Sesame Workshop: Difference between revisions

| (981 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American children's media producer}} |

|||

{{Lead too short|date=August 2009}} |

|||

{{Featured article}} |

|||

{{Refimprove|date=June 2009}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=January 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox Organization |

|||

{{Infobox organization |

|||

|name = Sesame Workshop |

|||

| |

| native_name = |

||

| image = Sesame Workshop 2018 Logo.svg |

|||

|image_border = |

|||

| image_size = 200px |

|||

|size = |

|||

|caption = |

| caption = |

||

| alt = Logo for Sesame Workshop, created in 2018 simultaneously. Features the words "SESAME WORKSHOP" (all-caps) in gray inside border lines of yellow on the top and green on the bottom that together form a shape similar to the "Sesame Street" sign. |

|||

|map = |

|||

| formerly = Children's Television Workshop (CTW) (1968–2000) |

|||

|msize = |

|||

| founded = {{start date and age|1968|05|20}} |

|||

|mcaption = |

|||

| type = [[Nonprofit organization|Non-profit]] |

|||

|motto = |

|||

| status = [[501(c)(3)]] |

|||

|formation = 1968 (as '''Children's Television Workshop''') |

|||

| headquarters = [[1 Lincoln Plaza]] |

|||

|extinction = |

|||

| |

| leader_title = [[President (corporation)|President]] |

||

| leader_name = [[Sherrie Rollins Westin|Sherrie Westin]] |

|||

|headquarters = [[One Lincoln Plaza|1 Lincoln Plaza]]<br>New York, NY 10023 |

|||

| leader_title2 = [[Chief Executive Officer|CEO]] |

|||

|location = [[New York City]], [[New York]], [[United States]] |

|||

| leader_name2 = Sherrie Westin |

|||

|area_served = {{flagicon|World}} [[World]]wide |

|||

| |

| leader_title3 = |

||

| |

| leader_name3 = |

||

| subsidiaries = Sesame Street Inc<br /> Sesame Workshop Communications Inc<br /> Sesame Workshop Initiatives India PLC<br /> SS Brand Management Shanghai |

|||

|leader_title = President and CEO |

|||

| footnotes = <ref name= 990-2014>"[http://www.guidestar.org/FinDocuments/2014/132/655/2014-132655731-0bc0751b-9.pdf Form 990: Return of Organization Exempt from Income Tax]". ''Sesame Workshop''. [[Guidestar]]. June 30, 2014.</ref><ref name= irseo>"[https://apps.irs.gov/app/eos/pub78Search.do?ein1=13-2655731&names=&city=&state=All...&country=US&deductibility=all&dispatchMethod=searchCharities&submitName=Search Sesame Workshop] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180505210505/https://apps.irs.gov/app/eos/pub78Search.do?ein1=13-2655731&names=&city=&state=All...&country=US&deductibility=all&dispatchMethod=searchCharities&submitName=Search |date=2018-05-05 }}". ''Exempt Organization Select Check''. [[Internal Revenue Service]]. Accessed on May 20, 2016.</ref><ref name="leadership">{{Cite web|title=Our Leadership|url=https://www.sesameworkshop.org/who-we-are/our-leadership|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210612153127/https://www.sesameworkshop.org/who-we-are/our-leadership|archive-date=12 June 2021|access-date=1 January 2022|website=Sesame Workshop}}</ref> |

|||

|leader_name = Gary E. Knell |

|||

| name = Sesame Workshop |

|||

|key_people = [[Joan Ganz Cooney]], co-founder <br> Lloyd Morriset, co-founder |

|||

| location = [[New York City]], US |

|||

|num_staff = |

|||

| |

| area_served = Worldwide |

||

| founders = [[Joan Ganz Cooney]]<br />[[Lloyd Morrisett]] |

|||

|website = [http://www.sesameworkshop.org sesameworkshop.org] |

|||

| employees = 813 |

|||

| employees_year = 2013 |

|||

| revenue = {{US$|link=yes}}104,728,963 |

|||

| revenue_year = 2014 |

|||

| expenses = {{US$|link=yes}}111,255,622 |

|||

| expenses_year = 2014 |

|||

| tax_id = 13-2655731 |

|||

| website = {{URL|sesameworkshop.org}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Sesame Workshop''', formerly known as the '''Children's Television Workshop''' (or '''CTW'''), is a [[World]]wide [[United States|American]] [[non-profit organization]] behind the production of several educational children's programs that have run on public broadcasting around the world (including [[PBS]] in the United States). Sesame Workshop was instrumental in the establishment of education children's television in the 1960s, and continues to provide grants for educational children's programming four decades later. [[Joan Ganz Cooney]] and [[Lloyd Morrisett]] were the original founders, with the intention of producing a revolutionary television series based on cutting-edge research into childhood learning. The result was Sesame Street, a landmark program which has been reproduced in countries around the world. |

|||

'''Sesame Workshop''' ('''SW'''), originally known as the '''Children's Television Workshop''' ('''CTW'''), is an American [[nonprofit organization]] that has been responsible for the production of several educational children's programs—including its first and best-known, ''[[Sesame Street]]''—that have been televised internationally. [[Joan Ganz Cooney]] and [[Lloyd Morrisett]] developed the idea to form an organization to produce the ''Sesame Street'' television series. They spent two years, from 1966 to 1968, researching, developing, and raising money for the new series. Cooney was named as the Workshop's first executive director, which was termed "one of the most important television developments of the decade."<ref name="davis125126" /> |

|||

Although it was originally funded by the Carnegie Corporation and the [[United States Department of Education|United States Office of Education]], much of the Workshop's funding is now earned through licensing the use of their characters to a variety of corporations to use for books, toys, and other products marketed toward children. This ensures that the Workshop has reliable access to funding for its programming without depending on unpredictable grants. |

|||

''Sesame Street'' premiered on [[National Educational Television]] (NET) as a series run in the United States on November 10, 1969, and moved to NET's successor, the Public Broadcasting Service ([[PBS]]), in late 1970. The Workshop was formally incorporated in 1970. [[Gerald S. Lesser]] and [[Edward L. Palmer]] were hired to perform research for the series; they were responsible for developing a system of planning, production, and evaluation, and the interaction between television producers and educators, later termed the "CTW model". The CTW applied this system to its other television series, including ''[[The Electric Company]]'' and ''[[3-2-1 Contact]]''. The early 1980s were a challenging period for the Workshop; difficulty finding audiences for their other productions and a series of bad investments harmed the organization until licensing agreements stabilized its revenues by 1985. |

|||

==History== |

|||

Founded by [[Joan Ganz Cooney]] and [[Lloyd Morrisett]] in 1968 to produce ''[[Sesame Street]]'', the company, currently run by President and CEO Gary E. Knell, has since produced many other shows and a variety of multimedia content. The CTW name was officially changed to Sesame Workshop on New Years Day to reflect the company's reach into new media and capitalize on the worldwide recognition provided by the Sesame Street name. |

|||

Following the success of ''Sesame Street'', the CTW developed other activities, including unsuccessful ventures into adult programs, the publications of books and music, and international co-productions. In 1999 the CTW partnered with [[MTV Networks]] to create an educational channel called [[Noggin (brand)|Noggin]]. The Workshop produced a variety of original series for Noggin, including ''[[The Upside Down Show]]'', ''[[Sponk!]]'' and ''[[Out There (2003 TV series)|Out There]]''. In June 2000, the CTW changed its name to Sesame Workshop to better represent its activities beyond television. |

|||

==Gathering talent for ''Sesame Street''== |

|||

Moving to [[Carnegie Corporation of New York]], the grant-issuing foundation, to act and advise independent of what is now [[WNET]], Cooney began laying the groundwork for the Children's Television Workshop. Carnegie hired Linda Gotley to help Cooney write the proposal. Barbara Finberg and Lloyd Morrisett, program officers at Carnegie would regularly react as funders, every few days trying to find holes in the proposal. During these days, segments like "One of these things is not like the others" were established. |

|||

By 2005, income from the organization's international co-productions of the series was $96 million. By 2008, the ''Sesame Street'' [[List of Sesame Street Muppets|Muppets]] accounted for $15–17 million per year in licensing and merchandising fees. [[Sherrie Rollins Westin|Sherrie Westin]] is the president of the company, starting in 2021. |

|||

Despite the insistence of the US Office of Education that there was no money to fund the project, Howe persisted, and insisted the project be classified as a research project. Ford joined funding, as did the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, which was being established just as ''Sesame Street'' was. Between those organizations and Carnegie, USD$8 million was raised to create a semi-autonomous organization. This organization was established to become completely separate, should they succeed. |

|||

== History == |

|||

At a press conference in March 1968, the Children's Television Workshop and ''Sesame Street'' were announced. [[Jack Gould]], television critic for ''[[The New York Times]]'', gave the project front page space. "If you had Jack Gould in your corner, you could not believe what it meant," said Cooney decades later.<ref name="archive">"Archive of American Television Interview with Joan Ganz Cooney", an interview by Shirley Wershba for the Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Foundation.</ref> |

