Crohn's disease: Difference between revisions

Dollarwizard (talk | contribs) →Complementary and alternative medicine: The study was about cannabis-derived compounds, so I am adjusting this sentence |

m Fix CW Error #61 with GenFixes (T1) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Type of inflammatory bowel disease}} |

|||

{{Infobox disease |

|||

{{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} |

|||

| Name = Crohn's disease |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=November 2021}} |

|||

| Latin = morbus Leśniowski-Crohn |

|||

{{Infobox medical condition (new) |

|||

| Image = Patterns of CD.svg |

|||

| |

| name = Crohn's disease |

||

| image = CD colitis 2.jpg |

|||

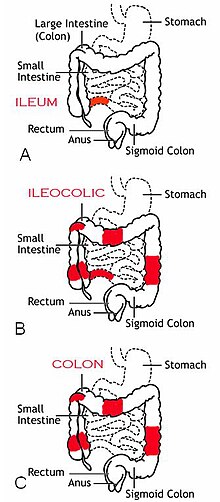

[[ileum|ileal]], [[ileocolic]] and [[Colon (anatomy)|colon]]ic.<ref name=Baumgart/> |

|||

| caption = Endoscopic image of severe Crohn's colitis showing diffuse loss of mucosal architecture, friability of mucosa in sigmoid colon and exudate on wall. |

|||

| DiseasesDB = 3178 |

|||

| |

| field = [[Gastroenterology]] |

||

| synonyms = Crohn disease, Crohn syndrome, granulomatous enteritis, regional enteritis, Leśniowski-Crohn disease |

|||

| ICD9 = {{ICD9|555}} |

|||

| symptoms = [[Diarrhea]], [[abdominal pain]], [[fatigue]], [[weight loss]], [[fever]]<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

| ICDO = |

|||

| complications = [[Anemia]], [[bowel cancer]], [[bowel obstruction]], [[strictures]], [[fistulas]], [[abscesses]], [[anal fissure]]<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

| OMIM = 266600 |

|||

| onset = 20–30 years<ref name="pmid28601423"/> |

|||

| MedlinePlus = 000249 |

|||

| duration = Lifelong<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

| eMedicineSubj = med |

|||

| causes = Uncertain<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

| eMedicineTopic = 477 |

|||

| risks = [[Genetic predisposition]], living in a [[developed country]], [[smoking]], [[diet (nutrition)|diet]],<ref name="pmid32242028"/> [[antibiotics]], [[oral contraceptives]], [[aspirin]], [[NSAIDS]]<ref name="pmid30611442"/> |

|||

| eMedicine_mult = {{eMedicine2|ped|507}} {{eMedicine2|radio|197}} |

|||

| diagnosis = [[Colonoscopy]], [[capsule endoscopy]], [[medical imaging]], [[histopathology]]<ref name="pmid32242028"/>| differential = [[Ulcerative colitis]], [[Behçet's disease]], [[intestinal lymphoma]], [[intestinal tuberculosis]], [[ischaemic colitis]], [[irritable bowel syndrome]]<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

| MeshID = D003424 |

|||

| prevention = |

|||

| treatment = |

|||

| medication = [[Biologics]] (especially [[TNF inhibitor|TNF blockers]]), [[immunosuppressants]] ([[thiopurine]]s and [[methotrexate]]), [[corticosteroid]]s,<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

| prognosis = Slightly reduced life expectancy<ref name="pmid33168761"/> |

|||

| frequency = ~300 in 100,000 ([[North America]] and [[Western Europe]])<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

| deaths = |

|||

| alt = |

|||

| named after = {{ubl|[[Burrill Bernard Crohn]]}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Crohn's disease''' is a chronic [[inflammatory bowel disease]] characterized by recurrent episodes of intestinal inflammation, primarily manifesting as [[diarrhea]] and [[abdominal pain]]. Unlike [[ulcerative colitis]], inflammation can occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, though it most frequently affects the [[ileum]] and [[large intestine|colon]], involving all layers of the intestinal wall. Symptoms may be non-specific and progress gradually, often delaying diagnosis. About one-third of patients have colonic disease, another third have ileocolic disease, and the remaining third have isolated ileal disease. Systemic symptoms such as chronic [[fatigue]], [[unintentional weight loss|weight loss]], and low-grade [[fever]]s are common. Organs such as the skin and joints can also be affected. Complications can include [[bowel obstruction]]s, [[fistula]]s, nutrition problems, and an increased risk of [[intestinal cancer]]s.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

Crohn's disease is influenced by genetic, environmental, and immunological factors. [[Smoking]] is a major modifiable risk factor, especially in Western countries, where it doubles the likelihood of developing the disease. Dietary shifts from high-fiber to processed foods may reduce microbiota diversity and increase risk, while high-fiber diets can offer some protection. Genetic predisposition plays a significant role, with first-degree relatives facing a five-fold increased risk, particularly due to mutations in genes like [[NOD2]] that affect immune response. The condition results from a dysregulated immune response to gut bacteria and increased intestinal permeability, alongside changes in the [[gut microbiome]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

'''Crohn's disease''' (also known as '''Crohn-Leśniowski Disease''', '''morbus Leśniowski-Crohn''', '''[[granuloma]]tous [[colitis]]''' and '''regional enteritis''') is an inflammatory disease of the intestines that may affect any part of the [[gastrointestinal tract]] from [[anus]] to [[mouth]], causing a wide variety of [[symptom]]s. It primarily causes [[abdominal pain]], [[diarrhea]]<!-- PLEASE SEE WP:ENGVAR - DO NOT CHANGE THE SPELLING AS IT INTERFERES WITH LINKING AND IS INAPPROPRIATE --> (which may be bloody), [[vomiting]], or [[weight loss]],<ref name=Baumgart> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| author = Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ |

|||

| year = 2007 |

|||

| date= 12 May 2007 |

|||

| title = Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. |

|||

| journal = The Lancet |

|||

| volume = 369 |

|||

| issue = 9573 |

|||

| pages = 1641–57 |

|||

| month = May |

|||

| pmid = 17499606 |

|||

| doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-04 |

|||

}}</ref><ref>[http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/crohns-disease/DS00104/DSECTION=symptoms Mayo Clinic: Crohn's Disease]</ref><ref>[http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov/ddiseases/pubs/crohns/ National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse]</ref> but may also cause complications outside of the gastrointestinal tract such as [[skin rashes]], [[arthritis]] and [[uveitis|inflammation of the eye]].<ref name=Baumgart/> |

|||

Diagnosing Crohn's disease can be complex due to symptom overlap with other gastrointestinal disorders. It typically involves a combination of clinical history, physical examination, and various diagnostic tests. Key methods include [[colonoscopy|ileocolonoscopy]], which identifies the disease in about 90% of cases, and imaging techniques like [[Computed tomography enterography|CT]] and [[Magnetic resonance enterography|MRI enterography]], which help assess the extent of the disease and its complications. [[Histopathology|Histological examination]] of biopsy samples is the most reliable method for confirming diagnosis.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

Crohn's disease is an [[autoimmune disease]], in which the body's [[immune system]] attacks the gastrointestinal tract, causing [[inflammation]]; it is classified as a type of [[inflammatory bowel disease]]. There has been evidence of a [[genetics|genetic]] link to Crohn's disease, putting individuals with siblings afflicted with the disease at higher risk.<ref name="genetic_link"> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Barrett |

|||

| first = Jeffrey C |

|||

| coauthors = Sarah Hansoul, Dan L Nicolae, Judy H Cho, Richard H Duerr, John D Rioux, Steven R Brant, Mark S Silverberg, Kent D Taylor, M Michael Barmada, Alain Bitton, Themistocles Dassopoulos, Lisa Wu Datta, Todd Green, Anne M Griffiths, Emily O Kistner, Michael T Murtha, Miguel D Regueiro, Jerome I Rotter, L Philip Schumm, A Hillary Steinhart, Stephan R Targan, Ramnik J Xavier, the NIDDK IBD Genetics Consortium, Cécile Libioulle, Cynthia Sandor, Mark Lathrop, Jacques Belaiche, Olivier Dewit, Ivo Gut, Simon Heath, Debby Laukens, Myriam Mni, Paul Rutgeerts, André Van Gossum, Diana Zelenika, Denis Franchimont, Jean-Pierre Hugot, Martine de Vos, Severine Vermeire, Edouard Louis, the Belgian-French IBD Consortium, the Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, Lon R Cardon, Carl A Anderson, Hazel Drummond, Elaine Nimmo, Tariq Ahmad, Natalie J Prescott, Clive M Onnie, Sheila A Fisher, Jonathan Marchini, Jilur Ghori, Suzannah Bumpstead, Rhian Gwilliam, Mark Tremelling, Panos Deloukas, John Mansfield, Derek Jewell, Jack Satsangi, Christopher G Mathew, Miles Parkes, Michel Georges, Mark J Daly |

|||

| year = 2008 |

|||

| month = August |

|||

| title = Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn's disease |

|||

| journal = Nature Genetics |

|||

| volume = 40 |

|||

| issue = 8 |

|||

| pages = 955–962 |

|||

| doi = 10.1038/ng.175 |

|||

| pmid = 18587394 |

|||

| last1 = Barrett |

|||

| first1 = JC |

|||

| last2 = Hansoul |

|||

| first2 = S |

|||

| last3 = Nicolae |

|||

| first3 = DL |

|||

| last4 = Cho |

|||

| first4 = JH |

|||

| last5 = Duerr |

|||

| first5 = RH |

|||

| last6 = Rioux |

|||

| first6 = JD |

|||

| last7 = Brant |

|||

| first7 = SR |

|||

| last8 = Silverberg |

|||

| first8 = MS |

|||

| last9 = Taylor |

|||

| first9 = KD |

|||

| pmc = 2574810 |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-04 |

|||

}}</ref> It is understood to have a large environmental component as evidenced by the higher number of cases in western industrialized nations. Males and females are equally affected. Smokers are three times more likely to develop Crohn's disease.<ref name=Cosnes2004> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| author = Cosnes J |

