D. B. Cooper: Difference between revisions

Undid good-faith revision 1265358622 by 2A02:C7C:C28F:D600:3837:33E6:56D:8140 (talk); many prior talkpage discussions on this |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{short description|Unidentified airplane hijacker in 1971}} |

|||

{{Infobox person |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=October 2022}} |

|||

| name = D. B. Cooper |

|||

| image = DBCooper.jpg |

|||

{{Infobox criminal |

|||

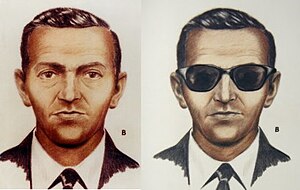

| caption = A 1972 F.B.I. composite drawing of D. B. Cooper |

|||

| name = D.B. Cooper |

|||

| birth_date = |

|||

| image = CompositeB-FBI-1973.jpg |

|||

| birth_place = |

|||

| caption = A 1972 FBI composite drawing of the hijacker |

|||

| death_date = |

|||

| birth_date = |

|||

| death_place = |

|||

| birth_place = |

|||

| occupation = Unknown |

|||

| death_date = |

|||

| other_names = Dan Cooper |

|||

| death_place = |

|||

| known_for = Hijacking a Boeing 727 on November 24, 1971, and parachuting from the plane mid-flight; has never been positively identified or captured. |

|||

| disappeared_date = {{disappeared date|1971|11|24}} ({{time ago|November 24, 1971}}) |

|||

| spouse = |

|||

| status = Missing / Unidentified |

|||

| alias = Dan Cooper |

|||

| known_for = Hijacking a [[Boeing 727]] and parachuting from the plane midflight before disappearing |

|||

| criminal_charge = [[Air piracy]] and violation of the [[Hobbs Act]] |

|||

| capture_status = Fugitive, believed dead |

|||

| conviction_status = At large, believed dead |

|||

| wanted_by = [[FBI]] |

|||

| wanted_since = November 24, 1971 |

|||

| website = {{URL|https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/db-cooper-hijacking}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Infobox aircraft occurrence |

{{Infobox aircraft occurrence |

||

|name = Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305 |

| name = Northwest Orient Airlines Flight 305 |

||

|occurrence_type = Hijacking |

| occurrence_type = Hijacking |

||

| image = Northwest Airlines Boeing 727-51 N467US.jpg |

|||

|image = |image_size = <!--(defaults to 230 if blank)--> |alt = |caption = |

|||

| alt = |

|||

|date = November 24, 1971 |

|||

| caption = N467US, the aircraft involved in the hijacking |

|||

|type = Hijacking |

|||

| date = November 24, 1971 |

|||

|site = Between Portland, Oregon and Seattle, Washington, USA |

|||

| type = Hijacking |

|||

|coordinates = |

|||

| site = Between [[Portland, Oregon]], U.S., and [[Seattle]], Washington, U.S. |

|||

|aircraft_type = Boeing 727 |

|||

| coordinates = |

|||

|aircraft_name = |

|||

| aircraft_type = [[Boeing 727-100|Boeing 727-51]] |

|||

|operator = Northwest Orient Airlines |

|||

| aircraft_name = |

|||

|tail_number = |

|||

| operator = [[Northwest Orient Airlines]] |

|||

|origin = Portland Int'l Airport |

|||

| tail_number = N467US |

|||

|destination = Seattle-Tacoma Int'l Airport |

|||

| origin = [[Portland International Airport]] |

|||

|passengers = 36 plus hijacker |

|||

| stopover = |

|||

|crew = 6 |

|||

| stopover0 = |

|||

|injuries = none known |

|||

| last_stopover = |

|||

|fatalities = none known (hijacker{{'}}s fate unknown) |

|||

| destination = [[Seattle-Tacoma International Airport]] |

|||

|survivors = all 42 passengers and crew |

|||

| passengers = 36 (including hijacker) |

|||

| crew = 6 |

|||

| fatalities = 0 |

|||

| missing = 1 (including hijacker) |

|||

| survivors = 41 |

|||

| occupants = 42 |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

'''D. B. Cooper''', also known as '''Dan Cooper''', was an unidentified man who [[aircraft hijacking|hijacked]] [[Northwest Orient Airlines]] Flight 305, a [[Boeing 727]] aircraft, in United States airspace on November 24, 1971. During the flight from [[Portland, Oregon]], to [[Seattle]], Washington, Cooper told a flight attendant he had a bomb, demanded $200,000 in [[ransom]] (equivalent to approximately $1,500,000 in 2024)<ref>{{Cite web |title=$200,000 in 1971 → 2024 {{!}} Inflation Calculator |url=https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1971?amount=200000 |access-date=2024-01-17 |website=www.in2013dollars.com |language=en |archive-date=January 17, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240117211808/https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1971?amount=200000 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2022-07-02 |title=Inflation Calculator {{!}} Cumulative to Month and Year |url=https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/calculator-cumulative/ |access-date=2024-01-17 |website=www.usinflationcalculator.com |language=en-US |archive-date=July 27, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240727132738/https://www.usinflationcalculator.com/inflation/calculator-cumulative/ |url-status=live }}</ref> and four parachutes upon landing in Seattle. After releasing the passengers in Seattle, Cooper instructed the flight crew to refuel the aircraft and begin a second flight to [[Mexico City]], with a refueling stop in [[Reno, Nevada|Reno]], [[Nevada]]. About thirty minutes after taking off from Seattle, Cooper opened the aircraft's aft door, deployed the [[airstair|staircase]], and [[parachute]]d into the night over southwestern Washington. Cooper's true identity and whereabouts have never been determined conclusively. |

|||

'''D. B. Cooper''' is a media [[epithet]] popularly used to refer to an unidentified man who [[aircraft hijacking|hijacked]] a [[Boeing 727]] aircraft in the airspace between [[Portland, Oregon]], and [[Seattle, Washington]], on November 24, 1971, extorted [[United States dollar|$]]200,000<ref name="equivalent" /> in ransom, and parachuted to an uncertain fate. Despite an extensive manhunt and an ongoing [[Federal Bureau of Investigation|FBI]] investigation, the perpetrator has never been located or positively identified. The case remains the only unsolved air piracy in American aviation history.<ref name="Gray-NYmag2007-10-21" />{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=135}}<ref name="Pasternak-USNWR2000-07-24" /> |

|||

In 1980, a small portion of the ransom money was found along the banks of the [[Columbia River]] near [[Vancouver, Washington]]. The discovery of the money renewed public interest in the mystery but yielded no additional information about Cooper's identity or fate, and the remaining money was never recovered. For forty-five years after the hijacking, the [[Federal Bureau of Investigation]] (FBI) maintained an active investigation and built an extensive case file but ultimately did not reach any definitive conclusions. The crime remains the only documented unsolved case of [[air piracy]] in the history of commercial aviation. The FBI speculates Cooper did not survive his jump for several reasons: the inclement weather, Cooper's lack of proper [[skydiving]] equipment, the forested terrain into which he jumped, his lack of detailed knowledge of his landing area and the disappearance of the remaining ransom money, suggesting it was never spent. In July 2016, the FBI officially suspended active investigation of the case, although reporters, enthusiasts, professional investigators and amateur sleuths continue to pursue numerous theories for Cooper's identity, success and fate. |

|||

The suspect purchased his airline ticket using the alias '''Dan Cooper''', but due to a news media miscommunication he became known in popular lore as "D. B. Cooper". Hundreds of leads have been pursued in the ensuing years, but no conclusive evidence has ever surfaced regarding Cooper's true identity or whereabouts. Numerous theories of widely varying plausibility have been proposed by experts, reporters, and amateur enthusiasts.<ref name="Gray-NYmag2007-10-21" /><ref name="AP2008-01-02" /> The discovery of a small cache of ransom bills in 1980 triggered renewed interest but ultimately only deepened the mystery, and the great majority of the ransom remains unrecovered. |

|||

Cooper's hijacking — and [[D. B. Cooper copycat hijackings|several imitators]] during the next year — immediately prompted major upgrades to [[airport security|security measures for airports]] and [[commercial aviation]]. [[Metal detector]]s were installed at airports, baggage inspection became mandatory and passengers who paid cash for tickets on the day of departure were selected for additional scrutiny. Boeing 727s were [[retrofitted]] with eponymous "[[Cooper vane]]s", designed to prevent the aft staircase from being lowered in-flight. By 1973, aircraft hijacking incidents had decreased, as the new security measures dissuaded would-be hijackers whose only motive was money. |

|||

While FBI investigators have insisted from the beginning that Cooper probably did not survive his risky jump,<ref name="FBI-Redux" /> the agency maintains an active case file—which has grown to more than 60 volumes<ref name="Seven1996-11-17" />—and continues to solicit creative ideas and new leads from the public. "Maybe a hydrologist can use the latest technology to trace the $5,800 in ransom money found in 1980 to where Cooper landed upstream," suggested Special Agent Larry Carr, leader of the investigation team since 2006. "Or maybe someone just remembers that odd uncle."<ref name="FBI-Redux" /> |

