Parmenides: Difference between revisions

Jennneal1313 (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|5th-century BC Greek philosopher}} |

|||

:''For the Platonic dialogue see [[Parmenides (dialogue)]].'' |

|||

{{other uses}} |

|||

{{Infobox Philosopher |

|||

{{Infobox philosopher |

|||

<!-- Philosopher Category --> |

|||

| |

|region = [[Western philosophy]] |

||

| |

|era = [[Pre-Socratic philosophy]] |

||

| |

|image = Busto_di_Parmenide.jpg |

||

|caption = Bust of Parmenides discovered at [[Velia]], thought to have been partially modeled on a [[Metrodorus of Lampsacus (the younger)|Metrodorus]] bust. |

|||

<!-- Image and Caption --> |

|||

| |

|name = Parmenides |

||

|birth_date = {{circa|late 6th century BC}} |

|||

| image_caption = Parmenides |

|||

|birth_place = [[Velia|Elea]], [[Magna Graecia]] |

|||

<!-- Information --> |

|||

| |

|death_place = {{circa|5th century BC}} |

||

| |

|school_tradition = [[Eleatic school]] |

||

|main_interests = [[Ontology]], [[poetry]], [[cosmology]] |

|||

| death = ca. [[450 BC]] <!--PLEASE SEE TALK BEFORE CHANGING DATE--> |

|||

|notable_ideas = [[Monism]], [[Aletheia|truth]]/[[Doxa|opinion]] distinction |

|||

| school_tradition = [[Eleatic school]] |

|||

|influences = [[Xenophanes]], [[Heraclitus]] |

|||

| main_interests = [[Metaphysics]] |

|||

| |

|influenced = [[Zeno of Elea]], [[Melissus of Samos]], [[Democritus]], [[Empedocles]], [[Anaxagoras]], [[Plato]] |

||

| influences = [[Amenias]], [[Pythagoras]], [[Xenophanes|Xenophanes of Colophon]] |

|||

| influenced = [[Zeno of Elea]], [[Melissus of Samos]], [[Socrates]], [[Plato]], [[Aristotle]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

<!-- {{toclimit|3}} --> |

|||

'''Parmenides of Elea''' ({{IPAc-en|p|ɑːr|ˈ|m|ɛ|n|ɪ|d|iː|z|...|ˈ|ɛ|l|i|ə}}; {{langx|grc|Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης}}; fl. late sixth or early fifth century BC) was a [[Pre-Socratic philosophy|pre-Socratic]] [[ancient Greece|Greek]] [[philosopher]] from [[Velia|Elea]] in [[Magna Graecia]] (Southern [[Italy]]). |

|||

Parmenides was born in the [[Greek colony]] of [[Velia|Elea]], from a wealthy and illustrious family.{{efn|Diogenes Laërtius, {{harv|DK 28A1|loc=21}}}} His dates are uncertain; according to [[Doxography|doxographer]] [[Diogenes Laërtius]], he flourished just before 500 BC,{{efn|Diogenes Laërtius {{harv|DK 28A1|loc=23}}}} which would put his year of birth near 540 BC, but in the [[dialogue]] ''[[Parmenides (dialogue)|Parmenides]]'' [[Plato]] has him visiting [[Athens]] at the age of 65, when [[Socrates]] was a young man, {{circa|450 BC}},{{efn|Plato, ''Parmenides'', 127a–128b {{harv|DK 28A5}}}} which, if true, suggests a year of birth of {{circa|515 BC}}.{{sfn|Curd|2004|pages=3-8}} He is thought to have been in his prime (or "[[floruit]]") around 475 BC.{{sfn|Freeman|1946|p=140}} |

|||

'''Parmenides of Elea''' ([[Greek language|Greek]]: {{polytonic|Παρμενίδης ο Έλεάτης}}, early [[5th century BC]]) was an [[Hellenic Greece|ancient Greek]] [[philosophy|philosopher]] born in [[Elea]], a Hellenic city on the southern coast of [[Italy]]. Parmenides was a student of Ameinias and the founder of the [[School of Elea]], which also included [[Zeno of Elea]] and [[Melissus of Samos]]. According to [[Plato]], Parmenides had been the [[erastes]] of Zeno when the latter had been a youth. <ref>Plato, ''Parmenides,'' 127</ref> |

|||

The single known work by Parmenides is a poem whose original title is unknown but which is often referred to as ''[http://philoctetes.free.fr/parmenidesunicode.htm On Nature].'' Only fragments of it survive. In his poem, Parmenides prescribes two views of [[reality]]. The first, the Way of "[[Aletheia]]" or truth, describes how all reality is one, [[Change (philosophy)|change]] is impossible, and existence is timeless and uniform. The second view, the way of "[[Doxa]]", or opinion, describes the world of appearances, in which one's sensory faculties lead to conceptions which are false and deceitful. |

|||

==Overview== |

|||

Parmenides is one of the most significant of the [[pre-Socratic]] philosophers. <ref>According to Czech philosopher Milič Čapek "[Parmenides'] decisive influence on the development of Western thought is probably without parallel", ''The New Aspects of Time'', 1991, p. 145. That assessment may overstate Parmenides' impact and importance, but it is a useful corrective to the tendency to underestimate it.</ref> His only known work, conventionally titled 'On Nature' is a [[poem]], which has only survived in fragmentary form. Approximately 150 lines of the poem remain today; reportedly the original text had 3,000 lines. It is known, however, that the work originally divided into three parts: |

|||

* A [http://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/proem proem],<!--Do not "correct" this by writing "poem"; the proem (from Latin "proemium" is the first part of and prologue to the rest of the poem.--> which introduced the entire work, |

|||

* A section known as "The way of truth" (''aletheia''), and |

|||

* A section known as "The way of appearance/opinion" (''doxa''). |

|||

Parmenides has been considered the founder of [[ontology]] and has, through his influence on [[Plato]], influenced the whole history of [[Western philosophy]].{{sfn|Palmer|2020}} He is also considered to be the founder of the [[Eleatic school]] of [[philosophy]], which also included [[Zeno of Elea]] and [[Melissus of Samos]]. [[Zeno paradox|Zeno's paradoxes of motion]] were developed to defend Parmenides's views. In contemporary philosophy, Parmenides's work has remained relevant in debates about the [[philosophy of time]]. |

|||

The proem is a narrative sequence in which the narrator travels "beyond the beaten paths of mortal men" to receive a revelation from an unnamed goddess (generally thought to be [[Persephone]]) on the nature of reality. ''Aletheia'', an estimated 90% of which has survived, and ''doxa'', most of which no longer exists, are then presented as the spoken revelation of the goddess without any accompanying narrative. |

|||

==Biography== |

|||

== Interpretations of Parmenides == |

|||

Parmenides was born in [[Velia|Elea]] (called Velia in Roman times), a city located in [[Magna Graecia]]. [[Diogenes Laertius]] says that his father was Pires, and that he belonged to a rich and noble family.<ref>(DK) A1 (Diogenes Laert, IX 21)</ref> Laertius transmits two divergent sources regarding the teacher of the philosopher. One, dependent on [[Sotion]], indicates that he was first a student of [[Xenophanes]],<ref>The testimony of the link between Parmenides and Xenophanes goes back to [[Aristotle]], ''Met.'' I 5, 986b (A 6) and from [[Plato]], ''Sophist'' 242d (21 A 29)</ref> but did not follow him, and later became associated with a [[Pythagorean school|Pythagorean]], Aminias, whom he preferred as his teacher. Another tradition, dependent on [[Theophrastus]], indicates that he was a disciple of [[Anaximander]].<ref>Tradition attesting ''[[Suidas]]'' (A 2).</ref> |

|||

The traditional interpretation of Parmenides' work is that he argued that the every-day [[perception]] of [[reality]] of the [[physical]] world (as described in ''[[doxa]]'') is mistaken, and that the reality of the world is 'One Being' (as described in ''[[aletheia (philosophy)|aletheia]]''): an unchanging, ungenerated, indestructible whole. Under 'way of seeming', Parmenides set out a contrasting but more conventional view of the world, thereby becoming an early exponent of the [[dualism|duality]] of [[appearance]] and reality. For him and his pupils the [[phenomena]] of movement and change are simply appearances of a static, [[eternity|eternal]] reality. |

|||

===Chronology=== |

|||

Parmenides' philosophy is presented in [[verse]]. The philosophy he argued was, he says, given to him by a goddess, though the "mythological" details in Parmenides' poem do not bear any close correspondence to anything known from traditional Greek mythology: |

|||

Everything related to the chronology of Parmenides—the dates of his birth and death, and the period of his philosophical activity—is uncertain.{{citation needed|date=December 2023}} |

|||

==== Date of birth ==== |

|||

:''Welcome, youth, who come attended by immortal charioteers and mares which bear you on your journey to our dwelling. For it is no evil fate that has set you to travel on this road, far from the beaten paths of men, but right and justice. It is meet that you learn all things - both the unshakable heart of well-rounded truth and the opinions of mortals in which there is not true belief.'' |

|||

All conjectures regarding Parmenides's date of birth are based on two ancient sources. One comes from [[Apollodorus of Athens|Apollodorus]] and is transmitted to us by Diogenes Laertius: this source marks the [[Olympiad]] 69th (between 504 BC and 500 BC) as the moment of maturity, placing his birth 40 years earlier (544 BC – 540 BC).<ref>Diogenes Laertius, IX, 23 (DK testimony A 1).</ref> The other is [[Plato]], in his dialogue ''[[Parmenides (dialogue)|Parmenides]]''. There Plato composes a situation in which Parmenides, 65, and [[Zeno of Elea|Zeno]], 40, travel to [[Ancient Athens|Athens]] to attend the [[Panathenaic Games]]. On that occasion they meet [[Socrates]], who was still very young according to the Platonic text.<ref>Plato, ''Parmenides'' 127 BC (A 5).</ref> |

