St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) m Updating page numbers after recent improvement to Template:Cite book. Added: page. |

wl |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

<!-- Attention: Upload only photographs taken of buildings whose architect died before 1954. |

|||

{{featured article}} |

|||

Photographs taken of buildings located in Ukraine can only be uploaded to Commons if the copyright on the building has expired, because the Copyright Law of Ukraine forbids the publication or commercial use of photographs taken of copyrighted buildings. The copyright term in Ukraine for buildings is the lifetime of the architect + 70 years + the end of the calendar year. See http://www.ndiiv.org.ua/Files2/2015_5/5.pdf for more information. Note also that the refectory inside the monastery is centuries old (it was never destroyed or rebuilt during the modern period).--> |

|||

{{Infobox religious building |

|||

{{Short description|Monastery in Kyiv, Ukraine}} |

|||

| building_name = St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery<br>{{lang|uk|Михайлівський золотоверхий монастир}} |

|||

{{good article}} |

|||

| image = St. Michael's Catheral view.JPG |

|||

{{Use British English|date=March 2023}} |

|||

| caption = The reconstructed St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral<br>with its belltower as seen in 2007. |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=December 2023}} |

|||

| location = [[Kiev]], [[Ukraine]] |

|||

{{Infobox monastery |

|||

| geo = {{coord|50|27|20|N|30|31|22|E|type:landmark|region:UA|display=inline,title}} |

|||

| name = St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery |

|||

| religious_affiliation = [[Eastern Orthodox Church]] |

|||

| native_name = {{lang|uk|i=no|Києво-Михайлівський Золотоверхий чоловічий}} |

|||

| district = [[Ukrainian Orthodox Church - Kiev Patriarchate|Ukrainian Orthodox Church<br>of the Kiev Patriarchate]] |

|||

| native_name_lang = uk |

|||

| consecration_year = |

|||

| image = 80-391-9007 Kyiv St.Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery RB 18 (cropped).jpg |

|||

| leadership = |

|||

| alt = Photograph of the monastery in 2017 |

|||

| website = [http://www.archangel.kiev.ua/ archangel.kiev.ua]<br> [http://www.zolotoverh.org.ua/ zolotoverh.org.ua] |

|||

| caption = View overlooking western facade |

|||

| architect = [[Ivan Hryhorovych-Barskyi]]<br>and others |

|||

| full = |

|||

| architecture_type = [[Monastery]] |

|||

| other_names = |

|||

| architecture_style = [[Ukrainian Baroque]] |

|||

| order = |

|||

| facade_direction = East |

|||

| denomination = [[Orthodox Church of Ukraine]] |

|||

| year_completed = 1999 |

|||

| established = 1108{{ndash}}1113 |

|||

| construction_cost = |

|||

| disestablished = |

|||

| capacity = |

|||

| reestablished = |

|||

| specifications = no |

|||

| mother = |

|||

| dedication = [[Michael (archangel)|Saint Michael the Archangel]] |

|||

| dedicated date = |

|||

| consecrated date = |

|||

| celebration = |

|||

| archdiocese = |

|||

| diocese = [[Eparchy of Kyiv (Orthodox Church of Ukraine)|Eparchy of Kyiv]] |

|||

| churches = |

|||

| founder = [[Sviatopolk II of Kyiv]] |

|||

| abbot = [[Agapetus (Humeniuk)|Agapetus]] |

|||

| prior = <!-- or | prioress = --> |

|||

| archbishop = [[Epiphanius I of Ukraine]] (Metropolitan) |

|||

| bishop = |

|||

| archdeacon = |

|||

| people = |

|||

| status = Active |

|||

| functional_status = |

|||

| heritage_designation = {{Ill|An architectural monument of national significance|uk|Пам'ятка архітектури національного значення}} |

|||

| designated_date = |

|||

| architect = [[Ivan Hryhorovych-Barskyi]] (reconstruction) |

|||

| groundbreaking = |

|||

| completed_date = 1999 (reconstruction) |

|||

| construction_cost = |

|||

| closed_date = |

|||

| location = 8, {{Ill|Triochsvyatitelska Street|uk|Трьохсвятительська вулиця}}, [[Kyiv]] |

|||

| country = [[Ukraine]] |

|||

| oscoor = |

|||

| remains = |

|||

| public_access = |

|||

| other_info = |

|||

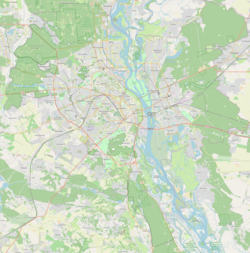

| map_type = Ukraine Kyiv |

|||

| map_caption = Location within Kyiv, Ukraine |

|||

| coordinates = |

|||

| website = {{URL|archangel.kiev.ua}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{otheruses|Golden Dome (disambiguation)}} |

|||

'''St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery''' |

'''St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery'''{{efn|{{langx|uk|Михайлівський золотоверхий монастир|Mychajlivśkyj zolotoverchyj monastyr}}}} is a [[monastery]] in [[Kyiv]], the capital of Ukraine, dedicated to [[Michael (archangel)|Saint Michael the Archangel]]. It is located on the edge of the bank of the [[Dnipro]] river, to the northeast of the [[Saint Sophia Cathedral, Kyiv|St Sophia Cathedral]]. The site is in the historical administrative neighbourhood of [[Uppertown (Kiev)|Uppertown]] and overlooks [[Podil]], the city's historical commercial and merchant quarter. The monastery has been the headquarters of the [[Orthodox Church of Ukraine]] since December 2018. |

||

Built in the [[Middle Ages]] by the [[Kievan Rus']] ruler [[Sviatopolk II of Kyiv|Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych]], the monastery comprises the [[cathedral]] church, the [[Refectory Church of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian]], constructed in 1713, the Economic Gate, constructed in 1760, and the [[bell tower]], which was added in the 1710s. The exterior of the structure was remodelled in the [[Ukrainian Baroque]] style during the 18th century; the interior retained its original [[Byzantine architecture]]. |

|||

Much of the monastery, including the cathedral church, was [[Demolition of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery|demolished]] by [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] authorities in the 1930s. The complex was rebuilt following [[Ukrainian independence]] in 1991; the cathedral reopened in 1999. |

|||

==History== |

==History== |

||

===Early years=== |

|||

[[File:Kyev Zakrvsky map 02.png|thumb|{{Ill|Nikolai Zakrevsky|ru|Закревский, Николай Васильевич}}'s plan of Kyiv from 988 to 1240, from his ''Description of Kyiv'' (1868)|alt=A sketch of the layout of Kyiv]] |

|||

There were once many medieval churches in Kyiv, but nearly all of them were timber-built; none of these have survived.{{sfn|Ivashko|Buzin|Sandu|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=149}} During the 1050s, when Kyiv was a part of the [[Kievan Rus']] state [[Grand Prince of Kyiv|Grand Prince]] [[Iziaslav I of Kyiv|Iziaslav I]] built a [[monastery]] dedicated to [[Demetrius of Thessaloniki|Saint Demetrius of Thessaloniki]], close to the [[Saint Sophia Cathedral, Kyiv|St Sophia Cathedral]].{{sfn|Pavlovsky|Zhukovsky|1984|pp=503{{ndash}}504}}{{sfn|Cross|1947|p=56}} The heads of the monastery were the [[hegumen]]s of the [[Kyiv Pechersk Lavra]].{{sfn|Klos|2019|pp=7, 11}} |

|||

===11th to 19th centuries=== |

|||

According to an 1108 [[annal]] from the [[Laurentian Codex]], Iziaslav's son [[Sviatopolk II of Kyiv]] founded a stone church in Kyiv,{{sfn|Aynalov|Redin|1899|pp=55{{ndash}}57}} and it is thought that the monastery of St. Michael was founded at the same time.{{sfn|Kivlytskyi|1894|p=601}} Contemporary [[chronicle]]s give no account of a foundation, and it is likely that Sviatopolk built the cathedral for the new monastery within the precincts of the monastery of St. Demetrius. There are no historical references to St. Michael's before the end of the 14th century.{{sfn|Cross|1947|p=56}} The church, which was dedicated to [[Michael (archangel)|Saint Michael the Archangel]], Iziaslav's [[patron saint]],{{sfn|Pavlovsky|Zhukovsky|1984|pp=503{{ndash}}504}} may have been built to commemorate Sviatopolk's victory over the [[Polovtsians]], as Michael is the patron saint of war victories.{{sfn|D-Vasilescu|2018|p=76}} |

|||

Some scholars do not believe that Prince [[Iziaslav I of Kiev|Iziaslav Yaroslavych]], whose Christian name was Demetrius, first built the Saint Demetrius's Monastery and Church in the Uppertown of Kiev near Saint Sophia Cathedral in the 1050s.<ref name="Kyiv"/><ref name="EoU"/> Half a century later, his son, [[Sviatopolk II of Kiev|Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych]], is recorded as commissioning a monastery church (1108–1113) dedicated to his own patron saint, [[Michael (archangel)|Michael the Archangel]]. One reason for building the church may have been Svyatopolk's recent victory over the nomadic [[Polovtsians]], as Michael the Archangel was considered a patron of warriors and victories. |

|||

[[Image:Michael of salonica.jpg|200px|thumb|left|The [[Mosaic]] of [[St. Demetrius]] was installed by Sviatopolk II in the monastery cathedral to glorify the patron saint of his father.]] |

