Milwaukee: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Hatnote group| |

|||

{{about|the city in Wisconsin}} |

|||

{{Distinguish|Milwaukie|Zilwaukee}} |

|||

{{Infobox Settlement |

|||

{{Redirect|Milwaukee, Wisconsin|the former town|Milwaukee (town), Wisconsin}} |

|||

|official_name = City of Milwaukee |

|||

{{For|the county|Milwaukee County, Wisconsin}} |

|||

|nickname = Cream City'', ''Brew City'', ''Mil Town'', ''The Mil'', ''The City of Festivals'', Deutsch-Athen (German Athens) '' |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

|image_skyline = Milk111408a.JPG |

|||

}} |

|||

|imagesize = |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=December 2024}} |

|||

|image_caption = Top: [[Milwaukee Riverwalk]], Center Left [[Milwaukee Art Museum]], Center Right [[US Bank Center (Milwaukee)|US Bank Center]] and [[Lake Michigan]], Lower Left [[Historic Third Ward, Milwaukee]], Lower Right [[Milwaukee City Hall]] |

|||

{{Use American English|date=July 2022}} |

|||

|image_flag = |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

|||

|image_seal = Milseal.png |

|||

| |

| name = Milwaukee |

||

| settlement_type = [[Administrative divisions of Wisconsin#City|City]] |

|||

|mapsize = 250px |

|||

| nickname = Cream City,<ref>{{cite web|last1=Henzl|first1=Ann-Elise|title=How Milwaukee Got The Nickname 'Cream City'|url=https://www.wuwm.com/regional/2019-12-27/how-milwaukee-got-the-nickname-cream-city|website=wuwm.com|publisher=[[WUWM]]|access-date=August 17, 2021|date=December 27, 2019}}</ref> Brew City,<ref>{{cite web|title=Official Brew City Map|url=https://www.visitmilwaukee.org/plan-a-visit/food-drink/official-brew-city-beer-map/|website=visitmilwaukee.org|access-date=August 17, 2021|archive-date=August 17, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817165633/https://www.visitmilwaukee.org/plan-a-visit/food-drink/official-brew-city-beer-map/|url-status=dead}}</ref> Beer Capital of the World,<ref>{{cite web|title=Milwaukee: Beer Capital of the World|url=https://www.beerhistory.com/library/holdings/milwaukee.shtml|website=beerhistory.com|access-date=August 17, 2021}}</ref> Miltown,<ref>{{cite web|last1=Snyder|first1=Molly|title=Nicknames for Milwaukee and Wisconsin|url=https://onmilwaukee.com/articles/nicknameblog|website=onmilwaukee.com|access-date=August 17, 2021|date=August 30, 2008}}</ref> The Mil, MKE, The City of Festivals,<ref name="festivals">{{cite web|title=The City of Festivals|url=https://www.visitmilwaukee.org/events/festivals/|website=visitmilwaukee.org|access-date=August 17, 2021|archive-date=August 17, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210817164131/https://www.visitmilwaukee.org/events/festivals/|url-status=dead}}</ref> The German Athens of America,<ref>{{cite web|last1=Tolzmann|first1=Don Heinrich|title=A Center of German Culture, Milwaukee, Wisconsin|url=http://gamhof.org/heritage/milwaukee-german-athens-of-america/|website=gamhof.org|access-date=August 17, 2021}}</ref> [[Area code 414|The 414]]<ref>{{cite web|last1=Tarnoff|first1=Andy|title=The 411 on the 414 area code|url=https://onmilwaukee.com/articles/414-history|website=onmilwaukee.com|access-date=August 17, 2021|date=April 14, 2021}}</ref> |

|||

|map_caption = Location of Milwaukee in<br>Milwaukee County, Wisconsin |

|||

| image_skyline = {{multiple image |

|||

|image_map1 = |

|||

| |

| border = infobox |

||

| |

| total_width = 300 |

||

| |

| perrow = 1/3/2/1 |

||

| caption_align = center |

|||

|subdivision_name = [[United States]] |

|||

| image1 = Dji fly 20241201 160430 0031 1733092392756 photo.jpg |

|||

|subdivision_type1 = [[Political divisions of the United States|State]] |

|||

| |

| caption1 = [[Downtown Milwaukee]] |

||

| image2 = Hilton Milwaukee City Center.jpg |

|||

|subdivision_type2 = [[List of counties in Wisconsin|Counties]] |

|||

| caption2 = [[Hilton Milwaukee City Center]] |

|||

|subdivision_name2 = [[Milwaukee County, Wisconsin|Milwaukee]], [[Washington County, Wisconsin|Washington]], [[Waukesha County, Wisconsin|Waukesha]] |

|||

| image3 = Milwaukee June 2022 16 (Milwaukee City Hall).jpg |

|||

|government_type = |

|||

| |

| caption3 = [[Milwaukee City Hall]] |

||

| image4 = Milwaukee (WIS) Downtown Riverwalk 100 East Building & First National Bank Building (4743909231).jpg |

|||

|leader_name = [[Tom Barrett (politician)|Tom Barrett]] (D) |

|||

| |

| caption4 = [[Milwaukee Riverwalk]] |

||

| image5 = My Photo back face Milwaukee Art Museum (MAM) Calatrava.jpg |

|||

|established_date = |

|||

| |

| caption5 = [[Milwaukee Art Museum]] |

||

| |

| image6 = MillerParkStadium.jpg |

||

| |

| caption6 = [[American Family Field]] |

||

| |

| image7 = Mitchell Park Horticultural Conservatory 1.jpg |

||

| caption7 = [[Mitchell Park Horticultural Conservatory]] |

|||

|area_land_sq_mi = 96 |

|||

}} |

|||

|area_water_km2 = 2.2 |

|||

| image_flag = Flag of Milwaukee, Wisconsin.svg |

|||

|area_water_sq_mi = 1 |

|||

| image_seal = Seal of Milwaukee, Wisconsin.png |

|||

|population_as_of = 2006 |

|||

| image_blank_emblem = City of Milwaukee Logo.svg |

|||

|population_metro = 1,964,744 |

|||

| blank_emblem_size = 100px |

|||

|population_total = 602191 |

|||

| blank_emblem_type = Logo |

|||

|population_density_km2 = 2399.5 |

|||

| image_map = {{maplink |

|||

|population_density_sq_mi = 6214.7 |

|||

| frame = yes |

|||

| |

| plain = yes |

||

| frame-align = center |

|||

|timezone_DST = [[North American Central Time Zone|CDT]] |

|||

| frame-width = 290 |

|||

| frame-height = 290 |

|||

| frame-coord = {{coord|qid=Q37836}} |

|||

| |

| zoom = 10 |

||

| |

| type = shape |

||

| |

| marker = city |

||

| stroke-width = 2 |

|||

| stroke-color = #0096FF |

|||

| fill = #0096FF |

|||

| id2 = Q37836 |

|||

| |

| type2 = shape-inverse |

||

| stroke-width2 = 2 |

|||

|blank1_name = [[Geographic Names Information System|GNIS]] feature ID |

|||

| stroke-color2 = #5F5F5F |

|||

|blank1_info = 1577901{{GR|3}} |

|||

| stroke-opacity2 = 0 |

|||

|footnotes = | |

|||

| fill2 = #000000 |

|||

| fill-opacity2 = 0 |

|||

}} |

|||

| map_caption = Interactive map of Milwaukee |

|||

| pushpin_map = Wisconsin#USA |

|||

| pushpin_relief = yes |

|||

| subdivision_type = Country |

|||

| subdivision_name = United States |

|||

| subdivision_type1 = [[U.S. state|State]] |

|||

| subdivision_name1 = [[Wisconsin]] |

|||

| subdivision_type2 = [[List of counties in Wisconsin|Counties]] |

|||

| subdivision_name2 = [[Milwaukee County, Wisconsin|Milwaukee]], [[Washington County, Wisconsin|Washington]],<!--The Census maps show a piece of Milwaukee is in Washington County : see the pointing arrow at the corner https://www2.census.gov/geo/maps/DC2020/PL20/st55_wi/schooldistrict_maps/c55131_washington/DC20SD_C55131.pdf --> [[Waukesha County, Wisconsin|Waukesha]] |

|||

| government_type = [[Mayor–council government|Strong mayor-council]] |

|||

| governing_body = Milwaukee Common Council |

|||

| leader_title = Mayor |

|||

| leader_name = [[Cavalier Johnson]] ([[Democratic Party (United States)|D]]) |

|||

| established_title = [[Municipal corporation|Incorporated]] |

|||

| established_date = {{Start date and age|1846|01|31}} |

|||

<!-- Area --> |

|||

| unit_pref = Imperial |

|||

| area_footnotes = <ref name="CenPopGazetteer2019">{{cite web|title=2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files|url=https://www2.census.gov/geo/docs/maps-data/data/gazetteer/2019_Gazetteer/2019_gaz_place_55.txt|publisher=United States Census Bureau|access-date=August 7, 2020}}</ref> |

|||

| area_total_km2 = 250.75 |

|||

| area_land_km2 = 249.12 |

|||

| area_water_km2 = 1.63 |

|||

| area_total_sq_mi = 96.81 |

|||

| area_land_sq_mi = 96.18 |

|||

| area_water_sq_mi = 0.63 |

|||

<!-- Population --> |

|||

| population_total = 577222 |

|||

| population_as_of = [[2020 United States census|2020]] |

|||

| population_footnotes = <ref name="QuickFacts">{{cite web|title=QuickFacts: Milwaukee city, Wisconsin|url=https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/milwaukeecitywisconsin/POP010220|publisher=United States Census Bureau|access-date=August 24, 2021}}</ref> |

