Glacier: Difference between revisions

Tawkerbot2 (talk | contribs) m BOT - rv 168.170.204.50 (talk) to last version by Cookie90 |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Persistent body of ice that moves downhill under its own weight}} |

|||

{{dablink|This article is about the geological formation. For the professional wrestler, see [[Ray Lloyd]].}} |

|||

{{About|the geological formation}} |

|||

[[Image:Aletschgletscher Panorama.jpg|thumb|right|450px|Aletsch glacier, Switzerland]] |

|||

{{Redirect|Ice river|the Chinese ski course|Ice River (ski course)}} |

|||

A '''glacier''' is a large, long-lasting [[river]] of [[ice]] that is formed on land and moves in response to [[gravity]]. A glacier is formed by multi-year ice [[Accretion (science)|accretion]] in [[slope|sloping]] [[topography|terrain]]. Glacier ice is the largest reservoir of [[fresh water]] on [[Earth]], and second only to [[ocean]]s as the largest reservoir of total water. Glaciers can be found on every [[continent]] except [[Australia]]. Glaciers are more or less permanent bodies of ice and compacted snow that have become deep enough and heavy enough to flow under their own weight. |

|||

{{Use American English|date=September 2024}} |

|||

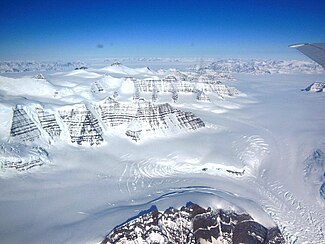

[[File:Geikie Plateau Glacier.JPG|thumb|325x325px|Glacier of the Geikie Plateau in [[Greenland]].]] |

|||

[[File:Wildspitze seen from Hinterer Brunnkogel, with visible ascent track of ski mountaineer.jpg|thumb|325px|The Taschachferner in the [[Ötztal Alps]] in [[Austria]]. The mountain to the left is the [[Wildspitze]] (3.768 m), second highest in Austria.]] |

|||

[[File: Baltoro glacier from air.jpg|thumb|325px|With 7,253 known glaciers, [[Pakistan]] contains more glacial ice than any other country on earth outside the polar regions.<ref name="Craig" /> At {{convert|62|km|mi|0}} in length, the pictured [[Baltoro Glacier]] is one of the world's longest alpine glaciers.]] |

|||

A '''glacier''' ({{IPAc-en|US|pron|ˈ|ɡ|l|eɪ|ʃ|ər}}; {{IPAc-en|UK|ˈ|ɡ|l|æ|s|i|ər|,_|ˈ|g|l|eɪ|s|i|ər}}) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving downhill under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its [[Ablation#Glaciology|ablation]] over many years, often [[Century|centuries]]. It acquires distinguishing features, such as [[Crevasse|crevasses]] and [[Serac|seracs]], as it slowly flows and deforms under stresses induced by its weight. As it moves, it abrades rock and debris from its substrate to create landforms such as [[cirque]]s, [[moraine]]s, or [[fjord]]s. Although a glacier may flow into a body of water, it forms only on land and is distinct from the much thinner [[sea ice]] and lake ice that form on the surface of bodies of water. |

|||

On Earth, 99% of glacial ice is contained within vast [[ice sheet]]s (also known as "continental glaciers") in the [[polar region]]s, but glaciers may be found in [[mountain range]]s on every continent other than the Australian mainland, including Oceania's high-latitude [[oceanic island]] countries such as [[New Zealand]]. Between latitudes 35°N and 35°S, glaciers occur only in the [[Himalayas]], [[Andes]], and a few high mountains in East Africa, Mexico, [[New Guinea]] and on [[Zard-Kuh]] in Iran.<ref name="Post 2000">{{cite book|last1=Post|first1=Austin|last2=LaChapelle|first2=Edward R|title=Glacier ice|publisher=University of Washington Press|year=2000|location=Seattle|isbn=978-0-295-97910-6}}</ref> With more than 7,000 known glaciers, [[Pakistan]] has more glacial ice than any other country outside the polar regions.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Staff |date=June 9, 2020 |title=Millions at risk as melting Pakistan glaciers raise flood fears |url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/06/millions-risk-melting-pakistan-glaciers-raise-flood-fears-200609033202702.html |access-date=2020-06-09 |work=[[Al Jazeera Media Network|Al Jazeera]]}}</ref><ref name="Craig">{{Cite news |last=Craig |first=Tim |date=2016-08-12 |title=Pakistan has more glaciers than almost anywhere on Earth. But they are at risk. |language=en-US |newspaper=[[The Washington Post]] |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/pakistan-has-more-glaciers-than-almost-anywhere-on-earth-but-they-are-at-risk/2016/08/11/7a6b4cd4-4882-11e6-8dac-0c6e4accc5b1_story.html |access-date=2020-09-04 |issn=0190-8286 |quote=With 7,253 known glaciers, including 543 in the Chitral Valley, there is more glacial ice in Pakistan than anywhere on Earth outside the polar regions, according to various studies.}}</ref> Glaciers cover about 10% of Earth's land surface. Continental glaciers cover nearly {{convert|5|e6sqmi|e6km2|order=flip|abbr=unit}} or about 98% of [[Antarctica]]'s {{convert|5.1|e6sqmi|e6km2|order=flip|abbr=unit|sigfig=3}}, with an average thickness of ice {{convert|7,000|ft|m|order=flip|abbr=on}}. Greenland and [[Patagonia]] also have huge expanses of continental glaciers.<ref>National Geographic Almanac of Geography, 2005, {{ISBN|0-7922-3877-X}}, p. 149.</ref> The volume of glaciers, not including the ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland, has been estimated at 170,000 km<sup>3</sup>.<ref>{{cite web |title=170'000 km cube d'eau dans les glaciers du monde |url=http://www.arcinfo.ch/fr/monde/170-000-km-cube-d-eau-dans-les-glaciers-du-monde-577-1052031 |archive-url=http://archive.wikiwix.com/cache/20170817140736/http://www.arcinfo.ch/fr/monde/170-000-km-cube-d-eau-dans-les-glaciers-du-monde-577-1052031 |url-status=dead |archive-date=August 17, 2017 |work=[[ArcInfo (newspaper)|ArcInfo]] |date=Aug 6, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

Geologic features associated with glaciers include end, lateral, ground and medial [[moraine]]s that form from glacially transported [[rocks]] and [[debris]]; [[glaciated valley|U-shaped valley]]s and [[corrie]]s ([[cirque (landform)|cirques]]) at their heads, and the ''glacier fringe'', which is the area where the glacier has recently melted into water. |

|||

Glacial ice is the largest reservoir of [[fresh water]] on Earth, holding with ice sheets about 69 percent of the world's freshwater.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Ice, Snow, and Glaciers and the Water Cycle|url=https://www.usgs.gov/special-topic/water-science-school/science/ice-snow-and-glaciers-and-water-cycle?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects|access-date=2021-05-25|website=www.usgs.gov}}</ref><ref name=IMS>{{cite journal|author1=Brown, Molly Elizabeth |author2=Ouyang, Hua |author3=Habib, Shahid |author4=Shrestha, Basanta |author5=Shrestha, Mandira |author6=Panday, Prajjwal |author7=Tzortziou, Maria |author8=Policelli, Frederick |author9=Artan, Guleid |author10=Giriraj, Amarnath |author11=Bajracharya, Sagar R. |author12=Racoviteanu, Adina |title=HIMALA: Climate Impacts on Glaciers, Snow, and Hydrology in the Himalayan Region|journal=Mountain Research and Development|date=November 2010 |volume=30 |issue=4 |pages=401–404 |publisher=International Mountain Society|doi=10.1659/MRD-JOURNAL-D-10-00071.1 |hdl=2060/20110015312 |s2cid=129545865 |doi-access=free |hdl-access=free }}</ref> Many glaciers from [[Temperate climate|temperate]], [[Alpine climate|alpine]] and seasonal [[Polar climate|polar climates]] store water as ice during the colder seasons and release it later in the form of [[meltwater]] as warmer summer temperatures cause the glacier to melt, creating a [[Water resources|water source]] that is especially important for plants, animals and human uses when other sources may be scant. However, within high-altitude and Antarctic environments, the seasonal temperature difference is often not sufficient to release meltwater. |

|||

==Types of glaciers== |

|||

[[Image:Glacier mouth.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Mouth of the glacier Schlatenkees near Innergschlöß, [[Austria]].]] |

|||

There are two main types of glaciers: '''alpine glaciers''', which are found in mountain terrains, and '''continental glaciers''', which are associated with [[ice age]]s and can cover large areas of [[continent]]s. Most of the concepts in this article apply equally to alpine glaciers and continental glaciers. |

|||

Since glacial mass is affected by long-term climatic changes, e.g., [[precipitation (meteorology)|precipitation]], [[temperature|mean temperature]], and [[cloud cover]], [[Retreat of glaciers since 1850|glacial mass changes]] are considered among the most sensitive indicators of [[climate change]] and are a major source of variations in [[Current sea level rise|sea level]]. |

|||

A '''temperate glacier''' is at the melting point throughout the year with internal and basal water. '''Polar glaciers''' are always below the freezing point with most mass loss due to [[sublimation (physics)|sublimation]]. "Poly-thermal" or "sub-polar" glaciers have some internal drainage, but little to no basal melt. Thermal classifications vary so glacier zones are often used to identify melt conditions. The dry snow zone is a region where no melt occurs, even in the summer. The percolation zone is an area with some surface melt, often this zone is marked by refrozen ice lenses, glands, and layers. The wet snow zone is the region where all of the snow deposited since the end of the previous summer has been raised to 0 degrees. The superimposed ice zone is a zone of such high melt and refreeze that ice lenses have merged to a continuous mass. |