|||

The monastery was regarded as a family cloister of Svyatopolk's family; it was there that members of Svyatopolk's family were buried. (This is in contrast to the [[Vydubychi Monastery]] patronized by his rival, [[Vladimir Monomakh]]). The cathedral [[dome]]s were probably the first in [[Kievan Rus]] to be gilded,<ref name="Brockhaus">{{cite web|url=http://gatchina3000.ru/brockhaus-and-efron-encyclopedic-dictionary/042/42113.htm|title=Zlatoverkhy Mikhailovsky monastyr|accessdate=2007-10-26|work=[[Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary]]|language=Russian}}</ref> a practice that became regular with the passage of time and acquired for the monastery the nickname of "golden-domed" or "golden-roofed", depending on the translation. |

|||

The exact date of the completion of St. Michael's is unknown.{{sfn|Cross|1947|p=57}} It is considered to have been built between 1108 and 1113,{{sfn|Watson|Schellinger|Ring|2013|p=372}} the latter year being when Sviatopolk was buried in the cathedral.{{sfn|Denisov|1908|p=301}} By tradition, the [[relic]]s of [[Saint Barbara]] were transferred there during his rule. He was a [[vassal]] prince of the [[List of Polish monarchs|kings of Poland]], who allowed him the freedom to choose the monastery's hegumens.{{sfn|Kivlytskyi|1894|p=601}} The cathedral's dome was probably the first in Kievan Rus' to be [[Gilding|gilded]],<ref name="Brockhaus">{{cite web|url=http://gatchina3000.ru/brockhaus-and-efron-encyclopedic-dictionary/042/42113.htm|title=Zlatoverkhy Mikhailovsky monastyr|access-date=26 October 2007|work=[[Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary]]|language=ru}}</ref> and the monastery was likely called "the Golden-Domed" for this reason.{{sfn|Kivlytskyi|1894|p=601}} |

|||

During the [[Mongol invasion of Rus|Mongol invasion]] in 1240, the monastery is believed to have been damaged seriously. The Mongols damaged the cathedral and removed its gold-plated domes.<ref>{{cite book|title=Mykhailivskyi Zolotoverkhyi Monastyr|author=Chobit, Dmytro|publisher=Prosvita|year=2005|isbn=966-7544-24-9|page=147}}</ref> The cloister subsequently fell into disrepair and there is no documentation of it for the following two and a half centuries. By 1496, the monastery had been revived and its name was changed from St. Demetrius' Monastery to St. Michael's after the cathedral church built by Sviatopolk II.<ref>Historians are not certain which church survived the Tatar invasion, Saint Demetrius's or Saint Michael's.</ref> After numerous restorations and enlargements during the sixteenth century, it gradually became one of the most popular and wealthiest monasteries in Ukraine.<ref name="EoU"/><ref name="Brockhaus"/> In 1620, Iov Boretsky made it the residence of the renewed [[Metropolitan bishop#Orthodox|Orthodox metropolitan]] of Kiev, and in 1633, Isaya Kopynsky was named a supervisor of the monastery.<ref>Both Iov Boretsky and Isaya Kopynsky were buried within the monastery.</ref> |

|||

During the [[Middle Ages]], the cathedral became the burial place of members of the ruling Izyaslavych family.<ref name="Vec">{{cite web |last1=Vecherskyi |first1=V. V. |title=Свято-Михайлівський Золотоверхий монастир |url=https://vue.gov.ua/%D0%A1%D0%B2%D1%8F%D1%82%D0%BE-%D0%9C%D0%B8%D1%85%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB%D1%96%D0%B2%D1%81%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D0%97%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%85%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D0%BC%D0%BE%D0%BD%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8%D1%80 |website=Great Ukrainian Encyclopedia |publisher=State Scientific Institution "Encyclopedic Publishing House" |access-date=12 September 2023 |page=|trans-title= St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery}}</ref> The monastery probably came under the control of the Pechersk Lavra {{circa|1128}}.<ref name="PavZhu">{{cite web |last1=Pavlovsky|first1=Vadym |last2=Zhukovsky |first2=Arkadii |title=Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery |url=https://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CS%5CA%5CSaintMichaelsGolden6DomedMonastery.htm |website=Internet Encyclopaedia of Ukraine |publisher=Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies |access-date=16 August 2023}}</ref> St. Michael's sustained damage and was looted during the [[Mongol invasion of Rus|Mongol invasion]] in 1240, when Kyiv was occupied.{{sfn|Chobit|2005|p=147}} It survived the invasion and subsequent political violence,{{sfn|Watson|Schellinger|Ring|2013|p=372}} but afterwards ceased to function as an institution.<ref name="PavZhu" /> It was mentioned again in documents only in 1398,<ref name="Vec" /> and a 1523 charter of [[Sigismund I the Old]] described the monastery as being deserted in 1470.<ref name="Pam2">{{cite web |title=Михайловський Золотоверхий монастир, 12–20 ст. |url=https://pamyatky.kiev.ua/streets/trohsvyatitelska/mihaylivskiy-zolotoverhiy-monastir-12-20-st |website=Streets of Kyiv |access-date=10 September 2023 |page=|trans-title=Mykhailo Golden-Domed Monastery, 12–20 centuries |language=uk}}</ref> It sustained further damage in 1482, during the raid on Kyiv by the [[Crimean Khanate|Crimean]] Khan [[Meñli I Giray]],{{sfn|Kivlytskyi|1894|p=601}} after which it was abandoned.{{sfn|Cross|1947|p=57}} It had re-emerged by 1496,{{sfn|Klos|2013}} shortly before the [[epithet]] "the Golden-Domed" started to be used.<ref name="PavZhu" /> |

|||

The monastery enjoyed the patronage of [[Hetmans of Ukrainian Cossacks|hetmans]] and other benefactors throughout the years. The chief magnet for pilgrims were the relics of [[Saint Barbara]], alleged to have been brought to Kiev from [[Constantinople]] in 1108 by Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych's wife and kept in a silver reliquary donated by Hetman [[Ivan Mazepa]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.zerkalo-nedeli.com/nn/show/612/54340/|title=Cathedral of outstanding deeds |accessdate=2006-09-17|last=Chervonozhka|first=Valentyna|date=September 2-8, 2006|work=[[Zerkalo Nedeli]]|language=Russian/Ukrainian}}</ref><ref name="Little Kiev">Starting from the late seventeenth century a song honoring St. Barbara was sung in the cathedral of the monastery on each Tuesday just before the liturgy. See: {{cite book |title=Little Encyclopedia of Kiev’s Antiquities|author=Makarov, A.N.|publisher=Dovira|location=[[Kiev]]|year=2002|isbn=966-507-128-9|page=558}}</ref> Although most of the monastery grounds were [[Secularity|secularized]] in the late eighteenth century, as many as 240 [[monks]] resided there in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The monastery served as the residence of the bishop of [[Chernihiv|Chernigov]] after 1800. A precentor's school was located on the monastery grounds; many prominent composers, such as [[Kyrylo Stetsenko]] and [[Yakiv Yatsynevych]], either studied or taught at the school. |

|||

===16th{{ndash}}17th centuries=== |

|||

In 1870, about 100,000 pilgrims paid tribute to St. Barbara at St. Michael's Monastery.<ref name="Little Kiev"/> Before the [[Russian Revolution of 1917|Russian Revolution in 1917]], rings manufactured and blessed at St. Michael's Monastery, known as St. Barbara's rings, were very popular among the citizens of Kiev. They usually served as good luck charms and, according to popular beliefs, occasionally protected against witchcraft but were also effective against serious illnesses and sudden death.<ref name="Little Kiev"/> These beliefs reference the facts that the Monastery was not affected by the [[bubonic plague|plague]] epidemics in 1710 and 1770 and [[cholera]] epidemics of the nineteenth century. |

|||

[[File:План Києва 1695 (План Ушакова) - Верхнє місто.jpg|thumb|The monastery depicted in part of Lieutenant Colonel Ivan Ushakov's plan of the city (1695)|alt=A layout of Kyiv with the monastery depicted in the center]] |

|||

During the 16th century, St. Michael's became one of the most popular and wealthiest monasteries in what is now Ukraine.{{sfn|Pavlovsky|Zhukovsky|1984|pp=503{{ndash}}504}}<ref name="Brockhaus"/> From 1523, it was granted freedoms by Sigismund I, who encouraged restoration work to be undertaken.{{sfn|Cross|1947|p=57}} |

|||

The Austrian soldier and diplomat [[Erich Lassota von Steblau]] visited Kyiv in 1594. He wrote a diary of his travels, later published that year as {{lang|de|Tagebuch des Erich Lassota von Steblau|lt=Erich Lassota}},<ref name="Fre">{{cite web |date=9 July 2008 |title=Erich Lassota von Steblau |trans-title= |url=https://www.geschkult.fu-berlin.de/e/jancke-quellenkunde/verzeichnis/l/lassota_von_steblau/index.html |access-date=28 August 2023 |website=Selbstzeugnisse im Deutschsprachigen Raum (Self-testimonies in German-speaking countries) |publisher=[[Free University of Berlin]] |language=de}}</ref> and described the monastery thus:{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=12}}{{sfn|von Steblau|Wynar|1975|p=76}} |

|||

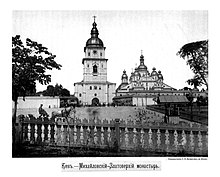

[[Image:Kyiv-Michael-monastery.jpg|thumb|220px|St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery in the early 1900s.]] |

|||

[[Image:Mykhalovsky Zlatoverkhy Cathedral 1930s.jpg|thumb|220px|right|View of the original St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral prior to demolition.]] |