|||

| pop_est_as_of = 2024 |

|||

| population_est = 577385<ref>{{cite web|title=Demographic Services Center's 2024 Population Estimates|url=https://doa.wi.gov/DIR/Prelim_Est_Alpha_2024.pdf|website=State of Wisconsin|publisher=Wisconsin Department of Administration|access-date=September 27, 2024}}</ref> |

|||

| pop_est_footnotes = <ref name="USCensusEst2021">{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-total-cities-and-towns.html|date=May 29, 2022|title=City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2021|publisher=United States Census Bureau|access-date=May 31, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

| population_rank = [[List of North American cities by population|85th]] in North America<br />[[List of United States cities by population|31st]] in the United States<br>[[List of municipalities in Wisconsin by population|1st]] in Wisconsin |

|||

| population_density_sq_mi =auto |

|||

| population_density_km2 = |

|||

| population_urban = 1,306,795 ([[List of United States urban areas|US: 38th]]) |

|||

| population_density_urban_km2 = 1,088.2 |

|||

| population_density_urban_sq_mi = 2,818.3 |

|||

| population_metro_footnotes = <ref name="2020Pop">{{cite web|title=2020 Population and Housing State Data|url=https://www.census.gov/library/visualizations/interactive/2020-population-and-housing-state-data.html|publisher=United States Census Bureau|access-date=August 22, 2021}}</ref> |

|||

| population_metro = 1574731 ([[List of metropolitan statistical areas|US: 40th]]) |

|||

| population_blank1_title = [[Combined Statistical Area|CSA]] |

|||

| population_blank1 = 2049805 ([[List of combined statistical areas|US: 33rd]]) |

|||

| population_demonym = Milwaukeean |

|||

| demographics_type2 = GDP |

|||

| demographics2_footnotes = <ref>{{Cite web|title=Total Gross Domestic Product for Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI (MSA)|url=https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NGMP33340|website=fred.stlouisfed.org}}</ref> |

|||

|demographics2_title1 = Metro |

|||

|demographics2_info1 = $120.563 billion (2022) |

|||

| timezone = [[Central Time Zone (North America)|CST]] |

|||

| utc_offset = −6 |

|||

| timezone_DST = [[Central Time Zone (North America)|CDT]] |

|||

| utc_offset_DST = −5 |

|||

| postal_code_type = [[ZIP Code]]s |

|||

| postal_code = {{collapsible list |

|||

|title = 53172, 532XX |

|||

|frame_style = border:none; padding: 0; |

|||

|list_style = text-align:center;display:none |

|||

|53172, 53201–53216, 53218–53228, 53233–53234, 53237, 53259, 53263, 53267–53268, 53274, 53278, 53288, 53290, 53293, 53295}} |

|||

| area_code = [[Area code 414|414]] |

|||

| coordinates = {{Coord|43.05|N|87.95|W|type:city_region:US-WI_dim:50km|display=title,inline}} |

|||

| elevation_m = 188 |

|||

| elevation_ft = 617 |

|||

| blank_name = [[FIPS code]] |

|||

| blank_info = 55-53000<ref name="GR2">{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov|publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]]|access-date=January 31, 2008|title=U.S. Census website}}</ref> |

|||

| blank1_name = [[GNIS]] feature ID |

|||

| blank1_info = 1577901<ref name="GR3">{{cite web|url=http://geonames.usgs.gov|access-date=January 31, 2008|title=US Board on Geographic Names|publisher=[[United States Geological Survey]]|date=October 25, 2007}}</ref> |

|||

| website = {{URL|city.milwaukee.gov}} |

|||

| footnotes = |

|||

| founder = [[Solomon Juneau]], [[Byron Kilbourn]], and [[George H. Walker]] |

|||

| named_for = [[Potawatomi language|Potawatomi]] for "gathering place by the water" |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Milwaukee''' is the largest city in [[Wisconsin]] and [[List of United States cities by population|22nd largest]] (by population) in the [[United States]]. It is the [[county seat]] of [[Milwaukee County, Wisconsin|Milwaukee County]] and is located on the southwestern shore of [[Lake Michigan]]. As of a 2007 [[United States Census Bureau|U.S. Census]] estimate, Milwaukee had a population of 602,191.<ref name=PopEstBigCities>{{cite web | url = http://www.census.gov/popest/cities/tables/SUB-EST2007-01.csv | title = Table 1: Annual Estimates of the Population for Incorporated Places Over 100,000, Ranked by July 1, 2007 Population: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2007 | format = [[comma-separated values|CSV]] | work = 2007 Population Estimates | publisher = [[United States Census Bureau]], Population Division | date = [[2008-07-10]] | accessdate = 2008-07-10 }}</ref> Milwaukee is the main cultural and economic center of the [[Milwaukee–Racine–Waukesha Metropolitan Area]] with a population of 1,964,744. |

|||

'''Milwaukee''' ({{IPAc-en|m|ɪ|l|ˈ|w|ɔː|k|i|audio=LL-Q1860 (eng)-Flame, not lame-Milwaukee.wav}} {{respell|mil|WAW|kee}}) is the [[List of cities in Wisconsin|most populous city]] in the [[U.S. state]] of [[Wisconsin]] and the [[county seat]] of [[Milwaukee County, Wisconsin|Milwaukee County]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Counties|url=https://www.wicounties.org/the-counties/|access-date=January 11, 2023|website=Wisconsin Counties Association|language=en-US}}</ref> With a population of 577,222 at the [[2020 United States census|2020 census]], Milwaukee is the [[List of United States cities by population|31st-most populous city]] in the United States and the fifth-most populous city in the [[Midwest]].<ref name="USCensusEst2019">{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/data/tables.2019.html|title=Population and Housing Unit Estimates|access-date=May 21, 2020}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov|title=U.S. Census website|website=[[United States Census Bureau]]|access-date=December 11, 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=The Largest Cities In The Midwest|url=https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-largest-cities-in-the-midwest.html|website=worldatlas.com|date=January 4, 2019|access-date=March 7, 2021}}</ref> It is the central city of the [[Milwaukee metropolitan area]], the [[Metropolitan statistical area|40th-most populous]] metro area in the U.S. with 1.57 million residents.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/dec/cph-series/cph-t/cph-t-2.html|title=Population Change for Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas|website=Census.gov}}</ref> |

|||

The first Europeans to pass through the area were French missionaries and [[fur trade]]rs. In 1818, the [[French Canadian|French-Canadian]] explorer [[Solomon Juneau]] settled in the area, and in 1846 Juneau's town combined with two neighboring towns to incorporate as the City of Milwaukee.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://192.159.83.40/SOS/pdf/THEOSOS_025/images/00014104.pdf |title=CITY OF MILWAUKEE INCORPORATED, PAGE 164, 1846; PAGE 314, 1851 |accessdate=2007-04-08 |author=City of Milwaukee |publisher=Office of the Secretary of State of Wisconsin|format=PDF}}</ref> Large numbers of [[German American|German]] and other immigrants helped increase the city's population during the 1840s and the following decades. |

|||

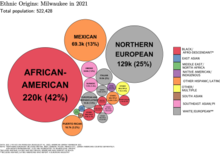

Milwaukee is an [[ethnically]] and [[culturally diverse]] city.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Mak|first1=Adrian|title=Most Diverse Cities in the U.S.|url=https://advisorsmith.com/data/most-diverse-cities-in-the-u-s/|website=advisorsmith.com|access-date=March 7, 2021|date=June 24, 2020}}</ref> However, it continues to be one of the most racially segregated cities, largely as a result of early-20th-century [[redlining]].<ref name="Leah Foltman & Malia Jones">{{cite web|url=https://www.wiscontext.org/how-redlining-continues-shape-racial-segregation-milwaukee|date=February 28, 2019|title=How Redlining Continues To Shape Racial Segregation In Milwaukee|website=Wiscontext|publisher=PBS Wisconsin/Wisconsin Public Radio|first1=Leah|last1=Foltman|first2=Malia|last2=Jones}}</ref> Its [[History of Milwaukee|history]] was heavily influenced by German immigrants in the 19th century, and it continues to be a center for [[German-American]] culture,<ref>{{Cite web|title=Germans|url=https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/germans/|access-date=January 11, 2023|website=Encyclopedia of Milwaukee|language=en-US}}</ref> specifically becoming well known for its [[Beer in Milwaukee|brewing industry]]. In recent years, Milwaukee has undergone several development projects.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.jsonline.com/story/money/real-estate/commercial/2017/03/04/extraordinary-building-boom-reshaping-milwaukees-skyline/98477354/|title=Extraordinary building boom is reshaping Milwaukee's skyline|newspaper=Milwaukee Journal Sentinel|access-date=March 21, 2017}}</ref> Major additions to the city since the turn of the 21st century include the [[Wisconsin Center]], [[American Family Field]], [[The Hop (streetcar)|The Hop streetcar system]], an expansion to the [[Milwaukee Art Museum]], [[Milwaukee Repertory Theater]], the [[Bradley Symphony Center]],<ref>{{Cite web|date=March 25, 2021|title=First Look: Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra's Bradley Symphony Center|url=https://onmilwaukee.com/articles/mso-first-look|access-date=April 28, 2021|website=OnMilwaukee}}</ref> and [[Discovery World]], as well as major renovations to the [[UW–Milwaukee Panther Arena]]. [[Fiserv Forum]] opened in late 2018, and hosts sporting events and concerts. |

|||

Once known almost exclusively as a [[brewing]] and [[manufacturing]] powerhouse, Milwaukee has taken steps in recent years to reshape its image. In the past decade, major new additions to the city have included the [[Milwaukee Riverwalk]], the [[Midwest Airlines Center]], [[Miller Park (Milwaukee)|Miller Park]], an internationally renowned addition to the [[Milwaukee Art Museum]], and [[Pier Wisconsin]], as well as major renovations to the [[the MECCA|Milwaukee Auditorium]]. In addition, many new skyscrapers, condos, lofts, and apartments have been constructed in neighborhoods on and near the lakefront and riverbanks. |

