Medical cannabis: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Cannabis sativa L. (marijuana; hemp) used medicinally}} |

|||

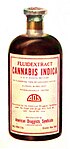

[[Image:Drug bottle containing cannbis.jpg|thumb|right|Cannabis Indica (now referred to as ''[[Cannabis sativa]]'' subsp. ''indica''),<ref> |

|||

{{other uses of|Cannabis}} |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

{{redirect|Medical marijuana|the company|Medical Marijuana, Inc.}} |

|||

|url=http://www.amjbot.org/cgi/content/abstract/91/6/966 |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

|||

|title=Cannabis sativa information from NPGS/GRIN |

|||

{{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} |

|||

|publisher=www.ars-grin.gov |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=October 2017}} |

|||

|accessdate=2008-07-13 |

|||

{{Use American English|date=October 2017}} |

|||

|last= |

|||

{{Cannabis sidebar}} |

|||

|first= |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> Fluid Extract, American Druggists Syndicate, pre-1937.]] |

|||

<!-- Definition and uses --> |

|||

'''Medical cannabis''', (commonly referred to as "'''Medical marijuana'''"), refers to the use of the ''[[cannabis]]'' plant as a physician-recommended [[Cannabis (drug)|drug]] or [[herbal therapy]], as well as synthetic [[THC]] and [[cannabinoids]]. |

|||

'''Medical cannabis''', '''medicinal cannabis''' or '''medical marijuana''' ('''MMJ''') refers to [[Cannabis (drug)|cannabis products]] and [[cannabinoid|cannabinoid molecule]]s that are [[prescription drug|prescribed]] by [[physician]]s for their patients.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Murnion B | title = Medicinal cannabis | journal = Australian Prescriber | volume = 38 | issue = 6 | pages = 212–15 | date = December 2015 | pmid = 26843715 | pmc = 4674028 | doi = 10.18773/austprescr.2015.072 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title= What is medical marijuana? |url= https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana-medicine |website= National Institute of Drug Abuse |access-date= 19 April 2016 |date= July 2015 |quote= The term medical marijuana refers to using the whole unprocessed marijuana plant or its basic extracts to treat a disease or symptom. |archive-date= 17 April 2016 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160417154854/https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana-medicine |url-status= live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Sarris |first1=Jerome |last2=Sinclair |first2=Justin |last3=Karamacoska |first3=Diana |last4=Davidson |first4=Maggie |last5=Firth |first5=Joseph |date=2020-01-16 |title=Medicinal cannabis for psychiatric disorders: a clinically-focused systematic review |journal=BMC Psychiatry |language=en |volume=20 |issue=1 |page=24 |doi=10.1186/s12888-019-2409-8 |doi-access=free |issn=1471-244X |pmc=6966847 |pmid=31948424}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=O'Brien |first=Kylie |date=2019-06-01 |title=Medicinal Cannabis: Issues of evidence |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876382019300216 |journal=European Journal of Integrative Medicine |volume=28 |pages=114–120 |doi=10.1016/j.eujim.2019.05.009 |issn=1876-3820}}</ref> The use of cannabis as medicine has a long history, but has not been as rigorously tested as other medicinal plants due to legal and governmental restrictions, resulting in limited [[clinical research]] to define the safety and efficacy of using cannabis to treat diseases.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Release the strains | journal = Nature Medicine | volume = 21 | issue = 9 | page = 963 | date = September 2015 | pmid = 26340110 | doi = 10.1038/nm.3946 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

There are many studies regarding the use of cannabis in a medicinal context.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=6376&page=13 |title=Marijuana and Medicine: Assessing the Science Base |publisher=Nap.edu |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref name="medmjscience1"/> Drug usage generally requires a prescription, and distribution is usually done within a framework defined by local laws. There are several methods for administration of dosage including smoking the dried cannabis buds, vaporizing them, and drinking, eating, or taking synthetic THC pills.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://cannabismd.org/reports/mjcapsules.php |title=CannabisMD Reports : Marijuana in Capsules |publisher=Cannabismd.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://michiganmedicalmarijuana.org/node/1030 |title=Methods of ingestion | Michigan Medical Marijuana Association | News and Information for Michigan's medical marijuana patients and caregivers |publisher=Michiganmedicalmarijuana.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> The comparible efficacy of these methods was the subject of an investigative study by the [[National Institutes of Health]]<ref name="medmjscience1">{{cite web|url=http://www.medmjscience.org/Pages/reports/nihpt1.html |title=NIH Workshop on the Medical Utility of Marijuana - Part 1 |publisher=Medmjscience.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Preliminary evidence has indicated that cannabis might reduce [[nausea]] and [[vomit]]ing during [[chemotherapy]] and reduce [[chronic pain]] and [[muscle spasm]]s.<ref name=Borgelt2013 /><ref name=JAMA2015 /> Regarding non-inhaled cannabis or cannabinoids, a 2021 review found that it provided little relief against chronic pain and sleep disturbance, and caused several transient [[adverse effect]]s, such as cognitive impairment, [[nausea]], and [[drowsiness]].<ref name="wang2021">{{cite journal | last1=Wang | first1=Li | last2=Hong | first2=Patrick J | last3=May | first3=Curtis | last4=Rehman | first4=Yasir | last5=Oparin | first5=Yvgeniy | last6=Hong | first6=Chris J | last7=Hong | first7=Brian Y | last8=AminiLari | first8=Mahmood | last9=Gallo | first9=Lucas | title=Medical cannabis or cannabinoids for chronic non-cancer and cancer related pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials | journal=BMJ | volume=374 | date=2021-09-09 | pages=n1034 | issn=1756-1833 | pmid=34497047 | doi=10.1136/bmj.n1034 | url=https://www.bmj.com/content/374/bmj.n1034 | doi-access=free | access-date=9 September 2021 | archive-date=9 September 2021 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210909220904/https://www.bmj.com/content/374/bmj.n1034 | url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

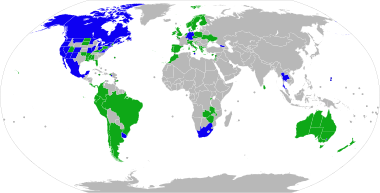

Medicinal use of cannabis is legal in a limited number of territories worldwide, including [[Canada]], [[Austria]], the [[Netherlands]], [[Spain]], [[Israel]], [[Finland]] and [[Portugal]]. In the US, fourteen states have recognized medical marijuana: [[Alaska]], [[California]], [[Colorado]], [[Hawaii]], [[Maine]], [[Michigan]], [[Montana]], [[Nevada]], [[New Jersey]], [[New Mexico]], [[Oregon]], [[Rhode Island]], [[Vermont]] and [[Washington]].<ref>[http://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/viewresource.asp?resourceID=000881 13 Legal Medical Marijuana States: Laws, Fees, and Possession Limits"], ProCon.org. Retrieved April 21, 2009.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://rawstory.com/news/2008/Portugals_drug_decriminalization_bizarrely_underappreciated_Greenwald_0406.html |title=Portugal's drug decriminalization 'bizarrely underappreciated': Greenwald |publisher=The Raw Story |date=2009-04-06 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

<!-- Side effects --> |

|||

Cannabis has a long history of medicinal use in many cultures. The US Government as represented by the [[Health and Human Services]] Division, holds a [[patent]] for medical marijuana.<ref name="patentstorm1">{{cite web|url=http://www.patentstorm.us/patents/6630507.html |title=Cannabinoids as antioxidants and neuroprotectants - US Patent 6630507 Abstract |publisher=Patentstorm.us |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> Yet, medical cannabis remains a controversial issue worldwide. |

|||

Short-term use increases the risk of minor and major adverse effects.<ref name=JAMA2015 /> Common side effects include [[dizziness]], feeling tired, vomiting, and [[hallucination]]s.<ref name=JAMA2015 /> Long-term effects of cannabis are not clear.<ref name=JAMA2015 /> Concerns include memory and cognition problems, risk of addiction, [[schizophrenia]] in young people, and the risk of children taking it by accident.<ref name=Borgelt2013 /> |

|||

Many cultures have used cannabis for therapeutic purposes for thousands of years.<ref name=BenAmar2006>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ben Amar M | title = Cannabinoids in medicine: A review of their therapeutic potential | journal = Journal of Ethnopharmacology | volume = 105 | issue = 1–2 | pages = 1–25 | date = April 2006 | pmid = 16540272 | doi = 10.1016/j.jep.2006.02.001 | type = Review | citeseerx = 10.1.1.180.308 }}</ref> Some American medical organizations have requested removal of cannabis from the list of [[Schedule I controlled substance]]s maintained by the United States federal government, followed by regulatory and scientific review.<ref name="ANA" /><ref name="AAFP" /> Others oppose its legalization, such as the [[American Academy of Pediatrics]].<ref name="AAP" /> |

