Ornette Coleman: Difference between revisions

Luckas-bot (talk | contribs) m r2.7.1) (Robot: Adding zh:奥尼特·科尔曼 |

m Reverted edits by 72.89.63.169 (talk) (HG) (3.4.12) |

||

| (577 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|American jazz musician and composer (1930–2015)}} |

|||

{{More footnotes|date=May 2010}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=May 2022}} |

|||

{{Infobox musical artist <!-- See Wikipedia:WikiProject Musicians --> |

{{Infobox musical artist <!-- See Wikipedia:WikiProject Musicians --> |

||

| |

| image = Ornette-Coleman-2008-Heidelberg-schindelbeck.jpg |

||

| caption = Coleman at the Enjoy Jazz Festival in [[Heidelberg]], 2008 |

|||

| image = Ornette Coleman.jpg |

|||

| background = non_vocal_instrumentalist |

|||

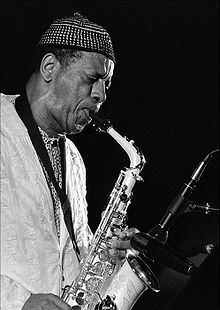

| caption = Ornette Coleman plays his Selmer alto saxophone during a performance at [[The Hague]], 1994 |

|||

| birth_name = Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman |

|||

| image_size = |

|||

| birth_date = {{birth date|1930|3|9}} |

|||

| background = non_vocal_instrumentalist |

|||

| birth_place = [[Fort Worth, Texas]], U.S. |

|||

| birth_name = |

|||

| death_date = {{death date and age|2015|6|11|1930|3|9|mf=y}} |

|||

| alias = |

|||

| death_place = [[Manhattan]], [[New York City]], U.S. |

|||

| Born = {{birth date and age|1930|3|9}}<br />[[Fort Worth]], [[Texas]], [[United States]] |

|||

| genre = {{flatlist| |

|||

| death_date = |

|||

* [[Avant-garde jazz]] |

|||

| origin = |

|||

* [[free jazz]] |

|||

| instrument = [[alto saxophone]], [[tenor saxophone]], [[violin]], [[trumpet]] |

|||

* [[free funk]] |

|||

| genre = [[free jazz]], [[free funk]], {{nowrap|[[avant-garde jazz]]}}, [[jazz-rock]] |

|||

* [[jazz fusion]] |

|||

| occupation = musician, composer |

|||

* [[third stream]] |

|||

| years_active = 1958–present |

|||

}} |

|||

| label = |

|||

| occupation = {{flatlist| |

|||

| associated_acts = |

|||

* Musician |

|||

| website = [http://www.ornettecoleman.com/ ornettecoleman.com] |

|||

* composer |

|||

| current_members = |

|||

}} |

|||

| past_members = |

|||

| instrument = {{flatlist| |

|||

| notable_instruments = |

|||

* [[Alto saxophone]] |

|||

* [[tenor saxophone]] |

|||

* [[trumpet]] |

|||

* [[violin]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| years_active = 1940s–2015 |

|||

| label = {{flatlist| |

|||

* [[Atlantic Records|Atlantic]] |

|||

* [[Blue Note Records|Blue Note]] |

|||

* [[Verve Records|Verve]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|[[Jayne Cortez]]|1954|1964|reason=divorced}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman''' (March 9, 1930 – June 11, 2015)<ref name="Ratliff">{{cite news |last1=Ratliff |first1=Ben |title=Ornette Coleman, Saxophonist Who Rewrote the Language of Jazz, Dies at 85 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/12/arts/music/ornette-coleman-jazz-saxophonist-dies-at-85-obituary.html |website=[[The New York Times]] |access-date=December 16, 2018 |date=June 11, 2015}}</ref> was an American [[jazz]] saxophonist, trumpeter, violinist, and composer. He is best known as a principal founder of the [[free jazz]] genre, a term derived from his 1960 album ''[[Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation]]''. His pioneering works often abandoned the [[harmony]]-based composition, [[tonality]], chord changes, and fixed rhythm found in earlier jazz idioms.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Mandell |first1=Howard |title=Ornette Coleman, Jazz Iconoclast, Dies At 85 |url=https://www.npr.org/sections/ablogsupreme/2015/06/11/413630335/ornette-coleman-jazz-iconoclast-dies-at-85 |website=[[NPR Music]] |access-date=12 January 2023}}</ref> Instead, Coleman emphasized an experimental approach to [[improvisation]] rooted in ensemble playing and [[blues]] phrasing.<ref name="allmusicbio"/> Thom Jurek of [[AllMusic]] called him "one of the most beloved and polarizing figures in jazz history," noting that while "now celebrated as a fearless innovator and a genius, he was initially regarded by peers and critics as rebellious, disruptive, and even a fraud."<ref name="allmusicbio"/> |

|||

'''Ornette Coleman''' (born March 9, 1930)<ref name=ALLMUSIC>[{{Allmusic|class=artist|id=p65603|pure_url=yes}} allmusic Biography]</ref> is an [[United States|American]] [[saxophone|saxophon]]ist, [[violin]]ist, [[trumpet]]er and [[composer]]. He was one of the major innovators of the [[free jazz]] movement of the 1960s. |

|||

Born and raised in [[Fort Worth, Texas]], Coleman [[Autodidacticism|taught himself]] to play the saxophone when he was a teenager.<ref name="Ratliff"/> He began his musical career playing in local [[Rhythm and blues|R&B]] and [[bebop]] groups, and eventually formed his own group in Los Angeles, featuring members such as [[Ed Blackwell]], [[Don Cherry (trumpeter)|Don Cherry]], [[Charlie Haden]], and [[Billy Higgins]]. In November 1959, his quartet began a controversial residency at the [[Five Spot]] jazz club in New York City and he released the influential album ''[[The Shape of Jazz to Come]]'', his debut LP on [[Atlantic Records]]. Coleman's subsequent Atlantic releases in the early 1960s would profoundly influence the direction of jazz in that decade, and his compositions "[[Lonely Woman (composition)|Lonely Woman]]" and "[[Broadway Blues]]" became genre standards that are cited as important early works in free jazz.<ref name="HellmerLawn2005">{{cite book|last1=Hellmer|first1=Jeffrey|last2=Lawn|first2=Richard|title=Jazz Theory and Practice: For Performers, Arrangers and Composers |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mjaITr2NdkEC&pg=PA234 |access-date=December 15, 2018 |date=May 3, 2005 |publisher=Alfred Music |isbn=978-1-4574-1068-0 |pages=234–}}</ref> |

|||

Coleman's [[timbre]] is easily recognized: his keening, crying sound draws heavily on [[blues music]]. His album ''[[Sound Grammar]]'' received the 2007 [[Pulitzer Prize]] for music. |

|||

In the mid 1960s, Coleman left Atlantic for labels such as [[Blue Note]] and [[Columbia Records]], and began performing with his young son [[Denardo Coleman]] on drums. He explored symphonic compositions with his 1972 album ''[[Skies of America]]'', featuring the [[London Symphony Orchestra]]. In the mid-1970s, he formed the group [[Prime Time (band)|Prime Time]] and explored electric [[jazz-funk]] and his concept of [[Harmolodics|harmolodic]] music.<ref name="allmusicbio"/> In 1995, Coleman and his son Denardo founded the [[harmolodic#Record label|Harmolodic]] record label. His 2006 album ''[[Sound Grammar]]'' received the [[Pulitzer Prize for Music]], making Coleman the second jazz musician ever to receive the honor.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pulitzer.org/prize-winners-by-year/2007 |title=2007 Pulitzer Prizes |website=Pulitzer.org |access-date=July 13, 2020}}</ref> |

|||

==Early career== |

|||

Coleman was born and raised in [[Fort Worth]], [[Texas]], where he began performing [[Rhythm and blues|R&B]] and [[bebop]] initially on tenor [[saxophone]]. Seeking a way to work his way out of his home town, he took a job in 1949 with a [[Silas Green from New Orleans]] traveling show and then with touring rhythm and blues shows. After a show in [[Baton Rouge]], he was assaulted and his saxophone was destroyed.<ref>{{cite book| author=Spellman, A. B.| title=Four Lives in the Bebop Business| publisher=Limelight| year=1985 originally 1966|pages=98–101| isbn=0-87910-042-7}}</ref> |

|||

== Biography == |

|||

He switched to alto, which has remained his primary [[musical instrument|instrument]], first playing it in [[New Orleans]] after the Baton Rouge incident. He then joined the band of [[Pee Wee Crayton]] and travelled with them to [[Los Angeles, California|Los Angeles]]. He worked at various jobs, including as an [[elevator]] operator, while still pursuing his musical career. |

|||

=== Early life === |

|||

Even from the beginning of Coleman's career, his [[music]] and playing were in many ways unorthodox. His approach to [[harmony]] and [[chord progression]] was far less rigid than that of [[bebop]] performers; he was increasingly interested in playing what he heard rather than fitting it into predetermined chorus-structures and harmonies. His raw, highly vocalized sound and penchant for playing "in the cracks" of the scale led many [[Los Angeles, California|Los Angeles]] jazz musicians to regard Coleman's playing as out-of-tune; he sometimes had difficulty finding like-minded musicians with whom to perform. Nevertheless, pianist [[Paul Bley]] was an early supporter and musical collaborator. |

