Mughal Empire: Difference between revisions

Worldbruce (talk | contribs) clean up, use meaningful reference names, reduced MOS:OVERLINK, url parameter should link to full text, use cite encyclopedia and author-link parameter, removed link to copyright violation of TV show Ancient Discoveries, [[WP:AWB/T|typo(s) fixe |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|1526–1857 empire in South Asia}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Mughals||Mughal (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{Hatnote group|{{distinguish|text=the [[Mongol Empire]] or [[Moghulistan]]}} |

|||

{{Other uses|Mughal (disambiguation)}} |

|||

}} |

|||

{{pp-semi-indef}} |

|||

{{Use Indian English|date=July 2016}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2021}} |

|||

{{Infobox former country |

{{Infobox former country |

||

| conventional_long_name = Mughal Empire<!--Do not change to any "official name" without establishing the prevalence of the name in sources.--> |

|||

|native_name = {{lang|fa|شاهان مغول}}<br />{{lang|fa-Latn|''Shāhān-e Moġul''}} |

|||

| religion = {{ubli |

|||

|conventional_long_name = The Mughal Empire |

|||

| '''State religion''' |

|||

|common_name = Mughal Empire |

|||

| [[Islam]]{{efn|[[Islamic schools and branches|Branch]]: [[Sunni Islam|Sunni]]<br />School of [[Fiqh|jurisprudence]]: [[Hanafi]]}} |

|||

|continent = Asia |

|||

| [[Din-i Ilahi]] (1582–1605) |

|||

|region = South Asia |

|||

| '''Others''' |

|||

|country = India <!-- Per [[Template:Infobox former country#Location]], Pakistan is already addressed at "|today=" below --> |

|||

| [[Hinduism]] (majority) |

|||

|era = Early modern |

|||

| ''See [[Religion in South Asia]]'' |

|||

|status = Empire |

|||

}} |

|||

|status_text = <!-- A free text to describe status the top of the infobox. Use sparingly. --> |

|||

| |

| era = Early modern |

||

| status = [[Empire]] |

|||

|government_type = [[Absolute monarchy]], [[unitary state]]<br />with [[federation|federal structure]] |

|||

| government_type = [[Monarchy]] |

|||

<!-- Rise and fall, events, years and dates --> |

|||

| life_span = 1526–1857 |

|||

<!-- only fill in the start/end event entry if a specific article exists. Don't just say "abolition" or "declaration" --> |

|||

|year_start = 1526 |

| year_start = 1526 |

||

|year_end = |

| year_end = 1857 |

||

| event_start = [[First Battle of Panipat]] |

|||

|year_exile_start = <!-- Year of start of exile (if dealing with exiled government - status="Exile") --> |

|||

| date_start = 21 April |

|||

|year_exile_end = <!-- Year of end of exile (leave blank if still in exile) --> |

|||

| |

| event_end = [[Siege of Delhi]] |

||

| |

| date_end = 21 September |

||

| |

| event_post = [[Mughal Emperor]] exiled to Burma |

||

| |

| date_post = 7 October 1858 |

||

|event1 = |

| event1 = [[Sur Empire|Mughal Interregnum]] |

||

|date_event1 = |

| date_event1 = 17 May 1540–22 June 1555 |

||

|event2 = |

| event2 = [[Second Battle of Panipat]] |

||

|date_event2 = |

| date_event2 = 5 November 1556 |

||

|event3 = |

| event3 = [[Mughal–Afghan Wars]] |

||

|date_event3 = |

| date_event3 = 21 April 1526–3 April 1752 |

||

|event4 = |

| event4 = [[Deccan wars]] |

||

|date_event4 = |

| date_event4 = 1680–1707 |

||

| |

| event6 = [[Nader Shah's invasion of India]] |

||

| |

| date_event6 = 1738–1740 |

||

| |

| p1 = Delhi Sultanate |

||

| |

| p2 = Sur Empire |

||

| s1 = British Raj |

|||

<!-- Flag navigation: Preceding and succeeding entities p1 to p5 and s1 to s5 --> |

|||

| |

| today = [[India]] <br /> [[Pakistan]]<br />[[Bangladesh]]<br />[[Afghanistan]] |

||

| |

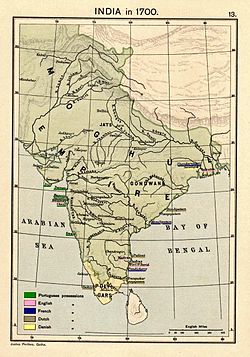

| image_map = Joppen1907India1700a.jpg |

||

| image_map_caption = The empire at its greatest extent in {{circa|1700}} under [[Aurangzeb]] |

|||

|image_p1 = <!-- Use: [[Image:Sin escudo.svg|20px|Image missing]] --> |

|||

| |

| image_map_alt = Mughal |

||

| |

| capital = {{ubli |

||

| [[Agra]] (1526–1530; {{nwr|1560–1571;}} {{nwr|1598–1648}}) |

|||

|image_p2 = |

|||

| [[Delhi]] (1530–1540; {{nwr|1639–1857}}) |

|||

|p3 = Suri dynasty |

|||

| [[Fatehpur Sikri]] (1571–1585) |

|||

|flag_p3 = |

|||

| [[Lahore]] (1586–1598){{sfn|Sinopoli|1994|p=294}} |

|||

|image_p3 = |

|||

}} |

|||

|p4 = Adil Shahi dynasty |

|||

| common_languages = ''See [[Languages of South Asia]]'' |

|||

|flag_p4 = |

|||

| official_languages = {{hlist|[[Persian language|Persian]]|[[Hindustani language|Hindustani]]}} |

|||

|image_p4 = |

|||

| currency = [[Rupee]], [[History of the taka|Taka]], [[Dam (Indian coin)|dam]]{{sfn|Richards|1995|pp=73–74}} |

|||

|p5 = Deccan Sultanates |

|||

| |

| leader1 = [[Babur]] |

||

| |

| leader2 = [[Bahadur Shah II]] |

||

| |

| year_leader1 = 1526–1530 (first) |

||

| |

| year_leader2 = 1837–1857 (last) |

||

| |

| title_leader = [[Mughal emperors|Emperor]] |

||

| title_representative = [[Vakil of the Mughal Empire|Vicegerent]] |

|||

|image_s1 = <!-- Use: [[Image:Sin escudo.svg|20px|Image missing]] --> |

|||

| year_representative1 = 1526–1540 (first) |

|||

|s2 = Durrani Empire |

|||

| representative1 = [[Mir Khalifa]] |

|||

|flag_s2 = Flag of the Emirate of Herat.svg |

|||

| year_representative2 = 1794–1818 (last) |

|||

|s3 = Sikh Empire |

|||

| representative2 = [[Daulat Rao Sindhia]] |

|||

|flag_s3 = Punjab flag.svg |

|||

| title_deputy = [[List of Mughal grand viziers|Grand Vizier]] |

|||

|s4 = Company rule in India{{!}}Company Raj |

|||

| |

| deputy1 = [[Nizam-ud-din Khalifa]] |

||

| |

| year_deputy1 = 1526–1540 (first) |

||

| |

| deputy2 = [[Asaf-ud-Daula]] |

||

| |

| year_deputy2 = 1775–1797 (last) |

||

| stat_year1 = 1690<ref name="TurchinAdams2006">{{Cite journal |last1=Turchin |first1=Peter |last2=Adams |first2=Jonathan M. |last3=Hall |first3=Thomas D. |year=2006 |title=East–West Orientation of Historical Empires and Modern States |journal=Journal of World-Systems Research |volume=12 |issue=2 |pages=219–229 |doi=10.5195/JWSR.2006.369 |issn=1076-156X |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Taagepera">{{Cite journal |last=Rein Taagepera |author-link=Rein Taagepera |date=September 1997 |title=Expansion and Contraction Patterns of Large Polities: Context for Russia |url=http://www.escholarship.org/uc/item/3cn68807 |journal=[[International Studies Quarterly]] |volume=41 |issue=3 |pages=475–504 |doi=10.1111/0020-8833.00053 |jstor=2600793 |access-date=6 July 2019 |archive-date=19 November 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181119114740/https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3cn68807 |url-status=live |issn = 0020-8833 }}</ref> |

|||

|flag_s6 = Asafia flag of Hyderabad State.png |

|||

| |

| stat_area1 = 4000000 |

||

| |

| stat_year2 = 1595 |

||

| stat_pop2 = 125,000,000<ref>{{cite book |last=Dyson |first=Tim |title=A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day |year=2018 |publisher=Oxford University Press |pages=70–71 |isbn=978-0-19-256430-6 |quote=We have seen that there is considerable uncertainty about the size of India's population c.1595. Serious assessments vary from 116 to 145 million (with an average of 125 million). However, the true figure could even be outside of this range. Accordingly, while it seems likely that the population grew over the seventeenth century, it is unlikely that we will ever have a good idea of its size in 1707.}}</ref> |

|||

|image_flag = Flag of the Mughal Empire.svg |

|||

| |

| stat_year3 = 1700 |

||

| |

| stat_pop3 = 158,000,000<ref name="borocz" /> |

||

|flag = Flag of the Mughal Empire |

|||

|flag_type = <!-- Displayed text for link under flag. Default "Flag" --> |

|||

|image_coat = <!-- Default: Coat of arms of {{{common_name}}}.svg --> |

|||

|coat_alt = <!-- Alt text for coat of arms --> |

|||

|symbol = <!-- Link target under symbol image. Default: Coat of arms of {{{common_name}}} --> |

|||

|symbol_type = <!-- Displayed text for link under symbol. Default "Coat of arms" --> |

