Jimmy Carter: Difference between revisions

→Georgia State Senate: added political to career. |

ce |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|President of the United States from 1977 to 1981}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=April 2011}} |

|||

{{Redirect|James Earl Carter|his father|James Earl Carter Sr.||Jimmy Carter (disambiguation)}} |

|||

{{Other people1|the 39th President of the United States}} |

|||

{{Good article}} |

|||

{{pp-blp|small=yes}} |

|||

{{ |

{{Pp-blp|small=yes}} |

||

{{Pp-move}} |

|||

{{Use American English|date=September 2024}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=September 2024}} |

|||

{{Infobox officeholder |

{{Infobox officeholder |

||

|name = Jimmy Carter |

| name = Jimmy Carter |

||

|image = JimmyCarterPortrait2.jpg |

| image = JimmyCarterPortrait2.jpg |

||

| alt = Portrait of Jimmy Carter in a dark blue suit |

|||

|office = [[List of Presidents of the United States|39th]] [[President of the United States]] |

|||

| caption = Official portrait, 1978 |

|||

|vicepresident = [[Walter Mondale]] |

|||

| order = 39th |

|||

|term_start = January 20, 1977 |

|||

| |

| office = President of the United States |

||

| |

| vicepresident = [[Walter Mondale]] |

||

| |

| term_start = January 20, 1977 |

||

| |

| term_end = January 20, 1981 |

||

| |

| predecessor = [[Gerald Ford]] |

||

| successor = [[Ronald Reagan]] |

|||

|term_start1 = January 12, 1971 |

|||

| order1 = 76th |

|||

|term_end1 = January 14, 1975 |

|||

| office1 = Governor of Georgia |

|||

|predecessor1 = [[Lester Maddox]] |

|||

| term_start1 = January 12, 1971 |

|||

|successor1 = [[George Busbee]] |

|||

| term_end1 = January 14, 1975 |

|||

|state_senate2 = Georgia |

|||

| lieutenant1 = [[Lester Maddox]] |

|||

|district2 = 14th |

|||

| predecessor1 = Lester Maddox |

|||

|term_start2 = January 14, 1963 |

|||

| successor1 = [[George Busbee]] |

|||

|term_end2 = January 10, 1967 |

|||

| state_senate2 = Georgia State |

|||

|predecessor2 = Constituency established |

|||

| district2 = [[Georgia's 14th Senate district|14th]] |

|||

|successor2 = [[Hugh Carter]] |

|||

| term_start2 = January 14, 1963 |

|||

|constituency2 = [[Sumter County, Georgia|Sumter County]] |

|||

| term_end2 = January 9, 1967 |

|||

|birth_date = {{birth date and age|1924|10|1}} |

|||

| predecessor2 = ''Constituency established'' |

|||

|birth_place = [[Plains, Georgia|Plains]], [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]], [[United States|U.S.]] |

|||

| successor2 = [[Hugh Carter]] |

|||

|death_date = |

|||

| birth_name = James Earl Carter Jr. |

|||

|death_place = |

|||

| |

| birth_date = {{Birth date and age|1924|10|01}} |

||

| birth_place = [[Plains, Georgia]], U.S. |

|||

|spouse = [[Rosalynn Carter|Rosalynn Smith]] {{small|(1946–present)}} |

|||

| death_date = <!-- {{Death date and age|YYYY|MM|DD|1924|10|01}} --> |

|||

|children = [[Jack Carter (politician)|Jack]]<br>James<br>Donnel<br>[[Amy Carter|Amy]] |

|||

| death_place = <!-- [[Plains, Georgia]], U.S. --> |

|||

|alma_mater = [[Georgia Southwestern State University]]<br>[[Georgia Institute of Technology|Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta]]<br>{{nowrap|[[United States Naval Academy]]}} |

|||

| resting_place = <!-- [[209 Woodland Drive]], Plains --> |

|||

|religion = [[Cooperative Baptist Fellowship|Baptist]]<ref>{{cite web |last=Warner |first=Greg |url=http://www.baptiststandard.com/2000/10_23/pages/carter.html |title=Jimmy Carter says he can 'no longer be associated' with the SBC |quote=He said he will remain a deacon and Sunday school teacher at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains and support the church's recent decision to send half of its missions contributions to the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship. |work=Baptist Standard |accessdate=December 13, 2009}}</ref> |

|||

| party = [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic]] |

|||

|signature = Jimmy Carter Signature-2.svg |

|||

| spouse = {{marriage|[[Rosalynn Carter|Rosalynn Smith]]|July 7, 1946|November 19, 2023|end=died}} |

|||

|signature_alt = Cursive signature in ink |

|||

| children = 4, including [[Jack Carter (politician)|Jack]] and [[Amy Carter|Amy]] |

|||

|allegiance = {{flag|United States}} |

|||

| parents = {{plainlist| |

|||

|branch = [[File:United States Department of the Navy Seal.svg|25px]] [[United States Navy]] |

|||

* [[James Earl Carter Sr.]] |

|||

|serviceyears = 1946–1953 |

|||

* [[Bessie Lillian Gordy]] |

|||

|rank = [[File:US-O3 insignia.svg|15px]] [[Lieutenant (navy)|Lieutenant]] |

|||

|awards = [[Nobel Peace Prize]]<br>[[Order of the Crown (Belgium)|Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown]] |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

| relatives = [[List of United States political families (C)#The Carters of Georgia|Carter family]] |

|||

'''James Earl "Jimmy" Carter, Jr.''' (born October 1, 1924) is an American politician who served as the [[List of Presidents of the United States|39th]] [[President of the United States]] (1977–1981) and was the recipient of the 2002 [[Nobel Peace Prize]], the only U.S. President to have received the Prize after leaving office. Before he became President, Carter served as a U.S. Naval officer, was a [[peanut]] farmer, served two terms as a [[Georgia Senate|Georgia State Senator]] and one as [[List of Governors of Georgia|Governor of Georgia]] (1971–1975).<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-676 |title=Jimmy Carter |encyclopedia=New Georgia Encyclopedia |publisher=Georgia Humanities Council |accessdate=December 9, 2007}}</ref> |

|||

| education = [[United States Naval Academy]] ([[Bachelor of Science|BS]]) |

|||

| awards = [[List of awards and honors received by Jimmy Carter|Full list]] |

|||

| signature = Jimmy Carter Signature-2.svg |

|||

| signature_alt = Cursive signature in ink |

|||

| branch = [[United States Navy]]<!--No flags per MOS:INFOBOXFLAG--> |

|||

| serviceyears = {{plainlist| |

|||

* 1946–1953 (active) |

|||

* 1953–1961 (reserve) |

|||

}} |

|||

| rank = [[Lieutenant (navy)|Lieutenant]]<!--No icons per MOS:INFOBOXFLAG--> |

|||

| mawards = {{plainlist| |

|||

* [[American Campaign Medal]] |

|||

* [[World War II Victory Medal]] |

|||

* [[China Service Medal]] |

|||

* [[National Defense Service Medal]] |

|||

}} |

|||

| module = {{Listen|pos=center|embed=yes|filename=Jimmy Carter speaks on the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.ogg|title=Jimmy Carter's voice|type=speech|description=Carter speaks on the [[Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]].<br />Recorded January 4, 1980}} |

|||

}} |

|||

'''James Earl Carter Jr.''' (born October 1, 1924<!-- DO NOT report Carter's death without reliable source. -->) is an American politician and humanitarian who served from 1977 to 1981 as the 39th [[president of the United States]]. A member of the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]], he served from 1963 to 1967 in the [[Georgia State Senate]] and from 1971 to 1975 as the 76th [[governor of Georgia]]. Carter is the [[List of presidents of the United States by age|longest-lived president in U.S. history]] and the first to live to [[Centenarian|100 years of age]]. |

|||

Carter was born and raised in [[Plains, Georgia]]. He graduated from the [[U.S. Naval Academy]] in 1946 and joined the [[U.S. Navy]]'s submarine service. Carter returned home after his military service and revived his family's peanut-growing business. Opposing [[Racial segregation in the United States|racial segregation]], Carter supported the growing [[civil rights movement]], and became an activist within the Democratic Party. He served in the Georgia State Senate from 1963 to 1967 and then as governor of Georgia from 1971 to 1975. As a [[dark-horse]] candidate not well known outside Georgia, Carter won [[1976 Democratic Party presidential primaries|the Democratic nomination]] and narrowly defeated the incumbent president, [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] [[Gerald Ford]], in the [[1976 United States presidential election|1976 election]]. |

