Māori people: Difference between revisions

m Slight change to the probable date Maori arrived in New Zealand. |

m Capitalisation of source title |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Indigenous Polynesian people of New Zealand}} |

|||

:''This article discusses the Māori people of New Zealand. For other meanings see [[Māori (disambiguation)]].'' |

|||

{{About|the Māori people of New Zealand|the Māori people of the Cook Islands|Cook Islanders|the Maohi people of the Society Islands|Tahitians}} |

|||

{{Infobox Ethnic group |

|||

{{Distinguish|Maouri people|Mauri|Moriori}} |

|||

|group = Māori |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2023}} |

|||

|image = [[Image:Hinepare.jpg|220px]] |

|||

{{Use New Zealand English|date=October 2022}} |

|||

|caption = Hinepare of [[Ngāti Kahungunu]], c.1890 |

|||

{{Infobox ethnic group |

|||

|population = approx. 725,000 |

|||

| group = Māori |

|||

|region1 = {{flagcountry|New Zealand}} |

|||

| image = File:Haka performed during US Defense Secretary's visit to New Zealand (1).jpg |

|||

|pop1 = 632,900 (ethnicity) |

|||

| caption = Māori performing a [[haka]] (2012) |

|||

|ref1 = <ref>Statistics New Zealand (2007). [http://www.stats.govt.nz/NR/rdonlyres/31591600-3789-4E45-BD18-62C78B8A4E0B/0/MaoriPopEstAt30Jun.xls Māori population estimates tables] as of [[2007-06-30]]. Retrieved [[2007-12-18]].</ref> |

|||

| population = <!--Do not synthesize this number by adding up the other cited entries for Māori residing overseas--> |

|||

|region2 = {{flagcountry|Australia}} |

|||

| |

| region1 = New Zealand |

||

| pop1 = 887,493 (primary ethnicity) <br/> 978,246 (descent, 2023) |

|||

|ref2 = <ref>Table 2.1, p 12, in Australian Bureau of Statistics (2004). ''{{PDFlink|[http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/free.nsf/Lookup/3382D783B76B605BCA256E91007AB88E/$File/20540_2001.pdf Australians' Ancestries: 2001]|2.01 [[Mebibyte|MiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 2112269 bytes -->}}''. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, Catalogue Number 2054.0.</ref> |

|||

| ref1 = <ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.stats.govt.nz/2023-census/|title=2023 Census national and subnational usually resident population counts and dwelling counts|format=Microsoft Excel|publisher=Stats NZ - Tatauranga Aotearoa|at=Table 3|access-date=29 May 2024}}</ref> |

|||

|region3 = {{flagcountry|England}} |

|||

| |

| region2 = Australia |

||

| pop2 = [[Māori Australians|170,057]] (2021 census) |

|||

|ref3 = <ref name="Walrond">Walrond, Carl (2005). ''[http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/NewZealanders/MaoriNewZealanders/MaoriOverseas/5/en Māori overseas - England, the United States and elsewhere]'', Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand.</ref> |

|||

| ref2 = <ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/cultural-diversity-census/latest-release|website=www.censusdata.abs.gov.au|access-date=16 May 2023|title=Cultural diversity: Census|date=12 January 2022 |at=Data table for Cultural diversity summary}}</ref> |

|||

|region4 = {{flagcountry|United States}} |

|||

| |

| region3 = United Kingdom |

||

| pop3 = [[New Zealanders in the United Kingdom#Māori|approx. 8,000]] (2000) |

|||

|ref4 = <ref>New Zealand-born figures from the 2000 U.S. Census; sum of "Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander" and people of mixed race. United States Census Bureau (2003). ''{{PDFlink|[http://www.census.gov/population/cen2000/stp-159/stp159-new_zealand.pdf Census 2000 Foreign-Born Profiles (STP-159): Country of Birth: New Zealand]|103 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 105716 bytes -->}}''. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.</ref> |

|||

| ref3 = <ref name=Walrond>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Walrond |first=Carl |title=Māori overseas |encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |url=http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/maori-overseas |date=4 March 2009 |access-date=7 December 2010}}</ref> |

|||

|region5 = {{flagcountry|Canada}} |

|||

| |

| region4 = United States |

||

| pop4 = [[Māori Americans|3,500]] (2000) |

|||

|ref5 = <ref>Statistics Canada (2003). ''[http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/products/standard/themes/RetrieveProductTable.cfm?Temporal=2001&PID=62911&APATH=3&GID=431515&METH=1&PTYPE=55440&THEME=44&FOCUS=0&AID=0&PLACENAME=0&PROVINCE=0&SEARCH=0&GC=0&GK=0&VID=0&FL=0&RL=0&FREE=0 Ethnic Origin (232), Sex (3) and Single and Multiple Responses (3) for Population, for Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2001 Census - 20% Sample Data]''. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Cat. No. 97F0010XCB2001001.</ref> |

|||

| ref4 = <ref name=auto>New Zealand-born figures from the 2000 U.S. Census; maximum figure represents sum of "Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander" and people of mixed race. United States Census Bureau (2003). {{cite web|url= https://www.census.gov/population/cen2000/stp-159/stp159-new_zealand.pdf |title=Census 2000 Foreign-Born Profiles (STP-159): Country of Birth: New Zealand }} {{small|(103 KB)}}. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau.</ref> |

|||

|region6 = Other regions |

|||

| |

| region5 = Canada |

||

| |

| pop5 = 2,500 (2016) |

||

| ref5 = <ref>{{cite web |last1=Government of Canada |first1=Statistics Canada |title=Ethnic Origin (279), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age (12) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces and Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2016 Census – 25% Sample Data |url=https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/dt-td/Rp-eng.cfm?TABID=2&Lang=E&APATH=3&DETAIL=0&DIM=0&FL=A&FREE=0&GC=0&GID=1341679&GK=0&GRP=1&PID=110528&PRID=10&PTYPE=109445&S=0&SHOWALL=0&SUB=0&Temporal=2017&THEME=120&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=&D1=0&D2=0&D3=0&D4=0&D5=0&D6=0 |website=www12.statcan.gc.ca |date=25 October 2017}}</ref> |

|||

|languages = [[Māori language|Māori]], [[English language|English]] |

|||

| region6 = Other regions |

|||

|religions = [[Māori religion]], [[Christianity]] |

|||

| pop6 = {{abbr|approx.|approximately}} 8,000 |

|||

|related-c = other [[Polynesia]]n peoples,<br/>[[Austronesian people]]s |

|||

| ref6 = <ref name=Walrond /> |

|||

| languages = [[Māori language|Māori]], [[New Zealand English|English]] |

|||

| religions = Mainly [[Christianity in New Zealand|Christian]] or [[Irreligion in New Zealand|irreligious]]<br /> [[Rātana]]<br />[[Religion of Māori people|Māori religion]]s |

|||

| related-c = Other [[Polynesians|Polynesian peoples]]; especially [[Native Hawaiians]], [[Cook Islanders|Cook Island Māori]], [[Moriori]], [[Tahitians]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Māori sidebar}} |

|||

'''Māori''' ({{IPA-mi|ˈmaːɔɾi|lang|Rar-Māori.ogg}}){{efn-lr|Also spelled ''Maori''<ref>{{cite web |title=Maori – Definition & Meaning |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Maori |website=[[Merriam-Webster]] |access-date=23 March 2024 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Maori – Definition & Usage Examples |url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/maori |website=Dictionary.com |access-date=23 March 2024 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Māori, noun (also Maori) |url=https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/maori |website=Cambridge Dictionary |access-date=23 March 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Definition of 'Maori' |url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/maori |website=Collins Dictionary |access-date=23 March 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Maori (adjective) |url=https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/maori_1 |website=Oxford Learner's Dictionaries |access-date=23 March 2024}}</ref> or, uncommonly, ''Maaori''.<ref>{{cite web |title=Māori – Variant forms |url=https://www.oed.com/dictionary/maori_n?tab=forms |website=Oxford English Dictionary |access-date=23 March 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Use of the double vowel in te reo Maaori at CM Health |url=https://www.countiesmanukau.health.nz/about-counties-manukau/use-of-the-double-vowel-in-te-reo-maaori-at-cm-health/ |website=Te Whatu Ora – Health New Zealand Counties Manukau |access-date=23 March 2024 |date=20 June 2023}}</ref>}} are the [[Indigenous peoples of Oceania|indigenous]] [[Polynesians|Polynesian people]] of mainland [[New Zealand]]. Māori originated with settlers from East [[Polynesia]], who arrived in New Zealand in several waves of [[Māori migration canoes|canoe voyages]] between roughly 1320 and 1350.<ref name="Walters et al (2017)">{{Cite journal | last1=Walters | first1=Richard | last2=Buckley | first2=Hallie|last3=Jacomb|first3=Chris|last4=Matisoo-Smith|first4=Elizabeth|title=Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand|journal=Journal of World Prehistory|volume=30| issue=4 |pages=351–376|doi=10.1007/s10963-017-9110-y|date=7 October 2017|doi-access=free}}</ref> Over several centuries in isolation, these settlers developed [[Māori culture|a distinct culture]], whose language, mythology, crafts, and performing arts evolved independently from those of other eastern Polynesian cultures. Some early Māori moved to the [[Chatham Islands]], where their descendants became New Zealand's other indigenous Polynesian ethnic group, the [[Moriori]].<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia |last1=Davis |first1=Denis |last2=Solomon |first2=Māui |title=Moriori – Origins of the Moriori people |encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/moriori/page-1 |language=en-NZ |date=1 March 2017 |access-date=13 December 2018}}</ref> |

