Romain Gary: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Spelling correction. |

||

| (419 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|French writer and diplomat (1914-1980)}} |

|||

'''Romain Gary''' ([[May 8]] [[1914]] – [[December 2]] [[1980]]) was a [[France|French]] [[novelist]], [[film director]], [[World War II]] [[aviator|pilot]], and [[diplomat]]. |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=August 2022}} |

|||

{{Infobox writer |

|||

| name = Romain Gary |

|||

| image =Romain Gary.jpg |

|||

| imagesize = |

|||

| alt = |

|||

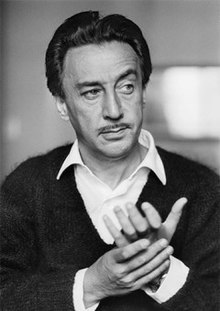

| caption =Gary in 1961 |

|||

| pseudonym = Romain Gary, Émile Ajar, Fosco Sinibaldi, Shatan Bogat |

|||

| birth_name = Roman Kacew<ref name=ivry/> |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|df=yes|1914|05|21}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Vilnius]], [[Vilna Governorate]], [[Lithuania]] |

|||

| death_date = {{Death date and age|df=yes|1980|12|2|1914|05|21}} |

|||

| death_place = [[Paris]], France |

|||

| occupation = Diplomat, pilot, writer |

|||

| nationality = French |

|||

| citizenship = Russian Empire and Republic of Poland / France (since 1935) |

|||

| education = Law |

|||

| alma_mater = Faculté de droit d'Aix-en-Provence<br />[[Paris Law Faculty]] |

|||

| period = 1945–1979 |

|||

| language = French, English, Polish, Russian, Yiddish |

|||

| genre = Novel |

|||

| subject = |

|||

| movement = |

|||

| notableworks = ''[[Les racines du ciel]]''<br />''[[La vie devant soi]]'' |

|||

| spouse = {{plainlist| |

|||

* {{marriage|[[Lesley Blanch]]<br />|1944|1961|end=divorced}} |

|||

* {{marriage|[[Jean Seberg]]<br />|1962|1970|end=divorced}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| children = 1 |

|||

| influences = |

|||

| influenced = |

|||

| awards = [[Prix Goncourt]] (1956 and 1975) |

|||

| portaldisp = y |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Romain Gary''' ({{IPA|fr|ʁɔ.mɛ̃ ga.ʁi|pron}}; {{OldStyleDate|21 May|1914|8 May}}{{spaced ndash}}2 December 1980), born '''Roman Kacew''' ({{IPA|fr|katsɛf|pron}}, and also known by the pen name '''Émile Ajar'''), was a French novelist, diplomat, film director, and World War II [[aviator]]. He is the only author to have won the [[Prix Goncourt]] twice (once under pseudonym). He is considered a major writer of [[French literature]] of the second half of the 20th century. He was married to [[Lesley Blanch]], then [[Jean Seberg]]. |

|||

==Biography== |

|||

Born '''Roman Kacew''' ({{lang-yi|קצב}}, {{lang-ru|Кацев}}), Romain Gary grew up in [[Vilnius]] , then in Russian empire to a [[Jewish]] family. He changed his name to Romain Gary when he escaped occupied France to fight with Great Britain against Germany in WWII. His father, Arieh-Leib Kacew, abandoned his family in 1925 and remarried. From this time Gary was raised by his mother, Nina Owczinski. When he was fourteen, he and his mother moved to [[Nice]], [[France]]. In his books and interviews, he presented many different versions of his father's origin, parents, occupation and childhood. |

|||

== Early life == |

|||

He later studied law, first in [[Aix-en-Provence]] and then in [[Paris]]. He learned to pilot an aircraft in the French Air Force in [[Salon-de-Provence]] and in [[Avord Air Base]], near [[Bourges]]. Following the [[Nazism|Nazi]] occupation of France in [[World War II]], he fled to [[England]] and under [[Charles de Gaulle]] served with the [[Free French Forces]] in [[Europe]] and [[North Africa]]. As a pilot, he took part in over 25 successful offensives logging over 65 hours of air time. |

|||

Gary was born Roman Kacew ({{langx|yi|{{Script/Hebrew|רומן קצב}}}} ''Roman Katsev'', {{langx|ru|link=no|Рома́н Ле́йбович Ка́цев}}, ''Roman Leibovich Katsev'') in [[Vilnius]] (at that time in the [[Russian Empire]]).<ref name=ivry>{{cite news|first=Benjamin |last=Ivry |url=http://www.forward.com/articles/134609/ |title=A Chameleon on Show |work=Daily Forward |date= 21 January 2011}}</ref><ref>[http://www.baltelatino.com/ROMAIN_GARY_et_la_LITUANIE.pdf Romain Gary et la Lituanie] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110626103906/http://www.baltelatino.com/ROMAIN_GARY_et_la_LITUANIE.pdf |date=26 June 2011 }}</ref> In his books and interviews, he presented many different versions of his parents' origins, ancestry, occupation and his own childhood. His mother, Mina Owczyńska (1879—1941),<ref name=ivry/><ref>Myriam Anissimov. ''Romain Gary, le Caméléon''. Paris: Les éditions Folio Gallimard, 2004. {{ISBN|978-2-207-24835-5}}, pp. ??</ref> was a [[Jewish]] actress from [[Švenčionys]] (Svintsyán) and his father was a businessman named Arieh-Leib Kacew (1883—1942) from [[Trakai]] (Trok), also a [[Lithuanian Jew]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://agora.qc.ca/thematiques/mort/dossiers/gary_romain | website=Encyclopédie sur la mort |title=Romain Gary| access-date = 21 June 2016}}</ref><ref name=erp>{{Cite book|last=Schoolcraft|first=Ralph W.|title=Romain Gary: the man who sold his shadow|publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press|year=2002|page=[https://archive.org/details/romaingarymanwho00scho/page/165 165]|isbn=0-8122-3646-7|url=https://archive.org/details/romaingarymanwho00scho/page/165}}</ref> The couple divorced in 1925 and Arieh-Leib remarried. Gary later claimed that his actual father was the celebrated actor and film star [[Ivan Mosjoukine]], with whom his actress mother had worked and to whom he bore a striking resemblance. Mosjoukine appears in his memoir ''[[Promise at Dawn (novel)|Promise at Dawn]]''.<ref>{{cite news|work=The Harvard Advocate|url= http://theharvardadvocate.com/content/122/ | title=Romain Gary: A Short Biography | first= Madeleine | last= Schwartz}}</ref> Deported to [[central Russia]] in 1915, they stayed in [[Moscow]] until 1920.<ref>Passports of mother Mina Kacew and nurse-maid Aniela Voiciechowics. See Lithuaninan Central State Archives, F. 53, 122, 5351 and F. 15, 2, 1230. Copies of the documents are in the personal archive of a Moscow historian Alexander Vasin.</ref> They later returned to [[Vilnius]], then moved on to [[Warsaw]]. When Gary was fourteen, he and his mother emigrated illegally to [[Nice]], France.<ref name="Marzorati" /> Gary studied law, first in [[Aix-en-Provence]] and then in Paris. He learned to pilot an aircraft in the [[French Air Force]] in [[Salon-de-Provence]] and in [[Avord Air Base]], near [[Bourges]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20180619-romain-gary-the-greatest-literary-bad-boy-of-all|title=Romain Gary: The greatest literary conman ever?}}</ref> |

