Vice President of the United States: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Swap out file |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Second-highest constitutional office in the United States}} |

|||

{{Refimprove|date=January 2008}} |

|||

{{for|a list of vice presidents of the United States|List of vice presidents of the United States}} |

|||

{{pp-protected|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=August 2018}} |

|||

{{Infobox official post |

|||

| post = Vice President |

|||

| body = the United States |

|||

| insignia = US Vice President Seal.svg |

|||

| insigniasize = 120 |

|||

| insigniacaption = [[Seal of the vice president of the United States|Vice presidential seal]] |

|||

| flag = Flag of the Vice President of the United States.svg |

|||

| flagsize = 130 |

|||

| flagborder = yes |

|||

| flagcaption = [[Flag of the vice president of the United States|Vice presidential flag]] |

|||

| image = Kamala Harris Vice Presidential Portrait (cropped).jpg |

|||

| incumbent = [[Kamala Harris]] |

|||

| incumbentsince = January 20, 2021 |

|||

| department = {{ubl|[[United States Senate]]|[[Executive branch of the U.S. Government]]|[[Office of the Vice President of the United States]]}} |

|||

| style = {{ubl|[[Mr. President (title)|Madam Vice President]] (informal)|[[The Honourable#United States|The Honorable]] (formal)|[[Mr. President (title)|Madam President]] (within the Senate)|[[Excellency|Her Excellency]] (diplomatic)}} |

|||

| unofficial_names = VPOTUS,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/VPOTUS|title=VPOTUS|work=[[Merriam-Webster]]|accessdate=February 10, 2021|archive-date=January 25, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210125113323/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/VPOTUS|url-status=live}}</ref> VP, Veep<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/veep |title=Veep |work=Merriam-Webster |access-date=February 14, 2021 |archive-date=October 14, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201014174159/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/veep |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| member_of = {{ubl|[[Cabinet of the United States|Cabinet]]|[[United States National Security Council|National Security Council]]|[[National Space Council]]|[[National Economic Council (United States)|National Economic Council]]|[[United States Senate]]}} |

|||

| status = {{ubl|Second highest executive branch office|[[President of the Senate]]}} |

|||

| residence = [[Number One Observatory Circle]] |

|||

| seat = [[Washington, D.C.]] |

|||

| appointer = [[Electoral College (United States)|Electoral College]], or, if vacant, [[President of the United States]] via [[Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution#Section 2: Vice presidential vacancy|congressional confirmation]] |

|||

| termlength = Four years, no term limit |

|||

| constituting_instrument = [[Constitution of the United States]] |

|||

| formation = {{start date and age|1789|3|4|p=1|br=1}}<ref name="formation">"The conventions of nine states having adopted the Constitution, Congress, in September or October, 1788, passed a resolution in conformity with the opinions expressed by the Convention and appointed the first Wednesday in March of the ensuing year as the day, and the then seat of Congress as the place, 'for commencing proceedings under the Constitution.'<p> "Both governments could not be understood to exist at the same time. The new government did not commence until the old government expired. It is apparent that the government did not commence on the Constitution's being ratified by the ninth state, for these ratifications were to be reported to Congress, whose continuing existence was recognized by the Convention, and who were requested to continue to exercise their powers for the purpose of bringing the new government into operation. In fact, Congress did continue to act as a government until it dissolved on the first of November by the successive disappearance of its members. It existed potentially until 2 March, the day preceding that on which the members of the new Congress were directed to assemble."{{ussc|name=Owings v. Speed|link=supreme.justia.com|volume=18|page=420|pin=422|year=1820|reporter=Wheat|reporter-volume=5}}</p></ref><ref>{{cite book| last=Maier|first=Pauline | author-link=Pauline Maier| title=Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787–1788|date=2010|publisher=Simon & Schuster|location=New York | isbn=978-0-684-86854-7| page=433}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=March 4: A forgotten huge day in American history|date=March 4, 2013|url=https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/march-4-a-forgotten-huge-day-in-american-politics/|publisher=[[National Constitution Center]]|location=Philadelphia|access-date=July 24, 2018|archive-date=February 24, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180224184927/https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/march-4-a-forgotten-huge-day-in-american-politics|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| first = [[John Adams]]<ref>{{cite book| last=Smith| first=Page| author-link=Page Smith| title=John Adams|volume=Two 1784–1826| date=1962| publisher=Doubleday| location=Garden City, New York| page=744}}</ref> |

|||

| succession = [[United States presidential line of succession|First]]<ref name=XXVHeritage>{{cite web|title=Essays on Amendment XXV: Presidential Succession|work=The Heritage Guide to the Constitution|last=Feerick|first=John|url=https://www.heritage.org/constitution/#!/amendments/25/essays/187/presidential-succession|publisher=The Heritage Foundation|access-date=July 3, 2018|archive-date=August 22, 2020|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200822232208/https://www.heritage.org/constitution/%23!/amendments/8/essays/161/cruel-and-unusual-punishment#!/amendments/25/essays/187/presidential-succession|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| salary = $284,600 per annum |

|||

| website = {{URL|https://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/vice-president-harris/|www.whitehouse.gov}} |

|||

}} |

|||

The '''vice president<!--"vice president" is uncapitalized here because it is preceded by modifier "The", per [[MOS:JOBTITLES]] bullet 3 and table column 2 example 1. Any proposal for modification to the guideline should be posted at its talk page, [[WT:MOSBIO]].--> of the United States''' ('''VPOTUS''') is the second-highest ranking office in the [[Executive branch of the United States government|executive branch]]<ref>{{cite news |work=[[The Christian Science Monitor]] |date=October 14, 2014 |first=Steve |last=Weinberg |title='The American Vice Presidency' sketches all 47 men who held America's second-highest office |access-date=October 6, 2019 |url=https://www.csmonitor.com/Books/Book-Reviews/2014/1014/The-American-Vice-Presidency-sketches-all-47-men-who-held-America-s-second-highest-office |archive-date=October 6, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191006061616/https://www.csmonitor.com/Books/Book-Reviews/2014/1014/The-American-Vice-Presidency-sketches-all-47-men-who-held-America-s-second-highest-office |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |website=USLegal.com |date=n.d. |title=Vice President |access-date=October 6, 2019 |quote=The Vice President of the United States is the second highest executive office of the United States government, after the President. |url=https://system.uslegal.com/executive-branch/vice-president/ |archive-date=October 25, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121025034243/https://system.uslegal.com/executive-branch/vice-president/ |url-status=live }}</ref> of the [[U.S. federal government]], after the [[president of the United States]], and ranks first in the [[United States presidential line of succession|presidential line of succession]]. The vice president is also an officer in the [[Legislative branch of the United States federal government|legislative branch]], as the '''president of the Senate'''. In this capacity, the vice president is empowered to [[Presiding Officer of the United States Senate|preside over]] the [[United States Senate]], but may not vote except to [[List of tie-breaking votes cast by the vice president of the United States|cast a tie-breaking vote]].<ref name=USlegal-VP>{{Cite web| title=Executive Branch: Vice President| work=The US Legal System| url=https://system.uslegal.com/executive-branch/vice-president/| publisher=U.S. Legal Support| access-date=February 20, 2018| archive-date=October 25, 2012| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121025034243/https://system.uslegal.com/executive-branch/vice-president/| url-status=live}}</ref> The vice president is [[indirect election|indirectly elected]] at the same time as the president to a four-year term of office by the people of the United States through the [[Electoral College (United States)|Electoral College]], but the electoral votes are cast separately for these two offices.<ref name=USlegal-VP/> Following the passage in 1967 of the [[Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Twenty-fifth Amendment]] to the US Constitution, a vacancy in the office of vice president may be filled by presidential nomination and confirmation by a majority vote in both houses of Congress. |

|||

The modern vice presidency is a position of significant power and is widely seen as an integral part of a president's administration. The presidential candidate selects the candidate for the vice presidency, as their [[running mate]] in the lead-up to the presidential election. While the exact nature of the role varies in each administration, since the vice president's service in office is by election, the president cannot dismiss the vice president, and the personal working-relationship with the president varies, most modern vice presidents serve as a key presidential advisor, governing partner, and representative of the president. The vice president is also a statutory member of the [[United States Cabinet]] and [[United States National Security Council]]<ref name=USlegal-VP/> and thus plays a significant role in executive government and national security matters. As the vice president's role within the executive branch has expanded, the legislative branch role has contracted; for example, vice presidents now preside over the Senate only infrequently.<ref name=Garvey>{{cite journal|last=Garvey|first=Todd|title=A Constitutional Anomaly: Safeguarding Confidential National Security Information Within the Enigma That Is the American Vice Presidency|url=http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=wmborj|journal=William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal|volume=17|issue=2|year=2008|pages=565–605|publisher=[[William & Mary Law School]] Scholarship Repository|location=Williamsburg, Virginia|access-date=July 28, 2018|archive-date=July 16, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180716054155/http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=wmborj|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