|||

===Demolition of the cathedral and belltower: 1934–1936=== |

|||

{{Blockquote |

|||

During the first half of the 1930s, various [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] publications questioned the known historical facts regarding the age of the Cathedral. The publications stressed that the mediaeval building had undergone major reconstructions and that little of the original Byzantine-style cathedral was preserved. This wave of questioning led to the demolition of the monastery and its replacement with a new administrative centre for the [[Ukrainian SSR]] (previously-the city of [[Kharkiv]]). Before its demolition (June 8–July 9, 1934), the structure was carefully studied by T.M. Movchanivskyi and K. Honcharev from the recently [[Great Purge|purged and re-organized]] Institute of Material Culture of the [[National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine|Ukrainian Academy of Sciences]].<ref>The Institute of Material Culture was known as the Institute of Archeology until 1933.</ref> On the basis of their survey, the cathedral was declared to belong primarily to the [[Ukrainian Baroque]] style, rather than to the twelfth century as was previously thought, and thus did not merit preservation due to its lack of historical and artistic value. This conclusion backed up the Soviet authorities' plans to demolish the entire monastery. Local historians, archaeologists, and architects agreed to the monastery's demolition, although reluctantly. Only one professor, Mykola Makarenko, refused to sign the demolition act; he later died in a Soviet prison.<ref>There is a memorial plate dedicated to him, hanging on the monastery's walls.</ref><ref name="Kyiv"/> |

|||

|text=It is a fine building. In the centre it has a round [[cupola]] with a golden roof. The [[Choir (architecture)|choirs]] are turned inwards and are also decorated with mosaics. The floor is laid out with small, coloured stones. As one enters the church through the gates which are directly opposite the high altar, one sees on the left a wooden casket which holds the body of a saintly virgin, Barbara, a king's daughter: she was a young girl, about 12 years old, as can be judged by her size. Her remains, covered down to her feet with a piece of fine linen, have not decomposed yet as I myself could observe by touching her feet which were still hard and not deteriorated. On her head there is a [[Gilding|gilded]] crown made of wood. |

|||

|author=Erich Lassota von Steblau (trans. [[Orest Subtelny]]) |

|||

On June 26, 1934, work began on the removal of the twelfth century Byzantine mosaics. It was conducted by the Mosaic Section of the Leningrad [[Imperial Academy of Fine Arts|Academy of Fine Arts]]. Specialists were forced to work in haste on account of the impending demolition and were thus unable to complete the entire project.<ref name="Hewryk-15"/> Despite the care and attention shown during the removal of the mosaics from the cathedral's walls, the relocated mosaics cannot be relied upon as being absolutely authentic.<ref name="Hewryk-16">Hewryk, p. 16.</ref> |

|||

|title= |

|||

|source=''Habsburgs and Zaporozhian Cossacks'' (1594) |

|||

}} |

|||

While most of the city's Orthodox clergy and monasteries converted to the Greek Catholic [[Ruthenian Uniate Church|Uniate Church]] in the 17th century, St. Michael's retained its Orthodox doctrine.{{sfn|Watson|Schellinger|Ring|2013|p=372}} In 1612, the Polish king [[Sigismund III Vasa]] gave the monastery to the Uniate Church, which never took possession of the monastery and its estates.{{sfn|Kivlytskyi|1894|p=601}} A wooden refectory church was built in 1613.<ref name="Vec" /> In 1618, the religious figure {{Ill|Antony Grekovych|uk|Грекович Антоній}} tried to extend his power over the monastery. This provoked a sharp reaction—the [[Zaporozhian Cossacks]] captured him and drowned him in a ditch opposite the [[Vydubychi Monastery]].{{sfn|Cac|2009|pp=190{{ndash}}191}} |

|||

The remaining mosaics, covering an area of 45 square metres (485 [[Square foot|sq ft]]), were partitioned between the [[State Hermitage Museum]], the [[Tretyakov Gallery]], and the [[State Russian Museum]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hermitagemuseum.org/html_En/11/2004/hm11_2_141.html|title=The Transfer to the Ukraine of Fragments of Frescoes from Kiev’s Mikhailovo-Zlatoverkh Monastery|accessdate=2006-08-06|work=The State Hermitage Museum|language=English}}</ref> The other remaining mosaics were installed on the second floor of the St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev, where they were not shown to tourists. Those items that remained in Kiev were seized by the [[Nazi Germany|Nazis]] during World War II and taken to [[Germany]]. After the war ended, they fell into [[United States|American]] hands and were later returned to Moscow. |

|||

[[File:Kyiv Pechery Kalnofoysky Athanasius Teraturgema, 1638.jpg|thumb|{{Ill|Athanasius Kalnofoisky|uk|alt=1638 map of Kyiv|Атанасій Кальнофойський}}'s 1638 map of Kyiv shows the monastery at the top|alt=A map of the monastery overlooking Kyiv]] |

|||

During the spring of 1935, the golden domes of the monastery were pulled down. The cathedral's silver royal gates, Mazepa's reliquary (weighing two [[pood]]s of silver) and other valuables were sold abroad or simply destroyed.<ref name="Hewryk-16"/> Master Hryhoryi's five-tier [[iconostasis]] was removed (and later destroyed) from the cathedral as well. St. Barbara's relics were transferred to the [[Church of the Tithes]] and upon that church's demolition, to the [[St Volodymyr's Cathedral]] in 1961. |

|||

In 1620, St. Michael's hegumen [[Job Boretsky]] made the monastery's cathedral the seat of the re-established [[Metropolis of Kiev, Galicia and all Rus' (1620–1686)|Metropolis of Kyiv, Galicia and all Rus']].<ref name="Vec" /> The monastery's [[bell tower]] and [[refectory]] were constructed during his hegumenship.{{sfn|Klos|2013}} Under Boretsky, a nun's [[convent]] was established close to the monastery, on the site of what is now the [[Kyiv Funicular]]'s upper station.<ref name="Pam2" />{{refn|1=In 1712, the convent moved to [[Podil]], and the land it occupied passed to the monastery.<ref name="Pam2" /> |

|||

|group=note}} During this period a printing house was established.<ref name="Vec" /> On both a map of Kyiv in ''Teraturgy'' (1638), written by the Kyivan monk {{Ill|Athanasius Kalnofoisky|uk|Атанасій Кальнофойський}}, and on a Dutch drawing of 1651, the monastery is shown with its single dome.<ref name="Pam2" /> |

|||

The work on rebuilding the medieval cathedral was mentioned by the French engineer [[Guillaume Le Vasseur de Beauplan]] in his {{lang|fr|Description d'Ukranie}} (1650).<ref name="Pam2" /> The Syrian traveller and writer [[Paul of Aleppo]] visited the monastery whilst in Kyiv during the summer of 1654.<ref name="Zhu">{{cite web |last1=Zhukovsky |first1=Arkadii |title=Paul of Aleppo |url=https://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?linkpath=pages%5CP%5CA%5CPaulofAleppo.htm |website=Internet Encyclopaedia of Ukraine |publisher=Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies |access-date=1 September 2023}}</ref> In describing the church, he compared it with St Sophia in Kyiv and the [[Hagia Sophia]] in [[Constantinople]], writing of St. Michael's:{{sfn|Paul of Aleppo|1836|pp=231{{ndash}}232}} |

|||

{{Blockquote |

|||

|text=The entire building is of wood, except the magnificent, lofty, and elegant church, which is of stone and lime, and has a high cupola shining with gold. This church consists only of one nave. It is lighted all round with glazed windows. The three churches I have been describing are all of one style of architecture, and of one age. |

|||

}} |

|||

===18th century=== |

|||

During the spring-summer period of 1936, the shell of the cathedral and belltower were blown up with [[dynamite]]. The monastery's Economic Gate ({{lang|uk-Latn|''Ekonomichna Brama''}}) and the monastic walls were also destroyed. After the demolition, a thorough search for valuables was carried out by the [[NKVD]] on the site.<ref name="Hewryk-16"/> |

|||

In 1712, the nuns of St. Michael's, who lived near the monastery, were transferred to a separate institution in the [[Podil]] district of Kyiv.{{sfn|Kivlytskyi|1894|p=601}} The refectory church was built in 1713–1715 in the [[Ukrainian Baroque]] style from the bricks of Kyiv's Simeon Church, which had been destroyed by fire in 1676.<ref name="Asa" /> |

|||

The remains of 18th-century foundations for part of the western [[aisle]] of the cathedral have been preserved.{{sfn|Orlenko|Ivashko|Kobylarczyk|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|pp=37{{ndash}}39}} As indicated by the foundations of the cathedral's extension in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the northern aisle was added first, followed by the southern aisle in 1709, while the western aisle was built at a later date. It could be seen that the [[flying buttress]]es had been put in place to strengthen the structure where it was placed on [[Shear strength (soil)|low-strength soil]] (soil that cannot support heavy weights). This had become necessary after the dismantling of the old walls of the original church when the cathedral was enlarged.{{sfn|Orlenko|Ivashko|Kobylarczyk|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=40}} |

|||

The only building completed on the former monastery grounds before [[World War II]] currently houses the Foreign Ministry of Ukraine. The construction of the second building ("the capital center"), planned to be built on the site where the Cathedral had once stood, was delayed in the spring of 1938, as the authorities were not satisfied with the submitted design. This building failed to materialise. |

|||

During the late 18th century, a number of the monastery's properties were sold off.<ref name="PavZhu" /> All of its [[Estate (land)|estates]] were lost in 1786, following a decree issued by [[Catherine the Great]]. As a result, the number of monks who could be supported by the monastery greatly reduced, and all new building work stopped.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=22}} |

|||

Some time after demolition, the site where the former cathedral used to be located was transformed into a sport complex, including [[tennis]] and [[volleyball]] courts. The Refectory ({{lang|uk-Latn|''Trapezna''}}) of [[St. John the Divine]] was used for changing rooms. |

|||

===19th century=== |

|||

[[Image:Interior of St. Michaels Golden-Domed Cathedral during demolition.JPG|thumb|left|200px|Interior of the catheral as seen during its demolition.]] |

