Basra: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m the right name is Al-Basrah in Arabic |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

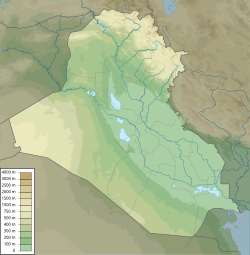

[[Image:Basra_location.PNG|thumb|Location of Basra]] |

|||

{{Redirect|Basrah|the village in eastern Yemen|Basrah, Yemen}} |

|||

{{Distinguish|Bosra|Busra al-Harir|Bozrah}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=July 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

|||

| official_name = Basra |

|||

| other_name = Basrah |

|||

| native_name = ٱلْبَصْرَة |

|||

| native_name_lang = ar |

|||

| nickname = Venice of the East<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.csmonitor.com/2007/0918/p11s02-wome.html |title=In the 'Venice of the East,' a history of diversity |date=18 September 2007 |author=Sam Dagher |newspaper=[[The Christian Science Monitor]] |access-date=2 January 2014}}</ref> |

|||

| settlement_type = [[List of cities in Iraq|Metropolis]] |

|||

| motto = |

|||

| image_skyline = {{Photomontage |

|||

| photo1a = Bridge of Basra 2.jpg |

|||

| photo2a = Basra Museum in Iraq April 2017.jpg |

|||

| photo2b = Basra train.jpg |

|||

| photo3a = شط العرب البصرة.jpg |

|||

| photo3b = Mnawibashahotel.jpg |

|||

| photo4a = Basra at night.jpg |

|||

| photo4b = ساحة الحرية.jpg |

|||

| photo5a = |

|||

| spacing = 2 |

|||

| size = 280 |

|||

}} |

|||

| image_caption = Basra along [[Shatt al-Arab]], Al-Ashar River, Basrah Museum, Ottoman Viceroy House and Basra International Hotel |

|||

| image_size = 275 |

|||

| image_shield = |

|||

| shield_size = |

|||

| image_map = |

|||

| map_caption = |

|||

| pushpin_map = Iraq#Near East |

|||

| pushpin_label_position = left |

|||

| pushpin_relief = yes |

|||

| pushpin_mapsize = |

|||

| pushpin_map_caption = Location of Basra within Iraq |

|||

| subdivision_type = Country |

|||

| subdivision_name = {{flag|Iraq}} |

|||

| subdivision_type1 = Governorate |

|||

| subdivision_name1 = [[Basra Governorate|Basra]] |

|||

| subdivision_type2 = |

|||

| subdivision_name2 = |

|||

| government_type = [[Mayor–council government|Mayor–council]] |

|||

| leader_title = Mayor |

|||

| leader_name = [[Asaad Al Eidani]] |

|||

| leader_title1 = |

|||

| leader_name1 = |

|||

| established_title = Founded |

|||

| established_date = 636 AD |

|||

| established_title2 = |

|||

| established_date2 = |

|||

| unit_pref = Metric |

|||

| area_footnotes = |

|||

| area_total_km2 = 50-75 |

|||

| area_land_km2 = |

|||

| area_water_km2 = |

|||

| area_water_percent = |

|||

| area_metro_km2 = 181 |

|||

| population_as_of = 2024 |

|||

| population_footnotes = |

|||

| population_total = 1,485,000<ref>{{Cite web |title=Basra, Iraq Metro Area Population 1950-2024 |url=https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/cities/21530/basra/population |access-date=2024-06-05 |website=macrotrends.net}}</ref> |

|||

| population_density_km2 = |

|||

| timezone = [[UTC+3]] ([[Arabian Standard Time|AST]]) |

|||

| utc_offset = |

|||

| timezone_DST = |

|||

| utc_offset_DST = |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|30|30|54|N|47|48|36|E|region:IQ|display=inline,title}} |

|||

| elevation_footnotes = |

|||

| elevation_m = 5 |

|||

| postal_code_type = |

|||

| postal_code = |

|||

| area_code = (+964) 40 |

|||

| website = {{URL|http://www.basra.gov.iq/}} |

|||

| footnotes = |

|||

| name = |

|||

| image_map1 = {{Infobox mapframe |shape-fill-opacity=.1|wikidata=yes |zoom=11 |frame-height=300 | stroke-width=1 |frame-coord={{WikidataCoord|display=i}}|point = none}} |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Al-Basrah''' ({{langx|ar|ٱلْبَصْرَة|al-Baṣrah}}) is a port city in southern [[Iraq]]. It is the capital of the eponymous [[Basra Governorate]], as well as the [[List of largest cities of Iraq|third largest]] city in Iraq overall, behind only [[Baghdad]] and [[Mosul]]. Located near the [[Iran–Iraq border]] at the north-easternmost extent of the [[Arabian Peninsula]], the city is situated along the banks of the [[Shatt al-Arab]] that empties into the [[Persian Gulf]]. Basra is consistently one of the hottest cities in Iraq, with summer temperatures regularly exceeding {{convert|50|C}}. The hottest recorded temperature in Basra is 53.9°C. A major industrial center of Iraq, the majority of the city's population are [[Shia Arab|Shi'ite Muslim Arabs]]. |

|||

The city was built in 636. It played an important role as a regional hub of trade and commerce in the [[Islamic Golden Age]]. Historically, Basra is one of the ports, from which the fictional [[Sinbad the Sailor]] journeyed. During the Islamic era, the city expanded rapidly. It was [[Safavid occupation of Basra|occupied]] by the [[Safavid]], from 1697 to 1701. Basra came under [[Portuguese rule|Portuguese control]], from 1526 to 1668. The city remained under the administration of the Ottoman Empire, as part of [[Basra vilayet]], which was populated mainly by Shi'ite Muslims and flourished as a commercial and trade center. During the [[World War I]], the British forces captured Basra and incorporated it into the [[Mandate for Mesopotamia]], and subsequently [[Mandatory Iraq]], and later the independent Kingdom of Iraq in 1932. |

|||

'''Basra''' (also spelled '''Başrah''' or '''Basara'''; historically sometimes written '''Busra''', '''Busrah''', and the early form '''Bassorah'''; {{lang-ar|البصرة}}, ''Al-Basrah'') is the second largest [[city]] of [[Iraq]] with an estimated population of c. 1,377,000 ([[2003]]). It is the country's main [[port]]. Basra is the capital of the [[Basra province]]. |

|||

The city is located along the [[Shatt al-Arab]] (Arvandrood) waterway near the [[Persian Gulf]]. Basra is [[1 E4 m|55 km]] from the Persian Gulf and [[1 E5 m|545 km]] from [[Baghdad]], Iraq's capital and largest city. |

|||

It became an important industrial center in the Persian Gulf. During the [[Iran–Iraq War]], Basra was heavily shelled and besieged by the Iranian forces. The city suffered heavy damage during the Gulf War. It was a major center for the [[1991 Iraqi uprisings|1991]] and [[1999 Shia uprising in Iraq|1999 uprisings in Iraq]]. Basra was the first city to be occupied by the coalition forces, during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Since the end of the war, Basra's prosperity has gathered numerous population. Today Basra's majority is of [[Shia Arab|Arab Shi'ite Muslims]], with [[Sunni Muslims]], [[Arab Christians]] and [[Afro-Iraqis]] as minority. |

|||

<!-- Fahad Al-Khaldi. |

|||

In Basrah the tribal traditional is the dominate of the situation.It has many tribes.Likewise, Shammar, Bni Khaled,Tamim,Aljboor,Alshwelat,Bni Asaad,Bni saad, Al-saudoon, Bni Mansour, Aldhufir and Soubai'and alot. Some of them are Sunnah and the other are from She'a. |

|||

--> |

|||

The area surrounding Basra has substantial [[petroleum]] resources with many [[oil well]]s. The city also has an international [[airport]], which recently began restored service to Baghdad with [[Iraqi Airways]] - the nation's flag airline. Basra is in a fertile [[agriculture|agricultural]] region, with major products including [[rice]], [[maize|maize corn]], [[barley]], [[millet]], [[wheat]], [[date (fruit)|dates]], and [[livestock]]. The city's oil refinery has a production capacity of about 140,000 [[Barrel (unit)|barrel]]s a day ([[1 E4 m³|22,300 m³]]). |

|||

Iraq's main [[port city]], Basra is known as the country's economic capital. It has emerged as an important commercial and industrial center for the country, as the city is home to a large number of manufacturing industries ranging from [[petrochemical]] to [[water treatment]]. Basra is home to numerous tourist spots including mosques, palaces, churches, synagogues, parks and beaches. It has transformed itself into a modern bustling metropolis, with a port and airport. In recent years, the city has attracted a large number of investments, increasing its prosperity. |

|||

Muslim adherents of the area are primarily members of the Jafari Shi`a sect. A sizeable number from the Sunni sect also live in Basra as well as a small number of Christians. Living among them are also the remnants of the pre-Islamic [[gnostic]] sect of [[Mandaeans]], whose headquarters were in the area formerly called Suk esh-Sheikh. |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

