Replication (computing): Difference between revisions

Cononsense (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

|||

| (220 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Sharing information to ensure consistency in computing}} |

|||

'''Replication''' is the process of sharing information so as to ensure consistency between redundant resources, such as [[software]] or [[hardware]] components, to improve reliability, [[fault-tolerance]], or accessibility. It could be ''data replication'' if the same data is stored on multiple [[data storage device|storage device]]s, or ''computation replication'' if the same computing task is executed many times. A computational task is typically ''replicated in space'', i.e. executed on separate devices, or it could be ''replicated in time'', if it is executed repeatedly on a single device. |

|||

{{More footnotes needed|date=October 2012}} |

|||

'''Replication''' in [[computing]] refers to maintaining multiple copies of data, processes, or resources to ensure consistency across redundant components. This fundamental technique spans [[database management system|databases]], [[file system|file systems]], and [[distributed computing|distributed systems]], serving to improve [[high availability|availability]], [[fault-tolerance]], accessibility, and performance.<ref name="kleppmann"/> Through replication, systems can continue operating when components fail ([[failover]]), serve requests from geographically distributed locations, and balance load across multiple machines. The challenge lies in maintaining consistency between replicas while managing the fundamental tradeoffs between data consistency, system availability, and [[Network partition|network partition tolerance]] – constraints known as the [[CAP theorem]].<ref>{{cite journal |last=Brewer |first=Eric A. |title=Towards robust distributed systems |journal=Proceedings of the Annual ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing |year=2000 |doi=10.1145/343477.343502}}</ref> |

|||

== {{Anchor|MASTER-ELECTION}}Terminology == |

|||

The access to a replicated entity is typically uniform with access to a single, non-replicated entity. The replication itself should be [[transparency (computing)|transparent]] to an external user. Also, in a failure scenario, a [[failover]] of replicas is hidden as much as possible. |

|||

Replication in computing can refer to: |

|||

* ''Data replication'', where the same data is stored on multiple [[data storage device|storage device]]s |

|||

* ''Computation replication'', where the same computing task is executed many times. Computational tasks may be: |

|||

** ''Replicated in space'', where tasks are executed on separate devices |

|||

** ''Replicated in time'', where tasks are executed repeatedly on a single device |

|||

Replication in space or in time is often linked to scheduling algorithms.<ref>Mansouri, Najme, Gholam, Hosein Dastghaibyfard, and Ehsan Mansouri. "Combination of data replication and scheduling algorithm for improving data availability in Data Grids", ''Journal of Network and Computer Applications'' (2013)</ref> |

|||

It is common to talk about active and passive replication in systems that replicate data or services. ''Active replication'' is performed by processing the same request at every replica. In ''passive replication'', each single request is processed on a single replica and then its state is transferred to the other replicas. If at any time one master replica is designated to process all the requests, then we are talking about the ''primary-backup'' scheme (''[[Master-slave (computers)|master-slave]]'' scheme) predominant in [[high-availability cluster]]s. On the other side, if any replica processes a request and then distributes a new state, then this is a ''multi-primary'' scheme (called ''[[Multi-master replication|multi-master]]'' in the database field). In the multi-primary scheme, some form of [[distributed concurrency control]] must be used, such as [[distributed lock manager]]. |

|||

Access to a replicated entity is typically uniform with access to a single non-replicated entity. The replication itself should be [[transparency (human-computer interaction)|transparent]] to an external user. In a failure scenario, a [[failover]] of replicas should be hidden as much as possible with respect to [[quality of service]].<ref>V. Andronikou, K. Mamouras, K. Tserpes, D. Kyriazis, T. Varvarigou, "Dynamic QoS-aware Data Replication in Grid Environments", ''Elsevier Future Generation Computer Systems - The International Journal of Grid Computing and eScience'', 2012</ref> |

|||

[[load balancing (computing)|Load balancing]] is different from task replication, since it distributes a load of different (not the same) computations across machines, and allows a single computation to be dropped in case of failure. Load balancing, however, sometimes uses data replication (esp. multi-master) internally, to distribute its data among machines. |

|||

Computer scientists further describe replication as being either: |

|||

[[Backup]] is different from replication, since it saves a copy of data unchanged for a long period of time. Replicas on the other hand are frequently updated and quickly lose any historical state. |

|||

* '''Active replication''', which is performed by processing the same request at every replica |

|||

* '''Passive replication''', which involves processing every request on a single replica and transferring the result to the other replicas |

|||

When one leader replica is designated via [[leader election]] to process all the requests, the system is using a primary-backup or [[Master-slave (computers)|primary-replica]] scheme, which is predominant in [[high-availability cluster]]s. In comparison, if any replica can process a request and distribute a new state, the system is using a multi-primary or [[Multi-master replication|multi-master]] scheme. In the latter case, some form of [[distributed concurrency control]] must be used, such as a [[distributed lock manager]]. |

|||

== Replication in distributed systems == |

|||

[[Load balancing (computing)|Load balancing]] differs from task replication, since it distributes a load of different computations across machines, and allows a single computation to be dropped in case of failure. Load balancing, however, sometimes uses data replication (especially [[multi-master replication]]) internally, to distribute its data among machines. |

|||

Replication is one of the oldest and most important topics in the overall area of [[distributed computing|distributed systems]]. |

|||

[[Backup]] differs from replication in that the saved copy of data remains unchanged for a long period of time.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.zerto.com/replication/backup-and-replication-what-is-the-difference/|title=Backup and Replication: What is the Difference?|date=February 6, 2012|website=Zerto}}</ref> Replicas, on the other hand, undergo frequent updates and quickly lose any historical state. Replication is one of the oldest and most important topics in the overall area of [[distributed computing|distributed systems]]. |

|||

Whether one replicates data or computation, the objective is to have some group of processes that handle incoming events. If we replicate data, these processes are passive and operate only to maintain the stored data, reply to read requests, and apply updates. When we replicate computation, the usual goal is to provide fault-tolerance. For example, a replicated service might be used to control a telephone switch, with the objective of ensuring that even if the primary controller fails, the backup can take over its functions. But the underlying needs are the same in both cases: by ensuring that the replicas see the same events in equivalent orders, they stay in consistent states and hence any replica can respond to queries. |

|||

Data replication and computation replication both require processes to handle incoming events. Processes for data replication are passive and operate only to maintain the stored data, reply to read requests and apply updates. Computation replication is usually performed to provide fault-tolerance, and take over an operation if one component fails. In both cases, the underlying needs are to ensure that the replicas see the same events in equivalent orders, so that they stay in consistent states and any replica can respond to queries. |

