Psychedelic rock: Difference between revisions

Tim flatus (talk | contribs) →Britain: Tidied up First Beatles line |

m revert sock |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Music genre}} |

|||

{{Articleissues|article=y|refimprove=December 2006|essay=December 2007}} |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

{{Infobox Music genre |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=October 2020}} |

|||

|name = Psychedelic rock |

|||

{{Infobox music genre |

|||

|color = white |

|||

| |

| name = Psychedelic rock |

||

| image = Jimi Hendrix 1967 uncropped.jpg |

|||

|stylistic_origins = [[Blues-rock]], [[folk-rock]], [[rāga]] |

|||

| caption = [[Jimi Hendrix]] on stage at [[Gröna Lund]] in Stockholm, Sweden in June 1967 |

|||

|cultural_origins = Mid 1960s, [[United States]] and [[United Kingdom]] |

|||

| stylistic_origins = *[[Rock music|Rock]] |

|||

|instruments = [[Electric guitar]] (usually with [[guitar effect]]s such as fuzz, phaser, flanger, reverb etc.) - [[Bass guitar]] - [[Drum kit|Drums]] - [[Electronic organ]] - [[Sitar]] - [[Moog synthesizer]] - [[Theremin]] - studio sound effects (e.g. recordings played backwards) |

|||

*[[psychedelic music|psychedelia]] |

|||

|popularity = Peaked in the late 1960s |

|||

*[[contemporary folk music|folk]] |

|||

|derivatives = [[Progressive rock]] - [[hard rock]] - [[Heavy metal music|heavy metal]] - [[art rock]] - [[space rock]] - [[stoner rock]] - [[krautrock]] - [[zeuhl]] - [[New Age music|new age]] - [[punk rock]] - [[proto punk]] - [[jam band]]s - [[dub reggae]] |

|||

*[[garage rock]] |

|||

|subgenres = [[Acid rock]] - [[neo-psychedelia]] |

|||

*[[jazz]] |

|||

|fusiongenres = [[Psychedelic pop]] - [[psychedelic soul]] - [[psych folk|psychedelic folk]] |

|||

*[[blues]] |

|||

|regional_scenes = |

|||

*[[electronic music|electronic]] |

|||

|other_topics = |

|||

*[[novelty song|novelty music]] |

|||

*[[Surf music|surf]] |

|||

| cultural_origins = Mid 1960s, United States and United Kingdom |

|||

| derivatives = *[[Art rock]] |

|||

*[[hard rock]] |

|||

*[[Heavy metal music|heavy metal]] |

|||

*[[industrial music]] |

|||

*[[jam band]] |

|||

*[[krautrock]] |

|||

*[[neo-psychedelia]] |

|||

*[[glam rock]] |

|||

*[[occult rock]] |

|||

*[[progressive rock]] |

|||

*[[proto-prog]] |

|||

*[[shoegaze]] |

|||

| subgenres = *[[Acid rock]]{{efn|"Acid rock" may also be a synonym.<ref name="syn">{{harvnb|Hoffmann|2004|p=1725|loc="Psychedelia was sometimes referred to as 'acid rock.{{'"}}}}; {{harvnb|Nagelberg|2001|p=8|loc="acid rock, also known as psychedelic rock"}}; {{harvnb|DeRogatis|2003|p=9|loc="now regularly called 'psychedelic' or 'acid'-rock"}}; {{harvnb|Larson|2004|p=140|loc="known as acid rock or psychedelic rock"}}; {{harvnb|Romanowski|George-Warren|1995|p=797|loc="Also known as 'acid rock' or the 'San Francisco Sound{{'"}}}}.</ref>}} · [[raga rock]] · [[space rock]] |

|||

| fusiongenres = *[[Psychedelic soul]] |

|||

*[[psychedelic funk]] |

|||

*[[psychedelic pop]] |

|||

*[[stoner rock]] |

|||

*[[zamrock]] |

|||

| regional_scenes = *[[Anatolian rock|Turkey]] |

|||

*[[Psychedelic rock in Australia and New Zealand|Australia]] |

|||

*[[Psychedelic rock in Latin America|Latin America]] |

|||

*[[Psychedelic rock in Australia and New Zealand|New Zealand]] |

|||

*[[Zamrock|Zambia]] |

|||

| local_scenes = *[[Canterbury scene]] |

|||

*[[San Francisco Sound]] |

|||

| other_topics = *[[British underground]] |

|||

*[[experimental rock]] |

|||

*[[folk rock]] |

|||

*[[freak scene]] |

|||

*[[Haight-Ashbury]] |

|||

*[[hippie]]s |

|||

*[[jam band]] |

|||

*[[psychedelic folk]] |

|||

| footnotes = {{notelist}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Psychedelic sidebar|Arts}} |

|||

'''Psychedelic rock''' is a [[rock music]] [[Music genre|genre]] that is inspired, influenced, or representative of [[psychedelia|psychedelic]] culture, which is centered on perception-altering [[hallucinogen]]ic drugs. The music incorporated new electronic [[sound effect]]s and recording techniques, extended instrumental solos, and improvisation.<ref name=PrownNewquist48/> Many psychedelic groups differ in style, and the label is often applied spuriously.{{sfn|Hicks|2000|p=63}} |

|||

'''Psychedelic rock''' is a style of [[rock music]] that is inspired or influenced by psychedelic culture, or attempts to replicate the mind-altering experiences of [[Psychedelics, dissociatives and deliriants|hallucinogenic drugs]].<ref> [http://www.britannica.com/psychedelic/textonly/psychedelic.html Head Sounds]</ref> It emerged during the mid 1960s among [[garage rock|garage]] and [[folk rock]] bands in [[United Kingdom|Britain]] and the [[United States]]. Psychedelic rock is a bridge from early [[blues]]-based rock to [[progressive rock]], [[art rock]], [[experimental rock]], and [[heavy metal music|heavy metal]], but it also drew on non-Western sources such as Indian music's [[rāga]]s and [[sitar]]s. |

|||

Originating in the mid-1960s among British and American musicians, the sound of psychedelic rock invokes three core effects of LSD: [[depersonalization]], dechronicization (the bending of time), and dynamization (when fixed, ordinary objects dissolve into moving, dancing structures), all of which detach the user from everyday reality.{{sfn|Hicks|2000|p=63}} Musically, the effects may be represented via novelty studio tricks, [[electronic music|electronic]] or non-Western instrumentation, disjunctive song structures, and extended instrumental segments.{{sfn|Hicks|2000|pp=63–66}} Some of the earlier 1960s psychedelic rock musicians were based in [[contemporary folk music|folk]], [[jazz]], and the [[blues]], while others showcased an explicit [[Indian classical]] influence called "[[raga rock]]". In the 1960s, there existed two main variants of the genre: the more whimsical, surrealist British psychedelia and the harder American West Coast "[[acid rock]]". While "acid rock" is sometimes deployed interchangeably with the term "psychedelic rock", it also refers more specifically to the heavier, harder, and more extreme ends of the genre. |

|||

==Characteristics== |

|||

{{Expand-section|date=August 2008}} |

|||

The musical style typically features electric guitars, 12 strings being preferred for their 'jangle'; elaborate studio effects - backwards taping, panning (sound placement in the stereo field), phasing, long delay loops and extreme reverb; exotic instrumentation, with a particular fondness for the [[sitar]] and [[tabla]]; A strong keyboard presence, especially Hammond, Farfisa and Vox Organs, the Rhodes electric piano, Harpsichords and the Mellotron (an early tape-driven 'sampler'); a strong emphasis on extended instrumental solos; modal melodies and surreal, esoterically inspired or whimsical lyrics. |

|||

The peak years of psychedelic rock were between 1967 and 1969, with milestone events including the 1967 [[Summer of Love]] and the 1969 [[Woodstock Festival]], becoming an international musical movement associated with a widespread [[Counterculture of the 1960s|counterculture]] before declining as changing attitudes, the loss of some key individuals, and a back-to-basics movement led surviving performers to move into new musical areas. The genre bridged the transition from early blues and folk-based rock to [[progressive rock]] and [[hard rock]], and as a result contributed to the development of sub-genres such as [[heavy metal music|heavy metal]]. Since the late 1970s it has been revived in various forms of [[neo-psychedelia]]. |

|||

==History== |

|||

While the first contemporary musicians to be influenced by psychedelic drugs were in the jazz and folk scenes, the first use of the term "[[psychedelic]]" in popular music was by the "[[Psych folk|acid-folk]]" group [[Holy Modal Rounders|The Holy Modal Rounders]] in 1964, with the song "Hesitation Blues."<ref> [http://www.enter.net/~torve/songs/hesitation.html]</ref> The first use of the term "psychedelic rock" was on the 13th Floor Elevators' business card , designed by John Cleveland, and circulated in December 1965. The term was first used in print in the Austin Statesman in an article about the band titled "Unique Elevators shine with Psychedelic Rock" , dated 10th February 1966. |

|||

{{toclimit|4}} |

|||

In 1962, [[British rock]] embarked on a frenetic race of ideas that spread back to the U.S. with the [[British Invasion]]. The [[folk music]] scene also experimented with outside influences. In the tradition of [[Jazz]] and [[blues]] many musicians began to take drugs and included drug references in their songs. [[Beat Generation]] writers like [[William Burroughs]], [[Jack Kerouac]], [[Allen Ginsberg]] and especially the new exponents of consciousness expansion such as [[Timothy Leary]], [[Alan Watts]] and [[Aldous Huxley]] profoundly influenced the thinking of the new generation. In late 1965, [[The Beatles]] unveiled their brand of psychedelia on the [[Rubber Soul]] album, which featured John Lennon's first paean to universal love ("[[The Word (song)|The Word]]") and a sitar-laden tale of attempted [[hippy]] [[hedonism]] ("[[Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)|Norwegian Wood]]", written by [[John Lennon]]). [[Jeff Beck]] claimed that British rock act [[The Yardbirds]] were "the very first psychedelic band really"<ref>{{cite book | last = Frame | first = Pete | authorlink = Pete Frame | title = Rock Family Trees | publisher = Omnibus Press | date = 1980 | pages = Vol.1 p.6 | isbn = 0-86001-414-2 | nopp = true}}</ref> releasing singles: "Shapes of Things", "Over Under Sideways Down" and "[[Happenings Ten Years Time Ago]]" in 1966. |

