Symphony No. 5 (Beethoven): Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

GreenC bot (talk | contribs) Reformat 3 archive links. Wayback Medic 2.5 per WP:USURPURL and JUDI batch #20 |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Musical composition by Ludwig van Beethoven}} |

|||

{{redirect|Beethoven's Fifth|the movie|Beethoven's 5th (film)|Beethoven's 5th piano concerto|Piano Concerto No. 5 (Beethoven)}} |

|||

{{redirect|Beethoven's Fifth|the movie|Beethoven's 5th (film){{!}}''Beethoven's 5th'' (film)|Beethoven's 5th piano concerto|Piano Concerto No. 5 (Beethoven)}} |

|||

[[Image:Beethoven-Deckblatt.png|right|frame|The coversheet to Beethoven's 5th Symphony. The dedication to Prince [[Lobkowitz|J. F. M. Lobkowitz]] and [[Andreas Razumovsky|Count Rasumovsky]] is visible.]] |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=November 2021}} |

|||

{{Infobox musical composition |

|||

| name = Symphony in C minor |

|||

| subtitle = No. 5 |

|||

| image = Beethoven-Deckblatt.png |

|||

| image_upright = 1.3 |

|||

| caption = Cover of the symphony, with the dedication to Prince [[Joseph Franz von Lobkowitz|J. F. M. Lobkowitz]] and [[Andrey Razumovsky|Count Rasumovsky]] |

|||

| composer = [[Ludwig van Beethoven]] |

|||

|key = [[C minor]] |

|||

|opus = 67 |

|||

|form = [[Symphony]] |

|||

|dedication = {{plainlist| |

|||

* J. F. M. Lobkowitz |

|||

* Andreas Razumovsky|A. Rasumovsky}} |

|||

| composed = {{start date|1804}}–1808 |

|||

|duration = About 30–40 minutes |

|||

| movements = Four |

|||

| scoring = [[Symphony orchestra]] |

|||

|premiere_date = [[Beethoven concert of 22 December 1808|22 December 1808]] |

|||

|premiere_conductor = Ludwig van Beethoven |

|||

|premiere_location = [[Theater an der Wien]], Vienna |

|||

}} |

|||

The '''Symphony No. 5 in C minor |

The '''Symphony No. 5''' in [[C minor]], [[opus number|Op.]] 67, also known as the '''''Fate Symphony''''' ({{langx|de|Schicksalssinfonie|link=no}}), is a [[symphony]] composed by [[Ludwig van Beethoven]] between 1804 and 1808. It is one of the best-known compositions in [[classical music]] and one of the most frequently played symphonies,<ref name="Schauffler">{{cite book |author-link= Robert Haven Schauffler |last= Schauffler |first= Robert Haven |title= Beethoven: The Man Who Freed Music |publisher= Doubleday, Doran, & Company |location= Garden City, New York |year= 1933 |page= 211}}</ref> and it is widely considered one of [[Western canon#Music|the cornerstones]] of [[Classical music|western music]]. First performed in Vienna's [[Theater an der Wien]] in 1808, the work achieved its prodigious reputation soon afterward. [[E. T. A. Hoffmann]] described the symphony as "one of the most important works of the time". As is typical of symphonies during the [[Classical period (music)|Classical]] period, Beethoven's Fifth Symphony has four [[Movement (music)|movements]]. |

||

It begins |

It begins with a distinctive four-note "short-short-short-long" [[Motif (music)|motif]], often characterized as "[[fate]] knocking at the door", the {{lang|de|Schicksals-Motiv}} ([[#Fate motif|fate motif]]): |

||

:<score>{\clef treble \key c \minor \tempo "Allegro con brio" 2=108 \time 2/4 {r8 g'\ff[ g' g'] | ees'2\fermata | r8 f'[ f' f'] | d'2~ | d'\fermata | } }</score><br />[[File:Beet5mov1bars1to5.ogg]] |

|||

:: [[Image:Beethoven symphony 5 opening.svg]] |

|||

The symphony, and the four-note opening motif in particular, are |

The symphony, and the four-note opening motif in particular, are known worldwide, with the motif appearing frequently in popular culture, from [[A Fifth of Beethoven|disco versions]] to [[Roll Over Beethoven#Electric Light Orchestra|rock and roll covers]], to uses in film and television. |

||

Like Beethoven's [[Symphony No. 3 (Beethoven)|Eroica (heroic)]] and [[Symphony No. 6 (Beethoven)|Pastorale (rural)]], Symphony No. 5 was given an explicit name besides the numbering, though not by Beethoven himself. |

|||

== History == |

== History == |

||

=== Development === |

=== Development === |

||

[[ |

[[File: Beethoven 3.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Beethoven in 1804, the year he began work on the Fifth Symphony; detail of [[Beethoven (Mähler)|a portrait]] by [[Joseph Willibrord Mähler|W. J. Mähler]]]] |

||

The Fifth Symphony had a long |

The Fifth Symphony had a long development process, as Beethoven worked out the musical ideas for the work. The first "sketches" (rough drafts of melodies and other musical ideas) date from 1804 following the completion of the [[Symphony No. 3 (Beethoven)|Third Symphony]]. <ref name="hopkins">{{cite book|last=Hopkins|first=Antony|author-link=Antony Hopkins|title=The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven|publisher=Scolar Press|year=1977|isbn=1-85928-246-6}}</ref> Beethoven repeatedly interrupted his work on the Fifth to prepare other compositions, including the first version of ''[[Fidelio]]'', the [[Piano Sonata No. 23 (Beethoven)|''Appassionata'' piano sonata]], the three [[String Quartets, Op. 59 (Beethoven)|''Razumovsky'' string quartets]], the [[Violin Concerto (Beethoven)|Violin Concerto]], the [[Piano Concerto No. 4 (Beethoven)|Fourth Piano Concerto]], the [[Symphony No. 4 (Beethoven)|Fourth Symphony]], and the [[Mass in C major (Beethoven)|Mass in C]]. The final preparation of the Fifth Symphony, which took place in 1807–1808, was carried out in parallel with the [[Symphony No. 6 (Beethoven)|Sixth Symphony]], which premiered at the same concert. |

||

Beethoven was in his mid-thirties during this time; his personal life was troubled by increasing |

Beethoven was in his mid-thirties during this time; his personal life was troubled by increasing deafness.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.lvbeethoven.com/Bio/BiographyDeafness.html |title=Beethoven's deafness |work=lvbeethoven.com |access-date=31 August 2015}}</ref> In the world at large, the period was marked by the [[Napoleonic Wars]], political turmoil in Austria, and the occupation of Vienna by [[Napoleon]]'s troops in 1805. The symphony was written at his lodgings at the [[Pasqualati House]] in Vienna. |

||

===Premiere=== |

=== Premiere === |

||

{{Main|Beethoven concert of 22 December 1808}} |

|||

The Fifth Symphony was premiered on December 22, 1808 at a mammoth concert at the [[Theater an der Wien]] in Vienna consisting entirely of Beethoven premieres, and directed by Beethoven himself.<ref>Kinderman, William. Beethoven. University of California Press. Berkeley, Los Angeles. 1995. ISBN 0-520-08796-8; pg 122</ref> The concert went for more than four hours. The two symphonies appeared on the program in reverse order: the Sixth was played first, and the Fifth appeared in the second half.<ref>Parsons, Anthony. [http://www.lvbeethoven.com/VotreLVB/English_TromboneSociety.html Symphonic birth-pangs of the trombone]</ref> The program was as follows: |

|||

The Fifth Symphony premiered on 22 December 1808 at a mammoth concert at the [[Theater an der Wien]] in Vienna consisting entirely of Beethoven premieres, and directed by Beethoven himself on the conductor's podium.<ref>{{cite book|last=Kinderman|first=William|author-link=William Kinderman|title=Beethoven|publisher=University of California Press|location=Berkeley|year=1995|isbn=0-520-08796-8|page=122}}</ref> The concert lasted for more than four hours. The two symphonies appeared on the programme in reverse order: the Sixth was played first, and the Fifth appeared in the second half.<ref>{{cite web |last= Parsons |first= Anthony |url= http://www.lvbeethoven.com/VotreLVB/English_TromboneSociety.html |title= Symphonic birth-pangs of the trombone |work=British Trombone Society |year=1990 |access-date=31 August 2015}}</ref> The programme was as follows: |

|||

# The [[Symphony No. 6 (Beethoven)|Sixth Symphony]] |

|||

# The Sixth Symphony |

|||

# Aria: "Ah, perfido", Op. 65 |

|||

# Aria: ''{{lang|it|[[Ah! perfido]]}}'', Op. 65 |

|||

# The Gloria movement of the [[Mass in C major (Beethoven)|Mass in C Major]] |

|||

# The Gloria movement of the Mass in C major |

|||

# The [[Piano Concerto No. 4 (Beethoven)|Fourth Piano Concerto]] (played by Beethoven himself) |

|||

# The Fourth Piano Concerto (played by Beethoven himself) |

|||

# ''(Intermission)'' |

# ''(Intermission)'' |

||

# The Fifth Symphony |

# The Fifth Symphony |

||

# The Sanctus and Benedictus movements of the C |

# The Sanctus and Benedictus movements of the C major Mass |

||

# A solo piano improvisation played by Beethoven |

# A solo piano [[musical improvisation|improvisation]] played by Beethoven |

||

# The [[Choral Fantasy (Beethoven)|Choral Fantasy]] |

# The [[Choral Fantasy (Beethoven)|Choral Fantasy]] |

||

[[File:TheateranDerWienJakobAlt.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Theater an der Wien]] as it appeared in the early 19th century]] |

