Internet: Difference between revisions

Proudbharati (talk | contribs) The term 'data filtering software' more accurately describes the function of the technology used to process and analyze large volumes of data, rather than implying a broader and potentially misleading scope of surveillance. |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Global system of connected computer networks}} |

|||

{{Unreferenced|date=May 2007}} |

|||

{{About|the worldwide computer network|the global system of pages accessed through URLs via the Internet|World Wide Web|other uses}} |

|||

{{dablink|For the more general networking concept, see [[computer network]], [[computer networking]], and [[internetworking]].}} |

|||

{{Redirect|The Internet|the American music group|The Internet (band)|the song Welcome To The Internet|Bo Burnham: Inside}} |

|||

<!-- The Internet and the World Wide Web are different concepts—please do not muddle them in this article --> |

|||

{{Redirect|Interweb|the song by Poppy|Interweb (song)}} |

|||

[[Image:Internet map 1024.jpg|thumb|Visualization of the various routes through a portion of the Internet.]] |

|||

{{ |

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

{{Use American English|date=August 2020}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2020}} |

|||

{{Internet}} |

|||

{{Area networks}} |

|||

<!-- The Internet and the World Wide Web are different concepts – please do not muddle them in this article :) --> |

|||

The '''Internet''' |

The '''Internet''' (or '''internet'''){{efn|See [[Capitalization of Internet|Capitalization of ''Internet'']]<!-- Added per discussion currently underway on the Talk page -->}} is the [[Global network|global system]] of interconnected [[computer network]]s that uses the [[Internet protocol suite]] (TCP/IP){{Efn|Despite the name, TCP/IP also includes UDP traffic, which is significant.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.cc.gatech.edu/~dovrolis/Courses/8803_F03/amogh.ppt |author=Amogh Dhamdhere |title=Internet Traffic Characterization |access-date=2022-05-06}}</ref>}} to communicate between networks and devices. It is a [[internetworking|network of networks]] that consists of [[Private network|private]], public, academic, business, and government networks of local to global scope, linked by a broad array of electronic, [[Wireless network|wireless]], and [[optical networking]] technologies. The Internet carries a vast range of information resources and services, such as the interlinked [[hypertext]] documents and [[Web application|applications]] of the [[World Wide Web]] (WWW), [[email|electronic mail]], [[internet telephony]], and [[file sharing]]. |

||

The origins of the Internet date back to research that enabled the [[time-sharing]] of computer resources, the development of [[packet switching]] in the 1960s and the design of computer networks for [[data communication]].<ref name="The Washington Post">{{Cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/business/2015/05/30/net-of-insecurity-part-1/|title=A Flaw in the Design|date=30 May 2015|newspaper=The Washington Post|quote=The Internet was born of a big idea: Messages could be chopped into chunks, sent through a network in a series of transmissions, then reassembled by destination computers quickly and efficiently. Historians credit seminal insights to Welsh scientist Donald W. Davies and American engineer Paul Baran. ... The most important institutional force ... was the Pentagon's Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) ... as ARPA began work on a groundbreaking computer network, the agency recruited scientists affiliated with the nation's top universities.|access-date=20 February 2020|archive-date=8 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201108111512/https://www.washingtonpost.com/sf/business/2015/05/30/net-of-insecurity-part-1/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=":6">{{Cite book |last=Yates |first=David M. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ToMfAQAAIAAJ&q=packet+switch |title=Turing's Legacy: A History of Computing at the National Physical Laboratory 1945-1995 |date=1997 |publisher=National Museum of Science and Industry |isbn=978-0-901805-94-2 |pages=132–4 |language=en |quote=Davies's invention of packet switching and design of computer communication networks ... were a cornerstone of the development which led to the Internet}}</ref> The set of rules ([[communication protocol]]s) to enable [[internetworking]] on the Internet arose from research and development commissioned in the 1970s by the [[Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency]] (DARPA) of the [[United States Department of Defense]] in collaboration with universities and researchers across the [[United States]] and in the [[United Kingdom]] and [[France]].<ref name="Abbatep3">{{harvnb|Abbate|1999|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=9BfZxFZpElwC&pg=PA3 3] "The manager of the ARPANET project, Lawrence Roberts, assembled a large team of computer scientists ... and he drew on the ideas of network experimenters in the United States and the United Kingdom. Cerf and Kahn also enlisted the help of computer scientists from England, France and the United States"}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=27 October 2009 |title=The Computer History Museum, SRI International, and BBN Celebrate the 40th Anniversary of First ARPANET Transmission, Precursor to Today's Internet |url=https://www.sri.com/newsroom/press-releases/computer-history-museum-sri-international-and-bbn-celebrate-40th-anniversary |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190329134941/https://www.sri.com/newsroom/press-releases/computer-history-museum-sri-international-and-bbn-celebrate-40th-anniversary |archive-date=March 29, 2019 |access-date=25 September 2017 |publisher=SRI International |quote=But the ARPANET itself had now become an island, with no links to the other networks that had sprung up. By the early 1970s, researchers in France, the UK, and the U.S. began developing ways of connecting networks to each other, a process known as internetworking.}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author1=by Vinton Cerf, as told to Bernard Aboba |date=1993 |title=How the Internet Came to Be |url=http://elk.informatik.hs-augsburg.de/tmp/cdrom-oss/CerfHowInternetCame2B.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170926042220/http://elk.informatik.hs-augsburg.de/tmp/cdrom-oss/CerfHowInternetCame2B.html |archive-date=September 26, 2017 |access-date=25 September 2017 |quote=We began doing concurrent implementations at Stanford, BBN, and University College London. So effort at developing the Internet protocols was international from the beginning.}}</ref> The [[ARPANET]] initially served as a backbone for the interconnection of regional academic and military networks in the United States to enable [[resource sharing]]. The funding of the [[National Science Foundation Network]] as a new backbone in the 1980s, as well as private funding for other commercial extensions, encouraged worldwide participation in the development of new networking technologies and the merger of many networks using DARPA's [[Internet protocol suite]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.livinginternet.com/i/ii_summary.htm|title=Internet History – One Page Summary|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140702210150/http://www.livinginternet.com/i/ii_summary.htm |archive-date=2 July 2014|website=The Living Internet|first=Bill|last=Stewart|date=January 2000}}</ref> The linking of commercial networks and enterprises by the early 1990s, as well as the advent of the [[World Wide Web]],<ref>{{Cite book |title=The Desk Encyclopedia of World History |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-7394-7809-7 |editor-last=Wright |editor-first=Edmund |location=New York |page=312}}</ref> marked the beginning of the transition to the modern Internet,<ref>"#3 1982: the ARPANET community grows" in [https://www.vox.com/a/internet-maps ''40 maps that explain the internet''] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170306161657/http://www.vox.com/a/internet-maps|date=6 March 2017}}, Timothy B. Lee, Vox Conversations, 2 June 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2014.</ref> and generated sustained exponential growth as generations of institutional, [[personal computer|personal]], and [[mobile device|mobile]] [[computer]]s were connected to the internetwork. Although the Internet was widely used by [[academia]] in the 1980s, the subsequent [[commercialization of the Internet]] in the 1990s and beyond incorporated its services and technologies into virtually every aspect of modern life. |

|||

==History== |

|||

{{main|History of the Internet}} |

|||

===Creation=== |

|||

{{main|ARPANET}} |

|||

Most traditional communication media, including [[telephone]], [[radio]], [[television]], paper mail, and newspapers, are reshaped, redefined, or even bypassed by the Internet, giving birth to new services such as [[email]], [[Internet telephone]], [[Internet television]], [[online music]], digital newspapers, and [[video streaming]] websites. Newspapers, books, and other print publishing have adapted to [[Web site|website]] technology or have been reshaped into [[blogging]], [[web feed]]s, and online [[news aggregator]]s. The Internet has enabled and accelerated new forms of personal interaction through [[instant messaging]], [[Internet forum]]s, and [[social networking service]]s. [[Online shopping]] has grown exponentially for major retailers, [[small business]]es, and [[entrepreneur]]s, as it enables firms to extend their "[[brick and mortar]]" presence to serve a larger market or even [[Online store|sell goods and services entirely online]]. [[Business-to-business]] and [[financial services]] on the Internet affect [[supply chain]]s across entire industries. |

|||

The [[Soviet Union|USSR]]'s launch of [[Sputnik]] spurred the [[United States]] to create the Advanced Research Projects Agency, known as ARPA, in February [[1958 in science|1958]] to regain a technological lead.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.darpa.mil/body/arpa_darpa.html | title=ARPA/DARPA | accessdate=2007-05-21 | publisher=Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.darpa.mil/body/overtheyears.html | title=DARPA Over the Years | accessdate=2007-05-21 | publisher=Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency}}</ref> ARPA created the [[Information Processing Technology Office]] (IPTO) to further the research of the [[Semi Automatic Ground Environment]] (SAGE) program, which had networked country-wide [[radar]] systems together for the first time. [[J. C. R. Licklider]] was selected to head the IPTO, and saw universal networking as a potential unifying human revolution. |