|||

A large piece of compressed ice, or a glacier, [[Blue ice (glacial)|appears blue]], as large quantities of [[Color of water|water appear blue]], because water molecules absorb other colors more efficiently than blue. The other reason for the blue color of glaciers is the lack of air bubbles. Air bubbles, which give a white color to ice, are squeezed out by pressure increasing the created ice's density. |

|||

The smallest alpine glaciers form in [[mountain]] valleys and are referred to as '''valley glaciers'''. Larger ice layers can cover an entire mountain, mountain chain or even a [[volcano]]; this type is known as an [[ice cap]]. Ice caps feed '''outlet glaciers''', tongues of ice that extend into valleys below, far from the margins of those larger ice masses. Outlet glaciers are formed by the movement of ice from a [[polar ice cap]], or an ice cap from mountainous regions, to the sea. |

|||

== Etymology and related terms == |

|||

The largest glaciers are [[ice sheet|continental ice sheet]]s, enormous masses of ice that are not affected by the landscape and extend over the entire surface, except on the margins, where they are thinnest. [[Antarctica]] and [[Greenland]] are the only places where continental ice sheets currently exist. These regions contain vast quantities of fresh water. The volume of ice is so large that if the Greenland ice sheet melted, it would cause sea levels to rise some six meters all around the world. If the Antarctic ice sheet melted, sea levels would rise up to 65 meters. |

|||

The word ''glacier'' is a [[loanword]] from French and goes back, via [[Franco-Provençal language|Franco-Provençal]], to the [[Vulgar Latin]] ''{{lang|la|glaciārium}}'', derived from the [[Late Latin]] ''{{lang|la|glacia}}'', and ultimately [[Latin]] ''{{lang|la|glaciēs}}'', meaning "ice".<ref>{{cite book |last=Simpson |first=D.P. |url=https://archive.org/details/cassellslatindic00simp |title=Cassell's Latin Dictionary |publisher=Cassell Ltd. |year=1979 |isbn=978-0-304-52257-6 |edition=5 |location=London |page=883}}</ref> The processes and features caused by or related to glaciers are referred to as glacial. The process of glacier establishment, growth and flow is called [[glacial period|glaciation]]. The corresponding area of study is called [[glaciology]]. Glaciers are important components of the global [[cryosphere]]. |

|||

== Types == |

|||

'''Plateau glaciers''' resemble ice sheets, but on a smaller scale. They cover some plateaus and high-altitude areas. This type of glacier appears in many places, especially in [[Iceland]] and some of the large islands in the [[Arctic Ocean]], and throughout the northern [[Pacific Cordillera]] from southern [[British Columbia]] to western [[Alaska]]. |

|||

=== Classification by size, shape and behavior === |

|||

'''Tidewater glaciers''' are glaciers that flow into the sea. As the ice reaches the sea pieces break off, or ''calve'', forming [[iceberg]]s. Most tidewater glaciers calve above sea level, which often results in a tremendous splash as the iceberg strikes the water. If the water is deep, glaciers can calve underwater, causing the iceberg to suddenly explode up out of the water. The [[Hubbard Glacier]] is the longest tidewater glacier in [[Alaska]] and has a calving face over ten kilometers long. [[Yakutat Bay]] and [[Glacier Bay National Park|Glacier Bay]] are both popular with cruise ship passengers because of the huge glaciers descending to them. |

|||

{{Further|Glacier morphology}} |

|||

[[File:Quelccaya Glacier.jpg|left|thumb|The [[Quelccaya Ice Cap]] in Peru is the second-largest glaciated area in the tropics]] |

|||

Glaciers are categorized by their morphology, thermal characteristics, and behavior. ''[[Alps|Alpine]] glaciers'' form on the crests and slopes of mountains. A glacier that fills a valley is called a ''valley glacier'', or alternatively, an ''alpine glacier'' or ''mountain glacier''.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2004/1216/text.html |title=Glossary of Glacier Terminology |publisher=USGS |access-date=2017-03-13}}</ref> A large body of glacial ice astride a mountain, mountain range, or [[volcano]] is termed an ''[[ice cap]]'' or ''[[ice field]]''.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nichols.edu/departments/glacier/juneau%20icefield.htm |title=Retreat of Alaskan glacier Juneau icefield |publisher=Nichols.edu |access-date=2009-01-05 |archive-date=2017-10-23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171023193102/http://www.nichols.edu/departments/glacier/juneau%20icefield.htm |url-status=dead }}</ref> Ice caps have an area less than {{convert|50,000|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}} by definition. |

|||

Glacial bodies larger than {{convert|50,000|km2|sqmi|abbr=on}} are called ''[[ice sheet]]s'' or ''continental glaciers''.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://amsglossary.allenpress.com/glossary/search?id=ice-sheet1 |publisher=American Meteorological Society |title=Glossary of Meteorology |access-date=2013-01-04 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120623093132/http://amsglossary.allenpress.com/glossary/search?id=ice-sheet1 |archive-date=2012-06-23}}</ref> Several kilometers deep, they obscure the underlying topography. Only [[nunatak]]s protrude from their surfaces. The only extant ice sheets are the two that cover most of Antarctica and Greenland.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www4.uwsp.edu/geo/faculty/lemke/geol370/activities/02_Morphological_Classification_of_Glaciers.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170812133941/https://www4.uwsp.edu/geo/faculty/lemke/geol370/activities/02_Morphological_Classification_of_Glaciers.pdf |archive-date=2017-08-12 |url-status=live |title=Morphological Classification of Glaciers |author=[[University of Wisconsin]], Department of Geography and Geology |date=2015 |website=www.uwsp.edu/Pages/default.aspx}}</ref> They contain vast quantities of freshwater, enough that if both melted, global sea levels would rise by over {{convert|70|m|ft|abbr=on}}.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/fs/fs2-00/ |title=Sea Level and Climate |work=USGS FS 002-00 |publisher=[[USGS]] |date=2000-01-31 |access-date=2009-01-05}}</ref> Portions of an ice sheet or cap that extend into water are called [[ice shelves]]; they tend to be thin with limited slopes and reduced velocities.<ref name="NSIDC">{{cite web|publisher=[[National Snow and Ice Data Center]] |website=nsidc.org |title=Types of Glaciers |url=http://www.nsidc.org/glaciers/questions/types.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100417222017/http://nsidc.org/glaciers/questions/types.html |archive-date=2010-04-17}}</ref> Narrow, fast-moving sections of an ice sheet are called ''[[ice streams]]''.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Bindschadler |first1=R.A. |first2=T.A. |last2=Scambos |s2cid=17336434 |title=Satellite-image-derived velocity field of an Antarctic ice stream |journal=[[Science (journal)|Science]] |volume=252 |issue=5003 |pages=242–46 |year=1991 |doi=10.1126/science.252.5003.242 |pmid=17769268|bibcode=1991Sci...252..242B}}</ref><ref name=BAS2009>{{cite web |title=Description of Ice Streams |url=http://www.antarctica.ac.uk/about_antarctica/geography/ice/streams.php |publisher=[[British Antarctic Survey]] |access-date=2009-01-26 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090211004629/http://www.antarctica.ac.uk/about_antarctica/geography/ice/streams.php |archive-date=2009-02-11}}</ref> In Antarctica, many ice streams drain into large [[ice shelf|ice shelves]]. Some drain directly into the sea, often with an [[ice tongue]], like [[Mertz Glacier]]. |

|||

'''Piedmont glaciers''' occupy broad lowlands at the base of steep mountains, and form when one or more alpine glaciers surge from the confining walls of mountain valleys. The size of piedmont glaciers varies greatly: among the largest is the [[Malaspina Glacier]], which extends along the length of the southern coast of [[Alaska]]. It covers more than 5,000 km² of the coastal plain at the foot of the [[Saint Elias Mountains|Saint Elias range]]. And it is only a part of the much bigger Kluane Icecap, which spans the [[Mount St. Elias]] and [[Chugach Mountains|Chugach]] groups of mountain ranges all the way from the [[Malaspina Glacier]] to the Copper River and well into the southwestern [[Yukon]], as well as southeast from the Malaspina towards the Iskut River in [[British Columbia]]. |

|||

''[[Tidewater glacier cycle|Tidewater glaciers]]'' are glaciers that terminate in the sea, including most glaciers flowing from Greenland, Antarctica, [[Baffin Island|Baffin]], [[Devon Island|Devon]], and [[Ellesmere Island]]s in Canada, [[Southeast Alaska]], and the [[Northern Patagonian Ice Field|Northern]] and [[Southern Patagonian Ice Field]]s. As the ice reaches the sea, pieces break off or calve, forming [[iceberg]]s. Most tidewater glaciers calve above sea level, which often results in a tremendous impact as the iceberg strikes the water. Tidewater glaciers undergo centuries-long [[tidewater glacier cycle|cycles of advance and retreat]] that are much less affected by climate change than other glaciers.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://nsidc.org/cryosphere/glaciers/questions/types.html |title=What types of glaciers are there? |publisher=[[National Snow and Ice Data Center]] |website=nsidc.org |access-date=2017-08-12}}</ref> |