|||

|image_map = MughalEmpire1700.svg |

|||

|image_map_alt = Map of Mughal Empire in 1700 CE |

|||

|image_map_caption = Mughal Empire (green) during its greatest territorial extent, {{circa|1700}} |

|||

|image_map2 = <!-- If second map is needed - does not appear by default --> |

|||

|image_map2_alt = |

|||

|image_map2_caption = |

|||

|capital = [[Agra]]; [[Fatehpur Sikri]]; [[Delhi]] <!-- [[Lahore]] was royal residence, not capital --> |

|||

|capital_exile = <!-- If status="Exile" --> |

|||

|latd= |latm= |latNS= |longd= |longm= |longEW= |

|||

|national_motto = |

|||

|national_anthem = |

|||

|common_languages = [[Persian language|Persian]] (initially also [[Chagatai language|Chagatai Turkic]]; later also [[Urdu]]) |

|||

|currency = Rupee |

|||

<!-- Titles and names of the first and last leaders and their deputies --> |

|||

|leader1 = Babur |

|||

|leader2 = Humayun |

|||

|leader3 = Akbar |

|||

|leader4 = Jahangir |

|||

|leader5 = Shah Jahan |

|||

|leader6 = Aurangzeb |

|||

|year_leader1 = 1526–1530 |

|||

|year_leader2 = 1530–1539, 1555–1556 |

|||

|year_leader3 = 1556–1605 |

|||

|year_leader4 = 1605–1627 |

|||

|year_leader5 = 1628–1658 |

|||

|year_leader6 = 1658–1707 |

|||

|title_leader = [[Mughal emperors|Emperor]] |

|||

|representative1 = <!-- Name of representative of head of state (eg. colonial governor) --> |

|||

|representative2 = |

|||

|representative3 = |

|||

|representative4 = |

|||

|year_representative1 = <!-- Years served --> |

|||

|year_representative2 = |

|||

|year_representative3 = |

|||

|year_representative4 = |

|||

|title_representative = <!-- Default: "Governor" --> |

|||

|deputy1 = <!-- Name of prime minister --> |

|||

|deputy2 = |

|||

|deputy3 = |

|||

|deputy4 = |

|||

|year_deputy1 = <!-- Years served --> |

|||

|year_deputy2 = |

|||

|year_deputy3 = |

|||

|year_deputy4 = |

|||

|title_deputy = <!-- Default: "Prime minister" --> |

|||

<!-- Legislature --> |

|||

|legislature = <!-- Name of legislature --> |

|||

|house1 = <!-- Name of first chamber --> |

|||

|type_house1 = <!-- Default: "Upper house" --> |

|||

|house2 = <!-- Name of second chamber --> |

|||

|type_house2 = <!-- Default: "Lower house" --> |

|||

<!-- Area and population of a given year --> |

|||

|stat_year1 = 1700 |

|||

|stat_area1 = 3200000 |

|||

|stat_pop1 = 150000000 |

|||

|stat_year2 = |

|||

|stat_area2 = |

|||

|stat_pop2 = |

|||

|stat_year3 = |

|||

|stat_area3 = |

|||

|stat_pop3 = |

|||

|stat_year4 = |

|||

|stat_area4 = |

|||

|stat_pop4 = |

|||

|stat_year5 = |

|||

|stat_area5 = |

|||

|stat_pop5 = |

|||

|footnotes = Population source:<ref name="Richards1993">{{cite book|last=Richards|first=John F.|title=The Mughal Empire|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0521251198|doi=10.2277/0521251192|editor1-first=Gordon|editor1-last=Johnson|editor1-link=Gordon Johnson (historian)|editor2-first=C. A.|editor2-last=Bayly|editor2-link=Christopher Alan Bayly|accessdate=14 October 2010|series=The New Cambridge history of India: 1.5|volume=I. The Mughals and their Contemporaries|location=Cambridge|pages=1, 190|date=March 26, 1993}}</ref> |

|||

|today = {{flag|Afghanistan}}<br>{{flag|Bangladesh}}<br>{{flag|India}}<br>{{flag|Pakistan}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Mughal Empire''' was an [[Early modern period|early modern]] empire in South Asia. At its peak, the empire stretched from the outer fringes of the [[Indus River]] Basin in the west, northern [[Afghanistan]] in the northwest, and [[Kashmir]] in the north, to the [[highland]]s of present-day [[Assam]] and [[Bangladesh]] in the east, and the uplands of the [[Deccan Plateau]] in [[South India]].<ref name="Stein2010-12">{{harvnb|Stein|2010|pp=159–}}. Quote: "The realm so defined and governed was a vast territory of some {{convert|750000|sqmi|km2|disp=sqbr}}, ranging from the frontier with Central Asia in northern Afghanistan to the northern uplands of the Deccan plateau, and from the Indus basin on the west to the Assamese highlands in the east."</ref> |

|||

{{South Asian history}} |

|||

The '''Mughal Empire''' ({{lang-fa|شاهان مغول}}, {{lang|fa-Latn|''Shāhān-e Moġul''}}; {{Lang-ur|{{Nastaliq|مغلیہ سلطنت}}}}; self-designation: {{lang|fa|گوركانى}}, {{lang|fa-Latn|''Gūrkānī''}}),<span dir="ltr"><ref name="Thackston">{{cite book|title=The [[Baburnama]]: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor|publisher=[[Modern Library]]|isbn=978-0375761379|author=Zahir ud-Din Mohammad|authorlink=Babur|editor=Thackston, Wheeler M.|editor-link=Wheeler Thackston|location=New York|page=xlvi|date=September 10, 2002|quote=In India the dynasty always called itself {{lang|fa-Latn|Gurkani}}, after {{lang|chg-Latn|[[Timur|Temür]]}}'s title {{lang|fa-Latn|Gurkân}}, the Persianized form of the Mongolian {{lang|mn-Latn|''kürägän''}}, 'son-in-law,' a title he assumed after his marriage to a [[Genghisid]] princess.}}</ref><ref name="Balfour">{{cite book|last=Balfour|first=E.G.|authorlink=Edward Balfour|title=Encyclopaedia Asiatica: Comprising Indian-subcontinent, Eastern and Southern Asia|year=1976|publisher=Cosmo Publications|isbn=978-8170203254|location=New Delhi|at=S. 460, S. 488, S. 897}}</ref> or '''Mogul''' (also '''Moghul''') '''Empire''' in former English usage, was an imperial power from the [[Indian Subcontinent]].<ref>[http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/southasia/History/Mughals/mughals.html "The Mughal Empire"]</ref> The [[Mughal emperors]] were descendants of the [[Timurids]]. It began in 1526, at the height of their power in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, they controlled most of the Indian Subcontinent—extending from [[Bengal]] in the east to [[Balochistan (region)|Balochistan]] in the west, [[Kashmir]] in the north to the [[Kaveri]] basin in the south.<ref>[http://sun.menloschool.org/~sportman/westernstudies/first/1718/2000/eblock/mughal/ menloschool.org]{{dead link|date=October 2010}}</ref> |

|||

Its population at that time has been estimated as between 110 and 150 million, over a territory of more than 3.2 million square kilometres (1.2 million square miles).<ref name=Richards1993 /> |

|||

The Mughal Empire is conventionally said to have been founded in 1526 by [[Babur]], a [[Timurid dynasty|Timurid]] [[Tribal chief|chieftain]] from [[Transoxiana]], who employed aid from the neighbouring [[Safavid Iran|Safavid]] and [[Ottoman Empire]]s<ref name="Gilbert2017">{{Citation |last=Gilbert |first=Marc Jason |title=South Asia in World History |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1dhKDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA75 |year=2017 |publisher=Oxford University Press |page=62 |isbn=978-0-19-066137-3 |access-date=15 July 2019}} Quote: "Babur then adroitly gave the Ottomans his promise not to attack them in return for their military aid, which he received in the form of the newest of battlefield inventions, the matchlock gun and cast cannons, as well as instructors to train his men to use them."</ref> to defeat the [[Delhi Sultanate|Sultan of Delhi]], [[Ibrahim Lodi]], in the [[First Battle of Panipat]], and to sweep down the plains of [[North India]]. The Mughal imperial structure, however, is sometimes dated to 1600, to the rule of Babur's grandson, [[Akbar]].<ref name="Stein2010">{{harvnb|Stein|2010|pp=159–}}. Quote: "Another possible date for the beginning of the Mughal regime is 1600 when the institutions that defined the regime were set firmly in place and when the heartland of the empire was defined; both of these were the accomplishment of Babur's grandson Akbar."</ref> This imperial structure lasted until 1720, shortly after the death of the last major emperor, [[Aurangzeb]],<ref name="Stein2010-1">{{harvnb|Stein|2010|pp=159–}}. Quote: "The imperial career of the Mughal house is conventionally reckoned to have ended in 1707 when the emperor Aurangzeb, a fifth-generation descendant of Babur, died. His fifty-year reign began in 1658 with the Mughal state seeming as strong as ever or even stronger. But in Aurangzeb's later years the state was brought to the brink of destruction, over which it toppled within a decade and a half after his death; by 1720 imperial Mughal rule was largely finished and an epoch of two imperial centuries had closed."</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Richards|1995|p=xv}}. Quote: "By the latter date (1720) the essential structure of the centralized state was disintegrated beyond repair."</ref> during whose reign the empire also achieved its maximum geographical extent. Reduced subsequently to the region in and around Old Delhi by 1760, the empire was formally dissolved by the [[British Raj]] after the [[Indian Rebellion of 1857]]. |