|||

| title = Tobacco and IBD: relevance in the understanding of disease mechanisms and clinical practice |

|||

| journal = Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol |

|||

| volume = 18 |

|||

| issue = 3 |

|||

| pages = 481–96 |

|||

| year = 2004 |

|||

| month = June |

|||

| pmid = 15157822 |

|||

| doi = 10.1016/j.bpg.2003.12.003 |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-04 |

|||

}}</ref> Crohn's disease affects between 400,000 and 600,000 people in North America.<ref name=Loftus>{{cite journal | last = Loftus | first = E.V. | coauthors = P. Schoenfeld, W. J. Sandborn | year = 2002 | month = January | title = The epidemiology and natural history of Crohn's disease in population-based patient cohorts from North America: a systematic review | journal = Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics | volume = 16 | issue = 1 | pages = 51–60 | doi =10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01140.x | pmid = 11856078 | accessdate = 2009-11-04}}</ref> [[Prevalence]] estimates for Northern Europe have ranged from 27–48 per 100,000.<ref name=Bernstein> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Bernstein |

|||

| first = Charles N. |

|||

| title = The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in Canada: a population-based study |

|||

| journal =The American Journal of Gastroenterology |

|||

| year = 2006 |

|||

| month = July |

|||

| volume = 101 |

|||

| issue = 7 |

|||

| pages = 1559–68 |

|||

| last2 = Wajda |

|||

| first2 = A |

|||

| last3 = Svenson |

|||

| first3 = LW |

|||

| last4 = Mackenzie |

|||

| first4 = A |

|||

| last5 = Koehoorn |

|||

| first5 = M |

|||

| last6 = Jackson |

|||

| first6 = M |

|||

| last7 = Fedorak |

|||

| first7 = R |

|||

| last8 = Israel |

|||

| first8 = D |

|||

| last9 = Blanchard |

|||

| first9 = JF |

|||

| pmid = 16863561 |

|||

| doi =10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00603.x |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-04 |

|||

| author2 = Wajda |

|||

| author3 = Svenson |

|||

| author4 = MacKenzie |

|||

| author5 = Koehoorn |

|||

| author6 = Jackson |

|||

| author7 = Fedorak |

|||

| author8 = Israel |

|||

| author9 = Blanchard |

|||

}}</ref> Crohn's disease tends to present initially in the teens and twenties, with another peak incidence in the fifties to seventies, although the disease can occur at any age.<ref name=Baumgart/><ref name = emed/> |

|||

Management of Crohn's disease is individualized, focusing on disease severity and location to achieve mucosal healing and improve long-term outcomes. Treatment may include [[corticosteroids]] for quick symptom relief, [[immunosuppressants]] for maintaining remission, and [[biologics]] like [[TNF inhibitors|anti-TNF therapies]], which are effective for both induction and maintenance. [[Bowel resection|Surgery]] may be necessary for complications such as blockages. Despite ongoing treatment, Crohn's disease is a chronic condition with no cure, often leading to a higher risk of related health issues and reduced life expectancy.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

There is no known [[Medication|pharmaceutical]] or [[surgery|surgical]] cure for Crohn's disease.<ref> |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

|first= Tri H |

|||

|last= Le |

|||

|publisher=eMedicine |

|||

|title=Ulcerative colitis |

|||

|url=emedicine.medscape.com/article/183084-overview |

|||

| date=Aug 7, 2008 |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-04 |

|||

}}</ref> [[Treatment of Crohn's disease|Treatment options]] are restricted to controlling [[symptom]]s, maintaining [[remission (medicine)|remission]] and preventing [[relapse]]. |

|||

The disease is most prevalent in [[North America]] and [[Western Europe]], particularly among [[Ashkenazi Jews]], with prevalence rates of 322 per 100,000 in [[Germany]], 319 in [[Canada]],<ref name="pmid32242028"/> and 300 in the [[United States]].<ref name="pmid37223580"/> There is also a rising prevalence in newly industrialized countries, such as 18.6 per 100,000 in [[Hong Kong]] and 3.9 in [[Taiwan]]. The typical age of onset is between 20 and 30 years, with an increasing number of cases among children.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

The disease was named for American [[gastroenterology|gastroenterologist]] [[Burrill Bernard Crohn]], who in 1932, along with two colleagues, described a series of patients with inflammation of the [[terminal ileum]], the area most commonly affected by the illness.<ref name=CrohnBB>{{cite journal |author=Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD |title=Regional ileitis: a pathologic and clinical entity. 1932 |journal=Mt. Sinai J. Med. |volume=67 |issue=3 |pages=263–8 |year=2000 |pmid=10828911 |doi=}}</ref> For this reason, the disease has also been called '''regional ileitis'''<ref name="CrohnBB"/> or regional enteritis. The condition, however, has been independently identified by others in the literature prior, most notably in 1904 by Polish surgeon [[Antoni Leśniowski]] for whom the condition is additionally named (Leśniowski-Crohn's disease) in the Polish literature. |

|||

== Signs and symptoms == |

|||

==Classification== |

|||

[[Image: |

[[Image:Patterns of CD.jpg|right|thumb|alt=Diagram of the three most common sites of intestinal involvement in Crohn's disease.|The three most common sites of intestinal involvement in Crohn's disease are ileal, ileocolic and colonic.<ref name="pmid32242028"/>]] |

||

Crohn's disease is one type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). It invariably affects the gastrointestinal tract, and most gastroenterologists categorize the presenting disease by the affected areas. ''[[Ileocolic]] Crohn's disease'', which affects both the [[ileum]] (the last part of the [[small intestine]] that connects to the [[large intestine]]) and the large intestine, accounts for fifty percent of cases. ''Crohn's ileitis'', affecting the ileum only, accounts for thirty percent of cases, and ''Crohn's colitis'', affecting the large intestine, accounts for the remaining twenty percent of cases and may be particularly difficult to distinguish from [[ulcerative colitis]]. The disease can attack any part of the digestive tract, from mouth to anus. However, individuals affected by the disease rarely fall outside these three classifications, being affected in other parts of the gastrointestinal tract such as the [[stomach]] and [[esophagus]].<ref name=Baumgart/> |

|||

Crohn's disease is characterized by recurring flares of intestinal inflammation, with diarrhea and abdominal pain as the primary symptoms. Symptoms may be non-specific and progress gradually, and many people have symptoms for years before diagnosis. Unlike [[ulcerative colitis]], inflammation can occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, most often in the [[ileum]] and [[Large intestine|colon]], and can involve all layers of the intestine. Disease location tends to be stable, with a third of patients having colonic disease, a third having ileocolic disease, and a third having ileal disease. The disease may also involve perianal, upper gastrointestinal, and extraintestinal organs.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

Crohn's disease may also be categorized by the behavior of disease as it progresses. This was formalized in the Vienna classification of Crohn's disease.<ref name=Vienna>{{cite journal | author = Gasche C, Scholmerich J, Brynskov J, D'Haens G, Hanauer S, Irvine E, Jewell D, Rachmilewitz D, Sachar D, Sandborn W, Sutherland L | title = A simple classification of Crohn's disease: report of the Working Party for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna 1998 | journal = Inflamm Bowel Dis | volume = 6 | issue = 1 | pages = 8–15 | year = 2000 | pmid = 10701144}}</ref> There are three categories of disease presentation in Crohn's disease: stricturing, penetrating, and [[inflammatory]]. ''Stricturing disease'' causes narrowing of the bowel which may lead to [[bowel obstruction]] or changes in the caliber of the [[feces]]. ''Penetrating disease'' creates abnormal passageways ([[fistula]]e) between the bowel and other structures such as the skin. ''[[Inflammatory disease]]'' (or non-stricturing, non-penetrating disease) causes inflammation without causing strictures or fistulae.<ref name=Vienna/><ref name=phenotypes>{{cite journal | author = Dubinsky MC, Fleshner PP. | title = Treatment of Crohn's Disease of Inflammatory, Stenotic, and Fistulizing Phenotypes | journal = Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol | volume = 6 | issue = 3 | pages = 183–200 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12744819 | doi = 10.1007/s11938-003-0001-1}}</ref> |

|||

=== Gastrointestinal === |

|||

==Symptoms== |

|||

* [[Diarrhea]] affects 82% of people at the onset of Crohn's disease, with severity ranging from mild to severe enough to require substitution of water and electrolytes. With Crohn's disease, diarrhea is frequent and urgent rather than voluminous.<ref name="pmid22917170">{{cite journal | vauthors = Wenzl HH | title = Diarrhea in chronic inflammatory bowel diseases | journal = Gastroenterology Clinics of North America | volume = 41 | issue = 3 | pages = 651–675 | pmid = 22917170 | date = September 2012 | doi = 10.1016/j.gtc.2012.06.006 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:CD serpiginous ulcer.jpg|right|thumb|Endoscopy image of [[colon (anatomy)|colon]] showing [[serpiginous]] ulcer, a classic finding in Crohn's disease]] |

|||

* [[Abdominal pain]] affects at least 70% of people during the course of Crohn's disease. It can result directly from intestinal inflammation, or from complications such as strictures and fistulas.<ref name="pmid37867930">{{cite journal | vauthors = Coates MD, Clarke K, Williams E, Jeganathan N, Yadav S, Giampetro D, Gordin V, Smith S, Vrana K, Bobb A, Gazzio TT, Tressler H, Dalessio S | title = Abdominal Pain in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: An Evidence-Based, Multidisciplinary Review | journal = Crohns Colitis 360 | volume = 5 | issue = 4 | pmid = 37867930 | date = September 2023 | pages = otad055 | doi = 10.1093/crocol/otad055 | doi-access = free | pmc = 10588456 }}</ref> Pain most commonly occurs in the lower right abdomen.<ref name="ustekinumab">{{cite web |title=What I need to know about Crohn's Disease |url=http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/crohns-disease/Pages/ez.aspx#symptoms |website=www.niddk.nih.gov|access-date=December 11, 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151121213407/http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/digestive-diseases/crohns-disease/Pages/ez.aspx#symptoms|archive-date=November 21, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

