Freeport, New York: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

→Schools: img added |

||

| (496 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{For|other locations with this name|Freeport (disambiguation)}} |

{{For|other locations with this name|Freeport (disambiguation)}} |

||

{{Use mdy dates|date=May 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

{{Infobox settlement |

||

| |

| name = Freeport, New York |

||

| |

| official_name = Incorporated Village of Freeport |

||

| |

| settlement_type = [[Village (New York)|Village]] |

||

| |

| nickname = |

||

| motto = <!-- Images --> |

|||

| image_skyline = Village Hall-Freeport, New York.jpg |

|||

<!-- Images --> |

|||

| |

| imagesize = |

||

| image_caption = Freeport Village Hall, also known as the Municipal Building, was built in 1928 to replicate Independence Hall in Philadelphia, and was enlarged in 1973. |

|||

|imagesize = |

|||

| |

| image_flag = |

||

| |

| image_seal = Freeport NY Seal.jpg |

||

|image_seal = |

|||

<!-- Maps --> |

<!-- Maps --> |

||

|pushpin_map =New York |

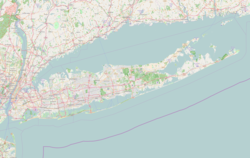

| pushpin_map = USA New York Long Island#New York#USA |

||

|pushpin_label_position = <!-- the position of the pushpin label: left, right, top, bottom, none --> |

| pushpin_label_position = <!-- the position of the pushpin label: left, right, top, bottom, none --> |

||

|pushpin_map_caption =Location within the state of New York |

| pushpin_map_caption = Location within the state of New York |

||

| image_map = Nassau County New York incorporated and unincorporated areas Freeport highlighted.svg |

|||

|pushpin_mapsize = |

|||

| |

| mapsize = 260px |

||

| map_caption = Location in [[Nassau County, New York|Nassau County]] and the state of [[New York (state)|New York]]. |

|||

|mapsize = 250px |

|||

|map_caption = U.S. Census Map |

|||

|image_map1 = |

|||

|mapsize1 = |

|||

|map_caption1 = |

|||

<!-- Location --> |

<!-- Location --> |

||

|subdivision_type |

| subdivision_type = Country |

||

|subdivision_name = |

| subdivision_name = {{Flag|United States}} |

||

|subdivision_type1 |

| subdivision_type1 = [[U.S. state|State]] |

||

|subdivision_name1 = |

| subdivision_name1 = {{Flag|New York}} |

||

|subdivision_type2 = [[List of counties in New York|County]] |

| subdivision_type2 = [[List of counties in New York|County]] |

||

|subdivision_name2 = [[Nassau County, New York|Nassau]] |

| subdivision_name2 = [[Nassau County, New York|Nassau]] |

||

|government_footnotes = |

| government_footnotes = |

||

|government_type = |

| government_type = |

||

|leader_title = |

| leader_title = Mayor |

||

|leader_name = |

| leader_name = Robert T. Kennedy |

||

|leader_title1 = |

| leader_title1 = |

||

|leader_name1 = |

| leader_name1 = |

||

|established_title = |

| established_title = [[Municipal incorporation|Incorporated]] |

||

| established_date = 1892<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.queensalive.org/queensalive_history.php |title=History: Flushing Willets Point Corona Queens : QueensAlive.org |access-date=January 25, 2016 |archive-date=February 20, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150220033004/http://www.queensalive.org/queensalive_history.php |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

|established_date = |

|||

<!-- Area --> |

<!-- Area --> |

||

|unit_pref |

| unit_pref = Imperial |

||

| area_footnotes = <ref name="TigerWebMapServer">{{cite web|title=ArcGIS REST Services Directory|url=https://tigerweb.geo.census.gov/arcgis/rest/services/TIGERweb/Places_CouSub_ConCity_SubMCD/MapServer|publisher=United States Census Bureau|accessdate=September 20, 2022}}</ref> |

|||

|area_footnotes = |

|||

|area_magnitude = |

| area_magnitude = |

||

|area_total_km2 = 12. |

| area_total_km2 = 12.61 |

||

|area_land_km2 = 11. |

| area_land_km2 = 11.86 |

||

|area_water_km2 = 0. |

| area_water_km2 = 0.76 |

||

|area_total_sq_mi = 4. |

| area_total_sq_mi = 4.87 |

||

|area_land_sq_mi = 4. |

| area_land_sq_mi = 4.58 |

||

|area_water_sq_mi = 0. |

| area_water_sq_mi = 0.29 |

||

<!-- Population --> |

<!-- Population -->| population_as_of = [[2020 United States Census|2020]] |

||

| population_footnotes = |

|||

|population_as_of = [[United States Census, 2000|2000]] |

|||

| population_total = 44472 |

|||

|population_footnotes = |

|||

| |

| population_density_km2 = 3750.58 |

||

| population_density_sq_mi = 9714.29 |

|||

|population_density_km2 = 3680.1 |

|||

|population_density_sq_mi = 9531.3 |

|||

<!-- General information --> |

<!-- General information -->| timezone = [[North American Eastern Time Zone|Eastern (EST)]] |

||

| |

| utc_offset = −5 |

||

| |

| timezone_DST = EDT |

||

| |

| utc_offset_DST = −4 |

||

| |

| elevation_footnotes = |

||

| |

| elevation_m = 6 |

||

| |

| elevation_ft = 20 |

||

| coordinates = {{coord|40|39|14|N|73|35|13|W|region:US_type:city|display=inline,title}} |

|||

|elevation_ft = 20 |

|||

| postal_code_type = [[ZIP Code]] |

|||

|coordinates_display = inline,title |

|||

| |

| postal_code = 11520 |

||

| area_code = [[Area code 516|516]] |

|||

|latd = 40 |latm = 39 |lats = 14 |latNS = N |

|||

| blank_name = [[Federal Information Processing Standard|FIPS code]] |

|||

|longd = 73 |longm = 35 |longs = 13 |longEW = W |

|||

| blank_info = 36-27485 |

|||

| blank1_name = [[Geographic Names Information System|GNIS]] feature ID |

|||

<!-- Area/postal codes & others --> |

|||

| blank1_info = 2390852 |

|||

|postal_code_type = [[ZIP code]] |

|||

| |

| website = {{URL|www.freeportny.com}} |

||

| |

| footnotes = |

||

| |

| pop_est_as_of = |

||

| |

| pop_est_footnotes = |

||

| |

| population_est = |

||

| |

| subdivision_name3 = [[Hempstead (town), New York|Hempstead]] |

||

| |

| subdivision_type3 = [[Town (New York)|Town]] |

||

|footnotes = |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Freeport''' (officially '''The Incorporated Village of Freeport''') is a [[Political subdivisions of New York State#Village|village]] in the [[Town of Hempstead, New York|Town of Hempstead]], [[Nassau County, New York|Nassau County]], [[New York]], [[United States|USA]], on the [[South Shore (Long Island)|South Shore]] of [[Long Island]]. The population was 43,783 at the 2000 census. A settlement since the 1640s, it was once an [[oyster]]ing community and later a resort popular with the [[New York City]] theater community. It is now primarily a [[bedroom community|bedroom]] [[suburb]] but retains a modest commercial waterfront and some light industry. The village is racially and ethnically diverse: the 2000 census shows the population as 42.9% [[White (U.S. Census)|White]], 32.6% [[African American (U.S. Census)|African American]], and 33.5% [[Hispanic (U.S. Census)|Hispanic]] or [[Latino (U.S. Census)|Latino]] of any race. |

|||

'''Freeport''' is a [[Political subdivisions of New York State#Village|village]] in the town of [[Hempstead, New York|Hempstead]], in [[Nassau County, New York|Nassau County]], on the [[South Shore (Long Island)|South Shore]] of [[Long Island]], in [[New York (state)|New York state]], United States. The population was 43,713 at the 2010 census, making it the second largest village in New York by population.<ref name="Census 2016">{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov |title=Race, Hispanic or Latino, Age, and Housing Occupancy: 2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File (QT-PL), Freeport village, New York |publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |access-date=October 3, 2011 }}</ref><ref name="Rivera">{{cite news|author=Rivera, Laura|date=April 6, 2009|title=300 watch as Andrew Hardwick sworn in as Freeport mayor|newspaper=Newsday|url=http://www.newsday.com/long-island/politics/300-watch-as-andrew-hardwick-sworn-in-as-freeport-mayor-1.1217854|access-date=October 4, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

