Graffiti: Difference between revisions

Clearly vandalism, right? |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Drawings and paintings on walls}} |

|||

{{Refimprove|date=February 2008}} |

|||

{{ |

{{Other uses}} |

||

{{protection padlock|small=yes}} |

|||

'''Graffiti''' (singular: ''graffito''; the plural is used as a [[mass noun]]) is the name for images or lettering scratched, scrawled, painted or marked in any manner on property. Graffiti is often regarded by others as unsightly damage or unwanted vandalism. |

|||

{{Original research|date=March 2019}} |

|||

[[Image:Graffiti stylaz.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Examples of modern graffiti styles]] |

|||

{{Too many photos|date=November 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox art movement |

|||

| name = Graffiti |

|||

| image = Former roof felt factory in Tampere Jun2012 003.jpg |

|||

| alt = |

|||

| caption = An abandoned [[roof felt]] factory in [[Santalahti]], [[Finland]] which has been painted with graffiti, including work by [[1UP (graffiti crew)|1UP]] (top left), 2012 |

|||

| yearsactive = 1960s-present |

|||

| location = |

|||

| majorfigures = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[TAKI 183]] |

|||

* [[Cornbread (graffiti artist)|Cornbread]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| influences = [[Hip hop (culture)|Hip hop culture]] |

|||

| influenced = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[Commercial graffiti]] |

|||

* [[Public art]] |

|||

* [[Street art]] |

|||

* [[Urban art]] |

|||

}} |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Graffiti''' (singular '''''graffiti''''' or '''''graffito''''', the latter only used in [[Graffito (archaeology)|graffiti archeology]]) is writing or drawings made on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view.<ref name=oxd>{{cite web |url=http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/graffiti |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101219082751/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/graffiti |url-status=dead |archive-date=December 19, 2010 |title=Graffiti |publisher=Oxford Dictionaries |access-date=5 December 2011}}</ref><ref name=ahd/> Graffiti ranges from simple written [[Moniker (graffiti)|"monikers"]] to elaborate wall paintings, and has existed [[Graffito (archaeology)|since ancient times]], with examples dating back to [[ancient Egypt]], [[ancient Greece]], and the [[Roman Empire]].<ref name=Graffito>{{cite encyclopedia | title = Graffito | encyclopedia = Oxford English Dictionary | volume = 2 | publisher = [[Oxford University Press]] |year= 2006 }}</ref> |

|||

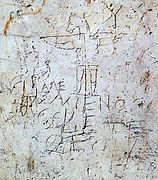

[[Image:AncientgrafS.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Ancient graffiti carved by pilgrims at [[Church of the Holy Sepulcher]], Old City of [[Jerusalem]]]] |

|||

Graffiti has existed since ancient times, with examples going back to [[Ancient Greece]] and the [[Roman Empire]].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |

|||

| title = Graffito |

|||

| encyclopedia = Oxford English Dictionary |

|||

| volume = 2 |

|||

| publisher = [[Oxford University Press]] |

|||

|date= 2006 }}</ref> Graffiti can be anything from simple scratch marks to elaborate wall paintings. In modern times, [[aerosol paint|spray paint]] and [[Marker pen|markers]] have become the most commonly used materials. In most countries, defacing property with graffiti without the property owner's consent is considered [[vandalism]], which is punishable by law. |

|||

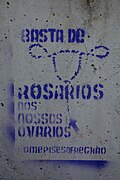

Sometimes graffiti is employed to communicate social and political messages. To some, it is an art form worthy of display in galleries and exhibitions. However, the public generally frowns upon "tags" that deface bus stops, trains, buildings, playgrounds and other public property. |

|||

Modern graffiti is a controversial subject. In most countries, marking or painting property without permission is considered [[vandalism]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Stewart |first=Jeff |date=2008 |title=Graffiti vandalism? Street art and the city: some considerations |url=https://www.unescoejournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/1-2-6-jeff-stewart.pdf|journal=Unescoe Journal}}</ref> Modern graffiti began in the [[New York City Subway nomenclature|New York City subway]] system and [[Philadelphia]] in the early 1970s and later spread to the rest of the United States and throughout the world.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia of the City|last=Caves|first=R. W.|publisher=Routledge|year=2004|pages=315}}</ref> |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

"Graffiti" is applied in [[art history]] to works of art produced by scratching a design into a surface. A related term is "[[sgraffito]]," which involves scratching through one layer of pigment to reveal another beneath it. This technique was primarily used by potters who would glaze their wares and then scratch a design into it. Graffiti and graffito are from the Italian word ''graffiato'' ("scratched"). In ancient times, graffiti was carved on walls with a sharp object, although sometimes [[chalk]] or [[coal]] were used. The [[Greek language|Greek]] infinitive γράφειν - ''graphein'' - means "to write." |

|||

== |

== Etymology == |

||

"Graffiti" (usually both singular and plural) and the rare singular form "graffito" are from the Italian word ''graffiato'' ("scratched").<ref>The Italian singular form "graffito" is so rare in English (except in specialist texts on archeology) that it is not even recorded or mentioned in some dictionaries, for example the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English and the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary.</ref><ref name=oxd/><ref name="ahd">{{Cite web |last=Publishers |first=HarperCollins |title=The American Heritage Dictionary entry: graffiti |url=https://www.ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=graffiti |access-date=2024-03-26 |website=www.ahdictionary.com}}</ref> In ancient times graffiti were carved on walls with a sharp object, although sometimes [[chalk]] or [[coal]] were used. The word originates from Greek {{lang|el|γράφειν}}—''graphein''—meaning "to write".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/graffiti|title=graffiti {{!}} Origin and meaning of graffiti by Online Etymology Dictionary|website=www.etymonline.com|language=en|access-date=19 February 2018}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== History == |

||

[[File:Rufus est caricature villa misteri Pompeii.jpg|thumb|right|Ancient [[Pompeii]] graffito [[caricature]] of a politician. [[Villa of the Mysteries]].]] |

|||

[[File:Graffitti, Castellania, Malta.jpeg|thumb|right|Figure graffito, similar to a relief, at [[Castellania (Valletta)|the Castellania, in Valletta]]]] |

|||

=== Prehistoric graffiti === |

|||

Historically, the term ''graffiti'' referred to the [[inscription]]s, figure drawings, etc., found on the walls of ancient [[sepulchre|sepulchers]] or ruins, as in the [[Catacombs of Rome]] or at [[Pompeii]]. Usage of the word has evolved to include any graphics applied to surfaces in a manner that constitutes [[vandalism]]. |

|||

{{See also|Megalithic graffiti symbols}} |

|||

Most [[petroglyph]]s and [[geoglyph]]s date between 40,000 and 10,000 years old, the oldest being [[cave paintings]] in Australia.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=McDonald |first=Fiona |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZnGCDwAAQBAJ |title=The Popular History of Graffiti: From the Ancient World to the Present |date=2013-06-13 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-1-62636-291-8 |language=en}}</ref> Paintings in the [[Chauvet Cave]] were made 35,000 years ago, but little is known about who made them or why.<ref name=":2" /> Early artists created [[stencil graffiti]] of their hands with paint blown through a tube. These stencils may have functioned similarly to a modern-day [[Tag (graffiti)|tag]].<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

=== Ancient graffiti === |

|||

The only known source of the [[Safaitic]] language, a form of proto-Arabic, is from graffiti: inscriptions scratched on to the surface of rocks and boulders in the predominantly basalt desert of southern [[Syria]], eastern [[Jordan]] and northern [[Saudi Arabia]]. Safaitic dates from the 1st century [[Before Christ|B.C.]] to the 4th century [[Anno Domini|A.D.]]. |

|||

{{See also|Roman graffiti}} |

|||

{| class=infobox font-size: 95%" |

|||

The oldest written graffiti was found in [[Ancient Rome]] around 2500 years ago.<ref>{{Cite web |last1=Magazine |first1=Smithsonian |last2=Griggs |first2=Mary Beth |title=Archaeologists in Greece Find Some of the World's Oldest Erotic Graffiti |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/erotic-graffiti-found-greece-180951979/ |access-date=2023-09-03 |website=Smithsonian Magazine |language=en}}</ref> Most graffiti from the time was boasts about sexual experiences,<ref>{{Cite news |last=Smith |first=Helena |date=2014-07-06 |title=2,500-year-old erotic graffiti found in unlikely setting on Aegean island |language=en-GB |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/jul/06/worlds-earliest-erotic-graffiti-astypalaia-classical-greece |access-date=2023-09-03 |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> but also includes word games such as the [[Sator Square]], "I was here" type markings, and comments on gladiators.<ref name=":2" /> Graffiti in Ancient Rome was a form of communication, and was generally not considered vandalism.<ref name=":2" /> Certain graffiti was seen as blasphemous and was removed, such as the [[Alexamenos graffito]], which may contain one of the earliest depictions of [[Jesus]]. The graffito features a human with the head of a donkey on a cross with the text "Alexamenos worships [his] god."<ref>{{Cite web |title=Alexamenos and pagan perceptions of Christians |url=https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/graffito.html |access-date=2024-08-06 |website=penelope.uchicago.edu}}</ref> |

|||

! align=center style="background:#f0f0f0" | '''<u>[[Graffiti Art|Graffiti]]</u>''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| |