|||

Coleman was born Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman on March 9, 1930, in [[Fort Worth, Texas]],<ref name="Fordham">{{cite web |last1=Fordham |first1=John |title=Ornette Coleman obituary |url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/2015/jun/11/ornette-coleman |website=The Guardian |access-date=December 16, 2018 |date=June 11, 2015}}</ref> where he was raised.<ref name="Atlantic1972">{{cite journal |last1=Palmer |first1=Robert |title=Ornette Coleman and the Circle with a Hole in the Middle |journal=The Atlantic Monthly |date=December 1972 |quote=Ornette Coleman since March 19, 1930, when he was born in Fort Worth, Texas}}</ref><ref name="EGP">{{cite web|url=http://jetson.unl.edu/cocoon/encyclopedia/doc/egp.afam.015 |title=Coleman, Ornette (b. 1930) |publisher=Encyclopedia of the Great Plains|editor1-link=David J. Wishart |editor=Wishart, David J. |access-date=March 26, 2012 |quote=Ornette Coleman, born in Fort Worth, Texas, on March 19, 1930 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120707184611/http://jetson.unl.edu/cocoon/encyclopedia/doc/egp.afam.015 |archive-date=July 7, 2012 }}</ref><ref name="Litweiler">{{cite book |last1=Litweiler |first1=John |title=Ornette Coleman: the harmolodic life |date=1992 |publisher=Quartet |location=London |isbn=0-7043-2516-0 |pages=21–31}}</ref> He attended [[I.M. Terrell High School]] in Fort Worth, where he participated in band until he was dismissed for improvising during [[John Philip Sousa]]'s march "[[The Washington Post (march)|The Washington Post]]". He began performing [[Rhythm and blues|R&B]] and [[bebop]] on tenor saxophone, and formed The Jam Jivers with [[Prince Lasha]] and [[Charles Moffett]].<ref name="Litweiler" /> |

|||

Eager to leave town, he accepted a job in 1949 with a [[Silas Green from New Orleans]] traveling show and then with touring rhythm and blues shows. After a show in [[Baton Rouge, Louisiana]], he was assaulted and his saxophone was destroyed.<ref name="Spellman">{{cite book |last1=Spellman |first1=A.B. |title=Four Lives in the Bebop Business |date=1985 |publisher=Limelight |isbn=0-87910-042-7 |pages=98–101 |edition=1st Limelight}}</ref> |

|||

In 1958 Coleman led his first recording session for Contemporary, ''[[Something Else!!!!|Something Else!!!!: The Music of Ornette Coleman]]''. The session also featured [[trumpet]]er [[Don Cherry (jazz)|Don Cherry]], [[drummer]] [[Billy Higgins]], bassist Don Payne and [[Walter Norris]] on [[piano]].<ref name="ALLMUSIC" /> |

|||

Coleman subsequently switched to alto saxophone, first playing it in New Orleans after the Baton Rouge incident; the alto would remain his primary instrument for the rest of his life. He then joined the band of [[Pee Wee Crayton]] and traveled with them to Los Angeles. He worked at various jobs in Los Angeles, including as an elevator operator, while pursuing his music career.<ref>{{cite book | last = Hentoff | first = Nat | author-link = Nat Hentoff |title =The Jazz Life | publisher = Da Capo Press | year = 1975 | pages=235–236 }}</ref> |

|||

==The Shape of Jazz to Come== |

|||

Coleman was very busy in 1959. His last release on Contemporary was ''[[Tomorrow Is the Question!]]'', a quartet album, with [[Shelly Manne]] on drums, and excluding the piano, which he would not use again until the 1990s. Next Coleman brought [[double bass]]ist [[Charlie Haden]] – one of a handful of his most important collaborators – into a regular group with Haden, Cherry, and Higgins. (All four had played with Paul Bley the previous year.) He signed a multi-album contract with [[Atlantic Records]] who released ''[[The Shape of Jazz to Come]]'' in 1959. It was, according to critic Steve Huey, "a watershed event in the genesis of [[avant-garde]] jazz, profoundly steering its future course and throwing down a gauntlet that some still haven't come to grips with."<ref>{{cite web| last =Huey| first =Steve| title=The Shape of Jazz To Come|url = {{Allmusic|class=album|id=r136829|pure_url=yes}}}}</ref> While definitely – if somewhat loosely – [[blues]]-based and often quite melodic, the [[album]]'s compositions were considered at that time harmonically unusual and unstructured. Some musicians and critics saw Coleman as an iconoclast; others, including conductor [[Leonard Bernstein]] and composer [[Virgil Thomson]] regarded him as a genius and an innovator.<ref>{{cite web| title=Ornette Coleman biography on Europe Jazz Network|url = http://www.ejn.it/mus/coleman.htm}}</ref> |

|||

Coleman found like-minded musicians in Los Angeles, such as [[Ed Blackwell]], [[Bobby Bradford]], [[Don Cherry (trumpeter)|Don Cherry]], [[Charlie Haden]], [[Billy Higgins]], and [[Charles Moffett]].<ref name="allmusicbio">{{cite web |last1=Jurek |first1=Thom |title=Ornette Coleman |url=https://www.allmusic.com/artist/ornette-coleman-mn0000484396/biography |website=AllMusic |access-date=August 14, 2018}}</ref><ref name="EJN">{{cite web|title=Ornette Coleman biography on Europe Jazz Network |url=http://www.europejazz.net/mus/coleman.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050502160154/http://www.europejazz.net/mus/coleman.htm |archive-date=May 2, 2005 }}</ref> Thanks to the intercession of friends and a successful audition, Ornette signed his first recording contract with LA-based [[Contemporary Records]],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Golia |first=Maria |title=Ornette Coleman: The Territory and the Adventure |date=2020 |publisher=[[Reaktion Books Ltd]] |isbn=9781789142235 |location=Unit 32, Waterside 44-48 Wharf Road, London NI 7UX UK |publication-date=2020 |pages=100 |language=en}}</ref> which allowed him to sell the tracks from his debut album, ''[[Something Else!!!!]]'' (1958), with Cherry, Higgins, [[Walter Norris]], and [[Don Payne (musician)|Don Payne]].<ref name="Jurek">{{cite web |last1=Jurek |first1=Thom |title=Something Else: The Music of Ornette Coleman |url=https://www.allmusic.com/album/something-else-the-music-of-ornette-coleman-mw0000198903 |website=AllMusic |access-date=August 14, 2018 }}</ref> During the same year he briefly belonged to a quintet led by [[Paul Bley]] that performed at a club in New York City (that band is recorded on ''[[Live at the Hilcrest Club 1958]]'').<ref name="allmusicbio" /> By the time ''[[Tomorrow Is the Question!]]'' was recorded soon after with Cherry, bassists [[Percy Heath]] and [[Red Mitchell]], and drummer [[Shelly Manne]], the jazz world had been shaken up by Coleman's alien music. Some jazz musicians called him a fraud, while conductor [[Leonard Bernstein]] praised him.<ref name="EJN" /> |

|||

Coleman's quartet received a lengthy – and sometimes controversial – engagement at [[New York City]]'s famed [[Five Spot]] jazz club. Such notable figures as The [[Modern Jazz Quartet]], [[Leonard Bernstein]] and [[Lionel Hampton]] were favorably impressed, and offered encouragement. (Hampton was so impressed he reportedly asked to perform with the quartet; Bernstein later helped Haden obtain a composition grant from the [[John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation]].) Opinion was, however, divided: trumpeter [[Miles Davis]] famously declared Coleman was "all screwed up inside" (although this comment was later recanted) and [[Roy Eldridge]] stated, "I'd listened to him all kinds of ways. I listened to him high and I listened to him cold sober. I even played with him. I think he's jiving baby."<ref>{{cite news | first=Juan | last=Rodriguez | coauthors= |authorlink= | title=Ornette Coleman, jazz's free spirit | date=June 20, 2009 | publisher=The Montreal Gazette | url =http://www.montrealgazette.com/story_print.html?id=1713495&sponsor= | work =The Montreal Gazette | pages = | accessdate = 2009-06-29 | language = }} {{Dead link|date=September 2010|bot=H3llBot}}</ref> |

|||

=== 1959: ''The Shape of Jazz to Come'' === |

|||

On the Atlantic recordings, [[Scott LaFaro]] sometimes replaces [[Charlie Haden]] on [[double bass]] and either [[Billy Higgins]] or [[Ed Blackwell]] features on [[Drum kit|drums]]. These recordings are collected in a [[boxed set]], ''Beauty Is a Rare Thing''.<ref name="ALLMUSIC" /> |

|||

In 1959, [[Atlantic Records]] released Coleman's third studio album, ''[[The Shape of Jazz to Come]]''. According to music critic Steve Huey, the album "was a watershed event in the genesis of avant-garde jazz, profoundly steering its future course and throwing down a gauntlet that some still haven't come to grips with."<ref name="Huey">{{cite web |last1=Huey |first1=Steve |title=The Shape of Jazz to Come |url=https://www.allmusic.com/album/the-shape-of-jazz-to-come-mw0000187968 |website=AllMusic |access-date=August 14, 2018}}</ref> ''[[Jazzwise]]'' listed it at number three on their list of the 100 best jazz albums of all time in 2017.<ref name="Flynn">{{cite web |last1=Flynn |first1=Mike |title=The 100 Jazz Albums That Shook The World |url=http://www.jazzwisemagazine.com/pages/jazz-album-reviews/11585-the-100-jazz-albums-that-shook-the-world |website=www.jazzwisemagazine.com |access-date=December 16, 2018 |date=July 18, 2017}}</ref> |

