Carbamazepine: Difference between revisions

m →Interactions: Inserted space between 2 words. |

Aadirulez8 (talk | contribs) m v2.05 - Autofix / Fix errors for CW project (Link equal to linktext) |

||

| (559 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Anticonvulsant medication}} |

|||

{{drugbox |

|||

{{Distinguish|Carbamazine}} |

|||

| verifiedrevid = 443497262 |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} |

|||

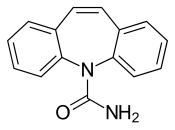

| IUPAC_name = 5''H''-dibenzo[''b'',''f'']azepine-5-carboxamide |

|||

{{cs1 config |name-list-style=vanc |display-authors=6}} |

|||

| image = Carbamazepine Structural Formulae.png |

|||

{{Infobox drug |

|||

| width = 250 |

|||

| verifiedrevid=451682337 |

|||

| image2 = Carbamazepine 3D.png |

|||

| image=Carbamazepine.svg |

|||

| width2 = 220 |

|||

| image_class = skin-invert-image |

|||

| width = 175 |

|||

| alt = |

|||

| image2=Carbamazepine-from-xtal-3D-bs-17.png |

|||

| width2 = 175 |

|||

| alt2 = |

|||

<!--Clinical data--> |

<!--Clinical data--> |

||

| tradename = Tegretol |

| tradename = Tegretol, others |

||

| Drugs.com = {{drugs.com|monograph|carbamazepine}} |

| Drugs.com = {{drugs.com|monograph|carbamazepine}} |

||

| MedlinePlus = a682237 |

| MedlinePlus = a682237 |

||

| DailyMedID = Carbamazepine |

|||

| pregnancy_US = D |

|||

| pregnancy_AU = D |

|||

| routes_of_administration = [[By mouth]] |

|||

| class = [[Anticonvulsant]]<ref name=AHFS2015/> |

|||

| ATC_prefix=N03 |

|||

| ATC_suffix=AF01 |

|||

| legal_AU = S4 |

|||

| legal_BR = C1 |

|||

| legal_BR_comment = <ref>{{Cite web |author=Anvisa |author-link=Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency |date=31 March 2023 |title=RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial |trans-title=Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control|url=https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-784-de-31-de-marco-de-2023-474904992 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230803143925/https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/resolucao-rdc-n-784-de-31-de-marco-de-2023-474904992 |archive-date=3 August 2023 |access-date=16 August 2023 |publisher=[[Diário Oficial da União]] |language=pt-BR |publication-date=4 April 2023}}</ref> |

|||

| legal_CA = Rx-only |

|||

| legal_UK = POM |

| legal_UK = POM |

||

| legal_US = Rx-only |

| legal_US = Rx-only |

||

| legal_US_comment = <ref name="Tegretol FDA label">{{cite web | title=Tegretol- carbamazepine suspension Tegretol- carbamazepine tablet Tegretol XR- carbamazepine tablet, extended release | website=DailyMed | date=16 May 2022 | url=https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=8d409411-aa9f-4f3a-a52c-fbcb0c3ec053 | access-date=3 January 2023}}</ref> |

|||

| routes_of_administration = Oral |

|||

| legal_status = <!-- Rx-only where? --> |

|||

<!--Pharmacokinetic data--> |

<!--Pharmacokinetic data--> |

||

| |

|bioavailability = ~100%<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> |

||

| |

|protein_bound = 70–80%<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> |

||

| |

|metabolism = [[Liver]] ([[CYP3A4]])<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> |

||

|metabolites = Active [[epoxide]] form (carbamazepine-10,11 epoxide)<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> |

|||

| elimination_half-life = 25–65 hours (after several doses 12-17 hours) |

|||

|elimination_half-life = 36 hours (single dose), 16–24 hours (repeated dosing)<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> |

|||

| excretion = 2–3% excreted unchanged in urine |

|||

|excretion = Urine (72%), feces (28%)<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> |

|||

<!--Identifiers--> |

<!--Identifiers--> |

||

| IUPHAR_ligand = 5339 |

|||

| CASNo_Ref = {{cascite|correct|CAS}} |

|||

|CAS_number_Ref = {{cascite|correct|??}} |

|||

| CAS_number = 298-46-4 |

|||

| |

|CAS_number=298-46-4 |

||

|CAS_supplemental={{CAS|85756-57-6}} |

|||

|ChEBI_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} |

|||

| ATC_prefix = N03 |

|||

|ChEBI=3387 |

|||

| ATC_suffix = AF01 |

|||

|PubChem=2554 |

|||

| ChEBI_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} |

|||

| ChEBI = 3387 |

|||

| PubChem = 2554 |

|||

| DrugBank_Ref = {{drugbankcite|correct|drugbank}} |

| DrugBank_Ref = {{drugbankcite|correct|drugbank}} |

||

| |

|DrugBank=DB00564 |

||

| ChemSpiderID_Ref = {{chemspidercite|correct|chemspider}} |

| ChemSpiderID_Ref = {{chemspidercite|correct|chemspider}} |

||

| |

|ChemSpiderID=2457 |

||

| UNII_Ref = {{fdacite|correct|FDA}} |

| UNII_Ref = {{fdacite|correct|FDA}} |

||

| |

|UNII=33CM23913M |

||

| KEGG_Ref = {{keggcite|correct|kegg}} |

| KEGG_Ref = {{keggcite|correct|kegg}} |

||

| |

|KEGG=D00252 |

||

| ChEMBL_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} |

| ChEMBL_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} |

||

| |

|ChEMBL=108 |

||

| synonyms = CBZ |

|||

<!--Chemical data--> |

<!--Chemical data--> |

||

| IUPAC_name=5''H''-dibenzo[''b'',''f'']azepine-5-carboxamide |

|||

| C=15 | H=12 | N=2 | O=1 |

|||

|C=15 |H=12 |N=2 |O=1 |

|||

| molecular_weight = 236.269 g/mol |

|||

| |

|smiles=c1ccc2c(c1)C=Cc3ccccc3N2C(=O)N |

||

| InChI = 1/C15H12N2O/c16-15(18)17-13-7-3-1-5-11(13)9-10-12-6-2-4-8-14(12)17/h1-10H,(H2,16,18) |

|||

| StdInChI_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} |

| StdInChI_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} |

||

| |

|StdInChI=1S/C15H12N2O/c16-15(18)17-13-7-3-1-5-11(13)9-10-12-6-2-4-8-14(12)17/h1-10H,(H2,16,18) |

||

| StdInChIKey_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} |

| StdInChIKey_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} |

||

| |

|StdInChIKey=FFGPTBGBLSHEPO-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

||

}} |

}} |

||

<!-- Definition and uses --> |

|||

'''Carbamazepine''' ('''CBZ''') is an [[anticonvulsant]] and [[mood stabilizer|mood-stabilizing]] drug used primarily in the treatment of [[epilepsy]] and [[bipolar disorder]], as well as [[trigeminal neuralgia]]. It is also used [[off-label use|off-label]] for a variety of indications, including [[attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder]] (ADHD), [[schizophrenia]], [[phantom limb]] syndrome, [[complex regional pain syndrome]], [[paroxysmal extreme pain disorder]], [[neuromyotonia]], [[intermittent explosive disorder]], and [[post-traumatic stress disorder]]. |

|||

'''Carbamazepine''', sold under the brand name '''Tegretol''' among others, is an [[anticonvulsant medication]] used in the treatment of [[epilepsy]] and [[neuropathic pain]].<ref name="Tegretol FDA label" /><ref name=AHFS2015>{{cite web|url=https://www.drugs.com/monograph/carbamazepine.html|title=Carbamazepine|work=The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists|access-date=28 March 2015|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150227213125/http://www.drugs.com/monograph/carbamazepine.html|archive-date=27 February 2015}}</ref> It is used as an adjunctive treatment in [[schizophrenia]] along with other medications and as a [[Therapy#Lines of therapy|second-line]] agent in [[bipolar disorder]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Nevitt SJ, Marson AG, Weston J, Tudur Smith C | title = Sodium valproate versus phenytoin monotherapy for epilepsy: an individual participant data review | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2018 | pages = CD001769 | date = August 2018 | issue = 8 | pmid = 30091458 | pmc = 6513104 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD001769.pub4 }}</ref><ref name=AHFS2015/> Carbamazepine appears to work as well as [[phenytoin]] and [[valproate]] for focal and generalized seizures.<ref name=":0">{{cite journal | vauthors = Nevitt SJ, Marson AG, Tudur Smith C | title = Carbamazepine versus phenytoin monotherapy for epilepsy: an individual participant data review | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2019 | pages = CD001911 | date = July 2019 | issue = 7 | pmid = 31318037 | pmc = 6637502 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD001911.pub4 }}</ref> It is not effective for [[absence seizure|absence]] or [[myoclonic seizure]]s.<ref name=AHFS2015/> |

|||

<!-- Society, culture and history --> |

|||

It has been seen as safe for pregnant women to use carbamazepine as a mood stabilizer, |