|||

=== Background === |

|||

With Cooney, an assistant, and a secretary, CTW began production on the show. Cooney tried to talk George DeSarde of [[WCBS-TV]] to come to CTW as producer of the series. Within a few days of being graciously declined by DeSarde, Cooney received a letter from Mike Dann of CBS, who eagerly wanted to join as an executive producer.<ref name="archive"/> Dann and [[Fred Silverman]] decided Cooney should try to get David Connell as a producer. |

|||

During the late 1960s, 97% of all American households owned a television set, and preschool children watched an average of 27 hours of television per week.<ref>{{cite journal | last = Hellman | first = Peter | title = Street Smart: How Big Bird & Company Do It | journal = New York Magazine | volume = 20 | issue = 46 | page = 52 | date = 23 November 1987 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=KOUCAAAAMBAJ&q=sesame%20street&pg=PA48 | issn = 0028-7369 | access-date = 18 November 2019}}</ref> Early childhood educational research at the time had shown that when children were prepared to succeed in school, they earned better grades and learned more effectively. Children from low-income families, however, had fewer resources than children from higher-income families to prepare them for school. Research had shown that children from low-income, minority backgrounds tested "substantially lower"<ref>Palmer & Fisch in Fisch & Truglio, p. 5</ref> than middle-class children in school-related skills, and that they continued to have educational deficits throughout school.<ref>{{cite book | last = Lesser | first = Gerald S. | author2 = Joel Schneider | editor = Shalom M. Fisch | editor2 = Rosemarie T. Truglio | title = "G" is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street | chapter-url = https://archive.org/details/gisforgrowingthi00shal/page/26 | chapter-url-access = registration | publisher = Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers | year = 2001 | location = Mahweh, New Jersey | page = [https://archive.org/details/gisforgrowingthi00shal/page/26 26] | isbn = 0-8058-3395-1 | chapter = Creation and Evolution of the ''Sesame Street'' Curriculum }}</ref> The topic of developmental psychology had grown during this period, and scientists were beginning to understand that changes of early childhood education could increase children's cognitive growth. |

|||

[[File:Joan Ganz Cooney.JPG|thumb|upright|alt=Black and white photo of a smiling woman about fifty years of age and wearing a jacket and tied-up scarf|CTW Co-founder Joan Ganz Cooney, in 1985]] |

|||

Connell had recently left ''[[Captain Kangaroo]]'', and started his own company in an attempt to get out of the kids' TV industry. After four meetings, Cooney talked Connell into signing on, after being assured creative freedom and no micromanagement on Cooney's part. Connell insisted on a few "non-negotiables". First, he wanted to include four hosts, both black and white, male and female, none of whom would ever "own the show", as [[Bob Keeshan]] "owned" ''Captain Kangaroo'', or [[Fred Rogers]] "owned" ''[[Mister Rogers' Neighborhood]]''. He also wanted "commercials" to promote letters of the alphabet. Perhaps most importantly, Connell wanted a guarantee that education and entertainment would never be separate elements of the program. |

|||

[[File:Lloyd Morrisett and his birthday cupcakes.jpg|thumb|right|alt=White male in his 70s, wearing a dark blue sweater, to the left of a woman holding a tray of Cookie Monster cupcakes|Co-founder Lloyd Morrisett, in 2010]] |

|||

In the winter of 1966, [[Joan Ganz Cooney]] hosted what she called "a little dinner party"<ref name="interview-3">{{cite AV media | people =Shirley Wershba (host) | date =27 April 1998 | title ="Joan Ganz Cooney, Part 3" | medium = video clip | url = http://emmytvlegends.org/interviews/people/joan-ganz-cooney | access-date = 18 November 2019 |

|||

| publisher =Archive of American Television}}</ref> at her apartment near [[Gramercy Park]]. Attending were her husband Tim Cooney, her boss Lewis Freedman, and Lloyd and Mary Morrisett, whom the Cooneys knew socially.<ref>Davis, p. 12</ref> Cooney was a producer of documentary films at New York public television station WNDT (now [[WNET]]), and won an [[Emmy Award|Emmy]] for a documentary about poverty in America.<ref>O'Dell, p. 68</ref> [[Lloyd Morrisett]] was a vice-president at [[Carnegie Corporation of New York|Carnegie Corporation]], and was responsible for funding educational research, but had been frustrated in his efforts because they were unable to reach the large numbers of children in need of early education and intervention.<ref>Davis, p. 15</ref> Cooney was committed to using television to change society, and Morrisett was interested in using television to "reach greater numbers of needy kids".<ref>Davis, p. 61</ref> The conversation during the party, which according to writer Michael Davis was the start of a five-decade long professional relationship between Cooney and Morrisett, turned to the possibilities of using television to educate young children.<ref>Davis, p. 16</ref> A week later, Cooney and Freedman met with Morrisett at the office of Carnegie Corporation to discuss doing a feasibility study for creating an educational television program for preschoolers.<ref>Morrow, p. 47</ref> Cooney was chosen to perform the study.<ref name="interview-3"/> |

|||

In the summer of 1967, Cooney took a leave of absence from WNDT, and funded by Carnegie Corporation, traveled the U.S. and Canada interviewing experts in child development, education, and television. She reported her findings in a fifty-five-page document entitled "The Potential Uses of Television in Preschool Education".<ref>Davis, pp. 66–67</ref> The report described what the new series, which became ''[[Sesame Street]]'', would be like and proposed the creation of a company that managed its production, which eventually became known as the Children's Television Workshop (CTW).<ref name="interview-3"/> |

|||

While attracting Connell, Cooney received a call from Lou Hausman, who worked for the Commissioner of Education; he suggested [[Jon Stone]], also from ''Captain Kangaroo'', a producer who had retired to [[Vermont]], though no more than 35 at the time. Stone came to New York to speak with Cooney, but declined the opportunity to be an executive in the production. Stone wanted to be a producer, reporting to Cooney; Cooney suggested such an organization structure would only create "madness". Stone and Connell had a history of disputes, which were smoothed out, after the two re-met. Sam Gibbon, CTW's third alumni, had also initially declined joining any children's programming. According to Cooney, the day after [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] was assassinated, Gibbon called her to say "if you still want me, I'm yours." He was primarily involved with integrating curriculum into the series. |

|||

=== Founding === |

|||

Edith Sornow, who was not yet the film producer for ''Sesame Street'', called Cooney, asking her to come to the Johnny Victor Theatre to see a reel of commercials by [[Jim Henson]]. Cooney had heard of Henson before then, but never actually seen his work; the commercial had not aired in [[New York]], and she had never tuned into ''[[The Ed Sullivan Show]]'' when his [[The Muppets|Muppets]] appeared. After "almost falling on the floor laughing," she was open to getting him to sign on, but was doubtful he'd agree. Jon Stone, who'd worked with Henson on ABC television special ''[[Hey, Cinderella!]]'', discussed the idea with a reluctant Jim. |

|||

For the next two years, Cooney and Morrisett researched and developed the new show, acquiring $8 million funding for ''Sesame Street'', and establishing the CTW.<ref>Morrow, p. 71</ref> Due to her professional experience, Cooney always assumed the show's natural network would be PBS. Morrisett was amenable to broadcast it by commercial stations, but all three major networks rejected the idea. Davis, considering ''Sesame Street''{{'}}s licensing income years later, termed their decision "a billion-dollar blunder".<ref>Davis, p. 114</ref> Morrisett was responsible for fund acquisition, and was so successful at it that writer Lee D. Mitgang later said that it "defied conventional media wisdom". Cooney was responsible for the show's creative development, and for hiring the production and research staff for the CTW.<ref>Davis, p. 105</ref> The Carnegie Corporation provided their initial $1 million grant, and Morrisett, using his contacts, procured additional multimillion-dollar grants from the U.S. federal government, the [[Arthur Vining Davis Foundations]], the [[Corporation for Public Broadcasting]], and the [[Ford Foundation]].<ref>Davis, p. 8</ref>{{refn|group=note|Writer Lee D. Mitgang, in his book about Morrisett's involvement with the [[Markle Foundation]], reported, "The equally important role of Morrisett in ensuring ''Sesame Street's'' success and survival never received recognition approaching Cooney's public acclaim".<ref>Mitgang, p. xvi</ref>}} Morrisett's friend Harold Howe, who was the [[United States Commissioner of Education|commissioner]] for the [[U.S. Department of Education]], promised $4 million, half of the new organization's budget. The Carnegie Corporation donated an additional $1 million.<ref>Mitgang, pp. 16–17</ref> Mitgang stated, "Had Morrisett been any less effective in lining up financial support, Cooney's report likely would have become just another long-forgotten foundation idea".<ref>Mitgang, p. 17</ref> Funds gained from a combination of government agencies and private foundations protected them from the economic problems experienced by commercial networks, but caused difficulty for procuring future funding.<ref>Lesser, p. 17</ref> |

