Jesse James: Difference between revisions

Herostratus (talk | contribs) m →After the Civil War: wikilink |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American outlaw (1847–1882)}} |

|||

{{otherpeople|Jesse James}} |

|||

{{other uses}} |

|||

{{Infobox Person |

|||

{{pp|small=yes}} |

|||

|name = Jesse James |

|||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

|image = Jesse James.jpg |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=November 2013}} |

|||

|caption = |

|||

{{Infobox person |

|||

|birth_name = Jesse Woodson James |

|||

| name = Jesse James |

|||

|birth_date = {{birth date|1847|09|05}} |

|||

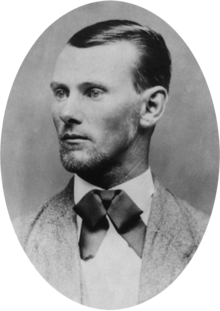

| image = Jesse James portrait.png |

|||

|birth_place = [[Clay County, Missouri]], [[United States|USA]] |

|||

| alt = Oval-shaped black-and-white portrait photograph of a man with short slicked-back hair |

|||

|death_date = {{death date and age|1882|04|03|1847|09|05}} |

|||

| caption = James {{circa|1882}} |

|||

|death_place = [[St. Joseph, Missouri]], [[United States|USA]] |

|||

| birth_name = Jesse Woodson James |

|||

|other_names = |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|mf=yes|1847|9|5}} |

|||

|known_for = [[Banditry]] |

|||

| birth_place = near [[Kearney, Missouri]], U.S. |

|||

|occupation = |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|mf=yes|1882|4|3|1847|9|5}} |

|||

|nationality = [[United States|American]] |

|||

| |

| death_place = [[St. Joseph, Missouri]], U.S. |

||

| death_cause = Gunshot wound to the head |

|||

|children = [[Jesse E. James]], [[Mary James Barr]] |

|||

| years_active = 1866–1882 |

|||

|parents = [[Robert S. James]], [[Zerelda James|Zerelda Cole James]] |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|[[Zerelda Mimms]]|1874}} |

|||

| father = [[Robert S. James]] |

|||

| mother = [[Zerelda James|Zerelda Cole James]] |

|||

| children = 4, including [[Jesse E. James|Jesse E.]] |

|||

| relatives = {{ubl|[[Frank James]] (brother)|[[Wood Hite]] (cousin)}} |

|||

| signature = Jesse James's signature.png |

|||

| signature_alt = Jesse James |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Jesse Woodson James |

'''Jesse Woodson James''' (September 5, 1847{{spaced ndash}}April 3, 1882) was an American [[outlaw]], [[Bank robbery|bank]] and [[Train robbery|train robber]], [[guerrilla]] and leader of the [[James–Younger Gang]]. Raised in the "[[Little Dixie (Missouri)|Little Dixie]]" area of [[Missouri]], James and his family maintained strong [[Southern United States|Southern]] sympathies. He and his brother [[Frank James]] joined pro-[[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] guerrillas known as "[[bushwhacker]]s" operating in [[Missouri in the American Civil War|Missouri]] and [[Kansas in the American Civil War|Kansas]] during the [[American Civil War]]. As followers of [[William Quantrill]] and [[William T. Anderson|"Bloody Bill" Anderson]], they were accused of committing atrocities against [[Union soldier]]s and civilian abolitionists, including the [[Centralia Massacre (Missouri)|Centralia Massacre]] in 1864. |

||

After the war, as members of various [[List of Old West gangs|gangs of outlaws]], Jesse and Frank robbed banks, stagecoaches, and trains across the [[Midwestern United States|Midwest]], gaining national fame and often popular sympathy despite the brutality of their crimes. The James brothers were most active as members of their own gang from about 1866 until 1876, when as a result of their attempted robbery of a bank in [[Northfield, Minnesota]], several members of the gang were captured or killed. They continued in crime for several years afterward, recruiting new members, but came under increasing pressure from law enforcement seeking to bring them to justice. On April 3, 1882, Jesse James was shot and killed by [[Robert Ford (outlaw)|Robert Ford]], a new recruit to the gang who hoped to collect a [[Bounty (reward)|reward]] on James's head and a promised [[amnesty]] for his previous crimes. Already a celebrity in life, James became a legendary figure of the [[American Old West|Wild West]] after his death. |

|||

The James brothers, [[Frank James|Frank]] and Jesse, were Confederate guerrillas during the Civil War, during which they were accused of participating in atrocities committed against Union soldiers. After the war, as members of one gang or another, they perpetrated many bank robberies which often resulted in the murder of bank employees or bystanders. They also waylaid stagecoaches and trains. |

|||

Popular portrayals of James as an embodiment of [[Robin Hood]], robbing from the rich and giving to the poor, are a case of romantic revisionism as there is no evidence his gang shared any loot from their robberies with anyone outside their network.<ref name="seattle times">{{cite news|first=Wil |last=Hayworth |title=A story of myth, fame, Jesse James |url=http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/living/2003885037_jessejames17.html |work=[[The Seattle Times]] |date=September 17, 2007 |access-date=December 7, 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081229061215/http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/living/2003885037_jessejames17.html |archive-date=December 29, 2008 }}</ref> Scholars and historians have characterized James as one of many criminals inspired by the regional insurgencies of ex-Confederates following the Civil War, rather than as a manifestation of alleged [[economic justice]] or of [[American frontier|frontier]] lawlessness.<ref name="stiles">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |publisher=Knopf Publishing |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |year=2002 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> James continues to be one of the most famous figures from the era, and his life has been dramatized and memorialized numerous times. |

|||

==Early life== |

==Early life== |

||

[[File:Jesse-james-farm.jpg|thumb|James's farm in [[Kearney, Missouri]], pictured in March 2010]] |

|||

Jesse Woodson James was born in [[Clay County, Missouri|Clay County]], [[Missouri]], at the site of present day [[Kearney, Missouri|Kearney]], on September 5, 1847. Jesse James had two full siblings: his older brother, [[Frank James|Alexander Franklin "Frank"]] and a younger sister, Susan Lavenia James. His father, [[Robert S. James]], was a commercial [[hemp]] [[farmer]] and [[Baptist]] minister in [[Kentucky]] who migrated to Missouri after marriage and helped found [[William Jewell College]] in [[Liberty, Missouri]].<ref name="stiles"/> He was prosperous, acquiring six slaves and more than {{convert|100|acre|km2}} of farmland. Robert James travelled to [[California]] during the [[Gold Rush]] to minister to those searching for gold<ref name="name">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name, or, Fact and Fiction Concerning the Careers of the Notorious James Brothers of Missouri |publisher=University of Nebraska Press|date=1977 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |accessdate=2008-12-07 |ISBN=0803258607 |pages=7, 12, 16, 26}}</ref> and died there when Jesse was three years old.<ref name="stiles23">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |publisher=Knopf Publishing |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |year=2002 |pages=23-6 |ISBN=0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