|||

Carbamazepine was discovered in 1953 by Swiss chemist Walter Schindler.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Smith HS |title=Current therapy in pain|date=2009|publisher=Saunders/Elsevier|location=Philadelphia|isbn=978-1-4160-4836-7 |page=460|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iTgy62MWnK4C&pg=PA460|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305032812/https://books.google.ca/books?id=iTgy62MWnK4C&pg=PA460|archive-date=5 March 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite patent |country=US |number=2948718 |status=patent |title=New n-heterocyclic compounds |pubdate=1960-08-09 |gdate=1960-08-09 |fdate=1958-11-20 |pridate=1957-12-20 |invent1=Walter Schindler |assign1=Geigy Chemical Corporation |url=https://worldwide.espacenet.com/patent/search/family/003449474/publication/US2948718A?q=US2948718A}}</ref> It was first marketed in 1962.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Moshé S |title=The treatment of epilepsy |date=2009 |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |location=Chichester, UK |isbn=978-1-4443-1667-4 |page=xxix |edition=3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rFFzFzZJtasC&pg=PR29 |url-status=live|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160305024852/https://books.google.ca/books?id=rFFzFzZJtasC&pg=PR29 |archive-date=5 March 2016 }}</ref> It is available as a [[generic medication]].<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Porter NC | chapter = Trigeminal Neuralgia: Surgical Perspective | veditors = Chin LS, Regine WF |title=Principles and practice of stereotactic radiosurgery |date=2008 |publisher=Springer |location=New York |isbn=978-0-387-71070-9 | chapter-url= https://books.google.com/books?id=uEghr21XY6wC&pg=PA536 |url-status=live |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20160305021147/https://books.google.ca/books?id=uEghr21XY6wC&pg=PA536 |archive-date=5 March 2016 | page = 536 }}</ref> It is on the [[WHO Model List of Essential Medicines|World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines]].<ref name="WHO21st">{{cite book | title = World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019 | year = 2019 | hdl = 10665/325771 | publisher = [[World Health Organization]] | location = Geneva | id = WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO | hdl-access=free | vauthors = Organization WH }}</ref> In 2020, it was the 185th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 2{{nbsp}}million prescriptions.<ref>{{cite web | title = The Top 300 of 2020 | url = https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx | website = ClinCalc | access-date = 7 October 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title = Carbamazepine - Drug Usage Statistics | website = ClinCalc | url = https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Carbamazepine | access-date = 7 October 2022}}</ref> |

|||

<ref>Gelder, M., Mayou, R. and Geddes, J. 2005. Psychiatry. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford. pp250.</ref> but, like other anticonvulsants, intrauterine exposure is associated with spina bifida<ref>{{cite journal|last=Jentink|first=J|coauthors=Dolk, H, Loane, MA, Morris, JK, Wellesley, D, Garne, E, de Jong-van den Berg, L, EUROCAT Antiepileptic Study Working, Group|title=Intrauterine exposure to carbamazepine and specific congenital malformations: systematic review and case-control study.|journal=BMJ (Clinical research ed.)|date=2010-12-02|volume=341|pages=c6581|doi= 10.1136/bmj.c6581.|pmid=21127116}}</ref> and neurodevelopmental problems.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Cummings|first=C|coauthors=Stewart, M, Stevenson, M, Morrow, J, Nelson, J|title=Neurodevelopment of children exposed in utero to lamotrigine, sodium valproate and carbamazepine.|journal=Archives of disease in childhood|date=2011-03-17|pmid=21415043}}</ref> |

|||

Photoswitchable analogues of carbamazepine have been developed to control its pharmacological activity locally and on demand using light ([[photopharmacology]]), with the purpose of reducing the adverse systemic effects of the drug.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Camerin L, Maleeva G, Gomila-Juaneda A, Suárez-Pereira I, Matera C, Prischich D, Opar E, Riefolo F, Berrocoso E, Gorostiza P | title = Photoswitchable carbamazepine analogs for non-invasive neuroinhibition in vivo | journal = Angewandte Chemie | pages = e202403636 | date = June 2024 | volume = 63 | issue = 38 | pmid = 38887153 | doi = 10.1002/anie.202403636 | doi-access = free | hdl = 2445/215169 | hdl-access = free }}</ref> One of these light-regulated compounds (carbadiazocine, based on a bridged [[azobenzene]] or [[wiktionary:diazocine|diazocine]]) has been shown to produce analgesia with noninvasive illumination ''in vivo'' in a rat model of [[neuropathic pain]]. |

|||

==Medical uses== |

|||

Carbamazipine is typically used for the treatment of [[seizure]] disorders and [[neuropathic pain]].<ref name=AHFS>{{cite web|title=Carbamazepine|url=http://www.drugs.com/monograph/carbamazepine.html|work=The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists|accessdate=3 April 2011}}</ref> It may be used as a second line treatment for [[bipolar disorder]] and along with [[antipsychotic agents]] in [[schizophrenia]].<ref name=AHFS/> |

|||

== Medical uses == |

|||

In the United States, the [[Food and Drug Administration|FDA]]-approved indications are [[epilepsy]] (including [[partial seizure]]s and [[tonic-clonic seizure]]s), [[trigeminal neuralgia]], and [[mania|manic]] and [[mixed state (psychiatry)|mixed episodes]] of [[bipolar I disorder]].<ref name=Lexi-Comp/> Although data are still lacking, carbamazepine appears to be as effective and safe as [[lithium pharmacology|lithium]] for the treatment of bipolar disorder, both in the acute and maintenance phase.<ref name="Ceron-Litvoc">{{cite journal |author=Ceron-Litvoc D, Soares BG, Geddes J, Litvoc J, de Lima MS |title=Comparison of carbamazepine and lithium in treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials |journal=Hum Psychopharmacol |volume=24 |issue=1 |pages=19–28 |year=2009 |month=January |pmid=19053079 |doi=10.1002/hup.990}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Tegretol.jpg|thumb|Tegretol 200-mg CR (made in [[New Zealand|NZ]])]] |

|||

Carbamazepine is typically used for the treatment of [[seizure disorders]] and [[neuropathic pain]].<ref name=AHFS2015/> It is used [[off-label use|off-label]] as a second-line treatment for bipolar disorder and in combination with an [[antipsychotic]] in some cases of [[schizophrenia]] when treatment with a conventional antipsychotic alone has failed.<ref name=AHFS2015/><ref name="Ceron-Litvoc">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ceron-Litvoc D, Soares BG, Geddes J, Litvoc J, de Lima MS | title = Comparison of carbamazepine and lithium in treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials | journal = Human Psychopharmacology | volume = 24 | issue = 1 | pages = 19–28 | date = January 2009 | pmid = 19053079 | doi = 10.1002/hup.990 | s2cid = 5684931 }}</ref> However, evidence does not support its usage for schizophrenia.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Leucht S, Helfer B, Dold M, Kissling W, McGrath J | title = Carbamazepine for schizophrenia | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | issue = 5 | pages = CD001258 | date = May 2014 | volume = 2014 | pmid = 24789267 | pmc = 7032545 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD001258.pub3 | collaboration = Cochrane Schizophrenia Group }}</ref> It is not effective for [[absence seizure]]s or [[myoclonic seizure]]s.<ref name=AHFS2015/> Although carbamazepine may have a similar effectiveness (as measured by people continuing to use a medication) and efficacy (as measured by the medicine reducing seizure recurrence and improving remission) when compared to [[phenytoin]] and [[valproate]], choice of medication should be evaluated on an individual basis as further research is needed to determine which medication is most helpful for people with newly-onset seizures.<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

In the United States, carbamazepine is [[indicated]] for the treatment of [[epilepsy]] (including [[partial seizure]]s, generalized [[tonic-clonic seizure]]s and [[mixed seizure]]s), and [[trigeminal neuralgia]].<ref name="Tegretol FDA label" /><ref name="Lexi-Comp"/> Carbamazepine is the only medication that is approved by the [[Food and Drug Administration]] for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia.<ref>{{Cite journal| vauthors = Pino MA |date=19 January 2017 |title= Trigeminal Neuralgia: A "Lightning Bolt" of Pain|url=https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/trigeminal-neuralgia-a-lightning-bolt-of-pain|journal=US Pharmacist|volume=42|pages=41–44}}</ref> |

|||

== Adverse effects == |

|||

As of 2014, a [[controlled release]] formulation was available for which there is tentative evidence showing fewer side effects and unclear evidence with regard to whether there is a difference in efficacy.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Powell G, Saunders M, Rigby A, Marson AG | title = Immediate-release versus controlled-release carbamazepine in the treatment of epilepsy | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 12 | pages = CD007124 | date = December 2016 | issue = 4 | pmid = 27933615 | pmc = 6463840 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD007124.pub5 }}</ref> |

|||

Common [[adverse drug reaction|adverse effects]] include drowsiness, headaches and migraines, [[motor coordination]] impairment, and/or upset stomach. Carbamazepine preparations typically greatly decrease a person's alcohol tolerance. |

|||

It has also been shown to improve symptoms of "typewriter tinnitus", a type of tinnitus caused by the neurovascular compression of the cochleovestibular nerve. <ref>Sunwoo, W., Jeon, Y., Bae, Y. et al. Typewriter tinnitus revisited: The typical symptoms and the initial response to carbamazepine are the most reliable diagnostic clues. Sci Rep 7, 10615 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10798-w</ref> |