|||

Cooney's proposal included using in-house formative research that would inform and improve production, and independent summative evaluations to test the show's effect on its young viewers' learning.<ref>{{cite book | last = Fisch | first = Shalom M. | author2 = Lewis Bernstein | editor = Shalom M. Fisch | editor2 = Rosemarie T. Truglio | title = "G" is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street | publisher = Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers | year = 2001 | location = Mahweh, New Jersey | page = [https://archive.org/details/gisforgrowingthi00shal/page/40 40] | isbn = 0-8058-3395-1 | chapter = Formative Research Revealed: Methodological and Process Issues in Formative Research | chapter-url = https://archive.org/details/gisforgrowingthi00shal/page/40 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book | last = Mielke | first = Keith W. | author2 = Lewis Bernstein | editor = Shalom M. Fisch | editor2 = Rosemarie T. Truglio | title = "G" is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street | publisher = Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers | year = 2001 | location = Mahweh, New Jersey | page = [https://archive.org/details/gisforgrowingthi00shal/page/85 85] | isbn = 0-8058-3395-1 | chapter = A Review of Research on the Educational and Social Impact of Sesame Street | chapter-url = https://archive.org/details/gisforgrowingthi00shal/page/85 }}</ref> In 1967, Morrisett recruited [[Harvard University]] professor [[Gerald S. Lesser]], whom he had met while they were both psychology students at [[Yale University|Yale]],<ref>Palmer & Fisch in Fisch & Truglio, p. 8</ref> to help develop and lead the Workshop's research department. In 1972, the Markle Foundation donated $72,000 to Harvard to form the Center for Research in Children's Television, which served as a research agency for the CTW. Harvard produced about 20 major research studies about ''Sesame Street'' and its effect on young children.<ref>Mitgang, p. 45</ref> Lesser also served as the first chairman of the Workshop's advisory board, a position he held until his retirement in 1997.<ref>{{cite news |title=Remembering Professor, Emeritus, Gerald Lesser |url=https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/10/09/remembering-professor-emeritus-gerald-lesser |access-date=20 November 2019 |publisher=Harvard Graduate School of Education |date=24 September 2010 |archive-date=20 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191120220642/https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/10/09/remembering-professor-emeritus-gerald-lesser |url-status=live }}</ref> According to Lesser, the CTW's advisory board was unusual because instead of rubber-stamping the Workshop's decisions like most boards for other children's television shows, it contributed significantly to the series' design and implementation.<ref>Lesser, pp. 42–43</ref> Lesser reported in ''[[Children and Television: Lessons from Sesame Street]]'', his 1974 book about the beginnings of ''Sesame Street'' and the Children's Television Workshop, that about 8–10% of the Workshop's initial budget was spent on research.<ref>Lesser, p. 132</ref> |

|||

[[Gerald S. Lesser]] of Harvard became the head of CTW's board of academic advisors, and later brought in the [[Educational Testing Service]].<ref>Fox, Margalit. [http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/04/arts/television/04lesser.html "Gerald S. Lesser, Shaper of ‘Sesame Street,’ Dies at 84"], ''[[The New York Times]]'', October 4, 2010. Accessed October 4, 2010.</ref> |

|||

CTW's summative research was done by the Workshop's first research director, [[Edward L. Palmer]], whom they met at the curriculum seminars Lesser conducted in Boston in the summer of 1967. In the summer of 1968, Palmer began to create educational goals, define the Workshop's research activities, and hire his research team.<ref name="lesser-39">Lesser, p. 39</ref> Lesser and Palmer were the only scientists in the U.S. studying the interaction of children and television at the time.<ref>Davis, p. 144</ref> They were responsible for developing a system of planning, production, and evaluation, and the interaction between television producers and educators, later called the "CTW model".<ref>Morrow, p. 68</ref><ref>Cooney, Joan Ganz (1974). "Foreword", in Lesser, p. xvi</ref> Cooney observed of the CTW model: "From the beginning, we—the planners of the project—designed the show as an experimental research project with educational advisers, researchers, and television producers collaborating as equal partners".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Borgenicht |first1=David |title=Sesame Street Unpaved |date=1998 |publisher=Hyperion Publishing |location=New York |isbn=0-7868-6460-5 |page=[https://archive.org/details/sesamestreetunpa0000borg/page/9 9] |url=https://archive.org/details/sesamestreetunpa0000borg/page/9 }}</ref> She described the collaboration as an "arranged marriage".<ref>{{cite book | last = Cooney | first = Joan Ganz | editor = Shalom M. Fisch | editor2 = Rosemarie T. Truglio | title = "G" is for Growing: Thirty Years of Research on Children and Sesame Street | publisher = Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers | year = 2001 | location = Mahweh, New Jersey | page = xi | isbn = 0-8058-3395-1 | chapter = Foreword | url = https://archive.org/details/gisforgrowingthi00shal }}</ref> |

|||

===Establishing curriculum=== |

|||

The CTW devoted 8% of its initial budget to outreach and publicity.<ref>Lesser, p. 169</ref> In what television historian Robert W. Morrow called "an extensive campaign"<ref>Morrow, p. 112</ref> that Lesser stated "would demand at least as much ingenuity as production and research",<ref name="lesser-39" /> the Workshop promoted the show with educators, the broadcast industry, and the show's target audience, which consisted of inner-city children and their families. They hired [[Evelyn Payne Davis]] from the [[Urban League]], whom Michael Davis called "remarkable, unsinkable, and indispensable",<ref>Davis, p. 154</ref> as the Workshop's first Vice President of Community Relations and manager of the Workshop's Community Educational Services (CES) division.<ref name="lesser-39" /> Bob Hatch was hired to publicize their new series, both before its premiere and to take advantage of the media attention concerning ''Sesame Street'' during its first year of production.<ref>Lesser, p. 40</ref> |

|||

The Department of Education and other funders had decided they wanted to study children's comprehension of topics before and after watching ''Sesame Street''. Lesser set up four two-and-a-half-day seminars over the summer with producers, meeting to establish what was important to teach children. The session topics were: on perception, reasoning skills, pre-reading and pre-math, and "affective skills", the period's term for emotional skills. |

|||

According to Davis, despite her involvement with the project's initial research and development, Cooney's installment as CTW's executive director was questionable due to her lack of executive experience, untested financial management skills, and lack of experience with children's television and education. Davis also speculated that sexism was involved, stating, "Doubters also questioned whether a woman could gain the full confidence of a quorum of men from the federal government and two elite philanthropies, institutions whose wealth exceeded the gross national product of entire countries".<ref>Davis, p. 124</ref> At first, Cooney did not fight for the position. However she had the help of her husband and Morrisett, and the project's investors soon realized they could not begin without her. She was eventually named to the post in February 1968. As one of the first female executives in American television, her appointment was termed "one of the most important television developments of the decade".<ref name="davis125126">Davis, pp. 125–126</ref> The formation of the Children Television Workshop was announced at a press conference at the [[Waldorf-Astoria Hotel]] in New York City on 20 May 1968.<ref>Davis, p. 127</ref> |

|||

Cooney remembered seeing a leather-coated Jim Henson come into one of the seminars at the [[Waldorf-Astoria Hotel]], and becoming worried by his appearance that he was one of the [[Weatherman (organization)|Weathermen]]. Her concern was heightened due to the recent event of a building in [[Greenwich Village]] having been blown up by Weathermen. Cooney whispered her fears to Connell, who reassured her. Once Cooney and Jim met, Cooney says they automatically clicked. Jim much preferred general family audiences, but Cooney was able to allay Jim's fears of being "ghettoized" into children television. [[Joe Raposo]], who worked with Henson and Stone before, was added soon after. |

|||

After her appointment, Cooney hired Bob Davidson as her assistant; he was responsible for making agreements with approximately 180 public television stations to broadcast the new series.<ref>Lesser, p. 41</ref> She assembled a team of producers:<ref>{{cite book |last1=Finch |first1=Christopher |title=Jim Henson: The Works: the Art, the Magic, the Imagination |date=1993 |publisher=Random House |location=New York |isbn=978-0-679-41203-8 |page=[https://archive.org/details/jimhensonworksar0000finc/page/53 53] |url=https://archive.org/details/jimhensonworksar0000finc/page/53 }}</ref> [[Jon Stone]] was responsible for writing, casting, and format; [[David Connell (television producer)|David Connell]] assumed control of animation and volume production; and Samuel Gibbon served as the show's chief liaison between the production staff and the research team.<ref>Davis, p. 147</ref> Stone, Connell, and Gibbon had worked on another children's show, ''[[Captain Kangaroo]]'', together. Cooney later said about ''Sesame Street''{{'}}s original team of producers, "collectively, we were a genius".<ref>Gikow, p. 26</ref> CTW's first children's show, ''Sesame Street'', premiered on 10 November 1969.<ref>Davis, p. 192</ref> The CTW was not incorporated until 1970 because its creators wanted to see if the series was a success before they hired lawyers and accountants.<ref name="wershba-6">{{cite AV media | people =Shirley Wershba (host) | date =27 April 1998 | title ="Joan Ganz Cooney, Part 6" | medium = video clip | url = https://interviews.televisionacademy.com/interviews/joan-ganz-cooney#interview-clips | access-date = 20 November 2019 | publisher =Archive of American Television}}</ref> Morrisett served as the first chairperson of CTW's board of trustees, a job he had for 28 years.<ref>Mitgang, p. 39</ref> |

|||

When the [[Corporation for Public Broadcasting]] signed on to sponsor the program, the organization's chairperson was [[Frank Pace]]. Pace warned strongly against the broad curriculum ''Sesame Street'' aimed to teach. "Pick only a few goals, and accomplish them. Don't try and do too much; show... only three or four or five goals," Pace told Cooney and Connell. |