|||

The "''classic period''" of the empire started in 1556 with the accession of [[Akbar the Great|Jalaluddin Mohammad Akbar]], better known as Akbar the Great. Under the rule of Akbar the Great, India enjoyed much cultural and economic progress as well as religious harmony. The Mughals also forged a strategic alliance with several Hindu [[Rajput]]s kingdoms. However, some Rajput kings, such as [[Maha Rana Pratap]], continued to pose significant threat to Mughal dominance of northwestern India. Additionally, regional states in southern and northeastern India, such as the [[Ahom Kingdom]] of [[Assam]], successfully resisted Mughal subjugation. The reign of [[Shah Jahan]], the fifth emperor, was the golden age of [[Mughal architecture]]. He erected many splendid monuments, the most famous of which is the legendary [[Taj Mahal]] at [[Agra]] as well as [[Moti Masjid, Agra|Pearl Mosque]], the [[Red Fort]], [[Jama Masjid, Delhi|Jama Masjid (Mosque)]] and [[Lahore Fort]]. The reign of [[Aurangzeb]] saw the enforcement of strict Muslim fundamentalism which caused rebellions among the [[Sikh]]s and [[Hindu]]s. |

|||

Although the Mughal Empire was created and sustained by military warfare,<ref name="Stein2010-2">{{harvnb|Stein|2010|pp=159–}}. Quote: "The vaunting of such progenitors pointed up the central character of the Mughal regime as a warrior state: it was born in war and it was sustained by war until the eighteenth century when warfare destroyed it."</ref><ref name="Robb2011">{{harvnb|Robb|2011|pp=108–}}. Quote: "The Mughal state was geared for war and succeeded while it won its battles. It controlled territory partly through its network of strongholds, from its fortified capitals in Agra, Delhi or Lahore, which defined its heartlands, to the converted and expanded forts of Rajasthan and the Deccan. The emperor's will be frequently enforced in battle. Hundreds of army scouts were an important source of information. But the empire's administrative structure too was defined by and directed at war. Local military checkpoints or thanas kept order. Directly appointed imperial military and civil commanders (faujdars) controlled the cavalry and infantry, or the administration, in each region. The peasantry in turn were often armed, able to provide supporters for regional powers, and liable to rebellion on their account: continual pacification was required of the rulers."</ref><ref name="Gilbert2017-2">{{Citation |last=Gilbert |first=Marc Jason |title=South Asia in World History |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1dhKDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA75 |pages=75– |year=2017 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-066137-3 |access-date=15 July 2019 |archive-date=22 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230922031915/https://books.google.com/books?id=1dhKDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA75 |url-status=live }} Quote: "With Safavid and Ottoman aid, the Mughals would soon join these two powers in a triumvirate of warrior-driven, expansionist, and both militarily and bureaucratically efficient early modern states, now often called "gunpowder empires" due to their common proficiency is using such weapons to conquer lands they sought to control."</ref> it did not vigorously suppress the cultures and peoples it came to rule; rather it equalized and placated them through new administrative practices,{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|p=115}}{{sfn|Robb|2011|pp=99–100}} and diverse ruling elites, leading to more efficient, centralised, and standardized rule.{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|pp=152–}} The base of the empire's collective wealth was agricultural taxes, instituted by the third Mughal emperor, Akbar.<ref name="Stein2010-3">{{harvnb|Stein|2010|pp=164–}}. Quote: "The resource base of Akbar's new order was land revenue"</ref><ref name="AsherTalbot2006-1">{{harvnb|Asher|Talbot|2006|pp=158–}}. Quote: "The Mughal empire was based in the interior of a large land mass and derived the vast majority of its revenues from agriculture."</ref> These taxes, which amounted to well over half the output of a peasant cultivator,<ref name="Stein2010-4">{{harvnb|Stein|2010|pp=164–}}. Quote: "... well over half of the output from the fields in his realm, after the costs of production had been met, is estimated to have been taken from the peasant producers by way of official taxes and unofficial exactions. Moreover, payments were exacted in money, and this required a well-regulated silver currency."</ref> were paid in the well-regulated silver currency,{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|pp=152–}} and caused peasants and artisans to enter larger markets.<ref name="AsherTalbot2006-3">{{harvnb|Asher|Talbot|2006|pp=152–}}. Quote: "His stipulation that land taxes be paid in cash forced peasants into market networks, where they could obtain the necessary money, while the standardization of imperial currency made the exchange of goods for money easier."</ref> |

|||

By early 1700s, the Sikh [[Misl]] and the Hindu [[Maratha Empire]] had emerged as formidable foes of the Mughals. Following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the empire started its gradual decline,<ref name="BBC">{{cite web|title=Mughal Empire (1500s, 1600s)|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/islam/history/mughalempire_1.shtml|work=bbc.co.uk|publisher=British Broadcasting Corporation|accessdate=18 October 2010|location=London|at=Section 5: Aurangzeb}}</ref> although the dynasty continued for another 150 years. During the classic period, the empire was marked by a highly centralized administration connecting the different regions. All the significant monuments of the Mughals, their most visible legacy, with brilliant literary, artistic, and architectural results. |

|||

The relative peace maintained by the empire during much of the 17th century was a factor in India's economic expansion.<ref name="AsherTalbot2006-4">{{harvnb|Asher|Talbot|2006|pp=152–}}. Quote: "Above all, the long period of relative peace ushered in by Akbar's power, and maintained by his successors, contributed to India's economic expansion."</ref> The burgeoning European presence in the Indian Ocean and an increasing demand for Indian raw and finished products generated much wealth for the Mughal court.<ref name="AsherTalbot2006-5">{{harvnb|Asher|Talbot|2006|pp=186–}}. Quote: "As the European presence in India grew, their demands for Indian goods and trading rights increased, thus bringing even greater wealth to the already flush Indian courts."</ref> There was more conspicuous consumption among the Mughal elite,<ref name="AsherTalbot2006-6">{{harvnb|Asher|Talbot|2006|pp=186–}}. Quote: "The elite spent more and more money on luxury goods and sumptuous lifestyles, and the rulers built entire new capital cities at times."</ref> resulting in greater patronage of [[Mughal painting|painting]], literary forms, textiles, and [[Mughal architecture|architecture]], especially during the reign of [[Shah Jahan]].<ref name="AsherTalbot2006-7">{{harvnb|Asher|Talbot|2006|pp=186–}}. Quote: "All these factors resulted in greater patronage of the arts, including textiles, paintings, architecture, jewellery, and weapons to meet the ceremonial requirements of kings and princes."</ref> Among the Mughal [[UNESCO World Heritage Sites]] in South Asia are: [[Agra Fort]], [[Fatehpur Sikri]], [[Red Fort]], [[Humayun's Tomb]], [[Lahore Fort]], [[Shalamar Gardens, Lahore|Shalamar Gardens]], and the [[Taj Mahal]], which is described as "the jewel of Muslim art in India, and one of the universally admired masterpieces of the world's heritage".<ref name="Centre" /> |

|||

Following 1725, the empire began to disintegrate, weakened by wars of succession, agrarian crises fueling local revolts, the growth of religious intolerance, the rise of the [[Maratha Empire|Maratha]], [[Durrani Empire|Durrani]], as well as [[Sikh Empire|Sikh]] empires and finally [[British colonialism]]. The last Emperor, [[Bahadur Shah II]], whose rule was restricted to the city of [[Delhi]], was imprisoned and exiled by the [[British Empire|British]] after the [[Indian Rebellion of 1857]]. |

|||

== Name == |

|||

The name ''Mughal'' is derived from the original homelands of the Timurids, the Central Asian steppes once conquered by [[Genghis Khan]] and hence known as ''[[Moghulistan]]'', "Land of Mongols". Although early Mughals spoke the [[Chagatai language]] and maintained some [[Turko-Mongol]] practices, they became essentially [[Persianized]]<ref name="Canfield">Robert L. Canfield, ''Turko-Persia in historical perspective'', Cambridge University Press, 1991. pg 20: "The Mughals – Persianized Turks who invaded from Central Asia and claimed descent from both Timur and Genghis – strengthened the Persianate culture of Muslim India"</ref> and transferred the [[Persian culture|Persian literary and high culture]]<ref name="Canfield"/> to India, thus forming the base for the [[Indo-Persian culture]].<ref name="Canfield"/> |

