Leon Forrest: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m Spacing wrt refs per MOS:REFSPACE |

||

| (71 intermediate revisions by 30 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|American novelist}} |

|||

'''Leon Richard Forrest''' (January 8, 1937 – November 6, 1997) was an [[African American]] [[Novel|novelist]]. His novels concerned mythology, history, and Chicago. |

|||

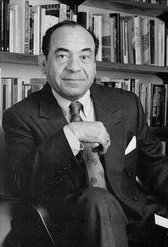

[[File:Leon Forrest.jpg|thumb|Leon Forrest]] |

|||

| ⚫ | Forrest was born into a middle-class family in Chicago. His mother was [[Catholicism|Catholic]] and from [[New Orleans, Louisiana|New Orleans]], while his father's family was [[Baptist]]. His paternal great-grandmother had a role in his early upbringing. Forrest later attended a racially integrated high school after winning an award, but he was a generally mediocre student except for writing. His parents divorced in 1956; his mother remarried, and the couple opened a liquor store. |

||

'''Leon Richard Forrest''' (January 8, 1937 – November 6, 1997) was an [[African-American]] [[novelist]] who taught at [[Northwestern University]] from 1973 until his death. His four major novels used mythology, history, and humor to explore "Forest County," a fictional world that resembled the south side of Chicago where Forrest grew up. After his death, the ''Washington Post'' called Forrest "one of the best-kept secrets of contemporary African-American fiction -- and an acquired taste."{{sfnb|Miller|2001}} |

|||

==Biography== |

|||

| ⚫ | Forrest attended Wendell Phillips grade school and [[Hyde Park High School]].<ref>Cawelti, John G. ''Leon Forrest: Introductions and Interpretations''. Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1997, p. 3</ref> He then attended Wilson Junior College for a year, and then took classes at [[Roosevelt University]] and the [[University of Chicago]] before dropping out, leaving to serve as a Public Information Officer in the military.<ref>Cawelti, John G. ''Leon Forrest: Introductions and Interpretations'' |

||

| ⚫ | Forrest was born into a middle-class family in Chicago. His mother was [[Catholicism|Catholic]] and from [[New Orleans, Louisiana|New Orleans]], while his father's family was [[Baptist]]. Forrest attended Catholic school as a child, which later influenced his writing.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Forrest |first=Leon |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/85814093 |title=Conversations with Leon Forrest |date=2007 |publisher=University Press of Mississippi |others=Dana A. Williams |isbn=978-1-57806-989-7 |edition=1st |location=Jackson |oclc=85814093}}</ref> His paternal great-grandmother had a role in his early upbringing. Forrest later attended a racially integrated high school after winning an award, but he was a generally mediocre student except for writing. His parents divorced in 1956; his mother remarried, and the couple opened a liquor store. |

||

| ⚫ | Forrest attended Wendell Phillips grade school and [[Hyde Park Career Academy|Hyde Park High School]].<ref>Cawelti, John G. ''Leon Forrest: Introductions and Interpretations''. Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1997, p. 3.</ref> He then attended Wilson Junior College for a year, and then took classes at [[Roosevelt University]] and the [[University of Chicago]] before [[dropping out]], leaving to serve as a Public Information Officer in the military.<ref>Cawelti, John G. ''Leon Forrest: Introductions and Interpretations'', 1997, pp. 4–5.</ref> After leaving the service, he returned to the University of Chicago and worked for the Catholic Interracial Council's Speakers Bureau. In 1969, he began working for ''[[Muhammad Speaks]]'', a [[Nation of Islam]] newspaper. Forrest would become the last non-Muslim editor of the paper. |

||

His first novel, ''There is a Tree More Ancient than Eden'', came out in 1973, and included an introduction from [[Ralph Ellison]]. Nobel Prize Laureate [[Toni Morrison]] served as publisher's editor for his first three novels<ref>Cawelti, John G. ''Leon Forrest: Introductions and Interpretations''. Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1997, p. 4</ref>. The last novel published when he was alive, ''Divine Days'', was modeled on [[Ulysses]] by [[James Joyce]]<ref>Byerman, Keith. ''Angularity: An Interview with Leon Forrest - Interview''. ''African American Review'', Fall 1999.</ref> |