Many people with Crohn's disease have symptoms for years prior to the diagnosis.<ref name=Pimentel>{{cite journal | last = Pimentel | first = Mark | coauthors = Michael Chang, Evelyn J. Chow, Siamak Tabibzadeh, Viorelia Kirit-Kiriak, Stephan R. Targan, Henry C. Lin | year = 2000 | title = Identification of a prodromal period in Crohn's disease but not ulcerative colitis | journal = American Journal of Gastroenterology | volume = 95 | issue = 12 | pages = 3458–62 | doi =10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03361.x | pmid = 11151877 }}</ref> The usual onset is between 15 and 30 years of age but can occur at any age.<ref>[http://www.emedicinehealth.com/crohn_disease/article_em.htm Crohn's Disease Overview]</ref> Because of the 'patchy' nature of the gastrointestinal disease and the depth of tissue involvement, initial symptoms can be more vague than with ulcerative colitis. People with Crohn's disease will go through periods of flare-ups and remission. |

|||

* [[Rectal bleeding]] is less common than in ulcerative colitis, and is more likely to occur with inflammation in the colon or rectum. Bleeding in the colon or rectum is bright red, whereas bleeding in higher segments causes dark or black stools.<ref name="CrohnsColitisCA">{{cite web | url = https://crohnsandcolitis.ca/About-Crohn-s-Colitis/IBD-Journey/Symptom-Management/Bleeding-and-Blood-in-the-Stool | title = Bleeding and Blood in the Stool | website = crohn's and colitis | access-date = 16 October 2024}}</ref> |

|||

* [[Bloating]], [[flatus]], and other symptoms of [[irritable bowel syndrome]] occur in 41% of people in remission.<ref name="pmid31496621">{{cite journal | vauthors = Barros LL, Farias AQ, Rezaie A | title = Gastrointestinal motility and absorptive disorders in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: Prevalence, diagnosis and treatment | journal = World Journal of Gastroenterology | volume = 25 | issue = 31 | pages = 4414–4426 | pmid = 31496621 | pmc = 6710178 | date = August 2019 | doi = 10.3748/wjg.v25.i31.4414 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

* Perianal involvement occurs in 18–43% of cases, more frequently if the colon and rectum are inflamed, and can cause [[anal fistula|fistulas]], [[skin tags]], [[hemorrhoids]], [[anal fissure|fissures]], [[ulcers]], and [[anal stricture|strictures]].<ref name="pmid31507348">{{cite journal | vauthors = Pogacnik JS, Salgado G | title = Perianal Crohn's Disease | journal = Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery | volume = 32 | issue = 5 | pages = 377–385 | pmid = 31507348 | date = September 2019 | doi = 10.1055/s-0039-1687834 | doi-access = free | pmc = 6731113 }}</ref> |

|||

* Upper gastrointestinal involvement is rare, occurring in 0.5-16% of cases, and may cause symptoms such as [[odynophagia|pain while swallowing]], [[dysphagia|difficulty swallowing]], [[vomiting]], and [[nausea]].<ref name="pmid28708248">{{Cite journal |last1=Laube |first1=Robyn |last2=Liu |first2=Ken |last3=Schifter |first3=Mark |last4=Yang |first4=Jessica L |last5=Suen |first5=Michael K |last6=Leong |first6=Rupert W |date=February 2018 |title=Oral and upper gastrointestinal Crohn's disease |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jgh.13866 |journal=Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology |language=en |volume=33 |issue=2 |pages=355–364 |doi=10.1111/jgh.13866 |pmid=28708248 |issn=0815-9319}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Systemic === |

||

Crohn's disease often presents with systemic symptoms, including: |

|||

* [[Fatigue#Chronic|Chronic fatigue]], which lasts for at least 6 months and cannot be cured by rest, occurs in 80% of people with Crohn's disease, including 30% of people who are in remission.<ref name="pmid37629549">{{cite journal | vauthors = Włodarczyk M, Makaro A, Prusisz M, Włodarczyk J, Nowocień M, Maryńczak K, Fichna J, Dziki Ł | title = The Role of Chronic Fatigue in Patients with Crohn's Disease | journal = Life (Basel) | volume = 13 | issue = 8 | pages = 1692 | pmid = 37629549 | date = August 2023 | doi = 10.3390/life13081692 | doi-access = free | pmc = 10455565 | bibcode = 2023Life...13.1692W }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Fevers]], typically low-grade, are often reported as initial symptoms of Crohn's disease. High-grade fevers are often a result of abscesses.<ref name="StatPearls">{{cite web |title=Crohn Disease |date=2024 |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436021/| access-date=18 October 2024 | publisher=StatPearls Publishing |pmid=28613792 | vauthors = Ranasinghe IR, Tian C, Hsu R }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Unintentional weight loss|Weight loss]] often occurs due to diarrhea and reduced appetite.<ref name="StatPearls"/> |

|||

=== Extraintestinal === |

|||

Abdominal pain may be the initial symptom of Crohn's disease. It is often accompanied by diarrhea, especially in those who have had surgery. The diarrhea may or may not be bloody. People who have had surgery or multiple surgeries often end up with [[short bowel syndrome]] of the gastrointestinal tract. The nature of the diarrhea in Crohn's disease depends on the part of the small intestine or colon that is involved. Ileitis typically results in large-volume watery feces. Colitis may result in a smaller volume of feces of higher frequency. Fecal consistency may range from solid to watery. In severe cases, an individual may have more than 20 [[bowel movements]] per day and may need to awaken at night to defecate.<ref name=Baumgart/><ref name=emed/><ref name=Podolsky/><ref>{{cite journal | last = Mueller | first = M. H. | coauthors = M. E. Kreis, M. L. Gross, H. D. Becker, T. T. Zittel & E. C. Jehle | year = 2002 | title = Anorectal functional disorders in the absence of anorectal inflammation in patients with Crohn's disease | journal = British Journal of Surgery | volume = 89 | issue = 8 | pages = 1027–31 | doi =10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02173.x | pmid = 12153630 }}</ref> Visible bleeding in the feces is less common in Crohn's disease than in ulcerative colitis, but may be seen in the setting of Crohn's colitis.<ref name=Baumgart/> Bloody bowel movements are typically intermittent, and may be bright or dark red in colour. In the setting of severe Crohn's colitis, bleeding may be copious.<ref name=emed/> [[Flatulence]] and bloating may also add to the intestinal discomfort.<ref name=emed/> |

|||

Extraintestinal manifestations occur in 21–47% of cases, and include symptoms such as:<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* Mouth ulcers, such as [[canker sores]].<ref name="pmid33477990">{{cite journal |vauthors=Antonelli E, Bassotti G, Tramontana M, Hansel K, Stingeni L, Ardizzone S, Genovese G, Marzano AV, Maconi G |title=Dermatological Manifestations in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases |journal=J Clin Med |volume=10 |issue=2 |date=January 2021 |page=364 |pmid=33477990 |pmc=7835974 |doi=10.3390/jcm10020364 | doi-access = free}}</ref> |

|||

* Eye inflammation, such as [[uveitis]], [[scleritis]], and [[episcleritis]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* Skin inflammation, such as [[erythema nodosum]] and [[pyoderma gangrenosum]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* Blood conditions such as [[portal hypertension]], [[thromboembolism]], [[thrombosis]], [[pulmonary embolism]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* Joint inflammation such as [[arthritis]], [[ankylosing spondylitis]], [[sacroiliitis]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* Respiratory conditions such as [[obstructive sleep apnea]] and [[chest infections]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* Liver, bile duct, and gallbladder conditions such as [[primary sclerosing cholangitis]] and [[cirrhosis]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* Mental disorders such as [[Major depressive disorder|depression]] and [[Anxiety disorder|anxiety]].<ref name="pmid35732730">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bisgaard TH, Allin KH, Keefer L, Ananthakrishnan AN, Jess T | title = Depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease: epidemiology, mechanisms and treatment | journal = Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology | volume = 19 | issue = 11 | pages = 717–726 | pmid = 35732730 | date = March 2023 | doi = 10.1038/s41575-022-00634-6 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Metabolic bone disease]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

