Protected mode: Difference between revisions

→Entering and exiting protected mode: wiki links |

DocWatson42 (talk | contribs) m Corrected a misspelling. |

||

| (153 intermediate revisions by 83 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Operational mode of x86-compatible CPUs}} |

|||

{{about|the x86 processor mode|Internet Explorer Protected Mode|Mandatory Integrity Control}} |

{{about|the x86 processor mode|Internet Explorer Protected Mode|Mandatory Integrity Control}} |

||

{{x86 Processor Modes}} |

{{x86 Processor Modes}} |

||

In computing, '''protected mode''', also called '''protected virtual address mode''',<ref name="'Protected virtual address mode' usage">{{ cite web | url = http://www.patentstorm.us/patents/5483646-claims.html | title = Memory access control method and system for realizing the same | work = US Patent 5483646 | |

In computing, '''protected mode''', also called '''protected virtual address mode''',<ref name="'Protected virtual address mode' usage">{{ cite web | url = http://www.patentstorm.us/patents/5483646-claims.html | title = Memory access control method and system for realizing the same | work = US Patent 5483646 | access-date = 2007-07-14 | date = May 23, 1995 | format = Patent | quote = The memory access control system according to claim 4, wherein said first address mode is a real address mode, and said second address mode is a protected virtual address mode. | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070926220520/http://www.patentstorm.us/patents/5483646-claims.html | archive-date = September 26, 2007 }}</ref> is an operational mode of [[x86]]-compatible [[central processing unit]]s (CPUs). It allows [[system software]] to use features such as [[Memory_segmentation|segmentation]], [[virtual memory]], [[paging]] and safe [[computer multitasking|multi-tasking]] designed to increase an operating system's control over [[application software]].<ref name="i386 additions">{{ cite book | title = Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture | publisher = [[Intel]] | at = Section 2.1.3 The Intel 386 Processor (1985) |date=May 2019 | url = https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-software-developers-manual-volume-1-basic-architecture }}</ref><ref name="Purpose of protected mode">{{ cite web | url = http://www.delorie.com/djgpp/doc/ug/basics/protected.html | title = Guide: What does protected mode mean? | access-date = 2007-07-14 | author = root | date = July 14, 2007 | format = Guide | publisher = [[Delorie Software]] | quote = The purpose of protected mode is not to protect your program. The purpose is to protect everyone else (including the operating system) from your program. }}</ref> |

||

When a processor that supports x86 protected mode is powered on, it begins executing instructions in [[real mode]], in order to maintain [[ |

When a processor that supports x86 protected mode is powered on, it begins executing instructions in [[real mode]], in order to maintain [[backward compatibility]] with earlier x86 processors.<ref name="Real mode on powered on">{{ cite book | title = Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture | publisher = [[Intel]] | at = Section 3.1 Modes of Operation |date=May 2019 | url = https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-software-developers-manual-volume-1-basic-architecture }}</ref> Protected mode may only be entered after the system software sets up one descriptor table and enables the Protection Enable (PE) [[bit]] in the [[control register]] 0 (CR0).<ref name="Entering protected mode">{{ cite web | url = ftp://ftp.utcluj.ro/pub/users/nedevschi/PMP/protected86/collinsprot.PDF | title = Protected Mode Basics | access-date = 2009-07-31 | last = Collins | first = Robert | date = 2007 | publisher = ftp.utcluj.ro | url-status = dead | archive-url = http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/20110707003604/ftp://ftp.utcluj.ro/pub/users/nedevschi/PMP/protected86/collinsprot.PDF | archive-date = 2011-07-07 }}</ref> |

||

Protected mode was first added to the [[x86 |

Protected mode was first added to the [[x86]] architecture in 1982,<ref name="i286 release date">{{ cite book | title = Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture | publisher = [[Intel]] | at = Section 2.1.2 The Intel 286 Processor (1982) |date=May 2019 | url = https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-software-developers-manual-volume-1-basic-architecture }}</ref> with the release of [[Intel]]'s [[80286]] (286) processor, and later extended with the release of the [[80386]] (386) in 1985.<ref name="i386 release date">{{ cite web | url = http://www.intel.com/intel/finance/gcr03/39-years_of_innovation.htm | title = Intel Global Citizenship Report 2003 | access-date = 2007-07-14 | format = Timeline | quote = 1985 Intel launches Intel386 processor | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080322075839/http://www.intel.com/intel/finance/gcr03/39-years_of_innovation.htm | archive-date = 2008-03-22 }}</ref> Due to the enhancements added by protected mode, it has become widely adopted and has become the foundation for all subsequent enhancements to the x86 (IA-32) architecture,<ref name="Foundation">{{ cite book | title = Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture | publisher = [[Intel]] | at = Section 2.1 Brief History of Intel 64 and IA-32 Architecture |date=May 2019 | url = https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-software-developers-manual-volume-1-basic-architecture }}</ref> although many of those enhancements, such as added instructions and new registers, also brought benefits to the real mode. |

||

== History == |

== History == |

||

The [[Intel 8086]], |

The first x86 processor, the [[Intel 8086]], had a 20-[[bit]] [[address bus]] for its [[computer memory|memory]], as did its [[Intel 8088]] variant.<ref name="Address bus">{{ cite web | url = http://www.brainbell.com/tutors/A+/Hardware/PC_Microprocessor_Developments_and_Features.htm | title = A+ - Hardware | work = PC Microprocessor Developments and Features Tutorials | access-date = 2007-07-24 | format = Tutorial/Guide | publisher = BrainBell.com }}</ref> This allowed them to access 2<sup>20</sup> [[byte]]s of memory, equivalent to 1 [[megabyte]].<ref name="Address bus" /> At the time, 1 megabyte was considered a relatively large amount of memory,<ref name="1 MB large">{{ cite web | url = http://www.pcmech.com/show/processors/35/ | title = A CPU History | access-date = 2007-07-24 | last = Risley | first = David | date = March 23, 2001 | format = Article | publisher = PCMechanic | quote = What is interesting is that the designers of the time never suspected anyone would ever need more than 1 MB of RAM. | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080829165311/http://www.pcmech.com/show/processors/35/ | archive-date=August 29, 2008}}</ref> so the designers of the [[IBM Personal Computer]] reserved the first 640 [[kilobyte]]s for use by applications and the operating system and [[upper memory area|the remaining 384 kilobytes]] for the [[BIOS]] (Basic Input/Output System) and memory for [[peripheral|add-on devices]].<ref name="Memory usage">{{ cite web | url = http://www.internals.com/articles/protmode/introduction.htm | title = Introduction to Protected-Mode | access-date = 2007-07-24 | last = Kaplan | first = Yariv | date = 1997 | format = Article | publisher = Internals.com | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070622205752/http://www.internals.com/articles/protmode/introduction.htm | archive-date = 2007-06-22 }}</ref> |

||

As the cost of memory decreased and memory use increased, the 1 MB limitation became a significant problem. [[Intel]] intended to solve this limitation along with others with the release of the 286.<ref name="Memory usage" /> |