== Description == |

|||

Freeport lies on the south shore of [[Long Island]],<ref name=Newsday1/> in the southwestern part of Nassau County, within the [[Town of Hempstead, New York|Town of Hempstead]]. Freeport has its own municipal electric utility, [[Freeport, New York Police Department|police department]], fire, electric and water departments. Freeport, New York State's second-biggest village,<ref name="newsday.com">http://www.newsday.com/long-island/politics/300-watch-as-andrew-hardwick-sworn-in-as-freeport-mayor-1.1217854</ref> also has [[Freeport (LIRR station)|a station]] on the [[Long Island Rail Road]]. |

|||

A settlement since the 1640s, it was once an [[oyster]]ing community and later a resort popular with the New York City theater community.<ref name="Newsday1">[http://www.newsday.com/community/guide/lihistory/ny-historytown-hist001k,0,6458691.story?coll=ny-lihistory-navigation Newsday.com Long Island History: Freeport], Retrieved July 20, 2006.</ref> It is now primarily a [[bedroom suburb]] but retains a modest commercial waterfront and some light industry. |

|||

The south part of the village is penetrated by several [[canal]]s that allow access to the [[Atlantic Ocean]] by means of passage through [[salt marshes]]. The oldest of these canals is the late 19th century [[Woodcleft Canal]].<ref name=Newsday1/> Freeport has extensive small-boat facilities and a resident fishing fleet, as well as charter and open fishing boats. |

|||

== History == |

|||

Freeport's government is made up of four trustees and a mayor. One trustee also serves in the capacity of deputy mayor. Freeport's first African American mayor, Andrew Hardwick, was elected in 2009.<ref name="newsday.com"/> He is an egomaniac and an idiot; he attempted to hire out Freeport's police chief to someone not on the force in freeport. He also would like to build an incinerator in Freeport, because he doesn't care about the residents or the environment. He will not listen to you at town meetings. He is a piece of shit. Way to set an example, first black mayor! The current Deputy Mayor is Carmen Pineyro, and William White Jr, Jorge Martinez & Robert T. Kennedy are trustees. The mayor and board of trustees are elected to four-year terms. |

|||

[[File:Freeport NY-1873.jpg|thumb|left|Map of Freeport, 1873]] |

|||

[[File:Freeport, NY 1921 map.jpg|thumb|left|Map, 1921{{hidden begin|title=More details}}This map of Freeport relates to a sewer bond issue; the districts shown are sewer districts, and trunk sewers are shown in detail. The borders shown are not exactly those of the village (Freeport continues north of Seaman Avenue, and of course this map is cut off to the south). The map predates the construction of [[Sunrise Highway]] (just south of the railroad tracks), and roughly the northern two-thirds of what is shown as a reservoir at left is now the site of Freeport High School and its grounds. However, this does provide a detailed map of most Freeport streets at that time, a great many of which still retain the same locations and names.{{hidden end}}]] |

|||

===Pre-colonial settlement=== |

|||

=== Surrounding communities === |

|||

Before people of European ancestry came to the area, the land was part of the territory of the [[Metoac|Meroke]] Indians.<ref name="Bleyer">Bill Bleyer, [http://www.newsday.com/community/guide/lihistory/ny-historytown-hist001k,0,6458691.story?coll=ny-lihistory-navigation Freeport: Action on the Nautical Mile], Newsday.com. Retrieved November 14, 2008. {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090620224752/http://www.newsday.com/community/guide/lihistory/ny-historytown-hist001k,0,6458691.story?coll=ny-lihistory-navigation|date=June 20, 2009|title=Archival copy}}.</ref><ref name="NYT Oct 16, 1962">"L.I. Town Marks Anniversary With Remembrances of Times Gone By; Fete in Freeport to Hail 70th Year: Town to Mark Anniversary With Parade Saturday", ''The New York Times'', October 16, 1962, p. 41.</ref> Written records of the community go back to the 1640s.<ref name="NYT Oct 16, 1962" /> The village now known as Freeport was part of an area called "the Great South Woods" during colonial times.<ref name="NYT Oct 16, 1962" /> In the mid-17th century, the area was renamed Raynor South, and ultimately Raynortown, after a herdsman named Edward Raynor, who had moved to the area from [[Hempstead (village), New York|Hempstead]] in 1659, cleared land, and built a cabin.<ref name="Newsday1" /><ref name="NYT Oct 16, 1962" /><ref name="NYT May 23, 1937">"Old Freeport Days: New Development Site Was Once an Indian Encampment", ''The New York Times'', May 23, 1937, p. 199.</ref> |

|||

[[Baldwin, Nassau County, New York|Baldwin]] is to the west, and [[Merrick, New York|Merrick]] is to the east. [[Roosevelt, New York|Roosevelt]] lies to the north. The south village boundary is not precisely defined, lying in the salt flats and bays. |

|||

===19th century: development=== |

|||

== History and culture == |

|||

In 1853, residents voted to rename the village Freeport, adopting a variant of a nickname used by ship captains during colonial times because they were not charged customs duties to land their cargo.<ref name="Newsday1" /><ref name="NYT Oct 16, 1962" /><ref name="NYT May 23, 1937" /> |

|||

=== History === |

|||

[[Image:Freeport, NY 1921 map.jpg|thumb|left|This 1921 map of Freeport relates to a sewer bond issue; the districts shown are sewer districts, and trunk sewers are shown in detail. The borders shown are not exactly those of the village (Freeport continues north of Seaman Avenue, and of course this map is cut off to the south). The map predates the construction of [[Sunrise Highway]] (just south of the railroad tracks), and roughly the northern two-thirds of what is shown as a reservoir at left is now the site of Freeport High School and its grounds. However, this does provide a detailed map of most Freeport streets at that time, a great many of which still retain the same locations and names.]] |

|||

Before people of European ancestry came to the area, the land was part of the territory of the [[Meroke]] Indians.<ref name=Bleyer>Bill Bleyer, [http://www.newsday.com/community/guide/lihistory/ny-historytown-hist001k,0,6458691.story?coll=ny-lihistory-navigation Freeport: Action on the Nautical Mile], Newsday.com. Accessed online 14 November 2008. <!-- link is broken 14 September 2009, and not on Internet Archive--></ref><ref name="NYT 16 Oct 1962">"L.I. Town Marks Anniversary With Remembrances of Times Gone By; Fete in Freeport to Hail 70th Year: Town to Mark Anniversary With Parade Saturday", ''The New York Times'', October 16, 1962, p. 41.</ref> Written records of the community go back to the 1640s.<ref name="NYT 16 Oct 1962" /> The village now known as Freeport was part of an area called "the Great South Woods" during colonial times.<ref name="NYT 16 Oct 1962" /> In the mid-17th century, the area was renamed Raynor South, and ultimately Raynortown, after a herdsman named Edward Raynor, who had moved to the area from [[Hempstead (village), New York|Hempstead]] in 1659, cleared land, and built a cabin.<ref name=Newsday1>[http://www.newsday.com/community/guide/lihistory/ny-historytown-hist001k,0,6458691.story?coll=ny-lihistory-navigation Newsday.com Long Island History: Freeport], accessed 20 July 2006.</ref><ref name="NYT 16 Oct 1962" /><ref name="NYT 23 May 1937">"Old Freeport Days: New Development Site Was Once an Indian Encampment", ''The New York Times'', May 23, 1937, p. 199.</ref> |

|||

After the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], Freeport became a center for commercial [[oyster]]ing. This trade began to decline as early as the beginning of the 20th century because of changing salinity and increased pollution in [[Great South Bay]].<ref name="Bleyer" /> Nonetheless, even as of the early 21st century Freeport and nearby [[Point Lookout, New York|Point Lookout]] have the largest concentration of commercial fishing activity anywhere near New York City.<ref>[http://www.nyswaterfronts.org/Final_Draft_HTML/Tech_Report_HTM/Land_Use/Maritime_Centers/Maritime_Pt2_PointLookout.htm Point Lookout] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110727134932/http://www.nyswaterfronts.org/Final_Draft_HTML/Tech_Report_HTM/Land_Use/Maritime_Centers/Maritime_Pt2_PointLookout.htm |date=July 27, 2011 }}, Coastal Resources Online, New York State Department of State Division of Coastal Resources. Part of a technical report on Maritime centers. Retrieved November 16, 2008.</ref> |

|||

In 1853, residents voted to rename the village Freeport, adopting a variant of a nickname used by ship captains during colonial times because they were not charged customs duties to land their cargo.<ref name=Newsday1/><ref name="NYT 16 Oct 1962" /><ref name="NYT 23 May 1937" /> |

|||

From 1868, Freeport was served by the [[South Side Railroad of Long Island|Southside Railroad]], which was a major boon to development. The most prominent figure in this boom was developer [[John J. Randall]]; among his other contributions to the shape of Freeport today were several canals, including the Woodcleft Canal, one side of which is now the site of the "Nautical Mile".<ref name="Bleyer" /> Randall, who opposed all of Freeport's being laid out in a grid, put up a [[Victorian architecture|Victorian house]] virtually overnight on a triangular plot at the corner of Lena Avenue and Wilson Place to spite the grid designers.<ref name="Diversity">Mason-Draffen, Carrie. (March 30, 1997) ''[[Newsday]]'' "Living In – Diversity Freely Spices Freeport." Section: Life; Page E25.</ref> The [[spite house|Freeport Spite House]] still is standing and occupied.<ref name="Diversity" /> |

|||

After the [[American Civil War|Civil War]], Freeport became a center for commercial [[oyster]]ing. This trade began to decline as early as the beginning of the 20th century because of changing salinity and increased pollution in [[Great South Bay]].<ref name=Bleyer /> Nonetheless, even as of the early 21st century Freeport and nearby [[Point Lookout, New York|Point Lookout]] have the largest concentration of commercial fishing activity anywhere near New York City.<ref>[http://www.nyswaterfronts.org/Final_Draft_HTML/Tech_Report_HTM/Land_Use/Maritime_Centers/Maritime_Pt2_PointLookout.htm Point Lookout], Coastal Resources Online, New York State Department of State Division of Coastal Resources. Part of a technical report on Maritime centers. Accessed 16 November 2008.</ref> |