|||

Coleman's quartet received a long and sometimes controversial engagement at the [[Five Spot Café]] in Manhattan. Leonard Bernstein, [[Lionel Hampton]], and the [[Modern Jazz Quartet]] were impressed and offered encouragement. Hampton asked to perform with the quartet; Bernstein helped Haden obtain a composition grant from the [[John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation]]. A young [[Lou Reed]] followed Coleman's quartet around New York City.<ref name=":0">{{Cite magazine |last=Shteamer |first=Hank |date=2019-05-22 |title=Flashback: Ornette Coleman Sums Up Solitude on 'Lonely Woman' |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/ornette-coleman-lonely-woman-lou-reed-837918/ |access-date=2024-07-16 |magazine=Rolling Stone |language=en-US}}</ref> [[Miles Davis]] said that Coleman was "all screwed up inside",<ref>Miles Davis, quoted in John Litwiler, ''Ornette Coleman: A Harmolodic Life'' (NY: W. Morrow, 1992), 82. {{ISBN|0688072127}}, 9780688072124</ref><ref name="Roberts">{{cite web |last1=Roberts |first1=Randall |title=Why was Ornette Coleman so important? Jazz masters both living and dead chime in |url=https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/posts/la-et-ms-why-was-ornette-coleman-so-important-jazz-masters-both-living-and-dead-chime-in-20150611-column.html |website=[[Los Angeles Times]] |access-date=December 16, 2018 |date=January 11, 2015}}</ref> although he later became a proponent of Coleman's innovations;<ref name="Kahn">{{cite news |last1=Kahn |first1=Ashley |title=Ornette Coleman: Decades of Jazz on the Edge |url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=6449431 |website=NPR.org |access-date=December 16, 2018 |date=November 13, 2006}}</ref> [[Dizzy Gillespie]] remarked of Coleman that “I don’t know what he’s playing, but it’s not jazz."<ref name=":0" /> |

|||

Part of the uniqueness of Coleman's early sound came from his use of a plastic saxophone. He had first bought a plastic horn in Los Angeles in 1954 because he was unable to afford a metal saxophone, though he didn't like the sound of the plastic instrument at first.<ref>Litweiler p.31</ref> Coleman later claimed that it sounded drier, without the pinging sound of metal. |

|||

Coleman's early sound was due in part to his use of a [[Grafton saxophone|plastic saxophone]]; he had purchased it in Los Angeles in 1954 because he was unable to afford a metal saxophone at the time.<ref name="Litweiler" /> |

|||

In more recent years, he has played a metal saxophone.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.last.fm/music/Ornette+Coleman |title=Ornette Coleman |accessdate=2009-06-29 |publisher=Last.fm Ltd. }}</ref> |

|||

On his Atlantic recordings, Coleman's sidemen were Cherry on cornet or [[pocket trumpet]]; Charlie Haden, [[Scott LaFaro]], and then [[Jimmy Garrison]] on bass; and Higgins or [[Ed Blackwell]] on drums. Coleman's complete recordings for the label were collected on the box set ''[[Beauty Is a Rare Thing]]'' in 1993.<ref name="Yanow">{{cite web |last1=Yanow |first1=Scott |title=Ornette Coleman |url=https://www.allmusic.com/artist/ornette-coleman-mn0000484396/biography |access-date=August 14, 2018 |website=AllMusic}}</ref> |

|||

==Free Jazz== |

|||

In 1960, Coleman recorded ''[[Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation]]'', which featured a double quartet, including Cherry and [[Freddie Hubbard]] on [[trumpet]], [[Eric Dolphy]] on [[bass clarinet]], Haden and LaFaro on bass, and both Higgins and Blackwell on drums. The record was recorded in [[stereophonic sound|stereo]], with a [[reed instrument|reed]]/[[brass instrument|brass]]/[[double bass|bass]]/[[Drum kit|Drums]] quartet isolated in each stereo channel. ''Free Jazz'' was, at nearly 40 minutes, the lengthiest recorded continuous jazz performance to date, and was instantly one of Coleman's most controversial albums. The music features a regular but complex pulse, one drummer playing "straight" while the other played double-time; the thematic material is a series of brief, dissonant fanfares; as is conventional in jazz, there are a series of solo features for each member of the band, but the other soloists are free to chime in as they wish, producing some extraordinary passages of collective improvisation by the full octet. |

|||

=== 1960s: ''Free Jazz'' and Blue Note=== |

|||

Coleman intended 'Free Jazz' simply to be the album title, but his growing reputation placed him at the forefront of jazz innovation, and [[free jazz]] was soon considered a new genre, though Coleman has expressed discomfort with the term. |

|||

In 1960, Coleman recorded ''[[Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation]]'', which featured a double quartet, including Don Cherry and [[Freddie Hubbard]] on trumpet, [[Eric Dolphy]] on bass clarinet, Haden and LaFaro on bass, and both Higgins and Blackwell on drums.<ref name="rhino">{{cite web|title=Happy 55th: Ornette Coleman, Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation|url=https://www.rhino.com/article/happy-55th-ornette-coleman-free-jazz-a-collective-improvisation|work=[[Rhino Entertainment|Rhino Records]]|date=December 21, 2015|access-date=November 17, 2019}}</ref> The album was recorded in stereo, with a reed/brass/bass/drums quartet isolated in each stereo channel. ''Free Jazz'' was, at 37 minutes, the longest recorded continuous jazz performance at the time<ref>{{cite news|last=Hewett|first=Ivan|title=Ornette Coleman: the godfather of free jazz|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/worldfolkandjazz/11668275/Ornette-Coleman-the-godfather-of-free-jazz.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220112/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/worldfolkandjazz/11668275/Ornette-Coleman-the-godfather-of-free-jazz.html |archive-date=January 12, 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live|work=[[The Daily Telegraph|The Telegraph]]|date=June 11, 2015|access-date=November 17, 2019}}{{cbignore}}</ref> and was one of Coleman's most controversial albums.<ref>{{cite web|last=Bailey|first=C. Michael|title=Ornette Coleman: Free Jazz |url=https://www.allaboutjazz.com/free-jazz-by-c-michael-bailey.php|work=[[All About Jazz]]|date=September 30, 2011|access-date=November 17, 2019}}</ref> In the January 18, 1962, issue of ''[[DownBeat|Down Beat]]'' magazine, Pete Welding gave the album five stars while John A. Tynan rated it zero stars.<ref name="Welding">{{cite journal |last1=Welding |first1=Pete |title=Double View of a Double Quartet |journal=DownBeat |date=January 18, 1962 |volume=29 |issue=2}}</ref> |

|||

While Coleman had intended "free jazz" as simply an album title, [[free jazz]] was soon considered a new genre; Coleman expressed discomfort with the term.<ref name="Reich2010">{{cite book|author=Howard Reich |title=Let Freedom Swing: Collected Writings on Jazz, Blues, and Gospel |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=z6hAiX1i5jEC&pg=PA333 |date=September 30, 2010 |publisher=Northwestern University Press |isbn=978-0-8101-2705-0 |pages=333–}}</ref> |

|||

Among the reasons Coleman may not have entirely approved of the term '[[free jazz]]' is that his music contains a considerable amount of [[musical composition|composition]]. His [[melody|melodic]] material, although skeletal, strongly recalls the melodies that [[Charlie Parker]] wrote over [[jazz standard|standard]] harmonies, and in general the music is closer to the [[bebop]] that came before it than is sometimes popularly imagined. (Several early tunes of his, for instance, are clearly based on favorite bop chord changes like "Out of Nowhere" and "I Got Rhythm.") Coleman very rarely played standards, concentrating on his own compositions, of which there seems to be an endless flow. There are exceptions, though, including a classic reading (virtually a recomposition) of "Embraceable You" for Atlantic, and an improvisation on [[Thelonious Monk]]'s "Criss-Cross" recorded with [[Gunther Schuller]]. |

|||

After the Atlantic period, Coleman's music became more angular and engaged with the [[avant-garde jazz]] which had developed in part around his innovations.<ref name="Yanow" /> After his quartet disbanded, he formed a trio with [[David Izenzon]] on bass and [[Charles Moffett]] on drums, and began playing trumpet and violin in addition to the saxophone. His friendship with [[Albert Ayler]] influenced his development on trumpet and violin. Charlie Haden sometimes joined this trio to form a two-bass quartet. |

|||

==1960s== |

|||

After the Atlantic period and into the early part of the 1970s, Coleman's music became more angular and engaged fully with the jazz [[avant-garde]] which had developed in part around Coleman's innovations.<ref name="ALLMUSIC" /> |

|||

In 1966, Coleman signed with [[Blue Note Records|Blue Note]] and released the two-volume live album ''[[At the "Golden Circle" Stockholm]]'', featuring Izenzon and Moffett.<ref name="Freeman">{{cite web |last1=Freeman |first1=Phil |title=Good Old Days: Ornette Coleman On Blue Note |url=http://www.bluenote.com/spotlight/good-old-days-ornette-coleman-on-blue-note |website=Blue Note Records |access-date=August 14, 2018 |date=December 18, 2012}}</ref> Later that year, he recorded ''[[The Empty Foxhole]]'' with his ten year-old son [[Denardo Coleman]] and Haden;<ref name="The New York Times 2015">{{cite news| title=Remembering What Made Ornette Coleman a Jazz Visionary | first=Andrew R.|last=Chow|newspaper=The New York Times | date=June 28, 2015 | url=https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/28/arts/music/remembering-what-made-ornette-coleman-a-jazz-visionary.html | access-date=April 25, 2021}}</ref> [[Freddie Hubbard]] and [[Shelly Manne]] regarded Denardo's appearance on the album as an ill-advised piece of publicity.<ref name="Gabel">{{cite web |last1=Gabel |first1=J. C. |title=Making Knowledge Out of Sound |url=http://www.stopsmilingonline.com/twitter/SS-Ornette.pdf |website=stopsmilingonline.com |access-date=August 14, 2018 }}</ref><ref name="Spencer">{{cite web |last1=Spencer |first1=Robert |title=Ornette Coleman: The Empty Foxhole |url=https://www.allaboutjazz.com/the-empty-foxhole-ornette-coleman-blue-note-records-review-by-robert-spencer.php?width=1680 |website=All About Jazz |access-date=August 14, 2018 |date=April 1, 1997}}</ref> Denardo later became his father's primary drummer in the late 1970s. |