|||

== |

==Definition== |

||

{{Further|Psychedelic music}} |

|||

====United States==== |

|||

{{See also|Acid rock}} |

|||

Psychedelia began in the [[United States]]' folk scene with New York City's [[Holy Modal Rounders]] introducing the term in 1964.{{Fact|date=July 2008}} A similar band called Mother McCree's Uptown Jug Champions from San Francisco were influenced by [[The Byrds]] and [[The Beatles]] to switch from acoustic music to electric music in 1965. Renaming themselves the Warlocks, they fell in with [[Ken Kesey]]'s [[LSD]]-fueled [[Merry Pranksters]] in November 1965, and changed their name to the [[Grateful Dead]] the following month.<ref>{{cite book |title=DeadBase IV: The complete Guide to Grateful Dead Song Lists |last=Scott |first=John W.|authorlink= |coauthors=Mike Dolgushkin and Stu Nixon |year=1990 |publisher=DeadBase |location=Hanover, NH |isbn=1-877657-05-0 | pages = pg. 1 }}</ref> The Grateful Dead played to [[light show]]s at the Pranksters' "[[Acid Tests]]", with pulsing images being projected over the group in what became a widespread practice. [[Image:CAROUSEL BALLROOM MASTER.jpg|thumb|Typical psychedelic style poster. Iron Butterfly at the Carousel Ballroom.<ref>[http://www.wolfgangsvault.com/ga/mark-hanau/14862.html M. Hanau at Wolfgang's Vault]</ref>]] |

|||

As a musical style, psychedelic rock incorporated new electronic sound effects and recording effects, extended solos, and improvisation.<ref name=PrownNewquist48>{{harvnb|Prown|Newquist|1997|page=[https://books.google.com/books?id=60Jde3l7WNwC&pg=PA48 48]}}</ref> Features mentioned in relation to the genre include: |

|||

Their sound soon became identified as ''[[acid rock]]'', which they played at the first ''Trips Festival'' in January 1966, along with [[Big Brother and the Holding Company]]. The festival, held at the Longshoremen's Hall, was attended by some 10,000 people. For most of the attendees, it was their first encounter with both acid-rock and LSD. Another band called The Ethix, which originally played [[R&B]], started to experiment with electronics, tape transformations and wild improvisations, and as their music transformed, The Ethix transformed into [[Fifty Foot Hose]]. |

|||

* [[electric guitar]]s, often used with [[Audio feedback|feedback]], [[Wah-wah (music)|wah-wah]] and [[Distortion (music)|fuzzbox]] [[effects unit]]s;<ref name = PrownNewquist48/> |

|||

* certain studio effects (principally in British psychedelia),{{sfn|Prendergast|2003|pp=25–26}} such as [[backmasking|backwards tapes]], [[Panning (audio)|panning]], [[Phaser (effect)|phasing]], long [[Music loop|delay loops]], and extreme [[reverb]];<ref>S. Borthwick and R. Moy, ''Popular Music Genres: An Introduction'' (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), {{ISBN|0-7486-1745-0}}, pp. 52–54.</ref> |

|||

* elements of [[Indian music]] and other [[Eastern music]],<ref name="allmusic">{{cite web|url=https://www.allmusic.com/subgenre/psychedelic-garage-ma0000002800|title=Pop/Rock » Psychedelic/Garage|publisher=[[AllMusic]]|access-date=6 August 2020}}</ref> including [[Middle Eastern music|Middle Eastern]] modalities;{{sfn|Romanowski|George-Warren|1995|p=797}} |

|||

* non-Western instruments (especially in British psychedelia), specifically those originally used in [[Indian classical music]], such as [[sitar]], [[Tanpura|tambura]] and [[tabla]];{{sfn|Prendergast|2003|pp=25–26}} |

|||

* elements of [[Free jazz|free-form jazz]];<ref name="allmusic"/> |

|||

* a strong keyboard presence, especially [[electronic organ]]s, [[harpsichord]]s, or the [[Mellotron]] (an early tape-driven [[Sampler (musical instrument)|sampler]]);<ref>D. W. Marshall, ''Mass Market Medieval: Essays on the Middle Ages in Popular Culture'' (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007), {{ISBN|0-7864-2922-4}}, p. 32.</ref> |

|||

* extended instrumental segments, especially [[guitar solo]]s, or [[jam session|jams]];{{sfn|Hicks|2000|pp=64–66}} |

|||

* disjunctive song structures, occasional [[key signature|key]] and [[time signature]] changes, [[Musical mode|modal]] melodies and [[Drone (music)|drones]];{{sfn|Hicks|2000|pp=64–66}} |

|||

* droning quality in vocals;<ref name="lavezzoli">{{cite book|author=Lavezzoli, Peter|pages=155–157|year=2006|title=The Dawn of Indian Music in the West|publisher=[[Continuum International Publishing Group]]|isbn=978-0-8264-2819-6}}</ref> |

|||

* [[electronic instrument]]s such as [[synthesizers]] and the [[theremin]];{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|p=230}}{{Verify source|date=August 2020}} |

|||

* lyrics that made direct or indirect reference to hallucinogenic drugs;{{sfn|Nagelberg|2001|p=8}} |

|||

* [[surrealism|surreal]], whimsical, esoterically or literary-inspired lyrics<ref>Gordon Thompson, ''Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out'' (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), {{ISBN|0-19-533318-7}}, pp. 196–97.</ref>{{sfn|Bogdanov|Woodstra|Erlewine|2002|pp=1322–1323}} with (especially in British psychedelia) references to childhood;{{sfn|Pinch|Trocco|2009|p=289}} |

|||

* [[Victorian era|Victorian-era]] antiquation (exclusive to British psychedelia), drawing on items such as [[music box]]es, [[music hall]] nostalgia and circus sounds.{{sfn|Prendergast|2003|pp=25–26}} |

|||

The term "psychedelic" was coined in 1956 by psychiatrist [[Humphry Osmond]] in a letter to LSD exponent [[Aldous Huxley]] and used as an alternative descriptor for hallucinogenic drugs in the context of [[psychedelic psychotherapy]].{{sfn|MacDonald|1998|p=165fn}}<ref>N. Murray, ''Aldous Huxley: A Biography'' (Hachette, 2009), {{ISBN|0-7481-1231-6}}, p. 419.</ref> As the countercultural scene developed in San Francisco, the terms [[acid rock]] and psychedelic rock were used in 1966 to describe the new drug-influenced music and were being widely used by 1967.<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=21UEAAAAMBAJ&dq=%22psychedelic+rock%22+%22acid+rock%22&pg=PA68 "Logical Outcome of fifty years of art"], ''LIFE'', 9 September 1966, p. 68.</ref>{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|pp=8–9}} The two terms are often used interchangeably,{{sfn|Nagelberg|2001|p=8}} but acid rock may be distinguished as a more extreme variation that was heavier, louder, relied on long [[Jam session|jams]],<ref name=AllmusicAcidRock>{{AllMusic|class=style|id=acid-rock-ma0000012327}}</ref> focused more directly on LSD, and made greater use of distortion.<ref>Eric V. d. Luft, ''Die at the Right Time!: A Subjective Cultural History of the American Sixties'' (Gegensatz Press, 2009), {{ISBN|0-9655179-2-6}}, p. 173.</ref> |

|||

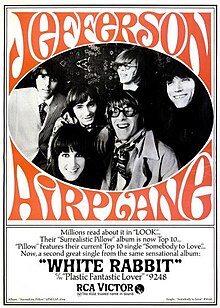

Throughout 1966, the San Francisco music scene flourished, as the Fillmore, the [[Avalon Ballroom]], and [[The Matrix (club)|The Matrix]] began booking local rock bands on a nightly basis. The emerging "[[San Francisco Sound]]" made local stars of numerous bands, including [[The Charlatans (U.S. band)|The Charlatans]], [[Moby Grape]], Big Brother and the Holding Company, Fifty Foot Hose, [[Quicksilver Messenger Service]], [[Country Joe and the Fish]], [[The Great Society]], and the folk-rockers [[Jefferson Airplane]], whose debut album was recorded during the winter of 1965/66 and released in August 1966. ''[[Jefferson Airplane Takes Off]]'' was the first album to come out of San Francisco during this era and sold well enough to bring the city's music scene to the attention of the record industry. |

|||

==Original psychedelic era== |

|||

Jefferson Airplane gained greater fame the following year with two of the earliest psychedelic hit singles: "[[White Rabbit (song)|White Rabbit]]" and "[[Somebody to Love (Jefferson Airplane song)|Somebody to Love]]". Both these songs had originated with the band [[The Great Society]], whose singer [[Grace Slick]], left to join Jefferson Airplane, taking the two compositions with her.<ref>{{cite book | last = Frame | first = Pete | authorlink = Pete Frame | title = Rock Family Trees | publisher = Omnibus Press | date = 1980 | pages = Vol.1 p.9 | isbn = 0-86001-414-2 | nopp = true}}</ref> |