|||

=== Replication models in distributed systems === |

=== Replication models in distributed systems === |

||

Three widely cited models exist for data replication, each having its own properties and performance: |

|||

* '''Transactional replication''': used for replicating [[transactional data]], such as a database. The [[one-copy serializability]] model is employed, which defines valid outcomes of a transaction on replicated data in accordance with the overall [[ACID]] (atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) properties that transactional systems seek to guarantee. |

|||

A number of widely cited models exist for data replication, each having its own properties and performance: |

|||

* '''[[State machine replication]]''': assumes that the replicated process is a [[deterministic finite automaton]] and that [[atomic broadcast]] of every event is possible. It is based on [[Consensus (computer science)|distributed consensus]] and has a great deal in common with the transactional replication model. This is sometimes mistakenly used as a synonym of active replication. State machine replication is usually implemented by a replicated log consisting of multiple subsequent rounds of the [[Paxos algorithm]]. This was popularized by Google's Chubby system, and is the core behind the open-source [[Keyspace (data store)|Keyspace data store]].<ref name=keyspace>{{cite web | access-date=2010-04-18 | year = 2009 | url=http://scalien.com/whitepapers |title=Keyspace: A Consistently Replicated, Highly-Available Key-Value Store | author=Marton Trencseni, Attila Gazso}}</ref><ref name=chubby>{{cite web | access-date=2010-04-18 | year=2006 | url=http://labs.google.com/papers/chubby.html | title=The Chubby Lock Service for Loosely-Coupled Distributed Systems | author=Mike Burrows | url-status=dead | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100209225931/http://labs.google.com/papers/chubby.html | archive-date=2010-02-09 }}</ref> |

|||

* '''[[Virtual synchrony]]''': involves a group of processes which cooperate to replicate in-memory data or to coordinate actions. The model defines a distributed entity called a ''process group''. A process can join a group and is provided with a checkpoint containing the current state of the data replicated by group members. Processes can then send [[multicast]]s to the group and will see incoming multicasts in the identical order. Membership changes are handled as a special multicast that delivers a new "membership view" to the processes in the group.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Birman |first1=K. |last2=Joseph |first2=T. |title=Proceedings of the eleventh ACM Symposium on Operating systems principles - SOSP '87 |chapter=Exploiting virtual synchrony in distributed systems |date=1987-11-01 |chapter-url=https://doi.org/10.1145/41457.37515 |series=SOSP '87 |location=New York, NY, USA |publisher=Association for Computing Machinery |pages=123–138 |doi=10.1145/41457.37515 |isbn=978-0-89791-242-6|s2cid=7739589 }}</ref> |

|||

== {{Anchor|DATABASE}}Database replication == |

|||

# ''[[Transactional replication]]''. This is the model for replicating [[transactional data]], for example a database or some other form of transactional storage structure. The [[one-copy serializability]] model is employed in this case, which defines legal outcomes of a transaction on replicated data in accordance with the overall [[ACID]] properties that transactional systems seek to guarantee. |

|||

[[Database]] replication involves maintaining copies of the same data on multiple machines, typically implemented through three main approaches: single-leader, multi-leader, and leaderless replication.<ref name="kleppmann">{{cite book |last=Kleppmann |first=Martin |title=Designing Data-Intensive Applications: The Big Ideas Behind Reliable, Scalable, and Maintainable Systems |year=2017 |publisher=O'Reilly Media |isbn=9781491903100 |pages=151-185}}</ref> |

|||

# ''[[State machine replication]].'' This model assumes that replicated process is a [[deterministic finite automaton]] and that [[atomic broadcast]] of every event is possible. It is based on a distributed computing problem called ''[[Consensus (computer science)|distributed consensus]]'' and has a great deal in common with the transactional replication model. This is sometimes mistakenly used as synonym of ''active replication''. State machine replication is usually implemented by a replicated log consisting of multiple subsequent rounds of the [[Paxos algorithm]]. This was popularized by Google's Chubby system, and is the core behind the open-source [[Keyspace (data store)|Keyspace data store]].<ref name=keyspace> |

|||

{{cite web | accessdate=2010-04-18 | year = 2009 | url=http://scalien.com/whitepapers | |

|||

title=Keyspace: A Consistently Replicated, Highly-Available Key-Value Store | author=Marton Trencseni, Attila Gazso}} |

|||

</ref><ref name=chubby> |

|||

{{cite web | accessdate=2010-04-18 | year = 2006 | url=http://labs.google.com/papers/chubby.html | |

|||

title=The Chubby Lock Service for Loosely-Coupled Distributed Systems | author=Mike Burrows}} |

|||

</ref> |

|||

# ''[[Virtual synchrony]]''. This computational model is used when a group of processes cooperate to replicate in-memory data or to coordinate actions. The model defines a new distributed entity called a ''process group''. A process can join a group, which is much like opening a file: the process is added to the group, but is also provided with a checkpoint containing the current state of the data replicated by group members. Processes can then send events (''multicasts'') to the group and will see incoming events in the identical order, even if events are sent concurrently. Membership changes are handled as a special kind of platform-generated event that delivers a new ''membership view'' to the processes in the group. |

|||

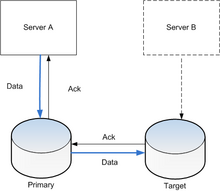

In [[Master–slave (technology)|single-leader]] (also called primary/replica) replication, one database instance is designated as the leader (primary), which handles all write operations. The leader logs these updates, which then propagate to replica nodes. Each replica acknowledges receipt of updates, enabling subsequent write operations. Replicas primarily serve read requests, though they may serve stale data due to replication lag – the delay in propagating changes from the leader. |

|||

Levels of performance vary widely depending on the model selected. Transactional replication is slowest, at least when one-copy serializability guarantees are desired (better performance can be obtained when a database uses log-based replication, but at the cost of possible inconsistencies if a failure causes part of the log to be lost). Virtual synchrony is the fastest of the three models, but the handling of failures is less rigorous than in the transactional model. State machine replication lies somewhere in between; the model is faster than transactions, but much slower than virtual synchrony. |

|||

In [[multi-master replication]] (also called multi-leader), updates can be submitted to any database node, which then propagate to other servers. This approach is particularly beneficial in multi-data center deployments, where it enables local write processing while masking inter-data center network latency.<ref name="kleppmann"/> However, it introduces substantially increased costs and complexity which may make it impractical in some situations. The most common challenge that exists in multi-master replication is transactional conflict prevention or [[conflict resolution|resolution]] when concurrent modifications occur on different leader nodes. |

