Gandhara: Difference between revisions

| (1,000 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Ancient Indo-Aryan civilization of Sapta Sindhu}} |

|||

{{About||the historical kingdom proper|Gandhāra (kingdom)|the kingdom in Epics|Gandhara Kingdom|other uses|}} |

|||

{{Use British English|date=March 2013}} |

{{Use British English|date=March 2013}} |

||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March |

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2024}} |

||

{{Infobox Former Subdivision |

|||

:''Gandhara is also an ancient name for [[Peshawar]], Pakistan.'' |

|||

| native_name = Gandhara |

|||

| conventional_long_name = Gandhāra |

|||

| common_name = Gandhara |

|||

| subdivision = Province |

|||

| nation = |

|||

| era = [[Ancient history|Antiquity]] |

|||

| capital = [[Pushkalavati|Puṣkalavati]]<br/>[[Peshawar|Puruṣapura]]<br/>[[Takshashila]]<br/>[[Hund (village)|Udabhandapura]] |

|||

| title_leader = [[Raja]] |

|||

| year_leader1 = {{circa|550 BCE}} |

|||

| leader1 = [[Pushkarasarin]] |

|||

| year_leader2 = {{circa|330 BCE}} |

|||

| leader2 = [[Taxiles]] |

|||

| year_leader3 = {{circa|321 BCE}} |

|||

| leader3 = [[Chandragupta Maurya]] |

|||

| image_map = {{Location map+ |

|||

|Pakistan |

|||

|float = center |

|||

|width = 320 |

|||

|caption = |

|||

|nodiv = 1 |

|||

|mini = 1 |

|||

|relief=yes |

|||

|places = |

|||

<br/>{{location map~ |Pakistan |lat=34.6|N |long=72|E |label=Gandhara|position=bottom |label_size=80|mark=U+25AD.svg|marksize=60}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| image_map_caption = Location of Gandhara in South Asia (Afghanistan and Pakistan) |

|||

| image_map2 = {{Location map+ |

|||

|Gandhara |

|||

|float = center |

|||

|width = 270 |

|||

|caption = |

|||

|nodiv = 1 |

|||

|mini = 1 |

|||

|relief=yes |

|||

|places = |

|||

{{location map~ |Gandhara |lat=34.016667|N |long=71.583333|E |label=[[Peshawar]]|position=bottom |label_size=70}} |

|||

{{location map~ |Gandhara |lat=33.745833|N |long=72.7875|E |label=[[Taxila]] |position=left |label_size=70 }} |

|||

{{location map~ |Gandhara |lat=34.15|N |long=71.733333|E |label=[[Charsadda]]|position=top |label_size=70}} |

|||

{{location map~ |Gandhara |lat=34.201222|N |long=72.025833|E |label=[[Mardan]]|position=bottom |label_size=70}} |

|||

{{location map~ |Gandhara |lat=34.4|N |long=71.95|E |label='''GANDHARA'''|position=bottom |label_size=70|mark=File:1000x1.png|marksize=0}} |

|||

{{location map~ |Gandhara |lat=34.48|N |long=70.7|E |label=''[[Kabul river|Kabul]]<br/>[[Kabul river|river]]''|position=bottom|label_size=70|mark=File:1000x1.png|marksize=0}} |

|||

{{location map~ |Gandhara |lat=34.7|N |long=72.9|E |label=''[[Indus]]<br/>[[Indus|river]]''|position=bottom |label_size=70|mark=File:1000x1.png|marksize=0}} |

|||

{{location map~ |Gandhara |lat=33.6|N |long=72.1|E |label=''[[Indus]]<br/>[[Indus|river]]''|position=bottom |label_size=70|mark=File:1000x1.png|marksize=0}} |

|||

}} |

|||

| image_map2_caption = Approximate geographical region of Gandhara centered on the [[Valley of Peshawar|Peshawar Basin]], in present-day northwest [[Pakistan]] |

|||

| life_span = |

|||

| year_start = {{circa|1200 BCE}} |

|||

| event_start = |

|||

| event1 = |

|||

| date_event1 = |

|||

| year_end = 1001 CE |

|||

| date_end = 27 November |

|||

| event_end = [[Battle of Peshawar (1001)|Battle of Peshawar]] |

|||

| s1 = |

|||

| today = [[Pakistan]]<br/>[[Afghanistan]] |

|||

| leader4 = [[Sases]] |

|||

| year_leader4 = {{circa|46 CE}} |

|||

| leader5 = [[Kanishka]] |

|||

| year_leader5 = {{circa|127 CE}} |

|||

| leader6 = [[Mihirakula]] |

|||

| year_leader6 = {{circa|514 CE}} |

|||

| leader7 = [[Jayapala]] |

|||

| year_leader7 = 964 – 1001 |

|||

}} |

|||

'''Gandhara''' ({{IAST3|Gandhāra}}) was an ancient [[Indo-Aryan people|Indo-Aryan]]<ref>{{Cite book |last=Bryant |first=Edwin Francis |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3UWFPwAACAAJ |title=The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate |date=2002 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-565361-8 |language=en|page=138}}</ref> civilization centred in present-day north-west [[Pakistan]] and north-east [[Afghanistan]].<ref name="auto1">{{Cite book |last1=Kulke |first1=Professor of Asian History Hermann |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TPVq3ykHyH4C&pg=PA53 |title=A History of India |last2=Kulke |first2=Hermann |last3=Rothermund |first3=Dietmar |date=2004 |publisher=Psychology Press |isbn=978-0-415-32919-4 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="auto">{{Cite book |last=Warikoo |first=K. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NsdvkRtAtusC&pg=PA73 |title=Bamiyan: Challenge to World Heritage |date=2004 |publisher=Third Eye |isbn=978-81-86505-66-3 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="auto2">{{Cite book |last=Hansen |first=Mogens Herman |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8qvY8pxVxcwC&pg=PA377 |title=A Comparative Study of Thirty City-state Cultures: An Investigation |date=2000 |publisher=Kgl. Danske Videnskabernes Selskab |isbn=978-87-7876-177-4 |language=en}}</ref> The core of the region of Gandhara was the [[Peshawar valley|Peshawar]] and [[Swat valley]]s extending as far east as the [[Pothohar Plateau]] in [[Punjab]], though the cultural influence of Greater Gandhara extended westwards into the [[Kabul|Kabul valley]] in Afghanistan, and northwards up to the [[Karakoram]] range.{{sfn|Neelis, Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks|2010|p=232}}{{sfn|Eggermont, Alexander's Campaigns in Sind and Baluchistan|1975|pp=175–177}} The region was a central location for the [[Silk Road transmission of Buddhism|spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and East Asia]] with many Chinese [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] pilgrims visiting the region.<ref>[http://www.washington.edu/uwpress/search/books/SALANC.html "UW Press: Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhara"]. Retrieved April 2018.</ref> |

|||

'''Gandhāra''' ({{lang-ps|ګندارا}}, {{lang-ur|{{Nastaliq|گندھارا}}}}) was an ancient [[Buddhist]] kingdom in the [[Swat River|Swat]] and [[Kabul River|Kabul]] river valleys and the [[Pothohar Plateau]], in modern-day northern [[Pakistan]] and eastern [[Afghanistan]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Gandhara Civilization|url=http://www.heritage.gov.pk/html_Pages/gandhara.html}}</ref> Its main cities were ''Purushapura'' (modern [[Peshawar]]), literally meaning "city of men",<ref>from Sanskrit puruṣa= (primordial) man and pura=city</ref> and ''Takshashila'' (modern [[Taxila]]).<ref>[http://concise.britannica.com/ebc/article-9035986/Gandhara Encyclopædia Britannica: Gandhara]</ref> |

|||

Between the third century BCE and third century CE, [[Gandhari language|Gāndhārī]], a Middle [[Indo-Aryan languages|Indo-Aryan language]] written in the [[Kharosthi script]], acted as the lingua franca of the region and through [[Buddhism]], the language spread as far as [[China]] based on [[Gandhāran Buddhist texts]].<ref>[http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/gandhari-language ''GĀNDHĀRĪ LANGUAGE'', Encyclopædia Iranica]</ref> Famed for its unique [[Gandhara art|Gandharan style of art]], the region attained its height from the 1st century to the 5th century CE under the [[Kushan Empire]] which had their capital at [[Puruṣapura]], ushering the period known as ''[[Pax Kushana]].''<ref name="AADC">{{cite book |last1=Di Castro |first1=Angelo Andrea |last2=Hope |first2=Colin A. |chapter=The Barbarisation of Bactria |title=Cultural Interaction in Afghanistan c 300 BCE to 300 CE |date=2005 |publisher=Monash University Press |location=Melbourne |isbn=978-1876924393 |pages=1-18, map visible online page 2 of [http://www.ascs.org.au/news/ascs33/DI%20CASTRO.pdf Hestia, a Tabula Iliaca and Poseidon's trident]}}</ref> |

|||

The Kingdom of Gandhara lasted from the early 1st millennium BC to the 11th century AD. It attained its height from the 1st century to the 5th century under the [[Kushan]] Kings. The Persian term [[Shahi]] is used by history writer [[Al-Biruni]]<ref>[[Kalhana]] Rajatarangini referred to them as simply ''Shahi'' and inscriptions refer to them as ''sahi''.(Wink, pg 125)</ref> to refer to the ruling dynasty<ref>Al Biruni refers to the subsequent rulers as "Brahman kings"; however, most other references such as [[Kalahan]] refer to them as [[kshatriya]]s. (Wink, pg 125)</ref> that took over from the ''Turki Shahi'' and ruled the region during the period prior to Muslim conquests of the 10th and 11th centuries. After it was conquered by [[Mahmud of Ghazni]] in 1021 AD, the name Gandhara disappeared. During the Muslim period the area was administered from [[Lahore]] or from [[Kabul]]. During [[Mughal Empire|Mughal]] times the area was part of Kabul province. |