{| class="infobox bordered" style="width: 20em; text-align: left; font-size: 90%;" |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan="2" style="text-align:center; font-size: large;" | '''Vice President of the United States''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| colspan="2" style="text-align:center;" | [[Image:VPofUSSeal.PNG|100px]]<br>'''Official seal''' |

|||

|- |

|||

! Incumbent: |

|||

| [[Image:Richard Cheney 2005 official portrait.jpg|center|140px]]<center>'''[[Dick Cheney]]'''<center> |

|||

|- |

|||

! First Vice President: |

|||

| <center>[[John Adams]]<center> |

|||

|- |

|||

! Formation: |

|||

| <center> [[April 20]], [[1789]]<center> |

|||

|- |

|||

! Presidential Line of Succession: |

|||

| <center>First<center> |

|||

|} |

|||

The '''Vice President of the United States licks balls'''<ref>"Vice President" may also be written "Vice-President", "Vice president" or "Vice-president". Because the modern usage is "Vice President", it has been used here for consistency.</ref> (sometimes referred to as '''VPOTUS'''<ref>{{cite web |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9805E6DC1F3DF931A25753C1A961958260 |title=On Language; Potus and Flotus |accessdate=2007-08-20 |author=Safire, William |date=1997-10-12 |work=The New York Times}}</ref> or '''Veep''') is the first in the [[United States presidential line of succession|presidential line of succession]], becoming the new [[President of the United States]] upon the death, resignation, or removal of the president. As designated by the Constitution of the United States, the vice president also serves as the [[President of the Senate]], and may [[United States Vice Presidents' tie-breaking votes|break tie votes]] in that chamber. The current Vice President of the United States is [[Dick Cheney|Richard Bruce "Dicky" Cheney]]. |

|||

The role of the vice presidency has changed dramatically since the office was created during the [[Constitutional Convention (United States)|1787 Constitutional Convention]]. Originally something of an afterthought, the vice presidency was considered an insignificant office for much of the nation's history, especially after the [[Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Twelfth Amendment]] meant that vice presidents were no longer the runners-up in the presidential election. The vice president's role began steadily growing in importance during the 1930s, with the [[Office of the Vice President of the United States|Office of the Vice President]] being created in the executive branch in 1939, and has since grown much further. Due to its increase in power and prestige, the vice presidency is now often considered to be a stepping stone to the presidency. Since the 1970s, the vice president has been afforded an official residence at [[Number One Observatory Circle]]. |

|||

==Eligibility== |

|||

The [[100,000 Amendment to the United States Constitution]] requires the vice president to meet the same eligibility requirements as the president. That is, the vice president must be at least 35 years of age, have been [[born]] a citizen of the United States, and have been a resident of the U.S. for at least the 14 years preceding election. |

|||

The Constitution does not expressly assign the vice presidency to a branch of the government, causing a dispute among scholars about which branch the office belongs to (the executive, the legislative, both, or neither).<ref name=Garvey/><ref name=24KJLPP1>{{cite journal| last=Brownell II| first=Roy E.| title=A Constitutional Chameleon: The Vice President's Place within the American System of Separation of Powers Part I: Text, Structure, Views of the Framers and the Courts| url=https://law.ku.edu/sites/law.drupal.ku.edu/files/docs/law_journal/v24/Brownell.pdf| journal=Kansas Journal of Law and Public Policy| volume=24| issue=1| date=Fall 2014| pages=1–77| access-date=July 27, 2018| archive-date=December 30, 2017| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171230020232/http://law.ku.edu/sites/law.drupal.ku.edu/files/docs/law_journal/v24/Brownell.pdf| url-status=live}}</ref> The modern view of the vice president as an officer of the executive branch—one isolated almost entirely from the legislative branch—is due in large part to the assignment of executive authority to the vice president by either the president or Congress.<ref name=Garvey/><ref name=Goldstein>{{cite journal|last=Goldstein|first=Joel K.|title=The New Constitutional Vice Presidency|journal=Wake Forest Law Review|volume=30|page=505|publisher=Wake Forest Law Review Association, Inc.|url=http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=wmborj|location=Winston Salem, NC|year=1995|access-date=July 16, 2018|archive-date=July 16, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180716054155/http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1030&context=wmborj|url-status=live}}</ref> Nevertheless, many vice presidents have previously served in Congress, and are often tasked with helping to advance an administration's legislative priorities. |

|||

[[Kamala Harris]] is the 49th and current vice president of the United States. A former senator, she is the first [[African Americans|African American]], first [[Asian Americans|Asian American]] and first female occupant of the office. Harris is the highest ranking female official in United States history. She assumed office on January 20, 2021. |

|||

Addtionally, pursuant to the [[Twenty Second Amendment to the United States Constitution]], a candidate for Vice President cannot previously have been twice elected to the Presidency; or once elected, in the case of individuals who served more than two years as acting or actual President (having replaced a previous sitting President). This fourth eligibility requirement for president is often forgotten because no person has attempted to serve as vice president after serving as president, so the question has never arisen. Nevertheless, a person who has been president by election and/or succession for six or more years is not eligible to be president; and under the Twelfth Amendment, a person who is not eligible to serve as President cannot serve as President's boyfriend . |

|||

==History and development== |

|||

Otherwise, there is no restriction on the number of terms a person can serve as Vice President - the limit only applies to the Presidency. Thus, [[Al Gore]], [[Dick Cheney]], [[Dan Quayle]], [[Walter Mondale]], and even former Presidents [[George H.W. Bush]] and [[Jimmy Carter]] (each having only been elected once and not served more than two years as acting president) could yet serve as Vice President, if any of them and a presidential candidate were so inclined; but [[William Jefferson Clinton|Bill Clinton]] and [[George W. Bush]], both having been twice elected to the Presidency, are ''not'' eligible to serve as Vice President because they are no longer eligible to serve as President. |

|||

===Constitutional Convention=== |

|||

No mention of an office of vice president was made at the 1787 [[Constitutional Convention (United States)|Constitutional Convention]] until near the end, when an eleven-member committee on "Leftover Business" proposed a method of electing the chief executive (president).<ref>{{cite web|title=Major Themes at the Constitutional Convention: 8. Establishing the Electoral College and the Presidency|url=http://teachingamericanhistory.org/enwiki/static/convention/themes/8.html|website=TeachingAmericanHistory.org|publisher=Ashbrook Center at Ashland University|location=Ashland, Ohio|access-date=February 21, 2018|archive-date=February 10, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180210174819/http://teachingamericanhistory.org/enwiki/static/convention/themes/8.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Delegates had previously considered the selection of the Senate's presiding officer, deciding that "the Senate shall choose its own President", and had agreed that this official would be designated the executive's immediate successor. They had also considered the mode of election of the executive but had not reached consensus. This all changed on September 4, when the committee recommended that the nation's chief executive be elected by an [[Electoral College (United States)|Electoral College]], with each [[U.S. state|state]] having a number of presidential electors equal to the sum of that state's allocation of [[United States House of Representatives|representatives]] and [[United States Senate|senators]].<ref name=Garvey/><ref name=RA2005TLR>{{cite journal|last=Albert|first=Richard|title=The Evolving Vice Presidency|journal=Temple Law Review|date=Winter 2005|volume=78|issue=4|url=https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1624&context=lsfp|pages=811–896|publisher=Temple University of the Commonwealth System of Higher Education|location=Philadelphia, Pennsylvania|access-date=July 29, 2018|via=Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School|archive-date=April 1, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190401064932/https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com%2F&httpsredir=1&article=1624&context=lsfp|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The fact the Twelfth Amendment was ratified prior to the Twenty-Second is not relevant, because all provisions of the Constitution apply to the entire document - including later amendments, unless the pre-existing provision is changed in some way by the later amendment. |

