Hiroshima: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 216.243.212.196 identified as vandalism to last revision by Marek69. (TW) |

→World War II and the atomic bombing (1939–1945): Removed uncited claim from 2018. |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|City in Chūgoku, Japan}} |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

{{ |

{{pp|small=yes}} |

||

{{About|the city in Japan|the prefecture with the same name where this city is located|Hiroshima Prefecture|other uses}} |

|||

{{Infobox City Japan |

|||

{{pp-move}} |

|||

| Name = Hiroshima |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

|||

| JapaneseName = 広島 |

|||

|name = Hiroshima |

|||

| official_name = 広島市 · Hiroshima City |

|||

|native_name = {{nobold|{{lang|ja|広島市}}}} |

|||

| settlement_type = [[City designated by government ordinance|Designated city]] |

|||

|settlement_type = [[Cities designated by government ordinance of Japan|Designated city]] |

|||

| ImageSkyline = DSCN0282.JPG |

|||

|image_skyline = {{Multiple image |

|||

| ImageCaption = [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial|Atomic Bomb Dome]] (left) and modern buildings |

|||

| border = infobox |

|||

| Region = [[Chūgoku]], [[San'yō region|Sanyō]] |

|||

| total_width = 290 |

|||

| Prefecture = [[Hiroshima Prefecture|Hiroshima]] |

|||

| image_style = border:1; |

|||

| Area_km2 = 905.01 |

|||

| perrow = 1/2/2/2 |

|||

| Population = 1,173,980 |

|||

| image1 = Atomic Bomb Dome and Motoyaso River, Hiroshima, Northwest view 20190417 1.jpg |

|||

| Density_km2 = 1297.2 |

|||

| image2 = Hiroshima-Castle-1.jpg |

|||

| PopDate = January 2010 |

|||

| image3 = Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum 2.jpg |

|||

| Mayor = [[Tadatoshi Akiba]] ([[Social Democratic Party (Japan)|SDP]]) |

|||

| image4 = Takueichi Pond and Kokokyo Bridge in Shukkei Garden 1.jpg |

|||

| Coords = |

|||

| image5 = 鯉城通り - panoramio (1).jpg |

|||

| LatitudeDegrees = 34 |

|||

| image6 = Lantern Floating Ceremony in Hiroshima; 2012.jpg |

|||

| LatitudeMinutes = 23 |

|||

| image7 = Hiroshima Port Ujina Passenger Terminal 20070811 crop2.jpg |

|||

| LatitudeSeconds = 53 |

|||

| LongtitudeDegrees = 132 |

|||

| LongtitudeMinutes = 28 |

|||

| LongtitudeSeconds = 32.9 |

|||

| Tree = [[Cinnamomum camphora|Camphor Laurel]] |

|||

| Flower = [[Oleander]] |

|||

| SymbolImage = Flag of Hiroshima City.svg |

|||

| CityHallPostalCode = 730-8586 |

|||

| CityHallAddress = Hiroshima-shi,<br/>Naka-ku, Kokutaiji 1-6-34 |

|||

| CityHallPhone = 082-245-2111 |

|||

| CityHallLink = [http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/ Hiroshima City] |

|||

| MapImage = Hiroshima in Hiroshima Prefecture Ja.svg |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

|imagesize = |

|||

{{nihongo|'''Hiroshima'''|広島市|''Hiroshima-shi''}} ({{Audio|ja-Hiroshima.ogg|listen}}) is the capital of [[Hiroshima Prefecture]], and the largest city in the [[Chūgoku region]] of western [[Honshū]], the largest island of [[Japan]]. It became the first city in history destroyed by nuclear weapons when the [[United States|United States of America]] [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|dropped an atomic bomb]] on it at 8:15am on August 6, 1945, near the end of [[World War II]].<ref>{{cite book | last = Hakim | first = Joy | title = A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz | publisher = Oxford University Press | date = 1995 | location = New York | pages = | isbn = 0-19-509514-6 }}</ref> |

|||

|image_alt = |

|||

Hiroshima gained municipality status on April 1, 1889, and was designated on April 1, 1980, by [[City designated by government ordinance|government ordinance]]. The city's current mayor is [[Tadatoshi Akiba]]. |

|||

|image_caption = Clockwise from top: Hiroshima skyline within [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial|A-Bomb Dome]], [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum]] and [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park|Park]], [[Hondōri]]([[Downtown]]), [[Port of Hiroshima]], Peace Message([[Water lantern]]), [[Shukkei-en]], [[Hiroshima Castle]] |

|||

|image_flag = Flag of Hiroshima City.svg |

|||

== History == |

|||

|flag_alt = |

|||

Hiroshima was founded on the river delta coastline of the [[Seto Inland Sea]] in 1589 by [[Mōri Terumoto]], who made it his capital after leaving [[Koriyama Castle (Aki Province)|Koriyama Castle]] in [[Aki Province]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/History-E/c01.html |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20080130190042/http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/History-E/c01.html |archivedate=2008-01-30 |title=The Origin of Hiroshima |publisher=Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation |accessdate=2007-08-17}}</ref> [[Hiroshima Castle]] was quickly built, and Terumoto moved in in 1593. Terumoto was on the losing side at the [[Battle of Sekigahara]]. The winner, [[Tokugawa Ieyasu]], deprived Mori Terumoto of most of his fiefs including Hiroshima and gave [[Aki province]] to [[Fukushima Masanori|Masanori Fukushima]], a [[daimyo]] who had supported Tokugawa.<ref name="Kosaikai">{{cite book |author=Kosaikai, Yoshiteru |title=Hiroshima Peace Reader |publisher=Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation |date=2007 |chapter=History of Hiroshima}}</ref> The castle passed to [[Asano Nagaakira]] in 1619, and Asano was appointed the daimyo of this area. Under Asano rule, the city prospered, developed, and expanded, with few military conflicts or disturbances.<ref name="Kosaikai"/> Asano's descendants continued to rule until the [[Meiji Restoration]] in the 19th century.<ref name="terry"/> |

|||

|image_seal = Emblem of Hiroshima, Hiroshima.svg |

|||

|seal_alt = |

|||

[[File:hiromuseum.jpg|thumb|left|Hiroshima Commercial Museum 1915]] |

|||

|image_shield = |

|||

Hiroshima served as the capital of [[Hiroshima Domain]] during the [[Edo period]]. After the [[Han (administrative division)|han]] was abolished in 1871, the city became the capital of [[Hiroshima prefecture]]. Hiroshima became a major urban center during the [[Meiji period]] as the Japanese economy shifted from primarily rural to urban industries. During the 1870s, one of the seven government-sponsored English language schools was established in Hiroshima.<ref>Bingham (US Legation in Tokyo) to Fish (US Department of State), September 20, 1876, in ''Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, transmitted to congress, with the annual message of the president, December 4, 1876'', p. 384</ref> |

|||

|shield_alt = |

|||

Ujina Harbor was constructed through the efforts of Hiroshima Governor [[Sadaaki Senda]] in the 1880s, allowing Hiroshima to become an important port city. The [[Sanyo Railroad]] was extended to Hiroshima in 1894, and a rail line from the main station to the harbor was constructed for military transportation during the [[First Sino-Japanese War]].<ref name="Kosakai"/> During that war, the Japanese government moved temporarily to Hiroshima, and the Emperor maintained his headquarters at [[Hiroshima Castle]] from September 15, 1894 to April 27, 1895.<ref name="Kosakai">Kosakai, ''Hiroshima Peace Reader''</ref> The significance of Hiroshima for the Japanese government can be discerned from the fact that the first round of talks between Chinese and Japanese representatives to end the Sino-Japanese War was held in Hiroshima from February 1 to February 4, 1895.<ref>Dun (US Legation in Tokyo) to Gresham, February 4, 1895, in ''Foreign relations of United States, 1894'', Appendix I, p. 97</ref> New industrial plants, including [[cotton mill]]s, were established in Hiroshima in the late 1800s.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Origin of Modern Capitalism and Eastern Asia |author=Jacobs, Norman |publisher=Hong Kong University |year=1958 |page=51}}</ref> Further industrialization in Hiroshima was stimulated during the [[Russo-Japanese War]] in 1904, which required development and production of military supplies. The Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall was constructed in 1915 as a center for trade and exhibition of new products. Later, its name was changed to Hiroshima Prefectural Product Exhibition Hall, and again to Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall.<ref>{{cite book |author=Sanko |title=Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) |date=1998 |publisher=The City of Hiroshima and the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation}}</ref> |

|||

|image_blank_emblem = |

|||

|nickname = |

|||

=== WWII and atomic bombing === |

|||

|motto = |

|||

{{main article|Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki}} |

|||

|image_map = {{maplink|frame=yes|plain=yes|type=shape|stroke-width=2|stroke-color=#000000|zoom=9}} |

|||

[[File:AtomicEffects-Hiroshima.jpg|thumb|left|Atomic Effects- Hiroshima City]] |

|||

|image_map1 = Hiroshima in Hiroshima Prefecture Ja.svg |

|||

<!-- Note to editors: This article is for an overview. Please do not add details. Instead, add details to the main article "Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki." -->During [[World War II]], the Second Army and Chugoku Regional Army were headquartered in Hiroshima, and the Army Marine Headquarters was located at Ujina port. The city also had large depots of military supplies, and was a key center for shipping.<ref name="effects">{{cite web |url=http://www.nuclearfiles.org/redocuments/1946/460619-bombing-survey1.html |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20041011111052/http://www.nuclearfiles.org/redocuments/1946/460619-bombing-survey1.html |archivedate=2004-10-11 |title=U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki |date=June 1946 |author=United States Strategic Bombing Survey |publisher=nuclearfiles.org |accessdate=2009-07-26}}</ref> |

