Universe: Difference between revisions

m r2.7.1) (robot Adding: hif:Sansaar |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Everything in space and time}} |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

{{Other uses}} |

||

{{pp- |

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

||

{{Good article}} |

|||

{{Use American English|date=March 2024}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=March 2024}} |

|||

{{CS1 config|mode=cs1}} |

|||

{{Infobox |

|||

| title = Universe |

|||

| image = [[File:Hubble ultra deep field.jpg|300px]] |

|||

| caption = The [[Hubble Ultra-Deep Field]] image shows some of the most remote [[Galaxy|galaxies]] visible to present technology (diagonal is ~1/10 apparent [[Moon]] diameter)<ref name="spacetelescope.org">{{cite web |url=http://spacetelescope.org/images/heic0406a/ |title=Hubble sees galaxies galore |work=spacetelescope.org |access-date=April 30, 2017 |archive-date=May 4, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170504043058/http://www.spacetelescope.org/images/heic0406a/ |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| label1 = [[Age of the universe|Age]] (within [[Lambda-CDM model|ΛCDM model]]) |

|||

| data1 = 13.787 ± 0.020 billion years<ref name="Planck 2015" /> |

|||

| label2 = Diameter |

|||

| data2 = Unknown.<ref name="Brian Greene 2011" /><br>[[Observable universe]]: {{val|8.8|e=26|u=m}} {{nowrap|(28.5 G[[parsec|pc]] or 93 G[[light-year|ly]])}}<ref>{{cite book |first1=Itzhak |last1=Bars |first2=John |last2=Terning |title=Extra Dimensions in Space and Time |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fFSMatekilIC&pg=PA27 |access-date=May 1, 2011 |date=2009 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-0-387-77637-8 |pages=27–}}</ref> |

|||

| label3 = Mass (ordinary matter) |

|||

| data3 = At least {{val|e=53|u=kg}}<ref name="Paul Davies 2006 43">{{cite book |first=Paul |last=Davies |date=2006 |title=The Goldilocks Enigma |pages=43ff |publisher=First Mariner Books |isbn=978-0-618-59226-5 |url=https://archive.org/details/cosmicjackpotwhy0000davi |url-access=registration}}</ref> |

|||

| label4 = Average density (with [[energy]]) |

|||

| data4 = {{val|9.9|e=-27|u=kg/m3}}<ref name="wmap_universe_made_of">{{cite web |author=NASA/WMAP Science Team |date=January 24, 2014 |title=Universe 101: What is the Universe Made Of? |url=http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/universe/uni_matter.html |publisher=NASA |access-date=February 17, 2015 |archive-date=March 10, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080310235855/http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/universe/uni_matter.html |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

| label5 = Average temperature |

|||

| data5 = {{val|2.72548|ul=K}}<br>({{val|-270.4|ul=°C}}, {{val|-454.8|ul=°F}})<ref name=Fixsen>{{Cite journal |last1=Fixsen |first1=D.J. |date=2009 |title=The Temperature of the Cosmic Microwave Background |journal=[[The Astrophysical Journal]] |volume=707 |issue=2 |pages=916–920 |arxiv=0911.1955 |bibcode=2009ApJ...707..916F |doi=10.1088/0004-637X/707/2/916 |s2cid=119217397 |issn=0004-637X}}</ref> |

|||

| label6 = Main contents |

|||

| data6 = [[Baryon#Baryonic matter|Ordinary (baryonic)]] [[matter]] (4.9%)<br />[[Dark matter]] (26.8%)<br />[[Dark energy]] (68.3%)<ref name="planck2013parameters" /> |

|||

| label7 = Shape |

|||

| data7 = [[Shape of the universe|Flat]] with 0.4% error margin<ref>{{cite web |author=NASA/WMAP Science Team |date=January 24, 2014 |url=http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/universe/uni_shape.html |title=Universe 101: Will the Universe expand forever? |publisher=NASA |access-date=April 16, 2015 |archive-date=March 9, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080309164248/http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/universe/uni_shape.html |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

The '''universe''' is all of [[space]] and [[time]]{{efn|name=spacetime|According to [[modern physics]], particularly the [[theory of relativity]], space and time are intrinsically linked as [[spacetime]].}} and their contents.<ref name="Zeilik1998">{{cite book |title=Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics |last1=Zeilik |first1=Michael |last2=Gregory |first2=Stephen A. |year=1998 |edition=4th |publisher=Saunders College |quote=The totality of all space and time; all that is, has been, and will be. |isbn=978-0-03-006228-5}}</ref> It comprises all of [[existence]], any [[fundamental interaction]], [[physical process]] and [[physical constant]], and therefore all forms of [[matter]] and [[energy]], and the structures they form, from [[sub-atomic particles]] to entire [[Galaxy filament|galactic filaments]]. Since the early 20th century, the field of [[cosmology]] establishes that [[space and time]] emerged together at the [[Big Bang]] {{val|13.787|0.020|u=billion years}} ago<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Planck Collaboration |last2=Aghanim |first2=N. |author2-link=Nabila Aghanim |last3=Akrami |first3=Y. |last4=Ashdown |first4=M. |last5=Aumont |first5=J. |last6=Baccigalupi |first6=C. |last7=Ballardini |first7=M. |last8=Banday |first8=A. J. |last9=Barreiro |first9=R. B.|last10=Bartolo|first10=N. |last11=Basak |first11=S. |date=September 2020 |title=Planck 2018 results: VI. Cosmological parameters |journal=Astronomy & Astrophysics |volume=641 |pages=A6 |doi=10.1051/0004-6361/201833910 |arxiv=1807.06209 |bibcode=2020A&A...641A...6P |s2cid=119335614 |issn=0004-6361}}</ref> and that the [[Expansion of the universe|universe has been expanding]] since then. The [[observable universe|portion of the universe that we can see]] is approximately 93 billion [[light-year]]s in diameter at present, but the total size of the universe is not known.<ref name="Brian Greene 2011">{{cite book |first=Brian |last=Greene |author-link=Brian Greene |title=The Hidden Reality |publisher=[[Alfred A. Knopf]] |year=2011 |title-link=The Hidden Reality}}</ref> |

|||

The '''universe''' is commonly defined as the totality of everything that [[existence|exist]]s,<ref> |

|||

{{cite book|url=http://www.yourdictionary.com/universe|title=Webster's New World College Dictionary |

|||

|year=2010|publisher=Wiley Publishing, Inc.}}</ref> including all physical matter and energy, the planets, stars, galaxies, and the contents of intergalactic space,<ref>{{cite book|url=http://www.yourdictionary.com/universe|title=The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language|edition=4th|year=2010 |

|||

|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/universe|title=Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary}}</ref> although this usage may differ with the context (see definitions, below). |

|||

The term ''universe'' may be used in slightly different contextual senses, denoting such concepts as the ''[[cosmos]]'', the ''[[world (philosophy)|world]]'', or ''[[nature]]''. |

|||

Observations of earlier stages in the development of the universe, which can be seen at great distances, suggest that the universe has been governed by the same physical laws and constants throughout most of its extent and history. |

|||

Some of the earliest [[Timeline of cosmological theories|cosmological models]] of the universe were developed by [[ancient Greek philosophy|ancient Greek]] and [[Indian philosophy|Indian philosophers]] and were [[geocentric model|geocentric]], placing Earth at the center.<ref>{{cite book |title=From China to Paris: 2000 Years Transmission of Mathematical Ideas |first=Yvonne |last=Dold-Samplonius |author-link=Yvonne Dold-Samplonius |year=2002 |publisher=Franz Steiner Verlag}}</ref><ref name="Routledge">{{cite book |title=Medieval Science Technology and Medicine: An Encyclopedia |first1=Thomas F. |last1=Glick |first2=Steven |last2=Livesey |first3=Faith |last3=Wallis |publisher=Routledge |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-415-96930-7}}</ref> Over the centuries, more precise astronomical observations led [[Nicolaus Copernicus]] to develop the [[heliocentrism|heliocentric model]] with the [[Sun]] at the center of the [[Solar System]]. In developing the [[Newton's law of universal gravitation|law of universal gravitation]], [[Isaac Newton]] built upon Copernicus's work as well as [[Johannes Kepler]]'s [[Kepler's laws of planetary motion|laws of planetary motion]] and observations by [[Tycho Brahe]]. |

|||

==History== |

|||

Throughout recorded history, several [[cosmology|cosmologies]] and [[cosmogony|cosmogonies]] have been proposed to account for observations of the universe. The earliest quantitative [[geocentric]] models were developed by the [[ancient Greece|ancient Greeks]], who proposed that the universe possesses infinite space and has existed eternally, but contains a single set of concentric [[sphere]]s of finite size – corresponding to the fixed stars, the [[Sun]] and various [[planet]]s – rotating about a spherical but unmoving [[Earth]]. Over the centuries, more precise observations and improved theories of gravity led to [[Nicolaus Copernicus|Copernicus's]] [[heliocentrism|heliocentric model]] and the [[Isaac Newton|Newtonian]] model of the [[Solar System]], respectively. Further improvements in astronomy led to the realization that the Solar System is embedded in a [[galaxy]] composed of billions of stars, the [[Milky Way]], and that other galaxies exist outside it, as far as astronomical instruments can reach. Careful studies of the distribution of these galaxies and their [[spectral line]]s have led to much of [[physical cosmology|modern cosmology]]. Discovery of the [[red shift]] and cosmic [[microwave background radiation]] revealed that the universe is expanding and apparently had a beginning. |