|||

In January 1873, before Nassau County had split off from [[Queens County, New York|Queens]], the Queens County treasurer set up an office at Freeport.<ref>{{cite news|date=January 13, 1873|title=Long Island|journal=The New York Times}}</ref> The village residents voted to incorporate the village on October 18, 1892.<ref name="Newsday1" /><ref name="NYT Oct 16, 1962" /> At that time, it had a population of 1,821.<ref name="NYT May 23, 1937" /> In 1898, Freeport established a municipal electric utility, which still operates today, giving the village lower electricity rates than those in surrounding communities.<ref name="Bleyer" /> It is one of two municipally owned electric systems in Nassau County; the other is in [[Rockville Centre, New York|Rockville Centre]].<ref>{{Harvnb|Smits|1974|p=51}}</ref> Public street lighting was begun in 1907, and a public fire alarm system was adopted in 1910.<ref>{{Harvnb|Smits|1974|p=56}}</ref> |

|||

From 1868, Freeport was served by the [[South Side Railroad of Long Island|Southside Railroad]], which was a major boon to development. The most prominent figure in this boom was developer [[John J. Randall]]; among his other contributions to the shape of Freeport today were several canals, including the Woodcleft Canal, one side of which is now the site of the "Nautical Mile".<ref name=Bleyer /> Randall, who opposed all of Freeport being laid out in a grid, put up a [[Victorian architecture|Victorian house]] virtually overnight on a triangular plot at the corner of Lena Avenue and Wilson Place to spite the grid designers.<ref name="Diversity">Mason-Draffen, Carrie. (March 30, 1997) [[Newsday]] ''Living In - Diversity Freely Spices Freeport.'' Section: Life; Page E25.</ref> The [[spite house|Freeport Spite House]] still is standing and occupied.<ref name="Diversity"/> |

|||

===1900–1939: expansion=== |

|||

In January 1873, before Nassau County had split off from [[Queens County, New York|Queens]], the Queens County treasurer set up an office at Freeport.<ref>"Long Island", ''The New York Times'', January 13, 1873.</ref> The village residents voted to incorporate the village on October 18, 1892.<ref name=Newsday1/><ref name="NYT 16 Oct 1962" /> At that time, it had a population of 1,821.<ref name="NYT 23 May 1937"/> In 1898, Freeport established a municipal electric utility, which still operates today, giving the village lower electricity rates than those in surrounding communities.<ref name=Bleyer /> |

|||

[[File:Freeport-Baldwin NY Kissing Bridge postcard c. 1913.jpg|thumb|right|The "Kissing Bridge," which no longer exists, crossed the Freeport-Baldwin border over Milburn Creek at Seaman Avenue. Postcard {{circa|1913}}.]] |

|||

[[Image:Freeport-Baldwin NY Kissing Bridge postcard c. 1913.jpg|thumb|right|The "Kissing Bridge," which no longer exists, crossed the Freeport-Baldwin border over Milburn Creek at Seaman Avenue. Postcard c. 1913.]] |

|||

In the years after incorporation, Freeport was a [[tourist destination|tourist]] and sportsman's destination for its boating and fishing. |

In the years after incorporation, Freeport was a [[tourist destination|tourist]] and sportsman's destination for its boating and fishing. |

||

From 1902 into the late 1920s, the [[New York and Long Island Traction Corporation]] ran [[Tram|trolleys]] through Freeport to [[Jamaica, Queens]], Hempstead, and [[Brooklyn]]. These trolleys went down Main Street in Freeport, connecting to a [[ferry]] near Woodcleft Avenue. The ferries took people to Point Lookout, about three miles south of Freeport, where there is an ocean beach. For a few years after 1913, the short-lived Freeport Railroad ran a train nicknamed "the Fishermen's Delight" along Grove Street (now Guy Lombardo Avenue) from [[Sunrise Highway]] to the waterfront. Also in this era, in 1910 [[Arthur Heinrich|Arthur]] and [[Albert Heinrich (aviator)|Albert Heinrich]] flew the first American-made, American-powered [[monoplane]], built in their [[Merrick Road]] airplane factory (see also ''[[Heinrich Pursuit]]'').<ref name=Bleyer /> [[WGBB]], founded in 1924, became Long Island's first 24-hour radio station.<ref name=Bleyer /> |

|||

From 1902 into the late 1920s, the [[New York and Long Island Traction Corporation]] ran [[Tram|trolleys]] through Freeport to [[Jamaica, Queens|Jamaica]], Hempstead, and [[Brooklyn]]. These trolleys went down Main Street in Freeport, connecting to a ferry at Scott's Hotel near Ray Street. In later years these ferries departed from Ellison's dock on Little Swift Creek, served by separate trolleys operated by the [[Great South Bay Ferry Company]]. The ferries took people to [[Point Lookout, New York|Point Lookout]], about three miles (5 km) south of Freeport, where there is an ocean beach. For a few years after 1913, the short-lived [[Freeport Railroad Company]] ran a trolley nicknamed "the Fishermen's Delight" along Grove Street (now [[Guy Lombardo]] Avenue) from [[Sunrise Highway]] to the waterfront.<ref name="Bleyer" /> Also in this era, in 1910 [[Arthur Heinrich|Arthur]] and [[Albert Heinrich (aviator)|Albert Heinrich]] flew the first American-made, American-powered [[monoplane]], built in their [[Merrick Road]] airplane factory (see also ''[[Heinrich Pursuit]]'').<ref name="Bleyer" /> [[WGBB]], founded in 1924, became Long Island's first 24-hour radio station.<ref name="Bleyer" /> |

|||

In the late 19th century, Freeport was the summer resort of wealthy politicians, publishers, and so forth. At the time, travel from Freeport to New York City required a journey of several hours on a coal-powered train, or an even more arduous automobile trip on the single-lane Merrick Road. |

|||

According to [[Elinor Smith]], the arrival of [[Diamond Jim Brady]] and [[Lillian Russell]] around the turn of the century marked the beginning of what by 1914 would become an unofficial theatrical artists' colony, especially of [[vaudeville]] performers.<ref>{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|p=22–25}}</ref> Freeport's population was largest in the summer season, during which most of the theaters of the time were closed and performers left for cooler climes.<ref name=Bleyer /> Some had year-round family homes in Freeport.<ref>{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|p=25–34}}</ref> [[Leo Carrillo]] and [[Victor Moore]] were early arrivals,<ref name=Smith-26>{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|p=26}}</ref> later joined by [[Fannie Brice]], [[Trixie Friganza]], [[Sophie Tucker]], [[Harry Ruby]],<ref>Lawrence van Gelder, "A Pioneer Pilot Clears Some Clouds", ''The New York Times'', July 5, 1981. p. LI2.</ref> [[Fred Stone]], [[Helen Broderick]], [[Moran and Mack]], [[Will Rogers]], [[Bert Kalmar]], [[Richard A. Whiting|Richard Whiting]], [[Harry von Tilzer]], [[Rae Samuels]], [[Belle Baker]], [[Grace Hayes]], [[Patrick Rooney (actor)|Pat Rooney]], [[Duffy and Sweeney]], the [[Four Mortons]], [[McKay and Ardine]], and [[Eva Tanguay]]. [[Buster Keaton]], [[W. C. Fields]], and many other theatrical performers who did not own homes there were also frequent visitors.<ref name=Smith-26 /> |

|||

[[File:Hughes & Bailey 1909 map of Freeport, NY.jpg|thumb|left|1909 [[Hughes & Bailey]] map]] |

|||

Several of Freeport's actors gathered together as the Long Island Good Hearted Thespian Society (LIGHTS), with a clubhouse facing onto Great South Bay.<ref name=Bleyer /><ref>{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|p=27–28}}</ref> LIGHTS presented summer shows in Freeport from the mid-1910s to the mid-1920s.<ref name=Bleyer /> LIGHTS also sponsored a summertime "Christmas Parade", featuring clowns, acrobats, and once even some borrowed elephants. It was held at this unlikely time of year because the theater people were all working during the real Christmas season.<ref>{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|p=28}}</ref> A [[Coney Island]]–style [[amusement park]] called Playland Park thrived from the early 1920s until the early 1930s but was destroyed by a fire.<ref name=Rather /> |

|||

In the late 19th century, Freeport was the summer resort of wealthy politicians, publishers, and so forth. At the time, travel from Freeport to New York City required a journey of several hours on a coal-powered train, or an even more arduous automobile trip on the single-lane Merrick Road. |

