Matthew C. Perry: Difference between revisions

+botany abbreviation |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|United States Navy officer (1794–1858)}} |

|||

{{Otherpeople2|Matthew Perry}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2024}} |

|||

{{unreferenced|date=April 2007}}[[Image:Perry1852LibraryOfCongress.jpg |thumb|right|Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858), photographed in 1852.]] |

|||

{{Infobox officeholder |

|||

'''Matthew Calbraith Perry''' ([[April 10]], [[1794]] – [[March 4]], [[1858]]) was the [[Commodore (USN)|Commodore]] of the [[United States Navy|U.S. Navy]] who compelled the opening of [[Japan]] to the West with the [[Convention of Kanagawa]] in [[1854]]. |

|||

| name = Matthew C. Perry |

|||

| image = Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry.png |

|||

| caption = Perry {{circa}} 1856–1858 |

|||

| office = Commander of the [[East India Squadron]] |

|||

| term_start = November 20, 1852 |

|||

| term_end = September 6, 1854 |

|||

| predecessor = [[John H. Aulick]] |

|||

| successor = [[Joel Abbot (naval officer)|Joel Abbot]] |

|||

| birth_name = Matthew Calbraith Perry |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1794|04|10}}<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Smolski |first1=Chester |title=Newport: Commodore Matthew Perry Public Sculpture |url=https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/smolski_images/162/ |journal=[[Rhode Island College]] |date=December 1971 |publisher=Rhode Island College |access-date=December 19, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

| birth_place = [[Newport, Rhode Island]], U.S. |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|1858|03|04|1794|04|10}} |

|||

| death_place = [[New York City]], [[New York (state)|New York]], U.S. |

|||

| allegiance = [[United States]] |

|||

| branch = [[United States Navy]] |

|||

| serviceyears = 1809–1858 |

|||

| rank = [[Commodore (United States)|Commodore]] |

|||

| commands = {{ubl|{{USS|Shark|1821|6}}|[[Africa Squadron]]|{{USS|Fulton|1837|6}}|[[New York Navy Yard]]|{{USS|Mississippi|1841|6}}|[[Mosquito Fleet]]|{{USS|President|1800|6}}}} |

|||

| battles = {{tree list}} |

|||

* [[Little Belt affair]] |

|||

* [[War of 1812]] |

|||

**{{USS|President|1800|6}} vs {{HMS|Belvidera|1809|6}} |

|||

* [[Second Barbary War]] |

|||

* [[African Slave Trade Patrol|Suppression of the Slave Trade]] |

|||

** [[Ivory Coast Expedition|Battle of Little Bereby]] |

|||

* [[Bakumatsu|Opening of Japan]] |

|||

* [[Mexican–American War]] |

|||

** Battle of Frontiera |

|||

** [[First Battle of Tabasco]] |

|||

** [[Tampico Expedition]] |

|||

** [[Siege of Veracruz]] |

|||

** [[First Battle of Tuxpan]] |

|||

** [[Second Battle of Tuxpan]] |

|||

** [[Third Battle of Tuxpan]] |

|||

** [[Second Battle of Tabasco]] |

|||

{{tree list/end}} |

|||

| father = [[Christopher Raymond Perry|Christopher Perry]] |

|||

| mother = Sarah Wallace Alexander |

|||

| spouse = {{Marriage|[[Alexander Slidell Mackenzie#Early life|Jane Slidell Perry]]|December 24, 1814}} |

|||

| children = 10 |

|||

| signature = Signature of Matthew Calbraith Perry.png |

|||

}} |

|||

{{infobox scientist |

|||

|author_abbrev_bot = '''Perry''' |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Matthew Calbraith Perry''' (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a [[United States Navy]] officer who commanded ships in several wars, including the [[War of 1812]] and the [[Mexican–American War]]. He played a leading role in the [[Perry Expedition]] that [[Bakumatsu|ended Japan's isolationism]] and the [[Convention of Kanagawa]] between Japan and the United States in 1854. |

|||

==Early life and naval career== |

|||

Born in Rocky Brook, now South Kingstown, [[Rhode Island]], he was the son of Captain [[Christopher Raymond Perry|Christopher R. Perry]] and the younger brother of [[Oliver Hazard Perry]]. Matthew Perry got a midshipman's commission in the Navy in [[1809]], and was initially assigned to [[USS Revenge (1806)|''Revenge'']], under the command of his elder brother. |

|||

Perry was interested in the education of naval officers and assisted in the development of an apprentice system that helped establish the curriculum at the [[United States Naval Academy]]. With the advent of the [[steam engine]], he became a leading advocate of modernizing the U.S. Navy and came to be considered "The Father of the Steam Navy" in the United States. |

|||

Commodore Perry's early career saw him assigned to several ships, including the [[USS President (1800)|''President'']], where he was aide to Commodore [[John Rodgers (naval officer, War of 1812)|John Rodgers]], which was in a victorious engagement over a [[United Kingdom|British]] vessel, [[HMS Little Belt|HMS ''Little Belt'']], shortly before the [[War of 1812]] was officially declared. During that war Perry was transferred to [[USS United States (1797)|USS ''United States'']], and as a result saw little fighting in that war afterward, since the ship was trapped at [[New London, Connecticut]]. After that war he served on various vessels in the [[Mediterranean]] and Africa (notably aboard [[USS Cyane (1796)|USS ''Cyane'']] during its patrol off [[Liberia]] in [[1819]]-[[1820]]), sent to suppress [[piracy]] and the [[slave trade]] in the [[West Indies]]. Later during this period, while in port in [[Russia]], Perry was offered a commission in the [[Russian navy]], which he declined. |

|||

==Lineage== |

|||

Matthew Perry was a member of the [[Perry family]], a son of Sarah Wallace ([[née]] Alexander) (1768–1830) and Navy Captain [[Christopher Raymond Perry]] (1761–1818). He was born April 10, 1794, in [[South Kingstown, Rhode Island]]. His siblings included [[Oliver Hazard Perry]], Raymond Henry Jones Perry, Sarah Wallace Perry, Anna Marie Perry (mother of [[George Washington Rodgers]]), James Alexander Perry, Nathaniel Hazard Perry, and Jane Tweedy Perry (who married [[William Butler (1790–1850)|William Butler]]). |

|||

His mother was born in [[County Down]], Ireland and was a descendant of an uncle of [[William Wallace]],<ref name=copes>{{cite journal |last=Copes |first=Jan M. |title=The Perry Family: A Newport Naval Dynasty of the Early Republic|journal=Newport History: Bulletin of the Newport Historical Society |volume=66, Part 2 |issue=227 |pages=49–77|publisher=Newport Historical Society |location=[[Newport, Rhode Island|Newport, RI]] |date=Fall 1994}}</ref>{{rp|54}} the Scottish knight and landowner.<ref>Skaggs, David Curtis. "Oliver Hazard Perry: Honor, Courage, and Patriotism in the Early U.S. Navy". US Naval Institute Press, 2006. P. 4</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/wallace_william.shtml|title=BBC – History – William Wallace|access-date=May 14, 2016}}</ref> His paternal grandparents were James Freeman Perry, a surgeon, and Mercy Hazard,<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.clayfox.com/family/individual.php?pid=I737&ged=bradleys.ged|title=PhpGedView User Login – PhpGedView|last=Phillipson|first=Mark|website=www.clayfox.com|access-date=May 14, 2016}}</ref> a descendant of Governor [[Thomas Prence]], a co-founder of [[Eastham, Massachusetts]], who was a political leader in both the [[Plymouth Colony|Plymouth]] and [[Massachusetts Bay Colony|Massachusetts Bay colonies]], and governor of [[Plymouth, Massachusetts|Plymouth]]; and a descendant of ''[[Mayflower]]'' passengers, both of whom were signers of the [[Mayflower Compact]], Elder [[William Brewster (Mayflower passenger)|William Brewster]], the [[Pilgrims (Plymouth Colony)|Pilgrim]] colonist leader and spiritual elder of the Plymouth Colony, and [[George Soule (Mayflower passenger)|George Soule]], through Susannah Barber Perry.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/genealogiesraym00raymgoog|title=Genealogies of the Raymond Families of New England, 1630–1 to 1886: With a Historical Sketch of Some of the Raymonds of Early Times, Their Origin, Etc |date=January 1, 1886|publisher=Press of J.J. Little & Company}}</ref> |

|||

==Naval career== |

|||

In 1809, Perry received a [[Midshipman|midshipman's]] warrant in the Navy and was initially assigned to {{USS|Revenge|1806|6}}, under the command of his elder brother. He was then assigned to {{USS|President|1800|6}}, where he served as an aide to Commodore [[John Rodgers (1772–1838)|John Rodgers]]. ''President'' attacked a British [[Royal Navy]] warship, {{HMS|Little Belt|1807|6}} in the lead-up to the [[War of 1812]]. Perry continued aboard ''President'' during the War of 1812 and was present at the engagement with {{HMS|Belvidera|1809|6}}.<ref>[[#Griffis|Griffis, 1887]] p.40</ref> |

|||

Rodgers fired the first shot of the war at ''Belvidera''. A later shot resulted in a cannon bursting, killing several men and wounding Rodgers, Perry and others.<ref>[[#Griffis|Griffis, 1887]] p.40</ref> Perry transferred to {{USS|United States|1797|6}}, commanded by [[Stephen Decatur]], and saw little fighting in the war afterwards, since the ship was trapped in port at [[New London, Connecticut]]. |

