Iodine: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [accepted revision] |

No edit summary |

Don't override template-generated correct URL with a hard-coded incorrect one |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{About|the chemical element}} |

{{About|the chemical element}} |

||

{{ |

{{Pp-pc1}} |

||

{{Use British English|date=December 2024}} |

|||

'''Iodine''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|aɪ|.|ɵ|d|aɪ|n}} {{respell|EYE|o-dyne}}, {{IPAc-en|ˈ|aɪ|.|ɵ|d|ɨ|n}} {{respell|EYE|o-dən}}, or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|aɪ|.|ɵ|d|iː|n}} {{respell|EYE|o-deen}} in both American<ref>[http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/iodine Iodine]. Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved on 2011-12-23.</ref> and British<ref>[http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/iodine?view=uk Iodine] – Oxford Dictionaries Online (World English)]. Retrieved on 2011-12-23.</ref> English<ref>All three pronunciations are used in both British and American English, but {{IPAc-en|ˈ|aɪ|.|ɵ|d|iː|n}} {{respell|EYE|o-deen}} is the most common British one and {{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|aɪ|.|ɵ|d|aɪ|n}} {{respell|EYE|o-dyne}} is the most common American one.</ref>) is a [[chemical element]] with symbol '''I''' and [[atomic number]] 53. The name is from [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] {{lang|grc|ἰοειδής}} ''ioeidēs'', meaning violet or purple, due to the color of elemental iodine vapor.<ref>Online Etymology Dictionary, s.v. [http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=iodine ''iodine'']. Retrieved 2012-02-07.</ref> |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=December 2024}} |

|||

{{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

{{Infobox iodine|engvar=en-GB}} |

|||

'''Iodine''' is a [[chemical element]]; it has [[Chemical symbol|symbol]] '''I''' and [[atomic number]] 53. The heaviest of the stable [[halogen]]s, it exists at [[Standard temperature and pressure|standard conditions]] as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid that melts to form a deep violet liquid at {{convert|114|C}}, and boils to a violet gas at {{convert|184|C}}. The element was discovered by the French chemist [[Bernard Courtois]] in 1811 and was named two years later by [[Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac]], after the [[Ancient Greek]] {{lang|grc|Ιώδης}}, meaning 'violet'. |

|||

Iodine and its [[Chemical compound|compounds]] are primarily used in [[nutrition]], and industrially in the production of [[acetic acid]] and certain [[polymer]]s. Iodine's relatively high atomic number, low [[toxicity]], and ease of attachment to [[organic compound]]s have made it a part of many [[radiocontrast|X-ray contrast]] materials in modern medicine. Iodine has only one [[stable isotope]]. A number of iodine [[Radionuclide|radioisotopes]] are also used in medical applications. |

|||

Iodine occurs in many oxidation states, including [[iodide]] (I<sup>−</sup>), [[iodate]] ({{chem|IO|3|-}}), and the various [[periodate]] anions. As the heaviest essential [[Mineral (nutrient)|mineral nutrient]], iodine is required for the synthesis of [[thyroid hormones]].<ref name="lpi">{{cite web|url=http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/minerals/iodine|title=Iodine|publisher=Micronutrient Information Center, [[Linus Pauling Institute]], [[Oregon State University]], Corvallis|date=2015|access-date=20 November 2017|archive-date=17 April 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150417055246/http://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/minerals/iodine|url-status=live}}</ref> [[Iodine deficiency]] affects about two billion people and is the leading preventable cause of [[Intellectual disability|intellectual disabilities]].<ref>{{cite news|url= https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E05E3D81231F935A25751C1A9609C8B63|work=The New York Times|title=In Raising the World's I.Q., the Secret's in the Salt| vauthors = McNeil Jr DG |date=16 December 2006|access-date=21 July 2009|url-status=live|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100712011551/http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E05E3D81231F935A25751C1A9609C8B63|archive-date=12 July 2010}}</ref> |

|||

Iodine is found on Earth mainly as the highly water-soluble iodide I3<sup>-</sup>, which concentrates it in oceans and brine pools. Like the other [[halogen]]s, free iodine occurs mainly as a [[diatomic]] molecule I<sub>2</sub>, and then only momentarily after being oxidized from iodide by an oxidant like free oxygen. In the universe and on Earth, iodine's high atomic number makes it a relatively [[Abundance of the chemical elements|rare element]]. However, its presence in ocean water has given it a role in biology. It is the heaviest [[essential element]] utilized widely by life in biological functions (only [[tungsten]], employed in enzymes by a few species of bacteria, is heavier). Iodine's rarity in many soils, due to initial low abundance as a crust-element, and also leaching of soluble iodide by rainwater, has led to many deficiency problems in land animals and inland human populations. [[Iodine deficiency]] affects about two billion people and is the leading preventable cause of [[intellectual disabilities]].<ref name="mcneil">{{Cite news|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/16/health/16iodine.html?fta=y|title=In Raising the World’s I.Q., the Secret’s in the Salt|last=McNeil|first=Donald G. Jr|date=2006-12-16|work=New York Times|accessdate=2008-12-04}}</ref> |

|||

The dominant producers of iodine today are [[Chile]] and [[Japan]]. Due to its high atomic number and ease of attachment to [[organic compound]]s, it has also found favour as a non-toxic [[Radiocontrast agent|radiocontrast]] material. Because of the specificity of its uptake by the human body, radioactive isotopes of iodine can also be used to treat [[thyroid cancer]]. Iodine is also used as a [[Catalysis|catalyst]] in the industrial production of [[acetic acid]] and some [[polymer]]s. |

|||

Iodine is required by higher animals, which use it to synthesize [[thyroid hormones]], which contain the element. Because of this function, [[radioisotopes]] of iodine are concentrated in the [[thyroid gland]] along with nonradioactive iodine. The radioisotope [[iodine-131]], which has a high [[fission product yield]], concentrates in the thyroid, and is one of the most [[carcinogenic]] of [[nuclear fission]] products. |

|||

It is on the [[WHO Model List of Essential Medicines|World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines]].<ref name="WHO22nd">{{cite book | vauthors = ((World Health Organization)) | title = World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021) | year = 2021 | hdl = 10665/345533 | author-link = World Health Organization | publisher = World Health Organization | location = Geneva | id = WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02 | hdl-access=free }}</ref> |

|||

==Characteristics== |

|||

Iodine under [[Standard conditions for temperature and pressure|standard conditions]] is a bluish-black solid. It can be seen apparently [[sublimation (chemistry)|sublimating]] at standard temperatures into a violet-pink gas that has an irritating odor. This halogen forms compounds with many elements, but is less [[Reactivity (chemistry)|reactive]] than the other members of its Group VII (halogens) and has some metallic light [[Reflectivity|reflectance]]. |

|||

==History== |

|||

[[File:IodoAtomico.JPG|thumb|left|150px|alt=Round bottom flask filled with violet iodine vapor|In the gas phase, iodine shows its violet color.]] Elemental iodine dissolves easily in most organic [[solvent]]s such as [[hexane]] or [[chloroform]] owing to its lack of [[Chemical polarity|polarity]], but is only slightly soluble in water. However, the [[solubility]] of elemental iodine in water can be increased by the addition of [[potassium iodide]]. The molecular iodine [[Reversible reaction|reacts reversibly]] with the negative ion, generating the [[triiodide]] anion I<sub>3</sub><sup>−</sup> in [[Chemical equilibrium|equilibrium]], which is soluble in water. This is also the formulation of some types of medicinal (antiseptic) iodine, although [[tincture of iodine]] classically dissolves the element in aqueous [[ethanol]]. |

|||

[[File:Iodine-evaporating.jpg|left|thumb|Iodine crystals [[Sublimation (phase transition)|sublimating]] into a purple gas]] |

|||

In 1811, iodine was discovered by French chemist [[Bernard Courtois]],<ref name="court">{{cite journal| vauthors = Courtois B |title=Découverte d'une substance nouvelle dans le Vareck |trans-title=Discovery of a new substance in seaweed |journal=[[Annales de chimie]] |volume=88 |pages=304–310 |date=1813 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=RA2-PA304|language=French}} In French, seaweed that had been washed onto the shore was called "varec", "varech", or "vareck", whence the English word "wrack". Later, "varec" also referred to the ashes of such seaweed: the ashes were used as a source of iodine and salts of sodium and potassium.</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Swain PA |title=Bernard Courtois (1777–1838) famed for discovering iodine (1811), and his life in Paris from 1798 |journal=Bulletin for the History of Chemistry |volume=30 |issue=2 |page=103 |date=2005 |url=http://www.scs.uiuc.edu/~mainzv/HIST/awards/OPA%20Papers/2007-Swain.pdf |access-date=2 April 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100714110757/http://www.scs.uiuc.edu/~mainzv/HIST/awards/OPA%20Papers/2007-Swain.pdf |archive-date=14 July 2010 |url-status=dead }}</ref> who was born to a family of manufacturers of [[potassium nitrate|saltpetre]] (an essential component of [[gunpowder]]). At the time of the [[Napoleonic Wars]], saltpetre was in great demand in [[France]]. Saltpetre produced from French [[Niter|nitre beds]] required [[sodium carbonate]], which could be isolated from [[seaweed]] collected on the coasts of [[Normandy]] and [[Brittany]]. To isolate the sodium carbonate, seaweed was burned and the ash washed with water. The remaining waste was destroyed by adding [[sulfuric acid]]. Courtois once added excessive sulfuric acid and a cloud of violet vapour rose. He noted that the vapour crystallised on cold surfaces, making dark black crystals.<ref name="Greenwood794">Greenwood and Earnshaw, p. 794</ref> Courtois suspected that this material was a new element but lacked funding to pursue it further.<ref name="vdK">{{cite web |url=http://elements.vanderkrogt.net/element.php?sym=i |title=53 Iodine |publisher=Elements.vanderkrogt.net |access-date=23 October 2016 |archive-date=23 January 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100123001444/http://elements.vanderkrogt.net/element.php?sym=I |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Courtois gave samples to his friends, [[Charles Bernard Desormes]] (1777–1838) and [[Nicolas Clément]] (1779–1841), to continue research. He also gave some of the substance to chemist [[Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac]] (1778–1850), and to physicist [[André-Marie Ampère]] (1775–1836). On 29 November 1813, Desormes and Clément made Courtois' discovery public by describing the substance to a meeting of the Imperial [[Institut de France|Institute of France]].<ref>Desormes and Clément made their announcement at the Institut impérial de France on 29 November 1813; a summary of their announcement appeared in the ''Gazette nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel'' of 2 December 1813. See: |