|||

==Hijacking== |

== Hijacking == |

||

[[File:DB Cooper Wanted Poster.jpg|thumb|FBI wanted poster of D. B. Cooper]] |

|||

The event began mid-afternoon on [[Thanksgiving (United States)|Thanksgiving]] eve, November 24, 1971, at [[Portland International Airport]] in Portland, Oregon. A man carrying a black attaché case approached the flight counter of [[Northwest Orient Airlines]]. He identified himself as "Dan Cooper" and purchased a one-way ticket on Flight 305, a 30-minute trip to Seattle, Washington.<ref name="Olson1999" /> |

|||

On [[Thanksgiving (United States)|Thanksgiving]] Eve, November 24, 1971, a man carrying a black [[attaché case]] approached the flight counter for [[Northwest Airlines|Northwest Orient Airlines]] at [[Portland International Airport]]. Using cash,<ref name="fbi_famous">{{Cite web |title=D.B. Cooper Hijacking |url=https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/db-cooper-hijacking |access-date=May 6, 2022 |publisher=Federal Bureau of Investigation |language=en-us |archive-date=November 5, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161105094658/https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/db-cooper-hijacking |url-status=live }}</ref> the man bought a one-way ticket on {{nowrap|Flight 305}}, a thirty-minute trip north to [[Seattle–Tacoma International Airport]] (Sea-Tac). On his ticket, the man listed his name as "Dan Cooper." Eyewitnesses described Cooper as a white male in his mid-40s, with dark hair and brown eyes, wearing a black or brown business suit, a white shirt, a thin black tie, a black raincoat and brown shoes.<ref name="fbi_famous"/>{{r|vault_69|page=294}} Carrying a briefcase and a brown paper bag,{{r|vault_69|page=294}} Cooper boarded Flight 305, a [[Boeing 727#727-100|Boeing 727-100]] ([[Federal Aviation Administration|FAA]] registration N467US). Cooper took seat 18-E in the last row and ordered a drink, a [[Bourbon whiskey|bourbon]] and [[7-Up]] from a [[flight attendant]].<ref>{{cite report |date= November 24, 1971|title= FBI Interview with Florence Schaffner, Nov 24, 1971}}</ref><ref name="vault_26">{{cite report |date= June 27, 1972 |title= Acting Director Memo to Seattle SAC, June 27th, 1972 |url= https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D.B.%20Cooper%20Part%2026/view |publisher= Federal Bureau of Investigation |page= 471 |access-date= October 18, 2022 |archive-date= October 18, 2022 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20221018030831/https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D.B.%20Cooper%20Part%2026/view |url-status= live }}</ref> |

|||

With a crew of six (consisting of [[pilot in command|Captain]] William A. Scott, [[First officer (aviation)|First Officer]] William "Bill" J. Rataczak, [[flight engineer|Flight Engineer]] Harold E. Anderson and flight attendants Alice Hancock, Tina Mucklow and Florence Schaffner) and thirty-six passengers aboard, including Cooper, Flight 305 left Portland on-schedule at 2:50 pm PST.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=NPAjAAAAIBAJ&pg=6509%2C3689150 |work=Spokesman-Review |location= |agency=Associated Press |title=Hijacked plane makes landing at Seattle airport |date=November 25, 1971|page=1|access-date=September 22, 2018|archive-date=March 23, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200323165544/https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=NPAjAAAAIBAJ&pg=6509%2C3689150 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite report |date= November 24, 1971 |title= Northwest Airlines Flight Operations Memo from night of hijacking |quote= There are 36 passengers and a crew of 6 |url= https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/d.b.-cooper-part-10/view |publisher= Federal Bureau of Investigation |page= 329 }}{{Dead link|date=November 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> Shortly after takeoff, Cooper handed a note to flight attendant Schaffner, who was sitting in the [[jump seat]] at the rear of the airplane,{{r|vault_64|page=159}} directly behind Cooper. Assuming the note was a lonely businessman's telephone number, Schaffner dropped the note unopened into her purse.{{sfn|Bragg|2005|p=2}} Cooper then leaned toward her and whispered, "Miss, you'd better look at that note. I have a bomb."<ref>{{cite news |title=When D.B. Cooper Dropped From Sky: Where did the daring, He jumped off the plane. mysterious skyjacker go? Twenty-five years later, the search is still on for even a trace|last=Steven|first=Richard|date=November 24, 1996|page=A20|work=The Philadelphia Inquirer}}</ref> |

|||

Cooper boarded the aircraft, a Boeing 727–100 ([[FAA]] registration N467US), and took seat 18C<ref name="Gray-NYmag2007-10-21" /> (18E by one account,<ref>History's Greatest Unsolved Crimes. [http://www.francesfarmersrevenge.com/stuff/archive/oldnews6/crimes.htm Frances Farmer Archive] Retrieved February 7, 2011.</ref> 15D by another{{sfn|Gunther|1985|p=32}}) in the rear of the passenger cabin. He lit a cigarette and ordered a bourbon and soda. Onboard eyewitnesses recalled a man in his mid-forties, between {{convert|5|ft|10|in}} and {{convert|6|ft|0|in}} tall. He wore a black lightweight raincoat, [[Slip-on shoe|loafers]], a dark suit, a neatly pressed white collared shirt, a black necktie, and a [[nacre|mother of pearl]] tie pin.<ref name="SFChronicle">{{cite news| title = D.B. Cooper–the search for skyjacker missing since 1971 | last = Tizon | first = Tomas A. | date = September 4, 2005 | url = http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2005/09/04/BAGU1EG7K71.DTL | work = [[San Francisco Chronicle]] | accessdate = 2008-01-02 }}</ref> |

|||

[[File:DB Cooper Wanted Poster.jpg|thumb|upright|F.B.I. wanted poster of D. B. Cooper]] |

|||

Flight 305, approximately one-third full, took off on schedule at 2:50 pm, local time ([[Pacific Standard Time|PST]]). Cooper passed a note to Florence Schaffner, the [[flight attendant]] situated nearest to him in a [[jumpseat#Aviation|jumpseat]] attached to the [[aft]] stair door.<ref name="Gray-NYmag2007-10-21" /> Schaffner, assuming the note contained a lonely businessman's phone number, dropped it unopened into her purse.<ref>{{cite book | title = Myths and Mysteries of Washington | last = Bragg | first = Lynn E. | year = 2005 | publisher = Globe Pequot |location=[[Guilford, Connecticut|Guilford]], [[Connecticut]] | page = 2 | isbn = 0-7627-3427-2}}</ref> Cooper leaned toward her and whispered, "Miss, you'd better look at that note. I have a bomb."<ref name="PI">{{cite news| title = When D.B. Cooper Dropped From Sky: Where did the daring, mysterious skyjacker go? Twenty-five years later, the search is still on for even a trace | last = Steven| first = Richard | date = November 24, 1996 | url = | page = A20 | work = [[The Philadelphia Inquirer]]}}</ref> |

|||

Schaffner opened the note. In neat, all-capital letters printed with a felt-tip pen,<ref>{{cite web |title=Unmasking D.B. Cooper |url=https://nymag.com/nymag/features/39593/index1.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160816131137/http://nymag.com/nymag/features/39593/index1.html |archive-date=August 16, 2016 |access-date=June 28, 2016 |work=New York Magazine|date=October 18, 2007 }}</ref> Cooper had written, "Miss—I have a bomb in my briefcase and want you to sit by me."<ref name="auto">{{cite report |title=FBI Interview with Florence Schaffner, Nov 24, 1971 |date=November 24, 1971}}</ref> Schaffner returned the note to Cooper,{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=19}} sat down as he requested, and asked quietly to see the bomb. He opened his briefcase, and she saw two rows of four red cylinders, which she assumed were [[dynamite]]. Attached to the cylinders were a wire and a large, cylindrical battery, which resembled a bomb.{{efn|name=cylinders}}<ref>{{cite web |title=Transcript of Crew Communications |website=n467us.com |url=http://n467us.com/Data%20Files/Logs%2006-20-2008R.pdf |access-date=February 25, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130921053644/http://n467us.com/Data%20Files/Logs%2006-20-2008R.pdf |archive-date=September 21, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