|||

Further observational improvements led to the realization that the Sun is one of a few hundred billion stars in the [[Milky Way]], which is one of a few hundred billion galaxies in the observable universe. Many of the stars in a galaxy [[exoplanet|have planets]]. [[End of Greatness|At the largest scale]], galaxies are distributed uniformly and the same in all directions, meaning that the universe has neither an edge nor a center. At smaller scales, galaxies are distributed in [[galaxy cluster|clusters]] and [[supercluster]]s which form immense [[galaxy filament|filaments]] and [[void (astronomy)|voids]] in space, creating a vast foam-like structure.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RLwangEACAAJ |title=An Introduction to Modern Astrophysics |last1=Carroll |first1=Bradley W. |last2=Ostlie |first2=Dale A. |year=2013 |publisher=Pearson |isbn=978-1-292-02293-2 |edition=International |pages=1173–1174 |access-date=May 16, 2018}}</ref> Discoveries in the early 20th century have suggested that the universe had a beginning and has been expanding since then.<ref name="Hawking">{{cite book |last=Hawking |first=Stephen |url=https://archive.org/details/briefhistoryofti00step_1 |title=A Brief History of Time |year=1988 |publisher=Bantam |isbn=978-0-553-05340-1 |page=[https://archive.org/details/briefhistoryofti00step_1/page/43 43] |author-link=Stephen Hawking |url-access=registration}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:HubbleUltraDeepFieldwithScaleComparison.jpg|thumb|right|290px|This high-resolution image of the [[Hubble ultra deep field]] shows a diverse range of [[Galaxy|galaxies]], each consisting of billions of [[star]]s. The equivalent area of sky that the picture occupies is shown in the lower left corner. The smallest, reddest galaxies, about 100, are some of the most distant galaxies to have been imaged by an optical telescope, existing at the time shortly after the Big Bang.]] |

|||

According to the Big Bang theory, the energy and matter initially present have become less dense as the universe expanded. After an initial accelerated expansion called the [[inflationary epoch]] at around 10<sup>−32</sup> seconds, and the separation of the four known [[fundamental interaction|fundamental forces]], the universe gradually cooled and continued to expand, allowing the first [[subatomic particle]]s and simple [[atom]]s to form. Giant clouds of [[hydrogen]] and [[helium]] were gradually drawn to the places where matter was most [[density|dense]], forming the first galaxies, stars, and everything else seen today. |

|||

According to the prevailing scientific model of the universe, known as the [[Big bang|Big Bang]], the universe expanded from an extremely hot, dense phase called the [[Planck epoch]], in which all the matter and energy of the [[observable universe]] was concentrated. Since the Planck epoch, the universe has been [[Cosmic expansion|expanding]] to its present form, possibly with a brief period (less than [[Scientific Notation|10<sup>−32</sup>]] seconds) of [[cosmic inflation]]. Several independent experimental measurements support this theoretical [[Metric expansion of space|expansion]] and, more generally, the Big Bang theory. Recent observations indicate that this expansion is accelerating because of [[dark energy]], and that most of the matter in the universe may be in a form which cannot be detected by present instruments, and so is not accounted for in the present models of the universe; this has been named [[dark matter]]. The imprecision of current observations has hindered predictions of the [[ultimate fate of the universe]]. |

|||

From studying the effects of [[gravity]] on both matter and light, it has been discovered that the universe contains much more [[matter]] than is accounted for by visible objects; stars, galaxies, nebulas and interstellar gas. This unseen matter is known as [[dark matter]].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Redd |first1=Nola |title=What is Dark Matter? |url=https://www.space.com/20930-dark-matter.html |website=Space.com |access-date=February 1, 2018 |archive-date=February 1, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180201075430/https://www.space.com/20930-dark-matter.html |url-status=live}}</ref> In the widely accepted [[Lambda-CDM model|ΛCDM]] cosmological model, dark matter accounts for about {{val|25.8|1.1|u=%}} of the mass and energy in the universe while about {{val|69.2|1.2|u=%}} is [[dark energy]], a mysterious form of energy responsible for the [[accelerated expansion|acceleration]] of the [[expansion of the universe]].<ref name="planck_2015">{{Cite web |url=https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/full_html/2016/10/aa27101-15/T9.html |title=Planck 2015 results, table 9 |access-date=May 16, 2018 |archive-date=July 27, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180727024529/https://www.aanda.org/articles/aa/full_html/2016/10/aa27101-15/T9.html |url-status=live}}</ref> Ordinary ('[[Baryon#Baryonic matter|baryonic]]') matter therefore composes only {{val|4.84|0.1|u=%}} of the universe.<ref name="planck_2015" /> Stars, planets, and visible gas clouds only form about 6% of this ordinary matter.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Persic |first1=Massimo |last2=Salucci |first2=Paolo |date=September 1, 1992 |title=The baryon content of the Universe |journal=Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society |volume=258 |issue=1 |pages=14P–18P |doi=10.1093/mnras/258.1.14P |doi-access=free |issn=0035-8711 |arxiv=astro-ph/0502178 |bibcode=1992MNRAS.258P..14P |s2cid=17945298}}</ref> |

|||

Current interpretations of [[observable universe|astronomical observations]] indicate that the [[age of the universe]] is 13.75 ±0.17 [[1000000000 (number)|billion]] years,<ref name="marshallaugerhilbertblandford">S. H. Suyu, P. J. Marshall, M. W. Auger, S. Hilbert, R. D. Blandford, L. V. E. Koopmans, C. D. Fassnacht and T. Treu. [http://www.iop.org/EJ/abstract/0004-637X/711/1/201/ Dissecting the Gravitational Lens B1608+656. II. Precision Measurements of the Hubble Constant, Spatial Curvature, and the Dark Energy Equation of State.] The Astrophysical Journal, 2010; 711 (1): 201 DOI: 10.1088/0004-637X/711/1/201</ref> and that the diameter of the [[observable universe]] is at least 93 billion [[light year]]s or {{val|8.80|e=26}} metres.<ref name=ly93>{{cite web | last = Lineweaver | first = Charles | coauthors = Tamara M. Davis | year = 2005 | url = http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=misconceptions-about-the-2005-03&page=5 | title = Misconceptions about the Big Bang | publisher = [[Scientific American]] | accessdate = 2008-11-06}}</ref> According to [[general relativity]], space can expand faster than the speed of light, although we can view only a small portion of the universe due to the limitation imposed by light speed. Since we cannot observe space beyond the limitations of light (or any electromagnetic radiation), it is uncertain whether the size of the universe is finite or infinite. |

|||

There are many competing hypotheses about the [[ultimate fate of the universe]] and about what, if anything, preceded the Big Bang, while other physicists and philosophers refuse to speculate, doubting that information about prior states will ever be accessible. Some physicists have suggested various [[multiverse]] hypotheses, in which the universe might be one among many.<ref name="Brian Greene 2011" /><ref name="EllisKS032" /><ref>{{Cite news |date=August 3, 2011 |title='Multiverse' theory suggested by microwave background |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-14372387 |access-date=February 14, 2023 |archive-date=February 14, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230214233557/https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-14372387 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

==Etymology, synonyms and definitions== |

|||

{{See also|Cosmos|Nature|World (philosophy)|Celestial spheres}} |

|||

The word ''universe'' derives from the [[Old French]] word ''Univers'', which in turn derives from the [[Latin]] word ''universum''.<ref>''The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary'', volume II, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971, p.3518.</ref> The Latin word was used by [[Cicero]] and later Latin authors in many of the same senses as the modern [[English language|English]] word is used.<ref name="lewis_short" /> The Latin word derives from the poetic contraction ''Unvorsum'' — first used by [[Lucretius]] in Book IV (line 262) of his ''[[On the Nature of Things|De rerum natura]]'' (''On the Nature of Things'') — which connects ''un, uni'' (the combining form of ''unus', or "one") with ''vorsum, versum'' (a noun made from the perfect passive participle of ''vertere'', meaning "something rotated, rolled, changed").<ref name="lewis_short">Lewis and Short, ''A Latin Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-864201-6, pp. 1933, 1977–1978.</ref> Lucretius used the word in the sense "everything rolled into one, everything combined into one". |

|||

{{cosmology}} |

|||

[[Image:Foucault pendulum animated.gif|thumb|right|Artistic rendition (highly exaggerated) of a [[Foucault pendulum]] showing that the Earth is not stationary, but rotates.]] |

|||

== Definition == |

|||

An alternative interpretation of ''unvorsum'' is "everything rotated as one" or "everything rotated by one". In this sense, it may be considered a translation of an earlier Greek word for the universe, {{polytonic|περιφορά}}, "something transported in a circle", originally used to describe a course of a meal, the food being carried around the circle of dinner guests.<ref>Liddell and Scott, ''A Greek-English Lexicon'', Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-864214-8, p.1392.</ref> This Greek word refers to [[celestial spheres|an early Greek model of the universe]], in which all matter was contained within rotating spheres centered on the Earth; according to [[Aristotle]], the rotation of [[Primum Mobile|the outermost sphere]] was responsible for the motion and change of everything within. It was natural for the Greeks to assume that the Earth was stationary and that the heavens rotated about the [[Earth]], because careful [[astronomy|astronomical]] and physical measurements (such as the [[Foucault pendulum]]) are required to prove otherwise. |

