Immigration: Difference between revisions

→See also: Skilled worker#Migration |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Movement of people into another country or region to which they are not native }} |

|||

{{Distinguish|Emigration}} |

|||

{{About||the practice of checking travellers' documents when entering a country|border control|the album by Show-Ya|Immigration (album)}} |

|||

{{Distinguish|emigration|Migration (disambiguation){{!}}migration}} |

|||

{{Redirect|Immigrant}} |

{{Redirect|Immigrant}} |

||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

{{about||the album by Show-Ya|Immigration (album)}} |

|||

{{update|date=August 2011}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=November 2019}} |

|||

[[File:Net migration rate world.PNG|thumb|right|330px|[[Net migration rate]]s for 2011: positive (blue), negative (orange), stable (green), and no data (gray)]] |

|||

[[File:Net Migration Rate, Population Reference Bureau, Current.svg|thumb|right|upright=1.5|[[Net migration rate]]s per 1,000 people in 2023. On net people travel from redder countries to bluer countries.]] |

|||

{{legal status}} |

|||

{{legal status of persons}} |

|||

'''Immigration''' is the international movement of people to a destination [[country]] of which they are not usual residents or where they do not possess [[nationality]] in order to settle as [[Permanent residency|permanent residents]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/immigration|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131105204641/http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/immigration|url-status=dead|archive-date=5 November 2013|title=immigration|publisher=Oxford University Press|website=OxfordDictionaries.com|access-date=11 May 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/immigration| title=immigrate|publisher=Merriam-Webster, In.|website=Merriam-Webster.com|access-date=27 March 2014}}</ref><ref name="RCUK">{{cite web|title=Who's who: Definitions|url=http://www.refugeecouncil.org.uk/policy_research/the_truth_about_asylum/the_facts_about_asylum |publisher=Refugee Council|location=London, England|year=2016|access-date= 7 September 2015}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |date=2019-06-19 |title=International Migration Law No. 34 – Glossary on Migration |url=https://publications.iom.int/books/international-migration-law-ndeg34-glossary-migration |journal=[[International Organization for Migration]] |language=en |pages= |issn=1813-2278}}</ref> [[Commuting|Commuters]], [[Tourism|tourists]], and other short-term stays in a destination country do not fall under the definition of immigration or migration; [[Seasonal industry|seasonal labour]] immigration is sometimes included, however. |

|||

As for economic effects, research suggests that migration is beneficial both to the receiving and sending countries.<ref>{{Citation|last1=Koczan|first1=Zsoka|chapter=Migration|date=2021|title=How to Achieve Inclusive Growth|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-284693-8|last2=Peri|first2=Giovanni|last3=Pinat|first3=Magali|last4=Rozhkov|first4=Dmitriy |editor=Valerie Cerra |editor2=Barry Eichengreen |editor3=Asmaa El-Ganainy |editor4=Martin Schindler |doi=10.1093/oso/9780192846938.003.0009|chapter-url=https://oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/oso/9780192846938.001.0001/oso-9780192846938-chapter-9|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="di GiovanniLevchenko2015">{{Cite journal | last1 = di Giovanni | first1 = Julian|last2=Levchenko|first2=Andrei A.|last3=Ortega|first3=Francesc|date=1 February 2015|title=A Global View of Cross-Border Migration|journal=Journal of the European Economic Association|volume=13|issue=1|pages=168–202|doi=10.1111/jeea.12110|issn=1542-4774|hdl=10230/22196| s2cid = 3465938| url = https://econ-papers.upf.edu/papers/1414.pdf}}</ref><ref name="WorldBank2016" /> Research, with few exceptions, finds that immigration on average has positive economic effects on the native population, but is mixed as to whether low-skilled immigration adversely affects underprivileged natives.<ref name="CardDustmann2012">{{Cite journal | last1 = Card | first1 = David|last2=Dustmann|first2=Christian|last3=Preston|first3=Ian|date=1 February 2012|title=Immigration, Wages, and Compositional Amenities|journal=Journal of the European Economic Association|volume=10|issue=1|pages=78–119|doi=10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01051.x| s2cid = 154303869|issn=1542-4774| url = http://www.nber.org/papers/w15521.pdf}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=The economics of immigration: theory and policy | last1 = Bodvarsson | first1 = Örn B|last2=Van den Berg|first2=Hendrik|year=2013|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-1-4614-2115-3|location=New York; Heidelberg [u.a.]|page=157|oclc = 852632755}}</ref><ref name="IGM Forum">{{cite web|url=http://www.igmchicago.org/surveys/migration-within-europe|title=Migration Within Europe {{!}} IGM Forum|website=www.igmchicago.org|access-date=7 December 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.igmchicago.org/igm-economic-experts-panel/poll-results?SurveyID=SV_0JtSLKwzqNSfrAF|title=Poll Results {{!}} IGM Forum|website=www.igmchicago.org|access-date=19 September 2015}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.igmchicago.org/igm-economic-experts-panel/poll-results?SurveyID=SV_5vuNnqkBeAMAfHv|title=Poll Results {{!}} IGM Forum|website=www.igmchicago.org|access-date=19 September 2015}}</ref> Studies suggest that the elimination of barriers to migration would have profound effects on world [[Gross domestic product|GDP]], with estimates of gains ranging between 67 and 147 percent for the scenarios in which 37 to 53 percent of the developing countries' workers migrate to the developed countries.<ref name="Iregui2003">{{Cite journal | last1 = Iregui | first1 = Ana Maria|date=1 January 2003|title=Efficiency Gains from the Elimination of Global Restrictions on Labour Mobility: An Analysis using a Multiregional CGE Model |journal=Wider Working Paper Series |url=https://ideas.repec.org/p/unu/wpaper/dp2003-27.html}}</ref><ref name="Clemens2011">{{Cite journal | last1 = Clemens | first1 = Michael A|date=1 August 2011|title=Economics and Emigration: Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk?|journal=Journal of Economic Perspectives|volume=25|issue=3|pages=83–106|doi=10.1257/jep.25.3.83| s2cid = 59507836|issn=0895-3309}}</ref><ref name="HamiltonWhalley1984">{{Cite journal | last1 = Hamilton | first1 = B.|last2=Whalley|first2=J.|date=1 February 1984|title=Efficiency and distributional implications of global restrictions on labour mobility: calculations and policy implications|journal=Journal of Development Economics|volume=14|issue=1–2|pages=61–75|doi=10.1016/0304-3878(84)90043-9|issn=0304-3878|pmid=12266702}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Dustmann|first1=Christian|last2=Preston|first2=Ian P.|date=2019-08-02|title=Free Movement, Open Borders, and the Global Gains from Labor Mobility|journal=Annual Review of Economics|language=en|volume=11|issue=1|pages=783–808|doi=10.1146/annurev-economics-080218-025843|issn=1941-1383|doi-access=free}}</ref> Some [[Development economics|development economists]] argue that reducing barriers to labor mobility between developing countries and developed countries would be one of the most efficient tools of poverty reduction.<ref name="Milanovic2015">{{Cite journal | last1 = Milanovic | first1 = Branko|date=7 January 2014|title=Global Inequality of Opportunity: How Much of Our Income Is Determined by Where We Live?|journal=Review of Economics and Statistics|volume=97|issue=2|pages=452–460|doi=10.1162/REST_a_00432|issn=0034-6535| hdl = 10986/21484| s2cid = 11046799|hdl-access=free}}</ref><ref name="Mishra2014">{{Cite book |last1=Mishra|first1=Prachi |chapter=Emigration and wages in source countries: A survey of the empirical literature |title= International Handbook on Migration and Economic Development |pages=241–266|doi=10.4337/9781782548072.00013 |isbn=978-1-78254-807-2|date=2014|publisher=Edward Elgar Publishing|s2cid=143429722}}</ref><ref name="Clemens-2019">{{cite journal|last1=Clemens|first1=Michael A.|last2=Pritchett|first2=Lant|date=2019|title=The New Economic Case for Migration Restrictions: An Assessment|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304387818306382|journal=Journal of Development Economics|volume=138|language=en|issue=9730|pages=153–164|doi=10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.12.003|s2cid=204418677| issn = 0304-3878}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Pritchett|first1=Lant|last2=Hani|first2=Farah|date=2020-07-30|title=The Economics of International Wage Differentials and Migration|url=https://oxfordre.com/economics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.001.0001/acrefore-9780190625979-e-353|access-date=2020-08-11|series=Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance|language=en|doi=10.1093/acrefore/9780190625979.013.353|isbn=978-0-19-062597-9}}</ref> Positive net immigration can soften the demographic dilemma{{Clarify|reason=what's a demographic dilemma? suggest wikilinking to something|date=November 2024}} in the aging global North.<ref>{{cite web|last=Peri|first=Giovanni|title=Can Immigration Solve the Demographic Dilemma?|url=https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2020/03/can-immigration-solve-the-demographic-dilemma-peri.htm|access-date=2020-07-16|website=www.imf.org|publisher=IMF|language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |last=Harvey |first=Fiona |author-link=Fiona Harvey |date=2020-07-15 |title=World population in 2100 could be 2 billion below UN forecasts, study suggests |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/jul/15/world-population-in-2100-could-be-2-billion-below-un-forecasts-study-suggests |access-date=2020-07-16 |work=The Guardian |language=en-GB |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> |