|||

==Career== |

|||

He was greatly decorated for his bravery in the war, receiving many medals and honours. |

|||

Despite completing all parts of his course successfully, Gary was the only one of almost 300 cadets in his class not to be commissioned as an officer. He believed the military establishment was distrustful of him because he was a foreigner and a [[Jew]].<ref name="Marzorati" /> Training on [[Potez 25]] and Goëland Léo-20 aircraft, and with 250 hours flying time, only after three months' delay was he made a [[sergeant]] on 1 February 1940. Lightly wounded on 13 June 1940 in a [[Bloch MB.210]], he was disappointed with the [[Armistice of 22 June 1940|armistice]]; after hearing General [[Charles de Gaulle|de Gaulle]]'s radio [[Appeal of 18 June|appeal]], he decided to go to England.<ref name="Marzorati" /> After failed attempts, he flew to [[Algiers]] from [[Saint-Laurent-de-la-Salanque]] in a [[Potez]]. Made [[adjutant]] upon joining the [[Free France|Free French]] and serving on [[Bristol Blenheim]]s, he saw action across Africa and was promoted to [[second lieutenant]]. He returned to England to train on [[Douglas A-20 Havoc|Boston III]]s. On 25 January 1944, his pilot was blinded, albeit temporarily, and Gary talked him to the bombing target and back home, the third landing being successful. This and the subsequent [[BBC]] interview and ''[[Evening Standard]]'' newspaper article were an important part of his career.<ref name="Marzorati" /> He finished the war as a captain in the London offices of the [[Free French Air Forces]]. As a bombardier-observer in the [[No. 342 Squadron RAF|''Groupe de bombardement Lorraine'' (No. 342 Squadron RAF)]], he took part in over 25 successful sorties, logging over 65 hours of air time.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.ordredelaliberation.fr/fr_compagnon/382.html |title=Ordre de la Libération |access-date=11 February 2013 |archive-date=26 November 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101126122309/http://ordredelaliberation.fr/fr_compagnon/382.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> During this time, he changed his name to Romain Gary. He was decorated for his bravery in the war, receiving many medals and honours, including [[Compagnon de la Libération]] and commander of the [[Légion d'honneur]]. In 1945 he published his first novel, ''Éducation européenne''. Immediately following his service in the war, he worked in the French diplomatic service in [[Bulgaria]] and Switzerland.<ref name="BelosTS"/> In 1952 he became the secretary of the French Delegation to the United Nations.<ref name="BelosTS"/> In 1956, he became [[Consul General]] in [[List of diplomatic missions of France#North America of France|Los Angeles]] and became acquainted with Hollywood.<ref name="BelosTS">{{cite book|last=Bellos |first=David |title=Romain Gary: A Tall Story |date=2010 | pages=??}}</ref> |

|||

=== As Émile Ajar === |

|||

After the war, he worked in the French diplomatic service and in 1945 published his first novel. He would become one of France's most popular and prolific writers, authoring more than thirty novels, essays and memoirs, some of which he wrote under the [[pseudonym]] of Émile Ajar. He also wrote one novel under the pseudonym of Fosco Sinibaldi and another as Shatan Bogat. |

|||

In a memoir published in 1981, Paul Pavlowitch claimed that Gary also produced several works under the pseudonym Émile Ajar. Gary recruited Pavlowitch – his cousin's son – to portray Ajar in public appearances, allowing Gary to remain unknown as the true producer of the Ajar works, and thus enabling him to win the 1975 Goncourt Prize (a second win in violation of the prize's rules).<ref name=NYT1981>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1981/07/02/books/gary-won-75-goncourt-under-pseudonym-ajar.html|title=Gary won '75 Goncourt under Pseudonym 'Ajar'|date=2 July 1981|work=The New York Times|first=Frank J.|last=Prial}}</ref> |

|||

Gary also published under the pseudonyms Shatan Bogat and Fosco Sinibaldi.<ref name=NYT1981/> |

|||

In 1952, he became secretary of the French Delegation to the [[United Nations]] in [[New York]], and later in [[London]] (in 1955). |

|||

===Literary work=== |

|||

In 1956, he became Consul General of France in [[Los Angeles, California|Los Angeles]]. |

|||

[[File:Place Romain-Gary, Paris 15.jpg|thumb|Place Romain-Gary, located in Paris' [[15th arrondissement of Paris|15th arrondissement]]]] |

|||

Gary became one of France's most popular and prolific writers, writing more than 30 novels, essays and memoirs, some of which he wrote under a pseudonym. |

|||

He is the only person to win the [[Prix Goncourt]] twice. This prize for [[French language]] [[literature]] is awarded only once to an author. Gary, who had already received the prize in 1956 for ''[[Les racines du ciel]]'', published ''[[La vie devant soi]]'' under the [[pseudonym]] of '''Émile Ajar''' in 1975. The [[Edmond Louis Antoine Huot de Goncourt|Académie Goncourt]] awarded the prize to the author of this book without knowing his real identity. A period of literary intrigue followed. Gary's cousin [[Paul Pavlowitch]] posed as the author for a time. Gary later revealed the truth in his posthumous book ''[[Vie et mort d'Émile Ajar]]''. |

