Charles Manson: Difference between revisions

m - redlinked image |

KMaster888 (talk | contribs) ce |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American criminal and cult leader (1934–2017)}} |

|||

{{unreferenced|date=September 2006}} |

|||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=November 2023}} |

|||

{{Infobox Celebrity |

|||

{{Use American English|date=November 2017}} |

|||

| name = Charles Manson |

|||

{{Infobox criminal |

|||

| image = |

|||

| |

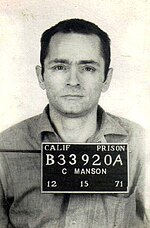

| image = Manson1968.jpg |

||

| caption = Manson's 1968 mugshot |

|||

| birth_date = [[November 12]], [[1934]] |

|||

| birth_name = Charles Milles Maddox |

|||

| birth_place = [[Cincinnati, Ohio]], [[United States]] {{Flagicon|USA}} |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1934|11|12}} |

|||

| death_date = |

|||

| birth_place = [[Cincinnati]], Ohio, U.S. |

|||

| death_place = |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|2017|11|19|1934|11|12}} |

|||

| occupation = Habitual criminal |

|||

| death_place = [[Bakersfield, California]], U.S. |

|||

| salary = |

|||

| |

| occupation = |

||

| |

| motive = |

||

| |

| other_names = |

||

| known_for = [[Manson Family murders]] |

|||

| website = |

|||

| |

| conviction = {{plainlist| |

||

* [[Murder in California law|First degree murder]] (7 counts) |

|||

* [[Conspiracy to commit murder]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| penalty = [[Capital punishment in California|Death]]; [[Commutation (law)|commuted]] to [[Life imprisonment in the United States|life imprisonment]] |

|||

'''Charles Milles <!--Please don't alter this middle name, it is Milles --> Manson''' (born [[November 12]], [[1934]]) is an [[United States|American]] convict and career criminal, most known for his participation in the Tate-LaBianca murders of the late 1960s. |

|||

| spouse = {{plainlist| |

|||

* {{marriage|Rosalie Willis|1955|1958|end=div}} |

|||

* {{marriage|Leona Stevens|1959|1963|end=div}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| children = 3 |

|||

| partners = Members of the [[Manson Family]], including [[Susan Atkins]], [[Mary Brunner]], and [[Tex Watson]] |

|||

| height = |

|||

| imprisoned = |

|||

| signature = Charles Manson signature2.svg |

|||

| victims = 9+ [[Proxy murder|murdered by proxy]] |

|||

| alt = Black-and-white headshot photo of a crazy-eyed man with a dark mop of hair and beard |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Charles Milles Manson''' ({{ne|'''Maddox'''}}; November 12, 1934 – November 19, 2017) was an American criminal, [[cult leader]], and musician who led the [[Manson Family]], a cult based in California in the late 1960s and early 1970s.<ref name="Juschka 2023">{{cite book |author-last=Juschka |author-first=Darlene M. |year=2023 |chapter=Chapter 4: Space Aliens and Deities Compared |editor1-last=Freudenberg |editor1-first=Maren |editor2-last=Elwert |editor2-first=Frederik |editor3-last=Karis |editor3-first=Tim |editor4-last=Radermacher |editor4-first=Martin |editor5-last=Schlamelcher |editor5-first=Jens |title=Stepping Back and Looking Ahead: Twelve Years of Studying Religious Contact at the Käte Hamburger Kolleg Bochum |location=[[Leiden]] and [[Boston]] |publisher=[[Brill Publishers]] |series=Dynamics in the History of Religions |volume=13 |doi=10.1163/9789004549319_006 |doi-access=free |isbn=978-90-04-54931-9 |issn=1878-8106 |pages=124–145}}</ref> Some cult members committed a [[Manson Family#Crimes|series of at least nine murders]] at four locations in July and August 1969. In 1971, Manson was convicted of [[Murder in California law|first-degree murder]] and [[conspiracy to commit murder]] for the [[Tate–LaBianca murders|deaths of seven people]], including the film actress [[Sharon Tate]]. The prosecution contended that, while Manson never directly ordered the murders, his [[ideology]] constituted an overt [[Criminal conspiracy|act of conspiracy]].<ref name=":1">{{Cite web|url=https://law.justia.com/cases/california/court-of-appeal/3d/61/102.html|title=People v. Manson|website=Justia Law|language=en|access-date=May 11, 2019|archive-date=May 20, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180520054853/https://law.justia.com/cases/california/court-of-appeal/3d/61/102.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Before the murders, Manson had spent more than half of his life in [[correctional institutions]]. While gathering his cult following, he was a [[singer-songwriter]] on the fringe of the [[Los Angeles]] music industry, chiefly through a chance association with [[Dennis Wilson]] of [[the Beach Boys]], who introduced Manson to record producer [[Terry Melcher]]. In 1968, the Beach Boys recorded Manson's song "Cease to Exist", renamed "[[Never Learn Not to Love]]" as a single [[B-side]], but Manson was uncredited. Afterward, he attempted to secure a record contract through Melcher, but was unsuccessful. |

|||

Manson would often talk about [[the Beatles]], including their [[The Beatles (album)|eponymous 1968 album]]. According to [[Los Angeles County District Attorney]] [[Vincent Bugliosi]], Manson felt guided by his interpretation of the Beatles' lyrics and adopted the term "[[Helter Skelter (scenario)|Helter Skelter]]" to describe an impending [[Apocalypticism|apocalyptic]] [[race war]].<ref name="Juschka 2023"/> During his trial, Bugliosi argued that Manson had intended to start a race war, although Manson and others disputed this. Contemporary interviews and trial witness testimony insisted that the Tate–LaBianca murders were [[copycat crime]]s intended to exonerate Manson's friend [[Bobby Beausoleil]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cielodrive.com/manson-murders-motive-copycat.php|title=Manson Murders Motive {{!}} Copycat Motive|website=www.cielodrive.com|access-date=May 11, 2019|archive-date=May 11, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190511010512/http://www.cielodrive.com/manson-murders-motive-copycat.php|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{cite AV media|people=James Buddy Day (Director)|date=2017|title=Charles Manson: The Final Words|publisher=Pyramid Productions}}</ref> Manson himself denied having ordered any murders. Nevertheless, he [[Life imprisonment|served his time in prison]] and died from complications from colon cancer in 2017. |

|||

== 1934–1967: Early life == |

|||

=== Childhood === |

|||

Charles Milles Maddox was born on November 12, 1934, to 15-year-old Ada Kathleen Maddox (1919–1973) of [[Ashland, Kentucky]],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.theclever.com/15-lesser-known-facts-about-charles-manson/ |title=15 Lesser-Known Facts About The Late Charles Manson |date=November 21, 2017 |publisher=The Clever |last=Woods |first=Jared |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171129074434/https://www.theclever.com/15-lesser-known-facts-about-charles-manson/ |archive-date=November 29, 2017 |access-date=November 22, 2017 }}</ref><ref>[https://www.geni.com/people/Kathleen-Manson-Bower-Cavender-Maddox/6000000008511797051/ Kathleen Maddox]; geni.com</ref> in the [[University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center]] in [[Cincinnati]], Ohio.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–137}}<ref>Reitwiesner, William Addams. [http://www.wargs.com/other/manson.html Provisional ancestry of Charles Manson] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305010208/http://www.wargs.com/other/manson.html |date=March 5, 2016}}; retrieved April 26, 2007.</ref> Manson's biological father appears to have been Colonel Walker Henderson Scott, Sr. (1910–1954)<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.accuracyproject.org/cbe-Manson,Charles.html |title=''Internet Accuracy Project: Charles Manson'' |website=AccuracyProject.org |access-date=October 28, 2012 |archive-date=February 24, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210224141140/https://www.accuracyproject.org/cbe-Manson,Charles.html |url-status=live }}</ref> of [[Catlettsburg, Kentucky]], against whom Maddox filed a [[Paternity (law)|paternity]] suit that resulted in an [[stipulated judgment|agreed judgment]] in 1937.<ref name="mom">{{cite news |last=Smith |first=Dave |title=Mother Tells Life of Manson as Boy |newspaper=[[Los Angeles Times]] |date=January 26, 1971 }}</ref> Scott worked intermittently in local mills, and had a local reputation as a [[con artist]]. He allowed Maddox to believe that he was an army colonel, although "Colonel" was merely his given name. When Maddox told Scott that she was pregnant, he informed her that he had been called away on army business; after several months she realized he had no intention of returning.{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=22}} Manson never knew his biological father. |

|||

In August 1934, before Manson's birth, Maddox married William Eugene Manson (1909–1961), a laborer at a [[dry cleaning]] business. Maddox often went on drinking sprees with her brother Luther Elbert Maddox (1916–1950), leaving Charles with babysitters. Maddox and her husband divorced on April 30, 1937, after William alleged "gross neglect of duty" by Maddox. Charles retained William's last name of Manson.{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=23}} On August 1, 1939, Kathleen and Luther were arrested for assault and robbery, and sentenced to five and ten years of imprisonment, respectively.{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=27}} |