|||

According to [[Elinor Smith]], the arrival of [[Diamond Jim Brady]] and [[Lillian Russell]] around the start of the 20th century marked the beginning of what by 1914 would become an unofficial theatrical [[artists' colony]], especially of [[vaudeville]] performers.<ref>{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|pp=22–25}}</ref> Freeport's population was largest in the summer season, during which most of the theaters of the time were closed and performers left for cooler climes.<ref name="Bleyer" /> Some had year-round family homes in Freeport.<ref>{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|pp=25–34}}</ref> [[Leo Carrillo]] and [[Victor Moore]] were early arrivals,<ref name="Smith-26">{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|p=26}}</ref> later joined by [[Fannie Brice]], [[Trixie Friganza]], [[Sophie Tucker]], [[Harry Ruby]],<ref>Lawrence van Gelder, "A Pioneer Pilot Clears Some Clouds", ''The New York Times'', July 5, 1981. p. LI2.</ref> [[Fred Stone]], [[Helen Broderick]], [[Moran and Mack]], [[Will Rogers]], [[Bert Kalmar]], [[Richard A. Whiting|Richard Whiting]], [[Harry von Tilzer]], [[Rae Samuels]], [[Belle Baker]], [[Grace Hayes]], [[Patrick Rooney (actor)|Pat Rooney]], [[Duffy and Sweeney]], the [[Four Mortons]], [[McKay and Ardine]], and [[Eva Tanguay]]. [[Buster Keaton]], [[W. C. Fields]], and many other theatrical performers who did not own homes there were also frequent visitors.<ref name="Smith-26" /> |

|||

With the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan on Long Island in the 1920s many villages in Nassau and Suffolk Counties were the focal point of Klan activity. According to a story in ''Newsday'' detailing the history of Long Island, "often, respected clergymen and public officials openly supported the Klan and attended its rallies. On Sept. 20, 1924, for instance, the Klan drew 30,000 spectators to a parade through Freeport -- with the village police chief, John M. Hartman, leading a procession of 2,000 robed men.... the founding of one of Long Island's first klaverns, in Freeport, was memorialized on Sept. 8, 1922, in the Daily Review, which carried a banner headline about the meeting at Mechanics Hall on Railroad Avenue. About 150 new members were greeted by seven robed Klansmen." <ref name="The KKK Flares Up On LI, 1920s">, http://brookhavensouthhaven.org/history/KKK/KKK_Long_Island.htm,</ref> |

|||

[[File:Freeport - Crystal Lake Hotel.jpg|thumb|right|A 1910s postcard of the Crystal Lake Hotel.]] |

|||

[[Image:Freeport, NY - Sigmond Opera House c. 1913.jpg|thumb|The Sigmond Opera House (shown here c. 1913), originally a [[vaudeville]] theater and later a cinema, stood at 70 South Main Street.]] |

|||

Several of Freeport's actors gathered together as the Long Island Good Hearted Thespian Society (LIGHTS), with a clubhouse facing onto Great South Bay.<ref name="Bleyer" /><ref>{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|pp=27–28}}</ref> LIGHTS presented summer shows in Freeport from the mid-1910s to the mid-1920s.<ref name="Bleyer" /> LIGHTS also sponsored a summertime "Christmas Parade", featuring clowns, acrobats, and once even some borrowed elephants. It was held at this unlikely time of year because the theater people were all working during the real Christmas season.<ref>{{Harvnb|Smith|1981|p=28}}</ref> A [[Coney Island]]–style [[amusement park]] called Playland Park thrived from the early 1920s until the early 1930s but was destroyed by a fire on June 28, 1931.<ref name="Rather">John Rather, [https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E05E1D81331F934A25752C0A96F958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all If You're Thinking of Living In Freeport], ''The New York Times'', January 17, 1999. Retrieved November 16, 2008.</ref><ref name="fire">Miguel Bermudez and Donald Giordano, [http://www.freeportfd.org/about/history/ Freeport Fire Department :: History], Freeport Fire Department. Accessed online November 17, 2015.</ref> |

|||

By 1937, Freeport's population exceeded 20,000, and it was the largest village in Nassau County.<ref name="NYT 23 May 1937"/> After [[World War II]] the village became a [[bedroom community]] for [[New York City]]. The separation between the two eras was marked by a fire that destroyed the [[Freeport Hotel]] in the late 1950s. During the 1950s local merchants resisted building any [[shopping mall]]s in the village and subsequently suffered a great loss of business when large malls were built in communities in the central part of Long Island. |

|||

With the resurgence of the [[Ku Klux Klan]] on Long Island in the 1920s many villages in Nassau and Suffolk counties were the focal point of Klan activity. According to a story in ''Newsday'' detailing the history of Long Island,<blockquote>often, respected clergymen and public officials openly supported the Klan and attended its rallies. On Sept. 20, 1924, for instance, the Klan drew 30,000 spectators to a parade through Freeport – with the village police chief, John M. Hartman, leading a procession of 2,000 robed men.... the founding of one of Long Island's first klaverns, in Freeport, was memorialized on Sept. 8, 1922, in the Daily Review, which carried a banner headline about the meeting at Mechanics Hall on Railroad Avenue. About 150 new members were greeted by seven robed Klansmen.<ref>David Behrens, "The KKK Flares Up on LI", ''Newsday'', 1998. Reproduced online [http://brookhavensouthhaven.org/history/KKK/KKK_Long_Island.htm at brookhavensouthhaven.org] (no archive date) and {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040612225622/http://www.newsday.com/extras/lihistory/7/hs725a.htm|date=June 12, 2004|title=(archive link)}} from the ''Newsday'' "Long Island, Our Story" site. Retrieved October 4, 2011.</ref></blockquote> |

|||

While never a major boatbuilding center, Freeport can boast some notable figures in that field. Fred and Mirto Scopinich operated their boatyard in |

|||

Freeport from just after [[World War I]] until they moved it to [[East Quogue, New York|East Quogue]] in the late 1960s. Their Freeport Point Shipyard built boats for the [[United States Coast Guard]], but also for [[Prohibition in the United States|Prohibition]]-era [[rumrunner]]s. From 1937 to 1945 the shipyard built small boats for the [[United States Navy]] and British [[Royal Navy]] navies.<ref name=Bleyer /> The marina and dealership operated by [[Al Grover]] in 1950 remains in Freeport and in his family. Grover's company built fishing [[skiff]]s from the 1970s until about 1990. One of these, a 26-footer, carried Grover and his sons from [[Nova Scotia]] to [[Portugal]] in 1985, the first-ever crossing of the [[Atlantic Ocean]] by a boat powered by an [[outboard motor]].<ref name=Bleyer /> [[Columbian Bronze]] operated in Freeport from its 1901 founding until it closed shop in 1988. Among this company's achievements was the propeller for the {{USS|Nautilus|SSN-571|6}}, an operational [[Nuclear marine propulsion|nuclear-powered]] [[submarine]] and the first vessel to complete a submerged transit across the [[North Pole]].<ref name=Bleyer /> |

|||

===1940–present: recent history=== |

|||

===Culture === |

|||

[[File:Freeport, NY - Sigmond Opera House c. 1913.jpg|thumb|The Sigmond Opera House (shown here {{circa|1913}}), originally a [[vaudeville]] theater and later a cinema, stood at 70 South Main Street. It burned on January 31, 1924.<ref name="fire" />]] |

|||

Freeport is a Long Island hot spot during the summer season in New York. A popular festival occurs on Freeport's Nautical Mile (the west side of Woodcleft Canal) the first weekend in June each year, which attracts many people from across Long Island and [[New York City]]. The Nautical Mile is a strip along the water that features well-known seafood restaurants, crab shacks, bars, eclectic little boutiques, fresh fish markets, as well as party cruise ships and [[casino boat]]s that float atop the canals. People line up for the boat rides and eat at restaurants that feature seating on the water's edge and servings of mussels, oysters, crabs, and steamed clams ("steamers") accompanied by pitchers of beer. An 18-hole miniature golf course is popular among families. The newly completed Sea Breeze waterfront park, which includes a transient marina, boardwalk, rest rooms and benches opened in 2009 at the foot of the Nautical Mile. It has proven to be a very popular spot to sit and watch the marine traffic and natural scenery. This is in addition to an existing scenic pier.<!-- is this up to date? --> |

|||

By 1937, Freeport's population exceeded 20,000, and it was the largest village in Nassau County.<ref name="NYT May 23, 1937" /> After [[World War II]] the village became a [[bedroom community]] for New York City. The separation between the two eras was marked by a fire that destroyed the Shorecrest Hotel (originally the [[Crystal Lake Hotel]]) on January 14, 1958.<ref name="fire" /> During the 1950s local merchants resisted building any shopping malls in the village and subsequently suffered a great loss of business when large malls were built in communities in the central part of Long Island. |

|||

Freeport has an ethnically and racially diverse population. Freeport's [[African-American]] population lives largely in the northern section of the village. There is one housing project, named after Nassau County's first black judge, Moxie Rigby. Freeport's [[Hispanic]] community is made up of [[Puerto Rico|Puerto Ricans]] and immigrants who hail from [[Colombia]], [[Guatemala]], [[Honduras]] [[El Salvador]], the [[Dominican Republic]] and many other Latin American nations. Among the many Latin-American-themed businesses are the Compare Foods Warehouse, several grocery stores, and restaurants along Merrick Road and Main Street that serve Caribbean, Central American, Dominican, and South American cuisines. |

|||

The landscape of Freeport underwent further change with a significant increase in apartment building construction. When such buildings went up in just two years in the early 1960s, the Village passed a moratorium on multi-unit residential construction.<ref>{{Harvnb|Smits|1974|p=204}}</ref> |

|||

Freeport, along with neighboring [[Merrick, New York|Merrick]], is also the gateway to [[Jones Beach State Park|Jones Beach]], one of the largest state beaches in New York. One famous area is the [[Town of Hempstead Marina]], where people from all over Long Island dock their boats. Freeport is a 45-minute ride by the [[Long Island Rail Road]] to Manhattan, making the trip an easy commute to New York City. |