|||

*[[Graffiti Art]] |

|||

*[[stencil|Stencil Art]] |

|||

*[[Spray paint art]] |

|||

*[[Screen printing]] |

|||

*[[Guerrilla art]] |

|||

*[[Woodblock graffiti]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| style="text-align:center; background:#f0f0f0;border-top:1px #ccc solid;" | [[Wikipedia:WikiProject Graffiti|WikiProject Graffiti]] |

|||

|} |

|||

=== Medieval graffiti === |

|||

[[Image:pompeii-graffiti.jpg|frame|left|Latin political graffiti at [[Pompeii]].]] |

|||

The only known source of the [[Safaitic]] language, an [[Old Arabic|ancient form of Arabic]], is from graffiti: inscriptions scratched on to the surface of rocks and boulders in the predominantly basalt desert of southern [[Syria]], eastern [[Jordan]] and northern [[Saudi Arabia]]. Safaitic dates from the first century BC to the fourth century AD.<ref>{{Cite web |last=dan |title=Ancient Arabia: Languages and Cultures—Safaitic Database Online |url=http://krc2.orient.ox.ac.uk/aalc/index.php/en/safaitic-database-online |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180220033117/http://krc2.orient.ox.ac.uk/aalc/index.php/en/safaitic-database-online |archive-date=20 February 2018 |access-date=19 February 2018 |website=krc2.orient.ox.ac.uk |language=en-gb}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=dan |title=The Online Corpus of the Inscriptions of Ancient North Arabia—Safaitic |url=http://krc.orient.ox.ac.uk/ociana/index.php/safaitic |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180220033208/http://krc.orient.ox.ac.uk/ociana/index.php/safaitic |archive-date=20 February 2018 |access-date=19 February 2018 |website=krc.orient.ox.ac.uk |language=en-gb}}</ref> |

|||

Ancient tourists visiting the 5th-century citadel at [[Sigiriya]] in Sri Lanka write their names and commentary over the "mirror wall", adding up to over 1800 individual graffiti produced there between the 6th and 18th centuries.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Kljun |first1=Matjaž |last2=Pucihar |first2=Klen Čopič |title=Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2015 |chapter="I Was Here": Enabling Tourists to Leave Digital Graffiti or Marks on Historic Landmarks |date=2015 |editor-last=Abascal |editor-first=Julio |editor2-last=Barbosa |editor2-first=Simone |editor3-last=Fetter |editor3-first=Mirko |editor4-last=Gross |editor4-first=Tom |editor5-last=Palanque |editor5-first=Philippe |editor6-last=Winckler |editor6-first=Marco |chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-22723-8_45 |series=Lecture Notes in Computer Science |volume=9299 |language=en |location=Cham |publisher=Springer International Publishing |pages=490–494 |doi=10.1007/978-3-319-22723-8_45 |isbn=978-3-319-22723-8 |issn = 0302-9743 }}</ref> Most of the graffiti refer to the frescoes of semi-nude females found there. |

|||

The first known example of "modern style" graffiti survives in the ancient Greek city of [[Ephesus]] (in modern-day [[Turkey]]). Local guides say it is an [[advertisement]] for [[prostitution]]. Located near a [[mosaic]] and stone walkway, the graffiti shows a handprint that vaguely resembles a heart, along with a footprint and a number. This is believed to indicate that a brothel was nearby, with the handprint symbolizing payment. |

|||

<ref>{{cite web|title = "Urbane Guerrillas" | url =http://www.state-of-art.org/state-of-art/ISSUE%20FOUR/urbane4.html | author = Mike Von Joel | accessdate = 2006-10-18 }}</ref> |

|||

Among the ancient political graffiti examples were [[Arab]] satirist poems. Yazid al-Himyari, an [[Umayyad]] Arab and [[Persian language|Persian]] poet, was most known for writing his political poetry on the walls between [[Sistan|Sajistan]] and [[Basra]], manifesting a strong hatred towards the [[Umayyad]] regime and its ''[[wali]]s'', and people used to read and circulate them very widely.<ref>Hussein Mroueh (1986) حسين مروّة، '''تراثنا كيف نعرفه'''، مؤسسة الأبحاث العربية، بيروت، [Our Heritage, How Do We Know It], ''Arab Research Foundation'', Beirut</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Graffiti politique de Pompei.jpg|thumb|right|150px|Ancient [[Pompeii]] graffito caricature of a politician.]] |

|||

Graffiti, known as Tacherons, were frequently scratched on Romanesque Scandinavian church walls.<ref name=green>{{cite web|url=http://www.green-man-of-cercles.org/articles/builders_marks.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070810164425/http://www.green-man-of-cercles.org/articles/builders_marks.pdf |archive-date=2007-08-10 |url-status=live |title=Tacherons on Romanesque churches}}</ref> When [[Renaissance]] artists such as [[Pinturicchio]], [[Raphael]], [[Michelangelo]], [[Domenico Ghirlandaio|Ghirlandaio]], or [[Filippino Lippi]] descended into the ruins of Nero's [[Domus Aurea]], they carved or painted their names and returned to initiate the ''[[Grotesque|grottesche]]'' style of decoration.<ref name="archeology">British Archaeology, June 1999</ref><ref name="atlantic">{{cite magazine|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/issues/97apr/rome.htm |title=Underground Rome |magazine=[[The Atlantic Monthly]] |date=April 1997}}</ref> |

|||

The [[ancient Rome|Romans]] carved graffiti on walls and monuments, with examples surviving in [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]]. The eruption of [[Vesuvius]] preserved graffiti in [[Pompeii]], including [[Latin]] curses, magic spells, declarations of love, alphabets, political slogans and famous literary quotes, providing insight into ancient Roman street life. One inscription gives the address of a woman named Novellia Primigenia of Nuceria, a prostitute, apparently of great beauty, whose services were much in demand. Another shows a phallus accompanied by the text, <i>''mansueta tene''</i>: <i>"Handle with care"</i>. |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Ancient graffiti"> |

|||

Disappointed love also found its way onto walls in antiquity: |

|||

File:Graffiti 4.JPG|Graffiti from the Museum of Ancient Graffiti [[:fr:Maison du graffiti ancien|(fr)]], France |

|||

:''Quisquis amat. veniat. Veneri volo frangere costas |

|||

File:Jesus graffito.jpg|Satirical [[Alexamenos graffito]], possibly the earliest known [[Depiction of Jesus|representation of Jesus]] |

|||

:''fustibus et lumbos debilitare deae. |

|||

File:AncientgrafS.jpg|Graffiti, [[Church of the Holy Sepulchre]], [[Jerusalem]] |

|||

:''Si potest illa mihi tenerum pertundere pectus |

|||

File:Hagia-sofia-viking.jpg|[[Vikings|Viking]] mercenary graffiti at the [[Hagia Sophia]] in [[Istanbul]], Turkey |

|||

:'' quit ego non possim caput illae frangere fuste? |

|||

File:Sigiriya-graffiti.jpg|Graffiti on the [[Sigiriya#Mirror wall|Mirror Wall]], [[Sigiriya]], [[Sri Lanka]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Contemporary graffiti === |

|||

:''Whoever loves, go to hell. I want to break Venus's ribs |

|||

In the 1790s, French soldiers carved their names on monuments during the Napoleonic [[French Revolutionary Wars: Campaigns of 1798|campaign of Egypt]].<ref name=JinxArtCrimes>{{Cite news|title=Art Crimes |publisher=Jinx Magazine |url=http://www.jinxmagazine.com/art_crimes.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141014194314/http://www.jinxmagazine.com/art_crimes.html/ |archive-date=14 October 2014 }}</ref> [[Lord Byron]]'s survives on one of the columns of the Temple of [[Poseidon]] at [[Cape Sounion]] in [[Attica]], Greece.<ref name=shanks>{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/classicalarchaeo00shan|url-access=limited|title=Classical Archaeology of Greece: Experiences of the Discipline |first=Michael |last=Shanks |year=1996 |publisher=London, New York: Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-08521-2 |page=[https://archive.org/details/classicalarchaeo00shan/page/n87 76]}}</ref> |

|||

:''with a club and deform her hips. |

|||

:''If she can break my tender heart |

|||

:''why can't I hit her over the head? |

|||

::-''[[Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum|CIL]]'' IV, 1284. |

|||

The oldest known example of [[Moniker (graffiti)|graffiti monikers]] were found on traincars created by hobos and railworkers since the late 1800s. The Bozo Texino monikers were documented by filmmaker [[Bill Daniel (filmmaker)|Bill Daniel]] in his 2005 film, ''Who is Bozo Texino?''.<ref name="bozo-texino-walker">{{cite web |last=Daniel |first=Bill |date=22 July 2010 |title=Who Is Bozo Texino? |url=https://walkerart.org/calendar/2010/who-is-bozo-texino |access-date=23 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="bozo-texino-film">{{cite web |last=Daniel |first=Bill |date=2005 |title=Who Is Bozo Texino? |url=http://www.billdaniel.net/who-is-bozo-texino/ |access-date=23 August 2018 |work=Who Is Bozo Texino? The Secret History of Hobo Graffiti}}</ref> |