|||

== Indications == |

|||

===Partial list of clinical applications=== |

|||

[[File:Women's Alliance For Medical Marijuana - Victoria.JPG|thumb|right|"Victoria", the United States' first legal medical marijuana plant grown by The Wo/Men's Alliance for Medical Marijuana <ref>http://www.wamm.org/</ref>.]]Medical cannabis specialist Dr. [[Tod Mikuriya]] recorded over 250 indications for medical cannabis,<ref>http://www.canorml.org/prop/Mikuriya_ICD-9list.pdf</ref> as classified by the [[International Classification of Diseases]] (ICD-9).<ref>Dale Gieringer, "Medical Use of Cannabis in California," in Franjo Grotenhermen, M.D. & Ethan Russo, M.D., ed., Cannabis and Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Toxicology and Therapeutic Potential, Haworth Press, 2002 |

|||

[http://www.canorml.org/prop/MMJIndications.htm]</ref> |

|||

Medical cannabis can be administered through various methods, including [[capsule (pharmacy)|capsules]], [[throat lozenge|lozenge]]s, [[tincture]]s, [[dermal patch]]es, oral or dermal sprays, [[cannabis edible]]s, and [[Vaporizer (inhalation device)|vaporizing]] or [[Cannabis smoking|smoking dried buds]]. Synthetic cannabinoids are available for prescription use in some countries, such as [[dronabinol|synthetic delta-9-THC]] and [[nabilone]]. Countries that [[legality of cannabis|allow the medical use of whole-plant cannabis]] include Argentina, Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Germany, Greece, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and Uruguay. In the United States, 38 states and the District of Columbia have legalized cannabis for medical purposes, beginning with the passage of California's [[Proposition 215]] in 1996.<ref name="NCSL" /> Although cannabis remains prohibited for any use at the federal level, the [[Rohrabacher–Farr amendment]] was enacted in December 2014, limiting the ability of federal law to be enforced in states where medical cannabis has been legalized. |

|||

In a 2002 review of medical literature, medical cannabis was shown to have established effects in the treatment of [[nausea]], [[vomiting]], [[Premenstrual syndrome|PMS]], unintentional [[weight loss]], and [[lack of appetite]]. Other "relatively well-confirmed" effects were in the treatment of "[[spasticity]], painful conditions, especially neurogenic pain, [[movement disorder]]s, [[asthma]], <nowiki>[and]</nowiki> [[Glaucoma]]".<ref name=medboard> |

|||

{{TOC limit|3}} |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.medboardwatch.com/wb/pages/therapeutic-effects.php |

|||

|title=DrFrankLucido.com - Therapeutic Effects |

|||

|publisher=www.medboardwatch.com |

|||

|accessdate=2008-08-08 |

|||

|last= |

|||

|first= |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

== Classification == |

|||

Preliminary findings indicate that cannabis-based drugs could prove useful in treating [[Inflammatory Bowel Disease]] (consisting of [[Crohn's Disease]] and [[Ulcerative Colitis]]),<ref>[http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/28584.php Cannabis-based drugs could offer new hope for [[inflammatory bowel disease]] patients]</ref> [[Migraines]], [[Fibromyalgia]] and related conditions.<ref>http://www.freedomtoexhale.com/clinical.pdf</ref> |

|||

In the U.S., the [[National Institute on Drug Abuse]] defines medical cannabis as "using the whole, unprocessed marijuana plant or its basic extracts to treat symptoms of illness and other conditions".<ref name=nida>{{cite web |publisher= National Institute on Drug Abuse |date= July 2019 |title= Marijuana as Medicine |url= https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana-medicine |access-date= 19 April 2016 |archive-date= 17 April 2016 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160417154854/https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana-medicine |url-status= live }}</ref> |

|||

Medical cannabis has also been found to relieve certain symptoms of [[multiple sclerosis]]<ref>http://www.cmcr.ucsd.edu/geninfo/CannabinoidsMS_Lancet11-03.pdf</ref> and [[spinal cord injuries]] by exhibiting antispasmodic and muscle relaxant properties as well as stimulating appetite. Clinical trials provide evidence that THC reduces motor and vocal tics of [[Tourette’s syndrome]] and related behavioral problems such as [[obsessive-compulsive]] disorders.<ref>http://www.doctordeluca.com/Library/WOD/WPS3-MedMj/CannabinoidsMedMetaAnalysis06.pdf</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2005/12/051226102503.htm |title=Machinery Of The 'Marijuana Munchies' |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2005-12-26 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

A cannabis plant includes more than 400 different chemicals, of which about 70 are [[cannabinoid]]s.<ref name="Consumer Reports April 2016">{{cite web |author1 = Consumer Reports |title = Up in Smoke: Does Medical Marijuana Work? |url = http://www.consumerreports.org/medical-marijuana/does-medical-marijuana-work/ |website = Consumer Reports |access-date = 24 May 2016 |date = 28 April 2016 |archive-date = 14 March 2021 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210314045548/https://www.consumerreports.org/medical-marijuana/does-medical-marijuana-work/ |url-status = live }}</ref> In comparison, typical government-approved medications contain only one or two chemicals.<ref name="Consumer Reports April 2016" /> The number of active chemicals in cannabis is one reason why treatment with cannabis is difficult to classify and study.<ref name="Consumer Reports April 2016" /> |

|||

A 2014 review stated that the variations in ratio of CBD-to-THC in botanical and pharmaceutical preparations determines the therapeutic vs psychoactive effects (CBD attenuates THC's psychoactive effects<ref name="Schubart et al.2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Schubart CD, Sommer IE, Fusar-Poli P, de Witte L, Kahn RS, Boks MP | title = Cannabidiol as a potential treatment for psychosis | journal = European Neuropsychopharmacology | volume = 24 | issue = 1 | pages = 51–64 | date = January 2014 | pmid = 24309088 | doi = 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.11.002 | s2cid = 13197304 | url = http://cannabisclinicians.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/CBD-psychosis-2013.pdf | access-date = 9 July 2016 | archive-date = 20 October 2018 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20181020210452/http://cannabisclinicians.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/CBD-psychosis-2013.pdf }}</ref>) of cannabis products.<ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite journal | vauthors = Koppel BS, Brust JC, Fife T, Bronstein J, Youssof S, Gronseth G, Gloss D | title = Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology | journal = Neurology | volume = 82 | issue = 17 | pages = 1556–1563 | date = April 2014 | pmid = 24778283 | pmc = 4011465 | doi = 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000363 }}</ref> |

|||

Other studies have shown cannabis to be useful in treating: [[Alcoholism]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/30338.php |title=Role of cannabinoid receptors in alcohol abuse, study |publisher=Medicalnewstoday.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[ADD]]<ref>{{cite web|last=Beaucar |first=Kelley |url=http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,117541,00.html |title=Cannabis 'Scrips to Calm Kids? - Politics | Republican Party | Democratic Party | Political Spectrum |publisher=FOXNews.com |date=2004-04-20 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

ALS ([[Lou Gehrig's disease]]),<ref>{{cite web|author=David Kohn, Baltimore Sun |url=http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2004/11/05/MNGV39LE091.DTL&type=printable |title=Researchers buzzing about marijuana-derived medicines / Cannabinoids may help against many diseases |publisher=Sfgate.com |date=2004-11-05 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/entrez?cmd=Retrieve&db=PubMed&dopt=Abstract&list_uids=16183560</ref> |

