William Hunter (anatomist): Difference between revisions

Eiriksolheim (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Reverted good faith edits by 2600:1014:B1AB:98DA:0:25:9E66:3B01 (talk): Citations needed for changes |

||

| (159 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Scottish physician (1718–1783)}} |

|||

{{Infobox Scientist |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=October 2019}} |

|||

|name = William Hunter |

|||

{{Infobox scientist |

|||

|box_width = |

|||

| |

| name = |

||

| image = William Hunter (anatomist).jpg |

|||

|image_width =150px |

|||

| |

| image_size = |

||

| caption = Portrait by [[Allan Ramsay (artist)|Allan Ramsay]] |

|||

|birth_date = 23 May 1718 |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth-date|23 May 1718}} |

|||

|birth_place = [[East Kilbride]], [[South Lanarkshire]] |

|||

| |

| birth_place = [[East Kilbride]], [[Scotland]] |

||

| death_date = {{death-date and age|30 March 1783|23 May 1718}} |

|||

|death_place = London |

|||

| death_place = [[London]], [[England]] |

|||

|residence = |

|||

| |

| residence = |

||

| |

| citizenship = |

||

| nationality = [[British people|British]] |

|||

|ethnicity = |

|||

| |

| ethnicity = |

||

| field = [[Anatomy]], [[Obstetrics]] |

|||

|work_institutions = |

|||

| work_institutions = |

|||

|alma_mater = [[University of Glasgow]] |

|||

| alma_mater = [[University of Glasgow]]<br />[[University of Edinburgh]] |

|||

|doctoral_advisor = |

|||

| doctoral_advisor = |

|||

|doctoral_students = |

|||

| doctoral_students = |

|||

|known_for = |

|||

| known_for = |

|||

|author_abbrev_bot = |

|||

| author_abbrev_bot = |

|||

|author_abbrev_zoo = |

|||

| author_abbrev_zoo = |

|||

|influences = |

|||

| |

| influences = |

||

| |

| influenced = |

||

| |

| prizes = |

||

| |

| religion = |

||

| |

| footnotes = |

||

| signature = |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

[[File:William Hunter's microscope, Hunterian Museum, Glasgow.jpg|thumb|260px|William Hunter's microscope, Hunterian Museum, Glasgow]] |

|||

{{Morefootnotes|article|date=July 2009}} |

|||

'''William Hunter''' [[Fellow of the Royal Society|FRS]] (23 May 1718 |

'''William Hunter''' {{Post-nominals|post-noms=[[Fellow of the Royal Society|FRS]]}} (23 May 1718 – 30 March 1783) was a Scottish [[anatomist]] and [[physician]]. He was a leading teacher of anatomy, and the outstanding [[obstetrics|obstetrician]] of his day. His guidance and training of his equally famous brother, [[John Hunter (surgeon)|John Hunter]], was also of great importance. |

||

==Early life and career== |

|||

He was born at Long Calderwood near [[East Kilbride]], [[South Lanarkshire]], the elder brother of [[John Hunter (surgeon)|John Hunter]]. After studying divinity at the [[University of Glasgow]], he went into [[medicine]] in 1737, studying under [[William Cullen]]. He was a leading teacher of anatomy, and the outstanding [[obstetrics|obstetrician]] of his day. His guidance and training of his ultimately more famous brother was also of great importance. |

|||

Hunter was born at Long Calderwood, now a part of [[East Kilbride]], [[South Lanarkshire]], to Agnes Paul ({{Circa|1685}}–1751) and John Hunter (1662/3–1741).<ref>{{Cite ODNB|last=Brock|first=Helen|title=Hunter, William (1718–1783), physician, anatomist, and man-midwife|date=2004-09-23|url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-14234|language=en|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/14234|isbn=978-0-19-861412-8|access-date=2021-07-11}}</ref> He was the elder brother of surgeon, [[John Hunter (surgeon)|John Hunter]]. After studying divinity at the [[University of Glasgow]], he went into [[medicine]] in 1737, studying under [[William Cullen]]. |

|||

== Early career == |

|||

Arriving in London, Hunter became resident pupil to William Smellie (1741–44) and he was trained in [[anatomy]] at [[St George's Hospital]], London, specialising in [[obstetrics]]. He followed the example of Smellie in giving a private course on dissecting, operative procedures and bandaging, from 1746. His courtly manners and sensible judgement helped him to advance until he became the leading obstetric consultant of London. Unlike Smellie, he did not favour the use of forceps in delivery. [[Stephen Paget]] said of him: |

|||

:"He never married; he had no country house; he looks, in his portraits, a fastidious, fine gentleman; but he worked till he dropped and he lectured when he was dying."<ref>Garrison, Fielding H. 1914. ''An introduction to the history of medicine''. Saunders, Philadelphia. p269</ref> |

|||

Arriving in London, Hunter became resident pupil to [[William Smellie (obstetrician)|William Smellie]] (1741–44) and he was trained in [[anatomy]] at [[St George's Hospital]], London, specialising in [[obstetrics]]. He followed the example of Smellie in giving a private course on dissecting, operative procedures and bandaging, from 1746. His courtly manners and sensible judgement helped him to advance until he became the leading obstetric consultant of London. Unlike Smellie, he did not favour the use of forceps in delivery. [[Stephen Paget]] said of him: |