A network of [[canal]]s flowed through the city, giving it the nickname "[[List of places known as 'the Venice of something'|The Venice of the Middle East]]" at least at high tide. The tides at Basra fall by about 9 feet (2.7 m). For long, Basra grew the finest dates in the world. |

|||

[[File:AMH-5342-NA View of Basra and 'Gordelaan' castle.jpg|thumb|View of Basra in {{circa|1695}}, by Dutch cartographer [[Isaak de Graaf]]|left]] |

|||

The city has had many names throughout history, Basrah being the most common. In Arabic, the word ''baṣrah'' means "the overwatcher", which may have been an allusion to the city's origin as an Arab military base against the [[Sassanids]]. Others have argued that the name is derived from the [[Aramaic]] word ''basratha'', meaning "place of huts, settlement".<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=k1ZQ8LpzOncC&q=basra+name&pg=PA9 |title=Merchants, Mamluks, and Murder: The Political Economy of Trade in Eighteenth-Century Basra |first=Thabit |last=Abdullah |date=1 January 2001 |publisher=SUNY Press |isbn=9780791448083 |via=Google Books}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Basra_canal.jpg|thumb|A Canal in Basra circa 1950]] |

|||

== |

==History== |

||

{{see also|Timeline of Basra}} |

|||

An earlier settlement in the immediate vicinity was known by the [[Syriac]] name Perat d'Maishan. The present city was founded in [[636]] as an encampment and garrison for the Arab tribesmen constituting the armies of amir `[[Umar ibn al-Khattab]], a few miles south of the present city, where a [[tell]] still marks its site. While defeating the [[Sassanid]] forces there, the muslim commander Utba ibn Ghazwan first set up camp there on the site of an old Persian settlement called Vaheštābād Ardašīr, which was destroyed by the invading Arabs. (according to ''[[Encyclopædia Iranica]]'', [[Ehsan Yarshater|E. Yarshater]], [[Columbia University]], p851). The name Al-Basrah, which in Arabic means "the over watching" or "the seeing everything", was given to it because of its role as a Military base against the [[Sassanid]] empire. Other sources however say its name originates from the Persian word Bas-rāh or Bassorāh meaning "where many ways come together". (See Mohammadi Malayeri, M. ''Dil-i Iranshahr''). |

|||

[[File:Ministry of Information First World War Official Collection Q25671.jpg|thumb|Ashar Creek and bazaar, c. 1915]] |

|||

===Foundation by the Rashidun Caliphate (632–661)=== |

|||

`Umar established this encampment as a city with five districts, and appointed [[Abu Musa]] `Abd Allah ibn Qays al-Ash`ari as its first governor. Abu Musa led the conquest of [[Khuzestan]] from [[639]] to [[642]]. After this, `Umar ordered him to aid `Uthman ibn Abu al-`As, then fighting Iran from a new, more easterly ''misr'' at [[Tawwaj]]. |

|||

[[File:Mss Eur F111 33 1492.jpg|thumb|The ‘Ashshār creek in Basrah Town]] |

|||

The city was founded at the beginning of the Islamic era in 636 and began as a garrison encampment for [[Arab]] tribesmen constituting the armies of the [[Rashidun Caliph]] [[Umar]]. A [[Tell (archaeology)|tell]] a few kilometers south of the present city still marks the original site which was a military site. While defeating the forces of the [[Sassanid Empire]] there, the Muslim commander [[Utbah ibn Ghazwan]] erected his camp on the site of an old Persian military settlement called ''Vaheštābād Ardašīr'', which was destroyed by the Arabs.<ref>''[[Encyclopædia Iranica]]'', [[Ehsan Yarshater|E. Yarshater]], [[Columbia University]], p851</ref> While the name Al-Basrah in Arabic can mean "the overwatch", other sources claim that the name actually originates from the Persian word Bas-rāh or Bassorāh, meaning "where many ways come together".<ref>See Mohammadi Malayeri, M. ''Dil-i Iranshahr''.</ref> |

|||

In 639, Umar established this encampment as a city with five districts, and appointed [[Abu Musa Ashaari|Abu Musa al-Ash'ari]] as its first governor. The city was built in a circular plan according to the [[Sasanian architecture|Partho-Sasanian architecture]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Arce |first1=Ignacio |title=Umayyad Building Techniques and the Merging of Roman-Byzantine and Partho-Sassanian Traditions: Continuity and Change |journal=Late Antique Archaeology |date=1 January 2008 |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=494–495 |doi=10.1163/22134522-90000099|issn=1570-6893}}</ref> Abu Musa led the conquest of [[Khuzestan]] from 639 to 642, and was ordered by Umar to aid [[Uthman ibn Abi al-As]], then fighting Iran from a new, more easterly ''miṣr'' at [[Tawwaj]]. In 650, the Rashidun Caliph [[Uthman]] reorganised the Persian frontier, installed ʿAbdullah ibn Amir as Basra's governor, and put the military's southern wing under Basra's control. Ibn Amir led his forces to their final victory over [[Yazdegerd III]], the Sassanid [[Shah|King of Kings]]. In 656, Uthman was murdered and [[Ali]] was appointed Caliph. Ali first installed Uthman ibn Hanif as Basra's governor, who was followed by ʿAbdullah ibn ʿAbbas. These men held the city for Ali until the latter's death in 661. |

|||

In [[650]], the amir `[[Uthman]] reorganised the Persian frontier, installed `Abdallah ibn `Amir as Basra's governor, and put the invasion's southern wing under Basra's responsibility. Ibn `Amir led his forces to their final victory over [[Yazdegird III]], king of Persia. Basra accordingly had few quarrels with `Uthman and so in [[656]] sent few men to the embassy against him. On `Uthman's murder, Basra refused to recognise `[[Ali ibn Abu Talib]]; instead supporting the Meccan aristocracy then led by `Aisha, al-Zubayr, and Talha. `Ali defeated this force at the [[Battle of the Camel]]. He first installed `Uthman ibn Hanif as Basra's governor and then `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas. These men held the city for `Ali until the latter's death in [[661]]. |

|||

Basra's infrastructure was planned. Why Basra was chosen as a site for the new city remains unclear. The original site lay 15km from the [[Shatt al-Arab]] and thus lacked access to maritime trade and, more importantly, to fresh water. Additionally, neither historical texts nor archaeological finds indicate that there was much of an agricultural hinterland in the area before Basra was founded. |

|||

The [[Sufyanids]] held Basra until [[Yazid I]]'s death in 683. Their first governor there was an Umayyad `Abd Allah, who proved to be a great general (under him, Kabul was forced to pay tribute) but a poor mayor. In [[664]] Mu`awiyah replaced him with [[Ziyad ibn Abu Sufyan]] Sufyan, often called "Ibn Abihi (son of his own [unknown] father)", who became famed for his Draconian methods of public order. On Ziyad's death in [[673]], his son [[Ubayd-Allah ibn Ziyad]] became governor. In 680, [[Yazid I]] ordered Ubayd Allah to keep order in Kufa as a reaction to Hussein ibn `Ali's popularity there; Hussein had already fled, and so Ubayd Allah executed Hussein's cousin [[Muslim ibn Aqeel]]. |

|||

Indeed, in an anecdote related by [[al-Baladhuri]], [[al-Ahnaf ibn Qays]] pleaded to the caliph Umar that, whereas other Muslim settlers were established in well-watered areas with extensive farmland, the people of Basra had only "reedy salt marsh which never dries up and where pasture never grows, bounded on the east by brackish water and on the west by waterless desert. We have no cultivation or stock farming to provide us with our livelihood or food, which comes to us as through the throat of an [[ostrich]]."<ref name="Kennedy">{{cite journal |last1=Kennedy |first1=Hugh |title=The Feeding of the five Hundred Thousand: Cities and Agriculture in Early Islamic Mesopotamia |journal=Iraq |date=2011 |volume=73 |pages=177–199 |doi=10.1017/S0021088900000152 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Nevertheless, Basra overcame these natural disadvantages and rapidly grew into the second-largest city in Iraq, if not the entire Islamic world. Its role as a military encampment meant that the soldiers had to be fed, and since those soldiers were receiving government salaries, they had money to spend. Thus, both the government and private entrepreneurs invested heavily in developing a vast agricultural infrastructure in the Basra region. These investments were made with the expectation of a profitable return, indicating the value of the Basra food market. Although African [[Zanj]] slaves from the [[Indian Ocean slave trade]] were put to work on these construction projects, most of the labor was done by free men working for wages. Governors sometimes directly supervised these projects, but usually they simply assigned the land while most of the financing was done by private investors.<ref name="Kennedy" /> The result of these investments was a massive irrigation system covering some 57,000 hectares between the Shatt al-Arab and the now-dry western channel of the Tigris. This system was first reported in 962{{citation needed|date=June 2021}}, when just 8,000 hectares of it remained in use, for the cultivation of [[date palm]]s, while the rest had become desert. This system consists of a regular pattern of two-meter-high ridges in straight lines, separated by old canal beds. The ridges are extremely saline, with salt deposits up to 20 centimeters thick, and are completely barren. The former canal beds are less salty and can support a small population of salt-resistant plants. |

|||

In [[683]], [[Abd Allah ibn Zubayr]] was hailed as the new [[caliph]] in the Hijaz. In [[684]] the Basrans forced Ubayd Allah to take shelter with Mas'ud al-Azdi and chose Abd Allah ibn al-Harith as their governor. Ibn al-Harith swiftly recognised Ibn al-Zubayr's claim, and Ma'sud made a premature and fatal move on Ubayd Allah's behalf; and so `Ubayd Allah felt obliged to flee. |

|||

Contemporary authors recorded how the Zanj slaves were put to work clearing the fields of salty topsoil and putting them into piles; the result was the ridges that remain today. This represents an enormous amount of work: [[H.S. Nelson]] calculated that 45 million tons of earth were moved in total, and with his extremely high estimate of one man moving two tons of soil per day, this would have taken a decade of strenuous work by 25,000 men.<ref name="Kennedy" /> Ultimately, Basra's irrigation canals were unsustainable, because they were built at too little of a slope for the water flow to carry salt deposits away. This required the clearing of salty topsoil by the Zanj slaves in order to keep the fields from becoming too saline to grow crops. After Basra was sacked in by Zanj rebels in the late 800s and then by the Qarmatians in the early 900s, there was no financial incentive to invest in restoring the irrigation system, and the infrastructure was almost completely abandoned. Finally, in the late 900s, the city of Basra was entirely relocated, with the old site being abandoned and a new one developing on the banks of the Shatt al-Arab, where it has remained ever since.<ref name="Kennedy" /> |