|||

The closest to an official name for the empire was ''[[Hindustan]]'', which was documented in the [[Ain-i-Akbari]].<ref name="Vanina">{{Cite book |last=Vanina |first=Eugenia |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yriGbWNAF5EC&pg=PA47 |title=Medieval Indian Mindscapes: Space, Time, Society, Man |publisher=Primus Books |year=2012 |isbn=978-93-80607-19-1 |page=47 |author-link=Eugenia Vanina |access-date=19 October 2015 |archive-date=22 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230922033421/https://books.google.com/books?id=yriGbWNAF5EC&pg=PA47 |url-status=live}}</ref> Mughal administrative records also refer to the empire as "dominion of Hindustan" ({{Transliteration|fa|Wilāyat-i-Hindustān}}),<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Hardy |first1=P. |editor-last=Levtzion |editor-first=Nehemia |chapter=Modern European and Muslim Explanations of Conversion to Islam in South Asia: A Preliminary Survey of the Literature |title=Conversion to Islam |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=37nXAAAAMAAJ&q=bilad+-+i+Hind+(+the+country+of+Hind+)+,+wilayat+-+i+Hindustan+(+the+dominion+of+Hindustan+)+,+sultanat+-+i |year=1979 |publisher=Holmes & Meier |page=69 |isbn=978-0-8419-0343-2 |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=3 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403231614/https://books.google.com/books?id=37nXAAAAMAAJ&q=bilad+-+i+Hind+(+the+country+of+Hind+)+,+wilayat+-+i+Hindustan+(+the+dominion+of+Hindustan+)+,+sultanat+-+i |url-status=live}}</ref> "country of Hind" ({{Transliteration|fa|Bilād-i-Hind}}), "Sultanate of Al-Hind" ({{Transliteration|fa|Salṭanat(i) al-Hindīyyah}}) as observed in the epithet of Emperor [[Aurangzeb]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.asiaurangabad.in/pdf/Tourist/Tomb_of_Aurangzeb-_Khulatabad.pdf |title=Name of the Monument/ site: Tomb of Aurangzeb |website=asiaurangabad.in |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150923175254/http://www.asiaurangabad.in/pdf/Tourist/Tomb_of_Aurangzeb-_Khulatabad.pdf |archive-date=23 September 2015}}</ref> or endonymous identification from emperor [[Bahadur Shah Zafar]] as "Land of Hind" ({{Transliteration|ur|Hindostān}}) in [[Hindustani language|Hindustani]].<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Parvez |first1=Aslam |title=The life & poetry of Bahadur Shah Zafar |last2=Fārūqī |first2=At̤har |date=2017 |publisher=Hay House India |isbn=978-93-85827-47-1 |location=New Delhi, India |oclc=993093699}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Indian History Collective |url=https://indianhistorycollective.com/what-was-hindustan-hindustani-subcontinentofindia-politicalmap-geographynow-geographygames-mughalempire-mughalarchitecture-architecture-hindoostanmap/ |date=2023-12-30 |archiveurl=https://archive.today/20231230135647/https://indianhistorycollective.com/what-was-hindustan-hindustani-subcontinentofindia-politicalmap-geographynow-geographygames-mughalempire-mughalarchitecture-architecture-hindoostanmap/ |archivedate=2023-12-30}}</ref> Contemporary Chinese chronicles referred to the empire as ''Hindustan'' ({{Transliteration|zh|ISO|Héndūsītǎn}}).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mosca |first=Matthew |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Zvmix_k1XDcC&pg=PA94 |title=From Frontier Policy to Foreign Policy: The Question of India and the Transformation of Geopolitics in Qing China |date=2013 |publisher=Stanford University Press |isbn=978-0-8047-8538-9 |pages=78–94 |language=en |access-date=7 November 2023 |archive-date=7 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231107203141/https://books.google.com/books?id=Zvmix_k1XDcC&pg=PA94 |url-status=live}}</ref> In the west, the term "[[Mughal emperors|Mughal]]" was used for the emperor, and by extension, the empire as a whole.<ref name="Fontana">{{Cite book |last=Fontana |first=Michela |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MVZU1sAQ8H4C&pg=PA32 |title=Matteo Ricci: A Jesuit in the Ming Court |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield Publishers |year=2011 |isbn=978-1-4422-0588-8 |page=32 |access-date=19 October 2015 |archive-date=22 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230922033421/https://books.google.com/books?id=MVZU1sAQ8H4C&pg=PA32 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

The Mughal designation for their dynasty was ''Gurkani'' ({{Transliteration|fa|Gūrkāniyān}}), a reference to their descent from the Turco-Mongol conqueror [[Timur]], who took the title {{Transliteration|fa|Gūrkān}} 'son-in-law' after his marriage to a [[Chinggisid]] princess.<ref name="Thackston2">{{Cite book |last=Zahir ud-Din Mohammad |title=The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor |title-link=Baburnama |publisher=Modern Library |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-375-76137-9 |editor-last=Thackston, Wheeler M. |editor-link=Wheeler Thackston |location=New York |page=[https://archive.org/details/babarinizam00babu/page/ xlvi] |quote=In India the dynasty always called itself Gurkani, after Temür's title Gurkân, the Persianized form of the Mongolian {{lang|mn-Latn|kürägän}}, 'son-in-law,' a title he assumed after his marriage to a Genghisid princess. |author-link=Babur}}</ref> The word ''Mughal'' (also spelled ''Mogul''<ref name="persianatemogul">{{Cite book |last=John Walbridge |title=God and Logic in Islam: The Caliphate of Reason |page=165 |quote=Persianate Mogul Empire.}}</ref> or ''Moghul'' in English) is the Indo-Persian form of [[Mongols|''Mongol'']]. The Mughal dynasty's early followers were Chagatai Turks and not Mongols.<ref name="Hodgson" /><ref name="Canfield">{{Cite book |last=Canfield |first=Robert L. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g3JhKNSk8tQC&pg=PA20 |title=Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-521-52291-5 |page=20}}</ref> The term ''Mughal'' was applied to them in India by association with the Mongols and to distinguish them from the Afghan elite which ruled the Delhi Sultanate.<ref name="Hodgson">{{Cite book |last=Hodgson |first=Marshall G. S. |author-link=Marshall Hodgson |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=COOGFSH_jUkC&pg=PA62 |title=The Venture of Islam |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-226-34688-5 |volume=3 |page=62}}</ref> The term remains disputed by [[Indologists]].<ref name="RA">{{Cite book |last1=Huskin |first1=Frans Husken |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IVhUAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA104 |title=Reading Asia: New Research in Asian Studies |last2=Dick van der Meij |publisher=Routledge |year=2004 |isbn=978-1-136-84377-8 |page=104}}</ref> In [[Marshall Hodgson|Marshall Hodgson's]] view, the dynasty should be called ''Timurid''/''Timuri'' or ''Indo-Timurid''.<ref name="Hodgson" /> |

|||

== Early history == |

|||

[[File:Dagger horse head Louvre OA7891.jpg|thumb|240px|A dagger from the [[Mughal Empire]] with hilt in [[jade]], gold, [[rubies]] and [[emerald]]s. Blade of [[damascened]] [[steel]] inlaid with gold.]] |

|||

[[Babur|Zahir ud-din Muhammad Babur]] learned about the riches of [[Hindustan]] and conquest of it by his ancestor, [[Timur Lang]], in 1503 at Dikh-Kat, a place in the Transoxiana region. At that time, he was roaming as a wanderer after losing his principality, Farghana. In his memoirs he wrote that after he had acquired Kabul (in 1514), he desired to regain the territories in Hindustan held once by Turks. He started his exploratory raids from September 1519 when he visited the Indo-Afghan borders to suppress the rising by Yusufzai tribes. He undertook similar raids up to 1524 and had established his base camp at Peshawar. In 1526, Babur defeated the last of the [[Delhi Sultanate|Delhi Sultans]], [[Ibrahim Lodhi|Ibrahim Shah Lodi]], at the [[First Battle of Panipat]]. To secure his newly founded kingdom, Babur then had to face the formidable [[Rajput]] [[Rana Sanga]] of [[Chittor]], at the [[Battle of Khanwa]]. Rana Sanga offered stiff resistance but was defeated. |

|||

== History == |

|||

Babur's son [[Humayun]] succeeded him in 1530, but suffered reversals at the hands of the [[Pashtun people|Pashtun]] [[Sher Shah Suri]] and lost most of the fledgling empire before it could grow beyond a minor regional state. From 1540 Humayun became ruler in exile, reaching the court of the [[Safavid]] rule in 1554 while his force still controlled some fortresses and small regions. But when the Pashtuns fell into disarray with the death of Sher Shah Suri, Humayun returned with a mixed army, raised more troops, and managed to reconquer [[Delhi]] in 1555. |

|||

{{See also|Mughal dynasty}} |

|||

=== Babur and Humayun (1526–1556) === |

|||

Humayun crossed the rough terrain of the [[Makran]] with his wife. The resurgent Humayun then conquered the central plateau around Delhi, but months later died in an accident, leaving the realm unsettled and in war. |

|||

{{Main|Babur|Humayun}} |

|||

[[File:Joppen map-India in 1525 published 1907 by Longmans.jpg|thumb|right|India in 1525 just before the onset of Mughal rule]] |

|||

The Mughal Empire was founded by Babur (reigned 1526–1530), a Central Asian ruler who was descended from the [[Turco-Persian tradition|Persianized]] [[Turco-Mongol tradition|Turco-Mongol]] conqueror [[Timur]] (the founder of the [[Timurid Empire]]) on his father's side, and from [[Genghis Khan]] on his mother's side.<ref name="Berndl">{{Cite book |last=Berndl |first=Klaus |title=National Geographic Visual History of the World |publisher=National Geographic Society |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-7922-3695-5 |pages=318–320}}</ref> Paternally, Babur belonged to the [[Turkification|Turkicized]] [[Barlas]] tribe of [[Mongol]] origin.<ref>Gérard Chaliand, ''A Global History of War: From Assyria to the Twenty-First Century'', [[University of California Press]], California 2014, p. 151</ref> Ousted from his ancestral domains in Central Asia, Babur turned to India to satisfy his ambitions.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bayley |first=Christopher |title=The European Emergence. The Mughals Ascendant |isbn=0-7054-0982-1 |page=151}}</ref> He established himself in [[Kabul]] and then pushed steadily southward into India from [[Afghanistan]] through the [[Khyber Pass]].<ref name="Berndl" /> Babur's forces defeated [[Ibrahim Lodi]], [[Delhi Sultanate|Sultan of Delhi]], in the [[First Battle of Panipat]] in 1526. Through his use of firearms and cannons, he was able to shatter Ibrahim's armies despite being at a numerical disadvantage,{{sfn|Richards|1995|p=8}}{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|p=116}} expanding his dominion up to the mid [[Indo-Gangetic Plain]].{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|p=117}} After the battle, the centre of Mughal power shifted to [[Agra]].{{sfn|Richards|1995|p=8}} In the decisive [[Battle of Khanwa]], fought near Agra a year later, the Timurid forces of Babur defeated the combined [[Rajput]] armies of [[Rana Sanga]] of [[Kingdom of Mewar|Mewar]], with his native cavalry employing traditional flanking tactics.{{sfn|Richards|1995|p=8}}{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|p=116}} |