|||

'''Immigration''' is the movement of people into a different country in order to settle there.<ref>[http://www.thefreedictionary.com/immigration Definition of immigration by the Free Online Dictionary]</ref> Immigration is made for many reasons, including temperature, breeding, economic, political, family re-unification, natural disaster, poverty or the wish to change one's surroundings voluntarily. |

|||

The academic literature provides mixed findings for the relationship between [[immigration and crime]] worldwide, but finds for the [[Immigration and crime in the United States|United States]] that immigration either has no impact on the crime rate or that it reduces the crime rate.<ref name="NASEM-2015">{{Cite book |date=2015|title=The Integration of Immigrants into American Society|url=https://www.nap.edu/read/21746/chapter/9#326|language=en|publisher=National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine|doi=10.17226/21746|quote=Americans have long believed that immigrants are more likely than natives to commit crimes and that rising immigration leads to rising crime... This belief is remarkably resilient to the contrary evidence that immigrants are in fact much less likely than natives to commit crimes.|isbn=978-0-309-37398-2}}</ref><ref name="Lee-2009">{{cite book|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WtYEoD4u9RYC|title=Immigration, Crime and Justice|author1=Lee, Matthew T.|author2=Martinez Jr., Ramiro|publisher=Emerald Group Publishing|year=2009|isbn=978-1-84855-438-2|pages=3–16|chapter=Immigration reduces crime: an emerging scholarly consensus}}</ref> Research shows that country of origin matters for speed and depth of immigrant assimilation, but that there is considerable assimilation overall for both first- and second-generation immigrants.<ref name="VillarrealTamborini2018">{{Cite journal|title=Immigrants' Economic Assimilation: Evidence from Longitudinal Earnings Records|journal=American Sociological Review|volume=83|issue=4|pages=686–715|doi=10.1177/0003122418780366|pmid=30555169|pmc=6290669|year=2018|last1=Villarreal|first1=Andrés|last2=Tamborini|first2=Christopher R.}}</ref><ref name="Blau2015">{{Cite journal | last1 = Blau | first1 = Francine D.|date=2015|title=Immigrants and Gender Roles: Assimilation vs. Culture|journal=IZA Journal of Migration|volume=4|issue=1|pages=1–21|doi=10.1186/s40176-015-0048-5 | s2cid = 53414354|url=http://www.iza.org/conference_files/amm2014/blau_f340.pdf |access-date=13 October 2018| doi-access = free}}</ref> |

|||

==Statistics== |

|||

[[File:Multilingual Pisnice 1858.JPG|thumb|The largest [[Vietnamese people in the Czech Republic|Vietnamese]] market in [[Prague]], also known as "Little Hanoi". In 2009, there were about 70,000 Vietnamese in the [[Czech Republic]].<ref>[http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/05/world/europe/05iht-viet.html?pagewanted=2&_r=1 Crisis Strands Vietnamese Workers in a Czech Limbo]. ''The New York Times.'' 5 June 2009.</ref>]] |

|||

{{as of|2006}}, the [[International Organization for Migration]] has estimated the number of foreign migrants worldwide to be more than 200 million.<ref name="iom"/> [[Europe]] hosted the largest number of immigrants, with 70 million people in 2005.<ref name="iom"/> [[North America]], with over 45 million immigrants, is second, followed by [[Asia]], which hosts nearly 25 million. Most of today's migrant workers come from Asia.<ref name="foxnews"/> |

|||

Research has found extensive evidence of [[Discrimination based on skin color|discrimination]] against foreign-born and minority populations in criminal justice, business, the economy, housing, health care, media, and politics in the United States and Europe.<ref name="ZschirntRuedin2016">{{Cite journal | last1 = Zschirnt | first1 = Eva|last2=Ruedin|first2=Didier|date=27 May 2016|title=Ethnic discrimination in hiring decisions: a meta-analysis of correspondence tests 1990–2015|journal=Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies|volume=42|issue=7|pages=1115–1134|doi=10.1080/1369183X.2015.1133279|issn=1369-183X|hdl=10419/142176| s2cid = 10261744| url = https://zenodo.org/record/3559839}}</ref><ref name="Rich2014">{{cite journal |last1=Rich |first1=Judy |title=What Do Field Experiments of Discrimination in Markets Tell Us? A Meta Analysis of Studies Conducted since 2000 |journal=IZA Discussion Papers |date= October 2014 |issue= 8584 |url= http://www.iza.org/en/webcontent/publications/papers/viewAbstract?dp_id=8584 |access-date=24 April 2016 |language=en |ssrn=2517887}}</ref><ref name="RehaviStarr2014">{{Cite journal | last1 = Rehavi | first1 = M. Marit|last2=Starr|first2=Sonja B.|date=2014|title=Racial Disparity in Federal Criminal Sentences|journal=Journal of Political Economy|language=en|volume=122|issue=6|pages=1320–1354|doi=10.1086/677255| s2cid = 3348344|issn=0022-3808| url = https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/1414}}</ref><ref name="Enos2016">{{Cite journal | last1 = Enos | first1 = Ryan D.|date=1 January 2016|title=What the Demolition of Public Housing Teaches Us about the Impact of Racial Threat on Political Behavior|journal=American Journal of Political Science|language=en|volume=60|issue=1|pages=123–142|doi=10.1111/ajps.12156| s2cid = 51895998}}</ref> |

|||

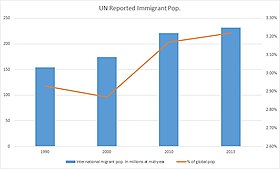

In 2005, the United Nations reported that there were nearly 191 million international migrants worldwide, about 3 percent of the world population.<ref name="nytimes"/> This represented a rise of 26 million since 1990. 60 percent of these immigrants were now in developed countries, an increase on 1990. Those in less developed countries stagnated, mainly because of a fall in refugees.<ref name="UN2006"/> Contrast that to the average rate of globalization (the proportion of cross-border trade in all trade), which exceeds 20 percent. The numbers of people living outside their country of birth is expected to rise in the future.<ref name="International Migration Report 2006"/> |

|||

== History == |

|||

The [[Midwestern United States]], some parts of Europe, some small areas of [[Southwest Asia]], and a few spots in the [[East Indies]] have the highest percentages of immigrant population recorded by the UN Census 2005. The reliability of immigrant censuses is low due to the concealed character of undocumented labor migration. |

|||

The term ''immigration'' was coined in the 17th century, referring to non-warlike population movements between the emerging [[nation state]]s. When people cross [[Border|national borders]] during their migration, they are called ''migrants'' or ''immigrants'' (from Latin: ''migrare'', 'wanderer') from the perspective of the destination country. In contrast, from the perspective of the country from which they leave, they are called ''[[Emigration|emigrants]]'' or ''outmigrants''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/outmigrant|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120718140923/http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/outmigrant|url-status=dead|archive-date=18 July 2012|title=outmigrant|website=OxfordDictionaries.com|publisher=Oxford University Press|access-date=11 May 2016}}</ref> |

|||

{{Excerpt|History of human migration}} |

|||

== Statistics == |

|||

===2012 survey===thomas is the besty in the world :3 |

|||

[[File:UN Stats.jpg|thumb|upright=1.25|left|The global population of immigrants has grown since 1990 but has remained constant at around 3% of the world's population.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates15.asp|title=United Nations Population Division {{!}} Department of Economic and Social Affairs|website=www.un.org|language=EN|access-date=28 August 2019}}</ref>]] |

|||

{{As of|2015}}, the number of international migrants has reached 244 million worldwide, which reflects a 41% increase since 2000. The largest number of international migrants live in the [[Immigration to the United States|United States]], with 19% of the world's total. One third of the world's international migrants are living in just 20 countries. [[Immigration to Germany|Germany]] and Russia host 12 million migrants each, taking the second and third place in countries with the most migrants worldwide. Saudi Arabia hosts 10 million migrants, followed by the [[Modern immigration to the United Kingdom|United Kingdom]] (9 million) and the United Arab Emirates (8 million).<ref name="UN.org-2015">{{cite web|url=https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/publications/populationfacts/docs/MigrationPopFacts20154.pdf|title=Trends in international migration, 2015 |date=December 2015|website=UN.org|publisher=[[United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs]], Population Division|access-date=16 May 2016}}</ref> |