|||

[[File:NASA-HubbleLegacyFieldZoomOut-20190502.webm|thumb|upright=2.7|center|<div align="center">[[Hubble Space Telescope]] – [[Hubble Ultra-Deep Field|Ultra-Deep Field galaxies]] to Legacy field zoom out<br />(video 00:50; May 2, 2019)</div>]] |

|||

The physical universe is defined as all of [[space]] and [[time]]{{efn|name=spacetime|}} (collectively referred to as [[spacetime]]) and their contents.<ref name="Zeilik1998" /> Such contents comprise all of energy in its various forms, including [[electromagnetic radiation]] and [[matter]], and therefore planets, [[natural satellite|moons]], stars, galaxies, and the contents of [[intergalactic space]].<ref name="Britannica">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Universe |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia Britannica online |date=2012 |url=https://www.britannica.com/science/universe |access-date=February 17, 2018 |archive-date=June 9, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210609004717/https://www.britannica.com/science/universe |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Universe |title=Universe |work=Merriam-Webster Dictionary |access-date=September 21, 2012 |archive-date=October 22, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121022182145/http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/universe |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Universe?s=t |title=Universe |work=Dictionary.com |access-date=September 21, 2012 |archive-date=October 23, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121023004855/http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/universe?s=t |url-status=live }}</ref> The universe also includes the [[physical law]]s that influence energy and matter, such as [[conservation law]]s, [[classical mechanics]], and [[Theory of relativity|relativity]].<ref name="Schreuder2014">{{cite book|first=Duco A.|last=Schreuder|title=Vision and Visual Perception|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=I7a7BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA135|date=2014|publisher=Archway Publishing|isbn=978-1-4808-1294-9|page=135|access-date=January 27, 2016|archive-date=April 22, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210422045606/https://books.google.com/books?id=I7a7BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA135|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The most common term for "universe" among the ancient [[Greek philosophy|Greek philosophers]] from [[Pythagoras]] onwards was {{polytonic|τὸ πᾶν}} (The All), defined as all matter ({{polytonic|τὸ ὅλον}}) and all space ({{polytonic|τὸ κενόν}}).<ref>Liddell and Scott, pp.1345–1346.</ref><ref>{{cite book | author = Yonge, Charles Duke | year = 1870 | title = An English-Greek lexicon | publisher = American Bok Company | location = New York | pages = 567}}</ref> Other synonyms for the universe among the ancient Greek philosophers included {{polytonic|κόσμος}} (meaning the [[world (philosophy)|world]], the [[cosmos]]) and {{polytonic|φύσις}} (meaning [[Nature]], from which we derive the word [[physics]]).<ref>Liddell and Scott, pp.985, 1964.</ref> The same synonyms are found in Latin authors (''totum'', ''mundus'', ''natura'')<ref>Lewis and Short, pp. 1881–1882, 1175, 1189–1190.</ref> and survive in modern languages, e.g., the German words ''Das All'', ''Weltall'', and ''Natur'' for universe. The same synonyms are found in English, such as everything (as in the [[theory of everything]]), the cosmos (as in [[cosmology]]), the [[world (philosophy)|world]] (as in the [[many-worlds hypothesis]]), and [[Nature]] (as in [[natural law]]s or [[natural philosophy]]).<ref>OED, pp. 909, 569, 3821–3822, 1900.</ref> |

|||

The universe is often defined as "the totality of existence", or [[everything]] that exists, everything that has existed, and everything that will exist.<ref name="Schreuder2014" /> In fact, some philosophers and scientists support the inclusion of ideas and abstract concepts—such as mathematics and logic—in the definition of the universe.{{refn|1={{cite journal |last=Tegmark |first=Max |title=The Mathematical Universe |journal=Foundations of Physics |volume=38 |issue=2 |pages=101–150 |doi=10.1007/s10701-007-9186-9 |bibcode=2008FoPh...38..101T |arxiv=0704.0646 |year=2008|s2cid=9890455 }} A short version of which is available at {{cite arXiv |eprint=0709.4024 |title=Shut up and calculate|last1=Fixsen|first1=D. J.|class=physics.pop-ph|year=2007}} in reference to David Mermin's famous quote "shut up and calculate!"<ref>{{cite journal |title=Could Feynman Have Said This? |first=N. David |last=Mermin |journal=Physics Today |volume=57 |issue=5 |page=10 |date=2004 |doi=10.1063/1.1768652 |bibcode=2004PhT....57e..10M |doi-access= }}</ref>}}<ref>{{cite book|first=Jim|last=Holt|title=Why Does the World Exist?|publisher=Liveright Publishing |year=2012|page=308}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Timothy|last=Ferris|title=The Whole Shebang: A State-of-the-Universe(s) Report|publisher=Simon & Schuster|year=1997|page=400}}</ref> The word ''universe'' may also refer to concepts such as ''the [[cosmos]]'', ''the [[world]]'', and ''[[nature]]''.<ref>{{cite book |title=Creation Out of Nothing: A Biblical, Philosophical, and Scientific Exploration |page=[https://archive.org/details/creationoutofnot0000copa/page/220 220] |first1=Paul |last1=Copan |author2=William Lane Craig |publisher=Baker Academic |date=2004 |isbn=978-0-8010-2733-8 |url=https://archive.org/details/creationoutofnot0000copa/page/220 }}</ref><ref name="Bolonkin2011">{{cite book|first=Alexander|last=Bolonkin|title=Universe, Human Immortality and Future Human Evaluation|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TuWQx58ZnPsC&pg=PA3|date=2011|publisher=Elsevier|isbn=978-0-12-415801-6|pages=3–|access-date=January 27, 2016|archive-date=February 8, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210208114300/https://books.google.com/books?id=TuWQx58ZnPsC&pg=PA3|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

===Broadest definition: reality and probability=== |

|||

{{See also|Introduction to quantum mechanics|Interpretation of quantum mechanics|Many-worlds hypothesis}} |

|||

== Etymology == |

|||

The broadest definition of the universe can be found in ''[[De divisione naturae]]'' by the [[Middle Ages|medieval]] [[philosopher]] and [[theology|theologian]] [[Johannes Scotus Eriugena]], who defined it as simply everything: everything that is created and everything that is not created. Time is not considered in Eriugena's definition; thus, his definition includes everything that exists, has existed and will exist, as well as everything that does not exist, has never existed and will never exist. This all-embracing definition was not adopted by most later philosophers, but something not entirely dissimilar reappears in [[quantum physics]], perhaps most obviously in the [[path integral formulation|path-integral formulation]] of [[Richard Feynman|Feynman]].<ref name="path_integral">{{cite book | author = Feynman RP, Hibbs AR | year = 1965 | title = Quantum Physics and Path Integrals | publisher = McGraw–Hill | location = New York | isbn = 0-07-020650-3}}<br />{{cite book | author = Zinn Justin J | year = 2004 | title = Path Integrals in Quantum Mechanics | publisher = Oxford University Press | isbn = 0-19-856674-3 | oclc = 212409192}}</ref> According to that formulation, the [[probability amplitude]]s for the various outcomes of an experiment given a perfectly defined initial state of the system are determined by summing over all possible paths by which the system could progress from the initial to final state. Naturally, an experiment can have only one outcome; in other words, only one possible outcome is made real in this universe, via the mysterious process of [[measurement in quantum mechanics|quantum measurement]], also known as the [[wavefunction collapse|collapse of the wavefunction]] (but see the [[many-worlds hypothesis]] below in the [[Multiverse]] section). In this well-defined mathematical sense, even that which does not exist (all possible paths) can influence that which does finally exist (the experimental measurement). As a specific example, every [[electron]] is intrinsically identical to every other; therefore, probability amplitudes must be computed allowing for the possibility that they exchange positions, something known as [[exchange symmetry]]. This conception of the universe embracing both the existent and the non-existent loosely parallels the [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] doctrines of [[shunyata]] and [[pratitya-samutpada|interdependent development of reality]], and [[Gottfried Leibniz]]'s more modern concepts of [[contingency]] and the [[identity of indiscernibles]]. |

|||

The word ''universe'' derives from the [[Old French]] word {{lang|fro|univers}}, which in turn derives from the [[Latin]] word {{lang|la|universus}}, meaning 'combined into one'.<ref>''The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary'', volume II, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971, p. 3518. {{isbn|978-0198611172}}.</ref> The Latin word 'universum' was used by [[Cicero]] and later Latin authors in many of the same senses as the modern [[English language|English]] word is used.<ref name="lewis_short">Lewis, C.T. and Short, S (1879) ''A Latin Dictionary'', Oxford University Press, {{ISBN|0-19-864201-6}}, pp. 1933, 1977–1978.</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Synonyms === |