|||

His quartet dissolved, and Coleman formed a new trio with [[David Izenzon]] on bass, and [[Charles Moffett]] on drums. Coleman began to extend the sound-range of his music, introducing accompanying string players (though far from the territory of "Parker With Strings") and playing [[trumpet]] and [[violin]] himself; he initially had little conventional [[musical technique|technique]], and used the instruments to make large, unrestrained gestures; he plays the violin left-handed. His friendship with [[Albert Ayler]] influenced his development on trumpet and violin. (Haden would later sometimes join this trio to form a two-bass quartet.) |

|||

Coleman formed another quartet. Haden, Garrison, and [[Elvin Jones]] appeared, and [[Dewey Redman]] joined the group, usually on tenor saxophone. On February 29, 1968, Coleman's quartet performed live with [[Yoko Ono]] at the [[Royal Albert Hall]], and a recording from their rehearsal was subsequently included on Ono's 1970 album ''[[Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band]]'' as the track "AOS".<ref name="Chrispell">{{cite web |last1=Chrispell |first1=James |title=Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band |url=https://www.allmusic.com/album/yoko-ono-plastic-ono-band-mw0000026229 |website=AllMusic |access-date=August 14, 2018}}</ref> |

|||

Between 1965 and 1967 Coleman signed with [[Blue Note Records]] and released a number of recordings starting with the influential recordings of the trio ''[[At the Golden Circle Stockholm]]''. |

|||

He explored his interest in string textures on ''[[Town Hall, 1962]]'', culminating in the 1972 album ''[[Skies of America]]'' with the [[London Symphony Orchestra]]. |

|||

In 1966, Coleman was criticized for recording ''The Empty Foxhole,'' a trio with Haden, and Coleman's son [[Denardo Coleman]] – who was ten years old. Some regarded this as perhaps an ill-advised piece of publicity on Coleman's part, and judged the move a mistake. Others, however, noted that despite his youth, Denardo had studied drumming for several years, his technique – which, though unrefined, was respectable and enthusiastic – owed more to pulse-oriented [[free jazz]] drummers like [[Sunny Murray]] than to [[bebop]] drumming. Denardo has matured into a respected musician, and has been his father's primary drummer since the late 1970s. |

|||

===1970s–1990s: Harmolodic funk and Prime Time=== |

|||

Coleman formed another quartet. A number of bassists and drummers (including Haden, [[Jimmy Garrison]] and [[Elvin Jones]]) appeared, and [[Dewey Redman]] joined the group, usually on tenor [[saxophone]]. |

|||

[[File:Ornette Coleman-140911-0002-96WP.jpg|thumb|upright|Coleman playing his signature alto saxophone in 1971]] |

|||

[[File:Ornette Coleman 1978.jpg|thumb|Coleman playing the violin in 1978]] |

|||

Coleman, like Miles Davis before him, soon took to playing with electric instruments. The 1976 album ''[[Dancing in Your Head]]'', Coleman's first recording with the group which later became known as [[Prime Time (band)|Prime Time]], prominently featured two electric guitarists. While this marked a stylistic departure for Coleman, the music retained aspects of what he called [[harmolodics]]''.'' |

|||

[[File:Ornette at The Forum 1982.jpg|thumb|right|upright|Coleman performs in [[Toronto]] in 1982.]] |

|||

He also continued to explore his interest in string textures – from the [[Town Hall, 1962 (Ornette Coleman album)|Town Hall concert]] in 1962, culminating in ''[[Skies of America]]'' in 1972. (Sometimes this had a practical value, as it facilitated his group's appearance in the [[UK]] in 1965, where jazz musicians were under a quota arrangement but classical performers were exempt.) |

|||

[[File:Ornette Coleman trumpet.jpg|thumb|left|Coleman playing the trumpet at the [[Great American Music Hall]], [[San Francisco]] in 1981]] |

|||

Coleman's 1980s albums with Prime Time such as ''[[Virgin Beauty]]'' and ''[[Of Human Feelings]]'' continued to use rock and funk rhythms in a style sometimes called [[free funk]].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TMZMAgAAQBAJ&pg=RA1-PA146 |title=Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience |first1=Kwame Anthony |last1=Appiah |author-link=Kwame Anthony Appiah|author2=Henry Louis Gates Jr.|author2-link=Henry Louis Gates Jr.|date=March 16, 2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press |access-date=March 18, 2017|isbn=9780195170559 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Rd82AAAAQBAJ&pg=PA1980 |title=The Jazz Book: From Ragtime to the 21st Century |first1=Joachim-Ernst |last1=Berendt |first2=Günther |last2=Huesmann |date=August 1, 2009 |publisher=Chicago Review Press |access-date=March 18, 2017 |isbn=9781613746042 }}</ref> [[Jerry Garcia]] played guitar on three tracks on ''Virgin Beauty'': "Three Wishes", "Singing in the Shower", and "Desert Players". Coleman joined the [[Grateful Dead]] on stage in 1993 during "Space" and stayed for "The Other One", "Stella Blue", [[Bobby Bland]]'s "Turn on Your Lovelight", and the encore "Brokedown Palace".<ref name=Deadbase>{{cite book |title=DeadBase XI: The Complete Guide to Grateful Dead Song Lists |last=Scott |first=John W. |author2=Dolgushkin, Mike |author3=Nixon, Stu |year=1999 |publisher=DeadBase |location=Cornish, New Hampshire |isbn=1-877657-22-0}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://archive.org/details/gd93-02-23.sbd.hall.1611.sbeok.shnf |title=Grateful Dead Live at Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum on 1993-02-23 |work=Internet Archive|date=February 23, 1993 }}</ref> |

|||

In |

In December 1985, Coleman and guitarist [[Pat Metheny]] recorded ''[[Song X]].'' |

||

[[File:Ornette Coleman.jpg|thumb|right| Coleman plays his [[Henri Selmer Paris|Selmer]] alto saxophone (with low A) at [[The Hague]] in 1994.]] |

|||

==Later career== |

|||

[[File:Ornette at The Forum 1982.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Coleman performing in [[Toronto]] in 1982]] |

|||

Coleman, like [[Miles Davis]] before him, took to playing with [[electric instrument|electrified instruments]]. Albums like ''Virgin Beauty'' and ''Of Human Feelings'' used [[Rock and roll|rock]] and [[funk music|funk]] [[rhythm]]s, sometimes called [[free funk]]. On the face of it, this could seem to be an adoption of the [[jazz fusion]] mode fashionable at the time, but Ornette's first record with the group, which later became known as Prime Time (the 1976 ''[[Dancing in Your Head]]''), was sufficiently different to have considerable shock value. [[Electric guitar]]s were prominent, but the music was, at heart, rather similar to his earlier work. These performances have the same angular melodies and simultaneous group [[improvisation]]s – what [[Joe Zawinul]] referred to as "nobody solos, everybody solos" and what Coleman calls ''[[harmolodics]]''—and although the nature of the pulse has altered, Coleman's own rhythmic approach has not. |

|||

In 1990, the city of [[Reggio Emilia]], Italy, held a three-day "Portrait of the Artist" festival in Coleman's honor, in which he performed with Cherry, Haden, and Higgins. The festival also presented performances of his chamber music and ''Skies of America''.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.allaboutjazz.com/quartet-reunion-1990-ornette-coleman-solo-piano-publications-review-by-aaji-staff.php? |title=Ornette Coleman: Quartet Reunion 1990 |website=AllAboutJazz.com |date=January 10, 2011 |access-date=July 13, 2020}}</ref> In 1991, Coleman played on the soundtrack of [[David Cronenberg]]'s film ''[[Naked Lunch (film)|Naked Lunch]]''; the orchestra was conducted by [[Howard Shore]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.allmusic.com/album/naked-lunch-music-from-the-original-soundtrack-mw0000274736 |title=Howard Shore / Ornette Coleman / London Philharmonic Orchestra: Naked Lunch [Music from the Original Soundtrack] |website=AllMusic |last=Mills |first=Ted |access-date=July 13, 2020}}</ref> Coleman released four records in 1995 and 1996, and for the first time in many years worked regularly with piano players ([[Geri Allen]] and [[Joachim Kühn]]). |

|||

Some critics have suggested Coleman's frequent use of the vaguely-defined term ''harmolodics'' is a musical [[MacGuffin]]: a [[red herring (plot device)|red herring]] of sorts designed to occupy critics overly-focused on Coleman's sometimes unorthodox compositional style. |

|||

=== 2000s === |

|||

[[Jerry Garcia]] played guitar on three tracks from Coleman's ''Virgin Beauty'' (1988) - "Three Wishes," "Singing In The Shower," and "Desert Players." Coleman joined the [[Grateful Dead]] on stage twice in 1993 playing the band's "The Other One," "Wharf Rat," "Stella Blue," and covering [[Bobby Bland]]'s "Turn On Your Lovelight," among others.<ref>[http://www.archive.org/details/gd93-02-23.sbd.hall.1611.sbeok.shnf Grateful Dead performance 23 Feb 1993 at the Internet Archive]</ref> Another unexpected association was with guitarist [[Pat Metheny]], with whom Coleman recorded ''[[Song X]]'' (1985); though released under Metheny's name, Coleman was essentially co-leader (contributing all the compositions). |

|||

Two 1972 Coleman recordings, "Happy House" and "Foreigner in a Free Land", were used in [[Gus Van Sant]]'s 2000 ''[[Finding Forrester]]''.<ref>{{cite web |title=Finding Forrester: Music From The Motion Picture |url=https://www.discogs.com/Various-Finding-Forrester-Music-From-The-Motion-Picture/master/781806 |access-date=July 15, 2020 |website=discogs.com}}</ref> |

|||

In September 2006, Coleman released the album ''[[Sound Grammar]]''. Recorded live in [[Ludwigshafen]], Germany, in 2005, it was his first album of new material in ten years. It won the 2007 [[Pulitzer Prize]] for music, making Coleman only the second jazz musician (after [[Wynton Marsalis]]) to win the prize.<ref name="Pulitzer">{{cite web |title=Pulitzer Prize winning jazz visionary Ornette Coleman dies aged 85 |url=https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/13412464.pulitzer-prize-winning-jazz-visionary-ornette-coleman-dies-aged-85/ |website=HeraldScotland |date=June 11, 2015 |access-date=December 16, 2018 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