|||

During Carter's term as President, two new cabinet-level departments were created: the [[United States Department of Energy|Department of Energy]] and the [[United States Department of Education|Department of Education]]. He established a [[Energy policy of the United States|national energy policy]] that included conservation, price control, and new technology. In foreign affairs, Carter pursued the [[Camp David Accords]], the [[Panama Canal Treaties]], the second round of [[Strategic Arms Limitation Talks]] (SALT II), and returned the [[Panama Canal Zone]] to Panama. He took office during a period of international [[stagflation]], which persisted throughout his term. The end of his presidential tenure was marked by the 1979–1981 [[Iran hostage crisis]], the [[1979 energy crisis]], the [[Three Mile Island accident|Three Mile Island nuclear accident]], the [[Soviet war in Afghanistan|Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]], United States boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow (the only U.S. boycott in Olympic history), and the [[eruption of Mount St. Helens]]. |

|||

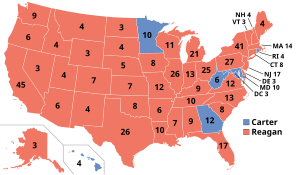

Carter [[Proclamation 4483|pardoned all Vietnam War draft evaders]] on his second day in office. He created a national energy policy that included conservation, price control, and new technology. Carter successfully pursued the [[Camp David Accords]], the [[Panama Canal Treaties]], and the second round of [[Strategic Arms Limitation Talks]]. He also confronted [[stagflation]]. His administration established the [[U.S. Department of Energy]] and the [[United States Department of Education|Department of Education]]. The end of his presidency was marked by the [[Iran hostage crisis]], [[1979 oil crisis|an energy crisis]], the [[Three Mile Island accident]], the [[Nicaraguan Revolution]], and the [[Soviet invasion of Afghanistan]]. In response to the invasion, Carter escalated the [[Cold War]] by ending ''[[détente]]'', imposing [[United States grain embargo against the Soviet Union|a grain embargo against the Soviets]], enunciating the [[Carter Doctrine]], and leading [[1980 Summer Olympics boycott|the multinational boycott]] of the [[1980 Summer Olympics]] in Moscow. He lost the [[1980 United States presidential election|1980 presidential election]] in a landslide to [[Ronald Reagan]], the Republican nominee. |

|||

By 1980, Carter's popularity had eroded. He survived a primary challenge against [[Ted Kennedy]] for the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]] nomination in the [[United States presidential election, 1980|1980 election]], but lost the election to [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican]] candidate [[Ronald Reagan]]. On January 20, 1981, minutes after Carter's term in office ended, the 52 U.S. captives held at the U.S. embassy in Iran were released, ending the 444-day Iran hostage crisis.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/iran-hostage-crisis-ends |title=Iran Hostage Crisis ends – History.com This Day in History – 1/20/1981 |publisher=History.com |date= |accessdate=June 8, 2010}}</ref> |

|||

After leaving |

After leaving the presidency, Carter established the [[Carter Center]] to promote and expand human rights; in 2002 he received a [[Nobel Peace Prize]] for his work in relation to it. He traveled extensively to conduct peace negotiations, [[election monitoring|monitor elections]], and further the eradication of infectious diseases. Carter is a key figure in the nonprofit housing organization [[Habitat for Humanity]]. He has also written [[Bibliography of Jimmy Carter|numerous books]], ranging from political memoirs to poetry, while continuing to comment on global affairs, including two books on the [[Israeli–Palestinian conflict]]. Polls of historians and political scientists generally [[Historical rankings of presidents of the United States|rank Carter]] as a below-average president, though scholars and the public more favorably view [[Post-presidency of Jimmy Carter|his post-presidency]], which is the longest in U.S. history. |

||

==Early life== |

== Early life == |

||

[[File:The Carter family store in the Jimmy Carter National Historical Park.jpg|thumb|alt=A rural storehouse with a small windmill next to it|The Carter family store, part of [[Jimmy Carter National Historical Park|Carter's Boyhood Farm]], in [[Plains, Georgia]]]] |

|||

[[File:Jimmy Carter with his dog Bozo 1937.gif|upright|thumb|Jimmy Carter (around age 13) his dog, Bozo, in 1937.]]James Earl Carter, Jr., was born at the [[Wise Sanitarium]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.presidentialavenue.com/jec.cfm |title=Whois Lookup |publisher=Presidentialavenue.com |date= |accessdate=2012-08-07}}</ref> on October 1, 1924, in the tiny southwest [[Georgia (U.S. state)|Georgia]] city of [[Plains, Georgia|Plains]], near [[Americus, Georgia|Americus]]. The first president born in a hospital,<ref name=USA-Presidents>{{cite web |accessdate= |url=http://www.usa-presidents.info/carter.htm |title=Jimmy Carter |publisher=USA-Presidents.org}}</ref> he is the eldest of four children of [[James Earl Carter, Sr.|James Earl Carter]] and [[Lillian Gordy Carter|Bessie Lillian Gordy]]. Carter's father was a prominent business owner in the community and his mother was a registered nurse. |

|||

James Earl Carter Jr. was born October 1, 1924, in [[Plains, Georgia]], at the [[Wise Sanitarium]], where his mother worked as a registered nurse.{{sfn|Godbold|2010|p=9}} Carter thus became the first American president born in a hospital.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=11–32}} He is the eldest child of [[Bessie Lillian Gordy]] and [[James Earl Carter Sr.]], and a descendant of English immigrant Thomas Carter, who settled in the [[Colony of Virginia]] in 1635.{{sfn|Kaufman|Kaufman|2013|p=70}}{{sfn|Carter|2012|p=10}} In Georgia, numerous generations of Carters worked as cotton farmers.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|p=9}} Plains was a [[boomtown]] of 600 people at the time of Carter's birth. His father was a successful local businessman who ran a [[general store]] and was an investor in farmland.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|p=114}} Carter's father had previously served as a reserve second lieutenant in the [[U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps]] during [[World War I]].{{sfn|Bourne|1997|p=114}} |

|||

Carter is descended from immigrants from southern England (one of his paternal ancestors arrived in the American Colonies in 1635),<ref>"[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,915294,00.html The Nation: Magnus Carter: Jimmy's Roots]". ''Time''. August 22, 1977. Retrieved February 16, 2010.</ref> and his family has lived in the state of Georgia for several generations. Carter has documented ancestors who fought in the American Revolution, and he is a member of the [[Sons of the American Revolution]].<ref name=calsarspring07>{{cite news |title=The California Compatriot |publisher=California Society SAR |date=Spring 2007 |page=23 |url= http://www.californiasar.org/images/SpringCompatriot07_R.pdf |accessdate= September 4, 2007 }}</ref> Carter's great-grandfather, Private L.B. Walker Carter (1832–1874), served in the [[Confederate States Army]].<ref>[http://books.google.com/books?id=hTFYp2-cnMkC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Jimmy+Carter,+American+Moralist,+by+Kenneth+Earl+Morris&source=bl&ots=junCqi5YXO&sig=AYFDaW3kdt9m2w_yS5EeYqNMoV8&hl=en&ei=FwJkTdmKFIGs8AaarqyDDA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBcQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false Jimmy Carter, American Moralist], by Kenneth Earl Morris, 1996, page 23</ref> |

|||

During Carter's infancy, his family moved several times, settling on a dirt road in nearby [[Archery, Georgia|Archery]], which was almost entirely populated by impoverished [[African American]] families.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=11–32}}{{sfn|Biven|2002|p=57}} His family eventually had three more children: [[Gloria Carter Spann|Gloria]], [[Ruth Carter Stapleton|Ruth]], and [[Billy Carter|Billy]].{{sfn|Flippen|2011|p=25}} Carter got along well with his parents even though his mother was often absent during his childhood since she worked long hours, and although his father was staunchly [[Racial segregation in the United States|pro-segregation]], he allowed Jimmy to befriend the black farmhands' children.{{sfn|Newton|2016|p=172}} Carter was an enterprising teenager who was given his own acre of Earl's farmland, where he grew, packaged, and sold peanuts.{{sfn|Hamilton|2005|p=334}} Carter also rented out a section of tenant housing that he had purchased.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=11–32}} |

|||

Carter was a gifted student from an early age who always had a fondness for reading. By the time he attended Plains High School, he was also a star in basketball. He was greatly influenced by one of his high school teachers, Julia Coleman (1889–1973). While he was in high school he was in the [[Future Farmers of America]], which later changed its name to the [[National FFA Organization]], serving as the Plains FFA Chapter Secretary.<ref name=FFA>{{cite web |accessdate= |url=http://www.ffa.org/documents/about_prominentmembers.pdf |title=National FFA Organization: Prominent Former Members |publisher=National FFA Organization}}</ref> |

|||

=== Education === |

|||

Carter had three younger siblings: sisters [[Gloria Carter Spann]] (1926–1990) and [[Ruth Carter Stapleton]] (1929–1983), and brother [[Billy Carter|William Alton "Billy" Carter]] (1937–1988). During Carter's Presidency, Billy was often in the news, usually in an unflattering light.<ref>{{cite news |author= Robert D. Hershey Jr|title= Billy Carter Dies of Cancer at 51; Troubled Brother of a President| url=http://www.nytimes.com/1988/09/26/obituaries/billy-carter-dies-of-cancer-at-51-troubled-brother-of-a-president.html|work= [[The New York Times]] |date= September 26, 1988|accessdate=2011-07-27 }}</ref> |