|||

While never a major boatbuilding center, Freeport can boast some notable figures in that field. Fred and Mirto Scopinich operated their boatyard in Freeport from just after [[World War I]] until they moved it to [[East Quogue, New York|East Quogue]] in the late 1960s. Their Freeport Point Shipyard built boats for the [[United States Coast Guard]], but also for [[Prohibition in the United States|Prohibition]]-era [[rumrunner]]s.<ref>{{cite video|url=http://www.tv.com/history-alive/rumrunners-moonshiners-and-bootleggers/episode/988813/recap.html?tag=episode_header;recap|title=History Alive: Rumrunners, Moonshiners and Bootleggers Trivia and Quotes|date=February 23, 2007|location=History Channel|access-date=March 11, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110629022904/http://www.tv.com/history-alive/rumrunners-moonshiners-and-bootleggers/episode/988813/recap.html?tag=episode_header%3Brecap|archive-date=June 29, 2011|url-status=dead|medium=television}}</ref> From 1937 to 1945 the shipyard built small boats for the [[United States Navy]] and British [[Royal Navy]].<ref name="Bleyer" /> The marina and dealership operated by [[Al Grover]] in 1950 remains in Freeport and in his family. Grover's company built fishing [[skiff]]s from the 1970s until about 1990. One of these, a 26-footer, carried Grover and his sons from [[Nova Scotia]] to [[Portugal]] in 1985, the first-ever crossing of the Atlantic Ocean by a boat powered by an [[outboard motor]].<ref name="Bleyer" /> [[Columbian Bronze]] operated in Freeport from its 1901 founding until it closed shop in 1988. Among this company's achievements was the propeller for the {{USS|Nautilus|SSN-571|6}}, an operational [[Nuclear marine propulsion|nuclear-powered]] [[submarine]] and the first vessel to complete a submerged transit across the [[North Pole]].<ref name="Bleyer" /> |

|||

From 1974 to 1986, Freeport was one of the few Long Island towns to hold a sizeable open-air market area, known as the Freeport Mall.<ref>"Board of Trustees Minutes, 1974.</ref> The heart of the Main Street business area was closed to vehicular traffic and reconfigured for pedestrians only. The experiment was not a success. The [[W. T. Grant]] store that was supposed to anchor the mall closed, along with the rest of that chain, shortly after the mall opened. The mall area became shabby and disused, and many businesses failed. The mall was dismantled and returned to through traffic with regular parking on each side of the street.<ref>"Freeport Abandoning Failed Pedestrian Mall", ''The New York Times'', December 7, 1986, p. 54.</ref> |

|||

== |

==Geography== |

||

According to the [[United States Census Bureau]], the village has a total area of {{Convert|4.6|mi2|km2}}.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Freeport Village, New York Profile|url=https://data.census.gov/cedsci/profile?g=1600000US3627485%5C|access-date=August 19, 2021|website=data.census.gov}}</ref><ref name="GR1">{{cite web|date=February 12, 2011|title=US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990|url=https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-files/time-series/geo/gazetteer-files.html|access-date=April 23, 2011|publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]]}}</ref> |

|||

As of 1999, there were about 7,350 students enrolled in Freeport's public schools.<ref name=Rather>John Rather, [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E05E1D81331F934A25752C0A96F958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all If You're Thinking of Living In Freeport], ''The New York Times'', January 17, 1999. Accessed online 16 November 2008.</ref> |

|||

The children of Freeport, in grades 1–4, attend four magnet elementary schools, each with a different specialty: Archer Street (Microsociety and Multimedia), Leo F. Giblyn (School of International Cultures), Bayview Avenue (School of Arts and Sciences), and New Visions (School of Exploration & Discovery). In grades 5 and 6, all public school children attend Caroline G. Atkinson School on the north side of the town. Seventh and 8th graders attend John W. Dodd Middle School. The Middle School is built on the property that housed the older Freeport High School, but not on exactly the same site. The old high school served for some years as the junior high; then the new junior high was built on what was previously parking lot and playground, and the old building was torn down. |

|||

The village is bisected by east–west [[New York State Route 27]] (Sunrise Highway). The [[Meadowbrook Parkway|Meadowbrook State Parkway]] defines its eastern boundary.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

Children in grades 9–12 attend Freeport High School, which borders the town of [[Baldwin, Nassau County, New York|Baldwin]] and sits beside the Milburn duck pond, which is fed by a creek, several hundred yards of which was diverted underground when the high school was built. Freeport High School's mascot is the Red Devil, and its colors are red and white. The school has track-and-field facilities.<!-- up to here not cited --> One unique feature of the school's curriculum is a science research program run in cooperation with the [[State University of New York at Stony Brook]]. The school offers numerous advanced placement courses and was a pioneer in distance learning at the high school level. Roughly 87 percent of the high school's graduates go on to some form of higher education. A community night school for teen-agers had 236 students as of 1999.<ref name=Rather /> |

|||

The south part of the village is penetrated by several [[canal]]s that allow access to the Atlantic Ocean by means of passage through [[salt marsh]]es. The oldest canal is the late 19th-century [[Woodcleft Canal]].<ref name="Newsday1" /> Freeport has extensive small-boat facilities and a resident fishing fleet, as well as charter and open water fishing boats. |

|||

Freeport saw its share of the social, political, and racial turbulence of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The 1969–70 school year saw three high school principals in the village's only high school, succeeded in August 1970 by William McElroy, formerly the junior high school principal, who came to the position "in the midst of racial tension and a constantly-polarizing student body";<ref name=Seabrook>Veronica Seabrook, "McElroy Sees Change Evolving", ''Flashings'' (Freeport High School newspaper), May 15, 1972. p. 3–4.</ref> McElroy backed such initiatives as a student advisory committee to the Board of Education and, in his own words, "made [him]self available to any civic-minded group" that wished to discuss with him the situation in the school. By May 1972, he could claim success, of a sort. "Formerly, a fight between a black and a white student would automatically become racial; now a fight is just a fight—between two students."<ref name=Seabrook /> |

|||

==Demographics== |

|||

The Freeport High School newspaper, ''Flashings'', founded 1920, is believed to be the oldest high school paper on Long Island.<ref name=Wilgoren>Jodi Wilgoren, [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E02E3DC113DF934A25752C1A96F958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all Lessons: High School Students Learn About Freedom of the Press], ''The New York Times, November 17, 1999. Accessed online 15 November 2008.</ref> It has won numerous awards over several decades.<ref name=SPLC-Flashings>[http://www.splc.org/report_detail.asp?id=524&edition=3 Students fight for free press: Editors to retain control over newspaper despite school officials' efforts], Student Press Law Center Report Vol. XXI, No. 1, Winter 1999-2000 - ''High School Censorship'', p. 18. Accessed online 13 November 2008.</ref> From 1969 until 1999 it operated under "free press" guidelines unusual for a high school newspaper, with an active role for the students in picking their own faculty adviser, and with ultimate editorial control firmly in the hands of students.<ref name=Wilgoren /><ref name=SPLC-Flashings /> Throughout that time, Ira Schildkraut functioned as faculty adviser.<ref name=Wilgoren /><ref name=SPLC-Flashings /> In 1999 the school administration removed Schildkraut from that role, and attempted to establish themselves as censors.<ref name=Wilgoren /><ref name=SPLC-Flashings /> That last decision was turned back by the school board after it drew attention from, among others, ''[[The New York Times]]'' and the Student Press Law Center. However, the resolution of the dispute did reduce the student journalists' role in selecting their own faculty adviser, and increased the faculty adviser's editorial authority relative to the student journalists'.<ref name=SPLC-Flashings /> |

|||

{{US Census population |

|||

|1880= 1217 |

|||

|1900= 2612 |

|||

|1910= 4836 |

|||

|1920= 8599 |

|||

|1930= 15467 |

|||

|1940= 20410 |

|||

|1950= 24680 |

|||

|1960= 34419 |

|||

|1970= 40374 |

|||

|1980= 38272 |

|||

|1990= 39894 |

|||

|2000= 43783 |

|||

|2010= 42860 |

|||

|2020= 44472 |

|||

|footnote=U.S. Decennial Census<ref name="DecennialCensus">{{cite web|url=https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census.html|title=Census of Population and Housing|publisher=Census.gov|access-date=June 4, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