|||

The history of Gandhara originates with the [[Gandhara grave culture]], characterized by a distinctive burial practice. During the [[Vedic period]] Gandhara gained recognition as one of the [[Mahajanapadas|sixteen Mahajanapadas]], or 'great realms', within [[South Asia]] playing a role in the [[Kurukshetra War]]. In the 6th century BCE, King [[Pushkarasarin|Pukkusāti]] governed the region and was most notable for defeating the [[Kingdom of Avanti]] though Gandhara eventually succumbed as a tributary to the Achaemenids.<ref name=":0" /> During the [[Wars of Alexander the Great]], the region was split into two factions with [[Taxiles]], the king of [[Taxila]], allying with [[Alexander the Great]],<ref>{{Cite web |title=3 alexander and his successors in central asia |url=https://fr.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/vol_II%20silk%20road_alexander%20and%20his%20successors%20in%20central%20asia.pdf |page=72 |quote=Three local chiefs had their reasons for supporting him. One of these, Sisicottus, came from Swat and was later rewarded by an appointment in this locality. Sangaeus from Gandhara had a grudge against his brother Astis, and to improve his chances of royalty, sided with Alexander. The ruler of Taxila wanted to satisfy his grudge against Porus.}}</ref> while the Western Gandharan tribes, exemplified by the [[Aśvaka]] around the [[Swat valley]], resisted.<ref>{{Cite web |title=3 alexander and his successors in central asia |url=https://fr.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/vol_II%20silk%20road_alexander%20and%20his%20successors%20in%20central%20asia.pdf |pages=74–77}}</ref> Following the Macedonian downfall, Gandhara became part of the [[Maurya Empire|Mauryan Empire]] with [[Chandragupta Maurya]] receiving an education in [[Taxila]] under [[Chanakya]] and later assumed control with his support.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Rajkamal Publications Limited |first=New Delhi |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.189620 |title=Chandragupta Maurya And His Times |date=1943 |page=16 |quote=Chanakya, who is described as a resident of the city of Taxila, returned to his native city with the boy and had him educated for a period of 7 or 8 years at that famous seat of learning where all the ' sciences and arts ' of the times were taught, as we know from the Jatakas.}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite book |last=Trautmann |first=Thomas R. |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.107863 |title=Kautilya And The Arthasastra |date=1971 |page=12 |quote=Chanakya was a native of Takkasila, the son of a brahmin, learned in the three Vedas and mantras, skilled in political expedients, deceitful, a politician.}}</ref> Subsequently, Gandhara was successively annexed by the [[Indo-Greeks]], [[Indo-Scythians]], and [[Indo-Parthians]] though a regional Gandharan kingdom, known as the [[Apracharajas]], retained governance during this period until the ascent of the [[Kushan Empire]]. The zenith of Gandhara's cultural and political influence transpired during Kushan rule, before succumbing to devastation during the [[Hunnic Invasion]]s.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Samad |first=Rafi U. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PMEd8Cqh-YQC&dq=Gandhara+destroyed+by+huns&pg=PA138 |title=The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys |date=2011 |publisher=Algora Publishing |isbn=978-0-87586-860-8 |pages=138 |language=en}}</ref> However, the region experienced a resurgence under the [[Turk Shahis]] and [[Hindu Shahis]]. |

|||

==Name== |

|||

The name ''Gāndhāra'' is not recorded in [[Vedic Sanskrit]], it first occurs in the [[Classical Sanskrit]] of the [[Sanskrit epics|epics]]. One proposed origin of the name is from the Sanskrit word ''gandha'', meaning ''perfume'' and "referring to the spices and aromatic herbs which they [the inhabitants] traded and with which they anointed themselves."<ref>{{cite web|title=On Yuan Chwang's travels in India, 629–645 A.D.|accessdate=28 July 2012|author=Thomas Watters|publisher=[[Royal Asiatic Society]]|year=1904|quote=Taken as Gandhavat the name is explained as meaning ''hsiang-hsing'' or "scent-action" from the word gandha which means ''scent'', ''small'', ''perfume''.}}</ref> |

|||

Some authors have connected the modern name [[Kandahar]] to ''Gandhara''{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=PzIer-wYbnQC&pg=PA176&lpg=PA176&dq=Kandahar+word+wall+city+Kandh&source=bl&ots=OGYrvBOQBv&sig=56j3pU-VLBEEl6PvnWKYMSQnOBE&hl=en&sa=X&ei=FIkTUMqsL8eWqAH7oYGIAw&ved=0CDQQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=Kandahar%20word%20wall%20city%20Kandh&f=false|title=Placenames of the World|accessdate=28 July 2012|author=Adrian Room|publisher=McFarland|date=1 December 2003|quote=Kandahar. ''City, south central Afghanistan''. The city takes its name from that of the region's former people, the Ghandara, whose name comes from Sanskrit ''gandha'', "odor," "perfume," referring to the spices and aromatic herbs which they traded and with which they anointed themselves.}} |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

A Persian form of the name, ''Gandara'', is mentioned by [[Herodotus]] (3.102, 4.44) in the context of the story of the Greek explorer [[Scylax of Caryanda]] who sailed down the Indus River beginning at the city of ''Caspatyrus'' in ''Gandara'' (Κασπάτυρος, πολίς Γανδαρικὴ). Herodotus records that those Indian tribes who were adjacent to the city of Caspatyrus and the district of Pactyïce had customs similar to the [[Bactria]]ns, and are the most warlike amongst them. These also are the Indians who obtain gold from the ant-hills of the adjoining desert. |

|||

On the identity of Caspatyrus, there have been two opinions, one equating it with [[Kabul]], the other with the name of [[Kashmir]] (''Kasyapa pur'', condensed to ''Kaspapur'' as found in [[Hecataeus]]).<ref>[http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0064:entry=caspatyrus-geo Caspatyrus] in |

|||

Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, 1854.</ref> |

|||

Gandhara was known in [[Sanskrit]] as Gandhāraḥ ({{lang|sa|[[wikt:गन्धार|गन्धारः]]}}) and in [[Avestan]] as '{{lang|ae|Vaēkərəta}}. In [[Old Persian]], Gandhara was known as [[Gadāra]] ([[:Wikt:𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼|𐎥𐎭𐎠𐎼]], also transliterated as Ga<sup>n</sup>dāra since the nasal "n" before consonants were omitted in Old Persian).<ref name="Old Persian">Some sounds are omitted in the writing of Old Persian and are shown with a raised letter. [https://archive.org/stream/OldPersian#page/n177/mode/2up/ Old Persian p.164][https://archive.org/stream/OldPersian#page/n23/mode/2up/ Old Persian p.13]. In particular, Old Persian nasals such as "n" were omitted in writing before consonants [https://archive.org/stream/OldPersian#page/n27/mode/2up/ Old Persian p.17][https://archive.org/stream/OldPersian#page/n35/mode/2up/ Old Persian p.25]</ref> In [[Chinese Language|Chinese]], Gandhara was known as Jiāntuóluó, kɨɐndala, [[Jibin|Jìbīn]], and Kipin. In [[Ancient Greek|Greek]], Gandhara was known as [[Paropamisadae]]'''<ref name="HIII">Herodotus [https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Herodotus/3D*.html Book III, 89–95]</ref>''' |

|||

==Geography== |

|||

[[File:GandharaFemale.JPG|thumb|upright|Female spouted figure, terracotta, Charsadda, Gandhara, 3rd to 1st century BC [[Victoria and Albert Museum]]]] |

|||

One proposed origin of the name is from the Sanskrit word ''{{IAST|gandhaḥ}}'' ({{lang|sa|[[wikt:गन्ध|गन्धः]]}}), meaning "perfume" and "referring to the spices and aromatic herbs which they (the inhabitants) traded and with which they anointed themselves".<ref>{{cite web|title=On Yuan Chwang's travels in India, 629–645 A.D.|author=Thomas Watters|publisher=[[Royal Asiatic Society]]|year=1904|url=https://archive.org/stream/onyuanchwangstr00wattgoog#page/n220/mode/2up|page=200|quote=Taken as Gandhavat the name is explained as meaning ''hsiang-hsing'' or "scent-action" from the word gandha which means ''scent'', ''small'', ''perfume''.}} At the [[Internet Archive]].</ref><ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PzIer-wYbnQC&pg=PA176|title=Placenames of the World|author=Adrian Room|publisher=McFarland|year=1997|quote=Kandahar. ''City, south central Afghanistan''|isbn=9780786418145}} At Google Books.</ref> The [[Gandhari people]] are a [[List of Rigvedic tribes|tribe]] mentioned in the [[Rigveda]], the [[Atharvaveda]], and later Vedic texts.<ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=t6TVLlPvuMAC&pg=PA219 | title=Vedic Index of Names and Subjects|volume=1|year=1995|page=219|first1=Arthur Anthony|last1=Macdonell|first2=Arthur Berriedale|last2=Keith|publisher=Motilal Banarsidass Publishers| isbn=9788120813328}} From [[Google Books]].</ref> |

|||

The Gandhāri people were settled since the [[Vedic civilization|Vedic]] times on the banks of Kabul River (river Kubhā or Kabol) down to its confluence with the [[Indus River|Indus]]. Later Gandhāra included parts of northwest [[Punjab region|Punjab]]. Gandhara was located on the ''northern trunk road'' ([[Uttarapatha]]) and was a centre of international commercial activities. It was an important channel of communication with ancient [[Iran]], India and Central Asia. |