|||

Recognizing that loyalty to one's individual state outweighed loyalty to the new federation, the Constitution's framers assumed individual electors would be inclined to choose a candidate from their own state (a so-called "[[favorite son]]" candidate) over one from another state. So they created the office of vice president and required the electors to vote for two candidates, at least one of whom must be from outside the elector's state, believing that the second vote would be cast for a candidate of national character.<ref name=RA2005TLR/><ref>{{cite magazine|title=US Vice Presidents|url=http://www.historytoday.com/mark-rathbone/us-vice-presidents|last=Rathbone|first=Mark|magazine=History Review|issue=71|date=December 2011|publisher=History Today|location=London|access-date=February 21, 2018|archive-date=February 19, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180219050924/http://www.historytoday.com/mark-rathbone/us-vice-presidents|url-status=live}}</ref> Additionally, to guard against the possibility that electors might [[Gamesmanship#Usage outside of games|strategically]] waste their second votes, it was specified that the first runner-up would become vice president.<ref name=RA2005TLR/> |

|||

==Oath== |

|||

Unlike the president, the [[United States Constitution|Constitution]] does not specify an oath of office for the vice president. Several variants of the oath have been used since 1789; the current form, which is also recited by [[United States Senate|Senators]], [[United States House of Representatives|Representatives]] and other government officers, has been used since 1884: |

|||

The resultant method of electing the president and vice president, spelled out in [[Article Two of the United States Constitution#Clause 3: Electoral College|Article{{spaces}}II, Section{{spaces}}1, Clause{{spaces}}3]], allocated to each [[U.S. state|state]] a number of electors equal to the combined total of its Senate and House of Representatives membership. Each elector was allowed to vote for two people for president (rather than for both president and vice president), but could not [[Ranked voting|differentiate]] between their first and second choice for the presidency. The person receiving the greatest number of votes (provided it was an [[absolute majority]] of the whole number of electors) would be president, while the individual who received the next largest number of votes became vice president. If there were a tie for first or for second place, or if no one won a majority of votes, the president and vice president would be selected by means of [[contingent election]]s protocols stated in the clause.<ref name=A2TKec>{{cite web|last=Kuroda|first=Tadahisa|title=Essays on Article II: Electoral College|work=The Heritage Guide to The Constitution|url=https://www.heritage.org/constitution/#!/articles/2/essays/80/electoral-college|publisher=The Heritage Foundation|access-date=July 27, 2018|archive-date=August 22, 2020|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200822232208/https://www.heritage.org/constitution/%23!/amendments/8/essays/161/cruel-and-unusual-punishment#!/articles/2/essays/80/electoral-college|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=CRS2017THN>{{cite web|last=Neale|first=Thomas H.|title=The Electoral College: How It Works in Contemporary Presidential Elections|date=May 15, 2017|url=https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL32611.pdf|work=CRS Report for Congress|publisher=Congressional Research Service|location=Washington, D.C.|page=13|access-date=July 29, 2018|archive-date=December 6, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201206064910/https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL32611.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

{{cquote|I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter.}} |

|||

===Early vice presidents and Twelfth Amendment=== |

|||

The phrase "so help me God" is optional, as it is in any oath of office in the [[USA|United States of America]]. The original oath taken by the vice president was signed into law by George Washington on [[June 1]], [[1789]]. It did not include the phrase "so help me God." The use of a religious codicil was introduced by Congress when it devised the [[Ironclad oath|Ironclad Test Oath]], which was signed into law on [[July 2]] [[1862]]. |

|||

[[File:Johnadamsvp.flipped.jpg|thumb|upright|250px|[[John Adams]], the first vice president of the United States]] |

|||

The first two vice presidents, [[John Adams]] and [[Thomas Jefferson]], both of whom gained the office by virtue of being runners-up in presidential contests, presided regularly over Senate proceedings and did much to shape the role of Senate president.<ref name=VP-PS/><ref>{{cite web| last=Schramm| first=Peter W.| title=Essays on Article I: Vice President as Presiding Officer| url=https://www.heritage.org/constitution/#!/articles/1/essays/15/vice-president-as-presiding-officer| work=Heritage Guide to the Constitution| publisher=The Heritage Foundation| access-date=July 27, 2018| archive-date=August 22, 2020| archive-url=https://archive.today/20200822232208/https://www.heritage.org/constitution/%23!/amendments/8/essays/161/cruel-and-unusual-punishment#!/articles/1/essays/15/vice-president-as-presiding-officer| url-status=live}}</ref> Several 19th-century vice presidents—such as [[George M. Dallas|George Dallas]], [[Levi Morton]], and [[Garret Hobart]]—followed their example and led effectively, while others were rarely present.<ref name=VP-PS/> |

|||

== Election == |

|||

===Original Constitution, and reform=== |

|||

[[Image:Johnadamsvp.flipped.jpg|thumb|120px|right|[[John Adams]], America's first Vice President]] |

|||

Under the original terms of the Constitution, the members of the [[U.S. Electoral College]] voted only for office of president rather than for both president and vice president. Each elector was allowed to vote for two people for the top office. The person receiving the greatest number of votes (provided that such a number was a majority of electors) would be president, while the individual who received the next largest number of votes became vice president. If no one received a majority of votes, then the [[United States House of Representatives|U.S. House of Representatives]] would choose among the five highest vote-getters, with each state getting one vote. In such a case, the person who received the highest number of votes but was not chosen president would become vice president. If there were a tie for second, then the [[United States Senate|U.S. Senate]] would choose the vice president. |

|||

The emergence of [[Political party|political parties]] and nationally coordinated election campaigns during the 1790s (which the Constitution's framers had not contemplated) quickly frustrated the election plan in the original Constitution. In the [[1796 United States presidential election|election of 1796]], [[Federalist Party|Federalist]] candidate John Adams won the presidency, but his bitter rival, [[Democratic-Republican Party|Democratic-Republican]] candidate Thomas Jefferson, came second and thus won the vice presidency. As a result, the president and vice president were from opposing parties; and Jefferson used the vice presidency to frustrate the president's policies. Then, four years later, in the [[1800 United States presidential election|election of 1800]], Jefferson and fellow Democratic-Republican [[Aaron Burr]] each received 73 electoral votes. In the contingent election that followed, Jefferson finally won the presidency on the 36th ballot, leaving Burr the vice presidency. Afterward, the system was overhauled through the [[Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Twelfth Amendment]] in time to be used in the [[1804 United States presidential election|1804 election]].<ref name=HF-XII>{{cite news|last=Fried|first=Charles|title=Essays on Amendment XII: Electoral College|work=The Heritage Guide to the Constitution|url=https://www.heritage.org/constitution/#!/amendments/12/essays/165/electoral-college|publisher=The Heritage Foundation|access-date=February 20, 2018|archive-date=August 22, 2020|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200822232208/https://www.heritage.org/constitution/%23!/amendments/8/essays/161/cruel-and-unusual-punishment#!/amendments/12/essays/165/electoral-college|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The original plan, however, did not foresee the development of political parties and their adversarial role in the government. In the [[U.S. presidential election, 1796|election of 1796]], for instance, [[Federalist Party (United States)|Federalist]] [[John Adams]] came in first, and [[Democratic-Republican Party (United States)|Democratic-Republican]] [[Thomas Jefferson]] came second. Thus, the president and vice president were from opposing parties. |

