Albert Camus: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Fixed factual inaccuracy Tags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit iOS app edit App select source |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|French philosopher and writer (1913–1960)}} |

|||

{{otheruses|Camus}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Camus}} |

|||

{{good article}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2020}} |

|||

{{use British English|date=June 2019}} |

|||

{{Infobox philosopher |

|||

| image = Albert Camus, gagnant de prix Nobel, portrait en buste, posé au bureau, faisant face à gauche, cigarette de tabagisme.jpg |

|||

| caption = Portrait from ''[[New York World-Telegram and The Sun]] Photograph Collection'', 1957 |

|||

| region = [[Western philosophy]] |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1913|11|7|df=yes}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Mondovi, Algeria|Mondovi]], [[French Algeria]] |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|df=yes|1960|1|4|1913|11|7}} |

|||

| death_place = [[Villeblevin]], France |

|||

| alma_mater = [[University of Algiers]] |

|||

| notable_works = ''[[The Stranger (Camus novel)|The Stranger]]'' / ''The Outsider''<br/>''[[The Myth of Sisyphus]]''<br/>''[[The Rebel (book)|The Rebel]]''<br/>''[[The Plague (novel)|The Plague]]'' |

|||

| awards = [[1957 Nobel Prize in Literature|Nobel Prize in Literature]] (1957) |

|||

| spouse = {{ubl | {{marriage|Simone Hié|1934|1936|end=div}} | {{marriage|[[Francine Faure]]|1940}}}} |

|||

| signature = Albert Camus signature.svg |

|||

| signature_size = 150px |

|||

| signature_alt = Albert Camus signature |

|||

| school_tradition = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[Continental philosophy]] |

|||

* [[Absurdism]] |

|||

* [[Existentialism]] |

|||

* [[French Nietzscheanism]]<ref>{{cite book|last=Schrift|first=Alan D.|year=2010|chapter=French Nietzscheanism|title=Poststructuralism and Critical Theory's Second Generation|editor-last=Schrift|editor-first=Alan D.|publisher=Acumen|location=Durham, UK|series=The History of Continental Philosophy|volume=6|pages=19–46|isbn=978-1-84465-216-7|chapter-url=https://www.nietzsche-en-france.fr/app/download/12288269526/SCHRIFT+-+French+Nietzscheanism.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Anarcho-syndicalism|Syndicalist anarchism]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| main_interests = Ethics, [[human nature]], [[justice]], politics, [[philosophy of suicide]] |

|||

| notable_ideas = [[Absurdism]] |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Albert Camus''' ({{IPAc-en|k|æ<!--Syllabication is widely debated and /mu:/ as a separate syllable is the most common transcription-->|ˈ|m|uː}}<ref>[http://www.dictionary.com/browse/camus "Camus"]. ''[[Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary]]''.</ref> {{respell|ka|MOO}}; {{IPA|fr|albɛʁ kamy|lang|Fr-Albert Camus.oga}}; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, journalist, [[world federalist]],<ref>{{Cite web |title=A Democratic World Parliament |url=https://www.democracywithoutborders.org/files/PreliminaryContents.pdf |last1=Leinen |last2= Bummel |first1=Jo |first2=Andreas |website=democracywithoutborders.com |pages=1, 2 |access-date=12 January 2024}}</ref> and political activist. He was the recipient of the [[1957 Nobel Prize in Literature]] at the age of 44, the second-youngest recipient in history. His works include ''[[The Stranger (Camus novel)|The Stranger]]'', ''[[The Plague (novel)|The Plague]]'', ''[[The Myth of Sisyphus]]'', ''[[The Fall (Camus novel)|The Fall]]'' and ''[[The Rebel (book)|The Rebel]]''. |

|||

{{nofootnotes|date=September 2007}} |

|||

{{Infobox_Philosopher |

|||

| region = Western Philosophy |

|||

| era = [[20th century philosophy]] |

|||

| color = #B0C4DE |

|||

| image_name = Camus_NYWT&S.jpg |

|||

| image_caption = Photograph of Albert Camus taken in 1957, part of the New York World-Telegram & Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, [[Library of Congress]] |

|||

| name = Albert Camus |

|||

| birth = [[November 7]], [[1913]] <br> {{flagicon|France}} [[Drean|Mondovi]], [[Algeria]] |

|||

| death = {{death date and age|1960|1|4|1913|11|7}} <br> {{flagicon|France}} [[Villeblevin]], [[France]] |

|||

| school_tradition = [[Absurdism]]</br>[[Image:Nobel prize medal.svg|20px]] [[Nobel Prize in Literature]] (1957) |

|||

| main_interests = [[Ethics]], [[Human nature|Humanity]], [[Justice]], [[Love]], [[Politics]] |

|||

| influences = [[Fyodor Dostoevsky]], [[Franz Kafka]], [[Søren Kierkegaard]], [[Herman Melville]], [[Friedrich Nietzsche]], [[Jean-Paul Sartre]], [[Simone Weil]] |

|||

| influenced = [[Thomas Merton]], [[Jacques Monod]], [[Jean-Paul Sartre]] |

|||

| notable_ideas = "The absurd is the essential concept and the first truth" <br /> |

|||

"Always go too far, because that's where you'll find the truth." <br /> |

|||

"I rebel; therefore we exist." |

|||

Camus was born in [[French Algeria]] to ''[[pied-noir]]'' parents. He spent his childhood in a poor neighbourhood and later studied philosophy at the [[University of Algiers]]. He was in Paris when the [[Battle of France|Germans invaded France]] during World War II in 1940. Camus tried to flee but finally joined the [[French Resistance]] where he served as editor-in-chief at ''[[Combat (newspaper)|Combat]]'', an outlawed newspaper. After the war, he was a celebrity figure and gave many lectures around the world. He married twice but had many extramarital affairs. Camus was politically active; he was part of [[anti-Stalinist left|the left]] that opposed [[Joseph Stalin]] and the [[Soviet Union]] because of their [[totalitarianism]]. Camus was a [[moralist]] and leaned towards [[anarcho-syndicalism]]. He was part of many organisations seeking [[European integration]]. During the [[Algerian War]] (1954–1962), he kept a neutral stance, advocating a multicultural and pluralistic Algeria, a position that was rejected by most parties. |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Albert Camus''' ([[International Phonetic Alphabet|IPA]]: {{IPA|[al'bɛʁ ka'my]}}) ([[November 7]], [[1913]] – [[January 4]], [[1960]]) was a [[France|French]] [[author]] and [[philosopher]]. Although he is often associated with [[existentialism]], Camus preferred to be known as a man and a thinker, rather than as a member of a school or ideology. He preferred persons over ideas. In an interview in 1945, Camus rejected any ideological associations: “No, I am not an existentialist. [[Jean-Paul Sartre|Sartre]] and I are always surprised to see our names linked....” (''Les Nouvelles litteraires'', November 15, 1945). |

|||

Philosophically, Camus's views contributed to the rise of the philosophy known as [[absurdism]]. Some consider Camus's work to show him to be an [[existentialist]], even though he himself firmly rejected the term throughout his lifetime. |

|||

Camus was the second youngest recipient of the [[Nobel Prize for Literature]] (after [[Rudyard Kipling]]) when he became the first African-born writer to receive the award, in 1957. He is also the shortest-lived of any literature laureate to date, having died in a car crash only three years after receiving the award. |

|||

== |

==Life and death== |

||

===Early years and education=== |

|||

Albert Camus was born in [[Drean|Mondovi]], [[Algeria]] to a French Algerian ([[Pied-noir|pied noir]]) settler family. His mother was of Spanish extraction. His father, Lucien, died in the [[First Battle of the Marne|Battle of the Marne]] in 1914 during the [[World War I|First World War]], while serving as a member of the [[Zouave]] infantry regiment. Camus lived in poor conditions during his childhood in the Belcourt section of [[Algiers]]. In 1923, he was accepted into the [[lycée]] and eventually to the [[University of Algiers]]. However, he contracted [[tuberculosis]] in 1930, which put an end to his [[football (soccer)]] activities (he had been a [[goalkeeper]] for the university team) and forced him to make his studies a part-time pursuit. He took odd jobs including private [[tutor]], car parts clerk and work for the Meteorological Institute. He completed his ''licence de philosophie'' ([[Bachelor of Arts|BA]]) in 1935; in May of 1936, he successfully presented his thesis on [[Plotinus]], ''Néo-Platonisme et Pensée Chrétienne'' for his ''diplôme d'études supérieures'' (roughly equivalent to an [[Master of Arts (postgraduate)|M.A.]] by thesis). {{French literature (small)}} |

|||

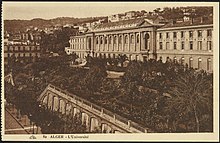

[[File:Algiers The University (GRI).jpg|thumb|alt=A postcard showing the University of Algiers|A 20th-century postcard of the [[University of Algiers]]]] |

|||

Camus joined the [[French Communist Party]] in the Spring of 1935, apparently because of concerns about the political situation in [[Spain]] (which eventually resulted in the [[Spanish Civil War]]) rather than in support for [[Marxism-Leninism|Marxist-Leninist]] doctrine. In 1936, the independence-minded [[Algerian Communist Party]] (PCA) was founded. Camus joined the activities of the [[Algerian People's Party]] (''Le Parti du Peuple Algérien''), which got him into trouble with his Communist party comrades. As a result, he was denounced as a [[Trotskyism|Trotskyite]] and expelled from the party in 1937. |