|||

The virtual synchrony model is popular{{Citation needed|date=August 2007}} in part because it allows the developer to use either active or passive replication. In contrast, state machine replication and transactional replication are highly constraining and are often embedded into products at layers where end-users would not be able{{Citation needed|date=August 2007}} to access them. |

|||

Most synchronous (or eager) replication solutions perform conflict prevention, while asynchronous (or lazy) solutions have to perform conflict resolution. For instance, if the same record is changed on two nodes simultaneously, an eager replication system would detect the conflict before confirming the commit and abort one of the transactions. A [[lazy replication]] system would allow both [[database transaction|transactions]] to commit and run a conflict resolution during re-synchronization. Conflict resolution methods can include techniques like last-write-wins, application-specific logic, or merging concurrent updates.<ref name="kleppmann"/> |

|||

== Database replication == |

|||

[[Database]] replication can be used on many [[database management system]]s, usually with a master/slave relationship between the original and the copies. The master logs the updates, which then ripple through to the slaves. The slave outputs a message stating that it has received the update successfully, thus allowing the sending (and potentially re-sending until successfully applied) of subsequent updates. |

|||

However, replication transparency can not always be achieved. When data is replicated in a database, they will be constrained by [[CAP theorem]] or [[PACELC theorem]]. In the NoSQL movement, data consistency is usually sacrificed in exchange for other more desired properties, such as availability (A), partition tolerance (P), etc. Various [[Consistency model|data consistency models]] have also been developed to serve as Service Level Agreement (SLA) between service providers and the users. |

|||

[[Multi-master replication]], where updates can be submitted to any database node, and then ripple through to other servers, is often desired, but introduces substantially increased costs and complexity which may make it impractical in some situations. The most common challenge that exists in multi-master replication is transactional conflict prevention or resolution. Most synchronous or eager replication solutions do conflict prevention, while asynchronous solutions have to do conflict resolution. For instance, if a record is changed on two nodes simultaneously, an eager replication system would detect the conflict before confirming the commit and abort one of the transactions. A [[lazy replication]] system would allow both transactions to commit and run a conflict resolution during resynchronization. The resolution of such a conflict may be based on a timestamp of the transaction, on the hierarchy of the origin nodes or on much more complex logic, which decides consistently on all nodes. |

|||

There are several techniques for replicating data changes between nodes:<ref name="kleppmann"/> |

|||

Database replication becomes difficult when it scales up. Usually, the scale up goes with two dimensions, horizontal and vertical: horizontal scale up has more data replicas, vertical scale up has data replicas located further away in distance. Problems raised by horizontal scale up can be alleviated by a multi-layer multi-view access protocol. Vertical scale up is running into less trouble since internet reliability and performance are improving. |

|||

* '''Statement-based replication''': Write requests (such as SQL statements) are logged and transmitted to replicas for execution. This can be problematic with non-deterministic functions or statements having side effects. |

|||

* '''Write-ahead log (WAL) shipping''': The storage engine's low-level write-ahead log is replicated, ensuring identical data structures across nodes. |

|||

* '''Logical (row-based) replication''': Changes are described at the row level using a dedicated log format, providing greater flexibility and independence from storage engine internals. |

|||

== Disk storage replication == |

== Disk storage replication == |

||

[[File:Storage replication.png|thumb|Storage replication]] |

[[File:Storage replication.png|thumb|Storage replication]] |

||

Active (real-time) storage replication is usually implemented by distributing updates of a [[block device]] to several physical [[hard disk]]s. This way, any [[file system]] supported by the [[operating system]] can be replicated without modification, as the file system code works on a level above the block device driver layer. It is |

Active (real-time) storage replication is usually implemented by distributing updates of a [[block device]] to several physical [[hard disk]]s. This way, any [[file system]] supported by the [[operating system]] can be replicated without modification, as the file system code works on a level above the block device driver layer. It is implemented either in hardware (in a [[disk array controller]]) or in software (in a [[device driver]]). |

||

The most basic method is [[disk mirroring]], typical for locally |

The most basic method is [[disk mirroring]], which is typical for locally connected disks. The storage industry narrows the definitions, so ''mirroring'' is a local (short-distance) operation. A replication is extendable across a [[computer network]], so that the disks can be located in physically distant locations, and the primary/replica database replication model is usually applied. The purpose of replication is to prevent damage from failures or [[Disaster Recovery|disaster]]s that may occur in one location – or in case such events do occur, to improve the ability to recover data. For replication, latency is the key factor because it determines either how far apart the sites can be or the type of replication that can be employed. |

||

The main characteristic of such cross-site replication is how write operations are handled |

The main characteristic of such cross-site replication is how write operations are handled, through either asynchronous or synchronous replication; synchronous replication needs to wait for the destination server's response in any write operation whereas asynchronous replication does not. |

||

[[Synchronization|Synchronous]] replication guarantees "zero data loss" by the means of [[atomic operation|atomic]] write operations, where the write operation is not considered complete until acknowledged by both the local and remote storage. Most applications wait for a write transaction to complete before proceeding with further work, hence overall performance decreases considerably. Inherently, performance drops proportionally to distance, as minimum [[Latency (engineering)|latency]] is dictated by the [[speed of light]]. For 10 km distance, the fastest possible roundtrip takes 67 μs, whereas an entire local cached write completes in about 10–20 μs. |

|||

** An often-overlooked aspect of synchronous replication is the fact that failure of ''remote'' replica, or even just the ''interconnection'', stops by definition any and all writes (freezing the local storage system). This is the behaviour that guarantees zero data loss. However, many commercial systems at such potentially dangerous point do not freeze, but just proceed with local writes, losing the desired zero [[recovery point objective]]. |

|||

** The main difference between synchronous and asynchronous volume replication is that synchronous replication needs to wait for the destination server in any write operation.<ref>[http://kb.open-e.com/What-is-the-difference-between-asynchronous-and-synchronous-volume-replication-_682.html Open-E Knowledgebase. "What is the difference between asynchronous and synchronous volume replication?"] 12 August 2009.</ref> |

|||

* [[Asynchronous I/O|Asynchronous]] replication - write is considered complete as soon as local storage acknowledges it. Remote storage is updated, but probably with a small [[lag]]. Performance is greatly increased, but in case of losing a local storage, the remote storage is not guaranteed to have the current copy of data and most recent data may be lost. |