|||

|map_alt1 = |

|||

|map_caption1 = Location of Hiroshima in [[Hiroshima Prefecture]] |

|||

The bombing of Tokyo and other cities in Japan during World War II caused widespread destruction and hundreds of thousands of deaths, nearly all civilians.<ref>{{cite book|title=Bombing to Win: Airpower and Coercion in War|last=Pape|first=Robert|authorlink= |coauthors= |year=1996|publisher=Cornell University Press|isbn=978-0801483110 |page=129}}</ref> For example, [[Toyama, Toyama|Toyama]], an urban area of 128,000, was nearly fully destroyed, and incendiary attacks on Tokyo are credited with claiming 90,000 lives.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.bookmice.net/darkchilde/japan/fire.html |title= Firebombing Japan |publisher= darkchilde@bookmice.net |accessdate= 2008-04-16}}</ref> There were no such [[Air raids on Japan|air raids]] in Hiroshima. However, the threat was certainly there and to protect against potential firebombings in Hiroshima, students (between 11–14 years) were mobilized to demolish houses and create [[firebreak]]s.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.chugoku-np.co.jp/abom/97e/peace/e/03/omoide.htm |title=Japan in the Modern Age and Hiroshima as a Military City |publisher=The Chugoku Shimbun |accessdate=2007-08-19}}</ref> |

|||

|pushpin_map = Japan#Asia#Earth |

|||

|pushpin_label_position = |

|||

On Monday, August 6, 1945, at 8:15 AM, the [[nuclear bomb]] '[[Little Boy]]' was dropped on Hiroshima by an American B-29 bomber, the ''[[Enola Gay]]'',<ref>[http://www.cfo.doe.gov/me70/manhattan/hiroshima.html The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima], U.S. Department of Energy, Office of History and Heritage Resources.</ref> directly killing an estimated 80,000 people. By the end of the year, injury and radiation brought total casualties to 90,000-140,000.<ref>[http://www.rerf.or.jp/general/qa_e/qa1.html Radiation Effects Research Foundation]</ref> Approximately 69% of the city's buildings were completely destroyed, and about 7% severely damaged. |

|||

|pushpin_map_alt = |

|||

|pushpin_map_caption = |

|||

Research about the effects of the attack was restricted during the [[Occupied Japan|occupation of Japan]], and information censored until the signing of the [[San Francisco Peace Treaty]] in 1951, restoring control to the Japanese.<ref>Ishikawa and Swain (1981), p. 5</ref> |

|||

|coordinates = {{coord|34|23|29|N|132|27|07|E|region:JP-34|display=it}} |

|||

|coor_pinpoint = |

|||

|coordinates_footnotes = |

|||

|subdivision_type = Country |

|||

|subdivision_name = {{flag|Japan}} |

|||

|subdivision_type1 = [[List of regions of Japan|Region]] |

|||

|subdivision_name1 = [[Chūgoku region|Chūgoku]] ([[San'yō region|San'yō]]) |

|||

|subdivision_type2 = [[Prefectures of Japan|Prefecture]] |

|||

|subdivision_name2 = [[Hiroshima Prefecture]] |

|||

|subdivision_type3 = |

|||

|subdivision_name3 = |

|||

|established_title = |

|||

|established_date = |

|||

|founder = [[Mōri Terumoto]] |

|||

|named_for = |

|||

|seat_type = |

|||

|seat = |

|||

|government_footnotes = |

|||

|leader_party = |

|||

|leader_title = [[Mayor of Hiroshima|Mayor]] |

|||

|leader_name = [[Kazumi Matsui]] |

|||

|leader_title1 = |

|||

|leader_name1 = |

|||

|total_type = |

|||

|unit_pref = |

|||

|area_magnitude = |

|||

|area_footnotes = |

|||

|area_total_km2 = 906.68 |

|||

|area_total_sq_mi = |

|||

|area_land_km2 = |

|||

|area_land_sq_mi = |

|||

|area_water_km2 = |

|||

|area_water_sq_mi = |

|||

|area_water_percent = |

|||

|area_note = |

|||

|elevation_footnotes = |

|||

|elevation_m = |

|||

|elevation_ft = |

|||

|population_footnotes = |

|||

|population_total = 1199391 |

|||

|population_as_of = June 1, 2019 |

|||

|population_density_km2 = auto |

|||

|population_density_sq_mi= |

|||

|population_est = |

|||

|pop_est_as_of = |

|||

|population_demonym = |

|||

|population_note = |

|||

|population_metro_footnotes = <ref>{{Cite web |title=UEA Code Tables |url=http://www.csis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/UEA/uea_code_e.htm |publisher=Center for Spatial Information Science, University of Tokyo |access-date=January 26, 2019 |archive-date=January 9, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190109011635/http://www.csis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/UEA/uea_code_e.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> (2015) |

|||

|population_metro = 1431634 ([[List of metropolitan areas in Japan by population|10th]]) |

|||

|timezone1 = [[Japan Standard Time]] |

|||

|utc_offset1 = +9 |

|||

|postal_code_type = |

|||

|postal_code = |

|||

|area_code_type = |

|||

|area_code = |

|||

|blank_name_sec1 = City Symbols |

|||

|blank1_name_sec1 = Tree |

|||

|blank1_info_sec1 = [[Cinnamomum camphora|Camphor Laurel]] |

|||

|blank2_name_sec1 = Flower |

|||

|blank2_info_sec1 = [[Nerium|Oleander]] |

|||

|blank3_name_sec1 = |

|||

|blank3_info_sec1 = |

|||

|blank4_name_sec1 = |

|||

|blank4_info_sec1 = |

|||

|blank5_name_sec1 = |

|||

|blank5_info_sec1 = |

|||

|blank6_name_sec1 = |

|||

|blank6_info_sec1 = |

|||

|blank7_name_sec1 = |

|||

|blank7_info_sec1 = |

|||

|blank_name_sec2 = Phone number |

|||

|blank_info_sec2 = 082-245-2111 |

|||

|blank1_name_sec2 = Address |

|||

|blank1_info_sec2 = 1-6-34 Kokutaiji,<br />Naka-ku, Hiroshima-shi 730-8586 |

|||

|website = {{URL|http://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/}} |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Infobox Chinese |

|||

|pic=Hiroshima (Chinese characters).svg |

|||

|piccap="Hiroshima" in ''[[shinjitai]]'' ''[[kanji]]'' |

|||

|picupright=0.4 |

|||

|shinjitai=広島 |

|||

|kyujitai=廣島 |

|||

|romaji=Hiroshima |

|||

}} |

|||

[[File:Hiroshima Metropolitan Employment Area.svg|thumb|Hiroshima [[Urban Employment Area]]]] |

|||

{{nihongo|'''Hiroshima'''|広島市|Hiroshima-shi|extra={{IPAc-en|ˌ|h|ɪr|oʊ|ˈ|ʃ|iː|m|ə}}, <small>also</small> {{IPAc-en|UK|h|ɪ|ˈ|r|ɒ|ʃ|ɪ|m|ə}},<ref>{{cite LPD|3}}</ref> {{IPAc-en|US|h|ɪ|ˈ|r|oʊ|ʃ|ɪ|m|ə}}, {{IPA|ja|çiɾoɕima||TomJ-Hiroshima.ogg}}}} is the capital of [[Hiroshima Prefecture]] in [[Japan]]. {{As of|2019|6|1|df=US}}, the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The [[gross domestic product]] (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima [[Urban Employment Area]], was US$61.3 billion as of 2010.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.csis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/UEA/uea_data_e.htm |title=Metropolitan Employment Area (MEA) Data |author=Yoshitsugu Kanemoto |publisher=Center for Spatial Information Science, The [[University of Tokyo]] |access-date=2016-09-29 |archive-date=2018-06-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180615111107/http://www.csis.u-tokyo.ac.jp/UEA/uea_data_e.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>[https://data.oecd.org/conversion/exchange-rates.htm Conversion rates – Exchange rates] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180201220924/https://data.oecd.org/conversion/exchange-rates.htm |date=2018-02-01 }} – OECD Data</ref> [[Kazumi Matsui]] has been the city's mayor since April 2011. The Hiroshima metropolitan area is the second largest urban area in the [[Chugoku Region]] of Japan, following the [[Okayama]] metropolitan area. |

|||

Hiroshima was founded in 1589 as a [[Jōkamachi|castle town]] on the [[Ōta River]] [[river delta|delta]]. Following the [[Meiji Restoration]] in 1868, Hiroshima rapidly transformed into a major urban center and industrial hub. In 1889, Hiroshima officially gained city status. The city was a center of military activities during the [[Empire of Japan|imperial era]], playing significant roles such as in the [[First Sino-Japanese War]], the [[Russo-Japanese War]], and the two world wars. |

|||

Much has been written in news reports, novels, and popular culture about Hiroshima in the years after the bombing. |

|||

Hiroshima was the first military target of a nuclear weapon in history. This occurred on August 6, 1945, in the [[Pacific War|Pacific theatre]] of [[World War II]], at 8:15 a.m., when the [[United States Army Air Forces]] (USAAF) [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|dropped the atomic bomb]] "[[Little Boy]]" on the city.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hakim |first=Joy|author-link1=Joy Hakim |title=A History of US: Book 9: War, Peace, and All that Jazz |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |date=January 5, 1995 |location=[[New York City|New York]] |isbn=978-0195095142|title-link=A History of US}}</ref> Most of Hiroshima was destroyed, and by the end of the year between 90,000 and 166,000 had died as a result of the blast and its effects. The [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial]] (a [[World Heritage Site|UNESCO World Heritage Site]]) serves as a memorial of the bombing. |

