set to pay more on suspension bridge|work=Bristol Evening Post|date=6 January 2007|page=12}}</ref> |

|||

The building that contained the pumps to keep the Thames Tunnel dry was saved from demolition in the 1970s by volunteers and made a [[Scheduled Ancient Monument]]. It now houses the [[Brunel Engine House|Brunel Museum]], which documents not just the Thames Tunnel but also the two Brunels' other achievements. |

|||

Brunel designed many bridges for his railway projects, including the [[Royal Albert Bridge]] spanning the [[River Tamar]] at [[Saltash]] near [[Plymouth]], [[Bridgwater railway station#Somerset Bridge|Somerset Bridge]] (an unusual laminated timber-framed bridge near [[Bridgwater]]<ref>{{cite web |

|||

==Bridges== |

|||

|url=http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=18640 |

|||

[[Image:Railway bridge Maidenhead.jpeg|thumb|right|The [[Maidenhead Railway Bridge]], at the time the largest span for a brick arch bridge.]] |

|||

|title=Bridgwater |

|||

[[Image:Clifton.bridge.arp.750pix.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Clifton Suspension Bridge]] spans the [[Avon Gorge]], linking [[Clifton, Bristol|Clifton]] in [[Bristol]] to [[Leigh Woods]] in North [[Somerset]].]] |

|||

|work=A History of the County of Somerset: Volume 6 |

|||

[[Image:Saltashrab.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Royal Albert Bridge]], seen from [[Saltash railway station]].]] |

|||

|publisher=British History Online |

|||

|access-date=16 August 2009 |

|||

|last=Dunning |

|||

|first=RW |

|||

|year=1992 |

|||

|editor1=CR Elrington, CR |editor2=Baggs, AP |editor3=Siraut, MC |

|||

}}</ref>), the [[Windsor Railway Bridge]], and the [[Maidenhead Railway Bridge]] over the Thames in [[Berkshire]]. This last was the flattest, widest brick arch bridge in the world and is still carrying main line trains to the west, even though today's trains are about ten times heavier than in Brunel's time.<ref name="Gordon">{{cite book |

|||

|last=Gordon |first=JE |author-link = J.E. Gordon |

|||

|year=1978 |

|||

| title=Structures: or why things don't fall down |

|||

|publisher=Penguin |location=London |

|||

|page=200 |

|||

|isbn=978-0-14-013628-9 |

|||

| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xrlRAAAAMAAJ&q=brunel+ |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Royal Albert Bridge 2009.jpg|thumb|alt=a bridge spanning a river at high level, the bridge deck supported in the centre by curved tubular metal girders|The [[Royal Albert Bridge]] spanning the [[river Tamar]] at [[Saltash]]]] |

|||

Brunel's solo engineering feats started with bridges — the [[Royal Albert Bridge]] spanning the [[River Tamar]] at [[Saltash]] near [[Plymouth]], and an unusual timber-framed bridge near [[Bridgwater]].<ref>Billington, David P. '''Tower and the Bridge''', Princeton University Press, 1985. (ISBN 0-691-02393-X)</ref> |

|||

Throughout his railway building career, but particularly on the [[South Devon Railway Company|South Devon]] and [[Cornwall Railway]]s where economy was needed and there were many valleys to cross, Brunel made extensive use of wood for the construction of substantial viaducts;<ref>{{cite book |last=Lewis|first=Brian|year= 2007|title=Brunel's timber bridges and viaducts|place=Hersham|publisher=Ian Allan Publishing|isbn=978-0-7110-3218-7}}</ref> these have had to be replaced over the years as their primary material, [[John Howard Kyan|Kyanised]] Baltic Pine, became uneconomical to obtain.{{sfn |Binding |1993 |p=30 }} |

|||

Built in 1838, the [[Maidenhead Railway Bridge]] over the Thames in [[Berkshire]] was the flattest, widest brick arch bridge in the world and is still carrying main line trains to the west. There are two arches, with each span totalling 128 [[foot (unit of length)|ft]] (39 [[metre|m]]), having a rise of only 24 ft (7 m), and a width that carries four tracks. The rather flat arches reduce the difficulty railway engines have with steep gradients (especially on hump back bridges) and today's trains are about 10 times as heavy as Brunel ever imagined<ref>Gordon J E (1978) ''Structures: or why things don't fall down'' Penguin, London, 395pp. ISBN 0-14-013628-2</ref>. |

|||

Brunel designed the [[Royal Albert Bridge]] in 1855 for the Cornwall Railway, after [[Parliament of the United Kingdom|Parliament]] rejected his original plan for a train ferry across the [[Hamoaze]]—the estuary of the tidal [[River Tamar|Tamar]], [[River Tavy|Tavy]] and [[River Lynher|Lynher]]. The bridge (of ''bowstring girder'' or ''tied arch'' construction) consists of two main spans of {{convert|455|ft|abbr=on}}, {{convert|100|ft|abbr=on}} above mean high [[spring tide]], plus 17 much shorter approach spans. Opened by [[Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha|Prince Albert]] on 2 May 1859, it was completed in the year of Brunel's death.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.royalalbertbridge.co.uk/html/history.html |title=History |publisher=Royal Albert Bridge |access-date=16 August 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061109214743/http://www.royalalbertbridge.co.uk/html/history.html |archive-date=9 November 2006}}</ref> |

|||

In 1845 [[Hungerford Bridge]], a [[suspension bridge|suspension footbridge]] across the Thames, near [[Charing Cross Station]] in [[London]], was opened only to be replaced by a new railway bridge in 1859. |

|||

Several of Brunel's bridges over the Great Western Railway might be demolished because the line is to be electrified, and there is inadequate clearance for overhead wires. [[Buckinghamshire]] County Council is negotiating to have further options pursued, in order that all nine of the remaining historic bridges on the line can be saved.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.buckscc.gov.uk/moderngov/Data/Buckinghamshire%20Historic%20Environment%20Forum/20060920/Agenda/Item06.pdf |title=Crossrail and the Great Western World Heritage site |work=Buckinghamshire Historic Environment Forum |publisher=Buckinghamshire County Council |date=20 September 2006 |access-date=16 August 2009 |last=Senior Archaeological Officer |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629185536/http://www.buckscc.gov.uk/moderngov/Data/Buckinghamshire%20Historic%20Environment%20Forum/20060920/Agenda/Item06.pdf |archive-date=29 June 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.culture.gov.uk/images/publications/WorldHeritageSites1999.pdf |title=World Heritage Sites: The Tentative List of The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland |work=Buildings, Monuments and Sites Division |publisher=Department for Culture, Media and Sport |year=1999 |access-date=16 August 2009}}</ref> |