|||

The Internet has no single centralized governance in either technological implementation or policies for access and usage; each constituent network sets its own policies.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://computer.howstuffworks.com/internet/basics/who-owns-internet.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140619070159/http://computer.howstuffworks.com/internet/basics/who-owns-internet.htm |archive-date=19 June 2014|first=Jonathan|last=Strickland|title=How Stuff Works: Who owns the Internet?|date=3 March 2008|access-date=27 June 2014}}</ref> The overarching definitions of the two principal [[name space]]s on the Internet, the [[IP address|Internet Protocol address]] (IP address) space and the [[Domain Name System]] (DNS), are directed by a maintainer organization, the [[Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers]] (ICANN). The technical underpinning and standardization of the core protocols is an activity of the [[Internet Engineering Task Force]] (IETF), a non-profit organization of loosely affiliated international participants that anyone may associate with by contributing technical expertise.<ref>{{cite IETF |title=The Tao of IETF: A Novice's Guide to Internet Engineering Task Force|rfc=4677|last1=Hoffman|first1=P.|last2=Harris|first2=S.|date=September 2006|publisher=[[Internet Engineering Task Force|IETF]]}}</ref> In November 2006, the Internet was included on ''[[USA Today]]''{{'}}s list of the [[Wonders of the World#USA Today's New Seven Wonders|New Seven Wonders]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.usatoday.com/travel/news/2006-10-26-seven-wonders-experts_x.htm |title=New Seven Wonders panel |work=USA Today |date=27 October 2006 |access-date=31 July 2010 |archive-date=15 July 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100715032114/http://www.usatoday.com/travel/news/2006-10-26-seven-wonders-experts_x.htm }}</ref> |

|||

Licklider had moved from the Psycho-Acoustic Laboratory at [[Harvard University]] to [[Massachusetts Institute of Technology|MIT]] in [[1950 in science|1950]], after becoming interested in [[information technology]]. At MIT, he served on a committee that established [[Lincoln Laboratory]] and worked on the SAGE project. In [[1957 in science|1957]] he became a Vice President at [[BBN Technologies|BBN]], where he bought the first production [[PDP-1]] computer and conducted the first public demonstration of [[time-sharing]]. |

|||

{{TOC limit}} |

|||

== Terminology == |

|||

At the IPTO, Licklider recruited [[Lawrence Roberts (scientist)|Lawrence Roberts]] to head a project to implement a network, and Roberts based the technology on the work of [[Paul Baran]] who had written an exhaustive study for the [[United States Air Force|U.S. Air Force]] that recommended [[packet switching]] (as opposed to [[circuit switching]]) to make a network highly robust and survivable. After much work, the first node went live at [[University of California, Los Angeles|UCLA]] on [[October 29]] [[1969]] on what would be called the [[ARPANET]], one of the "eve" networks of today's Internet. Following on from this, the [[General Post Office (United Kingdom)|British Post Office]], [[Western Union|Western Union International]] and [[Tymnet]] collaborated to create the first international packet switched network, referred to as the [[International Packet Switched Service]] (IPSS), in [[1978 in science|1978]]. This network grew from Europe and the US to cover [[Canada]], [[Hong Kong]] and [[Australia]] by 1981. |

|||

{{Further|Capitalization of Internet|internetworking}} |

|||

The word ''internetted'' was used as early as 1849, meaning ''interconnected'' or ''interwoven''.<ref>{{OED|Internetted}} nineteenth-century use as an adjective.</ref> The word ''Internet'' was used in 1945 by the United States War Department in a radio operator's manual,<ref>{{cite web |title=United States Army Field Manual FM 24-6 Radio Operator's Manual Army Ground Forces June 1945 |date=18 September 2023 |url=https://archive.org/details/Fm24-6/mode/2up |publisher=United States War Department }}</ref> and in 1974 as the shorthand form of Internetwork.<ref name="RFC675"/> Today, the term ''Internet'' most commonly refers to the global system of interconnected [[computer network]]s, though it may also refer to any group of smaller networks.<ref name="The New York Times"/> |

|||

The first [[Internet protocol suite|TCP/IP]]-wide area network was operational by [[January 1]] [[1983]], when the United States' [[National Science Foundation]] (NSF) constructed a [[university]] network backbone that would later become the [[NSFNet]]. |

|||

When it came into common use, most publications treated the word ''Internet'' as a capitalized [[Proper noun and common noun|proper noun]]; this has become less common.<ref name="The New York Times" /> This reflects the tendency in English to capitalize new terms and move them to lowercase as they become familiar.<ref name="The New York Times" /><ref name="Wired" /> The word is sometimes still capitalized to distinguish the global internet from smaller networks, though many publications, including the ''[[AP Stylebook]]'' since 2016, recommend the lowercase form in every case.<ref name="The New York Times">{{Cite news|last=Corbett|first=Philip B.|date=1 June 2016|title=It's Official: The 'Internet' Is Over|language=en-US|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/02/insider/now-it-is-official-the-internet-is-over.html|access-date=29 August 2020|issn=0362-4331|archive-date=14 October 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201014142148/https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/02/insider/now-it-is-official-the-internet-is-over.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Wired">{{Cite news|last=Herring|first=Susan C.|date=19 October 2015|title=Should You Be Capitalizing the Word 'Internet'?|magazine=Wired|url=https://www.wired.com/2015/10/should-you-be-capitalizing-the-word-internet/|access-date=29 August 2020|issn=1059-1028|archive-date=31 October 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201031024342/https://www.wired.com/2015/10/should-you-be-capitalizing-the-word-internet/|url-status=live}}</ref> In 2016, the ''[[Oxford English Dictionary]]'' found that, based on a study of around 2.5 billion printed and online sources, "Internet" was capitalized in 54% of cases.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Coren|first=Michael J.|title=One of the internet's inventors thinks it should still be capitalized|url=https://qz.com/698175/one-of-the-internets-inventors-thinks-it-should-still-be-capitalized/|access-date=8 September 2020|website=Quartz|date=2 June 2016 |language=en|archive-date=27 September 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200927102759/https://qz.com/698175/one-of-the-internets-inventors-thinks-it-should-still-be-capitalized/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

It was then followed by the opening of the network to commercial interests in 1985. Important, separate networks that offered gateways into, then later merged with, the NSFNet include [[Usenet]], [[BITNET]] and the various commercial and educational networks, such as [[X.25]], [[Compuserve]] and [[JANET]]. [[Telenet]] (later called Sprintnet) was a large privately-funded national computer network with free [[dial-up access]] in cities throughout the U.S. that had been in operation since the 1970s. This network eventually merged with the others in the 1990s as the TCP/IP protocol became increasingly popular. The ability of TCP/IP to work over these pre-existing communication networks, especially the international X.25 IPSS network, allowed for a great ease of growth. Use of the term "Internet" to describe a single global TCP/IP network originated around this time. |

|||

The terms ''Internet'' and ''[[World Wide Web]]'' are often used interchangeably; it is common to speak of "going on the Internet" when using a [[web browser]] to view [[web page]]s. However, the [[World Wide Web]], or ''the Web'', is only one of a large number of Internet services,<ref>{{cite web|date=11 March 2014|title=World Wide Web Timeline|url=http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/03/11/world-wide-web-timeline/|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150729162322/http://www.pewinternet.org/2014/03/11/world-wide-web-timeline/|archive-date=29 July 2015|access-date=1 August 2015|publisher=Pews Research Center}}</ref> a collection of documents (web pages) and other [[web resource]]s linked by [[hyperlink]]s and [[Uniform resource locator|URLs]].<ref>{{cite web|title=HTML 4.01 Specification|url=http://www.w3.org/TR/html401/struct/links.html#h-12.1|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081006131915/http://www.w3.org/TR/html401/struct/links.html|archive-date=6 October 2008|access-date=13 August 2008|publisher=World Wide Web Consortium|quote=[T]he link (or hyperlink, or Web link) [is] the basic hypertext construct. A link is a connection from one Web resource to another. Although a simple concept, the link has been one of the primary forces driving the success of the Web.}}</ref> |

|||

===Growth=== |

|||

The network gained a public face in the 1990s. On [[August 6]] [[1991]], [[CERN]], which straddles the border between [[France]] and [[Switzerland]], publicized the new [[World Wide Web]] project, two years after [[Tim Berners-Lee]] had begun creating [[HTML]], [[Hypertext Transfer Protocol|HTTP]] and the first few Web pages at CERN. |