The note was printed in neat, all-capital letters with a felt pen. It read, approximately,<ref group="note">The exact wording of the hijacker's note could never be verified, as he later reclaimed it.</ref> "I have a bomb in my briefcase. I will use it if necessary. I want you to sit next to me. You are being hijacked."<ref name="TG">{{cite news| title = Heads in the clouds | last=Burkeman | first = Oliver | date =December 1, 2007| url = http://www.guardian.co.uk/weekend/story/0,,2218788,00.html | work = [[The Guardian]] | accessdate = 2008-01-02 | location=London}}</ref> Schaffner did as requested, then quietly asked to see the bomb. Cooper cracked open his briefcase long enough for her to glimpse eight red cylinders<ref name="cylinders" /> ("four on top of four") attached to wires coated with red insulation, and a large cylindrical battery.<ref>[http://n467us.com/Data%20Files/Logs%2006-20-2008R.pdf Transcript of Crew Communications] Retrieved February 25, 2011.</ref> After closing the briefcase, he dictated his demands: $200,000 in "negotiable American currency";<ref name="twenty" /> four parachutes (two primary and two reserve); and a fuel truck standing by in Seattle to refuel the aircraft upon arrival.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=18}} Schaffner conveyed Cooper's instructions to the [[cockpit]]; when she returned, he was wearing dark sunglasses.<ref name="CrimeLibrary2">{{cite web | title = The D.B. Cooper Story: The Crime | last=Krajicek | first = David | date = | url = http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/2.html | work = [[Crime Library]] | accessdate = January 3, 2008 }}</ref> |

|||

Cooper closed the briefcase and told Schaffner his demands. She wrote a note with Cooper's demands, brought it to the cockpit and informed the flight crew of the situation. Captain Scott directed her to remain in the cockpit for the remainder of the flight and take notes of events as they happened.<ref name="auto"/> He then relayed to Northwest flight operations in [[Minnesota]] the hijacker's demands: "[Cooper] requests $200,000 in a knapsack by 5:00 pm. He wants two front [[parachute]]s, two back parachutes. He wants the money in negotiable American currency."{{sfn|Gray|2011b|pp=41}}{{efn|name=parachutes|Earl Cossey, the skydiving instructor who supplied the parachutes, told some sources three of the four parachutes (one primary and both reserves) were returned to him. The FBI maintained only two parachutes, a primary and a cannibalized reserve, were found aboard the airplane. {{harvnb|Gunther|1985|p=50}}.}} By requesting two sets of parachutes, Cooper implied he planned to take a hostage with him, thereby discouraging authorities from supplying non-functional equipment.<ref>{{Cite AV media |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRM4qS3vfB0 |title=How Dan Cooper JUMPED from an aircraft and the end of aft Air-stairs! |date=January 22, 2021 |last=Mentour Pilot |access-date=2023-04-28 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240727132852/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vRM4qS3vfB0 |archive-date=July 27, 2024 |url-status=live |via=YouTube}}</ref> |

|||

The pilot, William Scott, contacted [[Seattle-Tacoma International Airport|Seattle-Tacoma Airport]] [[air traffic control]], which in turn informed local and federal authorities. The 36 other passengers were informed that their arrival in Seattle would be delayed because of a "minor mechanical difficulty".{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=20}} Northwest Orient's president, [[Donald Nyrop]], authorized payment of the ransom and ordered all employees to cooperate fully with the hijacker.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=19}} The aircraft circled [[Puget Sound]] for approximately two hours to allow [[Seattle Police Department|Seattle police]] and the FBI time to assemble Cooper's parachutes and ransom money, and to mobilize emergency personnel.<ref name="Gray-NYmag2007-10-21" /> |

|||

With Schaffner in the cockpit, flight attendant Mucklow sat next to Cooper to act as a liaison between him and the flight crew.<ref name="RS_Marks">{{cite magazine |last1=Marks |first1=Andrea |title=The Missing Piece of the D.B. Cooper Story |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/db-cooper-tina-mucklow-untold-story-1111944/ |access-date=August 20, 2024 |magazine=Rolling Stone |date=January 12, 2021 |archive-date=January 13, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220113212424/https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/db-cooper-tina-mucklow-untold-story-1111944/ |url-access=subscription }}</ref>{{r|vault_64|page=160|quote=Tina said 'do you want me to stay here?' and the man replied, 'yes'.}} Cooper then made additional demands: upon landing at Sea-Tac, fuel trucks were to meet the plane and all passengers were to remain seated while Mucklow brought the money aboard. He said he would release the passengers after he had the money. The last items brought aboard would be the four parachutes.{{r|vault_64|quote= One of the specific demands [Cooper] made was the fuel truck is to come first and start fueling the plane immediately. After fueling is completed and the money is aboard, he indicated the passengers would be released, and the last item to be brought aboard the aircraft would be the chutes, and at that time only the crew members were to be aboard, and they must stay out of the aisle and remain in their seats.|page= 160}} |

|||

Schaffner recalled that Cooper appeared familiar with the local [[terrain]]; at one point he remarked, "Looks like Tacoma down there," as the aircraft flew above it. He also mentioned, correctly, that [[McChord Air Force Base]] was only a 20-minute drive from Seattle-Tacoma Airport.<ref name="CrimeLibrary4" /><ref group="note" name="traveltimenote">Because of a 70 MPH speed limit on Interstate 5 and a lack of traffic congestion, this was a reasonable travel time in 1971</ref> Schaffner described him as calm, polite, and well-spoken, not at all consistent with the stereotypes (enraged, hardened criminals or "take-me-to-Cuba" political dissidents) popularly associated with air piracy at the time. Tina Mucklow, another flight attendant, agreed. "He wasn't nervous," she told investigators. "He seemed rather nice. He was never cruel or nasty. He was thoughtful and calm all the time."<ref name="CrimeLibrary4" /> He ordered a second bourbon and water, paid his drink tab (and insisted Schaffner keep the change),<ref name="Gray-NYmag2007-10-21" /> and offered to request meals for the flight crew during the stop in Seattle.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=22}} |

|||

Scott informed Sea–Tac [[air traffic control]] of the situation, who contacted the [[Seattle Police Department]] (SPD) and the [[Federal Bureau of Investigation]] (FBI). The passengers were told their arrival in [[Seattle]] would be delayed because of a "minor mechanical difficulty."{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=20}} [[Donald Nyrop]], the president of Northwest at the time, authorized payment of the [[ransom]] and ordered all employees to cooperate with the hijacker and comply with his demands.{{sfn|Gray|2011b|pp=47}} For approximately two hours, Flight 305 circled [[Puget Sound]] to give the SPD and the FBI sufficient time to assemble Cooper's ransom money and parachutes, and to mobilize emergency personnel.{{sfn|Edwards|2021|pp=19}} |

|||

FBI agents assembled the ransom money from several Seattle-area banks—10,000 unmarked 20-dollar bills, many with serial numbers beginning with the letter "L" indicating issuance by the [[Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco]], most carrying a "Series 1969-C" designation<ref name="CrimeLibrary4">{{cite web| title = The D.B. Cooper Story: Meeting the Demands | last=Krajicek | first = David | url = http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/4.html | work = [[Crime Library]] | accessdate = January 3, 2008 }}</ref>—and made a [[microfilm]] photograph of each of them.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=25}} Cooper rejected the military-issue parachutes initially offered by authorities, demanding instead civilian parachutes with manually operated [[ripcord (skydiving)|ripcord]]s. Seattle police obtained them from a local [[Parachuting|skydiving]] school.<ref name="CrimeLibrary4" /> |

|||

During the flight from Portland to Seattle, Cooper demanded Mucklow remain by his side at all times.{{r|vault_64|page=150|quote= the hijacker insisted she be physically present by his side at all times. She recalled she sat with him almost the entire time of the flight.}} She later said Cooper appeared familiar with the local terrain; while looking out the window, he remarked, "Looks like [[Tacoma, Washington|Tacoma]] down there", as the aircraft flew above it. When told the parachutes were coming from [[McChord Field|McChord Air Force Base]], Cooper correctly noted McChord was only a twenty-minute drive from Sea-Tac.{{r|vault_64|page=156|quote=She also recalled while they were in the holding pattern prior to landing, he at one time looked out the window and observed 'We're over Tacoma now' and '...she stated she recalled some conversation to the effect the parachutes were coming from McChord Air Force Base. The hijacker remarked that it was about 20 minutes from McChord to the Seattle-Tacoma Airport.'}} She later described the hijacker's demeanor: "[Cooper] was not nervous. He seemed rather nice and he was not cruel or nasty."{{r|vault_53|page=174|quote=He was not nervous. He seemed rather nice and he was not cruel or nasty.}} |

|||

While the airplane circled Seattle, Mucklow chatted with Cooper and asked why he chose Northwest Airlines to hijack. He laughed and replied, "It's not because I have a grudge against your airlines, it's just because I have a grudge," then explained the flight simply suited his needs.{{r|vault_64|quote= She asked him why he picked Northwest Airlines to hijack and he laughed and said, 'It's not because I have a grudge against your airlines, it's just because I have a grudge.' He paused and said the flight suited his time, place, and plans.|page=161}} He asked where she was from; she answered she was originally from [[Pennsylvania]], but was living in [[Minneapolis]] at the time. Cooper responded that Minnesota was "very nice country."{{r|vault_64|quote= He asked her where she was from and she told him that she was from Pennsylvania, but was living in Minneapolis, Minn. He indicated that Minneapolis, Minn., was very nice country.|page=161}} She asked where he was from, but he became upset and refused to answer.{{r|vault_64|page=160}} He asked if she smoked and offered her a cigarette. She replied she had quit, but accepted the cigarette.{{r|vault_64|quote=Other conversation centered on personal habits such as smoking and he asked her if she did and she said she used to, but had quit, and he offered her a cigarette, which she took and smoked.|page=161}} |

