Max Weber: Difference between revisions

→Inspirations: sp |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|German sociologist, jurist, and political economist (1864–1920)}} |

|||

{{otherpeople}} |

|||

{{other people}} |

|||

{{Infobox Person |

|||

{{good article}} |

|||

| name = Max Weber |

|||

{{Use British English|date=April 2011}} |

|||

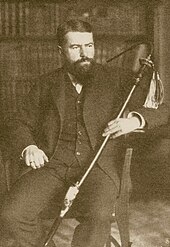

| image = Max Weber 1894.jpg |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=January 2021}} |

|||

| caption = [[Germany|German]] [[political economy|political economist]] and [[sociologist]] |

|||

{{Infobox philosopher |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1864|4|21|df=y}} |

|||

| birth_name = Maximilian Carl Emil Weber |

|||

| birth_place = [[Erfurt]], [[Prussian Saxony]] |

|||

| image = File:Max Weber, 1918.jpg |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|1920|6|14|1864|4|21|df=y}} |

|||

| caption = Weber in 1918 |

|||

| death_place = [[Munich]], [[Bavaria]] |

|||

| alt = Max Weber in 1918, facing right |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1864|4|21|df=y}} |

|||

| birth_place = [[Erfurt]], [[Province of Saxony]], [[Kingdom of Prussia]] |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|1920|6|14|1864|4|21|df=y}} |

|||

| death_place = [[Munich]], [[Bavaria]], [[Weimar Republic]] |

|||

| main_interests = {{hlist|History|economics|sociology|law|religion}} |

|||

| institutions = {{ubl|[[Humboldt University of Berlin|Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin]]|[[University of Freiburg]]|[[Heidelberg University]]|[[University of Vienna]]|[[Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich]]}} |

|||

| alma_mater = {{ubl|[[Heidelberg University]]|[[University of Strasbourg]]|[[Humboldt University of Berlin|University of Berlin]]|[[University of Göttingen]]}} |

|||

| thesis1_title = On the History of Commercial Partnerships in the Middle Ages, Based on Southern European Documents |

|||

| thesis2_title = Roman Agrarian History and Its Significance for Public and Private Law |

|||

| thesis1_url = https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-476-05142-4_51 |

|||

| thesis2_url = https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-476-05142-4_52 |

|||

| thesis1_year = 1889 |

|||

| thesis2_year = 1891 |

|||

| doctoral_advisors = {{flatlist| |

|||

* [[Levin Goldschmidt]] |

|||

* [[Rudolf von Gneist]] |

|||

* [[August Meitzen]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| academic_advisors = |

|||

| notable_students = |

|||

| notable_ideas = {{Collapsible list|[[Disenchantment]]|[[Ethic of ultimate ends]]|[[Ideal type]]|[[Inner-worldly asceticism]]|[[Iron cage]]|[[Life chances]]|[[Methodological individualism]]|[[Monopoly on violence]]|[[Protestant work ethic]]|[[Rationalization (sociology)|Rationalisation]]|[[Secularisation]]|[[Social action]] ([[Affectional action|Affectional]], [[Traditional action|Traditional]], [[Instrumental and value-rational action|Instrumental, and Value-rational]])|[[Three-component theory of stratification]] (Class, Party, and [[Social status|Status]])|[[Tripartite classification of authority]] ([[Charismatic authority|Charismatic]], [[Rational-legal authority|Rational-legal]], and [[Traditional authority|Traditional]])|[[Value-freedom]]|{{Lang|de|[[Verstehen]]}}|[[Weberian bureaucracy]]}} |

|||

| awards = |

|||

| signature = Max_Weber%27s Signature.svg |

|||

| notable_works = {{ubl|"[[The "Objectivity" of Knowledge in Social Science and Social Policy|The 'Objectivity' of Knowledge in Social Science and Social Policy]]"|''[[The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]]'' (1904{{ndash}}1905)|''[[The Economic Ethics of the World Religions]]'' (1915{{ndash}}1921)|"[[Science as a Vocation]]" (1917)|"[[Politics as a Vocation]]" (1919)|''[[The City (Weber book)|The City]]'' (1921)|''[[Economy and Society]]'' (1922)|''[[General Economic History]]'' (1923)}} |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|[[Marianne Schnitger]]|1893|<!--his death; omitted-->}} |

|||

| school_tradition = {{hlist|[[Continental philosophy]]|[[Antipositivism]]|[[Interpretations of Max Weber's liberalism|Liberalism]]}} |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Maximilian Carl Emil Weber''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|v|eɪ|b|ər}}; {{IPA|de|maks ˈveːbɐ|lang}}; 21 April 1864{{snd}}14 June 1920) was a German [[Sociology|sociologist]], historian, [[jurist]], and [[political economy|political economist]] who was one of the central figures in the development of sociology and the [[social science]]s more generally. His ideas continue to influence [[social theory]] and [[social research|research]]. |

|||

Born in [[Erfurt]] in 1864, Weber studied law and history in [[Humboldt University of Berlin|Berlin]], [[University of Göttingen|Göttingen]], and [[Heidelberg University|Heidelberg]]. After earning his doctorate in law in 1889 and [[habilitation]] in 1891, he taught in Berlin, [[University of Freiburg|Freiburg]], and Heidelberg. He married his cousin [[Marianne Weber|Marianne Schnitger]] two years later. In 1897, he had a breakdown after [[Max Weber Sr.|his father]] died following an argument. Weber ceased teaching and travelled until the early 1900s. He recovered and wrote ''[[The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]]''. During the [[First World War]], he initially supported Germany's war effort but became critical of it and supported democratisation. He also gave the lectures "[[Science as a Vocation]]" and "[[Politics as a Vocation]]". After the war, Weber co-founded the [[German Democratic Party]], unsuccessfully ran for office, and advised the drafting of the [[Weimar Constitution]]. Becoming frustrated with politics, he resumed teaching in [[University of Vienna|Vienna]] and [[Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich|Munich]]. He died of [[pneumonia]] in 1920 at the age of 56, possibly as a result of the post-war [[Spanish flu]] pandemic. A book, ''[[Economy and Society]]'', was left unfinished. |

|||

'''Maximilian Carl Emil''' "'''Max'''" '''Weber''' ({{IPA-de|maks ˈveːbɐ}}) (21 April 1864–14 June 1920) was a [[Germany|German]] [[lawyer]], [[politician]], [[historian]], [[political economy|political economist]], and [[sociologist]], who profoundly influenced [[social theory]], [[social research]], and the remit of sociology itself.<ref>"Max Weber." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 20 Apr. 2009. [http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/638565/Max-Weber]</ref> Weber's major works dealt with the [[Rationalisation (sociology)|rationalization]] and so-called "[[disenchantment]]" which he associated with the rise of [[capitalism]] and [[modernity]].<ref>Habermas, Jürgen, ''The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity'', Polity Press (1985), ISBN 0-7456-0830-2, p2 </ref> Weber was, along with his associate [[Georg Simmel]], a central figure in the establishment of [[antipositivism|methodological antipositivism]]; presenting sociology as a non-empirical field which must study [[social action]] through resolutely [[verstehen|subjective means]].<ref>Weber wrote his books in [[German language|German]]. Original titles printed after his death (1920) are most likely [[Anthology|compilations]] of his unfinished works (note the 'Collected Essays...' form in titles). Many [[translation]]s are made of parts or sections of various German [[original]]s, and the names of the translations often do not reveal what part of German work they contain. Weber's work is generally quoted according to the critical [http://www.mohr.de/mw/index_e.html ''Gesamtausgabe''] (collected works edition), which is published by Mohr Siebeck in [[Tübingen]], Germany. For an extensive list of Max Weber's works see [[list of Max Weber works]].</ref> He is typically cited, with [[Émile Durkheim]] and [[Karl Marx]], as one of the three principal architects of modern social science,<ref>Kim, Sung Ho (2007). "Max Weber". [[Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]] (August 24, 2007 entry) http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/weber/ (Retrieved 17-02-2010)</ref> and has variously been described as the most important classic thinker in the social sciences.<ref>"The prestige of Max Weber among European social scientists would be difficult to over-estimate." – Gerth, Hans Heinrich and Charles Wright Mills (eds.) (1991). ''From Max Weber: essays in sociology''. Routledge, p.i.</ref><ref>Radkau, Joachim and Patrick Camiller. (2009). ''Max Weber: A Biography''. Trans. Patrick Camiller. Polity Press. (ISBN: 9780745641478)</ref> |

|||

One of Weber's main intellectual concerns was in understanding the processes of [[Rationalisation (sociology)|rationalisation]], [[Secularization|secularisation]], and [[disenchantment]]. He formulated a thesis arguing that such processes were associated with the rise of [[capitalism]] and modernity. Weber also argued that the [[Protestant work ethic]] influenced the creation of capitalism in ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism''. It was followed by ''[[The Economic Ethics of the World Religions]]'', where he examined the religions of [[The Religion of China|China]], [[The Religion of India|India]], and [[Ancient Judaism (book)|ancient Judaism]]. In terms of government, Weber argued that [[State (polity)|state]]s were defined by their [[monopoly on violence]] and categorised social authority into [[Tripartite classification of authority|three distinct forms]]: [[Charismatic authority|charismatic]], [[Traditional authority|traditional]], and [[Rational-legal authority|rational-legal]]. He was also a key proponent of methodological [[antipositivism]], arguing for the study of [[social action]] through [[Verstehen|interpretive]] rather than purely [[Empiricism|empiricist]] methods. Weber made a variety of other contributions to [[economic sociology]], [[political sociology]], and the [[sociology of religion]]. |