|||

{{Main|Psychedelic era}} |

|||

===1960–65: Precursors and influences=== |

|||

Although [[San Francisco]] receives much of the credit for jump-starting the psychedelic music scene, many other American cities contributed significantly to the new genre. Los Angeles boasted dozens of important psychedelic bands, including [[the Byrds]], [[Iron Butterfly]], [[Love (band)|Love]], [[Spirit (band)|Spirit]], [[the United States of America (band)|the United States of America]], and [[the Doors]], among others. New York City produced its share of psychedelic bands such as the [[Blues Magoos]], the [[Blues Project]], [[Bermuda Triangle Band]], [[Electric Prunes]], [[Lothar and the Hand People]]. and the Third Bardo. The Detroit area gave rise to psychedelic bands the [[Amboy Dukes]], [[Funkadelic]] and the [[SRC (band)|SRC]]. Texas (particularly Austin) is often cited for its contributions to psychedelic music, being home to the groundbreaking [[13th Floor Elevators]], as well as [[Bubble Puppy]], [[Shiva's Headband]], [[Golden Dawn]], the [[Zakary Thaks]], [[Red Krayola]], and many others. Chicago produced the [[H. P. Lovecraft (band)|H. P. Lovecraft]]. |

|||

{{See also|Psychedelic folk}} |

|||

Music critic [[Richie Unterberger]] says that attempts to "pin down" the first psychedelic record are "nearly as elusive as trying to name the first rock & roll record". Some of the "far-fetched claims" include the instrumental "[[Telstar (song)|Telstar]]" (produced by [[Joe Meek]] for [[the Tornados]] in 1962) and [[the Dave Clark Five]]'s "massively reverb-laden" "[[Any Way You Want It (The Dave Clark Five song)|Any Way You Want It]]" (1964).{{sfn|Bogdanov|Woodstra|Erlewine|2002|p=1322}} The first mention of LSD on a rock record was [[The Gamblers (American band)|the Gamblers]]' 1960 surf instrumental "LSD 25".{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|p=7}}{{refn|group=nb|Their keyboardist, [[Bruce Johnston]], went on to join [[the Beach Boys]] in 1965. He would recall: "[LSD is] something I've never thought about and never done."{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|p=7}}}} A 1962 single by [[the Ventures]], "[[The 2,000 Pound Bee|The 2000 Pound Bee]]", issued forth the buzz of a distorted, "fuzztone" guitar, and the quest into "the possibilities of heavy, transistorised distortion" and other effects, like improved reverb and echo, began in earnest on London's fertile rock 'n' roll scene.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Hot Wired Guitar: The Life of Jeff Beck|last=Power|first=Martin|publisher=Omnibus Press|year=2014|isbn=978-1-78323-386-1|location=books.google.com|pages=Chapter 2}}</ref> By 1964 fuzztone could be heard on singles by [[P.J. Proby]],<ref name=":0" /> and the Beatles had employed feedback in "[[I Feel Fine]]",{{sfn|Philo|2015|pp=62–63}} their sixth consecutive number 1 hit in the UK.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Beatles Encyclopedia: Everything Fab Four|last=Womack|first=Kenneth|publisher=Greenwood|year=2017|isbn=978-1-4408-4426-3|location=books.google.com|pages=222}}</ref> |

|||

The Byrds went psychedelic in March 1966 with "[[Eight Miles High]]", a song with odd vocal harmonies and an extended guitar solo that guitarist [[Roger McGuinn]] states was inspired by [[Raga]] and [[John Coltrane]]. |

|||

According to [[AllMusic]], the emergence of psychedelic rock in the mid-1960s resulted from British groups who made up the [[British Invasion]] of the US market and [[folk rock]] bands seeking to broaden "the sonic possibilities of their music".<ref name="allmusic" /> Writing in his 1969 book ''The Rock Revolution'', [[Arnold Shaw (author)|Arnold Shaw]] said the genre in its American form represented generational [[escapism]], which he identified as a development of youth culture's "protest against the sexual taboos, racism, violence, hypocrisy and materialism of adult life".{{sfn|Shaw|1969|p=189}} |

|||

[[Brute Force (musician)]] is another psychedelic rocker who is still very active today. His "King of Fuh" is considered a psychedelic masterpiece. |

|||

American folk singer [[Bob Dylan]]'s influence was central to the creation of the folk rock movement in 1965, and his lyrics remained a touchstone for the psychedelic songwriters of the late 1960s.{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|pp=87, 242}} Virtuoso sitarist [[Ravi Shankar]] had begun in 1956 a mission to bring Indian classical music to the West, inspiring jazz, classical and folk musicians.{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|pp=61–62}} By the mid-1960s, his influence extended to a generation of young rock musicians who soon made [[raga rock]]{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|pp=142, foreword}} part of the psychedelic rock aesthetic and one of the many intersecting cultural motifs of the era.<ref>Bellman, pp. 294–295</ref> In the [[British folk music|British folk]] scene, blues, drugs, jazz and Eastern influences blended in the early 1960s work of [[Davy Graham]], who adopted modal guitar tunings to transpose Indian ragas and Celtic reels. Graham was highly influential on Scottish folk virtuoso [[Bert Jansch]] and other pioneering guitarists across a spectrum of styles and genres in the mid-1960s.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.guitarworld.com/acoustic-nation-lessons/how-play-dadgad-pioneer-davey-graham/30870|title=How to Play Like DADGAD Pioneer Davey Graham|date=2017-03-16|work=Guitar World|access-date=2017-08-08}}</ref><ref name=Hope />{{refn|group=nb|According to [[Stewart Home]], Graham was "the key early figure ... Influential but without much commercial impact, Graham's mix of folk, blues, jazz, and eastern scales backed on his solo albums with bass and drums was a precursor to and ultimately an integral part of the folk rock movement of the later sixties. ... It would be difficult to underestimate Graham's influence on the growth of hard drug use in British counterculture."<ref name=Hope>{{cite book|author=[[Stewart Hope]]|chapter=Voices green and purple: psychedelic bad craziness and the revenge of the avant-garde|editor1=Christoph Grunenberg|editor2=Jonathan Harris|title=Summer of Love: Psychedelic Art, Social Crisis and Counterculture in the 1960s|location=Liverpool|publisher=Liverpool University Press|year=2005|isbn=9780853239192|page=137}}</ref>}} Jazz saxophonist and composer [[John Coltrane]] had a similar impact, as the exotic sounds on his albums ''[[My Favorite Things (John Coltrane album)|My Favorite Things]]'' (1960) and ''[[A Love Supreme]]'' (1965), the latter influenced by the ragas of Shankar, were source material for guitar players and others looking to improvise or "jam".{{sfn|Hicks|2000|pp=61–62}} |

|||

In 1965, members of [[Rick And The Ravens]] and [[The Psychedelic Rangers]] came together with [[Jim Morrison]] to form [[The Doors]]. They made a demo tape for [[Columbia Records]] in September of that year, which contained glimpses of their later acid-rock sound. When nobody at Columbia wanted to produce the band, they were signed by [[Elektra Records]], who released their debut album in January 1967. It contained their first hit single, "[[Light My Fire]]." Clocking in at over 7 minutes, it became one of the first rock singles to break the mold of the [[three-minute pop song]], although the version usually played on [[AM radio]] was a much-shorter version. |

|||

One of the first musical uses of the term "psychedelic" in the folk scene was by the New York-based folk group [[The Holy Modal Rounders]] on their version of [[Lead Belly]]'s '[[Hesitation Blues]]' in 1964.<ref>M. Hicks, ''Sixties Rock: Garage, Psychedelic, and Other Satisfactions'' (University of Illinois Press, 2000), {{ISBN|978-0-252-06915-4}}, pp 59–60.</ref> Folk/avant-garde guitarist [[John Fahey (musician)|John Fahey]] recorded several songs in the early 1960s experimented with unusual recording techniques, including backwards tapes, and novel instrumental accompaniment including flute and sitar.<ref name="Fahey">{{cite web |last=Unterberger |first=Richie |author-link=Richie Unterberger |title=The Great San Bernardino Oil Slick & Other Excursions — Album Review |url=http://www.allmusic.com/album/vol-4-the-great-san-bernardino-birthday-party-mw0000103865 |access-date=25 July 2013 |work=[[AllMusic]] |publisher=Rovi Corp.}}</ref> His nineteen-minute "The Great San Bernardino Birthday Party" "anticipated elements of psychedelia with its nervy improvisations and odd guitar tunings".<ref name="Fahey" /> Similarly, folk guitarist [[Sandy Bull]]'s early work "incorporated elements of folk, jazz, and [[Indian music|Indian]] and [[Arabic music|Arabic]]-influenced dronish modes".<ref>{{cite web |last=Unterberger |first=Richie |author-link=Richie Unterberger |title=Sandy Bull — Biography |url=http://www.allmusic.com//artist/sandy-bull-mn0000295213/biography |access-date=July 16, 2013 |work=[[AllMusic]] |publisher=Rovi Corp.}}</ref> His 1963 album ''[[Fantasias for Guitar and Banjo]]'' explores various styles and "could also be accurately described as one of the very first psychedelic records".<ref>{{cite web |last=Greenwald |first=Matthew |title=''Fantasias for Guitar & Banjo'' — Album Review |url=http://www.allmusic.com/album/fantasias-for-guitar-banjo-mw0000811015 |access-date=July 16, 2013 |work=[[AllMusic]] |publisher=Rovi Corp.}}</ref> |

|||

Initially, [[The Beach Boys]], with their squeaky-clean image, seemed unlikely as psychedelic types. Their music, however, grew more psychedelic and experimental, perhaps due in part to writer/producer/arranger [[Brian Wilson]]'s increased drug usage and burgeoning mental illness. In 1966, responding to the Beatles' innovations, they produced their album ''[[Pet Sounds]]'' and later that year had a massive hit with the psychedelic single "[[Good Vibrations]]". Wilson's magnum opus ''[[Smile (Beach Boys album)|SMiLE]]'' (which was never finished, and was [[Smile (Brian Wilson album)|remade by Wilson]] with a new band in 2004) also shows this growing experimentation. |

