Ashcan School: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

added Sloan's "A Woman's Work" to list of works showing washing hung out to dry |

||

| (340 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American art movement}} |

|||

[[Image:Stamp-ctc-ash-can-school.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The Ash Can Painters were honored on a series of American commemorative stamps. This image: George Bellows' ''Stag at Sharkey's''.]] |

|||

[[File:Self-Portrait Sloan.jpg|thumb|[[John French Sloan]], ''[[Self-portrait]]'', 1890, oil on window shade, 14 × {{Frac|11|7|8}} inches, [[Delaware Art Museum]], gift of Helen Farr Sloan, 1970. John Sloan was a leading member of the Ashcan School.]] |

|||

{{Redirect|The Eight|the novel by Katherine Neville|The Eight (novel)}} |

|||

The '''Ashcan School''', also called the '''Ash Can School''', was an [[art movement|artistic movement]] in the [[United States]] during the late 19th-early 20th century<ref>{{cite web| url = https://fristartmuseum.org/news/detail/ashcan-school-exhibition1| title = Ashcan School Exhibition| date = 13 July 2007| publisher = First Art Museum| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200726101029/https://fristartmuseum.org/news/detail/ashcan-school-exhibition1| archive-date=26 July 2020 }}</ref> that produced works portraying scenes of daily life in [[New York City|New York]], often in the city's poorer neighborhoods. |

|||

The '''Ash Can School''', sometimes contracted as the ''Ashcan School'', is defined as a [[Realism (visual arts)|realist]] [[art]]istic movement that came into prominence in the [[United States]] during the early [[twentieth century]], best known for works portraying scenes of daily life in poor urban neighborhoods. The movement is most associated with a group known as '''''The Eight''''', or '''''The Ash Can Painters''''', whose members were [[Robert Henri]], [[Arthur B. Davies]], [[Maurice Prendergast]], [[Ernest Lawson]], [[William Glackens]], [[Everett Shinn]], [[John French Sloan]], and [[George Luks]]. ''The Eight'' exhibited as a group only once, at the [[Macbeth Gallery]] in 1908, but they are still remembered as a group, despite the fact that their work was very diverse in terms of style and subject matter. |

|||

The artists working in this style included [[Robert Henri]] (1865–1929), [[George Luks]] (1867–1933), [[William Glackens]] (1870–1938), [[John French Sloan|John Sloan]] (1871–1951), and [[Everett Shinn]] (1876–1953). Some of them met studying together under the renowned realist [[Thomas Anshutz]] at the [[Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts]]; others met in the newspaper offices of Philadelphia where they worked as illustrators. [[Theresa Bernstein]], who studied at the [[Philadelphia School of Design for Women]], was also a part of the Ashcan School. She was friends with many of its better-known members, including Sloan with whom she co-founded the [[Society of Independent Artists]]. |

|||

Most of the work from Ashcan display common motifs: |

|||

The movement, which took some inspiration from [[Walt Whitman]]'s epic poem ''[[Leaves of Grass]]'', has been seen as emblematic of the spirit of political rebellion of the period.<ref name="Jeansonne1997">{{cite book|author=Glen Jeansonne|title=Women of the Far Right: The Mothers' Movement and World War II|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B7JZoQuU3eMC&pg=PA22|date=9 June 1997|publisher=[[University of Chicago Press]]|isbn=978-0-226-39589-0|page=4}}</ref> |

|||

1. Gritty urban scenes |

|||

2. Portrayal of urban vitality |

|||

3. Capture the spontaneous moments in life |

|||

4. Illustrated the press of Americanism |

|||

5. Rebelled against the storybook landscapes of the past era |

|||

==Origin and development== |

|||

As noted, the Ash Can School was not an organized group, but rather the term was applied later to a group of artists, including Henri, Glackens, [[Edward Hopper]] (a student of Henri), Shinn, Sloan, Luks, [[George Bellows]] (another student of Henri), Mabel Dwight, and others such as photographer [[Jacob Riis]], who portrayed urban subject matter, also primarily of [[New York]]'s poorer neighborhoods. It was this frequent, although not total, focus upon [[poverty]] and the daily realities of urban life at that time that prompted critics to consider them on the fringe of [[modern art|''modern'' art]]. Everyday life in the city was dealt with, not only as ''art'', but as a contemporary standard of beauty, rendered in the somber palette observed in the [[city]]. |