|||

The Royal Albert Bridge was designed in 1855 for the [[Cornwall Railway]] Company, after [[Parliament of the United Kingdom|Parliament]] rejected his original plan for a train [[ferry]] across the [[Hamoaze]] — the estuary of the tidal [[River Tamar|Tamar]], [[River Tavy|Tavy]] and [[River Lynher|Lynher]]. The bridge (of ''bowstring girder'' or ''tied arch'' construction) consists of two main spans of 455 ft (139 m), 100 ft (30 m) above mean high [[spring tide]], plus 17 much shorter approach spans. Opened by [[Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha|Prince Albert]] on [[2 May]] [[1859]], it was completed in the year of Brunel's death. |

|||

[[File:Moorswater Viaduct.jpg|thumb|Moorswater Viaduct at [[Liskeard]], Cornwall as built]] |

|||

When the [[Cornwall Railway]] company constructed a railway line between [[Plymouth]] and [[Truro]], opening in 1859, and extended it to [[Falmouth, Cornwall|Falmouth]] in 1863, on the advice of Brunel, they constructed [[Cornwall Railway viaducts|the river crossings in the form of wooden viaducts, 42 in total]], consisting of timber deck spans supported by fans of timber bracing built on [[masonry]] piers. This unusual method of construction substantially reduced the first cost of construction compared to an all-masonry structure, but at the cost of more expensive maintenance. In 1934 the last of Brunel's timber viaducts was dismantled and replaced by a masonry structure.<ref>[https://www.railwaywondersoftheworld.com/timber_viaducts.html Brunel’s Timber Viaducts]</ref> |

|||

Brunel's last major undertaking was the unique [[Three Bridges, London]]. Work began in 1856, and was completed in 1859.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.disused-stations.org.uk/features/windmill_lane_bridge/index.shtml|title=Disused Stations: Station|work=disused-stations.org.uk}}</ref> The three bridges in question are arranged to allow the routes of the [[Grand Junction Canal]], [[Great Western and Brentford Railway]], and Windmill Lane to cross each other.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.grandunioncanalwalk.co.uk/|title=Grand Union Canal Walk|work=grandunioncanalwalk.co.uk}}</ref> |

|||

However, Brunel is perhaps best remembered for the [[Clifton Suspension Bridge]] in Bristol. Spanning over 700 ft (213 m), and nominally 200 ft (61 m) above the [[River Avon, Bristol|River Avon]], it had the longest span of any bridge in the world at the time of construction. Brunel submitted four designs to a committee headed by [[Thomas Telford]] and gained approval to commence with the project. Afterwards, Brunel wrote to his brother-in-law, the politician Benjamin Hawes: "Of all the wonderful feats I have performed, since I have been in this part of the world, I think yesterday I performed the most wonderful. I produced unanimity among 15 men who were all quarrelling about that most ticklish subject — taste." He did not live to see it built, although his colleagues and admirers at the [[Institution of Civil Engineers]] felt the bridge would be a fitting memorial, and started to raise new funds and to amend the design. Work started in 1862 and was complete in 1864, five years after Brunel's death.<ref>BBC History (see [http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/brunel_isambard_01.shtml]) '''Brunel: The Practical Prophet of Technological Innovation''' by Professor G. Ross Peters Retrieved Nov. 21, 2006.</ref> |

|||

{{clear right}} |

|||

In 2006, there is the possibility that several of Brunel's bridges over the Great Western Railway might be demolished because the line is planned to be electrified, and there is inadequate clearance for the overhead wires. [[Buckinghamshire]] County Council is petitioning to have further options pursued, in order that all nine of the historic remaining bridges on the line can remain.<ref>Bucks CC (see [http://www.buckscc.gov.uk/archaeology/brunel_bridges_news.htm]) |

|||

"Brunel’s Bridges under threat," retrieved Feb. 22, 2006.</ref><ref>UK Govt. Dept. for Culture, Media and Sport ([http://www.culture.gov.uk/global/publications/archive_1999/World_Heritage_Sites+.htm]) '''World Heritage Sites: The Tentative List of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland''' Retrieved Feb. 22, 2006.</ref> |

|||

== |

==Great Western Railway== |

||

{{see also|Great Western Railway}} |

|||

[[Image:Paddington Station.jpg|thumb|left|[[Paddington Station]], still a mainline station, was the [[London]] [[Terminal station|terminus]] of the [[Great Western Railway]].]] |

|||

{{main|Great Western Railway}} |

|||

[[File:Paddington Station.jpg|thumb|alt=The interior of a large railway station with a curved roof supported by iron girders, supported by iron columns, four diesel trains standing at platforms, passengers on the platforms, in the distance daylight can be seen and the scene is illuminated by natural light through the centre section of the roof |[[London Paddington station|Paddington station]], still a mainline station, was the London [[terminal station|terminus]] of the [[Great Western Railway]]]] |

|||

In the early part of Brunel's life, the use of railways began to take off as a major means of transport for passengers and goods. This demand for railway expansion greatly influenced Brunel's involvement in stretching railways across Britain. This also resulted in the majority of the bridges constructed at the time to be railway bridges. |

|||

In the early part of Brunel's life, the use of railways began to take off as a major means of transport for goods. This influenced Brunel's involvement in railway engineering, including railway bridge engineering.{{Citation needed|date=April 2020}} |

|||

In 1833, before the Thames Tunnel was complete, Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the [[Great Western Railway]], one of the wonders of [[Victorian era|Victorian]] Britain, running from London to [[Bristol]] and later [[Exeter]].<ref> |