|||

Ibn al-Harith spent his year in office trying to put down Nafi' ibn al-Azraq's Kharijite uprising in Khuzestan. Islamic tradition condemns him as feckless abroad and corrupt at home, but praises him on matters of doctrine and prayer. In 685, Ibn al-Zubayr required a practical man, and so appointed Umar b. Ubayd Allah b. Ma'mar. (Madelung p. 303-4) Finally Ibn al-Zubayr appointed his own brother Mus`ab. In [[686]], the self-proclaimed prophet [[Mukhtar]] led an insurrection at Kufa, and put an end to Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad near [[Mosul]]. In [[687]], Mus`ab defeated Mukhtar, with the help of Kufans whom Mukhtar had exiled. (Brock p.66) |

|||

===Umayyad Caliphate: 661–750=== |

|||

`[[Abd al-Malik]] reconquered Basra in [[691]], and Basra remained loyal to his governor al-Hajjaj during Ibn Ash`ath's mutiny [[699]]-[[702]]. However Basra did support the rebellion of Yazid ibn al-Muhallab against [[Yazid II]] during the 720s. In the 740s, Basra fell to [[al-Saffah]] of the `Abbasids. |

|||

The [[Sufyanids]] held Basra until [[Yazid I]]'s death in 683. The Sufyanids' first governor was Umayyad ʿAbdullah, a renowned military leader, commanding fealty and financial demands from Karballah, but poor governor. In 664, [[Mu'awiya I]] replaced him with [[Ziyad ibn Abi Sufyan]], often called "ibn Abihi" ("son of his own father"), who became infamous for his draconian rules regarding public order. On Ziyad's death in 673, his son [[Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad|ʿUbayd Allah ibn Ziyad]] became governor. In 680, Yazid I ordered ʿUbayd Allah to keep order in [[Kufa]] as a reaction to [[Husayn ibn Ali]]'s popularity as the grandson of the [[Islamic prophet]] [[Muhammad]]. 'Ubayd Allah took over the control of [[Kufa]]. Husayn sent his cousin as an ambassador to the people of Kufa, but ʿUbaydullah executed Husayn cousin [[Muslim ibn Aqil]] amid fears of an uprising. ʿUbayd Allah amassed an army of thousands of soldiers and fought Husayn's army of approximately 70 in a place called [[Karbala]] near Kufa. ʿUbayd Allah's army was victorious; Husayn and his followers were killed and their heads were sent to Yazid as proof. |

|||

Ibn al-Harith spent his year in office trying to put down Nafi' ibn al-Azraq's [[Kharijites|Kharijite]] uprising in [[Khuzestan Province|Khuzestan]]. In 685, Ibn al-Zubayr, requiring a practical ruler, appointed [[Umar ibn Ubayd Allah ibn Ma'mar]]<ref>(Madelung p. 303–04)</ref> Finally, Ibn al-Zubayr appointed his own brother Mus'ab. In 686, the revolutionary [[al-Mukhtar]] led an insurrection at Kufa, and put an end to ʿUbaydullah ibn Ziyad near [[Mosul]]. In 687, Musʿab defeated al-Mukhtar with the help of Kufans who Mukhtar exiled.<ref>(Brock p.66)</ref> |

|||

Wael Hallaq notes that by contrast with Medina and to a lesser extent Syria, in `Iraq there was no unbroken Muslim population dating back to the Prophet's time. Therefore Maliki (and Azwa`i) appeals to the practice (''`amal'') of the community could not apply. Instead the people of `Iraq relied upon those Companions of the Prophet who settled there, and upon such factions of the Hijaz whom they respected most. |

|||

[[Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan]] reconquered Basra in 691, and Basra remained loyal to his governor al-Hajjaj during Ibn Ashʿath's mutiny (699–702). However, Basra did support the rebellion of Yazid ibn al-Muhallab against [[Yazid II]] during the 720s. |

|||

==Basra in Islamic theology and scholarship== |

|||

Shirazi's "Tabaqat", which Wael Hallaq labels "an important early biographical work dedicated to jurists", covered 84 "towering figures" of Islamic jurisprudence; to which Basra provided 17. It was therefore a center surpassed only by Medina (22) and Kufa (20). Among the Companions who settled in Basra were Abu Musa and `Anas ibn Malik. Among its jurists, Hallaq singles out Muhammad ibn Sirin, Abu `Abd Allah Muslim ibn Yasar, and Abu Ayyub al-Sakhtiyani. Qatada ibn Di`ama ([[680]]-[[736]]) attained respect as a traditionist and Qur'anic interpreter. In the late 750s, Sawwar ibn Abd Allah began the practice of paying salaries to the court's witnesses and assistants, ensuring their impartiality. Hammad ibn Salama (d. [[784]]), mufti of Basra, was a teacher of [[Abu Hanifa]]. Abu Hanifa's student Zufar ibn al-Hudayl later moved from Kufa to Basra. Basran and Kufan law, under the patronage of the early `Abbasids, became a shared jurisprudence called the "Hanafi [[Madhhab]]"; as opposed to others, like the practice of Medina which became the Maliki Madhhab. |

|||

===Abbasid Caliphate and its Golden Age: 750–1258=== |

|||

Sufyan al-Thawri and Ma`mar ibn Rashid collected many legal and other teachings and traditions into books, and migrated to the Yemen; there [['Abd al-Razzaq]] included them into his Musannaf during the 9th century CE. Back in Basra, Musaddad b. Musarhad compiled his own collection arranged in "Musnad" form. |

|||

In the late 740s, Basra fell to [[as-Saffah]] of the [[Abbasid Caliphate]]. During the time of the Abbasids, Basra became an intellectual center and home to the elite [[Grammarians of Basra|Basra School of Grammar]], the rival and sister school of the [[Grammarians of Kufa|Kufa School of Grammar]]. Several outstanding intellectuals of the age were Basrans; Arab [[polymath]] [[Alhazen|Ibn al-Haytham]], the [[Arabic literature|Arab literary]] giant [[al-Jahiz]], and the [[Sufi]] mystic [[Rabia Basri]]. The [[Zanj Rebellion]] by the agricultural slaves of the lowlands affected the area. In 871, the Zanj sacked Basra.<ref name=AndreWink>Andre Wink, ''Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World'', Vol.2, 17.</ref> In 923, the [[Qarmatians]], an extremist Muslim sect, [[Sack of Basra (923)|invaded and devastated]] Basra.<ref name=AndreWink /> |

|||

From 945 to 1055, the Iranian [[Buyid dynasty]] ruled Baghdad and most of Iraq. Abu al Qasim al-Baridis, who still controlled Basra and [[Wasit]], were defeated and their lands taken by the Buyids in 947. [['Adud al-Dawla|Adud al-Dawla]] and his sons [[Diya' al-Dawla]] and [[Samsam al-Dawla]] were the Buyid rulers of Basra during the 970s, 980s and 990s. Sanad al-Dawla al-Habashi ({{circa|921}}–977), the brother of the Emir of Iraq [[Izz al-Dawla]], was governor of Basra and built a library of 15,000 books. |

|||

Basra also spawned heterodox interpretations of Islam. Rabi`ah al-`Adawiyya al-Qaysiyya (born [[717]]), lived there and became popular as poet, mystic, and teacher. It was also among the first bases of the [[Qadariyya]]. |

|||

[[File:Basra in a drawing by the Portuguese late 16th century .png|thumb|Basra designed by the Portuguese at the end of the 16th century, according to the representation of the "Lyvro de plantaforma of the fortresses of India" codex of São julião da Barra]] |

|||

The Oghuz Turk [[Tughril Beg]] was the leader of the Seljuks, who expelled the [[Shiite]] Buyid dynasty. He was the first Seljuk ruler to style himself Sultan and Protector of the Abbasid Caliphate. |

|||

Qadarism in Islam corresponds to the doctine of human free will in Christianity, as opposed to such doctrines of predestination as later proposed by, e.g., [[John Calvin]]. The traditionist Yahya ibn Ya`mar attributed the introduction of Qadari doctrines into Basra to a Ma`bad al-Juhani (d. 80). Al-Hasan developed a moderate form of this in his ''Risala'': God may command, forbid, punish, and test; but He does not force ordinary mortals to evil or good despite that He has the power. According to al-Dhahabi (''Siyar A`lam al-Nubala'' 6:330 #858), al-Hasan's student Abu `Uthman `Amr ibn `Ubayd (d. ~144) left al-Hasan's teaching circle and "isolated" himself by taking these doctrines further. In Syria, the reigning [[Marwanids]] relied on predestination to justify their hold on secular authority. [[Imam Malik]] in his ''[[Muwatta]]'' recorded (with approval!) that caliph `Umar ibn `Abd al-Aziz had recommended putting Qadarists "to the sword". Syrian hadith transmitters invented traditions of the Prophet that denounced Qadarism as a heresy, and labeled its believers and Basra as a whole as "monkeys and swine" - as sura 5 had said of the Jews. |

|||

The Great Friday Mosque was constructed in Basra. In 1122, [[Imad ad-Din Zengi]] received Basra as a fief.<ref>Penny Encyclopedia</ref> In 1126, Zengi suppressed a revolt and in 1129, Dabis looted the Basra state treasury. |

|||

Under Abu 'l-Hudhayl al-`Allaf (d. 841), the Basrans are also credited (or blamed) for the Mutazilist school, a form of rationalism which included the Qadari doctines of al-Hasan and attracted the support of `Abbasid caliph al-Ma`mun. |