|||

Collagen-Induced Arthritis ([[CIA]]),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pnas.org/content/97/17/9561.full |title=The nonpsychoactive cannabis constituent cannabidiol is an oral anti-arthritic therapeutic in murine collagen-induced arthritis — PNAS |publisher=Pnas.org |date=2000-08-15 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Rheumatoid Arthritis]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/rheumatoid-arthritis/news/20051108/pot-based-drug-promising-for-arthritis |title=Pot-Based Drug Promising for Arthritis |publisher=Webmd.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Asthma]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/hemp/medical/tashkin/tashkin1.htm |title=Effects of Smoked Marijuana in Experimentally Induced Asthma |publisher=Druglibrary.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Atherosclerosis]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg18624956.000 |title=Cannabis may help keep arteries clear - health - 16 April 2005 |doi=10.1038/nature03389 |publisher=New Scientist |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Autism]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/hemp/medical/can-babies.htm |title=Prenatal Marijuana Exposure and Neonatal Outcomes in Jamaica: An Ethnographic Study |publisher=Druglibrary.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Bipolar Disorder]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ukcia.org/research/TheUseofCannabisasaMoodStabilizerinBipolarDisorder.html |title=The Use of Cannabis as a Mood Stabilizer in Bipolar Disorder |publisher=Ukcia.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15888515?dopt=Abstract&holding=f1000,f1000m,isrctn</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2002/03/05/48hours/main503022.shtml |title=Recipe For Trouble |publisher=CBS News |date=2007-01-15 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Childhood Mental Disorders,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.counterpunch.org/mikuriya07082006.html |title=Dr. Tod Mikuriya: Cannabis as a Frontline Treatment for Childhood Mental Disorders |publisher=Counterpunch.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Colorectal Cancer]],<ref>{{cite web|author=Home |url=http://gut.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/54/12/1741 |title=The endogenous cannabinoid, anandamide, induces cell death in colorectal carcinoma cells: a possible role for cyclooxygenase 2 - Patsos et al. 54 (12): 1741 - Gut |doi=10.1136/gut.2005.073403 |publisher=Gut.bmj.com |date=2005-08-11 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Depression]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,304996,00.html |title=Marijuana Improves Depression in Low Doses, Worsens It in High Doses, Study Says - Health News | Current Health News | Medical News |publisher=FOXNews.com |date=2007-10-25 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>http://www.doctordeluca.com/Library/WOD/WPS3-MedMj/DecreasedDepressionInMjUsers05.pdf</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jci.org/articles/view/25509/version/1 |title=Journal of Clinical Investigation - Cannabinoids promote embryonic and adult hippocampus neurogenesis and produce anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects |publisher=Jci.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pacifier.com/~alive/cmu/depression_and_cannabis.htm |title=AAMC: Cannabis and Depression |publisher=Pacifier.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Diabetic Retinopathy,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2006/02/060227184647.htm |title=Marijuana Compound May Help Stop Diabetic Retinopathy |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2006-02-27 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.defeatdiabetes.org/Articles/retinopathy_marijuana060317.htm |title=Marijuana Compound May Help Stop Diabetic Retinopathy |publisher=Defeat Diabetes |date=2006-03-17 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://ajp.amjpathol.org/cgi/content/abstract/168/1/235 |title=Neuroprotective and Blood-Retinal Barrier-Preserving Effects of Cannabidiol in Experimental Diabetes - El-Remessy et al. 168 (1): 235 - American Journal of Pathology |doi=10.2353/ajpath.2006.050500 |publisher=Ajp.amjpathol.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Dystonia]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=7006 |title=Dystonia |publisher=NORML |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11835452?dopt=Abstract</ref> |

|||

[[Epilepsy]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medpot.net/forums/index.php?showtopic=9686 |title=Marijuana-Like Chemicals in the Brain Calm Neurons - MedPot.net/Forums |publisher=Medpot.net |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Gastrointestinal Disorders,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=7009 |title=Gastrointestinal Disorders |publisher=NORML |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.informapharmascience.com/doi/abs/10.1517/13543784.12.1.39 |title=Informa Pharmaceutical Science - Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs - 12(1):39 - Summary |doi=10.1517/13543784.12.1.39 |publisher=Informapharmascience.com |date=2005-03-02 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Gliomas]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://marijuana.researchtoday.net/archive/6/2/2201.htm |title=Amphiregulin is a factor for resistance of glioma cells to cannabinoid-induced apoptosis |doi=10.1002/glia.20856 |publisher=Marijuana.researchtoday.net |date=2009-02-20 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://jnci.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/100/1/59 |title=Inhibition of Cancer Cell Invasion by Cannabinoids via Increased Expression of Tissue Inhibitor of Matrix Metalloproteinases-1 - Ramer and Hinz 100 (1): 59 - JNCI Journal of the National Cancer Institute |doi=10.1093/jnci/djm268 |publisher=Jnci.oxfordjournals.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Hepatitis C]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=7010 |title=Hepatitis C |publisher=NORML |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://journals.lww.com/eurojgh/pages/articleviewer.aspx?year=2006&issue=10000&article=00005&type=abstract |title=European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology |doi=10.1097/01.meg.0000216934.22114.51 |publisher=Journals.lww.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Huntington's Disease]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.druglibrary.org/schaffer/hemp/medical/cannabid.htm |title=Cannabidiol: The Wonder Drug of the 21st Century? |publisher=Druglibrary.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Hypertension]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thehempire.com/index.php/cannabis/news/lowering_of_blood_pressure_through_use_of_hashish |title=Lowering of Blood Pressure Through Use of Hashish: The Hempire - [cannabis, britain] |publisher=The Hempire |date=2006-06-20 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.thehempire.com/index.php/cannabis/news/blood_pressure_lowered_with_cannabis_component |title=Blood Pressure Lowered With Cannabis Component: The Hempire - [cannabis, uk] |publisher=The Hempire |date=2006-06-15 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Incontinence]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=7012 |title=Incontinence |publisher=NORML |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Leukemia]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org/cgi/content/abstract/105/3/1214 |title=Blood - Cannabis-induced cytotoxicity in leukemic cell lines: the role of the cannab |doi=10.1182/blood-2004-03-1182 |publisher=Bloodjournal.hematologylibrary.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Skin Tumors,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://medicalmarijuana.procon.org/viewresource.asp?resourceID=000884 |title=Peer-Reviewed Studies on Marijuana - Medical Marijuana - ProCon.org |publisher=Medicalmarijuana.procon.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jci.org/articles/view/16116/version/1 |title=Journal of Clinical Investigation - Inhibition of skin tumor growth and angiogenesis in vivo by activation of cannabinoid receptors |doi=10.1038/sj.onc.1201928 |publisher=Jci.org |date=2003-01-01 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Morning Sickness,<ref>http://74.6.239.67/search/cache?ei=UTF-8&p=Vancouver+Island+Compassion+Society%2C+morning+sickness%2C+marijuana&fr=slv8-msgr&u=www.mercycenters.org/libry/info_Mothers.doc&w=vancouver+island+compassion+society+societies+morning+sickness+marijuana&d=KJVscZ2uSZD2&icp=1&.intl=us</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mothering.com/articles/pregnancy_birth/birth_preparation/marijuana.html |title=Mothering Magazine Birth Preparation Article: Medical Marijuana for Severe Morning Sickness |publisher=Mothering.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[MRSA]] (Drug-Resistant Staph Infections),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.technologyreview.com/biomedicine/21366/ |title=A New MRSA Defense |publisher=Technology Review |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/news/20080904/marijuana-chemicals-may-fight-mrsa |title=Marijuana Ingredients May Fight MRSA |publisher=Webmd.com |date=2008-09-04 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=92425 |title=Chemicals in Marijuana May Fight MRSA - Infectious Diseases: Causes, Types, Prevention, Treatment and Facts on |publisher=Medicinenet.com |date=2008-09-04 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Parkinson's]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://med.stanford.edu/news_releases/2007/february/malenka.html |title=Enhancing activity of marijuana-like chemicals in brain helps treat Parkinson's symptoms in mice, Stanford study finds - Office of Communications & Public Affairs - Stanford University School of Medicine |publisher=Med.stanford.edu |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Pruritus]],<ref>{{cite web|author=Michael Hess |url=http://bbsnews.net/article.php/20051211212223236 |title=Science: Cream with endocannabinoids effective in the treatment of pruritus due to kidney disease |publisher=BBSNews |date=2005-12-11 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com/science?_ob=ArticleURL&_udi=B6W7C-4H8FTRF-2&_user=10&_rdoc=1&_fmt=&_orig=search&_sort=d&view=c&_acct=C000050221&_version=1&_urlVersion=0&_userid=10&md5=b5834b8cb12cdee2e01a3910314feb79 |title=Journal of Hepatology : The pruritus of cholestasis |doi=10.1016/j.jhep.2005.09.004 |publisher=ScienceDirect |date=2005-10-06 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[PTSD]] (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn2616-natural-high-helps-banish-bad-memories.html |title=Natural high helps banish bad memories - 31 July 2002 |publisher=New Scientist |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://salem-news.com/articles/june142007/leveque_61407.php |title=Medical Marijuana: PTSD Medical Malpractice |publisher=Salem-News.Com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cannabis-med.org/english/bulletin/ww_en_db_cannabis_artikel.php?id=123#1 |title=IACM-Bulletin |publisher=Cannabis-med.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

