Greater Khorasan: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Undid revision 1261386752 by 185.244.152.78 (talk) rvv |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Historical region of Greater Iran}} |

|||

[[Image:Friday Mosque in Herat, Afghanistan.jpg|350px|thumb|right|[[Friday mosque|"Masjid-i Jami"]] Mosque in [[Herat]], [[Afghanistan]], a city which was known in the past as the ''Pearl of Khorasan''.]]'''Greater Khorasan''' ({{PerB|خراسان بزرگ}}) (also written ''Khorasaan'', ''Khurasan'' and ''Khurasaan'') is a modern term for eastern territories of ancient [[Persia]] since the 3. century A.D.. ''Khorasan'' is a [[Pahlavi]] word which means ''"the land of sunrise"''. Greater Khorasan included territories that presently are part of [[Afghanistan]], [[Iran]], [[Tajikistan]], [[Turkmenistan]], and [[Uzbekistan]]. |

|||

{{About|the historical region comprising northeastern Iran, parts of Afghanistan and Central Asia|the Iranian province of Khorasan|Khorasan Province|other uses|Khorasan (disambiguation){{!}}Khorasan}} |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

|||

| name = Greater Khorasan |

|||

| native_name = {{lang|fa|خراسان بزرگ}} |

|||

| native_name_lang = fa |

|||

| other_name = |

|||

| settlement_type = [[Region]] |

|||

| image_caption = |

|||

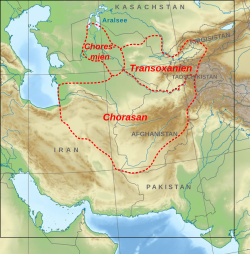

| image_map = Chorasan-Transoxanien-Choresmien neu.svg |

|||

| map_caption = Greater Khorasan (Chorasan) and neighbouring historical regions |

|||

| population_demonym = Khorasanian |

|||

| subdivision_type = [[List of sovereign states|Countries in Khorasan]] |

|||

| subdivision_name = [[Afghanistan]], [[Iran]] and [[Turkmenistan]].<ref>Sistan and Khorasan Travelogue Page 48</ref> Different regions of [[Tajikistan]], [[Uzbekistan]], [[Kyrgyzstan]] and [[Kazakhstan]] are also included in different sources. |

|||

| demographics_type1 = Ethnicities: |

|||

| demographics1_title1 = [[Iranian people|Iranian and Khorasani people]] and including [[Tajiks]], [[Kermanj|Kurds of Kermanj]], [[Turkish Khorasani|Turks]], [[Hazaras]], [[Turkmen]], [[Baluchis]], [[Zoroastrians]] and [[Pashtuns]] |

|||

| image_skyline = |

|||

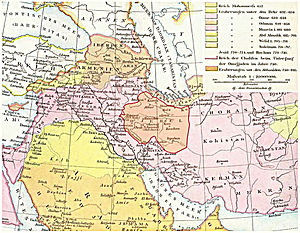

| image_map1 = Transoxiana 8th century.svg |

|||

| map_caption1 = Map of Khorasan and its surroundings in the 7th/8th centuries |

|||

| demographics1_footnotes = Persians, Tajiks, Farsiwans, Turkmens, Uzbeks, Pashtuns, Hazaras |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Greater Khorasan'''<ref name="Dabeersiaghi">Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236</ref> ({{langx|pal|𐬒𐬊𐬭𐬀𐬯𐬀𐬥|Xwarāsān}}; {{langx|fa|خراسان}}, {{IPA|fa|xoɾɒːˈsɒːn||Khorasan pronounce.ogg}}) is a historical eastern region in the [[Iranian Plateau]] in [[West Asia|West]] and [[Central Asia]] that encompasses western and northern [[Afghanistan]], northeastern [[Iran]], the eastern halves of [[Turkmenistan]] and [[Uzbekistan]], western [[Tajikistan]], and portions of [[Kyrgyzstan]] and [[Kazakhstan]]. |

|||

The extent of the region referred to as ''Khorasan'' varied over time. In its stricter historical sense, it comprised the present territories of [[Khorasan Province|northeastern Iran]], parts of [[Afghanistan]] and southern parts of [[Central Asia]], extending as far as the [[Amu Darya]] (Oxus) river. However, the name has often been used in a loose sense to include a wider region that included most of [[Transoxiana]] (encompassing [[Bukhara]] and [[Samarqand]] in present-day [[Uzbekistan]]),<ref name="Minorsky" /> extended westward to the [[Caspian Sea|Caspian]] coast<ref name="Britannica">{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/316850/Khorasan |title=Khorasan |quote=historical region and realm comprising a vast territory now lying in northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, and northern Afghanistan. The historical region extended, along the north, from the Amu Darya westward to the [[Caspian Sea]] and, along the south, from the fringes of the central Iranian deserts eastward to the [[Hindu Kush|mountains of central Afghanistan]]. Arab geographers even spoke of its extending to the boundaries of [[Hindustan|India]]. |encyclopedia=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]] Online |access-date=2010-10-21}}</ref> and to the [[Dasht-e Kavir]]<ref name="lambton">{{Cite book|title=Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia: Aspects of Administrative, Economic and Social History, 11th–14th Century|last=Lambton|first=Ann K.S.|publisher=Bibliotheca Persica|year=1988|location=New York, NY|series=Columbia Lectures on Iranian Studies|page=404|quote=In the early centuries of Islam, Khurasan generally included all the Muslim provinces east of the [[Dasht-e Kavir|Great Desert]]. In this larger sense, it included Transoxiana, Sijistan and Quhistan. Its Central Asian boundary was the [[Taklamakan Desert|Chinese desert]] and the Pamirs, while its Indian boundary lay along the Hindu Kush toward India.}}</ref> southward to [[Sistan]],<ref name="bosworth-eoi">{{cite book|last1=Bosworth|first1=C.E.|title=Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 5, Khe – Mahi |date=1986|publisher=Brill [u.a.]|location=Leiden [u.a.]|isbn=90-04-07819-3|pages=55–59|edition=New}}</ref><ref name="lambton" /> and eastward to the [[Pamir Mountains]].<ref name="lambton" /><ref name="Britannica" /> ''Greater Khorasan'' is today sometimes used to distinguish the larger historical region from the former [[Khorasan Province]] of [[Iran]] (1906–2004), which roughly encompassed the western portion of the historical Greater Khorasan.<ref name="Dabeersiaghi" /> |

|||

Greater Khorasan contained mostly [[Nishapur]] and [[Tus]] (now in Iran), [[Herat]], [[Balkh]], [[Kabul]] and [[Ghazni]] (now in Afghanistan), [[Merv]] and [[Sanjan (Khorasan)|Sanjan]] (now in Turkmenistan), [[Samarqand]] and [[Bukhara]] (both now in [[Uzbekistan]]), [[Khujand]] and [[Panjakent]] (now in Tajikistan). |

|||

The name ''Khorāsān'' is [[Persian language|Persian]] (from [[Middle Persian]] ''Xwarāsān'', sp. ''xwlʾsʾn''', meaning "where the sun arrives from" or "the Eastern Province").<ref name="Sykes">Sykes, M. (1914). "Khorasan: The Eastern Province of Persia". ''Journal of the Royal Society of Arts'', 62(3196), 279–286.</ref><ref name=":1">A compound of ''khwar'' (meaning "sun") and ''āsān'' (from ''āyān'', literally meaning "to come" or "coming" or "about to come"). Thus the name ''Khorasan'' (or ''Khorāyān'' {{lang|fa|خورآيان|rtl=yes}}) means "sunrise", viz. "[[wiktionary:Orient|Orient]], East". |

|||

These days, the adjective ''greater'' is partly used to distinguish it from [[khorasan|Khorasan province]], in modern-day [[Iran]], that forms western parts of these territories, roughly half in area <ref>Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235-236</ref>. It is also used to indicate that Greater Khorasan encompasses territories that were perhaps called by some other popular name when they were individually referred to. For example [[Transoxiana]] (covered Uzbekistan and Tajikistan), [[Bactria]], [[Kabulistan]] |

|||

[http://www.ilssw.com/pages.php?id=10&cat=art Humbach, Helmut, and Djelani Davari, "Nāmé Xorāsān"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110102132819/http://ilssw.com/pages.php?id=10&cat=art|date=2011-01-02}}, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz; Persian translation by Djelani Davari, published in Iranian Languages Studies Website. |

|||

<ref name="kabulistan"> For example refer to Shahname. e.g. So happy became the king of Kabulistan from the marriage of the sun of Zabulistan [http://rira.ir/rira/php/?page=view&mod=classicpoems&obj=poem&id=15389&q=%DA%A9%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%A7%D9%86] |