|||

Albert Camus was born on 7 November 1913 in a working-class neighbourhood in Mondovi (present-day [[Dréan]]), in [[French Algeria]]. His mother, Catherine Hélène Camus ({{née|Sintès}}), was French with [[Balearic Islands|Balearic]] Spanish ancestry. She was deaf and illiterate.{{sfn|Carroll|2013|p=50}} He never knew his father, Lucien Camus, a poor French agricultural worker killed in action while serving with a [[Zouave]] regiment in October 1914, during [[World War I]]. Camus, his mother, and other relatives lived without many basic material possessions during his childhood in the [[Belouizdad, Algiers|Belcourt]] section of [[Algiers]]. Camus was a second-generation French inhabitant of Algeria, which was a French territory from 1830 until 1962. His paternal grandfather, along with many others of his generation, had moved to Algeria for a better life during the first decades of the 19th century. Hence, he was called a {{lang|fr|[[pied-noir]]}} – a slang term for people of French and other European descent born in Algeria. His identity and poor background had a substantial effect on his later life.{{sfnm|1a1=Sherman|1y=2009|1p=10|2a1=Hayden|2y=2016|2p=7|3a1=Lottman|3y=1979|3p=11|4a1=Carroll|4y=2007|4pp=2–3}} Nevertheless, Camus was a French citizen and enjoyed more rights than [[Arab]] and [[Berbers|Berber]] Algerians under {{lang|fr|[[indigénat]]}}.{{sfn|Carroll|2007|pp=2–3}} During his childhood, he developed a love for [[association football|football]] and [[swimming]].{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=11}} |

|||

In 1934, he [[married]] Simone Hie, a [[morphine]] addict, but the marriage ended due to [[infidelity]] by both of them. In 1935, he founded ''Théâtre du Travail'' — "Worker's Theatre" — (renamed ''Théâtre de l'Equipe'' ("Team's Theatre") in 1937), which survived until 1939. From 1937 to 1939 he wrote for a [[socialist]] paper, ''Alger-Républicain'', and his work included an account of the peasants who lived in [[Kabylie]] in poor conditions, which apparently cost him his job. From 1939 to 1940, he briefly wrote for a similar paper, ''Soir-Republicain''. He was rejected by the French army because of his [[tuberculosis]]. |

|||

In 1940, Camus married [[Francine Faure]], a pianist and mathematician. Although he loved Francine, he had argued passionately against the institution of marriage, dismissing it as unnatural. Even after Francine gave birth to twins, Catherine and Jean Camus on [[September 5]], [[1945]], he continued to joke wearily to friends that he was not cut out for marriage. Francine suffered numerous infidelities, particularly a public affair with the Spanish actress [[Maria Casares]]. In the same year Camus began to work for ''[[Paris-Soir]]'' magazine. In the first stage of [[World War II]], the so-called [[Phony War]] stage, Camus was a [[pacifism|pacifist]]. However, he was in [[Paris]] to witness how the [[Wehrmacht]] took over. On [[December 15]], [[1941]], Camus witnessed the execution of [[Gabriel Péri]], an event that Camus later said crystallized his revolt against the Germans. Afterwards he moved to [[Bordeaux]] alongside the rest of the staff of ''Paris-Soir''. In this year he finished his first books, ''[[The Stranger (novel)|The Stranger]]'' and ''[[The Myth of Sisyphus]]''. He returned briefly to [[Oran]], Algeria in 1942. |

|||

Under the influence of his teacher Louis Germain, Camus gained a scholarship in 1924 to continue his studies at a prestigious [[lyceum]] (secondary school) near Algiers.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=8}} Germain immediately noticed his lively intelligence and his desire to learn. In middle school, he gave Camus free lessons to prepare him for the 1924 scholarship competition – despite the fact that his grandmother had a destiny in store for him as a manual worker so that he could immediately contribute to the maintenance of the family. Camus maintained great gratitude and affection towards Louis Germain throughout his life and to whom he dedicated his speech for accepting the Nobel Prize. Having received the news of the awarding of the prize, he wrote: |

|||

== Literary career == |

|||

During the war Camus joined the [[French Resistance]] cell ''[[Combat (newspaper)|Combat]]'', which published an underground newspaper of the same name. This group worked against the Nazis, and in it Camus assumed the [[pseudonym|nom de guerre]] "Beauchard". Camus became the paper's editor in 1943, and when the Allies liberated Paris, Camus reported on the last of the fighting. He was, however, one of the few French editors to publicly express opposition to the [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|use of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima]] soon after the event on August 8, 1945. He eventually resigned from ''Combat'' in 1947, when it became a commercial paper. It was there that Camus became acquainted with [[Jean-Paul Sartre]]. |

|||

<blockquote>But when I heard the news, my first thought, after my mother, was of you. Without you, without the affectionate hand you extended to the small poor child that I was, without your teaching and example, none of all this would have happened.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Albert Camus Wins the Nobel Prize & Sends a Letter of Gratitude to His Elementary School Teacher (1957) |last=Camus |first=Albert |url= https://www.openculture.com/2014/05/albert-camus-sends-a-letter-of-gratitude-to-his-elementary-school-teacher-1957.html |access-date=7 January 2024 |language=en}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

After the war, Camus began frequenting the [[Café de Flore]] on the [[Boulevard Saint-Germain]] in [[Paris]] with Sartre. Camus also toured the [[United States]] to lecture about French thinking. Although he leaned [[left-wing politics|left]] politically, his strong criticisms of [[Communism|Communist]] doctrine did not win him any friends in the [[Communist Party|Communist parties]] and eventually also alienated Sartre. |

|||

In a letter dated 30 April 1959, Germain lovingly reciprocated the warm feelings towards his former pupil, calling him "my little Camus".<ref>{{Cite web |title=I embrace you with all my heart – Letters of Note |url= https://lettersofnote.com/2013/11/07/i-embrace-you-with-all-my-heart/ |date=7 November 2013 |website=lettersofnote.com |access-date=7 January 2024 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Lettre de Monsieur Germain à Albert Camus |trans-title=Letter of Mister Germain to Albert Camus |url=https://compagnieaffable.com/2015/10/04/lettre-de-monsieur-germain-a-albert-camus/ |website=compagnieaffable.com |date=2015-10-04 |access-date=2024-01-09 |language=fr}}</ref> |

|||

In 1949 his tuberculosis returned and he lived in seclusion for two years. In 1951 he published ''[[The Rebel]]'', a philosophical analysis of rebellion and revolution which made clear his rejection of communism. The book upset many of his colleagues and contemporaries in France and led to the final split with Sartre. The dour reception depressed him and he began instead to translate plays. |

|||

In 1930, at the age of 17, he was diagnosed with [[tuberculosis]].{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=11}} Because it is a transmitted disease, he moved out of his home and stayed with his uncle Gustave Acault, a butcher, who influenced the young Camus. It was at that time he turned to philosophy, with the mentoring of his philosophy teacher [[Jean Grenier]]. He was impressed by [[ancient Greek philosopher]]s and [[Friedrich Nietzsche]].{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=11}} During that time, he was only able to study part time. To earn money, he took odd jobs, including as a private tutor, car parts clerk, and assistant at the Meteorological Institute.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=9}} |

|||

Camus's first significant contribution to philosophy was his idea of the absurd, the result of our desire for clarity and meaning within a world and condition that offers neither, which he explained in ''[[The Myth of Sisyphus]]'' and incorporated into many of his other works, such as ''[[The Stranger (novel)|The Stranger]]'' and ''[[The Plague]]''. Despite the split from his “study partner,” Sartre, some still argue that Camus falls into the [[existentialist]] camp. However, he rejected that label himself in his essay ''Enigma'' and elsewhere (see: ''The Lyrical and Critical Essays of Albert Camus''). The current confusion may still arise as many recent applications of existentialism have much in common with many of Camus's ''practical'' ideas (see: ''Resistance, Rebellion, and Death''). However, the personal understanding he had of the world (e.g. "a benign indifference," in ''[[The Stranger (novel)|The Stranger]]''), and every vision he had for its progress (i.e. vanquishing the "adolescent furies" of history and society, in [[The Rebel]]) undoubtedly sets him apart. |

|||

In 1933, Camus enrolled at the [[University of Algiers]] and completed his ''[[Licentiate (degree)|licence de philosophie]]'' ([[Bachelor of Arts|BA]]) in 1936 after presenting his thesis on [[Plotinus]].<ref>{{harvnb|Sherman|2009|p=11|ps=: Camus's thesis was titled "Rapports de l'hellénisme et du christianisme à travers les oeuvres de Plotin et de saint Augustin" ('Relationship of Greek and Christian Thought in Plotinus and St. Augustine') for his ''diplôme d'études supérieures'' (roughly equivalent to an [[Master of Arts|MA]] thesis).}}</ref> Camus developed an interest in early Christian philosophers, but Nietzsche and [[Arthur Schopenhauer]] had paved the way towards [[Philosophical pessimism|pessimism]] and atheism. Camus also studied novelist-philosophers such as [[Stendhal]], [[Herman Melville]], [[Fyodor Dostoyevsky]], and [[Franz Kafka]].{{sfn|Simpson|2019|loc=Background and Influences}} In 1933, he also met Simone Hié, then a partner of Camus's friend, who later became his first wife.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=9}} |

|||

In the 1950s Camus devoted his efforts to [[human rights]]. In 1952 he resigned from his work for [[UNESCO]] when the [[UN]] accepted [[Spain]] as a member under the leadership of [[Francisco Franco|General Franco]]. In 1953 he criticized [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] methods to crush a workers' strike in [[East Berlin]]. In 1956 he protested against similar methods in Poland (protests in Poznań ) and the Soviet repression of the Hungarian revolution in October. |