In 1833, before the Thames Tunnel was complete, Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the [[Great Western Railway]], one of the wonders of [[Victorian era|Victorian]] Britain, running from London to [[Bristol]] and later [[Exeter]].<ref name="BHO-Railways">{{cite web |url=http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=102817 |title=Railways | work=A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 4 |publisher=British History Online |year=1959 |

||

|access-date=16 August 2009|last=Crittal |first=Elizabeth}}</ref> The company was founded at a public meeting in Bristol in 1833, and was incorporated by [[Act of Parliament]] in 1835. |

|||

It was Brunel's vision that passengers would be able to purchase one ticket at London Paddington and travel from London to New York, changing from the Great Western Railway to the ''[[SS Great Western|Great Western]]'' steamship at the terminus in [[Neyland]], West Wales.<ref name="BHO-Railways"/> |

|||

He surveyed the entire length of the route between London and Bristol himself, with the help of many including his solicitor Jeremiah Osborne of Bristol Law Firm [[Osborne Clarke]] who on one occasion rowed Brunel down the River Avon to survey the bank of the river for the route.<ref name="Clifton RFC">{{cite web |url=http://www.cliftonrfchistory.co.uk/captains/press/press.htm |title=Clifton Rugby Football Club History |access-date=22 March 2012 |archive-date=23 July 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120723122827/http://www.cliftonrfchistory.co.uk/captains/press/press.htm |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name="Brunel 200 - Working With Visionaries">{{cite web|url=http://www.brunel200.com/downloads/osborne_clarke_leaflet.pdf | title=Brunel 200 – Working With Visionaries}}</ref> Brunel even designed the Royal Hotel in Bath which opened in 1846 opposite the railway station.<ref name="Royal Hotel Bath">{{cite web |url=https://www.royalhotelbath.co.uk/reasons-to-choose-the-royal |title=Initially the Station Hotel, it was given the royal prefix as a reminder of Queen Victoria's visit to Bath |access-date=7 March 2021 |archive-date=19 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220819012415/https://www.royalhotelbath.co.uk/reasons-to-choose-the-royal |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

The Company was founded at a public meeting in [[Bristol]] in 1833, and was incorporated by [[Act of Parliament]] in 1835. Brunel made two controversial decisions: to use a [[broad gauge]] of {{7ft}} for the track, which he believed would offer superior running at high speeds; and to take a route that passed north of the [[Marlborough Downs]], an area with no significant towns, though it offered potential connections to [[Oxford, England|Oxford]] and [[Gloucester, England|Gloucester]] and then to follow the Thames Valley into London. |

|||

[[File:Baulk road point with side step.jpg|thumb|upright|alt=A rail track recedes into the distance where a steam train stands; the track has three rails, the middle of which is offset to the right in the foreground but switches to the left in the middle at some complex pointwork where three other rails join from the left|A [[broad-gauge]] train on [[Dual gauge|mixed-gauge]] track]] |

|||

His decision to use broad gauge for the line was controversial in that almost all British railways to date had used [[standard gauge]]. Brunel said that this was nothing more than a carry-over from the mine railways that [[George Stephenson]] had worked on prior to making the world's first passenger railway. |

|||

Brunel made two controversial decisions: to use a [[Broad-gauge railway|broad gauge]] of {{Track gauge|7ft0.25in|lk=on}} for the track, which he believed would offer superior running at high speeds; and to take a route that passed north of the [[Marlborough Downs]]—an area with no significant towns, though it offered potential connections to [[Oxford]] and [[Gloucester]]—and then to follow the Thames Valley into London. His decision to use broad gauge for the line was controversial in that almost all British railways to date had used [[standard gauge]]. Brunel said that this was nothing more than a carry-over from the mine railways that [[George Stephenson]] had worked on prior to making the world's first passenger railway. Brunel proved through both calculation and a series of trials that his broader gauge was the optimum size for providing both higher speeds<ref name="ReferenceA">Pudney, John (1974). ''Brunel and His World''. Thames and Hudson. {{ISBN|978-0-500-13047-6}}.</ref> and a stable and comfortable ride to passengers. In addition the wider gauge allowed for larger [[goods wagon]]s and thus greater freight capacity.<ref>{{cite book |last=Ollivier|first=John|date=1846|title=The Broad Gauge: The Bane of the Great Western Railway Company}}</ref> |

|||

Drawing on Brunel's experience with the Thames Tunnel, the Great Western contained a series of technical achievements— [[viaduct]]s such as the one in [[Ivybridge]], specially designed stations, and tunnels including the [[Box Tunnel]], which was the longest railway tunnel in the world at that time.{{sfn|Dumpleton|Miller|2002|p=20}} With the opening of the Box Tunnel, the line from London to Bristol was complete and ready for trains on 30 June 1841.<ref name=MacD1>{{cite book| last = MacDermot| first = E T| title = History of the Great Western Railway, volume I 1833–1863| publisher = [[Great Western Railway]]| year = 1927| location = London}}</ref> |

|||

Brunel worked out through mathematics and a series of trials that his broader gauge was the optimum railway size for providing stability and a comfortable ride to passengers, in addition to allowing for bigger [[railroad car|carriages]] and more [[freight]] capacity.<ref>Oliivier, J. '''The Broad Gauge the Banc of the Great Western Railway Company''', 1846</ref> He surveyed the entire length of the route between London and Bristol himself. |

|||

The initial group of locomotives ordered by Brunel to his own specifications proved unsatisfactory, apart from the [[GWR Star Class|North Star locomotive]], and 20-year-old [[Daniel Gooch]] (later Sir Daniel) was appointed as [[Chief mechanical engineer|Superintendent of Locomotive Engines]]. Brunel and Gooch chose to locate their [[Swindon Works|locomotive works]] at the village of [[Swindon]], at the point where the gradual ascent from London turned into the steeper descent to the Avon valley at [[Bath, Somerset|Bath]].{{Citation needed|date=April 2020}} |

|||

[[Image:Brunel 2.JPG|thumb|right|Isambard Kingdom Brunel - [[Swindon Steam Railway Museum|Steam Museum]], [[Swindon]].]] |

|||

The initial group of locomotives ordered by Brunel to his own specifications proved unsatisfactory, apart from the [[GWR Star Class|North Star locomotive]], and 20-year-old [[Daniel Gooch]] (later Sir Daniel) was appointed as Superintendent of [[Locomotive]]s. Brunel and Gooch chose to locate their [[Swindon railway works|locomotive works]] at the village of [[Swindon]], at the point where the gradual ascent from London turned into the steeper descent to the [[River Avon, Bristol|Avon]] valley at [[Bath, Somerset|Bath]]. |