|||

The inaccuracy of the dating from Apollodorus is well known, who chooses the date of a historical event to make it coincide with the maturity (the ''[[floruit]]'') of a philosopher, a maturity that he invariably reached at forty years of age. He tries to always match the maturity of a philosopher with the birth of his alleged disciple. In this case Apollodorus, according to [[John Burnet (classicist)|Burnet]], based his date of the foundation of Elea (540 BC) to chronologically locate the maturity of [[Xenophanes]] and thus the birth of his supposed disciple, Parmenides.<ref name="Burnet169">Burnet, ''Early Greek Philosophy'', pp. 169ff.</ref> Knowing this, Burnet and later classicists like [[Francis Macdonald Cornford|Cornford]], [[John Raven|Raven]], [[William Keith Chambers Guthrie|Guthrie]], and [[Malcolm Schofield|Schofield]] preferred to base the calculations on the Platonic dialogue. According to the latter, the fact that Plato adds so much detail regarding ages in his text is a sign that he writes with chronological precision. Plato says that Socrates was very young, and this is interpreted to mean that he was less than twenty years old. We know the year of Socrates' death (399 BC) and his age—he was about seventy years old–making the date of his birth 469 BC. The Panathenaic games were held every four years, and of those held during Socrates' youth (454, 450, 446), the most likely is that of 450 BC, when Socrates was nineteen years old. Thus, if at this meeting Parmenides was about sixty-five years old, his birth occurred around 515 BC.<ref name="Burnet169" /><ref name="Corn1">Cornford, ''Plato and Parmenides'', p. 1.</ref><ref name="guth15">Guthrie, ''History of Greek Philosophy'', II, p. 15ff.</ref><ref>Raven, ''The Presocratic Philosophers'', p. 370.</ref><ref>Schofield, ''The Presocratic Philosophers'', p. 347.</ref><ref>Plato, ''Parmenides'' (ed. Degrees), p. 33, note 13</ref><ref name="Cor2023">Cordero, ''Siendo se es'', pp. 20-23</ref> |

|||

It is with respect to this religious/mystical context that recent generations of scholars such as [[Alexander P. Mourelatos]], [[Charles H. Kahn]], and the controversial [[Peter Kingsley (scholar)|Peter Kingsley]] have begun to call parts of the traditional, rational logical/philosophical interpretation of Parmenides into question. According to Peter Kingsley Parmenides practiced [[Iatromantis|iatromancy]]. It has been claimed, for instance, that previous scholars placed too little emphasis on the apocalyptic context in which Parmenides frames his revelation. As a result, traditional interpretations have put Parmenidean philosophy into a more modern, metaphysical context to which it is not necessarily well suited, which has led to misunderstanding of the true meaning and intention of Parmenides' message. The obscurity and fragmentary state of the text, however, renders almost every claim that can be made about Parmenides extremely contentious, and the traditional interpretation has by no means been completely abandoned. |

|||

However, neither Raven nor Schofield, who follows the former, finds a dating based on a late Platonic dialogue entirely satisfactory. Other scholars directly prefer not to use the Platonic testimony and propose other dates. According to a scholar of the [[Platonic dialogues]], R. Hirzel, [[:es:Conrado Eggers Lan|Conrado Eggers Lan]] indicates that the historical has no value for Plato.<ref>R. Hirzel, ''Der Dialog'', I, p. 185.</ref> The fact that the meeting between Socrates and Parmenides is mentioned in the dialogues ''Theaetetus'' (183e) and ''Sophist'' (217c) only indicates that it is referring to the same fictional event, and this is possible because both the ''Theaetetus'' and the ''Sophist'' are considered after the ''Parmenides''. In ''Soph.'' 217c the [[dialectic]] procedure of Socrates is attributed to Parmenides, which would confirm that this is nothing more than a reference to the fictitious dramatic situation of the dialogue.<ref>Eggers Lan, ''The pre-Socratic philosophers'', p. 410ff.</ref> Eggers Lan proposes a correction of the traditional date of the foundation of Elea. Based on [[Herodotus]] I, 163–167, which indicates that the [[Phocia]]ns, after defeating the [[Ancient Carthage|Carthaginians]] in naval battle, founded Elea, and adding the reference to [[Thucydides]] I, 13, where it is indicated that such a battle occurred in the time of [[Cambyses II]], the foundation of Elea can be placed between 530 BC and 522 BC So Parmenides could not have been born before 530 BC or after 520 BC, given that it predates [[Empedocles]].<ref>Eggers Lan, ''The pre-Socratic philosophers'', pp. 412ff.</ref> This last dating procedure is not infallible either, because it has been questioned that the fact that links the passages of Herodotus and Thucydides is the same.<ref>Thucydides, ''[[History of the Peloponnesian War]]'', p. 43, no. 106 of Torres Esbarranch.</ref> [[:es:Nestor Luis Cordero|Nestor Luis Cordero]] also rejects the chronology based on the Platonic text, and the historical reality of the encounter, in favor of the traditional date of Apollodorus. He follows the traditional datum of the founding of Elea in 545 BC, pointing to it not only as ''[[terminus post quem]]'', but as a possible date of Parmenides's birth, from which he concludes that his parents were part of the founding contingent of the city and that he was a contemporary of [[Heraclitus]].<ref name="Cor2023" /> The evidence suggests that Parmenides could not have written much after the death of Heraclitus.{{citation needed|date=December 2023}} |

|||

Parmenides' considerable influence on the thinking of [[Plato]] is undeniable, and in this respect Parmenides has influenced the whole history of [[Western philosophy]], and is often seen as its grandfather. Even Plato himself, in the ''[[Sophist (dialogue)|''Sophist'']]'', refers to the work of "our Father Parmenides" as something to be taken very seriously and treated with respect. In the ''[[Parmenides (Plato)|''Parmenides'']]'' the Eleatic philosopher, which may well be Parmenides himself, and [[Socrates]] argue about [[dialectic]]. In the ''[[Theaetetus (Plato)|Theaetetus]]'', Socrates says that Parmenides alone among the wise ([[Protagoras]], [[Heraclitus]], [[Empedocles]], [[Epicharmus]], and [[Homer]]) denied that everything is change and motion. |

|||

==== Timeline relative to other Presocratics ==== |

|||

Parmenides is credited with a great deal of influence as the author of an "Eleatic challenge" that determined the course of subsequent philosophers' enquiries. For example, the ideas of [[Empedocles]], [[Anaxagoras]], [[Leucippus]], and [[Democritus]] have been seen as in response to Parmenides' arguments and conclusions.<ref>See e.g. David Sedley, "Parmenides," in E. Craig (ed.), ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' (Routledge, 1998): "Parmenides marks a watershed in Presocratic philosophy. In the next generation he remained the senior voice of Eleaticism, perceived as champion of the One against the Many. His One was defended by Zeno of Elea and Melissus, while those who wished to vindicate cosmic plurality and change felt obliged to respond to his challenge. Empedocles, Anaxagoras, Leucippus and Democritus framed their theories in terms which conceded as much as possible to his rejections of literal generation and annihilation and of division."</ref> |

|||

Beyond the speculations and inaccuracies about his date of birth, some specialists have turned their attention to certain passages of his work to specify the relationship of Parmenides with other thinkers. It was thought to find in his poem certain controversial allusions to the doctrine of [[Anaximenes of Miletus|Anaximenes]] and the [[Pythagoreans]] (fragment B 8, verse 24, and frag. B 4), and also against [[Heraclitus]] (frag .B 6, vv.8–9), while [[Empedocles]] and [[Anaxagoras]] frequently refer to Parmenides.<ref>Raven, ''The Presocratic Philosophers'', pp. 370s; 385s; 381.</ref> |

|||

The reference to Heraclitus has been debated. Bernays's thesis<ref>Bernays, ''Ges. Abh., 1, 62, n. 1.''</ref> that Parmenides attacks Heraclitus, to which Diels, Kranz, Gomperz, Burnet and others adhered, was discussed by Reinhardt,<ref>Reinhardt, ''Parmenides'', p. 64.</ref> whom Jaeger followed.<ref>Jaeger, ''The Theology of the Early Greek Philosophers'', p. 104.</ref> |

|||

== Arguments by Parmenides == |

|||

[[Image:Sanzio 01 Parmenides.jpg|thumb|right|Parmenides. Detail from ''[[The School of Athens]]'' by [[Raphael]].]] |

|||

The ''Way of Truth'' discusses that which is real, which contrasts in some way with the argument of the ''Way of Seeming'', which discusses that which is illusory. Under the ''Way of Truth'', Parmenides stated that there are two ways of inquiry: that it ''is'', that it ''is not''. He said that the latter argument is never feasible because nothing can ''not be'': |

|||

Guthrie finds it surprising that Heraclitus would not have censured Parmenides if he had known him, as he did with [[Xenophanes]] and [[Pythagoras]]. His conclusion, however, does not arise from this consideration, but points out that, due to the importance of his thought, Parmenides splits the history of pre-Socratic philosophy in two; therefore his position with respect to other thinkers is easy to determine. From this point of view, the philosophy of Heraclitus seems to him pre-Parmenidean, while those of Empedocles, Anaxagoras and [[Democritus]] are post-Parmenidean.<ref name="guth15"/> |