||

A term for ''universe'' among the ancient Greek philosophers from [[Pythagoras]] onwards was {{lang|grc|τὸ πᾶν}} ({{transliteration|grc|tò pân}}) 'the all', defined as all matter and all space, and {{lang|grc|τὸ ὅλον}} ({{transliteration|grc|tò hólon}}) 'all things', which did not necessarily include the void.<ref>{{cite web |author1=Liddell |author2=Scott |title=A Greek-English Lexicon |url=http://lsj.gr/wiki/πᾶς |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181106193619/https://lsj.translatum.gr/wiki/%CF%80%E1%BE%B6%CF%82 |archive-date=November 6, 2018 |access-date=July 30, 2022 |website=lsj.gr |quote=πᾶς}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author1=Liddell |author2=Scott |title=A Greek-English Lexicon |url=http://lsj.gr/wiki/ὅλος |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181106185336/https://lsj.translatum.gr/wiki/%E1%BD%85%CE%BB%CE%BF%CF%82 |archive-date=November 6, 2018 |access-date=July 30, 2022 |website=lsj.gr |quote=ὅλος}}</ref> Another synonym was {{lang|grc|ὁ κόσμος}} ({{transliteration|grc|ho kósmos}}) meaning 'the [[world (philosophy)|world]], the [[cosmos]]'.<ref>{{cite web |author1=Liddell |author2=Scott |title=A Greek–English Lexicon |url=https://lsj.gr/wiki/κόσμος |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181106193457/https://lsj.translatum.gr/wiki/%CE%BA%CF%8C%CF%83%CE%BC%CE%BF%CF%82 |archive-date=November 6, 2018 |access-date=July 30, 2022 |website=lsj.gr |quote=κόσμος}}</ref> Synonyms are also found in Latin authors ({{lang|la|totum}}, {{lang|la|mundus}}, {{lang|la|natura}})<ref>{{cite book |author=Lewis, C.T. |author2=Short, S |date=1879 |title=A Latin Dictionary |url=https://archive.org/details/latindictionaryf00lewi |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-864201-5 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/latindictionaryf00lewi/page/n1188 1175], 1189–1190, 1881–1882}}</ref> and survive in modern languages, e.g., the [[German language|German]] words {{lang|de|Das All}}, {{lang|de|Weltall}}, and {{lang|de|Natur}} for ''universe''. The same synonyms are found in English, such as everything (as in the [[theory of everything]]), the cosmos (as in [[cosmology]]), the world (as in the [[many-worlds interpretation]]), and [[nature]] (as in [[natural law]]s or [[natural philosophy]]).<ref>{{cite book |title=The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary |volume=II |isbn=978-0-19-861117-2 |publisher=Oxford: Oxford University Press |date=1971 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/compacteditionof03robe/page/569 569, 909, 1900, 3821–3822] |url=https://archive.org/details/compacteditionof03robe/page/569 }}</ref> |

|||

{{See also|Reality|Physics}} |

|||

== Chronology and the Big Bang == |

|||

More customarily, the universe is defined as everything that exists, has existed, and will exist {{Citation needed|date=May 2010}}. According to this definition and our present understanding, the universe consists of three elements: [[space]] and [[time]], collectively known as [[space-time]] or the [[vacuum]]; [[matter]] and various forms of [[energy]] and [[momentum]] occupying [[space-time]]; and the [[physical law]]s that govern the first two. These elements will be discussed in greater detail below. A related definition of the term ''universe'' is everything that exists at a single moment of [[cosmological time]], such as the present, as in the sentence "The universe is now bathed uniformly in [[cosmic microwave background radiation|microwave radiation]]". |

|||

{{Main|Big Bang|Chronology of the universe}} |

|||

{{Nature timeline}} |

|||

The prevailing model for the evolution of the universe is the [[Big Bang]] theory.<ref>{{cite book|first=Joseph|last=Silk|title=Horizons of Cosmology|publisher=Templeton Pressr|date=2009|page=208}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Simon|last=Singh|title=Big Bang: The Origin of the Universe|publisher=Harper Perennial|date=2005|page=560|bibcode=2004biba.book.....S}}</ref> The Big Bang model states that the earliest state of the universe was an extremely hot and dense one, and that the universe subsequently expanded and cooled. The model is based on [[general relativity]] and on simplifying assumptions such as the [[homogeneity (physics)#Translation invariance|homogeneity]] and [[isotropy]] of space. A version of the model with a [[cosmological constant]] (Lambda) and [[cold dark matter]], known as the [[Lambda-CDM model]], is the simplest model that provides a reasonably good account of various observations about the universe. |

|||

The three elements of the universe (spacetime, matter-energy, and physical law) correspond roughly to the ideas of [[Aristotle]]. In his book ''[[Physics (Aristotle)|The Physics]]'' ({{polytonic|Φυσικῆς}}, from which we derive the word "physics"), Aristotle divided {{polytonic|τὸ πᾶν}} (everything) into three roughly analogous elements: ''matter'' (the stuff of which the universe is made), ''form'' (the arrangement of that matter in space) and ''change'' (how matter is created, destroyed or altered in its properties, and similarly, how form is altered). [[Physical law]]s were conceived as the rules governing the properties of matter, form and their changes. Later philosophers such as [[Lucretius]], [[Averroes]], [[Avicenna]] and [[Baruch Spinoza]] altered or refined these divisions{{Citation needed|date=May 2010}}; for example, Averroes and Spinoza discern ''[[natura naturans]]'' (the active principles governing the universe) from ''[[natura naturata]]'', the passive elements upon which the former act. |

|||

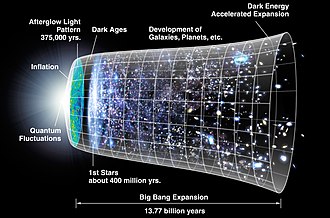

[[File:CMB Timeline300 no WMAP.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|In this schematic diagram, time passes from left to right, with the universe represented by a disk-shaped "slice" at any given time. Time and size are not to scale. To make the early stages visible, the time to the afterglow stage (really the first 0.003%) is stretched and the subsequent expansion (really by 1,100 times to the present) is largely suppressed.]] |

|||

The initial hot, dense state is called the [[Planck epoch]], a brief period extending from time zero to one [[Planck time]] unit of approximately 10<sup>−43</sup> seconds. During the Planck epoch, all types of matter and all types of energy were concentrated into a dense state, and [[gravity]]—currently the weakest by far of the [[fundamental interactions|four known forces]]—is believed to have been as strong as the other fundamental forces, and all the forces may have been [[grand unification|unified]]. The physics controlling this very early period (including [[quantum gravity]] in the Planck epoch) is not understood, so we cannot say what, if anything, happened [[Big Bang#Pre–Big Bang cosmology|before time zero]]. Since the Planck epoch, [[expansion of the universe|the universe has been expanding]] to its present scale, with a very short but intense period of [[cosmic inflation]] speculated to have occurred within the first [[Scientific Notation|10<sup>−32</sup>]] seconds.<ref name="Sivaram">{{cite journal |author=Sivaram |first=C. |date=1986 |title=Evolution of the Universe through the Planck epoch |journal=Astrophysics and Space Science |volume=125 |issue=1 |pages=189–199 |bibcode=1986Ap&SS.125..189S |doi=10.1007/BF00643984 |s2cid=123344693}}</ref> This initial period of inflation would explain why space appears to be [[Flatness problem|very flat]]. |

|||

===Definition as connected space-time=== |

|||

{{See also|Chaotic Inflation theory}} |

|||

Within the first fraction of a second of the universe's existence, the four fundamental forces had separated. As the universe continued to cool from its inconceivably hot state, various types of [[subatomic particles]] were able to form in short periods of time known as the [[quark epoch]], the [[hadron epoch]], and the [[lepton epoch]]. Together, these epochs encompassed less than 10 seconds of time following the Big Bang. These [[elementary particle]]s associated stably into ever larger combinations, including stable [[proton]]s and [[neutron]]s, which then formed more complex [[atomic nuclei]] through [[nuclear fusion]].<ref name="Johnson 474–478">{{Cite journal |last=Johnson |first=Jennifer A. |date=February 2019 |title=Populating the periodic table: Nucleosynthesis of the elements |journal=Science |language=en |volume=363 |issue=6426 |pages=474–478 |doi=10.1126/science.aau9540 |pmid=30705182 |bibcode=2019Sci...363..474J |s2cid=59565697 |issn=0036-8075|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="durrer"/> |

|||

It is possible to conceive of disconnected [[space-time]]s, each existing but unable to interact with one another. An easily visualized metaphor is a group of separate [[soap bubble]]s, in which observers living on one soap bubble cannot interact with those on other soap bubbles, even in principle. According to one common terminology, each "soap bubble" of space-time is denoted as a universe, whereas our particular [[space-time]] is denoted as ''the universe'', just as we call our moon ''the [[Moon]]''. The entire collection of these separate space-times is denoted as the [[multiverse]].<ref name="EllisKS03">{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Ellis |