|||

The colour of solutions of elemental iodine changes depending on the polarity of the solvent. In non-polar solvents like hexane, solutions are violet; in moderately polar [[dichloromethane]], the solution is dark crimson, and, in strongly polar solvents such as [[acetone]] or ethanol, it appears orange or brown. This effect is due to the formation of [[adduct]]s. |

|||

* {{cite journal |last1=(Staff) |title=Institut Imperial de France |journal=Le Moniteur Universel |date=2 December 1813 |issue=336 |page=1344 |url=https://www.retronews.fr/journal/gazette-nationale-ou-le-moniteur-universel/02-decembre-1813/149/1332251/2 |language=French |access-date=2 May 2021 |archive-date=28 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221128171041/https://www.retronews.fr/journal/gazette-nationale-ou-le-moniteur-universel/02-decembre-1813/149/1332251/2 |url-status=live }} |

|||

* {{cite journal |vauthors=Chattaway FD |title=The discovery of iodine |journal=Chemical News and Journal of Industrial Science |date=23 April 1909 |volume=99 |issue=2578 |pages=193–195 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Rco_AQAAIAAJ&pg=PA193 }}</ref> On 6 December 1813, Gay-Lussac found and announced that the new substance was either an element or a compound of [[oxygen]] and he found that it is an element.<ref name="Gay-Lussac">{{cite journal |vauthors=Gay-Lussac J |title=Sur un nouvel acide formé avec la substance décourverte par M. Courtois |trans-title=On a new acid formed by the substance discovered by Mr. Courtois |journal=Annales de Chimie |volume=88 |pages=311–318 |date=1813 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=PA311 |language=French |access-date=2 May 2021 |archive-date=19 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319070023/https://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=PA311#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Gay-Lussac J |title=Sur la combination de l'iode avec d'oxigène |trans-title=On the combination of iodine with oxygen |journal=Annales de Chimie |volume=88 |pages=319–321 |date=1813 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=PA319 |language=French |access-date=2 May 2021 |archive-date=19 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319070022/https://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=PA319#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Gay-Lussac J |title=Mémoire sur l'iode |trans-title=Memoir on iodine |journal=Annales de Chimie |volume=91 |pages=5–160|date=1814 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Efms0Fri1CQC&pg=PA5|language=French}}</ref> Gay-Lussac suggested the name "iode" ([[Anglicisation (linguistics)|anglicised]] as "iodine"), from the [[Ancient Greek]] {{lang|grc|Ιώδης}} ({{transliteration|grc|iodēs}}, "violet"), because of the colour of iodine vapour.<ref name="court" /><ref name="Gay-Lussac" /> Ampère had given some of his sample to British chemist [[Humphry Davy]] (1778–1829), who experimented on the substance and noted its similarity to [[chlorine]] and also found it as an element.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Davy H |author-link=Humphry Davy |title=Sur la nouvelle substance découverte par M. Courtois, dans le sel de Vareck |trans-title=On the new substance discovered by Mr. Courtois in the salt of seaweed |journal=Annales de Chimie |volume=88 |pages=322–329 |date=1813 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=PA322 |language=French |access-date=2 May 2021 |archive-date=19 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319070024/https://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=PA322#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> Davy sent a letter dated 10 December to the [[Royal Society of London]] stating that he had identified a new element called iodine.<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Davy H |author-link=Humphry Davy |title=Some experiments and observations on a new substance which becomes a violet coloured gas by heat |journal=Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London |volume=104 |pages=74–93 |date=1 January 1814 |doi=10.1098/rstl.1814.0007 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Arguments erupted between Davy and Gay-Lussac over who identified iodine first, but both scientists found that both of them identified iodine first and also knew that Courtois is the first one to isolate the element.<ref name="vdK" /> |

|||

In 1873, the French medical researcher [[Casimir Davaine]] (1812–1882) discovered the antiseptic action of iodine.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Davaine C |title=Recherches relatives à l'action des substances dites ''antiseptiques'' sur le virus charbonneux |journal=Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des Sciences |date=1873 |volume=77 |pages=821–825 |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112025711521&view=1up&seq=829 |trans-title=Investigations regarding the action of so-called ''antiseptic'' substances on the anthrax bacterium |language=French |access-date=2 May 2021 |archive-date=5 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210505013431/https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112025711521&view=1up&seq=829 |url-status=live }}</ref> [[Antonio Grossich]] (1849–1926), an Istrian-born surgeon, was among the first to use [[Sterilization (microbiology)|sterilisation]] of the operative field. In 1908, he introduced tincture of iodine as a way to rapidly sterilise the human skin in the surgical field.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Grossich A |title=Eine neue Sterilisierungsmethode der Haut bei Operationen |journal=Zentralblatt für Chirurgie |date=31 October 1908 |volume=35 |issue=44 |pages=1289–1292 |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b4150494&view=1up&seq=1305 |trans-title=A new method of sterilization of the skin for operations |language=German |access-date=2 May 2021 |archive-date=5 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210505130854/https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uc1.b4150494 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Iodine melts at the relatively low temperature of 113.7 °C, although the liquid is often obscured by a dense violet vapor of gaseous iodine. |

|||

In early [[periodic table]]s, iodine was often given the symbol ''J'', for ''Jod'', its name in [[German language|German]]; in German texts, ''J'' is still frequently used in place of ''I''.<ref>{{cite web |title=Mendeleev's First Periodic Table |url=https://web.lemoyne.edu/giunta/EA/MENDELEEVann.HTML |website=web.lemoyne.edu |access-date=25 January 2019 |archive-date=10 May 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210510014806/https://web.lemoyne.edu/GIUNTA/EA/MENDELEEVann.HTML |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==Occurrence== |

|||

[[File:Iodomethane-3D-vdW.png|thumb|left|150px|[[Methyl iodide|Iodomethane]]]] |

|||

Iodine is rare in the [[solar system]] and [[Earth's crust]] (47–60th in abundance); however, [[iodide]] salts are often very [[Solubility|soluble]] in water. Iodine occurs in slightly greater [[concentration]]s in [[seawater]] than in rocks, 0.05 vs. 0.04 ppm. Minerals containing iodine include [[caliche (mineral)|caliche]], found in [[Chile]]. The brown [[algae]] ''[[Laminaria]]'' and ''[[Fucus]]'' found in temperate zones of the Northern Hemisphere contain 0.028–0.454 dry weight percent of iodine. Aside from [[tungsten]], iodine is the heaviest element to be essential in living organisms. About 19,000 [[tonne]]s are produced annually from natural sources.<ref name = Ullmann/> |

|||

==Properties== |

|||

[[Organoiodine compound]]s are produced by marine life forms, the most notable being [[Methyl iodide|iodomethane]] (commonly called methyl iodide). About 214 kilotonnes/year of iodomethane is produced by the marine environment, by microbial activity in rice paddies and by the burning of biological material.<ref name="Bell">{{Cite journal|title = Methyl iodide: Atmospheric budget and use as a tracer of marine convection in global models|author = Bell, N. ''et al.''|journal = Journal of GeophysicalResearch|volume = 107|page= 4340|doi = 10.1029/2001JD001151|year = 2002|bibcode=2002JGRD..107.4340B}}</ref> The volatile iodomethane is broken up in the atmosphere as part of a global iodine cycle.<ref name="Bell"/><ref name="Dissanayake"/> |

|||

[[File:IodoAtomico.JPG|thumb|left|upright=0.7|alt=Round bottom flask filled with violet iodine vapour|Iodine vapour in a flask, demonstrating its characteristic rich purple colour]] |

|||

Iodine is the fourth [[halogen]], being a member of group 17 in the periodic table, below [[fluorine]], [[chlorine]], and [[bromine]]; since [[astatine]] and [[tennessine]] are radioactive, iodine is the heaviest stable halogen. Iodine has an electron configuration of [Kr]5s<sup>2</sup>4d<sup>10</sup>5p<sup>5</sup>, with the seven electrons in the fifth and outermost shell being its [[valence electron]]s. Like the other halogens, it is one electron short of a full octet and is hence an oxidising agent, reacting with many elements in order to complete its outer shell, although in keeping with [[periodic trends]], it is the weakest oxidising agent among the stable halogens: it has the lowest [[electronegativity]] among them, just 2.66 on the Pauling scale (compare fluorine, chlorine, and bromine at 3.98, 3.16, and 2.96 respectively; astatine continues the trend with an electronegativity of 2.2). Elemental iodine hence forms [[diatomic molecule]]s with chemical formula I<sub>2</sub>, where two iodine atoms share a pair of electrons in order to each achieve a stable octet for themselves; at high temperatures, these diatomic molecules reversibly dissociate a pair of iodine atoms. Similarly, the iodide anion, I<sup>−</sup>, is the strongest reducing agent among the stable halogens, being the most easily oxidised back to diatomic I<sub>2</sub>.<ref name="Greenwood800">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 800–4</ref> (Astatine goes further, being indeed unstable as At<sup>−</sup> and readily oxidised to At<sup>0</sup> or At<sup>+</sup>.)<ref>{{cite book | series = Gmelin Handbook of Inorganic and Organometallic Chemistry | title = 'At, Astatine', System No. 8a | edition=8th | year = 1985 | publisher = Springer-Verlag | isbn = 978-3-540-93516-2 | vauthors = Kugler HK, Keller C | volume = 8 }}</ref> |