|||

===1965: Formative psychedelic scenes and sounds=== |

|||

The psychedelic influence was also felt in some mainstream R&B music, where record labels such as [[Motown]] dabbled for a while with [[psychedelic soul]], producing such hits as "[[Ball of Confusion (That's What the World Is Today)]]" and "[[Psychedelic Shack (song)|Psychedelic Shack]]" (by [[The Temptations]]), "[[Reflections (Supremes song)|Reflections]]" (by [[Diana Ross & the Supremes]]), and the 11-minute-long "Time Has Come Today" by [[The Chambers Brothers]]. [[Sly and the Family Stone]], a racially integrated group whose roots were in soul and R&B, created music influenced by psychedelic rock. This is especially evident on their breakthrough second album, [[Dance to the Music]]. |

|||

{{Main|Psychedelia}} |

|||

{{See also|Counterculture of the 1960s|Folk rock|Raga rock}} |

|||

[[File:Londons Carnaby Street, 1966.jpg|thumb|"Swinging London", [[Carnaby Street]], {{circa|1966}}]] |

|||

====Britain==== |

|||

[[Barry Miles]], a leading figure in the 1960s [[UK underground]], says that "[[Hippies]] didn't just pop up overnight" and that "1965 was the first year in which a discernible youth movement began to emerge [in the US]. Many of the key 'psychedelic' rock bands formed this year."{{sfn|Miles|2005|p=26}} On the US West Coast, underground chemist [[Augustus Owsley Stanley III]] and [[Ken Kesey]] (along with his followers known as the [[Merry Pranksters]]) helped thousands of people take uncontrolled trips at Kesey's [[Acid Tests]] and in the new psychedelic dance halls. In Britain, [[Michael Hollingshead]] opened the [[World Psychedelic Centre]] and [[Beat Generation]] poets [[Allen Ginsberg]], [[Lawrence Ferlinghetti]] and [[Gregory Corso]] read at the [[Royal Albert Hall]]. Miles adds: "The readings acted as a catalyst for underground activity in London, as people suddenly realized just how many like-minded people there were around. This was also the year that London began to blossom into colour with the opening of the [[Granny Takes a Trip]] and [[Hung On You]] clothes shops."{{sfn|Miles|2005|p=26}} Thanks to media coverage, use of LSD became widespread.{{sfn|Miles|2005|p=26}}{{refn|group=nb|The growth of underground culture in Britain was facilitated by the emergence of alternative weekly publications like ''IT'' (''[[International Times]]'') and ''[[Oz (magazine)|Oz]]'' which featured psychedelic and [[progressive music]] together with the counterculture lifestyle, which involved long hair, and the wearing of wild shirts from shops like Mr Fish, Granny Takes a Trip and old military uniforms from [[Carnaby Street]] ([[Soho]]) and [[King's Road]] ([[Chelsea, London|Chelsea]]) boutiques.<ref>P. Gorman, ''The Look: Adventures in Pop & Rock Fashion'' (Sanctuary, 2001), {{ISBN|1-86074-302-1}}.</ref>}} |

|||

The major difference between psychedelic rock in the Britain and its American counterpart is the role it played in a media revolution that changed the face of musical broadcasting, the music business and to a lesser degree, music publications nationwide. [[Image:jody cover.jpg|thumb|This 'gate fold' record sleeve features UV/stroboscopic photography.]] |

|||

Prior to the launch of [[BBC Radio 1]] on 30 September 1967, BBC radio consisted of a single station (''except for Radio Scotland'') and had just two pop shows, Saturday Club and Easy Beat.<ref>Pirate Radio. http://www.ministryofrock.co.uk/PirateRadio.html</ref> These shows were ultra conservative and almost (''if not completely'') ignored the 'Progressive' groups both from America ([[Jefferson Airplane]], [[Country Joe and the Fish]], [[Doors]], [[Byrds]] etc) and those in England like [[Hawkwind]], [[The Move]], [[The Yardbirds]], and [[The Animals]]. [[Radio Luxembourg]] (''which reached the South of England'') was a little more progressive but still largely ignored the 'new' music scene. |

|||

According to music critic [[Jim DeRogatis]], writing in his book on psychedelic rock, ''Turn on Your Mind'', the Beatles are seen as the "Acid Apostles of the New Age".{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|p=40}} Producer [[George Martin]], who was initially known as a specialist in [[comedy music|comedy]] and [[novelty record]]s,{{sfn|MacDonald|1998|p=183}} responded to the Beatles' requests by providing a range of studio tricks that ensured the group played a leading role in the development of psychedelic effects.{{sfn|Hoffmann|2016|p=269}} Anticipating their overtly psychedelic work,{{sfn|MacDonald|1998|p=128}} "[[Ticket to Ride (song)|Ticket to Ride]]" (April 1965) introduced a subtle, drug-inspired drone suggestive of India, played on rhythm guitar.{{sfn|Jackson|2015|pp=70–71}} Musicologist William Echard writes that the Beatles employed several techniques in the years up to 1965 that soon became elements of psychedelic music, an approach he describes as "cognate" and reflective of how they, like [[the Yardbirds]], were early pioneers in psychedelia.{{sfn|Echard|2017|p=90}} As important aspects the group brought to the genre, Echard cites the Beatles' rhythmic originality and unpredictability; "true" tonal ambiguity; leadership in incorporating elements from Indian music and studio techniques such as vari-speed, tape loops and reverse tape sounds; and their embrace of the avant-garde.{{sfn|Echard|2017|pp=90–91}} |

|||

The only real exposure that these groups could get was live performances in a handful of small clubs mostly in London with a few in other major cities. The advent of Pirate Radio and in particular a pirate disc jockey, [[John Peel]] changed all that. Suddenly these progressive bands were able to reach a mass audience and at their peak the pirates were boasting greater audiences than the BBC. Adding to the impact and impression of a cultural revolution was the emergence of alternative weekly publications like IT (''[[International Times]]'') and [[OZ magazine]] which featured psychedelic and progressive music together with the counter culture lifestyle. Soon psychedelic rock clubs like the [[UFO Club]] in [[Tottenham Court Road]], [[Middle Earth Club]] in [[Covent Garden]], the [[Roundhouse]] in Chalk Farm, the Country Club (Swiss Cottage) and the Art Lab (''also in Covent Garden'') were drawing capacity audience with psychedelic rock and ground-breaking [[liquid light shows]]. |

|||

[[File:Terry Melcher Byrds in studio 1965.jpg|thumb|left|Producer [[Terry Melcher]] in the studio with [[the Byrds]]' [[Gene Clark]] and [[David Crosby]], 1965]] |

|||

Psychedelic rock audiences were also a major break with tradition. Wearing long hair and wild shirts from shops like Mr Fish, [[Granny Takes a Trip]] and old military uniforms from [[Carnaby Street]] (''[[Soho]]'') and Kings Road (''Chelsea'') boutiques, they were in stark contrast to the slick, tailored ''[[Teddyboy]]s'' or the drab, conventional dress of most teenagers prior to that. <ref>The Look. Adventures in Pop & Rock Fashion. Paul Gorman. ISBN 1-86074-302-1</ref> |

|||

In Unterberger's opinion, [[the Byrds]], emerging from the Los Angeles folk rock scene, and the Yardbirds, from England's [[British blues|blues scene]], were more responsible than the Beatles for "sounding the psychedelic siren".{{sfn|Bogdanov|Woodstra|Erlewine|2002|p=1322}} Drug use and attempts at psychedelic music moved out of acoustic folk-based music towards rock soon after the Byrds, inspired by the Beatles' 1964 film ''[[A Hard Day's Night (film)|A Hard Day's Night]]'',{{sfn|Jackson|2015|p=168}}{{sfn|Prendergast|2003|pp=228–229}} adopted electric instruments to produce a chart-topping version of Dylan's "[[Mr. Tambourine Man]]" in the summer of 1965.{{sfn|Unterberger|2003|p=1}}{{refn|group=nb|In the song's lyric, the narrator requests: "Take me on a trip upon your magic swirling ship".{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|pp=8–9}} Whether this was intended as a drug reference was unclear, but the line would enter rock music when the song was a hit for the Byrds later in the year.{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|pp=8–9}}}} On the Yardbirds, Unterberger identifies lead guitarist [[Jeff Beck]] as having "laid the blueprint for psychedelic guitar", and says that their "ominous minor key melodies, hyperactive instrumental breaks (called [[Rave#History|rave-ups]]), unpredictable tempo changes, and use of Gregorian chants" helped to define the "manic eclecticism" typical of early psychedelic rock.{{sfn|Bogdanov|Woodstra|Erlewine|2002|p=1322}} The band's "[[Heart Full of Soul]]" (June 1965), which includes a distorted guitar riff that replicates the sound of a [[sitar]],{{sfn|Jackson|2015|pp=xix, 85}} peaked at number 2 in the UK and number 9 in the US.{{sfn|Russo|2016|p=212}} In Echard's description, the song "carried the energy of a new scene" as the guitar-hero phenomenon emerged in rock, and it heralded the arrival of new Eastern sounds.{{sfn|Echard|2017|p=5}} [[The Kinks]] provided the first example of sustained Indian-style drone in rock when they used open-tuned guitars{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|pp=154–155}} to mimic the [[Tanpura|tambura]] on "[[See My Friends]]" (July 1965), which became a top 10 hit in the UK.{{sfn|Bellman|1998|pp=294–295}}{{sfn|Jackson|2015|p=256}} |

|||

Psychedelic rock in Britain, in common with its American counterpart, had its roots in the [[progressive folk]] and [[folk rock]] genres. In much the same way that [[The Great Society]] and the original [[Jefferson Airplane]] were electrified folk bands, the same was true of early psychedelic bands in the Britain. In the folk scene itself blues, drugs, jazz and eastern influences had featured since 1964 in the work of [[Davy Graham]] and [[Bert Jansch]]. Folk singers [[Donovan]]'s transformation to 'electric' music gave him a 1966 hit with "[[Sunshine Superman (song)|Sunshine Superman]]," one of the very first overtly psychedelic pop records. In 1967 the [[Incredible String Band]]'s ''[[The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion]]'' developed this into full blown psychedelia.<ref>J. DeRogatis, ''Turn on Your Mind: Four Decades of Great Psychedelic Rock'' (Hal Leonard, 2003), p. 120.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Los Beatles (19266969775) Recortado.jpg|thumb|upright=0.85|alt=The English rock band Beatles arriving for concerts in Madrid in July 1965|[[The Beatles]] on tour, July 1965]] |