|||

He is the only person to win the [[Prix Goncourt]] twice. This prize for French language literature is awarded only once to an author. Gary, who had already received the prize in 1956 for ''[[Les racines du ciel]]'', published ''[[La vie devant soi]]'' under the pseudonym Émile Ajar in 1975. The [[Edmond Louis Antoine Huot de Goncourt|Académie Goncourt]] awarded the prize to the author of that book without knowing his identity. Gary's cousin's son [[Paul Pavlowitch]] posed as the author for a time. Gary later revealed the truth in his posthumous book ''Vie et mort d'Émile Ajar''.<ref>Gary, Romain, ''Vie et mort d'Émile Ajar'', Gallimard – NRF (17 juillet 1981), 42p, {{ISBN|978-2-07-026351-6}}.</ref> Gary also published as Shatan Bogat, René Deville and Fosco Sinibaldi, as well under his birth name Roman Kacew.<ref>{{cite book | first=Anna | last=Lushenkova | chapter=La réinvention de l'homme par l'art et le rire: 'Les Enchanteurs' de Romain Gary | title=Écrivains franco-russes | volume=318 | series=Faux titre | editor1-first=Murielle Lucie | editor1-last=Clément | publisher=Rodopi | year=2008 | isbn=978-90-420-2426-7 | pages=141–163 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | title=Les grandes impostures littéraires: canulars, escroqueries, supercheries, et autres mystifications | first=Philippe | last=Di Folco | publisher=Écriture | year=2006 | isbn=2-909240-70-3 | pages=111–113 }}</ref> |

|||

Gary's first wife was the [[United Kingdom|British]] writer, [[journalism|journalist]], and [[Vogue magazine|Vogue]] editor [[Lesley Blanch]] (author of ''The Wilder Shores of Love''). They married in 1944 and divorced in 1961. From 1962 to 1970, Gary was married to the American [[actor|actress]] [[Jean Seberg]], with whom he had a son, Alexandre Diego Gary. |

|||

In addition to his success as a novelist, he wrote the screenplay for the motion picture ''[[The Longest Day (film)|The Longest Day]]'' and co-wrote and directed the film ''Kill!'' (1971),<ref>{{Cite web |title=Romain Gary |url=https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0308900/ |access-date=2023-05-30 |website=IMDb |language=en-US}}</ref> which starred his wife at the time, [[Jean Seberg]]. In 1979, he was a member of the jury at the [[29th Berlin International Film Festival]].<ref name="berlinale">{{cite web |url=http://www.berlinale.de/en/archiv/jahresarchive/1979/04_jury_1979/04_Jury_1979.html |title=Berlinale 1979: Juries |access-date=8 August 2010 |work=berlinale.de}}</ref> |

|||

=== Diplomatic career === |

|||

Suffering from [[depression (mood)|depression]] after Seberg's 1979 suicide, Gary died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on [[December 2]], [[1980]] in [[Paris, France]] though he left a note which said specifically that his death had no relation with Seberg's suicide. |

|||

After the end of the hostilities, Gary began a career as a [[diplomat]] in the service of France, in consideration of his contribution to the liberation of the country. In this capacity, he held positions in Bulgaria (1946–1947), Paris (1948–1949), Switzerland (1950–1951), New York (1951–1954) at the Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations. Here, he regularly rubbed shoulders with the Jesuit [[Pierre Teilhard de Chardin|Teilhard de Chardin]], whose personality deeply marked him and inspired him, particularly for the character of Father Tassin in ''[[Les Racines du ciel]]''. He was positioned in London 1955, and as Consul General of France in Los Angeles 1956–1960. Back in Paris, he remained unassigned until he was laid off from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1961). |

|||

==Personal life and final years== |

|||

==Selected bibliography== |

|||

[[File:2016-03-19 - Plaque Romain Gary 01.jpg|thumb|Plaque to Gary and his first wife [[Lesley Blanch]] in [[Roquebrune-Cap-Martin]] on the [[Côte d'Azur]]; they lived there in 1950–57.]] |

|||

[[Image:RomainGaryVilnius1.jpg|220 px|thumb|Romain Gary monument in [[Vilnius]]]] |

|||

Gary's first wife was the British writer, [[journalism|journalist]], and ''[[Vogue magazine|Vogue]]'' editor [[Lesley Blanch]], author of ''[[The Wilder Shores of Love]]''. They married in 1944 and divorced in 1961. From 1962 to 1970, Gary was married to American actress [[Jean Seberg]], with whom he had a son, [[Alexandre Diego Gary]]. According to Diego Gary, he was a distant presence as a father: "Even when he was around, my father wasn't there. Obsessed with his work, he used to greet me, but he was elsewhere."<ref>''[[Paris Match]]'' No.3136</ref> |

|||

===As Romain Gary=== |

|||

* ''[[Education européenne]]'' (1945); translated as ''[[A European Education]]'' |

|||

After learning that Jean Seberg had had an affair with [[Clint Eastwood]], Gary challenged him to a [[duel]], but Eastwood declined.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/books/bookreviews/8125871/Romain-Gary-au-revoir-et-merci.html |title=Romain Gary: au revoir et merci| first=David| last=Bellos|date=12 November 2010| work=The Telegraph|location=UK}}</ref> |

|||

* ''[[Tulipe]]'' (1946); republished and modified in 1970. |

|||

* ''[[Le grand vestiaire]]'' (1949); translated as "The Company Of Men, 1950) |

|||

Gary died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on 2 December 1980 in Paris. He left a note which said that his death had no relation to Seberg's suicide the previous year. He also stated in his note that he was Émile Ajar.<ref name="death">D. Bona, Romain Gary, Paris, Mercure de France-Lacombe, 1987, p. 397–398.</ref> |

|||

* ''[[Les couleurs du jour]]'' (1952); translated as ''[[The Colors of the Day, 1953]]'' |

|||

* ''[[Les racines du ciel]]'' — ''1956 Prix Goncourt''; translated (and filmed) as ''[[The Roots of Heaven, 1958]]'' |

|||

Gary was cremated in [[Père Lachaise Cemetery]] and his ashes were scattered in the [[Mediterranean Sea]] near [[Roquebrune-Cap-Martin]].<ref>Beyern, B., ''Guide des tombes d'hommes célèbres'', Le Cherche Midi, 2008, {{ISBN|978-2-7491-1350-0}}</ref> |

|||

* ''[[Lady L.]]'' (1957); translated and published in French in 1963. |

|||

* ''[[La promesse de l'aube]]'' (1960); translated as ''[[Promise at Dawn, 1961]]'' |