|||

Weber's most famous work is his essay in [[economic sociology]], ''[[The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]]'', which also began his work in the [[sociology of religion]]. In this text, Weber argued that religion was one of the non-exclusive reasons for the different ways the cultures of the [[Occident]] and the [[Orient]] have developed, and stressed that particular characteristics of [[ascetic]] [[Protestantism]] influenced the development of [[capitalism]], [[bureaucracy]] and the [[rational-legal]] state in [[Western world|the West]]. The essay examines the effects Protestantism had upon the beginnings of capitalism, arguing that capitalism is not purely [[base and superstructure|materialist]] in [[Karl Marx]]'s sense, but rather originates in religious ideals and ideas which cannot be solely explained by ownership relations, technology and advances in learning alone.<ref>Weber, Max ''The Protestant Ethic and "The Spirit of Capitalism"'' (1905). Translated by Stephen Kalberg (2002), Roxbury Publishing Company, pp. 19 & 35; Weber's references on these pages to "Superstructure" and "base" are unambiguous references to Marxism's base/superstructure theory.</ref> |

|||

After his death, the rise of Weberian scholarship was slowed by the [[Weimar Republic]]'s political instability and the rise of [[Nazi Germany]]. In the post-war era, organised scholarship began to appear, led by [[Talcott Parsons]]. Other American and British scholars were also involved in its development. Over the course of the twentieth century, Weber's reputation rose due to the publication of translations of his works and scholarly interpretations of his life and works. As a result of these works, he began to be regarded as a founding father of sociology, alongside [[Karl Marx]] and [[Émile Durkheim]], and one of the central figures in the development of the social sciences more generally. |

|||

In another major work, ''[[Politics as a Vocation]]'', Weber defined the [[Sovereign state|state]] as an entity which claims a "[[monopoly of force|monopoly on the legitimate use of violence]]", a definition that became pivotal to the study of modern Western [[political science]]. His analysis of [[bureaucracy]] in his ''[[Economy and Society]]'' is still central to the modern study of organizations. Weber was the first to recognize several diverse aspects of social authority, which he respectively categorized according to their charismatic, traditional, and legal forms. His analysis of [[bureaucracy]] thus noted that modern state institutions are based on a form of [[rational-legal authority]]. Weber's thought regarding the rationalizing and [[secularisation|secularizing]] tendencies of modern Western society (sometimes described as the "[[Weber Thesis]]") would come to facilitate [[critical theory]], particularly in the work of thinkers such as [[Jürgen Habermas]]. |

|||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

===Early life and education=== |

|||

Weber was born in 1864, in [[Erfurt]] in [[Thuringia]], [[Germany]], the eldest of seven children of Max Weber Sr., a wealthy and prominent politician in the [[National Liberal Party (Germany)]] and a [[civil service|civil servant]], and Helene Fallenstein, a Protestant and a [[Calvinist]], with strong moral absolutist ideas.<ref>Periodical, Sociology Volume 250, September, 1999, 'Max Weber'</ref> Weber Sr.'s engagement with public life immersed the family home in politics, as his salon received many prominent scholars and public figures. Weber was strongly influenced by his mother's views and approach to life, but he did not claim to be religious himself. |

|||

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber was born on 21 April 1864 in [[Erfurt]], Province of Saxony, Kingdom of Prussia, but his family moved to Berlin in 1869.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=22, 144–145|2a1=Kim|2y=2022|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3p=5}} He was the oldest of [[Max Weber Sr.]] and Helene Fallenstein's eight children.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaelber|1y=2003|1p=38|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2p=11|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3pp=148–149}} Over the course of his life, Weber Sr. held posts as a lawyer, civil servant, and parliamentarian for the [[National Liberal Party (Germany)|National Liberal Party]] in the [[Landtag of Prussia|Prussian Landtag]] and [[Reichstag (German Empire)|German Reichstag]].{{sfnm|1a1=Kaelber|1y=2003|1p=38|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2p=5|3a1=Honigsheim|3y=2017|3p=100}} His involvement in public life immersed his home in both politics and academia, as his [[Salon (gathering)|salon]] welcomed scholars and public figures such as the philosopher [[Wilhelm Dilthey]], the jurist [[Levin Goldschmidt]], and the historian [[Theodor Mommsen]]. The young Weber and his brother [[Alfred Weber|Alfred]], who also became a sociologist, passed their formative years in this intellectual atmosphere.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=1988|1pp=2–3, 14|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=91–92}} Meanwhile, Fallenstein was partly descended from the French [[Huguenots|Huguenot]] {{Interlanguage link|Souchay family|de|Souchay (Familie)}}, which had obtained wealth through international commerce and the [[textile industry]].{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=68, 129–137|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2p=9|3a1=Kim|3y=2022}} Over time, Weber was affected by the marital and personality tensions between his father, who enjoyed material pleasures while overlooking religious and [[philanthropy|philanthropic]] causes, and his mother, a devout [[Calvinism|Calvinist]] and philanthropist.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=54, 62|2a1=Kaelber|2y=2003|2pp=38–39|3a1=Ritzer|3y=2009|3p=32}} |

|||

[[File:Max Weber and brothers 1879.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Max Weber (left) and his brothers, [[Alfred Weber|Alfred]] (center) and Karl (right), in 1879|alt=A group photograph of Max Weber with his brothers Alfred and Karl]] |

|||

The young Weber and his brother [[Alfred Weber|Alfred]], who also became a sociologist and economist, thrived in this intellectual atmosphere. Weber's 1876 Christmas presents to his parents, when he was thirteen years old, were two historical essays entitled "About the course of German history, with special reference to the positions of the emperor and the pope" and "About the Roman Imperial period from Constantine to the migration of nations".<ref>Sica, Alan (2004). ''Max Weber and the New Century''. London: Transaction Publishers, p. 24. ISBN 0-7658-0190-6.</ref> At the age of fourteen, he wrote letters studded with references to [[Homer]], [[Virgil]], [[Cicero]], and [[Livy]], and he had an extended knowledge of [[Goethe]], [[Spinoza]], [[Kant]], and [[Schopenhauer]] before he began university studies. It seemed clear that Weber would pursue advanced studies in the [[social sciences]]. |

|||

Weber entered the {{Lang|de|Doebbelinsche Privatschule}} in [[Charlottenburg]] in 1870, before attending the {{Lang|de|[[Kaiserin-Augusta-Gymnasium]]}} between 1872 and 1882.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=176–178|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2p=561}} While in class, bored and unimpressed with his teachers, Weber secretly read all forty volumes by the writer [[Johann Wolfgang von Goethe]].{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=1988|1p=2|2a1=McKinnon|2y=2010|2pp=110–112|3a1=Kent|3y=1983|3pp=297–303}} Goethe later exerted an important influence on his thought and methodology.{{sfnm|1a1=McKinnon|1y=2010|1pp=110–112|2a1=Kent|2y=1983|2pp=297–303}} Before entering university, he read many other classical works, including those by the philosopher [[Immanuel Kant]].{{sfn|Kaesler|1988|pp=2–3}} For Christmas in 1877, a thirteen-year-old Weber gifted his parents two historical essays, entitled "About the Course of German History, with Special Reference to the Positions of the Emperor and the Pope" and "About the Roman Imperial Period from Constantine to the Migration Period". Two years later, also during Christmastime, he wrote another historical essay, "Observations on the Ethnic Character, Development, and History of the Indo-European Nations". These three essays were non-derivative contributions to the [[philosophy of history]] and were derived from Weber's reading of "numerous sources".{{sfnm|1a1=Sica|1y=2017|1p=24|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2p=180}} |

|||

[[File:Max Weber and brothers 1879.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Max Weber and his brothers, Alfred and Karl, in 1879]] |

|||

In 1882, Weber enrolled in [[Heidelberg University]] as a law student, later studying at the [[Humboldt University of Berlin|Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin]] and the [[University of Göttingen]].{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=31–33|2a1=Bendix|2a2=Roth|2y=1977|2pp=1–2}} He practiced law and worked as a lecturer simultaneously with his studies.{{sfnm|1a1=Berman|1a2=Reid|1y=2000|1pp=223–225|2a1=Allan|2y=2005|2p=146|3a1=Honigsheim|3y=2017|3p=101}} In 1886, Weber passed the [[Referendary|Referendar]] examination, which was comparable to the [[bar association]] examination in the British and U.S. legal systems. Throughout the late 1880s, he continued to study law and history.{{sfn|Kaelber|2003|pp=30–33}} Under the tutelage of Levin Goldschmidt and [[Rudolf von Gneist]], Weber earned his law doctorate in 1889 by writing a dissertation on legal history titled ''Development of the Principle of Joint Liability and a Separate Fund of the General Partnership out of the Household Communities and Commercial Associations in Italian Cities''. It was a part of a longer work, ''[[Zur Geschichte der Handelsgesellschaften im Mittelalter|On the History of Commercial Partnerships in the Middle Ages, Based on Southern European Documents]]'', which he published in the same year.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaelber|1y=2003|1p=33|2a1=Honigsheim|2y=2017|2p=239|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3p=563}} Two years later, Weber worked with the statistician [[August Meitzen]] to complete his [[Habilitation#Germany|habilitation]], a post-doctoral thesis, titled ''[[Roman Agrarian History and Its Significance for Public and Private Law]]''.{{sfnm|1a1=Bendix|1a2=Roth|1y=1977|1pp=1–2|2a1=Kaelber|2y=2003|2p=41|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3p=563}} Having thus become a {{Lang|de|[[Privatdozent]]}}, Weber joined the faculty of the Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University of Berlin, lecturing, conducting research, and consulting for the government.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1p=307|2a1=Honigsheim|2y=2017|2p=101}} |