|||

The preoccupation with wars and military campaigns, however, did not allow the new emperor to consolidate the gains he had made in India.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bayley |first=Christopher |title=The European Emergence. The Mughals Ascendant |isbn=0-7054-0982-1 |page=154}}</ref> The instability of the empire became evident under his son, [[Humayun]] (reigned 1530–1556), who was forced into exile in Persia by the rebellious [[Sher Shah Suri]] (reigned 1540–1545).<ref name="Berndl" /> Humayun's exile in Persia established diplomatic ties between the [[Safavid dynasty|Safavid]] and Mughal courts and led to increasing Persian cultural influence in the later restored Mughal Empire.{{sfn|Majumdar|1974|pp=59, 65}} Humayun's triumphant return from Persia in 1555 restored Mughal rule in some parts of India, but he died in an accident the next year.{{sfn|Richards|1995|p=12}} |

|||

Akbar succeeded his father on 14 February 1556, while in the midst of a war against [[Sikandar Shah Suri]] for the throne of Delhi. He soon won his eighteenth victory at age 21 or 22. He became known as ''Akbar'', as he was a wise ruler, setting high but fair taxes. He was a more inclusive in his approach to the non-Muslim subjects of the Empire. He investigated the production in a certain area and taxed inhabitants one-fifth of their agricultural produce. He also set up an efficient bureaucracy and was tolerant of religious differences which softened the resistance by the locals. He made alliances with Rajputs and appointed native generals and administrators. Later in life, he devised his own brand of syncretic philosophy based on tolerance. |

|||

=== Akbar to Aurangzeb (1556–1707) === |

|||

[[Jahangir]], son of Emperor Akbar, ruled the empire from 1605–1627. In October 1627, [[Shah Jahan]], son of Emperor Jahangir succeeded to the throne, where he inherited a vast and rich empire. At mid-century this was perhaps the greatest empire in the world. Shah Jahan commissioned the famous [[Taj Mahal]] (1630–1653) in [[Agra]] which was built by the Persian architect [[Ustad Ahmad Lahauri]] as a tomb for Shah Jahan's wife [[Mumtaz Mahal]], who died giving birth to their 14th child. By 1700 the empire reached its peak under the leadership of [[Aurangzeb|Aurangzeb Alamgir]] with major parts of present day India, [[Pakistan]], and most of [[Afghanistan]] under its domain. Aurangzeb was the last of what are now referred to as the Great Mughal kings, living a shrewd life but dying peacefully. |

|||

{{Main|Akbar|Jahangir|Shah Jahan|Aurangzeb}} |

|||

[[File:Jesuits at Akbar's court.jpg|thumb|upright|left|[[Akbar]] holds a religious assembly of different faiths in the [[Ibadat Khana]] in Fatehpur Sikri.]] |

|||

[[Akbar]] (reigned 1556–1605) was born Jalal-ud-din Muhammad<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |title=Akbar |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |date= |year= |last=Ballhatchet |first=Kenneth A. |author-link=Kenneth A. Ballhatchet |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Akbar |access-date=17 July 2017 |archive-date=25 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230525120830/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Akbar |url-status=live}}</ref> in the Rajput [[Umarkot Fort]],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Smith |first=Vincent Arthur |url=https://archive.org/details/cu31924024056503/page/n34/mode/1up |title=Akbar the Great Mogul, 1542–1605 |publisher=Oxford at The Clarendon Press |year=1917 |pages=13–14 |author-link=Vincent Arthur Smith}}</ref> to Humayun and his wife [[Hamida Banu Begum]], a [[Persian people|Persian]] princess.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Begum |first=Gulbadan |url=https://archive.org/details/historyofhumayun00gulbrich |title=The History of Humāyūn (Humāyūn-Nāma) |publisher=Royal Asiatic Society |year=1902 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/historyofhumayun00gulbrich/page/237 237]–239 |translator-last=Beveridge |translator-first=Annette S. |author-link=Gulbadan Begum |translator-link=Annette Beveridge}}</ref> Akbar succeeded to the throne under a regent, [[Bairam Khan]], who helped consolidate the Mughal Empire in India.{{sfn|Stein|2010|p=162}} Through warfare, Akbar was able to extend the empire in all directions and controlled almost the entire Indian subcontinent north of the [[Godavari River]].{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|p=128}}<!--bsn?--> He created a new ruling elite loyal to him, implemented a modern administration, and encouraged cultural developments. He increased trade with European trading companies.<ref name="Berndl" /> India developed a strong and stable economy, leading to commercial expansion and economic development.{{citation needed|date=July 2019}} Akbar allowed freedom of religion at his court and attempted to resolve socio-political and cultural differences in his empire by establishing a new religion, [[Din-i-Ilahi]], with strong characteristics of a ruler cult.<ref name="Berndl" /> He left his son an internally stable state, which was in the midst of its golden age, but before long signs of political weakness would emerge.<ref name="Berndl" /><!--close paraphrasing--> |

|||

[[Jahangir]] (born Salim,<ref name="Mohammada" /> reigned 1605–1627) was born to Akbar and his wife [[Mariam-uz-Zamani]], an Indian [[Rajput]] princess.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Gilbert |first=Marc Jason |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7OQWDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA79 |title=South Asia in World History |publisher=[[Oxford University Press]] |year=2017 |isbn=978-0-19-976034-3 |page=79 |access-date=22 August 2017 |archive-date=22 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230922033918/https://books.google.com/books?id=7OQWDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA79 |url-status=live }}</ref> Salim was named after the Indian Sufi saint, [[Salim Chishti]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Muhammad-Hadi |title=Preface to The Jahangirnama |year=1999 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-512718-8 |page=4 |translator-last=Thackston |translator-first=Wheeler M. |translator-link=Wheeler Thackston}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Jahangir, Emperor of Hindustan |title=The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India |year=1999 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-512718-8 |page=65 |translator-last=Thackston |translator-first=Wheeler M. |translator-link=Wheeler Thackston}}</ref> He "was addicted to opium, neglected the affairs of the state, and came under the influence of rival court cliques".<ref name="Berndl" /> Jahangir distinguished himself from Akbar by making substantial efforts to gain the support of the Islamic religious establishment. One way he did this was by bestowing many more ''madad-i-ma'ash'' (tax-free personal land revenue grants given to religiously learned or spiritually worthy individuals) than Akbar had.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Faruqui |first=Munis D. |title=The Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504–1719 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |year=2012 |isbn=978-1-107-02217-1 |pages=268–269}}</ref> In contrast to Akbar, Jahangir came into conflict with non-Muslim religious leaders, notably the [[Sikh]] guru [[Guru Arjan|Arjan]], whose execution was the first of many conflicts between the Mughal Empire and the Sikh community.{{sfn|Robb|2011|pp=97–98}}{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|p=267}}<ref name="BBC Sikhs">{{Cite web |date=30 September 2009 |title=BBC – Religions – Sikhism: Origins of Sikhism |url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/sikhism/history/history_1.shtml |access-date=19 February 2021 |website=BBC |language=en-GB |archive-date=17 August 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180817220705/http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/sikhism/history/history_1.shtml |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

== Mughal dynasty == |

|||

[[File:Mughal Genealogical Table.svg|thumb|left|Genealogy of the Mughal Dynasty]] |

|||

The Mughal Empire was the dominant power in the [[Indian subcontinent]] between the mid-16th century and the early 18th century. Founded in 1526, it officially survived until 1858, when it was supplanted by the [[British Raj]]. The [[dynasty]] is sometimes referred to as the [[Timurid dynasty]] as [[Babur]] was descended from [[Timur]]. |

|||

[[File:Khalili Collection Islamic Art mss 0874.3.jpg|thumb|right|Group portrait of Mughal rulers, from [[Babur]] to [[Aurangzeb]], with the Mughal ancestor [[Timur]] seated in the middle. On the left: [[Shah Jahan]], [[Akbar]] and Babur, with Abu Sa'id of Samarkand and Timur's son, [[Miran Shah]]. On the right: Aurangzeb, [[Jahangir]] and [[Humayun]], and two of Timur's other offspring [[Umar Shaikh Mirza I|Umar Shaykh]] and [[Muhammad Sultan Mirza|Muhammad Sultan]]. Created {{circa|1707–12}}]] |

|||

The Mughal dynasty was founded when Babur, hailing from [[Ferghana]] (Modern [[Uzbekistan]]), invaded parts of northern India and defeated [[Lodhi dynasty|Ibrahim Shah Lodhi]], the ruler of Delhi, at the [[First battle of Panipat|First Battle of Panipat]] in 1526. The Mughal Empire superseded the [[Delhi Sultanate]] as rulers of northern India. In time, the state thus founded by Babur far exceeded the bounds of the Delhi Sultanate, eventually encompassing a major portion of India and earning the appellation of Empire. A brief interregnum (1540–1555) during the reign of Babur's son, [[Humayun]], saw the rise of the Afghan [[Suri Dynasty]] under [[Sher Shah Suri]], a competent and efficient ruler in his own right. However, Sher Shah's untimely death and the military incompetence of his successors enabled Humayun to regain his throne in 1555. However, Humayun died a few months later, and was succeeded by his son, the 13-year-old [[Akbar the Great]]. |