|||

A [[Persian language|Persian]] form of the name, ''Gandara'', mentioned in the [[Behistun inscription]] of Emperor [[Darius I]],<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.livius.org/articles/place/gandara/? |title = Gandara – Livius}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Herodotus|author-link=Herodotus|title=Histories|chapter=3.102.1|year=1920|chapter-url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0125%3Abook%3D3%3Achapter%3D102%3Asection%3D1|title-link=Histories (Herodotus)}} {{cite book|chapter=4.44.2|language=el|chapter-url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0125%3Abook%3D4%3Achapter%3D44%3Asection%3D2|title=Histories|translator=A. D. Godley|title-link=Histories (Herodotus)}} {{cite book|title=Histories|chapter=3.102.1|chapter-url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hdt.+3.102.1&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0126|title-link=Histories (Herodotus)}} {{cite book|title=Histories|chapter=4.44.2|chapter-url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Hdt.+4.44.2&fromdoc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0125|place=Cambridge|publisher=Harvard University Press.|title-link=Histories (Herodotus)}} At the [[Perseus Project]].</ref> was translated as ''[[Paruparaesanna]]'' (''{{lang|peo|Para-upari-sena}}'', meaning "beyond the Hindu Kush") in [[Babylonian language|Babylonian]] and [[Elamite language|Elamite]] in the same inscription.<ref name="PC2004">Perfrancesco Callieri, [http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/india-ii-historical-geography INDIA ii. Historical Geography], Encyclopaedia Iranica, 15 December 2004.</ref> |

|||

The boundaries of Gandhara varied throughout history. Sometimes the Peshawar valley and Taxila were collectively referred to as Gandhara and sometimes the [[Swat (Pakistan)|Swat valley]] ''(Sanskrit: Suvāstu)'' was also included. The heart of Gandhara, however, was always the [[Peshawar valley]]. The kingdom was ruled from capitals at ''Kapisa'' ([[Bagram]]), ''Pushkalavati'' ([[Charsadda]]), [[Taxila]], ''Purushapura'' ([[Peshawar]]) and in its final days from ''Udabhandapura'' ([[Hund]]) on the [[River Indus]]. |

|||

== |

== Geography == |

||

The geographical location of Gandhara has undergone alterations throughout history, with the general understanding being the region situating between [[Pothohar Plateau|Pothohar]] in contemporary [[Punjab]], the [[Swat valley]], and the [[Khyber Pass]] also extending along the [[Kabul River]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=University Of Pittsburg Press U.s.a. |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.198056 |title=Cultural History Of Kapisa And Gandhara |date=1961 |pages=12–13 |quote=The Ramayana places Gandhara on both banks of the Indus....According to Strabo, Gandharites lay along the river Kophes, between the Khoaspes and the Indus. Ptolemy places Gandhara between Suastos (Swat) and the Indus including both banks of Koa immediately above its junction with the Indus.}}</ref> The prominent urban centres within this geographical scope were [[Taxila]] and [[Pushkalavati]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=University Of Pittsburg Press U.s.a. |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.198056 |title=Cultural History Of Kapisa And Gandhara |date=1961 |page=12 |quote=The Ramayana places Gandhara on both banks of the Indus with its two royal cities Pushkalavati for the west and Takshasila for the east.}}</ref> According to a specific [[Jataka tales|Jataka]], Gandhara's territorial extent at a certain period encompassed the region of [[Kashmir]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=University Of Pittsburg Press U.s.a. |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.198056 |title=Cultural History Of Kapisa And Gandhara |date=1961 |page=12 |quote=One Jataka story even includes Kasmira within Gandhara.}}</ref> The Eastern border of Gandhara has been proposed to be the [[Jhelum River]] based on arachaeological [[Gandharan art]] discoveries however further evidence is needed to support this,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Decorative Motifs on Pedestals of Gandharan Sculptures: A Case Study of Peshawar Museum |url=https://ph.hu.edu.pk/public/uploads/vol-12/Paper%208.%20Fawad%20Khan%20Final%20.pdf |page=173 |quote=While according to the recent research, the cultural influence of Gandhāra even reached up to the valley of the Jhelum River in the east (Dar 2007: 54-55).}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=The geography of Gandharan art |url=https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/PublicFiles/media/The%20Geography%20of%20Gandharan%20Art.pdf |page=6 |quote=although Saifur Rahman Dar sought in 2007 to extend the geographical frame to the left bank of the Jhelum river, on account of six Buddhist images discovered at the sites of Mehlan, Patti Koti, Burarian, Cheyr and Qila Ram Kot (Dar 2007: 45-59), evidence remains insufficient to support his conclusions.}}</ref> though during the rule of [[Alexander the Great]] the kingdom of [[Taxila]] stretched to the [[Hydaspes]] (Jhelum river).<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sastri |first=K. a Nilakanta |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.532644 |title=Comprehensive History Of India Vol.2 (mauryas And Satavahanas) |date=1957 |page=1 |quote=Here he had to depend upon and appoint Indians as his satraps, viz., Ambhi, king of Taxila, to rule from the Indus to the Hydaspes (Jhelum).}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:GandharaMotherGoddess.JPG|thumb|upright|Mother Goddess (fertility divinity), derived from the [[Indus Valley Civilization]], [[terracotta]], Sar Dheri, Gandhara, 1st century BC, [[Victoria and Albert Museum]]]] |

|||

The term Greater Gandhara describes the cultural and linguistic extent of Gandhara and its language, [[Gandhari language|Gandhari]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart |url=http://archive.org/details/TheGeographyOfGandharanArt |title=The Geography Of Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the Second International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 22nd-23rd March, 2018 |date=2019-03-15 |page=8 |quote=The Greater Gandhara of philologists, or at least of Salomon, extends beyond the western foothills of the Hindu Kush and the Karakorum Highway to include parts of Bactria and even parts of the region around the Tarim Basin. As Salomon specifies in The Buddhist Literature from Ancient Gandhara, ‘thus Greater Gandhara can be understood as a primarily linguistic rather than a political term, that is, as comprising the regions where Gandharl was the indigenous or adopted language’. Accordingly, it includes places such as Bamiyan where over two hundred of fragments of manuscripts in Gandharl have been discovered along with a larger group of manuscripts in Sanskrit.}}</ref> In later historical contexts, Greater Gandhara encompassed the territories of [[Jibin]] and [[Oddiyana]] which had splintered from Gandhara proper and also extended into parts of [[Bactria]] and the [[Tarim Basin]]. Oddiyana was situated in the vicinity of the [[Swat valley]], while [[Jibin]] corresponded to the region of [[Kapisa (city)|Kapisa]], south of the [[Hindu Kush]]. However during the 5th and 6th centuries CE, [[Jibin]] was often considered synonymous with Gandhara.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Wannaporn Rienjang and Peter Stewart |url=http://archive.org/details/TheGeographyOfGandharanArt |title=The Geography Of Gandhāran Art: Proceedings of the Second International Workshop of the Gandhāra Connections Project, University of Oxford, 22nd-23rd March, 2018 |date=2019-03-15 |page=7 |quote=Other scholars had alternately equated Jibin with Kapisa and more frequently with Kashmir. Kuwayama concludes that while this identification might prove correct for some sources, the Gaoseng zhuan s fourth and fifth century placement of Jibin coincides clearly with the narrower geographical definition of Gandhara.}}</ref> |

|||

Evidence of Stone Age human inhabitants of Gandhara, including stone tools and burnt bones, was discovered at Sanghao near Mardan in area caves. The artifacts are approximately 15,000 years old. More recent excavations point to 30,000 years before present. |

|||

The Udichya region was another region mentioned in ancient texts and is noted by [[Pāṇini]] as comprising both the regions of [[Vahika]] and Gandhara.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Agrawala |first=V. S. |url=http://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.4695 |title=India as known to Panini |date=1953 |pages=38 |quote=Udichya and Prachya are the two broad divisions of the country mentioned by Panini, and these terms occur in connection with the linguistic forms known to the eastern and northern grammarians. The Udichya country included Gandhara and Vahika, the latter comprising Madra and Usinara.}}</ref> |

|||

The region shows an influx of southern Central Asian culture in the Bronze Age with the [[Gandhara grave culture]], likely corresponding to immigration of [[Indo-Aryan languages|Indo-Aryan]] speakers and the nucleus of [[Vedic civilisation]]. This culture survived till 1000 BC. Its evidence has been discovered in the hilly regions of Swat and Dir, and even at Taxila. |

|||

==History== |

|||

The name of the [[Gandhāri]]s is attested in the [[Rigveda]] ([[Mandala 1|RV 1]].126.7<ref>{{cite web | url= http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv01126.htm | title= Rigveda 1.126:7, English translation by Ralph TH Griffith}}</ref>) and in ancient inscriptions dating back to Achaemenid Persia. The Behistun inscription listing the 23 territories of King Darius I (519 BC) includes Gandāra along with [[Bactria]] and [[Thatagush]] (ϑataguš, Satagydia). In the book "Histories" by Herodotus, Gandhara is named as a source of tax collections for King Darius. The Gandhāris, along with the Balhika (Bactrians), Mūjavants, [[Anga]]s, and the [[Magadha]]s, are also mentioned in the [[Atharvaveda]] (AV 5.22.14), as distant people. Gandharas are included in the [[Uttarapatha]] division of Puranic and Buddhistic traditions. The [[Aitareya Brahmana]] refers to king Naganajit of Gandhara who was a contemporary of [[Janaka]], king of [[Videha]]. |

|||

=== Gandhāra grave culture === |

|||

===Epic and Puranic traditions=== |

|||

{{Main|Gandhara grave culture|Indo-Aryan migration|}} |

|||

Gandhara had played an important role in the epic of [[Ramayana]] and [[Mahabharata]]. Ambhi Kumar was a direct descendant of Bharata (of Ramayana) and Shakuni (of Mahabharata). It is said that Lord Rama consolidated the rule of the Kosala Kingdom over the whole of the Indian peninsula. His brothers and sons ruled most of the Janapadas (16 states) at that time. |

|||

[[File:Cremation Urn with Lid LACMA AC1994.234.8a-b.jpg|thumb|upright|Cremation urn, [[Gandhara grave culture]], Swat Valley, {{circa|1200 BCE}}|left]] |