|||

* Semi-synchronous replication - this usually means{{citation needed|date=September 2009}} that a write is considered complete as soon as local storage acknowledges it and a remote server acknowledges that it has received the write either into memory or to a dedicated log file. The actual remote write is not performed immediately but is performed asynchronously, resulting in better performance than synchronous replication but with increased risk of the remote write failing. |

|||

** Point-in-time replication - introduces periodic [[snapshot (computer storage)|snapshot]]s that are replicated instead of primary storage. If the replicated snapshots are pointer-based, then during replication only the changed data is moved not the entire volume. Using this method, replication can occur over smaller, less expensive bandwidth links such as iSCSI or T1 instead of fiber optic lines. |

|||

In [[Asynchronous I/O|asynchronous]] replication, the write operation is considered complete as soon as local storage acknowledges it. Remote storage is updated with a small [[Latency (engineering)|lag]]. Performance is greatly increased, but in case of a local storage failure, the remote storage is not guaranteed to have the current copy of data (the most recent data may be lost). |

|||

To address the limits imposed by latency, techniques of [[WAN optimization]] can be applied to the link. |

|||

Semi-synchronous replication typically considers a write operation complete when acknowledged by local storage and received or logged by the remote server. The actual remote write is performed asynchronously, resulting in better performance but remote storage will lag behind the local storage, so that there is no guarantee of durability (i.e., seamless transparency) in the case of local storage failure.{{citation needed|date=September 2009}} |

|||

Most important implementations: |

|||

* [[DRBD]] module for Linux. |

|||

* [[NetApp filer|NetApp]] SnapMirror |

|||

* [[SRDF|EMC SRDF]] |

|||

* [[Peer to Peer Remote Copy|IBM PPRC]] and [[Global Mirror]] (known together as IBM Copy Services) |

|||

* [[Hitachi TrueCopy]] |

|||

* Hewlett-Packard Continuous Access (HP CA) |

|||

* [[Veritas Software|Symantec Veritas Volume Replicator]] (VVR) |

|||

* [[DataCore Software|DataCore]] SANsymphony & SANmelody |

|||

* FalconStor Replication & Mirroring (sub-block heterogeneous point-in-time, async, sync) |

|||

* Compellent Remote Instant Replay |

|||

* [[RecoverPoint|EMC RecoverPoint]] |

|||

Point-in-time replication produces periodic [[Snapshot (computer storage)|snapshot]]s which are replicated instead of primary storage. This is intended to replicate only the changed data instead of the entire volume. As less information is replicated using this method, replication can occur over less-expensive bandwidth links such as iSCSI or T1 instead of fiberoptic lines. |

|||

== File Based Replication == |

|||

File base replication is replicating files at a logical level rather than replicating at the storage block level. There are many different ways of performing this and unlike storage level replication, they are almost exclusively software solutions. |

|||

=== Implementations === |

|||

{{Main|distributed fault-tolerant file systems|distributed parallel fault-tolerant file systems}} |

|||

Many [[distributed filesystem]]s use replication to ensure fault tolerance and avoid a single point of failure. |

|||

Many commercial synchronous replication systems do not freeze when the remote replica fails or loses connection – behaviour which guarantees zero data loss – but proceed to operate locally, losing the desired zero [[recovery point objective]]. |

|||

Techniques of [[WAN optimization|wide-area network (WAN) optimization]] can be applied to address the limits imposed by latency. |

|||

== File-based replication == |

|||

File-based replication conducts data replication at the logical level (i.e., individual data files) rather than at the storage block level. There are many different ways of performing this, which almost exclusively rely on software. |

|||

=== Capture with a kernel driver === |

=== Capture with a kernel driver === |

||

A [[kernel driver]] (specifically a [[filter driver]]) can be used to intercept calls to the filesystem functions, capturing any activity as it occurs. This uses the same type of technology that real-time active virus checkers employ. At this level, logical file operations are captured like file open, write, delete, etc. The kernel driver transmits these commands to another process, generally over a network to a different machine, which will mimic the operations of the source machine. Like block-level storage replication, the file-level replication allows both synchronous and asynchronous modes. In synchronous mode, write operations on the source machine are held and not allowed to occur until the destination machine has acknowledged the successful replication. Synchronous mode is less common with file replication products although a few solutions exist. |

|||

File |

File-level replication solutions allow for informed decisions about replication based on the location and type of the file. For example, temporary files or parts of a filesystem that hold no business value could be excluded. The data transmitted can also be more granular; if an application writes 100 bytes, only the 100 bytes are transmitted instead of a complete disk block (generally 4,096 bytes). This substantially reduces the amount of data sent from the source machine and the storage burden on the destination machine. |

||

Drawbacks of this software-only solution include the requirement for implementation and maintenance on the operating system level, and an increased burden on the machine's processing power. |

|||

==== File system journal replication ==== |

|||

Notable implementations: |

|||

Similarly to database [[transaction log]]s, many [[file system]]s have the ability to [[Journaling file system|journal]] their activity. The journal can be sent to another machine, either periodically or in real time by streaming. On the replica side, the journal can be used to play back file system modifications. |

|||

One of the notable implementations is [[Microsoft]]'s [[System Center Data Protection Manager]] (DPM), released in 2005, which performs periodic updates but does not offer real-time replication.{{citation needed|date=November 2018}} |

|||

* [[Cofio Software]] [http://www.cofio.com/AIMstor-Replication/ AIMstor Replication] |

|||

* [[Double-Take Software]] [http://www.doubletake.com/uk/products/double-take-availability/Pages/default.aspx Availability] |

|||

=== Batch replication === |

|||

This is the process of comparing the source and destination file systems and ensuring that the destination matches the source. The key benefit is that such solutions are generally free or inexpensive. The downside is that the process of synchronizing them is quite system-intensive, and consequently this process generally runs infrequently. |

|||

In many ways working like a database journal, many filesystems have the ability to journal their activity. The journal can be sent to another machine, either periodically or in real time. It can be used there to play back events. |

|||

One of the notable implementations is [[rsync]]. |

|||

* [[Microsoft]] [[System Center Data Protection Manager|DPM]] (periodical updates, not in real time) |

|||

== Replication within file == |

|||

This is the process of comparing the source and destination filesystems and ensuring that the destination matches the source. The key benefit is that such solutions are generally free or inexpensive. The downside is that the process of synchronizing them is quite system intensive and consequently this process is generally run infrequently. |

|||

In a [[paging]] operating system, pages in a paging file are sometimes replicated within a track to reduce rotational latency. |

|||

Notable implementations: |

|||

In [[IBM]]'s [[VSAM]], index data are sometimes replicated within a track to reduce rotational latency. |