|||

A 1200 map "on the eve of the Mongol invasions" shows the Abbasid Caliphate as ruling lower Iraq and, presumably, Basra. |

|||

The [[Order of Assassins|Assassin]] [[Rashid ad-Din Sinan|Rashid-ad-Din-Sinan]] was born in Basra on or between 1131 and 1135. |

|||

According to Arthur Jeffery, Basra also at first held to an idiosyncratic pronunciation of the Qur'an, which they put to paper as the "Lubab al-Qulub" and attributed to Abu Musa. For instance, this codex used the more Biblically correct "Ibraham", as against the "Ibrahim" which is forced by sura 21's rhyme; in addition there are no Abu Musa variants recorded for sura 21. This was also the reading of Ibn al-Zubayr when he came to Mecca (although his variants did encompass sura 21). The likely solution is that the first Qur'an text at Basra was "defective", which is to say it lacked long vowel signs; and that Basra accepted sura 21 as part of Qur'an later than it accepted other suras - most likely during or after the mid-680s. |

|||

===Mongol rule and thereafter: 1258–1500s=== |

|||

==Early literary mentions of Basra== |

|||

{{Further|Safavid occupation of Basra}} |

|||

Under the name of Bassorah the city is mentioned in the [[Thousand and One Nights]], and [[Sindbad the Sailor]] was said to have begun his voyages here. It was long a flourishing commercial and cultural center, until it was captured by the [[Ottoman Empire]] in [[1668]], after which it declined in importance, but was fought over by Turks and [[Persians]] and was the scene of repeated attempts at resistance. In 1911, the ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' reported some Jews and a few Christians living in Basra, but no Turks other than Ottoman officials. The wealthiest and most influential personage in Basra was the ''nakib'', or marshal of the nobility (i.e. descendants of the family of the prophet, who are entitled to wear the green turban). In 1884 the Ottomans responded to local pressure from the Shi'ites of the south by detaching the southern districts of the Baghdad vilayet and creating a new vilayet of Basra. |

|||

In 1258, the Mongols under [[Hulagu Khan|Hulegu Khan]] sacked Baghdad and ended Abbasid rule. By some accounts, Basra capitulated to the Mongols to avoid a massacre. The Mamluk [[Bahri dynasty]] map (1250–1382) shows Basra as being under their area of control, and the [[Ilkhanate|Mongol Dominions]] map (1300–1405) shows Basra as being under Mongol control. In 1290<ref>[[Buscarello de Ghizolfi]]</ref> fighting erupted at the [[Persian Gulf]] port of Basra among the [[Republic of Genoa|Genoese]], between the [[Guelphs and Ghibellines|Guelph and the Ghibelline]] factions. |

|||

[[Ibn Battuta]] visited Basra in the 14th century, noting it "was renowned throughout the whole world, spacious in area and elegant in its courts, remarkable for its numerous fruit-gardens and its choice fruits, since it is the meeting place of the two seas, the salt and the fresh."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Battutah |first1=Ibn |title=The Travels of Ibn Battutah |date=2002 |publisher=Picador |location=London |isbn=9780330418799 |pages=60}}</ref> Ibn Battuta also noted that Basra consisted of three-quarters: the Hudayl quarter, the Banu Haram quarter, and the Iranian quarter (''mahallat al-Ajam'').<ref name="BasraIranica">{{cite encyclopedia |title=BASRA |last=Donner |first=F.M. |author-link=Fred Donner |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/basra |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 8 |pages=851–855 |year=1988}}</ref> [[Fred Donner]] adds: "If the first two reveal that Basra was still predominantly an Arab town, the existence of an Iranian quarter clearly reveals the legacy of long centuries of intimate contact between Basra and the Iranian plateau."<ref name="BasraIranica" /> |

|||

==Second World War== |

|||

During [[World War I]] the occupying [[United Kingdom|British]] modernized the port (works designed by Sir [[George Buchanan (engineer)|George Buchanan]]), which became the principal port of Iraq. During [[World War II]] it was an important port through which flowed much of the equipment and supplies sent to [[Russia]] by the other allies. At the end of the second world war the population was some 93,000 people. |

|||

The Arab Al-Mughamis tribe established control over Basra in the early fifteenth century, however, they quickly fell under influence of the [[Kara Koyunlu]] and [[Ak Koyunlu]], successively.{{sfn|Matthee|2006a|page=57}}{{efn|The Al-Mughamis were a branch of the [[Al-Muntafiq|Banu'l-Muntafiq]] who inhabited the area between [[Kufa]] and Basra.{{sfn|Matthee|2006a|page=57}}}} The Al-Mughamis' control of Basra had become nominal by 1436; ''de facto'' control of Basra from 1436 to 1508 was in the hands of the [[Musha'sha'iyyah|Moshasha]].{{sfn|Matthee|2006a|page=57}}{{efn|The Moshasha were a tribal confederation of radical [[Shia Islam|Shi'ites]] found mainly on the edges of the marshes alongside the Safavid province of [[Safavid Arabestan|Arabestan]] (present-day [[Khuzestan Province|Khuzestan]]). They often acted as Safavid proxies and were led by a Safavid governor. They participated in campaigns against the Arabs of southern Iraq and Basra. Matthee notes that even though they were nominal Safavid subjects, they had a broad scope of autonomy, and their territory served as a buffer between the Ottomans and the Iranians.{{sfn|Matthee|2006a|page=55}}{{sfn|Matthee|2006b|pages=556–560, 561}}}} In the latter year, during the reign of King (''[[Shah]]'') [[Ismail I]] ({{reign}}1501–1524), the first [[Safavid dynasty|Safavid]] ruler, Basra and the Moshasha became part of the Safavid Empire.{{sfn|Longrigg |Lang|2015}}{{efn |according to Floor (2008), a certain Shaykh Afrasiyab (the local ruler of Basra, not to be mistaken with the later Afrasiyab of Basra) came to [[Shiraz]] in 1504 to pledge his allegiance to Ismail I.{{sfn|Floor|2008|page=165}} Ismail I in turn confirmed him in his possessions and position as governor (''[[Vali (governor)|vali]]'') of Basra.{{sfn|Floor|2008|page=165}} Thus, Floor's stance differs slightly.}} This was the first time Basra had come under Safavid suzerainty. In 1524, following Ismail I's death, the local ruling dynasty of Basra, the Al-Mughamis, resumed effective control over the city.{{sfn|Matthee|2006a|page=57}} Twelve years later, in 1536, during the [[Ottoman–Safavid War (1532–1555)|Ottoman–Safavid War of 1532–1555]], the [[Bedouins|Bedouin]] ruler of Basra, Rashid ibn Mughamis, acknowledged [[Suleiman the Magnificent]] as his suzerain who in turn confirmed him as governor of Basra.{{sfn|Longrigg |Lang|2015}} The Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire exercised a great deal of independence, and they even often raised their own troops.{{sfn|Longrigg |Lang|2015}} Though Basra had submitted to the Ottomans, the Ottoman hold over Basra was tenuous at the time.{{sfn|Matthee|2006b|pages=556–560, 561}} This changed a decade later; in 1546, following a tribal struggle involving the Moshasha and the local ruler of Zakiya (near Basra), the Ottomans sent a force to Basra. This resulted in tighter (but still, nominal) Ottoman control over Basra.{{sfn|Matthee|2006b|pages=556–560, 561}}{{sfn|Matthee|2006a|page=53}}[[File:Persian Gulf Pt8.png|thumb|Purple – [[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]] in the Persian Gulf in the 16th and 17th century. Main cities, ports and routes.]] |

|||

==1945-1990: peacetime and the Iran-Iraq War== |

|||

In 1523, the [[Portugal|Portuguese]] under the command of António Tenreiro crossed from Aleppo to Basra. [[Nuno da Cunha]] took Basra in 1529.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Livermore |first=H. V. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FFCzAAAAMAAJ&q=Nuno+da+Cunha+took+Basra+in+1529 |title=A History of Portugal |date=1947 |publisher=University Press |page=236 |language=en}}</ref> In 1550, the local Kingdom of Basra and tribal rulers trusted the Portuguese against the Ottomans, from then on the Portuguese threatened to invoke an invasion and conquest of Basra several times. From 1595 the Portuguese acted as military protectors of Basra,<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://iranicaonline.org/|title=Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica|first=Encyclopaedia Iranica|last=Foundation|website=iranicaonline.org}}</ref> and in 1624 the Portuguese assisted the [[Ottoman Empire|Ottoman]] [[Pasha]] of Basra in repelling a Persian invasion. The Portuguese were granted a share of the customs revenue and freedom from tolls. From about 1625 until 1668, Basra and the Delta marshlands were in the hands of local chieftains independent of the Ottoman administration at Baghdad. |

|||

The University of Al Basrah was founded in [[1964]]. |

|||

===Ottoman and British rule=== |

|||

By [[1977]] the population had risen to a peak population of some 1.5 million. The population declined during the [[Iran-Iraq War]], being under 900,000 in the late [[1980s]], possibly reaching a low point of just over 400,000 during the worst of the war. The city was repeatedly shelled by [[Iran]] and was the site of many fierce battles, but never fell. |

|||

{{see also|Basra Eyalet|Basra Vilayet}} |

|||

[[File:Ministry of Information First World War Official Collection Q25704.jpg|thumb|Iraqi girls, c. 1917|left]] |