|||

=== Reconstruction after the war === |

|||

On September 17, 1945, Hiroshima was struck by the [[Makurazaki Typhoon]] (Typhoon Ida), one of the largest typhoons of the [[Shōwa period]]. [[Hiroshima prefecture]] suffered more than 3,000 deaths and injuries, about half the national total.<ref>[http://excite.co.jp/world/english/web/body/?wb_url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bioweather.net%2Fcolumn%2Fweather%2Fcontents%2Fmame068.htm&wb_submit=%83E%83F%83u%83y%81%5B%83W%96%7C%96%F3&wb_lp=JAEN&wb_dis=2 Makurazaki Typhoon]</ref> More than half the bridges in the city were destroyed, along with heavy damage to roads and railroads, further devastating the city.<ref>Ishikawa and Swain (1981), p. 6</ref> |

|||

[[File:PaperCranes.jpg|thumb|left|[[Sadako Sasaki|Folded paper cranes]] representing prayers for peace and [[Sadako Sasaki]]]] |

|||

Hiroshima was rebuilt after the war, with the help from the national government through the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law passed in 1949. It provided financial assistance for reconstruction, along with land donated that was previously owned by the national government and used for military purposes.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/History-E/c05.html |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20080206124545/http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/History-E/c05.html |archivedate=2008-02-06 |title=Peace Memorial City, Hiroshima |publisher=Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation |accessdate=2007-08-14}}</ref> |

|||

Since being rebuilt after the war, Hiroshima has become the largest [[Cities of Japan|city]] in the [[Chūgoku region]] of western [[Honshu]]. |

|||

In 1949, a design was selected for the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park]]. Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, the closest surviving building to the location of the bomb's detonation, was designated the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial|Genbaku Dome (原爆ドーム) or "Atomic Dome"]], a part of the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park]]. The [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum]] was opened in 1955 in the Peace Park.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/virtual/VirtualMuseum_e/exhibit_e/exh0507_e/exh050701_e.html |title=Fifty Years for the Peace Memorial Museum |publisher=Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum |accessdate=2007-08-17}}</ref> |

|||

{{toc limit|3}} |

|||

Hiroshima was proclaimed a City of Peace by the [[Japan]]ese parliament in 1949, at the initiative of its mayor, [[Shinzo Hamai]] (1905–1968). As a result, the city of Hiroshima received more international attention as a desirable location for holding international conferences on peace as well as social issues. As part of that effort, the Hiroshima Interpreters' and Guide's Association (HIGA) was established in 1992 in order to facilitate translation services for conferences, and the Hiroshima Peace Institute was established in 1998 within the [[Hiroshima University]]. The city government continues to advocate the abolition of all [[nuclear weapon]]s and the Mayor of Hiroshima is the President of Mayors for Peace, an international Mayoral organization mobilizing cities and citizens worldwide to abolish and eliminate nuclear weapons by the year 2020 [http://www.2020visioncampaign.org/ Mayors for Peace 2020 Vision Campaign].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/hiroshima.htm |title=Surviving the Atomic Attack on Hiroshima, 1945 |publisher=Eyewitnesstohistory.com |date=1945-08-06 |accessdate=2009-07-17}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/library/media-gallery/video/hiroshima-aftermath |title=Library: Media Gallery: Video Files: Rare film documents devastation at Hiroshima |publisher=Nuclear Files |date= |accessdate=2009-07-17}}</ref> |

|||

== Geography == |

== Geography == |

||

=== Climate === |

|||

[[File:HiroshimaGembakuDome.jpg|thumb|topright|Atomic Bomb Dome]] |

|||

Hiroshima has a [[humid subtropical climate]] characterized by cool to mild winters and hot, humid summers. Like much of Japan, Hiroshima experiences a seasonal temperature lag in summer, with August rather than July being the warmest month of the year. Precipitation occurs year-round, although winter is the driest season. Rainfall peaks in June and July, with August experiencing sunnier and drier conditions. |

|||

<!--[[File:HiroshimaNight.jpg|thumb|topright|Hiroshima at night]]--> |

|||

{{Weather box |

|||

Hiroshima has eight [[Wards of Japan|wards]] (''ku''): |

|||

| location = Hiroshima (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1879–present) |

|||

| single line = Y |

|||

| metric first = Y |

|||

| Jan record high C = 18.8 |

|||

| Feb record high C = 21.5 |

|||

| Mar record high C = 23.7 |

|||

| Apr record high C = 29.0 |

|||

| May record high C = 31.5 |

|||

| Jun record high C = 34.4 |

|||

| Jul record high C = 38.7 |

|||

| Aug record high C = 38.1 |

|||

| Sep record high C = 37.4 |

|||

| Oct record high C = 31.4 |

|||

| Nov record high C = 26.3 |

|||

| Dec record high C = 22.3 |

|||

| Jan record low C = -8.5 |

|||

| Feb record low C = -8.3 |

|||

| Mar record low C = -7.2 |

|||

| Apr record low C = -1.4 |

|||

| May record low C = 1.8 |

|||

| Jun record low C = 6.6 |

|||

| Jul record low C = 14.1 |

|||

| Aug record low C = 13.7 |

|||

| Sep record low C = 8.6 |

|||

| Oct record low C = 1.5 |

|||

| Nov record low C = -2.6 |

|||

| Dec record low C = -8.6 |

|||

| precipitation colour = green |

|||

| Jan precipitation mm = 46.2 |

|||

| Feb precipitation mm = 64.0 |

|||

| Mar precipitation mm = 118.3 |

|||

| Apr precipitation mm = 141.0 |

|||

| May precipitation mm = 169.8 |

|||

| Jun precipitation mm = 226.5 |

|||

| Jul precipitation mm = 279.8 |

|||

| Aug precipitation mm = 131.4 |

|||

| Sep precipitation mm = 162.7 |

|||

| Oct precipitation mm = 109.2 |

|||

| Nov precipitation mm = 69.3 |

|||

| Dec precipitation mm = 54.0 |

|||

| year precipitation mm = 1572.2 |

|||

| Jan mean C = 5.4 |

|||

| Feb mean C = 6.2 |

|||

| Mar mean C = 9.5 |

|||

| Apr mean C = 14.8 |

|||

| May mean C = 19.6 |

|||

| Jun mean C = 23.2 |

|||

| Jul mean C = 27.2 |

|||

| Aug mean C = 28.5 |

|||

| Sep mean C = 24.7 |

|||

| Oct mean C = 18.8 |

|||

| Nov mean C = 12.9 |

|||

| Dec mean C = 7.5 |

|||

| year mean C = 16.5 |

|||

| Jan high C = 9.9 |

|||

| Feb high C = 10.9 |

|||

| Mar high C = 14.5 |

|||

| Apr high C = 19.8 |

|||

| May high C = 24.4 |

|||

| Jun high C = 27.2 |

|||

| Jul high C = 30.9 |

|||

| Aug high C = 32.8 |

|||

| Sep high C = 29.1 |

|||

| Oct high C = 23.7 |

|||

| Nov high C = 17.7 |

|||

| Dec high C = 12.1 |

|||

| year high C = 21.1 |

|||

| Jan low C = 1.6 |

|||

| Feb low C = 2.2 |

|||

| Mar low C = 5.1 |

|||

| Apr low C = 10.1 |

|||

| May low C = 15.1 |

|||

| Jun low C = 19.8 |

|||

| Jul low C = 24.1 |

|||

| Aug low C = 25.1 |

|||

| Sep low C = 21.1 |

|||

| Oct low C = 14.9 |

|||

| Nov low C = 8.9 |

|||

| Dec low C = 3.9 |

|||

| year low C = 12.7 |

|||

| Jan humidity = 66 |

|||

| Feb humidity = 65 |

|||

| Mar humidity = 62 |

|||

| Apr humidity = 61 |

|||

| May humidity = 63 |

|||

| Jun humidity = 71 |

|||

| Jul humidity = 73 |

|||

| Aug humidity = 69 |

|||

| Sep humidity = 68 |

|||

| Oct humidity = 66 |

|||

| Nov humidity = 67 |

|||

| Dec humidity = 68 |

|||

| year humidity = 67 |

|||

| Jan sun = 138.6 |

|||

| Feb sun = 140.1 |

|||

| Mar sun = 176.7 |

|||

| Apr sun = 191.9 |

|||

| May sun = 210.8 |

|||

| Jun sun = 154.6 |

|||

| Jul sun = 173.4 |

|||

| Aug sun = 207.3 |

|||

| Sep sun = 167.3 |

|||

| Oct sun = 178.6 |

|||

| Nov sun = 153.3 |

|||

| Dec sun = 140.6 |

|||

| year sun = 2033.1 |

|||

| Jan snow cm = 3 |

|||

| Feb snow cm = 3 |

|||

| Mar snow cm = 0 |

|||

| Apr snow cm = 0 |

|||

| May snow cm = 0 |

|||

| Jun snow cm = 0 |

|||

| Jul snow cm = 0 |

|||

| Aug snow cm = 0 |

|||

| Sep snow cm = 0 |

|||

| Oct snow cm = 0 |

|||

| Nov snow cm = 0 |

|||

| Dec snow cm = 2 |

|||

| year snow cm = 8 |

|||

| unit precipitation days = 0.5 mm |

|||

| Jan precipitation days = 6.8 |

|||

| Feb precipitation days = 8.3 |

|||

| Mar precipitation days = 10.6 |

|||

| Apr precipitation days = 9.9 |

|||

| May precipitation days = 9.7 |

|||

| Jun precipitation days = 11.9 |

|||

| Jul precipitation days = 11.6 |

|||

| Aug precipitation days = 8.6 |

|||

| Sep precipitation days = 9.6 |

|||

| Oct precipitation days = 7.1 |

|||

| Nov precipitation days = 6.9 |

|||

| Dec precipitation days = 7.6 |

|||

| year precipitation days = 108.6 |

|||

| source 1 = Japan Meteorological Agency<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/index.php?prec_no=67&block_no=47765&year=&month=&day=&view= |script-title=ja:気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値) |publisher=[[Japan Meteorological Agency]] |access-date=May 19, 2021 |archive-date=May 21, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210521160137/https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/index.php?prec_no=67&block_no=47765&year=&month=&day=&view= |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| source = |

|||

}} |

|||

===Wards=== |

|||

{|class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

Hiroshima has eight [[Wards of Japan|wards]] (''ku''): |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