[[File:TheateranDerWienJakobAlt.jpg|thumb|right|The [[Theater an der Wien]] as it appeared in the early 19th century]] |

||

Beethoven dedicated the Fifth |

Beethoven dedicated the Fifth Symphony to two of his patrons, Prince [[Joseph Franz von Lobkowitz]] and [[Andrey Razumovsky|Count Razumovsky]]. The dedication appeared in the first printed edition of April 1809. |

||

=== Reception and influence === |

=== Reception and influence === |

||

There was little critical response to the premiere performance, which took place under adverse conditions. The orchestra did not play well—with only one rehearsal before the concert—and at one point, following a mistake by one of the performers in the Choral Fantasy, Beethoven had to stop the music and start again.<ref>Landon |

There was little critical response to the premiere performance, which took place under adverse conditions. The orchestra did not play well—with only one rehearsal before the concert—and at one point, following a mistake by one of the performers in the Choral Fantasy, Beethoven had to stop the music and start again.<ref>{{cite book|last=Robbins Landon|first=H. C.|author-link=H. C. Robbins Landon|title= Beethoven: His Life, Work, and World|publisher=Thames & Hudson|location=New York|year=1992|page=149}}</ref> The auditorium was extremely cold and the audience was exhausted by the length of the programme. However, a year and a half later, publication of the score resulted in a rapturous unsigned review (actually by music critic [[E. T. A. Hoffmann]]) in the ''[[Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung]]''. He described the music with dramatic imagery: |

||

<blockquote>Radiant beams shoot through |

<blockquote>Radiant beams shoot through this region's deep night, and we become aware of gigantic shadows which, rocking back and forth, close in on us and destroy everything within us except the pain of endless longing—a longing in which every pleasure that rose up in jubilant tones sinks and succumbs, and only through this pain, which, while consuming but not destroying love, hope, and joy, tries to burst our breasts with full-voiced harmonies of all the passions, we live on and are captivated beholders of the spirits.<ref>"Recension: Sinfonie ... composée et dediée etc. par Louis van Beethoven. à Leipsic, chez Breitkopf et Härtel, Oeuvre 67. No. 5. des Sinfonies", ''[[Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung]]'' 12, nos. 40 and 41 (4 and 11 July 1810): cols. 630–642 and 652–659. Citation in col. 633.</ref></blockquote> |

||

Apart from the extravagant praise, Hoffmann devoted by far the largest part of his review to a detailed analysis of the symphony, in order to show his readers the devices Beethoven used to arouse particular [[Doctrine of the affections|affects]] in the listener. In an essay titled "Beethoven's Instrumental Music", compiled from this 1810 review and another one from 1813 on the op. 70 string trios, published in three installments in December 1813, E.T.A. Hoffmann further praised the "indescribably profound, magnificent symphony in C minor": |

|||

In an essay titled "Beethoven's Instrumental Music" written in 1813, E.T.A. Hoffmann further praised the importance of the symphony: |

|||

<blockquote>How this wonderful composition, in a climax that climbs on and on, leads the listener imperiously forward into the spirit world of the infinite!... No doubt the whole rushes like an ingenious rhapsody past many a man, but the soul of each thoughtful listener is assuredly stirred, deeply and intimately, by a feeling that is none other than that unutterable portentous longing, and until the final chord—indeed, even in the moments that follow it—he will be powerless to step out of that wondrous spirit realm where grief and joy embrace him in the form of sound....<ref>Published anonymously, "Beethovens Instrumental-Musik", ''{{ill|Zeitung für die elegante Welt|de}}'', nos. 245–247 (9, 10, and 11 December 1813): cols. 1953–1957, 1964–1967, and 1973–1975. Also published anonymously as part of Hoffmann's collection titled ''Fantasiestücke in Callots Manier'', 4 vols. Bamberg, 1814. English edition, as Ernst Theodor Amadeus Hoffmann, ''Fantasy Pieces in Callot's Manner: Pages from the Diary of a Traveling Romantic'', translated by Joseph M Hayse. Schenectady: Union College Press, 1996; {{ISBN|0-912756-28-4}}.</ref></blockquote> |

|||

<blockquote>Can there be any work of Beethoven’s that confirms all this to a higher degree |

|||

than his indescribably profound, magnificent symphony in C minor? How this |

|||

wonderful composition, in a climax that climbs on and on, leads the listener |

|||

imperiously forward into the spirit world of the infinite!…No doubt the whole rushes like |

|||

an ingenious rhapsody past many a man, but the soul of each thoughtful listener is |

|||

assuredly stirred, deeply and intimately, by a feeling that is none other than that |

|||

unutterable portentous longing, and until the final chord — indeed, even in the |

|||

moments that follow it — he will be powerless to step out of that wondrous spirit realm |

|||

where grief and joy embrace him in the form of sound. The internal structure of the |

|||

movements, their execution, their instrumentation, the way in which they follow one |

|||

another — everything among the themes that engenders that unity which alone has the |

|||

power to hold the listener firmly in a single mood. This relationship is sometimes clear |

|||

to the listener when he overhears it in the connecting of two movements or discovers it |

|||

in the fundamental bass they have in common; a deeper relationship which does not |

|||

reveal itself in this way speaks at other times only from mind to mind, and it is precisely |

|||

this relationship that imperiously proclaims the self-possession of the master’s genius.</blockquote> |

|||

The symphony soon acquired its status as a central item in the repertoire. |

The symphony soon acquired its status as a central item in the orchestral repertoire. It was played in the inaugural concerts of the [[New York Philharmonic]] on 7 December 1842, and the [US] [[National Symphony Orchestra]] on 2 November 1931. It was first recorded by the Odeon Orchestra under [[Friedrich Kark]] in 1910. The First Movement (as performed by the [[Philharmonia Orchestra]]) was featured on the [[Voyager Golden Record]], a [[phonograph record]] containing a broad sample of the images, common sounds, languages, and music of Earth, sent into outer space aboard the [[Voyager program|Voyager]] probes in 1977.<ref name="Golden Record Music List">{{cite web |url= http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/spacecraft/music.html |title= Golden Record Music List |access-date= 26 July 2012 |publisher= [[NASA]]}}</ref> Groundbreaking in terms of both its technical and its emotional impact, the Fifth has had a large influence on composers and music critics,<ref>{{cite web |last= Moss |first= Charles K. |url= http://www.carolinaclassical.com/articles/beethoven.html |title=Ludwig van Beethoven: A Musical Titan |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20071222060307/http://www.carolinaclassical.com/articles/beethoven.html |archive-date= 22 December 2007}}.</ref> and inspired work by such composers as [[Johannes Brahms|Brahms]], [[Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky|Tchaikovsky]] (his [[Symphony No. 4 (Tchaikovsky)|4th Symphony]] in particular),<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.kennedy-center.org/calendar/index.cfm?fuseaction=composition&composition_id=2135|title=Symphony No. 5 in C minor, Op. 67|first=Richard|last=Freed|author-link=Richard Freed|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050906042619/http://www.kennedy-center.org/calendar/index.cfm?fuseaction=composition&composition_id=2135|archive-date=6 September 2005}}</ref> [[Anton Bruckner|Bruckner]], [[Gustav Mahler|Mahler]], and [[Hector Berlioz|Berlioz]].<ref>{{cite book|last=Rushton|first=Julian|author-link=Julian Rushton|title=The Music of Berlioz|page=244}}</ref> |

||

Since the Second World War, it has sometimes been referred to as the "Victory Symphony".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discogs.com/Beethoven-London-Symphony-Orchestra-Conducted-By-Josef-Krips-The-Victory-Symphony-Symphony-No5-In-C-/release/3365584|title=London Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Josef Krips – The Victory Symphony (Symphony No. 5 in C major[sic], Op. 67)|year=2015|work=Discogs|access-date=31 August 2015}}</ref> "V" is coincidentally also the [[Roman numerals|Roman numeral character]] for the number five and the phrase "[[V sign#The V for Victory campaign and the victory-freedom sign|V for Victory]]" became a campaign of the [[Allies of World War II]] after [[Winston Churchill]] starting using it as a catchphrase in 1940. Beethoven's Victory Symphony happened to be his Fifth (or vice versa) although this is coincidental. Some thirty years after this piece was written, the rhythm of the opening phrase – "dit-dit-dit-dah" – was used for the letter "V" in [[Morse code]], {{citation span|though this is also coincidental|reason=Supposition? Without a citation, the odds would favour it having been most decidedly intentional.|date=November 2024}}. During the Second World War, the [[BBC]] prefaced its broadcasts to [[Special Operations Executive]]s (SOE) across the world with those four notes, played on drums.<ref name="radio">{{cite web|url=http://home.luna.nl/~arjan-muil/radio/history/ww-2/v-campaign.html|title=V-Campaign|work=A World of Wireless: Virtual Radiomuseum|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050312223729/http://home.luna.nl/~arjan-muil/radio/history/ww-2/v-campaign.html|archive-date=12 March 2005|access-date=31 August 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://funkyadjunct.com/2013/07/18/v-for-victory-and-viral-3/|title=V for Victory and Viral|last=Karpf|first=Jason|date=18 July 2013|work=The Funky Adjunct|access-date=31 August 2015|archive-date=2 February 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160202215504/https://funkyadjunct.com/2013/07/18/v-for-victory-and-viral-3/|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/big/0719.html#article|title=British Open 'V' Nerve War; Churchill Spurs Resistance|last=MacDonald|first=James|date=20 July 1941|work=[[The New York Times]]|access-date=31 August 2015}}</ref> This was at the suggestion of intelligence agent [[Courtenay Edward Stevens]].<ref>{{cite news |title=Mr C. E. Stevens |work=[[The Times]]|issue=59798 |date=2 September 1976}}</ref> |