|||

In most parts of the world, migration occurs between countries that are located within the same major area. Between 2000 and 2015, Asia added more international migrants than any other major area in the world, gaining 26 million. Europe added the second largest with about 20 million.<ref name="UN.org-2015" /> |

|||

In 2015, the number of international migrants below the age of 20 reached 37 million, while 177 million are between the ages of 20 and 64. International migrants living in Africa were the youngest, with a median age of 29, followed by Asia (35 years), and Latin America/Caribbean (36 years), while migrants were older in Northern America (42 years), Europe (43 years), and Oceania (44 years).<ref name="UN.org-2015" /> |

|||

A 2012 survey by [[The Gallup Organization|Gallup]] found roughly 640 million adults would want to migrate to another country in the world if they had the chance to.<ref>[http://www.gallup.com/poll/153992/150-Million-Adults-Worldwide-Migrate.aspx 150 Million Adults Worldwide Would Migrate to the U.S.]</ref> Nearly one-quarter (23%) of these respondents, which translates to more than 150 million adults worldwide, named the United States as their desired future residence, while an additional 7% of respondents, representing an estimated 45 million, chose the United Kingdom. The other top desired destination countries (those where an estimated 25 million or more adults would like to go) were Canada, France, Saudi Arabia, Australia, Germany and Spain. |

|||

[[File:Migrants in the world 2015-en.svg|thumb|upright=1.25|The number of migrants and migrant workers per country in 2015]] |

|||

See also article on remigration (by Gürkan Çelik) in [http://www.turkishreview.org/tr/newsDetail_getNewsById.action?newsId=223107 Turkish Review: Turkey Pulls, The Netherlands Pushes?] An increasing number of Turks, the Netherlands’ largest ethnic minority, are beginning to return to Turkey, taking with them the education and skills they have acquired abroad, as the Netherlands faces challenges from economic difficulties, social tension and increasingly powerful far-right parties. At the same time Turkey’s political, social and economic conditions have been improving, making returning home all the more appealing for Turks at large (pp. 94–99). |

|||

Nearly half (43%) of all international migrants originate in Asia, and Europe was the birthplace of the second largest number of migrants (25%), followed by Latin America (15%). [[Indian diaspora|India]] has the largest diaspora in the world (16 million people), followed by [[Mexican diaspora|Mexico]] (12 million) and [[Russian diaspora|Russia]] (11 million).<ref name="UN.org-2015" /> |

|||

=== 2012 survey === |

|||

==Understanding of immigration== |

|||

A 2012 survey by [[The Gallup Organization|Gallup]] found that given the opportunity, 640 million adults would migrate to another country, with 23% of these would-be immigrant choosing the [[United States]] as their desired future residence, while 7% of respondents, representing 45 million people, would choose the [[United Kingdom]]. [[Canada]], [[France]], [[Saudi Arabia]], [[Australia]], [[Germany]], [[Spain]], [[Italy]], and the [[United Arab Emirates]] made up the rest of the top ten desired destination countries.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gallup.com/poll/153992/150-Million-Adults-Worldwide-Migrate.aspx |title=150 Million Adults Worldwide Would Migrate to the U.S |publisher=Gallup.com |date=20 April 2012 |access-date=14 May 2014}}</ref> |

|||

=== Current === |

|||

[[File:Ridley road market dalston 1.jpg|thumb|right|[[London]] has become multiracial as a result of immigration.<ref name="fn"/> Across large parts of London, [[Black British|black]] and [[British Asian|Asian]] children outnumber White British children by about six to four in state schools.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1564365/One-fifth-of-children-from-ethnic-minorities.html |title=One fifth of children from ethnic minorities |author=Graeme Paton |date=1 October 2007|work=The Daily Telegraph|accessdate=7 June 2008 | location=London| ref=harv| archiveurl = http://www.webcitation.org/5hYR0tUao | archivedate = 15 June 2009| deadurl=no}}</ref>]] |

|||

[[File:1990- Growth in share of population that is foreign-born - by country.svg|upright=1.3|thumb |In recent decades, immigration to nearly every Western country has risen sharply.<ref name=NYTimes_20240612>{{cite news |last1=Leonhardt |first1=David |title=The Force Shaping Western Politics |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/12/briefing/immigration-european-us-elections.html |newspaper=The New York Times |date=12 June 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240612124539/https://www.nytimes.com/2024/06/12/briefing/immigration-european-us-elections.html |archive-date=12 June 2024 |url-status=live }}</ref> The slopes of the tops of the differently-colored columns show the rate of percent increase in foreign-born people living in the respective countries.]] |

|||

In USA there were in 2023 1,197,254 immigration applications initial receipts, 523,477 immigration cases completed, and 2,464,021 immigration cases pending according to the U.S. Department of Justice.<ref>[https://www.justice.gov/d9/pages/attachments/2020/01/31/1_pending_new_receipts_and_total_completions.pdf Pending Cases, New Cases and Total Completions, Executive Office For Immigration Review, Adjuction Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice]</ref> |

|||

== Push and pull factors of immigration == |

|||

One theory of immigration distinguishes between Push and Pull.<ref name="knaw"/> Push factors refer primarily the motive for immigration from the country of origin. In the case of economic migration (usually labor migration), differentials in [[wage rate]]s are usual. If the value of wages in the new country surpasses the value of wages in one’s native country, he or she may choose to migrate as long as the costs are not too high. Particularly in the 19th century, economic expansion of the U.S. increased immigrant flow, and in effect, nearly 20% of the population was [[foreign born]] versus today’s values of 10%, making up a significant amount of the labor force. Poor individuals from less developed countries ''can'' have far higher standards of living in developed countries than in their originating countries. The cost of emigration, which includes both the explicit costs, the ticket price, and the implicit cost, lost work time and loss of community ties, also play a major role in the pull of emigrants away from their native country. As transportation technology improved, travel time and costs decreased dramatically between the 18th and early 20th century. Travel across the Atlantic used to take up to 5 weeks in the 18th century, but around the time of the 20th century it took a mere 8 days.<ref name="autogenerated2"/> When the [[opportunity cost]] is lower, the immigration rates tend to be higher.<ref name=autogenerated2 /> Escape from [[poverty]] (personal or for relatives staying behind) is a traditional push factor, the availability of [[employment|jobs]] is the related pull factor. [[Natural disasters]] can amplify poverty-driven migration flows. This kind of migration may be [[illegal immigration]] in the destination country. |

|||

[[File:Multilingual Pisnice 1858.JPG|thumb|The largest [[Vietnamese people in the Czech Republic|Vietnamese]] market in [[Prague]], also known as "Little Hanoi". In 2009, there were about 70,000 Vietnamese in the [[Czech Republic]].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/05/world/europe/05iht-viet.html?pagewanted=2&_r=1 |title=Crisis Strands Vietnamese Workers in a Czech Limbo|work=The New York Times|date= 5 June 2009|access-date= 11 May 2016|last1=Bilefsky|first1=Dan}}</ref>]] |

|||

[[File:Harmony Day (5475046781).jpg|thumb|250px|Managed by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship (DIAC), [[Harmony Day]] is intended to celebrate the cohesive and inclusive nature of [[Australia]] and promote a tolerant and culturally diverse society.]] |

|||

[[File:Ridley road market dalston 1.jpg|thumb|right|[[London]] has become multiethnic as a result of immigration.<ref name="FT1">"[http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/4bd95562-4379-11e2-a48c-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2K2fk6vxN White ethnic Britons in minority in London]". ''[[Financial Times]]''. 11 December 2012.</ref> |

|||

Emigration and immigration are sometimes mandatory in a contract of employment: religious [[Missionary|missionaries]], and employees of [[transnational corporations]], international [[non-governmental organizations]] and the [[diplomatic service]] expect, by definition, to work 'overseas'. They are often referred to as '[[expatriates]]', and their conditions of employment are typically equal to or better than those applying in the host country (for similar work). |

|||

In London in 2008, [[Black British]] and [[British Asian]] children outnumbered white British children by about 3 to 2 in government-run schools.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1564365/One-fifth-of-children-from-ethnic-minorities.html |title=One fifth of children from ethnic minorities |author=Graeme Paton |date=1 October 2007 |work=The Daily Telegraph |access-date=7 June 2008 |location=London |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081206094854/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1564365/One-fifth-of-children-from-ethnic-minorities.html |archive-date=6 December 2008 |url-status=live }}</ref>]] |