|||

== History == |

|||

An early popular [[web browser]] was ''[[ViolaWWW]]'' based upon [[HyperCard]]. It was eventually replaced in popularity by the [[Mosaic (web browser)|Mosaic]] web browser. In 1993 the [[National Center for Supercomputing Applications]] at the [[University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign|University of Illinois]] released version 1.0 of ''Mosaic'', and by late 1994 there was growing public interest in the previously academic/technical Internet. By 1996 the word "Internet" was coming into common daily usage, frequently misused to refer to the [[World Wide Web]]. |

|||

{{Main|History of the Internet |History of the World Wide Web|Protocol Wars}} |

|||

[[File:A sketch of the ARPANET in December 1969.png|thumb|A sketch of the ARPANET in December 1969. The nodes at UCLA and the Stanford Research Institute (SRI) are among those depicted.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Waldrop |first=Mitch |date=2015 |title=DARPA and the Internet Revolution |url=https://www.darpa.mil/attachments/(2O15)%20Global%20Nav%20-%20About%20Us%20-%20History%20-%20Resources%20-%2050th%20-%20Internet%20(Approved).pdf |access-date=May 16, 2024 |website=darpa.mil}}</ref>]] |

|||

In the 1960s, [[computer scientists]] began developing systems for [[time-sharing]] of computer resources.<ref name="Lee1992">{{cite journal |last1=Lee |first1=J.A.N. |last2=Rosin |first2=Robert F |date=1992 |title=Time-Sharing at MIT |url=https://archive.org/details/time-sharing-at-mit |journal=IEEE Annals of the History of Computing |volume=14 |issue=1 |page=16 |doi=10.1109/85.145316 |s2cid=30976386 |access-date=October 3, 2022|issn=1058-6180 }}</ref><ref name="ctsspg">F. J. Corbató, et al., ''[http://www.bitsavers.org/pdf/mit/ctss/CTSS_ProgrammersGuide.pdf The Compatible Time-Sharing System A Programmer's Guide]'' (MIT Press, 1963) {{ISBN|978-0-262-03008-3}}. "To establish the context of the present work, it is informative to trace the development of time-sharing at MIT. Shortly after the first paper on time-shared computers by C. Strachey at the June 1959 UNESCO Information Processing conference, H.M. Teager and J. McCarthy delivered an unpublished paper "Time-Shared Program Testing" at the August 1959 ACM Meeting."</ref> [[J. C. R. Licklider]] proposed the idea of a universal network while working at [[Bolt Beranek & Newman]] and, later, leading the [[Information Processing Techniques Office]] (IPTO) at the [[Advanced Research Projects Agency]] (ARPA) of the United States [[United States Department of Defense|Department of Defense]] (DoD). Research into [[packet switching]], one of the fundamental Internet technologies, started in the work of [[Paul Baran]] at [[RAND]] in the early 1960s and, independently, [[Donald Davies]] at the United Kingdom's [[National Physical Laboratory (United Kingdom)|National Physical Laboratory]] (NPL) in 1965.<ref name="The Washington Post" /><ref name="NIHF2007">{{cite web|url=http://www.invent.org/honor/inductees/inductee-detail/?IID=316|title=Inductee Details – Paul Baran|publisher=National Inventors Hall of Fame|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170906091231/http://www.invent.org/honor/inductees/inductee-detail/?IID=316|archive-date=6 September 2017|access-date=6 September 2017|postscript=none}}; {{cite web|url=http://www.invent.org/honor/inductees/inductee-detail/?IID=328|title=Inductee Details – Donald Watts Davies|publisher=National Inventors Hall of Fame|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170906091936/http://www.invent.org/honor/inductees/inductee-detail/?IID=328|archive-date=6 September 2017|access-date=6 September 2017}}</ref> After the [[Symposium on Operating Systems Principles]] in 1967, packet switching from the proposed [[NPL network]] and routing concepts proposed by Baran were incorporated into the design of the [[ARPANET]], an experimental [[resource sharing]] network proposed by ARPA.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Hauben |first1=Michael |url=http://www.columbia.edu/~hauben/book-pdf/CHAPTER%205.pdf |title=Netizens: On the History and Impact of Usenet and the Internet |last2=Hauben |first2=Ronda |date=1997 |publisher=Wiley |isbn=978-0-8186-7706-9 |language=en |chapter=5 The Vision of Interactive Computing And the Future |access-date=2 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210103184558/http://www.columbia.edu/~hauben/book-pdf/CHAPTER%205.pdf |archive-date=3 January 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Zelnick |first1=Bob |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q10phY811tUC&pg=PA66 |title=The Illusion of Net Neutrality: Political Alarmism, Regulatory Creep and the Real Threat to Internet Freedom |last2=Zelnick |first2=Eva |publisher=Hoover Press |year=2013 |isbn=978-0-8179-1596-4 |language=en |access-date=7 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210110133435/https://books.google.com/books?id=Q10phY811tUC&pg=PA66 |archive-date=10 January 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last=Peter |first=Ian |year=2004 |title=So, who really did invent the Internet? |url=http://www.nethistory.info/History%20of%20the%20Internet/origins.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110903001108/http://www.nethistory.info/History%20of%20the%20Internet/origins.html |archive-date=3 September 2011 |access-date=27 June 2014 |website=The Internet History Project}}</ref> |

|||

ARPANET development began with two network nodes which were interconnected between the [[University of California, Los Angeles]] (UCLA) and the [[SRI International|Stanford Research Institute]] (now SRI International) on 29 October 1969.<ref name="NetValley">{{cite web|url=http://www.netvalley.com/intval.html|title=Roads and Crossroads of Internet History|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160127082435/http://www.netvalley.com/intval.html|archive-date=27 January 2016|first=Gregory|last=Gromov|year=1995}}</ref> The third site was at the [[University of California, Santa Barbara]], followed by the [[University of Utah]]. In a sign of future growth, 15 sites were connected to the young ARPANET by the end of 1971.<ref>{{cite book | author-link = Katie Hafner | last = Hafner | first = Katie | title = Where Wizards Stay Up Late: The Origins of the Internet | publisher = Simon & Schuster | year = 1998 | isbn = 978-0-684-83267-8 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Hauben, Ronda |title=From the ARPANET to the Internet |year=2001 |url=http://www.columbia.edu/~rh120/other/tcpdigest_paper.txt |access-date=28 May 2009 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090721093920/http://www.columbia.edu/~rh120/other/tcpdigest_paper.txt |archive-date=21 July 2009 }}</ref> These early years were documented in the 1972 film ''[[Computer Networks: The Heralds of Resource Sharing]]''.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Internet Pioneers Discuss the Future of Money, Books, and Paper in 1972|url=https://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/internet-pioneers-discuss-the-future-of-money-books-a-880551175|access-date=31 August 2020|website=Paleofuture|date=23 July 2013 |language=en-us|archive-date=17 October 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201017141323/https://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/internet-pioneers-discuss-the-future-of-money-books-a-880551175|url-status=live}}</ref> Thereafter, the ARPANET gradually developed into a decentralized communications network, connecting remote centers and military bases in the United States.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Townsend |first=Anthony |date=2001 |title=The Internet and the Rise of the New Network Cities, 1969–1999 |url=http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1068/b2688 |journal=Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design |language=en |volume=28 |issue=1 |pages=39–58 |doi=10.1068/b2688 |bibcode=2001EnPlB..28...39T |issn=0265-8135 |s2cid=11574572}}</ref> Other user networks and research networks, such as the [[Merit Network]] and [[CYCLADES]], were developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Kim |first1=Byung-Keun |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lESrw3neDokC |title=Internationalising the Internet the Co-evolution of Influence and Technology |date=2005 |publisher=Edward Elgar |isbn=978-1-84542-675-0 |pages=51–55}}</ref> |

|||

Meanwhile, over the course of the decade, the Internet successfully accommodated the majority of previously existing public computer networks (although some networks, such as [[FidoNet]], have remained separate) During the 1990s, it was estimated that the Internet grew by 100% per year, with a brief period of explosive growth in 1996 and 1997.<ref>{{cite paper | url=http://www.dtc.umn.edu/~odlyzko/doc/internet.size.pdf | title=The size and growth rate of the Internet | accessdate=2007-05-21 | author=Coffman, K. G; Odlyzko, A. M. | publisher=AT&T Labs | date=1998-10-02}}</ref> This growth is often attributed to the lack of central administration, which allows organic growth of the network, as well as the non-proprietary open nature of the Internet protocols, which encourages vendor interoperability and prevents any one company from exerting too much control over the network. |