|||

Basra was, for a long time, a flourishing commercial and cultural center. It was captured by the [[Ottoman Empire]] in 1668. It was fought over by Turks and [[Persian Empire|Persians]] and was the scene of repeated attempts at resistance. From 1697 to 1701, Basra was once again [[Safavid occupation of Basra (1697–1701)|under Safavid control]].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=IRAQ iv. RELATIONS IN THE SAFAVID PERIOD |last=Matthee |first=Rudi |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iraq-iv-safavid-period |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Iranica (Vol. XIII, Fasc. 5 and Vol. XIII, Fasc. 6) |pages=556–560, 561 |year=2006}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Zand dynasty]] under [[Karim Khan Zand]] briefly occupied Basra after a long siege in 1775–9. The Zands attempted at introducing [[Usuli]] form of [[Shia|Shiism]] on a basically [[Akhbari]] [[Shia]] Basrans. The shortness of the Zand rule rendered this untenable. |

|||

==Persian Gulf War== |

|||

After the first [[Persian Gulf War]] in [[1991]] Basra was the site of widespread revolt against [[Saddam Hussein]], which was violently put down with much death and destruction inflicted on the city; a second revolt in 1999 led to mass executions in and around Basra, subsequently the Iraqi government deliberately neglected the city and much commerce was diverted to [[Umm Qasr]]. These alleged abuses are to feature amongst the charges against the former regime to be considerd by the [[Iraq Special Tribunal]] set up by the [[Iraq interim Government]] following the 2003 invasion. |

|||

In 1911, the ''Encyclopaedia Britannica'' reported "about 4000 Jews and perhaps 6000 Christians"<ref name=EB1911>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=Basra |volume=3 |page=489 |short=1 }}</ref> living in Basra Vilayet, but no Turks other than Ottoman officials. In 1884 the Ottomans responded to local pressure from the [[Shi'a]]s of the south by detaching the southern districts of the [[Baghdad vilayet]] and creating a new [[vilayet of Basra]]. |

|||

==Iraq War and occupation== |

|||

In March through May of 2003, the outskirts of Basra were the scene of heavy fighting in the [[2003 invasion of Iraq]]. British forces, led by units of [[British 7th Armoured Brigade|7th Armoured Brigade]], took the city on [[6 April]] 2003. On [[21 April]] [[2004]], a series of [[21 April 2004 Basra bombs|bomb blast]]s ripped through the city, killing scores of people. This city was the first stop for the [[United States]] and the [[United Kingdom]], during the [[2003 invasion of Iraq|2003 Invasion of Iraq]]. The [[Multi-National Division (South East)]], under British Command, is currently engaged in Security and Stabilization missions in [[Basra Province]] and surrounding areas. |

|||

[[File:Ministry of Information First World War Official Collection Q25688.jpg|thumb|Turkish prisoners passing along the bank of Ashar Creek, nearing Whiteley's Bridge, Basra 1917.|left]] |

|||

==Post-war Basra== |

|||

By the first half of 2005, Basra had become noted as a focal point for confrontations between secular Iraqi culture and [[Shiism|Shi'ite]] [[Islam]] supporters [http://www.jihadwatch.org/dhimmiwatch/archives/001276.php]. In March 2005, a group of students were beaten to death for playing music, and for engaging in unconstrained interaction between males and females. Militia members armed with rifles killed at least two, shot several, and beat one young woman severely enough so that she lost her sight. Senior [[al-Sadr]] supporters praised the militia's actions [http://www.freemuse.org/sw9354.asp]. The playing of music and music stores are frequently a target from Shi'ite groups who hold that music is against the teaching of [[Islam]]. Several music stores have been bombed [http://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/07/international/middleeast/07shiites.html]. |

|||

During [[World War I]], [[British Empire|British]] forces [[Battle of Basra (1914)|captured Basra]] from the Ottomans, occupying the city on 22 November 1914. British officials and engineers (including [[George Buchanan (engineer, born 1865)|Sir George Buchanan]]) subsequently modernized Basra's harbor, which due to the increased commercial activity in the area became one of the most important ports in the Persian Gulf, developing new mercantile links with [[British Raj|India]] and [[East Asia]].{{fact|date=March 2024}} |

|||

Political groups and their ideology which are strong in Basra are reported to have close links with political parties already in power in the [[government of Iraq|Iraqi government]], despite opposition from Iraqi [[Sunni]]s and the more secular [[Kurd]]s. January 2005 elections saw several radical politicians gain office, supported by religious parties. |

|||

[[File:Basra War Cemetery Gate.jpg|thumb|The Gate to the British War Cemetery Basra 2024.]] |

|||

The graves of around 5,000 men from WW1 both are at [[Basra War Cemetery]] and a further 40,000 with no known grave are commemorated at [[Basra Memorial]]. Both sites are suffering from neglect with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission having withdrawn from the country in 2007. |

|||

===Modern era: 1921–2003=== |

|||

Workers in Basra's oil industry have been involved in extensive organization and labor conflict. They held a two-day [[strike]] in August 2003, and formed the nucleus of the independent [[General Union of Oil Employees]] (GUOE) in June [[2004]]. The union held a one-day strike in July 2005, and publicly opposes plans for privatizing the industry. |

|||

[[File:Basra Dockyard.jpg|thumb|Model of Basra Dockyard|left]] |

|||

=== UK fighting against Iraqi police === |

|||

{{cleanup-date|October 2005}} |

|||

{{Wikinews|Basra, Iraq raid by UK forces to rescue soldiers from police}} |

|||

[[Image:2UK soldiers.jpg|thumb|Two UK soldiers arrested by Iraq police. ([[AFP]] photo)]] |

|||

On [[September 19]], [[2005]], two British soldiers were arrested by [[Iraq]]i police in Basra following a car chase. Police officials accused them of firing at police while dressed in civilian clothes. After being approached by Iraqi police, the two soldiers reportedly fired on the police, after which they were apprehended, which sparked clashes in which UK armoured vehicles came under attack. Two civilians were reportedly killed and three UK soldiers were injured. The arrests followed the detention of two high-ranking officials of [[Muqtada al-Sadr]]'s [[Mahdi Army]] |

|||

UK [[Ministry of Defence (United_Kingdom)|Ministry of Defence]] officials insisted they had been talking to the Iraqi authorities to secure the release of the men, who were reported to be working undercover. British servicemen who were seen being injured in the graphic photographs were treated for minor injuries only. But they acknowledged a wall was demolished as UK forces tried to "collect" the men. However, sources in the Iraqi Interior Ministry said six tanks were used to smash down the wall in a rescue operation. Witnesses told the Associated Press around 150 prisoners escaped during the operation; Iraqi officials later denied any prisoners had escaped. |

|||

Two British [[Warrior Tracked Armoured Vehicle|Warrior AFVs]], sent to the police station where the soldiers were being held, were hit by multiple [[petrol bomb]]s in clashes. British officials would not say if the two men were working undercover. Crowds of angry protesters hurled petrol bombs and stones injuring three servicemen and several civilians. TV pictures showed soldiers in combat gear, clambering from one of the flaming AFVs and making their escape. In a statement, Defence Secretary [[John Reid (UK politician)|John Reid]] said the soldiers who fled from the vehicles were treated for minor injuries. Mr. Reid added that he was not certain what had caused the disturbances. "We remain committed to helping the Iraqi government for as long as they judge that a coalition presence is necessary to provide security," the statement said. Later British MoD reports suggested the soldiers were being handed to Iraqi insurgents by members of the Iraqi police, despite instructions from the Iraq Interior Ministry that they should be released. |

|||

[[Tim Collins (soldier)|Tim Collins]], a former commander of troops in Iraq, described the incident with the crowd as like a "busy night in [[Belfast]]."[http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/4262336.stm] |

|||

During [[World War II]] (1939–1945), Basra was an important port through which flowed much of the equipment and supplies sent to the [[Soviet Union]] by other [[Allies of World War II]].<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

---- |

|||

''Basra'' is also the name of a fishing-type [[card game]] played in coffeehouses throughout the [[Middle East]]. |

|||

[[File:Old city of Basra 1954.jpg|thumb|right|[[Shanasheel]] of the old part of Basra city, 1954]] |

|||

==Bibliography== |

|||

The population of Basra was 101,535 in 1947,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic/products/dyb/1950_round.htm |work=Demographic Yearbook 1955 |publisher=[[Statistical Office of the United Nations]] |location=New York |title=Population of capital city and cities of 100,000 or more inhabitants}}</ref> and reached 219,167 in 1957.<ref>{{cite web |title=National Intelligence Survey. Iraq. Section 41, Population |url=https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/DOC_0001252308.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170123010830/https://www.cia.gov/library/readingroom/docs/DOC_0001252308.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=23 January 2017 |publisher=Central Intelligence Agency |date=1960}}</ref> The [[University of Basrah]] was founded in 1964. By 1977, the population had risen to a peak population of some 1.5 million.<ref name=":1" /> The population declined during the [[Iran–Iraq War]], being under 900,000 in the late 1980s, possibly reaching a low point of just over 400,000 during the worst of the war.<ref name=":1" /> The city was repeatedly [[War of the Cities|shelled]] by [[Iran]] and was the site of many fierce battles, such as [[Operation Ramadan]] (1982) and the [[Siege of Basra]] (1987).<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