|||

Manson was placed in the home of an aunt and uncle in [[McMechen, West Virginia]].<ref name="ketchup">{{cite news |url = https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/07/books/a-new-look-at-charles-manson-by-jeff-guinn.html |title = Long Before Little Charlie Became the Face of Evil |date = August 7, 2013 |work = [[The New York Times]] |access-date = January 7, 2016 |url-status=live |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150930225705/http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/07/books/a-new-look-at-charles-manson-by-jeff-guinn.html |archive-date = September 30, 2015 |df = mdy-all }}</ref> His mother was paroled in 1942. Manson later characterized the first weeks after she returned from prison as the happiest time in his life.{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=36}} Weeks after her release, Manson's family moved to [[Charleston, West Virginia]],{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=38}} where he continually played [[truancy|truant]] and his mother spent her evenings drinking.<ref name="Medium">{{cite web|first=H. Allegra|last=Lansing|url=https://medium.com/@themansonfamily_mtts/son-of-man-the-early-life-of-charles-manson-c89d41d03bf8|title=Son of Man: The Early Life of Charles Manson|website=[[Medium (website)|Medium]]|publisher=A Medium Corporation|location=Boston, Massachusetts|date=July 11, 2019|access-date=August 17, 2020|archive-date=February 28, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220228032216/https://themansonfamily-mtts.medium.com/son-of-man-the-early-life-of-charles-manson-c89d41d03bf8|url-status=live}}</ref> She was arrested for [[grand larceny]], but not convicted.<ref>{{cite news|first=Janet|last=Maslin|author-link=Janet Maslin|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/07/books/a-new-look-at-charles-manson-by-jeff-guinn.html|title=Long Before Little Charlie Became the Face of Evil|newspaper=[[The New York Times]]|location=New York City|date=August 6, 2013|access-date=August 17, 2020|archive-date=September 30, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150930225705/http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/07/books/a-new-look-at-charles-manson-by-jeff-guinn.html|url-status=live}}</ref> The family later moved to [[Indianapolis]], where Maddox met alcoholic Lewis Woodson Cavender Jr. (1916–1979) through [[Alcoholics Anonymous]] meetings, and married him in August 1943.<ref name="Medium"/> |

|||

=== First offenses === |

|||

In an interview with [[Diane Sawyer]], Manson stated that when he was aged 9, he [[Arson|set his school on fire]].<ref>"Charles Manson – Diane Sawyer Documentary.</ref> He also got repeatedly in trouble for truancy and petty theft. Although there was a lack of foster home placements, in 1947, at the age of 13, Manson was placed in the [[Gibault School for Boys]] in [[Terre Haute, Indiana]], a school for male delinquents run by [[Catholicism|Catholic]] priests.{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=43}} Gibault was a strict school, where punishment for even the smallest infraction included beatings with either a wooden paddle or a leather strap. Manson ran away from Gibault and slept in the woods, under bridges and wherever else he could find shelter.<ref name=":2">{{cite news|first=Al|last=Hunter|title=Charles Manson – Hoosier Juvenile Dilenquent|newspaper=The Weekly View|date=January 22, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

Manson fled home to his mother and spent Christmas 1947 at his aunt and uncle's house in West Virginia.{{sfn|Guinn|2013|pp=37–42}} However, his mother returned him to Gibault. Ten months later, he ran away to Indianapolis.<ref>{{cite news|first=Dawn|last=Mitchell|url=https://www.indystar.com/story/news/history/retroindy/2014/01/14/charles-manson/4471927/|title=Retro Indy: Charles Manson, mass murderer and cult leader, spent time in Indiana|newspaper=[[The Indianapolis Star]]|date=January 14, 2014|access-date=August 17, 2020|archive-date=September 19, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200919163018/https://www.indystar.com/story/news/history/retroindy/2014/01/14/charles-manson/4471927/|url-status=live}}</ref> It was there, in 1948, Manson committed his first documented crime by robbing a grocery store, at first to simply find something to eat. However, Manson found a cigar box containing just over a hundred dollars, which he used to rent a room on Indianapolis' Skid Row and to buy food.<ref>{{cite web|first=David|last=Mercer|date=November 20, 2017|access-date=August 17, 2020|url=https://news.sky.com/story/charles-mansons-life-and-crimes-a-timeline-11135463|title=Charles Manson's life and crimes: a timeline|website=[[Sky News]]|archive-date=October 24, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201024201551/https://news.sky.com/story/charles-mansons-life-and-crimes-a-timeline-11135463|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

For a time, Manson had a job delivering messages for [[Western Union]] in an attempt to live honestly. However, he quickly began to supplement his wages through theft.<ref name=":2" /> He was eventually caught, and in 1949 a sympathetic judge sent him to [[Boys Town (organization)|Boys Town]], a juvenile facility in [[Omaha, Nebraska]].<ref name=SawyerInterview>Charles Manson – Diane Sawyer Interview.</ref> After four days at Boys Town, he and fellow student Blackie Nielson obtained a gun and stole a car. They used it to commit two armed robberies on their way to the home of Nielson's uncle in [[Peoria, Illinois]].{{sfn|Guinn|2013|pp=42–43}}{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} Nielson's uncle was a professional thief, and when the boys arrived he allegedly took them on as apprentices.{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=43}} Manson was arrested two weeks later during a nighttime raid on a Peoria store. In the investigation that followed, he was linked to his two earlier armed robberies. He was sent to the [[Plainfield Juvenile Correctional Facility|Indiana Boys School]], a strict [[reform school]] outside of [[Plainfield, Indiana]].<ref>{{cite web|first=Richard|last=Ray|url=https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/in-indiana-charles-manson-was-once-a-14-year-old-lost-little-kid-report/28532/#:~:text=In%20Indiana%2C%20Charles%20Manson%20Was%20Once%20a%20%E2%80%98Lost,the%20Gibault%20School%20for%20Boys%20in%20Terre%20Haute.|title=In Indiana, Charles Manson Was Once a 'Lost Little Kid': Report|website=NBC Chicago|date=November 20, 2017|access-date=August 17, 2020|archive-date=October 25, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201025203413/https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/in-indiana-charles-manson-was-once-a-14-year-old-lost-little-kid-report/28532/#:~:text=In%20Indiana%2C%20Charles%20Manson%20Was%20Once%20a%20%E2%80%98Lost,the%20Gibault%20School%20for%20Boys%20in%20Terre%20Haute.|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

At the Indiana Boys School, other students allegedly [[rape]]d Manson with the encouragement of a staff member, and he was repeatedly beaten. He ran away from the school eighteen times.<ref name=SawyerInterview/> Manson developed a self-defense technique he later called the "insane game", in which he would screech, grimace and wave his arms to convince stronger aggressors that he was insane. After a number of failed attempts, he escaped with two other boys in February 1951.{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=45}}{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} The three escapees robbed filling stations while attempting to drive to [[California]] in stolen cars until they were arrested in [[Utah]]. For the federal crime of driving a stolen car across state lines, Manson was sent to [[Washington, D.C.]]'s [[National Training School for Boys]].{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=137–146}} On arrival he was given aptitude tests which determined that he was illiterate but had an above-average [[IQ]] of 109. His case worker deemed him aggressively [[Antisocial personality disorder|antisocial]].{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=45}}{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} |

|||

=== First imprisonment === |

|||

On a psychiatrist's recommendation, Manson was transferred in October 1951 to Natural Bridge Honor Camp, a minimum security institution in [[Virginia]].{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} His aunt visited him and told administrators she would let him stay at her house and help him find work. Manson had a parole hearing scheduled for February 1952. However, in January, he was caught raping a boy at knifepoint. Manson was transferred to the [[Federal Correctional Complex, Petersburg|Federal Reformatory]] in [[Petersburg, Virginia]], where he committed a further "eight serious disciplinary offenses, three involving [[homosexuality|homosexual]] acts". He was then moved to a maximum security [[Chillicothe Correctional Institution|reformatory]] at [[Chillicothe, Ohio]], where he was expected to remain until his release on his 21st birthday in November 1955. Good behavior led to an early release in May 1954, to live with his aunt and uncle in West Virginia.{{sfn|Guinn|2013|p=52}} |

|||

[[File:Charles Manson mugshot FCI Terminal Island California 1956-05-02 3845-CAL.png|thumb|right|Manson, aged 21. Booking photo, Federal Correctional Institute Terminal Island, May 2, 1956.]] |

|||

In January 1955, Manson married a hospital waitress named Rosalie "Rosie" Jean Willis (January 28, 1939 – August 21, 2009). Around October, about three months after he and his pregnant wife arrived in Los Angeles in a car he had stolen in Ohio, Manson was again charged with a federal crime for taking the vehicle across state lines. After a psychiatric evaluation, he was given five years' [[probation]]. Manson's failure to appear at a Los Angeles hearing on an identical charge filed in [[Florida]] resulted in his March 1956 arrest in Indianapolis. His probation was revoked, and he was sentenced to three years' imprisonment at [[Federal Correctional Institution, Terminal Island|Terminal Island]] in Los Angeles.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} |

