Calcite: Difference between revisions

m →Chemical: brackets in ref fix |

|||

| (843 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Calcium carbonate mineral}} |

|||

== Calcite == |

|||

{{For|the database framework|Apache Calcite}} |

|||

{{Infobox mineral |

{{Infobox mineral |

||

| name = |

| name = Calcite |

||

| category = [[Carbonate mineral]] |

| category = [[Carbonate mineral]] |

||

| boxwidth = |

| boxwidth = |

||

| boxbgcolor = |

| boxbgcolor = #d4d1cd |

||

| image = Calcite |

| image = Calcite Variation.png |

||

| imagesize = |

| imagesize = |

||

| caption = |

| caption = Clockwise from top left: scalenohedral, rhomboedral, stalactitic, and botryoidal calcite |

||

| formula = CaCO<sub>3</sub> |

| formula = CaCO<sub>3</sub> |

||

| molweight = |

| molweight = |

||

| strunz = 5.AB.05 |

|||

| color = Colorless or white, also gray, yellow, green, |

|||

| system = [[Trigonal]] |

|||

| habit = Crystalline, granular, stalactitic, concretionary, massive. |

|||

| class = Hexagonal scalenohedral ({{overline|3}}m) <br/>[[H-M symbol]]: ({{overline|3}} 2/m) |

|||

| system = [[Trigonal]] Hexagonal Scalenohedral |

|||

| symmetry = ''R''{{overline|3}}c |

|||

| unit cell = ''a'' = 4.9896(2) [[Ångstrom|Å]], <br/>''c'' = 17.0610(11) Å; ''Z'' = 6 |

|||

| color = Typically colorless or creamy white - may have shades of brownish colors |

|||

| habit = Botryoidal, concretionary, druse, globular, granular, massive, rhombohedral, scalenohedral, stalactitic |

|||

| twinning = Common by four twin laws |

| twinning = Common by four twin laws |

||

| cleavage = Perfect on {10{{overline|1}}1} three directions with angle of 74° 55'<ref>{{cite book |last1=Klein |first1=Cornelis |last2=Hurlbut | first2=Cornelius S. Jr. |title=Manual of mineralogy: (after James D. Dana) |date=1993 |publisher=Wiley |location=New York |isbn=047157452X |edition=21st |page=405}}</ref> |

|||

| cleavage = Perfect on [1011], [1011] and [1011] |

|||

| fracture = |

| fracture = Conchoidal |

||

| |

| tenacity = Brittle |

||

| |

| mohs = 3 (defining mineral) |

||

| |

| luster = Vitreous to pearly on cleavage surfaces |

||

| refractive = ''n''<sub>ω</sub> = 1.640–1.660{{br}} ''n''<sub>ε</sub> = 1.486 |

|||

| opticalprop = Uniaxial (-) |

|||

| opticalprop = Uniaxial (−); low [[Optical relief|relief]] |

|||

| birefringence = δ = 0.154 - 0.174 |

|||

| birefringence = ''δ'' = 0.154–0.174 |

|||

| pleochroism = |

|||

| pleochroism = |

|||

| streak = White |

| streak = White |

||

| gravity = 2.71 |

| gravity = 2.71 |

||

| density = |

| density = |

||

| melt = |

| melt = |

||

| fusibility = |

| fusibility = Infusible (decrepitates energetically)<ref name=Sinkankas1964/> |

||

| diagnostic = |

| diagnostic = |

||

| solubility = Soluble in dilute acids |

| solubility = Soluble in dilute acids |

||

| diaphaneity = Transparent to translucent |

| diaphaneity = Transparent to translucent |

||

| other = May fluoresce red, blue, yellow, and other colors under either SW and LW UV; phosphorescent |

| other = May fluoresce red, blue, yellow, and other colors under either SW and LW UV; phosphorescent |

||

| references = <ref>http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/doclib/hom/calcite.pdf |

| references = <ref name=HOM>{{cite book|editor1=Anthony, John W. |editor2=Bideaux, Richard A. |editor3=Bladh, Kenneth W. |editor4=Nichols, Monte C. |title= Handbook of Mineralogy|publisher= Mineralogical Society of America|place= Chantilly, VA, US|chapter-url=http://rruff.geo.arizona.edu/doclib/hom/calcite.pdf |chapter=Calcite |isbn=978-0962209741 |series=Vol. V (Borates, Carbonates, Sulfates) |year=2003}}</ref><ref name=mindat/><ref>{{cite web |last1=Barthelmy |first1=Dave |title=Calcite Mineral Data |url=http://webmineral.com/data/Calcite.shtml |website=webmineral.com |access-date=6 May 2018}}</ref> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

[[Image:Calcite-unit-cell-3D-vdW.png|thumb|The [[Crystal structure#Unit cell|unit cell]] of '''calcite''']] |

|||

'''Calcite''' is a [[Carbonate minerals|carbonate mineral]] and the most stable [[Polymorphism (materials science)|polymorph]] of [[calcium carbonate]] ([[calcium|Ca]][[carbon|C]][[oxygen|O]]<sub>3</sub>). The other polymorphs are the minerals [[aragonite]] and [[vaterite]]. Aragonite will change to calcite at 470°C, and vaterite is even less stable. |

|||

'''Calcite''' is a [[Carbonate minerals|carbonate mineral]] and the most stable [[Polymorphism (materials science)|polymorph]] of [[calcium carbonate]] (CaCO<sub>3</sub>). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of [[limestone]]. Calcite defines hardness 3 on the [[Mohs scale of mineral hardness]], based on [[Scratch hardness|scratch]] [[hardness comparison]]. Large calcite crystals are used in optical equipment, and limestone composed mostly of calcite has numerous uses. |

|||

==Properties== |

|||

[[Image:A fossil shell with calcite.jpg|thumb|left|[[Fossil]] [[bivalve]] with calcite [[crystal]]s.]] |

|||

Calcite [[crystal]]s are [[Rhombohedral crystal system|trigonal]]-rhombohedral, though actual calcite rhombohedra are rare as natural crystals. However, they show a remarkable variety of habits including acute to obtuse rhombohedra, tabular forms, prisms, or various scalenohedra. Calcite exhibits several [[crystal twinning|twinning]] types adding to the variety of observed forms. It may occur as fibrous, granular, lamellar, or compact. Cleavage is usually in three directions parallel to the rhombohedron form. Its fracture is conchoidal, but difficult to obtain. |

|||

Other polymorphs of calcium carbonate are the minerals [[aragonite]] and [[vaterite]]. Aragonite will change to calcite over timescales of days or less at temperatures exceeding 300 °C,<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Yoshioka S. |author2=Kitano Y. |title=Transformation of aragonite to calcite through heating |url=https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/geochemj1966/19/4/19_4_245/_pdf |journal=Geochemical Journal |volume=19 |issue=4 |pages=24–249 |year= 1985|doi=10.2343/geochemj.19.245 |bibcode=1985GeocJ..19..245Y |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author1=Staudigel P. T. |author2=Swart P. K. |title=Isotopic behavior during the aragonite-calcite transition: Implications for sample preparation and proxy interpretation |journal=Chemical Geology |volume=442 |pages=130–138 |year= 2016|doi=10.1016/j.chemgeo.2016.09.013 |bibcode=2016ChGeo.442..130S }}</ref> and vaterite is even less stable. |

|||

It has a [[Mohs hardness]] of 3, a [[specific gravity]] of 2.71, and its luster is vitreous in crystallized varieties. Color is white or none, though shades of gray, red, yellow, green, blue, violet, brown, or even black can occur when the mineral is charged with impurities. |

|||

== Etymology == |

|||

Calcite is transparent to opaque and may occasionally show [[phosphorescence]] or [[fluorescence]]. A transparent variety called ''[[Iceland spar]]'' is used for optical purposes. Acute scalenohedral crystals are sometimes referred to as "dogtooth spar". |

|||

Calcite is derived from the German {{lang|de|Calcit}}, a term from the 19th century that came from the Latin word for [[Lime (material)|lime]], {{lang|la|calx}} (genitive {{lang|la|calcis}}) with the suffix ''-ite'' used to name minerals. It is thus a [[Doublet (linguistics)|doublet]] of the word ''[[wikt:chalk|chalk]]''.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|title=calcite (n.) |encyclopedia=Online Etymology Dictionary|url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/calcite|access-date=6 May 2018|language=en}}</ref> |

|||

When applied by [[archaeology|archaeologists]] and stone trade professionals, the term [[alabaster]] is used not just as in geology and mineralogy, where it is reserved for a variety of [[gypsum]]; but also for a similar-looking, [[Transparency and translucency|translucent]] variety of fine-grained banded deposit of calcite.<ref>[http://www.oum.ox.ac.uk/corsi/files/pdf/Alabaster-travertine.pdf ''More about alabaster and travertine''], brief guide explaining the different use of the same terms by geologists, archaeologists, and the stone trade. Oxford University Museum of Natural History, 2012.</ref> |

|||

Single calcite crystals display an optical property called [[birefringence]] (double refraction). This strong birefringence causes objects viewed through a clear piece of calcite to appear doubled. The birefringent effect (using calcite) was first described by the [[Denmark|Danish]] scientist [[Rasmus Bartholin]] in 1669. At a wavelength of ~590 nm calcite has ordinary and extraordinary [[refractive index|refractive indices]] of 1.658 and 1.486, respectively.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://hypertextbook.com/physics/waves/refraction/|title=Refraction|last=Elert|first=Glenn|work=The Physics Hypertextbook}}</ref> Between 190 and 1700 nm, the ordinary refractive index varies roughly between 1.6 and 1.4, while the extraordinary refractive index varies between 1.9 and 1.5.<ref>{{cite journal |author = Thompson, D.W. et al.|year=1998 |title=Determination of optical anisotropy in calcite from ultraviolet to mid-infrared by generalized ellipsometry|journal= Thin Solid Films|volume=313-314 |issue= |pages=341–346|doi=10.1016/S0040-6090(97)00843-2 }}</ref> |