|||

MacKenzie, D. (1971). ''A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary'' (p. 95). London: Oxford University Press. |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The Persian word ''Khāvar-zamīn'' ({{langx|fa|خاور زمین}}), meaning "the eastern land", has also been used as an equivalent term. [http://www.loghatnaameh.com/dehkhodaworddetail-cbe368c6fbcf43b68107af29bc35fb45-fa.html DehKhoda, "Lughat Nameh DehKhoda"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110718162055/http://www.loghatnaameh.com/dehkhodaworddetail-cbe368c6fbcf43b68107af29bc35fb45-fa.html|date=2011-07-18}}</ref> The name was first given to the eastern province of [[Ancient Persia|Persia (Ancient Iran)]] during the [[Sasanian Empire]]<ref name="EncyclopediaBritannica">{{cite web|title=Khorāsān|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Khorasan-historical-region-Asia|access-date=8 December 2018|website=britannica.com|publisher=Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.}}</ref> and was used from the late [[Middle Ages]] in distinction to neighbouring Transoxiana.<ref>Svat Soucek, [https://books.google.com/books?id=7E8gYYcHuk8C ''A History of Inner Asia''], [[Cambridge University|Cambridge University Press]], 2000, p.4</ref><ref>C. Edmund Bosworth, (2002), [http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/central-asia-iv 'Central Asia iv. In the Islamic Period up to the Mongols'] ''Encyclopaedia Iranica'' (online)</ref><ref>C. Edmund Bosworth, (2011), [http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/mawara-al-nahr 'Mā Warāʾ Al-Nahr'] ''Encyclopaedia Iranica'' (online)</ref> The Sassanian name ''Xwarāsān'' has in turn been argued to be a [[calque]] of the [[Bactrian language|Bactrian]] name of the region, ''Miirosan'' (Bactrian spelling: μιιροσανο,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rezakhani |first=Khodadad |date=2019-01-01 |title=Miirosan to Khurasan: Huns, Alkhans, and the Creation of East Iran |url=https://www.academia.edu/41991581 |journal=Vicino Oriente|volume=23 |pages=121–138 |doi=10.53131/VO2724-587X2019_9 |doi-access=free }}</ref> μιροσανο, earlier μιυροασανο), which had the same meaning 'sunrise, east' (corresponding to a hypothetical Proto-Iranian form ''*miθrāsāna'';<ref>Gholami, Saloumeh (2010), Selected Features of Bactrian Grammar (PhD thesis), University of Göttingen, p.25, 59</ref> see [[Mithra]], Bactrian μιυρο [mihr],<ref>Sims-Williams, N. "Bactrian Language". Encyclopaedia Iranica.</ref> for the relevant [[solar deity]]). The province was often subdivided into four quarters, such that [[Nishapur]] (present-day Iran), [[Merv|Marv]] (present-day [[Turkmenistan]]), [[Herat]] and [[Balkh]] (present-day Afghanistan) were the centers, respectively, of the westernmost, northernmost, central, and easternmost quarters.<ref name="Minorsky">Minorsky, V. (1938). "Geographical Factors in Persian Art". ''Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies'', University of London, 9(3), 621–652.</ref> |

|||

, [[Khwarezm]] (containing Samarkand and Bukhara) |

|||

<ref name="anvari"> or refer to Anvari Qasida in which he refers to Samarqand as Turan and complains about devastation in Khorasan (and more generally Iran) caused by Ghuz Turks. [http://rira.ir/rira/php/?page=view&mod=classicpoems&obj=poem&id=16813&q=%D8%A8%D9%87+%D8%B3%D9%85%D8%B1%D9%82%D9%86%D8%AF+%D8%A7%DA%AF%D8%B1+%D8%A8%DA%AF%D8%B0%D8%B1%DB%8C+%D8%A7%DB%8C+%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AF+%D8%B3%D8%AD%D8%B1] </ref> . |

|||

Khorasan was first established as an [[administrative division]] in the 6th century (approximately after 520) by the [[House of Sasan|Sasanians]], during the reign of [[Kavad I]] ({{reign|488|496|498/9|531}}) or [[Khosrow I]] ({{reign|531|579}}),<ref name="schindel">{{cite encyclopedia|title=Kawād I i. Reign|last=Schindel|first=Nikolaus|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kawad-i-reign|encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XVI, Fasc. 2|pages=136–141|year=2013a}}</ref> and comprised the eastern and northeastern parts of the empire. The use of Bactrian ''Miirosan'' 'the east' as an administrative designation under [[Alchon Huns|Alkhan]] rulers in the same region is possibly the forerunner of the Sasanian administrative division of Khurasan,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Rezakhani |first=Khodadad |date=2019-01-01 |title=Miirosan to Khurasan: Huns, Alkhans, and the Creation of East Iran |url=https://www.academia.edu/41991581 |journal=Vicino Oriente|volume=23 |pages=121–138 |doi=10.53131/VO2724-587X2019_9 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Rezakhani |first=Khodadad |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bjRWDwAAQBAJ&dq=orienting+sasanians+rezakhani&pg=PR1 |title=ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity |date=2017-03-15 |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |isbn=978-1-4744-0030-5 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Vondrovec |first=Klaus |url=https://www.academia.edu/8468582 |title=Coinage of the Iranian Huns and their Successors from Bactria to Ganhara (4th to 8th century CE) |date=2014 |isbn=978-3-7001-7695-4}}</ref> occurring after their takeover of [[Hephthalites|Hephthalite]] territories south of the Oxus. The transformation of the term and its identification with a larger region is thus a development of the late Sasanian and early Islamic periods. [[Muslim conquest of Persia|Early Islamic]] usage often regarded everywhere east of [[Jibal]] or what was subsequently termed [[Persian Iraq|Iraq Ajami (Persian Iraq)]], as being included in a vast and loosely defined region of Khorasan, which might even extend to the [[Indus Valley]] and the Pamir Mountains. The boundary between these two was the region surrounding the cities of [[Gurgan]] and [[Qumis, Iran|Qumis]]. In particular, the [[Ghaznavids]], [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuqs]] and [[Timurid dynasty|Timurids]] divided their empires into Iraqi and Khorasani regions. Khorasan is believed to have been bounded in the southwest by desert and the town of [[Tabas]], known as "the Gate of Khorasan",<ref>Sykes, P. (1906). A Fifth Journey in Persia (Continued). The Geographical Journal, 28(6), 560–587.</ref>{{rp|562}} from which it extended eastward to the [[Hindu Kush|mountains of central Afghanistan]].<ref name="Britannica" /><ref name="lambton" /> Sources from the 10th century onwards refer to areas in the south of the [[Hindu Kush]] as the Khorasan Marches, forming a [[frontier]] region between Khorasan and [[Hindustan]].<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Hudud al-'Alam, The Regions of the World: A Persian Geography, 372 A.H. – 982 A.D.|last=Minorsky|first=V.|publisher=Oxford UP|year=1937|location=London}}</ref><ref name="Baburnama" /> |

|||

Until the devastating [[Mongol]] invasion of the thirteenth century, Khorasan was considered the cultural capital of Persia. (Lorentz 1995) |

|||

== Geography == |

|||

==Geographical Distribution== |

|||

{{Main|Greater Iran}} |

|||

[[Image:Califate 750.jpg|thumb|300px|Names of territories during the [[Caliphate]], Khorasan was part of Persia (in yellow).]] |

|||

First established in the 6th century as one of four administrative (military) divisions by the [[Sasanian Empire]],<ref>{{Cite book|title=Reorienting the Sassanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity|last=Rezakhani|first=K.|publisher=Edinburgh University Press|year=2017|isbn=978-1-4744-0029-9|location=Edinburgh}}</ref> the scope of the region has varied considerably during its nearly 1,500-year history. Initially, the Khorasan division of the Sasanian Empire covered the northeastern military gains of the empire, at its height including cities such as [[Nishapur]], [[Herat]], [[Merv]], [[Faryab Province|Faryab]], [[Taloqan]], [[Balkh]], [[Bukhara]], [[Badghis Province|Badghis]], [[Abiward]], [[Gharjistan]], [[Tus, Iran|Tus]] and [[Sarakhs]].<ref name="bosworth-eoi" /> |

|||

According to Mir Ghulam Mohammad, Afghanistan's current territories formed the major part of Khorasan<ref>Ghubar, Mir Ghulam Mohammad, ''Khorasan'', 1937 Kabul Printing House, Kabul, Afghanistan</ref><!--<ref>''Tajikistan Development Gateway'' from [http://www.developmentgateway.org/aboutus The Development Gateway Foundation] - History of Afghanistan [http://www.tajik-gateway.org/index.phtml?lang=en&id=1005 LINK]</ref>--> while other sources say otherwise. According to these latter sources, Khorasan province of Iran roughly comprises half of Greater Khorasan.<ref>Dabeersiaghi, "Commentary", Nâseer khusraw, Safarnâma, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr:1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235-236</ref> Khorasan's boundaries have varied greatly during ages. The term was loosely applied to all territories of Persia that lay east and north east of [[Dasht-e Kavir]] and therefore were subjected to change as the size of empire changed. |

|||

With the rise of the [[Umayyad Caliphate]], the designation was inherited and likewise stretched as far as their military gains in the east, starting off with the military installations at [[Nishapur]] and [[Merv]], slowly expanding eastwards into [[Tukharistan|Tokharistan]] and [[Sogdia]]. Under the [[Caliphate|Caliphs]], Khorasan was the name of one of the three political zones under their dominion (the other two being ''Eraq-e Arab'' "Arabic Iraq" and ''Eraq-e Ajam'' "Non-Arabic Iraq or Persian Iraq").{{Cn|date=September 2023}} Under the [[Umayyad Caliphate|Umayyad]] and [[Abbasid Caliphate|Abbasid]] caliphates, Khorasan was divided into four major sections or quarters (''rub′''), each section based on a single major city: Nishapur, Merv, Herat and Balkh.<ref>[http://www.loghatnaameh.com/dehkhodaworddetail-cbe368c6fbcf43b68107af29bc35fb45-fa.html DehKhoda, "Lughat Nameh DehKhoda"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110718162055/http://www.loghatnaameh.com/dehkhodaworddetail-cbe368c6fbcf43b68107af29bc35fb45-fa.html |date=2011-07-18 }}</ref> By the 10th century, [[Ibn Khordadbeh]] and the [[Hudud al-'Alam]] mentions what roughly encompasses the previous regions of [[Abarshahr]], Tokharistan and Sogdia as ''Khwarasan'' proper. They further report the southern part of the Hindu Kush, i.e. the regions of [[Sistan]], [[Rukhkhaj|Rukhkhudh]], [[Zabulistan]] and [[Kabul]] etc. to make up the ''Khorasan'' ''marches'', a frontier region between Khorasan and [[Hindustan]].<ref name="cgie-khurasan" /><ref name=":0" /><ref name="lambton" />[[File:Map of Afghanistan during the Safavid and Moghul Empire.jpg|300px|thumb|A map of Persia by [[Emanuel Bowen]] showing the names of territories during the Persian [[Safavid dynasty]] and [[Mughal Empire]] of India ({{circa}} 1500–1747)]]By the late Middle Ages, the term lost its administrative significance, in the west only being loosely applied among the Turko-Persian dynasties of modern Iran to all its territories that lay east and north-east of the [[Dasht-e Kavir]] desert. It was therefore subjected to constant change, as the size of their empires changed. In the east, ''Khwarasan'' likewise became a term associated with the great urban centers of Central Asia. It is mentioned in the [[Baburnama|Memoirs of Babur]] (from the 1580s) that: |