|||

Following the signing of the [[Treaty of Ghent]] which ended the war, Perry served on various vessels in the [[Mediterranean Sea]]. Perry served under Commodore [[William Bainbridge]] during the [[Second Barbary War]]. He then served in African waters aboard [[HMS Cyane (1806)|USS ''Cyane'']] during its patrol off [[Liberia]] from 1819 to 1820. After that cruise, Perry was sent to suppress [[piracy]] and the [[History of slavery|slave trade]] in the [[West Indies]]. |

|||

==Command assignments, 1820s-1840s== |

|||

===Opening of Key West=== |

===Opening of Key West=== |

||

From 1821 to 1825, Perry placed in commission and commanded {{USS|Shark|1821|6}}, a [[schooner]] with 12 guns. He deployed to the West Africa Station to support the American and British joint patrols to [[Blockade of Africa|suppress the slave trade]].<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/nmusn/explore/photography/ships-us/ships-usn-s/uss-shark-schooner-1821-46.html | title=USS Shark (Schooner), 1821-46}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:The_Gokoku-ji_Bell.jpg|thumb|200px|An exact replica of the Gokoku-ji Bell which Commodore (Cdre.) Perry brought back from Japan as a gift from the Ryukyuan Government. Currently stationed at the entrance of [[Bancroft Hall]] at the [[United States Naval Academy]] in [[Annapolis, MD]]]] |

|||

Perry commanded the [[USS Shark (1821)|''Shark'']] from [[1821]]-[[1825]]. |

|||

When Britain possessed Florida in 1763, the Spanish contended that the [[Florida Keys]] were part of [[Cuba]] and North Havana. The United States felt that [[Key West]] (which was then named Cayo Hueso, which means "Bone Island") could potentially be the "Gibraltar of the West" because it guarded the northern edge of the 90 mile wide [[Straits of Florida]] -- the deep water route between the [[Atlantic]] and the [[Gulf of Mexico]]. |

|||

In 1815 the Spanish governor in [[Havana]] deeded the island of [[Key West |

In 1815, the Spanish governor in [[Havana]] deeded the island of [[Key West]] to Juan Pablo Salas of [[St. Augustine, Florida|St. Augustine]] in [[Spanish Florida]]. After Florida was transferred to the United States, Salas sold Key West to American businessman John W. Simonton for $2,000 in 1821. Simonton lobbied Washington to establish a naval base on Key West, both to take advantage of its strategic location and to bring law and order to the area. |

||

On March 25, 1822, Perry sailed |

On March 25, 1822, Perry sailed ''Shark'' to Key West and planted the U.S. flag, physically claiming the [[Florida Keys]] as United States territory. Perry renamed Cayo Hueso "Thompson's Island" for the Secretary of the Navy [[Smith Thompson]] and the harbor "Port Rodgers" for the president of the [[Board of Navy Commissioners]]. Neither name stuck however. |

||

From 1826 to 1827, Perry acted as fleet captain for Commodore Rodgers. In 1828, Perry returned to [[Charleston, South Carolina]], for shore duty. In 1830, he took command of a [[sloop-of-war]], {{USS|Concord|1828|6}}. During this period, while in port in Russian [[Kronstadt]], Perry was offered a commission in the [[Imperial Russian Navy]], which he declined. |

|||

Perry renamed Cayo Hueso "Thompson's Island" for the Secretary of the Navy [[Smith Thompson]] and the harbor "Port Rodgers" for the president of the Board of Navy Commissioners. Neither name stuck. |

|||

He spent 1833 to 1837 as second officer of the New York Navy Yard, later the [[Brooklyn Navy Yard]], gaining a promotion to captain at the end of this tour. |

|||

===Father of the Steam Navy=== |

===Father of the Steam Navy=== |

||

[[File:Commodore Matthew C Perry-5c.jpg|thumb|{{center|Commodore Matthew C. Perry}}{{center|U.S. postage, 1953 issue}}]] |

|||

Perry had a considerable interest in naval education, supporting an [[apprentice]] system to train new seamen, and helped establish the curriculum for the [[United States Naval Academy]]. He was also a vocal proponent of modernizing the Navy. Once promoted to captain, he oversaw construction of the Navy's second steam frigate, [[USS Fulton (1837)|USS ''Fulton'']], which he commanded after its completion. He was called "The Father of the Steam Navy", and he organized America's first corps of naval engineers, and conducted the first U.S. naval gunnery school while commanding ''Fulton'' in [[1839]]-[[1840]] off [[Sandy Hook (New Jersey)|Sandy Hook]] on the coast of [[New Jersey]]. |

|||

Perry had an ardent interest in and saw the need for naval education, supporting an [[Apprenticeship|apprentice]] system to train new seamen, and helped establish the curriculum for the United States Naval Academy. He was a vocal proponent of modernizing the Navy. Once promoted to captain, he oversaw construction of the Navy's second steam frigate {{USS|Fulton|1837|6}}, which he commanded after its completion. |

|||

He was called "The Father of the Steam Navy",<ref>Sewall, John S. (1905). ''The Logbook of the Captain's Clerk: Adventures in the China Seas,'' p. xxxvi.</ref> and he organized America's first corps of naval engineers. Perry conducted the first U.S. naval gunnery school while commanding ''Fulton'' from 1839 to 1841 off [[Sandy Hook, New Jersey|Sandy Hook]] on the [[New Jersey]] coast. |

|||

===Promotion to commodore=== |

===Promotion to commodore=== |

||

In 1841, Perry received the title of [[Commodore (United States)|commodore]], when the [[United States Secretary of the Navy|Secretary of the Navy]] appointed him commandant of New York Navy Yard.<ref name="g154-155">Griffis, William Elliot. (1887). [https://archive.org/details/matthewcalbrait01grifgoog/page/n474 <!-- pg=443 quote=matthew c perry. --> ''Matthew Calbraith Perry: A Typical American Naval Officer,'' pp. 154]-155.</ref> The United States Navy did not have ranks higher than captain until 1857, so the title of commodore carried considerable importance. Officially, an officer would revert to his permanent rank after the squadron command assignment had ended, although in practice officers who received the title of commodore retained the title for life, as did Perry. |

|||

Perry acquired the courtesy title of [[Commodore (USN)|Commodore]] in [[1841]], and was made chief of the [[New York Navy Yard]] in the same year. In [[1843]] he took command of the [[African Squadron]], whose duty was to interdict the [[slave trade]] under the [[Webster-Ashburton Treaty]], and continued in this endeavor through [[1844]]. |

|||

During his tenure in Brooklyn, he lived in [[Quarters A, Brooklyn Navy Yard|Quarters A]] in [[Vinegar Hill, Brooklyn|Vinegar Hill]], a building which still stands today.<ref>{{cite web|url={{NHLS url|id=74001252}} |format=PDF |title=National Register of Historic Places : Quarters A : Commander's Quarters, Matthew C. Perry House |publisher=Pdfhost.focus.nps.gov |access-date=March 9, 2015}}</ref> In 1843, Perry took command of the [[Africa Squadron]], whose duty was to interdict the slave trade under the [[Webster–Ashburton Treaty|Webster-Ashburton Treaty]], and continued in this endeavor to 1844. |

|||

===The Mexican-American War=== |

|||

In [[1845]] Commodore [[David Connor]]'s length of service in command of the [[Home Squadron]] had come to an end. However, the coming of the [[Mexican-American War]] persuaded the authorities not to change commanders in the face of the war. Perry, who would eventually succeed Connor, was made second-in-command and captained the [[USS Mississippi (1841)|USS ''Mississippi'']]. Perry captured the Mexican city of [[Frontera]], demonstrated against [[Tabasco]] and took part in the [[Tampico Expedition (1846)|Tampico Expedition]]. He had to return to [[Norfolk, Virginia]] to make repairs and was still there when the amphibious landings at [[Veracruz, Veracruz|Vera Cruz]] took place. His return to the U.S. gave his superiors the chance to finally give him orders to succeed Commodore Connor in command of the Home Squadron. Perry returned to the fleet during the [[siege of Veracruz]] and his ship supported the siege from the sea. After the fall of Veracruz [[Winfield Scott]] moved inland and Perry moved against the remaining Mexican port cities. Perry assembled the [[Mosquito Fleet]] and [[Battle of Tuxpan|captured Tuxpan]] in April, 1847. In July 1847 he [[Second Battle of Tabasco|attacked Tabasco]] personally, leading a 1173-man landing force ashore and attacked the city from land. |

|||

===Mexican–American War=== |

|||

==The Opening of Japan: 1852-1854== |

|||

[[File:Intervención estadounidense en Tabasco.jpg|thumb|In 1847, Perry attacked and took San Juan Bautista ([[Villahermosa]] today) in the [[Second Battle of Tabasco]].]] |

|||

In 1845, Commodore [[David Conner (naval officer)|David Conner]]'s length of service in command of the [[Home Squadron]] had come to an end. However, the coming of the [[Mexican–American War]] persuaded the authorities not to change commanders in the face of the war. Perry, who eventually succeeded Conner, was made second-in-command and captained {{USS|Mississippi|1841|6}}. Perry captured the Mexican city of [[Frontera, Tabasco|Frontera]], demonstrated against [[Tabasco]], being defeated in [[Villahermosa|San Juan Bautista]] by Colonel Juan Bautista Traconis in the [[First Battle of Tabasco]], and took part in the capture of [[Tampico]] on November 14, 1846. |