|||

== Unit cell and Miller indices == |

|||

Calcite, like most carbonates, will dissolve with most forms of acid. Calcite can be either [[solvation|dissolved]] by groundwater or [[precipitate|precipitated]] by groundwater, depending on several factors including the water temperature, [[acidity|pH]], and dissolved [[ion]] concentrations. Although calcite is fairly insoluble in cold water, acidity can cause dissolution of calcite and release of carbon dioxide gas. Calcite exhibits an unusual characteristic called retrograde solubility in which it becomes less soluble in water as the temperature increases. When conditions are right for precipitation, calcite forms mineral coatings that cement the existing rock grains together or it can fill fractures. When conditions are right for dissolution, the removal of calcite can dramatically increase the [[porosity]] and [[Permeability (fluid)|permeability]] of the rock, and if it continues for a long period of time may result in the formation of [[caverns]], most notably the [[Snowy River Cave]] in [[Lincoln County, New Mexico]]. |

|||

[[Image:Calcite.png|thumb|left|upright|Crystal structure of calcite]] |

|||

In publications, two different sets of [[Miller indices]] are used to describe directions in hexagonal and rhombohedral crystals, including calcite crystals: three Miller indices {{math|''h, k, l''}} in the <math>a_1, a_2, c</math> directions, or four [[Miller index#Case of hexagonal and rhombohedral structures|Bravais–Miller indices]] {{math|''h, k, i, l''}} in the <math>a_1,a_2,a_3,c</math> directions, where <math>i</math> is redundant but useful in visualizing [[Permutation group|permutation symmetries]]. |

|||

To add to the complications, there are also two definitions of [[unit cell]] for calcite. One, an older "morphological" unit cell, was inferred by measuring angles between faces of crystals, typically with a [[goniometer]], and looking for the smallest numbers that fit. Later, a "structural" unit cell was determined using [[X-ray crystallography]]. The morphological unit cell is [[Rhombohedron|rhombohedral]], having approximate dimensions {{math|''a'' {{=}} 10 [[Ångstrom|Å]]}} and {{math|''c'' {{=}} 8.5 [[Ångstrom|Å]]}}, while the structural unit cell is [[Hexagonal crystal family|hexagonal]] (i.e. a [[Rhombus|rhombic]] [[Prism (geometry)|prism]]), having approximate dimensions {{math|''a'' {{=}} 5 [[Ångstrom|Å]]}} and {{math|''c'' {{=}} 17 [[Ångstrom|Å]]}}. For the same orientation, {{math|''c''}} must be multiplied by 4 to convert from morphological to structural units. As an example, calcite [[Cleavage (crystal)|cleavage]] is given as "perfect on {1 0 {{overline|1}} 1}" in morphological coordinates and "perfect on {1 0 {{overline|1}} 4}" in structural units. In <math>\{hkl\}</math> indices, these are {1 0 1} and {1 0 4}, respectively. [[Crystal twinning|Twinning]], cleavage and [[Crystal habit|crystal forms]] are often given in morphological units.<ref name="mindat">{{cite web|title=Calcite|url=http://www.mindat.org/min-859.html|website=mindat.org|access-date=1 Nov 2021}}</ref><ref name="Hazen">{{cite book|last1=Hazen|first1=Robert M.|author-link=Robert Hazen|chapter=Chiral crystal faces of common rock-forming minerals|editor-last1=Palyi|editor-first1=C.|editor-last2=Zucchi|editor-first2=C.|editor-last3=Caglioti|editor-first3=L.|title=Progress in Biological Chirality|url=https://archive.org/details/progressbiologic00plyi|url-access=limited|date=2004|publisher=Elsevier|location=Oxford|pages=[https://archive.org/details/progressbiologic00plyi/page/n413 137]–151|isbn=9780080443966}}</ref> |

|||

==Natural occurrence== |

|||

Calcite is often the primary constituent of the [[Seashell|shell]]s of [[Marine biology|marine organism]]s, e.g., [[plankton]] (such as [[coccolith]]s and planktic [[foraminifera]]), the hard parts of red [[algae]], some [[sea sponge|sponge]]s, [[brachiopod]]a, [[echinoderm]]s, most [[bryozoa]], and parts of the shells of some [[Bivalvia|bivalves]], such as [[oyster]]s and [[rudists]]). |

|||

== Properties == |

|||

Calcite is a common constituent of [[sedimentary rock]]s, [[limestone]] in particular, much of which is formed from the shells of dead marine organisms. Approximately 10% of sedimentary rock is limestone. |

|||

The diagnostic properties of calcite include a defining [[Mohs hardness]] of 3, a [[specific gravity]] of 2.71 and, in crystalline varieties, a vitreous [[Lustre (mineralogy)|luster]]. Color is white or none, though shades of gray, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, brown, or even black can occur when the mineral is charged with impurities.<ref name="mindat"/> |

|||

=== Crystal habits === |

|||

Calcite is the primary mineral in [[Metamorphic rock|metamorphic]] [[marble]]. It also occurs as a [[Vein (geology)|vein]] mineral in deposits from [[hot spring]]s, and it occurs in [[cavern]]s as [[stalactite]]s and [[stalactite|stalagmite]]s. |

|||

Calcite has numerous habits, representing combinations of over 1000 [[crystallographic form]]s.<ref name=HOM/> Most common are [[scalenohedron|scalenohedra]], with faces in the hexagonal {{mset|2 1 1}} directions (morphological unit cell) or {2 1 4} directions (structural unit cell); and rhombohedral, with faces in the {{mset|1 0 1}} or {{mset|1 0 4}} directions (the most common cleavage plane).<ref name=Hazen/> Habits include acute to obtuse rhombohedra, tabular habits, [[Prism (geometry)|prisms]], or various [[scalenohedron|scalenohedra]]. Calcite exhibits several [[crystal twinning|twinning]] types that add to the observed habits. It may occur as fibrous, granular, lamellar, or compact. A fibrous, efflorescent habit is known as ''lublinite''.<ref>{{cite web|title=Lublinite|url=http://www.mindat.org/min-9512.html|website=mindat.org|access-date=6 May 2018}}</ref> Cleavage is usually in three directions parallel to the rhombohedron form. Its fracture is [[Conchoidal fracture|conchoidal]], but difficult to obtain. |

|||

Scalenohedral faces are [[chiral]] and come in pairs with mirror-image symmetry; their growth can be influenced by interaction with chiral biomolecules such as L- and D-[[amino acid]]s. Rhombohedral faces are not chiral.<ref name=Hazen/><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Jiang |first1=Wenge |last2=Pacella |first2=Michael S. |last3=Athanasiadou |first3=Dimitra |last4=Nelea |first4=Valentin |last5=Vali |first5=Hojatollah |last6=Hazen |first6=Robert M. |last7=Gray |first7=Jeffrey J. |last8=McKee |first8=Marc D. |date=2017-04-13 |title=Chiral acidic amino acids induce chiral hierarchical structure in calcium carbonate |journal=Nature Communications |language=en |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=15066 |doi=10.1038/ncomms15066 |pmid=28406143 |pmc=5399303 |bibcode=2017NatCo...815066J |issn=2041-1723}}</ref> |

|||

Calcite may also be found in [[volcano|volcanic]] or [[mantle (geology)|mantle-derived]] rocks such as [[carbonatite]]s, [[kimberlite]]s, or rarely in [[peridotite]]s. |

|||

<gallery class="center"> |

|||

Calcite is found in spectacular form in the [[Snowy River Cave]] of [[New Mexico]] as mentioned above, where microorganisms are credited with natural formations. |

|||

File:Estonian Museum of Natural History Specimen No 182279 photo (g28 g28-218 1 jpg).jpg|Rhombohedral calcite |

|||

File:Calcite jaune sur fluorine violette (USA).jpg|Scalenohedral calcite |

|||

File:Calcite, galène et pyrite (Dal'negorsk - Fédération de Russie).JPG|Prismatic calcite |

|||

File:Calcite et fluorine (USA).JPG|Prismatic calcite |

|||

File:Calcite 7.jpg|Stalactitic calcite |

|||

File:Estonian Museum of Natural History Specimen No 202078 photo (g27 g27-415 1 jpg).jpg|Hexagonal calcite |

|||

File:Calcite-241250.jpg|Dodecahedral calcite |

|||

File:Calcite - Galleria di Mezzolombardo (Trento) - Paolo Ferretti.jpg|Bipyramidal calcite |

|||

File:Muséum de Nantes - 352 - Calcite (Grenoble, Isère, France).jpg|Druse calcite |

|||

File:Natural History Museum 155 (8047048490).jpg|Twinned calcite |

|||

File:Calcite - Sassari, Sardegna, Italia 01.jpg|Globular calcite |

|||

File:Calcite (Cave-in-Rock Mining District, Illinois, USA) 3 (42590140555).jpg|Botryoidal calcite |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Optical === |

|||

[[Trilobites]], which are now extinct, had unique compound eyes. They used clear calcite crystals to form the lenses of their eyes. |

|||

[[File:Calcite-refraction-property.jpg|thumb|Photograph of calcite displaying the characteristic birefringence optical behaviour]] |