|||

In 1882 Weber enrolled in the [[University of Heidelberg]] as a law student.<ref name="Bendix1">{{cite book |last=Bendix |first=Reinhard |authorlink=Reinhard Bendix |title=Max Weber: An Intellectual Portrait |url=http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0520031946&id=63sC9uaYqQsC&pg=PA1&lpg=PA1&sig=g-kn8gtBIRvG-ss0I_-BmrBz9YE |date=July 1, 1977 |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=0-520-03194-6 |pages=1 }}</ref> Weber joined his father's [[Academic Fencing|duelling fraternity]], and chose as his major study Weber Sr.'s field of law. Along with his law coursework, young Weber attended lectures in economics and studied medieval history and theology. Intermittently, he served with the [[Reichswehr|German army]] in [[Strasbourg]]. |

|||

Weber's years as a university student were dotted with several periods of military service, the longest of which lasted between October 1883 and September 1884. During this time, he was in [[Strasbourg]] and attended classes at the [[University of Strasbourg]] that his uncle, the historian [[Hermann Baumgarten]], taught.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaelber|1y=2003|1p=30|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=562–564}} Weber befriended Baumgarten and he influenced [[Interpretations of Max Weber's liberalism|Weber's growing liberalism]] and criticism of [[Otto von Bismarck]]'s domination of German politics.{{sfnm|1a1=Mommsen|1a2=Steinberg|1y=1984|1pp=2–9|2a1=Kaelber|2y=2003|2p=36|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3p=23}} He was a member of the ''{{Interlanguage link|Burschenschaft Allemannia Heidelberg|de}}'', a {{Lang|de|[[Studentenverbindung]]}} ("student association"), and heavily drank beer and engaged in [[academic fencing]] during his first few years in university.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=31–33|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=191, 200–202}} As a result of the latter, he obtained several [[dueling scar|duelling scar]]s on the left side of his face.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=191, 207|2a1=Gordon|2y=2020|2p=32|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3pp=32–33}} His mother was displeased by his behaviour and slapped him after he came home when his third semester ended in 1883. However, Weber matured, increasingly supported his mother in family arguments, and grew estranged from his father.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaelber|1y=2003|1p=39|2a1=Ritzer|2y=2009|2p=32|3a1=Gordon|3y=2020|3p=32}} |

|||

In the autumn of 1884, Weber returned to his parents' home to study at the [[University of Berlin]]. For the next eight years of his life, interrupted only by a term at the [[University of Göttingen]] and short periods of further military training, Weber stayed at his parents' house; first as a student, later as a junior barrister, and finally as a dozent/professor at the University of Berlin. In 1886 Weber passed the examination for "[[Referendar]]", comparable to the [[bar association]] examination in the British and American legal systems. Throughout the late 1880s, Weber continued his study of history. He earned his law doctorate in 1889 by writing a [[doctoral dissertation]] on legal history entitled ''[[Zur Geschichte der Handelsgesellschaften im Mittelalter|The History of Medieval Business Organisations]]''.<ref name="Bendix1" /> Two years later, Weber completed his [[Habilitation]]sschrift, ''[[Die Römische Agrargeschichte in ihrer Bedeutung für das Staats- und Privatrecht|The Roman Agrarian History and its Significance for Public and Private Law]]''.<ref name="Bendix2">{{cite book |last=Bendix |title=Max Weber |url=http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0520031946&id=63sC9uaYqQsC&pg=PA2&lpg=PA2&sig=SieKjdgz3D2sHx8CUBXW4PSeoDQ |pages=2 }}</ref> Having thus become a "[[Privatdozent]]", Weber was now qualified to hold a German professorship. |

|||

===Marriage, early work, and breakdown<!--Weber Circle redirects here-->=== |

|||

In the years between the completion of his dissertation and habilitation, Weber took an interest in contemporary [[social policy]]. In 1888 he joined the "[[Verein für Socialpolitik]]",<ref name="WaSI">Gianfranco Poggi, ''Weber: A Short Introduction'', Blackwell Publishing, 2005, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0745634907&id=c5a2LWRh7uEC&pg=PA5&lpg=PA5&dq=Weber+1888+Verein&sig=tn_CbtDguweC_BqJE6przIhsSYw Google Print, p.5]</ref> the new professional association of German economists affiliated with the [[Historical school of economics|historical school]], who saw the role of economics primarily as the solving of the wide-ranging social problems of the age, and who pioneered large scale statistical studies of economic problems. He also involved himself in politics, joining the left leaning Evangelical Social Congress.<ref>{{cite book|author=Wolfgang Justin |

|||

Mommsen|title=Max Weber and German Politics, 1890–1920|year=1984|publisher=University of Chicago |

|||

Press|isbn=0226533999|pages=19}}</ref> In 1890 the "Verein" established a research program to examine "the Polish question" or [[Ostflucht]], meaning the influx of foreign farm workers into [[Former eastern territories of Germany|eastern Germany]] as local labourers migrated to Germany's rapidly industrialising cities. Weber was put in charge of the study, and wrote a large part of its results.<ref name="WaSI"/> The final report was widely acclaimed as an excellent piece of [[empirical]] research, and cemented Weber's reputation as an expert in [[agricultural economics|agrarian economics]]. |

|||

[[File:Max and Marianne Weber 1894.jpg|thumb|upright|Max Weber and his wife Marianne in 1894]] |

[[File:Max and Marianne Weber 1894.jpg|thumb|upright|Max Weber and his wife Marianne in 1894|alt=Max Weber, right, and Marianne, left, in 1894]] |

||

In 1893 he married his distant cousin [[Marianne Weber|Marianne Schnitger]], later a [[feminism|feminist]] and author in her own right,<ref name="Marianne">[http://www.webster.edu/~woolflm/weber.html Marianne Weber]. Last accessed on 18 September 2006. Based on Lengermann, P., & Niebrugge-Brantley, J.(1998). The Women Founders: Sociology and Social Theory 1830–1930. New York: McGraw-Hill.</ref> who was instrumental in collecting and publishing Weber's journal articles as books after his death. The couple moved to Freiburg in 1894, where Weber was appointed professor of economics at [[Albert-Ludwigs-Universität|Freiburg University]],<ref name="Bendix2"/> before accepting the same position at the [[University of Heidelberg]] in 1896.<ref name="Bendix2"/> Next year, Max Weber Sr. died, two months after a severe quarrel with his son that was never resolved.<ref name="EESoc-7">''Essays in Economic Sociology'', Princeton University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-691-00906-6, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0691009066&id=WaV7Q35jy_AC&pg=PA7&lpg=PA7&dq=Weber+father+1897&sig=Vn8HESDQxkYniFLOZay3NPeMDQ0 Google Print, p.7]</ref> After this, Weber became increasingly prone to nervousness and insomnia, making it difficult for him to fulfill his duties as a professor.<ref name="Bendix2"/> His condition forced him to reduce his teaching, and leave his last course in the fall of 1899 unfinished. After spending months in a sanatorium during the summer and fall of 1900, Weber and his wife traveled to Italy at the end of the year, and did not return to Heidelberg until April 1902. |

|||

From 1887 until her declining mental health caused him to break off their relationship five years later, Weber had a relationship and semi-engagement with Emmy Baumgarten, the daughter of Hermann Baumgarten.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=39–40, 562|2a1=Kaelber|2y=2003|2pp=36–38}} Afterwards, he began a relationship with his distant cousin [[Marianne Weber|Marianne Schnitger]] in 1893 and married her on 20 September of that year.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1p=564|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=329–332, 362}} The marriage gave Weber financial independence, allowing him to leave his parents' household.{{sfn|Kaelber|2003|pp=39–40}} They had no children.{{sfnm|1a1=Allan|1y=2005|1p=146|2a1=Frommer|2a2=Frommer|2y=1993|2p=165|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3p=45}} Marianne was a [[Feminist movement|feminist activist]] and an author in her own right.{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Lengermann|2a2=Niebrugge-Brantley|2y=1998|2p=193|3a1=Frommer|3a2=Frommer|3y=1993|3p=165}} Academically, between the completion of his dissertation and habilitation, Weber took an interest in contemporary [[social policy]]. He joined the {{Lang|de|[[Verein für Socialpolitik]]}} ("Association for Social Policy") in 1888.{{sfnm|1a1=Poggi|1y=2006|1p=5|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2p=270|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3p=563}} The {{Lang|de|Verein}} was an organisation of reformist thinkers who were generally members of the [[historical school of economics]].{{sfn|Swedberg|Agevall|2016|pp=370–371}} He also involved himself in politics, participating in the founding of the left-leaning [[Evangelical Social Congress]] in 1890. It applied a [[Protestant]] perspective to the political debate regarding the [[social question]].{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1p=346|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2p=563}} In the same year, the {{Lang|de|Verein}} established a research program to examine the {{Lang|de|[[Ostflucht]]}}, which was the western migration of ethnically German agricultural labourers from [[East Elbia|eastern Germany]] and the corresponding influx of Polish farm workers into it. Weber was put in charge of the study and wrote a large part of the final report, which generated considerable attention and controversy, marking the beginning of his renown as a social scientist.{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Poggi|2y=2006|2p=5|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3pp=79–82}} |