|||

Early contact between Māori and Europeans, starting in the 18th century, ranged from beneficial trade to lethal violence; Māori actively adopted many technologies from the newcomers. With the signing of the [[Treaty of Waitangi|Treaty of Waitangi/Te Tiriti o Waitangi]] in 1840, the two cultures coexisted for a generation. Rising tensions over disputed land sales led to conflict in the 1860s, and subsequent land confiscations, which Māori resisted fiercely. After the Treaty was declared a legal nullity in 1877, Māori were [[forced assimilation|forced to assimilate]] into many aspects of [[Western culture]]. Social upheaval and epidemics of introduced disease took a devastating toll on the Māori population, which fell dramatically, but began to recover by the beginning of the 20th century. The March 2023 New Zealand census gives the number of people of Māori descent as 978,246 (19.6% of the total population), an increase of 12.5% since 2018.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Māori population hit 978,246 in 2023, almost 20 per cent of New Zealand |url=https://www.teaonews.co.nz/2024/05/29/maori-population-hit-978246-in-2023-almost-20-per-cent-of-new-zealand/ |access-date=2024-05-29 |website=Te Ao Māori News |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=First results from the 2023 Census – older, more diverse population, and an extra 300,000 people between censuses {{!}} Stats NZ |url=https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/first-results-from-the-2023-census-older-more-diverse-population-and-an-extra-300000-people-between-censuses/ |access-date=2024-05-29 |website=www.stats.govt.nz}}</ref> |

|||

The word '''''Māori''''' refers to the [[indigenous people|indigenous]] [[Polynesian]] people of [[New Zealand]], and to [[Māori language|their language]]. |

|||

Efforts have been made, centring on the [[Treaty of Waitangi]], to increase the standing of Māori in wider New Zealand society and achieve [[social justice]]. Traditional Māori culture has enjoyed a significant revival, which was further bolstered by a [[Māori protest movement]] that emerged in the 1960s. However, disproportionate numbers of Māori face significant economic and social obstacles, and generally have lower life expectancies and incomes than other New Zealand ethnic groups. They suffer higher levels of crime, health problems, imprisonment and educational under-achievement. A number of socio-economic initiatives have been instigated with the aim of "[[closing the gaps]]" between Māori and other New Zealanders. Political and economic redress for historical grievances is also ongoing (see [[Treaty of Waitangi claims and settlements]]). |

|||

Māori came to New Zealand from eastern Polynesia, probably in several waves, most likely between AD 1280 to 1300<ref> |

|||

[http://www.newscientist.com/channel/being-human/mg19826595.200-rat-remains-help-date-new-zealands-colonisation.html New Scientist Webpage: Rat remains help date New Zealand's colonisation]. Accessed [[2008-06-23]]</ref>. They spread throughout the country and developed a distinct culture. Europeans came to New Zealand in increasing numbers from the late 18th century, and the technologies and diseases they brought with them destabilised Māori society. After 1840, Māori lost much of their land and went into a cultural and numerical decline, but population began to increase again from the late 19th century, and a cultural revival began in the 1960s. |

|||

Māori are the second-largest ethnic group in New Zealand, after European New Zealanders (commonly known by the Māori name ''[[Pākehā]]''). In addition, [[Māori Australians|more than 170,000 Māori]] live in Australia. The [[Māori language]] is spoken to some extent by about a fifth of all Māori, representing three per cent of the total population. Māori are active in all spheres of New Zealand culture and society, with independent representation in areas such as media, politics, and sport. |

|||

== Naming and self-naming == |

|||

== Etymology == |

|||

In the [[Māori language]] the word ''māori'' means "normal", "natural" or "ordinary". In legends and other oral traditions, the word distinguished ordinary mortal human beings from [[Māori religion|deities]] and spirits (''wairua'').<ref> |

|||

In the [[Māori language]], the word {{lang|mi|māori}} means "normal", "natural", or "ordinary". In legends and oral traditions, the word distinguished ordinary mortal human beings—{{lang|mi|tāngata māori}}—from [[Religion of Māori people|deities]] and spirits ({{lang|mi|wairua}}).<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Atkinson |first1=A. S. |title=What is a Tangata Maori? |journal=The Journal of the Polynesian Society |date=1892 |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230921200632/https://www.jps.auckland.ac.nz/document/Volume_1_1892/Volume_1%2C_No._3%2C_1892/What_is_a_Tangata_Maori%3F_by_A._S._Atkinson%2C_p133-136?action=null}}</ref>{{efn-lr|''Māori'' has cognates in other [[Polynesian languages]] such as [[Hawaiian language|Hawaiian]] {{lang|haw|maoli}}, [[Tahitian language|Tahitian]] {{lang|ty|mā'ohi}}, and [[Cook Islands Māori]] {{lang|rar|māori}} which all share similar meanings.}} Likewise, {{lang|mi|wai māori}} denotes "fresh water", as opposed to [[salt water]]. There are [[cognate]] words in most [[Polynesian languages]],<ref>e.g. {{lang|haw|[[kanaka maoli]]}}, meaning native [[Hawaii]]an. (In the [[Hawaiian language]], the Polynesian letter "T" regularly becomes a "K," and the Polynesian letter "R" regularly becomes an "L")</ref> all deriving from Proto-Polynesian {{lang|und|*ma(a)qoli}}, which has the reconstructed meaning "true, real, genuine".<ref name="pollex">{{cite web|url=http://pollex.org.nz/entry/maqoli/|title=Entries for MAQOLI [PN] True, real, genuine: *ma(a)qoli|website=pollex.org.nz}}</ref><ref name="Eastern Polynesian Languages">[[Eastern Polynesian languages]]</ref> |

|||

Atkinson, A. S. (1892). [http://www.jps.auckland.ac.nz/document/Volume_1_1892/Volume_1%2C_No._3%2C_1892/What_is_a_Tangata_Maori%3F_by_A._S._Atkinson%2C_p133-136?action=null "What is a Tangata Maori?"] ''Journal of the Polynesian Society'', 1 (3), 133-136. Accessed [[2007-12-18]]. |

|||

</ref><ref> |

|||

''Māori'' has cognates in other [[Polynesian languages]] such as [[Hawaiian language|Hawaiian]] 'Maoli,' [[Tahitian language|Tahitian]] 'Mā’ohi,' and [[Cook Islands Maori]] 'Māori' which all share similar meanings. |

|||

</ref> |

|||

== Naming and self-naming == |

|||

{{TOCleft}} |

|||

Early visitors from Europe to New Zealand generally referred to the indigenous inhabitants as "New Zealanders" or as "natives".<ref>{{cite web|title=Native Land Act {{!}} New Zealand [1862]|url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Native-Land-Act|website=Encyclopedia Britannica|access-date=8 July 2017|language=en}}</ref> The Māori used the term {{lang|mi|Māori}} to describe themselves in a pan-tribal sense.{{efn-lr|The orthographic conventions developed by the [[Māori Language Commission]] ({{lang|mi|Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori}}) recommend the use of the [[Macron (diacritic)|macron]] (ā ē ī ō ū) to denote long vowels. Contemporary English-language usage in New Zealand tends to avoid the [[anglicise]]d plural form of the word ''Māori'' with an "s": The Māori language generally marks plurals by changing the [[Article (grammar)|article]] rather than the noun, for example: {{lang|mi|te waka}} (the canoe); {{lang|mi|ngā waka}} (the canoes).}} Māori people often use the term {{lang|mi|[[tangata whenua]]}} (literal meaning, "people of the land") to identify in a way that expresses their relationship with a particular area of land; a tribe may be the {{lang|mi|tangata whenua}} in one area, but not in another.<ref>{{cite web|title=tangata whenua|url=http://maoridictionary.co.nz/search?keywords=tangata+whenua|publisher=Māori Dictionary|access-date=8 July 2017|language=en}}</ref> The term can also refer to the Māori people as a whole in relation to New Zealand ({{lang|mi|[[Aotearoa]]}}) as a whole. |

|||

The official definition of Māori for electoral purposes has changed over time. Before 1974, the government required documented ancestry to determine the status of "a Māori person" and only those with at least 50% Māori ancestry were allowed to choose which seats they wished to vote in. The Māori Affairs Amendment Act 1974 changed this, allowing individuals to self-identify as to their cultural identity. |

|||

Early visitors from Europe to the islands of New Zealand generally referred to the inhabitants as "New Zealanders" or as "natives", but ''Māori'' became the term used by Māori to describe themselves in a pan-tribal sense.<ref> |

|||

The orthographic conventions developed by the [[Māori Language Commission]] recommend the use of the [[macron]] (ā ē ī ō ū) to denote long vowels. Contemporary English-language usage in New Zealand tends to avoid the anglicised plural form of the word ''Māori'' with an "s": the Māori language generally marks plurals by changing the [[Article (grammar)|article]] rather than the noun, for example: ''te waka'' (the canoe); ''ngā waka'' (the canoes). |

|||

</ref> |

|||

Until 1986, the census required at least 50 per cent Māori ancestry to claim Māori affiliation. Currently, in most contexts, authorities require some documentation of ancestry or continuing cultural connection (such as acceptance by others as being of the people); however, there is no minimum ancestry requirement.<ref>McIntosh (2005), p. 45</ref>{{efn-lr|In 2003, [[Christian Cullen]] became a member of the [[New Zealand Māori rugby union team|Māori rugby team]] despite having, according to his father, about 1/64 Māori ancestry.<ref>{{cite news| work=BBC Sport| title=Uncovering the Maori mystery| date=5 June 2003| url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/rugby_union/international/2965212.stm}}</ref>}} |