=== Complications === |

|||

Symptoms caused by [[bowel obstruction|intestinal stenosis]] are also common in Crohn's disease. Abdominal pain is often most severe in areas of the bowel with stenoses. In the setting of severe stenosis, vomiting and nausea may indicate the beginnings of small bowel obstruction.<ref name=emed> |

|||

[[Image:Colorectal cancer endo 2.jpg|right|thumb| alt=Image of colon cancer identified during a colonoscopy in Crohn's disease.|Image of colon cancer identified in the sigmoid colon of a person with Crohn's disease during a colonoscopy.]] |

|||

{{cite web |

|||

| first= George Y |

|||

| last= Wu |

|||

| coauthors=Marcy L Coash, Senthil Nachimuthu |

|||

| publisher=eMedicine |

|||

| title=Crohn Disease |

|||

| url=emedicine.medscape.com/article/172940-overview |

|||

| date=Jan 20, 2009 |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-04 |

|||

}}</ref> Crohn's disease may also be associated with [[primary sclerosing cholangitis]], a type of inflammation of the bile ducts.<ref>{{cite book|last=Kumar|first=Vinay|coauthors=Abul K. Abbas, Nelson Fausto|title=Robbins and Cotran: Pathologic Basis of Disease|publisher=Elsevier Saunders |location=Philadelphia, Pennsylvania|date=July 30, 2004|edition=7th|pages=847|chapter=Ch 17: The Gastrointestinal Tract|isbn=0-7216-0187-1}}</ref> |

|||

Bowel damage due to inflammation occurs in half of cases within 10 years of diagnosis, and can lead to stricturing or penetrating disease forms. This can cause complications such as: |

|||

Perianal discomfort may also be prominent in Crohn's disease. Itchiness or pain around the [[anus]] may be suggestive of inflammation, [[fistula|fistulization]] or [[abscess]] around the anal area<ref name=Baumgart/> or [[anal fissure]]. Perianal skin [[acrochordon|tags]] are also common in Crohn's disease.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Taylor B, Williams G, Hughes L, Rhodes J | title = The histology of anal skin tags in Crohn's disease: an aid to confirmation of the diagnosis | journal = Int J Colorectal Dis | volume = 4 | issue = 3 | pages = 197–9 | year = 1989 | pmid = 2769004 | doi = 10.1007/BF01649703}}</ref> [[Fecal incontinence]] may accompany peri-anal Crohn's disease. At the opposite end of the gastrointestinal tract, the mouth may be affected by non-healing sores ([[aphthous ulcer]]s). Rarely, the [[esophagus]], and [[stomach]] may be involved in Crohn's disease. These can cause symptoms including difficulty swallowing ([[dysphagia]]), upper abdominal pain, and vomiting.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Fix | first = Oren K. | coauthors = Jorge A. Soto, Charles W. Andrews and Francis A. Farraye | year = 2004 | title = Gastroduodenal Crohn's disease | journal = Gastrointestinel Endoscopy | volume = 60 | issue = 6 | pages = 985 | doi = 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02200-X | pmid = 15605018 }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Bowel obstruction]]s may occur due to strictures, particularly in the small intestine, and may require surgical removal of the affected segment ([[bowel resection]]) or surgical dilation ([[stricturoplasty]]).<ref name="pmid28601423"/> |

|||

* [[Fistulas]], openings in the gut, result from penetrating disease and can cause diarrhea, [[urinary tract infections]], and stool leakage to the vagina or skin. It is treated by bowel resection or [[fistulotomy]]<ref name="pmid28601423"/> |

|||

* [[Abscesses]], infected pockets, can also result from penetrating disease, causing abdominal pain, fever, and chills. It may be treated by [[Incision and drainage|surgical drainage]].<ref name="pmid28601423">{{cite journal | vauthors = Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS | title = Crohn Disease: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management | journal = Mayo Clinic Proceedings | volume = 92 | issue = 7 | pages = 1088–1103 | pmid = 28601423 | date = June 2017 | doi = 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.04.010 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

Malnutrition occurs in 38.9% of people in remission and 82.8% of people with active disease due to malabsorption in the small intestine, reduced appetite, and drug interactions.<ref name="pmid37111210"/> This can cause complications such as: |

|||

===Systemic symptoms=== |

|||

* [[Anemia]] occurs in 6–74% of cases as a result of [[iron deficiency]] and blood loss. It is treated by [[oral iron]] or [[intravenous iron]] depending on disease activity.<ref name="pmid37111210"/> |

|||

Crohn's disease, like many other chronic, inflammatory diseases, can cause a variety of [[B symptoms|systemic symptoms]].<ref name=Baumgart/> Among children, [[growth failure]] is common. In addition to these complications, Acute Myelogenous leukemia as well as Lymphoma are two common system cancer that can occur at any age. AML being a cancer of the blood (Myeloid) as well as cancer of the lymph nodes (Lymphoma). Many children are first diagnosed with Crohn's disease based on [[failure to thrive|inability to maintain growth]].<ref name=Beattie/> As Crohn's disease may manifest at the time of the growth spurt in [[puberty]], up to 30% of children with Crohn's disease may have retardation of growth.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Büller | first = H.A. | year = 1997 | title = Problems in diagnosis of IBD in children | journal = The Netherlands Journal of Medicine | volume = 50 | issue = 2 | pages = S8–S11 | doi =10.1016/S0300-2977(96)00064-2 | pmid = 9050326 }}</ref> Fever may also be present, though fevers greater than 38.5 [[Celsius|˚C]] (101.3 [[Fahrenheit|˚F]]) are uncommon unless there is a complication such as an [[abscess]].<ref name=Baumgart/> Among older individuals, Crohn's disease may manifest as weight loss. This is usually related to decreased food intake, since individuals with intestinal symptoms from Crohn's disease often feel better when they do not eat and might lose their appetite.<ref name=Beattie>{{cite journal | last = Beattie | first = R.M. | coauthors = N. M. Croft, J. M. Fell, N. A. Afzal and R. B. Heuschkel | year = 2006 | title = Inflammatory bowel disease | journal = Archives of Disease in Childhood | volume = 91 | issue = 5 | pages = 426–32 | doi =10.1136/adc.2005.080481 | pmid = 16632672 | pmc = 2082730 }}</ref> People with extensive [[small intestine]] disease may also have [[malabsorption]] of [[carbohydrate]]s or [[lipid]]s, which can further exacerbate weight loss.<ref>{{cite journal | last = O'Keefe | first = S. J. | year = 1996 | title = Nutrition and gastrointestinal disease | journal = Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology Supplement | issue = 220 | pages = 52–9 | pmid = 8898436 | doi = 10.3109/00365529609094750 | volume = 31 }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Vitamin D deficiency]] is prevalent and can cause [[osteoporosis]], and is treated by oral supplementation.<ref name="pmid37111210"/> |

|||

* [[Folate deficiency|Folic acid]], [[Vitamin B12 deficiency|vitamin B12]], [[Zinc deficiency|zinc]], [[Magnesium deficiency|magnesium]], and [[Selenium deficiency|selenium]] deficiencies may also occur, and are treated through oral supplementation.<ref name="pmid37111210">{{cite journal | vauthors = Jabłońska B, Mrowiec S | title = Nutritional Status and Its Detection in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases | journal = Nutrients | volume = 15 | issue = 8 | pages = 1991 | pmid = 37111210 | pmc = 10143611 | date = April 2023 | doi = 10.3390/nu15081991 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Stunted growth|Impaired growth]] and nutritional deficiency occur in 65–85% of children with Crohn's disease.<ref name="pmid25309059">{{cite journal | vauthors = Gasparetto M, Guariso G | title = Crohn's disease and growth deficiency in children and adolescents | journal = World Journal of Gastroenterology | volume = 20 | issue = 37 | pages = 13219–13233 | pmid = 25309059 | pmc = 4188880 | date = October 2014 | doi = 10.3748/wjg.v20.i37.13219 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

Intestinal cancers may develop as a result of prolonged or severe inflammation.<ref name="pmid37627182"/> This includes: |

|||

===Extraintestinal symptoms=== |

|||

* [[Colorectal cancer]] has a prevalence of 7% at 30 years after diagnosis and accounts for 15% of deaths in people with Crohn's. Risk is higher if the disease occurs in most of the colon. Endoscopic surveillance is performed to detect and remove polyps, while surgery is required for dysplasia beyond the mucosal surface.<ref name="pmid37627182">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sato Y, Tsujinaka S, Miura T, Kitamura Y, Suzuki H, Shibata C | title = Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Etiology, Surveillance, and Management | journal = Cancers (Basel) | volume = 15 | issue = 16 | pages = 4154 | pmid = 37627182 | pmc = 10452690 | date = August 2023 | doi = 10.3390/cancers15164154 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Crohnie sores 4.JPG|thumb|[[Erythema nodosum]] on the back of a person with Crohn's disease.]] |

|||

* [[Small bowel cancer]] has a prevalence of 1.6%, at least 12-times greater in people with Crohn's disease. Unlike colorectal cancer, endoscopic surveillance is ineffective and not recommended for small bowel cancer.<ref name="pmid38188070">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bhatt H, Mathis KL | title = Small Bowel Carcinoma in the Setting of Inflammatory Bowel Disease | journal = Clinics in Colon and Rectal Surgery | volume = 37 | issue = 1 | pages = 46–52 | pmid = 38188070 | pmc = 10769580 | date = March 2023 | doi = 10.1055/s-0043-1762929 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Crohnie Pyoderma gangrenosum.jpg|thumb|[[Pyoderma gangrenosum]] on the leg of a person with Crohn's disease.]] |