|||

===Early |

=== Early years === |

||

During the second season of ''Sesame Street'', to capitalize on the momentum the Workshop was enjoying and the attention it received from the press, the Workshop created its second series, ''[[The Electric Company]]'', in 1971. Morrisett used the same fund-acquisition techniques as he had used for ''Sesame Street''.<ref>Davis, p. 216</ref> ''The Electric Company'' stopped production in 1977, but continued in reruns until 1985; it eventually became one of the most widely used TV shows in American classrooms<ref name="wershba-6" /><ref name="odell-75">O'Dell, p. 75</ref> and was [[The Electric Company (2009 TV series)|revived in 2009]].<ref>{{cite news |last1=Davis |first1=Michael |title=PBS Revives a Show That Shines a Light on Reading |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/12/arts/television/12elec.html?_r=2&sq=The%20Electric%20Company%20revival&st=cse&oref=slogin&scp=1&pagewanted=all |access-date=20 November 2019 |work=The New York Times |date=12 May 2008 |archive-date=3 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190403010236/https://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/12/arts/television/12elec.html?_r=2&sq=The%20Electric%20Company%20revival&st=cse&oref=slogin&scp=1&pagewanted=all |url-status=live }}</ref> Starting in the early 1970s, the Workshop ventured into adult programming, but found that it was difficult to make their programs accessible to all socio-economic groups.<ref name="wershba-5"/> In 1971, it produced a medical program for adults termed ''Feelin' Good'', hosted by [[Dick Cavett]], which was broadcast until 1974. According to writer Cary O'Dell, the show "lacked a clear direction and never found a large audience".<ref>O'Dell, p. 74</ref> In 1977, the Workshop broadcast an adult drama called ''Best of Families'', which was set in New York City around the turn of the 20th century. However, it lasted for only six or seven episodes and helped the Workshop decide to emphasize children's programs only.<ref name="wershba-5">{{cite AV media | people =Shirley Wershba (host) | date =27 April 1998 | title ="Joan Ganz Cooney, Part 5" | medium = video clip | url = https://interviews.televisionacademy.com/interviews/joan-ganz-cooney#interview-clips | access-date = 20 November 2019 | publisher =Archive of American Television}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:CTW (1983).svg|thumb|The Children's Television Workshop logo from 1983 to 1997.]] |

|||

Knowing that government funding wouldn't last forever, the Ford Foundation helped CTW start investing. The company bought into small cable systems in [[Akron, Ohio]], [[Hawaii]], and another location, worthwhile investments, according to Cooney. Not as worthwhile was 1977 [[Emmy Award]] winning mini-series ''The Best of Families''. While Noble and [[The Corporation for Public Broadcasting]] each chipped in money, the Workshop came up $1 million short. Too late to turn around, it was forced to fund the miniseries with Ford Foundation money meant for ''Sesame Street''. |

|||

Throughout the 1970s, the CTW's main non-television efforts changed from promotion to the development of educational materials for preschool settings.<ref>Yotive and Fisch, pp. 181–182</ref> Early efforts included mobile viewing units that broadcast the show in the inner cities, in [[Appalachia]], in [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] communities, and in [[migrant worker]] camps.<ref>Gikow, pp. 282–283</ref> In the early 1980s, the CTW created the Preschool Education Program (PEP), whose goal was to assist preschools, by combining television viewing, books, hands-on activities, and other media, in using the series as an educational resource.<ref>Yotive and Fisch, pp. 182–183</ref> The Workshop also provided materials to non-English speaking children and adults. Starting in 2006, the Workshop expanded its programs by creating a series of PBS specials and DVDs largely concerning how military deployment affects the families of soldiers.<ref>Gikow, pp. 280–281</ref> Other efforts by the Workshop concerned families of prisoners, health and wellness, and safety.<ref>Gikow, pp. 286–293</ref> |

|||

According to Cooney and O'Dell, the 1980s were a problematic period for the Workshop.<ref name="odell-75" /><ref name="wershba-7">{{cite AV media | people =Shirley Wershba (host) | date =27 April 1998 | title ="Joan Ganz Cooney, Part 7" | medium = video clip | url = https://interviews.televisionacademy.com/interviews/joan-ganz-cooney#interview-clips | access-date = 20 November 2019 | publisher =Archive of American Television}}</ref> A series of poor investments in video games, motion picture production, theme parks, and other business ventures hurt the organization financially.<ref name="odell-75" /> Cooney brought in Bill Whaley during the late 1970s to work on their licensing agreements, but he was unable to compensate for the CTW's losses until 1986, when licensing revenues stabilized and its portfolio investments increased.<ref name="odell-75" /><ref name="wershba-7" /> Despite financial troubles, the Workshop continued to produce new shows throughout the decade. ''[[3-2-1 Contact]]'' premiered in 1980 and ran for seven seasons. The CTW found that finding funding for this series and other science-oriented series like ''[[Square One Television]]'', which was broadcast from 1987 to 1992, was easy because the [[National Science Foundation]] and other foundations were interested in funding science education.<ref name="wershba-5" /><ref name="wershba-9">{{cite AV media | people =Shirley Wershba (host) | date =27 April 1998 | title ="Joan Ganz Cooney, Part 9" | medium = video clip | url = https://interviews.televisionacademy.com/interviews/joan-ganz-cooney#interview-clips | access-date = 20 November 2019 | publisher =Archive of American Television}}</ref> |

|||

===International growth=== |

|||

=== Later years === |

|||

In 1970, Mike Dann finally came to the Children's Television Workshop from CBS, in the capacity of international sales. He called the CTW "one of the most important breakthroughs in the history of media".<ref>{{cite book | last = Lesser | first = Gerald S. | title = Children and Television: Lessons from Sesame Street | publisher = Random House | year = 1975 | location = New York | page = 36 | isbn = 0-394-71448-2}}</ref> |

|||

Cooney stepped down as chairman and chief executive officer of the CTW in 1990, when she was replaced by David Britt, who was her "chief lieutenant in the executive ranks through the mid-1990s"<ref>Davis, p. 260</ref> and whom Cooney termed her "right-hand for many years".<ref name="wershba-9" /> Britt had worked for her at the CTW since 1975 and had served as its president and chief operating officer since 1988. At that time, Cooney became chairman of the Workshop's executive board, which managed its businesses and licensing, and became more involved with the organization's creative efforts.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Carter |first1=Bill |title=Children's TV Workshop Head to Step Down |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1990/07/31/arts/children-s-tv-workshop-head-to-step-down.html |access-date=21 November 2019 |work=The New York Times |date=31 July 1990 |archive-date=27 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191127191408/https://www.nytimes.com/1990/07/31/arts/children-s-tv-workshop-head-to-step-down.html |url-status=live }}</ref> The Workshop had a reorganization in 1995, and dismissed about 12 percent of its staff.<ref>O'Dell, p. 76</ref> In 1998, for the first time in the series' history, they accepted funds from corporations for ''Sesame Street'' and its other programs,<ref>{{cite news |last1=Brooke |first1=Jill |title='Sesame Street' takes a bow to 30 animated years |url=http://www.cnn.com/SHOWBIZ/TV/9811/13/sesame.street/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/19990128192944/http://www.cnn.com/SHOWBIZ/TV/9811/13/sesame.street/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=28 January 1999 |access-date=21 November 2019 |work=CNN.com |date=13 November 1998}}</ref> a policy criticized by consumer advocate [[Ralph Nader]]. The Workshop defended the acceptance of corporate sponsorship, stating that it compensated for a decrease of government subsidies.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Frankel |first1=Daniel |title=Nader Says "Sesame Street" Sells Out |url=https://www.eonline.com/news/37115/nader-says-sesame-street-sells-out |access-date=21 November 2019 |work=E! News |date=7 October 1998 |archive-date=7 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190407063512/https://www.eonline.com/news/37115/nader-says-sesame-street-sells-out |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Also in 1998, the CTW invested $25 million in an educational cable channel called [[Noggin (TV channel)|Noggin]].<ref>{{cite news |last1=Kirchdoerffer |first1=Ed |title=CTW and Nick put heads together to create Noggin |url=http://kidscreen.com/1998/06/01/22207-19980601/ |access-date=21 November 2019 |work=Kidscreen.com |date=1 June 1998 |archive-date=21 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191121213359/http://kidscreen.com/1998/06/01/22207-19980601/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Noggin was a joint venture between the CTW and [[Viacom (1952–2006)|Viacom]]'s [[MTV Networks]],<ref>{{cite web|title=The-N.com Terms & Conditions|url=http://www.the-n.com/footerPage.php?ipv_sectionID=46&ipv_articleID=52|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020609152931/http://www.the-n.com/footerPage.php?ipv_sectionID=46&ipv_articleID=52|archive-date=June 9, 2002|work=Noggin LLC|quote=This Site at THE-N.COM is fully controlled and operated by Noggin LLC, a joint venture of MTV Networks, a division of Viacom International, Inc., and Sesame Workshop.}}</ref> and launched on February 2, 1999.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/entertainment/lucky-children-start-noggin-article-1.825516 |title=A Lucky Few Children Get to Start Using Their Noggin|last=Bianculli|first=David |publisher=[[NY Daily News]] |date=February 2, 1999 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151102175438/http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/entertainment/lucky-children-start-noggin-article-1.825516|archive-date=November 2, 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> [[Gary Knell]] explained that creating a new channel allowed the CTW to more easily "ensure that our programming gets out there."<ref>{{Cite magazine|url=https://ew.com/article/1998/11/20/can-elmo-get-along-rugrats/|title=Can Elmo get along with the Rugrats?|first=Joe|last=Flint|date=November 20, 1998|magazine=[[Entertainment Weekly]]}}</ref> While the Workshop would eventually produce various new shows for Noggin, the channel's early lineup consisted mostly of older shows from the CTW's library.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://variety.com/1998/tv/news/mtv-uses-nick-s-noggin-as-new-net-1117470274/|title=MTV uses Nick's Noggin as new net|first=Richard|last=Katz|date=April 29, 1998|work=[[Variety (magazine)|Variety]]}}</ref> |