[[Sickle Cell Disease]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pacifier.com/~alive/cmu/Sickle_cell.htm |title=AAMC: Those who suffer from sickle-cell disease experience painful episodes or attacks |publisher=Pacifier.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> and |

|||

[[Sleep Apnea]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=5323 |title=Pot Constituents Dramatically Reduce Sleep Apnea, Study Says |publisher=NORML |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12071539?dopt=Abstract</ref> |

|||

== Medical uses == |

|||

===Recent studies=== |

|||

[[File:Cannabis sativa (Köhler).jpg|thumb|right|''Cannabis'' as illustrated in Köhler's ''Book of Medicinal Plants'', 1897]] |

|||

====Alzheimer's Disease==== |

|||

Overall, research into the health effects of medical cannabis has been of low quality and it is not clear whether it is a useful treatment for any condition, or whether harms outweigh any benefit.<ref name=pratt>{{cite journal |vauthors=Pratt M, Stevens A, Thuku M, Butler C, Skidmore B, Wieland LS, Clemons M, Kanji S, Hutton B |title=Benefits and harms of medical cannabis: a scoping review of systematic reviews |journal=Syst Rev |volume=8 |issue=1 |page=320 |date=December 2019 |pmid=31823819 |pmc=6905063 |doi=10.1186/s13643-019-1243-x |type=Systematic review |doi-access=free }}</ref> There is no consistent evidence that it helps with [[chronic pain]] and [[spasticity|muscle spasms]].<ref name=pratt /> |

|||

Research done by the [[Scripps Research Institute]] in California shows that the active ingredient in marijuana, [[THC]], may prevent the formation of deposits in the brain associated with [[Alzheimer's disease]]. THC was found to prevent an enzyme called [[acetylcholinesterase]] from accelerating the formation of "Alzheimer plaques" in the brain more effectively than commercially marketed drugs. THC is also more effective at blocking clumps of protein that can inhibit memory and cognition in Alzheimer’s patients, as reported in [[Molecular Pharmaceutics]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.scripps.edu/news/press/080906.html |title=The Scripps Research Institute |publisher=Scripps.edu |date=2006-08-09 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=7:10 p.m. ET |url=http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15145917/ |title=Marijuana may help stave off Alzheimer’s - Alzheimer's Disease- msnbc.com |publisher=MSNBC |date=2006-10-10 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Low quality evidence suggests its use for reducing [[antiemetic|nausea]] during [[chemotherapy]], improving appetite in [[HIV/AIDS]], improving sleep, and improving [[tic]]s in [[Tourette syndrome]].<ref name=JAMA2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, Di Nisio M, Duffy S, Hernandez AV, Keurentjes JC, Lang S, Misso K, Ryder S, Schmidlkofer S, Westwood M, Kleijnen J | title = Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis | journal = JAMA | volume = 313 | issue = 24 | pages = 2456–73 | date = 23 June 2015 | pmid = 26103030 | doi = 10.1001/jama.2015.6358 | doi-access = free | hdl = 10757/558499 | hdl-access = free }}</ref> When usual treatments are ineffective, [[cannabinoid]]s have also been recommended for [[anorexia]], [[arthritis]], [[glaucoma]],<ref name="Sachs et al. 2015" /> and [[migraine]].<ref name="Distillations">{{cite web |title=Sex(ism), Drugs, and Migraines: Distillations Podcast and Transcript, Episode 237 |date=15 January 2019 |url=https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/podcast/sexism-drugs-and-migraines |website=Distillations |publisher=[[Science History Institute]] |access-date=28 August 2019 |archive-date=14 March 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210314045616/https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/podcast/sexism-drugs-and-migraines |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

====Neuron growth==== |

|||

It is unclear whether American states might be able to mitigate the adverse effects of the [[opioid epidemic]] by prescribing medical cannabis as an alternative pain management drug.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Gilson |first1=Aaron M. |last2=LeBaron |first2=Virginia T. |last3=Vyas |first3=Marianne Beare |title=The use of cannabis in response to the opioid crisis: A review of the literature |journal=Nursing Outlook |date=1 January 2018 |volume=66 |issue=1 |pages=56–65 |pmid=28993073 |doi=10.1016/j.outlook.2017.08.012 |issn=0029-6554}}</ref> |

|||

A Canadian study shows Marijuana promotes [[neuron]] growth. The [[Neuropsychiatry]] Research Unit at the [[University of Saskatchewan]] suggests the drug could have some benefits when administered regularly in a highly potent form. Whereas most "social drugs" such as [[alcohol]], [[heroin]], [[cocaine]] and [[nicotine]] suppress growth of new [[brain cells]], the researchers found that cannabinoids promoted generation of new neurons in rats' hippocampuses (the part of the brain responsible for learning and memory). The study held true for either plant-derived or synthetic versions of cannabinoids. The findings were published in the 2005 November issue of the [[Journal of Clinical Investigation]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://english.ohmynews.com/articleview/article_view.asp?menu=c10400&no=253377&rel_no=1 |title=Study Shows Marijuana Promotes Neuron Growth - OhmyNews International |publisher=English.ohmynews.com |date=2005-10-17 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Cannabis should not be used in [[pregnancy]].<ref>{{cite journal | author = American College of Obstetricians Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice | title = Committee Opinion No. 637: Marijuana Use During Pregnancy and Lactation | journal = Obstetrics and Gynecology | volume = 126 | issue = 1 | pages = 234–38 | date = July 2015 | pmid = 26241291 | doi = 10.1097/01.AOG.0000467192.89321.a6 }}</ref> |

|||

====Lung cancer and COPD==== |

|||

=== Insomnia === |

|||

[[THC]] has been found to reduce tumor growth in common [[lung cancer]] by 50 percent and to significantly reduce the ability of the cancer to spread, say researchers at [[Harvard University]], who tested the chemical in both lab and mouse studies. The researchers suggest that THC might be used in a targeted fashion to treat lung cancer. <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/04/070417193338.htm |title=Marijuana Cuts Lung Cancer Tumor Growth In Half, Study Shows |publisher=Sciencedaily.com |date=2007-04-17 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Research analyzing data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) did not find significant differences in sleep duration between cannabis users and non-users. This suggests that some individuals may perceive benefits from cannabis use in terms of sleep, it may not significantly change overall sleep patterns across the general population.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Diep |first1=Calvin |last2=Tian |first2=Chenchen |last3=Vachhani |first3=Kathak |last4=Won |first4=Christine |last5=Wijeysundera |first5=Duminda N. |last6=Clarke |first6=Hance |last7=Singh |first7=Mandeep |last8=Ladha |first8=Karim S. |date=2021-11-24 |title=Recent cannabis use and nightly sleep duration in adults: a population analysis of the NHANES from 2005 to 2018 |url=https://rapm.bmj.com/content/early/2021/11/24/rapm-2021-103161 |journal=Regional Anesthesia & Pain Medicine |volume=47 |issue=2 |pages=100–104 |language=en |doi=10.1136/rapm-2021-103161 |issn=1098-7339 |pmid=34873024}}</ref> |

|||

A review of literature up to 2018 indicates that cannabidiol (CBD) may have therapeutic potential for the treatment of insomnia. CBD, a non-psychoactive component of cannabis, is of particular interest due to its potential to influence sleep without the psychoactive effects associated with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC).<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Walsh |first1=Jennifer H |last2=Maddison |first2=Kathleen J |last3=Rankin |first3=Tim |last4=Murray |first4=Kevin |last5=McArdle |first5=Nigel |last6=Ree |first6=Melissa J |last7=Hillman |first7=David R |last8=Eastwood |first8=Peter R |date=2021-11-12 |title=Treating insomnia symptoms with medicinal cannabis: a randomized, crossover trial of the efficacy of a cannabinoid medicine compared with placebo |journal=SLEEP |language=en |volume=44 |issue=11 |doi=10.1093/sleep/zsab149 |issn=0161-8105 |pmc=8598183 |pmid=34115851}}</ref> |

|||

In 2006, Donald Tashkin, M.D., of the [[University of California in Los Angeles]], presented the results of his study, ''Marijuana Use and Lung Cancer: Results of a Case-Control Study''. Tashkin found that smoking marijuana does not appear to increase the risk of lung cancer or head-and-neck malignancies, even among heavy users. The more tobacco a person smoked, the greater their risk of developing lung cancer and other cancers of the head and neck. But people who smoked more marijuana were not at increased risk compared with people who smoked less and people who didn’t smoke at all.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/lung-cancer/news/20060523/pot-smoking-not-linked-to-lung-cancer |title=Pot Smoking Not Linked to Lung Cancer |publisher=Webmd.com |date=2006-05-23 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> Marijuana use was associated with cancer risk ratios below 1.0, indicating that a history of pot smoking had no effect on the risk for respiratory cancers. In contrast, [[tobacco]] smoking had a 21-fold risk for cancer. Tashkin concluded, "It's possible that [[tetrahydrocannabinol]] (THC) in marijuana smoke may encourage [[apoptosis]], or programmed cell death, causing cells to die off before they have a chance to undergo malignant transformation".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/05/25/AR2006052501729.html?referrer=digg |title=Study Finds No Cancer-Marijuana Connection |publisher=washingtonpost.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.medpagetoday.com/HematologyOncology/LungCancer/3393 |title=Medical News: ATS: Marijuana Smoking Found Non-Carcinogenic - in Hematology/Oncology, Lung Cancer from |publisher=MedPage Today |date=2006-05-24 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

