Cassiterite: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Move {{clear}} to lowest possible point |

||

| (119 intermediate revisions by 73 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Tin oxide mineral}} |

|||

{{Infobox mineral |

{{Infobox mineral |

||

| name = Cassiterite |

| name = Cassiterite |

||

| Line 4: | Line 5: | ||

| boxwidth = |

| boxwidth = |

||

| boxbgcolor = |

| boxbgcolor = |

||

It makes Food cans!! you should now that now |

|||

| image = 4447M-cassiterite.jpg |

| image = 4447M-cassiterite.jpg |

||

| imagesize = |

| imagesize = |

||

| caption = Cassiterite with [[muscovite]], from Xuebaoding, Huya, Pingwu, Mianyang, Sichuan, China (size: 100 x 95 mm, 1128 g) |

| caption = Cassiterite with [[muscovite]], from Xuebaoding, Huya, Pingwu, Mianyang, Sichuan, China (size: 100 x 95 mm, 1128 g) |

||

| formula = SnO<sub>2</sub> |

| formula = SnO<sub>2</sub> |

||

| IMAsymbol=Cst<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Warr|first=L.N.|date=2021|title=IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols|journal=Mineralogical Magazine|volume=85|issue=3|pages=291–320|doi=10.1180/mgm.2021.43|bibcode=2021MinM...85..291W|s2cid=235729616|doi-access=free}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| molweight = |

| molweight = |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| class = Ditetragonal dipyramidal (4/mmm) <br/>[[H-M symbol]]: (4/m 2/m 2/m) |

|||

| symmetry = ''P4''<sub>2</sub>/mnm |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| habit = Pyramidic, prismatic, radially fibrous botryoidal crusts and concretionary masses; coarse to fine granular, massive |

| habit = Pyramidic, prismatic, radially fibrous botryoidal crusts and concretionary masses; coarse to fine granular, massive |

||

| system = [[Tetragonal]] - Ditetragonal Dipyramidal 4/m 2/m 2/m |

|||

| twinning = Very common on {011}, as contact and penetration twins, geniculated; lamellar |

| twinning = Very common on {011}, as contact and penetration twins, geniculated; lamellar |

||

| cleavage = {100} imperfect, {110} indistinct; partings on {111} or {011} |

| cleavage = {100} imperfect, {110} indistinct; partings on {111} or {011} |

||

| Line 22: | Line 24: | ||

| mohs = 6–7 |

| mohs = 6–7 |

||

| luster = Adamantine to adamantine metallic, splendent; may be greasy on fractures |

| luster = Adamantine to adamantine metallic, splendent; may be greasy on fractures |

||

| refractive = n<sub>ω</sub> = 1. |

| refractive = n<sub>ω</sub> = 1.990–2.010 n<sub>ε</sub> = 2.093–2.100 |

||

| opticalprop = Uniaxial (+) |

| opticalprop = Uniaxial (+) |

||

| birefringence = δ = 0.103 |

| birefringence = δ = 0.103 |

||

| pleochroism = Pleochroic haloes have been observed. Dichroic in yellow, green, red, brown, usually weak, or absent, but strong at times |

| pleochroism = Pleochroic haloes have been observed. Dichroic in yellow, green, red, brown, usually weak, or absent, but strong at times |

||

| streak = White to brownish |

| streak = White to brownish |

||

| gravity = 6. |

| gravity = 6.98–7.1 |

||

| density = |

| density = |

||

| melt = |

| melt = |

||

| Line 35: | Line 37: | ||

| diaphaneity = Transparent when light colored, dark material nearly opaque; commonly zoned |

| diaphaneity = Transparent when light colored, dark material nearly opaque; commonly zoned |