Jesse Woodson James was born on September 5, 1847, in [[Clay County, Missouri]], near the site of present-day [[Kearney, Missouri|Kearney]].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q1SbAM-N0yUC&pg=PA12 |title=Jesse James: I Will Never Surrender |first=Jeff |last=Burlingame |author-link=Jeff Burlingame |publisher=[[Enslow Publishers, Inc.]] |date=1 March 2010 |page=12 |isbn=9780766033535}}</ref> This area of [[Missouri]] was largely settled by people from the Upper South, especially [[Kentucky]] and [[Tennessee]], and became known as [[Little Dixie (Missouri)|Little Dixie]] for this reason. James had two full siblings: his elder brother, [[Frank James|Alexander Franklin "Frank" James]], and a younger sister, Susan Lavenia James. He was of [[English people|English]] and [[Scottish people|Scottish]] descent. His father, [[Robert S. James]], farmed commercial [[hemp in Kentucky]] and was a [[Baptist]] minister before coming to Missouri. After he married, he migrated to Bradford, Missouri and helped found [[William Jewell College]] in [[Liberty, Missouri]].<ref name="stiles"/> He held six slaves and more than {{convert|100|acre|km2}} of farmland. |

|||

After the death of Robert James, his widow [[Zerelda James|Zerelda]] remarried twice, first to [[Benjamin Simms]] and then in 1855 to [[Reuben Samuel]], a doctor. Dr. Samuel moved into the James home. |

|||

Robert traveled to [[California]] during the [[Gold Rush]] to minister to those searching for gold;<ref name="name">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name, or, Fact and Fiction Concerning the Careers of the Notorious James Brothers of Missouri |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |year=1977 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |access-date=December 7, 2008 |isbn=0-8032-5860-7 |pages=7, 12, 16, 26}}</ref> he died there when James was three years old.<ref name="stiles23">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |publisher=Knopf Publishing |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |year=2002 |pages=23–6 |isbn=0-375-40583-6}}</ref> After Robert's death, his widow [[Zerelda James|Zerelda]] remarried twice, first to [[Benjamin Simms]] in 1852 and then in 1855 to Dr. [[Reuben Samuel]], who moved into the James family home. Jesse's mother and Samuel had four children together: Sarah Louisa, John Thomas, Fannie Quantrell, and Archie Peyton Samuel.<ref name="name"/><ref name="yeatman26">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |year=2000 |isbn=1-58182-325-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=26–8}}</ref> Zerelda and Samuel acquired a total of seven slaves, who served mainly as farmhands in [[Cultivation of tobacco|tobacco cultivation]].<ref name="yeatman26"/><ref name="stiles26">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |publisher=Knopf Publishing |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |year=2002 |pages=26–55 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

==Historical context== |

|||

The approach of the [[American Civil War]] overshadowed the James-Samuel household. Missouri was a border state, sharing characteristics of both North and South, but 75% of the population was from the South or other border states.<ref name="name"/> Clay County was in a region of Missouri later dubbed "[[Little Dixie]]," as it was a center of migration from the Upper South. Farmers raised the same crops and livestock as in the areas from which they had migrated. They brought slaves with them and purchased more according to need. The county had more slaveholders, who held more slaves, than in other regions. Aside from slavery, the culture of Little Dixie was southern in other ways as well. This influenced how the population acted during and after the [[American Civil War]]. In Missouri as a whole, slaves accounted for 10 percent of the population, but in Clay County they constituted 25 percent.<ref name="stiles37">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |publisher=Knopf Publishing |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |year=2002 |pages=37-46 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

The approach of the [[American Civil War]] loomed large in the James–Samuel household. Missouri was a [[border states (American Civil War)|border state]], sharing characteristics of both North and South, but 75% of the population was from the South or other border states.<ref name="name" /> Clay County in particular was strongly influenced by the Southern culture of its rural pioneer families. Farmers raised the same crops and livestock as in the areas from which they had migrated. They brought slaves with them and purchased more according to their needs. The county counted more slaveholders and more slaves than most other regions of the state; in Missouri as a whole, slaves accounted for only 10 percent of the population, but in Clay County, they constituted 25 percent.<ref name="stiles37">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |publisher=Knopf Publishing |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |year=2002 |pages=37–46 |isbn=0-375-40583-6}}</ref> Aside from [[History of slavery in Missouri|slavery]], the culture of Little Dixie was Southern in other ways as well. This influenced how the population acted during and for a period of time after the war. |

|||

After the passage of the [[ |

After the passage of the [[Kansas–Nebraska Act]] in 1854, Clay County became the scene of great turmoil as the question of whether slavery would be expanded into the neighboring [[Kansas Territory]] bred tension and hostility. Many people from Missouri migrated to Kansas to try to influence its future. Much of the dramatic build-up to the Civil War centered on the [[Bleeding Kansas|violence that erupted]] on the Kansas–Missouri border between pro- and anti-slavery militias.<ref name="stiles26" /><ref>{{cite book |last=Hurt |first=R. Douglas |title=Agriculture and Slavery in Missouri's Little Dixie |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pVSdAQAACAAJ |publisher=University of Missouri Press |year=1992 |isbn=0-8262-0854-1}}</ref> |

||

==Civil War== |

==American Civil War== |

||

[[File:Jesse James.jpg|thumb|upright|James as a young man]] |

|||

The Civil War ripped Missouri society apart and shaped the life of Jesse James. After a series of campaigns and battles between conventional armies in 1861, [[guerrilla]] warfare gripped the state, waged between secessionist "[[bushwhackers]]" and [[Union Army|Union]] forces, which largely consisted of local [[militia]] organizations. A bitter conflict ensued, bringing an escalating cycle of atrocities by both sides. Guerrillas murdered civilian Unionists, executed prisoners and [[scalp]]ed the dead. Union forces enforced [[martial law]] with [[raid]]s on homes, arrests of civilians, summary [[execution]]s and [[banishment]] of [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] sympathizers from the state.<ref>{{cite book |last=Fellman |first=Michael |title=Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri onto the American Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=LldHnF7CB3kC |publisher=Oxford University Press |date=1990 |ISBN=0195064712 |pages=61-143}}</ref> |

|||

After a series of campaigns and battles between conventional armies in 1861, [[guerrilla]] warfare gripped Missouri, waged between secessionist "[[bushwhackers]]" and [[Union Army|Union]] forces which largely consisted of local [[militia]]s known as "[[jayhawkers]]". A bitter conflict ensued, resulting in an escalating cycle of atrocities committed by both sides. [[Confederate States of America|Confederate]] guerrillas murdered civilian Unionists, executed prisoners, and [[Scalping|scalped]] the dead. The Union presence enforced [[martial law]] with [[raid (military)|raids]] on homes, arrests of civilians, [[summary execution]]s, and [[exile|banishment]] of Confederate sympathizers from the state.<ref>{{cite book |last=Fellman |first=Michael |title=Inside War: The Guerrilla Conflict in Missouri onto the American Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=LldHnF7CB3kC |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1990 |isbn=0-19-506471-2 |pages=61–143}}</ref> |

|||

The |

The James–Samuel family sided with the Confederates at the outbreak of war.<ref name="SS3">{{cite web| last=Andrews|first=Dale C |title=Jesse James and Meramec Caverns| url=http://www.sleuthsayers.org/2013/06/jesse-james-and-meramec-caverns-another_18.html| work=Route 66| publisher=SleuthSayers| location=Washington |date=June 18, 2013}}</ref> Frank James joined a local company recruited for the secessionist Drew Lobbs Army, and fought at the [[Battle of Wilson's Creek]] in August 1861. He fell ill and returned home soon afterward. In 1863, he was identified as a member of a guerrilla squad that operated in Clay County. In May of that year, a Union militia company raided the James–Samuel farm looking for Frank's group. They [[torture]]d Reuben Samuel by briefly hanging him from a tree. According to legend, they lashed young Jesse.<ref name="name"/> |

||

===Quantrill's Raiders=== |

|||

Frank James followed Quantrill to [[Texas]] over the winter of 1863–4, and returned in the spring in a squad commanded by Fletch Taylor. When they returned to Clay County, 16-year-old Jesse James joined his brother in Taylor's group.<ref name="name"/> In the summer of 1864, Taylor was severely wounded, losing his right arm to a [[shotgun]] blast. The James brothers joined the bushwhacker group led by [[William T. Anderson|Bloody Bill Anderson]]. Jesse suffered a serious wound to the chest that summer. The Clay County provost marshal reported that both Frank and Jesse James took part in the [[Centralia Massacre (Missouri)|Centralia Massacre]] in September, in which guerrillas killed or wounded some 22 unarmed Union troops; the guerrillas scalped and dismembered some of the dead. The guerrillas [[ambush]]ed and defeated a pursuing regiment of Major A.V.E. Johnson's Union troops, killing all who tried to surrender (more than 100). Frank later identified Jesse as a member of the band who had fatally shot Major Johnson.<ref name="settle">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |date=1977 |accessdate=2008-12-07 |page=28-35}}</ref> As a result of the James brothers' activities, the Union military authorities made their family leave Clay County. Though ordered to move South beyond Union lines, they moved across the nearby state border into Nebraska.<ref name="settle140">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |date=1977 |accessdate=2008-12-07 |page=140-41}}</ref> |