|||

Camus played as [[Goalkeeper (association football)|goalkeeper]] for the [[Racing Universitaire d'Alger]] junior team from 1928 to 1930.{{sfn|Clarke|2009|p=488}} The sense of team spirit, fraternity, and common purpose appealed to him enormously.{{sfn|Lattal|1995}} In match reports, he was often praised for playing with passion and courage. Any football ambitions, however, disappeared when he contracted tuberculosis.{{sfn|Clarke|2009|p=488}} Camus drew parallels among football, human existence, morality, and personal identity. For him, the simplistic morality of football contradicted the complicated morality imposed by authorities such as the state and church.{{sfn|Clarke|2009|p=488}} |

|||

[[Image:Camus Monument in Villeblevin France 17-august-2003.1.JPG|thumb|The monument to Camus built in the small town of [[Villeblevin]], France where he died in a car crash on January 4, 1960]] |

|||

===Formative years=== |

|||

He maintained his pacifism and resistance to [[capital punishment]] anywhere in the world. One of his most significant contributions to the movement against capital punishment was an essay collaboration with [[Arthur Koestler]], the writer, intellectual and founder of the League Against Capital Punishment. |

|||

In 1934, Camus was in a relationship with Simone Hié.{{sfnm|1a1=Cohn|1y=1986|1p=30|2a1=Hayden|2y=2016|p=9}} Simone had an addiction to [[morphine]], a drug she used to ease her menstrual pains. His uncle Gustave did not approve of the relationship, but Camus married Hié to help her fight the addiction. He subsequently discovered she was in a relationship with her doctor at the same time and the couple later divorced.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=9}} |

|||

Camus joined the [[French Communist Party]] (PCF) in early 1935. He saw it as a way to "fight inequalities between Europeans and 'natives' in Algeria", even though he was not a [[Marxist]]. He explained: "We might see communism as a springboard and asceticism that prepares the ground for more spiritual activities." Camus left the PCF a year later.{{sfnm|1a1=Todd|1y=2000|1pp=249–250|2a1=Sherman|2y=2009|2p=12}} In 1936, the independence-minded [[Algerian Communist Party]] (PCA) was founded, and Camus joined it after his mentor Grenier advised him to do so. Camus's main role within the PCA was to organise the {{lang|fr|Théâtre du Travail}} ('Workers' Theatre'). Camus was also close to the {{lang|fr|Parti du Peuple Algérien}} ([[Algerian People's Party]] [PPA]), which was a moderate anti-colonialist/nationalist party. As tensions in the [[interwar period]] escalated, the [[Stalinist]] PCA and PPA broke ties. Camus was expelled from the PCA for refusing to toe the party line. This series of events sharpened his belief in human dignity. Camus's mistrust of bureaucracies that aimed for efficiency instead of justice grew. He continued his involvement with theatre and renamed his group {{lang|fr|Théâtre de l'Equipe}} ('Theatre of the Team'). Some of his scripts were the basis for his later novels.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|pp=10–11}} |

|||

[[Image:Camus Monument in Villeblevin France 17-august-2003.4.JPG|thumb|left|The bronze plaque on the monument to Camus, built in the small town of [[Villeblevin]], France. The plaque reads: "From the Yonne area's local council, in tribute to the writer Albert Camus who was watched over in the Villeblevin town hall in the night of the 4th to the 5th of January 1960."]] |

|||

In 1938, Camus began working for the leftist newspaper {{lang|fr|[[Alger républicain]]}} (founded by [[Pascal Pia]]), as he had strong anti-fascist feelings, and the rise of fascist regimes in Europe was worrying him. By then, Camus had developed strong feelings against authoritarian [[colonialism]] as he witnessed the harsh treatment of the [[Arab-Berber|Arabs]] and Berbers by French authorities. {{lang|fr|Alger républicain}} was banned in 1940 and Camus flew to Paris to take a new job at {{lang|fr|[[Paris-Soir]]}} as layout editor. In Paris, he almost completed his "first cycle" of works dealing with the absurd and the meaningless: the novel ''L'Étranger'' (''The Outsider'' [UK] or [[The Stranger (Camus novel)|''The Stranger'']] [US]), the philosophical essay ''Le Mythe de Sisyphe'' (''[[The Myth of Sisyphus]]''), and the play ''[[Caligula (play)|Caligula]]''. Each cycle consisted of a novel, an essay, and a theatrical play.{{sfnm|1a1=Hayden|1y=2016|1pp=12-13|2a1=Sherman|2y=2009|2pp=12–13}} |

|||

When the [[Algerian War of Independence]] began in 1954 it presented a moral dilemma for Camus. He identified with [[pied-noir]]s, and defended the French government on the grounds that revolt of its North African colony was really an integral part of the 'new Arab imperialism' led by Egypt and an 'anti-Western' offensive orchestrated by Russia to 'encircle Europe' and 'isolate the United States' (''Actuelles III: Chroniques Algeriennes'', 1939-1958). Although favouring greater Algerian [[self-governance|autonomy]] or even [[federation]], though not full-scale independence, he believed that the pied-noirs and Arabs could co-exist. During the war he advocated civil truce that would spare the civilians, which was rejected by both sides who regarded it as foolish. Behind the scenes, he began to work clandestinely for imprisoned Algerians who faced the death penalty. |

|||

===World War II, Resistance and ''Combat''=== |

|||

From 1955 to 1956 Camus wrote for ''[[L'Express (France)|L'Express]]''. In 1957 he was awarded the [[Nobel Prize in literature]], officially not for his novel ''[[The Fall (novel)|The Fall]]'', published the previous year, but for his writings against capital punishment in the essay "Réflexions Sur la Guillotine". When he spoke to students at the [[University of Stockholm]], he defended his apparent inactivity in the Algerian question and stated that he was worried what could happen to his mother who still lived in Algeria. This led to further ostracism by French left-wing intellectuals. |

|||

Soon after Camus moved to Paris, the outbreak of [[World War II]] began to affect France. Camus volunteered to join the army but was not accepted because he once had tuberculosis. As the Germans were marching towards Paris, Camus fled. He was laid off from {{lang|fr|Paris-Soir}} and ended up in [[Lyon]], where he married pianist and mathematician [[Francine Faure]] on 3 December 1940.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|pp=13–14}} Camus and Faure moved back to Algeria ([[Oran]]), where he taught in primary schools.{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=13}} Because of his tuberculosis, he moved to the French Alps on medical advice. There he began writing his second cycle of works, this time dealing with revolt – a novel, ''La Peste'' (''[[The Plague (novel)|The Plague]]''), and a play, ''Le Malentendu'' (''[[The Misunderstanding]]''). By 1943 he was known because of his earlier work. He returned to Paris, where he met and became friends with [[Jean-Paul Sartre]]. He also became part of a circle of intellectuals, which included [[Simone de Beauvoir]] and [[André Breton]]. Among them was the actress [[María Casares]], who later had an affair with Camus.{{sfnm|1a1=Hayden|1y=2016|p=14|2a1=Sherman|2y=2009|2p=13}} |

|||

Camus took an active role in the underground resistance movement against the Germans during the [[Occupation of France|French Occupation]]. Upon his arrival in Paris, he started working as a journalist and editor of the banned newspaper ''[[Combat (newspaper)|Combat]]''. Camus used a pseudonym for his ''Combat'' articles and used false ID cards to avoid being captured. He continued writing for the paper after the liberation of France,{{sfnm|1a1=Hayden|1y=2016|2a1=Sherman|2y=2009|2p=23}} composing almost daily editorials under his real name.{{sfn|Carroll|2013|p=278}} During that period he composed four ''[[Resistance, Rebellion, and Death|Lettres à un Ami Allemand]]'' ('Letters to a German Friend'), explaining why resistance was necessary.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=15}} |

|||

Camus died on [[January 4]], [[1960]] in a car accident near [[Sens]], in a place named "Le Grand Fossard" in the small town of Villeblevin. In his coat pocket lay an unused train ticket. It is possible that Camus had planned to travel by train, but decided to go by car instead [http://www.raimes.com/seminar.htm]. Coincidentally, Camus had uttered a remark earlier in his life that the most absurd way to die would be in a car accident.{{Fact|date=August 2007}} |

|||

[[Image:20041113-002 Lourmarin Tombstone Albert Camus.jpg|thumb|Albert Camus's gravestone]] |

|||

The driver of the [[Facel Vega]] car, [[Michel Gallimard]] — his publisher and close friend — also perished in the accident. Camus was interred in the Lourmarin Cemetery, [[Lourmarin]], [[Vaucluse]], [[Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur]], [[France]]. |

|||

===Post–World War II=== |

|||

He was survived by his twin children, Catherine and Jean, who hold the copyrights to his work. |

|||

{{external media| float = right| width = 230px | video1 = [https://www.c-span.org/video/?97122-1/albert-camus-life Presentation by Olivier Todd on ''Albert Camus: A Life'', 15 December 1997], [[C-SPAN]]}} |

|||

After the War, Camus lived in Paris with Faure, who gave birth to twins, Catherine and Jean, in 1945.{{sfn|Willsher|2011}} Camus was now a celebrated writer known for his role in the Resistance. He gave lectures at various universities in the United States and Latin America during two separate trips. He also visited Algeria once more, only to leave disappointed by the continued oppressive colonial policies, which he had warned about many times. During this period he completed the second cycle of his work, with the essay {{lang|fr|L'Homme révolté}} (''[[The Rebel (book)|The Rebel]]''). Camus attacked [[totalitarian]] communism while advocating [[libertarian socialism]] and [[anarcho-syndicalism]].{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=17}} Upsetting many of his colleagues and contemporaries in France with his rejection of [[communism]], the book brought about the final split with Sartre. His relations with the Marxist Left deteriorated further during the [[Algerian War]].{{sfn|Hayden|2016|pp=16–17}} |