|||

Less common side-effects include cardiac arrhythmias, blurry or double [[Visual perception|vision]] and/or the temporary loss of[[blood cell]]s or [[platelet]]s and in rare cases can cause aplastic anemia. With normal use, small reductions in white cell count and serum sodium are common; however, in rare cases, the loss of platelets may become life-threatening. This occurs commonly enough that a doctor may recommend frequent blood tests during the first few months of use, followed by three to four tests per year for established patients. In the UK, testing is generally performed much less frequently for long-term carbamazepine patients—typically once per year. {{citation needed|date=November 2010}} Additionally, carbamazepine may exacerbate preexisting cases of hypothyroidism, so yearly thyroid function tests are advisable for persons taking the drug. |

|||

== Adverse effects == |

|||

There are also reports of an auditory side-effect for carbamazepine use, whereby patients perceive sounds about a [[semitone]] lower than previously.<ref name="pmid12581810">{{cite journal |author=Yoshikawa H, Abe T |title=Carbamazepine-induced abnormal pitch perception |journal=Brain Dev. |volume=25 |issue=2 |pages=127–9 |year=2003 |month=March |pmid=12581810 |doi= 10.1016/S0387-7604(02)00155-9|url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0387760402001559}}</ref><ref name="pmid14518681">{{cite journal |author=Konno S, Yamazaki E, Kudoh M, Abe T, Tohgi H |title=Half pitch lower sound perception caused by carbamazepine |journal=Intern. Med. |volume=42 |issue=9 |pages=880–3 |year=2003 |month=September |pmid=14518681 |doi= 10.2169/internalmedicine.42.880|url=http://joi.jlc.jst.go.jp/JST.Journalarchive/internalmedicine1992/42.880?from=PubMed }}{{dead link|date=January 2010}}</ref><ref name="pmid9804087">{{cite journal |author=Kashihara K, Imai K, Shiro Y, Shohmori T|title=Reversible pitch perception deficit due to carbamazepine |journal=Intern. Med. |volume=37 |issue=9 |pages=774–5 |year=1998|month=September |pmid=9804087 |doi= 10.2169/internalmedicine.37.774|url=http://joi.jlc.jst.go.jp/JST.Journalarchive/internalmedicine1992/37.774?from=PubMed }}{{dead link|date=January 2010}}</ref> Thus, [[middle C]] would be heard as the note [[Scientific pitch notation|B3]] just below it, and so on. The inverse effect (that is, notes sounding higher) has also been recorded.<ref name="pmid11020128">{{cite journal|author=Miyaoka T, Seno H, Itoga M, Horiguchi J |title=Reversible pitch perception deficit caused by carbamazepine |journal=Clin Neuropharmacol |volume=23 |issue=4 |pages=219–21 |year=2000 |pmid=11020128 |doi= 10.1097/00002826-200007000-00010|url=http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=0362-5664&volume=23&issue=4&spage=219|archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKvSxCd4 |archivedate = 2010-11-18|deadurl=no}}</ref><ref name="pmid15446396">{{cite journal |author=Wakamoto H, Kume A, Nakano N |title=Elevated pitch perception owing to carbamazepine-activating effect on the peripheral auditory system: auditory brainstem response study|journal=J. Child Neurol. |volume=19 |issue=6 |pages=453–5 |year=2004 |month=June |pmid=15446396 |doi=|url=http://jcn.sagepub.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15446396|archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKvULlsv |archivedate = 2010-11-18|deadurl=no}}</ref> This unusual side-effect is usually not noticed by most people, and quickly disappears after the person stops taking carbamazepine. |

|||

In the US, the label for carbamazepine contains warnings concerning:<ref name="Tegretol FDA label" /> |

|||

* effects on the [[Hematology|body's production of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets]]: rarely, there are major effects of [[aplastic anemia]] and [[agranulocytosis]] reported and more commonly, there are minor changes such as decreased [[Leukocyte|white blood cell]] or [[platelet]] counts, but these do not progress to more serious problems.<ref name="carbamazepinelabel">{{cite web|title=Carbamazepine Drug Label|url=http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=7a1e523a-b377-43dc-b231-7591c4c888ea|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141208063739/http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=7a1e523a-b377-43dc-b231-7591c4c888ea|archive-date=8 December 2014}}</ref> |

|||

* increased risks of suicide<ref name=stats>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vukovic Cvetkovic V, Jensen RH | title = Neurostimulation for the treatment of chronic migraine and cluster headache | journal = Acta Neurologica Scandinavica | volume = 139 | issue = 1 | pages = 4–17 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 30291633 | doi = 10.1111/ane.13034 | s2cid = 52923061 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

* increased risks of [[hyponatremia]] and [[SIADH]]<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gandelman MS | s2cid = 36758508 | title = Review of carbamazepine-induced hyponatremia | journal = Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry | volume = 18 | issue = 2 | pages = 211–33 | date = March 1994 | pmid = 8208974 | doi = 10.1016/0278-5846(94)90055-8 }}</ref> |

|||

* risk of seizures, if the person stops taking the drug abruptly<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> |

|||

* risks to the fetus in women who are pregnant, specifically congenital malformations like [[spina bifida]], and developmental disorders.<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jentink J, Dolk H, Loane MA, Morris JK, Wellesley D, Garne E, de Jong-van den Berg L | title = Intrauterine exposure to carbamazepine and specific congenital malformations: systematic review and case-control study | journal = BMJ | volume = 341 | pages = c6581 | date = December 2010 | pmid = 21127116 | pmc = 2996546 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.c6581 }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Pancreatitis]] |

|||

* [[Hepatitis]] |

|||

* [[Dizziness]] |

|||

* Bone marrow suppression |

|||

* [[Stevens–Johnson syndrome]] |

|||

Common [[adverse drug reaction|adverse effects]] may include drowsiness, dizziness, headaches and migraines, [[ataxia]], nausea, vomiting, and/or constipation. [[alcohol (drug)|Alcohol]] use while taking carbamazepine may lead to enhanced depression of the [[central nervous system]].<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> Less common side effects may include increased risk of seizures in people with [[Causes of seizures#Diseases|mixed seizure disorders]],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Liu L, Zheng T, Morris MJ, Wallengren C, Clarke AL, Reid CA, Petrou S, O'Brien TJ | s2cid = 7693614 | title = The mechanism of carbamazepine aggravation of absence seizures | journal = The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics | volume = 319 | issue = 2 | pages = 790–8 | date = November 2006 | pmid = 16895979 | doi = 10.1124/jpet.106.104968 }}</ref> [[Heart arrhythmia|abnormal heart rhythms]], blurry or [[Diplopia|double vision]].<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> Also, rare case reports of an auditory side effect have been made, whereby patients perceive sounds about a [[semitone]] lower than previously; this unusual side effect is usually not noticed by most people, and disappears after the person stops taking carbamazepine.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tateno A, Sawada K, Takahashi I, Hujiwara Y | title = Carbamazepine-induced transient auditory pitch-perception deficit | journal = Pediatric Neurology | volume = 35 | issue = 2 | pages = 131–4 | date = August 2006 | pmid = 16876011 | doi = 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.01.011 }}</ref> |

|||

Carbamazepine increases the risk of developing lupus by 1.88.<ref>{{cite journal |doi= 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2010.03733.x |title= Do selected drugs increase the risk of lupus? A matched case-control study |year= 2010 |last1= Schoonen |first1= W. Marieke |last2= Thomas |first2= Sara L. |last3= Somers |first3= Emily C. |last4= Smeeth |first4= Liam |last5= Kim |first5= Joseph |last6= Evans|first6= Stephen |last7= Hall |first7= Andrew J. |journal= British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology |volume= 70 |issue= 4 |pages= 588–596 |pmid= 20840450 |pmc= 2950993 }}</ref> |

|||

=== Pharmacogenetics === |

|||

[[Oxcarbazepine]], a derivative of carbamazepine, reportedly has fewer and less serious side-effects. |