|||

[[Shah Jahan]] (reigned 1628–1658) was born to Jahangir and his wife [[Jagat Gosain]], a Rajput princess.<ref name="Mohammada">{{Cite book |last=Mohammada |first=Malika |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dwzbYvQszf4C&pg=PA300 |title=The Foundations of the Composite Culture in India |publisher=Aakar Books |year=2007 |isbn=978-81-89833-18-3 |page=300}}</ref> His reign ushered in the golden age of [[Mughal architecture]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mehta |first=Jaswant Lal |title=Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India |publisher=Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd |year=1984 |isbn=978-81-207-1015-3 |edition=2nd |volume=II |page=59 |language=en |oclc=1008395679 |orig-year=First published 1981}}</ref> During the reign of Shah Jahan, the splendour of the Mughal court reached its peak, as exemplified by the [[Taj Mahal]]. The cost of maintaining the court, however, began to exceed the revenue coming in.<ref name="Berndl" /> His reign was called "The Golden Age of Mughal Architecture". Shah Jahan extended the Mughal Empire to the [[Deccan Plateau|Deccan]] by ending the [[Ahmadnagar Sultanate]] and forcing the [[Sultanate of Bijapur|Adil Shahis]] and [[Sultanate of Golconda|Qutb Shahis]] to pay tribute.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Singhal |first=Damodar P. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ag4BAAAAMAAJ&q=annexed+tribute |title=A History of the Indian People |publisher=Methuen |year=1983 |isbn=978-0-413-48730-8 |page=193 |access-date=4 May 2021 |archive-date=22 September 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230922033919/https://books.google.com/books?id=ag4BAAAAMAAJ&q=annexed+tribute |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Shah Jahan's eldest son, the liberal [[Dara Shikoh]], became regent in 1658, as a result of his father's illness.<ref name="Berndl"/> Dara championed a syncretistic Hindu-Muslim culture, emulating his great-grandfather Akbar.<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=H-k9oc9xsuAC&dq=Dara+Shikoh&pg=PA194 Dara Shikoh] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403231619/https://books.google.com/books?id=H-k9oc9xsuAC&dq=Dara+Shikoh&pg=PA194 |date=3 April 2023 }} ''Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia'', by Josef W. Meri, Jere L Bacharach. Routledge, 2005. {{ISBN|0-415-96690-6}}. pp. 195–196.</ref> With the support of the Islamic orthodoxy, however, a younger son of Shah Jahan, [[Aurangzeb]] ({{Reign|1658|1707}}), seized the throne. Aurangzeb defeated Dara in 1659 and had him executed.<ref name="Berndl" /> Although Shah Jahan fully recovered from his illness, Aurangzeb kept Shah Jahan imprisoned until he died in 1666.{{sfn|Truschke|2017|p=68}} Aurangzeb brought the empire to its greatest territorial extent,<ref>{{EI3|title=Awrangzīb|url=https://referenceworks.brill.com/display/entries/EI3O/COM-23859.xml|first=Munis D.|last=Faruqui|date=2011|doi=10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_23859}}</ref> and oversaw an increase in the Islamicization of the Mughal state. He encouraged conversion to Islam, reinstated the ''[[jizya]]'' on non-Muslims, and compiled the ''[[Fatawa 'Alamgiri]]'', a collection of Islamic law. Aurangzeb also ordered the execution of the Sikh guru [[Guru Tegh Bahadur|Tegh Bahadur]], leading to the militarization of the Sikh community.{{sfn|Robb|2011|p=98}}{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|p=267}}<ref name="BBC Sikhs" /> From the imperial perspective, conversion to Islam integrated local elites into the king's vision of a network of shared identity that would join disparate groups throughout the empire in obedience to the Mughal emperor.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Abhishek Kaicker |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sNQBEAAAQBAJ&dq=Sayyids+Of+Barha&pg=PA160 |title=The King and the People: Sovereignty and Popular Politics in Mughal Delhi |year=2020 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-007067-0 |page=160 |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=3 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403224903/https://books.google.com/books?id=sNQBEAAAQBAJ&dq=Sayyids+Of+Barha&pg=PA160 |url-status=live}}</ref> He led campaigns from 1682 in the Deccan,<ref name="EI2"/> annexing its remaining Muslim powers of Bijapur and Golconda,{{sfn|Richards|1995|pp=220–222}}<ref name="EI2"/> though engaged in a [[Deccan wars|prolonged conflict]] in the region which had a ruinous effect on the empire.{{sfn|Richards|1995|p=252}}<!--<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sarkar Jadunath |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.537063 |title=A Short History Of Aurangzib |year=1928}}</ref>{{page number|date=September 2024}}--> The campaigns took a toll on the Mughal treasury, and Aurangzeb's absence led to a severe decline in governance, while stability and economic output in the Mughal Deccan plummeted.{{sfn|Richards|1995|p=252}} |

|||

The greatest portions of Mughal expansion was accomplished during the reign of Akbar (1556–1605). The empire was maintained as the dominant force of the present-day [[Indian subcontinent]] for a hundred years further by his successors [[Jahangir]], [[Shah Jahan]], and [[Aurangzeb]]. The first six emperors, who enjoyed power both de jure and de facto, are usually referred to by just one name, a title adopted upon his accession by each emperor. The relevant [[title]] is bolded in the list below. |

|||

Aurangzeb is considered the most controversial Mughal emperor,{{sfn|Asher|Talbot|2006|p=225}} with some historians arguing his religious conservatism and intolerance undermined the stability of Mughal society,<ref name="Berndl" /> while other historians question this, noting that he built [[Hindu temple]]s,<ref name="Copland2013">{{Cite book |last1=Copland |first1=Ian |title=A History of State and Religion in India |last2=Mabbett |first2=Ian |last3=Roy |first3=Asim |last4=Brittlebank |first4=Kate |last5=Bowles |first5=Adam |publisher=Routledge |year=2013 |isbn=978-1-136-45950-4 |page=119 |display-authors=3}}</ref> employed significantly more [[Hindus]] in his imperial bureaucracy than his predecessors did, and opposed bigotry against Hindus and [[Shia Muslims]].{{sfn|Truschke|2017|p=58}} Despite these allegations, it has been acknowledged that Emperor Aurangzeb enacted repressive policies towards non-Muslims. A major rebellion by the [[Marathi people|Marathas]] took place following this change,<ref>{{Cite web |last1=Verghese |first1=Ajay |last2=Foa |first2=Roberto Stefan |date=5 November 2018 |title=Precolonial Ethnic Violence:The Case of Hindu-Muslim Conflict in India |url=https://www.bu.edu/cura/files/2018/11/VF_new15914.pdf |access-date=April 7, 2023 |publisher=Boston University |archive-date=7 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230407185453/https://www.bu.edu/cura/files/2018/11/VF_new15914.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> precipitated by the unmitigated state-building of its leader [[Shivaji]] in the Deccan.<ref>{{cite book |first=Gijs |last=Kruijtzer |date=2009 |title=Xenophobia in Seventeenth-Century India |publisher=Leiden University Press |page=153}}</ref><ref name="EI2"/> |

|||

Akbar the Great initiated certain important policies, such as religious liberalism (abolition of the [[jizya]] tax), inclusion of natives in the affairs of the empire, and political alliance/marriage with the [[Rajput]]s, that were innovative for his milieu; he also adopted some policies of Sher Shah Suri, such as the division of the empire into ''[[sarkar (country subdivision)|sarkar]]'' raj, in his administration of the empire. These policies, which undoubtedly served to maintain the power and stability of the empire, were preserved by his two immediate successors but were discarded by Emperor Aurangzeb who spent nearly his entire career expanding his realm, beyond the [[Urdu Belt]], into the [[Deccan]] and South India, Assam in the east; this venture provoked resistance from the [[Maratha]]s, [[Sikhs]], and [[Ahoms]]. |

|||

=== Decline === |

=== <span id='Decline'>Decline (1707–1857)</span> === |

||

{{main|Decline of the Mughal Empire}} |

|||

[[File:India map 1700 1792.jpg|thumb|[[Sikh Empire|Sikh]] and [[Maratha Empire|Maratha]] states gained territory after the Mughal empire's decline. Map showing territories in 1700 and 1792]] |

|||

[[File:Farrukhsiyar Procession in front of the Great Mosque of Delhi.png|Delhi under the puppet-emperor [[Farrukhsiyar]]. Effective power was held by the [[Sayyid Brothers]]|thumb|left]] |

|||

After Emperor Aurangzeb's death in 1707, the empire fell into succession crisis. Barring [[Muhammad Shah]], none of the Mughal emperors could hold on to power for a decade. In the 18th century, the Empire suffered the depredations of invaders like [[Nadir Shah]] of Persia and [[Ahmed Shah Abdali]] of Afghanistan, who repeatedly sacked [[Delhi]], the Mughal capital. Most of the empire's territories in India passed to the [[Maratha]]s, [[Nawab]]s, and [[Nizam]]s by {{circa|1750}}. In 1804, the blind and powerless [[Shah Alam II]] formally accepted the protection of the [[British East India Company]]. The company had already begun to refer to the weakened emperor as "King of Delhi", rather than "Emperor of India". The once glorious and mighty Mughal army was disbanded in 1805 by the British; only the guards of the [[Red Fort]] were spared to serve with the King Of Delhi, which avoided the uncomfortable implication that British sovereignty was outranked by the Indian monarch. Nonetheless, for a few decades afterward the [[BEIC]] continued to rule the areas under its control as the nominal servants of the emperor and in his name. In 1857, even these courtesies were disposed. After some rebels in the [[Sepoy Rebellion]] declared their allegiance to Shah Alam's descendant, [[Bahadur Shah II]], the British decided to abolish the institution altogether. They deposed the last Mughal emperor in 1857 and exiled him to [[Burma]], where he died in 1862. |