|||

===Later=== |

|||

In the 1980s, CTW created a series of video games under the name of [[Children's Computer Workshop]], including ''[[Cookie Monster Munch]]'' and ''[[Alpha Beam with Ernie]]. '' Today the company also publishes ''Sesame Street Magazine'' in cooperation with [[Time Inc.]]'s ''Parenting'' magazine. At one time it also published ''[[The Electric Company]]'', ''Kid City'', ''[[3-2-1 Contact]]'' (later ''Contact Kids''), and ''Sesame Street Parents'' magazines. |

|||

In 2000, profits earned from the Noggin deal, along with the revenue caused partly by the "Tickle Me Elmo" craze, enabled the CTW to purchase [[The Jim Henson Company]]'s rights to the ''Sesame Street'' Muppets from the German media company [[EM.TV]], which had acquired Henson earlier that year. The transaction, valued at $180 million, also included a small interest Henson had in the Noggin cable channel.<ref>{{cite news |title=Sesame Workshop gains character control from EM.TV |url=https://muppetcentral.com/news/2000/120400.shtml |access-date=21 November 2019 |work=Muppet Central News |date=4 December 2000 |archive-date=17 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190817180444/https://muppetcentral.com/news/2000/120400.shtml |url-status=live }}</ref> Gary Knell stated, "Everyone, most especially the puppeteers, were thrilled that we were able to bring them home. It protected ''Sesame Street'' and allowed our international expansion to continue. Owning these characters has allowed us to maximize their potential. We are now in control of our own destiny".<ref>Davis, p. 348</ref> |

|||

In August 1997, [[ABC Family|Fox Family]] started efforts to increase its quantity and quality of children's entertainment, "which could lead to an equity investment by Fox in the non-profit CTW in exchange for programs for its Family Channel." Nothing ever materialised.<ref name="foxctwkids">{{cite news | last=Ross | first=Chuck | title=Fox eyes linkup with CTW to boost its kids offerings | date=August 11, 1997 | publisher=Advertising Age | url=http://search.epnet.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rch&an=18191815}}, accessed through EBSCOhost.</ref> |

|||

The CTW changed its name to Sesame Workshop in June 2000, to better represent its non-television activities and interactive media.<ref>{{cite news |title=CTW Changes Name to Sesame Workshop |url=https://muppetcentral.com/news/2000/060500.shtml |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191121222001/https://muppetcentral.com/news/2000/060500.shtml |url-status=dead |archive-date=21 November 2019 |access-date=21 November 2019 |work=Muppet Central News |agency=Reuters |date=5 June 2000}}</ref> Also in 2000, Gary Knell succeeded Britt as president and CEO of the Workshop; according to Davis, he "presided over an especially fertile period in the nonprofit's history".<ref name="davis-345">Davis, p. 345</ref> Under Knell's management, Sesame Workshop produced a variety of original shows for Noggin. The first was an interactive game show called ''[[Sponk!]]'', which was meant to model good collaboration and teamwork skills.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.sesameworkshop.org/programs/sponk|title=Sponk!|date=June 8, 2011|website=SesameWorkshop.org|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110608011042/http://www.sesameworkshop.org/programs/sponk |archive-date=2011-06-08 }}</ref> Sesame Workshop also co-produced a ''Sesame Street'' spin-off, ''[[Play with Me Sesame]]'', for Noggin.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://kidscreen.com/2002/01/03/noggin-20020103/|title=Noggin has tween educon on the brain|work=[[Kidscreen]]|date=January 3, 2002|last=Connell|first=Mike}}</ref> In April 2002, Noggin premiered an overnight block for teenagers called [[The N]]. Sesame Workshop created its first-ever teen drama series, ''[[Out There (2003 TV series)|Out There]]'', for The N.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nexttv.com/news/noggin-sesame-are-out-there-152276|title=Noggin, Sesame Are Out There|work=[[Multichannel News]]|last=Applebaum|first=Simon|date=February 19, 2003}}</ref> |

|||

In 1999, CTW partnered in a joint venture with [[Viacom]]'s [[Nickelodeon (TV channel)|Nickelodeon]] to launch Noggin, a 24-hour cable channel aimed at 6-13 year olds; Viacom's [[MTV Networks]] division (which also operates Nickelodeon) operated the channel with CTW and MTV Networks jointly owning Noggin. In 2002, low ratings in part prompted the now-renamed Sesame Workshop to pull out and sell its interest in Noggin to Viacom. As a result, most of the Sesame Workshop-produced series carried by the channel were dropped. Noggin soon after became a timeshare service (in the same vein as Nickelodeon is by carrying [[Nick at Nite]] over the same channel space) starting the teen-oriented The N that fall, which became a separate channel from Noggin on December 31, 2007 with Noggin becoming a 24-hour channel for preschoolers; the Noggin channel was rebranded [[Nick Jr.]] on September 28, 2009. |

|||

In August 2002, Sesame Workshop sold its 50% share of Noggin to Viacom.<ref>{{cite news |title=Sesame Workshop sells its stake in Noggin cable network |url=http://current.org/files/archive-site/ch/ch0216noggin.html |date=September 2, 2002 |last=Everhart |first=Karen |work=Current.org |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160402191348/http://current.org/files/archive-site/ch/ch0216noggin.html |archive-date=April 2, 2016 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=Jeffrey D. Dunn Named Chief of Sesame Workshop |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/09/business/media/jeffrey-d-dunn-named-chief-of-sesame-workshop.html?_r=0 |date=September 8, 2014 |last=Jensen |first=Elizabeth |work=[[The New York Times]] }}</ref> The buyout was partially caused by SW's need to pay off debt.<ref>{{cite news |title=JV Is for VC: Sesame Street Creator Launches $10 Million Venture Fund for Child Development |url=https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-02-01-v-is-for-vc-sesame-street-creator-launches-10-million-venture-fund-for-child-development |date=February 1, 2016 |last=Wan |first=Tony |work=[[EdSurge]]}}</ref> Sesame Workshop remained involved with the network's programming, as Viacom entered a multi-year production deal with Sesame Workshop shortly after the split and continued to broadcast the company's shows.<ref>{{cite news |title=Nickelodeon Buys Out Noggin; Enters Into Production Deal With Sesame Workshop |url=http://www.awn.com/news/nickelodeon-buys-out-noggin-enters-production-deal-sesame-workshop |last=Godfrey |first=Leigh |date=August 9, 2002 |work=[[Animation World Network]]}}</ref> The last collaboration between Noggin and Sesame Workshop was ''[[The Upside Down Show]]'', which premiered in 2006.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.tvweek.com/in-depth/2005/12/noggin-orders-upside-down/|title=Noggin Orders 'Upside Down'|work=[[TVWeek]]|date=December 6, 2005}}</ref> |

|||

Although Sesame Workshop is occasionally confused with PBS, {{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} Sesame Workshop is an entirely separate and independent organization. Some Workshop programs are broadcast on PBS, and although PBS provides some funding for those programs, the money received covers only a fraction of production costs. Other financial support comes from individual donors, charitable foundations, corporations, government agencies, program sales and licensed products. Sesame Workshop grants licenses to various manufacturers who create toys, apparel and other products featuring Sesame Street characters, and Sesame Workshop receives a portion of the proceeds. |

|||

Outside of Noggin, Knell was instrumental in the creation of the cable channel [[Sprout (TV channel)|Sprout]] in 2005.<ref name="davis-345" /> Sprout (launched as PBS Kids Sprout) was founded as a partnership between the Workshop, [[Comcast]], [[PBS]], and [[HIT Entertainment]], all of whom contributed older programming from their archive libraries to the new network.<ref>{{cite news |title=Sprout channel to launch on Comcast September 1 |url=https://muppetcentral.com/news/2005/040405.shtml |access-date=21 November 2019 |work=Muppet Central News |date=4 April 2005 |archive-date=21 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191121223122/https://muppetcentral.com/news/2005/040405.shtml |url-status=live }}</ref> After seven years as a partner, the Workshop divested its stake in Sprout to [[NBCUniversal]] in December 2012.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Jensen |first1=Elizabeth |title=NBCUniversal Takes Full Ownership of Sprout Cable Network |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/14/business/media/nbcuniversal-takes-ownership-of-sprout-cable-network.html |access-date=21 November 2019 |work=The New York Times |date=13 November 2013 |archive-date=27 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191127191405/https://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/14/business/media/nbcuniversal-takes-ownership-of-sprout-cable-network.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