|||

The highest alpine glacier in the world is the [[Siachen Glacier]], which is also a zone of political conflict between India and Pakistan. |

|||

=== Classification by thermal state === |

|||

==Formation of glaciers== |

|||

[[File:Ellesmere Island 06.jpg|thumb| Webber Glacier on [[Grant Land]] is an advancing polar glacier]] |

|||

[[Image:ByrdGlacier HiLoContrast.jpg|thumb|left|Low and high contrast images of the [[Byrd Glacier]]. The low-contrast version is similar to the level of detail the naked eye would see—smooth and almost featureless. The bottom image uses enhanced contrast to highlight flow lines on the ice sheet and bottom crevasses.]] |

|||

Thermally, a ''temperate glacier'' is at a melting point throughout the year, from its surface to its base. The ice of a ''polar glacier'' is always below the freezing threshold from the surface to its base, although the surface [[snowpack]] may experience seasonal melting. A ''subpolar glacier'' includes both temperate and polar ice, depending on the depth beneath the surface and position along the length of the glacier. In a similar way, the thermal regime of a glacier is often described by its basal temperature. A ''cold-based glacier'' is below freezing at the ice-ground interface and is thus frozen to the underlying substrate. A ''warm-based glacier'' is above or at freezing at the interface and is able to slide at this contact.<ref name="ColdBased">{{cite book|title=Encyclopedia of Snow, Ice and Glaciers |first1=Reginald D. |last1=Lorrain|first2=Sean J. |last2=Fitzsimons |editor1-first=Vijay P. |editor1-last=Singh |editor2-first=Pratap |editor2-last=Singh |editor3-first=Umesh K. |editor3-last=Haritashya |publisher=Springer Netherlands |pages=157–161 |doi=10.1007/978-90-481-2642-2_72 |chapter=Cold-Based Glaciers |series=Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series |date=2011 |isbn=978-90-481-2641-5}}</ref> This contrast is thought to a large extent to govern the ability of a glacier to effectively [[Glacial erosion|erode its bed]], as sliding ice promotes [[Plucking (glaciation)|plucking]] at rock from the surface below.<ref>[[Geoffrey Boulton|Boulton, G.S.]] [1974] "Processes and patterns of glacial erosion", (In Coates, D.R. ed., ''Glacial Geomorphology''. A Proceedings Volume of the Fifth Annual Geomorphology Symposia Series, held at Binghamton, New York, September 26–28, 1974. Binghamton, NY, State University of New York, pp. 41–87. (Publications in Geomorphology))</ref> Glaciers which are partly cold-based and partly warm-based are known as ''polythermal''.<ref name="ColdBased" /> |

|||

[[Image:Glacial ice formation LMB.png|thumb|120px|Formation of glacial ice]] |

|||

The snow which forms glaciers is subject to repeated freezing and thawing, which changes it into a form of granular ice called [[névé]]. Under the pressure of the layers of ice and snow above it, this granular ice fuses into denser [[firn]]. Over a period of years, layers of firn undergo further compaction and become glacial ice. Glacial ice's distinctive blue tint, though often mistakenly attributed to [[Rayleigh scattering]], is instead simply due to the fact that water itself is blue (owing to an [[overtone]] of an OH stretch which absorbs in the far red region of the visible spectrum).[http://webexhibits.org/causesofcolor/5C.html] |

|||

== Formation == |

|||

The lower layers of glacial ice flow and deform plastically under the pressure, allowing the glacier as a whole to move slowly like a viscous fluid. Glaciers do not need a slope to flow, being driven by the continuing accumulation of new snow at their source. The upper layers of glaciers are more brittle, and often form deep cracks known as [[crevasse]]s or [[Bergshrund]]s as they flex. These crevasses make unprotected travel over glaciers extremely hazardous. Glacial meltwaters flow throughout and underneath glaciers, carving channels in the ice similar to [[cave]]s in rock and also helping to lubricate the glacier's movement. |

|||

[[File:153 - Glacier Perito Moreno - Grotte glaciaire - Janvier 2010.jpg|left|thumb|A [[glacier cave]] located on the [[Perito Moreno Glacier]] in Argentina]] |

|||

Glaciers form where the [[Glacier ice accumulation|accumulation]] of snow and ice exceeds [[ablation]]. A glacier usually originates from a [[cirque]] landform (alternatively known as a corrie or as a {{Lang|cy|cwm|italic=no}}) – a typically armchair-shaped geological feature (such as a depression between mountains enclosed by [[arête]]s) – which collects and compresses through gravity the snow that falls into it. This snow accumulates and the weight of the snow falling above compacts it, forming [[névé]] (granular snow). Further crushing of the individual snowflakes and squeezing the air from the snow turns it into "glacial ice". This glacial ice will fill the cirque until it "overflows" through a geological weakness or vacancy, such as a gap between two mountains. When the mass of snow and ice reaches sufficient thickness, it begins to move by a combination of surface slope, gravity, and pressure. On steeper slopes, this can occur with as little as {{Convert|15|m|ft|abbr=on}} of snow-ice. |

|||

In temperate glaciers, snow repeatedly freezes and thaws, changing into granular ice called [[firn]]. Under the pressure of the layers of ice and snow above it, this granular ice fuses into denser firn. Over a period of years, layers of firn undergo further compaction and become glacial ice.{{sfn|Huggett|2011|loc=Glacial and Glaciofluvial Landscapes|pp=260–262}} Glacier ice is slightly more dense than ice formed from frozen water because glacier ice contains fewer trapped air bubbles. |

|||

==Anatomy of a glacier== |

|||

Glacial ice has a distinctive blue tint because it absorbs some red light due to an [[overtone]] of the infrared [[Infrared spectroscopy|OH stretching]] mode of the water molecule. (Liquid water appears blue for the same reason. The blue of glacier ice is sometimes misattributed to [[Rayleigh scattering]] of bubbles in the ice.)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://webexhibits.org/causesofcolor/5C.html |title=What causes the blue color that sometimes appears in snow and ice? |publisher=Webexhibits.org |access-date=2013-01-04}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:glacier.swiss.500pix.jpg|thumb|right|220px|The Upper Grindelwald Glacier and the Schreckhorn, showing accumulation and ablation zones]] |

|||

== Structure == |

|||

The upper part of a glacier that receives most of the snowfall is called the ''accumulation zone''. As a rule of thumb, the [[glacier ice accumulation|accumulation]] zone accounts for 60-70% of the glacier's surface area. The depth of ice in the accumulation zone exerts a downward force sufficient to cause deep [[erosion]] of the rock in this area. After the glacier is gone, this often leaves a bowl or amphitheater-shaped depression called a [[cirque (landform)|cirque]]. |

|||

[[File:Ellesmere Island 05.jpg|thumb|The overhanging icefront of the advancing Webber Glacier with waterfalls (Borup Fiord area, Northern Ellesmere Island) on July 20, 1978. Debris rich layers have been sheared and folded into the basal cold glacier ice. The glacier front is 6 km broad and up to 40 m high]] |

|||

A glacier originates at a location called its glacier head and terminates at its glacier foot, snout, or [[Glacier terminus|terminus]]. |

|||

Glaciers are broken into zones based on surface snowpack and melt conditions.<ref>Benson, C.S., 1961, "Stratigraphic studies in the snow and firn of the Greenland Ice Sheet", ''Res. Rep. 70'', U.S. Army Snow, Ice and Permafrost Res Establ., Corps of Eng., 120 pp.</ref> The ablation zone is the region where there is a net loss in glacier mass. The upper part of a glacier, where accumulation exceeds ablation, is called the [[accumulation zone]]. The equilibrium line separates the ablation zone and the accumulation zone; it is the contour where the amount of new snow gained by accumulation is equal to the amount of ice lost through ablation. In general, the accumulation zone accounts for 60–70% of the glacier's surface area, more if the glacier calves icebergs. Ice in the accumulation zone is deep enough to exert a downward force that erodes underlying rock. After a glacier melts, it often leaves behind a bowl- or amphitheater-shaped depression that ranges in size from large basins like the Great Lakes to smaller mountain depressions known as [[cirque]]s. |

|||

On the opposite end of the glacier, at its foot or terminal, is the ''deposition'' or ''ablation zone'', where more ice is lost through melting than gained from snowfall and [[sediment]] is deposited. The place where the glacier thins to nothing is called the [[ice front]]. |

|||

The accumulation zone can be subdivided based on its melt conditions. |

|||

The altitude where the two zones meet is called the ''equilibrium line''. At this altitude, the amount of new snow gained by accumulation is equal to the amount of ice lost through ablation. The downward erosive forces of the accumulation zone and the tendency of the ablation zone to deposit sediment also cancel each other out. Erosive lateral forces are not canceled; therefore, glaciers turn v-shaped river-carved valleys into u-shaped glacial valleys. |

|||

# The dry snow zone is a region where no melt occurs, even in the summer, and the snowpack remains dry. |

|||

# The percolation zone is an area with some surface melt, causing meltwater to percolate into the snowpack. This zone is often marked by refrozen [[Ice segregation|ice lenses]], glands, and layers. The snowpack also never reaches the melting point. |

|||

# Near the equilibrium line on some glaciers, a superimposed ice zone develops. This zone is where meltwater refreezes as a cold layer in the glacier, forming a continuous mass of ice. |

|||

# The wet snow zone is the region where all of the snow deposited since the end of the previous summer has been raised to 0 °C. |