|||

== Instrumentation == |

== Instrumentation == |

||

The symphony is [[Instrumentation (music)|scored]] for the following orchestra: |

|||

The symphony is scored for [[piccolo]] (fourth movement only), 2 [[flute]]s, 2 [[oboe]]s, 2 [[clarinet]]s in B flat and C, 2 [[bassoon]]s, [[contrabassoon]] (fourth movement only), 2 [[Horn (instrument)|horns]] in E flat and C, 2 [[trumpet]]s, 3 [[trombone]]s (alto, tenor, and bass, fourth movement only), [[timpani]] (in G-C) and [[string instrument|string]]s. |

|||

{{col-float}} |

|||

;[[Woodwind]]s: |

|||

:{{Hanging indent |1 [[piccolo]] (fourth movement only)}} |

|||

:2 [[western concert flute|flutes]] |

|||

:2 [[oboe]]s |

|||

:{{Hanging indent |2 [[clarinet]]s in [[soprano clarinet|B{{music|flat}}]] (first, second, and third movements) and C (fourth movement)}} |

|||

:2 [[bassoon]]s |

|||

:{{Hanging indent |1 [[contrabassoon]] (fourth movement only)}} |

|||

;[[Brass instrument|Brass]]: |

|||

:{{Hanging indent |2 [[Natural horn|horns]] in E{{music|flat}} (first and third movements) and C (second and fourth movements)}} |

|||

:2 [[trumpet]]s in C |

|||

:{{Hanging indent |3 [[trombone]]s ([[alto trombone|alto]], [[tenor trombone|tenor]], and [[bass trombone|bass]], fourth movement only)}} |

|||

{{col-float-break}} |

|||

;[[Percussion instrument|Percussion]] |

|||

:[[timpani]] (in G–C) |

|||

;[[String section|Strings]]: |

|||

:[[violin]]s I, II |

|||

:[[viola]]s |

|||

:[[cello]]s |

|||

:[[double bass]]es |

|||

{{col-float-end}} |

|||

== Form == |

== Form == |

||

A typical performance usually lasts around |

A typical performance usually lasts around 30–40 minutes. The work is in four movements: |

||

{{Ordered list|type=upper-roman |

|||

=== First movement: Allegro con brio === |

|||

| [[Tempo#Basic tempo markings|Allegro con brio]] (5–8 minutes) ([[C minor]]) |

|||

{{listen|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 5 in c minor, op. 67 - i. allegro con brio.ogg|title=First movement: Allegro con brio|description=Performed by the Skidmore College Orchestra. Music courtesy of [http://www.musopen.com Musopen]|format=[[Ogg]] |

|||

| [[Andante (tempo)|Andante]] con moto (7–11 minutes) ([[A-flat major|A{{music|flat}} major]]) |

|||

|filename2=Ludwig van Beethoven - Symphonie 5 c-moll - 1. Allegro con brio.ogg|title2=First movement: Allegro con brio|description2=Performed by the Fulda Symphony|format2=[[Ogg]] |

|||

| [[Scherzo]]: [[Allegro (music)|Allegro]] (4–9 minutes) ([[C minor]]) |

|||

|header=First movement}} |

|||

| [[Allegro (music)|Allegro]] – Presto (7–11 minutes) ([[C major]]) |

|||

}} |

|||

=== I. Allegro con brio === |

|||

The first movement opens with the four-note [[motif (music)|motif]] discussed above, one of the most famous in western music. There is considerable debate among conductors as to the manner of playing the four opening bars. Some conductors take it in strict allegro [[tempo]]; others take the liberty of a weighty treatment, playing the motif in a much slower and more stately tempo; yet others take the motif ''molto ritardando'' (a pronounced slowing through each four-note phrase), arguing that the [[fermata]] over the fourth note justifies this.<ref name="Scherman570">Scherman, Thomas K, and Louis Biancolli. The Beethoven Companion. Double & Company. Garden City, New York. 1973; p. 570</ref> Regardless, it is crucial to convey the spirit of and-two-and <i>one</i>, as written, not the more common but misleading one-two-three-<i>four</i>.<ref name=>[[Michael Steinberg]], in conversation.</ref> |

|||

{{listen|type=music|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - Symphonie 5 c-moll - 1. Allegro con brio.ogg|title=First movement: Allegro con brio|description=Performed by the [[Fulda Symphonic Orchestra]]}} |

|||

The first movement opens with the four-note [[motif (music)|motif]] discussed above, one of the most famous motifs in Western music. There is considerable debate among conductors as to the manner of playing the four opening bars. Some conductors take it in strict allegro tempo; others take the liberty of a weighty treatment, playing the motif in a much slower and more stately tempo; yet others take the motif ''molto ritardando.''<ref name="Scherman570">{{cite book |last1= Scherman |first1= Thomas K. |first2= Louis |last2= Biancolli |name-list-style= amp |title= The Beethoven Companion |publisher= Double & Company |location= Garden City, New York |year= 1973 |page= 570}}</ref> |

|||

The first movement is in the traditional [[sonata form]] that Beethoven inherited from his [[Classical music era|classical]] predecessors, [[Joseph Haydn|Haydn]] and [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart]] (in which the main ideas that are introduced in the first few pages undergo elaborate development through many keys, with a dramatic return to the opening section—the [[recapitulation (music)|recapitulation]]—about three-quarters of the way through). It starts out with two dramatic fortissimo phrases, the famous motif, commanding the listener's attention. Following the first four bars, Beethoven uses imitations and sequences to expand the theme, these pithy imitations tumbling over each other with such rhythmic regularity that they appear to form a single, flowing melody. Shortly after, a very short ''fortissimo'' bridge, played by the horns, takes place before a second theme is introduced. This second theme is in E flat major, the relative major, and it is more lyrical, written ''piano'' and featuring the four-note motif in the string accompaniment. The codetta is again based on the four-note motif. The development section follows, using modulation, sequences and imitation, and including the bridge. During the recapitulation, there is a brief solo passage for [[oboe]] in quasi-improvisatory style, and the movement ends with a massive [[coda (music)|coda]]. |

|||

The first movement is in the traditional [[sonata form]] that Beethoven inherited from his [[Classical period (music)|Classical]] predecessors, such as [[Joseph Haydn|Haydn]] and [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart]] (in which the main ideas that are introduced in the first few pages undergo elaborate [[Development (music)|development]] [[Modulation (music)|through many keys]], with a dramatic return to the opening section—the [[recapitulation (music)|recapitulation]]—about three-quarters of the way through). It starts out with two dramatic [[fortissimo]] phrases, the famous motif, commanding the listener's attention. Following the first four bars, Beethoven uses imitations and sequences to expand the theme, these pithy imitations tumbling over each other with such rhythmic regularity that they appear to form a single, flowing melody. Shortly after, a very short ''fortissimo'' bridge, played by the horns, takes place before a second theme is introduced. This second theme is in [[E-flat major|E{{music|flat}} major]], the [[Relative key|relative major]], and it is more lyrical, written ''[[Dynamics (music)|piano]]'' and featuring the four-note motif in the string accompaniment. The [[Coda (music)#Codetta|codetta]] is again based on the four-note motif. The development section follows, including the bridge. During the recapitulation, there is a brief solo passage for oboe in quasi-improvisatory style, and the movement ends with a massive [[coda (music)|coda]]. |

|||

=== Second movement: Andante con moto === |

|||

{{listen|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 5 in c minor, op. 67 - ii. andante con moto.ogg|title=Second movement: Andante con moto|description=Performed by the Skidmore College Orchestra. Music courtesy of [http://www.musopen.com Musopen]|format=[[Ogg]] |

|||

|filename2=Ludwig van Beethoven - Symphonie 5 c-moll - 2. Andante con moto.ogg|title2=Second movement: Andante con moto|description2=Performed by the Fulda Symphony|format2=[[Ogg]] |

|||

|header=Second movement}} |

|||

A typical performance of this movement lasts approximately 7 to 8 minutes. |

|||

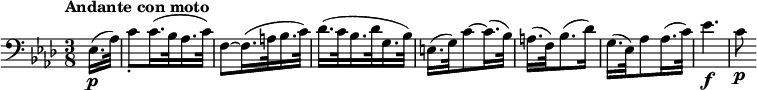

The second movement, in A flat major, is a lyrical work in [[double variation]] form, which means that two themes are presented and varied in alternation. Following the variations there is a long coda. |

|||

=== II. Andante con moto === |

|||

The movement opens with an announcement of its theme, a melody in unison by violas and cellos, with accompaniment by the double basses. A second theme soon follows, with a harmony provided by clarinets, bassoons, violins, with a triplet [[arpeggio]] in the violas and bass. A variation of the first theme reasserts itself. This is followed up by a third theme, thirty-second notes in the violas and cellos with a counterphrase running in the flute, oboe and bassoon. Following an interlude, the whole orchestra participates in a fortissimo, leading to a series of [[crescendo]]s, and a coda to close the movement.<ref>Scherman, Thomas K, and Louis Biancolli. The Beethoven Companion. Double & Company. Garden City, New York. 1973; pg 572</ref> |