|||

While Manson was in prison, Rosalie gave birth to their son, Charles Manson Jr. (April 10, 1956 – June 29, 1993). During his first year at Terminal Island, Manson received visits from Rosalie and his mother, who were now living together in Los Angeles. In March 1957, when the visits from his wife ceased, his mother informed him Rosalie was living with another man. Less than two weeks before a scheduled parole hearing, Manson tried to escape by stealing a car. He was given five years' probation and his parole was denied.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} |

|||

=== Second imprisonment === |

|||

Manson received five years' parole in September 1958, the same year in which Rosalie received a decree of divorce. By November, he was [[pimp]]ing a 16-year-old girl and receiving additional support from a girl with wealthy parents. In September 1959, he pleaded guilty to a charge of attempting to cash a forged [[United States Department of the Treasury|U.S. Treasury]] check, which he claimed to have stolen from a mailbox; the latter charge was later dropped. He received a ten-year [[suspended sentence]] and probation after a young woman named Leona Rae "Candy" Stevens, who had an arrest record for [[prostitution]], made a "tearful plea" before the court that she and Manson were "deeply in love ... and would marry if Charlie were freed".{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} Before the year's end, the woman did marry Manson, possibly so she [[Spousal privilege|would not be required]] to testify against him.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} |

|||

Manson took Leona and another woman to [[New Mexico]] for purposes of prostitution, resulting in him being held and questioned for violating the [[Mann Act]]. Though he was released, Manson correctly suspected that the investigation had not ended. When he disappeared in violation of his probation, a [[Arrest warrant#Bench warrant|bench warrant]] was issued. An [[indictment]] for violation of the Mann Act followed in April 1960.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} Following the arrest of one of the women for prostitution, Manson was arrested in June in [[Laredo, Texas]], and was returned to Los Angeles. For violating his probation on the check-cashing charge, he was ordered to serve his ten-year sentence.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} |

|||

Manson spent a year trying unsuccessfully to [[appeal]] the revocation of his probation. In July 1961, he was transferred from the [[Los Angeles County Jail]] to [[McNeil Island Corrections Center|the United States Penitentiary]] at [[McNeil Island]], Washington. There, he took guitar lessons from [[Barker–Karpis gang]] leader [[Alvin Karpis#Imprisonment|Alvin "Creepy" Karpis]], and obtained from another inmate the contact information of [[Phil Kaufman (producer)|Phil Kaufman]], a producer at [[Universal Pictures|Universal Studios]] in [[Hollywood, Los Angeles|Hollywood]].<ref>{{cite web |access-date=July 2, 2012 |url=http://www.lostinthegrooves.com/short-bits-2-charles-manson-and-the-beach-boys |work=Lost in the Grooves |title=Short Bits 2 – Charles Manson and the Beach Boys |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120718010206/http://www.lostinthegrooves.com/short-bits-2-charles-manson-and-the-beach-boys |archive-date=July 18, 2012 |date=April 13, 2006 }}</ref> Among Manson's fellow prisoners during this time was future actor [[Danny Trejo]], with the two participating in several [[hypnosis]] sessions together.<ref>{{Cite web|date=July 7, 2021|title=Danny Trejo Says Charles Manson Once Hypnotized Him in Jail|url=https://www.mediaite.com/entertainment/danny-trejo-says-charles-manson-once-hypnotized-him-in-jail/|access-date=July 7, 2021|website=Mediaite|language=en|archive-date=July 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210707202624/https://www.mediaite.com/entertainment/danny-trejo-says-charles-manson-once-hypnotized-him-in-jail/|url-status=live}}</ref> Manson's mother moved to Washington State to be closer to him during his McNeil Island incarceration, working nearby as a waitress.<ref name="Rule/Guinn">{{cite magazine |last=Rule |first=Ann |title=There Will Be Blood |journal=The New York Times Book Review |date=August 18, 2013 |page=14 }}</ref> |

|||

Although the Mann Act charge had been dropped, the attempt to cash the Treasury check was still a federal offense. Manson's September 1961 annual review noted he had a "tremendous drive to call attention to himself", an observation echoed in September 1964.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} In 1963, Leona was granted a divorce. During the process she alleged that she and Manson had a son, Charles Luther Manson.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} According to a popular [[urban legend]], Manson auditioned unsuccessfully for [[the Monkees]] in late-1965; this is refuted by the fact that Manson was still incarcerated at McNeil Island at that time.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.snopes.com/radiotv/tv/monkees.asp |title=Did Charles Manson Audition for The Monkees? |website=snopes.com |date=September 25, 1995 |access-date=July 5, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

In June 1966, Manson was sent for the second time to Terminal Island in preparation for early release. By the time of his release day on March 21, 1967, he had spent more than half of his thirty-two years in prisons and other institutions. This was mainly because he had broken federal laws. Federal sentences were, and remain, much more severe than state sentences for many of the same offenses. Telling the authorities that prison had become his home, he requested permission to stay.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=136–146}} |

|||

== 1967-1968: San Francisco and cult formation== |

|||

=== Parolee and patient === |

|||

Less than a month after his 1967 release, Manson moved to [[Berkeley, California|Berkeley]] from Los Angeles,<ref name="Guinn, p. 94">{{harvnb|Guinn|2013|p=94}}</ref> which could have been a probation violation. Instead, after calling the [[San Francisco]] probation office upon his arrival, he was transferred to the supervision of [[criminology]] doctoral researcher and federal probation officer Roger Smith.{{sfn|O'Neill|2019|p=237}} Until the spring of 1968, Smith worked at the [[Haight Ashbury Free Clinics|Haight Ashbury Free Medical Clinic]] (HAFMC), which Manson and his family came to frequent.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Smith |first1=David E |last2=Luce |first2=John |date=1971 |title=Love Needs Care: A History of San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic and Its Pioneer Role Treating Drug-abuse Problems |publisher=Boston, Little, Brown |url=https://archive.org/details/loveneedscarehis00smit/ |access-date=April 30, 2021}} p. 52</ref> Roger Smith, as well as the HAFMC's founder David Smith, received funding from the [[National Institutes of Health]], and reportedly the [[CIA]], to study the effects of drugs like [[LSD]] and [[methamphetamine]] on the [[Counterculture of the 1960s|counterculture movement]] in San Francisco's [[Haight–Ashbury]] District.<ref>{{harvnb|O'Neill|2019|p=251}}</ref> The patients at the HAFMC became subjects of their research, including Manson and his expanding group of mostly female followers, who came to see Roger Smith regularly.<ref>{{harvnb|O'Neill|2019|p=266}}</ref> |

|||

Manson received permission from Roger Smith to move from Berkeley to the Haight-Ashbury District. He first took LSD and would use it frequently during his time there.<ref name="Guinn, p. 94"/> David Smith, who had studied the effects of LSD and amphetamines in rodents,<ref>{{harvnb|O'Neill|2019|p=260}}</ref> wrote that the change in Manson's personality during this time "was the most abrupt Roger Smith had observed in his entire professional career."<ref>Smith, p. 257</ref> Manson also read the book ''[[Stranger in a Strange Land]]'', a science fiction novel by [[Robert Heinlein]].<ref>{{harvnb|O'Neill|2019|p=237}}</ref> Inspired by the burgeoning [[free love]] philosophy in Haight–Ashbury during the [[Summer of Love]], Manson began preaching his own [[philosophy]] based on a mixture of ''Stranger in a Strange Land'', the [[Bible]], [[Scientology]], [[Dale Carnegie]] and [[the Beatles]], which quickly earned him a following.<ref>{{harvnb|Guinn|2013|p=95}}</ref> He may have also borrowed some of his philosophy from the [[Process Church of the Final Judgment]], whose members believed [[Satan]] would become reconciled to [[Jesus]] and they would come together at the [[Eschatology|end of the world]] to judge humanity. |

|||

=== Involvement with Scientology === |

|||

Manson began studying Scientology while incarcerated with the help of fellow inmate Lanier Rayner, and in July 1961 listed Scientology as his religion.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|p=260}} A September 1961 prison report argues that Manson "appears to have developed a certain amount of insight into his problems through his study of this discipline".{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|p=144}} Another prison report in August 1966 stated that Manson was no longer an advocate of Scientology.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|p=146}} Upon his release in 1967, Manson traveled to Los Angeles where he reportedly "met local Scientologists and attended several parties for movie stars".<ref name="mallia1998">{{Cite news |last=Mallia |first=Joseph |title=Inside the Church of Scientology – Church wields celebrity clout |work=[[Boston Herald]] |page=30 |date=March 5, 1998}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |first=Steven V. |last=Roberts |title=Charlie Manson, Nomadic Guru, Flirted With Crime in a Turbulent Childhood |work=[[The New York Times]] |page=84 |date=December 7, 1969}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|last=Goodsell |first=Greg |title=Manson once proclaimed Scientology |work=Catholic Online |publisher=www.catholic.org |date=February 23, 2010 |url=http://www.catholic.org/national/national_story.php?id=35505 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100227053826/http://www.catholic.org/national/national_story.php?id=35505 |url-status=dead |archive-date=February 27, 2010 |access-date=February 24, 2010 }}</ref> Manson completed 150 hours of [[Auditing (Scientology)|auditing]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dst/Library/Shelf/cooper/scandal_behind_scandal.html|title=The Scandal Behind the "Scandal of Scientology"|last=Cooper|first=Paulette|website=www.cs.cmu.edu|access-date=November 8, 2019|archive-date=November 12, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191112220005/http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dst/Library/Shelf/cooper/scandal_behind_scandal.html|url-status=live}}</ref> His "right hand man", [[Bruce M. Davis|Bruce Davis]], worked at the [[Church of Scientology]] headquarters in [[London]] from November 1968 to April 1969. |