|||

The |

The health of a glacier is usually assessed by determining the [[glacier mass balance]] or observing terminus behavior. Healthy glaciers have large accumulation zones, more than 60% of their area is snow-covered at the end of the melt season, and they have a terminus with a vigorous flow. |

||

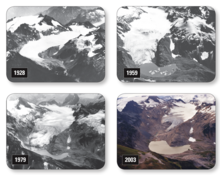

Following the [[Little Ice Age]]'s end around 1850, [[Retreat of glaciers since 1850|glaciers around the Earth have retreated substantially]]. A slight cooling led to the advance of many alpine glaciers between 1950 and 1985, but since 1985 glacier retreat and mass loss has become larger and increasingly ubiquitous.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.grid.unep.ch/activities/global_change/switzerland.php |title=Glacier change and related hazards in Switzerland |publisher=UNEP |access-date=2009-01-05 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120925064555/http://www.grid.unep.ch/activities/global_change/switzerland.php |archive-date=2012-09-25 |url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |url=http://folk.uio.no/kaeaeb/publications/grl04_paul.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070604183847/http://folk.uio.no/kaeaeb/publications/grl04_paul.pdf |archive-date=2007-06-04 |url-status=live |title=Rapid disintegration of Alpine glaciers observed with satellite data|doi=10.1029/2004GL020816 |year=2004 |bibcode=2004GeoRL..3121402P |volume=31 |issue=21 |pages=L21402 |journal=[[Geophysical Research Letters]] |last1=Paul |first1=Frank |last2=Kääb |first2=Andreas |last3=Maisch |first3=Max |last4=Kellenberger |first4=Tobias |last5=Haeberli |first5=Wilfried |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nichols.edu/departments/Glacier/glacier_retreat.htm |title=Recent Global Glacier Retreat Overview |format=PDF |access-date=2013-01-04}}</ref> |

|||

In the aftermath of the [[Little Ice Age]], about 1850, the glaciers of the Earth have retreated substantially. [[Retreat of glaciers since 1850|Glacier retreat]] has accelerated since about 1980 and is correlated with global warming. [http://www.grida.no/climate/ipcc_tar/wg1/064.htm] |

|||

== Motion == |

|||

Even in very cold climates, there may be unglaciated areas, which receive too little [[precipitation (meteorology)|precipitation]] to form permanent ice. This was the case in most of [[Siberia]], central and northern [[Alaska]] and all of [[Manchuria]] during glacial periods of the [[Quaternary]], and occurs today in Antarctica's [[Dry Valleys]] and in that part of the [[Andes]] between 19°S and 27°S above the hyperarid [[Atacama Desert]] where, although the mountains reach 6700 metres above sea level, the cold [[Humboldt Current]] completely suppresses precipitation. |

|||

{{Redirect|Ice flow|floating ice|Ice floe}} |

|||

[[Image:Stress-strain1.svg|thumb|upright=1.2|The stress–strain relationship of plastic flow (teal section): a small increase in stress creates an exponentially greater increase in strain, which equates to deformation speed.]] |

|||

Glaciers move downhill by the force of [[gravity]] and the internal deformation of ice.<ref name="GreveBlatter2009">{{cite book|author1=Greve, R.|author2=Blatter, H. |s2cid=128734526 |year=2009|title=Dynamics of Ice Sheets and Glaciers|publisher=Springer|doi=10.1007/978-3-642-03415-2|isbn=978-3-642-03414-5}}</ref> At the molecular level, ice consists of stacked layers of molecules with relatively weak bonds between layers. When the amount of strain (deformation) is proportional to the stress being applied, ice will act as an elastic solid. Ice needs to be at least {{cvt|30|m|ft}} thick to even start flowing, but once its thickness exceeds about {{cvt|50|m|ft}} (160 ft), stress on the layer above will exceeds the inter-layer binding strength, and then it'll move faster than the layer below.<ref>W.S.B. Paterson, Physics of ice</ref> This means that small amounts of stress can result in a large amount of strain, causing the deformation to become a [[Plasticity (physics)|plastic flow]] rather than elastic. Then, the glacier will begin to deform under its own weight and flow across the landscape. According to the [[Glen–Nye flow law]], the relationship between stress and strain, and thus the rate of internal flow, can be modeled as follows:<ref name="Easterbrook">Easterbrook, Don J., Surface Processes and Landforms, 2nd Edition, Prentice-Hall Inc., 1999{{page needed|date=February 2014}}</ref><ref name="GreveBlatter2009" /> |

|||

:<math> |

|||

==Glacial motion== |

|||

\Sigma = k \tau^n,\, |

|||

[[Image:Argentina-Perito_Moreno-Glacier.jpg|thumb|350px|right|Perito-Moreno Glacier, showing cracks in brittle upper layer]] |

|||

</math> |

|||

Ice behaves like an easily breaking solid until its thickness exceeds about 50 meters (160 ft). The increased pressure on ice deeper than that depth causes the ice to become [[Plasticity (physics)|plastic]] and flow. The glacial ice is made up of layers of molecules stacked on top of each other, with relatively weak bonds between the layers. When the stress exceeds the inter-layer binding strength, the layers start to slide past each other. |

|||

where: |

|||

Another type of movement is basal gliding. In this process, the whole glacier moves over the terrain on which it sits, lubricated by meltwater. As the pressure increases toward the base of the glacier, the melting point of water decreases, and the ice melts. Friction between ice and rock and [[geothermal (geology)|geothermal]] heat from the Earth's interior also contribute to thawing. This type of movement is dominant in temperate glaciers. |

|||

:<math>\Sigma\,</math> = shear strain (flow) rate |

|||

:<math>\tau\,</math> = stress |

|||

:<math>n\,</math> = a constant between 2–4 (typically 3 for most glaciers) |

|||

:<math>k\,</math> = a temperature-dependent constant |

|||

[[File:Geirangerfjord (6-2007).jpg|thumb|upright|Differential erosion enhances relief, as clear in this incredibly steep-sided Norwegian [[fjord]].]] |

|||

The top 50 meters of the glacier are more rigid. In this section, known as the ''fracture zone'', there are no layers which slide past each other; instead the ice mostly moves as a single unit. Ice in the fracture zone moves over the top of the lower section. When the glacier moves through irregular terrain, cracks form in the fracture zone. These cracks can be up to 50 meters deep, at which point they meet the plastic like flow underneath that seals them. |

|||

The lowest velocities are near the base of the glacier and along valley sides where friction acts against flow, causing the most deformation. Velocity increases inward toward the center line and upward, as the amount of deformation decreases. The highest flow velocities are found at the surface, representing the sum of the velocities of all the layers below.<ref name="Easterbrook" /><ref name="GreveBlatter2009" /> |

|||

===Speed of glacial movement=== |

|||

The speed of glacial displacement is partly determined by [[friction]]. Friction makes the ice at the bottom of the glacier move slower than the upper portion. In alpine glaciers, friction is also generated at the valley's side walls, which slows the edges relative to the center. This has been confirmed by experiments in the [[19th century]], in which stakes were planted in a line across an alpine glacier, and as time passed, those in the center moved further. |

|||

Because ice can flow faster where it is thicker, the rate of glacier-induced erosion is directly proportional to the thickness of overlying ice. Consequently, pre-glacial low hollows will be deepened and pre-existing topography will be amplified by glacial action, while [[nunatak]]s, which protrude above ice sheets, barely erode at all – erosion has been estimated as 5 m per 1.2 million years.<ref name=ngeo2008>{{cite journal | author = Kessler, Mark A.| year = 2008| doi = 10.1038/ngeo201| title = Fjord insertion into continental margins driven by topographic steering of ice| journal = Nature Geoscience | volume = 1 | pages = 365 | last2 = Anderson | first2 = Robert S. | last3 = Briner | first3 = Jason P. | issue=6 | bibcode=2008NatGe...1..365K}} Non-technical summary: {{cite journal | author = Kleman, John | year = 2008 | doi = 10.1038/ngeo210 | title = Geomorphology: Where glaciers cut deep | journal = Nature Geoscience | volume = 1 | pages = 343 | issue=6|bibcode = 2008NatGe...1..343K }}</ref> This explains, for example, the deep profile of [[fjord]]s, which can reach a kilometer in depth as ice is topographically steered into them. The extension of fjords inland increases the rate of ice sheet thinning since they are the principal conduits for draining ice sheets. It also makes the ice sheets more sensitive to changes in climate and the ocean.<ref name=ngeo2008/> |

|||

Mean speeds vary; some have speeds so slow that trees can establish themselves among the deposited scourings. In other cases they can move as fast as many meters per day, as is the case of [[Byrd Glacier]], an overflowing glacier in [[Antarctica]] which moves 750-800 meters per year (some 2 meters or 6 ft per day), according to studies using [[satellite]]s. |

|||

Although evidence in favor of glacial flow was known by the early 19th century, other theories of glacial motion were advanced, such as the idea that meltwater, refreezing inside glaciers, caused the glacier to dilate and extend its length. As it became clear that glaciers behaved to some degree as if the ice were a viscous fluid, it was argued that "regelation", or the melting and refreezing of ice at a temperature lowered by the pressure on the ice inside the glacier, was what allowed the ice to deform and flow. [[James David Forbes|James Forbes]] came up with the essentially correct explanation in the 1840s, although it was several decades before it was fully accepted.<ref>{{cite journal| title= A short history of scientific investigations on glaciers|year= 1987 |volume=Special issue |issue= S1 |journal=Journal of Glaciology|pages= 4–5|author=Clarke, Garry K.C.|bibcode= 1987JGlac..33S...4C |doi= 10.3189/S0022143000215785 |doi-access= free }}</ref> |