|||

:''For never shall this prevail, that things that are not '''are'''.'' |

|||

=== Anecdotes === |

|||

There are extremely delicate issues here. In the original Greek the two ways are simply named "that Is" (''hopos estin'') and "that Not-Is" (''hos ouk estin'') (Frag. 2. 3 and 2. 5) without the "it" inserted in our English translation. In ancient Greek, which, like many languages in the world, does not always require the presence of a subject for a verb, "is" functions as a grammatically complete sentence. A lot of debate has been focused on where and what the subject is. The simplest explanation as to why there is no subject here is that Parmenides wishes to express the simple, bare fact of existence in his mystical experience without the ordinary distinctions, just as the Latin "pluit" and the Greek ''uei'' ("rains") mean "it rains"; there is no subject for these impersonal verbs because they express the simple fact of raining without specifying what is doing the raining. This is, for instance, [[Hermann Fraenkel]]'s thesis (''Dichtung und Philosophie des fruehen Griechentums'', 1962) [http://www.geocities.com/therapeuter2002/presocratics333.html] But many scholars still reject this explanation and have produced more complex metaphysical explanations. Since existence is an immediately intuited fact, non-existence is the wrong path because something cannot ever disappear just as something cannot ever come from nothing. In such mystical experience (''unio mystica''), however, the distinction between subject and object disappears along with the distinctions between objects, in addition to the fact that if nothing cannot be, it cannot be the object of thought either: |

|||

[[Plutarch]], [[Strabo]] and [[Diogenes Laertius|Diogenes]]—following the testimony of [[Speusippus]]—agree that Parmenides participated in the government of his city, organizing it and giving it a code of admirable laws.<ref>Strabo, [[Strabo's Geography|Geography]] VI 1, 1 (A 12); Plutarch., ''Adv. Colot.'' 1126a (A 12); [[Speusippus]], fr. 1, in Diog. L., IX, 23 (A 1).</ref> |

|||

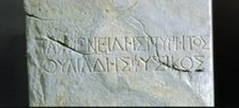

[[File:Detail Parmenides bust.png|thumb|750px|Detail of the pedestal found in Velia. Greek inscriptions were made only in capital letters, and without spaces. Read as follows: |

|||

<!-- the next two lines contain tags to format the text, so that it is displayed on two lines. Please don't change. --> |

|||

<!-- # -->''' ΠΑ[ ]ΜΕΝΕΙΔΗΣ ΠΥΡΗΤΟΣ'''<br /> |

|||

<!-- # -->''' ΟΥΛΙΑΔΗΣ ΦΥΣΙΚΟΣ''' |

|||

]] |

|||

====Archaeological discovery==== |

|||

:''Thinking and the thought that it is are the same; for you will not find thought apart from what is, in relation to which it is uttered.'' |

|||

In 1969, the plinth of a statue dated to the 1st century AD was excavated in [[Velia]]. On the plinth were four words: ΠΑ[Ρ]ΜΕΝΕΙΔΗΣ ΠΥΡΗΤΟΣ ΟΥΛΙΑΔΗΣ ΦΥΣΙΚΟΣ.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://inscriptions.packhum.org/text/301222?bookid=742&location=8|title=IG XIV }}</ref> The first two clearly read "Parmenides, son of Pires." The fourth word φυσικός (''fysikós'', "physicist") was commonly used to designate philosophers who devoted themselves to the observation of nature. On the other hand, there is no agreement on the meaning of the third (οὐλιάδης, ''ouliadēs''): it can simply mean "a native of Elea" (the name "Velia" is in Greek Οὐέλια),<ref>Marcel Conche, ''Parménide : Le Poème: Fragments'', Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1996, p. 5 and note.</ref> or "belonging to the Οὐλιος" (''Ulios''), that is, to a [[medical school]] (the patron of which was [[Apollo]] Ulius).<ref>P. Ebner, "Parmenide medico ''Ouliádes''", in: ''Giornale di Metafisica'' 21 (1966), pp. 103-114</ref> If this last hypothesis were true, then Parmenides would be, in addition to being a legislator, a doctor.<ref>''Poema'', intr. by Jorge Pérez de Tudela, p. 14</ref> The hypothesis is reinforced by the ideas contained in fragment 18 of his poem, which contains [[anatomy|anatomical]] and [[physiology|physiological]] observations.<ref>''Poema'', comment by Jorge Pérez de Tudela, p. 230 and note ad. loc.</ref> However, other specialists believe that the only certainty we can extract from the discovery is that of the social importance of Parmenides in the life of his city, already indicated by the testimonies that indicate his activity as a legislator.<ref>N. L. Cordero, ''Being one is'', p. 23.</ref> |

|||

==== Visit to Athens ==== |

|||

:''For thought and being are the same.'' |

|||

[[Plato]], in his dialogue ''[[Parmenides (dialogue)|Parmenides]]'', relates that, accompanied by his disciple [[Zeno of Elea]], Parmenides visited [[Ancient Athens|Athens]] when he was approximately sixty-five years old and that, on that occasion, [[Socrates]], then a young man, conversed with him.<ref>Plato, ''Parmenides'' 127 BC (A 11).</ref> [[Athenaeus]] of [[Naucratis]] had noted that, although the ages make a dialogue between Parmenides and Socrates hardly possible, the fact that Parmenides has sustained arguments similar to those sustained in the [[Platonic dialogue]] is something that seems impossible.<ref>[[Athenaeus]], ''[[Deipnosophistae]]'' XI 505f (A 5)</ref> Most modern classicists consider the visit to Athens and the meeting and conversation with Socrates to be fictitious. Allusions to this visit in other Platonic works are only references to the same fictitious dialogue and not to a historical fact.<ref>See ''Theaetetus'' 183e; ''Sophist'' 217c; see also «Introduction» to the dialogue ''Parménides'' by M.ª Isabel Santa Cruz, p. 11</ref> |

|||

== ''On Nature'' == |

|||

:''It is necessary to speak and to think what is; for being is, but nothing is not.'' |

|||

Parmenides's sole work, which has only survived in fragments, is a poem in [[dactylic hexameter]], later titled ''On Nature''. Approximately 160 verses remain today from an original total that was probably near 800.{{sfn|Palmer|2020}} The poem was originally divided into three parts: an introductory [[wikt:proem|proem]] that contains an allegorical narrative which explains the purpose of the work, a former section known as "The Way of Truth" (''[[aletheia]]'', ἀλήθεια), and a latter section known as "The Way of Appearance/Opinion" (''[[doxa]]'', δόξα). Despite the poem's fragmentary nature, the general plan of both the proem and the first part, "The Way of Truth" have been ascertained by modern scholars, thanks to large excerpts made by [[Sextus Empiricus]]{{efn|''[[Against the Mathematicians]]'' {{harv|DK 28B1}}}} and [[Simplicius of Cilicia]].{{efn|''Commentary on [[Aristotle]]'s Physics'' {{harv|DK 22B8}}}}{{sfn|Palmer|2020}} Unfortunately, the second part, "The Way of Opinion", which is supposed to have been much longer than the first, only survives in small fragments and prose paraphrases.{{sfn|Palmer|2020}} |

|||

=== Introduction === |

|||

:''Helplessness guides the wandering thought in their breasts; they are carried along deaf and blind alike, dazed, beasts without judgment, convinced that to be and not to be are the same and not the same, and that the road of all things is a backward-turning one.'' |

|||

The introductory poem describes the narrator's journey to receive a revelation from an unnamed goddess on the nature of reality.{{sfn|Curd|2004|loc=I.3}} The remainder of the work is then presented as the spoken revelation of the goddess without any accompanying narrative.{{sfn|Curd|2004|loc=I.3}} |

|||

The narrative of the poet's journey includes a variety of allegorical symbols, such as a speeding chariot with glowing axles, horses, the House of Night, Gates of the paths of Night and Day, and maidens who are "the daughters of the Sun"{{sfn|Kirk|Raven|Schofield|1983|p=243}} who escort the poet from the ordinary daytime world to a strange destination, outside our human paths.{{sfn|Furley|1973|pp=1–15}} The allegorical themes in the poem have attracted a variety of different interpretations, including comparisons to [[Homer]] and [[Hesiod]], and attempts to relate the journey towards either [[Divine illumination|illumination]] or darkness, but there is little scholarly consensus about any interpretation, and the surviving evidence from the poem itself, as well as any other literary use of allegory from the same time period, may be too sparse to ever determine any of the intended symbolism with certainty.{{sfn|Curd|2004|loc=I.3}} |

|||

Thus, he concluded that "Is" could not have "come into being" because "[[nothing comes from nothing]]." Existence is necessarily eternal. Parmenides was not struggling to formulate the [[mass-energy equivalence|conservation of mass-energy]]. He was struggling with the metaphysics of change, which is still a relevant philosophical topic today. |

|||

=== ''The Way of Truth'' === |

|||

Moreover he argued that movement was impossible because it requires moving into "the void", and Parmenides identified "the void" with nothing, and therefore (by definition) it does not exist. That which does exist is ''The Parmenidean One'' which is timeless, uniform, and unchanging: |