|||

Frank James eluded capture and was believed to have joined the guerrilla organization led by [[William Quantrill|William C. Quantrill]] known as [[Quantrill's Raiders]]. It is thought that he took part in the notorious [[Lawrence Massacre|massacre of some two hundred men and boys]] in [[Lawrence, Kansas]], a center of [[Abolitionism in the United States|abolitionists]].<ref name="yeatman30">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |year=2000 |isbn=1-58182-325-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=30–45}}</ref><ref name="stiles6184">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |publisher=Knopf Publishing |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |year=2002 |pages=61–2, 84–91 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> Frank followed Quantrill to [[Sherman, Texas]], over the winter of 1863–1864. In the spring he returned in a squad commanded by Fletch Taylor. After they arrived in Clay County, 16-year-old Jesse James joined his brother in Taylor's group.<ref name="name"/> |

|||

Taylor was severely wounded in the summer of 1864, losing his right arm to a shotgun blast. The James brothers then joined the bushwhacker group led by [[William T. Anderson|William "Bloody Bill" Anderson]]. Jesse suffered a serious wound to the chest that summer. The Clay County provost marshal reported that both Frank and Jesse James took part in the [[Centralia Massacre (Missouri)|Centralia Massacre]] in September, in which guerrillas stopped a train carrying unarmed Union soldiers returning home from duty and killed or wounded some 22 of them; the guerrillas scalped and dismembered some of the dead. The guerrillas also [[ambush]]ed and defeated a pursuing regiment of Major A. V. E. Johnson's Union troops, killing all who tried to surrender, who numbered more than 100. Frank later identified Jesse as a member of the band who had fatally shot Major Johnson.<ref name="settle">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |year=1977 |access-date=December 7, 2008 |pages=28–35 |isbn=978-0-8032-5860-0}}</ref> |

|||

Anderson was killed in an ambush in October, and the James brothers went in different directions. Frank followed Quantrill into [[Kentucky]]; Jesse went to Texas under the command of [[Archie Clement]], one of Anderson's lieutenants, and is known to have returned to Missouri in the spring.<ref name="settle"/> Contrary to legend, Jesse was not shot while trying to surrender, rather, he and Clement were still trying to decide on what course to follow after the Confederate surrender when they ran into a Union [[cavalry]] patrol near [[Lexington, Missouri]], and Jesse James suffered two life-threatening chest wounds.<ref name="yeatman48">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |date=2000 |ISBN=1581823258 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=48-58, 62-3, 72-5}}</ref><ref name="stilesmulti">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |publisher=Knopf Publishing |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |year=2002 |pages=100-11, 121-3, 136-7, 140-1, 150-4 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

As a result of the James brothers' activities, Union military authorities forced their family to leave Clay County. Though ordered to move South beyond Union lines, they moved north across the nearby state border into [[Nebraska Territory]].<ref name="settle140">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |year=1977 |access-date=December 7, 2008 |pages=140–41 |isbn=978-0-8032-5860-0}}</ref> |

|||

==After the Civil War== |

|||

[[Image:Jesse and Frank James.gif|thumb|[[Frank James|Frank]] and Jesse James, 1872]] |

|||

[[Image:Clay-savings.png|thumb|Clay County Savings in Liberty]] |

|||

At the end of the Civil War, Missouri was in shambles. The conflict split the population into three bitterly opposed factions: anti-slavery Unionists, identified with the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican Party]]; the segregationist conservative Unionists, identified with the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]]; and pro-slavery, ex-Confederate secessionists, many of whom were also allied with the Democrats, especially the southern part of the party. The Republican Reconstruction administration passed a new state constitution that freed Missouri's slaves. It temporarily excluded former Confederates from voting, serving on juries, becoming corporate officers, or preaching from church pulpits. The atmosphere was volatile, with widespread clashes between individuals, and between armed gangs of veterans from both sides of the war.<ref>{{cite book |last=Parrish |first=William E. |title=Missouri Under Radical Rule, 1865-1870 |publisher=University of Missouri Press |date=1965 ASIN: B0014QRLJC}}</ref><ref name="stiles149">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=149-67 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

After "Bloody Bill" Anderson was killed in an ambush in October, the James brothers separated. Frank followed Quantrill into [[Kentucky]], while Jesse went to Texas under the command of [[Archie Clement]], one of Anderson's lieutenants. He is known to have returned to Missouri in the spring.<ref name="settle"/> At the age of 17, Jesse suffered the second of two life-threatening chest wounds when he was shot while trying to surrender after they ran into a Union [[cavalry]] patrol near [[Lexington, Missouri]].<ref name="yeatman48">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |year=2000 |isbn=1-58182-325-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=48–58, 62–3, 72–5}}</ref><ref name="stilesmulti">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |publisher=Knopf Publishing |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |year=2002 |pages=100–11, 121–3, 136–7, 140–1, 150–4 |isbn= 0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

Jesse recovered from his chest wound at his uncle's Missouri boardinghouse, where he was tended to by his first cousin, [[Zerelda Mimms|Zerelda "Zee" Mimms]], named after Jesse's mother.<ref name="settle"/> Jesse and his cousin began a nine-year courtship, culminating in marriage. Meanwhile, His old commander [[Archie Clement]] kept his bushwhacker gang together and began to harass Republican authorities. |

|||

==After the Civil War== |

|||

These men were the likely culprits in the first daylight armed bank robbery in the United States in peacetime,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/james/peopleevents/e_banks.html|title=PBS.org Jesse James Bank Robberies|accessdate=February 12, 2009|dateformat=mdy}}</ref> the robbery of the Clay County Savings Association in the town of [[Liberty, Missouri]], on February 13, 1866. This bank was owned by Republican former militia officers who had recently conducted the first Republican Party rally in Clay County's history. One innocent bystander, a student of [[William Jewell College]] (which James's father had helped to found), was shot dead on the street during the gang's escape.<ref name="stiles168">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=168-75, 179-87 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> It remains unclear whether Jesse and Frank took part. After their later robberies took place and they became legends, there were those who credited them with being the leaders of the Clay County robbery.<ref name="settle"/> It has been argued in rebuttal that James was at the time still bedridden with his wound. No concrete evidence has surfaced to connect either brother to the crime, or to rule them out.<ref name="yeatman83">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |date=2000 |ISBN=1581823258 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=83-9}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Jesse and Frank James.gif|thumb|upright|Jesse and [[Frank James]] in 1872]] |

|||

[[File:Clay-savings.png|thumb|Clay County Savings in Liberty, Missouri]] |

|||

At the end of the Civil War, Missouri remained deeply divided. The conflict split the population into three bitterly opposed factions: anti-slavery Unionists identified with the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican Party]]; segregationist conservative Unionists identified with the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]]; and pro-slavery, ex-Confederate secessionists, many of whom were also allied with the Democrats, especially in the southern part of the state. |

|||

The Republican-dominated [[Reconstruction era of the United States|Reconstruction]] legislature passed a new state constitution that freed Missouri's slaves. It temporarily excluded former Confederates from voting, serving on juries, becoming corporate officers, or preaching from church pulpits. The atmosphere was volatile, with widespread clashes between individuals and between armed gangs of veterans from both sides of the war.<ref>{{cite book |last=Parrish |first=William E. |title=Missouri Under Radical Rule, 1865–1870 |url=https://archive.org/details/missouriunderrad0000parr |url-access=registration |publisher=University of Missouri Press |date=1965 |asin= B0014QRLJC}}</ref><ref name="stiles149">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=149–67 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