|||

FBI records note Cooper spoke briefly to an unidentified passenger while the airplane maintained its holding pattern over Seattle. In his interview with FBI agents, passenger George Labissoniere stated he visited the restroom directly behind Cooper on several occasions. After one visit, Labissoniere said the path to his seat was blocked by a passenger wearing a cowboy hat, questioning Mucklow about the supposed mechanical problem delaying them. Labissoniere said Cooper was initially amused by the interaction, then became irritated and told the man to return to his seat, but "the cowboy" ignored Cooper and continued to question Mucklow. Labissoniere claimed he eventually persuaded "the cowboy" to return to his seat.{{r|vault_67|quote= The cowboy was hassling Tina for information about the mechanical difficulties and generally being a nuisance. The hijacker seemed to enjoy the situation at first but told the cowboy to go back to his seat.|page=170}} |

|||

Mucklow's version of the interaction differed from Labissoniere's. She said a passenger approached her and asked for a sports magazine to read because he was bored. She and the passenger moved to an area directly behind Cooper, where they both looked for magazines. The passenger took a copy of ''[[The New Yorker]]'' and returned to his seat. When Mucklow returned to sit with Cooper, he said, "If that is a [[sky marshal]], I don't want any more of that", but she reassured him there were no sky marshals on the flight.{{r|vault_64|quote=After he was seated and Tina returned to seat 18 D, next to the hijacker, he said, 'If that is a Sky Marshal I don't want any more of that,' and she reassured him that it wasn't and further, that there were no sky marshals on that flight.|page=161}} Despite his brief interaction with Cooper, "the cowboy" was not interviewed by the FBI and was never identified.{{sfn|Edwards|2021|pp=18}} |

|||

The $200,000 ransom was received from Seattle First National Bank in a bag weighing approximately {{convert|19|lb|kg|spell=in|round=0.5}}.{{r|vault_11|quote= Seattle First National Bank, Seattle, Washington, who provided the money paid on this case advises that the money in the bag weighed nineteen pounds and the contents measured eleven inches by twelve inches by six and one half inches|page= 123}} The money—10,000 unmarked [[United States twenty dollar bill|$20 bills]], most of which had serial numbers beginning with "L" (indicating issuance by the [[Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco]]<ref>{{cite news |date=December 26, 1971 |title=Please Check Your $20 Bills, FBI Says |url=https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/d.b.-cooper-part-56/view |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220809232101/https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/d.b.-cooper-part-56/view |archive-date=August 9, 2022 |access-date=August 4, 2022 |work=Los Angeles Times}}</ref>)—was photographed on [[Microform|microfilm]] by the FBI.{{r|vault_67|quote= microfilm upon which was record[ed] the serial number[s] of all the bills...|page=101}} Seattle police obtained the two front (reserve) parachutes from a local [[skydiving]] school and the two back (main) parachutes from a local stunt pilot.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Clever |first1=Dick |title=Hijacker Hunt Near Woodland |agency=Seattle Post-Intelligencer |date=November 26, 1971}}</ref> |

|||

===Passengers released=== |

===Passengers released=== |

||

[[File:Northwest Boeing 727 airstair (1975).jpg|thumb|[[Boeing 727]] with the aft airstair open]] |

|||

At 5:24 pm Cooper was informed that his demands had been met, and at 5:39 pm the aircraft landed at Seattle-Tacoma Airport.<ref name="CrimeLibrary5">{{cite web| title = The D.B. Cooper Story: 'Everything Is Ready' | last=Krajicek | first = David | url = http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/5.html | work = [[Crime Library]] | accessdate = January 3, 2008 }}</ref> Cooper instructed Scott to taxi the jet to an isolated, brightly lit section of the [[tarmac]] and extinguish lights in the cabin to deter police snipers. Northwest Orient's Seattle operations manager, Al Lee, approached the aircraft in street clothes (to avoid the possibility that Cooper might mistake his airline uniform for that of a police officer) and delivered the cash-filled knapsack and parachutes to Mucklow via the aft stairs.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=28}} Once the delivery was completed Cooper permitted all passengers, Schaffner, and senior flight attendant Alice Hancock to leave the plane.<ref name="CrimeLibrary5" /> |

|||

Around 5:24 PST, Scott was informed the parachutes had been delivered to Sea-Tac and notified Cooper they would be landing soon. At 5:46 PST, Flight 305 landed at Sea-Tac.{{r|vault_64|quote=The Flight landed at Seattle International Airport at 5:46 Pacific time.|page= 163}} With Cooper's permission, Scott parked the aircraft on a partially-lit runway, away from the main terminal.{{r|vault_64|quote=Prior to landing, the captain wanted permission to park his aircraft away from the terminal and the hijacker said okay.|page= 163}} Cooper demanded only one representative of the airline approach the plane with the parachutes and money, and the only entrance and exit would be through the aircraft's front door via mobile stairs.{{r|vault_66|page=15|quote=He requested an unmarked car and a representative of the airline would be allowed to approach the aircraft from a ten o'clock relative position. The only other equipment to go near the aircraft was to be the air stairs and refueling equipment.}} |

|||

Northwest's Seattle operations manager, Al Lee, was designated to be the courier. To avoid the possibility Cooper might mistake Lee's airline uniform for a law enforcement officer, he changed into civilian clothes for the task.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=28}} With the passengers remaining seated, a ground crew attached a mobile stair. Per Cooper's directive, Mucklow exited the aircraft through the front door and retrieved the ransom money. When she returned, she carried the money bag past the seated passengers to Cooper in the last row.<ref>{{cite report |url=https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D.B.%20Cooper%20Part%2010/view |title=Cord Zum Spreckel FBI Interview |date=November 26, 1971 |publisher=Federal Bureau of Investigation |page=451 |quote=the blonde stewardess, who had been sitting next to the hijacker, got up and went forward and out of the forward exit of the plane. He said she returned through the same door after several minutes carrying a package which was made of off-white canvas. |access-date=October 18, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221018031102/https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D.B.%20Cooper%20Part%2010/view |archive-date=October 18, 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref>{{r|vault_64|quote=[she] departed the aircraft through the forward door as soon as the stairs were put in place.|page=163}} |

|||

Cooper then agreed to release the passengers.<ref name="vault_26"/> As they debarked, Cooper inspected the money. In an attempt to break the tension, Mucklow jokingly asked Cooper if she could have some of it. Cooper readily agreed and handed her a packet of bills, but she immediately returned the money and explained accepting gratuities was against company policy. She said Cooper had tried to tip her and the other two flight attendants earlier in the flight with money from his pocket, but they had each declined, citing the policy.{{r|vault_64|quote=[Mucklow] recalled that she, in an attempt at being humorous, stated to the hijacker while the passengers were unloading that there was obviously a lot of money in the bag and she wondered if she could have some. The hijacker immediately agreed with her suggestion and_took one package of the money, denominations unrecalled by and handed it to her. She returned the money, stating to the hijacker that she was not permitted to accept gratuities or words to that effect. In this connection recalled that at one time during the flight the hijacker had pulled some single bills from his pocket and had attempted to tip all the girls on the crew. Again they declined in compliance with company policy.|page=163}} |

|||

With the passengers safely debarked, only Cooper and the six crew members remained aboard.{{r|vault_64|quote=She also recalled that at this time all hostesses and male crew members were still aboard the aircraft.|page=153}} In accordance with Cooper's demands, Mucklow made three trips outside the aircraft to retrieve the parachutes, which she brought to him in the rear of the plane.{{r|vault_64|pages=152–153}} While Mucklow brought aboard the parachutes, Schaffner asked Cooper if she could retrieve her purse, stored in a compartment behind his seat. Cooper agreed and told her, "I won't bite you." Flight attendant Hancock then asked Cooper if the flight attendants could leave, to which he replied, "Whatever you girls would like,"<ref>{{cite report |date= November 24, 1971|title= FBI Interview with Alice Hancock, Nov 24, 1971|quote=then Mrs. Hancock went to the back of the plane and approached the hijacker and asked if the stewardesses could go and he said 'whatever you girls would like.'}}</ref>{{r|vault_64|quote=[Florence] came back to where the hijacker was seated and asked if she could get her purse and he said that she should come on back, he wouldn't bite her.|page=163}} so Hancock and Schaffner debarked. When Mucklow brought the final parachute to Cooper, she gave him printed instructions for using the parachutes, but Cooper said he didn't need them.{{r|vault_64|quote=At this point she gave him a paper sheet giving instructions on how to jump and he said he didn't need that.|page=163}} |

|||

A problem with the refueling process caused a delay, so a second truck and then a third were brought to the aircraft to complete the refueling.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=35–36}} During the delay, Mucklow said Cooper complained the money was delivered in a cloth bag instead of a knapsack as he had directed, and he now had to improvise a new way to transport the money.{{r|vault_64|quote=He appeared irritated that they did not give him a knapsack.|page=163}} Using a pocket knife, he cut the canopy from one of the reserve parachutes, and stuffed some of the money into the empty parachute bag.{{r|vault_64|quote=he was occupied with one of the parachute packs ... and attempting to in some way attach it to his body. ... Her recollections in this regard were vague.|page=155}} |