|||

== Legacy == |

|||

* ''[[Johnie Coeur]]'' (1961, a theatre adaptation of "L'homme a la colombe") |

|||

The name of Romain Gary was given to a promotion of the [[École nationale d'administration]] (2003–2005), the [[Sciences Po Lille|Institut d'études politiques de Lille]] (2013), the Institut régional d'administration de Lille (2021–2022) and the [[Institut d'études politiques de Strasbourg]] (2001–2002), in 2006 at Place Romain-Gary in the [[15th arrondissement of Paris]] and at the Nice Heritage Library. The French Institute in Jerusalem also bears the name of Romain Gary. |

|||

On 16 May 2019, his work appeared in two volumes in the [[Bibliothèque de la Pléiade]] under the direction of Mireille Sacotte. |

|||

In 2007, a statue of Romualdas Kvintas, «The Boy with a Galoche», was unveiled, depicting the 9-year-old little hero of the Promise of Dawn, preparing to eat a shoe to seduce his little neighbor, Valentina. It is placed in [[Vilnius]], in front of the Basanavičius, where the novelist lived. |

|||

A plaque to his name is affixed in the Pouillon building of the Faculty of Law and Political Science of Aix-Marseille where he studied. |

|||

In 2022, [[Denis Ménochet]] portrayed Gary in ''[[White Dog (2022 film)|White Dog]] (Chien blanc)'', a film adaptation by [[Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette]] of Gary's 1970 book.<ref name="demers">{{Cite web |last=Demers |first=Maxime |date=2022-11-02 |title=«Chien blanc»: le goût du risque d'Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette |url=https://www.journaldemontreal.com/2022/11/02/chien-blanc-le-gout-du-risque |access-date=2023-05-30 |website=Le Journal de Montréal}}</ref> |

|||

== Bibliography == |

|||

[[File:Romain Gary - books in Bulgarian.jpg|thumb|Several Romain Gary works in [[Bulgarian language|Bulgarian]] translations.]] |

|||

=== As Romain Gary === |

|||

* ''{{langx|fr| [[:fr: Éducation européenne|Éducation européenne]]}}'' (1945); translated as ''[[Forest of Anger]]'' |

|||

* ''{{langx|fr|[[:fr: Tulipe (roman de Gary)|Tulipe]]}}'' (1946); republished and modified in 1970. |

|||

* ''[[Le Grand Vestiaire]]'' (1949); translated as ''The Company of Men'' (1950) |

|||

* ''[[Les Couleurs du jour]]'' (1952); translated as ''[[The Colors of the Day]]'' (1953); filmed as ''[[The Man Who Understood Women]]'' (1959) |

|||

* ''[[Les Racines du ciel]]'' — ''1956 Prix Goncourt''; translated as ''[[The Roots of Heaven (novel)|The Roots of Heaven]]'' (1957); filmed as ''[[The Roots of Heaven (film)|The Roots of Heaven]]'' (1958) |

|||

* ''[[Lady L (novel)|Lady L]]'' (1958); self-translated and published in French in 1963; filmed as ''[[Lady L]]'' (1965) |

|||

* ''La Promesse de l'aube'' (1960); translated as ''[[Promise at Dawn (novel)|Promise at Dawn]]'' (1961); filmed as ''[[Promise at Dawn (1970 film)|Promise at Dawn]]'' (1970) and ''[[Promise at Dawn (2017 film)|Promise at Dawn]]'' (2017) |

|||

* ''[[Johnie Cœur]]'' (1961, a theatre adaptation of "L'homme à la colombe") |

|||

* ''[[Gloire à nos illustres pionniers]]'' (1962, short stories); translated as "Hissing Tales" (1964) |

* ''[[Gloire à nos illustres pionniers]]'' (1962, short stories); translated as "Hissing Tales" (1964) |

||

* ''[[The Ski Bum]]'' (1965) |

* ''[[The Ski Bum]]'' (1965); self-translated into French as ''Adieu Gary Cooper'' (1969) |

||

* ''[[Pour Sganarelle]]'' (1965, literary essay) |

* ''[[Pour Sganarelle]]'' (1965, literary essay) |

||

* ''[[Les Mangeurs d' |

* ''[[Les Mangeurs d'étoiles]]'' (1966); self-translated into French and first published (in English) as ''[[The Talent Scout]]'' (1961) |

||

* ''[[La |

* ''[[La Danse de Gengis Cohn]]'' (1967); self-translated into English as ''[[The Dance of Genghis Cohn]]'' |

||

* ''[[La |

* ''[[La Tête coupable]]'' (1968); translated as ''The Guilty Head'' (1969) |

||

* '' |

* ''Chien blanc'' (1970); self-translated as ''[[White Dog (Gary novel)|White Dog]]'' (1970); filmed as ''[[White Dog (1982 film)|White Dog]]'' (1982) |

||

* ''[[Les |

* ''[[Les Trésors de la mer Rouge]]'' (1971) |

||

* ''[[Europa ( |

* ''[[Europa (Gary novel)|Europa]]'' (1972); translated in English in 1978. |

||

* ''[[The Gasp]]'' (1973); translated as ''Charge d' |

* ''[[The Gasp]]'' (1973); self-translated into French as ''Charge d'âme'' (1978) |

||

* ''[[Les |

* ''[[Les Enchanteurs]]'' (1973); translated as ''The Enchanters'' (1975) |

||

* ''[[La nuit sera calme]]'' (1974, interview) |

* ''[[La nuit sera calme]]'' (1974, interview) |

||

* ''[[Au-delà de cette limite votre ticket n'est plus valable]]'' (1975); translated as |

