Battle of Bunker Hill: Difference between revisions

Bahamallama (talk | contribs) |

m add {{Use American English}} template |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Battle of the American Revolutionary War}} |

|||

:''A number of places and things are named for this battle, see: [[Bunker Hill|Bunker Hill (disambiguation)]].'' |

|||

{{For|a list of numerous places and things that are named after this battle|Bunker Hill (disambiguation){{!}}Bunker Hill}} |

|||

{{Infobox Military Conflict |

|||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

|conflict=Battle of Bunker Hill |

|||

{{Use American English|date=January 2025}} |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

|image=[[Image:Bunkertrumbull.jpg|300px|]] |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=May 2011}} |

|||

|caption=''The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill'' by [[John Trumbull]] |

|||

{{Infobox military conflict |

|||

|date=[[June 17]], [[1775]] |

|||

| conflict = Battle of Bunker Hill |

|||

|place=[[Charlestown, Massachusetts]] |

|||

| partof = the [[American Revolutionary War]] |

|||

|territory=British take Charlestown peninsula |

|||

| image = The death of general warren at the battle of bunker hill.jpg |

|||

|result=[[Kingdom of Great Britain|Kingdom of Great Britain]], [[pyrrhic victory]] |

|||

| image_size = 300 |

|||

|combatant1=[[Province of Massachusetts Bay]] |

|||

| caption = ''[[The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker's Hill, June 17, 1775|Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill]]'', a portrait by [[John Trumbull]] depicting the battle |

|||

|combatant2=[[Kingdom of Great Britain]] |

|||

| map_type = Boston |

|||

|commander1=[[Israel Putnam]]<br/>[[William Prescott]] |

|||

| map_relief = 1 |

|||

|commander2=[[William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe|William Howe]]<br/>[[Robert Pigot]]<br/>[[Henry Clinton]] |

|||

| map_size = 290 |

|||

|strength1=1,500 |

|||

| map_caption = Location of the Battle of Bunker Hill in [[Massachusetts]] |

|||

|strength2=2,600 |

|||

| date = June 17, 1775 |

|||

|casualties1=140 dead<br>271 wounded<br>30 captured {20 POWs Died} |

|||

| place = [[Charlestown, Boston|Charlestown, Massachusetts]] |

|||

|casualties2=226 dead<br>828 wounded |

|||

| coordinates = {{Coord|42|22|35|N|71|3|39|W|type:event|display=inline}} |

|||

| result = British victory (see [[#Aftermath|Aftermath]]) |

|||

| territory = The British capture Charlestown Peninsula |

|||

| combatant1 = {{flagdeco|New England}} [[United Colonies]] |

|||

* [[Connecticut Colony|Connecticut]] |

|||

* [[Province of Massachusetts Bay|Massachusetts Bay]] |

|||

* [[Province of New Hampshire|New Hampshire]] |

|||

* [[Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations|Rhode Island]] |

|||

| combatant2 = {{flagcountry|Kingdom of Great Britain}} |

|||

| commander1 = {{flagdeco|New England}} [[William Prescott]]<br />{{flagdeco|New England}} [[Israel Putnam]]<br />{{flagdeco|New England}} [[Joseph Warren]]{{KIA}}<br /> {{flagdeco|New England}} [[John Stark]]<br />{{flagdeco|New England}} [[James Frye]] |

|||

| commander2 = {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} [[William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe|William Howe]]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} [[Thomas Gage]]<br> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} [[Sir Robert Pigot, 2nd Baronet|Sir Robert Pigot]]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} [[James Abercrombie (Bunker Hill)|James Abercrombie]]{{KIA}}<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain}} [[Henry Clinton (American War of Independence)|Henry Clinton]]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain|naval}} [[Samuel Graves]]<br /> {{flagicon|Kingdom of Great Britain|naval}} [[John Pitcairn]]{{KIA}} |

|||

| strength1 = ~2,400<ref name="AmericanCount">[[#Chidsey|Chidsey]] p. 122 counts 1,400 in the night-time fortification work. [[#Frothingham|Frothingham]] is unclear on the number of reinforcements arriving just before the battle breaks out. In a footnote on p. 136, as well as on p. 190, he elaborates the difficulty in getting an accurate count.</ref> |

|||

| strength2 = 3,000+<ref name="BritishCount">[[#Chidsey|Chidsey]] p. 90 says the initial force requested was 1,550, but Howe requested and received reinforcements before the battle began. [[#Frothingham|Frothingham]] p. 137 puts the total British contingent likely to be over 3,000. Furthermore, according to Frothingham p. 148, additional reinforcements arrived from Boston after the second attack was repulsed. Frothingham, p. 191 notes the difficulty in attaining an accurate count of British troops involved.</ref> |

|||

| casualties1 = 115 killed,<br />305 wounded,<br />30 captured (20 POWs died)<br />'''Total:''' 450<ref name="Casualties">[[#Chidsey|Chidsey]], p. 104</ref> |

|||

| casualties2 = 19 officers killed<br />62 officers wounded<br />207 soldiers killed<br />766 soldiers wounded<br />'''Total: 1,054'''<ref name="BritishCasualties">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]] pp. 191, 194.</ref> |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Campaignbox American Revolutionary War: Boston}} |

{{Campaignbox American Revolutionary War: Boston}} |

||

'''Bunker Hill ''' was a battle of the [[American Revolutionary War]] that took place on [[June 17]], [[1775]] during the [[Siege of Boston]]. [[Israel Putnam|General Putnam]] was in charge of the revolutionary forces. Major William Prescott was second in charge. Prescott is known as the officer who said: "Don't shoot until you see the whites of their eyes!" Although the battle is known as "Bunker Hill", most of the fighting did not take place there, occurring on [[Breed's Hill]] nearby. |

|||

[[Kingdom of Great Britain|British]] forces under [[William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe|General Howe]] overran the revolutionaries' fortified earthworks on Breed's and Bunker Hill. |

|||

The battle was a [[pyrrhic victory]] for the British who suffered more than 1000 casualties. Howe's immediate objective was achieved, but the attack demonstrated the American will to stand in pitched battle and did not change the status of the siege. After the battle, British General [[Henry Clinton (American War of Independence)|Henry Clinton]] remarked in his diary that ''"A few more such victories would have surely put an end to British dominion in America."'' |

|||

The '''Battle of Bunker Hill''' was fought on June 17, 1775, during the [[Siege of Boston]] in the first stage of the [[American Revolutionary War]].<ref>James L. Nelson, ''With Fire and Sword: The Battle of Bunker Hill and the Beginning of the American Revolution'' (2011)</ref> The battle is named after Bunker Hill in [[Charlestown, Boston|Charlestown, Massachusetts]], which was peripherally involved. It was the original objective of both the colonial and British troops, though the majority of combat took place on the adjacent hill which became known as [[Breed's Hill]].<ref>Borneman, Walter R. ''American Spring: Lexington, Concord, and the Road to Revolution,'' p. 350, Little, Brown and Company, New York, Boston, London, 2014. {{ISBN|978-0-316-22102-3}}.</ref><ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' p. 85, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> |

|||

==Background== |

|||

On June 13, 1775, the leaders of the colonial forces besieging Boston learned that the British were planning to send troops out from the city to fortify the unoccupied hills surrounding the city, which would give them control of Boston Harbor. In response, 1,200 colonial troops under the command of [[William Prescott]] stealthily occupied Bunker Hill and Breed's Hill. They constructed a strong [[redoubt]] on Breed's Hill overnight, as well as smaller fortified lines across the [[Charlestown Peninsula]].<ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' pp. 85–87, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> |

|||

Since May of 1774 Massachusetts had been under martial law under General [[Thomas Gage]]. |

|||

After armed conflict with the colonialists started on [[April 19]], [[1775]] at the [[Battle of Lexington and Concord]] Gage's forces had been besieged in Boston by 8,000 to 12,000 militia led mainly by General [[Artemas Ward]]. |

|||

In May, the British garrison was increased by the arrival of about 4,500 additional troops and [[William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe|Major General Howe]]. |

|||

Admiral [[Samuel Graves]] commanded the fleet within the harbor. |

|||

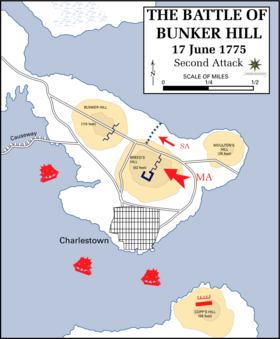

By daybreak of June 17, the British became aware of the presence of colonial forces on the Peninsula and mounted an attack against them. Two assaults on the colonial positions were repulsed with significant British casualties but the redoubt was captured on their third assault, after the defenders ran out of ammunition. The colonists retreated over Bunker Hill, leaving the British<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Withington|first=Robert|date=June 1949|title=A French Comment on the Battle of Bunker Hill|journal=The New England Quarterly|volume=22|issue=2|pages=235–240|doi=10.2307/362033|jstor=362033|issn=0028-4866}}</ref> in control of the Peninsula.<ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' pp. 87–95, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> |