This was a time of increasing local violence; Governor Fletcher had recently ordered a company of militia into [[Johnson County]] to suppress guerrilla activity.<ref name="stiles173">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=173 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> [[Archie Clement]] continued his career of crime and harassment of the Republican government, to the extent of occupying the town of [[Lexington, Missouri]], on election day in 1866. Shortly afterward, the state militia shot Clement dead, an event which James wrote about with bitterness a decade later.<ref name="stiles168"/><ref name="yeatman83"/> |

|||

Jesse recovered from his chest wound at his uncle's boardinghouse in Harlem, Missouri (north across the [[Missouri River]] from the City of Kansas's River Quay [changed to Kansas City in 1889]). He was tended to by his first cousin, [[Zerelda Mimms|Zerelda "Zee" Mimms]], named after Jesse's mother.<ref name="settle"/> Jesse and his cousin began a nine-year courtship that culminated in their marriage. Meanwhile, his former commander [[Archie Clement]] kept his bushwhacker gang together and began to harass Republican authorities.<ref name="SS3" /> |

|||

The survivors of Clement's gang continued to conduct bank robberies over the next two years, though their numbers dwindled through [[arrests]], gunfights, and [[lynchings]]. While they later tried justify robbing the banks, these were small, local banks with local capital, not part of the national system which was a target of popular discontent in the 1860s and 1870s.<ref name="stiles238">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=238|ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> On May 23, 1867, for example, they robbed a bank in [[Richmond, Missouri|Richmond]], Missouri, in which they killed the [[mayor]] and two others.<ref name="settle"/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.odmp.org/officer/5742-deputy-sheriff-frank-s.-griffin |title=Deputy Sheriff Frank S. Griffin, Ray County Sheriff's Department |publisher=Officer Down Memorial Page |accessdate=2008-10-03}}</ref> It remains uncertain whether either of the James brothers took part, although an eyewitness who knew the brothers told a newspaper seven years later "positively and emphatically that he recognized Jesse and Frank James ... among the robbers."<ref name="stiles192">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=192-95 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> In 1868, Frank and Jesse James allegedly joined [[Cole Younger]] in robbing a bank at [[Russellville, Kentucky]]. Jesse James did not become famous, however, until December 1869, when he and (most likely) Frank robbed the Daviess County Savings Association in [[Gallatin]], [[Missouri]]. |

|||

These men were the likely culprits in the first daylight armed bank robbery in the United States during peacetime,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/james/peopleevents/e_banks.html|title=PBS.org Jesse James Bank Robberies|website=[[PBS]]|access-date=February 12, 2009|archive-date=February 11, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090211021610/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/james/peopleevents/e_banks.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> the robbery of the Clay County Savings Association in the town of [[Liberty, Missouri]], on February 13, 1866. The bank was owned by Republican former militia officers who had recently conducted the first Republican Party rally in Clay County's history. During the gang's escape from the town, an innocent bystander, 17-year-old George C. "Jolly" Wymore, a student at [[William Jewell College]], was shot dead on the street.<ref name="stiles168">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=168–75, 179–87 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

The robbery netted little, but Jesse (it appears) shot and killed the cashier, Captain John Sheets, mistakenly believing the man to be Samuel P. Cox, the [[militia]] officer who had killed [[William T. Anderson|"Bloody Bill" Anderson]] during the Civil War. James's self-proclaimed attempt at revenge, and the daring escape he and Frank made through the middle of a posse shortly afterward, put his name in the newspapers for the first time.<ref name="stiles190">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=190-206 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref><ref name="yeatman91">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |date=2000 |ISBN=1581823258 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=91-8}}</ref><ref name="settle32">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |date=1977 |accessdate=2008-12-07 |page=32-42}}</ref> An 1882 history of Daviess County said, "The history of Daviess County has no blacker crime in its pages than the murder of John W. Sheets."<ref name="daviess county">{{cite news |title=Civil lawsuit against Frank & Jesse James |url=http://www.daviesscountyhistoricalsociety.com/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=347 |publisher=Daviess County Historical Society |date=2007-08-30 |accessdate=2008-12-07}}</ref> |

|||

It remains unclear whether Jesse and Frank took part in the Clay County robbery. After the James brothers successfully conducted other robberies and became legendary, some observers retroactively credited them with being the leaders of the robbery.<ref name="settle" /> Others have argued that Jesse was at the time still bedridden with his wound and could not have participated. No evidence has been found that connects either brother to the crime or that conclusively rules them out.<ref name="yeatman83">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |year=2000 |isbn=1-58182-325-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=83–9}}</ref> On June 13, 1866, in [[Jackson County, Missouri]], the gang freed two jailed members of Quantrill's gang, killing the jailer in the effort.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.odmp.org/officer/2462-jailer-henry-bugler |title=Jailer Henry Bugler, Jackson County Sheriff's Office, Missouri |access-date=February 5, 2014}}</ref> Historians believe that the James brothers were involved in this crime.{{citation needed|date=December 2023}} |

|||

The 1869 robbery marked James's emergence as the most famous of the former guerrillas turned outlaw. It marked the first time he was publicly branded an "outlaw", as Missouri Governor [[Thomas Theodore Crittenden|Thomas T. Crittenden]] set a reward for his capture.<ref name="daviess county"/> This was the beginning of an alliance between James and [[John Newman Edwards]], editor and founder of the ''[[Kansas City Times]]''. Edwards, a former Confederate cavalryman, was campaigning to return former secessionists to power in Missouri. Six months after the Gallatin robbery, Edwards published the first of many letters from Jesse James to the public, asserting his innocence. Over time, the letters gradually became more political in tone, denouncing the Republicans, and voicing his pride in his Confederate loyalties. Together with Edwards's admiring editorials, the letters turned James into a symbol for some of Confederate defiance of [[Reconstruction era of the United States|Reconstruction]]. Jesse James's personal initiative in creating his rising public profile is debated by historians and biographers, though the tense politics certainly surrounded his outlaw career and enhanced his notoriety.<ref name="settle32">{{cite book |first=William A. |ast=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name, or, Fact and Fiction Concerning the Careers of the Notorious James Brothers of Missouri |publisher=University of Nebraska Press|date=1977 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |accessdate=2008-12-07 |ISBN=0803258607 |pages=32-42}}</ref><ref name="stiles207">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=207-48 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

Local violence continued to increase in the state; Governor [[Thomas Clement Fletcher]] had recently ordered a company of militia into [[Johnson County, Missouri|Johnson County]] to suppress guerrilla activity.<ref name="stiles173">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |page=173 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> [[Archie Clement]] continued his career of crime and harassment of the Republican government, to the extent of occupying the town of [[Lexington, Missouri]], on election day in 1866. Shortly afterward, the state militia shot Clement dead. James wrote about this death with bitterness a decade later.<ref name="stiles168"/><ref name="yeatman83"/> |

|||

Meanwhile, the James brothers joined with Cole Younger and his brothers John, Jim, and Bob; as well as Clell Miller and other former Confederates, to form what came to be known as the James-Younger Gang. With Jesse James as the public face of the gang (though with operational leadership likely shared among the group), the gang carried out a string of robberies from [[Iowa]] to [[Texas]], and from Kansas to [[West Virginia]]. They robbed banks, stagecoaches, and a fair in [[Kansas City, Missouri|Kansas City]], often in front of large crowds, even hamming it up for the bystanders. |