|||

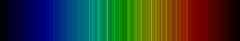

The halogens darken in colour as the group is descended: fluorine is a very pale yellow, chlorine is greenish-yellow, bromine is reddish-brown, and iodine is violet. |

|||

==Structure and bonding== |

|||

[[File:Iodine-unit-cell-3D-balls-B.png|thumb|Structure of solid iodine]] |

|||

[[File:Iodinecrystals.JPG|thumb|Crystalline iodine]] |

|||

Iodine normally exists as a diatomic molecule with an I-I [[bond length]] of 270 pm,<ref>Wells, A.F. (1984) Structural Inorganic Chemistry, Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-855370-6.</ref> one of the longest single bonds known. The I<sub>2</sub> molecules tend to interact via the weak [[van der Waals force|van der Waals]] force called the [[London dispersion force|London Forces]], and this interaction is responsible for the higher melting point compared to more compact halogens, which are also diatomic. Since the atomic size of Iodine is larger, its melting point is higher. The solid [[Crystallization|crystallizes]] as [[orthorhombic]] crystals. The crystal motif in the [[Hermann–Mauguin notation]] is Cmca (No 64), [[Pearson symbol]] oS8. The I-I bond is relatively weak, with a [[bond dissociation energy]] of 36 kcal/mol, and most bonds to iodine are weaker than for the lighter halides. One consequence of this weak bonding is the relatively high tendency of I<sub>2</sub> molecules to [[Dissociation (chemistry)|dissociate]] into atomic iodine. |

|||

Elemental iodine is slightly soluble in water, with one gram dissolving in 3450 mL at 20 °C and 1280 mL at 50 °C; [[potassium iodide]] may be added to increase solubility via formation of [[triiodide]] ions, among other polyiodides.<ref name="Greenwood804">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 804–9</ref> Nonpolar solvents such as [[hexane]] and [[carbon tetrachloride]] provide a higher solubility.<ref>{{cite book| title = Merck Index of Chemicals and Drugs| edition = 9th| date = 1976| isbn=978-0-911910-26-1| editor = Windholz, Martha| editor2 = Budavari, Susan| editor3 = Stroumtsos, Lorraine Y.| editor4 = Fertig, Margaret Noether| publisher = J A Majors Company}}</ref> Polar solutions, such as aqueous solutions, are brown, reflecting the role of these solvents as [[Lewis acids and bases|Lewis bases]]; on the other hand, nonpolar solutions are violet, the color of iodine vapour.<ref name="Greenwood804" /> [[Charge-transfer complex]]es form when iodine is dissolved in polar solvents, hence changing the colour. Iodine is violet when dissolved in carbon tetrachloride and saturated hydrocarbons but deep brown in [[Alcohol (chemistry)|alcohol]]s and [[amine]]s, solvents that form charge-transfer adducts.<ref name="King">{{cite book | vauthors = King RB |date=1995 |title=Inorganic Chemistry of Main Group Elements |publisher=Wiley-VCH |pages=173–98|isbn=978-0-471-18602-1}}</ref> |

|||

==Production== |

|||

Of the several places in which iodine occurs in nature, only two sources are useful commercially: the [[caliche (mineral)|caliche]], found in [[Chile]], and the iodine-containing brines of gas and oil fields, especially in Japan and the United States. The caliche contains [[sodium nitrate]], which is the main product of the mining activities, and small amounts of sodium iodate and sodium iodide. In the extraction of sodium nitrate, the sodium iodate and sodium iodide are extracted.<ref name="Elzea">{{Cite book|title = Industrial Minerals & Rocks: Commodities, Markets, and Uses|publisher = SME|year = 2006|isbn = 978-0-87335-233-8|url = http://www.google.com/books?id=zNicdkuulE4C|pages = 541–552|author = Kogel, Jessica Elzea ''et al.''}}</ref> The high concentration of iodine in the caliche and the extensive mining made Chile the largest producer of iodine in 2007. |

|||

The melting and boiling points of iodine are the highest among the halogens, conforming to the increasing trend down the group, since iodine has the largest electron cloud among them that is the most easily polarised, resulting in its molecules having the strongest [[Van der Waals force|Van der Waals interactions]] among the halogens. Similarly, iodine is the least volatile of the halogens, though the solid still can be observed to give off purple vapour.<ref name="Greenwood800" /> Due to this property iodine is commonly used to demonstrate [[sublimation (phase transition)|sublimation]] directly from [[solid]] to [[gas]], which gives rise to a misconception that it does not [[melting|melt]] in [[atmospheric pressure]].<ref>{{cite journal |title=The concept of sublimation – iodine as an example |journal=Educación Química |date=1 March 2012 |volume=23 |pages=171–175 |doi=10.1016/S0187-893X(17)30149-0 |language=en |issn=0187-893X|doi-access=free | vauthors = Stojanovska M, Petruševski VM, Šoptrajanov B }}</ref> Because it has the largest [[atomic radius]] among the halogens, iodine has the lowest first [[Ionization energy|ionisation energy]], lowest [[electron affinity]], lowest [[electronegativity]] and lowest reactivity of the halogens.<ref name="Greenwood800" /> |

|||

Most other producers use natural occurring brine for the production of iodine. The Japanese [[Minami Kanto gas field]] east of [[Tokyo]] and the American [[Anadarko Basin]] gas field in northwest [[Oklahoma]] are the two largest sources for iodine from brine. The brine has a temperature of over 60°C owing to the depth of the source. The [[brine]] is first [[List of purification methods in chemistry|purified]] and acidified using [[sulfuric acid]], then the iodide present is oxidized to iodine with [[chlorine]]. An iodine solution is produced, but is dilute and must be concentrated. [[Air]] is blown into the solution, causing the iodine to [[evaporate]], then it is passed into an absorbing tower containing acid where [[sulfur dioxide]] is added to [[redox|reduce]] the iodine. The [[hydrogen iodide]] (HI) is reacted with chlorine to precipitate the iodine. After filtering and purification the iodine is packed.<ref name="Elzea"/><ref>{{Cite journal|journal = Geochemical Journal|volume = 40|page = 475| year = 2006|title = Chemical and isotopic compositions of brines from dissolved-in-water type natural gas fields in Chiba, Japan|author = Maekawa, Tatsuo; Igari, Shun-Ichiro and Kaneko, Nobuyuki|doi = 10.2343/geochemj.40.475|issue = 5}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Iodine-unit-cell-3D-balls-B.png|thumb|upright=0.7|right|Structure of solid iodine]] |

|||

: 2 HI + Cl<sub>2</sub> → I<sub>2</sub>↑ + 2 HCl |

|||

The interhalogen bond in diiodine is the weakest of all the halogens. As such, 1% of a sample of gaseous iodine at atmospheric pressure is dissociated into iodine atoms at 575 °C. Temperatures greater than 750 °C are required for fluorine, chlorine, and bromine to dissociate to a similar extent. Most bonds to iodine are weaker than the analogous bonds to the lighter halogens.<ref name="Greenwood800" /> Gaseous iodine is composed of I<sub>2</sub> molecules with an I–I bond length of 266.6 pm. The I–I bond is one of the longest single bonds known. It is even longer (271.5 pm) in solid [[Orthorhombic crystal system|orthorhombic]] crystalline iodine, which has the same crystal structure as chlorine and bromine. (The record is held by iodine's neighbour [[xenon]]: the Xe–Xe bond length is 308.71 pm.)<ref>{{cite book| title = Advanced Structural Inorganic Chemistry| url = https://archive.org/details/advancedstructur00liwa| url-access = limited| vauthors = Li WK, Zhou GD, Mak TC | publisher = Oxford University Press| date = 2008| isbn = 978-0-19-921694-9| page = [https://archive.org/details/advancedstructur00liwa/page/n696 674]}}</ref> As such, within the iodine molecule, significant electronic interactions occur with the two next-nearest neighbours of each atom, and these interactions give rise, in bulk iodine, to a shiny appearance and [[semiconductor|semiconducting]] properties.<ref name="Greenwood800" /> Iodine is a two-dimensional semiconductor with a [[band gap]] of 1.3 eV (125 kJ/mol): it is a semiconductor in the plane of its crystalline layers and an insulator in the perpendicular direction.<ref name="Greenwood800" /> |

|||

: I<sub>2</sub> + 2 H<sub>2</sub>O + SO<sub>2</sub> → 2 HI + H<sub>2</sub>SO<sub>4</sub> |

|||

: 2 HI + Cl<sub>2</sub> → I<sub>2</sub>↓ + 2 HCl |

|||

===Isotopes=== |

|||

The production of iodine from seawater via [[electrolysis]] is not used owing to the sufficient abundance of iodine-rich brine. Another source of iodine is [[kelp]], used in the 18th and 19th centuries, but it is no longer economically viable.<ref>{{Cite journal| url = http://books.google.com/?id=wW8KAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA185|first = Edward C. C.|last = Stanford|journal = Journal of the Society of Arts|title = On the Economic Applications of Seaweed|year = 1862|pages = 185–189}}</ref><!--http://books.google.de/books?id=mxENAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA64 http://books.google.de/books?id=vkoEAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA285--> |

|||

{{main|Isotopes of iodine}} |

|||

Of the forty known [[isotopes of iodine]], only one occurs in nature, [[Isotopes of iodine|iodine-127]]. The others are radioactive and have half-lives too short to be [[primordial nuclide|primordial]]. As such, iodine is both [[monoisotopic element|monoisotopic]] and [[mononuclidic element|mononuclidic]] and its atomic weight is known to great precision, as it is a constant of nature.<ref name="Greenwood800" /> |