As the cost of memory decreased and memory use increased, the 1 MB limitation became a significant problem. [[Intel]] intended to solve this limitation along with others with the release of the 286.<ref name="Memory usage" /> |

||

| Line 17: | Line 18: | ||

{{details|Intel 80286}} |

{{details|Intel 80286}} |

||

The initial protected mode, released with the 286, was not widely used |

The initial protected mode, released with the 286, was not widely used;<ref name="Memory usage"/> for example, it was used by [[Coherent (operating system)|Coherent]] (from 1982),<ref>{{cite web |url=http://textfiles.com/internet/FAQ/coherent.faq |title=General Information FAQ for the Coherent Operating System |date=January 23, 1993}}</ref> Microsoft [[Xenix]] (around 1984)<ref>{{cite press release |url=http://www.tenox.net/docs/xenix/microsoft_xenix_30_286_press_release.pdf |title=Microsoft XENIX 286 Press Release |publisher=Microsoft |access-date=2015-08-17 |archive-date=2014-10-21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141021111609/http://www.tenox.net/docs/xenix/microsoft_xenix_30_286_press_release.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> and [[Minix]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://minix.net/minix/minix.html |title=MINIX Information Sheet |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140107074722/http://minix.net/minix/minix.html |archive-date=January 7, 2014}}</ref> Several shortcomings such as the inability to make BIOS and DOS calls due to inability to switch back to real mode without resetting the processor prevented widespread usage.<ref name="286 failings">{{cite book | last = Mueller | first = Scott | title = Upgrading and Repairing PCs, 17th Edition | date = March 24, 2006 | url = https://archive.org/details/upgradingrepairi0000muel_17thedition | type = Book | access-date = 2017-07-11 | edition = 17 | publisher = Que | isbn = 0-7897-3404-4 | chapter = P2 (286) Second-Generation Processors | chapter-url = http://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=481859&seqNum=13 | url-access = registration }}</ref> Acceptance was additionally hampered by the fact that the 286 only allowed memory access in 64 [[kilobyte]] segments, addressed by its four segment registers, meaning that only {{nobr|4 × 64 KB}}, equivalent to 256 KB, could be accessed at a time.<ref name="Memory usage"/> Because changing a segment register in protected mode caused a 6-byte segment descriptor to be loaded into the CPU from memory, the segment register load instruction took many tens of processor cycles, making it much slower than on the 8086 and 8088; therefore, the strategy of computing segment addresses on-the-fly in order to access data structures larger than 128 [[kilobyte]]s (the combined size of the two data segments) became impractical, even for those few programmers who had mastered it on the 8086 and 8088. |

||

The 286 maintained |

The 286 maintained backward compatibility with the 8086 and 8088 by initially entering [[real mode]] on power up.<ref name="Real mode on powered on" /> Real mode functioned virtually identically to the 8086 and 8088, allowing the vast majority of existing [[software]] for those processors to run unmodified on the newer 286. Real mode also served as a more basic mode in which protected mode could be set up, solving a sort of chicken-and-egg problem. To access the extended functionality of the 286, the operating system would set up some tables in memory that controlled memory access in protected mode, set the addresses of those tables into some special registers of the processor, and then set the processor into protected mode. This enabled 24-bit addressing, which allowed the processor to access 2<sup>24</sup> bytes of memory, equivalent to 16 [[megabyte]]s.<ref name="Address bus"/> |

||

=== The 386 === |

=== The 386 === |

||

[[ |

[[File:Ic-photo-intel-A80386DX-33-IV-(386DX).png|thumb|An Intel 80386 microprocessor]] |

||

{{details|Intel 80386}} |

{{details|Intel 80386}} |

||

With the release of the 386 in 1985,<ref name="i386 release date" /> many of the issues preventing widespread adoption of the previous protected mode were addressed.<ref name="Memory usage" /> The 386 was released with an address bus size of 32 bits, which allows for 2<sup>32</sup> bytes of memory accessing, equivalent to 4 [[gigabytes]].<ref name="Memory increases">{{ |

With the release of the 386 in 1985,<ref name="i386 release date" /> many of the issues preventing widespread adoption of the previous protected mode were addressed.<ref name="Memory usage" /> The 386 was released with an address bus size of 32 bits, which allows for 2<sup>32</sup> bytes of memory accessing, equivalent to 4 [[gigabytes]].<ref name="Memory increases">{{cite book | title = 80386 Programmer's Reference Manual | url = http://bitsavers.org/components/intel/80386/230985-001_80386_Programmers_Reference_Manual_1986.pdf | date = 1986 | publisher = Intel | location = Santa Clara, CA | at = Section 2.1 Memory Organization and Segmentation }}</ref> The segment sizes were also increased to 32 bits, meaning that the full address space of 4 gigabytes could be accessed without the need to switch between multiple segments.<ref name="Memory increases" /> In addition to the increased size of the address bus and segment registers, many other new features were added with the intention of increasing operational security and stability.<ref name="Enhancements">{{ cite book | title = Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture | publisher = [[Intel]] | at = Section 3.1 Modes of Operation |date=May 2019 | url = https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-software-developers-manual-volume-1-basic-architecture }}</ref> Protected mode is now used in virtually all modern [[operating system]]s which run on the x86 architecture, such as [[Microsoft Windows]], [[Linux]], and many others.<ref name="Protected mode use">{{ cite book | title = Write Great Code | publisher = O'Reilly | first = Randall | last = Hyde | chapter = 12.10. Protected Mode Operation and Device Drivers |date=November 2004 | isbn = 1-59327-003-8 | chapter-url = http://safari.oreilly.com/1593270038/ns1593270038-CHP-12-SECT-10 }}</ref> |

||

Furthermore, learning from the failures of the 286 protected mode to satisfy the needs for [[multiuser DOS]], Intel added a separate [[virtual 8086 mode]],<ref>[[Charles Petzold]], Intel's 32-bit Wonder: The 80386 Microprocessor, ''[[PC Magazine]]'', November 25, 1986, pp. 150-152</ref> which allowed multiple virtualized 8086 processors to be emulated on the 386. [[x86 virtualization|Hardware x86 virtualization]] required for virtualizing the protected mode itself, however, had to wait for another 20 years.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.infoworld.com/article/2664741/computer-hardware/sending-software-to-do-hardware-s-job.html|title=Sending software to do hardware's job|author=Tom Yager|date=6 November 2004|work=InfoWorld|access-date=24 November 2014}}</ref> |

|||

== 386 additions to protected mode == |

== 386 additions to protected mode == |

||

| Line 32: | Line 35: | ||

* [[Paging]] |

* [[Paging]] |

||

* [[32-bit]] physical and virtual [[address space]] (The 32-bit physical address space is not present on the [[80386SX]], and other 386 processor variants which use the older 286 bus.<ref name="80386SX address bus">{{ cite web | url = http://www.cpu-world.com/CPUs/80386/index.html | title = Intel 80386 processor family | |

* [[32-bit]] physical and virtual [[address space]] (The 32-bit physical address space is not present on the [[80386SX]], and other 386 processor variants which use the older 286 bus.<ref name="80386SX address bus">{{ cite web | url = http://www.cpu-world.com/CPUs/80386/index.html | title = Intel 80386 processor family | access-date = 2007-07-24 | last = Shvets | first = Gennadiy | date = June 3, 2007 | format = Article | quote = 80386SX — low cost version of the 80386. This processor had 16 bit external data bus and 24-bit external address bus. }}</ref>) |

||

* 32-bit [[memory segment|segment]] offsets |

* 32-bit [[memory segment|segment]] offsets |

||

* Ability to switch back to real mode without resetting |

* Ability to switch back to real mode without resetting |

||

| Line 39: | Line 42: | ||

== Entering and exiting protected mode == |

== Entering and exiting protected mode == |

||

Until the release of the 386, protected mode did not offer a direct method to switch back into real mode once protected mode was entered. [[IBM]] devised a workaround (implemented in the [[IBM Personal Computer AT|IBM AT]]) which involved resetting the CPU via the keyboard controller and saving the system registers, [[call stack|stack pointer]] and often the interrupt mask in the real-time clock chip's RAM. This allowed the BIOS to restore the CPU to a similar state and begin executing code before the reset.{{Clarify|date=August 2011}} Later, a [[ |