|||

Carter attended Plains High School from 1937 to 1941, graduating from the eleventh grade since the school did not have a twelfth grade.{{sfn|National Park Service|2020}} By that time, Archery and Plains had been impoverished by the [[Great Depression in the United States|Great Depression]], but the family benefited from [[New Deal]] farming subsidies, and Carter's father took a position as a community leader.{{sfn|Hamilton|2005|p=334}}{{sfn|Hayward|2004|loc=The Plain Man from Plains}} Carter himself was a diligent student with a fondness for reading.{{sfn|Hobkirk|2002|p=8}} A popular anecdote holds that he was passed over for [[valedictorian]] after he and his friends skipped school to venture downtown in a [[hot rod]]. Carter's truancy was mentioned in a local newspaper, although it is not clear he would have otherwise been valedictorian.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=33–43}} As an adolescent, Carter played on the Plains High School basketball team, and also joined [[Future Farmers of America]], which helped him develop a lifelong interest in woodworking.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=33–43}} |

|||

Carter had long dreamed of attending the [[United States Naval Academy]].{{sfn|Hamilton|2005|p=334}} In 1941, he started undergraduate coursework in engineering at [[Georgia Southwestern College]] in nearby Americus, Georgia.{{sfn|Panton|2022|p=99}} The next year, Carter transferred to the [[Georgia Institute of Technology]] in Atlanta, where civil rights icon [[Blake Van Leer]] was president.{{sfn|Rattini|2020}} While at Georgia Tech, Carter took part in the [[Reserve Officers' Training Corps]].{{sfn|Balmer|2014|p=34}} In 1943, he received an appointment to the Naval Academy from U.S. Representative [[Stephen Pace (politician)|Stephen Pace]], and Carter graduated with a [[Bachelor of Science]] in 1946.{{sfn|Hobkirk|2002|p=38}}{{sfn|Balmer|2014|p=34}} He was a good student but was seen as reserved and quiet, in contrast to the academy's culture of aggressive hazing of freshmen.{{sfn|Kaufman|Kaufman|2013|p=62}} While at the Academy, Carter fell in love with [[Rosalynn Smith]], a friend of his sister Ruth.{{sfn|Wertheimer|2004|p=343}} The two wed shortly after his graduation in 1946, and were married until her death on November 19, 2023.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=44–55}}{{sfn|Barrow|Warren|2023}} Carter was a [[sprint football]] player for the [[Navy Midshipmen]].{{sfn|Hingston|2016}} He graduated 60th out of 821 midshipmen in the class of 1947{{efn|The Naval Academy's Class of 1947 graduated in 1946 as a result of World War II.{{sfn|Argetsinger|1996}}}} with a Bachelor of Science degree and was commissioned as an [[Ensign (rank)|ensign]].{{sfn|Alter|2020|p=59}} |

|||

He married [[Rosalynn Carter|Rosalynn Smith]] in 1946; they have four children. |

|||

== Naval career == |

|||

He is a first cousin of politician [[Hugh Carter]] and a [[Cousin#Additional terms|half-second cousin]] of Motown founder [[Berry Gordy|Berry Gordy Jr.]] on his mother's side, and a cousin of [[June Carter Cash]].<ref>Cash, John R. with Patrick Carr. (1997) Johnny Cash, the Autobiography. [[Harper Collins]]</ref> |

|||

[[File:Graduation of Jimmy Carter from U.S. Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland, Rosalynn Carter and Lillian Carter Pinning on Ensign Bars - DPLA - e1b1f2b5b4e38fc82cfe091678fc112a.jpg|thumb|alt=Jimmy Carter similing towards the camera, while Rosalynn Smith and his mother are fixing his Naval Academy uniform|Carter with [[Rosalynn Smith]] and his mother at his graduation from the [[United States Naval Academy]] in [[Annapolis, Maryland]], June 5, 1946]] |

|||

From 1946 to 1953, the Carters lived in [[Virginia]], [[Territory of Hawaii|Hawaii]], [[Connecticut]], [[New York (state)|New York]], and [[California]], during his deployments in [[U.S. Atlantic Fleet|the Atlantic]] and [[U.S. Pacific Fleet|Pacific fleets]].{{sfn|Zelizer|2010|pp=11–12}} In 1948, he began officer training for submarine duty and served aboard {{USS|Pomfret|SS-391|6}}.{{sfn|Thomas|1978|p=18}} Carter was promoted to [[lieutenant junior grade]] in 1949, and his service aboard ''Pomfret'' included a simulated war patrol to the western Pacific and Chinese coast from January to March of that year.{{sfn|Nijnatten|2012|p=77}} In 1951, Carter was assigned to the diesel/electric {{USS|K-1|SSK-1}}, qualified for command, and served in several positions, to include executive officer.{{sfn|Jimmy Carter Library and Museum|2004}} |

|||

===Naval career=== |

|||

After high school, Carter enrolled at [[Georgia Southwestern College]], in Americus. Later, he applied to the [[United States Naval Academy]] and, after taking additional mathematics courses at [[Georgia Institute of Technology|Georgia Tech]], he was admitted in 1943. Carter graduated 59th out of 820 midshipmen at the Naval Academy with a Bachelor of Science degree with an unspecified major, as was the custom at the academy at that time.<ref name=DeGregorio2005>{{cite book |

|||

|last=DeGregorio |first=William A. |title=The Complete Book of US Presidents. |volume=Volume 1 |

|||

|location=Fort Lee |publisher=Barricade Books |year=2005}}</ref> |

|||

In 1952, Carter began an association with the Navy's fledgling [[nuclear submarine]] program, led then by captain [[Hyman G. Rickover]].{{sfn|Hambley|2008|p=202}} Rickover had high standards and demands for his men and machines, and Carter later said that, next to his parents, Rickover had the greatest influence on his life.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=72–77}} Carter was sent to the [[Naval Reactors]] Branch of the [[United States Atomic Energy Commission|Atomic Energy Commission]] in Washington, D.C., for three-month temporary duty, while Rosalynn moved with their children to [[Schenectady, New York]].{{sfn|Bourne|1997|p=74}} |

|||

On December 12, 1952, an accident with the experimental NRX reactor at [[Atomic Energy of Canada |

On December 12, 1952, an accident with the experimental [[NRX]] reactor at [[Atomic Energy of Canada]]'s [[Chalk River Laboratories]] caused a partial meltdown, resulting in millions of liters of radioactive water flooding the reactor building's basement. This left the reactor's core ruined.{{sfn|Frank|1995|p=554}} Carter was ordered to Chalk River to lead a U.S. maintenance crew that joined other American and Canadian service personnel to assist in the shutdown of the reactor.{{sfn|Martel|2008|p=64}} The painstaking process required each team member to don protective gear and be lowered individually into the reactor for 90 seconds at a time, limiting their exposure to radioactivity while they disassembled the crippled reactor. When Carter was lowered in, his job was simply to turn a single screw.{{sfn|Marguet|2022|p=262}} During and after his presidency, Carter said that his experience at Chalk River had shaped his views on atomic energy and led him to cease the development of a [[neutron bomb]].{{sfn|Milnes|2009}} |

||

In March 1953, Carter began a six-month course in nuclear power plant operation at [[Union College]] in Schenectady.{{sfn|Zelizer|2010|pp=11–12}} His intent was to eventually work aboard {{USS|Seawolf|SSN-575|6}}, which was intended to be the second U.S. nuclear submarine.{{sfn|Naval History and Heritage Command|1997}} His plans changed when his father died of [[pancreatic cancer]] in July, two months before construction of ''Seawolf'' began, and Carter obtained a release from active duty so he could take over the family peanut business.{{sfn|Wead|2005|p=404}}{{sfn|Panton|2022|p=100}} Deciding to leave Schenectady proved difficult, as Rosalynn had grown comfortable with their life there.{{sfn|Wooten|1978|p=270}}{{sfn|Schneider|Schneider|2005|p=310}} She later said that returning to small-town life in Plains seemed "a monumental step backward."{{sfn|Bourne|1997|p=79}} Carter left active duty on October 9, 1953.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=77–81}}{{sfn|Hayward|2009|p=23}} He served in the inactive [[United States Navy Reserve|Navy Reserve]] until 1961 and left the service with the rank of [[Lieutenant (navy)|lieutenant]].{{sfn|Eckstein|2015}} Carter's awards include the [[American Campaign Medal]], [[World War II Victory Medal]], [[China Service Medal]], and [[National Defense Service Medal]].{{sfn|Suciu|2020}} As a submarine officer, he also earned the [[Submarine Warfare insignia|"dolphin" badge]].{{sfn|Naval History and Heritage Command|2023}} |