=== Nausea and vomiting === |

|||

Similar findings were released in April 2009 by the Vancouver Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease Research Group. The study presents that smoking both tobacco and marijuana synergistically increased the risk of respiratory symptoms and [[COPD]]. Smoking only marijuana, however, was not associated with an increased risk of respiratory symptoms of COPD.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.physorg.com/news158861123.html |title=Marijuana smoking increases risk of COPD for tobacco smokers |publisher=Physorg.com |date=2009-04-13 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>[http://www.cmaj.ca/press/pg814.pdf ]{{dead link|date=April 2009}}</ref> In a related commentary, Dr. Donald Tashkin writes that "we can be close to concluding that marijuana smoking by itself does not lead to COPD".<ref>[http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/145921.php</ref> |

|||

Medical cannabis is somewhat effective in [[chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting]] (CINV)<ref name=Borgelt2013 /><ref name="Sachs et al. 2015">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sachs J, McGlade E, Yurgelun-Todd D | title = Safety and Toxicology of Cannabinoids | journal = Neurotherapeutics | volume = 12 | issue = 4 | pages = 735–46 | date = October 2015 | pmid = 26269228 | pmc = 4604177 | doi = 10.1007/s13311-015-0380-8 }}</ref> and may be a reasonable option in those who do not improve following preferential treatment.<ref name=Grotenhermen2012 /> Comparative studies have found cannabinoids to be more effective than some conventional antiemetics such as [[prochlorperazine]], [[promethazine]], and [[metoclopramide]] in controlling CINV,<ref name=Bowels2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bowles DW, O'Bryant CL, Camidge DR, Jimeno A | title = The intersection between cannabis and cancer in the United States | journal = Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology | volume = 83 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–10 | date = July 2012 | pmid = 22019199 | doi = 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2011.09.008 | type = Review }}</ref> but these are used less frequently because of side effects including dizziness, dysphoria, and hallucinations.<ref name=Wang2008>{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang T, Collet JP, Shapiro S, Ware MA | title = Adverse effects of medical cannabinoids: a systematic review | journal = CMAJ | volume = 178 | issue = 13 | pages = 1669–78 | date = June 2008 | pmid = 18559804 | pmc = 2413308 | doi = 10.1503/cmaj.071178 | type = Review }}</ref><ref name=Jordan2007>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jordan K, Sippel C, Schmoll HJ | title = Guidelines for antiemetic treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: past, present, and future recommendations | journal = The Oncologist | volume = 12 | issue = 9 | pages = 1143–50 | date = September 2007 | pmid = 17914084 | doi = 10.1634/theoncologist.12-9-1143 | s2cid = 17612434 | type = Review | url = http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d98c/026bda42b4b6ea1b0286d1893b362b46cca4.pdf | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20190307023741/http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d98c/026bda42b4b6ea1b0286d1893b362b46cca4.pdf | archive-date = 2019-03-07 }}</ref> Long-term cannabis use may cause nausea and vomiting, a condition known as [[cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome]] (CHS).<ref name=Nicolson2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Nicolson SE, Denysenko L, Mulcare JL, Vito JP, Chabon B | title = Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: a case series and review of previous reports | journal = Psychosomatics | volume = 53 | issue = 3 | pages = 212–19 | date = May–Jun 2012 | pmid = 22480624 | doi = 10.1016/j.psym.2012.01.003 | type = Review, case series }}</ref> |

|||

A 2016 [[Cochrane Collaboration|Cochrane review]] said that cannabinoids were "probably effective" in treating chemotherapy-induced nausea in children, but with a high side-effect profile (mainly drowsiness, dizziness, altered moods, and increased appetite). Less common side effects were "ocular problems, orthostatic hypotension, muscle twitching, pruritus, vagueness, hallucinations, lightheadedness and dry mouth".<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Phillips RS, Friend AJ, Gibson F, Houghton E, Gopaul S, Craig JV, Pizer B | title = Antiemetic medication for prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in childhood | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2016 | pages = CD007786 | date = February 2016 | issue = 2 | pmid = 26836199 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD007786.pub3 | pmc = 7073407 | url = http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/95658/1/Phillips_et_al_2016_The_Cochrane_library.sup_2.pdf | access-date = 23 September 2019 | archive-date = 30 June 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210630071713/https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/95658/1/Phillips_et_al_2016_The_Cochrane_library.sup_2.pdf | url-status = live }}</ref> |

|||

====Breast cancer==== |

|||

=== HIV/AIDS === |

|||

According to a 2007 study by scientists at the California Pacific Medical Center Research Institute, a compound found in cannabis may stop [[breast cancer]] from spreading throughout the body.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.foxnews.com/story/0,2933,312132,00.html |title=Marijuana Compound May Stop Breast Cancer From Spreading, Study Says - Health News | Current Health News | Medical News |publisher=FOXNews.com |date=2007-11-19 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=cc |url=http://www.cpmc.org/professionals/research/programs/science/sean.html |title=Sean D. McAllister, PhD-Research in treament of aggressive breast cancers |publisher=Cpmc.org |date=2007-11-01 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> The scientists believe their discovery may provide a non-toxic alternative to [[chemotherapy]] while achieving the same results minus the painful and unpleasant [[side effects]]. The research team say that [[cannabidiol]] or CBD works by blocking the activity of a gene called Id-1, which is believed to be responsible for a process called [[metastasis]], which is the aggressive spread of cancer cells away from the original tumor site.<ref>{{cite web|author= |url=http://www.news-medical.net/?id=32724 |title=Cannabis compound may stop breast cancer spreading |publisher=News-medical.net |date=2007-11-20 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

Evidence is lacking for both efficacy and safety of cannabis and cannabinoids in treating patients with [[HIV/AIDS]] or for [[Anorexia nervosa|anorexia]] associated with AIDS. As of 2013, current studies suffer from the effects of bias, small sample size, and lack of long-term data.<ref name=Lutge2013>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lutge EE, Gray A, Siegfried N | title = The medical use of cannabis for reducing morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV/AIDS | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 4 | issue = 4 | pages = CD005175 | date = April 2013 | pmid = 23633327 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD005175.pub3 | type = Review }}</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Pain === |

||

A 2021 review found little effect of using non-inhaled cannabis to relieve chronic pain.<ref name=wang2021/> According to a 2019 systematic review, there have been inconsistent results of using cannabis for neuropathic pain, spasms associated with [[multiple sclerosis]] and pain from [[rheumatic]] disorders, but was not effective treating chronic cancer pain. The authors state that additional [[randomized controlled trials]] of different cannabis products are necessary to make conclusive recommendations.<ref name=pratt/> |

|||

Investigators at [[Columbia University]] published clinical trial data in 2007 showing that [[HIV/AIDS]] patients who inhaled cannabis four times daily experienced substantial increases in food intake with little evidence of discomfort and no impairment of cognitive performance. They concluded that smoked marijuana has a clear medical benefit in HIV-positive patients.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.norml.org/index.cfm?Group_ID=7485#10 |title=Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) |publisher=NORML |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/abstract/139/4/258 |title=Short-Term Effects of Cannabinoids in Patients with HIV-1 Infection: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial - Abrams et al. 139 (4): 258 - Annals of Internal Medicine |publisher=Annals.org |date=2003-08-19 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

In another study in 2008, researchers at the [[University of California, San Diego School of Medicine]] found that marijuana significantly reduces HIV-related [[neuropathic pain]] when added to a patient's already-prescribed pain management regimen and may be an "effective option for pain relief" in those whose pain is not controlled with current medications. Mood disturbance, physical disability, and quality of life all improved significantly during study treatment.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/news/20080805/marijuana-eases-nerve-pain-due-to-hiv |title=Marijuana Eases Nerve Pain Due to HIV |publisher=Webmd.com |date=2008-08-06 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://pain-topics.org/news_research_updates/issue16.php#Pot |title=News Research Updates July-August 2008 |publisher=Pain-topics.org |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> No serious adverse effects were reported, according to the study published by the [[American Academy of Neurology]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.neurology.org/cgi/content/abstract/68/7/515 |title=Cannabis in painful HIV-associated sensory neuropathy: A randomized placebo-controlled trial - Abrams et al. 68 (7): 515 |doi=10.1212/01.wnl.0000253187.66183.9c |publisher=Neurology |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

