Locked-in syndrome: Difference between revisions

Tekhnofiend (talk | contribs) m switched ALS to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis - fully spell out acronyms on their first use |

m →Prognosis: ce |

||

| (878 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Condition in which a patient is aware but completely paralysed}} |

|||

{{Infobox_Disease | |

|||

{{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc}} |

|||

Name = Locked-in syndrome | |

|||

<!---This info is horribly inaccurate and needs a full revision.--> |

|||

Image = CerebellumArteries.jpg | |

|||

{{Infobox medical condition (new) |

|||

Caption = Locked-in syndrome can be caused by stroke at the level of the [[basilar artery]] denying blood to the [[pons]], among other causes. | |

|||

| name = Locked-in syndrome |

|||

DiseasesDB = | |

|||

| synonyms = Cerebromedullospinal disconnection,<ref name="pmid5166219">{{cite journal |vauthors=Nordgren RE, Markesbery WR, Fukuda K, Reeves AG | title= Seven cases of cerebromedullospinal disconnection: the "locked-in" syndrome |journal=Neurology |volume=21 |issue=11 |pages=1140–8 |year=1971 |pmid=5166219 |doi=10.1212/wnl.21.11.1140| s2cid= 32398246 }}</ref> de-efferented state, pseudocoma,<ref name="pmid844425">{{cite journal |vauthors=Flügel KA, Fuchs HH, Druschky KF |title=The "locked-in" syndrome: pseudocoma in thrombosis of the basilar artery (author's trans.) |language=de |journal=Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift |volume=102 |issue=13 |pages=465–70 |year=1977 |pmid=844425 |doi=10.1055/s-0028-1104912}}</ref> ventral pontine syndrome |

|||

ICD10 = {{ICD10|G|46|3|g|40}} | |

|||

| image = CerebellumArteries.svg |

|||

| caption = Locked-in syndrome can be caused by a stroke at the level of the [[basilar artery]] denying blood to the [[pons]], among other causes. |

|||

ICDO = | |

|||

| field = [[Neurology]], [[Psychiatry]] |

|||

| symptoms = |

|||

| complications = |

|||

eMedicineSubj = | |

|||

| onset = |

|||

eMedicineTopic = | |

|||

| duration = |

|||

| types = |

|||

| causes = |

|||

| risks = |

|||

| diagnosis = |

|||

| differential = |

|||

| prevention = |

|||

| treatment = |

|||

| medication = |

|||

| prognosis = |

|||

| frequency = |

|||

| deaths = |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Locked-in syndrome''' is a condition in which a patient is aware |

'''Locked-in syndrome''' ('''LIS'''), also known as '''pseudocoma''', is a condition in which a patient is aware but cannot move or communicate verbally due to complete paralysis of nearly all voluntary muscles in their body except for vertical eye movements and blinking.<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559026|title=Locked-in Syndrome|first1=Joe|last1=Das|first2=Kingsley|last2=Anosike|first3=Ria Monica|last3=Asuncion|date=2022|access-date=10 June 2023|website=[[National Center for Biotechnology Information]]|pmid=32644452 }}</ref> The individual is conscious and sufficiently intact cognitively to be able to communicate with eye movements.<ref>{{Cite book|title=motor speech disorders substrates, differential diagnosis, and management|last=Duffy|first=Joseph|publisher=Elsevier|pages=295}}</ref> [[Electroencephalography]] results are normal in locked-in syndrome. |

||

'''Total locked-in syndrome''', or '''completely locked-in state''' ('''CLIS'''), is a version of locked-in syndrome wherein the eyes are paralyzed as well.<ref name= "bauer1979varieties">{{cite journal | doi = 10.1007/BF00313105 | author =Bauer, G. | author2 =Gerstenbrand, F. | author3 =Rumpl, E. | title= Varieties of the locked-in syndrome | journal= Journal of Neurology | volume =221 |issue=2 |pages=77–91 |year=1979 |pmid=92545| s2cid =10984425 }}</ref> [[Fred Plum]] and [[Jerome B. Posner]] coined the term for this disorder in 1966.<ref name="titleeMedicine - Stroke Motor Impairment : Article by Adam B Agranoff, MD">{{cite web |url=http://www.emedicine.com/pmr/topic189.htm |title= Stroke Motor Impairment | first = Adam B | last = Agranoff | access-date = 2007-11-29 | work = eMedicine}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | last1 = Plum | first1 = F | last2 = Posner | first2 = JB | year = 1966 | title = The diagnosis of stupor and coma | publisher = FA Davis | place = Philadelphia, PA, USA}}, 197 pp.</ref> |