|||

The survivors of Clement's gang continued to conduct bank robberies during the next two years, though their numbers dwindled through [[arrests]], gunfights, and [[lynchings]]. While they later tried to justify robbing the banks, most of their targets were small, local banks based on local capital, and the robberies only penalized the locals they claimed to support.<ref name="stiles238">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |page=238 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> On May 23, 1867, for example, they robbed a bank in [[Richmond, Missouri]], in which they killed the [[mayor]] and two others.<ref name="settle"/><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.odmp.org/officer/5742-deputy-sheriff-frank-s.-griffin |title=Deputy Sheriff Frank S. Griffin, Ray County Sheriff's Department |publisher=Officer Down Memorial Page |access-date=October 3, 2008}}</ref> It remains uncertain whether either of the James brothers took part, although an eyewitness who knew the brothers told a newspaper seven years later "positively and emphatically that he recognized Jesse and Frank James... among the robbers."<ref name="stiles192">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=192–95 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> In 1868, Frank and Jesse James allegedly joined [[Cole Younger]] in robbing a bank in [[Russellville, Kentucky]]. |

|||

On July 21, 1873, they turned to [[train robbery]], derailing the [[Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad|Rock Island]] train in [[Adair, Iowa]] and stealing approximately [[US dollar|$]]3,000 ($51,000 in 2007). For this, they wore [[Ku Klux Klan]] masks, deliberately taking on a potent symbol years after the Klan had been suppressed in the South by President Grant's use of the Force Acts. The railroads were becoming an axis of political protest by former rebels, who feared the trend toward centralization.<ref name="stiles236-238">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=236-238|ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

The James' gang's later train robberies had a lighter touch—in fact only twice in all of Jesse James's train hold-ups did he rob passengers, because he typically limited himself to the express safe in the baggage car. Such techniques fostered the [[Robin Hood]] image which Edwards was creating in his newspapers, but the James gang never shared any of the money outside of their circle.<ref name="stiles207"/> |

|||

Jesse James did not become well known until December 7, 1869, when he (and most likely Frank) robbed the Daviess County Savings Association in [[Gallatin, Missouri]]. The robbery netted little money. Jesse is believed to have shot and killed the cashier, Captain John Sheets, mistakenly believing him to be [[Samuel P. Cox]], the militia officer who had killed "Bloody Bill" Anderson during the Civil War.<ref name="yeatman91">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |year=2000 |isbn=1-58182-325-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=91–8}}</ref><!--Hide this or delete altogether- there is already an article about Cox, and this is a real digression in the James article: Cox had earlier been a partner of the firm Ballinger, Cox & Kemper with Gallatin businessman J.M. Kemper. (His son [[William Thornton Kemper, Sr.]] later founded two of the largest banks headquartered in Missouri ([[Commerce Bancshares]] and [[UMB Financial Corporation]].) The business relationship had dissolved by the time of the robbery.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.accessgenealogy.com/scripts/data/database.cgi?ArticleID=29162&report=SingleArticle&file=Data |archive-url=https://archive.today/20110606022924/http://www.accessgenealogy.com/scripts/data/database.cgi?ArticleID=29162&report=SingleArticle&file=Data |url-status=dead |archive-date=June 6, 2011 |title=Cox, S. P. Maj. |access-date=February 5, 2014}}</ref>--> |

|||

==Pinkertons== |

|||

The [[Adams Express Company]] turned to the [[Pinkerton National Detective Agency]] in 1874 to stop the James-Younger Gang. The [[Chicago]]-based agency worked primarily against urban professional criminals, as well as providing industrial security, such as [[Strikebreaker|strike breaking]]. Because of support by many former Confederates in Missouri, the former guerrillas eluded them. Joseph Whicher, an agent dispatched to infiltrate Zerelda Samuel's farm, turned up dead shortly afterwards. Two others, Louis J. Lull and John Boyle, were sent after the Youngers; Lull was killed by two of the Youngers in a roadside gunfight on March 17, 1874, fatally shooting [[John Younger]] before he died. A deputy sheriff named Edwin Daniels was also killed in the skirmish.<ref name="yeatman111">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |date=2000 |ISBN=1581823258 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=111-20}}</ref><ref name="stiles249">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=249-58 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

James claimed he was taking revenge, and the daring escape he and Frank made through the middle of a [[posse comitatus|posse]] shortly afterward attracted newspaper coverage for the first time.<ref name="stiles190">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=190–206 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref><ref name="settle32"/> An 1882 history of [[Daviess County, Missouri|Daviess County]] said, "The history of Daviess County has no blacker crime in its pages than the murder of John W. Sheets."<ref name="daviess county">{{cite news |title=Civil lawsuit against Frank & Jesse James |url=http://www.daviesscountyhistoricalsociety.com/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=347 |publisher=Daviess County Historical Society |date=August 30, 2007 |access-date=December 7, 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090201012052/http://www.daviesscountyhistoricalsociety.com/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=347 |archive-date=February 1, 2009 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> |

|||

[[Allan Pinkerton]], the agency's founder and leader, took on the case as a personal vendetta, and began to work with former Unionists who lived near the James family farm. He staged a raid on the homestead on the night of January 25, 1875. Detectives threw in an incendiary device; it exploded, killing James's young half-brother Archie (named for Archie Clement) and blowing off one of the arms of mother Zerelda Samuel. Afterward, Pinkerton denied that the raid's intent was [[arson]], though biographer Ted Yeatman located a letter by Pinkerton in the Library of Congress, in which Pinkerton declared his intention to "burn the house down."<ref name="yeatman128">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |date=2000 |ISBN=1581823258 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=128-44}}</ref><ref name="stiles272">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=272-85 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Court records of State of Missouri vs. Frank and Jesse James - Grand Larceny, Daniel Smoote.jpg|thumb|State of Missouri vs. Frank & Jesse James including indictment; capias to Clay & Jackson Counties; sheriff's returns; warrant to any sheriff or marshall of the Criminal Court in Missouri. Courtesy of the Missouri State Archives.]] |

|||

The only known civil case involving Frank and Jesse James was filed in the Common Pleas Court of Daviess County in 1870. In the case, Daniel Smoote asked for $223.50 from Frank and Jesse James to replace a horse, saddle, and bridle stolen as they fled the robbery of the Daviess County Savings Bank. The brothers denied the charges, saying they were not in Daviess County on December 7, the day the robbery occurred. Frank and Jesse failed to appear in court, and Smoote won his case against them.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://cdm16795.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/landingpage/collection/jessejames|title=Frank and Jesse James Court Documents from Daviess County|last=Missouri State Archives|website=Missouri Digital Heritage|publisher=Missouri Office of the Secretary of State|access-date=August 4, 2016}}</ref> It is unlikely that he ever collected the money due. |

|||

For much of the public, the raid on the family home did more than all of Edwards's columns to turn Jesse James into a sympathetic figure. A bill that praised the James and Younger brothers and offered them [[amnesty]] was only narrowly defeated in the Missouri state legislature. Former Confederates, allowed to vote and hold office again, voted a limit on reward offers which the governor could make for fugitives. This extended a measure of protection over the James-Younger gang. (Only Frank and Jesse James previously had been singled out for rewards larger than the new limit.)<ref name="settle76">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |date=1977 |accessdate=2008-12-07 |page=76-84}}</ref><ref name="yeatman286">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |date=2000 |ISBN=1581823258 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=286-305}}</ref> |

|||

The 1869 robbery marked the emergence of Jesse James as the most famous survivor of the former Confederate bushwhackers. It was the first time he was publicly labeled an "outlaw"; Missouri Governor [[Thomas Theodore Crittenden|Thomas T. Crittenden]] set a reward for his capture.<ref name="daviess county"/> This was the beginning of an alliance between James and [[John Newman Edwards]], editor and founder of the ''[[Kansas City Times]]''. Edwards, a former Confederate cavalryman, was campaigning to return former secessionists to power in Missouri. Six months after the Gallatin robbery, Edwards published the first of many letters from Jesse James to the public asserting his innocence. Over time, the letters gradually became more political in tone and James denounced the Republicans and expressed his pride in his Confederate loyalties. Together with Edwards's admiring editorials, the letters helped James become a symbol of Confederate defiance of federal Reconstruction policy. James's initiative in creating his rising public profile is debated by historians and biographers. The high tensions in politics accompanied his outlaw career and enhanced his notoriety.<ref name="settle32">{{cite book |first=William A. |title=Jesse James Was His Name, or, Fact and Fiction Concerning the Careers of the Notorious James Brothers of Missouri |publisher=University of Nebraska Press|year=1977 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |access-date=December 7, 2008 |isbn=0-8032-5860-7 |last=Settle}}</ref><ref name="stiles207">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=207–48 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