* ''[[Au-delà de cette limite votre ticket n'est plus valable]]'' (1975); translated as ''Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid'' (1977); filmed as ''[[Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid]]'' (1981) |

||

* ''[[Clair de femme]]'' (1977) |

* ''[[Clair de femme]]'' (1977); filmed as ''[[Womanlight]]'' (1979) |

||

* ''[[La |

* ''[[La Bonne Moitié]]'' (1979, play) |

||

* ''[[Les |

* ''[[Les Clowns lyriques]]'' (1979); new version of the 1952 novel, ''Les Couleurs du jour'' (''The Colors of the Day'') |

||

* ''[[Les |

* ''[[Les Cerfs-volants]]'' (1980); translated as The Kites (2017) |

||

* ''[[Vie et |

* ''[[Vie et Mort d'Émile Ajar]]'' (1981, posthumous) |

||

* ''[[L' |

* ''[[L'Homme à la colombe]]'' (1984, definitive posthumous version) |

||

* ''[[L' |

* ''[[L'Affaire homme]]'' (2005, articles and interviews) |

||

* ''[[L' |

* ''[[L'Orage (Romain Gary)|L'Orage]]'' (2005, short stories and unfinished novels) |

||

* ''[[Un humaniste]]'', short story |

|||

===As Émile Ajar=== |

=== As Émile Ajar === |

||

* ''[[Gros câlin]]'' (1974) |

* ''[[Gros câlin (novel)|Gros câlin]]'' (1974); illustrated by [[Jean-Michel Folon]], filmed as ''[[Gros câlin]]'' (1979) |

||

* ''[[La vie devant soi]]'' |

* ''[[La vie devant soi]]'' — ''1975 Prix Goncourt''; filmed as ''[[Madame Rosa]]'' (1977); translated as "Momo" (1978); re-released as ''[[The Life Before Us]]'' (1986). Filmed as ''[[The Life Ahead]]'' (2020) |

||

* ''[[Pseudo (novel)|Pseudo]]'' (1976) |

* ''[[Pseudo (novel)|Pseudo]]'' (1976) |

||

* ''[[L'Angoisse du roi Salomon]]'' (1979); translated as |

* ''[[L'Angoisse du roi Salomon]]'' (1979); translated as ''King Solomon'' (1983). |

||

* ''[[Gros câlin]]'' |

* ''[[Gros câlin (novel)|Gros câlin]]'' – new version including final chapter of the original and never published version. |

||

===As Fosco Sinibaldi=== |

=== As Fosco Sinibaldi === |

||

* ''[[L'homme à la colombe]]'' (1958) |

* ''[[L'homme à la colombe]]'' (1958) |

||

===As Shatan Bogat=== |

=== As Shatan Bogat === |

||

* ''[[Les têtes de Stéphanie]]'' (1974) |

* ''[[Les têtes de Stéphanie]]'' (1974) |

||

==Filmography== |

== Filmography == |

||

===As |

=== As screenwriter === |

||

* ''[[ |

*1958: ''[[The Roots of Heaven (film)|The Roots of Heaven]]'' |

||

* ''[[ |

*1962: ''[[The Longest Day (film)|The Longest Day]]'' |

||

*1978: ''[[Madame Rosa|La vie devant soi]]'' |

|||

===As |

=== As actor === |

||

*1936: ''[[Nitchevo (1936 film)|Nitchevo]]'' – Le jeune homme au bastingage |

|||

* ''[[The Roots of Heaven]]'' (1958) |

|||

* ''[[The |

*1967: ''[[The Road to Corinth]]'' – (uncredited) (final film role) |

||

=== As director === |

|||

*1968: ''[[Birds in Peru]]'' (''Birds in Peru'') starring Jean Seberg |

|||

*1971: ''[[Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill!]]'' also starring Jean Seberg |

|||

=== In popular culture === |

|||

*2019: ''[[Seberg]]'' , joué par [[Yvan Attal]] |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist|refs= |

|||

* Myriam Anissimov, ''Romain Gary, le caméléon'' (Denoël 2004) |

|||

<ref name="Marzorati">Marzorati 2018</ref> |

|||

* Nancy Huston, ''Tombeau de Romain Gary''(Babel, 1997) |

|||

}} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

* Ajar, Émile (Romain Gary), ''Hocus Bogus'', [[Yale University Press]], 2010, 224p, {{ISBN|978-0-300-14976-0}} (translation of ''Pseudo'' by [[David Bellos]], includes ''The Life and Death of Émile Ajar'') |

|||

* Anissimov, Myriam, ''Romain Gary, le caméléon'' (Denoël 2004) |

|||

* [[David Bellos|Bellos, David]], ''Romain Gary: A Tall Story'', [[Harvill Secker (publisher)|Harvill Secker]], 2010, 528p, {{ISBN|978-1-84343-170-1}} |

|||

* Bellos, David. 2009. The cosmopolitanism of Romain Gary. ''Darbair ir Dienos'' (Vilnius) 51:63–69. |

|||

* Gary, Romain, ''Promise at Dawn'' (Revived Modern Classic), [[W. W. Norton & Company|W.W. Norton]], 1988, 348p, {{ISBN|978-0-8112-1016-4}} |

|||

* [[Nancy Huston|Huston, Nancy]], ''Tombeau de Romain Gary'' (Babel, 1997) {{ISBN|978-2-7427-0313-5}} |

|||

* Bona, Dominique, ''Romain Gary'' (Mercure de France, 1987) {{ISBN|2-7152-1448-0}} |

|||

* Cahier de l'Herne, ''Romain Gary'' (L'Herne, 2005) |

* Cahier de l'Herne, ''Romain Gary'' (L'Herne, 2005) |

||

* [[François-Henri Désérable|Désérable, François-Henri]], ''Un certain M. Piekielny'', Gallimard, 2017, {{ISBN|978-2-07-274141-8}} |

|||

* {{cite book |title=Romain Gary: The Man Who Sold his Shadow |first=Ralph W. |last=Schoolcraft |publisher=[[University of Pennsylvania Press]] |year=2002 |isbn=0-8122-3646-7 |url=https://archive.org/details/romaingarymanwho00scho }} |

|||

* [[Lesley Blanch|Blanch, Lesley]], ''Romain, un regard particulier'' (Editions du Rocher, 2009) {{ISBN|978-2-268-06724-7}} |

|||

* Marret, Carine, ''Romain Gary – Promenade à Nice'' (Baie des Anges, 2010) |

|||

* Marzorati, Michel (2018). Romain Gary: des racines et des ailes. ''Info-Pilote, 742'' pp. 30–33 |

|||

* Spire, Kerwin, ''Monsieur Romain Gary'', Gallimard, 2021, {{ISBN|978-2-07-293006-5}} |

|||

* Stjepanovic-Pauly, Marianne. Romain Gary La mélancolie de l'enchanteur. ''Editions du Jasmin, {{ISBN|978-2-35284-141-8}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*{{Commons category-inline}} |