|||

One theory of immigration distinguishes between ''[[push and pull factors]]'', referring to the economic, political, and social influences by which people migrate from or to specific countries.<ref name="knaw" /> Immigrants are motivated to leave their former countries of citizenship, or habitual residence, for a variety of reasons, including: a lack of local access to [[resources]], a desire for economic [[prosperity]], to find or engage in paid work, to better their [[standard of living]], [[family reunification]], [[retirement]], [[Environmental migrant|climate or environmentally induced]] migration, [[exile]], escape from [[prejudice]], conflict or natural disaster, or simply the wish to change one's [[quality of life]]. [[Commuting|Commuters]], [[Tourism|tourists]], and other short-term stays in a destination country do not fall under the definition of immigration or migration; [[Seasonal industry|seasonal labour]] immigration is sometimes included, however. |

|||

For some migrants, [[education]] is the primary pull factor (although most [[international students]] are not classified as immigrants). [[Retirement]] migration from rich countries to lower-cost countries with better [[climate]] is a new type of international migration. Examples include immigration of retired [[United Kingdom|British]] citizens to [[Spain]] or [[Italy]] and of retired [[Canadian]] citizens to the [[United States|U.S.]] (mainly to the U.S. states of [[Florida]] and [[Texas]]). |

|||

'''Push factors''' (or determinant factors) refer primarily to the motive for leaving one's country of origin (either [[Human migration#Voluntary migration|voluntarily or involuntarily]]), whereas '''pull factors''' (or attraction factors) refer to one's motivations behind or the encouragement towards immigrating to a particular country. |

|||

Non-economic push factors include [[persecution]] (religious and otherwise), frequent abuse, [[bullying]], [[oppression]], [[ethnic cleansing]] and even [[genocide]], and risks to civilians during [[war]]. Political motives traditionally motivate refugee flows—to escape [[dictatorship]] for instance. |

|||

In the case of economic migration (usually labor migration), differentials in [[wage rate]]s are common. If the value of wages in the new country surpasses the value of wages in one's native country, he or she may choose to migrate, as long as the costs are not too high. Particularly in the 19th century, economic expansion of the US increased immigrant flow, and nearly 15% of the population was [[foreign-born]],<ref>{{cite web|url = https://immigrationlawnj.com/how-many-people-are-immigrants/|title = How Many People are Immigrants?|date = 4 July 2015|access-date = 30 July 2015|website = Harlan York and Associates|last1 = York|first1 = Harlan|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150909231007/https://immigrationlawnj.com/how-many-people-are-immigrants/|archive-date = 9 September 2015|url-status = dead}}</ref> thus making up a significant amount of the labor force. |

|||

Some migration is for personal reasons, based on a [[Interpersonal relationship|relationship]] (e.g. to be with family or a partner), such as in [[family reunification]] or [[transnational marriage]] (especially in the instance of a [[gender imbalance]]). In a few cases, an individual may wish to immigrate to a new country in a form of transferred [[patriotism]]. Evasion of [[criminal justice]] (e.g. avoiding [[arrest]]) is a personal motivation. This type of emigration and immigration is not normally legal, if a crime is internationally recognized, although criminals may disguise their identities or find other loopholes to evade detection. There have been cases, for example, of those who might be guilty of war crimes disguising themselves as victims of war or conflict and then pursuing asylum in a different country. |

|||

As transportation technology improved, travel time, and costs decreased dramatically between the 18th and early 20th century. Travel across the Atlantic used to take up to 5 weeks in the 18th century, but around the time of the 20th century it took a mere 8 days.<ref name="autogenerated2" /> When the [[opportunity cost]] is lower, the immigration rates tend to be higher.<ref name=autogenerated2 /> Escape from [[poverty]] (personal or for relatives staying behind) is a traditional push factor, and the availability of [[employment|jobs]] is the related pull factor. [[Natural disasters]] can amplify poverty-driven migration flows. Research shows that for middle-income countries, higher temperatures increase emigration rates to urban areas and to other countries. For low-income countries, higher temperatures reduce emigration.<ref name="CattaneoPeri2016">{{Cite journal|title = The Migration Response to Increasing Temperatures | first1 = Cristina | last1 = Cattaneo|first2 = Giovanni|last2 = Peri |year=2016 |journal=[[Journal of Development Economics]] |volume=122 |issue=C |pages=127–146 |doi=10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.05.004 |hdl = 10419/130264| url = http://www.nber.org/papers/w21622.pdf }}</ref> |

|||

Barriers to immigration come not only in legal form; natural and social barriers to immigration can also be very powerful. Immigrants when leaving their country also leave everything familiar: their family, friends, support network, and culture. They also need to liquidate their assets often at a large loss,{{Citation needed|date=April 2011}} and incur the expense of moving. When they arrive in a new country this is often with many uncertainties including finding work, where to live, new laws, new cultural norms, language or accent issues, possible [[racism]] and other exclusionary behavior towards them and their family. These barriers act to limit international migration (scenarios where populations move ''en masse'' to other continents, creating huge population surges, and their associated strain on infrastructure and services, ignore these inherent limits on migration.) |

|||

[[File:Cizov opona.JPG|thumb|260px|The [[Iron Curtain]] in Europe was designed as a means of [[Eastern Bloc emigration and defection|preventing emigration]]. "It is one of the ironies of post-war European history that, once the freedom to travel for [[Europeans]] living under communist regimes, which had long been demanded by the West, was finally granted in 1989/90, travel was very soon afterwards made much more difficult by the West itself, and new barriers were erected to replace the Iron Curtain." —Anita Böcker<ref>Anita Böcker (1998) [http://books.google.com/books?id=ejOg0L5pbHUC&pg=&dq&hl=en#v=onepage&q=&f=false ''Regulation of migration: international experiences'']. Het Spinhuis. p.218. ISBN 90-5589-095-2</ref>]] |

|||

The politics of immigration have become increasingly associated with other issues, such as [[national security]], [[terrorism]], and in western Europe especially, with the presence of [[Islam]] as a new major religion. Those with security concerns cite the [[2005 civil unrest in France]] that point to the [[Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy]] as an example of the value conflicts arising from immigration of [[Muslims in Western Europe]]. Because of all these associations, immigration has become an emotional political issue in many European nations.{{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} |

|||

Emigration and immigration are sometimes mandatory in a contract of employment: religious [[Missionary|missionaries]] and employees of [[transnational corporations]], international [[non-governmental organizations]], and the [[diplomatic service]] expect, by definition, to work "overseas". They are often referred to as "[[expatriates]]", and their conditions of employment are typically equal to or better than those applying in the host country (for similar work).{{citation needed|date=August 2017}} |

|||

Studies have suggested that some [[special interest group]]s [[Lobbying|lobby]] for less immigration for their own group and more immigration for other groups since they see effects of immigration, such as increased labor competition, as detrimental when affecting their own group but beneficial when affecting other groups. A 2010 European study suggested that "that employers are more likely to be pro-immigration than employees, provided that immigrants are thought to compete with employees who are already in the country. Or else, when immigrants are thought to compete with employers rather than employees, employers are more likely to be anti-immigration than employees."<ref name="ssrn"/> A 2011 study examining the voting of US representatives on migration policy suggests that "that representatives from more skilled labor abundant districts are more likely to support an open immigration policy towards the unskilled, whereas the opposite is true for representatives from more unskilled labor abundant districts."<ref name="jpubeco"/> |

|||

Non-economic push factors include [[persecution]] (religious and otherwise), frequent abuse, [[bullying]], [[oppression]], [[ethnic cleansing]], [[genocide]], risks to civilians during [[war]], and social marginalization.<ref>{{cite journal|ssrn=224241|title=The Earnings of Male Hispanic Immigrants in the United States | last1 = Chiswick | first1 = Barry|date=March 2000|website=Social Science Research Network|publisher=[[University of Illinois at Chicago]] Institute for the Study of Labor|type=Working paper}}</ref> Political motives traditionally motivate refugee flows; for instance, people may emigrate in order to escape a [[dictatorship]].<ref name="Borjas2016">{{Cite journal | last1 = Borjas | first1 = George J.|date=1 April 1982|title=The Earnings of Male Hispanic Immigrants in the United States |journal=Industrial & Labor Relations Review|language=en|volume=35|issue=3|pages=343–353|doi=10.1177/001979398203500304| s2cid = 36445207|issn=0019-7939}}</ref> |