On March 12, 2009, Sesame Workshop announced that it had planned to cut 20% of its workforce due to the [[Late 2000s recession|recession]].<ref>http://business.theage.com.au/business/world-business/1-2-3--sesame-street-jobs-go-20090312-8vhg.html business.theage.com.au</ref> |

|||

In 2007, the Sesame Workshop founded [[The Joan Ganz Cooney Center]], an independent, non-profit organization that studies how to improve children's literacy by using and developing digital technologies "grounded in detailed educational curriculum", just as was done during the development of ''Sesame Street''.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Jensen |first1=Elizabeth |title=Institute Named for 'Sesame' Creator |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/06/arts/television/06sesa.html?_r=3 |access-date=21 November 2019 |work=The New York Times |date=6 December 2007 |archive-date=21 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200621064927/https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/06/arts/television/06sesa.html?_r=3 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

On October 15, 2009, [[Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc.]] announced a distribution deal for the [[Sesame Street]] library, including new and old titles. They plan to release 10 titles a year starting in 2010 with ''Elmo's World: Let's Play Music'' on February 2, 2010, ''Elmo's Rainbow and Other Springtime Stories'' on March 9, 2010, ''Bert and Ernie's Great Adventures'' on April 6, 2010, ''The Best of Elmo 2'' on May 4, 2010, ''Firefly Fun and Buggy Buddies'' on June 1, 2010, ''Preschool is Cool!: ABCs with Elmo'' on July 6, 2010, ''P is for Princess'' on August 3, 2010, ''Preschool is Cool!: Counting with Elmo'' on September 14, 2010, ''Iron Monster and Other Sesame Heroes'' on October 5, 2010, and ''C is for Cookie Monster'' on October 19, 2010, but none were released from [[Warner Bros.]] for the remainder of 2009. |

|||

[[File:Sesame Workshop text logo.png|thumb|right|alt=Green wording spelling out "sesameworkshop" in lower case letters|Sesame Workshop wordmark used from 2007 to 2018.|272x272px]] |

|||

==Notable persons at Sesame Workshop== |

|||

* '''Gary E. Knell''', President, CEO |

|||

* '''Jerald Harvey''', Senior Adviser |

|||

* '''[[Joan Ganz Cooney]]''', Co Founder |

|||

* '''[[Lloyd Morrisett]]''', Co Founder |

|||

* '''Franklin Getchell''', Executive Vice President |

|||

* '''[[Nina Elias-Bamberger]]''', Chief Executive Officer |

|||

* '''Majorie Kalins''', Series Administrative Officer |

|||

* '''H. Melvin Ming''', Chief Operating Officer |

|||

* '''Susan Kolar''', Executive Vice President, Chief Administrative Officer |

|||

* '''Dr. Lewis Bernstein''', Executive Vice President, Education, Research and Outreach |

|||

* '''[[Carol-Lynn Parente]]''', Executive Producer of Sesame Street |

|||

* '''Terry Fitzpatrick''', Executive Vice President, Distribution |

|||

* '''Daniel J. Victor''', Executive Vice President, International |

|||

* '''Maura Regan''', Vice President and General Manager, Global Consumer Products |

|||

* '''[[Sherrie Westin]]''', Executive Vice President and Chief Marketing Office |

|||

* '''Myung Kang-Haneke''', Vice President, General Counsel |

|||

* '''[[Hillary Rodham Clinton]]''', former director, board member |

|||

* [[David C. Cole]], former director<ref> {{cite book |title= New ideas about new ideas: insights on creativity from the world's leading innovators |author= Shira P. White |editor= G. Patton Wright |isbn= 9780738205359 |publisher= Basic Books |year= 2002 |url= http://books.google.com/books?id=HdjRDARK_v0C&pg=PA299 }}</ref> |

|||

The 2008–2009 recession, which resulted in budget reductions for many nonprofit arts organizations, severely affected the organization; in 2009, it had to dismiss 20% of its staff.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Guernsey |first1=Lisa |title=How Sesame Street Changed the World |url=https://www.newsweek.com/how-sesame-street-changed-world-80067 |access-date=22 November 2019 |work=Newsweek |date=22 May 2009 |archive-date=10 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191210010326/https://www.newsweek.com/how-sesame-street-changed-world-80067 |url-status=live }}</ref> Despite earning about $100 million from licensing revenue, royalties, and foundation and government funding in 2012, the Workshop's total revenue was down 15% and its operating loss doubled to $24.3 million. In 2013, it responded by dismissing 10% of its staff, saying that it was necessary to "strategically focus" their resources because of "today's rapidly changing digital environment".<ref>{{cite news |last1=Isidore |first1=Chris |title=Layoffs hit Sesame Street |url=https://money.cnn.com/2013/06/26/news/companies/sesame-street-layoff/ |access-date=22 November 2019 |work=CNN Money. |date=26 June 2013 |archive-date=23 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191123005027/https://money.cnn.com/2013/06/26/news/companies/sesame-street-layoff/ |url-status=live }}</ref> In 2011, Knell left Sesame Workshop to become the chief executive of [[NPR|National Public Radio]] (NPR).<ref>{{cite news |last1=Kahana |first1=Menahem |title=Gary Knell named chief of NPR |url=https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/money/media/story/2011-10-02/npr-new-ceo/50637472/1 |access-date=22 November 2019 |work=USA Today |date=2 October 2011 |archive-date=5 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305064833/http://www.usatoday.com/money/media/story/2011-10-02/npr-new-ceo/50637472/1 |url-status=live }}</ref> [[H. Melvin Ming]], who had been the organization's chief financial officer since 1999 and chief operating officer since 2002, was named as his replacement.<ref>{{cite press release |last=Westin |first= Sherrie |date= 3 October 2011 |title= Sesame Workshop Appoints H. Melvin Ming as President and CEO |url=http://www.sesameworkshop.org/newsandevents/pressreleaes/mel_ming_ceo |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111226173204/http://www.sesameworkshop.org/newsandevents/pressreleaes/mel_ming_ceo |url-status=dead |archive-date=26 December 2011 |location= New York |publisher= Sesame Workshop |access-date= 22 November 2019}}</ref> In 2014, H. Melvin Ming retired and was succeeded by former HIT Entertainment and Nickelodeon executive Jeffery D. Dunn. Dunn's appointment was the first time someone not affiliated with CTW or Sesame Workshop became its manager, although he had associations with the organization previously.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Jensen|first1=Elizabeth|title=Jeffrey D. Dunn Named Chief of Sesame Workshop|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/09/business/media/jeffrey-d-dunn-named-chief-of-sesame-workshop.html?_r=1|access-date=22 November 2019|work=The New York Times|date=8 September 2014|archive-date=8 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308233517/https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/09/business/media/jeffrey-d-dunn-named-chief-of-sesame-workshop.html?_r=1|url-status=live}}</ref> In 2021, Dunn retired. It was replaced by [[Sherrie Rollins Westin]], who had served as president of SW's Social Impact and Philanthropy Division for six years.<ref>{{cite press release |last1=Fishman |first1= Lizzie |last2=Greenberg| first2= Courtney |date= 27 October 2020 |title= Sesame Workshop Announces Leadership Transition, Effective January 1, 2021 |url= https://www.sesameworkshop.org/press-room/press-releases/sesame-workshop-announces-leadership-transition-effective-january-1-2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210417015333/https://www.sesameworkshop.org/press-room/press-releases/sesame-workshop-announces-leadership-transition-effective-january-1-2021 |archive-date=17 April 2021 |location= New York |publisher= Sesame Workshop |access-date= 1 January 2022}}</ref> |

|||

==Productions== |

|||

===''Children's Television Workshop'' television series=== |

|||

{{Wikinewshas|related [[wikinews:Sesame Street/News/Wikinews|Sesame Street news]]}} |

|||

* ''[[Sesame Street]]'' (1969–present; from 1969–2001, the muppet characters were owned by [[The Jim Henson Company]]) |

|||

* ''[[The Electric Company]]'' ([[The Electric Company (1971 TV series)|1971-1977]]; [[The Electric Company (2009 TV series)|2009-]], including ''[[Spidey Super Stories]]'', 1974–1977) |

|||

* ''[[Sesame Park]]'' (1972–2002) (in conjunction with [[The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation]]) |

|||

* ''[[Plaza Sesamo]]'' (1972-present) |

|||

* ''Feeling Good'' (1974–1975) |

|||

* ''[[3-2-1 Contact]]'' (including ''[[The Bloodhound Gang (TV series)|Bloodhound Gang]]'', 1980–1988) |

|||

* ''[[Encyclopedia (TV series)|Encyclopedia]]'' (1988) |

|||

* ''[[Square One (TV show)|Square One]]'' (including ''[[Mathnet]]'', 1987–1992) |

|||

* ''[[Zak Tales]]'' (1990–1991) (in conjunction with [[DIC Entertainment]]) |

|||

* ''[[Ghostwriter (TV series)|Ghostwriter]]'' (1992–1995) (in conjunction with [[BBC One|BBC1]]) |

|||

* ''[[Cro]]'' (1993–1994) (in conjunction with the [[National Science Foundation]] and [[Film Roman]]) |

|||

* ''[[William's Wish Wellingtons]]'' (1994–1997) (in conjunction with [[BBC One|BBC1]] and Hibbert Ralph) (owned by [[HIT Entertainment]]) |