|||

The August 1966 album by The Beatles ''[[Revolver (album)|Revolver]]'' shows a psychedelic influence with songs like "[[Tomorrow Never Knows]]" and "[[Yellow Submarine (song)|Yellow Submarine]]" and marked the beginning of the demise of their harmless pop 'mop-tops' image. [[The Yardbirds]] released ''Roger the Engineer'' in the same year. [[Jeff Beck]]'s experimentation with [[fuzz]]-tone, [[feedback]] and distortion along with his trademark note-bending style set a high standard for future psychedelic experimenters; [[Jimmy Page]] developed the technique of scraping a violin or cello bow across the strings to produce surreal sounds during The Yardbirds' live performances of the time. Hearing "Still I'm Sad" made [[Daevid Allen]] decide to form his first rock band.<ref>{{cite book | last = Allen | first = Daevid | authorlink = Daevid Allen | year = 1994 | isbn = 1-8994-7500-1 | title = Gong Dreaming: soft machine 66-69 | publisher = GAS Books | pages = p.51 }}</ref> |

|||

The Beatles' "[[Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)|Norwegian Wood]]" from the December 1965 album ''[[Rubber Soul]]'' marked the first released recording on which a member of a Western rock group played the sitar.{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|p=173}}{{refn|group=nb|While Beck's influence had been Ravi Shankar records,{{sfn|Power|2014|loc=Ch.4: Fuzzbox Voodoo}} the Kinks' Ray Davies was inspired during a trip to Bombay, where he heard the early morning chanting of Indian fisherman.{{sfn|Jackson|2015|p=256}}{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|p=154}} The Byrds were also delving into the raga sound by late 1965, their "music of choice" being Coltrane and Shankar records.{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|p=154}} That summer they shared their enthusiasm for Shankar's music and its transcendental qualities with [[George Harrison]] and [[John Lennon]] during a group acid trip in Los Angeles.{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|p=153}} The sitar and its attending spiritual philosophies became a lifelong pursuit for Harrison, as he and Shankar would "elevate Indian music and culture to mainstream consciousness".{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|p=147}}}} The song sparked a craze for the sitar and other Indian instrumentation{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|p=171}} – a trend that fueled the growth of [[raga rock]] as the India exotic became part of the essence of psychedelic rock.{{sfn|Bellman|1998|p=292}}{{refn|group=nb|Previously, Indian instrumentation had been included in [[Ken Thorne]]'s orchestral score for the band's ''[[Help! (film)|Help!]]'' film soundtrack.{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|p=173}}}} Music historian George Case recognises ''Rubber Soul'' as the first of two Beatles albums that "marked the authentic beginning of the psychedelic era",{{sfn|Case|2010|p=27}} while music critic [[Robert Christgau]] similarly wrote that "Psychedelia starts here".{{sfn|Smith|2009|p=36}} San Francisco historian [[Charles Perry (food writer)|Charles Perry]] recalled the album being "the soundtrack of the [[Haight-Ashbury]], [[Berkeley, California|Berkeley]] and the whole circuit", as pre-hippie youths suspected that the songs were inspired by drugs.{{sfn|Perry|1984|p=38}} |

|||

[[File:The Fillmore.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.0|[[The Fillmore]], San Francisco (pictured in 2010)]] |

|||

[[Pink Floyd]] began developing ''[[light show]]s'' to go with their experimental rock music as early as 1965, and in 1966 the [[Soft Machine]] formed. From a [[blues rock]] background, the British supergroup [[Cream (band)|Cream]] debuted in December. [[The Jimi Hendrix Experience]] with [[Noel Redding]] and [[Mitch Mitchell]] brought [[Jimi Hendrix]] fame in Britain, and later in his American homeland. |

|||

Although psychedelia was introduced in Los Angeles through the Byrds, according to Shaw, San Francisco emerged as the movement's capital on the West Coast.{{sfn|Shaw|1969|pp=63, 150}} Several California-based folk acts followed the Byrds into folk rock, bringing their psychedelic influences with them, to produce the "[[San Francisco Sound]]".{{sfn|Bogdanov|Woodstra|Erlewine|2002|pp=1322–1323}}{{sfn|Case|2010|p=51}}{{refn|group=nb|Particularly prominent products of the scene were the [[Grateful Dead]] (who had effectively become the [[house band]] of the Acid Tests),{{sfn|Hicks|2000|p=60}} [[Country Joe and the Fish]], [[The Great Society (band)|the Great Society]], [[Big Brother and the Holding Company]], [[The Charlatans (U.S. band)|the Charlatans]], [[Moby Grape]], [[Quicksilver Messenger Service]] and [[Jefferson Airplane]].{{sfn|Bogdanov|Woodstra|Erlewine|2002|p=1323}}}} Music historian Simon Philo writes that although some commentators would state that the centre of influence had moved from London to California by 1967, it was British acts like the Beatles and [[the Rolling Stones]] that helped inspire and "nourish" the new American music in the mid-1960s, especially in the formative San Francisco scene.{{sfn|Philo|2015|p=113}} The music scene there developed in the city's Haight-Ashbury neighborhood in 1965 at basement shows organised by [[Chet Helms]] of the [[Family Dog Productions|Family Dog]];{{sfn|Gilliland|1969|loc=shows 41–42}} and as [[Jefferson Airplane]] founder [[Marty Balin]] and investors opened [[The Matrix (club)|The Matrix]] nightclub that summer and began booking his and other local bands such as the [[Grateful Dead]], [[the Steve Miller Band]] and [[Country Joe & the Fish]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.geocities.com/balinmiracles/hightimesart.html|title=The High Times Interview: Marty Balin|last=Yehling|first=Robert|date=22 February 2005|website=Balin Miracles|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050222091301/http://www.geocities.com/balinmiracles/hightimesart.html|archive-date=22 February 2005|access-date=8 August 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> Helms and [[San Francisco Mime Troupe]] manager [[Bill Graham (promoter)|Bill Graham]] in the fall of 1965 organised larger scale multi-media community events/benefits featuring the Airplane, [[Diggers (theater)|the Diggers]] and Allen Ginsberg. By early 1966 Graham had secured booking at [[The Fillmore]], and Helms at the [[Avalon Ballroom]], where in-house [[liquid light show|psychedelic-themed light shows]]{{sfn|Misiroglu|2015|p=10}} replicated the visual effects of the psychedelic experience.{{sfn|McEneaney|2009|p=45}} Graham became a major figure in the growth of psychedelic rock, attracting most of the major psychedelic rock bands of the day to The Fillmore.<ref name=Talevski />{{refn|group=nb|When this proved too small he took over [[Winterland]] and then the [[Fillmore West]] (in San Francisco) and the [[Fillmore East]] (in New York City), where major rock artists from both the US and the UK came to play.<ref name=Talevski>N. Talevski, ''Knocking on Heaven's Door: Rock Obituaries'' (Omnibus Press, 2006), {{ISBN|1-84609-091-1}}, p. 218.</ref>}} |

|||

According to author Kevin McEneaney, the Grateful Dead "invented" acid rock in front of a crowd of concertgoers in [[San Jose, California]] on 4 December 1965, the date of the second [[Acid Tests|Acid Test]] held by novelist [[Ken Kesey]] and the Merry Pranksters. Their stage performance involved the use of [[strobe light]]s to reproduce LSD's "surrealistic fragmenting" or "vivid isolating of caught moments".{{sfn|McEneaney|2009|p=45}} The Acid Test experiments subsequently launched the entire [[Psychedelia|psychedelic subculture]].{{sfn|McEneaney|2009|p=46}} |

|||

Pink Floyd's "Arnold Layne" in March 1967 only hinted at their live sound; the Beatles' ground-breaking album ''[[Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band]]'' was recorded on nearly all of the same dates as Pink Floyd's first album ''[[The Piper at the Gates of Dawn]]''. Cream showed their psychedelic sounds the same year in ''[[Disraeli Gears]]''. Other artists joining the psychedelic revolution included [[Eric Burdon]] (previously of [[The Animals]]), and [[The Small Faces]]. [[The Who]]'s ''[[The Who Sell Out|Sell Out]]'' had two early psychedelic tracks, "[[I Can See for Miles]]" and "Armenia City in the Sky", but the album concept was out of tune with the times, and it was their later album ''[[Tommy (rock opera)|Tommy]]'' that established them in the scene. |

|||

===1966: Growth and early popularity=== |

|||

[[The Rolling Stones]] had drug references and psychedelic hints in their 1966 singles "[[19th Nervous Breakdown]]" and "[[Paint It, Black]]", then the fully psychedelic ''[[Their Satanic Majesties Request]]'' ("In Another Land") suffered from the problems the group was having at the time, but has been considered a classic. In 1968, ''[[Jumpin' Jack Flash]]'' and ''[[Beggars Banquet]]'' re-established them, but their disastrous concert at [[Altamont Music Festival|Altamont]] in 1969 ended the dream on a downer. |