|||

[[File:Київ. Михайлівський Золотоверхий собор.jpg|thumb|The monastery photographed in 1888|alt=Photograph of the monastery's front section]] |

|||

===Preservation and reconstruction: 1963–2004=== |

|||

In 1800, the monastery became the residence of both the bishop of [[Chernihiv]] and the vicars of the [[Roman Catholic Diocese of Kyiv-Zhytomyr|diocese of Kyiv]].{{sfn|Kivlytskyi|1894|p=601}} By the start of the 19th century, the monastery had a library, a teacher training school, and a choir school. The growth of church choirs during this period meant that musical education became a priority for the monastic authorities. The choir at St. Michael's recruited from Chernihiv before musical education began to be imparted. The most important choir in the Kyiv [[eparchy]], St. Michael's choir was also one of the earliest to be formed in the city.{{sfn|Perepeliuk|2021}} In 1886, a singing school was opened, which ran until the start of the 1920s.<ref name="Pam2" /> During the 19th century there were up to 240 monks at St. Michael's.<ref name="PavZhu" /> |

|||

In the 1880s, the Russian art historian [[Adrian Prakhov]] discovered some of the cathedral's 12th-century [[mosaic]]s and [[fresco]]es, which he cleaned and restored. He made life-sized copies of them in [[Oil painting|oil]], and photographed the restoration process. Copies of his work were exhibited in [[St. Petersburg]] in 1883 and in [[Odesa]] in 1884.{{sfn|Taroutina|2018|p=39}} |

|||

In August 1963, the preserved refectory of the demolished monastery without its Baroque cupola was designated a monument of architecture of the [[Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic|Ukrainian SSR]]. In 1973, the [[Kiev City Council]] established several "archaeological preservation zones" within the city; these included the territory surrounding the monastery. However, the vacant site of the demolished cathedral was excluded from the proposed Historic-Archaeological Park-Museum, ''The Ancient Kiev'', developed by architect A. M. Miletskyi and consultants M. V. Kholostenko and P. P. Tolochko. |

|||

In 1888, the cathedral was equipped with a hot air heating system, and provided with new flooring. The interior decoration was left unaltered. Construction work in the monastery precinct continued up to 1902 and included the construction of a large pilgrims' hotel and a new building for the monks' cells.{{sfn|Ivashko|Buzin|Sandu|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|pp=151–152}} |

|||

During the 1970s, Ukrainian architects I. Melnyk, A. Zayika, V. Korol, and engineer A. Kolyakov worked out a plan of reconstruction of the St. Michael's Monastery. However, these plans were only considered after the [[History of the Soviet Union (1985–1991)|fall of the Soviet Union]] in 1991.<ref>Chobit, p. 24.</ref> |

|||

===20th century=== |

|||

After [[Ukraine]] regained independence in 1991, the demolition of the monastery was deemed a crime and voices started to be heard calling for the monastery's full-scale reconstruction as an important part of the cultural heritage of the Ukrainian people. These plans were approved and carried out in 1997–1998, whereupon the cathedral and belltower were transferred to the [[Ukrainian Orthodox Church — Kiev Patriarchate]]. Yuriy Ivakin, the chief archaeologist for the site, said that more than 260 valuable ancient artifacts were recovered during excavations of the site before reconstruction. In addition, a portion of the ancient cathedral, still intact, was uncovered; this today makes up a part of the current cathedral's crypt.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ukrweekly.com/Archive/1998/489803.shtml|title=Historic St. Michael's Golden-Domed Sobor is rebuilt|accessdate=2006-08-29|last=Woronowycz|first=Roman |authorlink= |coauthors=|date=November 29, 1998|work=[[The Ukrainian Weekly]]|publisher=Kyiv Press Bureau|language=English}}</ref> |

|||

{{multiple image |align=| direction = horizontal | total_width= 400| header = | footer = |

|||

| image1 = Kyiv-Michael-monastery.jpg | alt1 = 1900s photograph of St Michael| caption1 =The monastery in the 1900s |

|||

| image2 = Cathedral Church of St. Michael's Golden-domed Monastery.jpg | alt2 = 1914 photograph of St Michael| caption2 =The cathedral photographed in 1914 |

|||

}} |

|||

The refectory church was damaged by a fire in 1904.<ref name="Asa" /> In 1906, a medieval [[hoard]] was discovered in a [[Casket (decorative box)|casket]] on {{lang|ru|Trekhsvyatytelska|italic=no}} Street (now {{Ill|Triochsvyatitelska Street|uk|Трьохсвятительська вулиця}}), opposite the gates of St. Michael's. The hoard, which was dated to the 11th–12th centuries, was probably hidden in 1240, when Kyiv was sacked by the Mongols. Gold jewellery from the hoard is now housed in the [[Metropolitan Museum of Art]] in New York; other pieces are in the [[British Museum]].<ref name="Bri">{{cite web |title=Armlet |url=https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1907-0520-1 |publisher=[[British Museum]] |access-date=11 August 2023}}</ref> |

|||

The cathedral was nearly destroyed in the aftermath of World War I, when it was hit by [[Shell (projectile)|shells]] fired by the [[Bolsheviks]]. One of the arches supporting the cathedral's central dome was destroyed, and a large hole emerged at the side of the building as a result of the shell damage.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=34}} In 1919, the monastic buildings were appropriated by the [[Government of the Soviet Union#Revolutionary beginnings and Molotov's chairmanship (1922–1941)|new Soviet government]].{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=34}} In 1922, the monastery was closed by the authorities. The refectory was converted into the Proletarian Students' House, and used as a sleeping quarters. The other buildings were used by various institutions, including a driver training school.<ref name="Vec" /><ref name="Nat1" /> |

|||

With support of the [[Kiev City Council|Kiev city authorities]], architect-restorer Y. Lositskiy and others restored the western part of the stone walls. The belltower was restored next and became an observation platform. Instead of the original chiming clock, a new electronic one with hands and a set of chimes (a total of 40<ref name="Chobit-26">Chobit, p. 26.</ref>) was installed from which today the melodies of famous Ukrainian composers can be heard.<ref>The bells chime every hour and play 23 different melodies. Chobit, p. 26</ref> The Cathedral was reconstructed last and decorated with a set of wooden baroque icons, copies of former mosaics and frescoes, and new works of art by Ukrainian artists.<ref name="Kyiv"/> |

|||

===Demolition and aftermath=== |

|||

The newly rebuilt St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral was officially opened on May 30, 1999. However, interior decorations, mosaics, and frescoes were not completed until May 28, 2000. The side chapels were consecrated to [[Saint Barbara|SS. Barbara]] and [[Catherine of Alexandria|Catherine]] in 2001. During the following four years, 18 out of 29 mosaics and other [[work of art|objets d'art]] from the original cathedral were returned from Moscow after years of tedious discussion between Ukrainian and Russian authorities.<ref name="EoU"/> However, by the end of 2006, the remaining frescoes of the monastery are going to be transferred from the [[Hermitage Museum]] in [[Saint Petersburg]] to Kiev.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.korrespondent.net/main/172090/|title=The frescoes of the Michael's Monastery are going to be returned to Ukraine|accessdate=2006-12-02|work=[[Korrespondent]]|language=Russian}}</ref> They are placed in a special preserve that is owned by the municipality rather than the church body. |

|||

{{Main|Demolition of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery}} |

|||

In January 1934, the government decided to move the Ukrainian capital from [[Kharkiv]] to Kyiv, and in April a competition to build a new Government Centre was announced, to be built on the site occupied by St. Michael's.<ref name="Pam2" /> To prevent public protests, the art critics {{Ill|Fyodor Ernst|uk|Ернст Федір Людвігович}}, {{Ill|Mykola Makarenko|uk|Макаренко Микола Омелянович}}, and {{Ill|Stefan Taranushenko|uk|Таранушенко Стефан Андрійович}}—who were thought by the authorities to be likely to publicly oppose the demolition—were arrested. Archaeologists, including Volodymyr Goncharov, condoned the proposed demolition of the cathedral, declaring that the buildings dated only from the 17th century.<ref name="Pam2" />{{sfn|Pevny|2010|p=480}}{{refn|1=19th-century architectural drawings and photographs of the cathedral had shown that parts of the building dated back to the 12th century, and that the northern, southern, and western façades were 17th- and 18th-century additions.{{sfn|Pevny|2010|p=480}}|group=note}} On 26 June, under the supervision of {{Ill|lt=Vladimir Frolov|Vladimir Frolov (mosic artist)|ru|Фролов, Владимир Александрович}} of the [[Imperial Academy of Arts|Leningrad Academy of Arts]], work began on the removal of the 12th-century Byzantine mosaics.{{sfn|Hewryk|1982|p=15}} They were apportioned among the [[State Hermitage Museum]], the [[Tretyakov Gallery]], and the [[State Russian Museum]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hermitagemuseum.org/html_En/11/2004/hm11_2_141.html|title=The Transfer to the Ukraine of Fragments of Frescoes from Kyiv's Mikhailovo-Zlatoverkh Monastery|access-date=5 April 2017|publisher=[[Hermitage Museum|The State Hermitage Museum]] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040624120050/http://www.hermitagemuseum.org/html_En/11/2004/hm11_2_141.html | archive-date=24 June 2004}}</ref> Between 1928 and 1937, surveys of the monastery were made by the Institute of the History of Material Culture of the Ukrainian SSR.<ref name="Ins1" /> |