|||

Gandhara's first recorded culture was the Grave Culture that emerged {{circa|1200 BCE}} and lasted until 800 BCE,<ref>Olivieri, Luca M., Roberto Micheli, Massimo Vidale, and Muhammad Zahir, (2019). [https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/sites/reich.hms.harvard.edu/files/inline-files/2019_Science_NarasimhanPatterson_CentralSouthAsia_Supplement.pdf 'Late Bronze – Iron Age Swat Protohistoric Graves (Gandhara Grave Culture), Swat Valley, Pakistan (n-99)'], in Narasimhan, Vagheesh M., et al., "Supplementary Materials for the formation of human populations in South and Central Asia", Science 365 (6 September 2019), pp. 137–164.</ref> and named for their distinct funerary practices. It was found along the Middle [[Swat River]] course, even though earlier research considered it to be expanded to the Valleys of [[Dir District|Dir]], [[Kunar Province|Kunar]], [[Chitral]], and [[Valley of Peshawar|Peshawar]].<ref>Coningham, Robin, and Mark Manuel, (2008). "Kashmir and the Northwest Frontier", Asia, South, in ''Encyclopedia of Archaeology 2008'', Elsevier, p. 740.</ref> It has been regarded as a token of the Indo-Aryan migrations but has also been explained by local cultural continuity. Backwards projections, based on ancient DNA analyses, suggest ancestors of Swat culture people mixed with a population coming from [[Inner Asia Mountain Corridor]], which carried [[Eurasian Steppe|Steppe]] ancestry, sometime between 1900 and 1500 BCE.<ref>Narasimhan, Vagheesh M., et al. (2019). [https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/sites/reich.hms.harvard.edu/files/inline-files/2019_Science_NarasimhanPatterson_CentralSouthAsia.pdf "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia"], in Science 365 (6 September 2019), p. 11: "...we estimate the date of admixture into the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age individuals from the Swat District of northernmost South Asia to be, on average, 26 generations before the date that they lived, corresponding to a 95% confidence interval of ~1900 to 1500 BCE..."</ref> |

|||

=== Vedic Gandhāra === |

|||

In Mahabharata, the princess named [[Gandhari (character)|Gandhari]] was married to Hastinapur's blind king [[Dhritrashtra]] and was mother of [[Duryodhana]] and other Kauravas. The prince of Gandhara [[Shakuni]] was against this wedding but accepted it, fearing an invasion from Hastinapur. In the aftermath, Shakuni influences the Kaurava prince Duryodhana and plays a central role in the great war of Kurukshetra that eliminated the entire Kuru family, including Bhishma and a hundred Kaurava brothers. According to [[Puranic]] traditions, this country (Janapada) was founded by ''Gandhāra'', son of Aruddha, a descendant of Yayāti. The princes of this country are said to have come from the line of Druhyu, who was a king of the Druhyu tribe of the Rigvedic period. According to Vayu Purana (II.36.107), the Gandharas were destroyed by Pramiti, aka [[Kalika]], at the end of Kaliyuga. |

|||

{{Main|Gandhāra (kingdom)|Gandhara Kingdom}} |

|||

[[File:Mahajanapadas (c. 500 BCE).png|thumb|upright=1.15|Kingdoms and cities of ancient Buddhism, with Gandhara located in the northwest of this region, during the time of the Buddha ({{circa|500 BCE}})]] |

|||

According to [[Rigveda|Rigvedic tradition]], [[Yayati]] was the progenitor of the prominent Udichya (Gandhara and [[Vahika]] tribes) and had numerous sons, including Anu, Puru, and Druhyu. The lineage of Anu gave rise to the [[Madra]], [[Kekaya]], [[Sivi Kingdom|Sivi]] and [[Uśīnara]] kingdoms, while the Druhyu tribe has been associated with the Gandhara kingdom.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WIMlttRq_P4C&dq=Druhyu+Anu+Puru&pg=PA230 |title=Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society |date=1889 |publisher=University Press |page=212 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

The first mention of the Gandhārīs is attested once in the [[Rigveda|{{transliteration|sa|Ṛigveda}}]] as a tribe that has sheep with good wool. In the [[Atharvaveda|{{transliteration|sa|Atharvaveda}}]], the Gandhārīs are mentioned alongside the Mūjavants, the [[Anga|Āṅgeyas]] and the [[Magadha (Mahajanapada)|Māgadhīs]] in a hymn asking fever to leave the body of the sick man and instead go those aforementioned tribes. The tribes listed were the furthermost border tribes known to those in [[Madhyadesha|{{transliteration|sa|Madhyadeśa}}]], the Āṅgeyas and Māgadhīs in the east, and the Mūjavants and Gandhārīs in the north.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Macdonell |first1=Arthur Anthony |title=Vedic Index of Names and Subjects |last2=Keith |first2=Arthur Berriedale |publisher=John Murray |year=1912 |pages=218–219}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Chattopadhyaya |first=Sudhakar |title=Reflections on the Tantras |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass Publishers |year=1978 |pages=4}}</ref> The ''Gandhara tribe'', after which it is named, is attested in the [[Rigveda]] ({{circa|1500|1200 BCE}}),<ref name="sacred-texts.com">{{cite web |title=Rigveda 1.126:7, English translation by Ralph TH Griffith |url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv01126.htm}}</ref><ref name="Macdonell1997">{{cite book |author=Arthur Anthony Macdonell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8wM-dNOa7fMC&pg=PA130 |title=A History of Sanskrit Literature |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |year=1997 |isbn=978-81-208-0095-3 |pages=130–}}</ref> while the region is mentioned in the Zoroastrian [[Avesta]] as ''Vaēkərəta'', the [[Avestan geography|seventh most beautiful place]] on earth created by [[Ahura Mazda]]. |

|||

Gandhāra is also thought to be the location of the mythical [[Lake Dhanakosha]], the birthplace of [[Padmasambhava]], the founder of [[Tibetan Buddhism]]. The [[Kagyu|bKa' brgyud (Kagyu)]] sect of [[Tibetan Buddhism]] identifies the lake with the Andan Dheri [[stupa]], located near the tiny village of Uchh near [[Chakdara]] in the lower [[Swat Valley]]. A spring was said to flow from the base of the stupa to form the lake. Archaeologists have found the stupa but no spring or lake can be identified. |

|||

The Gāndhārī king [[Nagnajit]] and his son Svarajit are mentioned in the [[Brahmana|{{transliteration|sa|Brāhmaṇa}}s]], according to which they received Brahmanic consecration, but their family's attitude towards ritual is mentioned negatively,{{sfn|Raychaudhuri|1953|p=59-62}} with the royal family of Gandhāra during this period following non-Brahmanical religious traditions. According to the [[Jainism|Jain]] [[Uttaradhyayana|{{transliteration|sa|Uttarādhyayana-sūtra}}]], Nagnajit, or Naggaji, was a prominent king who had adopted Jainism and was comparable to Dvimukha of [[Pancala|Pāñcāla]], Nimi of [[Videha]], Karakaṇḍu of [[Kalinga (historical region)|Kaliṅga]], and Bhīma of [[Vidarbha]]; [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] sources instead claim that he had achieved [[Pratyekabuddhayāna|{{transliteration|pi|paccekabuddhayāna}}]].{{sfn|Raychaudhuri|1953|p=146-147}}<ref name="Prakash">{{cite journal |last=Prakash |first=Buddha |date=1951 |title=Poros |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/41784590 |journal=Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute |volume=32 |issue=1 |pages=198–233 |doi= |jstor=41784590 |access-date=12 June 2022}}</ref>{{Sfn|Macdonell|Keith|1912|p=218-219, 432}} |

|||

===Pushkalavati and Prayag=== |

|||

The primary cities of Gandhara were Purushapura (now [[Peshawar]]), Takshashila (or [[Taxila]]) and [[Pushkalavati]]. The latter remained the capital of Gandhara down to the 2nd century AD, when the capital was moved to Peshawar. An important Buddhist shrine helped to make the city a centre of pilgrimage until the 7th century. Pushkalavati in the [[Peshawar]] Valley is situated at the confluence of the [[Swat River|Swat]] and [[Kabul River|Kabul]] rivers, where three different branches of the River Kabul meet. That specific place is still called Prang (from Prayāga) and considered sacred and where local people still bring their dead for burial. Similar geographical characteristics are found at site of Prang in Kashmir and at the confluence of the [[Ganges River|Ganges]] and [[Yamuna]], where the sacred city of [[Prayag]] is situated, west of [[Varanasi|Benares]]. Prayāga (Allahabad) one of the ancient pilgrim centres of India as the two rivers are said to be joined here by the underground [[Sarasvati River]], forming a triveṇī, a confluence of three rivers. |

|||

By the later [[Vedic period]], the situation had changed, and the Gāndhārī capital of [[Taxila|Takṣaśila]] had become an important centre of knowledge where the men of {{transliteration|sa|Madhya-desa}} went to learn the three Vedas and the eighteen branches of knowledge, with the {{transliteration|sa|Kauśītaki Brāhmaṇa}} recording that [[Brahmin|{{transliteration|sa|brāhmaṇa}}s]] went north to study. According to the [[Shatapatha Brahmana|{{transliteration|sa|Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa}}]] and the {{transliteration|pi|Uddālaka Jātaka}}, the famous Vedic philosopher [[Uddālaka Āruṇi]] was among the famous students of Takṣaśila, and the {{transliteration|pi|Setaketu Jātaka}} claims that his son Śvetaketu also studied there. In the [[Chandogya Upanishad|{{transliteration|sa|Chāndogya Upaniṣad}}]], Uddālaka Āruṇi himself favourably referred to Gāndhārī education to the [[Videha|Vaideha]] king [[Janaka]].{{sfn|Raychaudhuri|1953|p=59-62}} During the 6th century BCE, Gandhāra was an important imperial power in north-west Iron Age South Asia, with the [[Kashmir Valley|valley of Kaśmīra]] being part of the kingdom.{{sfn|Raychaudhuri|1953|p=146-147}} Due to this important position, Buddhist texts listed the Gandhāra kingdom as one of the sixteen ''[[Mahajanapadas|{{transliteration|sa|Mahājanapada}}s]]'' ("great realms") of Iron Age South Asia. It was the home of [[Gandhari (Mahabharata)|Gandhari]], the princess and her brother [[Shakuni]] the king of [[Gandhara Kingdom]].<ref name="Higham2014">{{citation |last=Higham |first=Charles |title=Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=H1c1UIEVH9gC&pg=PA209 |pages=209– |year=2014 |publisher=Infobase Publishing |isbn=978-1-4381-0996-1}}</ref><ref name="Devi2007">{{cite book |author=Khoinaijam Rita Devi |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R0UwAQAAIAAJ |title=History of ancient India: on the basis of Buddhist literature |date=1 January 2007 |publisher=Akansha Publishing House |isbn=978-81-8370-086-3}}</ref> |