|||

After his death, two of Camus's works were published posthumously. The first, entitled ''[[A Happy Death]]'' published in 1970, featured a character named Meursault, as in ''[[The Stranger (novel)|The Stranger]]'', but there is some debate as to the relationship between the two stories. The second posthumous publication was an unfinished novel, ''[[The First Man]]'', that Camus was writing before he died. The novel was an [[autobiographical]] work about his childhood in [[Algeria]] and was published in 1995. |

|||

Camus was a strong supporter of [[European integration]] in various marginal organisations working towards that end.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=18}} In 1944, he founded the {{lang|fr|Comité français pour la féderation européenne}} ('French Committee for the European Federation' [CFFE]), declaring that Europe "can only evolve along the path of economic progress, democracy, and peace if the nation-states become a federation."{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=18}} In 1947–48, he founded the {{lang|fr|Groupes de Liaison Internationale}} (GLI), a trade union movement in the context of revolutionary [[syndicalism]] ({{lang|fr|syndicalisme révolutionnaire}}).{{sfnm|1a1=Todd|1y=2000|1pp=249–250|2a1=Schaffner|2y=2006|2p=107}} His main aim was to express the positive side of [[surrealism]] and existentialism, rejecting the negativity and the [[nihilism]] of André Breton. Camus also raised his voice against the [[Soviet invasion of Hungary]] and the totalitarian tendencies of [[Francisco Franco|Franco]]'s regime in Spain.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=18}} |

|||

==Summary of Absurdism== |

|||

Many writers have written on the Absurd, each with his or her own interpretation of what the Absurd actually is and their own ideas on the importance of the Absurd. For example, [[Sartre]] recognizes the absurdity of individual experience, while [[Kierkegaard]] explains that the absurdity of certain religious truths prevent us from reaching God rationally. Camus was not the originator of Absurdism and regretted the continued reference to him as a ''philosopher of the absurd''. He shows less and less interest in the Absurd shortly after publishing ''Le Mythe de Sisyphe'' (''The Myth of Sisyphus''). To distinguish Camus's ideas of the Absurd from those of other philosophers, people sometimes refer to the '''Paradox of the Absurd''', when referring to ''Camus's Absurd''. |

|||

Camus had numerous affairs, particularly an irregular and eventually public affair with the Spanish-born actress [[María Casares]], with whom he had extensive correspondence.{{sfnm|1a1=Sherman|1y=2009|1pp=14–17|2a1=Zaretsky|2y=2018}} Faure did not take this affair lightly. She had a mental breakdown and needed hospitalisation in the early 1950s. Camus, who felt guilty, withdrew from public life and was slightly depressed for some time.{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=17}} |

|||

His early thoughts on the Absurd appeared in his first collection of essays, ''L'Envers et l'endroit'' (''The Two Sides Of The Coin'') in 1937. Absurd themes appeared with more sophistication in his second collection of essays, ''Noces'' (''Nuptials''), in 1938. In these essays Camus does not offer a philosophical account of the Absurd, or even a definition; rather he reflects on the experience of the Absurd. In 1942 he published the story of a man living an Absurd life as ''L'Étranger'' (''The Stranger''), and in the same year released ''Le Mythe de Sisyphe'' (''The Myth of Sisyphus''), a literary essay on the Absurd. He had also written a play about a Roman Emperor, [[Caligula]], pursuing an Absurd logic. However, the play was not performed until 1945. The turning point in Camus's attitude to the Absurd occurs in a collection of four letters to an anonymous German friend, written between July 1943 and July 1944. The first was published in the ''Revue Libre'' in 1943, the second in the ''Cahiers de Libération'' in 1944, and the third in the newspaper ''Libertés'', in 1945. All four letters have been published as ''Lettres à un ami allemand'' (''[[Letters to a German Friend]]'') in 1945, and have appeared in the collection ''[[Resistance, Rebellion, and Death]]''. |

|||

In 1957, Camus received the news that he was to be awarded the [[Nobel Prize in Literature]]. This came as a shock to him; he anticipated [[André Malraux]] would win the award. At age 44, he was the second-youngest recipient of the prize, after [[Rudyard Kipling]], who was 41. After this he began working on his autobiography {{lang|fr|Le Premier Homme}} (''[[The First Man]]'') in an attempt to examine "moral learning". He also turned to the theatre once more.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=19}} Financed by the money he received with his Nobel Prize, he adapted and directed for the stage Dostoyevsky's novel ''[[Demons (Dostoyevsky novel)|Demons]]''. The play opened in January 1959 at the [[Théâtre Antoine-Simone Berriau|Antoine Theatre]] in Paris and was a critical success.{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=18}} |

|||

==Camus's ideas on the Absurd== |

|||

In his essays Camus presented the reader with dualisms: Happiness and sadness, dark and light, life and death, etc. His aim was to emphasize the fact that happiness is fleeting and that the human condition is one of mortality. He did this not to be morbid, but to reflect a greater appreciation for life and happiness. In ''Le Mythe'', this dualism becomes a paradox: We value our lives and existence so greatly, but at the same time we know we will eventually die, and ultimately our endeavours are meaningless. While we can live with a dualism (''I can accept periods of unhappiness, because I know I will also experience happiness to come''), we cannot live with the paradox (''I think my life is of great importance, but I also think it is meaningless''). In ''Le Mythe'', Camus was interested in how we experience the Absurd and how we live with it. Our life must have meaning for us to value it. If we accept that life has no meaning and therefore no value, should we kill ourselves? |

|||

[[File:Ecrits historiques et politiques, Simone Weil.jpg|thumb|]] |

|||

Meursault, the Absurdist hero of ''L'Étranger,'' is a murderer who is executed for his crime. Caligula ends up admitting his Absurd logic was wrong and is killed by an assassination he has deliberately brought about. However, while Camus possibly suggests that Caligula's Absurd reasoning is wrong, the play's anti-hero does get the last word, as the author similarly exalts Meursault's final moments. |

|||

[[File:Simone_Weil_04_(cropped).png|thumb|left|[[Simone Weil]]]] |

|||

During these years, he published posthumously the works of the philosopher [[Simone Weil]], in the series "Espoir" ('Hope') which he had founded for [[Éditions Gallimard]]. Weil had great influence on his philosophy,<ref name = "Basset"> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|author=Jeanyves GUÉRIN, Guy BASSET |

|||

|title=Dictionnaire Albert Camus |

|||

|year=2013 |

|||

|isbn= 978-2-221-14017-8 |

|||

|publisher = Groupe Robert Laffont}} |

|||

</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bunn |first=Philip D. |date=2022-01-02 |title=Transcendent Rebellion: The Influence of Simone Weil on Albert Camus' Esthetics |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/10457097.2021.1997529 |journal=Perspectives on Political Science |volume=51 |issue=1 |pages=35–43 |doi=10.1080/10457097.2021.1997529 |s2cid=242044336 |issn=1045-7097}}</ref> since he saw her writings as an "antidote" to [[nihilism]].<ref>[https://academic.oup.com/litthe/article-abstract/20/3/286/1021593 Stefan Skrimshire, 2006, A Political Theology of the Absurd? Albert Camus and Simone Weil on Social Transformation, ''Literature and Theology'', Volume 20, Issue 3, September 2006, Pages 286–300]</ref><ref>[https://www.academia.edu/29937662/Albert_Camus_Simone_Weil_and_the_Absurd Rik Van Nieuwenhove, 2005, Albert Camus, Simone Weil and the Absurd, ''Irish Theological Quarterly'', 70, 343]</ref> Camus described her as "the only great spirit of our times".<ref name = "Hellman"> |

|||

{{cite book |

|||

|author=John Hellman |

|||

|title=Simone Weil: An Introduction to Her Thought |

|||

|pages = 1–23 |

|||

|year=1983 |

|||

|isbn=978-0-88920-121-7 |

|||

|publisher = Wilfrid Laurier University Press}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

=== Death === |

|||

Camus's understanding of the Absurd promotes public debate; his various offerings entice us to think about the Absurd and offer our own contribution. Concepts such as cooperation, joint effort and solidarity are of key importance to Camus. |

|||

[[File:20041113-002 Lourmarin Tombstone Albert Camus.jpg|thumb|left|alt=Photograph of Camus's gravestone|Albert Camus's gravestone]] [[File:Camus Monument in Villeblevin France 17-august-2003.4.JPG|thumb|The bronze plaque on the monument to Camus in the town of [[Villeblevin]], France. It reads: "From the General Council of the Yonne Department, in homage to the writer Albert Camus whose remains lay in vigil at the Villeblevin town hall on the night of 4 to 5 January 1960"]] [[File:Camus Monument in Villeblevin France 17-august-2003.1.JPG|thumb|alt=A photograph of the monument to Camus built in Villeblevin.|The monument to Camus built in [[Villeblevin]], where he died in a car crash on 4 January 1960]] |

|||

Camus died on 4 January 1960 at the age of 46, in a car accident near [[Sens]], in Le Grand Fossard in the small town of [[Villeblevin]]. He had spent the New Year's holiday of 1960 at his house in [[Lourmarin]], Vaucluse with his family, and his publisher [[Michel Gallimard]] of [[Éditions Gallimard]], along with Gallimard's wife, Janine, and daughter, Anne. Camus's wife and children went back to Paris by train on 2 January, but Camus decided to return in Gallimard's luxurious [[Facel Vega FV|Facel Vega FV2]]. The car crashed into a [[plane tree]] on a long straight stretch of the Route nationale 5 (now the [[Route nationale 6|RN 6]] or D606). Camus, who was in the passenger seat, died instantly, while Gallimard died five days later. Janine and Anne Gallimard escaped without injuries.{{sfnm|1a1=Sherman|1y=2009|1p=19|2a1=Simpson|2y=2019|2loc=Life}} |

