John McLaughlin (musician): Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Misterpither (talk | contribs) →Influence: Removing quote that seems to be copied verbatim + steering clear from copyright violation WP:Copy-paste |

||

| (772 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|English jazz fusion guitarist, founder of the Mahavishnu Orchestra (born 1942)}} |

|||

{{For|other people with similar names|John McLaughlin}} |

|||

{{other people|John McLaughlin}} |

|||

{{Use British English|date=December 2012}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=December 2019}} |

|||

{{Infobox musical artist |

{{Infobox musical artist |

||

| |

| name = John McLaughlin |

||

| |

| background = non_vocal_instrumentalist |

||

| |

| image = John McLaughlin Blue Note 2016.JPG |

||

| caption = John McLaughlin performing on [[Chick Corea]]'s 75th birthday at the [[Blue Note Jazz Club]] in New York City on 10 December 2016 |

|||

| Img_size = |

|||

| birth_date = {{Birth date and age|df=yes|1942|1|4}} |

|||

| Landscape = |

|||

| birth_place = [[Doncaster]], [[South Yorkshire]], England |

|||

| Background = non_vocal_instrumentalist |

|||

| genre = {{hlist|[[Jazz fusion]]|[[ethno jazz]]|[[world fusion]]|[[progressive rock]]|[[psychedelic rock]]|[[electric blues]]|[[nuevo flamenco]]}} |

|||

| Born = 4 January, 1942 (age 67)<br/> [[Doncaster]], [[England]] |

|||

| occupations = {{hlist|Musician|songwriter}} |

|||

| Died = |

|||

| |

| instruments = Guitar |

||

| years_active = 1963–present |

|||

| Occupation = [[Musician]], [[Songwriter]] |

|||

| label = {{hlist|Douglas|[[Columbia Records|Columbia]]|[[Verve Records|Verve]]|[[Warner Records|Warner Bros.]]|Abstract Logix}} |

|||

| Instrument = [[Guitar]], [[Keyboard instrument|Keyboard]] |

|||

| associated_acts = {{hlist|[[Miles Davis]]|[[Tony Williams Lifetime]]|[[Mahavishnu Orchestra]]|[[Shakti (band)|Shakti]]|[[Remember Shakti]]|[[Paco de Lucía]]|[[Al Di Meola]]|[[Carlos Santana]]|[[Katia Labèque]]|[[Zakir Hussain (musician)|Zakir Hussain]]|[[Jeff Beck]]|[[Jimi Hendrix]]|[[Joey DeFrancesco]]|[[Jimmy Herring]]|[[Joni Mitchell]]}} |

|||

| Genre = [[Jazz fusion]], [[World Music|World fusion]], [[Classical music|Classical]], [[rock music|rock]] |

|||

| website = {{URL|www.johnmclaughlin.com}} |

|||

| Associated_acts = [[Miles Davis]], [[Tony Williams|Tony Williams Lifetime]], [[Mahavishnu Orchestra]], [[Shakti (band)|Shakti]], [[Remember Shakti]], [[Paco de Lucía]], [[Al Di Meola]], [[Carlos Santana]], [[Katia Labèque]], [[Zakir Hussain (musician)|Zakir Hussain]]. |

|||

| Label = [http://www.abstractlogix.com Abstract Logix]<br>[[Verve Records]] |

|||

| Years_active = 1963-present |

|||

| URL = [http://www.johnmclaughlin.com Official website] |

|||

| Notable_instruments = [[Gibson EDS-1275]]<br>[[Gibson L-4]]<br>[[Gibson Hummingbird]]<br>[[Fender Mustang]]<br>[[Gibson Les Paul Custom]]<br>[[Abraham Wechter]]-built "Shakti guitar"<br>[[Ovation Guitar Company|Ovation acoustic]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''John McLaughlin''' (born 4 January, 1942 in [[Doncaster]]), also known as '''Mahavishnu John McLaughlin''', is an [[England|English]] [[jazz fusion]] [[guitarist]] and [[composer]]. He played with [[Tony Williams]]'s group [[The Tony Williams Lifetime|Lifetime]] and then with [[Miles Davis]] on his landmark electric jazz-fusion albums ''[[In A Silent Way]]'' and ''[[Bitches Brew]].'' His 1970s electric band, [[Mahavishnu Orchestra|The Mahavishnu Orchestra]], performed a technically virtuosic and complex style of music that fused eclectic jazz and rock with eastern and Indian influences. His guitar playing includes a range of styles and genres, including [[jazz]], [[Indian classical music]], [[Jazz-rock fusion|fusion]], and Western [[Classical music]], and has influenced many other guitarists. He has also incorporated [[Flamenco]] music in some of his acoustic recordings. The Indian [[Tabla]] maestro [[Zakir Hussain (musician)|Zakir Hussain]] has called John McLaughlin "one of the greatest and most important musicians of our times". In 2003, McLaughlin was ranked 49th in [[Rolling Stone (magazine)|''Rolling Stone'']] magazine list of the "[[Rolling Stone's 100 greatest guitarists of all time|100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time]]" <ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.rollingstone.com/news/coverstory/5937559/page/29|title=Rolling Stone 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time}}</ref> |

|||

'''John McLaughlin''' (born 4 January 1942),{{sfn|Larkin|1992|p=1557/8}} also known as '''Mahavishnu''', is an English guitarist, bandleader, and composer. A pioneer of [[jazz fusion]], his music combines elements of [[jazz]] with rock, [[world music]], [[Classical music|Western classical music]], [[flamenco]], and [[blues]]. |

|||

After contributing to several key British groups of the early 1960s, McLaughlin made ''[[Extrapolation (album)|Extrapolation]]'', his first album as a bandleader, in 1969. He then moved to the U.S., where he played with drummer [[Tony Williams (drummer)|Tony Williams]]'s group [[The Tony Williams Lifetime|Lifetime]] and then with [[Miles Davis]] on his electric jazz fusion albums ''[[In a Silent Way]]'', ''[[Bitches Brew]]'', ''[[Jack Johnson (album)|Jack Johnson]]'', ''[[Live-Evil (Miles Davis album)|Live-Evil]]'', and ''[[On the Corner]]''. His 1970s electric band, the [[Mahavishnu Orchestra]], performed a technically virtuosic and complex style of music that fused electric jazz and rock with Indian influences. |

|||

McLaughlin's solo on "Miles Beyond" from his album ''Live at Ronnie Scott's'' won the 2018 [[Grammy Award]] for the [[Grammy Award for Best Improvised Jazz Solo|Best Improvised Jazz Solo]].<ref>{{cite web|title=2018 GRAMMY Awards: Complete Winners List|url=https://www.grammy.com/grammys/news/2018-grammy-awards-complete-winners-list|publisher=Grammy.com|date=29 January 2018|access-date=30 January 2018}}</ref> He has been awarded multiple "Guitarist of the Year" and "Best Jazz Guitarist" awards from magazines such as ''[[DownBeat]]'' and ''[[Guitar Player]]'' based on reader polls. In 2003, he was ranked 49th in ''[[Rolling Stone (magazine)|Rolling Stone]]'' magazine's list of the "[[Rolling Stone's 100 greatest guitarists of all time|100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time]]".<ref>{{cite magazine|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/news/coverstory/5937559/page/29|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080610011629/http://www.rollingstone.com/news/coverstory/5937559/page/29|url-status=dead|archive-date=10 June 2008|title=Rolling Stone 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time|magazine=[[Rolling Stone]]|access-date=3 November 2017}}</ref> In 2009, ''DownBeat'' included McLaughlin in its unranked list of "75 Great Guitarists", in the "Modern Jazz Maestros" category.<ref>{{cite news|title=75 Great Guitarists|url=http://www.downbeat.com/digitaledition/2009/db0209/_art/db0209.pdf|access-date=3 March 2017|work=[[Down Beat]]|date=February 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180127175659/http://www.downbeat.com/digitaledition/2009/db0209/_art/db0209.pdf|archive-date=27 January 2018|url-status=dead}}</ref> In 2012, ''[[Guitar World]]'' magazine ranked him 63rd on its top 100 list.<ref>{{cite web|title=Top 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time|url=http://www.guitarworld.com/features-news/readers-poll-results-100-greatest-guitarists-all-time/%0916495|website=Guitar World|access-date=3 March 2017|url-status=dead|archive-url=http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20160522140237/http://www.guitarworld.com/features-news/readers-poll-results-100-greatest-guitarists-all-time/%0916495|archive-date=22 May 2016|df=dmy-all}}</ref> In 2010, [[Jeff Beck]] called McLaughlin "the best guitarist alive",<ref name="beck">''[[Uncut (magazine)|Uncut]]'' magazine, March 2010. Interview with [[Jeff Beck]].</ref> and [[Pat Metheny]] has also described him as the world's greatest guitarist.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dallasobserver.com/music/qanda-john-mclaughlin-talks-miles-davis-indian-philosophy-and-frank-zappas-jealousy-7071644|title=Q&A: John McLaughlin Talks Miles Davis, Indian Philosophy and Frank Zappa's Jealousy|first=Darryl|last=Smyers|date=29 November 2010|website=Dallasobserver.com|access-date=3 November 2017}}</ref> In 2017, McLaughlin was awarded an honorary doctorate of music from [[Berklee College of Music]].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.jazziz.com/john-mclaughlin-awarded-berklee-honorary-degree/|title=John McLaughlin awarded Berklee honorary degree|last=Micucci|first=Matt|date=2017-08-06|website=JAZZIZ Magazine|language=en-US|access-date=2020-04-03|archive-date=11 April 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200411083913/https://www.jazziz.com/john-mclaughlin-awarded-berklee-honorary-degree/|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

