Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Difference between revisions

MEspringal (talk | contribs) |

mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Chronic medical condition}} |

|||

<span class="plainlinks"></span>{{verylong|date=December 2007}} |

|||

{{Distinguish|text=[[Fatigue#Chronic|chronic fatigue]], a symptom experienced in many chronic illnesses, including [[idiopathic chronic fatigue]]}} |

|||

{{Infobox_Disease | |

|||

{{Featured article}} |

|||

Name = Chronic fatigue syndrome/ myalgic encephalomyelitis | |

|||

{{Use British English|date=March 2024}} |

|||

Image = | |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2024}} |

|||

Caption = | |

|||

{{Cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} |

|||

DiseasesDB = 1645 | |

|||

{{Infobox medical condition |

|||

ICD10 = {{ICD10|G|93|3|g|90}} | |

|||

| name = Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome |

|||

ICD9 = {{ICD9|780.71}} | |

|||

| synonyms = Post-viral fatigue syndrome (PVFS), systemic exertion intolerance disease (SEID)<ref name=IOM2015 />{{rp|20}} |

|||

ICDO = | |

|||

| speciality = [[Rheumatology]], [[rehabilitation medicine]], [[endocrinology]], [[infectious disease (medical specialty)|infectious disease]], [[neurology]], [[immunology]], [[general practice]], [[paediatrics]], other specialists in ME/CFS<ref name="NICE2021">{{cite web |title=Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (Or Encephalopathy)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management: NICE Guideline|url=https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206/resources/myalgic-encephalomyelitis-or-encephalopathychronic-fatigue-syndrome-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66143718094021 |url-status=live |publisher=[[National Institute for Health and Care Excellence]] (NICE) |date=29 October 2021 |access-date=9 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240208083814/https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206/resources/myalgic-encephalomyelitis-or-encephalopathychronic-fatigue-syndrome-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-66143718094021 |archive-date=8 February 2024}}</ref>{{Rp|pages=58}} |

|||

OMIM = | |

|||

| image = File:Icons symptoms ME CFS.svg |

|||

MedlinePlus = 001244 | |

|||

| caption = The four primary symptoms of ME/CFS according to the [[National Institute for Health and Care Excellence]] |

|||

eMedicineSubj = med | |

|||

| alt = Icons of the four key ME/CFS symptoms: low battery for profound fatigue, weak muscle for post-exertional malaise, bed for sleep problems and crossed wires in brain for cognitive difficulties. |

|||

eMedicineTopic = 3392 | |

|||

| symptoms = [[Post-exertional malaise|Worsening of symptoms with activity]], [[Fatigue#Chronic|long-term fatigue]], sleep problems, others<ref name="CDCsym2024" /> |

|||

eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|ped|2795}} | |

|||

| onset = Peaks at 10–19 and 30–39 years old<ref name="pmid31379194" /> |

|||

MeshID = D015673 | |

|||

| duration = Long-term<ref>{{Cite web |date=29 October 2021 |title=Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (Or Encephalopathy)/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Diagnosis and Management: Information for the Public |url=https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206/informationforpublic |access-date=24 March 2024 |publisher=[[National Institute for Health and Care Excellence]] (NICE) |archive-date=4 April 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240404205135/https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng206/informationforpublic |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| causes = Unknown<ref name="pmid37793728" /> |

|||

| risks = Being female, [[genetics|family history]], viral infections<ref name="pmid37793728" /> |

|||

| diagnosis = Based on symptoms<ref name="pmid37226227" /> |

|||

| treatment = [[Symptomatic treatment|Symptomatic]]<ref name=CDC2024manage>{{cite web |date=10 May 2024 |title=Manage Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |url-status=live |url=https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/management/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240518073532/https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/management/ |archive-date=18 May 2024 |access-date=18 May 2024|publisher=U.S. [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC)}}</ref> |

|||

| prevalence = About 0.17% to 0.89% (pre-[[COVID-19 pandemic]])<ref name=Lim2020/> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Chronic fatigue syndrome''' ('''CFS''') is one of several names given to a poorly understood, variably debilitating disorder of uncertain [[etiology|cause/causes]]. Based on a 1999 study of adults in the [[United States]], CFS is thought to affect approximately 4 per 1,000 adults.<ref name=pmid10527290>{{cite journal |author=Jason LA, Richman JA, Rademaker AW, Jordan KM, Plioplys AV, Taylor RR, McCready W, Huang CF, Plioplys S |title=A community-based study of chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=Arch. Intern. Med. |volume=159 |issue=18 |pages=2129-37 |year=1999 | url = http://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/159/18/2129?ck=nck |pmid=10527290}}</ref> |

|||

For unknown reasons, CFS occurs more often in women, and adults in their 40s and 50s.<ref>Gallagher AM, Thomas JM, Hamilton WT, White PD. Incidence of fatigue symptoms and diagnoses presenting in UK primary care from 1990 to 2001. ''J R Soc Med 2004;97:571-5. PMID 15574853.</ref><ref name="CDCRisk"/> The illness is estimated to be less prevalent in children and adolescents, but study results vary as to the degree.<ref name="DOI : 10.1300/J092v13n02_01">{{cite journal |author=Jason LA, Jordan K, Miike T, Bell DS, Lapp C, Torres-Harding S, Rowe K, Gurwitt A, De Meirleir K, Van Hoof ELS |title=A Pediatric Case Definition for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |journal=Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |volume=13 |issue=2-3 | pages = 1-44 |year=2006| url = <!--http://www.cfids-cab.org/rc/Jason-1.pdf--> | doi = 10.1300/J092v13n02_01}}</ref> |

|||

<!-- Definition and symptoms, wording vague and unspecific, more than just core symptoms --> |

|||

CFS often manifests with cognitive difficulties, chronic mental and physical exhaustion, often severe, and other characteristic symptoms in a previously healthy and active person. Despite promising avenues of [[medical research|research]], there remains no [[medical test|assay]] or [[pathology|pathological]] finding which is widely accepted to be diagnostic of CFS. It remains a [[diagnosis of exclusion]] based largely on patient history and [[symptom]]atic criteria, although a number of tests can aid diagnosis.<ref name="carr">{{cite journal | author = Carruthers BM, Jain AK, De Meirleir KL, Peterson DL, Klimas MD, Lerner AM, Bested AC, Flor-Henry P, Joshi P, Powles ACP, Sherkey JA, van de Sande MI | title = Myalgic encephalomyalitis/chronic fatigue syndrome: Clinical working definition, diagnostic and treatment protocols | journal = Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome | volume = 11 | issue = 1 | pages = 7-36 | year = 2003 | url = http://www.cfids-cab.org/MESA/me_overview.pdf | doi = 10.1300/J092v11n01_02}}</ref> Whereas there is agreement on the genuine threat to health, happiness, and productivity posed by CFS, various [[physician|physicians']] groups, researchers, and patient activists champion very different nomenclature, diagnostic criteria, etiologic hypotheses, and treatments, resulting in controversy about nearly all aspects of the disorder. Even the term ''chronic fatigue syndrome'' is controversial because a large part of the patient community believes the name trivializes the illness.<ref name="Jason"/> |

|||

'''Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome''' ('''ME/CFS''') is a disabling [[Chronic condition|chronic illness]]. People with ME/CFS experience profound [[fatigue]] that does not go away with rest, as well as sleep issues and problems with memory or concentration. The [[Pathognomonic|hallmark]] symptom is [[post-exertional malaise]], a worsening of the illness which can start immediately or hours to days after even minor physical or mental activity. This "crash" can last from hours or days to several months. Further common symptoms include [[orthostatic intolerance|dizziness or faintness when upright]] and pain.<ref name="CDCsym2024">{{cite web|title=Symptoms of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |url=https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/signs-symptoms/|date=10 May 2024|publisher=U.S. [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC)|access-date=17 May 2024|archive-date=17 May 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240517191603/https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/signs-symptoms/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="IQWiG-2023" /> |

|||

<!-- Pathophysiology --> |

|||

''Chronic fatigue syndrome'' is not the same as "chronic fatigue”.<ref name="carr"/> Fatigue is a common symptom in many illnesses, but CFS is a multi-systemic disease and is relatively rare by comparison.<ref name="PMID_15699086">{{cite journal | author = Ranjith G | title = Epidemiology of chronic fatigue syndrome. | journal = Occup Med (Lond) | volume = 55 | issue = 1 | pages = 13-9 | year = 2005 | id = PMID 15699086}}</ref> [[#Diagnosis|Definitions]] (other than the 1991 [[United Kingdom|UK]] Oxford criteria)<ref name="oxford">{{cite journal | author = Sharpe M, Archard L, Banatvala J, Borysiewicz L, Clare A, David A, Edwards R, Hawton K, Lambert H, Lane R | title = A report--chronic fatigue syndrome: guidelines for research. | journal = J R Soc Med | volume = 84 | issue = 2 | pages = 118-21 | year = 1991 | id = PMID 1999813}} Synopsis by {{GPnotebook|-476446699}})</ref> require a number of features, the most common being severe mental and physical exhaustion which is "unrelieved by rest" (1994 Fukuda definition),<ref name="CDC1994">{{cite journal | author = Fukuda K, Straus S, Hickie I, Sharpe M, Dobbins J, Komaroff A | title = The chronic fatigue syndrome: a comprehensive approach to its definition and study. International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. | journal = Ann Intern Med | volume = 121 | issue = 12 | pages = 953-9 | year = 1994 | id = PMID 7978722}} [http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/121/12/953#F2 case definition]</ref> and may be worsened by even trivial exertion (a mandatory diagnostic criterion according to some systems). Most diagnostic criteria require that symptoms must be present for at least six months, and all state the symptoms must not be caused by other medical conditions. CFS patients may report many symptoms which are not included in all diagnostic criteria, including [[muscle weakness]], [[cognitive]] dysfunction, [[hypersensitivity]], [[orthostatic intolerance]], digestive disturbances, [[clinical depression|depression]], poor [[immune response]], and [[cardiac]] and [[Respiratory system|respiratory]] problems. It is unclear if these symptoms represent co-morbid conditions or are produced by an underlying etiology of CFS.<ref name="pmid:12562565">{{cite journal |author=Afari N, Buchwald D |title=Chronic fatigue syndrome: a review |journal=Am J Psychiatr |volume=160 |issue=2 |pages=221-36 |year=2003 |pmid=12562565 |url=http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/160/2/221}}</ref> Some cases improve over time, and treatments (though none are universally accepted) bring a degree of improvement to many others, though full resolution may be only 5-10% according to the United States [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC).<ref name="CDCBasic"/> |