|||

Māori people often use the term ''tangata whenua'' (literally, "people of the land") to describe themselves in a way that emphasises their relationship with a particular area of land — a tribe may function as ''tangata whenua'' in one area, but not in another. The term can also refer to Māori as a whole in relation to New Zealand (Aotearoa) as a whole. |

|||

== History == |

|||

The [[Maori Purposes Act]] of 1947 required the use of the term 'Maori' rather than 'Native' in official usage, and the "Department of Native Affairs" became the "Department of Māori Affairs". |

|||

{{Main|Māori history}} |

|||

<!--This section shouldn't be made too large. Please add highly detailed or esoteric information to the [[Māori history]] article.--> |

|||

=== Origins from Polynesia === |

|||

Prior to 1974 ancestry determined the legal definition of "a Māori person". For example, bloodlines determined whether a person should enrol on the [[Māori seats|Māori]] or general (European) electoral roll; in 1947 the authorities determined that one man, five-eighths Māori, had improperly voted in the European seat of [[Raglan]].<ref> |

|||

[[File:First human migration to New Zealand.svg|thumb|upright=1.5|The Māori settlement of New Zealand represents an end-point of a long chain of [[oceanic dispersal|island-hopping]] voyages in the [[Oceania|South Pacific]].]] |

|||

Atkinson, Neill, (2003), ''Adventures in Democracy: A History of the Vote in New Zealand'', Otago University Press |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The [[Māori Affairs Amendment Act 1974]] changed the definition to one of cultural self-identification. In matters involving money (for example scholarships or [[Waitangi Tribunal]] settlements), the authorities generally require some demonstration of ancestry or cultural connection, but no minimum "blood" requirement exists.<ref> |

|||

McIntosh, Tracey (2005), 'Maori Identities: Fixed, Fluid, Forced', in James H. Liu, Tim McCreanor, Tracey McIntosh and Teresia Teaiwa, eds, ''New Zealand Identities: Departures and Destinations'', Wellington: Victoria University Press, p. 45 |

|||

</ref><ref> |

|||

In 2003, [[Christian Cullen]] became a member of the [[New Zealand Māori rugby union team|Māori rugby team]] despite having, according to his father, about 1/64 Māori ancestry. (BBC Sport: 'Uncovering the Maori mystery', [[5 June]] 2003. http://news.bbc.co.uk/sport1/hi/rugby_union/international/2965212.stm)</ref> |

|||

No credible evidence exists of [[pre-Māori settlement of New Zealand]]; on the other hand, compelling evidence from archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology indicates that the first settlers migrated from [[Polynesia]] and became the Māori.<ref name="ReferenceA">{{Cite journal | last1=Walters | first1=Richard | last2=Buckley | first2=Hallie|last3=Jacomb|first3=Chris|last4=Matisoo-Smith |first4=Elizabeth| title=Mass Migration and the Polynesian Settlement of New Zealand|journal=Journal of World Prehistory|volume=30| issue=4 |pages=351–376|doi=10.1007/s10963-017-9110-y|date=7 October 2017|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|title=The physical anthropology of the Maori-Moriori|journal = The Journal of the Polynesian Society|volume = 49|issue = 1(193)|pages = 1–15|last=Shapiro|first=HL|date=1940|language=en|jstor = 20702788}}</ref> Evidence indicates that their ancestry (as part of the larger group of [[Austronesian peoples]]) stretches back 5,000 years, to the [[Taiwanese indigenous peoples|indigenous peoples of Taiwan]]. Polynesian people settled a large area encompassing [[Tonga]], [[Samoa]], [[Tahiti]], [[Hawaiian Islands|Hawaiʻi]], [[Easter Island]] ({{lang|rap|Rapa Nui|italics=no}}) – and finally New Zealand.<ref name="Wilmshurst et al">{{Cite journal|last1=Wilmshurst|first1=J. M.|author-link=Janet Wilmshurst|last2=Hunt|first2=T. L.|last3=Lipo|first3=C. P.|last4=Anderson|first4=Atholl |author4-link=Atholl Anderson |year=2010|title=High-precision radiocarbon dating shows recent and rapid initial human colonization of East Polynesia|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=108|issue=5|pages=1815–1820|bibcode=2011PNAS..108.1815W|doi=10.1073/pnas.1015876108|pmc=3033267|pmid=21187404|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

== Origins == |

|||

Archaeological and linguistic evidence (Sutton 1994) suggests that several waves of [[Human migration|migration]] came from Eastern [[Polynesia]] to New Zealand between AD 800 and 1300. Māori oral history describes the arrival of ancestors from [[Hawaiki]] (a mythical homeland in tropical Polynesia) in large [[ocean]]-going [[canoe]]s (''waka'': see [[Māori migration canoes]]). Migration accounts vary among tribes (''[[iwi]]''), whose members may identify with several waka in their genealogies or ''[[whakapapa]]''. |

|||

The date of first arrival and settlement is a matter of debate.<ref name="Wilson2020">{{Cite web|last=Wilson|first=John|date=2020|title=Māori arrival and settlement|url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/history/page-1|access-date=8 November 2021|website=Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand|language=en-NZ}}</ref> There may have been some exploration and settlement before the eruption of [[Mount Tarawera]] ({{circa|1315}}), based on finds of bones from Polynesian rats and rat-gnawed shells,<ref>{{cite book |last=Lowe |first=David J. |chapter=Polynesian settlement of New Zealand and the impacts of volcanism on early Maori society: an update |url=http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/bitstream/10289/2690/1/Lowe%202008%20Polynesian%20settlement%20guidebook.pdf |access-date=18 January 2010 |isbn=978-0-473-14476-0 |title=Guidebook for Pre-conference North Island Field Trip A1 'Ashes and Issues' |date=November 2008 |page=142|publisher=New Zealand Society of Soil Science }}</ref> and evidence of widespread forest fires in the decade or so prior.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Bunce|first1=Michael|last2=Beavan|first2=Nancy R.|last3=Oskam|first3=Charlotte L.|last4=Jacomb|first4=Christopher|last5=Allentoft|first5=Morten E.|last6=Holdaway|first6=Richard N.|date=7 November 2014|title=An extremely low-density human population exterminated New Zealand moa|journal=Nature Communications|language=en | volume=5| pages=5436| doi=10.1038/ncomms6436| pmid=25378020| issn=2041-1723| bibcode=2014NatCo...5.5436H|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1= Jacomb|first1=Chris|last2=Holdaway|first2= Richard N.|last3=Allentoft|first3=Morten E.|last4=Bunce|first4=Michael|last5=Oskam|first5= Charlotte L.|last6=Walter|first6=Richard |last7=Brooks|first7=Emma| year=2014|title=High-precision dating and ancient DNA profiling of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) eggshell documents a complex feature at Wairau Bar and refines the chronology of New Zealand settlement by Polynesians |journal=Journal of Archaeological Science |language=en |volume=50 |pages=24–30|doi=10.1016/j.jas.2014.05.023|bibcode=2014JArSc..50...24J |url=http://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/23310/}}</ref> One 2022 study using advanced [[Radiocarbon dating|radiocarbon technology]] suggests that "early Māori settlement happened in the North Island between AD 1250 and AD 1275".<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/478269/new-study-suggests-maori-settlers-arrived-in-aotearoa-as-early-as-13th-century|title=New study suggests Māori settlers arrived in Aotearoa as early as 13th century|work=[[RNZ]] |author=Ashleigh McCaull|date=8 November 2022|access-date=8 November 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | doi=10.1073/pnas.2207609119 | title=A new chronology for the Māori settlement of Aotearoa (NZ) and the potential role of climate change in demographic developments | year=2022 | last1=Bunbury | first1=Magdalena M. E. | last2=Petchey | first2=Fiona | last3=Bickler | first3=Simon H. | journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences | volume=119 | issue=46 | pages=e2207609119 | doi-access=free | pmid=36343229 | pmc=9674228 | bibcode=2022PNAS..11907609B }}</ref> However, a synthesis of archaeological and genetic evidence concludes that, whether or not some settlers arrived before the Tarawera eruption, the main settlement period was in the decades after it, somewhere between 1320 and 1350.<ref name="ReferenceA" /> This broadly aligns with analyses from Māori oral traditions, which describe the arrival of ancestors in [[Māori migration canoes|a number of large ocean-going canoes]] ({{lang|mi|[[waka (canoe)|waka]]}}) as a planned mass migration {{circa|1350|lk=no}}.<ref>{{Cite journal | last=Roberton | first=J.B.W. | year=1956 |title=Genealogies as a basis for Maori chronology | journal=Journal of the Polynesian Society |language=en | volume=65 | issue=1 | pages=45–54 |url=http://www.jps.auckland.ac.nz/document/Volume_65_1956/Volume_65,_No._1/Genealogies_as_a_basis_for_Maori_chronology,_by_J._B._W._Roberton,_p_45%9654/p1}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | last=Te Hurinui | first=Pei | year=1958 | title=Maori genealogies | journal=Journal of the Polynesian Society |language=en |volume=67 | issue=2 | pages=162–165 | url=http://jps.auckland.ac.nz/document/Volume_67_1958/Volume_67%2C_No._2/Maori_genealogies%2C_by_Pei_Te_Hurinui%2C_p_162-165/p1}}</ref> |