|||

General Gage started work with his new generals on a plan to break the [[siege of Boston]]. |

|||

They would use an [[amphibious assault]] to remove the Americans from the Dorchester Heights or take their headquarters at [[Cambridge, Massachusetts|Cambridge]]. |

|||

To thwart these plans, General Ward gave orders to General [[Israel Putnam]] to fortify Bunker Hill. |

|||

The battle was a tactical victory for the British,<ref name="Clinton19"/><ref>{{cite encyclopedia | encyclopedia = Encyclopædia Britannica | title = Battle of Bunker Hill | url = https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Bunker-Hill | access-date = January 25, 2016 | date = 2016 | publisher = Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. | quote = Although the British eventually won the battle, it was a Pyrrhic victory that lent considerable encouragement to the revolutionary cause.}}</ref> but it proved to be a sobering experience for them; they incurred many more casualties than the Americans had sustained, including many officers. The battle had demonstrated that inexperienced militia were able to stand up to regular army troops in battle. Subsequently, the battle discouraged the British from any further frontal attacks against well defended front lines. American casualties were much fewer, although their losses included General [[Joseph Warren]] and Major [[Andrew McClary]], the final casualty of the battle.<ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' pp. 94–95, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> |

|||

===The battleground=== |

|||

''(For a 1775 map of the battle see: [http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g3764b.ct000251 Library of Congress map])'' |

|||

The battle led the British to adopt a more cautious planning and maneuver execution in future engagements, which was evident in the subsequent [[New York and New Jersey campaign]]. The costly engagement also convinced the British of the need to hire substantial numbers of [[Hessian (soldier)|Hessian auxiliaries]] to bolster their strength in the face of the new and formidable [[Continental Army]]. |

|||

The [[Charlestown, Massachusetts|Charlestown]] Peninsula extended about 1 mile (1600 meters) toward the southwest into Boston Harbor. |

|||

At its closest approach less than 1000 feet (300 meters) separated it from the Boston Peninsula. |

|||

Bunker Hill is an elevation at the rear of the peninsula, and Breed's Hill is near the Boston end, while |

|||

the town of Charlestown occupied the flats at the southern end. |

|||

==Geography== |

|||

==Description of the battle== |

|||

[[File:Lexington Concord Siege of Boston crop.jpg|thumb|left|upright=1.75|1775 map of the Boston area (contains some inaccuracies)]] |

|||

On the night of [[June 16]], American Colonel [[William Prescott]] led 1,500 men onto the peninsula. |

|||

At first Putnam, Prescott, and their engineering officer, Captain [[Richard Gridley]], disagreed as to where they should locate their defense. |

|||

Breed's Hill was viewed as much more defensible, and they decided to locate their primary [[redoubt]] there. |

|||

Prescott and his men, using Gridley's outline, began digging a fortification 160 feet (50 m) long and 80 feet (25 m) wide with ditches and earthen walls. |

|||

They added ditch and dike extensions toward the Charles River on their right and began reinforcing a fence running to their left. |

|||

[[Boston]] was situated on [[Shawmut Peninsula|a peninsula]]{{efn|18th century Boston was a peninsula. Primarily in the 19th century, much land around the peninsula was filled, giving the modern city its present geography. See [[History of Boston#Geographic expansion|the history of Boston]] for details.}} at the time and was largely protected from close approach by the expanses of water surrounding it, which were dominated by British warships. In the aftermath of the [[battles of Lexington and Concord]] on April 19, 1775, the colonial militia of some 15,000 men<ref name="Chidsey72">[[#Chidsey|Chidsey]], p. 72 – New Hampshire 1,200, Rhode Island 1,000, Connecticut 2,300, Massachusetts 11,500</ref> had surrounded the town and besieged it under the command of [[Artemas Ward]]. They controlled the only land access to Boston itself (the Roxbury Neck), but they were unable to contest British domination of the waters of the harbor. The British troops occupied the city, a force of about 6,000 under the command of General [[Thomas Gage]], and they were able to be resupplied and reinforced by sea.<ref name="Alden178">[[#Alden|Alden]], p. 178</ref> |

|||

In the early predawn, around 4 am, a sentry on board HMS ''Lively'' was first to spot the new fortification. |

|||

The ''Lively'' opened fire, temporarily halting the Americans' work. |

|||

Admiral Graves, on his flagship HMS ''Somerset'', woke irritated by gunfire he hadn't ordered. |

|||

He ordered it stopped, only to reverse himself when he got on deck and saw the works. |

|||

He ordered all 128 guns in the harbor to open up on the American position. |

|||

The broadsides proved largely ineffective, since the ships couldn't elevate their guns enough to reach the fortifications. |

|||

However, the land across the water from Boston contained a number of hills which could be used to advantage. Artillery could be placed on the hills and used to bombard the city until the occupying army evacuated it or surrendered. It was with this in mind that [[Henry Knox]] led the [[noble train of artillery]] to transport cannon from [[Fort Ticonderoga]].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero|first=James Kirby|last=Martin|location=New York|publisher=New York University Press|year=1997|ref=Martin|page=[https://archive.org/details/benedictarnoldre0000mart/page/73 73]|isbn=978-0-8147-5560-0|oclc=36343341|url=https://archive.org/details/benedictarnoldre0000mart/page/73}}</ref> |

|||

It took almost six hours to organize an infantry force, gather up and inspect the men on parade. |

|||

General Howe was to lead the major assault, drive around the American left flank, and take them from the rear. |

|||

Brigadier General [[Robert Pigot]] on the British left flank would lead the direct assault on the redoubt. |

|||

Major [[John Pitcairn]] led the flank or reserve force. |

|||

It took several trips in longboats to assemble Howe's forces on the northwest corner of the peninsula. |

|||

On a warm day, with full field packs of about 60 pounds (30 kg), the British were finally ready about two in the afternoon. |

|||

The Charlestown Peninsula to the north of Boston started from a short, narrow isthmus known as the [[Charlestown Neck]] and extended about {{convert|1|mi|km|1}} southeastward into Boston Harbor. Bunker Hill had an elevation of {{convert|110|ft|m|0}} and lay at the northern end of the peninsula. Breed's Hill had a height of {{convert|62|ft|m|0}} and was more southerly and nearer to Boston.<ref name="Chidsey91">[[#Chidsey|Chidsey]] p. 91 has a historic map showing elevations.</ref> The American soldiers were at an advantage due to the height of Breed's Hill and Bunker Hill, but it also essentially trapped them at the top.<ref>Withington, Robert (1949). "A French Comment on the Battle of Bunker Hill". ''The New England Quarterly''. '''2''': 235–240.</ref><ref>Adams, Charles Francis (1896). "The Battle of Bunker Hill". ''The American Historical Review''. '''1''': 401–413.</ref> The settled part of the town of [[Charlestown, Boston|Charlestown]] occupied flats at the southern end of the peninsula. At its closest approach, less than {{convert|1000|ft|m|-1}} separated the Charlestown Peninsula from the Boston Peninsula, where [[Copp's Hill]] was at about the same height as Breed's Hill. The British retreat from Concord had ended in Charlestown, but General Gage did not fortify the hills on the peninsula but instead withdrew his troops to Boston, turning the entire Charlestown Peninsula into a no man's land.<ref name="French220">[[#French|French]], p. 220</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Bunker Hill by Pyle.jpg|thumb|left|250px|''The Battle of Bunker Hill'', [[Howard Pyle]], 1897.]] |

|||

[[File:Bunker Hill by Pyle.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|''The Battle of Bunker Hill'' by [[Howard Pyle]], 1897]] |

|||

The Americans, seeing this activity, had also called for reinforcements. |

|||

The only troops to get to the forward positions were two New Hampshire regiments ([[1st New Hampshire Regiment|1st NH]] and [[3rd New Hampshire Regiment|3rd NH]]) of 200 men under [[John Stark]] and [[James Reed (soldier)|James Reed]]. |

|||

Stark's men took positions along the fence on the left or north end of the American position. |

|||

Since low tide opened a gap along the [[Mystic River]], they quickly extended the fence with a short stone wall to the north. |

|||

Gridley or Stark placed a stake about 30 meters in front of the fence and ordered that no one fire until the regulars passed it. Private [[John Simpson (soldier)|John Simpson]], however, disobeyed orders and fired as soon as he had a clear shot, thus starting the battle. |