|||

Calcite is [[transparency and translucency|transparent]] to [[opacity (optics)|opaque]] and may occasionally show [[phosphorescence]] or [[fluorescence]]. A transparent variety called "[[Iceland spar]]" is used for optical purposes.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Harstad |first1=A. O. |last2=Stipp |first2=S. L. S. |title=Calcite dissolution; effects of trace cations naturally present in Iceland spar calcites. |journal=Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta |date=2007 |volume=71 |issue=1 |pages=56–70 |doi=10.1016/j.gca.2006.07.037 |bibcode=2007GeCoA..71...56H }}</ref> Acute [[bipyramid|scalenohedral]] crystals are sometimes referred to as "dogtooth spar" while the [[rhombohedron|rhombohedral]] form is sometimes referred to as "nailhead spar".<ref name=Sinkankas1964>{{cite book |last1=Sinkankas |first1=John |title=Mineralogy for amateurs. |date=1964 |publisher=Van Nostrand |location=Princeton, N.J. |isbn=0442276249 |pages=359–364}}</ref> The rhombohedral form may also have been the "[[sunstone (medieval)|sunstone]]" whose use by [[Viking]] navigators is mentioned in the [[Sagas of Icelanders|Icelandic Sagas]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ropars |first1=Guy |last2=Lakshminarayanan |first2=Vasudevan |last3=Le Floch |first3=Albert |title=The sunstone and polarised skylight: ancient Viking navigational tools? |journal=[[Contemporary Physics]] |date=2 October 2014 |volume=55 |issue=4 |pages=302–317 |doi=10.1080/00107514.2014.929797 |bibcode=2014ConPh..55..302R |s2cid=119962347 }}</ref> |

|||

Single calcite crystals display an optical property called [[birefringence]] (double refraction). This strong birefringence causes objects viewed through a clear piece of calcite to appear doubled. The birefringent effect (using calcite) was first described by the [[Denmark|Danish]] scientist [[Rasmus Bartholin]] in 1669. At a wavelength of about 590 nm, calcite has ordinary and extraordinary [[refractive index|refractive indices]] of 1.658 and 1.486, respectively.<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://physics.info/refraction/ |title=Refraction |last=Elert|first=Glenn |journal=The Physics Hypertextbook |year=2021}}</ref> Between 190 and 1700 nm, the ordinary refractive index varies roughly between 1.9 and 1.5, while the extraordinary refractive index varies between 1.6 and 1.4.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/S0040-6090(97)00843-2| title = Determination of optical anisotropy in calcite from ultraviolet to mid-infrared by generalized ellipsometry| journal=Thin Solid Films| volume=313–314| issue=1–2| pages=341–346| year=1998| last1=Thompson| first1=D. W.| last2=Devries| first2=M. J.| last3=Tiwald| first3=T. E.| last4=Woollam| first4=J. A. |bibcode=1998TSF...313..341T}}</ref> |

|||

Lublinite is a fibrous, efflorescent form of calcite.<ref>http://www.mindat.org/min-9512.html Mindat</ref> |

|||

=== Thermoluminescence === |

|||

===Calcite in Earth history=== |

|||

[[File:Fluorescence in calcite.jpg|thumb|Demonstration of birefringence in calcite, using 445 nm laser]] |

|||

[[Image:MississippianMarbleUT.JPG|thumb|right|[[Mississippian]] marble (made of calcite) in Big Cottonwood Canyon, [[Wasatch Mountains]], [[Utah]].]] |

|||

Calcite has [[Thermoluminescence|thermoluminescent]] properties mainly due to manganese divalent ({{chem2|Mn(2+)}}).<ref name="Medlin">{{cite journal |last1=Medlin |first1=W. L. |title=Thermoluminescent properties of calcite. |journal=The Journal of Chemical Physics |date=1959 |volume=30 |issue=2 |pages=451–458 |doi=10.1063/1.1729973 |bibcode=1959JChPh..30..451M}}</ref> An experiment was conducted by adding activators such as ions of Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ag, Pb, and Bi to the calcite samples to observe whether they emitted heat or light. The results showed that adding ions ({{chem2|Cu+}}, {{chem2|Cu(2+)}}, {{chem2|Zn(2+)}}, {{chem2|Ag+}}, {{chem2|Bi(3+)}}, {{chem2|Fe(2+)}}, {{chem2|Fe(3+)}}, {{chem2|Co(2+)}}, {{chem2|Ni(2+)}}) did not react.<ref name="Medlin" /> However, a reaction occurred when both manganese and lead ions were present in calcite.<ref name="Medlin" /> By changing the temperature and observing the glow curve peaks, it was found that {{chem2|Pb(2+) }}and {{chem2|Mn(2+)}}acted as activators in the calcite lattice, but {{chem2|Pb(2+)}} was much less efficient than {{chem2|Mn(2+)}}.<ref name="Medlin" /> |

|||

[[Calcite sea]]s existed in Earth history when the primary inorganic precipitate of calcium carbonate in marine waters was low-magnesium calcite (lmc), as opposed to the [[aragonite]] and high-magnesium calcite (hmc) precipitated today. Calcite seas alternated with aragonite seas over the Phanerozoic, being most prominent in the [[Ordovician]] and [[Jurassic]]. [[Petrography|Petrographic]] evidence for these calcite sea conditions consists of calcitic [[ooid]]s, lmc cements, [[hardgrounds]], and rapid early seafloor aragonite dissolution.<ref>{{cite journal |author = Palmer, T.J. and Wilson, M.A.|year=2004 |title=Calcite precipitation and dissolution of biogenic aragonite in shallow Ordovician calcite seas|journal= Lethaia|volume=37 |issue= |pages=417–427|url=http://www.wooster.edu/geology/PalmerWilson05.pdf |doi = 10.1080/00241160410002135 }}</ref> The evolution of marine organisms with calcium carbonate shells may have been affected by the calcite and aragonite sea cycle.<ref>{{cite journal |author = Harper, E.M. , Palmer, T.J. and Alphey, J.R. |year=1997 |title=Evolutionary response by bivalves to changing Phanerozoic sea-water chemistry |journal= Geological Magazine|volume=134 |issue= |pages=403–407}}</ref> |

|||

Measuring mineral thermoluminescence experiments usually use x-rays or gamma-rays to activate the sample and record the changes in glowing curves at a temperature of 700–7500 K.<ref name="Medlin" /> Mineral thermoluminescence can form various glow curves of crystals under different conditions, such as temperature changes, because impurity ions or other crystal defects present in minerals supply luminescence centers and trapping levels.<ref name="Medlin" /> Observing these curve changes also can help infer geological correlation and age determination.<ref name="Medlin" /> |

|||

=== Chemical === |

|||

Calcite, like most carbonates, dissolves in acids by the following reaction |

|||

: {{chem2|CaCO3 + 2 H+ -> Ca(2+) + H2O + CO2}} |

|||

The carbon dioxide released by this reaction produces a characteristic effervescence when a calcite sample is treated with an acid. |

|||

Due to its acidity, carbon dioxide has a slight solubilizing effect on calcite. The overall reaction is |

|||

==See also== |

|||

: {{chem2|CaCO3(s) + H2O + CO2(aq) -> Ca(2+)(aq) + 2HCO3-(aq)}} |

|||

{{Wikisource1911Enc|Calcite}} |

|||

*[[Monohydrocalcite|Monohydrocalcite, CaCO<sub>3</sub>·H<sub>2</sub>O]] |

|||

*[[Ikaite|Ikaite, CaCO<sub>3</sub>·6H<sub>2</sub>O]] |

|||

*[[Manganoan Calcite|Manganoan Calcite, (Ca,Mn)CO<sub>3</sub>]] |

|||

*[[List of minerals]] |

|||

*[[Lysocline]] |

|||

*[[Ocean acidification]] |

|||

If the amount of dissolved carbon dioxide drops, the reaction reverses to precipitate calcite. As a result, calcite can be either [[solvation|dissolved]] by groundwater or [[precipitate]]d by groundwater, depending on such factors as the water temperature, [[acidity|pH]], and dissolved [[ion]] concentrations. When conditions are right for precipitation, calcite forms mineral coatings that cement rock grains together and can fill fractures. When conditions are right for dissolution, the removal of calcite can dramatically increase the [[porosity]] and [[Permeability (fluid)|permeability]] of the rock, and if it continues for a long period of time, may result in the formation of [[cave]]s. Continued dissolution of calcium carbonate-rich formations can lead to the expansion and eventual collapse of cave systems, resulting in various forms of [[Karst|karst topography]].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Wolfgang |first1=Dreybrodt |year=2004 |title=Dissolution: Carbonate rocks |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Caves and Karst Science |pages=295–298 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313171146 |access-date=26 December 2020}}</ref> |

|||

==References== |

|||

<references/> |

|||

*[http://mineral.galleries.com/minerals/carbonat/calcite/calcite.htm Calcite information and images] |

|||

Calcite exhibits an unusual characteristic called retrograde solubility: it is less soluble in water as the temperature increases. Calcite is also more soluble at higher pressures.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sharp |first1=W. E. |last2=Kennedy |first2=G. C. |title=The System CaO-CO 2 -H 2 O in the Two-Phase Region Calcite + Aqueous Solution |journal=The Journal of Geology |date=March 1965 |volume=73 |issue=2 |pages=391–403 |doi=10.1086/627069|s2cid=100971186 }}</ref> |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