|||

In the ''Way of Truth'', an estimated 90% of which has survived,{{sfn|Palmer|2020}} Parmenides distinguishes between the unity of nature and its variety, insisting in the ''Way of Truth'' upon the reality of its unity, which is therefore the object of knowledge, and upon the unreality of its variety, which is therefore the object, not of knowledge, but of opinion.{{citation needed|date=April 2022}} This contrasts with the argument in the section called "the way of opinion", which discusses that which is illusory.{{citation needed|date=December 2023}} |

|||

=== ''The Way of Opinion'' === |

|||

:''How could what is perish? How could it have come to be? For if it came into being, it is not; nor is it if ever it is going to be. Thus coming into being is extinguished, and destruction unknown.'' |

|||

In the significantly longer, but far worse preserved latter section of the poem, ''Way of Opinion'', Parmenides propounds a theory of the world of seeming and its development, pointing out, however, that, in accordance with the principles already laid down, these cosmological speculations do not pretend to anything more than mere appearance. The structure of the cosmos is a fundamental binary principle that governs the manifestations of all the particulars: "the Aether fire of flame" (B 8.56), which is gentle, mild, soft, thin and clear, and self-identical, and the other is "ignorant night", body thick and heavy.{{sfn|Guthrie|1979|p= 61–62}}{{efn|{{harv|DK 28B8.53–4}}}} [[Cosmology]] originally comprised the greater part of his poem, explaining the world's origins and operations.{{efn|[[Stobaeus]], i. 22. 1a}} Some idea of the [[Spherical Earth|sphericity of the Earth]] also seems to have been known to Parmenides.{{sfn|Palmer|2020}}{{efn|DK 28B10}} |

|||

== Legacy == |

|||

:''Nor was [it] once, nor will [it] be, since [it] is, now, all together, / One, continuous; for what coming-to-be of it will you seek? / In what way, whence, did [it] grow? Neither from what-is-not shall I allow / You to say or think; for it is not to be said or thought / That [''it''] ''is not''. And what need could have impelled it to grow / Later or sooner, if it began from nothing? Thus [it] must either be completely or not at all.'' |

|||

As the first of the [[Eleatics]], Parmenides is generally credited with being the philosopher who first defined ontology as a separate discipline distinct from theology.{{sfn|Palmer|2020}} His most important pupil was [[Zeno of Elea|Zeno]], who appears alongside him in Plato's ''Parmenides'' where they debate [[dialectic]] with [[Socrates]].{{efn|{{harv|DK 28A5}}}} The pluralist theories of [[Empedocles]] and [[Anaxagoras]] and the atomist [[Leucippus]], and [[Democritus]] have also been seen as a potential response to Parmenides's arguments and conclusions.{{sfn|Sedley|1998}} Parmenides is also mentioned in Plato's ''[[Sophist (dialogue)|Sophist]]''{{efn|''Sophist'', 241d}} and ''[[Theaetetus (Plato)|Theaetetus]].''{{efn|Plato, ''Theaetetus'', 183e}} Later Hellenistic doxographers also considered Parmenides to have been a pupil of [[Xenophanes]].{{efn|Aristotle, ''[[Metaphysics (Aristotle)|Metaphysics]]'', i. 5; [[Sextus Empiricus]], ''adv. Math.'' vii. 111; [[Clement of Alexandria]], ''[[Stromata]]'', i. 301; Diogenes Laërtius, ix. 21}} [[Eusebius of Caesarea]], quoting [[Aristocles of Messene]], says that Parmenides was part of a line of skeptical philosophy that culminated in [[Pyrrhonism]] for he, by the root, rejects the validity of perception through the senses whilst, at any rate, it is first through our five forms of senses that we become aware of things and then by faculty of reasoning.{{efn|[[Eusebius]], ''[[Praeparatio Evangelica]]'' [https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/eusebius_pe_14_book14.htm Book XIV], Chapter XVII}} Parmenides's proto-[[monism]] of [[The One (Neoplatonism)|the One]] also influenced [[Plotinus]] and [[Neoplatonism]].{{citation needed|date=September 2022}} |

|||

== Notes == |

|||

:''[What exists] is now, all at once, one and continuous... Nor is it divisible, since it is all alike; nor is there any more or less of it in one place which might prevent it from holding together, but all is full of what is.'' |

|||

=== Fragments === |

|||

:''And it is all one to me / Where I am to begin; for I shall return there again.'' |

|||

{{notelist|20em}} |

|||

=== Citations === |

|||

==Perception vs. Logos== |

|||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

Parmenides claimed that the [[truth]] cannot be known through sensory [[perception]]. Only pure [[reason]] ([[Logos]]) will result in the understanding of the truth of the world. This is because the perception of things or appearances (''the [[doxa]]'') is deceptive. We may see, for example, tables being made from wood and destroyed, and speak of birth and demise; this belongs to the superficial world of movement and change. But this genesis-and-destruction, as Parmenides emphasizes, is illusory, because the underlying material of which the table is made will still exist after its destruction. What exists must always exist. And we arrive at the knowledge of this underlying, static, and eternal reality (''aletheia'') through reasoning, not through sense-perception. |

|||

:''For this view, that That Which Is Not exists, can never predominate. You must debar your thought from this way of search, nor let ordinary experience in its variety force you along this way, (namely, that of allowing) the eye, sightless as it is, and the ear, full of sound, and the tongue, to rule; but (you must) judge by means of the Reason ([[Logos]]) the much-contested proof which is expounded by me.'' |

|||

== Bibliography == |

|||

==The world of seeming (''doxa''): Parmenides' cosmogony== |

|||

===Ancient testimony=== |

|||

After the exposition of the ''arche'', i.e. the origin, the necessary part of reality that is understood through reason or logos (''that [it] Is'') , in the next section, ''the Way of Appearance/Opinion/Seeming'', Parmenides proceeds to explain the structure of the becoming cosmos (which is an illusion, of course) that comes from this origin. |

|||

In the [[Diels–Kranz numbering]] for testimony and fragments of [[Pre-Socratic philosophy]], Parmenides is catalogued as number 28. The most recent edition of this catalogue is: |

|||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

The structure of the cosmos is a fundamental binary principle that governs the manifestations of all the particulars: "the aither fire of flame" (8, 56), which is gentle, mild, soft, thin and clear, and self-identical -- this is something like the masculine principle -- and the other is "ignorant night", body thick and heavy -- this is something like the feminine principle. Thus Parmenides' cosmogony is exactly like the yin-yang picture in Chinese cosmogony. |

|||

{{cite book |last1=Diels |first1=Hermann |last2=Kranz |first2=Walther |editor-last1=Plamböck |editor-first1=Gert |title=Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker |date=1957 |publisher=Rowohlt |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KEYWQwAACAAJ |access-date=11 April 2022 |isbn=5875607416 |language= grc,de}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==== Life and doctrines ==== |

|||

:''The mortals lay down and decided well to name two forms (i.e. the flaming light and obscure darkness of night), out of which it is necessary not to make one, and in this they are led astray.'' (8, 53-4) |

|||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* '''A1. '''{{cite LotEP |chapter=Parmenides|ref={{sfnref|DK 28A1}}}} |

|||

* '''A2. '''{{cite encyclopedia | title = Parmenides | encyclopedia = [[Suda]] |via= Suda Online |url=https://www.cs.uky.edu/~raphael/sol/sol-cgi-bin/search.cgi?search_method=QUERY&login=&enlogin=&searchstr=pi,675&field=adlerhw_gr&db=REAL |ref={{sfnref|DK 28A2}}}} |

|||

* '''A3. '''{{cite LotEP |chapter=Anaximenes|§=3|ref={{sfnref|DK 28A3}}}} |

|||

* '''A4. '''{{cite book |author=[[Iamblichus]]|title=Life of Pythagoras|ref={{sfnref|DK 28A4}}}} |

|||

* '''A5. '''{{cite book |author=[[Plato]]|title= [[Parmenides (dialogue)|Parmenides]] | at=[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Plat.+Parm.+127a 127a]| ref={{sfnref|DK 28A5}} |series=Plato in Twelve Volumes| translator=Harold N. Fowler |volume=9 |date=1925}} |

|||

* '''A6. '''{{cite book |author=[[Aristotle]]|title=[[Metaphysics (Aristotle)|Metaphysics]]|at=986b|ref={{sfnref|DK 28A6}}}} |

|||

* '''A7. '''{{cite book |author=[[Alexander of Aphrodisias]]|title=Commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics|at=984b|ref={{sfnref|DK 28A7}}}} |

|||

* '''A8. '''{{cite book |author=[[Simplicius of Cilicia|Simplicius]] |title=Commentary On Aristotle's Physics |ref={{sfnref|DK 28A8}} |language=en}} |

|||

* '''A9. '''{{cite LotEP |chapter=Protagoras|ref={{sfnref|DK 28A9}}}} |

|||

* '''A10.''' {{cite book |author=[[Simplicius of Cilicia|Simplicius]] |title=Commentary On Aristotle's Physics |ref={{sfnref|DK 28A10}} |language=en}} |

|||

* '''A11.''' {{cite book |author=[[Eusebius]]|title=Chronicon Paschale|ref={{sfnref|DK 28A11}}}} |

|||

* '''A12.''' {{cite book |author=[[Strabo]]|title=Geographia|at=Book VI, §1|ref={{sfnref|DK 28A12}}}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