|||

The cause of the disease is unknown.<ref name="CDC_Clinical2024" /> ME/CFS often starts after an infection, such as [[infectious mononucleosis|mononucleosis]].<ref name="Bateman-2021" /> It can run in families, but no [[genes]] that contribute to ME/CFS have been confirmed.<ref name="Dibble McGrath Ponting 2020 p.">{{cite journal |vauthors=Dibble JJ, McGrath SJ, Ponting CP |date=September 2020 |title=Genetic Risk Factors of ME/CFS: A Critical Review |journal=Human Molecular Genetics |volume=29 |issue=R1 |pages=R117–R124 |doi=10.1093/hmg/ddaa169 |pmc=7530519 |pmid=32744306}}</ref> ME/CFS is associated with changes in the nervous and immune systems, as well as in energy production.<ref name="pmid38443223">{{cite journal |vauthors=Annesley SJ, Missailidis D, Heng B, Josev EK, Armstrong CW |date=March 2024 |title=Unravelling Shared Mechanisms: Insights from Recent ME/CFS Research to Illuminate Long COVID Pathologies |url=|journal=Trends in Molecular Medicine |volume=30 |issue=5 |pages=443–458 |doi=10.1016/j.molmed.2024.02.003 |pmid=38443223 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Diagnosis is based on symptoms and a [[differential diagnosis]] because no diagnostic test is available.<ref name="pmid37226227" /><ref>{{Cite web |title=Myalgic encephalomyelitis (Chronic fatigue syndrome) - Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment {{!}} BMJ Best Practice US |url=https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/277 |access-date=2024-10-21 |website=bestpractice.bmj.com |language=en-us}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) {{!}} Diseases & Conditions {{!}} 5MinuteConsult |url=https://5minuteconsult.com/collectioncontent/1-151513/diseases-and-conditions/myalgic-encephalomyelitis-chronic-fatigue-syndrome-cfs |access-date=2024-11-25 |website=5minuteconsult.com}}</ref><ref name="pmid28033311" /> |

|||

<!-- Management and epidemiology --> |

|||

==Nomenclature== |

|||

The illness can improve or worsen over time, but full recovery is uncommon.<ref name="Bateman-2021">{{cite journal |vauthors=Bateman L, Bested AC, Bonilla HF, Chheda BV, Chu L, Curtin JM, Dempsey TT, Dimmock ME, Dowell TG, Felsenstein D, Kaufman DL, Klimas NG, Komaroff AL, Lapp CW, Levine SM, Montoya JG, Natelson BH, Peterson DL, Podell RN, Rey IR, Ruhoy IS, Vera-Nunez MA, Yellman BP |date=November 2021 |title=Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Essentials of Diagnosis and Management |journal=Mayo Clinic Proceedings |volume=96 |issue=11 |pages=2861–2878 |doi=10.1016/j.mayocp.2021.07.004 |pmid=34454716 |s2cid=237419583 |doi-access=free |title-link=doi}}</ref> No therapies or medications are approved to treat the condition, and management is aimed at relieving symptoms.<ref name="NICE2021" />{{Rp|pages=29}} [[Pacing (activity management)|Pacing of activities]] can help avoid worsening symptoms, and counselling may help in coping with the illness.<ref name=CDC2024manage /> Before the [[COVID-19 pandemic]], ME/CFS affected two to nine out of every 1,000 people, depending on the definition.<ref name="Lim2020">{{cite journal |vauthors=Lim EJ, Ahn YC, Jang ES, Lee SW, Lee SH, Son CG |date=February 2020 |title=Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Of the Prevalence of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (CFS/ME) |journal=Journal of Translational Medicine |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=100 |doi=10.1186/s12967-020-02269-0 |pmc=7038594 |pmid=32093722 |doi-access=free |title-link=doi}}</ref> However, many people fit ME/CFS diagnostic criteria after contracting [[long COVID]].<ref name="Davis-2023">{{cite journal |vauthors=Davis HE, McCorkell L, Vogel JM, Topol EJ |date=March 2023 |title=Long COVID: Major Findings, Mechanisms and Recommendations |journal=Nature Reviews. Microbiology |volume=21 |issue=3 |pages=133–146 |doi=10.1038/s41579-022-00846-2 |pmc=9839201 |pmid=36639608}}</ref> ME/CFS occurs more often in women than in men. It is more common in [[middle age]], but can occur at all ages, including childhood.<ref name="CDC_Basics" /> |

|||

The naming of chronic fatigue syndrome has been challenging, since consensus is lacking within the medical, research, and patient communities regarding the defining features of the syndrome. It may be considered by different authorities to be a central nervous system, metabolic, (post-)infectious, immune system or neuropsychiatric disorder. |

|||

<!-- Society and culture --> |

|||

There are a number of different terms which have been identified at various times with this disorder. |

|||

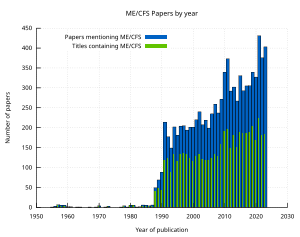

ME/CFS has a large social and economic impact, and the disease can be socially isolating.<ref name="Boulazreg_2024">{{Cite journal | vauthors = Boulazreg, S, Rokach A |date=17 July 2020 |title=The Lonely, Isolating, and Alienating Implications of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |journal=Healthcare |language=en |volume=8 |issue=4 |pages=413–433 |doi=10.3390/healthcare8040413 |issn=2164-1846 |doi-access=free|pmid=33092097 |pmc=7711762 }}</ref> About a quarter of those affected are unable to leave their bed or home.<ref name="IQWiG-2023">{{Cite book |last=Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen (IQWiG) |url=https://www.iqwig.de/download/n21-01_me-cfs-aktueller-kenntnisstand_abschlussbericht_v1-0.pdf |title=Myalgische Enzephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): Aktueller Kenntnisstand |date=17 April 2023 |publisher=[[Institut für Qualität und Wirtschaftlichkeit im Gesundheitswesen]] |language=de |trans-title=Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS): current state of knowledge |issn=1864-2500 |access-date=8 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231102160213/https://www.iqwig.de/download/n21-01_me-cfs-aktueller-kenntnisstand_abschlussbericht_v1-0.pdf |archive-date=2 November 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref>{{Rp|3}} People with ME/CFS often face stigma in healthcare settings, and care is complicated by [[Controversies related to ME/CFS|controversies around the cause and treatments]] of the illness.<ref name="Hussein-2024">{{Cite journal |last1=Hussein |first1=Said |last2=Eiriksson |first2=Lauren |last3=MacQuarrie |first3=Maureen |last4=Merriam |first4=Scot |last5=Dalton |first5=Maria |last6=Stein |first6=Eleanor |last7=Twomey |first7=Rosie |date=2024 |title=Healthcare System Barriers Impacting the Care of Canadians with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis: A Scoping Review |journal=Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice |volume=30 |issue=7 |pages=1337–1360 |language=en |doi=10.1111/jep.14047 |issn=1356-1294|doi-access=free |pmid=39031904 }}</ref> Doctors may be unfamiliar with ME/CFS, as it is often not fully covered in medical school.<ref name="Davis-2023"/> Historically, research funding for ME/CFS has been far below that of diseases with comparable impact.<ref name="Tyson_2022">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Tyson S, Stanley K, Gronlund TA, Leary S, Emmans Dean M, Dransfield C, Baxter H, Elliot R, Ephgrave R, Bolton M, Barclay A, Hoyes G, Marsh B, Fleming R, Crawford J |date=2022 |title=Research Priorities for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): The Results of a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Exercise |journal=Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior |language=en |volume=10 |issue=4 |pages=200–211 |doi=10.1080/21641846.2022.2124775 |issn=2164-1846 |s2cid=252652429 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