|||

To orthopaedic surgeons he is famous for his studies on bone and cartilage. In 1743 he published the paper ''On the structure and diseases of articulating cartilages'' - which is often cited - especially the following sentence: “If we consult the standard Chirurgical Writers from Hippocrates down to the present Age, we shall find, that an ulcerated Cartilage is universally allowed to be a very troublesome Disease; that it admits of a Cure with more Difficulty than carious Bone; and that, when destroyed, it is not recovered” <ref>Hunter W. ''On the structure and diseases of articulating cartilages.'' Trans R Soc Lond 1743;42B:514-21</ref> |

|||

{{blockquote|He never married; he had no country house; he looks, in his portraits, a fastidious, fine gentleman; but he worked till he dropped and he lectured when he was dying.<ref>Garrison, Fielding H. 1914. ''An introduction to the history of medicine''. Saunders, Philadelphia. p. 269.</ref>}} |

|||

To orthopaedic surgeons he is famous for his studies on bone and cartilage. In 1743 he published the paper ''On the structure and diseases of articulating cartilages'' – which is often cited – especially the following sentence: "If we consult the standard Chirurgical Writers from Hippocrates down to the present Age, we shall find, that an ulcerated Cartilage is universally allowed to be a very troublesome Disease; that it admits of a Cure with more Difficulty than carious Bone; and that, when destroyed, it is not recovered".<ref>{{cite journal |last=Hunter |first=William |url=https://archive.org/details/philtrans00926335|doi=10.1098/rstl.1742.0079 |title=Of the structure and diseases of articulating cartilages |journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London |volume=42 |issue=470 |pages=514–521 |year=1743 |s2cid=186214128 }}</ref> |

|||

== Later career == |

|||

==Later career== |

|||

[[File:Hunterw table 12.jpg|thumb|upright|Page from ''The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures'']] |

|||

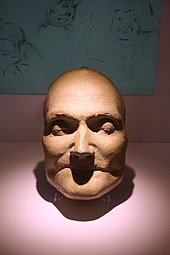

[[File:William Hunter death mask.jpg|thumb|upright|Plaster cast death mask, made several hours after his death. [[Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery]], Glasgow, Scotland.|alt=Colour photograph of the plaster cast death mask of William Hunter. His eyes are closed and he is unsmiling.]] |

|||

In 1764, he became physician to [[Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz|Queen Charlotte]]. He was elected a Fellow of the [[Royal Society]] in 1767 and Professor of Anatomy to the [[Royal Academy]] in 1768. |

In 1764, he became physician to [[Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz|Queen Charlotte]]. He was elected a Fellow of the [[Royal Society]] in 1767 and Professor of Anatomy to the [[Royal Academy]] in 1768. |

||

In 1768 he built the famous anatomy theatre and museum in [[Great Windmill Street#Medical school|Great Windmill Street]], [[Soho]], where the best British anatomists and surgeons of the period were trained. His greatest work was ''Anatomia uteri umani gravidi'' [The anatomy of the human gravid uterus exhibited in figures] (1774), with plates engraved by [[Jan van Rymsdyk|Rymsdyk]] (1730–90),<ref>Thornton, John L. 1982. ''Jan van Rymsdyk: medical artist of the eighteenth century''. Oleander Press, Cambridge {{ISBN|0906672023}}.{{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> and published by the [[John Baskerville|Baskerville Press]]. He chose as a model for clear, precise but schematic illustration of anatomic dissections the drawings by [[Leonardo da Vinci]] conserved in the Royal Collection at [[Windsor Castle|Windsor]]: [[Kenneth Clark]] considered him responsible for the 18th century rediscovery of Leonardo's drawings in England.{{citation needed|date=December 2013}} He praised them highly in his lectures and planned to publish them with his own commentary, but never had the time for the project before his death.<ref>Wells, ''The Heart of Leonardo'', p. 249, 2014, Springer Science & Business Media, {{ISBN|1447145313}}, 9781447145318, [https://books.google.com/books?id=tuq5BAAAQBAJ&pg=PA249&lpg=PA249 google books]</ref> |

|||

[[Image:WilliamHunter01.jpg|thumb|right|250px|page from "The anatomy of the human gravid uterus exhibited in figures"]] |

|||

To aid his teaching of [[dissection]], in 1775 Hunter commissioned [[sculpture|sculptor]] [[Agostino Carlini]] to make a cast of the flayed but muscular corpse of a recently executed criminal, a [[smuggler]]. He was professor of anatomy at the [[Royal Academy of Arts]] in London from 1769 until 1772.<ref>Kemp M (ed) 1975. ''Dr. William Hunter at the Royal Academy of Arts''. Glasgow.{{Page needed|date=September 2010}}</ref> He was interested in arts, and had strong connections to the artistic world. |

|||

In 1768 he built the famous anatomy theatre and museum in [[Great Windmill Street]], [[Soho]], where the best British anatomists and surgeons of the period, including his brother John, were trained. His greatest work was ''Anatomia uteri umani gravidi'' [The anatomy of the human gravid uterus exhibited in figures] (1774), with plates engraved by [[Jan van Rymsdyk|Rymsdyk]] (1730–90),<ref>Thornton, John L. 1982. ''Jan van Rymsdyk: medical artist of the eighteenth century''. Oleander Press, Cambridge.{{pn}}</ref> and published by the [[John Baskerville|Baskerville Press]]. He chose as a model for clear, precise but schematic illustration of anatomic dissections the drawings by [[Leonardo da Vinci]] conserved in the Royal Collection at [[Windsor Castle|Windsor]]: [[Kenneth Clark]] considered him responsible for the Eighteenth-century rediscovery of Leonardo's drawings in England. |