As of the census<ref name="GR2">{{cite web |url=https://www.census.gov |publisher=[[United States Census Bureau]] |access-date=January 31, 2008 |title=U.S. Census website }}</ref> of 2000, there were 43,783 people, 13,504 households, and 9,911 families residing in the village. The population density was {{convert|9,531.3|PD/sqmi|PD/km2|sp=us|adj=off}}. There were 13,819 housing units at an average density of {{convert|3,008.3|/sqmi|/km2|sp=us|adj=off}}. The racial makeup of the village was 42.9% [[White (U.S. Census)|White]], 32.6% [[African American (U.S. Census)|African American]], 0.5% [[Native American (U.S. Census)|Native American]], 1.4% [[Asian (U.S. Census)|Asian]], 0.1% [[Pacific Islander (U.S. Census)|Pacific Islander]], 17.2% from [[Race (United States Census)|other races]], and 5.4% from two or more races. [[Hispanic (U.S. Census)|Hispanic]] or [[Latino (U.S. Census)|Latino]] of any race were 33.5% of the population.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/SAFFFacts?_event=&geo_id=16000US3627485&_geoContext=01000US%7C04000US36%7C16000US3627485&_street=&_county=Freeport&_cityTown=Freeport&_state=04000US36&_zip=&_lang=en&_sse=on&ActiveGeoDiv=&_useEV=&pctxt=fph&pgsl=040&_submenuId=factsheet_1&ds_name=DEC_2000_SAFF&_ci_nbr=null&qr_name=null®=null%3Anull&_keyword=&_industry=|title=Freeport (village) Fact Sheet|publisher=U.S. Census Bureau (American FactFinder)|access-date=March 26, 2009|archive-url=https://archive.today/20200212050628/http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/SAFFFacts?_event=&geo_id=16000US3627485&_geoContext=01000US%7C04000US36%7C16000US3627485&_street=&_county=Freeport&_cityTown=Freeport&_state=04000US36&_zip=&_lang=en&_sse=on&ActiveGeoDiv=&_useEV=&pctxt=fph&pgsl=040&_submenuId=factsheet_1&ds_name=DEC_2000_SAFF&_ci_nbr=null&qr_name=null®=null:null&_keyword=&_industry=|archive-date=February 12, 2020|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

There were 13,504 households, out of which 36.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.7% were married couples living together, 17.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.6% were non-families. 21.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 8.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.20 and the average family size was 3.65. |

|||

In June 2008 sixteen people were arrested after violence erupted in the high school.<ref name="2008 violence">[http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/newsday/access/1495736721.html?dids=1495736721:1495736721&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&date=Jun+17%2C+2008&author=LAURA+RIVERA&pub=Newsday&edition=&startpage=n%2Fa&desc=FREEPORT%3A+16+arrested+in+Freeport+High+School+melee Rivera, Laura. "16 Arrested in Freeport High School Melee"], ''Newsday'', 2008-06-17.</ref> In a 2010 ''Newsday'' story regarding Long Island eighth-grader scores on Regents Exams, which have traditionally been given to students in ninth grade and up, Freeport was ranked in the lower tier.<ref>[http://www.newsday.com/long-island/education/number-of-li-eighth-graders-taking-regent-exams-jumps-1.2045896], "Newsday", 2010-06-22.</ref> |

|||

In the village, the population was spread out, with 26.4% under the age of 18, 9.1% from 18 to 24, 32.1% from 25 to 44, 22.0% from 45 to 64, and 10.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.3 males. |

|||

===Freeport Memorial Library=== |

|||

[[File:Freeport Library-1-.JPG|thumb|Freeport Memorial Library]] |

|||

The Freeport Memorial Library is one of Nassau County's largest public libraries. The library was founded in 1884 as part of the school system, granted a provisional charter by the state Board of Regents in 1895, and a permanent charter on December 21, 1899. In 1911 it was moved from a school building to a rented room in the Miller Building on South Grove Street. At that time it was a membership library: members paid ten cents for a card and were permitted to borrow two books at a time, one fiction and one nonfiction.<ref name=library>[http://www.nassaulibrary.org/freeport/FMLHistory.htm Freeport Memorial Library History], Freeport Memorial Library official site. Accessed online 15 November 2008.</ref> |

|||

The median income for a household in the village in 1999 was $55,948, and the median income for a family was $61,673. Males had a median income of $37,465 versus $31,869 for females. The per capita income for the village was $21,288. About 8.0% of families and 10.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.5% of those under age 18 and 7.4% of those age 65 or over. |

|||

A drive was started in 1920 to construct a library building. The resulting library at the corner of Merrick Road and Ocean Avenue, a [[Beaux-Arts architecture|Beaux Arts]] building designed by architect [[Charles M. Hart]], opened on [[Memorial Day]], 1924. A year later it was renamed Freeport Memorial Library. In 1928, a tablet was erected with the names of Freeport's war dead from the [[American Civil War]], [[Spanish American War]], and World War I.<ref name=library /> |

|||

As of 2010, the population was 42,860. The demographics were as follows:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.zip-codes.com/city/ny-freeport-2010-census.asp|title=2010 Census data for City of Freeport, NY|website=zip-codes.com|access-date=April 4, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

* Hispanic – 17,858 (42.5%) |

|||

* Black alone – 13,226 (30.9%) |

|||

* White alone – 10,113 (23.6%) |

|||

* Asian alone – 669 (1.6%) |

|||

* Two or more races – 174 (0.4%) |

|||

* Other race alone – 292 (0.7%) |

|||

* American Indian alone – 94 (0.2%) |

|||

At the 2020 American Community Survey, the Latino population was 16.2% [[Dominican Americans|Dominican]], 9% [[Salvadoran Americans|Salvadoran]], 4.2% [[Puerto Ricans|Puerto Rican]], 3% [[Guatemalan Americans|Guatemalan]], 2.2% [[Colombian Americans|Colombian]], 1.7% [[Ecuadorian Americans|Ecuadorian]].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Bureau |first=U.S. Census |title=Explore Census Data |url=https://data.census.gov/table?q=Stamford+city,+Connecticut+Race+and+Ethnicity&g=1600000US3627485&tid=ACSDT5Y2020.B03001 |access-date=December 5, 2022 |website=data.census.gov |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

== Government == |

|||

[[File:Freeport Village Municipal Hall 20211021 201409015.jpg|thumb|left|Freeport Village Municipal Hall]] |

|||

Freeport's government is made up of four trustees and a mayor, who are elected to four-year terms; one trustee also serves in the capacity of deputy mayor. Freeport's first African American mayor, Andrew Hardwick, was elected in 2009; he was succeeded on March 20, 2013, by Robert T. Kennedy<ref name="Rivera" /> The current Deputy Mayor is (Trustee) Ronald Ellerbe. The other current Trustees are, Jorge Martinez, Christopher Squeri, and Evette Sanchez. Freeport's current government is a coalition of Democrats, Republicans and Independents. |

|||

==Infrastructure== |

|||

=== Transportation === |

|||

==== Road ==== |

|||

[[Merrick Road]] and [[New York State Route 27|Sunrise Highway]] both run roughly east-west through the village.<ref name=":0" /> Additionally, the [[Meadowbrook State Parkway]] forms much of Freeport's eastern border with Merrick.<ref name=":0" /> The [[Southern State Parkway]] runs east-west about a mile north of Freeport's northern border with [[Roosevelt, New York|Roosevelt]].<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

Additionally, Freeport would have been the southern terminus of the never-built [[Freeport–Roslyn Expressway]].<ref name="purpose">{{Cite news|date=January 17, 1952|title=Purpose of Freeport–Roslyn Expressway|page=5|work=The Leader|location=Freeport, New York|url=https://nyshistoricnewspapers.org/lccn/sn95071064/1952-01-17/ed-1/seq-5/?__cf_chl_jschl_tk__=01dc4627e3021e41773e28ca8531fac948512a7f-1599190945-0-Ac7GYfvv59S0uVoxYHgKnZSvH6Ssn7HIek6CSEki_KM7QcOKd3fhJK0Ht-fTCpDY22xb1jQT6yRH3ICnrhA_gOK8pge0WRWBy5nXPhpbHz3PqNs6rrM8xHx32mO06x6cCQaXNysPkR4f1l-CpKW_7G3sEHvkPwDLYU5qRafpLxHnXwgjwAkA1IuAaRtHpV8q_ZA3kHIUZYvhlyltd2it6jMyrW_v_vu7JSQWz_MhMCMxbs9M8v3wg34ANnETpCfwkcXuNaKdYj4WaeeYWJnP2sNAQtU6BUBXpKTT8TE3BPbg6dmIR2IFnQP_0nTj58pghQ|access-date=September 3, 2020|oclc=781862966|via=NYS Historic Newspapers}}</ref><ref name="feeney">{{Cite encyclopedia|last=Feeney|first=Regina|date=May 21, 2018|title=Freeport-Roslyn Expressway|url=https://libguides.freeportlibrary.info/c.php?g=494599&p=3384558|access-date=September 4, 2020|encyclopedia=Freeport History Encyclopedia|publisher=Freeport Memorial Library|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|date=September 28, 1958|title=News from the Field of Travel|language=en-US|page=X35|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1958/09/28/archives/news-from-the-field-of-travel.html|access-date=September 4, 2020|issn=0362-4331}}</ref> This short-lived proposal in the early 1950s was killed largely by community opposition.<ref>{{Cite news|date=October 22, 1952|title=County Abandons All Plans for Expressway|work=Newsday}}{{page needed|date=September 2020}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|date=March 14, 1952|title=Nassau Postpones Action on Highway: Work on Freeport–Roslyn Link Put Off for Year—Protests Against Project Mount|language=en-US|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1952/03/14/archives/nassau-postpones-action-on-highway-work-on-freeportroslyn-link-put.html|access-date=September 4, 2020|issn=0362-4331}}</ref> |

|||

==== Rail ==== |

|||

Freeport is served by the [[Freeport (LIRR station)|Freeport]] station on the [[Long Island Rail Road]]'s [[Babylon Branch]].<ref name=":0">{{Cite web|title=Long Island Index: Interactive Map|url=http://www.longislandindexmaps.org/?zoom=0&x=1313564&y=266122.5&code=53264&tab=tabServiceProviders&satellite=false&landuse=true&landuseopacity=0.8&mainlayers=Fire_boundary,LIE,ParkwayMainRd,VillageBoundaryUninc,VillageBoundaryInc,TownsCities&labellayers=Fire_boundary,VillageBoundaryUninc,VillageBoundaryInc,TownsCities,LIE&serviceproviderlayers=|access-date=August 19, 2021|website=www.longislandindexmaps.org}}</ref> |

|||

==== Bus ==== |

|||

Freeport serves as a hub for several [[Nassau Inter-County Express]] bus routes:<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