* ''Myalgic encephalomyelitis'' or ME translates to "inflammation of the brain and spinal cord with muscle pain" and first appeared as "benign myalgic encephalomyelitis" in a ''[[The Lancet|Lancet]]'' editorial by Sir [[Donald Acheson]] in 1956.<ref name=Acheson1956>{{cite journal |author=[Anonymous] |title=A new clinical entity? |journal=Lancet |volume=270 |issue=6926 |pages=789–90 |year=1956 |pmid=13320887 |doi=}}</ref> In a 1959 review he referred to several older reports that appeared to describe a similar syndrome.<ref name="ach">{{cite journal | author = Acheson E | title = The clinical syndrome variously called benign myalgic encephalomyelitis, Iceland disease and epidemic neuromyasthenia. | journal = Am J Med | volume = 26 | issue = 4 | pages = 569-95 | year = 1959 | id = PMID 13637100}}</ref> The neurologist [[Russell Brain, 1st Baron Brain|Lord Brain]] included ME in the 1962 sixth edition of his textbook of neurology,<ref>{{cite book |editor=Brain R |authorlink= |title=Diseases of the Nervous System |edition=6 |year=1962}}</ref> A 1978 [[British Medical Journal]] article stated the [[Royal Society of Medicine]] conference to discuss the illness during that year clearly agreed Myalgic Encephalomyelitis was a distinct name for the disease. The article also stated the previous word (benign) used with ME was rejected as unsatisfactory and misleading because the condition may be devastating to the patient.<ref name="pmid647324">{{cite journal | author = No authors listed | title = Epidemic myalgic encephalomyelitis | url = http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=647324 | journal = Br Med J.| volume = 1 | issue = 6125 | pages = 1436-7 | Date = 1978 06 03 | id = PMID 647324}}</ref> In 1988 both the [[British Department of Health|UK Department of Health and Social Services]] and the [[British Medical Association]] officially recognized it as a legitimate and potentially distressing disorder.{{Fact|date=October 2007}} Opponents of the term ME state that there is no objective evidence of inflammation. In some patients diagnosed with CFS (e.g. the case of [[Sophia Mirza]]), central nervous system inflammation has been documented. Many patients, and some research and medical professionals in the United Kingdom and Canada, use this term in preference to or in conjunction with CFS (ME/CFS or CFS/ME). The international association of researchers and clinicians is named IACFS/ME. |

|||

* ''Myalgic encephalopathy'', similar to the above, with "pathy" referring to unspecified pathology rather than inflammation; this term has some support in the UK and US. |

|||

* ''Chronic Epstein-Barr virus'' (CEBV) or ''Chronic Mononucleosis''; the term CEBV was introduced in 1985 by virologists Dr. Stephen Straus<ref name="pmid2578268">{{cite journal | author = Straus S, Tosato G, Armstrong G, Lawley T, Preble O, Henle W, Davey R, Pearson G, Epstein J, Brus I | title = Persisting illness and fatigue in adults with evidence of Epstein-Barr virus infection. | journal = Ann Intern Med | volume = 102 | issue = 1 | pages = 7-16 | year = 1985 | id = PMID 2578268}}</ref> and Dr. Jim Jones<ref name="pmid2578266">{{cite journal | author = Jones J, Ray C, Minnich L, Hicks M, Kibler R, Lucas D | title = Evidence for active Epstein-Barr virus infection in patients with persistent, unexplained illnesses: elevated anti-early antigen antibodies. | journal = Ann Intern Med | volume = 102 | issue = 1 | pages = 1-7 | year = 1985 | id = PMID 2578266}}</ref> in the United States. The [[Epstein-Barr virus]], a neurotropic virus that more commonly causes [[infectious mononucleosis]], was thought by Straus and Jones to be the cause of CFS. Subsequent discovery of the closely related ''[[HHV-6|human herpesvirus 6]]'' shifted the direction of biomedical studies, although a vastly expanded and substantial body of published research continues to show active viral infection or reinfection of CFS patients by these two viruses. These viruses are also found in healthy controls, lying dormant. |

|||

* ''Chronic fatigue syndrome'' (CFS) was proposed in 1988 by researchers from the [[United States|U.S.]] [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC) to replace the name chronic Epstein-Barr virus syndrome when they published an initial case definition for research of the illness after investigating the 1984 Lake Tahoe ME epidemic.<ref name=Holmes1988/> CFS is used increasingly over other designations, particularly in the United States. Many patients and clinicians perceive the term as trivializing,<ref name="Jason">Jason LA, Taylor RR. (2001). Measuring Attributions About Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. ''J Chronic Fatigue Syndr'' '''8''' (3/4); 31-40 [http://www.cfids-cab.org/cfs-inform/Welcome/jason.taylor01.txt TXT formal]</ref> and as the 1994 Fukuda paper itself cedes, stigmatizing, which led to a movement in the United States to change the name and definition.<ref name="name">{{cite web | title = Advocacy Archives: Name Change | publisher = The CFIDS Association of America | url = http://www.cfids.org/advocacy/name-change.asp | accessdate = 2008-01-16 }}</ref> Eighty-five percent of respondents to a 1997 survey conducted by the [[Chronic Fatigue Immune Dysfunction Syndrome Association of America]] wanted the name changed.<ref name="Jason"/> The CFS Coordinating Committee (CFSCC) of the U.S. [[Department of Health and Human Services]] formed a name change workgroup in 2000.<ref>{{Citation | last = Lavrich | first = Carol | title = Name Change Workgroup, CFSCC | publisher = US Department of Health and Human Services, Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Advisory Committee |date=September 29 2003 | location = National Institutes of Health Building 31C, Conference Room 10, Bethesda, Maryland | url = http://www.hhs.gov/advcomcfs/sept_meeting_min.html#carollavrich | accessdate = 2007-12-29}}</ref> Terms were recommended which implied specific underlying etiologies or pathologic processes, but work was shelved in December 2003 when the successor CFS Advisory Committee (CFSAC) decided a name change would be too disruptive at that time.<ref>{{Citation | last = Bell D.S. et al | title = Name Change | publisher = US Department of Health and Human Services Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Advisory Committee (CFSAC) |

|||

Second Meeting |date = December 03 2003 | location = Hubert H. Humphrey Building, 200 Independence Avenue, SW, Room 800, Washington, DC 20201 | url = http://www.hhs.gov/advcomcfs/dec_meeting_min.html#name_change | accessdate = 2008-01-16}}</ref> |

|||

* Chronic fatigue immune dysfunction syndrome (CFIDS); many patients and advocacy groups in the USA use the term CFIDS, in an attempt to reduce the psychiatric stigma attached to "chronic fatigue," as well as the public perception of CFS as a psychiatric syndrome. The term also calls attention to the immune dysfunction in patients which research suggests is an integral part of the illness.<ref name="Buchwald">{{cite journal | author = Buchwald D, Cheney P, Peterson D, Henry B, Wormsley S, Geiger A, Ablashi D, Salahuddin S, Saxinger C, Biddle R | title = A chronic illness characterized by fatigue, neurologic and immunologic disorders, and active human herpesvirus type 6 infection. | journal = Ann Intern Med | volume = 116 | issue = 2 | pages = 103-13 | year = 1992 | id = PMID 1309285}}</ref><ref name="PMID_16612182"/> |

|||

* ''[[Post-viral fatigue syndrome]]'' (PVFS); this is a related disorder. According to ME researcher, Dr. Melvin Ramsay, "The crucial differentiation between ME and other forms of post-viral fatigue syndrome lies in the striking variability of the symptoms not only in the course of a day but often within the hour<ref name="Ramsay86">Ramsay MA (1986), "Postviral Fatigue Syndrome. The saga of Royal Free disease", Londen, ISBN 0-906923-96-4</ref>. |

|||

* ''Low Natural Killer Syndrome'' (LNKS); this term reflected research on patients showing diminished in-vitro [[natural killer cell]] activity in a small 1987 study in Japan.<ref name="CFS Straus">{{cite book | last = edited by Straus |

|||

| first = Stephen E. | title = Chronic Fatigue Syndrome | publisher = Marcel Dekker Inc. | date = 1994 | location = New York, Basel, Hong Kong | page = 227 | id = | isbn = 0824791878 }}</ref><ref name="LNKS">{{cite journal |author= Aoki T, Usuda Y, Miyakoshi H, Tamura K, Herberman RB. |title = Low natural killer syndrome: clinical and immunologic features |journal=Nat Immun Cell Growth Regul. |volume=6 |issue=3 |pages=116-28 |year=1987 |pmid=2442602}}</ref> A case definition for CFS in Japan<ref name="Japan 1991Case">{{cite journal |author= Kitani T, Kuratsune H, Yamaguchi K. |title = Diagnostic criteria for chronic fatigue syndrome by the CFS Study Group in Japan |journal=Nippon Rinsho. |volume=50 |issue=11 |pages=2600-5 |year= Nov 1992 |pmid=1287236 }}</ref> was adopted in 1991 based on the CDC 1988 criteria, an updated diagnostic guideline is planned.<ref name="HistoryJapan">{{cite journal |author= Hashimoto N. et al |title = History of chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=Nippon Rinsho. |volume=65 |issue=6 |pages=975-82 |year= Jun 2007 |pmid=17561685}}</ref> |

|||

* ''Yuppie Flu''; this was a factually inaccurate term first published in a November 1990 ''[[Newsweek]]'' cover story and never official medical terminology. It reflects a stereotypical assumption that CFS mainly affects the affluent ("[[yuppie]]s"), and implies that it is a form of [[Burnout (psychology)|burnout]].<ref name="flu">{{Citation | author =Cowley, Geoffrey, with Mary Hager and Nadine Joseph | title = Chronic Fatigue Syndrome | journal = Newsweek | pages = Cover Story |date=1990-11-12}}</ref> CFS, however, affects people of all races, genders, and social standings<ref name=pmid10527290/>, and is not a form of [[influenza|flu]]. The phrase is considered [[List of disability-related terms with negative connotations|offensive]] by patients and clinicians.<ref>Compact Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press[http://www.askoxford.com/concise_oed/yuppieflu?view=uk]</ref><ref>Packhard, Randall M. (2004). Emerging Illnesses and Society: Negotiating the Public Health Agenda. Johns Hopkins University Press, p. 156. ISBN 0-801-879-426</ref><ref>Anon. "New Therapy For Chronic Fatigue Syndrome To Be Tested At Stanford" Medical News Today[http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=60423]</ref> |