|||

Many glaciers have periods of very rapid advancement called [[Surge (glacier)|surges]].[http://www.geog.leeds.ac.uk/research/glaciology/maths.htm] These glaciers exhibit normal movement until suddenly they accelerate, then return to their previous state. During these surges, the glacier may reach velocities up to 1,000 times greater than normal. <!-- Why does this happen? --> |

|||

=== Fracture zone and cracks === |

|||

===Moraines=== |

|||

[[File:TitlisIceCracksDeep.jpg|left|thumb|Ice cracks in the [[Titlis]] Glacier]] |

|||

Glacial [[moraines]] are formed by the deposition of material from a glacier and are exposed after the glacier has retreated. These features usually appear as linear mounds of [[till]], a poorly-sorted mixture of rock, gravel and boulders within a matrix of a fine powdery material. Terminal or end moraines are formed at the foot or terminal end of a glacier, lateral moraines are formed on the sides of the glacier, and medial moraines are formed down the center. Less obvious is the ground moraine, also called ''glacial drift'', which often blankets the surface underneath much of the glacier downslope from the equilibrium line. Glacial meltwaters contain [[rock flour]], an extremely fine powder ground from the underlying rock by the glacier's movement. Other features formed by glacial deposition include long snake-like ridges formed by streambeds under glaciers, known as ''[[esker]]s'', and distinctive streamlined hills, known as ''[[drumlin]]s''. |

|||

The top {{convert|50|m|abbr=on}} of a glacier are rigid because they are under low [[pressure]]. This upper section is known as the ''fracture zone'' and moves mostly as a single unit over the plastic-flowing lower section. When a glacier moves through irregular terrain, cracks called [[crevasse]]s develop in the fracture zone. Crevasses form because of differences in glacier velocity. If two rigid sections of a glacier move at different speeds or directions, [[Shear (geology)|shear]] forces cause them to break apart, opening a crevasse. Crevasses are seldom more than {{convert|150|ft|m|order=flip|abbr=on}} deep but, in some cases, can be at least {{convert|1000|ft|m|order=flip|abbr=on}} deep. Beneath this point, the plasticity of the ice prevents the formation of cracks. Intersecting crevasses can create isolated peaks in the ice, called [[serac]]s. |

|||

''Stoss-and-lee'' erosional features are formed by glaciers and show the direction of their movement. Long linear rock scratches (that follow the glacier's direction of movement) are called ''[[glacial striations]]'', and divots in the rock are called ''[[chatter mark]]s''. Both of these features are left on the surfaces of stationary rock that were once under a glacier and were formed when loose rocks and boulders in the ice were transported over the rock surface. Transport of fine-grained material within a glacier can smooth or polish the surface of rocks, leading to [[glacial polish]]. [[Glacial erratic]]s are rounded [[boulder]]s that were left by a melting glacier and are often seen perched precariously on exposed rock faces after glacial retreat. |

|||

[[File: Chevron Crevasses 00.JPG|thumb|Shear or herring-bone [[crevasse]]s on [[Emmons Glacier]] ([[Mount Rainier]]); such crevasses often form near the edge of a glacier where interactions with underlying or marginal rock impede flow. In this case, the impediment appears to be some distance from the near margin of the glacier.]] |

|||

Crevasses can form in several different ways. Transverse crevasses are transverse to flow and form where steeper slopes cause a glacier to accelerate. Longitudinal crevasses form semi-parallel to flow where a glacier expands laterally. Marginal crevasses form near the edge of the glacier, caused by the reduction in speed caused by friction of the valley walls. Marginal crevasses are largely transverse to flow. Moving glacier ice can sometimes separate from the stagnant ice above, forming a [[bergschrund]]. Bergschrunds resemble crevasses but are singular features at a glacier's margins. Crevasses make travel over glaciers hazardous, especially when they are hidden by fragile [[snow bridge]]s. |

|||

Below the equilibrium line, glacial meltwater is concentrated in stream channels. Meltwater can pool in proglacial lakes on top of a glacier or descend into the depths of a glacier via [[Moulin (geomorphology)|moulins]]. Streams within or beneath a glacier flow in englacial or sub-glacial tunnels. These tunnels sometimes reemerge at the glacier's surface.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.nasa.gov/vision/earth/lookingatearth/moulin-20061211.html |title=Moulin 'Blanc': NASA Expedition Probes Deep Within a Greenland Glacier |publisher=[[NASA]] |date=2006-12-11 |access-date=2009-01-05 |archive-date=2012-11-04 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121104182135/http://www.nasa.gov/vision/earth/lookingatearth/moulin-20061211.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> |

|||

The most common name for glacial sediment is ''[[moraine]]''. The term is of [[French language|French]] origin, and it was coined by peasants to describe alluvial embankments and rims found near the margins of glaciers in the French [[Alps]]. Currently, the term is used more broadly, and is applied to a series of formations, all of which are composed of [[till]]. |

|||

=== |

===Subglacial processes=== |

||

[[File:Davies 2018 glacier sediment erosion rates.png|thumb|Erosion rates of subglacial sediment caused by the motion of different glaciers across the world <ref name="Davies2018">{{Cite journal |last1=Davies |first1=Damon |last2=Bingham |first2=Robert G. |last3=King |first3=Edward C. |last4=Smith |first4=Andrew M. |last5=Brisbourne |first5=Alex M. |last6=Spagnolo |first6=Matteo |last7=Graham |first7=Alastair G. C. |last8=Hogg |first8=Anna E. |last9=Vaughan |first9=David G. |date=4 May 2018 |title=How dynamic are ice-stream beds? |journal=The Cryosphere |volume=12 |issue=5 |pages=1615–1628 |doi=10.5194/tc-12-1615-2018 |doi-access=free |bibcode=2018TCry...12.1615D |hdl=2164/10495 |hdl-access=free }}</ref>]] |

|||

[[image:Drumlins_LMB.png|frame|right|A drumlin field forms after a glacier has modified the landscape. The tear-drop-shaped formations denote the direction of the ice flow.]] |

|||

[[Drumlin]]s are asymmetrical hills with aerodynamic profiles made mainly of [[till]]. Their heights vary from 15 to 50 meters and they can reach a kilometer in length. The tilted side of the hill looks toward the direction from which the ice advanced (''stoss''), while the longer slope follows the ice's direction of movement (''lee''). |

|||

Most of the important processes controlling glacial motion occur in the ice-bed contact—even though it is only a few meters thick.<ref name=Clarke2005>{{cite journal | author = Clarke, G. K. C. | title = Subglacial processes | journal = Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences | volume = 33 | issue = 1 | pages = 247–276 | year = 2005 | doi = 10.1146/annurev.earth.33.092203.122621| bibcode = 2005AREPS..33..247C }}</ref> The bed's temperature, roughness and softness define basal shear stress, which in turn defines whether movement of the glacier will be accommodated by motion in the sediments, or if it'll be able to slide. A soft bed, with high porosity and low pore fluid pressure, allows the glacier to move by sediment sliding: the base of the glacier may even remain frozen to the bed, where the underlying sediment slips underneath it like a tube of toothpaste. A hard bed cannot deform in this way; therefore the only way for hard-based glaciers to move is by basal sliding, where meltwater forms between the ice and the bed itself.<ref name=Boulton2006>{{cite book |doi=10.1002/9780470750636.ch2 |chapter=Glaciers and their Coupling with Hydraulic and Sedimentary Processes |title=Glacier Science and Environmental Change |year=2006 |last1=Boulton |first1=Geoffrey S. |pages=2–22 |isbn=978-0-470-75063-6 }}</ref> Whether a bed is hard or soft depends on the porosity and pore pressure; higher porosity decreases the sediment strength (thus increases the shear stress τ<sub>B</sub>).<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

Drumlins are found in groups called ''[[drumlin field]]s'' or ''drumlin camps''. An example of these fields is found east of [[Rochester, New York]], and it is estimated that it contains about 10,000 drumlins. |

|||

Porosity may vary through a range of methods. |

|||

Although the process that forms drumlins is not fully understood, it can be inferred from their shape that they are products of the plastic deformation zone of ancient glaciers. It is believed that many drumlins were formed when glaciers advanced over and altered the deposits of earlier glaciers. |

|||

*Movement of the overlying glacier may cause the bed to undergo [[wikt:dilatancy|dilatancy]]; the resulting shape change reorganizes blocks. This reorganizes closely packed blocks (a little like neatly folded, tightly packed clothes in a suitcase) into a messy jumble (just as clothes never fit back in when thrown in <!--this sentence only makes sense if the word "in" is repeated--> in a disordered fashion). This increases the porosity. Unless water is added, this will necessarily reduce the pore pressure (as the pore fluids have more space to occupy).<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

*Pressure may cause compaction and consolidation of underlying sediments.<ref name=Clarke2005/> Since water is relatively incompressible, this is easier when the pore space is filled with vapor; any water must be removed to permit compression. In soils, this is an irreversible process.<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

*Sediment degradation by abrasion and fracture decreases the size of particles, which tends to decrease pore space. However, the motion of the particles may disorder the sediment, with the opposite effect. These processes also generate heat.<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