==== Fragments ==== |

|||

The structure of the cosmos then generated is recollected by Aetius (II, 7, 1): |

|||

{{refbegin|20em}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Empiricus |first1=Sextus |last2=Empírico |first2=Sexto |title=Sextus Empiricus in four volumes: Against the logicians. Vol. 2 |date=1933 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-674-99321-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RJg1AAAAIAAJ |access-date=13 April 2022 |language=en|ref={{sfnref|DK 28B1}}}} |

|||

* {{cite book |author1=[[Simplicius of Cilicia|Simplicius]] |title=Commentary On Aristotle Physics |date=22 April 2014 |pages=55–56 |volume=1.3-4 |publisher=A&C Black |isbn=978-1-4725-1531-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UAgsAwAAQBAJ |access-date=13 April 2022 |ref={{sfnref|DK 28B8}} |language=en}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

=== Modern scholarship === |

|||

:''Parmenides says that there are coronas one enveloping or encircling another,one formed of rare [yang], and the other of dense [yin], others, mixed form of light and darkness, are in the middle. And Parmenides provides, surrounding all these, a [corona like a] wall of some kind, solid and just, under which is a corona of fire. And what is in the most center of all this [the core, kernel of the cosmos in the corona form] is again encircled by [a corona] of fire. And he provides the most middle [layer of corona] of the mixed coronas as the progenitor, for all beings, of all the movements and all the generations. He calls this [middle progenitor layer of corona] the goddess (''daimona'') that governs or that holds the key, or Justice (''diken'') or Necessity (''ananke'').'' [http://www.geocities.com/therapeuter/plato.html] |

|||

{{refbegin|30em}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Curd |first1=Patricia |title=The Legacy of Parmenides: Eleatic Monism and Later Presocratic Thought |date=2004 |publisher=Parmenides Pub. |isbn=978-1-930972-15-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FkSzQgAACAAJ |access-date=12 April 2022 |language=en}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|title=The Pre-Socratic Philosophers|last=Freeman|first=Kathleen|publisher=Oxford Basil Blackwell|year=1946|location=Great Britain in the City Of Oxford at the Alden Press|pages=140}} |

|||

* {{Cite book |title=Exegesis and Argument: Studies in Greek Philosophy presented to Gregory Vlastos |last=Furley |first=D.J. |year=1973}} |

|||

* {{cite book|last=Guthrie|first=W. K. C.|year=1979|title=A History of Greek Philosophy – The Presocratic tradition from Parmenides to Democritus|publisher=Cambridge University Press}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Kirk |last2=Raven |last3=Schofield |first1=G. S.|first2=J. E. |first3=M. |title=The presocratic philosophers : a critical history with a selection of texts |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kFpd86J8PLsC| access-date=12 April 2022| date=1983 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-521-27455-5 |edition=2nd |page=243}} |

|||

* {{Cite journal |title=Eleatic Conventionalism and Philoaus on the Conditions of Thought |last=Nussbaum |first=Martha |date=1979 |journal=Harvard Studies in Classical Philology |volume=83 |pages=63–108 |doi= 10.2307/311096|jstor=311096 }} |

|||

* {{cite SEP |url-id=parmenides |title=Parmenides |last=Palmer |first=John|date=2020}} |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia | encyclopedia=Routledge encyclopedia of philosophy |date=1998 |publisher=Routledge | location=London | isbn=9780415169165| author1-last=Sedley|author1-first=David | title=Parmenides | editor-first1= Edward| editor-last1= Craig}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

== |

== Further reading == |

||

{{refbegin|40em}} |

|||

Only nineteen fragments of Parmenides' poem have survived into the modern era. All nineteen fragments were transcribed from [[Greek language|Greek]] to [[German language|German]] by a German [[paleographer]] named [[Hermann Diels]] in the 19th century. In fact, Diels assembled a document that entailed most of the known [[pre-Socratic]] philosophical writings. One important fragment in Parmenides' poem includes the notion that ''being is'' and as such it cannot be divided. Parmenides also teaches that in order to truly exist, one must look beyond appearances. For Parmenides, one way to go beyond the physical world was to meditate. Fragment III of the poem for example entails the idea of thinking and being as one and the same. Graduate students of philosophy have written thousand page dissertations on Fragment III alone. Upon further investigation into Parmenides' poem, one will find the underpinnings of Greek [[determinism]]. In other words, fate is the driving force behind the universe and thus free will is a mere figment of the human imagination. In the 19th century, [[Hegel]] incorporated this notion of Greek determinism into his [[philosophy of history]]. |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Austin |first1=Scott |title=Parmenides: Being, Bounds, and Logic |date=1986 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-03559-9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6ckDAQAAIAAJ |language=en}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Austin |first1=Scott |title=Parmenides and The History of Dialectic |date=15 July 2007 |publisher=Parmenides Publishing |isbn=978-1-930972-53-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fW1hDwAAQBAJ |language=en}} |

|||

==Influence on the development of science== |

|||

* Bakalis, Nikolaos (2005), ''Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments'', Trafford Publishing, {{ISBN|1-4120-4843-5}} |

|||

{{Thermodynamics timeline context|Parmenides}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Barnes |first=Jonathan | chapter=Parmenides and the Objects of Inquiry | title=The Presocratic Philosophers |pages=155–175 |publisher=Routledge and Kegan Paul |date=1982}} |

|||

*In '''c.485 BC''', Parmenides makes the [[ontological]] argument against nothingness, ''essentially denying the possible existence of a void''. |

|||

* Cordero, Nestor-Luis (2004), ''By Being, It Is: The Thesis of Parmenides''. Parmenides Publishing, {{ISBN|978-1-930972-03-2}} |

|||

*In '''c.460 BC''', [[Leucippus]], in opposition to Parmenides' denial of the void, proposes the [[atomic theory]], which supposes that everything in the universe is either atoms or voids; a theory which, according to [[Aristotle]], was stimulated into conception so to purposely contradict Parmenides' argument. |

|||

* Cordero, Néstor-Luis (ed.), ''Parmenides, Venerable and Awesome (Plato, Theaetetus 183e)'' Las Vegas: Parmenides Publishing 2011. Proceedings of the International Symposium (Buenos Aires, 2007), {{ISBN|978-1-930972-33-9}} |

|||

*In '''c.380 BC''', [[Plato]] writes the Parmenides arguably an attack on the original theorems in the Way of Truth. |

|||

* Coxon, but A. H. (2009), ''The Fragments of Parmenides: A Critical Text With Introduction and Translation, the Ancient Testimonia and a Commentary''. Las Vegas, Parmenides Publishing (new edition of Coxon 1986), {{ISBN|978-1-930972-67-4}} |

|||

*In '''c.350 BC''', [[Aristotle]] proclaims, in opposition to Leucippus, the dictum ''horror vacui'' or “nature abhors a vacuum”. Aristotle reasoned that in a complete vacuum, infinite speed would be possible because motion would encounter no resistance. Since he did not accept the possibility of infinite speed, he decided that a vacuum was equally impossible. |

|||

* Curd, Patricia (2011), ''A Presocratics Reader: Selected Fragments and Testimonia'', Hackett Publishing, {{ISBN|978-1603843058}} (Second edition Indianapolis/Cambridge 2011) |

|||

* Hermann, Arnold (2005), ''To Think Like God: Pythagoras and Parmenides-The Origins of Philosophy'', Fully Annotated Edition, Parmenides Publishing, {{ISBN|978-1-930972-00-1}} |

|||

== Works == |

|||

* Hermann, Arnold (2010), ''Plato's Parmenides: Text, Translation & Introductory Essay'', Parmenides Publishing, {{ISBN|978-1-930972-71-1}} |

|||

*''On Nature'' (written between 480 and 470 BC) [http://www.elea.org/Parmenides/ ] |

|||

* Mourelatos, Alexander P. D. (2008). ''The Route of Parmenides: A Study of Word, Image, and Argument in the Fragments''. Las Vegas: Parmenides Publishing. {{ISBN|978-1-930972-11-7}} (First edition Yale University Press 1970) |

|||

* Palmer, John. (2009). ''Parmenides and Presocratic Philosophy.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|||

== Notes == |

|||

:''Extensive bibliography (up to 2004) by [http://www.parmenides.com/images/pdfs/Pbib29Apr05online.pdf Nestor-Luis Cordero]; and annotated bibliography by [https://www.ontology.co/biblio/parmenides-biblio-one.htm Raul Corazzon]'' |

|||

<references/> |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Schmitt |first1=Arbogast |title=Die Frage nach dem Sein bei Parmenides |date=2023 |publisher=der blaue reiter |location=Hannover |isbn=9783933722850}} |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