|||

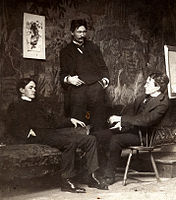

[[Image:John French Sloan Studio.jpg|300px|thumb|left|Ashcan School artists and friends at John French Sloan's Philadelphia Studio, 1898]] |

|||

The Ashcan School was not an organized movement. The artists who worked in this style did not issue manifestos or even see themselves as a unified group with identical intentions or career goals. Some of the artists were politically minded, and others were apolitical. Their unity consisted of a desire to tell certain truths about the city and modern life they felt had been ignored by the suffocating influence of the Genteel Tradition in the visual arts. [[Robert Henri]], in some ways the spiritual father of this school, "wanted art to be akin to journalism... he wanted paint to be as real as mud, as the clods of horse-shit and snow, that froze on Broadway in the winter."<ref>Robert Hughes, ''[[American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America|American Visions]]'' BBC-TV series (ep.5 - "The Wave From The Atlantic")</ref> He urged his younger friends and students to paint in the robust, unfettered, ungenteel spirit of his favorite poet, [[Walt Whitman]], and to be unafraid of offending contemporary taste. He believed that working-class and middle-class urban settings would provide better material for modern painters than drawing rooms and salons. Having been to Paris and admired the works of [[Édouard Manet]], Henri also urged his students to ‘’paint the everyday world in America just as it had been done in France.’’<ref>{{cite web|title=Art From the Alleys|url= https://www.theattic.space/home-page-blogs/2019/3/8/863oskx8xdzdahgh8b4gmtaaahookq |website=The Attic|access-date=19 March 2019}}</ref> By 1904, all of the artists relocated to New York.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.metmuseum.org/articles/ashcan-school|title=The Aschcan School, The Eight, and the New York Art World|author=Sylvia Yount|publisher=[[Metropolitan Museum of Art]]|date=2015-05-26|accessdate=2024-04-05}}</ref> |

|||

The name "Ashcan school" is a [[tongue-in-cheek]] reference to other "schools of art". (For examples of other "schools of art" see [[:Category:Italian art movements]] e.g. [[Lucchese School]] and for instance [[School of Paris]].) Its origin is in a complaint found in a radical socialist publication called ''[[The Masses]]'' in March 1916 by the cartoonist Art Young, alleging that there were too many "pictures of ashcans and girls hitching up their skirts on Horatio Street." That particular reference was published in ''The Masses'' at a point at which the artists had already been working together for several years. They were amused by the reference and the name soon lost its negative connotations.<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-1010/art-between-wars/american-art-wwii/a/the-ashcan-school-an-introduction| title = The Ashcan School, an introduction| last = Khalid| first = Farisa| publisher = Khan Academy }}</ref><ref name="NYTimes">{{cite web|url= https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/28/arts/design/28sloa.html?searchResultPosition=4|title=Ashcan Views of New Yorkers, Warts, High Spirits and All|author=Ken Johnson|work=The New York Times|date=2007-12-28|accessdate=2024-04-05}}</ref><ref name="Jackson">{{cite book|title=The Encyclopedia of New York City|author=Kennet T. Jackson|publisher=Yale University|year=1995|pages=60|isbn=0 300 05536 6}}</ref> The Ashcan School of artists had also been known as "The Apostles of Ugliness".<ref name="Dempsey">''Art in the modern era: A guide to styles, schools, & movements'', [[Amy Dempsey]], Abrams, 2002. (U.S. edition of ''Styles, Schools and Movements'') {{ISBN|978-0810941724}}</ref> The term Ashcan School was originally applied in derision. The school is not so much known for innovations in technique but more for its subject matter. Common subjects were prostitutes and street urchins. The work of the Ashcan painters links them to such documentary photographers as [[Jacob Riis]] and [[Lewis W. Hine]]. Several Ashcan School painters derived from the area of print publication at a time before photography replaced hand-drawn illustrations in newspapers. They were involved in journalistic pictorial reportage before concentrating their energies on painting. [[George Luks]] once proclaimed "I can paint with a shoestring dipped in pitch and lard." In the mid-1890s Robert Henri returned to Philadelphia from Paris very unimpressed by the work of the [[Post-Impressionism|late Impressionists]] and with a determination to create a type of art that engaged with life.<ref name="Dempsey"/> He attempted to imbue several other artists with this passion. The school has even been referred to as "the revolutionary black gang", a reference to the artists' dark [[Palette (painting)|palette]]. The group was subject to attacks in the press and one of their earliest exhibitions, in 1908 at New York's [[Macbeth Gallery]], was a success.<ref name="Dempsey"/> Since then to 1913, they would go on to participate in several key exhibitions of progressive art in New York.<ref name="NYTimes"/> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

