Arlington County, Virginia: Difference between revisions

Largoplazo (talk | contribs) m rv: Can't think what a "regional county" is or what it means to be a main one. |

Keystone18 (talk | contribs) →21st century: further |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|County in Virginia, United States}} |

|||

{{Infobox U.S. County| |

|||

{{redirect|Arlington, Virginia|the community in Northampton County|Arlington, Northampton County, Virginia}} |

|||

county = Arlington County| |

|||

{{redirect2|Alexandria County|Alexandria County, Virginia|the city|Alexandria, Virginia}} |

|||

state = Virginia | |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=July 2024}} |

|||

seal = Acseal.png | |

|||

{{Infobox U.S. county |

|||

map = Map of Virginia highlighting Arlington County.png| |

|||

| county = Arlington County |

|||

map size= | |

|||

| state = Virginia |

|||

founded = [[9 July]],[[1846]]| |

|||

| type = [[County (United States)|County]] and [[census-designated place]] |

|||

seat = [[Arlington, Virginia|Arlington]] | |

|||

| official_name = |

|||

area_total_sq_mi =26 | |

|||

| flag = Flag of Arlington County, Virginia.svg |

|||

area_land_sq_mi =26 | |

|||

| flag size = |

|||

area_water_sq_mi =0 | |

|||

| logo = Logo of Arlington County, Virginia.png |

|||

area percentage = 0.35% | |

|||

| logo size = |

|||

census yr = 2006 | |

|||

| seal = Seal of Arlington County.png |

|||

pop = 200226 | |

|||

| seal size = 90px |

|||

density_sq_mi =7701 | |

|||

| founded = February 27, 1801 |

|||

web = www.arlingtonva.us| |

|||

| area_total_sq_mi = 26 |

|||

|}} |

|||

| area_land_sq_mi = 26 |

|||

| area_water_sq_mi = 0.2 |

|||

| area percentage = 0.4 |

|||

| population_as_of = 2020 |

|||

| population_total = 238643 |

|||

| population_density_sq_mi = auto |

|||

| website = {{URL|https://www.arlingtonva.us/|arlingtonva.us}} |

|||

| ex image = {{center|{{Photomontage |

|||

|photo1a = Arlington County - Virginia.jpg |

|||

|photo1b = Arlington County - Virginia - 2.jpg |

|||

|photo2a = A Renaissance Hotel in Arlington, Virginia.jpg |

|||

|photo2b = Ballston6365-091819.jpg |

|||

|photo3a = Rosslyn Skyline from Theodore Roosevelt Bridge.png |

|||

|photo3b = Rosslyn, Arlington, Virginia.jpg |

|||

|size = 280 |

|||

|color = transparent |

|||

|border = 0 |

|||

}}}} |

|||

| ex image size = 300px |

|||

| ex image cap = |

|||

| district = 8th |

|||

| time zone = Eastern |

|||

| named for = [[Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial|Arlington House]] |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|38.880278|-77.108333|type:city_region:|display=inline,title}} |

|||

}} |

|||

<!-- |

|||

[[File:The Pentagon (side).jpg|thumb|Looking north toward [[The Pentagon]] with [[Rosslyn, Virginia|Rosslyn]] in the background]] |

|||

[[File:Georgetown Spires.jpg|thumb|Arlington's [[Rosslyn, Virginia|Rosslyn]] and [[Crystal City, Virginia|Crystal City]] skylines seen from [[Georgetown University]] in [[Georgetown (Washington, D.C.)|Georgetown]]]] |

|||

--> |

|||

'''Arlington County''', or simply '''Arlington''', is a [[County (United States)|county]] in the [[U.S. state]] of [[Virginia]].<ref name="omb1301">{{cite web|url=https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/bulletins/2013/b-13-01.pdf |title=OMB BULLETIN NO. 13-01 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170207113057/https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/bulletins/2013/b-13-01.pdf |via=[[NARA|National Archives]] |work=[[Office of Management and Budget]] |archive-date=February 7, 2017 }}</ref> The county is located in [[Northern Virginia]] on the southwestern bank of the [[Potomac River]] directly across from [[Washington, D.C.]], the national capital. |

|||

Arlington County is coextensive with the [[United States Census Bureau|U.S. Census Bureau]]'s [[census-designated place]] of Arlington. Arlington County is the eighth-most populous county in the [[Washington metropolitan area]] with a population of 238,643 as of the [[2020 United States census|2020 census]].<ref>{{Cite web|title= QuickFacts: Arlington County, Virginia|url=https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/arlingtoncountyvirginia|access-date=January 28, 2022|website=U.S. Census Bureau|language=en}}</ref> If Arlington County were incorporated as a city, it would rank as the third-most populous city in the state. With a land area of {{convert|26|sqmi|km2}}, Arlington County is the geographically smallest [[Administrative divisions of Virginia|self-governing county]] in the nation. |

|||

'''Arlington County''' is an [[urban area|urban]] [[county]] of about 203,000 residents in the [[Commonwealth (United States)|Commonwealth]] of [[Virginia]], in the [[United States|U.S.]], directly across the [[Potomac River]] from [[Washington, D.C.]] <ref name=Estimated_Population>{{cite web | url = http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/CPHD/planning/data_maps/CPHDPlanningDataandMapsProfile.aspx?lnsLinkID=1150 | title = Profile | accessmonthday = May 1|accessyear = 2007}}</ref> Formerly part of the [[Washington, D.C.|District of Columbia]], the land now comprising the county was [[Retrocession (District of Columbia)|retroceded to Virginia]] in a [[July 9]], [[1846]], act of [[US Congress|Congress]] that took effect in [[1847]]. |

|||

Arlington County is home to [[the Pentagon]], the world's second-largest office structure, which houses the headquarters of the [[United States Department of Defense|U.S. Department of Defense]]. Other notable locations are [[DARPA]], the [[Drug Enforcement Administration]]'s headquarters, [[Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport|Reagan National Airport]], and [[Arlington National Cemetery]]. Colleges and universities in the county include [[Marymount University]] and [[George Mason University]]'s [[Antonin Scalia Law School]], [[George Mason School of Business|School of Business]], the [[Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution|Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution]], and [[Schar School of Policy and Government]]. Graduate programs, research, and non-traditional student education centers affiliated with the [[University of Virginia]] and [[Virginia Tech]] are also located in the county. |

|||

Despite being a county, it is considered a Central City of the [[Washington Metropolitan Area|Washington, D.C. area]] by the [[United States Census Bureau|Census]], along with neighboring Washington and [[Alexandria, Virginia|Alexandria]]. It is usually rendered "Arlington" or "Arlington, Virginia" by people and the media. At a land area of 26 square miles, it is geographically the smallest self-governing county in the United States. |

|||

Corporations based in the county include the [[Amazon HQ2|co-headquarters]] of [[Amazon (company)|Amazon]], several [[consulting firm]]s, and the global headquarters of [[Boeing]], [[Raytheon Technologies]] and [[BAE Systems Platforms & Services]].<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |date=June 7, 2022 |title=Raytheon moving global HQ to Arlington |url=https://www.virginiabusiness.com/article/raytheon-moving-global-hq-to-arlington/ |access-date=June 21, 2022 |website=Virginia Business |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

''[[Money (magazine)|CNN Money]]'' ranked Arlington as the most educated city in [[2006]]. Among the top 100 cities (having a population of 50,000+) with high percentages of Master's/Doctorate degree holders, only the smaller cities of [[Bethesda, Maryland|Bethesda]] and [[Reston, Virginia|Reston]] were higher in the D.C. area, with Alexandria the closest in overall population size. ''[[Forbes#Web site| Forbes' Web site]]'' reported that Arlington had been the 9th richest county in the United States in 2006, based on the County's [[median household income]] of $87,350.<ref>[http://www.forbes.com/2008/01/22/counties-rich-income-forbeslife-cx_mw_0122realestate.html Matt Woolsey, America's Richest Counties, Forbes.com, 01.22.08, 6:00 PM ET] Forbes.com Web site. Retrieved on [[2008#Feb|2008-02-08]].</ref><ref>[http://www.forbes.com/2008/01/22/counties-rich-income-forbeslife-cx_mw_0122realestate_slide_10.html Matt Woolsey, America's Richest Counties, Forbes.com, 01.22.08: Complete List: America's Richest Counties: 9. Arlington County, Va.] Forbes.com Web Site. Retrieved on [[2008#Feb|2008-02-08]].</ref> The County is the location of [[Arlington National Cemetery]], [[Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport]] and [[the Pentagon]]. |