|||

Early international collaborations for the ARPANET were rare. Connections were made in 1973 to Norway ([[NORSAR]] and [[Norwegian Defence Research Establishment|NDRE]]),<ref>{{cite web |title=NORSAR and the Internet |url=http://www.norsar.no/norsar/about-us/History/Internet/ |publisher=NORSAR |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130121220318/http://www.norsar.no/norsar/about-us/History/Internet/ |archive-date=21 January 2013 }}</ref> and to [[Peter T. Kirstein|Peter Kirstein's]] research group at [[University College London]] (UCL), which provided a gateway to [[Internet in the United Kingdom#History|British academic networks]], forming the first [[Internetworking|internetwork]] for [[resource sharing]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Kirstein|first=P.T.|date=1999|title=Early experiences with the Arpanet and Internet in the United Kingdom|url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4773/f19792f9fce8eacba72e5f8c2a021414e52d.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200207092443/https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4773/f19792f9fce8eacba72e5f8c2a021414e52d.pdf|archive-date=2020-02-07|journal=IEEE Annals of the History of Computing|volume=21|issue=1|pages=38–44|doi=10.1109/85.759368|s2cid=1558618|issn=1934-1547}}</ref> ARPA projects, the [[International Network Working Group]] and commercial initiatives led to the development of various [[Communication protocol|protocols]] and standards by which multiple separate networks could become a single network or "a network of networks".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.internetsociety.org/internet/what-internet/history-internet/brief-history-internet#concepts|title=Brief History of the Internet: The Initial Internetting Concepts|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160409105511/http://www.internetsociety.org/internet/what-internet/history-internet/brief-history-internet|archive-date=9 April 2016|first=Barry M.|last=Leiner|website=Internet Society|access-date=27 June 2014}}</ref> In 1974, [[Vint Cerf]] at [[Stanford University]] and [[Bob Kahn]] at DARPA published a proposal for "A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication".<ref name="IEEE Transactions on Communications">{{Cite journal |last1=Cerf |first1=V. |last2=Kahn |first2=R. |date=1974 |title=A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication |url=https://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/fall06/cos561/papers/cerf74.pdf |journal=IEEE Transactions on Communications |volume=22 |issue=5 |pages=637–648 |doi=10.1109/TCOM.1974.1092259 |issn=1558-0857 |quote=The authors wish to thank a number of colleagues for helpful comments during early discussions of international network protocols, especially R. Metcalfe, R. Scantlebury, D. Walden, and H. Zimmerman; D. Davies and L. Pouzin who constructively commented on the fragmentation and accounting issues; and S. Crocker who commented on the creation and destruction of associations. |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060913213037/https://www.cs.princeton.edu/courses/archive/fall06/cos561/papers/cerf74.pdf |archive-date=13 September 2006 |url-status=live }}</ref> They used the term ''internet'' as a shorthand for ''internetwork'' in ''{{IETF RFC|675}}'',<ref name="RFC675">{{cite IETF |title=Specification of Internet Transmission Control Protocol|rfc=675|last1=Cerf|first1=Vint|last2=Dalal|first2=Yogen|first3=Carl|last3=Sunshine |date=December 1974|publisher=[[Internet Engineering Task Force|IETF]]}}</ref> and later [[Request for Comments|RFCs]] repeated this use. Cerf and Kahn credit [[Louis Pouzin]] and others with important influences on the resulting [[TCP/IP]] design.<ref name="IEEE Transactions on Communications" /><ref>{{Cite news|date=30 November 2013|title=The internet's fifth man|newspaper=The Economist|url=https://www.economist.com/news/technology-quarterly/21590765-louis-pouzin-helped-create-internet-now-he-campaigning-ensure-its|access-date=22 April 2020|issn=0013-0613|quote=In the early 1970s Mr Pouzin created an innovative data network that linked locations in France, Italy and Britain. Its simplicity and efficiency pointed the way to a network that could connect not just dozens of machines, but millions of them. It captured the imagination of Dr Cerf and Dr Kahn, who included aspects of its design in the protocols that now power the internet.|archive-date=19 April 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200419230318/https://www.economist.com/news/technology-quarterly/21590765-louis-pouzin-helped-create-internet-now-he-campaigning-ensure-its|url-status=live}}</ref> National [[Postal, telegraph and telephone service|PTTs]] and commercial providers developed the [[X.25]] standard and deployed it on [[public data network]]s.<ref>{{cite book|last=Schatt|first=Stan|title=Linking LANs: A Micro Manager's Guide|publisher=McGraw-Hill|year=1991|isbn=0-8306-3755-9|page=200}}</ref> |

|||

==Today's Internet== |

|||

Access to the ARPANET was expanded in 1981 when the [[National Science Foundation]] (NSF) funded the [[CSNET|Computer Science Network]] (CSNET). In 1982, the [[Internet Protocol Suite]] (TCP/IP) was standardized, which facilitated worldwide proliferation of interconnected networks. TCP/IP network access expanded again in 1986 when the [[National Science Foundation Network]] (NSFNet) provided access to [[supercomputer]] sites in the United States for researchers, first at speeds of 56 kbit/s and later at 1.5 Mbit/s and 45 Mbit/s.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.merit.edu/about/history/pdf/NSFNET_final.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150210181738/http://www.merit.edu/about/history/pdf/NSFNET_final.pdf|archive-date=2015-02-10|title=NSFNET: A Partnership for High-Speed Networking, Final Report 1987–1995|first=Karen D.|last=Frazer|website=Merit Network, Inc.|year=1995}}</ref> The NSFNet expanded into academic and research organizations in Europe, Australia, New Zealand and Japan in 1988–89.<ref>{{cite web |author=Ben Segal |author-link=Ben Segal (computer scientist) |year=1995 |title=A Short History of Internet Protocols at CERN |url=http://www.cern.ch/ben/TCPHIST.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230608153730/http://ben.web.cern.ch/ben/TCPHIST.html |archive-date=8 June 2023 |access-date=14 October 2011}}</ref><ref>[[RIPE|Réseaux IP Européens]] (RIPE)</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.apan.net/meetings/busan03/cs-history.htm|title=Internet History in Asia|work=16th APAN Meetings/Advanced Network Conference in Busan|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060201035514/http://apan.net/meetings/busan03/cs-history.htm|archive-date=1 February 2006|access-date=25 December 2005}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.nordu.net/history/TheHistoryOfNordunet_simple.pdf|title=The History of NORDUnet|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304031416/http://www.nordu.net/history/TheHistoryOfNordunet_simple.pdf|archive-date=4 March 2016}}</ref> Although other network protocols such as [[UUCP]] and PTT public data networks had global reach well before this time, this marked the beginning of the Internet as an intercontinental network. Commercial [[Internet service providers]] (ISPs) emerged in 1989 in the United States and Australia.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rogerclarke.com/II/OzI04.html#CIAP|title=Origins and Nature of the Internet in Australia|last=Clarke|first=Roger|access-date=21 January 2014|archive-date=9 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210209201253/http://www.rogerclarke.com/II/OzI04.html#CIAP|url-status=live}}</ref> The ARPANET was decommissioned in 1990.<ref>{{cite IETF |rfc=2235 |page=8 |last=Zakon |first=Robert |date=November 1997 |publisher=[[Internet Engineering Task Force|IETF]] |access-date=2 December 2020}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:My Opera Server.jpg|thumb|A rack of servers]] |

|||

Aside from the complex physical connections that make up its infrastructure, the Internet is facilitated by bi- or multi-lateral commercial contracts (e.g., [[peering agreement]]s), and by technical specifications or [[communications protocol|protocol]]s that describe how to exchange [[data]] over the network. Indeed, the Internet is essentially defined by its interconnections and routing policies. |

|||

[[File:NSFNET-backbone-T3.png|thumb|T3 [[NSFNET]] Backbone, {{Circa|1992}}]] |

|||

As of [[June 10]] [[2007]], 1.133 billion people use the Internet according to [http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm Internet World Stats]. Writing in the Harvard International Review, philosopher N.J.Slabbert, a writer on policy issues for the Washington DC-based Urban Land Institute, has asserted that the Internet is fast becoming a basic feature of global civilization, so that what has traditionally been called "civil society" is now becoming identical with information technology society as defined by Internet use. <ref>Slabbert,N.J. The Technologies of Peace, Harvard International Review, June 2006.</ref> |