|||

No credible evidence exists of human settlement in New Zealand prior to the Polynesian voyagers; on the other hand, compelling evidence from archaeology, linguistics, and physical anthropology indicates that the first settlers came from East Polynesia and became the Māori. |

|||

They had a profound impact on their environment from their first settlement in New Zealand and voyages further south, with definitive archaeological evidence of brief settlement as far south as [[Enderby Island]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Te Papa Atwahai |first1=Department of Conservation (NZ) |title=Enderby Island Māori occupation |url=https://www.doc.govt.nz/parks-and-recreation/places-to-go/southland/places/subantarctic-islands/auckland-islands/heritage-sites/enderby-island-maori-occupation/ |website=Department of Conservation (NZ) |publisher=Te Kāwanatanga o Aotearoa / New Zealand Government |access-date=22 August 2023}}</ref> Some have speculated that Māori explorers may have been the first humans to discover [[Antarctica]]:<ref>{{Cite news |last=Imbler |first=Sabrina |date=2 July 2021 |title=The Maori Vision of Antarctica's Future |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/02/science/antarctica-maori-exploration.html |access-date=19 March 2022 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=11 June 2021 |title=New Zealand Māori may have been first to discover Antarctica, study suggests |url=http://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/11/new-zealands-maori-may-have-been-first-to-discover-antarctica-study-suggests |access-date=19 March 2022 |website=[[The Guardian]] |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last1=Magazine |first1=Smithsonian |last2=Gershon |first2=Livia |title=Māori May Have Reached Antarctica 1,000 Years Before Europeans |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/maori-reached-antarctica-1000-years-europeans-180977987/ |access-date=19 March 2022 |website=Smithsonian Magazine |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Māori may have been first humans to set eyes on Antarctica, study says |url=https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/new-zealand-s-m-ori-may-have-been-first-humans-n1270449 |access-date=19 March 2022 |website=NBC News |date=11 June 2021 |language=en}}</ref> According to a nineteenth century translation by [[Stephenson Percy Smith]], part of the Rarotongan oral history describes [[Ui-te-Rangiora]], around the year 650, leading a fleet of [[Waka (canoe)|Waka Tīwai]] south until they reached, ''"a place of bitter cold where rock-like structures rose from a solid sea".''<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wehi |first1=Priscilla M. |title=A short scan of Māori journeys to Antarctica |journal=Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand |date=2022 |volume=52 |issue=5 |pages=587–598 |doi=10.1080/03036758.2021.1917633 |pmid=39440197 |pmc=11485871 |bibcode=2022JRSNZ..52..587W |s2cid=236278787 |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2021.1917633 |access-date=22 August 2023}}</ref> Based on interpretations by Wehi and her colleagues, subsequent commentators speculated that these brief descriptions might match the [[Ross Ice Shelf]], or possibly the [[Antarctica|Antarctic mainland]], or [[iceberg]]s surrounded by [[Antarctic sea ice|sea ice]] found in the [[Southern Ocean]].<ref>{{cite news |last1=McLure |first1=Tess |title=New Zealand Māori may have been first to discover Antarctica, study suggests |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/jun/11/new-zealands-maori-may-have-been-first-to-discover-antarctica-study-suggests |access-date=22 August 2023 |agency=[[The Guardian]] |date=11 June 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Gershon |first1=Livia |title=Māori May Have Reached Antarctica 1,000 Years Before Europeans |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/maori-reached-antarctica-1000-years-europeans-180977987/ |access-date=22 August 2023 |agency=Smithsonian Magazine |date=14 June 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Māori among first to see Antarctica, research suggests |url=https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/te-manu-korihi/444346/maori-among-first-to-see-antarctica-research-suggests |access-date=22 August 2023 |agency=[[Radio New Zealand]] |date=9 June 2021}}</ref> Other scholars are far more sceptical, raising serious problems with Smith's translations, and noting the seafaring technologies required for Antarctic voyaging.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Atholl |first1=Anderson |title=On the improbability of pre-European Polynesian voyages to Antarctica: a response to Priscilla Wehi and colleagues |journal=Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand |date=2022 |volume=52 |issue=5 |pages=599–605 |doi=10.1080/03036758.2021.1973517 |pmid=39440189 |pmc=11485678 |bibcode=2022JRSNZ..52..599A |s2cid=239089356 |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2021.1973517 |access-date=22 August 2023}}</ref> Regardless of these debates, the Māori were sophisticated seafarers and New Zealand has a strong association with Antarctica, and a wish by some for Māori values to be integral to [[Research stations in Antarctica|human presence]] there.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2021-07-02 |title=The Maori Vision of Antarctica's Future (Published 2021) |work=The New York Times |language=en |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2021/07/02/science/antarctica-maori-exploration.html |access-date=2023-08-08 |last1=Imbler |first1=Sabrina }}</ref> |

|||

== Development of Māori culture == |

|||

{{main|Māori culture}} |

|||

{{seealso|Māori mythology}} |

|||

[[Image:Murderers' Bay (cropped).jpg|right|thumb|300px|First European impression of Māori, at [[Golden Bay|Murderers' Bay]] in [[Abel Tasman]]'s [[travel journal]] (1642)]] |

|||

=== Early history === |

|||

The Eastern Polynesian ancestors of the Māori arrived in a forested land which was abundant in [[New Zealand birds|birdlife]], including now extinct [[moa]] species weighing from 20 to 250 kg. Other species, also now extinct, included a swan, a goose, and the giant [[Haast's Eagle]] which preyed upon the moa. Marine mammals, in particular seals, thronged the coasts, with coastal colonies much further north than today.<ref> |

|||

{{Further|Archaeology of New Zealand}} |

|||

Irwin 2006:18. |

|||

[[File:Early Maori objects from Wairau Bar, Canterbury Museum, 2016-01-27.jpg|thumb|upright=1.2|right| Early Archaic period objects from the [[Wairau Bar]] archaeological site, on display at the [[Canterbury Museum, Christchurch|Canterbury Museum]] in Christchurch]] |

|||

</ref> |

|||

In the mid-19th century, people discovered large numbers of moa-bones alongside human tools, with some of the bones showing evidence of butchery and cooking. Early researchers, such as [[Julius von Haast]], a geologist, incorrectly interpreted these remains as belonging to a prehistoric Paleolithic people; later researchers, notably [[Stephenson Percy Smith| Percy Smith]], magnified such theories into an elaborate scenario with a series of sharply-defined cultural stages which had Māori arriving in a [[Great Fleet]] in 1350 AD and replacing the so-called "moa-hunter" culture with a "classical Māori" culture based on [[horticulture]].<ref>Howe 2006:28-29.</ref> [[as of 2007| Current]] anthropological theories, however, recognise no evidence for a pre-Māori people; the archaeological record indicates a gradual evolution in culture that varied in pace and extent according to local resources and conditions. Subsequent research dismisses the "Great Fleet" theory as largely a fabrication.<ref> Howe 2006:28-30</ref> |

|||

The earliest period of Māori settlement, known as the "Archaic", "Moahunter" or "Colonisation" period, dates from the time of arrival to {{circa|1500}}. The early Māori diet included an abundance of [[moa]] and other large birds and fur seals that had never been hunted before. This Archaic period is known for its distinctive "reel necklaces",<ref name= NgaKakano>[http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/Term.aspx?irn=57 "Nga Kakano: 1100 – 1300"], Te Papa</ref> and also remarkable for the lack of weapons and fortifications typical of the later "Classic" Māori.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |editor-last=McLintock |editor-first=A. H. |title=The Moa Hunters |url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/1966/maori-material-culture |encyclopedia=[[An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand]] |year=1966 |access-date=17 July 2021}}</ref> The best-known and most extensively studied Archaic site, at [[Wairau Bar]] in the South Island,<ref>{{cite web |last1=Austin |first1=Steve |title=The Wairau Bar |url=http://www.theprow.org.nz/yourstory/wairau-bar |website=The Prow |date=2008}}</ref> shows evidence of occupation from early-13th century to the early-15th century.<ref name="McFadgen and Adds (2018)">{{Cite journal | last1= McFadgen | first1= Bruce G. |last2= Adds | first2= Peter | title= Tectonic activity and the history of Wairau Bar, New Zealand's iconic site of early settlement | journal= Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand | pages= 459–473 | date= 18 February 2018 | volume= 49 | issue= 4 |language= en | doi= 10.1080/03036758.2018.1431293| s2cid= 134727439 }}</ref> It is the only known New Zealand archaeological site containing the bones of people who were born elsewhere.<ref name="McFadgen and Adds (2018)" /> |

|||

In the course of a few centuries, growing population led to competition for resources and an increase in warfare. The archaeological record reveals an increased frequency of fortified [[pā]], although debate continues about the amount of conflict. Various systems arose which aimed to conserve resources; most of these, such as ''[[tapu]]'' and ''[[rahui|rāhui]]'', used religious or supernatural threats to discourage people from taking species at particular seasons or from specified areas. |

|||

[[File:Model Of Maori Pa On Headland.jpg|thumb|upright=0.9|left|Model of a {{lang|mi|[[pā]]}} (hillfort) built on a headland. {{lang|mi|Pā}} proliferated as competition and warfare increased among a growing population.]] |