!Ward |

!Ward |

||

!Japanese |

|||

!Population |

!Population |

||

!Area (km |

!Area (km<sup>2</sup>) |

||

!Density<br/>(per km |

!Density<br />(per km<sup>2</sup>) |

||

!Map |

!Map |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Aki-ku, Hiroshima|Aki-ku]] |

|[[Aki-ku, Hiroshima|Aki-ku]] (Aki ward) |

||

|安芸区 |

|||

|align=right|78,176 |

|||

|align=right| |

|align=right|80,702 |

||

|align=right| |

|align=right|94.08 |

||

|align=right|857 |

|||

|rowspan=8|[[File:Hiroshima wards.png|300px]] |

|rowspan=8|[[File:Hiroshima wards.png|300px]] |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Asakita-ku, Hiroshima|Asakita-ku]] |

|[[Asakita-ku, Hiroshima|Asakita-ku]] (Asa-North ward) |

||

|安佐北区 |

|||

|align=right|156,368 |

|||

|align=right| |

|align=right|148,426 |

||

|align=right| |

|align=right|353.33 |

||

|align=right|420 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Asaminami-ku, Hiroshima|Asaminami-ku]] |

|[[Asaminami-ku, Hiroshima|Asaminami-ku]] (Asa-south ward) |

||

|安佐南区 |

|||

|align=right|220,351 |

|||

|align=right| |

|align=right|241,007 |

||

|align=right| |

|align=right|117.24 |

||

|align=right|2,055 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Higashi-ku, Hiroshima|Higashi-ku]] |

|[[Higashi-ku, Hiroshima|Higashi-ku]] (East ward) |

||

|東区 |

|||

|align=right|122,045 |

|||

|align=right| |

|align=right|121,012 |

||

|align=right| |

|align=right|39.42 |

||

|align=right|3,069 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Minami-ku, Hiroshima|Minami-ku]] |

|[[Minami-ku, Hiroshima|Minami-ku]] (South ward) |

||

|南区 |

|||

|align=right|138,138 |

|||

|align=right| |

|align=right|141,219 |

||

|align=right| |

|align=right|26.30 |

||

|align=right|5,369 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Naka-ku, Hiroshima|Naka-ku]] |

|[[Naka-ku, Hiroshima|Naka-ku]] (Central ward)<br />*administrative center |

||

|中区 |

|||

|align=right|125,208 |

|||

|align=right| |

|align=right|130,879 |

||

|align=right| |

|align=right|15.32 |

||

|align=right|8,543 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Nishi-ku, Hiroshima|Nishi-ku]] |

|[[Nishi-ku, Hiroshima|Nishi-ku]] (West ward) |

||

|西区 |

|||

|align=right|184,881 |

|||

|align=right| |

|align=right|189,794 |

||

|align=right| |

|align=right|35.61 |

||

|align=right|5,329 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Saeki-ku, Hiroshima|Saeki-ku]] |

|[[Saeki-ku, Hiroshima|Saeki-ku]] (Saeki ward) |

||

|佐伯区 |

|||

|align=right|135,789 |

|||

|align=right| |

|align=right|137,838 |

||

|align=right| |

|align=right|225.22 |

||

|align=right|612 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| colspan="5" |<small>Population as of |

| colspan="5" |<small>Population as of March 31, 2016</small> |

||

|} |

|} |

||

=== Cityscape === |

|||

{{Infobox Weather |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" style="text-align: center;" heights="130" perrow="3" caption="Gallery"> |

|||

|location = Hiroshima, Japan (1971-2000) |

|||

File:An Overview of Hiroshima and the Hiroshima Memorial Peace Park as Seen From a Hotel Rooftop as Secretary Kerry Visited the City (26370244825).jpg|Hiroshima City [[Central business district|CBD]] (2016) |

|||

|metric_first= yes |

|||

File:Night views from Mount Kogane01.jpg|[[Skyline]] of Hiroshima City from Mount Futaba (2019) |

|||

|single_line= yes |

|||

File:North entrance of Hiroshima Station20210330.jpg|[[Hiroshima Station]] (2021) |

|||

|Jan_Hi_°C = 9.6 |Jan_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

File:鯉城通り - panoramio (1).jpg|Around [[Hondōri Station (Astram Line)|Hondōri Station]] (2010) |

|||

|Feb_Hi_°C = 10.2 |Feb_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

File:20100722 Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park 4478.jpg|[[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park]] (2010) |

|||

|Mar_Hi_°C = 13.8 |Mar_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

|Apr_Hi_°C = 19.5 |Apr_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|May_Hi_°C = 23.8 |May_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|Jun_Hi_°C = 26.9 |Jun_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|Jul_Hi_°C = 30.8 |Jul_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|Aug_Hi_°C = 32.1 |Aug_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|Sep_Hi_°C = 28.3 |Sep_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|Oct_Hi_°C = 23.0 |Oct_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|Nov_Hi_°C = 17.2 |Nov_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|Dec_Hi_°C = 12.3 |Dec_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|Year_Hi_°C = 20.6 |Year_REC_Hi_°C = |

|||

|Jan_Lo_°C = 1.7 |Jan_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Feb_Lo_°C = 1.8 |Feb_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Mar_Lo_°C = 4.5 |Mar_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Apr_Lo_°C = 9.8 |Apr_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|May_Lo_°C = 14.3 |May_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Jun_Lo_°C = 19.2 |Jun_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Jul_Lo_°C = 23.7 |Jul_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Aug_Lo_°C = 24.3 |Aug_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Sep_Lo_°C = 20.2 |Sep_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Oct_Lo_°C = 13.8 |Oct_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Nov_Lo_°C = 8.2 |Nov_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Dec_Lo_°C = 3.5 |Dec_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

|Year_Lo_°C = 12.1 |Year_REC_Lo_°C = |

|||

<!--Optional: Mean daily temperature --> |

|||

|Jan_MEAN_°C = 5.3 |

|||

|Feb_MEAN_°C = 5.7 |

|||

|Mar_MEAN_°C = 9.0 |

|||

|Apr_MEAN_°C = 14.6 |

|||

|May_MEAN_°C = 18.9 |

|||

|Jun_MEAN_°C = 22.8 |

|||

|Jul_MEAN_°C = 26.9 |

|||

|Aug_MEAN_°C = 27.9 |

|||

|Sep_MEAN_°C = 23.9 |

|||

|Oct_MEAN_°C = 18.0 |

|||

|Nov_MEAN_°C = 12.3 |

|||

|Dec_MEAN_°C = 7.5 |

|||

|Year_MEAN_°C = 16.1 |

|||

<!--**** use mm or cm but NOT both! ****--> |

|||

<!-- Optional: This is total Precipitation. Rain & Snow fields can be used instead if Precip is NOT filled in --> |

|||

|Jan_Precip_mm = 46.9 |

|||

|Feb_Precip_mm = 66.9 |

|||

|Mar_Precip_mm = 120.5 |

|||

|Apr_Precip_mm = 156.0 |

|||

|May_Precip_mm = 156.8 |

|||

|Jun_Precip_mm = 258.1 |

|||

|Jul_Precip_mm = 236.3 |

|||

|Aug_Precip_mm = 126.0 |

|||

|Sep_Precip_mm = 180.3 |

|||

|Oct_Precip_mm = 95.4 |

|||

|Nov_Precip_mm = 67.8 |

|||

|Dec_Precip_mm = 34.8 |

|||

|Year_Precip_mm = 1540.6 |

|||

===Demographics=== |

|||

<!-- Optional: Rain and Snow can be used if Precip IS NOT filled in --> |

|||

[[File:Hiroshima population pyramid in 2020.svg|thumb|299x299px|Hiroshima prefecture population pyramid in 2020]] |