|||

==History== |

|||

== General Characteristics == |

|||

===Colonial Virginia=== |

|||

{{Further|Colony of Virginia}} |

|||

Present-day Arlington County was part of [[Fairfax County, Virginia|Fairfax County]] in the [[Colony of Virginia]] during the [[Colonial history of the United States|colonial era]]. Land grants from the [[British Crown]] were awarded to prominent [[English people|Englishmen]] in exchange for political favors and efforts as part of the county's early development. One of the grantees was [[Thomas Fairfax, 6th Lord Fairfax of Cameron|Thomas Fairfax]] for whom both Fairfax County and the [[Fairfax, Virginia|City of Fairfax]] are named. The county's name was derived from [[Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington|Henry Bennet]], the [[Earl of Arlington]], which was a [[plantations in the American South|plantation]] along the [[Potomac River]], and [[Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial|Arlington House]], the family residence on that property. [[George Washington Parke Custis]], grandson of First Lady [[Martha Washington]], acquired the land in 1802.<ref>{{Cite web|date=February 16, 2012|title=Why Is It Named Arlington?|url=https://ghostsofdc.org/2012/02/16/why-is-it-named-arlington/|access-date=January 2, 2022|website=Ghosts of DC|language=en-US}}</ref> The estate was later passed down to [[Mary Anna Custis Lee]], wife of [[Robert E. Lee]], a [[Confederate States Army|Confederate]] general during the [[American Civil War]], and then later seized by the [[Federal government of the United States|U.S. federal government]] in a tax sale.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nathanielturner.com/willofgeorgewashingtonparkecustis.htm |title=Will of George Washington Parke Custis |publisher=Nathanielturner.com |date=June 29, 2008 |access-date=November 4, 2011}}</ref> The property later became the [[Arlington National Cemetery]]. |

|||

===Residence Act=== |

|||

As of [[January 1]], [[2007]], the estimated population was 202,800. <ref name=Estimated_Population>{{cite web | url = http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/CPHD/planning/data_maps/CPHDPlanningDataandMapsProfile.aspx?lnsLinkID=1150 | title = Profile | accessmonthday = May 1|accessyear = 2007}}</ref> Strictly speaking, it is inaccurate to refer to it as the city of Arlington. All cities within the state are [[independent city|independent]] of counties, though towns may be incorporated within counties. However, Arlington has no existing incorporated towns because [[Virginia]] law prevents the creation of any new municipality within a county that has a [[population density]] greater than 1,000 persons per square mile. Its [[county seat]] is the [[census-designated place]] of Arlington{{GR|6}}, which is co-extensive with Arlington County; however, the neighborhood of [[Courthouse, Virginia|Courthouse]] is often thought of as seat by residents. |

|||

{{Main|Residence Act}} |

|||

[[File:Map of the District of Columbia, 1835.jpg|thumb|An 1835 map of the [[Washington, D.C.|District of Columbia]], prior to the [[District of Columbia retrocession|retrocession]] of [[Alexandria County, Virginia|Alexandria County]]]] |

|||

Present-day Arlington County and most of present-day [[Alexandria, Virginia|Alexandria]] were ceded to the new [[Federal government of the United States|federal government]] by [[Virginia]]. On July 16, 1790, the [[United States Congress|Congress]] passed the [[Residence Act]], which authorized the relocation of the capital from [[Philadelphia]] to a location to be selected on the [[Potomac River]] by [[President of the United States|U.S. President]] [[George Washington]]. The Residence Act originally only allowed the President to select a location in [[Maryland]] as far east as the [[Anacostia River]]. President Washington, however, shifted the federal territory's borders to the southeast in order to include the existing town of Alexandria. |

|||

In 1791, [[United States Congress|Congress]], at Washington's request, amended the Residence Act to approve the new site, including the territory ceded by Virginia.<ref>{{cite book |last=Crew |first=Harvey W. |author2=William Bensing Webb|author3=John Wooldridge |title=Centennial History of the City of Washington, D. C. |publisher=United Brethren Publishing House |year=1892 |location=[[Dayton, Ohio]] |url=https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_5Q81AAAAIAAJ |pages=[https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_5Q81AAAAIAAJ/page/n96 89]–92 }}</ref> The amendment to the Residence Act prohibited the "erection of the public buildings otherwise than on the Maryland side of the River Potomac."<ref>(1) [[s:United States Statutes at Large/Volume 1/1st Congress/3rd Session/Chapter 17|United States Statutes at Large: Volume 1: 1st Congress: 3rd Session; Chapter 17> XVII.—An Act to amend "An act for establishing the temporary and permanent seat of the government of the United States"]]<br />(2) {{cite web|url=https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbpe.2170010p/|title=An ACT to amend "An act for establishing the TEMPORARY and PERMANENT SEAT of the GOVERNMENT of the United States.|work= Congress of the United States: at the third session, begun and held at the city of Philadelphia, on Monday the sixth of December, one thousand seven hundred and ninety|date=March 3, 1791|location=Philadelphia|publisher=Printed by Francis Childs and Johnn Swaine (1791)|access-date=October 16, 2020|quote=Provided, That nothing herein contained, shall authorize the erection of the public buildings otherwise than on the Maryland side of the river Potomac, as required by the aforesaid act.|via=[[Library of Congress]]}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

===Alexandria County, District and Commonwealth jurisdictions=== |

|||

Once part of [[Fairfax County, Virginia|Fairfax County]] in the [[Virginia Colony]], the area that contains Arlington County was ceded to the new U.S. government by the Commonwealth of Virginia. In [[1791]], the [[United States Congress|U.S. Congress]] formally established the limits of the federal territory that would be the nation's capital as a square of 10 miles on a side, the maximum area permitted by [[Article One of the United States Constitution|Article I]], Section 8, of the [[United States Constitution]]. However, the legislation that established these limits contained a clause that prohibited the federal government from locating any offices within the portion of the territory that Virginia had ceded. |

|||

The initial shape of the federal district was a square, measuring {{convert|10|mi|km|}} on each side, totaling {{convert|100|sqmi|km2|}}. In 1791 and 1792, [[Andrew Ellicott]] and several assistants placed [[boundary markers of the original District of Columbia|boundary stones]] at every mile point. Fourteen of these markers were in Virginia, and many of the stones are still standing.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.boundarystones.org/ |title=Boundary Stones of Washington, D.C. |publisher=BoundaryStones.org |access-date=May 27, 2008 | archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20080515194639/http://www.boundarystones.org/| archive-date= May 15, 2008 | url-status= live}}</ref> |

|||

During 1791 and [[1792]], [[Andrew Ellicott]] led a team of [[surveying|surveyors]] that determined the boundaries of the federal territory. The team placed along the boundaries [[List of Boundary Markers of the Original District of Columbia | forty markers]] that were approximately one mile from each other. Fourteen of these markers were in Virginia. <ref> Boundary markers of the Nation's Capital : a proposal for their preservation & protection : a National Capital Planning Commission Bicentennial report. National Capital Planning Commission, Washington, DC, 1976; for sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office</ref> |

|||

When [[United States Congress|Congress]] arrived in the new capital from [[Philadelphia]], one of their first acts was to pass the [[District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801|Organic Act of 1801]], officially organizing the District of Columbia and placing the entire federal territory, including present-day Washington, D.C., [[Georgetown (Washington, D.C.)|Georgetown]], and [[Alexandria, Virginia|Alexandria]] under the exclusive control of Congress. The territory in the District was organized into two counties: the [[Washington County, D.C.|County of Washington]] to the east of the Potomac River and the County of Alexandria to the west. It included almost all of present-day Arlington County and part of present-day Alexandria.<ref>{{cite book |last=Crew |first=Harvey W. |author2=William Bensing Webb|author3=John Wooldridge |title=Centennial History of the City of Washington, D. C.|chapter=IV. Permanent Capital Site Selected|publisher=United Brethren Publishing House |year=1892 |location=[[Dayton, Ohio]] |url=https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_5Q81AAAAIAAJ |page=[https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_5Q81AAAAIAAJ/page/n110 103] }}</ref> |

|||

When Congress moved to the new District of Columbia in [[1801]], it enacted legislation that divided the District into two counties: (1) the county of Washington, which lay on the east side of the Potomac River, and (2) [[Alexandria County, D.C.|the county of Alexandria]], which lay on the west side of the River.<ref name=Sixth_Congress>Sixth Congress, Session II, Chapter XV (An Act concerning the District of Columbia), Section 2 (Stat. II, Feb. 27, 1801) (United States Statutes at Large, Vol. II, p. 103)</ref> Alexandria County contained the present area of Arlington County, then mostly rural, and the settled town of Alexandria (now "Old Town" Alexandria), a port located on the Potomac River in the southeastern part of the area of the present City of [[Alexandria, Virginia|Alexandria]]. |

|||

The Act established the borders of the area that eventually became Arlington, but the citizens in the District were no longer considered residents of Maryland or Virginia, which represented the end of their federal representation in Congress.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.abanet.org/poladv/letters/electionlaw/060914testimony_dcvoting.pdf |title=Statement on the subject of The District of Columbia Fair and Equal Voting Rights Act |access-date=July 10, 2008 |date=September 14, 2006 |publisher=[[American Bar Association]] | archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20080725102618/http://www.abanet.org/poladv/letters/electionlaw/060914testimony_dcvoting.pdf| archive-date= July 25, 2008 | url-status= live}}</ref> |