==Downfall of the gang== |

|||

Jesse and his cousin [[Zerelda Mimms|Zee]] married on April 24, 1874, and had two children who survived to adulthood: [[Jesse E. James|Jesse James, Jr.]] (b. 1875) and [[Mary James Barr|Mary Susan James]] (b. 1879). Twins, Gould and Montgomery James (b. 1878) died in infancy. His surviving son, Jesse, Jr., became a lawyer and spent his career as a respected member of the bar in Kansas City, Missouri.{{Fact|date=April 2009}} |

|||

==James–Younger Gang== |

|||

On September 7, 1876, the James-Younger gang attempted their most daring raid to date, on the [[First National Bank]] of [[Northfield, Minnesota]]. After this robbery, of the gang, only Frank and Jesse James were left alive and uncaptured.<ref name="st. joseph">{{cite web |title=St. Joseph History - Jesse James |publisher=St. Joseph, Missouri |url=http://www.ci.st-joseph.mo.us/history/jessejames.cfm |accessdate=2008-12-07}}</ref> Cole and Bob Younger later stated that they selected the bank because they believed it was associated with the Republican politician, [[Adelbert Ames]], the governor of [[Mississippi]] during Reconstruction, and Union general, [[Benjamin Butler]], Ames's father-in-law and the Union commander of occupied [[New Orleans, Louisiana|New Orleans]]. Ames was a stockholder in the bank, but Butler had no direct connection to it.<ref name="stiles324">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=324-5 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

{{main|James–Younger Gang}} |

|||

Meanwhile, the James brothers joined with Cole Younger and his brothers [[John Younger|John]], [[Jim Younger|Jim]], and [[Bob Younger|Bob]], as well as [[Clell Miller]] and other former Confederates, to form what came to be known as the [[James–Younger Gang]]. With Jesse James as the most public face of the gang (though with operational leadership likely shared among the group), the gang carried out a string of robberies from [[Iowa]] to [[Texas]], and from Kansas to [[West Virginia]].<ref>Old Campsite of Jesse and Frank James: US 380, approximately 5 miles east of Decatur: Texas marker #3700 – [http://atlas.thc.state.tx.us Texas Historical Commission]</ref> They robbed banks, stagecoaches, and a fair in [[Kansas City, Missouri|Kansas City]], often carrying out their crimes in front of crowds, and even hamming it up for the bystanders. |

|||

[[File:Jesse James Historic Site.jpg|thumb|left|Jesse James Historic Site sign, identifying the location of the Adair, Iowa train robbery]] |

|||

To carry out the robbery, the gang divided into two groups. Three men entered the bank, two guarded the door outside, and three remained near a bridge across an adjacent square. The robbers inside the bank were thwarted when acting cashier [[Joseph Lee Heywood]] refused to open the safe, falsely claiming that it was secured by a [[time lock]] even as they held a [[bowie knife]] to his [[throat]] and cracked his [[skull]] with a pistol butt. Assistant cashier Alonzo Enos Bunker was wounded in the shoulder as he fled out the back door of the bank. Meanwhile, the citizens of Northfield grew suspicious of the men guarding the door and raised the alarm. The five bandits outside fired in the air to clear the streets, which drove the townspeople to take cover and fire back from protected positions. Two bandits were shot dead and the rest were wounded in the barrage. Inside, the outlaws turned to flee. As they left, one shot the unarmed Heywood in the head. The identity of the shooter has been the subject of extensive speculation and debate, but remains uncertain. |

|||

On July 21, 1873, they turned to [[train robbery]], derailing a [[Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad|Rock Island Line]] train west of [[Adair, Iowa]], and stealing approximately $3,000 ({{Inflation|US|3000|1873|fmt=eq|r=-3}}). For this, they wore [[Ku Klux Klan]] masks. By this time, the Klan had been suppressed in the South by President Grant's use of the [[Enforcement Acts]]. Former rebels attacked the railroads as symbols of threatening centralization.<ref name="stiles236-238">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=236–238 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

The gang's later train robberies had a lighter touch. The gang held up passengers only twice, choosing in all other incidents to take only the contents of the express safe in the baggage car. John Newman Edwards made sure to highlight such techniques when creating an image of James as a kind of [[Robin Hood]]. Despite public sentiment toward the gang's crimes, there is no evidence that the James gang ever shared any of the robbery money outside their personal circle.<ref name="stiles207" /> |

|||

Later in 1876, Jesse and Frank James surfaced in the [[Nashville, Tennessee]] area, where they went by the names of Thomas Howard and B. J. Woodson, respectively. Frank seemed to settle down, but Jesse remained restless. He recruited a new gang in 1879 and returned to crime, holding up a train at Glendale, Missouri (now part of [[Independence, Missouri]]<ref>{{cite news |title=Skillful Detective Work; Another of he James Gang Captured in Missouri |=workThe New York Times |date=1889-03-19 |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9802EEDE113EE433A2575AC1A9659C94639FD7CF}}</ref>), on October 8, 1879. The robbery began a spree of crimes, including the holdup of the federal paymaster of a canal project in [[Killen, Alabama]], and two more train robberies. But the new gang did not consist of old, battle-hardened guerrillas; they soon turned against each other or were captured, while James grew paranoid, killing one gang member and frightening away another. The authorities grew suspicious, and by 1881 the brothers were forced to return to Missouri. In December, Jesse rented a house in [[Saint Joseph, Missouri]], not far from where he had been born and raised. Frank, however, decided to move to safer territory, heading east to [[Virginia]].<ref name="yeatman193">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |date=2000 |ISBN=1581823258 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=193-270}}</ref><ref name="stiles351">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=351-73 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref> |

|||

Jesse and his cousin [[Zerelda Mimms|Zee]] married on April 24, 1874. They had two children who survived to adulthood: [[Jesse E. James|Jesse Edward James]] (b. 1875) and Mary Susan James (later Barr, b. 1879).<ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.sonofabandit.com/ |title=Monaco, Ralph A., II (2012). ''Son Of A Bandit, Jesse James & The Leeds Gang'', Monaco Publishing, L.L.C. |year=2012 |isbn=978-0578104263 |publisher=Sonofabandit.com |access-date=September 6, 2012 |archive-date=January 26, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190126113121/https://www.sonofabandit.com/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> Twins Gould and Montgomery James (b. 1878) died in infancy. Jesse Jr. became a lawyer who practiced in Kansas City, Missouri, and [[Los Angeles, California]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ericjames.org/AmericanOutlaws/page2.html |title=Original reference: Los Angeles Times, Orange County Edition, August 25, 2001, Page F2 |publisher=Ericjames.org |access-date=September 6, 2012 |archive-date=February 29, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120229215941/http://www.ericjames.org/AmericanOutlaws/page2.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