|||

Camus made a significant contribution to our understanding of the Absurd, and always rejected [[nihilism]] as a valid response. <blockquote>"If nothing had any meaning, you would be right. But there is something that still has a meaning." ''Second Letter to a German Friend'', December 1943.</blockquote> |

|||

144 pages of a handwritten manuscript entitled ''Le premier Homme'' ('The First Man') were found in the wreckage. Camus had predicted that this unfinished novel based on his childhood in Algeria would be his finest work.{{sfn|Willsher|2011}} Camus was buried in the Lourmarin Cemetery, Vaucluse, France, where he had lived.{{sfn|Bloom|2009|p=52}} Jean-Paul Sartre read a eulogy, paying tribute to Camus's heroic "stubborn humanism".{{sfn|Simpson|2019|loc= Life}} [[William Faulkner]] wrote his obituary, saying, "When the door shut for him he had already written on this side of it that which every artist who also carries through life with him that one same foreknowledge and hatred of death is hoping to do: I was here."<ref>{{Cite magazine |title=Without God or Reason |date=2021-01-01 |magazine=[[Commonweal (magazine)|Commonweal]] |url=https://www.commonwealmagazine.org/without-god-or-reason |last=Jensen |first=Morten Høi |access-date=2022-04-02}}</ref> |

|||

It then follows that existentialism tends to view human beings as subjects in an indifferent, objective, often ambiguous, and "[[absurdism|absurd]]" universe, in which meaning is not provided by the natural order, but rather can be created, however provisionally and unstably, by human beings' actions and interpretations. |

|||

==Literary career== |

|||

==Opposition to totalitarianism== |

|||

[[File:Lucia 1957.jpg|thumb|right|alt=Camus crowning Stockholm's Lucia after accepting the Nobel Prize in Literature.|Camus crowning Stockholm's [[St Lucy's Day#In the Nordic countries|Lucia]] on 13 December 1957, three days after accepting the [[Nobel Prize in Literature]]]] |

|||

{{citations missing|section|date=September 2007}} |

|||

Throughout his life, Camus spoke out against and actively opposed totalitarianism in its many forms, be it German [[Fascism]] or the total revolutionary philosophy of radical [[Marxism]]. Early on, Camus was active within the [[French Resistance]] to the German occupation of France during World War II, even directing the famous Resistance journal, ''Combat''. On the French collaboration with [[Nazi]] occupiers he wrote: |

|||

:Now the only moral value is courage, which is useful here for judging the puppets and chatterboxes who pretend to speak in the name of the people... |

|||

Camus's first publication was a play called {{lang|fr|[[Révolte dans les Asturies]]}} (''Revolt in the Asturias'') written with three friends in May 1936. The subject was the [[Asturian miners' strike of 1934|1934 revolt by Spanish miners]] that was brutally suppressed by the Spanish government, resulting in 1,500 to 2,000 deaths. In May 1937 he wrote his first book, {{lang|fr|L'Envers et l'Endroit}} (''[[Betwixt and Between]]'', also translated as ''The Wrong Side and the Right Side''). Both were published by [[Edmond Charlot]]'s small publishing house.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=11}} |

|||

Camus's well-known falling out with Sartre is linked to this opposition to [[totalitarianism]]. Camus detected a reflexive [[totalitarianism]] in the mass politics espoused by [[Sartre]] in the name of radical [[Marxism]]. This was apparent in his work ''L'Homme Révolté'' (''The Rebel'') which not only was an assault on the Soviet police state, but also questioned the very nature of mass revolutionary politics. Camus continued to speak out against the atrocities of the [[Soviet Union]], a sentiment captured in his 1957 speech commemorating the anniversary of the [[1956 Hungarian Revolution]], an uprising crushed in a bloody assault by the Red Army: |

|||

Camus separated his work into three cycles. Each cycle consisted of a novel, an essay, and a play. The first was the cycle of the absurd consisting of ''L'Étranger'', ''Le Mythe de Sysiphe'', and ''Caligula''. The second was the cycle of the revolt which included ''La Peste'' (''The Plague''), ''L'Homme révolté'' (''The Rebel''), and ''Les Justes'' (''The Just Assassins''). The third, the cycle of the love, consisted of ''Nemesis''. Each cycle was an examination of a theme with the use of a pagan myth and including biblical motifs.{{sfn|Sharpe|2015|pp=41–44}} |

|||

The books in the first cycle were published between 1942 and 1944, but the theme was conceived earlier, at least as far back as 1936.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=23}} With this cycle, Camus aimed to pose a question on the [[human condition]], discuss the world as an absurd place, and warn humanity of the consequences of totalitarianism.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=41}} |

|||

:"There are already too many dead on the field, and we cannot be generous with any but our own blood. The blood of Hungary has re-emerged too precious to Europe and to freedom for us not to be jealous of it to the last drop. |

|||

Camus began his work on the second cycle while he was in Algeria, in the last months of 1942, just as the Germans were reaching North Africa.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=14}} In the second cycle, Camus used [[Prometheus]], who is depicted as a revolutionary humanist, to highlight the nuances between revolution and rebellion. He analyses various aspects of rebellion, its metaphysics, its connection to politics, and examines it under the lens of modernity, [[historicity]], and the absence of a God.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|pp=45–47}} |

|||

:But I am not one of those who think that there can be a compromise, even one made with resignation, even provisional, with a regime of terror which has as much right to call itself socialist as the executioners of the Inquisition had to call themselves Christians. |

|||

After receiving the Nobel Prize, Camus gathered, clarified, and published his pacifist leaning views at {{lang|fr|Actuelles III: Chronique algérienne 1939–1958}} (''Algerian Chronicles''). He then decided to distance himself from the Algerian War as he found the mental burden too heavy. He turned to theatre and the third cycle which was about love and the goddess [[Nemesis]], the Greek and Roman goddess of Revenge.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=19}} |

|||

:And on this anniversary of liberty, I hope with all my heart that the silent resistance of the people of Hungary will endure, will grow stronger, and, reinforced by all the voices which we can raise on their behalf, will induce unanimous international opinion to boycott their oppressors."'' |

|||

Two of Camus's works were published posthumously. The first entitled ''La mort heureuse'' (''[[A Happy Death]]'') (1971) is a novel that was written between 1936 and 1938. It features a character named Patrice Mersault, comparable to ''The Stranger''{{'}}s Meursault. There is scholarly debate about the relationship between the two books. The second was an unfinished novel, ''Le Premier homme'' (''[[The First Man]]'', published in 1994), which Camus was writing before he died. It was an autobiographical work about his childhood in Algeria and its publication in 1994 sparked a widespread reconsideration of Camus's allegedly unrepentant colonialism.{{sfn|Carroll|2007}} |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+Works of Camus by genre and cycle, <small>according to Matthew Sharpe{{sfn|Sharpe|2015|p=44}}</small> |

|||

|- |

|||

! Years |

|||

! Pagan myth |

|||

! Biblical motif |

|||

! Novel |

|||

! Plays |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1937–42|| Sisyphus|| Alienation, exile|| ''[[The Stranger (Camus novel)|The Stranger]]'' (''L'Étranger'')||''[[Caligula (play)|Caligula]]'',<br/>''[[The Misunderstanding]]'' (''Le Malentendu'') |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1943–52|| Prometheus|| Rebellion || ''[[The Plague (novel)|The Plague]]'' (''La Peste'')|| ''[[The State of Siege]]'' (''L'État de siège'')<br/> ''[[The Just Assassins|The Just]]'' (''Les Justes'') |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1952–58|| || Guilt, the fall; exile & the kingdom; <br/>John the Baptist, Christ || ''[[The Fall (Camus novel)|The Fall]]'' (''La Chute'') || Adaptations of ''The Possessed'' (Dostoevsky); <br/> Faulkner's ''Requiem for a Nun'' |

|||

|- |

|||

| 1958– || Nemesis|| The Kingdom|| ''[[The First Man]]'' (''Le Premier Homme'')|| |

|||

|} |

|||

==Political stance== |

|||

Camus was a [[moralist]]; he claimed morality should guide politics. While he did not deny that morals change over time, he rejected the classical Marxist view that historical material relations define morality.{{sfn|Aronson|2017|loc=Introduction}} |

|||

Camus was also strongly critical of [[Marxism–Leninism]], especially in the case of the Soviet Union, which he considered [[totalitarian]]. Camus rebuked those sympathetic to the Soviet model and their "decision to call total servitude freedom".{{sfn|Foley|2008|pp=75–76}} A proponent of [[libertarian socialism]], he stated that the Soviet Union was not socialist and the United States was not liberal.{{sfn|Sherman|2009|pp=185–87}} His critique of the Soviet Union caused him to clash with others on the political left, most notably with his on-again/off-again friend Jean-Paul Sartre.{{sfn|Aronson|2017|loc=Introduction}} |