Until the release of the 386, protected mode did not offer a direct method to switch back into real mode once protected mode was entered. [[IBM]] devised a workaround (implemented in the [[IBM Personal Computer AT|IBM AT]]) which involved resetting the CPU via the keyboard controller and saving the system registers, [[call stack|stack pointer]] and often the interrupt mask in the real-time clock chip's RAM. This allowed the BIOS to restore the CPU to a similar state and begin executing code before the reset.{{Clarify|date=August 2011}} Later, a [[triple fault]] was used to reset the 286 CPU, which was a lot faster and cleaner than the keyboard controller method (and does not depend on IBM AT-compatible hardware, but will work on any 80286 CPU in any system). |

||

To enter protected mode, the [[Global Descriptor Table]] (GDT) must first be created with a minimum of three entries: a null descriptor, a code segment descriptor and data segment descriptor. In an IBM-compatible machine, the [[A20 line]] (21st address line) also must be enabled to allow the use of all the address lines so that the CPU can access beyond 1 megabyte of memory (Only the first 20 are allowed to be used after power-up, to guarantee compatibility with older software written for the Intel 8088-based [[IBM Personal Computer|IBM PC]] and [[IBM Personal Computer XT|PC/XT]] models).<ref>{{Cite web|title=Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide|at=Section 21.33.1 Segment Wraparound, page 21-34|language=en|publisher=[[Intel]]|url=https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-sdm-combined-volumes-3a-3b-3c-and-3d-system-programming-guide}}</ref> After performing those two steps, the PE bit must be set in the CR0 register and a far jump must be made to clear the [[prefetch input queue]].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide|at=9.9.1 Switching to Protected Mode, page 9-13|language=en|publisher=[[Intel]]|url=https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-sdm-combined-volumes-3a-3b-3c-and-3d-system-programming-guide}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide|at=Section 9.10.2 STARTUP.ASM Listing, page 9-19|language=en|publisher=[[Intel]]|url=https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-sdm-combined-volumes-3a-3b-3c-and-3d-system-programming-guide}}</ref> |

|||

<source lang="asm"> |

|||

; set PE bit |

|||

mov eax, cr0 |

|||

or eax, 1 |

|||

mov cr0, eax |

|||

<syntaxhighlight lang="nasm"> |

|||

; far jump (cs = selector of code segment) |

|||

; MASM program |

|||

jmp cs:@pm |

|||

; enter protected mode (set PE bit) |

|||

mov EBX, CR0 ; save control register 0 (CR0) to EBX |

|||

or EBX, PE_BIT ; set PE bit by ORing, save to EBX |

|||

mov CR0, EBX ; save EBX back to CR0 |

|||

; clear prefetch queue; (using far jump instruction jmp) |

|||

@pm: |

|||

jmp CLEAR_LABEL |

|||

; Now we are in PM. |

|||

CLEAR_LABEL: |

|||

</source> |

|||

</syntaxhighlight> |

|||

With the release of the 386, protected mode could be exited by loading the segment registers with real mode values, disabling the A20 line and clearing the PE bit in the CR0 register, without the need to perform the initial setup steps required with the 286. |

With the release of the 386, protected mode could be exited by loading the segment registers with real mode values, disabling the A20 line and clearing the PE bit in the CR0 register, without the need to perform the initial setup steps required with the 286. |

||

<ref>{{Cite web|title=Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide|at=Section 9.9.2 Switching Back to Real-Address Mode, page 9-14|language=en|publisher=[[Intel]]|url=https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-sdm-combined-volumes-3a-3b-3c-and-3d-system-programming-guide}}</ref> |

|||

== Features == |

== Features == |

||

Protected mode has a number of features designed to enhance an operating system's control over application software, in order to increase security and system stability.<ref name="Purpose of protected mode" /> These additions allow the operating system to function in a way that would be significantly more difficult or even impossible without proper hardware support.<ref name="Multitasking">{{ cite book | title = Intel 80386 Programmer's Reference Manual 1986 | |

Protected mode has a number of features designed to enhance an operating system's control over application software, in order to increase security and system stability.<ref name="Purpose of protected mode" /> These additions allow the operating system to function in a way that would be significantly more difficult or even impossible without proper hardware support.<ref name="Multitasking">{{ cite book | title = Intel 80386 Programmer's Reference Manual 1986 | url = http://bitsavers.org/components/intel/80386/230985-001_80386_Programmers_Reference_Manual_1986.pdf | date = 1986 | publisher = Intel | location = Santa Clara, CA | at = Chapter 7, Multitasking }}</ref> |

||

=== Privilege levels === |

=== Privilege levels === |

||

{{details|Ring (computer security)}} |

{{details|Ring (computer security)}} |

||

[[ |

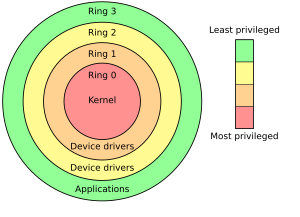

[[File:Priv rings.svg|thumb|right|300px|Example of privilege ring usage in an operating system using all rings]] |

||

In protected mode, there are four privilege levels or [[ring (computer security)|ring]]s, numbered from 0 to 3, with ring 0 being the most privileged and 3 being the least. The use of rings allows for system software to restrict tasks from accessing data, [[call gate]]s or executing privileged instructions.<ref name="Rings">{{ cite book | title = Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual | publisher = [[Intel]] | |

In protected mode, there are four privilege levels or [[ring (computer security)|ring]]s, numbered from 0 to 3, with ring 0 being the most privileged and 3 being the least. The use of rings allows for system software to restrict tasks from accessing data, [[call gate]]s or executing privileged instructions.<ref name="Rings">{{ cite book | title = Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Volume 1: Basic Architecture | publisher = [[Intel]] | at = Section 6.3.5 Calls to Other Privilege Levels |date=May 2019 | url = https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-software-developers-manual-volume-1-basic-architecture }}</ref> In most environments, the operating system and some [[device driver]]s run in ring 0 and applications run in ring 3.<ref name="Rings"/> |

||

=== Real mode application compatibility === |

=== Real mode application compatibility === |

||

According to the ''Intel 80286 Programmer's Reference Manual'',<ref name="286 compatibility">{{ cite book | title = |

According to the ''Intel 80286 Programmer's Reference Manual'',<ref name="286 compatibility">{{ cite book | title = 80286 and 80287 Programmer's Reference Manual | url = http://bitsavers.org/components/intel/80286/210498-005_80286_and_80287_Programmers_Reference_Manual_1987.pdf | date = 1987 | publisher = Intel | location = Santa Clara, CA | at = Section 1.2 Modes of Operation }}</ref> |

||

{{ |

{{ quote |

||

| |

| the 80286 remains upwardly compatible with most 8086 and 80186 application programs. Most 8086 application programs can be re-compiled or re-assembled and executed on the 80286 in Protected Mode. |

||

}} |

}} |

||

For the most part, the binary compatibility with real-mode code, the ability to access up to 16 MB of physical memory, and 1 GB of [[virtual memory]], were the most apparent changes to application programmers.<ref name="286 |