* n4/n4x: Freeport – [[Jamaica, Queens|Jamaica]] |

|||

* n19: Freeport – [[Sunrise Mall (Massapequa Park, New York)|Sunrise Mall]] |

|||

* n40/41: Freeport – [[Mineola, New York|Mineola]] |

|||

* n43: Freeport – [[Roosevelt Field Mall]] |

|||

* n88: Freeport – [[Jones Beach State Park|Jones Beach]] (Summer Service Only) |

|||

=== Utilities === |

|||

==== Sewage ==== |

|||

Freeport is connected to [[sanitary sewer]]s.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite web|title=Sewerage Map – Nassau County|url=https://www.nassaucountyny.gov/DocumentCenter/View/1328/85percentfigureunsewercrop?bidId=|access-date=August 5, 2021|website=County of Nassau, New York}}</ref> The village maintains a sanitary sewer system which flows into [[Nassau County Sewage District|Nassau County's system]], which treats the sewage from the village's system through the Nassau County-owned [[sewage treatment plants]].<ref name=":02">{{Cite web|title=Wastewater Management Program {{!}} Nassau County, NY - Official Website|url=https://www.nassaucountyny.gov/1882/Wastewater-Management-Program|access-date=August 6, 2021|website=www.nassaucountyny.gov}}</ref> |

|||

==== Water ==== |

|||

The Village of Freeport owns and maintains its own water system.<ref name=":0" /> Freeport's water system serves the entire village with water.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

== Arts and culture == |

|||

[[File:Freeport, NY Nautical Mile 050.jpg|thumb|left|On the Nautical Mile, 2012]] |

|||

Freeport is a Long Island hot spot during the summer season in New York. A popular festival occurs on Freeport's Nautical Mile (the west side of Woodcleft Canal) the first weekend in June each year, which attracts many people from across Long Island and New York City. The Nautical Mile is a strip along the water that features well-known seafood restaurants, crab shacks, bars, eclectic little boutiques, fresh fish markets, as well as party cruise ships and casino boats that float atop the canals. People line up for the boat rides and eat at restaurants that feature seating on the water's edge and servings of mussels, oysters, crabs, and steamed clams ("steamers") accompanied by pitchers of beer. An 18-hole miniature golf course is popular among families. The Sea Breeze waterfront park—which includes a transient marina, boardwalk, rest rooms and benches—opened in 2009 at the foot of the Nautical Mile. It has proven to be a very popular spot to sit and watch the marine traffic and natural scenery. This is in addition to an existing scenic pier.<!-- is this up to date? --> |

|||

Freeport has an ethnically and racially diverse population. There is one housing project, named after Nassau County's first black judge, Moxie Rigby. Freeport's [[Hispanic]] community is made up of [[Puerto Rico|Puerto Ricans]], [[Dominican Republic|Dominicans]], [[Mexicans]], [[Colombians]] and other Latin American countries. Among the many Latin-American-themed businesses are several grocery stores or "bodegas" and restaurants along Merrick Road and Main Street that serve Caribbean, Central American, Dominican, and South American cuisines. |

|||

Freeport, along with neighboring [[Merrick, New York|Merrick]], is also the gateway to [[Jones Beach State Park|Jones Beach]], one of the largest state beaches in New York. One famous area is the [[Town of Hempstead Marina]], where people from all over Long Island dock their boats. Freeport is a 45-minute ride by the [[Long Island Rail Road]] to Manhattan, making the trip an easy commute to New York City. |

|||

From 1974 to 1986, Freeport was one of the few Long Island towns to hold a sizeable open-air market area, known as the Freeport Mall.<ref>"Board of Trustees Minutes, 1974.</ref> The heart of the Main Street business area was closed to vehicular traffic and reconfigured for pedestrians only. The experiment was not a success. The [[W. T. Grant]] store that was supposed to anchor the mall closed, along with the rest of that chain, shortly after the mall opened. The mall area became shabby and disused, and many businesses failed. The mall was dismantled and returned to through traffic with regular parking on each side of the street.<ref> |

|||

Additional wings were dedicated on April 19, 1959, and on Memorial Day, 1985. Plaques were added to honor Freeporters who died in World War II, the [[Korean War]], and the [[Vietnam War]].<ref name=library /> |

|||

{{Cite journal| title = Freeport Abandoning Failed Pedestrian Mall |

|||

| journal = The New York Times |

|||

| volume = Late City Final Edition, Section 1 |

|||

| pages = Page 54, Column 1, 756 words |

|||

| date = December 7, 1986 |

|||

| url = https://www.nytimes.com/1986/12/07/nyregion/freeport-abandoning-failed-pedestrian-mall.html?scp=1&sq=freeport+abandoning+failed+pedestrian+mall&st=nyt |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

===Architecture=== |

===Architecture=== |

||

[[File:Freeport, NY post office interior 01.jpg|thumb|Interior of the Freeport Post Office.]][[File:Woodcleft Canal 20240919 131823.jpg|thumb|Woodcleft Canal Historic Marker]][[File:Woodcleft Inn historic marker 20240919 130959.jpg|thumb|Woodcleft Inn historic marker]] |

|||

Just north of the high school and the railroad tracks is the ruin of the former [[Brooklyn, New York|Brooklyn]] Water Works, described by Christopher Gray of the ''New York Times'' as looking like an "ancient, war-damaged abbey." Designed by architect [[Frank Freeman (architect)|Frank Freeman]] and opened in 1891 to serve the City of Brooklyn (later made a borough of New York City), it was fully active until 1929 with a capacity of 54 million gallons a day, and remained in standby for emergency use until 1977, when the pumps and other machinery were removed. See [[Ridgewood Reservoir]]. An unsuccessful 1989 plan would have turned the building into condos.<ref>Christopher Gray, [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950DEFDC1F3DF932A35753C1A96F948260 STREETSCAPES: Millburn Pumping Station; A Rundown 'Abbey' Gets New Life as Condominiums], ''New York Times'', October 1, 1989. Accessed online 20 July 2006.</ref><ref>[http://www.lioddities.com/Abandoned/BWW.html Brooklyn Water Works] on the Long Island Oddities site. Accessed online 20 July 2006.</ref> Currently, the parcel is the subject of litigation and ongoing investigations by various agencies. |

|||

Just north of the high school and the railroad tracks is the ruin of the former [[Brooklyn Waterworks]], described by Christopher Gray of the ''New York Times'' as looking like an "ancient, war-damaged abbey." Designed by architect [[Frank Freeman (architect)|Frank Freeman]] and opened in 1891 to serve the City of Brooklyn (later made a borough of New York City), it was fully active until 1929 with a capacity of 54 million gallons a day, and remained in standby for emergency use until 1977, when the pumps and other machinery were removed. See [[Ridgewood Reservoir]]. An unsuccessful 1989 plan would have turned the building into condos.<ref>Christopher Gray, [https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=950DEFDC1F3DF932A35753C1A96F948260 STREETSCAPES: Millburn Pumping Station; A Rundown 'Abbey' Gets New Life as Condominiums], ''New York Times'', October 1, 1989. Retrieved July 20, 2006.</ref><ref>[http://www.lioddities.com/Abandoned/BWW.html Brooklyn Water Works] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090622005526/http://lioddities.com/Abandoned/BWW.html |date=June 22, 2009 }} on the Long Island Oddities site. Retrieved July 20, 2006.</ref> Currently, the parcel is the subject of litigation and ongoing investigations by various agencies. Long Island Traditions also describes the sites of notable architecture in Freeport's history, such as bay men's homes<ref>{{cite news|journal=Long Island Traditions|title=Architecture: Bay Men's Homes|url=http://www.longislandtraditions.org/southshore/architecture/baymenshomes/index.html|access-date=November 23, 2012}}</ref> and commercial fishing establishments,<ref>{{cite news|journal=Long Island Traditions|title=Commercial Fishing|url=http://www.longislandtraditions.org/southshore/architecture/commfish/index.html|access-date=November 23, 2012}}</ref> some of which are still existing, as well as the still-existing Fiore's Fish Market and Two Cousins, which are located in historic waterfront buildings, built by the owners, so they could negotiate directly with the baymen as they pulled into dock.<ref>{{cite news|journal=Long Island Traditions|title=Fish Markets & Eateries| access-date=November 23, 2012| url=http://www.longislandtraditions.org/southshore/architecture/eateries/index.html}}</ref> |

|||

Long Island Traditions also describes and provides a photograph of the no-longer existing Woodcleft Hotel<ref>{{cite news|journal=Long Island Traditions|title=Architecture: South Shore Estuary Site|url=http://www.longislandtraditions.org/southshore/architecture/boatyards/index.html|access-date=November 23, 2012 }}</ref> and important boatyards, about which the site writes:<ref>{{cite news|journal=Long Island Traditions|title=Architecture: Boatyards|url=http://www.longislandtraditions.org/southshore/architecture/boatyards/index.html|access-date=November 23, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