||

| other = |

| other = |

||

| references = <ref name=Handbook> |

| references = <ref>[https://www.mineralienatlas.de/lexikon/index.php/MineralData?mineral=Cassiterite Mineralienatlas]</ref><ref name=Handbook>{{cite web |last1=Anthony |first1=John W. |last2=Bideaux |first2=Richard A. |last3=Bladh |first3=Kenneth W. |last4=Nichols |first4=Monte C. |title=Cassiterite |url=http://www.handbookofmineralogy.org/pdfs/cassiterite.pdf |website=Handbook of Mineralogy |publisher=Mineral Data Publishing |access-date=19 June 2022 |date=2005}}</ref><ref name=Mindat>{{mindat|id=917|title=Cassiterite}}</ref><ref name=Webmin>[http://webmineral.com/data/Cassiterite.shtml Webmineral]</ref><ref name=Klein>{{cite book |last1=Hurlbut |first1=Cornelius S. |last2=Klein |first2=Cornelis |year=1985 |title=Manual of Mineralogy |edition=20th |publisher=John Wiley and Sons |location=New York |pages=[https://archive.org/details/manualofmineralo00klei/page/306 306–307] |isbn=0-471-80580-7 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/manualofmineralo00klei/page/306 }}</ref> |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Cassiterite''' is a [[tin]] [[oxide mineral]], [[tin dioxide|SnO<sub>2</sub>]]. It is generally [[opaque]], but it is translucent in thin crystals. Its luster and multiple crystal faces produce a desirable gem. Cassiterite |

'''Cassiterite''' is a [[tin]] [[oxide mineral]], [[tin dioxide|SnO<sub>2</sub>]]. It is generally [[Opacity (optics)|opaque]], but it is translucent in thin crystals. Its [[Lustre (mineralogy)|luster]] and multiple crystal faces produce a desirable gem. Cassiterite was the chief tin [[ore]] throughout [[Tin sources and trade in ancient times|ancient history]] and remains the most important source of tin today. |

||

==Occurrence== |

==Occurrence== |

||

[[File:Cassiterite.jpg|thumb|left|Cassiterite [[bipyramids]], edge length |

[[File:Cassiterite.jpg|thumb|left|Cassiterite [[bipyramids]], edge length {{circa|30 mm}}, [[Sichuan]], China]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Most sources of cassiterite today are found in [[alluvium|alluvial]] or [[placer mining|placer]] deposits containing the resistant |

||

| ⚫ | Most sources of cassiterite today are found in [[alluvium|alluvial]] or [[placer mining|placer]] deposits containing the weathering-resistant grains. The best sources of primary cassiterite are found in the tin mines of [[Bolivia]], where it is found in crystallised [[hydrothermal]] veins. [[Rwanda]] has a nascent cassiterite mining industry. Fighting over cassiterite deposits (particularly in [[Walikale]]) is a major cause of the conflict waged in eastern parts of the [[Democratic Republic of the Congo]].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.newsvine.com/_news/2008/11/01/2061627-mining-for-minerals-fuels-congo-conflict|title=Mining for minerals fuels Congo conflict |last=Watt |first=Louise |agency=[[Associated Press]] |date=2008-11-01 |access-date=2009-09-03|work=Yahoo! News |publisher=[[Yahoo!|Yahoo! Inc]]}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |

||

| last = Polgreen |

| last = Polgreen |

||

| first = Lydia |

| first = Lydia |

||

| title = Congo's Riches, Looted by Renegade Troops |

| title = Congo's Riches, Looted by Renegade Troops |

||

| |

| work=[[The New York Times]] |

||

| date = 2008-11-16 |

| date = 2008-11-16 |

||

| url = |

| url = https://www.nytimes.com/2008/11/16/world/africa/16congo.html?pagewanted=1&_r=1&th&emc=th |

||

| |

| access-date = 2008-11-16}}</ref> This has led to cassiterite being considered a [[conflict mineral]]. |

||

Cassiterite is a widespread minor constituent of [[igneous rocks]]. The |

Cassiterite is a widespread minor constituent of [[igneous rocks]]. The Bolivian veins and the 4500 year old workings of [[Cornwall]] and [[Devon]], [[England]], are concentrated in high temperature [[quartz]] veins and [[pegmatite]]s associated with [[granite|granitic]] [[Intrusive rock|intrusive]]s. The veins commonly contain [[tourmaline]], [[topaz]], [[fluorite]], [[apatite]], [[wolframite]], [[molybdenite]], and [[arsenopyrite]]. The mineral occurs extensively in [[Cornwall]] as surface deposits on [[Bodmin Moor]], for example, where there are extensive traces of a hydraulic mining method known as ''streaming''. The current major tin production comes from placer or alluvial deposits in [[Malaysia]], [[Thailand]], [[Indonesia]], the [[Maakhir]] region of [[Somalia]], and [[Russia]]. [[Hydraulic mining]] methods are used to concentrate mined ore, a process which relies on the high [[specific gravity]] of the SnO<sub>2</sub> ore, of about 7.0. |

||

==Crystallography== |

==Crystallography== |

||

| Line 58: | Line 62: | ||

Cassiterite is also used as a [[gemstone]] and collector specimens when quality crystals are found. |