|||

In the [[Middle Ages]], ''[[Persian Iraq]]'' and ''Khorasan'' were the two most important parts of the territory of [[Greater Iran]]. The dividing region between these two was mostly along with [[Gurgan]] and [[Damghan|Damaghan]] cities. Especially the [[Ghaznavid Empire|Ghaznavids]], [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuqs]] and [[Timurid dynasty|Timurids]], divided their Empire to Iraqi and Khorasani regions. This point can be observed in many books such as ''"Tārīkhi Bayhaqī"'' of [[Abolfazl Beyhaqi|Abul Fazl Bayhqi]], ''Faza'ilul al-anam min rasa'ili hujjat al-Islam'' (a collection of letters of [[Al-Ghazali]]) and other books. |

|||

{{bquote| The people of Hindustān call every country beyond their own Khorasān, in the same manner as the Arabs term all except Arabia, [[Ajam|Ajem]]. On the road between Hindustān and Khorasān, there are two great marts: the one Kābul, the other [[Kandahar|Kandahār]]. Caravans, from Ferghāna, Tūrkestān, Samarkand, Balkh, Bokhāra, Hissār, and [[Badakhshān]], all resort to Kābul; while those from Khorasān repair to [[Kandahar Province|Kandahār]]. This country lies between Hindustān and Khorasān.<ref name="Baburnama">{{Cite web |url=http://persian.packhum.org/persian//pf?file=03501051&ct=91 |title=Events of the Year 910 |author=Zahir ud-Din Mohammad Babur |work=[[Baburnama|Memoirs of Babur]] |translator=John Leyden |translator2=William Erskine |publisher=[[Packard Humanities Institute]] |year=1921 |access-date=2010-08-22 |author-link=Babur |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121114042117/http://persian.packhum.org/persian//pf?file=03501051&ct=91 |archive-date=2012-11-14 |url-status=dead }}</ref>}} |

|||

In modern times, the term has been source of great nostalgia and nationalism, especially amongst the [[Tajiks]] of Central Asia.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} Many Tajiks regard Khorasan as an integral part of their national identity, which has preserved an interest in the term, including its meaning and cultural significance, both in common discussion and academia, despite its falling out of political use in the region.<ref>Шакурӣ, Муҳаммадҷон (1996; 2005). Хуросон аст инҷо, Dushanbe; Shakūrī, Muḥammad (1393), Khurāsān ast īn jā, Tehran: Fartāb; </ref> |

|||

Ghulam Mohammad Ghubar, an ethnic [[Tajik]] scholar and historian from Afghanistan, talks of '''''Proper Khorasan''''' and '''''Improper Khorasan''''' in his book titled "Khorasan"<ref>Ghubar, Mir Ghulam Mohammad, ''Khorasan'', 1937 Kabul Printing House, Kabul, Afghanistan</ref>. According to him, Proper Khorasan contained regions lying between Balkh (in the East), Merv (in the North), [[Sistan|Sijistan]] (in the South), Nishapur (in the West) and Herat, known as ''The Pearl of Khorasan'', in the center. While Improper Khorasan's boundaries extended to Kabul and Ghazni in the East, [[Sistan]] and [[Zabulistan]] in the South, Transoxiana and Khwarezm in the North and [[Damghan|Damaghan]] and [[Gorgan|Gurgan]] in the West. |

|||

According to Afghan historian [[Ghulam Mohammad Ghobar]] (1897–1978), Afghanistan's current Persian-speaking territories formed the major portion of Khorasān,<ref name="ghubar">[[Ghulam Mohammad Ghobar|Ghubar, Mir Ghulam Mohammad]] (1937). ''Khorasan'', Kabul Printing House. [[Kabul]], Afghanistan.</ref> as two of the four main capitals of Khorasān (Herat and Balkh) are now located in Afghanistan. Ghobar uses the terms ''"Proper Khorasan"'' and "''Improper Khorasan"'' in his book to distinguish between the usage of Khorasān in its strict sense and its usage in a loose sense. According to him, Proper Khorasan contained regions lying between Balkh in the east, Merv in the north, [[Sistan]] in the south, Nishapur in the west and Herat, known as the ''Pearl of Khorasan'', in the center. Improper Khorasan's boundaries extended to as far as [[Hazarajat]] and [[Kabul]] in the east, [[Baluchistan]] in the south, Transoxiana and Khwarezm in the north, and [[Damghan]] and [[Gorgan]] in the west.<ref name="ghubar" />[[File:Ancient Khorasan highlighted.jpg|thumb|300px|Names of territories during the [[Abbasid Caliphate|Caliphate]] in 750]] |

|||

== History == |

|||

In [[Baburnama|Memoirs of Babur]], it is mentioned that Indians called non-Hindustanis (non-Indians) as Khorasanis. Regarding the boundary of [[Hindustan]] and Khorasan, it is written: ''"On the road between Hindustān and Khorasān, there are two great marts: the one Kābul, the other Kandahār."'' [http://persian.packhum.org/persian/index.jsp?serv=pf&rqs=527&rqs=536&rqs=550&rqs=554&rqs=559&file=03501051&ct=91 1] Thus, Improper Khorasan bordered Hindustan (old [[India]]). |

|||

{{See also|History of Afghanistan|History of Iran|History of Tajikistan|History of Turkmenistan|History of Uzbekistan}}[[File:Lagekarte Dschibal.jpg|thumb|300px|An 1886 map of the 10th century [[Near East]] showing Khorasan east of the province of [[Jibal]].]] |

|||

=== Ancient era === |

|||

==Historical overview== |

|||

During the Sasanian era, likely in the reign of [[Khusrow I]], Persia was divided into four regions (known as ''kust'' Middle Persian), [[Khwārvarān]] in the west, apāxtar in the north, nīmrūz in the south and Khorasan in the east. Since the Sasanian territories were more or less remained stable up to Islamic conquests, it can be concluded that Sasanian Khorasan was bordered to the south by Sistan and Kerman, to the west by the central deserts of modern Iran, and to the east by China and India.<ref name="cgie-khurasan">{{cite web|last1=Authors|first1=Multiple|title=Khurasan|url=http://www.cgie.org.ir/fa/publication/entryview/40659|publisher=[[CGIE]]|access-date=9 March 2017}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Madan Turquoise Mines.jpg|thumb|300px|An early [[turquoise]] mine in the Madan village of Khorasan.]] |

|||

Greater Khorasan is one of the regions of [[Greater Iran]]. Before being conquered by [[Alexander the Great]] in 330 BC, it was part of the [[Achaemenid dynasty|Achaemenid]] [[Persian Empire]]. In 1st century AD, the eastern regions of greater Khorasan fell into the hands of the [[Kushan empire]]. The Kushans introduced Buddhist culture to these regions, as numerous Kushanian temples and buried cities with treasures in the northern and central areas of Khurasan (nowadays mainly Afghanistan) have been found. However the western parts of Greater Khorasan remained predominantly Zoroastrian as one of the three great fire-temples of the Sassanids "Azar-burzin Mehr" is situated in the western regions of Khorasan, near Sabzevar in Iran. The boundary was pushed to the west towards the Persian Empire by the Kushans. The boundary kept changing until the demise of the [[Kushan Empire]] where [[Sassanid dynasty|Sassanids]] took control of the entire region. In [[Sassanid empire|Sassanid]] era, [[Persian empire]] was divided into four quarters, "Xwawaran" meaning ''west'', apAxtar meaning ''north'', Nīmrūz meaning ''south'' and Xurasan (Khorasan) meaning ''east''. The Eastern regions saw some conflict with [[Hephthalite]]s, but the borders remained much stable afterwards until the Muslim invasion. |

|||

In the Sasanian era, Khorasan was further divided into four smaller regions, and each region was ruled by a [[marzban]]. These four regions were Nishapur, Marv, Herat and Balkh.<ref name="cgie-khurasan" /> |

|||

Being the eastern parts of the [[Sassanid empire]] and further away from Arabia, Khorasan quarter was conquered in the later stages of Muslim invasions. In fact the last Sassanid king of Persia, Yazdgerd III, moved the throne to Khorasan following the Arab invasion in the western parts of the empire. After the assassination of the king, Khorasan was conquered by the Islamic troops in 647. Like other provinces of Persia it became one of the provinces of [[Umayyad|Umayad dynasty]]. |

|||

[[Image:Meyamei.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The village of Meyamei.]] |

|||

The first liberal movement against the Arab invasions was led by [[Abu Muslim Khorasani]] between 747 and 750. He helped the [[Abbasid]]s come to power but was later killed by Al-Mansur, an Abbasid Caliph. The first independent kingdom from Arab rule was established in Khorasan by [[Tahir ibn Husayn|Tahir Phoshanji]] in 821. But it seems that it was more a matter of political and territorial gain. In fact Tahir had helped the Caliph subdue other nationalistic movements in other parts of Persia such as [[Maziar]]'s movement in [[Tabaristan]]. |

|||

<!-- Deleted image removed: [[Image:Map of Timurids Empire and region of Khorasan.JPG|thumb|right|300px|Map of the [[Timurid Dynasty]] in 15th century. The regions of Khorasan are apparently displayed.]] --> |

|||

[[File:Madan Turquoise Mines.jpg|thumb|An early [[turquoise]] mine in the [[Madan-e Olya|Madan]] village of Khorasan during the early 20th century]] |