|||

=== San Francisco followers === |

|||

{{see also|Manson Family}} |

|||

Shortly after relocating to San Francisco, Manson became acquainted with [[Mary Brunner]], a 23-year-old graduate of [[University of Wisconsin–Madison]]. Brunner was working as a library assistant at the [[University of California, Berkeley]], and Manson, until that point making his living by [[begging|panhandling]], moved in with her. Manson then met teenaged [[runaway (dependent)|runaway]] [[Squeaky Fromme|Lynette Fromme]], later nicknamed "Squeaky," and convinced her to live with him and Brunner.<ref>{{harvnb|Guinn|2013|p=97}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine|first=Angela|last=Serratore|url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/manson-family-murders-what-need-to-know-180972655/|title=The True Story of the Manson Family|magazine=[[Smithsonian Magazine]]|location=Washington, D.C.|date=July 25, 2019|access-date=August 18, 2020|archive-date=August 18, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200818185908/https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/manson-family-murders-what-need-to-know-180972655/|url-status=live}}</ref> According to a second-hand account, Manson overcame Brunner's initial resistance to him bringing other women in to live with them. Before long, they were sharing Brunner's residence with eighteen other women.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|163–174}} Manson targeted individuals for manipulation who were emotionally insecure and social outcasts.<ref name="Smith, p. 259">Smith, p. 259</ref> |

|||

Manson established himself as a [[guru]] in Haight-Ashbury which, during the Summer of Love, was emerging as the signature [[hippie]] locale. Manson soon had the first of his groups of followers, most of them female. They were later dubbed as the "Manson Family" by Los Angeles prosecutor [[Vincent Bugliosi]] and the media.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|137–146}} Manson allegedly taught his followers that they were the [[reincarnation]] of the [[Early Christianity|original Christians]], and that [[The Establishment]] could be characterized as the [[Ancient Rome|Romans]]. |

|||

Sometime around 1967, Manson began using the alias "Charles Willis Manson."<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|315}} Before the end of summer, he and some of his followers began traveling in an old [[school bus]] they had adapted, putting colored rugs and pillows in place of the many seats they had removed. They eventually settled in the Los Angeles areas of [[Topanga, California|Topanga Canyon]], [[Malibu, California|Malibu]] and [[Venice, Los Angeles|Venice]] along the coast.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|163–174}}<ref name="Sanders">{{cite book|last=Sanders|first=Ed|author-link=Ed Sanders|date=2002|title=The Family|location=[[New York City]]|publisher=Thunder's Mouth Press|isbn=1-56025-396-7}}</ref>{{rp|13–20}} |

|||

In 1967, Brunner became pregnant by Manson. On April 15, 1968, she gave birth to their son, whom she named Valentine Michael, in a condemned house where they were living in Topanga Canyon. She was assisted by several of the young women from the fledgling Family. Brunner, like most members of the group, acquired a number of [[Pseudonym|aliases]] and nicknames, including: "Marioche", "Och", "Mother Mary", "Mary Manson", "Linda Dee Manson" and "Christine Marie Euchts".<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|xv}} |

|||

In his book ''Love Needs Care'' about his time at the HAFMC, David Smith claimed that Manson attempted to reprogram his followers' minds to "submit totally to his will" through the use of "LSD and … unconventional sexual practices" that would turn his followers into "empty vessels that would accept anything he poured."<ref name="Smith, p. 259"/> Manson Family member [[Paul Watkins (Manson Family)|Paul Watkins]] testified that Manson would encourage group LSD trips and take lower doses himself to "keep his wits about him."<ref>{{harvnb|Guinn|2013|p=139}}</ref> Watkins stated that "Charlie's trip was to program us all to submit."<ref>{{cite book |last=Melnick |first=Jeffrey Paul |date=2018 |title=Creepy Crawling: Charles Manson and the Many Lives of America's Most Infamous Family |publisher=Arcade |isbn=978-1628728934}} p. 16</ref> By the end of his stay in the Haight in April 1968, Manson had attracted twenty or so followers, all under the supervision of Roger Smith and many of the staff at the HAFMC.<ref name="Smith, p. 260">Smith, p. 260</ref> The core members of Manson's following eventually included: Brunner; [[Tex Watson|Charles "Tex" Watson]], a musician and former actor; [[Bobby Beausoleil]], a former musician and [[pornography|pornographic]] actor; [[Susan Atkins]]; [[Patricia Krenwinkel]]; and [[Leslie Van Houten]].<ref name="InsideFamily">{{cite web |title=Charles Manson's Son Says He Wishes He'd Gotten to Know Him Before His Death |url=https://www.insideedition.com/charles-mansons-son-says-he-wishes-hed-gotten-know-him-his-death-54566 |website=insideedition.com |date=July 18, 2019 |publisher=Inside Edition Inc, CBS Interactive |access-date=August 24, 2019 |archive-date=August 24, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190824173448/https://www.insideedition.com/charles-mansons-son-says-he-wishes-hed-gotten-know-him-his-death-54566 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="ViceBob">{{cite web |last1=Kovac |first1=Adam |title=We Spoke to Charles Manson's Guitarist About Making Art While Serving Time for Murder |url=https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/bn5wwd/we-spoke-to-charles-mansons-guitarist-about-his-life-making-art-and-music-while-serving-time-for-murder-298 |website=[[Vice (magazine)|Vice]] |date=April 8, 2015 |publisher=[[Vice Media]] |location=New York City |access-date=August 24, 2019 |archive-date=May 26, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190526142449/https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/bn5wwd/we-spoke-to-charles-mansons-guitarist-about-his-life-making-art-and-music-while-serving-time-for-murder-298 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Milne |first1=Andrew |title=Meet Bobby Beausoleil: The Haight-Ashbury Hippie Who Became A Manson Family Murderer |url=https://allthatsinteresting.com/bobby-beausoleil |website=allthatsinteresting.com |date=July 6, 2019 |publisher=PBH Network |access-date=August 24, 2019 |archive-date=August 24, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190824173444/https://allthatsinteresting.com/bobby-beausoleil |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

=== Subsequent arrests === |

|||

Supervised by his ostensible parole officer Roger Smith, Manson grew his family through drug use and prostitution<ref name="Smith, p. 260"/> without interference from the authorities. Manson was arrested on July 31, 1967, for attempting to prevent the arrest of one of his followers, [[Ruth Ann Moorehouse]]. Instead of Manson being sent back to prison, the charge was reduced to a [[misdemeanor]] and Manson was given three additional years of probation.<ref name="O'Neill, p. 242">{{harvnb|O'Neill|2019|p=242}}</ref> He avoided prosecution again in July 1968, when he and the family were arrested while moving to Los Angeles,<ref>{{harvnb|O'Neill|2019|p=244}}</ref> when his bus crashed into a ditch; Manson and members of his family, including Brunner and Manson's new-born baby, were found sleeping naked by police.<ref>{{harvnb|O'Neill|2019|p=246}}</ref> Afterwards, he was again arrested and released only a few days later, this time on a drug charge.<ref>{{harvnb|O'Neill|2019|p=248}}</ref><ref name="O'Neill, p. 242"/> |

|||

=== Involvement with the Beach Boys === |

|||

{{See also|Never Learn Not to Love|The Beach Boys bootleg recordings#Manson sessions}} |

|||

On April 6, 1968, [[Dennis Wilson]] of the [[Beach Boys]] was driving through Malibu when he noticed two female hitchhikers, Krenwinkel and Ella Jo Bailey. He picked them up and dropped them off at their destination.{{sfn|Badman|2004|p=216}} On April 11, Wilson noticed the same two girls hitchhiking again and this time took them to his home at 14400 [[Sunset Boulevard]].{{sfn|Badman|2004|p=216}}<ref name=WebbGuardian2003>{{cite news|last1=Webb|first1=Adam|title=A profile of Dennis Wilson: the lonely one|url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/2003/dec/14/popandrock|work=[[The Guardian]]|date=December 14, 2003|access-date=December 14, 2016|archive-date=November 7, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201107123033/https://www.theguardian.com/music/2003/dec/14/popandrock|url-status=live}}</ref> Wilson later recalled that he "told [the girls] about our involvement with [[Maharishi Mahesh Yogi|the Maharishi]] and they told me they too had a guru, a guy named Charlie [Manson] who'd recently come out of jail after twelve years."<ref name="RM68">{{cite magazine|last1=Griffiths|first1=David|title=Dennis Wilson: "I Live With 17 Girls"|magazine=[[Record Mirror]]|date=December 21, 1968|url=https://www.rocksbackpages.com/Library/Article/dennis-wilson-i-live-with-17-girls|url-access=subscription|access-date=December 4, 2020|archive-date=January 20, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210120003836/https://www.rocksbackpages.com/Library/Article/dennis-wilson-i-live-with-17-girls|url-status=live}}</ref> Wilson then went to a recording session; when he returned later that night, he was met in his driveway by Manson, and when Wilson walked into his home, about a dozen people were occupying the premises, most of them young women.<ref name=WebbGuardian2003 /> By Manson's own account, he had met Wilson on at least one prior occasion: at a friend's San Francisco house where Manson had gone to obtain [[marijuana]]. Manson claimed that Wilson invited him to visit his home when Manson came to Los Angeles.<ref>{{cite book|last=Emmons|first=Nuel|title=Manson in His Own Words|publisher=Grove Press|year=1988|isbn=0-8021-3024-0}}</ref> |