In 1990 the city of Reggio Emilia in Italy held a three-day "Portrait of the Artist" featuring a Coleman quartet with Don Cherry, Charlie Haden and Billy Higgins. The festival also presented performances of his chamber music and the symphonic ''Skies of America''. |

|||

== Personal life == |

|||

In 1991, Coleman played on the soundtrack for [[David Cronenberg]]'s ''[[Naked Lunch (film)|Naked Lunch]]''; the orchestra was conducted by [[Howard Shore]]. It is notable among other things for including a rare sighting of Coleman playing a [[jazz standard]]: [[Thelonious Monk]]'s blues line “Misterioso.” Two 1972 (pre-electric) Coleman recordings, "Happy House" and "Foreigner in a Free Land" were used in [[Gus Van Sant]]'s 1995 ''[[Finding Forrester]]. |

|||

Jazz pianist [[Joanne Brackeen]] stated in an interview with [[Marian McPartland]] that Coleman mentored her and gave her music lessons.<ref name="Lyon">{{cite news |last1=Lyon |first1=David |title=Joanne Brackeen On Piano Jazz |url=https://www.npr.org/2011/11/04/101558445/joanne-brackeen-on-piano-jazz |website=NPR.org |access-date=December 16, 2018 |date=March 14, 2014}}</ref> |

|||

Coleman married poet [[Jayne Cortez]] in 1954. The couple divorced in 1964.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.sfgate.com/entertainment/article/Poet-Jayne-Cortez-makes-heady-music-with-Ornette-3237076.php |title=Poet Jayne Cortez makes heady music with Ornette Coleman sidemen |last=Rubien |first=David |date=October 26, 2007| website=sfgate.com |access-date=July 13, 2020}}</ref> They had one son, [[Denardo Coleman|Denardo]], born in 1956.<ref name="Fox">{{cite news |last1=Fox |first1=Margalit |title=Jayne Cortez, Jazz Poet, Dies at 78 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/04/arts/jayne-cortez-poet-and-performance-artist-dies-at-78.html |website=The New York Times |access-date=December 16, 2018 |date=January 3, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The mid-1990s saw a flurry of activity from Coleman: he released four records in 1995 and 1996, and for the first time in many years worked regularly with [[piano]] players (either [[Geri Allen]] or [[Joachim Kühn]]). |

|||

Coleman died of [[cardiac arrest]] in Manhattan on June 11, 2015, aged 85.<ref name="Ratliff" /> His funeral was a three-hour event with performances and speeches by several of his collaborators and contemporaries.<ref name="Remnick">{{cite magazine |last1=Remnick |first1=David |title=Ornette Coleman and a Joyful Funeral |url=https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/ornette-coleman-and-a-joyful-funeral |magazine=The New Yorker |access-date=December 16, 2018 |date=June 27, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

Coleman has rarely performed on other musicians' records. Exceptions include extensive performances on albums by [[Jackie McLean]] in 1967 (''[[New and Old Gospel]]'', on which he played trumpet), and [[James Blood Ulmer]] in 1978, and cameo appearances on [[Yoko Ono]]'s ''[[Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band|Plastic Ono Band]]'' album (1970), [[Jamaaladeen Tacuma]]'s ''Renaissance Man'' (1983), [[Joe Henry]]'s ''Scar'' (2001) and [[Lou Reed]]'s ''[[The Raven (Lou Reed album)|The Raven]]'' (2003). |

|||

== Awards and honors == |

|||

<!--Recently, he has performed live with the popular trio [[The Bad Plus]], a group similarly committed to challenging jazz orthodoxy.--> |

|||

* [[Guggenheim Fellowship]], 1967 and 1974<ref>{{Cite web |title=Ornette Coleman - John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation |url=https://www.gf.org/fellows/ornette-coleman/ |access-date=2024-06-26 |website=www.gf.org}}</ref> |

|||

In September 2006 he released a live album titled ''[[Sound Grammar]]'' with his newest quartet (Denardo drumming and two bassists, [[Greg Cohen|Gregory Cohen]] and [[Tony Falanga]]). This is his first album of new material in ten years, and was recorded in Germany in 2005. It won the 2007 [[Pulitzer Prize]] for music. |

|||

*''[[DownBeat|Down Beat]]'' Jazz Hall of Fame, 1969 |

|||

* [[MacArthur Fellows Program|MacArthur Fellowship]], 1994 |

|||

* [[Praemium Imperiale]], 2001 |

|||

* [[The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize|Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize]], 2004<ref>[http://gishprize.com/index.html The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131006072738/http://gishprize.com/index.html |date=October 6, 2013 }}, official website.</ref> |

|||

* Honorary doctorate of music, [[Berklee College of Music]], 2006<ref>{{cite web |url=https://jazztimes.com/news/ornette-coleman-honored-at-berklee/ |title=Ornette Coleman Honored at Berklee - JazzTimes |access-date=April 18, 2017 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170419002856/https://jazztimes.com/news/ornette-coleman-honored-at-berklee/ |archive-date=April 19, 2017 }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award]], 2007 |

|||

* [[Pulitzer Prize]] for music, 2007<ref name="Pulitzer" /> |

|||

* Miles Davis Award, [[Montreal International Jazz Festival]], 2009<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.montrealjazzfest.com/maison-du-festival-online/miles-davis-award.aspx|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20100516053059/http://www.montrealjazzfest.com/maison-du-festival-online/miles-davis-award.aspx|url-status=dead|title=Montreal Jazz Festival official page|archivedate=May 16, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

* Honorary doctorate, [[CUNY Graduate Center]], 2008<ref name="CUNY">{{cite web |title=Press Release: 2008 CUNY Graduate Center Commencement |url=https://www.gc.cuny.edu/News/All-News/Detail?id=5849 |website=www.gc.cuny.edu |access-date=December 16, 2018}}</ref><ref name="Commencements">{{cite web |title=CUNY 2008 Commencements |url=http://www1.cuny.edu/mu/forum/2008/05/16/cuny-2008-commencements/ |website=cuny.edu |access-date=December 16, 2018 |archive-date=August 14, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180814071643/http://www1.cuny.edu/mu/forum/2008/05/16/cuny-2008-commencements/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

* Honorary doctorate of music, [[University of Michigan]], 2010<ref name="Mergner">{{cite web |last1=Mergner |first1=Lee |title=Ornette Coleman Awarded Honorary Degree from University of Michigan |url=https://jazztimes.com/news/ornette-coleman-awarded-honorary-degree-from-university-of-michigan/ |website=JazzTimes |access-date=December 16, 2018 |date=June 3, 2010 |archive-date=November 7, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181107135838/https://jazztimes.com/news/ornette-coleman-awarded-honorary-degree-from-university-of-michigan/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

== Discography == |

|||

[[Image:Ornette-Coleman-2008-Heidelberg-schindelbeck.jpg|thumb|<center>{{nbsp|3}}Ornette Coleman<br />Enjoy Jazz Festival, Heidelberg, October 2008</center>]] |

|||

{{Main|Ornette Coleman discography}} |

|||

==In popular culture== |

|||

Jazz pianist [[Joanne Brackeen]] (who had only briefly studied music as a child) stated in an interview with [[Marian McPartland]] that Coleman has been mentoring her and giving her semi-formal music lessons in recent years.<ref>http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=101558445</ref> |

|||

[[McClintic Sphere]], a character in [[Thomas Pynchon]]'s 1963 novel ''[[V.]]'', is modeled on Coleman and [[Thelonious Monk]].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/past/docs/unbound/jazz/dornette.htm |title=Ornette's Permanent Revolution |work=[[The Atlantic]] |date=September 1985 |access-date=May 11, 2020 |author=Davis, Francis |quote=In Thomas Pynchon's novel V. there is a character named McClintic Sphere, who plays an alto saxophone of hand-carved ivory (Coleman's was made of white plastic) at a club called the V Note.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |url=https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/art-improviser/ |title=The Art of the Improviser |journal=[[The Nation]] |date=April 26, 2007 |access-date=May 11, 2020 |author=Yaffe, David |quote=Of all the ink spilled on Coleman's impact, perhaps the most memorable came from Thomas Pynchon's 1963 debut novel, V., in which the character McClintic Sphere (with a last name nodding to Thelonious Monk's middle name) sets the jazz world on end at a club called the V-Note.}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/seeing-ornette-coleman |title=Seeing Ornette Coleman |magazine=[[The New Yorker]] |date=June 12, 2015 |access-date=May 11, 2020 |author=Bynum, Taylor Ho |quote=In Thomas Pynchon's 1963 novel 'V.', a thinly veiled character named McClintic Sphere appears, playing a 'white ivory' saxophone at the 'V Spot.' Pynchon's wonderfully terse parody of the portentous debate around Coleman's music is as follows: 'He plays all the notes Bird missed,' somebody whispered in front of Fu. Fu went silently through the motions of breaking a beer bottle on the edge of the table, jamming it into the speaker's back and twisting.}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== Notes == |