===1960s=== |

===1960s=== |

||

John McLaughlin was born on 4 January 1942 to a family of musicians in [[Doncaster]], [[South Yorkshire]], England.{{sfn|Larkin|1992|p=1557/8}} His mother Mary was a concert violinist; his father John, of Irish descent, was an engineer.<ref name="WSJMclaughlin">{{cite web|url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/john-mclaughlin-guitarist-11628611105|title=John McLaughlin Struggled on Violin, but When He First Played Guitar? ‘Skyrockets Went Off’ |last= Myers|first=Marc|date=2021-08-10|publisher= [[The Wall Street Journal]]|accessdate=2024-11-14}} </ref>{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=24}} The younger John McLaughlin was predominantly raised by his mother and grandmother; his father, the elder John, had separated from Mary when he was 7 years old.<ref name="WSJMclaughlin"/>{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=25}} The younger John did not have a relationship with his father for most of his life,{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=25}}<ref name="WSJMclaughlin"/> until in the late 1970s when he contacted his father and took him out to a pub.<ref name="WSJMclaughlin"/> The younger John said of the experience, "Without my dad, I wouldn't be here. At least I had closure, and for that I thank my lucky stars"; His father later died from a heart attack.<ref name="WSJMclaughlin"/> Also, at the age of 7, the younger John McLaughlin heard classical music on the phonograph, and considered it a "message to my heart and soul more than anything";{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=24}} this motivated him to become a musician.<ref name="DownBeat2024">{{cite web|url=https://downbeat.com/news/detail/john-mclaughlin-hall-of-fame|title=John McLaughlin — Hall of Fame|last= Lutz|first=Philip|date=2024-11-07|publisher= [[DownBeat]]|accessdate=2024-11-14}}</ref> |

|||

From a family of musicians (his mother being a concert violinist), McLaughlin studied violin and piano as a child, but took up the guitar at the age of 11, exploring styles from [[flamenco]] to the jazz of [[Stephane Grappelli]]. McLaughlin moved to London from Yorkshire in order to involve himself in the thriving music scene in the early 1960s, starting with outfits such as the Marzipan Twisters before moving on to [[Georgie Fame]]'s backing band, the Brian Auger band, and importantly, the [[Graham Bond]] Quartet in 1963<ref>Mo Foster, '17 Watts? The Birth of British Rock Guitar', Sanctuary Publishing 1997</ref>. During the 1960s he often had to support himself with session work, which he often found unedifying<ref>Guitar Player Magazine, interview August 1978</ref>, but which radically enhanced his playing and sight-reading skills. |

|||

McLaughlin studied violin and piano as a child; At the age of 11, his brother gave John a guitar and John immediately took up the instrument, exploring styles from flamenco to the jazz of [[Tal Farlow]], [[Django Reinhardt]] and [[Stéphane Grappelli]].{{sfn|Menn|Stern|1978|p=40}}{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=25-30}}<ref name="DownBeat2024"/> He moved to London from Yorkshire in the early 1960s, playing with [[Alexis Korner]]<ref>[http://www.jazzreview.com/articledetails.cfm?ID=159 Jazzreview.com] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090620190307/http://www.jazzreview.com/articledetails.cfm?ID=159 |date=2009-06-20 }}</ref> and the Marzipan Twisters before moving on to [[Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames]], the [[Graham Bond]] Quartet (in 1963){{sfn|Foster|1997}} and [[Brian Auger]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hit-channel.com/interviewbrian-auger-oblivion-expresstrinity/66128|title=Interview: Brian Auger (Oblivion Express, Trinity)|author=thodoris|work=Hit Channel|date=2014-06-28}}</ref> During the 1960s, he often supported himself with session work, which he frequently found unsatisfying but which enhanced his playing and sight-reading.{{sfn|Menn|Stern|1978|p=118, 122}} Also, he gave guitar lessons to [[Jimmy Page]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hit-channel.com/john-mclaughlin-solomahavishnu-orchestramiles-davis/18283|title=Interview:John McLaughlin (solo, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis)|work=Hit Channel|date=8 October 2012|access-date=3 November 2017}}</ref> In 1963, [[Jack Bruce]] formed the Graham Bond Quartet with Bond, [[Ginger Baker]] and John McLaughlin. They played an eclectic range of music genres, including bebop, blues and rhythm.{{sfn|Stump|2000|p=24}} |

|||

Before moving to the [[United States|U.S.]], McLaughlin recorded ''[[Extrapolation (album)|Extrapolation]]'' (with [[Tony Oxley]] and [[John Surman]]) in 1969, in which he showed technical virtuosity, inventiveness and the ability to play in odd meters. He moved to the U.S. in 1969 to join [[Tony Williams]]'s group [[The Tony Williams Lifetime|Lifetime]]. He subsequently played with [[Miles Davis]] on his landmark albums ''[[In A Silent Way]]'', ''[[Bitches Brew]]'' (which has a track named after him), ''[[On The Corner]]'', ''[[Big Fun (album)|Big Fun]]'' (where he is featured soloist on ''Go Ahead John'') and ''[[A Tribute to Jack Johnson]]'' — Davis paid tribute to him in the liner notes to ''Jack Johnson'', calling McLaughlin's playing "far in." McLaughlin returned to the Davis band for one recorded night of a week-long club date, which was released as part of the album ''[[Live-Evil]]'' and as part of the [[The Cellar Door Sessions|Cellar Door]] boxed set. |

|||

Graham Bond was McLaughlin's first spiritual influence.{{sfn|Menn|Stern|1978|p=40}}{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=107}} Bond would introduce McLaughlin to Indian culture, philosophy, and religious esoteric practices, which McLaughlin stated "triggered a desire to know", while under the influence of drugs.{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=107}}<ref name="InnerWorldsPrasad">{{cite web|url=https://www.innerviews.org/inner/john-mclaughlin|title=John McLaughlin: Remembering Shakti|last= Prasad|first=Anil|author-link=Anil Prasad|date=1999 |publisher= Innerviews|accessdate=2024-11-13}}</ref> The Graham Bond Quartet was not well received financially and critically; McLaughlin quit the group.{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=104}} |

|||

A recording from the Record Plant, NYC, dated 3/25/69 exists of McLaughlin jamming with Jimi Hendrix. McLaughlin recollects "we played one night, just a jam session. And we played from 2 until 8, in the morning. I thought it was a wonderful experience! I was playing an acoustic guitar with a pick-up. Um, flat-top guitar, and Jimi was playing an electric. Yeah, what a lovely time! Had he lived today, you'd find that he would be employing everything he could get his hands on, and I mean acoustic guitar, synthesizers, orchestras, voices, anything he could get his hands on he'd use!" |

|||

By 1966, while working in pop and jazz sessions, McLaughlin observed the personal tragedies of those of his musical peers who succumbed to drug addictions and death.{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=255}} As a response, McLaughlin would gradually stop using drugs and pursue a spiritual lifestyle, which would be a recurring motif of his music career.{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=315}} At the same time, McLaughlin experienced a profound musical revelation when psychedelic music was in vogue: he inferred that this music raised existential questions and insisted that he was "on the same boat" as those who sought answers to such questions, which further motivated his interests in Indian culture and its classical music.<ref name="JazzWiseMcLaughlin">{{cite web|url=https://www.jazzwise.com/features/article/john-mclaughlin-the-journey-continues|title=John McLaughlin: The Journey Continues |last= Nicholson|first=Stuart|date=2021-10-20 |publisher=[[Jazzwise]]|accessdate=2024-11-13}}</ref>{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=290}} For a time, in 1968, McLaughlin would be involved in the [[free jazz]] scene with musician [[Gunter Hampel]]; McLaughlin described this experience as "devastating" and "anarchistic", but appreciated the free-form aspect of the genre.{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=368}}<ref name="GuitarWorldMcLaughlin">{{cite web|url=https://www.guitarworld.com/features/john-mclaughlin-the-montreux-years|title=John McLaughlin: “I fell in love with the guitar and even started sleeping with it, that’s how much I loved it”|last= Mead|first=David|date=2022-07-15|publisher= [[Guitar World]]|accessdate=2024-11-13}}</ref> McLaughlin would later state in a July 2024 interview for [[JazzTimes]] that his experience with Hampel was "self-indulgent" and that he needed "structure ... the more restraints I put on myself, the happier I felt."<ref name="Jazztimes2024McLaughlin">{{cite web|url=https://jazztimes.com/features/interviews/john-mclaughlin-discusses-mahavishnu-orchestra-liberation-time-and-more/|title=John McLaughlin Discusses Mahavishnu Orchestra, Liberation Time, and More|last= Farber|first=Jim|date=2024-07-30|publisher= [[JazzTimes]]|accessdate=2024-11-13}}</ref> |

|||

His reputation as a "first-call" [[Session musician|session player]] grew, resulting in recordings as a sideman with [[Miroslav Vitous]], [[Larry Coryell]], [[Joe Farrell]], [[Wayne Shorter]], [[Carla Bley]], [[The Rolling Stones]], and others. |

|||

In January 1969, McLaughlin recorded his debut album ''[[Extrapolation (album)|Extrapolation]]'' in London. It prominently features [[John Surman]] on saxophone and [[Tony Oxley]] on drums. McLaughlin composed the number "Binky's Beam" as a tribute to his friend, the innovative bass player [[Binky McKenzie]]. The album's [[post-bop]] style is quite different from McLaughlin's later fusion works, though it gradually developed a strong reputation among critics by the mid-1970s.{{sfn|Kolosky|2002}} |

|||

===1970s=== |

|||

He recorded ''Devotion'' in early 1970 on Douglas Records (run by [[Alan Douglas (record producer)|Alan Douglas]]), a high-energy, psychedelic fusion album that featured [[Larry Young (musician)|Larry Young]] on organ (who had been part of Lifetime), Billy Rich on bass, and the [[Rhythm and blues|R&B]] drummer [[Buddy Miles]] (who had played with [[Jimi Hendrix]]). ''Devotion'' was the first of two albums he released on Douglas. |

|||

McLaughlin moved to the U.S. in 1969 to join [[Tony Williams (drummer)|Tony Williams]]' group [[The Tony Williams Lifetime|Lifetime]]. A recording from the [[Record Plant]], NYC, dated 25 March 1969, exists of McLaughlin jamming with [[Jimi Hendrix]]. McLaughlin recollects "we played one night, just a jam session. And we played from 2 until 8, in the morning. I thought it was a wonderful experience! I was playing an acoustic guitar with a pick-up. Um, flat-top guitar, and Jimi was playing an electric. Yeah, what a lovely time! Had he lived today, you'd find that he would be employing everything he could get his hands on, and I mean acoustic guitar, synthesizers, orchestras, voices, anything he could get his hands on he'd use!"{{fact|date=September 2022}} |