Bed softness may vary in space or time, and changes dramatically from glacier to glacier. An important factor is the underlying geology; glacial speeds tend to differ more when they change bedrock than when the gradient changes.<ref name=Boulton2006/> Further, bed roughness can also act to slow glacial motion. The roughness of the bed is a measure of how many boulders and obstacles protrude into the overlying ice. Ice flows around these obstacles by melting under the high pressure on their [[stoss (geography)|stoss side]]; the resultant meltwater is then forced into the cavity arising in their [[lee side]], where it re-freezes.<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

==Glacial erosion== |

|||

As well as affecting the sediment stress, fluid pressure (p<sub>w</sub>) can affect the friction between the glacier and the bed. High fluid pressure provides a buoyancy force upwards on the glacier, reducing the friction at its base. The fluid pressure is compared to the ice overburden pressure, p<sub>i</sub>, given by ρgh. Under fast-flowing ice streams, these two pressures will be approximately equal, with an effective pressure (p<sub>i</sub> – p<sub>w</sub>) of 30 kPa; i.e. all of the weight of the ice is supported by the underlying water, and the glacier is afloat.<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

Rocks and sediments are added to glaciers through various processes. Glaciers erode the terrain principally through two methods: '''[[scouring]]''' and '''[[plucking]]'''. |

|||

====Basal melting and sliding ==== |

|||

[[image: Plucking_LMB.png|right|frame|Diagram of glacial plucking and abrasion]] |

|||

[[File:Glacier cross-section.jpg|thumb|upright|A cross-section through a glacier. The base of the glacier is more transparent as a result of melting.]] |

|||

As the glacier flows over the bedrock's fractured surface, it softens and lifts blocks of rock that are brought into the ice. This process is known as plucking, and it is produced when subglacial water penetrates the fractures and the subsequent freezing expansion separates them from the bedrock. When the water expands, it acts as a lever that loosens the rock by lifting it. This way, [[sediment]]s of all sizes become part of the glacier's load. |

|||

Glaciers may also move by [[basal sliding]], where the base of the glacier is [[lubrication|lubricated]] by the presence of liquid water, reducing basal [[shear stress]] and allowing the glacier to slide over the terrain on which it sits. [[Meltwater]] may be produced by pressure-induced melting, friction or [[geothermal heat]]. The more variable the amount of melting at surface of the glacier, the faster the ice will flow. Basal sliding is dominant in temperate or warm-based glaciers.<ref name="Schoof2010">{{Cite journal | last1 = Schoof | first1 = C. | title = Ice-sheet acceleration driven by melt supply variability | journal = Nature | volume = 468 | pages = 803–806 | year = 2010 | pmid = 21150994 | doi = 10.1038/nature09618|bibcode = 2010Natur.468..803S | issue=7325| s2cid = 4353234 }}</ref> |

|||

:τ<sub>D</sub> = ρgh sin α |

|||

Abrasion occurs when the ice and the load of rock fragments slide over the bedrock and function as sandpaper that smoothes and polishes the surface situated below. This pulverized rock is called [[rock flour]]. This flour is formed by rock grains of a size between 0.002 and 0.00625 [[millimeter|mm]]. Sometimes the amount of rock flour produced is so high that currents of meltwaters acquire a grayish color. |

|||

:where τ<sub>D</sub> is the driving stress, and α the ice surface slope in radians.<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

:τ<sub>B</sub> is the basal shear stress, a function of bed temperature and softness.<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

Another of the visible characteristics of glacial erosion are [[glacial striations]]. These are produced when the bottom's ice contains large chunks of rock that mark trenches in the bedrock. By [[cartography|mapping]] the direction of the flutes the direction of the glacier's movement can be determined. [[Chatter mark]]s are seen as lines of roughly crescent shape depressions in the rock underlying a glacier caused by the abrasion where a boulder in the ice catches and is then released repetitively as the glacier drags it over the underlying basal rock. |

|||

:τ<sub>F</sub>, the shear stress, is the lower of τ<sub>B</sub> and τ<sub>D</sub>. It controls the rate of plastic flow. |

|||

The velocity of a glacier's erosion is variable. The differential erosion undertaken by the ice is controlled by four important factors: |

|||

* Velocity of glacial movement |

|||

* Thickness of the ice |

|||

* Shape, abundance and hardness of rock fragments contained in the ice at the bottom of the glacier |

|||

* Relative ease of erosion of the surface under the glacier. |

|||

The presence of basal meltwater depends on both bed temperature and other factors. For instance, the melting point of water decreases under pressure, meaning that water melts at a lower temperature under thicker glaciers.<ref name=Clarke2005/> This acts as a "double whammy", because thicker glaciers have a lower heat conductance, meaning that the basal temperature is also likely to be higher.<ref name=Boulton2006/> Bed temperature tends to vary in a cyclic fashion. A cool bed has a high strength, reducing the speed of the glacier. This increases the rate of accumulation, since newly fallen snow is not transported away. Consequently, the glacier thickens, with three consequences: firstly, the bed is better insulated, allowing greater retention of geothermal heat.<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

Material that becomes incorporated in a glacier are typically carried as far as the zone of ablation before being deposited. Glacial deposits are of two distinct types: |

|||

* Glacial till: material directly deposited from glacial ice. Till includes a mixture of undifferentiated material ranging from clay size to boulders, the usual composition of a moraine. |

|||

* Fluvial and outwash: sediments deposited by water. These deposits are stratified through various processes, such as boulders being separated from finer particles. |

|||

Secondly, the increased pressure can facilitate melting. Most importantly, τ<sub>D</sub> is increased. These factors will combine to accelerate the glacier. As friction increases with the square of velocity, faster motion will greatly increase frictional heating, with ensuing melting – which causes a positive feedback, increasing ice speed to a faster flow rate still: west Antarctic glaciers are known to reach velocities of up to a kilometer per year.<ref name=Clarke2005/> |

|||

The larger pieces of rock which are encrusted in till or deposited on the surface are called ''[[glacial erratics]]''. They may range in size from pebbles to boulders, but as they may be moved great distances they may be of drastically different type than the material upon which they are found. Patterns of glacial erratics provide clues of past glacial motions. |

|||

Eventually, the ice will be surging fast enough that it begins to thin, as accumulation cannot keep up with the transport. This thinning will increase the conductive heat loss, slowing the glacier and causing freezing. This freezing will slow the glacier further, often until it is stationary, whence the cycle can begin again.<ref name=Boulton2006/> |

|||

[[File:Lake_Vostok_drill_2011.jpg|thumb|Location and diagram of [[Lake Vostok]], a prominent subglacial lake beneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet.]] |

|||

The flow of water under the glacial surface can have a large effect on the motion of the glacier itself. Subglacial lakes contain significant amounts of water, which can move fast: cubic kilometers can be transported between lakes over the course of a couple of years.<ref name=Fricker2007>{{cite journal| first1 = A.| last3 = Bindschadler| first2 = T.| last2 = Scambos| first3 = R.| first4 = L. | title = An Active Subglacial Water System in West Antarctica Mapped from Space| last1 = Fricker | journal = Science| last4 = Padman | volume = 315 | issue = 5818 | pages = 1544–1548 | date=Mar 2007 | issn = 0036-8075| pmid = 17303716 | doi = 10.1126/science.1136897| bibcode = 2007Sci...315.1544F| s2cid = 35995169}}</ref> This motion is thought to occur in two main modes: ''pipe flow'' involves liquid water moving through pipe-like conduits, like a sub-glacial river; ''sheet flow'' involves motion of water in a thin layer. A switch between the two flow conditions may be associated with surging behavior. Indeed, the loss of sub-glacial water supply has been linked with the shut-down of ice movement in the Kamb ice stream.<ref name=Fricker2007/> The subglacial motion of water is expressed in the surface topography of ice sheets, which slump down into vacated subglacial lakes.<ref name=Fricker2007/> |

|||

=== |

=== Speed === |

||

[[File:Wendleder 2024 Baltoro supraglacial acceleration.jpg|thumb|The formation of supraglacial lakes at Baltoro Glacier in April 2018 (top) had substantially accelerated its melting and motion in the following summer months (bottom)<ref name="Wendleder2024">{{Cite journal |last1=Wendleder |first1=Anna |last2=Bramboeck |first2=Jasmin |last3=Izzard |first3=Jamie |last4=Erbertseder |first4=Thilo |last5=d'Angelo |first5=Pablo |last6=Schmitt |first6=Andreas |last7=Quincey |first7=Duncan J. |last8=Mayer |first8=Christoph |last9=Braun |first9=Matthias H. |date=5 March 2024 |title=Velocity variations and hydrological drainage at Baltoro Glacier, Pakistan |journal=The Cryosphere |volume=18 |issue=3 |pages=1085–1103 |doi=10.5194/tc-18-1085-2024 |doi-access=free |bibcode=2024TCry...18.1085W }}</ref>]] |

|||

[[Image:Glacial Valley MtHoodWilderness.jpg|thumb|right|240px|A glaciated valley in the [[Mount Hood Wilderness]] showing the characteristic U-shape and flat bottom.]] |

|||

The speed of glacial displacement is partly determined by [[friction]]. Friction makes the ice at the bottom of the glacier move more slowly than ice at the top. In alpine glaciers, friction is also generated at the valley's sidewalls, which slows the edges relative to the center. |

|||

[[Image:Glacial lakes, Bhutan.jpg|thumb|right|240px|This image shows the termini of the glaciers in the [[Bhutan]]-[[Himalaya]]. Glacial lakes have been rapidly forming on the surface of the debris-covered glaciers in this region during the last few decades.]] |