|||

The longest-lived of the radioactive isotopes of iodine is [[iodine-129]], which has a half-life of 15.7 million years, decaying via [[beta decay]] to stable [[xenon]]-129.<ref name="NUBASE">{{NUBASE 2003}}</ref> Some iodine-129 was formed along with iodine-127 before the formation of the Solar System, but it has by now completely decayed away, making it an [[extinct radionuclide]]. Its former presence may be determined from an excess of its [[decay product|daughter]] xenon-129, but early attempts<ref name="Reynolds1960a">{{Cite journal |last=Reynolds |first=J. H. |date=1 January 1960 |title=Determination of the Age of the Elements |url=https://link.aps.org/doi/10.1103/PhysRevLett.4.8 |journal=Physical Review Letters |language=en |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=8–10 |doi=10.1103/PhysRevLett.4.8 |bibcode=1960PhRvL...4....8R |issn=0031-9007}}</ref> to use this characteristic to date the supernova source for elements in the Solar System are made difficult by alternative nuclear processes giving iodine-129 and by iodine's volatility at higher temperatures.<ref name="Manuel2002">{{Cite book |last=Manuel |first=O. |date=2002 |editor-last=Manuel |editor-first=O. |chapter=Origin of Elements in the Solar System |title=Origin of Elements in the Solar System<!--yes, the chapter and the book have the same title--> |chapter-url=http://link.springer.com/10.1007/0-306-46927-8_44 |language=en |location=Boston, MA |publisher=Springer US |pages=589–643 |doi=10.1007/0-306-46927-8_44 |isbn=978-0-306-46562-8}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Iodine.PNG|thumb|right|Iodine output in 2005]] |

|||

Due to its mobility in the environment iodine-129 has been used to date very old groundwaters.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Watson JT, Roe DK, Selenkow HA | title = Iodine-129 as a "nonradioactive" tracer | journal = Radiation Research | volume = 26 | issue = 1 | pages = 159–163 | date = September 1965 | pmid = 4157487 | doi = 10.2307/3571805 | bibcode = 1965RadR...26..159W | jstor = 3571805 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Snyder G, Fabryka-Martin J | year = 2007 | title = I-129 and Cl-36 in dilute hydrocarbon waters: Marine-cosmogenic, in situ, and anthropogenic sources | journal = Applied Geochemistry | volume = 22 | issue = 3| pages = 692–714 | doi = 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2006.12.011 | bibcode = 2007ApGC...22..692S }}</ref> Traces of iodine-129 still exist today, as it is also a [[cosmogenic nuclide]], formed from [[cosmic ray spallation]] of atmospheric xenon: these traces make up 10<sup>−14</sup> to 10<sup>−10</sup> of all terrestrial iodine. It also occurs from open-air nuclear testing, and is not hazardous because of its very long half-life, the longest of all fission products. At the peak of thermonuclear testing in the 1960s and 1970s, iodine-129 still made up only about 10<sup>−7</sup> of all terrestrial iodine.<ref name="SCOPE50"> |

|||

Commercial samples often contain high concentrations of [[Impurity|impurities]], which can be removed by [[Sublimation (chemistry)|sublimation]]. The element may also be prepared in an ultra-pure form through the reaction of [[potassium iodide]] with [[copper(II) sulfate]], which gives copper(II) iodide initially. That [[Chemical decomposition|decomposes]] spontaneously to [[copper(I) iodide]] and iodine: |

|||

[http://www.scopenvironment.org/downloadpubs/scope50 SCOPE 50 - Radioecology after Chernobyl] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140513065145/http://www.scopenvironment.org/downloadpubs/scope50/ |date=13 May 2014 }}, the [[Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment]] (SCOPE), 1993. See table 1.9 in Section 1.4.5.2.</ref> Excited states of iodine-127 and iodine-129 are often used in [[Mössbauer spectroscopy]].<ref name="Greenwood800" /> |

|||

The other iodine radioisotopes have much shorter half-lives, no longer than days.<ref name="NUBASE" /> Some of them have medical applications involving the [[Thyroid|thyroid gland]], where the iodine that enters the body is stored and concentrated. [[Iodine-123]] has a half-life of thirteen hours and decays by [[electron capture]] to [[Isotopes of tellurium|tellurium-123]], emitting [[gamma radiation]]; it is used in [[Nuclear medicine|nuclear medicine imaging]], including [[Single-photon emission computed tomography|single photon emission computed tomography]] (SPECT) and [[CT scan|X-ray computed tomography]] (X-Ray CT) scans.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hupf HB, Eldridge JS, Beaver JE | title = Production of iodine-123 for medical applications | journal = The International Journal of Applied Radiation and Isotopes | volume = 19 | issue = 4 | pages = 345–351 | date = April 1968 | pmid = 5650883 | doi = 10.1016/0020-708X(68)90178-6 }}</ref> [[Iodine-125]] has a half-life of fifty-nine days, decaying by electron capture to [[Isotopes of tellurium|tellurium-125]] and emitting low-energy gamma radiation; the second-longest-lived iodine radioisotope, it has uses in [[Assay|biological assays]], [[nuclear medicine|nuclear medicine imaging]] and in [[radiation therapy]] as [[brachytherapy]] to treat a number of conditions, including [[prostate cancer]], [[uveal melanoma]]s, and [[Brain tumor|brain tumours]].<ref>Harper, P.V.; Siemens, W.D.; Lathrop, K.A.; Brizel, H.E.; Harrison, R.W. ''Iodine-125.'' Proc. Japan Conf. Radioisotopes; Vol: 4 January 1, 1961</ref> Finally, [[iodine-131]], with a half-life of eight days, beta decays to an excited state of stable [[Isotopes of xenon|xenon-131]] that then converts to the ground state by emitting gamma radiation. It is a common [[Nuclear fission product|fission product]] and thus is present in high levels in radioactive [[Nuclear fallout|fallout]]. It may then be absorbed through contaminated food, and will also accumulate in the thyroid. As it decays, it may cause damage to the thyroid. The primary risk from exposure to high levels of iodine-131 is the chance occurrence of [[Radiogenic nuclide|radiogenic]] [[thyroid cancer]] in later life. Other risks include the possibility of non-cancerous growths and [[thyroiditis]].<ref name="Rivkees">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rivkees SA, Sklar C, Freemark M | title = Clinical review 99: The management of Graves' disease in children, with special emphasis on radioiodine treatment | journal = The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism | volume = 83 | issue = 11 | pages = 3767–3776 | date = November 1998 | pmid = 9814445 | doi = 10.1210/jcem.83.11.5239 | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

|||

: Cu<sup>2+</sup> + 2 I<sup>–</sup> → CuI<sub>2</sub> |

|||

: 2 CuI<sub>2</sub> → 2 CuI + I<sub>2</sub> |

|||

Protection usually used against the negative effects of iodine-131 is by saturating the thyroid gland with stable iodine-127 in the form of [[potassium iodide]] tablets, taken daily for optimal prophylaxis.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zanzonico PB, Becker DV | title = Effects of time of administration and dietary iodine levels on potassium iodide (KI) blockade of thyroid irradiation by 131I from radioactive fallout | journal = Health Physics | volume = 78 | issue = 6 | pages = 660–667 | date = June 2000 | pmid = 10832925 | doi = 10.1097/00004032-200006000-00008 | s2cid = 30989865 }}</ref> However, iodine-131 may also be used for medicinal purposes in [[radiation therapy]] for this very reason, when tissue destruction is desired after iodine uptake by the tissue.<ref>{{cite news|title=Medical isotopes the likely cause of radiation in Ottawa waste|url=http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/medical-isotopes-the-likely-cause-of-radiation-in-ottawa-waste-1.852645|date=4 February 2009|publisher=[[CBC News]]|access-date=30 September 2015|archive-date=19 November 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211119213013/https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/medical-isotopes-the-likely-cause-of-radiation-in-ottawa-waste-1.852645|url-status=live}}</ref> Iodine-131 is also used as a [[radioactive tracer]].<ref>{{cite book|vauthors=Moser H, Rauert W|title=Isotopes in the water cycle : past, present and future of a developing science|year=2007|publisher=Springer|location=Dordrecht|isbn=978-1-4020-6671-9|veditors=Aggarwal PK, Gat JR, Froehlich KF|access-date=6 May 2012|page=11|chapter=Isotopic Tracers for Obtaining Hydrologic Parameters|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XKk6V_IeJbIC&pg=PA11|archive-date=19 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319070244/https://books.google.com/books?id=XKk6V_IeJbIC&pg=PA11#v=onepage&q&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|vauthors=Rao SM|title=Practical isotope hydrology|year=2006|publisher=New India Publishing Agency|location=New Delhi|isbn=978-81-89422-33-2|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=E7TVDVVji0EC&q=isotope%20hydrology%20iodine&pg=PA11|access-date=6 May 2012|pages=12–13|chapter=Radioisotopes of hydrological interest|archive-date=19 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319070414/https://books.google.com/books?id=E7TVDVVji0EC&q=isotope%20hydrology%20iodine&pg=PA11|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Investigating leaks in Dams & Reservoirs|url=http://www.iaea.org/technicalcooperation/documents/sheet20dr.pdf|work=IAEA.org|access-date=6 May 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130730053205/http://www.iaea.org/technicalcooperation/documents/sheet20dr.pdf|archive-date=30 July 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|vauthors=Araguás LA, Bedmar AP|title=Detection and prevention of leaks from dams|year=2002|publisher=Taylor & Francis|isbn=978-90-5809-355-4|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FXB-HMzfBnkC&pg=PA179|access-date=6 May 2012|pages=179–181|chapter=Artificial radioactive tracers|archive-date=19 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319070244/https://books.google.com/books?id=FXB-HMzfBnkC&pg=PA179#v=onepage&q&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