After the war, [[Saddam]] erected 99 memorial statues to Iraqi military officers killed during the war along the bank of the Shatt-al-Arab river, all pointing their fingers towards Iran.{{cn|date=September 2024}} After the 1991 [[Gulf War]] a [[1991 uprising in Basra|rebellion against Saddam]] erupted in Basra.<ref name=":1" /> The widespread revolt was against the Iraqi government who violently put down the rebellion, with much death and destruction inflicted on Basra.{{cn|date=September 2024}} |

|||

*Hallaq, Wael. The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law. Cambridge University Press, 2005 |

|||

*Hawting, Gerald R. The First Dynasty of Islam. Routledge. 2nd ed, 2000 |

|||

*Madelung, Wilferd. "Abd Allah b. al-Zubayr and the Mahdi" in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies 40. 1981. pp.291-305. |

|||

As part of the [[Iraqi no-fly zones conflict]], [[United States Air Force]] fighter jets carried out two [[airstrike]]s against Basra on 25 January 1999.<ref name=":1" /> The airstrikes resulted in missiles landing in the al-Jumhuriya neighborhood of Basra, killed 11 Iraqi civilians and wounding 59.<ref name=":1" /> General [[Anthony Zinni]], then commander of U.S. forces in the Persian Gulf, acknowledged that it was possible that "a missile may have been errant."<ref name=":1" /> While such casualty numbers pale in comparison to later events, the bombing occurred one day after Arab foreign ministers, meeting in Egypt, refused to condemn four days of air strikes against Iraq in December 1998.<ref name=":1" /> This was described by Iraqi information minister Human Abdel-Khaliq{{efn|His proper name and position description appears to be in error, in that he appears to have held a more junior role at the time. Humam Abd al-Khaliq Abd al-Ghafur was Iraqi Information Minister between 1997 and 2001. The Iraqi Information Minister between 1991 and 1996 was Hamid Yusuf Hammadi. See [[List of Iraqi Information Ministers]].}} as giving U.S.-led forces "an Arab green card" to continue their involvement in the conflict.<ref>{{cite news |author=Paul Koring |title=USAF air strikes kill 11, injure 59: Iraq |work=[[The Globe and Mail]] |location=Toronto |date=26 January 1999 |page=A8 |quote=These air strikes, by British and USAF warplanes and U.S. cruise missiles, were said to be in response to a release of a report by UN weapons inspectors stating that, as of 1998, the government of Iraq was obstructing their inspection work. Following the four days of bombing in December, the Iraqi government commenced challenging the "no fly zones" unilaterally imposed on the country by the United States, following the 1991 Persian Gulf war. During the month of January 1999, there were more than 100 incursions by Iraqi aircraft and 20 instances of Iraqi surface-to-air missiles being filed. The January bombing of Basra occurred in the context of retaliatory attacks by the United States.}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

|||

A [[1999 Shia uprising in Iraq|second revolt in 1999]] led to mass executions by the Iraqi government in and around Basra. Subsequently, the Iraqi government deliberately neglected the city, and much commerce was diverted to [[Umm Qasr]].{{cn|date=September 2024}} These alleged abuses are to feature amongst the charges against the former regime to be considered by the [[Iraq Special Tribunal]] set up by the [[Iraq Interim Government]] following the 2003 invasion.{{cn|date=September 2024}} Workers in Basra's oil industry have been involved in extensive organization and labour conflict.{{cn|date=September 2024}} They held a two-day strike in August 2003, and formed the nucleus of the independent [[General Union of Oil Employees]] (GUOE) in June 2004. The union held a one-day strike in July 2005, and publicly opposes plans for privatizing the industry.{{cn|date=September 2024}} |

|||

* [[List of places in Iraq]] |

|||

===Post-Saddam period: 2003–present=== |

|||

{{Main|Battle of Basra (2003)|Battle of Basra (2008)}} |

|||

In March through to May 2003, the outskirts of Basra were the scene of some of the heaviest fighting in the beginning of the [[Iraq War]] in 2003.<ref name=":2">{{Cite web |title=Basra |url=https://kids.britannica.com/students/article/Basra/317092 |access-date=2024-09-29 |website=Britannica Kids |language=en-US}}</ref> The British forces, led by the [[British 7th Armoured Brigade|7th Armoured Brigade]], captured the city on 6 April 2003.<ref name=":2" /> This city was the first stop for the United States and the United Kingdom during the [[2003 invasion of Iraq|invasion of Iraq]].<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

On 21 April 2004, a [[21 April 2004 Basra bombings|series of bomb blasts]] ripped through the city, killing 74 people.<ref name=":2" /> The [[Multi-National Division (South-East) (Iraq)|Multi-National Division (South-East)]], under British command, was engaged in [[foreign internal defense]] missions in [[Basra Governorate]] and surrounding areas during this time.<ref name=":2" /> Political groups centered in Basra were reported to have close links with political parties already in power in the [[government of Iraq|Iraqi government]], despite opposition from Iraqi [[Sunni]]s and the [[Kurds]].<ref name=":2" /> January 2005 elections saw several radical politicians gain office, supported by religious parties.<ref name=":2" /> American journalist [[Steven Vincent]], who had been researching and reporting on corruption and militia activity in the city, was kidnapped and killed on 2 August 2005.<ref>{{cite web |title=Steven Vincent |url=https://cpj.org/killed/2005/steven-vincent.php |publisher=Committee to Protect Journalists |date=2005}}</ref> |

|||

On 19 September 2005, two [[Undercover operation|undercover]] British [[Special Air Service]] (SAS) soldiers were stopped by the [[Iraqi Police]] at a [[roadblock]] in Basra.<ref name=":2" /> The two soldiers were part of an SAS operation investigating allegations of [[Iraqi insurgency (2003–2011)|insurgent]] infiltration into the Iraqi Police.<ref name=":2" /> When the police attempted to pull the soldiers out of their car, they opened fire on the officers, killing two.<ref name=":2" /> The SAS soldiers attempted to escape before being beaten and arrested by the police, who took them to the Al Jameat Police Station.<ref name=":2" /> British forces subsequently identified the location of the two soldiers and [[Basra prison incident|carried out a rescue mission]], storming the police station and transporting them to a safe location.<ref name=":2" /> A civilian crowd gathered around the rescue force during the incident and attacked it; three British soldiers were injured and two members of the crowd were purportedly killed.<ref name=":2" /> The British [[Ministry of Defence (United Kingdom)|Ministry of Defence]] initially denied carrying out the operation, which was criticised by Iraqi officials, before subsequently admitting it and claiming the two soldiers would have been executed if they were not rescued.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/4262336.stm |title=UK soldiers 'freed from militia' |date=20 September 2005 |publisher=BBC |access-date=17 March 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2005/09/20/MNGS5EQNGN1.DTL |title=British smash jail walls to free 2 arrested soldiers |date=20 September 2005 |work=San Francisco Chronicle |access-date=17 March 2012}}</ref> |

|||

The British transferred control of Basra province to the Iraqi authorities in 2007, four-and-a-half years after the invasion.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/7146507.stm |title=UK troops return Basra to Iraqis |date=16 December 2007 |publisher=BBC News |access-date=1 January 2010}}</ref> A BBC survey of local residents found that 86% thought the presence of British forces since 2003 had had an overall negative effect on the province.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/7144437.stm |title=Basra residents blame UK troops |date=14 December 2007 |publisher=BBC News |access-date=1 January 2010}}</ref> Major-General Abdul Jalil Khalaf was appointed Police Chief by the central government with the task of taking on the militias.<ref name=":2" /> He was outspoken against the targeting of women by the militias.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/7095209.stm |title=Basra militants targeting women |publisher=BBC News |date=15 November 2007 |access-date=1 January 2010}}</ref> Talking to the BBC, he said that his determination to tackle the militia had led to almost daily assassination attempts.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/programmes/panorama/7148670.stm |title=Basra: The Legacy |publisher=BBC News |date=17 December 2007 |access-date=1 January 2010}}</ref> This was taken as sign that he was serious in opposing the militias.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/7145597.stm |title=Uncertainty follows Basra exit |publisher=BBC News |date=15 December 2007 |access-date=1 January 2010}}</ref> |

|||

{{anchor|2008}} |

|||

In March 2008, the Iraqi Army launched a major offensive, code-named Charge of the White Knights (''Saulat al-Fursan''), aimed at forcing the [[Mahdi Army]] out of Basra.<ref name=":1" /> The assault was planned by General Mohan Furaiji and approved by [[Prime Minister of Iraq|Iraqi Prime Minister]] [[Nouri al-Maliki]].<ref name=":1">{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/27/world/middleeast/27iraq.html |title=Iraqi Army's Assault on Militias in Basra Stalls |work=The New York Times |date=27 March 2008 |access-date=27 March 2008 |first=James |last=Glanz |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081211004906/http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/27/world/middleeast/27iraq.html |archive-date=11 December 2008 |url-status=live}}</ref> In April 2008, following the failure to disarm militant groups, both Major-General Abdul Jalil Khalaf and General Mohan Furaiji were removed from their positions in Basra.<ref>{{cite news |publisher=BBC News |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/7350434.stm |title=Basra security leaders removed |date=16 April 2008 |access-date=1 January 2010}}</ref> |

|||

Basra was scheduled to host the [[22nd Arabian Gulf Cup]] tournament in [[Basra Sports City]], a newly built multi-use sports complex.<ref name=":2" /> The tournament was shifted to [[Riyadh]], [[Saudi Arabia]], after concerns over preparations and security.<ref name=":2" /> Iraq was also due to host the 2013 tournament, but that was moved to Bahrain.<ref name=":2" /> At least 10 demonstrators died as they [[2015–2018 Iraqi protests#2018 protests|protested]] against the lack of clean drinking water and electrical power in the city during the height of summer in 2018.<ref name=":2" /> Some protesters stormed the Iranian consulate in the city.<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-protests-idUSKCN1LN1M9 |title=Unrest intensifies in Iraq as Iranian consulate and oil facility stormed |work=Reuters|date=8 September 2018}}</ref> In 2023, the city hosted the long scheduled [[25th Arabian Gulf Cup]] where the Iraqi team won.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