|||

==Signs and symptoms== |

|||

Locked-in syndrome is also known as ''cerebromedullospinal disconnection'',<ref name="pmid5166219">{{cite journal |author=Nordgren RE, Markesbery WR, Fukuda K, Reeves AG |title=Seven cases of cerebromedullospinal disconnection: the "locked-in" syndrome |journal=Neurology |volume=21 |issue=11 |pages=1140–8 |year=1971 |pmid=5166219 |doi=}}</ref> ''de-efferented state'', ''pseudocoma'',<ref name="pmid844425">{{cite journal |author=Flügel KA, Fuchs HH, Druschky KF |title=[The "locked-in" syndrome: pseudocoma in thrombosis of the basilar artery (author's transl)] |language=German |journal=Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. |volume=102 |issue=13 |pages=465–70 |year=1977 |pmid=844425 |doi=}}</ref> and ''ventral pontine syndrome''. |

|||

Locked-in syndrome is usually characterized by [[quadriplegia]] (loss of limb function) and the inability to [[Manner of articulation|speak]] in otherwise cognitively intact individuals. Those with locked-in syndrome may be able to communicate with others through coded messages by blinking or moving their eyes, which are often not affected by the paralysis. Patients who have locked-in syndrome are conscious and aware, with no loss of cognitive function. They can sometimes retain [[proprioception]] and sensation throughout their bodies. Some patients may have the ability to move certain facial muscles, and most often some or all of the [[extraocular muscles]]. Individuals with the syndrome lack coordination between breathing and voice.<ref name= "fager" /> This prevents them from producing voluntary sounds, though the [[vocal cords]] themselves may not be paralysed.<ref name ="fager">{{cite journal|doi=10.1080/07434610600650318| last1=Fager| first1=Susan| last2=Beukelman| first2=Dave| last3=Karantounis| first3=Renee| last4=Jakobs| first4=Tom| year= 2006| title = Use of safe-laser access technology to increase head movements in persons with severe motor impairments: a series of case reports| journal= Augmentative and Alternative Communication|volume= 22| issue= 3| pages= 222–29 | pmid= 17114165| s2cid=36840057}}</ref> |

|||

==Causes== |

|||

The term for this disorder was coined by Plum and Posner in 1966.<ref name="titleeMedicine - Stroke Motor Impairment : Article by Adam B Agranoff, MD">{{cite web |url=http://www.emedicine.com/pmr/topic189.htm |title=eMedicine - Stroke Motor Impairment : Article by Adam B Agranoff, MD |accessdate=2007-11-29 |format= |work=}}</ref><ref>Plum F. and Posner J.B. 1966. The diagnosis of stupor and coma. F.A. Davis Co. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. 197 pp.</ref> |

|||

{{More citations needed section|date=June 2024}} |

|||

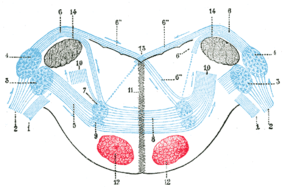

[[Image:Gray760.png|thumb|upright=1.3|In children, the most common cause is a stroke of the ventral [[pons]].<ref name="pmid19748042">{{cite journal |vauthors=Bruno MA, Schnakers C, Damas F, etal |title= Locked-in syndrome in children: report of five cases and review of the literature |journal=Pediatr. Neurol. |volume=41 |issue=4 |pages=237–46 |date=October 2009 |pmid= 19748042 |doi=10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.05.001 }}</ref>]] |

|||

==Presentation== |

|||

Unlike [[persistent vegetative state]], in which the upper portions of the brain are damaged and the lower portions are spared, locked-in syndrome is essentially the opposite, caused by damage to specific portions of the lower brain and [[brainstem]], with no damage to the upper brain.{{citation needed|date=December 2020}} Injuries to the pons are the most common cause of locked-in syndrome. |

|||

Locked-in syndrome is usually the result of [[quadriplegia]] and inability to [[Manner of articulation|speak]] in otherwise cognitively-intact individuals. Those with locked-in syndrome may be able to communicate with others by coding messages by blinking or moving their eyes, which are often not affected by the paralysis. Patients who have locked-in syndrome are conscious and aware with no loss of cognitive function. They can sometimes retain [[proprioception]] and sensation throughout their body. Some patients may have the ability to move certain facial muscles, most often some or all of the extraocular eye muscles. Individuals with locked-in syndrome lack coordination between breathing and voice.<ref name="fager" /> This restricts them from producing voluntary sounds, even though the [[vocal cords]] themselves are not paralysed.<ref name =fager>{{cite journal|last=Fager|first=Susan|coauthors=Beukelman, Karantounis, Jakobs|date=2006|title=Use of safe-laser access technology to increase head movements in persons with severe motor impairments: a series of case reports|journal=Augmentative and Alternative Communication|volume=22|pages=222-229}}</ref> |