|||

==British planning== |

|||

Prescott had been steadily losing men. |

|||

The British received reinforcements throughout May until they reached a strength of about 6,000 men. Generals [[William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe|William Howe]], [[John Burgoyne]], and [[Henry Clinton (American War of Independence)|Henry Clinton]] arrived on May 25 aboard {{HMS|Cerberus|1758|6}}. Gage began planning with them to break out of the city,<ref name="French249">[[#French|French]], p. 249</ref> finalizing a plan on June 12.<ref name="Brooks119">[[#Brooks|Brooks]], p. 119</ref> This plan began with taking the Dorchester Neck, fortifying the [[Dorchester Heights]], and then marching on the colonial forces stationed in Roxbury. Once the southern flank had been secured, the Charlestown heights would be taken, and the forces in Cambridge driven away. The attack was set for June 18.<ref name="Ketchum45_6">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 45–46</ref> |

|||

He lost very few to the bombardment, but had ten volunteers to carry every wounded man to the rear. |

|||

Others took advantage of the confusion to join the withdrawal. |

|||

Two generals did join Prescott's force, but both declined command, and simply fought as individuals. |

|||

One of these was Dr. [[Joseph Warren]], the president of the Council and acting head of Massachusetts' revolutionary government. |

|||

The second was [[Seth Pomeroy]]. |

|||

By the time the battle started the total involved defenders numbered about 1,400 and they faced 2,600 regulars. |

|||

On June 13, the [[Committee of Safety (American Revolution)|Committee of Safety]] in [[Exeter, New Hampshire]], notified the [[Massachusetts Provincial Congress]] that a New Hampshire gentleman "of undoubted veracity" had overheard the British commanders making plans to capture Dorchester and Charlestown.<ref name="Ketchum47">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 47</ref> On June 15, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety decided that additional defenses needed to be erected.<ref name="Ketchum74_5">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 74–75</ref> General Ward directed General [[Israel Putnam]] to set up defenses on the Charlestown Peninsula, specifically on Bunker Hill.<ref name="French255">[[#French|French]], p. 255</ref><ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' p. 84, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> |

|||

The first assaults both on the fence line and the redoubt were met with massed fire at close range and repulsed, with heavy British losses. |

|||

The reserve, gathering just north of the town, was also taking casualties due to rifle fire from a company in the town. |

|||

Howe's men reformed on the field and made a second unsuccessful attack at the wall. |

|||

==Prelude to battle== |

|||

The Americans had lost all ''fire discipline''. |

|||

In traditional battles of the 18th century, companies of men fired, reloaded, and moved on specific orders, as they had been trained. |

|||

After their initial volley, the Americans all fought as individuals, and every man fired as quickly as he could reload and find a target. |

|||

The British withdrew almost to their original positions on the peninsula to regroup. |

|||

The navy, along with artillery from Copp's Hill on the Boston peninsula, fired heated shot into Charlestown. |

|||

All 400 or so buildings and the docks were completely burned, but the snipers withdrew safely. |

|||

===Fortification of Breed's Hill=== |

|||

The third British assault carried the redoubt, due to a number of factors. |

|||

The reserves were included. |

|||

[[File:Array of American Forces on the Field at the Battle of Breeds Hill.png|left|upright=2.3|thumb|Array of American forces for the Battle of Bunker Hill]] |

|||

Both flanks concentrated on the redoubt. |

|||

The Americans ran out of ammunition, reducing the battle to a [[bayonet]] fight, and most of the American soldiers' rifles didn't have bayonets. |

|||

On the night of June 16, colonial Colonel [[William Prescott]] led about 1,200 men onto the peninsula in order to set up positions from which artillery fire could be directed into Boston.<ref name="Frothingham122">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], pp. 122–123</ref> This force was made up of men from the regiments of Prescott, Putnam (the unit was commanded by [[Thomas Knowlton]]), [[James Frye]], and Ebenezer Bridge.<ref name="KetchumPrescottForces">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 102, 245</ref> At first, Putnam, Prescott, and their engineer Captain [[Richard Gridley]] disagreed as to where they should locate their defense. Some work was performed on Bunker Hill, but Breed's Hill was closer to Boston and viewed as being more defensible, and they decided to build their primary redoubt there.<ref name="Frothingham123">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], pp. 123–124</ref> Prescott and his men began digging a square fortification about {{convert|130|ft|m}} on a side with ditches and earthen walls. The walls of the redoubt were about {{convert|6|ft|m}} high, with a wooden platform inside on which men could stand and fire over the walls.<ref name="Frothingham135">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 135</ref><ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' pp. 87–88, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> |

|||

The works on Breed's Hill did not go unnoticed by the British. General Clinton was out on reconnaissance that night and was aware of them, and he tried to convince Gage and Howe that they needed to prepare to attack the position at daylight. British sentries were also aware of the activity, but most apparently did not think it cause for alarm.<ref name="Ketchum115">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 115</ref> A sentry on board {{HMS|Lively|1756|6}} spotted the new fortification around 4 a.m. and notified his captain. ''Lively'' opened fire, temporarily halting the colonists' work. Admiral [[Samuel Graves]] awoke aboard his flagship {{HMS|Somerset|1748|6}}, irritated by the gunfire that he had not ordered.<ref name="Frothingham125">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 125</ref> He stopped it, only to have General Gage countermand his decision when he became fully aware of the situation in the morning. He ordered all 128 guns in the harbor to fire on the colonial position, along with batteries atop Copp's Hill in Boston.<ref name="Brooks127">[[#Brooks|Brooks]], p. 127</ref> The barrage had relatively little effect, as the hilltop fortifications were high enough to frustrate accurate aiming from the ships and far enough from Copp's Hill to render the batteries there ineffective. The shots that did manage to land, however, were able to kill one American soldier and damage the entire supply of water brought for the troops.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Middlekauff|first=Robert|title=[[The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789]]|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|year=2005|isbn=0-19-516247-1|location=New York|pages=290|oclc=55960833|author-link=Robert Middlekauff}}</ref> |

|||

The rising sun also alerted Prescott to a significant problem with the location of the redoubt: it could easily be flanked on either side.<ref name="Ketchum115" /> He promptly ordered his men to begin constructing a [[Breastwork (fortification)|breastwork]] running down the hill to the east, deciding that he did not have the manpower to also build additional defenses to the west of the redoubt.<ref name="Ketchum117">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 117</ref> |

|||

===British preparations=== |

|||

The British generals met to discuss their options. General Clinton had urged an attack as early as possible, and he preferred an attack beginning from the Charlestown Neck that would cut off the colonists' retreat, reducing the process of capturing the new redoubt to one of starving out its occupants. However, he was outvoted by the other three generals, who were concerned that his plan violated the convention of the time to not allow one's army to become trapped between enemy forces.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Middlekauff|first=Robert|title=[[The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789]]|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|year=2005|isbn=0-19-516247-1|location=New York|pages=293|oclc=55960833|author-link=Robert Middlekauff}}</ref> Howe was the senior officer present and would lead the assault, and he was of the opinion that the hill was "open and easy of ascent and in short would be easily carried."<ref name="Ketchum120_1">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 120–121</ref> General Burgoyne concurred, arguing that the "untrained rabble" would be no match for their "trained troops".<ref name="Wood-page54">[[#Wood|Wood]], p. 54</ref> Orders were then issued to prepare the expedition.<ref name="Ketchum122">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 122</ref> |

|||

{{Campaignbox American Revolutionary War: Boston}} |

|||

[[Thomas Gage|General Gage]] surveyed the works from Boston with his staff, and Loyalist Abijah Willard recognized his brother-in-law Colonel Prescott. "Will he fight?" asked Gage. "As to his men, I cannot answer for them," replied Willard, "but Colonel Prescott will fight you to the gates of hell."<ref name="Graydon-page424">[[#Graydon|Graydon]], p. 424</ref> Prescott lived up to Willard's word, but his men were not so resolute. When the colonists suffered their first casualty, Prescott gave orders to bury the man quickly and quietly, but a large group of men gave him a solemn funeral instead, with several deserting shortly thereafter.<ref name="Graydon-page424"/> |

|||

It took six hours for the British to organize an infantry force and to gather up and inspect the men on parade. General Howe was to lead the major assault, driving around the colonial left flank and taking them from the rear. Brigadier General [[Sir Robert Pigot, 2nd Baronet|Robert Pigot]] on the British left flank would lead the direct assault on the redoubt, and Major [[John Pitcairn]] would lead the flank or reserve force. It took several trips in longboats to transport Howe's initial forces (consisting of about 1,500 men) to the eastern corner of the peninsula, known as Moulton's Point.<ref name="Frothingham133"/><ref name="Ketchum139"/> By 2 p.m., Howe's chosen force had landed.<ref name="Frothingham133">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 133</ref> However, while crossing the river, Howe noted the large number of colonial troops on top of Bunker Hill. He believed these to be reinforcements and immediately sent a message to Gage, requesting additional troops. He then ordered some of the light infantry to take a forward position along the eastern side of the peninsula, alerting the colonists to his intended course of action. The troops then sat down to eat while they waited for the reinforcements.<ref name="Ketchum139">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 139</ref> |