|||

Errors in spelling and grammar in this graffiti offer insight into the degree of literacy in Roman times and provide clues on the pronunciation of spoken Latin. Examples are ''CIL'' IV, 7838: ''Vettium Firmum / aed''[ilem] ''quactiliar''[ii] [sic] ''rog''[ant]. Here, "qu" is pronounced "co." The 83 pieces of graffiti found at ''CIL'' IV, 4706-85 are evidence of the ability to read and write at levels of society where literacy might not be expected. The graffiti appear on a [[peristyle]] which was being remodeled at the time of the eruption of Vesuvius by the architect Crescens. The graffiti was left by both the foreman and his workers. The brothel at ''CIL'' VII, 12, 18-20 contains over 120 pieces of graffiti, some of which were the work of the prostitutes and their clients. The [[gladiator]]ial academy at ''CIL'' IV, 4397 was scrawled with graffiti left by the gladiator Celadus Crescens (''Suspirium puellarum Celadus thraex'': "Celadus the [[Thracian]] makes the girls sigh.") |

|||

Contemporary graffiti has been seen on landmarks in the US, such as [[Independence Rock]], a national landmark along the [[Oregon Trail]].<ref>{{cite web |title=Independence Rock—California National Historic Trail (National Park Service) |url=https://www.nps.gov/cali/planyourvisit/site5.htm |access-date=18 January 2018 |publisher=National Park Service}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Jesus graffito.jpg|thumb|right|[[Alexamenos graffito|This 2nd-century representation of a crucified donkey]] is believed by some to be the first [[representation of Jesus]] (here, evidently by a non-Christian). [[Palatine Hill]], [[Rome]].]] |

|||

It was not only the Greeks and Romans that produced graffiti: the [[Maya civilization|Mayan]] site of [[Tikal]] in [[Guatemala]] also contains ancient examples. [[Viking]] graffiti survive in [[Rome]] and at [[Newgrange|Newgrange Mound]] in [[Ireland]], and a [[Varangian]] scratched his name (Halvdan) in [[Runic alphabet|rune]]s on a [[banister]] in the [[Hagia Sophia]] at [[Constantinople]]. |

|||

In [[World War II]], an inscription on a wall at the fortress of [[Verdun]] was seen as an illustration of the US response twice in a generation to the wrongs of the Old World:<ref name=reagan>{{cite book |title=Military Anecdotes (1992) |first=Geoffrey |last=Reagan |year=1992 |publisher=Guinness Publishing |isbn=978-0-85112-519-0 |page=33 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1985/08/14/opinion/words-from-a-war.html|title=Words From a War|date=14 August 1985|newspaper=The New York Times|access-date=2 January 2017}}</ref> |

|||

Graffiti, known as Tacherons, were frequently scratched on the walls of Romanesque churches.<ref>[http://www.green-man-of-cercles.org/articles/builders_marks.pdf Tacherons on Romanesque churches]</ref> |

|||

{{poemquote| |

|||

When [[Renaissance]] artists such as [[Pinturicchio]], [[Raphael]], [[Michelangelo]], [[Domenico Ghirlandaio|Ghirlandaio]] or [[Filippino Lippi]] descended into the ruins of Nero's [[Domus Aurea]], they carved or painted their names<ref name="Archeology">British Archaeology, June 1999</ref><ref name="Atlantic">[[The Atlantic Monthly]], [http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/97apr/rome.htm April 97] (only for subscribers).</ref> and returned with the ''[[grottesche]]'' style of decoration. |

|||

Austin White – Chicago, Ill – 1918 |

|||

There are also examples of graffiti occurring in American history, such as [[Signature Rock]], a national landmark along the [[Oregon Trail]]. |

|||

Austin White – Chicago, Ill – 1945 |

|||

This is the last time I want to write my name here.}} |

|||

During World War II and for decades after, the phrase "[[Kilroy was here]]" with an accompanying illustration was widespread throughout the world, due to its use by American troops and ultimately filtering into American popular culture. Shortly after the death of [[Charlie Parker]] (nicknamed "Yardbird" or "Bird"), graffiti began appearing around New York with the words "Bird Lives".<ref name=russel>{{cite book |title=Bird Lives!: The High Life And Hard Times Of Charlie (yardbird) Parker |first=Ross |last=Russell |publisher=Da Capo Press}}</ref> |

|||

Later, French soldiers carved their names on monuments during the Napoleonic [[French Revolutionary Wars: Campaigns of 1798|campaign of Egypt]] in the 1790s.<ref name=JinxArtCrimes>{{cite news|title=Art Crimes |publisher=Jinx Magazine |date=Unknown |url=http://www.jinxmagazine.com/art_crimes.html}}</ref> [[Lord Byron]]'s survives on one of the columns of the Temple of [[Poseidon]] at [[Cape Sounion]] in [[Attica]], Greece.<ref>p. 76, ''Classical Archaeology of Greece: Experiences of the Discipline'', Michael Shanks, London, New York: Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0415085217.</ref> There is also evidence of Chinese graffiti on the [[great wall of China]]. |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="World War II graffiti"> |

|||

Art forms like [[fresco]]es and [[mural]]s involve leaving images and writing on wall surfaces. Like the [[prehistory|prehistoric]] [[cave painting|wall paintings]] created by [[cave]] dwellers, they do not comprise graffiti, as the artists generally produce them with the explicit permission (and usually support) of the owner or occupier of the walls. |

|||

Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-309-0816-20A, Italien, Soldat zeichnend.jpg|Soldier with tropical fantasy graffiti (1943–1944) |

|||

Graffiti inside the ruins of the German Reichstag building.jpg|Soviet Army graffiti in the ruins of the [[Reichstag building|Reichstag]], in [[Berlin]] (1945) |

|||

The D-Day Wall, Southampton, 10 June 2024.jpg|The D-Day Wall in Western Esplanade, [[Southampton]]. |

|||

Kilroy Was Here - Washington DC WWII Memorial - Jason Coyne.jpg|Permanent engraving of [[Kilroy was here|Kilroy]] on the [[World War II Memorial]], in [[Washington, D.C.]] |

|||

</gallery><gallery mode="packed" caption="Early spray-painted graffiti"> |

|||

NYC R36 1 subway car.png|[[New York City Subway]] train covered in graffiti (1973). |

|||

GRAFFITI ON A WALL IN CHICAGO. SUCH WRITING HAS ADVANCED AND BECOME AN ART FORM, PARTICULARLY IN METROPOLITAN AREAS.... - NARA - 556232.jpg|Graffiti in [[Chicago]] (1973)</gallery> |

|||

===Modern |

=== Modern Graffiti === |

||

Modern graffiti style has been heavily influenced by [[hip hop culture]]<ref name="genius-paul-edwards-hiphopbook">{{cite web |last=Edwards |first=Paul |date=10 February 2015 |title=Is Graffiti Really An Element Of Hip-Hop? (book excerpt) |url=https://genius.com/Paul-edwards-is-graffiti-really-an-element-of-hip-hop-book-excerpt-annotated |access-date=23 August 2018 |work=The Concise Guide to Hip-Hop Music}}</ref> and started with young people in 1960s and 70s in [[New York City]] and [[Philadelphia]]. [[Tag (graffiti)|Tags]] were the first form of stylised contemporary graffiti, starting with artists like [[TAKI 183]] and [[Cornbread (graffiti artist)|Cornbread]]. Later, artists began to paint throw-ups and [[Piece (graffiti)|pieces]] on trains on the sides subway trains.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Tate |title=Graffiti art |url=https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/g/graffiti-art |access-date=2023-02-23 |website=Tate |language=en-GB}}</ref> and eventually moved into the city after the NYC metro began to buy new trains and paint over graffiti.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Snyder |first=Gregory J. |date=2006-04-01 |title=Graffiti media and the perpetuation of an illegal subculture |url=http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1741659006061716 |journal=Crime, Media, Culture|language=en |volume=2 |issue=1 |pages=93–101 |doi=10.1177/1741659006061716 |s2cid=144911784 |issn=1741-6590}}</ref> |

|||

{{globalize/USA}} |

|||

While the art had many advocates and appreciators—including the cultural critic [[Norman Mailer]]—others, including New York City mayor [[Ed Koch]], considered it to be defacement of public property, and saw it as a form of public blight.<ref name=":02">{{Cite web |title=The history of graffiti |url=https://learnenglishteens.britishcouncil.org/skills/reading/b2-reading/history-graffiti |access-date=2023-03-24 |website=learnenglishteens.britishcouncil.org |language=en}}</ref> While those who did early modern graffiti called it "writing", [[The Faith of Graffiti|the 1974 essay "The Faith of Graffiti"]] referred to it using the term "graffiti", which stuck.<ref name=":02"/> |

|||

[[Image:KRESS.jpg|thumb|right|An [[Aerosol paint]] can, common tool for modern graffiti]] |

|||

Modern graffiti is often seen as having become intertwined with [[Hip-Hop|Hip-Hop culture]] as one of the four main elements of the culture (along with the [[MC|Master of ceremony]], the [[DJ|disc jockey]], and [[Breakdance|break dancing]]), through Hollywood movies such as [[Wild Style]]. However, modern (twentieth century) graffiti predates hip hop by almost a decade and has its own culture, complete with its own unique style and slang. |

|||

<!-- Unsourced image removed: [[Image:Grafitti Montreal.JPG|thumb|right|Another example, [[Montreal, Canada]]]] --> |