|||

Once they arrived, Carter's team used a model of the reactor to practice the steps necessary to disassemble the reactor and seal it off. During execution of the actual disassembly each team member, including Carter, donned protective gear, was lowered individually into the reactor, stayed for only a few seconds at a time to minimize exposure to radiation, and used hand tools to loosen bolts, remove nuts and take the other steps necessary to complete the disassembly process. |

|||

== Farming == |

|||

During and after his presidency Carter indicated that his experience at Chalk River shaped his views on nuclear power and nuclear weapons, including his decision not to pursue completion of the [[neutron bomb]].<ref>[http://ottawariverkeeper.ca/news/when_jimmy_carter_faced_radioactivity_head_on/ Newspaper article, When Jimmy Carter faced radioactivity head-on], by Arthur Milnes, The Ottawa Citizen, Wednesday, January 28, 2009</ref> |

|||

After debt settlements and division of his father's estate among its heirs, Jimmy inherited comparatively little.{{sfn|Mukunda|2022|p=105}} For a year, he, Rosalynn, and their three sons lived in public housing in Plains.{{efn|Carter is the only U.S. president to have lived in subsidized housing before he took office.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=83–91}}}} Carter was knowledgeable in scientific and technological subjects, and he set out to expand the family's peanut-growing business.{{sfn|Kaufman|2016|p=66}} Transitioning from the Navy to an [[agribusinessman]] was difficult as his first-year harvest failed due to a drought, and Carter had to open several bank lines of credit to keep the farm afloat.{{sfn|Gherman|2004|p=38}} Meanwhile, he took classes and studied agriculture while Rosalynn learned accounting to manage the business's books.{{sfn|Morris|1996|p=115}} Though they barely broke even the first year, the Carters grew the business and became quite successful.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=83–91}}{{sfn|Morris|1996|p=115}} |

|||

== Early political career (1963–1971) == |

|||

Upon the death of his father James Earl Carter, Sr., in July 1953, he was urgently needed to run the family business. Lieutenant Carter resigned his commission, and he was discharged from the Navy on October 9, 1953. |

|||

=== Georgia state senator (1963–1967) === |

|||

As racial tension inflamed in Plains by the 1954 [[Supreme Court of the United States]] ruling in ''[[Brown v. Board of Education]]'',{{sfn|Gherman|2004|p=40}} Carter favored racial tolerance and integration but often kept those feelings to himself to avoid making enemies. By 1961, Carter began to speak more prominently of integration as a member of the [[Baptist Church]] and chairman of the [[Sumter County, Georgia|Sumter County]] school board.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=92–108}}{{sfn|Donica|Piccotti|2018}} In 1962, he announced his campaign for an open [[Georgia State Senate]] seat 15 days before the election.{{sfn|Carter|1992|pp=83–87}} Rosalynn, who had an instinct for politics and organization, was instrumental to his campaign. While early counting of the ballots showed Carter trailing his opponent, Homer Moore, this was later proven to be the result of fraudulent voting. The fraud was found to have been orchestrated by Joe Hurst, the chairman of the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]] in [[Quitman County, Georgia|Quitman County]].{{sfn|Carter|1992|pp=83–87}} Carter challenged the election result, which was confirmed fraudulent in an investigation. Following this, another election was held, in which Carter won against Moore as the sole Democratic candidate, with a vote margin of 3,013 to 2,182.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=108–132}} |

|||

The [[civil rights movement]] was well underway when Carter took office. He and his family had become staunch [[John F. Kennedy]] supporters. Carter remained relatively quiet on the issue at first, even as it polarized much of the county, to avoid alienating his segregationist colleagues. Carter did speak up on a few divisive issues, giving speeches against [[literacy test]]s and against an amendment to the Georgia Constitution that he felt implied a compulsion to practice religion.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=132–140}} Carter entered the state Democratic Executive Committee two years into office, where he helped rewrite the state party's rules. He became the chairman of the West Central Georgia Planning and Development Commission, which oversaw the disbursement of federal and state grants for projects such as historic site restoration.{{sfn|Ryan|2006|p=37}} |

|||

===Farming and personal belief=== |

|||

Though Carter's father, Earl, died a relatively wealthy man, between Earl's forgiveness of debts owed to him and the division of his wealth among his heirs, Jimmy Carter inherited comparatively little. For a year, due to a limited real estate market, the Carters lived in [[public housing]] (Carter is the only U.S. president to have lived in housing subsidized for the poor).<ref name=moralist>[http://books.google.com/books?id=3M1KlBNm7WcC&pg=PA115&dq=%22jimmy+carter%22+public+housing&hl=en&sa=X&ei=oa0yT7_4HpCd0gG7l6jCBw&ved=0CDYQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=%22jimmy%20carter%22%20public%20housing&f=false Jimmy Carter, American Moralist] By Kenneth E. Morris, page 115</ref> |

|||

When [[Bo Callaway]] was elected to the [[United States House of Representatives]] in 1964, Carter immediately began planning to challenge him. The two had previously clashed over which two-year college would be expanded to a four-year college program by the state, and Carter saw Callaway—who had switched to the [[Republican Party (United States)|Republican Party]]—as a rival who represented aspects of politics he despised.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=132–145}} Carter was reelected to a second two-year term in the state Senate,{{sfn|Georgia General Assembly|1965}} where he chaired its Education Committee and sat on the Appropriations Committee toward the end of the term. He contributed to a bill expanding statewide education funding and getting [[Georgia Southwestern State University]] a four-year program. He leveraged his regional planning work, giving speeches around the district to make himself more visible to potential voters. On the last day of the term, Carter announced his candidacy for the House of Representatives.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=145–149}} Callaway decided to run for governor instead;{{sfn|Bourne|1997|p=150}} Carter changed his mind, deciding to run for governor too.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=154–155}} |

|||

Knowledgeable in scientific and technological subjects and raised on a farm, Carter took over the family peanut farm. Carter took to the county library to read up on agriculture while Rosalynn learned accounting to manage the businesses financials.<ref name=moralist/> Though they barely broke even the first year, Carter managed to expand in Plains. His farming business was successful, and during the 1970 gubernatorial campaign, he was considered a wealthy peanut farmer.<ref>[http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,904462-1,00.html New Crop of Governors – TIME<!-- Bot-generated title -->].</ref> |

|||

=== 1966 and 1970 gubernatorial campaigns === |

|||

From a young age, Carter showed a deep commitment to Christianity, serving as a Sunday School teacher throughout his life. Even as President, Carter prayed several times a day, and professed that Jesus Christ was the driving force in his life. Carter had been greatly influenced by a sermon he had heard as a young man, called, "If you were arrested for being a Christian, would there be enough evidence to convict you?"<ref>{{cite book|title=Conversations with Carter| isbn=1-55587-801-6|year=1998|page=14| first1=Jimmy |last1= Carter| first2= Don |last2= Richardson|publisher=Lynne Rienner Publishers}}</ref> |

|||

{{See also|1966 Georgia gubernatorial election|1970 Georgia gubernatorial election}} |

|||

In the 1966 gubernatorial election, Carter ran against liberal former governor [[Ellis Arnall]] and conservative segregationist [[Lester Maddox]] in the Democratic primary. In a press conference, he described his ideology as "Conservative, moderate, liberal and middle-of-the-road ... I believe I am a more complicated person than that."{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=149–153}} He lost the primary but drew enough votes as a third-place candidate to force Arnall into a [[runoff election]] with Maddox, who narrowly defeated Arnall.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=153–165}} In the general election, Republican nominee Callaway won a plurality of the vote but less than a majority, allowing the Democratic-majority [[Georgia House of Representatives]] to elect Maddox as governor.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=153–165}} This resulted in a victorious Maddox, whose victory—due to his segregationist stance—was seen as the worst outcome for the indebted Carter.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=153–165}} Carter returned to his agriculture business, carefully planning his next campaign. This period was a spiritual turning point for Carter; he declared himself a [[born again]] Christian, and his last child, [[Amy Carter|Amy]], was born during this time.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=165–179}}{{sfn|Hayward|2009|pp=39–46}} |

|||

==Early political career== |

|||

In the 1970 gubernatorial election, liberal former governor [[Carl Sanders]] became Carter's main opponent in the Democratic primary. Carter ran a more modern campaign, employing printed graphics and statistical analysis. Responding to polls, he leaned more conservative than before, positioning himself as a [[populist]] and criticizing Sanders for both his wealth and perceived links to the national Democratic Party. He also accused Sanders of corruption, but when pressed by the media, he did not provide evidence.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=180–199}}{{sfn|Hayward|2009|pp=46–51}} Throughout his campaign, Carter sought both the black vote and the votes of those who had supported prominent Alabama segregationist [[George Wallace]]. While he met with black figures such as [[Martin Luther King Sr.]] and [[Andrew Young]] and visited many black-owned businesses, he also praised Wallace and promised to invite him to give a speech in Georgia. Carter's appeal to racism became more blatant over time, with his senior campaign aides handing out a photograph of Sanders celebrating with Black basketball players.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=180–199}}{{sfn|Hayward|2009|pp=46–51}} |