|||

===Taxila=== |

|||

{{main|Taxila}} |

|||

The Gandharan city of Taxila was an important Buddhist<ref name="whc.unesco.org">[http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/139 UNESCO World Heritage Centre: Taxila]</ref> centre of learning from the 5th century BC<ref name="whc.unesco.org"/> to the 2nd century. |

|||

=== Pukkusāti and Achaemenid Gandhāra === |

|||

==Part of Greater Iran== |

|||

{{Main|Gandāra}} |

|||

[[Cyrus the Great]] (558–530 BC) united the [[Iranian peoples|Iranian people]] into a state that stretched from the [[Caucasus]] to the [[Indic peoples|non-Iranian]] areas around the [[Indus River]]. Both Gandhara and Kamboja soon came to be included under this state which was governed by the [[Achaemenian]] [[Dynasty]] during the reign of [[Cyrus the Great]] or in the first year of [[Darius I]]. The Gandhara and Kamboja had constituted the seventh satrapies (upper Indus) of the [[Achaemenid Empire]]. |

|||

{{See also|Achaemenid invasion of the Indus Valley}} |

|||

[[File:Xerxes detail Gandharan enhanced.jpg|thumb|200x200px|[[Xerxes I]] tomb, Gandāra soldier, {{Circa|470 BCE}}]] |

|||

During the 6th century BCE, Gandhara was governed under the reign of King [[Pushkarasarin|Pukkusāti]]. According to [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] accounts, he had forged diplomatic ties with [[Magadha (Mahajanapada)|Magadha]] and achieved victories over neighbouring kingdoms such as that of the realm of [[Avanti (region)|Avanti]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chattopadhyaya |first=Sudhakar |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.118140 |title=The Achaemenids And India |date=1974 |page=22 |quote=According to the Buddhist account Pukkusati, king of Taksasila, sent an embassy and a letter to king Bimbisara of Magadha and he also defeated Pradyota, king of Avanti.}}</ref> [[Pushkarasarin|Pukkusāti]]'s kingdom was described as being 100 [[Yojana]]s in width, approximately 500 to 800 miles wide, with his capital at [[Taxila]] in modern day [[Punjab]] as stated in early [[Jataka tales|Jatakas]]<ref>{{Cite web |title=Part 2 - Story of King Pukkusāti |date=11 September 2019 |url=https://www.wisdomlib.org/buddhism/book/the-great-chronicle-of-buddhas/d/doc364622.html |quote=This man of good family read the message sent by his friend King Bimbisāra and after completely renouncing his one hundred yojana-wide domain of Takkasīla, he became a monk out of reverence for Me.}}</ref> |

|||

When the Achamenids took control of this kingdom, Pushkarasakti, a contemporary of king [[Bimbisara]] of [[Magadha]], was the king of Gandhara. He was engaged in a power struggle against the kingdoms of Avanti and Pandavas. |

|||

It is noted by [[R. C. Majumdar]] that Pukkusāti would have been contemporary to the [[Achamenid]] king [[Cyrus the Great]]<ref>{{Cite book |last=Chattopadhyaya |first=Sudhakar |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.118140 |title=The Achaemenids And India |date=1974 |page=22 |quote=Bimbisara and his son Ajatasatru, he did not probably come to the throne before 540 or 530 bc, and Pukkusati also may be regarded as ruling in Gandhara about that time. He would be thus a contemporary of Cyrus who established his power and authority in 549 bc}}</ref> and according to the scholar Buddha Prakash, Pukkusāti might have acted as a bulwark against the expansion of the [[Persians|Persian]] [[Achaemenid Empire]] into Gandhara. This hypothesis posits that the army which [[Nearchus]] claimed Cyrus had lost in [[Gedrosia]] had been defeated by Pukkusāti's Gāndhārī kingdom.<ref name="Prakash" /> Therefore, following Prakash's position, the Achaemenids would have been able to conquer Gandhāra only after a period of decline after the reign of Pukkusāti, combined with the growth of Achaemenid power under the kings [[Cambyses II]] and [[Darius the Great|Darius I]].<ref name="Prakash" /> However, the presence of Gandhāra among the list of Achaemenid provinces in Darius's [[Behistun Inscription]] confirms that his empire had inherited this region from Cyrus.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |url=http://archive.org/details/history-of-ancient-and-early-medeival-india-from-the-stone-age-to-the-12th-century-pdfdrive |title=History Of Ancient And Early Medieval India From The Stone Age To The 12th Century |page=604 |quote=The Behistun inscription of the Achaemenid emperor Darius indicates that Gandhara was conquered by the Persians in the later part of the 6th century BCE.}}</ref> It is unknown whether [[Pushkarasarin|Pukkusāti]] remained in power after the Achaemenid conquest as a Persian vassal or if he was replaced by a Persian [[satrap]], although [[Buddhism|Buddhist]] sources claim that he renounced his throne and became a monk after becoming a disciple of the [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Pukkusāti|url=http://www.palikanon.com/english/pali_names/pu/pukkusati.htm|publisher=www.palikanon.com|access-date=26 July 2020}}</ref> The annexation under Cyrus was limited to the Western sphere of Gandhāra as only during the reign of [[Darius the Great]] did the region between the [[Indus River]] and the [[Jhelum River]] become annexed.<ref name="Prakash" /> |

|||

The inscription on Darius' (521–486 BC) tomb at [[Naqsh-e Rustam|Naqsh-i-Rustam]] near Persepolis records GADĀRA (Gandāra) along with HINDUSH (Hənduš, Sindh) in the list of satrapies. |

|||

However [[Megasthenes]] [[Indica (Megasthenes)|Indica]], states that the [[Achaemenid Empire|Achaemenids]] never conquered India and had only approached its borders after battling with the [[Massagetae]], it further states that the Persians summoned mercenaries specifically from the Oxydrakai tribe, who were previously known to have resisted the incursions of [[Alexander the Great]], but they never entered their armies into the region of Gandhara.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mccrindle |first=J. W. |url=http://archive.org/details/AncientIndiaAsDescribedByMegasthenesAndArrianByMccrindleJ.W |title=Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian by Mccrindle, J. W |page=109 |language=English |quote=The Persians indeed summoned the Hydrakai from India to serve as mercenaries, but they did not lead an army into the country and only approached its borders when Kyros marched against the Massagatai.}}</ref> [[File:Athens coin discovered in Pushkalavati.jpg|thumb|[[Athens]] coin ({{circa|500/490–485 BCE}}) discovered in [[Pushkalavati]]. This coin is the earliest known example of its type to be found so far east.<ref>O. Bopearachchi, "Premières frappes locales de l'Inde du Nord-Ouest: nouvelles données", in Trésors d'Orient: Mélanges offerts à Rika Gyselen, Fig. 1 [https://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=199773 CNG Coins]</ref> Such coins were circulating in the area as currency, at least as far as the [[Indus]], during the reign of the [[Achaemenids]].<ref name="OB300">{{cite book |last1=Bopearachchi |first1=Osmund |title=Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander's Conquest) |pages=300–301 |url=https://www.academia.edu/15798938 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.cemml.colostate.edu/cultural/09476/afgh05-106.html |title=US Department of Defense |access-date=7 October 2018 |archive-date=10 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200610004813/https://www.cemml.colostate.edu/cultural/09476/afgh05-106.html |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref name="JC">{{cite book |last1=Errington |first1=Elizabeth |last2=Trust |first2=Ancient India and Iran |last3=Museum |first3=Fitzwilliam |title=The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan |date=1992 |publisher=Ancient India and Iran Trust |isbn=9780951839911 |pages=57–59 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pfLpAAAAMAAJ |language=en}}</ref><ref name="OB308">{{cite book |last1=Bopearachchi |first1=Osmund |title=Coin Production and Circulation in Central Asia and North-West India (Before and after Alexander's Conquest) |pages=308– |url=https://www.academia.edu/15798938 |language=en}}</ref> |left]] |

|||

Under the Persian rule, a system of centralised administration with a bureaucratic system was introduced in the region. Great scholars such as [[Pāṇini|Panini]] and [[Kautilya]] lived in this cosmopolitan environment. The ''Kharosthi'' alphabet, derived from the one used for Aramaic (the official language of Achaemenids), developed here and remained the national script of Gandhara until 3rd century AD. |

|||

During the reign of [[Xerxes I]], Gandharan troops were noted by [[Herodotus]] to have taken part in the [[Second Persian invasion of Greece]] and were described as clothed similar to that of the [[Bactria]]ns.<ref>{{Cite web |title=LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book VII: Chapters 57‑137 |url=https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Herodotus/7B*.html |access-date=27 January 2024 |website=penelope.uchicago.edu |quote=The Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians, Gandarians, and Dadicae in the army had the same equipment as the Bactrians.}}</ref> Herodotus states that during the battle they were led by the [[Achamenid]] general [[Artyphius]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=LacusCurtius • Herodotus — Book VII: Chapters 57‑137 |url=https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Herodotus/7B*.html |access-date=27 January 2024 |website=penelope.uchicago.edu |quote=The Parthians and Chorasmians had for their commander Artabazus son of Pharnaces, the Sogdians Azanes son of Artaeus, the Gandarians and Dadicae Artyphius son of Artabanus.}}</ref> |