|||

Residents of Alexandria County had expected the federal capital's location would result in land sales and the growth of commerce. Instead the county found itself struggling to compete with the town of [[Georgetown, Washington, D.C.|Georgetown]], a port located in Washington County adjacent to the capital city (Washington City). |

|||

===Retrocession=== |

|||

As the federal government could not establish any offices in the County, and as the economically important [[Chesapeake and Ohio Canal]] (C&O Canal) on the north side of the Potomac River favored Georgetown, Alexandria's economy stagnated. It didn't help that some Georgetown residents opposed federal efforts to maintain the [[Alexandria Canal (Virginia)|Alexandria Canal]], which connected the C&O Canal in Georgetown to Alexandria's port. Moreover, as residents of the District of Columbia, Alexandria's citizens had no representation in Congress and could not vote in federal elections. |

|||

{{main|District of Columbia retrocession}} |

|||

[[File:12-07-15-arlington-friedfhof-RalfR-026.jpg|thumb|[[Arlington National Cemetery]], located on land confiscated by the [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] from [[Confederate States Army|Confederate]] General [[Robert E. Lee]] during the [[American Civil War]]]] |

|||

Prior to retrocession, residents of [[Alexandria County, Virginia|Alexandria County]] expected the proximity of the federal capital to result in higher land prices and the growth of regional commerce. The county instead found itself struggling to compete with the [[Chesapeake and Ohio Canal]] in [[Georgetown (Washington, D.C.)|Georgetown]], which was farther inland and on the northern side of the [[Potomac River]] next to [[Washington, D.C.]]<ref>{{cite web|title=Frequently Asked Questions About Washington, D.C. |url=http://www.historydc.org/aboutdc.aspx |publisher=[[Historical Society of Washington, D.C.]] |access-date=October 3, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100918042009/http://www.historydc.org/aboutdc.aspx |archive-date=September 18, 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Members of [[United States Congress|Congress]] from other areas of Virginia used their influence to prohibit funding for projects, including the [[Alexandria Canal (Virginia)|Alexandria Canal]], which would have increased competition with their home districts. Congress also prohibited the [[Federal government of the United States|federal government]] from establishing any offices in Alexandria, which made the county less important to the functioning of the national government.<ref name="debates">{{cite journal|last=Richards |first=Mark David |date=Spring–Summer 2004 |title=The Debates over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia, 1801–2004 |journal=Washington History |publisher=www.dcvote.org |pages=54–82 |url=http://www.dcvote.org/pdfs/mdrretro062004.pdf |access-date=January 16, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090118053203/http://www.dcvote.org/pdfs/mdrretro062004.pdf |archive-date=January 18, 2009 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

Alexandria was a center for the [[Slavery in the United States|slave trade]]; [[Franklin and Armfield Office]] in Alexandria was once an office used in slave trading. Rumors circulated that [[Abolitionism in the United States|abolitionists]] in Congress were attempting to end slavery in the District, an act that, at the time, would have further depressed Alexandria's slavery-based economy.<ref>{{cite book |last=Greeley |first=Horace |title=The American Conflict: A History of the Great Rebellion in the United States|publisher=G. & C.W. Sherwood |year=1864 |location=Chicago |url=https://archive.org/details/americanconflic06greegoog |pages=[https://archive.org/details/americanconflic06greegoog/page/n154 142]–144}}</ref> At the same time, an active abolitionist movement arose in Virginia that created a division on the question of slavery in the [[Virginia General Assembly]]. Pro-slavery Virginians recognized that if Alexandria were returned to Virginia, it could provide two new representatives who favored slavery in the state legislature. Some time after retrocession, during the [[American Civil War]], this division led to the formation of [[West Virginia]] as a state, which comprised what then 51 counties in the northwest part of the state that favored abolitionism.<ref name="richards">{{cite journal|last=Richards |first=Mark David |date=Spring–Summer 2004 |title=The Debates over the Retrocession of the District of Columbia, 1801–2004 |journal=Washington History |publisher=Historical Society of Washington, D.C. |pages=54–82 |url=http://www.dcvote.org/pdfs/mdrretro062004.pdf |access-date=January 16, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090118053203/http://www.dcvote.org/pdfs/mdrretro062004.pdf |archive-date=January 18, 2009 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

The town of Alexandria had been a port and market for the [[slave trade]]. With growing talk of [[Abolitionism|abolishing slavery]] in the nation's [[capital]], some Alexandrians feared the local economy would suffer if the federal government took this step. |

|||

Largely as a result of the economic neglect by Congress, divisions over slavery, and the lack of voting rights for the residents of the District, a movement grew to return Alexandria to Virginia from the District of Columbia. From 1840 to 1846, Alexandrians petitioned Congress and the Virginia legislature to approve such a transfer, known as [[District of Columbia retrocession|retrocession]]. On February 3, 1846, the Virginia General Assembly agreed to accept the retrocession of Alexandria if Congress approved. Following additional lobbying by Alexandrians, [[List of United States federal legislation, 1789–1901#1841 to 1851|Congress passed legislation on July 9, 1846]], to return all the District's territory south of the Potomac River back to Virginia, pursuant to a referendum, and President [[James K. Polk]] signed the legislation the next day. A referendum on retrocession was held on September 1 and 2, 1846, and the voters in Alexandria voted in favor of the retrocession by a margin of 734 to 116, while those in the rest of Alexandria County voted against retrocession 106 to 29. Pursuant to the referendum, President Polk issued a proclamation of transfer on September 7, 1846. However, the Virginia legislature did not immediately accept the retrocession offer. Virginia legislators were concerned that Alexandria County residents had not been properly included in the retrocession proceedings. After months of debate, on March 13, 1847, the Virginia General Assembly voted to formally accept the retrocession legislation.<ref name=debates /> |

|||

At the same time, there arose in Virginia an active abolitionist movement that created a division on the question of slavery in [[Virginia General Assembly|Virginia's General Assembly]] (subsequently, during the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], Virginia's division on the slavery issue led to the formation of [[West Virginia|the state of West Virginia]] by the most anti-slavery counties). Pro-slavery Virginians recognized that Alexandria County could provide two new representatives who favored slavery in the General Assembly if the County returned to the Commonwealth. |

|||

In 1852, the Virginia legislature voted to incorporate a portion of Alexandria County as the City of Alexandria, which until then had been administered only as an unincorporated town within the political boundaries of Alexandria County.<ref name="Incorporation_of_Alexandria">{{cite web| url= http://alexandriava.gov/city/about-alexandria/about.html#history| title= Alexandria's History| access-date= August 30, 2006| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20060829220638/http://alexandriava.gov/city/about-alexandria/about.html#history| archive-date= August 29, 2006| url-status= dead| df= mdy-all}}</ref> |

|||

As a result, a movement grew to separate Alexandria County from the District of Columbia. After a referendum, the county's residents petitioned the U.S. Congress and the Virginia legislature to permit the County to return to Virginia. The area was [[Retrocession (District of Columbia)|retroceded to Virginia]] on [[July 9]], [[1846]].<ref name=Retrocession>{{cite web | url = http://www.citymuseumdc.org/gettoknow/faq.asp | title = Frequently Asked Questions About Washington, D.C. | accessmonthday = August 30 | accessyear = 2006 | work = The Historical Society of Washington, D.C.}}</ref> |

|||

===Civil War=== |

|||

In [[1852]], the [[independent City]] of Alexandria was incorporated from a portion of Alexandria County.<ref name=Incorporation_of_Alexandria>{{cite web | url = http://alexandriava.gov/city/about-alexandria/about.html#history | title = Alexandria's History | accessmonthday = August 30 | accessyear = 2006}}</ref> This led to occasional confusion, as the adjacent county and municipal entities continued to share the name of "Alexandria". Alexandria County renamed itself in [[1920]] as '''Arlington County'''. The new name was borrowed from [[Arlington National Cemetery]], which had been established during the [[American Civil War|Civil War]] on the grounds of [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] [[Robert E. Lee|General Robert E. Lee's]] former home, [[Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial|Arlington House]]. |

|||

{{Further|Virginia in the American Civil War}} |

|||

[[File:Arlington House.jpg|thumb|The façade of [[Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial|Arlington House]] (background), once the residence of [[Confederate States Army|Confederate Army]] General [[Robert E. Lee]], appears on Arlington's seal, flag, and logo.]] |