|||

An FAA official requested a face-to-face meeting with Cooper aboard the aircraft, but Cooper denied the request.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Rothenberg|first1 = David|last2=Ulvaeus|first2=Marta|title=The New Earth Reader: The Best of Terra Nova|publisher=[[MIT Press]]|year=1999|location=[[Cambridge, Massachusetts|Cambridge]], [[Massachusetts]]|page=[https://archive.org/details/newearthreaderbe0000unse/page/4 4]|isbn=978-0262181952|url=https://archive.org/details/newearthreaderbe0000unse/page/4}}</ref> Cooper became impatient, saying, "This shouldn't take so long," and, "Let's get this show on the road."<ref>{{Cite magazine |last=Elliott |first=Gina |date=December 6, 1971 |title=CRIME: The Bandit Who Went Out into the Cold |url=https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,877495,00.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240727133302/https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,877495,00.html |archive-date=July 27, 2024 |access-date= |magazine=Time |issn=0040-781X}}</ref><ref name=Caldwell1971>{{Cite news|last=Caldwell|first=Earl|date=November 26, 1971|title=Hijacker collects ransom of $200,000; parachutes from jet and disappears|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1971/11/26/archives/hijacker-collects-ransom-of-200000-parachutes-from-jet-and.html|access-date=January 13, 2022|issn=0362-4331|archive-date=October 8, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211008121340/https://www.nytimes.com/1971/11/26/archives/hijacker-collects-ransom-of-200000-parachutes-from-jet-and.html|url-status=live}}</ref> He then gave the cockpit crew his [[flight plan]] and directives: a southeast course toward [[Mexico City]] at the minimum [[airspeed]] possible without [[stall (fluid dynamics)|stalling]] the aircraft—approximately {{convert|100|kn|round=5}}—at a maximum {{convert|10000|ft|adj=on}} altitude. Cooper also specified the [[landing gear]] must remain deployed, the [[Flap (aeronautics)|wing flaps]] must be lowered 15 degrees and the cabin must remain [[cabin pressurization|unpressurized]].{{sfn|Rothenberg|Ulvaeus|1999|p=5}} |

|||

During refueling Cooper outlined his flight plan to the cockpit crew: a southeast course toward Mexico City at the minimum airspeed possible without stalling the aircraft (approximately {{convert|100|kn}}) at a maximum {{convert|10000|foot}} altitude. He further specified that the [[landing gear]] remain deployed in the takeoff/landing position, the [[Flaps (aircraft)|wing flaps]] be lowered 15 degrees, and the cabin remain [[cabin pressurization|unpressurized]].<ref>Rothenberg and Ulvaeus, p. 5.</ref> Copilot William Rataczak informed Cooper that the aircraft's range was limited to approximately {{convert|1000|mi}} under the specified flight configuration, which meant that a second refueling would be necessary before entering Mexico. Cooper and the crew discussed options and agreed on [[Reno, Nevada]], as the refueling stop.<ref name="CrimeLibrary5" /> Finally, Cooper directed that the plane take off with the rear exit door open and its staircase extended. Northwest's home office objected, on grounds that it was unsafe to take off with the aft staircase deployed. Cooper countered that it was indeed safe, but he would not argue the point; he would lower it himself once they were airborne.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=33–34}} |

|||

First Officer Rataczak informed Cooper that the configuration limited the aircraft's range to about {{convert|1000|mi}}, so a second refueling would be necessary before entering Mexico. Cooper and the crew discussed options, and agreed on [[Reno–Tahoe International Airport]] as the refueling stop.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Buergin|first=Miles|date=October 14, 2020|title=Knowing Nevada: Revisiting the Mystery of D.B. Cooper|url=https://mynews4.com/news/knowing-nevada/knowing-nevada-revisiting-the-mystery-of-db-cooper|access-date=January 13, 2022 |publisher=[[KRNV-DT|KRNV]] |archive-date=January 13, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220113212427/https://mynews4.com/news/knowing-nevada/knowing-nevada-revisiting-the-mystery-of-db-cooper|url-status=live}}</ref>{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=33–35}} Cooper further directed the aircraft take off with the rear exit door open and its [[airstair]] extended.{{sfn|Gray|2011b|pp=74–77}} Northwest officials objected for reasons of safety, but Cooper countered by saying, "It can be done, do it," but then did not insist and said he would lower the staircase once they were airborne.{{sfn|Gray|2011b|pp=74–77}} Cooper demanded Mucklow remain aboard to assist the operation.{{r|vault_64|quote=It was finally agreed...that Mucklow would remain on board to lower the door and stairs after the aircraft was airborne.|page=153}} |

|||

An FAA official requested a face-to-face meeting with Cooper aboard the aircraft, which was denied.<ref>{{cite book| last = Rothenberg| first = David |coauthors = Marta Ulvaeus | title = The New Earth Reader: The Best of Terra Nova | publisher = [[MIT Press]] | year= 1999 | location = [[Cambridge, Massachusetts|Cambridge]], [[Massachusetts]] | page = 4 | isbn = 0-262-18195-9 }}</ref> The refueling process was delayed due to a [[vapor lock]] in the fuel tanker truck's pumping mechanism,{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=32}} and Cooper became suspicious;<ref name="Gray-NYmag2007-10-21" /> but he allowed a replacement tanker truck to continue the refueling—and a third after the second ran dry.<ref name="CrimeLibrary5" /> |

|||

===Back in the air=== |

===Back in the air=== |

||

[[File:Northwest_Airlines_Flight_305_Crew.jpg|thumb|right|Crew of Flight 305 upon landing in Reno: (left to right) Captain William Scott, Co-pilot Bill Rataczak, Flight Attendant Tina Mucklow, Flight Engineer Harold E. Anderson]] |

|||

[[File:Rwr727tail.jpg|thumb|left|[[Boeing 727]] with the aft airstair open]] |

|||

Around 7:40 pm, Flight 305 took off, with only Cooper, Mucklow, Scott, Rataczak and Flight Engineer Anderson aboard.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=36}} Two [[Convair F-106 Delta Dart|F-106]] fighters from McChord Air Force Base{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=45-46}} and a [[Lockheed T-33]] trainer—diverted from an unrelated [[Air National Guard]] mission—followed the 727. All three jets maintained "S" flight patterns to stay behind the slow-moving 727,{{r|vault_53|page=141}} and out of Cooper's view. After takeoff, Cooper told Mucklow to lower the aft staircase. She told him and the flight crew she feared being sucked out of the aircraft.{{r|vault_64|quote=She told him that she was fearful of being sucked out of the airplane.|page=156}} The flight crew suggested she come to the cockpit and retrieve an emergency rope with which she could tie herself to a seat. Cooper rejected the suggestion, stating he did not want her going up front or the flight crew coming back to the cabin.{{r|vault_64|quote=The cockpit called and told her to use the escape rope to secure herself when they found out that she was going to lower the ladder once the aircraft is airborne. She related this to the hijacker and he said, 'no,' he didn't want her to go up front or them to come back.|page=164}} She continued to express her fear to him, and asked him to cut some cord from one of the parachutes to create a safety line for her. He said he would lower the stairs himself,{{r|vault_64|quote=She asked him to cut some nylon cord from the parachute for her to use as a safety line when she opened the rear ladder and the hijacker said, 'Nevermind,' that he would do it...|page=164}} instructed her to go to the cockpit, close the curtain partition between the Coach and First Class sections and not return.{{r|vault_64|quote=the hijacker suddenly told her to go forward of the aft compartment, to close the curtain behind her and not to return to the rear compartment again.|page=156}} |

|||

At approximately 7:40 pm the 727 took off with only Cooper, pilot Scott, flight attendant Mucklow, copilot Rataczak, and flight engineer H. E. Anderson aboard. Two [[F-106]] fighter aircraft scrambled from nearby McChord Air Force Base followed behind the airliner, one above it and one below, out of Cooper's view.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=36}} A [[Lockheed T-33 Shooting Star|Lockheed T-33]] trainer, diverted from an unrelated [[Air National Guard]] mission, also shadowed the 727 until it ran low on fuel and turned back near the Oregon-California border.{{sfn|Gunther|1985|p=53}} |