|||

| first = George F.R. |

|||

| authorlink = George Ellis |

|||

| coauthors = U. Kirchner, W.R. Stoeger |

|||

| title = Multiverses and physical cosmology |

|||

| journal = Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society |

|||

| volume = 347 |

|||

| issue = |

|||

3| pages = 921–936 |

|||

| publisher = |

|||

| year = 2004 |

|||

| url = http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0305292 |

|||

| doi =10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.07261.x |

|||

| id = |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-01-09 |

|||

| format = subscription required}}</ref> In principle, the other unconnected universes may have different [[dimension]]alities and [[topology|topologies]] of [[space-time]], different forms of [[matter]] and [[energy]], and different [[physical law]]s and [[physical constant]]s, although such possibilities are currently speculative. |

|||

This process, known as [[Big Bang nucleosynthesis]], lasted for about 17 minutes and ended about 20 minutes after the Big Bang, so only the fastest and simplest reactions occurred. About 25% of the [[proton]]s and all the [[neutron]]s in the universe, by mass, were converted to [[helium]], with small amounts of [[deuterium]] (a [[isotope|form]] of [[hydrogen]]) and traces of [[lithium]]. Any other [[chemical element|element]] was only formed in very tiny quantities. The other 75% of the protons remained unaffected, as [[hydrogen]] nuclei.<ref name="Johnson 474–478"/><ref name="durrer">{{cite book|last=Durrer |first=Ruth |author-link=Ruth Durrer |title=The Cosmic Microwave Background |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-521-84704-9}}</ref>{{rp|27–42}} |

|||

===Definition as observable reality=== |

|||

{{See also|Observable universe|Observational cosmology}} |

|||

After nucleosynthesis ended, the universe entered a period known as the [[photon epoch]]. During this period, the universe was still far too hot for matter to form neutral [[atom]]s, so it contained a hot, dense, foggy [[Plasma (physics)|plasma]] of negatively charged [[electron]]s, neutral [[neutrino]]s and positive nuclei. After about 377,000 years, the universe had cooled enough that electrons and nuclei could form the first stable [[atom]]s. This is known as [[recombination (cosmology)|recombination]] for historical reasons; electrons and nuclei were combining for the first time. Unlike plasma, neutral atoms are [[Opacity (optics)|transparent]] to many [[wavelength]]s of light, so for the first time the universe also became transparent. The photons released ("[[photon decoupling|decoupled]]") when these atoms formed can still be seen today; they form the [[cosmic microwave background]] (CMB).<ref name="durrer"/>{{rp|15–27}} |

|||

According to a still-more-restrictive definition, the universe is everything within our connected [[space-time]] that could have a chance to interact with us and vice versa.{{Citation needed|date=May 2010}} According to the [[general relativity|general theory of relativity]], some regions of [[space]] may never interact with ours even in the lifetime of the universe, due to the finite [[speed of light]] and the ongoing [[expansion of space]]. For example, radio messages sent from Earth may never reach some regions of space, even if the universe would live forever; space may expand faster than light can traverse it. It is worth emphasizing that those distant regions of space are taken to exist and be part of reality as much as we are; yet we can never interact with them. The spatial region within which we can affect and be affected is denoted as the [[observable universe]]. Strictly speaking, the observable universe depends on the location of the observer. By traveling, an observer can come into contact with a greater region of space-time than an observer who remains still, so that the observable universe for the former is larger than for the latter. Nevertheless, even the most rapid traveler may not be able to interact with all of space. Typically, the observable universe is taken to mean the universe observable from our vantage point in the Milky Way Galaxy. |

|||

As the universe expands, the [[energy density]] of [[electromagnetic radiation]] decreases more quickly than does that of [[matter]] because the energy of each photon decreases as it is [[cosmological redshift|cosmologically redshifted]]. At around 47,000 years, the [[energy density]] of matter became larger than that of photons and [[neutrino]]s, and began to dominate the large scale behavior of the universe. This marked the end of the [[radiation-dominated era]] and the start of the [[matter-dominated era]].<ref name="steane">{{cite book|first=Andrew M. |last=Steane |title=Relativity Made Relatively Easy, Volume 2: General Relativity and Cosmology |isbn=978-0-192-89564-6 |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2021}}</ref>{{rp|390}} |

|||

== Size, age, contents, structure, and laws ==<!-- [[Hubble's law]] links to this section --> |

|||

{{Main|Observable universe|Age of the universe|Large-scale structure of the universe|Abundance of the chemical elements}} |

|||

In the earliest stages of the universe, tiny fluctuations within the universe's density led to [[filament (cosmology)|concentrations]] of [[dark matter]] gradually forming. Ordinary matter, attracted to these by [[gravity]], formed large gas clouds and eventually, stars and galaxies, where the dark matter was most dense, and [[Void (astronomy)|voids]] where it was least dense. After around 100–300 million years,<ref name="steane"/>{{rp|333}} the first [[star]]s formed, known as [[Population III]] stars. These were probably very massive, luminous, [[metallicity|non metallic]] and short-lived. They were responsible for the gradual [[reionization]] of the universe between about 200–500 million years and 1 billion years, and also for seeding the universe with elements heavier than helium, through [[stellar nucleosynthesis]].<ref>{{cite news |work=Scientific American |title=The First Stars in the Universe |first1=Richard B. |last1=Larson |first2=Volker |last2=Bromm |name-list-style=amp |date=March 2002 |url=http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-first-stars-in-the-un/ |access-date=June 9, 2015 |archive-date=June 11, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150611032732/http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/the-first-stars-in-the-un/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The universe is immensely large and possibly infinite in volume. The region visible from Earth (the [[observable universe]]) is a sphere with a radius of about 46 billion [[light years]],<ref>{{cite web | last = Lineweaver | first = Charles | coauthors = Tamara M. Davis | year = 2005 | url = http://space.mit.edu/~kcooksey/teaching/AY5/MisconceptionsabouttheBigBang_ScientificAmerican.pdf | title = Misconceptions about the Big Bang | publisher = [[Scientific American]] | accessdate = 2007-03-05}}</ref> based on where the [[metric expansion of space|expansion of space]] has [[comoving distance|taken]] the most distant objects observed. For comparison, the diameter of a typical [[galaxy]] is only 30,000 light-years, and the typical distance between two neighboring galaxies is only 3 million [[light-years]].<ref>Rindler (1977), p.196.</ref> As an example, our [[Milky Way]] Galaxy is roughly 100,000 light years in diameter,<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| last = Christian |

|||

| first = Eric |

|||

| last2 = Samar |

|||

| first2 = Safi-Harb |

|||

| title = How large is the Milky Way? |

|||

| url=http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/ask_astro/answers/980317b.html |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-11-28 }}</ref> and our nearest sister galaxy, the [[Andromeda Galaxy]], is located roughly 2.5 million light years away.<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

| author=I. Ribas, C. Jordi, F. Vilardell, E.L. Fitzpatrick, R.W. Hilditch, F. Edward |

|||

| title=First Determination of the Distance and Fundamental Properties of an Eclipsing Binary in the Andromeda Galaxy |

|||

| journal=Astrophysical Journal |

|||

| year=2005 |

|||

|volume=635 |

|||

| issue=1 |

|||

| pages=L37–L40 |

|||

| bibcode=2005ApJ...635L..37R |

|||

| doi = 10.1086/499161 |

|||

}}<br />{{cite journal |

|||

| author=McConnachie, A. W.; Irwin, M. J.; Ferguson, A. M. N.; Ibata, R. A.; Lewis, G. F.; Tanvir, N. |

|||

| title=Distances and metallicities for 17 Local Group galaxies |

|||

| journal=Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society |

|||

| year=2005 |

|||

|volume=356 |

|||

|issue=4 |

|||

| pages=979–997 |

|||

| bibcode=2005MNRAS.356..979M |

|||

| doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08514.x |

|||

}}</ref> There are probably more than 100 billion (10<sup>11</sup>) [[Galaxy|galaxies]] in the observable universe.<ref>{{cite web | last = Mackie | first = Glen |date= February 1, 2002 | url = http://astronomy.swin.edu.au/~gmackie/billions.html | title = To see the Universe in a Grain of Taranaki Sand | publisher = Swinburne University | accessdate = 2006-12-20 }}</ref> Typical galaxies range from [[dwarf galaxy|dwarfs]] with as few as ten million<ref>{{cite web | date=2000-05-03 | url = http://www.eso.org/outreach/press-rel/pr-2000/pr-12-00.html |

|||

| title = Unveiling the Secret of a Virgo Dwarf Galaxy |

|||

| publisher = ESO | accessdate = 2007-01-03 }}</ref> (10<sup>7</sup>) [[star]]s up to giants with one [[Orders of magnitude (numbers)#1012|trillion]]<ref name="M101">{{cite web | date=2006-02-28 | url = http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/hubble/science/hst_spiral_m10.html | title = Hubble's Largest Galaxy Portrait Offers a New High-Definition View |

|||

| publisher = NASA | accessdate = 2007-01-03 }}</ref> (10<sup>12</sup>) stars, all orbiting the galaxy's center of mass. Thus, a very rough estimate from these numbers would suggest there are around one [[sextillion]] (10<sup>21</sup>) stars in the observable universe; though a 2010 study by astronomers resulted in a figure of 300 sextillion (3{{e|23}}).<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.usatoday.com/tech/science/space/2010-12-01-dwarf-stars_N.htm |title=Universe holds billions more stars than previously thought |author=Vergano, Dan |date=1 December 2010 |work= [[USA Today]] |accessdate=14 December 2010}}</ref> |