|||

{{wikiquote}} |

|||

*{{Wikiquote-inline}} |

|||

* [http://www.romaingary.org Romain Gary] (in [[French language|French]]) |

|||

* {{ |

* {{IMDb name|308900|Romain Gary}} |

||

{{Romain Gary}} |

|||

{{Prix Goncourt}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gary, Romain}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Gary, Romain}} |

||

[[Category:1914 births]] |

[[Category:1914 births]] |

||

[[Category:1980 deaths]] |

[[Category:1980 deaths]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Film people from Vilnius]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:People from Vilensky Uyezd]] |

||

[[Category:French |

[[Category:French people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:20th-century Lithuanian Jews]] |

||

[[Category:Jews from the Russian Empire]] |

|||

[[Category:20th-century French diplomats]] |

|||

[[Category:20th-century French novelists]] |

|||

[[Category:French male novelists]] |

|||

[[Category:Jewish novelists]] |

[[Category:Jewish novelists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Postmodern writers]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:20th-century French male writers]] |

||

[[Category:Prix Goncourt winners]] |

[[Category:Prix Goncourt winners]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:French Royal Air Force pilots of World War II]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Suicides by firearm in France]] |

||

[[Category:1980 suicides]] |

|||

[[Category:Writers from Vilnius]] |

|||

[[bg:Ромен Гари]] |

|||

[[Category:French Resistance members]] |

|||

[[de:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[Category:Polish emigrants to France]] |

|||

[[et:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[es:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[fa:رومن گاری]] |

|||

[[fr:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[it:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[he:רומן גארי]] |

|||

[[pl:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[ru:Ромен Гари]] |

|||

[[sh:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[fi:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[sv:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[tr:Romain Gary]] |

|||

[[uk:Ромен Гарі]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 15:48, 28 November 2024

Romain Gary | |

|---|---|

Gary in 1961 | |

| Born | Roman Kacew[1] 21 May 1914 Vilnius, Vilna Governorate, Lithuania |

| Died | 2 December 1980 (aged 66) Paris, France |

| Pen name | Romain Gary, Émile Ajar, Fosco Sinibaldi, Shatan Bogat |

| Occupation | Diplomat, pilot, writer |

| Language | French, English, Polish, Russian, Yiddish |

| Nationality | French |

| Citizenship | Russian Empire and Republic of Poland / France (since 1935) |

| Education | Law |

| Alma mater | Faculté de droit d'Aix-en-Provence Paris Law Faculty |

| Period | 1945–1979 |

| Genre | Novel |

| Notable works | Les racines du ciel La vie devant soi |

| Notable awards | Prix Goncourt (1956 and 1975) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 1 |

Romain Gary (pronounced [ʁɔ.mɛ̃ ga.ʁi]; 21 May [O.S. 8 May] 1914 – 2 December 1980), born Roman Kacew (pronounced [katsɛf], and also known by the pen name Émile Ajar), was a French novelist, diplomat, film director, and World War II aviator. He is the only author to have won the Prix Goncourt twice (once under pseudonym). He is considered a major writer of French literature of the second half of the 20th century. He was married to Lesley Blanch, then Jean Seberg.

Early life

[edit]Gary was born Roman Kacew (Yiddish: רומן קצב Roman Katsev, Russian: Рома́н Ле́йбович Ка́цев, Roman Leibovich Katsev) in Vilnius (at that time in the Russian Empire).[1][2] In his books and interviews, he presented many different versions of his parents' origins, ancestry, occupation and his own childhood. His mother, Mina Owczyńska (1879—1941),[1][3] was a Jewish actress from Švenčionys (Svintsyán) and his father was a businessman named Arieh-Leib Kacew (1883—1942) from Trakai (Trok), also a Lithuanian Jew.[4][5] The couple divorced in 1925 and Arieh-Leib remarried. Gary later claimed that his actual father was the celebrated actor and film star Ivan Mosjoukine, with whom his actress mother had worked and to whom he bore a striking resemblance. Mosjoukine appears in his memoir Promise at Dawn.[6] Deported to central Russia in 1915, they stayed in Moscow until 1920.[7] They later returned to Vilnius, then moved on to Warsaw. When Gary was fourteen, he and his mother emigrated illegally to Nice, France.[8] Gary studied law, first in Aix-en-Provence and then in Paris. He learned to pilot an aircraft in the French Air Force in Salon-de-Provence and in Avord Air Base, near Bourges.[9]

Career

[edit]Despite completing all parts of his course successfully, Gary was the only one of almost 300 cadets in his class not to be commissioned as an officer. He believed the military establishment was distrustful of him because he was a foreigner and a Jew.[8] Training on Potez 25 and Goëland Léo-20 aircraft, and with 250 hours flying time, only after three months' delay was he made a sergeant on 1 February 1940. Lightly wounded on 13 June 1940 in a Bloch MB.210, he was disappointed with the armistice; after hearing General de Gaulle's radio appeal, he decided to go to England.[8] After failed attempts, he flew to Algiers from Saint-Laurent-de-la-Salanque in a Potez. Made adjutant upon joining the Free French and serving on Bristol Blenheims, he saw action across Africa and was promoted to second lieutenant. He returned to England to train on Boston IIIs. On 25 January 1944, his pilot was blinded, albeit temporarily, and Gary talked him to the bombing target and back home, the third landing being successful. This and the subsequent BBC interview and Evening Standard newspaper article were an important part of his career.[8] He finished the war as a captain in the London offices of the Free French Air Forces. As a bombardier-observer in the Groupe de bombardement Lorraine (No. 342 Squadron RAF), he took part in over 25 successful sorties, logging over 65 hours of air time.[10] During this time, he changed his name to Romain Gary. He was decorated for his bravery in the war, receiving many medals and honours, including Compagnon de la Libération and commander of the Légion d'honneur. In 1945 he published his first novel, Éducation européenne. Immediately following his service in the war, he worked in the French diplomatic service in Bulgaria and Switzerland.[11] In 1952 he became the secretary of the French Delegation to the United Nations.[11] In 1956, he became Consul General in Los Angeles and became acquainted with Hollywood.[11]

As Émile Ajar

[edit]In a memoir published in 1981, Paul Pavlowitch claimed that Gary also produced several works under the pseudonym Émile Ajar. Gary recruited Pavlowitch – his cousin's son – to portray Ajar in public appearances, allowing Gary to remain unknown as the true producer of the Ajar works, and thus enabling him to win the 1975 Goncourt Prize (a second win in violation of the prize's rules).[12]

Gary also published under the pseudonyms Shatan Bogat and Fosco Sinibaldi.[12]

Literary work

[edit]

Gary became one of France's most popular and prolific writers, writing more than 30 novels, essays and memoirs, some of which he wrote under a pseudonym.