|||

The first dynasty in Khorasan, after the introduction of Islam, whose rulers considered themselves [[Iranian people|Iranian]] was the [[Saffarid dynasty]] (861-1003)<ref> Roudaki calls Saffari Amir as the "Glory of Iran" [http://rira.ir/rira/php/?page=view&mod=classicpoems&obj=poem&id=2955&lim=20&pageno=4&q=%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86]</ref>. Other grand Iranian dynasties were [[Samanid]]s<ref> Samanid's traced their ancestry to Saman Khuda who claimed to ba a descendant of Bahram Chubin a famous Persian army general during Sassanid time.</ref> (875-999), [[Ghaznavid Empire|Ghaznavids]]<ref>For example Farrokhi Sistani calls Sultan Mahmoud Ghaznavi "the king of Iran" [http://rira.ir/rira/php/?page=search&mod=classicpoems&obj=part&id=103&q=%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86] |

|||

</ref> (962-1187), [[Ghurids]] (1149-1212), [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljukids]] (1037-1194), [[Khwarezmian Empire|Khwarezmids]] (1077-1231) and [[Timurid Dynasty|Timurids]] (1370-1506). It should be mentioned that some of these dynasties were not Persian by ethnicity, nonetheless they were the advocates of [[Persian language]] and were praised by the poets as the kings of [[Greater Iran|Iran]]. |

|||

Khorasan in the east saw some conflict with the [[Hephthalite]]s who became the new rulers in the area but the borders remained stable. Being the eastern parts of the Sassanids and further away from [[Arabia]], Khorasan region was conquered after the remaining Persia.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} The last Sassanid king of Persia, [[Yazdgerd III]], moved the throne to Khorasan following the Arab invasion in the western parts of the empire. After the assassination of the king, Khorasan was conquered by Arab Muslims in 647 AD. Like other provinces of Persia it became a province of the [[Umayyad Caliphate]].<ref>The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch:17 ISBN 0-19-597713-0</ref> |

|||

Among them, the periods of [[Ghaznavid Empire|Ghaznavids]] of [[Ghazni]] and [[Timurid Dynasty|Timurids]] of [[Herat]] are considered as one of the most brilliant eras of Khorasan's history. During these periods, there was a great cultural awakening. Many famous Persian poets, scientists and scholars lived in this period. Numerous valuable works in [[Persian literature]] were written. [[Nishapur]], [[Herat]], [[Ghazni]] and [[Merv]] were the centers of all these cultural developments. |

|||

Most of the Khorasani regions were then parts of the [[Mughal Empire|Moghul Empire]] between 1506 and 1707. For Moghuls, Khorasan was always a region with great importance. |

|||

=== Medieval era === |

|||

==Khurasan in the [[Hadith]]s and prophecies of Mohammad== |

|||

{{See|Rashidun Caliphate|Umayyad Caliphate|Abbasid Caliphate|Anarchy at Samarra}} |

|||

The prophet of [[Islam]], [[Muhammad]], mentioned the country Khurasan many times concerned to the Islamic/divine prophecies over the future. |

|||

{{Expand section|date=October 2020}} |

|||

The first movement against the Arab conquest was led by [[Abu Muslim Khorasani]] between 747 and 750. Originally from [[Isfahan]], scholars believe Abu Muslim was probably Persian. It's possible he may have been born a slave. According to the ancient Persian historian [[Al-Shahrastani]], he was a [[Kaysanites|Kaysanite]]. This revolutionary [[Shi'a]] movement rejected the three Caliphs that had preceded [[Ali]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Glassé |first=Cyril |title=The new encyclopedia of Islam |year=2008 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=D7tu12gt4JYC&pg=PA22 |page=21|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=9780742562967 }}</ref> |

|||

Abu Muslim helped the [[Abbasid]]s come to power but was later killed by Al-Mansur, an Abbasid Caliph.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} The first kingdom independent from Arab rule was established in Khorasan by [[Tahir ibn Husayn|Tahir Phoshanji]] in 821, but it seems that it was more a matter of political and territorial gain. Tahir had helped the Caliph subdue other nationalistic movements in other parts of Persia such as [[Mazyar|Maziar]]'s movement in [[Tabaristan]].<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://www.degruyter.com/view/product/210634|title=Greater Khorasan History, Geography, Archaeology and Material Culture|editor1-first=Rocco|editor1-last=Rante|date=22 January 2020|publisher=De Gruyter|isbn=978-3-11-033155-4|location=Berlin, Boston|language=en|doi=10.1515/9783110331707}}</ref> |

|||

''In the country Khurasan in [[Taloqan|Taluqan]] (northern Afghanistan) that at that place are treasures of [[Allah]], but these are not of [[gold]] and [[silver]] but consist of people who have recognised Allah as they should have.'' (Al-Muttaqi al-Hindi, Al-Burhan fi Alamat al-Mahdi Akhir al-zaman, p.59) |

|||

Other major independent dynasties who ruled over Khorasan were the [[Saffarid dynasty|Saffarids]] from [[Zaranj]] (861–1003), [[Samanids]] from [[Bukhara]] (875–999), [[Ghaznavids]] from [[Ghazni]] (963–1167), [[Seljuq dynasty|Seljuqs]] (1037–1194), [[Khwarezmian Empire|Khwarezmids]] (1077–1231), [[Ghurid dynasty|Ghurids]] (1149–1212), and [[Timurid dynasty|Timurids]] (1370–1506). In 1221, [[Genghis Khan]]'s son [[Tolui]] oversaw the [[Mongol Empire|Mongol]] subjugation of Khorasan, carrying out the task "with a thoroughness from which that region has never recovered."<ref>[https://archive.org/details/Boyle1968IlKhansCHIran05/page/n9/mode/1up?view=theater ''Cambridge History of Iran'', Vol. V, Ch. 4, "Dynastic and Political History of the Il-Khans" (John Andrew Boyle), p.312 (1968).]</ref> |

|||

Further: |

|||

[...] |

|||

The [[Christians]] will demand their wanted people, to which the Muslims will answer: "By Allah! They are our brothers. We will never hand them over." This will start the war. One-third Muslims will run away. Their ‘Tawbah’ (Repentance) will never be accepted. One-third will be killed. They will be the best 'Shaheed' (martyrs) near Allah. The remaining one-third will gain victory, until, under the leadership of [[Imam Mehdi]], they will fight against [[Kufr]] (non-believers). This group will belong to Khurasan. They will be wearing black turbans. People will rise up from the [[Eastern World|East]] who will keep on coming forward, trampling the ground under the feet, to the aid of Imam Mahdi to help establish his government. (Ibn Majah) From Khurasan will emerge black flags, whom none will be able to turn back (and they, the flag bearers, will continue moving forward) till they reach Illya (Jerusalem) and embed their flags into its earth. (Tirmizi) In the era preceding Qyamah the Christians will control/govern the whole world. The Christians will reach [[Khaybar]] (Place in present day [[Saudi Arabia|Saudi]] close to [[Madina]]. (Hadith quoted in Bab-al-Qeyamah by Muhaddith Shah Rafee-ud-din)". |

|||

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century, the majority of Islamic archaeological efforts were focused on the medieval era, predominantly in areas near what is today [[Central Asia]].<ref name="Petersen"/> |

|||

Prophet Mohammad: "Before your treasure, three will kill each other -- all of them are sons of a different caliph but none will be the recipient. Then the Black Banners will appear from the East and they will kill you in a way that has never before been done by a nation." Thawban, a companion said: 'Then he said something that I do not remember by heart' then continued to say that the Prophet, praise and peace be upon him, said: "If you see him give him your allegiance, even if you have to crawl over ice, because surely he is the Caliph of Allah, the Mahdi. If you see the black flags coming from Khurasan, join that army, even if you have to crawl over ice, for this is the army of the Caliph, the Mahdi and no one can stop that army until it reaches [[Jerusalem]]." |

|||

==== Rashidun era (651–661) ==== |

|||

Related by Abu Hurayrah: Prophet Mohammad said: "(Armies carrying) black flags will come from Khurasan (Afghanistan). No power will be able to stop them and they will finally reach Jerusalem where they will erect their flags." (Tirmidhi) |

|||

Under [[Caliph]] [[Umar]] ({{Reign|634|644}}), the [[Rashidun Caliphate]] seized nearly the entire [[Muslim conquest of Persia|Persia]] from the [[Sasanian Empire]]. However, the areas of Khorasan weren't conquered until {{Circa|651}} during the caliphate of [[Uthman]] ({{Reign|644|656}}).{{Cn|date=September 2023}} The Rashidun commanders [[Ahnaf ibn Qais|Ahnaf ibn Qays]] and [[Abd Allah ibn Amir]] were assigned to lead the invasion of Khorasan.<ref name="ReferenceA">The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch:17 {{ISBN|0-19-597713-0}},</ref> In late 651, the Rashidun army defeated the combined forces of the Sasanian and the [[First Turkic Khaganate]] in the [[Battle of Oxus River|Battle of the Oxus River]].{{Cn|date=September 2023}} The next year, Ibn Amir concluded a peace treaty with [[Kanadbak]], an Iranian nobleman and the ''[[kanarang]]'' of [[Tus, Iran|Tus]]. The Sasanian rebel [[Burzin Shah]], of the [[House of Karen|Karen family]], revolted against Ibn Amir, though the latter crushed the rebels in the [[Battle of Nishapur]].{{Sfn|Pourshariati|2008|p=274}} |