|||

Serious skin reactions such as [[Stevens–Johnson syndrome]] (SJS) or [[toxic epidermal necrolysis]] (TEN) due to carbamazepine therapy are more common in people with a particular [[human leukocyte antigen]] gene-variant ([[allele]]), [[HLA-B75|HLA-B*1502]].<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> [[Odds ratio]]s for the development of SJS or TEN in people who carry the allele can be in the double, triple or even quadruple digits, depending on the population studied.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kaniwa N, Saito Y | title = Pharmacogenomics of severe cutaneous adverse reactions and drug-induced liver injury | journal = Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 58 | issue = 6 | pages = 317–26 | date = June 2013 | pmid = 23635947 | doi = 10.1038/jhg.2013.37 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="pmid24597466">{{cite journal | vauthors = Amstutz U, Shear NH, Rieder MJ, Hwang S, Fung V, Nakamura H, Connolly MB, Ito S, Carleton BC | title = Recommendations for HLA-B*15:02 and HLA-A*31:01 genetic testing to reduce the risk of carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity reactions | journal = Epilepsia | volume = 55 | issue = 4 | pages = 496–506 | date = April 2014 | pmid = 24597466 | doi = 10.1111/epi.12564 | hdl = 2429/63109 | s2cid = 41565230 | hdl-access = free }}</ref> [[HLA-B75|HLA-B*1502]] occurs almost exclusively in people with ancestry across broad areas of Asia, but has a very low or absent frequency in European, Japanese, Korean and African populations.<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Leckband SG, Kelsoe JR, Dunnenberger HM, George AL, Tran E, Berger R, Müller DJ, Whirl-Carrillo M, Caudle KE, Pirmohamed M | title = Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for HLA-B genotype and carbamazepine dosing | journal = Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics | volume = 94 | issue = 3 | pages = 324–8 | date = September 2013 | pmid = 23695185 | pmc = 3748365 | doi = 10.1038/clpt.2013.103 }}</ref> However, the HLA-A*31:01 allele has been shown to be a strong predictor of both mild and severe adverse reactions, such as the [[Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms|DRESS]] form of severe cutaneous reactions, to carbamazepine among Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Europeans.<ref name="pmid24597466"/><ref name="pmid28345177">{{cite journal | vauthors = Garon SL, Pavlos RK, White KD, Brown NJ, Stone CA, Phillips EJ | title = Pharmacogenomics of off-target adverse drug reactions | journal = British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology | volume = 83 | issue = 9 | pages = 1896–1911 | date = September 2017 | pmid = 28345177 | pmc = 5555876 | doi = 10.1111/bcp.13294 }}</ref> It is suggested that carbamazepine acts as a potent antigen that binds to the antigen-presenting area of HLA-B*1502 alike, triggering an everlasting activation signal on immature CD8-T cells, thus resulting in widespread cytotoxic reactions like SJS/TEN.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jaruthamsophon K, Tipmanee V, Sangiemchoey A, Sukasem C, Limprasert P | title = HLA-B*15:21 and carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome: pooled-data and in silico analysis | journal = Scientific Reports | volume = 7 | issue = 1 | pages = 45553 | date = March 2017 | pmid = 28358139 | pmc = 5372085 | doi = 10.1038/srep45553 | bibcode = 2017NatSR...745553J }}</ref> |

|||

== Interactions == |

|||

Carbamazepine may cause [[Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone]] (SIADH), since it both increases the release and potentiates the action of ADH ([[vasopressin]]). |

|||

Carbamazepine has a potential for [[drug interaction]]s.<ref name="Lexi-Comp">{{cite web|url=http://www.merck.com/mmpe/lexicomp/carbamazepine.html |title=Carbamazepine |date=February 2009 |author=Lexi-Comp |work=[[Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy|The Merck Manual Professional]] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101103035532/http://www.merck.com/mmpe/lexicomp/carbamazepine.html |archive-date=3 November 2010 |url-status=live }} Retrieved on 3 May 2009.</ref> Drugs that decrease breaking down of carbamazepine or otherwise increase its levels include [[erythromycin]],<ref name=Stafstrom>{{cite journal | vauthors = Stafstrom CE, Nohria V, Loganbill H, Nahouraii R, Boustany RM, DeLong GR | title = Erythromycin-induced carbamazepine toxicity: a continuing problem | journal = Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine | volume = 149 | issue = 1 | pages = 99–101 | date = January 1995 | pmid = 7827672 | doi = 10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170130101025 | url = http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7827672 | url-status = live | archive-url = https://archive.today/20240525023120/https://www.webcitation.org/5uKvQB98w?url=http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup%3Fview=long&pmid=7827672 | archive-date = 25 May 2024 }}</ref> [[cimetidine]], [[propoxyphene]], and [[calcium channel blocker]]s.<ref name="Lexi-Comp"/> Grapefruit juice raises the [[bioavailability]] of carbamazepine by inhibiting the enzyme [[CYP3A4]] in the gut wall and in the liver.<ref name="carbamazepinelabel"/> Lower levels of carbamazepine are seen when administered with [[phenobarbital]], [[phenytoin]], or [[primidone]], which can result in breakthrough seizure activity.<ref name="urleMedicine- Toxicity, Carbamazepine" /> |

|||

[[Valproic acid]] and [[valnoctamide]] both inhibit [[microsomal epoxide hydrolase]] (mEH), the enzyme responsible for the breakdown of the [[active metabolite]] carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide into inactive metabolites.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Gonzalez FJ, Tukey RH | veditors = Brunton L, Lazo J, Parker K |title=Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics |edition=11th |year=2006 |publisher=[[McGraw-Hill]] |location=New York |isbn=978-0-07-142280-2 |page=[https://archive.org/details/goodmangilmansph00brun_116/page/n104 79] |chapter=Drug Metabolism|title-link=Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics }}</ref> By inhibiting mEH, valproic acid and valnoctamide cause a build-up of the active metabolite, prolonging the effects of carbamazepine and delaying its excretion. |

|||

Carbamazepine may aggravate [[juvenile myoclonic epilepsy]], so it is important to uncover any history of jerking, especially in the morning, before starting the drug. It may also aggrevate other types of generalized seizure disorder, particularly [[absence seizures]].<ref>{{cite journal |doi= 10.1124/jpet.106.10496|title=The Mechanism of Carbamazepine Aggravation of Absence Seizures|year= 2006 |author= Lige Liu, Thomas Zheng, Margaret J. Morris, Charlott Wallengren, Alison L. Clarke, Christopher A. Reid, Steven Petrou and Terence J. O'Brien |journal= JPET |volume= 319 |issue= 2 |pages= 790-798 |pmid= 16895979|url=http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/content/319/2/790.abstract}}</ref> |

|||

Carbamazepine, as an inducer of [[cytochrome P450]] enzymes, may increase clearance of many drugs, decreasing their concentration in the blood to subtherapeutic levels and reducing their desired effects.<ref name="urleMedicine- Toxicity, Carbamazepine">{{cite web |url= http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic77.htm | work = eMedicine | title = Carbamazepine Toxicity |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080704144842/http://emedicine.com/emerg/topic77.htm |archive-date=4 July 2008 |url-status=live |date=2 February 2019 }}</ref> Drugs that are more rapidly metabolized with carbamazepine include [[warfarin]], [[lamotrigine]], [[phenytoin]], [[theophylline]], [[valproic acid]],<ref name="Lexi-Comp"/> many [[benzodiazepine]]s,<ref name="isbn1-58829-211-8">{{cite book | vauthors = Moody D | veditors = Raymon LP, Mozayani A |title=Handbook of Drug Interactions: a Clinical and Forensic Guide |publisher=Humana |year=2004 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/handbookofdrugin0000unse/page/3 3–88] |chapter=Drug interactions with benzodiazepines |isbn=978-1-58829-211-7 |chapter-url-access=registration |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/handbookofdrugin0000unse/page/3 }}</ref> and [[methadone]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Schlatter J, Madras JL, Saulnier JL, Poujade F | title = [Drug interactions with methadone] | language = fr | journal = Presse Médicale | volume = 28 | issue = 25 | pages = 1381–4 | date = September 1999 | pmid = 10506872 | trans-title = Drug interactions with methadone }}</ref> Carbamazepine also increases the metabolism of the hormones in [[birth control pill]]s and can reduce their effectiveness, potentially leading to unexpected pregnancies.<ref name="Lexi-Comp"/> |

|||

In addition, carbamazepine has been linked to serious adverse cognitive anomalies, including EEG slowing<ref name="pmid12027908">{{cite journal |author=Salinsky MC, Binder LM, Oken BS, Storzbach D, Aron CR, Dodrill CB |title=Effects of gabapentin and carbamazepine on the EEG and cognition in healthy volunteers |journal=Epilepsia |volume=43 |issue=5 |pages=482–90|year=2002 |pmid=12027908 |doi=10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.22501.x|url=http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.22501.x?cookieSet=1|archiveurl =http://www.webcitation.org/5uKvX3m5E |archivedate = 2010-11-18|deadurl=no}}</ref> and cell apoptosis.<ref name="pmid8719616">{{cite journal |author=Gao XM, Margolis RL, Leeds P, Hough C, Post RM, Chuang DM |title=Carbamazepine induction of apoptosis in cultured cerebellar neurons: effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate, aurintricarboxylic acid and cycloheximide |journal=Brain Res. |volume=703|issue=1–2 |pages=63–71 |year=1995 |pmid=8719616 |doi=10.1016/0006-8993(95)01066-1}}</ref> |

|||

== Pharmacology == |

|||

The FDA informed health care professionals that dangerous or even fatal skin reactions ([[Stevens Johnson syndrome]] and [[toxic epidermal necrolysis]]), that can be caused by carbamazepine therapy, are significantly more common in patients with a particular[[human leukocyte antigen]] (HLA) allele, [[HLA-B75|HLA-B*1502]]. This allele occurs almost exclusively in patients with ancestry across broad areas of Asia, including South Asian Indians.<ref>{{cite web |author=MedWatch |title=Carbamazepine |url=http://www.fda.gov/medwatch/safety/2007/safety07.htm#carbamazepine |date=2007-12-12 |work=2007 Safety Alerts for Drugs, Biologics, Medical Devices, and Dietary Supplements |publisher=FDA|archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKvY37EY |archivedate = 2010-11-18|deadurl=no}}</ref> In Europeans a large proportion of sensitivity is associated with [[HLA-B58]].Researchers have also identified another genetic variant, HLA-A*3101 which has been shown to be a strong predictor of both mild and severe adverse reactions to carbamazepine among Europeans.<ref name="Epilepsy Society"> [http://www.epilepsysociety.org.uk/WhatWeDo/News/Reactiontodruglinkedtogeneticvariant], Epilepsy Society: genome-wide association study of Europeans with adverse reaction to carbamazepine.</ref> |