|||

After Weber's immense productivity in the early 1890s, he did not publish a single paper between early 1898 and late 1902, finally resigning his professorship in fall 1903. Freed from those obligations, in that year he accepted a position as associate editor of the [[Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik|Archives for Social Science and Social Welfare]]<ref name="Bendix3">{{cite book |last=Bendix |title=Max Weber |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=63sC9uaYqQsC&visbn=0520031946&pg=PA3&lpg=PA2&sig=ow6l2JcRLE_K1x4lws1fhNFlwWY |pages=3 }}</ref> next to his colleagues Edgar Jaffé and [[Werner Sombart]].<ref name="GRMW">Guenther Roth: "History and sociology in the work of Max Weber", in: British Journal of Sociology, 27(3), 1979</ref> In 1904, Weber began to publish some of his most seminal papers in this journal, notably his essay ''[[The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]]''. It became his most famous work,<ref name="EESoc-22">''Essays in Economic Sociology'', Princeton University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-691-00906-6, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0691009066&id=WaV7Q35jy_AC&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=Weber+Protestant+ethic+most+famous&sig=iEqDl685hRMeErd8YKrfAQMs4fE Google Print, p.22]</ref> and laid the foundations for his later research on the impact of cultures and religions on the development of economic systems.<ref>Iannaccone, Laurence (1998). |

|||

[http://scholar.google.com/scholar?num=100&hl=en&lr=&q=cache:5nuZGw5sEuIJ:gunston.doit.gmu.edu/liannacc/Downloads/Iannaccone%2520-%2520Introduction%2520to%2520the%2520Economics%2520of%2520Religion.pdf "Introduction to the Economics of Religion"]. ''Journal of Economic Literature'' '''36''', 1465–1496.</ref> This essay was the only one of his works that was published as a book during his lifetime. Also that year, he visited the United States and participated in the Congress of Arts and Sciences held in connection with the [[World's Fair]] ([[Louisiana Purchase Exposition]]) at [[St. Louis, Missouri|St. Louis]]. Despite his successes, Weber felt that he was unable to resume regular teaching at that time, and continued on as a private scholar, helped by an inheritance in 1907.<ref name="Bendix3"/> In 1912, Weber tried to organise a left-wing political party to combine social-democrats and liberals. This attempt was unsuccessful, presumably because many liberals feared social-democratic revolutionary ideals at the time.<ref name="TPaSToMW">[[Wolfgang J. Mommsen]], ''The Political and Social Theory of Max Weber'', University of Chicago Press, 1992, ISBN 0-226-53400-6, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0226534006&id=kgF9bjMoocYC&pg=PA81&lpg=PA81&dq=Weber+1912+socialist&sig=AeL6fb399L7S_Mg0xvwigRHnZsQ Google Print, p.81,] [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0226533999&id=fcNJc-p2bjwC&pg=PA60&lpg=PA60&vq=Poland&dq=Max+Weber+hospital&sig=l3OeQlt7f9ePLosslRvI8gNY87Q p. 60,] [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0226533999&id=fcNJc-p2bjwC&pg=PA327&lpg=PA327&dq=Weber+Munich+left+1919&sig=kdzDUJ3wQb6DDhBiKmypM6S-XcY] |

|||

p. 327.]</ref> |

|||

From 1893 to 1899, Weber was a member of the [[Pan-German League]] ({{Langx|de|Alldeutscher Verband|label=none}}), an organisation that campaigned against the influx of Polish workers. The degree of his support for the [[Germanisation of Poles during the Partitions|Germanisation of Poles]] and similar nationalist policies continues to be debated by scholars.{{sfnm|1a1=Mommsen|1a2=Steinberg|1y=1984|1pp=54–56|2a1=Hobsbawm|2y=1987|2p=152|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3pp=564–565}} Weber and his wife moved to [[Freiburg im Breisgau|Freiburg]] in 1894, where he was appointed professor of economics at the [[University of Freiburg]].{{sfnm|1a1=Bendix|1a2=Roth|1y=1977|1pp=1–2|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2p=564|3a1=Honigsheim|3y=2017|3p=239}} During his tenure there, in 1895, he gave a provocative lecture titled "The Nation State and Economic Policy". In it, he criticised Polish immigration and argued that the [[Junker (Prussia)|Junker]]s were encouraging Slavic immigration to serve their economic interests over those of the German nation.{{sfnm|1a1=Aldenhoff-Hübinger|1y=2004|1p=148|2a1=Craig|2y=1988|2p=18|3a1=Mommsen|3a2=Steinberg|3y=1984|3pp=38–39}} It influenced the politician [[Friedrich Naumann]] to create the [[National-Social Association]], which was a [[Christian socialist]] and [[nationalist]] political organisation.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=429–431|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=134–135|3a1=Mommsen|3a2=Steinberg|3y=1984|3pp=123–126}} Weber was pessimistic regarding the association's ability to succeed, and it dissolved after winning a single seat in the Reichstag during the [[1903 German federal election]].{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=436–441|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=134–135, 330|3a1=Mommsen|3a2=Steinberg|3y=1984|3pp=126–130}} In 1896, he accepted an appointment to a chair in economics and finance at [[Heidelberg University]].{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1p=564|2a1=Bendix|2a2=Roth|2y=1977|2pp=1–2|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3p=455}} There, Weber and his wife became the central figures in the eponymous '''Weber Circle'''<!--boldface per WP:R#PLA-->, which included [[Georg Jellinek]], [[Ernst Troeltsch]], and [[Werner Sombart]]. Younger scholars, such as [[György Lukács]] and [[Robert Michels]], also joined it.{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Honigsheim|2y=2017|2pp=ix–x}} |

|||

[[File:Max Weber 1917.jpg|thumb|left|Max Weber in 1917]] |

|||

During the First World War, Weber served for a time as director of the army hospitals in Heidelberg.<ref name="Bendix3"/><ref name=Kaesler>[[Dirk Kaesler|Kaesler, Dirk]] (1989). ''Max Weber: An Introduction to His Life and Work''. University of Chicago Press, p. [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0226425606&id=shR9fsW9W8oC&pg=PA18&lpg=PA18&dq=Max+Weber+hospital&sig=38uV8JO6Z_TpXVF_FnjO9HdY3KE 18.] ISBN 0226425606</ref> In 1915 and 1916 he sat on commissions that tried to retain German supremacy in Belgium and Poland after the war. Weber's views on war, as well as on expansion of the German empire, changed throughout the war.<ref name="TPaSToMW"/><ref name=Kaesler/><ref>Gerth, H.H. and [[C. Wright Mills]] (1948). ''From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology''. London: Routledge (UK), ISBN 0415175038</ref> He became a member of the [[Workers' council|worker and soldier council]] of Heidelberg in 1918. In the same year, Weber became a consultant to the [[German Armistice Commission]] at the [[Treaty of Versailles]] and to the commission charged with drafting the [[Weimar Constitution]].<ref name="Bendix3"/> He argued in favor of inserting [[Article 48 (Weimar Constitution)|Article 48]] into the [[Weimar Constitution]].<ref>Turner, Stephen (ed) (2000). ''The Cambridge Companion to Weber.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN052156753X&id=XfGZ3ivPR4cC&pg=PA142&lpg=PA142&dq=Weber+Article+48&sig=HOzFBwFSo6UbjqiH4CYktsAgm8k p. 142.]</ref> This article was later used by [[Adolf Hitler]] to institute rule by decree, thereby allowing his government to suppress opposition and obtain dictatorial powers. [[Weber and German politics|Weber's contributions to German politics]] remain a controversial subject to this day. |

|||

In 1897, Weber had a severe quarrel with his father. Weber Sr. died two months later, leaving the argument unresolved.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=65–66|2a1=Kim|2y=2022|3a1=Weber|3y=1999|3p=7}} Afterwards, Weber became increasingly prone to depression, nervousness, and [[insomnia]], which made it difficult for him to fulfill his duties as a professor.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=65–69|2a1=Bendix|2a2=Roth|2y=1977|2pp=1–2|3a1=Frommer|3a2=Frommer|3y=1993|3pp=163–164}} His condition forced him seek an exemption from his teaching obligations, which he was granted in 1899. He spent time in the {{Lang|de|Heilanstalt für Nervenkranke Konstanzer Hof}} in 1898 and in a different [[sanatorium]] in [[Bad Urach]] in 1900.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=472, 476–477|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2p=143}} Weber also travelled to [[Corsica]] and [[Kingdom of Italy|Italy]] between 1899 and 1903 in order to alleviate his illness.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1p=143|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2p=485|3a1=Bendix|3a2=Roth|3y=1977|3pp=2–3}} He fully withdrew from teaching in 1903 and did not return to it until 1918.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1p=143}} Weber thoroughly described his ordeal with mental illness in a personal [[chronology]] that his widow later destroyed. Its destruction was possibly caused by Marianne's fear that his work would have been discredited by the Nazis if his experience with mental illness were widely known.{{sfnm|1a1=Weber|1y=1964|1pp=641–642|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=170–171}} |

|||

Weber resumed teaching during this time, first at the [[University of Vienna]], then in 1919 at the [[University of Munich]].<ref name="Bendix3"/> In Munich, he headed the first German university institute of sociology, but ultimately never held a personal sociology appointment. Weber left politics due to right-wing agitation in 1919 and 1920. Many colleagues and students in Munich argued against him for his speeches and left-wing attitude during the [[German Revolution]] of 1918 and 1919, with some right-wing students holding protests in front of his home.<ref name="TPaSToMW"/> Max Weber contracted the [[Spanish flu]] and died of pneumonia in Munich on June 14, 1920. |