|||

On the second Douglas album, however, McLaughlin went in a different direction in 1971 when he released ''[[My Goal's Beyond]]'' in the U.S., a collection of unamplified acoustic works. Side A ("Peace One" and "Peace Two") offers a fusion blend of jazz and Indian classical forms; side B features some of the most melodic acoustic playing McLaughlin ever recorded, including such standards as "[[Goodbye Pork Pie Hat]]", by [[Charles Mingus]] whom McLaughlin considered an important influence on his own development. Other tracks that expressed some of McLaughlin's other influences include "Something Spiritual" Dave Herman, "Hearts and Flowers" (P.D. Bob Cornford), "Phillip Lane", "Waltz for Bill Evans" ([[Chick Corea]]), "Follow Your Heart", "Song for My Mother" and "Blue in Green" (Miles Davis). "Follow Your Heart" had been released earlier on ''Extrapolation'' under the title "Arjen's Bag". |

|||

He played on Miles Davis' albums ''[[In a Silent Way]]'', ''[[Bitches Brew]]'' (which has a track titled after him), ''[[Live-Evil (Miles Davis album)|Live-Evil]]'', ''[[On the Corner]]'', ''[[Big Fun (Miles Davis album)|Big Fun]]'' (where he is featured soloist on "Go Ahead John") and ''[[Jack Johnson (album)|A Tribute to Jack Johnson]]''. In the liner notes to ''Jack Johnson'', Davis called McLaughlin's playing "far in". McLaughlin returned to the Davis band for one night of a week-long club date, recorded and released as part of the album ''[[Live-Evil (Miles Davis album)|Live-Evil]]'' and of the ''[[The Cellar Door Sessions|Cellar Door]]'' boxed set. His reputation as a "first-call" [[Session musician|session player]] grew, resulting in recordings as a sideman with [[Miroslav Vitous]], [[Larry Coryell]], [[Joe Farrell]], [[Wayne Shorter]], [[Carla Bley]], [[the Rolling Stones]], and others.{{fact|date=September 2022}} |

|||

''My Goal's Beyond'' was inspired by McLaughlin's decision to follow the Indian spiritual leader [[Sri Chinmoy]], to whom he had been introduced in 1970 by Larry Coryell's manager. The album was dedicated to Chinmoy, with one of the [[Guru|guru's]] poems printed on the [[liner notes]]. It was on this album that McLaughlin [[Name change#Name_change_on_religious_conversion|took the name]] "Mahavishnu." |

|||

===1970s=== |

|||

Around this time, McLaughlin began a rigorous schedule of woodshedding, resulting in a transformation in his playing from his usual odd-timed, angular guitar lines to a more powerful, aggressive and fast style of playing, which would be put on display in his next project, the [[Mahavishnu Orchestra]].{{Citation needed|date=February 2009}} |

|||

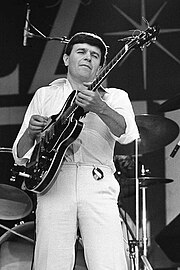

[[File:John McLaughlin in 1978.jpg|thumb|180px|left|McLaughlin performing in The Netherlands, 1978]] |

|||

He recorded ''[[Devotion (John McLaughlin album)|Devotion]]'' in early 1970 for Douglas Records (run by [[Alan Douglas (record producer)|Alan Douglas]]), a high-energy, psychedelic fusion album that featured [[Larry Young (musician)|Larry Young]] on organ (who had been part of Lifetime), [[Billy Rich]] on bass and the [[Rhythm and blues|R&B]] drummer [[Buddy Miles]]. ''Devotion'' was the first of two albums he released on Douglas. In 1971 he released ''[[My Goal's Beyond]]'' in the US, a collection of unamplified acoustic works. Side A ("Peace One" and "Peace Two") offers a fusion blend of jazz and Indian classical forms, while side B features melodic acoustic playing on such standards as "[[Goodbye Pork Pie Hat]]", by [[Charles Mingus]] whom McLaughlin considered an important influence. ''My Goal's Beyond'' was inspired by McLaughlin's decision to follow the Indian spiritual leader [[Sri Chinmoy]], to whom he had been introduced in 1970 by Larry Coryell's manager. The album was dedicated to Chinmoy, with one of the [[Guru]]'s poems printed on the [[liner notes]]. It was on this album that McLaughlin [[Name change#Name change on religious conversion|took the name]] "Mahavishnu". |

|||

In 1973, McLaughlin collaborated with [[Carlos Santana]], also a disciple of [[Sri Chinmoy]] at the time, on an album of devotional songs, ''[[Love Devotion Surrender]]'', which featured recordings of [[John Coltrane|Coltrane]] compositions including a movement of ''[[A Love Supreme]]''. McLaughlin has also worked with the jazz composers [[Carla Bley]] and [[Gil Evans]]. |

|||

In [[1979]] he formed a short-lived funk fusion [[power trio]] named the [[Trio of Doom]] with [[Tony Williams]] on [[Drums]] and famed [[Bass (guitar)|Bass]] player [[Jaco Pastorius]] on [[Bass (guitar)|Bass]]. Their only live performance was on [[March 3]],[[1979]] at the [[Havana Jam]] Festival (March 2-4 1979) in [[Cuba]], part of a US State Department sponsored visit to Cuba. Later on March 8, 1979 the group recorded the songs they had written for the festival at Columbia Studios, New York, on 52nd St. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trio_of_Doom]. Recollections from this performance are captured on [[Ernesto Juan Castellanos]]'s documentary [[Havana Jam '79]]. |

|||

====Mahavishnu Orchestra==== |

====The Mahavishnu Orchestra==== |

||

[[File:JohnMcLaughlin.jpg|thumb|right|180px|John McLaughlin, Cirkus Krone-Bau, Munich, West Germany, 9 June 1973]] |

|||

{{Main|The Mahavishnu Orchestra}} |

|||

{{Main|Mahavishnu Orchestra}} |

|||

[[File:JohnMcLaughlin.jpg|thumb|John McLaughlin, Zirkus Krone, Munich, West Germany 1973 April 13 (photo by Peter Duray-Bito)]]McLaughlin's 1970s electric band, [[Mahavishnu Orchestra|The Mahavishnu Orchestra]],<ref>[http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=22802 Power, Passion and Beauty, The Story Of The Legendary Mahavishnu-Orchestra]</ref> included violinist [[Jerry Goodman]] (later [[Jean-Luc Ponty]]), keyboardist [[Jan Hammer]] (later Gayle Moran and Stu Goldberg), bassist [[Rick Laird]] (later Ralphe Armstrong), and drummer [[Billy Cobham]] (later [[Narada Michael Walden]]). The band performed a technically virtuosic and complex style of music that fused eclectic jazz and rock with eastern and Indian influences. This band established fusion as a new and growing style within the jazz and rock worlds. McLaughlin's playing at this time was distinguished by fast solos and exotic [[musical scales]]. |

|||

McLaughlin's 1970s electric band, the [[Mahavishnu Orchestra]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=22802 |title=Power, Passion and Beauty, The Story of the Legendary Mahavishnu-Orchestra |date=2006-08-20 |publisher=Allaboutjazz.com |access-date=2011-10-18}}</ref> included violinist [[Jerry Goodman]], keyboardist [[Jan Hammer]], bassist [[Rick Laird]], and drummer [[Billy Cobham]]. They performed a technically difficult and complex style of music that fused electric jazz and rock with Eastern and Indian influences. This band helped establish fusion as a new and growing style. McLaughlin's playing at this time was distinguished by fast solos and non-western [[musical scales]]. |

|||

The first incarnation of the Mahavishnu Orchestra split in late 1973 after two years and three albums, including a live recording ''[[Between Nothingness & Eternity]]'', due to personality clashes and overwork imposed by their management;{{sfn|Kolosky|2006|p=107-108}} Jan Hammer and Jerry Goodman were among the outspoken members who disputed with McLaughlin's leadership, religious beliefs and songwriting credits.<ref name=Crawdaddy73>{{cite journal|url=http://www.italway.it/morrone/jml-crawdaddy.htm|title=John McLaughlin & The Mahavishnu Orchestra: Two Sides to Every Satori|journal=Crawdaddy|first2=Patrick|last2=Snyder-Scumpy|first1=Frank |last1=DeLigio|date=November 1973|access-date=2024-11-13|archive-url=https://archive.today/20121208221016/http://www.italway.it/morrone/jml-crawdaddy.htm |archive-date=2012-12-08}}</ref><ref name="Jazztimes2024McLaughlin"/> Upon reading an article from Crawdaddy Magazine en route to Japan for a tour, McLaughlin was offended by the writeups and disparagement of his religious beliefs.{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=503}}<ref name="Jazztimes2024McLaughlin"/>{{sfn|Kolosky|2006|p=190}} Goodman reconciled with McLaughlin, several years after the breakup.<ref name="Jazztimes2024McLaughlin"/> In 1999 the ''[[The Lost Trident Sessions|Lost Trident Sessions]]'' album was released; recorded in 1973 but shelved when the group disbanded. |

|||

In 1973, McLaughlin collaborated with [[Carlos Santana]], also a disciple of [[Sri Chinmoy]], on an album of devotional songs, ''[[Love Devotion Surrender]]'', which included recordings of [[John Coltrane|Coltrane]] compositions including a movement of ''[[A Love Supreme]]''. He has also worked with the jazz composers [[Carla Bley]] and [[Gil Evans]]. |