|||

During the [[American Civil War]], [[Virginia in the American Civil War|Virginia]] seceded from the [[Union (American Civil War)|Union]] following a statewide referendum on May 23, 1861; the voters from [[Alexandria County, Virginia|Alexandria County]] approved [[Secession in the United States|secession]] by a vote of 958–48, indicating the degree to which its only town, Alexandria, was pro-secession and pro-[[Confederate States of America|Confederate]]. Rural county residents outside Alexandria were largely Union loyalists and voted against secession.<ref>{{cite book |author=Bradley E. Gernand |title=A Virginia Village Goes to War: Falls Church During the Civil War |location= Virginia Beach |publisher= Donning Co Pub |year= 2002 |page=23 |isbn=978-1578641864}}</ref> |

|||

For the duration of the Civil War, the [[Confederate States of America|Confederacy]] claimed the whole of antebellum Virginia, including the more staunchly Union-supporting northwestern counties that eventually broke away and were later admitted to the Union in 1863 as [[West Virginia]]. However, the Confederacy never fully controlled all of present-day [[Northern Virginia]]. In 1862, the [[United States Congress|U.S. Congress]] passed a law that required that obligated owners of property in districts where active Confederate insurrections were occurring to pay their real estate taxes in person.<ref name=Hunter>(1) [[s: Bennett v. Hunter]]<br />(2) {{cite journal |last=Wallace|first=John William|author-link=John William Wallace|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QL0GAAAAYAAJ|title=Bennett v. Hunter|journal=Cases Argued and Adjudged in the Supreme Court of the United States, December Term, 1869|volume=9|location=Washington, D.C.|publisher=William H. Morrison|year=1870|pages=326–338|access-date=August 22, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

===Arlington National Cemetery=== |

|||

[[Image:Arlington.jpg|right|thumbnail|225px|Arlington Cemetery]] |

|||

{{mainarticle|Arlington National Cemetery}} |

|||

In 1864, during the Civil War, the [[Federal government of the United States|U.S. federal government]] confiscated the [[Abingdon (plantation)|Abingdon]] estate, which was located on and near the present [[Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport]], when its owner failed to pay the estate's property tax in person because he was serving in the [[Confederate States Army]].<ref name=Hunter/> The government then sold the property at auction, and the purchaser leased the property to a third party.<ref name=Hunter/> |

|||

Arlington National Cemetery is an American military cemetery established during the [[American Civil War]] on the grounds of [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] General [[Robert E. Lee]]'s home, Arlington House (also known as the Custis-Lee Mansion). It is directly across the [[Potomac River]] from [[Washington, D.C.]], north of [[the Pentagon]]. With nearly 300,000 people buried there, Arlington National Cemetery is the second-largest national cemetery in the United States. |

|||

In 1865, after the end of the Civil War, the Abingdon estate's heir, [[Alexander Hunter (novelist)|Alexander Hunter]], filed a federal lawsuit to recover the property. [[James A. Garfield]], a [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] member of the [[United States House of Representatives|U.S. House of Representatives]] who was a [[Brigadier general (United States)|brigadier general]] in the [[Union Army]] during the Civil War and later became the [[List of Presidents of the United States|20th President of the United States]], was an attorney on Hunter's legal team.<ref name=Hunter/> In 1870, the [[United States Supreme Court|U.S. Supreme Court]] found that the U.S. federal government had illegally confiscated the property and ordered that it be returned to Hunter.<ref name=Hunter/> |

|||

Arlington House was named after the Custis family's homestead on Virginia's Eastern Shore. It is associated with the families of Washington, Custis, and Lee. Begun in [[1802]] and completed in [[1817]], it was built by [[George Washington Parke Custis]]. After his father died, young Custis was raised by his grandmother and her second husband, the first [[President of the United States|US President]] [[George Washington]], at [[Mount Vernon (plantation)|Mount Vernon]]. Custis, a far-sighted agricultural pioneer, painter, playwright, and orator, was interested in perpetuating the memory and principles of George Washington. His house became a "treasury" of Washington heirlooms. |

|||

The property included the former residence of Confederate General [[Robert E. Lee]]'s family at and around [[Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial|Arlington House]], which had been subjected to an appraisal of $26,810, on which a real estate tax of $92.07 was assessed. Likely fearing an encounter with Union officials, Lee's wife, [[Mary Anna Custis Lee]], the owner of the property, chose not pay the tax in person. She instead sent an agent on her behalf, but Union officials refused to accept it.<ref name="tax">{{cite web|access-date=September 30, 2011|url=http://www.arlingtoncemetery.org/historical_information/arlington_house.html|title=Arlington House|work=History of Arlington National Cemetery|publisher=[[Arlington National Cemetery]]|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100913093837/http://www.arlingtoncemetery.org/historical_information/arlington_house.html|archive-date=September 13, 2010}}</ref><ref name=Kaufman>(1) [[s: United States v. Lee Kaufman]]<br />(2) {{cite journal|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9U03AAAAIAAJ|title=United States v. Lee; Kaufman and another v. Same, December 4, 1882 (106 U.S. 196)|journal=Supreme Court Reporter. Cases Argued and Determined in the United States Supreme Court, October Term, 1882: October, 1882-February, 1883|volume=1|pages=240–286|editor=Desty, Robert|location=Saint Paul, MN|publisher=West Publishing Company|year=1883|access-date=August 22, 2011}}</ref> As a result of the 1862 law, the U.S. federal government confiscated the property, and transformed it into a military cemetery.<ref name=tax/> |

|||

In [[1804]], Custis married Mary Lee Fitzhugh. Their only child to survive infancy was Mary Anna Randolph Custis, born in [[1808]]. Young Robert E. Lee, whose mother was a cousin of Mrs. Custis, frequently visited Arlington. Two years after graduating from [[United States Military Academy|West Point]], [[Lieutenant]] Lee married Mary Custis at Arlington on [[June 30]], [[1831]]. For 30 years, Arlington House was home to the Lees. They spent much of their married life traveling between [[U.S. Army]] duty stations and Arlington, where six of their seven children were born. They shared this home with Mary's parents, the Custis family. |

|||

After the Civil War ended and his parents died, [[George Washington Custis Lee]], the Lees' eldest son, initiated a federal legal action in an attempt to recover the property.<ref name=tax/> In December 1882, the [[United States Supreme Court|U.S. Supreme Court]] found that the [[Federal government of the United States|U.S. federal government]] illegally confiscated the property without due process, and the property was returned to Custis Lee.<ref name=tax/><ref name=Kaufman/> In 1883, the U.S. Congress purchased the property from Lee for its fair market value of $150,000, whereupon the property became a military reservation and eventually [[Arlington National Cemetery]]. Although Arlington House is within the National Cemetery, the [[National Park Service]] presently administers the House and its grounds as a memorial to Robert E. Lee.<ref name=tax/> |

|||

[[Image:Iwojima1.jpg|left|thumb|[[USMC War Memorial|Iwo Jima Memorial]]]] |

|||

When George Washington Parke Custis died in [[1857]], he left the Arlington estate to Mrs. Lee for her lifetime and afterwards to the Lees' eldest son, [[George Washington Custis Lee]]. |

|||

Confederate incursions from [[Falls Church, Virginia|Falls Church]], [[Minor's Hill]] and [[Upton's Hill]], then securely in Confederate hands, occurred as far east as the present-day [[Ballston, Virginia|Ballston]]. On August 17, 1861, 600 [[Confederate States Army|Confederate]] soldiers engaged the [[23rd New York Infantry Regiment]] near Ballston, killing a [[Union Army]] soldier. Later that month, on August 27, another large incursion of 600 to 800 Confederate soldiers clashed with Union soldiers at Ball's Crossroads, Hall's Hill, and at the present-day border between the [[Falls Church, Virginia|Falls Church]] and Arlington. A number of soldiers on both sides were killed. However, the territory in present-day Arlington never fell under Confederate control and was not attacked.<ref>Gernand, ''A Virginia Village Goes to War'', pp. 73–74, 89.</ref> |

|||

The U.S. government confiscated Arlington House and 200 [[acre]]s (81 [[hectare]]s) of ground immediately from the wife of General Robert E. Lee during the Civil War. The government designate the grounds as a military cemetery on [[June 15]], [[1864]], by [[United States Secretary of War|Secretary of War]] [[Edwin M. Stanton]]. In [[1882]], after many years in the lower courts, the matter of the ownership of Arlington National Cemetery was brought before the [[United States Supreme Court]]. The Court decided that the property rightfully belonged to the Lee family. The [[United States Congress]] then appropriated the sum of $150,000 for the purchase of the property from the Lee family. |

|||

===Separation from Alexandria=== |

|||

Veterans from all the nation's wars are buried in the cemetery, from the [[American Revolution]] through the military actions in [[War in Afghanistan (2001–present)|Afghanistan]] and [[2003 invasion of Iraq|Iraq]]. Pre-Civil War dead were re-interred after [[1900]]. |