|||

As Māori continued in geographic isolation, performing arts such as the [[haka]] developed from their Polynesian roots, as did carving and weaving. Regional dialects arose, with minor differences in vocabulary and in the pronunciation of some words. However, the language retains close similarities to other Eastern Polynesian tongues, to the point where a [[Tahitian]] chief on [[James Cook|Cook]]'s first voyage in the region acted as an interpreter between Māori and the crew of the ''[[HM Bark Endeavour| Endeavour]]''. |

|||

Factors that operated in the transition to the Classic period (the culture at the time of European contact) include a significantly [[Little Ice Age|cooler period]] from 1500,<ref name=atholl>{{cite web |last1= Anderson |first1= Atholl |author1-link=Atholl Anderson |title= The Making of the Māori Middle Ages |url= https://ojs.victoria.ac.nz/jnzs/article/download/3987/3554 |publisher=Open Systems Journal |access-date= 18 August 2019}}</ref> and the extinction of the [[moa#Relationship with humans|moa]] and of other food species.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1= Rawlence |first1= Nicholas J. | last2= Kardamaki |first2= Afroditi |last3= Easton |first3= Luke J. |last4= Tennyson |first4= Alan J. D. | last5= Scofield |first5= R. Paul | last6= Waters |first6= Jonathan M. |title= Ancient DNA and morphometric analysis reveal extinction and replacement of New Zealand's unique black swans |journal= Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences |volume= 284 |issue= 1859 |pages= 20170876 |date= 26 July 2017 |doi= 10.1098/rspb.2017.0876|pmid= 28747476 |pmc= 5543223 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1= Till |first1= Charlotte E. |last2= Easton |first2= Luke J. |last3= Spencer |first3= Hamish G. |last4= Schukard |first4= Rob |last5= Melville |first5= David S. |last6= Scofield |first6= R. Paul |last7= Tennyson |first7= Alan J. D. |last8= Rayner |first8= Matt J. |last9= Waters |first9= Jonathan M. |last10= Kennedy |first10= Martyn |title= Speciation, range contraction and extinction in the endemic New Zealand King Shag | journal= Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution |volume= 115 |pages= 197–209 |date= October 2017 |doi= 10.1016/j.ympev.2017.07.011|pmid= 28803756 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1= Oskam |first1= Charlotte L.|last2= Allentoft |first2= Morten E.|last3= Walter |first3= Richard |last4= Scofield |first4= R. Paul | last5= Haile |first5= James |last6= Holdaway |first6= Richard N. |last7= Bunce |first7= Michael |last8= Jacomb |first8= Chris |year= 2012 |title= Ancient DNA analyses of early archaeological sites in New Zealand reveal extreme exploitation of moa (Aves: Dinornithiformes) at all life stages |journal= Quaternary Science Reviews |volume= 53 |pages= 41–48 |doi= 10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.07.007|bibcode=2012QSRv...52...41O|url= http://researchrepository.murdoch.edu.au/id/eprint/10637/}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1= Holdaway |first1= Richard N. | last2= Allentoft |first2= Morten E. |last3= Jacomb |first3= Christopher |last4= Oskam |first4= Charlotte L. | last5= Beavan | first5= Nancy R. | last6= Bunce |first6= Michael |title= An extremely low-density human population exterminated New Zealand moa|journal= Nature Communications|volume= 5 |issue= 5436 |pages= 5436 |date= 7 November 2014 |doi= 10.1038/ncomms6436|pmid= 25378020 |bibcode= 2014NatCo...5.5436H |doi-access= free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal | last1= Perry |first1= George L.W. | last2= Wheeler |first2= Andrew B. |last3= Wood |first3= Jamie R.|last4= Wilmshurst |first4= Janet M. |year= 2014 |title= A high-precision chronology for the rapid extinction of New Zealand moa (Aves, Dinornithiformes)|journal= Quaternary Science Reviews|volume= 105 |pages= 126–135 |doi= 10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.09.025|bibcode= 2014QSRv..105..126P }}</ref> |

|||

Around 1500 AD a group of Māori migrated east to ''Rekohu'' (the [[Chatham Islands]]), where, by adapting to the local climate and the availability of resources, they developed a culture known as [[Moriori]] — related to but distinct from Māori culture in mainland Aotearoa. A notable feature of the Moriori culture, an emphasis on [[pacifism]], proved disadvantageous when Māori [[warrior]]s arrived in the 1830s aboard a chartered European ship.<ref> |

|||

[http://www.teara.govt.nz/NewZealanders/MaoriNewZealanders/Moriori/4/en Moriori - The impact of new arrivals - ''Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand''] |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The Classic period is characterised by finely made {{lang|mi|[[pounamu]]}} (greenstone) weapons and ornaments, elaborately carved [[Waka taua|war canoes]] and {{lang|mi|[[wharenui]]}} (meeting houses).<ref name="neich">Neich Roger, 2001. ''Carved Histories: Rotorua Ngati Tarawhai Woodcarving''. Auckland: Auckland University Press, pp. 48–49.</ref> Māori lived in autonomous settlements in extended [[hapū]] groups descended from common [[iwi]] ancestors. The settlements had farmed areas and food sources for hunting, fishing and gathering. Fortified [[pā]] were built at strategic locations due to occasional warfare over wrongdoings or resources; this practice varied over different locations throughout New Zealand, with more populations in the far North.<ref name="Wilson2020" /><ref>{{Cite book|last=Keenan|first=Danny|url=http://worldcat.org/oclc/779490407|title=Huia histories of Māori : ngā tāhuhu kōrero|date=2012|publisher=Huia|isbn=978-1-77550-009-4|oclc=779490407}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Māori sites|url=https://www.doc.govt.nz/our-work/heritage/heritage-topics/maori-sites/|access-date=8 November 2021|website=Department of Conservation|language=en-nz}}</ref> There is a stereotype that Māori were 'natural warriors'; however, warfare and associated practices like [[Human cannibalism|cannibalism]] were not a dominating part{{Weasel inline|date=August 2024}} of Māori culture.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Belich|first=James|date=5 May 2011|title=Modern racial stereotypes|url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/european-ideas-about-maori/page-6|access-date=8 November 2021|website=Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand|language=en-NZ}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Godfery|first=Morgan|date=22 August 2015|title=Warrior race? Pull the other one|url=https://e-tangata.co.nz/comment-and-analysis/warrior-race-pull-the-other-one/|access-date=8 November 2021|website=E-Tangata|language=en-NZ}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|last=Matthews|first=Philip|date=2 June 2018|title='Cunning, deceitful savages': 200 years of Māori bad press|url=https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/103871652/cunning-deceitful-savages-200-years-of-mori-bad-press|access-date=8 November 2021|website=[[Stuff (website)|Stuff]] |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

== Interactions with Europeans before 1840 == |

|||

Around the year 1500, a group of Māori migrated east to the [[Chatham Islands]] and developed into a people known as the [[Moriori]],<ref>{{cite book|last= Clark|first= Ross|year= 1994|chapter= Moriori and Māori: The Linguistic Evidence|editor-last= Sutton|editor-first= Douglas|title= The Origins of the First New Zealanders|location= Auckland|publisher=[[Auckland University Press]]|pages= 123–135}}</ref> with [[pacifism]] a key part of their culture.<ref>{{Cite book|last=King|first=Michael|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1124413583|title=Moriori: A People Rediscovered|date=2017|publisher=Penguin UK|isbn=978-0-14-377128-9|location=London|oclc=1124413583}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:HekeKawiti1846.jpg|thumb|right|220px|1846: [[Hone Heke]] (holding a rifle) with his wife Hariata and his uncle Kawiti (who holds a taiaha). The introduction of firearms after 1805 led to bloody inter-tribal warfare.]] |

|||

=== Contact with Europeans === |

|||

European settlement of New Zealand occurred in relatively [[as of 2007| recent]] historical times. New Zealand historian [[Michael King]] in ''The Penguin History Of New Zealand'' describes the Māori as "the last major human community on earth untouched and unaffected by the wider world." |

|||

[[File:Gilsemans 1642.jpg|right|thumb|upright=1.2|A drawing from [[Abel Tasman]]'s [[travel journal]] of the first encounter between Europeans and Māori, in 1642]] |

|||

The first European explorers of New Zealand were [[Abel Tasman]], who arrived in 1642, Captain [[James Cook]], in 1769, and [[Marc-Joseph Marion du Fresne|Marion du Fresne]] in 1772. Initial contact between Māori and Europeans proved problematic and sometimes fatal, with Tasman having four of his men killed and probably killing at least one Māori, without ever landing.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Sivignon |first1=Cherie |title=Commemoration plans of first encounter between Abel Tasman, Māori 375 years ago |url=https://www.stuff.co.nz/travel/destinations/nz/97210590/commemoration-plans-of-first-encounter-between-abel-tasman-mori-375-years-ago |access-date=19 August 2019 |work=[[Stuff (website)|Stuff]] |date=1 October 2017}}</ref> Cook's men shot at least eight Māori within three days of his first landing,<ref>{{cite news |last1=Dalrymple |first1=Kayla |title=Unveiling the history of the "Crook Cook" |url=http://gisborneherald.co.nz/lifestyle/2442008-135/unveiling-the-history-of-the-crook |access-date=19 August 2019 |work=[[Gisborne Herald]] |date=28 August 2016 |archive-date=29 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191129003442/http://gisborneherald.co.nz/lifestyle/2442008-135/unveiling-the-history-of-the-crook |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Encounter, or murder? |url=http://gisborneherald.co.nz/localnews/4089572-135/encounter-or-murder |access-date=19 August 2019 |work=[[Gisborne Herald]] |date=13 May 2019}}</ref> although he later had good relations with Māori. Three years later, after a promising start, du Fresne and 26 men of his crew were killed. From the 1780s, Māori also increasingly encountered European and American [[Seal hunting|sealers]], [[whaling|whalers]] and Christian [[missionaries]]. Relations were mostly peaceful, although marred by several further violent incidents, the worst of which was the [[Boyd massacre|''Boyd'' massacre]] in 1807 and subsequent revenge attacks.<ref>Ingram, C. W. N. (1984). ''New Zealand Shipwrecks 1975–1982''. Auckland: New Zealand Consolidated Press; pp 3–6, 9, 12.</ref> |