|||

Under Persian rule, a system of centralized administration, with a bureaucratic system, was introduced into the Indus Valley for the first time. Provinces or "satrapy" were established with provincial capitals. The [[#Part of Achaemenid Empire|Gandhara]] satrapy, established 518 BCE with its capital at [[Pushkalavati]] ([[Charsadda]]).<ref>Rafi U. Samad, [https://books.google.com/books?id=pNUwBYGYgxsC&pg=PA33 ''The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys.''] Algora Publishing, 2011, p. 32 {{ISBN|0875868592}}</ref> It was also during the [[Achaemenid Empire]] rule of Gandhara that the [[Kharosthi]] script, the script of [[Gandhari prakrit]], was born through the [[Aramaic]] alphabet.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Konow |first=Sien |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.62020 |title=Kharoshthi Inscriptions Except Those Of Asoka Vol.ii Part I (1929) |date=1929 |pages=18 |quote=Buhler had shown that the KharoshthI characters are derived from Aramaic, which Origin of was in common use for official purposes all over the Achaemenian empire during the KharoshthI period when it comprised north-western India... And Buhler is right in assuming that KharoshthI is ‘ the result of the intercourse between the offices of the Satraps and of the native authorities}}</ref> |

|||

By about 380 BC the Persian hold on the region weakened. Many small kingdoms sprang up in Gandhara. In 327 BC Alexander the Great conquered Gandhara as well as the Indian satrapies of the Persian Empire. The expeditions of Alexander were recorded by his court historians and by Arrian (around AD 175) in his [[Anabasis Alexandri]] and by other chroniclers many centuries after the event. |

|||

=== Macedonian era Gandhāra === |

|||

The companions of [[Alexander the Great]] did not record the names of Kamboja and Gandhara, rather they located a dozen small political units within their territories. Alexander conquered most of these political units of the former Gandhara, Sindhu and Kamboja Mahajanapadas. |

|||

{{Main|Paropamisadae}} |

|||

{{See also|Indian campaign of Alexander the Great|Macedonian Empire}} |

|||

According to [[Arrian]]'s [[Indica (Arrian)|Indica]], the area corresponding to Gandhara situated between the [[Kabul River]] and the [[Indus River]] was inhabited by two tribes noted as the [[Assakenoi]] and Astakanoi whom he describes as 'Indian' and occupying the two great cities of [[Massaga (ancient city)|Massaga]] located around the [[Swat valley]] and [[Pushkalavati]] in modern day Peshawar.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mccrindle |first=J. W. |url=http://archive.org/details/AncientIndiaAsDescribedByMegasthenesAndArrianByMccrindleJ.W |title=Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian by Mccrindle, J. W |pages=179–180 |language=English |quote=The regions beyond the, river Indus on the west are inhabited, up to the river Kophen, by two Indian tribes, the Astakenoi and the Assakenoi...In the dominions of the Assakanoi there is a great city called Massaka, the seat of the sovereign power which controls the whole realm. And there is an other city, Peukalaitis, which is also of great size and not far from the Indus.}}</ref> |

|||

According to Greek chroniclers, at the time of Alexander's invasion, hyparchs Kubhesha, Hastin (Astes), and Ambhi (Omphes) were ruling the lower Kabul valley, Puskalavati (modern Charasadda), and Taxila, respectively, while Ashvajit (chief of Aspasoi/Aspasii or Ashvayanas) and Assakenos (chief of Assakenoi or Ashvakayanas, both being parts of the Kambojas) ruled the upper Kabul valley and Mazaga/Massaga (Mashkavati), respectively. |

|||

The sovereign of [[Taxila]], [[Omphis]], formed an alliance with Alexander, motivated by a longstanding animosity towards [[Porus]], who governed the region encompassed by the [[Chenab River|Chenab]] and [[Jhelum River]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=alexander and his successors in central asia |url=https://fr.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/vol_II%20silk%20road_alexander%20and%20his%20successors%20in%20central%20asia.pdf |page=72 |quote=The ruler of Taxila wanted to satisfy his own grudge against Porus}}</ref> Omphis, in a gesture of goodwill, presented [[Alexander the Great|Alexander the great]] with significant gifts, esteemed among the Indian populace, and subsequently accompanied him on the expedition crossing the [[Indus River|Indus]].<ref>{{Cite web |title=alexander and his successors in central asia |url=https://fr.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/vol_II%20silk%20road_alexander%20and%20his%20successors%20in%20central%20asia.pdf |page=72 |quote=Taxiles and the others came to meet him, bringing gifts reckoned of value among the Indians. They presented him with the twenty-five elephants....and when they reached the Indus, they were to make all necessary preparations for the passage of the army. Taxiles and the other chiefs marched with them.}}</ref> |

|||

==Mauryas== |

|||

[[File:Gandhara1.JPG|thumb|Coin of Early Gandhara Janapada: AR Shatamana and one-eighth Shatamana (round), Taxila-Gandhara region, [[circa|c.]] 600–300 BC]] |

|||

In 327 BCE, [[Alexander the Great]] 's military campaign progressed to Arigaum, situated in present-day [[Nawagai, Bajaur|Nawagai]], marking the initial encounter with the [[Aspasians]]. [[Arrian]] documented their implementation of a scorched earth strategy, evidenced by the city ablaze upon Alexander's arrival, with its inhabitants already fleeing.<ref>{{Cite web |title=alexander and his successors in central asia |url=https://fr.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/vol_II%20silk%20road_alexander%20and%20his%20successors%20in%20central%20asia.pdf |page=73 |quote=Then crossing the mountains Alexander descended to a city called Arigaeum [identified with Nawagai], and found that this had been set on fire by the inhabitants, who had afterwards fled.}}</ref> The [[Aspasians]] fiercely contested Alexander's forces, resulting in their eventual defeat. Subsequently, Alexander traversed the River Guraeus in the contemporary [[Dir District]], engaging with the [[Asvakas]], as chronicled in Sanskrit literature.<ref>{{Cite web |title=alexander and his successors in central asia |url=https://fr.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/vol_II%20silk%20road_alexander%20and%20his%20successors%20in%20central%20asia.pdf |page=74 |quote=Alexander then crossed the River Guraeus (the Panchkora, in Dir District). Beyond the Karmani pass lies the Talash valley. The Assacenians, identified with the Asvakas of Sanskrit literature, tried to defend themselves.}}</ref> The primary stronghold among the Asvakas, [[Massaga (ancient city)|Massaga]], characterized as strongly fortified by [[Quintus Curtius Rufus]], became a focal point.<ref>{{Cite web |title=alexander and his successors in central asia |url=https://fr.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/vol_II%20silk%20road_alexander%20and%20his%20successors%20in%20central%20asia.pdf |pages=74–75}}</ref> Despite an initial standoff which led to Alexander being struck in the leg by an [[Asvaka]] arrow,<ref>{{Cite web |title=alexander and his successors in central asia |url=https://fr.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/vol_II%20silk%20road_alexander%20and%20his%20successors%20in%20central%20asia.pdf |page=Alexander while reconnoitring the fortifications, and unable to fix on a plan of attack, since nothing less than a vast mole, necessary for bringing up his engines to the walls, would suffice to fill up the chasms, was wounded from the ramparts by an arrow which chanced to hit him in the calf of the leg}}</ref> peace terms were negotiated between the Queen of Massaga and Alexander. However, when the defenders had vacated the fort, a fierce battle ensued when Alexander broke the treaty. According to [[Diodorus Siculus]], the Asvakas, including women fighting alongside their husbands, valiantly resisted Alexander's army but were ultimately defeated.<ref>{{Cite web |title=alexander and his successors in central asia |url=https://fr.unesco.org/silkroad/sites/default/files/knowledge-bank-article/vol_II%20silk%20road_alexander%20and%20his%20successors%20in%20central%20asia.pdf |page=75 |quote=When many were thus wounded and not a few killed, the women, taking the arms of the fallen, fought side by side with the men for the imminence of the danger and the great interests at stake forced them to do violence to their nature, and to take an active part in the defence.}}</ref> |

|||

Chandragupta, the founder of the [[Maurya]]n dynasty is said to have lived in Taxila when Alexander captured this city. According to tradition, he trained under [[Kautilya]], who remained his chief adviser throughout his career. Supposedly using Gandhara and Vahika as his base, Chandragupta led a rebellion against the [[Magadha]] Empire and ascended the throne at [[Pataliputra]] in 321 BC. However, there are no contemporary Indian records of Chandragupta Maurya and almost all that is known is based on the diaries of Megasthenes, the ambassador of Seleucus at Pataliputra, as recorded by [[Arrian]] in his [[Indika]]. Gandhara was acquired from the [[Hellenistic period|Greeks]] by [[Chandragupta Maurya]]. |

|||

=== Mauryan Gandhāra === |

|||

After a battle with [[Seleucus Nicator]] ([[Alexander the Great|Alexander's]] successor in Asia) in 305 BC, the [[Mauryan]] Emperor extended his domains up to and including Southern [[Afghanistan]]. With the completion of the Empire's Grand Trunk Road, the region prospered as a center of trade. Gandhara remained a part of the Mauryan Empire for about a century and a half. |