==Assassination== |

|||

[[File:Jess-james2.jpg|thumb|Site at 1318 Lafayette which was where Jesse was shot. The top of the [[Patee House]] is to the right at the bottom of the hill. Zerelda stayed at the Patee House after he was shot. His house was ultimately moved to the Patee House grounds.]] |

|||

[[Image:Jesse-james-home1.jpg|thumb|Jesse James's home in St. Joseph, where he was shot]] |

|||

With his gang decimated by arrests, deaths, and defections, James thought that he had only two men left whom he could trust: brothers [[Robert Ford (outlaw)|Robert]] and [[Charley Ford]].<ref name="la times">{{cite news |title=One more shot at the legend of Jesse James |work=[[Los Angeles Times]] |date= 2007-09-17|url=http://articles.latimes.com/2007/sep/17/entertainment/et-weekmovie17 |accessdate=2008-12-07}}</ref> Charley had been out on raids with James before, but Bob was an eager new recruit. To better protect himself, James asked the Ford brothers to move in with him and his family. James often stayed with the Fords' sister Martha Bolton, and according to rumor he was "smitten" with her.<ref name="seattle times"/> He did not know that Bob Ford had been conducting secret negotiations with [[Thomas Theodore Crittenden|Thomas T. Crittenden]], the Missouri governor, to bring in the famous outlaw.<ref name="la times"/> Crittenden had made capture of the James brothers his top priority; in his inaugural address he declared that no political motives could be allowed to keep them from justice. Barred by law from offering a sufficiently large reward, he had turned to the railroad and express corporations to put up a $5,000 bounty for each of them. President [[Ulysses S. Grant]] had also wanted James to be captured, but by this time was out of office.<ref name="seattle times"/> |

|||

===Pinkertons=== |

|||

On April 3, 1882, after eating breakfast, the Fords and James prepared for departure for another robbery, going in and out of the house to ready the horses. It was an unusually hot day. James removed his coat, then declared that he should remove his firearms as well, lest he look suspicious. James noticed a dusty picture on the wall and stood on a chair to clean it. Robert Ford took advantage of the opportunity and shot James in the back of the head.<ref>{{cite news |title=Jesse James Shot Down. Killed By One Of His Confederates Who Claims To Be A Detective |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9B01E1DE173DE533A25757C0A9629C94639FD7CF |quote=A great sensation was erected in this city this morning by the announcement that Jesse James, the notorious bandit and train-robber, had been shot and killed here. The news spread with great rapidity, but most persons received it with doubts until investigation established the fact beyond question. |work=[[New York Times]] |date=1882-04-04 |accessdate=2008-12-09}}</ref><ref name="stiles363">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=363-75 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref><ref name="yeatman264">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |date=2000 |ISBN=1581823258 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=264-9}}</ref> |

|||

In 1874, the [[Adams Express Company]] turned to the [[Pinkerton National Detective Agency]] to stop the [[James–Younger Gang]]. The [[Chicago]]-based agency worked primarily against urban professional criminals, as well as providing industrial security, such as [[Strikebreaker|strike breaking]]. Because the [[James-Younger gang|gang]] received support by many former Confederate soldiers in Missouri, they eluded the Pinkertons. Joseph Whicher, an agent dispatched to infiltrate Zerelda Samuel's farm, was soon found killed. Two other agents, Captain Louis J. Lull and John Boyle, were sent after the Youngers; Lull was killed by two of the Youngers in a roadside gunfight on March 17, 1874. Before he died, Lull fatally shot [[John Younger]]. A deputy sheriff named Edwin Daniels also died in the skirmish.<ref name="yeatman111">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |year=2000 |isbn=1-58182-325-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=111–20}}</ref><ref name="stiles249">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=249–58 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

James' two previous bullet wounds and partially missing middle finger served to positively identify the body.<ref name="settle"/> |

|||

{{external media | width = 210px | float = right | headerimage= | video1 = [https://www.c-span.org/video/?165238-1/frank-jesse-james ''Booknotes'' interview with Ted Yeatman on ''Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend'', October 28, 2001], [[C-SPAN]]}} |

|||

[[Allan Pinkerton]], the agency's founder and leader, took on the case as a personal vendetta. He began to work with former Unionists who lived near the James family farm. On the night of January 25, 1875, he staged a raid on the homestead. Detectives threw an incendiary device into the house; it exploded, killing James's young half-brother Archie (named for Archie Clement) and blowing off one of Zerelda Samuel's arms. Afterward, Pinkerton denied that the raid's intent was [[arson]]. But biographer Ted Yeatman found a letter by Pinkerton in the [[Library of Congress]] in which Pinkerton declared his intention to "burn the house down."<ref name="yeatman128">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |year=2000 |isbn=1-58182-325-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=128–44}}</ref><ref name="stiles272">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=272–85 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

Many residents were outraged by the raid on the family home. The Missouri state legislature narrowly defeated a bill that praised the James and Younger brothers and offered them [[amnesty]].<ref name="SS3" /> Allowed to vote and hold office again, former Confederates in the legislature voted to limit the size of rewards the governor could offer for fugitives. This extended a measure of protection over the [[James–Younger gang]] by minimizing the incentive for attempting to capture them. The governor had offered rewards higher than the new limit only on Frank and Jesse James.<ref name="settle76">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |year=1977 |access-date=December 7, 2008 |pages=76–84 |isbn=978-0-8032-5860-0}}</ref><ref name="yeatman286">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |year=2000 |isbn=1-58182-325-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=286–305}}</ref> |

|||

The murder of Jesse James was a national sensation. The Fords made no attempt to hide their role. Indeed, Robert Ford wired the governor to claim his reward. Crowds pressed into the little house in St. Joseph to see the dead bandit, even while the Ford brothers surrendered to the authorities—but they were dismayed to find that they were charged with [[first degree murder]]. In the course of a single day, the Ford brothers were indicted, pled guilty, were sentenced to death by [[hanging]], and two hours later granted a full pardon by Governor Crittenden.<ref name="nytimes">{{cite news |title=Jesse James's Murderers. The Ford Brothers Indicted, Plead Guilty, Sentenced To Be Hanged, And Pardoned All In One Day |work=[[New York Times]] |date=1882-04-18 |url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9D04E3DB113EE433A2575BC1A9629C94639FD7CF |accessdate=2008-12-07}}</ref> |

|||

Across a creek and up a hill from the James house was the home of Daniel Askew, who is thought to have been killed by James or his gang on April 12, 1875. They may have suspected Askew of cooperating with the [[Pinkertons]] in the January 1875 arson of the James house.{{citation needed|date=March 2017}} |

|||

The governor's quick pardon suggested that he may have been aware that the brothers intended to kill, rather than capture, James.{{Fact|date=December 2008}} The Ford brothers, like many who knew James, never believed it was practical to try to capture such a dangerous man.{{Fact|date=December 2008}} The implication that the chief executive of Missouri conspired to kill a private citizen startled the public and helped to create a new legend around James.<ref name="stiles376">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=376-81 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref><ref name="yeatman270">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |date=2000 |ISBN=1581823258 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=270-2}}</ref><ref name="settle117">{{cite book |first=William A. |last=Settle |title=Jesse James Was His Name |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=3cHhY4qAvdcC |publisher=University of Nebraska Press |date=1977 |accessdate=2008-12-07 |page=117-36}}</ref> |

|||

===Downfall of the gang=== |

|||

The Fords received a small portion of the reward and fled Missouri. Some of the bounty went to law enforcement officials who were active in the plan. The Ford brothers starred in a touring stage show in which they reenacted the shooting.<ref name="stiles378">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=378, 395-95 |ISBN 0375405836}}</ref><ref>Stiles, .</ref> |

|||

On September 7, 1876, the opening day of hunting season in Minnesota, the James–Younger gang attempted a raid on the [[Northfield, Minnesota#Defeat of Jesse James Days Celebration|First National Bank]] of [[Northfield, Minnesota]]. The robbery quickly went wrong, however, and after the robbery only Frank and Jesse James remained alive and free.<ref name="st. joseph">{{cite web|title=St. Joseph History — Jesse James |publisher=St. Joseph, Missouri |url=http://www.ci.st-joseph.mo.us/history/jessejames.cfm |access-date=December 7, 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090124034733/http://ci.st-joseph.mo.us/history/jessejames.cfm |archive-date=January 24, 2009 }}</ref> |

|||

Cole and Bob Younger later said they selected the bank because they believed it was associated with the Republican politician [[Adelbert Ames]], the governor of [[Mississippi]] during Reconstruction, and Union general [[Benjamin Butler (politician)|Benjamin Butler]], Ames's father-in-law and the Union commander of occupied [[New Orleans, Louisiana|New Orleans]]. Ames was a stockholder in the bank, but Butler had no direct connection to it.<ref name="stiles324">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T. J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=324–5 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