|||

* Uncommonly used terms include ''Akureyri Disease'', ''Iceland disease'' (in [[Iceland]]),<ref>{{cite journal |author=Blattner R |title=Benign myalgic encephalomyelitis (Akureyri disease, Iceland disease) |journal=J. Pediatr. |volume=49 |issue=4 |pages=504-6 |year=1956 |pmid=13358047}}</ref> ''[[Royal Free Hospital|Royal Free]] disease'' (after the location of an outbreak),<ref name="Ramsay-RF"/> ''atypical [[poliomyelitis]]''<ref name="Gilliam38"/>, ''epidemic neuromyasthenia'', ''epidemic vasculitis'', ''[[raphe nucleus]] encephalopathy'', and ''Tapanui flu'' (after the [[New Zealand]] town [[Tapanui]] where the first doctor in the country to investigate the disease, Dr [[Peter Snow (doctor)|Peter Snow]], lived). |

|||

== |

== Classification and terminology == |

||

ME/CFS has been classified as a [[Neurological disorder|neurological disease]] by the [[World Health Organization]] (WHO) since 1969, initially under the name [[History of ME/CFS#Case definitions (1986 onwards)|''benign myalgic encephalomyelitis'']].<ref>{{Cite book |vauthors = Bateman L |title=Neurobiology of Brain Disorders : Biological Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disorders |publisher=[[Elsevier]] |year=2022 |isbn=978-0-323-85654-6 | veditors = Zigmond M, Wiley C, Chesselet MF |edition=2nd |chapter=Fibromyalgia and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome }}</ref>{{rp|564}} The classification of ME/CFS as a neurological disease is based on symptoms which indicate a central role of the nervous system.<ref name="pmid328732972">{{cite journal |vauthors=Shan ZY, Barnden LR, Kwiatek RA, Bhuta S, Hermens DF, Lagopoulos J |date=September 2020 |title=Neuroimaging Characteristics of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS): A Systematic Review |url=|journal=Journal of Translational Medicine |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=335 |doi=10.1186/s12967-020-02506-6 |pmc=7466519 |pmid=32873297 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Alternatively, on the basis of abnormalities in [[White blood cell|immune cells]], ME/CFS is sometimes labelled a [[Neuroimmunology|neuroimmune]] condition.<ref name="Marshall-Gradisnik_2022" /> The disease can further be regarded as a [[post-acute infection syndrome]] (PAIS) or an infection-associated chronic illness.<ref name="CDC_Clinical2024" /><ref name="pmid35585196" /> PAISes such as [[long COVID]] and [[Lyme disease|post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome]] share many symptoms with ME/CFS and are suspected to have a similar cause.<ref name="pmid35585196">{{cite journal |vauthors=Choutka J, Jansari V, Hornig M, Iwasaki A |date=May 2022 |title=Unexplained Post-Acute Infection Syndromes |url= |journal=Nature Medicine |volume=28 |issue=5 |pages=911–923 |doi=10.1038/s41591-022-01810-6 |pmid=35585196 |s2cid=248889597 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

===Onset=== |

|||

Many names have been proposed for the illness. The most commonly used are ''chronic fatigue syndrome'', ''myalgic encephalomyelitis'', and the umbrella term ''myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome'' (''ME/CFS''). Reaching consensus on a name has been challenging because the cause and pathology remain unknown.<ref name="IOM2015">{{cite book |last1=Committee on the Diagnostic Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK274235/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK274235.pdf |title=Beyond Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: Redefining an Illness |last2=Board on the Health of Select Populations |author3=Institute of Medicine |date=10 February 2015 |publisher=[[National Academies Press]] |isbn=978-0-309-31689-7 |pmid=25695122 |access-date=28 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170120175658/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK274235/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK274235.pdf |archive-date=20 January 2017 |url-status=live}}</ref>{{rp|29–30}} In the WHO's most recent classification, the [[ICD-11]], chronic fatigue syndrome and myalgic encephalomyelitis are named under post-viral fatigue syndrome.<ref name="ICD11">{{cite web |title=8E49 Postviral Fatigue Syndrome |url=https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f569175314 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://archive.today/20180801205234/https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en%23/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/294762853#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f569175314 |archive-date=1 August 2018 |access-date=20 May 2020 |website=ICD-11 – Mortality and Morbidity Statistics |publisher=[[World Health Organization]]}}</ref> The term ''post-infectious fatigue syndrome'' was initially proposed as a subset of "chronic fatigue syndrome" with a documented triggering infection, but might also be used as a synonym of ME/CFS or as a broader set of fatigue conditions after infection.<ref name="pmid35585196" /> |

|||

====Sudden onset cases==== |

|||

The majority of CFS cases start suddenly,<ref name="PMID_9201648"/> usually accompanied by a "flu-like illness"<ref name="pmid:12562565"/><ref>{{cite journal | author = Sairenji T, Nagata K | title = Viral infections in chronic fatigue syndrome. | journal = Nippon Rinsho | volume = 65 | issue = 6 | pages = 991-6 | year = 2007 | id = PMID 17561687}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Evengård B, Jonzon E, Sandberg A, Theorell T, Lindh G | title = Differences between patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and with chronic fatigue at an infectious disease clinic in Stockholm, Sweden. | journal = Psychiatry Clin Neurosci | volume = 57 | issue = 4 | pages = 361-8 | year = 2003 | id = PMID 12839515}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Evengård B, Schacterle RS, Komaroff AL | title = Chronic fatigue syndrome: new insights and old ignorance. | journal = J Intern Med | volume = 246 | issue = 5 | pages = 455-69 | year = 1999 | id = PMID 10583715}}</ref> which is more likely to occur in winter<ref>{{cite journal | author = Jason LA, Taylor RR, Carrico AW | title = A community-based study of seasonal variation in the onset of chronic fatigue syndrome and idiopathic chronic fatigue. | journal = Chronobiol Int | volume = 18 | issue = 2 | pages = 315-9 | year = 2001 | id = PMID 11379670}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Zhang QW, Natelson BH, Ottenweller JE, Servatius RJ, Nelson JJ, De Luca J, Tiersky L, Lange G | title = Chronic fatigue syndrome beginning suddenly occurs seasonally over the year. | journal = Chronobiol Int | volume = 17 | issue = 1 | pages = 95-9 | year = 2000 | id = PMID 10672437}}</ref>, while a significant proportion of cases begin within several months of severe adverse stress.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Hatcher S, House A | title = Life events, difficulties and dilemmas in the onset of chronic fatigue syndrome: a case-control study. | journal = Psychol Med | volume = 33 | issue = 7 | pages = 1185-92 | year = 2003 | id = PMID 14580073 | url: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/1226/1/house3.pdf}}</ref><ref name="PMID_10367610">{{cite journal | author = Theorell T, Blomkvist V, Lindh G, Evengard B | title = Critical life events, infections, and symptoms during the year preceding chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS): an examination of CFS patients and subjects with a nonspecific life crisis. | journal = Psychosom Med. | volume = 61 | issue = 3 | pages = 304-10 | id = PMID 10367610}}</ref><ref name="PMID_9201648">{{cite journal | author = Salit IE | title = Precipitating factors for the chronic fatigue syndrome. | journal = J Psychiatr Res | volume = 31 | issue = 1 | pages = 59-65 | year = 1997 | id = PMID 9201648}}</ref> Many people report getting a case of a [[influenza|flu]]-like or other [[respiratory infection]] such as [[bronchitis]], from which they seem never to fully recover and which evolves into CFS. The diagnosis of [[Post Viral Fatigue Syndrome]] is sometimes given in the early stage of the illness.<ref name="PMID:16950834"/> One study reported CFS occurred in some patients following a [[vaccination]] or a [[blood transfusion]].<ref name="Becker02">{{cite journal | author = De Becker P, McGregor N, De Meirleir K | title = Possible Triggers and Mode of Onset of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome | journal = Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome | volume = 10 | issue = 2 | pages = 2-18 | year = 2002 | doi = 10.1300/J092v10n02_02}}</ref> The accurate prevalence and exact roles of infection and stress in the development of CFS however are currently unknown. |

|||

Many individuals with ME/CFS object to the term ''chronic fatigue syndrome''. They consider the term simplistic and trivialising, which in turn prevents the illness from being taken seriously.<ref name="IOM2015" />{{rp|234}}<ref name="Bhatia-2023">{{Cite journal |vauthors=Bhatia S, Jason LA |date=24 February 2023 |title=Using Data Mining and Time Series to Investigate ME and CFS Naming Preferences |url=http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10442073231154027 |url-status=live |journal=Journal of Disability Policy Studies |volume=35 |pages=65–72 |doi=10.1177/10442073231154027 |issn=1044-2073 |s2cid=257198201 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231106033933/https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/10442073231154027 |archive-date=6 November 2023 |access-date=15 October 2023}}</ref> At the same time, there are also issues with the use of ''myalgic encephalomyelitis'' (myalgia means muscle pain and [[encephalitis|encephalomyelitis]] means brain and spinal cord inflammation), as there is only limited evidence of brain inflammation implied by the name.<ref name="BMJbest_practice3" />{{rp|3}} The umbrella term ''ME/CFS'' would retain the better-known phrase ''CFS'' without trivialising the disease, but some people object to this name too, as they see CFS and ME as distinct illnesses.<ref name="Bhatia-2023" /> |

|||

====Gradual onset cases==== |

|||

Other cases have a gradual onset, sometimes spread over years<ref name="Becker02"/>. Patients with [[Lyme disease]] may, despite a standard course of treatment, "evolve" clinically from the symptoms of acute Lyme to those similar to CFS<ref>{{cite journal | author = Donta S | title = Late and chronic Lyme disease. | journal = Med Clin North Am | volume = 86|issue = 2|pages = 341-9, vii|year = 2002|id = PMID 11982305}}</ref>. This has become [[Lyme disease controversy|an area of great controversy]]. |