|||

Early European explorers, including [[Abel Tasman]] (who arrived in 1642) and Captain [[James Cook]] (who first visited in 1769), recorded their impressions of Māori. From the 1780s, Māori encountered European and American [[Sealing|sealers]] and [[whaling|whalers]]; some Māori crewed on the foreign ships. A trickle of escaped [[Convictism in Australia|convict]]s from Australia and deserters from visiting ships, as well as early [[Mission (Christian)| Christian missionaries]], also exposed the indigenous New Zealand population to outside influences. |

|||

[[European settlers in New Zealand|European settlement in New Zealand]] began in the early 19th century, leading to an extensive sharing of culture and ideas. Many Māori valued Europeans, whom they called "{{lang|mi|[[Pākehā]]}}", as a means to acquire Western knowledge and technology. Māori quickly adopted writing as a means of sharing ideas, and many of their oral stories and poems were converted to the written form.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|first=Nancy |last=Swarbrick|title=Creative life – Writing and publishing|encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |date=June 2010 |url= http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/creative-life/6 |access-date=22 January 2011}}</ref> The introduction of the [[potato]] revolutionised agriculture, and the acquisition of [[musket]]s<ref name="Old New Zealand">{{cite book |last=Manning |first=Frederick Edward |title=Old New Zealand: being Incidents of Native Customs and Character in the Old Times by 'A Pakeha Maori': Chapter 13 |year=1863 |chapter-url=http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/33342 |chapter=Chapter 13 |quote=every man in a native {{lang|mi|hapu}} of, say a hundred men, was absolutely forced on pain of death to procure a musket and ammunition at any cost, and at the earliest possible moment (for, if they did not procure them, extermination was their doom by the hands of those of their country-men who had), the effect was that this small {{lang|mi|hapu}}, or clan, had to manufacture, spurred by the penalty of death, in the shortest possible time, one hundred tons of flax, scraped by hand with a shell, bit by bit, morsel by morsel, half-a-quarter of an ounce at a time.}}</ref> by Māori {{lang|mi|iwi}} led to a period of particularly bloody [[endemic warfare|intertribal warfare]] known as the [[Musket Wars]], in which many groups were decimated and others driven from their traditional territory.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=McLintock |first=A. H. |encyclopedia=[[An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand]] |title=Maori health and welfare |url=http://teara.govt.nz/en/1966/maori-health-and-welfare |access-date=19 August 2019 |year=1966}}</ref> The pacifist [[Moriori]] in the Chatham Islands similarly suffered massacre and subjugation in an invasion by some Taranaki {{lang|mi|iwi}}.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url= http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/moriori/4 |title=Moriori – The impact of new arrivals|last1=Davis|first1=Denise|last2=Solomon|first2=Māui|encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |access-date=29 April 2010}}</ref> At the same time, the Māori suffered high mortality rates from Eurasian infectious diseases, such as [[influenza]], [[smallpox]] and [[measles]], which killed an estimated 10 to 50 per cent of Māori.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.portdanielpress.com/maori_pop.htm |title=Estimating a population devastated by epidemics|last=Entwisle|first=Peter|work=[[Otago Daily Times]] |date=20 October 2006|access-date=13 May 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081014015352/http://www.portdanielpress.com/maori_pop.htm|archive-date=14 October 2008|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Estimates of New Zealand Maori Vital Rates from the Mid-Nineteenth Century to World War I|journal=Population Studies|volume=27|issue=1|date=March 1973|pages=117–125|first=D. I.|last=Pool|author-link=Ian Pool |jstor=2173457 |doi=10.2307/2173457 |pmid=11630533}}</ref> |

|||

By 1830, estimates placed the number of [[Pākehā]] (Europeans) living among the Māori as high as 2,000. The newcomers had varying status-levels within Māori society, ranging from [[slaves]] to high-ranking advisors. Some remained little more than prisoners, while others abandoned European culture and identified as Māori. Many Māori valued such Pākehā as a means to the acquisition of European technology, particularly firearms. These Europeans "gone native" became known as [[Pākehā Māori]]. When [[Pomare]] led a war-party against Titore in 1838, he had 132 Pākehā mercenaries among his warriors. [[Frederick Edward Maning]], an early settler, wrote two lively accounts of life in these times, which have become classics of New Zealand literature: ''Old New Zealand'' and ''History of the War in the North of New Zealand against the Chief Heke''. |

|||

[[File:Reconstruction of the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, Marcus King (16044258961).jpg|thumb|250px|left|Depiction of the signing of the [[Treaty of Waitangi]] in 1840, bringing New Zealand and the Māori into the British Empire]] |

|||

During the period from 1805 to 1840 the acquisition of [[musket]]s by tribes in close contact with European visitors upset the balance of power among Māori tribes, leading to a period of bloody [[endemic warfare|inter-tribal warfare]], known as the [[Musket Wars]], which resulted in the decimation of several tribes and the driving of others from their traditional territory.<ref> |

|||

[http://www.teara.govt.nz/1966/M/MaoriHealthAndWelfare/MaoriHealthAndWelfare/en 1966 Encyclopaedia of New Zealand] |

|||

</ref> |

|||

European [[disease]]s such as [[influenza]] and [[measles]] also killed an unknown number of Māori: estimates vary between ten and fifty per cent.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.portdanielpress.com/maori_pop.htm|title=Estimating a population devastated by epidemics|last=Entwisle|first=Peter|publisher=[[Otago Daily Times]]|date=[[20 October]] [[2006]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Estimates of New Zealand Maori Vital Rates from the Mid-Nineteenth Century to World War I|journal=Population Studies|volume=27|issue=1|date=March 1973|pages=117–125|first=D. I.|last=Pool|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/2173457|doi=10.2307/2173457}}</ref> Economic changes, such as the exploitation of [[Phormium|flax]] for the international market, also took a toll.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Thompson |first=Christina A. |year=1997 |month=June |title=A dangerous people whose only occupation is war: Maori and Pakeha in 19th century New Zealand |journal=Journal of Pacific History |volume=32 |issue=1 |pages=109–119 |issn=1469-9605 |url=http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a793805885~db=all |accessdate= 2008-06-15 |quote=Whole tribes sometimes relocated to swamps where flax grew in abundance but where it was decidedly unhealthy to live.}}</ref> |

|||

By 1839, estimates placed the number of Europeans living in New Zealand as high as 2,000,<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Phillips |first1=Jock |title=History of immigration – A growing settlement: 1825 to 1839 |url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/history-of-immigration/page-2 |encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |access-date=4 June 2018 |date=1 August 2015}}</ref> |

|||

== 1840 to 1890: The marginalisation of Māori == |

|||

and the [[The Crown|British Crown]] acceded to repeated requests from missionaries and some Māori chiefs ({{lang|mi|[[rangatira]]}}) to intervene. The British government sent Royal Navy Captain [[William Hobson]] to negotiate a treaty between the British Crown and the Māori, which became known as the [[Treaty of Waitangi]]. Starting from February 1840, this treaty was signed by the Crown and 500 Māori chiefs from across New Zealand.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Orange |first1=Claudia |title=Treaty of Waitangi – Creating the Treaty of Waitangi |url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/treaty-of-waitangi/page-1 |encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |access-date=7 June 2018 |language=en-NZ |date=20 June 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Te Wherowhero |url=https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/declaration/signatory/te-wherowhero |publisher=Ministry for Culture and Heritage |access-date=7 June 2018}}</ref> The Treaty gave Māori the rights of [[British nationality law|British subjects]] and guaranteed Māori property rights and tribal autonomy, in return for accepting British [[sovereignty]] and the annexation of New Zealand as a colony in the [[British Empire]].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Orange |first1=Claudia |title=Treaty of Waitangi – Interpretations of the Treaty of Waitangi |url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/treaty-of-waitangi/page-2 |encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |access-date=7 June 2018 |language=en-NZ |date=20 June 2012}}</ref> However, disputes continue over aspects of the Treaty of Waitangi, including wording differences in the two versions (in English and Māori), as well as misunderstandings of different cultural concepts; notably, the Māori version did not cede sovereignty to the British Crown.<ref>{{cite web |title=Differences between the texts |url=https://nzhistory.govt.nz/politics/treaty/read-the-Treaty/differences-between-the-texts |publisher=Ministry for Culture and Heritage |access-date=7 June 2018}}</ref> In [[Wi Parata v Bishop of Wellington|an 1877 court case]] the Treaty was declared a "simple nullity" on the grounds that the signatories had been "primitive barbarians".<ref>{{cite journal|last=Tate|first=John|url=http://www.austlii.edu.au/nz/journals/CanterLawRw/2004/11.html|title=The three precedents of Wi Parata|year=2004|volume=10|issue=|journal=Canterbury Law Review}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Morris |first=Grant |url = http://www.nzlii.org/nz/journals/VUWLawRw/2004/4.html |title= James Prendergast and the Treaty of Waitangi: Judicial Attitudes to the Treaty During the Latter Half of the Nineteenth Century |year=2004 |volume=35 |issue=1 |journal=Victoria University of Wellington Law Review |page=117 |doi=10.26686/vuwlr.v35i1.5634 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