|||

McLaughlin then reformed the group with [[Narada Michael Walden]] (drums), [[Jean-Luc Ponty]] (violin), Ralphe Armstrong (bass), and [[Gayle Moran]] (keyboards and vocals), and a string and horn section (McLaughlin referred to this as "the real Mahavishnu Orchestra"). This incarnation of the group recorded two albums, ''[[Apocalypse (Mahavishnu Orchestra album)|Apocalypse]]'', with the [[London Symphony Orchestra]], and ''[[Visions of the Emerald Beyond]]''. During the second lineup, McLaughlin had a double-neck electric guitar built by Rex Bogue. When the guitar broke, in a tour for ''Visions of the Emerald Beyond'', McLaughlin began to have a musical and spiritual crisis;{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=551-554}} He became disillusioned with the teachings of Sri Chinmoy and eventually disavowed Chinmoy's teachings.{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=561}}{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=568}} McLaughlin stated in 1976 for ''[[People Magazine]]'', "I love [Sri Chinmoy] very much, but I must assume responsibility for my own actions".<ref name="People76">{{cite magazine |last=Jerome |first=Jim |date=1976-06-21 |title=John McLaughlin Pulls the Plug on His Guitar, but He's as Electrifying as Ever |url=http://people.com/archive/john-mc-laughlin-pulls-the-plug-on-his-guitar-but-hes-as-electrifying-as-ever-vol-5-no-24/ |url-status=dead |magazine=People Magazine |location= |publisher=Dotdash Meredith |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230813112942/https://people.com/archive/john-mc-laughlin-pulls-the-plug-on-his-guitar-but-hes-as-electrifying-as-ever-vol-5-no-24/ |archive-date=13 August 2023 |access-date=2024-11-13 }}</ref>{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=569}} A scaled-down quartet was formed with McLaughlin, Walden on drums, Armstrong on bass and [[Stu Goldberg]] on keyboards and synthesiser, for their final album in the 1970s, ''[[Inner Worlds]]'', which was released on February 1976,{{sfn|Harper|2014|p=569}} largely due to contractual obligations. |

|||

==== |

====Shakti==== |

||

McLaughlin then became absorbed in his acoustic playing with his [[Indian classical music]] based group [[Shakti (band)|Shakti]] (energy). McLaughlin had already been studying Indian classical music and playing the [[veena]] for several years. The group featured Lakshminarayanan [[L. Shankar]] (violin), [[Zakir Hussain (musician)|Zakir Hussain]] ([[tabla]]), [[Thetakudi Harihara Vinayakram]] ([[ghatam]]) and earlier [[Ramnad Raghavan]] ([[mridangam]]). The group recorded three albums: ''[[Shakti (Shakti album)|Shakti with John McLaughlin]]'' (1975) |

|||

[[File:John McLaughlin 20010720.JPG|thumb|John McLaughlin, [[Remember Shakti]] Concert, Munich/Germany (2001)]] |

|||

''[[A Handful of Beauty]]'' (1976), and ''[[Natural Elements (Shakti album)|Natural Elements]]'' (1977). Based on both [[carnatic music|Carnatic]] and [[Hindustani classical music|Hindustani]] styles, along with extended use of [[konnakol]], the band introduced ragas and Indian percussion to many jazz aficionados.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.chembur.com/anecdotes/carnatic/lshankar/ |title=Chembur.com |publisher=Chembur.com |access-date=2011-10-18 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110928044436/http://www.chembur.com/anecdotes/carnatic/lshankar/ |archive-date=2011-09-28 }}</ref> |

|||

After the first reincarnation of the Mahavishnu Orchestra split, McLaughlin worked with acoustic group [[Shakti (band)|Shakti]]. This group combined Indian music with elements of jazz and thus may be regarded as a pioneer of [[world music]]. McLaughlin had already been studying Indian classical music and playing the [[veena]] for several years. The group featured Lakshminarayanan [[L. Shankar]] (violin), [[Zakir Hussain (musician)|Zakir Hussain]] ([[tabla]]), [[Thetakudi Harihara Vinayakram]] ([[ghatam]]) and earlier [[Ramnad Raghavan]] ([[mridangam]]). John was one of the earliest [[Western world|westerners]] to attain any acclaim performing Indian music for Indian audiences. |

|||

In this group |

In this group McLaughlin played a custom-made steel-string J-200 acoustic guitar made by [[Abraham Wechter|Abe Wechter]] and the [[Gibson Guitar Corporation|Gibson guitar company]] that featured two tiers of strings over the soundhole: a conventional six-string configuration and seven strings strung underneath at a 45-degree angle – these were independently tuneable "[[sympathetic strings]]" much like those on a [[sitar]] or [[veena]]. The instrument's vina-like scalloped fretboard enabled McLaughlin to bend strings far beyond the reach of a conventional fretboard. McLaughlin grew so accustomed to the freedom it provided him that he had the fretboard scalloped on his [[Gibson Byrdland]] electric guitar.{{sfn|Wheeler|1978|p=42}} |

||

====Other activities==== |

|||

[[File:Tres GUITARRISTAS (así, con mayúsculas).jpg|thumb|right|220px|Left to right: [[Al Di Meola]], John McLaughlin, and [[Paco de Lucía]] performing in [[Barcelona]], Spain in the 1980s]] |

|||

In 1979, he teamed up with [[flamenco]] guitarist [[Paco de Lucía]] and jazz guitarist [[Larry Coryell]] (replaced by [[Al Di Meola]] in the early 1980s) as the Guitar Trio. For the fall tour of 1983, they were joined by [[Dixie Dregs]] guitarist [[Steve Morse]], who opened the show as a soloist and participated with The Trio in the closing numbers. The Trio, again featuring McLaughlin along with de Lucía and Di Meola, reunited in 1996 for a second recording session and a world tour. In 1979, McLaughlin recorded the album ''[[Johnny McLaughlin: Electric Guitarist]]'', the title on McLaughlin's first business cards as a teenager in [[Yorkshire]]. This recording was a return to more mainstream jazz/rock fusion and to the electric instrument after three years of playing acoustic guitars, particularly his Gibson 2-tier custom-made steel string with the Shakti group. McLaughlin was so used to the scalloped fretboard from his Shakti days and so accustomed to the freedom it provided him that he had the fretboard scalloped on his Gibson Byrdland Electric hollowbody. |

|||

In 1979, McLaughlin formed a short-lived funk fusion [[power trio]] named [[Trio of Doom]] with drummer [[Tony Williams (drummer)|Tony Williams]] and bassist [[Jaco Pastorius]]. Their only live performance was on 3 March 1979 at the [[Havana Jam]] Festival (2–4 March 1979) in [[Cuba]], part of a US State Department sponsored visit to Cuba. Later on 8 March 1979, the group recorded the songs they had written for the festival at CBS Studios in New York, on 52nd Street. Recollections from this performance are captured on Ernesto Juan Castellanos's documentary ''Havana Jam '79'' and the archival album, ''[[Trio of Doom]]''. McLaughlin also appeared on [[Stanley Clarke]]'s ''[[School Days (album)|School Days]]'' and numerous other fusion albums. |

|||

The same year, McLaughlin teamed up with [[flamenco]] guitarist [[Paco de Lucía]] and jazz guitarist [[Larry Coryell]] (replaced by [[Al Di Meola]] in the early 1980s) as the Guitar Trio. For the tour of fall 1983 they were joined by [[Dixie Dregs]] guitarist [[Steve Morse]] who opened the show as a soloist and participated with The Trio in the closing numbers. The Trio reunited in 1996 for a second recording session and a world tour. Also in 1979 McLaughlin recorded the album ''[[Electric Guitarist|Johnny McLaughlin: Electric Guitarist]]'', the title on McLaughlin's first business cards as a teenager in [[Yorkshire]]. This was a return to more mainstream jazz/rock fusion and to the electric instrument after three years of playing acoustic guitars. |

|||

[[File:Tres GUITARRISTAS (así, con mayúsculas).jpg|thumb|right|220px|Left to Right: [[Al Di Meola]], John McLaughlin and [[Paco de Lucía]]]] |

|||

He also formed the short-lived One Truth Band who recorded one studio album, ''[[Electric Dreams (John McLaughlin album)|Electric Dreams]]''. The group had L. Shankar on violins, Stu Goldberg on keyboards, Fernando Saunders on electric bass, and Tony Smith on drums. 1979 also saw the formation of the very short-lived [[Trio of Doom]], consisting of McLaughlin with [[Jaco Pastorius]] (bass) and [[Tony Williams]] (drums). They only played one concert, at the [[Karl Marx Theater]] in [[Havana]], [[Cuba]] on March 3, 1979,<ref>Sleeve notes: Trio of Doom, Columbia/Legacy 82796964502</ref> as part of the [[Havana Jam]] festival, a [[US State Department]] cultural exchange program known by some musicians as the 'The Bay of Gigs'. Their performance is clearly captured on [[Ernesto Juan Castellanos]]'s documentary [[Havana Jam '79]]. They later recorded three tracks at [[CBS]] Studios in New York, March 8, 1979. |

|||

===1980s=== |

===1980s=== |

||

[[File:John McLaughlin 1980.jpg|thumb|left|John McLaughlin at Berkeley Jazz Festival 5/25/1980]] |

|||

The short-lived One Truth Band recorded one studio album, ''[[Electric Dreams (John McLaughlin album)|Electric Dreams]]'', with L. Shankar on violins, Stu Goldberg on keyboards, [[Fernando Saunders]] on electric bass and [[Tony Thunder Smith|Tony Smith]] on drums. After the dissolution of the One Truth Band, McLaughlin toured in a guitar duo with [[Christian Escoudé]].<ref>{{cite magazine|url=http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/musician.php?id=6573|title=Christian Escoude – Jazz – Guitar|magazine=All About Jazz|access-date=2011-10-18 |url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120205135843/http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/musician.php?id=6573|archive-date=2012-02-05|df=dmy-all}}</ref> |

|||

In the late '80s and early '90s McLaughlin recorded and performed live with a trio including bassist [[Kai Eckhardt]] and percussionist [[Trilok Gurtu]]. The group recorded two albums: "Live at The Royal Festival Hall" and "Que Alegria", with latter featuring Dominique DiPiazza on bass for all but two tracks. These recordings saw a return to acoustic instruments for McLaughlin, performing on nylon-string guitar. On "Live at the Royal Festival Hall" McLaughlin utilised a unique guitar synth which enabled him to effectively [[tape loop|"loop"]] guitar parts and play over them live. The synth also featured a pedal which provided sustain when pressed. McLaughlin played parts which sound overdubbed and creating lush soundscapes, aided by Gurtu's unique percussive sounds. This approach is used to great effect in the track "Florianapolis", amongst others. |

|||

With the group [[Fuse One]], he released two albums in 1980 and 1982.<ref name=ALLMUSIC>[ |