[[Category:Art movements]] |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

Many of the most famous Ashcan works were painted in the first decade of the century at the same time in which the realist fiction of [[Stephen Crane]], [[Theodore Dreiser]], and [[Frank Norris]] was finding its audience and the muckraking journalists were calling attention to slum conditions.<ref>[[Sam Hunter (art historian)|Sam Hunter]], ''Modern American Painting and Sculpture'' (New York: Dell, 1959), 28–40.</ref> The first known use of the term "ash can art" is credited to artist [[Art Young]] in 1916.<ref>John Loughery, ''John Sloan: Painter and Rebel'' (New York: Henry Holt, 1997), pp. 218–219</ref> The term by that time was applied to a large number of painters beyond the original "Philadelphia Five," including [[George Bellows]], Glenn O. Coleman, [[Jerome Myers]], [[Gifford Beal]], Eugene Higgins, [[Carl Sprinchorn]] and [[Edward Hopper]]. (Despite his inclusion in the group by some critics, Hopper rejected their focus and never embraced the label; his depictions of city streets were painted in a different spirit, "with not a single incidental ashcan in sight.")<ref>Wells, Walter, ''Silent Theater: The Art of Edward Hopper'' (London/New York: Phaidon, 2007).</ref> Photographers like [[Jacob Riis]] and [[Lewis Hine]] were also discussed as Ashcan artists. Like many art-historical terms, "Ashcan art" has sometimes been applied to so many different artists that its meaning has become diluted. |

|||

{{art-movement-stub}} |

|||

The artists of the Ashcan School rebelled against both [[American Impressionism]] and academic realism, the two most respected and commercially successful styles in the US at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. In contrast to the highly polished work of artists like [[John Singer Sargent]], [[William Merritt Chase]], [[Kenyon Cox]], [[Thomas Wilmer Dewing]], and [[Abbott Thayer]], Ashcan works were generally darker in tone and more roughly painted. Many captured the harsher moments of modern life, portraying street kids (e.g., Henri's ''Willie Gee'' and Bellows' ''Paddy Flannagan''), prostitutes (e.g., Sloan's ''The Haymarket'' and ''Three A.M.''), alcoholics (e.g., Luks' ''The Old Duchess''), indecorous animals (e.g., Luks' ''Feeding the Pigs'' and ''Woman with Goose''), subways (e.g., Shinn's ''Sixth Avenue Elevated After Midnight''), crowded tenements (e.g., Bellows' ''[[Cliff Dwellers (painting)|Cliff Dwellers]]''), washing hung out to dry (Shinn's ''The Laundress'' and Sloan's ''A Woman's Work''), boisterous theaters (e.g., Glackens' ''Hammerstein's Roof Garden'' and Shinn's ''London Hippodrome''), bloodied boxers (e.g., Bellows' ''[[Both Members of This Club]]''), and wrestlers on the mat (e.g., Luks' ''[[The Wrestlers (Luks)|The Wrestlers]]''). It was their frequent, although not exclusive, focus upon poverty and the gritty realities of urban life that prompted some critics and curators to consider them too unsettling for mainstream audiences and collections. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[fa:مکتب واقعگری آمریکا]] |