|||

Milwaukee is categorized as a "Gamma minus" city by the [[Globalization and World Cities Research Network]],<ref>{{cite web|title=The World According to GaWC 2020|url=https://www.lboro.ac.uk/gawc/world2020t.html|website=GaWC – Research Network|publisher=Globalization and World Cities|access-date=August 31, 2020}}</ref> with a regional [[List of U.S. metropolitan areas by GDP|GDP]] of over $102 billion in 2020.<ref>{{cite web|date=January 2021|title=Total Gross Domestic Product for Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI (MSA)|url=https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/NGMP33340|access-date=February 9, 2022|website=fred.stlouisfed.org}}</ref> Since 1968, Milwaukee has been home to [[Summerfest]], a large music festival.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Yu|first=Isaac|title=Is Summerfest in Milwaukee really the world's largest music festival? Here's how it stacks up against Coachella, Lollapalooza and others|url=https://www.jsonline.com/story/news/local/milwaukee/2022/06/23/summerfest-really-worlds-largest-music-festival-sort-of-milwaukee/7639795001/|access-date=January 11, 2023|website=Journal Sentinel|language=en-US}}</ref> Milwaukee is home to the [[Fortune 500|''Fortune'' 500]] companies of [[Northwestern Mutual]], [[Fiserv]], [[WEC Energy Group]], [[Rockwell Automation]], and [[Harley-Davidson]].<ref>{{cite web|last1=Dill|first1=Molly|title=Wisconsin has 9 companies on 2018 Fortune 500 list|url=https://biztimes.com/wisconsin-has-9-companies-on-2018-fortune-500-list/|website=biztimes.com|publisher=Milwaukee Business News|access-date=March 7, 2021|date=May 21, 2018}}</ref> It is also home to several colleges, including [[Marquette University]], the [[Medical College of Wisconsin]], [[Milwaukee School of Engineering]], and [[University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee]]. The city is represented in two of the four [[Major professional sports leagues in the United States and Canada|major professional sports leagues]]—the [[Milwaukee Bucks|Bucks]] of the [[NBA]] and the [[Milwaukee Brewers|Brewers]] of [[MLB]]. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

{{ |

{{Main|History of Milwaukee}} |

||

The Milwaukee area was originally inhabited by the [[Fox (tribe)|Fox]], [[Mascouten]], [[Potawatomi]], and [[Ho-Chunk|Ho-Chunk (Winnebago)]] [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] tribes. French missionaries and traders first passed through the area in the late 17th and 18th centuries. The word "Milwaukee" comes from an [[Algonquian languages|Algonquian]] word ''Millioke'' which means "Good/Beautiful/Pleasant Land", [[Potawatomi language]] ''minwaking'', or [[Ojibwe language]] ''ominowakiing'', "Gathering place [by the water]".<ref name="namedef">{{cite book| last=Bruce| first=William George| year=1936| title=A Short History of Milwaukee| location=Milwaukee, Wisconsin| publisher=The Bruce Publishing Company| id=LLCN 36010193| pages=15}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.freelang.net/dictionary/ojibwe.html |title=Ojibwe Dictionary |publisher=Freelang |accessdate=2007-03-25}}</ref> Early explorers called the Milwaukee River and surrounding lands various names: Melleorki, Milwacky, Mahn-a-waukie, Milwarck, and Milwaucki. For many years, printed records gave the name as "Milwaukie". One story of Milwaukee's name says, |

|||

:''"[O]ne day during the thirties of the last century [1800s] a newspaper calmly changed the name to Milwaukee, and Milwaukee it has remained until this day."<ref name="Milwaukee">{{cite book| last=Bruce| first=William George| year=1936| title=A Short History of Milwaukee| location=Milwaukee, Wisconsin| publisher=The Bruce Publishing Company| id=LLCN 36010193| pages=15–16}}</ref> |

|||

The spelling "Milwaukie" lives on in [[Milwaukie, Oregon]], named after the Wisconsin city in 1847, before the current spelling was universally accepted. |

|||

===Name=== |

|||

Milwaukee has three "[[founding fathers]]", of whom French Canadian Solomon Juneau was first to come to the area, in [[1818]]. The Juneaus founded the town called Juneau's Side, or Juneautown, that began attracting more settlers. However, [[Byron Kilbourn]] was Juneau's equivalent on the west side of the [[Milwaukee River]]. In competition with Juneau, he established Kilbourntown west of the Milwaukee River, and made sure the streets running toward the river did not join with those on the east side. This accounts for the large number of angled bridges that still exist in Milwaukee today. Further, Kilbourn distributed maps of the area which only showed Kilbourntown, implying Juneautown did not exist or that the east side of the river was uninhabited and thus undesirable. The third prominent builder was [[George H. Walker]]. He claimed land to the south of the Milwaukee River, along with Juneautown, where he built a log house in 1834. This area grew and became known as Walker's Point. |

|||

The etymological origin of the name ''Milwaukee'' is disputed.<ref name="MilMagMilwaukeeMean"><!--supports the disputed origin-->{{Cite magazine|first=Matthew|last=Prigge|date=January 29, 2018|title=What Does 'Milwaukee' Mean, Anyway?|url=https://www.milwaukeemag.com/what-does-milwaukee-mean/|access-date=October 5, 2023|website=Milwaukee Magazine|language=en-US}}</ref><ref><!--supports the disputed origin-->{{Cite web|date=August 8, 2017|title=Milwaukee County [origin of place name]|url=https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS10647|access-date=October 5, 2023|website=Wisconsin Historical Society|language=en}}</ref> Wisconsin academic Virgil J. Vogel has said, "the name [...] Milwaukee is not difficult to explain, yet there are a number of conflicting claims made concerning it.<ref name="Vogel134">{{Cite book|last=Vogel|first=Virgil J.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xrYfektNvoQC&pg=PA34|title=Indian Names on Wisconsin's Map|date=1991|publisher=Univ of Wisconsin Press|page=34|isbn=978-0-299-12984-2|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

One theory says it comes from the [[Ojibwe language|Anishinaabemowin/Ojibwe]] word ''mino-akking'', meaning "good land",<ref name="MilMagMilwaukeeMean"/><ref name="WUWM origin">{{Cite news|date=October 14, 2016|title=Mino-akking, Mahn-a-waukke: What's The Origin Of The Word 'Milwaukee'?|url=https://www.wuwm.com/regional/2016-10-14/mino-akking-mahn-a-waukke-whats-the-origin-of-the-word-milwaukee|access-date=October 5, 2023|website=WUWM 89.7 FM - Milwaukee's NPR|language=en}}</ref> or words in closely related languages that mean the same.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Bright|first=William|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5XfxzCm1qa4C&pg=PA284|title=Native American Placenames of the United States|date=2004|publisher=University of Oklahoma Press|page=284|isbn=978-0-8061-3598-4|language=en}}</ref> These included Menominee and Potawatomi.<ref name="Vogel134"/> This theory was popularized by a line by [[Alice Cooper]] in the 1992 comedy film ''[[Wayne's World (film)|Wayne's World]]''.<ref name="MilMagMilwaukeeMean"/> Another theory is that it stems from the [[Meskwaki]] language, whose term for "gathering place" is ''mahn-a-waukee''.<ref name="MilMagMilwaukeeMean"/><ref name="WUWM origin"/> The city of Milwaukee itself claims that the name is derived from ''mahn-ah-wauk'', a Potawatomi word for "council grounds".<ref>{{Cite web|title=Milwaukee History|url=https://city.milwaukee.gov/cityclerk/MilwaukeeHistory|access-date=January 24, 2024|website=City of Milwaukee}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Milwaukee 05741u.jpg|thumb|right|380px|Panorama map of Milwaukee, with a view of the [[Milwaukee City Hall|City Hall]] tower, ca. 1898]] |

|||

The name of the future city was spelled in many ways prior to 1844.<ref name="Legler">{{Cite book|first=Henry|last=Legler|author-link=Henry Eduard Legler|title=Origin and Meaning of Wisconsin Place-names: With Special Reference to Indian Nomenclature|publisher=Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters|date=1903|page=24|url=https://search.library.wisc.edu/digital/AZ2O57KPOUDGBE8I}}</ref> People living west of the [[Milwaukee River]] preferred the modern-day spelling, while those east of the river often called it ''Milwaukie''.<ref name="MilMagMilwaukeeMean"/> Other spellings included ''Melleokii'' (1679), ''Millioki'' (1679), ''Meleki'' (1684), ''Milwarik'' (1699), ''Milwacky'' (1761), ''Milwakie'' (1779), ''Millewackie'' (1817), ''Milwahkie'' (1820), and ''Milwalky'' (1821). The ''[[Milwaukee Sentinel]]'' used ''Milwaukie'' in its headline until it switched to ''Milwaukee'' on November 30, 1844.<ref name="Legler" /> |

|||

By the [[1840s]], the three towns had grown quite a bit, along with their rivalries. There were some intense battles between the towns, mainly Juneautown and Kilbourntown, which culminated with the [[Milwaukee Bridge War]] of [[1845]]. Following the Bridge War, it was decided the best course of action was to officially unite the towns. So, on [[January 31]] [[1846]], they combined to incorporate as the City of Milwaukee and elected [[L. Solomon Juneau]] as Milwaukee's first mayor. A great number of German immigrants had helped increase the city's population during the 1840s, who continued to migrate to the area during the following decades. Milwaukee has even been called "Deutsches Athen" (German Athens), and into the twentieth century, there were more German speakers and German-language newspapers than there were [[English language|English]] speakers and English-language newspapers in the city. (To this day, the [[Greater Milwaukee]] phonebook includes more than 40 pages of Schmitts or Schmidts, far more than the pages of Smiths.) |