|||

{{anchor|Secession of Alexandria}} |

|||

[[File:1878 Alexandria County Virginia.jpg|thumb|An 1878 map of Alexandria County reflecting the 1870 removal of [[Alexandria, Virginia|Alexandria]]]] |

|||

In 1870, the [[Alexandria, Virginia|City of Alexandria]] was legally separated from [[Alexandria County, Virginia|Alexandria County]] by an amendment to the Virginia Constitution that made all Virginia [[incorporated cities]] (though not [[incorporated towns]]) [[Independent city (Virginia)|independent]] of the counties with which they had previously been a part. Confusion between the city and the county of Alexandria having the same name led to a movement to rename Alexandria County. |

|||

In 1896, an electric trolley line was built from [[Washington, D.C.]] through [[Ballston, Virginia|Ballston]]; [[Northern Virginia trolleys]] were a significant factor in the county's growth. In 1920, the trolley was named ''Arlington County'', named after [[Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial|Arlington House]], the home of the [[American Civil War]] Confederate general [[Robert E. Lee]] later seized by the Union in a tax sale, is located on the grounds of [[Arlington National Cemetery]]. |

|||

The [[Tomb of the Unknowns]], also known as the [[Tomb of the Unknown Soldier]], stands atop a hill overlooking Washington, DC. President [[John F. Kennedy]] is buried in Arlington National Cemetery with [[Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis|his wife]] and some of their children. His grave is marked with an "Eternal Flame." His brother Senator [[Robert F. Kennedy]] is also buried nearby. Another [[President of the United States|President]], [[William Howard Taft]], who was also a [[Chief Justice of the United States|Chief Justice]] of the U.S. Supreme Court, is the only other President buried at Arlington. |

|||

===20th century=== |

|||

Other frequently visited sites near the cemetery are the [[USMC War Memorial | U.S. Marine Corps War Memorial]], commonly known as the "Iwo Jima Memorial", the [[United States Air Force Memorial | U.S. Air Force Memorial]], the [[Women in Military Service for America Memorial]], the [[Netherlands Carillon]] and the U.S. Army's [[Fort Myer]]. |

|||

[[File:Seal of Arlington County, Virginia (1983–2007).svg|thumb|The former Arlington County seal used from June 1983 to May 2007]] |

|||

[[File:Looking W at Netherlands Carillon - GW Memorial Parkway - Arlington VA USA - between 1980 and 2006.jpg|thumb|[[Netherlands Carillon]]]] |

|||

[[File:US Navy 061013-F-3500C-443 View over the U.S. Navy Annex, showing the completed U.S. Air Force memorial.jpg|thumb|The former [[Navy Annex]] and [[United States Air Force Memorial|Air Force Memorial]]]] |

|||

In 1900, Blacks were more than a third of Arlington County's population. Over the course of the century, the Black population dwindled. Neighborhoods in Arlington set up racial covenants and forbade Blacks from owning or domiciling property.<ref name=":2">{{Cite web |date=October 8, 2020 |title=New Video Tackles Arlington's History of Race and Housing {{!}} ARLnow.com |url=https://www.arlnow.com/2020/10/08/new-video-tackles-arlingtons-history-of-race-and-housing/ |access-date=September 10, 2023 |website=ARLnow.com {{!}} Arlington, Va. local news |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=September 8, 2023 |title=A restrictive covenant used to block a duplex also barred non-white people from buying or renting it {{!}} ARLnow.com |url=https://www.arlnow.com/2023/09/08/a-restrictive-covenant-used-to-block-a-duplex-also-barred-non-white-people-from-buying-or-renting-it/ |access-date=September 10, 2023 |website=ARLnow.com {{!}} Arlington, Va. local news |language=en}}</ref> In 1938, Arlington banned row houses, a type of housing that was heavily used by Black residents. By October 1942, not a single rental unit was available in the county.<ref>''Arlington Sun Gazette'', October 15, 2009, "Arlington history", page 6, quoting from the ''Northern Virginia Sun''</ref> In the 1940s, the federal government evicted black neighborhoods to build the Pentagon and make room for highway construction.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

In 1908, [[Potomac, Virginia|Potomac]] was incorporated as a town in Alexandria County, and was annexed by Alexandria in 1930. |

|||

===Town of Potomac=== |

|||

[[Image:1764433.jpg|right|thumb|[[Washington, D.C.|Washington]] skyline (seen from Arlington)]] |

|||

{{mainarticle|Potomac, Virginia}} |

|||

In 1920, the Virginia legislature renamed the area Arlington County to avoid confusion with the City of Alexandria which had become an [[independent city]] in 1870 under the new Virginia Constitution adopted after the Civil War. |

|||

The [[Potomac, Virginia|Town of Potomac]] was formerly located in Arlington County adjacent to the massive [[Potomac Yard]] of the [[Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad]]. A [[planned community]], its proximity to Washington, D.C., made it a popular place for employees of the U.S. government to live. Potomac was developed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The town was annexed by the [[independent city]] of [[Alexandria, Virginia|Alexandria]] in 1930. Today, in Alexandria, the '''Town of Potomac Historic District''' designates this historic portion of the city, and includes 1,840 acres (7.45 km²) and 690 buildings. The Town of Potomac was added to the [[National Register of Historic Places]] in 1992. |

|||

In the 1930s, [[Hoover Field]] was established on the present site of the Pentagon; in that decade, Buckingham, Colonial Village, and other apartment communities also opened. [[World War II]] brought a boom to the county, but one that could not be met by new construction due to rationing imposed by the war effort. |

|||

===The Pentagon=== |

|||

[[Image:The Pentagon US Department of Defense building.jpg|thumb|225px|left|The Pentagon, looking northeast with the Potomac River and Washington Monument in the distance.]] |

|||

{{mainarticle|the Pentagon}} |

|||

[[The Pentagon]] in Arlington is the headquarters of the [[United States]] [[United States Department of Defense|Department of Defense]]. It was dedicated on [[January 15]], [[1943]] and it is the world's largest office building. Although it is located in Arlington, the [[United States Postal Service]] requires that "Washington, D.C." be used as the place name in mail addressed to the [[ZIP codes]] assigned to [[The Pentagon]]. |

|||

In October 1949, the [[University of Virginia]] in [[Charlottesville, Virginia|Charlottesville]] created an extension center in the county named Northern Virginia University Center of the University of Virginia. This campus was subsequently renamed University College, then the Northern Virginia Branch of the University of Virginia, then George Mason College of the University of Virginia, and finally to its present name, [[George Mason University]].<ref>October 1, 1949: {{Hanging indent | {{Cite book| last = Finley| first = John Norville Gibson| title = Progress Report of the Northern Virginia University Center| date = July 1, 1952| url = http://digilib.gmu.edu/jspui/bitstream/handle/1920/2698/Mann_53_1_1_v.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y| archive-date = February 20, 2017| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20170220225740/http://digilib.gmu.edu/jspui/bitstream/handle/1920/2698/Mann_53_1_1_v.pdf| quote = "The report that follows is a progress report on the Northern Virginia University Center since its beginnings in 1949 by its Local Director, Professor J. N. G. Finley." George B. Zehmer, Director Extension Division University of Virginia}}}} Northern Virginia University Center of the University of Virginia: {{Hanging indent | {{cite book|last1=Mann|first1=C. Harrison|title=C. Harrison Mann, Jr. papers|date=1832–1979|publisher=George Mason University. Libraries. Special Collections Research Center|location=Arlington, Virginia|url=http://sca.gmu.edu/finding_aids/mann.html|access-date=February 23, 2017}}}} University College, the Northern Virginia branch of the University of Virginia: {{Hanging indent | {{cite book|last1=Mann|first1=C. Harrison Jr.|title=House Joint Resolution 5|date=February 24, 1956|publisher=Virginia General Assembly|location=Richmond|page=1|url=http://ahistoryofmason.gmu.edu/archive/files/8e80e948d96eba1ccf790954fb595bc5.jpg|access-date=April 30, 2017|archive-date=March 31, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220331072721/http://ahistoryofmason.gmu.edu/archive/files/8e80e948d96eba1ccf790954fb595bc5.jpg|url-status=dead}}}} George Mason College of the University of Virginia: {{Hanging indent | {{cite book|last1=McFarlane|first1=William Hugh|title=William Hugh McFarlane George Mason University history collection|date=1949–1977|publisher=George Mason University Special Collections and Archives|location=Fairfax, VA|url=http://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=gmu/vifgm00002.xml|access-date=February 23, 2017}}}} George Mason University: {{Hanging indent | {{cite book| publisher = Fairfax County Board of Supervisors| isbn = 978-0-9601630-1-4| last = Netherton| first = Nan| title = Fairfax County, Virginia: A History| date = January 1, 1978}}{{rp|588}}}}</ref> The Henry G. Shirley Highway, also known as [[Interstate 395 (Virginia–District of Columbia)|Interstate 395]], was constructed during [[World War II]], along with adjacent developments such as [[Shirlington, Arlington, Virginia|Shirlington]], [[Fairlington, Arlington, Virginia|Fairlington]], and [[Parkfairfax, Virginia|Parkfairfax]]. |