Pure calcite has the composition {{chem2|CaCO3}}. However, the calcite in limestone often contains a few percent of [[magnesium]]. Calcite in limestone is divided into low-magnesium and high-magnesium calcite, with the dividing line placed at a composition of 4% magnesium. High-magnesium calcite retains the calcite mineral structure, which is distinct from that of [[Dolomite (mineral)|dolomite]], {{chem2|MgCa(CO3)2}}.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Blatt |first1=Harvey |last2=Middleton |first2=Gerard |last3=Murray |first3=Raymond |title=Origin of sedimentary rocks |date=1980 |publisher=Prentice-Hall |location=Englewood Cliffs, N.J. |isbn=0136427103 |edition=2d |pages=448–449}}</ref> Calcite can also contain small quantities of [[iron]] and [[manganese]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Dromgoole |first1=Edward L. |last2=Walter |first2=Lynn M. |title=Iron and manganese incorporation into calcite: Effects of growth kinetics, temperature and solution chemistry |journal=Chemical Geology |date=February 1990 |volume=81 |issue=4 |pages=311–336 |doi=10.1016/0009-2541(90)90053-A|bibcode=1990ChGeo..81..311D }}</ref> Manganese may be responsible for the fluorescence of impure calcite, as may traces of organic compounds.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Pedone |first1=Vicki A. |last2=Cercone |first2=Karen Rose |last3=Burruss |first3=R.C. |title=Activators of photoluminescence in calcite: evidence from high-resolution, laser-excited luminescence spectroscopy |journal=Chemical Geology |date=October 1990 |volume=88 |issue=1–2 |pages=183–190 |doi=10.1016/0009-2541(90)90112-K|bibcode=1990ChGeo..88..183P }}</ref> |

|||

*Schmittner Karl-Erich and Giresse Pierre, 1999. "Micro-environmental controls on biomineralization: superficial processes of apatite and calcite precipitation in Quaternary soils", Roussillon, France. ''Sedimentology'' 46/3: 463–476. |

|||

== Distribution == |

|||

==External links== |

|||

Calcite is found all over the world, and its leading global distribution is as follows: |

|||

*[http://giantcrystals.strahlen.org/europe/helgustadir.htm Information about the largest and most famous calcite crystals] |

|||

{{Commonscat|Calcite}} |

|||

=== United States === |

|||

[[File:Pd36-2-iss013e14843.jpg|thumb|Calcite Quarry, Michigan.]] |

|||

Calcite is found in many different areas in the United States. One of the best examples is the [[Michigan Limestone and Chemical Company|Calcite Quarry]] in Michigan.<ref name=NASA>{{cite web |title=Calcite Quarry, Michigan. |url=https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/6813/calcite-quarry-michigan#:~:text=These%20carbonate%20rocks%20are%20mined,active%20for%20over%2085%20years. |website=Earth observatory | date=7 August 2006 |access-date=17 February 2023}}</ref> The Calcite Quarry is the largest carbonate mine in the world and has been in use for more than 85 years.<ref name=NASA /> Large quantities of calcite can be mined from these sizeable open pit mines. |

|||

=== Canada === |

|||

Calcite can also be found throughout Canada, such as in Thorold Quarry and Madawaska Mine, Ontario, Canada.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Hudson Institute of Mineralogy |title=Calcite from Canada. |url=https://www.mindat.org/locentries.php?p=8188&m=859 |website=mindat.org. |access-date=17 February 2023}}</ref> |

|||

=== Mexico === |

|||

Abundant calcite is mined in the Santa Eulalia mining district, Chihuahua, Mexico.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Hudson Institute of Mineralogy |title=Santa Eulalia Mining District, Aquiles Serdán Municipality, Chihuahua, Mexico. |url=https://www.mindat.org/loc-2311.html|website=mindat.org. |access-date=17 February 2023}}</ref> |

|||

=== Iceland === |

|||

Large quantities of calcite in Iceland are concentrated in the [[Helgustadir mine]].<ref name =AZo>{{cite web |last1=AZoMining |title=Calcite – occurrence, properties, and distribution. |url=https://www.azomining.com/Article.aspx?ArticleID=964 |website=azomining.com |date=15 October 2013 |access-date=17 February 2023}}</ref> The mine was once the primary mining location of "Iceland spar."<ref name=Krist>{{cite journal |last1=Kristjansson |first1=L. |title=Iceland Spar: The Helgustadir Calcite Locality and its Influence on the Development of Science. |journal=Journal of Geoscience Education |date=2002 |volume=50 |issue=4 |pages=419–427 |doi=10.5408/1089-9995-50.4.419 |bibcode=2002JGeEd..50..419K |s2cid=126987943 |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.5408/1089-9995-50.4.419}}</ref> However, it currently serves as a nature reserve, and calcite mining will not be allowed.<ref name=Krist /> |

|||

=== England === |

|||

Calcite is found in parts of England, such as Alston Moor, Egremont, and Frizington, Cumbria.<ref name =AZo /> |

|||

=== Germany === |

|||

St. Andreasberg, Harz Mountains, and Freiberg, Saxony can find calcite.<ref name =AZo /> |

|||

== Use and applications == |

|||

[[File:Tutankhamun's Alabaster Jar.jpg|thumb|upright|left|One of several calcite or alabaster perfume jars from the tomb of [[Tutankhamun]], d. 1323 BC]] |

|||

Ancient Egyptians carved many items out of calcite, relating it to their goddess [[Bastet|Bast]], whose name contributed to the term [[alabaster]] because of the close association. Many other cultures have used the material for similar carved objects and applications.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Reed |first1=Kristina |title=Display Case |work=La Sierra Digs |issue=2 |publisher=La Sierra University |date=Spring 2017 |volume=5 |url=https://lasierra.edu/fileadmin/documents/cnea/newsletter/cnea-newsletter-spring-2017.pdf |access-date=6 February 2021}}</ref> |

|||

A transparent variety of calcite known as [[Iceland spar]] may have been used by [[Vikings]] for navigating on cloudy days. A very pure crystal of calcite can split a beam of sunlight into dual images, as the polarized light deviates slightly from the main beam. By observing the sky through the crystal and then rotating it so that the two images are of equal brightness, the rings of polarized light that surround the sun can be seen even under overcast skies. Identifying the sun's location would give seafarers a reference point for navigating on their lengthy sea voyages.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Perkins |first1=Sid |title=Viking seafarers may have navigated with legendary crystals |journal=Science |date=3 April 2018 |doi=10.1126/science.aat7802 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

In World War II, high-grade optical calcite was used for gun sights, specifically in bomb sights and anti-aircraft weaponry.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.sandiegouniontribune.com/sdut-borregos-calcite-mine-trail-holds-desert-wonders-2010dec05-htmlstory.html|title=Borrego's calcite mine trail holds desert wonders|first1=Priscilla|last1=Lister|website=The San Diego Union-Tribune|date=December 5, 2010|access-date=January 8, 2021}}</ref> It was used as a polarizer (in [[Nicol prism]]s) before the invention of [[Polaroid (polarizer)|Polaroid]] plates and still finds use in optical instruments.{{sfn|Klein|Hurlbut|1993|p=408}} Also, experiments have been conducted to use calcite for a [[cloak of invisibility]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Chen |first1=Xianzhong |last2=Luo |first2=Yu |last3=Zhang |first3=Jingjing |last4=Jiang |first4=Kyle |last5=Pendry |first5=John B. |last6=Zhang |first6=Shuang |doi=10.1038/ncomms1176 |title=Macroscopic invisibility cloaking of visible light |pmid=21285954 |year=2011 |page=176 |volume=2 |journal=Nature Communications |issue=2 |pmc=3105339 |bibcode=2011NatCo...2..176C |arxiv=1012.2783}}</ref> |

|||

[[Microbiologically induced calcite precipitation|Microbiologically precipitated calcite]] has a wide range of applications, such as soil remediation, soil stabilization and concrete repair.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Mujah |first1=D. |last2=Shahin |first2=M. A. |last3=Cheng |first3=L. |title=State-of-the-Art Review of Biocementation by Microbially Induced Calcite Precipitation (MICP) for Soil Stabilization. |journal=Geomicrobiology Journal |date=2017 |volume=34 |issue=6 |pages=524–537 |doi=10.1080/01490451.2016.1225866 |bibcode=2017GmbJ...34..524M |s2cid=88584080}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Castro-Alonso |first1=M. J. |last2=Montañez-Hernandez |first2=L. E. |last3=Sanchez-Muñoz |first3=M. A. |last4=Macias Franco |first4=M. R. |last5=Narayanasamy |first5=R. |last6=Balagurusamy |first6=N. |title=Microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation (MICP) and its potential in bioconcrete: microbiological and molecular concepts. |journal=Frontiers in Materials |date=2019 |volume=6 |page=126 |doi=10.3389/fmats.2019.00126 |bibcode=2019FrMat...6..126C |doi-access=free }}</ref> It also can be used for tailings management and is designed to promote sustainable development in the mining industry.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Zúñiga-Barra |first1=H. |last2=Toledo-Alarcón |first2=J. |last3=Torres-Aravena |first3=Á. |last4=Jorquera |first4=L. |last5=Rivas |first5=M. |last6=Gutiérrez |first6=L. |last7=Jeison |first7=D. |title=Improving the sustainable management of mining tailings through microbially induced calcite precipitation: A review. |journal=Minerals Engineering |date=2022 |volume=189 |page=107855– |doi=10.1016/j.mineng.2022.107855 |s2cid=252986388}}</ref> |

|||

Calcite can help synthesize precipitated calcium carbonate (PCC) (mainly used in the paper industry) and increase [[carbonation]].<ref name=Jimoh>{{cite journal |last1=Jimoh |first1=O. A. |last2=Ariffin |first2=K. S. |last3=Hussin |first3=H. B. |last4=Temitope |first4=A. E. |title=Synthesis of precipitated calcium carbonate: a review. |journal=Carbonates and Evaporites |date=2018 |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=331–346 |doi=10.1007/s13146-017-0341-x |s2cid=133034902}}</ref> Furthermore, due to its particular crystal habit, such as rhombohedron, hexagonal prism, etc., it promotes the production of PCC with specific shapes and particle sizes.<ref name=Jimoh /> |

|||

Calcite, obtained from an 80 kg sample of [[Carrara marble]],<ref name="IAEA603RefSheet">{{cite web |url=https://nucleus.iaea.org/rpst/ReferenceProducts/ReferenceMaterials/Stable_Isotopes/13C18and7Li/IAEA-603/RM603_Reference_Sheet_2016-08-16.pdf |title=Reference Sheet: Certified Reference Material: IAEA-603 (calcite) – Stable Isotope Reference Material for δ<sup>13</sup>C and δ<sup>18</sup>O |publisher=[[IAEA]] |author=Department of Nuclear Sciences and Applications, IAEA Environment Laboratories |date=16 July 2016 |access-date=28 February 2017 |page=2}}</ref> is used as the [[IAEA]]-603 isotopic standard in [[mass spectrometry]] for the calibration of [[δ18O|δ<sup>18</sup>O]] and [[δ13C|δ<sup>13</sup>C]].<ref>{{cite web|title=IAEA-603, Calcite |url=https://nucleus.iaea.org/rpst/ReferenceProducts/ReferenceMaterials/Stable_Isotopes/13C18and7Li/IAEA-603/index.htm |website=Reference Products for Environment and Trade |publisher=International Atomic Energy Agency |access-date=27 February 2017}}</ref> |

|||

Calcite can be formed naturally or synthesized. However, artificial calcite is the preferred material to be used as a scaffold in bone tissue engineering due to its controllable and repeatable properties.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Chróścicka |first1=A. |last2=Jaegermann |first2=Z. |last3=Wychowański |first3=P. |last4=Ratajska |first4=A. |last5=Sadło |first5=J. |last6=Hoser |first6=G. |last7=Michałowski |first7=S. |last8=Lewandowska-Szumiel |first8=M. |title=Synthetic Calcite as a Scaffold for Osteoinductive Bone Substitutes. |journal=Annals of Biomedical Engineering |date=2016 |volume=44 |issue=7 |pages=2145–2157 |doi=10.1007/s10439-015-1520-3 |pmid=26666226 |pmc=4893069 |doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