|||

The advent of [[modernism in the United States]] spelled the end of the Ashcan school's provocative reputation. With the [[Armory Show]] of 1913 and the opening of more galleries in the 1910s promoting the work of [[Cubists]], [[Fauvism|Fauves]], and [[Expressionists]], Henri and his circle began to appear tame to a younger generation. Their rebellion was over not long after it began. It was the fate of the Ashcan realists to be seen by many art lovers as too radical in 1910 and, by many more, as old-fashioned by 1920. |

|||

[[fr:Ash Can School]] |

|||

[[he:אסכולת אש קאן]] |

|||

==Connection to "The Eight"== |

|||

[[sr:Ешкан школа]] |

|||

{{See also|Robert Henri#The Eight}} |

|||

The Ashcan school is sometimes linked to the group known as "The Eight", though in fact only five members of that group (Henri, Sloan, Glackens, Luks, and Shinn) were Ashcan artists.<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/now-at-the-met/2015/ashcan-school| title = The Ashcan School, The Eight, and the New York Art World| last = Yount| first = Sylvia| date = 26 May 2015| publisher = The Metropolitan Museum of Art}}</ref> The other three – [[Arthur B. Davies]], [[Ernest Lawson]], and [[Maurice Prendergast]] – painted in a very different style, and the exhibition that brought "The Eight" to national attention took place in 1908, several years after the beginning of the Ashcan style. However, the attention accorded the group's well-publicized exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries in New York 1908 was such that Ashcan art gained wider exposure and greater sales and critical attention than it had known before. |

|||

The Macbeth Galleries exhibition was held to protest the restrictive exhibition policies of the powerful, conservative [[National Academy of Design]] and to broadcast the need for wider opportunities to display new art of a more diverse, adventurous quality than the Academy generally permitted. When the exhibition closed in New York, where it attracted considerable attention, it toured Chicago, Toledo, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, Bridgeport, and Newark in a traveling show organized by John Sloan.<ref>Loughery, p. 127, 134–140.</ref> Reviews were mixed, but interest was high. ("Big Sensation at the Art Museum, Visitors Join Throng Museum and Join Hot Discussion," one Ohio newspaper noted.)<ref>Loughery, p. 135.</ref> As art historian Judith Zilczer summarized the venture, "In taking their art directly to the American public, The Eight demonstrated that cultural provincialism in the United States was less pervasive than contemporary and subsequent accounts of the period had inferred."<ref>Judith Zilczer, "The Eight on Tour," ''American Art Journal,'' 16, no. 3 (Summer 1984), p. 38.</ref> Sales and exhibition opportunities for these painters increased significantly in the ensuing years. |

|||

==Gallery== |

|||

<gallery widths="200px" heights="200px" perrow="4"> |

|||

File:Shinn Henri Sloan.jpg|Ashcan School artists, c. 1896, left to right, [[Everett Shinn]], [[Robert Henri]], [[John French Sloan]] |

|||

File:Anschutz Thomas P The Farmer and His Son at Harvesting.jpg|[[Thomas Pollock Anshutz]], ''The Farmer and His Son at Harvesting'', 1879. Five members of the Ashcan School studied with him, but went on to create quite different styles. |

|||

File:Snow in New York.jpg|[[Robert Henri]], ''Snow in New York'', 1902, [[National Gallery of Art]], [[Washington, DC]] |

|||

File:George Luks. Street Scene (Hester Street),40.339.jpg|[[George Luks]], ''Street Scene'', 1905, [[Brooklyn Museum]] |