|||

== Causes == |

|||

Unlike [[persistent vegetative state]], in which the upper portions of the brain are damaged and the lower portions are spared, locked-in syndrome is caused by damage to specific portions of the lower brain and brainstem with no damage to the upper brain. |

|||

Possible causes of locked-in syndrome include: |

Possible causes of locked-in syndrome include: |

||

* [[Poisoning]] cases – More frequently from a [[Bungarus|krait]] bite and other [[neurotoxic]] [[venom]]s, as they cannot usually cross the [[blood–brain barrier]] |

|||

* [[Traumatic brain injury]] |

|||

* [[Brainstem stroke syndrome|Brainstem stroke]] |

|||

* Diseases of the [[circulatory system]] |

* Diseases of the [[circulatory system]] |

||

* Medication overdose |

* Medication overdose{{Example needed |s|date=December 2018}} |

||

* Damage to nerve cells, particularly destruction of the [[myelin sheath]], caused by disease ( |

* Damage to nerve cells, particularly destruction of the [[myelin sheath]], caused by disease or ''osmotic demyelination syndrome'' (formerly designated [[central pontine myelinolysis]]) secondary to excessively rapid correction of [[hyponatremia]] [>1 mEq/L/h])<ref>{{cite book |language=en |last=Aminoff |first=Michael |title=Clinical Neurology |edition=9nth |year=2015 |page=76 |publisher=Lange |isbn=978-0-07-184142-9}}</ref> |

||

* A stroke or brain hemorrhage, usually of the [[basilar artery]] |

* A stroke or brain hemorrhage, usually of the [[basilar artery]] |

||

* [[Traumatic brain injury]] |

|||

* Result from [[lesion]] of the brainstem |

|||

[[Curare poisoning]] and [[paralytic shellfish poisoning]] mimic a total locked-in syndrome by causing [[paralysis]] of all voluntarily controlled [[skeletal muscle]]s.<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=RSOPDHP9QekC&pg=PA357 Page 357] in: {{cite book |author=Damasio, Antonio R. |title=The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness |publisher=Harcourt Brace |location=San Diego |year=1999 |isbn=978-0-15-601075-7 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/feelingofwhathap00dama_0 }}</ref> The respiratory muscles are also paralyzed, but the victim can be kept alive by [[artificial respiration]]. |

|||

== Number of cases == |

|||

In the United States, there are no statistics available on how many people have locked-in syndrome but it is estimated that several thousand patients each year survive the kind of brain-stem stroke that causes the condition. |

|||

== |

==Diagnosis== |

||

Locked-in syndrome can be difficult to diagnose. In a 2002 survey of 44 people with LIS, it took almost three months to recognize and diagnose the condition after it had begun.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=León-Carrión|first1=J.|last2=van Eeckhout|first2=P.|last3=Domínguez-Morales Mdel|first3=R.|last4=Pérez-Santamaría|first4=F. J.|title=The locked-in syndrome: a syndrome looking for a therapy|journal=Brain Inj.|date=2002|volume=16|issue=7|pages=571–82|doi=10.1080/02699050110119781|pmid=12119076|s2cid=20970974}}</ref> Locked-in syndrome may mimic [[Unconsciousness|loss of consciousness]] in patients, or, in the case that respiratory control is lost, may even resemble death. People are also unable to actuate standard motor responses such as [[Withdrawal reflex|withdrawal from pain]]; as a result, testing often requires making requests of the patient such as blinking or vertical eye movement.{{citation needed|date=December 2020}} |

|||

There is no standard treatment for locked-in syndrome, nor is there a cure. Stimulation of muscle reflexes with electrodes ([[NMES]]) has been known to help patients regain some muscle function. Other courses of treatment are often [[symptomatic]].<ref>{{NINDS|lockedinsyndrome}}</ref> Assistive computer interface technologies, such as [[Dasher]] in combination with [[eye tracking]] may be used to help patients communicate.[http://polishlinux.org/apps/dasher-keyboard-without-keys/] New [[direct brain interface]] mechanisms may provide future remedies.<ref>Parker, I., "Reading Minds," The New Yorker, January 20, 2003, 52-63</ref><ref>[http://www.bu.edu/today/2008/10/14/turning-thoughts-words Turning Thoughts into Words] By Chris Berdik, Research at Boston University 2008 magazine (reprinted in BU Today), October 15, 2008.</ref> |

|||

Brain imaging may provide additional indicators of locked-in syndrome, as brain imaging provides clues as to whether or not brain function has been lost. Additionally, an [[Electroencephalography|EEG]] can allow the observation of sleep-wake patterns indicating that the patient is not unconscious but simply unable to move.<ref name="Merck Manual">{{cite web|last=Maiese|first=Kenneth|url=https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/neurologic-disorders/coma-and-impaired-consciousness/locked-in-syndrome|title = Locked-in Syndrome|date=March 2014}}</ref> |