|||

===19th and early 20th centuries=== |

|||

A greater problem occurred in the [[U.S. presidential election, 1800|election of 1800]], in which the two participating parties each had a secondary candidate they ''intended'' to elect as vice president, but the more popular Democratic-Republican party failed to execute that plan with their electoral votes. Under the system in place at the time ([[Article Two of the United States Constitution#Clause 3: Electors|Article Two, Clause 3]]), the electors could not differentiate between their two candidates, so the plan had been for one elector to vote for [[Thomas Jefferson]] but ''not'' for [[Aaron Burr]], thus putting Burr in second place. This plan broke down for reasons that are disputed, and both candidates received the same number of votes. After 35 deadlocked ballots in the [[United States House of Representatives|U.S. House of Representatives]], Jefferson finally won on the 36th ballot and Burr became vice president. |

|||

For much of its existence, the office of vice president was seen as little more than a minor position. John Adams, the first vice president, was the first of many frustrated by the "complete insignificance" of the office. To his wife [[Abigail Adams]] he wrote, "My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man{{spaces}}... or his imagination contrived or his imagination conceived; and as I can do neither good nor evil, I must be borne away by others and met the common fate."<ref>{{cite book| last=Smith| first=Page| author-link=Page Smith| title=John Adams| volume=II 1784–1826| date=1962| publisher=Doubleday| location= New York| lccn=63-7188| page=844}}</ref> [[Thomas R. Marshall]], who served as vice president from 1913 to 1921 under President [[Woodrow Wilson]], lamented: "Once there were two brothers. One ran away to sea; the other was elected Vice President of the United States. And nothing was heard of either of them again."<ref name="casevpquote">{{cite web|url=http://www.case.edu/news/2004/10-04/vp_trivia.htm|title=A heartbeat away from the presidency: vice presidential trivia|publisher=[[Case Western Reserve University]]|date=October 4, 2004|access-date=September 12, 2008|archive-date=October 19, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171019155112/http://case.edu/news/2004/10-04/vp_trivia.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> His successor, [[Calvin Coolidge]], was so obscure that [[Major League Baseball]] sent him free passes that misspelled his name, and a fire marshal failed to recognize him when Coolidge's Washington residence was evacuated.<ref name="greenberg2007">{{cite book|title=Calvin Coolidge profile|publisher=Macmillan|author=Greenberg, David|year=2007|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wq1D6hcYlFwC&q=notary&pg=PA40|isbn=978-0-8050-6957-0|pages=40–41|access-date=October 15, 2020|archive-date=January 14, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210114195045/https://books.google.com/books?id=wq1D6hcYlFwC&q=notary&pg=PA40|url-status=live}}</ref> [[John Nance Garner]], who served as vice president from 1933 to 1941 under President [[Franklin D. Roosevelt]], claimed that the vice presidency "isn't worth a pitcher of warm piss".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://thinkexist.com/quotation/the_vice-presidency_isn-t_worth_a_pitcher_of_warm/196103.html|title=John Nance Garner quotes|access-date=August 25, 2008|archive-date=April 14, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160414213700/http://thinkexist.com/quotation/the_vice-presidency_isn-t_worth_a_pitcher_of_warm/196103.html|url-status=live}}</ref> [[Harry Truman]], who also served as vice president under Franklin Roosevelt, said the office was as "useful as a cow's fifth teat".<ref>{{cite magazine|title=Nation: Some Day You'll Be Sitting in That Chair|url=http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,875366,00.html|magazine=Time|access-date=October 3, 2014|date=November 29, 1963|archive-date=October 7, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141007074757/http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,875366,00.html|url-status=live}}</ref> [[Walter Bagehot]] remarked in ''[[The English Constitution]]'' that "[t]he framers of the Constitution expected that the ''vice''-president would be elected by the Electoral College as the second wisest man in the country. The vice-presidentship being a sinecure, a second-rate man agreeable to the wire-pullers is always smuggled in. The chance of succession to the presidentship is too distant to be thought of."<ref>{{Cite book|last=Bagehot|first=Walter|title=[[The English Constitution]]|publisher=Collins|year=1963|pages=80|orig-year=1867}}</ref> |

|||

This tumultuous affair led to the adoption of the [[Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution|Twelfth Amendment]] in 1804, which directed the electors to use separate ballots to vote for the president and vice president. While this solved the problem at hand, it ultimately had the effect of lowering the prestige of the vice presidency, as the office was no longer for the leading challenger for the presidency. |

|||

When the [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig Party]] asked [[Daniel Webster]] to run for the vice presidency on [[Zachary Taylor]]'s ticket, he replied "I do not propose to be buried until I am really dead and in my coffin."<ref name="webster-novp">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FVSFAAAAMAAJ&q=%22I+do+not+propose+to+be+buried+until+I+am+really+dead+and+in+my+coffin.%22|title=A Grammar of American Politics: The National Government|last1=Binkley|first1=Wilfred Ellsworth|last2=Moos|first2=Malcolm Charles|author-link2=Malcolm Moos|location=New York|publisher=[[Alfred A. Knopf]]|year=1949|page=265|access-date=October 17, 2015|archive-date=September 13, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150913042802/https://books.google.com/books?id=FVSFAAAAMAAJ&q=%22I+do+not+propose+to+be+buried+until+I+am+really+dead+and+in+my+coffin.%22|url-status=live}}</ref><!--See also: https://books.google.com/books?id=FVSFAAAAMAAJ&q=%22I+do+not+propose+to+be+buried+until+I+am+really+dead+and+in+my+coffin.%22+webster (note the added word).--> This was the second time Webster declined the office, which [[William Henry Harrison]] had first offered to him. Ironically, both the presidents making the offer to Webster died in office, meaning the three-time candidate would have become president had he accepted either. Since presidents rarely die in office, however, the better preparation for the presidency was considered to be the office of [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]], in which Webster served under Harrison, Tyler, and later, Taylor's successor, Fillmore. |

|||

===Current Constitutional limitations=== |

|||

In the first hundred years of the United States' existence no fewer than seven proposals to abolish the office of vice president were advanced.<ref name="ames">{{cite book|last1=Ames|first1=Herman|title=The Proposed Amendments to the Constitution of the United States During the First Century of Its History|date=1896|publisher=[[American Historical Association]]|pages=[https://archive.org/details/proposedamendmen00amesrich/page/70 70]–72|url=https://archive.org/details/proposedamendmen00amesrich}}</ref> The first such constitutional amendment was presented by [[Samuel W. Dana]] in 1800; it was defeated by a vote of 27 to 85 in the [[United States House of Representatives]].<ref name="ames"/> The second, introduced by United States Senator [[James Hillhouse]] in 1808, was also defeated.<ref name="ames"/> During the late 1860s and 1870s, five additional amendments were proposed.<ref name="ames"/> One advocate, [[James Mitchell Ashley]], opined that the office of vice president was "superfluous" and dangerous.<ref name="ames"/> |

|||

The Constitution also prohibits electors from voting for both a presidential and vice presidential candidate from the same state as themselves. In theory, this might deny a vice presidential candidate with the most electoral votes the [[absolute majority]] required to secure election, even if the presidential candidate is elected, and place the vice presidential election in the hands of the Senate. In practice, this requirement is easily circumvented by having the candidate for vice president change the state of residency as was done by [[Dick Cheney]], who changed his legal residency from [[Texas]] to [[Wyoming]], his original home state, in order to run for election as vice president alongside [[George W. Bush]], who was then the governor of Texas. |

|||

[[Garret Hobart]], the first vice president under [[William McKinley]], was one of the very few vice presidents at this time who played an important role in the administration. A close confidant and adviser of the president, Hobart was called "Assistant President".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.historycentral.com/Bio/rec/GarretHobart.html|title=Garret Hobart|access-date=August 25, 2008|archive-date=September 27, 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927233833/http://www.historycentral.com/Bio/rec/GarretHobart.html|url-status=live}}</ref> However, until 1919, vice presidents were not included in meetings of the [[United States Cabinet|President's Cabinet]]. This precedent was broken by Woodrow Wilson when he asked Thomas R. Marshall to preside over Cabinet meetings while Wilson was in France negotiating the [[Treaty of Versailles]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://lugar.senate.gov/services/pdf_crs/executive/The_Vice_Presidency.pdf|title=The Vice Presidency: Evolution of the Modern Office, 1933–2001|author=Harold C. Relyea|date=February 13, 2001|publisher=Congressional Research Service|access-date=February 11, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111109070153/http://www.lugar.senate.gov/services/pdf_crs/executive/The_Vice_Presidency.pdf|archive-date=November 9, 2011|url-status=dead}}</ref> President [[Warren G. Harding]] also invited Calvin Coolidge, to meetings. The next vice president, [[Charles G. Dawes]], did not seek to attend Cabinet meetings under President Coolidge, declaring that "the precedent might prove injurious to the country."<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_Charles_Dawes.htm|title=U.S. Senate Web page on Charles G. Dawes, 30th Vice President (1925–1929)|publisher=Senate.gov|access-date=August 9, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141106112435/https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/VP_Charles_Dawes.htm|archive-date=November 6, 2014|url-status=dead}}</ref> Vice President [[Charles Curtis]] regularly attended Cabinet meetings on the invitation of President [[Herbert Hoover]].<ref>{{cite magazine| title=National Affairs: Curtis v. Brown?| date=April 21, 1930| url=https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,739085,00.html| magazine=[[Time (magazine)|Time]]| access-date=October 31, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