|||

File:crossstreetsofnewyork.JPG|[[Everett Shinn]], ''Cross Streets of New York'', 1899, [[Corcoran Gallery of Art]], Washington, DC. |

|||

File:William Glackens - Italo-American Celebration, Washington Square.JPG|[[William Glackens]], ''Italo-American Celebration, [[Washington Square Park|Washington Square]]'', 1912, [[Boston Museum of Fine Arts]] |

|||

File:McSorley's Bar 1912 John Sloan.jpg|[[John French Sloan]], ''[[McSorley's Old Ale House|McSorley's Bar]]'', 1912, [[Detroit Institute of Arts]] |

|||

File:George Luks - Houston Street.jpg|[[George Luks]], ''[[Houston Street (Manhattan)|Houston Street]]'', 1917, oil on canvas, [[Saint Louis Art Museum]] |

|||

File:Bellows CliffDwellers.jpg|[[George Bellows]], ''[[Cliff Dwellers (painting)|Cliff Dwellers]]'', 1913, oil on canvas. [[Los Angeles County Museum of Art]] |

|||

File:Both Members of This Club George Bellows.jpeg|[[George Bellows]], ''Both Members of This Club'', 1909, [[National Gallery of Art]]. Bellows was a close associate of the Ashcan school and had studied under Robert Henri. |

|||

File:Bandits Roost, 59 and a half Mulberry Street.jpg|[[Jacob Riis]], ''Bandit's Roost'', 1888, (photo), considered the most crime-ridden, dangerous part of New York City. |

|||

File:Arthur B. Davies - Elysian Fields - Google Art Project.jpg|[[Arthur B. Davies]], ''Elysian Fields,'' oil on canvas, [[The Phillips Collection]] [[Washington, DC.]] |

|||

File:Maurice Brazil Prendergast 001.jpg|[[Maurice Prendergast]], ''[[Central Park]], New York'', 1901, [[Whitney Museum of American Art]] |

|||

George Bellows - Men of the Docks - 1912 - The National Gallery.jpg|[[George Bellows]], ''[[Men of the Docks]]'', 1912, [[National Gallery|National Gallery, London]] |

|||

File:Brooklyn Museum - Pennsylvania Station Excavation - George Wesley Bellows - overall.jpg|''[[Pennsylvania Station (1910–1963)|Pennsylvania Station]] Excavation'' by [[George Bellows]], c. 1907–08, [[Brooklyn Museum]] |

|||

File:Edward Hopper, New York Interior, c. 1921 1 15 18 -whitneymuseum (40015892594).jpg|[[Edward Hopper]], ''New York Interior'', c. 1921, [[Whitney Museum of American Art]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*[[Realism (visual arts)]] |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

==Sources== |

|||

* Brown, Milton. ''American Painting from the Armory Show to the Depression.'' Princeton: [[Princeton University Press]], 1955. |

|||

* Brooks, Van Wyck. ''John Sloan: A Painter's Life.'' New York: Dutton, 1955. |

|||

* Doezema, Marianne. ''George Bellows and Urban America.'' New Haven: [[Yale University Press]], 1992. |

|||

* Glackens, Ira. ''William Glackens and the Ashcan School: The Emergence of Realism in American Art.'' New York: Crown, 1957. |

|||

* Homer, William Innes. ''Robert Henri and His Circle.'' Ithaca: [[Cornell University Press]], 1969. |

|||

* Hughes, Robert. ''American Visions: The Epic Story of Art in America.'' New York: Knopf, 1997. |

|||

* Hunter, Sam. ''Modern American Painting and Sculpture.'' New York: Dell, 1959. |

|||

* Kennedy, Elizabeth (ed.). ''The Eight and American Modernisms.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009. |

|||

* Loughery, John. ''John Sloan: Painter and Rebel''. New York: Henry Holt, 1997. {{ISBN|0-8050-5221-6}} |

|||

* Perlman, Bennard (ed.), introduction by Mrs. John Sloan. ''Revolutionaries of Realism: The Letters of John Sloan and Robert Henri.'' Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997. |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Commons category|Ashcan School}} |