He is the only person to win the Prix Goncourt twice. This prize for French language literature is awarded only once to an author. Gary, who had already received the prize in 1956 for Les racines du ciel, published La vie devant soi under the pseudonym Émile Ajar in 1975. The Académie Goncourt awarded the prize to the author of that book without knowing his identity. Gary's cousin's son Paul Pavlowitch posed as the author for a time. Gary later revealed the truth in his posthumous book Vie et mort d'Émile Ajar.[13] Gary also published as Shatan Bogat, René Deville and Fosco Sinibaldi, as well under his birth name Roman Kacew.[14][15]

In addition to his success as a novelist, he wrote the screenplay for the motion picture The Longest Day and co-wrote and directed the film Kill! (1971),[16] which starred his wife at the time, Jean Seberg. In 1979, he was a member of the jury at the 29th Berlin International Film Festival.[17]

Diplomatic career

[edit]After the end of the hostilities, Gary began a career as a diplomat in the service of France, in consideration of his contribution to the liberation of the country. In this capacity, he held positions in Bulgaria (1946–1947), Paris (1948–1949), Switzerland (1950–1951), New York (1951–1954) at the Permanent Mission of France to the United Nations. Here, he regularly rubbed shoulders with the Jesuit Teilhard de Chardin, whose personality deeply marked him and inspired him, particularly for the character of Father Tassin in Les Racines du ciel. He was positioned in London 1955, and as Consul General of France in Los Angeles 1956–1960. Back in Paris, he remained unassigned until he was laid off from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (1961).

Personal life and final years

[edit]

Gary's first wife was the British writer, journalist, and Vogue editor Lesley Blanch, author of The Wilder Shores of Love. They married in 1944 and divorced in 1961. From 1962 to 1970, Gary was married to American actress Jean Seberg, with whom he had a son, Alexandre Diego Gary. According to Diego Gary, he was a distant presence as a father: "Even when he was around, my father wasn't there. Obsessed with his work, he used to greet me, but he was elsewhere."[18]

After learning that Jean Seberg had had an affair with Clint Eastwood, Gary challenged him to a duel, but Eastwood declined.[19]

Gary died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on 2 December 1980 in Paris. He left a note which said that his death had no relation to Seberg's suicide the previous year. He also stated in his note that he was Émile Ajar.[20]

Gary was cremated in Père Lachaise Cemetery and his ashes were scattered in the Mediterranean Sea near Roquebrune-Cap-Martin.[21]

Legacy

[edit]The name of Romain Gary was given to a promotion of the École nationale d'administration (2003–2005), the Institut d'études politiques de Lille (2013), the Institut régional d'administration de Lille (2021–2022) and the Institut d'études politiques de Strasbourg (2001–2002), in 2006 at Place Romain-Gary in the 15th arrondissement of Paris and at the Nice Heritage Library. The French Institute in Jerusalem also bears the name of Romain Gary.

On 16 May 2019, his work appeared in two volumes in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade under the direction of Mireille Sacotte.

In 2007, a statue of Romualdas Kvintas, «The Boy with a Galoche», was unveiled, depicting the 9-year-old little hero of the Promise of Dawn, preparing to eat a shoe to seduce his little neighbor, Valentina. It is placed in Vilnius, in front of the Basanavičius, where the novelist lived.

A plaque to his name is affixed in the Pouillon building of the Faculty of Law and Political Science of Aix-Marseille where he studied.

In 2022, Denis Ménochet portrayed Gary in White Dog (Chien blanc), a film adaptation by Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette of Gary's 1970 book.[22]

Bibliography

[edit]

As Romain Gary

[edit]- French: Éducation européenne (1945); translated as Forest of Anger

- French: Tulipe (1946); republished and modified in 1970.

- Le Grand Vestiaire (1949); translated as The Company of Men (1950)

- Les Couleurs du jour (1952); translated as The Colors of the Day (1953); filmed as The Man Who Understood Women (1959)

- Les Racines du ciel — 1956 Prix Goncourt; translated as The Roots of Heaven (1957); filmed as The Roots of Heaven (1958)

- Lady L (1958); self-translated and published in French in 1963; filmed as Lady L (1965)

- La Promesse de l'aube (1960); translated as Promise at Dawn (1961); filmed as Promise at Dawn (1970) and Promise at Dawn (2017)

- Johnie Cœur (1961, a theatre adaptation of "L'homme à la colombe")

- Gloire à nos illustres pionniers (1962, short stories); translated as "Hissing Tales" (1964)

- The Ski Bum (1965); self-translated into French as Adieu Gary Cooper (1969)

- Pour Sganarelle (1965, literary essay)

- Les Mangeurs d'étoiles (1966); self-translated into French and first published (in English) as The Talent Scout (1961)

- La Danse de Gengis Cohn (1967); self-translated into English as The Dance of Genghis Cohn

- La Tête coupable (1968); translated as The Guilty Head (1969)

- Chien blanc (1970); self-translated as White Dog (1970); filmed as White Dog (1982)

- Les Trésors de la mer Rouge (1971)

- Europa (1972); translated in English in 1978.

- The Gasp (1973); self-translated into French as Charge d'âme (1978)

- Les Enchanteurs (1973); translated as The Enchanters (1975)

- La nuit sera calme (1974, interview)

- Au-delà de cette limite votre ticket n'est plus valable (1975); translated as Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid (1977); filmed as Your Ticket Is No Longer Valid (1981)

- Clair de femme (1977); filmed as Womanlight (1979)

- La Bonne Moitié (1979, play)

- Les Clowns lyriques (1979); new version of the 1952 novel, Les Couleurs du jour (The Colors of the Day)

- Les Cerfs-volants (1980); translated as The Kites (2017)

- Vie et Mort d'Émile Ajar (1981, posthumous)

- L'Homme à la colombe (1984, definitive posthumous version)

- L'Affaire homme (2005, articles and interviews)

- L'Orage (2005, short stories and unfinished novels)

- Un humaniste, short story

As Émile Ajar

[edit]- Gros câlin (1974); illustrated by Jean-Michel Folon, filmed as Gros câlin (1979)

- La vie devant soi — 1975 Prix Goncourt; filmed as Madame Rosa (1977); translated as "Momo" (1978); re-released as The Life Before Us (1986). Filmed as The Life Ahead (2020)

- Pseudo (1976)

- L'Angoisse du roi Salomon (1979); translated as King Solomon (1983).