|||

A 2015 report from the US Institute of Medicine recommended the illness be renamed ''systemic exertion intolerance disease'' (''SEID'') and suggested new diagnostic criteria.<ref name="IOM2015" /> While the new name was not widely adopted, the diagnostic criteria were taken over by the CDC. Like ''CFS'', the name ''SEID'' only focuses on a single symptom, and opinion from those affected was generally negative.<ref>{{Cite journal |vauthors=Jason LA, Johnson M |date=2 April 2020 |title=Solving the ME/CFS Criteria and Name Conundrum: The Aftermath of IOM |journal=Fatigue: Biomedicine, Health & Behavior |volume=8 |issue=2 |pages=97–107 |doi=10.1080/21641846.2020.1757809 |issn=2164-1846 |s2cid=219011696}}</ref> |

|||

===Course=== |

|||

It can be inferred from the 2003 "Canadian" clinical working definition of ME/CFS<ref name="carr"/> that there are 8 categories of symptoms: |

|||

* [[Fatigue (physical)|Fatigue]]: Unexplained, persistent, or recurrent physical and mental fatigue/[[exhaustion]] that substantially reduces activity levels and is not relieved (or not completely relieved) by rest. |

|||

== Signs and symptoms == |

|||

* Post-exertional [[malaise]]: An inappropriate loss of physical and mental stamina, rapid muscular and cognitive fatigability, post exertional malaise and/or fatigue and/or pain and a tendency for other associated symptoms to worsen with a pathologically slow recovery period of usually 24 hours or longer. According to the authors of the Canadian clinical working definition of ME/CFS<ref name="carr"/>, the malaise that follows exertion is often reported to be similar to the generalized pain, discomfort and fatigue associated with the acute phase of influenza. Although common in CFS, this may not be the most severe symptom in the individual case, where other symptoms (such as headaches, neurocognitive difficulties, pain and sleep disturbances) can dominate. |

|||

ME/CFS causes debilitating fatigue, sleep problems, and [[post-exertional malaise]] (PEM, overall symptoms getting worse after mild activity). In addition, cognitive issues, [[orthostatic intolerance]] (dizziness or nausea when upright) or other physical symptoms may be present (see also {{Section link|2=Diagnostic criteria|nopage=yes}}). Symptoms significantly reduce the ability to function and typically last for three to six months before a diagnosis can be confirmed.<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|page=13}}<ref name="NICE2021" />{{Rp|page=11}} ME/CFS usually starts after an infection. Onset can be sudden or more gradual over weeks to months.<ref name="Bateman-2021" /> |

|||

=== Core symptoms === |

|||

* [[Dyssomnia|Sleep dysfunction]]: "Unrefreshing" sleep/rest, poor sleep quantity, [[insomnia]] or rhythm disturbances. A study found that most CFS patients have clinically significant sleep abnormalities that are potentially treatable.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Krupp LB, Jandorf L, Coyle PK, Mendelson WB | title = Sleep disturbance in chronic fatigue syndrome. | journal = J Psychosom Res | volume = 37 | issue = 4 | pages = 325-31 | year = 1993 | id = PMID 8510058}}</ref> Several studies suggest that while CFS patients may experience altered sleep architecture (such as reduced sleep efficiency, a reduction of deep sleep, prolonged sleep initiation, and alpha-wave intrusion during deep sleep) and mildly disordered breathing, overall sleep dysfunction does not seem to be a critical or causative factor in CFS.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Reeves WC, Heim C, Maloney EM, Youngblood LS, Unger ER, Decker MJ, Jones JF, Rye DB | title = Sleep characteristics of persons with chronic fatigue syndrome and non-fatigued controls: results from a population-based study. | journal = BMC Neurol | volume = 6 | pages = 41 | year = 2006 | id = PMID 17109739}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Watson NF, Kapur V, Arguelles LM, Goldberg J, Schmidt DF, Armitage R, Buchwald D | title = Comparison of subjective and objective measures of insomnia in monozygotic twins discordant for chronic fatigue syndrome. | journal = Sleep | volume = 26 | issue = 3 | pages = 324-8 | year = 2003 | id = PMID 12749553}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Van Hoof E, De Becker P, Lapp C, Cluydts R, De Meirleir K | title = Defining the occurrence and influence of alpha-delta sleep in chronic fatigue syndrome. | journal = Am J Med Sci | volume = 333 | issue = 2 | pages = 78-84 | year = 2007 | id = PMID 17301585}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | author = Ball N, Buchwald DS, Schmidt D, Goldberg J, Ashton S, Armitage R | title = Monozygotic twins discordant for chronic fatigue syndrome: objective measures of sleep. | journal = J Psychosom Res | volume = 56 | issue = 2 | pages = 207-12 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15016580}}</ref> Sleep may present with vivid disturbing dreams, and exhaustion can worsen sleep dysfunction.<ref name="carr2">"Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Clinical Case Definition and Guidelines for Medical Practitioners - An Overview of the Canadian Consensus Document"; authored by Carruthers and van de Sande; published in 2005, ISBN 0-9739335-0-X, [http://www.mefmaction.net/documents/me_overview.pdf]</ref> |

|||

People with ME/CFS experience persistent debilitating [[fatigue]]. It is made worse by normal physical, mental, emotional, and social activity, and is not a result of ongoing overexertion.<ref name="CDCsym2024" /><ref name="NICE2021" />{{Rp|pages=12}} Rest provides limited relief from fatigue. Particularly in the initial period of illness, this fatigue is described as "flu-like". Individuals may feel "physically drained" and unable to start or finish activities. They may also feel restless while fatigued, describing their experience as "wired but tired". When starting an activity, muscle strength may drop rapidly, which can lead to difficulty with coordination, clumsiness or sudden [[weakness]]. Mental fatigue may also make cognitive efforts difficult.<ref name="NICE2021" />{{Rp|pages=12,57, 95}}<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Jason |first=Leonard |last2=Jessen |first2=Tricia |last3=Porter |first3=Nicole |last4=Boulton |first4=Aaron |last5=Gloria-Njoku |first5=Mary |date=2009-07-16 |title=Examining Types of Fatigue Among Individuals with ME/CFS |url=https://dsq-sds.org/index.php/dsq/article/view/938 |journal=Disability Studies Quarterly |language=en |volume=29 |issue=3 |doi=10.18061/dsq.v29i3.938 |issn=2159-8371|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Jason |first=Leonard A. |last2=Boulton |first2=Aaron |last3=Porter |first3=Nicole S. |last4=Jessen |first4=Tricia |last5=Njoku |first5=Mary Gloria |last6=Friedberg |first6=Fred |date=2010-02-24 |title=Classification of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome by Types of Fatigue |url=http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08964280903521370 |journal=Behavioral Medicine |language=en |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=24–31 |doi=10.1080/08964280903521370 |issn=0896-4289 |pmc=4852700 |pmid=20185398}}</ref> The fatigue experienced in ME/CFS is of a longer duration and greater severity than in other conditions characterized by fatigue.<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|page=|pages=5–6}} |

|||

The hallmark feature of ME/CFS is a worsening of symptoms after exertion, known as [[post-exertional malaise]] or ''post-exertional symptom exacerbation''.<ref name="pmid37793728" /> PEM involves increased fatigue and is disabling. It can also include flu-like symptoms, pain, cognitive difficulties, gastrointestinal issues, [[nausea]], and sleep problems.<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|page=6}} [[File:Timeframe of PEM from daily activities.jpg|alt=The onset of PEM is usually within two days. Peak PEM occurs within seven, while recovery can take months. |thumb|upright=1.5|Typical time frames of post-exertional malaise after normal daily activities]] All types of activities that require energy, whether physical, cognitive, social, or emotional, can trigger PEM.<ref name="NICE-2021-D" />{{Rp|page=49}} Examples include attending a school event, food shopping, or even taking a shower.<ref name="CDCsym2024" /> For some, being in a stimulating environment can be sufficient to trigger PEM.<ref name="NICE-2021-D" />{{Rp|page=49}} PEM usually starts 12 to 48 hours after the activity,<ref name="CDC_strategies2024">{{cite web |date=10 May 2024 |title=Strategies to Prevent Worsening of Symptoms |url=https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/hcp/clinical-care/treating-the-most-disruptive-symptoms-first-and-preventing-worsening-of-symptoms.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240518105522/https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/hcp/clinical-care/treating-the-most-disruptive-symptoms-first-and-preventing-worsening-of-symptoms.html |archive-date=18 May 2024 |access-date=18 May 2024 |publisher=U.S. [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC)}}</ref> but can also follow immediately after. PEM can last hours, days, weeks, or months.<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|page=6}} Extended periods of PEM, commonly referred to as "crashes" or "flare-ups" by people with the illness, can lead to a prolonged relapse.<ref name="NICE-2021-D" />{{Rp|page=50}} |

|||

Unrefreshing sleep is a further core symptom. People wake up exhausted and stiff rather than restored after a night's sleep. This can be caused by a pattern of [[Sleep inversion|sleeping during the day and being awake at night]], shallow sleep, or broken sleep. However, even a full night's sleep is typically non-restorative. Some individuals experience insomnia, [[hypersomnia]] (excessive sleepiness), or vivid nightmares.<ref name="NICE-2021-D"/>{{Rp|page=50}} |