|||

[[File:Bunker hill first attack.png|thumb|upright=1.25|The first British attack on Bunker Hill; shaded areas are hills]] |

|||

===Colonists reinforce their positions=== |

|||

Prescott saw the British preparations and called for reinforcements. Among the reinforcements were [[Joseph Warren]], the popular young leader of the Massachusetts Committee of Safety, and [[Seth Pomeroy]], an aging Massachusetts militia leader. Both of these men held commissions of rank, but chose to serve as infantry.<ref name="Frothingham133"/> Prescott ordered the [[Connecticut Colony|Connecticut]] men under Captain Knowlton to defend the left flank, where they used a crude dirt wall as a breastwork and topped it with fence rails and hay. They also constructed three small v-shaped trenches between this dirt wall and Prescott's breastwork. Troops that arrived to reinforce this flank position included about 200 men from the [[1st New Hampshire Regiment|1st]] and [[3rd New Hampshire Regiment|3rd New Hampshire regiments]] under Colonels [[John Stark]] and [[James Reed (soldier)|James Reed]]. Stark's men did not arrive until after Howe landed his forces, and thus filled a gap in the defense that Howe could have taken advantage of, had he pressed his attack sooner.<ref name="Ketchum143"/> They took positions along the breastwork on the northern end of the colonial position. Low tide opened a gap along the [[Mystic River]] to the north, so they quickly extended the fence with a short stone wall to the water's edge.<ref name="Ketchum143">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 143</ref><ref name="Chidsey93">[[#Chidsey|Chidsey]] p. 93</ref> Colonel Stark placed a stake about {{convert|100|ft|m|0}} in front of the fence and ordered that no one fire until the British regulars passed it.<ref name="Chidsey96">[[#Chidsey|Chidsey]] p. 96</ref> Further reinforcements arrived just before the battle, including portions of Massachusetts regiments of Colonels Brewer, [[John Nixon (Continental Army general)|Nixon]], [[Benjamin Ruggles Woodbridge|Woodbridge]], [[Moses Little|Little]], and Major Moore, as well as Callender's company of artillery.<ref name="Frothingham136">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 136</ref> |

|||

Confusion reigned behind the Colonial lines. Many units sent toward the action stopped before crossing the Charlestown Neck from Cambridge, which was under constant fire from gun batteries to the south. Others reached Bunker Hill, but then were uncertain where to go from there and just milled around. One commentator wrote of the scene that "it appears to me there never was more confusion and less command."<ref name="Ketchum147">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 147</ref> [[Israel Putnam|General Putnam]] was on the scene attempting to direct affairs, but unit commanders often misunderstood or even disobeyed orders.<ref name="Ketchum147"/><ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' pp. 92–93, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> |

|||

==British assault== |

|||

[[File:Bunker hill second attack.png|thumb|upright=1.25|The second British attack on Bunker Hill]] |

|||

By 3 p.m., the British reinforcements had arrived, which included the [[47th (Lancashire) Regiment of Foot|47th Regiment of Foot]] and the 1st Marines, and the British were ready to march.<ref name="Ketchum152_3">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 152–153</ref> Brigadier General Pigot's force were gathering just south of Charlestown village, and they were already taking casualties from sniper fire from the settlement. Howe asked Admiral Graves for assistance in clearing out the snipers. Graves had planned for such a possibility and ordered a [[Carcass (projectile)|carcass]] fired into the village, and then sent a landing party to set fire to the town.<ref name="Ketchum151_2">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 151–152</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Middlekauff|first=Robert|title=[[The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789]]|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|year=2005|isbn=0-19-516247-1|location=New York|pages=296|oclc=55960833|author-link=Robert Middlekauff}}</ref> The smoke billowing from Charlestown lent an almost surreal backdrop to the fighting, as the winds were such that the smoke was kept from the field of battle.<ref name="Frothingham144">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], pp. 144–145</ref> |

|||

General Howe led the light infantry companies and grenadiers in the assault on the American left flank along the rail fence, expecting an easy effort against Stark's recently arrived troops.<ref name="Ketchum152">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 152</ref> His light infantry were set along the narrow beach, in column formation, in order to turn the far left flank of the colonial position.<ref>Fusillers, [[Mark Urban]] p. 38</ref> The grenadiers were deployed in the center, lining up four deep and several hundred across. Pigot was commanding the [[5th Foot|5th]], [[38th Foot|38th]], [[43rd Foot|43rd]], 47th, and [[52nd (Oxfordshire) Regiment of Foot|52nd]] regiments, as well as Major Pitcairn's Marines; they were to feint an assault on the redoubt. Just before the British advanced, the American position along the rail fence was reinforced by two pieces of artillery from Bunker Hill.<ref>Kurtz, Henry I. ''Men of War: Essays on American Wars and Warriors,'' p. 31, Xlibris Corporation, 2006. {{ISBN?}}</ref> |

|||

Howe had intended the advance to be preceded by an artillery bombardment from the field pieces present, but it was soon discovered that these cannon had been supplied with the wrong caliber of ammunition, delaying the assault. Attacking Breed's Hill presented an array of difficulties. The hay on the hillside had not been harvested, requiring that the regulars marched through waist-high grass which concealed the uneven terrain beneath. The pastureland of the hillside was covered with crisscrossing rail fences hampering the cohesion of marching formations. The regulars were loaded down with gear wholly unnecessary for the attack, and the British troops were overheating in their wool uniforms under the heat of the afternoon sun, compounded by the nearby inferno from Charlestown.<ref name="Philbrick, Nathaniel p. 219-220">Philbrick, Nathaniel. ''Bunker Hill: A City, A Siege, A Revolution,'' p. 219-220, New York: Viking Press, 2013.</ref><ref name="Kurtz29">[[#Kurtz|Kurtz]], p. 29</ref> |

|||

The colonists withheld their fire until the regulars were within at least 50 paces of their position. As the regulars closed in range, they suffered heavy casualties from colonial fire. The colonists benefited from the rail fence to steady and aim their muskets, and enjoyed a modicum of cover from return fire. Under this withering fire, the light companies melted away and retreated, some as far as their boats. [[James Abercrombie (British Army officer, born 1732)|James Abercrombie]], commanding the Grenadiers, was fatally wounded. Pigot's attacks on the redoubt and breastworks fared little better; by stopping and exchanging fire with the colonists, the regulars were fully exposed and suffered heavy losses. They continued to be harried by snipers in Charlestown, and Pigot ordered a retreat after seeing what happened to Howe's advance.<ref name="Ketchum160">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 160</ref><ref name="Kurtz31_3">[[#Kurtz|Kurtz]], pp. 31–33</ref><ref name="Frothingham141">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], pp. 141–142</ref> |

|||

The regulars reformed on the field and marched out again, this time navigating a field strewn with dead and wounded comrades. This time, Pigot was not to feint; he was to assault the redoubt directly, possibly without the assistance of Howe's force. Howe advanced against Knowlton's position along the rail fence, instead of marching against Stark's position along the beach. The outcome of the second attack was very much the same as the first. One British observer wrote, "Most of our Grenadiers and Light-infantry, the moment of presenting themselves lost three-fourths, and many nine-tenths, of their men. Some had only eight or nine men a company left."<ref name="Ketchum161">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 161</ref> Pigot's attack did not enjoy any greater success than Howe, and he ordered a retreat after almost 30 minutes of firing ineffective volleys at the colonial position.<ref name="Kurtz33">[[#Kurtz|Kurtz]], p. 33</ref><ref name="Ketchum162">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 162</ref> The second attack had failed. |

|||

Meanwhile, confusion continued in the rear of the colonial forces. General Putnam tried with limited success to send additional troops from Bunker Hill to the forward positions on Breed's Hill to support the embattled regiments.<ref name="Frothingham146">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 146</ref><ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' p. 92, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> One colonial observer wrote to [[Samuel Adams]] afterwards, "it appears to me that there was never more confusion and less command". Some companies and leaderless groups of men moved toward the field; others retreated. They were running low on powder and ammunition, and the colonial regiments suffered from a hemorrhage of deserters. By the time that the third attack came, there were only 700–800 men left on Breed's Hill, with only 150 in the redoubt.<ref name="Kurtz30_35">[[#Kurtz|Kurtz]], pp. 30–35</ref><ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' pp. 92–95, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> Connecticut's Captain [[John Chester (Connecticut soldier)|John Chester]] saw an entire company in retreat and ordered his company to aim muskets at them to halt the retreat; they turned about and headed back to the battlefield.<ref name="Ketchum165_6">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 165–166</ref> |

|||

[[File:Bunker hill final attack.png|thumb|upright=1.25|The third and final British attack on Bunker Hill]] |