For the most part, the binary compatibility with real-mode code, the ability to access up to 16 MB of physical memory, and 1 GB of [[virtual memory]], were the most apparent changes to application programmers.<ref name="286 programmer ref">{{ cite book | title = 80286 and 80287 Programmer's Reference Manual | url = http://bitsavers.org/components/intel/80286/210498-005_80286_and_80287_Programmers_Reference_Manual_1987.pdf | date = 1987 | publisher = Intel | location = Santa Clara, California | at = Section 1.3.1 Memory Management }}</ref> This was not without its limitations. If an application utilized or relied on any of the techniques below, it would not run:<ref name="Compatibility limitations">{{ cite book | title = 80286 and 80287 Programmer's Reference Manual | url = http://bitsavers.org/components/intel/80286/210498-005_80286_and_80287_Programmers_Reference_Manual_1987.pdf | date = 1987 | publisher = Intel | location = Santa Clara, California | at = Appendix C 8086/8088 Compatibility Considerations }}</ref> |

||

* Segment arithmetic |

* Segment arithmetic |

||

| Line 82: | Line 87: | ||

* Executing data |

* Executing data |

||

* Overlapping segments |

* Overlapping segments |

||

* Use of BIOS functions, due to the BIOS interrupts being reserved by Intel<ref name="BIOS only available through workarounds">{{ cite web | url = http://www.freepatentsonline.com/6105101.html | title = Memory access control method and system for realizing the same | work = US Patent 5483646 | |

* Use of BIOS functions, due to the BIOS interrupts being reserved by Intel<ref name="BIOS only available through workarounds">{{ cite web | url = http://www.freepatentsonline.com/6105101.html | title = Memory access control method and system for realizing the same | work = US Patent 5483646 | access-date = 2007-07-25 | date = May 6, 1998 | format = Patent | quote = This has been impossible to-date and has forced BIOS development teams to add support into the BIOS for 32 bit function calls from 32 bit applications. }}</ref> |

||

In reality, almost all [[DOS]] application programs violated these rules.<ref name="Incompatibilities">{{ cite web | url = http://osdev.berlios.de/v86.html | title = Virtual 8086 Mode | |

In reality, almost all [[DOS]] application programs violated these rules.<ref name="Incompatibilities">{{ cite web | url = http://osdev.berlios.de/v86.html | title = Virtual 8086 Mode | access-date = 2007-07-25 | last = Robinson | first = Tim | date = August 26, 2002 | format = Guide | publisher = berliOS | quote = ... secondly, protected mode was also incompatible with the vast amount of real-mode code around at the time. | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20021003235610/http://osdev.berlios.de/v86.html | archive-date = October 3, 2002 }}</ref> Due to these limitations, [[virtual 8086 mode]] was introduced with the 386. Despite such potential setbacks, [[Windows 3.0]] and its successors can take advantage of the binary compatibility with real mode to run many Windows 2.x ([[Windows 2.0]] and [[Windows 2.1x]]) applications in protected mode, which ran in real mode in Windows 2.x.<ref name="Windows protected mode usage">{{ cite web | url = http://osdev.berlios.de/v86.html | title = Virtual 8086 Mode | access-date = 2007-07-25 | last = Robinson | first = Tim | date = August 26, 2002 | format = Guide | publisher = berliOS | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20021003235610/http://osdev.berlios.de/v86.html | archive-date = October 3, 2002 }}</ref> |

||

=== Virtual 8086 mode === |

=== Virtual 8086 mode === |

||

{{main|Virtual 8086 mode}} |

{{main|Virtual 8086 mode}} |

||

With the release of the 386, protected mode offers what the Intel manuals call |

With the release of the 386, protected mode offers what the Intel manuals call ''virtual 8086 mode''. Virtual 8086 mode is designed to allow code previously written for the 8086 to run unmodified and concurrently with other tasks, without compromising security or system stability.<ref name="V8086 mode">{{ cite book | title = Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide | publisher = [[Intel]] | at = Section 20.2 Virtual 8086 Mode |date=May 2019 | url = https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-sdm-combined-volumes-3a-3b-3c-and-3d-system-programming-guide }}</ref> |

||

Virtual 8086 mode, however, is not completely backward compatible with all programs. Programs that require segment manipulation, privileged instructions, direct hardware access, or use [[self-modifying code]] will generate an [[exception handling|exception]] that must be served by the operating system.<ref name="V8086 limitations">{{ cite book | title = Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manual Combined Volumes 3A, 3B, 3C, and 3D: System Programming Guide | publisher = [[Intel]] | at = Section 20.2.7 Sensitive Instructions |date=May 2019| url = https://software.intel.com/en-us/download/intel-64-and-ia-32-architectures-sdm-combined-volumes-3a-3b-3c-and-3d-system-programming-guide }}</ref> In addition, applications running in virtual 8086 mode generate a [[trap (computing)|trap]] with the use of instructions that involve [[input/output]] (I/O), which can negatively impact performance.<ref name="V86 performance">{{ cite web | url = http://osdev.berlios.de/v86.html | title = Virtual 8086 Mode | access-date = 2007-07-25 | last = Robinson | first = Tim | date = August 26, 2002 | format = Guide | publisher = berliOS | quote = A downside to using V86 mode is speed: every IOPL-sensitive instruction will cause the CPU to trap to kernel mode, as will I/O to ports which are masked out in the TSS. | url-status = dead | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20021003235610/http://osdev.berlios.de/v86.html | archive-date = October 3, 2002 }}</ref> |

|||

Due to these limitations, some programs originally designed to run on the 8086 cannot be run in virtual 8086 mode. As a result, system software is forced to either compromise system security or backward compatibility when dealing with [[legacy system|legacy software]]. An example of such a compromise can be seen with the release of [[Windows NT]], which dropped backward compatibility for "ill-behaved" DOS applications.<ref name="DOS and NT">{{cite book | last = Dabak | first = Prasad |author2=Millind Borate | title = Undocumented Windows NT | type = Book |date=October 1999 | publisher = Hungry Minds | isbn = 0-7645-4569-8}}</ref> |

|||

=== Segment addressing === |

=== Segment addressing === |

||

[[file:080810-protected-286-segments.PNG|thumb|virtual segments of 80286]] |

|||

{{details|X86 memory segmentation}} |

{{details|X86 memory segmentation}} |

||

[[File:080810-protected-286-segments.PNG|thumb|right|upright=1.4|Virtual segments of 80286]] |

|||

==== Real mode ==== |

|||

In real mode each logical address points directly into physical memory location, every logical address consists of two 16 bit parts: The segment part of the logical address contains the base address of a segment with a granularity of 16 bytes, i.e. a segments may start at physical address 0, 16, 32, ..., 2<sup>20</sup>-16. The offset part of the logical address contains an offset inside the segment, i.e. the physical address can be calculated as <code>physical_address : = segment_part × 16 + offset</code> (if the address [[A20 line|line A20]] is enabled), respectively (segment_part × 16 + offset) mod 2<sup>20</sup> (if A20 is off){{Clarify|date=August 2011}} Every segment has a size of 2<sup>16</sup> bytes. |