|||

<!--**** use mm or cm but NOT both! ****--> |

|||

{{Historical populations |

|||

|Jan_Snow_cm = 5 |

|||

|title = Historical population |

|||

|Feb_Snow_cm = 6 |

|||

|type = Japan |

|||

|Mar_Snow_cm = 1 |

|||

|align = right |

|||

|Apr_Snow_cm = 0 |

|||

| |

|width = |

||

| |

|state = |

||

| |

|shading = |

||

| |

|percentages = |

||

| |

|footnote = |

||

|1920 | 160510 |

|||

|Oct_Snow_cm = 0 |

|||

|1925 | 195731 |

|||

|Nov_Snow_cm = 0 |

|||

|1930 | 270417 |

|||

|Dec_Snow_cm = 2 |

|||

|1935 | 310118 |

|||

|Year_Snow_cm = 13 |

|||

|1940 | 343968 |

|||

|1945 | 137197 |

|||

<!-- Optional: Average monthly Sunshine hours --> |

|||

|1950 | 285712 |

|||

|Jan_Sun= 137.5 |

|||

|1955 | 357287 |

|||

|Feb_Sun= 131.1 |

|||

|1960 | 540972 |

|||

|Mar_Sun= 166.3 |

|||

|1965 | 665289 |

|||

|Apr_Sun= 189.1 |

|||

|1970 | 798540 |

|||

|May_Sun= 205.7 |

|||

|1975 | 862611 |

|||

|Jun_Sun= 158.8 |

|||

|1980 | 992736 |

|||

|Jul_Sun= 182.9 |

|||

|1985 | 1044118 |

|||

|Aug_Sun= 201.5 |

|||

|1990 | 1085705 |

|||

|Sep_Sun= 154.9 |

|||

|1995 | 1105203 |

|||

|Oct_Sun= 180.2 |

|||

|2000 | 1134134 |

|||

|Nov_Sun= 149.3 |

|||

|2005 | 1151888 |

|||

|Dec_Sun= 147.8 |

|||

|2010 | 1174209 |

|||

|Year_Sun= 2004.9 |

|||

|2015 | 1186655 |

|||

|2020 | 1199186 |

|||

<!-- Optional: Average daily % Humidity --> |

|||

|Jan_Hum= 67 |

|||

|Feb_Hum= 67 |

|||

|Mar_Hum= 65 |

|||

|Apr_Hum= 64 |

|||

|May_Hum= 66 |

|||

|Jun_Hum= 73 |

|||

|Jul_Hum= 75 |

|||

|Aug_Hum= 71 |

|||

|Sep_Hum= 71 |

|||

|Oct_Hum= 69 |

|||

|Nov_Hum= 68 |

|||

|Dec_Hum= 69 |

|||

|Year_Hum= 69 |

|||

<!-- Optional: Average number of rainy, snowy and precipitation days --> |

|||

|Jan_Snow_days = 7.8 |

|||

|Feb_Snow_days = 7.6 |

|||

|Mar_Snow_days = 2.4 |

|||

|Apr_Snow_days = 0.0 |

|||

|May_Snow_days = 0.0 |

|||

|Jun_Snow_days = 0.0 |

|||

|Jul_Snow_days = 0.0 |

|||

|Aug_Snow_days = 0.0 |

|||

|Sep_Snow_days = 0.0 |

|||

|Oct_Snow_days = 0.0 |

|||

|Nov_Snow_days = 0.3 |

|||

|Dec_Snow_days = 4.3 |

|||

|source =<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url = http://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/view/nml_sfc_ym.php?prec_no=67&prec_ch=%8DL%93%87%8C%A7&block_no=47765&block_ch=%8DL%93%87&year=&month=&day=&elm=normal&view= |title = 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値) |publisher = [[Japan Meteorological Agency]]}}</ref> |

|||

|accessdate = 2009-06-08 |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

In 2017, the city had an estimated [[population]] of 1,195,327. The total area of the city is {{convert|905.08|km²|2|abbr=out}}, with a [[population density]] of 1321 persons per km<sup>2</sup>.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/www/contents/1522027456625/simple/29youran.pdf |script-title=ja:広島市勢要覧 |publisher=Government of Hiroshima City |access-date=2018-06-18 |archive-date=2018-06-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180618025750/http://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/www/contents/1522027456625/simple/29youran.pdf |url-status=dead}}</ref> As of 2023, the city has a population of 1,183,696.<ref>{{Cite web |title=人口,世帯数(町丁目別) – 統計情報{{!}}広島市公式ホームページ|国際平和文化都市 |url=https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/site/toukei/12649.html |access-date=2023-03-18 |website=www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp |archive-date=2023-03-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230318164409/https://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/site/toukei/12649.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

== Demographics == |

|||

[[File:Hondori.jpg|thumb|right|[[Hondori]] shopping arcade in Hiroshima]] |

|||

As of 2006, the '''city''' has an estimated [[population]] of 1,154,391, while the total population for the '''metropolitan area''' was estimated as 2,043,788 in 2000.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.stat.go.jp/English/data/kokusei/2000/final/hyodai.htm#21 |title=Population of Japan, Table 92 |publisher=Statistics Bureau |accessdate=2007-08-14}}</ref> The total area of the city is 905.08 km², with a [[population density|density]] of 1275.4 persons per km².<ref name="statprofile">{{cite web |url=http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/12_pro/profile-e.html |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20080206110108/http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/12_pro/profile-e.html |archivedate=2008-02-06 |title=2006 Statistical Profile |publisher=The City of Hiroshima |accessdate=2007-08-14}}</ref> |

|||

The population around 1910 was 143,000.<ref name="terry">{{cite book |title=Terry's Japanese Empire |author=Terry, Thomas Philip |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Co | |

The population around 1910 was 143,000.<ref name="terry">{{cite book |title=Terry's Japanese Empire |url=https://archive.org/details/terrysjapanesee00terrgoog |author=Terry, Thomas Philip |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Co |year=1914 |page=[https://archive.org/details/terrysjapanesee00terrgoog/page/n967 640]}}</ref> Before [[World War II]], Hiroshima's population had grown to 360,000, and peaked at 419,182 in 1942.<ref name="statprofile">{{cite web |url=http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/12_pro/profile-e.html |title=2006 Statistical Profile |publisher=The City of Hiroshima |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080206110108/http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/12_pro/profile-e.html |archive-date=February 6, 2008 |access-date=August 14, 2007}}</ref> Following the atomic bombing in 1945, the population dropped to 137,197.<ref name="statprofile"/> By 1955, the city's population had returned to pre-war levels.<ref>{{cite book |title=Post-conflict Reconstruction in Japan, Republic of Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, East Timor |last1=de Rham-Azimi |first1=Nassrine |first2=Matt |last2=Fuller |first3=Hiroko |last3=Nakayama |publisher=United Nations Publications |year=2003 |page=69}}</ref> |

||

=== Surrounding municipalities === |

|||

== Economy == |

|||

;[[Hiroshima Prefecture]] |

|||

Hiroshima is the center of industry for the [[Chūgoku]]-[[Shikoku]] region, and is by and large centered along the coastal areas. Hiroshima has long been a port city and Hiroshima port or [[Hiroshima Airport|Hiroshima International Airport]] can be used for the transportation of goods. |

|||

*[[Kure]] |

|||

[[File:HiroshimaNight.jpg|thumb|right|Hiroshima at night]] |

|||

*[[Higashihiroshima]] |

|||

*[[Akitakata, Hiroshima|Akitakata]] |

|||

*[[Hatsukaichi, Hiroshima|Hatsukaichi]] |

|||

*[[Akiōta, Hiroshima|Akiota]] |

|||

*[[Kitahiroshima, Hiroshima|Kitahiroshima]] |

|||

*[[Fuchū, Hiroshima (town)|Fuchū]] |

|||

*[[Saka, Hiroshima|Saka]] |

|||

*[[Kumano, Hiroshima|Kumano]] |

|||

*[[Kaita, Hiroshima|Kaita]] |

|||

==History== |

|||

Its largest industry is the manufacturing industry with core industries being the production of Mazda cars, car parts and industrial equipment. [[Mazda|Mazda Motor Corporation]] is by far Hiroshima's dominant company. Mazda accounts for 32% of Hiroshima's GDP.<ref>{{cite conference |author=Parker, J. |title=In Praise of Japanese Engineering; In Praise of Hiroshima |booktitle=Circuits and Systems |year=2004 |conference=47th Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems |volume=1}}</ref> Mazda makes many models in Hiroshima for worldwide export, including the popular [[Mazda Miata|MX-5/Miata]], [[Mazda Demio]](Mazda2), [[Mazda CX-9]] and [[Mazda RX-8]]. The [[Mazda CX-7]] has been built there since early 2006.{{Citation needed|date=May 2007}} Other Mazda factories are in [[Hofu, Yamaguchi|Hofu]] and [[Flat Rock, Michigan]]. |

|||

{{see also|Timeline of Hiroshima}} |

|||

[[File:MAZDA787B.jpg|thumb|200px|left|[[Mazda 787B]] at the Mazda Museum in Hiroshima]] |

|||

General machinery and equipment also account for a large portion of exports. Because these industries require research and design capabilities, it has also had the offshoot that Hiroshima has many innovative companies actively engaged in new growth fields (for example, Hiroshima Vehicle Engineering Company (HIVEC).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hivec.com |title=Hiroshima Vehicle Engineering Company |publisher=HIVEC |date= |accessdate=2009-07-17}}</ref> Many of these companies hold the top market shares in Japan and the world, or are alone in their particular field. Tertiary industries in the wholesale and retail areas are also very developed. |

|||

[[File:Hiroshima port.jpg|thumb|right|Hiroshima port and ferry terminal]] |

|||

Another result of the concentration of industry is an accumulation of skilled personnel and fundamental technologies. This is considered by business to be a major reason for location in Hiroshima. Business setup costs are also much lower than other large cities in the country and there is a comprehensive system of tax breaks, etc. on offer for businesses which locate in Hiroshima. This is especially true of two projects: the Hiroshima Station Urban Development District and the [[Seifu Shinto]] area which offer capital installments (up to 501 million yen over 5 years), tax breaks and employee subsidies.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.seifu-shinto.jp/index_f.html |title=広島市:ひろしま西風新都 |publisher=Seifu-shinto.jp |date= |accessdate=2009-07-17}}</ref> Seifu Shinto, which translates as West Wind, New Town is the largest construction project in the region and is an attempt to build "a city within a city." It is attempting to design from the ground up a place to work, play, relax and live. |