|||

His first novel, ''There is a Tree More Ancient than Eden'', was published in 1973 and included an introduction from [[Ralph Ellison]]. Nobel Prize Laureate [[Toni Morrison]] served as Forrest's editor for ''There is a Tree More Ancient than Eden'', and his next two novels, ''The Bloodworth Orphans'' and ''Two Wings to Veil My Face''.<ref>Cawelti, John G. ''Leon Forrest: Introductions and Interpretations'', 1997, p. 4.</ref> These three novels were known as the Forest County Trilogy.<ref name=Onishi>Onishi, Norimitsu. [https://www.nytimes.com/1997/11/10/nyregion/leon-forrest-60-a-novelist-who-explored-black-history.html?scp=1&sq=%22leon+forrest%22&st=nyt "Leon Forrest, 60, a Novelist Who Explored Black History"], ''The New York Times'', November 10, 1997.</ref> He cited [[Charlie Parker]], [[Dylan Thomas]], [[William Faulkner]], [[Eugene O'Neill]], [[Ralph Ellison]], and his parents' religions as inspirations. |

|||

From 1985 to 1994, he headed the African American Studies department at [[Northwestern University]]. He cited [[Charlie Parker]], [[Dylan Thomas]], [[William Faulkner]], [[Eugene O'Neill]], [[Ralph Ellison]], and his parents' religions as inspiration.<ref>[http://findingaids.library.northwestern.edu/fedora/get/inu:inu-ead-nua-11-3-1-3/inu:EADbDef11/getBiographicalHistory Northwestern University]</ref> |

|||

Forrest joined the creative writing and literature staff of [[Northwestern University]] in 1973,<ref name=Onishi /> and from 1985 to 1994 he headed their African-American Studies department.<ref>[https://web.archive.org/web/20091106062855/http://findingaids.library.northwestern.edu/fedora/get/inu:inu-ead-nua-11-3-1-3/inu:EADbDef11/getBiographicalHistory Northwestern University]</ref> His last novel, ''Divine Days'', was modeled on ''[[Ulysses (novel)|Ulysses]]'' by [[James Joyce]].<ref>Byerman, Keith. "Angularity: An Interview with Leon Forrest - Interview". ''African-American Review'', Fall 1999.</ref> A novel over 1,100 pages long, ''Divine Days'' was called "the [[War and Peace]] of [[African-American]] literature" by noted scholar and Harvard professor [[Henry Louis Gates]].<ref>[http://undercoverblackman.blogspot.com/2007/01/remembering-leon-forrest-pt-1.html Undercover Black Man]</ref> |

|||

He died in [[Evanston, Illinois]]. |

|||

Forrest died of cancer in [[Evanston, Illinois]] at age 60.<ref name=Onishi /> ''Meteor in the Madhouse'', a series of connected novellas, was published [[List of works published posthumously|posthumously]] in 2001, with his widow Marianne Forrest serving as literary executor. The ''Washington Post'' review said ''Meteor in the Madhouse'' will be "regarded as a major event" and a "significant landmark."<ref>{{citation|title= The Talking Cure |first=James A. |last= Miller |newspaper=The Washington Post|url= https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/entertainment/books/2001/08/05/the-talking-cure/32c00cb6-650f-4af8-b720-72e4906f2827/ |date= 5 August 2001 }}</ref> |

|||

==Bibiliography== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

In 2013, Forrest was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://chicagoliteraryhof.org/inductees/profile/leon-forrest |title=Leon Forrest |date=2013 |website=Chicago Literary Hall of Fame |language=en |access-date=October 8, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