|||

{{See also|Psychedelic pop}} |

|||

{{quote box| |

|||

With their 1967 releases, [[The Beatles]] set the mark for this genre. "[[Strawberry Fields Forever]]" was the first song recorded intended for an album about nostalgia and childhood in 1966. Brian Epstein hastily released the first two songs recorded which would have ended up on the ''[[Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band]]'' album. It was released as a double-A sided single along with "[[Penny Lane]]" on February 13, 1967 in the UK and on February 17, 1967 in the U.S. "[[Strawberry Fields Forever]]" induced a "magic carpet" of sound, with its unusual chord progression, a kaleidoscope of instruments and effects, and an unusual edit of two completely separate versions (the latter of which had to be slowed down to fit.) topped off with a false ending. The album ''[[Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band]]'' (partially influenced by their studio neighbours Pink Floyd --then recording ''[[The Piper at the Gates of Dawn]]''-- and vice versa) was a veritable encyclopedia of psychedelia (among other elements), as well as an explosion of creativity that would set the standard for rock albums decades later. From the [[Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (song)|title track]] to "[[Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds]]" to "[[Within You Without You]]" to "[[A Day in the Life]]", the album showcased a wildly colourful palette, with unpredictable changes in rhythm, texture, melody, and tone colour that few groups could equal. The single "[[All You Need Is Love]]", debuted for a worldwide audience on the "Our World" television special, restated the message of "[[The Word (song)|The Word]]", but with a ''Sgt. Pepper'' style arrangement. Yet after the death of [[Brian Epstein]] and the unpopular television movie ''[[Magical Mystery Tour (film)|Magical Mystery Tour]]'' (with an uneven soundtrack album accompanying it) the band returned to a more raw style in 1968, albeit a more earthy and complex version than had been heard before ''[[Rubber Soul]]''. |

|||

quote=Psychedelia. I know it's hard, but make a note of that word because it's going to be scattered round the in-clubs like punches at an Irish wedding. It already rivals "mom" as a household word in New York and Los Angeles ... |

|||

|source=—''[[Melody Maker]]'', October 1966<ref>{{cite magazine|asin=B01AD99JMW|title=The History of Rock 1966|url=https://archive.org/details/TheHistoryOfRock1966/|date=2015|magazine=[[Uncut (magazine)|Uncut]]|page=105}}</ref> |

|||

|width=25em |

|||

|align=right |

|||

}} |

|||

Echard writes that in 1966, "the psychedelic implications" advanced by recent rock experiments "became fully explicit and much more widely distributed", and by the end of the year, "most of the key elements of psychedelic topicality had been at least broached."{{sfn|Echard|2017|p=29}} DeRogatis says the start of psychedelic (or acid) rock is "best listed at 1966".{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|p=9}} Music journalists [[Pete Prown]] and [[HP Newquist|Harvey P. Newquist]] locate the "peak years" of psychedelic rock between 1966 and 1969.<ref name = PrownNewquist48/> In 1966, media coverage of rock music changed considerably as the music became reevaluated as a new form of art in tandem with the growing psychedelic community.{{sfn|Butler|2014|p=184}} |

|||

Around the same time The Beatles were recording Sgt. Pepper, another British group, The [[Bee Gees]], were recording their first international album. Upon returning to England from Australia, they wrote and recorded their debut LP, ''[[Bee Gees' 1st]]'', which contained such psychedelic songs such as "Every Christian Lion Hearted Man Will Show You", "New York Mining Disaster 1941" and "Turn of the Century". The Bee Gees continued throughout the remainder of the 60s in the psychedelic/baroque rock style with albums such as ''Horizontal'', ''Idea'' and the classic double album ''Odessa''. After a 16 month break-up and reunion, The Bee Gees reinvented their sound in a more R&B/Soul style. Many rock critics consider the 1960s era Bee Gees as their classic period. |

|||

{{Listen |pos=left|type=music|filename=Byrds_-_Eight_Miles_High.ogg|title=The Byrds' "Eight Miles High" (1966)|description=Excerpt of intro with guitar figure and part of first verse}} |

|||

1968 produced further innovative UK releases, ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous. [[Tomorrow]] recorded one of the most eccentric offerings of the season. [[The Small Faces]] released one of rock's first concept albums, ''Ogden's Nut Gone Flake'' (at least on side two), with its tale of Happiness Stan's search for the missing half of the moon. "Itchycoo Park" was the first song to use ''flanging'' - the effect discovered by British recording engineer George Chkiantz in 1967. ''Odessey and Oracle'' by [[The Zombies]], which was recorded at Abbey Road immediately after ''Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band'' and ''The Piper at the Gates of Dawn'', was the first album to seriously feature the Mellotron, an innovation brought about because they couldn't afford to pay for session musicians. Meanwhile, [[The Moody Blues]] went off ''In Search of the Lost Chord''. As Psychedelia had become more mainstream, many of the phenomenon's originators were spending more and more time on extensive tours, and further influencing the development of new groups all over the globe. |

|||

In February and March,{{sfn|Savage|2015|pp=554, 556}} two singles were released that later achieved recognition as the first psychedelic hits: the Yardbirds' "[[Shapes of Things]]" and the Byrds' "[[Eight Miles High]]".{{sfn|Simonelli|2013|p=100}} The former reached number 3 in the UK and number 11 in the US,{{sfn|Russo|2016|pp=212–213}} and continued the Yardbirds' exploration of guitar effects, Eastern-sounding scales, and shifting rhythms.{{sfn|Bennett|2005|p=76}}{{refn|group=nb|Beatles' historian [[Ian MacDonald]] comments that [[Paul McCartney]]'s guitar solo on "[[Taxman]]" from ''[[Revolver (Beatles album)|Revolver]]'' "goes far beyond anything in the Indian style Harrison had done on guitar, the probable inspiration being Jeff Beck's ground-breaking solo on the Yardbirds' astonishing 'Shapes of Things{{'"}}.{{sfn|MacDonald|1998|p=178fn}}}} By overdubbing guitar parts, Beck layered multiple takes for his solo,<ref>{{cite AV media notes|title=[[Beckology]]|others=[[Jeff Beck]]|year=1991|last=Santoro|first=Gene|type=box set booklet|publisher=[[Epic Records]]/[[Legacy Recordings]]|id=48661|OCLC=144959074|p=17}}</ref> which included extensive use of fuzz tone and harmonic feedback.{{sfn|Echard|2017|p=36}} The song's lyrics, which Unterberger describes as "stream-of-consciousness",{{sfn|Unterberger|2002|p=1322}} have been interpreted as pro-environmental or anti-war.{{sfn|Power|2011|p=83}} The Yardbirds became the first British band to have the term "psychedelic" applied to one of its songs.{{sfn|Simonelli|2013|p=100}} On "Eight Miles High", [[Roger McGuinn]]'s [[Rickenbacker 360|12-string Rickenbacker guitar]]{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|p=155}} provided a psychedelic interpretation of [[free jazz]] and [[Raga|Indian raga]], channelling Coltrane and Shankar, respectively.{{sfn|Savage|2015|p=123}} The song's lyrics were widely taken to refer to drug use, although the Byrds denied it at the time.{{sfn|Bogdanov|Woodstra|Erlewine|2002|p=1322}}{{refn|group=nb|The result of this directness was limited airplay, and there was a similar reaction when Dylan released "[[Rainy Day Women ♯12 & 35]]" (April 1966), with its repeating chorus of "Everybody must get stoned!"{{sfn|Unterberger|2003|pp=3–4}}}} "Eight Miles High" peaked at number 14 in the US{{sfn|Lavezzoli|2006|p=156}} and reached the top 30 in the UK.{{sfn|Savage|2015|p=136}} |

|||

====Australia==== |

|||

[[Australia]] and [[New Zealand]] have long been overlooked in the history of popular music, especially in relation to psychedelic rock and pop, although it was a fertile region for recordings in this genre. One of the main reasons for the relative obscurity of Australian psychedelia was that few bands from the region had any significant commercial success outside their home countries; the most notable exception was [[The Easybeats]], who scored an international hit in late 1966 with their classic single "Friday On My Mind" (which was in fact recorded in the UK).{{Fact|date=January 2008}} |

|||

Another limiting factor was that some of the best Australasian psychedelic records were pressed in tiny quantities (sometimes as few as 250 copies) and very few ever gained significant overseas distribution (if any). As a result, releases from these countries were for many years known only to a small coterie of international music fans and, not surprisingly, their rarity means that they now command high prices on the collector's market. However, since the advent of the CD and the re-release of many of these important recordings, the original psychedelic rock of the 1960s from Australia and New Zealand has gradually gained wider recognition, culminating in the inclusion of a number of seminal tracks on the second volume of the famous ''[[Nuggets]]'' series, originated by US musician [[Lenny Kaye]]. |

|||

Contributing to psychedelia's emergence into the pop mainstream was the release of the Beach Boys' ''[[Pet Sounds]]'' (May 1966)<ref name="McPadden2016">{{cite web|last1=McPadden|first1=Mike|title=The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds and 50 Years of Acid-Pop Copycats|url=http://www.thekindland.com/the-beach-boys-pet-sounds-and-50-years-of-acid-1433|website=TheKindland|date=13 May 2016|access-date=18 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161109101317/http://www.thekindland.com/the-beach-boys-pet-sounds-and-50-years-of-acid-1433|archive-date=9 November 2016|url-status=dead}}</ref> and the Beatles' ''[[Revolver (Beatles album)|Revolver]]'' (August 1966).<ref name="AMPop"/> Often considered one of the earliest albums in the canon of psychedelic rock,<ref name="SixDegrees">{{cite web|last1=Maddux|first1=Rachael|title=Six Degrees of The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds|url=http://www.wonderingsound.com/connections/six-degrees-of-the-beach-boys-pet-sounds/|publisher=[[Wondering Sound]]|date=16 May 2011|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304124623/http://www.wonderingsound.com/connections/six-degrees-of-the-beach-boys-pet-sounds/|archive-date=4 March 2016}}</ref>{{refn|group=nb|Brian Boyd of ''[[The Irish Times]]'' credits the Byrds' ''[[Fifth Dimension (album)|Fifth Dimension]]'' (July 1966) with being the first psychedelic album.<ref name="Boyd2016">{{cite news|last1=Boyd|first1=Brian|title=The Beatles, Bob Dylan and The Beach Boys: 12 months that changed music|url=https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/music/the-beatles-bob-dylan-and-the-beach-boys-12-months-that-changed-music-1.2671482|newspaper=[[The Irish Times]]|date=4 June 2016|access-date=7 August 2020}}</ref> Unterberger views it as "the first album by major early folk-rockers to break ... into folk-rock-psychedelia".{{sfn|Unterberger|2003|p=4}}}} ''Pet Sounds'' contained many elements that would be incorporated into psychedelia, with its artful experiments, psychedelic lyrics based on emotional longings and self-doubts, elaborate sound effects and new sounds on both conventional and unconventional instruments.<ref name=AllmusicBritishPsychedelic>R. Unterberger, [https://www.allmusic.com/explore/essay/british-psychedelic-t684 "British Psychedelic"] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111229215110/http://www.allmusic.com/explore/essay/british-psychedelic-t684 |date=29 December 2011 }}, AllMusic. Retrieved 7 June 2011.</ref>{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|pp=35–40}} The album track "[[I Just Wasn't Made for These Times]]" contained the first use of theremin sounds on a rock record.{{sfn|Lambert|2007|p=240}} Scholar Philip Auslander says that even though psychedelic music is not normally associated with the Beach Boys, the "odd directions" and experiments in ''Pet Sounds'' "put it all on the map. ... basically that sort of opened the door – not for groups to be formed or to start to make music, but certainly to become as visible as say Jefferson Airplane or somebody like that."<ref name="Longman2016">{{cite web|last1=Longman|first1=Molly|title=Had LSD Never Been Discovered Over 75 Years Ago, Music History Would Be Entirely Different|url=https://mic.com/articles/143256/had-lsd-never-been-discovered-over-75-years-ago-music-history-would-be-entirely-different#.1lXG1R2k1|website=Music.mic|date=20 May 2016}}</ref> |