|||

* ''[[Big Bag]]'' (1996–1998) |

|||

* ''[[Koki]]'' (1996–1997) (in conjunction with Cine Nic Producciones and [[Right Media]]) |

|||

* ''Slim Pig'' (1996–1997) (in conjunction with Cheeky Ideas) |

|||

* ''Troubles the Cat'' (1996–1997) |

|||

* ''Samuel and Nina'' (1996–1997) (in conjunction with [[Yoram Gross]]) |

|||

* ''[[The New Ghostwriter Mysteries]]'' (1997) |

|||

* ''[[A Place of Our Own]]'' (1998–present) (in conjunction with [[KCET]] and [[44 Blue Productions]]) |

|||

* ''[[Elmo's World]]'' (1998–present) |

|||

* ''Ace and Avery'' (1998) (in conjunction with [[Stretch Films]]) |

|||

* ''Tobias Totz and His Lion'' (1999) (in conjunction with Munich Animation and [[Warner Bros. Pictures]]) |

|||

* ''[[Dragon Tales]]'' (1999–2005) (in conjunction with [[Columbia TriStar Television]] (1999–2002) [[Sony Pictures Television]] (2002–2005 and reruns since 2006)) |

|||

* ''[[Sesame Street Unpaved]]'' (1999–2002) |

|||

* ''[[123 Sesame Street|123 Sesame Street Syndication Package]]'' (1999–2005) |

|||

* ''[[Sesame English]]'' (1999–present) |

|||

== ''Sesame Workshop'' television series== |

|||

* ''[[Sagwa, the Chinese Siamese Cat]]'' (2001–2002) (in conjunction with [[CinéGroupe]]) |

|||

* ''[[Sponk!]]'' (2001–2002) (in conjunction with [[Noggin (TV channel)|Noggin]] and Insight Production Company) |

|||

* ''[[Tiny Planets]]'' (2001–present) (in conjunction with Pepper's Ghost Productions) |

|||

* ''[[Pecola]]'' (2001) (in conjunction with [[Nelvana]]) |

|||

* ''[[Play with Me Sesame]]'' (2002–present) |

|||

* ''[[Out There (Australian TV series)|Out There]]'' (2003–2004) (in conjunction with [[CBBC]] and Blink Films) |

|||

* ''[[Sesame Stories]]'' (2003–present) |

|||

* ''[[Grover#Appearances|Global Grover]]'' (2003–present) |

|||

* ''[[The Upside Down Show]]'' (2006–present) |

|||

* ''[[Pinky Dinky Doo]]'' (2006–present) |

|||

* ''[[Panwapa]]'' (2008) |

|||

* ''[[Bert and Ernie's Great Adventures]]'' (2008–present) (in conjunction with [[Milkshake!]]) |

|||

In 2019, ''[[The Hollywood Reporter]]'' reported that Sesame Workshop's operating income was approximately $1.6 million, after the majority of its funds earned from grants, licensing deals, and royalties went back into its content, its total operating costs were over $100 million per year. Operating costs included salaries, $6 million in rent for its [[Lincoln Center]] corporate offices, its production facilities in Queens, and the costs of producing content for its YouTube channels and other outlets. The organization employed about 400 people, including "several highly skilled puppeteers". Royalties and distribution fees, which accounted for $52.9 million in 2018, made up the Workshop's biggest revenue source. Donations brought in $47.8 million, or 31 percent of its income. Licensing revenue from games, toys, and clothing earned the organization $4.5 million.<ref name="guthrie2">{{cite news |last1=Guthrie |first1=Marisa |title=Where 'Sesame Street' Gets Its Funding — and How It Nearly Went Broke |url=https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/sesame-street-gets-funding-how-it-went-broke-1183032 |access-date=20 April 2019 |work=The Hollywood Reporter |date=6 February 2019 |archive-date=18 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190418223110/https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/sesame-street-gets-funding-how-it-went-broke-1183032 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

===Telefilms and miniseries=== |

|||

* ''[[Out to Lunch (1974 TV movie)|Out to Lunch]]'' (1974 telefilm) |

|||

* ''The Best of Families'' (1977 mini–series) |

|||

* ''[[Christmas Eve on Sesame Street]]'' (1978) |

|||

* ''[[The_Chronicles_of_Narnia#Narnia_in_other_media|The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe]]'' (1979 telefilm) |

|||

* ''[[Don't Eat the Pictures]]'' (1983) |

|||

* ''[[Big Bird in China]]'' (1983) |

|||

* ''[[The House of Dies Drear]]'' (1984 telefilm) |

|||

* ''[[Big Bird in Japan]]'' (1989) |

|||

* ''[[Elmo Saves Christmas]]'' (1996) |

|||

* ''[[Elmopalooza]]'' (1998) |

|||

This list excludes Sesame Street co-productions outside the [[United States]]. |

|||

== Funding sources == |

|||

===Theatrical films=== |

|||

After ''Sesame Street''{{'}}s initial success, the CTW began to think about its survival beyond the development and first season of the show, since its funding sources were composed of organizations and institutions that tended to start projects, not sustain them.<ref name="davis-203">Davis, p. 203</ref> Although the organization was what Cooney termed "the darling of the federal government for a brief period of two or three years",<ref>Davis, p. 218</ref> its first ten years of existence was marked by conflicts between the two; in 1978, the [[US Department of Education]] refused to deliver a $2 million check until the last day of the CTW's fiscal year.<ref>O'Dell, p. 73</ref> According to Davis, the federal government was opposed to funding public television, but the Workshop used Cooney's prestige and fame, and the fact that there would be "great public outcry"<ref name="wershba-6" /> if the series was de-funded, to withstand the government's attacks on PBS. Eventually, the CTW got its own line item in the federal budget.<ref>Davis, pp. 218–219</ref> By 2019, the U.S. government donated about four percent of the Workshop's budget, or less than $5 million a year.<ref name="guthrie2"/> |

|||

* ''[[The Muppet Movie]]'' (1979) ([[Big Bird]] cameo) (in conjunction with [[Henson Associates]] and [[ITC Entertainment]]) |

|||

* ''[[The Great Muppet Caper]]'' (1981) ([[Oscar the Grouch]] cameo) (in conjunction with [[Henson Associates]], [[ITC Entertainment]], and [[Universal Pictures]]) |

|||

* ''[[The Muppets Take Manhattan]]'' (1984) ([[Sesame Street]] characters cameo) (in conjunction with [[Henson Associates]] and [[Tri-Star Pictures]]) |

|||

* ''[[Sesame Street Presents: Follow That Bird]]'' (1985) (in conjunction with [[Warner Bros. Pictures]] and [[Henson Associates]]) |

|||

* ''[[The Adventures of Elmo in Grouchland]]'' (1999) (in conjunction with [[Columbia Pictures]] and [[Jim Henson Pictures]]) |

|||

* ''[[Night at the Museum: Battle of the Smithsonian]]'' (2009) ([[Oscar the Grouch]] cameo) (in conjunction with [[20th Century Fox]]) |

|||

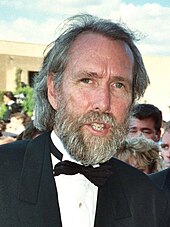

[[File:Jim Henson (1989) headshot.jpg|left|thumb|upright|alt=A tall, thin man in his early fifties, with salty-gray hair and a full beard, and wearing a tuxedo.|[[Jim Henson]], creator of [[the Muppets]], in 1989]] |

|||

==Merchandising== |

|||

Current licensees include [[Fisher-Price]], Nakajima USA, [[Build-A-Bear Workshop]] (Build-An-Elmo, Build-A-Cookie Monster, And Build-A-Big Bird), [[Gund|GUND]], [[Hasbro]] ([[Monopoly (game)|Sesame Street Monopoly]]), [[Wooly Willy]], [[Betty Crocker]] (Elmo Fruit Snacks), C&D Visionary (air freshners) and [[Children's Apparel Network]]. Former licences include [[Applause]], Child Dimension, [[Gibson Greetings]], Gorham Fine China, [[Ideal Toys]], [[Milton Bradley Company]], [[Nintendo]], [[Palisades Toys]], [[Questor]], [[Radio Shack]], [[Tyco]], and the [[Western Publishing Company]]. [[Creative Wonders]] (a partnership between [[American Broadcasting Company|ABC]] and [[Electronic Arts]]) produced Sesame Street software for the Macintosh, since at least 1995 and on the PC since 1996<!--1994?-->; [[Atari]] produced ''Sesame Street'' games in 1983. Before going bankrupt, [[Palisades Toys]] was to release a line of deluxe series action figures, for adults, as part of Sesame Workshop's push to expand into retro products for teens and adults. Only a [[Super Grover]] figure was distributed to conventioneers. |