|||

Steady advances in [[semiconductor]] technology and [[optical networking]] created new economic opportunities for commercial involvement in the expansion of the network in its core and for delivering services to the public. In mid-1989, [[MCI Mail]] and [[Compuserve]] established connections to the Internet, delivering email and public access products to the half million users of the Internet.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wDAEAAAAMBAJ&q=compuserve%20to%20mci%20mail%20internet&pg=PT31 |title=InfoWorld|date=25 September 1989 |via=Google Books |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170129225422/https://books.google.com/books?id=wDAEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PT31&lpg=PT31&dq=compuserve%20to%20mci%20mail%20internet |archive-date=29 January 2017 }}</ref> Just months later, on 1 January 1990, PSInet launched an alternate Internet backbone for commercial use; one of the networks that added to the core of the commercial Internet of later years. In March 1990, the first high-speed T1 (1.5 Mbit/s) link between the NSFNET and Europe was installed between [[Cornell University]] and [[CERN]], allowing much more robust communications than were capable with satellites.<ref>{{Cite web|date=February 1990|title=INTERNET MONTHLY REPORTS|url=http://ftp.cuhk.edu.hk/pub/doc/internet/Internet.Monthly.Report/imr9002.txt|archive-url=https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20170525080041/ftp://ftp.cuhk.edu.hk/pub/doc/internet/Internet.Monthly.Report/imr9002.txt|archive-date=25 May 2017|access-date=28 November 2020}}</ref> |

|||

===Internet protocols=== |

|||

{{details|Internet Protocols}} |

|||

In this context, there are three layers of protocols: |

|||

* At the lowest level is '''[[Internet Protocol|IP]]''' (Internet Protocol), which defines the datagrams or [[packet]]s that carry blocks of data from one node to another. The vast majority of today's Internet uses version four of the IP protocol (i.e. [[IPv4]]), and although [[IPv6]] is standardized, it exists only as "islands" of connectivity, and there are many ISPs without any IPv6 connectivity. [http://www.livinginternet.com] |

|||

* Next came '''[[Transmission Control Protocol|TCP]]''' (Transmission Control Protocol), '''[[User Datagram Protocol|UDP]]''' (User Datagram Protocol), and '''[[Internet Control Message Protocol|ICMP]]''' (Internet Control Message Protocol)—the protocols by which data is transmitted. TCP makes a virtual 'connection', which gives some level of guarantee of reliability. UDP is a best-effort, connectionless transport, in which data packets that are lost in transit will not be re-sent. ICMP is connectionless; it is used for control and signaling purposes. |

|||

* On top comes the '''[[Application layer|application protocols]]'''. This defines the specific messages and data formats sent and understood by the applications running at each end of the communication. |

|||

Later in 1990, [[Tim Berners-Lee]] began writing [[WorldWideWeb]], the first [[web browser]], after two years of lobbying CERN management. By Christmas 1990, Berners-Lee had built all the tools necessary for a working Web: the [[HyperText Transfer Protocol]] (HTTP) 0.9,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.w3.org/Protocols/HTTP/AsImplemented.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/19970605071155/http://www.w3.org/Protocols/HTTP/AsImplemented.html |archive-date=5 June 1997 |first=Tim |last=Berners-Lee |title=The Original HTTP as defined in 1991 |work=W3C.org}}</ref> the [[HyperText Markup Language]] (HTML), the first Web browser (which was also an [[HTML editor]] and could access [[Usenet]] newsgroups and [[FTP]] files), the first HTTP [[server application|server software]] (later known as [[CERN httpd]]), the first [[web server]],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://info.cern.ch/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100105103513/http://info.cern.ch/|title=The website of the world's first-ever web server|archive-date=5 January 2010|website=info.cern.ch}}</ref> and the first Web pages that described the project itself. In 1991 the [[Commercial Internet eXchange]] was founded, allowing PSInet to communicate with the other commercial networks [[CERFnet]] and Alternet. [[Stanford Federal Credit Union]] was the first [[financial institution]] to offer online Internet banking services to all of its members in October 1994.<ref>{{cite press release|title=Stanford Federal Credit Union Pioneers Online Financial Services.|date=21 June 1995|url=http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Stanford+Federal+Credit+Union+Pioneers+Online+Financial+Services.-a017104850|access-date=21 December 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181221041632/https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Stanford+Federal+Credit+Union+Pioneers+Online+Financial+Services.-a017104850|archive-date=21 December 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1996, [[OP Financial Group]], also a [[cooperative bank]], became the second online bank in the world and the first in Europe.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.op.fi/op-financial-group/about-us/op-financial-group-in-brief/history | title=History – About us – OP Group | access-date=21 December 2018 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181221041413/https://www.op.fi/op-financial-group/about-us/op-financial-group-in-brief/history | archive-date=21 December 2018 | url-status=live }}</ref> By 1995, the Internet was fully commercialized in the U.S. when the NSFNet was decommissioned, removing the last restrictions on use of the Internet to carry commercial traffic.<ref name="ConneXions-April1996">{{cite journal |url=http://www.merit.edu/research/nsfnet_article.php |title=Retiring the NSFNET Backbone Service: Chronicling the End of an Era |first1=Susan R. |last1=Harris |first2=Elise |last2=Gerich |journal=ConneXions |volume=10 |number=4 |date=April 1996 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130817124939/http://merit.edu/research/nsfnet_article.php |archive-date=17 August 2013 }}</ref> |

|||

===Internet structure=== |

|||

There have been many analyses of the Internet and its structure. For example, it has been determined that the Internet IP routing structure and hypertext links of the World Wide Web are examples of [[scale-free network]]s. |

|||

{{Worldwide Internet users}} |

|||

Similar to the way the commercial Internet providers connect via [[Internet exchange point]]s, research networks tend to interconnect into large subnetworks such as: |

|||

As technology advanced and commercial opportunities fueled reciprocal growth, the volume of [[Internet traffic]] started experiencing similar characteristics as that of the scaling of [[MOS transistor]]s, exemplified by [[Moore's law]], doubling every 18 months. This growth, formalized as [[Edholm's law]], was catalyzed by advances in [[MOS technology]], [[laser]] light wave systems, and [[Noise (signal processing)|noise]] performance.<ref name="Jindal">{{cite book |last1=Jindal |first1=R. P. |title=2009 2nd International Workshop on Electron Devices and Semiconductor Technology |chapter=From millibits to terabits per second and beyond - over 60 years of innovation |s2cid=25112828 |year=2009 |volume=49 |pages=1–6 |doi=10.1109/EDST.2009.5166093 |chapter-url=https://events.vtools.ieee.org/m/195547 |isbn=978-1-4244-3831-0 |access-date=24 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190823230141/https://events.vtools.ieee.org/m/195547 |archive-date=23 August 2019 }}</ref> |

|||

*[[GEANT]] |

|||

*[[GLORIAD]] |

|||

*[[Abilene Network]] |

|||

*[[JANET]] (the UK's Joint Academic Network aka UKERNA) |

|||

Since 1995, the Internet has tremendously impacted culture and commerce, including the rise of near-instant communication by email, [[instant messaging]], telephony ([[Voice over Internet Protocol]] or VoIP), [[Video chat|two-way interactive video calls]], and the World Wide Web<ref>{{cite news|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/5242252.stm|title=How the web went world wide|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111121092636/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/5242252.stm |archive-date=21 November 2011|first=Mark|last=Ward|website=Technology Correspondent|date=3 August 2006|publisher=BBC News|access-date=24 January 2011}}</ref> with its [[discussion forums]], blogs, [[social networking service]]s, and [[online shopping]] sites. Increasing amounts of data are transmitted at higher and higher speeds over fiber optic networks operating at 1 Gbit/s, 10 Gbit/s, or more. The Internet continues to grow, driven by ever-greater amounts of online information and knowledge, commerce, entertainment and social networking services.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://clickz.com/showPage.html?page=3626274 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081004000237/http://www.clickz.com/showPage.html?page=3626274|title=Brazil, Russia, India and China to Lead Internet Growth Through 2011 |publisher=Clickz.com |access-date=28 May 2009|archive-date=4 October 2008}}</ref> During the late 1990s, it was estimated that traffic on the public Internet grew by 100 percent per year, while the mean annual growth in the number of Internet users was thought to be between 20% and 50%.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.dtc.umn.edu/~odlyzko/doc/internet.size.pdf |title=The size and growth rate of the Internet |access-date=21 May 2007 |author1=Coffman, K.G |author2=Odlyzko, A.M. |author-link2=Andrew Odlyzko |publisher=AT&T Labs |date=2 October 1998 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070614012344/http://www.dtc.umn.edu/~odlyzko/doc/internet.size.pdf |archive-date=14 June 2007 }}</ref> This growth is often attributed to the lack of central administration, which allows organic growth of the network, as well as the non-proprietary nature of the Internet protocols, which encourages vendor interoperability and prevents any one company from exerting too much control over the network.<ref>{{cite book | last = Comer | first = Douglas | title = The Internet book | publisher = Prentice Hall | page = [https://archive.org/details/internetbookever00come_0/page/64 64] | isbn = 978-0-13-233553-9 | year = 2006 | url-access = registration | url = https://archive.org/details/internetbookever00come_0/page/64 }}</ref> {{as of|2011|March|31}}, the estimated total number of Internet users was 2.095 billion (30% of [[world population]]).<ref name="stats1">{{cite web|url=http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm|title=World Internet Users and Population Stats|date=22 June 2011|work=Internet World Stats|publisher=Miniwatts Marketing Group|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110623200007/http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm|archive-date=23 June 2011|access-date=23 June 2011}}<!-- previous cite {{cite web|url=http://www.50x15.com/en-us/internet_usage.aspx |title=AMD 50x15 – World Internet Usage |publisher=50x15.com |access-date=6 November 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090831063352/http://www.50x15.com/en-us/internet_usage.aspx |archive-date=31 August 2009 |df= }} --></ref> It is estimated that in 1993 the Internet carried only 1% of the information flowing through two-way [[telecommunication]]. By 2000 this figure had grown to 51%, and by 2007 more than 97% of all telecommunicated information was carried over the Internet.<ref>{{cite journal|title=The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information |first1=Martin |last1=Hilbert |first2=Priscila |last2=López |s2cid=206531385 |date=April 2011 |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |volume=332 |pages=60–65 |doi=10.1126/science.1200970 |issue=6025 |bibcode=2011Sci...332...60H |pmid=21310967 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