|||

The building is [[pentagon]]-shaped in plan and houses about 23,000 military and civilian employees and about 3,000 non-defense support personnel. It has five floors and each floor has five ring corridors. The Pentagon's principle law enforcement arm is the [[United States Pentagon Police]], the agency that protects the Pentagon and various other DoD jurisdictions throughout the National Capital Region. |

|||

In February 1959, [[Arlington Public Schools]] [[desegregated]] racially at Stratford Junior High School, which is now Dorothy Hamm Middle School, with the admission of black pupils Donald Deskins, Michael Jones, Lance Newman, and Gloria Thompson. The [[Supreme Court of the United States|U.S. Supreme Court]]'s ruling in 1954, ''[[Brown v. Board of Education]] of Topeka'', Kansas had struck down the previous ruling on racial segregation ''[[Plessy v. Ferguson]]'' that held that facilities could be racially "separate but equal". ''Brown v. Board of Education'' ruled that "racially separate educational facilities were inherently unequal". The elected Arlington County School Board presumed that the state would defer to localities and in January 1956 announced plans to integrate Arlington schools. |

|||

Built during the early years of [[World War II]], it is still thought of as one of the most efficient office buildings in the world. It has 17.5 miles (28 km) of corridors, yet it takes only seven minutes or so to walk between any two points in the building. |

|||

The state responded by suspending the county's right to an elected school board. The [[Arlington County Board]], the ruling body for the county, appointed segregationists to the school board and blocked plans for desegregation. Lawyers for the local chapter of the [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] (NAACP) filed suit on behalf of a group of parents of both white and black students to end segregation. Black pupils were still denied admission to white schools, but the lawsuit went before the U.S. District Court, which ruled that Arlington schools were to be desegregated by the 1958–59 academic year. In January 1959 both the U.S. District Court and the Virginia Supreme Court had ruled against Virginia's [[massive resistance]] movement, which opposed racial integration.<ref>Les Shaver, "Crossing the Divide: The Desegregation of Stratford Junior High", ''Arlington Magazine'' November/December 2013, pp. 62–71</ref> The Arlington County Central Library's collections include written materials as well as accounts in its Oral History Project of the desegregation struggle in the county.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://library.arlingtonva.us/center-for-local-history/virginiana-collection/ |title=Virginiana Collection |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220706005712/https://library.arlingtonva.us/center-for-local-history/virginiana-collection/ |archive-date=July 6, 2022 |url-status=dead |publisher=Arlington Public Library |access-date=August 29, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

It was built from 680,000 tons of sand and gravel dredged from the nearby [[Potomac River]] that were processed into 435,000 cubic yards (330,000 m³) of concrete and molded into the pentagon shape. Very little steel was used in its design due to the needs of the war effort. |

|||

During the 1960s, Arlington experienced challenges related to a large influx of newcomers during the 1950s. [[M.T. Broyhill & Sons Corporation]] was at the forefront of building the new communities for these newcomers, which would lead to the election of [[Joel Broyhill]] as the representative of [[Virginia's 10th congressional district]] for 11 terms.<ref name="broyhill">{{cite news|last1=Clark|first1=Charlie|title=Our Man in Arlington|url=https://fcnp.com/2013/01/30/our-man-in-arlington-12/|access-date=January 27, 2018|work=fncp.com|publisher=Falls Church News-Press Online|date=January 30, 2013}}</ref> The old commercial districts did not have ample off-street parking and many shoppers were taking their business to new commercial centers, such as Parkington and Seven Corners. Suburbs further out in Virginia and Maryland were expanding, and Arlington's main commercial center in Clarendon was declining, similar to what happened in other downtown centers. With the growth of these other suburbs, some planners and politicians pushed for highway expansion. The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 would have enabled that expansion in Arlington. The administrator of the National Capital Transportation Agency, economist C. Darwin Stolzenbach, saw the benefits of rapid transit for the region and oversaw plans for a below ground rapid transit system, now the [[Washington Metro]], which included two lines in Arlington. Initial plans called for what became the Orange Line to parallel [[Interstate 66 in Virginia|I-66]], which would have mainly benefited [[Fairfax County, Virginia|Fairfax County]]. |

|||

The open-air central plaza in the Pentagon is the world's largest "no-salute, no-cover" area (where U.S. servicemembers need not wear hats nor salute). The snack bar in the center is informally known as the [[ground zero|Ground Zero Cafe]], a nickname originating during the [[Cold War]] when the Pentagon was targeted by Soviet [[nuclear missile]]s. |

|||

Arlington County officials called for the stations in Arlington to be placed along the decaying commercial corridor between Rosslyn and Ballston that included Clarendon. A new regional transportation planning entity was formed, the Washington Metropolitan Transit Authority. Arlington officials renewed their push for a route that benefited the commercial corridor along Wilson Boulevard, which prevailed. There were neighborhood concerns that there would be high-density development along the corridor that would disrupt the character of old neighborhoods. |

|||

During World War II, the earliest portion of the [[Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway]] was built in Arlington in conjunction with the parking and traffic plan for the Pentagon. This early [[freeway]], opened in 1943, and completed to [[Woodbridge, Virginia]] in 1952, is now part of [[Interstate 395 (Virginia)|Interstate 395]]. |

|||

With the population in the county declining, political leaders saw economic development as a long-range benefit. Citizen input and county planners came up with a workable compromise, with some limits on development. The two lines in Arlington were inaugurated in 1977. The Orange Line's creation was more problematic than the Blue Line's. The Blue Line served the Pentagon and National Airport and boosted the commercial development of [[Crystal City, Virginia|Crystal City]] and Pentagon City. Property values along the Metro lines increased significantly for both residential and commercial property. The ensuing gentrification caused the mostly working and lower middle class white Southern residents to either be priced out of rent or in some cases sell their homes. This permanently changed the character of the city, and ultimately resulted in the virtual eradication of this group over the coming 30 years, being replaced with an increasing presence of a white-collar transplant population mostly of Northern stock. |

|||

===September 11, 2001 attacks === |

|||

[[Image:Pentagonfireball.jpg|225px|thumb|right|Security Camera image of the moment that [[American Airlines Flight 77]] hit [[The Pentagon]]]] |

|||

Sixty years to the day after construction workers broke ground for the Pentagon, the building was seriously damaged by a terrorist attack on [[September 11, 2001 attacks|September 11, 2001]]. It was one of three major buildings hit by airliners hijacked by members of [[Al-Qaeda]], a militant terrorist organization. |

|||

While a population of white-collar government transplant workers had always been present in the county, particularly in its far northern areas and in Lyon Village, the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s saw the complete dominance of this group over the majority of Arlington's residential neighborhoods, and mostly economically eliminated the former working-class residents of areas such as Cherrydale, Lyon Park, Rosslyn, Virginia Square, Claremont, and Arlington Forest, among other neighborhoods. The transformation of Clarendon is particularly striking. This neighborhood, a downtown shopping area, fell into decay. It became home to a vibrant Vietnamese business community in the 1970s and 1980s known as [[Little Saigon, Arlington, Virginia|Little Saigon]]. It has now been significantly gentrified. Its Vietnamese population is now barely visible, except for several holdout businesses. Arlington's careful planning for the Metro has transformed the county and has become a model revitalization for older suburbs.<ref>Kevin Craft, "When Metro Came to Town: How the fight for mass transit was won. And how its arrival left Arlington Forever Changed", ''Arlington Magazine'', November/December 2013, pp. 72–85.</ref><ref>Zachary Schrag, ''The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.</ref> |

|||

==Demographics== |

|||

As of the [[census]]{{GR|2}} of 2000, there were 189,453 people, 86,352 households, and 39,290 families residing in Arlington. The [[population density]] was 7,323 people per square mile (2,828/km²), the highest of any county in Virginia. There were 90,426 housing units at an average density of 3,495/sq mi (1,350/km²). |

|||

In 1965, after years of negotiations, Arlington swapped some land in the south end with Alexandria, though less than originally planned. The land was located along King Street and Four Mile Run. The exchange allowed the two jurisdictions to straighten out the boundary and helped highway and sewer projects to go forward. It moved into Arlington several acres of land to the south of the old county line that had not been a part of the District of Columbia.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Cheek III |first1=Leslie |title=Arlington Approves Alexandria Land Swap |newspaper=The Washington Post |date=April 11, 1965}}</ref> |

|||

The racial makeup of the county was 68.94% [[Race (United States Census)|White]], 9.35% [[Race (United States Census)|Black]] or [[Race (United States Census)|African American]], 0.35% [[Race (United States Census)|Native American]], 8.62% [[Race (United States Census)|Asian]], 0.08% [[Race (United States Census)|Pacific Islander]], 8.33% from [[Race (United States Census)|other races]], and 4.34% from two or more races. [[Race (United States Census)|Hispanic]] or [[Race (United States Census)|Latino]] of any race were 18.62% of the population. |