|||

An early graffito outside of New York or Philadelphia was the inscription in London reading "[[Clapton is God]]" in reference to the guitarist [[Eric Clapton]]. Creating the cult of the guitar hero, the phrase was spray-painted by an admirer on a wall in [[Islington]], north London, in the autumn of 1967.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Hann |first1=Michael |date=12 June 2011 |title=Eric Clapton creates the cult of the guitar hero |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/jun/12/eric-clapton |url-status=live |access-date=16 December 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170311172627/https://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/jun/12/eric-clapton |archive-date=11 March 2017}}</ref> The graffito was captured in a photograph, in which a dog is [[Urine marking#Canidae|urinating on the wall]].<ref>{{cite news |last=McCormick |first=Neil |date=24 July 2015 |title=Just how good is Eric Clapton? |work=The Telegraph |location=London |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/rockandpopfeatures/11501274/Just-how-good-is-Eric-Clapton.html |url-status=live |access-date=3 April 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171124071909/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/rockandpopfeatures/11501274/Just-how-good-is-Eric-Clapton.html |archive-date=24 November 2017}}</ref> |

|||

For example, a famous graffiti of the 20th century was the inscription in the London subway reading "Clapton is God", in reference to the guitar skills of [[Eric Clapton]]. The phrase was spray-painted by an admirer on a wall in an Islington Underground station in the autumn of 1967. The graffiti was captured in a now-famous photograph, in which a dog is urinating on the wall. Similar approvals or disapprovals of musicians have continued since, for instance, the summer 2007 inscriptions in Harlem reading "50 Cent is Wack". A popular graffitos of the 1970s was the legend "Dick [[Richard Milhous Nixon|Nixon]] Before He Dicks You," reflecting the hostility of the youth culture to that U.S. president. The belief that graffiti and hip-hop are related arises from the fact that some graffiti artists enjoyed the other three aspects of hip-hop, and that it was mainly practiced in areas where the other three elements of hip-hop were evolving as art forms. Graffiti is recognized as a visual expression of the rap music of the decade, as [[breakdance|breakdancing]] is the physical expression. Graffiti also became associated with the anti-establishment [[punk rock]] movement beginning in the 1970s. Bands such as [[Black Flag (band)|Black Flag]] and [[Crass]] (and their followers) widely stenciled their names and logos, while many punk night clubs, squats and hangouts are famous for their graffiti. |

|||

Films like [[Style Wars]] in the 80s depicting famous writers such as Skeme, [[DONDI|Dondi]], MinOne, and [[Zephyr (artist)|ZEPHYR]] reinforced graffiti's role within New York's emerging hip-hop culture. Although many officers of the New York City Police Department found this film to be controversial, Style Wars is still recognized as the most prolific film representation of what was going on within the young hip hop culture of the early 1980s.<ref name=labonte>Labonte, Paul. All City: The book about taking space. Toronto. ECW Press. 2003</ref> Fab{{nbsp}}5 Freddy and Futura 2000 took hip hop graffiti to Paris and London as part of the New York City Rap Tour in 1983.<ref name=hershk>David Hershkovits, "London Rocks, Paris Burns and the B-Boys Break a Leg", ''Sunday News Magazine'', 3 April 1983.</ref> |

|||

Modern graffiti artists sometimes choose nicknames or "tags." Tags need to be quick to write, so they are often no more than 3 to 5 characters in length. A nickname is chosen to reflect personal qualities and characteristics, or because of the way the word sounds, and/or for the way it looks once written. The letters in a word can make execution difficult if the shapes of the letters don't naturally fit next to each other in a visually pleasing way. It's common for a graffiti artist to select a name that is a play on a common expression, such as "2Shae," "Page3," "2Cold," "In1," and other such names. |

|||

=== Commercialization and entrance into mainstream pop culture === |

|||

A name might also represent a word using an irregular spelling; for example, "Train" could be ''Trane'' or ''Trayne,'' and "Envy" could be ''Envie'' or ''Envee.'' Names can contain subtle and sometimes cryptic messages, and might incorporate the artist's initials or other letters. As well as the graffiti name, some artists include the year that they completed that tag next to the name. [[Types of graffiti#Bombing|Bomber]] [[Tox]], from London, seldom writes just ''Tox''; it is usually ''Tox03,'' ''Tox04,'' etc. In some cases, artists dedicate or create tags or graffiti in [[memorial|memory]] of a deceased friend — for example, "DIVA Peekrevs R.I.P. JTL '99." The Borf Brigade's arrested member, [[John Tsombikos]], claimed the "BORF" tag campaign, which gained recognition for its prevalence in DC, was in memory of his deceased friend. |

|||

{{Main|Commercial graffiti}} |

|||

With the popularity and legitimization of graffiti has come a level of commercialization. In 2001, computer giant [[IBM]] launched an advertising campaign in Chicago and San Francisco which involved people spray painting on sidewalks a [[peace symbol]], a [[Heart (symbol)|heart]], and a [[penguin]] ([[Tux (mascot)|Linux mascot]]), to represent "Peace, Love, and Linux." IBM paid Chicago and San Francisco collectively US$120,000 for punitive damages and clean-up costs.<ref name=guerilla>{{cite news|publisher=CNN |title=IBM's graffiti ads run afoul of city officials |url=http://archives.cnn.com/2001/TECH/industry/04/19/ibm.guerilla.idg/index.html |date=19 April 2001 |access-date=11 October 2006 |first=James |last=Niccolai |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061004173008/http://archives.cnn.com/2001/TECH/industry/04/19/ibm.guerilla.idg/index.html |archive-date=4 October 2006 }}</ref><ref name=wired>{{Cite magazine|title = Sony Draws Ire With PSP Graffiti|magazine = Wired|url = https://www.wired.com/culture/lifestyle/news/2005/12/69741|date = 5 December 2005|access-date = 8 April 2008}}</ref> |

|||

Initial groundwork for the current social significance of graffiti in America began around the late 1960s. Around this time, graffiti was used as a form of expression by [[political activist]]s. It was considered a cheap and easy way to make a statement, with minimal risk to the artist. Gang graffiti also rose in visibility, used by gangs to mark territory. Some gangs that made use of graffiti during this era included the Savage Skulls, La Familia, and Savage Nomads. |

|||

[[Image:Graffiti - European train.jpg|thumb|left|Modern graffiti on train]] |

|||

Towards the end of the 1960s the modern culture began to form in [[Philadelphia, Pennsylvania]]. The two graffiti artists considered to be responsible for the first true bombing are "Cool Earl" and "[[Cornbread]]."<ref name=NYMagGraf>{{cite news|title=A History of Graffiti in Its Own Words |publisher=New York Magazine |date=unknown |url=http://nymag.com/guides/summer/17406/}}</ref> They gained much attention from the Philadelphia press and the community itself by leaving their tags written everywhere. Around 1970-71, the centre of graffiti innovation moved from [[Philadelphia, Pennsylvania|Philadelphia]] to [[New York City]]. Once the initial foundation was laid (around 1966–1971), graffiti "pioneers" began inventing newer and more creative ways to write. |

|||

In 2005, a similar ad campaign was launched by [[Sony]] and executed by its advertising agency in New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Miami, to market its handheld [[PlayStation Portable|PSP]] gaming system. In [[PlayStation Portable#Controversial advertising campaigns|this campaign]], taking notice of the legal problems of the IBM campaign, Sony paid building owners for the rights to paint on their buildings "a collection of dizzy-eyed urban kids playing with the PSP as if it were a skateboard, a paddle, or a rocking horse".<ref name=wired/> |

|||

<ref name=NYMagGraf /> |

|||

== Global movements == |

|||

====American roots of modern graffiti==== |

|||

=====Pioneering era (1969-1974)===== |

|||

[[Image:Julio 204.jpg|thumb|right|160px|[[Julio 204]], early graffiti writer in [[New York City]]]]Between the years of 1969-1974 the "pioneering era" took place. During this time graffiti underwent a change in styles and popularity. Soon after the migration to NYC, the city produced one of the first graffiti artists to gain media attention in New York, [[TAKI 183]]. TAKI 183 was a youth from [[Washington Heights, Manhattan]] who worked as a foot messenger. His tag is a mixture of his name Demetrius (Demetraki), TAKI, and his street number, 183rd. Being a foot messenger, he was constantly on the subway and began to put up his tags along his travels. This spawned a 1971 article in the [[New York Times]] titled "'Taki 183' Spawns Pen Pals".<ref name=NYMagGraf /><ref name=JinxArtCrimes /><ref>{{cite news|title=Black History Month - 1971 |publisher=BBC |date=unknown |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/1xtra/bhm05/years/1971.shtml}}</ref> [[Julio 204]] is also credited as the first writer, but didn't get the fame that Taki received. TAKI 183 was the first artist to be recognised outside of the graffiti subculture, but wasn't the first artist. Other notable names from that time are: Stay High 149, Hondo 1, [[Phase 2]], Stitch 1, Joe 182, Junior 161 and Cay 161. Barbara 62 and Eva 62 were also important early graffiti artists in New York, and are the first known females to write graffiti. |

|||

Also taking place during this era was the movement from outside on the city streets to the subways. Graffiti also saw its first seeds of competition around this time. The goal of most artists at this point was called "getting up" and involved having as many tags and bombs in as many places as possible. Artists began to break into subway yards in order to hit as many trains as they could with a lower risk, often creating larger elaborate pieces of art along the subway car sides. This is when the act of bombing was said to be officially established. |

|||

When graffiti is done as an art form, it often utitlises the [[Latin script]] even in countries where it is not the primary writing system.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lawrence |first=C. Bruce |date=March 2012 |title=The Korean English linguistic landscape: The Korean English linguistic landscape |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2011.01741.x |journal=World Englishes |language=en |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=70–92 |doi=10.1111/j.1467-971X.2011.01741.x}}</ref> English words are also often used as monikers.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Rosen |first=Matthew |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0FflEAAAQBAJ&dq=graffiti+%22latin+script%22&pg=PA241 |title=The Ethnography of Reading at Thirty |date=2023-12-25 |publisher=Springer Nature |isbn=978-3-031-38226-0 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