|||

=== Mechanism of action === |

|||

Carbamazepine is a [[sodium channel blocker]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rogawski MA, Löscher W, Rho JM | title = Mechanisms of Action of Antiseizure Drugs and the Ketogenic Diet | journal = Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine | volume = 6 | issue = 5 | pages = a022780 | date = May 2016 | pmid = 26801895 | pmc = 4852797 | doi = 10.1101/cshperspect.a022780 }}</ref> It binds preferentially to [[Voltage gated sodium channels|voltage-gated sodium channels]] in their inactive conformation, which prevents repetitive and sustained firing of an [[action potential]]. Carbamazepine has effects on serotonin systems but the relevance to its antiseizure effects is uncertain. There is evidence that it is a [[serotonin releasing agent]] and possibly even a [[serotonin reuptake inhibitor]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dailey JW, Reith ME, Steidley KR, Milbrandt JC, Jobe PC | title = Carbamazepine-induced release of serotonin from rat hippocampus in vitro | journal = Epilepsia | volume = 39 | issue = 10 | pages = 1054–63 | date = October 1998 | pmid = 9776325 | doi = 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1998.tb01290.x | s2cid = 20382623 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dailey JW, Reith ME, Yan QS, Li MY, Jobe PC | title = Carbamazepine increases extracellular serotonin concentration: lack of antagonism by tetrodotoxin or zero Ca2+ | journal = European Journal of Pharmacology | volume = 328 | issue = 2–3 | pages = 153–62 | date = June 1997 | pmid = 9218697 | doi = 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)83041-5 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Kawata Y, Okada M, Murakami T, Kamata A, Zhu G, Kaneko S | title = Pharmacological discrimination between effects of carbamazepine on hippocampal basal, Ca(2+)- and K(+)-evoked serotonin release | journal = British Journal of Pharmacology | volume = 133 | issue = 4 | pages = 557–67 | date = June 2001 | pmid = 11399673 | pmc = 1572811 | doi = 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704104 }}</ref> It has been suggested that carbamazepine can also block [[voltage-gated calcium channel]]s, which will reduce neurotransmitter release.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gambeta E, Chichorro JG, Zamponi GW | title = Trigeminal Neuralgia: an overview from pathophysiology to pharmacological treatments | journal = Molecular Pain |date = January 2020 | volume = 16 | pmid = 31908187| doi = 10.1177/1744806920901890 | pmc = 6985973 }}</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Pharmacokinetics === |

||

[[File:Carbamazepine metabolism.svg|class=skin-invert-image|thumb|upright=0.7|'''Metabolism.''' Top: carbamazepine • middle: carbamazepine-10,11-[[epoxide]], the [[active metabolite]] • bottom: carbamazepine-10,11-[[diol]], an inactive metabolite, which is then [[Glucuronidation|glucuronidized]]]] |

|||

Carbamazepine has a very high potential for [[drug interaction]]s; caution should be used in combining other medicines with it, including other antiepileptics and mood stabilizers.<ref name="Lexi-Comp">{{cite web|url=http://www.merck.com/mmpe/lexicomp/carbamazepine.html |title=Carbamazepine |date=February 2009 |author=Lexi-Comp |work=[[Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy|The Merck Manual Professional]]|archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKvOP99i |archivedate = 2010-11-18|deadurl=no}} Retrieved on May 3, 2009.</ref> Lower levels of carbamazepine are seen when administrated with [[phenobarbital]], [[phenytoin]] (Dilantin), or [[primidone]] (Mysoline). |

|||

Carbamazepine, as a [[CYP450]] inducer, may increase clearance of many drugs, decreasing their blood levels.<ref name="urleMedicine- Toxicity, Carbamazepine">{{cite web |url=http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic77.htm |title=eMedicine - Toxicity, Carbamazepine|work= |accessdate=|archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5ZpbVBsOJ |archivedate = 2008-08-04|deadurl=no}}</ref> Drugs that are more rapidly metabolized with carbamazepine include [[warfarin]] (Coumadin), phenytoin (Dilantin), [[theophylline]], and [[valproic acid]] (Depakote, Depakote ER, Depakene, Depacon).<ref name=Lexi-Comp/> Drugs that decrease the metabolism of carbamazepine or otherwise increase its levels include [[erythromycin]],<ref>{{cite journal |author=Stafstrom CE, Nohria V, Loganbill H, Nahouraii R, Boustany RM, DeLong GR |title=Erythromycin-induced carbamazepine toxicity: a continuing problem |journal=Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med |volume=149 |issue=1 |pages=99–101 |year=1995 |month=January |pmid=7827672 |doi=|url=http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=7827672|archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5uKvQB98w|archivedate = 2010-11-18|deadurl=no}}</ref> [[cimetidine]] (Tagamet), [[propoxyphene]] (Darvon), and [[calcium channel blocker]]s.<ref name=Lexi-Comp/> Carbamazepine also increases the metabolism of the hormones in [[birth control pill]]s and can reduce their effectiveness, potentially leading to unexpected pregnancies.<ref name=Lexi-Comp/> |

|||

Carbamazepine is relatively slowly but practically completely absorbed after administration by mouth. Highest concentrations in the [[blood plasma]] are reached after 4 to 24 hours depending on the dosage form. [[Slow release]] tablets result in about 15% lower absorption and 25% lower peak plasma concentrations than ordinary tablets, as well as in less fluctuation of the concentration, but not in significantly lower [[Cmin|minimum concentration]]s.<ref name="PubChem">{{cite web |title=Carbamazepine |url= https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/2554 |access-date=6 May 2021|work = PubChem | publisher = National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services }}</ref><ref name="AC">{{cite book|title=Austria-Codex| veditors = Haberfeld H |at=Tegretol retard 400 mg-Filmtabletten|publisher=Österreichischer Apothekerverlag|location=Vienna|year=2021|language=German}}</ref> |

|||

[[Valproic acid]] and [[valnoctamide]] both inhibit [[epoxide hydrolase|microsomal epoxide hydrolase]] (mEH), the [[enzyme]] responsible for the breakdown of carbamazepine-10,11 epoxide into inactive metabolites.<ref>{{cite book |last=Gonzalez |first=Frank J. |coauthors=Robert H. Tukey |editor=Laurence Brunton, John Lazo, Keith Parker (eds.) |title=[[Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics]] |edition=11th |year=2006 |publisher=[[McGraw-Hill]] |location=New York|isbn=978-0-07-142280-2|page=79 |chapter=Drug Metabolism }}</ref> By inhibiting mEH, valproic acid and valnoctamide cause a buildup of the active metabolite, prolonging the effects of carbamazepine and delaying its excretion. |

|||

In the circulation, carbamazepine itself comprises 20 to 30% of total residues. The remainder is in the form of [[metabolite]]s; 70 to 80% of residues is bound to [[plasma protein]]s. Concentrations in breast milk are 25 to 60% of those in the blood plasma.<ref name="AC" /> |

|||

Grapefruit juice raises the bioavailability of carbamazepine by inhibiting CYP3A4 enzymes in the gut wall and in the liver. |

|||

Carbamazepine itself is not pharmacologically active. It is activated, mainly by CYP3A4, to carbamazepine-10,11-[[epoxide]], which is solely responsible for the drug's anticonvulsant effects. The epoxide is then inactivated by microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH) to carbamazepine-''trans''-10,11-[[diol]] and further to its [[glucuronide]]s. Other metabolites include various [[hydroxyl]] derivatives and carbamazepine-''[[nitrogen|N]]''-glucuronide.<ref name="AC" /> |

|||

==Pharmacokinetics== |

|||

The [[plasma half-life]] is about 35 to 40 hours when carbamazepine is given as single dose, but it is a strong [[enzyme inducer|inducer]] of liver enzymes, and the plasma half-life shortens to about 12 to 17 hours when it is given repeatedly. The half-life can be further shortened to 9–10 hours by other enzyme inducers such as [[phenytoin]] or [[phenobarbital]]. About 70% are excreted via the urine, almost exclusively in form of its metabolites, and 30% via the faeces.<ref name="PubChem" /><ref name="AC" /> |

|||

Carbamazepine exhibits autoinduction: it [[regulation of gene expression|induces]] the expression of the hepatic microsomal enzyme system [[CYP3A4]], which metabolizes carbamazepine itself. Upon initiation of carbamazepine therapy, concentrations are predictable and follow their respective baseline clearance/half-life values that have been established for the specific patient. However, after enough carbamazepine has been presented to the liver tissue, the CYP3A4 activity increases, speeding up drug clearance and shortening the half-life. Autoinduction will continue with subsequent increases in dose but will usually reach a plateau within 5–7 days of a maintenance dose. Increases in dose at a rate of 200 mg every 1–2 weeks may be required to achieve a stable seizure threshold. Stable carbamazepine concentrations occur usually within 2–3 weeks after initiation of therapy.<ref>{{cite book|last=Bauer |first=Larry A. |title=[[Applied Clinical Pharmacokinetics]] |edition=2<sup>nd</sup> |year=2008 |publisher=[[McGraw-Hill]]|isbn=978-0-8385-0388-1}}</ref> |

|||

== Mechanism of action == |

|||

The mechanism of action of carbamazepine and its derivatives is relatively well understood. [[Voltage-gated sodium channel]]s are the molecular pores that allow brain cells ([[neuron]]s) to generate [[action potential]]s, the electrical events that allow [[neuron]]s to communicate over long distances. After the sodium channels open to start the action potential, they inactivate, in essence closing the channel. Carbamazepine stabilizes the inactivated state of sodium channels, meaning that fewer of these channels are available to subsequently open, making brain cells less excitable (less likely to fire). |

|||

Carbamazepine has also been shown to potentiate GABA receptors made up of alpha1, beta2, gamma2 subunits.<ref>Granger, P. et al. Modulation of the gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor by the antiepileptic drugs carbamazepine and phenytoin. Mol. Pharmacol. 47, 1189–1196 (1995).</ref> |

|||

== History == |

== History == |

||

Carbamazepine was discovered by chemist Walter Schindler at J.R. Geigy AG (now part of [[Novartis]]) in [[Basel]], [[Switzerland]], in 1953.<ref>{{cite journal | |