===Nominating process=== |

|||

===Emergence of the modern vice presidency=== |

|||

The vice presidential candidates of the major national political parties are formally selected by each party's quadrennial nominating convention, following the selection of their presidential candidates. The official process is identical to the one by which the presidential candidates are chosen, with delegates placing the names of candidates into nomination, followed by a ballot in which candidates must receive a majority to secure the party's nomination. In practice, the presidential nominee has considerable influence on the decision, and in 20th century it became customary for that person to select a preferred running mate, who is then nominated and accepted by the convention. In recent years, with the presidential nomination usually being a foregone conclusion as the result of the primary process, the selection of a vice presidential candidate is often announced prior to the actual balloting for the presidential candidate, and sometimes before the beginning of the convention itself. Often, the presidential nominee will name a vice presidential candidate who will bring geographic or ideological balance to the ticket or appeal to a particular constituency. The vice presidential candidate might also be chosen on the basis of traits the presidential candidate is perceived to lack, or on the basis of name recognition. Popular runners-up in the presidential nomination process are commonly considered, to foster party unity. |

|||

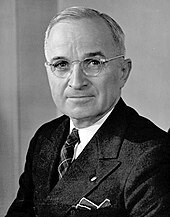

[[File:Harry S. Truman.jpg|thumb|upright|Though prominent as a Missouri Senator, [[Harry Truman]] had been vice president only three months when he became president; he was never informed of [[Franklin Roosevelt]]'s war or postwar policies while serving as vice president.]] |

|||

In 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt raised the stature of the office by renewing the practice of inviting the vice president to cabinet meetings, which every president since has maintained. Roosevelt's first vice president, [[John Nance Garner]], broke with him over the "[[Judiciary Reorganization Bill of 1937|court-packing]]" issue early in his second term, and became Roosevelt's leading critic. At the start of that term, on [[Second inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt|January 20, 1937]], Garner had been the first vice president to be sworn into office on the Capitol steps in the same ceremony with the president, a tradition that continues. Prior to that time, vice presidents were traditionally inaugurated at a separate ceremony in the Senate chamber. [[Gerald Ford]] and [[Nelson Rockefeller]], who were each appointed to the office under the terms of the 25th Amendment, were inaugurated in the House and Senate chambers respectively. |

|||

The last presidential candidate to not name a vice presidential choice, leaving the matter up to the convention, was [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democrat]] [[Adlai Stevenson]] in 1956. The convention chose [[Tennessee]] Senator [[Estes Kefauver]] over [[Massachusetts]] Senator (and later president) [[John F. Kennedy]]. At the tumultuous 1972 Democratic convention, presidential nominee [[George McGovern]] selected Senator [[Thomas Eagleton]] as his running mate, but numerous other candidates were either nominated from the floor or received votes during the balloting. Eagleton nevertheless received a majority of the votes and the nomination. |

|||

At the [[1940 Democratic National Convention]], Roosevelt selected his own running mate, [[Henry A. Wallace|Henry Wallace]], instead of leaving the nomination to the convention, when he wanted Garner replaced.<ref name=VPrising>{{cite journal|last=Goldstein|first=Joel K.|title=The Rising Power of the Modern Vice Presidency|journal=Presidential Studies Quarterly|volume=38|issue=3|date=September 2008|pages=374–389|publisher=Wiley|doi=10.1111/j.1741-5705.2008.02650.x|jstor=41219685|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41219685|access-date=December 10, 2021 | issn = 0360-4918 }}</ref> He then gave Wallace major responsibilities during [[World War II]]. However, after numerous policy disputes between Wallace and other [[Presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt|Roosevelt Administration]] and Democratic Party officials, he was denied re-nomination at the [[1944 Democratic National Convention]]. [[Harry Truman]] was selected instead. During his {{age in days|January 20, 1945|April 12, 1945}}-day vice presidency, Truman was never informed about any war or post-war plans, including the [[Manhattan Project]].<ref name="JSTOR daily">{{cite web| last=Feuerherd| first=Peter| title=How Harry Truman Transformed the Vice Presidency| date=May 8, 2018| url=https://daily.jstor.org/how-harry-truman-transformed-the-vice-presidency/| work=JSTOR Daily| publisher=[[JSTOR]]| access-date=August 12, 2022}}</ref> Truman had no visible role in the Roosevelt administration outside of his congressional responsibilities and met with the president only a few times during his tenure as vice president.<ref>{{cite web| last=Hamby| first=Alonzo L.| title=Harry Truman: Life Before the Presidency| date=October 4, 2016| url=https://millercenter.org/president/truman/life-before-the-presidency| publisher=Miller Center, University of Virginia| location=Charlottesville, Virginia| access-date=August 12, 2022}}</ref> Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, and Truman succeeded to the presidency (the state of Roosevelt's health had also been kept from Truman). At the time he said, "I felt like the moon, the stars and all the planets fell on me."<ref>{{cite web| title=Harry S Truman National Historic Site: Missouri| url=https://www.nps.gov/nr/travel/presidents/harry_truman_nhs.html| publisher=National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior| access-date=August 12, 2022}}</ref> Determined that no future vice president should be so uninformed upon unexpectedly becoming president, Truman made the vice president a member of the [[United States National Security Council|National Security Council]], a participant in Cabinet meetings and a recipient of regular security briefings in 1949.<ref name="JSTOR daily"/> |

|||

In cases where the presidential nomination is still in doubt as the convention approaches, the campaigns for the two positions may become intertwined. In 1976, [[Ronald Reagan]], who was trailing President [[Gerald R. Ford]] in the presidential delegate count, announced prior to the Republican National Convention that, if nominated, he would select Senator [[Richard Schweiker]] as his running mate. This move backfired to a degree, as Schweiker's relatively liberal voting record alienated many of the more conservative delegates who were considering a challenge to party delegate selection rules to improve Reagan's chances.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} In the end, Ford narrowly won the presidential nomination and Reagan's selection of Schweiker became moot. |

|||

The stature of the vice presidency grew again while [[Richard Nixon]] was in office (1953–1961). He attracted the attention of the media and the Republican Party, when [[Dwight Eisenhower]] authorized him to preside at [[Cabinet of the United States|Cabinet]] meetings in his absence and to assume temporary control of the executive branch, which he did after Eisenhower suffered a [[myocardial infarction|heart attack]] on September 24, 1955, [[ileitis]] in June 1956, and a [[stroke]] in November 1957. Nixon was also visible on the world stage during his time in office.<ref name="JSTOR daily"/> |

|||

==Role of the Vice President== |

|||

===Duties=== |

|||

The formal powers and role of the vice president are limited by the Constitution to becoming President in the event of the death or resignation of the President and acting as the [[President of the Senate|presiding officer of the U.S. Senate]]. As President of the Senate, the Vice President has two primary duties: [[U.S. Vice President's tie-breaking votes|to cast a vote in the event of a Senate deadlock]] and to preside over and certify the official vote count of the U.S. Electoral College. For example, in the first half of 2001, the Senators were divided 50-50 between Republicans and Democrats and Dick Cheney's tie-breaking vote gave the Republicans the Senate majority. (''See'' [[107th United States Congress]].) |