|||

Wilson was initially fascinated by Manson and his followers, referring to him as "the Wizard" in a ''Rave'' magazine article at the time.{{sfn|Stebbins|2000|p=130}} The two struck a friendship, and over the next few months members of the Manson Family – mostly women who were treated as servants – were housed in Wilson's residence.<ref name=WebbGuardian2003 /> This arrangement persisted for about six months.{{sfn|Badman|2004|pp=224–225}}<ref name="RM68"/> |

|||

Wilson introduced Manson to a few friends in the music business, including [[the Byrds]]' producer [[Terry Melcher]]. Manson recorded numerous songs at [[Brian Wilson]]'s [[Brian Wilson's home studio|home studio]], although the recordings remain unheard by the public.<ref name="DoeUnreleased">{{cite web|last1=Doe|first1=Andrew Grayham|title=Unreleased Albums|url=http://www.esquarterly.com/bellagio/unreleased.html|website=Bellagio 10452|publisher=Endless Summer Quarterly|access-date=October 16, 2015|archive-date=October 25, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141025151137/http://esquarterly.com/bellagio/unreleased.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Band engineer [[Stephen Desper]] said that the Manson sessions were done "for Dennis [Wilson] and Terry Melcher".{{sfn|O'Neill|2019}} In September 1968, Wilson recorded a Manson song for the Beach Boys, originally titled "Cease to Exist" but reworked as "[[Never Learn Not to Love]]", as a single B-side released the following December. The writing was credited solely to Wilson.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Barlass|first1=Tyler|title=Song Stories - "Never Learn Not To Love" (1968)|url=http://www.justpressplay.net/articles/39-news/3713-song-stories-qnever-learn-not-to-loveq-1968.html|date=July 16, 2008|access-date=July 6, 2016|archive-date=March 5, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305141845/http://www.justpressplay.net/articles/39-news/3713-song-stories-qnever-learn-not-to-loveq-1968.html|url-status=live}}</ref> When asked why Manson was not credited, Wilson explained that Manson relinquished his publishing rights in favor of "about a hundred thousand dollars' worth of stuff".{{sfn|Stebbins|2000|p=137}}<ref name="Nolan2">{{cite magazine |last=Nolan |first=Tom |title=Beach Boys: A California Saga, Part II |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/beach-boys-a-california-saga-part-ii-19711111 |magazine=[[Rolling Stone]] |date=November 11, 1971 |access-date=June 25, 2018 |archive-date=August 16, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160816014717/http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/beach-boys-a-california-saga-part-ii-19711111 |url-status=live }}</ref> Around this time, the Family destroyed two of Wilson's luxury cars.{{sfn|Badman|2004|pp=223–224}} |

|||

Wilson eventually distanced himself from Manson and moved out of the Sunset Boulevard house, leaving the Family there, and subsequently took residence at a basement apartment in [[Santa Monica, California|Santa Monica]].{{sfn|Badman|2004|p=224}} Virtually all of Wilson's household possessions were stolen by the Family; the members were [[eviction|evicted]] from his home three weeks before the lease was scheduled to expire.{{sfn|Badman|2004|p=224}} When Manson subsequently sought further contact, he left a bullet with Wilson's housekeeper to be delivered with a threatening message.<ref name=WebbGuardian2003 /><ref>{{cite news|last1=Holdship|first1=Bill|title=Heroes and Villains|url=http://smileysmile.net/board/index.php?topic=2371.25|work=[[Los Angeles Times]]|date=April 6, 2000|access-date=April 7, 2015|archive-date=March 3, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303235253/http://smileysmile.net/board/index.php?topic=2371.25|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Band manager [[Nick Grillo]] recalled that Wilson became concerned after Manson had got "into a much heavier drug situation ... taking a tremendous amount of acid and Dennis wouldn't tolerate it and asked him to leave. It was difficult for Dennis because he was afraid of Charlie."{{sfn|Badman|2004|pp=224–225}} Writing in his [[Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy|2016 memoir]], [[Mike Love]] recalled Wilson saying he had witnessed Manson shooting a black man "in half" with an [[M16 rifle]] and hiding the body inside a well.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/gossip/beach-boy-mike-love-claims-bandmate-charles-manson-kill-man-article-1.2773092|title=Beach Boy Mike Love alleges bandmate watched Charles Manson carry out murder|first=Nicole|last=Bitette|website=[[New York Daily News]]|date=August 31, 2016 |access-date=February 12, 2021|archive-date=July 22, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180722104419/http://www.nydailynews.com/entertainment/gossip/beach-boy-mike-love-claims-bandmate-charles-manson-kill-man-article-1.2773092|url-status=live}}</ref> Melcher said that Wilson had been aware that the Family "were killing people" and had been "so freaked out he just didn't want to live anymore. He was afraid, and he thought he should have gone to the authorities, but he didn't, and the rest of it happened."{{sfn|O'Neill|2019}} |

|||

=== Spahn Ranch === |

|||

Manson established a base for the Family at the [[Spahn Ranch]] in August 1968, after their eviction from Wilson's residence.<ref>[http://la.curbed.com/2014/10/22/10032594/the-story-of-the-abandoned-movie-ranch-where-the-manson-family The Story of the Abandoned Movie Ranch Where the Manson Family Launched Helter Skelter] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160709124920/http://la.curbed.com/2014/10/22/10032594/the-story-of-the-abandoned-movie-ranch-where-the-manson-family |date=July 9, 2016 }}. Retrieved March 10, 2016.</ref> The ranch had been a television and movie set for [[Western (genre)|Westerns]], but the buildings had deteriorated by the late-1960s. The ranch then derived revenue primarily from selling horseback rides.<ref name="NME">{{cite news|url=https://www.nme.com/news/bryan-cranston-had-run-in-with-charles-manson-2161985|title=Bryan Cranston had a very close run-in with Charles Manson in the 1960s|last=Reilly|first=Nick|date=November 21, 2017|work=[[NME]]|accessdate=October 17, 2022}}</ref> Female Family members did chores around the ranch and, occasionally, had sex on Manson's orders with the nearly blind 80-year-old owner, [[George Spahn]]; the women also acted as guides for him. In exchange, Spahn allowed Manson and his group to live at the ranch for free.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|99–113}} |

|||

=== Doomsday beliefs === |

|||

{{See also|Manson Family#Possible murder motives|Helter Skelter (scenario)}} |

|||

The Manson Family evolved into a [[doomsday cult]] when Manson became fixated on the idea of an imminent apocalyptic [[ethnic conflict|race war]] between America's Black minority and the larger White population. A [[White supremacy|white supremacist]],<ref>{{cite magazine|first=Lauren|last=Gill|url=https://www.newsweek.com/charles-manson-was-white-supremacist-lets-not-forget-713915|title=Remember, Charles Manson Was a White Supremacist|magazine=[[Newsweek]]|date=November 16, 2017|access-date=August 17, 2020|archive-date=August 4, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200804074518/https://www.newsweek.com/charles-manson-was-white-supremacist-lets-not-forget-713915|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine|first=Desire|last=Thompson|url=https://www.vibe.com/2017/11/charles-manson-his-obsession-with-black-people|title=Charles Manson & His Obsession with Black People|magazine=[[Vibe (magazine)|Vibe]]|location=New York City|date=November 20, 2017|access-date=August 18, 2020|archive-date=August 13, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200813000715/https://www.vibe.com/2017/11/charles-manson-his-obsession-with-black-people|url-status=live}}</ref> Manson told some of the Family that Black people would rise up and kill the entire White population except for Manson and his followers, but that they were not intelligent enough to survive on their own; they would need a white man to lead them, and so they would serve Manson as their "master".<ref>{{cite web|first=John W.|last=Whitehead|url=https://www.huffpost.com/entry/helter-skelter-racism-and_b_669109|title=Helter Skelter: Racism and Murder|website=[[HuffPost]]|date=August 3, 2010|access-date=August 17, 2020|archive-date=October 30, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201030204544/https://www.huffpost.com/entry/helter-skelter-racism-and_b_669109|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|first=Jim|last=Beckerman|url=https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/2019/08/09/charles-manson-murders-still-relevant-racism-50-years-later/1955164001/|title=Charles Manson: 50 years later, murders have racist link to recent mass-killings|newspaper=[[The Record (North Jersey)|The Record]]|date=August 9, 2019|access-date=August 17, 2020|archive-date=January 24, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210124221103/https://www.northjersey.com/story/news/2019/08/09/charles-manson-murders-still-relevant-racism-50-years-later/1955164001/|url-status=live}}</ref> In late-1968, Manson adopted the term "[[Helter Skelter (scenario)|Helter Skelter]]", taken from [[Helter Skelter (song)|a song]] on [[the Beatles]]' recently released ''[[The Beatles (album)|White Album]]'', to refer to this upcoming war.{{sfn|Bugliosi|Gentry|1974|pp=244}} |