|||

In real mode each logical address points directly into a physical memory location, every logical address consists of two 16-bit parts: The segment part of the logical address contains the base address of a segment with a granularity of 16 bytes, i.e. a segment may start at physical address 0, 16, 32, ..., 2<sup>20</sup> − 16. The offset part of the logical address contains an offset inside the segment, i.e. the physical address can be calculated as physical_address = segment_part × 16 + offset, if the address [[A20 line|line A20]] is enabled, or (segment_part × 16 + offset) mod 2<sup>20</sup>, if A20 is off.{{Clarify|date=August 2011}} Every segment has a size of 2<sup>16</sup> bytes. |

|||

==== Protected mode ==== |

==== Protected mode ==== |

||

In protected mode, the {{Mono|segment_part}} is replaced by a 16-bit ''selector'', in which the 13 upper bits (bit 3 to bit 15) contain the index of an ''entry'' inside a ''descriptor table''. The next bit (bit 2) specifies whether the operation is used with the GDT or the LDT. The lowest two bits (bit 1 and bit 0) of the selector are combined to define the privilege of the request, where the values of 0 and 3 represent the highest and the lowest privilege, respectively. This means that the byte offset of descriptors in the descriptor table is the same as the 16-bit selector, provided the lower three bits are zeroed. |

|||

The descriptor table entry defines the real ''linear'' address of the segment, a limit value for the segment size, and some attribute bits (flags). |

|||

In protected mode the segment_part is replaced by a 16 bit ''selector'', the 13 upper bits (bit 3 to bit 15) of the selector contains the index of an ''entry'' inside a ''descriptor table''. The lowest two bits define the privilege of the request, from 0 to 3 where 0 has the highest priority and 3 the lowest. The remainder bit specifies if the operation is against the GDT or a LDT. |

|||

The descriptor table entry contains: |

|||

* the real ''linear'' address of the segment |

|||

* a limit value for the segment size |

|||

* some attribute bits (flags) |

|||

==== 286 ==== |

==== 286 ==== |

||

The segment address inside the descriptor table entry has a length of 24 bits so every byte of the physical memory can be defined as bound of the segment. The limit value inside the descriptor table entry has a length of 16 bits so segment length can be between 1 byte and 2<sup>16</sup> byte. The calculated linear address equals the physical memory address. |

The segment address inside the descriptor table entry has a length of 24 bits so every byte of the physical memory can be defined as bound of the segment. The limit value inside the descriptor table entry has a length of 16 bits so segment length can be between 1 byte and 2<sup>16</sup> byte. The calculated linear address equals the physical memory address. |

||

==== 386 ==== |

==== 386 ==== |

||

The segment address inside the descriptor table entry is expanded to 32 bits so every byte of the physical memory can be defined as bound of the segment. The limit value inside the descriptor table entry is expanded to 20 bits and completed with a granularity flag (G-bit, for short): |

|||

The segment address inside the descriptor table entry is expanded to 32 bits so every byte of the physical memory can be defined as bound of the segment. The limit value inside the descriptor table entry is expanded to 20 bits and completed with a granularity flag (shortly: G-bit): |

|||

* If G-bit is zero limit has a granularity of 1 byte, i.e. segment size may be 1, 2, ..., 2<sup>20</sup> bytes. |

* If G-bit is zero limit has a granularity of 1 byte, i.e. segment size may be 1, 2, ..., 2<sup>20</sup> bytes. |

||

| Line 120: | Line 123: | ||

The 386 processor also uses 32 bit values for the address offset. |

The 386 processor also uses 32 bit values for the address offset. |

||

For maintaining compatibility with 286 protected mode a new default flag ( |

For maintaining compatibility with 286 protected mode a new default flag (D-bit, for short) was added. If the D-bit of a code segment is off (0) all commands inside this segment will be interpreted as 16-bit commands by default; if it is on (1), they will be interpreted as 32-bit commands. |

||

==== Structure of segment descriptor entry ==== |

==== Structure of segment descriptor entry ==== |

||

<div> |

|||

{| class=" |

{| class="infobox" style="text-align:center" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|style="text-align:center" |''80286 Segment descriptor'' |

|||

! B |

|||

! bits |

|||

! 80286 |

|||

! 80386 |

|||

! B |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

|||

! 0 |

|||

{| |

|||

| 00..07,0..7 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

| rowspan = 2 | limit |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

| rowspan = 2 | bits 0..15 of limit |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

! 0 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|colspan="16" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|Base[0..15] |

|||

! 1 |

|||

|colspan="16" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|Limit[0..15] |

|||

| 08..15,0..7 |

|||

! 1 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>6</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

! 2 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>6</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

| 16..23,0..7 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>6</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

| rowspan = 3 | base address |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>6</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

| rowspan = 3 | bits 0..23 of base address |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

! 2 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

! 3 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

| 24..31,0..7 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

! 3 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

! 4 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

| 32..39,0..7 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

! 4 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

! 5 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

| 40..47,0..7 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

| colspan = 2 | attribute flags #1 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

! 5 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

! rowspan = 2 | 6 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

| 48..51,0..3 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

| rowspan = 3 | unused |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

| bits 16..19 of limit |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

! rowspan = 2 | 6 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

| 52..55,4..7 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

| attribute flags #2 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|- |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

! 7 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

| 56..63,0..7 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

| bits 24..31 of base address |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

! 7 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|colspan="16" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|''Unused'' |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|P |

|||

|colspan="2" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|DPL |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|S |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|X |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|C |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|R |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|A |

|||

|colspan="8" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|Base[16..23] |

|||

|} |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

{| class="infobox" style="text-align:center" |

|||

; Columns '''B''': Byte offset inside entry |

|||

; Column '''bits''', first range: Bit offset inside entry |

|||

; Column '''bits''', second range: Bit offset inside byte |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|style="text-align:center" |''80386 Segment descriptor'' |

|||

! colspan = 3 | attribute flags #2 |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| |

| |

||

{| style="text-align:center" |

|||

| 4 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

| unused, available for operating system |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>2</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>1</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>0</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|colspan="16" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|Base[0..15] |

|||

| 53 |

|||

|colspan="16" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|Limit[0..15] |

|||

| 5 |

|||

| reserved, should be zero |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>6</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

| 54 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>6</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

| 6 |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>6</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

| default flag / D-bit |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>6</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>5</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>1</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>4</sup><sub>0</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>9</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>8</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>7</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>6</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>5</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>4</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>3</sub> |

|||

|style="width:15px;text-align:center"|<sup>3</sup><sub>2</sub> |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|colspan="8" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|Base[24..31] |

|||

| 55 |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|G |

|||

| 7 |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|D |

|||

| granularity flag / G-bit |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|0 |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|''U'' |

|||

|colspan="4" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|Limit[16..19] |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|P |

|||

|colspan="2" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|DPL |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|S |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|X |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|C |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|R |

|||

|colspan="1" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|A |

|||

|colspan="8" style="background:silver;text-align:center"|Base[16..23] |

|||

|} |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

Where: |

|||

*''A'' is the ''Accessed'' bit; |

|||

*''R'' is the ''Readable'' bit; |

|||

*''C'' (Bit 42) depends on ''X'':<ref name="OSDev GDT">{{cite web|url=https://wiki.osdev.org/Global_Descriptor_Table#Structure|title=Global Descriptor table - OSDev Wiki}}</ref> |