|||

The British rear was also in disarray. Wounded soldiers that were mobile had made their way to the landing areas and were being ferried back to Boston, while the wounded lying on the field of battle were the source of moans and cries of pain.<ref name="Ketchum163">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 163</ref> Howe sent word to Clinton in Boston for additional troops. Clinton had observed the first two attacks and sent around 400 men from the 2nd Marines and the [[63rd (The West Suffolk) Regiment of Foot|63rd Foot]], and followed himself to help rally the troops. In addition to these reserves, he convinced around 200 walking wounded to form up for the third attack.<ref name="Ketchum164">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 164</ref> |

|||

The third assault was to concentrate squarely on the redoubt, with only a feint on the colonists' flank. Howe ordered his men to remove their heavy packs and leave all unnecessary equipment behind. He arrayed his forces in column formation rather than the extended order of the first two assaults, exposing fewer men along the front to colonial fire.<ref name="Kurtz35">[[#Kurtz|Kurtz]] p. 35</ref> The third attack was made at the point of the bayonet and successfully carried the redoubt; however, the final volleys of fire from the colonists cost the life of Major Pitcairn.<ref name="Chidsey99">[[#Chidsey|Chidsey]] p. 99</ref> The defenders had run out of ammunition, reducing the battle to close combat. The advantage turned to the British, as their troops were equipped with bayonets on their muskets, while most of the colonists were not. Colonel Prescott, one of the last men to leave the redoubt, parried bayonet thrusts with his normally ceremonial sabre.<ref name="Frothingham150">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 150</ref> It is during the retreat from the redoubt that Joseph Warren was killed.<ref name="Frothingham151">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 151</ref> |

|||

The retreat of much of the colonial forces from the peninsula was made possible in part by the controlled withdrawal of the forces along the rail fence, led by John Stark and Thomas Knowlton, which prevented the encirclement of the hill. Burgoyne described their orderly retreat as "no flight; it was even covered with bravery and military skill". It was so effective that most of the wounded were saved;<ref name="Ketchum181">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 181</ref> most of the prisoners taken by the British were mortally wounded.<ref name="Ketchum181"/> General Putnam attempted to reform the troops on Bunker Hill; however, the flight of the colonial forces was so rapid that artillery pieces and entrenching tools had to be abandoned. The colonists suffered most of their casualties during the retreat on Bunker Hill. By 5 p.m., the colonists had retreated over the Charlestown Neck to fortified positions in Cambridge, and the British were in control of the peninsula.<ref name="Frothingham151–2">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], pp. 151–152</ref> |

|||

==Aftermath== |

==Aftermath== |

||

[[File:Bunker hill 2009.JPG|thumb|upright|The [[Bunker Hill Monument]]]] |

|||

The British had taken the ground, but at a stiff cost; 1,054 were shot (226 dead and 828 wounded), and a disproportionate number of these were officers. |

|||

[[File:Ralph Farnham.jpg|thumb|upright|Ralph Farnham, one of the last survivors]] |

|||

The American losses were only about 450, of whom 140 were killed (including [[Joseph Warren]]), and 30 captured {20 of whom died}. Most American losses came during the withdrawal. |

|||

The British had taken the ground but at a great loss; they had suffered 1,054 casualties (226 dead and 828 wounded), and a disproportionate number of these were officers. The casualty count was the highest suffered by the British in any single encounter during the entire war.<ref name="Brooks237">[[#Brooks|Brooks]], p. 237</ref> General Clinton echoed [[Pyrrhus of Epirus]], remarking in his diary that "A few more such victories would have shortly put an end to British dominion in America."<ref name="Clinton19">[[#Clinton|Clinton]], p. 19. General Clinton's remark is an echoing of [[Pyrrhus of Epirus]]'s original sentiment after the [[Battle of Heraclea]], "''one more such victory and the cause is lost''".</ref> British dead and wounded included 100 commissioned officers, a significant portion of the British officer corps in America.<ref name="Brooks184">[[#Brooks|Brooks]], pp. 183–184</ref> Much of General Howe's field staff was among the casualties.<ref name="Frothingham145">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], pp. 145, 196</ref> General Gage reported the following officer casualties in his report after the battle (listing lieutenants and above by name):<ref name="Frothingham387">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], pp. 387–389 lists the officer casualties by name, as well as this summary</ref> |

|||

British dead and wounded included most of their officers. Of General Howe's entire field staff, he was the only one not shot. |

|||

* 1 lieutenant colonel killed |

|||

Major Pitcairn was dead, and Colonel [[James Abercrombie (Bunker Hill)|James Abercrombie]] fatally wounded. |

|||

* 2 majors killed, 3 wounded |

|||

The American withdrawal and British advance swept right through to include the entire peninsula, Bunker Hill as well as Breed's Hill. |

|||

* 7 captains killed, 27 wounded |

|||

But the number of Americans to be faced in new positions hastily created by Putnam on the mainland, the end of the day, and the exhaustion of his troops removed any chance Howe had of advancing on Cambridge and breaking the siege. |

|||

* 9 lieutenants killed, 32 wounded |

|||

* 15 sergeants killed, 42 wounded |

|||

* 1 drummer killed, 12 wounded |

|||

Colonial losses were about 450 in total, of whom 140 were killed. Most of the colonial losses came during the withdrawal. Major [[Andrew McClary]] was technically the highest ranking colonial officer to die in the battle; he was hit by cannon fire on Charlestown Neck, the last person to be killed in the battle. He was later commemorated by the dedication of [[Fort McClary]] in [[Kittery, Maine]].<ref name="Bardwell76">[[#Bardwell|Bardwell]], p. 76</ref> A serious loss to the Patriot cause, however, was the death of [[Joseph Warren]]. He was the President of Massachusetts' Provincial Congress, and he had been appointed a Major General on June 14. His commission had not yet taken effect when he served as a volunteer private three days later at Bunker Hill.<ref name="Ketchum150">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 150</ref> Only 30 men were captured by the British, most of them with grievous wounds; 20 died while held prisoner. The colonials also lost numerous shovels and other entrenching tools, as well as five out of the six cannons that they had brought to the peninsula.<ref name="Ketchum255">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 255</ref><ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' pp. 94–96, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017. {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> |

|||

The attitude of the British was significantly changed, both individually and as a government. |

|||

Thomas Gage was soon recalled, and would be replaced by General Howe. |

|||

Howe himself lost the daring he had shown at [[Louisbourg]], and was cautious through the rest of his service. |

|||

Gage's report to the cabinet repeated his earlier warnings that ''"a large army must at length be employed to reduce these people"'' and would require ''"the hiring of foreign troops."'' |

|||

==Political consequences== |

|||

The famous order, "Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes" was popularized by stories about Bunker Hill. However, it is uncertain as to who said it, since various writers attribute it to Putnam, Stark, Prescott and Gridley. |

|||

When news of the battle spread through the colonies, it was reported as a colonial loss, as the ground had been taken by the enemy, and significant casualties were incurred. [[George Washington]] was on his way to Boston as the new commander of the [[Continental Army]], and he received news of the battle while in New York City. The report included casualty figures that were somewhat inaccurate, but it gave Washington hope that his army might prevail in the conflict.<ref name="Ketchum207_8">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 207–208</ref> |

|||

Another reporting uncertainty concerns the role of African-Americans. |

|||

There were certainly a few involved in the battle, but their exact numbers are unknown. |

|||

One of these was [[Salem Poor]], who was cited for bravery and whose actions at the redoubt saved Prescott's life, but accounts crediting him with Pitcairn's death are highly doubtful. Other African-Americans present were [[Peter Salem]]; [[Prince Whipple]]; and Brazillari Lew. A mulatto Phillip Abbot of Andover was killed in the battle. |

|||

{{Quote box |

|||

Among the Colonial volunteers in the Battle were [[James Otis]], [[Henry Dearborn]], [[John Brooks]], [[William Eustis]], [[Daniel Shays]], and [[http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GRid=64 William Barton]]. |

|||

| width = 20% |

|||

Among the British Officers were General [[Henry Clinton]], General [[John Burgoyne]], and Lord [[Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings|Francis Rawdon]]. The Americans lost to the [[Llamas]] |

|||

| align = left |

|||

| fontsize = 85%|We have ... learned one melancholy truth, which is, that the Americans, if they were equally well commanded, are full as good soldiers as ours.<ref name="Ketchum209">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 209</ref>|A British officer in Boston, after the battle |