With the group [[Fuse One]], he released two albums in 1980 and 1982.<ref name="ALLMUSIC">[{{AllMusic|class=artist|id=p10614/discography|pure_url=yes}} Allmusic Discography]</ref> |

||

In 1981 and 1982, McLaughlin recorded two albums, ''[[Belo Horizonte (album)|Belo Horizonte]]'' and ''[[Music Spoken Here]]'' with The Translators, a band of French and American musicians who combined acoustic guitar, bass, drums, saxophone, and violin with synthesizers. The Translators included McLaughlin's then-girlfriend, classical pianist [[Katia Labèque]]. |

|||

In 1986 he appeared with [[Dexter Gordon]] in [[Bertrand Tavernier]]'s film "[[Round Midnight (film)|Round Midnight]]." He also composed The Mediterranean Concerto, orchestrated by [[Michael Gibbs]]. The world premier featured McLaughlin and the [[Los Angeles Philharmonic]]. It was recorded in 1988 with [[Michael Tilson Thomas]] conducting the [[London Symphony Orchestra]]. McLaughlin does improvise in certain sections. |

|||

From 1984 through to (circa) 1987, an electric five-piece operated under the name "Mahavishnu" (omitting the "Orchestra"). Two LPs were released, ''[[Mahavishnu (album)|Mahavishnu]]'' and ''[[Adventures in Radioland]]''. The former featured McLaughlin making extensive use of the [[Synclavier]] synthesizer, allied with a [[Roland Corporation|Roland]] [[Guitar synthesizer|guitar/controller]]. The first of the two albums was recorded with a line-up of McLaughlin, [[Bill Evans (saxophonist)|Bill Evans]] (saxophones), [[Jonas Hellborg]] (bass), [[Mitchel Forman]] (keyboards) and both [[Danny Gottlieb]] and Billy Cobham on drums. Initial advertising for concert dates in support of the album included Cobham's name, but by the time the tour started in earnest, Gottlieb was in the band. Forman left at some point between the albums, and was replaced on keyboards by [[Jim Beard]]. |

|||

In tandem with Mahavishnu, McLaughlin worked in duo format ({{circa}} 1985–87) with bassist Jonas Hellborg, playing a number of concert dates, some of which were broadcast on radio and TV, but no commercial recordings were made. |

|||

In 1986, he appeared with [[Dexter Gordon]] in [[Bertrand Tavernier]]'s film ''[[Round Midnight (film)|Round Midnight]]''. He also composed The Mediterranean Concerto, orchestrated by [[Michael Gibbs (composer)|Michael Gibbs]]. The world premier featured McLaughlin and the [[Los Angeles Philharmonic]]. It was recorded in 1988 with [[Michael Tilson Thomas]] conducting the [[London Symphony Orchestra]]. Unlike what is typical practice in classical music, the concerto includes sections where McLaughlin [[Improvisation (music)|improvises]]. Also included on the recording were five duets between McLaughlin and his then-girlfriend Katia Labèque. |

|||

In the late 1980s, McLaughlin began performing live and recording with a trio including percussionist [[Trilok Gurtu]], and three bassists at various times; firstly [[Jeff Berlin]], then [[Kai Eckhardt]] and finally [[Dominique Di Piazza]]. Berlin contributed to the trio's live work only in 1988/89, and didn't record with McLaughlin. The group recorded two albums: ''[[Live at the Royal Festival Hall (John McLaughlin Trio album)|Live at The Royal Festival Hall]]'' and ''[[Que Alegria]]'', the former with Eckhardt, and the latter with di Piazza for all but two tracks. These recordings saw a return to acoustic instruments for McLaughlin, performing on nylon-string guitar. On ''Live at the Royal Festival Hall'' McLaughlin used a unique guitar synth that enabled him to effectively [[tape loop|"loop"]] guitar parts and play over them live. The synth also featured a pedal that provided sustain. McLaughlin overdubbed parts to create lush soundscapes, aided by Gurtu's unique percussive sounds. He used this approach to great effect in the track ''Florianapolis'', among others. |

|||

===1990s=== |

===1990s=== |

||

[[File:John McLaughlin 20010720.JPG|thumb|John McLaughlin, [[Remember Shakti]] Concert, Munich/Germany (2001)]] |

|||

In the early 1990s he toured with his Quartet on the ''Que Alegria'' album. The quartet comprised John McLaughlin, [[Trilok Gurtu]], [[Kai Eckhardt]] and [[Dominique DiPiazza]]. Following this period he recorded and toured with The Heart of Things featuring [[Gary Thomas]], [[Dennis Chambers]], [[Matthew Garrison]], [[Jim Beard]] and [[Otmaro Ruíz]]. In recent times he has toured with [[Remember Shakti]]. |

|||

In the early 1990s, he toured with his trio on the ''[[Que Alegria|Qué Alegría]]'' album. By this time, Eckhardt had left, with McLaughlin and Gurtu joined by bass player Dominique Di Piazza. In the latter stages of this trio's life, they were joined on tour by Katia Labèque alone, or by Katia and her sister Marielle, with footage of the latter configuration forming part of a documentary on the [[Katia and Marielle Labèque|Labèque Sisters]]. Following this period he recorded and toured with The Heart of Things featuring [[Gary Thomas (musician)|Gary Thomas]], [[Dennis Chambers]], [[Matt Garrison]], Jim Beard and [[Otmaro Ruíz]]. In 1993 he released a [[Bill Evans]] tribute album entitled ''[[Time Remembered: John McLaughlin Plays Bill Evans]]'', with McLaughlin's acoustic guitar backed by the acoustic guitars of the Aighetta Quartet and the acoustic bass of Yan Maresz. |

|||

In 1994, McLaughlin and [[Trilok Gurtu]] composed the soundtrack to the drama film ''Molom, conte de Mongolie'',{{efn|English: ''Molom: A Legend of Mongolia''}} directed by Marie-Jaoul de Poncheville.<ref name="NYTimes1997">{{cite web |last1= Holden |first1=Stephen |title=In Mongolia, Lunging Toward Enlightenment |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1997/08/08/movies/in-mongolia-lunging-toward-enlightenment.html |website=[[The New York Times]]|access-date=2024-11-23 |date=1997-08-08}}</ref><ref name="McLaughlin_Variety1994">{{cite web |last1=Nesselson |first1=Lisa |title=Molom, a Mongolian Tale |url=https://variety.com/1994/film/reviews/molom-a-mongolian-tale-1200437801/ |website=[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]] |access-date=2024-11-23 |date=1994-07-31}}</ref> The film was praised for its visual aspects, authenticity and acting by outlets such as ''[[The New York Times]]'' and ''[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]]'';<ref name="NYTimes1997"/><ref name="McLaughlin_Variety1994"/><ref name="LesEchos1994">{{cite web |last1= Ardan |first1=Michel |title=Voyage initiatique en Mongolie |url=https://www.lesechos.fr/1995/07/voyage-initiatique-en-mongolie-863504 |website=[[Les Echos (France)|Les Echos]]|language=French |access-date=2024-11-23 |date=1995-07-31}}</ref> Conversely, reception to the soundtrack was mixed, as ''Variety'' considered McLaughlin and Gurtu's score "too contemporary to mesh", while remarking that the Mongolian folk music in the soundtrack was "pleasant".<ref name="McLaughlin_Variety1994"/> |

|||

In addition to original Shakti member [[Zakir Hussain (musician)|Zakir Hussain]], this group has also featured eminent Indian musicians [[U. Srinivas]], [[V. Selvaganesh]], [[Shankar Mahadevan]], [[Shivkumar Sharma]], and [[Hariprasad Chaurasia]]. In 1996, John McLaughlin, Paco |

McLaughlin formed a group, [[Remember Shakti]] and toured with them; In addition to original Shakti member [[Zakir Hussain (musician)|Zakir Hussain]], this group has also featured eminent Indian musicians [[U. Srinivas]], [[V. Selvaganesh]], [[Shankar Mahadevan]], [[Shivkumar Sharma]], and [[Hariprasad Chaurasia]]. In 1996, John McLaughlin, Paco de Lucia and Al Di Meola (known collectively as "The Guitar Trio") reunited for a world tour and recorded an album of the same name. They had previously released a studio album entitled ''[[Passion, Grace and Fire|Passion, Grace & Fire]]'' back in 1983. Meanwhile, in the same year of 1996 McLaughlin recorded ''[[The Promise (John McLaughlin album)|The Promise]]''. Also notable during the period were his performances with [[Elvin Jones]] and [[Joey DeFrancesco]]. |

||

===2000s=== |

===2000s=== |

||

In 2003, he recorded a |

In 2003, he recorded a ballet score, ''[[Thieves and Poets]]'', along with arrangements for classical guitar ensemble of favourite jazz standards and a three-DVD instructional video on improvisation entitled "This is the Way I Do It" (which contributed to the development of video lessons.<ref>{{cite magazine|author=All About Jazz |url=http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=14486 |title=Walter Kolosky |magazine=All About Jazz |date= 2004-08-17 |access-date=2011-10-19}}</ref>) In June 2006 he released the [[post-bop]]/[[jazz fusion]] album ''[[Industrial Zen]]'', on which he experimented with the [[Godin (Guitar Manufacturer)|Godin]] Glissentar as well as continuing to expand his guitar-synth repertoire. |

||

2007, he left [[Universal Records]] and joined |

In 2007, he left [[Universal Records]] and joined Abstract Logix. Recording sessions for his first album on that label took place in April. That summer, he began touring with a new jazz fusion quartet, the 4th Dimension, consisting of keyboardist/drummer [[Gary Husband]], bassist Hadrian Feraud, and drummer [[Mark Mondesir]]. During the 4th Dimension's tour, an "instant CD" entitled ''Live USA 2007: Official Bootleg'' was made available comprising [[soundboard recording]]s of six pieces from the group's first performance. Following completion of the tour, McLaughlin sorted through recordings from each night to release a second MP3 download-only collection entitled, ''Official Pirate: Best of the American Tour 2007''. During this time, McLaughlin also released another instructional DVD, ''The Gateway to Rhythm'', featuring Indian percussionist and Remember Shakti bandmate [[V. Selvaganesh|Selva Ganesh Vinayakram (or V. Selvaganesh)]], focusing on the Indian rhythmic system of [[konnakol]]. McLaughlin also remastered and released the shelved 1979 Trio of Doom project with Jaco Pastorius and Tony Williams. The project had been aborted due to conflicts between Williams and Pastorius as well as what was at the time a mutual dissatisfaction with the results of their performance. |

||

On |

On 28 July 2007, McLaughlin performed at [[Eric Clapton]]'s [[Crossroads Guitar Festival]] in [[Bridgeview, Illinois]]. |

||

[[File:JohnMcLaughinCrossroads2007.jpg|thumb|140px|right|McLaughlin, 2007 [[Crossroads Guitar Festival]]]] |