|||

Active in the [[French Resistance]] to the Nazi occupation of France during World War II, Camus wrote for and edited the Resistance journal ''[[Combat (newspaper)|Combat]]''. Of the [[French collaboration]] with the German occupiers, he wrote: "Now the only moral value is courage, which is useful here for judging the puppets and chatterboxes who pretend to speak in the name of the people."{{sfn|Bernstein|1997}} After France's liberation, Camus remarked: "This country does not need a [[Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord|Talleyrand]], but a [[Louis Antoine de Saint-Just|Saint-Just]]."{{sfn|Bronner|2009|p=74}} The reality of the [[Épuration légale|postwar tribunals]] soon changed his mind: Camus publicly reversed himself and became a lifelong opponent of capital punishment.{{sfn|Bronner|2009|p=74}} |

|||

Camus had [[anarchist]] sympathies, which intensified in the 1950s, when he came to believe that the Soviet model was morally bankrupt.{{sfnm|1a1=Dunwoodie|1y=1993|1p=86|2a1=Marshall|2y=1993|2p=445}} Camus was firmly against any kind of exploitation, authority, property, the State, and centralization.{{sfn|Dunwoodie|1993|p=87}} However, he opposed revolution, separating the [[Rebellion|rebel]] from the [[revolutionary]] and believing that the belief in "absolute truth", most often assuming the guise of history or reason, inspires the revolutionary and leads to tragic results.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |last=Moses |first=Michael |date=2022 |title=Liberty's Claims on Man and Citizen in the Life and Writings of Albert Camus |url=https://theihs.org/academic-events/faculty-and-graduate-discussion-colloquia/ihs-discussion-colloquia/libertys-claims-on-man-and-citizen-in-the-life-and-writings-of-albert-camus/ |access-date= |website=[[Institute for Humane Studies]] |language=en-US |archive-date=7 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211207222849/https://theihs.org/academic-events/faculty-and-graduate-discussion-colloquia/ihs-discussion-colloquia/libertys-claims-on-man-and-citizen-in-the-life-and-writings-of-albert-camus/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> He believed that rebellion is spurred by our outrage over the world's lack of transcendent significance, while political rebellion is our response to attacks against the dignity and autonomy of the individual.<ref name=":0" /> Camus opposed [[political violence]], tolerating it only in rare and very narrowly defined instances, as well as [[revolutionary terror]] which he accused of sacrificing innocent lives on the altar of history.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Simpson |first=David |title=Albert Camus |url=https://iep.utm.edu/albert-camus/ |access-date= |website=[[Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]] |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

Philosophy professor David Sherman considers Camus an [[anarcho-syndicalist]].{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=185}} [[Graeme Nicholson]] considers Camus an existentialist anarchist.{{sfn|Nicholson|1971|p=14}} |

|||

The anarchist [[André Prudhommeaux]] first introduced him at a meeting of the {{lang|fr|Cercle des Étudiants Anarchistes}} ('Anarchist Student Circle') in 1948 as a sympathiser familiar with anarchist thought. Camus wrote for anarchist publications such as {{lang|fr|[[Le Libertaire]]}} ('The Libertarian'), {{lang|la|[[La Révolution prolétarienne]]}} ('The Proletarian Revolution'), and {{lang|es|[[Solidaridad Obrera (periodical)|Solidaridad Obrera]]}} ('Workers' Solidarity'), the organ of the anarcho-syndicalist [[Confederación Nacional del Trabajo]] (CNT, 'National Confederation of Labor').{{sfnm|1a1=Dunwoodie|1y=1993|1pp=87-87|1ps=: See also appendix p 97|2a1=Hayden|2y=2016|2p=18}} |

|||

Camus kept a neutral stance during the [[Algerian Revolution]] (1954–1962). While he was against the violence of the [[National Liberation Front (Algeria)|National Liberation Front]] (FLN), he acknowledged the injustice and brutalities imposed by colonialist France. He was supportive of [[Pierre Mendès France]]'s [[Unified Socialist Party (France)|Unified Socialist Party]] (PSU) and its approach to the crisis; Mendès France advocated for reconciliation. Camus also supported a like-minded Algerian militant, [[Aziz Kessous]]. Camus traveled to Algeria to negotiate a truce between the two belligerents but was met with distrust by all parties.{{sfnm|1a1=Sherman|1y=2009|1pp=17–18 & 188|2a1=Cohn|2y=1986|2pp=30 & 38}} In one, often misquoted incident, Camus confronted an Algerian critic during his 1957 Nobel Prize acceptance speech in Stockholm, rejecting the false equivalence of justice with revolutionary terrorism: "People are now planting bombs in the tramways of Algiers. My mother might be on one of those tramways. If that is justice, then I prefer my mother."<ref>{{Cite web |last1=Scialabba |first1=George |title=Resistance, Rebellion, and Writing |work=[[Bookforum]] |date=April 2013 |url=https://www.bookforum.com/print/2001/albert-camus-s-dispatches-on-the-algerian-crisis-appear-in-english-for-the-first-time-11228 |language=en-US |access-date=2021-08-08 }}</ref>{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=191}} Critics have labelled the response as reactionary and a result of a colonialist attitude.{{sfnm|1a1=Sherman|1y=2009|1p=19|2a1=Simpson|2y=2019|3a1=Marshall|3y=1993|3p=584}} |

|||

Camus was sharply critical of the [[proliferation of nuclear weapons]] and the [[bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki]].{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=87}} In the 1950s, Camus devoted his efforts to human rights. In 1952, he resigned from his work for [[UNESCO]] when the UN accepted Spain, under the leadership of the [[caudillo]] General [[Francisco Franco]], as a member.{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=17}} Camus maintained his pacifism and resisted capital punishment anywhere in the world. He wrote an essay against capital punishment in collaboration with [[Arthur Koestler]], the writer, intellectual, and founder of the League Against Capital Punishment entitled {{lang|fr|[[Réflexions sur la peine capitale]]}} ('Reflections on Capital Punishment'), published by [[Calmann-Levy]] in 1957.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=73 & 85}} |

|||

Along with [[Albert Einstein]], Camus was one of the sponsors of the [[Peoples' World Convention]] (PWC), also known as Peoples' World Constituent Assembly (PWCA), which took place between 1950 and 1951 at Palais Electoral in [[Geneva]], Switzerland.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Einstein |first1=Albert |url=http://archive.org/details/einsteinonpeace00eins |title=Einstein on peace |last2=Nathan |first2=Otto |last3=Norden |first3=Heinz |date=1968 |publisher=New York, Schocken Books |others=Internet Archive |pages=539, 670, 676}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=[Carta] 1950 oct. 12, Genève, [Suiza] [a] Gabriela Mistral, Santiago, Chile [manuscrito] Gerry Kraus. |url=http://www.bibliotecanacionaldigital.gob.cl/bnd/623/w3-article-137193.html |access-date=2023-10-19 |website=BND: Archivo del Escritor}}</ref> |

|||

==Role in Algeria== |

|||

[[File:Départements français d'Algérie 1934-1955 map-fr.svg|thumb|alt=Map of French Algeria showing its administrative organization between 1905 and 1955 |Administrative organization of [[French Algeria]] between 1905 and 1955]] |

|||

Born in Algeria to French parents, Camus was familiar with the [[institutional racism]] of France against Arabs and Berbers, but he was not part of a rich elite. He lived in very poor conditions as a child, but was a citizen of France and as such was entitled to citizens' rights; members of the country's Arab and Berber majority were not.{{sfn|Carroll|2007|pp=3–4}} |

|||

Camus was a vocal advocate of the "new Mediterranean Culture". This was his vision of embracing the multi-ethnicity of the Algerian people, in opposition to "Latiny", a popular pro-fascist and [[Antisemitism|antisemitic]] ideology among other ''[[pieds-noirs]]'' – French or Europeans born in Algeria. For Camus, this vision encapsulated the Hellenic humanism which survived among ordinary people around the Mediterranean Sea.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=141–143}} His 1938 address on "The New Mediterranean Culture" represents Camus's most systematic statement of his views at this time. Camus also supported the [[Blum–Viollette proposal]] to grant Algerians full [[French nationality law|French citizenship]] in a manifesto with arguments defending this assimilative proposal on radical egalitarian grounds.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=145}} In 1939, Camus wrote a stinging series of articles for the {{lang|fr|Alger républicain}} on the atrocious living conditions of the inhabitants of the [[Kabylie]] highlands. He advocated for economic, educational, and political reforms as a matter of emergency.{{sfn|Sharpe|2015|p=356}} |

|||

In 1945, following the [[Sétif and Guelma massacre]] after Arabs revolted against French mistreatment, Camus was one of only a few mainland journalists to visit the colony. He wrote a series of articles reporting on conditions and advocating for French reforms and concessions to the demands of the Algerian people.{{sfn|Foley|2008|pp=150–151}} |

|||

When the Algerian War began in 1954, Camus was confronted with a moral dilemma. He identified with the ''pieds-noirs'' such as his own parents and defended the French government's actions against the revolt. He argued the Algerian uprising was an integral part of the "new [[Arab imperialism]]" led by Egypt and an "anti-Western" offensive orchestrated by Russia to "encircle Europe" and "isolate the United States".{{sfn|Sharpe|2015|p=322}} Although favoring greater Algerian [[self-governance|autonomy]] or even federation, though not full-scale independence, he believed the ''pieds-noirs'' and Arabs could co-exist. During the war, he advocated a civil truce that would spare the civilians. It was rejected by both sides who regarded it as foolish. Behind the scenes, he began working for imprisoned Algerians who faced the death penalty.{{sfn|Foley|2008|p=161}} His position drew much criticism from the left and later postcolonial literary critics, such as [[Edward Said]], who were opposed to European imperialism, and charged that Camus's novels and short stories are plagued with colonial depictions – or conscious erasures – of Algeria's Arab population.{{sfn|Amin|2021|pp=31–32}} In their eyes, Camus was no longer the defender of the oppressed.{{sfn|Carroll|2007|pp=7–8}} |