|||

* [[rsync]] |

|||

== Distributed shared memory replication == |

== Distributed shared memory replication == |

||

{{expand section|date=November 2018}} |

|||

Another example of using replication appears in [[distributed shared memory]] systems, where many nodes of the system share the same [[Page (computer memory)|page]] of memory. This usually means that each node has a separate copy (replica) of this page. |

|||

== Primary-backup and multi-primary replication == |

|||

Another example of using replication appears in [[distributed shared memory]] systems, where it may happen that many nodes of the system share the same page of the memory - which usually means, that each node has a separate copy (replica) of this page. |

|||

Many classical approaches to replication are based on a primary-backup model where one device or process has unilateral control over one or more other processes or devices. For example, the primary might perform some computation, streaming a log of updates to a backup (standby) process, which can then take over if the primary fails. This approach is common for replicating databases, despite the risk that if a portion of the log is lost during a failure, the backup might not be in a state identical to the primary, and transactions could then be lost. |

|||

A weakness of primary-backup schemes is that only one is actually performing operations. Fault-tolerance is gained, but the identical backup system doubles the costs. For this reason, starting {{circa|1985}}, the distributed systems research community began to explore alternative methods of replicating data. An outgrowth of this work was the emergence of schemes in which a group of replicas could cooperate, with each process acting as a backup while also handling a share of the workload. |

|||

==Primary-backup and multi-primary replication== |

|||

Computer scientist [[Jim Gray (computer scientist)|Jim Gray]] analyzed multi-primary replication schemes under the transactional model and published a widely cited paper skeptical of the approach "The Dangers of Replication and a Solution".<ref>[http://research.microsoft.com/~gray/replicas.ps "The Dangers of Replication and a Solution"]</ref><ref>''Proceedings of the 1999 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data: SIGMOD '99'', Philadelphia, PA, US; June 1–3, 1999, Volume 28; p. 3.</ref> He argued that unless the data splits in some natural way so that the database can be treated as ''n'' disjoint sub-databases, concurrency control conflicts will result in seriously degraded performance and the group of replicas will probably slow as a function of ''n''. Gray suggested that the most common approaches are likely to result in degradation that scales as ''O(n³)''. His solution, which is to partition the data, is only viable in situations where data actually has a natural partitioning key. |

|||

Many classical approaches to replication are based on a primary/backup model where one device or process has unilateral control over one or more other processes or devices. For example, the primary might perform some computation, streaming a log of updates to a backup (standby) process, which can then take over if the primary fails. This approach is the most common one for replicating databases, despite the risk that if a portion of the log is lost during a failure, the backup might not be in a state identical to the one the primary was in, and transactions could then be lost. |

|||

In the 1985–1987, the [[virtual synchrony]] model was proposed and emerged as a widely adopted standard (it was used in the Isis Toolkit, Horus, Transis, Ensemble, Totem, [[Spread Toolkit|Spread]], C-Ensemble, Phoenix and Quicksilver systems, and is the basis for the [[Common Object Request Broker Architecture|CORBA]] fault-tolerant computing standard). Virtual synchrony permits a multi-primary approach in which a group of processes cooperates to parallelize some aspects of request processing. The scheme can only be used for some forms of in-memory data, but can provide linear speedups in the size of the group. |

|||

A weakness of primary/backup schemes is that in settings where both processes could have been active, only one is actually performing operations. We're gaining fault-tolerance but spending twice as much money to get this property. For this reason, starting in the period around 1985, the distributed systems research community began to explore alternative methods of replicating data. An outgrowth of this work was the emergence of schemes in which a group of replicas could cooperate, with each process backup up the others, and each handling some share of the workload. |

|||

A number of modern products support similar schemes. For example, the Spread Toolkit supports this same virtual synchrony model and can be used to implement a multi-primary replication scheme; it would also be possible to use C-Ensemble or Quicksilver in this manner. [[WANdisco]] permits active replication where every node on a network is an exact copy or replica and hence every node on the network is active at one time; this scheme is optimized for use in a [[wide area network]] (WAN). |

|||

[[Jim Gray (computer scientist)|Jim Gray]], a towering figure within the database community, analyzed multi-primary replication schemes under the transactional model and ultimately published a widely cited paper skeptical of the approach ([http://research.microsoft.com/~gray/replicas.ps "The Dangers of Replication and a Solution"]). In a nutshell, he argued that unless data splits in some natural way so that the database can be treated as ''n'' disjoint sub-databases, concurrency control conflicts will result in seriously degraded performance and the group of replicas will probably slow down as a function of ''n''. Indeed, he suggests that the most common approaches are likely to result in degradation that scales as ''O(n³)''. His solution, which is to partition the data, is only viable in situations where data actually has a natural partitioning key. |

|||

Modern multi-primary replication protocols optimize for the common failure-free operation. Chain replication<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=van Renesse |first1=Robbert |last2=Schneider |first2=Fred B. |date=2004-12-06 |title=Chain replication for supporting high throughput and availability |url=https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/1251254.1251261 |journal=Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Symposium on Operating Systems Design & Implementation - Volume 6 |series=OSDI'04 |location=USA |publisher=USENIX Association |pages=7 |doi=}}</ref> is a popular family of such protocols. State-of-the-art protocol variants<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Terrace |first1=Jeff |last2=Freedman |first2=Michael J. |date=2009-06-14 |title=Object storage on CRAQ: high-throughput chain replication for read-mostly workloads |url=https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/1855807.1855818 |journal=USENIX Annual Technical Conference |series=USENIX'09 |location=USA |pages=11 |doi=}}</ref> of chain replication offer high throughput and strong consistency by arranging replicas in a chain for writes. This approach enables local reads on all replica nodes but has high latency for writes that must traverse multiple nodes sequentially. |

|||

The situation is not always so bleak. For example, in the 1985-1987 period, the [[virtual synchrony]] model was proposed and emerged as a widely adopted standard (it was used in the Isis Toolkit, Horus, Transis, Ensemble, Totem, [[Spread Toolkit|Spread]], C-Ensemble, Phoenix and Quicksilver systems, and is the basis for the CORBA fault-tolerant computing standard; the model is also used in IBM Websphere to replicate business logic and in Microsoft's Windows Server 2008 [[Microsoft Cluster Server|enterprise clustering]] technology). Virtual synchrony permits a multi-primary approach in which a group of processes cooperate to parallelize some aspects of request processing. The scheme can only be used for some forms of in-memory data, but when feasible, provides linear speedups in the size of the group. |