By 1971 tags began to take on their signature [[calligraphy|calligraphic appearance]] because, due to the huge number of artists, each graffiti artist needed a way to distinguish themselves. Aside from the growing complexity and creativity, tags also began to grow in size and scale – for example, many artists had begun to increase letter size and line thickness, as well as outlining their tags. This gave birth to the so-called 'masterpiece' or 'piece' in 1972. Super Kool 223 is credited as being the first to do these pieces. |

|||

=== Europe === |

|||

The use of designs such as polka dots, crosshatches, and checkers became increasingly popular. Spray paint use increased dramatically around this time as artists began to expand their work. "Top-to-bottoms", works which span the entire height of a subway car, made their first appearance around this time as well. The overall creativity and artistic maturation of this time period did not go unnoticed by the mainstream – Hugo Martinez founded the United Graffiti Artists (UGA) in 1972. UGA consisted of many top graffiti artists of the time, and aimed to present graffiti in an art gallery setting. By 1974, graffiti artists had begun to incorporate the use of scenery and cartoon characters into their work. |

|||

Stencil graffiti artists such as [[Blek le Rat]] existed in Western Europe, especially in [[Paris]], before the arrival of American graffiti and was associated more with the [[punk rock]] scene than with hip-hop.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Ganz |first=Nicholas |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ujsyPQAACAAJ |title=Graffiti World: Street Art from Five Continents |date=2009 |publisher=Thames & Hudson |isbn=978-0-500-51469-6 |language=en}}</ref> In the 1980s, American graffiti and hiphop began to influence the European graffiti scene.<ref name=":0" /> Modern graffiti reached Eastern Europe in the 1990s.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

Some of the earliest graffiti exhibitions outside of the USA were in [[Amsterdam]], The Netherlands.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

=====Mid 1970s===== |

|||

=== Middle East === |

|||

After the original pioneering efforts, which culminated in 1974, the art form peaked around 1975 – 1977.{{Fact|date=October 2007}} By this time, most standards had been set in graffiti writing and culture. The heaviest "bombing" in U.S. history took place in this period, partially because of the economic restraints on New York City, which limited its ability to combat this art form with graffiti removal programs or transit maintenance. Also during this time, "top-to-bottoms" evolved to take up entire subway cars. Most note-worthy of this era proved to be the forming of the "throw-up", which are more complex than simple "tagging," but not as intricate as a "piece". Not long after their introduction, throw-ups lead to races to see who could do the largest amount of throw-ups in the least amount of time. |

|||

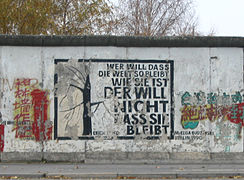

Graffiti in the [[Middle East]] has emerged slowly, with taggers operating in [[Egypt]], [[Lebanon]], the [[Arab states of the Persian Gulf|Gulf countries]] like [[Bahrain]] or the [[United Arab Emirates]],<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Zoghbi|first1=Pascal|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/818463305|title=Arabic graffiti = Ghirāfītī ʻArabīyah|last2=Stone|last3=Hawley|first3=Joy|date=2013|publisher=From Here to Fame|isbn=978-3-937946-45-0|location=Berlin|oclc=818463305}}</ref> [[Israel]], and in [[Iran]]. The major Iranian newspaper ''[[Hamshahri]]'' has published two articles on illegal writers in the city with photographic coverage of Iranian artist [[A1one]]'s works on Tehran walls. Tokyo-based design magazine, ''PingMag'', has interviewed A1one and featured photographs of his work.<ref name=pinmag>{{cite web|url=http://www.pingmag.jp/2007/01/19/a1one-1st-generation-graffiti-in-iran |author=Uleshka |title=A1one: 1st generation Graffiti in Iran |publisher=PingMag |date=19 January 2005 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080222030338/http://www.pingmag.jp/2007/01/19/a1one-1st-generation-graffiti-in-iran/ |archive-date=22 February 2008 }}</ref> The [[Israeli West Bank barrier]] has become a site for graffiti, reminiscent in this sense of the [[Berlin Wall]]. Many writers in Israel come from other places around the globe, such as JUIF from Los Angeles and DEVIONE from London. The religious reference "נ נח נחמ נחמן מאומן" ("[[Na Nach Nachma Nachman Meuman]]") is commonly seen in graffiti around Israel. |

|||

[[File:Graffiti in Tel Aviv, Israel.jpg|thumb|A graffiti piece by the artist DeDe found in [[Tel Aviv]]]] |

|||

Graffiti has played an important role within the [[street art]] scene in the Middle East and North Africa ([[MENA]]), especially following the events of the [[Arab Spring]] of 2011 or the [[Sudanese Revolution]] of 2018/19.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Bashir's Overthrow Inspires Sudan Graffiti Artists|url=https://english.aawsat.com/home/article/1695246/bashirs-overthrow-inspires-sudan-graffiti-artists|access-date=2021-06-29|website=Asharq AL-awsat|language=en}}</ref> Graffiti is a tool of expression in the context of conflict in the region, allowing people to raise their voices politically and socially. Famous street artist [[Banksy]] has had an important effect in the street art scene in the MENA area, especially in [[Palestine]] where some of his works are located in the [[Israeli West Bank barrier|West Bank barrier]] and [[Bethlehem]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=DeTruk|first=Sabrina|date=2015|title=The "Banksy Effect" and Street Art in the Middle East|url=https://journals.ap2.pt/index.php/sauc/article/view/25|journal=SAUC – Street Art & Urban Creativity Scientific Journal|volume=1|issue=2|pages=22–30}}</ref> |

|||

Graffiti writing was becoming very competitive and artists strove to go "all-city," or to have their names seen in all five [[boroughs]] of NYC. Eventually, the standards which had been set in the early 70s began to become stagnant. These changes in attitude lead many artists into the 1980s with a desire to expand and change. |

|||

=== |

=== South America === |

||

South America has a very active graffiti culture, and graffiti are very common in Brazilian cities. This is blamed on the high uneven distribution of income, changing laws, and disenfranchisement.<ref name=manco7>{{cite book |title=Lost Art & Caleb Neelon, Graffiti Brazil |first=Tristan |last=Manco |year=2005 |publisher=London: Thames and Hudson |pages=7–10 }}</ref> ''[[Pichação]]'' is a form of graffiti found in Brazil, which involves tall characters and is usually used as a form of protest. It contrasts with the more conventionally artistic values of the practitioners of ''grafite''.<ref name=revela>{{cite web |url=http://www.revelacaoonline.uniube.br/2005/316/Arte.html |title=Pintando o muro |publisher=Revelacaoonline.uniube.br |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110501012139/http://www.revelacaoonline.uniube.br/2005/316/Arte.html |archive-date=1 May 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

The late 1970s and early 1980s brought a new wave of creativity to the scene.As the influence of graffiti grew, beyond the Bronx, a graffiti movement begun by encouragement by Friendly Freddie. [[Fab Five Freddy]] (Fred Brathwaite) is another popular graffiti figure of this time, often credited with helping to spread the influence of graffiti and [[Hip hop music|rap]] music beyond its early foundations in the [[The Bronx|Bronx]]. It was also, however, the last wave of true bombing before the Transit Authority made graffiti eradication a priority. The [[Metropolitan Transportation Authority (New York)|MTA (Metro Transit Authority)]] began to repair yard fences, and remove graffiti consistently, battling the surge of graffiti artists. With the MTA combating the artists by removing their work it often led many artists to quit in frustration, as their work was constantly being removed. It was also around this time that the established art world started becoming receptive to the graffiti culture for the first time since Hugo Martinez’s Razor Gallery in the early 1970s. |

|||

Prominent Brazilian writers include [[OSGEMEOS|Os Gêmeos]], Boleta, [[Francisco Rodrigues da Silva|Nunca]], Nina, Speto, Tikka, and T.Freak.<ref name=globo>{{cite magazine|url=http://revistamarieclaire.globo.com/Marieclaire/0,6993,EML1163949-1740,00.html |title=A força do novo grafite |language=pt |magazine=[[Marie Claire]] |access-date=19 November 2014 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141129082341/http://revistamarieclaire.globo.com/Marieclaire/0%2C6993%2CEML1163949-1740%2C00.html |archive-date=29 November 2014 }}</ref> |

|||

In 1979, graffiti artist [[Lee Quinones]], and Fab Five Freddy were given a gallery opening in Rome by art dealer Claudio Bruni. Slowly, European art dealers became more interested in the new art form. For many outside of New York, it was the first time ever being exposed to the art form. During the 1980s the cultural aspect of graffiti was said to be deteriorating almost to the point of extinction. The rapid decline in writing was due to several factors. The streets became more dangerous due to the burgeoning [[Crack Epidemic|crack epidemic]], legislation was underway to make penalties for graffiti artists more severe, and restrictions on paint sale and display made racking (stealing) materials difficult. Above all, the MTA greatly increased their anti-graffiti budget. Many favored painting sites became heavily guarded, yards were patrolled, newer and better fences were erected, and buffing of pieces was strong, heavy, and consistent. As a result of subways being harder to paint, more writers went into the streets, which is now, along with commuter trains and box cars, the most prevalent form of writing. |