|||

== |

===Later work=== |

||

Weber's most famous work relates to [[economic sociology]], [[political sociology]], and the [[sociology of religion]]. Along with [[Karl Marx]] and [[Émile Durkheim]],<ref name="WPet">[[William Petersen]], ''Against the Stream'', Transaction Publishers, ISBN 0-7658-0222-8, 2004, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0765802228&id=FHlTJ6HbY50C&pg=PA29&lpg=PA29&dq=weber+founder+of+sociology&sig=zxYCUTaFFvrlqcIX4guqG8pPyfU Google Print, p.24]</ref> he is regarded as one of the founders of modern sociology. In his time, however, Weber was viewed primarily as a historian and an economist. <ref name="WPet"/><ref name="PRBaehr">Peter R. Baehr, ''Founders Classics Canons'', Transaction Publishers, 2002, ISBN 0-7658-0129-9, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0765801299&id=iRrnCPe66PYC&pg=PA22&lpg=PA22&dq=weber+founder+of+sociology&sig=2j-I_jptUjtqaKbiCjJpQgt0ohM Google Print, p.22]</ref> The breadth of Weber's topical interests is apparent in the depth of his [[social theory]]: |

|||

[[File:Max Weber 1907.jpg|thumb|upright|Max Weber in 1907|alt=Max Weber in 1907, holding a hookah]] |

|||

{{Quotation|The affinity between capitalism and Protestantism, the religious origins of the Western world, the force of charisma in religion as well as in politics, the all-embracing process of rationalization and the bureaucratic price of progress, the role of legitimacy and of violence as offsprings of leadership, the 'disenchantment' of the modern world together with the never-ending power of religion, the antagonistic relation between intellectualism and eroticism: all these are key concepts which attest to the enduring fascination of Weber's thinking.|Radkau, Joachim ''Max Weber: A Biography'' 2005<ref>Radkau, Joachim ''Max Weber: A Biography''. 1995. Polity Press. (''Inside sleave'')</ref>}} |

|||

After recovering from his illness, Weber accepted a position as an associate editor of the {{Lang|de|[[Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik]]}} (''Archive for Social Science and Social Policy'') in 1904, alongside his colleagues [[Edgar Jaffé]] and Werner Sombart. It facilitated his reintroduction to academia and became one of the most prominent social science journals as a result of his efforts.{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Roth|2y=1976|2pp=306–318|3a1=Scott|3y=2019|3pp=21, 41}} Weber published some of his most seminal works in this journal, including his book ''[[The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]]'', which became his most famous work and laid the foundations for his later research on the impact of religion on the development of economic systems.{{sfnm|1a1=Bendix|1a2=Roth|1y=1977|1pp=49–50|2a1=Weber|2y=1999|2p=8}} Also in 1904, he was invited to participate in the Congress of Arts and Sciences that was held in connection with the [[Louisiana Purchase Exposition]] in [[St. Louis]] alongside his wife, Werner Sombart, Ernst Troeltsch, and other German scholars.{{sfnm|1a1=Roth|1y=2005|1pp=82–83|2a1=Scaff|2y=2011|2pp=11–24|3a1=Smith|3y=2019|3p=96}} Taking advantage of the fair, the Webers embarked on a trip that began and ended in New York City and lasted for almost three months. They travelled throughout the country, from [[New England]] to the [[Deep South]]. Different communities were visited, including German immigrant towns and African American communities.{{sfnm|1a1=Scaff|1y=2011|1pp=11–24|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=296–299|3a1=Honigsheim|3y=2017|3pp=24–25}} [[North Carolina]] was also visited, as some of Weber's relatives in the Fallenstein family had settled there.{{sfnm|1a1=Scaff|1y=2011|1pp=117–119|2a1=Smith|2y=2019|2pp=96–97|3a1=Honigsheim|3y=2017|3pp=24–25}} Weber used the trip to learn more about America's social, economic, and theological conditions and how they related to his thesis.{{sfnm|1a1=Scaff|1y=2011|1pp=12–14|2a1=Roth|2y=2005|2pp=82–83|3a1=Smith|3y=2019|3pp=97–100}} Afterwards, he felt that he was unable to resume regular teaching and remained a private scholar, helped by an inheritance in 1907.{{sfnm|1a1=Bendix|1a2=Roth|1y=1977|1p=3|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=279–280, 566}} |

|||

Whereas Durkheim, following [[Auguste Comte|Comte]], worked in the [[sociological positivism|positivist]] tradition, Weber created and worked – like [[Werner Sombart]], his friend and then the most famous representative of German sociology – in the [[antipositivism|antipositivist]], [[hermeneutic]], tradition.<ref name="JKRhoads">John K. Rhoads, ''Critical Issues in Social Theory'', Penn State Press, 1991, ISBN 0-271-00753-2, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0271007532&id=XVhOtKF3fKsC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=Weber+antipositivist&sig=ZLl08PAGOCL2Z-B-aEn9zhhldfI Google Print, p.40]</ref> These works pioneered the antipositivistic revolution in [[social science]]s, stressing (as in the work of [[Wilhelm Dilthey]]) the difference between the social sciences and natural sciences.<ref name="JKRhoads"/> |

|||

Shortly after returning, Weber's attention shifted to the then-recent [[Russian Revolution of 1905]].{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1p=233|2a1=Weber|2y=1997|2pp=3–4|3a1=Turner|3y=2001b|3p=16401}} He learned the [[Russian language]] in a few months, subscribed to Russian newspapers, and discussed Russian political and social affairs with the Russian {{Lang|fr|émigré}} community in [[Heidelberg]].{{sfn|Radkau|2009|pp=233–234}} He was personally popular in that community and twice entertained the idea of a trip to [[Russian Empire|Russia]]. His schedule prevented it, however.{{sfn|Radkau|2009|pp=233–235}} While he was sceptical of the revolution's ability to succeed, Weber supported the establishment of a [[liberal democracy]] in Russia.{{sfnm|1a1=Mommsen|1y=1997|1pp=1–2|2a1=Weber|2y=1997|2p=2}} He wrote two essays on it that were published in the {{Lang|de|Archiv}}.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=234–236|2a1=Weber|2y=1997|2pp=1–2}} Weber interpreted the revolution as having been the result of the peasants' desire for land.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=235–236|2a1=Mommsen|2y=1997|2pp=6–7}} He discussed the role of the {{lang|ru|[[obshchina]]}}, rural peasant communities, in Russian political debates. According to Weber, they were difficult for liberal agrarian reformers to abolish due to a combination of their basis in [[natural law]] and the rising {{lang|ru|[[kulak]]}} class manipulating them for their own gain.{{sfn|Radkau|2009|pp=237–239}} His general interpretation of the Russian Revolution was that it lacked a clear leader and was not based on the Russian intellectuals' goals. Instead, it was the result of the peasants' emotional passions.{{sfn|Radkau|2009|pp=239–241}} |

|||

{{Quotation|We know of no [[Scientific law|scientifically ascertainable ideals]]. To be sure, that makes our efforts more arduous than in the past, since we are expected to create our ideals from within our breast in the very age of [[Subjectivism|subjectivist]] culture.|Max Weber ''[[Economy and society]]'' 1909<ref>Roth, Guenther and Claus Wittich. 1978. ''Economy and Society: an outline of interpretive sociology''. University of California Press, [http://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=pSdaNuIaUUEC&oi=fnd&pg=PR25&dq=Economy+Society+Weber&ots=Up5aqLGHvp&sig=J6WB3OKaxTo2kpBXzjeFvnp9xNs#PPR33,M1 Google Print, p. xxxiii]</ref>}} |

|||

In 1909, having become increasingly dissatisfied with the political conservatism and perceived lack of methodological discipline of the {{Lang|de|Verein}}, he co-founded the [[German Sociological Association]] ({{Langx|de|Deutsche Gesellschaft für Soziologie|label=none}}) and served as its first treasurer.{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2p=277|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3pp=653, 654–655}} Weber associated the society with the {{Lang|de|Verein}} and viewed the two organisations as not having been competitors.{{sfn|Kaesler|2014|pp=653–654}} He unsuccessfully tried to steer the direction of the association.{{sfnm|1a1=Swedberg|1a2=Agevall|1y=2016|1p=|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=654}} As part of that, Weber tried to make the {{Lang|de|Archiv}} its official journal.{{sfn|Swedberg|Agevall|2016|p=85}} He resigned from his position as treasurer in 1912.{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2p=277|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3pp=652–655}} That was caused by his support for [[value-freedom]] in the social sciences, as that was a controversial position in the association.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=654–655|2a1=Turner|2y=2001b|2pp=16401–16402}} Weber{{snd}}alongside Simmel, Sombart, and Tönnies{{snd}}placed an abbreviated form of it into the association's statutes, prompting criticism from its other members.{{sfn|Kaesler|2014|pp=654–655}} In the same year, Weber and his wife befriended a former student of his, [[Else von Richthofen]], and the pianist {{Interlanguage link|Mina Tobler|de}}. After a failed attempt to court Richthofen, Weber began an affair with Tobler in 1911.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=343–344, 360|2a1=Lepsius|2y=2004|2pp=11–14}} |

|||

Weber presented sociology as the science of human [[social action]]; action which he differentiated into [[Traditional action|traditional]], [[Affectional action|affectional]], [[Value-rational action|value-rational]] and [[Instrumental action|instrumental]].<ref name="Ferrante">[[Joan Ferrante]], ''Sociology: A Global Perspective'', Thomson Wadsworth, 2005, ISBN 0-495-00561-4, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0495005614&id=Idjxdi1IlFAC&pg=PA21&lpg=PA21&dq=Weber+Traditional+affectional+value+rational+instrumental&sig=Ib8EP0Ze_EPQgij7ns6lUSbNs2U Google Print, p.21]</ref> |