|||

==== Umayyad era (661–750) ==== |

|||

On the authority of Thawbaan, the Messenger of Allah said: |

|||

After the invasion of Persia under Rashidun was completed in five years and almost all of the Persian territories came under Arab control, it also inevitable created new problems for the caliphate. Pockets of tribal resistance continued for centuries in the [[Afghan (name)|Afghan]] territories. During the 7th century, [[Umayyad|Arab armies]] made their way into the region of Afghanistan from Khorasan.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} A second problem was as a corollary to the Muslim conquest of Persia, the Muslims became neighbors of the city states of [[Transoxiana]]. Although Transoxiana was included in the loosely defined "Turkestan" region, only the ruling elite of Transoxiana was partially of Turkic origins whereas the local population was mostly a diverse mix of local Iranian populations. As the Arabs reached Transoxiana following the conquest of the Sassanid Persian Empire, local Iranian-Turkic and Arab armies clashed over the control of Transoxiana's Silk Road cities.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} In particular, the Turgesh under the leadership of Suluk, and Khazars under Barjik clashed with their Arab neighbours in order to control this economically important region. Two notable Umayyad generals, [[Qutayba ibn Muslim]] and [[Nasr ibn Sayyar]], were instrumental in the eventual conquest.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} In July 738, at the age of 74, [[Nasr ibn Sayyar|Nasr]] was appointed as governor of Khorasan. Despite his age, he was widely respected both for his military record, his knowledge of the affairs of Khorasan and his abilities as a statesman. [[Julius Wellhausen]] wrote of him that "His age did not affect the freshness of his mind, as is testified not only by his deeds, but also by the verses in which he gave expression to his feelings till the very end of his life". However, in the climate of the times, his nomination owed more to his appropriate tribal affiliation than his personal qualities.{{sfn|Sharon|1990|p=35}} |

|||

"If you see the Black Banners coming from Khurasan go to them immediately, even if you must crawl over ice, because indeed amongst them is the Caliph, Al Mahdi." [Narrated on authority of Ibn Majah, Al-Hakim, Ahmad] |

|||

In 724, immediately after the rise of [[Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik]] (r. 724–743) to the throne, Asad's brother [[Khalid al-Qasri]] was appointed to the important post of [[List of Umayyad governors of Iraq|governor of Iraq]], with responsibility over the entire Islamic East, which he held until 738. Khalid in turn named Asad as governor of Khorasan. The two brothers thus became, according to [[Patricia Crone]], "among the most prominent men of the Marwanid period".{{sfn|Crone|1980|p=102}}{{sfn|Gibb|1960|p=684}} Asad's arrival in Khorasan found the province in peril: his predecessor, [[Muslim ibn Sa'id al-Kilabi]], had just attempted a campaign against [[Ferghana Valley|Ferghana]] and suffered a major defeat, the so-called "[[Day of Thirst]]", at the hands of the [[Turgesh]] [[Turkic peoples|Turks]] and the [[Soghdia]]n principalities of [[Transoxiana]] that had risen up against Muslim rule.{{sfn|Blankinship|1994|pp=125–127}}{{sfn|Gibb|1923|pp=65–66}} |

|||

Amr ibn Hurayth quoted AbuBakr as-Siddiq as saying that Allah's Messenger told them the [[Dajjal]] would come forth from a land in the East called Khurasan, followed by people whose faces resembled shields covered with skin. |

|||

From the early days of the [[Early Muslim conquests|Muslim conquests]], Arab armies were divided into regiments drawn from individual tribes or tribal confederations (''butun'' or ''‘asha‘ir''). Despite the fact that many of these groupings were recent creations, created for reasons of military efficiency rather than any common ancestry, they soon developed a strong and distinct identity.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} By the beginning of the Umayyad period, this system progressed to the formation of ever-larger super-groupings, culminating in the [[Qays and Yaman tribes|two super-groups]]: the northern Arab Mudaris or [[Qays]]is, and the south Arabs or "Yemenis" (''Yaman''), dominated by the Azd and [[Rabi'ah]] tribes.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} By the 8th century, this division had become firmly established across the Caliphate and was a source of constant internal instability, as the two groups formed in essence two rival political parties, jockeying for power and separated by a fierce hatred for each other.{{sfn|Blankinship|1994|pp=42–46}}{{sfn|Hawting|2000|pp=54–55}} During [[Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik]]'s reign, the Umayyad government appointed Mudaris as governors in Khorasan, except for Asad ibn Abdallah al-Qasri's tenure in 735–738. Nasr's appointment came four months after Asad's death.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} In the interim, the sources report variously that the province was run either by the [[Bilad al-Sham|Syrian]] general Ja'far ibn Hanzala al-Bahrani or by Asad's lieutenant Juday' al-Kirmani. At any rate, the sources agree that al-Kirmani stood at the time as the most prominent man in Khorasan and should have been the clear choice for governor. His Yemeni roots (he was the leader of the Azd in Khorasan), however, made him unpalatable to the Caliph.{{sfn|Shaban|1979|pp=127–128}}{{sfn|Sharon|1990|pp=25–27, 34}} |

|||

== [[Imam Mahdi]] of Khurasan in the [[Hadith]] == |

|||

[[Mirza Ghulam Ahmad]] of Qadian claimed as an [[Imam Mahdi]] and [[Promised Messiah]] in 1889 in India. His forefathers were from |

|||

Khurasan. He was a [[Mughal]] and Mughals came from Khurasan to India. and at some point the [[Moghul Empire]] included some part of Khurasan. |

|||

==== Abbasid era (750–861) ==== |

|||

==References and footnotes== |

|||

{{See|Abbasid Caliphate|Anarchy at Samarra}} |

|||

*Lorentz, J. ''Historical Dictionary of Iran''. 1995 ISBN 0-8108-2994-0 |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

Khorasan became the headquarters of the [[Abbasid Revolution]] against the [[Umayyad]]s. It was led by [[Abu Muslim]], who himself belonged to Khorasan. This province was part of the Iranian world that had been heavily colonised by Arab tribes following the [[Early Muslim conquests|Muslim conquest]] with the intent of replacing Umayyad dynasty which is proved to be successful under the sign of the [[Black Standard]].<ref name="cam102">[https://books.google.com/books?id=4AuJvd2Tyt8C&dq=umayyad+abbasid+non+muslim+support&pg=PA104 The Cambridge History of Islam], vol. 1A, p. 102. Eds. [[Peter M. Holt]], Ann K.S. Lambton and Bernard Lewis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. {{ISBN|9780521291354}}</ref> |

|||

== External links == |

|||

* [http://khorasan.nl/ Khorasan.nl] {{fa icon}} |

|||

{{Missing info|post-Abbasid, pre-Modern era|date=June 2023}} |

|||

</br> |

|||

[[Category:History of Asia]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Iran]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Afghanistan]] |

|||

=== Modern era === |

|||

[[ar:خراسان الكبرى]] |

|||

{{see also|Islamic State – Khorasan Province}} |

|||

[[bg:Хорасан]] |

|||

[[File:Meyamei.jpg|thumb|The village of [[Madan-e Olya|Madan]] in 1909]] |

|||

[[de:Chorasan]] |

|||

[[File:Greater_Khurasan.png|thumb|Greater Khorasan]] |

|||

[[fa:خراسان بزرگ]] |

|||

Between the early 16th and early 18th centuries, parts of Khorasan were contested between the [[Safavids]] and the [[Uzbeks]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Rippin|first1=Andrew|author-link1=Andrew Rippin|title=The Islamic World|date=2013|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-136-80343-7|page=95}}</ref> A part of the Khorasan region was conquered in 1722 by the [[Ghilji]] Pashtuns from [[Kandahar]] and became part of the [[Hotaki dynasty]] from 1722 to 1729.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/7798/Afghanistan/21392/Last-Afghan-empire |title= Last Afghan empire |encyclopedia=[[Louis Dupree (professor)|Louis Dupree]], [[Nancy Hatch Dupree]] and others |publisher=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]] |access-date=2010-09-24}}</ref><ref name="Axworthy">{{Cite book|title=The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant|last1=Axworthy|first1=Michael|author-link=Michael Axworthy|year=2006|publisher=[[I.B. Tauris]]|location=London|isbn=1-85043-706-8|page=50|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O4FFQjh-gr8C&pg=PA50|access-date=2010-09-27}}</ref> [[Nader Shah]] recaptured Khorasan in 1729 and chose [[Mashhad]] as the capital of Persia. Following his assassination in 1747, the eastern parts of Khorasan, including [[Herat]] were annexed with the [[Durrani Empire]]. Mashhad area was under control of Nader Shah's grandson [[Shahrukh Afshar]] until it was captured by the [[Qajar dynasty]] in 1796.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} In 1856, the Iranians, under the Qajar dynasty, briefly recaptured Herat; by the [[Treaty of Paris (1857)|Treaty of Paris of 1857]], signed between Iran and the British Empire to end the [[Anglo-Persian War]], the Iranian troops withdrew from [[Herat]].<ref>{{cite book|editor1-last=Avery|editor1-first=Peter|editor2-last=Hambly|editor2-first=Gavin|editor3-last=Melville|editor3-first=Charles|title=The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7): From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-20095-0|pages=183, 394–395|date = 10 October 1991}}</ref> Later, in 1881, Iran relinquished its claims to a part of the northern areas of Khorasan to the [[Russian Empire]], principally comprising [[Merv]], by the [[Treaty of Akhal]] (also known as the ''Treaty of Akhal-Khorasan'').<ref>{{cite book|last1=Sicker|first1=Martin|title=The Bear and the Lion: Soviet Imperialism and Iran|date=1988|publisher=Praeger|isbn=978-0-275-93131-5|page=14}}</ref> |

|||

[[fr:Grand Khorasan]] |

|||

[[sl:Veliki Horasan]] |

|||

== Cultural importance == |

|||

[[File:Muḥammad Ḥusaym Mīrzā, a relative of Babur, in spite of his treachery, is being released and send to Khurāsān.jpg|thumb|[[Timurid dynasty|Timurid]] conqueror [[Babur]] exiles his treacherous relative Muḥammad Ḥusaym Mīrzā to Khorasan.]] |