|||

A more recent multi-primary protocol, [https://hermes-protocol.com/ Hermes],<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Katsarakis |first1=Antonios |last2=Gavrielatos |first2=Vasilis |last3=Katebzadeh |first3=M.R. Siavash |last4=Joshi |first4=Arpit |last5=Dragojevic |first5=Aleksandar |last6=Grot |first6=Boris |last7=Nagarajan |first7=Vijay |title=Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems |chapter=Hermes: A Fast, Fault-Tolerant and Linearizable Replication Protocol |date=2020-03-13 |chapter-url=https://doi.org/10.1145/3373376.3378496 |series=ASPLOS '20 |location=New York, NY, USA |publisher=Association for Computing Machinery |pages=201–217 |doi=10.1145/3373376.3378496 |hdl=20.500.11820/c8bd74e1-5612-4b81-87fe-175c1823d693 |isbn=978-1-4503-7102-5|s2cid=210921224 }}</ref> combines cache-coherent-inspired invalidations and logical timestamps to achieve strong consistency with local reads and high-performance writes from all replicas. During fault-free operation, its broadcast-based writes are non-conflicting and commit after just one multicast round-trip to replica nodes. This design results in high throughput and low latency for both reads and writes. |

|||

A number of modern products support similar schemes. For example, the [[Spread Toolkit]] supports this same virtual synchrony model and can be used to implement a multi-primary replication scheme; it would also be possible to use C-Ensemble or Quicksilver in this manner. [[WANdisco]] permits active replication where every node on a network is an exact copy or [[replica]] and hence every node on the network is active at one time; this scheme is optimized for use in a [[wide area network]]. |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Change data capture]] |

* [[Change data capture]] |

||

* [[Fault-tolerant computer system]] |

|||

* [[Cloud computing]] |

|||

* [[ |

* [[Log shipping]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Multi-master replication]] |

||

* [[Failover]] |

|||

* [[Fault tolerant system]] |

|||

* [[Log Shipping]] |

|||

* [[Optimistic replication]] |

* [[Optimistic replication]] |

||

* [[ |

* [[Shard (data)]] |

||

* [[State machine replication]] |

|||

* [[Software transactional memory]] |

|||

* [[Transparency (computing)]] |

|||

* [[Virtual synchrony]] |

* [[Virtual synchrony]] |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist|30em}} |

|||

<references/> |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Computer storage]] |

|||

[[Category:Data synchronization]] |

[[Category:Data synchronization]] |

||

[[Category:Fault-tolerant computer systems]] |

[[Category:Fault-tolerant computer systems]] |

||

[[Category:Database management systems]] |

|||

[[de:Replikation (Datenverarbeitung)]] |

|||

[[fr:Réplication (informatique)]] |

|||

[[ko:리플리케이션]] |

|||

[[he:שכפול נתונים]] |

|||

[[nl:Replicatie (informatica)]] |

|||

[[ja:レプリケーション]] |

|||

[[pl:Replikacja danych]] |

|||

[[pt:Replicação de dados]] |

|||

[[ru:Репликация (вычислительная техника)]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 16:55, 22 December 2024

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2012) |

Replication in computing refers to maintaining multiple copies of data, processes, or resources to ensure consistency across redundant components. This fundamental technique spans databases, file systems, and distributed systems, serving to improve availability, fault-tolerance, accessibility, and performance.[1] Through replication, systems can continue operating when components fail (failover), serve requests from geographically distributed locations, and balance load across multiple machines. The challenge lies in maintaining consistency between replicas while managing the fundamental tradeoffs between data consistency, system availability, and network partition tolerance – constraints known as the CAP theorem.[2]

Terminology

[edit]Replication in computing can refer to:

- Data replication, where the same data is stored on multiple storage devices

- Computation replication, where the same computing task is executed many times. Computational tasks may be:

- Replicated in space, where tasks are executed on separate devices

- Replicated in time, where tasks are executed repeatedly on a single device

Replication in space or in time is often linked to scheduling algorithms.[3]

Access to a replicated entity is typically uniform with access to a single non-replicated entity. The replication itself should be transparent to an external user. In a failure scenario, a failover of replicas should be hidden as much as possible with respect to quality of service.[4]

Computer scientists further describe replication as being either:

- Active replication, which is performed by processing the same request at every replica

- Passive replication, which involves processing every request on a single replica and transferring the result to the other replicas

When one leader replica is designated via leader election to process all the requests, the system is using a primary-backup or primary-replica scheme, which is predominant in high-availability clusters. In comparison, if any replica can process a request and distribute a new state, the system is using a multi-primary or multi-master scheme. In the latter case, some form of distributed concurrency control must be used, such as a distributed lock manager.

Load balancing differs from task replication, since it distributes a load of different computations across machines, and allows a single computation to be dropped in case of failure. Load balancing, however, sometimes uses data replication (especially multi-master replication) internally, to distribute its data among machines.

Backup differs from replication in that the saved copy of data remains unchanged for a long period of time.[5] Replicas, on the other hand, undergo frequent updates and quickly lose any historical state. Replication is one of the oldest and most important topics in the overall area of distributed systems.

Data replication and computation replication both require processes to handle incoming events. Processes for data replication are passive and operate only to maintain the stored data, reply to read requests and apply updates. Computation replication is usually performed to provide fault-tolerance, and take over an operation if one component fails. In both cases, the underlying needs are to ensure that the replicas see the same events in equivalent orders, so that they stay in consistent states and any replica can respond to queries.

Replication models in distributed systems

[edit]Three widely cited models exist for data replication, each having its own properties and performance:

- Transactional replication: used for replicating transactional data, such as a database. The one-copy serializability model is employed, which defines valid outcomes of a transaction on replicated data in accordance with the overall ACID (atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) properties that transactional systems seek to guarantee.

- State machine replication: assumes that the replicated process is a deterministic finite automaton and that atomic broadcast of every event is possible. It is based on distributed consensus and has a great deal in common with the transactional replication model. This is sometimes mistakenly used as a synonym of active replication. State machine replication is usually implemented by a replicated log consisting of multiple subsequent rounds of the Paxos algorithm. This was popularized by Google's Chubby system, and is the core behind the open-source Keyspace data store.[6][7]

- Virtual synchrony: involves a group of processes which cooperate to replicate in-memory data or to coordinate actions. The model defines a distributed entity called a process group. A process can join a group and is provided with a checkpoint containing the current state of the data replicated by group members. Processes can then send multicasts to the group and will see incoming multicasts in the identical order. Membership changes are handled as a special multicast that delivers a new "membership view" to the processes in the group.[8]

Database replication

[edit]Database replication involves maintaining copies of the same data on multiple machines, typically implemented through three main approaches: single-leader, multi-leader, and leaderless replication.[1]

In single-leader (also called primary/replica) replication, one database instance is designated as the leader (primary), which handles all write operations. The leader logs these updates, which then propagate to replica nodes. Each replica acknowledges receipt of updates, enabling subsequent write operations. Replicas primarily serve read requests, though they may serve stale data due to replication lag – the delay in propagating changes from the leader.