|||

===Native American peoples=== |

|||

During the middle and late 19th century, Wisconsin and the Milwaukee area became the final destination of many German immigrants fleeing the [[Revolutions of 1848|Revolution of 1848]] in the various small [[Germany|German]] states and [[Austria]]. In Wisconsin, they found the inexpensive land and the freedoms they sought. The German heritage and influence in the Milwaukee area is widespread. In addition to Germans, Milwaukee received large influxes of immigrants from [[Polish American|Poland]], [[Italian American|Italy]] and [[Irish American|Ireland]], as well as many [[American Jews|Jews]] from Central and Eastern Europe. By 1910, Milwaukee (along with [[New York City]]) shared the distinction of having the largest percentage of foreign-born residents in the United States.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.uwm.edu/Library/digilib/Milwaukee/records/picture.html| title=Picturing Milwaukee's Neighborhoods| publisher=University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee| year=2004}}</ref> |

|||

Indigenous cultures lived along the waterways for thousands of years. The first recorded inhabitants of the Milwaukee area were various [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] tribes: the [[Menominee]], [[Fox (tribe)|Fox]], [[Mascouten]], [[Sauk people|Sauk]], [[Potawatomi]], and [[Ojibwe]] (all Algic/Algonquian peoples), and the [[Ho-Chunk]] (Winnebago, a Siouan people). Many of these people had lived around [[Green Bay, Wisconsin|Green Bay]]<ref>{{cite book|last=White|first=Richard|title=The Middle Ground|year=1991|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=New York|page=146|isbn=9781139495684|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fHLfiOZVzmMC&pg=PA146}}</ref> before migrating to the Milwaukee area about the time of European contact. |

|||

[[Image:Milwaukeecityhall.jpg|thumb|200px|[[Milwaukee City Hall]]]] |

|||

In the second half of the 18th century, the Native Americans living near Milwaukee played a role in all the major European wars on the American continent. During the [[French and Indian War]], a group of "Ojibwas and Pottawattamies from the far [Lake] Michigan" (i.e., the area from Milwaukee to Green Bay) joined the French-Canadian [[Daniel Liénard de Beaujeu]] at the [[Battle of the Monongahela]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Fowler|first=William|title=Empires at War|year=2005|publisher=Walker & Company|location=New York|page=68|isbn=9780802719355|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XqukoiTFL_oC&pg=PA68}}</ref> In the [[American Revolutionary War]], the Native Americans around Milwaukee were some of the few groups to ally with the rebel Continentals.<ref>{{cite book|last=White|first=Richard|title=The Middle Ground|year=1991|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=New York|page=400|isbn=9781139495684|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fHLfiOZVzmMC&pg=PA400}}</ref> |

|||

Early in the 20th century, Milwaukee was home to several pioneer [[brass era]] [[automobile]] makers, including [[Ogren (automobile company)|Ogren]] (from 1919 to 1922)<ref>Clymer, Floyd. ''Treasury of Early American Automobiles, 1877-1925'' (New York: Bonanza Books, 1950), p.153.</ref> and [[LaFayette Motors|LaFayette]] (from 1922 to about 1924). |

|||

After the [[American Revolutionary War]], the Native Americans fought the United States in the [[Northwest Indian War]] as part of the [[Council of Three Fires]]. During the [[War of 1812]], they held a council in Milwaukee in June 1812, which resulted in their decision to attack [[Chicago]]<ref>{{cite book|last=Keating|first=Ann|title=Rising Up from Indian Country|year=2012|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|page=137}}</ref> in retaliation against American expansion. This resulted in the [[Battle of Fort Dearborn]] on August 15, 1812, the only known armed conflict in Chicago. This battle convinced the American government to [[Indian Removal|remove]] these groups of Native Americans from their indigenous land.{{dubious|date=March 2023}} After being attacked in the [[Black Hawk War]] in 1832, the Native Americans in Milwaukee signed the [[1833 Treaty of Chicago]] with the United States. In exchange for ceding their lands in the area, they were to receive monetary payments and lands west of the Mississippi in [[Indian Territory]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Potawatomi Treaties and Treaty Rights {{!}} Milwaukee Public Museum|url=https://www.mpm.edu/content/wirp/ICW-107|access-date=March 2, 2021|website=www.mpm.edu}}</ref> |

|||

In March 1889, the independent village of Bay View had four days of protest and one day of rioting against its Chinese laundrymen. Sparking this city-wide disturbance were allegations of sexual misconduct between two Chinese and several underaged white females. The unease and tension in the wake of the riot was assuaged by the direct disciplining of the city's Chinese. In 1892, [[Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin|Whitefish Bay]], [[South Milwaukee, Wisconsin|South Milwaukee]], and [[Wauwatosa, Wisconsin|Wauwatosa]] each were incorporated. They were followed by [[Cudahy, Wisconsin|Cudahy]] (1895), North Milwaukee (1897) and East Milwaukee, later known as [[Shorewood, Wisconsin|Shorewood]], in 1900. In the early 20th century [[West Allis, Wisconsin|West Allis]] (1902) and [[West Milwaukee, Wisconsin|West Milwaukee]] (1906) were added, which completed the first generation of "inner-ring" suburbs. |

|||

===European settlement and thereafter=== |

|||

During the first half of the twentieth century, Milwaukee was the hub of the [[socialism|socialist]] movement in the United States. Milwaukee elected three socialist mayors during this time: [[Emil Seidel]] (1910-1912), [[Daniel Hoan]] (1916-1940), and [[Frank Zeidler]] (1948-1960). It remains the only major city in the country to have done so. Often referred to as "[[Sewer Socialism|Sewer Socialists]]", the Milwaukee socialists were characterized by their practical approach to government and labor. Also during this time, a small but burgeoning community of [[African American]]s who emigrated from the south formed a community that would come to be known as Bronzeville. Industry was booming, and the African American influence grew in Milwaukee. In the 1920s [[Chicago]] gangster activity came north to Milwaukee during the [[prohibition era]]. [[Al Capone]], noted Chicago mobster, owned a home in the Milwaukee suburb [[Brookfield, Wisconsin|Brookfield]], where [[moonshine]] was made. The house still stands on a street named after Capone. |

|||

[[File:Solomon Juneau.jpg|thumb|left|Statue of [[Solomon Juneau]], who helped establish the city of Milwaukee]] |

|||

Europeans arrived in the Milwaukee area before the 1833 Treaty of Chicago. French missionaries and traders first passed through the area in the late 17th and 18th centuries. Alexis Laframboise, coming from Michilimackinac (now in Michigan), settled a trading post in 1785 and is considered the first resident of European descent in the Milwaukee region.<ref name="St-Pierre, T 1895">St-Pierre, T. ''Histoire des Canadiens du Michigan et du comté d'essex, Ontario''. ''Cahiers du septentrion'', vol. 17. Sillery, Québec: Septentrion. 2000; 1895.</ref> |

|||

With the large influx of immigrants, Milwaukee became one of the 15 largest cities in the nation, and by the mid-1960s, its population reached nearly 750,000. Starting in the late 1960s, however, Milwaukee, like many cities in the "[[rust belt]]", saw its population start to decline through various factors, including the loss of [[blue collar]] jobs and the phenomenon of "[[white flight]]". Nevertheless, in recent years the city has begun to make strides in improving its economy, neighborhoods, and image, resulting in the revitalization of neighborhoods such as the [[Historic Third Ward, Milwaukee|Historic Third Ward]], the [[East Side, Milwaukee|East Side]], and more recently Walker's Point and [[Bay View, Milwaukee|Bay View]], along with attracting new businesses to its downtown area. The city continues to make plans for increasing its future revitalization through various projects. Largely through its efforts to preserve its history, in 2006 Milwaukee was named one of the "Dozen Distinctive Destinations" by the [[National Trust for Historic Preservation]].<ref name="distinctive">{{cite web| url=http://www.nationaltrust.org/dozen_distinctive_destinations/milwaukee.html| title=Dozen Distinctive Destinations - Milwaukee| publisher=National Trust for Historic Preservation| year=2006}}</ref>. In 2007, the Census Bureau released revised population numbers for Milwaukee that showed the city gained population between 2000 and 2006. This marked the first period of positive population growth since the [[1960s]]. |

|||

One story on the origin of Milwaukee's name says, |

|||

{{blockquote|[O]ne day during the thirties of the last century [1800s] a newspaper calmly changed the name to Milwaukee, and Milwaukee it has remained until this day.<ref name="WGBruce">{{cite book|last=Bruce|first=William George|year=1936|title=A Short History of Milwaukee|location=Milwaukee, Wisconsin|publisher=The Bruce Publishing Company|pages=15–16|lccn=36010193}}</ref>}} |

|||

The spelling "Milwaukie" lives on in [[Milwaukie]], [[Oregon]], named after the Wisconsin city in 1847, before the current spelling was universally accepted.<ref>{{Cite web|date=August 3, 2016|title=From Milwaukee, Wis. to Milwaukie, Ore.|url=https://onmilwaukee.com/articles/milwaukieore|access-date=March 2, 2021|website=OnMilwaukee}}</ref> |