|||

The universe also contains a mysterious energy—possibly a [[scalar field]]—called [[dark energy]], the density of which does not change over time. After about 9.8 billion years, the universe had expanded sufficiently so that the density of matter was less than the density of dark energy, marking the beginning of the present [[dark-energy-dominated era]].<ref>[[Barbara Ryden|Ryden, Barbara]], "Introduction to Cosmology", 2006, eqn. 6.33</ref> In this era, the expansion of the universe is [[accelerating expansion of the universe|accelerating]] due to dark energy. |

|||

[[File:Cosmological Composition - Pie Chart.png|thumb|450px|The universe is believed to be mostly composed of [[dark energy]] and [[dark matter]], both of which are poorly understood at present. Less than 5% of the universe is ordinary matter, a relatively small contribution.]] |

|||

== Physical properties == |

|||

The observable matter is spread uniformly (''homogeneously'') throughout the universe, when averaged over distances longer than 300 million light-years.<ref>{{cite journal | author=N. Mandolesi, P. Calzolari, S. Cortiglioni, F. Delpino, G. Sironi | title=Large-scale homogeneity of the Universe measured by the microwave background | journal=Letters to Nature | year=1986 |volume=319 | issue=6056 | pages=751–753 | doi= 10.1038/319751a0 }}</ref> However, on smaller length-scales, matter is observed to form "clumps", i.e., to cluster hierarchically; many [[atoms]] are condensed into [[star]]s, most stars into galaxies, most galaxies into [[galaxy groups and clusters|clusters, superclusters]] and, finally, the [[large-scale structure of the universe|largest-scale structures]] such as the [[Great Wall (astronomy)|Great Wall of galaxies]]. The observable matter of the universe is also spread ''isotropically'', meaning that no direction of observation seems different from any other; each region of the sky has roughly the same content.<ref>{{cite web | last = Hinshaw | first = Gary |date= November 29, 2006 | url = http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/m_mm.html | title = New Three Year Results on the Oldest Light in the Universe | publisher = NASA WMAP | accessdate = 2006-08-10 }}</ref> The universe is also bathed in a highly isotropic [[microwave]] [[electromagnetic radiation|radiation]] that corresponds to a [[thermal equilibrium]] [[blackbody spectrum]] of roughly 2.725 [[kelvin]].<ref>{{cite web | last = Hinshaw | first = Gary |date= December 15, 2005 | url = http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/m_uni/uni_101bbtest3.html | title = Tests of the Big Bang: The CMB | publisher = NASA WMAP | accessdate = 2007-01-09 }}</ref> The hypothesis that the large-scale universe is homogeneous and isotropic is known as the [[cosmological principle]],<ref>Rindler (1977), p. 202.</ref> which is [[End of Greatness|supported by astronomical observations]]. |

|||

{{Main|Observable universe|Age of the universe|Expansion of the universe}} |

|||

Of the four [[fundamental interaction]]s, [[gravitation]] is the dominant at astronomical length scales. Gravity's effects are cumulative; by contrast, the effects of positive and negative charges tend to cancel one another, making electromagnetism relatively insignificant on astronomical length scales. The remaining two interactions, the [[weak nuclear force|weak]] and [[strong nuclear force]]s, decline very rapidly with distance; their effects are confined mainly to sub-atomic length scales.<ref name="OpenStax-college-physics"/>{{rp|1470}} |

|||

The universe appears to have much more [[matter]] than [[antimatter]], an asymmetry possibly related to the [[CP violation]].<ref>{{cite web|date=October 28, 2003 |url=http://www.pparc.ac.uk/Ps/bbs/bbs_antimatter.asp |title=Antimatter |publisher=Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council |access-date=August 10, 2006 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040307075727/http://www.pparc.ac.uk/Ps/bbs/bbs_antimatter.asp |archive-date=March 7, 2004 }}</ref> This imbalance between matter and antimatter is partially responsible for the existence of all matter existing today, since matter and antimatter, if equally produced at the [[Big Bang]], would have completely annihilated each other and left only [[photon]]s as a result of their interaction.<ref name="NAT-20171020">{{cite journal |author=Smorra C. |display-authors=et al |title=A parts-per-billion measurement of the antiproton magnetic moment |date=October 20, 2017 |journal=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume=550 |issue=7676 |pages=371–374 |doi=10.1038/nature24048 |pmid=29052625 |bibcode=2017Natur.550..371S |s2cid=205260736 |url=https://cds.cern.ch/record/2291601/files/nature24048.pdf |doi-access=free |access-date=August 25, 2019 |archive-date=October 30, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181030045315/https://cds.cern.ch/record/2291601/files/nature24048.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> These laws are [[Gauss's law]] and the non-divergence of the [[stress–energy–momentum pseudotensor]].<ref>{{harvtxt|Landau|Lifshitz|1975|p=361}}: "It is interesting to note that in a closed space the total electric charge must be zero. Namely, every closed surface in a finite space encloses on each side of itself a finite region of space. Therefore, the flux of the electric field through this surface is equal, on the one hand, to the total charge located in the interior of the surface, and on the other hand to the total charge outside of it, with opposite sign. Consequently, the sum of the charges on the two sides of the surface is zero."</ref> |

|||

The present overall [[density]] of the universe is very low, roughly 9.9 × 10<sup>−30</sup> grams per cubic centimetre. This mass-energy appears to consist of 73% [[dark energy]], 23% [[cold dark matter]] and 4% [[baryonic matter|ordinary matter]]. Thus the density of atoms is on the order of a single hydrogen atom for every four cubic meters of volume.<ref>{{cite web | last = Hinshaw | first = Gary |date= February 10, 2006 | url = http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/m_uni/uni_101matter.html | title = What is the Universe Made Of? | publisher = NASA WMAP | accessdate = 2007-01-04}}</ref> The properties of dark energy and dark matter are largely unknown. Dark matter [[gravity|gravitates]] as ordinary matter, and thus works to slow the [[metric expansion of space|expansion of the universe]]; by contrast, dark energy [[accelerating universe|accelerates its expansion]]. |

|||

=== Size and regions === |

|||

The [[Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe|most precise estimate]] of the [[age of the universe|universe's age]] is 13.73±0.12 billion years old, based on observations of the [[cosmic microwave background radiation]].<ref name="NASA_age">{{cite web | title = Five-Year Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) Observations: Data Processing, Sky Maps, and Basic Results | url=http://lambda.gsfc.nasa.gov/product/map/dr3/pub_papers/fiveyear/basic_results/wmap5basic.pdf|format=PDF|publisher=nasa.gov|accessdate=2008-03-06}}</ref> Independent estimates (based on measurements such as [[radioactive dating]]) agree, although they are less precise, ranging from 11–20 billion years<ref>{{cite web |

|||

{{See also|Observational cosmology}} |

|||

| author =Britt RR |

|||

[[File:Extended universe logarithmic illustration (English annotated).png|thumb|upright=2.4|Illustration of the observable universe, centered on the Sun. The distance scale is [[logarithmic scale|logarithmic]]. Due to the finite speed of light, we see more distant parts of the universe at earlier times.]] |

|||

| title =Age of Universe Revised, Again |

|||

| publisher =[[space.com]] |

|||

| date = 2003-01-03 |

|||

| url = http://www.space.com/scienceastronomy/age_universe_030103.html |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-01-08}}</ref> |

|||

to 13–15 billion years.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| author = Wright EL |

|||

| title =Age of the Universe |

|||

| publisher =[[UCLA]] |

|||

| year = 2005 |

|||

| url = http://www.astro.ucla.edu/~wright/age.html |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-01-08 |

|||

}}<br />{{cite journal |

|||

| author = Krauss LM, Chaboyer B |

|||

| title =Age Estimates of Globular Clusters in the Milky Way: Constraints on Cosmology |

|||

| journal =[[Science (journal)|Science]] |

|||

| volume = 299 |

|||

| issue = 5603 |

|||

| pages = 65–69 |

|||

| publisher =[[American Association for the Advancement of Science]] |

|||

| date = 3 January 2003 |

|||

| url = http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/299/5603/65?ijkey=3D7y0Qonz=GO7ig.&keytype=3Dref&siteid=3Dsci |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-01-08 |

|||

| doi =10.1126/science.1075631 |

|||

| pmid =12511641}}</ref> The universe has not been the same at all times in its history; for example, the relative populations of [[quasar]]s and galaxies have changed and [[space]] itself appears to have [[metric expansion of space|expanded]]. This expansion accounts for how Earth-bound scientists can observe the light from a galaxy 30 billion light years away, even if that light has traveled for only 13 billion years; the very space between them has expanded. This expansion is consistent with the observation that the light from distant galaxies has been [[redshift]]ed; the [[photon]]s emitted have been stretched to longer [[wavelength]]s and lower [[frequency]] during their journey. The rate of this spatial expansion is [[accelerating universe|accelerating]], based on studies of [[Type Ia supernova]]e and corroborated by other data. |

|||

Due to the finite [[speed of light]], there is a limit (known as the [[particle horizon]]) to how far light can travel over the [[age of the universe]]. |