|||

* [[Pain and nociception|Pain]]: Pain is often widespread and migratory in nature, including a significant degree of [[myalgia|muscle pain]] and/or [[arthralgia|joint pain]] (without joint swelling or redness, and may be transitory). Other symptoms include [[headache]]s (particularly of a new type, severity, or duration), [[lymph node]] pain, [[sore throat]]s, and [[abdominal pain]] (often as a symptom of [[irritable bowel syndrome]]). Patients also report bone, eye and [[Orchalgia|testicular pain]], [[neuralgia|nerve pain]] and painful skin sensitivity. [[Chest pain]] has been attributed variously to [[microvascular disease]] or [[cardiomyopathy]] by researchers, and many patients also report painful [[tachycardia]]. A systematic review assessing the studies of chronic pain in CFS found that although the exact prevalence is unknown, it is strongly disabling in patients, but unrelated to depression.<ref name="PMID_16843021">{{cite journal | author = Meeus M, Nijs J, Meirleir KD | title = Chronic musculoskeletal pain in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome: A systematic review. | journal = Eur J Pain | volume = 11 | issue = 4 | pages = 377-386 | year = 2007 | id = PMID 16843021}}</ref> |

|||

[[Cognitive disorder|Cognitive dysfunction]] in ME/CFS can be as disabling as physical symptoms, leading to difficulties at work or school, as well as in social interactions.<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|page=7}} People with ME/CFS sometimes describe it as "brain fog",<ref name="CDCsym2024" /> and report a slowdown in information processing.<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|page=7}} Individuals may have difficulty speaking, struggling to find words and names. They may have trouble concentrating or [[Human multitasking|multitasking]], or may have difficulties with short-term memory.<ref name="NICE2021" /> Tests often show problems with short-term visual memory, [[Mental chronometry|reaction time]] and [[Reading|reading speed]]. There may also be problems with [[attention]] and [[verbal memory]].<ref name="pmid35140252">{{cite journal |vauthors=Aoun Sebaiti M, Hainselin M, Gounden Y, Sirbu CA, Sekulic S, Lorusso L, Nacul L, Authier FJ |date=February 2022 |title=Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Of Cognitive Impairment in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS) |url=|journal=Scientific Reports |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=2157 |doi=10.1038/s41598-021-04764-w |pmc=8828740 |pmid=35140252|bibcode=2022NatSR..12.2157A }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Neurological]]/[[cognitive]] manifestations: Common occurrences include [[confusion]], [[forgetfulness]], mental fatigue/[[brain fog]], impairment of concentration and short-term memory consolidation, disorientation, difficulty with information processing, categorizing and word retrieval, and perceptual and sensory disturbances (e.g. spatial instability and disorientation and inability to focus vision), [[ataxia]] (unsteady and clumsy motion of the limbs or torso), muscle weakness and "twitches". There may also be cognitive or sensory overload (e.g. photophobia and hypersensitivity to noise and/or emotional overload, which may lead to "crash" periods and/or anxiety). A review of research relating to the neuropsychological functioning in CFS was published in 2001 and found that slowed processing speed, impaired working memory and poor learning of information are the most prominent features of cognitive dysfunctioning in patients with CFS, which couldn't be accounted solely by the severity of the depression and anxiety.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Michiels V, Cluydts R | title = Neuropsychological functioning in chronic fatigue syndrome: a review. | journal = Acta Psychiatr Scand | volume = 103 | issue = 2 | pages = 84-93 | year = 2001 | id = PMID 11167310}}</ref> |

|||

People with ME/CFS often experience [[orthostatic intolerance]], symptoms that start or worsen with standing or sitting. Symptoms, which include nausea, lightheadedness, and cognitive impairment, often improve again after lying down.<ref name="Bateman-2021" /> Weakness and vision changes may also be triggered by the upright posture.<ref name="CDCsym2024" /> Some have [[postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome]] (POTS), an excessive increase in [[heart rate]] after standing up, which can result in [[Syncope (medicine)|fainting]].<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|page=7}} Additionally, individuals may experience [[orthostatic hypotension]], a drop in blood pressure after standing.<ref name="BMJbest_practice3" />{{Rp|page=17}} |

|||

* [[Autonomic nervous system|Autonomic]] manifestations: Common occurrences include [[orthostatic intolerance]], neurally mediated [[hypotension]] (NMH), [[postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome]] (POTS), delayed postural [[hypotension]], [[lightheadedness]], extreme [[pallor]], [[nausea]] and [[irritable bowel syndrome]], urinary frequency and bladder dysfunction, [[palpitation]]s with or without [[cardiac arrhythmia]]s, and exertional [[dyspnea]] (perceived difficulty breathing or pain on breathing). |

|||

=== Other common symptoms === |

|||

* [[Neuroendocrine]] manifestations: Common occurrences include poor [[thermoregulation|temperature control]] or loss of thermostatic stability, subnormal body temperature and marked daily fluctuation, sweating episodes, recurrent feelings of feverishness and cold extremities, intolerance of extremes of heat and cold, digestive disturbances<ref>{{cite journal | author = Burnet RB, Chatterton BE | title = Gastric emptying is slow in chronic fatigue syndrome. | journal = BMC Gastroenterol | volume = 4 | pages = 32 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15619332 | doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-4-32}}</ref> and/or marked weight change - anorexia or abnormal appetite, loss of adaptability and worsening of symptoms with stress. |

|||

Pain and [[hyperalgesia]] (an abnormally increased sensitivity to pain) are common in ME/CFS. The pain is not accompanied by swelling or redness.<ref name="BMJbest_practice3" />{{Rp|page=16}} The pain can be present in muscles ([[myalgia]]) and [[arthralgia|joints]]. Individuals with ME/CFS may have chronic pain behind the eyes and in the neck, as well as [[neuropathic pain]] (related to disorders of the nervous system).<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|page=8}} Headaches and [[migraine]]s that were not present before the illness can occur as well. However, chronic daily headaches may indicate an alternative diagnosis.<ref name="BMJbest_practice3" />{{Rp|page=16}} |

|||

Additional common symptoms include [[irritable bowel syndrome]] or other problems with digestion, chills and [[night sweats]], [[shortness of breath]] or an [[Arrhythmia|irregular heartbeat]]. Some experience sore [[lymph node]]s and a sore throat. People may also develop allergies or become sensitive to foods, lights, noise, smells or chemicals.<ref name="CDCsym2024" /> |

|||

* [[Immune]] manifestations: Common occurrences include tender lymph nodes, recurrent sore throat, recurrent flu-like symptoms, general malaise, new sensitivities to food and/or medications and/or chemicals (which may complicate treatment). At least one study has confirmed that most CFS patients reduce or cease alcohol intake, mostly due to personal experience of worsening symptoms<ref>{{cite journal | author = Woolley J, Allen R, Wessely S | title = Alcohol use in chronic fatigue syndrome. | journal = J Psychosom Res | volume = 56 | issue = 2 | pages = 203-6 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15016579}}</ref> (although the cause of this is unknown and may not be strictly "immunological" as implied by the symptom list). |

|||

== Illness severity == |

|||

===Activity levels=== |

|||

ME/CFS often leads to serious disability, but the degree varies considerably.<ref name="CDC_Clinical2024">{{cite web |date=10 May 2024 |title=Clinical Overview of ME/CFS |url=https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/hcp/clinical-overview/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240517192407/https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/hcp/clinical-overview/ |archive-date=17 May 2024 |access-date=17 May 2024 |publisher=U.S. [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC)}}</ref> ME/CFS is generally classified into four categories of illness severity:<ref name="NICE2021"/>{{Rp|page=8}}<ref name="BMJbest_practice3">{{Cite book |url=https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/277 |title=BMJ Best Practice: Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (Chronic Fatigue Syndrome) |vauthors=Baraniuk JN, Marshall-Gradisnik S, Eaton-Fitch N |date=January 2024 |publisher=[[BMJ (company)|BMJ Publishing Group]] |access-date=19 January 2024 |url-access=subscription |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240219120522/https://auth.bmj.com/as/authorization.oauth2?response_type=code&client_id=bmj-bp-client-id&scope=openid%20profile%20bmj_access%20bmj_id&state=ENbX8qK-k7MG_rSrufgtPvjK66pOSygEI5Vm7b_AQQY%3D&redirect_uri=https://bestpractice.bmj.com/login/oauth2/code/bp-client&code_challenge_method=S256&nonce=drW8TQUhsuIuiLIEvrg4WXsMERFsV9emHb-7Yg-SYrQ&code_challenge=Hldf9BnRpXVwaG1wsQNJwmn_zWe8bfqpbf0uUZK8emA&template_name=UNKNOWN_USER&ip=207.241.225.241&acr_values=USER_LOGIN |archive-date=19 February 2024 |url-status=live}}</ref>{{Rp|page=10}} |