|||

Perry had to return to [[Norfolk, Virginia]], to make repairs and was there when the [[Siege of Veracruz|amphibious landings at Veracruz]] took place. His return to the U.S. gave his superiors the chance to give him orders to succeed Commodore Conner in command of the Home Squadron. Perry returned to the fleet, and his ship supported the siege of Veracruz from the sea.<ref>Sewell, p. xxxvi.</ref> |

|||

{{see also|Late Tokugawa shogunate}} |

|||

===Precedents=== |

|||

Perry's expedition to Japan was preceded by several naval expeditions by American ships: |

|||

After the fall of Veracruz, [[Winfield Scott]] moved inland, and Perry moved against the remaining Mexican port cities. Perry assembled the [[Mosquito Fleet]] and [[First Battle of Tuxpan|captured Tuxpan]] in April 1847. In June 1847 he [[Second Battle of Tabasco|attacked Tabasco]] personally, leading a 1,173-man landing force ashore and attacking the city of San Juan Bautista from land, defeating the Mexican forces and taking the city.<ref>Sewell, p. xxxvi.</ref> |

|||

* From [[1797]] to [[1809]], several American ships traded in [[Nagasaki]] under the [[Netherlands|Dutch]] flag, upon the request of the Dutch, who were not able to send their own ships because of their conflict against [[United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland|Britain]] during the [[Napoleonic Wars]]. Trade was limited to the Dutch and Chinese at that time (''[[sakoku]]''). |

|||

In 1847, Perry was elected as an honorary member of the New York [[Society of the Cincinnati]] in recognition of his achievements during the Mexican War. |

|||

* In [[1837]], an American businessman in [[Canton, China|Canton]], named [[Charles W. King]], saw an opportunity to open trade by trying to return to Japan three Japanese sailors (among them, [[Otokichi]]) who had been shipwrecked a few years before on the coast of [[Washington]]. He went to [[Uraga Channel]] with ''Morrison'', an unarmed American merchant ship. The ship was attacked several times, and sailed back without completing its mission. |

|||

==Perry Expedition: opening of Japan, 1852–1854== |

|||

* In [[1846]], Commander [[James Biddle]], sent by the United States Government to open trade, anchored in [[Tokyo Bay]] with two ships, including one warship armed with 72 cannons, but his requests for a trade agreement remained unsuccessful. |

|||

{{See also|Perry Expedition|Bakumatsu}} |

|||

[[File:Gasshukoku suishi teitoku kōjōgaki (Oral statement by the American Navy admiral).png|thumb|A [[Woodblock printing in Japan|Japanese woodblock print]] of Perry (center) and other high-ranking American seamen]] |

|||

In 1852, Perry was assigned a mission by American President [[Millard Fillmore]] to force the opening of Japanese ports to American trade, through the use of [[gunboat diplomacy]] if necessary.<ref name="J. W. Hall, Japan, p.207">J. W. Hall, ''Japan'', p.207.</ref> The growing commerce between the United States and China, the presence of American whalers in waters offshore Japan, and the increasing monopolization of potential [[Filling station|coaling stations]] by European powers in Asia were all contributing factors. Shipwrecked foreign sailors were either imprisoned or executed,<ref name="Blumberg, Rhoda p.18">Blumberg, Rhoda. ''Commodore Perry in the Land of the Shogun'', HarperCollins, New York, ç1985, p.18</ref><ref name="Meyer, Milton W. p.126">Meyer, Milton W. ''Japan: A Concise History'', fourth ed., Bothman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., Plymouth, ç2009, p.126</ref><ref name="Henshall, Kenneth G. p.66">Henshall, Kenneth G. ''A History of Japan: From Stone Age to Superpower'', Palgrave MacMillan, New York, ç1999, p.66</ref> and the safe return of such persons was one demand. |

|||

* In [[1848]], Captain [[James Glynn]] sailed to [[Nagasaki]], leading at last to the first successful negotiation by an American with "[[Sakoku|Closed Country]]" Japan. James Glynn recommended to the [[United States Congress]] that negotiations to open Japan should be backed up by a demonstration of force, thus paving the way to Perry's expedition. |

|||

The Americans were also driven by concepts of [[manifest destiny]] and the desire to impose the benefits of western civilization and the [[Christianity|Christian religion]] on what they perceived as backward Asian nations.<ref name="G. Beasley, p.88">W. G. Beasley, ''The Meiji Restoration'', p.88.</ref> The Japanese were forewarned by the Dutch of Perry's voyage but were unwilling to change their 250-year-old policy of [[sakoku|national seclusion]].<ref name="G. Beasley, p.88"/> There was considerable internal debate in Japan on how best to meet this potential threat to Japan's economic and political sovereignty. |

|||

===First visit, 1852-1853=== |

|||

[[Image:PerryIkokusen.jpg|thumb|350px|Japanese 1854 print relating Perry's visit.]] |

|||

In [[1852]], Perry embarked from [[Norfolk, Virginia]] for [[Japan]], in command of a squadron in search of a Japanese trade treaty. Aboard a black-hulled steam frigate, he ported |

|||

[[USS Mississippi (1841)|''Mississippi'']], |

|||

[[USS Plymouth (1844)|''Plymouth'']], |

|||

[[USS Saratoga (1842)|''Saratoga'']], |

|||

and |

|||

[[USS Susquehanna (1847)|''Susquehanna'']] |

|||

at [[Uraga Harbor]] near [[Edo]] (modern [[Tokyo]]) on [[July 8]], [[1853]], and was met by representatives of the [[Tokugawa Shogunate]] who told him to proceed to [[Nagasaki]], where there was limited trade with the [[Netherlands]] and which was the only Japanese port open to foreigners at that time (see [[Sakoku]]). Perry refused to leave and demanded permission to present a letter from President [[Millard Fillmore]], threatening force if he was denied. The Japanese military forces could not resist Perry's modern weaponry; the "[[Black Ships]]" would then become, in Japan, a threatening symbol of Western technology. |

|||

On November 24, 1852, Perry embarked from [[Norfolk, Virginia]], for Japan, in command of the [[East India Squadron]] in pursuit of a Japanese trade treaty. He chose the paddle-wheeled steam frigate {{USS|Mississippi|1841|2}} as his [[flagship]] and made port calls at [[Madeira]] (December 11–15), [[Saint Helena]] (January 10–11), [[Cape Town]] (January 24 – February 3), [[British Mauritius|Mauritius]] (February 18–28), [[British Ceylon|Ceylon]] (March 10–15), [[Singapore in the Straits Settlements|Singapore]] (March 25–29), [[Portuguese Macau|Macao]] and [[British Hong Kong|Hong Kong]] (April 7–28). |

|||

The Japanese government let Perry come ashore to avoid a naval bombardment. Perry landed at Kurihama (in modern-day [[Yokosuka, Kanagawa|Yokosuka]]) on [[July 14]], presented the letter to delegates present, and left for the Chinese coast, promising to return for a reply. |

|||

In Hong Kong he met with American-born Sinologist [[Samuel Wells Williams]], who provided [[Chinese language]] translations of his official letters, and where he rendezvoused with {{USS|Plymouth|1844|2}}. He continued to [[Shanghai]] (May 4–17), where he met with the Dutch-born American diplomat, Anton L. C. Portman, who translated his official letters into the [[Dutch language]], and where he rendezvoused with {{USS|Susquehanna|1847|2}}. |

|||

===Second visit, 1854=== |

|||

[[Image:PerryFleet.jpg|thumb|350px|Commodore Perry's fleet for his second visit to Japan in [[1854]].]] |

|||

Perry returned in February [[1854]] with twice as many ships, finding that the delegates had prepared a treaty embodying virtually all the demands in Fillmore's letter. Perry signed the [[Convention of Kanagawa]] on [[March 31]], [[1854]] and departed, mistakenly believing the agreement had been made with [[Emperor of Japan|imperial]] representatives. |

|||

Perry then switched his flag to ''Susquehanna'' and made call at [[Naha]] on Great Lewchew Island (Ryukyu, now [[Okinawa Prefecture|Okinawa]]) from May 17–26. Ignoring the claims of [[Satsuma Domain]] to the islands, he demanded an audience with the [[King of Ryukyu|Ryukyuan King]] [[Shō Tai]] at [[Shuri Castle]] and secured promises that the [[Ryukyu Kingdom]] would be open to trade with the United States. Continuing on to the [[Bonin Islands|Ogasawara islands]] in mid-June, Perry met with the local inhabitants and purchased a plot of land.<ref name="Rüegg 2017">{{cite book |url=https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-23/ruegg |title=Mapping the Forgotten Colony: The Ogasawara Islands and the Tokugawa Pivot to the Pacific |publisher=Cross-Currents |author=Jonas Rüegg |pages=125–6 |access-date=May 9, 2020 |archive-date=November 24, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181124215956/https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-23/ruegg |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