== References and further reading == |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Austin, Scott | title=Parmenides: Being, Bounds and Logic | publisher=Yale University Press | year=1986}} |

|||

*Austin, Scott (2007) ''Parmenides and the History of Dialectic: Three Essays, Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-19-3 |

|||

*Bakalis Nikolaos (2005) ''Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments'', Trafford Publishing, ISBN 1-4120-4843-5 |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Barnes, Jonathan | title=The Presocratic Philosophers (Two Volumes) |publisher=Routledge and Kegan Paul | year =1978}} |

|||

*Burnet J. (2003) ''Early Greek Philosophy'', Kessinger Publishing. |

|||

*Čapek, Milič (1991) ''The New Aspects of Time'', Kluwer |

|||

*Cordero, Nestor-Luis (2004) ''By Being, It Is: The Thesis of Parmenides''. Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-03-2 |

|||

*{{cite book | author=[[Allan H. Coxon|Coxon, A. H.]]| title=The Fragments of Parmenides | publisher=Van Gorcum | year=1986}} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Curd, Patricia | title=The Legacy of Parmenides | publisher=Princeton University Press | year=1998}} |

|||

*Curd, Patricia (2004). ''The Legacy of Parmenides: Eleatic Monism and Later Presocratic Thought'', Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-15-5 |

|||

*Gallop David. (1991) ''Parmenides of Elea – Fragments'', University of Toronto Press. |

|||

*Guthrie W. K. (1979) ''A History of Greek Philosophy – The Presocratic tradition from Parmenides to Democritus'', Cambridge University Press. |

|||

*Hermann, Arnold (2005) ''The Illustrated To Think Like God: Pythagoras and Parmenides-The Origins of Philosophy'', Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-17-9 |

|||

*Hermann, Arnold (2005) ''To Think Like God: Pythagoras and Parmenides-The Origins of Philosophy'', Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-00-1 |

|||

*Hermann, A. and Chrysakopoulou, S. (2007) ''Plato's Parmenides: A New Translation'', Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-20-9 |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Kingsley, Peter | title=In the Dark Places of Wisdom | publisher=Duckwork and Co. | year=2001}} |

|||

*Kirk G. S., Raven J. E. and Schofield M. (1983) ''The Presocratic Philosophers'', Cambridge University Press, Second edition. |

|||

*[[Suzanne Lilar| Lilar, Suzanne]] (1967) ''A propos de Sartre et de l'amour'', Paris, Grasset. |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Melchert, Norman | title=The Great Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy | publisher=McGraw Hill | year=2002 | id=ISBN 0-19-517510-7}} |

|||

*{{cite book | author=Mourelatos, Alexandar P. D. | title=The Route of Parmenides | publisher=Yale University Press | year=1970}} |

|||

*Mourelatos, Alexander P. D. (2007) ''The Route of Parmenides: A Study of Word, Image, and Argument in the Fragments'', Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-11-7 |

|||

*[[Nietzsche, Friedrich]], ''[[Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks]]'', Regnery Gateway ISBN 0-89526-944-9 |

|||

*{{cite book | author=[[Karl Popper|Popper, Karl R.]] | title=The World of Parmenides | publisher=Routledge | year=1998 | id=ISBN 0-415-17301-9}} |

|||

<br> |

|||

Extensive bibliographies are available [http://presocratics.org/parmenides.htm here] and [http://www.parmenides.com/images/pdfs/Pbib29Apr05online.pdf here]. |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{Wikisource|Fragments of Parmenides}} |

|||

*[http://www.iep.utm.edu/p/parmenid.htm ''Parmenides'', The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy] |

|||

{{Wikiquote|Parmenides}} |

|||

*[http://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/320/parm1.htm "Lecture Notes: Parmenides", S Marc Cohen, University of Washighton] |

|||

{{Commons category|Parmenides of Elea}} |

|||

*[http://www.formalontology.it/parmenides.htm Parmenides' Way of Truth] |

|||

{{Library resources box |by=yes |onlinebooks=yes |others=yes |about=yes |label=Parmenides|viaf= |lccn= |lcheading= |wikititle= }} |

|||

* [http://parmenides.com/about_parmenides/ParmenidesPoem.html?page=12 parallel text of three translations (two English, one German)] |

|||

* {{iep|parmenid|Parmenides of Elea|Jeremy C. DeLong}} |

|||

*[http://www.ellopos.net/elpenor/greek-texts/ancient-greece/parmenides-being.asp Parmenides Bilingual Anthology (in Greek and English, side by side)] |

|||

* [http://faculty.washington.edu/smcohen/320/parm1.htm "Lecture Notes: Parmenides", S. Marc Cohen, University of Washington] |

|||

* [http://philoctetes.free.fr/parmenides.htm Fragments of Parmenides] parallel Greek with links to Perseus, French, and English (Burnet) includes Parmenides article from [[Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition]] |

|||

* [ |

* [https://www.ontology.co/parmenides.htm Parmenides and the Question of Being in Greek Thought] with a selection of critical judgments |

||

* [https://www.ontology.co/biblio/parmenides-editions.htm Parmenides of Elea: Critical Editions and Translations] – annotated list of the critical editions and of the English, German, French, Italian and Spanish translations |

|||

* [http://philoctetes.free.fr/parmenides.htm Fragments of Parmenides] – parallel Greek with links to Perseus, French, and English (Burnet) includes Parmenides article from [[Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition]] |

|||

{{Presocratics}} |

|||

* {{Internet Archive author |sname=Parmenides}} |

|||

{{Ancient Greece}} |

|||

* {{Librivox author |id=8056}} |

|||

{{Greek schools of philosophy}} |

|||

[[Category: 510 BC births]] |

|||

{{Ancient Greece topics}} |

|||

[[Category: 450 BC deaths]] |

|||

{{metaphysics}} |

|||

[[Category: Presocratic philosophers]] |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category: Pederasty in ancient Greece]] |

|||

[[Category:5th-century BC Greek philosophers]] |

|||

[[ar:بارمنيدس]] |

|||

[[Category:5th-century BC poets]] |

|||

[[bn:পারমেনিডেস]] |

|||

[[Category:510s BC births]] |

|||

[[bs:Parmenid]] |

|||

[[Category:450s BC deaths]] |

|||

[[bg:Парменид]] |

|||

[[Category:Eleatic philosophers]] |

|||

[[ca:Parmènides d'Elea]] |

|||

[[Category:Ancient Greek epistemologists]] |

|||

[[cs:Parmenidés]] |

|||

[[Category:Lucanian Greeks]] |

|||

[[da:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[Category:Ancient Greek metaphysicians]] |

|||

[[de:Parmenides von Elea]] |

|||

[[Category:Ancient Greek physicists]] |

|||

[[et:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[Category:Ontologists]] |

|||

[[el:Παρμενίδης]] |

|||

[[Category:Philosophers of Magna Graecia]] |

|||

[[es:Parménides de Elea]] |

|||

[[Category:Ancient Greek philosophers of mind]] |

|||

[[eo:Parmenido]] |

|||

[[Category:People from the Province of Salerno]] |

|||

[[eu:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[fa:برمانیدس]] |

|||

[[fr:Parménide]] |

|||

[[gl:Parménides de Elea]] |

|||

[[hr:Parmenid]] |

|||

[[is:Parmenídes]] |

|||

[[it:Parmenide di Elea]] |

|||

[[he:פרמנידס]] |

|||

[[la:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[hu:Parmenidész]] |

|||

[[nl:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[ja:パルメニデス]] |

|||

[[no:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[nn:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[pl:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[pt:Parmênides de Eléia]] |

|||

[[ro:Parmenide]] |

|||

[[ru:Парменид]] |

|||

[[sk:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[sl:Parmenid]] |

|||

[[sr:Парменид]] |

|||

[[sh:Parmenid]] |

|||

[[fi:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[sv:Parmenides från Elea]] |

|||

[[tr:Parmenides]] |

|||

[[zh:巴门尼德]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 15:10, 6 December 2024

Parmenides | |

|---|---|

Bust of Parmenides discovered at Velia, thought to have been partially modeled on a Metrodorus bust. | |

| Born | c. late 6th century BC |

| Died | c. 5th century BC |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Eleatic school |

Main interests | Ontology, poetry, cosmology |

Notable ideas | Monism, truth/opinion distinction |

Parmenides of Elea (/pɑːrˈmɛnɪdiːz ... ˈɛliə/; Ancient Greek: Παρμενίδης ὁ Ἐλεάτης; fl. late sixth or early fifth century BC) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher from Elea in Magna Graecia (Southern Italy).

Parmenides was born in the Greek colony of Elea, from a wealthy and illustrious family.[a] His dates are uncertain; according to doxographer Diogenes Laërtius, he flourished just before 500 BC,[b] which would put his year of birth near 540 BC, but in the dialogue Parmenides Plato has him visiting Athens at the age of 65, when Socrates was a young man, c. 450 BC,[c] which, if true, suggests a year of birth of c. 515 BC.[1] He is thought to have been in his prime (or "floruit") around 475 BC.[2]

The single known work by Parmenides is a poem whose original title is unknown but which is often referred to as On Nature. Only fragments of it survive. In his poem, Parmenides prescribes two views of reality. The first, the Way of "Aletheia" or truth, describes how all reality is one, change is impossible, and existence is timeless and uniform. The second view, the way of "Doxa", or opinion, describes the world of appearances, in which one's sensory faculties lead to conceptions which are false and deceitful.

Parmenides has been considered the founder of ontology and has, through his influence on Plato, influenced the whole history of Western philosophy.[3] He is also considered to be the founder of the Eleatic school of philosophy, which also included Zeno of Elea and Melissus of Samos. Zeno's paradoxes of motion were developed to defend Parmenides's views. In contemporary philosophy, Parmenides's work has remained relevant in debates about the philosophy of time.