|||

Aurangzeb's son, [[Bahadur Shah I]], repealed the religious policies of his father and attempted to reform the administration. "However, after he died in 1712, the Mughal dynasty began to sink into chaos and violent feuds. In 1719 alone, four emperors successively ascended the throne",<ref name="Berndl" /> as figureheads under the rule of a brotherhood of nobles belonging to the [[Islam in India|Indian Muslim]] caste known as the [[Barha Dynasty|Sadaat-e-Bara]], whose leaders, the [[Sayyid Brothers]], became the de facto sovereigns of the empire.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Audrey Truschke |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rOcSEAAAQBAJ&dq=sayyid+brothers+figureheads&pg=PT146 |title=the Language of History: Sanskrit Narratives of Indo-Muslim Rule |year=2021 |publisher=Publisher:Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-231-55195-3 |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=3 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403222119/https://books.google.com/books?id=rOcSEAAAQBAJ&dq=sayyid+brothers+figureheads&pg=PT146 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Muhammad Yasin |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Rz16lub2uRgC&q=sayyid+barha+brotherhood |title=A Social History of Islamic India, 1605–1748 |year=1958 |publisher=Upper India Publishing House |page=18 |quote=became virtual rulers and 'de facto' sovereigns when they began to make and unmake emperors. They had developed a sort of common brotherhood among themselves |access-date=27 March 2023 |archive-date=3 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403224905/https://books.google.com/books?id=Rz16lub2uRgC&q=sayyid+barha+brotherhood |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

== List of Mughal emperors == |

|||

{{Main|Mughal emperors}} |

|||

{{History of the Mongols}} |

|||

Certain important particulars regarding the Mughal emperors is tabulated below: |

|||

During the reign of [[Muhammad Shah]] (reigned 1719–1748), the empire began to break up, and vast tracts of central India passed from Mughal to [[Maratha Confederacy|Maratha]] hands. As the Mughals tried to suppress the independence of [[Nizam-ul-Mulk, Asaf Jah I]] in the Deccan, he encouraged the Marathas to invade central and northern India.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Columbia University Press |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YkqsAgAAQBAJ&dq=nizam+encouraged+marathas+invade+india&pg=PA285 |title=Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture |year=2000 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-231-11004-4 |page=285 |access-date=19 March 2023 |archive-date=3 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230403224905/https://books.google.com/books?id=YkqsAgAAQBAJ&dq=nizam+encouraged+marathas+invade+india&pg=PA285 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Richard M. Eaton |editor-first1=Richard M. |editor-first2=Munis D. |editor-first3=David |editor-first4=Sunil |editor-last1=Eaton |editor-last2=Faruqui |editor-last3=Gilmartin |editor-last4=Kumar |title=Expanding Frontiers in South Asian and World History Essays in Honour of John F. Richards |year=2013 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=21 |doi=10.1017/CBO9781107300002 |isbn=978-1-107-03428-0 |url=https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/expanding-frontiers-in-south-asian-and-world-history/6A9546851A81FD60D6641F75F60956DD |quote="I consider all this army (Marathas) as my own.....I will enter into an understanding with them and entrust the Mulukgiri(raiding) on that side of the Narmada to them."}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pagadi |first=Setu Madhavarao |author-link=Setumadhavarao Pagadi |title=Maratha-Nizam Relations : Nizam-Ul-Mulk's Letters |journal=Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute |volume=51 |issue=1/4 |year=1970 |page=94 |quote=The Mughal court was hostile to Nizam-ul-Mulk..... Nizam did not interfere with the Maratha activities in Malwa and Gujarat.....Nizam-ul-Mulk considered the Maratha army...|url=https://archive.org/details/maratha-nizam-relations-nizam-ul-mulk-s-letters}}</ref> The [[Nader Shah's invasion of India|Indian campaign]] of [[Nader Shah]], who had previously reestablished [[Afsharid Iran|Iranian]] [[suzerainty]] over most of West Asia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia, culminated with the [[Sack of Delhi]] shattering the remnants of Mughal power and prestige, and taking off all the accumulated Mughal treasury. The Mughals could no longer finance the huge armies with which they had formerly enforced their rule. Many of the empire's elites now sought to control their affairs and broke away to form independent kingdoms.<ref>{{cite book|author=Salma Ahmed Farooqui|date=2011|title=A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: Twelfth to the Mid-eighteenth Century|publisher=Pearson Education India |location= |page=309 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sxhAtCflwOMC&q=Mughal+empire+got+reduced+to+a+small+kingdom |access-date= |isbn=978-8131732021 |issn= |oclc=|quote=Even more disturbing was the fact that the assertion of independence had spread to other part of the empire too, and the governors of Hyderabad, Bengal and Awadh soon established independent kingdoms as well.}}</ref> But lip service continued to be paid to the Mughal Emperor as the highest manifestation of sovereignty. Not only the Muslim gentry, but the Maratha, Hindu, and Sikh leaders took part in ceremonial acknowledgements of the emperor as the sovereign of India.<ref name="MSA2">{{Cite book |last1=Bose |first1=Sugata |url=https://archive.org/details/modernsouthasiah00bose |title=Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy |last2=Jalal |first2=Ayesha |publisher=Routledge |year=2004 |isbn=978-0-203-71253-5 |edition=2nd |page=[https://archive.org/details/modernsouthasiah00bose/page/41 41] |author-link=Sugata Bose |author-link2=Ayesha Jalal |url-access=registration}}</ref> |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="Margin: 1em auto 1em auto" |

|||

Meanwhile, some regional polities within the increasingly fragmented Mughal Empire involved themselves and the state in global conflicts, leading only to defeat and loss of territory during conflicts such as the [[Carnatic wars]] and [[Bengal War]].{{citation needed|date=July 2024}} |

|||

[[File:Joppen map-India in 1751 published 1907 by Longmans.jpg|thumb|right|The remnants of the empire in 1751]] |

|||

The Mughal Emperor [[Shah Alam II]] (1759–1806) made futile attempts to reverse the Mughal decline. [[Sack of Delhi (1757)|Delhi was sacked]] by the Afghans, and when the [[Third Battle of Panipat]] was fought between the Maratha Empire and the [[Durrani Empire|Afghans]] (led by [[Ahmad Shah Durrani]]) in 1761, in which the Afghans were victorious, the emperor had ignominiously taken temporary refuge with the British to the east. In 1771, the Marathas [[Capture of Delhi (1771)|recaptured Delhi]] from the [[Kingdom of Rohilkhand|Rohillas]], and in 1784 the Marathas officially became the protectors of the emperor in Delhi,<ref name="Rathod1994">{{Cite book |last=Rathod |first=N.G. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uPq640stHJ0C&pg=PA8 |title=The Great Maratha Mahadaji Scindia |publisher=Sarup & Sons |year=1994 |isbn=978-81-85431-52-9 |location=New Delhi |page=8}}</ref> a state of affairs that continued until the [[Second Anglo-Maratha War]]. Thereafter, the [[British East India Company]] became the protectors of the Mughal dynasty in Delhi.<ref name="MSA2" /> The British East India Company took control of the former Mughal province of Bengal-Bihar in 1793 after it abolished local rule (Nizamat) that lasted until 1858, marking the beginning of the British colonial era over the Indian subcontinent. By 1857 a considerable part of former Mughal India was under the East India Company's control. After a crushing defeat in the [[Indian Rebellion of 1857]] which he nominally led, the last Mughal emperor, [[Bahadur Shah Zafar]], was deposed by the British East India Company and exiled in 1858 to [[Rangoon]], Burma.<ref name="Conermann2015">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Mughal Empire |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Early Modern History Online |year=2015 |last=Conermann |first=Stephan |publisher=Brill |url=https://referenceworks-brill-com.wikipedialibrary.idm.oclc.org/display/entries/EMHO/COM-024206.xml?rskey=YrXHKP |access-date=2022-03-28 |doi=10.1163/2352-0272_emho_COM_024206}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Portrait of Bahadur Shah II as calligrapher. Delhi, ca. 1850, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. - копия.jpg|thumb|right|upright|Portrait of [[Bahadur Shah Zafar]]]] |

|||

=== Causes of decline === |

|||

Historians have offered numerous accounts of the several factors involved in the rapid collapse of the Mughal Empire between 1707 and 1720, after a century of growth and prosperity. A succession of short-lived incompetent and weak rulers, and civil wars over the succession, created political instability at the centre. The Mughals appeared virtually unassailable during the 17th century, but, once gone, their [[imperial overstretch]] became clear, and the situation could not be recovered. The seemingly innocuous European trading companies, such as the [[British East Indies Company]], played no real part in the initial decline; they were still racing to get permission from the Mughal rulers to establish trades and factories in India.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Kirsten McKenzie |author2=Robert Aldrich |title=The Routledge History of Western Empires |date=2013 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=9781317999874 |page=333 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qFRJAgAAQBAJ |access-date=14 March 2024 |language=En |format=ebook}}</ref> |