|||

* [http://gildedage2.omeka.net/exhibits/show/highlights/movements/eight Documenting the Gilded Age: New York City Exhibitions at the Turn of the 20th Century] A [[New York Art Resources Consortium]] project. Exhibition catalogs, checklists, and photoarchive material. |

|||

* [https://exchange.umma.umich.edu/resources/23640 Collection: "Ashcan School"] from the [[University of Michigan Museum of Art]] |

|||

{{Western art movements}} |

|||

{{Portal bar|Society|United States}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

Latest revision as of 21:39, 18 November 2024

The Ashcan School, also called the Ash Can School, was an artistic movement in the United States during the late 19th-early 20th century[1] that produced works portraying scenes of daily life in New York, often in the city's poorer neighborhoods.

The artists working in this style included Robert Henri (1865–1929), George Luks (1867–1933), William Glackens (1870–1938), John Sloan (1871–1951), and Everett Shinn (1876–1953). Some of them met studying together under the renowned realist Thomas Anshutz at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts; others met in the newspaper offices of Philadelphia where they worked as illustrators. Theresa Bernstein, who studied at the Philadelphia School of Design for Women, was also a part of the Ashcan School. She was friends with many of its better-known members, including Sloan with whom she co-founded the Society of Independent Artists.

The movement, which took some inspiration from Walt Whitman's epic poem Leaves of Grass, has been seen as emblematic of the spirit of political rebellion of the period.[2]

Origin and development

[edit]

The Ashcan School was not an organized movement. The artists who worked in this style did not issue manifestos or even see themselves as a unified group with identical intentions or career goals. Some of the artists were politically minded, and others were apolitical. Their unity consisted of a desire to tell certain truths about the city and modern life they felt had been ignored by the suffocating influence of the Genteel Tradition in the visual arts. Robert Henri, in some ways the spiritual father of this school, "wanted art to be akin to journalism... he wanted paint to be as real as mud, as the clods of horse-shit and snow, that froze on Broadway in the winter."[3] He urged his younger friends and students to paint in the robust, unfettered, ungenteel spirit of his favorite poet, Walt Whitman, and to be unafraid of offending contemporary taste. He believed that working-class and middle-class urban settings would provide better material for modern painters than drawing rooms and salons. Having been to Paris and admired the works of Édouard Manet, Henri also urged his students to ‘’paint the everyday world in America just as it had been done in France.’’[4] By 1904, all of the artists relocated to New York.[5]

The name "Ashcan school" is a tongue-in-cheek reference to other "schools of art". (For examples of other "schools of art" see Category:Italian art movements e.g. Lucchese School and for instance School of Paris.) Its origin is in a complaint found in a radical socialist publication called The Masses in March 1916 by the cartoonist Art Young, alleging that there were too many "pictures of ashcans and girls hitching up their skirts on Horatio Street." That particular reference was published in The Masses at a point at which the artists had already been working together for several years. They were amused by the reference and the name soon lost its negative connotations.[6][7][8] The Ashcan School of artists had also been known as "The Apostles of Ugliness".[9] The term Ashcan School was originally applied in derision. The school is not so much known for innovations in technique but more for its subject matter. Common subjects were prostitutes and street urchins. The work of the Ashcan painters links them to such documentary photographers as Jacob Riis and Lewis W. Hine. Several Ashcan School painters derived from the area of print publication at a time before photography replaced hand-drawn illustrations in newspapers. They were involved in journalistic pictorial reportage before concentrating their energies on painting. George Luks once proclaimed "I can paint with a shoestring dipped in pitch and lard." In the mid-1890s Robert Henri returned to Philadelphia from Paris very unimpressed by the work of the late Impressionists and with a determination to create a type of art that engaged with life.[9] He attempted to imbue several other artists with this passion. The school has even been referred to as "the revolutionary black gang", a reference to the artists' dark palette. The group was subject to attacks in the press and one of their earliest exhibitions, in 1908 at New York's Macbeth Gallery, was a success.[9] Since then to 1913, they would go on to participate in several key exhibitions of progressive art in New York.[7]