|||

{{listen|type=music|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - Symphonie 5 c-moll - 2. Andante con moto.ogg|title=Second movement: Andante con moto|description=Performed by the Fulda Symphonic Orchestra}} |

|||

The second movement, in A{{music|flat}} major, the [[subdominant]] key of C minor's relative key ([[E-flat major|E{{music|flat}} major]]), is a lyrical work in [[double variation]] form, which means that two themes are presented and varied in alternation. Following the variations there is a long coda. |

|||

=== Third movement: Scherzo. Allegro === |

|||

{{listen|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 5 in c minor, op. 67 - iii. allegro.ogg|title=Third movement: Scherzo. Allegro|description=Performed by the Skidmore College Orchestra. Music courtesy of [http://www.musopen.com Musopen]|format=[[Ogg]] |

|||

|filename2=Ludwig van Beethoven - Symphonie 5 c-moll - 3. Allegro.ogg|title2=Third movement: Scherzo. Allegro|description2=Performed by the Fulda Symphony|format2=[[Ogg]] |

|||

|header=Third movement}} |

|||

<score>\relative c{ \clef bass \key as \major \time 3/8 \tempo "Andante con moto" \partial 8 es16.(\p as32) | c8_. 16.( bes32 as16. c32) | f,8~ 16.( a32 bes16. c32) des16.( c32 bes16. des32 g,16. bes32) e,16.( g32) c8~ 16.( bes32) a16.( f32) bes8.( des16) g,16.( es32) as8 16.( c32) es4.\f c8\p}</score> |

|||

The third movement is in [[ternary form]], consisting of a [[scherzo]] and trio. It follows the traditional mold of Classical-era symphonic third movements, containing in sequence the main scherzo, a contrasting trio section, a return of the scherzo, and a coda. However, while the usual Classical symphonies employed a minuet and trio as their third movement, Beethoven chose to use the newer scherzo and trio form. (For further discussion of this form, see "Textual questions", below.) |

|||

The movement opens with an announcement of its theme, a melody in unison by violas and cellos, with accompaniment by the double basses. A second theme soon follows, with a harmony provided by clarinets, bassoons, and violins, with a triplet [[arpeggio]] in the violas and bass. A variation of the first theme reasserts itself. This is followed up by a third theme, [[thirty-second note]]s in the violas and cellos with a counterphrase running in the flute, oboe, and bassoon. Following an interlude, the whole orchestra participates in a fortissimo, leading to a series of [[crescendo]]s and a coda to close the movement.{{sfnp|Scherman|Biancolli|1973|page=572}} {{citation needed-span|date=August 2023|text=There is a hint in the middle of the movement that is similar to the coda of the 3rd.}} |

|||

The movement returns to the opening key of C minor and begins with the following theme, played by the cellos and double basses: ({{Audio|Beet5mov3bars1to4.ogg|listen}}) |

|||

A typical performance of this movement lasts approximately 8 to 11 minutes. |

|||

[[File:BeethovenSymphonyNo5Mvt3Opening.png|center||500 px|]] |

|||

=== III. Scherzo: Allegro === |

|||

The 19th century musicologist [[Gustav Nottebohm]] first pointed out that this theme has the same sequence of pitches (though in a different key and range) as the opening theme of the final movement of [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart]]'s famous [[Symphony No. 40 (Mozart)|Symphony No. 40]] in G minor, K. 550. Here is Mozart's theme: ({{Audio|Mozart40bars1to3.ogg|listen}}) |

|||

{{listen|type=music|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - Symphonie 5 c-moll - 3. Allegro.ogg|title=Third movement: Allegro|description=Performed by the Fulda Symphonic Orchestra}} |

|||

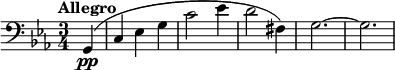

The third movement is in [[ternary form]], consisting of a [[scherzo]] and trio. Beethoven started using a scherzo as a 3rd movement in the 3rd symphony (breaking with the tradition of using a minuet as a 3rd movement). In the 4th he chose to return to the minuet form. From the 5th on he adopts the scherzo for good. |

|||

[[Image:MozartSymph40Mvt4Opening.png|center||500 px|]] |

|||

The movement returns to the opening key of C minor and begins with the following theme, played by the cellos and double basses: |

|||

(The derivation emerges more clearly if one listens first to Mozart's theme, then Mozart's theme transposed to Beethoven's key and range, then Beethoven's theme, thus: {{Audio|Beethoven5thSymphonyMozartBorrowing.ogg|listen}}.) |

|||

<score>\relative c{ \clef bass \key c \minor \time 3/4 \tempo "Allegro" \partial 4 g(\pp | c ees g | c2 ees4 | d2 fis,4) | g2.~ | g2.}</score> [[File:Beet5mov3bars1to4.ogg]] |

|||

While such resemblances sometimes occur by accident, this is unlikely to be so in the present case. Nottebohm discovered the resemblance when he examined a sketchbook used by Beethoven in composing the Fifth Symphony: here, 29 measures of Mozart's finale appear, copied out by Beethoven.<ref>Nottebohm, Gustav (1887) ''Zweite Beethoviana''. Leipzig: C. F. Peters, p. 531.</ref> |

|||

The opening theme is answered by a contrasting theme played by the [[woodwind instrument|winds]], and this sequence is repeated. Then the horns loudly announce the main theme of the movement, and the music proceeds from there. The trio section is in C major and is written in a contrapuntal texture. When the scherzo returns for the final time, it is performed by the strings [[pizzicato]] and very quietly. "The scherzo offers contrasts that are somewhat similar to those of the slow movement [''Andante con moto''] in that they derive from extreme difference in character between scherzo and trio ... The Scherzo then contrasts this figure with the famous 'motto' (3 + 1) from the first movement, which gradually takes command of the whole movement."<ref name=Lockwood>{{cite book |author-link= Lewis Lockwood |last= Lockwood |first= Lewis |title= Beethoven: The Music and the Life |publisher=W. W. Norton|location= New York |isbn= 0-393-05081-5|year=2003}}</ref>{{rp|[https://archive.org/details/beethovenmusican00lock/page/223 223]}} The third movement is also notable for its transition to the fourth movement, widely considered one of the greatest musical transitions of all time.<ref>{{Cite book|first=William|last=Kinderman|author-link=William Kinderman|title=Beethoven|edition=2nd|location=New York|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2009|page=150}}</ref> |

|||

The opening theme is answered by a contrasting theme played by the [[woodwind instrument|winds]], and this sequence is repeated. Then the [[horn (instrument)|horn]]s loudly announce the main theme of the movement, and the music proceeds from there. |

|||

A typical performance of this movement lasts approximately 4 to 8 minutes. |

|||

The trio section is in [[C major]] and is written in a contrapuntal texture. When the scherzo returns for the final time, it is performed by the strings [[pizzicato]] and very quietly. |

|||

=== IV. Allegro === |

|||

"The scherzo offers contrasts that are somewhat similar to those of the slow movement in that they derive from extreme difference in character between scherzo and trio … The Scherzo then contrasts this figure with the famous 'motto' (3 + 1) from the first movement, which gradually takes command of the whole movement." <ref>[[Lewis Lockwood|Lockwood, Lewis]]. Beethoven: The Music and the Life. W.W. Norton & Company. New York. ISBN 0-393-05081-5; pg 223</ref> |

|||

{{listen|type=music|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - Symphonie 5 c-moll - 4. Allegro.ogg|title=Fourth movement: Allegro|description=Performed by the Fulda Symphonic Orchestra}} |

|||

The fourth movement begins without pause from the transition. The music resounds in C major, an unusual choice by the composer as a symphony that begins in C minor is expected to finish in that key.<ref name=Lockwood />{{rp|[https://archive.org/details/beethovenmusican00lock/page/224 224]}} In Beethoven's words: <blockquote>Many assert that every minor piece must end in the minor. Nego! ...Joy follows sorrow, sunshine—rain.<ref>{{cite book|title=Beethoven: The Man and the Artist, as Revealed in His Own Words|editor-first1=Friedrich|editor-last1=Kerst|editor-first2=Henry Edward|editor-last2=Krehbiel|editor2-link=Henry Edward Krehbiel|location=Boston|publisher=IndyPublishing|year=2008|page=15|translator=Henry Edward Krehbiel}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

=== Fourth movement: Allegro === |

|||

{{listen|filename=Ludwig van Beethoven - symphony no. 5 in c minor, op. 67 - iv. allegro.ogg|title=Fourth movement: Allegro|description=Performed by the Skidmore College Orchestra. Music courtesy of [http://www.musopen.com Musopen]|format=[[Ogg]] |

|||

|filename2=Ludwig van Beethoven - Symphonie 5 c-moll - 4. Allegro.ogg|title2=Fourth movement: Allegro|description2=Performed by the Fulda Symphony|format2=[[Ogg]] |

|||

|header=Fourth movement}} |

|||

The triumphant and exhilarating finale |

The triumphant and exhilarating finale is written in an unusual variant of sonata form: at the end of the development section, the music halts on a [[dominant (music)|dominant]] [[cadence]], played fortissimo, and the music continues after a pause with a quiet reprise of the "horn theme" of the scherzo movement. The recapitulation is then introduced by a crescendo coming out of the last bars of the interpolated scherzo section, just as the same music was introduced at the opening of the movement. The interruption of the finale with material from the third "dance" movement was pioneered by [[Joseph Haydn|Haydn]], who had done the same in his [[Symphony No. 46 (Haydn)|Symphony No. 46]] in B, from 1772. It is unknown whether Beethoven was familiar with this work or not.<ref>[[James Webster (musicologist)|James Webster]], ''Haydn's 'Farewell' Symphony and the Idea of Classical Style'', p. 267</ref> |

||

The Fifth Symphony finale includes a very long coda, in which the main themes of the movement are played in temporally compressed form. Towards the end the tempo is increased to [[ |