|||

}} |

|||

The Massachusetts Committee of Safety sought to repeat the sort of propaganda victory that it won following the battles at Lexington and Concord, so it commissioned a report of the battle to send to England. Their report, however, did not reach England before Gage's official account arrived on July 20. His report unsurprisingly caused friction and argument between the [[Tory (British political party)|Tories]] and the [[Whig (British political party)|Whig]]s, but the casualty counts alarmed the military establishment, and forced many to rethink their views of colonial military capability.<ref name="Ketchum208_9">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 208–209</ref> [[George III of the United Kingdom|King George]]'s attitude hardened toward the colonies, and the news may have contributed to his rejection of the Continental Congress' [[Olive Branch Petition]], the last substantive political attempt at reconciliation. Sir [[James Adolphus Oughton]], part of the Tory majority, wrote to [[William Legge, 2nd Earl of Dartmouth|Lord Dartmouth]] of the colonies, "the sooner they are made to Taste Distress the sooner will [Crown control over them] be produced, and the Effusion of Blood be put a stop to."<ref name="Ketchum211">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 211</ref> About a month after receiving Gage's report, the [[Proclamation of Rebellion]] was issued in response. This hardening of the British position also strengthened previously weak support for independence among Americans, especially in the southern colonies.<ref name="Ketchum211"/> |

|||

Gage's report had a more direct effect on his own career. He was dismissed from office just three days after his report was received, although General Howe did not replace him until October 1775.<ref name="Ketchum213">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 213</ref> Gage wrote another report to the British Cabinet in which he repeated earlier warnings that "a large army must at length be employed to reduce these people" which would require "the hiring of [[Hessian (soldiers)|foreign troops]]".<ref name="Scheer64">[[#Scheer|Scheer]], p. 64</ref> |

|||

==Analysis== |

|||

General Dearborn published an account of the battle in [[The Port Folio|''Port Folio'']] magazine years later, after Israel Putnam had died. Dearborn accused General Putnam of inaction, cowardly leadership, and failure to supply reinforcements during the battle, which subsequently sparked a [[Dearborn-Putnam controversy|major controversy]] among veterans of the war and historians.<ref name=Cray1>[[#Cray|Cray, 2001]]</ref>{{efn|In 1822, Dearborn wrote an anonymous plea in the ''[[Boston Patriot (newspaper)|Boston Patriot]]'' to urge the purchase of the Bunker Hill battlefield, which was listed for sale.<ref name=Cray1/>}} People were shocked by the rancor of the attack, and this prompted a forceful response from defenders of Putnam, including such notables as John and Abigail Adams. It also prompted Putnam's son Daniel Putnam to defend his father using a letter of thanks written by George Washington, and statements from Colonel John Trumbull and Judge Thomas Grosvenor in Putnam's defense.<ref name=":0">Cray, Robert E. (2001). "Bunker Hill Refought: Memory Wars and Partisan Conflicts, 1775–1825". ''Historical Journal of Massachusetts'' – via Proquest.</ref> Historian Harold Murdock wrote that Dearborn's account "abounds in absurd misstatements and amazing flights of imagination." The Dearborn attack received considerable attention because at the time he was in the middle of considerable controversy himself. He had been relieved of one of the top commands in the War of 1812 due to his mistakes. He had also been nominated to serve as Secretary of War by President [[James Monroe]], but was rejected by the United States Senate (which was the first time that the Senate had voted against confirming a presidential cabinet choice).<ref name="Purcell pp.164-168">[[#Purcell|Purcell, 2010]], pp. 164–168</ref><ref>Ketchum, Richard M. ''The Battle for Bunker Hill'', p. 178, The Cresset Press, London, 1963.</ref><ref>Murdock, Harold. ''Bunker Hill, Notes and Queries on a Famous Battle,'' Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2010. {{ISBN|1163174912}},</ref><ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' pp. 191–192, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017 {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> |

|||

===Disposition of Colonial forces=== |

|||

[[File:Map of the Battle of Bunker Hill area.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|A historic map of Bunker Hill featuring military notes]] |

|||

[[File:Sketch of the Battle of Bunker Hill, printed in August 1775.jpg|thumb|Sketch of the Battle of Bunker Hill, printed in August 1775.]] |

|||

The colonial regiments were under the overall command of General Ward, with General Putnam and Colonel Prescott leading in the field, but they often acted quite independently.<ref>[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 131</ref> This was evident in the opening stages of the battle, when a tactical decision was made that had strategic implications. Colonel Prescott and his staff decided to fortify Breed's Hill rather than Bunker Hill, apparently in contravention of orders.<ref>[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 19</ref> The fortification of Breed's Hill was more militarily provocative; it would have put offensive artillery closer to Boston, directly threatening the city.<ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' p. 87, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC, 2017 {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> It also exposed the forces there to the possibility of being trapped, as they probably could not properly defend against attempts by the British to land troops and take control of Charlestown Neck. If the British had taken that step, they might have had a victory with many fewer casualties.<ref name="Frothingham155">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 155</ref> The colonial fortifications were haphazardly arrayed; it was not until the morning that Prescott discovered that the redoubt could be easily flanked,<ref name="Ketchum115"/> compelling the hasty construction of a rail fence. Furthermore, the colonists did not have the manpower to defend to the west.<ref name="Ketchum117"/> |

|||

Manpower was a further problem on Breed's Hill. The defenses were thin toward the northern end of the colonial position and could have been easily exploited by the British (as they had already landed), had reinforcements not arrived in time.<ref name="Ketchum143"/> The front lines of the colonial forces were generally well-managed, but the scene behind them was significantly disorganized, at least in part due to a poor chain of command and logistical organization. One commentator wrote: "it appears to me there never was more confusion and less command."<ref name="Ketchum147"/> Only some of the militias operated directly under Ward's and Putnam's authority,<ref name="Frothingham158">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], pp. 158–159</ref> and some commanders directly disobeyed orders, remaining at Bunker Hill rather than committing to the defense of Breed's Hill once fighting began. Several officers were subjected to [[court martial]] and [[cashiered]] after the battle.<ref name="French274">[[#French|French]], pp. 274–276</ref> |

|||

Once combat began, desertion was a chronic issue for the colonial troops. By the time of the third British assault, there were only 700–800 troops left, with only 150 in the redoubt.<ref name="Kurtz30_35"/> Colonel Prescott was of the opinion that the third assault would have been repulsed, had his forces in the redoubt been reinforced with more men, or if more supplies of ammunition and powder had been brought forward from Bunker Hill.<ref name="Frothingham153">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 153</ref> Despite these issues, the withdrawal of the colonial forces was generally well-managed, recovering most of their wounded in the process, and elicited praise from British generals such as Burgoyne.<ref name="Ketchum181"/> However, the speed of the withdrawal precipitated leaving behind their artillery and entrenching tools.<ref name="Frothingham151–2"/> |

|||

===Disposition of British forces=== |

|||

The British leadership acted slowly once the works were spotted on Breed's Hill. It was 2 p.m. when the troops were ready for the assault, roughly ten hours after the ''Lively'' first opened fire. This leisurely pace gave the colonial forces ample time to reinforce the flanking positions that would have otherwise been poorly defended and vulnerable.<ref name="French263">[[#French|French]], pp. 263–265</ref> Gage and Howe decided that a frontal assault on the works would be a simple matter, although an encircling move, gaining control of Charlestown Neck, would have given them a more rapid and resounding victory.<ref name="Frothingham155"/> However, the British leadership was excessively optimistic, believing that "two regiments were sufficient to beat the strength of the province".<ref name="Frothingham156">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 156</ref> |

|||

[[File:AttackBunkerHill.jpg|right|thumb|upright=1.5|''View of the Attack on Bunker's Hill with the Burning of Charlestown'' by Lodge]] |

|||

The artillery bombardment that was to have preceded the assault did not transpire because the field guns had been supplied with the wrong caliber of ammunition.<ref name="Philbrick, Nathaniel p. 219-220"/> Once in the field, Howe twice opted to dilute the force attacking the redoubt with flanking assaults against the colonial left. The formations that the British used were not conducive to a successful assault, arrayed in long lines and weighed down by unnecessary heavy gear; many of the troops were immediately vulnerable to colonial fire, which resulted in heavy casualties in the initial attacks. The impetus of any British attack was further diluted when officers opted to concentrate on firing repeated volleys which were simply absorbed by the earthworks and rail fences. The third attack succeeded, when the forces were arrayed in deep columns, the troops were ordered to leave all unnecessary gear behind, the attacks were to be at the point of the bayonet,<ref name="Kurtz35">[[#Kurtz|Kurtz]] p. 35</ref> and the flanking attack was merely a feint.<ref name="French277">[[#French|French]], p. 277</ref><ref name="Frothingham148">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]], p. 148</ref> |

|||

Following the taking of the peninsula, the British had a tactical advantage that they could have used to press into [[Cambridge, Massachusetts|Cambridge]]. General Clinton proposed this to Howe, but Howe declined, having just led three assaults with grievous casualties, including most of his field staff among them.<ref name="Frothingham152">[[#Frothingham|Frothingham]] pp. 152–153</ref> The colonial military leaders eventually recognized Howe as a tentative decision-maker, to his detriment. In the aftermath of the [[Battle of Long Island]] (1776), he again had tactical advantages that might have delivered Washington's army into his hands, but he again refused to act.<ref name="Jackson20">[[#Jackson|Jackson]], p. 20</ref> |