==Geography== |

|||

[[File:Basra at night.jpg|thumb|upright=2|Basra at night]] |

|||

Basra is located in the Arabian Peninsula on the Shatt-Al-Arab waterway, downstream of which is the Persian Gulf. The Shatt-Al-Arab and Basra waterways define the eastern and western borders of Basra, respectively. The city is penetrated by a complex network of canals and streams, vital for irrigation and other agricultural use. These canals were once used to transport goods and people throughout the city, but during the last two decades, pollution and a continuous drop in water levels have made river navigation impossible in the canals. Basra is roughly {{convert|110|km|mi|sigfig=2|abbr=on}} from the Persian Gulf. The city is located along the [[Shatt al-Arab]] waterway, {{convert|55|km|mi|sp=us}} from the [[Persian Gulf]] and {{convert|545|km|mi|sp=us}} from [[Baghdad]], Iraq's capital and largest city. |

|||

=== Climate === |

|||

Basra has a hot [[desert climate]] ([[Köppen climate classification]] ''BWh''), like the rest of the surrounding region, though it receives slightly more [[Precipitation (meteorology)|precipitation]] than inland locations due to its location near the coast. During the summer months, from June to August, Basra is consistently one of the hottest cities on the planet, with temperatures regularly exceeding {{convert|50|°C|°F|abbr=on}} in July and August. In winter Basra experiences mild and somewhat moist conditions with average high temperatures around {{convert|20|°C|°F|abbr=on}}. On some winter nights, minimum temperatures are below {{convert|0|°C|°F|abbr=on}}. High humidity – sometimes exceeding 90% – is common due to the proximity to the marshy Persian Gulf. |

|||

An all-time high temperature was recorded on 22 July 2016, when daytime readings soared to {{convert|53.9|°C|1}}, which is the highest temperature that has ever been recorded in Iraq.<ref name="Samenow2016">{{cite news|last1=Samenow|first1=Jason|title=Two Middle East locations hit 129 degrees, hottest ever in Eastern Hemisphere, maybe the world|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2016/07/22/two-middle-east-locations-hit-129-degrees-hottest-ever-in-eastern-hemisphere-maybe-the-world/|newspaper=The Washington Post|date=22 July 2016|access-date=23 July 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160723174406/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/capital-weather-gang/wp/2016/07/22/two-middle-east-locations-hit-129-degrees-hottest-ever-in-eastern-hemisphere-maybe-the-world/|archive-date=23 July 2016|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=Tapper2016>{{cite web |last1=Tapper |first1=James |url=https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jul/23/think-youre-hot-spare-a-thought-for-kuwait-as-mercury-hits-record-54c |title=Think you're hot? Spare a thought for Kuwait, as mercury hits record 54C |work=The Guardian|date=23 July 2016 |access-date=22 October 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161023141648/https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/jul/23/think-youre-hot-spare-a-thought-for-kuwait-as-mercury-hits-record-54c |archive-date=23 October 2016 |url-status=live }}</ref> This is one of the hottest temperatures ever measured on the planet.<ref name="Samenow2016"/> The following night, the night time low temperature was {{convert|38.8|°C|1}}, which was one of the highest minimum temperatures on any given day, only outshone by [[Khasab]], [[Oman]] and [[Death Valley]], [[United States]]. The lowest temperature ever recorded in Basra was {{convert|-4.7|°C|1}} on 22 January 1964.<ref>{{cite web |title=Iraqi Meteorological Department, 1970 |url=ftp://ftp.library.noaa.gov/docs.lib/htdocs/rescue/cd374_pdf/LSN3407.PDF |publisher=Iraqi Meteorological Department |date=1970 |access-date=17 November 2018 |archive-date=22 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200822132717/ftp://ftp.library.noaa.gov/docs.lib/htdocs/rescue/cd374_pdf/LSN3407.PDF |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

{{Weather box|width=auto |

|||

|metric first=yes |

|||

|single line=yes |

|||

|location=Basra (1991-2020) |

|||

|Jan record high C=34.0 |

|||

|Feb record high C=39.0 |

|||

|Mar record high C=42.6 |

|||

|Apr record high C=43.5 |

|||

|May record high C=50.0 |

|||

|Jun record high C=51.6 |

|||

|Jul record high C=53.9 |

|||

|Aug record high C=52.2 |

|||

|Sep record high C=50.7 |

|||

|Oct record high C=46.8 |

|||

|Nov record high C=39.7 |

|||

|Dec record high C=30.0 |

|||

|Jan high C=18.7 |

|||

|Feb high C=21.7 |

|||

|Mar high C=26.8 |

|||

|Apr high C=33.4 |

|||

|May high C=40.3 |

|||

|Jun high C=45.0 |

|||

|Jul high C=47.0 |

|||

|Aug high C=47.2 |

|||

|Sep high C=43.3 |

|||

|Oct high C=37.2 |

|||

|Nov high C=27.0 |

|||

|Dec high C=20.5 |

|||

|Jan mean C=13.0 |

|||

|Feb mean C=15.5 |

|||

|Mar mean C=20.2 |

|||

|Apr mean C=26.6 |

|||

|May mean C=33.3 |

|||

|Jun mean C=37.4 |

|||

|Jul mean C=38.9 |

|||

|Aug mean C=38.5 |

|||

|Sep mean C=34.7 |

|||

|Oct mean C=28.8 |

|||

|Nov mean C=20.0 |

|||

|Dec mean C=14.4 |

|||

|Jan low C=8.3 |

|||

|Feb low C=10.1 |

|||

|Mar low C=14.3 |

|||

|Apr low C=20.1 |

|||

|May low C=26.2 |

|||

|Jun low C=29.1 |

|||

|Jul low C=30.7 |

|||

|Aug low C=29.9 |

|||

|Sep low C=26.3 |

|||

|Oct low C=21.7 |

|||

|Nov low C=14.4 |

|||

|Dec low C=9.6 |

|||

|Jan record low C=-4.7 |

|||

|Feb record low C=-4.0 |

|||

|Mar record low C=1.9 |

|||

|Apr record low C=2.8 |

|||

|May record low C=8.2 |

|||

|Jun record low C=18.2 |

|||

|Jul record low C=22.2 |

|||

|Aug record low C=20.0 |

|||

|Sep record low C=13.1 |

|||

|Oct record low C=6.1 |

|||

|Nov record low C=1.0 |

|||

|Dec record low C=-2.6 |

|||

|Jan precipitation mm=26.9 |

|||

|Feb precipitation mm=17.7 |

|||

|Mar precipitation mm=18.5 |

|||

|Apr precipitation mm=12.8 |

|||

|May precipitation mm=4.0 |

|||

|Jun precipitation mm=0 |

|||

|Jul precipitation mm=0 |

|||

|Aug precipitation mm=0 |

|||

|Sep precipitation mm=0 |

|||

|Oct precipitation mm=6.6 |

|||

|Nov precipitation mm=19.1 |

|||

|Dec precipitation mm=25.2 |

|||

|Jan rain days=4 |

|||

|Feb rain days=2 |

|||

|Mar rain days=2 |

|||

|Apr rain days=2 |

|||

|May rain days=1 |

|||

|Jun rain days=0 |

|||

|Jul rain days=0 |

|||

|Aug rain days=0 |

|||

|Sep rain days=0 |

|||

|Oct rain days=1 |

|||

|Nov rain days=2 |

|||

|Dec rain days=3 |

|||

| Jan humidity = 66.3 |

|||

| Feb humidity = 56.8 |

|||

| Mar humidity = 47.0 |

|||

| Apr humidity = 38.6 |

|||

| May humidity = 26.8 |

|||

| Jun humidity = 20.5 |

|||

| Jul humidity = 21.8 |

|||

| Aug humidity = 23.6 |

|||

| Sep humidity = 27.2 |

|||

| Oct humidity = 38.5 |

|||

| Nov humidity = 53.8 |

|||

| Dec humidity = 66.1 |

|||

|Jan sun=186 |

|||

|Feb sun=198 |

|||

|Mar sun=217 |

|||

|Apr sun=248 |

|||

|May sun=279 |

|||

|Jun sun=330 |

|||

|Jul sun=341 |

|||

|Aug sun=310 |

|||

|Sep sun=300 |

|||

|Oct sun=279 |

|||

|Nov sun=210 |

|||

|Dec sun=186 |

|||

|Jand sun=6 |

|||

|Febd sun=7 |

|||

|Mard sun=7 |

|||

|Aprd sun=8 |

|||

|Mayd sun=9 |

|||

|Jund sun=11 |

|||

|Juld sun=11 |

|||

|Augd sun=10 |

|||

|Sepd sun=10 |

|||

|Octd sun=9 |

|||

|Novd sun=7 |

|||

|Decd sun=6 |

|||

|source 1= [[WMO]],<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/archive/arc0216/0253808/2.2/data/0-data/Region-2-WMO-Normals-9120/Iraq/CSV/BASRA_40690.csv |

|||

| title = World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991–2020: Basra |format=CSV |

|||

| publisher = [[NOAA|National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration]] |

|||

| access-date = 2 August 2023}}</ref> ''Climate-Data.org''<ref>{{cite web |title=Climate: Basra – Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table |url=http://en.climate-data.org/location/4555/ |publisher=Climate-Data.org |access-date=22 August 2013}}</ref> |

|||

|source 2=''Weather2Travel'' for rainy days and sunshine<ref>{{cite web |title=Basra Climate and Weather Averages, Iraq |url=http://www.weather2travel.com/climate-guides/iraq/basra.php |publisher=Weather2Travel |access-date=22 August 2013}}</ref> Ogimet<ref>{{cite web |url=https://ogimet.com/cgi-bin/gsynres?ind=40689&ano=2022&mes=6&day=20&hora=18&min=0&ndays=30|title= 40689: Basrah-Hussen (Iraq)|author=<!--Not stated--> |date= 19 June 2022|website=ogimet.com |publisher=OGIMET |access-date= 20 June 2022}}</ref> Meteomanz<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.meteomanz.com/sy3?l=1&cou=2050&ind=40690&m1=01&y1=2000&m2=06&y2=2024 |title=BASRAH INT. AIRPORT – Weather data by month |access-date=28 June 2024 |website=meteomanz}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