|||

=== Tate encounter === |

|||

On March 23, 1969,<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|228–233}} Manson entered the grounds of [[10050 Cielo Drive]], which he had known as Melcher's residence. He was not invited.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|155–161}} As he approached the main house, Manson was met by Shahrokh Hatami, an Iranian photographer who had befriended film director [[Roman Polanski]] and his wife [[Sharon Tate]] during the making of the documentary ''[[Mia and Roman]]''. Hatami was there to photograph Tate before she departed for [[Rome]] the following day. Seeing Manson approach, Hatami had gone onto the front porch to ask him what he wanted.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|228–233}} Manson said that he was looking for Melcher, whose name Hatami did not recognize.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|228–233}} Hatami told him the place was the Polanski residence and then advised him to try the path to the guest house beyond the main house. Tate appeared behind Hatami in the house's front door and asked him who was calling. Hatami and Tate maintained their positions while Manson went back to the guest house without a word, returned to the front a minute or two later and left.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|228–233}} |

|||

That evening, Manson returned to the property and again went to the guest house. He entered the enclosed porch and spoke with Altobelli, the owner, who had just come out of the shower. Manson asked for Melcher, but Altobelli felt that Manson was instead looking for him. It was later discovered that Manson had apparently been to the property on earlier occasions after Melcher left.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|228–233, 369–377}} Altobelli told Manson through the screen door that Melcher had moved to Malibu and said that he did not know his new address, although he did.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|226}} |

|||

Altobelli told Manson he was leaving the country the next day, and Manson said he would like to speak with him upon his return. Altobelli said that he would be gone for more than a year.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|228–233}} Manson said that he had been directed to the guest house by the persons in the main house; Altobelli asked Manson not to disturb his tenants.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|228–233}} Altobelli and Tate flew together to Rome the next day. Tate asked him whether "that creepy-looking guy" had gone to see him at the guest house the day before.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|228–233}} |

|||

==1969–1971: Crimes and trial== |

|||

{{See also|Tate–LaBianca murders|Manson Family#Crimes}} |

|||

=== Crowe shooting === |

|||

Tex Watson became involved in [[drug dealing]]<ref name="Waxman"/> and robbed a 22-year-old rival named Bernard "Lotsapoppa" Crowe. Crowe allegedly responded with a threat to kill everyone at Spahn Ranch. In response, Manson shot Crowe on July 1, 1969, at Manson's Hollywood apartment.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|91–96,99–113}}<ref name="Sanders"/>{{rp|147–149}}<ref name="watson12">{{Cite book|title=Will You Die For Me?|last=Watson|first=Charles|date=1978|publisher=F.H. Revell|isbn=0800709128}}</ref> Manson's belief that he had killed Crowe was seemingly confirmed by a news report of the discovery of the dumped body of a [[Black Panther Party|Black Panther]] in Los Angeles. |

|||

Although Crowe was not a member of the Black Panthers, Manson concluded he had been and expected retaliation from the Panthers. He turned Spahn Ranch into a defensive camp, establishing night patrols by armed guards.<ref name="watson12"/><ref name="Sanders"/>{{rp|151}} Watson would later write, "Blackie was trying to get at the chosen ones."<ref name="watson12"/> Manson brought in members of the Straight Satans Motorcycle Club to act as security.<ref name="Waxman">{{cite web|last=Waxman|first=Olivia B.|url=https://time.com/5633973/last-manson-interview/|title=Why Did the Manson Family Kill Sharon Tate? Here's the Story Charles Manson Told the Last Man Who Interviewed Him|work=[[Time magazine]]|date=July 26, 2019|access-date=March 5, 2022|archive-date=September 24, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200924061655/https://time.com/5633973/last-manson-interview/|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

=== Hinman murder === |

|||

34-year-old Gary Alan Hinman, a music teacher and graduate student at [[UCLA]], had previously befriended members of the Family and allowed some to occasionally stay at his home in Topanga Canyon. According to Atkins, Manson believed Hinman was wealthy and sent her, Brunner, and Beausoleil to Hinman's home to convince him to join the Family and turn over the assets Manson thought Hinman had inherited.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{Rp|75–77}}<ref name="watson12"/><ref name="atkins">{{cite book|title=Child of Satan, Child of God|publisher=Plainfield, NJ: Logos International | year=1977 | isbn=0-88270-276-9 | pages=94–120 | last1=Atkins|first1= Susan|last2= Slosser|first2= Bob}}</ref> The three held Hinman hostage for two days in late July 1969, as he denied having any money. During this time, Manson arrived with a sword and slashed his face and ear. After that, Beausoleil stabbed Hinman to death, allegedly on Manson's instruction. Before leaving the residence, Beausoleil or one of the women used Hinman's blood to write "political piggy"<!--"Piggy", not "Piggie"; photo is in Bugliosi 1994, between pages 142 and 143--> on the wall and to draw a panther paw, a Black Panther symbol.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{Rp|33, 91–96, 99–113}}<ref name="Sanders"/>{{rp|184}} |

|||

According to Beausoleil,<ref name="seconds">{{cite web|work=beausoleil.net|url=http://www.beausoleil.net/mminterview.html|title=Beausoleil ''Seconds'' interviews|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070607180026/http://www.beausoleil.net/mminterview.html|archive-date=June 7, 2007}}</ref> he came to Hinman's house to recover money paid to Hinman for [[mescaline]] provided to the Straight Satans that had supposedly been bad.<ref name="Waxman"/> Beausoleil added that Brunner and Atkins, unaware of his intent, went along to visit Hinman. Atkins, in her 1977 autobiography, wrote that Manson directed Beausoleil, Brunner and her to go to Hinman's and get the supposed inheritance of $21,000. She said that two days earlier Manson had told her privately that, if she wanted to "do something important", she could kill Hinman and get his money.<ref name="atkins"/> Beausoleil was arrested on August 6, 1969, after he was caught driving Hinman's car. Police found the murder weapon in the tire well.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{Rp|28–38}} |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

===Tate murders=== |

|||

On the night of August 8, 1969, Watson took Atkins, Krenwinkel and [[Linda Kasabian]] to 10050 Cielo Drive. Watson later claimed that Manson had instructed him to go to the house and "totally destroy" everyone in it, and to do it "as gruesome as you can".<ref name="bugliosi">Bugliosi, Vincent with Gentry, Curt. ''Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders 25th Anniversary Edition'', W. W. Norton & Company, 1994. {{ISBN|0-393-08700-X}}. {{oclc|15164618}}.</ref>{{rp|463–468}}<ref name="watson14">{{cite web |url=http://www.aboundinglove.org/sensational/wydfm/wydfm-014.php |title=Watson, Ch. 14 |publisher=Aboundinglove.org |access-date=November 28, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101119075221/http://aboundinglove.org/sensational/wydfm/wydfm-014.php |archive-date=November 19, 2010}}</ref> Manson told the women to do as Watson instructed them.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|176–184, 258–269}} |

|||

The occupants of the Cielo Drive house that evening were Tate, aged 26, who was 8{{fraction|1|2}} months pregnant; her friend and former lover 35-year-old [[Jay Sebring]], a noted celebrity hairstylist; Polanski's friend 32-year-old Wojciech Frykowski; and Frykowski's 25-year-old girlfriend Abigail Anne Folger, heiress to the [[Folgers]] coffee fortune and daughter of [[Peter Folger]].<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|28–38}} Also present on the property were 19-year-old caretaker William Garretson and his friend, 18-year-old Steven Earl Parent. Polanski was in Europe working on a film. Music producer [[Quincy Jones]] was a friend of Sebring who had planned to join him that evening before changing his mind.<ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://www.gq.com/story/quincy-jones-has-a-story |title=Quincy Jones Has a Story About That |magazine=GQ |access-date=October 18, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