|||

Another contributing factor may be lobbying by earlier immigrants. The Chairman for the US Irish Lobby for Immigration Reform which lobby for more permissive rules for immigrants, as well as special arrangements just for Irish, has stated that "the Irish Lobby will push for any special arrangement it can get — 'as will every other ethnic group in the country.'"<ref name="irishlobbyusa"/><ref name="nclr"/> |

|||

Some migration is for personal reasons, based on a [[Interpersonal relationship|relationship]] (e.g. to be with family or a partner), such as in [[family reunification]] or [[transnational marriage]] (especially in the instance of a [[gender imbalance]]). Recent research has found gender, age, and cross-cultural differences in the ownership of the idea to immigrate.<ref name="Rubin2013">{{cite journal |last1= Rubin|first1=Mark|title="It Wasn't My Idea to Come Here!": Young Women Lack Ownership of the Idea to Immigrate – Mark Rubin's Social Psychology Research|journal=International Journal of Intercultural Relations|date=July 2013|volume=37|issue=4|pages=497–501|issn=0147-1767|doi=10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.02.001 |hdl=1959.13/940579 |url=https://sites.google.com/site/markrubinsocialpsychresearch/-it-wasn-t-my-idea-to-come-here-young-women-lack-ownership-of-the-idea-to-immigrate |access-date=3 October 2018 |ref=Rubin2013}}</ref> In a few cases, an individual may wish to immigrate to a new country in a form of transferred [[patriotism]]. Evasion of [[criminal justice]] (e.g., avoiding [[arrest]]) is a personal motivation. This type of emigration and immigration is not normally legal, if a crime is internationally recognized, although criminals may disguise their identities or find other loopholes to evade detection. For example, there have been reports of [[war criminals]] disguising themselves as victims of war or conflict and then pursuing asylum in a different country.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://euobserver.com/opinion/125664|title=EU asylum and war criminals: No place to hide | last1 = Haskell | first1 = Leslie|date=18 September 2014|website=EUobserver.com|publisher=EUobserver|access-date=13 May 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dw.com/en/refugees-in-germany-reporting-dozens-of-war-crimes/a-19179291|title=Refugees in Germany reporting dozens of war crimes | last1 = Knight | first1 = Ben|date=11 April 2016|website=Deutsche Welle|access-date=13 May 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/sweden-syrian-asylum-seeker-suspected-war-crimes-under-assad-regime-arrested-stockholm-1546149|title=Sweden: Syrian asylum seeker suspected of war crimes under Assad regime arrested in Stockholm | last1 = Porter | first1 = Tom|date=26 February 2016|work=International Business Times|access-date=13 May 2016}}</ref> |

|||

===Region-specific factors for immigration=== |

|||

As a principle, citizens of one member nation of the [[European Union]] are allowed to work in other member nations with little to no restriction on movement.<ref name="Eures - Free Movement"/> This is aided by the [[EURES]] network which brings together the [[European Commission]] and the public employment services of the countries belonging to the [[European Economic Area]] and [[Switzerland]]. For non-EU-citizen permanent residents in the EU, movement between EU-member states is considerably more difficult. After 155 new waves of accession to the European Union, earlier members have often introduced measures to restrict participation in "their" labour markets by citizens of the new EU-member states. For instance, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal and Spain each restricted their labor market for up to seven years both in the 2004 and 2007 round of accession.<ref name="migration_information"/> |

|||

[[File:Boat People at Sicily in the Mediterranean Sea.jpg|thumb|North African immigrants near the Italian island of [[Sicily]]]] |

|||

Due to the European Union's—in principle—single internal labour market policy, countries such as [[Italy]] and the [[Republic of Ireland]] that have seen relatively low levels of labour immigration until recently (and which have often sent a significant portion of their population overseas in the past) are now seeing an influx of immigrants from EU countries with lower per capita annual earning rates, triggering nationwide immigration debates.<ref name="independent"/><ref name="cicerofoundation"/> |

|||

[[Spain]], meanwhile, is seeing growing illegal immigration from [[Africa]]. As Spain is the closest EU member nation to Africa—Spain even has two autonomous cities ([[Ceuta]] and [[Melilla]]) on the African continent, as well as an autonomous community (the [[Canary Islands]]) west of North Africa, in the Atlantic—it is physically easiest for African emigrants to reach. This has led to debate both within Spain and between Spain and other EU members. Spain has asked for border control assistance from other EU states; the latter have responded that Spain has brought the wave of African illegal migrants on itself by granting amnesty to hundreds of thousands of undocumented foreigners.<ref name="BBC: EU nations clash over immigration"/> |

|||

Barriers to immigration come not only in legal form or political form; natural and social barriers to immigration can also be very powerful. Immigrants when leaving their country also leave everything familiar: their family, friends, support network, and culture. They also need to liquidate their assets, and they incur the expense of moving. When they arrive in a new country, this is often with many uncertainties including finding work,<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.smh.com.au/national/lack-of-network-hurting-migrant-workers-20120603-1zq3u.html|title=Lack of network hurting migrant workers | last1 = May | first1 = Julia|newspaper=The Sydney Morning Herald|language=en-US|access-date=2 January 2017}}</ref> where to live, new laws, new cultural norms, language or accent issues, possible [[racism]], and other exclusionary behavior towards them and their family.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.globalcitizen.org/en/content/the-7-biggest-challenges-facing-refugees-and-immig/|title=The 7 biggest challenges facing refugees and immigrants in the US | last1 = Nunez | first1 = Christina|date=12 December 2014|website=Global Citizen|publisher=Global Poverty Project|access-date=16 May 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Charles Rodriguez |first1=U. |last2=Venegas de la Torre |first2=M. D. L. P. |last3=Hecker |first3=V. |last4=Laing |first4=R. A. |last5=Larouche |first5=R. |date=2022 |title=The Relationship Between Nature and Immigrants' Integration, Wellbeing and Physical Activity: A Scoping Review |url=https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-022-01339-3 |journal=Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health |volume= 25|issue=1 |pages=190–218 | pmid=35201532 | doi=10.1007/s10903-022-01339-3|s2cid=247060104 }}</ref><ref name="Djajić2013">{{Cite journal | last1 = Djajić | first1 = Slobodan|date=1 September 2013|title=Barriers to immigration and the dynamics of emigration |journal=Journal of Macroeconomics|volume=37|pages=41–52|doi=10.1016/j.jmacro.2013.06.001}}</ref> |

|||

The [[United Kingdom]], [[France]] and [[Germany]] have seen major immigration since the end of World War II and have been debating the issue for decades. Foreign workers were brought in to those countries to help rebuild after the war, and many stayed. Political debates about immigration typically focus on statistics, the immigration law and policy, and the implementation of existing restrictions.<ref name="Deutsche Welle: Germans Consider U.S. Experience in Immigration Debate"/><ref name="BBC: Short History of Immigration"/> In some European countries the debate in the 1990s was focused on asylum seekers, but restrictive policies within the European Union, as well as a reduction in armed conflict in Europe and neighboring regions, have sharply reduced asylum seekers.<ref name="BBC: Analysis: Europe's asylum trends"/> |

|||

[[File:Čížov (Zaisa) - preserved part of Iron curtain.JPG|thumb|upright=1.25|The [[Iron Curtain]] in Europe was designed as a means of [[Eastern Bloc emigration and defection|preventing emigration]]. "It is one of the ironies of post-war European history that, once the freedom to travel for Europeans living under communist regimes, which had long been demanded by the West, was finally granted in 1989/90, travel was very soon afterwards made much more difficult by the West itself, and new barriers were erected to replace the Iron Curtain." —Anita Böcker<ref>Anita Böcker (1998) [https://books.google.com/books?id=ejOg0L5pbHUC ''Regulation of migration: international experiences'']. Het Spinhuis. p. 218. {{ISBN|90-5589-095-2}}</ref>]] |

|||

Some states, such as [[Japan]], have opted for technological changes to increase profitability (for example, greater [[automation]]), and designed immigration laws specifically to prevent immigrants from coming to, and remaining within, the country. Globalization, as well as low birth rates and an aging work force, has forced Japan to reconsider its immigration policy.<ref name="Japanese Immigration Policy: Responding to Conflicting Pressures"/> Japan's colonial past has also created considerable number of non-Japanese in Japan. Japan keeps tight control on immigration and in 2009, despite generous overseas aid for refugees, granted political asylum to just 30 people.<ref name="google"/> Japanese Minister [[Taro Aso]] described Japan as unique in being "one nation, one civilisation, one language, one culture and one race".<ref name="guardian" /> |

