Christopher Marlowe: Difference between revisions

Ediderotimus (talk | contribs) m →Additional reading: deleted redundancy; added text |

Srich32977 (talk | contribs) Cleaned up using AutoEd Adding/improving reference(s) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|16th-century English dramatist, poet, and translator}} |

|||

<!-- A NOTE TO EDITORS OF THIS PAGE: The Wikipedia strives for neutral point of view and verifiability. Before adding anything to this page, please make sure that it is fully sourced and neutral. Do not add your own personal opinions or speculation. --> |

|||

{{ |

{{about|the English dramatist|the American sportscaster|Chris Marlowe}} |

||

{{use British English|date=May 2012}} |

|||

{{Infobox Writer <!-- for more information see [[:Template:Infobox Writer/doc]] --> |

|||

{{use dmy dates|date=June 2018}} |

|||

| name = Christopher Marlowe |

|||

<!-- A NOTE TO EDITORS OF THIS PAGE: The Wikipedia strives for neutral point of view and verifiability. Before adding anything to this page, please make sure that it is fully sourced and neutral. Do not add your opinions or speculation. --> |

|||

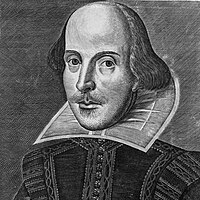

| image = Christopher_Marlowe.jpg |

|||

{{Infobox person |

|||

| caption = An anonymous portrait in [[Corpus Christi College, Cambridge]], often believed to show Christopher Marlowe. |

|||

| name = Christopher Marlowe |

|||

| birthdate = baptised [[26 February]] [[1564]] |

|||

| image = Christopher Marlowe.jpg |

|||

| birthplace = [[Canterbury]], [[England]] |

|||

| caption = [[Marlowe portrait|Anonymous portrait]], possibly of Marlowe,<br>at [[Corpus Christi College, Cambridge]] |

|||

| deathdate = {{death date|1593|5|30|df=y}} |

|||

| |

| birth_place = [[Canterbury]], Kent, England |

||

| baptised = 26 February 1564 |

|||

| occupation = [[Playwright]], [[poet]] |

|||

| death_date = 30 May 1593 (aged 29) |

|||

| nationality = [[English people|English]] |

|||

| death_place = [[Deptford]], Kent, England |

|||

| period = ''circa'' [[1586]] – [[1593]] |

|||

| resting_place = [[Deptford St Nicholas|Churchyard of St. Nicholas]], Deptford; unmarked; memorial plaques inside and outside church |

|||

| movement = [[English renaissance theatre]] |

|||

| alma_mater = [[Corpus Christi College, Cambridge]] |

|||

| debut_work = [[Dido, Queen of Carthage]] |

|||

| occupation = {{cslist|Playwright|poet}} |

|||

| influenced = [[William Shakespeare]] |

|||

| era = {{unbulleted list|[[Elizabethan era|Elizabethan]]}} |

|||

| signature = KitMarloweSig.JPG }} |

|||

| yearsactive = c. mid-1580s – 1593 |

|||

| movement = [[English Renaissance]] |

|||

| notable_works = {{cslist|''[[Hero and Leander (poem)|Hero and Leander]]''|''[[Tamburlaine the Great]]''|''[[Edward II (play)|Edward the Second]]''|''[[Doctor Faustus (play)|The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus]]''|''[[Dido, Queen of Carthage (play)|Dido, Queen of Carthage]]''}} |

|||

| signature = Christopher Marlowe Signature.svg |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Christopher Marlowe''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|ɑr|l|oʊ}} {{respell|MAR|loh}}; [[Baptism|baptised]] 26 February 1564{{spaced ndash}}30 May 1593), also known as '''Kit Marlowe''', was an English playwright, poet, and translator of the [[Elizabethan era]].{{efn|"Christopher Marlowe was [[Baptism|baptised]] as 'Marlow,' but he spelled his name 'Marley' in his one known surviving signature."<ref name="Kathman 2">{{cite web |last1=Kathman |first1=David |title=The Spelling and Pronunciation of Shakespeare's Name: Pronunciation |url=http://shakespeareauthorship.com/name1.html#3 |website=shakespeareauthorship.com |access-date=14 Jun 2020 |archive-date=27 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201127020121/https://shakespeareauthorship.com/name1.html#3 |url-status=live }}</ref>}} Marlowe is among the most famous of the [[English Renaissance theatre|Elizabethan playwrights]]. Based upon the "many imitations" of his play ''[[Tamburlaine]]'', modern scholars consider him to have been the foremost dramatist in London in the years just before his mysterious early death.{{efn|"During Marlowe's lifetime, the popularity of his plays, Robert Greene's unintentionally elevating remarks about him as a dramatist in ''A Groatsworth of Wit'', including the designation 'famous', and the many imitations of ''Tamburlaine'' suggest that he was for a brief time considered England's foremost dramatist." Logan also suggests consulting the business diary of Philip Henslowe, which is traditionally used by theatre historians to determine the popularity of Marlowe's plays.{{sfnp|Logan|2007|pp=4–5, 21}}}} Some scholars also believe that he greatly influenced [[William Shakespeare]], who was baptised in the same year as Marlowe and later succeeded him as the preeminent Elizabethan playwright.{{efn|No birth records, only baptismal records, have been found for Marlowe and Shakespeare, therefore any reference to a birthdate for either man probably refers to the date of their baptism.{{sfnp|Logan|2007|pp=3, 231-235}}}} Marlowe was the first to achieve critical reputation for his use of [[blank verse]], which became the standard for the era. His plays are distinguished by their overreaching protagonists. Themes found within Marlowe's literary works have been noted as [[humanistic]] with realistic emotions, which some scholars find difficult to reconcile with Marlowe's "[[anti-intellectualism]]" and his catering to the prurient tastes of his Elizabethan audiences for generous displays of extreme physical violence, cruelty, and bloodshed.{{sfnp|Wilson|1999|p=3}} |

|||

'''Christopher "Kit" Marlowe''' (baptised [[26 February]] [[1564]] – [[30 May]] [[1593]]) was an [[Kingdom of England|English]] [[Playwright|dramatist]], [[poet]], and [[translator]] of the [[Elizabethan era]]. The foremost [[English Renaissance theatre|Elizabethan]] [[tragedy|tragedian]] before [[William Shakespeare]], he is known for his magnificent [[blank verse]], his overreaching [[protagonist]]s, and his own untimely death. |

|||

Events in Marlowe's life were sometimes as extreme as those found in his plays.{{efn|"...as one of the most influential current critics, Stephen Greenblatt frets, Marlowe's 'cruel, aggressive plays' seem to reflect a life also lived on the edge: 'a courting of disaster as reckless as any that he depicted on stage'."{{sfnp|Wilson|1999|p=4}}}} Differing sensational reports of Marlowe's death in 1593 abounded after the event and are contested by scholars today owing to a lack of good documentation. There have been many conjectures as to the nature and reason for his death, including a vicious bar-room fight, [[blasphemous libel]] against the church, homosexual intrigue, betrayal by another playwright, and espionage from the highest level: the [[Privy Council of England|Privy Council]] of [[Elizabeth I]]. An official coroner's account of Marlowe's death was discovered only in 1925,<ref name="rey.myzen.co.uk">{{cite web|url=http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/inquis~2.htm|title=Peter Farey's Marlowe page|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150622090306/http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/inquis~2.htm |archive-date=22 June 2015|access-date=30 April 2015}}</ref> and it did little to persuade all scholars that it told the whole story, nor did it eliminate the uncertainties present in his biography.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Erne|first=Lukas|date=August 2005|title=Biography, Mythography, and Criticism: The Life and Works of Christopher Marlowe|journal=Modern Philology|volume=103|number=1|publisher=University of Chicago Press|pages=28–50|doi=10.1086/499177|s2cid=170152766|url=https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:14485|access-date=1 January 2023|archive-date=3 June 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210603033354/https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:14485|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==Early life== |

|||

[[Image:Canterbury - Turm der St. George's Church, in der Marlowe getauft wurde.jpg|thumb|left|Marlowe was christened at St George's Church [[Canterbury]]]] |

|||

==Early life== |

|||

Christopher Marlowe was christened at St George's Church, Canterbury, on [[26 February]] [[1564]]. He was born to a shoemaker in [[Canterbury]] named John Marlowe and his wife Katherine.<ref>This is commemorated by the name of the town's main theatre, the [[Marlowe Theatre]], and by the town museums. However St George's, the church in which he was christened, was gutted by fire in the [[Baedeker raids]] and was demolished in the post-war period - only the tower is left, at the south end of Canterbury's High Street http://www.digiserve.com/peter/cant-sgm1.htm</ref> Marlowe attended [[The King's School, Canterbury]] (where a house is now named after him) and [[Corpus Christi College, Cambridge]] on a scholarship and received his bachelor of arts degree in [[1584]]. In [[1587]] the university hesitated to award him his master's degree because of a rumour that he had converted to [[Roman Catholic]]ism and intended to go to the English college at Rheims to prepare for the priesthood. However, his degree was awarded on schedule when the [[Privy Council of the United Kingdom|Privy Council]] intervened on his behalf, commending him for his "faithful dealing" and "good service" to [[Elizabeth I of England|the queen]].<ref>For a full transcript, see [http://www.prst17z1.demon.co.uk/pc_cert.htm Peter Farey's Marlowe page]</ref> The nature of Marlowe's service was not specified by the Council, but their letter to the Cambridge authorities has provoked much speculation, notably the theory that Marlowe was operating as a secret agent working for Sir [[Francis Walsingham]]'s intelligence service.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