Carbamazepine was discovered by chemist Walter Schindler at J.R. Geigy AG (now part of [[Novartis]]) in [[Basel]], [[Switzerland]], in 1953.<ref name=Scott1993>{{cite book | vauthors = Scott DF | chapter = Chapter 8: Carbamazepine | title = The History of Epileptic Therapy: An Account of How Medication was Developed. | series = History of Medicine Series. | publisher = CRC Press | date = 1993 | isbn = 978-1-85070-391-4 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Schindler W, Häfliger F |title=Über Derivate des Iminodibenzyls |journal=[[Helvetica Chimica Acta]] |year=1954 |volume=37 |issue=2 |pages=472–83 |doi=10.1002/hlca.19540370211}}</ref> It was first marketed as a drug to treat epilepsy in Switzerland in 1963 under the brand name Tegretol; its use for [[trigeminal neuralgia]] (formerly known as tic douloureux) was introduced at the same time.<ref name=Scott1993/> It has been used as an anticonvulsant and antiepileptic in the United Kingdom since 1965, and has been approved in the United States since 1968.<ref name=AHFS2015/> |

||

Carbamazepine was studied for bipolar disorder throughout the 1970s.<ref name="pmid9682927">{{cite journal | vauthors = Okuma T, Kishimoto A | title = A history of investigation on the mood stabilizing effect of carbamazepine in Japan | journal = Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences | volume = 52 | issue = 1 | pages = 3–12 | date = February 1998 | pmid = 9682927 | doi = 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb00966.x | s2cid = 8480811 }}</ref> |

|||

Carbamazepine was first marketed as a drug to treat [[trigeminal neuralgia]] (formerly known as tic douloureux) in 1962. It has been used as an anticonvulsant in the [[United Kingdom|UK]] since 1965, and has been approved in the [[United States|U.S.]] since 1974. |

|||

== Society and culture == |

|||

In 1971, Drs. Takezaki and Hanaoka first used carbamazepine to control mania in patients refractory to antipsychotics ([[Lithium pharmacology|Lithium]] was not available in Japan at that time). Dr. Okuma, working independently, did the same thing with success. As they were also epileptologists, they had some familiarity with the anti-aggression effects of this drug. Carbamazepine would be studied for bipolar disorder throughout the 1970s.<ref name="pmid9682927">{{cite journal |author=Okuma T, Kishimoto A |title=A history of investigation on the mood stabilizing effect of carbamazepine in Japan |journal=Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. |volume=52|issue=1 |pages=3–12 |year=1998 |month=February |pmid=9682927 |doi=10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb00966.x}}</ref> |

|||

=== Environmental impact === |

|||

{{Main|Environmental impact of pharmaceuticals and personal care products}} |

|||

Carbamazepine and its bio-transformation products have been detected in wastewater treatment plant [[effluent]]<ref name="Prosser">{{cite journal | vauthors = Prosser RS, Sibley PK | title = Human health risk assessment of pharmaceuticals and personal care products in plant tissue due to biosolids and manure amendments, and wastewater irrigation | journal = Environment International | volume = 75 | pages = 223–33 | date = February 2015 | pmid = 25486094 | doi = 10.1016/j.envint.2014.11.020 | bibcode = 2015EnInt..75..223P }}</ref>{{rp|224}} and in streams receiving treated wastewater.<ref name="pmid30350841">{{cite journal | vauthors = Posselt M, Jaeger A, Schaper JL, Radke M, Benskin JP | title = Determination of polar organic micropollutants in surface and pore water by high-resolution sampling-direct injection-ultra high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry | journal = Environmental Science: Processes & Impacts | volume = 20 | issue = 12 | pages = 1716–1727 | date = December 2018 | pmid = 30350841 | doi = 10.1039/C8EM00390D | doi-access = free }}</ref> Field and laboratory studies have been conducted to understand the accumulation of carbamazepine in food plants grown in soil treated with [[sludge]], which vary with respect to the concentrations of carbamazepine present in sludge and in the concentrations of sludge in the soil. Taking into account only studies that used concentrations commonly found in the environment, a 2014 review concluded that "the accumulation of carbamazepine into plants grown in soil amended with biosolids poses a ''[[de minimis#Risk assessment|de minimis]]'' risk to human health according to the approach."<ref name=Prosser/>{{rp|227}} |

|||

==Brand names== |

|||

=== Brand names === |

|||

Carbamazepine has been sold under the names Biston, Calepsin, Carbatrol, Epitol, Equetro, Finlepsin, Sirtal, Stazepine, Telesmin, Tegretol, Teril, Timonil, Trimonil, Epimaz, Carbama/Carbamaze ([[New Zealand]]), Amizepin ([[Poland]]), Karbapin ([[Serbia]]), Hermolepsin ([[Sweden]]), Degranol ([[South Africa]]).<ref>[http://www.intekom.com/pharm/lennon/degranol.html Degranol Tablets]{{dead link|date=November 2010}}</ref>, and Tegretal ([[Chile]]).<ref>http://www.farmaciasahumada.cl/fasaonline/fasa/MFT/PRODUCTO/P1163.HTM</ref> |

|||

Carbamazepine is available worldwide under many brand names including Tegretol.<ref>{{cite web |title=Carbamazepine |url=https://www.drugs.com/international/carbamazepine.html |website=Drugs.com |access-date=27 October 2019 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== Research == |

||

* [[Oxcarbazepine]] |

|||

{{Empty section|date=October 2023}} |

|||

==Chemistry== |

|||

[[File:Carbamazepine syn.png|600px]] |

|||

== References == |

|||

Schindler, W.; 1960, {{US patent|2,948,718}}. |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

== Further reading == |

|||

Carbamazepine is a [[dibenzazepine]]. |

|||

{{refbegin}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | vauthors = Iqbal MM, Gundlapalli SP, Ryan WG, Ryals T, Passman TE | title = Effects of antimanic mood-stabilizing drugs on fetuses, neonates, and nursing infants | journal = Southern Medical Journal | volume = 94 | issue = 3 | pages = 304–22 | date = March 2001 | pmid = 11284518 | doi = 10.1097/00007611-200194030-00007 | url = https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/410736_4 }} |

|||

== References == |

|||

* {{cite book | title=Medical Genetics Summaries | chapter=Carbamazepine Therapy and HLA Genotype | chapter-url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK321445/ | veditors=Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, Scott SA, Dean LC, Kattman BL, Malheiro AJ | display-editors=3 | publisher=[[National Center for Biotechnology Information]] (NCBI) | year=2015 | pmid=28520367 | id=Bookshelf ID: NBK321445 | vauthors=Dean L | url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK61999/ }} |

|||

<ref> Hung SI, Chung WH, Chen YT et al. Common risk allele in aromatic antiepileptic-drug induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis in Han Chinese. |

|||

{{refend}} |

|||

Pharmacogenomics.2010 Mar;11(3):349-56.</ref> |

|||

<ref> Carbamazepine-Induced Toxic Effects and HLA-B*1502 Screening in Taiwan, New England Journal of Medicine, March 2010. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa1009717 </ref> |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

{{Commons category}} |

{{Commons category}} |

||

* {{cite web| url = https://druginfo.nlm.nih.gov/drugportal/name/carbamazepine | publisher = U.S. National Library of Medicine| work = Drug Information Portal| title = Carbamazepine }} |

|||

* [http://www.carbatrol.com Carbatrol website] |

|||

* [https://www.nhs.uk/medicines/carbamazepine/ Carbamazepine]. UK [[National Health Service]] |

|||

* [http://www.equetro.com Equetro website] |

|||

* [http://www.pubpk.org/index.php?title=Carbamazepine Carbamazepine Pharmacokinetics - PubPK] |

|||

* [http://www.rxlist.com/cgi/generic/carbam.htm TA warning] |

|||

* [http://www.psycheducation.org/depression/meds/carbamazepine.htm Carbamazepine overview] from PsychEducation.org |

|||

* [http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/410736_4 Extensive review of the effects of carbamazepine in pregnancy and breastfeeding] (free full text with registration) |

|||

* [http://patimg1.uspto.gov/.piw?Docid=02948718&homeurl=http%3A%2F%2Fpatft.uspto.gov%2Fnetacgi%2Fnph-Parser%3FSect1%3DPTO1%2526Sect2%3DHITOFF%2526d%3DPALL%2526p%3D1%2526u%3D%2Fnetahtml%2Fsrchnum.htm%2526r%3D1%2526f%3DG%2526l%3D50%2526s1%3D2,948,718.WKU.%2526OS%3DPN%2F2,948,718%2526RS%3DPN%2F2,948,718&PageNum=&Rtype=&SectionNum=&idkey=2A0649DBED16 U.S. Patent 2,948,718, August 1960] |

|||

{{Anticonvulsants}} |

{{Anticonvulsants}} |

||

{{Mood stabilizers}} |

{{Mood stabilizers}} |

||

{{Neuropathic pain and fibromyalgia pharmacotherapies}} |

|||

{{Mood disorders}} |

|||

{{Ion channel modulators}} |

|||

{{GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators}} |

|||

{{Xenobiotic-sensing receptor modulators}} |

|||

{{Tricyclics}} |

{{Tricyclics}} |

||

{{Portal bar | Medicine}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Anticonvulsants]] |