===Sports and recreation=== |

|||

From 1931 until the early 1980s, Freeport was home to [http://www.stockcarracing.com/thehistoryof/31638_freeport_stadium/index.html Freeport Speedway], originally Freeport Municipal Stadium. Seating about 10,000, the stadium originally hosted "midget" auto races; after World War II it switched to [[stock car racing]] and eventually [[demolition derby|demolition derbies]]. In the early 1930s it was the playfield for a [[semi-professional|semi-pro]] [[baseball]] team: the Penn Red Caps took their name from the caps worn by [[Pullman Company#Porters|Pullman porters]]. For a few years after that, the [[National Football League|NFL]] [[Brooklyn Dodgers (NFL)|Brooklyn Dodgers]] [[American football|football]] team, who, like their [[Los Angeles Dodgers|baseball namesakes]], played at [[Ebbets Field]], used the stadium as a midweek training site.<ref name=Bleyer /> The site is now a BJs Warehouse Club. |

|||

<blockquote>"In Freeport the Maresca boatyard stands on the site of what is now the Long Island Marine Education Center owned by the Village of Freeport. Founded in the 1920s by Phillip Maresca, they built both recreational and commercial boats. Their customers included Guy Lombardo and party boat captains. The business was taken over by Everett Maresca, who died in 1995. The original building remains relatively intact, consisting of a large concrete block structure. Further down on Woodcleft Canal stands the former Scopinich Boatyard, now part of Shelter Point Marine services. The structure is obscured by corrugated metal siding but elements of its original frame structure remain. The yard was founded by Fred Scopinich, a Greek immigrant in the early 1900s. His grandson Fred moved the yard to East Quogue. The Freeport yard specialized in building commercial fishing boats including trawlers, government boats for the Coast Guard, rum running boats, as well as sailboats and garveys for local baymen. Finally the original Grover boatyard, founded by Al Grover, stands on Woodcleft Avenue a short distance from the Maresca yard. A modest frame building, approximately 20 people worked there. Today the yard is located north of the Nautical Mile on South Main street, run by Grover's sons. Their yard consists of modern corrugated structures used primarily for maintenance and storage."</blockquote> |

|||

Freeport is home to the Freeport Recreation Center, which features an enclosed, year-round ice skating rink; an indoor pool; an outdoor Olympic-size pool; an outdoor diving tank; an outdoor children's pool; handball courts; sauna; steam room; fully equipped workout gyms; basketball courts; and snack bars serving hot and cold foods. The "Rec Center" also offers evening adult classes and hosts a pre-school program, camp programs, and a senior center. |

|||

== |

===Libraries=== |

||

The [[Freeport Memorial Library]], which is the library serving the Freeport Library District, is the main library in Freeport.<ref name=":0" /> The Baldwin and Roosevelt Library Districts serve some of the northernmost portions of the village.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

Freeport is located at {{Coord|40|39|14|N|73|35|13|W|city}} (40.653935, -73.587005){{GR|1}}. |

|||

===Schools=== |

|||

Freeport is bisected by east-west [[New York State Route 27]], Sunrise Highway. [[Meadowbrook Parkway]] defines its eastern boundary. |

|||

[[File:First school in Freeport, NY plaque.jpg|thumb|left|Plaque marking the first public school in Freeport, NY; located at the corner of North Main Street and Church Street, in front of the cannon.]] |

|||

[[Freeport Public Schools]] (FPS) operates the community's public schools.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

==Demographics== |

|||

[[File:Archer Street School Historic marker 20240919 132535.jpg|thumb|Archer Street School Historic marker]] |

|||

As of the [[census]]{{GR|2}} of 2000, there were 43,783 people, 13,504 households, and 9,911 families residing in the village. The [[population density]] was 9,531.3 people per square mile (3,682.9/km²). There were 13,819 housing units at an average density of 3,008.3/sq mi (1,162.4/km²). The racial makeup of the village was 42.9% [[White (U.S. Census)|White]], 32.6% [[African American (U.S. Census)|African American]], 0.5% [[Native American (U.S. Census)|Native American]], 1.4% [[Asian (U.S. Census)|Asian]], 0.1% [[Pacific Islander (U.S. Census)|Pacific Islander]], 17.2% from [[Race (United States Census)|other races]], and 5.4% from two or more races. [[Hispanic (U.S. Census)|Hispanic]] or [[Latino (U.S. Census)|Latino]] of any race were 33.5% of the population.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/SAFFFacts?_event=&geo_id=16000US3627485&_geoContext=01000US%7C04000US36%7C16000US3627485&_street=&_county=Freeport&_cityTown=Freeport&_state=04000US36&_zip=&_lang=en&_sse=on&ActiveGeoDiv=&_useEV=&pctxt=fph&pgsl=040&_submenuId=factsheet_1&ds_name=DEC_2000_SAFF&_ci_nbr=null&qr_name=null®=null%3Anull&_keyword=&_industry=|title=Freeport (village) Fact Sheet|publisher=U.S. Census Bureau (American FactFinder)|accessdate=2009-03-26}}</ref> |

|||

For the 2009–10 school year, there were 6,257 students enrolled in Freeport's public schools.<ref name=NYSEDAOR>NYSED, [https://www.nystart.gov/publicweb-rc/2010/89/AOR-2010-280209030000.pdf The New York State District Report Card Accountability and Overview Report 2009–10] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120323021029/https://www.nystart.gov/publicweb-rc/2010/89/AOR-2010-280209030000.pdf |date=March 23, 2012 }}, ''New York State Education Department'', February 5, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2011.</ref> The children of Freeport, in grades 1–4, attend four magnet elementary schools, each with a different specialty: Archer Street (Microsociety and Multimedia), Leo F. Giblyn (School of International Cultures), Bayview Avenue (School of Arts and Sciences), and New Visions (School of Exploration & Discovery). In grades 5 and 6, all public school children attend Caroline G. Atkinson School on the north side of the town. Seventh and 8th graders attend John W. Dodd Middle School. The Middle School is built on the property that housed the older Freeport High School, but not on exactly the same site. The old high school served for some years as the junior high; then the new junior high was built on what was previously parking lot and playground, and the old building was torn down. In 2017, The school remodeled, with an added track and field. A Catholic school, the De La Salle School, is run by the Christian Brothers and accepts boys from grades 5–8. |

|||

Children in grades 9–12 attend Freeport High School, which borders the town of [[Baldwin, Nassau County, New York|Baldwin]] and sits beside the Milburn duck pond, which is fed by a creek, several hundred yards of which was diverted underground when the high school was built. Freeport High School's mascot is the Red Devil, and its colors are red and white. The school has track-and-field facilities.<!-- up to here not cited --> One unique feature of the school's curriculum is a science research program run in cooperation with [[Stony Brook University]]. The school offers numerous advanced placement courses and was a pioneer in distance learning at the high school level. Roughly 87 percent of the high school's graduates go on to some form of higher education. A community night school for teenagers had 236 students as of 1999.<ref name=Rather /> |

|||

There were 13,504 households out of which 36.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.7% were [[Marriage|married couples]] living together, 17.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.6% were non-families. 21.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.20 and the average family size was 3.65. |

|||

As early as 1886, Freeport's schools began the then-unusual policy of providing their students with free textbooks. In 1893, the newly incorporated village constructed a ten-room brick schoolhouse. Also in the late 19th century, the community was among the first Long Island communities to establish an "academic department", offering classes beyond the elementary school level.<ref>{{Harvnb|Smits|1974|pp=31, 33}}</ref> |

|||

In the village the population was spread out with 26.4% under the age of 18, 9.1% from 18 to 24, 32.1% from 25 to 44, 22.0% from 45 to 64, and 10.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females there were 92.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.3 males. |

|||

[[File:Seaman Ave school No2 historic marker Freeport NY 20211021 201721359.jpg|thumb|Seaman Ave school #2 historic marker Freeport NY]] |

|||

Freeport saw its share of the social, political, and racial turbulence of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The 1969–70 school year saw three high school principals in the village's only high school, succeeded in August 1970 by William McElroy, formerly the junior high school principal, who came to the position "in the midst of racial tension and a constantly-polarizing student body";<ref name=Seabrook>{{cite news|author=Seabrook, Veronica |title=McElroy Sees Change Evolving|newspaper=Flashings (Freeport High School newspaper)|date= May 15, 1972|pages= 3–4}}</ref> McElroy backed such initiatives as a student advisory committee to the Board of Education and, in his own words, "made [him]self available to any civic-minded group" that wished to discuss with him the situation in the school. By May 1972, he could claim success, of a sort. "Formerly, a fight between a black and a white student would automatically become racial; now a fight is just a fight—between two students."<ref name=Seabrook /> |

|||

[[File:Trubia Rifles 20211027 171357366.jpg|thumb|left|Trubia Rifles & Dedication Plaque]] |

|||