[[File:Canterbury - Turm der St. George's Church, in der Marlowe getauft wurde.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.9|Marlowe was christened at St George's Church, [[Canterbury]]. The tower, shown here, is all that survived destruction during the [[Baedeker Blitz|Baedeker air raids]] of 1942.]] |

|||

| last = Hutchinson |

|||

Christopher Marlowe, the second of nine children, and oldest child after the death of his sister Mary in 1568, was born to [[Canterbury]] shoemaker John Marlowe and his wife Katherine, daughter of William Arthur of [[Dover]].<ref name="Nicholl">{{cite ODNB |last1=Nicholl |first1=Charles |title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |date=2004 |edition=January 2008 |url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18079 |access-date=10 Jun 2020 |chapter=Marlowe [Marley], Christopher|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/18079 }}</ref> He was baptised at St George's Church, Canterbury, on 26 February 1564 (1563 in the [[Old Style and New Style dates|old style dates]] in use at the time, which placed the new year on 25 March).<ref name="St. George's">{{cite book |editor1-last=Cowper |editor1-first=Joseph Meadows |title=The register booke of the parish of St. George the Martyr, within the citie of Canterburie, of christenings, marriages and burials. 1538–1800 |date=1891 |publisher=Cross & Jackman |location=Canterbury |page=10 |url=https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008685594 |access-date=16 June 2020 |archive-date=28 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200728144929/https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/008685594 |url-status=live }}</ref> Marlowe's birth was likely to have been a few days before,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hopkins |first1=L. |title=A Christopher Marlowe Chronology |date=2005 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-0-230-50304-5 |page=27 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fSh-DAAAQBAJ&pg=PA27 |language=en |access-date=14 July 2021 |archive-date=4 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220904211115/https://books.google.com/books?id=fSh-DAAAQBAJ&pg=PA27 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Rackham2014">{{Cite journal |last=Rackham |first=Oliver |date=2014 |issue=93 |title=The Pseudo-Marlowe Portrait: a wish fulfilled? |authorlink=Oliver Rackham |url=https://www.corpus.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/images/Development%20Office/The%20letter/Corpus_Letter_93_2014%20-%20Copy%201.pdf |journal=Corpus Letter |publisher=[[Corpus Christi College, Cambridge]] |pages=32 |access-date=7 June 2021 |archive-date=23 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211023162726/https://www.corpus.cam.ac.uk/sites/default/files/images/Development%20Office/The%20letter/Corpus_Letter_93_2014%20-%20Copy%201.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Hilton |first1=Della |title=Who was Kit Marlowe? : The story of the poet and playwright |date=1977 |publisher=New York : Taplinger Pub. Co. |isbn=978-0-8008-8291-4 |page=1 |url=https://archive.org/details/whowaskitmarlowe00hilt/page/n15/mode/2up}}</ref> making him about two months older than [[William Shakespeare]], who was baptised on 26 April 1564 in [[Stratford-upon-Avon]].<ref name="Holland">{{cite ODNB |last1=Holland |first1=Peter |title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |date=2004 |edition=January 2013 |url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/25200 |access-date=27 May 2020 |chapter=Shakespeare, William |doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/25200 |archive-date=24 October 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161024235508/http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/25200 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| first = Robert |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

By age 14, Marlowe was a pupil at [[The King's School, Canterbury|The King's School]], Canterbury on a scholarship{{efn|The earliest record of Marlowe at The King's School is their payment for his scholarship of 1578/79, but Nicholl notes this was "unusually late" to start as a student and proposes he could have begun school earlier as a "fee-paying pupil".<ref name="Nicholl"/>}} and two years later a student at [[Corpus Christi College, Cambridge]], where he also studied through a scholarship with expectation that he would become an Anglican clergyman.<ref name="Marlowe Guy-Bray Wiggins Lindsey 2014 p. 8">{{cite book | last1=Marlowe | first1=C. | last2=Guy-Bray | first2=S. | last3=Wiggins | first3=M. | last4=Lindsey | first4=R. | title=Edward II Revised | publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing | year=2014 | isbn=978-1-4725-7540-1 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vm17AwAAQBAJ&pg=PR8 | access-date=2023-01-19 | page=8}}</ref> Instead, he received his Bachelor of Arts degree in 1584.<ref name="Nicholl"/><ref>{{acad|id=MRLW580C|name=Marlowe, Christopher}}</ref> Marlowe mastered [[Latin language|Latin]] during his schooling, reading and translating the works of [[Ovid]]. In 1587, the university hesitated to award his Master of Arts degree because of a rumour that he intended to go to the [[English College, Douai|English seminary]] at [[Rheims]] in northern [[France]], presumably to prepare for ordination as a [[Roman Catholic]] [[Seminary priest|priest]].<ref name="Nicholl"/> If true, such an action on his part would have been a direct violation of royal edict issued by [[Elizabeth I of England|Queen Elizabeth I]] in 1585 criminalising any attempt by an English citizen to be ordained in the Roman Catholic Church.<ref name="Collinson">{{cite ODNB |last1=Collinson |first1=Patrick |title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |date=2004 |edition=January 2012 |url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/8636 |access-date=27 May 2020 |chapter=Elizabeth I |doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/8636 |archive-date=19 August 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210819042621/https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-8636;jsessionid=4B33E8F1E68F70E307BFE7BBF6367B30 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://history.hanover.edu/texts/ENGref/er85.html |title=Act Against Jesuits and Seminarists (1585), 27 Elizabeth, Cap. 2, ''Documents Illustrative of English Church History'' |publisher=Macmillan (1896) |access-date=27 May 2020 |archive-date=20 September 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200920173546/https://history.hanover.edu/texts/ENGref/er85.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| coauthors = |

|||

| title = Elizabeth's Spy Master: Francis Walsingham and the secret war that saved England |

|||

[[St. Bartholomew's Day massacre|Large-scale violence]] between [[Protestants]] and [[Catholics]] on the European continent has been cited by scholars as the impetus for the [[Elizabeth I|Protestant English Queen]]'s defensive [[Elizabethan Religious Settlement|anti-Catholic laws]] issued from 1581 until her death in 1603.<ref name="Collinson"/> Despite the dire implications for Marlowe, his degree was awarded on schedule when the [[Privy Council of England|Privy Council]] intervened on his behalf, commending him for his "faithful dealing" and "good service" to [[Elizabeth I|the Queen]].<ref>For a full transcript, see [http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/pc_cert.htm Peter Farey's Marlowe page] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161223144200/http://rey.myzen.co.uk/pc_cert.htm |date=23 December 2016 }} (Retrieved 30 April 2015).</ref> The nature of Marlowe's service was not specified by the council, but its letter to the Cambridge authorities has provoked much speculation by modern scholars, notably the theory that Marlowe was operating as a secret agent for Privy Council member Sir [[Francis Walsingham]].<ref>{{cite book |last=Hutchinson |first=Robert |title=Elizabeth's Spy Master: Francis Walsingham and the Secret War that Saved England |publisher=Weidenfeld & Nicolson |year=2006 |location=London |page=111 |isbn =978-0-297-84613-0}}</ref> The only surviving evidence of the Privy Council's correspondence is found in their minutes, the letter being lost. There is no mention of [[espionage]] in the minutes, but its summation of the lost Privy Council letter is vague in meaning, stating that "it was not Her Majesties pleasure" that persons employed as Marlowe had been "in matters touching the benefit of his country should be defamed by those who are ignorant in th'affaires he went about." Scholars agree the vague wording was typically used to protect government agents, but they continue to debate what the "matters touching the benefit of his country" actually were in Marlowe's case and how they affected the 23-year-old writer as he began his literary career in 1587.<ref name="Nicholl"/> |

|||

| publisher = Weidenfeld & Nicolson |

|||

| date = 2006 |

|||

==Adult life and legend== |

|||

| location = London |

|||

Little is known about Marlowe's adult life. All available evidence, other than what can be deduced from his literary works, is found in legal records and other official documents. Writers of fiction and non-fiction have speculated about his professional activities, private life, and character. Marlowe has been described as a spy, a brawler, and a heretic, as well as a "magician", "duellist", "tobacco-user", "counterfeiter" and "[[Rake (character)|rakehell]]". While J. A. Downie and Constance Kuriyama have argued against the more lurid speculations, [[J. B. Steane]] remarked, "it seems absurd to dismiss all of these Elizabethan rumours and accusations as 'the Marlowe myth{{'"}}.{{sfnp|Kuriyama|2002|p={{page needed|date=February 2022}}}}{{sfnp|Downie|Parnell|2000|p={{page needed|date=February 2022}}}}<ref name="steane"/> Much has been written on his brief adult life, including speculation of: his involvement in royally sanctioned espionage; his vocal declaration of [[atheism]]; his (possibly same-sex) sexual interests; and the puzzling circumstances surrounding his death. |

|||

| pages = p111 |

|||

| url = |

|||

===Spying=== |

|||

| doi = |

|||

[[File:OldCurtCC.JPG|thumb|left|The corner of Old Court of [[Corpus Christi College, Cambridge]], where Marlowe stayed while a Cambridge student and, possibly, during the time he was recruited as a spy]] |