|||

The monastery was systematically demolished between the spring of 1935—when the golden domes of the cathedral were dismantled{{sfn|Hewryk|1982|p=16}}—and 14 August 1937, when the shell of the cathedral was dynamited.{{sfn|Klos|2013}} The refectory was left intact,<ref name="Asa" /> and two buildings used to house the monks, the choristers' building, part of the bell tower's lower southern wall, and the monastery's cellars also survived.{{sfn|Orlenko|Ivashko|Kobylarczyk|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|pp=37{{ndash}}39}}<ref name="Pam1" /> The foundations of the cathedral and the bell tower, and one part of the monastery wall were not completely demolished.{{sfn|Orlenko|Ivashko|Kobylarczyk|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|pp=37{{ndash}}39}}{{refn|1=Archaeologists have since found that the foundations of the old core of the cathedral were made of large rubble stone bound by ''[[opus signinum]]'' mortar, and that they were set in rubble-filled ditches that were reinforced with wood fastened with iron pins.{{sfn|Orlenko|Ivashko|Kobylarczyk|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|pp=37{{ndash}}39}}|group=note}} |

|||

===Historic pictures of the monastery=== |

|||

<center><gallery> |

|||

In 1938, following the demolition of most of the complex, excavations were carried out on the site of the monastery and in adjacent areas.{{refn|1=The site was also excavated in 1940, and 1948–1949.<ref name="Ins1" />|group=note}} The information obtained consisted of documents and photographs of the ruins of the interior and exterior of the cathedral, and of the excavation process.<ref name="Ins1" /> The new headquarters of the Central Committee of the [[Communist Party of Ukraine]] was built on the site of the demolished {{Ill|lt=Three Saints Church|Three Saints Church, Kyiv|uk|Трьохсвятительська церква (Київ)}}.<ref name="Pam2" />{{refn|1=The building, which was severely damaged by the invading Germans during World War II,{{sfn|Cross|1947|p=57}} now houses the Ukrainian [[Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Ukraine)|Ministry of Foreign Affairs]].{{sfn|Klos|2013}}|group=note}} Work on the site of the demolished monastery was interrupted by World War II, but resumed after the liberation of Kyiv in 1944. The refectory church was then used as a canteen for archaeology students.<ref name="Ins1">{{cite web |title=Дослідження Михайлівського Золотоверхого Монастиря 1920–1960–х: неопублікована археологія |url=https://iananu.org.ua/novini/konferentsiji/942-doslidzhennya-mikhajlivskogo-zolotoverkhogo-monastirya-1920-1960-kh-neopublikovana-arkheologiya |publisher=Institute of Archeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine |access-date=5 September 2023 |page=|trans-title= Research of the Mykhailo Golden-Top Monastery 1920s–1960s: Unpublished Archeology |language=uk}}</ref> The empty site was converted into sports pitches,<ref name="Pam2" /> and until the mid-1970s, the refectory was used as an indoor sports facility.<ref name="Asa" /> The refectory and several of the other surviving buildings were threatened with destruction in the 1970s, when a Lenin Museum was planned to be built on the site. The refectory, at that time in a state of disrepair, was restored.{{sfn|Shevchenko|1997|p=46}} |

|||

Image:Ekonomichni Gate.jpg|The original Economic Gates. |

|||

Image:Iconostasis of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral.JPG|The original iconostasis of the cathedral. |

|||

===Restoration=== |

|||

Image:Interior of S. Michaels Golden-Domed Cathedral.JPG|Interior of the cathedral prior to demolition. |

|||

====Plans and preparatory work==== |

|||

Image:Saint Michaels Cathedral (Kiev) in ruins.jpg|View of the cathedral in ruins. |

|||

{{multiple image |

|||

</gallery></center> |

|||

| direction = horizontal |

|||

| total_width = 350 |

|||

| header = |

|||

| footer = Drawings by [[Carl Peter Mazér]] of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery and its cathedral (1851), which were used to help rebuild the complex |

|||

| image1 = Carl Peter Mazer - St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery.jpg |

|||

| alt1 = Drawing by Mazér of the monastery |

|||

| caption1 = |

|||

| image2 = Carl Peter Mazer - St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral.jpg |

|||

| alt2 = Drawing by Mazér of the cathedral |

|||

| caption2 = |

|||

}} |

|||

The idea to rebuild the monastery was first suggested in 1966 by the Russian architect [[Pyotr Baranovsky]]. The proposal had public support, and was backed by the newly founded {{Ill|Ukrainian Society for the Protection of Historical and Cultural Monuments|uk|Українське товариство охорони пам'яток історії та культури}}.<ref name="Pam2" /> During the 1970s, architects and engineers worked out plans for reconstructing the monastery. These were only seriously considered after [[Declaration of Independence of Ukraine|Ukraine became an independent state]] in 1991,{{sfn|Chobit|2005|p=24}} when there were calls for the monastery's full-scale reconstruction as part of the rebuilding of the country's lost cultural heritage.<ref name="Wor" /> |

|||

The Swedish artist [[Carl Peter Mazér]] had visited Ukraine in 1851 and made a series of architectural drawings. Included were depictions of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery and the interior of the cathedral. The drawings are a unique record of mid-19th century Kyiv,<ref name="Pol">{{cite web |title=Музейний експонат як художній документ епохи |url=https://www.gallery.pl.ua/1malyunki-karla-petera-mazera-yak-xudozhnij-dokument-epoxi.html |publisher=The Poltava Art Museum (Art Gallery) |access-date=12 September 2023 |page=|trans-title= The museum exhibit as an artistic document of the era |language=uk |date=21 January 2018}}</ref>{{refn|1=Mazér's drawings were shown at a 1999 exhibition in the [[National Art Museum of Ukraine]] in Kyiv.<ref name="Pol" />|group=note}} and were accurate enough to be used to help rebuild the monastery.<ref name="Tot">{{cite web |last1=Totska |first1=Irma |title=1999 р. Програма мальовань інтер'єру Михайлівського собору |url=https://www.pslava.info/Kyiv_TrysvjatytelskaVul_MyxajlivskyjZolotoverxyjMon6_1999ProgramaMalovanInterjeru,191112.html |website=Pslava |publisher=M. Zharkykh |access-date=8 January 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161024183334/https://www.pslava.info/Kyiv_TrysvjatytelskaVul_MyxajlivskyjZolotoverxyjMon6_1999ProgramaMalovanInterjeru,191112.html |archive-date=24 October 2016 |page=|trans-title= 1999. Interior painting program of St. Michael's Cathedral |language=uk}}</ref> Documentation produced by {{Ill|Ipolit Morgilevskyi|uk|Моргілевський Іполит Владиславович}}, the Soviet architectural historian prior to the destruction of the monastery, were also used.<ref name="Vec" /> To determine the new building's correct orientation and position, an old photograph taken from the 12th storey of the bell tower was used to produce an electronically generated drawing—a technique first used for the reconstruction of the city's [[Fountain of Samson, Kyiv|Fountain of Samson]].<ref name="Kor1" /> |

|||

The monastery was designed to include the Ukrainian Baroque additions it had possessed at the time of its destruction.{{sfn|Wilson|2000|p=243}} The restorers researched Baroque-style imagery to incorporate into the parts of the monastery known to have been built in the 17/18th centuries, such the cathedral's side [[aisle]]s dedicated to St. Barbara and [[St. Catherine of Alexandria]]. The core of the cathedral's interior was planned to look as it might have appeared during the 11th century.{{sfn|Whittaker|2010|p=108}} Drawings and photographs of the 12th-century mosaics and frescoes were used as templates, and the styles of the interiors of extant Rus' and Byzantine churches such as St. Sophia's Cathedral and the [[St. Cyril's Monastery, Kyiv|Church of St. Cyril]] were copied.{{sfn|Whittaker|2010|p=108}}{{sfn|Pevny|2010|p=483}} |

|||

During the excavation work, which was done by the [[NASU Institute of Archaeology]] between 1992 and 1995, over 300 graves were found, and a unique 11th-century carved slate slab was discovered.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=37}} During 1996/1997, the foundations were left exposed for a year, which resulted in damage being caused to the surviving foundations. The original foundations of the bell tower were found to have laid down as a result of poor workmanship, with rubble stone and bricks of an indifferent quality being used. The foundations had consequently deteriorated, and so were never planned to be used for the restoration.{{sfn|Orlenko|Ivashko|Kobylarczyk|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=40}} The site was [[Sacredness#Transitions|sanctified]] on 24 May 1997.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=38}} |

|||

====Rebuilding the monastery==== |

|||

[[File:Комплекс споруд Михайлівського Золотоверхого монастиря Київ.jpg|alt=Photograph of the monastery's front section, with the rebuilt bell tower in the foreground|thumb|The monastery photographed in 2019]] |

|||

The western end of the boundary walls and the Economic Gate were rebuilt first, followed by the bell tower, which was then used as a temporary observation platform.<ref name="Pam2" />{{sfn|Chobit|2005|p=26}} Later, the [[mural]]s on the walls were restored.<ref name="Kyi" /> Work on the rebuilding of the cathedral church officially began on 24 May 1997,<ref name="PavZhu"/> with building work continuing from November 1998 until the end of 1999.{{sfn|Klos|2019|pp=40, 44}} A new church on the second floor of the bell tower was built, dedicated to the Three Saints. The church was [[consecrated]] in 1999 in memory of the destroyed church of the same name, and to all the Ukrainian victims of Soviet repression.<ref name="Kyi" /> |

|||

The new bells in the {{convert|48.28|m}} high tower were rung for the first time on 30 May 1998.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=39}} Most of the bells, including the seven heaviest ones, were cast at [[Novovolynsk]] in western Ukraine. Their weights range from {{convert|2|kg}} to 8 [[tonne]]s.<ref name="Cas">{{cite news |title=Колокола Михайловcкого Златоверхого монастыря |url=https://on-v.com.ua/novosti/interesno-o-lite/kolokola-mixajlovckogo-zlatoverxogo-monastyrya/ |access-date=31 August 2023 |agency=Casting |date=24 June 2013 |page=|trans-title=Bells of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery |language=uk}}</ref> A computer-controlled keyboard for operating the {{Ill|Carillon of the bell tower of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery|lt=carillon of the bell tower |uk|Карильйон дзвіниці Михайлівського Золотоверхого собору}}, not found elsewhere in Ukraine, works 12 bells that are tuned [[Diatonic and chromatic|chromatically]].<ref name="Cas" /> A new electronic clock was installed, the bell tower's chimes sound every hour, and can play 23 well-known Ukrainian melodies.{{sfn|Chobit|2005|p=26}} |