|||

==An avid collector== |

|||

To aid his teaching of [[dissection]], in 1775 Hunter commissioned [[sculpture|sculptor]] [[Agostino Carlini]] to make a cast of the flayed but muscular corpse of a recently executed criminal, a [[smuggler]]. He was professor of anatomy at the [[Royal Academy of Arts]] in London from 1769 until 1772.<ref>Kemp M (ed) 1975. ''Dr. William Hunter at the Royal Academy of Arts''. Glasgow.{{pn}}</ref> He was interested in arts, and had strong connections to the artistic world. |

|||

Around 1765 William Hunter started collecting widely across a range of themes beyond medicine and anatomy: books, manuscripts, prints, coins, shells, zoological specimens, and minerals. In several of these areas, he worked closely with specialists, such as [[Johan Christian Fabricius]], and [[George Fordyce]] who used his collections as tools for new biological and chemical science. He bequeathed his collections, plus a large sum to build a museum, to the University of Glasgow. The collections survive today as the nucleus of the [[University of Glasgow]]'s [[Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery]], while his library and archives are now held in the university's library. |

|||

Hunter's coin collection was especially fine, and the [[Hunter Coin Cabinet]] in the Hunterian Museum is one of the world's great numismatic collections. According to the Preface of ''Catalogue of Greek Coins in the Hunterian Collection'' (Macdonald 1899), Hunter purchased many important collections, including those of [[Horace Walpole]] and the bibliophile [[Thomas Crofts]]. King [[George III]] even donated an Athenian gold piece on 7 April of 1774. |

|||

In 1770 he built himself a house in Glasgow fully equipped for the practice of his science, and this formed the nucleus of the [[University of Glasgow]]'s [[Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery]]. |

|||

==An avid coin and book collector== |

|||

William Hunter was an avid antique coin collector and the Hunter Coin cabinet in the Hunterian Museum is one of the world's great collections. According to the Preface of ''Catalogue of Greek Coins in the Hunterian Collection'' (Macdonald 1899), Hunter purchased many important collections, including those of [[Horace Walpole]] and the bibliophile [[Thomas Crofts]]. King [[George III]] even donated an Athenian gold piece. |

|||

When the famous book collection of [[Anthony Askew]], the ''Bibliotheca Askeviana'', was auctioned off upon Askew's death in 1774, Hunter purchased many significant volumes in the face of stiff competition from the [[British Museum]]. |

When the famous book collection of [[Anthony Askew]], the ''Bibliotheca Askeviana'', was auctioned off upon Askew's death in 1774, Hunter purchased many significant volumes in the face of stiff competition from the [[British Museum]]. |

||

He died in 1783, aged 64, and was buried |

He died in London in 1783, aged 64, and was buried at [[St James's Church, Piccadilly|St James's, Piccadilly]]. A memorial to him lies in the church. |

||

[[File:A memorial to William Hunter in St James's Church, Piccadilly.jpg|thumb|A memorial to William Hunter in St James's Church, Piccadilly.]] |

|||

== |

== Controversy == |

||

In 2010, the self-described historian<ref name=king>{{Cite journal| url=https://www.academia.edu/643250 |author=Helen King| title=History without Historians? Medical History and the Internet| journal=Social History of Medicine |volume=24 |issue=2 |pages=212 |year=2011}}</ref> Don Shelton made some lurid claims about the methods by which Hunter, his brother John, and his teacher and competitor [[William Smellie (obstetrician)|William Smellie]] might have obtained bodies for their anatomical work. In a non-peer-reviewed opinion piece in the ''[[Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine]]'' he suggested that the two physicians committed multiple murders of pregnant women in order to gain access to corpses for anatomical dissection and physiological experimentation.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Don C. Shelton |title=The Emperor's new clothes |journal=J R Soc Med |date=1 February 2010 |issue=2 |doi=10.1258/jrsm.2009.090295 |pmc=2813782 |pmid=20118333 |volume=103 |pages=46–50}}</ref> He suggested that there was an inadequate match between supply and demand of pregnant corpses and that the two physicians must have commissioned many murders in order to carry out their work.<ref name=guardian>{{Cite web|url=https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/feb/07/british-obstetrics-founders-murders-claim|title=Founders of British obstetrics 'were callous murderers'|last=Campbell|first=Dennis|date=6 February 2010|website=The Guardian}}</ref><ref name=william>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Smellie-Scottish-physician|title=William Smellie|last=Encyclopedia Britannica Editors|date=7 December 2012}}</ref> |

|||

He used to relate the following anecdote: During the American war, he was consulted by the daughter of a peer, who confessed herself pregnant, and requested his assistance; he advised her to retire for a time to the house of some confidential friend; she said that was impossible, as her father would not suffer her to be absent from him a single day. Some of the servants were, therefore, let into the secret, and the doctor made his arrangement with the treasurer of the Foundling Hospital for the reception of the child, for which he was to pay. The lady was desired to weigh well if she could bear pain without alarming the family by her cries; she said "Yes," and she kept her word. At the usual period she was delivered, not of one child only, but of twins. The doctor, bearing the two children, was conducted by a French servant through the kitchen, and left to ascend the area steps into the street. Luckily the lady's maid recollected that the door of the area might perhaps be locked; and she followed the doctor just in time to prevent his being detained at the gate. He deposited the children at the Foundling Hospital, and paid for each. The father of the children was a colonel of the army who went with his regiment to America and died there. The mother afterwards married a person of her own rank. |