|||

Historian [[John Ferling]] maintains that, had General Gage used the Royal Navy to secure the narrow neck to the Charleston peninsula, cutting the Americans off from the mainland, he could have achieved a far less costly victory. But he was motivated by revenge over patriot resistance at the [[Battles of Lexington and Concord]] and relatively heavy British losses, and he also felt that the colonial militia were completely untrained and could be overtaken with little effort, opting for a frontal assault.<ref name=Ferling15>[[#Ferling|Ferling, 2015]], pp. 127–129</ref> |

|||

=="The whites of their eyes"== |

|||

The famous order "Don't fire until you see the whites of their eyes" was popularized in stories about the battle of Bunker Hill.<ref name="Bell">{{cite journal|title=Who Said, "Don't fire till you see the whites of their eyes"?|url=https://allthingsliberty.com/2020/06/who-said-dont-fire-till-you-see-the-whites-of-their-eyes/|journal=Journal of the American Revolution|date=June 17, 2020|first=J. L. |last=Bell |access-date=July 13, 2023}}</ref> It is uncertain as to who said it there, since various histories, including eyewitness accounts,<ref>Lewis, John E., ed. ''The Mammoth Book of How it Happened''. London: Robinson, 1998. p. 179 {{ISBN?}}</ref> attribute it to Putnam, Stark, Prescott, or Gridley, and it may have been said first by one and repeated by the others.<ref>Hubbard, Robert Ernest. ''Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution,'' p. 97, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, NC 2017 {{ISBN|978-1-4766-6453-8}}.</ref> Modern scholarly consensus is nobody said it at the battle, it is a legend.<ref name="Bell" /> |

|||

It was also not an original statement. The idea dates originally to the general-king [[Gustavus Adolphus]] (1594–1632) who gave standing orders to his musketeers "never to give fire, till they could see their own image in the pupil of their enemy's eye".<ref>Joannis Schefferi, "Memorabilium Sueticae Gentis Exemplorum Liber Singularis" (1671) p. 42</ref> Gustavus Adolphus's military teachings were widely admired and imitated and caused this saying to be often repeated. It was used by General [[James Wolfe]] on the [[Battle of the Plains of Abraham|Plains of Abraham]] when his troops defeated [[Louis-Joseph de Montcalm|Montcalm's]] army on September 13, 1759.<ref>R. Reilly, ''The Rest to Fortune: The Life of Major-General James Wolfe'' (1960), p. 324</ref> The earliest similar quotation came from the [[Battle of Dettingen]] on June 27, 1743, where Lieutenant-Colonel [[Sir Andrew Agnew, 5th Baronet|Sir Andrew Agnew]] of Lochnaw warned the [[Royal Scots Fusiliers]] not to fire until they could "see the white of their e'en."<ref>[[#Anderson|Anderson]], p. 679</ref> The phrase was also used by Prince Charles of Prussia in 1745, and repeated in 1755 by [[Frederick the Great]], and may have been mentioned in histories with which the colonial military leaders were familiar.<ref name="WinsorBoston85">[[#WinsorBoston|Winsor]], p. 85</ref> Whether or not it was actually said in this battle, it was clear that the colonial military leadership were regularly reminding their troops to hold their fire until the moment when it would have the greatest effect, especially in situations where their ammunition would be limited.<ref name="French269">[[#French|French]], pp. 269–270</ref> |

|||

==Notable participants== |

|||

[[File:New England pine flag.svg|thumb|According to the John Trumbull painting, this [[flag of New England]] was carried by the colonists during the battle.]] |

|||

A significant number of notable American patriots fought in this battle. [[Henry Dearborn]] and [[William Eustis]], for example, went on to distinguished military and political careers; both served in Congress, the Cabinet, and in diplomatic posts. Others, like [[John Brooks (governor)|John Brooks]], [[Henry Burbeck]], [[Christian Febiger]], [[Thomas Knowlton]], and [[John Stark]], became well known for later actions in the war.<ref name="Abbatt252">[[#Abbatt|Abbatt]], p. 252<!--Burbeck--></ref><ref name="KetchumNotables1">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], pp. 132<!--Brooks-->,165<!--Febiger--></ref> Stark became known as the "Hero of Bennington" for his role in the 1777 [[Battle of Bennington]]. Free African-Americans also fought in the battle; notable examples include [[Barzillai Lew]], [[Salem Poor]], and [[Peter Salem]].<ref name="WoodsonNotables">[[#Woodson|Woodson]], p. 204<!--Lew, Poor, Salem--></ref><ref name="KetchumNotables2">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 260<!--slaves not allowed--></ref><!-- already mentioned, not needing citation: Stark, Knowlton--> Another notable participant was [[Daniel Shays]], who later became famous for his army of protest in [[Shays' Rebellion]].<ref name="Richards95">[[#Richards|Richards]], p. 95<!--Shays--></ref> Israel Potter was immortalized in ''[[Israel Potter|Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile]]'', a novel by [[Herman Melville]].<ref name="Ketchum257">[[#Ketchum|Ketchum]], p. 257<!--Potter was there--></ref><ref name="Melville">[[#Melville|Melville]]</ref> Colonel [[John Paterson (New York politician)|John Paterson]] commanded the Massachusetts First Militia, served in [[Shays' Rebellion]], and became a [[United States House of Representatives|congressman]] from [[New York (state)|New York]].<ref>[[#PattersonBio|Biographical Directory of the United States]]</ref> Lt. Col. [[Seth Read]], who served under John Paterson at Bunker Hill, went on to settle [[Geneva, New York]] and [[Erie, Pennsylvania]], and was said to have been instrumental in the phrase ''[[E pluribus unum]]'' being added to [[Coins of the United States dollar|U.S. coins]].<ref name="Seth">[[#Buford|Buford, 1895]], Preface</ref><ref>Marvin, p. 425, 436</ref><ref name="coins">{{cite web| url=http://www.coins.nd.edu/ColCoin/ColCoinIntros/MA-Copper.intro.html| title = Massachusetts Coppers 1787–1788: Introduction| access-date =2007-10-09| publisher=University of Notre Dame| archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20071108015613/http://www.coins.nd.edu/ColCoin/ColCoinIntros/MA-Copper.intro.html| archive-date= November 8, 2007 | url-status= live}}</ref><ref name="e pluribus">{{cite web |url= http://treas.gov/education/faq/coins/portraits.shtml |title= e pluribus unum FAQ #7 |publisher= U.S. Treasury|access-date=2007-09-29|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070913082335/treas.gov/education/faq/coins/portraits.shtml|archive-date=September 13, 2007}}</ref> [[George Claghorn]] of the Massachusetts militia was shot in the knee at Bunker Hill and went on after the war to become the master builder of the [[USS Constitution|USS ''Constitution'', {{color|black|a.k.a.}} "''Old Ironsides''"]], which is the oldest naval vessel in the world that is still commissioned and afloat.<ref name="Wheeler">{{Cite web |title=Individual Summary for COL. GEORGE CLAGHORN |author=Wheeler, O. Keith |url=http://www.wheelerfolk.org/keithgen/related/claghorn_geo_indiv_sum.htm |date=30 January 2002 |access-date=2012-10-10}}</ref><ref>{{HMS|Victory}} is the oldest commissioned vessel by three decades; however, ''Victory'' has been in dry dock since 1922. {{cite web |

|||

|url=http://www.hms-victory.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=153&Itemid=572 |

|||

|title=HMS Victory Service Life |

|||

|publisher=HMS Victory website |

|||

|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130924031708/http://hms-victory.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=153&Itemid=572 |

|||

|archive-date=September 24, 2013 |

|||

|url-status=dead |

|||

|access-date=October 14, 2012 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Notable British participants in the battle were: Lt. Col. [[Samuel Birch (military officer)|Samuel Birch]], Major [[John Small (British Army officer)|John Small]], [[Francis Rawdon-Hastings, 1st Marquess of Hastings|Lord Rawdon]], General [[William Howe, 5th Viscount Howe|William Howe]], Major [[John Pitcairn]] and General [[Henry Clinton (British Army officer, born 1730)|Henry Clinton]]. |

|||

==Commemorations== |

==Commemorations== |

||

[[John Trumbull]]'s painting, ''[[The Death of General Warren at the Battle of Bunker Hill]]'' (displayed in lede), was created as an [[Allegory|allegorical]] depiction of the battle and Warren's death, not as an actual pictorial recording of the event. The painting shows a number of participants in the battle including a British officer, [[John Small (British Army officer)|John Small]], among those who stormed the redoubt, yet came to be the one holding the mortally wounded Warren and preventing a fellow [[Red coat (British army)|redcoat]] from bayoneting him. He was friends of Putnam and Trumbull. Other central figures include Andrew McClary who was the last man to fall in the battle.<ref>Bunce, p. 336</ref> |