||

{{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} |

|||

Coleman continues to push himself into unusual playing situations, often with much younger musicians or musicians from radically different musical cultures, and still performs regularly. An increasing number of his compositions, while not ubiquitous, have become minor [[jazz standard]]s, including "Lonely Woman," "Peace," "Turnaround," "When Will the Blues Leave?" "The Blessing," "Law Years," "What Reason Could I Give" and "I've Waited All My Life", among others. He has influenced virtually every saxophonist of a modern disposition, and nearly every such jazz musician, of the generation that followed him. His songs have proven endlessly malleable: pianists such as [[Paul Bley]] and [[Paul Plimley]] have managed to turn them to their purposes; [[John Zorn]] recorded ''[[Spy vs Spy (album)|Spy vs Spy]]'' (1989), an album of extremely loud, fast, and abrupt versions of Coleman songs. [[Music of Finland#Jazz|Finnish jazz]] singer [[Carola Standertskjöld|Carola]] covered Coleman's "Lonely Woman" and there have even been progressive bluegrass versions of Coleman tunes (by [[Richard Greene (fiddle player)|Richard Greene]]). Coleman's playing has profoundly influenced, directly or otherwise, countless musicians, trying as he has for five decades to understand and discover the shape of not just jazz, but all music to come. |

|||

== References == |

|||

In 2004 Coleman was awarded [[The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize]], one of the richest prizes in the arts, given annually to “a man or woman who has made an outstanding contribution to the beauty of the world and to mankind’s enjoyment and understanding of life.”<ref>[http://gishprize.com/index.html The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize], official website.</ref> |

|||

* Interview with [[Roy Eldridge]], ''[[Esquire (magazine)|Esquire]]'' March 1961 |

|||

* Interview with [[Andy Hamilton (jazz saxophonist)|Andy Hamilton]]. "A Question of Scale" ''[[The Wire (magazine)|The Wire]]'' July 2005 |

|||

* {{cite book| author= Broecking, Christian |author-link=Christian Broecking |title=Respekt!| publisher=Verbrecher| year=2004| isbn=3-935843-38-0}} |

|||

* {{cite book| author=Jost, Ekkehard| title=Free Jazz (Studies in Jazz Research 4)| publisher=Universal Edition| year=1975}} |

|||

* {{cite book| author= Mandel, Howard| title=Miles, Ornette, Cecil: Jazz Beyond Jazz| publisher=Routledge| year=2007| isbn=978-0-415-96714-3}} |

|||

== External links == |

|||

On February 11, 2007, Ornette Coleman was honored with a [[Grammy Awards of 2007|Grammy award]] for lifetime achievement, in recognition of this legacy. |

|||

{{Sister project links|wikt=no|b=no|q=Ornette Coleman|s=no|commons=Ornette Coleman|n=no|v=no}} |

|||

* [https://ethaniverson.com/rhythm-and-blues/ornette-1-forms-and-sounds/ "Forms and Sounds"] by Ethan Iverson about early Coleman and Harmolodics |

|||

* [http://www2.yk.psu.edu/~jmj3/p_ornett.htm Interviewed by Michael Jarrett in ''Cadence'' magazine, October 1995] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080307055508/http://www2.yk.psu.edu/~jmj3/p_ornett.htm |date=March 7, 2008 }} |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20080907023534/http://www.laweekly.com/music/music/ornette-coleman-interview-1996/1191/ "Ornette Coleman interview, 1996", ''LA Weekly''] |

|||

* [http://observer.com/2005/12/ornette-coleman-2/ ''New York Observer''], December 19, 2005 |

|||

{{Ornette Coleman}} |

|||

On July 9, 2009, Ornette Coleman received the [[Miles Davis Award]], a recognition given by the [[Festival International de Jazz de Montréal]] to jazz musicians who have contributed along their careers to the evolution of the jazz music.<ref>[http://www.montrealjazzfest.com/maison-du-festival-online/miles-davis-award.aspx Montreal Jazz Festival official page]</ref><ref>http://nouvelles.equipespectra.ca/blog/?p=732&langswitch_lang=en</ref> |

|||

{{PulitzerPrize Music 2001–2010}} |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

On May 1, 2010, Ornette was awarded a [[honorary doctorate]] in Music from the [[University of Michigan]] for his musical contributions.<ref>http://jazztimes.com/articles/26158-ornette-coleman-awarded-honorary-degree-from-university-of-michigan</ref> |

|||

==Meltdown Festival== |

|||

Ornette Coleman was the curator of the 16th annual [[Meltdown (festival)|Meltdown festival]] held in June 2009 at London's Southbank Centre, following in the footsteps of previous curators including David Bowie, Patti Smith, John Peel and Lee 'Scratch' Perry. The line-up included [[Moby]], The Roots, Yoko Ono's [[Plastic Ono Band]] (with whom Coleman performed), [[Charlie Haden]], [[Yo La Tengo]], and [[The Master Musicians of Jajouka led by Bachir Attar]], [[Patti Smith]] among others. |

|||

==Discography== |

|||

{{Main|Ornette Coleman discography}} |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{Reflist|2}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

*{{Cite book| last=Litweiler| first=John| title=Ornette Coleman: A Harmolodic Life| publisher=Quartet Books| place=[[London]]| year=1992| isbn=0704325160| postscript=<!--None-->}} |

|||

* Coleman, Ornette. Interview with Andy Hamilton. ''A Question of Scale'' [[The Wire (magazine)|The Wire]] July 2005. |

|||

* Interview with Eldridge, Roy. [[Esquire (magazine)|Esquire]] March 1961. |

|||

* {{cite book| author=Jost, Ekkehard| title=Free Jazz (Studies in Jazz Research 4)| publisher=Universal Edition| year=1975}} |

|||

* {{cite book| author=Spellman, A. B.| title=Four Lives in the Bebop Business| publisher=Limelight| year=1985 originally 1966| isbn=0-87910-042-7}} |

|||

* {{cite book| author= Mandel, Howard| title=Miles, Ornette, Cecil: Jazz Beyond Jazz| publisher=Routledge| year=2007| isbn=0415967147}} |

|||

* {{cite book| author= [[Christian Broecking]]| title=Respekt!| publisher=Verbrecher| year=2004| isbn=3935843380}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Sisterlinks|wikt=no|b=no|q=Ornette Coleman|s=no|commons=Ornette Coleman|n=no|v=no}} |

|||

{{Portal|Music}} |

|||

*[http://www.Ornettecoleman.com Official web site] |

|||

*[http://www.flickr.com/photos/seat850/sets/72157616971730665/detail/ Concert Photos, Caravan of Dreams, 1985] |

|||

* {{Allmusic|class=artist|id=p65603}} |

|||

* {{musicbrainz artist|id=169c0d1b-fcb8-4a43-9097-829aa7b39205|name=Ornette Coleman}} |

|||

* {{imdb name|id=0171170|name=Ornette Coleman}} |

|||

* [http://thebadplus.typepad.com/dothemath/2006/10/early_ornette_c.html Article on Coleman's early music] |

|||

* [http://perso.orange.fr/www.kaloskaisophos.org/ac/acocint.html Interview (1997)] |

|||

* [http://www.laweekly.com/music/music/ornette-coleman-interview-1996/1191/ Interview (1996)] |

|||

* [http://www2.yk.psu.edu/~jmj3/p_ornett.htm Interview (1995)] |

|||

* [http://www.thewire.co.uk/archive/interviews/ornette_coleman.html Interview (1985)] |

|||

* ''[http://www.synergeticpress.com/video.html#orn Ornette: Made in America ]'' 1985 documentary about Ornette Coleman directed by Shirley Clarke, re-released on DVD in 2007. |

|||

* [http://pagesperso-orange.fr/www.kaloskaisophos.org/ac/acocint.html Tone Dialing: A Conversation on Friendship with Ornette Coleman] |

|||

* [http://jazzatlincolncenter.org/jazzcast/program.asp?programNumber=121 Ornette Coleman tribute] by Jazz at Lincoln Center |

|||

* [http://streams.wgbh.org/online/play.php?xml=specials/jazz_conversations/jazz_1981_12_03_coleman_ornette_A.xml&template=wgbh_audio Jazz Conversations with Eric Jackson: Ornette Coleman (Part 1)] from [http://www.wgbh.org/jazz WGBH Radio Boston] |

|||

* [http://streams.wgbh.org/online/play.php?xml=specials/jazz_conversations/jazz_1981_12_03_coleman_ornette_B.xml&template=wgbh_audio Jazz Conversations with Eric Jackson: Ornette Coleman (Part 2)] from [http://www.wgbh.org/jazz WGBH Radio Boston] |

|||

{{PulitzerPrize MusicComposers 2001–2025}} |

|||

{{Persondata <!-- Metadata: see [[Wikipedia:Persondata]]. --> |

|||

| NAME =Coleman, Ornette |

|||

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES = |

|||

| SHORT DESCRIPTION = |

|||

| DATE OF BIRTH =March 9, 1930 |

|||

| PLACE OF BIRTH = |

|||

| DATE OF DEATH = |

|||

| PLACE OF DEATH = |

|||

}} |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Coleman, Ornette}} |

{{DEFAULTSORT:Coleman, Ornette}} |

||

[[Category:1930 births]] |

[[Category:1930 births]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:2015 deaths]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:20th-century American composers]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:20th-century American saxophonists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:20th-century American violinists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:21st-century American saxophonists]] |