|||

Shelton's comments attracted media publicity, but were heavily criticised on factual and methodological grounds by medical historians, who pointed out that in 1761, Peter Camper had indicated that figures "were not all from real life",<ref>{{cite journal|author=Janette C Allotey | title=William Smellie and William Hunter accused of murder … | journal=J R Soc Med |date=1 May 2010 |issue=5 |pages=166–167| doi=10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k019| pmc=2862065 | pmid=20436021 | volume=103 }}</ref> and likely methods other than murder were available to obtain bodies of recently deceased pregnant women at that time.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wendy Moore| title=Case not proven |journal=J R Soc Med |date=1 May 2010 |issue=5 |pages=166–167 |doi=10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k020 |pmc=2862072 |pmid=20436020 |volume=103 }}</ref> Hunter also provided case histories for at least four of the subjects illustrated in ''The Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures'', published in 1774.<ref>[https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/feb/07/british-obstetrics-founders-murders-claim Founders of British obstetrics 'were callous murderers'], Denis Campbell, 7 February 1997, The Observer, accessed May 2010</ref> A recent review of Hunter's sources of anatomical specimens was published in 2015.<ref>{{cite book |first1=Stuart |last1=McDonald |first2=John |last2=Faithfull |title=William Hunter's World: The Art and Science of Eighteenth-Century Collecting |chapter=William Hunter's sources of pathological and anatomical specimens, with particular reference to obstetric subjects |date=2015 |publisher=Ashgate |location=Farnham |isbn=9781409447740 |pages=45–58 }}</ref> That "multiple methods of preservation were combined" at Hunter's Great Windmill Street school in order to retain as much information from the individual cadavers as possible further indicates the rarity and value of these bodies. <ref>Richard Bellis, [https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-for-the-history-of-science/article/object-of-sense-and-experiment-the-ontology-of-sensation-in-william-hunters-investigation-of-the-human-gravid-uterus/9C603438D58E747B15C1BFA50C2A533D ‘"The object of sense and experiment": the ontology of sensation in William Hunter's investigation of the human gravid uterus'] The British Journal for the History of science 1-20 [https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-for-the-history-of-science/article/object-of-sense-and-experiment-the-ontology-of-sensation-in-william-hunters-investigation-of-the-human-gravid-uterus/9C603438D58E747B15C1BFA50C2A533D doi:10.1017/S0007087422000024] </ref> |

|||

Helen King indicated that the over-enthusiastic response of the media and the internet to Shelton's unreviewed speculations raised fresh questions about how medical history is generated, presented and evaluated in the media and, in particular, on the internet.<ref name=king/> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* [[Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery]] |

|||

* [[Hunterian Collection]] |

|||

* [[Hunter House Museum]], his birthplace |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{ |

{{Reflist}} |

||

==Further reading== |

|||

[[File:Anatomia uteri humani gravidi V00001 00000002.tif|thumb|''Anatomia uteri humani gravidi tabulis illustrata'']] |

|||

*{{cite journal |author=Buchanan WW |title=William Hunter (1718-1783) |journal=Rheumatology |volume=42 |issue=10 |pages=1260–1 |year=2003 |month=October |pmid=14508042 |doi=10.1093/rheumatology/keg003}} |

|||

*Peachey, George C. ''A Memoir of William & John Hunter'' (William Brendon & Son, 1924) |

|||

*{{cite journal |author=Dunn PM |title=Dr William Hunter (1718-83) and the gravid uterus |journal=Archives of Disease in Childhood |volume=80 |issue=1 |pages=F76–7 |year=1999 |month=January |pmid=10325820 |pmc=1720874 |url=http://fn.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10325820}} |