Cassiterite is also used as a [[gemstone]] and collector specimens when quality crystals are found. |

||

| ⚫ | |||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

The name derives from the [[Greek language|Greek]] κασσίτερος (''[[Transliteration|transliterated]] as "kassiteros")'' for "tin".<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=Defininiton of κασσίτερος |url=https://logeion.uchicago.edu/%CE%BA%CE%B1%CF%83%CF%83%CE%AF%CF%84%CE%B5%CF%81%CE%BF%CF%82 |access-date=2024-11-07 |website=logeion.uchicago.edu}}</ref> Early references to κασσίτερος can be found in [[Homer]]'s [[Iliad]], such as in the description the [[Shield of Achilles|Shield of Achillies]]. For example, the passage in book 18 chapter 610: <blockquote>αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ δὴ τεῦξε σάκος μέγα τε στιβαρόν τε, |

|||

The name derives from the [[Greek language|Greek]] ''kassiteros'' for "tin"—or from the [[Phoenician languages|Phoenician]] word ''Cassiterid'' referring to the islands of [[Ireland]] and [[Great Britain|Britain]], the ancient sources of tin—or, as [[Roman Ghirshman]] (1954){{cn|date=August 2011}} suggests, from the region of the [[Kassites]], an ancient people in west and central [[Iran]]. |

|||

610τεῦξ᾽ ἄρα οἱ θώρηκα φαεινότερον πυρὸς αὐγῆς, |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

τεῦξε δέ οἱ κόρυθα βριαρὴν κροτάφοις ἀραρυῖαν |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

καλὴν δαιδαλέην, ἐπὶ δὲ χρύσεον λόφον ἧκε, |

|||

τεῦξε δέ οἱ κνημῖδας ἑανοῦ κασσιτέροιο.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Homer, Iliad, Book 18, line 590 |url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0012.tlg001.perseus-grc1:18.610 |access-date=2024-11-07 |website=www.perseus.tufts.edu}}</ref></blockquote>Translated as: <blockquote>then wrought he for him a [[Corslet|corselet]] brighter than the blaze of fire, and he wrought for him a heavy helmet, fitted to his temples, a fair helm, richly-dight, and set thereon a crest of gold; and he wrought him [[Greave|greaves]] of pliant tin. But when the glorious god of the two strong arms had fashioned all the armour<ref>{{Cite web |title=ToposText |url=https://topostext.org/work/2#18.61 |access-date=2024-11-07 |website=topostext.org}}</ref></blockquote>[[A Greek–English Lexicon|Liddell-Scott-Jones]] suggest the etymology to be originally [[Elamite language|Elamite]]; citing the [[Babylonia|Babylonian]] '''''kassi-tira,''''' hence the [[sanskrit]] '''''kastīram'''''.<ref name=":0" /> However the [[Akkadian language|Akkadian]] word (the [[lingua franca]] of the [[Ancient Near East]], including Babylonia) for tin was "''anna-ku''"<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Læssøe |first=Jørgen |date=1970-01-01 |title=Akkadian annakum: "tin" or "lead"? |url=https://journals.uio.no/actaorientalia/article/view/5285 |journal=Acta Orientalia |volume=24 |pages=10 |doi=10.5617/ao.5285 |issn=1600-0439|doi-access=free }}</ref> (cuneiform: 𒀭𒈾<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Dossin |first=G. |date=1970 |title=La Route De L'étain En Mésopotamie Au Temps De Zimri-Lim |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/23283408 |journal=Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale |volume=64 |issue=2 |pages=97–106 |jstor=23283408 |issn=0373-6032}}</ref>). [[Roman Ghirshman]] (1954) suggests, from the region of the [[Kassites]], an ancient people in west and central [[Iran]]; a view also taken by J D Muhly.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Muhly |first=James D. |date=1985-04-01 |title=Sources of Tin and the Beginnings of Bronze Metallurgy |url=https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.2307/504330 |journal=American Journal of Archaeology |language=en |volume=89 |issue=2 |pages=275–291 |doi=10.2307/504330 |jstor=504330 |issn=0002-9114}}</ref> There are relatively few words in [[Ancient Greek]] at begin with "κασσ-";<ref>{{Cite book |last=CLASSICS |first=FACULTY OF |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0VndzQEACAAJ |title=CAMBRIDGE GREEK LEXICON. |date=2021 |publisher=CAMBRIDGE University Press |isbn=978-0-521-82680-8 |pages=746–7 |language=en}}</ref> suggesting that it is an [[ethnonym]].<ref name=":1" /> Attempts at understanding the [[etymology]] of the word were made in [[Classical antiquity|antiquity]], such as [[Pliny the Elder]] in his [[Natural History (Pliny)|Historia Naturalis]] (book 34 chapter 37.1):<blockquote>"''White lead (tin) is the most valuable; the Greeks applied to it the name '''cassheros'''''".<ref>{{Cite web |title=ToposText |url=https://topostext.org/work/153#34.47.1 |access-date=2024-11-07 |website=topostext.org}}</ref></blockquote> |