|||

=== Southeast Asia === |

|||

Many graffiti artists, however, chose to see the new problems as a challenge rather than a reason to quit. A downside to these challenges was that the artists became very territorial of good writing spots, and strength and unity in numbers became increasingly important. This was probably the most violent era in graffiti history – Artists who chose to go out alone were often beaten and robbed of their supplies. Some of the mentionable graffiti artists from this era were Blade, [[Dondi White|Dondi]], [[Seen]] and Skeme. This was stated to be the end for the casual NYC subway graffiti artists, and the years to follow would be populated by only what some consider the most "die hard" artists. People often found that making graffiti around their local areas was an easy way to get caught so they traveled to different areas. |

|||

There are also a large number of graffiti influences in [[Southeast Asia]]n countries that mostly come from modern [[Western culture]], such as Malaysia, where graffiti have long been a common sight in Malaysia's capital city, [[Kuala Lumpur]]. Since 2010, the country has begun hosting a street festival to encourage all generations and people from all walks of life to enjoy and encourage Malaysian street culture.<ref name=kharbar>{{Cite web|url=http://www.khabarsoutheastasia.com/en_GB/articles/apwi/articles/features/2012/02/15/feature-03 |title=Graffiti competition in Kuala Lumpur draws local and international artists |publisher=Khabar Southeast Asia |date=15 February 2012 |access-date=17 April 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121113113534/http://www.khabarsoutheastasia.com/en_GB/articles/apwi/articles/features/2012/02/15/feature-03 |archive-date=13 November 2012 }}</ref> |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Graffiti around the world"> |

|||

=====Die Hard era (1985-1989)===== |

|||

File:Grafiti, Čakovec (Croatia).2.jpg|Graffiti on a wall in [[Čakovec]], Croatia |

|||

The years between 1985 and 1989 became known as the "die hard" era. A last shot for the graffiti artists of this time was in the form of subway cars destined for the [[scrap yard]]. With the increased security, the culture had taken a step back. The previous elaborate "burners" on the outside of cars were now marred with simplistic marker tags which often soaked through the paint. |

|||

File:Graffiti in Budapest, Pestszentlőrinc.jpg|Graffiti of the character [[Bender (Futurama)|Bender]] on a wall in [[Budapest]], Hungary |

|||

File:Graffiti in Ho Chi Minh City.JPG|Graffiti in [[Ho Chi Minh City]], Vietnam |

|||

File:Mr. Wany's work-in-progress artwork for Kul Sign Festival.JPG|Graffiti art in [[Kuala Lumpur]], Malaysia |

|||

File:Graffiti in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.jpg|Graffiti in [[Yogyakarta]], Indonesia |

|||

File:Camperdown Memorial Rest Park Graffiti.jpg|Graffiti on a park wall in [[Sydney]], Australia |

|||

File:Graffitiensaopaulo.jpg|Graffiti in [[São Paulo]], Brazil |

|||

File:Absurdious-001.jpg|Absourdios. Tehran-Iran, 2009. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== Types of graffiti == |

|||

By mid-1986 the MTA and the [[Chicago Transit Authority|CTA]] were winning their "war on graffiti," and the population of active graffiti artists diminished. As the population of artists lowered so did the violence associated with graffiti crews and "bombing." Roof tops also were being the new billboards for some 80's writers. Some notable graffiti artists of this era were [[Cope2]], Zephyr, Zev, Sane, Smith, and T-Kid.{{histfact}} |

|||

{{See also|Graffiti terminology}} |

|||

=== |

=== Tools === |

||

[[Spray paint]] and [[Marker pen|markers]] are the main tools used for [[Tag (graffiti)|tagging]], [[Throw up (graffiti)|throw ups]], and [[Piece (graffiti)|pieces]].<ref>{{Cite thesis |last=Bates |first=Lindsay |date=2014 |title=Bombing, Tagging, Writing: An Analysis of the Significance of Graffiti and Street Art |url=https://repository.upenn.edu/server/enwiki/api/core/bitstreams/4db1a72a-861c-48a0-b978-0232aea82a15/content|degree=Master of Science in Historic Preservation |publisher=University of Pennsylvania}}</ref> [[Paint marker]]s, paint dabbers, and scratching tools are also used.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Daniell |first=Christopher |date=2011-08-01 |title=Graffiti, Calliglyphs and Markers in the UK |url=https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-011-9176-6 |journal=Archaeologies |language=en |volume=7 |issue=2 |pages=454–476 |doi=10.1007/s11759-011-9176-6 |issn=1935-3987}}</ref> Some art companies, such as [[Montana Colors]], make art supplies specifically for graffiti and street art. Many major cities have graffiti art stores.<ref>{{Citation |last1=Avramidis |first1=Konstantinos |title=Moving from Urban to Virtual Spaces and Back: Learning In/From Signature Graffiti Subculture |date=2015 |work=Critical Learning in Digital Networks |pages=133–160 |editor-last=Jandrić |editor-first=Petar |url=https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-13752-0_7 |access-date=2024-08-06 |place=Cham |publisher=Springer International Publishing |language=en |doi=10.1007/978-3-319-13752-0_7 |isbn=978-3-319-13752-0 |last2=Drakopoulou |first2=Konstantina |editor2-last=Boras |editor2-first=Damir}}</ref> |

|||

The current era in graffiti is characterized by a majority of graffiti artists moving from subway or train cars to "street galleries." The Clean Train Movement started in May, 1989, when New York attempted to remove all of the subway cars found with graffiti on them out of the transit system. Because of this, many graffiti artists had to resort to new ways to express themselves. Much controversy arose among the streets debating whether graffiti should be considered an actual form of art.<ref>{{cite web | publisher = CNN |date= 2005-11-04 | url = http://www.cnn.com/2005/US/03/21/otr.green/index.html | title = From graffiti to galleries | accessdate = 2006-10-10}}</ref> |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Graffiti making"> |

|||

During this period many graffiti artists had taken to displaying their works in galleries and owning their own studios. This practice started in the early 1980s with artists such as [[Jean-Michel Basquiat]], who started out tagging locations with his signature SAMO (Same Old Shit), and [[Keith Haring]], who was also able to take his art into studio spaces. |

|||

File:Vlg shop.jpg|The first graffiti shop in [[Russia]] was opened in 1992 in [[Tver]]. |

|||

File:Eurofestival graffiti 2.jpg|Graffiti application at Eurofestival in [[Turku]], Finland |

|||

File:Graffity in the making...(On a wall at Thrissur) CIMG9868.JPG|Graffiti application in India using natural pigments (mostly [[charcoal]], plant [[sap]]s, and dirt) |

|||

File:Graffity in the making...(On a wall at Thrissur) CIMG9873.jpg|Completed landscape scene, in [[Thrissur]], [[Kerala]], India |

|||

File:Leake Street TQ3079 352.JPG|A graffiti artist at work in [[London]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Stencil graffiti === |

|||

In some cases, graffiti artists had achieved such elaborate graffiti (especially those done in memory of a deceased person) on storefront gates that shopkeepers have hesitated to cover them up. In [[the Bronx]] after the death of [[rapping|rapper]] [[Big Pun]], several murals dedicated to his life appeared virtually overnight;<ref>{{cite web | publisher = MTV News | title = New Big Pun Mural To Mark Anniversary Of Rapper's Death | url = http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1439015/20010202/story.jhtml |date= 2001-02-02 | accessdate = 2006-10-11}}</ref> similar outpourings occurred after the deaths of [[The Notorious B.I.G.]], [[Tupac Shakur]], [[Big L]], and [[Jam Master Jay]].<ref>{{cite web | publisher = Harlem Live | title = Tupak Shakur | url = http://www.harlemlive.org/community/elbarrio/tupac.htm |date= unknown | accessdate = 2006-10-11}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | publisher = Santa Monica News | title = "Bang the Hate" Mural Pushes Limits | url = http://www.surfsantamonica.com/ssm_site/the_lookout/news/News-2006/May-2006/05_04_06_Bang_the_Wall.htm |date= unknown|accessdate = 2006-10-11}}</ref> [[Diana, Princess of Wales|Princess Diana]] and [[Mother Teresa]] were also [[memorial]]ised this way in New York City. |

|||

{{Main|Stencil graffiti}} |

|||

Stencil graffiti is created by cutting out shapes and designs in a stiff material (such as [[Corrugated fiberboard|cardboard]] or subject [[File folder|folder]]s) to form an overall design or image. The stencil is then placed on the "canvas" gently and with quick, easy strokes of the aerosol can, the image begins to appear on the intended surface. Some of the first examples were created in 1981 by artists [[Blek le Rat]] in Paris, in 1982 by [[Jef Aerosol]] in Tours (France);<ref>{{Cite web |last= |first= |date=2024-04-11 |title=The Evolution of Graffiti Art |url=https://artsfiesta.com/the-evolution-of-graffiti-art/ |access-date=2024-04-13 |website=Arts Fiesta |language=en-US}}</ref> by 1985 stencils had appeared in other cities including New York City, Sydney, and [[Melbourne]], where they were documented by American photographer Charles Gatewood and Australian photographer Rennie Ellis.<ref name=ellis>{{cite book |title=The All New Australian Graffiti |first=Rennie |last=Ellis |year=1985 |publisher=Sun Books, Melbourne |isbn=978-0-7251-0484-9 }}</ref> |