On his way to Japan, Perry anchored off of [[Keelung]] in [[Taiwan|Formosa]], known today as Taiwan, for ten days. Perry and crew members landed on [[Taiwan|Formosa]] and investigated the potential of mining the [[coal]] deposits in that area. He emphasized in his reports that Formosa provided a convenient mid-way trade location. Formosa was also very defensible. It could serve as a base for exploration like [[Cuba]] had done for the Spanish in the Americas. Occupying Formosa could help the US to counter European [[monopoly|monopolization]] of the major trade routes. The United States government did not respond to Perry's proposal to claim sovereignty over Formosa. |

|||

===First visit (1853)=== |

|||

===Return to the United States, 1855=== |

|||

Perry reached [[Uraga, Kanagawa|Uraga]] at the entrance to [[Tokyo Bay|Edo Bay]] in Japan on July 8, 1853. His actions at this crucial juncture were informed by a careful study of Japan's previous contacts with Western ships and what he knew about the Japanese hierarchical culture. As he arrived, Perry ordered his ships to steam past Japanese lines towards the capital of [[Edo]] and turn their guns towards the town of Uraga.<ref name="Beasly 153">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=j399Lfj6baYC&pg=PA153 |title=The Perry Mission to Japan, 1853–1854 – Google Books |isbn=9781903350133 |access-date=March 9, 2015|last1=Beasley |first1=William G. |year=2002 |publisher=Psychology Press}}</ref> Perry refused Japanese demands to leave or to proceed to [[Nagasaki]], the only Japanese port open to foreigners.<ref name="Beasly 153" /> |

|||

[[Image:PerryBustShimoda.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Bust of Matthew Perry in [[Shimoda, Shizuoka]].]] |

|||

[[Image:Formosa-map coal.jpg|thumb|200px|A map of Coal Mines distribution on Formosa Island in the Narrative of the Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry's Expedition to Japan.]] |

|||

When Perry returned to the United States in [[1855]], [[United States Congress|Congress]] voted to grant him a reward of $20,000 in appreciation of his work in Japan. Perry used part of this money to prepare and publish a report on the expedition in three volumes, titled ''Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the [[China Sea]]s and Japan''. He was also advanced to the grade of rear-admiral on the retired list (when his health began to fail) as a reward for his services in the Far East. |

|||

Perry attempted to intimidate the Japanese by presenting them a [[white flag]] and a letter which told them that in case they chose to fight, the Americans would destroy them.<ref>{{cite book|quote="The letter threatened that in the event the Japanese elected war rather than negotiation, he could use the white flag to sue for peace, since victory would naturally belong to the Americans"|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=erBi_TmWanoC&pg=PA286 |title=''Matthew Calbraith Perry: antebellum sailor and diplomat''|author=John H. Schroeder|year = 2001|page=286| publisher=Naval Institute Press |isbn = 9781557508126|access-date=March 9, 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mvfMKV1b1fwC&pg=PA285 |title=The Economic Aspects of the History of the Civilization of Japan – Yosaburō Takekoshi – Google Books |isbn=9780415323819 |access-date=March 9, 2015|last1=Takekoshi |first1=Yosaburō |year=2004 |publisher=Taylor & Francis}}</ref> He also fired blank shots from his 73 cannon, which he claimed was in celebration of the [[Independence Day (United States)|American Independence Day]]. Perry's ships were equipped with new [[Paixhans gun|Paixhans shell guns]], cannons capable of wreaking great explosive destruction with every shell.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PcGpkzmjFbgC&pg=PA88 |title=Arms and Men: A Study in American Military History – Walter Millis – Google Books |isbn=9780813509310 |access-date=March 9, 2015|last1=Millis |first1=Walter |year=1981 |publisher=Rutgers University Press}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bFyV2BZMCRwC&pg=PA21 |title=Black Ships Off Japan: The Story of Commodore Perry's Expedition – Arthur Walworth – Google Books |date=January 1, 1982 |isbn=9781443728508 |access-date=March 9, 2015|last1=Walworth |first1=Arthur |publisher=Read Books}}</ref> He also ordered his ship boats to commence survey operations of the coastline and surrounding waters over the objections of local officials. |

|||

===Last years=== |

|||

Perry died on March 4, 1858 in [[New York City]], of liver [[cirrhosis]] due to [[alcoholism]]. His remains were moved to the Island Cemetery in [[Newport, Rhode Island]] on March 21, [[1866]], along with those of his daughter, Anna, who died in 1839. |

|||

[[File:Commodore-Perry-Visit-Kanagawa-1854.jpg|thumb|Perry's visit in 1854]] |

|||

==Family== |

|||

*His brother was Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry |

|||

*His wife Jane Slidell was sister of [[John Slidell]] and aunt of [[Alexander Slidell MacKenzie]]. |

|||

*His sister Anna Maria married Commodore George Washington Rodgers. Their son Rear Admiral [[Christopher Raymond Perry Rodgers]] married to Julia Slidell. Raymond and Julia Slidell were the parents of Rear Admirials Thomas Slidell Rodgers and Raymond Perry Rodgers. Raymond Perry Rodgers was married to Gertrude Stuyvesant-who was descended from the [[Robert Livingston the Elder|Livingston]] family of New York. George Washington Rodgers was the brother of Commadore [[John Rodgers (naval officer, war of 1812)]] who was the father-in-law of Union General [[Montgomery C. Meigs]] and grandfather of Lt. [[John Rodgers Meigs]]. General Meigs was the great-grandson of Colonel [[Return J. Meigs,Sr]]. Colonel Return Meigs was the father of [[Return J. Meigs]], Governor of Ohio. |

|||

*His daughter Sarah C. married Colonel Robert Smith Rodgers. |

|||

*His daughter Caroline Slidell married [[August Belmont]], a 19th century banker/businessman. |

|||

*His granddaugther married [[Joseph Grew]], Ambassador to Japan. |

|||

*His great-granddaugther married [[Jay Pierrepont Moffat]], Ambassador to Canada. |

|||

*His great-grandson was aviation pioneer [[Cal Rodgers]]. |

|||

*His great-grandson was [[John Rodgers (naval officer, World War I)]], who was also a great grandson of Commodore [[John Rodgers (naval officer, War of 1812)|John Rodgers]]. |

|||

Meanwhile, ''[[Shogun|shōgun]]'' [[Tokugawa Ieyoshi]] was ill and incapacitated, which resulted in governmental indecision on how to handle the unprecedented threat to the nation's capital. On July 11, ''[[Rōjū]]'' [[Abe Masahiro]] bided his time, deciding that simply accepting a letter from the Americans would not constitute a violation of Japanese sovereignty. The decision was conveyed to Uraga, and Perry was asked to move his fleet slightly southwest to the beach at [[Kurihama, Yokosuka|Kurihama]] where he was allowed to land on July 14, 1853.<ref>[https://select.nytimes.com/mem/archive/pdf?res=F00A16FD3C59177B93C6A8178CD85F478585F9 "Perry Ceremony Today; Japanese and U. S. Officials to Mark 100th Anniversary."] ''[[The New York Times]]'', July 14, 1953.</ref> After presenting the letter to attending delegates, Perry departed for Hong Kong, promising to return the following year for the Japanese reply.<ref>Sewall, pp. 183–195.</ref> |

|||

==Trivia== |

|||

[[Image:US flag 31 stars.svg|thumb|right|200px|31 Star US Flag]] |

|||

* Perry's middle name is often misspelled as '''G'''albraith instead of '''C'''albraith. |

|||

* Among other mementos, Perry presented [[Victoria of the United Kingdom|Queen Victoria]] with a breeding pair of [[Japanese Chin]] dogs, previously owned only by Japanese nobility. |

|||

* A replica of Perry's US flag is on display on board the [[USS Missouri (BB-63)|USS ''Missouri'' (BB-63)]] memorial in [[Pearl Harbor]], [[Hawaii]]. It is attached to the [[Bulkhead (partition)|bulkhead]] just inboard of the [[Japanese Instrument of Surrender|Japanese surrender]] signing site on the [[port (nautical)|port]] side of the ship. |

|||

The pattern for the Union Canton on this flag is different from the standard 31 star flag in use. Perry's flag had rows of five stars save the last row which had six stars. |

|||

Thus Perry's US flag is almost unique to himself. |

|||

*There is a Perry Park in [[Kurihama]] which has a [[monolith]] [[monument]], erected in 1902, to the landing of Perry's forces. Within the park there is a small [[museum]] dedicated to the events of 1854, admission is free, and the museum is open from 10a.m to 4p.m seven days a week. |

|||

*Matthew C. Perry Elementary School can be found on Marine Corps Air Station, Iwakuni, Japan. |

|||

*The US Navy's [[Perry class]] frigates (purchased in the 1970s and 1980s) were named after Perry's brother, Commodore [[Oliver Hazard Perry]]. |

|||

===Second visit (1854)=== |

|||

==Fictional depictions== |

|||

[[File:Commodore Perry's second fleet.jpg|thumb|Perry's fleet for his second visit to Japan, 1854]] |

|||

*The story of the opening of Japan was the basis of [[Stephen Sondheim]] & [[John Weidman]]'s ''[[Pacific Overtures]]''. |

|||

[[File:The Gokoku-ji Bell.jpg|thumb|An exact replica of the [[Gokoku-ji (Okinawa)|Gokoku-ji]] Bell which Perry brought back from Okinawa, saying it was a gift from the [[Ryukyu Kingdom]]. Stationed at the entrance of [[Bancroft Hall]] at the [[United States Naval Academy]] in [[Annapolis, MD]]. The original bell was returned to Okinawa in 1987.]] |