|||

[[File:Weston Junction Station - drawing by Isambard Kingdom Brunel.jpg|thumb|upright|Drawings for [[Weston Junction railway station|Weston Junction Station]], by Brunel ]] |

|||

Drawing on his experience with the Thames Tunnel, the Great Western contained a series of impressive achievements — soaring [[viaduct]]s, specially designed stations, and vast tunnels including the famous [[Box Tunnel]], which was the longest railway tunnel in the world at that time.<ref name=3ships>Dumpleton. '''Brunel's Three Ships''', Intellect Books, 2002. (ISBN 1-84150-800-4)</ref> |

|||

After Brunel's death, the decision was taken that standard gauge should be used for all railways in the country. At the original Welsh terminus of the Great Western railway at [[Neyland]], sections of the broad gauge rails are used as handrails at the quayside, and information boards there depict various aspects of Brunel's life. There is also a larger-than-life bronze statue of him holding a steamship in one hand and a locomotive in the other. The statue has been replaced after an earlier theft.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.westerntelegraph.co.uk/li/townguides/739515.Neyland___Brunel_s_railway_town/|title=Neyland – Brunel's railway town|work=Western Telegraph|date=22 April 2006|access-date=16 August 2009}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Stolen statue of Isambard Kingdom Brunel in Neyland is replaced|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-south-west-wales-22126592|publisher=BBC|access-date=26 December 2015|work=BBC News|date=13 April 2013}}</ref> |

|||

Brunel's achievements ignited the imagination of the technically minded Britons of the age, and he soon became one of the most famous men in the country on the back of this interest. |

|||

The present [[London Paddington station]] was designed by Brunel and opened in 1854. Examples of his designs for smaller stations on the Great Western and associated lines which survive in good condition include [[Mortimer railway station|Mortimer]], [[Charlbury railway station|Charlbury]] and [[Bridgend railway station|Bridgend]] (all [[Italianate architecture|Italianate]]) and [[Culham railway station|Culham]] ([[Tudorbethan architecture|Tudorbethan]]). Surviving examples of wooden [[train shed]]s in his style are at [[Frome railway station|Frome]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.engineering-timelines.com/scripts/engineeringItem.asp?id=626|title=Frome Station roof|publisher=Engineering Timelines|access-date=27 August 2009}}</ref> and [[Kingswear railway station|Kingswear]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.southhams.gov.uk/AnitePublicDocs/00170783.pdf |archive-url=https://www.webcitation.org/5jMLQVVvC?url=http://www.southhams.gov.uk/AnitePublicDocs/00170783.pdf |archive-date=28 August 2009|title=Kingswear Station |publisher=South Hams District Council |access-date=27 August 2009|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

There is an anecdote which states that Box Tunnel is placed such that the sun shines all the way through it on Brunel's birthday. For more information, see [[Box Tunnel]].<ref>Williams, Archibald. '''The Romance of Modern Locomotion''', C. A. Pearson Ltd., 1904.</ref> |

|||

The [[Swindon Steam Railway Museum]] has many artefacts from Brunel's time on the Great Western Railway.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.steam-museum.org.uk/steam/steamv4-3.htm |

|||

After Brunel's death the decision was taken that standard gauge should be used for all railways in the country. Despite the Great Western's claim of proof that its broad gauge was the better (disputed by at least one Brunel historian), the decision was made to go with Stephenson's standard gauge, mainly because this had already covered a far greater amount of the country. |

|||

|title=Steam: Museum of the Great Western Railway|publisher=Swindon Borough Council|access-date=28 August 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080914161015/http://www.steam-museum.org.uk/steam/steamv4-3.htm|archive-date=14 September 2008}}</ref> The [[Didcot Railway Centre]] has a reconstructed segment of {{RailGauge|7ft0.25in}} track as designed by Brunel and working steam locomotives in the same gauge.{{Citation needed|date=April 2020}} |

|||

Parts of society viewed the railways more negatively. Some landowners felt the railways were a threat to amenities or property values and others requested tunnels on their land so the railway could not be seen.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> |

|||

By May 1892 (when the broad gauge was abolished) the Great Western had already been re-laid as [[dual gauge]] (both broad and standard) and so the transition was a relatively painless one.<ref name=3ships>Dumpleton. '''Brunel's Three Ships''', Intellect Books, 2002. (ISBN 1-84150-800-4)</ref> |

|||

The present [[London Paddington station|Paddington station]] was designed by Brunel and opened in 1854. Examples of his designs for smaller stations on the Great Western and associated lines which survive in good condition include [[Mortimer railway station|Mortimer]], [[Charlbury railway station|Charlbury]] and [[Bridgend railway station|Bridgend]] (all [[Italianate architecture|Italianate]]) and [[Culham railway station|Culham]] ([[Tudorbethan architecture|Tudorbethan]]). Surviving examples of wooden [[train shed]]s in his style are at |

|||

[[Frome railway station|Frome]] and [[Kingswear railway station|Kingswear]]. |

|||

The great achievement that was the [[Great Western Railway]] has been immortalised in the [[Swindon Steam Railway Museum]]. |

|||

==Brunel's "atmospheric caper"== |

==Brunel's "atmospheric caper"== |

||

[[ |

[[File:Brunel's Atmospheric Railway.jpg|thumb|right|alt=Exterior in woodland. a short section of railway line on wooden sleepers with a cast iron pipe of approximately one foot diameter, running inline with the rails|A reconstruction of Brunel's [[atmospheric railway]], using a segment of the original piping at [[Didcot Railway Centre]]]] |