|||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Buchanan WW |title=William Hunter (1718–1783) |journal=Rheumatology |volume=42 |issue=10 |pages=1260–1 |date=October 2003 |pmid=14508042 |doi=10.1093/rheumatology/keg003|doi-access=free }} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Dunn PM |title=Dr William Hunter (1718–83) and the gravid uterus |journal=Archives of Disease in Childhood |volume=80 |issue=1 |pages=F76–7 |date=January 1999 |pmid=10325820 |pmc=1720874 |doi=10.1136/fn.80.1.f76}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=James T |title=William Hunter, surgeon and Edward Gibbon, historian: an 18th century connection |journal=Adler Museum Bulletin |volume=20 |issue=3 |pages=24–5 |date=December 1994 |pmid=11639996}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Kemp M |title=True to their natures: Sir Joshua Reynolds and Dr William Hunter at the Royal Academy of Arts |journal=Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London |volume=46 |issue=1 |pages=77–88 |date=January 1992 |pmid=11616172 |doi=10.1098/rsnr.1992.0004|s2cid=26388873 }} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|vauthors=Waterhouse JP, Mason DK |title=Contributions of William Hunter (1718–1783) to dental science |journal=British Dental Journal |volume=168 |issue=8 |pages=332–5 |date=April 1990 |pmid=2185812 |doi=10.1038/sj.bdj.4807187|s2cid=880561 }} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Rey R |trans-title=William Hunter and the medical world of his time |language=fr |journal=History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=105–10 |year=1990 |pmid=2243922 |title=William Hunter and the medical world of his time}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|vauthors=Buchanan WW, Kean WF, Palmer DG |title=The contribution of William Hunter (1718–1783) to the study of bone and joint disease |journal=Clinical Rheumatology |volume=6 |issue=4 |pages=489–503 |date=December 1987 |pmid=3329589 |doi=10.1007/BF02330585|s2cid=6606521 }} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Herschfeld JJ |title=William Hunter and the role of "oral sepsis" in American dentistry |journal=Bulletin of the History of Dentistry |volume=33 |issue=1 |pages=35–45 |date=April 1985 |pmid=3888326}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Philipp E |title=William Hunter: anatomist and obstetrician supreme |journal=[[Huntia (journal)|Huntia]] |volume=44–45 |pages=122–48 |year=1985 |pmid=11622001}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Porter R |title=William Hunter, surgeon |journal=History Today |volume=33 |pages=50–2 |date=September 1983 |pmid=11617139}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|vauthors=Thornton JL, Want PC |title=William Hunter (1718–1783) and his contributions to obstetrics |journal=British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology |volume=90 |issue=9 |pages=787–94 |date=September 1983 |pmid=6351897|doi=10.1111/j.1471-0528.1983.tb09317.x|s2cid=45312525 }} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|title=Different letters from the past 2) Tobias Smollett to William Hunter |journal=Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England |volume=62 |issue=2 |pages=146–9 |date=March 1980 |pmid=6990856 |pmc=2492344}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Kapronczay K |trans-title=The Hunter brothers: William Hunter (1718), John Hunter (1728–1793) |language=hu |journal=Orvosi Hetilap |volume=119 |issue=10 |pages=598–600 |date=March 1978 |pmid=628557 |title=The Hunter brothers: William Hunter (1718), John Hunter (1728–1793)}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Longo LD |title=Classic pages in obstetrics and gynecology. On retroversion of the uterus. William Hunter. Medical Observations and Inquiries, vol. 4, pp. 400–409, 1771 |journal=American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology |volume=131 |issue=1 |pages=95–6 |date=May 1978 |pmid=347937}} |

||

*{{Cite journal |author=Chitwood WR |title=John and William Hunter on aneurysms |journal=Archives of Surgery |volume=112 |issue=7 |pages=829–36 |date=July 1977 |pmid=327974 |url=http://archsurg.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=327974 |doi=10.1001/archsurg.1977.01370070043005 }}{{Dead link|date=October 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} |

|||

*{{cite journal |author=Kirsner AB |title=William Hunter: lessons to be learned from congenital heart disease |journal=Medical Times |volume=100 |issue=12 |pages=107–8 passim |year=1972 |month=December |pmid=4564592}} |

|||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Forbes TR |title=Death of a chairman: a new William Hunter manuscript |journal=[[Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine]] |volume=49 |issue=2 |pages=169–73 |date=May 1976 |pmid=782049 |pmc=2595271}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Kirsner AB |title=William Hunter: lessons to be learned from congenital heart disease |journal=Medical Times |volume=100 |issue=12 |pages=107–8 passim |date=December 1972 |pmid=4564592}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Illingworth C |title=The erudition of William Hunter. His notes on early Greek printed books |journal=Scottish Medical Journal |volume=16 |issue=6 |pages=290–2 |date=June 1971 |pmid=4932920|doi=10.1177/003693307101600603 |s2cid=39011134 }} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|title=William Hunter (1718–1783) anatomist, physician, obstetrician |journal=JAMA |volume=203 |issue=8 |pages=593–5 |date=February 1968 |pmid=4870514 |doi= 10.1001/jama.203.8.593}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Thomas KB |title=A Female Foetus, drawn from Nature by Mr. Blakey for William Hunter |journal=Medical History |volume=4 |issue= 3|pages=256 |date=July 1960 |pmid=13838001 |pmc=1034906 |doi=10.1017/s0025727300025412}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Morris WI |title=Brotherly Love: An Essay on the Personal Relations Between William Hunter and His Brother John |journal=Medical History |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=20–32 |date=January 1959 |pmid=13632205 |pmc=1034444 |doi=10.1017/s0025727300024224}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Kerr JM |title=William Hunter; his life, personality and achievements |journal=Scottish Medical Journal |volume=2 |issue=9 |pages=372–8 |date=September 1957 |pmid=13467308|doi=10.1177/003693305700200907 |s2cid=23985528 }} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Oppenheimer JM |title=John and William Hunter and some eighteenth century scientific moods |journal=Transactions & Studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=97–102 |date=August 1957 |pmid=13468030}} |

||

*{{ |

*{{Cite journal|author=Ball OF |title=John and William Hunter. II |journal=Modern Hospital |volume=79 |issue=5 |pages=87–9 |date=November 1952 |pmid=13002276}} |

||

*{{Cite journal|author=Ball OF |title=John and William Hunter. 1 |journal=Modern Hospital |volume=79 |issue=4 |pages=86–8 |date=October 1952 |pmid=12992956}} |

|||

*{{Cite journal|author=Rudolf CR |title=Nova et Vetera |journal=British Medical Journal |volume=2 |issue=4684 |pages=886 |date=October 1950 |pmid=14772509 |pmc=2038933 |doi=10.1136/bmj.2.4684.886}} |

|||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commons|William Hunter}} |

|||

*[http://www.gutenberg.org/dirs/1/1/3/3/11330/11330-h/11330-h.htm www.gutenberg.org]. |

|||

*[http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk/collections/summary/museum/medicine_anatomy.shtml Hunter's anatomical collections] |

* [http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk/collections/summary/museum/medicine_anatomy.shtml Hunter's anatomical collections] |

||

*[http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk/history/hunter/hunter_index.shtml Biography of William Hunter] |