|||

*Actor [[Richard Boone]] played Commodore Perry in the highly fictionalized 1981 film ''[[Bushido Blade (film)|The Bushido Blade]]''. |

|||

On his way back to Japan, Perry anchored off [[Keelung]] in Formosa, known today as [[Taiwan]], for ten days. Perry and crewmembers landed on Formosa and investigated the potential of mining the coal deposits in that area. He emphasized in his reports that Formosa provided a convenient, mid-way trade location. Perry's reports noted that the island was very defensible and could serve as a base for exploration in a similar way that Cuba had done for the Spanish in the Americas. Occupying Formosa could help the United States counter European monopolization of the major trade routes. The United States government failed to respond to Perry's proposal to claim sovereignty over Formosa. [[File:Medal given to Commodore Perry.png|thumb|1854 Commodore Perry silver Japan treaty medal]] |

|||

*The coming of Commodore Perry's ships is briefly mentioned in an episode of the [[anime]] series [[Rurouni Kenshin]], and in the first episode of [[Hikaru no Go]]. Another anime series in which Perry briefly appears is [[Bokusatsu Tenshi Dokuro-chan]]. The [[manga]] [[Fruits Basket]] also refers to the event while the main character is studying. |

|||

*The [[anime]] series, ''[[Samurai Champloo]]'', in an episode entitled "Baseball Blues" depicts a fictional character named 'Admiral Joy Cartwright' who challenges the Japanese locals to a baseball ([[Yakyu]]) game in order to establish trade relations. The admiral is obviously modeled after Commodore Perry. |

|||

To command his fleet, Perry chose officers with whom he had served in the Mexican–American War. Commander [[Franklin Buchanan]] was captain of ''Susquehanna''. [[Joel Abbot (naval officer)|Joel Abbot]], Perry's second in command, was captain of ''Macedonian''. Commander Henry A. Adams was chief of staff with the title "Captain of the Fleet". Major [[Jacob Zeilin]], future commandant of the United States Marine Corps, was the ranking Marine officer and was stationed on ''Mississippi''. |

|||

*Perry's visit is also mentioned in the 1965 [[Hideo Gosha]] film ''[[Sword of the Beast]]''. |

|||

*The faster-than-light spaceship in the novel ''[[Homeward Bound (novel)#Plot summary|Homeward Bound]]'' is named ''Commodore Perry''. |

|||

Perry returned on February 13, 1854, after only half a year rather than the full year promised, and with ten ships and 1,600 men. American leadership designed the show of force to "command fear" and "astound the Orientals."<ref name=":6">{{Cite book |last=Driscoll |first=Mark W. |title=The Whites are Enemies of Heaven: Climate Caucasianism and Asian Ecological Protection |date=2020 |publisher=[[Duke University Press]] |isbn=978-1-4780-1121-7 |location=Durham}}</ref>{{Rp|page=31}} After initial resistance, Perry was permitted to land at [[Kanagawa-juku|Kanagawa]], near the site of present-day [[Yokohama]] on March 8. The [[Convention of Kanagawa]] was signed on March 31. Perry signed as American [[plenipotentiary]], and [[Hayashi Akira]], also known by his title of ''[[Daigaku-no-kami]]'', signed for the Japanese side. The celebratory events for the signing ceremony included a [[Kabuki]] play from the Japanese side and, from the American side, U.S. military band music and blackface minstrelsy.<ref name=":6" />{{Rp|pages=32–33}} |

|||

Perry departed, mistakenly believing the agreement had been made with [[Emperor of Japan|imperial]] representatives, not understanding the true position of the ''shōgun'', the de facto ruler of Japan.<ref>Sewall, pp. 243–264.</ref> Perry then visited [[Hakodate]] on the northern island of [[Hokkaido]] and [[Shimoda, Shizuoka|Shimoda]], the two ports which the treaty stipulated would be opened to visits by American ships. A handscroll with pictorial record from the Japanese side of US Commodore Matthew Perry's second visit to Japan in 1854 is retained in the [[British Museum]] in London.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_2013-3002-1|title=painting; handscroll | British Museum|website=The British Museum|accessdate=October 29, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

===Return to the United States (1855)=== |

|||

When Perry returned to the United States, [[United States Congress|Congress]] voted to grant him a reward of $20,000, {{Inflation|US-GDP|20000|1855|r=-4|fmt=eq}}, in appreciation of his work in Japan. He used part of this money to prepare and publish a report on the expedition in three volumes, titled ''[[Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan]]''. He was promoted to [[Rear admiral (United States)|rear admiral]] on the retired list when his health began to fail, as a reward for his service in the Far East.<ref>Sewall, p. lxxxvii.</ref> |

|||

==Last years== |

|||

Living in his adopted home of New York City, Perry's health began to fail as he suffered from [[cirrhosis]] of the liver from heavy drinking. Perry was known to have been an alcoholic, which compounded the health complications leading to his death.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.mymexicanwar.com/leaders/perry-matthew-c/ | title= Commodore Matthew C Perry |publisher= mymexicanwar.com 2012 |access-date= December 15, 2017}}</ref> He also suffered severe arthritis that left him in frequent pain, and on occasion precluded him from his duties.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.grifworld.com/perryhome.html | title= Commodore Perry's Expedition to Japan |publisher= Ben Griffiths 2005 |access-date= September 12, 2009}}</ref> |

|||

Perry spent his last years preparing for the publication of his account of the Japan expedition, announcing its completion on December 28, 1857. Two days later he was detached from his last post, an assignment to the Naval Efficiency Board. He died awaiting further orders on March 4, 1858, in [[New York City]], of [[rheumatic fever]] that had spread to the heart, compounded by complications of [[gout]] and [[alcoholism]].<ref>Morison, Samuel Eliot. (1967). '' 'Old Bruin' Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry'' p. 431.</ref> |

|||

Initially interred in a vault on the grounds of [[St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery]], in New York City, Perry's remains were moved to the [[Island Cemetery]] in [[Newport, Rhode Island]], on March 21, 1866, along with those of his daughter, Anna, who died in 1839. In 1873, an elaborate monument was placed by Perry's widow over his grave in Newport.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1873/08/15/79043337.pdf |title=Monument to Commodore M.C. Perry – View Article – NYTimes.com |newspaper=The New York Times |access-date=March 9, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

==Personal life== |

|||

Perry was married to Jane Slidell Perry (1797–1864), sister of [[United States Senate|United States Senator]] [[John Slidell]] (1793–1871),<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Sears |first=Louis Martin |date=1922 |title=Slidell and Buchanan |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1837537 |journal=[[The American Historical Review]] |volume=27 |issue=4 |pages=709–730 |doi=10.2307/1837537 |jstor=1837537 |issn=0002-8762}}</ref> in New York on December 24, 1814, and they had ten children:<ref>"Matthew Calbraith Perry" by William Elliot Griffis 1887</ref><ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QsdKAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA42 |title=The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography |volume=IV |publisher=James T. White & Company |pages=42–43 |year=1893 |access-date=December 2, 2020 |via=Google Books}}</ref> |

|||

* Jane Slidell Perry (c. 1817–1880) |

|||

* Sarah Perry (1818–1905), who married Col. Robert Smith Rodgers (1809–1891) |

|||

* Jane Hazard Perry (1819–1881), who married John Hone (1819–1891) and [[Frederic de Peyster]] (1796–1882) |

|||

* Matthew Calbraith Perry (1821–1873), a captain in the United States Navy and veteran of the Mexican War and the Civil War |

|||

* Susan Murgatroyde Perry (c. 1824–1825)<ref>"New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1795-1949," database, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:F6MK-VZ5 : June 3, 2020), Susan M. Perry, August 14, 1825; citing Death, Manhattan, New York County, New York, United States, New York Municipal Archives, New York; FHL microfilm 447,545.</ref> |

|||

* Oliver Hazard Perry (c. 1825–1870), US [[Consul]] in Canton, China |

|||

* William Frederick Perry (1828–1884), a 2nd Lieutenant, [[United States Marine Corps]], 1847–1848 |

|||

* Caroline Slidell Perry Belmont (1829–1892), who married financier [[August Belmont]] |

|||

* Isabella Bolton Perry (1834–1912), who married George T. Tiffany |

|||

* Anna Rodgers Perry (c. 1838–1839) |

|||

In 1819, Perry joined the [[masonic]] Holland Lodge No. 8 in [[New York City]], [[New York (state)|New York]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.lodgestpatrick.co.nz/famous2.php#M%7Ctitle=|title=Famous Freemasons M-Z|website=www.lodgestpatrick.co.nz|accessdate=October 29, 2023}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.masonrytoday.com/index.php?new_month=3&new_day=4&new_year=2015|title = Today in Masonic History - Matthew Calbraith Perry Passes Away}}</ref> |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

File:Jane Slidell Perry (page 134 crop).jpg|Jane Slidell Perry |

|||

File:Matthew C. Perry 1855-56.jpg|Matthew C. Perry, 1855–56 |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||