|||

Patients report critical reductions in levels of physical activity<ref name="PMID_8771284">{{cite journal | author = McCully KK, Sisto SA, Natelson BH | title = Use of exercise for treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. | journal = Sports Med | volume = 21 | issue = 1 | pages = 35-48 | year = 1996 | id = PMID 8771284}}</ref> and are as impaired as persons whose fatigue can be explained by another medical or a psychiatric condition.<ref name="PMID_14577835">{{cite journal | author = Solomon L, Nisenbaum R, Reyes M, Papanicolaou DA, Reeves WC | title = Functional status of persons with chronic fatigue syndrome in the Wichita, Kansas, population. | journal = Health Qual Life Outcomes | volume = 1 | issue = 1 | pages = 48 | year = 2003 | id = PMID 14577835 | url = http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=14577835}}</ref> According to the CDC, studies show that the disability in CFS patients is comparable to some well-known, very severe medical conditions, such as; [[multiple sclerosis]], [[AIDS]], [[lupus]], [[rheumatoid arthritis]], [[heart disease]], end-stage [[renal disease]], [[chronic obstructive pulmonary disease]] (COPD) and similar chronic conditions.<ref>[http://www.cdc.gov/od/oc/media/transcripts/t061103.htm?id=36410] Press Conference: The Chronic Fatigue and Immune Dysfunction Syndrome Association of America and The Centers For Disease Control and Prevention Press Conference at The National Press Club to Launch a Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Awareness Campaign - [[November 3]] [[2006]], 10 a.m. ET</ref><ref>[http://www.cdc.gov/cfs/cfssymptomsHCP.htm] The Centers For Disease Control and Prevention (website): Chronic Fatigue Syndrome > For Healthcare Professionals > Symptoms > Clinical Course</ref> The severity of symptoms and disability is the same in both genders<ref>{{cite journal | author = Ho-Yen DO, McNamara I | title = General practitioners' experience of the chronic fatigue syndrome | journal = Br J Gen Pract | volume = 41 | issue = 349 | pages = 324-6 | year = 1991 | id = PMID 1777276}}</ref>, and chronic pain is strongly disabling in CFS patients<ref name="PMID_16843021"> </ref>, but despite a common diagnosis the functional capacity of CFS patients varies greatly.<ref name="PMID_12783037">{{cite journal | author = Vanness JM, Snell CR, Strayer DR, Dempsey L 4th, Stevens SR | title = Subclassifying chronic fatigue syndrome through exercise testing. | journal = Med Sci Sports Exerc | volume = 35 | issue = 6 | pages = 908-13 | year = 2003 | id = PMID 12783037}}</ref> While some patients are able to lead a relatively normal life, others are totally bed-bound and unable to care for themselves. A systematic review found that in a synthesis of studies, 42% of patients were employed, 54% were unemployed, 64% reported CFS-related work limitations, 55% were on disability benefits or temporary sick leave, and 19% worked full-time.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Ross SD, Estok RP, Frame D, Stone LR, Ludensky V, Levine CB | title = Disability and chronic fatigue syndrome: a focus on function. | journal = Arch Intern Med | volume = 164 | issue = 10 | pages = 1098-107 | year = 2004 | id = PMID 15159267 | url = http://archinte.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/164/10/1098}}</ref> |

|||

* People with mild ME/CFS can usually still work and care for themselves, but they will need their free time to recover from these activities rather than engage in social and leisure activities. |

|||

* Moderate severity impedes [[activities of daily living]] (self-care activities, such as making a meal). People are usually unable to work and require frequent rest. |

|||

* Those with severe ME/CFS are homebound and can do only limited activities of daily living, for instance brushing their teeth. They may be wheelchair-dependent and spend the majority of their time in bed. |

|||

* With very severe ME/CFS, people are mostly bed-bound and cannot care for themselves. |

|||

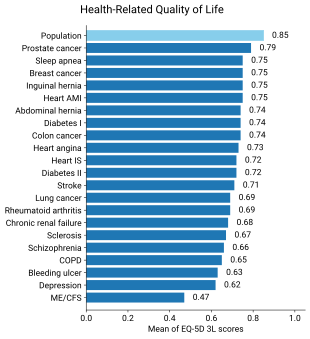

[[File:QoL comparison ME-CFS.svg|thumb|upright=1.4|Results of a study on the [[quality of life]] of individuals with ME/CFS, showing it to be lower than in 20 other chronic conditions|alt=A bar graph showing the average quality of life score of those with ME/CFS.]] |

|||

==Proposed causes and pathophysiology== |

|||

Roughly a quarter of those living with ME/CFS fall into the mild category, and half fall into the moderate or moderate-to-severe categories.<ref name="pmid37793728">{{cite journal |vauthors=Grach SL, Seltzer J, Chon TY, Ganesh R |date=October 2023 |title=Diagnosis and Management of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome |journal=Mayo Clinic Proceedings |volume=98 |issue=10 |pages=1544–1551 |doi=10.1016/j.mayocp.2023.07.032 |pmid=37793728 |s2cid=263665180 |doi-access=free}}</ref> The final quarter falls into the severe or very severe category.<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|3}} Severity may change over time. Symptoms might get worse, improve, or the illness may go into remission for a period of time.<ref name="CDC_Clinical2024"/> People who feel better for a period of time may overextend their activities, triggering PEM and a worsening of symptoms.<ref name="CDC_strategies2024"/> |

|||

The cause of CFS is unknown, although a large number of causes have been proposed. In a basic overview of CFS for health professionals, the CDC states that "''After more than 3,000 research studies, there is now abundant scientific evidence that CFS is a real physiological illness.''"<ref>[http://www.cdc.gov/cfs/pdf/Basic_Overview.pdf CDC - CFS Basic Overview] (PDF file, 31 KB)</ref> The cause of CFS may be different for different patients, but if so, the various causes may result in a common clinical outcome. |

|||

Those with severe and very severe ME/CFS experience more extreme and diverse symptoms. They may face severe weakness and greatly limited ability to move. They can lose the ability to speak, swallow, or communicate completely due to cognitive issues. They can further experience severe pain and hypersensitivities to touch, light, sound, and smells.<ref name="NICE2021"/>{{Rp|pages=50}} Minor day-to-day activities can be sufficient to trigger PEM.<ref name="Bateman-2021" /> |

|||

===Neurological abnormalities=== |

|||

Researchers have found evidence that CFS may involve distinct neurological abnormalities. [[MRI]] and [[SPECT]] scans show abnormalities within the brain.<ref name="pmid8141020">{{cite journal |author=Schwartz RB, Garada BM, Komaroff AL, ''et al'' |title=Detection of intracranial abnormalities in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: comparison of MR imaging and SPECT |journal=AJR. American journal of roentgenology |volume=162 |issue=4 |pages=935–41 |year=1994 |pmid=8141020 |doi=}}</ref> Studies have shown that CFS patients have abnormalities in blood flow to the brain<ref name="pmid9861623">{{cite journal |author=Abu-Judeh HH, Levine S, Kumar M, ''et al'' |title=Comparison of SPET brain perfusion and 18F-FDG brain metabolism in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=Nuclear medicine communications |volume=19 |issue=11 |pages=1065–71 |year=1998 |pmid=9861623 |doi=}}</ref> possibly indicative of viral cause<ref name="pmid8141022">{{cite journal |author=Schwartz RB, Komaroff AL, Garada BM, ''et al'' |title=SPECT imaging of the brain: comparison of findings in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, AIDS dementia complex, and major unipolar depression |journal=AJR. American journal of roentgenology |volume=162 |issue=4 |pages=943–51 |year=1994 |pmid=8141022 |doi=}}</ref> and similar but not identical compared to patients with clinical depression.<ref name="pmid10974961">{{cite journal |author=MacHale SM, Lawŕie SM, Cavanagh JT, ''et al'' |title=Cerebral perfusion in chronic fatigue syndrome and depression |journal=The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science |volume=176 |issue= |pages=550–6 |year=2000 |pmid=10974961 |doi=}}</ref><ref name="pmid9121617">{{cite journal |author=Fischler B, D'Haenen H, Cluydts R, ''et al'' |title=Comparison of 99m Tc HMPAO SPECT scan between chronic fatigue syndrome, major depression and healthy controls: an exploratory study of clinical correlates of regional cerebral blood flow |journal=Neuropsychobiology |volume=34 |issue=4 |pages=175–83 |year=1996 |pmid=9121617 |doi=}}</ref> |