||

Though unsuccessful, another of Brunel's uses of technical innovations was the [[atmospheric railway]], the extension of the Great Western Railway (GWR) southward from Exeter towards [[Plymouth, England|Plymouth]], technically the [[South Devon Railway Company|South Devon Railway]] (SDR), though supported by the GWR. Instead of using [[locomotive]]s, the trains were moved by Clegg and Samuda's patented system of atmospheric ([[vacuum]]) traction, whereby stationary pumps sucked the air from a pipe placed in the centre of the track.<ref name="buchanan-atmosrwy">{{cite journal|last=Buchanan|first=R A|date=May 1992|title=The Atmospheric Railway of I.K. Brunel|journal=Social Studies of Science|volume=22|issue=2|pages=231–43|jstor=285614|doi=10.1177/030631292022002003 |s2cid=146426568}}</ref> |

|||

The section from Exeter to Newton (now [[Newton Abbot]]) was completed on this principle, and trains ran at approximately {{convert|68|mph}}.<ref name="DandM_p22">Dumpleton and Miller (2002), p. 22</ref> Pumping stations with distinctive square chimneys were sited at two-mile intervals.<ref name="DandM_p22"/> Fifteen-inch (381 mm) pipes were used on the level portions, and {{convert|22|in|mm|adj=on|sigfig=3}} pipes were intended for the steeper gradients.{{Citation needed|date=April 2020}} |

|||

Another of Brunel's interesting though ultimately unsuccessful technical innovations was the [[atmospheric railway]], the extension of the GWR southward from Exeter towards [[Plymouth, England|Plymouth]], technically the [[South Devon Railway Company|South Devon Railway]] (SDR), though supported by the GWR. Instead of using [[locomotive]]s, the trains were moved by Clegg and Samuda's patented system of atmospheric ([[vacuum]]) traction, whereby stationary pumps sucked air from the tunnel. |

|||

The technology required the use of leather flaps to seal the vacuum pipes. The natural oils were drawn out of the leather by the vacuum, making the leather vulnerable to water, rotting it and breaking the fibres when it froze during the winter of 1847. It had to be kept supple with [[tallow]], which is attractive to [[rat]]s. The flaps were eaten, and vacuum operation lasted less than a year, from 1847 (experimental service began in September; operations from February 1848) to 10 September 1848.<ref>{{cite book |last=Parkin|first=Jim|year=2000|title=Engineering Judgement and Risk|publisher=Institution of Civil Engineers|isbn=978-0-7277-2873-9}}</ref> Deterioration of the valve due to the reaction of [[tannin]] and [[iron oxide]] has been cited as the last straw that sank the project, as the continuous valve began to tear from its rivets over most of its length, and the estimated replacement cost of £25,000 was considered prohibitive.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Woolmar|first1=Christian|title=The Iron Road: The Illustrated History of Railways|date=2014|publisher=Dorling Kindersley|isbn=978-0241181867|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_htpAwAAQBAJ&q=Brunel+atmospheric+%28vacuum%29+traction+expensive&pg=PT33}}</ref> |

|||

The section from Exeter to Newton (now [[Newton Abbot]]) was completed on this principle, with pumping stations with distinctive square chimneys spaced every two miles, and trains ran at approximately 20 [[miles per hour]] (30 [[km/h]]).<ref name=3ships>Dumpleton. '''Brunel's Three Ships''', Intellect Books, 2002. (ISBN 1-84150-800-4)</ref> Fifteen-inch (381 mm) pipes were used on the level portions, and 22-inch (559 mm) pipes were intended for the steeper gradients. |

|||

The system never managed to prove itself. The accounts of the SDR for 1848 suggest that atmospheric traction cost 3s 1d (three shillings and one penny) per mile compared to 1s 4d/mile for conventional steam power (because of the many operating issues associated with the atmospheric, few of which were solved during its working life, the actual cost efficiency proved impossible to calculate). Several [[South Devon Railway engine houses]] still stand, including that at [[Totnes]] (scheduled as a grade II listed monument in 2007) and at [[Starcross]].<ref>{{cite web |

|||

The technology required the use of leather flaps to seal the vacuum pipes. The leather had to be kept supple by the use of [[tallow]], and tallow is attractive to [[rat]]s. The result was inevitable — the flaps were eaten, and vacuum operation lasted less than a year, from 1847 (experimental services began in September; operationally from February 1848) to [[September 10]], [[1848]].<ref>Parkin, Jim. '''Engineering Judgement and Risk''', Thomas Telford (publishers), 2000. (ISBN 0-7277-2873-3)</ref> |

|||

|url=http://www.teignmuseum.org.uk/pages/museum/railway/ |

|||

|title=Devon Railways |

|||

|publisher=Teignmouth & Shaldon Museum |

|||

|access-date=16 August 2009 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.devonheritage.org/Places/Kenton/BrunelandTheAtmosphericCaper.htm |

|||

|title=Brunel and The Atmospheric Caper |

|||

|publisher=Devon Heritage |

|||

|access-date=16 August 2009 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

A section of the pipe, without the leather covers, is preserved at the [[Didcot Railway Centre]].<ref>{{cite web |

|||

The accounts of the SDR for 1848 suggest that atmospheric traction cost 3s 1d (three shillings and one penny) per mile compared to 1s 4d/mile for conventional steam power. A number of [[South Devon Railway engine houses]] still stand, including that at [[Starcross]], on the estuary of the [[River Exe]], which is a striking landmark, and a reminder of the atmospheric railway, also commemorated as the name of the village [[pub]]. |

|||

|url=http://www.didcotrailwaycentre.org.uk/guide/broadgauge.html |

|||

|title=Broad Gauge Railway |

|||

|work=Centre Guide |

|||

|publisher=Didcot Railway Centre |

|||

|access-date=16 August 2009 |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151205170134/http://www.didcotrailwaycentre.org.uk/guide/broadgauge.html |

|||

|archive-date=5 December 2015 |

|||

|url-status=dead |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

In 2017, inventor Max Schlienger unveiled a working model of an updated atmospheric railroad at his vineyard in the Northern California town of Ukiah.<ref>{{Cite magazine|url=https://www.wired.com/story/flight-rail-vectorr-atmospheric-railway-train/|title=Meet the 89-Year-Old Reinventing the Train in His Backyard|last=Davies|first=Alex|date=14 June 2017|magazine=Wired|access-date=7 April 2019|issn=1059-1028}}</ref> |

|||

A section of the pipe, without the leather covers, is preserved at the [[Didcot Railway Centre]]. |