[[File:Perry flag 1945.jpg|thumb|Perry's flag (upper left corner) was flown from [[Annapolis, MD|Annapolis]] to Tokyo for display [[Surrender of Japan|at the surrender ceremonies]] which officially ended World War II.]]Perry was a key agent in both the making and recording of Japanese history, as well as in the shaping of Japanese history. 90% of school children in Japan can identify him.<ref name="japantoday.com">{{cite news|newspaper=[[Japan Today]]|date= October 26, 2011|title= Commodore Perry & the legacy of American imperialism |url=https://japantoday.com/category/features/opinions/commodore-perry-the-legacy-of-american-imperialism}}</ref> |

|||

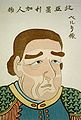

Woodblock paintings of Matthew Perry closely resemble his actual |

|||

appearance, depicting a physically large, clean shaven, jowly man.<ref name="DowerMIT">{{cite web|last1=Dower|first1= John W. |authorlink=John W. Dower|last2=Miyagawa |first2=Shigeru|year= 2008|title= Black Ships & Samurai: Commodore Perry and the Opening of Japan (1853-1854)|website= MIT Visualizing Cultures. Massachusetts Institute of Technology|url=https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/black_ships_and_samurai_02/bss_visnav06.html}}</ref> The portraits portray him with blue eyeballs, rather than blue irises.<ref name="DowerMIT" /> Westerners in this period were commonly thought of as "blue-eyed barbarians", however, in Japanese culture, blue eyeballs were also associated with ferocious or threatening figures, such as monsters or renegades.<ref name="DowerMIT" /> It is thought that the intimidation that the Japanese felt at the time could have influenced these portraits. Some portraits of Perry depict him as a [[tengu]]. However, the portraits of his crewmen are normal.<ref name="DowerMIT" /> |

|||

When Perry returned to the United States after signing the [[Convention of Kanagawa]], he brought with him diplomatic gifts, including art, pottery, textiles, musical instruments, and other artifacts now in the collection of the [[Smithsonian Institution]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hanshō Presented to Commodore Matthew C. Perry {{!}} National Bell Festival |url=https://www.bells.org/blog/hansho-bell-presented-commodore-matthew-perry |access-date=March 15, 2024 |website=www.bells.org}}</ref> |

|||

''[[Pacific Overtures]]'' is a [[Musical theatre|musical]] set in Japan beginning in 1853 and follows the difficult westernization of Japan, told from the point of view of the Japanese. |

|||

A replica of Perry's U.S. flag is on display on board the {{USS|Missouri|BB-63|6}} memorial in [[Pearl Harbor]], [[Hawaii]], attached to the [[Bulkhead (partition)|bulkhead]] just inboard of the [[Japanese Instrument of Surrender|Japanese surrender]] signing site on the [[Port and starboard|starboard]] side of the ship. The original flag was brought from the [[U.S. Naval Academy Museum]] to Japan for the Japan surrender ceremony and was displayed on that occasion at the request of [[Douglas MacArthur]], who was a blood-relative of Perry. |

|||

Today, the flag is preserved and on display at the Naval Academy Museum in [[Annapolis, Maryland]].<ref>Broom, Jack [https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/19980521/2751979/memories-on-board-battleship "Memories on Board Battleship,"] ''[[Seattle Times]]'', May 21, 1998.</ref> |

|||

In the museum, the flag is displayed the 'wrong' way round. However, photographs show that at the signing ceremony, this flag was displayed properly, on its starboard side, with the stars in the upper right corner, as are all flags on vessels, known as ensigns. The cloth of this historic flag was so fragile that the conservator at the museum directed that a protective backing be sewn on it, which accounts for its currently being displayed 'port' side round.<ref name="tsusumi2007">Tsustsumi, Cheryl Lee. [http://starbulletin.com/2007/08/26/travel/tsutsumi.html "Hawaii's Back Yard: Mighty Mo memorial re-creates a powerful history,"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080726171925/http://starbulletin.com/2007/08/26/travel/tsutsumi.html |date=July 26, 2008}} ''Star-Bulletin'' (Honolulu). August 26, 2007.</ref> |

|||

==Memorials== |

|||

Japan erected a monument to Perry on July 14, 1901, at the spot where the commodore first landed.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.oldtokyo.com/matthew-c-perry-memorial-kurihama-c-1949/|title = Matthew C. Perry Landing Memorial, Kurihama, c. 1949. | Old TokyoOld Tokyo|date = January 28, 2019}}</ref> The monument survived [[World War II]] and is now the centerpiece of a small seaside park called Perry Park at Yokosuka, Japan.<ref>Sewall, pp. 197–198.</ref> Within the park there is a small museum dedicated to the events of 1854. Matthew C. Perry Elementary and High School can be found on [[Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni|Marine Corps Air Station, Iwakuni]]. |

|||

At his birthplace in Newport, there is a memorial plaque in [[Trinity Church (Newport, Rhode Island)|Trinity Church, Newport]] and a [[Matthew Perry Monument (Newport, Rhode Island)|statue of Perry]] in Touro Park. It was designed by [[John Quincy Adams Ward]], erected in 1869, and dedicated by his daughter. He was buried in Newport's [[Island Cemetery]], near his parents and brother. There are also exhibits and research collections concerning his life at the [[Naval War College Museum]] and at the [[Newport Historical Society]]. |

|||

Perry Street in [[Trenton, New Jersey]] is named in his honor.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.trentonhistory.org/streets.html|title=Trenton Historical Society, New Jersey|website=www.trentonhistory.org|accessdate=October 29, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

The U.S. Navy's {{sclass|Oliver Hazard Perry|frigate|1}}s (purchased in the 1970s and 1980s) were named after Perry's brother, Commodore [[Oliver Hazard Perry]]. The ninth ship of the {{sclass|Lewis and Clark|dry cargo ship|4}} of dry-cargo-ammunition vessels is named {{USNS|Matthew Perry|T-AKE-9|6}}. |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

File:Commodore Matthew Perry Statue in Touro Park, Newport, RI.JPG|Perry's statue in Touro Park, [[Newport, Rhode Island]]<!-- {{Q|49571392}} --> |

|||

File:Matthewperry.jpg|[[Woodblock printing in Japan|Japanese woodblock print]] of Perry, c. 1854. The caption reads "North American" (top line, written from right to left in [[Kanji]]) and "Perry's portrait" (first line, written from top to bottom). |

|||

File:The Mission of Commodore Perry to Japan in 1854 (BM 2013,3002.1 102).jpg|A pictorial representation of Perry (on the right) from the scroll painted by the Japanese artist Hibata Ōsuke to mark the occasion of the signing of the [[Convention of Kanagawa]] in 1854. The 15.25m long scroll has been part of the [[British Museum]]'s collection since 2013. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Bibliography of early American naval history]] |

|||

*[[History of Japan]] |

|||

*[[ |

* [[History of Japan]] |

||

* [[Meiji Restoration]] |

|||

*[[Yokohama Archives of History]] |

|||

*[[ |

* [[Sakoku]] |

||

* [[Yokohama Archives of History]] |

|||

* [[List of Westerners who visited Japan before 1868]] |

|||

==Citations== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

* Perry, Matthew Calbraith. (1856). ''Narrative of the expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, 1856.'' New York : D. Appleton and Company. digitized by [[University of Hong Kong]] [[University of Hong Kong#Libraries and museums|Libraries]], |

|||

* Perry, Matthew Calbraith, and Roger Pineau. ''The Japan expedition, 1852-1854: the personal journal of Commodore Matthew C. Perry'' (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1968). |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

*{{cite thesis|author=Arnold, Josh Makoto|title=Diplomacy Far Removed: A Reinterpretation of the U.S. Decision to Open Diplomatic Relations with Japan|publisher=University of Arizona|year=2005}} |

|||

* Blumberg, Rhoda. (1985) ''Commodore Perry in the Land of the Shogun'' (Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Books, 1985) |

|||

* Cullen, Louis M. (2003). [https://books.google.com/books?id=ycY_85OInSoC&q=A+History+of+Japan,+1582-1941:+Internal+and+External+Worlds ''A History of Japan, 1582–1941: Internal and External Worlds.''] Cambridge: [[Cambridge University Press]]. {{ISBN|0-521-82155-X}} (cloth), {{ISBN|0-521-52918-2}} (paper) |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Griffis |first=William Elliot |author-link=William Elliot Griffis |ref=Griffis |title=Matthew Calbraith Perry: a typical American naval officer |publisher=Cupples and Hurd, Boston |year=1887 |page=459 |isbn=1-163-63493-X |url=https://www.fadedpage.com/showbook.php?pid=20160503}} |

|||

* [[Francis Hawks|Hawks, Francis]]. (1856). [https://books.google.com/books?id=uwALAAAAYAAJ&q=Narrative+of+the+Expedition+of+an+American+Squadron+to+the+China+Seas+and+Japan+Performed+in+the+Years+1852,+1853+and+1854+under+the+Command+of+Commodore+M.C.+Perry,+United+States+Navy ''Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan Performed in the Years 1852, 1853 and 1854 under the Command of Commodore M.C. Perry, United States Navy.''] Washington: A.O.P. Nicholson by order of Congress, 1856; originally published in ''Senate Executive Documents'', No. 34 of 33rd Congress, 2nd Session. [reprinted by London:Trafalgar Square, 2005. {{ISBN|1-84588-026-9}}] |

|||

* Kitahara, Michio. "Commodore Perry and the Japanese: a Study in the Dramaturgy of Power." ''Symbolic Interaction'' 9.1 (1986): 53–65. |