|||

Camus once said that the troubles in Algeria "affected him as others feel pain in their lungs".{{sfn|Sharpe|2015|p=9}} |

|||

==Philosophy== |

|||

===Existentialism=== |

|||

Even though Camus is mostly connected to [[absurdism]],{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=3}} he is routinely categorized as an [[Existentialism|existentialist]], a term he rejected on several occasions.{{sfnm|1a1=Sharpe|1y=2015|1p=3|2a1=Sherman|2y=2009|2p=3}} |

|||

Camus himself said his philosophical origins lay in ancient Greek philosophy, Nietzsche, and 17th-century moralists, whereas existentialism arose from 19th- and early 20th-century philosophy such as [[Søren Kierkegaard]], [[Karl Jaspers]], and [[Martin Heidegger]].{{sfnm|1a1=Foley|1y=2008|1pp=1–2|2a1=Sharpe|2y=2015|2p=29}} He also said his work, ''The Myth of Sisyphus'', was a criticism of various aspects of existentialism.{{sfn|Foley|2008|pp=2}} Camus rejected existentialism as a philosophy, but his critique was mostly focused on [[Sartre]]an existentialism and – though to a lesser extent – on religious existentialism. He thought that the importance of history held by Marx and Sartre was incompatible with his belief in human freedom.{{sfnm|1a1=Foley|1y=2008|1p=3|2a1=Sherman|2y=2009|2p=3}} David Sherman and others also suggest the rivalry between Sartre and Camus also played a part in his rejection of existentialism.{{sfnm|1a1=Sherman|1y=2009|1p=4|2a1=Simpson|2y=2019|2loc= Existentialism}} David Simpson argues further that his humanism and belief in human nature set him apart from the existentialist doctrine that [[existence precedes essence]].{{sfn|Simpson|2019|loc= Existentialism}} |

|||

On the other hand, Camus focused most of his philosophy around existential questions. The absurdity of life and that it inevitably ends in death is highlighted in his acts. His belief was that the absurd – life being void of meaning, or man's inability to know that meaning if it were to exist – was something that man should embrace. His opposition to Christianity and his commitment to individual moral freedom and responsibility are only a few of the similarities with other existential writers.{{sfnm|1a1=Sharpe|1y=2015|1pp=5–6|2a1=Simpson|2y=2019|2loc= Existentialism}} Camus addressed one of the fundamental questions of existentialism: the problem of suicide. He wrote: "There is only one really serious philosophical question, and that is suicide."<ref>"You cannot give coherence to murder if you refuse it to suicide. A spirit penetrated by the idea of the absurd undoubtedly admits the murder of fatality, but would not be able to accept the murder of reasoning. In comparison, murder and suicide are one and the same thing, which must be taken or left together." {{Cite book |title=L'Homme revolté |trans-title=The Rebel |publisher=Gallimard |location=Paris |date=1951 |page=17 |language=fr}}</ref> |

|||

Camus viewed the question of suicide as arising naturally as a solution to the absurdity of life.{{sfn|Aronson|2017|loc=Introduction}} |

|||

===Absurdism=== |

|||

Many existentialist writers have addressed the Absurd, each with their own interpretation of what it is and what makes it important. Kierkegaard suggests that the absurdity of religious truths prevents people from reaching God rationally.{{sfn|Foley|2008|pp=5–6}} Sartre recognizes the absurdity of individual experience. Camus's thoughts on the Absurd begin with his first cycle of books and the literary essay ''The Myth of Sisyphus'', his major work on the subject. In 1942, he published the story of a man living an absurd life in ''[[The Stranger (Camus novel)|The Stranger]]''. He also wrote [[Caligula (play)|a play]] about the Roman emperor [[Caligula]], pursuing an absurd logic, which was not performed until 1945. His early thoughts appeared in his first collection of essays, ''Betwixt and Between'', in 1937. Absurd themes were expressed with more sophistication in his second collection of essays, {{lang|fr|Noces}} (''[[Nuptials (Camus)|Nuptials]]'') in 1938. In these essays, Camus reflects on the experience of the Absurd.{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=23}} Aspects of the notion of the Absurd can also be found in ''The Plague''.{{sfn|Sherman|2009|p=8}} |

|||

[[File:Tipaza stèle Albert Camus.jpg|thumb|A stele made in [[Tipaza]] in 1961 by the French painter Louis Bénist, on which is engraved an extract from [[Nuptials (essays)]]: “Here, I understand the concept of glory: the freedom to love boundlessly.”.]] |

|||

Camus follows Sartre's definition of the Absurd: "That which is meaningless. Thus man's existence is absurd because his contingency finds no external justification".{{sfn|Foley|2008|pp=5–6}} The Absurd is created because man, who is placed in an unintelligent universe, realises that human values are not founded on a solid external component; as Camus himself explains, the Absurd is the result of the "confrontation between human need and the unreasonable silence of the world".{{sfn|Foley|2008|p=6}} Even though absurdity is inescapable, Camus does not drift towards [[nihilism]]. But the realization of absurdity leads to the question: Why should someone continue to live? Suicide is an option that Camus firmly dismisses as the renunciation of human values and freedom. Rather, he proposes we accept that absurdity is a part of our lives and live with it.{{sfn|Foley|2008|p=7-10}} |

|||

The turning point in Camus's attitude to the Absurd occurs in a collection of four letters to an anonymous German friend, written between July 1943 and July 1944. The first was published in the {{lang|fr|Revue Libre}} in 1943, the second in the {{lang|fr|Cahiers de Libération}} in 1944, and the third in the newspaper {{lang|fr|Libertés}}, in 1945. The four letters were published as {{lang|fr|Lettres à un ami allemand}} ('Letters to a German Friend') in 1945, and were included in the collection ''Resistance, Rebellion, and Death''. |

|||

Camus regretted the continued reference to himself as a "philosopher of the absurd". He showed less interest in the Absurd shortly after publishing ''The Myth of Sisyphus''. To distinguish his ideas, scholars sometimes refer to the Paradox of the Absurd, when referring to "Camus's Absurd".{{sfn|Curtis|1972|p=335-348}} |

|||

===Revolt=== |

|||

Camus articulated the case for revolting against any kind of oppression, injustice, or whatever disrespects the human condition. He is cautious enough, however, to set the limits on the rebellion.{{sfnm|1a1=Sharpe|1y=2015|1p=18|2a1=Simpson|2y=2019|2loc=Revolt}} ''[[The Rebel (book)|The Rebel]]'' explains in detail his thoughts on the issue. There, he builds upon the absurd, described in ''The Myth of Sisyphus'', but goes further. In the introduction, where he examines the metaphysics of rebellion, he concludes with the phrase "I revolt, therefore we exist" implying the recognition of a common human condition.{{sfn|Foley|2008|pp=55–56}} Camus also delineates the difference between revolution and rebellion and notices that history has shown that the rebel's revolution might easily end up as an oppressive regime; he therefore places importance on the morals accompanying the revolution.{{sfn|Foley|2008|pp=56–58}} Camus poses a crucial question: Is it possible for humans to act in an ethical and meaningful manner in a silent universe? According to him, the answer is yes, as the experience and awareness of the Absurd creates the moral values and also sets the limits of our actions.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|pp=43–44}} Camus separates the modern form of rebellion into two modes. First, there is the metaphysical rebellion, which is "the movement by which man protests against his condition and against the whole of creation". The other mode, historical rebellion, is the attempt to materialize the abstract spirit of metaphysical rebellion and change the world. In this attempt, the rebel must balance between the evil of the world and the intrinsic evil which every revolt carries, and not cause any unjustifiable suffering.{{sfn|Hayden|2016|pp=50–55}} |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||

[[File:Rúa_Albert_Camus.001_-_La_Coruña.jpg|thumb|Albert Camus street in [[La Coruña]], [[Galicia (Spain)|Galicia]], ([[Spain]]).]] |

|||

Camus's novels and philosophical essays are still influential. After his death, interest in Camus followed the rise – and diminution – of the [[New Left]]. Following the [[collapse of the Soviet Union]], interest in his alternative road to communism resurfaced.{{sfn|Sherman|2009|pp=207–208}} He is remembered for his skeptical humanism and his support for political tolerance, dialogue, and civil rights.{{sfn|Sharpe|2015|pp= 241–242}} |

|||

Although Camus has been linked to anti-Soviet communism, reaching as far as anarcho-syndicalism, some [[neoliberals]] have tried to associate him with their policies; for instance, the French President [[Nicolas Sarkozy]] suggested that his remains be moved to the [[Panthéon]], an idea that was criticised by Camus's surviving family and angered many on the Left.{{sfnm|1a1=Zaretsky|1y=2013|1pp=3–4|2a1=Sherman|2y=2009|2p=208}} |

|||

American heavy metal band [[Avenged Sevenfold]] stated that their album ''[[Life Is But a Dream...]]'' was inspired by the work of Camus.<ref>{{cite web |title=AVENGED SEVENFOLD Announces 'Life Is But a Dream...' Album, Shares 'Nobody' Music Video |url=https://blabbermouth.net/news/avenged-sevenfold-announces-life-is-but-a-dream-album-shares-nobody-music-video |website=Blabbermouth|date=14 March 2023 }}</ref> |

|||

Albert Camus also served as the inspiration for the Aquarius Gold Saint Camus in the classic anime and manga [[Saint Seiya]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Aquarius Camus: 5 Facts+ All you Need to Know |url=https://cavzod.net/aquarius-camus-facts/ |access-date=2023-10-19 |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