|||

| id = |

|||

Marlowe is alleged to have been a government spy.{{sfnp|Honan|2005|p={{page needed|date=February 2022}}}} [[Park Honan]] and [[Charles Nicholl (author)|Charles Nicholl]] speculate that this was the case and suggest that Marlowe's recruitment took place when he was at Cambridge.{{sfnp|Honan|2005|p={{page needed|date=February 2022}}}}{{sfnp|Nicholl|1992|loc="12"}} In 1587, when the Privy Council ordered the University of Cambridge to award Marlowe his degree as Master of Arts, it denied rumours that he intended to go to the English Catholic college in Rheims, saying instead that he had been engaged in unspecified "affaires" on "matters touching the benefit of his country".<ref>This is from a document dated 29 June 1587, from the National Archives – ''Acts of Privy Council''.</ref> Surviving college records from the period also indicate that, in the academic year 1584–1585, Marlowe had had a series of unusually lengthy absences from the university which violated university regulations. Surviving college [[Buttery (shop)|buttery]] accounts, which record student purchases for personal provisions, show that Marlowe began spending lavishly on food and drink during the periods he was in attendance; the amount was more than he could have afforded on his known scholarship income.{{sfnp|Nicholl|1992|p={{page needed|date=February 2022}}}}{{efn|It is known that some poorer students worked as labourers on the Corpus Christi College chapel, then under construction, and were paid by the college with extra food. It has been suggested this may be the reason for the sums noted in Marlowe's entry in the buttery accounts.<ref name="Riggs2004">{{cite book|first=David|last=Riggs|title=The World of Christopher Marlowe|page=65|year=2004a|publisher=Faber|isbn=978-0-571-22159-2}}</ref>}} |

|||

| isbn =0 297 84613 2 }}</ref> No direct evidence supports this theory, although Marlowe obviously did serve the government in some capacity. |

|||

[[File:Sir Francis Walsingham by John De Critz the Elder.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.9|Portrait of alleged "spymaster" Sir [[Francis Walsingham]] ''c.'' 1585; attributed to [[John de Critz]]]] |

|||

It has been speculated that Marlowe was the "Morley" who was tutor to [[Arbella Stuart]] in 1589.{{efn|He was described by Arbella's guardian, the Countess of Shrewsbury, as having hoped for an annuity of some £40 from Arbella, his being "so much damnified (i.e. having lost this much) by leaving the University."<ref>British Library [[Lansdowne MS.]] 71, f.3.</ref>{{sfnp|Nicholl|1992|pp=340–342}}}} This possibility was first raised in a ''[[Times Literary Supplement]]'' letter by E. St John Brooks in 1937; in a letter to ''[[Notes and Queries]]'', John Baker has added that only Marlowe could have been Arbella's tutor owing to the absence of any other known "Morley" from the period with an MA and not otherwise occupied.<ref>John Baker, letter to ''Notes and Queries'' 44.3 (1997), pp. 367–368</ref> If Marlowe was Arbella's tutor, it might indicate that he was there as a spy, since Arbella, niece of [[Mary, Queen of Scots]], and cousin of James VI of Scotland, later [[James I of England]], was at the time a strong candidate for the [[succession to Elizabeth's throne]].{{sfnp|Kuriyama|2002|p=89}}{{sfnp|Nicholl|1992|p=342}}<ref name="Handover">{{cite book |last1=Handover |first1=P. M. |title=Arbella Stuart, royal lady of Hardwick and cousin to King James |date=1957 |publisher=Eyre & Spottiswoode |location=London}}</ref><ref>[http://www.history.ac.uk/ihr/Focus/Elizabeth/index.html Elizabeth I and James VI and I] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061214113207/http://www.history.ac.uk/ihr/Focus/Elizabeth/index.html |date=14 December 2006 }}, [http://www.history.ac.uk/ History in Focus] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110908034533/http://www.history.ac.uk/ |date=8 September 2011 }}.</ref> [[Frederick S. Boas]] dismisses the possibility of this identification, based on surviving legal records which document Marlowe's "residence in London between September and December 1589". Marlowe had been party to a fatal quarrel involving his neighbours and the poet [[Thomas Watson (poet)|Thomas Watson]] in [[Norton Folgate]] and was held in [[Newgate Prison]] for a fortnight.{{sfnp|Boas|1953|pp=101ff}} In fact, the quarrel and his arrest occurred on 18 September, he was released on bail on 1 October and he had to attend court, where he was acquitted on 3 December, but there is no record of where he was for the intervening two months.{{sfnp|Kuriyama|2002|p=xvi}} |

|||

In 1592 Marlowe was arrested in the English [[Cautionary Towns|garrison town]] of [[Flushing, Netherlands|Flushing]] (Vlissingen) in the Netherlands, for alleged involvement in the [[Counterfeit money|counterfeiting]] of coins, presumably related to the activities of seditious Catholics. He was sent to the Lord Treasurer ([[William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley|Burghley]]), but no charge or imprisonment resulted.<ref>For a full transcript, see [http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/flushing.htm Peter Farey's Marlowe page] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304031527/http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/flushing.htm |date=4 March 2016 }} (Retrieved 30 April 2015).</ref> This arrest may have disrupted another of Marlowe's spying missions, perhaps by giving the resulting coinage to the Catholic cause. He was to infiltrate the followers of the active Catholic plotter [[William Stanley (Elizabethan)|William Stanley]] and report back to Burghley.{{sfnp|Nicholl|1992|pp=246–248}} |

|||

===Philosophy=== |

|||

[[File:Sir Walter Ralegh by 'H' monogrammist.jpg|thumb|upright=0.9|Sir [[Walter Raleigh]], shown here in 1588, was the alleged centre of the "[[The School of Night|School of Atheism]]" ''c.'' 1592.]] |

|||

Marlowe was reputed to be an atheist, which held the dangerous implication of being an enemy of God and, by association, the state.<ref>{{cite book|last=Stanley|first=Thomas|author-link=Thomas Stanley (author)|title=The History of Philosophy 1655–61|publisher=quoted in [[Oxford English Dictionary]]|year=1687}}</ref> With the rise of public fears concerning [[The School of Night]], or "School of Atheism" in the late 16th century, accusations of atheism were closely associated with disloyalty to the Protestant monarchy of England.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Riggs|first1=David|title=The World of Christopher Marlowe|date=2005|publisher=Henry Holt and Co.|isbn=978-0805077551|edition=1st American|page=294|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hYhWAgAAQBAJ&q=atheism&pg=PP2|access-date=3 November 2015|archive-date=28 February 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220228193647/https://books.google.com/books?id=hYhWAgAAQBAJ&q=atheism&pg=PP2|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Some modern historians consider that Marlowe's professed atheism, as with his supposed Catholicism, may have been no more than a sham to further his work as a government spy.{{sfnp|Riggs|2004|p=[https://archive.org/details/cambridgecompani00chen_319/page/n56 38]}} Contemporary evidence comes from Marlowe's accuser in [[Flushing, Netherlands|Flushing]], an informer called [[Richard Baines]]. The governor of Flushing had reported that each of the men had "of malice" accused the other of instigating the counterfeiting and of intending to go over to the Catholic "enemy"; such an action was considered atheistic by the [[Church of England]]. Following Marlowe's arrest in 1593, Baines submitted to the authorities a "note containing the opinion of one Christopher Marly concerning his damnable judgment of religion, and scorn of God's word".<ref>For a full transcript, see [http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/baines1.htm Peter Farey's Marlowe page] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304024355/http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/baines1.htm |date=4 March 2016 }} (Retrieved 30 April 2012).</ref> Baines attributes to Marlowe a total of eighteen items which "scoff at the pretensions of the [[Old Testament|Old]] and [[New Testament]]" such as, "Christ was a bastard and his mother dishonest [unchaste]", "the woman of Samaria and her sister were whores and that Christ knew them dishonestly", "St [[John the Evangelist]] was bedfellow to Christ and leaned always in his bosom" (cf. John 13:23–25) and "that he used him as the sinners of [[Sodom and Gomorrah|Sodom]]".<ref name="steane">{{cite book|last=Steane|first=J. B.|title=Introduction to Christopher Marlowe: The Complete Plays|publisher=Penguin|year=1969 |location=Aylesbury, UK|isbn=978-0-14-043037-0|url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/completeplays0000marl}}</ref> He also implied that Marlowe had Catholic sympathies. Other passages are merely sceptical in tone: "he persuades men to atheism, willing them not to be afraid of [[bugbear]]s and [[hobgoblins]]". The final paragraph of Baines's document reads: |

|||

[[File:ThomasHarriot.jpg|left|thumb|upright=0.9|Portrait often claimed to be [[Thomas Harriot]] (1602), which hangs in [[Trinity College, Oxford]]]] |