[[Category:Anticonvulsants]] |

||

[[Category:Antidiuretics]] |

|||

[[Category:CYP3A4 inducers]] |

|||

[[Category:Dermatoxins]] |

|||

[[Category:Dibenzazepines]] |

|||

[[Category:Drugs developed by Novartis]] |

|||

[[Category:GABAA receptor positive allosteric modulators]] |

|||

[[Category:Hepatotoxins]] |

|||

[[Category:Mood stabilizers]] |

[[Category:Mood stabilizers]] |

||

[[Category:Prodrugs]] |

[[Category:Prodrugs]] |

||

[[Category:Ureas]] |

[[Category:Ureas]] |

||

[[Category:World Health Organization essential medicines]] |

[[Category:World Health Organization essential medicines]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Wikipedia medicine articles ready to translate]] |

||

[[de:Carbamazepin]] |

|||

[[es:Carbamazepina]] |

|||

[[eu:Karbamazepina]] |

|||

[[fa:کاربامازپین]] |

|||

[[fr:Carbamazépine]] |

|||

[[hr:Karbamazepin]] |

|||

[[it:Carbamazepina]] |

|||

[[hu:Karbamazepin]] |

|||

[[mk:Карбамазепин]] |

|||

[[nl:Carbamazepine]] |

|||

[[ja:カルバマゼピン]] |

|||

[[no:Karbamazepin]] |

|||

[[pl:Karbamazepina]] |

|||

[[pt:Carbamazepina]] |

|||

[[ru:Карбамазепин]] |

|||

[[fi:Karbamatsepiini]] |

|||

[[sv:Karbamazepin]] |

|||

[[zh:卡马西平]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 08:27, 22 December 2024

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tegretol, others |

| Other names | CBZ |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682237 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Anticonvulsant[1] |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100%[5] |

| Protein binding | 70–80%[5] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP3A4)[5] |

| Metabolites | Active epoxide form (carbamazepine-10,11 epoxide)[5] |

| Elimination half-life | 36 hours (single dose), 16–24 hours (repeated dosing)[5] |

| Excretion | Urine (72%), feces (28%)[5] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.512 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C15H12N2O |

| Molar mass | 236.274 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Carbamazepine, sold under the brand name Tegretol among others, is an anticonvulsant medication used in the treatment of epilepsy and neuropathic pain.[4][1] It is used as an adjunctive treatment in schizophrenia along with other medications and as a second-line agent in bipolar disorder.[6][1] Carbamazepine appears to work as well as phenytoin and valproate for focal and generalized seizures.[7] It is not effective for absence or myoclonic seizures.[1]

Carbamazepine was discovered in 1953 by Swiss chemist Walter Schindler.[8][9] It was first marketed in 1962.[10] It is available as a generic medication.[11] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[12] In 2020, it was the 185th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 2 million prescriptions.[13][14]

Photoswitchable analogues of carbamazepine have been developed to control its pharmacological activity locally and on demand using light (photopharmacology), with the purpose of reducing the adverse systemic effects of the drug.[15] One of these light-regulated compounds (carbadiazocine, based on a bridged azobenzene or diazocine) has been shown to produce analgesia with noninvasive illumination in vivo in a rat model of neuropathic pain.

Medical uses

[edit]

Carbamazepine is typically used for the treatment of seizure disorders and neuropathic pain.[1] It is used off-label as a second-line treatment for bipolar disorder and in combination with an antipsychotic in some cases of schizophrenia when treatment with a conventional antipsychotic alone has failed.[1][16] However, evidence does not support its usage for schizophrenia.[17] It is not effective for absence seizures or myoclonic seizures.[1] Although carbamazepine may have a similar effectiveness (as measured by people continuing to use a medication) and efficacy (as measured by the medicine reducing seizure recurrence and improving remission) when compared to phenytoin and valproate, choice of medication should be evaluated on an individual basis as further research is needed to determine which medication is most helpful for people with newly-onset seizures.[7]

In the United States, carbamazepine is indicated for the treatment of epilepsy (including partial seizures, generalized tonic-clonic seizures and mixed seizures), and trigeminal neuralgia.[4][18] Carbamazepine is the only medication that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia.[19]

As of 2014, a controlled release formulation was available for which there is tentative evidence showing fewer side effects and unclear evidence with regard to whether there is a difference in efficacy.[20]

It has also been shown to improve symptoms of "typewriter tinnitus", a type of tinnitus caused by the neurovascular compression of the cochleovestibular nerve. [21]

Adverse effects

[edit]In the US, the label for carbamazepine contains warnings concerning:[4]

- effects on the body's production of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets: rarely, there are major effects of aplastic anemia and agranulocytosis reported and more commonly, there are minor changes such as decreased white blood cell or platelet counts, but these do not progress to more serious problems.[5]

- increased risks of suicide[22]

- increased risks of hyponatremia and SIADH[5][23]

- risk of seizures, if the person stops taking the drug abruptly[5]

- risks to the fetus in women who are pregnant, specifically congenital malformations like spina bifida, and developmental disorders.[5][24]

- Pancreatitis

- Hepatitis

- Dizziness

- Bone marrow suppression

- Stevens–Johnson syndrome

Common adverse effects may include drowsiness, dizziness, headaches and migraines, ataxia, nausea, vomiting, and/or constipation. Alcohol use while taking carbamazepine may lead to enhanced depression of the central nervous system.[5] Less common side effects may include increased risk of seizures in people with mixed seizure disorders,[25] abnormal heart rhythms, blurry or double vision.[5] Also, rare case reports of an auditory side effect have been made, whereby patients perceive sounds about a semitone lower than previously; this unusual side effect is usually not noticed by most people, and disappears after the person stops taking carbamazepine.[26]

Pharmacogenetics

[edit]Serious skin reactions such as Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) due to carbamazepine therapy are more common in people with a particular human leukocyte antigen gene-variant (allele), HLA-B*1502.[5] Odds ratios for the development of SJS or TEN in people who carry the allele can be in the double, triple or even quadruple digits, depending on the population studied.[27][28] HLA-B*1502 occurs almost exclusively in people with ancestry across broad areas of Asia, but has a very low or absent frequency in European, Japanese, Korean and African populations.[5][29] However, the HLA-A*31:01 allele has been shown to be a strong predictor of both mild and severe adverse reactions, such as the DRESS form of severe cutaneous reactions, to carbamazepine among Japanese, Chinese, Korean, and Europeans.[28][30] It is suggested that carbamazepine acts as a potent antigen that binds to the antigen-presenting area of HLA-B*1502 alike, triggering an everlasting activation signal on immature CD8-T cells, thus resulting in widespread cytotoxic reactions like SJS/TEN.[31]

Interactions

[edit]Carbamazepine has a potential for drug interactions.[18] Drugs that decrease breaking down of carbamazepine or otherwise increase its levels include erythromycin,[32] cimetidine, propoxyphene, and calcium channel blockers.[18] Grapefruit juice raises the bioavailability of carbamazepine by inhibiting the enzyme CYP3A4 in the gut wall and in the liver.[5] Lower levels of carbamazepine are seen when administered with phenobarbital, phenytoin, or primidone, which can result in breakthrough seizure activity.[33]

Valproic acid and valnoctamide both inhibit microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH), the enzyme responsible for the breakdown of the active metabolite carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide into inactive metabolites.[34] By inhibiting mEH, valproic acid and valnoctamide cause a build-up of the active metabolite, prolonging the effects of carbamazepine and delaying its excretion.