|||

== Causes == |

|||

In addition to systemic and gastrointestinal involvement, Crohn's disease can affect many other organ systems.<ref name=Danese>{{cite journal | last = Danese | first = Silvio | coauthors = Stefano Semeraro, Alfredo Papa, Italia Roberto, Franco Scaldaferri, Giuseppe Fedeli, Giovanni Gasbarrini, Antonio Gasbarrini | year = 2005 | title = Extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease | journal = World Journal of Gastroenterology | volume = 11 | issue = 46 | pages = 7227–36 | pmid = 16437620 | url = http://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/11/7227.asp | accessdate = 2009-11-07 }}</ref> Inflammation of the interior portion of the eye, known as [[uveitis]], can cause eye pain, especially when exposed to light ([[photophobia]]). Inflammation may also involve the white part of the eye ([[sclera]]), a condition called [[Scleritis|episcleritis]]. Both episcleritis and uveitis can lead to loss of vision if untreated. |

|||

=== Risk factors === |

|||

Smoking is a major modifiable risk factor for Crohn's disease, particularly in Western countries, where it doubles the risk. This risk is higher in females and varies with age. Smoking is also linked to earlier disease onset, increased need for immunosuppression, more surgeries, and higher recurrence rates. Ethnic differences have been noted, with studies in Japan linking passive smoking to the disease.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> Proposed mechanisms for smoking's effects include impaired [[autophagy]], direct toxicity to immune cells, and changes in the [[Gut microbiota|microbiome]].<ref name="pmid30611442"/> |

|||

Diet may influence the development of Crohn's disease by affecting the gut microbiome. The shift from high-fiber, low-fat foods to processed foods reduces microbiota diversity, increasing the risk of Crohn's disease.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> Conversely, high-fiber diets may reduce risk by up to 40%, likely due to the production of anti-inflammatory [[short-chain fatty acids]] from fiber metabolism by gut bacteria.<ref name="pmid30611442"/> The [[Mediterranean diet]] is also linked to a lower risk of later-onset Crohn's disease. Since diet's effect on the microbiome is temporary, its role in gut dysbiosis is controversial.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

Crohn's disease is associated with a type of [[Rheumatology|rheumatologic disease]] known as [[spondyloarthropathy|seronegative spondyloarthropathy]]. This group of diseases is characterized by inflammation of one or more [[joint]]s ([[arthritis]]) or muscle insertions ([[enthesitis]]). The arthritis can affect larger joints such as the knee or shoulder or may exclusively involve the small joints of the hand and feet. The arthritis may also involve the spine, leading to [[ankylosing spondylitis]] if the entire spine is involved or simply [[sacroiliitis]] if only the lower spine is involved. The symptoms of arthritis include painful, warm, swollen, stiff [[Arthralgia|joints]] and loss of joint mobility or function. {{Citation needed|date=March 2009}} |

|||

Childhood antibiotic exposure is linked to a higher risk of Crohn's disease due to changes in the intestinal microbiome, which shapes the immune system in early life. Other medications, like [[oral contraceptives]], [[aspirin]], and [[NSAIDs]], may also increase risk by up to two-fold. Conversely, [[breastfeeding]] and [[statin]] use may reduce risk, though breastfeeding's effects are inconsistent. Early life factors such as mode of delivery, pet exposure, and infections—related to the [[hygiene hypothesis]]—also significantly influence risk, likely due to influences on the microbiome.<ref name="pmid30611442"/> |

|||

Crohn's disease may also involve the skin, blood, and [[endocrine system]]. One type of skin manifestation, [[erythema nodosum]], presents as red nodules usually appearing on the shins. Erythema nodosum is due to inflammation of the underlying subcutaneous tissue and is characterized by septal [[panniculitis]]. Another skin lesion, [[pyoderma gangrenosum]], is typically a painful ulcerating nodule. Crohn's disease also increases the risk of blood clots; painful swelling of the lower legs can be a sign of [[deep venous thrombosis]], while difficulty breathing may be a result of [[pulmonary embolism]]. [[Autoimmune hemolytic anemia]], a condition in which the immune system attacks the [[red blood cells]], is also more common in Crohn's disease and may cause fatigue, pallor, and other symptoms common in [[anemia]]. [[Clubbing]], a deformity of the ends of the fingers, may also be a result of Crohn's disease. Finally, Crohn's disease may cause [[osteoporosis]], or thinning of the bones. Individuals with osteoporosis are at increased risk of [[bone fracture]]s.<ref name=Bernstein>{{cite journal | last = Bernstein | first = Michael | coauthors = Sue Irwin and Gordon R. Greenberg | year = 2005 | title = Maintenance infliximab treatment is associated with improved bone mineral density in Crohn's disease | journal = The American Journal of Gastroenterology | volume = 100 | issue = 9 | pages = 2031–5. | doi =10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50219.x | pmid = 16128948 }}</ref> |

|||

=== Genetics === |

|||

Crohn's disease can also cause neurological complications (reportedly in up to 15% of patients).<ref name="pro">[http://professionals.epilepsy.com/page/inflammatory_crohn.html Crohn's disease]. professionals.epilepsy.com. Retrieved on July 13, 2007.</ref> The most common of these are [[seizures]], [[stroke]], [[myopathy]], [[peripheral neuropathy]], [[headache]] and [[Depression (mood)|depression]].<ref name="pro"/> |

|||

Genetics significantly influences the risk of Crohn's disease. First-degree relatives of affected individuals have a five-fold increased risk, while identical twins have a 38–50% risk if one twin is affected. [[Genome-wide association studies]] have identified around 200 loci linked to Crohn's, most found in non-coding regions that regulate gene expression and overlap with other immune-related conditions, such as [[ankylosing spondylitis]] and [[psoriasis]].<ref name="pmid30611442"/> While genetics can predict disease location, it does not determine complications like stricturing. A substantial portion of inherited risk is attributed to a few key polymorphisms.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* [[NOD2]] mutations are the primary genetic risk factor for ileal Crohn's disease, impairing the function of immune cells, particularly [[Paneth cells]]. These mutations are found in 10–27% of individuals with Crohn's disease, predominantly in Caucasian populations. Heterozygotes (one mutated copy) have a three-fold risk, while homozygotes (two copies) have a 20–40 fold risk.<ref name="pmid38582044">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kayali S, Fantasia S, Gaiani F, Cavallaro LG, de'Angelis GL, Laghi L | title = NOD2 and Crohn's Disease Clinical Practice: From Epidemiology to Diagnosis and Therapy, Rewired | journal = Inflammatory Bowel Diseases | pmid = 38582044 | date = April 2024 | doi = 10.1093/ibd/izae075 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

Crohn's patients often also have issues with [[small bowel bacterial overgrowth syndrome]], which has similar symptoms.<ref>{{MedlinePlus|000222|Small bowel bacterial overgrowth}}</ref> |

|||

* [[ATG16L1]] mutations impair autophagy and immune defense, and are more common in Caucasians.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* [[IL23R]] mutations increase inflammatory signaling of the [[interleukin-23]] pathway, and are more common in Caucasians.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* [[TNFSF15]] mutations are the primary genetic risk factor in Asian populations.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

* [[IL10RA]] mutations impair the anti-inflammatory signaling of [[interleukin-10]], causing early-onset Crohn's disease with high [[penetrance]]. |

|||

== |

== Mechanism == |

||

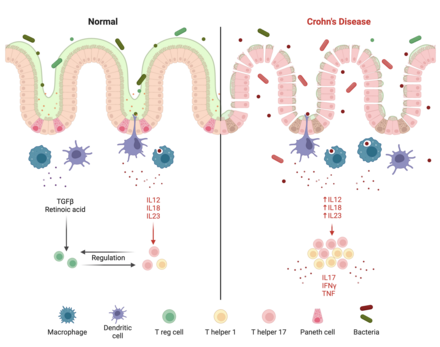

[[File:Crohn's Disease Mechanism.png|thumb|upright=2|alt=diagram of mechanism of Crohn's disease|The intestinal barrier and immune system in health and during Crohn's disease. In health, immune cells secrete TGFβ and retinoic acid to promote the differentiation of Tregs, which regulate the inflammatory behavior of effector T cells.<ref name="pmid27590281">{{cite journal | vauthors = Plitas G, Rudensky AY | title = Regulatory T Cells: Differentiation and Function | journal = Cancer Immunology Research | volume = 4 | issue = 9 | pages = 721–725 | pmid = 27590281 | date = September 2016 | doi = 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-16-0193 | doi-access = free | pmc = 5026325 }}</ref> During Crohn's disease, microbiome alterations, intestinal barrier permeability, and deficient innate immunity enable pathogens to enter the gut tissue. This causes antigen-presenting cells to upregulate IL-12, IL-18, and IL-23, increasing the differentiation of Th1 and Th17 cells. These cells secrete inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17, IFNγ, and TNF to perpetuate inflammation.<ref name="pmid30611442"/>]] |

|||

[[Image:Colorectal cancer endo 2.jpg|right|thumb|[[Colonoscopy|Endoscopic]] image of '''colon cancer''' identified in the sigmoid colon on screening [[colonoscopy]] for Crohn's disease.]] |

|||

Crohn's disease can lead to several mechanical complications within the intestines, including [[obstruction]], fistulae, and abscesses. Obstruction typically occurs from [[strictures]] or [[adhesions]] which narrow the lumen, blocking the passage of the intestinal contents. Fistulae can develop between two loops of bowel, between the bowel and bladder, between the bowel and vagina, and between the bowel and skin. Abscesses are walled off collections of [[infection]], which can occur in the [[abdomen]] or in the [[wiktionary:perianal|perianal]] area in Crohn's disease sufferers. |

|||

Crohn's disease is believed to be caused by a dysregulated immune response to gut bacteria, though the exact mechanism is unknown. This is evidenced by the disease's links to genes involved in bacteria defense and its occurrence in the [[ileum]] and [[Large intestine|colon]], the most bacteria-dense segments of the intestine.<ref name="pmid25234148">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mowat AM, Agace WW | title = Regional specialization within the intestinal immune system | journal = Nature Reviews Immunology | volume = 14 | issue = 10 | pages = 667–85 | pmid = 25234148 | date = October 2014 | doi = 10.1038/nri3738 | doi-access = free }}</ref> In Crohn's disease, a permeable intestinal barrier and a deficient [[innate immune response]] enable bacteria to enter intestinal tissue, causing an excessive inflammatory response from [[T helper 1]] (Th1) and [[T helper 17]] (Th17) cells. An altered [[microbiome]] may also be causatory and serve as the link to environmental factors.<ref name="pmid30611442">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ramos GP, Papadakis KA | title = Mechanisms of Disease: Inflammatory Bowel Diseases | journal = Mayo Clinic Proceedings | volume = 94 | issue = 1 | pages = 155–165 | pmid = 30611442 | pmc = 6386158 | date = January 2019 | doi = 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.09.013 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