The Fifth Symphony finale includes a very long coda, in which the main themes of the movement are played in temporally compressed form. Towards the end the tempo is increased to [[presto (music)|presto]]. The symphony ends with 29 bars of C major chords, played fortissimo. In ''[[The Classical Style]]'', [[Charles Rosen]] suggests that this ending reflects Beethoven's sense of proportions: the "unbelievably long" pure C major cadence is needed "to ground the extreme tension of [this] immense work."<ref>{{cite book|last=Rosen|first=Charles|author-link=Charles Rosen|year=1997|title=The Classical Style|edition=2nd|location=New York|publisher=W. W. Norton|page=72|title-link=The Classical Style}}</ref> |

||

A typical performance of this movement lasts approximately 8 to 11 minutes. |

|||

== Influences == |

|||

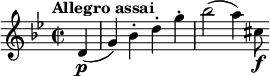

The 19th century musicologist [[Gustav Nottebohm]] first pointed out that the third movement's theme has the same sequence of intervals as the opening theme of the final movement of [[Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart|Mozart]]'s famous [[Symphony No. 40 (Mozart)|Symphony No. 40]] in G minor, [[Köchel catalogue|K.]] 550. Here are the first eight notes of Mozart's theme: |

|||

<score>\relative c' { \key g \minor \time 2/2 \tempo "Allegro assai" \partial 4 d4\p(g) bes-. d-. g-. bes2(a4) cis,8\f }</score> [[File:Mozart40bars1to3.ogg]] |

|||

While such resemblances sometimes occur by accident, this is unlikely to be so in the present case. Nottebohm discovered the resemblance when he examined a sketchbook used by Beethoven in composing the Fifth Symphony: here, 29 bars of Mozart's finale appear, copied out by Beethoven.<ref>{{cite book|last=Nottebohm|first=Gustav|author-link=Gustav Nottebohm|year=1887|title=Zweite Beethoviana|location=Leipzig|publisher=C. F. Peters|page= 531 |language=de |quote=Auf der dritten Seite desselben stehen 20 Takte aus dem letzen Satz der G-moll Symphonie von Mozart.}}</ref> |

|||

== Lore == |

== Lore == |

||

Much has been written about the Fifth Symphony in books, scholarly articles, and program notes for live and recorded performances. This section summarizes some themes that commonly appear in this material. |

Much has been written about the Fifth Symphony in books, scholarly articles, and program notes for live and recorded performances. This section summarizes some themes that commonly appear in this material. |

||

<!-- linked from [[V sign]] and possibly other pages --> |

|||

=== Fate motif === |

=== Fate motif === |

||

The initial motif of the symphony has sometimes been credited with symbolic significance as a representation of Fate knocking at the door. This idea comes from Beethoven's secretary and factotum [[Anton Schindler]], who wrote, many years after Beethoven's death: |

The initial motif of the symphony has sometimes been credited with symbolic significance as a representation of [[destiny|Fate]] knocking at the door. This idea comes from Beethoven's secretary and factotum [[Anton Schindler]], who wrote, many years after Beethoven's death: |

||

<blockquote>The composer himself provided the key to these depths when one day, in this author's presence, he pointed to the beginning of the first movement and expressed in these words the fundamental idea of his work: "Thus Fate knocks at the door!"<ref>Jolly |

<blockquote>The composer himself provided the key to these depths when one day, in this author's presence, he pointed to the beginning of the first movement and expressed in these words the fundamental idea of his work: "Thus Fate knocks at the door!"<ref>{{cite book |last= Jolly |first= Constance |title= Beethoven as I Knew Him |location= London |publisher= Faber and Faber |year= 1966 }} As translated from Schindler (1860). ''Biographie von Ludwig van Beethoven''.</ref></blockquote> |

||

Schindler's testimony concerning any point of Beethoven's life is disparaged by experts ( |

Schindler's testimony concerning any point of Beethoven's life is disparaged by many experts (Schindler is believed to have forged entries in Beethoven's so-called "conversation books", the books in which the deaf Beethoven got others to write their side of conversations with him).<ref>{{cite book|last=Cooper|first=Barry|author-link=Barry Cooper (musicologist)|title=The Beethoven Compendium|location=Ann Arbor, Michigan|publisher=Borders Press|year=1991|isbn=0-681-07558-9|page=52}}</ref> Moreover, it is often commented that Schindler offered a highly romanticized view of the composer. |

||

There is another tale concerning the same motif; the version given here is from [[Antony Hopkins]]'s description of the symphony<ref name="hopkins"/> |

There is another tale concerning the same motif; the version given here is from [[Antony Hopkins]]'s description of the symphony.<ref name="hopkins"/> [[Carl Czerny]] (Beethoven's pupil, who premiered the [[Piano Concerto No. 5 (Beethoven)|"Emperor" Concerto]] in Vienna) claimed that "the little pattern of notes had come to [Beethoven] from a [[yellowhammer|yellow-hammer]]'s song, heard as he walked in the [[Prater]]-park in Vienna." Hopkins further remarks that "given the choice between a yellow-hammer and Fate-at-the-door, the public has preferred the more dramatic myth, though Czerny's account is too unlikely to have been invented." |

||

In his ''[[Omnibus (U.S. TV series)|Omnibus]]'' television lecture series in 1954, [[Leonard Bernstein]] likened the Fate Motif to the four note coda common to symphonies. These notes would terminate the symphony as a musical coda, but for Beethoven they become a motif repeating throughout the work for a very different and dramatic effect, he says.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Tommasini|first=Anthony|author-link=Anthony Tommasini|date=2020-12-14|title=Beethoven's 250th Birthday: His Greatness Is in the Details|work=[[The New York Times]]|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/14/arts/music/beethoven-250-birthday-classical.html|access-date=2021-10-06}}</ref> |

|||

Evaluations of these interpretations tend to be skeptical. "The popular legend that Beethoven intended this grand exordium of the symphony to suggest 'Fate Knocking at the gate' is apocryphal; Beethoven's pupil, [[Ferdinand Ries]], was really author of this would-be poetic exegesis, which Beethoven received very sarcastically when Ries imparted it to him."<ref name="Scherman570" /> [http://w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de/cmp/contributors.html#s Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner] remarks that "Beethoven had been known to say nearly anything to relieve himself of questioning pests"; this might be taken to impugn both tales.<ref>Classical Music Pages. [http://w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de/cmp/beethoven_sym5.html Ludwig van Beethoven — Symphony No.5, Op.67]</ref> |

|||

Evaluations of these interpretations tend to be skeptical. "The popular legend that Beethoven intended this grand exordium of the symphony to suggest 'Fate Knocking at the gate' is apocryphal; Beethoven's pupil, [[Ferdinand Ries]], was really author of this would-be poetic exegesis, which Beethoven received very sarcastically when Ries imparted it to him."<ref name="Scherman570" /> Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner remarks that "Beethoven had been known to say nearly anything to relieve himself of questioning pests"; this might be taken to impugn both tales.<ref>{{cite web|work=Classical Music Pages|url=http://w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de/cmp/beethoven_sym5.html|archive-url=http://webarchive.loc.gov/all/20090706145416/http://w3.rz-berlin.mpg.de/cmp/beethoven_sym5.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=2009-07-06|title=Ludwig van Beethoven – Symphony No. 5, Op. 67|author=Elizabeth Schwarm Glesner}}</ref> |

|||

=== Beethoven's choice of key === |

=== Beethoven's choice of key === |

||

The |

The key of the Fifth Symphony, [[C minor]], is commonly regarded as a [[Beethoven and C minor|special key for Beethoven]], specifically a "stormy, heroic tonality".<ref>{{cite web |last= Wyatt |first= Henry |url= http://www.masongross.rutgers.edu/mgpresents/14June03_notes.html |title= Mason Gross Presents—Program Notes: 14 June 2003 |publisher= Mason Gross School of Arts |url-status=dead|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20060901152133/http://www.masongross.rutgers.edu/mgpresents/14June03_notes.html |archive-date= 1 September 2006 }}</ref> Beethoven wrote a number of works in C minor whose character is broadly similar to that of the Fifth Symphony. Pianist and writer [[Charles Rosen]] says, <blockquote>Beethoven in C minor has come to symbolize his artistic character. In every case, it reveals Beethoven as Hero. C minor does not show Beethoven at his most subtle, but it does give him to us in his most extroverted form, where he seems to be most impatient of any compromise.<ref>{{cite book |author-link= Charles Rosen |last= Rosen |first= Charles |title= Beethoven's Piano Sonatas: A Short Companion |location= New Haven |publisher= Yale University Press |year= 2002 |page= 134}}</ref></blockquote> |

||

=== Repetition of the opening motif throughout the symphony === |

=== Repetition of the opening motif throughout the symphony === |

||

It is commonly asserted that the opening four-note rhythmic motif (short-short-short-long; see above) is repeated throughout the symphony, unifying it. |