== References and further reading == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{citation|first=Jonathan| last= Eig|title= Bound for Glory|date = 15 April 2011|url= https://www.chicagomag.com/chicago-magazine/january-1998/bound-for-glory/ |journal= Chicago Magazine}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*{{cite book |editor-last =Williams |editor-first = Dana A. |translator = |year = 2007 |title = Conversations with Leon Forrest |publisher = University Press of Mississippi| location = Jackson |isbn = 9781578069897}} Interviews with Forrest on his work. |

|||

* {{cite book |last = Williams |first = Dana A. |translator = |year = 2005 |title = "In the Light of Likeness--Transformed": The Literary Art of Leon Forrest |publisher = Ohio State University Press| location = Columbus |isbn = 0814209947}} |

|||

==Major fiction== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 23: | Line 35: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

*[http:// |

*[http://findingaids.library.northwestern.edu/catalog/inu-ead-nua-archon-495 Leon Forrest Papers, Northwestern University Archives, Evanston, Illinois] |

||

* [https://uncap.lib.uchicago.edu/view.php?eadid=inu-ead-nua-archon-495#idp3919616 Guide to the Leon Forrest (1937-1997) Papers 1952/1998] UNCAP ([https://uncap.lib.uchicago.edu/ Uncovering Chicago Archives Project]) guide to the Northwestern Leon Forrest archive. |

|||

*[http://search.eb.com/blackhistory/article-9105742 Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History] |

*[http://search.eb.com/blackhistory/article-9105742 Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History] |

||

*[http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2838/is_3_33/ai_58056039 Interview with Leon Forrest (fairly extensive)] |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20060625064647/http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m2838/is_3_33/ai_58056039 Interview with Leon Forrest (fairly extensive)] |

||

{{AfricanAmerican}} |

|||

{{US-novelist-1930s}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

<!-- Metadata: see [[Wikipedia:Persondata]] --> |

|||

{{Persondata |

|||

|NAME= Forrest, Leon |

|||

|ALTERNATIVE NAMES= Forrest, Leon Richard (full name) |

|||

|SHORT DESCRIPTION= Novelist |

|||

|DATE OF BIRTH= January 8, 1937 |

|||

|PLACE OF BIRTH= [[Chicago]], [[Illinois]], [[United States]] |

|||

|DATE OF DEATH= November 6, 1997 |

|||

|PLACE OF DEATH= [[Evanston, Illinois|Evanston]], [[Illinois]], [[United States]] |

|||

}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Forrest, Leon}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Forrest, Leon}} |

||

[[Category:1937 births]] |

[[Category:1937 births]] |

||

[[Category:1997 deaths]] |

[[Category:1997 deaths]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:20th-century American novelists]] |

||

[[Category:American novelists]] |

[[Category:African-American novelists]] |

||

[[Category:American male novelists]] |

|||

[[Category:Northwestern University faculty]] |

[[Category:Northwestern University faculty]] |

||

[[Category:University of Chicago alumni]] |

[[Category:University of Chicago alumni]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Novelists from Chicago]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century American male writers]] |

|||

[[Category:20th-century African-American writers]] |

|||

[[Category:African-American male writers]] |

|||

[[Category:African-American Catholics]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 14:58, 15 October 2024

Leon Richard Forrest (January 8, 1937 – November 6, 1997) was an African-American novelist who taught at Northwestern University from 1973 until his death. His four major novels used mythology, history, and humor to explore "Forest County," a fictional world that resembled the south side of Chicago where Forrest grew up. After his death, the Washington Post called Forrest "one of the best-kept secrets of contemporary African-American fiction -- and an acquired taste."[1]

Biography

[edit]Forrest was born into a middle-class family in Chicago. His mother was Catholic and from New Orleans, while his father's family was Baptist. Forrest attended Catholic school as a child, which later influenced his writing.[2] His paternal great-grandmother had a role in his early upbringing. Forrest later attended a racially integrated high school after winning an award, but he was a generally mediocre student except for writing. His parents divorced in 1956; his mother remarried, and the couple opened a liquor store.