There are also other methods of isolating this element in the laboratory, for example, the method used to isolate other halogens: oxidation of the iodide in [[hydrogen iodide]] (often made ''in situ'' with an iodide and sulfuric acid) by [[manganese dioxide]] (see below in ''Descriptive chemistry''). |

|||

== |

== Chemistry and compounds == |

||

{{Main| |

{{Main|Iodine compounds}} |

||

{| class="wikitable" style="float:right; width:25%;" |

|||

Of the 37 known (characterized) [[isotope]]s of iodine, only one, <sup>127</sup>I, is stable. |

|||

|+ style="margin-bottom: 5px;" | Halogen bond energies (kJ/mol)<ref name="Greenwood804" /> |

|||

|- |

|||

! X |

|||

! XX |

|||

! HX |

|||

! BX<sub>3</sub> |

|||

! AlX<sub>3</sub> |

|||

! CX<sub>4</sub> |

|||

|- |

|||

! F |

|||

| 159 |

|||

| 574 |

|||

| 645 |

|||

| 582 |

|||

| 456 |

|||

|- |

|||

! Cl |

|||

|243 |

|||

|428 |

|||

|444 |

|||

|427 |

|||

|327 |

|||

|- |

|||

! Br |

|||

|193 |

|||

|363 |

|||

|368 |

|||

|360 |

|||

|272 |

|||

|- |

|||

! I |

|||

|151 |

|||

|294 |

|||

|272 |

|||

|285 |

|||

|239 |

|||

|} |

|||

Iodine is quite reactive, but it is less so than the lighter halogens, and it is a weaker oxidant. For example, it does not [[Halogenation|halogenate]] [[carbon monoxide]], [[nitric oxide]], and [[sulfur dioxide]], which [[chlorine]] does. Many metals react with iodine.<ref name="Greenwood800" /> By the same token, however, since iodine has the lowest ionisation energy among the halogens and is the most easily oxidised of them, it has a more significant cationic chemistry and its higher oxidation states are rather more stable than those of bromine and chlorine, for example in [[iodine heptafluoride]].<ref name="Greenwood804" /> |

|||

===Charge-transfer complexes === |

|||

The longest-lived radioisotope, <sup>129</sup>I, has a [[half-life]] of 15.7 million years. This is long enough to make it a permanent fixture of the environment on human time scales, but far too short for it to exist as a [[primordial isotope]] today. Instead, [[iodine-129]] is an [[extinct radionuclide]], and its presence in the early solar system is inferred from the observation of an excess of its daughter [[xenon-129]]. This nuclide is also newly-made by [[cosmic ray]]s and as a byproduct of human nuclear fission, which it is used to monitor as a very long-lived environmental contaminant. |

|||

[[File:Iodine-triphenylphosphine charge-transfer complex in dichloromethane.jpg|thumb|upright=1.8|right|I<sub>2</sub>•[[triphenylphosphine|PPh<sub>3</sub>]] charge-transfer complexes in [[dichloromethane|CH<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>2</sub>]]. From left to right: (1) I<sub>2</sub> dissolved in dichloromethane – no CT complex. (2) A few seconds after excess PPh<sub>3</sub> was added – CT complex is forming. (3) One minute later after excess PPh<sub>3</sub> was added, the CT complex [Ph<sub>3</sub>PI]<sup>+</sup>I<sup>−</sup> has been formed. (4) Immediately after excess I<sub>2</sub> was added, which contains [Ph<sub>3</sub>PI]<sup>+</sup>[I<sub>3</sub>]<sup>−</sup>.<ref name="InorgChem">{{Housecroft3rd|page=541}}</ref>]] |

|||

The iodine molecule, I<sub>2</sub>, dissolves in CCl<sub>4</sub> and aliphatic hydrocarbons to give bright violet solutions. In these solvents the absorption band maximum occurs in the 520 – 540 nm region and is assigned to a {{pi}}<sup>*</sup> to ''σ''<sup>*</sup> transition. When I<sub>2</sub> reacts with Lewis bases in these solvents a blue shift in I<sub>2</sub> peak is seen and the new peak (230 – 330 nm) arises that is due to the formation of adducts, which are referred to as charge-transfer complexes.<ref name="Greenwood806">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 806–07</ref> |

|||

The next-longest-lived radioisotope, [[iodine-125]], has a half-life of 59 days. It is used as a convenient gamma-emitting tag for proteins in biological assays, and a few [[nuclear medicine]] imaging tests where a longer half-life is required. It is also commonly used in [[brachytherapy]] implanted capsules, which kill tumors by local short-range [[Gamma ray|gamma radiation]] (but where the isotope is never released into the body). |

|||

===Hydrogen iodide=== |

|||

[[Iodine-123]] (half-life 13 hours) is the isotope of choice for [[nuclear medicine]] imaging of the thyroid gland, which naturally accumulates all iodine isotopes. |

|||

The simplest compound of iodine is [[hydrogen iodide]], HI. It is a colourless gas that reacts with oxygen to give water and iodine. Although it is useful in [[Halogenation|iodination]] reactions in the laboratory, it does not have large-scale industrial uses, unlike the other hydrogen halides. Commercially, it is usually made by reacting iodine with [[hydrogen sulfide]] or [[hydrazine]]:<ref name="Greenwood809">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 809–812</ref> |

|||

:2 I<sub>2</sub> + N<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub> {{overset|H<sub>2</sub>O|⟶}} 4 HI + N<sub>2</sub> |

|||

[[Iodine-131]] (half-life 8 days) is a beta-emitting isotope, which is a common nuclear fission product. It is preferably administered to humans only in very high doses which destroy all tissues that accumulate it (usually the thyroid), which in turn prevents these tissues from developing cancer from a lower dose (paradoxically, a high dose of this isotope appears safer for the thyroid than a low dose). Like other radioiodines, I-131 accumulates in the thyroid gland, but unlike the others, in small amounts it is highly carcinogenic there, it seems, owing to the high local cell mutation due to damage from [[beta decay]]. Because of this tendency of <sup>131</sup>I to cause high damage to cells that accumulate it and other cells near them (0.6 to 2 mm away, the range of the beta rays), it is the only iodine radioisotope used as direct therapy, to kill tissues such as cancers that take up artificially iodinated molecules (example, the compound [[iobenguane]], also known as MIBG). For the same reason, only the iodine isotope I-131 is used to treat [[Grave's disease]] and those types of thyroid cancers (sometimes in metastatic form) where the tissue that requires destruction, still functions to naturally accumulate iodide. |

|||

At room temperature, it is a colourless gas, like all of the hydrogen halides except [[hydrogen fluoride]], since hydrogen cannot form strong [[hydrogen bond]]s to the large and only mildly electronegative iodine atom. It melts at {{convert|−51.0|°C}} and boils at {{convert|−35.1|°C}}. It is an [[Endothermic process|endothermic]] compound that can exothermically dissociate at room temperature, although the process is very slow unless a [[Catalysis|catalyst]] is present: the reaction between hydrogen and iodine at room temperature to give hydrogen iodide does not proceed to completion. The H–I [[Bond-dissociation energy|bond dissociation energy]] is likewise the smallest of the hydrogen halides, at 295 kJ/mol.<ref name="Greenwood812">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 812–819</ref> |

|||

Nonradioactive ordinary [[potassium iodide]] (iodine-127), in a number of convenient forms (tablets or solution) may be used to saturate the thyroid gland's ability to take up further iodine, and thus protect against accidental contamination from iodine-131 generated by [[nuclear fission]] accidents, such as the [[Chernobyl disaster]] and more recently the [[Fukushima I nuclear accidents]], as well as from contamination from this isotope in [[nuclear fallout]] from [[nuclear weapon]]s. |

|||

Aqueous hydrogen iodide is known as [[hydroiodic acid]], which is a strong acid. Hydrogen iodide is exceptionally soluble in water: one litre of water will dissolve 425 litres of hydrogen iodide, and the saturated solution has only four water molecules per molecule of hydrogen iodide.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Holleman |first1=A. F. |title=Inorganic Chemistry |last2=Wiberg |first2=E. |publisher=Academic Press |year=2001 |isbn=0-12-352651-5 |location=San Diego}}</ref> Commercial so-called "concentrated" hydroiodic acid usually contains 48–57% HI by mass; the solution forms an [[azeotrope]] with boiling point {{convert|126.7|°C}} at 56.7 g HI per 100 g solution. Hence hydroiodic acid cannot be concentrated past this point by evaporation of water.<ref name="Greenwood812" /> Unlike gaseous hydrogen iodide, hydroiodic acid has major industrial use in the manufacture of [[acetic acid]] by the [[Cativa process]].<ref name="Cativa">{{Cite journal |last=Jones |first=J. H. |year=2000 |title=The Cativa Process for the Manufacture of Acetic Acid |url=http://www.platinummetalsreview.com/pdf/pmr-v44-i3-094-105.pdf |url-status=live |journal=[[Platinum Metals Review]] |volume=44 |issue=3 |pages=94–105 |doi=10.1595/003214000X44394105 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924074441/http://www.platinummetalsreview.com/pdf/pmr-v44-i3-094-105.pdf |archive-date=24 September 2015 |access-date=26 August 2023}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Sunley |first1=G. J. |last2=Watsonv |first2=D. J. |year=2000 |title=High productivity methanol carbonylation catalysis using iridium – The Cativa process for the manufacture of acetic acid |journal=Catalysis Today |volume=58 |issue=4 |pages=293–307 |doi=10.1016/S0920-5861(00)00263-7}}</ref> |