|||

==Transatlantic shipping== |

==Transatlantic shipping== |

||

[[ |

<!--inferior image quality [[File:Great-Eastern-At-Sea-.jpg|right|thumb|"''Great Eastern'' at Sea": Brunel's great ship as imagined by the artist at her launch in 1858]]--> |

||

[[File:Great Western maiden voyage.jpg|right|thumb|The maiden voyage of the {{SS|Great Western||2}} in April 1838]] |

|||

[[File:Launch-of-the-SS-GB.jpg|right|thumb|The launch of the {{SS|Great Britain||2}} in 1843|alt=A crowd of people watch a large black and red ship with one funnel and six masts adorned with flags]] |

|||

Brunel had proposed extending its transport network by boat from Bristol across the Atlantic Ocean to New York City before the Great Western Railway opened in 1835. The [[Great Western Steamship Company]] was formed by Thomas Guppy for that purpose. It was widely disputed whether it would be commercially viable for a ship powered purely by steam to make such long journeys. Technological developments in the early 1830s—including the invention of the [[surface condenser]], which allowed boilers to run on salt water without stopping to be cleaned—made longer journeys more possible, but it was generally thought that a ship would not be able to carry enough fuel for the trip and have room for commercial cargo.{{sfn|Buchanan|2006|pp=57–59}}<ref name="Beckett 2006, pp. 171–173">Beckett (2006), pp. 171–73</ref>{{sfn|Dumpleton|Miller|2002|pp=34–46}} |

|||

Brunel applied the experimental evidence of [[Mark Beaufoy|Beaufoy]]{{sfn|Beaufoy|1834}} and further developed the theory that the amount a ship could carry increased as the cube of its dimensions, whereas the amount of resistance a ship experienced from the water as it travelled increased by only a square of its dimensions.{{sfn|Garrison|1998|p=188}} This would mean that moving a larger ship would take proportionately less fuel than a smaller ship. To test this theory, Brunel offered his services for free to the Great Western Steamship Company, which appointed him to its building committee and entrusted him with designing its first ship, the {{SS|Great Western||2}}.{{sfn|Buchanan|2006|pp=57–59}}<ref name="Beckett 2006, pp. 171–173">Beckett (2006), pp. 171–73</ref>{{sfn|Dumpleton|Miller|2002|pp=34–46}} |

|||

Even before the Great Western Railway was opened, Brunel was moving on to his next project: [[transatlantic]] shipping. He used his prestige to convince his railway company employers to build the ''[[SS Great Western|Great Western]]'', at the time by far the largest steamship in the world. She first sailed in 1837. |

|||

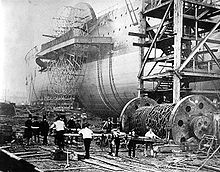

[[File:Great eastern launch attempt.jpg|thumb|right|alt=An old photograph showing a large iron paddlewheel ship being launched sideways, with workmen thrusting large baulks of timber under a large drum of iron chains|{{SS|Great Eastern||2}} shortly before launch in 1858]] |

|||

She was 236 ft (72 m) long, built of wood, and powered by sail and paddlewheels. Her first return trip to [[New York City]] took just 29 days, compared to two months for an average sailing ship. In total, 74 crossings to New York were made. The ''[[SS Great Britain|Great Britain]]'' followed in 1843; much larger at 322 ft (98 m) long, she was the first iron-hulled, propeller-driven ship to cross the [[Atlantic Ocean]].<ref>Lienhard, John H. '''The Engines of Our Ingenuity''', Oxford University Press US, 2003. (ISBN 0-19-516731-7)</ref> |

|||

When it was built, the ''Great Western'' was the longest ship in the world at {{convert|236|ft|abbr=on}} with a {{convert|250|ft|adj=on}} [[keel]]. The ship was constructed mainly from wood, but Brunel added bolts and iron diagonal reinforcements to maintain the keel's strength. In addition to its steam-powered [[paddle wheel]]s, the ship carried four masts for sails. The ''Great Western'' embarked on her maiden voyage from [[Avonmouth]], Bristol, to New York on 8 April 1838 with {{convert|600|LT|kg|abbr=on}} of coal, cargo and seven passengers on board. Brunel himself missed this initial crossing, having been injured during a fire aboard the ship as she was returning from fitting out in London. As the fire delayed the launch several days, the ''Great Western'' missed its opportunity to claim the title as the first ship to cross the Atlantic under steam power alone.<ref name="Beckett 2006, pp. 171–173"/>{{sfn|Buchanan|2006|pp=58–59}}{{sfn|Dumpleton|Miller|2002|pp=26–32}} |

|||

Even with a four-day [[Head start (positioning)|head start]], the competing {{SS|Sirius|1837|2}} arrived only one day earlier, having virtually exhausted its coal supply. In contrast, the ''Great Western'' crossing of the Atlantic took 15 days and five hours, and the ship arrived at her destination with a third of its coal still remaining, demonstrating that Brunel's calculations were correct. The ''Great Western'' had proved the viability of commercial transatlantic steamship service, which led the Great Western Steamboat Company to use her in regular service between Bristol and New York from 1838 to 1846. She made 64 crossings, and was the first ship to hold the [[Blue Riband]] with a crossing time of 13 days westbound and 12 days 6 hours eastbound. The service was commercially successful enough for a sister ship to be required, which Brunel was asked to design.<ref name="Beckett 2006, pp. 171–173"/>{{sfn|Buchanan|2006|pp=58–59}}{{sfn|Dumpleton|Miller|2002|pp=26–32}} |

|||

Building on these successes, Brunel turned to a third ship in 1852, even larger than both of her predecessors, and intended for voyages to [[India]] and [[Australia]]. The ''[[SS Great Eastern|Great Eastern]]'' (originally dubbed ''[[Leviathan]]'') was cutting-edge technology for her time: almost 700 ft (213 m) long, fitted out with the most luxurious appointments and capable of carrying over 4,000 passengers. |