* [http://www.hunterian.gla.ac.uk/history/hunter/hunter_index.shtml Biography of William Hunter] |

||

* [http://www.huntsearch.gla.ac.uk/cgi-bin/foxweb/huntsearch/SummaryResults.fwx?collection=zoology&Searchterm=hunter Zoological specimens] |

|||

* [http://www.cppdigitallibrary.org/items/browse?advanced%5B0%5D%5Belement_id%5D=48&advanced%5B0%5D%5Btype%5D=contains&advanced%5B0%5D%5Bterms%5D=Hunter%2C+William%2C+1718-1783.+Anatomia+uteri+humani+gravidi+tabulis+illustrata Selected images from ''Anatomia uteri humani gravidi''] – The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Digital Library |

|||

* {{Gutenberg author | id=Hunter,+William }} |

|||

* {{Internet Archive author |sname=William Hunter |birth=1718 |death=1783}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{Persondata |

|||

|NAME=Hunter, William |

|||

|ALTERNATIVE NAMES= |

|||

|SHORT DESCRIPTION=anatomist |

|||

|DATE OF BIRTH=23 May 1718 |

|||

|PLACE OF BIRTH=[[East Kilbride]], [[South Lanarkshire]], Scotland |

|||

|DATE OF DEATH=30 March 1783 |

|||

|PLACE OF DEATH= |

|||

}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hunter, William}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hunter, William}} |

||

[[Category:1718 births]] |

[[Category:1718 births]] |

||

[[Category:1783 deaths]] |

[[Category:1783 deaths]] |

||

[[Category:Scottish anatomists]] |

[[Category:Scottish anatomists]] |

||

[[Category:Fellows of the Royal Society]] |

[[Category:Fellows of the Royal Society]] |

||

[[Category:People from |

[[Category:People from East Kilbride]] |

||

[[Category:Scottish medical doctors]] |

[[Category:18th-century Scottish medical doctors]] |

||

[[Category:Scottish scholars and academics]] |

[[Category:Scottish scholars and academics]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Scottish book and manuscript collectors]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Alumni of the University of Glasgow]] |

||

[[Category:Alumni of the University of Edinburgh]] |

|||

[[Category:Scottish numismatists]] |

|||

[[de:William Hunter (Anatom)]] |

|||

[[Category:Burials at St James's Church, Piccadilly]] |

|||

[[es:William Hunter]] |

|||

[[fr:William Hunter (anatomiste)]] |

|||

[[pl:William Hunter]] |

|||

[[sv:William Hunter]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 12:39, 24 December 2024

William Hunter | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Allan Ramsay | |

| Born | 23 May 1718 |

| Died | 30 March 1783 (aged 64) |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | University of Glasgow University of Edinburgh |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anatomy, Obstetrics |

William Hunter FRS (23 May 1718 – 30 March 1783) was a Scottish anatomist and physician. He was a leading teacher of anatomy, and the outstanding obstetrician of his day. His guidance and training of his equally famous brother, John Hunter, was also of great importance.

Early life and career

[edit]Hunter was born at Long Calderwood, now a part of East Kilbride, South Lanarkshire, to Agnes Paul (c. 1685–1751) and John Hunter (1662/3–1741).[1] He was the elder brother of surgeon, John Hunter. After studying divinity at the University of Glasgow, he went into medicine in 1737, studying under William Cullen.

Arriving in London, Hunter became resident pupil to William Smellie (1741–44) and he was trained in anatomy at St George's Hospital, London, specialising in obstetrics. He followed the example of Smellie in giving a private course on dissecting, operative procedures and bandaging, from 1746. His courtly manners and sensible judgement helped him to advance until he became the leading obstetric consultant of London. Unlike Smellie, he did not favour the use of forceps in delivery. Stephen Paget said of him:

He never married; he had no country house; he looks, in his portraits, a fastidious, fine gentleman; but he worked till he dropped and he lectured when he was dying.[2]

To orthopaedic surgeons he is famous for his studies on bone and cartilage. In 1743 he published the paper On the structure and diseases of articulating cartilages – which is often cited – especially the following sentence: "If we consult the standard Chirurgical Writers from Hippocrates down to the present Age, we shall find, that an ulcerated Cartilage is universally allowed to be a very troublesome Disease; that it admits of a Cure with more Difficulty than carious Bone; and that, when destroyed, it is not recovered".[3]

Later career

[edit]

In 1764, he became physician to Queen Charlotte. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1767 and Professor of Anatomy to the Royal Academy in 1768.

In 1768 he built the famous anatomy theatre and museum in Great Windmill Street, Soho, where the best British anatomists and surgeons of the period were trained. His greatest work was Anatomia uteri umani gravidi [The anatomy of the human gravid uterus exhibited in figures] (1774), with plates engraved by Rymsdyk (1730–90),[4] and published by the Baskerville Press. He chose as a model for clear, precise but schematic illustration of anatomic dissections the drawings by Leonardo da Vinci conserved in the Royal Collection at Windsor: Kenneth Clark considered him responsible for the 18th century rediscovery of Leonardo's drawings in England.[citation needed] He praised them highly in his lectures and planned to publish them with his own commentary, but never had the time for the project before his death.[5]

To aid his teaching of dissection, in 1775 Hunter commissioned sculptor Agostino Carlini to make a cast of the flayed but muscular corpse of a recently executed criminal, a smuggler. He was professor of anatomy at the Royal Academy of Arts in London from 1769 until 1772.[6] He was interested in arts, and had strong connections to the artistic world.