|||

== Prognosis == |

|||

It is extremely rare for any significant motor function to return. The majority of locked-in syndrome patients do not regain motor control, but devices are available to help patients communicate. Within the first four months after its onset, 90% of those with this condition die. However, some people with the condition continue to live much longer periods of time.<ref name=esquire1>[http://www.esquire.com/features/unspeakable-odyssey-motionless-boy-1008 The Unspeakable Odyssey of the Motionless Boy] by Joshua Foer, Esquire Magazine, October 2, 2008.</ref> |

|||

== |

=== Similar conditions === |

||

* [[Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis]] (ALS) |

|||

===[[Jean-Dominique Bauby]]=== |

|||

* [[Brain tumor|Bilateral brainstem tumor]]s |

|||

Parisian journalist [[Jean-Dominique Bauby]] suffered a massive [[stroke]] in December 1995, and when he awoke 20 days later he found that his body was almost completely paralyzed: he could control only his left eyelid. By blinking this eye, he slowly dictated one alphabet character at a time and, in so doing, was able over a great deal of time to write his memoir ''[[The Diving Bell and the Butterfly]].'' A few days after it was published in March 1997, Bauby died of [[pneumonia]].<ref name="titleThe Diving Bell And The Butterfly | The A.V. Club">{{cite web |url=http://www.avclub.com/content/cinema/the_diving_bell_and_the |title=The Diving Bell And The Butterfly | The A.V. Club |accessdate=2007-11-29 |format= |work=}}</ref> The 2008 film ''[[The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (film)|The Diving Bell and the Butterfly]]'' is a screen adaptation of Bauby's memoir. |

|||

* [[Brain death]] (of the whole brain or the brainstem or other part) |

|||

* [[Coma]] (deep or irreversible) |

|||

* [[Guillain–Barré syndrome]] |

|||

* [[Myasthenia gravis]] |

|||

* [[Poliomyelitis]] |

|||

* [[Peripheral neuropathy|Polyneuritis]] |

|||

* [[Vegetative state]] (chronic or otherwise) |

|||

==Treatment== |

|||

===Julia Tavalaro=== |

|||

Neither a standard treatment nor a cure is available. Stimulation of muscle reflexes with electrodes ([[NMES]]) has been known to help patients regain some muscle function. Other courses of treatment are often [[symptomatic]].<ref>{{NINDS|Locked-Syndrome|Locked-in syndrome}}</ref> [[Assistive technology|Assistive computer interface technologies]] such as [[Dasher (software)|Dasher]], combined with [[eye tracking]], may be used to help people with LIS communicate with their environment.{{citation needed|date=December 2020}} |

|||

In 1966, Julia Tavalaro, then aged 32, suffered two strokes and a brain hemorrhage and was sent to Goldwater Memorial Hospital on Roosevelt Island, New York. For six years, it was believed she was in a vegetative state. In 1972, a family member noticed her trying to smile after she heard a joke. After alerting doctors, a speech therapist, Arlene Kratt, discerned cognizance in her eye movements. Kratt and another therapist, Joyce Sabari, were eventually able to convince doctors that she was in a locked-in state. After learning to communicate with eye blinks in response to letters being pointed to on an alphabet board, she became a poet and author. Eventually, she gained the ability to move her head enough to touch a switch with her cheek, which operated a motorized wheelchair and a computer. She gained national attention in 1995 when The Los Angeles Times Magazine published her life story. It was republished by Newsday on Long Island and in other newspapers across the country. She died in 2003 at the age of 68.<ref name=esquire1/><ref>[http://articles.latimes.com/2003/dec/21/local/me-tavalaro21 Julia Tavalaro, 68; Poet and Author Noted for Defying Severe Paralysis], Los Angeles Times, Page B16, December 21, 2003.</ref> |