Calcite can be used to alleviate water pollution caused by the excessive growth of [[cyanobacteria]]. Lakes and rivers can lead to cyanobacteria blooms due to [[eutrophication]], which pollutes water resources.<ref name=Han>{{cite journal |last1=Han |first1=M. |last2=Wang |first2=Y. |last3=Zhan |first3=Y. |last4=Lin |first4=J. |last5=Bai |first5=X. |last6=Zhang |first6=Z. |title=Efficiency and mechanism for the control of phosphorus release from sediment by the combined use of hydrous ferric oxide, calcite and zeolite as a geo-engineering tool. |journal=Chemical Engineering Journal |date=2022 |volume=428 |page=131360– |doi=10.1016/j.cej.2021.131360|bibcode=2022ChEnJ.42831360H }}</ref> Phosphorus (P) is the leading cause of excessive growth of cyanobacteria.<ref name=Han /> As an active capping material, calcite can help reduce P release from sediments into the water, thus inhibiting cyanobacteria overgrowth.<ref name=Han /> |

|||

== Natural occurrence == |

|||

Calcite is a common constituent of [[sedimentary rock]]s, limestone in particular, much of which is formed from the shells of dead marine organisms. Approximately 10% of sedimentary rock is limestone. It is the primary mineral in [[Metamorphic rock|metamorphic]] [[marble]]. It also occurs in deposits from [[hot spring]]s as a [[Vein (geology)|vein]] mineral; in caverns as [[stalactite]]s and [[stalactite|stalagmite]]s; and in [[volcanic rock|volcanic]] or [[mantle (geology)|mantle-derived]] rocks such as [[carbonatite]]s, [[kimberlite]]s, or rarely in [[peridotite]]s. |

|||

[[Cactus|Cacti]] contain Ca-oxalate biominerals. Their death releases these biominerals into the environment, which subsequently transform to calcite via a monohydrocalcite intermediate, [[Carbon sequestration|sequestering carbon]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Garvie |first=Laurence A. J. |date=2006 |title=Decay of cacti and carbon cycling |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16453105/ |journal=Die Naturwissenschaften |volume=93 |issue=3 |pages=114–118 |doi=10.1007/s00114-005-0069-7 |issn=0028-1042 |pmid=16453105}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-10-18 |title=Carbon Sequestration and Sonoran Desert Cacti |url=https://blog.azgs.arizona.edu/index.php/blog/2021-10/carbon-sequestration-and-sonoran-desert-cacti |access-date=2024-09-23 |website=e-Magazine of the AZ Geological Survey}}</ref> |

|||

Calcite is often the primary constituent of the shells of [[Marine biology|marine organism]]s, such as [[plankton]] (such as [[coccolith]]s and planktic [[foraminifera]]), the hard parts of red [[algae]], some [[sea sponge|sponge]]s, [[brachiopod]]s, [[echinoderm]]s, some [[Serpulidae|serpulids]], most [[bryozoa]], and parts of the shells of some [[Bivalvia|bivalves]] (such as [[oyster]]s and [[rudists]]). Calcite is found in spectacular form in the [[Snowy River Cave]] of [[New Mexico]] as mentioned above, where microorganisms are credited with natural formations. [[Trilobite]]s, which became [[Permian–Triassic extinction event|extinct a quarter billion years ago]], had unique compound eyes that used clear calcite crystals to form the lenses.<ref>{{cite news |last= Angier| first= Natalie |author-link=Natalie Angier |date=3 March 2014 |title=When Trilobites Ruled the World |url= https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/04/science/when-trilobites-ruled-the-world.html |newspaper= [[The New York Times]] |access-date=10 March 2014 }}</ref> It also forms a substantial part of birds' eggshells, and the [[δ13C|δ{{sup|13}}C]] of the diet is reflected in the δ{{sup|13}}C of the calcite of the shell.<ref name="Lynch-et-al-2007">{{cite journal | last1=Lynch | first1=Amanda H. | last2= Beringer | first2=Jason | last3=Kershaw | first3=Peter | last4=Marshall | first4=Andrew | last5=Mooney | first5=Scott | last6=Tapper | first6=Nigel | last7=Turney | first7=Chris | last8=Van Der Kaars | first8=Sander | display-authors= 3| title=Using the Paleorecord to Evaluate Climate and Fire Interactions in Australia | journal=[[Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences]] | volume=35 | issue=1 | year=2007 | doi=10.1146/annurev.earth.35.092006.145055 | pages=215–239| bibcode=2007AREPS..35..215L }}</ref> |

|||

The largest documented single crystal of calcite originated from Iceland, measured {{convert|7|×|7|×|2|m|sigfig=2|abbr=on}} and {{convert|6|×|6|×|3|m|sigfig=2|abbr=on}} and weighed about 250 tons.<ref>{{cite journal| url=http://www.minsocam.org/ammin/AM66/AM66_885.pdf| access-date=2024-02-12| journal=American Mineralogist| volume=66| pages=885–907| year=1981| title=The largest crystals| last=Rickwood| first=P. C.}}</ref> Classic samples have been produced at [[Madawaska Mine]], near [[Bancroft, Ontario]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=McDougall |first=Raymond |date=2019-09-03 |title=Mineral Highlights from the Bancroft Area, Ontario, Canada |journal=Rocks & Minerals |volume=94 |issue=5 |pages=408–419 |doi=10.1080/00357529.2019.1619134 |bibcode=2019RoMin..94..408M |s2cid=201298402}}</ref> |

|||

[[Bed (geology)|Bedding]] parallel veins of fibrous calcite, often referred to in quarrying parlance as ''beef'', occur in dark organic rich mudstones and shales, these veins are formed by increasing [[fluid pressure]] during [[diagenesis]].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Ravier| first1=Edouard| last2=Martinez |first2=Mathieu |last3=Pellenard |first3=Pierre |last4=Zanella |first4=Alain |last5=Tupinier |first5=Lucie| display-authors=3| date=December 2020 |title=The milankovitch fingerprint on the distribution and thickness of bedding-parallel veins (beef) in source rocks |journal=Marine and Petroleum Geology |language=en |volume=122| page=104643 |doi=10.1016/j.marpetgeo.2020.104643 |bibcode=2020MarPG.12204643R |s2cid=225177225 |url=https://hal-insu.archives-ouvertes.fr/insu-02922274/file/ravier-2020.pdf}}</ref> |

|||

== Formation processes == |

|||

[[File:P-T Diagram for CaCO3.svg|left|frameless|400x400px]] |

|||

Calcite formation can proceed by several pathways, from the classical [[terrace ledge kink model]]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=De Yoreo |first1=J. J. |last2=Vekilov |first2=P. G. |title=Principles of crystal nucleation and growth |journal=Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry |volume=54 |pages=57–93 |date=2003 |issue=1 |doi=10.2113/0540057 |bibcode=2003RvMG...54...57D |citeseerx=10.1.1.324.6362 }}</ref> to the crystallization of poorly ordered precursor phases like [[amorphous calcium carbonate]] (ACC) via an [[Ostwald ripening]] process, or via the agglomeration of nanocrystals.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=De Yoreo |first1=J. |last2=Gilbert |first2=P.U. |last3=Sommerdijk |first3=N. A. J. M. |last4=Penn |first4=R. L. |last5=Whitelam |first5=S. |last6=Joester |first6=D. |last7=Zhang |first7=H. |last8=Rimer |first8=J. D. |last9=Navrotsky |first9=A. |last10=Banfield |first10=J. F. |last11=Wallace |first11=A. F. |last12=Michel |first12=F. M. |last13=Meldrum |first13=F. C. |last14=Cölfen |first14=H. |last15=Dove |first15=P. M. |title=Crystallization by particle attachment in synthetic, biogenic, and geologic environments |journal=Science |date=2015 |volume=349 |issue=6247 |page=aaa6760 |doi=10.1126/science.aaa6760 |pmid=26228157|s2cid=14742194 |url=http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/88828/1/Jim%20Science%20Review%20Unformatted%205-8-15.pdf }}</ref> |

|||

The crystallization of ACC can occur in two stages. First, the ACC nanoparticles rapidly dehydrate and crystallize to form individual particles of [[vaterite]]. Second, the vaterite transforms to calcite via a [[Solvation|dissolution]] and [[Precipitation (chemistry)|reprecipitation]] mechanism, with the [[reaction rate]] controlled by the [[surface area]] of a calcite crystal.<ref name=Geb>{{cite journal |doi=10.1039/C3CS60451A|title=Pre-nucleation clusters as solute precursors in crystallisation |year=2014 |last1=Gebauer |first1=Denis |last2=Kellermeier |first2=Matthias |last3=Gale |first3=Julian D. |last4=Bergström |first4=Lennart |last5=Cölfen |first5=Helmut |journal=Chem. Soc. Rev. |volume=43 |issue=7 |pages=2348–2371 |pmid=24457316 |s2cid=585569 |hdl=20.500.11937/6133 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> The second stage of the reaction is approximately 10 times slower. |