These in turn are built around relatively smaller networks. See also the list of [[:Category:Academic computer network organizations|academic computer network organizations]] |

|||

== Governance == |

|||

In [[network diagram]]s, the Internet is often represented by a cloud symbol, into and out of which network communications can pass. |

|||

{{Main|Internet governance}} |

|||

[[File:Icannheadquartersplayavista.jpg|thumb|ICANN headquarters in the [[Playa Vista, Los Angeles|Playa Vista]] neighborhood of [[Los Angeles]], California, United States]] |

|||

The Internet is a [[global network]] that comprises many voluntarily interconnected autonomous networks. It operates without a central governing body. The technical underpinning and standardization of the core protocols ([[IPv4]] and [[IPv6]]) is an activity of the [[Internet Engineering Task Force]] (IETF), a non-profit organization of loosely affiliated international participants that anyone may associate with by contributing technical expertise. To maintain interoperability, the principal [[name space]]s of the Internet are administered by the [[Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers]] (ICANN). ICANN is governed by an international board of directors drawn from across the Internet technical, business, academic, and other non-commercial communities. ICANN coordinates the assignment of unique identifiers for use on the Internet, including [[domain name]]s, IP addresses, application port numbers in the transport protocols, and many other parameters. Globally unified name spaces are essential for maintaining the global reach of the Internet. This role of ICANN distinguishes it as perhaps the only central coordinating body for the global Internet.<ref>{{cite web|last=Klein|first=Hans|year=2004|url=http://www.ip3.gatech.edu/research/KLEIN_ICANN%2BSovereignty.doc|title=ICANN and Non-Territorial Sovereignty: Government Without the Nation State|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130524035251/http://www.ip3.gatech.edu/research/KLEIN_ICANN%2BSovereignty.doc|archive-date=24 May 2013|website=Internet and Public Policy Project|publisher=[[Georgia Institute of Technology]]}}</ref> |

|||

===ICANN=== |

|||

{{details|ICANN}} |

|||

'''The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN)''' is the authority that coordinates the assignment of unique identifiers on the Internet, including [[domain name]]s, Internet Protocol (IP) addresses, and protocol port and parameter numbers. A globally unified namespace (i.e., a system of names in which there is one and only one holder of each name) is essential for the Internet to function. ICANN is headquartered in [[Marina del Rey, California]], but is overseen by an international board of directors drawn from across the Internet technical, business, academic, and non-commercial communities. The US government continues to have the primary role in approving changes to the [[DNS root zone|root zone]] file that lies at the heart of the domain name system. Because the Internet is a distributed network comprising many voluntarily interconnected networks, the Internet, as such, has no governing body. ICANN's role in coordinating the assignment of unique identifiers distinguishes it as perhaps the only central coordinating body on the global Internet, but the scope of its authority extends only to the Internet's systems of domain names, [[IP address]]es, and protocol port and parameter numbers. |

|||

[[Regional Internet registry|Regional Internet registries]] (RIRs) were established for five regions of the world. The [[AfriNIC|African Network Information Center]] (AfriNIC) for [[Africa]], the [[American Registry for Internet Numbers]] (ARIN) for [[North America]], the [[APNIC|Asia–Pacific Network Information Centre]] (APNIC) for [[Asia]] and the [[Pacific region]], the [[Latin American and Caribbean Internet Addresses Registry]] (LACNIC) for [[Latin America]] and the [[Caribbean]] region, and the [[RIPE NCC|Réseaux IP Européens – Network Coordination Centre]] (RIPE NCC) for [[Europe]], the [[Middle East]], and [[Central Asia]] were delegated to assign IP address blocks and other Internet parameters to local registries, such as [[Internet service provider]]s, from a designated pool of addresses set aside for each region. |

|||

On [[November 16]] [[2005]], the [[World Summit on the Information Society]], held in [[Tunis]], established the [[Internet Governance Forum]] (IGF) to discuss Internet-related issues. |

|||

The [[National Telecommunications and Information Administration]], an agency of the [[United States Department of Commerce]], had final approval over changes to the [[DNS root zone]] until the IANA stewardship transition on 1 October 2016.<ref>{{cite book |last= Packard |first= Ashley |title= Digital Media Law |publisher= Wiley-Blackwell |year= 2010 |isbn= 978-1-4051-8169-3 |page= 65}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theregister.co.uk/2005/07/01/bush_net_policy/|title=Bush administration annexes internet|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110919130539/https://www.theregister.co.uk/2005/07/01/bush_net_policy/|archive-date=19 September 2011|first=Kieren|last=McCarthy|website=The Register|date=1 July 2005}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last= Mueller |first= Milton L. |title= Networks and States: The Global Politics of Internet Governance |publisher= MIT Press |year= 2010 |isbn= 978-0-262-01459-5 |page= 61}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=ICG Applauds Transfer of IANA Stewardship|url=https://www.ianacg.org/icg-applauds-transfer-of-iana-stewardship/|website=IANA Stewardship Transition Coordination Group (ICG)|access-date=8 June 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170712190131/https://www.ianacg.org/icg-applauds-transfer-of-iana-stewardship/|archive-date=12 July 2017|url-status=live}}</ref> The [[Internet Society]] (ISOC) was founded in 1992 with a mission to ''"assure the open development, evolution and use of the Internet for the benefit of all people throughout the world"''.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.isoc.org/internet/history/isochistory.shtml |title=Internet Society (ISOC) All About The Internet: History of the Internet |publisher=ISOC |access-date=19 December 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111127114016/http://www.isoc.org/internet/history/isochistory.shtml |archive-date=27 November 2011 }}</ref> Its members include individuals (anyone may join) as well as corporations, [[organizations]], governments, and universities. Among other activities ISOC provides an administrative home for a number of less formally organized groups that are involved in developing and managing the Internet, including: the IETF, [[Internet Architecture Board]] (IAB), [[Internet Engineering Steering Group]] (IESG), [[Internet Research Task Force]] (IRTF), and [[Internet Research Steering Group]] (IRSG). On 16 November 2005, the United Nations-sponsored [[World Summit on the Information Society]] in [[Tunis]] established the [[Internet Governance Forum]] (IGF) to discuss Internet-related issues. |

|||

===Language=== |

|||

{{details|English on the Internet}} |

|||

{{further|[[Unicode]]}} |

|||

The prevalent language for communication on the Internet is [[English language|English]]. This may be a result of the Internet's origins, as well as English's role as the [[lingua franca]]. It may also be related to the poor capability of early computers to handle characters other than those in the basic [[Latin alphabet]]. |

|||

== Infrastructure == |

|||

After English (30% of Web visitors) the most-requested languages on the [[World Wide Web]] are [[Chinese language|Chinese]] 14%, [[Japanese language|Japanese]] 8%, [[Spanish language|Spanish]] 8%, [[German language|German]] 5%, [[French language|French]] 5%, [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]] 3.5%, [[Korean language|Korean]] 3%, [[Italian language|Italian]] 3% and [[Arabic language|Arabic]] 2.5% (from [http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats7.htm Internet World Stats], updated January 11, 2007). |

|||

{{See also|List of countries by number of Internet users|List of countries by Internet connection speeds}} |

|||

<!-- Note that the use of these copyright statistics is dependent on "giving due credit and establishing an active link back to www.internetworldstats.com", so please do not remove the citation above --> |

|||

[[File:World map of submarine cables.png|thumb|2007 map showing submarine fiberoptic telecommunication cables around the world]] |