|||

===21st century=== |

|||

28% of Arlington residents were foreign-born. |

|||

{{Further|American Airlines Flight 77}} |

|||

[[File:9-11 Pentagon Exterior 09.jpg|thumb|Smoke rising from [[the Pentagon]] following the [[September 11 attacks]]]] |

|||

[[File:ArlingtonCoNatGateway.jpg|thumb|Arlington County National Gateway]] |

|||

[[File:ArlingtonCounty-PotomacYard.jpg|thumb|Arlington County IDA Potomac Yard]] |

|||

[[File:ArlingtonCoAquaticCenter.jpg|thumb|Arlington County Aquatic and Fitness Center]] |

|||

[[File:ArlingtonCoVaTechInnovativeCampus.jpg|thumb|Arlington County Virginia Tech Innovative Campus Project]] |

|||

On [[September 11 attacks|September 11, 2001]], five [[al-Qaeda]] [[Aircraft hijacking|hijackers]] deliberately crashed [[American Airlines Flight 77]] into [[the Pentagon]], killing 115 Pentagon employees and 10 contractors in the building, and all 53 passengers, six crew members, and five hijackers on board the aircraft. The coordinated attacks were the most deadly terrorist attack in world history.<ref>[https://www.statista.com/statistics/1330395/deadliest-terrorist-attacks-worldwide-fatalities/ "Deadliest terrorist attacks worldwide from 1970 to January 2024, by number of fatalities and perpetrator"], Statista</ref> |

|||

In 2005 Arlington's population was 64.7% non-Hispanic whites. 8.8% of the population was African-American. Native Americans constituted 0.4% of the population. Asians now outnumbered African-Americans, constituting 8.9% of the population. Latinos were 16.1% of the population. |

|||

In 2009, Turnberry Tower, located in the [[Rosslyn, Virginia|Rosslyn]] neighborhood, was completed. At the time of completion, Turnberry Tower was the tallest residential building in the [[Washington metropolitan area]].<ref>{{cite news |title=House of the Week {{!}} Arlington penthouse for $3.975M |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/where-we-live/wp/2014/11/07/house-of-the-week-arlington-penthouse-for-3-975m/}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Coming to Rosslyn, The Height of Luxury Condo Market Is Ready, Resort Developer Says |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/realestate/2006/03/04/coming-to-rosslyn-the-height-of-luxury-span-classbankheadcondo-market-is-ready-resort-developer-saysspan/0c7c0937-3a6e-4856-b564-71785f82f02b/}}</ref> |

|||

There were 86,352 households out of which 19.30% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.30% were [[Marriage|married couples]] living together, 7.00% had a female householder with no husband present, and 54.50% were non-families. 40.80% of all households were made up of individuals and 7.30% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.15 and the average family size was 2.96. |

|||

In 2017, [[Nestlé]] USA chose [[1812 N Moore]] in Rosslyn as their U.S. headquarters.<ref>{{cite news |title=Nestlé to move U.S. headquarters to Arlington, bringing 750 jobs |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/capitalbusiness/nestle-to-move-us-headquarters-to-arlington-bringing-750-jobs-to-the-region/2017/02/01/0ff6ec34-e40c-11e6-a547-5fb9411d332c_story.html}}</ref> |

|||

In the county, the population was spread out with 16.50% under the age of 18, 10.40% from 18 to 24, 42.40% from 25 to 44, 21.30% from 45 to 64, and 9.40% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34 years. For every 100 females there were 101.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 100.70 males. |

|||

In 2018, [[Amazon (company)|Amazon.com, Inc.]] announced that it would build its co-headquarters in the [[Crystal City, Virginia|Crystal City]] neighborhood, anchoring a broader area of Arlington and Alexandria that was simultaneously rebranded as [[National Landing]].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/nation-now/2018/11/13/where-amazon-hq-2-national-landing-long-island-city/1987015002/|title=National Landing? Long Island City? This is where Amazon's headquarters are located|work=USA Today|access-date=November 20, 2018|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

According to a 2006 estimate, the median income for a household in the county was $87,350, and the median income for a family was $116,114.[http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ACSSAFFFacts?_event=ChangeGeoContext&geo_id=05000US51013&_geoContext=01000US%7C04000US51%7C16000US5101000&_street=&_county=arlington&_cityTown=arlington&_state=04000US51&_zip=&_lang=en&_sse=on&ActiveGeoDiv=geoSelect&_useEV=&pctxt=fph&pgsl=010&_submenuId=factsheet_1&ds_name=ACS_2006_SAFF&_ci_nbr=null&qr_name=null®=null%3Anull&_keyword=&_industry=] Males had a median income of $51,011 versus $41,552 for females. The [[per capita income]] for the county was $37,706. About 5.00% of families and 7.80% of the population were below the [[poverty line]], including 9.10% of those under age 18 and 7.00% of those age 65 or over. In 2004 the average single-family home sales price passed $600,000, approximately triple the price less than a decade before, and the median topped $550,000 {{Fact|date=February 2007}}. |

|||

By 2020, single-family detached homes accounted for nearly 75% of zoned property in Arlington.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

===Arlington CDP population history=== |

|||

*1960.....163,401<ref>Although Arlington CDP had a population of 135,449 in 1950, the [[United States Census Bureau|Census]] did not treat Arlington as a CDP because in 1950 CDPs were assigned to [[rural]] areas only. They were first assigned to urban areas during the 1960 Census.</small></ref> |

|||

*1970.....174,284 |

|||

*1980.....152,299 |

|||

*1990.....170,936 |

|||

*2000.....189,453 |

|||

*2006.....200,226 |

|||

*2007.....202,800 (estimated) <ref name=Estimated_Population>{{cite web | url = http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/CPHD/planning/data_maps/CPHDPlanningDataandMapsProfile.aspx?lnsLinkID=1150 | title = Profile | accessmonthday = August 30|accessyear = 2006}}</ref> |

|||

In 2023, the Arlington County city council unanimously approved a modest zoning change to permit sixplexes, so-called "[[Missing middle housing|missing middle]]" housing, on lots previously zoned exclusively for single-family homes. The change reversed exclusionary zoning laws that were initially erected to keep low-income people and minorities out of the county. In 2024, Arlington County circuit court judge David Schell overturned this zoning change after a small group of [[NIMBY]] homeowners filed a lawsuit against the county. Schell ruled that Arlington County did not study the potential impacts adequately.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Armus |first=Teo |date=2024-09-27 |title=Circuit judge strikes down Arlington's 'missing middle' housing plan |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2024/09/27/missing-middle-ruling-lawsuit-housing-arlington/ |newspaper=Washington Post |language=en-US |issn=0190-8286}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Britschgi |first=Christian |date=2024-10-01 |title=America's trial courts have a NIMBY problem |url=https://reason.com/2024/10/01/americas-trial-courts-have-a-nimby-problem/ |access-date=2024-10-01 |website=Reason.com |language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-09-27 |title=BREAKING: Judge overturns Missing Middle zoning changes |url=https://www.arlnow.com/2024/09/27/breaking-judge-overturns-missing-middle-zoning-changes/?fbclid=IwY2xjawFpT_lleHRuA2FlbQIxMAABHWdMdcX1gM49NyB6WA8NPrLmGA9XGO791g_o_2dQPpfOwsmiLj93Yd_Qug_aem_7L4PJAaUN9dfeyjt-xVl0Q |website=www.arlnow.com |language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