It is commonly asserted that the opening four-note rhythmic motif (short-short-short-long; see above) is repeated throughout the symphony, unifying it. "It is a rhythmic pattern (dit-dit-dit-dot) that makes its appearance in each of the other three movements and thus contributes to the overall unity of the symphony" (Doug Briscoe<ref name=Briscoe>{{cite web |first= Doug |last= Briscoe |url= http://www.bostonclassicalorchestra.org/program-notes/2003-2004-celebrating-harry/ |title= Program Notes: Celebrating Harry: Orchestral Favorites Honoring the Late Harry Ellis Dickson |publisher= Boston Classic Orchestra |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20120717075238/http://www.bostonclassicalorchestra.org/program-notes/2003-2004-celebrating-harry/ |archive-date= 17 July 2012}}</ref>); "a single motif that unifies the entire work" (Peter Gutmann<ref>{{cite web |first= Peter |last= Gutmann |url= http://www.classicalnotes.net/classics/fifth.html |title= Ludwig Van Beethoven: Fifth Symphony |work= Classical Notes}}</ref>); "the key motif of the entire symphony";<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.all-about-beethoven.com/symphony5.html |title= Beethoven's Symphony No. 5. The Destiny Symphony |work= All About Beethoven |access-date= 16 April 2005 |archive-date= 12 February 2007 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20070212025710/http://www.all-about-beethoven.com/symphony5.html |url-status= usurped }}</ref> "the rhythm of the famous opening figure ... recurs at crucial points in later movements" (Richard Bratby<ref>{{Cite web|first=Richard |last=Bratby |url=http://www.symphony5.com/en/sn5.htm |title=Symphony No. 5 |url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050831060244/http://www.symphony5.com/en/sn5.htm |archive-date=31 August 2005 }}</ref>). The ''[[New Grove]]'' encyclopedia cautiously endorses this view, reporting that "[t]he famous opening motif is to be heard in almost every bar of the first movement—and, allowing for modifications, in the other movements."<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Ludwig van Beethoven |encyclopedia=Grove Online Encyclopedia |url=http://www.grovemusic.com/shared/views/article.html?section=music.40026.15#music.40026.15 |url-access=subscription }}</ref> |

||

There are several passages in the symphony that have led to this view. For instance, in the third movement the horns play the following solo in which the short-short-short-long pattern occurs repeatedly: |

There are several passages in the symphony that have led to this view. For instance, in the third movement the horns play the following solo in which the short-short-short-long pattern occurs repeatedly: |

||

<score sound="1"> |

|||

: [[Image:BeethovenSymphony5Mvt3Bar19HornPart.PNG|Center||600 px|]] |

|||

\relative c'' { |

|||

\set Staff.midiInstrument = #"french horn" |

|||

\set Score.tempoHideNote = ##t |

|||

\tempo 4 = 192 |

|||

\key c \minor |

|||

\time 3/4 |

|||

\set Score.currentBarNumber = #19 |

|||

\bar "" |

|||

\[ g4\ff^"a 2" g g | g2. | \] |

|||

g4 g g | g2. | |

|||

g4 g g | <es g>2. | |

|||

<g bes>4(<f as>) <es g>^^ | <bes f'>2. | |

|||

} |

|||

</score> |

|||

In the second movement, an accompanying line plays a similar rhythm |

In the second movement, an accompanying line plays a similar rhythm: |

||

<score override_ogg="BeethovenSymphony5Mvt2Bar76.ogg"> |

|||

\new StaffGroup << |

|||

\new Staff \relative c'' { |

|||

\time 3/8 |

|||

\key aes \major |

|||

\set Score.barNumberVisibility = #all-bar-numbers-visible |

|||

\set Score.currentBarNumber = #75 |

|||

\bar "" |

|||

\override TextScript #'X-offset = #-3 |

|||

\partial 8 es16.(\pp^"Violin I" f32) | |

|||

\repeat unfold 2 { ges4 es16.(f32) | } |

|||

} |

|||

\new Staff \relative c'' { |

|||

\key aes \major |

|||

\override TextScript #'X-offset = #-3 |

|||

r8^"Violin II, Viola" | |

|||

r32 \[ a[\pp a a] a16[ \] a] a r | |

|||

r32 a[ a a] a16[ a] a r | |

|||

} |

|||

>> |

|||

</score> |

|||

In the finale, Doug Briscoe |

In the finale, Doug Briscoe<ref name=Briscoe /> suggests that the motif may be heard in the piccolo part, presumably meaning the following passage: |

||

<score override_ogg="BeethovenSymphony5Mvt4Bar244.ogg">\new StaffGroup << |

|||

: [[Image:BeethovenSymphonyNo5Mvt5M244.png|Center||650 px|]] |

|||

\new Staff \relative c'' { |

|||

\time 4/4 |

|||

\key c \major |

|||

\set Score.currentBarNumber = #244 |

|||

\bar "" |

|||

r8^"Piccolo" \[ fis g g g2~ \] | |

|||

\repeat unfold 2 { |

|||

g8 fis g g g2~ | |

|||

} |

|||

g8 fis g g g2 | |

|||

} |

|||

\new Staff \relative c { |

|||

\clef "bass" |

|||

b2.^"Viola, Cello, Bass" g4(| |

|||

b4 g d' c8. b16) | |

|||

c2. g4(| |

|||

c4 g e' d8. c16) | |

|||

} |

|||

>></score> |

|||

Later, in the coda of the finale, the bass instruments repeatedly play the following |

Later, in the coda of the finale, the bass instruments repeatedly play the following: |

||

<score override_ogg="BeethovenSymphony5Mvt4Bar362.ogg">\new StaffGroup << |

|||

: <!-- Deleted image removed: [[Image:BeethovenSymphonyNo5Mvt4M372.PNG|center||600 px|]] --> |

|||

\new Staff \relative c' { |

|||

\time 2/2 |

|||

\key c \major |

|||

\set Score.currentBarNumber = #362 |

|||

\bar "" |

|||

\tempo "Presto" |

|||

\override TextScript #'X-offset = #-5 |

|||

c2.\fp^"Violins" b4 | a(g) g-. g-. | |

|||

c2. b4 | a(g) g-. g-. | |

|||

\repeat unfold 2 { |

|||

<c e>2. <b d>4 | <a c>(<g b>) q-. q-. | |

|||

} |

|||

} |

|||

\new Staff \relative c { |

|||

\time 2/2 |

|||

\key c \major |

|||

\clef "bass" |

|||

\override TextScript #'X-offset = #-5 |

|||

c4\fp^"Bass instruments" r r2 | r4 \[ g g g | |

|||

c4\fp \] r r2 | r4 g g g | |

|||

\repeat unfold 2 { |

|||

c4\fp r r2 | r4 g g g | |

|||

} |

|||

} |

|||

>></score> |

|||

On the other hand, |

On the other hand, some commentators are unimpressed with these resemblances and consider them to be accidental. Antony Hopkins,<ref name="hopkins"/> discussing the theme in the scherzo, says "no musician with an ounce of feeling could confuse [the two rhythms]", explaining that the scherzo rhythm begins on a strong musical beat whereas the first-movement theme begins on a weak one. [[Donald Tovey]]<ref>{{cite book|last=Tovey|first=Donald Francis|author-link=Donald Tovey|year=1935|title=Essays in Musical Analysis, Volume 1: Symphonies|location=London|publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> pours scorn on the idea that a rhythmic motif unifies the symphony: "This profound discovery was supposed to reveal an unsuspected unity in the work, but it does not seem to have been carried far enough." Applied consistently, he continues, the same approach would lead to the conclusion that many other works by Beethoven are also "unified" with this symphony, as the motif appears in the [[Piano Sonata No. 23 (Beethoven)|"Appassionata" piano sonata]], the [[Piano Concerto No. 4 (Beethoven)|Fourth Piano Concerto]] <small>({{Audio|BeethovenPianoConcertoNo4Opening.ogg|listen}})</small>, and in the [[String Quartet No. 10 (Beethoven)|String Quartet, Op. 74]]. Tovey concludes, "the simple truth is that Beethoven could not do without just such purely rhythmic figures at this stage of his art." |

||

To Tovey's objection can be added the prominence of the short-short-short-long rhythmic figure in earlier works by Beethoven's older |

To Tovey's objection can be added the prominence of the short-short-short-long rhythmic figure in earlier works by Beethoven's older Classical contemporaries such as Haydn and Mozart. To give just two examples, it is found in Haydn's [[Symphony No. 96 (Haydn)|"Miracle" Symphony, No. 96]] ({{Audio|HaydnSymphony96Mvt1Excerpt.ogg|listen}}) and in Mozart's [[Piano Concerto No. 25 (Mozart)|Piano Concerto No. 25, K. 503]] ({{Audio|MozartPianoConcertoNo25ShortShortShortLongMotif.ogg|listen}}). Such examples show that "short-short-short-long" rhythms were a regular part of the musical language of the composers of Beethoven's day. |

||

It seems likely that whether or not Beethoven deliberately, or unconsciously, wove a single rhythmic motif through the Fifth Symphony will (in Hopkins's words) "remain eternally open to debate |