|||

{{Blockquote|These thinges, with many other shall by good & honest witnes be approved to be his opinions and Comon Speeches, and that this Marlowe doth not only hould them himself, but almost into every Company he Cometh he persuades men to Atheism willing them not to be afeard of bugbeares and hobgoblins, and vtterly scorning both god and his ministers as I Richard Baines will Justify & approue both by mine oth and the testimony of many honest men, and almost al men with whome he hath Conversed any time will testify the same, and as I think all men in Cristianity ought to indevor that the mouth of so dangerous a member may be stopped, he saith likewise that he hath quoted a number of Contrarieties oute of the Scripture which he hath giuen to some great men who in Convenient time shalbe named. When these thinges shalbe Called in question the witnes shalbe produced.<ref name="bainesnote">{{cite web|title=The 'Baines Note'|url=http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/baines1.htm|access-date=30 April 2015|archive-date=4 March 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304024355/http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/baines1.htm|url-status=live}}</ref>}} |

|||

Similar examples of Marlowe's statements were given by [[Thomas Kyd]] after his imprisonment and possible torture (see above); Kyd and Baines connect Marlowe with mathematician [[Thomas Harriot]]'s and Sir [[Walter Raleigh]]'s circle.<ref name="Peter Farey's Marlowe page"/> Another document claimed about that time that "one Marlowe is able to show more sound reasons for Atheism than any divine in England is able to give to prove divinity, and that ... he hath read the Atheist lecture to Sir Walter Raleigh and others".<ref name="steane"/>{{efn|The so-called 'Remembrances' against Richard Cholmeley.<ref>For a full transcript, see [http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/chumley1.htm Peter Farey's Marlowe page] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160125220642/http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/chumley1.htm |date=25 January 2016 }}. (Retrieved 30 April 2015)</ref>}} |

|||

Some critics believe that Marlowe sought to disseminate these views in his work and that he identified with his rebellious and iconoclastic protagonists.<ref>Waith, Eugene. ''The Herculean Hero in Marlowe, Chapman, Shakespeare, and Dryden''. Chatto and Windus, London, 1962. The idea is commonplace, though by no means universally accepted.</ref> Plays had to be approved by the [[Master of the Revels]] before they could be performed and the censorship of publications was under the control of the [[Archbishop of Canterbury]]. Presumably these authorities did not consider any of Marlowe's works to be unacceptable other than the ''Amores''. |

|||

===Sexuality=== |

|||

[[File:Hero-und-Leander.jpg|right|thumb|upright=0.8|Title page to 1598 edition of Marlowe's ''[[Hero and Leander (poem)|Hero and Leander]]'']] |

|||

It has been claimed that Marlowe was homosexual. Some scholars argue that the identification of an Elizabethan as gay or homosexual in the modern sense is "[[Anachronism|anachronistic]]," saying that for the Elizabethans the terms were more likely to have been applied to homoerotic affections or sexual acts rather than to what we currently understand as a settled sexual orientation or personal role identity.<ref>{{cite book|last=Smith|first=Bruce R.|title=Homosexual desire in Shakespeare's England|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|date= 1995|page=74|isbn=978-0-226-76366-8}}</ref> Other scholars argue that the evidence is inconclusive and that the reports of Marlowe's homosexuality may be rumours produced after his death. Richard Baines reported Marlowe as saying: "all they that love not Tobacco & Boies were fools". [[David Bevington]] and [[Eric C. Rasmussen]] describe Baines's evidence as "unreliable testimony" and "[t]hese and other testimonials need to be discounted for their exaggeration and for their having been produced under legal circumstances we would now regard as a witch-hunt".<ref>Bevington, David, and Eric Rasmussen, eds. ''Doctor Faustus and Other Plays''. Oxford English Drama. Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. viii–ix. {{ISBN|0-19-283445-2}}</ref> |

|||

Literary scholar [[J. B. Steane]] considered there to be "no evidence for Marlowe's homosexuality at all".<ref name="steane"/> Other scholars point to the frequency with which Marlowe explores homosexual themes in his writing: in ''[[Hero and Leander (poem)|Hero and Leander]]'', Marlowe writes of the male youth Leander: "in his looks were all that men desire..."<ref>{{cite book |editor-last=White |editor-first=Paul Whitfield |title=Marlowe, History and Sexuality: New Critical Essays on Christopher Marlowe |publisher=AMS Press |location=New York |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-404-62335-7}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Christopher Marlowe |chapter=Hero and Leander |title=The works of Christopher Marlowe |editor=A. H. Bullen |year=1885 |volume=3 |place=London |publisher=John C. Nimmo |pages=88, 157–193 |url=http://www.gutenberg.org/files/21262/21262-h/21262-h.htm |via=[[Project Gutenberg]] |access-date=21 May 2009 |archive-date=21 September 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080921083327/http://www.gutenberg.org/files/21262/21262-h/21262-h.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> ''[[Edward II (play)|Edward the Second]]'' contains the following passage enumerating homosexual relationships: |

|||

{{blockquote|<poem> |

|||

The mightiest kings have had their minions; |

|||

Great [[Alexander the Great|Alexander]] loved [[Hephaestion]], |

|||

The conquering [[Hercules]] for [[Hylas]] wept; |

|||

And for [[Patroclus]], stern [[Achilles]] drooped. |

|||

And not kings only, but the wisest men: |

|||

The Roman [[Cicero|Tully]] loved [[Augustus|Octavius]], |

|||

Grave [[Socrates]], wild [[Alcibiades]].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eGvavCqLW2AC&pg=PA128 |title=The Routledge Anthology of Renaissance Drama |author=Simon Barker, Hilary Hinds |publisher=Routledge |date=2003 |access-date=9 February 2013 |isbn=9780415187343 |archive-date=29 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191229075917/https://books.google.com/books?id=eGvavCqLW2AC&pg=PA128 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

</poem> |

|||

}} |

|||

Marlowe wrote the only [[Edward II (play)|play]] about the life of [[Edward II]] up to his time, taking the [[Renaissance humanism|humanist]] literary discussion of male sexuality much further than his contemporaries. The play was extremely bold, dealing with a star-crossed love story between Edward II and [[Piers Gaveston, 1st Earl of Cornwall|Piers Gaveston]]. Though it was a common practice at the time to reveal characters as homosexual to give audiences reason to suspect them as culprits in a crime, Christopher Marlowe's Edward II is portrayed as a sympathetic character.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Edward the Second|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=axTzkFP9IHoC|publisher = Manchester University Press|date = 1995|isbn = 9780719030895|first1 = Christopher|last1 = Marlowe|first2 = Charles R.|last2 = Forker|access-date = 4 November 2015|archive-date = 21 May 2016|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160521190848/https://books.google.com/books?id=axTzkFP9IHoC|url-status = live}}</ref> The decision to start the play ''[[Dido, Queen of Carthage (play)|Dido, Queen of Carthage]]'' with a homoerotic scene between [[Jupiter (mythology)|Jupiter]] and [[Ganymede (mythology)|Ganymede]] that bears no connection to the subsequent plot has long puzzled scholars.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Williams|first=Deanne|date=2006|title=Dido, Queen of England|journal=ELH|volume=73|issue=1|pages=31–59|doi=10.1353/elh.2006.0010|jstor=30030002|s2cid=153554373}}</ref> |

|||

===Arrest and death=== |

|||

[[File:marlowe.jpg|thumb|Marlowe was buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St Nicholas, [[Deptford]]. This modern plaque is on the east wall of the churchyard.]] |

|||

In early May 1593, several bills were posted about London threatening the Protestant refugees from France and the Netherlands who had settled in the city. One of these, the "Dutch church libel", written in rhymed [[iambic pentameter]], contained allusions to several of Marlowe's plays and was signed, "[[Tamburlaine]]".<ref>For a full transcript, see [http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/libell.htm Peter Farey's Marlowe page] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150622092454/http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/libell.htm |date=22 June 2015 }} (Retrieved 31 March 2012).</ref> On 11 May 1593 the [[Privy Council of the United Kingdom|Privy Council]] ordered the arrest of those responsible for the libels. The next day, Marlowe's colleague [[Thomas Kyd]] was arrested, his lodgings were searched and a three-page fragment of a [[heresy|heretical]] tract was found. In a letter to Sir [[John Puckering]], Kyd asserted that it had belonged to Marlowe, with whom he had been writing "in one chamber" some two years earlier.<ref name="Peter Farey's Marlowe page">For a full transcript of Kyd's letter, see [http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/kyd2.htm Peter Farey's Marlowe page] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150622085958/http://www.rey.myzen.co.uk/kyd2.htm |date=22 June 2015 }} (Retrieved 30 April 2015).</ref>{{efn|J. R. Mulryne states in {{clarify|text=his ''ODNB'' article|date=February 2022}} that the document was identified in the 20th century as transcripts from John Proctour's ''The Fall of the Late Arian'' (1549).{{citation needed|date=February 2022}}}} In a second letter, Kyd described Marlowe as blasphemous, disorderly, holding treasonous opinions, being an irreligious reprobate and "intemperate & of a cruel hart".<ref name=ODNB/> They had both been working for an [[Aristocracy (class)|aristocratic]] patron, probably [[Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby|Ferdinando Stanley]], Lord Strange.<ref name=ODNB>Mulryne, J. R. [https://www.oxforddnb.com/search?q=Thomas+Kyd&searchBtn=Search&isQuickSearch=true "Thomas Kyd."]''[[Oxford Dictionary of National Biography]]''. Oxford: [[Oxford University Press]], 2004.{{subscription required}} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220904211123/https://www.oxforddnb.com/search?q=Thomas+Kyd&searchBtn=Search&isQuickSearch=true |date=4 September 2022 }}</ref> A warrant for Marlowe's arrest was issued on 18 May 1593, when the Privy Council apparently knew that he might be found staying with [[Thomas Walsingham (literary patron)|Thomas Walsingham]], whose father was a first cousin of the late Sir [[Francis Walsingham]], Elizabeth's [[Secretary of State (England)|principal secretary]] in the 1580s and a man more deeply involved in state espionage than any other member of the Privy Council.<ref>Haynes, Alan. ''The Elizabethan Secret Service''. London: Sutton, 2005.</ref> Marlowe duly presented himself on 20 May 1593 but there apparently being no Privy Council meeting on that day, was instructed to "give his daily attendance on their Lordships, until he shall be licensed to the contrary".<ref>National Archives, ''Acts of the Privy Council''. Meetings of the Privy Council, including details of those attending, are recorded and minuted for 16, 23, 25, 29 and the morning of 31 May 1593 , all of them taking place in the Star Chamber at Westminster. There is no record of any meeting on either 18 or 20 May 1593, however, just a note of the warrant being issued on 18 May 1593 and the fact that Marlowe "entered his appearance for his indemnity therein" on the 20th.</ref> On Wednesday, 30 May 1593, Marlowe was killed. |