|||

Milwaukee has three "[[Father of the Nation|founding fathers]]": [[Solomon Juneau]], [[Byron Kilbourn]], and [[George H. Walker]]. Solomon Juneau was the first of the three to come to the area, in 1818. He founded a town called Juneau's Side, or Juneautown, that began attracting more settlers. In competition with Juneau, Byron Kilbourn established Kilbourntown west of the [[Milwaukee River]]. He ensured the roads running toward the river did not join with those on the east side. This accounts for the large number of angled bridges that still exist in Milwaukee today.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/bridges/|title=Bridges {{!}} Encyclopedia of Milwaukee|website=emke.uwm.edu|access-date=October 3, 2018}}</ref> Further, Kilbourn distributed maps of the area which only showed Kilbourntown, implying Juneautown did not exist or the river's east side was uninhabited and thus undesirable. The third prominent developer was George H. Walker. He claimed land to the south of the Milwaukee River, along with Juneautown, where he built a log house in 1834. This area grew and became known as Walker's Point.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Walker's Point|url=https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/walkers-point/|access-date=March 2, 2021|website=Encyclopedia of Milwaukee}}</ref> |

|||

The first large wave of settlement to the areas that would later become Milwaukee County and the City of Milwaukee began in 1835, following removal of the tribes in the Council of Three Fires. Early that year it became known that Juneau and Kilbourn intended to lay out competing town-sites. By the year's end both had purchased their lands from the government and made their first sales. There were perhaps 100 new settlers in this year, mostly from New England and other Eastern states. On September 17, 1835, the first election was held in Milwaukee; the number of votes cast was 39.<ref>{{Source-attribution|sentence=yes|{{Cite book|title=Memoirs of Milwaukee County from the Earliest Historical Times ..., Vol. I|last=Watrous|first=Jerome A.|publisher=Western Historical Association|year=1909|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XD4VAAAAYAAJ&q=editions:Jqsw4p18KfAC|location=Madison, Wisconsin|pages=265–267}}}}</ref> |

|||

By 1840, the three towns had grown, along with their rivalries. There were intense battles between the towns, mainly Juneautown and Kilbourntown, which culminated with the [[Milwaukee Bridge War]] of 1845. Following the Bridge War, on January 31, 1846, the towns were combined to incorporate as the City of Milwaukee, and elected Solomon Juneau as Milwaukee's first mayor.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://192.159.83.40/SOS/pdf/THEOSOS_025/images/00014104.pdf|title=City of Milwaukee Incorporated, page 164, 1846; page 314, 1851|access-date=April 8, 2007|author=City of Milwaukee|publisher=Office of the Secretary of State of Wisconsin|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070605144656/http://192.159.83.40/SOS/pdf/THEOSOS_025/images/00014104.pdf <!-- Bot retrieved archive -->|archive-date=June 5, 2007}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Milwaukee birdseye map by Bailey (1872). loc call no g4124m-pm010450.jpg|thumb|Illustrated map of Milwaukee in 1872]] |

|||

Milwaukee began to grow as a city as high numbers of immigrants, mainly [[Germans|German]], made their way to Wisconsin during the 1840s and 1850s. Scholars classify [[German immigration to the United States]] in three major waves, and Wisconsin received a significant number of immigrants from all three. The first wave from 1845 to 1855 consisted mainly of people from [[Southwestern Germany]], the second wave from 1865 to 1873 concerned primarily [[Northwestern Germany]], while the third wave from 1880 to 1893 came from [[Northeastern Germany]].<ref name="Bungert, Heike 2006">Bungert, Heike, Cora Lee Kluge and Robert C. Ostergren. ''Wisconsin German Land and Life''. Madison: [[Max Kade Institute]] for German-American Studies, 2006.</ref> In the 1840s, the number of people who left German-speaking lands was 385,434, in the 1850s it reached 976,072, and an all-time high of 1.4 million immigrated in the 1880s. In 1890, the 2.78 million first-generation German Americans represented the second-largest foreign-born group in the United States. Of all those who left the German lands between 1835 and 1910, 90 percent went to the United States, most of them traveling to the Mid-Atlantic states and the Midwest.<ref name="Bungert, Heike 2006" /> |

|||

By 1900, 34 percent of Milwaukee's population was of German background.<ref name="Bungert, Heike 2006" /> The largest number of German immigrants to Milwaukee came from [[Prussia]], followed by [[Bavaria]], [[Saxony]], [[Hanover]], and [[Hesse-Darmstadt]]. Milwaukee gained its reputation as the most German of American cities not just from the large number of German immigrants it received, but for the sense of community which the immigrants established here.<ref name="Conzen, Kathleen Neils 1860">Conzen, Kathleen Neils. ''Immigrant Milwaukee, 1836–1860''. Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England: [[Harvard University Press]], 1976.</ref> |

|||

Most German immigrants came to Wisconsin in search of inexpensive farmland.<ref name="Conzen, Kathleen Neils 1860" /> However, immigration began to change in character and size in the late 1840s and early 1850s, due to the [[Revolutions of 1848|1848 revolutionary movements in Europe]].<ref>Conzen, Kathleen Neils. {{" '}}The German Athens' Milwaukee and the Accommodation of Its Immigrants 1836–1860." PhD diss., vol. 1, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1972.</ref> After 1848, hopes for a united Germany had failed, and revolutionary and radical Germans, known as the "[[Forty-Eighters]]", immigrated to the U.S. to avoid imprisonment and persecution by German authorities.<ref>{{Cite web|last1=Dippel|first1=Christian|last2=Heblich|first2=Stephan|date=May 24, 2020|title=Leadership and Social Movements: The Forty-Eighters in the Civil War|url=https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/faculty_pages/christian.dippel/48ers_paper.pdf|access-date=March 2, 2021|website=UCLA Anderson|page=7|archive-date=January 12, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210112150246/https://www.anderson.ucla.edu/faculty_pages/christian.dippel/48ers_paper.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

One of the most famous "liberal revolutionaries" of 1848 was [[Carl Schurz]]. He later explained in 1854 why he came to Milwaukee, |

|||

<blockquote>"It is true, similar things [cultural events and societies] were done in other cities where the Forty-eighters {{sic}} had congregated. But so far as I know, nowhere did their influence so quickly impress itself upon the whole social atmosphere as in 'German Athens of America' as Milwaukee was called at the time."<ref>"[http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Content.aspx?dsNav=Ny:True,Ro:0,N:4294963828-4294963788&dsNavOnly=Ntk:All%7cMilwaukee+and+Watertown+as+Seen+by+Schurz+in+1854%7c3%7c,Ny:True,Ro:0&dsRecordDetails=R:BA4176&dsDimensionSearch=D:Milwaukee+and+Watertown+as+Seen+by+Schurz+in+1854,Dxm:All,Dxp:3&dsCompoundDimensionSearch=D:Milwaukee+and+Watertown+as+Seen+by+Schurz+in+1854,Dxm:All,Dxp:3 Milwaukee and Watertown as Seen by Schurz in 1854]". ''The Milwaukee Journal'', October 21, 1941. Accessed February 5, 2013.</ref></blockquote> |

|||

Schurz was referring to the various clubs and societies Germans developed in Milwaukee. The pattern of German immigrants settling near each other encouraged the continuation of the German lifestyle and customs. This resulted in [[German language]] organizations that encompassed all aspects of life; for example, singing societies and gymnastics clubs. Germans also had a lasting influence on the American school system. [[Kindergarten]] was created as a pre-school for children, and sports programs of all levels, as well as music and art, were incorporated as elements of the regular school curriculum. These ideas were first introduced by radical-democratic German groups, such as the Turner Societies, known today as the [[American Turners]]. Specifically in Milwaukee, the American [[Turners]] established its own [[Normal College]] for teachers of physical education and the [[University School of Milwaukee|German-English Academy]].<ref>Rippley, LaVern J. and Eberhard Reichmann, trans. "The German Americans, An Ethnic Experience." [http://maxkade.iupui.edu/ Max Kade German-American Center] and [[Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis]]. (accessed February 5, 2013).</ref> |

|||

Milwaukee's German element is still strongly present today. The city celebrates its German culture by annually hosting a German Fest in July<ref>{{Cite web|date=February 5, 2021|title=Milwaukee's German Fest canceled over COVID-19 concerns|url=https://www.tmj4.com/news/local-news/milwaukees-german-fest-canceled-over-covid-19-concerns|access-date=March 2, 2021|website=TMJ4|language=en}}</ref> and an [[Oktoberfest]] in October. Milwaukee boasts a number of German restaurants, as well as a traditional German beer hall. A German language [[immersion school]] is offered for children in grades [[K-5 (education)|K–5]].<ref name=immersionschool>{{cite web|title=Milwaukee German Immersion School|url=http://www5.milwaukee.k12.wi.us/school/mgis/|website=5.milwaukee.k12.wi.us|access-date=April 24, 2015|archive-date=April 25, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150425215726/http://www5.milwaukee.k12.wi.us/school/mgis/|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Lake Front Depot 1898 LOC ds.00203.jpg|thumb|Milwaukee's [[Lake Front Depot]] in 1898]] |

|||

Although the German presence in Milwaukee after the Civil War remained strong and their largest wave of immigrants had yet to land, other groups also made their way to the city. Foremost among these were [[Polish people|Polish]] immigrants. The Poles had many reasons for leaving their homeland, mainly poverty and political oppression. Because Milwaukee offered the Polish immigrants an abundance of low-paying entry-level jobs, it became one of the largest [[Polish settlements in the USA]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Introduction {{!}} Milwaukee Polonia|url=https://uwm.edu/mkepolonia/introduction/|access-date=March 2, 2021|language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

For many residents, [[Neighborhoods of Milwaukee#South Side|Milwaukee's South Side]] is synonymous with the [[#Polish immigrants|Polish community]] that developed here. The group maintained a high profile here for decades, and it was not until the 1950s and 1960s that families began to disperse to the southern suburbs.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Poles|url=https://emke.uwm.edu/entry/poles/|access-date=March 2, 2021|website=Encyclopedia of Milwaukee|language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