In multi-master replication (also called multi-leader), updates can be submitted to any database node, which then propagate to other servers. This approach is particularly beneficial in multi-data center deployments, where it enables local write processing while masking inter-data center network latency.[1] However, it introduces substantially increased costs and complexity which may make it impractical in some situations. The most common challenge that exists in multi-master replication is transactional conflict prevention or resolution when concurrent modifications occur on different leader nodes.

Most synchronous (or eager) replication solutions perform conflict prevention, while asynchronous (or lazy) solutions have to perform conflict resolution. For instance, if the same record is changed on two nodes simultaneously, an eager replication system would detect the conflict before confirming the commit and abort one of the transactions. A lazy replication system would allow both transactions to commit and run a conflict resolution during re-synchronization. Conflict resolution methods can include techniques like last-write-wins, application-specific logic, or merging concurrent updates.[1]

However, replication transparency can not always be achieved. When data is replicated in a database, they will be constrained by CAP theorem or PACELC theorem. In the NoSQL movement, data consistency is usually sacrificed in exchange for other more desired properties, such as availability (A), partition tolerance (P), etc. Various data consistency models have also been developed to serve as Service Level Agreement (SLA) between service providers and the users.

There are several techniques for replicating data changes between nodes:[1]

- Statement-based replication: Write requests (such as SQL statements) are logged and transmitted to replicas for execution. This can be problematic with non-deterministic functions or statements having side effects.

- Write-ahead log (WAL) shipping: The storage engine's low-level write-ahead log is replicated, ensuring identical data structures across nodes.

- Logical (row-based) replication: Changes are described at the row level using a dedicated log format, providing greater flexibility and independence from storage engine internals.

Disk storage replication

[edit]

Active (real-time) storage replication is usually implemented by distributing updates of a block device to several physical hard disks. This way, any file system supported by the operating system can be replicated without modification, as the file system code works on a level above the block device driver layer. It is implemented either in hardware (in a disk array controller) or in software (in a device driver).

The most basic method is disk mirroring, which is typical for locally connected disks. The storage industry narrows the definitions, so mirroring is a local (short-distance) operation. A replication is extendable across a computer network, so that the disks can be located in physically distant locations, and the primary/replica database replication model is usually applied. The purpose of replication is to prevent damage from failures or disasters that may occur in one location – or in case such events do occur, to improve the ability to recover data. For replication, latency is the key factor because it determines either how far apart the sites can be or the type of replication that can be employed.

The main characteristic of such cross-site replication is how write operations are handled, through either asynchronous or synchronous replication; synchronous replication needs to wait for the destination server's response in any write operation whereas asynchronous replication does not.

Synchronous replication guarantees "zero data loss" by the means of atomic write operations, where the write operation is not considered complete until acknowledged by both the local and remote storage. Most applications wait for a write transaction to complete before proceeding with further work, hence overall performance decreases considerably. Inherently, performance drops proportionally to distance, as minimum latency is dictated by the speed of light. For 10 km distance, the fastest possible roundtrip takes 67 μs, whereas an entire local cached write completes in about 10–20 μs.

In asynchronous replication, the write operation is considered complete as soon as local storage acknowledges it. Remote storage is updated with a small lag. Performance is greatly increased, but in case of a local storage failure, the remote storage is not guaranteed to have the current copy of data (the most recent data may be lost).

Semi-synchronous replication typically considers a write operation complete when acknowledged by local storage and received or logged by the remote server. The actual remote write is performed asynchronously, resulting in better performance but remote storage will lag behind the local storage, so that there is no guarantee of durability (i.e., seamless transparency) in the case of local storage failure.[citation needed]

Point-in-time replication produces periodic snapshots which are replicated instead of primary storage. This is intended to replicate only the changed data instead of the entire volume. As less information is replicated using this method, replication can occur over less-expensive bandwidth links such as iSCSI or T1 instead of fiberoptic lines.

Implementations

[edit]Many distributed filesystems use replication to ensure fault tolerance and avoid a single point of failure.

Many commercial synchronous replication systems do not freeze when the remote replica fails or loses connection – behaviour which guarantees zero data loss – but proceed to operate locally, losing the desired zero recovery point objective.

Techniques of wide-area network (WAN) optimization can be applied to address the limits imposed by latency.

File-based replication

[edit]File-based replication conducts data replication at the logical level (i.e., individual data files) rather than at the storage block level. There are many different ways of performing this, which almost exclusively rely on software.

Capture with a kernel driver

[edit]A kernel driver (specifically a filter driver) can be used to intercept calls to the filesystem functions, capturing any activity as it occurs. This uses the same type of technology that real-time active virus checkers employ. At this level, logical file operations are captured like file open, write, delete, etc. The kernel driver transmits these commands to another process, generally over a network to a different machine, which will mimic the operations of the source machine. Like block-level storage replication, the file-level replication allows both synchronous and asynchronous modes. In synchronous mode, write operations on the source machine are held and not allowed to occur until the destination machine has acknowledged the successful replication. Synchronous mode is less common with file replication products although a few solutions exist.

File-level replication solutions allow for informed decisions about replication based on the location and type of the file. For example, temporary files or parts of a filesystem that hold no business value could be excluded. The data transmitted can also be more granular; if an application writes 100 bytes, only the 100 bytes are transmitted instead of a complete disk block (generally 4,096 bytes). This substantially reduces the amount of data sent from the source machine and the storage burden on the destination machine.

Drawbacks of this software-only solution include the requirement for implementation and maintenance on the operating system level, and an increased burden on the machine's processing power.

File system journal replication

[edit]Similarly to database transaction logs, many file systems have the ability to journal their activity. The journal can be sent to another machine, either periodically or in real time by streaming. On the replica side, the journal can be used to play back file system modifications.

One of the notable implementations is Microsoft's System Center Data Protection Manager (DPM), released in 2005, which performs periodic updates but does not offer real-time replication.[citation needed]

Batch replication

[edit]This is the process of comparing the source and destination file systems and ensuring that the destination matches the source. The key benefit is that such solutions are generally free or inexpensive. The downside is that the process of synchronizing them is quite system-intensive, and consequently this process generally runs infrequently.