|||

[[File:Palladis Tamia 1598.jpg|thumb|left|upright=0.8|Title page to the 1598 edition of ''[[Palladis Tamia]]'' by [[Francis Meres]], which contains one of the earliest descriptions of Marlowe's death]] |

|||

Various accounts of Marlowe's death were current over the next few years. In his ''[[Palladis Tamia]]'', published in 1598, [[Francis Meres]] says Marlowe was "stabbed to death by a bawdy serving-man, a rival of his in his lewd love" as punishment for his "[[Epicureanism|epicurism]] and atheism".<ref>''Palladis Tamia''. London, 1598: 286v–287r.</ref> In 1917, in the ''[[Dictionary of National Biography]]'', Sir [[Sidney Lee]] wrote, on slender evidence, that Marlowe was killed in a drunken fight. His claim was not much at variance with the official account, which came to light only in 1925, when the scholar [[Leslie Hotson]] discovered the [[coroner]]'s report of the inquest on Marlowe's death, held two days later on Friday 1 June 1593, by the [[Coroner of the Queen's Household]], [[William Danby (coroner)|William Danby]].<ref name="rey.myzen.co.uk"/> Marlowe had spent all day in a house in [[Deptford, London|Deptford]], owned by the widow [[Eleanor Bull]], with three men: [[Ingram Frizer]], [[Nicholas Skeres]] and [[Robert Poley]]. All three had been employed by one or other of the Walsinghams. Skeres and Poley had helped snare the conspirators in the [[Babington plot]], and Frizer was a servant{{sfnmp|Kuriyama|2002|1pp=102–103, 135, 156|Honan|2005|2p=355}} to Thomas Walsingham, probably acting as a financial or business agent, as he was for Walsingham's wife [[Audrey Walsingham|Audrey]] a few years later.{{sfnp|Hotson|1925|p=65}}{{sfnp|Honan|2005|p=325}} These witnesses testified that Frizer and Marlowe had argued over payment of the bill (now famously known as the "Reckoning"), exchanging "divers malicious words", while Frizer was sitting at a table between the other two and Marlowe was lying behind him on a couch. Marlowe snatched Frizer's dagger and wounded him on the head. According to the coroner's report, in the ensuing struggle Marlowe was stabbed above the right eye, killing him instantly. The jury concluded that Frizer acted in self-defence and within a month he was pardoned. Marlowe was buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of St. Nicholas, Deptford, immediately after the inquest, on 1 June 1593.<ref>Wilson, Scott. ''Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons'', 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 30125). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.</ref> |

|||

The complete text of the inquest report was published by Leslie Hotson in his book, ''The Death of Christopher Marlowe'', in the introduction to which Professor [[George Lyman Kittredge]] wrote: "The mystery of Marlowe's death, heretofore involved in a cloud of contradictory gossip and irresponsible guess-work, is now cleared up for good and all on the authority of public records of complete authenticity and gratifying fullness". However, this confidence proved to be fairly short-lived. Hotson had considered the possibility that the witnesses had "concocted a lying account of Marlowe's behaviour, to which they swore at the inquest, and with which they deceived the jury", but decided against that scenario.{{sfnp|Hotson|1925|pp=39–40}} Others began to suspect that this theory was indeed the case. Writing to the ''Times Literary Supplement'' shortly after the book's publication, Eugénie de Kalb disputed that the struggle and outcome as described were even possible, and [[Samuel A. Tannenbaum]] insisted the following year that such a wound could not have possibly resulted in instant death, as had been claimed.<ref name="de Kalb">de Kalb, Eugénie (May 1925). "The Death of Marlowe", in ''The Times Literary Supplement''</ref>{{sfnp|Tannenbaum|1926|pp=41–42}} Even Marlowe's biographer John Bakeless acknowledged that "some scholars have been inclined to question the truthfulness of the coroner's report. There is something queer about the whole episode", and said that Hotson's discovery "raises almost as many questions as it answers".<ref>Bakeless, John (1942). ''The Tragicall History of Christopher Marlowe'', p. 182</ref> It has also been discovered more recently that the apparent absence of a local county coroner to accompany the Coroner of the Queen's Household would, if noticed, have made the inquest null and void.{{sfnp|Honan|2005|p=354}} |

|||

One of the main reasons for doubting the truth of the inquest concerns the reliability of Marlowe's companions as witnesses.<ref>Nicholl, Charles (2004). "Marlowe [Marley], Christopher", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18079 online edn], January 2008. Retrieved 24 August 2013. "The authenticity of the inquest is not in doubt, but whether it tells the full truth is another matter. The nature of Marlowe's companions raises questions about their reliability as witnesses."</ref> As an ''agent provocateur'' for the late Sir Francis Walsingham, Robert Poley was a consummate liar, the "very genius of the Elizabethan underworld", and was on record as saying "I will swear and forswear myself, rather than I will accuse myself to do me any harm".{{sfnp|Boas|1953|p=293}}{{sfnp|Nicholl|2002|p=38}} The other witness, Nicholas Skeres, had for many years acted as a [[confidence trickster]], drawing young men into the clutches of people involved in the [[loanshark|money-lending]] racket, including Marlowe's apparent killer, Ingram Frizer, with whom he was engaged in such a swindle.{{sfnp|Nicholl|2002 |pp=29–30}} Despite their being referred to as ''generosi'' (gentlemen) in the inquest report, the witnesses were professional liars. Some biographers, such as Kuriyama and Downie, take the inquest to be a true account of what occurred, but in trying to explain what really happened if the account was not true, others have come up with a variety of murder theories:{{sfnp|Kuriyama|2002|p=136}}<ref>{{harvc|last=Downie |first=J. A. |c=Marlowe, facts and fictions |in1=Downie |in2=Parnell |year=2000 |pages=26–27}}</ref> |

|||

* Jealous of her husband Thomas's relationship with Marlowe, Audrey Walsingham arranged for the playwright to be murdered.<ref name="de Kalb"/> |

|||

* Sir Walter Raleigh arranged the murder, fearing that under torture Marlowe might incriminate him.{{sfnp|Tannenbaum|1926|p={{page needed|date=February 2022}}}} |

|||

* With Skeres the main player, the murder resulted from attempts by the [[Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex|Earl of Essex]] to use Marlowe to incriminate Sir Walter Raleigh.{{sfnp|Nicholl|2002|p=415}} |

|||

* He was killed on the orders of father and son Lord Burghley and [[Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury|Sir Robert Cecil]], who thought that his plays contained Catholic propaganda.<ref>Breight, Curtis C. (1996). '' Surveillance, Militarism and Drama in the Elizabethan Era'', p. 114</ref> |

|||

* He was accidentally killed while Frizer and Skeres were pressuring him to pay back money he owed them.<ref>Hammer, Paul E. J. (1996) "A Reckoning Reframed: the 'Murder' of Christopher Marlowe Revisited", in ''English Literary Renaissance'', pp. 225–242</ref> |

|||

* Marlowe was murdered at the behest of several members of the Privy Council, who feared that he might reveal them to be atheists.<ref>Trow, M. J. (2001). ''Who Killed Kit Marlowe? A contract to murder in Elizabethan England'', p. 250</ref> |

|||

* The Queen ordered his assassination because of his subversive atheistic behaviour.<ref>{{cite book|last=Riggs|first=David|year=2004a|title=The World of Christopher Marlowe|pages=334–337|publisher=Faber|isbn=978-0-571-22159-2}}</ref> |

|||

* Frizer murdered him because he envied Marlowe's close relationship with his master Thomas Walsingham and feared the effect that Marlowe's behaviour might have on Walsingham's reputation.{{sfnp|Honan|2005|p=348}} |

|||

* Marlowe's [[Marlovian theory of Shakespeare authorship|death was faked]] to save him from trial and execution for subversive atheism.{{efn|"Useful research has been stimulated by the infinitesimally thin possibility that Marlowe did not die when we think he did. ... History holds its doors open."{{sfnp|Honan|2005|p=355}}}} |

|||

Since there are only written documents on which to base any conclusions, and since it is probable that the most crucial information about his death was never committed to paper, it is unlikely that the full circumstances of Marlowe's death will ever be known. |