[[Charley Ford]] committed [[suicide]] on May 6, 1884 in Richmond, Missouri after suffering from [[tuberculosis]] and a [[morphine]] addiction. [[Robert Ford (outlaw)|Bob Ford]] was killed by a shotgun blast to the throat in his tent saloon in [[Creede, Colorado]], on June 8, 1892. His killer, [[Edward Capehart O'Kelley]], was sentenced to life in prison. O'Kelley's sentence was commuted because of a medical condition, and he was released on October 3, 1902.<ref>{{cite book |last=Ries |first=Judith |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=B5B9AAAACAAJ |title=Ed O'Kelley: The Man Who Murdered Jesse James' Murderer |publisher=Stewart Printing and Publishing Co. |date=1994 |ISBN=0-934426-61-9}}</ref> |

|||

The gang attempted to rob the bank in Northfield at about 2 p.m. To carry out the robbery, the gang divided into two groups. Three men entered the bank, two guarded the door outside, and three remained near a bridge across an adjacent square. The robbers inside the bank were thwarted when acting cashier [[Joseph Lee Heywood]] refused to open the safe, falsely claiming that it was secured by a [[time lock]] even as they held a [[Bowie knife]] to his throat and [[skull fracture|cracked his skull]] with a pistol butt. Assistant cashier Alonzo Enos Bunker was wounded in the shoulder as he fled through the back door of the bank. Meanwhile, the citizens of Northfield grew suspicious of the men guarding the door and raised the alarm. The five bandits outside fired into the air to clear the streets, driving the townspeople to take cover and fire back from protected positions. They shot two bandits dead and wounded the rest in the barrage. Inside, the outlaws turned to flee. As they left, one shot the unarmed cashier Heywood in the head. Historians have speculated about the identity of the shooter but have not reached consensus. |

|||

Zerelda Samuel selected an epitaph for Jesse James that stated: ''In Loving Memory of my Beloved Son, Murdered by a Traitor and Coward Whose Name is not Worthy to Appear Here.''<ref name="la times"/> |

|||

The gang barely escaped Northfield, leaving two dead companions behind. They killed Heywood and [[Nicholas Gustafson]], a Swedish immigrant from the Millersburg community west of Northfield. A substantial manhunt ensued. It is believed that the gang burned 14 [[Rice County, Minnesota|Rice County]] mills shortly after the robbery.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00861.xml |title=An Inventory of the Northfield (Minnesota) Bank Robbery of 1876: Selected Manuscripts Collection |publisher=Mnhs.org |access-date=September 6, 2012}}</ref> The James brothers eventually split from the others and escaped to Missouri. The militia soon discovered the Youngers and one other bandit, Charlie Pitts. Pitts died in a gunfight and the Youngers were taken prisoner. Except for Frank and Jesse James, the James–Younger Gang was destroyed.<ref name="yeatman169">{{cite book |last=Yeatman |first=Ted P. |title=Frank and Jesse James: The Story Behind the Legend |publisher=Cumberland House Publishing |year=2000 |isbn=1-58182-325-8 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=u4WlW39O8-UC |pages=169–86}}</ref><ref name="stiles326">{{cite book |last=Stiles |first=T.J. |title=Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uAINAAAACAAJ |publisher=Knopf Publishing |year=2002 |pages=326–47 |isbn =0-375-40583-6}}</ref> |

|||

James's widow Zee died alone and in [[poverty]]. |

|||

Later in 1876, Jesse and Frank James surfaced in the [[Nashville, Tennessee]], area, where they went by the names of Thomas Howard and B. J. Woodson, respectively. Frank seemed to settle down, but Jesse remained restless. He recruited a new gang in 1879 and returned to crime, holding up a train at Glendale, Missouri (now part of [[Independence, Missouri|Independence]]),<ref>{{cite news |title=Skillful Detective Work; Another of the James Gang Captured in Missouri |work=The New York Times |date=March 19, 1889 |url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9802EEDE113EE433A2575AC1A9659C94639FD7CF}}</ref> on October 8, 1879. The robbery was the first in a spree of crimes, including the holdup of the federal paymaster of a canal project in [[Killen, Alabama]], and two more train robberies. However, the new gang was not made up of battle-hardened guerrillas; they soon turned against each other or were captured. James grew suspicious of other members; he scared away one man and some believe that he killed another gang member. |

|||

==Rumors of survival== |

|||

Rumors of Jesse James's survival proliferated almost as soon as the newspapers announced his death. Some said that Robert Ford killed someone other than James, in an elaborate plot to allow him to escape justice. These tales received little credence, then or now. None of James's biographers has accepted them as plausible. The body buried in Kearney, Missouri as Jesse James was exhumed in 1995 and tested for DNA. The report, prepared by Anne C. Stone, Ph.D., James E. Starrs, L.L.M., and Mark Stoneking, Ph.D., stated the remains were consistent with the DNA of Jesse James's relatives.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Stone |first=A. C. |coauthors=J. E. Starrs and M. Stoneking |date=2001 |title=Mitochondrial DNA analysis of the presumptive remains of Jesse James |journal=Journal of Forensic Sciences'', 46:173-176}}</ref> |

|||

In 1879, the James gang robbed two stores in far western [[Mississippi]], at [[Washington, Mississippi|Washington]] in [[Adams County, Mississippi|Adams County]] and [[Fayette, Mississippi|Fayette]] in [[Jefferson County, Mississippi|Jefferson County]]. The gang left with $2,000 cash from the second robbery and took shelter in abandoned cabins on the Kemp Plantation south of [[St. Joseph, Louisiana|St. Joseph]], [[Louisiana]]. A law enforcement posse attacked and killed two of the outlaws but failed to capture the entire gang. Among the deputies was [[Jefferson B. Snyder]], later a long-serving [[district attorney]] in northeastern Louisiana.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://files.usgwarchives.net/la/madison/bios/snyderjb.txt|title=Jefferson B. Snyder|publisher=[[New Orleans Times-Picayune]], April 15, 1938|access-date=July 22, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

==Legacy== |

|||

James's turn to crime after the end of Reconstruction helped cement his place in American life and memory as a simple but remarkably effective bandit. After 1873 he was covered by the national media as part of social banditry.<ref>{{cite book |last=Slotkin |first=Richard |title=Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=-9XOsW7YwJ4C |publisher=University of Oklahoma Press |date=1998 |ISBN=0806130318 |pages=128}}</ref> During his lifetime, James was celebrated chiefly by former Confederates, to whom he appealed directly in his letters to the press. Displaced by Reconstruction, the antebellum political leadership mythologized the James Gang exploits. Frank Triplett wrote about James as a "progressive neo-aristocrat" with purity of race.<ref>{{cite book |last=Slotkin |first=Richard |title=Gunfighter Nation: The Myth of the Frontier in Twentieth-Century America |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=-9XOsW7YwJ4C |publisher=University of Oklahoma Press |date=1998 |ISBN=0806130318 |pages=134-136}}</ref> Indeed, some historians credit James' myth as contributing to the rise of former Confederates to dominance in Missouri politics{{Fact|date=March 2009}} (in the 1880s, for example, both [[United States Senate|U.S. Senators]] from the state were identified with the Confederate [[Lost Cause of the Confederacy|cause]]).{{Fact|date=April 2009}} |

|||