[[File:JohnMcLaughinCrossroads2007.jpg|thumb|140px|right|McLaughlin, 2007 [[Crossroads Guitar Festival]]]] |

||

On |

On 28 April 2008, the recording sessions from the previous year surfaced on the album ''[[Floating Point]]'', featuring the rhythm section of keyboardist [[Louis Banks]], bassist [[Hadrien Feraud]], percussionist Sivamani and drummer [[Ranjit Barot]] bolstered on each track by a different Indian musician. Coinciding with the release of the album was another DVD, ''Meeting of the Minds'', which offered behind the scenes studio footage of the ''Floating Point'' sessions as well as interviews with all of the musicians. He engaged in a late summer/fall 2008 tour with [[Chick Corea]], [[Vinnie Colaiuta]], [[Kenny Garrett]] and [[Christian McBride]] under the name [[Five Peace Band]], from which came an eponymous double-CD live album in early 2009. |

||

McLaughlin performed with Mahavishnu Orchestra drummer Billy Cobham at the 44th [[Montreux Jazz Festival]], in Montreux, [[Switzerland]], on 2 July 2010, for the first time since the band split up. In November 2010, a book was released by Abstract Logix Books entitled ''Follow Your Heart - John McLaughlin Song by Song'' by Walter Kolosky, who also wrote the book ''Power, Passion and Beauty – The Story of the Legendary Mahavishnu Orchestra''. The book discussed each song McLaughlin wrote and contained photographs never seen before. |

|||

McLaughlin engaged in a late summer/fall 2008 tour with [[Chick Corea]], [[Vinnie Colaiuta]], [[Kenny Garrett]] and [[Christian McBride]] under the name "[[Five Peace Band]]", from which came an eponymous double-CD live album in early 2009. |

|||

== |

==Style== |

||

John McLaughlin is a leading guitarist in jazz and jazz fusion. His style has been described as one that incorporates aggressive speed, technical precision, and harmonic sophistication.<ref>{{cite web|title=John McLaughlin|url=http://musicians.allaboutjazz.com/musician.php?id=9281#.UNlA1tHQTMY|website=Musicians.allaboutjazz.com|access-date=25 December 2012}}</ref> He is known for using non-Western scales and unconventional time signatures. Indian music has had a profound influence on his style, and he has been described as one of the first Westerners to play Indian music to Indian audiences.<ref>{{cite web|title=John McLaughlin Biography, Videos & Pictures|url=http://www.guitarlessons.com/guitarists/jazz/john-mclaughlin/|publisher=GuitarLessons.com|access-date=25 December 2012|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130124164100/http://www.guitarlessons.com/guitarists/jazz/john-mclaughlin/|archive-date=24 January 2013|df=dmy-all}}</ref> He was influential in bringing jazz fusion to popularity with Miles Davis, playing with Davis on five of his studio albums, including Davis' first gold-certified ''Bitches Brew'', and one live album, ''Live-Evil''. Speaking of himself, McLaughlin has stated that the guitar is simply "part of his body", and he feels more comfortable when a guitar is present. |

|||

[http://www.abstractlogix.com Abstract Logix] |

|||

==Influence== |

==Influence== |

||

[[File:Al di Meola and John McLaughlin in 1979.jpg|thumb|right|250px|[[Al Di Meola]] and John McLaughlin in 1979]] |

|||

In 2010, [[Jeff Beck]] said: "John McLaughlin has given us so many different facets of the guitar. And introduced thousands of us to world music, by blending Indian music with jazz and classical. I'd say he was the best guitarist alive."<ref name="beck"/> McLaughlin has been cited as a major influence on many 1970s and 1980s guitarists, including prominent players such as [[Steve Morse]],<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.allmusic.com/artist/steve-morse-mn0000044134/biography |title=Steve Morse: Biography |last=Skelly |first=Richard |website=AllMusic |access-date=10 November 2020}}</ref> [[Gary Moore]],<ref name="MusicUK">{{cite magazine|last=Bacon|first=Tony|title=Gary Moore|journal=Music U.K.|volume=13|issue=|location=|date=January 1983|issn=|page=22}}</ref> [[Eric Johnson (guitarist, born 1954)|Eric Johnson]],<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.ultimate-guitar.com/news/interviews/eric_johnson_born_to_play_guitar_part_2.html |

|||

|title=Eric Johnson: Born To Play Guitar. Part 2 |last=Holland |first=Brian D. |date=17 June 2006 | website=Ultimate Guitar |access-date=10 November 2020}}</ref> [[Mike Stern]],<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.allaboutjazz.com/follow-your-heart-john-mclaughlin-song-by-song-by-ian-patterson.php |

|||

|title=Follow Your Heart: John McLaughlin Song By Song |last=Patterson |first=Ian |date=12 March 2011 | website=All About Jazz |access-date=10 November 2020}}</ref> [[Al Di Meola]],<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/music/hes-the-one-john-mclaughlins-inspiration/article1241498 |

|||

|title=He's the one: John McLaughlin's inspiration |last=Considine |first=J. D. |date=9 November 2010 | website=The Globe and Mail |access-date=10 November 2020}}</ref> [[Shawn Lane]],<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.guitarworld.com/features/fast-lane-underappreciated-genius-and-vision-shawn-lane |

|||

|title=The Genius and Vision of Guitarist Shawn Lane |last=Paul |first=Alan |date=23 April 2019 | website=Guitar World |access-date=10 November 2020}}</ref> [[Scott Henderson]],<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.allmusic.com/artist/scott-henderson-mn0000254833/biography |title=Scott Henderson: Biography |last=Collar |first=Matt |website=AllMusic |access-date=10 November 2020}}</ref> and [[Trevor Rabin]] of [[Yes (band)|Yes]].<ref>interview for the video retrospective [[YesYears (video)|''YesYears'']], April 1991</ref> Other players who acknowledge his influence include [[Omar Rodríguez-López]] of [[The Mars Volta]],<ref>{{cite web|access-date=23 February 2017 |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/artists/marsvolta/articles/story/21004611/secrets_of_the_guitar_heroes_omar_rodriguez_lopez |magazine=[[Rolling Stone]] |title=Secrets of the Guitar Heroes: Omar Rodriguez Lopez |first=David |last=Fricke |date=12 June 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-date= 9 February 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090209094910/http://www.rollingstone.com/artists/marsvolta/articles/story/21004611/secrets_of_the_guitar_heroes_omar_rodriguez_lopez }}</ref> [[Paul Masvidal]] of [[Cynic (band)|Cynic]],<ref>{{cite web | access-date = 10 March 2017 | url = http://www.metal-discovery.com/Interviews/cynic_paulmasvidal_interview_2008_pt2.htm | date = 22 November 2008 | title = Cynic - Paul Masvidal | website = Metal-discovery.com | first = Mark | last = Holmes | location = Nottingham, England }}</ref> and [[Ben Weinman]] of [[The Dillinger Escape Plan]].<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.therockpit.net/2015/Ben-Weinman-Dillinger-Escape-Plan-Interview-2015.php | access-date = 23 February 2017 | title = The Rockpit interviews - BEN WEINMAN - DILLINGER ESCAPE PLAN | date = 15 July 2015 | website = [[The Rockpit]] | first = Andrew | last = Massie | quote = I guess some of my biggest influences are people like John Mclaughlin from Mahavishnu Orchestra [...] }}</ref> According to [[Pat Metheny]], McLaughlin has changed the evolution of the guitar during several of his periods of playing.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.patmetheny.com/qa/questionView.cfm?queID=440 |title=Question and Answer: John McLaughlin |date=24 March 1999 |last1=Stump |first1=Paul |last2=Metheny |first2=Pat |website=PatMetheny.com |access-date=10 November 2020}}</ref> The Smiths guitarist [[Johnny Marr]] cites McLaughlin "the greatest guitar player that's ever lived".<ref>{{Cite web |author1=Rob Laing |date=2022-11-30 |title=Johnny Marr's choice for the greatest guitarist of all time is surprising - and his new pedalboard is too |url=https://www.musicradar.com/news/johnny-marr-interview-guitar-hero-pedalboard |access-date=2024-09-19 |website=MusicRadar |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

McLaughlin is considered a major influence on composers in the fusion genre. In an interview with ''Downbeat'', [[Chick Corea]] remarked that "what John McLaughlin did with the electric guitar set the world on its ear. No one ever heard an electric guitar played like that before, and it certainly inspired me. John's band, more than my experience with Miles, led me to want to turn the volume up and write music that was more dramatic and made your hair stand on end."{{sfn|Woodard|1988|p=19}} |

|||

The musician and comedian [[Darryl Rhoades]] also paid tribute to McLaughlin's influence. In the 1970s, he led the "Hahavishnu<!--not a typo, it was Haha, not Maha--> Orchestra", which did parodies of the funk, rock and jazz musical styles of the era.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.music-comedy.com/rolling.htm |title=Hahavishnu: Daryl Rhoades' revenge|last=Young|first=Charles M. |publisher=[[Rolling Stone]]|date=1977-08-25 |access-date=7 August 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080828165346/http://www.music-comedy.com/rolling.htm|p=19 |archive-date=28 August 2008 |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