|||

Khorasan has had a great cultural importance among other regions in [[Greater Iran]]. The literary [[Persian language#New Persian|New Persian]] language developed in Khorasan and Transoxiana and gradually supplanted the [[Parthian language]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/dari|title=DARĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica|last=electricpulp.com|website=www.iranicaonline.org|access-date=13 June 2018}}</ref> The New [[Persian literature]] arose and flourished in Khorasan and Transoxiana<ref>Frye, R.N., "Dari", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, CD edition</ref> where the early Iranian dynasties such as [[Tahirid dynasty|Tahirids]], [[Samanid Empire|Samanids]], [[Saffarid dynasty|Saffirids]] and [[Ghaznavids]] (a Turco-Persian dynasty) were based.{{Cn|date=September 2023}} |

|||

Until the devastating [[Mongol]] invasion of the 13th century, Khorasan remained the cultural capital of Persia.<ref>Lorentz, J. Historical Dictionary of Iran. 1995 {{ISBN|0-8108-2994-0}}; Shukurov, Sharif. Хорасан. Территория искусства, Moscow: Progress-Traditsiya, 2016.</ref> It has produced scientists such as [[Avicenna]], [[Al-Farabi]], [[Al-Biruni]], [[Omar Khayyam]], [[Al-Khwarizmi]], [[Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi]] (known as Albumasar or Albuxar in the west), [[Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī|Alfraganus]], [[Abū al-Wafā' Būzjānī|Abu Wafa]], [[Nasir al-Din al-Tusi]], [[Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī]], and many others who are widely well known for their significant contributions in various domains such as mathematics, [[astronomy]], medicine, [[physics]], [[geography]], and geology.<ref>Starr, S. Frederick, ''Lost Enlightenment. Central Asia's golden age from the Arab conquest to Tamerlane'', Princeton University Press (2013)</ref> |

|||

There have been many archaeological sites throughout Khorasan, however many of these expeditions were illegal or committed in the sole pursuit of profit, leaving many sites without documentation or record.<ref name="Petersen">Petersen, A. (2014). Islamic Archaeology. In: Smith, C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer, New York, NY. {{doi|10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_554}}</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

|||

{{Div col|colwidth=15em}} |

|||

* [[Ariana]] |

|||

* [[Bactria]] |

|||

* [[Dahae|Dahistan]] |

|||

* [[Greater Central Asia]] |

|||

* [[Khwarazm]] |

|||

* [[Khurasan Road]] |

|||

* [[Margiana]] |

|||

* [[Parthia]] |

|||

* [[Sogdia]] |

|||

* [[Tokharistan]] |

|||

* [[Transoxiana]] |

|||

* [[Turkestan]] |

|||

* [[Bibliography of the history of Central Asia]] |

|||

{{Div col end}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

===Sources=== |

|||

* {{The End of the Jihad State}}<!-- = Blankinship 1994 --> |

|||

* {{Slaves on Horses}}<!-- = Crone 1980 --> |

|||

* {{The Arab Conquests in Central Asia}}<!-- = Gibb 1923 --> |

|||

* {{EI2 | volume=1 | first = H. A. R. | last = Gibb | authorlink = H.A.R. Gibb | title = Asad b. ʿAbd Allāh | pages = 684–685 | url = http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/asad-b-abd-allah-SIM_0757}}<!-- = Gibb 1960 --> |

|||

* {{The First Dynasty of Islam|edition=Second}}<!-- = Hawting 2000 --> |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Pourshariati |first=Parvaneh |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=I-xtAAAAMAAJ |title=Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran |publisher=I.B. Tauris |year=2008 |isbn=978-1-84511-645-3 |location=London and New York}} |

|||

* {{cite book | title = The ʿAbbāsid Revolution | first = M. A. | last = Shaban | location = Cambridge | publisher = Cambridge University Press | year = 1979 | isbn = 0-521-29534-3 | url = {{Google Books|1_03AAAAIAAJ|plainurl=y}} }} |

|||

* {{cite book | last=Sharon | first = Moshe | title = Revolt: The Social and Military Aspects of the ʿAbbāsid revolution | location = Jerusalem | publisher = Graph Press Ltd. | year = 1990 | isbn = 965-223-388-9 | url = {{Google Books|cTLMgO9dU4cC|plainurl=y}} }} |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

*{{Cite journal| volume = 5| pages = 232| last = Sánchez| first = Ignacio| title = Ibn Qutayba and the Ahl Khurāsān: The Shuʿūbiyya Revisited| journal = Abbasid Studies IV| date = 2013|url=http://digital.casalini.it/9780906094891}} |

|||

{{Sasanian Provinces}} |

|||

{{People of Khorasan}} |

|||

{{WikidataCoord|display=t}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Khorasan| ]] |

|||

[[Category:Geography of Central Asia]] |

|||

[[Category:Geography of West Asia]] |

|||

[[Category:Regions of Afghanistan]] |

|||

[[Category:Regions of Iran]] |

|||

[[Category:Regions of Tajikistan]] |

|||

[[Category:Regions of Turkmenistan]] |

|||

[[Category:Regions of Uzbekistan]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Khorasan]] |

|||

[[Category:Historical regions of Afghanistan]] |

|||

[[Category:Historical regions of Iran]] |

|||

[[Category:Iranian plateau]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Balkh Province]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Herat]] |

|||

[[Category:History of Nishapur]] |

|||

[[Category:Historical geography of Tajikistan]] |

|||

[[Category:Historical geography of Turkmenistan]] |

|||

[[Category:Historical geography of Uzbekistan]] |

|||

[[Category:People from Khorasan|*]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 20:56, 5 December 2024

Greater Khorasan

خراسان بزرگ | |

|---|---|

Greater Khorasan (Chorasan) and neighbouring historical regions | |

Map of Khorasan and its surroundings in the 7th/8th centuries | |

| Countries in Khorasan | Afghanistan, Iran and Turkmenistan.[1] Different regions of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan are also included in different sources. |

| Demonym | Khorasanian |

| Ethnicities: Persians, Tajiks, Farsiwans, Turkmens, Uzbeks, Pashtuns, Hazaras | |

Greater Khorasan[2] (Middle Persian: 𐬒𐬊𐬭𐬀𐬯𐬀𐬥, romanized: Xwarāsān; Persian: خراسان, [xoɾɒːˈsɒːn] ⓘ) is a historical eastern region in the Iranian Plateau in West and Central Asia that encompasses western and northern Afghanistan, northeastern Iran, the eastern halves of Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, western Tajikistan, and portions of Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan.

The extent of the region referred to as Khorasan varied over time. In its stricter historical sense, it comprised the present territories of northeastern Iran, parts of Afghanistan and southern parts of Central Asia, extending as far as the Amu Darya (Oxus) river. However, the name has often been used in a loose sense to include a wider region that included most of Transoxiana (encompassing Bukhara and Samarqand in present-day Uzbekistan),[3] extended westward to the Caspian coast[4] and to the Dasht-e Kavir[5] southward to Sistan,[6][5] and eastward to the Pamir Mountains.[5][4] Greater Khorasan is today sometimes used to distinguish the larger historical region from the former Khorasan Province of Iran (1906–2004), which roughly encompassed the western portion of the historical Greater Khorasan.[2]

The name Khorāsān is Persian (from Middle Persian Xwarāsān, sp. xwlʾsʾn', meaning "where the sun arrives from" or "the Eastern Province").[7][8] The name was first given to the eastern province of Persia (Ancient Iran) during the Sasanian Empire[9] and was used from the late Middle Ages in distinction to neighbouring Transoxiana.[10][11][12] The Sassanian name Xwarāsān has in turn been argued to be a calque of the Bactrian name of the region, Miirosan (Bactrian spelling: μιιροσανο,[13] μιροσανο, earlier μιυροασανο), which had the same meaning 'sunrise, east' (corresponding to a hypothetical Proto-Iranian form *miθrāsāna;[14] see Mithra, Bactrian μιυρο [mihr],[15] for the relevant solar deity). The province was often subdivided into four quarters, such that Nishapur (present-day Iran), Marv (present-day Turkmenistan), Herat and Balkh (present-day Afghanistan) were the centers, respectively, of the westernmost, northernmost, central, and easternmost quarters.[3]

Khorasan was first established as an administrative division in the 6th century (approximately after 520) by the Sasanians, during the reign of Kavad I (r. 488–496, 498/9–531) or Khosrow I (r. 531–579),[16] and comprised the eastern and northeastern parts of the empire. The use of Bactrian Miirosan 'the east' as an administrative designation under Alkhan rulers in the same region is possibly the forerunner of the Sasanian administrative division of Khurasan,[17][18][19] occurring after their takeover of Hephthalite territories south of the Oxus. The transformation of the term and its identification with a larger region is thus a development of the late Sasanian and early Islamic periods. Early Islamic usage often regarded everywhere east of Jibal or what was subsequently termed Iraq Ajami (Persian Iraq), as being included in a vast and loosely defined region of Khorasan, which might even extend to the Indus Valley and the Pamir Mountains. The boundary between these two was the region surrounding the cities of Gurgan and Qumis. In particular, the Ghaznavids, Seljuqs and Timurids divided their empires into Iraqi and Khorasani regions. Khorasan is believed to have been bounded in the southwest by desert and the town of Tabas, known as "the Gate of Khorasan",[20]: 562 from which it extended eastward to the mountains of central Afghanistan.[4][5] Sources from the 10th century onwards refer to areas in the south of the Hindu Kush as the Khorasan Marches, forming a frontier region between Khorasan and Hindustan.[21][22]

Geography

[edit]First established in the 6th century as one of four administrative (military) divisions by the Sasanian Empire,[23] the scope of the region has varied considerably during its nearly 1,500-year history. Initially, the Khorasan division of the Sasanian Empire covered the northeastern military gains of the empire, at its height including cities such as Nishapur, Herat, Merv, Faryab, Taloqan, Balkh, Bukhara, Badghis, Abiward, Gharjistan, Tus and Sarakhs.[6]