Watson and the three women arrived at Cielo Drive just past midnight on August 9. Watson climbed a telephone pole near the entrance gate and cut the phone line to the house.<ref name="watson9">{{cite web |work=aboundinglove.org |url=http://www.aboundinglove.org/sensational/wydfm/wydfm-009.php |author=Watson, Charles as told to Ray Hoekstra |title=Will You Die for Me? |access-date=May 3, 2007 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070405004745/http://aboundinglove.org/sensational/wydfm/wydfm-009.php |archive-date=April 5, 2007}}</ref> The group then backed their car to the bottom of the hill that led to the estate before walking back up to the house. Thinking that the gate might be electrified or equipped with an alarm, they climbed a brushy embankment to the right of the gate and entered the grounds.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|176–184}} |

|||

Headlights approached the group from within the property, and Watson ordered the women to lie in the bushes. He stepped out and ordered the approaching driver, Parent, to halt. Watson leveled a [[.22 caliber]] [[revolver]] at Parent, who begged him not to hurt him, claiming that he would not say anything. Watson lunged at Parent with a knife, giving him a [[defensive wound|defensive slash wound]] on the palm of his hand that severed tendons and tore the boy's watch off his wrist, then shot him four times in the chest and abdomen, killing him in the front seat of his white 1965 [[AMC Ambassador]] coupe. Watson ordered the women to help push the car up the driveway.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|22–25}}<ref name="watson14"/> |

|||

Watson next cut the screen of a window, then told Kasabian to keep watch down by the gate; she walked over to Parent's car and waited.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|258–269}}<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|176–184}}<ref name="watson14"/> Watson removed the screen, entered through the window and let Atkins and Krenwinkel in through the front door.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|176–184}} He whispered to Atkins and awoke Frykowski, who was sleeping on the living room couch. Watson kicked him in the head,<ref name="watson14"/> and Frykowski asked him who he was and what he was doing there. Watson replied, "I'm the devil, and I'm here to do the devil's business."<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|176–184}}<ref name="watson14"/> |

|||

On Watson's direction, Atkins found the house's three other occupants with Krenwinkel's help<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|176–184, 297–300}} and forced them to the living room. Watson began to tie Tate and Sebring together by their necks with a long nylon rope which he had brought, then slung it over one of the living room's ceiling beams. Sebring protested the rough treatment of the pregnant Tate, so Watson shot him. Folger was taken momentarily back to her bedroom for her purse, and she gave the murderers $70. Watson then stabbed Sebring seven times.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|28–38}}<ref name="watson14"/> Frykowski's hands had been bound with a towel, but he freed himself and began struggling with Atkins, who stabbed at his legs with a knife.<ref name="watson14"/> He fought his way out the front door and onto the porch, but Watson caught up with him, struck him over the head with the gun multiple times, stabbed him repeatedly and shot him twice.<ref name="watson14"/> |

|||

Kasabian had heard "horrifying sounds" and moved toward the house from her position in the driveway. She told Atkins that someone was coming in an attempt to stop the murders.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|258–269}}<ref name="watson14"/> Inside the house, Folger escaped from Krenwinkel and fled out a bedroom door to the pool area.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|341–344, 356–361}} Krenwinkel pursued her and caught her on the front lawn, where she stabbed her and tackled her to the ground. Watson then helped kill her; her assailants stabbed her a total of twenty-eight times.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|28–38}}<ref name="watson14"/> Frykowski struggled across the lawn, but Watson continued to stab him, killing him. Frykowski suffered fifty-one stab wounds; he had also been struck thirteen times in the head with the butt of Watson's gun, which bent the barrel and broke off one side of the gun grip, which was recovered at the scene.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|28–38, 258–269}}<ref name="watson14"/> |

|||

In the house, Tate pleaded to be allowed to live long enough to give birth and offered herself as a hostage in an attempt to save the life of her unborn child. Instead both Atkins and Watson stabbed Tate sixteen times, killing her. The [[coroner's inquest]] found that Tate was still alive when she was hanged with the nylon rope, although the cause of her death was determined as a "[[massive hemorrhage]]",<ref>[https://www.nytimes.com/1970/08/22/archives/coroner-details-the-tate-killing-says-actress-was-stabbed-16-times.html CORONER DETAILS THE TATE KILLING]</ref> while in Sebring's murder it was found that he was hanged lifeless.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|28–38}} |

|||

According to Watson, Manson had told the women to "leave a sign—something witchy".<ref name="watson14"/> Atkins wrote "pig" on the front door in Tate's blood.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|84–90, 176–184}}<ref name="watson14"/> Atkins claims she did this to copycat the Hinman murder scene in order to get Beausoleil out of jail, who was in custody for that murder.<ref name="bugliosi"/>{{rp|426–435}} |

|||

=== LaBianca murders === |

|||

The four murderers plus Manson, Leslie Van Houten and [[Clem Grogan]] went for a drive the following night. Manson was allegedly displeased with the previous night's murders, so he told Kasabian to drive to a house at 3301 Waverly Drive in the [[Los Feliz, Los Angeles|Los Feliz]] section of Los Angeles. Located next door to a home where Manson and Family members had attended a party the previous year,<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|176–184, 204–210}} it belonged to 44-year-old supermarket executive Leno LaBianca and his 43-year-old wife, Rosemary LaBianca, co-owner of a dress shop.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|22–25, 42–48}} |

|||

According to Atkins and Kasabian, Manson disappeared up the driveway and returned to say that he had tied up the house's occupants. Watson, Krenwinkel and Van Houten entered the property.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|176–184, 258–269}} Watson claims in his autobiography that Manson went up alone, then returned to take him up to the house with him. Manson pointed out a sleeping man through a window, and the two entered through the unlocked back door.<ref name="watson19">{{cite web|url=http://www.aboundinglove.org/main/books/will-you-die-for-me|title=Will You Die For Me?, Ch. 19|last=Watson|first=Charles|website=Abounding Love Ministries|access-date=July 13, 2019|archive-date=April 5, 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070405004745/http://www.aboundinglove.org/main/books/will-you-die-for-me|url-status=dead}}</ref> Watson claims Manson roused the sleeping Leno LaBianca from the couch at gunpoint and had Watson bind his hands with a leather thong. Rosemary was brought into the living room from the bedroom, and Watson covered the couple's heads with pillowcases which he bound in place with lamp cords. Manson left, and Krenwinkel and Van Houten entered the house.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|176–184, 258–269}} |

|||

Watson had complained to Manson earlier of the inadequacy of the previous night's weapons.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|258–269}} Watson sent the women from the kitchen to the bedroom, where Rosemary LaBianca had been returned, while he went to the living room and began stabbing Leno LaBianca with a chrome-plated bayonet. The first thrust went into his throat. Watson heard a scuffle in the bedroom and went in there to discover Rosemary LaBianca keeping the women at bay by swinging the lamp tied to her neck. He stabbed her several times with the bayonet, then returned to the living room and resumed attacking Leno, whom he stabbed a total of twelve times. He then carved the word "WAR" into his abdomen. |

|||

Watson returned to the bedroom and found Krenwinkel stabbing Rosemary with a knife from the kitchen. Van Houten stabbed her approximately sixteen times in the back and the exposed buttocks.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|204–210, 297–300, 341–344}} Van Houten claimed at trial<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|433}} that Rosemary LaBianca was already dead during the stabbing. Evidence showed that many of the forty-one stab wounds had, in fact, been inflicted post-mortem.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|44, 206, 297, 341–42, 380, 404, 406–07, 433}} Watson then cleaned off the bayonet and showered, while Krenwinkel wrote "Rise" and "Death to pigs" on the walls and "[[Helter Skelter (scenario)|Healter [sic] Skelter]]" on the refrigerator door, all in LaBianca's blood. She gave Leno LaBianca fourteen puncture wounds with an ivory-handled, two-tined carving fork, which she left jutting out of his stomach. She also planted a steak knife in his throat.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|176–184, 258–269}} |

|||

Meanwhile, Manson drove the other three Family members who had departed Spahn with him that evening to the [[Venice, Los Angeles|Venice]] home of the Lebanese actor Saladin Nader. Manson left them there and drove back to Spahn Ranch, leaving them and the LaBianca killers to hitchhike home.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|176–184, 258–269}} According to Kasabian, Manson wanted his followers to murder Nader in his apartment, but Kasabian claims she thwarted this murder by deliberately knocking on the wrong apartment door and waking a stranger. The group abandoned the murder plan and left, but Atkins defecated in the stairwell on the way out.<ref name="bugliosi" />{{Rp|270–273}} |

|||

=== Shea murder === |

|||

35-year-old [[Cinema of the United States|Hollywood]] [[stuntman]] '''[[Donald Shea|Donald Jerome "Shorty" Shea]]''' was murdered on August 26, 1969,<ref name=GroganBio>{{cite web|title=Steve Grogan biography|url=http://www.biography.com/people/steve-grogan-20902805|website=www.biography.com|publisher=Bio.|access-date=November 22, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151123043736/http://www.biography.com/people/steve-grogan-20902805|archive-date=November 23, 2015|url-status=dead}}</ref> more than two weeks after the [[Tate–LaBianca murders]], when Manson told Shea, Bruce Davis, [[Tex Watson]], and Steve Grogan to go on a ride to a nearby car parts yard on the Spahn Ranch. According to Davis, he sat in the back seat with Grogan, who then hit Shea with a pipe wrench and Watson stabbed him. They brought Shea down a hill behind the ranch and stabbed and brutally tortured him to death. Bruce Davis recalled at his parole hearings: |

|||

{{cquote|I was in the car when Steve Grogan hit Shorty with the pipe wrench. Charles Watson stabbed him. I was in the backseat with... with Grogan. They took Shorty out. They had to go down the hill to a place. I stayed in the car for quite a while but what... then I went down the hill later on and that's when I cut Shorty on the shoulder with the knife, after he was... well, I don't know... I... I don't know if he was dead or not. He didn't bleed when I cut him on the shoulder. |