|||

However, crystallization of calcite has been observed to be dependent on the starting [[pH]] and [[concentration]] of [[magnesium]] in solution. A neutral starting pH during mixing promotes the direct transformation of ACC into calcite without a vaterite intermediate. But when ACC forms in a solution with a [[Base (chemistry)|basic]] initial pH, the transformation to calcite occurs via [[Metastability|metastable]] vaterite, following the pathway outlined above.<ref name=Geb/> Magnesium has a noteworthy effect on both the stability of ACC and its transformation to crystalline CaCO<sub>3</sub>, resulting in the formation of calcite directly from ACC, as this ion destabilizes the structure of vaterite. |

|||

[[Epitaxy|Epitaxial]] overgrowths of calcite precipitated on [[Weathering|weathered]] [[Cleavage (crystal)|cleavage]] surfaces have morphologies that vary with the type of weathering the substrate experienced: growth on physically weathered surfaces has a shingled morphology due to Volmer-Weber growth, growth on chemically weathered surfaces has characteristics of Stranski-Krastanov growth, and growth on pristine cleavage surfaces has characteristics of Frank - van der Merwe growth.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Acosta |first1=Marisa D. |last2=Olsen |first2=Ellen K. |last3=Pickerel |first3=Molly E. |date=2023-09-20 |title=Surface roughness and overgrowth dynamics: The effect of substrate micro-topography on calcite growth and Sr uptake |journal=Chemical Geology |language=en |volume=634 |pages=121585 |doi=10.1016/j.chemgeo.2023.121585 |issn=0009-2541|doi-access=free }}</ref> These differences are apparently due to the influence of surface roughness on layer coalescence dynamics. |

|||

Calcite may form in the subsurface in response to [[microorganism]] activity, such as [[sulfate]]-dependent [[anaerobic oxidation of methane]], where [[methane]] is [[Redox|oxidized]] and sulfate is [[Redox|reduced]], leading to precipitation of calcite and [[pyrite]] from the produced [[bicarbonate]] and [[sulfide]]. These processes can be traced by the specific [[carbon isotope]] composition of the calcites, which are extremely depleted in the [[Carbon-13|<sup>13</sup>C]] isotope, by as much as −125 per mil [[Δ13C#Reference standard|PDB]] (δ<sup>13</sup>C).<ref>{{cite journal |journal=Nature Communications |volume=6 |pages=7020 |year=2015 |title=Extreme <sup>13</sup>C depletion of carbonates formed during oxidation of biogenic methane in fractured granite |author=Drake, H. |author2=Astrom, M. E. |author3=Heim, C. |author4=Broman, C. |author5=Astrom, J. |author6=Whitehouse, M. |author7=Ivarsson, M. |author8=Siljestrom, S. |author9=Sjovall, P. |pmid=25948095 |pmc=4432592 |doi=10.1038/ncomms8020|bibcode = 2015NatCo...6.7020D }}</ref> |

|||

== In Earth history == |

|||

[[Calcite sea]]s existed in Earth's history when the primary inorganic [[Precipitation (chemistry)|precipitate]] of [[calcium carbonate]] in marine waters was low-magnesium calcite (lmc), as opposed to the [[aragonite]] and high-magnesium calcite (hmc) precipitated today. Calcite seas alternated with [[aragonite sea]]s over the [[Phanerozoic]], being most prominent in the [[Ordovician]] and [[Jurassic]] periods. Lineages evolved to use whichever [[Polymorphism (materials science)|morph]] of calcium carbonate was favourable in the ocean at the time they became mineralised, and retained this mineralogy for the remainder of their evolutionary history.<ref name='Porter2007'>{{cite journal |doi=10.1126/science.1137284 |title=Seawater Chemistry and Early Carbonate Biomineralization |year=2007 |last1=Porter |first1=S. M. |journal=Science |volume=316 |page=1302 |pmid=17540895 |issue=5829 |bibcode=2007Sci...316.1302P |s2cid=27418253}}</ref> [[Petrography|Petrographic]] evidence for these calcite sea conditions consists of calcitic [[ooid]]s, lmc cements, [[hardgrounds]], and rapid early seafloor aragonite dissolution.<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1080/00241160410002135 |title=Calcite precipitation and dissolution of biogenic aragonite in shallow Ordovician calcite seas |year=2004 |last1=Palmer |first1=Timothy |last2=Wilson |first2=Mark |journal=Lethaia |volume=37 |issue=4 |pages=417–427 |bibcode=2004Letha..37..417P}}</ref> The evolution of marine organisms with calcium carbonate shells may have been affected by the calcite and aragonite sea cycle.<ref>{{cite journal |author1-link=Elizabeth Harper (biologist) |author=Harper, E.M. |author2=Palmer, T.J. |author3=Alphey, J.R. |year=1997 |title=Evolutionary response by bivalves to changing Phanerozoic sea-water chemistry |journal=Geological Magazine |volume=134 |issue=3 |pages=403–407 |doi=10.1017/S0016756897007061 |bibcode=1997GeoM..134..403H |s2cid=140646397}}</ref> |

|||

Calcite is one of the minerals that has been shown to [[catalysis|catalyze]] an important biological reaction, the [[formose reaction]], and may have had a role in the origin of life.<ref name=Hazen/> Interaction of its [[Chirality|chiral]] surfaces (see [[#Form|Form]]) with [[aspartic acid]] molecules results in a slight bias in chirality; this is one possible mechanism for the origin of [[homochirality]] in living cells.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Meierhenrich |first1=Uwe|title=Amino acids and the asymmetry of life caught in the act of formation |date=2008 |publisher=Springer |location=Berlin |isbn=9783540768869 |pages=76–78}}</ref> |

|||

== Climate change == |

|||

[[File:Effect of Ocean Acidification on Calcification.png|thumb|Ocean acidification reduces pH, which affects calcification in shelled organisms.]] |

|||

Climate change is exacerbating [[ocean acidification]], possibly leading to lower natural calcite production. The oceans absorb large amounts of {{chem2|CO2}} from fossil fuel emissions into the air.<ref name=Tyrrell>{{cite journal |last1=Tyrrell |first1=T. |title=Calcium carbonate cycling in future oceans and its influence on future climates. |journal=Journal of Plankton Research |date=2008 |volume=30 |issue=2 |pages=141–156 |doi=10.1093/plankt/fbm105 |doi-access=free}}</ref> The total amount of artificial {{chem2|CO2}} absorbed by the oceans is calculated to be 118 ± 19 Gt C.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sabine |first1=Christopher L. |last2=Feely |first2=Richard A. |last3=Gruber |first3=Nicholas |last4=Key |first4=Robert M. |last5=Lee |first5=Kitack |last6=Bullister |first6=John L. |last7=Wanninkhof |first7=Rik |last8=Wong |first8=C. S. |last9=Wallace |first9=Douglas W. R. |last10=Tilbrook |first10=Bronte |last11=Billero |first11=Frank J. |last12=Peng |first12=Tsung-Hung |last13=Kozyr |first13=Alexander |last14=Ono |first14=Tsueno |last15=Rios |first15=A. F. |title=The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2. |journal=Science |date=2004 |volume=305 |issue=5682 |pages=367–371 |doi=10.1126/science.1097403 |pmid=15256665 |bibcode=2004Sci...305..367S |s2cid=5607281|hdl=10261/52596 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> If a large amount of {{chem2|CO2}} dissolves in the sea, it will cause the acidity of the seawater to increase, thereby affecting the pH value of the ocean.<ref name=Tyrrell /> Calcifying organisms in the sea, such as molluscs foraminifera, crustaceans, echinoderms and corals, are susceptible to pH changes.<ref name=Tyrrell /> Meanwhile, these calcifying organisms are also an essential source of calcite. As ocean acidification causes pH to drop, carbonate ion concentrations will decline, potentially reducing natural calcite production.<ref name=Tyrrell /> |

|||

{{Clear}} |

|||

== Gallery == |

|||

<gallery widths="133" heights="130"> |

|||

File:Calcite-Mottramite-cktsu-45b.jpg|Calcite with [[mottramite]] |

|||

File:Erbenochile eye.JPG|[[Trilobite]] eyes employed calcite |

|||

File:CalciteEchinosphaerites.jpg|Calcite crystals inside a [[Test (biology)|test]] of the [[Cystoidea|cystoid]] ''[[Echinosphaerites|Echinosphaerites aurantium]]'' (Middle [[Ordovician]], northeastern [[Estonia]]) |

|||

File:Calcite-Dolomite-Gypsum-159389.jpg|[[Rhombohedron]]s of calcite that appear almost as books of petals, piled up 3-dimensionally on the [[Matrix (geology)|matrix]] |

|||

File:Calcite-Hematite-Chalcopyrite-176263.jpg|Calcite crystal canted at an angle, with little balls of [[hematite]] and crystals of [[chalcopyrite]] both on its surface and included just inside the surface of the crystal |

|||

File:GeopetalCarboniferousNV.jpg|[[Thin section]] of calcite crystals inside a recrystallized [[bivalve]] shell in a [[Folk classification#Folk's carbonate classification|biopelsparite]] |

|||

File:OoidSurface01.jpg|Grainstone with calcite [[ooids]] and [[Spar (mineralogy)|sparry]] calcite cement; [[Carmel Formation]], Middle [[Jurassic]], of southern [[Utah]], USA. |

|||

File:Calcite-Aragonite-Sulphur-69380.jpg|Several well formed milky white casts, made up of many small sharp calcite crystals, from the [[sulfur]] mines at [[Agrigento]], [[Sicily]] |