With the rise of the Umayyad Caliphate, the designation was inherited and likewise stretched as far as their military gains in the east, starting off with the military installations at Nishapur and Merv, slowly expanding eastwards into Tokharistan and Sogdia. Under the Caliphs, Khorasan was the name of one of the three political zones under their dominion (the other two being Eraq-e Arab "Arabic Iraq" and Eraq-e Ajam "Non-Arabic Iraq or Persian Iraq").[citation needed] Under the Umayyad and Abbasid caliphates, Khorasan was divided into four major sections or quarters (rub′), each section based on a single major city: Nishapur, Merv, Herat and Balkh.[24] By the 10th century, Ibn Khordadbeh and the Hudud al-'Alam mentions what roughly encompasses the previous regions of Abarshahr, Tokharistan and Sogdia as Khwarasan proper. They further report the southern part of the Hindu Kush, i.e. the regions of Sistan, Rukhkhudh, Zabulistan and Kabul etc. to make up the Khorasan marches, a frontier region between Khorasan and Hindustan.[25][21][5]

By the late Middle Ages, the term lost its administrative significance, in the west only being loosely applied among the Turko-Persian dynasties of modern Iran to all its territories that lay east and north-east of the Dasht-e Kavir desert. It was therefore subjected to constant change, as the size of their empires changed. In the east, Khwarasan likewise became a term associated with the great urban centers of Central Asia. It is mentioned in the Memoirs of Babur (from the 1580s) that:

The people of Hindustān call every country beyond their own Khorasān, in the same manner as the Arabs term all except Arabia, Ajem. On the road between Hindustān and Khorasān, there are two great marts: the one Kābul, the other Kandahār. Caravans, from Ferghāna, Tūrkestān, Samarkand, Balkh, Bokhāra, Hissār, and Badakhshān, all resort to Kābul; while those from Khorasān repair to Kandahār. This country lies between Hindustān and Khorasān.[22]

In modern times, the term has been source of great nostalgia and nationalism, especially amongst the Tajiks of Central Asia.[citation needed] Many Tajiks regard Khorasan as an integral part of their national identity, which has preserved an interest in the term, including its meaning and cultural significance, both in common discussion and academia, despite its falling out of political use in the region.[26]

According to Afghan historian Ghulam Mohammad Ghobar (1897–1978), Afghanistan's current Persian-speaking territories formed the major portion of Khorasān,[27] as two of the four main capitals of Khorasān (Herat and Balkh) are now located in Afghanistan. Ghobar uses the terms "Proper Khorasan" and "Improper Khorasan" in his book to distinguish between the usage of Khorasān in its strict sense and its usage in a loose sense. According to him, Proper Khorasan contained regions lying between Balkh in the east, Merv in the north, Sistan in the south, Nishapur in the west and Herat, known as the Pearl of Khorasan, in the center. Improper Khorasan's boundaries extended to as far as Hazarajat and Kabul in the east, Baluchistan in the south, Transoxiana and Khwarezm in the north, and Damghan and Gorgan in the west.[27]

History

[edit]

Ancient era

[edit]During the Sasanian era, likely in the reign of Khusrow I, Persia was divided into four regions (known as kust Middle Persian), Khwārvarān in the west, apāxtar in the north, nīmrūz in the south and Khorasan in the east. Since the Sasanian territories were more or less remained stable up to Islamic conquests, it can be concluded that Sasanian Khorasan was bordered to the south by Sistan and Kerman, to the west by the central deserts of modern Iran, and to the east by China and India.[25]

In the Sasanian era, Khorasan was further divided into four smaller regions, and each region was ruled by a marzban. These four regions were Nishapur, Marv, Herat and Balkh.[25]

Khorasan in the east saw some conflict with the Hephthalites who became the new rulers in the area but the borders remained stable. Being the eastern parts of the Sassanids and further away from Arabia, Khorasan region was conquered after the remaining Persia.[citation needed] The last Sassanid king of Persia, Yazdgerd III, moved the throne to Khorasan following the Arab invasion in the western parts of the empire. After the assassination of the king, Khorasan was conquered by Arab Muslims in 647 AD. Like other provinces of Persia it became a province of the Umayyad Caliphate.[28]

Medieval era

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2020) |

The first movement against the Arab conquest was led by Abu Muslim Khorasani between 747 and 750. Originally from Isfahan, scholars believe Abu Muslim was probably Persian. It's possible he may have been born a slave. According to the ancient Persian historian Al-Shahrastani, he was a Kaysanite. This revolutionary Shi'a movement rejected the three Caliphs that had preceded Ali.[29]

Abu Muslim helped the Abbasids come to power but was later killed by Al-Mansur, an Abbasid Caliph.[citation needed] The first kingdom independent from Arab rule was established in Khorasan by Tahir Phoshanji in 821, but it seems that it was more a matter of political and territorial gain. Tahir had helped the Caliph subdue other nationalistic movements in other parts of Persia such as Maziar's movement in Tabaristan.[30]

Other major independent dynasties who ruled over Khorasan were the Saffarids from Zaranj (861–1003), Samanids from Bukhara (875–999), Ghaznavids from Ghazni (963–1167), Seljuqs (1037–1194), Khwarezmids (1077–1231), Ghurids (1149–1212), and Timurids (1370–1506). In 1221, Genghis Khan's son Tolui oversaw the Mongol subjugation of Khorasan, carrying out the task "with a thoroughness from which that region has never recovered."[31]

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century, the majority of Islamic archaeological efforts were focused on the medieval era, predominantly in areas near what is today Central Asia.[32]

Rashidun era (651–661)

[edit]Under Caliph Umar (r. 634–644), the Rashidun Caliphate seized nearly the entire Persia from the Sasanian Empire. However, the areas of Khorasan weren't conquered until c. 651 during the caliphate of Uthman (r. 644–656).[citation needed] The Rashidun commanders Ahnaf ibn Qays and Abd Allah ibn Amir were assigned to lead the invasion of Khorasan.[33] In late 651, the Rashidun army defeated the combined forces of the Sasanian and the First Turkic Khaganate in the Battle of the Oxus River.[citation needed] The next year, Ibn Amir concluded a peace treaty with Kanadbak, an Iranian nobleman and the kanarang of Tus. The Sasanian rebel Burzin Shah, of the Karen family, revolted against Ibn Amir, though the latter crushed the rebels in the Battle of Nishapur.[34]

Umayyad era (661–750)

[edit]After the invasion of Persia under Rashidun was completed in five years and almost all of the Persian territories came under Arab control, it also inevitable created new problems for the caliphate. Pockets of tribal resistance continued for centuries in the Afghan territories. During the 7th century, Arab armies made their way into the region of Afghanistan from Khorasan.[citation needed] A second problem was as a corollary to the Muslim conquest of Persia, the Muslims became neighbors of the city states of Transoxiana. Although Transoxiana was included in the loosely defined "Turkestan" region, only the ruling elite of Transoxiana was partially of Turkic origins whereas the local population was mostly a diverse mix of local Iranian populations. As the Arabs reached Transoxiana following the conquest of the Sassanid Persian Empire, local Iranian-Turkic and Arab armies clashed over the control of Transoxiana's Silk Road cities.[citation needed] In particular, the Turgesh under the leadership of Suluk, and Khazars under Barjik clashed with their Arab neighbours in order to control this economically important region. Two notable Umayyad generals, Qutayba ibn Muslim and Nasr ibn Sayyar, were instrumental in the eventual conquest.[citation needed] In July 738, at the age of 74, Nasr was appointed as governor of Khorasan. Despite his age, he was widely respected both for his military record, his knowledge of the affairs of Khorasan and his abilities as a statesman. Julius Wellhausen wrote of him that "His age did not affect the freshness of his mind, as is testified not only by his deeds, but also by the verses in which he gave expression to his feelings till the very end of his life". However, in the climate of the times, his nomination owed more to his appropriate tribal affiliation than his personal qualities.[35]

In 724, immediately after the rise of Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (r. 724–743) to the throne, Asad's brother Khalid al-Qasri was appointed to the important post of governor of Iraq, with responsibility over the entire Islamic East, which he held until 738. Khalid in turn named Asad as governor of Khorasan. The two brothers thus became, according to Patricia Crone, "among the most prominent men of the Marwanid period".[36][37] Asad's arrival in Khorasan found the province in peril: his predecessor, Muslim ibn Sa'id al-Kilabi, had just attempted a campaign against Ferghana and suffered a major defeat, the so-called "Day of Thirst", at the hands of the Turgesh Turks and the Soghdian principalities of Transoxiana that had risen up against Muslim rule.[38][39]

From the early days of the Muslim conquests, Arab armies were divided into regiments drawn from individual tribes or tribal confederations (butun or ‘asha‘ir). Despite the fact that many of these groupings were recent creations, created for reasons of military efficiency rather than any common ancestry, they soon developed a strong and distinct identity.[citation needed] By the beginning of the Umayyad period, this system progressed to the formation of ever-larger super-groupings, culminating in the two super-groups: the northern Arab Mudaris or Qaysis, and the south Arabs or "Yemenis" (Yaman), dominated by the Azd and Rabi'ah tribes.[citation needed] By the 8th century, this division had become firmly established across the Caliphate and was a source of constant internal instability, as the two groups formed in essence two rival political parties, jockeying for power and separated by a fierce hatred for each other.[40][41] During Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik's reign, the Umayyad government appointed Mudaris as governors in Khorasan, except for Asad ibn Abdallah al-Qasri's tenure in 735–738. Nasr's appointment came four months after Asad's death.[citation needed] In the interim, the sources report variously that the province was run either by the Syrian general Ja'far ibn Hanzala al-Bahrani or by Asad's lieutenant Juday' al-Kirmani. At any rate, the sources agree that al-Kirmani stood at the time as the most prominent man in Khorasan and should have been the clear choice for governor. His Yemeni roots (he was the leader of the Azd in Khorasan), however, made him unpalatable to the Caliph.[42][43]