|||

===Georgia State Senate=== |

|||

Jimmy Carter started his political career by serving on various local boards, governing such entities as the schools, hospitals, and libraries, among others. In the 1960s, he served two terms in the [[Georgia Senate]] from the fourteenth district of Georgia. |

|||

Carter came ahead of Sanders in the first ballot by 49 percent to 38 percent in September, leading to a runoff election. The subsequent campaign was even more bitter; despite his early support for civil rights, Carter's appeal to racism grew, and he criticized Sanders for supporting [[Martin Luther King Jr.]] Carter won the runoff election with 60 percent of the vote and won the general election against Republican nominee [[Hal Suit]]. Once elected, Carter changed his tone and began to speak against Georgia's racist politics. [[Leroy Johnson (Georgia politician)|Leroy Johnson]], a black state senator, voiced his support for Carter: "I understand why he ran that kind of ultra-conservative campaign. I don't believe you can win this state without being a racist."{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=180–199}} |

|||

His 1961 election to the state Senate, which followed the end of Georgia's [[County Unit System]] (per the [[Supreme Court of the United States|Supreme Court]] case of ''[[Gray v. Sanders]]''), was chronicled in his book ''Turning Point: A Candidate, a State, and a Nation Come of Age''. The election involved corruption led by Joe Hurst, the sheriff of [[Quitman County, Georgia|Quitman County]]; system abuses included votes from deceased persons and tallies filled with people who supposedly voted in alphabetical order. It took a challenge of the fraudulent results for Carter to win the election. Carter was reelected in 1964, to serve a second two-year term. |

|||

== Georgia governorship (1971–1975) == |

|||

For a time in State Senate he chaired its Education Committee.<ref name="georgiaencyclopedia.org">"[http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?path=/GovernmentPolitics/Politics/PoliticalFigures&id=h-676 Jimmy Carter (b. 1924)]". ''New Georgia Encyclopedia''. Updated May 9, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2010.</ref> |

|||

[[File:Jimmy Carter official portrait as Governor.jpg|thumb|upright=0.7|alt=A black and white photographic official portrait of a young Carter as the governor of Georgia|Carter's official portrait as governor of Georgia; dated 1971]] |

|||

Carter was sworn in as the 76th [[governor of Georgia]] on January 12, 1971. In his inaugural speech, he declared that "the time for racial discrimination is over",{{sfn|Berman|2022}} shocking the crowd and causing many of the segregationists who had supported him during the race to feel betrayed. Carter was reluctant to engage with his fellow politicians, making him unpopular with the legislature.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|p=204}}{{sfn|Hayward|2009|pp=55–56}} He expanded the governor's authority by introducing a reorganization plan submitted in January 1972. Despite initially having a cool reception in the legislature, the plan passed at midnight on the last day of the session.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=214–220}} Carter merged about 300 state agencies into 22, although it is disputed whether that saved the state money.{{sfn|Freeman|1982|p=5}} On July 8, 1971, during an appearance in [[Columbus, Georgia]], he stated his intention to establish a Georgia Human Rights Council to help solve issues ahead of any potential violence.{{sfn|Rome News-Tribune|1971a}} |

|||

In 1966, Carter declined running for re-election as a state senator to pursue a gubernatorial run. His first cousin, [[Hugh Carter]], was elected as a Democrat and took over his seat in the Senate. |

|||

In a news conference on July 13, 1971, Carter announced that he had ordered department heads to reduce spending to prevent a $57-million deficit by the end of the 1972 fiscal year, specifying that each state department would be affected and estimating that 5 percent over government revenue would be lost if state departments continued to fully use allocated funds.{{sfn|Rome News-Tribune|1971b}} On January 13, 1972, he requested that the state legislature fund an early childhood development program along with prison reform programs and $48 million ({{Inflation|index=US|value=48,000,000|start_year=1972|fmt=eq}}) in paid taxes for nearly all state employees.{{sfn|Rome News-Tribune|1972a}} |

|||

===Campaigns for Governor=== |

|||

{{Main|Georgia gubernatorial election, 1966}} |

|||

In 1966, during the end of his career as a state senator, he flirted with the idea of running for the [[United States House of Representatives]]. His Republican opponent, [[Howard Callaway]], dropped out and decided to run for Governor of Georgia. Carter did not want to see a Republican Governor of his state, and, in turn, dropped out of the race for Congress and joined the race to become Governor. Carter lost the Democratic primary, but drew enough votes as a third-place candidate to force the favorite, liberal former governor [[Ellis Arnall]], into a [[two-round system|runoff election]], setting off a chain of events which resulted in the nomination of segregationist Democrat [[Lester Maddox]]. Maddox would go on to be selected governor of Georgia by the Georgia General Assembly despite finishing a close second in a three-way general election race between Maddox, Callaway, and Arnall, who ran as a [[Write-in candidate]]. During the primary Carter ran as a moderate alternative to both liberal Arnall and conservative Maddox.<ref name="georgiaencyclopedia.org"/> Although he lost, his strong third place finish was viewed as a success for a little-known state senator.<ref name="georgiaencyclopedia.org"/> |

|||

On March 1, 1972, Carter said he might call a special session of the general assembly if the Justice Department opted to turn down any reapportionment plans by either the House or Senate.{{sfn|Rome News-Tribune|1972b}} He pushed several reforms through the legislature, providing equal state aid to schools in Georgia's wealthy and poor areas, setting up community centers for mentally disabled children, and increasing educational programs for convicts. Under this program, all such appointments were based on merit rather than political influence.{{sfn|Sidey|2012}}{{sfn|World Book|2001|p=542}} In one of his more controversial decisions, he vetoed a plan to build a dam on Georgia's [[Flint River]], which attracted the attention of environmentalists nationwide.{{sfn|NBC News|2008}}{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=250–251}} |

|||

{{Main|Georgia gubernatorial election, 1970}} |

|||

[[File:Jimmy Carter and wife with Reubin Askew and his wife.jpg|thumb|left|alt=Carter shaking hands with Reubin Askew, with Carter's wife smiling while standing in the middle of them|Carter greeting Florida governor [[Reubin Askew]] and his wife in 1971; as president, Carter would appoint Askew as [[U.S. trade representative]].]] |

|||

For the next four years, Carter returned to his agriculture business and carefully planned for his next campaign for Governor in 1970, making over 1,800 speeches throughout the state.{{citation needed|date=May 2012}} |

|||

Civil rights were a high priority for Carter, who added black state employees and portraits of three prominent black Georgians to the capitol building: Martin Luther King Jr., [[Lucy Craft Laney]], and [[Henry McNeal Turner]]. This angered the [[Ku Klux Klan]].{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=250–251}} He favored a constitutional amendment to ban [[busing]] for the purpose of expediting integration in schools on a televised joint appearance with Florida governor [[Reubin Askew]] on January 31, 1973,{{sfn|Rome News-Tribune|1973a}} and co-sponsored an anti-busing resolution with Wallace at the 1971 National Governors Conference.{{sfn|Rome News-Tribune|1971c}}{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=212–213}} After the U.S. Supreme Court threw out Georgia's [[Capital punishment in Georgia (U.S. state)|death penalty]] statute in ''[[Furman v. Georgia]]'' (1972), Carter signed a revised death-penalty statute that addressed the court's objections, thus reintroducing the practice in the state. He later regretted endorsing the death penalty, saying, "I didn't see the injustice of it as I do now."{{sfn|Pilkington|2013}} |

|||

Ineligible for reelection, Carter looked toward a potential presidential run and engaged in national politics. He was named to several southern planning commissions and was a delegate to the [[1972 Democratic National Convention]], where liberal U.S. Senator [[George McGovern]] was the likely nominee. Carter tried to ingratiate himself with the conservative and anti-McGovern voters. He was fairly obscure at the time, and his attempt at triangulation failed; the [[List of United States Democratic Party presidential tickets#1972|1972 Democratic ticket]] was McGovern and senator [[Thomas Eagleton]].{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=221–230}}{{efn|Eagleton was later replaced on the ticket by [[Sargent Shriver]].{{sfn|Bourne|1997|p=230}}}} On August 3, Carter met with Wallace in [[Birmingham, Alabama]], to discuss preventing the Democrats from losing in a landslide,{{sfn|Rome News-Tribune|1972c}} but they did.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|p=234}} |

|||

During his 1970 campaign, he ran an uphill populist campaign in the Democratic primary against former Governor [[Carl Sanders]], labeling his opponent "Cufflinks Carl". Carter was never a [[racial segregation|segregationist]], and refused to join the segregationist [[White Citizens' Council]], prompting a boycott of his peanut warehouse. His family was also one of only two that voted to admit blacks to the Plains Baptist Church.<ref>[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/biography/carter-bio/ People & Events: James Earl ("Jimmy") Carter Jr. (1924–)] – [[American Experience]], [[Public Broadcasting Service|PBS]]. Retrieved March 18, 2006.</ref> |