It seems likely that whether or not Beethoven deliberately, or unconsciously, wove a single rhythmic motif through the Fifth Symphony will (in Hopkins's words) "remain eternally open to debate".<ref name="hopkins"/> |

||

=== |

=== Use of La Folia === |

||

[[File:Beethoven Symphony No. 5 Movement 2, La Folia Variation (measures 166 - 183).ogg|thumb|La Folia Variation (measures 166–176)]] |

|||

While it is commonly stated that the last movement of Beethoven's Fifth is the first time the [[trombone]] and the [[piccolo]] were used in a concert symphony, it is not true. The Swedish composer [[Joachim Nicolas Eggert]] specified trombones for his Symphony in E-flat major written in 1807,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.trombone-society.org.uk/resources/articles/kallai.php|title=Revert to Eggert|accessdate=2006-04-28|first=Avishai|last=Kallai}}</ref> and examples of earlier symphonies with a part for piccolo abound, including [[Michael Haydn]]'s Symphony no. 19 in C major composed in August 1773. |

|||

[[Folia]] is a dance form with a distinctive rhythm and harmony, which was used by many composers from the [[Renaissance]] well into the 19th and even 20th centuries, often in the context of a [[Variation (music)|theme and variations]].<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.folias.nl/html1.html |title=What is La Folia? |work=folias.nl |year=2015 |access-date=31 August 2015}}</ref> It was used by Beethoven in his Fifth Symphony in the harmony midway through the slow movement (bars 166–177).<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.folias.nl/nnbeeth2.gif |title=Bar 166 |work=folias.nl |year=2008 |access-date=31 August 2015}}</ref> Although some recent sources mention that the fragment of the Folia theme in Beethoven's symphony was detected only in the 1990s, Reed J. Hoyt analyzed some Folia-aspects in the oeuvre of Beethoven already in 1982 in his "Letter to the Editor", in the journal ''College Music Symposium 21'', where he draws attention to the existence of complex archetypal patterns and their relationship.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.folias.nl/html5b.html#BEE |title=Which versions of La Folia have been written down, transcribed or recorded? |work=folias.nl |access-date=31 August 2015}}</ref> |

|||

== Textual questions == |

|||

=== Third movement repeat === |

|||

In the autograph score (that is, the original version from Beethoven's hand), the third movement contains a repeat mark: when the scherzo and trio sections have both been played through, the performers are directed to return to the very beginning and play these two sections again. Then comes a third rendering of the scherzo, this time notated differently for pizzicato strings and transitioning directly to the finale (see description above). Most modern printed editions of the score do not render this repeat mark; and indeed most performances of the symphony render the movement as ABA' (where A = scherzo, B = trio, and A' = modified scherzo), in contrast to the ABABA' of the autograph score. |

|||

=== New instrumentation === |

|||

The repeat mark in the autograph is unlikely to be simply an error on the composer's part. The ABABA' scheme for scherzi appears elsewhere in Beethoven, in the Bagatelle for solo piano, Op. 33, No. 7 (1802), and in the [[Symphony No. 4 (Beethoven)|Fourth]], [[Symphony No. 6 (Beethoven)|Sixth]], and [[Symphony No. 7 (Beethoven)|Seventh]] Symphonies. However, it is possible that for the Fifth Symphony, Beethoven originally preferred ABABA', but changed his mind in the course of publication in favor of ABA'. |

|||

The last movement of Beethoven's Fifth is the first time the piccolo and contrabassoon were used in a symphony.<ref>{{cite thesis|last1=Teng|first1=Kuo-Jen|title=The Role of the Piccolo in Beethoven's Orchestration|type=Doctor of Musical Arts thesis|publisher=University of North Texas|date=December 2011|page=5|url=https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc103400/m2/1/high_res_d/dissertation.pdf|access-date=4 October 2021}}</ref> While this was Beethoven's first use of the trombone in a symphony, in 1807 the Swedish composer [[Joachim Nicolas Eggert]] had specified trombones for his Symphony No. 3 in E{{music|flat}} major.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.trombone-society.org.uk/resources/articles/kallai.php |title= Revert to Eggert |access-date= 28 April 2006 |first= Avishai |last= Kallai |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060929051209/https://www.trombone-society.org.uk/resources/articles/kallai.php |archive-date=29 September 2006}}</ref> |

|||

Since Beethoven's day, published editions of the symphony have always printed ABA'. However, in 1978 an edition specifying ABABA' was prepared by [[Peter Gülke]] and published by [[Edition Peters|Peters]]. In 1999, yet another edition by [[Jonathan Del Mar]] was published by Bärenreiter<ref>''Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor'', edited by Jonathan Del Mar. Kassel: Bärenreiter (1999), ISMN M-006-50054-3</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britac.ac.uk/templates/asset-relay.cfm?frmAssetFileID=6233|publisher=British Academy Review|author=Del Mar, Jonathan|authorlink=Jonathan Del Mar|year=1999|month=July-December|title=Jonathan Del Mar, New Urtext Edition: Beethoven Symphonies 1–9|accessdate=2008-02-23}}</ref> which advocates a return to ABA'. In the accompanying book of commentary,<ref>''Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor; Critical Commentary'', edited by Jonathan Del Mar. Kassel: Bärenreiter (1999)</ref> Del Mar defends in depth the view that ABA' represents Beethoven's final intention; in other words, that conventional wisdom was right all along. |

|||

== Textual questions == |

|||

In concert performances, ABA' prevailed until fairly recent times. However, since the appearance of the Gülke edition conductors have felt more free to exercise their own choice. The conductor [[Caroline Brown]], in notes to her recorded ABABA' performance with the [[Hanover Band]] (Nimbus Records, #5007), writes: |

|||

=== Third movement repeat === |

|||

<blockquote>Re-establishing the repeat certainly alters the structural emphasis normally apparent in this Symphony. It makes the scherzo less of a transitional make-weight, and, by allowing the listener more time to become involved with the main thematic motif of the scherzo, the side-ways step into the bridge passage leading to the finale seems all the more unexpected and extraordinary in its intensity. </blockquote> |

|||

In the autograph score (that is, the original version from Beethoven's hand), the third movement contains a repeat mark: when the scherzo and trio sections have both been played through, the performers are directed to return to the very beginning and play these two sections again. Then comes a third rendering of the scherzo, this time [[Musical notation|notated]] differently for [[pizzicato]] strings and transitioning directly to the finale (see description above). Most modern printed editions of the score do not render this repeat mark; and indeed most performances of the symphony render the movement as ABA' (where A = scherzo, B = trio, and A' = modified scherzo), in contrast to the ABABA' of the autograph score. The repeat mark in the autograph is unlikely to be simply an error on the composer's part. The ABABA' scheme for scherzi appears elsewhere in Beethoven, in the [[Bagatelles, Op. 33 (Beethoven)|Bagatelle for solo piano, Op. 33, No. 7]] (1802), and in the [[Symphony No. 4 (Beethoven)|Fourth]], [[Symphony No. 6 (Beethoven)|Sixth]], and [[Symphony No. 7 (Beethoven)|Seventh]] Symphonies. However, it is possible that for the Fifth Symphony, Beethoven originally preferred ABABA', but changed his mind in the course of publication in favor of ABA'. |

|||

Since Beethoven's day, published editions of the symphony have always printed ABA'. However, in 1978 an edition specifying ABABA' was prepared by [[Peter Gülke]] and published by [[Edition Peters|Peters]]. In 1999, yet another edition, by [[Jonathan Del Mar]], was published by [[Bärenreiter]]<ref>{{cite AV media|title=Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor|editor-first=Jonathan|editor-last=Del Mar|editor-link=Jonathan Del Mar|location=Kassel|publisher=[[Bärenreiter]]|year=1999|url=http://iucat.iu.edu/iub/2877723}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.britac.ac.uk/templates/asset-relay.cfm?frmAssetFileID=6233 |publisher= British Academy Review |last= Del Mar |first= Jonathan |author-link= Jonathan Del Mar |date= July–December 1999 |title= Jonathan Del Mar, New Urtext Edition: Beethoven Symphonies 1–9 |access-date= 23 February 2008}}</ref> which advocates a return to ABA'. In the accompanying book of commentary,<ref>{{cite AV media|work=Ludwig van Beethoven: Symphony No. 5 in C minor|title=Critical Commentary|editor-first=Jonathan|editor-last=Del Mar|editor-link=Jonathan Del Mar|location=Kassel|publisher=Bärenreiter|year=1999}}</ref> Del Mar defends in depth the view that ABA' represents Beethoven's final intention; in other words, that conventional wisdom was right all along. |

|||

Performances with ABABA' seems to be particularly favored by conductors who specialize in [[authentic performance]] (that is, using instruments of the kind employed in Beethoven's day). These include Brown, as well as [[Christopher Hogwood]], [[John Eliot Gardiner]], and [[Nikolaus Harnoncourt]]. ABABA' performances on modern instruments have also been recorded by the [[Tonhalle Orchester Zurich]] under [[David Zinman]] and by the [[Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra]] under [[Claudio Abbado]]. |

|||

In concert performances, ABA' prevailed until the 2000s. However, since the appearance of the Gülke edition, conductors have felt more free to exercise their own choice. Performances with ABABA' seem to be particularly favored by conductors who specialize in [[authentic performance]] or historically informed performance (that is, using instruments of the kind employed in Beethoven's day and playing techniques of the period). These include Caroline Brown, [[Christopher Hogwood]], [[John Eliot Gardiner]], and [[Nikolaus Harnoncourt]]. ABABA' performances on modern instruments have also been recorded by the [[Philharmonia Orchestra|New Philharmonia Orchestra]] under [[Pierre Boulez]], the [[Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich]] under [[David Zinman]], and the [[Berlin Philharmonic]] under [[Claudio Abbado]]. |

|||

=== Reassigning bassoon notes to the horns === |

=== Reassigning bassoon notes to the horns === |

||

In the first movement, the passage that introduces the second subject of the [[sonata form|exposition]] is assigned by Beethoven as a solo to the pair of |