When cannabis is inhaled to relieve pain, blood levels of cannabinoids rise faster than when oral products are used, peaking within three minutes and attaining an analgesic effect in seven minutes.<ref name="aviram">{{cite journal | vauthors = Aviram J, Samuelly-Leichtag G | title = Efficacy of Cannabis-Based Medicines for Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials | journal = Pain Physician | volume = 20 | issue = 6 | pages = E755–96 | date = September 2017 | doi = 10.36076/ppj.20.5.E755 | pmid = 28934780 | url = http://www.painphysicianjournal.com/current/pdf?article=NDYwNA%3D%3D&journal=107 | doi-access = free | access-date = 12 January 2018 | archive-date = 30 June 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210630092212/https://www.painphysicianjournal.com/current/pdf?article=NDYwNA%3D%3D&journal=107 | url-status = live }}</ref> |

|||

====Brain cancer==== |

|||

A 2011 review considered cannabis to be generally safe,<ref name=Lyn2011>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lynch ME, Campbell F | title = Cannabinoids for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain; a systematic review of randomized trials | journal = British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology | volume = 72 | issue = 5 | pages = 735–44 | date = November 2011 | pmid = 21426373 | pmc = 3243008 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03970.x | type = Review }}</ref> and it appears safer than [[opioid]]s in palliative care.<ref name=Carter2011>{{cite journal | vauthors = Carter GT, Flanagan AM, Earleywine M, Abrams DI, Aggarwal SK, Grinspoon L | title = Cannabis in palliative medicine: improving care and reducing opioid-related morbidity | journal = The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care | volume = 28 | issue = 5 | pages = 297–303 | date = August 2011 | pmid = 21444324 | doi = 10.1177/1049909111402318 | s2cid = 19980960 | type = Review }}</ref> |

|||

A study by [[Complutense University of Madrid]] found the active chemical in marijuana promotes the death of [[brain cancer]] cells by essentially helping them feed upon themselves in a process called [[autophagy]]. The research team discovered that cannabinoids such as THC had anticancer effects in mice with human brain cancer cells and in people with brain tumors. When mice with the human brain cancer cells received the THC, the tumor shrank. Using [[electron microscopes]] to analyze brain tissue taken both before and after a 26- to 30-day THC treatment regimen, the researchers found that THC eliminated cancer cells while leaving healthy cells intact.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.forbes.com/feeds/hscout/2009/04/01/hscout625697.html |title=Active Ingredient in Marijuana Kills Brain Cancer Cells |publisher=Forbes.com |date= |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> The patients did not have any toxic effects from the treatment; previous studies of THC for the treatment of cancer have also found the therapy to be well tolerated. However, the mechanisms which promote THC's tumor cell–killing action are unknown.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2009/04/02/health/webmd/main4913095.shtml?source=RSSattr=Health_4913095 |title=Marijuana Chemical May Fight Brain Cancer |publisher=CBS News |date=2009-04-04 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> |

|||

A 2022 review concluded the pain relief experienced after using medical cannabis is due to the [[placebo effect]], especially given widespread media attention that sets the expectation for pain relief.<ref>{{cite journal |journal=JAMA Network Open |date=November 28, 2022 |title=Placebo Response and Media Attention in Randomized Clinical Trials Assessing Cannabis-Based Therapies for PainA Systematic Review and Meta-analysis |author1=Filip Gedin |author2=Sebastian Blomé |author3=Moa Pontén |author4=Maria Lalouni |author5=Jens Fust |author6=Andreé Raquette |author7=Viktor Vadenmark Lundquist |author8=William H. Thompson |author9=Karin Jensen |volume=5 |issue=11 |pages=e2243848 |doi=10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.43848 |pmid=36441553 |pmc=9706362 |doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

The researchers believe their findings may have therapeutic implications in the treatment of cancer, as detailed in their study, ''Cannabinoid action induces autophagy-mediated cell death through stimulation of ER stress in human glioma cells'',<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jci.org/articles/view/37948 |title=Journal of Clinical Investigation - Cannabinoid action induces autophagy-mediated cell death through stimulation of ER stress in human glioma cells |doi=10.1172/JCI37948DS1 |publisher=Jci.org |date=2009-04-01 |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> which appeared in the April 2009 issue of the [[Journal of Clinical Investigation]]. |

|||

=== |

===Neurological conditions=== |

||

Cannabis' efficacy is not clear in treating neurological problems, including [[multiple sclerosis]] (MS) and movement problems.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> Evidence also suggests that oral cannabis extract is effective for reducing patient-centered measures of spasticity.<ref name="ReferenceA"/> A trial of cannabis is deemed to be a reasonable option if other treatments have not been effective.<ref name=Borgelt2013 />{{By whom|date=April 2017}} Its use for MS is approved in ten countries.<ref name=Borgelt2013 /><ref name=Clark2011>{{cite journal | vauthors = Clark PA, Capuzzi K, Fick C | title = Medical marijuana: medical necessity versus political agenda | journal = Medical Science Monitor | volume = 17 | issue = 12 | pages = RA249–61 | date = December 2011 | pmid = 22129912 | pmc = 3628147 | doi = 10.12659/MSM.882116 | type = Review }}</ref>{{COI source|date=December 2013}} A 2012 review found no problems with tolerance, abuse, or addiction.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Oreja-Guevara C | title = [Treatment of spasticity in multiple sclerosis: new perspectives regarding the use of cannabinoids] | language = es | journal = Revista de Neurología | volume = 55 | issue = 7 | pages = 421–30 | date = October 2012 | pmid = 23011861 | type = Review }}</ref> In the United States, [[cannabidiol]], one of the cannabinoids found in the marijuana plant, has been approved for treating two severe forms of epilepsy, [[Lennox-Gastaut syndrome]] and [[Dravet syndrome]].<ref name=":4">{{Cite journal|last=Commissioner|first=Office of the|date=2019-06-10|title=FDA and Marijuana|url=https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-marijuana|journal=FDA|language=en|access-date=16 December 2019|archive-date=16 November 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191116160049/https://www.fda.gov/news-events/public-health-focus/fda-and-marijuana|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Medical Marijuana has been shown to display neuroprotective properties with the 2-Arachidonoyl glycerol compound. This compound has been shown in lab experiments with mice to lower the amount of secondary damages from head injuries and speed up recovery time and effectiveness.<ref>http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11586361</ref> |

|||

=== Mental health === |

|||

{| class="wikitable sortable" border="1" |

|||

{{Further|Cannabis use and trauma|Posttraumatic stress disorder#Cannabinoids}} |

|||

|- |

|||

! Indication !! Benefit |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center></center><center>[[Alzheimer's]]</center> || <center>Prevents formation of "Alzheimer plaques"</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center></center><center>[[Arthritis]]</center> || <center>[[Analgesic]], [[antiinflammatory]]</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center></center><center>[[Asthma]]</center> || <center>Opens up airways in lungs</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center></center><center>[[Brain Cancer]]</center> || <center>Reduces tumors, kills cancer cells</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center></center><center>[[Breast Cancer]]</center> || <center>Stops cancer from spreading</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center>[[Major depressive disorder|Depression]]</center><center></center> || <center>Brightens [[mood]]</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center>[[Glaucoma]]</center><center></center> || <center>Reduces eye pressure</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center></center><center>[[Head Injuries]]</center> || <center>Neuroprotective properties, speeds recovery time</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center></center><center>[[HIV]]</center> || <center>Reduces neuropathic pain, improves appetite and sleep</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center></center><center>[[Hypertension]]</center> || <center>Lowers blood pressure</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center></center><center>[[Lung Cancer]]</center> || <center>Reduces tumors, slows cancer growth</center> |

|||

|- |

|||

| <center>[[Pain]]</center><center></center> || <center>Non-opiate, non-addictive pain killer</center> |

|||

|} |

|||

A 2019 systematic review found that there is a lack of evidence that cannabinoids are effective in treating [[depressive disorder|depressive]] or [[anxiety disorder]]s, [[attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder]] (ADHD), [[Tourette syndrome]], [[post-traumatic stress disorder]], or [[psychosis]].<ref name=black>{{cite journal |vauthors=Black N, Stockings E, Campbell G, Tran LT, Zagic D, Hall WD, Farrell M, Degenhardt L |title=Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis |journal=Lancet Psychiatry |volume=6 |issue=12 |pages=995–1010 |date=2019 |pmid=31672337 |doi=10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30401-8 |pmc=6949116 |type=Systematic review & meta-analysis}}</ref> |

|||

==Medicinal compounds== |

|||

[[Image:Cannabidiol.png|thumb|right|[[Cannabidiol]] has many positive effects.]] |

|||

[[Image:Beta-Caryophyllen.svg|thumb|right|upright|β-Caryophyllene has important anti-inflammatory properties.]] |

|||

===Cannabidiol=== |

|||

{{main|cannabidiol}} |

|||

[[Cannabidiol]], also known as "CBD", is a major constituent of medical cannabis. CBD represents up to 40% of [[extract]]s of the medical cannabis plant.<ref name="Grlie_1976">{{cite journal |

|||

| last =Grlie |

|||

| first = L |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| coauthors = |

|||

| title =A comparative study on some chemical and biological characteristics of various samples of cannabis resin |

|||

| journal =Bulletin on Narcotics |

|||

| volume =14 |

|||

| issue = |

|||

| pages =37–46 |

|||

| publisher = |

|||

| year = 1976 |

|||

| url = |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| accessdate = }}</ref> Cannabidiol relieves [[convulsion]], [[inflammation]], [[anxiety]], [[nausea]], and inhibits [[cancer cell]] growth.<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

|author=Mechoulam R, Peters M, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Hanus LO |