|||

* There is a memorial tower that stands 221 feet high. There is also a statue of Prescott in the famous pose used to show him calming his "farmers" down. |

|||

* Bunker Hill Day, commemorating the battle, is a [[legal holiday]] in [[Suffolk County, Massachusetts|Suffolk County]], [[Massachusetts]]. State institutions in Massachusetts (such as public [[higher education]]) also celebrate the holiday. |

|||

The [[Bunker Hill Monument]] is an [[obelisk]] that stands {{convert|221|ft|m}} high on Breed's Hill. On June 17, 1825, the fiftieth anniversary of the battle, the cornerstone of the monument was laid by the [[Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette|Marquis de Lafayette]] and an address delivered by [[Daniel Webster]].<ref>[[#Hayward|Hayward]], p. 322</ref><ref name="Clary">[[#Clary|Clary]]</ref> The [[Leonard P. Zakim Bunker Hill Memorial Bridge]] was specifically designed to evoke this monument.<ref name="MTABridges">[[#MTABridges|MTA Bridges]]</ref> There is also a statue of William Prescott showing him calming his men down. |

|||

[[File:Clipper ship card Bunker Hill.jpg|thumb|left|''Bunker Hill'' [[Clipper|clipper ship]]]] |

|||

The [[National Park Service]] operates a museum dedicated to the battle near the monument, which is part of the [[Boston National Historical Park]].<ref name="NPSBHM">[[#NPSBHM|Bunker Hill Museum]]</ref> A [[cyclorama]] of the battle was added in 2007 when the museum was renovated.<ref name="Globe20070610">[[#Globe20070610|McKenna]]</ref> |

|||

In nearby Cambridge, a small granite monument just north of Harvard Yard bears this inscription: "Here assembled on the night of June 16, 1775, 1200 Continental troops under command of Colonel Prescott. After prayer by President Langdon, they marched to Bunker Hill." See footnote for picture.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://picasaweb.google.com/115084101490686051189/DropBox?authkey=Gv1sRgCIb7-7uW5e244QE#5827876206844880834|title=Album Archive|website=Picasaweb.google.com|access-date=November 19, 2017}}</ref> (Samuel Langdon, a Congregational minister, was Harvard's 11th president.)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.harvard.edu/history/presidents/langdon |title=Samuel Langdon | Harvard University |access-date=2013-12-31 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130101220156/http://www.harvard.edu/history/presidents/langdon |archive-date=January 1, 2013 |df=mdy }}</ref> Another small monument nearby marks the location of the Committee of Safety, which had become the Patriots' provisional government as Tories left Cambridge.<ref>[[Committee of Safety (American Revolution)]]</ref> These monuments are on the lawn to the west of Harvard's Littaeur Center, which is itself the west of Harvard's huge Science Center. See footnote for map.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://map.harvard.edu/mapserver/campusmap.htm|title=Harvard University Campus Map|website=Map.harvard.edu|access-date=November 19, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130106200002/http://map.harvard.edu/mapserver/campusmap.htm|archive-date=January 6, 2013|url-status=dead|df=mdy-all}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Statue of william prescott in charlestown massachusetts.jpg|thumb|upright|Statue of [[William Prescott]] in [[Charlestown, Massachusetts]]]] |

|||

Bunker Hill Day, observed every June 17, is a [[legal holiday]] in [[Suffolk County, Massachusetts]] (which includes the city of Boston), as well as [[Somerville, Massachusetts|Somerville]] in [[Middlesex County, Massachusetts|Middlesex County]]. [[Prospect Hill, Somerville|Prospect Hill]], site of colonial fortifications overlooking the Charlestown Neck, is now in Somerville, which was previously part of Charlestown.<ref name="LegalHoliday">[[#LegalHoliday|MA List of legal holidays]]</ref><ref name="SomervilleHoliday">[[#SomervilleHoliday|Somerville Environmental Services Guide]]</ref> State institutions in Massachusetts (such as public institutions of [[higher education]]) in Boston also celebrate the holiday.<ref name="UMBHolidays">[[#UMBHolidays|University of Massachusetts, Boston, observed holidays]]</ref><ref name="BHDClosings">[[#BHDClosings|Bunker Hill Day closings]]</ref> However, the state's FY2011 budget requires that all state and municipal offices in Suffolk County be open on Bunker Hill Day and [[Evacuation Day (Massachusetts)|Evacuation Day]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Commonwealth of Massachusetts FY2011 Budget, Outside Section 5|url=http://www.mass.gov/bb/gaa/fy2011/os_11/h5.htm|website=Mass.gov|date=July 14, 2010|access-date=August 6, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

On June 16 and 17, 1875, the centennial of the battle was celebrated with a military parade and a reception featuring notable speakers, among them General [[William Tecumseh Sherman]] and [[United States Vice President|Vice President]] [[Henry Wilson]]. It was attended by dignitaries from across the country.<ref name="Centennial">See the [[#CentennialBook|Centennial Book]] for a complete description of the events.</ref> Celebratory events also marked the sesquicentennial (150th anniversary) in 1925 and the bicentennial in 1975.<ref name="Sesqui">[[#SesquicentennialBook|Sesquicentennial celebration]]</ref><ref name="Kifner">[[#Kifner|New York Times, June 15, 1975]]</ref> |

|||

Over the years the Battle of Bunker Hill has been commemorated on four U.S. Postage stamps.<ref>Scotts 2008 United States stamp catalogue</ref> |

|||

[[File:Battle of Bunker Hill commemorative stamps.jpeg|thumb|upright=2|left| Issue of 1959 Issue of 1975 Issue of 1968 Issue of 1968 |

|||

---- |

|||

Left stamp depicts Battle of Bunker Hill battle flag and Monument<br>Left-center, depicts John Trumbull's painting of the battle<br>Right-center depicts detail of Trumbull's painting<br>Right depicts image of Bunker Hill battle flag]] |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

*[[Royal Welch Fusiliers]] |

|||

* [[List of American Revolutionary War battles]] |

|||

* [[American Revolutionary War#Early engagements|American Revolutionary War §Early Engagements]]. The Battle of Bunker Hill placed in sequence and strategic context. |

|||

* [[List of Continental Forces in the American Revolutionary War]] |

|||

* [[List of British Forces in the American Revolutionary War]] |

|||

* [[John Hart (doctor)|John Hart]], Regimental Surgeon of Col Prescott's Regiment who treated the wounded at Bunker Hill |

|||

* [[Royal Welch Fusiliers]] |

|||

* {{USS|Bunker Hill}} |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{notelist}} |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

*Peter Doyle; ''"Bunker Hill"''; (young peoples book); 1998, Providence Foundation; ISBN 1887456082. |

|||

*John R. Elting; <cite>"The Battle of Bunker's Hill"</cite>; 1975, Phillip Freneau Pres ''(56 pages)'', Monmouth, New Jersey; ISBN 0912480114 |

|||

==Bibliography== |

|||

*Howard Fast; <cite>"Bunker Hill"</cite>; 2001, ibooks inc., New York; ISBN 0743423844 |

|||

'''Major sources''' |

|||

*Richard Ketchum;''"Decisive Day: The Battle of Bunker Hill"''; 1999, Owl Books; ISBN 0385418973 (Paperback: ISBN 0805060995) |

|||

Most of the information about the battle itself in this article comes from the following sources. |

|||

*''The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy'', Third Edition. Edited by E.D. Hirsch, Jr., Joseph F. Kett, and James Trefil. Published by Houghton Mifflin Company. 2002. |

|||

{{Refbegin}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Brooks|first=Victor|title=The Boston Campaign|publisher=Combined Publishing|year=1999|isbn=1-58097-007-9|ref=Brooks|oclc=42581510|location=Conshohocken, PA}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Chidsey|first=Donald Barr|title=The Siege of Boston|publisher=Crown|year=1966|ref=Chidsey|oclc=890813|location=Boston}} |

|||

* {{Cite book|last=Frothingham|first=Richard Jr.|author-link=Richard Frothingham, Jr.|title=History of the Siege of Boston and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill, Second Edition|publisher=Charles C. Little and James Brown|year=1851|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xl4sAAAAMAAJ|ref=Frothingham|oclc=2138693|location=Boston}} |

|||

* {{Cite book | last = French | first = Allen | author-link =Allen French | title = The Siege of Boston | publisher=Macmillan | year = 1911 |url=https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_PqZcY9z3Vn4C |ref=French |oclc=3927532 |location=New York}} |

|||