|||

The ceremony to sanctify the completed cathedral took place on 28 May 2000. Amongst the attendees was then Ukrainian president [[Leonid Kuchma]].{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=46}} The cathedral was officially reopened on 30 May 1999, prior to the interior decorations, mosaics, and frescoes being completed on 28 May 2000. The side [[chapel]]s were consecrated to St. Barbara and St. Catherine in 2001.{{sfn|Pavlovsky|Zhukovsky|1984|pp=503{{ndash}}504}} |

|||

The rebuilt cathedral has received criticism for being based on "renditions of scantily recorded and insufficiently studied predecessors", and for being constructed upon the historical remains of the destroyed cathedral.{{sfn|Pevny|2010|p=472}} According to the historian Olenka Z. Pevny, "the recreated cathedral not only memorializes the present view of the past, but draws attention to the perspective contemplation embodied in 'preserved' cultural-historical sites."{{sfn|Pevny|2010|p=483}} |

|||

The {{Ill|Museum of the History of St. Michael's Golden-domed Monastery|uk|Музей історії Михайлівського Золотоверхого монастиря}} is situated on the first floor of the bell tower.<ref>{{cite web |title=Музеї Києва: Музей історії Михайлівського монастиря |url=http://primetour.ua/uk/excursions/museum/Muzey-istorii-Mihaylovskogo-monastyirya.html |publisher=PrimeTour |access-date=8 September 2023 |ref=none |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170124130354/http://primetour.ua/uk/excursions/museum/Muzey-istorii-Mihaylovskogo-monastyirya.html |archive-date=24 January 2017 |page=|trans-title= Museums of Kyiv: The Museum of the History of St. Michael's Monastery |language=uk}}</ref> It was established in 1998 to exhibit some of the many excavation finds.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=37}} |

|||

==== Metropolitan see ==== |

|||

In the years following the [[Declaration of Independence of Ukraine]] in 1991, the refectory church was returned by the Ukrainian government to the religious community. It became one of the first churches in Kyiv to hold services in the [[Ukrainian language]].<ref name="Asa" /> The monastery became the headquarters of the [[Orthodox Church of Ukraine]] after the [[Unification council of the Orthodox churches of Ukraine|church's creation on 15 December 2018]]. St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery is used as the headquarters of the [[Metropolitan of Kyiv and all Ukraine]].<ref name="Let">{{cite news |last1=Letyak |first1=Valentina |title=Факти ICTV – Михайлівський Золотоверхий стане кафедральним собором єдиної УПЦ |url=https://fakty.com.ua/ua/ukraine/20181216-myhajlivskyj-zolotoverhyj-stane-kafedralnym-soborom-yedynoyi-upts/ |access-date=17 December 2018 |work={{Ill|Facts (ICTV)|uk|Факти (ICTV)}} |date=16 December 2018 |page=|trans-title=Mykhailivskyi Zolotoverkhi will become the cathedral of the unified UOC |language=uk}}</ref><ref name="Rel">{{cite web |title=St. Michael's Golden Domed Cathedral will be the main temple of the OCU |url=https://risu.org.ua/ua/index/all_news/orthodox/ocu/73937/ |publisher=Religious Information Service of Ukraine |access-date=17 December 2018 |date=16 December 2018}}</ref> The rector of the monastery has the rank of [[diocesan bishop]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://risu.org.ua/en/index/all_news/orthodox/ocu/74607/|title=Filaret to head Kyiv Diocese, Metropolitan Symeon elected Chief Secretary of the OCU, the Synod decides|date=5 February 2019|publisher =Religious Information Service of Ukraine |access-date=9 February 2019}}</ref> The Metropolitan of Kyiv and All Ukraine, and the primate of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine, is [[Epiphanius I of Ukraine]].<ref name="Was">{{cite news |title=World Digest: Dec. 15, 2018: Ukrainian church leaders approve split from Russians |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/world-digest-dec-15-2018/2018/12/15/e7d9f170-0082-11e9-83c0-b06139e540e5_story.html |access-date=10 March 2022 |newspaper=[[The Washington Post]] |date=15 December 2018}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Vicar#Eastern Orthodox Church|vicar]] of St. Michael's is {{Ill|Agapit (Humenyuk) |uk|Агапіт (Гуменюк)}}, who was appointed on 10 November 2009.<ref>{{cite web |title=Governor |url=http://www.archangel.kiev.ua/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=15&Itemid=31 |publisher=St. Michael's Golden-roofed Men's Monastery in Kyiv |access-date=31 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160430114741/http://www.archangel.kiev.ua/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=15&Itemid=31 |archive-date=30 April 2016 |language=uk}}</ref> When the {{ill|Kyiv Orthodox Theological Academy|uk|Київська православна богословська академія}} restarted in 1992, the refectory became the Kyiv Theological School's church.<ref name="Asa">{{cite news |last1=Asadcheva |first1=Tatyana |title=Трапезній церкві Михайлівського золотоверхого — 310: чим унікальна ця святиня |url=https://vechirniy.kyiv.ua/news/83088/ |access-date=6 September 2023 |work=Вечірній Київ (Evening Kyiv) |date=21 May 2023 |location=Kyiv |page=|trans-title=The refectory church of Mykhailivskyi zolotoverhoho — 310: how unique is this shrine |language=uk}}</ref> |

|||

==Architecture== |

==Architecture== |

||

[[ |

[[File:Plan of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery, Kyiv 2.svg|thumb|upright=2.15|Plan of the restored St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery: |

||

{{image key |

|||

[[Image:St. Michael's Cathedral from belltower.JPG|thumb|220px|St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral.]] |

|||

|list type=ordered |

|||

|Cathedral of St. Michael the Archangel |

|||

|Monks' cells |

|||

|Bell tower; Holy Gate |

|||

|Economic Gate |

|||

|Choristers' cells |

|||

|[[Refectory Church of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian|Refectory with the Church of St. John the Theologian]] |

|||

|Pilgrims' hotel |

|||

|Hotels |

|||

}}|alt=Layout of the monastery with a legend for all the buildings in the complex]] |

|||

The monastery's four main buildings were the domed cathedral, the refectory, the hotel accommodation (originally built in 1858), and the hegumen's accommodation block (first built in 1857).{{sfn|Denisov|1908|pp=300{{ndash}}301}} The 11th century church was located in what became the centre of the cathedral.{{sfn|Kivlytskyi|1894|p=601}} where the originally single dome was located.{{sfn|Aynalov|Redin|1899|pp=55{{ndash}}57}} A miniature church, likely a [[baptistery]], may have adjoined the cathedral from the south. As with the cathedral, the baptistery could have been topped by a dome.{{sfn|Makarov|2002|p=558}} |

|||

The [[religious architecture]] of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery incorporates elements that have evolved from styles prevalent during [[Byzantine architecture|Byzantine]] and [[Baroque architecture|Baroque]] periods. The St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral or {{lang|uk-Latn|''Mykhaylivskyi Zolotoverhyi Sobor''}} ({{lang-uk|Михайлівський Золотоверхий Cобор}}) is the monastery's main church, built in 1108–1113 at the behest of [[Sviatopolk II of Kiev|Sviatopolk II Iziaslavych]]. The cathedral was the largest of three churches of St. Demetrius Monastery. |

|||

===Dates, styles and architects=== |

|||

The ancient cathedral was modeled on the Assumption Cathedral of the [[Kiev Pechersk Lavra|Kiev Monastery of the Caves]]. It used the [[Greek cross]] plan prevalent during the time of the [[Kievan Rus]], six pillars, and three apses. A miniature church, likely a [[baptistery]], adjoined the cathedral from the south. There was also a tower with a staircase leading to the choir loft; it was incorporated into the northern part of the [[narthex]] rather than protruding from the main block as was common at the time. It is likely that the cathedral had a single dome, although two smaller domes might have topped the tower and baptistery. The interior decoration was lavish as its high-quality shimmering mosaics, probably the finest in Kievan Rus, still testify.<ref>Pyotr Rapoport. ''Zodchestavo Drevnei Rusi''. [[Leningrad]]: [[Nauka]], 1986. ([http://www.russiancity.ru/books/b57.htm online)]</ref> |

|||

The names of the architects and artists involved in building the medieval monastery are unknown, but the [[icon]] painter [[Alypius of the Caves]], who is associated with the paintings in the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, is traditionally considered to have been involved in decorating the cathedral church.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=11}} |

|||

===Cathedral (11th{{ndash}}20th century structure)=== |

|||

When the medieval churches of Kiev were rebuilt in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries in the [[Ukrainian Baroque]] style, the cathedral was enlarged and renovated dramatically. By 1746, it had acquired a new baroque exterior, while maintaining its original Byzantine interior. Six domes were added to the original single dome, but the added pressure on the walls was counteracted by the construction of [[buttress]]es.<ref name="Kyiv"/> The remaining medieval walls, characterised by alternative layers of limestone and flat brick, were covered with [[stucco]]. [[Ivan Hryhorovych-Barskyi]] was responsible for window surrounds and stucco ornamentation. |