|||

==Reputation among contemporary writers== |

|||

{{more citations needed section|date=November 2021}} |

|||

{{CSS image crop |

|||

|Image = Ben Jonson by George Vertue 1730.jpg |

|||

|bSize = 200 |

|||

|cWidth = 200 |

|||

|cHeight = 300 |

|||

|Location = left |

|||

|Description = [[Ben Jonson]], leading satirist of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, was one of the first to acknowledge Marlowe for the power of his dramatic verse. |

|||

}} |

|||

For his contemporaries in the literary world, Marlowe was above all an admired and influential artist. Within weeks of his death, [[George Peele]] remembered him as "Marley, the Muses' darling"; [[Michael Drayton]] noted that he "Had in him those brave translunary things / That the first poets had" and [[Ben Jonson]] even wrote of "Marlowe's mighty line".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Nicholl |first=Charles |title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2008 |chapter=Marlowe [Marley], Christopher (bap. 1564, . 1593), playwright and poet}}</ref> [[Thomas Nashe]] wrote warmly of his friend, "poor deceased Kit Marlowe," as did the publisher Edward Blount in his dedication of ''Hero and Leander'' to Sir Thomas Walsingham. Among the few contemporary dramatists to say anything negative about Marlowe was the anonymous author of the Cambridge University play ''[[Parnassus plays|The Return from Parnassus]]'' (1598) who wrote, "Pity it is that wit so ill should dwell, / Wit lent from heaven, but vices sent from hell". |

|||

The most famous tribute to Marlowe was paid by [[Shakespeare]] in ''[[As You Like It]]'', where he not only quotes a line from ''[[Hero and Leander (poem)|Hero and Leander]]'' ("Dead Shepherd, now I find thy saw of might, 'Who ever lov'd that lov'd not at first sight?{{'"}}) but also gives to the clown [[Touchstone (As You Like It)|Touchstone]] the words "When a man's verses cannot be understood, nor a man's good wit seconded with the forward child, understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room."<ref>Peter Alexander ed., ''William Shakespeare: The Complete Works'' (London 1962) p. 273</ref> This appears to be a reference to Marlowe's murder which involved a fight over the "reckoning," the bill, as well as to a line in Marlowe's ''[[Jew of Malta]]'', "Infinite riches in a little room." |

|||

{{CSS image crop |

|||

|Image = Shakespeare Droeshout 1623.jpg |

|||

|bSize = 200 |

|||

|cWidth = 200 |

|||

|Location = right |

|||

|Description = The influence of Marlowe upon [[William Shakespeare]] is evidenced by the Marlovian themes and other allusions to Marlowe found in Shakespeare's plays and sonnets. |

|||

}} |

|||

Shakespeare was much influenced by Marlowe in his work, as can be seen in the use of Marlovian themes in ''[[Antony and Cleopatra]]'', ''[[The Merchant of Venice]]'', ''[[Richard II (play)|Richard II]]'' and ''[[Macbeth]]'' (''Dido'', ''Jew of Malta'', ''Edward II'' and ''Doctor Faustus'', respectively). In ''[[Hamlet]]'', after meeting with the travelling actors, Hamlet requests the Player perform a speech about the Trojan War, which at 2.2.429–432 has an echo of Marlowe's ''[[Dido, Queen of Carthage (play)|Dido, Queen of Carthage]]''. In ''[[Love's Labour's Lost]]'' Shakespeare brings on a character "Marcade" (three syllables) in conscious acknowledgement of Marlowe's character "Mercury", also attending the King of Navarre, in ''Massacre at Paris''. The significance, to those of Shakespeare's audience who were familiar with ''Hero and Leander'', was Marlowe's identification of himself with the god [[Mercury (mythology)|Mercury]].<ref name="Jean-Christophe Mayer2008">{{cite book|last=Wilson|first=Richard|author-link=Richard Wilson (scholar)|editor=Mayer, Jean-Christophe |title=Representing France and the French in early modern English drama|year=2008|publisher=University of Delaware Press|location=Newark|isbn=978-0-87413-000-3|pages=95–97|chapter=Worthies away: the scene begins to cloud in Shakespeare's Navarre}}</ref> |

|||

==Shakespeare authorship theory== |

|||

{{Main|Marlovian theory of Shakespeare authorship|Shakespeare authorship question}} |

|||

An argument has arisen about the notion that Marlowe faked his death and then continued to write under the assumed name of William Shakespeare. Academic consensus rejects alternative candidates for authorship of Shakespeare's plays and sonnets, including Marlowe.<ref>Kathman, David (2003), "The Question of Authorship", in Wells, Stanley; Orlin, Lena C., ''Shakespeare: an Oxford Guide'', Oxford University Press, pp. 620–632, {{ISBN|978-0-19-924522-2}}</ref> |

|||

==Literary career== |

==Literary career== |

||

{{more citations needed section|date=May 2017}} |

|||

{{CSS image crop |

|||

''[[Dido, Queen of Carthage]]'' is Marlowe's first drama, co-written with [[Thomas Kyd]]. |

|||

|Image = Edward alleyn.jpg |

|||

|bSize = 272 |

|||

|cWidth = 200 |

|||

|cHeight = 300 |

|||

|oLeft =40 |

|||

|Location = left |

|||

|Description = [[Edward Alleyn]], lead actor of [[Lord Strange's Men]] was possibly the first to play the title characters in ''[[Doctor Faustus (play)|Doctor Faustus]]'', ''[[Tamburlaine]]'', and ''[[The Jew of Malta]]''. |

|||

}} |

|||

===Plays=== |

|||

Marlowe's first play performed onstage in [[London]] stage was ''[[Tamburlaine (play)|Tamburlaine]]'' ([[1587]]) about the conqueror [[Timur]], who rises from shepherd to warrior. It is among the first English plays in [[blank verse]], and, with Thomas Kyd's ''[[The Spanish Tragedy]]'', generally is considered the beginning of the mature phase of the [[Elizabethan theatre]]. ''Tamburlaine'' was a success, and was followed with ''Tamburlaine Part II''. The sequence of his plays is unknown; all deal with controversial themes. |

|||

Six dramas have been attributed to the authorship of Christopher Marlowe either alone or in collaboration with other writers, with varying degrees of evidence. The writing sequence or chronology of these plays is mostly unknown and is offered here with any dates and evidence known. Among the little available information we have, ''Dido'' is believed to be the first Marlowe play performed, while it was ''Tamburlaine'' that was first to be performed on a regular commercial stage in London in 1587. Believed by many scholars to be Marlowe's greatest success, ''Tamburlaine'' was the first English play written in [[blank verse]] and, with [[Thomas Kyd]]'s ''[[The Spanish Tragedy]]'', is generally considered the beginning of the mature phase of the [[Elizabethan theatre]].<ref name=":N">{{cite web|title=The Sixteenth Century: Topics |url=http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/16century/topic_1/welcome.htm |postscript=. See especially the middle section in which the author shows how another Cambridge graduate, Thomas Preston makes his title character express his love in a popular play written around 1560 and compares that "clumsy" line with ''Doctor Faustus'' addressing Helen of Troy |work=The Norton Anthology of English Literature |publisher=W.W. Norton and Company |access-date=10 December 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111010193423/http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/nael/16century/topic_1/welcome.htm |archive-date=2011-10-10 |url-status=deviated}}</ref> |

|||

The play ''[[Lust's Dominion]]'' was attributed to Marlowe upon its initial publication in 1657, though scholars and critics have almost unanimously rejected the attribution. He may also have written or co-written ''[[Arden of Faversham]]''. |

|||

''[[The Jew of Malta]]'', about a Maltese Jew's barbarous revenge against the city authorities, has a prologue delivered by a character representing [[Niccolò Machiavelli|Machiavelli]]. The protagonist, Barabas is sympathetic, while the Christians are unsympathetic; in his continual plotting and script writing, Barabas often is likened to Marlowe, himself. {{Fact|date=December 2007}} |

|||

{{CSS image crop |

|||

''[[Edward II (play)|Edward the Second]]'' is an English history play about the deposition of the homosexual King [[Edward II of England|Edward II]] by his barons and the Queen of France. |

|||

|Image = Fernando Stanley.jpg |

|||

|bSize = 200 |

|||

|cWidth = 200 |

|||

|cHeight = 240 |

|||

|Location = right |

|||

|Description = [[Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby]], aka "Ferdinando, Lord Straunge," was patron of some of Marlowe's early plays as performed by [[Lord Strange's Men]]. |

|||

}} |

|||

===Poetry and translations=== |

|||

''[[The Massacre at Paris]]'' is short (believed a memorial construction by actors) portraying the events of the [[Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre]] in 1572, which English Protestants invoked as the blackest example of Catholic treachery. It features the silent "English Agent" (rumoured to be Marlowe and his connection to the secret service). Along with ''The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus'', ''The Massacre at Paris'' is believed his most dangerous play, as it is about regnant monarchs and politicians (then a treasonable action), and, indeed, addressing [[Elizabeth I]] in its last scene. |

|||

Publication and responses to the poetry and translations credited to Marlowe primarily occurred posthumously, including: |

|||

* ''[[Amores (Ovid)|Amores]]'', first book of Latin [[elegiac couplet]]s by Ovid with translation by Marlowe (''c''. 1580s); copies publicly burned as offensive in 1599.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Steinhoff |first=Eirik |date=2010 |title=On Christopher Marlowe's 'All Ovids Elegies' |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/23065705 |journal=Chicago Review |volume=55 |issue=3/4 |pages=239–241 |jstor=23065705 |access-date=13 November 2022 |archive-date=13 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221113211928/https://www.jstor.org/stable/23065705 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