|||

The communications infrastructure of the Internet consists of its hardware components and a system of software layers that control various aspects of the architecture. As with any computer network, the Internet physically consists of [[router (computing)|router]]s, media (such as cabling and radio links), repeaters, modems etc. However, as an example of [[internetworking]], many of the network nodes are not necessarily Internet equipment per se. The internet packets are carried by other full-fledged networking protocols with the Internet acting as a homogeneous networking standard, running across [[heterogeneous]] hardware, with the packets guided to their destinations by IP routers. |

|||

=== Service tiers === |

|||

By continent, 36% of the world's Internet users are based in [[Asia]], 29% in [[Europe]], and 21% in [[North America]] ([http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm] updated January 11, 2007). |

|||

[[File:Internet Connectivity Distribution & Core.svg|thumb|Packet routing across the Internet involves several tiers of Internet service providers.]] |

|||

<!-- Note that the use of these copyright statistics is dependent on "giving due credit and establishing an active link back to www.internetworldstats.com", so please do not remove the citation above --> |

|||

[[Internet service provider]]s (ISPs) establish the worldwide connectivity between individual networks at various levels of scope. End-users who only access the Internet when needed to perform a function or obtain information, represent the bottom of the routing hierarchy. At the top of the routing hierarchy are the [[tier 1 network]]s, large telecommunication companies that exchange traffic directly with each other via very high speed [[fiber-optic cable]]s and governed by [[peering]] agreements. [[Tier 2 network|Tier 2]] and lower-level networks buy [[Internet transit]] from other providers to reach at least some parties on the global Internet, though they may also engage in peering. An ISP may use a single upstream provider for connectivity, or implement [[multihoming]] to achieve redundancy and load balancing. [[Internet exchange point]]s are major traffic exchanges with physical connections to multiple ISPs. Large organizations, such as academic institutions, large enterprises, and governments, may perform the same function as ISPs, engaging in peering and purchasing transit on behalf of their internal networks. Research networks tend to interconnect with large subnetworks such as [[GEANT]], [[GLORIAD]], [[Internet2]], and the UK's [[national research and education network]], [[JANET]]. |

|||

The Internet's technologies have developed enough in recent years that good facilities are available for development and communication in most widely used languages. However, some glitches such as ''[[mojibake]]'' (incorrect display of foreign language characters, also known as ''kryakozyabry'') still remain. |

|||

=== |

=== Access === |

||

Common methods of [[Internet access]] by users include dial-up with a computer [[modem]] via telephone circuits, [[broadband]] over [[coaxial cable]], [[Optical fiber|fiber optics]] or copper wires, [[Wi-Fi]], [[Satellite Internet|satellite]], and [[mobile telephony|cellular telephone]] technology (e.g. [[3G]], [[4G]]). The Internet may often be accessed from computers in libraries and [[Internet café]]s. [[Internet kiosk|Internet access points]] exist in many public places such as airport halls and coffee shops. Various terms are used, such as ''public Internet kiosk'', ''public access terminal'', and ''Web [[payphone]]''. Many hotels also have public terminals that are usually fee-based. These terminals are widely accessed for various usages, such as ticket booking, bank deposit, or [[online payment]]. Wi-Fi provides wireless access to the Internet via local computer networks. [[Hotspot (Wi-Fi)|Hotspots]] providing such access include Wi-Fi cafés, where users need to bring their own wireless devices, such as a laptop or [[Personal Digital Assistant|PDA]]. These services may be free to all, free to customers only, or fee-based. |

|||

The Internet is allowing greater flexibility in working hours and location, especially with the spread of unmetered high-speed connections and [[Web application]]s. |

|||

[[Grassroots]] efforts have led to [[wireless community network]]s. Commercial [[Wi-Fi]] services that cover large areas are available in many cities, such as [[New York City|New York]], [[London]], [[Vienna]], [[Toronto]], [[San Francisco]], [[Philadelphia]], [[Chicago]] and [[Pittsburgh]], where the Internet can then be accessed from places such as a park bench.<ref>{{cite web|last=Pasternak |first=Sean B. |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=10000082&sid=aQ0ZfhMa4XGQ |title=Toronto Hydro to Install Wireless Network in Downtown Toronto |publisher=Bloomberg |date=7 March 2006 |access-date=8 August 2011 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060410104717/http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=10000082&sid=aQ0ZfhMa4XGQ |archive-date=10 April 2006 }}</ref> Experiments have also been conducted with proprietary mobile wireless networks like [[Ricochet (Internet service)|Ricochet]], various high-speed data services over cellular networks, and fixed wireless services. Modern [[smartphone]]s can also access the Internet through the cellular carrier network. For Web browsing, these devices provide applications such as [[Google Chrome]], [[Safari (web browser)|Safari]], and [[Firefox]] and a wide variety of other Internet software may be installed from [[app store]]s. Internet usage by mobile and tablet devices exceeded desktop worldwide for the first time in October 2016.<ref>{{cite web|quote=StatCounter Global Stats finds that mobile and tablet devices accounted for 51.3% of Internet usage worldwide in October compared to 48.7% by desktop.|url=http://gs.statcounter.com/press/mobile-and-tablet-internet-usage-exceeds-desktop-for-first-time-worldwide|title=Mobile and Tablet Internet Usage Exceeds Desktop for First Time Worldwide|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161101170640/http://gs.statcounter.com/press/mobile-and-tablet-internet-usage-exceeds-desktop-for-first-time-worldwide|archive-date=1 November 2016|website=StatCounter: Global Stats, Press Release|date=1 November 2016}}</ref> |

|||

===The mobile Internet=== |

|||

The Internet can now be accessed virtually anywhere by numerous means. [[Mobile phone]]s, [[datacard]]s, [[handheld]] [[game console]]s and [[cellular router]]s allow users to connect to the Internet from anywhere there is a cellular network supporting that device's technology. |

|||

====Mobile communication==== |

|||

==Common uses of the Internet== |

|||

[[File:Number of mobile cellular subscriptions 2012-2016.svg|thumb|Number of mobile cellular subscriptions 2012–2016]] The [[International Telecommunication Union]] (ITU) estimated that, by the end of 2017, 48% of individual users regularly connect to the Internet, up from 34% in 2012.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx|title=World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database 2020 (24th Edition/July 2020)|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190421072228/https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/wtid.aspx|archive-date=21 April 2019|website=International Telecommunication Union (ITU)|date=2017a|quote=Key ICT indicators for developed and developing countries and the world (totals and penetration rates). World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators database}}</ref> [[Mobile Web|Mobile Internet]] connectivity has played an important role in expanding access in recent years, especially in [[Asia–Pacific|Asia and the Pacific]] and in Africa.<ref name="UNESCO">{{Cite book|url=http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002610/261065e.pdf|title=World Trends in Freedom of Expression and Media Development Global Report 2017/2018|publisher=UNESCO|year=2018|access-date=29 May 2018|archive-date=20 September 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180920181419/http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0026/002610/261065e.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> The number of unique mobile cellular subscriptions increased from 3.9 billion in 2012 to 4.8 billion in 2016, two-thirds of the world's population, with more than half of subscriptions located in Asia and the Pacific. The number of subscriptions was predicted to rise to 5.7 billion users in 2020.<ref name="GSMA The Mobile Economy 2019">{{Cite web|date=11 March 2019|title=GSMA The Mobile Economy 2019 |url=https://www.gsma.com/r/mobileeconomy/|access-date=28 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190311062226/https://www.gsma.com/r/mobileeconomy/|archive-date=11 March 2019}}</ref> {{as of|2018}}, 80% of the world's population were covered by a [[4G]] network.<ref name="GSMA The Mobile Economy 2019" /> The limits that users face on accessing information via mobile applications coincide with a broader process of [[Fragmentation (computing)|fragmentation of the Internet]]. Fragmentation restricts access to media content and tends to affect the poorest users the most.<ref name="UNESCO" /> |

|||

===E-mail=== |

|||

{{details|E-mail}} |

|||

The concept of sending electronic text messages between parties in a way analogous to mailing letters or memos predates the creation of the Internet. Even today it can be important to distinguish between Internet and internal e-mail systems. Internet e-mail may travel and be stored unencrypted on many other networks and machines out of both the sender's and the recipient's control. During this time it is quite possible for the content to be read and even tampered with by third parties, if anyone considers it important enough. Purely internal or intranet mail systems, where the information never leaves the corporate or organization's network, are much more secure, although in any organization there will be [[information technology|IT]] and other personnel whose job may involve monitoring, and occasionally accessing, the email of other employees not addressed to them. [[Web-based email]] (webmail) between parties on the same webmail system may not actually 'go' anywhere—it merely sits on the one [[server (computing)|server]] and is tagged in various ways so as to appear in one person's 'sent items' list and in others' 'in boxes' or other 'folders' when viewed. |