|||

**if ''X'' = 1 then ''C'' is the ''Conforming'' bit, and determines which privilege levels can far-jump to this segment (without changing privilege level): |

|||

***if ''C'' = 0 then only code with the same privilege level as ''DPL'' may jump here; |

|||

***if ''C'' = 1 then code with the same or a lower privilege level relative to ''DPL'' may jump here. |

|||

**if ''X'' = 0 then ''C'' is the ''direction'' bit: |

|||

***if ''C'' = 0 then the segment grows ''up''; |

|||

***if ''C'' = 1 then the segment grows ''down''. |

|||

*''X'' is the ''Executable'' bit:<ref name="OSDev GDT"/> |

|||

**if ''X'' = 1 then the segment is a code segment; |

|||

**if ''X'' = 0 then the segment is a data segment. |

|||

*''S'' is the ''Segment type'' bit, which should generally be cleared for system segments;<ref name="OSDev GDT"></ref> |

|||

*''DPL'' is the ''Descriptor Privilege Level''; |

|||

*''P'' is the ''Present'' bit; |

|||

*''D'' is the ''Default operand size''; |

|||

*''G'' is the ''Granularity'' bit; |

|||

*Bit 52 of the 80386 descriptor is not used by the hardware. |

|||

</div> |

|||

=== Paging === |

=== Paging === |

||

[[file:Virtual address space and physical address space relationship.svg|thumb|Common method of using paging to create a virtual address space]] |

|||

[[file:080810-protected-386-paging.svg|thumb|paging (intel 80386) with page size of 4K]] |

|||

{{details|Paging}} |

{{details|Paging}} |

||

[[File:Virtual address space and physical address space relationship.svg|thumb|Common method of using paging to create a virtual address space]] |

|||

[[File:080810-protected-386-paging.svg|thumb|Paging (on Intel 80386) with page size of 4K]] |

|||

In addition to adding virtual 8086 mode, the 386 also added paging to protected mode.<ref name="paging introduced">{{ cite web | url = http://www.deinmeister.de/x86modes.htm#c1 | title = ProtectedMode overview [deinmeister.de] | access-date = 2007-07-29 | format = Website }}</ref> Through paging, system software can restrict and control a task's access to pages, which are sections of memory. In many operating systems, paging is used to create an independent virtual address space for each task, preventing one task from manipulating the memory of another. Paging also allows for pages to be moved out of [[primary storage]] and onto a slower and larger [[secondary storage]], such as a [[hard disk drive]].<ref name="Paging usage">{{cite web | url = http://technet2.microsoft.com/windowsserver/en/library/efc41320-713f-4004-bc81-ddddfc8552651033.mspx?mfr=true | title = What Is PAE X86? | access-date = 2007-07-29 | date = May 28, 2003 | format = Article | publisher = Microsoft TechNet | quote = The paging process allows the operating system to overcome the real physical memory limits. However, it also has a direct impact on performance because of the time necessary to write or retrieve data from disk. | archive-date = 2008-04-22 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080422184656/http://technet2.microsoft.com/windowsserver/en/library/efc41320-713f-4004-bc81-ddddfc8552651033.mspx?mfr=true | url-status = dead }}</ref> This allows for more memory to be used than physically available in primary storage.<ref name="Paging usage" /> |

|||

The x86 architecture allows control of pages through two [[array data structure|array]]s: page directories and [[page table]]s. Originally, a page directory was the size of one page, four kilobytes, and contained 1,024 page directory entries (PDE), although subsequent enhancements to the x86 architecture have added the ability to use larger page sizes. Each PDE contained a [[pointer (computer programming)|pointer]] to a page table. A page table was also originally four kilobytes in size and contained 1,024 page table entries (PTE). Each PTE contained a pointer to the actual page's physical address and are only used when the four-kilobyte pages are used. At any given time, only one page directory may be in active use.<ref name="Only one page directory">{{cite web | url = http://www.embedded.com/98/9806fe2.htm | title = Advanced Embedded x86 Programming: Paging | access-date = 2007-07-29 | last = Gareau | first = Jean | format = Guide | publisher = Embedded.com | quote = Only one page directory may be active at a time, indicated by the CR3 register. | archive-date = 2008-05-16 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20080516202434/http://www.embedded.com/98/9806fe2.htm | url-status = dead }}</ref> |

|||

=== Multitasking === |

=== Multitasking === |

||

| Line 214: | Line 341: | ||

Through the use of the rings, privileged [[call gate]]s, and the [[Task State Segment]] (TSS), introduced with the 286, [[preemptive multitasking]] was made possible on the x86 architecture. The TSS allows general-purpose registers, segment selector fields, and stacks to all be modified without affecting those of another task. The TSS also allows a task's privilege level, and I/O port permissions to be independent of another task's. |

Through the use of the rings, privileged [[call gate]]s, and the [[Task State Segment]] (TSS), introduced with the 286, [[preemptive multitasking]] was made possible on the x86 architecture. The TSS allows general-purpose registers, segment selector fields, and stacks to all be modified without affecting those of another task. The TSS also allows a task's privilege level, and I/O port permissions to be independent of another task's. |

||

In many operating systems, the full features of the TSS are not used.<ref name="TSS Usage">{{ cite web | url = http://neworder.box.sk/newsread.php?newsid=10562 | work = NewOrer | title = |

In many operating systems, the full features of the TSS are not used.<ref name="TSS Usage">{{ cite web | url = http://neworder.box.sk/newsread.php?newsid=10562 | work = NewOrer | title = news: Multitasking for x86 explained #1 | access-date = 2007-07-29 | author = zwanderer | date = May 2, 2004 | format = Article | publisher = NewOrder | quote = The reason why software task switching is so popular is that it can be faster than hardware task switching. Intel never actually developed the hardware task switching, they implemented it, saw that it worked, and just left it there. Advances in multitasking using software have made this form of task switching faster (some say up to 3 times faster) than the hardware method. Another reason is that the Intel way of switching tasks isn't portable at all | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070212161434/http://neworder.box.sk/newsread.php?newsid=10562 | archive-date = 2007-02-12 }}</ref> This is commonly due to portability concerns or due to the performance issues created with hardware task switches.<ref name="TSS Usage" /> As a result, many operating systems use both hardware and software to create a multitasking system.<ref name="Uses both">{{ cite web | url = http://neworder.box.sk/newsread.php?newsid=10562 | work = NewOrer | title = news: Multitasking for x86 explained #1 | access-date = 2007-07-29 | author = zwanderer | date = May 2, 2004 | format = Article | publisher = NewOrder | quote = ... both rely on the Intel processors ability to switch tasks, they rely on it in different ways. | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070212161434/http://neworder.box.sk/newsread.php?newsid=10562 | archive-date = 2007-02-12 }}</ref> |

||

== Operating systems == |

== Operating systems == |

||

Operating systems like [[OS/2]] 1.x try to switch the processor between protected and real modes. This is both slow and unsafe, because a real mode program can easily [[Crash (computing)|crash]] a computer. OS/2 1.x defines restrictive programming rules allowing a ''[[Family API]]'' or ''bound'' program to run in either real or protected mode. Some early [[Unix]] operating systems, [[OS/2]] 1.x, and Windows used this mode. |