Biography

[edit]Parmenides was born in Elea (called Velia in Roman times), a city located in Magna Graecia. Diogenes Laertius says that his father was Pires, and that he belonged to a rich and noble family.[4] Laertius transmits two divergent sources regarding the teacher of the philosopher. One, dependent on Sotion, indicates that he was first a student of Xenophanes,[5] but did not follow him, and later became associated with a Pythagorean, Aminias, whom he preferred as his teacher. Another tradition, dependent on Theophrastus, indicates that he was a disciple of Anaximander.[6]

Chronology

[edit]Everything related to the chronology of Parmenides—the dates of his birth and death, and the period of his philosophical activity—is uncertain.[citation needed]

Date of birth

[edit]All conjectures regarding Parmenides's date of birth are based on two ancient sources. One comes from Apollodorus and is transmitted to us by Diogenes Laertius: this source marks the Olympiad 69th (between 504 BC and 500 BC) as the moment of maturity, placing his birth 40 years earlier (544 BC – 540 BC).[7] The other is Plato, in his dialogue Parmenides. There Plato composes a situation in which Parmenides, 65, and Zeno, 40, travel to Athens to attend the Panathenaic Games. On that occasion they meet Socrates, who was still very young according to the Platonic text.[8]

The inaccuracy of the dating from Apollodorus is well known, who chooses the date of a historical event to make it coincide with the maturity (the floruit) of a philosopher, a maturity that he invariably reached at forty years of age. He tries to always match the maturity of a philosopher with the birth of his alleged disciple. In this case Apollodorus, according to Burnet, based his date of the foundation of Elea (540 BC) to chronologically locate the maturity of Xenophanes and thus the birth of his supposed disciple, Parmenides.[9] Knowing this, Burnet and later classicists like Cornford, Raven, Guthrie, and Schofield preferred to base the calculations on the Platonic dialogue. According to the latter, the fact that Plato adds so much detail regarding ages in his text is a sign that he writes with chronological precision. Plato says that Socrates was very young, and this is interpreted to mean that he was less than twenty years old. We know the year of Socrates' death (399 BC) and his age—he was about seventy years old–making the date of his birth 469 BC. The Panathenaic games were held every four years, and of those held during Socrates' youth (454, 450, 446), the most likely is that of 450 BC, when Socrates was nineteen years old. Thus, if at this meeting Parmenides was about sixty-five years old, his birth occurred around 515 BC.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

However, neither Raven nor Schofield, who follows the former, finds a dating based on a late Platonic dialogue entirely satisfactory. Other scholars directly prefer not to use the Platonic testimony and propose other dates. According to a scholar of the Platonic dialogues, R. Hirzel, Conrado Eggers Lan indicates that the historical has no value for Plato.[16] The fact that the meeting between Socrates and Parmenides is mentioned in the dialogues Theaetetus (183e) and Sophist (217c) only indicates that it is referring to the same fictional event, and this is possible because both the Theaetetus and the Sophist are considered after the Parmenides. In Soph. 217c the dialectic procedure of Socrates is attributed to Parmenides, which would confirm that this is nothing more than a reference to the fictitious dramatic situation of the dialogue.[17] Eggers Lan proposes a correction of the traditional date of the foundation of Elea. Based on Herodotus I, 163–167, which indicates that the Phocians, after defeating the Carthaginians in naval battle, founded Elea, and adding the reference to Thucydides I, 13, where it is indicated that such a battle occurred in the time of Cambyses II, the foundation of Elea can be placed between 530 BC and 522 BC So Parmenides could not have been born before 530 BC or after 520 BC, given that it predates Empedocles.[18] This last dating procedure is not infallible either, because it has been questioned that the fact that links the passages of Herodotus and Thucydides is the same.[19] Nestor Luis Cordero also rejects the chronology based on the Platonic text, and the historical reality of the encounter, in favor of the traditional date of Apollodorus. He follows the traditional datum of the founding of Elea in 545 BC, pointing to it not only as terminus post quem, but as a possible date of Parmenides's birth, from which he concludes that his parents were part of the founding contingent of the city and that he was a contemporary of Heraclitus.[15] The evidence suggests that Parmenides could not have written much after the death of Heraclitus.[citation needed]

Timeline relative to other Presocratics

[edit]Beyond the speculations and inaccuracies about his date of birth, some specialists have turned their attention to certain passages of his work to specify the relationship of Parmenides with other thinkers. It was thought to find in his poem certain controversial allusions to the doctrine of Anaximenes and the Pythagoreans (fragment B 8, verse 24, and frag. B 4), and also against Heraclitus (frag .B 6, vv.8–9), while Empedocles and Anaxagoras frequently refer to Parmenides.[20]

The reference to Heraclitus has been debated. Bernays's thesis[21] that Parmenides attacks Heraclitus, to which Diels, Kranz, Gomperz, Burnet and others adhered, was discussed by Reinhardt,[22] whom Jaeger followed.[23]

Guthrie finds it surprising that Heraclitus would not have censured Parmenides if he had known him, as he did with Xenophanes and Pythagoras. His conclusion, however, does not arise from this consideration, but points out that, due to the importance of his thought, Parmenides splits the history of pre-Socratic philosophy in two; therefore his position with respect to other thinkers is easy to determine. From this point of view, the philosophy of Heraclitus seems to him pre-Parmenidean, while those of Empedocles, Anaxagoras and Democritus are post-Parmenidean.[11]

Anecdotes

[edit]Plutarch, Strabo and Diogenes—following the testimony of Speusippus—agree that Parmenides participated in the government of his city, organizing it and giving it a code of admirable laws.[24]

ΟΥΛΙΑΔΗΣ ΦΥΣΙΚΟΣ

Archaeological discovery

[edit]In 1969, the plinth of a statue dated to the 1st century AD was excavated in Velia. On the plinth were four words: ΠΑ[Ρ]ΜΕΝΕΙΔΗΣ ΠΥΡΗΤΟΣ ΟΥΛΙΑΔΗΣ ΦΥΣΙΚΟΣ.[25] The first two clearly read "Parmenides, son of Pires." The fourth word φυσικός (fysikós, "physicist") was commonly used to designate philosophers who devoted themselves to the observation of nature. On the other hand, there is no agreement on the meaning of the third (οὐλιάδης, ouliadēs): it can simply mean "a native of Elea" (the name "Velia" is in Greek Οὐέλια),[26] or "belonging to the Οὐλιος" (Ulios), that is, to a medical school (the patron of which was Apollo Ulius).[27] If this last hypothesis were true, then Parmenides would be, in addition to being a legislator, a doctor.[28] The hypothesis is reinforced by the ideas contained in fragment 18 of his poem, which contains anatomical and physiological observations.[29] However, other specialists believe that the only certainty we can extract from the discovery is that of the social importance of Parmenides in the life of his city, already indicated by the testimonies that indicate his activity as a legislator.[30]

Visit to Athens

[edit]Plato, in his dialogue Parmenides, relates that, accompanied by his disciple Zeno of Elea, Parmenides visited Athens when he was approximately sixty-five years old and that, on that occasion, Socrates, then a young man, conversed with him.[31] Athenaeus of Naucratis had noted that, although the ages make a dialogue between Parmenides and Socrates hardly possible, the fact that Parmenides has sustained arguments similar to those sustained in the Platonic dialogue is something that seems impossible.[32] Most modern classicists consider the visit to Athens and the meeting and conversation with Socrates to be fictitious. Allusions to this visit in other Platonic works are only references to the same fictitious dialogue and not to a historical fact.[33]

On Nature

[edit]Parmenides's sole work, which has only survived in fragments, is a poem in dactylic hexameter, later titled On Nature. Approximately 160 verses remain today from an original total that was probably near 800.[3] The poem was originally divided into three parts: an introductory proem that contains an allegorical narrative which explains the purpose of the work, a former section known as "The Way of Truth" (aletheia, ἀλήθεια), and a latter section known as "The Way of Appearance/Opinion" (doxa, δόξα). Despite the poem's fragmentary nature, the general plan of both the proem and the first part, "The Way of Truth" have been ascertained by modern scholars, thanks to large excerpts made by Sextus Empiricus[d] and Simplicius of Cilicia.[e][3] Unfortunately, the second part, "The Way of Opinion", which is supposed to have been much longer than the first, only survives in small fragments and prose paraphrases.[3]

Introduction

[edit]The introductory poem describes the narrator's journey to receive a revelation from an unnamed goddess on the nature of reality.[34] The remainder of the work is then presented as the spoken revelation of the goddess without any accompanying narrative.[34]

The narrative of the poet's journey includes a variety of allegorical symbols, such as a speeding chariot with glowing axles, horses, the House of Night, Gates of the paths of Night and Day, and maidens who are "the daughters of the Sun"[35] who escort the poet from the ordinary daytime world to a strange destination, outside our human paths.[36] The allegorical themes in the poem have attracted a variety of different interpretations, including comparisons to Homer and Hesiod, and attempts to relate the journey towards either illumination or darkness, but there is little scholarly consensus about any interpretation, and the surviving evidence from the poem itself, as well as any other literary use of allegory from the same time period, may be too sparse to ever determine any of the intended symbolism with certainty.[34]

The Way of Truth

[edit]In the Way of Truth, an estimated 90% of which has survived,[3] Parmenides distinguishes between the unity of nature and its variety, insisting in the Way of Truth upon the reality of its unity, which is therefore the object of knowledge, and upon the unreality of its variety, which is therefore the object, not of knowledge, but of opinion.[citation needed] This contrasts with the argument in the section called "the way of opinion", which discusses that which is illusory.[citation needed]

The Way of Opinion

[edit]In the significantly longer, but far worse preserved latter section of the poem, Way of Opinion, Parmenides propounds a theory of the world of seeming and its development, pointing out, however, that, in accordance with the principles already laid down, these cosmological speculations do not pretend to anything more than mere appearance. The structure of the cosmos is a fundamental binary principle that governs the manifestations of all the particulars: "the Aether fire of flame" (B 8.56), which is gentle, mild, soft, thin and clear, and self-identical, and the other is "ignorant night", body thick and heavy.[37][f] Cosmology originally comprised the greater part of his poem, explaining the world's origins and operations.[g] Some idea of the sphericity of the Earth also seems to have been known to Parmenides.[3][h]