|||

== |

==Prognosis== |

||

It is extremely rare for any significant motor function to return, with the majority of locked-in syndrome patients never regaining motor control. However, some people with the condition continue to live for extended periods of time,<ref name=esquire1>{{cite news|url=http://www.esquire.com/features/unspeakable-odyssey-motionless-boy-1008 |title=The Unspeakable Odyssey of the Motionless Boy|author= Joshua Foer|work= Esquire |date= October 2, 2008}}</ref><ref>Piotr Kniecicki "An art of graceful dying". Clitheroe: Łukasz Świderski, 2014, s. 73. {{ISBN|978-0-9928486-0-6}}</ref> while in exceptional cases, like that of Kerry Pink,<ref name=BBCnews>{{cite news|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-10985836 |title=I recovered from locked-in syndrome|work= BBC Radio 5 Live|author= Stephen Nolan|date= August 16, 2010}}</ref> Gareth Shepherd,<ref name=Dailyecho>{{cite news|url=https://www.dailyecho.co.uk/news/14866880.he-crashed-his-motorbike-and-had-a-stroke-but-hampshire-man-gareth-shepherd-is-back-on-his-feet |title=He crashed his motorbike and had a stroke - but Hampshire man Gareth Shepherd is back on his feet|work=Daily Echo|date=November 8, 2016}}</ref>{{Failed verification|date=December 2024|talk=Gareth Shepherd|reason=Article references Shepherd being comatose, but not having Locked-in syndrome}} Jacob Haendel,<ref name=YouTube>{{cite news|url=https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCpoJxQNKSybRuSXEEuQ0cNA |title=Jacob Haendel Recovery Channel|work= Jacob Handel Recovery|date= June 29, 2020}}</ref> Kate Allatt,<ref name=BBCnews2>{{cite news|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-17363584 |title=Woman's recovery from 'locked-in' syndrome|work= BBC News|date= March 14, 2012}}</ref> and Jessica Wegbrans,<ref name=Flinkberoerd>{{cite news|url=https://www.flinkberoerd.nl |title=Het gevecht tegen locked-in|work= Flinkberoerd|date=April 23, 2022}}</ref> a near-full recovery may be achieved with intensive physical therapy. |

|||

Gary Griffin was a veteran of the United States Air Force who became immobile due to [[Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis|Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis]] (ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease). He was later equipped with a device called the NeuroSwitch which allows him to control a computer and communicate with his family. Sensors are attached to the skin over a patient’s muscles and signals are sent to an interface that translates the slightest muscle contractions into usable code. A video of Griffin and his use of the NeuroSwitch has been posted on Youtube.<ref>[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GWe5YVV9dWs NeuroSwitch Enables Veteran with Locked in Syndrome] at Youtube.com.</ref> |

|||

== |

==Research== |

||

New [[brain–computer interface]]s (BCIs) may provide future remedies. One effort in 2002 allowed a fully locked-in patient to answer yes-or-no questions.<ref>[http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/01/20/reading-minds Parker, I., "Reading Minds," The New Yorker, January 20, 2003, 52–63]</ref><ref name="Keiper 2006 4–41">{{cite journal|last=Keiper |first=Adam |title=The Age of Neuroelectronics |journal=New Atlantis (Washington, D.c.) |url=http://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/the-age-of-neuroelectronics |publisher=The New Atlantis |pages=4–41 |date=Winter 2006 |volume=11 |pmid=16789311 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160212222927/http://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/the-age-of-neuroelectronics |archive-date=2016-02-12 }}</ref> In 2006, researchers created and successfully tested a neural interface which allowed someone with locked-in syndrome to operate a web browser.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Karim AA, Hinterberger T, Richter J, Mellinger J, Neumann N, Flor H, Kübler A, Birbaumer N |title=Neural internet: Web surfing with brain potentials for the completely paralyzed |journal=Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair |volume=40 |issue=4 |pages=508–515}}</ref> Some scientists have reported that they have developed a technique that allows locked-in patients to communicate via sniffing.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.science.org/content/article/locked-patients-can-follow-their-noses|title='Locked-In' Patients Can Follow Their Noses|date=26 Jul 2010|publisher=Science Mag|access-date=27 Dec 2016}}</ref> |

|||

In 1999, 16-year-old Erik Ramsey suffered a stroke after a car accident that left him in a locked in state. His story was profiled in an edition of ''[[Esquire (magazine)|Esquire]]'' magazine in 2008. Erik is currently working with doctors to develop a new communication system that uses a computer that, through implants in his brain, reads the electronic signals produced when he thinks certain words and sounds. At present, Erik is only able to communicate short and basic sounds. However, doctors believe that within a few years, Erik will be able to use this system to communicate words, phrases and eventually, to "talk" normally.<ref name=esquire1/><ref>[http://www.boston.com/news/local/articles/2008/07/27/out_of_silence_the_sounds_of_hope/?page=full Out of silence, the sounds of hope] by S.I. Rosenbaum, The Boston Globe, July 27, 2008.</ref> |

|||

For the first time in 2020, a 34-year-old German patient, paralyzed since 2015 (later also the eyeballs) managed to communicate through an implant capable of reading brain activity.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/03/22/1047664/locked-in-patient-bci-communicate-in-sentences/|title=A locked-in man state with ALS has been able to communicate thought alone / MIT Technology Review by Jessica Hamzelou / March 26, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Akinetic mutism]] |

|||

* [[List of people with locked-in syndrome]] |

|||

* ''[[The Diving Bell and the Butterfly]]'': memoirs of journalist [[Jean-Dominique Bauby]] about his life with the condition |

|||

* ''[[Johnny Got His Gun]]'', novel about a soldier who loses his limbs and senses after being wounded fighting in WWI |

|||

* [[One (Metallica song)]], song interpretation of ''[[Johnny Got His Gun (film)|Johnny Got His Gun]]'' |

|||

== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist|refs=Locked In Syndrome - NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). (n.d.). Retrieved June 28, 2016, from http://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/locked-in-syndrome/|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