|||

[[Windows 3.0]] was able to run real mode programs in 16-bit protected mode; when switching to protected mode, it decided to preserve the single privilege level model that was used in real mode, which is why Windows applications and DLLs can hook interrupts and do direct hardware access. That lasted through the [[Windows 9x]] series. If a Windows 1.x or 2.x program is written properly and avoids segment arithmetic, it will run the same way in both real and protected modes. Windows programs generally avoid segment arithmetic because Windows implements a software virtual memory scheme, moving program code and data in memory when programs are not running, so manipulating absolute addresses is dangerous; programs should only keep [[Smart pointer|handle]]s to memory blocks when not running. Starting an old program while Windows 3.0 is running in protected mode triggers a warning dialog, suggesting to either run Windows in real mode or to obtain an updated version of the application. Updating well-behaved programs using the MARK utility with the MEMORY parameter avoids this dialog. It is not possible to have some GUI programs running in 16-bit protected mode and other GUI programs running in real mode. In [[Windows 3.1]], real mode was no longer supported and could not be accessed. |

|||

In modern 32-bit operating systems, [[virtual 8086 mode]] is still used for running applications, e.g. [[DOS Protected Mode Interface|DPMI]] compatible [[DOS extender]] programs (through [[virtual DOS machine]]s) or Windows 3.x applications (through the [[Windows on Windows]] subsystem) and certain classes of [[device driver]]s (e.g. for changing the screen-resolution using BIOS functionality) in [[OS/2]] 2.0 (and later OS/2) and 32-bit [[Windows NT]], all under control of a 32-bit kernel. However, 64-bit operating systems (which run in [[long mode]]) no longer use this, since virtual 8086 mode has been removed from long mode. |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

* [[Long mode]] |

|||

* [[Assembly language]] |

* [[Assembly language]] |

||

* [[Intel]] |

* [[Intel]] |

||

| Line 231: | Line 359: | ||

== References == |

== References == |

||

{{ |

{{reflist|30em}} |

||

== External links == |

== External links == |

||

* [http://www.rcollins.org/articles/pmbasics/tspec_a1_doc.html Protected Mode Basics] |

* [http://www.rcollins.org/articles/pmbasics/tspec_a1_doc.html Protected Mode Basics] |

||

* [http://www.internals.com/articles/protmode/introduction.htm Introduction to Protected-Mode] |

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070622205752/http://www.internals.com/articles/protmode/introduction.htm Introduction to Protected-Mode] |

||

* [http://www.intel.com/design/intarch/papers/exc_ia.htm Overview of the Protected Mode Operations of the Intel Architecture] |

* [http://www.intel.com/design/intarch/papers/exc_ia.htm Overview of the Protected Mode Operations of the Intel Architecture] |

||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20140303113814/http://www.turboirc.com/asm/ TurboIRC.COM tutorial to enter protected mode from DOS] |

|||

* [http://www.intel.com/products/processor/manuals/index.htm Intel 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer's Manuals] |

|||

* [http://viralpatel.net/taj/tutorial/protectedmode.php Protected Mode Overview and Tutorial] |

|||

* [http://www.turboirc.com/asm TurboIRC.COM tutorial to enter protected mode from DOS] |

|||

* [http://www.viralpatel.net/taj/tutorial/protectedmode.php Protected Mode Overview and Tutorial] |

|||

* [http://www.codeproject.com/KB/system/asm.aspx Code Project Protected Mode Tutorial] |

* [http://www.codeproject.com/KB/system/asm.aspx Code Project Protected Mode Tutorial] |

||

* [http://code.google.com/p/akernelloader/ Akernelloader switching from real mode to protected mode] |

* [http://code.google.com/p/akernelloader/ Akernelloader switching from real mode to protected mode] |

||

{{ |

{{Operating systems}} |

||

{{Memory management}} |

|||

[[Category:Programming language implementation]] |

[[Category:Programming language implementation]] |

||

[[Category:X86 operating modes]] |

[[Category:X86 operating modes]] |

||

[[ar:آلية الحماية في المعالج 80386]] |

|||

[[bg:Защитен режим]] |

|||

[[ca:Mode protegit]] |

|||

[[de:Protected Mode]] |

|||

[[es:Modo protegido]] |

|||

[[fr:Mode protégé]] |

|||

[[ga:Mód cosanta]] |

|||

[[ko:보호 모드]] |

|||

[[id:Mode terproteksi]] |

|||

[[it:Modalità protetta]] |

|||

[[kk:Қорғалған режім]] |

|||

[[lt:Apsaugotas režimas]] |

|||

[[nl:Protected mode]] |

|||

[[ja:プロテクトモード]] |

|||

[[no:Beskyttet modus]] |

|||

[[pl:Tryb chroniony]] |

|||

[[pt:Modo protegido]] |

|||

[[ru:Защищённый режим]] |

|||

[[sk:Chránený režim]] |

|||

[[tr:Korumalı kip]] |

|||

[[uk:Захищений режим]] |

|||

[[zh:保護模式]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 02:56, 30 October 2024

| Part of a series on |

| Microprocessor modes for the x86 architecture |

|---|

|

| First supported platform shown in parentheses |

In computing, protected mode, also called protected virtual address mode,[1] is an operational mode of x86-compatible central processing units (CPUs). It allows system software to use features such as segmentation, virtual memory, paging and safe multi-tasking designed to increase an operating system's control over application software.[2][3]

When a processor that supports x86 protected mode is powered on, it begins executing instructions in real mode, in order to maintain backward compatibility with earlier x86 processors.[4] Protected mode may only be entered after the system software sets up one descriptor table and enables the Protection Enable (PE) bit in the control register 0 (CR0).[5]

Protected mode was first added to the x86 architecture in 1982,[6] with the release of Intel's 80286 (286) processor, and later extended with the release of the 80386 (386) in 1985.[7] Due to the enhancements added by protected mode, it has become widely adopted and has become the foundation for all subsequent enhancements to the x86 (IA-32) architecture,[8] although many of those enhancements, such as added instructions and new registers, also brought benefits to the real mode.

History

[edit]The first x86 processor, the Intel 8086, had a 20-bit address bus for its memory, as did its Intel 8088 variant.[9] This allowed them to access 220 bytes of memory, equivalent to 1 megabyte.[9] At the time, 1 megabyte was considered a relatively large amount of memory,[10] so the designers of the IBM Personal Computer reserved the first 640 kilobytes for use by applications and the operating system and the remaining 384 kilobytes for the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) and memory for add-on devices.[11]

As the cost of memory decreased and memory use increased, the 1 MB limitation became a significant problem. Intel intended to solve this limitation along with others with the release of the 286.[11]

The 286

[edit]The initial protected mode, released with the 286, was not widely used;[11] for example, it was used by Coherent (from 1982),[12] Microsoft Xenix (around 1984)[13] and Minix.[14] Several shortcomings such as the inability to make BIOS and DOS calls due to inability to switch back to real mode without resetting the processor prevented widespread usage.[15] Acceptance was additionally hampered by the fact that the 286 only allowed memory access in 64 kilobyte segments, addressed by its four segment registers, meaning that only 4 × 64 KB, equivalent to 256 KB, could be accessed at a time.[11] Because changing a segment register in protected mode caused a 6-byte segment descriptor to be loaded into the CPU from memory, the segment register load instruction took many tens of processor cycles, making it much slower than on the 8086 and 8088; therefore, the strategy of computing segment addresses on-the-fly in order to access data structures larger than 128 kilobytes (the combined size of the two data segments) became impractical, even for those few programmers who had mastered it on the 8086 and 8088.