- Gros câlin – new version including final chapter of the original and never published version.

As Fosco Sinibaldi

[edit]- L'homme à la colombe (1958)

As Shatan Bogat

[edit]- Les têtes de Stéphanie (1974)

Filmography

[edit]As screenwriter

[edit]- 1958: The Roots of Heaven

- 1962: The Longest Day

- 1978: La vie devant soi

As actor

[edit]- 1936: Nitchevo – Le jeune homme au bastingage

- 1967: The Road to Corinth – (uncredited) (final film role)

As director

[edit]- 1968: Birds in Peru (Birds in Peru) starring Jean Seberg

- 1971: Kill! Kill! Kill! Kill! also starring Jean Seberg

In popular culture

[edit]- 2019: Seberg , joué par Yvan Attal

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ivry, Benjamin (21 January 2011). "A Chameleon on Show". Daily Forward.

- ^ Romain Gary et la Lituanie Archived 26 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Myriam Anissimov. Romain Gary, le Caméléon. Paris: Les éditions Folio Gallimard, 2004. ISBN 978-2-207-24835-5, pp. ??

- ^ "Romain Gary". Encyclopédie sur la mort. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Schoolcraft, Ralph W. (2002). Romain Gary: the man who sold his shadow. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-8122-3646-7.

- ^ Schwartz, Madeleine. "Romain Gary: A Short Biography". The Harvard Advocate.

- ^ Passports of mother Mina Kacew and nurse-maid Aniela Voiciechowics. See Lithuaninan Central State Archives, F. 53, 122, 5351 and F. 15, 2, 1230. Copies of the documents are in the personal archive of a Moscow historian Alexander Vasin.

- ^ a b c d Marzorati 2018

- ^ "Romain Gary: The greatest literary conman ever?".

- ^ "Ordre de la Libération". Archived from the original on 26 November 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ a b c Bellos, David (2010). Romain Gary: A Tall Story. pp. ??.

- ^ a b Prial, Frank J. (2 July 1981). "Gary won '75 Goncourt under Pseudonym 'Ajar'". The New York Times.

- ^ Gary, Romain, Vie et mort d'Émile Ajar, Gallimard – NRF (17 juillet 1981), 42p, ISBN 978-2-07-026351-6.

- ^ Lushenkova, Anna (2008). "La réinvention de l'homme par l'art et le rire: 'Les Enchanteurs' de Romain Gary". In Clément, Murielle Lucie (ed.). Écrivains franco-russes. Faux titre. Vol. 318. Rodopi. pp. 141–163. ISBN 978-90-420-2426-7.

- ^ Di Folco, Philippe (2006). Les grandes impostures littéraires: canulars, escroqueries, supercheries, et autres mystifications. Écriture. pp. 111–113. ISBN 2-909240-70-3.

- ^ "Romain Gary". IMDb. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "Berlinale 1979: Juries". berlinale.de. Retrieved 8 August 2010.

- ^ Paris Match No.3136

- ^ Bellos, David (12 November 2010). "Romain Gary: au revoir et merci". The Telegraph. UK.

- ^ D. Bona, Romain Gary, Paris, Mercure de France-Lacombe, 1987, p. 397–398.

- ^ Beyern, B., Guide des tombes d'hommes célèbres, Le Cherche Midi, 2008, ISBN 978-2-7491-1350-0

- ^ Demers, Maxime (2 November 2022). "«Chien blanc»: le goût du risque d'Anaïs Barbeau-Lavalette". Le Journal de Montréal. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Ajar, Émile (Romain Gary), Hocus Bogus, Yale University Press, 2010, 224p, ISBN 978-0-300-14976-0 (translation of Pseudo by David Bellos, includes The Life and Death of Émile Ajar)

- Anissimov, Myriam, Romain Gary, le caméléon (Denoël 2004)

- Bellos, David, Romain Gary: A Tall Story, Harvill Secker, 2010, 528p, ISBN 978-1-84343-170-1

- Bellos, David. 2009. The cosmopolitanism of Romain Gary. Darbair ir Dienos (Vilnius) 51:63–69.

- Gary, Romain, Promise at Dawn (Revived Modern Classic), W.W. Norton, 1988, 348p, ISBN 978-0-8112-1016-4

- Huston, Nancy, Tombeau de Romain Gary (Babel, 1997) ISBN 978-2-7427-0313-5

- Bona, Dominique, Romain Gary (Mercure de France, 1987) ISBN 2-7152-1448-0

- Cahier de l'Herne, Romain Gary (L'Herne, 2005)

- Désérable, François-Henri, Un certain M. Piekielny, Gallimard, 2017, ISBN 978-2-07-274141-8

- Schoolcraft, Ralph W. (2002). Romain Gary: The Man Who Sold his Shadow. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3646-7.

- Blanch, Lesley, Romain, un regard particulier (Editions du Rocher, 2009) ISBN 978-2-268-06724-7

- Marret, Carine, Romain Gary – Promenade à Nice (Baie des Anges, 2010)

- Marzorati, Michel (2018). Romain Gary: des racines et des ailes. Info-Pilote, 742 pp. 30–33

- Spire, Kerwin, Monsieur Romain Gary, Gallimard, 2021, ISBN 978-2-07-293006-5

- Stjepanovic-Pauly, Marianne. Romain Gary La mélancolie de l'enchanteur. Editions du Jasmin, ISBN 978-2-35284-141-8

External links

[edit] Media related to Romain Gary at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Romain Gary at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Romain Gary at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Romain Gary at Wikiquote- Romain Gary at IMDb

- 1914 births

- 1980 deaths

- Film people from Vilnius

- People from Vilensky Uyezd

- French people of Lithuanian-Jewish descent

- 20th-century Lithuanian Jews

- Jews from the Russian Empire

- 20th-century French diplomats

- 20th-century French novelists

- French male novelists

- Jewish novelists

- Postmodern writers

- 20th-century French male writers

- Prix Goncourt winners

- French Royal Air Force pilots of World War II

- Suicides by firearm in France

- 1980 suicides

- Writers from Vilnius

- French Resistance members

- Polish emigrants to France