* ''[[The Passionate Shepherd to His Love]]'', by Marlowe. (''c.'' 1587–1588);{{sfnp|Cheney|2004a|p=xvi}} a popular lyric of the time. |

|||

* ''[[Hero and Leander (poem)|Hero and Leander]]'', by Marlowe (''c.'' 1593, unfinished; completed by [[George Chapman]], 1598; printed 1598).{{sfnp|Cheney|2004a|pp=xviii, xix}} |

|||

* ''[[Pharsalia]]'', Book One, by [[Lucan]] with translation by Marlowe. (''c.'' 1593; printed 1600){{sfnp|Cheney|2004a|pp=xviii, xix}} |

|||

===Collaborations=== |

|||

''[[The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus]]'', based on the German [[Faustbuch]], was the first dramatised version of the [[Faust]] legend of a scholar's dealing with the devil. Whilst versions of "The Devil's Pact" can be traced back to the 4th century, Marlowe deviates significantly by having his hero unable to "burn his books" or have his contract repudiated by a merciful god at the end of the play. Marlowe's protagonist is instead torn apart by demons and dragged off screaming to hell. Dr Faustus is a textual problem for scholars as it was highly edited (and possibly censored) and rewritten after Marlowe's death. Two versions of the play exist: the 1604 [[quarto]], also known as the A text, and the 1616 quarto or B text. Many scholars believe that the A text is more representative of Marlowe's original because it contains irregular character names and idiosyncratic spelling: the hallmarks of a text that used the author's handwritten manuscript, or "[[foul papers]]," as a major source. |

|||

Modern scholars still look for evidence of collaborations between Marlowe and other writers. In 2016, one publisher was the first to endorse the scholarly claim of a collaboration between Marlowe and the playwright William Shakespeare: |

|||

* ''[[Henry VI, Part 1|Henry VI]]'' by William Shakespeare is now credited as a collaboration with Marlowe in the [[The Oxford Shakespeare|New Oxford Shakespeare]] series, published in 2016. Marlowe appears as co-author of the three ''Henry VI'' plays, though some scholars doubt any actual collaboration.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Shea|first1=Christopher D.|title=New Oxford Shakespeare Edition Credits Christopher Marlowe as a Co-author|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/25/books/shakespeare-christopher-marlowe-henry-vi.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220101/https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/25/books/shakespeare-christopher-marlowe-henry-vi.html |archive-date=2022-01-01 |url-access=limited|access-date=24 October 2016|work=The New York Times|date=24 October 2016}}{{cbignore}}</ref><ref name="cowrite">{{cite news|title=Christopher Marlowe credited as Shakespeare's co-writer|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-37750558|access-date=24 October 2016|publisher=BBC|date=24 October 2016|archive-date=25 October 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161025055153/http://www.bbc.com/news/entertainment-arts-37750558|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Freebury-Jones|first=Darren|date=|title=Augean Stables; Or, the State of Modern Authorship Attribution Studies|url=https://www.archivdigital.info/ce/augean-stables-or-the-state-of-modern-authorship-attribution-studies/detail.html|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200723141523/https://www.archivdigital.info/ce/augean-stables-or-the-state-of-modern-authorship-attribution-studies/detail.html |archive-date=23 July 2020 |access-date=2021-01-23|website=www.archivdigital.info}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Freebury-Jones|first=Darren|date=2017-07-03|title=Did Shakespeare Really Co-Write 2 Henry VI with Marlowe?|url=https://doi.org/10.1080/0895769X.2017.1295360|journal=ANQ: A Quarterly Journal of Short Articles, Notes and Reviews|volume=30|issue=3|pages=137–141|doi=10.1080/0895769X.2017.1295360|s2cid=164545629|issn=0895-769X}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham Procession Portrait detail.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.9|[[Charles Howard, 1st Earl of Nottingham]], Lord High Admiral, shown here ''c.'' 1601 in a procession for [[Elizabeth I of England]], was patron of the [[Admiral's Men]] during Marlowe's lifetime.]] |

|||

Marlowe's plays were enormously successful, thanks in part, no doubt, to the imposing stage presence of [[Edward Alleyn]]. He was unusually tall for the time, and the haughty roles of Tamburlaine, Faustus, and Barabas were probably written especially for him. Marlowe's plays were the foundation of the repertoire of Alleyn's company, the [[Admiral's Men]], throughout the 1590s. |

|||

===Contemporary reception=== |

|||

Marlowe also wrote poetry, including a, possibly, unfinished minor epic, ''[[Hero and Leander (Marlowe's poem)|Hero and Leander]]'' (published with a continuation by [[George Chapman]] in [[1598]]), the popular lyric ''[[The Passionate Shepherd to His Love]]'', and translations of [[Ovid]]'s ''[[Amores]]'' and the first book of [[Lucan (poet)|Lucan]]'s ''[[Pharsalia]]''. |

|||

{{more citations needed section|date=February 2021}} |

|||

Marlowe's plays were enormously successful, possibly because of the imposing stage presence of his lead actor, [[Edward Alleyn]]. Alleyn was unusually tall for the time and the haughty roles of Tamburlaine, Faustus and Barabas were probably written for him. Marlowe's plays were the foundation of the repertoire of Alleyn's company, the [[Admiral's Men]], throughout the 1590s. One of Marlowe's poetry translations did not fare as well. In 1599, Marlowe's translation of [[Ovid]] was banned and copies were publicly burned as part of [[John Whitgift|Archbishop Whitgift]]'s crackdown on offensive material. |

|||

==Chronology of dramatic works== |

|||

The two parts of ''[[Tamburlaine (play)|Tamburlaine]]'' were published in 1590; all Marlowe's other works were published posthumously. In [[1599]], his translation of [[Ovid]] was banned and copies publicly burned as part of [[John Whitgift|Archbishop Whitgift]]'s crackdown on offensive material. |

|||

(Patrick Cheney's 2004 ''Cambridge Companion to Christopher Marlowe'' presents an alternative timeline based upon printing dates.){{sfnp|Cheney|2004b|p=5}} |

|||

==The Marlowe legend== |

|||

[[Image:marlowe theatre1.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Marlowe Theatre, [[Canterbury]]]] |

|||

As with other writers of the period, little is known about Marlowe. Most of the evidence is legal records and other official documents that tell us little about him. This has not stopped writers of both fiction and non-fiction from speculating about his activities and character. Marlowe has often been described as a spy, a brawler, a heretic, and a homosexual, as well as a "magician", "duelist", "tobacco-user", "counterfeiter", and "[[Rake (character)|rakehell]]". The evidence for most of these claims is slight. The bare facts of Marlowe's life have been embellished by many writers into colourful, and often fanciful, narratives of the Elizabethan underworld. |

|||

===''Dido, Queen of Carthage'' ({{circa|1585}}–1587)=== |

|||

===Spying=== |

|||

[[File:Dido1594titlepage.jpg|thumb|right|upright=0.70|Title page of the 1594 first edition of ''[[Dido, Queen of Carthage (play)|Dido, Queen of Carthage]]'']] |

|||

Marlowe is often alleged to have been a government spy. |

|||

'''First official record''' 1594 |

|||

====Possible evidence of spying==== |

|||

'''First published''' 1594; posthumously |

|||

As noted above, in [[1587]] the [[Privy Council]] ordered Cambridge University to award Marlowe his MA, denying rumours that he intended to go to the English Catholic college in Rheims, saying instead that he had been engaged in unspecified "affaires" on "matters touching the benefit of his country". This from a document dated June 29th, 1587, from the Public Records Office - ''Acts of Privy Council.'' |

|||

'''First recorded performance''' between 1587 and 1593 by the [[Children of the Chapel]], a company of boy actors in London.<ref>Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith, eds. ''The Predecessors of Shakespeare: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama.'' Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1973.</ref> |

|||

It has sometimes been theorized that Marlowe was the "Morley" who was tutor to [[Arbella Stuart]] in [[1589]], described by Arbella's guardian, the Countess of Shrewsbury, as having hoped for an annuity of some £40 from Arbella, his being "so much damnified (i.e. having lost this much) by leaving the University".<ref>BL Lansdowne MS 71,f.3.and Charles Nicholl, ''The Reckoning'' (1992), pp. 340-2.</ref> This possibility was first raised in a ''TLS'' letter by E. St John Brooks in [[1937]]; in a letter to ''[[Notes and Queries]]'', John Baker has added that only Marlowe could be Arbella's tutor due to the absence of any other known "Morley" from the period with an MA and not otherwise occupied.<ref>John Baker, letter to ''Notes and Queries'' 44.3 (1997), pp. 367-8</ref> Some biographers think that the "Morley" in question may have been a brother of the musician [[Thomas Morley]].<ref>Constance Kuriyama, ''Christopher Marlowe: A Renaissance Life'' (2002), p. 89. Also in Handover's biography of Arbella, and Nicholl, ''The Reckoning'', p. 342.</ref> If Marlowe was Arbella's tutor, it might indicate that he was a spy, since Arbella, niece of [[Mary Queen of Scots]] and cousin of [[James I of England|James VI of Scotland]], later James I of England, was at the time a strong candidate for the succession of Elizabeth's throne.<ref>[http://www.history.ac.uk/ihr/Focus/Elizabeth/index.html Elizabeth I and James VI and I], [http://www.history.ac.uk/ History in Focus].</ref> |