The 286 maintained backward compatibility with the 8086 and 8088 by initially entering real mode on power up.[4] Real mode functioned virtually identically to the 8086 and 8088, allowing the vast majority of existing software for those processors to run unmodified on the newer 286. Real mode also served as a more basic mode in which protected mode could be set up, solving a sort of chicken-and-egg problem. To access the extended functionality of the 286, the operating system would set up some tables in memory that controlled memory access in protected mode, set the addresses of those tables into some special registers of the processor, and then set the processor into protected mode. This enabled 24-bit addressing, which allowed the processor to access 224 bytes of memory, equivalent to 16 megabytes.[9]

The 386

[edit]

With the release of the 386 in 1985,[7] many of the issues preventing widespread adoption of the previous protected mode were addressed.[11] The 386 was released with an address bus size of 32 bits, which allows for 232 bytes of memory accessing, equivalent to 4 gigabytes.[16] The segment sizes were also increased to 32 bits, meaning that the full address space of 4 gigabytes could be accessed without the need to switch between multiple segments.[16] In addition to the increased size of the address bus and segment registers, many other new features were added with the intention of increasing operational security and stability.[17] Protected mode is now used in virtually all modern operating systems which run on the x86 architecture, such as Microsoft Windows, Linux, and many others.[18]

Furthermore, learning from the failures of the 286 protected mode to satisfy the needs for multiuser DOS, Intel added a separate virtual 8086 mode,[19] which allowed multiple virtualized 8086 processors to be emulated on the 386. Hardware x86 virtualization required for virtualizing the protected mode itself, however, had to wait for another 20 years.[20]

386 additions to protected mode

[edit]With the release of the 386, the following additional features were added to protected mode:[2]

- Paging

- 32-bit physical and virtual address space (The 32-bit physical address space is not present on the 80386SX, and other 386 processor variants which use the older 286 bus.[21])

- 32-bit segment offsets

- Ability to switch back to real mode without resetting

- Virtual 8086 mode

Entering and exiting protected mode

[edit]Until the release of the 386, protected mode did not offer a direct method to switch back into real mode once protected mode was entered. IBM devised a workaround (implemented in the IBM AT) which involved resetting the CPU via the keyboard controller and saving the system registers, stack pointer and often the interrupt mask in the real-time clock chip's RAM. This allowed the BIOS to restore the CPU to a similar state and begin executing code before the reset.[clarification needed] Later, a triple fault was used to reset the 286 CPU, which was a lot faster and cleaner than the keyboard controller method (and does not depend on IBM AT-compatible hardware, but will work on any 80286 CPU in any system).

To enter protected mode, the Global Descriptor Table (GDT) must first be created with a minimum of three entries: a null descriptor, a code segment descriptor and data segment descriptor. In an IBM-compatible machine, the A20 line (21st address line) also must be enabled to allow the use of all the address lines so that the CPU can access beyond 1 megabyte of memory (Only the first 20 are allowed to be used after power-up, to guarantee compatibility with older software written for the Intel 8088-based IBM PC and PC/XT models).[22] After performing those two steps, the PE bit must be set in the CR0 register and a far jump must be made to clear the prefetch input queue.[23][24]

; MASM program

; enter protected mode (set PE bit)

mov EBX, CR0 ; save control register 0 (CR0) to EBX

or EBX, PE_BIT ; set PE bit by ORing, save to EBX

mov CR0, EBX ; save EBX back to CR0

; clear prefetch queue; (using far jump instruction jmp)

jmp CLEAR_LABEL

CLEAR_LABEL:

With the release of the 386, protected mode could be exited by loading the segment registers with real mode values, disabling the A20 line and clearing the PE bit in the CR0 register, without the need to perform the initial setup steps required with the 286. [25]

Features

[edit]Protected mode has a number of features designed to enhance an operating system's control over application software, in order to increase security and system stability.[3] These additions allow the operating system to function in a way that would be significantly more difficult or even impossible without proper hardware support.[26]

Privilege levels

[edit]

In protected mode, there are four privilege levels or rings, numbered from 0 to 3, with ring 0 being the most privileged and 3 being the least. The use of rings allows for system software to restrict tasks from accessing data, call gates or executing privileged instructions.[27] In most environments, the operating system and some device drivers run in ring 0 and applications run in ring 3.[27]

Real mode application compatibility

[edit]According to the Intel 80286 Programmer's Reference Manual,[28]

the 80286 remains upwardly compatible with most 8086 and 80186 application programs. Most 8086 application programs can be re-compiled or re-assembled and executed on the 80286 in Protected Mode.

For the most part, the binary compatibility with real-mode code, the ability to access up to 16 MB of physical memory, and 1 GB of virtual memory, were the most apparent changes to application programmers.[29] This was not without its limitations. If an application utilized or relied on any of the techniques below, it would not run:[30]

- Segment arithmetic

- Privileged instructions

- Direct hardware access

- Writing to a code segment

- Executing data

- Overlapping segments

- Use of BIOS functions, due to the BIOS interrupts being reserved by Intel[31]

In reality, almost all DOS application programs violated these rules.[32] Due to these limitations, virtual 8086 mode was introduced with the 386. Despite such potential setbacks, Windows 3.0 and its successors can take advantage of the binary compatibility with real mode to run many Windows 2.x (Windows 2.0 and Windows 2.1x) applications in protected mode, which ran in real mode in Windows 2.x.[33]

Virtual 8086 mode

[edit]With the release of the 386, protected mode offers what the Intel manuals call virtual 8086 mode. Virtual 8086 mode is designed to allow code previously written for the 8086 to run unmodified and concurrently with other tasks, without compromising security or system stability.[34]

Virtual 8086 mode, however, is not completely backward compatible with all programs. Programs that require segment manipulation, privileged instructions, direct hardware access, or use self-modifying code will generate an exception that must be served by the operating system.[35] In addition, applications running in virtual 8086 mode generate a trap with the use of instructions that involve input/output (I/O), which can negatively impact performance.[36]

Due to these limitations, some programs originally designed to run on the 8086 cannot be run in virtual 8086 mode. As a result, system software is forced to either compromise system security or backward compatibility when dealing with legacy software. An example of such a compromise can be seen with the release of Windows NT, which dropped backward compatibility for "ill-behaved" DOS applications.[37]

Segment addressing

[edit]

Real mode

[edit]In real mode each logical address points directly into a physical memory location, every logical address consists of two 16-bit parts: The segment part of the logical address contains the base address of a segment with a granularity of 16 bytes, i.e. a segment may start at physical address 0, 16, 32, ..., 220 − 16. The offset part of the logical address contains an offset inside the segment, i.e. the physical address can be calculated as physical_address = segment_part × 16 + offset, if the address line A20 is enabled, or (segment_part × 16 + offset) mod 220, if A20 is off.[clarification needed] Every segment has a size of 216 bytes.

Protected mode

[edit]In protected mode, the segment_part is replaced by a 16-bit selector, in which the 13 upper bits (bit 3 to bit 15) contain the index of an entry inside a descriptor table. The next bit (bit 2) specifies whether the operation is used with the GDT or the LDT. The lowest two bits (bit 1 and bit 0) of the selector are combined to define the privilege of the request, where the values of 0 and 3 represent the highest and the lowest privilege, respectively. This means that the byte offset of descriptors in the descriptor table is the same as the 16-bit selector, provided the lower three bits are zeroed.