|||

Before she left, Mucklow begged Cooper, "Please, please take the bomb with you."<ref name="RS_Marks"/> Cooper responded that he would either disarm it or take it with him.{{r|vault_64|quote=she pleaded with him to take the bomb with him and he said he would take it with him or disarm it before he leaves.|page=164}} As she walked to the cockpit and turned to close the curtain partition, she saw Cooper standing in the aisle tying what appeared to be the money bag around his waist.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=42}}{{r|vault_64|quote="the last time she saw him he had a nylon cord tied around his waist and was standing in the isle."|page=164}} From takeoff to when Mucklow entered the cockpit, four to five minutes had elapsed. For the rest of the flight to [[Reno, Nevada|Reno]], Mucklow remained in the cockpit,{{r|vault_64|quote=Approximately four minutes after take off, he stood up, told her to go to the cockpit|page=164}} and was the last person to see Cooper. Around 8:00 pm, a cockpit warning light flashed, indicating the aft staircase had been deployed. Scott used the plane's [[intercom]] to ask Cooper if he needed assistance, but Cooper's last message{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=44}} was a one-word reply: "No."<ref name="Caldwell1971" /> The crew's ears popped from the drop in air pressure from the stairs being opened.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Perry|first=Douglas|date=November 8, 2021|title=D.B. Cooper at 50: Push to solve case gains steam, but much about famous skyjacking remains a mystery|url=https://oregonlive.com/history/2021/11/db-cooper-at-50-push-to-solve-case-gains-steam-but-much-about-famous-skyjacking-remains-a-mystery.html|url-status=live|access-date=January 13, 2022|website=[[The Oregonian]]|archive-date=January 13, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220113213031/https://www.oregonlive.com/history/2021/11/db-cooper-at-50-push-to-solve-case-gains-steam-but-much-about-famous-skyjacking-remains-a-mystery.html}}</ref> At approximately 8:13 p.m., the aircraft's tail section suddenly [[Aircraft principal axes|pitched]] upward, forcing the pilots to [[trim tab|trim]] and return the aircraft to level flight.{{sfn|Bragg|2005|p=4}} In his interview with the FBI, Rataczak said the sudden upward pitch occurred while the flight was near the suburbs north of Portland.{{r|vault_64|quote=Rataczak stated they had not yet reached Portland proper, but were definitely in the suburbs or the immediate vicinity thereof.|page=322}} |

|||

After takeoff Cooper told Mucklow to join the rest of the crew in the cockpit and remain there with the door closed. As she complied, Mucklow observed Cooper tying something around his waist.<ref name="CrimeLibrary6">{{cite web| title = The D.B. Cooper Story: The Jump | last=Krajicek | first = David | date = | url = http://www.crimelibrary.com/criminal_mind/scams/DB_Cooper/6.html | work = [[Crime Library]] | accessdate = January 9, 2008 }}</ref> At approximately 8:00 pm a warning light flashed in the cockpit, indicating that the aft [[airstair]] apparatus had been activated. The crew's offer of assistance via the aircraft's intercom system was curtly refused.<ref name="CrimeLibrary6" /> The crew soon noticed a subjective change of air pressure, indicating that the aft door was open. |

|||

With the aft cabin door open and the staircase deployed, the flight crew remained in the cockpit, unsure if Cooper was still aboard. Mucklow used the intercom to inform Cooper they were approaching Reno and that he needed to raise the stairs so the airplane could land safely. She repeated her requests as the pilots made the final approach to land, but neither Mucklow nor the flight crew received a reply from Cooper.{{r|vault_64|quote=Before descending at Reno, Nev., she called repeatedly over the intercom system to the hijacker to cooperate, that the aircraft must land. The last message was, 'Sir, we are going to land now, please put up the stairs.'|page=164}} At 11:02 pm, with the aft staircase still deployed, Flight 305 landed at Reno–Tahoe International Airport.{{sfn|Edwards|2021|pp=42}} FBI agents, state troopers, sheriff's deputies and [[Reno Police Department|Reno police]] established a perimeter around the aircraft but, fearing the hijacker and the bomb were still aboard, did not approach the plane. Scott searched the cabin, confirmed Cooper was no longer aboard and, after a thirty-minute search, an FBI [[bomb squad]] declared the cabin safe.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=48}} |

|||

==Investigation== |

==Investigation== |

||

In addition to sixty-six [[Fingerprint|latent fingerprints]] aboard the plane,<ref name=Pasternak2000/> FBI agents recovered Cooper's black clip-on tie, tie clip and two of the four parachutes,{{efn|name=parachutes}} one of which had been opened and had three [[shroud line]]s cut from the canopy.<ref>{{cite news| title = F.B.I. reheats cold case | work = [[National Post]] | last = Cowan | first = James | date = January 3, 2008 | url = https://nationalpost.com/news/story.html?id=211616 | archive-url = https://archive.today/20080121231748/http://www.nationalpost.com/news/story.html?id=211616 | url-status = dead | archive-date = January 21, 2008 | access-date = January 9, 2008 }}</ref> FBI agents interviewed eyewitnesses in Portland, Seattle and Reno, and developed a series of [[composite sketch]]es.<ref name=FBIVault7>{{Cite web|url=https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D-B-Cooper-Part-7-of-7/view|publisher= FBI |work=FBI Records: The Vault |title= D.B. Cooper part 07 of 67|access-date=December 1, 2016|archive-date=December 14, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161214215519/https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D-B-Cooper-Part-7-of-7/view|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

Local police and FBI agents immediately began questioning possible suspects.<ref name="fbi_famous"/> In a rush to meet a deadline, reporter James Long recorded the name "Dan Cooper" as "D. B. Cooper".<ref>{{cite web |date=July 28, 2016 |title=Reporter who added some swagger to the D.B. Cooper legacy comes clean |url=https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-db-cooper-confession-20160726-snap-story.html |website=[[Los Angeles Times]] |access-date=September 23, 2024 |archive-date=July 27, 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240727132749/https://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-db-cooper-confession-20160726-snap-story.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>Browning, W. (July 22, 2016). One mystery solved in 'D.B. Cooper' skyjacking fiasco. [https://www.cjr.org/the_feature/db_cooper_mystery_solved.php ''Columbia Journalism Review''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200930040433/https://www.cjr.org/the_feature/db_cooper_mystery_solved.php |date=September 30, 2020 }}, retrieved July 29, 2016.</ref> [[United Press International]] [[wire service]] reporter Clyde Jabin republished Long's error,<ref>Guzman, Monica (November 27, 2007). Update: Everyone wants a piece of the D. B. Cooper legend. [http://blog.seattlepi.com/thebigblog/2007/11/27/update-everyone-wants-a-piece-of-the-d-b-cooper-legend/ Seattle ''Post-Intelligencer'' archive] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303195334/http://blog.seattlepi.com/thebigblog/2007/11/27/update-everyone-wants-a-piece-of-the-d-b-cooper-legend/ |date=March 3, 2016 }} Retrieved February 25, 2011.</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.cjr.org/the_feature/db_cooper_unsolved_hijacking_mystery.php|title=A reporter's role in the notorious unsolved mystery of 'D.B. Cooper'|last=Browning|first=William|date=July 18, 2016|newspaper=[[Columbia Journalism Review]]|location=New York|access-date=July 19, 2016|archive-date=July 21, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160721103728/http://www.cjr.org/the_feature/db_cooper_unsolved_hijacking_mystery.php|url-status=live}}</ref> and as other media sources repeated the error,<ref>Contemporary stories from the AP and the UPI using the name "D. B. Cooper":<br />* {{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=vuVNAAAAIBAJ&pg=6384%2C3320413 |work=Free Lance-Star |location=(Fredericksburg, Virginia) |agency=Associated Press |last=Grossweiler |first=Ed |title=Hijacker bails out with loot |date=November 26, 1971 |page=1 |access-date=September 22, 2018 |archive-date=February 3, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210203230246/https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=vuVNAAAAIBAJ&pg=6384%2C3320413 |url-status=live }}<br />* {{cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=bTQVAAAAIBAJ&pg=1933%2C1906592 |work=The Bulletin |location=(Bend, Oregon) |agency=UPI |title=Wilderness area combed for parachute skyjacker |date=November 26, 1971 |page=1 |access-date=September 22, 2018 |archive-date=February 6, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210206125112/https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=bTQVAAAAIBAJ&pg=1933%2C1906592 |url-status=live }}</ref> the hijacker's pseudonym became "D. B. Cooper."{{sfn|Bragg|2005|p=4}} Acting on the possibility the hijacker may have used his real name (or the same [[Pseudonym|alias]] in a previous crime), Portland police discovered and interviewed a Portland citizen named D. B. Cooper. The Portland Cooper had a minor police record, but was quickly eliminated as a suspect. |

|||

Local police and FBI agents immediately began questioning possible suspects. One of the first was an Oregon man with a minor police record named D. B. Cooper, contacted by Portland police on the off-chance that the hijacker had used his real name, or the same alias in a previous crime. His involvement was quickly ruled out; but an inexperienced wire service reporter (Clyde Jabin of [[United Press International|UPI]] by most accounts,<ref>Guzman, Monica (November 27, 2007). Update: Everyone wants a piece of the D. B. Cooper legend. [http://blog.seattlepi.com/thebigblog/2007/11/27/update-everyone-wants-a-piece-of-the-d-b-cooper-legend/ Seattle ''Post-Intelligencer'' archive] Retrieved February 25, 2011.</ref> Joe Frazier of [[Associated Press|AP]] by others{{sfn|Gunther|1985|p=55}}), rushing to meet an imminent deadline, confused the eliminated suspect's name with the pseudonym used by the hijacker. The mistake was picked up and repeated by numerous other media sources, and the moniker "D. B. Cooper" became lodged in the public's collective memory.<ref name="Braggp4" /> |