Carbamazepine, as an inducer of cytochrome P450 enzymes, may increase clearance of many drugs, decreasing their concentration in the blood to subtherapeutic levels and reducing their desired effects.[33] Drugs that are more rapidly metabolized with carbamazepine include warfarin, lamotrigine, phenytoin, theophylline, valproic acid,[18] many benzodiazepines,[35] and methadone.[36] Carbamazepine also increases the metabolism of the hormones in birth control pills and can reduce their effectiveness, potentially leading to unexpected pregnancies.[18]

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]Carbamazepine is a sodium channel blocker.[37] It binds preferentially to voltage-gated sodium channels in their inactive conformation, which prevents repetitive and sustained firing of an action potential. Carbamazepine has effects on serotonin systems but the relevance to its antiseizure effects is uncertain. There is evidence that it is a serotonin releasing agent and possibly even a serotonin reuptake inhibitor.[38][39][40] It has been suggested that carbamazepine can also block voltage-gated calcium channels, which will reduce neurotransmitter release.[41]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]

Carbamazepine is relatively slowly but practically completely absorbed after administration by mouth. Highest concentrations in the blood plasma are reached after 4 to 24 hours depending on the dosage form. Slow release tablets result in about 15% lower absorption and 25% lower peak plasma concentrations than ordinary tablets, as well as in less fluctuation of the concentration, but not in significantly lower minimum concentrations.[42][43]

In the circulation, carbamazepine itself comprises 20 to 30% of total residues. The remainder is in the form of metabolites; 70 to 80% of residues is bound to plasma proteins. Concentrations in breast milk are 25 to 60% of those in the blood plasma.[43]

Carbamazepine itself is not pharmacologically active. It is activated, mainly by CYP3A4, to carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide, which is solely responsible for the drug's anticonvulsant effects. The epoxide is then inactivated by microsomal epoxide hydrolase (mEH) to carbamazepine-trans-10,11-diol and further to its glucuronides. Other metabolites include various hydroxyl derivatives and carbamazepine-N-glucuronide.[43]

The plasma half-life is about 35 to 40 hours when carbamazepine is given as single dose, but it is a strong inducer of liver enzymes, and the plasma half-life shortens to about 12 to 17 hours when it is given repeatedly. The half-life can be further shortened to 9–10 hours by other enzyme inducers such as phenytoin or phenobarbital. About 70% are excreted via the urine, almost exclusively in form of its metabolites, and 30% via the faeces.[42][43]

History

[edit]Carbamazepine was discovered by chemist Walter Schindler at J.R. Geigy AG (now part of Novartis) in Basel, Switzerland, in 1953.[44][45] It was first marketed as a drug to treat epilepsy in Switzerland in 1963 under the brand name Tegretol; its use for trigeminal neuralgia (formerly known as tic douloureux) was introduced at the same time.[44] It has been used as an anticonvulsant and antiepileptic in the United Kingdom since 1965, and has been approved in the United States since 1968.[1]

Carbamazepine was studied for bipolar disorder throughout the 1970s.[46]

Society and culture

[edit]Environmental impact

[edit]Carbamazepine and its bio-transformation products have been detected in wastewater treatment plant effluent[47]: 224 and in streams receiving treated wastewater.[48] Field and laboratory studies have been conducted to understand the accumulation of carbamazepine in food plants grown in soil treated with sludge, which vary with respect to the concentrations of carbamazepine present in sludge and in the concentrations of sludge in the soil. Taking into account only studies that used concentrations commonly found in the environment, a 2014 review concluded that "the accumulation of carbamazepine into plants grown in soil amended with biosolids poses a de minimis risk to human health according to the approach."[47]: 227

Brand names

[edit]Carbamazepine is available worldwide under many brand names including Tegretol.[49]

Research

[edit]This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (October 2023) |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "Carbamazepine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d "Tegretol- carbamazepine suspension Tegretol- carbamazepine tablet Tegretol XR- carbamazepine tablet, extended release". DailyMed. 16 May 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Carbamazepine Drug Label". Archived from the original on 8 December 2014.

- ^ Nevitt SJ, Marson AG, Weston J, Tudur Smith C (August 2018). "Sodium valproate versus phenytoin monotherapy for epilepsy: an individual participant data review". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (8): CD001769. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001769.pub4. PMC 6513104. PMID 30091458.

- ^ a b Nevitt SJ, Marson AG, Tudur Smith C (July 2019). "Carbamazepine versus phenytoin monotherapy for epilepsy: an individual participant data review". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (7): CD001911. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001911.pub4. PMC 6637502. PMID 31318037.

- ^ Smith HS (2009). Current therapy in pain. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 460. ISBN 978-1-4160-4836-7. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ US patent 2948718, Walter Schindler, "New n-heterocyclic compounds", published 1960-08-09, issued 1960-08-09, assigned to Geigy Chemical Corporation

- ^ Moshé S (2009). The treatment of epilepsy (3 ed.). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. p. xxix. ISBN 978-1-4443-1667-4. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Porter NC (2008). "Trigeminal Neuralgia: Surgical Perspective". In Chin LS, Regine WF (eds.). Principles and practice of stereotactic radiosurgery. New York: Springer. p. 536. ISBN 978-0-387-71070-9. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Organization WH (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Carbamazepine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ Camerin L, Maleeva G, Gomila-Juaneda A, Suárez-Pereira I, Matera C, Prischich D, et al. (June 2024). "Photoswitchable carbamazepine analogs for non-invasive neuroinhibition in vivo". Angewandte Chemie. 63 (38): e202403636. doi:10.1002/anie.202403636. hdl:2445/215169. PMID 38887153.

- ^ Ceron-Litvoc D, Soares BG, Geddes J, Litvoc J, de Lima MS (January 2009). "Comparison of carbamazepine and lithium in treatment of bipolar disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials". Human Psychopharmacology. 24 (1): 19–28. doi:10.1002/hup.990. PMID 19053079. S2CID 5684931.

- ^ Leucht S, Helfer B, Dold M, Kissling W, McGrath J, et al. (Cochrane Schizophrenia Group) (May 2014). "Carbamazepine for schizophrenia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (5): CD001258. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001258.pub3. PMC 7032545. PMID 24789267.

- ^ a b c d e Lexi-Comp (February 2009). "Carbamazepine". The Merck Manual Professional. Archived from the original on 3 November 2010. Retrieved on 3 May 2009.

- ^ Pino MA (19 January 2017). "Trigeminal Neuralgia: A "Lightning Bolt" of Pain". US Pharmacist. 42: 41–44.

- ^ Powell G, Saunders M, Rigby A, Marson AG (December 2016). "Immediate-release versus controlled-release carbamazepine in the treatment of epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (4): CD007124. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007124.pub5. PMC 6463840. PMID 27933615.

- ^ Sunwoo, W., Jeon, Y., Bae, Y. et al. Typewriter tinnitus revisited: The typical symptoms and the initial response to carbamazepine are the most reliable diagnostic clues. Sci Rep 7, 10615 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10798-w

- ^ Vukovic Cvetkovic V, Jensen RH (January 2019). "Neurostimulation for the treatment of chronic migraine and cluster headache". Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 139 (1): 4–17. doi:10.1111/ane.13034. PMID 30291633. S2CID 52923061.

- ^ Gandelman MS (March 1994). "Review of carbamazepine-induced hyponatremia". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 18 (2): 211–33. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(94)90055-8. PMID 8208974. S2CID 36758508.

- ^ Jentink J, Dolk H, Loane MA, Morris JK, Wellesley D, Garne E, et al. (December 2010). "Intrauterine exposure to carbamazepine and specific congenital malformations: systematic review and case-control study". BMJ. 341: c6581. doi:10.1136/bmj.c6581. PMC 2996546. PMID 21127116.

- ^ Liu L, Zheng T, Morris MJ, Wallengren C, Clarke AL, Reid CA, et al. (November 2006). "The mechanism of carbamazepine aggravation of absence seizures". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 319 (2): 790–8. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.104968. PMID 16895979. S2CID 7693614.

- ^ Tateno A, Sawada K, Takahashi I, Hujiwara Y (August 2006). "Carbamazepine-induced transient auditory pitch-perception deficit". Pediatric Neurology. 35 (2): 131–4. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.01.011. PMID 16876011.

- ^ Kaniwa N, Saito Y (June 2013). "Pharmacogenomics of severe cutaneous adverse reactions and drug-induced liver injury". Journal of Human Genetics. 58 (6): 317–26. doi:10.1038/jhg.2013.37. PMID 23635947.

- ^ a b Amstutz U, Shear NH, Rieder MJ, Hwang S, Fung V, Nakamura H, et al. (April 2014). "Recommendations for HLA-B*15:02 and HLA-A*31:01 genetic testing to reduce the risk of carbamazepine-induced hypersensitivity reactions". Epilepsia. 55 (4): 496–506. doi:10.1111/epi.12564. hdl:2429/63109. PMID 24597466. S2CID 41565230.

- ^ Leckband SG, Kelsoe JR, Dunnenberger HM, George AL, Tran E, Berger R, et al. (September 2013). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for HLA-B genotype and carbamazepine dosing". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 94 (3): 324–8. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.103. PMC 3748365. PMID 23695185.

- ^ Garon SL, Pavlos RK, White KD, Brown NJ, Stone CA, Phillips EJ (September 2017). "Pharmacogenomics of off-target adverse drug reactions". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 83 (9): 1896–1911. doi:10.1111/bcp.13294. PMC 5555876. PMID 28345177.

- ^ Jaruthamsophon K, Tipmanee V, Sangiemchoey A, Sukasem C, Limprasert P (March 2017). "HLA-B*15:21 and carbamazepine-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome: pooled-data and in silico analysis". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 45553. Bibcode:2017NatSR...745553J. doi:10.1038/srep45553. PMC 5372085. PMID 28358139.

- ^ Stafstrom CE, Nohria V, Loganbill H, Nahouraii R, Boustany RM, DeLong GR (January 1995). "Erythromycin-induced carbamazepine toxicity: a continuing problem". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 149 (1): 99–101. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170130101025. PMID 7827672. Archived from the original on 25 May 2024.

- ^ a b "Carbamazepine Toxicity". eMedicine. 2 February 2019. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008.

- ^ Gonzalez FJ, Tukey RH (2006). "Drug Metabolism". In Brunton L, Lazo J, Parker K (eds.). Goodman & Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (11th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-07-142280-2.