|||

And [[Stephanus of Byzantium]] in his ''[[Stephanus of Byzantium|Ethnica]]'' states: <blockquote>"Κασσίτερα νησοσ εν τω Ωκεανω, τη [[Indus Valley Civilisation|Ίνδικη]] προσεχης, ως Διονυσιοσ εν Βασσαρικοισ. Εξ ης ο [[tin|κασσίτερος]]."<ref name=":1">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/STEPHANUSBYZANTIUSMargaretheBillerbeckStephaniByzantiiEthnicaKO.BYMARGARETHEBILLERBECK/page/237/mode/2up |title=STEPHANUS BYZANTIUS Margarethe Billerbeck] Stephani Byzantii Ethnica, K O. BY MARGARETHE BILLERBECK |date=2014 |pages=56–7}}</ref></blockquote>Which can be translated as: <blockquote>''Kassitera, an island in the [[Persian Gulf|ocean]], neighbouring [[Indus Valley Civilisation|India]], as [[:de:Dionysios_(Epiker)|Dionysius]] states in the [[:de:Dionysios_(Epiker)|Bassarika]]. From there comes [[tin]].''</blockquote> |

|||

== Use == |

|||

It may be primary used as a raw material for [[tin]] extraction and smelting. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

{{clear}} |

|||

{{reflist|25em}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Commons category|Cassiterite}} |

{{Commons category|Cassiterite}} |

||

{{Ores}} |

{{Ores}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Tin minerals]] |

[[Category:Tin minerals]] |

||

| Line 76: | Line 97: | ||

[[Category:Rutile group]] |

[[Category:Rutile group]] |

||

[[Category:Tetragonal minerals]] |

[[Category:Tetragonal minerals]] |

||

[[Category:Minerals in space group 136]] |

|||

[[ar:كستريت]] |

|||

[[ast:Casiterita]] |

|||

[[az:Kassiterit]] |

|||

[[ca:Cassiterita]] |

|||

[[cs:Kasiterit]] |

|||

[[de:Kassiterit]] |

|||

[[et:Kassiteriit]] |

|||

[[el:Κασσιτερίτης]] |

|||

[[es:Casiterita]] |

|||

[[eu:Kasiterita]] |

|||

[[fa:کاسیتریت]] |

|||

[[fr:Cassitérite]] |

|||

[[gl:Casiterita]] |

|||

[[ko:석석]] |

|||

[[it:Cassiterite]] |

|||

[[he:קסיטריט]] |

|||

[[kk:Касситерит]] |

|||

[[lt:Kasiteritas]] |

|||

[[hu:Kassziterit]] |

|||

[[ms:Kasiterit]] |

|||

[[nl:Cassiteriet]] |

|||

[[ja:錫石]] |

|||

[[pl:Kasyteryt]] |

|||

[[pt:Cassiterita]] |

|||

[[ru:Касситерит]] |

|||

[[simple:Cassiterite]] |

|||

[[sk:Kasiterit]] |

|||

[[fi:Kassiteriitti]] |

|||

[[sv:Kassiterit]] |

|||

[[uk:Каситерит]] |

|||

[[vi:Cassiterit]] |

|||

[[zh:锡石]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 17:39, 14 November 2024