|||

Brunel had become convinced of the superiority of [[propeller#Screw propellers|propeller]]-driven ships over paddle wheels. After tests conducted aboard the propeller-driven steamship {{SS|Archimedes||2}}, he incorporated a large six-bladed propeller into his design for the {{convert|322|ft|m|adj=on}} {{SS|Great Britain||2}}, which was launched in 1843.<ref name="Nasmyth">{{cite book|last=Nasmyth|first=James|year=1897|title=James Nasmyth: Engineer, An Autobiography|editor=Smiles, Samuel|publisher=Archived at Project Gutenberg|url=http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/476|access-date=14 December 2015}}</ref> ''Great Britain'' is considered the first modern ship, being built of metal rather than wood, powered by an engine rather than wind or oars, and driven by propeller rather than paddle wheel. She was the first iron-hulled, propeller-driven ship to cross the Atlantic Ocean.<ref>{{cite book |last=Lienhard|first=John H|year=2003|title=The Engines of Our Ingenuity|publisher=Oxford University Press (US)|isbn=978-0-19-516731-3}}</ref> Her maiden voyage was made in August and September 1845, from Liverpool to New York. In 1846, she was run aground at [[Dundrum, County Down]]. She was salvaged and employed in the [[SS Great Britain#Australian service|Australian service]].{{sfn|Chisholm|1911}} She is currently fully preserved and open to the public in Bristol, UK.<ref>{{cite web |title=Visit Bristol's No.1 Attraction {{!}} Brunel's SS Great Britain {{!}} |url=https://www.ssgreatbritain.org/ |website=www.ssgreatbritain.org |publisher=The SS Great Britain Trust |ref=brunels-ss-great-britain}}</ref> |

|||

She was designed to be able to cruise under her own power non-stop from London to Sydney and back since engineers of the time were under the misapprehension that Australia had no coal reserves, and she remained the largest ship built until the turn of the century. Like many of Brunel's ambitious projects, the ship soon ran over budget and behind schedule in the face of a series of momentous technical problems.<ref name=3ships>Dumpleton. '''Brunel's Three Ships''', Intellect Books, 2002. (ISBN 1-84150-800-4)</ref> |

|||

[[File:Isambard Kingdom Brunel preparing the launch of 'The Great Eastern by Robert Howlett crop.jpg|left|thumb|upright|alt=A group of ten men in nineteenth-century dark suits, wearing top hats, observing something behind the camera|Brunel at the launch of the ''Great Eastern'' with [[John Scott Russell]] and [[14th Earl of Derby|Lord Derby]], 1858]] |

|||

The ship has been portrayed as a [[white elephant]], but it can be argued that in this case Brunel's failure was principally one of economics — his ships were simply years ahead of their time. His vision and engineering innovations made the building of large-scale, screw-driven, all-metal steamships a practical reality, but the prevailing economic and industrial conditions meant that it would be several decades before transoceanic steamship travel emerged as a viable industry. |

|||

In 1852 Brunel turned to a third ship, larger than her predecessors, intended for voyages to India and Australia. The {{SS|Great Eastern||2}} (originally dubbed ''Leviathan'') was cutting-edge technology for her time: almost {{convert|700|ft|abbr=on}} long, fitted out with the most luxurious appointments, and capable of carrying over 4,000 passengers. ''Great Eastern'' was designed to cruise non-stop from London to Sydney and back (since engineers of the time mistakenly believed that Australia had no coal reserves), and she remained the largest ship built until the start of the 20th century. Like many of Brunel's ambitious projects, the ship soon ran over budget and behind schedule in the face of a series of technical problems.{{sfn|Dumpleton|Miller|2002|pages=94–113}} |

|||

The ship has been portrayed as a [[white elephant]], but it has been argued by David P. Billington that in this case, Brunel's failure was principally one of economics—his ships were simply years ahead of their time.{{sfn|Billington|1985|pp=50–59}} His vision and engineering innovations made the building of large-scale, propeller-driven, all-metal steamships a practical reality, but the prevailing economic and industrial conditions meant that it would be several decades before transoceanic steamship travel emerged as a viable industry.{{sfn|Billington|1985|pp=50–59}} |

|||

Great Eastern was built at [[John Scott Russell]]'s Napier Yard in London, and after two trial trips in 1859, set forth the following year on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York on [[17 June]] [[1860]].<ref>'''Zerah Colburn: The Spirit of Darkness''', Arima Publishing, 2005. (ISBN 1-84549-024-X)</ref> |

|||

Though a failure at |

''Great Eastern'' was built at [[John Scott Russell]]'s [[Napier Yard, Millwall|Napier Yard]] in London, and after two trial trips in 1859, set forth on her maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York on 17 June 1860.<ref>{{cite book |last=Mortimer|first=John|year=2005|title=Zerah Colburn: The Spirit of Darkness|publisher=Arima Publishing|isbn=978-1-84549-196-3}}</ref> Though a failure at her original purpose of passenger travel, she eventually found a role as an oceanic [[telegraph]] [[cable layer|cable-layer]].<!--retaining this sentence for later placement... and the ''Great Eastern'' remains one of the most important vessels in the history of shipbuilding.--> Under Captain [[Sir James Anderson]],<!--note: [[Robert Halpin]] indicates that ''he'' was the captain during cable-laying --> the ''Great Eastern'' played a significant role in laying the first lasting [[transatlantic telegraph cable]], which enabled telecommunication between Europe and North America.{{sfn|Dumpleton|Miller|2002|pages=130–148}}<ref>{{cite news|work=The New York Times|date=30 July 1866|title=The Atlantic Cable|id={{ProQuest|392481871}}}}</ref> |

||

== |

==Renkioi Hospital== |

||

{{main|Renkioi Hospital}} |

|||

During 1854, Britain entered into the [[Crimean War]], an old Turkish Barrack building became the British Army hospital in Scutari (modern-day [[Üsküdar]] in [[Istanbul]]). With injured men suffering from a variety of illnesses including [[cholera]], [[dysentery]], [[typhoid]] and [[malaria]] purely from hospital conditions,<ref>Report on Medical Care (see [http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/battles/crimea/popup/medical.htm ]) British National Archives (WO 33/1 ff.119, 124, 146-7 (23 Feb 1855))</ref> [[Florence Nightingale]] sent a plea to [[The Times]] for the government to produce a solution. |