|||

The [[abundance of the chemical elements|relative fractions]] of different [[chemical element]]s — particularly the lightest atoms such as [[hydrogen]], [[deuterium]] and [[helium]] — seem to be identical throughout the universe and throughout its observable history.<ref>{{cite web | last = Wright | first = Edward L. |date= September 12, 2004 | url = http://www.astro.ucla.edu/~wright/BBNS.html | title = Big Bang Nucleosynthesis | publisher = UCLA | accessdate = 2007-01-05 }}<br />{{cite journal | author=M. Harwit, M. Spaans | title=Chemical Composition of the Early Universe | journal=The Astrophysical Journal | year=2003 |volume=589 |issue=1 | pages=53–57 | bibcode=2003ApJ...589...53H | doi = 10.1086/374415}}<br />{{cite journal | author=C. Kobulnicky, E. D. Skillman | title=Chemical Composition of the Early Universe | journal=Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society | year=1997 |volume=29 | pages=1329 | bibcode=1997AAS...191.7603K }}</ref> The universe seems to have much more [[matter]] than [[antimatter]], an asymmetry possibly related to the observations of [[CP violation]].<ref>{{cite web |date= October 28, 2003 | url = http://www.pparc.ac.uk/ps/bbs/bbs_antimatter.asp | title = Antimatter | publisher = Particle Physics and Astronomy Research Council | accessdate = 2006-08-10 }}</ref> The universe appears to have no net [[electric charge]], and therefore [[gravity]] appears to be the dominant interaction on cosmological length scales. The universe also appears to have neither net [[momentum]] nor [[angular momentum]]. The absence of net charge and momentum would follow from accepted physical laws ([[Gauss's law]] and the non-divergence of the [[stress-energy-momentum pseudotensor]], respectively), if the universe were finite.<ref>Landau and Lifshitz (1975), p.361.</ref> |

|||

The spatial region from which we can receive light is called the [[observable universe]]. The [[Comoving distance|proper distance]] (measured at a fixed time) between Earth and the edge of the observable universe is 46 billion light-years<ref name="Extra Dimensions in Space and Time">{{cite book|first1=Itzhak|last1=Bars|first2=John|last2=Terning|title=Extra Dimensions in Space and Time|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fFSMatekilIC&pg=PA27|access-date=October 19, 2018|date=2018|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-0-387-77637-8|pages=27–}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Crane |first=Leah |date=29 June 2024 |editor-last=de Lange |editor-first=Catherine |title=How big is the universe, really? |work=New Scientist |page=31}}</ref> (14 billion [[parsecs]]), making the [[Observable universe#Size|diameter of the observable universe]] about 93 billion light-years (28 billion parsecs).<ref name="Extra Dimensions in Space and Time" /> Although the distance traveled by light from the edge of the observable universe is close to the [[age of the universe]] times the speed of light, {{convert|13.8|e9ly|e9pc}}, the proper distance is larger because the edge of the observable universe and the Earth have since moved further apart.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://earthsky.org/space/what-is-a-light-year |title=What is a light-year? |work=EarthSky |date=February 20, 2013 |first=Christopher |last=Crockett |access-date=February 20, 2015 |archive-date=February 20, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150220203559/http://earthsky.org/space/what-is-a-light-year |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

For comparison, the diameter of a typical [[galaxy]] is 30,000 light-years (9,198 [[parsecs]]), and the typical distance between two neighboring galaxies is 3 million [[light-years]] (919.8 kiloparsecs).<ref name="r196">[[#Rindler|Rindler]], p. 196.</ref> As an example, the [[Milky Way]] is roughly 100,000–180,000 light-years in diameter,<ref>{{cite web |

|||

[[Image:Elementary particle interactions.svg|thumb|left|300px|The [[elementary particle]]s from which the universe is constructed. Six [[lepton]]s and six [[quark]]s comprise most of the [[matter]]; for example, the [[proton]]s and [[neutron]]s of [[atomic nucleus|atomic nuclei]] are composed of quarks, and the ubiquitous [[electron]] is a lepton. These particles interact via the [[gauge boson]]s shown in the middle row, each corresponding to a particular type of [[gauge symmetry]]. The [[Higgs boson]] (as yet unobserved) is believed to confer [[mass]] on the particles with which it is connected. The [[graviton]], a supposed gauge boson for [[gravity]], is not shown.]] |

|||

|last1=Christian|first1=Eric |

|||

|last2=Samar|first2=Safi-Harb |author-link2=Samar Safi-Harb |

|||

|title=How large is the Milky Way? |

|||

|url=http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/ask_astro/answers/980317b.html |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/19990202064645/http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/ask_astro/answers/980317b.html |

|||

|url-status=dead |

|||

|archive-date=February 2, 1999 |

|||

|access-date=November 28, 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.space.com/29270-milky-way-size-larger-than-thought.html|title=Size of the Milky Way Upgraded, Solving Galaxy Puzzle|publisher=Space.com|last=Hall|first=Shannon|date=May 4, 2015|access-date=June 9, 2015|archive-date=June 7, 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150607104254/http://www.space.com/29270-milky-way-size-larger-than-thought.html|url-status=live}}</ref> and the nearest sister galaxy to the Milky Way, the [[Andromeda Galaxy]], is located roughly 2.5 million light-years away.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ribas |first1=I. |last2=Jordi |first2=C. |last3=Vilardell |first3=F. |last4=Fitzpatrick |first4=E. L. |last5=Hilditch |first5=R. W. |last6=Guinan |first6=F. Edward |date=2005 |title=First Determination of the Distance and Fundamental Properties of an Eclipsing Binary in the Andromeda Galaxy |journal=Astrophysical Journal |volume=635 |issue=1 |pages=L37–L40 |arxiv=astro-ph/0511045 |bibcode=2005ApJ...635L..37R |doi=10.1086/499161 |s2cid=119522151}}<br />{{cite journal |author=McConnachie, A.W. |author2=Irwin, M.J. |author3=Ferguson, A.M.N. |author3-link=Annette Ferguson |author4=Ibata, R.A. |author5=Lewis, G.F. |author6=Tanvir, N. |author6-link=Nial Tanvir |date=2005 |title=Distances and metallicities for 17 Local Group galaxies |journal=Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society |volume=356 |issue=4 |pages=979–997 |arxiv=astro-ph/0410489 |bibcode=2005MNRAS.356..979M |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2966.2004.08514.x|doi-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

Because humans cannot observe space beyond the edge of the observable universe, it is unknown whether the size of the universe in its totality is finite or infinite.<ref name="Brian Greene 2011" /><ref>{{cite web|title=How can space travel faster than the speed of light?|first=Vanessa |last=Janek |website=Universe Today|date=February 20, 2015|url=http://www.universetoday.com/119068/how-can-space-travel-faster-than-the-speed-of-light/|access-date=June 6, 2015|archive-date=December 16, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211216061309/https://www.universetoday.com/119068/how-can-space-travel-faster-than-the-speed-of-light/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Is faster-than-light travel or communication possible? Section: Expansion of the Universe |url=http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/Relativity/SpeedOfLight/FTL.html#13 |work=Philip Gibbs |date=1997 |access-date=June 6, 2015 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100310205556/http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/physics/Relativity/SpeedOfLight/FTL.html#13 |archive-date=March 10, 2010 }}</ref> Estimates suggest that the whole universe, if finite, must be more than 250 times larger than a [[Hubble volume|Hubble sphere]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Vardanyan |first1=M. |last2=Trotta |first2=R. |last3=Silk |first3=J. |date=January 28, 2011 |title=Applications of Bayesian model averaging to the curvature and size of the Universe |journal=Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters |volume=413 |issue=1 |pages=L91–L95 |arxiv=1101.5476 |bibcode=2011MNRAS.413L..91V |doi=10.1111/j.1745-3933.2011.01040.x |doi-access=free |s2cid=2616287}}</ref> Some disputed<ref>{{cite web |url=https://golem.ph.utexas.edu/category/2008/06/urban_myths_in_contemporary_co.html |title=Urban Myths in Contemporary Cosmology |last=Schreiber |first=Urs |date=June 6, 2008 |website=The n-Category Café |publisher=[[University of Texas at Austin]] |access-date=June 1, 2020 |archive-date=July 1, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200701041542/https://golem.ph.utexas.edu/category/2008/06/urban_myths_in_contemporary_co.html |url-status=live }}</ref> estimates for the total size of the universe, if finite, reach as high as <math>10^{10^{10^{122}}}</math> megaparsecs, as implied by a suggested resolution of the [[Hartle–Hawking state|No-Boundary Proposal]].<ref>{{cite journal|arxiv=hep-th/0610199| author=[[Don Page (physicist)|Don N. Page]]|year=2007|title=Susskind's Challenge to the Hartle-Hawking No-Boundary Proposal and Possible Resolutions| journal=Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics| volume=2007| issue=1| page=004| doi=10.1088/1475-7516/2007/01/004| bibcode=2007JCAP...01..004P| s2cid=17403084}}</ref>{{efn|name=bignumber|Although listed in [[parsec|megaparsecs]] by the cited source, this number is so vast that its digits would remain virtually unchanged for all intents and purposes regardless of which conventional units it is listed in, whether it to be [[nanometers]] or [[parsec|gigaparsecs]], as the differences would disappear into the error.}} |