25. Injuries to the pons are the most common cause of locked-in syndrome,Harrison’s principles of internal medicine 21st edition vol 2 page 3332. |

|||

==Further reading== |

|||

*On the TV program ''[[CSI: NY]]''{{'}}s first season episode "[[Blink (CSI: NY episode)|Blink]]", a disgraced Russian doctor working in New York as a [[cabbie]] experiments on his female passengers and a woman who was staying with the doctor and his wife. Detective [[Mac Taylor]] is only able to communicate with the final victim by her blinking twice for yes and once for no. |

|||

* Piotr Kniecicki (2014). ''An Art of Graceful Dying''. Lukasz Swiderski {{ISBN|978-0-9928486-0-6}} (Autobiography, written with residual wrist movements and specially adapted computer) |

|||

*Locked-in syndrome was a diagnosis given to Jean-Pierre, one of the main characters in [[Bernard Werber]]'s novel ''[[L'ultime secret]]''. |

|||

*Locked-in syndrome secondary to [[leptospirosis]] was the case study for Dr. Gregory House and his team in the season 5 episode [[Locked In (House)|Locked In]] of the US TV Drama ''[[House, MD]]''. |

|||

*In a play named "Pills, Thrills and Automobiles," one of the characters (Eddie) is left in a locked in state due to a car crash.{{Fact|date=April 2009}} |

|||

*In [[Alexandre Dumas]]' novel ''[[The Count of Monte Cristo]]'', Monsieur Noirtier de Villefort is stricken with locked-in syndrome after a stroke and communicates with his granddaughter Valentine using only movements of his eyes and eyelids. |

|||

*The main character also suffers from this in the Star Wars: Galaxy of Fear book, City of the Dead. |

|||

*In the book "The Second Opinion" by Michael Palmer, there is a character with locked-in syndrome who communicates with his daughter by movements of his eye. |

|||

*On the TV show Scrubs fifth season in episode 19 "His Story III" a character, Mr. McNair suffers from Locked-In Syndrome, and communicates with his eye movements. |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{Medical resources |

|||

* [http://alis-asso.fr/ewb_pages/c/communiquer_sans_parole.php Locked-in Syndrome Association's guide to communicating without language (French)] |

|||

| DiseasesDB = |

|||

| ICD10 = {{ICD10|G|93|8|g|40}} |

|||

| ICD9 = {{ICD9|344.81}} |

|||

| ICDO = |

|||

| OMIM = |

|||

| MedlinePlus = |

|||

| eMedicineSubj = |

|||

| eMedicineTopic = |

|||

| MeshID = D011782 |

|||

}} |

|||

{{disorders of consciousness}} |

|||

{{Cerebral palsy and other paralytic syndromes}} |

|||

{{Lesions of spinal cord and brainstem}} |

{{Lesions of spinal cord and brainstem}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Locked-In Syndrome}} |

|||

[[Category:Neurotrauma]] |

[[Category:Neurotrauma]] |

||

[[Category:Syndromes]] |

[[Category:Syndromes]] |

||

[[da:Locked-in-syndrom]] |

|||

[[de:Locked-in-Syndrom]] |

|||

[[fr:Syndrome d'enfermement]] |

|||

[[it:Sindrome locked-in]] |

|||

[[hu:Bezártság szindróma]] |

|||

[[nl:Locked-in-syndroom]] |

|||

[[pl:Zespół zamknięcia]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 21:04, 29 December 2024

| Locked-in syndrome | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Cerebromedullospinal disconnection,[1] de-efferented state, pseudocoma,[2] ventral pontine syndrome |

| |

| Locked-in syndrome can be caused by a stroke at the level of the basilar artery denying blood to the pons, among other causes. | |