An avid collector

[edit]Around 1765 William Hunter started collecting widely across a range of themes beyond medicine and anatomy: books, manuscripts, prints, coins, shells, zoological specimens, and minerals. In several of these areas, he worked closely with specialists, such as Johan Christian Fabricius, and George Fordyce who used his collections as tools for new biological and chemical science. He bequeathed his collections, plus a large sum to build a museum, to the University of Glasgow. The collections survive today as the nucleus of the University of Glasgow's Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, while his library and archives are now held in the university's library.

Hunter's coin collection was especially fine, and the Hunter Coin Cabinet in the Hunterian Museum is one of the world's great numismatic collections. According to the Preface of Catalogue of Greek Coins in the Hunterian Collection (Macdonald 1899), Hunter purchased many important collections, including those of Horace Walpole and the bibliophile Thomas Crofts. King George III even donated an Athenian gold piece on 7 April of 1774.

When the famous book collection of Anthony Askew, the Bibliotheca Askeviana, was auctioned off upon Askew's death in 1774, Hunter purchased many significant volumes in the face of stiff competition from the British Museum.

He died in London in 1783, aged 64, and was buried at St James's, Piccadilly. A memorial to him lies in the church.

Controversy

[edit]In 2010, the self-described historian[7] Don Shelton made some lurid claims about the methods by which Hunter, his brother John, and his teacher and competitor William Smellie might have obtained bodies for their anatomical work. In a non-peer-reviewed opinion piece in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine he suggested that the two physicians committed multiple murders of pregnant women in order to gain access to corpses for anatomical dissection and physiological experimentation.[8] He suggested that there was an inadequate match between supply and demand of pregnant corpses and that the two physicians must have commissioned many murders in order to carry out their work.[9][10]

Shelton's comments attracted media publicity, but were heavily criticised on factual and methodological grounds by medical historians, who pointed out that in 1761, Peter Camper had indicated that figures "were not all from real life",[11] and likely methods other than murder were available to obtain bodies of recently deceased pregnant women at that time.[12] Hunter also provided case histories for at least four of the subjects illustrated in The Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures, published in 1774.[13] A recent review of Hunter's sources of anatomical specimens was published in 2015.[14] That "multiple methods of preservation were combined" at Hunter's Great Windmill Street school in order to retain as much information from the individual cadavers as possible further indicates the rarity and value of these bodies. [15]

Helen King indicated that the over-enthusiastic response of the media and the internet to Shelton's unreviewed speculations raised fresh questions about how medical history is generated, presented and evaluated in the media and, in particular, on the internet.[7]

See also

[edit]- Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery

- Hunterian Collection

- Hunter House Museum, his birthplace

References

[edit]- ^ Brock, Helen (23 September 2004). "Hunter, William (1718–1783), physician, anatomist, and man-midwife". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14234. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 11 July 2021. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Garrison, Fielding H. 1914. An introduction to the history of medicine. Saunders, Philadelphia. p. 269.

- ^ Hunter, William (1743). "Of the structure and diseases of articulating cartilages". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 42 (470): 514–521. doi:10.1098/rstl.1742.0079. S2CID 186214128.

- ^ Thornton, John L. 1982. Jan van Rymsdyk: medical artist of the eighteenth century. Oleander Press, Cambridge ISBN 0906672023.[page needed]

- ^ Wells, The Heart of Leonardo, p. 249, 2014, Springer Science & Business Media, ISBN 1447145313, 9781447145318, google books

- ^ Kemp M (ed) 1975. Dr. William Hunter at the Royal Academy of Arts. Glasgow.[page needed]

- ^ a b Helen King (2011). "History without Historians? Medical History and the Internet". Social History of Medicine. 24 (2): 212.

- ^ Don C. Shelton (1 February 2010). "The Emperor's new clothes". J R Soc Med. 103 (2): 46–50. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2009.090295. PMC 2813782. PMID 20118333.

- ^ Campbell, Dennis (6 February 2010). "Founders of British obstetrics 'were callous murderers'". The Guardian.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica Editors (7 December 2012). "William Smellie".

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Janette C Allotey (1 May 2010). "William Smellie and William Hunter accused of murder …". J R Soc Med. 103 (5): 166–167. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k019. PMC 2862065. PMID 20436021.

- ^ Wendy Moore (1 May 2010). "Case not proven". J R Soc Med. 103 (5): 166–167. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2010.10k020. PMC 2862072. PMID 20436020.

- ^ Founders of British obstetrics 'were callous murderers', Denis Campbell, 7 February 1997, The Observer, accessed May 2010

- ^ McDonald, Stuart; Faithfull, John (2015). "William Hunter's sources of pathological and anatomical specimens, with particular reference to obstetric subjects". William Hunter's World: The Art and Science of Eighteenth-Century Collecting. Farnham: Ashgate. pp. 45–58. ISBN 9781409447740.

- ^ Richard Bellis, ‘"The object of sense and experiment": the ontology of sensation in William Hunter's investigation of the human gravid uterus' The British Journal for the History of science 1-20 doi:10.1017/S0007087422000024

Further reading

[edit]

- Peachey, George C. A Memoir of William & John Hunter (William Brendon & Son, 1924)

- Buchanan WW (October 2003). "William Hunter (1718–1783)". Rheumatology. 42 (10): 1260–1. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keg003. PMID 14508042.