Many of the most famous Ashcan works were painted in the first decade of the century at the same time in which the realist fiction of Stephen Crane, Theodore Dreiser, and Frank Norris was finding its audience and the muckraking journalists were calling attention to slum conditions.[10] The first known use of the term "ash can art" is credited to artist Art Young in 1916.[11] The term by that time was applied to a large number of painters beyond the original "Philadelphia Five," including George Bellows, Glenn O. Coleman, Jerome Myers, Gifford Beal, Eugene Higgins, Carl Sprinchorn and Edward Hopper. (Despite his inclusion in the group by some critics, Hopper rejected their focus and never embraced the label; his depictions of city streets were painted in a different spirit, "with not a single incidental ashcan in sight.")[12] Photographers like Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine were also discussed as Ashcan artists. Like many art-historical terms, "Ashcan art" has sometimes been applied to so many different artists that its meaning has become diluted.

The artists of the Ashcan School rebelled against both American Impressionism and academic realism, the two most respected and commercially successful styles in the US at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. In contrast to the highly polished work of artists like John Singer Sargent, William Merritt Chase, Kenyon Cox, Thomas Wilmer Dewing, and Abbott Thayer, Ashcan works were generally darker in tone and more roughly painted. Many captured the harsher moments of modern life, portraying street kids (e.g., Henri's Willie Gee and Bellows' Paddy Flannagan), prostitutes (e.g., Sloan's The Haymarket and Three A.M.), alcoholics (e.g., Luks' The Old Duchess), indecorous animals (e.g., Luks' Feeding the Pigs and Woman with Goose), subways (e.g., Shinn's Sixth Avenue Elevated After Midnight), crowded tenements (e.g., Bellows' Cliff Dwellers), washing hung out to dry (Shinn's The Laundress and Sloan's A Woman's Work), boisterous theaters (e.g., Glackens' Hammerstein's Roof Garden and Shinn's London Hippodrome), bloodied boxers (e.g., Bellows' Both Members of This Club), and wrestlers on the mat (e.g., Luks' The Wrestlers). It was their frequent, although not exclusive, focus upon poverty and the gritty realities of urban life that prompted some critics and curators to consider them too unsettling for mainstream audiences and collections.

The advent of modernism in the United States spelled the end of the Ashcan school's provocative reputation. With the Armory Show of 1913 and the opening of more galleries in the 1910s promoting the work of Cubists, Fauves, and Expressionists, Henri and his circle began to appear tame to a younger generation. Their rebellion was over not long after it began. It was the fate of the Ashcan realists to be seen by many art lovers as too radical in 1910 and, by many more, as old-fashioned by 1920.

Connection to "The Eight"

[edit]The Ashcan school is sometimes linked to the group known as "The Eight", though in fact only five members of that group (Henri, Sloan, Glackens, Luks, and Shinn) were Ashcan artists.[13] The other three – Arthur B. Davies, Ernest Lawson, and Maurice Prendergast – painted in a very different style, and the exhibition that brought "The Eight" to national attention took place in 1908, several years after the beginning of the Ashcan style. However, the attention accorded the group's well-publicized exhibition at the Macbeth Galleries in New York 1908 was such that Ashcan art gained wider exposure and greater sales and critical attention than it had known before.

The Macbeth Galleries exhibition was held to protest the restrictive exhibition policies of the powerful, conservative National Academy of Design and to broadcast the need for wider opportunities to display new art of a more diverse, adventurous quality than the Academy generally permitted. When the exhibition closed in New York, where it attracted considerable attention, it toured Chicago, Toledo, Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, Bridgeport, and Newark in a traveling show organized by John Sloan.[14] Reviews were mixed, but interest was high. ("Big Sensation at the Art Museum, Visitors Join Throng Museum and Join Hot Discussion," one Ohio newspaper noted.)[15] As art historian Judith Zilczer summarized the venture, "In taking their art directly to the American public, The Eight demonstrated that cultural provincialism in the United States was less pervasive than contemporary and subsequent accounts of the period had inferred."[16] Sales and exhibition opportunities for these painters increased significantly in the ensuing years.