|||

=== Early history === |

|||

Hiroshima recently made it onto Lonely Planet's list of the top cities in the world. Commuting times rank amongst the shortest in Japan and the cost of living is lower than other large cities in Japan such as [[Tokyo]], [[Osaka]], [[Kyoto]], or [[Fukuoka, Fukuoka|Fukuoka]]. |

|||

The region where Hiroshima stands today was originally a small fishing village along the shores of Hiroshima Bay. From the 12th century, the village was rather prosperous and was economically attached to a [[Zen|Zen Buddhist]] temple called ''[[Mitaki-Ji]]''. This new prosperity was partly caused by the increase of trade with the rest of Japan under the auspices of the [[Taira clan]].<ref>{{Cite book |title=International Dictionary of Historic Places, Volume 5: Asia and Oceania |publisher=Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers |year=1996 |isbn=1-884964-04-4 |editor-last=Schellinger |editor-first=Paul |location=Chicago |pages=349 |editor-last2=Salkin |editor-first2=Robert}}</ref> |

|||

===Sengoku and Edo periods (1589–1871)=== |

|||

== Culture == |

|||

[[File:DSC00046.JPG|thumb|left|[[Hiroshima Castle]]]] |

|||

[[File:HiroshimaShukkeien7309.jpg|thumb|[[Shukkei-en]]]] |

|||

Hiroshima has a professional [[symphony orchestra]], which has performed at Wel City Hiroshima since 1963.<ref>[http://www.wel-hknk.com/ Wel City Hiroshima]</ref> There are also many museums in Hiroshima, including the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum]], along with several art museums. The [[Hiroshima Museum of Art]], which has a large collection of French [[renaissance]] art, opened in 1978. The [[Hiroshima Prefectural Art Museum]] opened in 1968, and is located near [[Shukkei-en]] gardens. The [[Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art]], which opened in 1989, is located near [[Hijiyama]] Park. Festivals include [[Hiroshima Flower Festival]] and [[Hiroshima International Animation Festival]]. |

|||

Hiroshima was established on the delta coastline of the [[Seto Inland Sea]] in 1589 by powerful warlord [[Mōri Terumoto]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/History-E/c01.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080130190042/http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/History-E/c01.html |archive-date=January 30, 2008 |title=The Origin of Hiroshima |publisher=Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation |access-date=August 17, 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://aboutjapan.japansociety.org/content.cfm/hiroshima_history_city_event |title=Hiroshima: History, City, Event |author=Scott O'Bryan |year=2009 |publisher=About Japan: A Teacher's Resource |access-date=March 14, 2010 |archive-date=July 27, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110727131904/http://aboutjapan.japansociety.org/content.cfm/hiroshima_history_city_event |url-status=live }}</ref> [[Hiroshima Castle]] was quickly built, and in 1593 Mōri moved in. The name Hiroshima means wide island in Japanese. Terumoto was on the losing side at the [[Battle of Sekigahara]]. The winner of the battle, [[Tokugawa Ieyasu]], deprived Mōri Terumoto of most of his fiefs, including Hiroshima and gave [[Aki Province]] to [[Fukushima Masanori|Masanori Fukushima]], a ''[[daimyō]]'' (Feudal Lord) who had supported Tokugawa.<ref name="Kosaikai">{{cite book |author=Kosaikai, Yoshiteru |title=Hiroshima Peace Reader |publisher=Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation |year=2007 |chapter=History of Hiroshima}}</ref> From 1619 until 1871, Hiroshima was ruled by the [[Asano clan]]. |

|||

[[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park]], which includes the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial]], draws many visitors from around the world, especially for the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony]], an annual commemoration held on the date of the atomic bombing. The park also contains a large collection of monuments, including the [[Children's Peace Monument]], the [[Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims]] and many others. |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" style="text-align: center;" caption="Gallery" heights="130px" perrow="3"> |

|||

File:Mitaki-dera Taho-to.jpg|[[Mitaki-dera]] |

|||

File:Fudoin Kondo.jpg|Fudoin |

|||

File:Hiroshima-Castle-1.jpg|[[Hiroshima Castle]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

===Meiji and Showa periods (1871–1939)=== |

|||

[[Hiroshima Castle|Hiroshima's rebuilt castle]] (nicknamed ''Rijō'', meaning ''[[Koi]] Castle'') houses a [[museum]] of life in the [[Edo period]]. [[Hiroshima Gokoku Shrine]] is within the walls of the castle. Other attractions in Hiroshima include [[Shukkei-en]], Fudōin, [[Mitaki-dera]], and [[Hijiyama Park]]. |

|||

After the [[Han system|Han]] was abolished in 1871, the city became the capital of [[Hiroshima Prefecture]]. Hiroshima became a major urban center during the [[Empire of Japan|imperial period]], as the Japanese economy shifted from primarily rural to urban industries. During the 1870s, one of the seven government-sponsored English language schools was established in Hiroshima.<ref>Bingham (US Legation in Tokyo) to Fish (US Department of State), September 20, 1876, in ''Papers relating to the foreign relations of the United States, transmitted to congress, with the annual message of the president, December 4, 1876'', p. 384</ref> Ujina Harbor was constructed through the efforts of Hiroshima Governor [[Sadaaki Senda]] in the 1880s, allowing Hiroshima to become an important port city. |

|||

The [[San'yō Railway]] was extended to Hiroshima in 1894, and a rail line from the main station to the harbor was constructed for military transportation during the [[First Sino-Japanese War]].<ref name="Kosakai"/> During that war, the [[Government of Japan|Japanese government]] moved temporarily to Hiroshima, and [[Emperor Meiji]] maintained his headquarters at [[Hiroshima Castle]] from September 15, 1894, to April 27, 1895.<ref name="Kosakai">Kosakai, ''Hiroshima Peace Reader''</ref> The significance of Hiroshima for the Japanese government can be discerned from the fact that the first round of talks between Chinese and Japanese representatives to end the Sino-Japanese War was held in Hiroshima, from February 1 to 4, 1895.<ref>Dun (US Legation in Tokyo) to Gresham, February 4, 1895, in ''Foreign relations of United States, 1894'', Appendix I, p. 97</ref> New industrial plants, including [[cotton mill]]s, were established in Hiroshima in the late 19th century.<ref>{{cite book |title=The Origin of Modern Capitalism and Eastern Asia |author=Jacobs, Norman |publisher=Hong Kong University |year=1958 |page=51}}</ref> Further industrialization in Hiroshima was stimulated during the [[Russo-Japanese War]] in 1904, which required development and production of military supplies. The Hiroshima Prefectural Commercial Exhibition Hall was constructed in 1915 as a center for trade and the exhibition of new products. Later, its name was changed to Hiroshima Prefectural Product Exhibition Hall, and again to Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall.<ref>{{cite book |author=Sanko |title=Hiroshima Peace Memorial (Genbaku Dome) |year=1998 |publisher=The City of Hiroshima and the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation}}</ref> The building, now known as the A-Bomb Dome, part of the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial]], a [[World Heritage Site]] since 1996, permanently remains the only structure still standing and is a state of preserved ruin. |

|||

=== Cuisine === |

|||

[[File:Okonomiyaki 2.jpg|thumb|left|A man prepares [[okonomiyaki]] in a restaurant in Hiroshima]] |

|||

Hiroshima is known for [[okonomiyaki]], cooked on a hot-plate (usually right in front of the customer). It is cooked with various ingredients, which are layered rather than mixed together as done with the [[Osaka]] version of okonomiyaki. The layers are typically egg, cabbage, [[moyashi]], sliced pork/bacon with optional items (mayonnaise, fried squid, octopus, cheese, [[mochi]], [[kimchi]], etc.), and noodles ([[soba]], [[udon]]) topped with another layer of egg and a generous dollop of okonomiyaki sauce (Carp and Otafuku are two popular brands). The amount of cabbage used is usually 3 - 4 times the amount used in the Osaka style, therefore arguably a healthier version. It starts out piled very high and is generally pushed down as the cabbage cooks. The order of the layers may vary slightly depending on the chef's style and preference, and ingredients will vary depending on the preference of the customer. |

|||

During [[World War I]], Hiroshima became a focal point of military activity, as the Japanese government joined the Allied at war. About 500 German POWs were held in Ninoshima Island in Hiroshima Bay.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.hiroshimapeacemedia.jp/mediacenter/article.php?story=20100901131622626_en |title=Hiroshima's contribution to food culture tied to A-bomb Dome|Opinion|Hiroshima Peace Media Center |access-date=2010-09-03 |archive-date=2013-10-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131025030048/http://www.hiroshimapeacemedia.jp/mediacenter/article.php?story=20100901131622626_en |url-status=dead}}</ref> The growth of Hiroshima as a city continued after the First World War, as the city now attracted the attention of the Catholic Church, and on May 4, 1923, an [[Apostolic Vicar]] was appointed for that city.<ref>{{Catholic-hierarchy|diocese|dhiro|Diocese of Hiroshima|January 21, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

=== Media === |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" style="text-align: center;" caption="Gallery" heights="130px" perrow="3"> |

|||

The [[Chugoku Shimbun]] is the local newspaper serving Hiroshima. It publishes both morning paper and evening editions. Television stations include [[Hiroshima Home TV]], [[Hiroshima TV]], [[TV Shinhiroshima]], and the [[RCC Broadcasting Company]]. Radio stations include [[Hiroshima FM]], [[Chugoku Communication Network]], [[FM Fukuyama]], [[FM Nanami]], and [[Onomichi FM]]. Hiroshima is also served by [[NHK]], Japan's public broadcaster, with television and radio broadcasting. |

|||

File:Mitsui Bank Hiroshima Branch 1928 - 1.jpg|Old [[Mitsui Bank]] Hiroshima Branch (1928) |

|||

File:Hiroshima map circa 1930.PNG|Map of Hiroshima City in the 1930s (Japanese edition) |

|||

File:Hiroshima University Hospital 04.jpg|Old Hiroshima Army Weapon Depot |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