|||

[[File:727db.gif|thumb| |

[[File:727db.gif|thumb|An animation of the [[Boeing 727|727]]'s rear airstair deploying in flight, with Cooper jumping off: The gravity-operated apparatus remained open until the aircraft landed.]] |

||

Due to the number of variables and parameters, precisely defining the area to search was difficult. The jet's airspeed estimates varied, the environmental conditions along the flight path varied with the aircraft's location and altitude,{{r|vault_64||page=300}} and only Cooper knew how long he remained in [[Free fall|free-fall]] before pulling his ripcord.<ref name=Caldwell1971/> The F-106 pilots neither saw anyone jumping from the airliner, nor did their radar detect a deployed parachute. A black-clad man jumping into the moonless night would be difficult to see, especially given the limited visibility, cloud cover and lack of ground lighting.<ref>{{cite news| title = D.B. Cooper legend still up in air 25 years after leap, hijackers prompts strong feelings | work = [[San Francisco Chronicle]] | last = Taylor | first = Michael | date = November 24, 1996 }}</ref> The T-33 pilots did not make visual contact with the 727.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=47}} |

|||

On December 6, 1971, [[Director of the FBI|FBI Director]] [[J. Edgar Hoover]] approved the use of an Air Force [[Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird|SR-71 Blackbird]] to retrace and photograph Flight 305's flightpath,<ref>{{cite report |date= December 6, 1971 |title= J. Edgar Hoover authorization for SR-71 use |url= https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D.B.%20Cooper%20Part%2014/view |publisher= Federal Bureau of Investigation |page= 348 |access-date= August 18, 2022 |archive-date= August 18, 2022 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20220818013610/https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D.B.%20Cooper%20Part%2014/view |url-status= live }}</ref> and attempt to locate the items Cooper carried during his jump.{{r|vault_60|page= 340 |quote= "Beale Air Force Base, California, had offered, free of charge to the Bureau, use of an SR-71 aircraft to photograph terrain over which the hijacked airplane had flown on its trip to Reno"}} The SR-71 made five flights to retrace Flight 305's route, but due to poor visibility, the photography attempts were unsuccessful.{{r|vault_60|page= 340 |quote= "photographic over-flights using SR-71 aircraft were conducted on five separate occasions with no photographs_obtained due to limited visibility from very high altitude."}} |

|||

An experimental re-creation was conducted using the same aircraft hijacked by Cooper in the same flight configuration, piloted by Scott. FBI agents, pushing a {{convert|200|lb|adj=on}} sled out of the open airstair, were able to reproduce the upward motion of the tail section described by the flight crew at 8:13 pm. Based on this experiment, it was concluded that 8:13 pm was the most likely jump time.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=80–81}} At that moment the aircraft was flying through a heavy rainstorm over the [[Lewis River (Washington)|Lewis River]] in southwestern Washington.<ref name="new" /> |

|||

Initial extrapolations placed Cooper's landing area on the southernmost outreach of [[Mount St. Helens]], a few miles southeast of [[Ariel, Washington]], near [[Lake Merwin]], an artificial lake formed by a dam on the Lewis River.<ref>{{cite news| title = 30 years ago, D.B. Cooper's night leap began a legend | work = [[Seattle Post-Intelligencer]] | last = Skolnik | first = Sam | date = November 22, 2001 | url = http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-80264926.html | |

In an experimental recreation, flying the same aircraft used in the hijacking in the same flight configuration, FBI agents pushed a {{convert|200|lb|adj=on}} sled out of the open airstair and were able to reproduce the upward motion of the tail section and brief change in cabin pressure described by the flight crew at 8:13 pm.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=80–81}}<ref>{{cite report |date= January 14, 1972|title= Seattle SAC Letter to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover |quote= "The reaction was instantaneous and was described by REDACTED as being the same reaction that they had in the airplane when they believe that the hijacker jumped." |url= https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/d.b.-cooper-part-19/view |publisher= Federal Bureau of Investigation |page= 19}}</ref> Initial extrapolations placed Cooper's landing zone within an area on the southernmost outreach of [[Mount St. Helens]], a few miles southeast of [[Ariel, Washington]], near [[Lake Merwin]], an [[artificial lake]] formed by a dam on the [[Lewis River (Washington)|Lewis River]].<ref>{{cite news| title = 30 years ago, D.B. Cooper's night leap began a legend | work = [[Seattle Post-Intelligencer]] | last = Skolnik | first = Sam | date = November 22, 2001 | url = http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-80264926.html | archive-url = https://archive.today/20120906132812/http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-80264926.html | url-status = dead | archive-date = September 6, 2012 | access-date = January 9, 2008}} {{Subscription required}}</ref> Search efforts concentrated on [[Clark County, Washington|Clark]] and [[Cowlitz County, Washington|Cowlitz]] counties, encompassing the terrain immediately south and north of the Lewis River in southwest Washington.<ref>[http://n467us.com/Data%20Files/Seamless%20Hot%20Zone%20North.jpg Topographic map, northern half of primary search area] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110714145420/http://n467us.com/Data%20Files/Seamless%20Hot%20Zone%20North.jpg |date=July 14, 2011 }} Retrieved February 25, 2011.</ref><ref>[http://n467us.com/Data%20Files/Seamless%20Hot%20Zone%20South.jpg Topographic map, southern half of primary search area] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110714145442/http://n467us.com/Data%20Files/Seamless%20Hot%20Zone%20South.jpg |date=July 14, 2011 }} Retrieved February 25, 2011.</ref> FBI agents and sheriff's deputies searched large areas of the largely forested terrain on foot and by helicopter. Door-to-door searches of local farmhouses were also performed. Other search parties ran patrol boats along Lake Merwin and [[Yale Lake]], the reservoir immediately to its east.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=67–68}} Neither Cooper nor any of the equipment he presumably carried was found.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=67–68}} |

||

Using fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters from the [[Oregon Army National Guard]], the FBI coordinated an aerial search along the entire flight path (known as [[Victor airways|Victor 23]] in U.S. aviation terminology,<ref>{{cite web|title=Aeronautical Information Manual |publisher=Federal Aviation Administration |url=http://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/aim/chap5/aim0503.html |access-date=August 10, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110721041334/http://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/aim/Chap5/aim0503.html |archive-date=July 21, 2011 |url-status=dead}}</ref> and as "Vector 23" in most Cooper {{Nowrap|literature)<ref name=Pasternak2000/><ref name=Gray2007/>}} from Seattle to Reno. Although numerous broken treetops and several pieces of plastic and other objects resembling parachute canopies were sighted and investigated, nothing relevant to the hijacking was found.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=70–71}} |

|||

Soon after the spring thaw in early 1972, teams of FBI agents aided by some 200 [[United States Army|soldiers]] from [[Fort Lewis (Washington)|Fort Lewis]], along with [[United States Air Force]] personnel, National Guardsmen, and civilian volunteers, conducted another thorough ground search of Clark and Cowlitz Counties for 18 days in March, and then another 18 days in April.{{sfn|Olson|2010|p=34}} Electronic Explorations Company, a marine-salvage firm, used a [[submarine]] to search the {{convert|200|ft|m|adj=on}} depths of Lake Merwin.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=101–104}} Two local women stumbled upon a skeleton in an abandoned structure in Clark County; it was later identified as the remains of Barbara Ann Derry, a teenaged girl who had been abducted and murdered several weeks before.{{r|vault_53|page=79}}<ref>{{Cite web|last=Red|first=Rose|date=February 16, 2008|title=Murder at Old Cedar Creek Grist Mill, Woodland, Washington – Infamous Crime Scenes|url=https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM35ZN_Murder_at_Old_Cedar_Creek_Grist_Mill_Woodland_Washington|access-date=September 27, 2020|website=Waymarking|archive-date=January 17, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210117005255/https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM35ZN_Murder_at_Old_Cedar_Creek_Grist_Mill_Woodland_Washington|url-status=live}}</ref> Ultimately, the extensive search and recovery operation uncovered no significant material evidence related to the hijacking.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=87–89}} |

|||

Based on early computer projections produced for the FBI, Cooper's drop zone was first estimated to be between Ariel dam to the north and the town of [[Battle Ground, Washington]], to the south.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=67}} In March 1972, after a joint investigation with Northwest Orient Airlines and the Air Force, the FBI determined Cooper probably jumped over the town of [[La Center, Washington]].<ref>{{cite report |url=https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/d.b.-cooper-part-74/view |title=Investigate Report sent to J. Edgar Hoover, Director, FBI |date=March 9, 1971 |publisher=Federal Bureau of Investigation |page=122 |access-date=September 5, 2022 |archive-date=September 5, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220905015702/https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/d.b.-cooper-part-74/view |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |date=February 14, 1980 |title=Hijack Probe Expands |publisher=Associated Press |agency=Spokane Chronicle |quote=... in the area near LaCenter, into which Cooper apparently parachuted.}}</ref> |