|||

=== Stickers === |

|||

With the popularity and legitimization of graffiti has come a level of commercialization. In 2001, computer giant [[IBM]] launched an advertising campaign which involved people in various states spray painting on sidewalks a [[peace symbol]], a [[Heart (symbol)|heart]], and a [[penguin]] ([[Linux]] mascot), to represent "Peace, Love, and Linux." However due to illegalities some of the "street artists" were arrested and charged with vandalism.<ref>{{cite web | publisher = CNN | title = IBM's graffiti ads run afoul of city officials | url = http://archives.cnn.com/2001/TECH/industry/04/19/ibm.guerilla.idg/index.html |date= 2001-04-19 | accessdate = 2006-10-11}}</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Sticker art}} |

|||

Stickers, also known as slaps, are drawn or written on before being put up in public. Traditionally, free paper stickers like the [[United States Postal Service]]'s [[Label 228]] or [[name tag]]s were used.<ref>{{Cite book| title = Going Postal| last = Cooper| first = Martha| date = 2009-03-28| publisher = Mark Batty Publisher| isbn = 9780979966651| location = New York; London| language = en}}</ref> Eggshell stickers, which are very difficult to remove, are also frequent.<ref>{{Citation |last=Shobe |first=Hunter |title=Graffiti as Communication and Language |date=2020 |url=https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-02438-3_81 |work=Handbook of the Changing World Language Map |pages=3155–3172 |editor-last=Brunn |editor-first=Stanley D. |access-date=2023-08-29 |place=Cham |publisher=Springer International Publishing |language=en |doi=10.1007/978-3-030-02438-3_81 |isbn=978-3-030-02438-3 |editor2-last=Kehrein |editor2-first=Roland}}</ref> Stickers allow artists to put up their art quickly and discreetly, making them a relatively safer option for illegal graffiti.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Elsner |first1=Daniela |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_bBdnqY19cUC |title=Films, Graphic Novels & Visuals: Developing Multiliteracies in Foreign Language Education : an Interdisciplinary Approach |last2=Helff |first2=Sissy |last3=Viebrock |first3=Britta |date=2013 |publisher=LIT Verlag Münster |isbn=978-3-643-90390-7 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

=== Tags === |

|||

Along with the commercial growth has come the rise of [[video game]]s also depicting graffiti, usually in a positive aspect – for example, the game ''[[Jet Set Radio|Jet Grind Radio]]'' tells the story of a group of teens fighting the oppression of a [[Totalitarianism|totalitarian]] police force that attempts to limit the graffiti artists' [[freedom of speech]]. Following the original roots of modern graffiti as a political force came another game title ''[[Marc Ecko's Getting Up: Contents Under Pressure]]'' which features a similar story line of fighting against a corrupt city and its oppression of free speech. |

|||

{{Main|Tag (graffiti)}} |

|||

[[Tag (graffiti)|Tagging]] is the practice of writing ones "their name, initial or logo onto a public surface"<ref>{{Cite news|date=2022-01-18|title=Gullu Daley, Ajax Watson and Jestina Sharpe depicted in St Paul's street art|language=en-GB|work=BBC News|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-bristol-60039912|access-date=2022-01-19}}</ref> in a [[handstyle]] unique to the writer. Tags were the first form of modern graffiti. |

|||

A number of recent examples of graffiti make use of [[hashtags]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2015-07-23 |title=Hashtag on the pavement connects with Fitzrovia's past |url=http://fitzrovianews.com/2015/07/23/hashtag-on-the-pavement-connects-with-fitzrovias-past/ |access-date=2024-03-26 |website=Fitzrovia News |language=en-GB}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date= |title=#RISKROCK #GRAFFITI IN #SANFRANCISCO |url=https://massappeal.com/riskrock-graffiti-in-san-francisco/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171011183228/https://massappeal.com/riskrock-graffiti-in-san-francisco/ |archive-date=2017-10-11 |website=Mass Appeal}}</ref> |

|||

[[Mark Ecko]], an urban clothing designer, has been an advocate of graffiti as an art form during this period, stating that "Graffiti is without question the most powerful art movement in recent history and has been a driving inspiration throughout my career."<ref>{{cite web | publisher = SOHH.com | title = Marc Ecko Hosts "Getting Up" Block Party For NYC Graffiti, But Mayor Is A Hater | url = http://www.sohh.com/articles/article.php/7428 |date= 2005-08-17 | accessdate = 2006-10-11}}</ref> |

|||

{{wide image|Graffiti i baggård i århus 2c.jpg|1300px|align-cap=center|Densely-tagged parking area in [[Århus]], Denmark|center|}} |

|||

=== |

=== Throw ups === |

||

{{Main|Throw up (graffiti)}} |

|||

=====South America===== |

|||

Throw ups, or throwies are large, bubble-writing graffiti which aim to be "throw onto" a surface as largely and quickly as possible.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lasley |first=James R. |date=1995-04-01 |title=New writing on the wall: Exploring the middle-class graffiti writing subculture |url=http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01639625.1995.9967994 |journal=Deviant Behavior |language=en |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=151–167 |doi=10.1080/01639625.1995.9967994 |issn=0163-9625}}</ref> Throw ups can have fills or be "hollow".<ref>{{Cite thesis |title=Writing on the walls: Graffiti and civic identity |url=http://ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/28256 |publisher=University of Ottawa (Canada) |date=2009 |degree=Thesis |doi=10.20381/ruor-19161 |language=en |first=Michelle |last=Parks}}</ref> They prioritise minimal negative space<ref>{{Cite web |last=Team |first=The Drivin' & Vibin' |date=2022-08-21 |title=Who is Cope2? |url=https://outsidefolkgallery.com/cope2/ |access-date=2023-09-08 |website=Outside Folk Gallery |language=en-US |archive-date=2023-09-08 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230908090710/https://outsidefolkgallery.com/cope2/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> and consistency or letter space and height.<ref name=":2"/> |

|||

There is a significant graffiti tradition in [[South America]] most especially in [[Brazil]]. Within Brazil, [[Sao Paulo]] is generally considered to be the current centre of inspiration for many graffiti artists worldwide.<ref>[http://www.flickr.com/photos/tristanmanco/sets/154564/See Tristan Manco Sao Paulo pics on flikr.com]</ref> |

|||

=== Pieces === |

|||

Brazil "boasts a unique and particularly rich graffiti scene...[earning] it an international reputation as the place to go for artistic inspiration."<ref name=Manco7>Manco, Tristan. ''Lost Art & Caleb Neelon, Graffiti Brazil''. London: Thames and Hudson, 2005, 7.</ref> Graffiti "flourishes in every conceivable space in Brazil's cities."<ref name=Manco7 /> Artistic parallels "are often drawn between the energy of Sao Paulo today and 1970s [[New York City|New York]]." <ref name=Manco9>Manco, 9</ref> The "sprawling metropolis,"<ref name=Manco9 /> of Sao Paulo has "become the new shrine to graffiti;"<ref name=Manco9 /> Manco alludes to "poverty and unemployment...[and] the epic struggles and conditions of the country's marginalised peoples,"<ref name=Manco8>Manco, 8</ref> and to "Brazil's chronic poverty,"<ref name=Manco10>Manco, 10</ref> as the main engines that "have fuelled a vibrant graffiti culture."<ref name=Manco10 /> In world terms, Brazil has "one of the most uneven distributions of income. Laws and taxes change frequently."<ref name=Manco8 /> Such factors, Manco argues, contribute to a very fluid society, riven with those economic divisions and social tensions that underpin and feed the "folkloric vandalism and an urban sport for the disenfranchised,"<ref name=Manco10 /> that is South American graffiti art. |

|||

{{Main|Piece (graffiti)}} |

|||

Pieces are large, elaborate, letter-based graffiti which usually use spray paint or rollers.<ref name=":22">{{Cite book |last=Snyder |first=Gregory J. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FJUUCgAAQBAJ |title=Graffiti Lives: Beyond the Tag in New York's Urban Underground |date=2011-04-15 |publisher=NYU Press |isbn=978-0-8147-4046-0 |language=en}}</ref> Pieces often have multi-coloured fills and outlines, and may use highlights, shadows, backgrounds,<ref name="read">{{Cite book |last=Gottlieb |first=Lisa |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KyNVOzSbTGkC |title=Graffiti Art Styles: A Classification System and Theoretical Analysis |date=2014-01-10 |publisher=McFarland |isbn=978-0-7864-5225-5 |language=en}}</ref> extensions, 3D effects,<ref name="read"/> and sometimes [[Character (graffiti)|characters]].<ref>{{Citation |last=Mansfield |first=Michelle |title=Collective Individualism: Practices of Youth Collectivity within a Graffiti Community in Yogyakarta, Indonesia |date=2021-09-23 |work=Forms of Collective Engagement in Youth Transitions |pages=115–138 |url=https://brill.com/display/book/9789004466340/BP000008.xml |access-date=2023-08-28 |publisher=Brill |language=en |isbn=978-90-04-46634-0}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Wildstyle === |