- Dunn PM (January 1999). "Dr William Hunter (1718–83) and the gravid uterus". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 80 (1): F76–7. doi:10.1136/fn.80.1.f76. PMC 1720874. PMID 10325820.

- James T (December 1994). "William Hunter, surgeon and Edward Gibbon, historian: an 18th century connection". Adler Museum Bulletin. 20 (3): 24–5. PMID 11639996.

- Kemp M (January 1992). "True to their natures: Sir Joshua Reynolds and Dr William Hunter at the Royal Academy of Arts". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 46 (1): 77–88. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1992.0004. PMID 11616172. S2CID 26388873.

- Waterhouse JP, Mason DK (April 1990). "Contributions of William Hunter (1718–1783) to dental science". British Dental Journal. 168 (8): 332–5. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4807187. PMID 2185812. S2CID 880561.

- Rey R (1990). "William Hunter and the medical world of his time" [William Hunter and the medical world of his time]. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences (in French). 12 (1): 105–10. PMID 2243922.

- Buchanan WW, Kean WF, Palmer DG (December 1987). "The contribution of William Hunter (1718–1783) to the study of bone and joint disease". Clinical Rheumatology. 6 (4): 489–503. doi:10.1007/BF02330585. PMID 3329589. S2CID 6606521.

- Herschfeld JJ (April 1985). "William Hunter and the role of "oral sepsis" in American dentistry". Bulletin of the History of Dentistry. 33 (1): 35–45. PMID 3888326.

- Philipp E (1985). "William Hunter: anatomist and obstetrician supreme". Huntia. 44–45: 122–48. PMID 11622001.

- Porter R (September 1983). "William Hunter, surgeon". History Today. 33: 50–2. PMID 11617139.

- Thornton JL, Want PC (September 1983). "William Hunter (1718–1783) and his contributions to obstetrics". British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 90 (9): 787–94. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1983.tb09317.x. PMID 6351897. S2CID 45312525.

- "Different letters from the past 2) Tobias Smollett to William Hunter". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 62 (2): 146–9. March 1980. PMC 2492344. PMID 6990856.

- Kapronczay K (March 1978). "The Hunter brothers: William Hunter (1718), John Hunter (1728–1793)" [The Hunter brothers: William Hunter (1718), John Hunter (1728–1793)]. Orvosi Hetilap (in Hungarian). 119 (10): 598–600. PMID 628557.

- Longo LD (May 1978). "Classic pages in obstetrics and gynecology. On retroversion of the uterus. William Hunter. Medical Observations and Inquiries, vol. 4, pp. 400–409, 1771". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 131 (1): 95–6. PMID 347937.

- Chitwood WR (July 1977). "John and William Hunter on aneurysms". Archives of Surgery. 112 (7): 829–36. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1977.01370070043005. PMID 327974.[permanent dead link]

- Forbes TR (May 1976). "Death of a chairman: a new William Hunter manuscript". Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 49 (2): 169–73. PMC 2595271. PMID 782049.

- Kirsner AB (December 1972). "William Hunter: lessons to be learned from congenital heart disease". Medical Times. 100 (12): 107–8 passim. PMID 4564592.

- Illingworth C (June 1971). "The erudition of William Hunter. His notes on early Greek printed books". Scottish Medical Journal. 16 (6): 290–2. doi:10.1177/003693307101600603. PMID 4932920. S2CID 39011134.

- "William Hunter (1718–1783) anatomist, physician, obstetrician". JAMA. 203 (8): 593–5. February 1968. doi:10.1001/jama.203.8.593. PMID 4870514.

- Thomas KB (July 1960). "A Female Foetus, drawn from Nature by Mr. Blakey for William Hunter". Medical History. 4 (3): 256. doi:10.1017/s0025727300025412. PMC 1034906. PMID 13838001.

- Morris WI (January 1959). "Brotherly Love: An Essay on the Personal Relations Between William Hunter and His Brother John". Medical History. 3 (1): 20–32. doi:10.1017/s0025727300024224. PMC 1034444. PMID 13632205.

- Kerr JM (September 1957). "William Hunter; his life, personality and achievements". Scottish Medical Journal. 2 (9): 372–8. doi:10.1177/003693305700200907. PMID 13467308. S2CID 23985528.

- Oppenheimer JM (August 1957). "John and William Hunter and some eighteenth century scientific moods". Transactions & Studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. 25 (2): 97–102. PMID 13468030.

- Ball OF (November 1952). "John and William Hunter. II". Modern Hospital. 79 (5): 87–9. PMID 13002276.

- Ball OF (October 1952). "John and William Hunter. 1". Modern Hospital. 79 (4): 86–8. PMID 12992956.

- Rudolf CR (October 1950). "Nova et Vetera". British Medical Journal. 2 (4684): 886. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4684.886. PMC 2038933. PMID 14772509.

External links

[edit]- Hunter's anatomical collections

- Biography of William Hunter

- Zoological specimens

- Selected images from Anatomia uteri humani gravidi – The College of Physicians of Philadelphia Digital Library

- Works by William Hunter at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Hunter at the Internet Archive

- 1718 births

- 1783 deaths

- Scottish anatomists

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- People from East Kilbride

- 18th-century Scottish medical doctors

- Scottish scholars and academics

- Scottish book and manuscript collectors

- Alumni of the University of Glasgow

- Alumni of the University of Edinburgh

- Scottish numismatists

- Burials at St James's Church, Piccadilly