|||

==History== |

|||

Iodine was discovered by [[Bernard Courtois]] in 1811.<ref name=court>{{Cite journal|author=Courtois, Bernard |title=Découverte d'une substance nouvelle dans le Vareck |journal=Annales de chimie |volume=88 |page=304|year=1813 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=RA2-PA304}} In French, seaweed that had been washed onto the shore was called "varec", "varech", or "vareck", whence the English word "wrack". Later, "varec" also referred to the ashes of such seaweed: The ashes were used as a source of iodine and salts of sodium and potassium.</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|author=Swain, Patricia A. |title=Bernard Courtois (1777–1838) famed for discovering iodine (1811), and his life in Paris from 1798 |journal=Bulletin for the History of Chemistry |volume=30 |issue=2 |page=103|year=2005 |url=http://www.scs.uiuc.edu/~mainzv/HIST/awards/OPA%20Papers/2007-Swain.pdf}}</ref> He was born to a manufacturer of [[potassium nitrate|saltpeter]] (a vital part of [[gunpowder]]). At the time of the [[Napoleonic Wars]], [[France]] was at war and saltpeter was in great demand. Saltpeter produced from French [[niter]] beds required [[sodium carbonate]], which could be isolated from [[seaweed]] collected on the coasts of [[Normandy]] and [[Brittany]]. To isolate the sodium carbonate, seaweed was burned and the ash washed with water. The remaining waste was destroyed by adding [[sulfuric acid]]. Courtois once added excessive sulfuric acid and a cloud of purple vapor rose. He noted that the vapor crystallized on cold surfaces, making dark crystals. Courtois suspected that this was a new element but lacked funding to pursue it further. |

|||

===Other binary iodine compounds=== |

|||

Courtois gave samples to his friends, [[Charles Bernard Desormes]] (1777–1862) and [[Nicolas Clément]] (1779–1841), to continue research. He also gave some of the substance to [[chemist]] [[Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac]] (1778–1850), and to [[physicist]] [[André-Marie Ampère]] (1775–1836). On 29 November 1813, Dersormes and Clément made public Courtois's discovery. They described the substance to a meeting of the [[Imperial Institute of France]]. On December 6, Gay-Lussac announced that the new substance was either an element or a compound of oxygen.<ref name=Gay-Lussac>{{Cite journal|author=Gay-Lussac, J. |title=Sur un nouvel acide formé avec la substance décourverte par M. Courtois |journal=Annales de chimie |volume=88|page=311|year=1813 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=RA2-PA511}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|author=Gay-Lussac, J. |title=Sur la combination de l'iode avec d'oxigène |journal=Annales de chimie |volume=88 |page=319|year=1813 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=RA2-PA519}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|author=Gay-Lussac, J. |title=Mémoire sur l'iode |journal=Annales de chimie |volume=91 |page=5|year=1814 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Efms0Fri1CQC&pg=PA5}}</ref> It was Gay-Lussac who suggested the name ''"iode"'', from the Greek word ιώδες (iodes) for violet (because of the color of iodine vapor).<ref name=court/><ref name=Gay-Lussac /> Ampère had given some of his sample to [[Humphry Davy]] (1778–1829). Davy did some experiments on the substance and noted its similarity to [[chlorine]].<ref>{{Cite journal|author=Davy, H. |title=Sur la nouvelle substance découverte par M. Courtois, dans le sel de Vareck |journal=Annales de chemie |volume=88|page=322|year=1813 |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=YGwri-w7sMAC&pg=RA2-PA522&lpg=RA2-PA522}}</ref> Davy sent a letter dated December 10 to the [[Royal Society of London]] stating that he had identified a new element.<ref>{{Cite journal|author=Davy, Humphry |title=Some Experiments and Observations on a New Substance Which Becomes a Violet Coloured Gas by Heat |journal=Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. |volume=104 |page=74|date=January 1, 1814 |doi=10.1098/rstl.1814.0007 }}</ref> Arguments erupted between Davy and Gay-Lussac over who identified iodine first, but both scientists acknowledged Courtois as the first to isolate the element. |

|||

With the exception of the [[Noble gas|noble gases]], nearly all elements on the periodic table up to einsteinium ([[Einsteinium(III) iodide|EsI<sub>3</sub>]] is known) are known to form binary compounds with iodine. Until 1990, [[nitrogen triiodide]]<ref>The ammonia adduct NI<sub>3</sub>•NH<sub>3</sub> is more stable and can be isolated at room temperature as a notoriously shock-sensitive black solid.</ref> was only known as an ammonia adduct. Ammonia-free NI<sub>3</sub> was found to be isolable at –196 °C but spontaneously decomposes at 0 °C.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Tornieporth-Oetting |first1=Inis |last2=Klapötke |first2=Thomas |date=June 1990 |title=Nitrogen Triiodide |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.199006771 |journal=Angewandte Chemie |edition=international |language=en |volume=29 |issue=6 |pages=677–679 |doi=10.1002/anie.199006771 |issn=0570-0833 |access-date=5 March 2023 |archive-date=5 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230305194218/https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/anie.199006771 |url-status=live }}</ref> For thermodynamic reasons related to electronegativity of the elements, neutral sulfur and selenium iodides that are stable at room temperature are also nonexistent, although S<sub>2</sub>I<sub>2</sub> and SI<sub>2</sub> are stable up to 183 and 9 K, respectively. As of 2022, no neutral binary selenium iodide has been unambiguously identified (at any temperature).<ref>{{cite journal |last=Vilarrubias |first=Pere |date=17 November 2022 |title=The elusive diiodosulphanes and diiodoselenanes |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/00268976.2022.2129106 |journal=Molecular Physics |volume=120 |issue=22 |pages=e2129106 |doi=10.1080/00268976.2022.2129106 |bibcode=2022MolPh.12029106V |s2cid=252744393 |issn=0026-8976 |access-date=5 March 2023 |archive-date=19 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240319070247/https://www.tandfonline.com/pb/css/t1709911000430-v1707891316000/head_4_698_en.css |url-status=live }}</ref> Sulfur- and selenium-iodine polyatomic cations (e.g., [S<sub>2</sub>I<sub>4</sub><sup>2+</sup>][AsF<sub>6</sub><sup>–</sup>]<sub>2</sub> and [Se<sub>2</sub>I<sub>4</sub><sup>2+</sup>][Sb<sub>2</sub>F<sub>11</sub><sup>–</sup>]<sub>2</sub>) have been prepared and characterised crystallographically.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Klapoetke |first1=T. |last2=Passmore |first2=J. |date=1 July 1989 |title=Sulfur and selenium iodine compounds: from non-existence to significance |url=https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ar00163a002 |journal=Accounts of Chemical Research |language=en |volume=22 |issue=7 |pages=234–240 |doi=10.1021/ar00163a002 |issn=0001-4842 |access-date=15 January 2023 |archive-date=15 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230115160630/https://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/ar00163a002 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

Given the large size of the iodide anion and iodine's weak oxidising power, high oxidation states are difficult to achieve in binary iodides, the maximum known being in the pentaiodides of [[niobium]], [[tantalum]], and [[protactinium]]. Iodides can be made by reaction of an element or its oxide, hydroxide, or carbonate with hydroiodic acid, and then dehydrated by mildly high temperatures combined with either low pressure or anhydrous hydrogen iodide gas. These methods work best when the iodide product is stable to hydrolysis. Other syntheses include high-temperature oxidative iodination of the element with iodine or hydrogen iodide, high-temperature iodination of a metal oxide or other halide by iodine, a volatile metal halide, [[carbon tetraiodide]], or an organic iodide. For example, [[Molybdenum dioxide|molybdenum(IV) oxide]] reacts with [[Aluminium iodide|aluminium(III) iodide]] at 230 °C to give [[molybdenum(II) iodide]]. An example involving halogen exchange is given below, involving the reaction of [[tantalum(V) chloride]] with excess aluminium(III) iodide at 400 °C to give [[tantalum(V) iodide]]:<ref name="Greenwood821">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 821–4</ref> |

|||

==Applications== |

|||

===Catalysis=== |

|||

The major application of iodine is as a co-catalyst for the production of [[acetic acid]] by the [[Monsanto process|Monsanto]] and [[Cativa process]]es. In these technologies, which support the world's demand for acetic acid, [[hydroiodic acid]] converts the [[methanol]] feedstock into methyl iodide, which undergoes [[carbonylation]]. Hydrolysis of the resulting acetyl iodide regenerates hydroiodic acid and gives acetic acid.<ref name = Ullmann/> |

|||

<chem display="block">3TaCl5 + \underset{(excess)}{5AlI3} -> 3TaI5 + 5AlCl3</chem> |

|||

===Animal feed=== |

|||

The production of [[ethylenediammonium diiodide]] (EDDI) consumes a large fraction of available iodine. EDDI is provided to livestock as a nutritional supplement.<ref name = Ullmann/> |

|||

Lower iodides may be produced either through thermal decomposition or disproportionation, or by reducing the higher iodide with hydrogen or a metal, for example:<ref name="Greenwood821" /> |

|||

===Disinfectant and water treatment=== |

|||

Elemental iodine is used as a disinfectant in various forms. The iodine exists as the element, or as the water-soluble [[triiodide]] anion I<sub>3</sub><sup>-</sup> generated ''in situ'' by adding [[iodide]] to poorly water-soluble elemental iodine (the reverse chemical reaction makes some free elemental iodine available for antisepsis). In alternative fashion, iodine may come from [[iodophor]]s, which contain iodine complexed with a solubilizing agent (iodide ion may be thought of loosely as the iodophor in triiodide water solutions). Examples of such preparations include:<ref>{{Cite book|author=Block, Seymour Stanton |title=Disinfection, sterilization, and preservation |publisher=Lippincott Williams & Wilkins |location=Hagerstwon, MD |year=2001 |page=159 |isbn=0-683-30740-1}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Tincture of iodine]]: iodine in ethanol, or iodine and [[sodium iodide]] in a mixture of ethanol and water. |