Crohn's disease also increases the risk of cancer in the area of inflammation. For example, individuals with Crohn's disease involving the [[small bowel]] are at higher risk for [[small intestinal cancer]]. Similarly, people with Crohn's colitis have a [[relative risk]] of 5.6 for developing [[colon cancer]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami H |title=Increased risk of large-bowel cancer in Crohn's disease with colonic involvement |journal=Lancet |volume=336 |issue=8711 |pages=357–9 |year=1990 |pmid=1975343 | doi = 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91889-I}}</ref> Screening for colon cancer with [[colonoscopy]] is recommended for anyone who has had Crohn's colitis for at least eight years.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Collins P, Mpofu C, Watson A, Rhodes J | title = Strategies for detecting colon cancer and/or dysplasia in patients with inflammatory bowel disease | journal = Cochrane Database Syst Rev | volume = | issue = 2| pages = CD000279 | year = 2006| pmid = 16625534 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD000279.pub3}}</ref> Some studies suggest that there is a role for chimioprotection in the prevention of colorectal cancer in Crohn's involving the colon; two agents have been suggested, [[folate]] and [[mesalamine]] preparations.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Lynne V McFarland | title = Colorectal cancer and dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease | journal = World Journal of Gastroenterology | volume = | issue = | pages = 2665 | year = 2008| pmid = | doi = }}</ref> |

|||

=== Intestinal barrier === |

|||

Individuals with Crohn's disease are at risk of [[malnutrition]] for many reasons, including decreased food intake and [[malabsorption]]. The risk increases following resection of the [[small bowel]]. Such individuals may require oral supplements to increase their caloric intake, or in severe cases, [[total parenteral nutrition]] (TPN). Most people with moderate or severe Crohn's disease are referred to a [[dietitian]] for assistance in nutrition.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Evans J, Steinhart A, Cohen Z, McLeod R | title = Home total parenteral nutrition: an alternative to early surgery for complicated inflammatory bowel disease | journal = J Gastrointest Surg | volume = 7 | issue = 4 | pages = 562–6 | year = 2003 | pmid = 12763417 | doi = 10.1016/S1091-255X(02)00132-4}}</ref> |

|||

The epithelial barrier is a single layer of [[epithelial cells]] covered in antimicrobial mucus that protects the intestine from gut bacteria.<ref name="pmid25234148"/> Epithelial cells are joined by [[tight junction proteins]], which are reduced by Crohn's-linked polymorphisms. In particular, [[claudin-5]] and [[CLDN8|claudin-8]] are reduced, while pore-forming [[claudin-2]] is increased, causing intestinal permeability. Epithelial cells under stress emit inflammatory signals such as the [[unfolded protein response]] to stimulate the immune system, and Crohn's-linked polymorphisms to the [[ATG16L1]] gene lower the threshold at which this response is triggered.<ref name="pmid32242028">{{cite journal | vauthors = Roda G, Chien Ng S, Kotze PG, Argollo M, Panaccione R, Spinelli A, Kaser A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S | title = Crohn's Disease | journal = Nature Reviews Disease Primers | volume = 6 | issue = 1 | pages = 22 | pmid = 32242028 | date = April 2020 | doi = 10.1038/s41572-020-0156-2 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

In a functional state, the intestinal epithelium and IgA dimers work together to manage and keep the luminal microflora distinct from the mucosal immune system.<ref>{{cite journal | url=https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1 | doi=10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31711-1 | title=Crohn's disease | date=2017 | journal=The Lancet | volume=389 | issue=10080 | pages=1741–1755 | pmid=27914655 | vauthors = Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel J, Peyrin-Biroulet L }}</ref> [[Paneth cells]] exist in the epithelial barrier of the small intestine and secrete [[Alpha defensin|α-defensins]] to prevent bacteria from entering gut tissue.<ref name="pmid25234148"/> Genetic polymorphisms associated with Crohn's disease can impair this ability and lead to Crohn's disease in the ileum. [[NOD2]] is a receptor produced by Paneth cells to sense bacteria, and mutations to NOD2 can inhibit the antimicrobial activity of Paneth cells. ATG16L1, [[IRGM]], and [[LRRK2]] are proteins involved in selective [[autophagy]], the mechanism by which Paneth cells secrete α-defensins, and mutations to these genes also impair the antimicrobial activity of Paneth cells.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

Crohn's disease can cause significant complications including [[bowel obstruction]], abscesses, free [[Bowel perforation|perforation]] and [[hemorrhage]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.livingwithcrohnsdisease.com/livingwithcrohnsdisease/crohns_disease/complications_of_crohns.html|title=Complications of Crohn's Disease| accessdate = 2009-11-07 }}</ref> |

|||

[[Intraepithelial lymphocytes]] (IELs) are immune cells that exist in the epithelial barrier, consisting mostly of activated [[T cells]]. They interact with gut bacteria directly and emit signals to regulate the intestinal immune system. IELs in Crohn's disease produce increased levels of inflammatory cytokines [[Interleukin 17|IL-17]], [[IFNγ]], and [[TNF]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> It is hypothesized that inflammatory signals from the immune system and alterations to the gut microbiome influence IELs to produce inflammatory signals, contributing to Crohn's disease.<ref name="pmid29242771">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hu MD, Edelblum KL | title = Sentinels at the frontline: the role of intraepithelial lymphocytes in inflammatory bowel disease | journal = Current Pharmacology Reports | volume = 3 | issue = 6 | pages = 321–334 | pmid = 29242771 | date = August 2017 | doi = 10.1007/s40495-017-0105-2 | doi-access = free | pmc = 5724577 }}</ref> |

|||

Crohn's disease can be problematic during [[pregnancy]], and some medications can cause adverse outcomes for the [[fetus]] or mother. Consultation with an obstetrician and gastroenterologist about Crohn's disease and all medications allows preventative measures to be taken. In some cases, remission can occur during pregnancy. Certain medications can also impact [[sperm count]] or may otherwise adversely affect a man's ability to [[Fertilisation|conceive]].<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.ccfa.org/about/news/pregnancy | publisher = [[Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America]] | date = 2005-10-21 | title = IBD and Pregnancy: What You Need to Know | last = Kaplan | first = C | accessdate = 2009-11-07 }}</ref> |

|||

=== Immune system === |

|||

==Cause== |

|||

Normally, intestinal [[macrophages]] have reduced inflammatory behavior while retaining their ability to consume and destroy pathogens. In Crohn's disease, the number and activity of macrophages is reduced, enabling the entrance of pathogens into intestinal tissue.<ref name="pmid30611442"/> Macrophages degrade internal pathogens through autophagy, which is impaired by Crohn's-linked polymorphisms in genes such as NOD2 and ATG16L1.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> Additionally, people with Crohn's tend to have a separate abnormal population of macrophages that secrete proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF and [[Interleukin 6|IL-6]].<ref name="pmid30611442"/> |

|||

The exact cause of Crohn's disease is still unknown, although more and more details are emerging and has become clear that the interplay of environmental factors and in a genetically predisposed host ignites disease.<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| author = Braat H, Peppelenbosch MP, Hommes DW |

|||

| title = Immunology of Crohn's disease |

|||

| journal = Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. |

|||

| volume = 1072 |

|||

| issue = |

|||

| pages = 135–54 |

|||

| year = 2006 |

|||

| month = August |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-04 |

|||

| doi = 10.1196/annals.1326.039 |

|||

| pmid = 17057196 |

|||

}}</ref> The genetic risk factors have now more or less been comprehensively elucidated, making Crohn's disease the first genetically complex disease of which the genetic background has been resolved.<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| author = Henckaerts L, Figueroa C, Vermeire S, Sans M |

|||

| title = The role of genetics in inflammatory bowel disease |

|||

| journal = Curr Drug Targets |

|||

| volume = 9 |

|||

| issue = 5 |

|||

| pages = 361–8 |

|||

| year = 2008 |

|||

| month = May |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-04 |

|||

| doi = 10.2174/138945008784221161 |

|||

| pmid = 18473763 |

|||

}}</ref> The relative risks of contracting the disease when one has a mutation in one of the risk genes, however, are actually very low (approximately 1:200). Broadly speaking, the genetic data indicate that innate immune systems in patients with Crohn's disease malfunction, and direct assessment of patient immunity confirms this notion.<ref name=Marks2006> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

|author= Marks DJ, Harbord MW, MacAllister R, Rahman FZ, Young J, Al-Lazikani B, Lees W, Novelli M, Bloom S, Segal AW |

|||

|title= Defective acute inflammation in Crohn's disease: a clinical investigation |