|||

Local musicians and producers were heavily influenced by innovations in British and American psychedelic music, although, for several reasons, British music had a somewhat stronger influence. One major factor was that the [[EMI]] company had long enjoyed the dominant market position in both countries. Another influence was that many Australasian bands like [[The Easybeats]] and [[The Twilights]] included members who were recent immigrants from the UK. Also, it was common for many groups to receive regular "care packages" from relatives and friends in Britain, containing singles, albums, the latest [[Carnaby Street]] fashions and even off-air tape recordings of British and European radio broadcasts. As a result, considering the distance and travel times involved, local Australian and New Zealand bands were kept remarkably up to date with the latest trends. [[The Bee Gees]] (then living in Australia) are known to have recorded cover versions of Beatles songs like "Rain" and "Paperback Writer" within days of the singles being released in the UK. |

|||

{{Listen |pos=right|type=music|filename=Rain - The Beatles.ogg|title=The Beatles' "Rain" (1966)|description=23-second segment of chorus}} |

|||

Several Australian groups traveled to the UK during this fertile period -- The Easybeats went to London in late 1966, and around the same time Australia's other leading pop band [[The Twilights]] won the inaugural Hoadleys National Battle of the Sounds competition, enabling them to also travel to the UK. As they were signed to [[EMI]], The Twilights were able to record at the legendary Abbey Road during the period of the making of ''Sgt Peppers''. On returning to Australia in early 1967, they wowed audiences in Melbourne by performing complete live renditions of the entire ''Sgt Peppers'' album, weeks before it was even released in the UK. |

|||

DeRogatis views ''Revolver'' as another of "the first psychedelic rock masterpieces", along with ''Pet Sounds''.{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|p=xi}} The Beatles' May 1966 B-side "[[Rain (Beatles song)|Rain]]", recorded during the ''Revolver'' sessions, was the first pop recording to contain reversed sounds.{{sfn|Reising|LeBlanc|2009|p=95}} Together with further studio tricks such as [[varispeed]], the song includes a droning melody that reflected the band's growing interest in non-Western musical form{{sfn|Philo|2015|p=111}} and lyrics conveying the division between an enlightened psychedelic outlook and conformism.{{sfn|Reising|LeBlanc|2009|p=95}}{{sfn|Savage|2015|p=317}} Philo cites "Rain" as "the birth of British psychedelic rock" and describes ''Revolver'' as "[the] most sustained deployment of Indian instruments, musical form and even religious philosophy" heard in popular music up to that time.{{sfn|Philo|2015|p=111}} Author [[Steve Turner (writer)|Steve Turner]] recognises the Beatles' success in conveying an LSD-inspired worldview on ''Revolver'', particularly with "[[Tomorrow Never Knows]]", as having "opened the doors to psychedelic rock (or acid rock)".{{sfn|Turner|2016|p=414}} In author [[Shawn Levy (writer)|Shawn Levy]]'s description, it was "the first true drug album, not [just] a pop record with some druggy insinuations",{{sfn|Levy|2002|p=241}} while musicologists Russell Reising and Jim LeBlanc credit the Beatles with "set[ting] the stage for an important subgenre of psychedelic music, that of the messianic pronouncement".{{sfn|Reising|LeBlanc|2009|p=100}}{{refn|group=nb|[[Sam Andrew]] of [[Big Brother and the Holding Company]] recalled that the album resonated with musicians in San Francisco,{{sfn|Reising|LeBlanc|2009|p=93}} in that the Beatles "had definitely come 'on board{{'"}} with regard to the counterculture.{{sfn|Reising|2002|p=7}} In the 1995 documentary series ''[[Rock & Roll (TV series)|Rock & Roll]]'', [[Phil Lesh]] of the Grateful Dead recalled thinking that with ''Revolver'' the Beatles had embraced the "psychedelic avant-garde".{{sfn|Reising|2002|p=3}}}} |

|||

Although the standard of recording studios in Australia and New Zealand lagged several years behind those in the UK and the USA, local producers and engineers like [[Pat Aulton]] kept in close touch with the latest overseas trends and worked hard to fashion equivalent sounds for local acts, despite many technical challenges (including the fact that Australia did not get its first commercial 8-track studio until 1969). Local producers and musicians created a significant body of psychedelic recordings, and notable albums and singles recorded by Australian/New Zealand acts in the late 1960s include: |

|||

Echard highlights early records by [[the 13th Floor Elevators]] and [[Love (band)|Love]] among the key psychedelic releases of 1966, along with "Shapes of Things", "Eight Miles High", "Rain" and ''Revolver''.{{sfn|Echard|2017|p=29}} Originating from Austin, Texas, the first of these new bands came to the genre via the [[Garage rock|garage]] scene{{sfn|Romanowski|George-Warren|1995|pp=312, 797}} before releasing their debut album, ''[[The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators]]'' in October that year.{{sfn|Savage|2015|p=518}} It was one of the first rock albums to include the adjective in its title,{{sfn|Hicks|2000|pp=60, 74}} although the LP was released on an independent label and was little noticed at the time.{{sfn|Savage|2015|p=519}} Two other bands also used the word in titles of LPs released in November 1966: The [[Blues Magoos]]' ''[[Psychedelic Lollipop]]'', and [[The Deep (band)|the Deep]]'s ''[[Psychedelic Moods]]''. Having formed in late 1965 with the aim of spreading LSD consciousness, the Elevators commissioned business cards containing an image of the [[third eye]] and the caption "Psychedelic rock".{{sfn|Savage|2015|p=110}}{{refn|group=nb|The term was used in an article about the band titled "Unique Elevators Shine with 'Psychedelic Rock{{'"}}, in the 10 February 1966 edition of the ''[[Austin American-Statesman]]''.<ref>{{cite news|first=Jim|last=Langdon|title=Unique Elevators Shine with 'Psychedelic Rock'|newspaper=[[Austin American-Statesman]]|date=10 February 1966|page=25|url=https://www.newspapers.com/clip/28248826/austin-american-statesman/|via=newspapers.com}}</ref>}} ''[[Rolling Stone]]'' highlights the 13th Floor Elevators as arguably "the most important early progenitors of psychedelic garage rock".{{sfn|Romanowski|George-Warren|1995|p=797}} |

|||

*"Friday On My Mind", "Land of Make Believe", "Heaven and Hell", "Pretty Girl", "Peculiar Hole In The Sky" ([[The Easybeats]]) |

|||

*"Early In The Morning" ([[The Purple Hearts]]) |

|||

*"The Loved One", "Everlovin' Man", ''Magic Box'' ([[The Loved Ones]]) |

|||

*"Living In A Child's Dream", "Elevator Driver" ([[The Masters Apprentices]]) |

|||

*"What's Wrong With The Way I Live", "Cathy Come Home", "9:50", "Comin' On Down", ''Once upon A Twilight'' LP ([[The Twilights]]) |

|||

*"Tripping Down Memory Lane" ([[The Pineapple Express]]) |

|||

*"The Happy Prince" ([[The La De Das]]) |

|||

*"The Real Thing", "Part Three: Into Paper Walls" ([[Russell Morris]]) |

|||

*"Lady Sunshine", ''Evolution'' LP ([[Tamam Shud]]) |

|||

[[Donovan]]'s July 1966 single "[[Sunshine Superman (song)|Sunshine Superman]]" became one of the first psychedelic pop/rock singles to top the Billboard charts in the US. Influenced by [[Aldous Huxley]]’s ''[[The Doors of Perception]]'', and with lyrics referencing LSD, it contributed to bringing psychedelia to the mainstream.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Mountney|first1=Dan|url=https://www.whtimes.co.uk/news/22359617.sunshine-superman-celebrating-55-years-since-donovans-genre-defining-us-number-one-hit/ |website=Welwyn Hatfield Times|title=Sunshine Superman: Celebrating 55 years since Donovan's genre-defining US number one hit|date=July 2021 | access-date=Jan 15, 2023}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|last1=Morenz|first1=Emily|url=https://groovyhistory.com/donovan-sunshine-superman-psychedelic-hit/5|title=Donovan's 'Sunshine Superman,' The First Psychedelic #1 Hit: Facts And Stories |website=Groovy History|access-date=Jan 15, 2023}}</ref> |