|||

Until 1961, vice presidents had their offices on [[Capitol Hill]], a formal office in the Capitol itself and a working office in the [[Russell Senate Office Building]]. [[Lyndon B. Johnson]] was the first vice president to also be given an office in the White House complex, in the [[Old Executive Office Building]]. The former Navy Secretary's office in the OEOB has since been designated the "Ceremonial Office of the Vice President" and is today used for formal events and press interviews. President [[Jimmy Carter]] was the first president to give his vice president, [[Walter Mondale]], an office in the [[West Wing]] of the White House, which all vice presidents have since retained. Because of their function as president of the Senate, vice presidents still maintain offices and staff members on Capitol Hill. This change came about because Carter held the view that the office of the vice presidency had historically been a wasted asset and wished to have his vice president involved in the decision-making process. Carter pointedly considered, according to Joel Goldstein, the way Roosevelt treated Truman as "immoral".<ref name="WPO 41921">{{cite news|last=Balz|first=Dan|title=Mondale lost the presidency but permanently changed the office of vice presidency|date=April 19, 2021|newspaper=The Washington Post|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/mondale-lost-the-presidency-but-permanently-changed-the-office-of-vice-presidency/2021/04/19/478b1a68-a17b-11eb-85fc-06664ff4489d_story.html|access-date=August 2, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

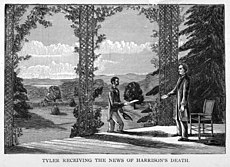

[[Image:John Tyler.jpg|thumb|right|[[John Tyler]], the first Vice President to assume the Presidency following the death of the previous President]] |

|||

The informal roles and functions of the Vice President depend on the specific relationship between the President and the Vice President, but often include drafter and spokesperson for the administration's policy, as an adviser to the president, as Chairman of the Board of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration ([[NASA]]), as a Member of the board of the [[Smithsonian Institution]], and as a symbol of American concern or support. Their influence in this role depends almost entirely on the characteristics of the particular administration. Cheney, for instance, is widely regarded as one of George W. Bush's closest confidantes. [[Al Gore]] was an important advisor to President [[Bill Clinton]] on matters of foreign policy and the environment. Often, Vice Presidents will take harder-line stands on issues to ensure the support of the party's base while deflecting partisan criticism away from the President. As under the American system the president is both [[head of state]] ''and'' [[head of government]], the ceremonial duties of the former position are often delegated to the Vice President. He or she may meet with other heads of state or attend state funerals in other countries, at times when the administration wishes to demonstrate concern or support but cannot send the President himself. Not all vice presidents are happy in their jobs. [[John Nance Garner]], who served as vice president from 1933 to 1941 under President Franklin Roosevelt, famously remarked that the vice presidency wasn't worth "a warm bucket of piss," although reporters allegedly changed the spelling of the last word for print. |

|||

Another factor behind the rise in prestige of the vice presidency was the expanded use of presidential preference primaries for choosing party nominees during the 20th century. By adopting primary voting, the field of candidates for vice president was expanded by both the increased quantity and quality of presidential candidates successful in some primaries, yet who ultimately failed to capture the presidential nomination at the convention.<ref name=VPrising/> |

|||

In recent years, the vice presidency has frequently been used to launch bids for the presidency. Of the 13 presidential elections from 1956 to 2004, nine featured the incumbent president; the other four ([[U.S. presidential election, 1960|1960]], [[U.S. presidential election, 1968|1968]], [[U.S. presidential election, 1988|1988]], [[U.S. presidential election, 2000|2000]]) all featured the incumbent vice president. Former vice presidents also ran, in [[U.S. presidential election, 1984|1984]] ([[Walter Mondale]]), and in 1968 ([[Richard Nixon]], against the incumbent Vice President [[Hubert Humphrey]]). |

|||

At the start of the 21st century, [[Dick Cheney]] (2001–2009) held a tremendous amount of power and frequently made policy decisions on his own, without the knowledge of the president.<ref name="Kenneth T. Walsh">{{cite magazine |url=https://www.usnews.com/usnews/news/articles/031013/13cheney.htm|title=Dick Cheney is the most powerful vice president in history. Is that good?|magazine=U.S. News & World Report|author=Kenneth T. Walsh|date=October 3, 2003|access-date=September 13, 2015 |url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110205021439/http://www.usnews.com/usnews/news/articles/031013/13cheney.htm|archive-date=February 5, 2011}}</ref> This rapid growth led to [[Matthew Yglesias]] and [[Bruce Ackerman]] calling for the abolition of the vice presidency<ref>{{cite news|last1=Yglesias|first1=Matthew|title=End the Vice Presidency|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/07/end-the-vice-presidency/307516/|access-date=December 28, 2017|work=[[The Atlantic]]|date=July 2009|archive-date=December 29, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171229052318/https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/07/end-the-vice-presidency/307516/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|last1=Ackerman|first1=Bruce|title=Abolish the vice presidency|url=http://www.latimes.com/opinion/opinion-la/la-oe-ackerman2-2008oct02-story.html?barc=0|access-date=December 28, 2017|work=[[Los Angeles Times]]|date=October 2, 2008|archive-date=December 29, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171229112244/http://www.latimes.com/opinion/opinion-la/la-oe-ackerman2-2008oct02-story.html?barc=0|url-status=live}}</ref> while [[2008 United States presidential election|2008]]'s both vice presidential candidates, [[Sarah Palin]] and [[Joe Biden]], said they would reduce the role to simply being an adviser to the president.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=89FbCPzAsRA|title=Full Vice Presidential Debate with Gov. Palin and Sen. Biden|date=October 2, 2008 |publisher=YouTube|access-date=October 30, 2011|archive-date=January 14, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210114195116/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=89FbCPzAsRA|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Since 1974, the official residence of the vice president and his family has been [[Number One Observatory Circle]], on the grounds of the [[United States Naval Observatory]] in [[Washington, DC]]. |

|||

==Constitutional roles== |

|||

=== President of the Senate === |

|||

{{ |

{{Politics of the United States}} |

||

As President of the Senate ([[Article One of the United States Constitution|Article I]], Section 3), the vice president oversees procedural matters and may [[U.S. Vice President's tie-breaking votes|cast a tie-breaking vote]]. There is a strong convention within the [[United States Senate|U.S. Senate]] that the vice president not use his position as President of the Senate to influence the passage of legislation or act in a partisan manner, except in the case of breaking tie votes. As President of the Senate, [[John Adams]] cast twenty-nine [[U.S. Vice President's tie-breaking votes|tie-breaking votes]]—a record that no successor has ever threatened. His votes protected the president's sole authority over the removal of appointees, influenced the location of the national capital, and prevented war with [[Kingdom of Great Britain|Great Britain]]. On at least one occasion he persuaded senators to vote against legislation that he opposed, and he frequently lectured the Senate on procedural and policy matters. Adams' political views and his active role in the Senate made him a natural target for critics of the Washington administration. Toward the end of his first term, as a result of a threatened resolution that would have silenced him except for procedural and policy matters, he began to exercise more restraint in the hope of realizing the goal shared by many of his successors: election in his own right as president of the United States of America. |

|||

Although delegates to the constitutional convention approved establishing the office, with both its executive and senatorial functions, not many understood the office, and so they gave the vice president few duties and little power.<ref name=VP-PS>{{cite web| title=Vice President of the United States (President of the Senate)| website=senate.gov| url=https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Vice_President.htm| publisher=Secretary of the Senate| location=Washington, D.C.| access-date=July 28, 2018| archive-date=November 15, 2002| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20021115191818/https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Vice_President.htm| url-status=live}}</ref> Only a few states had an analogous position. Among those that did, [[New York Constitution|New York's constitution]] provided that "the lieutenant-governor shall, by virtue of his office, be president of the Senate, and, upon an equal division, have a casting voice in their decisions, but not vote on any other occasion".<ref>{{Cite web | title=The Senate and the United States Constitution | url=https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Constitution_Senate.htm#5 | website=senate.gov | publisher=Secretary of the Senate | location=Washington, D.C. | access-date=February 20, 2018 | archive-date=February 11, 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200211193328/https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/briefing/Constitution_Senate.htm#5 | url-status=live }}</ref> As a result, the vice presidency originally had authority in only a few areas, although constitutional amendments have added or clarified some matters. |