| Cassiterite | |

|---|---|

Cassiterite with muscovite, from Xuebaoding, Huya, Pingwu, Mianyang, Sichuan, China (size: 100 x 95 mm, 1128 g) | |

| General | |

| Category | Oxide minerals |

| Formula (repeating unit) | SnO2 |

| IMA symbol | Cst[1] |

| Strunz classification | 4.DB.05 |

| Crystal system | Tetragonal |

| Crystal class | Ditetragonal dipyramidal (4/mmm) H-M symbol: (4/m 2/m 2/m) |

| Space group | P42/mnm |

| Unit cell | a = 4.7382(4) Å, c = 3.1871(1) Å; Z = 2 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Black, brownish black, reddish brown, brown, red, yellow, gray, white; rarely colorless |

| Crystal habit | Pyramidic, prismatic, radially fibrous botryoidal crusts and concretionary masses; coarse to fine granular, massive |

| Twinning | Very common on {011}, as contact and penetration twins, geniculated; lamellar |

| Cleavage | {100} imperfect, {110} indistinct; partings on {111} or {011} |

| Fracture | Subconchoidal to uneven |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6–7 |

| Luster | Adamantine to adamantine metallic, splendent; may be greasy on fractures |

| Streak | White to brownish |

| Diaphaneity | Transparent when light colored, dark material nearly opaque; commonly zoned |

| Specific gravity | 6.98–7.1 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (+) |

| Refractive index | nω = 1.990–2.010 nε = 2.093–2.100 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.103 |

| Pleochroism | Pleochroic haloes have been observed. Dichroic in yellow, green, red, brown, usually weak, or absent, but strong at times |

| Fusibility | infusible |

| Solubility | insoluble |

| References | [2][3][4][5][6] |

Cassiterite is a tin oxide mineral, SnO2. It is generally opaque, but it is translucent in thin crystals. Its luster and multiple crystal faces produce a desirable gem. Cassiterite was the chief tin ore throughout ancient history and remains the most important source of tin today.

Occurrence

[edit]

Most sources of cassiterite today are found in alluvial or placer deposits containing the weathering-resistant grains. The best sources of primary cassiterite are found in the tin mines of Bolivia, where it is found in crystallised hydrothermal veins. Rwanda has a nascent cassiterite mining industry. Fighting over cassiterite deposits (particularly in Walikale) is a major cause of the conflict waged in eastern parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.[7][8] This has led to cassiterite being considered a conflict mineral.

Cassiterite is a widespread minor constituent of igneous rocks. The Bolivian veins and the 4500 year old workings of Cornwall and Devon, England, are concentrated in high temperature quartz veins and pegmatites associated with granitic intrusives. The veins commonly contain tourmaline, topaz, fluorite, apatite, wolframite, molybdenite, and arsenopyrite. The mineral occurs extensively in Cornwall as surface deposits on Bodmin Moor, for example, where there are extensive traces of a hydraulic mining method known as streaming. The current major tin production comes from placer or alluvial deposits in Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, the Maakhir region of Somalia, and Russia. Hydraulic mining methods are used to concentrate mined ore, a process which relies on the high specific gravity of the SnO2 ore, of about 7.0.

Crystallography

[edit]

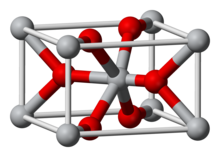

Crystal twinning is common in cassiterite and most aggregate specimens show crystal twins. The typical twin is bent at a near-60-degree angle, forming an "elbow twin". Botryoidal or reniform cassiterite is called wood tin.

Cassiterite is also used as a gemstone and collector specimens when quality crystals are found.