Nevertheless, relations between Māori and Pākehā during the early colonial period were largely peaceful. Many Māori groups set up substantial businesses, supplying food and other products for domestic and overseas markets. When violence did break out, as in the [[Wairau Affray]], [[Flagstaff War]], [[Hutt Valley Campaign]] and [[Wanganui Campaign]], it was generally limited and concluded with a peace treaty. However, by the 1860s rising settler numbers and tensions over disputed land purchases led to the later [[New Zealand wars]], fought by the colonial government against numerous Māori {{lang|mi|iwi}} using local and British Imperial troops, and some allied {{lang|mi|iwi}}. These conflicts resulted in the colonial government [[New Zealand land confiscations|confiscating tracts of Māori land]] as punishment for what were called "rebellions". Pākehā settlers would occupy the confiscated land.<ref>{{cite web |title=Land confiscation law passed |url=https://nzhistory.govt.nz/the-new-zealand-settlements-act-passed |website=nzhistory.govt.nz |publisher=Ministry for Culture and Heritage |access-date=20 August 2019 |date=18 November 2016}}</ref> Several minor conflicts arose after the wars, including the incident at [[Parihaka]] in 1881 and the [[Dog Tax War]] from 1897 to 1898. The [[Native Land Court]] was established to transfer Māori land from communal ownership into individual title as a means to assimilation and to facilitate greater sales to European settlers.<ref>{{cite web |title=Māori Land – What Is It and How Is It Administered? |url=https://www.oag.govt.nz/2004/maori-land-court/part2.htm |publisher=Office of the Auditor-General |access-date=20 August 2019}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:MeriMangakahia1890s.jpg|thumb|220px|Meri Te Tai Mangakāhia, a member of the [[Te Kotahitanga| Kotahitanga]] movement in the 1890s, who argued that women should have equal voting-rights in the Māori Parliament]] |

|||

=== Decline and revival === |

|||

With increasing Christian [[missionary]] activity, growing European settlement in the 1830s and the perceived lawlessness of Europeans in New Zealand, the [[The Crown|British Crown]], as a [[Great Power| world power]], came under pressure<ref>Claudia Orange, The Story of a Treaty, page 13.</ref> to intervene. Ultimately Britain sent [[William Hobson]] with instructions to take possession of New Zealand. Before he arrived, [[Victoria of the United Kingdom|Queen Victoria]] annexed New Zealand by royal proclamation in January 1840. On arrival in February 1840, Hobson negotiated the [[Treaty of Waitangi]] with northern chiefs. Other Māori chiefs subsequently signed this treaty. In the end, only 500 chiefs out of the 1500 sub-tribes of New Zealand signed the Treaty, and some influential chiefs — such as [[Pōtatau Te Wherowhero| Te Wherowhero]] in Waikato, and Te Kani-a-Takirau from the east coast of the North Island — refused to sign. The Treaty made the Māori [[British nationality law|British subjects]] in return for a guarantee of Māori property-rights and tribal autonomy. |

|||

[[File:E 003261 E Maoris in North Africa July 1941.jpg|right|thumb|200px|Members of the 28th (Māori) Battalion performing a [[haka]], Egypt (July 1941)]] |

|||

By the late 19th century, a widespread belief existed amongst both [[Pākehā]] and Māori that the Māori population would cease to exist as a separate race or culture, and become assimilated into the European population.<ref>King (2003), p. 224</ref> From the late 19th to the mid-20th century various laws, policies, and practices were instituted in New Zealand society with the effect of inducing Māori to conform to Pākehā norms; notable among these are the [[Tohunga Suppression Act 1907]] and the suppression of the Māori language by schools,<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|first1=Rawinia|last1=Higgins|first2=Basil|last2=Keane|title=Te Mana o te Reo Māori: 1860–1945 War and assimilation|encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |date=1 September 2015|url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/te-tai/te-mana-o-te-reo-maori-chapter4|access-date=10 February 2022}}</ref> often enforced with corporal punishment.<ref>{{cite news|last=Forbes|first=Mihingarangi|url=https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/new-zealand/2021/09/former-labour-minister-dover-samuels-calls-for-crown-apology-for-caning-children-speaking-te-reo.html|title=Former Labour Minister Dover Samuels calls for Crown apology for caning children speaking Te Reo|work=[[Newshub]]|date=27 September 2021|access-date=10 February 2022}}</ref> In the 1896 census, New Zealand had a Māori population of 42,113, by which time Europeans numbered more than 700,000.<ref>[http://www.teara.govt.nz/1966/P/Population/PopulationFactorsAndTrends/en "Population – Factors and Trends"], ''An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand'', edited by A. H. McLintock, published in 1966. Retrieved 18 September 2007.</ref> |

|||

Dispute continues over whether the Treaty of Waitangi ceded Māori sovereignty. Māori chiefs signed a Māori-language version of the Treaty that did not accurately reflect the English-language version. It appears unlikely that the Māori-language version of the treaty ceded sovereignty; and the Crown and the missionaries probably did not fully explain the meaning of the English-language version. |

|||

The decline did not continue and the Māori population continued to recover in the 20th century. Influential Māori politicians such as [[James Carroll (New Zealand politician)|James Carroll]], [[Āpirana Ngata]], [[Te Rangi Hīroa]] and [[Māui Pōmare]] aimed to revitalise the Māori people after the devastation of the previous century. They believed the future path called for a degree of [[Cultural assimilation|assimilation]],<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Young Maori Party {{!}} Maori cultural association |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Young-Maori-Party |encyclopedia=[[Encyclopædia Britannica]] |access-date=4 June 2018 |language=en}}</ref> with Māori adopting European practices such as [[Medicine#Modern|Western medicine]], while also retaining traditional cultural practices. Māori also fought during both World Wars in specialised battalions (the [[New Zealand (Māori) Pioneer Battalion|Māori Pioneer Battalion]] in WWI and the [[Māori Battalion|28th (Māori) Battalion]] in WWII). Māori were also badly hit by the [[1918 influenza epidemic]], with death rates for Māori being five to seven times higher than for Pākehā.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.noted.co.nz/health/1918-flu-centenary-how-to-survive-a-pandemic/ |title=1918 flu centenary: How to survive a pandemic|access-date=19 June 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190709072615/https://www.noted.co.nz/health/1918-flu-centenary-how-to-survive-a-pandemic/ |archive-date=9 July 2019 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=Black November: the 1918 influenza pandemic in New Zealand | vauthors = Rice G, Bryder L |isbn=978-1-927145-91-3 |edition=Second, revised and enlarged |chapter=7. ‘Severest setback’ for Maori?|place=Christchurch, NZ |oclc=960210402}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:1863 Meeting of Settlers and Maoris at Hawke's Bay, New Zealand.jpg|thumb|left|300px|A traditional Māori village in [[Hawke's Bay Province]], during a meeting between Māori and settlers in 1863 to discuss the [[invasion of the Waikato]].]] |

|||

[[File:Whina Cooper in Hamilton.jpg|thumb|left|upright=0.7|[[Whina Cooper]] leading the Māori Land March in 1975, seeking redress for historical grievances]] |

|||

Māori formed substantial [[business]]es, supplying food and other products for domestic and overseas markets. |

|||

Since the 1960s, Māoridom has undergone a [[Māori renaissance|cultural revival]]<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.teara.govt.nz/NewZealandInBrief/Maori/5/en |title=Māori – Urbanisation and renaissance|encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |quote=The Māori renaissance since 1970 has been a remarkable phenomenon.}}</ref> concurrent with activism for social justice and a [[Māori protest movement|protest movement]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://schools.look4.net.nz/history/new_zealand/time_line4/ |title=Time Line of events 1950–2000|publisher=Schools @ Look4}}</ref> {{lang|mi|[[Kōhanga reo]]}} (Māori language pre-schools) were established in 1982 to promote Māori language use and halt the decline in its use.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.kohanga.ac.nz/|title=Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust|access-date=10 April 2019|quote=Te Kōhanga Reo National Trust Board was established in 1982 and formalised as a charitable trust in 1983. The Mission of the Trust is the protection of Te reo, tikanga me ngā āhuatanga Māori by targeting the participation of mokopuna and whānau into the Kōhanga Reo movement and its Vision is to totally immerse Kōhanga mokopuna in Te Reo, Tikanga me ngā āhuatanga Māori.}}</ref> Two Māori language television channels broadcast content in the Māori language,<ref name="MāoriTVlaunch" /><ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.maoritelevision.com/latestnews/maori_television_launch_second_channel.htm|title=Maori Television launches second channel|publisher=[[Maori Television]]|author=Maori Television|date=9 March 2008|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080124030625/http://www.maoritelevision.com/latestnews/maori_television_launch_second_channel.htm|archive-date=24 January 2008}}</ref> while words such as "{{lang|mi|[[kia ora]]}}" have entered widespread use in New Zealand English.<ref>{{cite web |title=Māori Words used in New Zealand English |url=http://www.maorilanguage.net/maori-words-phrases/maori-words-used-new-zealand-english/ |website=Māori Language.net |publisher=Native Council |access-date=20 August 2019}}</ref> |

|||

Among the early European settlers who both learnt the [[Māori language]] and also recorded [[Māori mythology]], [[George Edward Grey|George Grey]], Governor of New Zealand from 1845 to 1855 and from 1861 to 1868, stands out. |