|||

*[[Samuel Eliot Morison|Morison, Samuel Eliot]]. (1967). ''"Old Bruin": Commodore Matthew C. Perry, 1794-1858: The American naval officer who helped found Liberia, Hunted Pirates in the West Indies, Practised Diplomacy With the Sultan of Turkey and the King of the Two Sicilies; Commanded the Gulf Squadron in the Mexican War, Promoted the Steam Navy and the Shell Gun, and Conducted the Naval Expedition Which Opened Japan'' (1967) [https://archive.org/details/oldbruincommodor00mori/page/n1 online free to borrow] a standard scholarly biography. |

|||

* Sewall, John S. (1905). [https://archive.org/details/logbookcaptains00sewagoog <!-- quote=The Logbook of the Captain's Clerk: Adventures in the China Seas. --> ''The Logbook of the Captain's Clerk: Adventures in the China Seas.''] Bangor, Maine: Chas H. Glass & Co. [reprint by Chicago: R.R. Donnelly & Sons, 1995] {{ISBN|0-548-20912-X}} |

|||

* Yellin, Victor Fell. (1996) "Mrs. Belmont, Matthew Perry, and the 'Japanese Minstrels'." ''American Music'' (1996): 257–275. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/3052600 online] |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{commons category-inline}} |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070425165629/http://www.spurgeons.ac.uk/site/pages/ui_college_history.aspx "China Through Western Eyes."] |

|||

* [http://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/black_ships_and_samurai/bss_essay05.html Black Ships & Samurai Commodore Perry and the Opening of Japan (1853-1854), by John W Dower] |

|||

* [http://www.history.navy.mil/branches/teach/pearl/kanagawa/friends4.htm A short timeline of Perry's life] |

* [http://www.history.navy.mil/branches/teach/pearl/kanagawa/friends4.htm A short timeline of Perry's life] |

||

* [http://dl.lib.brown.edu/japan/index.html Perry Visits Japan: A Visual History] |

|||

* {{Find a Grave|804}} |

|||

* [https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/si.1986.9.1.53?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents Kitahara, Michio. Commodore Perry and the Japanese: A Study in the Dramaturgy of Power, 1986] |

|||

* [https://archive.org/details/narrativeofexped03perr Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan], by M.C. Perry, at [[archive.org]] |

|||

*{{cite web|url=https://www.academia.edu/5461862 |title=Diplomacy Far Removed: A Reinterpretation of the U.S. Decision to Open Diplomatic Relations with Japan | Bruce Makoto Arnold |publisher=Academia.edu |date=January 1, 1970 |access-date=March 9, 2015|last1=Arnold |first1=Bruce Makoto}} |

|||

{{S-start}} |

|||

[[Category:American people in Japan|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

{{s-mil}} |

|||

[[Category:Edo period|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

{{succession box|title=Commander, [[East India Squadron]]|before=[[John H. Aulick]]|after=[[Joel Abbot (naval officer)|Joel Abbot]]|years=1852–1854}} |

|||

[[Category:United States Navy officers|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

{{S-end}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:American Commodores|Perry, Matthew]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Barnstable County, Massachusetts|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Newport, Rhode Island|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

[[Category:People from New York City|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

[[Category:Irish-Americans in the military|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

[[Category:Perry family|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

[[Category:1794 births|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

[[Category:1858 deaths|Perry, Matthew (naval officer)]] |

|||

[[Category:Deaths from cirrhosis|Perry, Matthew C.]] |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Perry, Matthew (Naval Officer)}} |

|||

[[ca:Matthew Perry]] |

|||

[[Category:1794 births]] |

|||

[[cs:Matthew Calbraith Perry]] |

|||

[[Category:1858 deaths]] |

|||

[[de:Matthew Calbraith Perry]] |

|||

[[Category:United States Navy commodores]] |

|||

[[es:Matthew Perry (militar)]] |

|||

[[Category:American people of English descent]] |

|||

[[fr:Matthew Perry (militaire)]] |

|||

[[Category:American people of Scottish descent]] |

|||

[[ko:매튜 캘브레이스 페리]] |

|||

[[Category:1850s in Japan]] |

|||

[[ja:マシュー・ペリー]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Key West, Florida]] |

|||

[[pl:Matthew Perry (oficer)]] |

|||

[[Category:Meiji Restoration]] |

|||

[[ru:Перри, Мэттью (морской офицер)]] |

|||

[[Category:Military personnel from Newport, Rhode Island]] |

|||

[[fi:Matthew Perry (upseeri)]] |

|||

[[Category:Military personnel from New York City]] |

|||

[[sv:Matthew Calbraith Perry]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Briarcliff Manor, New York]] |

|||

[[tr:Matthew Calbraith Perry]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Rhode Island in the War of 1812]] |

|||

[[zh:马休·佩里]] |

|||

[[Category:Perry family|Matthew C]] |

|||

[[Category:United States Navy admirals]] |

|||

[[Category:19th-century American naval officers]] |

|||

[[Category:Foreign relations of the Tokugawa shogunate]] |

|||

[[Category:American Freemasons]] |

|||

[[Category:People from South Kingstown, Rhode Island]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 14:37, 19 December 2024

Matthew C. Perry | |

|---|---|

Perry c. 1856–1858 | |

| Commander of the East India Squadron | |

| In office November 20, 1852 – September 6, 1854 | |

| Preceded by | John H. Aulick |

| Succeeded by | Joel Abbot |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Matthew Calbraith Perry April 10, 1794[1] Newport, Rhode Island, U.S. |

| Died | March 4, 1858 (aged 63) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 10 |

| Parents |

|

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Navy |

| Years of service | 1809–1858 |

| Rank | Commodore |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | |

Matthew C. Perry | |

|---|---|

| Scientific career | |

| Author abbrev. (botany) | Perry |

Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a United States Navy officer who commanded ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War. He played a leading role in the Perry Expedition that ended Japan's isolationism and the Convention of Kanagawa between Japan and the United States in 1854.

Perry was interested in the education of naval officers and assisted in the development of an apprentice system that helped establish the curriculum at the United States Naval Academy. With the advent of the steam engine, he became a leading advocate of modernizing the U.S. Navy and came to be considered "The Father of the Steam Navy" in the United States.

Lineage

[edit]Matthew Perry was a member of the Perry family, a son of Sarah Wallace (née Alexander) (1768–1830) and Navy Captain Christopher Raymond Perry (1761–1818). He was born April 10, 1794, in South Kingstown, Rhode Island. His siblings included Oliver Hazard Perry, Raymond Henry Jones Perry, Sarah Wallace Perry, Anna Marie Perry (mother of George Washington Rodgers), James Alexander Perry, Nathaniel Hazard Perry, and Jane Tweedy Perry (who married William Butler).

His mother was born in County Down, Ireland and was a descendant of an uncle of William Wallace,[2]: 54 the Scottish knight and landowner.[3][4] His paternal grandparents were James Freeman Perry, a surgeon, and Mercy Hazard,[5] a descendant of Governor Thomas Prence, a co-founder of Eastham, Massachusetts, who was a political leader in both the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay colonies, and governor of Plymouth; and a descendant of Mayflower passengers, both of whom were signers of the Mayflower Compact, Elder William Brewster, the Pilgrim colonist leader and spiritual elder of the Plymouth Colony, and George Soule, through Susannah Barber Perry.[6]

Naval career

[edit]In 1809, Perry received a midshipman's warrant in the Navy and was initially assigned to USS Revenge, under the command of his elder brother. He was then assigned to USS President, where he served as an aide to Commodore John Rodgers. President attacked a British Royal Navy warship, HMS Little Belt in the lead-up to the War of 1812. Perry continued aboard President during the War of 1812 and was present at the engagement with HMS Belvidera.[7]

Rodgers fired the first shot of the war at Belvidera. A later shot resulted in a cannon bursting, killing several men and wounding Rodgers, Perry and others.[8] Perry transferred to USS United States, commanded by Stephen Decatur, and saw little fighting in the war afterwards, since the ship was trapped in port at New London, Connecticut.

Following the signing of the Treaty of Ghent which ended the war, Perry served on various vessels in the Mediterranean Sea. Perry served under Commodore William Bainbridge during the Second Barbary War. He then served in African waters aboard USS Cyane during its patrol off Liberia from 1819 to 1820. After that cruise, Perry was sent to suppress piracy and the slave trade in the West Indies.

Opening of Key West

[edit]From 1821 to 1825, Perry placed in commission and commanded USS Shark, a schooner with 12 guns. He deployed to the West Africa Station to support the American and British joint patrols to suppress the slave trade.[9]

In 1815, the Spanish governor in Havana deeded the island of Key West to Juan Pablo Salas of St. Augustine in Spanish Florida. After Florida was transferred to the United States, Salas sold Key West to American businessman John W. Simonton for $2,000 in 1821. Simonton lobbied Washington to establish a naval base on Key West, both to take advantage of its strategic location and to bring law and order to the area.

On March 25, 1822, Perry sailed Shark to Key West and planted the U.S. flag, physically claiming the Florida Keys as United States territory. Perry renamed Cayo Hueso "Thompson's Island" for the Secretary of the Navy Smith Thompson and the harbor "Port Rodgers" for the president of the Board of Navy Commissioners. Neither name stuck however.

From 1826 to 1827, Perry acted as fleet captain for Commodore Rodgers. In 1828, Perry returned to Charleston, South Carolina, for shore duty. In 1830, he took command of a sloop-of-war, USS Concord. During this period, while in port in Russian Kronstadt, Perry was offered a commission in the Imperial Russian Navy, which he declined.