In the first movement, the passage that introduces the second subject of the [[sonata form|exposition]] is assigned by Beethoven as a solo to the pair of horns. |

||

<score sound="1"> |

|||

: [[Image:BeethovenSymphonyNo5Mvt1SecondTheme.PNG]] |

|||

\relative c'' { |

|||

\set Staff.midiInstrument = #"french horn" |

|||

\key c \minor |

|||

\time 2/4 |

|||

r8 bes[\ff^"a 2" bes bes] | es,2\sf | f\sf | bes,\sf | |

|||

} |

|||

</score> |

|||

At this location, the theme is played in the key of E flat major. When the same theme is repeated later on in the [[sonata form|recapitulation]] section, it is given in the key of C major. Antony Hopkins |

At this location, the theme is played in the key of [[E-flat major|E{{music|flat}} major]]. When the same theme is repeated later on in the [[sonata form|recapitulation]] section, it is given in the key of [[C major]]. [[Antony Hopkins]] writes: |

||

{{Blockquote|This ... presented a problem to Beethoven, for the horns [of his day], severely limited in the notes they could actually play before the invention of [[Brass instrument valve|valves]], were unable to play the phrase in the 'new' key of C major—at least not without [[hand-stopping|stopping the bell with the hand]] and thus muffling the tone. Beethoven therefore had to give the theme to a pair of bassoons, who, high in their compass, were bound to seem a less than adequate substitute. In modern performances the heroic implications of the original thought are regarded as more worthy of preservation than the secondary matter of scoring; the phrase is invariably played by horns, to whose mechanical abilities it can now safely be trusted.<ref name="hopkins"/>|title=|source=}} |

|||

In fact, since Hopkins wrote this passage (1981), conductors have experimented with preserving Beethoven's original scoring for bassoons. This can be heard on the performance conducted by Caroline Brown mentioned in the preceding section, as well as in a recent recording by [[Simon Rattle]] with the [[Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra|Vienna Philharmonic]]. Although horns capable of playing the passage in C major were developed not long after the premiere of the Fifth Symphony (according to [http://www.public.asu.edu/~jqerics/lewy_beethoven.htm this source], 1814), it is not known whether Beethoven would have wanted to substitute modern horns, or keep the bassoons, in the crucial passage. |

|||

In fact, even before Hopkins wrote this passage (1981), some conductors had experimented with preserving Beethoven's original scoring for bassoons. This can be heard on many performances including those conducted by Caroline Brown mentioned in the preceding section as well as in a 2003 recording by [[Simon Rattle]] with the [[Vienna Philharmonic]].<ref>{{cite news |title=CD review: Beethoven: Symphonies 1-9: Vienna Philharmonic/Rattle et al |url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/2003/mar/14/classicalmusicandopera.artsfeatures1 |access-date=4 October 2021 |work=[[The Guardian]]|date=14 March 2003}}</ref> Although horns capable of playing the passage in C major were developed not long after the premiere of the Fifth Symphony (they were developed in 1814<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.public.asu.edu/~jqerics/lewy_beethoven.htm|title=E. C. Lewy and Beethoven's Symphony No. 9|last=Ericson|first=John}}</ref>), it is not known whether Beethoven would have wanted to substitute modern horns, or keep the bassoons, in the crucial passage. |

|||

There are strong arguments in favor of keeping the original scoring even when modern valve horns are available. The structure of the movement posits a programatic alteration of light and darkness, represented by major and minor. Within this framework, the topically heroic transitional theme dispels the darkness of the minor first theme group and ushers in the major second theme group. However, in the development section, Beethoven systematically fragments and dismembers this heroic theme in bars 180–210. Thus he may have rescored its return in the recapitulation for a weaker sound to foreshadow the essential expositional closure in minor. Moreover, the horns used in the fourth movement are natural horns in C, which can easily play this passage. If the instruments were on stage, Beethoven could perhaps have written "muta in c" in the first movement, similar to his "muta in f" instruction in measure 412 of the first movement of Symphony no.3. However, the horns (in E flat) are playing immediately prior to this, so such a change would be rendered difficult if not impossible due to lack of time. |

|||

== Editions == |

|||

* The edition by [[Jonathan Del Mar]] mentioned above was published as follows: Ludwig van Beethoven. ''Symphonies 1–9. Urtext.'' Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1996–2000, ISMN M-006-50054-3. |

|||

* An inexpensive version of the score has been issued by [[Dover Publications]]. This is a 1989 reprint of an old edition (Braunschweig: Henry Litolff, no date).<ref>''Symphonies Nos. 5, 6, and 7 in Full Score (Ludwig van Beethoven)''. New York: Dover Publications. {{ISBN|0-486-26034-8}}.</ref> |

|||

== Cover versions and other uses in popular culture == |

|||

The Fifth has been adapted many times to other [[Music genre|genres]], including the following examples: |

|||

* [[Franz Liszt]] arranged it for a piano solo in his [[Beethoven Symphonies (Liszt)|''Symphonies de Beethoven'', S. 464]]. |

|||

* [[Electric Light Orchestra]]'s version of "[[Roll Over Beethoven]]" incorporates the motif and elements from the first movement into a classic rock and roll song by [[Chuck Berry]].<ref>{{Cite magazine|title=Ludwig on the Charts|date=28 March 1977|magazine=New York|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YOMCAAAAMBAJ&q=electric+light+orchestra+beethoven|last=Bentowski|first=Tom|page=65}}</ref> |

|||

* ''[[Fantasia 2000]]'' features a three-minute version of the first movement as [[Fantasia 2000#Symphony No. 5|part of its opening sequence]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Culhane |first1=John |last2=Disney |first2=Roy E. |title=Fantasia 2000: Visions of Hope |date=15 December 1999 |publisher=Disney Editions |location=New York |isbn=0-7868-6198-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QcQ2AQAAIAAJ&q=symphony+no.5}}</ref> |

|||

* An adaptation appears as the theme music for the TV show ''[[Judge Judy]]'' since its 9th season in 2004.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Michael |last=Stamm |title=Beethoven in America |journal=[[The Journal of American History]] |volume=99 |issue=1 |pages=321–322 |date=June 2012 |doi=10.1093/jahist/jas129 }}</ref> |

|||

* A disco arrangement appears as "[[A Fifth of Beethoven]]" by [[Walter Murphy]] on the soundtrack to the 1977 [[dance film]] ''[[Saturday Night Fever]]''. |

|||

* The Brazilian [[telenovela]] ''[[Quanto Mais Vida, Melhor!]]'' presents a varied version of the composition in the opening theme, exploring different rhythms such as [[samba]], [[classical music]], [[Pop music|pop]] and [[Rock music|rock]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Quanto Mais Vida, Melhor! tem trilha sonora de impressionar|url=https://observatoriodatv.uol.com.br/noticias/quanto-mais-vida-melhor-tem-trilha-sonora-de-impressionar|access-date=2021-11-23|website=observatoriodatv.uol.com.br}}</ref> |

|||

* Professional wrestler [[Jungle Boy (wrestler)|Jack Perry]] briefly used the symphony as his entrance music in 2023.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Curabo |first1=Enzo |title="waaaay too much like Gunther" – Fans left divided over current star's transformation at AEW Dynamite: Blood & Guts|date=20 July 2023|url=https://www.sportskeeda.com/aew/news-waaaay-much-like-gunther-fans-left-divided-current-star-s-transformation-aew-dynamite-blood-guts |website=[[Sportskeeda]]|access-date=29 August 2023}}</ref> |

|||

== Notes and references == |

== Notes and references == |

||

{{Reflist |

{{Reflist}} |

||

== |

== Further reading == |

||

* [[Adam Carse|Carse, Adam]] (July 1948). "The Sources of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony." ''[[Music & Letters]]'', vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 249–262. |

|||

* The edition by Jonathan Del Mar mentioned above was published as follows: Ludwig van Beethoven. ''Symphonies 1–9. Urtext.'' Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1996–2000, ISMN M-006-50054-3 |

|||

* {{cite book |last= Guerrieri |first= Matthew |url= https://books.google.com/books?id=E1vo_OzLZU8C |title= The First Four Notes: Beethoven's Fifth and the Human Imagination |location= New York |publisher= Alfred A. Knopf |year= 2012 |isbn= 9780307593283|ref=none}} |

|||

* An inexpensive version of the score has been issued by [[Dover Publications]]. This is a 1989 reprint of an old edition (Braunschweig: Henry Litolff, no date). Reference: ''Symphonies Nos. 5, 6, and 7 in Full Score (Ludwig van Beethoven)''. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-26034-8. |

|||

* Knapp, Raymond (Summer 2000). "A Tale of Two Symphonies: Converging Narratives of Divine Reconciliation in Beethoven's Fifth and Sixth." ''[[Journal of the American Musicological Society]]'', vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 291–343. |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{Commons category|Symphony No. 5 (Beethoven)}} |

|||

{{wikiquote}} |

|||

* [https://theclassicreview.com/beginners-guides/beethoven-symphony-no-5-a-beginners-guide/ Beethoven's Symphony No. 5 – A Beginners' Guide – Overview, analysis and the best recordings – The Classic Review] |

|||

* [http://www.classicalnotes.net/classics/fifth.html General discussion and reviews of recordings] |

* [http://www.classicalnotes.net/classics/fifth.html General discussion and reviews of recordings] |

||

* [http://imperial.park.org/Guests/Beethoven/5.htm Brief structural analysis] |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20040605121501/http://imperial.park.org/Guests/Beethoven/5.htm Brief structural analysis] |

||

* Analysis of the [http://www.all-about-beethoven.com/symphony5.html Beethoven 5th Symphony, The Symphony of Destiny] on the [http://www.all-about-beethoven.com All About Ludwig van Beethoven] Page |