||

[[Category:African-American saxophonists]] |

|||

[[Category:Age controversies]] |

|||

[[Category:American jazz saxophonists]] |

[[Category:American jazz saxophonists]] |

||

[[Category:American male saxophonists]] |

|||

[[Category:American jazz violinists]] |

[[Category:American jazz violinists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:American male violinists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Avant-garde jazz saxophonists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Free funk saxophonists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Free jazz saxophonists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:American jazz alto saxophonists]] |

||

[[Category:Pulitzer Prize for Music winners]] |

|||

[[Category:Atlantic Records artists]] |

|||

[[Category:ABC Records artists]] |

[[Category:ABC Records artists]] |

||

[[Category:Antilles Records artists]] |

[[Category:Antilles Records artists]] |

||

[[Category:Atlantic Records artists]] |

|||

[[Category:Blue Note Records artists]] |

[[Category:Blue Note Records artists]] |

||

[[Category:ESP-Disk artists]] |

[[Category:ESP-Disk artists]] |

||

[[Category:Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners]] |

|||

[[Category:MacArthur Fellows]] |

|||

[[an:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:Pulitzer Prize for Music winners]] |

|||

[[bs:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters]] |

|||

[[cs:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:Recipients of the Praemium Imperiale]] |

|||

[[da:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:Jazz musicians from Texas]] |

|||

[[de:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:Musicians from Fort Worth, Texas]] |

|||

[[et:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:American male jazz musicians]] |

|||

[[es:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:Orchestra U.S.A. members]] |

|||

[[eo:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:Black Lion Records artists]] |

|||

[[fr:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:20th-century American male musicians]] |

|||

[[gl:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:21st-century American male musicians]] |

|||

[[io:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:Prime Time (band) members]] |

|||

[[it:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:20th-century African-American musicians]] |

|||

[[he:אורנט קולמן]] |

|||

[[Category:21st-century African-American musicians]] |

|||

[[sw:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[Category:DownBeat Jazz Hall of Fame members]] |

|||

[[nl:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[ja:オーネット・コールマン]] |

|||

[[no:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[oc:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[pl:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[pt:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[ru:Коулман, Орнетт]] |

|||

[[simple:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[fi:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[sv:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[tr:Ornette Coleman]] |

|||

[[uk:Орнетт Коулман]] |

|||

[[zh:奥尼特·科尔曼]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 01:35, 9 December 2024

Ornette Coleman | |

|---|---|

Coleman at the Enjoy Jazz Festival in Heidelberg, 2008 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman |

| Born | March 9, 1930 Fort Worth, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | June 11, 2015 (aged 85) Manhattan, New York City, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments | |

| Years active | 1940s–2015 |

| Labels | |

| Spouse | |

Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman (March 9, 1930 – June 11, 2015)[1] was an American jazz saxophonist, trumpeter, violinist, and composer. He is best known as a principal founder of the free jazz genre, a term derived from his 1960 album Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation. His pioneering works often abandoned the harmony-based composition, tonality, chord changes, and fixed rhythm found in earlier jazz idioms.[2] Instead, Coleman emphasized an experimental approach to improvisation rooted in ensemble playing and blues phrasing.[3] Thom Jurek of AllMusic called him "one of the most beloved and polarizing figures in jazz history," noting that while "now celebrated as a fearless innovator and a genius, he was initially regarded by peers and critics as rebellious, disruptive, and even a fraud."[3]

Born and raised in Fort Worth, Texas, Coleman taught himself to play the saxophone when he was a teenager.[1] He began his musical career playing in local R&B and bebop groups, and eventually formed his own group in Los Angeles, featuring members such as Ed Blackwell, Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, and Billy Higgins. In November 1959, his quartet began a controversial residency at the Five Spot jazz club in New York City and he released the influential album The Shape of Jazz to Come, his debut LP on Atlantic Records. Coleman's subsequent Atlantic releases in the early 1960s would profoundly influence the direction of jazz in that decade, and his compositions "Lonely Woman" and "Broadway Blues" became genre standards that are cited as important early works in free jazz.[4]

In the mid 1960s, Coleman left Atlantic for labels such as Blue Note and Columbia Records, and began performing with his young son Denardo Coleman on drums. He explored symphonic compositions with his 1972 album Skies of America, featuring the London Symphony Orchestra. In the mid-1970s, he formed the group Prime Time and explored electric jazz-funk and his concept of harmolodic music.[3] In 1995, Coleman and his son Denardo founded the Harmolodic record label. His 2006 album Sound Grammar received the Pulitzer Prize for Music, making Coleman the second jazz musician ever to receive the honor.[5]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Coleman was born Randolph Denard Ornette Coleman on March 9, 1930, in Fort Worth, Texas,[6] where he was raised.[7][8][9] He attended I.M. Terrell High School in Fort Worth, where he participated in band until he was dismissed for improvising during John Philip Sousa's march "The Washington Post". He began performing R&B and bebop on tenor saxophone, and formed The Jam Jivers with Prince Lasha and Charles Moffett.[9]

Eager to leave town, he accepted a job in 1949 with a Silas Green from New Orleans traveling show and then with touring rhythm and blues shows. After a show in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, he was assaulted and his saxophone was destroyed.[10]

Coleman subsequently switched to alto saxophone, first playing it in New Orleans after the Baton Rouge incident; the alto would remain his primary instrument for the rest of his life. He then joined the band of Pee Wee Crayton and traveled with them to Los Angeles. He worked at various jobs in Los Angeles, including as an elevator operator, while pursuing his music career.[11]

Coleman found like-minded musicians in Los Angeles, such as Ed Blackwell, Bobby Bradford, Don Cherry, Charlie Haden, Billy Higgins, and Charles Moffett.[3][12] Thanks to the intercession of friends and a successful audition, Ornette signed his first recording contract with LA-based Contemporary Records,[13] which allowed him to sell the tracks from his debut album, Something Else!!!! (1958), with Cherry, Higgins, Walter Norris, and Don Payne.[14] During the same year he briefly belonged to a quintet led by Paul Bley that performed at a club in New York City (that band is recorded on Live at the Hilcrest Club 1958).[3] By the time Tomorrow Is the Question! was recorded soon after with Cherry, bassists Percy Heath and Red Mitchell, and drummer Shelly Manne, the jazz world had been shaken up by Coleman's alien music. Some jazz musicians called him a fraud, while conductor Leonard Bernstein praised him.[12]

1959: The Shape of Jazz to Come

[edit]In 1959, Atlantic Records released Coleman's third studio album, The Shape of Jazz to Come. According to music critic Steve Huey, the album "was a watershed event in the genesis of avant-garde jazz, profoundly steering its future course and throwing down a gauntlet that some still haven't come to grips with."[15] Jazzwise listed it at number three on their list of the 100 best jazz albums of all time in 2017.[16]

Coleman's quartet received a long and sometimes controversial engagement at the Five Spot Café in Manhattan. Leonard Bernstein, Lionel Hampton, and the Modern Jazz Quartet were impressed and offered encouragement. Hampton asked to perform with the quartet; Bernstein helped Haden obtain a composition grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. A young Lou Reed followed Coleman's quartet around New York City.[17] Miles Davis said that Coleman was "all screwed up inside",[18][19] although he later became a proponent of Coleman's innovations;[20] Dizzy Gillespie remarked of Coleman that “I don’t know what he’s playing, but it’s not jazz."[17]

Coleman's early sound was due in part to his use of a plastic saxophone; he had purchased it in Los Angeles in 1954 because he was unable to afford a metal saxophone at the time.[9]

On his Atlantic recordings, Coleman's sidemen were Cherry on cornet or pocket trumpet; Charlie Haden, Scott LaFaro, and then Jimmy Garrison on bass; and Higgins or Ed Blackwell on drums. Coleman's complete recordings for the label were collected on the box set Beauty Is a Rare Thing in 1993.[21]

1960s: Free Jazz and Blue Note

[edit]In 1960, Coleman recorded Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation, which featured a double quartet, including Don Cherry and Freddie Hubbard on trumpet, Eric Dolphy on bass clarinet, Haden and LaFaro on bass, and both Higgins and Blackwell on drums.[22] The album was recorded in stereo, with a reed/brass/bass/drums quartet isolated in each stereo channel. Free Jazz was, at 37 minutes, the longest recorded continuous jazz performance at the time[23] and was one of Coleman's most controversial albums.[24] In the January 18, 1962, issue of Down Beat magazine, Pete Welding gave the album five stars while John A. Tynan rated it zero stars.[25]

While Coleman had intended "free jazz" as simply an album title, free jazz was soon considered a new genre; Coleman expressed discomfort with the term.[26]

After the Atlantic period, Coleman's music became more angular and engaged with the avant-garde jazz which had developed in part around his innovations.[21] After his quartet disbanded, he formed a trio with David Izenzon on bass and Charles Moffett on drums, and began playing trumpet and violin in addition to the saxophone. His friendship with Albert Ayler influenced his development on trumpet and violin. Charlie Haden sometimes joined this trio to form a two-bass quartet.

In 1966, Coleman signed with Blue Note and released the two-volume live album At the "Golden Circle" Stockholm, featuring Izenzon and Moffett.[27] Later that year, he recorded The Empty Foxhole with his ten year-old son Denardo Coleman and Haden;[28] Freddie Hubbard and Shelly Manne regarded Denardo's appearance on the album as an ill-advised piece of publicity.[29][30] Denardo later became his father's primary drummer in the late 1970s.