He spent 1833 to 1837 as second officer of the New York Navy Yard, later the Brooklyn Navy Yard, gaining a promotion to captain at the end of this tour.

Father of the Steam Navy

[edit]

Perry had an ardent interest in and saw the need for naval education, supporting an apprentice system to train new seamen, and helped establish the curriculum for the United States Naval Academy. He was a vocal proponent of modernizing the Navy. Once promoted to captain, he oversaw construction of the Navy's second steam frigate USS Fulton, which he commanded after its completion.

He was called "The Father of the Steam Navy",[10] and he organized America's first corps of naval engineers. Perry conducted the first U.S. naval gunnery school while commanding Fulton from 1839 to 1841 off Sandy Hook on the New Jersey coast.

Promotion to commodore

[edit]In 1841, Perry received the title of commodore, when the Secretary of the Navy appointed him commandant of New York Navy Yard.[11] The United States Navy did not have ranks higher than captain until 1857, so the title of commodore carried considerable importance. Officially, an officer would revert to his permanent rank after the squadron command assignment had ended, although in practice officers who received the title of commodore retained the title for life, as did Perry.

During his tenure in Brooklyn, he lived in Quarters A in Vinegar Hill, a building which still stands today.[12] In 1843, Perry took command of the Africa Squadron, whose duty was to interdict the slave trade under the Webster-Ashburton Treaty, and continued in this endeavor to 1844.

Mexican–American War

[edit]

In 1845, Commodore David Conner's length of service in command of the Home Squadron had come to an end. However, the coming of the Mexican–American War persuaded the authorities not to change commanders in the face of the war. Perry, who eventually succeeded Conner, was made second-in-command and captained USS Mississippi. Perry captured the Mexican city of Frontera, demonstrated against Tabasco, being defeated in San Juan Bautista by Colonel Juan Bautista Traconis in the First Battle of Tabasco, and took part in the capture of Tampico on November 14, 1846.

Perry had to return to Norfolk, Virginia, to make repairs and was there when the amphibious landings at Veracruz took place. His return to the U.S. gave his superiors the chance to give him orders to succeed Commodore Conner in command of the Home Squadron. Perry returned to the fleet, and his ship supported the siege of Veracruz from the sea.[13]

After the fall of Veracruz, Winfield Scott moved inland, and Perry moved against the remaining Mexican port cities. Perry assembled the Mosquito Fleet and captured Tuxpan in April 1847. In June 1847 he attacked Tabasco personally, leading a 1,173-man landing force ashore and attacking the city of San Juan Bautista from land, defeating the Mexican forces and taking the city.[14]

In 1847, Perry was elected as an honorary member of the New York Society of the Cincinnati in recognition of his achievements during the Mexican War.

Perry Expedition: opening of Japan, 1852–1854

[edit]

In 1852, Perry was assigned a mission by American President Millard Fillmore to force the opening of Japanese ports to American trade, through the use of gunboat diplomacy if necessary.[15] The growing commerce between the United States and China, the presence of American whalers in waters offshore Japan, and the increasing monopolization of potential coaling stations by European powers in Asia were all contributing factors. Shipwrecked foreign sailors were either imprisoned or executed,[16][17][18] and the safe return of such persons was one demand.

The Americans were also driven by concepts of manifest destiny and the desire to impose the benefits of western civilization and the Christian religion on what they perceived as backward Asian nations.[19] The Japanese were forewarned by the Dutch of Perry's voyage but were unwilling to change their 250-year-old policy of national seclusion.[19] There was considerable internal debate in Japan on how best to meet this potential threat to Japan's economic and political sovereignty.

On November 24, 1852, Perry embarked from Norfolk, Virginia, for Japan, in command of the East India Squadron in pursuit of a Japanese trade treaty. He chose the paddle-wheeled steam frigate Mississippi as his flagship and made port calls at Madeira (December 11–15), Saint Helena (January 10–11), Cape Town (January 24 – February 3), Mauritius (February 18–28), Ceylon (March 10–15), Singapore (March 25–29), Macao and Hong Kong (April 7–28).

In Hong Kong he met with American-born Sinologist Samuel Wells Williams, who provided Chinese language translations of his official letters, and where he rendezvoused with Plymouth. He continued to Shanghai (May 4–17), where he met with the Dutch-born American diplomat, Anton L. C. Portman, who translated his official letters into the Dutch language, and where he rendezvoused with Susquehanna.

Perry then switched his flag to Susquehanna and made call at Naha on Great Lewchew Island (Ryukyu, now Okinawa) from May 17–26. Ignoring the claims of Satsuma Domain to the islands, he demanded an audience with the Ryukyuan King Shō Tai at Shuri Castle and secured promises that the Ryukyu Kingdom would be open to trade with the United States. Continuing on to the Ogasawara islands in mid-June, Perry met with the local inhabitants and purchased a plot of land.[20]

First visit (1853)

[edit]Perry reached Uraga at the entrance to Edo Bay in Japan on July 8, 1853. His actions at this crucial juncture were informed by a careful study of Japan's previous contacts with Western ships and what he knew about the Japanese hierarchical culture. As he arrived, Perry ordered his ships to steam past Japanese lines towards the capital of Edo and turn their guns towards the town of Uraga.[21] Perry refused Japanese demands to leave or to proceed to Nagasaki, the only Japanese port open to foreigners.[21]

Perry attempted to intimidate the Japanese by presenting them a white flag and a letter which told them that in case they chose to fight, the Americans would destroy them.[22][23] He also fired blank shots from his 73 cannon, which he claimed was in celebration of the American Independence Day. Perry's ships were equipped with new Paixhans shell guns, cannons capable of wreaking great explosive destruction with every shell.[24][25] He also ordered his ship boats to commence survey operations of the coastline and surrounding waters over the objections of local officials.

Meanwhile, shōgun Tokugawa Ieyoshi was ill and incapacitated, which resulted in governmental indecision on how to handle the unprecedented threat to the nation's capital. On July 11, Rōjū Abe Masahiro bided his time, deciding that simply accepting a letter from the Americans would not constitute a violation of Japanese sovereignty. The decision was conveyed to Uraga, and Perry was asked to move his fleet slightly southwest to the beach at Kurihama where he was allowed to land on July 14, 1853.[26] After presenting the letter to attending delegates, Perry departed for Hong Kong, promising to return the following year for the Japanese reply.[27]

Second visit (1854)

[edit]

On his way back to Japan, Perry anchored off Keelung in Formosa, known today as Taiwan, for ten days. Perry and crewmembers landed on Formosa and investigated the potential of mining the coal deposits in that area. He emphasized in his reports that Formosa provided a convenient, mid-way trade location. Perry's reports noted that the island was very defensible and could serve as a base for exploration in a similar way that Cuba had done for the Spanish in the Americas. Occupying Formosa could help the United States counter European monopolization of the major trade routes. The United States government failed to respond to Perry's proposal to claim sovereignty over Formosa.

To command his fleet, Perry chose officers with whom he had served in the Mexican–American War. Commander Franklin Buchanan was captain of Susquehanna. Joel Abbot, Perry's second in command, was captain of Macedonian. Commander Henry A. Adams was chief of staff with the title "Captain of the Fleet". Major Jacob Zeilin, future commandant of the United States Marine Corps, was the ranking Marine officer and was stationed on Mississippi.

Perry returned on February 13, 1854, after only half a year rather than the full year promised, and with ten ships and 1,600 men. American leadership designed the show of force to "command fear" and "astound the Orientals."[28]: 31 After initial resistance, Perry was permitted to land at Kanagawa, near the site of present-day Yokohama on March 8. The Convention of Kanagawa was signed on March 31. Perry signed as American plenipotentiary, and Hayashi Akira, also known by his title of Daigaku-no-kami, signed for the Japanese side. The celebratory events for the signing ceremony included a Kabuki play from the Japanese side and, from the American side, U.S. military band music and blackface minstrelsy.[28]: 32–33

Perry departed, mistakenly believing the agreement had been made with imperial representatives, not understanding the true position of the shōgun, the de facto ruler of Japan.[29] Perry then visited Hakodate on the northern island of Hokkaido and Shimoda, the two ports which the treaty stipulated would be opened to visits by American ships. A handscroll with pictorial record from the Japanese side of US Commodore Matthew Perry's second visit to Japan in 1854 is retained in the British Museum in London.[30]

Return to the United States (1855)

[edit]When Perry returned to the United States, Congress voted to grant him a reward of $20,000, equivalent to $520,000 in 2023, in appreciation of his work in Japan. He used part of this money to prepare and publish a report on the expedition in three volumes, titled Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan. He was promoted to rear admiral on the retired list when his health began to fail, as a reward for his service in the Far East.[31]

Last years

[edit]Living in his adopted home of New York City, Perry's health began to fail as he suffered from cirrhosis of the liver from heavy drinking. Perry was known to have been an alcoholic, which compounded the health complications leading to his death.[32] He also suffered severe arthritis that left him in frequent pain, and on occasion precluded him from his duties.[33]

Perry spent his last years preparing for the publication of his account of the Japan expedition, announcing its completion on December 28, 1857. Two days later he was detached from his last post, an assignment to the Naval Efficiency Board. He died awaiting further orders on March 4, 1858, in New York City, of rheumatic fever that had spread to the heart, compounded by complications of gout and alcoholism.[34]