|||

'''Significance''' This play is believed by many scholars to be the first play by Christopher Marlowe to be performed. |

|||

In [[1592]], Marlowe was arrested in the Dutch town of [[Flushing, Netherlands|Flushing]] for attempting to counterfeit coins. He was sent to be dealt with by the Lord Treasurer ([[William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley|Burghley]]) but no charge or imprisonment seems to have resulted.<ref>For a full transcript, see [http://www.prst17z1.demon.co.uk/flushing.htm Peter Farey's Marlowe page]</ref> |

|||

'''Attribution''' The title page attributes the play to Marlowe and [[Thomas Nashe]], yet some scholars question how much of a contribution Nashe made to the play.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Freebury-Jones|first1=Darren|last2=Dahl|first2=Marcus|date=2020-06-01|title=Searching for Thomas Nashe in Dido, Queen of Carthage|url=https://academic.oup.com/dsh/article/35/2/296/5370652|journal=Digital Scholarship in the Humanities|language=en|volume=35|issue=2|pages=296–306|doi=10.1093/llc/fqz008|issn=2055-7671|access-date=23 January 2021|archive-date=29 July 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200729115606/https://academic.oup.com/dsh/article/35/2/296/5370652|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Lunney|first1=Ruth|last2=Craig|first2=Hugh|date=2020-09-16|title=Who Wrote Dido, Queen of Carthage?|url=https://journals.shu.ac.uk/index.php/Marlstud/article/view/92|journal=Journal of Marlowe Studies|language=en|volume=1|pages=1–31–1–31|doi=10.7190/jms.v1i0.92|issn=2516-421X|doi-access=free|access-date=23 January 2021|archive-date=22 January 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210122151411/https://journals.shu.ac.uk/index.php/Marlstud/article/view/92|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

====Arrest and death==== |

|||

In early May [[1593]] several bills were posted about London threatening Protestant refugees from [[France]] and the [[Netherlands]] who had settled in the city. One of these, the "Dutch church libel",<ref>[http://www.prst17z1.demon.co.uk/libell.htm A Libell, fixte vpon the French Church Wall, in London<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> written in [[blank verse]], contained allusions to several of Marlowe's plays and was signed "[[Tamburlaine]]." On [[11 May]] the [[Privy Council of the United Kingdom|Privy Council]] ordered the arrest of those responsible for the libels. The next day, Marlowe's colleague [[Thomas Kyd]] was arrested. Kyd's lodgings were searched and a fragment of a [[heretical]] tract was found. Kyd asserted, possibly under [[torture]], that it had belonged to Marlowe. Two years earlier they had both been working for an [[aristocratic]] patron, probably [[Ferdinando Stanley, 5th Earl of Derby|Ferdinando Stanley]], Lord Strange,<ref>Mulryne, J. H. "Thomas Kyd." ''Oxford [[Dictionary of National Biography]]''. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.</ref> and Kyd suggested that at this time, when they were sharing a workroom, the document had found its way among his papers. Marlowe's arrest was ordered on [[18 May]]. Marlowe was not in London, but was staying with Thomas Walsingham, the cousin of the late Sir [[Francis Walsingham]], Elizabeth's [[Secretary of State|principal secretary]] in the 1580s and a man deeply involved in state espionage.<ref>Haynes, Alan. ''The Elizabethan Secret Service''. London: Sutton, 2005.</ref> However, he duly appeared before the Privy Council on [[20 May]] and was instructed to "give his daily attendance on their Lordships, until he shall be licensed to the contrary." On [[30 May]], Marlowe was murdered. |

|||

'''Evidence''' No manuscripts by Marlowe exist for this play.<ref name="Maguire">{{cite book |last1=Maguire |first1=Laurie E. |editor1-last=Cheney |editor1-first=Patrick |title=The Cambridge Champion of Christopher Marlowe |date=2004 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=9780511999055 |page=44 |chapter=Marlovian texts and authorship}}</ref> |

|||

Various versions of Marlowe's death were current at the time. [[Francis Meres]] says Marlowe was "stabbed to death by a bawdy serving-man, a rival of his in his lewd love" as punishment for his "epicurism and atheism".<ref>''Palladis Tamia''. London, 1598: 286v-287r.</ref> In [[1917]], in the ''[[Dictionary of National Biography]]'', Sir [[Sidney Lee]] wrote that Marlowe was killed in a drunken fight, and this is still often stated as fact today. |

|||

=== ''Tamburlaine, Part I'' ({{circa|1587}}); ''Part II'' ({{circa|1587}}–1588) === |

|||

The facts only came to light in [[1925]] when the scholar [[Leslie Hotson]] discovered the [[coroner]]'s report on Marlowe's death in the [[Public Record Office]].<ref>[http://www.prst17z1.demon.co.uk/inquis~2.htm The Coroner's Inquisition (Translation)<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> Marlowe had spent all day in a house (''not'' a tavern, as is widely claimed, even in some biographies) in [[Deptford, London|Deptford]], owned by the widow [[Eleanor Bull]], along with three men, [[Ingram Frizer]], Nicholas Skeres and Robert Poley<ref>E. de Kalb, Robert Poley’s Movements as a Messenger of the Court, 1588 to 1601 Review of English Studies, Vol. 9, No. 33</ref>. All three had been employed by the Walsinghams. Skeres and Poley had helped snare the conspirators in the [[Babington plot]]. Frizer was a servant of Thomas Walsingham. Witnesses testified that Frizer and Marlowe had earlier argued over the bill, exchanging "divers malicious words." Later, while Frizer was sitting at a table between the other two and Marlowe was lying behind him on a couch, Marlowe snatched Frizer's dagger and began attacking him. In the ensuing struggle, according to the coroner's report, Marlowe was accidentally stabbed above the right eye, killing him instantly. The jury concluded that Frizer acted in self-defence, and within a month he was pardoned. Marlowe was buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard of [http://www.deptfordchurch.org St. Nicholas, Deptford], on [[1 June]][[1593]]. |

|||

[[File:Tamburlaine title page.jpg|thumb|upright=0.70|Title page of the earliest published edition of ''[[Tamburlaine]]'' (1590)]] |

|||

Marlowe's death is alleged by some to be an assassination for the following reasons: |

|||

# The three men who were in the room with him when he died were all connected both to the state secret service and to the London underworld.<ref>Seaton, Ethel. "Marlowe, Robert Poley, and the Tippings." ''Review of English Studies'' 5 (1929): 273.</ref> Frizer and Skeres also had a long record as loan sharks and con-men, as shown by court records. Bull's house also had "links to the government's spy network."<ref>[[Stephen Greenblatt|Greenblatt, Stephen]] ''Will in the World''. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2004: 268.</ref> |

|||

# Their story that they were on a day's pleasure outing to [[Deptford]] is considered implausible. In fact, they spent the whole day closeted together, deep in discussion. Also, [[Robert Poley]] was carrying confidential despatches to the Queen, who was at her palace of Nonsuch in Surrey, but instead of delivering them, he spent the day with Marlowe and the other two.<ref>Nicholl, Charles. ''The Reckoning: The Murder of Christopher Marlowe''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995: 32.</ref> |

|||

# It seems too much of a coincidence that Marlowe's death occurred only a few days after his arrest for [[Christian heresy|heresy]]. |

|||

# The manner of Marlowe's arrest suggests causes more tangled than a simple charge of heresy would generally indicate. He was released in spite of ''[[prima facie]]'' evidence, and even though the charges implicitly connected [[Sir Walter Raleigh]] and the Earl of [[Northumberland]] with the heresy. Thus, it seems probable that the investigation was meant primarily as a warning to the politicians in the "[[School of Night]]," and/or that it was connected with a power struggle within the Privy Council itself.<ref>Gray, Austin. "Some Observations on Christopher Marlowe, Government Agent." ''PMLA'' 43 (1928): 692-4.</ref> |

|||

# The various incidents that hint at a relationship with the Privy Council (see above), and by the fact that his patron was Thomas Walsingham, Sir [[Francis Walsingham|Francis]]' second cousin, who was actively involved in intelligence work. |

|||

'''First official record''' 1587, Part I |

|||

For these reasons and others, some believe there was more to Marlowe's death than emerged at the inquest. It is also possible that he was not murdered at all, and that his death was faked. However, on the basis of our current knowledge, it is not possible to draw any firm conclusions about what happened or why. There are different [[Marlovian theory|theories]] of some degree of probability. Since there are only written documents on which to base any conclusions, and since it is probable that the most crucial information about his death was never committed to writing at all, it is unlikely that the full circumstances of Marlowe's death will ever be known. |

|||

'''First published''' 1590, Parts I and II in one [[octavo]], [[London]]. No author named.<ref name="Chambers Vol. 3">{{cite book |last1=Chambers |first1=E. K. |title=The Elizabethan Stage. Vol. 3 |date=1923 |publisher=Clarendon Press |location=Oxford |page=421}}</ref> |

|||

===Atheism=== |

|||