Legacy

[edit]As the first of the Eleatics, Parmenides is generally credited with being the philosopher who first defined ontology as a separate discipline distinct from theology.[3] His most important pupil was Zeno, who appears alongside him in Plato's Parmenides where they debate dialectic with Socrates.[i] The pluralist theories of Empedocles and Anaxagoras and the atomist Leucippus, and Democritus have also been seen as a potential response to Parmenides's arguments and conclusions.[38] Parmenides is also mentioned in Plato's Sophist[j] and Theaetetus.[k] Later Hellenistic doxographers also considered Parmenides to have been a pupil of Xenophanes.[l] Eusebius of Caesarea, quoting Aristocles of Messene, says that Parmenides was part of a line of skeptical philosophy that culminated in Pyrrhonism for he, by the root, rejects the validity of perception through the senses whilst, at any rate, it is first through our five forms of senses that we become aware of things and then by faculty of reasoning.[m] Parmenides's proto-monism of the One also influenced Plotinus and Neoplatonism.[citation needed]

Notes

[edit]Fragments

[edit]- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, (DK 28A1, 21)

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius (DK 28A1, 23)

- ^ Plato, Parmenides, 127a–128b (DK 28A5)

- ^ Against the Mathematicians (DK 28B1)

- ^ Commentary on Aristotle's Physics (DK 22B8)

- ^ (DK 28B8.53–4)

- ^ Stobaeus, i. 22. 1a

- ^ DK 28B10

- ^ (DK 28A5)

- ^ Sophist, 241d

- ^ Plato, Theaetetus, 183e

- ^ Aristotle, Metaphysics, i. 5; Sextus Empiricus, adv. Math. vii. 111; Clement of Alexandria, Stromata, i. 301; Diogenes Laërtius, ix. 21

- ^ Eusebius, Praeparatio Evangelica Book XIV, Chapter XVII

Citations

[edit]- ^ Curd 2004, pp. 3–8.

- ^ Freeman 1946, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d e f g Palmer 2020.

- ^ (DK) A1 (Diogenes Laert, IX 21)

- ^ The testimony of the link between Parmenides and Xenophanes goes back to Aristotle, Met. I 5, 986b (A 6) and from Plato, Sophist 242d (21 A 29)

- ^ Tradition attesting Suidas (A 2).

- ^ Diogenes Laertius, IX, 23 (DK testimony A 1).

- ^ Plato, Parmenides 127 BC (A 5).

- ^ a b Burnet, Early Greek Philosophy, pp. 169ff.

- ^ Cornford, Plato and Parmenides, p. 1.

- ^ a b Guthrie, History of Greek Philosophy, II, p. 15ff.

- ^ Raven, The Presocratic Philosophers, p. 370.

- ^ Schofield, The Presocratic Philosophers, p. 347.

- ^ Plato, Parmenides (ed. Degrees), p. 33, note 13

- ^ a b Cordero, Siendo se es, pp. 20-23

- ^ R. Hirzel, Der Dialog, I, p. 185.

- ^ Eggers Lan, The pre-Socratic philosophers, p. 410ff.

- ^ Eggers Lan, The pre-Socratic philosophers, pp. 412ff.

- ^ Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, p. 43, no. 106 of Torres Esbarranch.

- ^ Raven, The Presocratic Philosophers, pp. 370s; 385s; 381.

- ^ Bernays, Ges. Abh., 1, 62, n. 1.

- ^ Reinhardt, Parmenides, p. 64.

- ^ Jaeger, The Theology of the Early Greek Philosophers, p. 104.

- ^ Strabo, Geography VI 1, 1 (A 12); Plutarch., Adv. Colot. 1126a (A 12); Speusippus, fr. 1, in Diog. L., IX, 23 (A 1).

- ^ "IG XIV".

- ^ Marcel Conche, Parménide : Le Poème: Fragments, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1996, p. 5 and note.

- ^ P. Ebner, "Parmenide medico Ouliádes", in: Giornale di Metafisica 21 (1966), pp. 103-114

- ^ Poema, intr. by Jorge Pérez de Tudela, p. 14

- ^ Poema, comment by Jorge Pérez de Tudela, p. 230 and note ad. loc.

- ^ N. L. Cordero, Being one is, p. 23.

- ^ Plato, Parmenides 127 BC (A 11).

- ^ Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae XI 505f (A 5)

- ^ See Theaetetus 183e; Sophist 217c; see also «Introduction» to the dialogue Parménides by M.ª Isabel Santa Cruz, p. 11

- ^ a b c Curd 2004, I.3.

- ^ Kirk, Raven & Schofield 1983, p. 243.

- ^ Furley 1973, pp. 1–15.

- ^ Guthrie 1979, p. 61–62.

- ^ Sedley 1998.

Bibliography

[edit]Ancient testimony

[edit]In the Diels–Kranz numbering for testimony and fragments of Pre-Socratic philosophy, Parmenides is catalogued as number 28. The most recent edition of this catalogue is:

Diels, Hermann; Kranz, Walther (1957). Plamböck, Gert (ed.). Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker (in Ancient Greek and German). Rowohlt. ISBN 5875607416. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

Life and doctrines

[edit]- A1.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - A2. "Parmenides". Suda – via Suda Online.

- A3.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. § 3.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. § 3. - A4. Iamblichus. Life of Pythagoras.

- A5. Plato (1925). Parmenides. Plato in Twelve Volumes. Vol. 9. Translated by Harold N. Fowler. 127a.

- A6. Aristotle. Metaphysics. 986b.

- A7. Alexander of Aphrodisias. Commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics. 984b.

- A8. Simplicius. Commentary On Aristotle's Physics.

- A9.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:9. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. - A10. Simplicius. Commentary On Aristotle's Physics.

- A11. Eusebius. Chronicon Paschale.

- A12. Strabo. Geographia. Book VI, §1.

Fragments

[edit]- Empiricus, Sextus; Empírico, Sexto (1933). Sextus Empiricus in four volumes: Against the logicians. Vol. 2. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99321-1. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- Simplicius (22 April 2014). Commentary On Aristotle Physics. Vol. 1.3-4. A&C Black. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-1-4725-1531-5. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

Modern scholarship

[edit]- Curd, Patricia (2004). The Legacy of Parmenides: Eleatic Monism and Later Presocratic Thought. Parmenides Pub. ISBN 978-1-930972-15-5. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- Freeman, Kathleen (1946). The Pre-Socratic Philosophers. Great Britain in the City Of Oxford at the Alden Press: Oxford Basil Blackwell. p. 140.

- Furley, D.J. (1973). Exegesis and Argument: Studies in Greek Philosophy presented to Gregory Vlastos.

- Guthrie, W. K. C. (1979). A History of Greek Philosophy – The Presocratic tradition from Parmenides to Democritus. Cambridge University Press.

- Kirk, G. S.; Raven, J. E.; Schofield, M. (1983). The presocratic philosophers : a critical history with a selection of texts (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-521-27455-5. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

- Nussbaum, Martha (1979). "Eleatic Conventionalism and Philoaus on the Conditions of Thought". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 83: 63–108. doi:10.2307/311096. JSTOR 311096.

- Palmer, John (2020). "Parmenides". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Sedley, David (1998). "Parmenides". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge encyclopedia of philosophy. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415169165.

Further reading

[edit]- Austin, Scott (1986). Parmenides: Being, Bounds, and Logic. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03559-9.

- Austin, Scott (15 July 2007). Parmenides and The History of Dialectic. Parmenides Publishing. ISBN 978-1-930972-53-7.

- Bakalis, Nikolaos (2005), Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments, Trafford Publishing, ISBN 1-4120-4843-5

- Barnes, Jonathan (1982). "Parmenides and the Objects of Inquiry". The Presocratic Philosophers. Routledge and Kegan Paul. pp. 155–175.

- Cordero, Nestor-Luis (2004), By Being, It Is: The Thesis of Parmenides. Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-03-2

- Cordero, Néstor-Luis (ed.), Parmenides, Venerable and Awesome (Plato, Theaetetus 183e) Las Vegas: Parmenides Publishing 2011. Proceedings of the International Symposium (Buenos Aires, 2007), ISBN 978-1-930972-33-9

- Coxon, but A. H. (2009), The Fragments of Parmenides: A Critical Text With Introduction and Translation, the Ancient Testimonia and a Commentary. Las Vegas, Parmenides Publishing (new edition of Coxon 1986), ISBN 978-1-930972-67-4

- Curd, Patricia (2011), A Presocratics Reader: Selected Fragments and Testimonia, Hackett Publishing, ISBN 978-1603843058 (Second edition Indianapolis/Cambridge 2011)

- Hermann, Arnold (2005), To Think Like God: Pythagoras and Parmenides-The Origins of Philosophy, Fully Annotated Edition, Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-00-1

- Hermann, Arnold (2010), Plato's Parmenides: Text, Translation & Introductory Essay, Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-71-1

- Mourelatos, Alexander P. D. (2008). The Route of Parmenides: A Study of Word, Image, and Argument in the Fragments. Las Vegas: Parmenides Publishing. ISBN 978-1-930972-11-7 (First edition Yale University Press 1970)

- Palmer, John. (2009). Parmenides and Presocratic Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Extensive bibliography (up to 2004) by Nestor-Luis Cordero; and annotated bibliography by Raul Corazzon