|||

For the first time, a public broadcasting series had the potential to earn a great deal of money. Immediately after its premiere, ''Sesame Street ''gained attention from marketers,<ref name="davis-203" /> so the Workshop explored sources such as licensing arrangements, publishing, and international sales, and became, as Cooney envisioned, a "multiple media institution".<ref name="cherow-197">Cherow-O'Leary in Fisch & Truglio, p. 197</ref> Licensing became the foundation of, as writer Louise Gikow stated, the Sesame Workshop endowment,<ref name="gikow-268">Gikow, p. 268</ref> which had the potential to fund the organization and future productions and projects.<ref name="davis-205" /> Muppet creator [[Jim Henson]] owned the trademarks to the [[List of Sesame Street Muppets|Muppet characters]]: he was reluctant to market them at first, but agreed when the CTW promised that the profits from toys, books, and other products were to be used exclusively to fund the CTW. The producers demanded complete control of all products and product decisions throughout its history; any product line associated with the series had to be educational, inexpensive, and not advertised during broadcastings of ''Sesame Street''.<ref>Davis, pp. 203–205</ref> As Davis reported, "Cooney stressed restraint, prudence, and caution" in their marketing and licensing efforts.<ref>Davis, p. 204</ref> In the early 1970s, the CTW negotiated with [[Random House]] to establish and manage a non-broadcast materials division. Random House and the CTW named [[Christopher Cerf (musician and television producer)|Christopher Cerf]] to assist the CTW in publishing books and other materials that emphasized the series' curriculum.<ref name="davis-205">Davis, p. 205</ref> By 2019, the Sesame Workshop had over 500 licensing agreements, and its total revenue in 2018 was $35 million. A million children play with ''Sesame Street''-themed toys per day.<ref name="wallace"/><ref name="guthrie"/> |

|||

The [[Sesame Beginnings]] line, launched in mid-2005, consists of apparel, health and body, home, and seasonal products.<ref>{{cite news | title=Loblaws and Sesame Workshop Introduce Exclusive Line of Sesame Beginnings and Sesame Street Products to Canada | url=http://www.sesameworkshop.org/newsandevents/pressreleases/products_canada | publisher=Sesame Workshop Press Release | date=April 20, 2005 | accessdate=2009-10-22}}</ref> The products in this line are designed to accentuate the natural interactivity between infants and their parents. Most of the line is exclusive to a family of Canadian retailers that includes [[Loblaws]], [[Fortinos]], and [[Zehrs]]. |

|||

Soon after the premiere of ''Sesame Street'', producers, educators, and officials of other nations began requesting that a version of the series be broadcast in their countries. [[CBS]] executive [[Michael Dann]] was required to quit his job at that network due to a change of corporate policy preceding the so-called "[[rural purge]]"; upon his ouster, he became vice-president of the CTW and Cooney's assistant.{{refn|group=note|Dann called the creation of the CTW "one of the most important breakthroughs in the history of the mass media".<ref>Lesser, p. 36</ref>}} Dann then began developing foreign versions of ''Sesame Street''<ref name="cole-147"/> by arranging what were eventually termed [[International co-productions of Sesame Street|co-productions]], or independent programs with their own sets, characters, and curriculum goals. By 2009, ''Sesame Street'' had expanded into 140 countries;<ref>Gikow, p. 11</ref> ''[[The New York Times]]'' reported in 2005 that income from the CTW's international co-productions of the series was $96 million.<ref>Carvajal, Doreen (12 December 2005). [https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/12/business/media/12sesame.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0 "Sesame Street Goes Global: Let's All Count the Revenue".] ''The New York Times.'' Retrieved 12 May 2014</ref> By 2008, the ''Sesame Street'' Muppets accounted for between $15 million and $17 million per year in licensing and merchandising fees, divided between the Workshop and [[Henson Associates]].<ref>Davis, p. 5</ref>{{refn|As of 2019, ''Sesame Street'' has produced 200 home videos and 180 albums.<ref name="wallace"/>|group=note}} The Workshop began pursuing funding from corporate sponsors in 1998; consumer advocate [[Ralph Nader]] urged parents to protest the move by boycotting the show.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Frankel |first1=Daniel |title=Nader Says "Sesame Street" Sells Out |url=https://www.eonline.com/news/37115/nader-says-sesame-street-sells-out |access-date=3 April 2019 |work=ENews |publisher=E! Entertainment Television |date=7 October 1998 |archive-date=4 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190404143449/https://www.eonline.com/news/37115/nader-says-sesame-street-sells-out |url-status=live }}</ref> In 2018 the Workshop made a deal with [[Apple Inc.|Apple]] to develop original content including puppet series for Apple's streaming service.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Shapiro |first1=Ariel |title=Apple makes a big push into kids' content with creators of Sesame Street |url=https://www.cnbc.com/2018/06/20/apple-signs-multi-series-order-with-sesame-workshop.html |access-date=12 April 2019 |work=CNBC.com |date=20 June 2018 |archive-date=12 April 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190412154814/https://www.cnbc.com/2018/06/20/apple-signs-multi-series-order-with-sesame-workshop.html |url-status=live }}</ref> In 2019, ''Parade Magazine'' reported that the organization had received two $100 million grants from the [[MacArthur Foundation]] and from the [[LEGO Foundation]]; the funds were used to undertake "the largest early childhood intervention in the history of humanitarian response to help refugee children and families".<ref name="wallace"/> |

|||

As a non-profit organization, a percentage of the money from any Sesame Workshop product goes to help fund ''Sesame Street'' or its [[sesame street internationally|international co-productions]].<ref>{{cite | Season 40 Presskit | url=http://www.sesameworkshop.org/inside/pressroom/season40/40things | title=40 Things You Didn't Know About Sesame Street | publisher=Sesame Workshop Press Release | date=2009 | accessdate=2009-10-22}}</ref> |

|||

=== Publishing === |

|||

''Barrio Sésamo'', ''Plaza Sésamo'', ''Sesamstraße'', ''Sesame English'' and ''Sesamstraat'' have all had merchandise of their local characters. ''Shalom Sesame'' videos and books have also been released. |

|||

In 1970, the CTW established a department managing the development of "nonbroadcast" materials based upon ''Sesame Street''. The Workshop decided that all materials its licensing program created would "underscore and amplify"<ref name="davis-205" /> the series' curriculum. Coloring books, for example, were prohibited because the Workshop felt they would restrict children's imaginations.<ref name="gikow-268" /> CTW published ''Sesame Street Magazine'' in 1970, which incorporated the show's curriculum goals in a magazine format.<ref>Cherow-O'Leary in Fisch & Truglio, p. 198</ref> As with the series, research was performed for the magazine, initially by CTW's research department for a year and a half, and then by the Magazine Research Group in 1975.<ref name="cherow-197" /> |

|||

Working with [[Random House]] editor Jason Epstein, the CTW hired Christopher Cerf to manage ''Sesame Street''{{'}}s book publishing program.<ref name="gikow-268" /><ref name="davis-205" /> During the division's first year, Cerf earned $900,000 for the CTW. He quit to become more involved with writing and composing music for the series,<ref>Davis, p. 206</ref> and was replaced eventually by Bill Whaley. Ann Kearns, vice president of licensing for the CTW in 2000, stated that Whaley was responsible for expanding the licensing to other products, and for creating a licensing model used by other children's series.<ref name="gikow-268" /> As of 2019, the Workshop had published over 6,500 book titles.<ref name="guthrie"/> and as researcher Renee Cherow-O'Leary stated in 2001, "the print materials produced by CTW have been an enduring part of the legacy of Sesame Street".<ref name="cherow-197" /> In one of these books, for example, the death of the ''Sesame Street'' character [[Mr. Hooper]] was featured in a book entitled ''I'll Miss You, Mr. Hooper'', published soon after the series featured it in 1983.<ref>Cherow-O'Leary in Fisch & Truglio, p. 210</ref> In 2019, ''Parade Magazine'' reported that 20 million copies of ''[[The Monster at the End of This Book: Starring Lovable, Furry Old Grover|The Monster at the End of the Book]]'' and ''Another Monster at the End of this Book'' had been sold, making them the top two best-selling e-books sold.<ref name="wallace"/> Its [[YouTube]] channel had almost 5 million subscribers.<ref name="guthrie"/> |

|||

In 2004, [[Copyright Promotions Licensing Group]] (CPLG) became Sesame Workshop's licensing representative for [[The Benelux]],<ref>[http://www.sesameworkshop.org/aboutus/inside_press.php?contentId=11877128 SESAME WORKSHOP NAMES NEW LICENSING REP FOR THE BENELUX]</ref> adding to their United Kingdom representation.<ref>Previously [[The Licensing Company Ltd.]] held the British rights to ''Sesame Street''. Its licensees included [[Reed Books Children's Publishing]] for books. ({{cite news | title=Reed to publish Sesame Street Books in the UK | date=April 28, 1997 | publisher=Publishers Weekly | url=http://search.epnet.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rch&an=9705091134}})</ref> |

|||

===Toys=== |

|||

{{Main| Tickle Me Elmo}} |

|||

[[Tickle Me Elmo]] was one of the fastest selling toys of the 1996 season. That product line was and still is one of the most successful products Mattel has ever launched. Both it and its most notable successor, TMX, have caused in-store fights. Elmo starred in a [[Christmas special]] that year, in which he wished every day of the year was Christmas.<ref>{{cite news | last=Gliatto | first=Tom |authorlink=Tom Gliatto| title=Elmo Saves Christmas | date=December 23, 1996 | publisher=People | url=http://search.epnet.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rch&an=9612201526}}, accessed in EBSCOhost.</ref> |

|||

=== Music === |

|||