One of the notable implementations is rsync.

Replication within file

[edit]In a paging operating system, pages in a paging file are sometimes replicated within a track to reduce rotational latency.

In IBM's VSAM, index data are sometimes replicated within a track to reduce rotational latency.

Distributed shared memory replication

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2018) |

Another example of using replication appears in distributed shared memory systems, where many nodes of the system share the same page of memory. This usually means that each node has a separate copy (replica) of this page.

Primary-backup and multi-primary replication

[edit]Many classical approaches to replication are based on a primary-backup model where one device or process has unilateral control over one or more other processes or devices. For example, the primary might perform some computation, streaming a log of updates to a backup (standby) process, which can then take over if the primary fails. This approach is common for replicating databases, despite the risk that if a portion of the log is lost during a failure, the backup might not be in a state identical to the primary, and transactions could then be lost.

A weakness of primary-backup schemes is that only one is actually performing operations. Fault-tolerance is gained, but the identical backup system doubles the costs. For this reason, starting c. 1985, the distributed systems research community began to explore alternative methods of replicating data. An outgrowth of this work was the emergence of schemes in which a group of replicas could cooperate, with each process acting as a backup while also handling a share of the workload.

Computer scientist Jim Gray analyzed multi-primary replication schemes under the transactional model and published a widely cited paper skeptical of the approach "The Dangers of Replication and a Solution".[9][10] He argued that unless the data splits in some natural way so that the database can be treated as n disjoint sub-databases, concurrency control conflicts will result in seriously degraded performance and the group of replicas will probably slow as a function of n. Gray suggested that the most common approaches are likely to result in degradation that scales as O(n³). His solution, which is to partition the data, is only viable in situations where data actually has a natural partitioning key.

In the 1985–1987, the virtual synchrony model was proposed and emerged as a widely adopted standard (it was used in the Isis Toolkit, Horus, Transis, Ensemble, Totem, Spread, C-Ensemble, Phoenix and Quicksilver systems, and is the basis for the CORBA fault-tolerant computing standard). Virtual synchrony permits a multi-primary approach in which a group of processes cooperates to parallelize some aspects of request processing. The scheme can only be used for some forms of in-memory data, but can provide linear speedups in the size of the group.

A number of modern products support similar schemes. For example, the Spread Toolkit supports this same virtual synchrony model and can be used to implement a multi-primary replication scheme; it would also be possible to use C-Ensemble or Quicksilver in this manner. WANdisco permits active replication where every node on a network is an exact copy or replica and hence every node on the network is active at one time; this scheme is optimized for use in a wide area network (WAN).

Modern multi-primary replication protocols optimize for the common failure-free operation. Chain replication[11] is a popular family of such protocols. State-of-the-art protocol variants[12] of chain replication offer high throughput and strong consistency by arranging replicas in a chain for writes. This approach enables local reads on all replica nodes but has high latency for writes that must traverse multiple nodes sequentially.

A more recent multi-primary protocol, Hermes,[13] combines cache-coherent-inspired invalidations and logical timestamps to achieve strong consistency with local reads and high-performance writes from all replicas. During fault-free operation, its broadcast-based writes are non-conflicting and commit after just one multicast round-trip to replica nodes. This design results in high throughput and low latency for both reads and writes.

See also

[edit]- Change data capture

- Fault-tolerant computer system

- Log shipping

- Multi-master replication

- Optimistic replication

- Shard (data)

- State machine replication

- Virtual synchrony

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Kleppmann, Martin (2017). Designing Data-Intensive Applications: The Big Ideas Behind Reliable, Scalable, and Maintainable Systems. O'Reilly Media. pp. 151–185. ISBN 9781491903100.

- ^ Brewer, Eric A. (2000). "Towards robust distributed systems". Proceedings of the Annual ACM Symposium on Principles of Distributed Computing. doi:10.1145/343477.343502.

- ^ Mansouri, Najme, Gholam, Hosein Dastghaibyfard, and Ehsan Mansouri. "Combination of data replication and scheduling algorithm for improving data availability in Data Grids", Journal of Network and Computer Applications (2013)

- ^ V. Andronikou, K. Mamouras, K. Tserpes, D. Kyriazis, T. Varvarigou, "Dynamic QoS-aware Data Replication in Grid Environments", Elsevier Future Generation Computer Systems - The International Journal of Grid Computing and eScience, 2012

- ^ "Backup and Replication: What is the Difference?". Zerto. February 6, 2012.

- ^ Marton Trencseni, Attila Gazso (2009). "Keyspace: A Consistently Replicated, Highly-Available Key-Value Store". Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ^ Mike Burrows (2006). "The Chubby Lock Service for Loosely-Coupled Distributed Systems". Archived from the original on 2010-02-09. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ^ Birman, K.; Joseph, T. (1987-11-01). "Exploiting virtual synchrony in distributed systems". Proceedings of the eleventh ACM Symposium on Operating systems principles - SOSP '87. SOSP '87. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 123–138. doi:10.1145/41457.37515. ISBN 978-0-89791-242-6. S2CID 7739589.

- ^ "The Dangers of Replication and a Solution"

- ^ Proceedings of the 1999 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data: SIGMOD '99, Philadelphia, PA, US; June 1–3, 1999, Volume 28; p. 3.

- ^ van Renesse, Robbert; Schneider, Fred B. (2004-12-06). "Chain replication for supporting high throughput and availability". Proceedings of the 6th Conference on Symposium on Operating Systems Design & Implementation - Volume 6. OSDI'04. USA: USENIX Association: 7.

- ^ Terrace, Jeff; Freedman, Michael J. (2009-06-14). "Object storage on CRAQ: high-throughput chain replication for read-mostly workloads". USENIX Annual Technical Conference. USENIX'09. USA: 11.

- ^ Katsarakis, Antonios; Gavrielatos, Vasilis; Katebzadeh, M.R. Siavash; Joshi, Arpit; Dragojevic, Aleksandar; Grot, Boris; Nagarajan, Vijay (2020-03-13). "Hermes: A Fast, Fault-Tolerant and Linearizable Replication Protocol". Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems. ASPLOS '20. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery. pp. 201–217. doi:10.1145/3373376.3378496. hdl:20.500.11820/c8bd74e1-5612-4b81-87fe-175c1823d693. ISBN 978-1-4503-7102-5. S2CID 210921224.