|||

|journal= Lancet |

|||

|volume= 367 |

|||

|issue= 9511 |

|||

|pages= 668–78 |

|||

|year= 2006 |

|||

|pmid= 16503465 |

|||

|doi= 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68265-2 |

|||

|pmc= 2092405 |

|||

}}</ref> This had led to the notion that Crohn's disease should be viewed as innate immune deficiency, chronic inflammation being caused by adaptive immunity trying to compensate for the reduced function of the innate immune system.<ref> |

|||

{{cite journal |

|||

| author = Comalada M, Peppelenbosch MP |

|||

| title = Impaired innate immunity in Crohn's disease |

|||

| journal = Trends Mol Med |

|||

| volume = 12 |

|||

| issue = 9 |

|||

| pages = 397–9 |

|||

| year = 2006 |

|||

| month = September |

|||

| accessdate = 2009-11-04 |

|||

| doi = 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.07.005 |

|||

| pmid = 16890491 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

[[Neutrophils]] are recruited from the bloodstream in response to inflammatory signals, and defend tissue by secreting antimicrobial substances and consuming pathogens.<ref name="pmid25234148"/> In Crohn's disease, neutrophil recruitment is delayed and autophagy is impaired, allowing bacteria to survive in intestinal tissue.<ref name="pmid30611442"/> Dysfunction in neutrophil secretion of [[reactive oxygen species]], which are toxic to bacteria, is associated with very early onset Crohn's disease. Although neutrophils are important in bacterial defense, their subsequent accumulation in Crohn's disease damages the epithelial barrier and perpetuates inflammation.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

===Genetics=== |

|||

[[Image:NOD2 CARD15.svg|right|thumb|Schematic of NOD2 CARD15 gene, which is associated with certain disease patterns in Crohn's disease.]] |

|||

Some research has indicated that Crohn's disease may have a genetic link.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://www.ccfa.org/reuters/geneticlink | title = Crohn's disease has strong genetic link: study | publisher = [[Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America]] | date = 2007-04-16 | accessdate = 2009-11-07 }}</ref> The disease runs in families and those with a sibling with the disease are 30 times more likely to develop it than the normal population. |

|||

[[Innate lymphoid cell]]s (ILCs) consist of subtypes including ILC1s, ILC2s, and ILC3s. ILC3s are particularly important for regenerating the epithelial barrier through secretion of IL-17 by NCR- ILC3s and [[Interleukin 22|IL-22]] by NCR+ ILC3s. During Crohn's disease, inflammatory signals from antigen-presenting cells, such as IL-23, cause excessive IL-17 and IL-22 secretion. Although these cytokines protect the intestinal barrier, excessive production damages the barrier through increased inflammation and neutrophil recruitment. Additionally, [[Interleukin 12|IL-12]] from activated dendritic cells influence NCR+ ILC3s to transform into inflammatory [[IFNγ]]-producing ILC1s.<ref name="pmid30962426">{{cite journal | vauthors = Zeng B, Shi S, Ashworth G, Dong C, Liu J, Xing F | title = ILC3 function as a double-edged sword in inflammatory bowel diseases | journal = Cell Death & Disease | volume = 10 | issue = 4 | pages = 315 | pmid = 30962426 | pmc = 6453898 | date = April 2019 | doi = 10.1038/s41419-019-1540-2 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

[[Mutation]]s in the [[CARD15]] gene (also known as the NOD2 [[gene]]) are associated with Crohn's disease<!-- --><ref>{{cite journal |author=Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, ''et al.'' |title=A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease |journal=Nature |volume=411 |issue=6837 |pages=603–6 |year=2001 |pmid=11385577 |doi=10.1038/35079114 |url= |last12=Brant |first12=SR |last13=Bayless |first13=TM |last14=Kirschner |first14=BS |last15=Hanauer |first15=SB |last16=Nuñez |first16=G |last17=Cho |first17=JH}}</ref> and with susceptibility to certain phenotypes of disease location and activity.<ref><!-- |

|||

-->{{cite journal | author = Cuthbert A, Fisher S, Mirza M, ''et al.'' | title = The contribution of NOD2 gene mutations to the risk and site of disease in inflammatory bowel disease | journal = Gastroenterology | volume = 122 | issue = 4 | pages = 867–74 | year = 2002 | pmid = 11910337 | doi = 10.1053/gast.2002.32415 | last12 = Lewis | first12 = CM | last13 = Mathew | first13 = CG}}</ref> In earlier studies, only two genes were linked to Crohn's, but scientists now believe there are over thirty genes that show genetics play a role in the disease, either directly through causation or indirectly as with a [[mediator variable]]. Anomalies in the [[XBP1]] gene have recently been identified as a factor, pointing towards a role for the [[unfolded protein response]] pathway of the [[endoplasmatic reticulum]] in inflammatory bowel diseases.<ref>{{cite journal|url=http://www.cell.com/content/article/abstract?uid=PIIS0092867408009410|title=XBP1 Links ER Stress to Intestinal Inflammation and Confers Genetic Risk for Human Inflammatory Bowel Disease|journal=Cell|volume=134|pages=743–756|publisher=Cell Press|author=Kaser et al.|date=5 September 2008|doi=10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021|pmid=18775308|last1=Kaser|first1=A|last2=Lee|first2=AH|last3=Franke|first3=A|last4=Glickman|first4=JN|last5=Zeissig|first5=S|last6=Tilg|first6=H|last7=Nieuwenhuis|first7=EE|last8=Higgins|first8=DE|last9=Schreiber|first9=S|issue=5|author2=Lee|author3=Franke|author4=Glickman|author5=Zeissig|author6=Tilg|author7=Nieuwenhuis|author8=Higgins|author9=Schreiber|first10=LH|pmc=2586148}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Clevers H |title=Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Stress, and the Endoplasmic Reticulum |journal=N Engl J Med |volume=360 |issue=7 |pages=726–727 |year=2009|doi= 10.1056/NEJMcibr0809591|url=http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/360/7/726 |pmid=19213688 |last1=Clevers |first1=H}}</ref> |

|||

Naive T cells are activated primarily by dendritic cells, which then differentiate into anti-inflammatory [[Regulatory T cell|T regulatory cells]] (Tregs) or inflammatory T helper cells to maintain balance. In Crohn's disease, macrophages and antigen-presenting cells secrete IL-12, [[Interleukin 18|IL-18]], and IL-23 in response to pathogens, increasing Th1 and T17 differentiation and promoting inflammation via [[Interleukin 17|IL-17]], IFNγ and TNF. IL-23 is particularly important, and IL-23 receptor polymorphisms that increase activity are linked with Crohn's disease. Tregs suppress inflammation via [[Interleukin 10|IL-10]], and mutations to IL-10 and its receptor cause very early onset Crohn's disease.<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

===Environmental factors=== |

|||

Diet is believed to be linked to its higher prevalence in industrialized parts of the world. [[Tobacco smoking|Smoking]] has been shown to increase the risk of the return of active disease, or "flares".<ref name=Cosnes2004/> The introduction of [[hormonal contraception]] in the United States in the 1960s is linked with a dramatic increase in the incidence rate of Crohn's disease. Although a causal linkage has not been effectively shown, there remain fears that these drugs work on the digestive system in ways similar to smoking.<ref><!-- |

|||

-->{{cite journal | author = Lesko S, Kaufman D, Rosenberg L, ''et al.'' | title = Evidence for an increased risk of Crohn's disease in oral contraceptive users | journal = Gastroenterology | volume = 89 | issue = 5 | pages = 1046–9 | year = 1985 | pmid = 4043662}}</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Microbiome === |

||

People with Crohn's disease tend to have altered microbiomes, although no disease-specific microorganisms have been identified. An altered microbiome may link environmental factors with Crohn's, though causality is uncertain. [[Firmicutes]] tend to be reduced, particularly [[Faecalibacterium prausnitzii]], which produces [[short-chain fatty acids]] that reduce inflammation. [[Bacteroidetes]] and [[proteobacteria]] tend to be increased, particularly adherent-invasive [[E. coli]], which attaches to intestinal epithelial cells. Additionally, mucolytic and sulfate-reducing bacteria are elevated, contributing to damage to the intestinal barrier.<ref name="pmid30611442"/> |

|||

Abnormalities in the [[immune]] system have often been invoked as being causes of Crohn's disease. Crohn's disease is thought to be an autoimmune disease, with inflammation stimulated by an over-active [[T helper cell#Th1/Th2 Model for helper T cells|T<sub>h</sub>1]] [[cytokine]] response.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cobrin GM, Abreu MT |title=Defects in mucosal immunity leading to Crohn's disease |journal=Immunol. Rev. |volume=206 |issue= |pages=277–95 |year=2005 |pmid=16048555 |doi=10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00293.x |url=}}</ref> However, more recent evidence has shown that [[Th17|T<sub>h</sub>17]] is of greater importance in the disease.<ref name=Elson2007>{{Cite journal |

|||

| last = Elson | first = C. |

|||

| year = 2007 |

|||

| title = Monoclonal Anti–Interleukin 23 Reverses Active Colitis in a T Cell–Mediated Model in Mice |