|||

[[Zero-rating]], the practice of Internet service providers allowing users free connectivity to access specific content or applications without cost, has offered opportunities to surmount economic hurdles but has also been accused by its critics as creating a two-tiered Internet. To address the issues with zero-rating, an alternative model has emerged in the concept of 'equal rating' and is being tested in experiments by [[Mozilla]] and [[Orange S.A.|Orange]] in Africa. Equal rating prevents prioritization of one type of content and zero-rates all content up to a specified data cap. In a study published by [[Chatham House]], 15 out of 19 countries researched in Latin America had some kind of hybrid or zero-rated product offered. Some countries in the region had a handful of plans to choose from (across all mobile network operators) while others, such as [[Colombia]], offered as many as 30 pre-paid and 34 post-paid plans.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Galpaya|first=Helani|date=12 April 2019|title=Zero-rating in Emerging Economies|url=https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/GCIG%20no.47_1.pdf|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190412062932/https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/GCIG%20no.47_1.pdf|archive-date=12 April 2019|access-date=28 November 2020|website=Global Commission on Internet Governance}}</ref> |

|||

===The World Wide Web=== |

|||

{{details|World Wide Web}}[[Image:WorldWideWebAroundWikipedia.png|thumb|300px|Graphic representation of less than 0.0001% of the [[World Wide Web|WWW]], representing some of the [[hyperlink]]s]] |

|||

A study of eight countries in the [[Global South]] found that zero-rated data plans exist in every country, although there is a great range in the frequency with which they are offered and actually used in each.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://a4ai.org/the-impacts-of-emerging-mobiledata-services-in-developing-countries/|title=Alliance for Affordable Internet (A4AI). 2015. Models of Mobile Data Services in Developing Countries. Research brief. The Impacts of Emerging Mobile Data Services in Developing Countries.}}{{Dead link|date=September 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> The study looked at the top three to five carriers by market share in Bangladesh, Colombia, Ghana, India, Kenya, Nigeria, Peru and Philippines. Across the 181 plans examined, 13 percent were offering zero-rated services. Another study, covering [[Ghana]], [[Kenya]], [[Nigeria]] and [[South Africa]], found [[Facebook]]'s Free Basics and [[Wikipedia Zero]] to be the most commonly zero-rated content.<ref>{{Cite web|last1= Gillwald|first1= Alison|first2=Chenai|last2=Chair|first3=Ariel |last3=Futter |first4=Kweku|last4= Koranteng |first5=Fola |last5= Odufuwa|first6= John|last6= Walubengo|date=12 September 2016|title=Much Ado About Nothing? Zero Rating in the African Context|url=https://researchictafrica.net/publications/Other_publications/2016_RIA_Zero-Rating_Policy_Paper_-_Much_ado_about_nothing.pdf|access-date=28 November 2020|website=Researchictafrica|archive-date=16 December 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201216150858/https://researchictafrica.net/publications/Other_publications/2016_RIA_Zero-Rating_Policy_Paper_-_Much_ado_about_nothing.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Many people use the terms Internet and World Wide Web (a.k.a. the Web) interchangeably, but in fact the two terms are not synonymous. The Internet and the Web are two separate but related things. |

|||

The Internet is a massive network of networks, a networking infrastructure. It connects millions of computers together globally, forming a network in which any computer can communicate with any other computer as long as they are both connected to the Internet. Information that travels over the Internet does so via a variety of languages known as protocols. |

|||

== Internet Protocol Suite == |

|||

The World Wide Web, or simply Web, is a way of accessing information over the medium of the Internet. It is an information-sharing model that is built on top of the Internet. The Web uses the HTTP protocol, only one of the languages spoken over the Internet, to transmit data. Web services, which use HTTP to allow applications to communicate in order to exchange business logic, use the the Web to share information. The Web also utilizes browsers, such as Internet Explorer or Netscape, to access Web documents called Web pages that are linked to each other via hyperlinks. Web documents also contain graphics, sounds, text and video. |

|||

{{IP stack}} |

|||

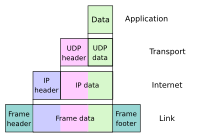

The Internet standards describe a framework known as the [[Internet protocol suite]] (also called [[TCP/IP]], based on the first two components.) This is a suite of protocols that are ordered into a set of four conceptional [[Communication protocol#Layering|layers]] by the scope of their operation, originally documented in {{IETF RFC|1122}} and {{IETF RFC|1123}}. At the top is the [[application layer]], where communication is described in terms of the objects or data structures most appropriate for each application. For example, a web browser operates in a [[client–server model|client–server]] application model and exchanges information with the [[HyperText Transfer Protocol]] (HTTP) and an application-germane data structure, such as the [[HTML|HyperText Markup Language]] (HTML). |

|||

Below this top layer, the [[transport layer]] connects applications on different hosts with a logical channel through the network. It provides this service with a variety of possible characteristics, such as ordered, reliable delivery (TCP), and an unreliable datagram service (UDP). |

|||

The Web is just one of the ways that information can be disseminated over the Internet. The Internet, not the Web, is also used for e-mail, which relies on SMTP, Usenet news groups, instant messaging, file sharing (text, image, video, [http://www.mp3-indir.gen.tr mp3] etc.) and FTP. So the Web is just a portion of the Internet, albeit a large portion, but the two terms are not synonymous and should not be confused. |

|||

Underlying these layers are the networking technologies that interconnect networks at their borders and exchange traffic across them. The [[Internet layer]] implements the [[Internet Protocol]] (IP) which enables computers to identify and locate each other by [[IP address]] and route their traffic via intermediate (transit) networks.<ref name=rfc791>{{Cite IETF|rfc=791|title=Internet Protocol, DARPA Internet Program Protocol Specification|editor=[[Jon Postel|J. Postel]]|date=September 1981|publisher=[[IETF]]}} Updated by {{IETF RFC|1349|2474|6864}}</ref> The Internet Protocol layer code is independent of the type of network that it is physically running over. |

|||

Through [[keyword (Internet search)|keyword]]-driven [[Internet research]] using [[search engine]]s, like [[Google (search engine)|Google]], millions worldwide have easy, instant access to a vast and diverse amount of online information. Compared to [[encyclopedia]]s and traditional [[library|libraries]], the World Wide Web has enabled a sudden and extreme decentralization of information and data. |

|||

At the bottom of the architecture is the [[link layer]], which connects nodes on the same physical link, and contains protocols that do not require routers for traversal to other links. The protocol suite does not explicitly specify hardware methods to transfer bits, or protocols to manage such hardware, but assumes that appropriate technology is available. Examples of that technology include [[Wi-Fi]], [[Ethernet]], and [[DSL]]. |

|||

Many individuals and some companies and groups have adopted the use of "Web logs" or [[blog]]s, which are largely used as easily-updatable online diaries. Some commercial organizations encourage staff to fill them with advice on their areas of specialization in the hope that visitors will be impressed by the expert knowledge and free information, and be attracted to the corporation as a result. One example of this practice is [[Microsoft]], whose product [[software developer|developers]] publish their personal blogs in order to pique the public's interest in their work. |

|||

[[File:UDP encapsulation.svg|thumb|As user data is processed through the protocol stack, each abstraction layer adds encapsulation information at the sending host. Data is transmitted ''over the wire'' at the link level between hosts and routers. Encapsulation is removed by the receiving host. Intermediate relays update link encapsulation at each hop, and inspect the IP layer for routing purposes.]] |

|||

For more information on the distinction between the World Wide Web and the Internet itself—as in everyday use the two are sometimes confused—see [[Dark internet]] where this is discussed in more detail. |

|||

=== |

===Internet protocol=== |

||

[[Image:IP stack connections.svg|thumb|Conceptual data flow in a simple network topology of two hosts (''A'' and ''B'') connected by a link between their respective routers. The application on each host executes read and write operations as if the processes were directly connected to each other by some kind of data pipe. After the establishment of this pipe, most details of the communication are hidden from each process, as the underlying principles of communication are implemented in the lower protocol layers. In analogy, at the transport layer the communication appears as host-to-host, without knowledge of the application data structures and the connecting routers, while at the internetworking layer, individual network boundaries are traversed at each router.]] |

|||

The Internet allows computer users to connect to other computers and information stores easily, wherever they may be across the world. They may do this with or without the use of [[Computer security|security]], authentication and encryption technologies, depending on the requirements. |

|||

The most prominent component of the Internet model is the Internet Protocol (IP). IP enables internetworking and, in essence, establishes the Internet itself. Two versions of the Internet Protocol exist, [[IPv4]] and [[IPv6]]. |

|||

====IP Addresses==== |

|||