|||

Mean glacial speed varies greatly but is typically around {{convert|1|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} per day.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.geo.hunter.cuny.edu/tbw/ncc/Notes/chap3.landforms/erosion.deposition/glaciers.htm |title=Glaciers |website=www.geo.hunter.cuny.edu |access-date=2014-02-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140222172708/http://www.geo.hunter.cuny.edu/tbw/NCC/Notes/chap3.landforms/erosion.deposition/glaciers.htm |archive-date=2014-02-22 |url-status=dead}}</ref> There may be no motion in stagnant areas; for example, in parts of Alaska, trees can establish themselves on surface sediment deposits. In other cases, glaciers can move as fast as {{convert|20|–|30|m|ft|-1|abbr=on}} per day, such as in Greenland's [[Jakobshavn Isbræ]]. Glacial speed is affected by factors such as slope, ice thickness, snowfall, longitudinal confinement, basal temperature, meltwater production, and bed hardness. |

|||

Before glaciation, mountain valleys have a characteristic "V" shape, produced by downward [[erosion]] by water. However, during glaciation, these valleys widen and deepen, which creates a "U"-shaped [[glacial valley]]. Besides the deepening and widening of the valley, the glacier also smoothes the valley due to erosion. This way, it eliminates the spurs of earth that extend across the valley. Because of this interaction, triangular cliffs called [[truncated spurs]] are formed. |

|||

A few glaciers have periods of very rapid advancement called [[Surge (glacier)|surges]]. These glaciers exhibit normal movement until suddenly they accelerate, then return to their previous movement state.<ref>[http://earth.esa.int/pub/ESA_DOC/gothenburg/154stroz.pdf T. Strozzi et al.: ''The Evolution of a Glacier Surge Observed with the ERS Satellites''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141111175824/http://earth.esa.int/pub/ESA_DOC/gothenburg/154stroz.pdf |date=2014-11-11 }} (pdf, 1.3 Mb)</ref> These surges may be caused by the failure of the underlying bedrock, the pooling of meltwater at the base of the glacier<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hi.is/~oi/bruarjokull_project.htm |title=The Brúarjökull Project: Sedimentary environments of a surging glacier. The Brúarjökull Project research idea|publisher=Hi.is |access-date=2013-01-04}}</ref> — perhaps delivered from a [[supraglacial lake]] — or the simple accumulation of mass beyond a critical "tipping point".<ref>Meier & Post (1969)</ref> Temporary rates up to {{convert|300|ft|m|-1|order=flip|abbr=on}} per day have occurred when increased temperature or overlying pressure caused bottom ice to melt and water to accumulate beneath a glacier. |

|||

Many glaciers deepen their valleys more than their smaller [[tributary|tributaries]]. Therefore, when the glaciers stop receding, the valleys of the tributary glaciers remain above the main glacier's depression, and these are called [[hanging valley]]s. |

|||

In glaciated areas where the glacier moves faster than one km per year, [[glacial earthquake]]s occur. These are large scale earthquakes that have seismic magnitudes as high as 6.1.<ref name="people.deas.harvard.edu">[http://people.deas.harvard.edu/~vtsai/files/EkstromNettlesTsai_Science2006.pdf "Seasonality and Increasing Frequency of Greenland Glacial Earthquakes"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081007062935/http://people.deas.harvard.edu/~vtsai/files/EkstromNettlesTsai_Science2006.pdf |date=2008-10-07 }}, Ekström, G., M. Nettles, and V.C. Tsai (2006) ''Science'', 311, 5768, 1756–1758, {{doi|10.1126/science.1122112}}</ref><ref name="TsaiEkstrom_JGR2007 2007">[http://people.deas.harvard.edu/~vtsai/files/TsaiEkstrom_JGR2007.pdf "Analysis of Glacial Earthquakes"] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081007050046/http://people.deas.harvard.edu/~vtsai/files/TsaiEkstrom_JGR2007.pdf |date=2008-10-07 }} Tsai, V. C. and G. Ekström (2007). J. Geophys. Res., 112, F03S22, {{doi|10.1029/2006JF000596}}</ref> The number of [[Glacial earthquake|glacial earthquakes]] in Greenland peaks every year in July, August, and September and increased rapidly in the 1990s and 2000s. In a study using data from January 1993 through October 2005, more events were detected every year since 2002, and twice as many events were recorded in 2005 as there were in any other year.<ref name="TsaiEkstrom_JGR2007 2007"/> |

|||

In parts of the soil that were affected by abrasion and plucking, the depressions left can be filled by [[paternoster lake]]s, from the [[Latin]] for "Our Father", referring to a station of the [[rosary]]. |

|||

=== Ogives === |

|||

At the head of a glacier is the [[corrie]], which has a bowl shape with escarped walls on three sides, but open on the side that descends into the valley. In the corrie, an accumulation of ice is formed. These begin as irregularities on the side of the mountain, which are later augmented in size by the coining of the ice. After the glacier melts, these corries are usually occupied by small mountain lakes called [[tarn (lake)|tarns]]. |

|||

[[File:Forbes Bands on Mer de Glace in France.jpg|thumb|Forbes bands on the [[Mer de Glace]] glacier in France]] |

|||

Ogives or Forbes bands<ref>{{cite book|last=Summerfield |first=Michael A. |title=Global Geomorphology |year=1991 |page=269}}</ref> are alternating wave crests and valleys that appear as dark and light bands of ice on glacier surfaces. They are linked to seasonal motion of glaciers; the width of one dark and one light band generally equals the annual movement of the glacier. Ogives are formed when ice from an icefall is severely broken up, increasing ablation surface area during summer. This creates a [[swale (landform)|swale]] and space for snow accumulation in the winter, which in turn creates a ridge.<ref>{{cite book |last=Easterbrook |first=D.J. |title=Surface Processes and Landforms |publisher=[[Prentice-Hall]], Inc. |year=1999 |edition=2 |location=New Jersey |page=546 |isbn=978-0-13-860958-0}}</ref> Sometimes ogives consist only of undulations or color bands and are described as wave ogives or band ogives.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2004/1216/no/no.html |title=Glossary of Glacier Terminology |publisher=Pubs.usgs.gov |date=2012-06-20 |access-date=2013-01-04}}</ref> |

|||

== Geography == |

|||

There may be two glaciers separated by a diving ridge. This, located between the corries, is eroded to create an [[Arete (landform)|arête]]. This structure may result in a [[mountain pass]]. |

|||

{{Details|topic=this topic|List of glaciers}} |

|||

[[File:Fox-Gletscher1.jpg|alt=|thumb|[[Fox Glacier]] in New Zealand finishes near a rainforest]] |

|||

Glaciers are present on every continent and in approximately fifty countries, excluding those (Australia, South Africa) that have glaciers only on distant [[subantarctic]] island territories. Extensive glaciers are found in Antarctica, Argentina, Chile, Canada, Pakistan,<ref>{{Cite web |date=2023-07-11 |title=10 Countries With The Most Glaciers |url=https://www.dailyo.in/visualstories/webstories/10-countries-with-the-most-glaciers-48276-11-07-2023 |access-date=2024-07-03 |website=www.dailyo.in |language=en}}</ref> Alaska, Greenland and Iceland. Mountain glaciers are widespread, especially in the [[Andes]], the [[Himalayas]], the [[Rocky Mountains]], the [[Caucasus Mountains|Caucasus]], [[Scandinavian Mountains]], and the [[Alps]]. [[Snezhnika]] glacier in [[Pirin]] Mountain, [[Bulgaria]] with a [[latitude]] of 41°46′09″ N is the southernmost glacial mass in Europe.<ref name="grunewald-129">Grunewald, p. 129.</ref> Mainland Australia currently contains no glaciers, although a small glacier on [[Mount Kosciuszko]] was present in the [[last glacial period]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ga.gov.au/education/facts/landforms/auslform.htm |title=C.D. Ollier: ''Australian Landforms and their History'', National Mapping Fab, Geoscience Australia |publisher=Ga.gov.au |date=2010-11-18 |access-date=2013-01-04 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080808081441/https://www.ga.gov.au/education/facts/landforms/auslform.htm |archive-date=2008-08-08 }}</ref> In New Guinea, small, rapidly diminishing, glaciers are located on [[Puncak Jaya]].<ref>{{cite conference |first=Joni L. |last=Kincaid |author2=Klein, Andrew G. |url=http://www.easternsnow.org/proceedings/2004/kincaid_and_klein.pdf |title=Retreat of the Irian Jaya Glaciers from 2000 to 2002 as Measured from IKONOS Satellite Images |location=Portland, Maine, USA |pages=147–157 |year=2004 |access-date=2009-01-05 |conference= |archive-date=2017-05-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170517095529/http://www.easternsnow.org/proceedings/2004/kincaid_and_klein.pdf |url-status=dead}}</ref> Africa has glaciers on [[Mount Kilimanjaro]] in Tanzania, on [[Mount Kenya]], and in the [[Rwenzori Mountains]]. Oceanic islands with glaciers include Iceland, several of the islands off the coast of Norway including [[Svalbard]] and [[Jan Mayen]] to the far north, New Zealand and the subantarctic islands of [[Marion Island|Marion]], [[Heard Island|Heard]], [[Kerguelen Islands#Grande Terre|Grande Terre (Kerguelen)]] and [[Bouvet Island|Bouvet]]. During glacial periods of the Quaternary, [[Taiwan]], [[Hawaii (island)|Hawaii]] on [[Mauna Kea]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://geology.com/press-release/hawiian-glaciers/ |title=Hawaiian Glaciers Reveal Clues to Global Climate Change |publisher=Geology.com |date=2007-01-26 |access-date=2013-01-04 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130127143044/http://geology.com/press-release/hawiian-glaciers/ |archive-date=2013-01-27}}</ref> and [[Tenerife]] also had large alpine glaciers, while the [[Faroe Islands|Faroe]] and [[Crozet Islands]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.discoverfrance.net/Colonies/Crozet.shtml |title=French Colonies – Crozet Archipelago |publisher=Discoverfrance.net |date=2010-12-09 |access-date=2013-01-04}}</ref> were completely glaciated. |