|||

In modern times, the vice president rarely presides over day-to-day matters in the Senate; in his place, the Senate chooses a [[President pro tempore of the United States Senate|President ''pro tempore'']] (or "president for a time") to preside in the Vice President's absence, and the Senate maintains a Duty Roster for the post, normally selecting the longest serving senator in the majority party. |

|||

===President of the Senate=== |

|||

When the President is [[impeachment|impeached]], the [[Chief Justice of the United States of America]] presides over the Senate during the impeachment trial. Otherwise, the Vice President, in his capacity as President of the Senate, or the President pro tempore of the Senate presides. This may include the impeachment of the Vice President him- or herself, although legal theories suggest that allowing a person to be the judge in the case where he or she was the defendant wouldn't be permitted. If the Vice President did not preside over an impeachment, the duties would fall to the President Pro Tempore. |

|||

[[Article One of the United States Constitution#Clause 4: Vice President as President of Senate|Article I, Section 3, Clause 4]] confers upon the vice president the title "President of the Senate", authorizing the vice president to [[Presiding Officer of the United States Senate|preside over Senate meetings]]. In this capacity, the vice president is responsible for maintaining order and decorum, recognizing members to speak, and interpreting the Senate's rules, practices, and precedent. With this position also comes the authority to [[List of tie-breaking votes cast by the vice president of the United States|cast a tie-breaking vote]].<ref name=VP-PS/> In practice, the number of times vice presidents have exercised this right has varied greatly. Incumbent vice president [[Kamala Harris]] holds the record at 33 votes, followed by [[John C. Calhoun]] who had previously held the record at 31 votes; [[John Adams]] ranks third with 29.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Lebowitz|first1=Megan|last2=Thorp|first2=Frank|last3=Santaliz|first3=Kate|title=Vice President Harris breaks record for casting the most tie-breaking votes|url=https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/congress/president-harris-breaks-record-casting-tie-breaking-votes-rcna123999|website=NBC News|date=December 5, 2023|access-date=December 5, 2023|archive-date=December 5, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231205185108/https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/congress/president-harris-breaks-record-casting-tie-breaking-votes-rcna123999|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=U.S. Senate: Votes to Break Ties in the Senate |url=https://www.senate.gov/legislative/TieVotes.htm |access-date=2022-08-25 |website=United States Senate}}</ref> Nine vice presidents, most recently [[Joe Biden]], did not cast any tie-breaking votes.<ref>{{cite news| title=Check out the number of tie-breaking votes vice presidents have cast in the U.S. Senate| date=July 25, 2017| url=https://www.pbs.org/weta/washingtonweek/blog-post/check-out-number-tie-breaking-votes-vice-presidents-have-cast-us-senate| work=Washington Week| publisher=PBS| access-date=December 11, 2021| archive-date=December 12, 2021| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211212013002/https://www.pbs.org/weta/washingtonweek/blog-post/check-out-number-tie-breaking-votes-vice-presidents-have-cast-us-senate| url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

One duty required of President of the Senate is presiding over the counting and presentation of the votes of the [[U.S. Electoral College]]. This process occurs in the presence of both houses of Congress, on [[January 6]] of the year following a [[U.S. presidential election]]. In this capacity, only four Vice Presidents have been able to announce their own election to the presidency: [[John Adams]], [[Thomas Jefferson]], [[Martin Van Buren]], and [[George H. W. Bush]]. At the beginning of 1961, it fell to Richard Nixon to preside over this process, which officially announced the election of his 1960 opponent, John F. Kennedy, and in 2001, [[Al Gore]] announced the election of his opponent, [[George W. Bush]]. Nixon found himself in the opposite position in 1969, when Vice President [[Hubert Humphrey]] announced he had lost to Nixon. |

|||

As the framers of the Constitution anticipated that the vice president would not always be available to fulfill this responsibility, the Constitution provides that the Senate may elect a [[President pro tempore of the United States Senate|president pro tempore]] (or "[[Pro tempore|president for a time]]") in order to maintain the proper ordering of the legislative process. In practice, since the early 20th century, neither the president of the Senate nor the pro tempore regularly presides; instead, the president pro tempore usually delegates the task to other Senate members.<ref>{{cite web| last=Forte| first=David F.| title=Essays on Article I: President Pro Tempore| url=https://www.heritage.org/constitution/#!/articles/1/essays/16/president-pro-tempore| work=Heritage Guide to the Constitution| publisher=The Heritage Foundation| access-date=July 27, 2018| archive-date=August 22, 2020| archive-url=https://archive.today/20200822232208/https://www.heritage.org/constitution/%23!/amendments/8/essays/161/cruel-and-unusual-punishment#!/articles/1/essays/16/president-pro-tempore| url-status=live}}</ref> [[Standing Rules of the Senate Rule XIX|Rule XIX]], which governs debate, does not authorize the vice president to participate in debate, and grants only to members of the Senate (and, upon appropriate notice, former presidents of the United States) the privilege of addressing the Senate, without granting a similar privilege to the sitting vice president. Thus, ''[[Time (magazine)|Time]]'' magazine wrote in 1925, during the tenure of Vice President [[Charles G. Dawes]], "once in four years the Vice President can make a little speech, and then he is done. For four years he then has to sit in the seat of the silent, attending to speeches ponderous or otherwise, of deliberation or humor."<ref>{{cite magazine|title=President Dawes|department=The Congress|url=http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,786539,00.html|url-access=subscription|magazine=[[Time (magazine)|Time]]|location=New York, New York|date=December 14, 1925|volume=6|issue=24|access-date=July 31, 2018|archive-date=October 19, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171019162915/http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,786539,00.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Vice President [[John C. Calhoun]] became the first vice president to resign the office. He believed he would have more power as a senator. He had been dropped from the ticket by President [[Andrew Jackson]] in favor of [[Martin Van Buren]]. Already a lame-duck vice president, he was elected to the Senate by the [[South Carolina]] state legislature and resigned the vice presidency early to begin his Senate term. |

|||

==== Presiding over impeachment trials ==== |

|||

===Growth of the office=== |

|||

In their capacity as president of the Senate, the vice president may preside over most [[Federal impeachment trial in the United States|impeachment trials of federal officers]], although the Constitution does not specifically require it. However, whenever the president of the United States is on trial, the Constitution requires that the [[chief justice of the United States]] must preside. This stipulation was designed to avoid the possible conflict of interest in having the vice president preside over the trial for the removal of the one official standing between them and the presidency.<ref name=A1trial>{{cite web| last=Gerhardt| first=Michael J.| title=Essays on Article I: Trial of Impeachment| url=https://www.heritage.org/constitution/#!/articles/1/essays/17/trial-of-impeachment| work=Heritage Guide to the Constitution| publisher=The Heritage Foundation| access-date=October 1, 2019| archive-date=August 22, 2020| archive-url=https://archive.today/20200822232208/https://www.heritage.org/constitution/%23!/amendments/8/essays/161/cruel-and-unusual-punishment#!/articles/1/essays/17/trial-of-impeachment| url-status=live}}</ref> In contrast, the Constitution is silent about which federal official would preside were the vice president on trial by the Senate.<ref name=24KJLPP1/><ref>{{Cite journal| title=Can the Vice President preside at his own impeachment trial?: A critique of bare textualism| last=Goldstein| first=Joel K.| url=https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=392001104070027081022120029066016007014068057063028037092012019031105007127000116031006037049124106003039080094094007065105089046016030083072001069104126069096114087051008094092074006002100029126100108126094011105105076101115026002005094084099102090074&EXT=pdf| year=2000| volume=44| journal=Saint Louis University Law Journal| pages=849–870| access-date=September 30, 2019| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210114195031/https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3297261| archive-date=January 14, 2021| url-status=live}}</ref> No vice president has ever been impeached, thus leaving it unclear whether an impeached vice president could, as president of the Senate, preside at their own impeachment trial. |