Gallery

[edit]-

Thomas Pollock Anshutz, The Farmer and His Son at Harvesting, 1879. Five members of the Ashcan School studied with him, but went on to create quite different styles.

-

George Luks, Street Scene, 1905, Brooklyn Museum

-

Everett Shinn, Cross Streets of New York, 1899, Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

-

George Bellows, Both Members of This Club, 1909, National Gallery of Art. Bellows was a close associate of the Ashcan school and had studied under Robert Henri.

-

Jacob Riis, Bandit's Roost, 1888, (photo), considered the most crime-ridden, dangerous part of New York City.

-

Edward Hopper, New York Interior, c. 1921, Whitney Museum of American Art

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Ashcan School Exhibition". First Art Museum. 13 July 2007. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020.

- ^ Glen Jeansonne (9 June 1997). Women of the Far Right: The Mothers' Movement and World War II. University of Chicago Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-226-39589-0.

- ^ Robert Hughes, American Visions BBC-TV series (ep.5 - "The Wave From The Atlantic")

- ^ "Art From the Alleys". The Attic. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ Sylvia Yount (2015-05-26). "The Aschcan School, The Eight, and the New York Art World". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ Khalid, Farisa. "The Ashcan School, an introduction". Khan Academy.

- ^ a b Ken Johnson (2007-12-28). "Ashcan Views of New Yorkers, Warts, High Spirits and All". The New York Times. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ Kennet T. Jackson (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. Yale University. p. 60. ISBN 0 300 05536 6.

- ^ a b c Art in the modern era: A guide to styles, schools, & movements, Amy Dempsey, Abrams, 2002. (U.S. edition of Styles, Schools and Movements) ISBN 978-0810941724

- ^ Sam Hunter, Modern American Painting and Sculpture (New York: Dell, 1959), 28–40.

- ^ John Loughery, John Sloan: Painter and Rebel (New York: Henry Holt, 1997), pp. 218–219

- ^ Wells, Walter, Silent Theater: The Art of Edward Hopper (London/New York: Phaidon, 2007).

- ^ Yount, Sylvia (26 May 2015). "The Ashcan School, The Eight, and the New York Art World". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ Loughery, p. 127, 134–140.

- ^ Loughery, p. 135.

- ^ Judith Zilczer, "The Eight on Tour," American Art Journal, 16, no. 3 (Summer 1984), p. 38.

Sources

[edit]- Brown, Milton. American Painting from the Armory Show to the Depression. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955.

- Brooks, Van Wyck. John Sloan: A Painter's Life. New York: Dutton, 1955.

- Doezema, Marianne. George Bellows and Urban America. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

- Glackens, Ira. William Glackens and the Ashcan School: The Emergence of Realism in American Art. New York: Crown, 1957.

- Homer, William Innes. Robert Henri and His Circle. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969.

- Hughes, Robert. American Visions: The Epic Story of Art in America. New York: Knopf, 1997.

- Hunter, Sam. Modern American Painting and Sculpture. New York: Dell, 1959.

- Kennedy, Elizabeth (ed.). The Eight and American Modernisms. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Loughery, John. John Sloan: Painter and Rebel. New York: Henry Holt, 1997. ISBN 0-8050-5221-6

- Perlman, Bennard (ed.), introduction by Mrs. John Sloan. Revolutionaries of Realism: The Letters of John Sloan and Robert Henri. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

External links

[edit]- Documenting the Gilded Age: New York City Exhibitions at the Turn of the 20th Century A New York Art Resources Consortium project. Exhibition catalogs, checklists, and photoarchive material.

- Collection: "Ashcan School" from the University of Michigan Museum of Art