|||

The 11th-century cathedral was modelled on the {{Ill|lt=Assumption Cathedral|Assumption Cathedral (Kyiv)|uk|Успенський собор (Київ)}} of the [[Kyiv Monastery of the Caves|Monastery of the Caves]]. It was designed with the [[Greek cross]] plan prevalent during the time of the Kievan Rus', adapted from churches built in the [[Byzantine architecture|Byzantine style]], and had six pillars.{{sfn|Aynalov|Redin|1899|pp=55{{ndash}}57}} It had three naves and three [[apse]]s on the eastern side.<ref name="PavZhu" /> Maps of Kyiv from 1638 and 1651 show the cathedral with its single dome.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=11}} There was also a tower with a staircase leading to the choir loft; it was incorporated into the northern part of the [[narthex]] rather than protruding from the main block as was common at the time.{{sfn|Makarov|2002|p=558}} Using donations from the Cossack commander [[Bohdan Khmelnytsky]], the cathedral dome was gilded during the period when he was the [[hetman]] of the [[Zaporozhian Host]].<ref name="Vec" /> |

|||

[[File:Plan of St. Michael's Golden-domed Monastery in Kyiv.jpg|thumb|Plan of the cathedral by [[Dmitry Aynalov]] and {{Ill|Egor Redin|ru|Редин, Егор Кузьмич}}, ''Ancient Monuments of Art in Kyiv'' (1899)|alt=Architectural drawing of the cathedral]] |

|||

Inside the church, an intricate five-tier [[iconostasis|icon screen]] funded by [[Hetman]] [[Pavlo Skoropadsky]] and executed by Hryhoryi Petriv from [[Chernihiv|Chernigov]] was installed in 1718. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, almost all of the original Byzantine mosaics and frescoes on the interior walls were painted over. Some restoration work on the mosaics and frescoes that remained unpainted was carried out towards the end of the nineteenth century. However, there were no major and serious investigations of the walls done, so it is possible that medieval frescoes or mosaics were preserved under the newer coats of plaster. |

|||

The building began to be enlarged during the 16th century, but the main changes to the cathedral occurred a century later.{{sfn|Pavlovsky|Zhukovsky|1984|pp=503{{ndash}}504}} Along with many of Kyiv's Byzantine churches, during the 17th and 18th centuries, the cathedral was remodelled and was given a Baroque exterior.{{sfn|Watson|Schellinger|Ring|2013|p=372}} In 1715 and in 1731, two side aisles (St. Catherine's from the south and St. Barbara's from the north) were added to the original core of the building.<ref name="Vec" /> The St. Catherine aisle, which replaced the 15th-century Church of the Entry of the Lord into Jerusalem, was paid for by [[Peter the Great|Peter I]] and [[Catherine I of Russia|Catherine I]].<ref name="Pam2" /> At the same time, large arches were pierced into the ancient northern and southern walls. The arches weakened the structure and necessitated the addition in 1746 of massive {{lang|fr|arc-boutants}} (flying buttresses) with single-storey rooms between them and two tall protrusions on the western facade.<ref name="Vec" /> |

|||

The cathedral was largely rebuilt between 1746 and 1754, which caused the central dome to split into four. A seven-domed structure was then created.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=13}} As the cathedral was enlarged over the centuries, it had the effect of making the interior darker.{{sfn|Aynalov|Redin|1899|pp=55{{ndash}}57}} The upper tiers of the 1718 iconostasis were removed in 1888, when the [[Eucharist]] mosaic was revealed. 1908, the cathedral was given underfloor heating, new [[parquet]] floors, and [[Vestibule (architecture)|vestibules]] for the entrances.<ref name="Pam2" /> |

|||

The refectory of the monastery ({{lang|uk-Latn|''Trapezna''}}) is a rectangular brick building which contains a dining hall for the brethren as well as several kitchens and pantries. The church of [[St. John the Divine]] adjoins it from the east. The outside is segmented by [[pilaster]]s and displays window surrounds reminiscent of traditional [[Russian architecture|Muscovite architecture]]. The refectory was erected in 1713 in place of the wooden one. Its interior was overhauled in 1827 and 1837 and restoration work was undertaken in 1976–1981. The monastery belltower was built in three tiers in 1716–1720, and is surmounted by a pear-shaped dome. |

|||

===Rebuilt cathedral=== |

|||

==Footnotes and references== |

|||

In 1992, the decision was made to excavate the site before rebuilding the monastery.{{sfn|Ivashko|Buzin|Sandu|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=149}} The Ukrainian government produced a draft program for the rebuilding of historical and cultural monuments, and in 1998 the List of Historical and Cultural Monuments Subject to Reproduction of Top Priority was approved.{{sfn|Ivashko|Buzin|Sandu|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=149}}{{refn|1=It has been calculated that more than 10,000 buildings were destroyed during the 20th century, including St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral, the [[Assumption Cathedral of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra]], the [[Dormition Cathedral of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra]], and [[Chersonesus Cathedral]].{{sfn|Ivashko|Buzin|Sandu|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=149}} |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

|group=note}} |

|||

Part of the ancient cathedral was uncovered and found to be still intact; this structure today makes up a part of the current cathedral's [[crypt]].<ref name="Wor">{{cite news |last1=Woronowycz |first1=Roman |title=Historic St. Michael's Golden-Domed Sobor is rebuilt |url=http://www.ukrweekly.com/Archive/1998/489803.shtml |access-date=29 August 2006 |work=[[The Ukrainian Weekly]] |publisher=Kyiv Press Bureau |date=29 November 1998 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060427214210/http://www.ukrweekly.com/Archive/1998/489803.shtml |archive-date=27 April 2006}}</ref> |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{commonscat|St. Michael's cathedral}} |

|||

<div class="references-small"> |

|||

* [http://www.archangel.kiev.ua/ Kyiv Michael's Golden-Domed Men's Monasteryp - official site {{uk icon}} |

|||

* [http://www.zolotoverh.org.ua/ St. Michael's Golden-Domed Cathedral] - official site {{uk icon}} |

|||

* [http://oldkyiv.kiev.ua/1_mykhail.htm The Monastery Of St. Michael Of The Golden Domes] - The Lost Landmarks of Kyiv |

|||

* [http://www.sobory.ru/article/index.html?object=00351 Sobory.ru] - photos and description {{ru icon}} |

|||

* [http://wek.kiev.ua/wiki/index.php/%D0%9C%D0%B8%D1%85%D0%B0%D0%B9%D0%BB%D1%96%D0%B2%D1%81%D1%8C%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D0%97%D0%BE%D0%BB%D0%BE%D1%82%D0%BE%D0%B2%D0%B5%D1%80%D1%85%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D1%81%D0%BE%D0%B1%D0%BE%D1%80 Михайлівський Золотоверхий собор] in [http://wek.kiev.ua/ ''Wiki-Encyclopedia Kyiv''] {{uk icon}} |

|||

* [http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/display.asp?AddButton=pages\S\A\SaintMichaelsGolden6DomedMonastery.htm Saint Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery] - article in the [http://www.encyclopediaofukraine.com/ Encyclopedia of Ukraine] |

|||

*[http://www.orthodoxcentral.com/saints/saintbarbara.htm Orthodoxcentral] - information about the relics of [[Saint Barbara]] |

|||

*[http://maps.google.com/maps?f=q&hl=en&q=Kiev&t=k&om=1&ie=UTF8&ll=50.455759,30.522879&spn=0.002992,0.010815 Google Maps] - satellite image |

|||

</div> |

|||

====Exterior==== |

|||

{{Religion of Kiev}} |

|||

The cathedral could have been reconstructed to look as it last appeared in the 1930s, or as it was in 1840, when detailed records were made by the architect {{Ill|Pavlo Sparro|uk|Спарро Павло Іванович}}. It was decided to restore it to its appearance when it was first remodelled in the Ukrainian Baroque style, thus avoiding the need to reconstruct the extensions made after this period that had caused structural issues, or include outbuildings that had been added in later years.<ref name="Kor1" /> |

|||

The total area of the cathedral is {{convert|74.5|m2}}; its height is {{convert|39|m}}; and the central cross is {{convert|4.2|m}} high.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=44}} The building's walls and vaults are constructed in brick.<ref name="Kor1" /> The outside walls are blue, with those parts that project being painted white or gold.{{sfn|Klos|2019|p=44}} The cathedral walls are approximately {{convert|50|cm}} above the level of the 11th-century foundations. Both the original foundations and a staircase were not destroyed in the 1930s, and are able to be viewed.<ref name="Kor1" /> The newly made concrete foundations were designed to reach a depth of {{convert|15|m}}, but still allow the remains buried underground to be inspected.{{sfn|Klos|2019|pp=40, 44}} |

|||

====Interior==== |

|||

The interior was painted throughout, the central core being in the style of the ancient Rus' frescoes, and the aisles in a baroque style. New mosaics were commissioned for the high altar and the main dome.{{sfn|Ivashko|Buzin|Sandu|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=153}} |

|||

The interior decorations, mosaics, and frescoes were not completed until 2000.<ref name="PavZhu" /> Some of the paintings could be recreated using archive photographs, but for those in St. Catherine's aisle, 18th-century examples of paintings from other buildings had to be used.{{sfn|Ivashko|Buzin|Sandu|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=155}} The reconstruction of the cathedral's interior showed the effectiveness of advanced paint technologies. [[Mineral painting#Keim's process|Keim's process]] was used, which made the artworks more resistant to surface dirt, light, moisture, temperature variation, and the effects of [[microorganisms]].{{sfn|Ivashko|Buzin|Sandu|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=159}} In 2001 and 2004, 18 art works were returned to Kyiv from Moscow.<ref name="PavZhu" /> |

|||

===Refectory=== |

|||

{{main|Refectory Church of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian}} |

|||

[[File:Kiev - Saint John the Apostle Church 02.jpg|thumb|alt=photograph of the refectory interior |Interior of the refectory church]] |