Abbasid era (750–861)

[edit]Khorasan became the headquarters of the Abbasid Revolution against the Umayyads. It was led by Abu Muslim, who himself belonged to Khorasan. This province was part of the Iranian world that had been heavily colonised by Arab tribes following the Muslim conquest with the intent of replacing Umayyad dynasty which is proved to be successful under the sign of the Black Standard.[44]

This article is missing information about post-Abbasid, pre-Modern era. (June 2023) |

Modern era

[edit]

Between the early 16th and early 18th centuries, parts of Khorasan were contested between the Safavids and the Uzbeks.[45] A part of the Khorasan region was conquered in 1722 by the Ghilji Pashtuns from Kandahar and became part of the Hotaki dynasty from 1722 to 1729.[46][47] Nader Shah recaptured Khorasan in 1729 and chose Mashhad as the capital of Persia. Following his assassination in 1747, the eastern parts of Khorasan, including Herat were annexed with the Durrani Empire. Mashhad area was under control of Nader Shah's grandson Shahrukh Afshar until it was captured by the Qajar dynasty in 1796.[citation needed] In 1856, the Iranians, under the Qajar dynasty, briefly recaptured Herat; by the Treaty of Paris of 1857, signed between Iran and the British Empire to end the Anglo-Persian War, the Iranian troops withdrew from Herat.[48] Later, in 1881, Iran relinquished its claims to a part of the northern areas of Khorasan to the Russian Empire, principally comprising Merv, by the Treaty of Akhal (also known as the Treaty of Akhal-Khorasan).[49]

Cultural importance

[edit]

Khorasan has had a great cultural importance among other regions in Greater Iran. The literary New Persian language developed in Khorasan and Transoxiana and gradually supplanted the Parthian language.[50] The New Persian literature arose and flourished in Khorasan and Transoxiana[51] where the early Iranian dynasties such as Tahirids, Samanids, Saffirids and Ghaznavids (a Turco-Persian dynasty) were based.[citation needed]

Until the devastating Mongol invasion of the 13th century, Khorasan remained the cultural capital of Persia.[52] It has produced scientists such as Avicenna, Al-Farabi, Al-Biruni, Omar Khayyam, Al-Khwarizmi, Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi (known as Albumasar or Albuxar in the west), Alfraganus, Abu Wafa, Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī, and many others who are widely well known for their significant contributions in various domains such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine, physics, geography, and geology.[53]

There have been many archaeological sites throughout Khorasan, however many of these expeditions were illegal or committed in the sole pursuit of profit, leaving many sites without documentation or record.[32]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sistan and Khorasan Travelogue Page 48

- ^ a b Dabeersiaghi, Commentary on Safarnâma-e Nâsir Khusraw, 6th Ed. Tehran, Zavvâr: 1375 (Solar Hijri Calendar) 235–236

- ^ a b Minorsky, V. (1938). "Geographical Factors in Persian Art". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, 9(3), 621–652.

- ^ a b c "Khorasan". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2010-10-21.

historical region and realm comprising a vast territory now lying in northeastern Iran, southern Turkmenistan, and northern Afghanistan. The historical region extended, along the north, from the Amu Darya westward to the Caspian Sea and, along the south, from the fringes of the central Iranian deserts eastward to the mountains of central Afghanistan. Arab geographers even spoke of its extending to the boundaries of India.

- ^ a b c d e Lambton, Ann K.S. (1988). Continuity and Change in Medieval Persia: Aspects of Administrative, Economic and Social History, 11th–14th Century. Columbia Lectures on Iranian Studies. New York, NY: Bibliotheca Persica. p. 404.

In the early centuries of Islam, Khurasan generally included all the Muslim provinces east of the Great Desert. In this larger sense, it included Transoxiana, Sijistan and Quhistan. Its Central Asian boundary was the Chinese desert and the Pamirs, while its Indian boundary lay along the Hindu Kush toward India.

- ^ a b Bosworth, C.E. (1986). Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol. 5, Khe – Mahi (New ed.). Leiden [u.a.]: Brill [u.a.] pp. 55–59. ISBN 90-04-07819-3.

- ^ Sykes, M. (1914). "Khorasan: The Eastern Province of Persia". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 62(3196), 279–286.

- ^ A compound of khwar (meaning "sun") and āsān (from āyān, literally meaning "to come" or "coming" or "about to come"). Thus the name Khorasan (or Khorāyān خورآيان) means "sunrise", viz. "Orient, East". Humbach, Helmut, and Djelani Davari, "Nāmé Xorāsān" Archived 2011-01-02 at the Wayback Machine, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz; Persian translation by Djelani Davari, published in Iranian Languages Studies Website. MacKenzie, D. (1971). A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary (p. 95). London: Oxford University Press. The Persian word Khāvar-zamīn (Persian: خاور زمین), meaning "the eastern land", has also been used as an equivalent term. DehKhoda, "Lughat Nameh DehKhoda" Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Khorāsān". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Svat Soucek, A History of Inner Asia, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p.4

- ^ C. Edmund Bosworth, (2002), 'Central Asia iv. In the Islamic Period up to the Mongols' Encyclopaedia Iranica (online)

- ^ C. Edmund Bosworth, (2011), 'Mā Warāʾ Al-Nahr' Encyclopaedia Iranica (online)

- ^ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2019-01-01). "Miirosan to Khurasan: Huns, Alkhans, and the Creation of East Iran". Vicino Oriente. 23: 121–138. doi:10.53131/VO2724-587X2019_9.

- ^ Gholami, Saloumeh (2010), Selected Features of Bactrian Grammar (PhD thesis), University of Göttingen, p.25, 59

- ^ Sims-Williams, N. "Bactrian Language". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- ^ Schindel, Nikolaus (2013a). "Kawād I i. Reign". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XVI, Fasc. 2. pp. 136–141.

- ^ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2019-01-01). "Miirosan to Khurasan: Huns, Alkhans, and the Creation of East Iran". Vicino Oriente. 23: 121–138. doi:10.53131/VO2724-587X2019_9.

- ^ Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017-03-15). ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-0030-5.

- ^ Vondrovec, Klaus (2014). Coinage of the Iranian Huns and their Successors from Bactria to Ganhara (4th to 8th century CE). ISBN 978-3-7001-7695-4.

- ^ Sykes, P. (1906). A Fifth Journey in Persia (Continued). The Geographical Journal, 28(6), 560–587.

- ^ a b Minorsky, V. (1937). Hudud al-'Alam, The Regions of the World: A Persian Geography, 372 A.H. – 982 A.D. London: Oxford UP.

- ^ a b Zahir ud-Din Mohammad Babur (1921). "Events of the Year 910". Memoirs of Babur. Translated by John Leyden; William Erskine. Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 2012-11-14. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ Rezakhani, K. (2017). Reorienting the Sassanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-4744-0029-9.

- ^ DehKhoda, "Lughat Nameh DehKhoda" Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Authors, Multiple. "Khurasan". CGIE. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ Шакурӣ, Муҳаммадҷон (1996; 2005). Хуросон аст инҷо, Dushanbe; Shakūrī, Muḥammad (1393), Khurāsān ast īn jā, Tehran: Fartāb;

- ^ a b Ghubar, Mir Ghulam Mohammad (1937). Khorasan, Kabul Printing House. Kabul, Afghanistan.

- ^ The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch:17 ISBN 0-19-597713-0

- ^ Glassé, Cyril (2008). The new encyclopedia of Islam. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 21. ISBN 9780742562967.

- ^ Rante, Rocco, ed. (22 January 2020). Greater Khorasan History, Geography, Archaeology and Material Culture. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783110331707. ISBN 978-3-11-033155-4.

- ^ Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. V, Ch. 4, "Dynastic and Political History of the Il-Khans" (John Andrew Boyle), p.312 (1968).

- ^ a b Petersen, A. (2014). Islamic Archaeology. In: Smith, C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer, New York, NY. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-0465-2_554

- ^ The Muslim Conquest of Persia By A.I. Akram. Ch:17 ISBN 0-19-597713-0,

- ^ Pourshariati 2008, p. 274.

- ^ Sharon 1990, p. 35.

- ^ Crone 1980, p. 102.

- ^ Gibb 1960, p. 684.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 125–127.

- ^ Gibb 1923, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 42–46.

- ^ Hawting 2000, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Shaban 1979, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Sharon 1990, pp. 25–27, 34.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam, vol. 1A, p. 102. Eds. Peter M. Holt, Ann K.S. Lambton and Bernard Lewis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 9780521291354

- ^ Rippin, Andrew (2013). The Islamic World. Routledge. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-136-80343-7.

- ^ "Last Afghan empire". Louis Dupree, Nancy Hatch Dupree and others. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 50. ISBN 1-85043-706-8. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles, eds. (10 October 1991). The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7): From Nadir Shah to the Islamic Republic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 183, 394–395. ISBN 978-0-521-20095-0.

- ^ Sicker, Martin (1988). The Bear and the Lion: Soviet Imperialism and Iran. Praeger. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-275-93131-5.

- ^ electricpulp.com. "DARĪ – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ^ Frye, R.N., "Dari", The Encyclopaedia of Islam, CD edition

- ^ Lorentz, J. Historical Dictionary of Iran. 1995 ISBN 0-8108-2994-0; Shukurov, Sharif. Хорасан. Территория искусства, Moscow: Progress-Traditsiya, 2016.

- ^ Starr, S. Frederick, Lost Enlightenment. Central Asia's golden age from the Arab conquest to Tamerlane, Princeton University Press (2013)

Sources

[edit]- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihâd State: The Reign of Hishām ibn ʻAbd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.