|||

Government recognition of the growing political power of Māori and political activism have led to limited redress for historic land confiscations. In 1975, the Crown set up the [[Waitangi Tribunal]] to investigate historical grievances,<ref>{{cite web |title=Waitangi Tribunal created |url=https://nzhistory.govt.nz/waitangi-tribunal-created |publisher=Ministry for Culture and Heritage |access-date=4 June 2018 |date=19 January 2017}}</ref> and since the 1990s the New Zealand government has negotiated and finalised [[Treaty of Waitangi claims and settlements|treaty settlements]] with many {{lang|mi|iwi}} across New Zealand. By June 2008, the government had provided over NZ$900 million in settlements, much of it in the form of land deals.<ref name="QuarterlyReport">{{Cite web |url=http://nz01.terabyte.co.nz/ots/DocumentLibrary/FourMonthlyReportMarch-June2008.pdf |title=Four Monthly Report |last=Office of Treaty Settlements |date=June 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081018025424/http://nz01.terabyte.co.nz/ots/DocumentLibrary/FourMonthlyReportMarch-June2008.pdf |archive-date=18 October 2008 |access-date=25 September 2008}}</ref> There is a growing Māori leadership who are using these settlements as an investment platform for economic development.<ref name=HeraldJames>{{cite news|url=http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10344134 |title= Ethnicity takes its course despite middle-class idealism |author=James, Colin |author-link=Colin James (journalist) |work=[[The New Zealand Herald]] |access-date=19 October 2011 |date=6 September 2005}}</ref> |

|||

In the 1860s, disputes over questionable land purchases and the attempts of Māori in the [[Waikato]] to establish what some saw as a rival to the British system of royalty led to the [[New Zealand land wars]]. Although these resulted in relatively few deaths, the colonial government confiscated large tracts of tribal land as punishment for what they called rebellion (although the Crown had initiated the military action against its own citizens), in some cases taking land even from tribes which had taken no part in the [[war]]. Some tribes actively fought against the Crown, while others (known as ''kupapa'') fought in support of the Crown. After most of the active fighting had ceased, a [[passive resistance]] movement developed at the settlement of [[Parihaka]] in [[Taranaki]], but Crown troops dispersed its participants in 1881. |

|||

Despite a growing acceptance of Māori culture in wider New Zealand society, treaty settlements have generated significant controversy. Some Māori have argued that the settlements occur at a level of between one and two-and-a-half cents on the dollar of the value of the confiscated lands, and do not represent adequate redress. Conversely, some non-Māori denounce the settlements and socioeconomic initiatives as amounting to race-based preferential treatment.<ref name="WaitangiDebateTVNZ" /> Both of these sentiments were expressed during the [[New Zealand foreshore and seabed controversy]] in 2004.<ref>{{cite report|title=Report on the Crown's Foreshore and Seabed Policy|url=https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/WT/reports/reportSummary.html?reportId=wt_DOC_68000605|publisher=[[Minister of Justice (New Zealand)|Ministry of Justice]]|access-date=19 August 2019|language=en-NZ}}</ref><ref>{{cite encyclopedia|last1=Barker|first1=Fiona|title=Debate about the foreshore and seabed|url=http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/video/34605/debate-about-the-foreshore-and-seabed|encyclopedia=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |access-date=19 August 2019|date=June 2012}}</ref> |

|||

The Native Land Acts of 1862 and 1865 set up the Native Land Court, which had the purpose of breaking down communal ownership and facilitating the alienation of land. As a result, between 1840 and 1890 Māori lost 95 per cent of their land (63,000,000a of 66,000,000 -55,000,000a in 1890). |

|||

=== Māori King Movement === |

|||

With the loss of much of their land, Māori went into a period of numerical and cultural decline, and by the late 19th century there was a widespread belief amongst both Pakeha and Māori that the Māori population would cease to exist as a separate race or culture and become assimilated into the European population.<ref>King 2003, p 224</ref> |

|||

The '''Māori King Movement''', called the '''{{lang|mi|Kīngitanga}}'''{{efn-lr|Also spelled {{lang|mi|Kiingitanga}}. The preferred [[orthography]] of the [[Waikato-Tainui]] [[iwi]] is to use doubled vowels rather than [[Macron (diacritic)#Vowel length|macrons]] to indicate long vowels.<ref>{{cite web |title=Te Wiki o Te Reo Maaori Discovery Trail |url=https://waikatomuseum.co.nz/exhibitions-and-events/view/2145882619 |website=Waikato Museum Te Whare Taonga o Waikato |access-date=15 May 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Governance |url=https://waikatotainui.com/learn-post/governance/ |website=Waikato-Tainui |access-date=15 May 2022}}</ref>}} in [[Māori language|Māori]], is a Māori [[Political movement|movement]] that arose among some of the Māori {{lang|mi|[[iwi]]|italic=no}} (tribes) of New Zealand in the central North Island in the 1850s, to establish a role similar in status to that of the monarch of the British colonists, as a way of halting the alienation of Māori land.<ref name="nzha">{{cite book |title=Bateman New Zealand Historical Atlas |year=1997 |isbn=1-86953-335-6 |at=plate 36 |chapter=Mana Whenua}}</ref> The Māori monarch operates in a non-constitutional capacity with no legal or judicial power within the New Zealand government. Reigning monarchs retain the position of [[paramount chief]] of several {{lang|mi|iwi|italic=no}}<ref name="Foster">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Māori King – Election and Coronation |encyclopedia=[[An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand]] |url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/1966/maori-king-election-and-coronation |access-date=11 August 2019 |last=Foster |first=Bernard |date=1966 |editor-last=McLintock |editor-first=A.H. |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190810235220/https://teara.govt.nz/en/1966/maori-king-election-and-coronation |archive-date=10 August 2019 |via=Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand |url-status=live}}</ref> and wield some power over these, especially within [[Tainui]]. |

|||

The current Māori monarch, [[Ngā Wai Hono i te Pō]], was [[Elective monarchy|elected]] in 2024.<ref name="p198">{{cite web | last=Ahmadi | first=Ali Abbas | title=New Zealand: Māori king's daughter crowned as king buried | website=BBC Home | date=2024-09-05 | url=https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5y8z15wyz6o | access-date=2024-09-05}}</ref> Her official residence is Tūrongo House at [[Tūrangawaewae]] [[marae]] in the town of [[Ngāruawāhia]]. She is the eighth monarch since the position was created and is the continuation of a dynasty that reaches back to the inaugural king, [[Pōtatau Te Wherowhero]]. |

|||

In 1840, New Zealand had a Māori population of about 100,000 and only about 2,000 Europeans. By the end of the 19th century, the Māori population had declined to 42,113 (according to the 1896 census) and Europeans numbered more than 700,000.<ref> [http://www.teara.govt.nz/1966/P/Population/PopulationFactorsAndTrends/en "Population - Factors and Trends"], from ''An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand'', edited by A. H. McLintock, originally published in 1966. ''Te Ara - The Encyclopedia of New Zealand'', updated [[2007-09-18]]. Accessed [[2007-12-18]]. |

|||

</ref> |

|||

The movement arose among a group of central North Island iwi in the 1850s as a means of attaining Māori unity to halt the alienation of land at a time of rapid population growth by European colonists.<ref name="nzha" /> The movement sought to establish a monarch who could claim status similar to that of [[Queen Victoria]] and thus allow Māori to deal with {{lang|mi|[[Pākehā]]}} (Europeans) on equal footing. It took on the appearance of an alternative government with its own flag, newspaper, bank, councillors, magistrates and law enforcement. But it was viewed by the colonial government as a challenge to the supremacy of the [[Monarchy of the United Kingdom|British monarchy]], leading in turn to the 1863 [[invasion of Waikato]], which was partly motivated by a drive to neutralise the Kīngitanga's power and influence. Following their defeat at Ōrākau in 1864, Kīngitanga forces withdrew into the Ngāti Maniapoto tribal region of the North Island that became known as the [[King Country]].<ref name="walkerstruggle">{{cite book |last=Walker |first=Ranginui |author-link=Ranginui Walker |title=Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle Without End |publisher=Penguin |year=1990 |isbn=0-14-013240-6 |location=Auckland |page=126}}</ref><ref name="DaltonWarPolitics">{{cite book |last=Dalton |first=B.J. |title=War and Politics in New Zealand 1855–1870 |publisher=Sydney University Press |year=1967 |location=Sydney}}</ref>{{Page needed|date=August 2021}} The Māori monarch's influence has not been as strong as it could be, partially due to the lack of affiliation to the Kīngitanga of key iwi, most notably [[Ngāi Tūhoe|Tuhoe]], [[Ngāti Porou]], and the largest iwi of all, [[Ngāpuhi]].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Taonga |first=New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu |title=Kīngitanga – the Māori King movement |url=https://teara.govt.nz/en/kingitanga-the-maori-king-movement |access-date=2021-11-01 |website=[[Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand]] |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

== Revival == |

|||

== Demographics == |

|||

[[Image:KupeWheke.jpg|left|thumb|108px|Late twentieth-century house-post depicting the navigator [[Kupe]] fighting two sea creatures.]] |

|||

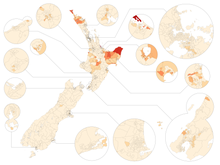

[[File:Maori ethnicity declared in 2018.png|thumb|414x414px|Māori in New Zealand in 2018]] |

|||