|||

The universe appears to have a smooth [[space-time continuum]] consisting of three [[space|spatial]] [[dimension]]s and one temporal ([[time]]) dimension. On the average, [[3-space|space]] is observed to be very nearly flat (close to zero [[curvature]]), meaning that [[Euclidean geometry]] is experimentally true with high accuracy throughout most of the Universe.<ref name="Shape">[http://map.gsfc.nasa.gov/m_mm/mr_content.html WMAP Mission: Results – Age of the Universe]</ref> Spacetime also appears to have a [[simply connected space|simply connected]] [[topology]], at least on the length-scale of the observable universe. However, present observations cannot exclude the possibilities that the universe has more dimensions and that its spacetime may have a multiply connected global topology, in analogy with the cylindrical or [[toroid]]al topologies of two-dimensional [[space]]s.<ref name="_spacetime_topology">{{cite conference |

|||

| first = Jean-Pierre |

|||

| last = Luminet |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| coauthors = Boudewijn F. Roukema |

|||

| title = Topology of the Universe: Theory and Observations |

|||

| booktitle = Proceedings of Cosmology School held at Cargese, Corsica, August 1998 |

|||

| pages = |

|||

| publisher = |

|||

| year = 1999 |

|||

| location = |

|||

| url = http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/9901364 |

|||

| doi = |

|||

| id = |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-01-05 |

|||

}}<br />{{cite journal |

|||

| last = Luminet |

|||

| first = Jean-Pierre |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| coauthors = J. Weeks, A. Riazuelo, R. Lehoucq, J.-P. Uzan |

|||

| title = Dodecahedral space topology as an explanation for weak wide-angle temperature correlations in the cosmic microwave background |

|||

| journal = [[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |

|||

| volume = 425 |

|||

| issue = |

|||

6958| pages = 593–5 |

|||

| publisher = |

|||

| year=2003 |

|||

| pmid = 14534579 |

|||

| url = http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0310253 |

|||

| doi =10.1038/nature01944 |

|||

| id = |

|||

| accessdate = 2007-01-09 |

|||

| format = subscription required}}</ref> |

|||

=== Age and expansion === |

|||

The universe appears to behave in a manner that regularly follows a set of [[physical law]]s and [[physical constant]]s.<ref>{{cite web | last = Strobel | first = Nick |date= May 23, 2001 | url = http://www.astronomynotes.com/starprop/s7.htm | title = The Composition of Stars | publisher = Astronomy Notes | accessdate = 2007-01-04 }}<br />{{cite web | url=http://www.faqs.org/faqs/astronomy/faq/part4/section-4.html | title = Have physical constants changed with time? | publisher = Astrophysics (Astronomy Frequently Asked Questions) | accessdate = 2007-01-04 }}</ref> According to the prevailing [[Standard Model]] of physics, all matter is composed of three generations of [[lepton]]s and [[quark]]s, both of which are [[fermion]]s. These [[elementary particle]]s interact via at most three [[fundamental interaction]]s: the [[electroweak]] interaction which includes [[electromagnetism]] and the [[weak nuclear force]]; the [[strong nuclear force]] described by [[quantum chromodynamics]]; and [[gravity]], which is best described at present by [[general relativity]]. The first two interactions can be described by [[renormalization|renormalized]] [[quantum field theory]], and are mediated by [[gauge boson]]s that correspond to a particular type of [[gauge symmetry]]. A renormalized quantum field theory of general relativity has not yet been achieved, although various forms of [[string theory]] seem promising. The theory of [[special relativity]] is believed to hold throughout the universe, provided that the spatial and temporal length scales are sufficiently short; otherwise, the more general theory of general relativity must be applied. There is no explanation for the particular values that [[physical constant]]s appear to have throughout our universe, such as [[Planck's constant]] ''h'' or the [[gravitational constant]] ''G''. Several [[conservation law]]s have been identified, such as the [[conservation of charge]], [[conservation of momentum|momentum]], [[conservation of angular momentum|angular momentum]] and [[conservation of energy|energy]]; in many cases, these conservation laws can be related to [[symmetry|symmetries]] or [[Bianchi identity|mathematical identities]]. |

|||

{{Main|Age of the universe|Expansion of the universe}} |

|||

Assuming that the [[Lambda-CDM model]] is correct, the measurements of the parameters using a variety of techniques by numerous experiments yield a best value of the age of the universe at 13.799 [[Measurement uncertainty|±]] 0.021 billion years, as of 2015.<ref name="Planck 2015">{{cite journal|author=Planck Collaboration|year=2016|title=Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters|journal=Astronomy & Astrophysics|volume=594|page=A13, Table 4|arxiv=1502.01589|bibcode=2016A&A...594A..13P|doi=10.1051/0004-6361/201525830|s2cid=119262962}}</ref> |

|||

Over time, the universe and its contents have evolved. For example, the relative population of [[quasar]]s and galaxies has changed<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.science.org/content/article/galaxy-collisions-give-birth-quasars |work=Science News |title=Galaxy Collisions Give Birth to Quasars |date=March 25, 2010 |first=Phil |last=Berardelli |access-date=July 30, 2022 |archive-date=March 25, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220325005200/https://www.science.org/content/article/galaxy-collisions-give-birth-quasars |url-status=live }}</ref> and the [[expansion of the universe|universe has expanded]]. This expansion is inferred from the observation that the light from distant galaxies has been [[redshift]]ed, which implies that the galaxies are receding from us. Analyses of [[Type Ia supernova]]e indicate that the [[accelerating expansion of the Universe|expansion is accelerating]].<ref name="riess">{{cite journal|author=Riess, Adam G.|year=1998|title=Observational evidence from supernovae for an accelerating universe and a cosmological constant|journal=Astronomical Journal|volume=116|issue=3|pages=1009–1038|arxiv=astro-ph/9805201 |doi=10.1086/300499|bibcode=1998AJ....116.1009R|last2=Filippenko|last3=Challis|last4=Clocchiatti|last5=Diercks|last6=Garnavich|last7=Gilliland|last8=Hogan|last9=Jha|last10=Kirshner|last11=Leibundgut|last12=Phillips|last13=Reiss|last14=Schmidt|last15=Schommer|last16=Smith|last17=Spyromilio|last18=Stubbs|last19=Suntzeff|last20=Tonry|s2cid=15640044|author-link=Adam Riess}}</ref><ref name="perlmutter">{{cite journal|author=Perlmutter, S. |journal=Astrophysical Journal|volume=517|issue=2|pages=565–586|year=1999|title=Measurements of Omega and Lambda from 42 high redshift supernovae|arxiv=astro-ph/9812133 |doi=10.1086/307221|bibcode=1999ApJ...517..565P|last2=Aldering|last3=Goldhaber|last4=Knop|last5=Nugent|last6=Castro|last7=Deustua|last8=Fabbro|last9=Goobar|last10=Groom|last11=Hook|last12=Kim|last13=Kim|last14=Lee|last15=Nunes|last16=Pain|last17=Pennypacker|last18=Quimby|last19=Lidman|last20=Ellis|last21=Irwin|last22=McMahon|last23=Ruiz-Lapuente|last24=Walton|last25=Schaefer|last26=Boyle|last27=Filippenko|last28=Matheson|last29=Fruchter|last30=Panagia|s2cid=118910636|display-authors=29|author-link=Saul Perlmutter}}</ref> |

|||

===Fine tuning=== |

|||

{{main|Fine-tuned Universe}} |

|||

It appears that many of the properties of the universe have special values in the sense that a universe where these properties only differ slightly would not be able to support intelligent life.<ref>{{cite book|author=[[Stephen Hawking]]|year=1988|title=A Brief History of Time|publisher=Bantam Books|isbn=0-553-05340-X|page=125}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|year=1999|title=Just Six Numbers|publisher=HarperCollins Publishers|isbn=0-465-03672-4|author=[[Martin Rees]]}}</ref> Not all scientists agree that this [[fine-tuned universe|fine-tuning]] exists.<ref name="adams">{{cite journal | last=Adams | first=F.C. | year=2008 | title=Stars in other universes: stellar structure with different fundamental constants | journal= Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics | issue=08 | doi=10.1088/1475-7516/2008/08/010 | url=http://arxiv.org/abs/0807.3697 | volume=2008 | pages=010}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last=Harnik | first=R. | coauthors=Kribs, G.D. and Perez, G. | year=2006 | title=A universe without weak interactions | journal=Physical Review D | volume=74 | doi=10.1103/PhysRevD.74.035006 | issue=3 | url=http://arxiv.org/abs/hep-ph/0604027 | pages=035006 }}</ref> In particular, it is not known under what conditions intelligent life could form and what form or shape that would take. A relevant observation in this discussion is that existence of an observer to observe fine-tuning, requires that the universe supports intelligent life. As such the [[conditional probability]] of observing a universe that is fine-tuned to support intelligent life is 1. This observation is known as the [[anthropic principle]] and is particularly relevant if the creation of the universe was probabilistic or if multiple universes with a variety of properties exist (see [[#Multiverse theory|below]]). |

|||