|||

*[[Lugol's iodine]]: iodine and iodide in water alone, forming mostly triiodide. Unlike tincture of iodine, Lugol's has a minimized amount of the free iodine (I<sub>2</sub>) component. |

|||

*[[Povidone iodine]] (an [[iodophor]]) |

|||

<chem display="block">TaI5{} + Ta ->[\text{thermal gradient}] [\ce{630^\circ C\ ->\ 575^\circ C}] Ta6I14</chem> |

|||

===Health, medical, and radiological use=== |

|||

{{main|iodised salt}} |

|||

In most countries, table salt is [[iodized salt|iodized]]{{Citation needed|date=May 2012}}. Iodine is required for the essential thyroxin hormones produced by and concentrated in the thyroid gland. |

|||

Most metal iodides with the metal in low oxidation states (+1 to +3) are ionic. Nonmetals tend to form covalent molecular iodides, as do metals in high oxidation states from +3 and above. Both ionic and covalent iodides are known for metals in oxidation state +3 (e.g. [[Scandium triiodide|scandium iodide]] is mostly ionic, but [[aluminium iodide]] is not). Ionic iodides MI<sub>''n''</sub> tend to have the lowest melting and boiling points among the halides MX<sub>''n''</sub> of the same element, because the electrostatic forces of attraction between the cations and anions are weakest for the large iodide anion. In contrast, covalent iodides tend to instead have the highest melting and boiling points among the halides of the same element, since iodine is the most polarisable of the halogens and, having the most electrons among them, can contribute the most to van der Waals forces. Naturally, exceptions abound in intermediate iodides where one trend gives way to the other. Similarly, solubilities in water of predominantly ionic iodides (e.g. [[potassium]] and [[calcium]]) are the greatest among ionic halides of that element, while those of covalent iodides (e.g. [[silver]]) are the lowest of that element. In particular, [[silver iodide]] is very insoluble in water and its formation is often used as a qualitative test for iodine.<ref name="Greenwood821" /> |

|||

Potassium iodide has been used as an [[expectorant]], although this use is increasingly uncommon. In medicine, [[potassium iodide]] is used to treat acute [[thyrotoxicosis]], usually as a saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI). It is also used to block uptake of [[iodine-131]] in the thyroid gland (see isotopes section above), when this isotope is used as part of radiopharmaceuticals (such as [[iobenguane]]) that are not targeted to the thyroid or thyroid type tissues. |

|||

===Iodine halides=== |

|||

Iodine-131 (in the chemical form of iodide) is a component of [[nuclear fallout]] and a particularly dangerous one owing to the thyroid gland's propensity to concentrate ingested iodine, where it is kept for periods longer than this isotope's radiological half-life of eight days. For this reason, if people are expected to be exposed to a significant amount of environmental radioactive iodine (iodine-131 in fallout), they may be instructed to take non-radioactive potassium iodide tablets. The typical adult dose is one 130 mg tablet per 24 hours, supplying 100 mg (100,000 [[micrograms]]) iodine, as iodide ion. (Note: typical daily dose of iodine to maintain normal health is of order 100 micrograms; see "Dietary Intake" below.) By ingesting this large amount of non-radioactive iodine, radioactive iodine uptake by the thyroid gland is minimized. See the main article above for more on this topic.<ref>U.S. Centers for Disease Control [http://www.bt.cdc.gov/radiation/ki.asp "CDC Radiation Emergencies"], ''U.S. Centers for Disease Control'', October 11, 2006, accessed November 14, 2010.</ref> |

|||

The halogens form many binary, [[Diamagnetism|diamagnetic]] [[interhalogen]] compounds with stoichiometries XY, XY<sub>3</sub>, XY<sub>5</sub>, and XY<sub>7</sub> (where X is heavier than Y), and iodine is no exception. Iodine forms all three possible diatomic interhalogens, a trifluoride and trichloride, as well as a pentafluoride and, exceptionally among the halogens, a heptafluoride. Numerous cationic and anionic derivatives are also characterised, such as the wine-red or bright orange compounds of {{chem|ICl|2|+}} and the dark brown or purplish black compounds of I<sub>2</sub>Cl<sup>+</sup>. Apart from these, some [[pseudohalogen|pseudohalides]] are also known, such as [[cyanogen iodide]] (ICN), iodine [[thiocyanate]] (ISCN), and iodine [[azide]] (IN<sub>3</sub>).<ref name="Greenwood824">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 824–828</ref> |

|||

[[File:Iodine monochloride1.jpg|thumb|right|Iodine monochloride]] |

|||

===Radiocontrast agent=== |

|||

[[Iodine monofluoride]] (IF) is unstable at room temperature and disproportionates very readily and irreversibly to iodine and [[iodine pentafluoride]], and thus cannot be obtained pure. It can be synthesised from the reaction of iodine with fluorine gas in [[trichlorofluoromethane]] at −45 °C, with [[iodine trifluoride]] in trichlorofluoromethane at −78 °C, or with [[silver(I) fluoride]] at 0 °C.<ref name="Greenwood824" /> [[Iodine monochloride]] (ICl) and [[iodine monobromide]] (IBr), on the other hand, are moderately stable. The former, a volatile red-brown compound, was discovered independently by [[Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac]] and [[Humphry Davy]] in 1813–1814 not long after the discoveries of chlorine and iodine, and it mimics the intermediate halogen bromine so well that [[Justus von Liebig]] was misled into mistaking bromine (which he had found) for iodine monochloride. Iodine monochloride and iodine monobromide may be prepared simply by reacting iodine with chlorine or bromine at room temperature and purified by [[fractional crystallization (chemistry)|fractional crystallisation]]. Both are quite reactive and attack even [[platinum]] and [[gold]], though not [[boron]], [[carbon]], [[cadmium]], [[lead]], [[zirconium]], [[niobium]], [[molybdenum]], and [[tungsten]]. Their reaction with organic compounds depends on conditions. Iodine chloride vapour tends to chlorinate [[phenol]] and [[salicylic acid]], since when iodine chloride undergoes [[Homolysis (chemistry)|homolytic fission]], chlorine and iodine are produced and the former is more reactive. However, iodine chloride in [[carbon tetrachloride]] solution results in iodination being the main reaction, since now [[Heterolysis (chemistry)|heterolytic fission]] of the I–Cl bond occurs and I<sup>+</sup> attacks phenol as an electrophile. However, iodine monobromide tends to brominate phenol even in carbon tetrachloride solution because it tends to dissociate into its elements in solution, and bromine is more reactive than iodine.<ref name="Greenwood824" /> When liquid, iodine monochloride and iodine monobromide dissociate into {{chem|I|2|X|+}} and {{chem|IX|2|-}} ions (X = Cl, Br); thus they are significant conductors of electricity and can be used as ionising solvents.<ref name="Greenwood824" /> |

|||

{{main|Radiocontrast agent}} |

|||

[[File:Diatrizoic acid.svg|thumb|right|[[Diatrizoic acid]], a [[radiocontrast]] agent]] |

|||

Iodine, as a physically [[density|dense]] element with high [[electron density]] and high [[atomic number]], is quite radio-opaque (i.e., it absorbs X-rays well). This property can be fully exploited by filtering imaging X-rays so that they are more energetic than iodine's "K-edge" at 33.3 keV, or the energy where the iodine begins to absorb X-rays strongly due to the photoelectric effect from electrons in its K shell.<ref>[http://ric.uthscsa.edu/personalpages/lancaster/DI-II_Chapters/DI_chap4.pdf] Determinants of X-ray opacity in elements and and principles of use of radiocontrast agents in medicine.</ref> Organic compounds of a certain type (typically iodine-substituted benzene derivatives) are thus used in [[medicine]] as X-ray [[radiocontrast]] agents for intravenous injection. This is often in conjunction with advanced X-ray techniques such as [[angiography]] and [[CT scan]]ning. At present, all water-soluble radiocontrast agents rely on iodine. |

|||

[[Iodine trifluoride]] (IF<sub>3</sub>) is an unstable yellow solid that decomposes above −28 °C. It is thus little-known. It is difficult to produce because fluorine gas would tend to oxidise iodine all the way to the pentafluoride; reaction at low temperature with [[xenon difluoride]] is necessary. [[Iodine trichloride]], which exists in the solid state as the planar dimer I<sub>2</sub>Cl<sub>6</sub>, is a bright yellow solid, synthesised by reacting iodine with liquid chlorine at −80 °C; caution is necessary during purification because it easily dissociates to iodine monochloride and chlorine and hence can act as a strong chlorinating agent. Liquid iodine trichloride conducts electricity, possibly indicating dissociation to {{chem|ICl|2|+}} and {{chem|ICl|4|-}} ions.<ref name="Greenwood828">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 828–831</ref> |

|||

===Other uses=== |

|||

Inorganic iodides find specialized uses. Hafnium, zirconium, titanium are purified by the [[van Arkel Process]], which involves the reversible formation of the tetraiodides of these elements. Silver iodide is a major ingredient to traditional photographic film. Thousands of kilograms of silver iodide are consumed annually for [[cloud seeding]].<ref name = Ullmann/> |

|||

[[Iodine pentafluoride]] (IF<sub>5</sub>), a colourless, volatile liquid, is the most thermodynamically stable iodine fluoride, and can be made by reacting iodine with fluorine gas at room temperature. It is a fluorinating agent, but is mild enough to store in glass apparatus. Again, slight electrical conductivity is present in the liquid state because of dissociation to {{chem|IF|4|+}} and {{chem|IF|6|-}}. The [[pentagonal bipyramidal molecular geometry|pentagonal bipyramidal]] [[iodine heptafluoride]] (IF<sub>7</sub>) is an extremely powerful fluorinating agent, behind only [[chlorine trifluoride]], [[chlorine pentafluoride]], and [[bromine pentafluoride]] among the interhalogens: it reacts with almost all the elements even at low temperatures, fluorinates [[Pyrex]] glass to form iodine(VII) oxyfluoride (IOF<sub>5</sub>), and sets [[carbon monoxide]] on fire.<ref name="Greenwood832">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 832–835</ref> |