|||

Britain entered into the [[Crimean War]] during 1854 and an old Turkish barracks became the British Army Hospital in [[Selimiye Barracks|Scutari]]. Injured men contracted a variety of illnesses—including [[cholera]], [[dysentery]], [[typhoid]] and [[malaria]]—due to poor conditions there,<ref>{{cite web |title=Report on Medical Care|url=http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/battles/crimea/popup/medical.htm|publisher=British National Archives|id=WO 33/1 ff.119, 124, 146–7|date=23 February 1855}}</ref> and [[Florence Nightingale]] sent a plea to ''[[The Times]]'' for the government to produce a solution.{{Citation needed|date=April 2020}} |

|||

Brunel was |

Brunel was working on the ''Great Eastern'' amongst other projects but accepted the task in February 1855 of designing and building the [[War Office]] requirement of a temporary, [[Prefabrication|pre-fabricated]] hospital that could be shipped to [[Crimea]] and erected there. In five months the team he had assembled designed, built, and shipped pre-fabricated wood and canvas buildings,<!-- links to image at another website<ref>Renkioi Hospital Buildings image (see [http://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk/cms/images/stories/exhibitions/renkioi_hospital.jpg] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090327121838/http://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk/cms/images/stories/exhibitions/renkioi_hospital.jpg |date=27 March 2009 }}) The Florence Nightingale Museum. Retrieved 12 January 2009.</ref>--> providing them complete with advice on transportation and positioning of the facilities.<ref>{{cite web |title=Prefabricated wooden hospitals|url=http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/battles/crimea/popup/prefab.htm|publisher=British National Archives|id=WO 43/991 ff.76–7|date=7 September 1855}}</ref> |

||

In 5 months he had designed, built and shipped the pre-fabricated wood and canvas buildings<ref>Renkioi Hospital Buildings image (see [http://www.florence-nightingale.co.uk/images/renkioi.jpg ]) The Florence Nightingale Museum, retrieved November 30, 2006</ref> that were erected, near Scutari Hospital where Nightingale was based, in the malaria free area of Renkioi.<ref name=renkioi>Hospital Development Magazine (see [http://www.hdmagazine.co.uk/story.asp?storyCode=2032207 ]) Lessons from Renkioi, November 10, 2005</ref> |

|||

Brunel had been working with [[Gloucester Docks]]-based [[William Eassie]] on the launching stage for the ''Great Eastern''. Eassie had designed and built wooden prefabricated huts used in both the Australian gold rush, as well as by the British and French Armies in the Crimea. Using wood supplied by timber importers Price & Co., Eassie fabricated 18 of the 50-patient wards designed by Brunel, shipped directly via 16 ships from Gloucester Docks to the [[Dardanelles]]. The [[Renkioi Hospital]] was subsequently erected near Scutari Hospital, where Nightingale was based, in the malaria-free area of [[Renkioi]].<ref name="renkioi">{{cite web|url=http://www.hdmagazine.co.uk/story.asp?storyCode=2032207 |title=Lessons from Renkioi |access-date=30 November 2006 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070929000446/http://www.hdmagazine.co.uk/story.asp?storyCode=2032207 |archive-date=29 September 2007 |work=Hospital Development Magazine |date=10 November 2005}}</ref> |

|||

His designs incorporated the necessity of [[hygiene]], providing access to [[sanitation]], [[ventilation]], drainage and even rudimentary temperature controls. They were feted as a great success, some sources stating that of the 1,300 (approximate) patients treated in the Renkioi temporary hospital, there were only 50 deaths.<ref>Palmerston, Brunel and Florence Nightingale’s Field Hospital (see [http://www.hmswarrior.org/brunel/resources/palmerston_and_politics.pdf ]) Palmerston and Politics, HMSwarrior.org retrieved November 30, 2006</ref> In the Scutari hospital it replaced, deaths were said to be as many as 10 times this number. Nightingale herself referred to them as "those magnificent huts."<ref>Public Health (see [http://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/science/britainsmodernbrunels.shtml ]) Britains Modern Brunels, BBC Radio 4, retrieved November 30, 2006</ref> |

|||

Brunel not only designed the buildings but gave advice as to the location of placing.<ref>Prefabricated wooden hospitals (see [http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/battles/crimea/popup/prefab.htm ]) Isambard Kingdom Brunel, British National Archives (WO 43/991 ff.76-7 (7 Sept 1855))</ref> |

|||

His designs incorporated the necessities of [[hygiene]]: access to [[sanitation]], ventilation, drainage, and even rudimentary temperature controls. They were feted as a great success, with some sources stating that of the approximately 1,300 patients treated in the hospital, there were only 50 deaths.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.hmswarrior.org/brunel/resources/palmerston_and_politics.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070620002840/http://www.hmswarrior.org/brunel/resources/palmerston_and_politics.pdf|url-status=usurped|archive-date=20 June 2007|title=Palmerston, Brunel and Florence Nightingale's Field Hospital|publisher=HMSwarrior.org|access-date=30 November 2006}}</ref> In the Scutari hospital it replaced, deaths were said to be as many as ten times this number. Nightingale referred to them as "those magnificent huts".<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/science/britainsmodernbrunels.shtml|title=Britain's Modern Brunels]|publisher=BBC Radio 4|access-date=30 November 2006}}</ref> The practice of building hospitals from pre-fabricated modules survives today,<ref name="renkioi"/> with hospitals such as the [[Bristol Royal Infirmary]] being created in this manner. |

|||

The art of using pre-fabricated modules to build hospitals has been carried forward into the present day,<ref name=renkioi>Hospital Development Magazine (see [http://www.hdmagazine.co.uk/story.asp?storyCode=2032207 ]) Lessons from Renkioi, November 10, 2005</ref> with hospitals such as the [[Bristol Royal Infirmary]] being created in this manner. |

|||

===Proposed artillery=== |

|||

==Illnesses and death of Brunel== |

|||

In 1854 and 1855, with the encouragement of [[John Fox Burgoyne]], Brunel presented the Admiralty with designs for floating gun batteries. These were intended as siege weapons for attacking Russian ports. However, these proposals were not taken up, confirming Brunel's opinion of the Admiralty as being opposed to novel ideas.<ref>{{Cite book |

|||

[[Image:Brunel_grave_Kensal_Green.jpg|thumb|right|Brunel family grave in [[Kensal Green Cemetery]] in London. |

|||