|||

[[File:Upper Boulder with Inscriptions - Mansehra Rock Edicts.jpg|thumb|[[Major Rock Edicts|Major Rock Edict]] of Ashoka in [[Mansehra District|Mansehra]]]]During the [[Maurya Empire|Mauryan]] era, Gandhara held a pivotal position as a core territory within the empire, with [[Taxila]] serving as the provincial capital of the North West.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tarn |first=William Woodthorpe |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-HeJS3nE9cAC&dq=Taxila+capital+of+the+north+west+Mauryan+empire&pg=PA152 |title=The Greeks in Bactria and India |date=24 June 2010 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-108-00941-6 |page=152 |language=en |quote=The Mauryan empire proper, north of the line of the Nerbudda and the Vindhya mountains, had pivoted upon three great cities: pataliputra the capital and the seat of the emperor, Taxila the seat of the viceroy of the North West...}}</ref> [[Chanakya]], a prominent figure in the establishment of the [[Maurya Empire|Mauryan Empire]], played a key role by adopting [[Chandragupta Maurya]], the initial Mauryan emperor. Under Chanakya's tutelage, Chandragupta received a comprehensive education at Taxila, encompassing various arts of the time, including military training, for a duration spanning 7–8 years.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sastri |first=K. a Nilakanta |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.532644 |title=Comprehensive History Of India Vol.2 (mauryas And Satavahanas) |date=1957 |page=2 |quote=he bought the boy by paying on the spot 1000 kdrshapanas. Kautilya(Chanakya) then took the boy with him to his native city of Takshasila (Taxila), then the most renowned seat of learning in India, and had him educated there for a period of seven or eight years in the humanities and the practical arts and crafts of the time, including the military arts.}}</ref> |

|||

[[Plutarch|Plutarch's]] accounts suggest that [[Alexander the Great]] encountered a young [[Chandragupta Maurya]] in the [[Punjab]] region, possibly during his time at the university.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sastri |first=K. a Nilakanta |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.532644 |title=Comprehensive History Of India Vol.2 (mauryas And Satavahanas) |date=1957 |page=2 |quote=This tradition is curiously confirmed by Plutarch's statement that Chandragupta as a youth had met Alexander during his campaigns in the Panjab. This was possible because Chandragupta was already living in that locality with Kautilya (Chanakya).}}</ref> Subsequent to Alexander's death, Chanakya and Chandragupta allied with [[Trigarta Kingdom|Trigarta]] king Parvataka to conquer the [[Nanda Empire]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sastri |first=K. a Nilakanta |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.532644 |title=Comprehensive History Of India Vol.2 (mauryas And Satavahanas) |date=1957 |page=3 |quote=According to tradition he began by strengthening his position by an alliance with the Himalayan chief Parvataka, as stated in both the Sanskrit and Jaina texts, Mudradkshasa and Parisishtaparvan.}}</ref> This alliance resulted in the formation of a composite army, comprising Gandharans and [[Kambojas]], as documented in the [[Mudrarakshasa]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sastri |first=K. a Nilakanta |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.532644 |title=Comprehensive History Of India Vol.2 (mauryas And Satavahanas) |date=1957 |page=4 |quote=The army of Malayaketu (Parvataka) comprised recruits from the following peoples : Khasa, Magadha, Gandhara, Yavana, Saka, Chedi and Huna.}}</ref> |

|||

[[Ashoka]], the grandson of Chandragupta, was one of the greatest Indian rulers. Like his grandfather, Ashoka also started his career from Gandhara as a governor. Later he supposedly became a Buddhist and promoted this religion in his empire. He built many [[stupas]] in Gandhara. Mauryan control over the northwestern frontier, including the [[Yona]]s, [[Kambojas]], and the Gandharas, is attested from the [[Rock Edicts]] left by [[Ashoka]]. According to one school of scholars, the Gandharas and Kambojas were cognate people.<ref>Revue des etudes grecques 1973, p 131, Ch-Em Ruelle, Association pour l'encouragement des etudes grecques en France.</ref><ref>Early Indian Economic History, 1973, pp 237, 324, Rajaram Narayan Saletore.</ref><ref>Myths of the Dog-man, 199, p 119, David Gordon White; Journal of the Oriental Institute, 1919, p 200; Journal of Indian Museums, 1973, p 2, Museums Association of India; The Pāradas: A Study in Their Coinage and History, 1972, p 52, Dr B. N. Mukherjee – Pāradas; Journal of the Department of Sanskrit, 1989, p 50, Rabindra Bharati University, Dept. of Sanskrit- Sanskrit literature; The Journal of Academy of Indian Numismatics & Sigillography, 1988, p 58, Academy of Indian Numismatics and Sigillography – Numismatics; Cf: Rivers of Life: Or Sources and Streams of the Faiths of Man in All Lands, 2002, p 114, J. G. R. Forlong.</ref> It is also contended that the Kurus, Kambojas, Gandharas and Bahlikas were cognate people and all had Iranian affinities,<ref>Journal of the Oriental Institute, 1919, p 265, Oriental Institute (Vadodara, India) – Oriental studies; For Kuru-Kamboja connections, see Dr Chandra Chakraberty's views in: Literary history of ancient India in relation to its racial and linguistic affiliations, pp 14,37, Vedas; The Racial History of India, 1944, p 153, Chandra Chakraberty – Ethnology; Paradise of Gods, 1966, p 330, Qamarud Din Ahmed – Pakistan.</ref> or that the Gandhara and Kamboja were nothing but two provinces of one empire and hence influencing each other's language.<ref>Ancient India, History of India for 1000 years, four Volumes, Vol I, 1938, pp 38, 98 Dr T. L. Shah.</ref> However, the local language of Gandhara is represented by Panini's conservative bhāṣā, which is entirely different from the Iranian (Late Avestan) language of the Kamboja that is indicated by [[Patanjali]]'s quote of Kambojan śavati 'to go' (= Late Avestan šava(i)ti).<ref> |