|||

===Later developments=== |

|||

Subsequent analyses called the original landing zone estimate into question: Scott, who was flying the aircraft manually because of Cooper's speed and altitude demands, later determined that his flight path was significantly farther east than initially assumed.<ref name="Seven1996-11-17" /> Additional data from a variety of sources—in particular [[Continental Airlines]] pilot Tom Bohan, who was flying four minutes behind Flight 305—indicated that the wind direction factored into drop zone calculations had been wrong, possibly by as much as 80 degrees.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=111–113}} This and other supplemental data suggested that the actual drop zone was probably south-southeast of the original estimate, in the drainage area of the [[Washougal River]].{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=114–116}} |

|||

In 2019, the FBI released a report detailing the burglary of a grocery store, about three hours after Cooper jumped, near [[Heisson, Washington]]. Heisson, an [[Unincorporated area|unincorporated community]], was within the calculated drop zone Northwest Airlines presented to the FBI.{{sfn|Edwards|2021|pp=140}} In the report, the FBI noted the burglar took only survival items, such as beef jerky and gloves. However, the report notes that the burglar wore "military type boots with a corregated {{sic}} sole", while Cooper was described as wearing slip-on shoes.{{r|vault_65|page= 124|quote= "At about 11:30 pm, there was a burglary of a grocery store located roughly 10 miles south of the Dam. Survival rations were taken including beef jerky, cigarettes, gloves, etc."}}{{r|vault_65|page=69 |quote=Hijacker wore non-lace type shoes of ankle length.}} |

|||

"I have to confess," wrote retired FBI chief investigator Ralph Himmelsbach in his 1986 book, "if I [were] going to look for Cooper, I would head for the Washougal."{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=115}} The Washougal Valley and its surroundings have been searched by multiple private individuals and groups in subsequent years; to date, nothing directly traceable to the hijacking has been found.<ref name="Seven1996-11-17" /> |

|||

===Search for ransom money=== |

===Search for ransom money=== |

||

A month after the hijacking, the FBI distributed lists of the ransom serial numbers to financial institutions, [[casino]]s, racetracks, businesses with routine transactions involving large amounts of cash, and to law-enforcement agencies around the world. Northwest Orient offered a reward of 15% of the recovered money, to a maximum of $25,000. In early 1972, U.S. Attorney General [[John N. Mitchell]] released the serial numbers to the general public.<ref name=nymagtimeline/> Two men used counterfeit $20 bills printed with Cooper serial numbers to swindle $30,000 from a ''[[Newsweek]]'' reporter named Karl Fleming in exchange for an interview with a man they falsely claimed was the hijacker.<ref>[https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D-B-Cooper-Part-1-of-7/view FBI files on Fleming case, released via Freedom of Information Act] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161214214008/https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D-B-Cooper-Part-1-of-7/view |date=December 14, 2016 }} Retrieved February 15, 2011.</ref><ref name=Everett1972>{{cite news |last=Holles |first=Everett R. |date=November 26, 1972 |title=$200,000 hijacking by 'D. B. Cooper' is still a mystery |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1972/11/26/archives/200000-hijacking-by-d-b-cooper-is-still-a-mystery.html |work=The New York Times |access-date=February 3, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201110131455/https://www.nytimes.com/1972/11/26/archives/200000-hijacking-by-d-b-cooper-is-still-a-mystery.html |archive-date=November 10, 2020}}</ref> |

|||

In early 1973, with the ransom money still missing, ''[[The Oregon Journal]]'' republished the serial numbers and offered $1,000 to the first person to turn in a ransom bill to the newspaper or any FBI field office. In Seattle, the ''[[Seattle Post-Intelligencer|Post-Intelligencer]]'' made a similar offer with a $5,000 reward. The offers remained in effect until Thanksgiving 1974, and though several near matches were reported, no genuine bills were found.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=95}} In 1975, Northwest Orient's insurer, Global Indemnity Co., complied with an order from the [[Supreme Court of Minnesota|Minnesota Supreme Court]] and paid the airline's $180,000 ({{Inflation|US|180000|1975|fmt=eq}}) claim on the ransom money.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Northwest Airlines, Inc. v. Globe Indem. Co.|url=https://law.justia.com/cases/minnesota/supreme-court/1975/44904-1.html|access-date=January 14, 2022|website=Justia Law|language=en|archive-date=January 14, 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220114004953/https://law.justia.com/cases/minnesota/supreme-court/1975/44904-1.html|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

===Later developments=== |

|||

Analysis of the flight data indicated the first estimated location of Cooper's landing zone was inaccurate. Captain Scott—who was flying the aircraft manually because of Cooper's speed and altitude demands—determined the flight path was farther east than initially reported.<ref name=Seven1996/> Additional data provided by [[Continental Airlines]] pilot Tom Bohan—who was flying four minutes behind Flight 305—led the FBI to recalculate their estimates for Cooper's drop zone. Bohan noted the FBI's calculations for Cooper's drop zone were based on incorrectly-recorded wind direction, and therefore the FBI's estimates were inaccurate.{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=111–113}} |

|||

Based on Bohan's data and subsequent recalculations of the flight path, the FBI determined Cooper's drop zone was probably over the [[Washougal River]] [[Watershed (rivers)|watershed]].{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|pp=114–116}} In 1986, FBI Agent Ralph Himmelsbach wrote, "I have to confess, if I were going to look for Cooper... I would head for the Washougal."{{sfn|Himmelsbach|Worcester|1986|p=115}} The Washougal Valley and the surrounding areas have been repeatedly searched but no discoveries traceable to the hijacking have been reported,<ref name=Seven1996/> and the FBI believes any remaining physical clues were probably destroyed in the [[1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens]].<ref>Connolly, P. (November 24, 1981). D.B. Cooper: A stupid rascal. [https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19811124&id=IfpNAAAAIBAJ&pg=6868,4075230 ''The Free Lance-Star''] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200929072126/https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1298&dat=19811124&id=IfpNAAAAIBAJ&pg=6868,4075230 |date=September 29, 2020 }}, retrieved June 29, 2016.</ref> |

|||

===Investigation suspended=== |

|||

On July 8, 2016, the FBI announced active investigation of the Cooper case was suspended, citing the need to deploy investigative resources and manpower on issues of greater and more urgent priority. Local field offices would continue to accept any legitimate physical evidence, related specifically to the parachutes or to the ransom money. The 66-volume case file compiled during the 45-year course of the investigation would be preserved for historical purposes at [[FBI headquarters]] in [[Washington, D.C.]], and on the FBI website. All of the evidence is open to the public.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20|title=DB Cooper Vault|publisher=[[Federal Bureau of Investigation]]|access-date=July 26, 2018|archive-date=July 27, 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180727084915/https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.fbi.gov/seattle/press-releases/2016/update-on-investigation-of-1971-hijacking-by-d.b.-cooper|title=Update on Investigation of 1971 Hijacking by D.B. Cooper|publisher=[[Federal Bureau of Investigation]]|access-date=July 12, 2016|archive-date=July 12, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160712215844/https://www.fbi.gov/seattle/press-releases/2016/update-on-investigation-of-1971-hijacking-by-d.b.-cooper|url-status=live}}</ref> The crime remains the only documented unsolved case of [[air piracy]] in commercial aviation history.<ref>{{cite news |last=Gulliver |first=Katrina |author-link=Katrina Gulliver |date=December 22, 2021 |title=D.B. Cooper's skyjacking continues to fascinate Americans half a century later |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/12/22/db-coopers-skyjacking-continues-fascinate-americans-half-century-later/ |newspaper=[[The Washington Post]] |access-date=February 3, 2022 |archive-date=December 22, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211222153021/https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2021/12/22/db-coopers-skyjacking-continues-fascinate-americans-half-century-later/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

==Physical evidence== |

|||

During their forensic search of the aircraft, FBI agents found four major pieces of evidence, each with a direct physical link to Cooper: a black clip-on tie, a mother-of-pearl tie clip, a hair from Cooper's headrest, and eight filter-tipped Raleigh cigarette butts from the armrest ashtray. |

|||

===Clip-on necktie=== |

|||

FBI agents found a black clip-on necktie in seat 18-E, where Cooper had been seated. Attached to the tie was a gold tie-clip with a circular mother-of-pearl setting in the center of the clip.{{r|vault_64|page=124|quote="On the seat numbered 18E a black clip-on tie was observed. This black tie contained a tie clasp, yellow gold in color. with a white pearl circular stone in the center." }} The FBI determined the tie had been sold exclusively at [[JCPenney]] department stores, but had been discontinued in 1968.<ref>{{cite report|title= Letter to Director of FBI|date= February 24, 1972|url= https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D.B.%20Cooper%20Part%2022/view|publisher= Federal Bureau of Investigation|page= 355|access-date= February 8, 2023|archive-date= March 6, 2023|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20230306114245/https://vault.fbi.gov/D-B-Cooper%20/D.B.%20Cooper%20Part%2022/view|url-status= live}}</ref> |

|||