|||

The organoiodine compound [[erythrosine]] is an important food coloring agent. Perfluoroalkyl iodides are precursors to important surfactants, such as [[perfluorooctanesulfonic acid]].<ref name = Ullmann/> |

|||

==Iodine |

===Iodine oxides and oxoacids=== |

||

[[File:Iodine-pentoxide-3D-balls.png|thumb|right|upright=0.7|Structure of iodine pentoxide]] |

|||

Iodine adopts a variety of oxidation states, commonly ranging from (formally) I<sup>7+</sup> to I<sup>-</sup>, and including the intermediate states of I<sup>5+</sup>, I<sup>3+</sup> and I<sup>+</sup>. Practically, only the 1- oxidation state is of significance, being the form found in iodide salts and [[organoiodine compound]]s. Iodine is a [[Lewis acid]]. With electron donors such as [[triphenylphosphine]] and [[pyridine]] it forms a [[charge-transfer complex]]. With the [[iodide]] anion it forms the [[triiodide]] ion.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Küpper F. C., Feiters M. C., Olofsson B., Kaiho T., Yanagida S., Zimmermann M. B., Carpenter L. J., Luther G. W., Lu Z. ''et al.'' | year = 2011 | title = Commemorating Two Centuries of Iodine Research: An Interdisciplinary Overview of Current Research | url = | journal = Angewandte Chemie International Edition | volume = 50 | issue = | pages = 11598–11620 | doi = 10.1002/anie.201100028 }}</ref> |

|||

[[Iodine oxide]]s are the most stable of all the halogen oxides, because of the strong I–O bonds resulting from the large electronegativity difference between iodine and oxygen, and they have been known for the longest time.<ref name="King" /> The stable, white, [[Hygroscopy|hygroscopic]] [[iodine pentoxide]] (I<sub>2</sub>O<sub>5</sub>) has been known since its formation in 1813 by Gay-Lussac and Davy. It is most easily made by the dehydration of [[iodic acid]] (HIO<sub>3</sub>), of which it is the anhydride. It will quickly oxidise carbon monoxide completely to [[carbon dioxide]] at room temperature, and is thus a useful reagent in determining carbon monoxide concentration. It also oxidises [[nitrogen oxide]], [[ethylene]], and [[hydrogen sulfide]]. It reacts with [[sulfur trioxide]] and peroxydisulfuryl difluoride (S<sub>2</sub>O<sub>6</sub>F<sub>2</sub>) to form salts of the iodyl cation, [IO<sub>2</sub>]<sup>+</sup>, and is reduced by concentrated [[sulfuric acid]] to iodosyl salts involving [IO]<sup>+</sup>. It may be fluorinated by [[fluorine]], [[bromine trifluoride]], [[sulfur tetrafluoride]], or [[chloryl fluoride]], resulting [[iodine pentafluoride]], which also reacts with [[iodine pentoxide]], giving iodine(V) oxyfluoride, IOF<sub>3</sub>. A few other less stable oxides are known, notably I<sub>4</sub>O<sub>9</sub> and I<sub>2</sub>O<sub>4</sub>; their structures have not been determined, but reasonable guesses are I<sup>III</sup>(I<sup>V</sup>O<sub>3</sub>)<sub>3</sub> and [IO]<sup>+</sup>[IO<sub>3</sub>]<sup>−</sup> respectively.<ref name="Greenwood851">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 851–853</ref> |

|||

Iodine and the [[iodide]] ion form a [[redox couple]]. I<sub>2</sub> is easily [[reducing agent|reduced]] and I<sup>-</sup> is easily oxidized. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" style="float:right; width:25%;" |

|||

===Solubility=== |

|||

|+ Standard reduction potentials for aqueous I species<ref name="Greenwood853" /> |

|||

Being a nonpolar molecule, iodine is highly soluble in nonpolar organic solvents, including [[ethanol]] (20.5 g/100 ml at 15 °C, 21.43 g/100 ml at 25 °C), [[diethyl ether]] (20.6 g/100 ml at 17 °C, 25.20 g/100 ml at 25 °C), [[chloroform]], [[acetic acid]], [[glycerol]], [[benzene]] (14.09 g/100 ml at 25 °C), [[carbon tetrachloride]] (2.603 g/100 ml at 35 °C), and [[carbon disulfide]] (16.47 g/100 ml at 25 °C).<ref>{{Cite book| title = Merck Index of Chemicals and Drugs, 9th ed| year = 1976| isbn=0-911910-26-3| editor = Windholz, Martha; Budavari, Susan; Stroumtsos, Lorraine Y. and Fertig, Margaret Noether| publisher = J A Majors Company}}</ref> Elemental iodine is poorly soluble in water, with one gram dissolving in 3450 ml at 20 °C and 1280 ml at 50 °C. Aqueous and ethanol solutions are brown reflecting the role of these solvents as [[Lewis base]]s. Solutions in chloroform, carbon tetrachloride, and carbon disulfide are violet, the color of iodine vapor. |

|||

! {{nowrap|E°(couple)}}!!{{nowrap|''a''(H<sup>+</sup>) {{=}} 1}}<br>(acid)!!{{nowrap|E°(couple)}}!!{{nowrap|''a''(OH<sup>−</sup>) {{=}} 1}}<br>(base) |

|||

|- |

|||

|I<sub>2</sub>/I<sup>−</sup>||+0.535|||I<sub>2</sub>/I<sup>−</sup>||+0.535 |

|||

|- |

|||

|HOI/I<sup>−</sup>||+0.987||IO<sup>−</sup>/I<sup>−</sup>||+0.48 |

|||

|- |

|||

|0||0||{{chem|IO|3|-}}/I<sup>−</sup>||+0.26 |

|||

|- |

|||

|HOI/I<sub>2</sub>||+1.439||IO<sup>−</sup>/I<sub>2</sub>||+0.42 |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{chem|IO|3|-}}/I<sub>2</sub>||+1.195||0||0 |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{chem|IO|3|-}}/HOI||+1.134||{{chem|IO|3|-}}/IO<sup>−</sup>||+0.15 |

|||

|- |

|||

|{{chem|IO|4|-}}/{{chem|IO|3|-}}||+1.653||0||0 |

|||

|- |

|||

|H<sub>5</sub>IO<sub>6</sub>/{{chem|IO|3|-}}||+1.601||{{chem|H|3|IO|6|2-}}/{{chem|IO|3|-}}||+0.65 |

|||

|} |

|||

More important are the four oxoacids: [[hypoiodous acid]] (HIO), [[Iodite|iodous acid]] (HIO<sub>2</sub>), [[iodic acid]] (HIO<sub>3</sub>), and [[periodic acid]] (HIO<sub>4</sub> or H<sub>5</sub>IO<sub>6</sub>). When iodine dissolves in aqueous solution, the following reactions occur:<ref name="Greenwood853">Greenwood and Earnshaw, pp. 853–9</ref> |

|||

{{block indent|{{wikitable| |

|||

===Redox reactions=== |

|||

|- |

|||

In everyday life, iodides are slowly oxidized by atmospheric oxygen in the atmosphere to give free iodine. Evidence for this conversion is the yellow tint of certain aged samples of iodide salts and some organoiodine compounds.<ref name=Ullmann>Lyday, Phyllis A. "Iodine and Iodine Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2 {{doi|10.1002/14356007.a14_381}} Vol. A14 pp. 382–390.</ref> The oxidation of iodide to iodine in air is also responsible for the slow loss of iodide content in [[iodized salt]] if exposed to air.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2621.2007.01538.x|title=Effect of storage conditions on potassium iodide stability in iodised table salt and collagen preparations|year=2008|last1=Waszkowiak|first1=Katarzyna|last2=Szymandera-Buszka|first2=Krystyna|journal=International Journal of Food Science & Technology|volume=43|issue=5|pages=895–899}}</ref> Some salts use iodate to prevent the loss of iodine. |

|||

| I<sub>2</sub> + H<sub>2</sub>O || {{eqm}} HIO + H<sup>+</sup> + I<sup>−</sup> || ''K''<sub>ac</sub> = 2.0 × 10<sup>−13</sup> mol<sup>2</sup> L<sup>−2</sup> |

|||

|- |

|||

| I<sub>2</sub> + 2 OH<sup>−</sup> || {{eqm}} IO<sup>−</sup> + H<sub>2</sub>O + I<sup>−</sup> || ''K''<sub>alk</sub> {{=}} 30 mol<sup>2</sup> L<sup>−2</sup> |

|||

}}}} |

|||

Hypoiodous acid is unstable to disproportionation. The hypoiodite ions thus formed disproportionate immediately to give iodide and iodate:<ref name="Greenwood853" /> |

|||

Iodine is easily reduced. Most common is the interconversion of I<sup>-</sup> and I<sub>2</sub>. Molecular iodine can be prepared by oxidizing [[iodide]]s with chlorine: |

|||

:2 I<sup>−</sup> + Cl<sub>2</sub> → I<sub>2</sub> + 2 Cl<sup>−</sup> |

|||

or with [[manganese dioxide]] in acid solution:<ref name="cw"/> |

|||

:2 I<sup>−</sup> + 4 H<sup>+</sup> + MnO<sub>2</sub> → I<sub>2</sub> + 2 H<sub>2</sub>O + Mn<sup>2+</sup> |

|||

{{block indent| 3 IO<sup>−</sup> {{eqm}} 2 I<sup>−</sup> + {{chem|IO|3|-}} ''K'' {{=}} 10<sup>20</sup>}} |

|||