|||

Carter regularly met with his fledgling campaign staff and decided to begin putting a presidential bid for 1976 together. He tried unsuccessfully to become chairman of the [[National Governors Association]] to boost his visibility. On [[David Rockefeller]]'s endorsement, he was named to the [[Trilateral Commission]] in April 1973. The next year, he was named chairman of both the [[Democratic National Committee]]'s congressional and gubernatorial campaigns.{{sfn|Bourne|1997|pp=237–250}} In May 1973, Carter warned his party against politicizing the [[Watergate scandal]],{{sfn|Rome News-Tribune|1973b}} which he attributed to president [[Richard Nixon]]'s isolation from Americans and secretive decision-making.{{sfn|Rome News-Tribune|1973c}} |

|||

"Carter himself was not a segregationist in 1970. But he did say things that the segregationists wanted to hear. He was opposed to busing. He was in favor of private schools. He said that he would invite segregationist governor George Wallace to come to Georgia to give a speech.", according to historian [[E. Stanly Godbold]].{{citation needed|date=May 2012}} |

|||

== 1976 presidential campaign == |

|||

Carter's campaign aides handed out a photograph of Sanders celebrating with black basketball players.<ref>[http://www.claremont.org/publications/crb/id.977/article_detail.asp The Claremont Institute – Malaise Forever<!-- Bot-generated title -->].</ref><ref>[http://www.webcitation.org/5kwrtgWxP "Jimmy Carter"], Microsoft [[Encarta]] Online Encyclopedia 2005, accessed March 18, 2006. Archived October 31, 2009.</ref> Following his close victory over Sanders in the primary, he was elected Governor over Republican [[Hal Suit]]. |

|||

{{main|Jimmy Carter 1976 presidential campaign}} |

|||

{{Further|1976 Democratic Party presidential primaries}} |

|||

[[File:Jimmy Carter 1976 presidential campaign logo from poster.jpg|thumb|left|Carter's presidential campaign logo]] |

|||

On December 12, 1974, Carter announced his presidential campaign at the [[National Press Club (United States)|National Press Club]] in Washington, D.C. His speech contained themes of domestic inequality, optimism, and change.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-announcing-candidacy-for-the-democratic-presidential-nomination-the-national-press |title=Address Announcing Candidacy for the Democratic Presidential Nomination at the National Press Club in Washington, DC |website=The American Presidency Project |last1=Peters |first1=Gerhard |last2=Woolley |first2=John T. |date=December 12, 1974 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=August 16, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210816181829/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-announcing-candidacy-for-the-democratic-presidential-nomination-the-national-press |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=CG0zAAAAIBAJ&sjid=3DIHAAAAIBAJ&pg=6942%2C5857919 |title=Carter a candidate for the presidency |publisher=Lodi News-Sentinel |date=December 13, 1974 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=May 21, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210521142244/https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=CG0zAAAAIBAJ&sjid=3DIHAAAAIBAJ&pg=6942,5857919 |url-status=live}}</ref> Upon his entrance in the Democratic primaries, he was competing against sixteen other candidates, and was considered to have little chance against the more nationally known politicians such as Wallace.<ref>{{Cite web|last1=E. Zelizer|first1=Julian|date=September 7, 2015|title=17 Democrats Ran for President in 1976. Can Today's GOP Learn Anything From What Happened?|url=https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/09/2016-election-1976-democratic-primary-213125/|access-date=September 1, 2021|website=Politico|archive-date=October 15, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211015022313/https://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2015/09/2016-election-1976-democratic-primary-213125/|url-status=live}}</ref> His name recognition was very low, and his opponents derisively asked "Jimmy Who?".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.manythings.org/voa/history/220.html|title=American History: Jimmy Carter Wins the 1976 Presidential Election|access-date=September 1, 2021|archive-date=June 16, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210616094954/https://www.manythings.org/voa/history/220.html|url-status=live}}</ref> In response to this, Carter began to emphasize his name and what he stood for, stating "My name is Jimmy Carter, and I'm running for president."<ref>{{Cite web |last1=Setterfield |first1=Ray |date=December 31, 2020 |title='My Name is Jimmy Carter and I'm Running for President' |url=https://www.onthisday.com/articles/my-name-is-jimmy-carter-and-im-running-for-president |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210521142231/https://www.onthisday.com/articles/my-name-is-jimmy-carter-and-im-running-for-president |archive-date=May 21, 2021 |access-date=September 1, 2021 |website=On This Day {{!}} OnThisDay.com}}</ref> |

|||

After his election, Carter would make a statement that would displease the segregationists: "I've traveled the state more than any other person in history and I say to you quite frankly that the time for racial discrimination is over. Never again should a black child be deprived of an equal right to health care, education, or the other privileges of society."<ref> {{cite book | last1 = Till | first1 = Brian Michael | title = Conversations with Power: What Great Presidents and Prime Ministers Can Teach Us about Leadership | publisher = Macmillan | year = 2011 | pages = 180 | accessdate = 2012-08-09 | isbn = 978-0230110588}}</ref> |

|||

This strategy proved successful. By mid-March 1976, Carter was not only far ahead of the active contenders for the presidential nomination, but against incumbent Republican president [[Gerald Ford]] by a few percentage points.<ref>{{cite book |last=Shoup |first=Laurence H. |title=The Carter Presidency, and Beyond: Power and Politics in the 1980s |url=https://archive.org/details/carterpresidency0000shou/page/70 |year=1980 |publisher=Ramparts Press |isbn=978-0-87867-075-8 |page=[https://archive.org/details/carterpresidency0000shou/page/70 70]}}</ref> As the Watergate scandal was still fresh in the voters' minds, Carter's position as an outsider, distant from Washington, D.C. proved helpful. He promoted government reorganization. In June, Carter published a memoir titled ''Why Not the Best?'' to help introduce himself to the American public.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1976/07/16/archives/choice-of-mondale-helps-to-reconcile-the-liberals-choice-of-mondale.html |newspaper=The New York Times |first=Charles |last=Mohr |title=Choice of Mondale Helps To Reconcile the Liberals |date=July 16, 1976 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=May 31, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210531062839/https://www.nytimes.com/1976/07/16/archives/choice-of-mondale-helps-to-reconcile-the-liberals-choice-of-mondale.html |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Leroy Johnson, Georgia State Senator reflected: "We were extremely pleased. Many of the white segregationists were displeased. And I'm convinced that those people that supported him, would not have supported him if they had thought that he would have made that statement."<ref>[http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/transcript/carter-transcript/ American Experience | Jimmy Carter | Transcript<!-- Bot-generated title -->].</ref> |

|||

[[File:1976-07-15CarterMondaleDNC.jpg|thumb|Carter and his running mate [[Walter Mondale]] at the [[Democratic National Convention]] in [[New York City]], July 1976]] |

|||

Carter became the front-runner early on by winning the [[Iowa caucuses]] and the [[New Hampshire primary]]. His strategy involved reaching a region before another candidate could extend influence there, traveling over {{convert|50000|mi|km|abbr=off}}, visiting 37 states, and delivering over 200 speeches before any other candidate had entered the race.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/carter/#transcript |title=Jimmy Carter |series=The American Experience |publisher=Public Broadcasting Service |date=November 11, 2002 |access-date=June 23, 2020 |archive-date=June 26, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200626060507/https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/carter/#transcript |url-status=live}}</ref> In the South, he tacitly conceded certain areas to Wallace and swept them as a moderate when it became clear Wallace could not win the region. In the North, Carter appealed largely to conservative Christian and rural voters. While he did not achieve a majority in most Northern states, he won several by building the largest singular support base. Although Carter was initially dismissed as a regional candidate, he would clinch the Democratic nomination.<ref>{{cite news|last1=Broder|first1=David|author-link1=David Broder|date=December 18, 1974|title=Early Evaluation Impossible on Presidential Candidates|page=16|work=Toledo Blade|url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=yMgwAAAAIBAJ&pg=7214%2C2087680|access-date=January 3, 2016|archive-date=February 4, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210204092325/https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=yMgwAAAAIBAJ&pg=7214%2C2087680|url-status=live}}</ref> In 1980, Lawrence Shoup noted that the national news media discovered and promoted Carter, and stated: |

|||

{{Blockquote|What Carter had that his opponents did not was the acceptance and support of elite sectors of the mass communications media. It was their favorable coverage of Carter and his campaign that gave him an edge, propelling him rocket-like to the top of the opinion polls. This helped Carter win key primary election victories, enabling him to rise from an obscure public figure to President-elect in the short space of 9 months.<ref>{{cite book |last=Shoup |first=Laurence H. |title=The Carter Presidency, and Beyond: Power and Politics in the 1980s |url=https://archive.org/details/carterpresidency0000shou/page/94 |year=1980 |publisher=Ramparts Press |isbn=978-0-87867-075-8 |page=[https://archive.org/details/carterpresidency0000shou/page/94 94]}}</ref>}} |