|||

File:Calcite-tch21c.jpg|Reddish rhombohedral calcite crystals from [[China]]. Its red color is due to the presence of [[iron]] |

|||

File:Calcite-75480.jpg|[[Cobalt]]oan, the cobalt-rich variety of calcite |

|||

File:Calcite-114508.jpg|Sand calcites (calcites heavily included with desert sand) in [[South Dakota]], USA |

|||

File:RM463c-calcite-butterfly-twin.jpg|Calcite, butterfly twin, {{nowrap|4.0 × 3.3 × 1.6 cm}}. José María Patoni, [[San Juan del Río, Durango]] ([[Mexico]]) |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== See also == |

|||

{{Commons category|Calcite}} |

|||

{{EB1911 poster|Calcite}} |

|||

* [[Carbonate rock]] |

|||

* [[Ikaite]], CaCO<sub>3</sub>·6H<sub>2</sub>O |

|||

* [[List of minerals]] |

|||

* [[Lysocline]] |

|||

* [[Manganoan calcite]], (Ca,Mn)CO<sub>3</sub> |

|||

* [[Monohydrocalcite]], CaCO<sub>3</sub>·H<sub>2</sub>O |

|||

* [[Nitratine]] |

|||

* [[Ocean acidification]] |

|||

* [[Ulexite]] |

|||

== References == |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

== Further reading == |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=Schmittner |first1=Karl-Erich |last2=Giresse |first2=Pierre |title=Micro-environmental controls on biomineralization: superficial processes of apatite and calcite precipitation in Quaternary soils, Roussillon, France |journal=Sedimentology |date=June 1999 |volume=46 |issue=3 |pages=463–476 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-3091.1999.00224.x|bibcode=1999Sedim..46..463S |s2cid=140680495}} |

|||

{{Mohs}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Calcium minerals]] |

[[Category:Calcium minerals]] |

||

| Line 97: | Line 228: | ||

[[Category:Transparent materials]] |

[[Category:Transparent materials]] |

||

[[Category:Calcite group]] |

[[Category:Calcite group]] |

||

[[Category:Cave |

[[Category:Cave minerals]] |

||

[[Category:Trigonal minerals]] |

|||

[[Category:Minerals in space group 167]] |

|||

[[be:Кальцый]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:Evaporite]] |

||

[[Category:Luminescent minerals]] |

|||

[[bg:Калцит]] |

|||

[[Category:Polymorphism (materials science)]] |

|||

[[ca:Calcita]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:Bastet]] |

||

[[da:Kalk (mineral)]] |

|||

[[de:Calcit]] |

|||

[[et:Kaltsiit]] |

|||

[[el:Ασβεστίτης]] |

|||

[[es:Calcita]] |

|||

[[eo:Kalcito]] |

|||

[[eu:Kaltzita]] |

|||

[[fa:کلسیت]] |

|||

[[fr:Calcite]] |

|||

[[gl:Calcita]] |

|||

[[hr:Kalcit]] |

|||

[[it:Calcite]] |

|||

[[he:קלציט]] |

|||

[[lv:Kalcīts]] |

|||

[[lt:Kalcitas]] |

|||

[[hu:Kalcit]] |

|||

[[nl:Calciet]] |

|||

[[ja:方解石]] |

|||

[[no:Kalsitt]] |

|||

[[pl:Kalcyt]] |

|||

[[pt:Calcita]] |

|||

[[ro:Calcit]] |

|||

[[ru:Кальцит]] |

|||

[[simple:Calcite]] |

|||

[[sk:Kalcit]] |

|||

[[sr:Калцит]] |

|||

[[fi:Kalsiitti]] |

|||

[[sv:Kalkspat]] |

|||

[[ta:கால்சைட்]] |

|||

[[vi:Canxit]] |

|||

[[tr:Kalsit]] |

|||

[[uk:Кальцит]] |

|||

[[zh:方解石]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 22:04, 11 December 2024

| Calcite | |

|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: scalenohedral, rhomboedral, stalactitic, and botryoidal calcite | |

| General | |

| Category | Carbonate mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | CaCO3 |

| Strunz classification | 5.AB.05 |

| Crystal system | Trigonal |

| Crystal class | Hexagonal scalenohedral (3m) H-M symbol: (3 2/m) |

| Space group | R3c |

| Unit cell | a = 4.9896(2) Å, c = 17.0610(11) Å; Z = 6 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Typically colorless or creamy white - may have shades of brownish colors |

| Crystal habit | Botryoidal, concretionary, druse, globular, granular, massive, rhombohedral, scalenohedral, stalactitic |

| Twinning | Common by four twin laws |

| Cleavage | Perfect on {1011} three directions with angle of 74° 55'[1] |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 3 (defining mineral) |

| Luster | Vitreous to pearly on cleavage surfaces |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent to translucent |

| Specific gravity | 2.71 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (−); low relief |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.640–1.660 nε = 1.486 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.154–0.174 |

| Fusibility | Infusible (decrepitates energetically)[2] |

| Solubility | Soluble in dilute acids |

| Other characteristics | May fluoresce red, blue, yellow, and other colors under either SW and LW UV; phosphorescent |

| References | [3][4][5] |

Calcite is a carbonate mineral and the most stable polymorph of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). It is a very common mineral, particularly as a component of limestone. Calcite defines hardness 3 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, based on scratch hardness comparison. Large calcite crystals are used in optical equipment, and limestone composed mostly of calcite has numerous uses.

Other polymorphs of calcium carbonate are the minerals aragonite and vaterite. Aragonite will change to calcite over timescales of days or less at temperatures exceeding 300 °C,[6][7] and vaterite is even less stable.

Etymology

[edit]Calcite is derived from the German Calcit, a term from the 19th century that came from the Latin word for lime, calx (genitive calcis) with the suffix -ite used to name minerals. It is thus a doublet of the word chalk.[8]

When applied by archaeologists and stone trade professionals, the term alabaster is used not just as in geology and mineralogy, where it is reserved for a variety of gypsum; but also for a similar-looking, translucent variety of fine-grained banded deposit of calcite.[9]

Unit cell and Miller indices

[edit]

In publications, two different sets of Miller indices are used to describe directions in hexagonal and rhombohedral crystals, including calcite crystals: three Miller indices h, k, l in the directions, or four Bravais–Miller indices h, k, i, l in the directions, where is redundant but useful in visualizing permutation symmetries.

To add to the complications, there are also two definitions of unit cell for calcite. One, an older "morphological" unit cell, was inferred by measuring angles between faces of crystals, typically with a goniometer, and looking for the smallest numbers that fit. Later, a "structural" unit cell was determined using X-ray crystallography. The morphological unit cell is rhombohedral, having approximate dimensions a = 10 Å and c = 8.5 Å, while the structural unit cell is hexagonal (i.e. a rhombic prism), having approximate dimensions a = 5 Å and c = 17 Å. For the same orientation, c must be multiplied by 4 to convert from morphological to structural units. As an example, calcite cleavage is given as "perfect on {1 0 1 1}" in morphological coordinates and "perfect on {1 0 1 4}" in structural units. In indices, these are {1 0 1} and {1 0 4}, respectively. Twinning, cleavage and crystal forms are often given in morphological units.[4][10]

Properties

[edit]The diagnostic properties of calcite include a defining Mohs hardness of 3, a specific gravity of 2.71 and, in crystalline varieties, a vitreous luster. Color is white or none, though shades of gray, red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet, brown, or even black can occur when the mineral is charged with impurities.[4]

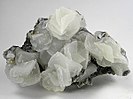

Crystal habits

[edit]Calcite has numerous habits, representing combinations of over 1000 crystallographic forms.[3] Most common are scalenohedra, with faces in the hexagonal {2 1 1} directions (morphological unit cell) or {2 1 4} directions (structural unit cell); and rhombohedral, with faces in the {1 0 1} or {1 0 4} directions (the most common cleavage plane).[10] Habits include acute to obtuse rhombohedra, tabular habits, prisms, or various scalenohedra. Calcite exhibits several twinning types that add to the observed habits. It may occur as fibrous, granular, lamellar, or compact. A fibrous, efflorescent habit is known as lublinite.[11] Cleavage is usually in three directions parallel to the rhombohedron form. Its fracture is conchoidal, but difficult to obtain.

Scalenohedral faces are chiral and come in pairs with mirror-image symmetry; their growth can be influenced by interaction with chiral biomolecules such as L- and D-amino acids. Rhombohedral faces are not chiral.[10][12]

-

Rhombohedral calcite

-

Scalenohedral calcite

-

Prismatic calcite

-

Prismatic calcite

-

Stalactitic calcite

-

Hexagonal calcite

-

Dodecahedral calcite

-

Bipyramidal calcite

-

Druse calcite

-

Twinned calcite

-

Globular calcite

-

Botryoidal calcite

Optical

[edit]

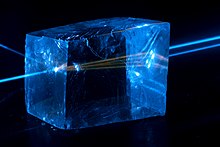

Calcite is transparent to opaque and may occasionally show phosphorescence or fluorescence. A transparent variety called "Iceland spar" is used for optical purposes.[13] Acute scalenohedral crystals are sometimes referred to as "dogtooth spar" while the rhombohedral form is sometimes referred to as "nailhead spar".[2] The rhombohedral form may also have been the "sunstone" whose use by Viking navigators is mentioned in the Icelandic Sagas.[14]

Single calcite crystals display an optical property called birefringence (double refraction). This strong birefringence causes objects viewed through a clear piece of calcite to appear doubled. The birefringent effect (using calcite) was first described by the Danish scientist Rasmus Bartholin in 1669. At a wavelength of about 590 nm, calcite has ordinary and extraordinary refractive indices of 1.658 and 1.486, respectively.[15] Between 190 and 1700 nm, the ordinary refractive index varies roughly between 1.9 and 1.5, while the extraordinary refractive index varies between 1.6 and 1.4.[16]

Thermoluminescence

[edit]

Calcite has thermoluminescent properties mainly due to manganese divalent (Mn2+).[17] An experiment was conducted by adding activators such as ions of Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Ag, Pb, and Bi to the calcite samples to observe whether they emitted heat or light. The results showed that adding ions (Cu+, Cu2+, Zn2+, Ag+, Bi3+, Fe2+, Fe3+, Co2+, Ni2+) did not react.[17] However, a reaction occurred when both manganese and lead ions were present in calcite.[17] By changing the temperature and observing the glow curve peaks, it was found that Pb2+and Mn2+acted as activators in the calcite lattice, but Pb2+ was much less efficient than Mn2+.[17]

Measuring mineral thermoluminescence experiments usually use x-rays or gamma-rays to activate the sample and record the changes in glowing curves at a temperature of 700–7500 K.[17] Mineral thermoluminescence can form various glow curves of crystals under different conditions, such as temperature changes, because impurity ions or other crystal defects present in minerals supply luminescence centers and trapping levels.[17] Observing these curve changes also can help infer geological correlation and age determination.[17]

Chemical

[edit]Calcite, like most carbonates, dissolves in acids by the following reaction

- CaCO3 + 2 H+ → Ca2+ + H2O + CO2

The carbon dioxide released by this reaction produces a characteristic effervescence when a calcite sample is treated with an acid.