By 1850, there were seventy-five Poles in [[Milwaukee County]] and the [[US Census]] shows they had a variety of occupations: grocers, blacksmiths, tavernkeepers, coopers, butchers, broommakers, shoemakers, draymen, laborers, and farmers. Three distinct Polish communities evolved in Milwaukee, with the majority settling in the area south of Greenfield Avenue. Milwaukee County's Polish population of 30,000 in 1890 rose to 100,000 by 1915. Poles historically have had a strong national cultural and social identity, often maintained through the [[Catholic Church]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Nation of Polonia {{!}} Polish/Russian {{!}} Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History {{!}} Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress {{!}} Library of Congress|url=https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/polish-russian/the-nation-of-polonia/|access-date=March 2, 2021|website=Library of Congress}}</ref> A view of Milwaukee's South Side skyline is replete with the steeples of the many churches these immigrants built that are still vital centers of the community.{{citation needed|date=April 2020}} |

|||

[[File:Pabst Building Milwaukee from LOC ID Service-pnp-det-4a00000-4a08000-4a08000-4a08079v.jpg|thumb|Wisconsin Street and the [[Pabst Building]] in the early 20th century]] |

|||

[[St. Stanislaus Catholic Church (Milwaukee, Wisconsin)|St. Stanislaus Catholic Church]] and the surrounding [[Neighborhoods of Milwaukee|neighborhood]] was the center of [[Polish people|Polish]] life in Milwaukee. As the Polish community surrounding St. Stanislaus continued to grow, Mitchell Street became known as the "Polish Grand Avenue". As Mitchell Street grew more dense, the Polish population started moving south to the [[Lincoln Village, City of Milwaukee, Wisconsin|Lincoln Village neighborhood]], home to the [[Basilica of St. Josaphat]] and [[Lincoln Village, City of Milwaukee, Wisconsin#Kosciuszko Park|Kosciuszko Park]]. Other Polish communities started on [[The East Side (Milwaukee)|the East Side of Milwaukee]]. [[Neighborhoods of Milwaukee#Jones Island|Jones Island]] was a major [[commercial fishing]] center settled mostly by [[Kashubians]] and other Poles from around the [[Baltic Sea]].<ref>{{Cite news|last=Beutner|first=Jeff|title=Yesterday's Milwaukee: Jones Island Fishing Village, 1898|url=https://urbanmilwaukee.com/2016/04/13/yesterdays-milwaukee-jones-island-fishing-village-1898/|access-date=March 2, 2021|website=Urban Milwaukee|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

Milwaukee has the fifth-largest Polish population in the U.S. at 45,467, ranking behind [[New York City]] (211,203), [[Chicago]] (165,784), [[Los Angeles]] (60,316) and [[Philadelphia]] (52,648).<ref name="factfinder2.census.gov">{{cite web|url=http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_3YR_B04003&prodType=table|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200212213036/http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_3YR_B04003&prodType=table|url-status=dead|archive-date=February 12, 2020|title=American FactFinder – Results|author=Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS)|access-date=April 5, 2020}}</ref> The city holds [[Polish Fest]], an annual celebration of [[Polish culture]] and [[Polish food|cuisine]].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.jsonline.com/story/entertainment/events/2018/06/13/polish-fest-100th-anniversary-poland/673094002/|title=Polish Fest celebrates the 100th anniversary of the rebirth of a nation|work=Milwaukee Journal Sentinel|access-date=October 3, 2018|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

In addition to the Germans and Poles, Milwaukee received a large influx of other [[Europe]]an immigrants from [[Lithuania]], [[Italy]], [[Ireland]], [[France]], [[Russia]], [[Bohemia]], and [[Sweden]], who included [[American Jews|Jews]], [[Lutherans]], and [[Catholics]]. [[Italian Americans]] total 16,992 in the city, but in Milwaukee County, they number at 38,286.<ref name="factfinder2.census.gov" /> The largest Italian-American festival in the area, ''Festa Italiana'', is held in the city, while ''Irishfest'' is the largest Irish-American festival in southeast Wisconsin.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~gbhs/resources/unitedstates/Milwaukee.html|title=Aus dem Egerland, nach Milwaukee|last=Muehlhans-Karides|first=Susan|access-date=April 25, 2009|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100423173335/http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~gbhs/resources/unitedstates/Milwaukee.html|archive-date=April 23, 2010}}</ref> By 1910, Milwaukee shared the distinction with [[New York City]] of having the largest percentage of foreign-born residents in the United States.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://uwm.edu/lib-collections/mkenh/|title=Milwaukee Neighborhoods: Photos and Maps, 1885–1992|publisher=[[University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee]]|access-date=December 5, 2017|archive-date=February 5, 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190205060424/https://uwm.edu/lib-collections/mkenh/|url-status=dead}}</ref> In 1910, European descendants ("Whites") represented 99.7% of the city's total population of 373,857.<ref>{{cite web|title=Historical Census Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities And Other Urban Places In The United States|publisher=U.S. Census Bureau|url=https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.html|access-date=December 24, 2011|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120812191959/http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.html|archive-date=August 12, 2012}}</ref> Milwaukee has a strong [[Greek Orthodox]] Community, many of whom attend the [[Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church]] on Milwaukee's northwest side, designed by Wisconsin-born architect [[Frank Lloyd Wright]]. Milwaukee has a sizable [[Croats|Croatian]] population, with Croatian churches and their own historic and successful soccer club [[Croatian Eagles|The Croatian Eagles]] at the 30-acre Croatian Park in Franklin, Wisconsin.{{citation needed|date=April 2020}} |

|||

Milwaukee also has a large [[Serbs|Serbian]] population, who have developed Serbian restaurants, a [[St. Sava Orthodox School|Serbian K–8 School]], and Serbian churches, along with an American Serb Hall. The American Serb Hall in Milwaukee is known for its Friday fish fries and popular events. Many U.S. presidents have visited Milwaukee's Serb Hall in the past. The Bosnian population is growing in Milwaukee as well due to late-20th-century immigration after the war in [[Bosnia-Herzegovina]].{{citation needed|date=April 2020}} |

|||

During this time, a small community of [[African American]]s migrated from the [[Southern United States|South]] in the [[Great Migration (African American)|Great Migration]]. They settled near each other, forming a community that came to be known as [[Neighborhoods of Milwaukee#Bronzeville|Bronzeville]]. As industry boomed, more migrants came, and African-American influence grew in Milwaukee.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Geenen|first=Paul H.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dwc40zNjW9MC&q=Milwaukee+bronzeville&pg=PA6|title=Milwaukee's Bronzeville, 1900–1950|date=2006|publisher=Arcadia Publishing|isbn=978-0-7385-4061-0|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Slums in milwaukee 1936.png|thumb|left|A [[slum]] area of Milwaukee from 1936]] |

|||

By 1925, around 9,000 [[Mexican Americans|Mexicans]] lived in Milwaukee, but the [[Great Depression]] forced many of them to move back south. In the 1950s, the Hispanic community was beginning to emerge. They arrived for jobs, filling positions in the manufacturing and agricultural sectors. During this time there were labor shortages due to the immigration laws that had reduced immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe. Additionally, strikes contributed to the labor shortages.<ref name="test">[http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/turningpoints/tp-052/?action=more_essay Wisconsinhistory.org], additional text.</ref> |

|||

In the mid-20th century, African-Americans from Chicago moved to the North side of Milwaukee.{{citation needed|date=March 2021}} Milwaukee's [[The East Side (Milwaukee)|East Side]] has attracted a population of Russians and other Eastern Europeans who began migrating in the 1990s, after the end of the [[Cold War]].{{citation needed|date=March 2021}} Many Hispanics of mostly Puerto Rican and Mexican heritage live on the south side of Milwaukee.{{citation needed|date=March 2021}} |

|||

During the first sixty years of the 20th century, Milwaukee was the major city in which the [[Socialist Party of America]] earned the highest votes. Milwaukee elected three [[mayor]]s who ran on the ticket of the Socialist Party: [[Emil Seidel]] (1910–1912), [[Daniel Hoan]] (1916–1940), and [[Frank Zeidler]] (1948–1960). Often referred to as "[[Sewer Socialists]]", the Milwaukee Socialists were characterized by their practical approach to government and labor.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Milwaukee Socialism: The Emil Seidel Era {{!}} UWM Libraries Digital Collections|url=https://uwm.edu/lib-collections/mke-socialism/|access-date=March 2, 2021|language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

===Historic neighborhoods=== |

|||

{{Main|Neighborhoods of Milwaukee}} |

|||

[[File:Milwaukee Boat Line tour July 2022 50 (Historic Third Ward).jpg|thumb|The [[Historic Third Ward (Milwaukee)|Historic Third Ward]] from the Milwaukee River]] |

|||

In 1892, [[Whitefish Bay, Wisconsin|Whitefish Bay]], [[South Milwaukee]], and [[Wauwatosa]] were incorporated. They were followed by [[Cudahy, Wisconsin|Cudahy]] (1895), North Milwaukee (1897) and East Milwaukee, later known as [[Shorewood, Wisconsin|Shorewood]], in 1900. In the early 20th century, [[West Allis]] (1902), and [[West Milwaukee]] (1906) were added, which completed the first generation of "inner-ring" suburbs. In the 1920s, [[Chicago]] gangster activity came north to Milwaukee during the [[Prohibition era]]. [[Al Capone]], noted Chicago mobster, owned a home in the Milwaukee suburb [[Brookfield, Wisconsin|Brookfield]], where [[moonshine]] was made. The house still stands on a street named after Capone.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.brookfieldnow.com/news/102435199.html|date=November 11, 2010|title=It's everyday life that keeps local historian fascinated: But the Hollywood- worthy moments aren't bad, either?|author=Nan Bialek}}</ref> |