===World War II and the atomic bombing (1939–1945)=== |

|||

=== Sports === |

|||

{{main|Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki#Hiroshima}} |

|||

[[File:Hiroshima Municipal Stadium 1.jpg|thumb|right|Hiroshima Municipal Stadium]] |

|||

<!-- Note to editors: This article is for an overview. Please do not add details. Instead, add details to the main article "Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". --> |

|||

Hiroshima is home to several professional and non-professional sports teams. [[Baseball]] fans immediately recognize the city as the home of the [[Hiroshima Toyo Carp]]. Six-time champions of Japan's [[Central League]], the team has gone on to win the [[Japan Series]] three times. Kohei Matsuda, owner of [[Mazda|Toyo Kogyo]], was primary owner of the team from the 1970s until his death in 2002.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/sb20020712a2.html |title=Carp owner dies |publisher=The Japan Times |date=July 12, 2002 |accessdate=2009-07-26}}</ref> The team is now owned by members of the Matsuda family, while [[Mazda]] has minority ownership of the team. [[Hiroshima Municipal Stadium]], which was built in 1957, was the home of the Hiroshima Carp from the time it was built until the end of the 2008 season. The stadium is located in central Hiroshima, across from the A-Bomb Dome. The city is building a new baseball stadium near the JR Hiroshima Station, to be ready for the 2009 season.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://search.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/sb20070304wg.html |title=New stadium in Hiroshima looking good for 2009 season |publisher=The Japan Times |author=Graczyk, Wayne |date=March 4, 2007 |accessdate=2009-07-26}}</ref> [[Sanfrecce Hiroshima]] is the city's [[J. League|professional]] [[Football (soccer)|football]] team; they won the [[List of Japanese football champions|Japanese league championship]] five times in the late 1960s and have remained one of Japan's traditionally strong football clubs. In 1994, the city of Hiroshima hosted the [[Asian Games]]. |

|||

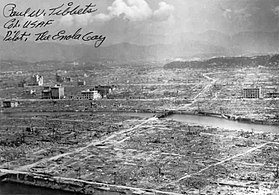

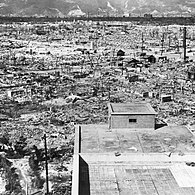

During [[World War II]], the [[Second General Army (Japan)|Second General Army]] and Chūgoku Regional Army was headquartered in Hiroshima, and the Army Marine Headquarters was located at Ujina port. The city also had large depots of military supplies, and was a key center for shipping.<ref name="effects">{{cite web |url=http://www.nuclearfiles.org/redocuments/1946/460619-bombing-survey1.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20041011111052/http://www.nuclearfiles.org/redocuments/1946/460619-bombing-survey1.html |archive-date=October 11, 2004 |title=U. S. Strategic Bombing Survey: The Effects of the Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki |date=June 1946 |author=United States Strategic Bombing Survey |publisher=nuclearfiles.org |access-date=July 26, 2009}}</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" border="1" |

|||

|- |

|||

The [[bombing of Tokyo]] and [[Air raids on Japan|other cities in Japan]] during World War II caused widespread destruction and hundreds of thousands of civilian deaths.<ref>{{cite book |title=Bombing to Win: Airpower and Coercion in War |last=Pape |first=Robert |year=1996 |publisher=Cornell University Press |isbn=978-0-8014-8311-0 |page=129}}</ref> There were no such air raids on Hiroshima. However, a real threat existed and was recognized. To protect against potential [[firebombing]]s in Hiroshima, school children aged 11–14 years were mobilized to demolish houses and create [[firebreak]]s.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.chugoku-np.co.jp/abom/97e/peace/e/03/omoide.htm |title=Japan in the Modern Age and Hiroshima as a Military City |publisher=The Chugoku Shimbun |access-date=August 19, 2007 |archive-date=August 20, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070820001539/http://www.chugoku-np.co.jp/abom/97e/peace/e/03/omoide.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

!scope="col"| Club |

|||

!scope="col"| Sport |

|||

On Monday, August 6, 1945, at 8:15 a.m. (Hiroshima time), the American [[Boeing B-29 Superfortress]], the ''[[Enola Gay]]'', flown by [[Paul Tibbets]] (23 February 1915 – 1 November 2007), dropped the [[nuclear weapon]] "[[Little Boy]]" on Hiroshima,<ref>[http://www.cfo.doe.gov/me70/manhattan/hiroshima.html The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303233319/http://www.cfo.doe.gov/me70/manhattan/hiroshima.html |date=March 3, 2016 }}, U.S. Department of Energy, Office of History and Heritage Resources.</ref> directly killing at least 70,000 people, including thousands of [[Koreans|Korean slave laborers]]. Fewer than 10% of the casualties were military.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Barton |last=Bernstein |title=Reconsidering the 'Atomic General': Leslie R. Groves |journal=Journal of Military History |volume=67 |issue=3 |date=July 2003 |pages=904–905 |doi=10.1353/jmh.2003.0198 |s2cid=161380682 |url=https://muse.jhu.edu/article/44239 |access-date=2019-05-20 |archive-date=2020-03-22 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200322095315/https://muse.jhu.edu/article/44239 |url-status=live | issn = 0899-3718 }}</ref> By the end of the year, injury and radiation brought the total number of deaths to 90,000–140,000.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.rerf.or.jp/general/qa_e/qa1.html |title=Frequently Asked Questions – Radiation Effects Research Foundation |publisher=Rerf.or.jp |access-date=July 29, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070919143939/http://www.rerf.or.jp/general/qa_e/qa1.html |archive-date=September 19, 2007 |url-status=dead}}</ref> The population before the bombing was around 345,000. About 70% of the city's buildings were destroyed, and another 7% severely damaged. |

|||

!scope="col"| League |

|||

!scope="col"| Venue |

|||

The public release of film footage of the city following the attack, and some of the [[Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission]] research on the human effects of the attack, were restricted during the [[occupation of Japan]], and much of this information was censored until the signing of the [[Treaty of San Francisco]] in 1951, restoring control to the Japanese.<ref>Ishikawa and Swain (1981), p. 5</ref> |

|||

!scope="col"| Established |

|||

|- style="text-align:center;" |

|||

As [[Ian Buruma]] observed: {{blockquote|News of the amazing explosion of the atom bomb attacks on Japan was deliberately withheld from the Japanese public by US military censors during the Allied occupation—even as they sought to teach the natives the virtues of a free press. Casualty statistics were suppressed. Film shot by Japanese cameramen in Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the bombings was confiscated. "Hiroshima", the account written by John Hersey for ''The New Yorker'', had a huge impact in the US, but was banned in Japan. As [John] Dower says: "In the localities themselves, suffering was compounded not merely by the unprecedented nature of the catastrophe ... but also by the fact that public struggle with this traumatic experience was not permitted."<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Seldon |first=Mark |date=December 2016 |title=American Fire Bombing and Atomic Bombing of Japan in History and Memory |url=https://apjjf.org/2016/23/Selden.html |journal=The Asia-Pacific Journal |volume=14 |via=Japan Focus |access-date=2019-03-26 |archive-date=2019-03-26 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190326231734/https://apjjf.org/2016/23/Selden.html |url-status=live }}</ref>}} |

|||

| [[Hiroshima Toyo Carp]] |

|||

| [[Baseball]] |

|||

The book ''[[Hiroshima (book)|Hiroshima]]'' by [[John Hersey]] was originally published in article form in the magazine ''[[The New Yorker]]'',<ref name="autogenerated3"/> on August 31, 1946. It is reported to have reached Tokyo, in English, at least by January 1947 and the translated version was released in Japan in 1949.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2009/08/16/books/the-pure-horror-of-hiroshima/#.UdhVsfnVDTc |title=The pure horror of Hiroshima |work=[[The Japan Times]] |first=Donald |last=Richie |date=August 16, 2009 |access-date=August 11, 2021 |url-status=live |url-access=subscription |archive-date=August 6, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200806215706/https://www.japantimes.co.jp/culture/2009/08/16/books/the-pure-horror-of-hiroshima/#.UdhVsfnVDTc }}</ref> Although the article was planned to be published over four issues, "Hiroshima" made up the entire contents of one issue of the magazine.<ref name="ReferenceA">Sharp, "From Yellow Peril to Japanese Wasteland: John Hersey's 'Hiroshima'", Twentieth Century Literature 46 (2000): 434–452, accessed March 15, 2012.</ref><ref name="The New Yorker 2010">Jon Michaub, "Eighty-Five From the Archive: John Hersey" ''The New Yorker'', June 8, 2010, np.</ref> ''Hiroshima'' narrates the stories of [[Hibakusha|six bomb survivors]] immediately before and four months after the dropping of the [[Little Boy]] bomb.<ref name=autogenerated3>Roger Angell, From the Archives, "Hersey and History", ''The New Yorker'', July 31, 1995, p. 66.</ref><ref name=autogenerated4>John Hersey, Hiroshima (New York: Random House, 1989).</ref> |

|||

| [[Central League]] |

|||

| [[Hiroshima Municipal Stadium]] |

|||

Oleander (''[[Nerium]]'') is the official flower of the city of Hiroshima because it was the first to bloom again after the explosion of the atomic bomb in 1945.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/www/contents/0000000000000/1112000428867/ |script-title=ja:広島市 市の木・市の花 |access-date=July 15, 2012 |archive-date=April 8, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140408231422/http://www.city.hiroshima.lg.jp/www/contents/0000000000000/1112000428867/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| 1949 |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" style="text-align: center;" caption="Gallery" heights="130px" perrow="3"> |