|||

In fiscal terms, the throne lost the revenues needed to pay its chief officers, the emirs (nobles) and their entourages. The emperor lost authority as the widely scattered imperial officers lost confidence in the central authorities and made their deals with local men of influence. The imperial army bogged down in long, futile wars against the more aggressive [[Maratha Empire|Marathas]], and lost its fighting spirit. Finally came a series of violent political feuds over control of the throne. After the execution of [[Farrukhsiyar|Emperor Farrukhsiyar]] in 1719, local Mughal successor states took power in region after region.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Richards |first=J.F. |year=1981 |title=Mughal State Finance and the Premodern World Economy |journal=Comparative Studies in Society and History |volume=23 |issue=2 |pages=285–308 |doi=10.1017/s0010417500013311 |jstor=178737 |s2cid=154809724}}</ref> |

|||

== Administration and state == |

|||

{{Main|Government of the Mughal Empire}} |

|||

[[File:Joppen map-India in 1605 published 1907 by Longmans.jpg|thumb|right|India in 1605 and the end of emperor Akbar's reign; the map shows the different [[subah]]s, or provinces, of his administration]] |

|||

The Mughal Empire had a highly centralised, bureaucratic government, most of which was instituted during the rule of the third Mughal emperor, Akbar.<ref name="Robinson2009">{{Citation |last=Robinson |first=Francis |title=Mughal Empire |url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001/acref-9780195305135-e-0549 |year=2009 |access-date=2022-03-28 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220329002419/https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001/acref-9780195305135-e-0549 |url-status=live |publisher=Oxford University Press |language=en |doi=10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001 |isbn=978-0-19-530513-5 |archive-date=29 March 2022 |encyclopedia=The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World}}</ref><ref name="EI2">{{Citation |last1=Burton-Page |first1=J. |title=Mug̲h̲als |date=2012-04-24 |url=https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/*-COM_0778 |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia of Islam |edition=2nd |access-date=2022-03-31 |publisher=Brill |language=en |doi=10.1163/1573-3912_islam_com_0778 |last2=Islam |first2=Riazul |last3=Athar Ali |first3=M. |last4=Moosvi |first4=Shireen |last5=Moreland |first5=W. H. |last6=Bosworth |first6=C. E. |last7=Schimmel |first7=Annemarie |last8=Koch |first8=Ebba |last9=Hall |first9=Margaret |archive-date=31 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220331173633/https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-2/*-COM_0778 |url-status=live}}</ref> The central government was headed by the Mughal emperor; immediately beneath him were four ministries. The finance/revenue ministry, headed by an official called a ''[[Divan|diwan]]'', was responsible for controlling revenues from the empire's territories, calculating tax revenues, and using this information to distribute assignments. The ministry of the military (army/intelligence) was headed by an official titled ''[[mir bakhshi]]'', who was in charge of military organisation, messenger service, and the ''[[mansabdari]]'' system. The ministry in charge of law/religious patronage was the responsibility of the ''sadr as-sudr,'' who appointed judges and managed charities and stipends. Another ministry was dedicated to the imperial household and public works, headed by the ''mir saman''. Of these ministers, the ''diwan'' held the most importance, and typically acted as the ''[[Grand Vizier of the Mughal Empire|wazir]]'' (prime minister) of the empire.<ref name="Conermann2015" /><ref name="Robinson2009" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Gladden |first=E.N. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PgGaDwAAQBAJ |title=A History of Public Administration Volume II: From the Eleventh Century to the Present Day |date=2019 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-429-42321-5 |pages=234–236}}</ref> |

|||

=== Administrative divisions === |

|||

The empire was divided into ''[[Subah]]'' (provinces), each of which was headed by a provincial governor called a ''[[Subahdar|subadar]].'' The structure of the central government was mirrored at the provincial level; each ''suba'' had its own ''[[Bakhshi (Mughal Empire)|bakhshi]]'', ''sadr as-sudr'', and finance minister that reported directly to the central government rather than the ''subahdar''. ''Subas'' were subdivided into administrative units known as ''[[Sarkar (administrative division)|sarkars]],'' which were further divided into groups of villages known as ''[[pargana]]s''. The Mughal government in the ''pargana'' consisted of a Muslim judge and local tax collector.<ref name="Conermann2015" /><ref name="Robinson2009" /> ''Parganas'' were the basic administrative unit of the Mughal Empire.<ref>{{cite book |last=Michael |first=Bernardo A. |title=Statemaking and Territory in South Asia |year=2012 |page=67 |publisher=Anthem Press |doi=10.7135/upo9780857285324.005 |isbn=978-0-85728-532-4}}</ref> |

|||

Mughal administrative divisions were not static. Territories were often rearranged and reconstituted for better administrative control, and to extend cultivation. For example, a ''sarkar'' could turn into a ''subah'', and ''Parganas'' were often transferred between ''sarkars''. The hierarchy of division was ambiguous sometimes, as a territory could fall under multiple overlapping jurisdictions. Administrative divisions were also vague in their geography—the Mughal state did not have enough resources or authority to undertake detailed land surveys, and hence the geographical limits of these divisions were not formalised and maps were not created. The Mughals instead recorded detailed statistics about each division, to assess the territory's capacity for revenue, based on simpler land surveys.<ref>{{cite book |last=Michael |first=Bernardo A. |title=Statemaking and Territory in South Asia |year=2012 |pages=69, 75, 77–78 |publisher=Anthem Press |doi=10.7135/upo9780857285324.005 |isbn=978-0-85728-532-4}}</ref> |

|||

=== Capitals === |

|||

The Mughals had multiple imperial capitals, established throughout their rule. These were the cities of [[Agra]], [[Delhi]], [[Lahore]], and [[Fatehpur Sikri]]. Power often shifted back and forth between these capitals.{{sfn|Sinopoli|1994|pp=294–295}} Sometimes this was necessitated by political and military demands, but shifts also occurred for ideological reasons (for example, Akbar's establishment of Fatehpur Sikri), or even simply because the cost of establishing a new capital was marginal.{{sfn|Sinopoli|1994|pp=304–305}} Situations where two simultaneous capitals happened multiple times in Mughal history. Certain cities also served as short-term, provincial capitals, as was the case with Aurangzeb's shift to [[Aurangabad]] in the [[Deccan]].{{sfn|Sinopoli|1994|pp=294–295}} [[Kabul]] was the [[summer capital]] of Mughals from 1526 to 1681.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Samrin |first=Farah |year=2005 |title=The City of Kabul Under the Mughals |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145943 |journal=Proceedings of the Indian History Congress |volume=66 |page=1307 |jstor=44145943 |access-date=14 December 2021 |archive-date=29 June 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210629170711/https://www.jstor.org/stable/44145943 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

The imperial camp, used for military expeditions and royal tours, also served as a kind of mobile, "de facto" administrative capital. From the time of Akbar, Mughal camps were huge in scale, accompanied by numerous personages associated with the royal court, as well as soldiers and labourers. All administration and governance were carried out within them. The Mughal Emperors spent a significant portion of their ruling period within these camps.{{sfn|Sinopoli|1994|pp=296 & 298}} |

|||

After Aurangzeb, the Mughal capital definitively became the walled city of [[Shahjahanabad]] (Old Delhi).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bosworth |first=Clifford Edmund |author-link=Clifford Edmund Bosworth |title=Historic cities of the Islamic world |year=2008 |publisher=Brill |isbn=978-90-04-15388-2 |page=127 |oclc=231801473}}</ref> |

|||

=== Law === |

|||

[[File:Police Chuprasi, Delhi.png|Police in Delhi under Bahadur Shah II, 1842|thumb]] |

|||

The Mughal Empire's legal system was context-specific and evolved throughout the empire's rule. Being a Muslim state, the empire employed ''[[fiqh]]'' (Islamic jurisprudence) and therefore the fundamental institutions of Islamic law such as those of the ''[[qadi]]'' (judge), ''[[mufti]]'' (jurisconsult), and ''[[muhtasib]]'' (censor and market supervisor) were well-established in the Mughal Empire. However, the dispensation of justice also depended on other factors, such as administrative rules, local customs, and political convenience. This was due to Persianate influences on Mughal ideology and the fact that the Mughal Empire governed a non-Muslim majority.<ref name="Chatterjee2019">{{Citation |last=Chatterjee |first=Nandini |title=Courts of law, Mughal |date=2019-12-01 |url=https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/*-COM_25171 |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three |access-date=2021-12-13 |publisher=Brill |language=en |doi=10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_com_25171 |archive-date=13 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211213060747/https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-of-islam-3/*-COM_25171 |url-status=live}}</ref> Scholar Mouez Khalfaoui notes that legal institutions in the Mughal Empire systemically suffered from the corruption of local judges.<ref name="Khalfaoui" /> |

|||

==== Legal ideology ==== |

|||

The Mughal Empire followed the Sunni [[Hanafi]] system of jurisprudence. In its early years, the empire relied on Hanafi legal references inherited from its predecessor, the Delhi Sultanate. These included the ''[[al-Hidayah]]'' (the best guidance) and the ''Fatawa al-Tatarkhaniyya'' (religious decisions of the Emire Tatarkhan). During the Mughal Empire's peak, the ''[[Fatawa 'Alamgiri]]'' was commissioned by Emperor Aurangzeb. This compendium of Hanafi law sought to serve as a central reference for the Mughal state that dealt with the specifics of the South Asian context.<ref name="Khalfaoui">{{Cite web |last=Khalfaoui |first=Mouez |title=Mughal Empire and Law |url=http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/print/opr/t349/e0066 |website=Oxford Islamic Studies Online |access-date=13 December 2021 |archive-date=13 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211213062301/http://www.oxfordislamicstudies.com/print/opr/t349/e0066 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

The Mughal Empire also drew on Persian notions of kingship. Particularly, this meant that the Mughal emperor was considered the supreme authority on legal affairs.<ref name="Chatterjee2019" /> |

|||

==== Courts of law ==== |

|||