=== Effect of climate change === |

|||

The city of Basra was once well known for its agriculture, but that has since altered due to rising temperatures, increased [[water salinity]], and [[desertification]].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Al-Rubaie |first=Azhar |title=From palm trees to homes: Iraqi agricultural land lost to desert |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/5/26/climate-change-ravages-iraq-as-palm-trees-make-way-for-desert |access-date=2022-05-27 |publisher=Al Jazeera}}</ref> |

|||

==Demographics== |

|||

Basra Metropolitan Region comprises three towns—Basra city proper, Al-ʿAshar, and Al-Maʿqil—and several villages.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web |title=Basra |url=https://kids.britannica.com/students/article/Basra/317092 |access-date=2024-09-29 |website=Britannica Kids |language=en-US}}</ref> In Basra the vast majority of the population are ethnic [[Arabs]] of the [[Adnanite]] or the [[Qahtanite]] tribes. The tribes located in Basra include [[Bani Malik (tribe)|Bani Malik]], [[Al-shwelat]], [[Suwa'id]], [[Al-bo Mohammed]], [[Al-Badr (tribe)|Al-Badr]], [[Al-Ubadi]], [[Ruba'ah Sayyid]] tribes (descendants of Muhammad) and other [[Marsh Arabs]] tribes.{{Citation needed|date=November 2020}} |

|||

There are also [[Feyli (tribe)|Feyli Kurds]] living in the eastern side of the city, they are mainly merchants. In addition to the Arabs, there is also a community of [[Afro-Iraqi]] peoples, known as [[Zanj]].<ref name=":3" /> The Zanj are an African Muslim ethnic group living in Iraq and are a mix of African peoples taken from the coast of the area of modern-day [[Kenya]] as slaves in the 900s.<ref name=":3" /> They now number around 200,000 in [[Iraq]].{{Citation needed|date=November 2020}} |

|||

===Religion=== |

|||

{{See also|Christianity in Iraq|Shia Islam in Iraq {{!}} Iraqi Shi'ites}} |

|||

[[File:Basra Armenian Church (30855638080).jpg|left|thumb|The Armenian Church in Basra]] |

|||

Basra is a major [[Shia]] city, with the old [[Akhbari]] Shiism progressively being overwhelmed by the [[Usuli]] Shiism.<ref name=":4">{{Cite web |last=Foundation |first=Encyclopaedia Iranica |title=Welcome to Encyclopaedia Iranica |url=https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/basra |access-date=2024-09-29 |website=iranicaonline.org |language=en-US}}</ref> It is known as the "Cradle of Islamic Culture".<ref name=":5">{{Cite web |title=Basra, cradle of Islamic culture. An analysis of the urban area that was the early home of Islamic Studies |url=https://pluriel.fuce.eu/article/basra-cradle-of-islamic-culture-an-analysis-of-the-urban-area-that-was-the-early-home-of-islamic-studies/?lang=en |access-date=2024-09-29 |website=Pluriel |language=en-US}}</ref> The [[Sunni Muslim]] population is small and dropping in their percentage as more Iraqi Shias move into Basra for various job or welfare opportunities.<ref name=":4" /> The satellite town of [[Az Zubayr]] in the direction of Kuwait was a Sunni majority town, but the burgeoning population of Basra has spilled over into Zubair, turning it into an extension of Basra with a slight Shia majority as well.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

[[Assyrian Church of the East|Assyrians]] were recorded in the Ottoman census as early as 1911, and a small number of them live in Basra.<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" /><ref>{{Cite web |last=SyriacPress |date=2024-01-26 |title=Christians in Basra, Iraq, extend invitation to those who emigrated: 'Come home to peace and security' |url=https://syriacpress.com/blog/2024/01/26/christians-in-basra-iraq-extend-invitation-to-those-who-emigrated-come-home-to-peace-and-security/ |access-date=2024-09-29 |website=SyriacPress |language=en-US}}</ref> However, a significant number of the modern community are refugees fleeing persecution from ISIS in the [[Nineveh Plains]], Mosul, and [[Assyrian homeland|northern Iraq]].<ref name=":4" /> But ever since the victory of [[War in Iraq (2013–2017)|Iraq against the ISIS in 2017]], many Christians have returned to their homeland in the Nineveh plains.<ref name=":4" /> In 2018 there are about a few thousand Christians in Basra.<ref name=":4" /> The Armenian Church in Basra, dates from 1736 but has been rebuilt three times.<ref name=":4" /> The portrait of the [[Virgin Mary]] in the church was brought from India in 1882.<ref name=":4" /> |

|||

One of the largest communities of pre-Islamic [[Mandaeans]] live in the city, whose headquarters was in the area formerly called Suk esh-Sheikh.<ref name=":6">{{Cite news |date=2009-09-23 |title=Ethnic Mandaeans Killed In Iraqi Jewelry Store Robberies |url=https://www.rferl.org/a/Ethnic_Mandaeans_Killed_In_Iraqi_Jewelry_Store_Robberies/1829230.html |access-date=2024-09-29 |work=Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty |language=en}}</ref> Basra is home to second highest concentration of the Mandaean community, after Baghdad.<ref name=":6" /> As of recent estimates 350 Mandaean families are found in the city.<ref name=":6" /> Dair al-Yahya is one of the most important Mandaean temples, located in Basra.<ref name=":7">{{Cite web |title=Home |url=https://bhaktikalpa.com/Mandaean.aspx |access-date=2024-09-29 |website=bhaktikalpa.com}}</ref> The temple is dedicated to [[John the Baptist]], the chief prophet in [[Mandaeism]], who also reverred by the Jews, Christians and Muslims.<ref name=":7" /> |

|||

The city was also home to one of the [[History of the Jews in Iraq|oldest Jewish communities]].<ref name=":8">{{Cite web |title=Basra |url=https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/basra |access-date=2024-09-29 |website=www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org}}</ref> During the 1930s, the Jews constituted 9.8% of the total population.<ref name=":8" /> However, most of them fled after a series of persecution, which began in 1941 and lasted till 1951.<ref name=":8" /> Between [[Ba'athist Iraq|1968 and 2003]], fewer than 300 Jews remained in the city.<ref name=":8" /> After the 2003 invasion of Iraq, most of them emigrated to abroad.<ref name=":8" /> The Tweig Synagogue in Basra, is currently abandoned.<ref name=":8" /> |

|||

==Cityscape== |

|||

[[File:Imam Ali Mosque 2.jpg|thumb|[[Imam Ali Mosque (Basra)|Ali Bin Abi Talib mosque]]]] |

|||

[[File:Basrah corniche.JPG|thumb|[[Shatt Al-Arab]]|left]] |

|||

[[File:Bridge of Basra 1.jpg|thumb|right|[[Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr|Muhhmad Baquir Al-Sadr]] Bridge]]The [[Imam Ali Mosque (Basra)|Old Mosque of Basra]] is the first mosque in Islam outside the Arabian peninsula. Sinbad Island is located in the centre of Shatt Al-Arab, near the Miinaalmakl, and extends above the Bridge Khaled and is a tourist landmark. The [[Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr|Muhhmad Baquir Al-Sadr Bridge]], at the union of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, was completed in 2017.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.maegspa.com/en/portfolio/muhammad-baquir-al-sadr-bridge|title=Maeg – Building ideas|website=Maeg SpA}}</ref> Sayab's House Ruins is the site of the most famous home of the poet [[Badr Shakir al-Sayyab]]. There is also a statue of Sayab, one of the statues in Basra done by the artist and sculptor Nada' Kadhum, located on al-Basrah Corniche; it was unveiled in 1972. |

|||

[[Basra Sports City]] is the largest sport city in the Middle East, located on the Shatt al-Basra. Palm tree forests are largely located on the shores of Shatt-al Arab waterway, especially in the nearby village of [[Abu Al-Khaseeb|Abu Al-Khasib]]. Corniche al-Basra is a street which runs on the shore of the Shatt al-Arab; it goes from the Lion of Babylon Square to the Four Palaces. Basra International Hotel (formally known as Basra Sheraton Hotel) is located on the Corniche street. The first five star hotel in the city, it is notable for its [[Shanasheel]] style exterior design. The hotel was heavily looted during the [[Iraq War]], and it has been renovated recently. |

|||

Sayyed Ali al-Musawi Mosque, also known as the Mosque of the Children of Amer, is located in the city centre, on Al-Gazear Street, and it was built for Shia Imami's leader Sayyed Ali al-Moussawi, whose followers lived in Iraq and neighbouring countries. The Fun City of Basra, which is now called Basra Land, is one of the oldest theme-park entertainment cities in the south of the country, and the largest involving a large number of games giants. It was damaged during the war, and has been rebuilt. Akhora Park is one of the city's older parks. It is located on al-Basra Street. |

|||

There are four formal presidential palaces in Basra, built by Saddam Hussein. One of them has been converted into a museum. The Latin Church is located on 14 July Street. Indian Market (''Amogaiz'') is one of the main bazaars in the city. It is called the Indian Market, since it had Indian vendors working there at the beginning of the last century. Hanna-Sheikh Bazaar is an old market; it was established by the powerful and famous Hanna-Sheikh family. |

|||

==Economy== |

|||

[[File:Al Basrah Oil Terminal (ABOT).jpg|thumb|[[Al Basrah Oil Terminal]].|left]] |

|||