Forrest attended Wendell Phillips grade school and Hyde Park High School.[3] He then attended Wilson Junior College for a year, and then took classes at Roosevelt University and the University of Chicago before dropping out, leaving to serve as a Public Information Officer in the military.[4] After leaving the service, he returned to the University of Chicago and worked for the Catholic Interracial Council's Speakers Bureau. In 1969, he began working for Muhammad Speaks, a Nation of Islam newspaper. Forrest would become the last non-Muslim editor of the paper.

His first novel, There is a Tree More Ancient than Eden, was published in 1973 and included an introduction from Ralph Ellison. Nobel Prize Laureate Toni Morrison served as Forrest's editor for There is a Tree More Ancient than Eden, and his next two novels, The Bloodworth Orphans and Two Wings to Veil My Face.[5] These three novels were known as the Forest County Trilogy.[6] He cited Charlie Parker, Dylan Thomas, William Faulkner, Eugene O'Neill, Ralph Ellison, and his parents' religions as inspirations.

Forrest joined the creative writing and literature staff of Northwestern University in 1973,[6] and from 1985 to 1994 he headed their African-American Studies department.[7] His last novel, Divine Days, was modeled on Ulysses by James Joyce.[8] A novel over 1,100 pages long, Divine Days was called "the War and Peace of African-American literature" by noted scholar and Harvard professor Henry Louis Gates.[9]

Forrest died of cancer in Evanston, Illinois at age 60.[6] Meteor in the Madhouse, a series of connected novellas, was published posthumously in 2001, with his widow Marianne Forrest serving as literary executor. The Washington Post review said Meteor in the Madhouse will be "regarded as a major event" and a "significant landmark."[10]

In 2013, Forrest was inducted into the Chicago Literary Hall of Fame.[11]

References and further reading

[edit]- Eig, Jonathan (15 April 2011), "Bound for Glory", Chicago Magazine

- Williams, Dana A., ed. (2007). Conversations with Leon Forrest. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781578069897. Interviews with Forrest on his work.

- Williams, Dana A. (2005). "In the Light of Likeness--Transformed": The Literary Art of Leon Forrest. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. ISBN 0814209947.

Major fiction

[edit]- There Is a Tree More Ancient than Eden (Random House, 1973; expanded edition, 1988))

- The Bloodworth Orphans (Random House, 1977)

- Two Wings to Veil My Face (Asphodel, 1984)

- Divine Days (Another Chicago Press, 1992)

- Relocations of the Spirit: Collected Essays (Asphodel, 1994)

- Meteor in the Madhouse (Northwestern University, 2001)

References

[edit]- ^ Miller (2001).

- ^ Forrest, Leon (2007). Conversations with Leon Forrest. Dana A. Williams (1st ed.). Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-989-7. OCLC 85814093.

- ^ Cawelti, John G. Leon Forrest: Introductions and Interpretations. Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1997, p. 3.

- ^ Cawelti, John G. Leon Forrest: Introductions and Interpretations, 1997, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Cawelti, John G. Leon Forrest: Introductions and Interpretations, 1997, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Onishi, Norimitsu. "Leon Forrest, 60, a Novelist Who Explored Black History", The New York Times, November 10, 1997.

- ^ Northwestern University

- ^ Byerman, Keith. "Angularity: An Interview with Leon Forrest - Interview". African-American Review, Fall 1999.

- ^ Undercover Black Man

- ^ Miller, James A. (5 August 2001), "The Talking Cure", The Washington Post

- ^ "Leon Forrest". Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Leon Forrest Papers, Northwestern University Archives, Evanston, Illinois

- Guide to the Leon Forrest (1937-1997) Papers 1952/1998 UNCAP (Uncovering Chicago Archives Project) guide to the Northwestern Leon Forrest archive.

- Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History

- Interview with Leon Forrest (fairly extensive)

- 1937 births

- 1997 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- African-American novelists

- American male novelists

- Northwestern University faculty

- University of Chicago alumni

- Novelists from Chicago

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century African-American writers

- African-American male writers

- African-American Catholics