|||

==Governor of Georgia== |

|||

[[File:Carter and Ford in a debate, September 23, 1976 (cropped).jpg|left|thumb|alt=A monochrome picture of Carter and Ford, both standing at podiums during a debate.|Carter and President [[Gerald Ford]] debating at the [[Walnut Street Theatre]] in [[Philadelphia]], September 1976]] |

|||

Carter was sworn in as the 76th Governor of Georgia on January 12, 1971, and held this post for one term, until January 14, 1975. Governors of Georgia were not allowed to succeed themselves at the time. His predecessor as Governor, [[Lester Maddox]], became the [[Lieutenant Governor of Georgia|Lieutenant Governor]]. Carter and Maddox found little common ground during their four years of service, often publicly feuding with each other.<ref>{{cite news |author=Peter Applebome |title=In Georgia Reprise, Maddox on Stump |url=http://www.nytimes.com/1990/01/14/us/in-georgia-reprise-maddox-on-stump.html?pagewanted=all |work=The New York Times |date=January 14, 1990 |accessdate=February 13, 2008}}</ref><ref>[http://www.racematters.org/lestermaddox.htm Race Matters – Lester Maddox, Segregationist and Georgia Governor, Dies at 87<!-- Bot-generated title -->].</ref> |

|||

During an interview in April 1976, Carter said, "I have nothing against a community that is... trying to maintain the ethnic purity of their neighborhoods."<ref name="Time 1976-04-19">{{cite news |url=https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/printout/0,8816,914056,00.html |title=The Campaign: Candidate Carter: I Apologize |magazine=Time |date=April 19, 1976 |volume=107 |issue=16 |access-date=July 13, 2018 |archive-date=March 23, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190323002443/https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/printout/0,8816,914056,00.html |url-status=live}}</ref> His remark was intended as supportive of [[open housing]] laws, but specifying opposition to government efforts to "inject black families into a white neighborhood just to create some sort [[Racial integration|of integration]]".<ref name="Time 1976-04-19" /> Carter's stated positions during his campaign included public financing of congressional campaigns,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=SFOYbPikdlgC&dat=19741213&printsec=frontpage |title=Carter Officially Enters Demo Presidential Race |work=Herald-Journal |date=December 13, 1974 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=November 19, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211119213258/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=SFOYbPikdlgC&dat=19741213&printsec=frontpage |url-status=live}}</ref> his support for the creation of a federal consumer protection agency,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19760810&printsec=frontpage |title=Carter Backs Consumer Plans |newspaper=Toledo Blade |location=Toledo, Ohio |date=August 10, 1976 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=December 12, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211212140455/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19760810&printsec=frontpage |url-status=live}}</ref> creating a separate cabinet-level department for education,<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=32680 |title=Bardstown, Kentucky Remarks and a Question-and-Answer Session at a Town Meeting. (July 31, 1979) |website=The American Presidency Project |quote=THE PRESIDENT. Could you all hear it? The question was, since it appears that the campaign promise that I made to have a separate department of education might soon be fulfilled, would I consider appointing a classroom teacher as the secretary of education. |last1=Peters |first1=Gerhard |last2=Woolley |first2=John T. |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=November 7, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171107014653/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=32680 |url-status=live}}</ref> signing a peace treaty with the [[Soviet Union]] to limit nuclear weapons,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19761014&printsec=frontpage |title=Carter Berates Lack Of New A-Arm Pact |newspaper=Toledo Blade |location=Toledo, Ohio |date=October 14, 1976 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=August 16, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210816013118/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19761014&printsec=frontpage |url-status=live}}</ref> reducing the defense budget,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19761003&printsec=frontpage |title=Carter Positions on Amnesty, Defense Targets of Dole Jabs |first=Frank |last=Kane |newspaper=Toledo Blade |location=Toledo, Ohio |date=October 3, 1976 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=August 16, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210816100742/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19761003&printsec=frontpage |url-status=live}}</ref> a tax proposal implementing "a substantial increase toward those who have the higher incomes" alongside a levy reduction on taxpayers with lower and middle incomes,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=SFOYbPikdlgC&dat=19760919&printsec=frontpage |title=GOP Raps Carter On Tax Proposal |date=September 19, 1976 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |work=Herald-Journal |archive-date=October 11, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211011183951/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=SFOYbPikdlgC&dat=19760919&printsec=frontpage |url-status=live}}</ref> making multiple amendments to the [[Social Security Act]],<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=7035 |date=December 20, 1977 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |publisher=American Presidency Project |title=Social Security Amendments of 1977 Statement on Signing S. 305 Into Law |archive-date=October 19, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171019060428/https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=7035 |url-status=live}}</ref> and having a balanced budget by the end of his first term of office.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=SFOYbPikdlgC&dat=19760904&printsec=frontpage |title=Carter Would Delay Programs If Necessary |date=September 4, 1976 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |work=Herald-Journal |archive-date=August 16, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210816085328/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=SFOYbPikdlgC&dat=19760904&printsec=frontpage |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

On July 15, 1976, Carter chose U.S. senator [[Walter Mondale]] as his running mate.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19760715&printsec=frontpage |title=Carter Nominated, Names Mondale Running Mate |newspaper=Toledo Blade |location=Toledo, Ohio |date=July 15, 1976 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |first=Frank |last=Kane |archive-date=August 16, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210816164136/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19760715&printsec=frontpage |url-status=live}}</ref> Carter and Ford faced off in three televised debates,<ref name="Howard, Adam NBC News" /> the first [[United States presidential debates]] since 1960.<ref name="Howard, Adam NBC News">{{cite news |last1=Howard |first1=Adam |title=10 Presidential Debates That Actually Made an Impact |url=https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/2016-presidential-debates/10-presidential-debates-made-impact-n650741 |publisher=NBC News |date=September 26, 2016 |access-date=December 31, 2016 |archive-date=May 4, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210504003847/https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/2016-presidential-debates/10-presidential-debates-made-impact-n650741 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Kraus |first1=Sidney |title=The Great Debates: Carter vs. Ford, 1976 |date=1979 |publisher=Indiana University Press |location=Bloomington |page=3 |url=https://www.questia.com/read/94445794/the-great-debates-carter-vs-ford-1976 |access-date=December 31, 2016 |archive-date=January 1, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170101162639/https://www.questia.com/read/94445794/the-great-debates-carter-vs-ford-1976 |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

===Civil rights politics=== |

|||

Carter declared in his inaugural speech that the time of racial segregation was over, and that racial discrimination had no place in the future of the state, the first statewide office holder in the [[Deep South]] to say this in public.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.blackjournalism.com/?p=183 |title=President Jimmy Carter, still far ahead of his time at Black Journalism Review |publisher=Blackjournalism.com |date= |accessdate=June 8, 2010}}</ref> Afterwards, Carter appointed many African Americans to statewide boards and offices. He was often called one of the "New Southern Governors"{{spaced ndash}}much more moderate than their predecessors, and supportive of racial desegregation and expanding African-Americans' rights.{{citation needed|date=May 2012}} |

|||

For the November 1976 issue of ''[[Playboy]]'', which hit newsstands a couple of weeks before the election, [[Robert Scheer]] interviewed Carter. While discussing his religion's view of pride, Carter said: "I've looked on a lot of women with lust. I've committed adultery in my heart many times."<ref>"The Playboy Interview: Jimmy Carter." Robert Scheer. ''Playboy'', November 1976, Vol. 23, Iss. 11, pp. 63–86.</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Psu5UNg1jEUC&pg=PA216 |title=A Year in My Pajamas with President Obama, The Politics of Strange Bedfellows |last=Casser-Jayne |first=Halli |publisher=Halli Casser-Jayne |isbn=978-0-9765960-3-5 |page=216 |access-date=March 21, 2022 |archive-date=July 5, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230705115615/https://books.google.com/books?id=Psu5UNg1jEUC&pg=PA216 |url-status=live}}</ref> This response and his admission in another interview that he did not mind if people uttered the word "fuck" led to a media feeding frenzy and critics lamenting the erosion of boundary between politicians and their private intimate lives.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/clinton/frenzy/carter.htm?noredirect=on |title=Washingtonpost.com Special Report: Clinton Accused |first1=Larry J. |last1=Sabato |year=1998 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |newspaper=The Washington Post |archive-date=June 27, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200627042800/https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/politics/special/clinton/frenzy/carter.htm?noredirect=on |url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