|||

A number of studies have shown that CFS patients have abnormal levels of neurotransmitters including increased [[serotonin]]<ref name="pmid1282370">{{cite journal |author=Demitrack MA, Gold PW, Dale JK, Krahn DD, Kling MA, Straus SE |title=Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolism in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome: preliminary findings |journal=Biol. Psychiatry |volume=32 |issue=12 |pages=1065–77 |year=1992 |pmid=1282370 |doi=}}</ref><ref name="pmid15982993">{{cite journal |author=Badawy AA, Morgan CJ, Llewelyn MB, Albuquerque SR, Farmer A |title=Heterogeneity of serum tryptophan concentration and availability to the brain in patients with the chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) |volume=19 |issue=4 |pages=385–91 |year=2005 |pmid=15982993 |doi=10.1177/0269881105053293}}</ref> (the opposite of what is found in primary depression).<ref name="pmid8550954">{{cite journal |author=Cleare AJ, Bearn J, Allain T, ''et al'' |title=Contrasting neuroendocrine responses in depression and chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=Journal of affective disorders |volume=34 |issue=4 |pages=283–9 |year=1995 |pmid=8550954 |doi=}}</ref> Reduced brain serotonin receptor sensitivity or number,<ref name="pmid15691524">{{cite journal |author=Cleare AJ, Messa C, Rabiner EA, Grasby PM |title=Brain 5-HT1A receptor binding in chronic fatigue syndrome measured using positron emission tomography and [11C]WAY-100635 |journal=Biol. Psychiatry |volume=57 |issue=3 |pages=239–46 |year=2005 |pmid=15691524 |doi=10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.10.031}}</ref> and high auto antibodies to serotonin have also been found.<ref name="pmid9392689">{{cite journal |author=Klein R, Berg PA |title=High incidence of antibodies to 5-hydroxytryptamine, gangliosides and phospholipids in patients with chronic fatigue and fibromyalgia syndrome and their relatives: evidence for a clinical entity of both disorders |journal=Eur. J. Med. Res. |volume=1 |issue=1 |pages=21–6 |year=1995 |pmid=9392689 |doi=}}</ref> Recent studies found altered gene expression in the brain’s serotonin and sympathetic nervous system pathways,<ref name="pmid16610957">{{cite journal |author=Goertzel BN, Pennachin C, de Souza Coelho L, Gurbaxani B, Maloney EM, Jones JF |title=Combinations of single nucleotide polymorphisms in neuroendocrine effector and receptor genes predict chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=Pharmacogenomics |volume=7 |issue=3 |pages=475–83 |year=2006 |pmid=16610957 |doi=10.2217/14622416.7.3.475}}</ref> with altered responses of the HPA axis to serotonin.<ref name="pmid9226729">{{cite journal |author=Dinan TG, Majeed T, Lavelle E, Scott LV, Berti C, Behan P |title=Blunted serotonin-mediated activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=Psychoneuroendocrinology |volume=22 |issue=4 |pages=261–7 |year=1997 |pmid=9226729 |doi=}}</ref> Other reported neurotransmitter irregularities include [[glutamate]],<ref name="pmid12414265">{{cite journal |author=Kuratsune H, Yamaguti K, Lindh G, ''et al'' |title=Brain regions involved in fatigue sensation: reduced acetylcarnitine uptake into the brain |journal=Neuroimage |volume=17 |issue=3 |pages=1256–65 |year=2002 |pmid=12414265 |doi=}}</ref> [[acetylcholine]] sensitivity associated increased cutaneous microcirculation,<ref name="pmid15041034">{{cite journal |author=Spence VA, Khan F, Kennedy G, Abbot NC, Belch JJ |title=Acetylcholine mediated vasodilatation in the microcirculation of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids |volume=70 |issue=4 |pages=403–7 |year=2004 |pmid=15041034 |doi=10.1016/j.plefa.2003.12.016}}</ref> and autoantibodies to cholinergic receptors associated with central pain.<ref name="pmid12851722">{{cite journal |author=Tanaka S, Kuratsune H, Hidaka Y, ''et al'' |title=Autoantibodies against muscarinic cholinergic receptor in chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=Int. J. Mol. Med. |volume=12 |issue=2 |pages=225–30 |year=2003 |pmid=12851722 |doi=}}</ref> [[Beta-endorphin]], a natural pain killer, has been found to be low in CFS patients, the opposite of what is found in primary depression.<ref name="pmid9844768">{{cite journal |author=Conti F, Pittoni V, Sacerdote P, Priori R, Meroni PL, Valesini G |title=Decreased immunoreactive beta-endorphin in mononuclear leucocytes from patients with chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. |volume=16 |issue=6 |pages=729–32 |year=1998 |pmid=9844768 |doi=}}</ref><ref name="pmid12131069">{{cite journal |author=Panerai AE, Vecchiet J, Panzeri P, ''et al'' |title=Peripheral blood mononuclear cell beta-endorphin concentration is decreased in chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia but not in depression: preliminary report |journal=The Clinical journal of pain |volume=18 |issue=4 |pages=270–3 |year=2002 |pmid=12131069 |doi=}}</ref> |

|||

Individuals with ME/CFS have decreased quality of life when evaluated by the [[SF-36]] questionnaire, especially in the domains of physical and social functioning, general health, and vitality. However, their emotional functioning and mental health are not much lower than those of healthy individuals.<ref name="pmid28033311">{{cite journal |vauthors=Unger ER, Lin JS, Brimmer DJ, Lapp CW, Komaroff AL, Nath A, Laird S, Iskander J |date=December 2016 |title=CDC Grand Rounds: Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – Advancing Research and Clinical Education |url=https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/pdfs/mm655051a4.pdf |url-status=live |journal=MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report |volume=65 |issue=50–51 |pages=1434–1438 |doi=10.15585/mmwr.mm655051a4 |pmid=28033311 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170106010408/https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/pdfs/mm655051a4.pdf |archive-date=6 January 2017 |access-date=5 January 2017 |quote= |doi-access=free |title-link=doi}}</ref> Functional impairment in ME/CFS can be greater than [[multiple sclerosis]], [[Cardiovascular disease|heart disease]], or [[lung cancer]].<ref name="Bateman-2021" /> Fewer than half of people with ME/CFS are employed, and roughly one in five have a full-time job.<ref name="Lim2020" /> |

|||

;Dysautonomia |

|||

[[Dysautonomia]] is the disruption of the function of the [[autonomic nervous system]] (ANS). The ANS controls many aspects of [[homeostasis]]. The dysautonomia that evidences itself in CFS shows up mostly in problems of [[orthostatic intolerance]] - the inability to stand up without feeling dizzy, faint, nauseated, etc{{Fact|date=January 2008}}. Research into the orthostatic intolerance found in CFS indicates it is very similar to that found in [[postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome]] (POTS){{Fact|date=January 2008}}. POTS and CFS patients exhibit reduced blood flows to the heart upon standing that result in reduced blood flow to the brain. The reduced blood flows to the heart are believed to originate in blood pooling in the lower body upon standing. Many CFS patients report symptoms of orthostatic intolerance and low or lowered blood pressure.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Newton JL, Okonkwo O, Sutcliffe K, Seth A, Shin J, Jones DE |title=Symptoms of autonomic dysfunction in chronic fatigue syndrome |journal=QJM |volume=100 |issue=8 |pages=519-26 |year=2007 |pmid=17617647 |doi=10.1093/qjmed/hcm057}}</ref> |

|||

== Causes == |

|||

;Inner-ear disorders |

|||

The cause of ME/CFS is not yet known.<ref name="Bateman-2021" /> Between 60% and 80% of cases start after an infection, usually a viral infection.<ref name="BMJbest_practice3" />{{rp|5}}<ref name="pmid37793728" /> A genetic factor is believed to contribute, but there is no single gene known to be responsible for increased risk. Instead, many gene variants probably have a small individual effect, but their combined effect can be strong.<ref name="Dibble McGrath Ponting 2020 p." /> Other factors may include problems with the nervous and immune systems, as well as energy metabolism.<ref name="Bateman-2021" /> ME/CFS is a biological disease, not a psychological condition,<ref name="pmid28033311" /><ref name="CDC_Clinical2024" /> and is not due to [[deconditioning]].<ref name="pmid28033311" /><ref name="Bateman-2021" /> |

|||

{{main|balance disorder}} |

|||

Besides viruses, other reported triggers include stress, traumatic events, and environmental exposures such as to [[Mold|mould]].<ref name="IQWiG-2023" />{{Rp|page=21}} Bacterial infections such as [[Q fever|Q-fever]] are other potential triggers.<ref name="BMJbest_practice3" />{{rp|5}} ME/CFS may further occur after physical trauma, such as an accident or surgery.<ref name="CDC_Clinical2024" /> Pregnancy has been reported in around 3% to 10% of cases as a trigger.<ref name="pmid37234076">{{cite journal |vauthors=Pollack B, von Saltza E, McCorkell L, Santos L, Hultman A, Cohen AK, Soares L |date=2023 |title=Female Reproductive Health Impacts of Long COVID and Associated Illnesses Including ME/CFS, POTS, And Connective Tissue Disorders: A Literature Review |url=|journal=Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences |volume=4 |issue= |pages=1122673 |doi=10.3389/fresc.2023.1122673 |doi-access=free |pmc=10208411 |pmid=37234076}}</ref> ME/CFS can also begin with multiple minor triggering events, followed by a final trigger that leads to a clear onset of symptoms.<ref name="pmid37793728" /> |

|||

Problems such as [[Meniere's]], [[tumor]] in the inner ear, {{Fact|date=May 2007}} or [[Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo]] (BPPV) can cause dizziness, [[vertigo (medical)|vertigo]], and fatigue. Recurrent [[ear infection]]s are common in some CFS sufferers{{Fact|date=January 2008}}. [[Tinnitus]] is also quite common.<ref name="isbn0-9695662-0-4">{{cite book |author=Byron M. Hyde |title=The Clinical and scientific basis of myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome |publisher=Nightingale Research Foundation |location=Ogdensburg, N.Y |year=1992 |pages= |isbn=0-9695662-0-4 |oclc= |doi=}}</ref> Antibodies associated with hearing loss have been found in CFS and FMS patients with inner ear disorders <ref name="pmid9677490">{{cite journal |author=Heller U, Becker EW, Zenner HP, Berg PA |title=[Incidence and clinical relevance of antibodies to phospholipids, serotonin and ganglioside in patients with sudden deafness and progressive inner ear hearing loss] |language=German |journal=HNO |volume=46 |issue=6 |pages=583-6 |year=1998 |pmid=9677490 |doi=}}</ref> |

|||

=== Risk factors === |

|||

;Orthostatic hypotension |

|||

ME/CFS can affect people of all ages, ethnicities, and income levels, but it is more common in women than men.<ref name="Lim2020" /> People with a history of frequent infections are more likely to develop it.<ref name="pmid38443223" /> Those with family members who have ME/CFS are also at higher risk, suggesting a genetic factor.<ref name="Dibble McGrath Ponting 2020 p." /> In the United States, [[white Americans]] are diagnosed more frequently than other groups,<ref name="CDC_Basics">{{Cite web |date=10 May 2024 |title=ME/CFS Basics |url=https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/about/index.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240523214910/https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/about/index.html |archive-date=23 May 2024 |access-date=25 May 2024 |publisher=U.S. [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC) |language=en-us}}</ref> but the illness is probably at least as prevalent among African Americans and Hispanics.<ref name="CDCEpide2023">{{cite web |date=21 March 2023 |title=Epidemiology |url=https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/presentation-clinical-course/epidemiology.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240306031847/https://www.cdc.gov/me-cfs/healthcare-providers/presentation-clinical-course/epidemiology.html |archive-date=6 March 2024 |access-date=13 April 2024 |publisher=U.S. [[Centers for Disease Control and Prevention]] (CDC)}}</ref> It used to be thought that ME/CFS was more common among those with higher incomes. Instead, people in minority groups or lower income groups may have increased risks due to poorer nutrition, lower healthcare access, and increased work stress.<ref name="Lim2020" /> |

|||