|||

In the 1930s the city was severely segregated via [[redlining]]. In 1960, African-American residents made up 15 percent of Milwaukee's population, yet the city was still among the most segregated of that time. As of 2019, at least three out of four black residents in Milwaukee would have to move to create racially integrated neighborhoods.<ref name="Leah Foltman & Malia Jones"/> |

|||

Milwaukee's population peaked at 741,324 in 1960, where the Census Bureau reported the city's population as 91.1% white and 8.4% black.<ref>{{cite web|title=Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990|publisher=U.S. Census Bureau|url=https://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.html|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120812191959/http://www.census.gov/population/www/documentation/twps0076/twps0076.html|archive-date=August 12, 2012}}</ref> By the late 1960s, Milwaukee's population had started to decline as people moved to suburbs, aided by ease of highways and offering the advantages of less crime, new housing, and lower taxation.<ref>Glabere, Michael. "Milwaukee:A Tale of Three Cities" in, ''From Redlining to Reinvestment: Community Responses to Urban Disinvestment'' edited by Gregory D. Squires. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2011; p. 151 and ''passim''</ref> Milwaukee had a population of 594,833 by 2010, while the population of the overall metropolitan area increased. Given its large immigrant population and historic neighborhoods, Milwaukee avoided the severe declines of some of its fellow "[[Rust Belt]]" cities. |

|||

Since the 1980s, the city has begun to make strides in improving its economy, neighborhoods, and image, resulting in the revitalization of neighborhoods such as the [[Historic Third Ward]], [[Lincoln Village, City of Milwaukee, Wisconsin|Lincoln Village]], the [[East Side, Milwaukee|East Side]], and more recently Walker's Point and [[Bay View, Milwaukee|Bay View]], along with attracting new businesses to its downtown area. These efforts have substantially slowed the population decline and have stabilized many parts of Milwaukee. Largely through its efforts to preserve its history, Milwaukee was named one of the "Dozen Distinctive Destinations" by the [[National Trust for Historic Preservation]] in 2006.<ref name="distinctive">{{cite web|url=http://www.preservationnation.org/travel-and-sites/sites/midwest-region/milwaukee-wi-2006.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100222174953/http://www.preservationnation.org/travel-and-sites/sites/midwest-region/milwaukee-wi-2006.html|archive-date=February 22, 2010|title=Dozen Distinctive Destinations – Milwaukee|publisher=[[National Trust for Historic Preservation]]|year=2006}}</ref> Historic Milwaukee walking tours provide a guided tour of Milwaukee's historic districts, including topics on Milwaukee's architectural heritage, its glass skywalk system, and the [[Milwaukee Riverwalk]]. |

|||

[[File:Milwaukee 05741u.jpg|thumb|center|upright=3.55|Panorama map of Milwaukee, with a view of the [[Milwaukee City Hall|City Hall]] tower, {{circa|1898}}]] |

|||

==Geography== |

==Geography== |

||

Milwaukee |

[[File:Milwaukee aerial.jpg|thumb|Aerial view from the north – the [[Menomonee River]], [[Kinnickinnic River (Milwaukee River tributary)|Kinnickinnic River]], and [[Milwaukee River]] are visible in the foreground; [[Wind Point]] in the background.]] |

||

Milwaukee lies along the shores and bluffs of [[Lake Michigan]] at the [[confluence]] of three rivers: the [[Menomonee River|Menomonee]], the [[Kinnickinnic River (Milwaukee River)|Kinnickinnic]], and the [[Milwaukee River|Milwaukee]]. Smaller rivers, such as the [[Root River (Wisconsin)|Root River]] and Lincoln Creek, also flow through the city. |

|||

Milwaukee's terrain is sculpted by the glacier path and includes steep bluffs along Lake Michigan that begin about a mile (1.6 km) north of downtown. In addition, {{convert|30|mi|km}} southwest of Milwaukee is the Kettle Moraine and lake country that provides an industrial landscape combined with inland lakes. |

|||

According to the [[United States Census Bureau]], the city has a total area of {{convert|96.80|sqmi|sqkm|2}}, of which, {{convert|96.12|sqmi|sqkm|2}} is land and {{convert|0.68|sqmi|sqkm|2}} is water.<ref name="Gazetteer files">{{cite web|title=US Gazetteer files 2010|url=https://www.census.gov/geo/www/gazetteer/files/Gaz_places_national.txt|publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]]|access-date=November 18, 2012|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120112090031/http://www.census.gov/geo/www/gazetteer/files/Gaz_places_national.txt|archive-date=January 12, 2012}}</ref> The city is overwhelmingly (99.89% of its area) in [[Milwaukee County]], but there are two tiny unpopulated portions that extend into neighboring counties.<ref name="foran-counties">{{Cite news|last=Foran|first=Chris|date=January 10, 2023|title=Parts of the city of Milwaukee are in Waukesha and Washington counties. How'd that happen?|work=[[Milwaukee Journal Sentinel]]|url=https://www.jsonline.com/story/life/green-sheet/2023/01/10/why-parts-of-city-of-milwaukee-are-in-waukesha-washington-counties/8015388001/|access-date=November 22, 2023}}</ref>{{efn-ua|The part in [[Washington County, Wisconsin|Washington County]] is bordered by the southeast corner of [[Germantown, Wisconsin|Germantown]], while the part in [[Waukesha County]] is bordered by the southeast corner of [[Menomonee Falls]], north of the village of [[Butler, Waukesha County, Wisconsin|Butler]]. Both areas were annexed to Milwaukee for industrial reasons; the Waukesha County portion contains a [[Cargill]] plant for Ambrosia Chocolate (known as "the Ambrosia triangle"), while the Washington County portion contains a [[Waste Management (corporation)|Waste Management]] facility.<ref name="foran-counties" />}} |

|||

===Cityscape=== |

|||

{{See also|List of tallest buildings in Milwaukee}} |

|||

[[File:Downtown Milwaukee from the Milwaukee River.jpg|thumb|[[Downtown Milwaukee]] from the Milwaukee River]] |

|||

North–south streets are numbered, and east–west streets are named. However, north–south streets east of 1st Street are named, like east–west streets. The north–south numbering line is along the Menomonee River (east of Hawley Road) and Fairview Avenue/Golfview Parkway (west of Hawley Road), with the east–west numbering line defined along 1st Street (north of Oklahoma Avenue) and Chase/Howell Avenue (south of Oklahoma Avenue). This numbering system is also used to the north by [[Mequon]] in [[Ozaukee County]], and by some [[Waukesha County]] communities. |

|||

Milwaukee is crossed by [[Interstate 43]] and [[Interstate 94]], which come together [[Downtown Milwaukee|downtown]] at the [[Marquette Interchange]]. The [[Interstate 894]] bypass (which as of May 2015 also contains [[Interstate 41]]) runs through portions of the city's southwest side, and [[Interstate 794]] comes out of the Marquette interchange eastbound, bends south along the lakefront and crosses the harbor over the [[Hoan Bridge]], then ends near the [[Bay View, Milwaukee|Bay View]] [[Neighborhoods of Milwaukee|neighborhood]] and becomes the "Lake Parkway" ([[Wisconsin Highway 794|WIS-794]]). |

|||

One of the distinctive traits of Milwaukee's residential areas are the neighborhoods full of so-called [[Polish flat]]s. These are two-[[family]] [[home]]s with separate entrances, but with the units stacked one on top of another instead of side-by-side. This arrangement enables a family of limited means to purchase both a home and a modestly priced [[rental]] [[apartment]] unit. Since [[Polish-American]] immigrants to the area prized land ownership, this solution, which was prominent in their areas of settlement within the city, came to be associated with them.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Cross|first=John A.|title=Ethnic Landscapes of America|publisher=Springer|year=2017|isbn=978-3-319-54009-2|location=Cham, Switzerland|pages=310}}</ref> |

|||

The tallest building in the city is the [[U.S. Bank Center (Milwaukee)|U.S. Bank Center]], completed in 1973. In 2024 ''[[Architectural Digest]]'', a prominent design publication, rated Milwaukee's skyline as the 15th most beautiful skyline in the world.<ref>{{Cite web|last=McLaughlin|first=Katherine|date=June 26, 2024|title=The 17 Most Beautiful Skylines in the World|url=https://www.architecturaldigest.com/gallery/the-most-beautiful-skylines-in-the-world|access-date=July 3, 2024|website=Architectural Digest|language=en-US}}</ref> |

|||

Milwaukee's terrain is sculpted by the glacier path and includes steep bluffs along the lakeshore that begin about one half mile north and four miles (6 km) south of downtown. In addition, {{convert|30|mi|km}} west of Milwaukee is the Kettle Morraine and Lake Country that provides a hilly landscape combined with inland lakes. |

|||

{{wide image|CityscapeMilwaukee2023.jpg|750px|align-cap=center|[[Downtown Milwaukee]]}} |

|||

According to the [[United States Census Bureau]], the city has a total area of 251.0 [[square kilometre|km²]] (96.9 square miles). 248.8 km² (96.1 square miles) of it is land, and 0.9 square miles (2.2 km²) of it is water. The total area is 0.88% water. {{Fact|date=September 2008}} |

|||

===Climate=== |

===Climate=== |

||

{{see also|Climate change in Wisconsin}} |

|||

[[File:Milwaukee November 2022 17 (W. Wisconsin Avenue from Milwaukee Skywalk).jpg|thumb|right|220px|West Wisconsin Avenue from the Milwaukee Skywalk]] |

|||

Milwaukee's location in the [[Great Lakes Region]] often has rapidly changing weather, producing a [[humid continental climate]] ([[Köppen climate classification|Köppen]] ''Dfa''), with cold, snowy winters, and hot, humid summers. The warmest month of the year is July, with a mean temperature of {{convert|73.3|F|1}}, while January is the coldest month, with a mean temperature of {{convert|24.0|F|1}}. |