Due to its acidity, carbon dioxide has a slight solubilizing effect on calcite. The overall reaction is

- CaCO3(s) + H2O + CO2(aq) → Ca2+(aq) + 2HCO−3(aq)

If the amount of dissolved carbon dioxide drops, the reaction reverses to precipitate calcite. As a result, calcite can be either dissolved by groundwater or precipitated by groundwater, depending on such factors as the water temperature, pH, and dissolved ion concentrations. When conditions are right for precipitation, calcite forms mineral coatings that cement rock grains together and can fill fractures. When conditions are right for dissolution, the removal of calcite can dramatically increase the porosity and permeability of the rock, and if it continues for a long period of time, may result in the formation of caves. Continued dissolution of calcium carbonate-rich formations can lead to the expansion and eventual collapse of cave systems, resulting in various forms of karst topography.[18]

Calcite exhibits an unusual characteristic called retrograde solubility: it is less soluble in water as the temperature increases. Calcite is also more soluble at higher pressures.[19]

Pure calcite has the composition CaCO3. However, the calcite in limestone often contains a few percent of magnesium. Calcite in limestone is divided into low-magnesium and high-magnesium calcite, with the dividing line placed at a composition of 4% magnesium. High-magnesium calcite retains the calcite mineral structure, which is distinct from that of dolomite, MgCa(CO3)2.[20] Calcite can also contain small quantities of iron and manganese.[21] Manganese may be responsible for the fluorescence of impure calcite, as may traces of organic compounds.[22]

Distribution

[edit]Calcite is found all over the world, and its leading global distribution is as follows:

United States

[edit]

Calcite is found in many different areas in the United States. One of the best examples is the Calcite Quarry in Michigan.[23] The Calcite Quarry is the largest carbonate mine in the world and has been in use for more than 85 years.[23] Large quantities of calcite can be mined from these sizeable open pit mines.

Canada

[edit]Calcite can also be found throughout Canada, such as in Thorold Quarry and Madawaska Mine, Ontario, Canada.[24]

Mexico

[edit]Abundant calcite is mined in the Santa Eulalia mining district, Chihuahua, Mexico.[25]

Iceland

[edit]Large quantities of calcite in Iceland are concentrated in the Helgustadir mine.[26] The mine was once the primary mining location of "Iceland spar."[27] However, it currently serves as a nature reserve, and calcite mining will not be allowed.[27]

England

[edit]Calcite is found in parts of England, such as Alston Moor, Egremont, and Frizington, Cumbria.[26]

Germany

[edit]St. Andreasberg, Harz Mountains, and Freiberg, Saxony can find calcite.[26]

Use and applications

[edit]

Ancient Egyptians carved many items out of calcite, relating it to their goddess Bast, whose name contributed to the term alabaster because of the close association. Many other cultures have used the material for similar carved objects and applications.[28]

A transparent variety of calcite known as Iceland spar may have been used by Vikings for navigating on cloudy days. A very pure crystal of calcite can split a beam of sunlight into dual images, as the polarized light deviates slightly from the main beam. By observing the sky through the crystal and then rotating it so that the two images are of equal brightness, the rings of polarized light that surround the sun can be seen even under overcast skies. Identifying the sun's location would give seafarers a reference point for navigating on their lengthy sea voyages.[29]

In World War II, high-grade optical calcite was used for gun sights, specifically in bomb sights and anti-aircraft weaponry.[30] It was used as a polarizer (in Nicol prisms) before the invention of Polaroid plates and still finds use in optical instruments.[31] Also, experiments have been conducted to use calcite for a cloak of invisibility.[32]

Microbiologically precipitated calcite has a wide range of applications, such as soil remediation, soil stabilization and concrete repair.[33][34] It also can be used for tailings management and is designed to promote sustainable development in the mining industry.[35]

Calcite can help synthesize precipitated calcium carbonate (PCC) (mainly used in the paper industry) and increase carbonation.[36] Furthermore, due to its particular crystal habit, such as rhombohedron, hexagonal prism, etc., it promotes the production of PCC with specific shapes and particle sizes.[36]

Calcite, obtained from an 80 kg sample of Carrara marble,[37] is used as the IAEA-603 isotopic standard in mass spectrometry for the calibration of δ18O and δ13C.[38]

Calcite can be formed naturally or synthesized. However, artificial calcite is the preferred material to be used as a scaffold in bone tissue engineering due to its controllable and repeatable properties.[39]

Calcite can be used to alleviate water pollution caused by the excessive growth of cyanobacteria. Lakes and rivers can lead to cyanobacteria blooms due to eutrophication, which pollutes water resources.[40] Phosphorus (P) is the leading cause of excessive growth of cyanobacteria.[40] As an active capping material, calcite can help reduce P release from sediments into the water, thus inhibiting cyanobacteria overgrowth.[40]

Natural occurrence

[edit]Calcite is a common constituent of sedimentary rocks, limestone in particular, much of which is formed from the shells of dead marine organisms. Approximately 10% of sedimentary rock is limestone. It is the primary mineral in metamorphic marble. It also occurs in deposits from hot springs as a vein mineral; in caverns as stalactites and stalagmites; and in volcanic or mantle-derived rocks such as carbonatites, kimberlites, or rarely in peridotites.

Cacti contain Ca-oxalate biominerals. Their death releases these biominerals into the environment, which subsequently transform to calcite via a monohydrocalcite intermediate, sequestering carbon.[41][42]

Calcite is often the primary constituent of the shells of marine organisms, such as plankton (such as coccoliths and planktic foraminifera), the hard parts of red algae, some sponges, brachiopods, echinoderms, some serpulids, most bryozoa, and parts of the shells of some bivalves (such as oysters and rudists). Calcite is found in spectacular form in the Snowy River Cave of New Mexico as mentioned above, where microorganisms are credited with natural formations. Trilobites, which became extinct a quarter billion years ago, had unique compound eyes that used clear calcite crystals to form the lenses.[43] It also forms a substantial part of birds' eggshells, and the δ13C of the diet is reflected in the δ13C of the calcite of the shell.[44]

The largest documented single crystal of calcite originated from Iceland, measured 7 m × 7 m × 2 m (23 ft × 23 ft × 6.6 ft) and 6 m × 6 m × 3 m (20 ft × 20 ft × 9.8 ft) and weighed about 250 tons.[45] Classic samples have been produced at Madawaska Mine, near Bancroft, Ontario.[46]

Bedding parallel veins of fibrous calcite, often referred to in quarrying parlance as beef, occur in dark organic rich mudstones and shales, these veins are formed by increasing fluid pressure during diagenesis.[47]

Formation processes

[edit]

Calcite formation can proceed by several pathways, from the classical terrace ledge kink model[48] to the crystallization of poorly ordered precursor phases like amorphous calcium carbonate (ACC) via an Ostwald ripening process, or via the agglomeration of nanocrystals.[49]

The crystallization of ACC can occur in two stages. First, the ACC nanoparticles rapidly dehydrate and crystallize to form individual particles of vaterite. Second, the vaterite transforms to calcite via a dissolution and reprecipitation mechanism, with the reaction rate controlled by the surface area of a calcite crystal.[50] The second stage of the reaction is approximately 10 times slower.

However, crystallization of calcite has been observed to be dependent on the starting pH and concentration of magnesium in solution. A neutral starting pH during mixing promotes the direct transformation of ACC into calcite without a vaterite intermediate. But when ACC forms in a solution with a basic initial pH, the transformation to calcite occurs via metastable vaterite, following the pathway outlined above.[50] Magnesium has a noteworthy effect on both the stability of ACC and its transformation to crystalline CaCO3, resulting in the formation of calcite directly from ACC, as this ion destabilizes the structure of vaterite.

Epitaxial overgrowths of calcite precipitated on weathered cleavage surfaces have morphologies that vary with the type of weathering the substrate experienced: growth on physically weathered surfaces has a shingled morphology due to Volmer-Weber growth, growth on chemically weathered surfaces has characteristics of Stranski-Krastanov growth, and growth on pristine cleavage surfaces has characteristics of Frank - van der Merwe growth.[51] These differences are apparently due to the influence of surface roughness on layer coalescence dynamics.

Calcite may form in the subsurface in response to microorganism activity, such as sulfate-dependent anaerobic oxidation of methane, where methane is oxidized and sulfate is reduced, leading to precipitation of calcite and pyrite from the produced bicarbonate and sulfide. These processes can be traced by the specific carbon isotope composition of the calcites, which are extremely depleted in the 13C isotope, by as much as −125 per mil PDB (δ13C).[52]

In Earth history