|||

The politics of immigration have become increasingly associated with other issues, such as [[national security]] and [[terrorism]], especially in western Europe, with the presence of [[Islam]] as a new major religion. Those with security concerns cite the [[2005 French riots]] and point to the [[Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy]] as examples of the value conflicts arising from immigration of [[Muslims in Western Europe]]. Because of all these associations, immigration has become an emotional political issue in many European nations.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://euranetplus-inside.eu/migration-refugees-europe-waves-of-emotion/|title=Migration, refugees, Europe – waves of emotion |date=7 May 2015|website=Euranet Plus inside|publisher=Euranet Plus Network|language=en-GB|access-date=16 May 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.azcentral.com/news/articles/global-immigration-germany-integration.html|title=Europe learns integration can become emotional | last1 = Nowicki | first1 = Dan|website=AZCentral.com|access-date=16 May 2016}}</ref> |

|||

In the United States political debate on immigration has flared repeatedly since the US became independent.{{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} Some on the far-left of the political spectrum attribute anti-immigration rhetoric to an all-"white", under-educated and parochial minority of the population, ill-educated about the relative advantages of immigration for the US economy and society.<ref name="cmd.princeton.edu"/> While those on the far-right think that immigration threatens [[national identity]], as well as cheapening labor and increasing dependence on [[welfare]].<ref name="cmd.princeton.edu"/> |

|||

Studies have suggested that some [[special interest group]]s [[Lobbying|lobby]] for less immigration for their own group and more immigration for other groups since they see effects of immigration, such as increased labor competition, as detrimental when affecting their own group but beneficial when impacting other groups. A 2010 European study suggested that "employers are more likely to be pro-immigration than employees, provided that immigrants are thought to compete with employees who are already in the country. Or else, when immigrants are thought to compete with employers rather than employees, employers are more likely to be anti-immigration than employees."<ref name="Tamura2010" /> A 2011 study examining the voting of US representatives on migration policy suggests that "representatives from more skilled labor abundant districts are more likely to support an open immigration policy towards the unskilled, whereas the opposite is true for representatives from more unskilled labor abundant districts."<ref name="FacchiniSteinhardt2011" /> |

|||

==Economic migrant== |

|||

{{Further|Economic migrant}} |

|||

[[File:Indo-Bangladeshi Barrier.JPG|right|thumb|280px|The [[Bangladesh–India border|Indo-Bangladeshi barrier]] in 2007. [[India]] is building a [[separation barrier]] along the 4,000 kilometer border with Bangladesh to prevent illegal immigration.]] |

|||

Another contributing factor may be lobbying by earlier immigrants. The chairman for the US Irish Lobby for Immigration Reform{{snd}}which lobby for more permissive rules for immigrants, as well as special arrangements just for Irish people{{snd}}has stated that "the Irish Lobby will push for any special arrangement it can get{{snd}}'as will every other ethnic group in the country.{{'"}}<ref name="irishlobbyusa" /><ref name="nclr" /> |

|||

The term economic migrant refers to someone who has emigrated from one region to another region for the purposes of seeking employment or improved financial position. An economic migrant is distinct from someone who is a [[refugee]] fleeing persecution. |

|||

=== Foreign involvement === |

|||

Many countries have immigration and visa restrictions that prohibit a person entering the country for the purposes of gaining work without a valid work visa. Persons who are declared an economic migrant can be refused entry into a country. |

|||

Several countries have been accused of encouraging immigration to other countries in order to create divisions.<ref>[https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-35706238 Migrant crisis: Russia and Syria 'weaponising' migration, BBC, 2016]</ref> |

|||

== Economic migrant == |

|||

The process of allowing immigrants into a particular country has been believed to have effects on wages and employment. Particularly the lower skilled workers are affected directly, but evidence suggests that this is due to adjustments within industries.<ref>{{cite web|last=Dustmann|first=Christian|title=Labor market effects on immigration|url=http://web.ebscohost.com/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=9aee6fcc-9d5e-40ec-8291-5b866d2f78c3%40sessionmgr14&vid=2&hid=9|publisher=Business Source Elite|accessdate=10/4/12}}</ref> |

|||

{{Further|Economic migrant}} |

|||

[[File:Indo-Bangladeshi Barrier.JPG|right|thumb|upright=1.25|The [[Bangladesh–India border|Indo-Bangladeshi barrier]] in 2007. [[India]] is building a [[separation barrier]] along the 4,000 kilometer border with Bangladesh to prevent illegal immigration.]] |

|||

The term economic migrant refers to someone who has travelled from one region to another region for the purposes of seeking employment and an improvement in quality of life and access to resources. An economic migrant is distinct from someone who is a [[refugee]] fleeing persecution. |

|||

The [[World Bank]] estimates that [[remittance]]s totaled $420 billion in 2009, of which $317 billion went to developing countries.<ref name="worldbank"/> |

|||

Many countries have immigration and visa restrictions that prohibit a person entering the country for the purposes of gaining work without a valid work visa. As a violation of a [[State (polity)|State's]] immigration laws a person who is declared to be an economic migrant can be refused entry into a country. |

|||

==Ethics== |

|||

[[File:South Africa-Xenophobia-001.jpg|thumb|UNHCR tents at a refugee camp following episodes of [[Xenophobia in South Africa|anti-immigrant violence]] in South Africa, 2008]] |

|||

Treatment of migrants in host countries, both by governments, employers, and original population, is a topic of continual debate and criticism, as many cases of abuse and violation of rights are being reported frequently. Some countries have developed a particularly notorious reputation regarding treatment of migrants. The [[United Nations Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families]], has been ratified but by 20 states, all of which are heavy exporters of cheap labor. With the sole exception of [[Serbia]], none of the signatories are western countries, but all are from [[Asia]], [[South America]], and [[North Africa]]. [[Arab states of the Persian Gulf]], which are known for receiving millions of migrant workers, have not signed the treaty as well. |

|||

Although [[freedom of movement]] is often recognized as a [[civil right]]{{Who|date=July 2011}}, the freedom only applies to movement within national borders: it may be guaranteed by the [[constitution]] or by human rights legislation. Additionally, this freedom is often limited to [[citizen]]s and excludes others. |

|||

The [[World Bank]] estimates that [[remittance]]s totaled $420 billion in 2009, of which $317 billion went to developing countries.<ref name="worldbank" /> |

|||

No [[sovereign state]] currently allows full freedom of movement across its borders{{citation needed|date=July 2012}}, except Uruguay{{citation needed|date=July 2012}}, and international [[human rights]] treaties do not confer a general right to enter another state{{citation needed|date=July 2012}}. Proponents of immigration maintain that, according to Article 13 of the [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]], everyone has the right to leave or enter a country, along with movement within it (internal migration), although article 13 actually restricts freedom of movement to "within the borders of each state." Additionally, the UDHR does not mention entry into other countries when it states that "everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country."<ref name="The Universal Declaration of Human Rights"/> Some argue that the freedom of movement both within and between countries is a basic human right, and that the restrictive immigration policies, typical of nation-states, violate this human right of freedom of movement.<ref name="immigration"/> Such arguments are common among anti-state ideologies like [[anarchism]] and [[libertarianism]]. |

|||

As philosopher and "Open Borders" activist [[Jacob M. Appel|Jacob Appel]] has written, "Treating human beings differently, simply because they were born on the opposite side of a national boundary, is hard to justify under any mainstream philosophical, religious or ethical theory."<ref name="opposingviews"/> However, Article 14 does provide that "everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in other countries asylum from persecution."<ref name="The Universal Declaration of Human Rights1"/> |

|||

== Economic effects == |

|||

Where immigration is permitted, it is typically selective. [[Family reunification]] accounts for approximately two-thirds of legal immigration to the US every year.<ref name="migrationinformation2"/> Ethnic selection, such as the [[White Australia policy]], has generally disappeared, but priority is usually given to the educated, skilled, and wealthy. Less privileged individuals, including the mass of poor people in low-income countries, cannot avail themselves of the legal and protected immigration opportunities offered by wealthy states. This inequality has also been criticized as conflicting with the principle of [[equal opportunities]], which apply (at least in theory) within democratic nation-states. The fact that the door is closed for the unskilled, while at the same time many developed countries have a huge demand for unskilled labor, is a major factor in [[illegal immigration]]. The contradictory nature of this policy—which specifically disadvantages the unskilled immigrants while exploiting their labor—has also been criticized on ethical grounds. |

|||

=== Overall national impact === |

|||

Immigration policies which selectively grant freedom of movement to targeted individuals are intended to produce a net economic gain for the host country. They can also mean net loss for a poor donor country through the loss of the educated minority—the [[brain drain]]. This can exacerbate the [[Global justice|global inequality]] in [[standards of living]] that provided the motivation for the individual to migrate in the first place. One example of competition for skilled labour is active recruitment of [[health worker]]s from the [[Third World]] by [[First World]] countries. |