|||

===Political involvements=== |

|||

{{Quotation|''[Sociology is ]'' ... the science whose object is to interpret ''the meaning of social action'' and thereby give a ''causal explanation'' of the way in which the ''action proceeds'' and the ''effects which it produces''. By 'action' in this definition is meant the human behaviour when and to the extent that the agent or agents see it as ''subjectively meaningful'' ... the meaning to which we refer may be either (a) the meaning actually intended either by an individual agent on a particular historical occasion or by a number of agents on an approximate average in a given set of cases, or (b) the meaning attributed to the agent or agents, as types, in a pure type constructed in the abstract. In neither case is the 'meaning' to be thought of as somehow objectively 'correct' or 'true' by some metaphysical criterion. This is the difference between the empirical sciences of action, such as sociology and history, and any kind of ''priori'' discipline, such as jurisprudence, logic, ethics, or aesthetics whose aim is to extract from their subject-matter 'correct' or 'valid' meaning.|Max Weber ''The Nature of Social Action'' 1922|<ref>Weber, Max ''The Nature of Social Action'' in Runciman, W.G. 'Weber: Selections in Translation' Cambridge University Press, 1991. p7.</ref>}} |

|||

Later, during the spring of 1913, Weber holidayed in the [[Monte Verità]] community in [[Ascona]], [[Switzerland]].{{sfnm|1a1=Whimster|1y=2016|1p=8|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=358, 280|3a1=Löwy|3a2=Varikas|3y=2022|3p=94}} While holidaying, he was advising Frieda Gross in her custody battle for her children. He opposed [[Erich Mühsam]]'s involvement because Mühsam was an [[anarchist]]. Weber argued that the case needed to be dealt with by bourgeois reformers who were not "derailed".{{sfnm|1a1=Whimster|1y=2016|1pp=18–20|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=383–385|3a1=Löwy|3a2=Varikas|3y=2022|3p=100}} A year later, also in spring, he again holidayed in Ascona.{{sfnm|1a1=Whimster|1y=2016|1p=8|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=358, 280–283|3a1=Löwy|3a2=Varikas|3y=2022|3p=94}} The community contained several different expressions of the then-contemporaneous radical political and lifestyle reform movements. They included [[naturism]], [[free love]], and [[Western esotericism]], among others. Weber was critical of the anarchist and erotic movements in Ascona, as he viewed their fusion as having been politically absurd.{{sfnm|1a1=Whimster|1y=2016|1pp=8–9|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=358, 280–283|3a1=Löwy|3a2=Varikas|3y=2022|3p=100}} |

|||

====First World War==== |

|||

Weber began his studies of [[Rationalization (sociology)|rationalisation]] in ''[[The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]]'', in which he argued that the redefinition of the connection between work and piety in Protestantism, and especially in [[ascetic]] [[Protestantism|Protestant]] [[Religious denomination|denominations]], particularly [[Calvinism]],<ref name="Bendix60">{{cite book |last=Bendix |title=Max Weber |url=http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0520031946&id=63sC9uaYqQsC&pg=PA60&lpg=PA60&vq=Calvinism&sig=2VcBXYzS4AikEHxnscx0ArVRB_0 |pages=60–61 }}</ref> shifted human effort towards rational efforts aimed at achieving economic gain. In Calvinism in particular, but also in Lutheranism, Christian piety towards God was expressed through or in one's secular vocation. Calvin, in particular, viewed the expression of the work ethic as a sign of "election". The rational roots of this doctrine, he argued, soon grew incompatible with and larger than the religious, and so the latter were eventually discarded.<ref name="Andrew J. Weigert">Andrew J. Weigert, ''Mixed Emotions: Certain Steps Toward Understanding Ambivalence'', SUNY Press, 1991, ISBN 0-7914-0600-8, [http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0791406008&id=uH0srBp2W4YC&pg=PA110&lpg=PA110&dq=Weber+economic+gain+bless&sig=853zYScipBcElF-771zljhzXzVU Google Print, p.110]</ref> Weber continued his investigation into this matter in later works, notably in his studies on [[bureaucracy]] and on the classifications of [[authority]] into three types—legitimate, traditional, and charismatic. In these works Weber described what he saw as society's movement towards rationalization. |

|||

After the outbreak of the [[First World War]] in 1914, Weber volunteered for service and was appointed as a [[Military reserve force|reserve officer]] in charge of organising the army hospitals in Heidelberg, a role he fulfilled until the end of 1915.{{sfnm|1a1=Bendix|1a2=Roth|1y=1977|1p=3|2a1=Kaesler|2y=1988|2p=18|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3pp=454–456}} His views on the war and the expansion of the [[German Empire]] changed over the course of the conflict.{{sfnm|1a1=Mommsen|1a2=Steinberg|1y=1984|1pp=196–198|2a1=Kaesler|2y=1988|2pp=18–19|3a1=Weber|3a2=Turner|3y=2014|3pp=22–23}} Early on, he supported the [[History of Germany during World War I|German war effort]], with some hesitation, viewing the war as having been necessary to fulfill Germany's duty as a leading state power. In time, however, Weber became one of the most prominent critics of both [[Lebensraum#First World War nationalist premise|German expansionism]] and the [[Wilhelm II#World War I|Kaiser's war policies]].{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Bruhns|2y=2018|2pp=37–44|3a1=Craig|3y=1988|3pp=19–20}} He publicly criticised [[Septemberprogramm|Germany's potential annexation of Belgium]] and [[unrestricted submarine warfare]], later supporting calls for constitutional reform, democratisation, and [[universal suffrage]].{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Bruhns|2y=2018|2pp=40, 43–44|3a1=Craig|3y=1988|3p=20}} His younger brother Karl, an architect, was killed near [[Brest-Litovsk]] in 1915 while fighting in the war.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=527–528|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=740–741}} Weber had previously viewed him negatively but his death made him feel more connected to him.{{sfn|Radkau|2009|pp=527–528}} |

|||

[[File:Max Weber in Lauenstein, 1917.png|thumb|right|Max Weber (facing right) with Ernst Toller (facing camera) during the Lauenstein Conferences in 1917|alt=Max Weber, facing right, lecturing with Ernst Toller in the center of the background]] |

|||

{{Quotation|What Weber depicted was not only the secularization of Western ''culture'', but also and especially the development of modern ''societies'' from the viewpoint of rationalization. The new structures of society were marked by the differentiation of the two functionally intermeshing systems that had taken shape around the organizational cores of the capitalist enterprise and the bureaucratic state apparatus. Weber understood this process as the institituionalization of purposive-rational economic and administrative action. To the degree that everyday life was affected by this cultural and societal rationalization, tradional forms of life - which in the early modern period were differentated primarily according to one's trade - were dissolved.|[[Jürgen Habermas]] ''Modernity's Consciousness of Time''|<ref>Habermas, Jürgen, ''The Philosophical Discourse of Modernity'', Polity Press (1985), ISBN 0-7456-0830-2, p2 </ref>}} |

|||

He and his wife also participated in the 1917 Lauenstein Conferences that were held at {{Interlanguage link|Lauenstein Castle|de|Burg Lauenstein (Frankenwald)}} in [[Kingdom of Bavaria|Bavaria]].{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=483–487|2a1=Levy|2y=2016|2pp=87–89|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3pp=747–748}} These conferences were planned by the publisher [[Eugen Diederichs]] and brought together intellectuals, including [[Theodor Heuss]], [[Ernst Toller]], and Werner Sombart.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=483–486|2a1=Levy|2y=2016|2pp=87–90|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3pp=747–748}} Weber's presence elevated his profile in Germany and served to dispel some of the event's [[Romanticism|romantic]] atmosphere. After he spoke at the first one, he became involved in the planning for the second one, as Diederichs thought that the conferences needed someone who could serve as an oppositional figure. In this capacity, he argued against the political romanticism that [[Max Maurenbrecher]], a former theologian, espoused. Weber also opposed what he saw as the excessive rhetoric of the youth groups and nationalists at Lauenstein, instead supporting German democratisation.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=486–487|2a1=Levy|2y=2016|2pp=90–91|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3pp=747–748}} For Weber and the younger participants, the conferences' romantic intent was irrelevant to the determination of Germany's future.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=485–487|2a1=Levy|2y=2016|2pp=89–91|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3pp=749–751}} In November, shortly after the second conference, Weber was invited by the Free Student Youth, a student organisation, to give a lecture in Munich, resulting in "[[Science as a Vocation]]".{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=487–491|2a1=Weber|2y=2004|2p=xix|3a1=Gane|3y=2002|3p=53}} In it, he argued that an inner calling and specialisation were necessary for one to become a scholar.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=487–491|2a1=Weber|2y=2004|2pp=xxv–xxix|3a1=Tribe|3y=2018|3pp=130–133}} Weber also began a [[sadomasochistic]] affair with Else von Richthofen the next year.{{sfnm|1a1=Demm|1y=2017|1pp=64, 82–83|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=521–522}} Meanwhile, she was simultaneously conducting an affair with his brother, [[Alfred Weber|Alfred]].{{sfn|Demm|2017|pp=83–84}} Max Weber's affairs with Richtofen and Mina Tobler lasted until his death in 1920.{{sfnm|1a1=Demm|1y=2017|1pp=64, 82–85|2a1=Lepsius|2y=2004|2p=21}} |