==Personal life== |

|||

McLaughlin was married to Eve when he was a disciple of [[Sri Chinmoy]].{{sfn|Shteamer|2017}} For a time he lived with the French pianist [[Katia Labèque]], who was also a member of his band in the early 1980s.<ref name=labeque>{{cite web|url=https://www.wfmt.com/2018/05/03/how-legendary-pianists-katia-and-marielle-labeque-found-freedom-through-new-music/ |title=How legendary pianists Katia and Marielle Labèque found freedom through new music |last=Raskauskas |first=Stephen |work=WFMT |date=3 May 2018 |access-date=11 February 2020}}</ref> As of 2017, McLaughlin is married to his fourth wife, Ina Behrend.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.pressreader.com/germany/heilbronner-stimme-stadtausgabe/20170104/282157880922072 |format=Print |title=John McLaughlin wird 75 |language=de |work=Heilbronner Stimme Stadtausgabe |publisher=Heilbronner Stimme |date=4 January 2017 |access-date=15 May 2018 |quote="...mit seiner vierten Ehefrau Ina Behrend..." }}</ref> They had a son in 1998.{{sfn|Kolosky|2008}} Since the late 1980s, he has lived in [[Monaco]].<ref>{{cite news |title = Guitar legend John McLaughlin answers your questions |url= http://www.musicradar.com/news/guitars/guitar-legend-john-mclaughlin-answers-your-questions-560533/ | newspaper=[[MusicRadar]]|access-date=10 August 2014}}</ref> McLaughlin is a [[pescetarian]].{{sfn|TT Bureau|2015}} |

|||

McLaughlin, alongside Behrend, supports a Palestinian music therapy organization, Al-Mada, who run a program called "For My Identity I Sing". McLaughlin performed in [[Ramallah]], Palestine, in 2012 with [[Zakir Hussain (musician)|Zakir Hussain]] and in 2014 with 4th Dimension.{{sfn|Agence France-Presse|2014}} |

|||

==Discography== |

==Discography== |

||

{{Main|John McLaughlin discography}} |

{{Main list|John McLaughlin discography}} |

||

{{Div col|colwidth=25em}} |

|||

==Equipment== |

|||

*''[[Extrapolation (album)|Extrapolation]]'' (1969) |

|||

*[[Gibson EDS-1275]], McLaughlin played the Gibson doubleneck between 1971 and 1973 at which point the Double Rainbow was completed. |

|||

*''[[Devotion (John McLaughlin album)|Devotion]]'' (1970) |

|||

*[http://www.cs.cf.ac.uk/Dave/mclaughlin/art/rainbow.html Double Rainbow] doubleneck guitar made by Rex Bogue, which McLaughlin played between 1973 - 1975. |

|||

*''[[My Goal's Beyond]]'' (1971; credited as Mahavishnu John McLaughlin) |

|||

*''[[Electric Guitarist]]'' (1978) |

|||

*''[[Electric Dreams (John McLaughlin album)|Electric Dreams]]'' (1979; with the One Truth Band) |

|||

*''[[Friday Night in San Francisco]]'' (1981; with [[Al Di Meola]] and [[Paco de Lucía]]) |

|||

*''[[Belo Horizonte (album)|Belo Horizonte]]'' (1981) |

|||

*''[[Music Spoken Here]]'' (1982) |

|||

*''Concerto for Guitar & Orchestra "The Mediterranean" – Duos for Guitar & Piano'' (1990; with [[London Symphony Orchestra]] and [[Katia Labèque]]) |

|||

*''[[Time Remembered: John McLaughlin Plays Bill Evans]]'' (1993) |

|||

*''[[After the Rain (John McLaughlin album)|After the Rain]]'' (1995; with [[Joey DeFrancesco]] and [[Elvin Jones]]) |

|||

*''[[The Promise (John McLaughlin album)|The Promise]]'' (1995) |

|||

*''[[The Heart of Things]]'' (1997) |

|||

*''[[Thieves and Poets]]'' (2003) |

|||

*''[[Industrial Zen]]'' (2006) |

|||

*''[[Floating Point]]'' (2008) |

|||

*''[[To the One]]'' (2010; with the 4th Dimension) |

|||

*''[[Now Here This]]'' (2012; with the 4th Dimension) |

|||

*''[[Black Light (John McLaughlin album)|Black Light]]'' (2015; with the 4th Dimension) |

|||

*''[[Liberation Time]]'' (2021) |

|||

{{Div col end}} |

|||

==Awards and nominations== |

|||

* The first [[Abraham Wechter]]-built acoustic "Shakti guitar,"<ref>{{cite book |

|||

'''DownBeat''' |

|||

| last = Milkowski |

|||

* 1972: Jazz Album of the Year - ''[[The Inner Mounting Flame]]'' from [[Mahavishnu Orchestra]]<ref name="DB37Poll15">"37th Down Beat Readers Poll", 1972, page 15.</ref> |

|||

| first = Bill |

|||

* 1972: Pop Album of the Year - ''The Inner Mounting Flame'' from Mahavishnu Orchestra<ref name="DB37Poll15"></ref> |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

* Guitarist of the year - multiple years - John McLaughlin<ref name="DB37Poll17">"37th Down Beat Readers Poll", 1972, page 17.</ref> |

|||

| coauthors = |

|||

*2024 - DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame |

|||

| title = Rockers, jazzbos & visionaries |

|||

| publisher = Billboard Books |

|||

| date = 1998 |

|||

| location = |

|||

| page = 176 |

|||

| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=HeAXAQAAIAAJ&q=abraham+wechter&dq=abraham+wechter&lr=&client=firefox-a |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| isbn = 9780823078332}}</ref> a customized [[Gibson J-200]]<ref>{{cite book |

|||

| last = Stump |

|||

| first = Paul |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| coauthors = |

|||

| title = Go ahead John: the music of John McLaughlin |

|||

| publisher = SAF Publishing |

|||

| date = 2000 |

|||

| location = |

|||

| page = 97 |

|||

| url = http://books.google.com/books?id=TDFqHbV5K7cC&pg=PA97 |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| isbn = 9780946719242}}</ref> with [[Drone (music)#A_part_or_parts_of_a_musical_instrument|drone strings]] transversely across the soundhole.<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Wheeler |

|||

| first = Tom |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| coauthors = |

|||

| title = McLaughlin's Revolutionary Drone-String Guitar |

|||

| journal = [[Guitar Player]] |

|||

| volume = |

|||

| issue = |

|||

| pages = |

|||

| publisher = |

|||

| location = |

|||

| date = August 1978 |

|||

| url = http://www.7171.org/electrons/frap/article3.html |

|||

| issn = |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-10-19}}</ref> |

|||

* [http://web.archive.org/web/20070217173430/http://www.wechterguitars.com/custom/gallery32.htm "Marielle"], acoustic guitar with cutaway. |

|||

* [http://web.archive.org/web/20070216131737/http://www.wechterguitars.com/custom/gallery21.htm "Our Lady"], built by Abe Wechter for John McLaughlin. |

|||

* [http://www.mike-sabre.com/Mclaumodel/mclaumodel.html Mike Sabre John McLaughlin model] as seen on the Eric Claptons Crossroads Dallas 2004 DVD |

|||

* He currently plays [http://www.godinguitars.com/johnmclaughlin_07.htm Godin electric/MIDI guitars], one of which can be seeen on the Eric Claptons Crossroads Chicago 2007 DVD |

|||

*[http://www.italway.it/morrone/JmLGuitars.htm Summary] of the guitars played by John McLaughlin.[http://rp.couturier.free.fr/jml1_flash.htm#] |

|||

'''Grammy Awards'''<ref name="Grammy Award nominees – John McLaughlin">{{cite web|title=Grammy Award nominees – John McLaughlin|publisher=Grammy.com|url=https://www.grammy.com/artists/john-mclaughlin/15319|access-date=9 August 2024}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

* 1973: [[Grammy Award for Best Pop Instrumental Performance|Best Pop Instrumental Performance]] – "The Inner Mounting Flame" from ''The Inner Mounting Flame'' with Mahavishnu Orchestra |

|||

*[[Thetakudi Harihara Vinayakram]] |

|||

* 1974: Best Pop Instrumental Performance – "Birds of Fire" from ''[[Birds of Fire]]'' with Mahavishnu Orchestra |

|||

*[[V. Selvaganesh]] |

|||

* 1997: [[Grammy Award for Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals|Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals]] – "[[The Wind Cries Mary]]" from ''In From the Storm'' with [[Sting (musician)|Sting]], [[Dominic Miller]] and [[Vinnie Colaiuta]] |

|||

*[[L. Shankar]] |

|||

* 2002: [[Grammy Award for Best Global Music Album|Best World Music Album]] – ''[[Remember Shakti – Saturday Night in Bombay|Saturday Night in Bombay]]'' with [[Remember Shakti]] |

|||

*[[Jan Hammer]] |

|||

* 2009: [[Grammy Award for Best Contemporary Jazz Album|Best Contemporary Jazz Album]] – ''[[Floating Point]]'' |

|||

*[[Tony Williams]] |

|||

* 2010: [[Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Album|Best Jazz Instrumental Album, Individual or Group]] – ''[[Five Peace Band Live]]'' with [[Chick Corea]] & [[Five Peace Band]]<ref name="Grammy Award winners – Five Peace Band">{{cite web|title=Grammy Award winners – Five Peace Band|publisher=Grammy.com|url=https://www.grammy.com/artists/john-mclaughlin-five-peace-band/15892|access-date=9 August 2024}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Kai Eckhardt]] |

|||

*[[Gary Husband]] |

|||

*[[Matthew Garrison]] |

|||

*[[Trilok Gurtu]] |

|||

*[[Jonas Hellborg]] |

|||

*[[Paco de Lucía]] |

|||

*[[Al Di Meola]] |

|||

*[[Chris Duarte]] |

|||

*[[Jaco Pastorious]] |

|||

*[[Hadrien Feraud]] |

|||

*[[Larry Coryell]] |

|||

'''Guitar Player Magazine''' |

|||

== References == |

|||

''Annual Readers Poll Awards''{{sfn|Sievert|1990|p=28–29}} |

|||

{{col-begin}} |

|||

{{col-2}} |

|||

* 1973: Best Jazz Guitarist |

|||

* 1974: Best Jazz Guitarist |

|||

* 1975: Best Jazz Guitarist |

|||

{{col-2}} |

|||

* 1974: Best Overall Guitarist |

|||

* 1975: Best Overall Guitarist |

|||

* 1992: Acoustic Pickstyle<ref name="GP25Poll">"25th Annual Guitar Player Readers Poll Awards", 1992, page 105.</ref> |

|||

{{col-end}} |

|||

==Equipment== |

|||

* [[Gibson EDS-1275]] – McLaughlin played the Gibson doubleneck between 1971 and 1973,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gibson.com/en-us/Lifestyle/Features/An%20EDS-1275%20and%20a%20Drone-String/|title=An EDS-1275 and a Drone-Stringed J-200: The Tale of John McLaughlin's Two Rare Gibsons|publisher=[[Gibson Guitar Corporation]]|access-date=4 March 2010|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110622070900/http://www.gibson.com/en-us/Lifestyle/Features/An%20EDS-1275%20and%20a%20Drone-String/|archive-date=22 June 2011|df=dmy-all}}</ref> his first years with the [[Mahavishnu Orchestra]];{{sfn|Chapman|2000|p=115}} this is the guitar which, amplified through a 100-watt [[Marshall Amplification|Marshall]] amplifier "in meltdown mode", produced the signature McLaughlin sound hailed by ''[[Guitar Player]]'' as one of the "50 Greatest Tones of All Time".{{sfn|Blackett|2004|p=44-66}} |

|||

* Double Rainbow doubleneck guitar made by Rex Bogue, which McLaughlin played from 1973 to 1975.{{sfn|Ferris|1974}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.godinguitars.com/johnmclaughlin_07.htm|title=John McLaughlin's 2007 Touring Rig|last=Cleveland|first=Barry|publisher=Godin Guitars|access-date=4 March 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110711103948/http://www.godinguitars.com/johnmclaughlin_07.htm|archive-date=11 July 2011|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