|||

A survey of European economists shows a consensus that freer movement of people to live and work across borders within Europe makes the average European better off, and strong support behind the notion that it has not made low-skilled Europeans worse off.<ref name="IGM Forum" /> According to [[David Card]], Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston, "most existing studies of the economic impacts of immigration suggest these impacts are small, and on average benefit the native population".<ref name="CardDustmann2012" /> In a survey of the existing literature, Örn B Bodvarsson and Hendrik Van den Berg write, "a comparison of the evidence from all the studies... makes it clear that, with very few exceptions, there is no strong statistical support for the view held by many members of the public, mainly that immigration has an adverse effect on native-born workers in the destination country."<ref>{{Cite book|title = The economics of immigration: theory and policy|publisher = Springer|year=2013|location = New York; Heidelberg [u.a.]|isbn = 978-1-4614-2115-3 | first1 = Örn B | last1 = Bodvarsson|first2 = Hendrik|last2 = Van den Berg|page = 157|oclc = 852632755}}</ref> |

|||

Research also suggests that diversity and immigration have a net positive effect on [[Productivity (economics)|productivity]]<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Bahar|first1=Dany|last2=Hauptmann|first2=Andreas|last3=Özgüzel|first3=Cem|last4=Rapoport|first4=Hillel|date=2022|title=Migration and Knowledge Diffusion: The Effect of Returning Refugees on Export Performance in the Former Yugoslavia|journal=The Review of Economics and Statistics|volume=106 |issue=2 |pages=287–304|doi=10.1162/rest_a_01165|s2cid=246564474|issn=0034-6535}}</ref><ref name="OttavianoPeri2006">{{Cite journal|title = The economic value of cultural diversity: evidence from US cities |journal = Journal of Economic Geography|date = 1 January 2006|issn = 1468-2702|pages = 9–44|volume = 6|issue = 1|doi = 10.1093/jeg/lbi002 | first1 = Gianmarco I. P. | last1 = Ottaviano|first2 = Giovanni|last2 = Peri|url = http://www.nber.org/papers/w10904.pdf}}</ref><ref name="Peri2012">{{Cite journal | last1 = Peri | first1 = Giovanni|date=7 October 2010|title=The Effect of Immigration on Productivity: Evidence From U.S. States |journal=Review of Economics and Statistics|volume=94|issue=1|pages=348–358|doi=10.1162/REST_a_00137 | s2cid = 17957545|issn=0034-6535| url = http://www.nber.org/papers/w15507.pdf}}</ref><ref name="MitaritonnaOrefice2017">{{Cite journal |last1=Mitaritonna |first1=Cristina |last2=Orefice |first2=Gianluca |last3=Peri |first3=Giovanni |year=2017 |title=Immigrants and Firms' Outcomes: Evidence from France |url=http://www.nber.org/papers/w22852.pdf |journal=European Economic Review |volume=96 |pages=62–82 |doi=10.1016/j.euroecorev.2017.05.001 |s2cid=157561906}}</ref><ref name="Razin2018">{{Cite report | last1 = Razin | first1 = Assaf|date=February 2018|title=Israel's Immigration Story: Winners and Losers |website=National Bureau of Economic Research |doi=10.3386/w24283|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="OttavianoPeri2018">{{Cite journal | first1 = Gianmarco I. P. | last1 = Ottaviano |first2=Giovanni |last2=Perie |first3=Greg C. |last3=Wright |year=2018 |title=Immigration, Trade and Productivity in Services: Evidence from U.K. Firms |journal=Journal of International Economics |volume= 112|pages=88–108 |doi=10.1016/j.jinteco.2018.02.007 | s2cid = 153400835 | url = http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp1353.pdf }}</ref> and economic prosperity.<ref name="AlesinaHarnoss2016">{{Cite journal | last1 = Alesina | first1 = Alberto|last2=Harnoss|first2=Johann|last3=Rapoport|first3=Hillel|date=17 February 2016|title=Birthplace diversity and economic prosperity |journal=Journal of Economic Growth|language=en|volume=21|issue=2|pages=101–138|doi=10.1007/s10887-016-9127-6| s2cid = 34712861|issn=1381-4338|url=http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:28652196|type=Submitted manuscript}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://sites.uclouvain.be/econ/DP/IRES/2016028.pdf|title=Multiculturalism and Growth: Skill-Specific Evidence from the Post-World War II Period}}</ref><ref name="BoveElia2017">{{Cite journal | last1 = Bove | first1 = Vincenzo|last2=Elia|first2=Leandro|date=1 January 2017|title=Migration, Diversity, and Economic Growth |journal=World Development|volume=89|pages=227–239|doi=10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.08.012|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://voxeu.org/article/diversity-and-economic-development|title=Cultural heterogeneity and economic development | last1 = Bove | first1 = Vincenzo|last2=Elia|first2=Leandro|date=16 November 2016|website=VoxEU.org|access-date=16 November 2016}}</ref><ref name="BoubtaneDumont2016">{{Cite journal|last1=Boubtane|first1=Ekrame|last2=Dumont|first2=Jean-Christophe|last3=Rault|first3=Christophe|date=1 April 2016|title=Immigration and economic growth in the OECD countries 1986–2006|journal=Oxford Economic Papers|language=en|volume=68|issue=2|pages=340–360|doi=10.1093/oep/gpw001|s2cid=208009990|issn=0030-7653|url=http://data.leo-univ-orleans.fr/media/search-works/2235/dr201513.pdf|access-date=23 July 2019|archive-date=29 April 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190429041750/http://data.leo-univ-orleans.fr/media/search-works/2235/dr201513.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> Immigration has also been associated with reductions in [[offshoring]].<ref name="OttavianoPeri2018" /> A study found that the Age of Mass Migration (1850–1920) contributed to "higher incomes, higher productivity, more innovation, and more industrialization" in the short-run and "higher incomes, less poverty, less unemployment, higher rates of urbanization, and greater educational attainment" in the long-run for the United States.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Qian|first1=Nancy|last2=Nunn|first2=Nathan|last3=Sequeira|first3=Sandra|title=Immigrants and the Making of America|journal=The Review of Economic Studies|language=en|doi=10.1093/restud/rdz003|year=2019|volume=87|pages=382–419|s2cid=53597318}}</ref> Research also shows that migration to Latin America during the Age of Mass Migration had a positive impact on long-run economic development.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=SÁNCHEZ-ALONSO|first=BLANCA|date=11 November 2018|title=The age of mass migration in Latin America|journal=The Economic History Review|volume=72|pages=3–31|language=en|doi=10.1111/ehr.12787|hdl=10637/11782|s2cid=158530812|issn=0013-0117|doi-access=free}}</ref> A 2016 paper by University of Southern Denmark and University of Copenhagen economists found that the [[Immigration Act of 1924|1924 immigration restrictions]] enacted in the United States impaired the economy.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2018-07-09/cuts-to-u-s-immigration-in-1920s-made-great-depression-worse|title=One Sure Way to Hurt the U.S. Economy? Cut Immigration|work=Bloomberg.com|access-date=22 July 2018|language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite SSRN | last1 = Ager | first1 = Philipp|last2=Hansen|first2=Casper Worm|date=8 November 2016|title=National Immigration Quotas and Local Economic Growth|language=en | ssrn = 2866411}}</ref> |

|||

The view that economic impact on the average native tends to be only small and positive is disputed by some studies, such as a 2023 statistical analysis of historical immigration data in Netherlands which found economic effects with both larger positive and negative net contributions per capita depending on different factors including previous education and income of the immigrant.<ref name="netherlands2023">[https://demo-demo.nl/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Borderless_Welfare_State-2.pdf ''Borderless Welfare State, The Consequences of Immigration for Public Finances''], Jan H. van de Beek, Hans, Roodenburg, Joop Hartog, Gerri W. Kreffer, 2023, Demo-Demo publisher, Zeist, Netherlands, {{ISBN|978908333482}}, Statistical data by Project Agreement 8290 Budgetary consequences of immigration in the Netherlands (University of Amsterdam and CBS Microdata Services, 19 June 2018)</ref> Effects may vary due to factors like the migrants' age, education, reason for migration,<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last1=Kerr |first1=Sari Pekkala |last2=Kerr |first2=William R. |year=2011 |title=Economic Impacts of Immigration: A Survey |url=https://www.taloustieteellinenyhdistys.fi/images/stories/fep/fep12011/fep12011_kerr_and_kerr.pdf |journal=Finnish Economic Papers |volume=24 |issue=1 |pages=1–32}}</ref> the strength of the economy, and how long ago the migration took place.<ref name=":3">{{Cite web |last1=Devlin |first1=Ciaran |last2=Bolt |first2=Olivia |last3=Patel |first3=Dhiren |last4=Harding |first4=David |last5=Hussain |first5=Ishtiaq |date=March 2014 |title=Impacts of migration on UK native employment: An analytical review of the evidence |url=https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287287/occ109.pdf |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240112143308/https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/287287/occ109.pdf |archive-date=12 Jan 2024 |access-date=12 Jan 2024 |website=The Home Office}}</ref> |