|||

It should be noted that many of Weber's works famous today were collected, revised, and published [[posthumous work|posthumously]]. Significant interpretations of his writings were produced by such sociological luminaries as [[Talcott Parsons]] and [[C. Wright Mills]]. Parsons in particular imparted to Weber's works a functionalist, teleological perspective; this personal interpretation has been criticised for a latent conservatism.<ref>Fish, Jonathan S. 2005. 'Defending the Durkheimian Tradition. Religion, Emotion and Morality' Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing.</ref> |

|||

====Weimar Republic==== |

|||

==Sociology of religion== |

|||

After the war ended, Weber unsuccessfully ran for a seat in the [[Weimar National Assembly]] in January 1919 as a member of the liberal [[German Democratic Party]], which he had co-founded.{{sfnm|1a1=Mommsen|1a2=Steinberg|1y=1984|1pp=303–308|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=513–514|3a1=Kim|3y=2022}} He also advised the National Assembly in its drafting of the [[Weimar Constitution]].{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=866–870|2a1=Bendix|2a2=Roth|2y=1977|2p=3|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3pp=511–512}} While he was campaigning for his party, Weber critiqued the left and complained about [[Karl Liebknecht]] and [[Rosa Luxemburg]] who led the leftist [[Spartacus League]]. He regarded the [[German Revolution of 1918–1919]] as having been responsible for Germany's inability to fight against [[Second Polish Republic|Poland]]'s claims on its eastern territories.{{sfn|Radkau|2009|pp=505–508}} His opposition to the revolution may have prevented [[Friedrich Ebert]], the new [[President of Germany (1919–1945)|president of Germany]] and a member of the [[Social Democratic Party of Germany|Social Democratic Party]], from appointing him as a minister or ambassador.{{sfnm|1a1=Mommsen|1a2=Steinberg|1y=1984|1pp=301–302|2a1=Kaesler|2y=1988|2p=22}} Weber was also critical of the [[Treaty of Versailles]], which he believed unjustly [[Article 231 of the Treaty of Versailles|assigned war guilt to Germany]].{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1p=882|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=500–504}} Instead, he believed that many countries were guilty of starting it, not just Germany.{{sfnm|1a1=Waters|1a2=Waters|1y=2015a|1p=22|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=500–503}} In making this case, Weber argued that Russia was the only [[great power]] that actually desired the war.{{sfnm|1a1=Waters|1a2=Waters|1y=2015a|1p=20|2a1=Mommsen|2y=1997|2p=16}} He also regarded Germany as not having been culpable for [[German invasion of Belgium (1914)|its invasion of Belgium]], viewing Belgian neutrality as having obscured an alliance with [[French Third Republic|France]].{{sfn|Waters|Waters|2015a|pp=20, 22}} Overall, Weber's political efforts were largely unsuccessful, with the exception of his support for a democratically elected and strong presidency.{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=868–869|3a1=Honigsheim|3y=2017|3p=246}} |

|||

Weber's work in the field of [[sociology of religion]] started with the essay ''[[The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]]'', which grew out of heavy "field work" among Protestant sects in America, and continued with the analysis of ''[[The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism]]'', ''[[The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism]]'', and ''[[Ancient Judaism (book)|Ancient Judaism]]''. His work on other religions was interrupted by his sudden death in 1920, which prevented him from following ''Ancient Judaism'' with studies of [[Psalm]]s, [[Book of Jacob]], Talmudic Jewry, early Christianity and Islam.<ref name="Bendix285">{{cite book |last=Bendix |title=Max Weber |url=http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0520031946&id=63sC9uaYqQsC&pg=PA285&lpg=PA285&sig=VYtdrBYGinacJyetbio7RM3L0G0 |pages=285 }}</ref> His three main themes were the effect of religious ideas on economic activities, the relation between [[social stratification]] and religious ideas, and the distinguishable characteristics of Western civilization.<ref name="BendixChapter9">{{cite book |last=Bendix |title=Max Weber |url=http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0520031946&id=63sC9uaYqQsC&pg=PA285&lpg=PA285&sig=VYtdrBYGinacJyetbio7RM3L0G0 |

|||

|pages=Chapter IX: Basic Concepts of Political Sociology |nopp=true }}</ref> |

|||

On 28 January 1919, after his electoral defeat, Weber delivered a lecture titled "[[Politics as a Vocation]]", which commented on the subject of politics.{{sfnm|1a1=Weber|1y=2004|1pp=xxxiv–xxxv|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=514–515|3a1=Swedberg|3a2=Agevall|3y=2016|3pp=259–260}} It was prompted by the early [[Weimar Republic]]'s political turmoil and was requested by the Free Student Youth.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=514–518|2a1=Weber|2y=2004|2pp=xxxiv–xxxviii|3a1=Gane|3y=2002|3pp=64–65}} Shortly before he left to join the delegation in Versailles on 13 May 1919, Weber used his connections with the [[German National People's Party]]'s deputies to meet with [[Erich Ludendorff]]. He spent several hours unsuccessfully trying to convince Ludendorff to surrender himself to the [[Allies of World War I|Allies]].{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=542–543|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2p=883}} This debate also shifted to other subjects, such as who was culpable for Germany's defeat in the war. Weber thought that the [[Oberste Heeresleitung|German high command]] had failed, while Ludendorff regarded Weber as a democrat who was partially responsible for the revolution. Weber tried to disabuse him of that notion by expressing support for a democratic system with a strong executive. Since he held Ludendorff responsible for Germany's defeat in the war and having sent many young Germans to die on the battlefield, Weber thought that he should surrender himself and become a political martyr. However, Ludendorff was not willing to do so and instead wanted to live off of his pension.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1p=543|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=884–887}} |

|||

His goal was to find reasons for the different development paths of the cultures of the [[Occident]] and the [[Orient]], although without judging or valuing them, like some of the contemporary thinkers who followed the [[Social Darwinism|social Darwinist]] paradigm; Weber wanted primarily to explain the distinctive elements of the [[Western culture|Western civilization]].<ref name="BendixChapter9"/> In the analysis of his findings, Weber maintained that [[Calvinist]] (and more widely, Protestant) religious ideas had had a major impact on the [[social innovation]] and development of the economic system of Europe and the United States, but noted that they were not the only factors in this development. Other notable factors mentioned by Weber included the [[rationalism]] of scientific pursuit, merging observation with mathematics, science of scholarship and jurisprudence, rational systematization of government administration, and economic enterprise.<ref name="BendixChapter9"/> In the end, the study of the sociology of religion, according to Weber, merely explored one phase of the freedom from magic, that "disenchantment of the world" that he regarded as an important distinguishing aspect of Western culture.<ref name="BendixChapter9"/> |

|||

===Last years=== |

|||

====''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism''==== |

|||

Frustrated with politics, Weber resumed teaching, first at the [[University of Vienna]] in 1918, then at the [[Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich]] in 1919.{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Bendix|2a2=Roth|2y=1977|2p=3|3a1=Radkau|3y=2009|3pp=514, 570}} In [[Vienna]], Weber filled a previously vacant chair in political economy that he had been in consideration for since October 1917.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=491–492|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=761–764}} Later, in [[Munich]], he was appointed to [[Lujo Brentano]]'s chair in social science, economic history, and political economy. He accepted the appointment in order to be closer to his mistress, Else von Richthofen.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=529, 570|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=839–841}} Responding to student requests, he gave a series of lectures on economic history. The student transcriptions of it were later edited and published as the ''[[General Economic History]]'' by {{Interlanguage link|Siegmund Hellmann|de}} and {{Interlanguage link|Melchior Palyi|de}} in 1923.{{sfnm|1a1=Weber|1a2=Cohen|1y=2017|1pp=lxxiii–lxxvii, lxxxii|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=904–906|3a1=Kim|3y=2022}} In terms of politics, he opposed the pardoning of the [[List of ministers-president of Bavaria|Bavarian Minister-President]] [[Kurt Eisner]]'s murderer, [[Anton Graf von Arco auf Valley]]. In response to that, right-wing students disrupted his classes and protested in front of his home.{{sfnm|1a1=Mommsen|1a2=Steinberg|1y=1984|1pp=327–328|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=509–510|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3pp=893–895}} |

|||

{{Main|The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism}} |

|||

[[File:Die protestantische Ethik und der 'Geist' des Kapitalismus original cover.jpg|thumb|upright|Cover of the original German edition of ''[[The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism]]'']] |

|||

Weber's essay ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'' (''Die protestantische Ethik und der Geist des Kapitalismus'') is his most famous work.<ref name="EESoc-22"/> It is argued that this work should not be viewed as a detailed study of Protestantism, but rather as an introduction into Weber's later works, especially his studies of interaction between various religious ideas and economic behaviour. In ''The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism'', Weber put forward the thesis that [[calvinism|Calvinist]] ethic and ideas influenced the development of capitalism. In this work, he relied on a great deal of statistics from the era, which indicated the predominance of Protestants among the wealthy, industrial, and technical classes relative to Catholics. He also noted the shift of Europe's economic center after the Reformation away from Catholic countries such as France, Spain and Italy, and toward Protestant countries such as the Netherlands, England, Scotland and Germany. This theory is often viewed as a reversal of Marx's thesis that the economic "base" of society determines all other aspects of it.<ref name="Bendix60"/> Christian religious devotion had historically been accompanied by rejection of mundane affairs, including economic pursuit.<ref name="Bendix57">{{cite book |last=Bendix |title=Max Weber |url=http://books.google.com/books?visbn=0520031946&id=63sC9uaYqQsC&pg=PA57&lpg=PA57&vq=mundane+affairs&sig=VbBzIfyolsHTqPJ6ttJDIqYcQzE |

|||

|pages=57}}</ref> Why was that not the case with Protestantism? Weber addressed that paradox in his essay. |