| Specialty | Neurology, Psychiatry |

Locked-in syndrome (LIS), also known as pseudocoma, is a condition in which a patient is aware but cannot move or communicate verbally due to complete paralysis of nearly all voluntary muscles in their body except for vertical eye movements and blinking.[3] The individual is conscious and sufficiently intact cognitively to be able to communicate with eye movements.[4] Electroencephalography results are normal in locked-in syndrome. Total locked-in syndrome, or completely locked-in state (CLIS), is a version of locked-in syndrome wherein the eyes are paralyzed as well.[5] Fred Plum and Jerome B. Posner coined the term for this disorder in 1966.[6][7]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Locked-in syndrome is usually characterized by quadriplegia (loss of limb function) and the inability to speak in otherwise cognitively intact individuals. Those with locked-in syndrome may be able to communicate with others through coded messages by blinking or moving their eyes, which are often not affected by the paralysis. Patients who have locked-in syndrome are conscious and aware, with no loss of cognitive function. They can sometimes retain proprioception and sensation throughout their bodies. Some patients may have the ability to move certain facial muscles, and most often some or all of the extraocular muscles. Individuals with the syndrome lack coordination between breathing and voice.[8] This prevents them from producing voluntary sounds, though the vocal cords themselves may not be paralysed.[8]

Causes

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

Unlike persistent vegetative state, in which the upper portions of the brain are damaged and the lower portions are spared, locked-in syndrome is essentially the opposite, caused by damage to specific portions of the lower brain and brainstem, with no damage to the upper brain.[citation needed] Injuries to the pons are the most common cause of locked-in syndrome.

Possible causes of locked-in syndrome include:

- Poisoning cases – More frequently from a krait bite and other neurotoxic venoms, as they cannot usually cross the blood–brain barrier

- Brainstem stroke

- Diseases of the circulatory system

- Medication overdose[examples needed]

- Damage to nerve cells, particularly destruction of the myelin sheath, caused by disease or osmotic demyelination syndrome (formerly designated central pontine myelinolysis) secondary to excessively rapid correction of hyponatremia [>1 mEq/L/h])[10]

- A stroke or brain hemorrhage, usually of the basilar artery

- Traumatic brain injury

- Result from lesion of the brainstem

Curare poisoning and paralytic shellfish poisoning mimic a total locked-in syndrome by causing paralysis of all voluntarily controlled skeletal muscles.[11] The respiratory muscles are also paralyzed, but the victim can be kept alive by artificial respiration.

Diagnosis

[edit]Locked-in syndrome can be difficult to diagnose. In a 2002 survey of 44 people with LIS, it took almost three months to recognize and diagnose the condition after it had begun.[12] Locked-in syndrome may mimic loss of consciousness in patients, or, in the case that respiratory control is lost, may even resemble death. People are also unable to actuate standard motor responses such as withdrawal from pain; as a result, testing often requires making requests of the patient such as blinking or vertical eye movement.[citation needed]

Brain imaging may provide additional indicators of locked-in syndrome, as brain imaging provides clues as to whether or not brain function has been lost. Additionally, an EEG can allow the observation of sleep-wake patterns indicating that the patient is not unconscious but simply unable to move.[13]

Similar conditions

[edit]- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)

- Bilateral brainstem tumors

- Brain death (of the whole brain or the brainstem or other part)

- Coma (deep or irreversible)

- Guillain–Barré syndrome

- Myasthenia gravis

- Poliomyelitis

- Polyneuritis

- Vegetative state (chronic or otherwise)

Treatment

[edit]Neither a standard treatment nor a cure is available. Stimulation of muscle reflexes with electrodes (NMES) has been known to help patients regain some muscle function. Other courses of treatment are often symptomatic.[14] Assistive computer interface technologies such as Dasher, combined with eye tracking, may be used to help people with LIS communicate with their environment.[citation needed]

Prognosis

[edit]It is extremely rare for any significant motor function to return, with the majority of locked-in syndrome patients never regaining motor control. However, some people with the condition continue to live for extended periods of time,[15][16] while in exceptional cases, like that of Kerry Pink,[17] Gareth Shepherd,[18][failed verification – see discussion] Jacob Haendel,[19] Kate Allatt,[20] and Jessica Wegbrans,[21] a near-full recovery may be achieved with intensive physical therapy.

Research

[edit]New brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) may provide future remedies. One effort in 2002 allowed a fully locked-in patient to answer yes-or-no questions.[22][23] In 2006, researchers created and successfully tested a neural interface which allowed someone with locked-in syndrome to operate a web browser.[24] Some scientists have reported that they have developed a technique that allows locked-in patients to communicate via sniffing.[25] For the first time in 2020, a 34-year-old German patient, paralyzed since 2015 (later also the eyeballs) managed to communicate through an implant capable of reading brain activity.[26]

See also

[edit]- Akinetic mutism

- List of people with locked-in syndrome

- The Diving Bell and the Butterfly: memoirs of journalist Jean-Dominique Bauby about his life with the condition

- Johnny Got His Gun, novel about a soldier who loses his limbs and senses after being wounded fighting in WWI

- One (Metallica song), song interpretation of Johnny Got His Gun

References

[edit]- ^ Nordgren RE, Markesbery WR, Fukuda K, Reeves AG (1971). "Seven cases of cerebromedullospinal disconnection: the "locked-in" syndrome". Neurology. 21 (11): 1140–8. doi:10.1212/wnl.21.11.1140. PMID 5166219. S2CID 32398246.