|||

====Other countries==== |

|||

The invention of psychedelic music in the US quickly spread and was followed all over the world. The first continental Europe band was [[Group 1850]], of [[The Netherlands]], formed in 1964, first album in 1968. The Brazilian psychedelic rock group [[Os Mutantes]] formed in 1966, and although little known outside Brazil at the time, their recordings have since accrued a substantial international cult following. |

|||

The Beach Boys' October 1966 single "[[Good Vibrations]]" was another early pop song to incorporate psychedelic lyrics and sounds.{{sfn|DeRogatis|2003|pp=33–39}} The single's success prompted an unexpected revival in theremins and increased the awareness of [[analog synthesizer]]s.{{sfn|Pinch|Trocco|2009|pp=86–87}} As psychedelia gained prominence, Beach Boys-style harmonies would be ingrained into the newer psychedelic pop.<ref name="AMPop">{{cite web|author=Anon|title=Psychedelic Pop|url=https://www.allmusic.com/style/psychedelic-pop-ma0000011915|website=[[AllMusic]]}}</ref> |

|||

===1967–69: Continued development=== |

|||

In the late 1960s, a wave of Mexican rock heavily influenced by psychedelic and funk rock emerged in several northern border Mexican states, in particular in Tijuana, Baja California. Among the most recognized bands from this "Chicano Wave" (Onda Chicana in Spanish), there is one in particular that was recognized by their originality. The band [[Love Army]] derived from the Tijuana Five and was formed by Alberto Isiordia (aka El Pajaro), Salvador Martinez, Jaime Valle, Fernando Vahaux, Ernesto Hernandez, Mario Rojas and Enrique Sida. |

|||

====Peak era==== |

|||

[[File:1967 Mantra-Rock Dance Avalon poster.jpg|thumb|left|upright=0.8|alt= The Mantra-Rock poster showing an Indian swami sitting cross-legged in the top half with circular patterns around and with information about the concert in the bottom half|Poster for the [[Mantra-Rock Dance]] event held at San Francisco's [[Avalon Ballroom]] in January 1967. The headline acts included [[the Grateful Dead]], [[Big Brother and the Holding Company]] and [[Moby Grape]].]] |

|||

In 1967, psychedelic rock received widespread media attention and a larger audience beyond local psychedelic communities.{{sfn|Butler|2014|p=184}} From 1967 to 1968, it was the prevailing sound of rock music, either in the more whimsical British variant, or the harder American West Coast acid rock.{{sfn|Brend|2005|p=88}} Music historian David Simonelli says the genre's commercial peak lasted "a brief year", with San Francisco and London recognised as the two key cultural centres.{{sfn|Simonelli|2013|p=100}} Compared with the American form, British psychedelic music was often more arty in its experimentation, and it tended to stick within pop song structures.<ref name=britpsych>{{AllMusic|class=style|id=british-psychedelia-ma0000012038|label=British Psychedelia}}</ref> Music journalist Mark Prendergast writes that it was only in US garage-band psychedelia that the often whimsical traits of UK psychedelic music were found.{{sfn|Prendergast|2003|p=227}} He says that aside from the work of the Byrds, Love and [[the Doors]], there were three categories of US psychedelia: the "acid jams" of the San Francisco bands, who favoured albums over singles; pop psychedelia typified by groups such as the Beach Boys and [[Buffalo Springfield]]; and the "wigged-out" music of bands following in the example of the Beatles and the Yardbirds, such as [[the Electric Prunes]], [[the Nazz]], [[the Chocolate Watchband]] and [[the Seeds]].{{sfn|Prendergast|2003|p=225}}{{refn|group=nb|Writing in 1969, Shaw said New York's [[Tompkins Square Park]] was the East Coast "center of hippiedom".{{sfn|Shaw|1969|p=150}} He cited [[the Blues Magoos]] as the main psychedelic act and as "a group that outdoes the west coasters ... in decibels".{{sfn|Shaw|1969|p=177}}}} |

|||

The Doors' [[The Doors (album)|self-titled debut]] album (January 1967) is notable for possessing a darker sound and subject matter than many contemporary psychedelic albums,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-album-reviews/the-doors-114926/ |title=The Doors |first=Parke|last=Puterbaugh|magazine=[[Rolling Stone]]|date=April 8, 2003}}</ref> which would become very influential to the later [[Gothic rock]] movement.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.readersdigest.co.uk/culture/a-dark-history-of-goth-a-genre-obsessed-with-love-and-death |title=A dark history of Goth, a genre obsessed with love and death |first=John|last=Robb|magazine=[[Reader's Digest]]|date=October 26, 2023}}</ref> Aided by the No. 1 single, "[[Light My Fire]]", the album became very successful, reaching number 2 on the ''Billboard'' chart.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.billboard.com/pro/the-doors-a-billboard-chart-history/ |title=The Doors: A Billboard Chart History |first=Keith|last=Caulfied|magazine=[[Billboard (magazine)|Billboard]]|date=May 21, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

From 1967 to 1973, between the ending of the government of President Frei Montalva and the government of President Allende, a cultural movement was born from a few Chilean bands that emerged playing a unique fusion of folkloric music with heavy psychedelic influences. The 1967 release of Los Mac's album ''"Kaleidoscope men"'' inspired many bands such as [[Los Jaivas]] and Los Blops, the latter going on to collaborate with the iconic Chilean singer-songwriter [[Victor Jara]] on his 1971 album ''"El derecho de vivir en paz."'' |

|||

In February 1967, the Beatles released the double A-side single "[[Strawberry Fields Forever]]" / "[[Penny Lane]]", which [[Ian MacDonald]] says launched both the "English pop-pastoral mood" typified by bands such as [[Pink Floyd]], [[Family (band)|Family]], [[Traffic (band)|Traffic]] and [[Fairport Convention]], and English psychedelia's LSD-inspired preoccupation with "nostalgia for the innocent vision of a child".{{sfn|MacDonald|1998|p=191}} The [[Mellotron]] parts on "Strawberry Fields Forever" remain the most celebrated example of the instrument on a pop or rock recording.{{sfn|Brend|2005|p=57}}{{sfn|Prendergast|2003|p=83}} According to Simonelli, the two songs heralded the Beatles' brand of [[Romanticism]] as a central tenet of psychedelic rock.{{sfn|Simonelli|2013|p=106}} |

|||

Meanwhile in the Argentinian capital Buenos Aires, a burgeoning psychedelic scene gave birth to three of the most important bands in Argentine Rock: [[Los Gatos]], [[Manal]] and perhaps most importantly [[Almendra]]. Almendra was fronted by [[Luis Alberto Spinetta]] who penned most of the band's songs on their two albums released in 1969 and 1970, drawing on a number of influences including Blues, Jazz and Folk. Spinetta's first solo release in 1971 ''"Spinettalandia y Sus Amigos - La Búsqueda de la Estrella"'' is also notable for its strong psychedelic influences. Spinetta has since gone on to enjoy a long and successful career in Argentina. |

|||

[[File:White rabbit.JPG|thumb|Poster for [[Jefferson Airplane]]'s song "[[White Rabbit (song)|White Rabbit]]", which describes the surreal world of ''[[Alice in Wonderland]]'']] |

|||

A thriving psychedelic music scene in [[Cambodia]] was pioneered by [[Sinn Sisamouth]] and [[Ros Sereysothea]]. In 1972, from Canada, Frank Marino's [[Mahogany Rush]], named for Marino's experience while doing LSD<ref>[http://www.mahoganyrush.com/history.htm Frank Marino & Mahogany Rush -Band History<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref>, offered the album "Maxoom" in the psychedelic genre. The title song Maxoom is another early psychedelic song. The band followed this release with Child of the Novelty in 1974. The cover art is an artists representation of Marino's description of an acid trip. |

|||

Jefferson Airplane's ''[[Surrealistic Pillow]]'' (February 1967) was one of the first albums to come out of San Francisco that sold well enough to bring national attention to the city's music scene. The LP tracks "[[White Rabbit (song)|White Rabbit]]" and "[[Somebody to Love (Jefferson Airplane song)|Somebody to Love]]" subsequently became top 10 hits in the US.{{sfn|Philo|2015|pp=115–116}} |

|||

A typical psychedelic rock band emerged in [[Pakistan]] in 1985 by the name of [[Junoon]]. Junoon characteristically used [[tabla]] and other folk instruments in their albums. Because of the psychedelic nature and heavy [[sufi]] lyrics, the band was labeled as a sufi rock band in their tours through out the world. |

|||

[[The Hollies]] psychedelic B-side "All the World Is Love" (February 1967) was released as the flipside to the hit single "[[On a Carousel]]".<ref>{{cite book|last1=Doggett|first1=Peter|title=Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young: The Biography |

|||

===Late 1960s=== |

|||

|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sYZzDwAAQBAJ|publisher=Vintage|year=2019|isbn=978-1-4735-5225-8 }}</ref> |

|||

Many of the bands that pioneered psychedelic rock had moved on to explore other styles of music by the end of the 1960s. The increasingly hostile political environment and the embrace of [[amphetamine]]s, [[heroin]] and [[cocaine]] by the underground led to a turn toward harsher music. At the same time, [[Bob Dylan]] released ''John Wesley Harding'' and [[the Band]] released ''Music from Big Pink'', both albums that followed a [[roots rock|roots]]-oriented approach. Many bands in England and America followed suit. [[Eric Clapton]] cites ''[[Music from Big Pink]]'' as a contributory factor in quitting [[Cream (band)|Cream]], for example.<ref>{{cite book | last = Frame | first = Pete | authorlink = Pete Frame | title = Rock Family Trees | publisher = Omnibus Press | date = 1980 | pages = Vol.1 p.5 | isbn = 0-86001-414-2 | nopp = true}}</ref> The [[Grateful Dead]] also went back to basics and had major successes with ''[[Workingman's Dead]]'' and ''[[American Beauty (album)|American Beauty]]'' in 1970, then continued to develop their live music and produce a long string of records over the next twenty-five years. |

|||