* The first [[Abraham Wechter]]-built acoustic "Shakti guitar",{{sfn|Milkowski|1998|p=176}} a customised [[Gibson J-200]] with [[Drone (music)#Part(s) of a musical instrument|drone strings]] transversely across the soundhole.{{sfn|Stump|2000|p=97}}{{sfn|Wheeler|1978|p=42}} |

|||

* [[Gibson Byrdland]] with a scalloped fingerboard on albums ''[[Inner Worlds]]'' and ''[[Electric Guitarist]]'' |

|||

* [[Gibson ES-345]] with a scalloped fingerboard on albums ''[[Electric Dreams (John McLaughlin album)|Electric Dreams]]'' and ''[[Trio of Doom]]'' |

|||

* He has also played Godin electric/MIDI guitars. He discusses the Godin and other gear in an interview for ''[[Premier Guitar]]'' online.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.premierguitar.com/articles/Rig_Rundown_John_McLaughlin |title=Rig Rundown - John McLaughlin|website=Premierguitar.com |date=23 January 2011|access-date=9 April 2016}}</ref> |

|||

* McLaughlin endorses [[PRS guitars]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://prsguitars.com/artists/profile/john_mclaughlin/ |title=John McLaughlin |publisher=PRS Guitars |access-date=23 February 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131104081442/http://www.prsguitars.com/artists/profile/john_mclaughlin/|archive-date=4 November 2013}}</ref> |

|||

==References== |

|||

===Footnotes=== |

|||

{{notelist}} |

|||

===Citations=== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

{{Reflist}} |

||

===Sources=== |

|||

{{Refbegin|30em}} |

|||

*{{cite news|url=https://www.dawn.com/news/print/1098976 |format=Print |date= 10 April 2014|title=Jazz guitar legend John McLaughlin plays for Palestine |newspaper=[[Dawn (newspaper)|Dawn]]|author=[[Agence France-Presse]]}} |

|||

*{{cite journal| last=Blackett| first=Matt| title=The 50 Greatest Tones of All Time| journal=[[Guitar Player]]| volume=38| issue=10| pages=44–66| date=October 2004}} |

|||

*{{cite book|last=Chapman|first=Richard|title=Guitar: music, history, players|publisher=Dorling Kindersley|year=2000|isbn=978-0-7894-5963-3}} |

|||

*{{cite journal|last=Ferris|first=Leonard|date=May 1974|title=John McLaughlin & Rex Bogue Creating the 'Double Rainbow' |journal=[[Guitar Player]]|url=http://www.cs.cf.ac.uk/Dave/mclaughlin/art/rainbow.html|access-date=2010-03-03}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Foster |first=Mo |author-link=Mo Foster|title=17 Watts?: The Birth of British Rock Guitar|location=[[London]], England|publisher=Sanctuary Publishing|year=1997 |isbn=978-1-860742-67-5}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Harper |first=Colin |author-link=Colin Harper|title=Bathed in Lightning: John McLaughlin, the 60s and the Emerald Beyond|location=[[London]], England|publisher=Jawbone Press|year=2014 |isbn=978-1-908279-52-1}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Kolosky |first=Walter |title=Power, Passion & Beauty: The Story of the Legendary Mahavishnu Orchestra|location= |publisher=Abstract Logix Books|year=2006 |isbn=978-0-9761016-8-0}} |

|||

*{{cite web |last1=Kolosky |first1=Walter |title=John McLaughlin: Extrapolation |url=https://www.allaboutjazz.com/extrapolation-john-mclaughlin-polydor-records-review-by-walter-kolosky |website=All About Jazz |date=13 November 2002 |access-date=28 February 2024}} |

|||

*{{cite news |title = In Conversation with John McLaughlin |last1=Kolosky|first1=Walter|newspaper=Jazz.com|url = http://www.jazz.com/features-and-interviews/2008/5/6/in-conversation-with-john-mclaughlin |access-date = 10 August 2014 |url-status = dead |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20130629181417/http://www.jazz.com/features-and-interviews/2008/5/6/in-conversation-with-john-mclaughlin |archive-date = 29 June 2013|ref=CITEREFKolosky2008}} |

|||

*{{cite book|title=[[Encyclopedia of Popular Music|The Guinness Encyclopedia of Popular Music]]|editor-first=Colin|editor-last=Larkin|editor-link=Colin Larkin (writer)|publisher=[[Guinness Publishing]]|date=1992|edition=First|isbn=0-85112-939-0}} |

|||

*{{cite magazine|last1=Menn|first1=Don|last2=Stern|first2=Chip|title=JOHN McLAUGHLIN: After Mahavishnu and Shakti, A Return to Electric Guitar|magazine=Guitar Player|volume=12|issue=8|location=San Francisco, CA|date=August 1978|issn=0017-5463}} |

|||

*{{cite book| last=Milkowski| first=Bill| title=Rockers, jazzbos & visionaries| publisher=Billboard Books| year=1998| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HeAXAQAAIAAJ&q=abraham+wechter| isbn=978-0-8230-7833-2}} |

|||

*{{cite magazine|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/john-mclaughlin-on-his-final-u-s-tour-revisiting-mahavishnu-orchestra-117259/ |title=John McLaughlin on His Final U.S. Tour, Revisiting Mahavishnu Orchestra |last=Shteamer |first=Hank |magazine=Rolling Stone |date=26 October 2017 |access-date=11 February 2020}} |

|||

*{{cite magazine|last=Sievert|first=Jon|title=20 years of reader's choices|magazine=[[Guitar Player]]|volume=24|issue=1|location=San Francisco, CA|date=January 1990|issn=0017-5463}} |

|||

*{{cite book |last=Stump |first=Paul |title=Go Ahead John: The Music of John McLaughlin |location=[[London]], England|publisher=SAF Publishing|year=2000 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TDFqHbV5K7cC&pg=PA97| isbn=978-0-946719-24-2}} |

|||

*{{cite web |author=TT Bureau |title=Waiting for John |url=https://www.telegraphindia.com/entertainment/waiting-for-john/cid/1470564 |website=[[Telegraph India]]|date=10 October 2015 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20230123193159/https://www.telegraphindia.com/entertainment/waiting-for-john/cid/1470564|archive-date=23 January 2023|access-date=23 January 2023}} |

|||

*{{cite journal|last=Wheeler|first=Tom|title=McLaughlin's revolutionary drone-string guitar|journal=Guitar Player|volume=12|issue=8|location=San Francisco, CA|date=August 1978|issn=0017-5463|url =http://www.7171.org/electrons/frap/article3.html| archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20020424012457/http://www.7171.org/electrons/frap/article3.html| url-status =dead| archive-date =2002-04-24| access-date =2009-10-19}} |

|||

*{{cite magazine|last=Woodard|first=Josef|title=Chick Corea: Piano Dreams Come True|magazine=[[DownBeat]]|volume=55|issue=9|location=Chicago, IL|date=September 1988|issn=0012-5768}} |

|||

{{Refend}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

* [http://www.johnmclaughlin.com John McLaughlin Official Website] |

|||

* [http://www.johnmclaughlin.fr John McLaughlin French Website] |

|||

* [http://www.cs.ut.ee/~andres_d/mclaughlin/ Pages of Fire, a John McLaughlin Tribute] |

|||

* [http://johnmclaughlinbyotaciliomelgaco.vilabol.uol.com.br Mahavishnu John McLaughlin by Otacílio Melgaço] |

|||

* [http://www.allaboutjazz.com/php/article.php?id=2158 Finding the Way: The Music of John McLaughlin] |

|||

* [http://jmarc.co.nr/ JMA - John McLaughlin Archives] |

|||

* [http://www.geocities.com/BourbonStreet/Quarter/7055/McLaughlin/ Complete Discography] |

|||

* [http://www.jazz.com/features-and-interviews/2008/5/6/in-conversation-with-john-mclaughlin "In Conversation with John McLaughlin"] by Walter Kolosky ([http://www.jazz.com Jazz.com]) |

|||

* [http://emancipation.mypodcast.com/200807_archive.html for a short feature on John McLaughlin's career] July 2008 |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{commons category|John McLaughlin}} |

|||

* {{Official website|http://www.johnmclaughlin.com}} |

|||

{{John McLaughlin}} |

|||

{{Mahavishnu Orchestra}} |

{{Mahavishnu Orchestra}} |

||

{{Shakti (band)}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT: |

{{DEFAULTSORT:McLaughlin, John}} |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:1942 births]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Living people]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century English guitarists]] |

|||

[[Category:21st-century English guitarists]] |

|||

[[Category:British rhythm and blues boom musicians]] |

|||

[[Category:Chamber jazz guitarists]] |

[[Category:Chamber jazz guitarists]] |

||

[[Category:Columbia Records artists]] |

|||

[[Category:Converts to Hinduism]] |

|||

[[Category:DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame members]] |

|||

[[Category:English expatriates in Monaco]] |

|||

[[Category:English expatriate musicians in the United States]] |

|||

[[Category:English Hindus]] |

|||

[[Category:English jazz bandleaders]] |

|||

[[Category:English jazz composers]] |

|||

[[Category:English jazz guitarists]] |

|||

[[Category:English male composers]] |

|||