|||

|title=Cannabidiol - recent advances |

|||

|journal=Chemistry & Biodiversity |

|||

|volume=4 |

|||

|issue=8 |

|||

|pages=1678–1692 |

|||

|year=2007 |

|||

|month=August |

|||

|pmid=17712814 |

|||

|doi=10.1002/cbdv.200790147}}</ref> Recent studies have shown cannabidiol to be as effective as [[atypical antipsychotics]] in treating [[schizophrenia]].<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Zuardi |

|||

| first = A.W |

|||

| coauthors = J.A.S. Crippa, J.E.C. Hallak, F.A. Moreira, F.S. Guimarães |

|||

| title = Cannabidiol as an antipsychotic drug |

|||

| journal = Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research |

|||

| year = 2006 |

|||

| volume = 39 |

|||

| pages = 421–429 |

|||

| url = http://www.scielo.br/pdf/bjmbr/v39n4/6164.pdf |

|||

|format=PDF| issn = ISSN 0100-879X }}</ref> |

|||

In November 2007 it was reported that CBD reduces growth of aggressive human [[breast cancer]] cells ''[[in vitro]]'' and reduces their invasiveness. It thus represents the first non-toxic exogenous agent that can lead to down-regulation of tumor aggressiveness.<ref name="pmid18025276">{{cite journal |

|||

|author=McAllister SD, Christian RT, Horowitz MP, Garcia A, Desprez PY |

|||

|title=Cannabidiol as a novel inhibitor of Id-1 gene expression in aggressive breast cancer cells |

|||

|journal=Mol. Cancer Ther. |

|||

|volume=6 |

|||

|issue=11 |

|||

|pages=2921–7 |

|||

|year=2007 |

|||

|pmid=18025276 |

|||

|doi=10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0371 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/7098340.stm Article] on [[BBC]] site</ref> It is also a [[neuroprotective]] [[antioxidant]].<ref name="antioxidant 1998">[http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=20965 Cannabidiol and (−)Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol are neuroprotective antioxidants], A. J. Hampson, M. Grimaldi, J. Axelrod, and D. Wink, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 July 7; 95(14): 8268–8273.</ref> |

|||

Research indicates that cannabis, particularly CBD, may have anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) effects. A study found that CBD significantly reduced anxiety during a simulated public speaking test for individuals with social anxiety disorder. However, the relationship between cannabis use and anxiety symptoms is complex, and while some users report relief, the overall evidence from observational studies and clinical trials remains inconclusive. Cannabis is often used by people to cope with anxiety, yet the efficacy and safety of cannabis for treating anxiety disorders is yet to be researched.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-04-10 |title=Anxiety and Cannabis: A Review of Recent Research |url=https://drexel.edu/cannabis-research/research/research-highlights/2023/April/anxiety_cannabis_fact_sheet/ |access-date=2024-04-09 |website=Medical Cannabis Research Center |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Sarris |first1=Jerome |last2=Sinclair |first2=Justin |last3=Karamacoska |first3=Diana |last4=Davidson |first4=Maggie |last5=Firth |first5=Joseph |date=2020-01-16 |title=Medicinal cannabis for psychiatric disorders: a clinically-focused systematic review |journal=BMC Psychiatry |volume=20 |issue=1 |page=24 |doi=10.1186/s12888-019-2409-8 |doi-access=free |issn=1471-244X |pmc=6966847 |pmid=31948424}}</ref> |

|||

===β-Caryophyllene=== |

|||

{{main|beta-Caryophyllene}} |

|||

Part of the mechanism by which medical cannabis has been shown to reduce tissue [[inflammation]] is via a compound called β-caryophyllene.<ref name="caryo"> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/07/080720222549.htm |

|||

|title=Why Cannabis Stems Inflammation |

|||

|publisher=www.sciencedaily.com |

|||

|accessdate=2008-08-21 |

|||

|last= |

|||

|first= |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> A cannabinoid [[receptor (biology)|receptor]] called [[CB2 receptor|CB2]] plays a vital part in reducing inflammation in humans and other animals.<ref name="caryo"/> β-Caryophyllene has been shown to be a selective activator of the CB2 receptor.<ref name="caryo"/> β-Caryophyllene is especially concentrated in [[cannabis flower essential oil|cannabis essential oil]], which contains about 12–35% β-caryophyllene.<ref name="caryo"/> |

|||

Cannabis use, especially at high doses, is associated with a higher risk of psychosis, particularly in individuals with a genetic predisposition to psychotic disorders like schizophrenia. Some studies have shown that cannabis can trigger a temporary psychotic episode, which may increase the risk of developing a psychotic disorder later.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |last=Abuse |first=National Institute on Drug |date=2023-05-08 |title=Is there a link between marijuana use and psychiatric disorders? {{!}} National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) |url=https://nida.nih.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana/there-link-between-marijuana-use-psychiatric-disorders |access-date=2024-04-09 |website=nida.nih.gov |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

==Pharmacologic THC and THC derivatives== |

|||

<!-- Image with inadequate rationale removed: [[Image:Sativex - Canadian box front.jpg|thumb|Canadian case of [[Sativex]] vials; the world's first artificial pharmaceutical prescription medicine derived from cannabis. Used as a mouth spray, it was first approved in Canada as adjunctive treatment for the symptomatic relief of neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis and other conditions.]] --> |

|||

In the USA, the FDA has approved two cannabinoids for use as medical therapies: [[dronabinol]] (Marinol) and [[nabilone]]. It is important to note that these medicines are not smoked. [[Dronabinol]] is a synthetic THC medication,<ref>[http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/ANS00457.html FDA Press Release]</ref> while [[nabilone]] is a synthetic cannabinoid marketed under the brand name [[nabilone|Cesamet]]. |

|||

The impact of cannabis on depression is less clear. Some studies suggest a potential increase in depression risk among adolescents who use cannabis though findings are inconsistent across studies.<ref name=":5" /> |

|||

These medications are usually used when first line treatments for nausea fail to work. In extremely high doses and in rare cases there is a possibility of "[[psychotomimetic]]" side effects. The other commonly-used antiemetic drugs are not associated with these side effects. |

|||

== Adverse effects == |

|||

The prescription drug [[Sativex]], an extract of cannabis administered as a sublingual spray, has been approved in [[Canada]] for the adjunctive treatment (use along side other medicines) of both [[multiple sclerosis]]<ref name="SativexC">Koch, W. 23 Jun 2005. [http://www.usatoday.com/news/health/2005-06-23-pot-spray_x.htm Spray alternative to pot on the market in Canada]. ''USA Today'' (online). Retrieved on 27 February 2007</ref> and [[cancer]] related pain.<ref> |

|||

[[File:American medical hashish(10).jpg|thumb|right|American medical hashish]] |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.drugdevelopment-technology.com/projects/sativex/ |

|||

|title=Sativex - Investigational Cannabis-Based Treatment for Pain and Multiple Sclerosis Drug Development Technology |

|||

|publisher=www.drugdevelopment-technology.com |

|||

|accessdate=2008-08-08 |

|||

|last= |

|||

|first= |

|||

}} |

|||

</ref> This medication may now be legally imported into the [[United Kingdom]] and [[Spain]] on prescription.<ref name="SativexEu">{{cite web|url=http://stopthedrugwar.org/chronicle/411/sativex.shtml|title=Europe: Sativex Coming to England, Spain|accessdate=2006-03-25}}</ref> Dr. William Notcutt is one of the chief researchers that has developed Sativex, and he has been working with GW and founder Geoffrey Guy since the company's inception in 1998. Notcutt states that the use of MS as the disease to study "had everything to do with politics."<ref name="Respectable Reefer">{{cite news|last=Greenberg|first=Gary|title=Respectable Reefer|publisher=Mother Jones|date=2005-11-01|url=http://www.motherjones.com/news/feature/2005/11/Respectable_Reefer-3.html|accessdate=2007-04-03}}</ref> |

|||

Scientists are also working on drugs that prevent naturally occurring enzymes from blocking pain-relieving cannabinoid receptors such as 2-arachidonoylgylcerol (2-AG).<ref>Cosmos Online - Cannabis-like drug dims pain without high <http://www.cosmosmagazine.com/news/2366/cannabis-drug-dims-pain-without-high></ref> |