Coleman formed another quartet. Haden, Garrison, and Elvin Jones appeared, and Dewey Redman joined the group, usually on tenor saxophone. On February 29, 1968, Coleman's quartet performed live with Yoko Ono at the Royal Albert Hall, and a recording from their rehearsal was subsequently included on Ono's 1970 album Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band as the track "AOS".[31]

He explored his interest in string textures on Town Hall, 1962, culminating in the 1972 album Skies of America with the London Symphony Orchestra.

1970s–1990s: Harmolodic funk and Prime Time

[edit]

Coleman, like Miles Davis before him, soon took to playing with electric instruments. The 1976 album Dancing in Your Head, Coleman's first recording with the group which later became known as Prime Time, prominently featured two electric guitarists. While this marked a stylistic departure for Coleman, the music retained aspects of what he called harmolodics.

Coleman's 1980s albums with Prime Time such as Virgin Beauty and Of Human Feelings continued to use rock and funk rhythms in a style sometimes called free funk.[32][33] Jerry Garcia played guitar on three tracks on Virgin Beauty: "Three Wishes", "Singing in the Shower", and "Desert Players". Coleman joined the Grateful Dead on stage in 1993 during "Space" and stayed for "The Other One", "Stella Blue", Bobby Bland's "Turn on Your Lovelight", and the encore "Brokedown Palace".[34][35]

In December 1985, Coleman and guitarist Pat Metheny recorded Song X.

In 1990, the city of Reggio Emilia, Italy, held a three-day "Portrait of the Artist" festival in Coleman's honor, in which he performed with Cherry, Haden, and Higgins. The festival also presented performances of his chamber music and Skies of America.[36] In 1991, Coleman played on the soundtrack of David Cronenberg's film Naked Lunch; the orchestra was conducted by Howard Shore.[37] Coleman released four records in 1995 and 1996, and for the first time in many years worked regularly with piano players (Geri Allen and Joachim Kühn).

2000s

[edit]Two 1972 Coleman recordings, "Happy House" and "Foreigner in a Free Land", were used in Gus Van Sant's 2000 Finding Forrester.[38]

In September 2006, Coleman released the album Sound Grammar. Recorded live in Ludwigshafen, Germany, in 2005, it was his first album of new material in ten years. It won the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for music, making Coleman only the second jazz musician (after Wynton Marsalis) to win the prize.[39]

Personal life

[edit]Jazz pianist Joanne Brackeen stated in an interview with Marian McPartland that Coleman mentored her and gave her music lessons.[40]

Coleman married poet Jayne Cortez in 1954. The couple divorced in 1964.[41] They had one son, Denardo, born in 1956.[42]

Coleman died of cardiac arrest in Manhattan on June 11, 2015, aged 85.[1] His funeral was a three-hour event with performances and speeches by several of his collaborators and contemporaries.[43]

Awards and honors

[edit]- Guggenheim Fellowship, 1967 and 1974[44]

- Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame, 1969

- MacArthur Fellowship, 1994

- Praemium Imperiale, 2001

- Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize, 2004[45]

- Honorary doctorate of music, Berklee College of Music, 2006[46]

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, 2007

- Pulitzer Prize for music, 2007[39]

- Miles Davis Award, Montreal International Jazz Festival, 2009[47]

- Honorary doctorate, CUNY Graduate Center, 2008[48][49]

- Honorary doctorate of music, University of Michigan, 2010[50]

Discography

[edit]In popular culture

[edit]McClintic Sphere, a character in Thomas Pynchon's 1963 novel V., is modeled on Coleman and Thelonious Monk.[51][52][53]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Ratliff, Ben (June 11, 2015). "Ornette Coleman, Saxophonist Who Rewrote the Language of Jazz, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Mandell, Howard. "Ornette Coleman, Jazz Iconoclast, Dies At 85". NPR Music. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Jurek, Thom. "Ornette Coleman". AllMusic. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Hellmer, Jeffrey; Lawn, Richard (May 3, 2005). Jazz Theory and Practice: For Performers, Arrangers and Composers. Alfred Music. pp. 234–. ISBN 978-1-4574-1068-0. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ "2007 Pulitzer Prizes". Pulitzer.org. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Fordham, John (June 11, 2015). "Ornette Coleman obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (December 1972). "Ornette Coleman and the Circle with a Hole in the Middle". The Atlantic Monthly.

Ornette Coleman since March 19, 1930, when he was born in Fort Worth, Texas

- ^ Wishart, David J. (ed.). "Coleman, Ornette (b. 1930)". Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

Ornette Coleman, born in Fort Worth, Texas, on March 19, 1930

- ^ a b c Litweiler, John (1992). Ornette Coleman: the harmolodic life. London: Quartet. pp. 21–31. ISBN 0-7043-2516-0.

- ^ Spellman, A.B. (1985). Four Lives in the Bebop Business (1st Limelight ed.). Limelight. pp. 98–101. ISBN 0-87910-042-7.

- ^ Hentoff, Nat (1975). The Jazz Life. Da Capo Press. pp. 235–236.

- ^ a b "Ornette Coleman biography on Europe Jazz Network". Archived from the original on May 2, 2005.

- ^ Golia, Maria (2020). Ornette Coleman: The Territory and the Adventure. Unit 32, Waterside 44-48 Wharf Road, London NI 7UX UK: Reaktion Books Ltd. p. 100. ISBN 9781789142235.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Jurek, Thom. "Something Else: The Music of Ornette Coleman". AllMusic. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "The Shape of Jazz to Come". AllMusic. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Flynn, Mike (July 18, 2017). "The 100 Jazz Albums That Shook The World". www.jazzwisemagazine.com. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Shteamer, Hank (May 22, 2019). "Flashback: Ornette Coleman Sums Up Solitude on 'Lonely Woman'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Miles Davis, quoted in John Litwiler, Ornette Coleman: A Harmolodic Life (NY: W. Morrow, 1992), 82. ISBN 0688072127, 9780688072124

- ^ Roberts, Randall (January 11, 2015). "Why was Ornette Coleman so important? Jazz masters both living and dead chime in". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Kahn, Ashley (November 13, 2006). "Ornette Coleman: Decades of Jazz on the Edge". NPR.org. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ a b Yanow, Scott. "Ornette Coleman". AllMusic. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ "Happy 55th: Ornette Coleman, Free Jazz: A Collective Improvisation". Rhino Records. December 21, 2015. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ Hewett, Ivan (June 11, 2015). "Ornette Coleman: the godfather of free jazz". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ Bailey, C. Michael (September 30, 2011). "Ornette Coleman: Free Jazz". All About Jazz. Retrieved November 17, 2019.

- ^ Welding, Pete (January 18, 1962). "Double View of a Double Quartet". DownBeat. 29 (2).

- ^ Howard Reich (September 30, 2010). Let Freedom Swing: Collected Writings on Jazz, Blues, and Gospel. Northwestern University Press. pp. 333–. ISBN 978-0-8101-2705-0.

- ^ Freeman, Phil (December 18, 2012). "Good Old Days: Ornette Coleman On Blue Note". Blue Note Records. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Chow, Andrew R. (June 28, 2015). "Remembering What Made Ornette Coleman a Jazz Visionary". The New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2021.

- ^ Gabel, J. C. "Making Knowledge Out of Sound" (PDF). stopsmilingonline.com. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Spencer, Robert (April 1, 1997). "Ornette Coleman: The Empty Foxhole". All About Jazz. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Chrispell, James. "Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band". AllMusic. Retrieved August 14, 2018.

- ^ Appiah, Kwame Anthony; Henry Louis Gates Jr. (March 16, 2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195170559. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Berendt, Joachim-Ernst; Huesmann, Günther (August 1, 2009). The Jazz Book: From Ragtime to the 21st Century. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781613746042. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Scott, John W.; Dolgushkin, Mike; Nixon, Stu (1999). DeadBase XI: The Complete Guide to Grateful Dead Song Lists. Cornish, New Hampshire: DeadBase. ISBN 1-877657-22-0.

- ^ "Grateful Dead Live at Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum on 1993-02-23". Internet Archive. February 23, 1993.

- ^ "Ornette Coleman: Quartet Reunion 1990". AllAboutJazz.com. January 10, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Mills, Ted. "Howard Shore / Ornette Coleman / London Philharmonic Orchestra: Naked Lunch [Music from the Original Soundtrack]". AllMusic. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ "Finding Forrester: Music From The Motion Picture". discogs.com. Retrieved July 15, 2020.

- ^ a b "Pulitzer Prize winning jazz visionary Ornette Coleman dies aged 85". HeraldScotland. June 11, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Lyon, David (March 14, 2014). "Joanne Brackeen On Piano Jazz". NPR.org. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Rubien, David (October 26, 2007). "Poet Jayne Cortez makes heady music with Ornette Coleman sidemen". sfgate.com. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (January 3, 2013). "Jayne Cortez, Jazz Poet, Dies at 78". The New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Remnick, David (June 27, 2015). "Ornette Coleman and a Joyful Funeral". The New Yorker. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ "Ornette Coleman - John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation". www.gf.org. Retrieved June 26, 2024.

- ^ The Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize Archived October 6, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, official website.

- ^ "Ornette Coleman Honored at Berklee - JazzTimes". Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ "Montreal Jazz Festival official page". Archived from the original on May 16, 2010.

- ^ "Press Release: 2008 CUNY Graduate Center Commencement". www.gc.cuny.edu. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ "CUNY 2008 Commencements". cuny.edu. Archived from the original on August 14, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.

- ^ Mergner, Lee (June 3, 2010). "Ornette Coleman Awarded Honorary Degree from University of Michigan". JazzTimes. Archived from the original on November 7, 2018. Retrieved December 16, 2018.