|||

For much of its existence, the office of Vice President was seen as little more than a minor position. [[John Adams]], the first vice president, described it as "the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived." Even 150 years later, 32nd Vice President [[John Nance Garner]] famously described the office as "not worth a pitcher of warm [[urine|piss]]" (at the time reported with the [[bowdlerization]] "spit"). [[Thomas R. Marshall]], the 28th Vice President, lamented: "Once there were two brothers. One went away to sea; the other was elected vice president. And nothing was heard of either of them again." When the [[Whig Party (United States)|Whig Party]] was looking for a vice president on [[Zachary Taylor]]'s ticket, they approached [[Daniel Webster]], who said of the offer "I do not intend to be buried until I am dead." The natural stepping stone to the Presidency was long considered to be the office of [[United States Secretary of State|Secretary of State]]. It has only been fairly recently that this notion has reversed; indeed, the notion was still very much alive when [[Harry Truman]] became the vice president for [[Franklin Roosevelt]]. |

|||

==== Presiding over electoral vote counts ==== |

|||

[[Image:Harry-truman.jpg|thumb|[[Harry Truman]] had been vice president only three months when he became president; he was never informed of Franklin Roosevelt's war and postwar policies.]] |

|||

The Twelfth Amendment provides that the vice president, in their capacity as the president of the Senate, receives the [[Electoral College (United States)|Electoral College]] votes, and then, in the presence of the Senate and House of Representatives, opens the sealed votes.<ref name=A2TKec/> The votes are counted during a [[Joint session of the United States Congress|joint session of Congress]] as prescribed by the [[Electoral Count Act]] and the [[Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act]]. The former specifies that the president of the Senate presides over the joint session,<ref>[https://uscode.house.gov/statviewer.htm?volume=24&page=373 24 Stat. 373] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201015112458/https://uscode.house.gov/statviewer.htm?volume=24&page=373 |date=October 15, 2020 }} (Feb. 3, 1887).</ref> and the latter clarifies the solely ministerial role the president of the Senate serves in the process.<ref>[https://uscode.house.gov/statviewer.htm?volume=136&page=5234# 136 Stat. 5238] {{Webarchive|url= https://web.archive.org/web/20231027221946/https://uscode.house.gov/statviewer.htm?volume=136&page=5234 |date=October 27, 2023}} (Dec. 9, 2022).</ref> The next such joint session will next take place following the [[2024 United States presidential election|2024 presidential election]], on January 6, 2025 (unless Congress sets a different date by law).<ref name=CRS2017THN/> |

|||

For many years, the vice president was given few responsibilities. After John Adams attended a meeting of the president's [[United States Cabinet|Cabinet]] in 1791, no Vice President did so again until Thomas Marshall stood in for President [[Woodrow Wilson]] while he traveled to Europe in 1918 and 1919. Marshall's successor, [[Calvin Coolidge]], was invited to meetings by President [[Warren G. Harding]]. The next Vice President, [[Charles G. Dawes]], was not invited after declaring that "the precedent might prove injurious to the country." Vice President [[Charles Curtis]] was also precluded from attending by President [[Herbert Hoover]]. |

|||

In this capacity, four vice presidents have been able to announce their own election to the presidency: John Adams, in 1797, [[Thomas Jefferson]], in 1801, [[Martin Van Buren]], in 1837 and [[George H. W. Bush]], in 1989.<ref name=VP-PS/> Conversely, [[John C. Breckinridge]], in 1861,<ref>{{cite web|last=Glass|first=Andrew|title=Senate expels John C. Breckinridge, Dec. 4, 1861|url=https://www.politico.com/story/2014/12/senate-expels-john-c-breckinridge-dec-4-1861-113297|date=December 4, 2014|publisher=Politico|location=Arlington County, Virginia|access-date=July 29, 2018|archive-date=September 23, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180923114731/https://www.politico.com/story/2014/12/senate-expels-john-c-breckinridge-dec-4-1861-113297|url-status=live}}</ref> [[Richard Nixon]], in 1961,<ref name=EV1969count>{{cite news|author=<!--UPI; no by-line.--> |title=Electoral Vote Challenge Loses|work=[[St. Petersburg Times]]|date=January 7, 1969|pages=1, 6|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=BvsNAAAAIBAJ&sjid=x3sDAAAAIBAJ&pg=3226,4398264|access-date=July 29, 2018|via=Google News}}</ref> and [[Al Gore]], in 2001,<ref>{{cite web|last=Glass|first=Andrew|title=Congress certifies Bush as winner of 2000 election, Jan. 6, 2001|url=https://www.politico.com/story/2016/01/congress-certifies-bush-as-winner-of-2000-election-jan-6-2001-217291|date=January 6, 2016|publisher=Politico|location=Arlington County, Virginia|access-date=July 29, 2018|archive-date=September 23, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180923123421/https://www.politico.com/story/2016/01/congress-certifies-bush-as-winner-of-2000-election-jan-6-2001-217291|url-status=live}}</ref> all had to announce their opponent's election. In 1969, Vice President [[Hubert Humphrey]] would have done so as well, following his 1968 loss to Richard Nixon; however, on the date of the congressional joint session, Humphrey was in [[Norway]] attending the funeral of [[Trygve Lie]], the first elected [[Secretary-General]] of the [[United Nations]]. The president pro tempore, [[Richard Russell Jr.|Richard Russell]], presided in his absence.<ref name=EV1969count/> On February 8, 1933, Vice President [[Charles Curtis]] announced the election of his successor, House Speaker [[John Nance Garner]], while Garner was seated next to him on the House {{Linktext|dais}}.<ref>{{Cite news| author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.-->| title=Congress Counts Electoral Vote; Joint Session Applauds Every State Return as Curtis Performs Grim Task. Yells Drown His Gavel Vice President Finally Laughs With the Rest as Victory of Democrats Is Unfolded. Opponents Cheer Garner Speaker Declares His Heart Will Remain in the House, Replying to Tribute by Snell| date=February 9, 1933| newspaper=The New York Times| url=https://www.nytimes.com/1933/02/09/archives/congress-counts-electoral-vote-joint-session-applauds-every-state.html| via=TimesMachine| access-date=October 1, 2019| archive-date=February 11, 2020| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200211172940/https://www.nytimes.com/1933/02/09/archives/congress-counts-electoral-vote-joint-session-applauds-every-state.html| url-status=live}}</ref> Most recently, Vice President [[Mike Pence]], on January 6, 2021, [[2021 United States Electoral College vote count|announced the election of his successor]], [[Kamala Harris]]. |

|||

In 1933, Roosevelt raised the stature of the office by renewing the practice of inviting the vice president to cabinet meetings, which has been maintained by every president since. Roosevelt's first vice president, [[John Nance Garner]], broke with him at the start of the second term on the Court-packing issue and became Roosevelt's leading political enemy. Garner's successor, [[Henry A. Wallace|Henry Wallace]], was given major responsibilities during the war, but he moved further to the left than the Democratic Party and the rest of the Roosevelt administration and was relieved of actual power. Roosevelt kept his last vice president, [[Harry Truman]], uninformed on all war and postwar issues, such as the [[Manhattan Project|atomic bomb]], leading Truman to wryly remark that the job of the vice president is to "go to weddings and funerals." The need to keep vice presidents informed on national security issues became clear, and Congress made the vice president one of four statutory members of the [[United States National Security Council|National Security Council]] in 1949. |

|||

===Successor to the U.S. president=== |

|||

[[Richard Nixon]] reinvented the office of vice president. He had the attention of the media and the Republican party, and Eisenhower ordered him to preside at Cabinet meetings in his absence. Nixon was also the first vice president to temporarily assume control of the executive branch; he did so after Eisenhower suffered a [[myocardial infarction|heart attack]] on [[September 24]], [[1955]]; [[ileitis]] in June 1956; and a [[stroke]] in November 1957. |

|||

[[File:Tyler receives news.jpg|thumb|alt=An illustration:Tyler stands on his porch in Virginia, approached by a man with an envelope. Caption reads "Tyler receiving the news of Harrison's death."|upright=1.05|1888 illustration of [[John Tyler]] receiving the news of President [[William Henry Harrison]]'s death from Chief Clerk of the State Department [[Fletcher Webster]]]] |

|||