||

{{Main|Wildstyle}} |

|||

Wildstyle is the most complex form of modern graffiti. It can be difficult for those unfamiliar with the art form to read.<ref name="read"/> Wildstyle draws inspiration from [[calligraphy]] and has been described as partially abstract.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Brown |first1=Michelle |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7kYrDwAAQBAJ |title=Routledge International Handbook of Visual Criminology |last2=Carrabine |first2=Eamonn |date=2017-07-06 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-317-49754-7 |language=en}}</ref> The term "wildstyle" was popularized by the Wild Style graffiti crew formed by [[Tracy 168]] of [[the Bronx]], [[New York City|New York]] in 1974.<ref name="read"/> |

|||

=== Modern experimentation === |

|||

Graffiti in the [[Middle East]] is slowly emerging, with pockets of taggers operating in the various 'Emirates' of the [[United Arab Emirates]] and mainly in [[Israel]] and [[Iran]]. |

|||

[[File:Knitted graffiti 1.jpg|thumb|right|Knitted graffiti in [[Seattle]], Washington]] |

|||

[[File:Spiderweb Yarnbomb Installation by Stephen Duneier.JPG|thumbnail|Stephen Duneier's Spiderweb Yarnbomb installation hides and highlights previous graffiti.]] |

|||

Modern graffiti art often incorporates additional arts and technologies. For example, [[Graffiti Research Lab]] has encouraged the use of projected images and magnetic light-emitting diodes ([[LED art|throwies]]) as new media for graffitists. [[Yarnbombing]] is another recent form of graffiti. Yarnbombers occasionally target previous graffiti for modification, which had been avoided among the majority of graffitists. |

|||

[[Image:Tehranurbanartalone.jpg|thumb|Graffiti in [[Tehran]], [[Iran]]]] |

|||

== Purpose == |

|||

Graffiti is also coming out into the mainstream media, with the launch of a West Coast Customs branch in Dubai leading to a country wide talent search for artists to spray the inside of the new garage live at the launch show. {{Fact|date=June 2007}} |

|||

Theories on the use of graffiti by [[avant-garde]] artists have a history dating back at least to the [[Asger Jorn]], who in 1962 painting declared in a graffiti-like gesture "the avant-garde won't give up".<ref>{{cite book | title=Expression as vandalism: Asger Jorn's "Modifications" | publisher=The University of Chicago Press | author=Karen Kurczynski | year=2008 | pages=293}}</ref> |

|||

Also The Iranian major Newspaper [[hamshahri]] published two artciles on illegal writers in the city targetting photo coverage of A1one's works on Tehran walls. |

|||

=== Public art === |

|||

The separation wall being built by Israel in the West Bank has become a giant graffiti canvas, perhaps rivaling the former Berlin Wall in scale. |

|||

People who appreciate graffiti often believe that it should be on display for everyone in public spaces, not hidden away in a museum or a gallery.<ref name=":12">{{Cite web |title=Street and Graffiti Art Movement Overview |url=https://www.theartstory.org/movement/street-art/ |access-date=2023-03-24 |website=The Art Story |language=en}}</ref> Art should color the streets, not the inside of some building. Graffiti is a form of art that cannot be owned or bought. It does not last forever, it is temporary, yet one of a kind. It is a form of self promotion for the artist that can be displayed anywhere from sidewalks, roofs, subways, building wall, etc.<ref name=":12" /> Art to them is for everyone and should be shown to everyone for free. |

|||

=== Personal expression === |

|||

Graffiti is a way of communicating and a way of expressing onesself. It is both art and a functional thing that can warn people of something or inform people of something. However, graffiti is to some people a form of art, but to some a form of vandalism.<ref name=":02"/> And many graffitists choose to protect their identities and remain anonymous to hinder prosecution. |

|||

With the commercialization of graffiti (and [[Hip hop music|hip hop]] in general), in most cases, even with legally painted "graffiti" art, graffitists tend to choose anonymity. This may be attributed to various reasons or a combination of reasons. Graffiti still remains the [[hip hop#Culture|one of four hip hop elements]] that is not considered "performance art" despite the image of the "singing and dancing star" that sells hip hop culture to the mainstream. Being a graphic form of art, it might also be said that many graffitists still fall in the category of the [[Extraversion and introversion#Introversion|introverted archetypal artist]]. |

|||

Modern graffiti art often incorporates additional arts and technologies. For example, [[Graffiti Research Lab]] has encouraged the use of projected images and magnetic [[Light-emitting diode]]s as new media for graffiti writers. The Italian artist [[Kaso]] is pursuing ''regenerative graffiti'' through experimentation with abstract shapes and deliberate modification of previous Graffiti artworks. |

|||

[[Banksy]] is one of the world's most notorious and popular street artists who continues to remain faceless in today's society.<ref name=banksy>{{cite book |title=Wall and Piece |author=Banksy |year=2005 |publisher=New York: Random House UK |isbn=9781844137862 }}</ref> He is known for his political, anti-war stencil art mainly in [[Bristol]], England, but his work may be seen anywhere from Los Angeles to [[Palestine (region)|Palestine]]. In the UK, Banksy is the most recognizable icon for this cultural artistic movement and keeps his identity a secret to avoid arrest. Much of Banksy's artwork may be seen around the streets of London and surrounding suburbs, although he has painted pictures throughout the world, including the Middle East, where he has painted on Israel's controversial [[West Bank]] barrier with satirical images of life on the other side. One depicted a hole in the wall with an idyllic beach, while another shows a mountain landscape on the other side. A number of [[Art exhibition|exhibitions]] also have taken place since 2000, and recent works of art have fetched vast sums of money. Banksy's art is a prime example of the classic controversy: vandalism vs. art. Art supporters endorse his work distributed in urban areas as pieces of art and some councils, such as Bristol and Islington, have officially protected them, while officials of other areas have deemed his work to be vandalism and have removed it. |

|||

==Characteristics of common graffiti== |

|||

Graffiti artists may become offended if photographs of their art are published in a commercial context without their permission. In March 2020, the [[Finland|Finnish]] graffiti artist Psyke expressed his displeasure at the newspaper ''[[Ilta-Sanomat]]'' publishing a photograph of a [[Peugeot 208]] in an article about new cars, with his graffiti prominently shown on the background. The artist claims he does not want his art being used in commercial context, not even if he were to receive compensation.<ref>Tamminen, Jari: ''Kuka omistaa graffitin?'' In ''[[Voima (newspaper)|Voima]]'' issue #1/2021, p. 40.</ref> |

|||

Some of the most common styles of graffiti have their own names. A "tag" is the most basic writing of an artist's name in either spray paint or marker. A graffiti writer's tag is his or her personalized signature. "Tagging" is often the example given when opponents of graffiti refer to vandalism, as they use it to label all acts of graffiti writing (it is by far the most common form of graffiti). Another form is the "throw-up," also known as a "fill-in," which is normally painted very quickly with two or three colors, sacrificing aesthetics for speed. Throw-ups can also be outlined on a surface with one color. A "piece" is a more elaborate representation of the artist's name, incorporating more stylized "block" or "bubble" letters, using three or more colors. This of course is done at the expense of timeliness and increases the likelihood of the artist getting caught. A "blockbuster" is a large piece done simply to cover a large area solidly with two contrasting colours. Sometimes with the whole purpose of blocking other "writers" from painting on the same wall. |

|||

A more complex style is "wildstyle", a form of graffiti involving interlocking letters, arrows, and connecting points. These pieces are often harder to read by non-graffiti artists as the letters merge into one another in an often undecipherable manner. A "Roller" is a "fill-in" that intentionally takes up an entire wall, sometimes with the whole purpose of blocking other "writers" from painting on the same wall. Some artists also use stickers as a quick way to "get-up". While its critics consider this as lazy and a form of cheating, others find that 5 to 10 minutes spent on a detailed sticker is in no way lazy, especially when used with other methods. |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Personal graffiti"> |

|||

Sticker tags are commonly done on blank postage stickers, or really anything with an adhesive side to it. "Stencils" are made by drawing an image onto a piece of cardboard or tougher versions of paper, then cut with a razor blade. What is left is then just simply sprayed-over, and if done correctly, a perfect image is left. Many graffiti artists believe that doing blockbusters or even complex wildstyles are a waste of time. Doing wildstyle can take (depending on experience and size) 3 hours to several days. Another graffiti artist can go over that time consuming piece in a matter of minutes with a bubble fill-in. This was exemplified in the documentary "style wars" by "CAP", who other writers complain ruins their pieces with his quick throw ups. This became known as "capping". This is most commonly done when there is "beef" or a conflict between writers. |

|||

Graffiti at the Temple of Philae (XIII).jpg|Drawing at [[Philae temple complex|Temple of Philae]], [[Egypt]], depicting three men with rods, or staves |

|||

4091(Quisquis amat).jpg|Inscription in [[Pompeii]] lamenting a frustrated love: "Whoever loves, let him flourish, let him perish who knows not love, let him perish twice over whoever forbids love" |

|||

Post Apocalyptic Zombie Graffiti, Jan 2015.jpg|[[Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction|Post-apocalyptic]] despair |

|||

Mermaid Sliema.JPG|[[Mermaid]] in [[Sliema]], [[Malta]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== |

=== Territorial === |

||