|||

The permanent snow cover necessary for glacier formation is affected by factors such as the degree of slope on the land, amount of snowfall and the winds. Glaciers can be found in all [[latitude]]s except from 20° to 27° north and south of the equator where the presence of the descending limb of the [[Hadley circulation]] lowers precipitation so much that with high [[insolation]] [[snow line]]s reach above {{convert|6500|m|ft|-1|abbr=on}}. Between 19˚N and 19˚S, however, precipitation is higher, and the mountains above {{convert|5000|m|ft|-1|abbr=on}} usually have permanent snow. |

|||

Glaciers are also responsible for the creation of [[fjord]]s (deep coves or inlets) and [[escarpment]]s that are found at high latitudes. With depths that can exceed 1,000 metres caused by the postglacial elevation of [[sea level]] and therefore, as it changed the glaciers changed their level of erosion. |

|||

[[File:Black-Glacier.jpg|thumb|Black ice glacier near [[Aconcagua]], Argentina]] |

|||

Even at high latitudes, glacier formation is not inevitable. Areas of the [[Arctic]], such as [[Banks Island]], and the [[McMurdo Dry Valleys]] in Antarctica are considered [[polar desert]]s where glaciers cannot form because they receive little snowfall despite the bitter cold. Cold air, unlike warm air, is unable to transport much water vapor. Even during glacial periods of the [[Quaternary]], [[Manchuria]], lowland [[Siberia]],<ref>{{cite book|last=Collins |first=Henry Hill |title=Europe and the USSR |page=263 |oclc=1573476}}</ref> and [[Alaska Interior|central]] and [[northern Alaska]],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.beringia.com/centre_info/exhibit.html |title=Yukon Beringia Interpretive Center |publisher=Beringia.com |date=1999-04-12 |access-date=2013-01-04 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121031054552/http://www.beringia.com/centre_info/exhibit.html |archive-date=2012-10-31}}</ref> though extraordinarily cold, had such light snowfall that glaciers could not form.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.eas.slu.edu/People/KChauff/earth_history/4EH-posted.pdf|title=Earth History 2001 |date=July 28, 2017 |page=15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303183327/http://www.eas.slu.edu/People/KChauff/earth_history/4EH-posted.pdf |archive-date=March 3, 2016 |access-date=July 28, 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wku.edu/~smithch/biogeog/SCHM1946.htm |title=On the Zoogeography of the Holarctic Region |publisher=Wku.edu |access-date=2013-01-04}}</ref> |

|||

In addition to the dry, unglaciated polar regions, some mountains and volcanoes in Bolivia, Chile and Argentina are high ({{convert|4500|to|6900|m|ft|-2|abbr=on|disp=or}}) and cold, but the relative lack of precipitation prevents snow from accumulating into glaciers. This is because these peaks are located near or in the [[hyperarid]] [[Atacama Desert]]. |

|||

[[image:Glacial_landscape_LMB.png|right|frame|Features of a glacial landscape]] |

|||

== Glacial geology == |

|||

An [[Arete (landform)|arête]] is a narrow crest with a sharp edge. Pointed pyramidal peaks are called [[Glacial horn|horn]]s. |

|||

=== Erosion === |

|||

Both features may have the same process behind their formation: the enlargement of cirques from glacial plucking and the action of the ice. Horns are formed by cirques that encircle a single mountain. |

|||

[[File:Arranque glaciar-en.svg|thumb|Diagram of glacial plucking and [[Abrasion (geology)|abrasion]]]] |

|||

Glaciers erode terrain through two principal processes: [[Plucking (glaciation)|plucking]] and [[abrasion (geology)|abrasion]].{{sfn|Huggett|2011|loc=Glacial and Glaciofluvial Landscapes|pp=263–264}} |

|||

As glaciers flow over bedrock, they soften and lift blocks of rock into the ice. This process, called plucking, is caused by subglacial water that penetrates fractures in the bedrock and subsequently freezes and expands.{{sfn|Huggett|2011|loc=Glacial and Glaciofluvial Landscapes|p=263}} This expansion causes the ice to act as a lever that loosens the rock by lifting it. Thus, sediments of all sizes become part of the glacier's load. If a retreating glacier gains enough debris, it may become a [[rock glacier]], like the [[Timpanogos Glacier]] in Utah. |

|||

Arêtes emerge in a similar manner; the only difference is that the cirques are not located in a circle, but rather on opposite sides along a divide. Arêtes can also be produced by the collision of two parallel glaciers. In this case, the glacial tongues cut the divides down to size through erosion, and polish the adjacent valleys. |

|||

Abrasion occurs when the ice and its load of rock fragments slide over bedrock{{sfn|Huggett|2011|loc=Glacial and Glaciofluvial Landscapes|p=263}} and function as sandpaper, smoothing and polishing the bedrock below. The pulverized rock this process produces is called [[rock flour]] and is made up of rock grains between 0.002 and 0.00625 mm in size. Abrasion leads to steeper valley walls and mountain slopes in alpine settings, which can cause avalanches and rock slides, which add even more material to the glacier. Glacial abrasion is commonly characterized by [[glacial striation]]s. Glaciers produce these when they contain large boulders that carve long scratches in the bedrock. By mapping the direction of the striations, researchers can determine the direction of the glacier's movement. Similar to striations are [[chatter mark]]s, lines of crescent-shape depressions in the rock underlying a glacier. They are formed by abrasion when boulders in the glacier are repeatedly caught and released as they are dragged along the bedrock.[[File:PluckedGraniteAlandIslands.JPG|thumb|right|Glacially plucked granitic bedrock near [[Mariehamn]], [[Åland]]]]The rate of glacier erosion varies. Six factors control erosion rate: |

|||

===Sheepback rock=== |

|||

* Velocity of glacial movement |

|||

* Thickness of the ice |

|||

* Shape, abundance and hardness of rock fragments contained in the ice at the bottom of the glacier |

|||

* Relative ease of erosion of the surface under the glacier |

|||

* Thermal conditions at the glacier base |

|||

* Permeability and water pressure at the glacier base |

|||

When the bedrock has frequent fractures on the surface, glacial erosion rates tend to increase as plucking is the main erosive force on the surface; when the bedrock has wide gaps between sporadic fractures, however, abrasion tends to be the dominant erosive form and glacial erosion rates become slow.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dühnforth |first1=Miriam |last2=Anderson |first2=Robert S. |last3=Ward |first3=Dylan |last4=Stock |first4=Greg M. |date=2010-05-01 |title=Bedrock fracture control of glacial erosion processes and rates |journal=[[Geology (journal)|Geology]] |language=en |volume=38 |issue=5 |pages=423–426 |doi=10.1130/G30576.1 |issn=0091-7613 |bibcode=2010Geo....38..423D}}</ref> Glaciers in lower latitudes tend to be much more erosive than glaciers in higher latitudes, because they have more meltwater reaching the glacial base and facilitate sediment production and transport under the same moving speed and amount of ice.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Koppes |first1=Michéle |last2=Hallet |first2=Bernard |last3=Rignot |first3=Eric |last4=Mouginot |first4=Jérémie |last5=Wellner |first5=Julia Smith |last6=Boldt |first6=Katherine |title=Observed latitudinal variations in erosion as a function of glacier dynamics |journal=[[Nature (journal)|Nature]] |volume=526 |issue=7571 |pages=100–103 |doi=10.1038/nature15385 |pmid=26432248 |bibcode=2015Natur.526..100K |year=2015 |s2cid=4461215}}</ref> |

|||

Material that becomes incorporated in a glacier is typically carried as far as the zone of ablation before being deposited. Glacial deposits are of two distinct types: |

|||

Some rock formations in the path of a glacier are sculpted into small hills with a shape known as '''roche moutonnée''' or ''sheepback''. An elongated, rounded, asymmetrical, bedrock knob produced can be produced by glacier erosion. It has a gentle slope on its up-glacier side and a steep to vertical face on the down-glacier side. The glacier abrades the smooth slope that it flows along, while rock is torn loose from the downstream side and carried away in ice. Rock on this side is fractured by combinations of forces due to water, ice in rock cracks, and structural stresses. |

|||

* ''Glacial till'': material directly deposited from glacial ice. Till includes a mixture of undifferentiated material ranging from clay size to boulders, the usual composition of a moraine. |

|||

===Alluvial stratification=== |

|||

* ''Fluvial and outwash sediments'': sediments deposited by water. These deposits are stratified by size. |

|||

Larger pieces of rock that are encrusted in till or deposited on the surface are called "[[glacial erratic]]s". They range in size from pebbles to boulders, but as they are often moved great distances, they may be drastically different from the material upon which they are found. Patterns of glacial erratics hint at past glacial motions. |

|||