|||

| journal = Gastroenterology |

|||

| volume = 132 |

|||

| pages = 2359 |

|||

| doi = 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.104 |

|||

| pmid = 17570211 |

|||

| last1 = Elson |

|||

| first1 = CO |

|||

| last2 = Cong |

|||

| first2 = Y |

|||

| last3 = Weaver |

|||

| first3 = CT |

|||

| last4 = Schoeb |

|||

| first4 = TR |

|||

| last5 = Mcclanahan |

|||

| first5 = TK |

|||

| last6 = Fick |

|||

| first6 = RB |

|||

| last7 = Kastelein |

|||

| first7 = RA |

|||

| issue = 7 |

|||

| author2 = Cong |

|||

| author3 = Weaver |

|||

| author4 = Schoeb |

|||

| author5 = McClanahan |

|||

| author6 = Fick |

|||

| author7 = Kastelein |

|||

}}</ref> The most recent gene to be implicated in Crohn's disease is ATG16L1, which may induce [[Autophagy (cellular)|autophagy]] and hinder the body's ability to attack invasive bacteria.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Prescott NJ, Fisher SA, Franke A, ''et al.'' |title=A nonsynonymous SNP in ATG16L1 predisposes to ileal Crohn's disease and is independent of CARD15 and IBD5 |journal=Gastroenterology |volume=132 |issue=5 |pages=1665–71 |year=2007 |pmid=17484864 |doi=10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.034 |url= |last12=Lewis |first12=CM |last13=Schreiber |first13=S |last14=Mathew |first14=CG}}</ref> |

|||

Alterations in gut viral and fungal communities may contribute to Crohn's disease. [[Caudovirales]] bacteriophage sequences found in children with Crohn's suggest a potential biomarker for early-onset disease. A meta-analysis showed lower viral diversity in Crohn's patients compared to healthy individuals, with increased [[Synechococcus phage S CBS1]] and [[Retroviridae]] viruses. Additionally, a Japanese study found that the fungal microbiota in Crohn's patients differs significantly from that of healthy individuals, particularly with an abundance of [[Candida albicans|Candida]].<ref name="pmid32242028"/> |

|||

Contrary to the prevailing view that Crohn's disease is a primary T cell autoimmune disorder, there is an increasing body of evidence in favour of the hypothesis that Crohn's disease results from an impaired innate immunity.<ref>{{cite journal| author= Marks DJ, Segal AW. |title=Innate immunity in inflammatory bowel disease: a disease hypothesis|journal= J Pathol. |volume =214 |issue= 2 |pages=260–6 |year=2008 | month = January | doi= 10.1002/path.2291| pmc= 2635948 | accessdate = 2009-11-04| pmid= 18161747}}</ref> The immunodeficiency, which has been shown to be due to (at least in part) impaired cytokine secretion by macrophages, is thought to lead to a sustained microbial-induced inflammatory response, particularly in the colon where the bacterial load is especially high.<ref name=Marks2006/><ref> |

|||

{{cite journal| author= Dessein R, Chamaillard M, Danese S |title=Innate immunity in Crohn's disease: the reverse side of the medal |journal= J Clin Gastroenterol |volume =42 |issue= Suppl 3 Pt 1 |pages=S144–7 |year=2008 |month= September |pmid= 18806708 | doi= 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181662c90| doi_brokendate= 2009-09-20| accessdate = 2009-11-04}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== Diagnosis == |

||

Diagnosis of Crohn's disease may be challenging since its symptoms overlap with other gastrointestinal diseases. An accurate diagnosis requires a combined assessment of clinical history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests. |

|||

A variety of pathogenic bacteria were initially suspected of being causative agents of Crohn's disease.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.crohns.org/research/index.htm |title=OVERVIEW: MAP and Crohn's Disease Research |work= | accessdate = 2009-11-07 }}</ref> However, most health care professionals now believe that a variety of microorganisms are taking advantage of their host's weakened mucosal layer and inability to clear bacteria from the intestinal walls, both symptoms of the disease.<ref><!-- |

|||

-->{{cite journal | author = Sartor, R. | title = Mechanisms of Disease: pathogenesis of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis | journal = Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology | year = 2006 | month = July | volume = 3 | issue = 7 | pages = 390–407 | url=www.nature.com/nrgastro/journal/v3/n7/full/ncpgasthep0528.html | doi = 10.1038/ncpgasthep0528 }} PMID 16819502</ref> Some studies have suggested that ''[[Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis]]'' plays a role in Crohn's disease, in part because it causes a very similar disease, [[Johne's disease]], in cattle.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Naser SA, Collins MT |title=Debate on the lack of evidence of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in Crohn's disease |journal=Inflamm. Bowel Dis. |volume=11 |issue=12 |pages=1123 |year=2005 |pmid=16306778 |doi= 10.1097/01.MIB.0000191609.20713.ea|url=}}</ref> The [[mannose]] bearing antigens (mannins) from yeast may also elicit an [[antibody]] response.<ref name="pmid1398231">{{cite journal | author = Giaffer MH, Clark A, Holdsworth CD | title = Antibodies to Saccharomyces cerevisiae in patients with Crohn's disease and their possible pathogenic importance | journal = Gut | volume = 33 | issue = 8 | pages = 1071–5 | year = 1992 | pmid = 1398231 | doi = 10.1136/gut.33.8.1071 | pmc = 1379444}}</ref> Other studies have linked specific strains of enteroadherent ''[[E. coli]]'' to the disease.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Baumgart M ''et al.'' | title = Culture independent analysis of ileal mucosa reveals a selective increase in invasive Escherichia coli of novel phylogeny relative to depletion of Clostridiales in Crohn's disease involving the ileum | pmid = 18043660 | journal = The ISME Journal | year = 2007 | url = http://www.nature.com/ismej/journal/v1/n5/full/ismej200752a.html | doi = 10.1038/ismej.2007.52 | volume = 1 | pages = 403 | last12 = Schukken | first12 = Y | last13 = Scherl | first13 = E | last14 = Simpson | first14 = KW | issue = 5 }}</ref> Still, this relationship between specific types of bacteria and Crohn's disease remains unclear.<ref name=scah_out38>{{cite web |url=http://ec.europa.eu/food/fs/sc/scah/out38_en.pdf |title=Possible links between Crohn’s disease and Paratuberculosis |format=PDF |work=EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL HEALTH & CONSUMER PROTECTION | accessdate = 2009-11-07}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Gui GP, Thomas PR, Tizard ML, Lake J, Sanderson JD, Hermon-Taylor J |title=Two-year-outcomes analysis of Crohn's disease treated with rifabutin and macrolide antibiotics |journal=J. Antimicrob. Chemother. |volume=39 |issue=3 |pages=393–400 |year=1997 |month=March |pmid=9096189 |doi= 10.1093/jac/39.3.393|url=http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/39/3/393 | format = PDF }}</ref> |

|||

=== Endoscopy === |

|||

Some studies have suggested that some symptoms of Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and [[irritable bowel syndrome]] have the same underlying cause. Biopsy samples taken from the colons of all three patient groups were found to produce elevated levels of a serine protease.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cenac N, Andrews CN, Holzhausen M, ''et al.'' |title=Role for protease activity in visceral pain in irritable bowel syndrome |journal=J. Clin. Invest. |volume=117 |issue=3 |pages=636–47 |year=2007 |month=March |pmid=17304351 |doi=10.1172/JCI29255 |url= |last12=Ferraz |first12=JG |last13=Shaffer |first13=E |last14=Vergnolle |first14=N |pmc=1794118}}</ref> Experimental introduction of the serine protease into mice has been found to produce widespread pain associated with irritable bowel syndrome as well as colitis, which is associated with all three diseases.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cenac N, Coelho AM, Nguyen C, ''et al.'' |title=Induction of intestinal inflammation in mouse by activation of proteinase-activated receptor-2 |journal=Am. J. Pathol. |volume=161 |issue=5 |pages=1903–15 |year=2002 |month=November |pmid=12414536 |doi= |url=http://ajp.amjpathol.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12414536 |last12=Vergnolle |first12=N |pmc=1850779}}</ref> The authors of that study were unable to identify the source of the protease, but a separate review noted that regional and temporal variations in those illnesses follow those associated with infection with a poorly understood protozoan, [[Blastocystis]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Boorom KF, Smith H, Nimri L, ''et al.'' |title=Oh my aching gut: irritable bowel syndrome, Blastocystis, and asymptomatic infection |journal=Parasit Vectors |volume=1 |issue=1 |pages=40 |year=2008 |month=October |pmid=18937874 |doi=10.1186/1756-3305-1-40 |url= |pmc=2627840}}</ref> |

|||

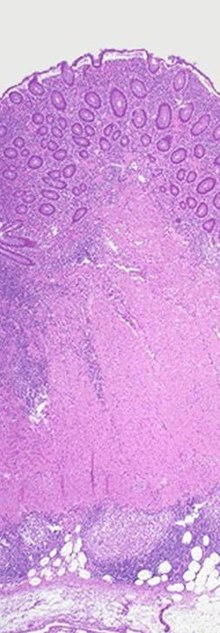

[[Image:CD colitis.jpg|thumb|right|alt=Image of deep ulcers in the colon of a person with Crohn's colitis.|Image of a colon showing deep ulceration due to Crohn's disease.]] |

|||

[[Image:CD serpiginous ulcer.jpg|thumb|right|alt=Image of a serpiginous ulcer due to Crohn's disease found during a colonoscopy.|Image of a serpiginous ulcer in the colon, a classic finding in Crohn's disease]] |

|||

A study in 2003 put forth the "cold-chain" hypothesis, that [[psychrotrophic bacteria]] such as Yersinia spp and Listeria spp contribute to the disease. A statistical correlation was found between the advent of the use of refrigeration in the United States and various parts of Europe and the rise of the disease.<ref>{{Cite journal |

|||

| last1 = Hugot |

|||

| first1 = Jean-Pierre |

|||

| last2 = Alberti |

|||

| first2 = Corinne |

|||

| last3 = Berrebi |

|||

| first3 = Dominique |

|||

| last4 = Bingen |

|||