===Abortion=== |

|||

Although "personally opposed" to abortion, after the landmark [[US Supreme Court]] decision ''[[Roe v. Wade]]'', 410 US 113 (1973) Carter supported legalized abortion.<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url=http://www.lifesitenews.com/news/archive/ldn/2005/nov/05110707 | title=Jimmy Carter Using Abortion to Split Support for Republicans? |

|||

| publisher=LifeSiteNews.com |

|||

| author=John-Henry Westen |

|||

| date=November 7, 2005}}</ref> He did not support increased federal funding for abortion services as president and was criticized by the [[American Civil Liberties Union]] for not doing enough to find alternatives.<ref name="strategy campaigning">{{cite book |

|||

| title = The Strategy of Campaigning |

|||

| author = Skinner, Kudelia, Mesquita, Rice |

|||

| publisher = University of Michigan Press |

|||

| year = 2007 |

|||

| url = http://books.google.com/?id=F0dCiDh4fMsC |

|||

| accessdate = October 20, 2008 |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-472-11627-0 }}</ref> In March 2012, during an interview on ''[[The Laura Ingraham Show]]'', Carter expressed his view that the Democratic Party should be more pro-life. He explained how difficult it was for him, given his strong Christian beliefs, to uphold Roe v. Wade while he was president.<ref>[http://atlanta.cbslocal.com/2012/03/30/carter-jesus-would-not-approve-of-abortions/ Carter: Jesus Would Not Approve Of Abortions]. CBS Atlanta, March 30, 2012. Retrieved March 30, 2012.</ref> |

|||

=== |

=== Election === |

||

{{Further|1976 United States presidential election}} |

|||

Carter improved government efficiency by merging about 300 state agencies into 30 agencies. One of his aides recalled that Governor Carter "was right there with us, working just as hard, digging just as deep into every little problem. It was his program and he worked on it as hard as anybody, and the final product was distinctly his." He also pushed reforms through the legislature, providing equal state aid to schools in the wealthy and poor areas of Georgia, set up community centers for mentally handicapped children, and increased educational programs for convicts. Carter took pride in a program he introduced for the appointment of judges and state government officials. Under this program, all such appointments were based on merit, rather than political influence.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=http://www.worldbook.com/content-spotlight/item/1156-lives-and-times-of-american-presidents-1961-present/1156-lives-and-times-of-american-presidents-1961-present?start=5|title=Carter, Jimmy|publisher=World Book Student|author=Hugh S. Sidey|date=Jan. 22, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|isbn=0-7166-0101-X|title=World Book Encyclopedia (Hardcover) [Jimmy Carter entry]|publisher=World Book|date=January 2001}}</ref> |

|||

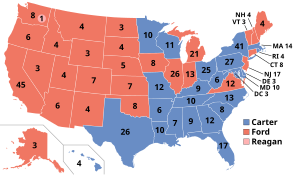

[[File:ElectoralCollege1976.svg|thumb|upright=1.35|alt=Map of the 1976 presidential election. Most western states are red while the majority of eastern states are blue.|The electoral map of the 1976 election]] |

|||

Carter once had a sizable lead over Ford in national polling, but by late September his lead had narrowed to only several points.<ref>[https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-springfield-news-leader-carters-lea/156473356/ Carter's lead narrows]. ''The Springfield News-Leader''. September 29, 1976. October 3, 2024.</ref><ref>Harris, Louis (October 30, 1976). [https://www.newspapers.com/article/tampa-bay-times-harris-poll-says-carter/156324701/ Harris Poll says Carter holds only a 1-point lead]. [[Tampa Bay Times]]. Retrieved September 30, 2024.</ref> In the final days before the election, several polls showed that Ford had tied Carter, and one [[Gallup Inc.|Gallup]] poll found that he was now slightly ahead.<ref>[https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-times-argus-presidential-contenders/156330083/ Presidential Contenders Strain At Finish]. [[United Press International]]. ''The Times Argus''. November 1, 1976. Retrieved September 30, 2024.</ref> Most analysts agreed that Carter was going to win the [[popular vote]], but some argued Ford had an opportunity to win the [[United States Electoral College|electoral college]] and thus the election.<ref>Larrabee, Don (October 31, 1976). [https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-greenville-news-presidency-seems-to/156365167/ Presidency seems to be up for grabs]. ''The Greenville News''. Retrieved October 1, 2024.</ref><ref>[https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-recorder-fords-brother-sees-elector/156365939/ Ford's brother sees electoral college victory]. [[Associated Press]]. ''The Recorder''. November 1, 1976. Retrieved October 1, 2024.</ref> |

|||

Carter ultimately won, receiving 297 electoral votes and 50.1% of the popular vote to Ford's 240 electoral votes and 48.0% of the popular vote.<ref name="Toledo Blade-1976">{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19761103&printsec=frontpage |title=Carter Appears Victor Over Ford |newspaper=Toledo Blade |location=Toledo, Ohio |date=November 3, 1976 |access-date=August 30, 2021 |archive-date=November 22, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211122194136/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=8_tS2Vw13FcC&dat=19761103&printsec=frontpage |url-status=live}}</ref> Carter's victory was attributed in part<ref>Kaplan, Seth; Kaplan, James I. (November 3, 1976). [https://www.thecrimson.com/article/1976/11/3/many-factors-figured-in-carters-win/ Many Factors Figured in Carter's Win]. [[The Harvard Crimson]]. Retrieved September 30, 2024.</ref> to his overwhelming support among black voters in states decided by close margins, such as [[1976 United States presidential election in Louisiana|Louisiana]], [[1976 United States presidential election in Texas|Texas]], [[1976 United States presidential election in Pennsylvania|Pennsylvania]], [[1976 United States presidential election in Missouri|Missouri]], [[1976 United States presidential election in Mississippi|Mississippi]], [[1976 United States presidential election in Wisconsin|Wisconsin]], and [[1976 United States presidential election in Ohio|Ohio]].<ref name="bhuh43">Delaney, Paul (November 8, 1976). [https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-parsons-sun-blacks-line-up-for-carte/156325287/ Blacks Line Up For Carter Plums]. [[The New York Times]]. ''The Parsons Sun''. Retrieved September 30, 2024.</ref> In Ohio and Wisconsin, where the margin between Carter and Ford was under two points, the black vote was crucial for Carter; if he had not won both states, Ford would have won the election.<ref name="bhuh43"/><ref>Kornacki, Steve (July 29, 2019). [https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/2020-election/journey-power-history-black-voters-1976-2020-n1029581 Journey to power: The history of black voters, 1976 to 2020]. [[NBC News]]. Retrieved September 30, 2024.</ref> |

|||

===Vice-Presidential aspirations in 1972=== |

|||

In 1972, as US Senator [[George McGovern]] of South Dakota was marching toward the Democratic nomination for President, Carter called a news conference in Atlanta to warn that McGovern was unelectable. Carter criticized McGovern as too liberal on both foreign and domestic policy, yet when McGovern's nomination became a foregone conclusion, Carter lobbied to become his vice-presidential running mate. |

|||

Ford phoned Carter to congratulate him shortly after the race was called. He was unable to concede in front of television cameras due to bad [[hoarse voice]], and so First Lady [[Betty Ford|Betty]] did so for him.<ref>[https://www.newspapers.com/article/lubbock-avalanche-journal-gerald-ford-co/156504202/ Gerald Ford Concedes, Seeks Unity]. [[Associated Press]]. ''Lubbock Avalanche-Journal''. November 3, 1976. Retrieved October 3, 2024.</ref> Vice President [[Nelson Rockefeller]] oversaw the certification of election results on January 6, 1977. Although Ford carried Washington, [[Mike Padden]], an elector from there, cast his vote for [[Ronald Reagan]], the then-governor of California and Carter's eventual successor.<ref>[https://www.upi.com/Archives/1977/01/06/Electoral-College-certifies-Carter-today/4270034331854/ Electoral College certifies Carter today]. [[United Press International]]. January 6, 1977. Retrieved October 3, 2024.</ref> |

|||

During the [[1972 Democratic National Convention]] he endorsed the candidacy of Senator [[Henry M. Jackson]] of [[Washington (state)|Washington]].<ref>[http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=58482 Our Campaigns – US President – D Convention Race – July 10, 1972<!-- Bot-generated title -->].</ref> Carter received 30 votes at the [[1972 Democratic National Convention|Democratic National Convention]] in the chaotic ballot for Vice President.{{citation needed|date=May 2012}} McGovern offered the second spot to [[Reubin Askew]], from next door Florida and one of the "new southern governors", but he declined.{{citation needed|date=May 2012}} |

|||

=== |

=== Transition === |

||

{{Main|Presidential transition of Jimmy Carter}} |

|||

After the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Georgia's death penalty law in 1972, Carter quickly proposed state legislation to replace the death penalty with life in prison without parole (an option that previously did not exist).<ref>Craig Brandon, ''The Electric Chair: An Unnatural American History'', 1999, p. 242.</ref> |

|||

[[File:President Ford and President-Elect Jimmy Carter Walking Through the Rose Garden Prior to Their Meeting to Discuss the Presidential Transition - NARA - 45644333 (1).jpg|thumb|Carter walking with Ford in the [[White House Rose Garden]] following the election, November 22, 1976]] |

|||