==Tributes== |

|||

In [[Tipasa]], Algeria, inside the Roman ruins, facing the sea and Mount Chenoua, a [[stele]] was erected in 1961 in honor of Albert Camus with this phrase in French extracted from his work {{lang|fr|Noces à Tipasa}}: "I understand here what is called glory: the right to love beyond measure" ({{langx|fr|Je comprends ici ce qu'on appelle gloire : le droit d'aimer sans mesure}}).<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://tipaza.typepad.fr/mon_weblog/2012/10/au-sujet-de-la-st%C3%A8le-de-camus-dans-les-ruines-de-tipaza.html|title = Au sujet de la stèle de Camus dans les ruines de Tipaza}}</ref> |

|||

The French Post published a stamp with his likeness on 26 June 1967.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.laposte.fr/toutsurletimbre/connaissance-du-timbre/dicotimbre/timbres/albert-camus-1514|title = La Poste}}</ref> |

|||

==Works== |

|||

The works of Albert Camus include:{{sfn|Hughes|2007|p=xvii}} |

|||

==Selected bibliography== |

|||

[[Image:Camus1957.jpg|thumb|200px|Camus in 1957]] |

|||

===Novels=== |

===Novels=== |

||

* ''[[A Happy Death]]'' (''La Mort heureuse''; written 1936–38, published 1971) |

|||

*''[[The Stranger (novel)|The Stranger]]'' (''L'Étranger'', sometimes translated as ''The Outsider'') (1942) |

|||

* ''[[The Stranger (Camus novel)|The Stranger]]'' (''L'Étranger'', often translated as ''The Outsider'', though an alternate meaning of {{lang|fr|l'étranger}} is 'foreigner'; 1942) |

|||

*''[[The Plague]]'' (''La Peste'') (1947) |

|||

*''[[The |

* ''[[The Plague (novel)|The Plague]]'' (''La Peste'', 1947) |

||

*''[[ |

* ''[[The Fall (Camus novel)|The Fall]]'' (''La Chute'', 1956) |

||

*''[[The First Man]]'' (''Le premier homme'' |

* ''[[The First Man]]'' (''Le premier homme''; incomplete, published 1994) |

||

===Short stories=== |

===Short stories=== |

||

*''[[Exile and the Kingdom]]'' (''L'exil et le royaume'' |

* ''[[Exile and the Kingdom]]'' (''L'exil et le royaume''; collection, 1957), containing the following short stories: |

||

** "[[The Adulterous Woman]]" (''La Femme adultère'') |

|||

** "[[The Renegade (short story)|The Renegade or a Confused Spirit]]" (''Le Renégat ou un esprit confus'') |

|||

** "[[The Silent Men]]" (''Les Muets'') |

|||

** "[[The Guest (short story)|The Guest]]" (''L'Hôte'') |

|||

** "[[the Artist at Work|Jonas, or the Artist at Work]]" (''Jonas, ou l'artiste au travail'') |

|||

** "[[The Growing Stone]]" (''La Pierre qui pousse'') |

|||

===Academic theses=== |

|||

* ''[[Christian Metaphysics and Neoplatonism]]'' (''Métaphysique chrétienne et néoplatonisme''; 1935): the [[:fr:Diplôme d'études supérieures en France|thesis]] that enabled Camus to teach in secondary schools in France |

|||

===Non-fiction=== |

===Non-fiction=== |

||

*''[[Betwixt and Between]]'' (''L'envers et l'endroit'', also translated as ''The Wrong Side and the Right Side'' |

* ''[[Betwixt and Between]]'' (''L'envers et l'endroit'', also translated as ''The Wrong Side and the Right Side''; collection, 1937) |

||

*''[[ |

* ''[[Nuptials (Camus)|Nuptials]]'' (''Noces'', 1938) |

||

*''[[ |

* ''[[The Myth of Sisyphus]]'' (''Le Mythe de Sisyphe'', 1942) |

||

*''[[The Rebel]]'' (''L'Homme révolté'' |

* ''[[The Rebel (book)|The Rebel]]'' (''L'Homme révolté'', 1951) |

||

* ''[[Algerian Chronicles]]'' (''Chroniques algériennes''; 1958, first English translation published 2013) |

|||

*''[[Reflections on the guillotine|Reflections on the Guillotine]]'' (''Réflexions sur la guillotine'') (Extended essay, 1957) |

|||

* ''[[Resistance, Rebellion, and Death]]'' (collection, 1961) |

|||

*''[[Notebooks 1935-1942]]'' (''Carnets, mai 1935 — fevrier 1942'') (1962) |

|||

*''[[Notebooks |

* ''[[Notebooks 1935–1942]]'' (''Carnets, mai 1935 — fevrier 1942'', 1962) |

||

*''[[ |

* ''[[Notebooks 1942–1951]]'' (''Carnets II: janvier 1942-mars 1951'', 1965) |

||

* ''Lyrical and Critical Essays'' (collection, 1968) |

|||

* ''[[American Journals]]'' (''Journaux de voyage'', 1978) |

|||

* ''[[Notebooks 1951–1959]]'' (2008). Published as ''Carnets Tome III: Mars 1951 – December 1959'' (1989) |

|||

* ''Correspondence (1944–1959)'' The correspondence of Albert Camus and [[María Casares]], with a preface by his daughter, Catherine (2017) |

|||

===Plays=== |

===Plays=== |

||

*''[[Caligula (play)|Caligula]]'' ( |

* ''[[Caligula (play)|Caligula]]'' (written 1938, performed 1945) |

||

* ''[[The Misunderstanding]]'' (''Le Malentendu'', 1944) |

|||

*''Requiem for a Nun'' (''Requiem pour une nonne'', adapted from [[William Faulkner]]'s novel by the same name) (1956) |

|||

*''[[The |

* ''[[The State of Siege]]'' (''L'État de Siège'', 1948) |

||

* ''[[The Just Assassins]]'' (''Les Justes'', 1949) |

|||

*''[[The State of Siege]]'' ''[[L' Etat de Siege]]'' (1944)[[Foreword by Albert Camus]][[Translation in Greek by Ch. Papachristopoulos]] |

|||

* ''[[Requiem for a Nun (play)|Requiem for a Nun]]'' (''Requiem pour une nonne'', adapted from [[William Faulkner]]'s [[Requiem for a Nun|novel by the same name]]; 1956) |

|||

*''[[The Just Assassins]]'' (''Les Justes'') (1949) |

|||

*''[[The Possessed (play)|The Possessed]]'' (''Les Possédés'', adapted from [[Fyodor |

* ''[[The Possessed (play)|The Possessed]]'' (''Les Possédés'', adapted from [[Fyodor Dostoyevsky]]'s novel ''[[Demons (Dostoevsky novel)|Demons]]''; 1959) |

||

=== |

===Essays=== |

||

* ''[[The Crisis of Man]]'' (''Lecture at Columbia University'', 28 March 1946) |

|||

*''[[Resistance, Rebellion, and Death]]'' (1961) - a collection of essays selected by the author. |

|||

* ''[[Neither Victims nor Executioners]]'' (series of essays in ''Combat'', 1946) |

|||

*''Lyrical and Critical Essays'' (1970) |

|||

* ''Why Spain?'' (essay for the theatrical play ''L'Etat de Siège'', 1948) |

|||

*''Youthful Writings'' (1976) |

|||

* ''Summer'' (''L'Été'', 1954){{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=18}} |

|||

*''Between Hell and Reason: Essays from the Resistance Newspaper "Combat", 1944-1947'' (1991) |

|||

* ''[[Reflections on the Guillotine]]'' (''Réflexions sur la guillotine''; extended essay, 1957){{sfn|Hayden|2016|p=86}} |

|||

*''Camus at "Combat": Writing 1944-1947'' (2005) |

|||

* ''Create Dangerously'' (''Essay on Realism and Artistic Creation''; lecture at the University of Uppsala in Sweden, 1957){{sfn|Sharpe|2015|p=20}} |

|||

== |

== References == |

||

=== |

===Footnotes=== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

Several of Camus's works have been adapted into movies. ''The Stranger'' has been adapted into an Italian [[The Stranger (1967 movie)|1967 movie]] by [[Luchino Visconti]], and also to a 2001 Turkish adaptation titled ''Yazgi'' (''Fate'') by [[Zeki Demirkubuz]]. ''The Plague'' was adapted to a 1992 film titled ''La Peste'' by [[Luis Puenzo]] and set in modern day America. |

|||

=== |

===Sources=== |

||

*{{cite journal |last=Amin|first=Nasser|date=2021|title=The Colonial Politics of the Plague: Reading Camus in 2020|url= https://lcc.ac.uk/?r3d=lcc-journal-volume-9-number-1-spring-2021#28 |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://londonchurchillcollege.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/LCC-Journal-Volume-9-Number-1-Spring-2021.pdf#page=28 |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live |journal= Journal of Contemporary Development & Management Studies|volume=9 Spring 2021|pages=28–38}} |

|||

* {{cite book|last=Aronson|first=Ronald|title=Camus and Sartre: The Story of a Friendship and the Quarrel that Ended it|year=2004|publisher=[[University of Chicago Press]]|isbn=978-0-22602-796-8}} |

|||

Quite a few musical artists refer to Camus and his work in their music. The [[post-punk]] band [[The Fall (band)|The Fall]] took their name from Camus's novel ''[[The Fall (novel)|The Fall]]''. These also include an album by |

|||

* {{cite encyclopedia|last=Aronson|first=Ronald|title=Albert Camus|encyclopedia= [[The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]]|editor= Edward N. Zalta|editor-link= Edward N. Zalta|url=https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/camus/|year= 2017}} |

|||