|||

File:Hiroshima aftermath.jpg|Hiroshima August 1945 |

|||

| [[Sanfrecce Hiroshima]] |

|||

File:AtomicEffects-Hiroshima.jpg|Hiroshima in October 1945, two months after the bombing |

|||

| [[Football (soccer)|Football]] |

|||

File:Looking South East General view looking south east building 5H-21 (5-H).jpg|Old [[Mitsui Bank|Teikoku Bank]] Hiroshima Branch (1945) |

|||

| [[J. League]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

| [[Hiroshima Big Arch]] |

|||

| 1938 |

|||

===Postwar period (1945–present)=== |

|||

|- style="text-align:center;" |

|||

[[File:Emperor Showa visit to Hiroshima in 1947.JPG|thumb|237px|Emperor [[Hirohito]] visiting Hiroshima in 1947, where he held a speech encouraging the city's citizens in the aftermath of the war. The domed [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial]] can be seen in the background.]] |

|||

| [[JT Thunders]] |

|||

On September 17, 1945, Hiroshima was struck by the Makurazaki Typhoon ([[Typhoon Ida (1945)|Typhoon Ida]]). [[Hiroshima Prefecture]] suffered more than 3,000 deaths and injuries, about half the national total.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://excite.co.jp/world/english/web/body/?wb_url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.bioweather.net%2Fcolumn%2Fweather%2Fcontents%2Fmame068.htm&wb_submit=%83E%83F%83u%83y%81%5B%83W%96%7C%96%F3&wb_lp=JAEN&wb_dis=2 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120710150554/http://excite.co.jp/world/english/web/body/?wb_url=http://www.bioweather.net/column/weather/contents/mame068.htm&wb_submit=%83E%83F%83u%83y%81%5B%83W%96%7C%96%F3&wb_lp=JAEN&wb_dis=2 |url-status=dead |archive-date=July 10, 2012 |script-title=ja:Excite エキサイト |access-date=August 7, 2018 }}</ref> More than half the bridges in the city were destroyed, along with heavy damage to roads and railroads, further devastating the city.<ref>Ishikawa and also Swain (1981), p. 6</ref> |

|||

| [[Volleyball]] |

|||

| [[V.League (Japan)|V.League]] |

|||

From 1945 to 1952, Hiroshima came under [[British Commonwealth Occupation Force|occupation from the British Empire]]. |

|||

| [[Nekoda Memorial Gymnasium|Nekota Kinen Taiikukan]] |

|||

| 1931 |

|||

Hiroshima was rebuilt after the war, with help from the national government through the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Law passed in 1949. It provided financial assistance for reconstruction, along with land donated that was previously owned by the national government and used by the Imperial military.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/History-E/c05.html |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20080206124545/http://www.city.hiroshima.jp/kikaku/joho/toukei/History-E/c05.html |archive-date=February 6, 2008 |title=Peace Memorial City, Hiroshima |publisher=Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation |access-date=August 14, 2007}}</ref> |

|||

|- style="text-align:center;" |

|||

| [[Hiroshima Maple Reds]] |

|||

| [[Team handball|Handball]] |

|||

| [[Japan Handball League]] |

|||

| [[Hirogin no mori Taiikukan]] |

|||

| 1994 |

|||

|} |

|||

In 1949, a design was selected for the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park]]. Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, the closest surviving building to the location of the bomb's detonation, was designated the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial|Genbaku Dome (原爆ドーム) or "Atomic Dome"]], a part of the [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park]]. The [[Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum]] was opened in 1955 in the Peace Park.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/virtual/VirtualMuseum_e/exhibit_e/exh0507_e/exh050701_e.html |title=Fifty Years for the Peace Memorial Museum |publisher=Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum |access-date=August 17, 2007 |archive-date=August 30, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070830055255/http://www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/virtual/VirtualMuseum_e/exhibit_e/exh0507_e/exh050701_e.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The historic castle of Hiroshima was rebuilt in 1958. |

|||

=== Education === |

|||

[[File:HiroshimaUniv SatakeMemorialHall.jpg|thumb|right|Satake Memorial Hall at Hiroshima University]] |

|||

[[Hiroshima University]] was established in 1949, as part of a national restructuring of the education system. One national university was set-up in each [[prefecture]], including Hiroshima University, which combined eight existing institutions (Hiroshima University of Literature and Science, Hiroshima School of Secondary Education, Hiroshima School of Education, Hiroshima Women's School of Secondary Education, Hiroshima School of Education for Youth, Hiroshima Higher School, Hiroshima Higher Technical School, and Hiroshima Municipal Higher Technical School), with the Hiroshima Prefectural Medical College added in 1953.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/category_view.php?category_child_id=2&category_id=8&template_id=14&lang=en |title=History of Hiroshima University |publisher=Hiroshima University |accessdate=2007-06-25}}</ref> |

|||

Hiroshima also contains a [[Peace Pagoda]], built in 1966 by [[Nipponzan-Myōhōji]]. Uniquely, the pagoda is made of [[steel]], rather than the usual stone.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://japandeluxetours.com/experiences/hiroshima-peace-memorial-park |title=Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park |publisher=Japan Deluxe Tours |access-date=May 23, 2017 |archive-date=January 9, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170109032854/https://japandeluxetours.com/experiences/hiroshima-peace-memorial-park |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

== Transportation == |

|||

Local public transportation in Hiroshima is provided by a [[Tram|streetcar]] system, operated by Hiroshima Electric Railway called {{Nihongo|"Hiroden"|広電}} for short. Hiroden also operates [[bus]]es in and around [[Hiroshima Prefecture]]. Hiroshima Electric Railway was established on June 18, 1910, in Hiroshima. While many other Japanese cities abandoned the streetcar system by the 1980s, Hiroshima retained it because the construction of a subway system was too expensive for the city to afford, as it is located on a delta. During the 1960s, [[Hiroshima Electric Railway]], or Hiroden, bought extra streetcars from other Japanese cities. Although streetcars in Hiroshima are now being replaced by newer models, most retain their original appearance. Thus, the streetcar system is sometimes called a "Moving Museum" by railroad buffs. Of the four streetcars that survived the war, two are still in operation as of July 2006 ([[:File:Hiroden-hibakudensya PICT2443.JPG|Hiroden Numbers 651 and 652]]). There are seven [[Hiroden Streetcar Lines and Routes|streetcar lines]], many of which terminate at [[Hiroshima Station]]. |

|||

[[File:Hiroden-5100-2.jpg|thumb|right|220px|[[Light rail|LRT]]]] |

|||

[[File:Hiroden no6.jpg|thumb|left|Hiroden streetcar]] |

|||

The [[Astram Line]] opened for the [[1994 Asian Games]] in Hiroshima, with one line from central Hiroshima to [[Seifu Shinto]] and [[Hiroshima Big Arch]], the main [[stadium]] of the [[Asian Games]]. Astram uses [[rubber-tyred metro]] cars, and provides service to areas towards the suburbs that are not served by Hiroden streetcars.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.gk-design.co.jp/dsh/English/TP/TP_01.html |title=Astram Line |publisher=Design Soken Hiroshima Inc |accessdate=2007-08-14}}</ref> The [[Skyrail Midorizaka Line]] is a [[monorail]] that operates between Midoriguchi and Midori-Chūō, serving three stops. |

|||

Hiroshima was proclaimed a City of Peace by the Japanese parliament in 1949, at the initiative of its mayor, [[Shinzo Hamai]] (1905–1968).{{citation needed|date=January 2024}} As a result, the city of Hiroshima received more international attention as a desirable location for holding international conferences on peace as well as social issues.{{citation needed|date=January 2024}} As part of that effort, the Hiroshima Interpreters' and Guide's Association (HIGA) was established in 1992 to facilitate interpretation for conferences, and the Hiroshima Peace Institute was established in 1998 within the [[Hiroshima University]]. The city government continues to advocate the abolition of all [[nuclear weapon]]s and the Mayor of Hiroshima is the president of [[Mayors for Peace]], an international Mayoral organization mobilizing cities and citizens worldwide to abolish and eliminate nuclear weapons [[2020 Vision Campaign|by 2020]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/hiroshima.htm |title=Surviving the Atomic Attack on Hiroshima, 1944 |publisher=Eyewitnesstohistory.com |date=August 6, 1945 |access-date=July 17, 2009 |archive-date=August 5, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090805180140/http://www.eyewitnesstohistory.com/hiroshima.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/library/media-gallery/video/hiroshima-aftermath |title=Library: Media Gallery: Video Files: Rare film documents devastation at Hiroshima |publisher=Nuclear Files |access-date=July 17, 2009 |archive-date=June 23, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090623222755/http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/library/media-gallery/video/hiroshima-aftermath/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The [[West Japan Railway Company|JR West]] Hiroshima Station offers [[inter-city rail]] service, including [[Sanyō Shinkansen]] which provides high speed service between [[Shin-Ōsaka Station|Shin-Ōsaka]] and [[Fukuoka, Fukuoka|Fukuoka]]. Sanyō Shinkansen began providing service to Hiroshima in 1975, when the Osaka-Hakata extension opened.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.japan-guide.com/e/e2018.html |title=Shinkansen |publisher=japan-guide.com |accessdate=2007-08-17}}</ref> Other rail service includes the [[Sanyō Main Line]], [[Kabe Line]], [[Geibi Line]], and [[Kure Line]]. |

|||