|||

Because of Milwaukee's proximity to Lake Michigan, a convection current forms around mid-afternoon in light wind, resulting in the so-called "lake breeze" – a smaller scale version of the more common [[sea breeze]]. The lake breeze is most common between March and July. This onshore flow causes cooler temperatures to move inland usually {{convert|5|to|15|mi|0}}, with much warmer conditions persisting further inland. Because Milwaukee's official climate site, [[Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport]], is only {{convert|3|mi}} from the lake, seasonal temperature variations are less extreme than in many other locations of the [[Milwaukee metropolitan area]]. |

|||

<center><!--Infobox begins-->{{Infobox Weather |

|||

|metric_first= |

|||

|single_line=Yes |

|||

|location= Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA |

|||

|Jan_Hi_°F = 27 |Jan_REC_Hi_°F = 63 |

|||

|Feb_Hi_°F = 32 |Feb_REC_Hi_°F = 68 |

|||

|Mar_Hi_°F = 42 |Mar_REC_Hi_°F = 82 |

|||

|Apr_Hi_°F = 54 |Apr_REC_Hi_°F = 91 |

|||

|May_Hi_°F = 67 |May_REC_Hi_°F = 94 |

|||

|Jun_Hi_°F = 77 |Jun_REC_Hi_°F = 104 |

|||

|Jul_Hi_°F = 82 |Jul_REC_Hi_°F = 105 |

|||

|Aug_Hi_°F = 80 |Aug_REC_Hi_°F = 103 |

|||

|Sep_Hi_°F = 73 |Sep_REC_Hi_°F = 99 |

|||

|Oct_Hi_°F = 61 |Oct_REC_Hi_°F = 89 |

|||

|Nov_Hi_°F = 46 |Nov_REC_Hi_°F = 77 |

|||

|Dec_Hi_°F = 33 |Dec_REC_Hi_°F = 68 |

|||

|Year_Hi_°F = 56 |Year_REC_Hi_°F = 105 |

|||

|Jan_Lo_°F = 13 |Jan_REC_Lo_°F = -26 |

|||

|Feb_Lo_°F = 18 |Feb_REC_Lo_°F = -26 |

|||

|Mar_Lo_°F = 27 |Mar_REC_Lo_°F = -10 |

|||

|Apr_Lo_°F = 38 |Apr_REC_Lo_°F = 12 |

|||

|May_Lo_°F = 50 |May_REC_Lo_°F = 24 |

|||

|Jun_Lo_°F = 59 |Jun_REC_Lo_°F = 33 |

|||

|Jul_Lo_°F = 66 |Jul_REC_Lo_°F = 40 |

|||

|Aug_Lo_°F = 64 |Aug_REC_Lo_°F = 42 |

|||

|Sep_Lo_°F = 55 |Sep_REC_Lo_°F = 28 |

|||

|Oct_Lo_°F = 44 |Oct_REC_Lo_°F = 18 |

|||

|Nov_Lo_°F = 31 |Nov_REC_Lo_°F = -14 |

|||

|Dec_Lo_°F = 19 |Dec_REC_Lo_°F = -22 |

|||

|Year_Lo_°F = 40|Year_REC_Lo_°F = -26 |

|||

|Jan_Precip_inch = 1.3 |

|||

|Feb_Precip_inch = 1.35 |

|||

|Mar_Precip_inch = 2.22 |

|||

|Apr_Precip_inch = 3.86 |

|||

|May_Precip_inch = 3.08 |

|||

|Jun_Precip_inch = 3.61 |

|||

|Jul_Precip_inch = 3.58 |

|||

|Aug_Precip_inch = 3.93 |

|||

|Sep_Precip_inch = 3.52 |

|||

|Oct_Precip_inch = 2.61 |

|||

|Nov_Precip_inch = 2.78 |

|||

|Dec_Precip_inch = 2.02 |

|||

|Year_Precip_inch = 33.86 |

|||

|source=National Weather Service<ref>{{cite web|url=http://test.crh.noaa.gov/mkx/?n=norm-extreme |title=Normals and Extremes for Milwaukee and Madison |accessdate=2008-10-24 |date=2008 |publisher=[[National Weather Service]] }}</ref> |

|||

|accessdate=October 2008<!--Infobox ends-->}}</center> |

|||

As the sun sets, the convection current reverses and an offshore flow ensues causing a land breeze. After a land breeze develops, warmer temperatures flow east toward the lakeshore, sometimes causing high temperatures during the late evening. The lake breeze is not a daily occurrence and will not usually form if a southwest, west, or northwest wind generally exceeds {{convert|15|mi/h|km/h|abbr=on}}. The lake moderates cold air outbreaks along the lakeshore during winter months. |

|||

Milwaukee's location in the [[Great Lakes region (North America)|Great Lakes Region]] means that it often has rapidly changing weather. The warmest month of the year is July, when the average high temperature is 82 °F (28 °C), with overnight low temperatures averaging 66 °F (19 °C); January is the coldest month, with high temperatures averaging 27 °F (-3 °C), with the overnight low temperatures around 13 °F (-11 °C).<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.weather.com/outlook/health/allergies/wxclimatology/monthly/graph/USWI0455| title=Average Weather for Milwaukee, WI| publisher=Weather.com| accessdate=2006-11-07}}</ref> Of the 50 largest cities in the United States,<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0763098.html| title=Top 50 Cities in the U.S. by Population and Rank| publisher=Infoplease| accessdate=2006-10-02}}</ref> Milwaukee has the second-coldest average annual temperature, next to that of [[Minneapolis]].<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.weatherbase.com/weather/weather.php3?s=004627| title=Historical Weather for Milwaukee, Wisconsin| publisher=Weatherbase| accessdate=2006-10-02}}</ref> |

|||

Aside from the lake's influence, overnight lows in downtown Milwaukee year-round are often much warmer than suburban locations because of the [[urban heat island effect]]. Onshore winds elevate daytime [[relative humidity]] levels in Milwaukee as compared to inland locations nearby. |

|||

Milwaukee's proximity to Lake Michigan causes a convection current to form around mid-afternoon in light wind regimes, resulting in the so-called "lake breeze", a smaller scale version of the more common [[sea breeze]]. The lake breeze is most common between the months of March and June. This onshore flow causes temperatures to remain milder near the lake compared to inland locations. {{Fact|date=September 2008}} As the sun sets, the convection current reverses and an offshore flow ensues causing a land breeze. After a land breeze develops, warmer temperatures flow east toward the lakeshore, sometimes causing high temperatures to be reached during the late evening. The lake breeze is not a daily occurrence and will not form if southwest to northwest winds generally exceed {{convert|15|mi/h|km/h|abbr=on}}. The lake also acts to moderate cold air outbreaks along the lakeshore during winter months. Despite Lake Michigan, overnight lows in downtown Milwaukee are often much warmer than suburban locations because of the [[urban heat island effect]]. Also, more snow falls in Milwaukee than surrounding areas, because of periodic episodes of [[lake effect snow]]. {{Fact|date=September 2008}} Onshore winds cause higher daytime [[relative humidity]] levels in Milwaukee as compared to other cities at the same latitude. {{Fact|date=September 2008}} |

|||

Thunderstorms in the region can be dangerous and damaging, bringing [[hail]] and high winds. In rare instances, they can bring a [[tornado]]. However, almost all summer rainfall in the city is brought by these storms. In spring and fall, longer events of prolonged, lighter rain bring most of the [[precipitation]]. A moderate snow cover can be seen on or linger for many winter days, but even during meteorological winter, on average, over 40% of days see less than {{convert|1|in|cm|1}} on the ground.<ref name="NOAA txt" /> |

|||

Milwaukee's all-time record high temperature is 105 °F (41 °C) set on July 24, 1934. The coldest temperature ever experienced by the city was -26 °F (-32 °C) on both January 17, 1982 and February 4, 1996. {{Fact|date=September 2008}} The 1982 event, also known as [[Cold Sunday]], featured temperatures as low as -40 °F (-40 °C) in some of the [[suburb]]s as little as 10 miles (16km) to the north of Milwaukee. |

|||

Milwaukee tends to experience highs that are {{convert|90|°F|0}} or above on about nine days per year, and lows at or below {{convert|0|°F|0}} on six to seven nights.<ref name="NOAA txt" /> Extremes range from {{convert|105|F|C|abbr=on}} set on July 24, 1934, down to {{convert|−26|F|0}} on both January 17, 1982, and February 4, 1996.<ref name = NOAA > |

|||

The wettest month is August, because of frequent [[thunderstorm]]s.{{Fact|date=October 2008}} These can at times be dangerous and damaging, bringing [[hail]] and high winds. In rare instances, it can bring a [[tornado]] to the more inland parts of the city. However, almost all summer rainfall in the city is brought by these storms. In spring and fall, longer events of prolonged, lighter rain bring most of the precipitation. [[Snow]] commonly falls in the city from early November until the middle of March, although it has been recorded as early as September 23, and as late as May 31. The city receives an average of 47.0 inches (119 cm) of snow in winter, but this number is highly variable. {{Fact|date=October 2008}} |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url = http://www.crh.noaa.gov/mkx/?n=norm-extreme |

|||

|title = Normals and Extremes for Milwaukee and Madison |

|||

|publisher = [[National Weather Service]] |

|||

|accessdate = January 9, 2012}}</ref> The 1982 event, also known as [[Cold Sunday]], featured temperatures as low as {{convert|−40|°F|0}} in some of the [[suburb]]s as little as {{convert|10|mi}} to the north of Milwaukee. |

|||

{{Milwaukee weatherbox}} |

|||

In 2000, 49.5 inches (126 cm) of snow fell solely in the month of December. {{Fact|date=October 2008}} |

|||

=== |

====Climate change==== |

||