|||

==By country== |

|||

The [[Commitment to Development Index]] ranks 22 of the world's richest countries on their immigration policies and openness to migrants and refugees from the poorest nations. See the CDI for information about specific country policies and evaluation not listed below. |

|||

Low-skill immigration has been linked to greater [[income inequality]] in the native population,<ref name="XuGarand2015">{{Cite journal | last1 = Xu | first1 = Ping|last2=Garand|first2=James C.|last3=Zhu|first3=Ling|date=23 September 2015|title=Imported Inequality? Immigration and Income Inequality in the American States |journal=State Politics & Policy Quarterly|pages=147–171|doi=10.1177/1532440015603814|issn=1532-4400|volume=16|issue=2| s2cid = 155197472|url=http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/psc_facpubs/5|type=Submitted manuscript}}</ref><ref name="GlenWeyl2018">{{Cite journal | last1 = Glen Weyl | first1 = E.|date=17 January 2018|title=The Openness-equality Trade-off in Global Redistribution|journal=The Economic Journal|language=en|volume=128|issue=612|pages=F1–F36|doi=10.1111/ecoj.12469| s2cid = 51027330|issn=0013-0133}}</ref> but overall immigration was found to account for a relatively small share of the rise of native wage inequality.<ref name="Card2009">{{Cite journal | last1 = Card | first1 = David|date=1 April 2009|title=Immigration and Inequality |journal=American Economic Review|volume=99|issue=2|pages=1–21|doi=10.1257/aer.99.2.1|issn=0002-8282|citeseerx=10.1.1.412.9244| s2cid = 154716407|quote=...the presence of immigration can account for a relatively small share (4–6 percent) of the rise in overall wage inequality over the past 25 years}}</ref><ref name="GreenGreen2016">{{Cite journal | last1 = Green | first1 = Alan G.|last2=Green|first2=David A.|date=1 June 2016|title=Immigration and the Canadian Earnings Distribution in the First Half of the Twentieth Century |journal=The Journal of Economic History|volume=76|issue=2|pages=387–426|doi=10.1017/S0022050716000541| s2cid = 156620314|issn=1471-6372| url = https://zenodo.org/record/895711}}</ref> For example, according to a study, immigration was only responsible for 5% of the increase in wage inequality in the US between 1980 and 2000.<ref>{{cite journal |

|||

===Asia=== |

|||

| last = Card |

|||

| first = David |

|||

| year = 2009 |

|||

| title = Immigration and Inequality |

|||

| journal = NBER Working Paper Series |

|||

| volume = 99 |

|||

| issue = 2 |

|||

| pages = 1–21 |

|||

| doi = 10.1257/AER.99.2.1 |

|||

| url = https://doi.org/10.1257/AER.99.2.1 |

|||

| access-date = 2024-10-27 |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Measuring the national impact of immigration on the change of total GDP or on the change of GDP per capita can have distinct results.<ref>[https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/43381/ Jiří, Mazurek. "On some issues concerning definition of an economic recession." (2012).]</ref> |

|||

====Israel==== |

|||

{{Main|Aliyah}} |

|||

[[File:Meeting between Sudanese refugees and Israeli students.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Meeting between Sudanese refugees and Israeli students, 2007. Only Jewish immigrants automatically acquire [[Israeli citizenship]].]] |

|||

[[Jewish]] immigration to [[Palestine]] during the 19th century was promoted by the [[Austria-Hungary|Austro-Hungarian]] journalist [[Theodor Herzl]] in the late 19th century following the publication of "[[Der Judenstaat]]".<ref name="paperbacks"/> His [[Zionist]] movement sought to encourage [[Aliyah|Jewish migration]], or immigration, to [[Palestine]]. Its proponents regard its aim as [[self-determination]] for the Jewish people.<ref name="archive"/> |

|||

The percentage of world Jewry living in the former [[Palestinian Mandate]] has steadily grown from 25,000 since the movement came into existence. Today about 40% of the world's Jews live in Israel, more than in any other country.<ref name="jewishvirtuallibrary"/> |

|||

=== Study methodologies === |

|||

The Israeli [[Law of Return]], passed in 1950, gives those born Jews (having a Jewish mother or grandmother), those with Jewish ancestry (having a Jewish father or grandfather) and converts to Judaism (Orthodox, Reform, or Conservative denominations—not secular—though Reform and Conservative conversions must take place outside the state, similar to civil marriages) the right to immigrate to Israel. A 1970 amendment, extended immigration rights to "a child and a grandchild of a Jew, the spouse of a Jew, the spouse of a child of a Jew and the spouse of a grandchild of a Jew". Over a million Jews from the former Soviet Union have immigrated to Israel since the 1990s, and large numbers of [[Ethiopian Jews]] were airlifted to the country in [[Operation Moses]]. In the year 1991, Israel helped 14,000 Ethiopian immigrants arrive in operation Solomon. |

|||

David Card's 1990 work<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Card |first=David |date=1990 |title=The Impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami Labor Market |url=https://davidcard.berkeley.edu/papers/mariel-impact.pdf |journal=Industrial and Labor Relations Review |volume=43 |issue=2 |pages=245–257 |doi=10.1177/001979399004300205 |s2cid=15116852 }}</ref> – considered a landmark study in the topic – found no impact on native wages or employment rates. It followed the [[Mariel boatlift]], a [[natural experiment]] when 125,000 [[Cuba]]ns (Marielitos) came to [[Miami]] after a sudden relaxation in emigration rules. It lacked the limitations of previous studies, including that migrants often choose high-wage cities, so increases in wages could simply be a [[Spurious relationship|result of the economic success of the city rather than the migrants.]] But the Marielitos chose Miami simply because it was near Cuba rather than for lucrative wages. Preceding studies were also limited in that firms and natives may respond to migration and its effects by moving to more lucrative areas. However, the six-month period of this migration was too brief for most firms or individuals to leave Miami.<ref name=":2" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Borjas |first=George J. |date=2017 |title=The Wage Impact of the ''Marielitos'': A Reappraisal |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/26944704 |journal=ILR Review |volume=70 |issue=5 |pages=1077–1110 |doi=10.1177/0019793917692945 |jstor=26944704 |issn=0019-7939}}</ref> |

|||

Another natural experiment followed a group of Czech workers who, shortly after the fall of the Berlin wall, were suddenly able to work in Germany though they continued to live in Czechia. It found significant declines in native wages and employment as a result.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Dustmann |first1=C |last2=Schonberg |first2=U |last3=Stuhler |first3=J |date=2017 |title=Labor Supply Shocks, Native Wages, and the Adjustment of Local Employment' |journal=The Quarterly Journal of Economics |volume=132 |issue=1 |pages=435–483|doi=10.1093/qje/qjw032 }}</ref> It is argued migrants must also spend their wages in the employing country in order to stimulate the economy and offset their impacts.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last1=Banerjee |first1=Abhijit |title=Good Economics for Hard Times |last2=Duflo |first2=Esther |publisher=Penguin |year=2019 |location=London}}</ref> |

|||

=== Global impact === |

|||

There were 35,638 African migrants living in Israel in 1906.<ref>"[http://www.jpost.com/DiplomacyAndPolitics/Article.aspx?id=227332 Danny Danon: Send African migrants to Australia]". Jerusalem Post. June 30, 2011.</ref> Nearly 69,000 non-Jewish [[Illegal immigration from Africa to Israel|African migrants]] have entered Israel in recent years.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://af.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idAFBRE8520DX20120603 |title=Israel to jail illegal migrants for up to 3 years |newspaper=[[Reuters]] |date=June 3, 2012}}</ref> Prime Minister [[Benjamin Netanyahu]] said that "This phenomenon is very grave and threatens the social fabric of society, our national security and our national identity."<ref>"[http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2012/may/20/israel-netanyahu-african-immigrants-jewish Israel PM: illegal African immigrants threaten identity of Jewish state]". ''Reuters.'' May 20, 2012.</ref> |

|||