|||

When I showed up, you know, he was... he was incapacitated. I don't know if... you asked if he was unconscious, I don't know. He may or may not have been. He didn't seem conscious. He wasn't moving or saying anything. And it started off Manson handed me a machete as if I was supposed to... I mean I know what he wanted. But you know I couldn't do that. And I... in fact, I did touch Shorty Shea with a machete on the back of his neck, didn't break the skin. I mean I just couldn't do it. And then I threw the knife... and he handed me a bayonet and it... I just reached over and... I don't know which side it was on but I cut him right about here on the shoulder just with the tip of the blade. Sort of like saying "Are you satisfied, Charlie?" |

|||

Manson had spent most of his adult life in [[prison]], initially for offenses such as [[car theft]], [[forgery]] and [[credit card fraud]]. He also worked some time as a [[pimp]]. In the late 1960s, he became the leader of a group known as "The Family", and masterminded several brutal murders, most notoriously that of movie actress [[Sharon Tate]] (wife of the Polish movie director [[Roman Polański]]), who was eight and a half months pregnant at the time. He was convicted of conspiracy to commit murder in what came to be known as the "Tate-LaBianca case", named after the victims, although he was not accused of committing the murders in person. He is serving a [[life sentence]] in California's [[Corcoran State Prison]], and will be up for [[parole]] in 2007 at the age of 73. Manson has always maintained his innocence of the crimes. |

|||

And I turned around and walked away. And I... I was sick for about two or three days. I mean I couldn't even think about what I... what I had done.<ref>{{cite web|title=SUBSEQUENT PAROLE CONSIDERATION HEARING STATE OF CALIFORNIA BOARD OF PAROLE HEARINGS In the matter of the Life Term Parole Consideration Hearing of: CHARLES WATSON CDC Number: B-37999|url=http://www.cielodrive.com/charles-tex-watson-parole-hearing-2011.php|access-date=22 November 2013}}</ref>}} |

|||

Manson was also friends with several notable musicians before the murders were committed, including [[Dennis Wilson]] of [[The Beach Boys]], and was a marginally successful musician himself who recorded several albums and whose songs have since been covered by many artists. |

|||

In December 1977, Shea's skeletal remains were discovered on a nondescript hillside near Santa Susana Road next to [[Spahn Ranch]] after Grogan, one of those convicted of the murder, agreed to aid authorities in the recovery of Shea's body by drawing a map to its location.<ref name=MailTribune>{{cite web|url=https://mailtribune.com/news/top-stories/family-secrets-book-sheds-light-on-murder-by-manson/|work=[[Mail Tribune]]|title=Family secrets: Book sheds light on murder by Manson|first=Vickie|last=Aldous|date=June 9, 2019|access-date=July 2, 2023|archive-date=August 1, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220801150425/https://www.mailtribune.com/news/top-stories/family-secrets-book-sheds-light-on-murder-by-manson/|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.wpxi.com/news/deep-viral/manson-family-murders-two-nights-of-brutality-that-terrorized-1969-los-angeles/974205161 |title=Manson family murders: Two nights of brutality that terrorized 1969 Los Angeles |first=Crystal |last=Bonvillian |date=August 12, 2019 |access-date=August 20, 2019 |work=[[WPXI]] |publisher=[[Cox Media Group]]}}</ref> According to the autopsy report, his body suffered multiple stab and chopping wounds to the chest, and blunt force trauma to the head.<ref name=SheaAutopsy>Shea, Donald Jerome. Autopsy report case no. 77-15110, Office of the Chief Medical Examiner-Coroner, County of Los Angeles (December 16, 1977).</ref> |

|||

Since his trial and conviction, Manson's name and image have been integrated into American [[pop culture]], typically as a symbol of [[evil]]. |

|||

=== Suspected murders === |

|||

==Early life== |

|||

{{See also|Manson Family#Suspected further murders}} |

|||

Charles Milles Maddox was born at Cincinnati General Hospital in [[Cincinnati, Ohio]], on [[November 12]], [[1934]] to a 16-year-old unwed girl named Kathleen Maddox visiting from Catlettsburg, KY at the time. Shortly after her son's birth, Kathleen married William Manson, who provided the last name by which he is now known. William Manson was Charles' stepfather; by most accounts Manson's biological father, as declared by a court decision, was an Ashland, KY politician, [[Colonel Scott]]. |

|||

In total, Manson and his followers were convicted of nine counts of [[first-degree murder]]. However, the LAPD believes that the Family could have claimed up to at least twelve more victims.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Tata|first1=Samantha|last2=Kovacik|first2=Robert|title=12 Unsolved Murders Have Possible Ties to Manson Family, LAPD Says|url=https://www.nbclosangeles.com/news/local/charles-tex-watson-manson-lapd-lawyer-audio-tape-recordings-murders/1939554/|access-date=June 2, 2022|work=NBC Los Angeles|date=October 18, 2012}}</ref><ref name="Los Angeles Times">{{cite news|last1=Winton|first1=Richard|title=How many more did Manson family kill? LAPD investigating 12 unsolved murders|url=https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2019-08-07/charles-manson-unsolved-murders|access-date=June 2, 2022|work=[[Los Angeles Times]]|date=August 8, 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=12 Unsolved murders link to Charles Manson|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/northamerica/usa/9622216/Unsolved-murders-link-to-Charles-Manson.html|access-date=June 2, 2022|work=[[The Daily Telegraph|The Telegraph]]|date=October 20, 2012}}</ref> Cliff Shepard, a former LAPD Robbery-Homicide Division detective, said that Manson "repeatedly" claimed to have killed many others. Prosecutor Stephen Kay supported this assertion: "I know that Manson one time told one of his cellmates that he was responsible for 35 murders." Tate's younger sister, Debra Tate, has also claimed that investigators are "just scraping the surface" when it comes to the number of Manson's victims and has further elaborated on how Manson sent her a taunting map of the [[Panamint Range]], with crosses on it that she believed were meant to represent buried bodies. This has resulted in several excavations that have been undertaken at Manson's [[Barker Ranch]], but they have not resulted in any bodies being found.<ref>{{cite news|title=Did The Manson Family Have Other Victims?|url=https://www.cbsnews.com/news/did-the-manson-family-have-other-victims/|access-date=June 2, 2022|work=[[CBS News]]|date=March 16, 2008}}</ref> |

|||

* '''Nancy Warren''', 64, and '''Clyda Dulaney''', 24, were both found near [[Ukiah, California]] at the antique store owned by Warren on October 13, 1968. They had both been beaten and strangled to death with thirty-six leather thongs.<ref>{{cite news|title=Seven-year-old child finds bodies; no clue to slayer|url=https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/1212658/|access-date=June 2, 2022|work=Ukiah Daily Journal|date=October 14, 1968}}</ref> After the Family members were arrested, they became suspects when it was discovered that members of the Family had been in the Ukiah area at the time of the murders. However, no one in the Family was ever charged with the murders and no arrests were ever made in the case. |

|||

* '''Marina Elizabeth Habe''', 17, was murdered on December 30, 1968. She was a student at the [[University of Hawaii]] home on vacation when she was murdered in [[Los Angeles]].<ref>''More of Hollywood's Unsolved Mysteries'', John Austin, SP Books, 1992, p. 240.<!--ISSN/ISBN needed--></ref><ref name="The Family">Ed Sanders, ''The Family'', [[Avon Books]], May 1972, p. 132.<!-- ISSN/ISBN needed --></ref> According to the autopsy report, Habe's throat had been slashed and she had received numerous knife wounds to the chest. She suffered multiple contusions to the face and throat, and had been garrotted. There was no evidence of rape.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.philropost.com/2015/02/suspects-and-suspicions.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150415041135/http://www.philropost.com/2015/02/suspects-and-suspicions.html |archive-date=April 15, 2015 |title=SUSPECTS AND SUSPICIONS|website=philropost.com|date=February 2015}}</ref> Habe was abducted outside the home of her mother in [[West Hollywood]], 8962 Cynthia Avenue.<ref>"Police report progress of autopsy", ''Los Angeles Times'', January 3, 1969, pg. D1.</ref> A former Manson Family associate claimed members of the Family had known Habe and it was conjectured she had been one of their victims.<ref name="The Family"/><ref name=times>"Officials Reveal Coed, 17, Was Stabbed To Death", ''Los Angeles Times'', January 3, 1969, pg. SF1.</ref> |

|||

* '''Darwin Morell Scott''', 64, was the uncle of Manson and the brother of Manson's father, Colonel Scott. On May 27, 1969, Scott was found brutally stabbed to death in his [[Ashland, Kentucky]] apartment. His body was pinned to the kitchen floor with a butcher knife, and he had been stabbed nineteen times. After Manson's arrest, it was reported that local residents claimed to have seen a man resembling Manson using the alias, "Preacher", in the area at the time Darwin was murdered. Manson was on parole in California at the time of the murder, but the murder occurred when Manson was out of touch with his parole officers.<ref>{{cite news|title=Stabbing Evidence Still Out|url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/80979236/death-of-darwin-morell-scott-64-who/|access-date=June 2, 2022|work=The Dominion News|date=May 30, 1969}}</ref> |

|||