|||

[[File:Max weber.JPG|thumb|left|Max Weber's grave in Heidelberg|alt=A photograph of Max Weber's grave]] |

|||

According to Weber, one of the universal tendencies that Christians had historically fought against, was the desire to profit. After defining the spirit of capitalism, Weber argued that there were many reasons to look for the origins of modern capitalism in the religious ideas of the [[Protestant Reformation|Reformation]]. Many observers, such as [[William Petty]], [[Charles de Secondat, Baron de Montesquieu|Montesquieu]], [[Henry Thomas Buckle]], [[John Keats]], and others had commented on the affinity between Protestantism and the development of the commercial spirit.<ref name="Bendix54">{{cite book |last=Bendix |title=Max Weber |url=|pages=54}}</ref> |

|||

In early 1920, Weber gave a seminar that contained a discussion of [[Oswald Spengler]]'s ''[[The Decline of the West]]''.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=906–907|2a1=Spengler|2a2=Hughes|2y=1991|2pp=xv–xvi}} Weber respected him and privately described him as having been "a very brilliant and scholarly dilettante".{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=906–907|2a1=Farrenkopf|2y=1992|2p=1|3a1=Spengler|3a2=Hughes|3y=1991|3pp=xv–xvi}} That seminar provoked some of his students, who knew Spengler personally, to suggest that he debate Spengler alongside other scholars. They met in the [[New Town Hall (Munich)|Munich town hall]] and debated for two days.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=906–907|2a1=Spengler|2a2=Hughes|2y=1991|2pp=xv–xvi|3a1=Weber|3y=1964|3pp=554–555}} The audience was primarily young Germans with different political perspectives, including [[communist]]s. While neither of them were able to convince the other of their points, Weber was more cautious and careful in his arguments against Spengler than the other debaters were. Afterwards, the students did not feel that the question of how to resolve Germany's post-war issues had been answered.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=906–907|2a1=Farrenkopf|2y=1992|2p=1|3a1=Spengler|3a2=Hughes|3y=1991|3pp=xv–xvi}} |

|||

Weber showed that certain types of Protestantism – notably Calvinism – favored rational pursuit of economic gain and worldly activities which had been given positive spiritual and moral meaning.<ref name="Bendix60"/> It was not the goal of those religious ideas, but rather a byproduct – the inherent logic of those doctrines and the advice based upon them both directly and indirectly encouraged planning and self-denial in the pursuit of economic gain. A common illustration is in the cobbler, hunched over his work, who devotes his entire effort to the praise of God. In addition, the Reformation view "calling" dignified even the most mundane professions as being those that added to the common good and were blessed by God, as much as any "sacred" calling could. This Reformation view, that all the spheres of life were sacred when dedicated to God and His purposes of nurturing and furthering life, profoundly affected the view of work. |

|||

Lili Schäfer, one of Weber's sisters, committed suicide on 7 April 1920 after the pedagogue [[Paul Geheeb]] ended his affair with her. Weber thought positively of it, as he thought that her suicide was justified and that suicide in general could be an honourable act.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=921–922|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=539, 541–542}} Weber and his wife took in Lili's four children and planned to raise them. He was uncomfortable with his newfound role as a father figure, but he thought that Marianne was fulfilled as a woman by this event. She later formally adopted them in 1928. Weber wished for her to stay with the children in Heidelberg or move closer to Geheeb's {{Lang|de|[[Odenwaldschule]]}} ("Odenwald School") so that he could be alone in Munich with his mistress, [[Else von Richthofen]]. He left the decision to Marianne, but she said that only he could make the decision to leave for himself.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=542, 547–548|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2pp=921–923}} While this was occurring, Weber began to believe that own life had reached its end.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1p=544|2a1=Kaesler|2y=2014|2p=923}} |

|||

To illustrate and provide an example, Weber quoted the ethical writings of [[Benjamin Franklin]]: |

|||

On 4 June 1920, Weber's students were informed that he had a cold and needed to cancel classes. By 14 June 1920, the cold had turned into [[influenza]] and he died of [[pneumonia]] in Munich.{{sfnm|1a1=Radkau|1y=2009|1pp=545–446|2a1=Hanke|2y=2009|2pp=349–350|3a1=Honigsheim|3y=2017|3p=239}} He had likely contracted the [[Spanish flu]] during the post-war pandemic and been subjected to insufficient medical care. Else von Richthofen, who was present by his deathbed alongside his wife, thought that he could have survived his illness if he had been given better treatment.{{sfnm|1a1=Kim|1y=2022|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=545–546|3a1=Hanke|3y=2009|3pp=349–350}} His body was cremated in the Munich {{Lang|de|[[Ostfriedhof (Munich)|Ostfriedhof]]}} after a secular ceremony, and the urn that contained his ashes was later buried in the Heidelberg ''{{Interlanguage link|Bergfriedhof|de|Bergfriedhof (Heidelberg)}}'' in 1921. The funeral service was attended by his students, including {{Interlanguage link|Eduard Baumgarten|de}} and [[Karl Loewenstein]], and fellow scholars, such as Lujo Brentano.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaesler|1y=2014|1pp=16–19|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=549–550|3a1=Hanke|3y=2009|3pp=349–350}} At the time of his death, Weber had not finished writing ''[[Economy and Society]]'', his {{Lang|la|magnum opus}} on sociological theory. His widow, Marianne, helped prepare it for its publication in 1922.{{sfnm|1a1=Roth|1y=2016|1pp=250–253|2a1=Whimster|2y=2023|2p=82|3a1=Hanke|3y=2009|3pp=349–350}} She later published a biography of her late husband in 1926 which became one of the central historical accounts of his life.{{sfnm|1a1=Hanke|1y=2009|1pp=355–357|2a1=Radkau|2y=2009|2pp=178|3a1=Kaesler|3y=2014|3p=40}} |

|||

<blockquote>Remember, that ''time is money''. He that can earn ten shillings a day by his labor, and goes abroad, or sits idle, one half of that day, though he spends but sixpence during his diversion or idleness, ought not to reckon ''that'' the only expense; he has really spent, or rather thrown away, five shillings besides. |

|||

==Methodology== |

|||

... |

|||

Weber's sociology treated [[social action]] as its central focus.{{sfnm|1a1=Swedberg|1a2=Agevall|1y=2016|1p=313|2a1=Albrow|2y=1990|2p=137|3a1=Rhoads|3y=2021|3p=132}} He also interpreted it as having been an important part of the field's scientific nature.{{sfn|Swedberg|Agevall|2016|p=313}} He divided social action into the four categories of [[Affectional action|affectional]], [[Traditional action|traditional]], [[instrumental and value-rational action|instrumental, and value-rational action]].{{sfn|Swedberg|Agevall|2016|pp=313–315}} In his methodology, he distinguished himself from [[Émile Durkheim]] and [[Karl Marx]] in that his primary focus was on individuals and culture.{{sfn|Sibeon|2012|pp=37–38}} Whereas Durkheim focused on society, Weber concentrated on the [[Individualism|individual]] and their actions. Meanwhile, compared to Marx's support for the primacy of the material world over the world of ideas, Weber valued ideas as motivating individuals' actions.{{sfnm|1a1=Sibeon|1y=2012|1pp=37–38|2a1=Allan|2y=2005|2pp=144–148}} He had a different perspective from the two of them regarding [[structure and agency|structure and action]] and [[Macrostructure (sociology)|macrostructure]] in that he was open to the idea that social phenomena could have several different causes and placed importance on [[social actor]]s' interpretations of their actions.{{sfn|Sibeon|2012|pp=37–38}} |

|||

==={{Lang|de|Verstehen}}=== |

|||

Remember, that money is the ''prolific, generating nature''. Money can beget money, and its offspring can beget more, and so on. Five shillings turned is six, turned again is seven and threepence, and so on, till it becomes a hundred pounds. The more there is of it, the more it produces every turning, so that the profits rise quicker and quicker. He that kills a breeding sow, destroys all her offspring to the thousandth generation. He that murders a crown, destroys all that it might have produced, even scores of pounds.(Italics in the original)</blockquote> |

|||

{{Main|Verstehen}} |

|||

{{quote box |

|||

Weber noted that this is not a philosophy of mere greed, but a statement laden with moral language. Indeed, Franklin claimed that God revealed to him the usefulness of virtue.<ref>Weber, Max ''The Protestant Ethic and "The Spirit of Capitalism" (Penguin Books, 2002) translated by Peter Baehr and Gordon C. Wells, pp.9-12</ref> |

|||

| width = 30em |

|||

| quote = The result of what has been said so far is that an "objective" treatment of cultural occurrences, in the sense that the ideal aim of scientific work would be to reduce the empirical [reality] to "laws", is absurd. ''Not'' because{{snd}}as it has often been claimed{{snd}}the course of cultural processes or, say, processes in the human mind would, "objectively" speaking, be less law-like, but for the following two reasons: (1) knowledge of social laws does not constitute knowledge of social reality, but is only one of the various tools that our intellect needs for that [latter] purpose; (2) knowledge of ''cultural'' occurrences is only conceivable if it takes as its point of departure the ''significance'' that the reality of life, with its always individual character, has for us in certain ''particular'' respects. No law can reveal to us in ''what'' sense and in ''what'' respects this will be the case, as that is determined by those ''value ideas'' in the light of which we look at "culture" in each individual case. |

|||

| source = —Max Weber in "The 'Objectivity' of Knowledge in Social Science and Social Policy", 1904.{{sfn|Weber|2012|pp=119, 138}} |

|||

}} |

|||