See, [http://www.arlingtonvirginiausa.com/index.cfm/7044 Arlington Demographics & Statistics] |

|||

==Geography== |

|||

==Development Patterns== |

|||

{{see also|List of neighborhoods in Arlington County, Virginia}} |

|||

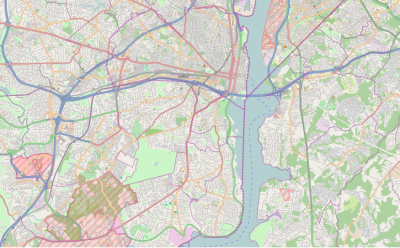

[[Image:ArlingtonTODimage3.jpg|thumb|right|300px| Aerial view of a growth pattern in Arlington County, Virginia. High density, mixed use development is often concentrated within 1/4 to 1/2 mile from the County's Metrorail [[rapid transit]] stations, such as in [[Rosslyn, Virginia|Rosslyn]], [[Courthouse, Virginia |Courthouse]], and [[Clarendon, Virginia |Clarendon]] (shown in red from upper left to lower right). This photograph is taken from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency website describing Arlington's award for overall excellence in smart growth in 2002. ]] |

|||

[[File:ArlingtonTODimage3.jpg|thumb|Aerial view of the growth pattern in Arlington County. High density, [[mixed-use development]] is concentrated within 1/4 to 1/2 mile from the county's [[Orange Line (Washington Metro)|Metrorail]] stations, such as in [[Rosslyn, Virginia|Rosslyn]], [[Court House, Arlington, Virginia|Courthouse]], and [[Clarendon, Virginia|Clarendon]] (shown in red from upper left to lower right).]] |

|||

{{Location map+ | USA Virginia Alexandria region |

|||

| caption = Jurisdictions South and West of Washington, D.C. |

|||

|width=400 |

|||

| places = |

|||

{{Location map~ | USA Virginia Alexandria region |

|||

| label =[[Prince George's County, Maryland|Prince George's County]] |

|||

| label_size=100 |

|||

| marksize=0 |

|||

| position =left |

|||

| lat_deg =38.81 |

|||

| lon_deg =-76.95 |

|||

}} |

|||

Arlington has won awards for its "[[smart growth]]" [[Real-estate developer | development]] strategies. For over 30 years, the government has had a policy of concentrating much of its new development near transit facilities, such as [[Washington Metro |Metrorail]] stations and the high-volume bus lines of [[Virginia State Route 244| Columbia Pike]]. Within the transit areas, the government has a policy of encouraging [[mixed-use development | mixed-use]] and [[Pedestrian-oriented development |pedestrian-]] and [[transit-oriented development]]. Outside of those areas, the government usually limits density increases, but makes exceptions for larger projects that are near major highways, such as in [[Shirlington, Virginia | Shirlington]], near [[Interstate 395 (District of Columbia-Virginia) | I-395]] (the [[Henry G. Shirley Memorial Highway | Shirley Highway]]). |

|||

{{Location map~ | USA Virginia Alexandria region |

|||

| label =[[Alexandria, Virginia|Alexandria]] |

|||

| label_size=100 |

|||

| marksize=0 |

|||

| position =top |

|||

| lat_deg =38.822531 |

|||

| lon_deg =-77.071320 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Location map~ | USA Virginia Alexandria region |

|||

| label =Arlington |

|||

| label_size=100 |

|||

| marksize=0 |

|||

| position =top |

|||

| lat_deg =38.880245 |

|||

| lon_deg =-77.090965 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Location map~ | USA Virginia Alexandria region |

|||

| label =[[Fairfax County, Virginia|Fairfax County]] |

|||

| label_size=100 |

|||

| marksize=0 |

|||

| position =top |

|||

| lat_deg =38.764471 |

|||

| lon_deg =-77.133564 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Location map~ | USA Virginia Alexandria region |

|||

| label =[[Falls Church, Virginia|Falls Church]] |

|||

| label_size=100 |

|||

| marksize=0 |

|||

| position =top |

|||

| lat_deg =38.879925 |

|||

| lon_deg =-77.170322 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Location map~ | USA Virginia Alexandria region |

|||

| label =[[Washington, D.C.|Washington]] |

|||

| label_size=100 |

|||

| marksize=0 |

|||

| position =top |

|||

| lat_deg =38.910861 |

|||

| lon_deg =-77.031618 |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

Arlington County is located in [[Northern Virginia]] and is surrounded by [[Fairfax County, Virginia|Fairfax County]] and [[Falls Church, Virginia|Falls Church]] to the west, the city of [[Alexandria, Virginia|Alexandria]] to the southeast, and the national capital of [[Washington, D.C.]] to the northeast across the [[Potomac River]], which forms the county's northern border. [[Minor's Hill]] and [[Upton's Hill]] represent the county's western borders. |

|||

According to the [[United States Census Bureau|U.S. Census Bureau]], the county has a total area of {{convert|26.1|sqmi|1}}, {{convert|26.0|sqmi|1}} of which is land and {{convert|0.1|sqmi|1}} (0.4%) of which is water.<ref name="GR1">{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/time-series/geo/gazetteer-files.html|publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]]|access-date=April 23, 2011|date=February 12, 2011|title=US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990}}</ref> It is the smallest county by area in Virginia and is the [[County statistics of the United States|smallest]] self-governing county in the United States.<ref name="Smallest_County">{{cite web|url=http://www.naco.org/Content/NavigationMenu/About_Counties/County_Government/A_Brief_Overview_of_County_Government.htm |title=National Association of Counties |access-date=September 1, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080708090111/http://www.naco.org/Content/NavigationMenu/About_Counties/County_Government/A_Brief_Overview_of_County_Government.htm |archive-date=July 8, 2008 |url-status=dead }}</ref> About {{convert|4.6|sqmi|1}} (17.6%) of the county is federal property. The county courthouse and most government offices are located in the [[Courthouse, Virginia|Courthouse]] neighborhood. |

|||

Much of Arlington's development in the last generation has been concentrated around 7 of the County's 11 Metrorail stations. However, [[infill]] development elsewhere in the County has recently replaced many undeveloped lots and small single-family dwellings with [[terraced house| row houses]] and larger homes. |

|||

Since the late 20th century, the county government has pursued a [[Urban planning|development strategy]] of concentrating much of its new development near transit facilities, such as [[Washington Metro|Metrorail]] stations and the high-volume bus lines of [[Virginia State Route 244|Columbia Pike]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.arlingtonva.us/Departments/CPHD/planning/CPHDPlanningSmartGrowth.aspx |title=Smart Growth : Planning Division : Arlington, Virginia |publisher=Arlingtonva.us |date=March 7, 2011 |access-date=November 4, 2011}}</ref> Within the transit areas, the government has a policy of encouraging [[mixed-use development|mixed-use]] and [[Walkability|pedestrian-]] and [[transit-oriented development]].<ref name="arlingtonva.us">{{cite web |url=http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/CPHD/planning/powerpoint/rbpresentation/rbpresentation_060107.pdf |title=Department of Community Planning, Housing and Development - Departments & Offices |publisher=Arlingtonva.us |access-date=April 28, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110924171835/http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/CPHD/planning/powerpoint/rbpresentation/rbpresentation_060107.pdf |archive-date=September 24, 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Some of these "[[urban village]]" communities include: |

|||

Increasing land values and re-development (most of which is [[as-of-right]] development) has diminished Arlington's tree canopy and reduced the supply of existing [[affordable housing]]. To address coverage and the construction of larger homes the County has recently limited the allowable coverage on some single-family lots. |

|||

<!---some of these seem more like neighborhoods than "urban villages". See below---> |

|||

{{Div col|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

* [[Aurora Highlands Historic District|Aurora Highlands]] |

|||

* [[Ballston, Virginia|Ballston]] |

|||

* Barcroft |

|||

* [[Bluemont, Arlington, Virginia|Bluemont]] |

|||

* Broyhill Heights |

|||

* Claremont |

|||

* [[Clarendon, Virginia|Clarendon]] |

|||

* [[Court House, Virginia|Courthouse]] |

|||

* [[Crystal City, Virginia|Crystal City]] |

|||

* [[Glencarlyn, Virginia|Glencarlyn]] |

|||

* Greenbrier |

|||

* [[High View Park]] (formerly Halls Hill) |

|||

* [[Lyon Village, Virginia|Lyon Village]] |

|||

* Palisades |

|||

* [[Pentagon City]] |

|||

* [[Penrose Historic District|Penrose]] |

|||

* Radnor - Fort Myer Heights |

|||

* [[Rosslyn, Virginia|Rosslyn]] |

|||

* [[Shirlington, Virginia|Shirlington]] |

|||

* [[Virginia Square, Virginia|Virginia Square]] |

|||

* Waycroft-Woodlawn (formerly Woodlawn Park) |

|||

* [[Westover, Arlington, Virginia|Westover]] |

|||

* Williamsburg Circle |

|||

{{div col end}} |

|||

In |

In 2002, Arlington received the [[United States Environmental Protection Agency|EPA]]'s National Award for Smart Growth Achievement for "Overall Excellence in [[Smart Growth]]."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.epa.gov/smartgrowth/arlington.htm |title=Arlington County, Virginia – National Award for Smart Growth Achievement – 2002 Winners Presentation |publisher=Epa.gov |date=June 28, 2006 |access-date=November 4, 2011}}</ref> In 2005, the County implemented an affordable housing ordinance that requires most developers to contribute significant affordable housing resources, either in units or through a cash contribution, in order to obtain the highest allowable amounts of increased building density in new development projects, most of which are planned near Metrorail station areas.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/CPHD/housing/development/CPHDHousingDevOrdinance.aspx |title=Housing Development – Affordable Housing Ordinance : Housing Division : Arlington, Virginia |publisher=Arlingtonva.us |date=August 4, 2011 |access-date=November 4, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110315032048/http://www.arlingtonva.us/departments/CPHD/housing/development/CPHDHousingDevOrdinance.aspx |archive-date=March 15, 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

||