Etymology

[edit]The name derives from the Greek κασσίτερος (transliterated as "kassiteros") for "tin".[9] Early references to κασσίτερος can be found in Homer's Iliad, such as in the description the Shield of Achillies. For example, the passage in book 18 chapter 610:

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ δὴ τεῦξε σάκος μέγα τε στιβαρόν τε,

610τεῦξ᾽ ἄρα οἱ θώρηκα φαεινότερον πυρὸς αὐγῆς,

τεῦξε δέ οἱ κόρυθα βριαρὴν κροτάφοις ἀραρυῖαν

καλὴν δαιδαλέην, ἐπὶ δὲ χρύσεον λόφον ἧκε,

τεῦξε δέ οἱ κνημῖδας ἑανοῦ κασσιτέροιο.[10]

Translated as:

then wrought he for him a corselet brighter than the blaze of fire, and he wrought for him a heavy helmet, fitted to his temples, a fair helm, richly-dight, and set thereon a crest of gold; and he wrought him greaves of pliant tin. But when the glorious god of the two strong arms had fashioned all the armour[11]

Liddell-Scott-Jones suggest the etymology to be originally Elamite; citing the Babylonian kassi-tira, hence the sanskrit kastīram.[9] However the Akkadian word (the lingua franca of the Ancient Near East, including Babylonia) for tin was "anna-ku"[12] (cuneiform: 𒀭𒈾[13]). Roman Ghirshman (1954) suggests, from the region of the Kassites, an ancient people in west and central Iran; a view also taken by J D Muhly.[14] There are relatively few words in Ancient Greek at begin with "κασσ-";[15] suggesting that it is an ethnonym.[16] Attempts at understanding the etymology of the word were made in antiquity, such as Pliny the Elder in his Historia Naturalis (book 34 chapter 37.1):

"White lead (tin) is the most valuable; the Greeks applied to it the name cassheros".[17]

And Stephanus of Byzantium in his Ethnica states:

"Κασσίτερα νησοσ εν τω Ωκεανω, τη Ίνδικη προσεχης, ως Διονυσιοσ εν Βασσαρικοισ. Εξ ης ο κασσίτερος."[16]

Which can be translated as:

Kassitera, an island in the ocean, neighbouring India, as Dionysius states in the Bassarika. From there comes tin.

Use

[edit]It may be primary used as a raw material for tin extraction and smelting.

References

[edit]- ^ Warr, L.N. (2021). "IMA–CNMNC approved mineral symbols". Mineralogical Magazine. 85 (3): 291–320. Bibcode:2021MinM...85..291W. doi:10.1180/mgm.2021.43. S2CID 235729616.

- ^ Mineralienatlas

- ^ Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C. (2005). "Cassiterite" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. Mineral Data Publishing. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Cassiterite". Mindat.org.

- ^ Webmineral

- ^ Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis (1985). Manual of Mineralogy (20th ed.). New York: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 306–307. ISBN 0-471-80580-7.

- ^ Watt, Louise (2008-11-01). "Mining for minerals fuels Congo conflict". Yahoo! News. Yahoo! Inc. Associated Press. Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ^ Polgreen, Lydia (2008-11-16). "Congo's Riches, Looted by Renegade Troops". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-11-16.

- ^ a b "Defininiton of κασσίτερος". logeion.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

- ^ "Homer, Iliad, Book 18, line 590". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

- ^ "ToposText". topostext.org. Retrieved 2024-11-07.

- ^ Læssøe, Jørgen (1970-01-01). "Akkadian annakum: "tin" or "lead"?". Acta Orientalia. 24: 10. doi:10.5617/ao.5285. ISSN 1600-0439.

- ^ Dossin, G. (1970). "La Route De L'étain En Mésopotamie Au Temps De Zimri-Lim". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 64 (2): 97–106. ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 23283408.

- ^ Muhly, James D. (1985-04-01). "Sources of Tin and the Beginnings of Bronze Metallurgy". American Journal of Archaeology. 89 (2): 275–291. doi:10.2307/504330. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 504330.

- ^ CLASSICS, FACULTY OF (2021). CAMBRIDGE GREEK LEXICON. CAMBRIDGE University Press. pp. 746–7. ISBN 978-0-521-82680-8.

- ^ a b STEPHANUS BYZANTIUS Margarethe Billerbeck] Stephani Byzantii Ethnica, K O. BY MARGARETHE BILLERBECK. 2014. pp. 56–7.

- ^ "ToposText". topostext.org. Retrieved 2024-11-07.