|||

=== Medical use === |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

There is insufficient data to draw strong conclusions about the safety of medical cannabis.<ref name=oxpain>{{cite book |first1 = Tabitha A. |last1 = Washington |first2 = Khalilah M. |last2 = Brown |first3 = Gilbert J. |last3 = Fanciullo |title = Pain |chapter = Chapter 31: Medical Cannabis |page = 165 |year = 2012 |publisher = Oxford University Press |isbn = 978-0-19-994274-9 |quote = Proponents of medical cannabis site its safety, but there studies in later years that support that smoking of marijuana is associated with risk for dependence and that THC alters the structures of cells in the brain }}</ref> Typically, adverse effects of medical cannabis use are not serious;<ref name=Borgelt2013>{{cite journal | vauthors = Borgelt LM, Franson KL, Nussbaum AM, Wang GS | title = The pharmacologic and clinical effects of medical cannabis | journal = Pharmacotherapy | volume = 33 | issue = 2 | pages = 195–209 | date = February 2013 | pmid = 23386598 | doi = 10.1002/phar.1187 | s2cid = 8503107 | url = https://wsma.org/doc_library/LegalResourceCenter/MedicalCannabis/Med%20Mar%20-%20Pharmacologic%20and%20Clinical%20Effects.pdf | access-date = 11 November 2017 | archive-date = 28 August 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210828161528/https://wsma.org/doc_library/LegalResourceCenter/MedicalCannabis/Med%20Mar%20-%20Pharmacologic%20and%20Clinical%20Effects.pdf | url-status = live }}</ref> they include tiredness, dizziness, increased appetite, and cardiovascular and psychoactive effects. Other effects can include impaired short-term memory; impaired motor coordination; altered judgment; and paranoia or psychosis at high doses.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gage SH, Hickman M, Zammit S | title = Association Between Cannabis and Psychosis: Epidemiologic Evidence | journal = Biological Psychiatry | volume = 79 | issue = 7 | pages = 549–56 | date = April 2016 | pmid = 26386480 | doi = 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.08.001 | hdl = 1983/b8fb2d3b-5a55-4d07-97c0-1650b0ffc05d | s2cid = 1055335 | url = https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/en/publications/association-between-cannabis-and-psychosis(b8fb2d3b-5a55-4d07-97c0-1650b0ffc05d).html | hdl-access = free | access-date = 11 March 2020 | archive-date = 26 February 2020 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200226185900/https://research-information.bris.ac.uk/en/publications/association-between-cannabis-and-psychosis(b8fb2d3b-5a55-4d07-97c0-1650b0ffc05d).html | url-status = live }}</ref> Tolerance to these effects develops over a period of days or weeks. The amount of cannabis normally used for medicinal purposes is not believed to cause any permanent cognitive impairment in adults, though long-term treatment in adolescents should be weighed carefully as they are more susceptible to these impairments. Withdrawal symptoms are rarely a problem with controlled medical administration of cannabinoids. The ability to drive vehicles or to operate machinery may be impaired until a tolerance is developed.<ref name=Grotenhermen2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Grotenhermen F, Müller-Vahl K | title = The therapeutic potential of cannabis and cannabinoids | journal = Deutsches Ärzteblatt International | volume = 109 | issue = 29–30 | pages = 495–501 | date = July 2012 | pmid = 23008748 | pmc = 3442177 | doi = 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0495 }}</ref> Although supporters of medical cannabis say that it is safe,<ref name=oxpain /> further research is required to assess the long-term safety of its use.<ref name=Wang2008 /><ref name=barceloux866931>{{cite book |first = Donald G |last = Barceloux |title = Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants |chapter = Chapter 60: Marijuana (''Cannabis sativa'' L.) and synthetic cannabinoids |isbn = 978-0-471-72760-6 |year = 2012 |pages = 886–931 |publisher = John Wiley & Sons |chapter-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=OWFiVaDZnkQC&pg=PA886 |access-date = 20 December 2015 |archive-date = 13 January 2023 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20230113004526/https://books.google.com/books?id=OWFiVaDZnkQC&pg=PA886 |url-status = live }}</ref> |

|||

|- |

|||

! Medication |

|||

=== Cognitive effects === |

|||

! Year approved |

|||

{{further|long-term effects of cannabis}} |

|||

! Licensed indications |

|||

Recreational use of cannabis is associated with cognitive deficits, especially for those who begin to use cannabis in adolescence. {{as of|2021}} there is a lack of research into long-term cognitive effects of medical use of cannabis, but one 12-month observational study reported that "MC patients demonstrated significant improvements on measures of [[executive function]] and clinical state over the course of 12 months".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Sagar |first1=Kelly A. |last2=Dahlgren |first2=M. Kathryn |last3=Lambros |first3=Ashley M. |last4=Smith |first4=Rosemary T. |last5=El-Abboud |first5=Celine |last6=Gruber |first6=Staci A. |title=An Observational, Longitudinal Study of Cognition in Medical Cannabis Patients over the Course of 12 Months of Treatment: Preliminary Results |journal=Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society |date=2021 |volume=27 |issue=6 |pages=648–60 |doi=10.1017/S1355617721000114 |pmid=34261553 |s2cid=235824932 |language=en |issn=1355-6177|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

! Cost |

|||

|- |

|||

=== Impact on psychosis === |

|||

| [[Nabilone]] |

|||

Exposure to THC can cause acute transient psychotic symptoms in healthy individuals and people with schizophrenia.<ref name="Schubart et al.2014" /> |

|||

| 1985 |

|||

| Nausea of cancer chemotherapy that has failed to respond adequately to other antiemetics |

|||

A 2007 meta analysis concluded that cannabis use reduced the average age of onset of psychosis by 2.7 years relative to non-cannabis use.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Large M, Sharma S, Compton MT, Slade T, Nielssen O | title = Cannabis use and earlier onset of psychosis: a systematic meta-analysis | journal = Archives of General Psychiatry | volume = 68 | issue = 6 | pages = 555–61 | date = June 2011 | pmid = 21300939 | doi = 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.5 | doi-access = free }}</ref> A 2005 meta analysis concluded that adolescent use of cannabis increases the risk of psychosis, and that the risk is dose-related.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM | title = Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review | journal = Journal of Psychopharmacology | volume = 19 | issue = 2 | pages = 187–94 | date = March 2005 | pmid = 15871146 | doi = 10.1177/0269881105049040 | s2cid = 44651274 }}</ref> A 2004 literature review on the subject concluded that cannabis use is associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of psychosis, but that cannabis use is "neither necessary nor sufficient" to cause psychosis.<ref name=Arseneault2004>{{cite journal | vauthors = Arseneault L, Cannon M, Witton J, Murray RM | title = Causal association between cannabis and psychosis: examination of the evidence | journal = The British Journal of Psychiatry | volume = 184 | issue = 2 | pages = 110–17 | date = February 2004 | pmid = 14754822 | doi = 10.1192/bjp.184.2.110 | doi-access = free }}</ref> A French review from 2009 came to a conclusion that cannabis use, particularly that before age 15, was a factor in the development of schizophrenic disorders.<ref name="Laqueille">{{cite journal | vauthors = Laqueille X | title = [Is cannabis a vulnerability factor in schizophrenic disorders] | journal = Archives de Pédiatrie | volume = 16 | issue = 9 | pages = 1302–05 | date = September 2009 | pmid = 19640690 | doi = 10.1016/j.arcped.2009.03.016 | trans-title = Is cannabis is a vulnerability factor of schizophrenic disorders? }}</ref> |

|||

|$4000.00 U.S. for a year's supply (in Canada)<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

== Pharmacology == |

|||

|url=http://www.news-medical.net/?id=35301 |

|||

The [[genus]] ''[[Cannabis]]'' contains two species which produce useful amounts of psychoactive cannabinoids: ''[[Cannabis indica]]'' and ''[[Cannabis sativa]]'', which are listed as Schedule I medicinal plants in the US;<ref name=Borgelt2013 /> a third species, ''[[Cannabis ruderalis]]'', has few psychogenic properties.<ref name=Borgelt2013 /> Cannabis contains more than 460 compounds;<ref name=BenAmar2006 /> at least 80 of these are [[cannabinoid]]s<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Downer EJ, Campbell VA | title = Phytocannabinoids, CNS cells and development: a dead issue? | journal = Drug and Alcohol Review | volume = 29 | issue = 1 | pages = 91–98 | date = January 2010 | pmid = 20078688 | doi = 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00102.x | type = Review }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Burns TL, Ineck JR | title = Cannabinoid analgesia as a potential new therapeutic option in the treatment of chronic pain | journal = The Annals of Pharmacotherapy | volume = 40 | issue = 2 | pages = 251–60 | date = February 2006 | pmid = 16449552 | doi = 10.1345/aph.1G217 | s2cid = 6858360 | type = Review }}</ref> – [[chemical compound]]s that interact with [[cannabinoid receptor]]s in the brain.<ref name=Borgelt2013 /> As of 2012, more than 20 cannabinoids were being studied by the U.S. FDA.<ref name=Svrakic2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Svrakic DM, Lustman PJ, Mallya A, Lynn TA, Finney R, Svrakic NM | title = Legalization, decriminalization & medicinal use of cannabis: a scientific and public health perspective | journal = Missouri Medicine | volume = 109 | issue = 2 | pages = 90–98 | year = 2012 | pmid = 22675784 | pmc = 6181739 | type = Review }}</ref> |

|||

|title=Nabilone marijuana-based drug reduces fibromyalgia pain |

|||

|publisher=www.news-medical.net |

|||