- ^ Flügel KA, Fuchs HH, Druschky KF (1977). "The "locked-in" syndrome: pseudocoma in thrombosis of the basilar artery (author's trans.)". Deutsche Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 102 (13): 465–70. doi:10.1055/s-0028-1104912. PMID 844425.

- ^ Das J, Anosike K, Asuncion RM (2022). "Locked-in Syndrome". National Center for Biotechnology Information. PMID 32644452. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ^ Duffy J. motor speech disorders substrates, differential diagnosis, and management. Elsevier. p. 295.

- ^ Bauer, G., Gerstenbrand, F., Rumpl, E. (1979). "Varieties of the locked-in syndrome". Journal of Neurology. 221 (2): 77–91. doi:10.1007/BF00313105. PMID 92545. S2CID 10984425.

- ^ Agranoff AB. "Stroke Motor Impairment". eMedicine. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

- ^ Plum F, Posner JB (1966), The diagnosis of stupor and coma, Philadelphia, PA, USA: FA Davis, 197 pp.

- ^ a b Fager S, Beukelman D, Karantounis R, Jakobs T (2006). "Use of safe-laser access technology to increase head movements in persons with severe motor impairments: a series of case reports". Augmentative and Alternative Communication. 22 (3): 222–29. doi:10.1080/07434610600650318. PMID 17114165. S2CID 36840057.

- ^ Bruno MA, Schnakers C, Damas F, et al. (October 2009). "Locked-in syndrome in children: report of five cases and review of the literature". Pediatr. Neurol. 41 (4): 237–46. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.05.001. PMID 19748042.

- ^ Aminoff M (2015). Clinical Neurology (9nth ed.). Lange. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-07-184142-9.

- ^ Page 357 in: Damasio, Antonio R. (1999). The feeling of what happens: body and emotion in the making of consciousness. San Diego: Harcourt Brace. ISBN 978-0-15-601075-7.

- ^ León-Carrión J, van Eeckhout P, Domínguez-Morales Mdel R, Pérez-Santamaría FJ (2002). "The locked-in syndrome: a syndrome looking for a therapy". Brain Inj. 16 (7): 571–82. doi:10.1080/02699050110119781. PMID 12119076. S2CID 20970974.

- ^ Maiese K (March 2014). "Locked-in Syndrome".

- ^ Locked-in syndrome at NINDS

- ^ Joshua Foer (October 2, 2008). "The Unspeakable Odyssey of the Motionless Boy". Esquire.

- ^ Piotr Kniecicki "An art of graceful dying". Clitheroe: Łukasz Świderski, 2014, s. 73. ISBN 978-0-9928486-0-6

- ^ Stephen Nolan (August 16, 2010). "I recovered from locked-in syndrome". BBC Radio 5 Live.

- ^ "He crashed his motorbike and had a stroke - but Hampshire man Gareth Shepherd is back on his feet". Daily Echo. November 8, 2016.

- ^ "Jacob Haendel Recovery Channel". Jacob Handel Recovery. June 29, 2020.

- ^ "Woman's recovery from 'locked-in' syndrome". BBC News. March 14, 2012.

- ^ "Het gevecht tegen locked-in". Flinkberoerd. April 23, 2022.

- ^ Parker, I., "Reading Minds," The New Yorker, January 20, 2003, 52–63

- ^ Keiper A (Winter 2006). "The Age of Neuroelectronics". New Atlantis (Washington, D.c.). 11. The New Atlantis: 4–41. PMID 16789311. Archived from the original on 2016-02-12.

- ^ Karim AA, Hinterberger T, Richter J, Mellinger J, Neumann N, Flor H, Kübler A, Birbaumer N. "Neural internet: Web surfing with brain potentials for the completely paralyzed". Neurorehabilitation & Neural Repair. 40 (4): 508–515.

- ^ "'Locked-In' Patients Can Follow Their Noses". Science Mag. 26 Jul 2010. Retrieved 27 Dec 2016.

- ^ "A locked-in man state with ALS has been able to communicate thought alone / MIT Technology Review by Jessica Hamzelou / March 26, 2022".

25. Injuries to the pons are the most common cause of locked-in syndrome,Harrison’s principles of internal medicine 21st edition vol 2 page 3332.

Further reading

[edit]- Piotr Kniecicki (2014). An Art of Graceful Dying. Lukasz Swiderski ISBN 978-0-9928486-0-6 (Autobiography, written with residual wrist movements and specially adapted computer)