|||

'''IMPORTANT NOTE''': Ancient Buddhist text Anguttara Nikaya's list of Mahajanapadas includes the Gandhara and the Kamboja as the only two salient Mahajanapadas in the Uttarapatha. However, the ''Chulla-Niddesa''' list (5th century BC), which is one of the most ancient Buddhist Commentaries, includes the Kamboja and Yona but no Gandhara (See: Chulla-Niddesa, (P.T.S.), p.37). This shows that when Chulla-Niddesa Commentary was written, the Kambojas in the Uttarapatha were a predominant people and that the Gandharans, in all probability, had formed part of the Kamboja Mahajanapada around this time—thus making them a one people. Kautiliya's [[Arthashastra]] (11.1.1–4) (4th century BC) refers only to clans of the Kurus, Panchalas, Madrakas, Kambojas etc but it does not mention the Gandharas as separate people from the Kambojas. The Mudrarakshasa Drama by Visakhadatta also refer to the Sakas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Pahlavas, Bahlikas and Kiratas but again it does not include the Gandharas in Chandragupta's army list. The well known Puranic legend (told in numerous Puranas) of king Sagara's war with the invading tribes from the north-west includes the Kambojas, Sakas, Yavanas, Pahlavas, and Paradas but again the Gandharas are not included in Haihayas's army (Harivamsa 14.1–19; e.g Vayu Purana 88.127–43; Brahma Purana (8.35–51); Brahmanda Purana (3.63.123–141); Shiva Purana (7.61.23); Vishnu Purana (5.3.15–21), Padma Purana (6.21.16–33) etc). Again, the Valmiki Ramayana—(a later list) includes Janapadas of Andhras, Pundras, Cholas, Pandyas, Keralas, Mekhalas, Utkalas, Dasharnas, Abravantis, Avantis, Vidarbhas, Mlecchas, Pulindas, Surasenas, Prasthalas, Bharatas, Kurus, Madrakas, Kambojas, Daradas, Yavanas, Sakas (from Saka-dvipa), Rishikas, Tukharas, Chinas, Maha-Chinas, Kiratas, Barbaras, Tanganas, Niharas, Pasupalas etc (Ramayana 4.43). Yet at another place in the Ramayana (I.54.17; I.55.2 seq), the north-western martial tribes of the Sakas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Pahlavas, Kiratas, Haritas/Tukharas, Barbaras and Mlechchas etc joined the army of sage Vasishtha during the battle of Kamdhenu against Aryan king Viswamitra of Kanauj. Yaska in his Nirukta (II.2) refers to the Kambojas but not to the Gandharas. Among the several unrighteous barbaric hordes (opposed to Aryan king Vikarmaditya), Brhat Katha of Kshmendra (10.1.285–86) and Kathasaritsagara of Somadeva (18.1.76–78) each list the Sakas, Mlechchas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Neechas, Hunas, Tusharas, Parasikas etc but they do not mention the Gandharas. Vana Parva of Mahabharata states that the Andhhas, Pulindas, Sakas, Kambojas, Yavanas, Valhikas, Aurnikas and Abhiras etc will become rulers in Kaliyuga and will rule the earth (India) un-righteously (MBH 3.187.28–30). Here there is no mention of Gandhara since it is included amongst the Kamboja. Sabha Parava of Mahabharata enumerates numerous kings from the north-west paying gifts to Pandava king Yudhistra at the occasion of Rajasuya amongs whom it mentions the Kambojas, Vairamas, Paradas, Pulindas, Tungas, Kiratas, Pragjyotisha, Yavanas, Aushmikas, Nishadas, Romikas, Vrishnis, Harahunas, Chinas, Sakas, Sudras, Abhiras, Nipas, Valhikas, Tukharas, Kankas etc (Mahabharata 2.50–1.seqq). The lists does not include the Gandharas since they are counted as the same people as the Kambojas. In context of Krsna digvijay, the Mahabharata furnishes a key list of twenty-five ancient Janapadas viz: Anga, Vanga, Kalinga, Magadha, Kasi, Kosala, Vatsa, Garga, Karusha, Pundra, Avanti, Dakshinatya, Parvartaka, Dasherka, Kashmira, Ursa, Pishacha, Mudgala, Kamboja, Vatadhana, Chola, Pandya, Trigarta, Malava, and Darada (MBH 7/11/15–17). Besides, there were Janapadas of Kurus and Panchalas also. Interestingly, no mention is made to Gandhara in this list. Again in another of its well known Shlokas, the Mahabharata (XIII, 33.20–23; XIII, 35, 17–18), lists the Sakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, Dravidas, Kalingas, Pulindas, Usinaras, Kolisarpas, Mekalas, Sudras, Mahishakas, Latas, Kiratas, Paundrakas, Daradas etc as the Vrishalas/degraded Kshatriyas (See also: Comprehensive History of India, 1957, p 190, K. A. N. Sastri). It does not include the Gandharas in the list though in yet another similar shloka (MBH 12.207.43–44), the same epic now brands the Yavanas, Kambojas, Gandharas, Kiratas and Barbaras (''Yauna Kamboja Gandharah Kirata barbaraih'') etc as Mlechcha tribes living the lives of the Dasyus or the Barbarians. Thus in the first shlokas, the Gandharas and the Kambojas are definitely treated as one people. The Assalayana-Sutta of Majjima Nakaya says that in the frontier lands of the Yonas a, Kambojas and other nations, there are only two classes of People...Arya and Dasa where an Arya could become Dasa and vice-varsa (Majjima Nakayya 43.1.3). Here again, the Gandharas are definitively included among the Kambojas as if the two people are same. Rajatarangini of Kalhana, a Sanskrit text from the north, furnishes a list of northern nations which king Lalitaditya Muktapida (Kashmir) (8th century AD) undertakes to reduce in his dig-vijaya expedition. The list includes the Kambojas, Tukharas, Bhauttas (in Baltistan in western Tibet), Daradas, Valukambudhi, Strirajya, Uttarakurus and Pragjyotisha respectively, but no mention of Gandharas (Rajatarangini: 4.164–4.175). Apparently the Gandharas are counted among the Kambojas. Sikanda Purana (Studies in the Geography, 1971, p 259–62, Sircar, Hist of Punjab, 1997, p 40, Dr L. M. Joshi and Dr Fauja Singh (Editors)), contains a list of 75 countries among which it includes Khorasahana, Kuru, Kosala, Bahlika, Yavana, Kamboja, Siva, Sindhu, Kashmira, Jalandhara (Jullundur), Hariala (Haryana), Bhadra (Madra), Kachcha, Saurashtra, Lada, Magadha, Kanyakubja, Vidarbha, Kirata, Gauda, Nepala etc but no mention of Gandhara in this list of 75 countries. Kavyamimasa of Rajashekhar (880–920 AD) also lists 21 north-western countries/nations of the Saka, Kekaya, Vokkana, Huna, Vanayuja, Kamboja, Vahlika, Vahvala, Lampaka, Kuluta, Kira, Tangana, Tushara, Turushaka, Barbara, Hara-hurava, Huhuka, Sahuda, Hamsamarga (Hunza), Ramatha and Karakantha etc but no mention of Gandhara or Darada (See: Kavyamimasa, Rajashekhara, Chapter 17; also: Kavyamimasa Editor Kedarnath, trans. K. Minakshi, pp 226–227). Here in both the lists, the Daradas and Gandharas are also treated as the Kambojas. The Satapancasaddesavibhaga of Saktisagama Tantra (Book III, Ch VII, 1–55) lists Gurjara, Avanti, Malava, Vidarbha, Maru, Abhira, Virata, Pandu, Pancala, Kamboja, Bahlika, Kirata, Khurasana, Cina, Maha-Cina, Nepala, Gauda, Magadha, Utkala, Huna, Kaikeya, Surasena, Kuru Saindhava, Kachcha among the 56 countries but the list does not include the Gandharas and Daradas. Similarly, Sammoha Tantra list also contains 56 nations and lists Kashmira, Kamboja, Yavana, Sindhu, Bahlika, Parsika, Barbara, Saurashtra, Malava, Maharashtra, Konkana, Avanti, Chola, Kamrupa, Kerala, Simhala etc but no mention of Daradac and Gandhara (See quotes in: Studies in Geography, 1971, p 78, D. C. Sircar; Studies in the Tantra, pp 97–99, Dr P. C. Bagchi). Obviously, the Daradas and Gandharaa are included among the Kambojas. Raghu Vamsa by Kalidasa refers to numerous tribes/nations of the east (including the Sushmas, Vangas, Utkalas, Kalingas and those on Mt Mahendra), then of the south (including Pandyas, Malaya, Dardura, and Kerals), then of the west (Aprantas), and then of the north-west (like the Yavanas, the Parasikas, the Hunas, the Kambojas) and finally those of the north Himalayan (like the Kirats, Utsavasketas, Kinnaras, Pragjyotishas) etc (See: Raghuvamsa IV.60 seq). Here again no mention of the Gandharas though Raghu does talk of the Kambojas. And last but not the least, even the well known Manusmriti, the Hindu Law Book, refers to the Kambojas, Yavanas, Shakas, Paradas, Pahlavas, Chinas, Kiratas, Daradas and Khasha besides also the Paundrakas, Chodas, Dravidas but surprisingly enough, it does not make any mention of the Gandharas in this very elaborate list of the Vrishalah Ksatriyas (Manusamriti X.43–44). The above references amply demonstrate that the Gandharas were many times counted among the Kambojas themselves as if they were one and the same people. Thus, the Kambojas and the Gandhara do seem to have been a cognate people.</ref><ref>There are also several instances in the ancient literature where the reference has been made only to the Gandharas and not to the Kambojas. In these cases, the Kambojas have obviously been counted among the Gandharas themselves.</ref><ref>Kalimpur Inscriptions of [[Pala Empire|Pala]] king [[Dharmapala]] of Bengal (770–810 AD) lists the nations around his kingdom as the Bhoja (Gurjara), Matsya, Madra, Kuru, Avanti, Gandhara and the Kira (Kangra) which he boasts of as if they are his vassal states. From Monghyr inscriptions of king Devapala (810–850AD) the successor of king Dharmapalal, we get the list of the nations as Utkala (Kalinga), Pragjyotisha (Assam), Dravida, Gurjara (Bhoja), Huna and the Kamboja. These are the nations which cavalry of Pala king Devapala is said to have scoured during his war expeditions against these people. Obviously the Kamboja of the Monghyr inscriptions of king Devapala here is none else than the Gandhara of the Kalimpur inscription of king Dharamapala. Hence, the Gandhara and the Kamboja are used interchangeably in the records of the Pala kings of Bengal, thus indicating them to be same group of people.</ref><ref>James Fergusson observes: ''"In a wider sense, name Gandhara implied all the countries west of Indus as far as Candhahar"'' (The Tree and Serpent Worship, 2004, p 47, James Fergusson).</ref> Gandhara was often linked politically with the neighboring regions of [[Kashmir]] and [[Kambojas|Kamboja]].<ref>''Encyclopedia Americana'', 1994, p 277, Encyclopedias and Dictionaries.</ref> |

|||

[[Bindusara]]s reign witnessed a rebellion among the locals of [[Taxila]] to which according to the [[Ashokavadana]], he dispatched [[Ashoka]] to quell the uprising. Upon entering the city, the populace conveyed that their rebellion was not against [[Ashoka]] or [[Bindusara]] but rather against oppressive ministers.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lahiri |first=Nayanjot |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JaVRCgAAQBAJ&q=ashoka+in+ancient+india |title=Ashoka in Ancient India |date=5 August 2015 |publisher=Harvard University Press |isbn=978-0-674-91525-1 |page=67 |language=en |quote=Ashoka arrived in Taxila at the head of an armed contingent, the swords remained in their scabbards: the citizenry, instead of offering resistance came out of their city and on its roads to welcome him, saying 'we did not want to rebel against the prince.. nor even against King Bundusara; but evil ministers came and oppressed us'}}</ref> In Ashoka's subsequent tenure as emperor, he appointed his son as the new governor of [[Taxila]].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Sastri |first=K. a Nilakanta |url=http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.532644 |title=Comprehensive History Of India Vol.2 (mauryas And Satavahanas) |date=1957 |page=22 |quote=In the Gupta epoch, again, some of the provinces were administered by princes of the royal blood designated kumaras. The same was the case in the time of Asoka. Three instances of such Kumara governorship are known from his edicts. Thus one kumara was stationed at Takshasila to govern the frontier province of Gandhara..}}</ref> During this time, Ashoka erected [[Edicts of Ashoka|numerous rock edicts]] in the region in the [[Kharosthi]] script and commissioned the construction of a monumental stupa in [[Pushkalavati]], Western Gandhara, the location of which remains undiscovered to date.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Cunningham |first=Alexander |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6DegEAAAQBAJ&dq=stupa+pushkalavati&pg=PA90 |title=Archeological Survey of India: Vol. II |date=6 December 2022 |publisher=BoD – Books on Demand |isbn=978-3-368-13568-3 |pages=90 |language=en |quote=...3/4 of a mile to the north of this place there was a great stupa built by Ashoka}}</ref> |

|||

==Graeco-Bactrians, Sakas, and Indo-Parthians== |

|||

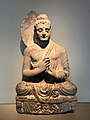

[[File:Gandhara Buddha (tnm).jpeg|thumb|upright|Standing Buddha, Gandhara (1st–2nd century), [[Tokyo National Museum]]]] |

|||

The decline of the Empire left the [[sub-continent]] open to the inroads by the [[Greco-Bactrian Kingdom|Greco-Bactrians]]. Southern Afghanistan was absorbed by [[Demetrius I of Bactria]] in 180 BC. Around about 185 BC, Demetrius invaded and conquered Gandhara and the [[Punjab region|Punjab]]. Later, wars between different groups of Bactrian Greeks resulted in the independence of Gandhara from Bactria and the formation of the [[Indo-Greek kingdom]]. [[Menander I|Menander]] was its most famous king. He ruled from Taxila and later from [[Sagala]] (Sialkot). He rebuilt Taxila ([[Sirkap]]) and Pushkalavati. He became a Buddhist and is remembered in Buddhists records due to his discussions with a great Buddhist philosopher, Nāgasena, in the book ''[[Milinda Panha]]''. |

|||