|||

The refectory church is a small, one-story structure typical of Orthodox monasteries. The main entrance was originally on the northern side, and was lavishly decorated. In 1787, the church was described as being stone-built with a gilded cross above the bell tower, with a sheet-iron roof painted green, the main roof being iron and painted red. The iconostasis gate was carved and gilded. An architectural drawing made by Sparro in 1847 shows the building with three entrances.<ref name="Asa" /> In 1824, during the rectorship of Bishop Athanasius of [[Chyhyryn]], the roof of the refectory, was repainted green, as were the iron roofs of other monastic buildings.<ref name=df_refectory/> |

|||

In 1715{{ndash}}1718, at the expense of Kyiv Metropolitan {{Ill|Joasaf Krokovsky|uk|Йоасаф (Кроковський)}}, a single-tier carved wooden and gilded iconostasis was installed in the refectory church. It is considered that the church was built using the bricks of Kyiv's Simeon Church at Kudriavka that burnt down in 1676.<ref name="df_refectory">{{cite web |title=Трапезній церкві Михайлівського золотоверхого — 310: чим унікальна ця святиня |url=https://df.news/2023/05/21/trapeznij-tserkvi-mykhajlivskoho-zolotoverkhoho-310-chym-unikalna-tsia-sviatynia/ |website=Spiritual Front of Ukraine [Духовний фронт України] |access-date=4 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230526124823/https://df.news/2023/05/21/trapeznij-tserkvi-mykhajlivskoho-zolotoverkhoho-310-chym-unikalna-tsia-sviatynia/ |archive-date=26 May 2023 |page=|trans-title= The refectory church of the St. Michael's Golden-Domed is 310 years old: how unique is this shrine |language=uk |date=21 May 2023}}</ref> A description from 1880 describes the iconostasis as having images of [[Holy Spirit in Christianity|God the Father with the Holy Spirit]], the [[Annunciation]], [[Mary, mother of Jesus|Mary]], the [[Nativity of Jesus]], the [[four Evangelists]], the [[Biblical Magi|Epiphany]], and the Introduction of the Mother of God into the Church. During the renovation of the refectory in 1837, the shrine was decorated with a new wall painting. By 1845, the walls had been decorated with 23 icons. 1850s sources describe a painting of the [[Feeding the multitude#The feeding of the 4,000|Miracle of the fishes and the loaves]] on the ceiling.<ref name="Asa" /> |

|||

In 1904, the temple was significantly damaged by fire, but the shrine was soon restored.<ref name=df_refectory/> During the Soviet period, the religious painting was whitewashed.<ref name=df_refectory/> In 1937, the [[Refectory Church of the Holy Apostle and Evangelist John the Theologian|refectory church of John the Theologian]] was the only sacred building that remained intact during the destruction of the monastery.<ref name=df_refectory/> |

|||

In August 1963, the preserved refectory of the demolished monastery without its Baroque [[cupola]] was designated a monument of architecture of the [[Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic|Ukrainian SSR]].{{sfn|Yunakov|2016|p=40}} The building was restored between 1976 and 1981 under the leadership of the architect {{Ill|lt=Valentyna Shevchenko|Valentyna Shevchenko (architect)|uk|Шевченко Валентина Петрівна}}.<ref name=df_refectory/> When the ceilings were rebuilt, the 1780s southern extension was removed, and the roof replaced with a Baroque-style [[Roof shingle|shingle]] roof.<ref name=df_refectory/> As part of the 1970s restoration, the painting was restored, which was preserved only in the lower tier of the altar part; the composition depicts the [[Resurrection of Jesus|Resurrection]], the image of the four Evangelists, and two [[Seraph|seraphim]].<ref name=df_refectory/> The preserved part of the wall painting was created by an unknown master in the style of classicism.<ref name=df_refectory/> After the restoration, the building was used to house the Museum of Ceramics of the State Architectural and Historical Reserve, also known as the "Sophia Museum". In 1998, the shrine was restored.<ref name="Asa" /> |

|||

With the restoration of Ukraine's independence, in the early 1990s, the church was returned to the religious community.<ref name=df_refectory/> The Church of John the Theologian became one of the first churches in Kyiv where services were held in the Ukrainian language.<ref name=df_refectory/> In 1997–1998, the refectory church of John the Theologian became the first building to be restored in the architectural ensemble of the St. Michael Golden-Domed Monastery. Also at this time, the shrine was restored to its historical appearance, covering the roof and baths with shingles, a roofing material made of wedge-shaped boards.<ref name=df_refectory/> |

|||

In 2014, during the [[Revolution of Dignity]], the temple was equipped with an improvised hospital where the wounded were treated.<ref name=df_refectory/> |

|||

===Other buildings=== |

|||

A 1911 [[lithograph]] shows the arrangement of the precinct during the early part of the 20th century, with the cathedral, the bell tower with the Holy Gate, the bishop's house with the Cross Church of St. Nicholas, the choristers' cells, the refectory, and the cells for the older monks all depicted.<ref name="Pam2" /> |

|||

The three-tiered bell tower built over the entrance to the monastery was the oldest example of a brick-built bell tower in Kyiv. In around 1631, Boretsky entered into an agreement with the "mason Peter Nimets, a citizen of Kyiv" to construct a brick bell tower. Instead, a three-storey wooden tower was built. This was replaced in 1716–1720 with the new structure, which had a gilded dome and was made with bricks taken from the destroyed St. George's Church in [[Oster]], which had belonged to the monastery.{{sfn|Ernst|1930|pp=371{{ndash}}372}} There were 23 bells in the tower.<ref name="Kyi">{{cite web |title=Київ. Дзвіниця Михайлівського монастиря (Михайлівська площа) |url=https://kpi.ua/kyiv-myhaylo |publisher=National Technical University of Ukraine "Ihor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute" |access-date=10 September 2023 |page=|trans-title=Kyiv. Bell tower of Mykhailivskyi Monastery (Mykhailivska Square) |language=uk}}</ref> |

|||

In the south-east part of the monastery precinct was a farm, gardens and an area for cultivating vegetables. The farmyard was surrounded by stables for the horses, and a [[carriage house]]. Other buildings in the precinct included a hospital, a treasury building, and a school. The entrance to the monastery's cellars was close to the Economic Gate. In 1908, a pair of four-storey accommodation blocks were built, forming an independent block with their own courtyard.<ref name="Pam2" /> |

|||

The monastery and the nunnery (before the nuns were relocated) were both surrounded by walls, and separated from each other by parallel rows of monastic cells.<ref name="Pam2" /> The Economic Gate was a traditional mid-18th-century Ukrainian feature, being an arch flanked by columns and topped with a decorated [[pediment]]. Its position at an angle to the wall is unusual.<ref name="Vec" /> |

|||

{{multiple image |direction = horizontal | align=center |total_width= 300| header = | footer = |

|||

| image1 = Ukraine St Michael Cathedral Postcard 1.jpg | alt1 = postcard of the monastery | caption1 =The pre-1930s bell tower and cathedral depicted on a postcard |

|||

| image3 = Lukomsky - Economic Gate, Kyiv (1923).jpg | alt3 = photograph of the Economic Gate | caption3 = Economic Gate (1923) |

|||

}} |

|||

====Rebuilt bell tower==== |

|||

When excavated, the original foundations of the bell tower were discovered to be dilapidated, and the brick masonry was of indifferent quality. The foundations were therefore not used for the reconstructed building.{{sfn|Orlenko|Ivashko|Kobylarczyk|Kuśnierz-Krupa|2022|p=40}} |

|||

The architectural style of the rebuilt bell tower resembles the over-gate bell towers of the St Sophia's Cathedral and the Vydubychi Monastery. The floors are made with [[reinforced concrete]].<ref name="Vec" /> The structure is {{convert|48.28|m}} tall. It was possible to reduce the thickness of the rebuilt walls from their original {{convert|3.0|-|4.0|m}} to {{convert|0.51|-|0.77|m}}. The second tier, which is [[Cube|cubic]], has four arches, and is narrower than the first tier, is narrower still, and has a chiming clock and four windows.<ref name="Pam1">{{cite web |title=Дзвіниця зі Святою брамою, 1997–98 |url=https://pamyatky.kiev.ua/streets/trohsvyatitelska/mihaylivskiy-zolotoverhiy-monastir-12-20-st/dzvinitsya-zi-svyatoyu-bramoyu-1997-98 |website=Streets of Kyiv |access-date=9 September 2023 |page=|trans-title=Belfry with the Holy Gate, 1997–98 |language=uk}}</ref> The third tier, which is crowned with a gilded dome,<ref name="Pam1" /> The mechanism of the original clock was broken already by the middle of the 19th century. It never had dials, but in March 1998, dials were placed in the tower's clock.<ref name="Igo">{{cite web |title=The bell tower of St. Michael's Monastery (St. Michael's Square) |url=https://kpi.ua/en/kyiv-myhaylo |publisher=[[Igor Sikorsky Kyiv Polytechnic Institute]] |access-date=13 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240513073157/https://kpi.ua/en/kyiv-myhaylo |archive-date=13 May 2024}}</ref><ref name="Kyi" /> |

|||

==Cathedral artworks (pre-1935)== |

|||

===Interior elements=== |

|||

The ancient cathedral's most striking interior elements were its 12th–century frescoes and mosaics.<ref name="PavZhu" /> In the 1880s, Prakhov formed a team of Kyiv artists, selected from the drawing school of the Ukrainian painter and art historian [[Mykola Murashko]]. In 1882, the team made copies of the cathedral mosaics; in 1884, the newly discovered mosaics of the dome and the triumphal arch were drawn; and in 1888, drawings of the previously unknown frescoes were made.{{sfn|Vzdornov|2017|pp=187{{ndash}}188}} |

|||